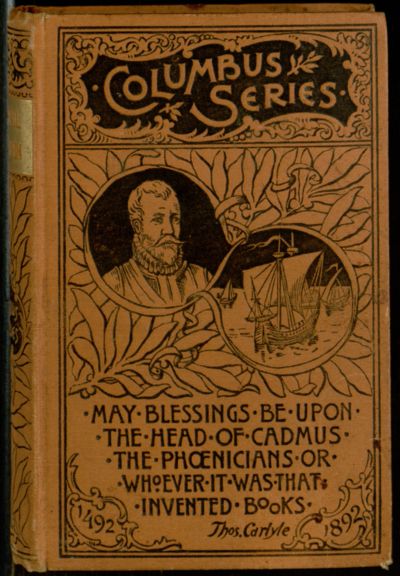

Title: A Dreadful Temptation; or, A Young Wife's Ambition

Author: Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller

Release date: October 8, 2013 [eBook #43911]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Demian Katz and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy

of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

BY

MRS. ALEX. McVEIGH MILLER

AUTHOR OF "QUEENIE'S TERRIBLE SECRET," "JAQUELINA," ETC.

NEW YORK

INTERNATIONAL BOOK COMPANY

3, 4, 5 AND 6-MISSION PLACE

Copyright, 1883,

by

NORMAN L. MUNRO

[All rights reserved.]

OR,

A Young Wife's Ambition.

By MRS. ALEX. McVEIGH MILLER.

"Hark! there's the wedding-march."

"Here they come!"

"Looks as white as a corpse, doesn't she?"

"Oh, no; as beautiful as a dream, to my notion. Pallor is becoming in brides, you know."

"He's a silly old dotard, though, not to know that she's taking him for his money."

"Of course he knows it. I dare say the old gray-beard is glad he had money enough to buy so much youth and loveliness."

"What a splendid veil and dress! They say her rich aunt furnished the trousseau."

"Her jewels are magnificent."

"The bridegroom's gift, of course. Well, he is able to cover her with diamonds."

These were but few of the remarks that were whispered in the fashionable throng gathered at Trinity to witness a marriage in high life—a marriage that was all the more interesting from the fact that the contracting parties were so totally dissimilar to each other that the whole affair in the eyes of the outsiders resolved itself into a simple matter of bargain and sale—so much youth and beauty for an old man's gold.

The bridegroom was John St. John, a millionaire of high birth and standing in the city where he lived, but so old and infirm that people said of him that "he had one foot in the grave and the other on the brink of it," and the[Pg 2] bride was the young daughter of some obscure country people.

An aunt in the city had given her some advantages, and kept her in town two seasons, hoping to bring about a good match for her, since she had no dowry of her own, save youth, talent and peerless beauty.

And Xenie Carroll was fulfilling her aunt's ambitious hopes and desires to their uttermost limit as she walked up the broad aisle of Trinity that night, clothed in her bridal white, and leaning on the arm of the decrepit old millionaire, John St. John.

His form was bent with age, his hair and beard were white, his eyes were dim and bleared; and she was in the bloom of youth and beauty. It was the union of winter and summer.

They passed slowly up the aisle to the grand music of the wedding-march, and after them came fair maidens, robed in white and adorned with flowers and jewels.

These stood round about the pair at the altar who were taking upon their lips the sacred vow of marriage.

It was over.

The holy man of God lifted reverent hands and invoked God's blessing upon this sordid bargain that desecrated the holy rite of marriage, the ring was slipped over the bride's white finger, and Xenie Carroll turned away from the altar Mrs. John St. John, mistress of the handsomest house in the city and the most princely private fortune.

There was a flash of triumph in her dark eyes as she received the congratulations of her friends, yet her cheeks and lips were cold and white as marble.

But the light and color came back to her beautiful face when, in the same carriage that had taken her from her aunt's roof a poor, dependent girl, she was whirled back to the millionaire's splendid home to take her place as its queen.

The aged bridegroom scarcely felt equal to an extended bridal tour, so he had wisely eschewed a trip, and determined to inaugurate the reign of the new social star by a brilliant reception at his splendid residence.

All the beauties of art and nature were called in to further his design.

The elegant drawing-rooms were almost transformed into bowers of tropical bloom.

Beautiful birds fluttered their tropical plumage and caroled their sweet songs in the gilded cages that swung in the flowery arches and niches.

Music filled the air with entrancing strains, wooing light feet to the giddy dance.

In the spacious supper-room the tables shone with silver and gold and crystal, and every delicacy that could tempt the appetite from home or foreign shores was daintily served for the wedding-guests, with wines of the purest vintage and greatest age.

There was no lack of wealth, there was no lack of beauty in the brilliant assemblage that graced the millionaire's proud house that night; and she, his bride, was now the wealthiest, as she had ever been the loveliest, of them all, yet she stole away at length from her aged bridegroom's flatteries, and sought the solitude of the conservatory.

The beautiful fragrance-breathing bower was deserted. The soft light of the wax-lights, half-hidden in flowers, streamed down upon her as she trod the leafy walks alone in her beautiful white satin robe, frosted with delicate lace, and her shining jewels that encircled a throat as white and round and queenly as if she had been a princess royal.

Yet none were here to praise the soft light of her dark eyes, the dazzling beauty of her smiles, the tender, tinted oval of her face.

Why was she here alone to "waste her sweetness on the desert air?"

Ah! in a moment she spoke in a stifled voice, her white hands twisted in the band of jewels that encircled her throat as if the beautiful flashing things burned her by their mere contact.

"I had to come here for a free breath away from that old man whose very presence stifles and smothers me. And yet—and yet, I am his wife! Oh, Heaven, what a terrible price I must pay for my revenge!"

She paused, and a strange look came into her eyes. It was a look of terrible dread and despair, inexplicably blended with passionate triumph.

"And yet," she began again, after a moment's silence, looking around at the evidences of wealth and taste so lavishly scattered about her, "what a glorious revenge it is! It was for this he scorned and deserted me! Yet I have stripped him of his heritage. I have stolen from him the empire he held so long. I have revenged myself tenfold for what I suffered at his hands. Ah! weak fool that I am, why regret the price of such a splendid triumph?"

Her face grew hard and cold, a cruel smile curled her scarlet lips, her eyes flashed with scorn.

Pride and passion spoke in every curve of her mobile, spirited face.

The lace hangings at the entrance parted noiselessly, and a man stepped lightly across the threshold.

Not a sound announced his presence, yet she looked up instantly, as if by some subtle inner sense she divined that he was there.

"Ah!" she breathed, in a hissing tone of hate and scorn.

A mocking smile curled the man's lip as he bowed before her.

"Ah! ma tante," he said, in a cool tone of scorn, "permit me to offer my congratulations."

Some emotion too great for utterance seemed to overpower her, so that she struggled vainly for speech a moment, while he stood silent, with folded arms, looking down at her from his haughty height with a look of veiled hatred in his dark-blue eyes.

They were deadly foes, this man and woman, yet nature had formed them as if for the perfect complement of each other.

He was tall, strong and fair, with the proud beauty and commanding air we fancy in the Grecian gods of old.

She was petite, dark, brilliant as a rose, and passionate as the tropical blood of the south could make her.

Breaking down the bars of her great emotion at last, she laughed aloud—a cool, insolent, incredulous laugh that made the hot blood bound faster through his veins, and a flush creep over his face.

"You call me aunt," she said; "ha! ha!"

"Yes, madam, you bear that relationship to me since your marriage with my uncle," he answered, with a formal bow.

"You expect to find me a most loving relative, no doubt?" she said, with exasperating coolness.

"I hope to do so, at least," he said, with calm frankness, "I cannot afford to quarrel with my uncle. I shall hope to keep on good terms with his wife."

"Ah! you don't wish to quarrel with your bread and butter," she said in a tone of cool contempt. "Well, mon ami, what do you suppose I married your uncle for?"

"The world says that you married him for his money," said the handsome young man, coolly.

"Yes, that is what the world says," she answered, with flashing eyes, and cresting her graceful head as haughtily as a young stag. "But you, Howard Templeton, you know better than that."

"Pardon me, how should I know better?" he rejoined, watching her keenly, as if it gave him a certain pleasure to irritate her. "The money seems to me the only reasonable[Pg 5] excuse you had for taking him. My uncle, kindly be it spoken, for he has been my kindest friend, is neither young nor handsome. I credited you with better taste than to love such a homely old man!"

