IN THE

EARLY HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

C. F. CLAY, Manager.

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

Glasgow: 50, WELLINGTON STREET.

Leipzig: P. A. BROCKHAUS.

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN & CO. Ltd.

Title: Domesday Book and Beyond: Three Essays in the Early History of England

Author: Frederic William Maitland

Release date: July 19, 2013 [eBook #43255]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by KD Weeks, Irma Spehar, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (http://archive.org/details/toronto)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Domesday Book and Beyond, by Frederic William Maitland

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/domesdaybook00maituoft |

Marginal descriptions

The marginal paragraph descriptions are placed at the beginning of each paragraph, and will be shown as can be seen here. On occasion, there are more than one for a single paragraph.

The copious footnotes have been renumbered, consecutively, and gathered at the end of this text. Internal references to those notes in the original have been modified to refer to the new numbers, and all have been hyperlinked.

The page references in the Index have also been linked to the physical page on which the topic appears.

There are two detailed maps. A link to the full image size has been added to each caption for optional viewing.

Please refer to the Notes at the end of this text for additional detail.

The greater part of what is in this book was written in order that it might be included in the History of English Law before the Time of Edward I. which was published by Sir Frederick Pollock and me in the year 1895. Divers reasons dictated a change of plan. Of one only need I speak. I knew that Mr Round was on the eve of giving to the world his Feudal England, and that thereby he would teach me and others many new lessons about the scheme and meaning of Domesday Book. That I was well advised in waiting will be evident to everyone who has studied his work. In its light I have suppressed, corrected, added much. The delay has also enabled me to profit by Dr Meitzen’s Siedelung und Agrarwesen der Germanen[1], a book which will assuredly leave a deep mark upon all our theories of old English history.

The title under which I here collect my three Essays is chosen for the purpose of indicating that I have followed that retrogressive method ‘from the known to the unknown,’ of which Mr Seebohm is the apostle. Domesday Book appears to me, not indeed as the known, but as the knowable. The Beyond is still very dark: but the way to it lies through the Norman record. A result is given to us: the problem is to find cause and process. That in some sort I have been endeavouring to answer Mr Seebohm, I can not conceal from myself or from others. A hearty admiration of his English Village Community is one main source of this book. That the task of disputing his conclusions might have fallen to stronger hands than mine I well know. I had hoped that by this time Prof. Vinogradoff’s Villainage in England would have had a sequel. When that sequel comes (and may it come soon) my provisional answer can be forgotten. One who by a few strokes of his pen has deprived the English nation of its land, its folk-land, owes us some reparation. I have been trying to show how we can best bear the loss, and abandon as little as may be of what we learnt from Dr Konrad von Maurer and Dr Stubbs.

For my hastily compiled Domesday Statistics I have apologized in the proper place. Here I will only add that I had but one long vacation to give to a piece of work that would have been better performed had it been spread over many years. Mr Corbett, of King’s College, has already shown me how by a little more patience and ingenuity I might have obtained some rounder and therefore more significant figures. But of this it is for him to speak.

Among the friends whom I wish to thank for their advice and assistance I am more especially grateful to Mr Herbert Fisher, of New College, who has borne the tedious labour of reading all my sheets, and to Mr W. H. Stevenson, of Exeter College, whose unrivalled knowledge of English diplomatics has been generously placed at my service.

F. W. M.

20 January, 1897.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | v |

| Table of Contents | vii |

| List of Abbreviations | xiv |

| ESSAY I. | |

| Domesday Book. | |

Domesday Book and its satellites, 1. Domesday and legal history, 2. Domesday a geld book, 3. The danegeld, 3. The inquest and the geld system, 5. Importance of the geld, 7. Unstable terminology of the record, 8. The legal ideas of century xi. 9. |

|

| § 1. Plan of the Survey, pp. 9–26. | |

|

The geographical basis, 9. The vill as the unit, 10. Modern and ancient vills, 12. Omission of vills, 13. Fission of vills, 14. The nucleated village and the vill of scattered steads, 15. Illustration by maps, 16. Size of the vill, 17. Population of the vill, 19. Contrasts between east and west, 20. Small vills, 20. Importance of the east, 21. Manorial and non-manorial vills, 22. Distribution of free men and serfs, 23. The classification of men, 23. The classes of men and the geld system, 24. Our course, 25. |

|

| § 2. The Serfs, pp. 26–36. | |

|

The servus of Domesday, 26. Legal position of the serf, 27. Degrees of serfdom, 27. Predial element in serfdom, 28. The serf and criminal law, 29. Serf and villein, 30. The serf of the Leges, 30. Return to the servus of Domesday, 33. Disappearance of servus, 35. |

|

| § 3. The Villeins, pp. 36–66. | |

|

The boors or coliberts, 36. The continental colibert, 37. The English boor, 37. Villani, bordarii, cotarii, 38. The villein’s tenement, 40. Villeins and cottiers, 41. Freedom and unfreedom of the villani, 41. Meaning of freedom, 42. The villein as free, 43. The villein as unfree, 45. Anglo-Saxon free-holding, 46. Free-holding and seignorial rights, 47. The scale of free-holding, 49. Free land and immunity, 50. Unfreedom of the villein, 50. Right of recapture, 50. Rarity of flight, 51. The villein and seignorial justice, 52. The villein and national justice, 52. The villein and his land, 53. The villein’s land and the geld, 54. The villein’s services, 56. The villein’s rent, 57. The English for villanus, 58. Summary of the villein’s position, 60. Depression of the peasants, 61. The Normans and the rustics, 61. Depression of the sokemen, 63. The peasants on the royal demesne, 65. |

|

| § 4. The Sokemen, pp. 66–79. | |

|

Sochemanni and liberi homines, 66. Lord and man, 67. Bonds between lord and man, 67. Commendation, 69. Commendation and protection, 70. Commendation and warranty, 71. Commendation and tenure, 71. The lord’s interest in commendation, 72. The seignory over the commended, 74. Commendation and service, 74. Land-loans and services, 75. The man’s consuetudines, 76. Nature of consuetudines, 78. Justiciary consuetudines, 78. |

|

| § 5. Sake and Soke, pp. 80–107. | |

Sake and soke, 80. Private jurisdiction in the Leges, 80. Soke in the Leges Henrici, 81. Kinds of soke in the Leges, 82. The Norman kings and private justice, 83. Sake and soke in Domesday, 84. Meaning of soke, 84. Meaning of sake, 84. Soke as jurisdiction, 86. Seignorial justice before the Conquest, 87. Soke as a regality, 89. Soke over villeins, 90. Private soke and hundredal soke, 91. Hundredal and manorial soke, 92. The seignorial court, 94. Soke and the earl’s third penny, 95. Soke and house-peace, 97. Soke over houses, 99. Vendible soke, 100. Soke and mund, 100. Justice and jurisdiction, 102. Soke and commendation, 103. Sokemen and ‘free men,’ 104. Holdings of the sokemen, 106. |

|

| § 6. The Manor, pp. 107–128. | |

|

What is a manor? 107. Manerium a technical term, 107. Manor and hall, 109. Difference between manor and hall, 110. Size of the maneria, 110. A large manor, 111. Enormous manors—Leominster, Berkeley, Tewkesbury, Taunton, 112. Large manors in the Midlands, 114. Townhouses and berewicks attached to manors, 114. Manor and soke, 115. Minute manors in the west, 116. Minute manors in the east, 117. The manor as a peasant’s holding, 118. Definition of a manor, 119. The manor and the geld, 120. Classification of men for the geld, 122. Proofs of connexion of the manor with the geld, 122. Land gelds in a manor, 124. Geld and hall, 124. The lord and the man’s taxes, 125. Distinction between villeins and sokemen, 125. The lord’s subsidiary liability, 126. Manors distributed to the Frenchmen, 127. Summary, 128. |

|

| § 7. Manor and Vill, pp. 129–150. | |

|

Manorial and non-manorial vills, 129. The vill of Orwell, 129. The Wetherley hundred of Cambridgeshire, 131. The Wetherley sokemen, 134. The sokemen and seignorial justice, 135. Changes in the Wetherley hundred, 135. Manorialism in Cambridgeshire, 136. The sokemen and the manors, 137. Hertfordshire sokemen, 138. The small maneria, 138. The Danes and freedom, 139. The Danish counties, 139. The contrast between villeins and sokemen, 140. Free villages, 141. Village communities, 142. The villagers as co-owners, 142. The waste land of the vill, 143. Co-ownership of mills and churches, 144. The system of virgates in a free village, 144. The virgates and inheritance, 145. The farm of the vill, 146. Round sums raised from the villages, 147. The township and police law, 147. The free village and Norman government, 149. Organization of the free village, 149. |