"You are right," she said, writhing under the keen sting of his words; "I did not marry him for love! Neither did I marry him for his money. I have never craved wealth for its own sake, though I have always known that a costly setting would befit beauty such as mine. I sold myself to that old man in yonder for revenge!"

"Revenge?" he repeated, inquiringly.

"Yes, upon you!" she repeated, with bitter frankness; "you sacrificed me that you might inherit your uncle's wealth. Love, hope, gladness, were stricken from my life at one fell blow. There was nothing left me but revenge upon my base deceiver. So I sold myself for the heritage you prized so highly that you might be left penniless."

"Yet once you loved me!" he muttered, half to himself.

"Yes, once I loved you," she answered, looking at him in proud scorn. "When my aunt brought me to the city two years ago a simple, unsophisticated country girl, you saw me and set yourself to win me by every art of which you were master. She encouraged you in your designs, for she knew that you were the reputed heir of your uncle, John St. John, and she thought it would be a fine match for the pretty little country girl. In the spring I went home with your ring upon my finger, the proudest girl in the world, and told mamma that you had promised to marry me. Then you came down to my country home and found out that the rich Mrs. Egerton's pretty niece was as poor as a church mouse. So you went back and told John St. John that you wanted to marry a girl who was beautiful but poor, and he—the old dotard, who had forgotten his youth, and transmuted his heart into gold—he bade you give me up on pain of disinheritance."

"And I obeyed him," said Howard Templeton, as she paused for breath.

"Yes, you obeyed him," she repeated; "you broke your plighted faith and word, you ruined my life, you broke my heart, you sold your truth and your honor to that cruel old man for his sordid gold, and now, to-night, you stand stripped of everything—and all because you turned a woman's love to hate."

She paused breathlessly and stood looking at him with blazing eyes and crimson cheeks, and lips parted in a smile of bitter triumph.

She had never looked more beautiful, yet it was a dangerous beauty, scathing to the man who looked upon her[Pg 6] and knew that his sin had roused the terrible passions of revenge and hatred in her young heart.

"But Xenie, think a moment," he said. "I had been brought up by Uncle John as his heir. I did not know how to work. I never earned a cent in my whole life! When he swore he would disinherit me if I married you, what could I do? I had to give you up. You must have starved if I had married you against his will!"

"I would have starved with you, I loved you so!" she exclaimed passionately.

"Would you, really?" he asked, with a slight air of wonder; "well, they say that women love like that. For myself, I have never reached a stage as idiotic, though I own that I loved you to the verge of distraction, Xenie."

"Well, and what will you do now?" she asked, sneeringly. "You will have to starve at last without the pleasure of my company, for my husband shall never leave you one dollar of his money; I will poison his mind against you, I will make him hate you even as I hate you! I have sworn to have the bitterest revenge for my wrongs, and I will surely keep my vow!"

"I defy you," he answered, looking down at her from his superb height, his proud Saxon beauty ablaze with wrath and scorn. "I defy you to rob me of my uncle's heart or even of his fortune. He shall know what a traitress he has taken to his heart. I will dispute your empire with you and you shall find me a foeman worthy of your steel. You will find that it is a terrible thing to make a man who has loved you hate and defy you!"

She quoted with a wild, defiant laugh. "Well, Howard Templeton, I take up the gage of defiance that you have thrown down. We will wage the deadliest feud the world ever knew between man and woman! From this moment it shall be war to the knife!"

"So be it," he answered with a scowl of hatred as he turned upon his heel and passed through the lace hangings to mingle with the gay and thoughtless throng outside, while curious glances followed him on every side, for all knew that the foolish old bridegroom had promised to make Howard Templeton his heir.

The beautiful bride remained motionless where Howard Templeton had left her until the rich lace curtains parted[Pg 7] noiselessly again and her lawful lord and master looked in upon her.

He did not speak for a moment, so beautiful she looked standing still and pale as a statue beneath a tall rose-tree that showered its scented petals down upon her night-black hair with its crown of orange blossoms.

No subtle instinct warned her of his presence as it had when that other came.

She stood silent and pale, the dark lashes shading her rounded cheek, her white hands loosely clasped before her until he spoke:

"Xenie, my darling!"

She started and shivered as she looked up.

Mr. St. John came slowly to her side and drew her hand through his arm.

"My dear, I have been seeking you everywhere. Supper is announced," he said.

"I only came here just a little while ago for a quiet minute to myself," she said, apologetically.

"Ah! then, you like quiet and repose sometimes," he said; "I am glad of that, for I am not fond of gayety myself, at least not too much of it. I suppose I am getting too far into the sere and yellow leaf to enjoy it, eh, my dear?"

"I hope not; sir," she said, making an effort to throw off her preoccupation and enter into the conversation with interest.

After the splendid banquet had been served, he led her to a quiet seat and begged her not to dance again that evening.

"I am too old to dance myself," he said, "but I am so selfish I want to keep you by my side that I may feast my eyes upon your peerless beauty. Can you be contented with my society, love?" he inquired, giving her a curious look.

"I will do whatever pleases you best, sir," she said, with an inward shudder of disgust.

"Very well; we will sit here hand in hand like a veritable Darby and Joan, and enjoy each other's company," he said, giving her an affectionate smile.

The bride looked at her lord in surprise. She had not known him long, for their marriage had followed upon a brief acquaintance and hurried courtship.

Xenie had never thought him very brilliant, and, indeed, she had heard people say maliciously that the old man was getting weak-minded, but after all, the proposition to hold her hand before all that brilliant array of wedding-guests nearly staggered her.

She made some plausible excuse for keeping her hands in her own possession, and sat quietly by his side, watching[Pg 8] the black coats of the men and the bright robes of the women as they fluttered through the joyous mazes of the dance.

"Do you see the lovely girl dancing with my nephew, Howard Templeton?" he said, to her after a short silence.

She looked up and saw Edith Wayland, one of her bridesmaids, whirling through the waltz in the arms of her deadly foe.

"Yes," she said, with a kind of stifled gasp.

"She's in love with my nephew," said the old man, with a low chuckle of pleasure.

"Indeed? Did she tell you so?" asked Mrs. St. John, half scornfully.

"Never mind how I found out. It's true, anyhow. And she is a great heiress, my dear, almost as rich as I am. I mean to make a match between her and my nephew."

"Do you?" she asked, but her voice was very low and faint, and the room swam around her so that the dancers seemed mingled in inextricable mazes.

"Yes, I do; but what is the matter with you, my darling?" he said, looking anxiously at her. "You have grown so pale!"

"It is nothing—a headache from the heat of the rooms," she murmured, confusedly, "but go on. You were saying——"

"That I am going to marry my nephew to Miss Wayland—yes. She is very rich, and he, well, the poor fellow, you know, Xenie, always expected to be my heir. And now, since my marriage, of course his prospects are entirely altered. He cannot expect much from me now. But I'm going to set him up with a few thousands, and marry him to the heiress. That's almost as well as leaving him my money—isn't it?" he laughed. "I've spoken to Howard about it, and he is pleased with the idea. There will be no difficulty with her, I am sure. Howard was always a lucky dog among the girls."

He laughed, and rubbed his withered palms softly together, and Xenie sat perfectly silent, her brain in a whirl, her pulse beating at fever heat.

Was this old man, whom she hated because his despotic will had blasted her brief dream of happiness, to despoil her of her revenge for which she had dared and risked so much?

And Howard Templeton—was her oath of vengeance of no avail, that fortune should make him her spoiled darling still?

The waltz music ceased with a great, passionate crash of melody, and the gentlemen led their partners to their seats.

Mr. St. John resigned his seat to Edith Wayland, and moved away on the arm of his nephew.

"What a handsome man Mr. Templeton is," said the lovely girl shyly to Mrs. St. John.

The bride looked after his retreating figure with a curl of her scarlet lip.

"Yes, he is as handsome as a Greek god," she said, "but then, he is utterly heartless—a mere fortune-hunter."

"Oh! Mrs. St. John, surely not," said Miss Wayland, in an anxious tone. "Why should you think so?"

"Perhaps it would suit you as well not to hear," said Mrs. St. John, with an arch insinuation in her look and tone.

"By no means. Pray tell me your reasons for what you said, Mrs. St. John," said the sweet, blue-eyed girl, blushing very much, and nervously fluttering her white satin fan.