|

| § 8. The Feudal Superstructure, pp. 150–172. | |

|

The higher ranks of men, 150. Dependent tenure, 151. Feudum, 152. Alodium, 153. Application of the formula of dependent tenure, 154. Military tenure, 156. The army and the land, 157. Feudalism and army service, 158. Punishment for default of service, 159. The new military service, 160. The thegns, 161. Nature of thegnship, 163. The thegns of Domesday, 165. Greater and lesser thegns, 165. The great lords, 166. The king as landlord, 166. The ancient demesne, 167. The comital manors, 168. Private rights and governmental revenues, 168. The English state, 170. |

|

| § 9. The Boroughs, pp. 172–219. | |

Borough and village, 172. The borough in century xiii., 173. The number of the boroughs, 173. The aid-paying boroughs of century xii, 174. List of aids, 175. The boroughs in Domesday, 176. The borough as a county town, 178. The borough on no man’s land, 178. Heterogeneous tenures in the boroughs, 179. Burgages attached to rural manors, 180. The burgess and the rural manor, 181. Tenure of the borough and tenure of land within the borough, 181. The king and other landlords, 182. The oldest burh, 183. The king’s burh, 184. The special peace of the burh, 184. The town and the burh, 185. The building of boroughs, 186. The shire and its borough, 186. Military geography, 187. The Burghal Hidage, 187. The shire’s wall-work, 188. Henry the Fowler and the German burgs, 189. The shire thegns and their borough houses, 189. The knights in the borough, 190. Burh-bót and castle-guard, 191. Borough and market, 192. Establishment of markets, 193. Moneyers in the burh, 195. Burh and port, 195. Military and commercial elements in the borough, 196. The borough and agriculture, 196. Burgesses as cultivators, 197. Burgage tenure, 198. Eastern and western boroughs, 199. Common property of the burgesses, 200. The community as landholders, 200. Rights of common, 202. Absence of communalism in the borough, 202. The borough community and its lord, 203. The farm of the borough, 204. The sheriff and the farm of the borough, 205. The community and the geld, 206. Partition of taxes, 207. No corporation farming the borough, 208. Borough and county organization, 209. Government of the boroughs, 209. The borough court, 210. The law-men, 211. Definition of the borough, 212. Mediatized boroughs, 212. Boroughs on the king’s land and other boroughs, 215. Attributes of the borough, 216. Classification of the boroughs, 217. National element in the boroughs, 219. |

|

| ESSAY II. | |

| England before the Conquest. | |

|

Object of this essay, 220. Fundamental controversies over Anglo-Saxon history, 221. The Romanesque theory unacceptable, 222. Feudalism as a normal stage, 223. Feudalism as progress and retrogress, 224. Progress and retrogress in the history of legal ideas, 224. The contact of barbarism and civilization, 225. Our materials, 226. |

|

| § 1. Book-land and the Land-book, pp. 226–244. | |

|

The lands of the churches, 226. How the churches acquired their lands, 227. The earliest land-books, 229. Exotic character of the book, 230. The book purports to convey ownership, 230. The book conveys a superiority, 231. A modern analogy, 232. Conveyance of superiorities in early times, 233. What had the king to give? 234. The king’s alienable rights, 234. Royal rights in land, 235. The king’s feorm, 236. Nature of the feorm, 237. Tribute and rent, 239. Mixture of ownership and superiority, 240. Growth of the seignory, 241. Book-land and church-right, 242. Book-land and testament, 243. |

|

| § 2. Book-land and Folk-land, pp. 244–258. | |

|

What is folk-land? 244. Folk-land in the laws, 244. Folk-land in the charters, 245. Land booked by the king to himself, 246. The consent of the witan, 247. Consent and witness in the land-books, 247. Attestation of the earliest books, 248, Confirmation and attestation, 250. Function of the witan, 251. The king and the people’s land, 252. King’s land and crown land, 253. Fate of the king’s land on his death, 253. The new king and the old king’s heir, 254. Immunity of the ancient demesne, 255. Rights of individuals in national land, 255. The alod, 256. Book-land and privilege, 257. Kinds of land and kinds of right, 257. |

|

| § 3. Sake and Soke, pp. 258–292. | |

|

Importance of seignorial justice, 258. Theory of the modern origin of seignorial justice, 258. Sake and soke in the Norman age, 259. The Confessor’s writs, 259. Cnut’s writs, 260. Cnut’s law, 261. The book and the writ, 261. Diplomatics, 262. The Anglo-Saxon writ, 264. Sake and soke appear when writs appear, 265. Traditional evidence of sake and soke, 267. Altitonantis, 268. Criticism of the earlier books, 269. The clause of immunity, 270. Dissection of the words of immunity, 272. The trinoda necessitas, 273. The ángild, 274. The right to wites and the right to a court, 275. The Taunton book, 276. The immunists and the wite, 277. Justice and jurisdiction, 277. The Frankish immunity, 278. Seignorial and ecclesiastical jurisdiction, 279. Criminal justice of the church, 281. Antiquity of seignorial courts, 282. Justice, vassalage and tenure, 283. The lord and the accused vassal, 284. The state, the lord and the vassal, 285. The landríca as immunist, 286. The immunist’s rights over free men, 288. Sub-delegation of justiciary rights, 289. Number of the immunists, 289. Note: The Ángild Clause, 290. |

|

| § 4. Book-land and Loan-land, pp. 293–318. | |

|

The book and the gift, 293. Book-land and service, 294. Military service, 295. Escheat of book-land, 295. Alienation of book-land, 297. The heriot and the testament, 298. The gift and the loan, 299. The precarium, 300. The English land-loan, 301. Loans of church land to the great, 302. The consideration for the loan, 303. St. Oswald’s loans, 303. Oswald’s letter to Edgar, 304. Feudalism in Oswald’s law, 307. Oswald’s riding-men, 308. Heritable loans, 309. Wardship and marriage, 310. Seignorial jurisdiction, 310. Oswald’s law and England at large, 311. Inferences from Oswald’s loans, 312. Economic position of Oswald’s tenants, 312. Loan-land and book-land, 313. Book-land in the dooms, 314. Royal and other books, 315. The gift and the loan, 317. Dependent tenure, 317. |

|

| § 5. The Growth of Seignorial Power, pp. 318–340. | |

|

Subjection of free men, 318. The royal grantee and the land, 318. Provender rents and the manorial economy, 319. The church and the peasants, 320. Growth of the manorial system, 321. Church-scot and tithes, 321. Jurisdictional rights of the lord, 322. The lord and the man’s taxes, 323. Depression of the free ceorl, 324. The slaves, 325. Growth of manors from below, 325. Theories which connect the manor with the Roman villa, 326. The Rectitudines, 327. Discussion of the Rectitudines, 328. The Tidenham case, 329. The Stoke case, 330. Inferences from these cases, 332. The villa and the vicus, 333. Manors in the land-books, 334. The mansus and the manens, 335. The hide, 336. The strip-holding and the villa, 337. The lord and the strips, 338. The ceorl and the slave, 339. The condition of the Danelaw, 339. |

|

| § 6. The Village Community, pp. 340–356. | |

|

Free villages, 340. Ownership by communities and ownership by individuals, 341. Co-ownership and ownership by corporations, 341. Ownership and governmental power, 342. Ownership and subordinate governmental power, 343. Evolution of sovereignty and ownership, 343. Communal ownership as a stage, 344. The theory of normal stages, 345. Was land owned by village communities? 346. Meadows, pastures and woods, 348. The bond between neighbours, 349. Feebleness of village communalism, 349. Absence of organization, 350. The German village on conquered soil, 351. Development of kingly power, 351. The free village in England, 352. The village meeting, 353. What might have become of the free village, 353. Mark communities, 354. Intercommoning between vills, 355. Last words, 356. |

|

| ESSAY III. | |

| The Hide. | |

|

What was the hide? 357. Importance of the question, 357. Hide and manse in Bede, 358. Hide and manse in the land-books, 358. The large hide and the manorial arrangement, 360. Our course, 361. |

|

| § 1. Measures and Fields, pp. 362–399. | |

|

Permanence and change in agrarian history, 362. Rapidity of change in old times, 363. Devastation of villages, 363. Village colonies, 365. Change of field systems, 365. Differences between different shires, 366. New and old villages, 367. History of land measures, 368. Growth of uniform measures, 369. Superficial measure, 370. The ancient elements of land measure, 372. The German acre, 373. English acres, 373. Small and large acres, 374. Anglo-Saxon rods and acres, 375. Customary acres and forest acres, 376. The acre and the day’s work, 377. The real acres in the fields, 379. The culturae or shots, 379. Delimitation of shots, 380. Real and ideal acres, 381. Irregular length of acres, 383. The seliones or beds, 383. Acres divided lengthwise, 384. The virgate, 385. Yard and yard-land, 385. The virgate a fraction of the hide, 385. The yard-land in laws and charters, 386. The hide as a measure, 387. The hide as a measure of arable, 388. The hide of 120 acres, 389. Real and fiscal hides, 389. Causes of divergence of fiscal from real hides, 390. Effects of the divergence, 392. Acreage of the hide in later days, 393. The carucate and bovate, 395. The ox-gang, 396. The fiscal carucate, 396. Acreage tilled by a plough, 397. Walter of Henley’s programme of ploughing, 398. |

|

| § 2. Domesday Statistics, pp. 399–490. | |

| Statistical Tables, 400–403. | |

|

Domesday’s three statements, 399. Northern formulas, 404. Southern formulas, 405. Kentish formulas, 406. Relation between the three statements, 406. Introduction of statistics, 407. Explanation of statistics, 407. Acreage, 407. Population, 408. Danegeld, 408. Hides, carucates, sulungs, 408. Reduced hidage, 410. The teamlands, 410. The teams, 411. The values, 411. The table of ratios, 411. Imperfection of statistics, 412. Constancy of ratios, 413. The team, 413. Variability of the caruca, 414. Constancy of the caruca, 414. The villein’s teams, 415. The villein’s oxen, 416. Light and heavy ploughs, 417. The team of Domesday and other documents, 417. The teamland, 418. Fractional parts of the teamland, 418. Land for oxen and wood for swine, 419. The teamland no areal unit, 419. The teamlands of Great and the teams of Little Domesday, 420. The Leicestershire formulas, 420. Origin of the inquiry touching the teamlands, 421. Modification of the inquiry, 423. The potential teams, 423. Normal relation between teams and teamlands, 424. The land of deficient teams, 425. Actual and potential teamlands, 426. The land of excessive teams, 427. Digression to East Anglia, 429. The teamland no areal measure, 431. Eyton’s theory, 431. Domesday’s lineal measure, 432. Measured teamlands, 433. Amount of arable in England, 435. Decrease of arable, 436. The food problem, 436. What was the population? 436. What was the field-system? 437. What was the acre’s yield? 437. Consumption of beer, 438. The Englishman’s diet, 440. Is the arable superabundant? 441. Amount of pasturage, 441. Area of the villages, 443. Produce and value, 444. Varying size of acres, 445. The teamland in Cambridgeshire, 445. The hides of Domesday, 446. Relation between hides and teamlands, 447. Unhidated estates, 448. Beneficial hidation, 448. Effect of privilege, 449. Divergence of hide from teamland, 450. Partition of the geld, 451. Distribution of hides among counties and hundreds, 451. The hidage of Worcestershire, 451. The County Hidage, 455. Its date, 456. The Northamptonshire Geld Roll, 457. Credibility of The County Hidage, 458. Reductions of hidage, 458. The county quotas, 459. The hundred and the hundred hides, 459. Comparison of Domesday hidage with Pipe Rolls, 460. Under-rated and over-rated counties, 461. Hidage and value, 462. One pound, one hide, 465. Equivalence of pound and hide, 465. Cases of under-taxation, 466. Kent, 466. Devon and Cornwall, 467. Cases of over-taxation, 468. Leicestershire, 468. Yorkshire, 469. Equity and hidage, 470. Distribution of hides and of teamlands, 471. Area and value as elements of geldability, 472. The equitable teamland, 473. Artificial valets, 473. The new assessments of Henry II., 473. Acreage of the fiscal hide, 475. Equation between hide and acres, 475. The hide of 120 acres, 476. Evidence from Cambridgeshire, 476. Evidence from the Isle of Ely, 476. Evidence from Middlesex, 477. Meaning of the Middlesex entries, 478. Evidence in the Geld Inquests, 478. Result of the evidence, 480. Evidence from Essex, 480. Acreage of the fiscal carucate, 483. Acreage of the fiscal sulung, 484. Kemble’s theory, 485. The ploughland and the plough, 486. The Yorkshire carucates, 487. Relation between teamlands and fiscal carucates, 487. The fiscal hide of 120 acres, 489. Antiquity of the large hide, 489. |

|

| § 3. Beyond Domesday, pp, 490–520. | |

|

The hide beyond Domesday, 490. Arguments in favour of small hides, 490. Continuity of the hide in the land-books, 491. Examples from charters of Chertsey, 492. Examples from charters of Malmesbury, 492. Permanence of the hidation, 493. Gifts of villages, 494. Gifts of manses in villages, 495. The largest gifts, 496. The Winchester estate at Chilcombe, 496. The Winchester estates at Downton and Taunton, 498. Kemble and the Taunton estate, 499. Difficulty of identifying parcels, 500. The numerous hides in ancient documents, 501. The Burghal Hidage, 502. The Tribal Hidage, 506. Bede’s hidage, 508. Bede and the land-books, 509. Gradual reduction of hidage, 510. Over-estimates of hidage, 510. Size of Bede’s hide, 511. Evidence from Iona, 512. Evidence from Selsey, 513. Conclusion in favour of the large hide, 515. Continental analogies, 515. The German Hufe, 515. The Königshufe, 516. The large hide on the continent, 517. The large hide not too large, 518. The large hide and the manor, 519. Last words, 520. |

p. 347, note 794. Instances of the periodic reallotment of the whole land of a vill, exclusive of houses and crofts, seem to have been not unknown in the north of England. Here the reallotment is found in connexion with a husbandry which knows no permanent severance of the arable from the grass-land, but from time to time ploughs up a tract and after a while allows it to become grass-land once more. See F. W. Dendy, The Ancient Farms of Northumberland, Archaeologia Aeliana, Vol. xvi. I have to thank Mr Edward Bateson for a reference to this paper.

Domesday Book and its satellites.

At midwinter in the year 1085 William the Conqueror wore his crown at Gloucester and there he had deep speech with his wise men. The outcome of that speech was the mission throughout all England of ‘barons,’ ‘legates’ or ‘justices’ charged with the duty of collecting from the verdicts of the shires, the hundreds and the vills a descriptio of his new realm. The outcome of that mission was the descriptio preserved for us in two manuscript volumes, which within a century after their making had already acquired the name of Domesday Book. The second of those volumes, sometimes known as Little Domesday, deals with but three counties, namely Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk, while the first volume comprehends the rest of England. Along with these we must place certain other documents that are closely connected with the grand inquest. We have in the so-called Inquisitio Comitatus Cantabrigiae, a copy, an imperfect copy, of the verdicts delivered by the Cambridgeshire jurors, and this, as we shall hereafter see, is a document of the highest value, even though in some details it is not always very trustworthy[2]. We have in the so-called Inquisitio Eliensis an account of the estates of the Abbey of Ely in Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and other counties, an account which has as its ultimate source the verdicts of the juries and which contains some particulars which were omitted from Domesday Book[3]. We have in the so-called Exon Domesday an account of Cornwall and Devonshire and of certain lands in Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire; this also seems to have been constructed directly or indirectly out of the verdicts delivered in those counties, and it contains certain particulars about the amount of stock upon the various estates which are omitted from what, for distinction’s sake, is sometimes called the Exchequer Domesday[4]. At the beginning of this Exon Domesday we have certain accounts relating to the payment of a great geld, seemingly the geld of six shillings on the hide that William levied in the winter of 1083–4, two years before the deep speech at Gloucester[5]. Lastly, in the Northamptonshire Geld Roll[6] we have some precious information about fiscal affairs as they stood some few years before the survey[7].