"Well, since you are not particularly interested in him, I will tell you," was the careless reply. "I was engaged to Mr. Templeton myself, two winters ago—when I first came out, you know, dear! I suppose he thought I was wealthy, for Aunt Egerton dressed me elegantly, and lent me her diamonds. The summer after our engagement he came to the country to see me, and then he found out my poverty—for I will tell you candidly, Edith, my people are as poor as church mice—and, would you believe it? he went back and wrote me a letter, and told me he could not afford to marry for love—he must have an heiress or none. So our little affair was all over with then, you know."

She paused and looked away, for she knew that she had stabbed the girl's heart deeply, and she did not wish to witness the pain she had inflicted.

In a moment, however, Miss Wayland exclaimed, indignantly:

"Oh! Mrs. St. John, is it possible that Mr. Templeton could have treated you so cruelly and heartlessly?"

"It is quite true, Miss Wayland. If you doubt my word I give you carte blanche to ask my aunt, Mrs. Egerton, or even Mr. Templeton himself. You see I have the best reason in the world for accusing him of being a fortune-hunter."

The beautiful young girl did not think of doubting Mrs. St. John's assertion, although it caused her the bitterest pain.

There was an earnestness in the words and tones of the bride that carried conviction with them.

Miss Wayland sat musing quietly a moment, then she said, hesitatingly:

"May I ask if you are friends with Mr. Templeton now, Mrs. St. John?"

Xenie lifted her dark eyes and looked at the gentle girl.

"Should you love a man that won your heart and threw it away like a broken toy?" she asked, slowly.

"I do not believe that I could ever forgive him," said Edith, frankly.

"Nor can I," answered Xenie, in a low voice of repressed passion. "No, I am not friends with him, Edith, and never shall be; I am not the kind of woman who could forgive such a cruel slight."

Neither of them said another word on the subject, but Edith knew quite well from that moment why Xenie had married Mr. St. John.

"It was not for the sake of the money, but simply to revenge herself on Howard Templeton," she said to herself, with a woman's ready wit.

And when Mr. Templeton, according to his uncle's desire, offered her his hand and heart, a few days later, expecting to have her for the asking, he was surprised to receive a cold, almost contemptuous refusal.

But she dropped a few words before they parted by which he knew plainly that his deadly foe had been working against him, and that her revengeful hand had struck a fortune from his grasp for the second time in the space of a week.

Several months of irksome quiet to Mrs. St. John succeeded the festivities that followed upon her marriage.

Her elderly bridegroom found that protracted gayeties did not agree with his age and health, and with the obstinacy common to a selfish old age, he prohibited his wife from participation in those scenes of pleasure in which, by reason of her youth and beauty, she was so pre-eminently fitted to shine.

He could not stand such excitement himself, he said, and he wanted his wife at home to cheer and solace his declining years.

So the beautiful bridal dresses hung in the wardrobe unworn, and the costly jewels hid their brightness locked away in their caskets.

Xenie had small need for these things in the lonely life to which she found herself condemned by her foolish, doting old husband.

Loving pleasure and excitement with all the ardor of a passionate, impulsive temperament like hers, it is quite possible that Mrs. St. John might have rebelled against her[Pg 11] liege lord's selfishness, but for one strong purpose to which she bent every energy, subordinating everything else to its accomplishment.

So she bore his selfish exactions with a patient, yielding sweetness, and ministered to his caprices with the beautiful devotion of a fireside angel.

She was using every sweet persuasion in her power to induce Mr. St. John to execute a will in her favor.

She had learned that in the event of his death, without a will, his widow would legally inherit only one-third of his great wealth, while the remaining two-thirds would descend to his next of kin—the next of kin in this case being her enemy, Howard Templeton.

Xenie knew that her revenge would not be secure until her husband had made his will and cut off his nephew without a dollar.

She had believed that Mr. St. John's infatuation for her would make her task easy, but she had not counted upon the uneasy sense in the old man's mind of a certain injustice done to the nephew he had reared, by his unexpected marriage.

"No, no, Xenie," he said, when she openly pleaded with him to make such a will. "It would be unjust to leave poor Howard without a dollar to support himself."

"He is a man," said Xenie, scornfully. "He has his head and hands to earn his living."

"Yes; but Howard does not know how to work, my darling, and it is all my fault. I brought him up as my heir and refused to let him have a profession or to learn anything useful. You see we are the last of our race, and I expected to leave him everything when I died. I did not know I should meet and marry you, my darling," he said, kissing her fondly, without noticing her uncontrollable shiver of disgust.

"Yes, but your marriage alters everything," she said, eagerly, lifting her melting, dark eyes to his face with a siren smile on the curve of her scarlet lips. "You would not wish to leave your money away from me, your poor, helpless little wife?"

"There is enough for you both, my dear," he said, persuasively. "Howard might have his share—the smaller share, of course—and you would still be a wealthy woman!"

"I hate Howard Templeton!" exclaimed Xenie, with sudden, passionate vehemence.

The old man looked at her half angrily.

"You hate my nephew?" he said. "Why do you hate him, Xenie, when next to you I love him, best of anyone in the world?"

Xenie's sober senses, that had almost deserted her in her sudden gust of passion, returned to her with a gasp.

"I—oh, forgive me," she said, with ready penitence, "I spoke foolishly. I do not like you to love him so. I am jealous of you, my darling!"

She leaned toward him and laid her white arm around his shoulder caressingly.

But suddenly, and even as she lifted her beautiful face for his caress, he drew back his hand, and without a word of warning, struck her a heavy blow across the face.

She reeled backward and fell upon the floor, the red blood spurting from her nostrils and from her lips that the terrible blow had driven against the points of her white teeth and terribly lacerated.

"You Jezebel," he shouted, hoarsely, rising and standing over her with his brandished fist. "How dare you hate him—my own nephew, my handsome Howard!"

With a moan of fear and pain Xenie sprang up and fled to the furthest corner of the room.

"Oh! you coward!" she cried, passionately. "To strike a woman—a helpless woman!"

She was trying to staunch the fast flowing blood with her lace handkerchief, but she stopped and stared at him in dumb terror as he approached her.

For the glare of madness shone in his dim eyes as they turned upon her—his foam-flecked lips were drawn away from his glistening set of false teeth, and his face presented a terrible appearance.

"Oh! my God, he is going to kill me!" she moaned to herself, crouching down in the corner with her arms raised wildly above her shrinking head.

He towered above her with his clenched fist raised threateningly and his eyes glaring ferociously upon her.

Xenie believed that a sudden frenzy of madness had come upon her husband and that he was going to take her life.

She was about to shriek aloud in the hope of rescue, when he suddenly clapped a strong hand over her lips.

"Hush!" he said, fearfully, "hush, Xenie, don't let anyone know I struck you! Does it hurt you much?—the blood, I mean—I'm sorry if it does."

The tone was that of a wheedling, penitent child that is sorry for its fault. In sheer surprise the frightened creature looked up at him.

The ferocious look of bloodthirsty madness had marvelously faded from his face, and left a pale, fearful, childish expression instead.

He dropped his hand and wiped the blood from it, shivering all over.

"Oh! the blood, how red it is!" he whined. "Did I hurt[Pg 13] you, my love? I'm sorry—very sorry. Don't tell anyone I struck you."

"I'll tell the whole world," she flashed forth, speaking with difficulty, for her lips were bruised and swollen. "I'll tell them that you are mad, and I'll have you put into an asylum for dangerous lunatics, you base coward!"

Mr. St. John's face grew livid at her angry threat. He trembled with fear.

"No, no, Xenie, you won't, you mustn't do it," he gasped forth. "I will never do so again. I'll be your slave if you won't tell!"

"I will tell it everywhere!" cried his young wife, rushing to the door, her whole passionate spirit aglow with the keenest resentment.

But with unlooked-for strength in one of his age, he ran forward, and stood with his back against the door.

"You shall not go till you promise to keep silent," he said, firmly; "I will do anything you ask me, Xenie, if you will only not tell on me!"

"Anything?" she exclaimed, turning quickly.

"Yes, anything," he reiterated, with a weak, imploring look, full of craven fear.

"Very well," she answered firmly; "make your will to-day, and cut Howard Templeton off with a shilling, and I'll keep your secret—otherwise the city shall ring with the story of your cruelty!"

"Won't you let me leave him ten thousand dollars, dear?" he asked, pitifully.

"Not a dollar!" she answered coldly.

"Five thousand dollars?"

"Not a dollar!" she reiterated firmly.