Domesday and legal history.

Such in brief are the documents out of which, with some small help from the Anglo-Saxon dooms and land-books, from the charters of Norman kings and from the so-called Leges of the Conqueror, the Confessor and Henry I., some future historian may be able to reconstruct the land-law which obtained in the conquered England of 1086, and (for our records frequently speak of the tempus Regis Edwardi) the unconquered England of 1065. The reflection that but for the deep speech at Gloucester, but for the lucky survival of two or three manuscripts, he would have known next to nothing of that law, will make him modest and cautious. At the present moment, though much has been done towards forcing Domesday Book to yield its meaning, some of the legal problems that are raised by it, especially those which concern the time of King Edward, have hardly been stated, much less solved. It is with some hope of stating, with little hope of solving them that we begin this essay. If only we can ask the right questions we shall have done something for a good end. If English history is to be understood, the law of Domesday Book must be mastered. We have here an absolutely unique account of feudalism in two different stages of its growth, the more trustworthy, though the more puzzling, because it gives us particulars and not generalities.

Puzzling enough it certainly is, and this for many reasons. Our task may be the easier if we state some of those reasons at the outset.

Domesday a geld book.

To say that Domesday Book is no collection of laws or treatise on law would be needless. Very seldom does it state any rule in general terms, and when it does so we shall usually find cause for believing that this rule is itself an exception, a local custom, a provincial privilege. Thus, if we are to come by general rules, we must obtain them inductively by a comparison of many thousand particular instances. But further, Domesday Book is no register of title, no register of all those rights and facts which constitute the system of land-holdership. One great purpose seems to mould both its form and its substance; it is a geld-book.

Danegeld.

When Duke William became king of the English, he found (so he might well think) among the most valuable of his newly acquired regalia, a right to levy a land-tax under the name of geld or danegeld. A detailed history of that tax cannot be written. It is under the year 991 that our English chronicle first mentions a tribute paid to the Danes[8]; £10,000 was then paid to them. In 994 the yet larger sum of £16,000[9] was levied. In 1002 the tribute had risen to £24,000[10], in 1007 to £30,000[11], in 1009 East Kent paid £3,000[12]; £21,000 was raised in 1014[13]; in 1018 Cnut when newly crowned took £72,000 besides £11,000 paid by the Londoners[14]; in 1040 Harthacnut took £21,099 besides a sum of £11,048 that was paid for thirty-two ships[15]. With a Dane upon the throne, this tribute seems to have become an occasional war-tax. How often it was levied we cannot tell; but that it was levied more than once by the Confessor is not doubtful[16]. We are told that he abolished it in or about the year 1051, some eight or nine years after his accession, some fifteen before his death. No sooner was William crowned than ‘he laid on men a geld exceeding stiff.’ In the next year ‘he set a mickle geld’ on the people. In the winter of 1083–4 he raised a geld of 72 pence (6 Norman shillings) upon the hide. That this tax was enormously heavy is plain. Taking one case with another, it would seem that the hide was frequently supposed to be worth about £1 a year and there were many hides in England that were worth far less. But grievous as was the tax which immediately preceded the making of the survey, we are not entitled to infer that it was of unprecedented severity. It brought William but £415 or thereabouts from Dorset and £510 or thereabouts from Somerset[17]. Worcestershire was deemed to contain about 1200 hides and therefore, even if none of its hides had been exempted, it would have contributed but £360. If the huge sums mentioned by the chronicler had really been exacted, and that too within the memory of men who were yet living, William might well regard the right to levy a geld as the most precious jewel in his English crown. To secure a due and punctual payment of it was worth a gigantic effort, a survey such as had never been made and a record such as had never been penned since the grandest days of the old Roman Empire. But further, the assessment of the geld sadly needed reform. Owing to one cause and another, owing to privileges and immunities that had been capriciously granted, owing also, so we think, to a radically vicious method of computing the geldable areas of counties and hundreds, the old assessment was full of anomalies and iniquities. Some estates were over-rated, others were scandalously under-rated. That William intended to correct the old assessment, or rather to sweep it away and put a new assessment in its stead, seems highly probable, though it has not been proved that either he or his sons accomplished this feat[18]. For this purpose, however, materials were to be collected which would enable the royal officers to decide what changes were necessary in order that all England might be taxed in accordance with a just and uniform plan. Concerning each estate they were to know the number of geldable units (‘hides’ or ‘carucates’) for which it had answered in King Edward’s day, they were to know the number of plough oxen that there were upon it, they were to know its true annual value, they were to know whether that value had been rising or falling during the past twenty years. Domesday Book has well been called a rate book, and the task of spelling out a land law from the particulars that it states is not unlike the task that would lie before any one who endeavoured to construct our modern law of real property out of rate books, income tax returns and similar materials. All the lands, all the land-holders of England may be brought before us, but we are told only of such facts, such rights, such legal relationships as bear on the actual or potential payment of geld. True, that some minor purposes may be achieved by the king’s commissioners, though the quest for geld is their one main object. About the rents and renders due from his own demesne manors the king may thus obtain some valuable information. Also he may learn, as it were by the way, whether any of his barons or other men have presumed to occupy, to ‘invade,’ lands which he has reserved for himself. Again, if several persons are in dispute about a tract of ground, the contest may be appeased by the testimony of shire and hundred, or may be reserved for the king’s audience; at any rate the existence of an outstanding claim may be recorded by the royal commissioners. Here and there the peculiar customs of a shire or a borough will be stated, and incidentally the services that certain tenants owe to their lords may be noticed. But all this is done sporadically and unsystematically. Our record is no register of title, it is no feodary, it is no custumal, it is no rent roll; it is a tax book, a geld book.

The survey and the geld system.

We say this, not by way of vain complaint against its meagreness, but because in our belief a care for geld and for all that concerns the assessment and payment of geld colours far more deeply than commentators have usually supposed the information that is given to us about other matters. We should not be surprised if definitions and distinctions which at first sight have little enough to do with fiscal arrangements, for example the definition of a manor and the distinction between a villein and a ‘free man,’ involved references to the apportionment and the levy of the land-tax. Often enough it happens that legal ideas of a very general kind are defined by fiscal rules; for example, our modern English idea of ‘occupation’ has become so much part and parcel of a system of assessment that lawyers are always ready to argue that a certain man must be an ‘occupier’ because such men as he are rated to the relief of the poor. It seems then a fair supposition that any line that Domesday Book draws systematically and sharply, whether it be between various classes of men or between various classes of tenements, is somehow or another connected with the main theme of that book—geldability, actual or potential.

Weight of the danegeld.

Since we have mentioned the stories told by the chronicler about the tribute paid to the Danes, we may make a comment upon them which will become of importance hereafter. Those stories look true, and they seem to be accepted by modern historians. Had we been told just once that some large number of pounds, for example £60,000, was levied, or had the same round sum been repeated in year after year, we might well have said that such figures deserved no attention, and that by £60,000 our annalist merely meant a big sum of money. But, as will have been seen, he varies his figures from year to year and is not always content with a round number; he speaks of £21,099 and of £11,048[19]. We can hardly therefore treat his statements as mere loose talk and are reluctantly driven to suppose that they are true or near the truth. If this be so, then, unless some discovery has yet to be made in the history of money, no word but ‘appalling’ will adequately describe the taxation of which he speaks. We know pretty accurately the amount of money that became due when Henry I. or Henry II. imposed a danegeld of two shillings on the hide. The following table constructed from the pipe rolls will show the sum charged against each county. We arrange the shires in the order of their indebtedness, for a few of the many caprices of the allotment will thus be visible, and our table may be of use to us in other contexts[20].

Approximate Charge of a Danegeld of Two Shillings on the Hide in the Middle of the Twelfth Century.

| £ | £ | ||

| Wiltshire | 389 | Cambridge | 114 |

| Norfolk | 330 | Derby and Nottingham | 110 |

| Somerset | 278 | Hertford | 110 |

| Lincoln | 266 | Bedford | 110 |

| Dorset | 248 | Kent | 105 |

| Oxford | 242 | Devon | 104 |

| Essex | 236 | Worcester | 101 |

| Suffolk | 235 | Leicester | 100 |

| Sussex | 210 | Hereford | 94 |

| Bucks | 205 | Middlesex | 100 |

| Berks | 202 | Huntingdon | 71 |

| Gloucester | 190 | Stafford | 44 |

| S. Hants | 180 | Cornwall | 44 |

| Surrey | 177 | Rutland | 44 |

| York | 160 | Northumberland | 44 |

| Warwick | 129 | Cheshire[21] | 0 |

| N. Hants | 120 | ||

| Salop | 118 | Total | 5198 |

The geld of old times.

Now be it understood that these figures do not show the amount of money that Henry I. and Henry II. could obtain by a danegeld. They had to take much less. When it was last levied, the tax was not bringing in £3500, so many were the churches and great folk who had obtained temporary or permanent exemptions from it. We will cite Leicestershire for example. The total of the geld charged upon it was almost exactly or quite exactly £100. On the second roll of Henry II.’s reign we find that £25. 7s. 6d. have been paid into the treasury, that £22. 8s. 3d. have been ‘pardoned’ to magnates and templars, that £51. 8s. 2d. are written off in respect of waste, and that 16s. 0d. are still due. On the eighth roll the account shows that £62. 12s. 7d. have been paid and that £37. 6s. 9d. have been ‘pardoned.’ No, what our table displays is the amount that would be raised if all exemptions were disregarded and no penny forborne. And now let us turn back to the chronicle and (not to take an extreme example) read of £30,000 being raised. Unless we are prepared to bring against the fathers of English history a charge of repeated, wanton and circumstantial lying, we shall think of the danegeld of Æthelred’s reign and of Cnut’s as of an impost so heavy that it was fully capable of transmuting a whole nation. Therefore the lines that are drawn by the incidence of this tribute will be deep and permanent; but still we must remember that primarily they will be fiscal lines.

Unstable terminology of the survey.

Then again, we ought not to look to Domesday Book for a settled and stable scheme of technical terms. Such a scheme could not be established in a brief twenty years. About one half of the technical terms that meet us, about one half of the terms which, as we think, ought to be precisely defined, are, we may say, English terms. They are ancient English words, or they are words brought hither by the Danes, or they are Latin words which have long been in use in England and have acquired special meanings in relation to English affairs. On the other hand, about half the technical terms are French. Some of them are old Latin words which have acquired special meanings in France, some are Romance words newly coined in France, some are Teutonic words which tell of the Frankish conquest of Gaul. In the one great class we place scira, hundredum, wapentac, hida, berewica, inland, haga, soka, saka, geldum, gablum, scotum, heregeat, gersuma, thegnus, sochemannus, burus, coscet; in the other comitatus, carucata, virgata, bovata, arpentum, manerium, feudum, alodium, homagium, relevium, baro, vicecomes, vavassor, villanus, bordarius, colibertus, hospes. It is not in twenty years that a settled and stable scheme can be formed out of such elements as these. And often enough it is very difficult for us to give just the right meaning to some simple Latin word. If we translate miles by soldier or warrior, this may be too indefinite; if we translate it by knight, this may be too definite, and yet leave open the question whether we are comparing the miles of 1086 with the cniht of unconquered England or with the knight of the thirteenth century. If we render vicecomes by sheriff we are making our sheriff too little of a vicomte. When comes is before us we have to choose between giving Britanny an earl, giving Chester a count, or offending some of our comites by invidious distinctions. Time will show what these words shall mean. Some will perish in the struggle for existence; others have long and adventurous careers before them. At present two sets of terms are rudely intermixed; the time when they will grow into an organic whole is but beginning.

Legal ideas of cent. xi.

To this we must add that, unless we have mistaken the general drift of legal history, the law implied in Domesday Book ought to be for us very difficult law, far more difficult than the law of the thirteenth century, for the thirteenth century is nearer to us than is the eleventh. The grown man will find it easier to think the thoughts of the school-boy than to think the thoughts of the baby. And yet the doctrine that our remote forefathers being simple folk had simple law dies hard. Too often we allow ourselves to suppose that, could we but get back to the beginning, we should find that all was intelligible and should then be able to watch the process whereby simple ideas were smothered under subtleties and technicalities. But it is not so. Simplicity is the outcome of technical subtlety; it is the goal not the starting point. As we go backwards the familiar outlines become blurred; the ideas become fluid, and instead of the simple we find the indefinite. But difficult though our task may be, we must turn to it.

The geographical basis.

England was already mapped out into counties, hundreds or wapentakes and vills. Trithings or ridings appear in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, lathes in Kent, rapes in Sussex, while leets appear, at least sporadically, in Norfolk[22]. These provincial peculiarities we must pass by, nor will we pause to comment at any length on the changes in the boundaries of counties and of hundreds that have taken place since the date of the survey. Though these changes have been many and some few of them have been large[23], we may still say that as a general rule the political geography of England was already stereotyped. And we see that already there are many curious anomalies, ‘detached portions’ of counties, discrete hundreds, places that are extra-hundredal[24], places that for one purpose are in one county and for another purpose in another county[25]. We see also that proprietary rights have already been making sport of arrangements which in our eyes should be fixed by public law. Earls, sheriffs and others have enjoyed a marvellous power of taking a tract of land out of one district and placing it, or ‘making it lie’ in another district[26]. Land is constantly spoken of as though it were the most portable of things; it can easily be taken from one vill or hundred and be added to or placed in or caused to lie in another vill or hundred. This ‘notional movability’ of land, if we may use such a term, will become of importance to us when we are studying the formation of manors.

The vill as the geographical unit.

For the present, however, we are concerned with the general truth that England is divided into counties, hundreds or wapentakes and vills. This is the geographical basis of the survey. That basis, however, is hidden from us by the form of our record. The plan adopted by those who fashioned Domesday Book out of the returns provided for them by the king’s commissioners is a curious, compromising plan. We may say that in part it is geographical, while in part it is feudal or proprietary. It takes each county separately and thus far it is geographical; but within the boundaries of each county it arranges the lands under the names of the tenants in chief who hold them. Thus all the lands in Cambridgeshire of which Count Alan is tenant in chief are brought together, no matter that they lie scattered about in various hundreds. Therefore it is necessary for us to understand that the original returns reported by the surveyors did not reach the royal treasury in this form. At least as regards the county of Cambridge, we can be certain of this. The hundreds were taken one by one; they were taken in a geographical order, and not until the justices had learned all that was to be known of Staplehow hundred did they call upon the jurors of Cheveley hundred for their verdict. That such was their procedure we might have guessed even had we not been fortunate enough to have a copy of the Cambridgeshire verdicts; for, though the commissioners seem to have held but one moot for each shire, still it is plain that each hundred was represented by a separate set of jurors[27]. But from these Cambridgeshire verdicts we learn what otherwise we could hardly have known. Within each hundred the survey was made by vills[28]. If we suppose the commissioners charging the jurors we must represent them as saying, not ‘Tell us what tenants in chief have lands in your hundred and how much each of them holds,’ but ‘Tell us about each vill in your hundred, who holds land in it.’ Thus, for example, the men of the Armingford hundred are called up. They make a separate report about each vill in it. They begin by stating that the vill is rated at a certain number of hides and then they proceed to distribute those hides among the tenants in chief. Thus, for example, they say that Abington was rated at 5 hides, and that those 5 hides are distributed thus[29]:

| hides | virgates | |

| Hugh Pincerna holds of the bishop of Winchester | 21⁄2 | 1⁄2 |

| The king | 1⁄2 | |

| Ralph and Robert hold of Hardouin de Eschalers | 1 | 11⁄2 |

| Earl Roger | 1 | |

| Picot the sheriff | 1⁄2 | |

| Alwin Hamelecoc the bedel holds of the king | 1⁄2 | |

| 5 | 0 |

Now in Domesday Book we must look to several different pages to get this information about the vill of Abington,—dash;to one page for Earl Roger’s land, to another page for Picot’s land, and we may easily miss the important fact that this vill of Abington has been rated as a whole at the neat, round figure of 5 hides. And then we see that the whole hundred of Armingford has been rated at the neat, round figure of 100 hides, and has consisted of six vills rated at 10 hides apiece and eight vills rated at 5 hides apiece[30]. Thus we are brought to look upon the vill as a unit in a system of assessment. All this is concealed from us by the form of Domesday Book.