"Very well," he answered, weakly. "I have said you shall name your own price. Shall I go to my lawyer now, Xenie?"

"Yes, now," she answered, with a flash of triumph in her eyes.

He stood still a moment looking at her with a half-insane look of cunning on the wrinkled features that but a moment ago had been transformed by maniacal rage.

"Poor boy!" he said, "you hate him very much, Xenie; I wonder what he has done to make you his enemy!"

She did not answer, and the old millionaire went out of the room, after turning upon her a strange look of blended cunning and triumph which she could not understand.

"Pshaw! he meant nothing by it," she said to herself to dispel the uneasy impression that glance had left. "The old man is getting weak and silly. One is scarcely safe alone with him."

She shuddered at the recollection of what she had passed[Pg 14] through, and going to her private room, locked the door and bathed her swollen, discolored face with a healing lotion.

Xenie remained alone in her chamber until darkness gathered like a pall over every luxurious object about her. Her maid came and tapped at the door once, but she sent her away, saying that her head ached and she did not wish to be disturbed.

It was quite true, for her heavy fall upon the floor had hurt her severely; so she remained quietly lying on a sofa until black darkness hid everything from her confused sight.

Then there came a light tap upon the door again. She thought it was the maid to light the gas.

"You may go away, Finette, I do not need you yet," she said, feeling that the darkness suited her mood the best.

"It is I, Xenie. Open the door. I wish to speak to you," said her husband's voice.

She went to the door, unlocked and threw it wide open. The light from the hall streamed in upon her pale and haggard face, her dress in disorder, her dark hair loose and dishevelled.

"It is dark in there, I cannot see you, my darling," he said; "come across into my smoking-room in the light. I want to tell you something."

He took her hand and drew her across the hall into a luxurious apartment he called his smoking-room.

It was elegantly furnished with cushioned easy-chairs and lounges, while the floor was covered with a soft, Persian carpet and beautiful rugs.

The marble mantel was decorated with costly meerschaums, and chibouques of various patterns and materials, and a richly gilded box stood in the center, containing cigars and perfumed smoking tobacco.

On a marble-topped table in the center of the room stood two bottles of wine, and two richly-chased drinking glasses.

"Well?" she inquired, half-fearfully, as he drew her in and carefully closed the door.

"I have made my will, dear," he said, looking at her with a curious smile.

"And you have cut Howard Templeton off without a shilling?" she said, anxiously.

"Yes, darling, I have made you the sole heir to all my wealth," answered the old man, drawing his arm around her shrinking form. "But perhaps you will wish the old[Pg 15] man dead, now, that you may enjoy his money without any incumbrance."

"Oh! no," she exclaimed quickly, for something in his words touched her heart, and made her forget for a moment that cruel blow from his hand. "Oh! no, I shall never wish you dead, and I thank you a thousand times for your generosity."

"Then you forgive me for my—for that—to-day?" he inquired in a flighty, half-frightened way, fixing his dim eyes on her beautiful face with an anxious expression.

"Yes, I forgive you freely," she said, touched again, as she scarcely thought she could be, by his looks and tones, and yet longing to get away, for she was half-frightened by a certain inexplicable wildness about him. "And now I must go and dress for dinner."

"Wait, I have not done with you yet," he said, catching her tightly around the wrist, his restlessness increasing. "I saw my nephew on the street, and brought him home with me to dinner. Do you care, Xenie?"

"No, I do not care," she answered, steadily, yet her heart gave a great passionate throb of bitter anger.

Still holding her tightly by the hand he pulled open the door and sent his voice ringing loudly down the hall.

"Howard, Howard, come here!"

Xenie heard the distant door of the library unclose, then shut again, and a man's footsteps ringing along the marble hall.

She tried to wrench her hand away and flee, but it was useless. He held her as in a vise.

"Let me go," she panted, "my hair is down, my dress is disarranged, my face is disfigured, I do not wish to meet him."

But he held her tightly, gnashing his teeth in sudden rage at her efforts to escape.

At that moment Howard Templeton entered the room.

He started back as his gaze encountered Mrs. St. John's, then with a cold bow stood still, turning an inquiring glance upon his uncle's excited face.

"I want you to take a glass of wine with me, Howard," said his uncle in a cordial tone. "Xenie, my love, you will pour the wine for us."

He led her forward, to the little marble-topped table where stood the wine and glasses.

She saw that the corks were both drawn from the bottles, and taking up one she poured some of its contents into the richly-chased glass beside it.

"Now pour from the second bottle into the second glass," commanded her husband.

Xenie silently obeyed him, without a thought as to the[Pg 16] strangeness of the request, for her heart was beating almost to suffocation with the bitter consciousness of her enemy's presence.

Mr. St. John watched her every motion with a strange, repressed excitement.

His eyes glittered, his lips worked as if he were talking to himself. He nodded to his nephew as she stepped back.

"Let us drink long life and happiness to Mrs. St. John," he said.

Howard Templeton took one glass, and his uncle took the remaining one.

Both bowed to the shrinking woman who stood watching them, drained their glasses, and set them back with a simultaneous clink upon the marble table.

Then a wild, maniacal laugh filled the room—so shrill, so exultant, so blood-curdling, it froze the blood in the veins of the man and woman who stood there listening.

"Ha, ha," cried Mr. St. John, "you thought I did not know your secret, you two! But I did. I heard your talk on my wedding-night. I knew then that I had taken the woman you loved. Howard, I knew that she had sought me, and won me, and married me, to revenge her wrongs at your hands. I said to myself her beautiful body is mine—I have bought it with my gold—but her heart is Howard Templeton's!"

"No, no," cried Xenie, stamping her foot passionately; "I hate him! I hate him!"

"Hush!" thundered the old man, turning on her with the wild glare of madness in his eyes, "hush, woman! I have thought it over for months—at last I have reached a conclusion. The world is not wide enough for us two men to live in. So I said to myself—one of us must die!"

"Must die!" repeated Howard Templeton, with a sudden strong shudder.

"Yes, die!" cried the maniac, with another horrible laugh. "So I put deadly poison into one of the bottles that chance might decide our fates. Xenie poured out death for one of us just now. In ten minutes either you or I will be dead, Howard Templeton!"

For one terrible moment Xenie St. John and Howard Templeton remained silently gazing at the excited old man, as if petrified with horror, then:

"My God, my uncle is a madman!" broke hoarsely from the young man's ashen lips, in tones of unutterable horror and grief.

Mrs. St. John rushed to the door, threw it wide open, and shrieked aloud in frenzied accents for help.

The servants came rushing in and found their old master crouching in a corner of the room, gibbering and mouthing like some terrible wild beast, his bloodshot eyes rolling in their sockets, his lips all flecked with foam, while Howard Templeton remained silent in the center of the room, like a statue of horror.

"A doctor—bring a doctor!" shrieked Xenie, wildly.

It was not five minutes before a physician, living close by, was brought in, but even as he crossed the threshold, the insane creature rolled over upon the floor in the agonies of death.

One or two desperate struggles, a gasp, a quiver from head to foot and the old millionaire lay dead before them.

The physician knelt down and felt his heart and his pulse.

"He is dead," he said, shaking his head slowly and sadly. "I apprehended a fit the last time he consulted me, some three weeks ago. His mind and body were both weakening fast. This mournful end was not unexpected by me."

Mrs. St. John made a quick step forward.

She was about to say, "He did not die in a fit, doctor, he died of poison," when a hand like steel gripped her wrist.

She looked up and met the stern, awful gaze of Howard Templeton.

"Hush!" he whispered, hurriedly and sternly. "Let the world accept the physician's verdict. Say nothing of what you know. Do not brand his memory with the terrible obloquy of insanity and self-murder!"

As he spoke he turned away, and crossed the room, and as he passed the marble-topped table, it fell over, no one could have told how, and the bottles and glasses were shivered upon the floor.

One of the servants removed the debris, and mopped up the spilled wine from the floor, and no one thought anything more of it.

Yet, by that simple act, Howard Templeton saved his uncle's name and his own from the shafts of malice and calumny that must have assailed them if the terrible truth had come to light.

So the physician's hasty verdict of apoplexy was universally accepted by the world, and the old millionaire was laid away in his costly tomb a few days later, regretted by all his friends, and the secret of his tragic death was locked in the breasts of two who kept that hideous story sacred, although they were deadly foes.

Yes, deadly foes, and destined to hate each other more and more, for when the old millionaire's papers were examined, the beautiful widow found that she was foiled of her dearly-bought revenge at last.

For no will was found, although Xenie protested passionately that her husband had made a will the very last day of his life.

The most careful and assiduous search failed to reveal the existence of any legal document like a will, and the lawyers gravely assured Mrs. St. John that she could claim only a third of her deceased husband's wealth, the remainder falling to the next of kin, Howard Templeton.

"You see, madam," said the old lawyer, whom she was anxiously questioning, "if Mr. St. John had left a child, you could claim the whole estate as its lawful guardian, even without the existence of a will. But there being no nearer kin than Mr. Templeton, it legally falls to him, after you receive your widow's portion."

The young widow brooded over those words night and day.

She hated Howard Templeton more than ever.

She would have given the whole world, had it been hers, to wrest that fortune from her enemy's grasp, and leave him poor and friendless to fight his way through the hard world.

"Oh! if I only could find that will," she thought wildly. "Is it true that Mr. St. John made it, or was he deceiving me? He was utterly insane. Could one expect truth from a madman?"

Gradually, as weary weeks flew by, she began to believe that Mr. St. John had deceived her.

She felt quite sure in her own mind, after a little while, that he had never made the will.

He had fully meant for Howard Templeton to inherit his wealth.

Yet bitterly as she regretted its loss she could not bring herself to hate the memory of the old man she had married, and who had loved her for a little while with so fond and foolish a passion.

The memory of his dreadful death was too strong upon her.

She woke at night from dreadful dreams that recalled that last awful day of her husband's life, and lay shuddering and weeping, and praying to forget that fearful face, and blood-curdling, maniacal laugh that still rung in her shocked hearing.

"You are growing thin and pale, Xenie," Mrs. Egerton said, when she came to condole with her, more for the loss of the fortune than the loss of her husband. "People are[Pg 19] talking of your ill looks, and they say you take Mr. St. John's death so hard, you must have cared for him more than anyone believed. I let them talk, for, of course, it is very much to your credit to have them think so, but as I know better myself, I cannot help wondering at your paleness and trouble."

"It was all so sudden and terrible," murmured the young widow, as she lay back in her easy-chair, looking very fragile and beautiful in her deep mourning dress.

"Yes it was very bad his going off in a fit that way," said her aunt. "Still, it was to be expected, Xenie. He was very old, and really growing childish, I thought. His going off without a will was the worst part of it. Of course it hurt you terribly for Templeton to have the money!"

The sudden flash in Mrs. St. John's dark eyes told plainer than words how much it had hurt her.

"However, Xenie, I would give over worrying about it," continued her aunt, soothingly.

"But my revenge, Aunt Egerton. Think how much I sacrificed for it. I married that foolish old man, and endured his caprices so long without a murmur, allowed myself to be shut up in solitude like a bird in a cage, and never murmured at his tiresome exactions. And all for what? Because I expected to get his whole fortune, and be revenged on the coward who broke my heart for the sake of it. And to be despoiled of my revenge like this is too hard for endurance," she exclaimed, walking up and down the room, and wringing her white hands in a perfect passion of despair and regret.

"Oh! let the wretch go," said Mrs. Egerton, complacently rustling in her silks and laces. "You have secured a large portion of the estate, anyhow. And you are so young and beautiful still, Xenie, you may even marry a greater fortune than that, when your year of mourning is expired."

Xenie stopped still in her excited walk, and looked at her aunt.

"I shall never marry again—never," she said earnestly. "I have as much money as I want, only—only I want to take that from Howard Templeton because I want to humble him and wring his heart. And there is but one way to do it, and that is to reduce him to poverty. Money is the only god he worships!" she added bitterly.

"He treated you villainously and deserves to be punished," said Mrs. Egerton, "but still I would try to forget it, Xenie. You will lose your youth and prettiness brooding over this idea of revenge."

"I will never forget it," cried Mrs. St. John, wrathfully. "I will wait and watch, and if ever I see a chance to[Pg 20] punish Howard Templeton, I shall strike swiftly and surely."

Her aunt arose, gathering her silken wrappings about her tall, elegant form.

"Well, I must go now," she said. "I see it is of no use talking to you. Come and see me when you feel better, Xenie."

"I am going to the country next week," said her niece, abruptly.

"Indeed? Has not your mother been up to see you in your trouble?" inquired Mrs. Egerton, pausing in her graceful exit.

"No. I wrote to her, but she has neither come nor written. I fear something has happened. She is usually very punctual. Anyway, I shall go down next week and stay with them a week or two."

"I hope the change may improve your spirits, love," said her aunt, kissing her and going out with an airy "Au revoir."

"Mamma, how pale and troubled you look. What ails you?"

Mrs. St. John was crossing the threshold of the little cottage home that looked, oh, so poor and cheap after the stately brown-stone palace she had left that morning, and after one quick glance into her mother's careworn face she saw that new lines of grief and trouble had come upon it since last they had met.

"Come up into my room, Xenie. I have much to say to you," said her mother, leading the way up the narrow stairway into her bedroom, a neat and scrupulously clean little room, but plainly and almost poorly furnished.

Mrs. Carroll was a widow with only a few barren acres of land, which she hired a man to till. Her husband was long since dead, and the burden of rearing her two children had been a heavy one to the lonely widow, who came of a good family and naturally desired to do well by her two daughters, both of them being gifted with uncommon beauty.

But poverty had hampered and crushed her desires, and made her an old woman while yet she was in the prime of life.

Xenie removed her traveling wraps and sat down before the little toilet glass to arrange her disordered hair.

"My dear, how pale and sad you look in your widow's weeds," said Mrs. Carroll, regarding her attentively. "I was very sorry to hear of your husband's death. It is very sad to be left a widow so young—barely twenty."

"Yes," answered Xenie, abstractedly; then she turned around and said abruptly: "Mamma, where is my sister?"

Mrs. Carroll looked at her daughter a moment without replying.

"I have brought her some beautiful presents," continued Mrs. St. John, "and you, too, dear mamma—things that you will like—both beautiful and useful."

Mrs. Carroll looked at her daughter a moment in utter silence, and her lips quivered strangely.

Then she caught up a corner of her homely check apron, and hiding her convulsed face in its folds, she burst into bitter weeping.

Xenie sprang up and threw her arms around the neck of the agitated woman.

"Oh, mamma," she cried, anxiously, "speak to me. Tell me what ails you? Where is Lora?"

As if that name had power to open the flood gates of emotion wider, Mrs. Carroll wept more bitterly than ever.

"Mamma, you frighten me," cried Xenie, terrified. "Oh, tell me where is Lora? Is she dead?"

"No, no—oh, better that she were!" sobbed her mother, wildly.

Mrs. St. John grew as pale as death. She shook her mother almost rudely by the arm.

"What has Lora done?" she cried. "Where is she? I will go and seek her."

She was rushing wildly to the door, but Mrs. Carroll sprang forward, and catching the skirt of her dress, pulled her back.

"Not now!" she gasped; "wait a little. That wretched girl has ruined her good name and disgraced us all."

Mrs. St. John dropped into a chair like one bereft of life, and her great, black eyes, dilated with terror, stared up into her mother's face.

"Yes, it is too true," said her mother, sitting down and rocking herself back and forth, while low and heart-broken moans escaped her white lips.

"But, mamma, poor, good, little Lora! it cannot be! She was truth and innocence itself," panted the young widow, in a voice of anguish.

"She deceived us all—she was a sly little piece. You will see for yourself, Xenie. She lies ill in her chamber, and—and in a few months there will be a"—she lowered her voice and gave a fearful glance around her—"a child!"

"Oh! mamma, then she was married? Of course Lora was married! Doesn't she say so?" exclaimed Xenie, confidently.

"Oh, yes, she swears to a marriage—a secret one—but[Pg 22] look you, Xenie—not a ring, not a witness, not a scrap of paper to prove it! And the man dead—lost at sea!" said Mrs. Carroll, despairingly.

"Oh! mamma, then it was——"

"Jack Mainwaring—yes. He was courting her this long time, you know. He asked for her, and I wouldn't give my consent. I thought he wasn't good enough for her—a sailor, and only second mate, you know. And Aunt Egerton had promised to give her a season in town this winter, and she might have made a better match than a sailor."

Mrs. Carroll broke down again and wept bitterly.

"Try to control yourself, mamma," said the young widow, stroking the bowed head tenderly. "And so Jack married her in spite of you?"