Stability of the vill.

When that book mentions the name of a place, when it says that Roger holds Sutton or that Ralph holds three hides in Norton, we regard that name as the name of a vill; it may or may not be also the name of a manor. Speaking very generally we may say that the place so named will in after times be known as a vill and in our own day will be a civil parish. No doubt in some parts of the country new vills have been created since the Conqueror’s time. Some names that occur in our record fail to obtain a permanent place on the roll of English vills, become the names of hamlets or disappear altogether; on the other hand, new names come to the front. Of course we dare not say dogmatically that all the names mentioned in Domesday Book were the names of vills; very possibly (if this distinction was already known) some of them were the names of hamlets; nor, again, do we imply that the villa of 1086 had much organization; but a place that is mentioned in Domesday Book will probably be recognized as a vill in the thirteenth, a civil parish in the nineteenth century. Let us take Cambridgeshire by way of example. Excluding the Isle of Ely, we find that the political geography of the Conqueror’s reign has endured until our own time. The boundaries of the hundreds lie almost where they lay, the number of vills has hardly been increased or diminished. The chief changes amount to this:—A small tract on the east side of the county containing Exning and Bellingham has been made over to Suffolk; four other names contained in Domesday no longer stand for parishes, while the names of five of our modern parishes—one of them is the significant name of Newton—are not found there[31]. But about a hundred and ten vills that were vills in 1086 are vills or civil parishes at the present day, and in all probability they then had approximately the same boundaries that they have now.

Omission of vills.

This may be a somewhat too favourable example of permanence and continuity. Of all counties Cambridgeshire is the one whose ancient geography can be the most easily examined; but wherever we have looked we have come to the conclusion that the distribution of England into vills is in the main as old as the Norman conquest[32]. Two causes of difficulty may be noticed, for they are of some interest. Owing to what we have called the ‘notional movability’ of land, we never can be quite sure that when certain hides or acres are said to be in or lie in a certain place they are really and physically in that place. They are really in one village, but they are spoken of as belonging to another village, because their occupants pay their geld or do their services in the latter. Manorial and fiscal geography interferes with physical and villar geography. We have lately seen how land rated at five hides was comprised, as a matter of fact, in the vill of Abington; but of those five hides, one virgate ‘lay in’ Shingay, a half-hide ‘lay in’ Litlington while a half-virgate ‘lay and had always lain’ in Morden[33]. This, if we mistake not, leads in some cases to an omission of the names of small vills. A great lord has a compact estate, perhaps the whole of one of the small southern hundreds. He treats it as a whole, and all the land that he has there will be ascribed to some considerable village in which he has his hall. We should be rash in supposing that there were no other villages on this land. For example, in Surrey there is now-a-days a hundred called Farnham which comprises the parish of Farnham, the parish of Frensham and some other villages. If we mistake not, all that Domesday Book has to say of the whole of this territory is that the Bishop of Winchester holds Farnham, that it has been rated at 60 hides, that it has been worth the large sum of £65 a year and that there are so many tenants upon it[34]. We certainly must not draw the inference that there was but one vill in this tract. If the bishop is tenant in chief of the whole hundred and has become responsible for all the geld that is levied therefrom, there is no great reason why the surveyors should trouble themselves about the vills. Thus the simple Episcopus tenet Ferneham may dispose of some 25,000 acres of land. So the same bishop has an estate at Chilcombe in Hampshire; but clearly the name Ciltecumbe covers a wide territory for there are no less than nine churches upon it[35]. We never can be very certain about the boundaries of these large and compact estates.

Fission of vills.

A second cause of difficulty lies in the fact that in comparatively modern times, from the twelfth century onwards, two or three contiguous villages will often bear the same name and be distinguished only by what we may call their surnames—thus Guilden Morden and Steeple Morden, Stratfield Saye, Stratfield Turgis, Stratfield Mortimer, Tolleshunt Knights, Tolleshunt Major, Tolleshunt Darcy. Such cases are common; in some districts they are hardly exceptional. Doubtless they point to a time when a single village by some process of colonization or subdivision become two villages. Now Domesday Book seldom enables us to say for certain whether the change has already taken place. In a few instances it marks off the little village from the great village of the same name[36]. In some other instances it will speak, for example, of Mordune and Mordune Alia, of Emingeforde and Emingeforde Alia, or the like, thus showing both that the change has taken place, and also that it is so recent that it is recognized only by very clumsy terms. In Cambridgeshire, since we have the original verdicts, we can see that the two Mordens are already distinct; the one is rated at ten hides, the other at five[37]. On the other hand, we can see that our Great and Little Shelford are rated as one vill of twenty hides[38], our Castle Camps and Shudy Camps as one vill of five hides[39]. Elsewhere we are left to guess whether the fission is complete, and the surnames that many of our vills ultimately acquire, the names of families which rose to greatness in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, will often suggest that the surveyors saw but one vill where we see two[40]. However, the broad truth stands out that England was divided into vills and that in general the vill of Domesday Book is still a vill in after days[41].

The nucleated village and the vill of scattered steads.

The ‘vill’ or ‘town’ of the later middle ages was, like the ‘civil parish’ of our own day, a tract of land with some houses on it, and this tract was a unit in the national system of police and finance[42], But we are not entitled to make for ourselves any one typical picture of the English vill. We are learning from the ordnance map (that marvellous palimpsest, which under Dr Meitzen’s guidance we are beginning to decipher) that in all probability we must keep at least two types before our minds. On the one hand, there is what we might call the true village or the nucleated village. In the purest form of this type there is one and only one cluster of houses. It is a fairly large cluster; it stands in the midst of its fields, of its territory, and until lately a considerable part of its territory will probably have consisted of spacious ‘common fields.’ In a country in which there are villages of this type the parish boundaries seem almost to draw themselves[43]. On the other hand, we may easily find a country in which there are few villages of this character. The houses which lie within the boundary of the parish are scattered about in small clusters; here two or three, there three or four. These clusters often have names of their own, and it seems a mere chance that the name borne by one of them should be also the name of the whole parish or vill[44]. We see no traces of very large fields. On the face of the map there is no reason why a particular group of cottages should be reckoned to belong to this parish rather than to the next. As our eyes grow accustomed to the work we may arrive at some extremely important conclusions such as those which Meitzen has suggested. The outlines of our nucleated villages may have been drawn for us by Germanic settlers, whereas in the land of hamlets and scattered steads old Celtic arrangements may never have been thoroughly effaced. Towards theories of this kind we are slowly winning our way. In the meantime let us remember that a villa of Domesday Book may correspond to one of at least two very different models or may be intermediate between various types. It may be a fairly large and agrarianly organic unit, or it may be a group of small agrarian units which are being held together in one whole merely by an external force, by police law and fiscal law[45].

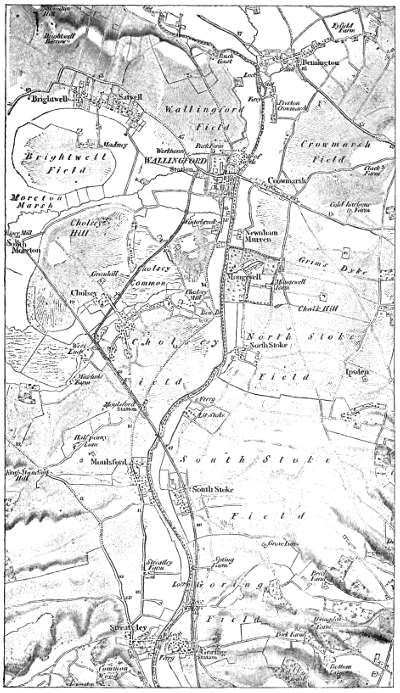

Illustrations by maps.