"Yes," sobbed her mother, "he married her secretly, she says. It was about the same time, or nearly, that you were married. He found out that Lora was going to town to be one of the bridesmaids, and was jealous, I suppose, thinking she might see someone she could like better. So he persuaded her into it, and they were to keep it secret until he came back from this voyage."

"And he is lost at sea, you say?" asked Xenie, thoughtfully.

"Yes; he went away in a few weeks after the marriage, to be gone six months; but the news came last week of the loss of his ship by fire, and his name was on the list of the dead. You see, Xenie, what a terrible position Lora was placed in. She fainted when she heard the news, and then I found out everything."

"Does anyone else know, mamma?" inquired Xenie, anxiously.

"Not yet. She has been ill, but I have cared for her myself, and did not call in the doctor. But we cannot keep it a secret always. Of course malicious people will not believe in the marriage, and Lora's fair fame will be ruined forever! Oh! if she had only never been born!" cried the proud and unhappy mother.

Mrs. St. John sat silent, her lily-white hands clasped in her lap, her dark eyes staring into vacancy with a strangely intent expression. She roused herself at last and looked at her mother.

"Mamma, we must devise ways and means of keeping this a secret! It would ruin the family to have it known," she said, decidedly.

"Yes, I know that," said Mrs. Carroll, gloomily. "I would do anything in the world to save Lora's fair fame if I only knew what to do!"

"I have a plan," said Xenie, rising quietly. "I will tell it you by-and-by, mamma. Everything shall come right[Pg 23] if you will be guided by me. Now take me to my sister, if you please."

Mrs. Carroll rose silently and opened the door. Xenie followed her down a narrow passage to a door at the further end, and they entered a pretty and neat little room.

A low wood fire burned on the cleanly swept hearth, and on the white bed, with her dark hair trailing loosely over the pillows, lay a beautiful, white-faced girl, enough like Xenie to be her twin.

She started up with a cry of mingled joy and pain as the new-comer came toward her.

"My poor darling!" Mrs. St. John murmured, in a tone of infinite love and compassion, as she twined her arms around the trembling form.

Lora clung to her sister, sobbing and weeping convulsively. At length she whispered against her shoulder:

"Mamma has told you all, Xenie?"

"Yes, dear," was the gentle answer.

"And you—you believe that I was married?" questioned the invalid.

"Yes, darling," whispered her sister, tenderly. "How could I believe evil of you, my innocent, little Lora?"

"Thank God!" cried the invalid, gratefully. "Oh! Xenie, mamma has been so angry it nearly broke my heart."

"She will forgive you, darling," murmured Mrs. St. John, fondly, as she stroked the dark head nestling on her breast.

"And, oh, Xenie, poor Jack—my Jack—he is dead!" sobbed Lora, bursting into a fit of wild, hysterical weeping.

"There, darling, hush—you must not excite yourself," said Mrs. St. John, laying her sister back upon the pillows, and trying to soothe her frenzied excitement.

"And no one will believe that I was Jack's wife—I am disgraced forever! Mamma says so. The finger of scorn will be pointed at me everywhere. But what do I care, since my heart is broken? I only want to die!" moaned the unhappy young creature, as she tossed to and fro upon the bed.

"Be quiet, Lora; listen to me," said Mrs. St. John, taking the restless, white hands in her own, and sitting down upon the bed. "I wish to talk to you as soon as you become reasonable."

Thus adjured, Lora hushed her sobs by a great effort, and lay perfectly still but for the uncontrollable heaving of her troubled breast, her large, hollow, dark eyes fixed earnestly on Xenie's pale and lovely face.

Mrs. Carroll crouched down in a chair by the side of the bed, the image of hopeless woe.

"Lora, dear," said her sister, in low, earnest tones, "of[Pg 24] course you know that, if this dreadful thing becomes known, the disgrace will be reflected upon us all."

Mrs. Carroll groaned, and Lora murmured a pitiful yes.

"I have thought of a plan to save you," continued Mrs. St. John. "A clever plan that would shield your fair fame forever. But it will require some co-operation on your part, and it may be that you and mamma may refuse for you to undertake it."

"You may count on my consent beforehand!" groaned Mrs. Carroll, desperately.

"I will do whatever mamma says," murmured Lora, weakly.

Mrs. St. John looked away from them a moment in silent thought; then she said, slowly:

"Of course, you know, mamma, that my husband died without a will, and that Howard Templeton inherited the greater part of his wealth?"

"Yes; you wrote me. I was very sorry that you were disappointed, dear," said her mother, gently, yet wondering what this had to do with Lora's forlorn case.

"Mamma," said Xenie, slowly, "if my husband had left me as Lora's left her, I could have kept that fortune out of Howard Templeton's hands."

"My dear, I hardly understand you," said her mother, blankly.

"Mamma, I mean that if I could hope for an heir to my husband, the child would inherit all that wealth, and Howard Templeton be left penniless."

"Oh, yes, I understand you now," was the quick reply, "but you have no prospect, no hope of such a thing—have you, dear?"

There was a moment's silence, and Mrs. St. John's fair face grew scarlet, then deadly white again. She looked away from her mother, and said, slowly:

"Yes, mamma, I have such a hope. Listen to me, you and Lora, and I will help you in your trouble, and you shall help me to complete my revenge."

Some three or four weeks after Mrs. St. John's visit to the country, Howard Templeton was sitting in his club one day, smoking and reading, after a most luxurious lunch.

The young fellow looked very comfortable as he leaned back in his cushioned chair, the blue smoke curling in airy rings over his curly, blonde head, a look of lazy contentment in his handsome blue eyes.

He was somewhat of a Sybarite in his tastes, this handsome[Pg 25] young fellow, over whose head twenty-five happy years had rolled serenely, without a shadow to mar their brightness save that unfortunate love affair two years before.

Howard was, emphatically, one of the "gilded youth" of his day. He "toiled not, neither did he spin." He had been cradled in luxury's silken lap all his life long.

Sorrow had passed him tenderly by as one exempt from the common ills of life.

He was so accustomed to his good luck that he seldom gave a thought to it. It simply seemed to him that he would go on that way forever.

Yet, to-day, for a wonder, he had been a little thoughtfully reviewing the events of the past six months.

"It was very kind in Uncle John to leave things so comfortable for me," he said to himself. "I thought his wife would influence him against me so much that he wouldn't have left me a penny. If he hadn't, what the deuce should I have done?"

He paused a moment, in comical amusement, to survey the situation; but the idea was too stupendous.

He could not even fancy himself the victim of adversity, much less tell what he would have done in that case. He laughed at it after a moment.

"I cannot even imagine it," he thought. "Poor little Xenie, how hard it went with her to be foiled in her revenge, as she called it. How she must have loved me to have turned against me so when I gave her up! Who would have believed that we two should ever hate each other with such a deadly hate?"

Something like a smothered sigh went upward with the blue cigar smoke, and just then a footstep crossed the threshold, and a man's voice said, lightly:

"Halloo, Doctor Templeton; enjoying yourself, as usual."

"Halloo, Doctor Shirley," returned Templeton, with a lazy nod at the new-comer. "Have a smoke?"

"I don't care if I do," said the doctor, throwing himself down in an easy-chair opposite the speaker, and lighting a weed. "How deuced comfortable you look, my boy!"

"Feel that way," lisped Templeton, in a lazy tone.

"Ah! I don't think you would feel so devil-may-care if you knew all that I know, old boy," laughed the doctor, significantly.

The old doctor was very well known at the club as a gossip, so Templeton only laughed carelessly as he said:

"What's the matter, doctor? Any of my sweethearts sick or dead?"

"Not that I know of," said Doctor Shirley. "However, Templeton, if any of your sweethearts has money, take my[Pg 26] advice, young fellow, and make up to her without delay."

Howard Templeton laughed at the doctor's sage advice.

"Thanks," he said, "but I do very well as I am, doctor. I don't care to become a subject for petticoat government, yet."

"Yet things looked that way two years ago," said Doctor Shirley, maliciously, for Templeton's ardent devotion to Mrs. Egerton's lovely debutante at that time had been no secret in society.

Templeton's blonde face flushed a dark red all over, yet he laughed carelessly.

"Oh, yes, I had the fever," he said. "However, its severity then precludes the danger of ever having a second attack. How little I dreamed that she would be my aunt."

"Or your bete noire," said the doctor.

"Hardly that," said Templeton, composedly, as he knocked the ashes from the end of his cigar. "True, she has taken a slice of my fortune away, but then there's yet enough to butter my bread."

"There may not be much longer," said Doctor Shirley, meaningly.

"What do you mean?" asked Templeton, looking at him as if he had serious doubts of his sanity. "Who's going to take it away from me? Has Mrs. St. John found the will she talked of so much?"

"No," said Doctor Shirley, "but she has found something that will serve her as well."

"Confound it, doctor, I don't understand you at all," said the young fellow, a little testily. "What are you driving at, anyway?"

"Templeton, honestly, I hate to tell you," said the physician, sobering down, "but I've bad news for you. You know that Mrs. St. John has been ill lately, I suppose?"

"Yes, I heard it—thought, perhaps, she meant to shuffle off this mortal coil and leave me the balance of my uncle's property," said the young man, imperturbably.

"Nothing further from her thoughts, I assure you," was the laughing reply. "She has been quite ill, but she is well enough to come down into the drawing-room to-day. Come, now, Templeton, guess what I have to tell you?"

"'Pon honor, doctor, I haven't the faintest idea. Does it refer to my fair and respected aunt? Is it a new freak of hers?"

"Yes, decidedly a new freak," said the doctor, laughing heartily, and enjoying his joke very much.

"Well, then, out with it," said Howard, growing impatient. "Does she accuse me of stealing and secreting that fabulous missing will?"

"Not that I am aware of," and Doctor Shirley rose and[Pg 27] threw away his half-smoked cigar, saying, carelessly: "I must be going. We poor devils of doctors never have time to smoke a whole cigar. Say, Templeton, Mrs. St. John has her mother and sister staying with her. Deuced handsome girl, that Lora Carroll! Very like her sister! And—don't go off in a fit, now, Templeton—in a very few months there will be a little heir to your deceased uncle's name and fortune!"

"I don't believe it!" exclaimed Howard Templeton, springing to his feet, while his handsome face grew white and red by turns.

"You don't believe it? That's because you don't want to believe it. But I give you my word and honor as a professional man and her medical attendant, that it is a self-evident fact," and laughing at his, little joke, the gossiping old doctor hurried away from the club-room.

"I don't believe it!" Howard Templeton repeated angrily, as he stood still where Doctor Shirley had left him, those unexpected words ringing through his brain.

"What is it you don't believe, Templeton?" inquired one of the "gilded youth," dawdling in and overhearing the remark.

"I don't believe anything—that's my creed," answered Templeton, snatching his hat, and hurrying out. He wanted to be out in the cold, fresh air. Somehow it seemed to him as if a hand grasped his throat, choking his life out.

He walked aimlessly up and down the crowded thoroughfare, seemingly blind and deaf to all that went on around him.

Men's eyes remarked the tall, well-proportioned form and handsome, blonde face with envy.

Women looked after him admiringly, thinking how splendid it would be to have such a man for a lover. Howard heeded nothing of it. He was accustomed to it. He simply took it for his due, and he had other things to engross his mind now.

"It can't be true, it can't be true," he said to himself, again and again in his restless walk. "It is the most undreamed of thing. Who could believe it?"

And yet it troubled him despite his incredulity. It troubled him so much that he went to see a lawyer about it.

He stated the case, and asked him frankly what were his chances if such a thing really should happen.

"No chance at all," was the grim reply. "If you did[Pg 28] not resign your claim, Mrs. St. John would naturally sue you for the money on behalf of the legal heir."

"And then?" asked Howard.

"The case would certainly go against you."

Howard went out again and took another walk. He tried to fancy himself—Howard Templeton, the golden youth—face to face with the grim fiend, poverty.

He wondered how it would feel to earn his dinner before he ate it, to wear out his old coats, and have to count the cost of new ones, as he had vaguely heard that poor men had to do.

"I can't imagine it," he said to himself. "Time enough to bother my brain with such conundrums if the thing really comes to pass. And if it does, what a glorious triumph it will be for 'mine enemy!' I'd like to see her—by Jove, I believe I'll go there."

He stopped short, filled with the new idea, then hurried on, recalled to himself by a stare of surprise from a casual passer-by.

"Yes; why shouldn't I go there, by George?" he went on. "It was my home before she came there. The world doesn't know that we are 'at outs,' although we are sworn foes privately. I'll pretend to call on Lora Carroll. Lora was a pretty girl enough when I was down there that summer, young and unformed, though time has remedied that defect, doubtless. Doctor Shirley thought her handsome. Yes, I will call on little Lora. A daring thing to do, perhaps, but then I'm in the mood for daring a great deal."

The lamps were lighted and the glare of the gas flared down upon him as he thus made up his mind.

He went to his hotel, made an elaborate and elegant toilet, as if anxious to please, then sallied forth toward the brown-stone palace where his enemy reigned in triumph.

A soft and subdued light shone through the curtains of rose-colored silk and creamy lace that shaded the windows of the drawing-room. A fancy seized upon Howard to peep through them before he went up the marble steps and sent in his card.

"For who knows that they may decline to see me," he thought, "and I am determined to get one look at Xenie. I want to see if she looks very happy over her triumph."

He glanced around, saw that no one was passing, and cautiously went up to the window.

It was as much as he could do, tall as he was, to peer into the room by standing on tiptoe.

He looked into the beautiful and spacious room where he had spent many happy hours with his deceased uncle in years gone by, and a sigh to the memory of those old days[Pg 29] breathed softly over his lips, and a dimness came into his bright blue eyes.

He brushed it away, and looked around for the beautiful woman who had come between him and the poor old man who had brought him up as his heir.

He saw two ladies in the room.

One of them was quite elderly, and had gray hair crimped beneath a pretty cap.

She wore black silk, and sat on a sofa trifling over a bit of fancy knitting.

"That is Mrs. Carroll," he said to himself. "She is a pretty old lady, though she looks so old and careworn. But she is poor, and that explains it. I dare say I shall grow gray and careworn too when Mrs. St. John takes my uncle's money from me, and I have to earn my bread before I eat it."

He saw another lady standing with her back to him by the piano.

She was petite and slender, with a crown of braided black hair, and her robe of rich, wine-colored silk and velvet trailed far behind her on the costly carpet.

She stood perfectly still for a few moments, then turned slowly around, and he saw her face.

"Why, it is Xenie herself!" he exclaimed. "Doctor Shirley lied to me, and I was fool enough to believe his silly joke. Heaven! what I have suffered through my foolish credulity! I've a mind to call Shirley out and shoot him for his atrocity!"

He remained silent a little while studying the lady's dark, beautiful, smiling face, when suddenly he saw the door unclose, and a lady, dressed in the deepest sables of mourning, entered and walked across the floor and sat down by Mrs. Carroll's side upon the sofa.

Howard Templeton started, and a hollow groan broke from his lips.

"My God!" he breathed to himself, "I was mistaken. It is Lora, of course, in that bright-hued dress. How like she is to Xenie! I ought to have remembered that my uncle's wife would be in mourning. Yes, that is Xenie by her mother's side, and Doctor Shirley told me the fatal truth!"

He walked away from the window, and made several hurried turns up and down before the house.

"Shall I go in?" he asked himself. "I know all I came for, now. Yes, I will be fool enough to go in anyhow."

He went up the steps and rang the bell, waiting nervously for the great, carved door to open.

The door swung slowly open, and the gray-haired old servitor whom Howard could remember from childhood, took his card and disappeared down the hallway.

Presently he returned, and informed the young man that the ladies would receive him; and Howard, half regretting, when too late, the hasty impulse that had prompted him enter, was ushered into the drawing-room.

The next moment he found himself returning a stiff, icy bow from his uncle's widow, a half-embarrassed greeting from Mrs. Carroll, and shaking hands with the beautiful Lora, who gave him a shy yet perfectly self-possessed welcome and referred to his visit to the country two years before in a pretty, naive way, showing that she remembered him perfectly; although, as she averred, she was little more than a child at the time.

They sat down, and he and Miss Carroll had the talk mostly to themselves, though now and then his glance strayed from her bright, vivacious countenance to the sad, white face of the young widow sitting beside her mother on the sofa, the dark lashes shading her colorless cheeks, a sorrowful droop about her beautiful lips as if her thoughts dwelt on some mournful theme.

Howard had heard people say that she looked ill and pale since Mr. St. John's death, and that after all she must have cared for him a little.

He knew better than that, of course, yet he could not but acknowledge that she played the part of a bereaved wife to perfection.