Two little fragments of ‘the original one inch ordnance map’ will be more eloquent than would be many paragraphs of written discourse. The one pictures a district on the border between Oxfordshire and Berkshire cut by the Thames and the main line of the Great Western Railway; the other a district on the border between Devon and Somerset, north of Collumpton and south of Wiveliscombe. Neither is an extreme example. True villages we may easily find. Cambridgeshire, for instance, would have afforded some beautiful specimens, for many of the ‘open fields’ were still open when the ordnance map of that county was made. But throughout large tracts of England, even though there has been an ‘inclosure’ and there are no longer any open fields, our map often shows a land of villages. When it does so and the district that it portrays is a purely agricultural district, we may generally assume without going far wrong that the villages are ancient, for during at least the last three centuries the predominant current in our agrarian history has set against the formation of villages and towards the distribution of scattered homesteads. To find the purest specimens of a land of hamlets we ought to go to Wales or to Cornwall or to other parts of ‘the Celtic fringe’; very fair examples might be found throughout the west of England. Also we may perhaps find hamlets rather than villages wherever there have been within the historic period large tracts of forest land. Very often, again, the parish or township looks on our map like a hybrid. We seem to see a village with satellitic hamlets. Much more remains to be done before we shall be able to construe the testimony of our fields and walls and hedges, but at least two types of vill must be in our eyes when we are reading Domesday Book[46].

[Between pp. 16–17]

Size of the vill.

To say that the villa of Domesday Book is in general the vill of the thirteenth century and the civil parish of the nineteenth is to say that the areal extent of the villa varied widely from case to case. More important is it for us to observe that the number of inhabitants of the villa varied widely from case to case. The error into which we are most likely to fall will be that of making our vill too populous. Some vills, especially some royal vills, are populous enough; a few contain a hundred households; but the average township is certainly much smaller than this[47]. Before we give any figures, it should first be observed that Domesday Book never enables us to count heads. It states the number of the tenants of various classes, sochemanni, villani, bordarii, and the like, and leaves us to suppose that each of these persons is, or may be, the head of a household. It also states how many servi there are. Whether we ought to suppose that only the heads of servile households are reckoned, or whether we ought to think of the servi as having no households but as living within the lord’s gates and being enumerated, men, women and able-bodied children, by the head—this is a difficult question. Still we may reach some results which will enable us to compare township with township. By way of fair sample we may take the Armingford hundred of Cambridgeshire, and all persons who are above the rank of servi we will include under the term ‘the non-servile population[48].’

Armingford Hundred.

Here in fourteen vills we have an average of thirty-two non-servile households for every vill. Now even in our own day a parish with thirty-two houses, though small, is not extremely small. But we should form a wrong picture of the England of the eleventh century if we filled all parts of it with such vills as these. We will take at random fourteen vills in Staffordshire held by Earl Roger[49].

| Non-servile population |

Servi | Total | |

| Claverlege | 4 | 0 | 45 |

| Nordlege | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Alvidelege | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| Halas | 40 | 2 | 42 |

| Chenistelei | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Otne | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Nortberie | 20 | 1 | 21 |

| Erlide | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Gaitone | 16 | 0 | 16 |

| Cressvale | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Dodintone | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Modreshale | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Almentone | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Metford | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 200 | 7 | 207 |

Here for fourteen vills we have an average of but fourteen non-servile households and the servi are so few that we may neglect them. We will next look at a page in the survey of Somersetshire which describes certain vills that have fallen to the lot of the bishop of Coutances[50].

| Non-servile population |

Servi | Total | |

| Winemeresham | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Chetenore | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Widicumbe | 21 | 6 | 27 |

| Harpetrev | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| Hotune | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Lilebere | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Wintreth | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Aisecome | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| Clutone | 22 | 1 | 23 |

| Temesbare | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Nortone | 16 | 3 | 19 |

| Cliveham | 15 | 1 | 16 |

| Ferenberge | 13 | 6 | 19 |

| Cliveware | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 153 | 36 | 189 |

Here we have on the average but eleven non-servile households for each village, and even if we suppose each servus to represent a household, we have not fourteen households. Yet smaller vills will be found in Devonshire, many vills in which the total number of the persons mentioned does not exceed ten and near half of these are servi. In Cornwall the townships, if townships we ought to call them, are yet smaller; often we can attribute no more than five or six families to the vill even if we include the servi.

Population of the vills.

Contrast between east and west.

Unless our calculations mislead us, the density of the population in the average vill of a given county varies somewhat directly with the density of the population in that county; at all events we can not say that where vills are populous, vills will be few. As regards this matter no precise results are attainable; our document is full of snares for arithmeticians. Still if for a moment we have recourse to the crude method of dividing the number of acres comprised in a modern county by the number of the persons who are mentioned in the survey of that county, the outcome of our calculation will be remarkable and will point to some broad truth[51]. For Suffolk the quotient is 46 or thereabouts; for Norfolk but little larger[52]; for Essex 61, for Lincoln 67; for Bedford, Berkshire, Northampton, Leicester, Middlesex, Oxford, Kent and Somerset it lies between 70 and 80, for Buckingham, Warwick, Sussex, Wiltshire and Dorset it lies between 80 and 90; Devon, Gloucester, Worcester, Hereford are thinly peopled, Cornwall, Stafford, Shropshire very thinly. Some particular results that we should thus attain would be delusive. Thus we should say that men were sparse in Cambridgeshire, did we not remember that a large part of our modern Cambridgeshire was then a sheet of water. Permanent physical causes interfere with the operation of the general rule. Thus Surrey, with its wide heaths has, as we might expect, but few men to the square mile. Derbyshire has many vills lying waste; Yorkshire is so much wasted that it can give us no valuable result; and again, Yorkshire and Cheshire were larger than they are now, while Rutland and the adjacent counties had not their present boundaries. For all this however, we come to a very general rule:—the density of the population decreases as we pass from east to west. With this we may connect another rule:—land is much more valuable in the east than it is in the west. This matter is indeed hedged in by many thorny questions; still whatever hypothesis we may adopt as to the mode in which land was valued, one general truth comes out pretty plainly, namely, that, economic arrangements being what they were, it was far better to have a team-land in Essex than to have an equal area of arable land in Devon.

Small vills.

Between eastern and western England there were differences visible to the natural eye. With these were connected unseen and legal differences, partly as causes, partly as effects. But for the moment let us dwell on the fact that many an English vill has very few inhabitants. We are to speak hereafter of village communities. Let us therefore reflect that a community of some eight or ten householders is not likely to be a highly organized entity. This is not all, for these eight or ten householders will often belong to two, three or four different social and economic, if not legal, classes. Some may be sokemen, some villani, bordarii, cotarii, and besides them there will be a few servi. If a vill consists, as in Devonshire often enough it will, of some three villani, some four bordarii and some two servi, the ‘township-moot,’ if such a moot there be, will be a queer little assembly, the manorial court, if such a court there be, will not have much to do. These men can not have many communal affairs; there will be no great scope for dooms or for by-laws; they may well take all their disputes into the hundred court, especially in Devonshire where the hundreds are small. Thus of the visible vill of the eleventh century and its material surroundings we may form a wrong notion. Often enough in the west its common fields (if common fields it had) were not wide fields; the men who had shares therein were few and belonged to various classes. Thus of two villages in Gloucestershire, Brookthorpe and Harescombe, all that we can read is that in Brostrop there were two teams, one villanus, three bordarii, four servi, while in Hersecome there were two teams, two bordarii and five servi[53]. Many a Devonshire township can produce but two or three teams. Often enough our ‘village community’ will be a heterogeneous little group whose main capital consists of some 300 acres of arable land and some 20 beasts of the plough.

Importance of the east.

On the other hand, we must be careful not to omit from our view the rich and thickly populated shires or to imagine or to speak as though we imagined that a general theory of English history can neglect the East of England. If we leave Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk out of account we are to all appearance leaving out of account not much less than a quarter of the whole nation[54]. Let us make three groups of counties: (1) a South-Western group containing Devon, Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire: (2) a Mid-Western group containing the shires of Gloucester, Worcester, Hereford, Salop, Stafford and Warwick: (3) an Eastern group containing Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk. The first of these groups has the largest; the third the smallest acreage. In Domesday Book, however, the figures which state their population seem to be these[55]:—

| South-Western Group: | 49,155 |

| Mid-Western Group: | 33,191 |

| Eastern Group: | 72,883 |

These figures are so emphatic that they may cause us for a moment to doubt their value, and on details we must lay no stress. But we have materials which enable us to check the general effect. In 1297 Edward I. levied a lay subsidy of a ninth[56]. The sums borne by our three groups of counties were these:—

| South-Western Group: | 4,038 |

| Mid-Western Group: | 3,514 |

| Eastern Group: | 7,329 |

There is a curious resemblance between these two sets of figures. Then in 1377 and 1381 returns were made for a poll-tax[57]. The number of polls returned in our three groups were these:—

| 1377 | 1381 | |

| South-Western Group: | 183,842 | 106,086 |

| Mid-Western Group: | 158,245 | 115,679 |

| Eastern Group: | 255,498 | 182,830 |

No doubt all inferences drawn from medieval statistics are exceedingly precarious; but, unless a good many figures have conspired to deceive us, Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk were at the time of the Conquest and for three centuries afterwards vastly richer and more populous than any tract of equal area in the West.