"It looks like real grief," he said to himself; "but, of course, I know that it is the loss of the money and not the man that weighs her spirits down so heavily."

"You resemble your sister very much, Miss Carroll," he said to Lora, after a little while. "If I were an Irishman, I should say that you look more like your sister than you do like yourself."

The careless, yet odd little speech seemed to have an inexplicable effect upon Lora Carroll. She started violently, her cheeks lost their soft, pink color, the bright smile faded from her lips, and she gave the speaker a keen, half-furtive glance from under her dark-fringed eyelashes.

She tried to laugh, but it sounded forced and unnatural.

Mrs. Carroll, who had been silently listening, broke in carelessly before Lora could speak:

"Yes, indeed, Lora and Xenie are exceedingly like each other, Mr. Templeton. Their aunt, Mrs. Egerton, says that Lora is now the living image of Xenie, when she first came to the city, two years ago."

"I quite agree with her," Mr. Templeton answered, in a light tone, and with a bow to Mrs. Carroll. "The resemblance is very striking."

As he spoke, he moved his chair forward, carelessly yet deliberately, so that he might look into Mrs. St. John's beautiful, pale face.

The young widow did not seem to relish his furtive contemplation. She flushed slightly, and her white hands clasped and unclasped themselves nervously, as they lay folded together in her lap.

She turned her head to one side that she might not encounter the full gaze of his eyes. He smiled to himself at her embarrassment and, turning from her, allowed his gaze to rest upon the bright fire burning behind the polished steel bars of the grate.

A momentary unpleasant silence fell upon them all. Lora broke it after a moment's thought by saying, carelessly, as she opened the piano:

"I remember that you used to sing very well, Mr. Templeton. Won't you favor us now?"

"Lora, my dear," Mrs. Carroll said, in a gently-shocked voice, "you forget that music may not be agreeable to your sister so recently bereaved."

"Oh, Xenie, dear, I beg your pardon," began Lora, turning around, but Mrs. St. John interrupted her by saying, wearily:

"Never mind, mamma, never mind, Lora. I—I—my head aches—I will retire if you will excuse me, and then you may have all the music you wish."

She arose from her seat, gave Mr. Templeton a chill, little bow which he returned as coldly, then went slowly from the room, trailing her sable robes behind her like a pall.

"As cold as ice, by Jove," was Howard's mental comment; "yet she did not appear particularly elated over her prospective triumph. Strange!"

He crossed over to the piano where Lora was restlessly turning over some sheets of music.

"Won't you sing to me, Miss Carroll?" he asked, in a soft, alluring voice.

Lora sat down on the music-stool and laughed as she ran her white fingers over the pearl keys.

"Excuse me—I do not sing," she said, carelessly. "But I will play your accompaniment if you will select a song."

"You do not sing," he said, as he began to turn over the music. "Ah! there is one point at least in which you do not resemble your sister. Mrs. St. John has a very fine voice."

"Yes. Xenie's voice has been well trained," she answered, carelessly; "but I do not care to sing, I would rather hear others."

"How will this please you?" he inquired, selecting a song and laying it up before her.

She glanced at it and answered composedly:

"As well as any. I remember this song. I heard you sing it with Xenie that summer."

"Yes, our voices went well together," he answered, as carelessly. "I wish you would sing it with me now?"

"I cannot, but I will play it for you. Shall we begin now?"

He was silent a moment, looking down at her as she sat there with down-drooped eyes, the gleam of the firelight and gaslight shining on the black braids of her hair and the rich, warm-hued dress that was so very becoming to her dark, bright beauty.

Suddenly he saw something on the white hand that was softly touching the piano keys. He took the slim fingers in his before she was aware.

"Let me see your ring," he said. "It looks familiar. Ah, it is the one I gave you that winter when we——"

She threw back her head and looked at him with wide, angry, black eyes.

"What do you mean?" she said imperiously. "Are you crazy, Mr. Templeton? It is the ring you gave Xenie, certainly, but not me!"

"Lora, love," said her mother's voice from the sofa, in mild reproval. "Do not be rude to Mr. Templeton."

"Mamma, I don't mean to," said Lora, without turning her head; "but he—he spoke as if I were Xenie."

"I beg your pardon, Miss Carroll," said the offender, with a teasing look in his blue eyes, which she did not see; "I did not mean to offend, but do you know that in talking with you, I constantly find myself under the impression that I am talking to your sister. It is one effect of the wonderful resemblance, I presume."

"Yes, I suppose so," admitted Lora; "but," she continued, in a tone of pretty, girlish pique, "I wish you would try and recollect the difference. I am two years younger than my sister, remember, and so it is not a compliment to be taken for a person older than myself!"

"Of course not," said Mr. Templeton, soothingly; "but it was the ring, please remember, that led me into error this time. You see, I gave it to——"

"Yes, you gave it to Xenie," broke in Lora, promptly and coolly; "yes, I know that, but you see she was tired of it, or rather she did not care for it any more—so she gave it to me."

His face whitened angrily, but he said, with assumed carelessness:

"And you—do you care for it, Miss Carroll?"

She lifted her hand and looked at the flashing ruby with a smile.

"Yes, I like it. It is very handsome, and must have cost a large sum of money—more than I ever saw, probably, at one time in my life, I suppose, for I am poor, as you know."

"I thought we were going to have some music, Lora," exclaimed Mrs. Carroll, gasping audibly over her knitting. "You weary Mr. Templeton with your idle talk."

"He began it, mamma," said Lora, carelessly. "Well, Mr. Templeton, I'm going to begin the accompaniment. Get ready."

She touched the keys with skillful fingers, waking a soft, melancholy prelude, and Howard sang in his full, rich, tenor voice:

"The poet has very happily blended truth and poesy in that very pathetic song," remarked Lora, with a touch of careless scorn in her voice, as the rich notes ceased. "Well, Mr. Templeton, will you try another song?"

"No, thank you, Miss Carroll—I must be going. I have already trespassed upon your time and patience."

Lora did not gainsay the assertion.

She rose with an almost audible sigh of relief, and stood waiting for him to say good-night.

"May I come and see you again?" he asked, as he bowed over the delicate hand that wore his ruby ring.

"I—we—that is, mamma and I—are going away soon. It may not—perhaps—be convenient for us to receive you again," stammered Lora, hesitating and blushing like the veriest school-girl.

"Ah! I am sorry," he said; "well, then, good-night, and good-bye."

He shook hands with both, holding Lora's hand a trifle longer than necessary, then courteously turned away.

When he was gone, the beautiful girl knelt down by her mother and lifted her flushed and brilliant face with a look of inquiry upon it.

"Well, mamma?" she questioned, gravely.

Mrs. Carroll smiled encouragingly.

"My dear, you acted splendidly," she said, "and so did your sister. I was afraid at first. I thought you were wrong to admit him. It was a terrible test, for the eyes of hatred are even keener than those of love. I trembled for you at first, but you stood the trial nobly. He was completely hoodwinked. No fear now. If you could blind Howard Templeton to the truth, there can be no trouble with the rest of the world."

"And yet once or twice I was terribly frightened," said the girl musingly. "The looks he gave me, the tones of his voice, sometimes his very words, made me tremble with fear. It was, as you say, a terrible test, but I am glad now that I risked it, for I believe that I have succeeded in blinding him. All goes well with us, mamma. Doctor Shirley and Howard Templeton have been completely deceived. The rest will be very easy of accomplishment."

Thanks to the gossiping tongue of old Doctor Shirley, the interesting news regarding Mrs. St. John speedily became a widespread and accepted fact in society.

It was quite a nine days' wonder at first, and in connection with its discussion a vast deal of speculation was indulged in regarding the possible future of Mr. Howard Templeton, the fair and gilded youth whose heritage might soon be wrested from him, leaving him to battle single-handed with the world.

Before people had stopped wondering over it, Mrs. Egerton added her quota to the excitement by the information that her niece, Mrs. St. John, had gone abroad, taking her mother and sister with her.

She had wanted Lora with her that season—she had long ago promised Mrs. Carroll to give Lora a season in the city—but the girl was so wild over the idea of travel that Xenie had taken her with her for company, acting on the advice of Doctor Shirley, who declared that change of scene and cheerful company were actually essential to the preservation of the young invalid's life.

The old doctor, when people interrogated him, confirmed Mrs. Egerton's assertion.

He said that Mrs. St. John had fallen into a state of depression and melancholy so deep as to threaten her health and even her life.