Manorial and non-manorial vills.

Another distinction between the eastern counties and the rest of England is apparent. In many shires we shall find that the name of each vill is mentioned once and no more. This is so because the land of each vill belongs in its entirety to some one tenant in chief. We may go further: we may say, though at present in an untechnical sense, that each vill is a manor. Such is the general rule, though there will be exceptions to it. On the other hand, in the eastern counties this rule will become the exception. For example, of the fourteen vills in the Armingford hundred of Cambridgeshire there is but one of which it is true that the whole of its land is held by a single tenant in chief. In this county it is common to find that three or four Norman lords hold land in the same vill. This seems true not only of Cambridgeshire but also of Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk, Lincoln, Nottingham, Derby, and some parts of Yorkshire. Even in other districts of England the rule that each vill has a single lord is by no means unbroken in the Conqueror’s day and we can see that there were many exceptions to it in the Confessor’s. A careful examination of all England vill by vill would perhaps show that the contrast which we are noting is neither so sharp nor so ancient as at first sight it seems to be: nevertheless it exists.

The distribution of free men and serfs.

A better known contrast there is. The eastern counties are the home of liberty[58]. We may divide the tillers of the soil into five great classes; these in order of dignity and freedom are (1) liberi homines, (2) sochemanni, (3) villani, (4) bordarii, cotarii etc., (5) servi. The two first of these classes are to be found in large numbers only in Norfolk, Suffolk, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Northamptonshire. We shall hereafter see that Cambridgeshire also has been full of sokemen, though since the Conquest they have fallen from their high estate. On the other hand, the number of servi increases pretty steadily as we cross the country from east to west. It reaches its maximum in Cornwall and Gloucestershire; it is very low in Norfolk, Suffolk, Derby, Leicester, Middlesex, Sussex; it descends to zero in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. This descent to zero may fairly warn us that the terms with which we are dealing may not bear precisely the same meaning in all parts of England, or that a small class is apt to be reckoned as forming part of a larger class. But still it is clear enough that some of these terms are used with care and express real and important distinctions.

The classification of men.

Of this we are assured by a document which seems to reproduce the wording of the instructions which defined the duty of at least one party of royal commissioners[59]. We are about to speak of the mode in which the occupants of the soil are classified by Domesday Book, and therefore this document deserves our best attention. It runs thus:—The King’s barons inquired by the oath of the sheriff of the shire and of all the barons and of their Frenchmen and of the whole hundred, the priest, reeve and six villani of every vill, how the mansion (mansio) is called, who held it in the time of King Edward, who holds it now, how many hides, how many plough-teams on the demesne, how many plough-teams of the men, how many villani, how many cotarii, how many servi, how many liberi homines, how many sochemanni, how much wood, how much meadow, how much pasture, how many mills, how many fisheries, how much has been taken away therefrom, how much added thereto, and how much there is now, how much each liber homo and sochemannus had and has:—All this thrice over, to wit as regards the time of King Edward, the time when King William gave it, and the present time, and whether more can be had thence than is had now[60].

Basis of classification.

Five classes of men are mentioned and they are mentioned in an order that is extremely curious:—villani, cotarii, servi, liberi homines, sochemanni. It descends three steps, then it leaps from the very bottom of the scale to the very top and thence it descends one step. A parody of it might speak of the rural population of modern England as consisting of large farmers, small farmers, cottagers, great landlords, small landlords. But a little consideration will convince us that beneath this apparent caprice there lies some legal principle. We shall observe that these five species of tenants are grouped into two genera. The king wants to know how much each liber homo, how much each sochemannus holds; he does not want to know how much each villanus, each cotarius, each servus holds. Connecting this with the main object of the whole survey, we shall probably be brought to the guess that between the sokeman and the villein there is some broad distinction which concerns the king as the recipient of geld. May it not be this:—the villein’s lord is answerable for the geld due from the land that the villein holds, the sokeman’s lord is not answerable, at least he is not answerable as principal debtor for the geld due from the land that the sokeman holds? If this be so, the order in which the five classes of men are mentioned will not seem unnatural. It proceeds outwards from the lord and his mansio. First it mentions the persons seated on land for the geld of which he is responsible, and them it arranges in an ‘order of merit.’ Then it turns to persons who, though in some way or another connected with the lord and his mansio, are themselves tax-payers, and concerning them the commissioners are to inquire how much each of them holds. Of course we can not say that this theory is proved by the statement that lies before us; but it is suggested by that statement and may for a while serve us as a working hypothesis. If this theory be sound, then we have here a distinction of the utmost importance. For one mighty purpose, the purpose that is uppermost in King William’s mind, the villanus is not a landowner, his lord is the landowner; on the other hand the sochemannus is a landowner, and is taxed as such. We are not saying that this is a purely fiscal distinction. In legal logic the lord’s liability for the geld that is apportioned on the land occupied by his villeins may be rather an effect than a cause. A lawyer might argue that the lord must pay because the occupier is his villanus, not that the occupier is a villanus because the lord pays. And yet, as we may often see in legal history, there will be action and reaction between cause and effect. The geld is no trifle. Levied at that rate of six shillings on the hide at which King William has just now levied it, it is a momentous force capable of depressing and displacing whole classes of men. In 1086 this tax is so much in everybody’s mind that any distinction as to its incidence will cut deeply into the body of the law.

Our course.

Now this classification of men we will take as the starting point for our enterprise. If we could define the liber homo, sochemannus, villanus, cotarius, servus, we should have solved some of the great legal problems of Domesday Book, for by the way we should have had to define two other difficult terms, namely manerium and soca. It would then remain that we should say something of the higher strata of society, of earls and sheriffs, of barons, knights, thegns and their tenures, of such terms as alodium and feudum, of the general theory of landownership or landholdership. We will begin with the lowest order of men, with the servi, and thence work our way upwards. But our course can not be straightforward. There are so many terms to be explained that sometimes we shall be compelled to leave a question but partially answered while we are endeavouring to find a partial answer for some yet more difficult question.

The serfs in Domesday Book.

The existence of some 25,000 serfs is recorded. In the thirteenth century servus and villanus are, at least among lawyers, equivalent words. The only unfree man is the ‘serf-villein’ and the lawyers are trying to subject him to the curious principle that he is the lord’s chattel but a free man in relation to all but his lord[61]. It is far otherwise in Domesday Book. In entry after entry and county after county the servi are kept well apart from the villani, bordarii, cotarii. Often they are mentioned in quite another context to that in which the villani are enumerated. As an instance we may take a manor in Surrey[62]:—‘In demesne there are 5 teams and there are 25 villani and 6 bordarii with 14 teams. There is one mill of 2 shillings and one fishery and one church and 4 acres of meadow, and wood for 150 pannage pigs, and 2 stone-quarries of 2 shillings and 2 nests of hawks in the wood and 10 servi.’ Often enough the servi are placed between two other sources of wealth, the church and the mill. In some counties they seem to take precedence over the villani; the common formula is ‘In dominio sunt a carucae et b servi et c villani et d bordarii cum e carucis.’ But this is delusive; the formula is bringing the servi into connexion with the demesne teams and separating them from the teams of the tenants. We must render it thus—‘On the demesne there are a teams and b servi; and there are c villani and d bordarii with e teams.’ Still we seem to see a gently graduated scale of social classes, villani, bordarii, cotarii, servi, and while the jurors of one county will arrange them in one fashion, the jurors of another county may adopt a different scheme. Thus in their classification of mankind the jurors will sometimes lay great stress on the possession of plough oxen. In Hertfordshire we read:—‘There are 6 teams in demesne and 41 villani and 17 bordarii have 20 teams ... there are 22 cotarii and 12 servi[63].’—‘The priest, 13 villani and 4 bordarii have 6 teams ... there are two cotarii and 4 servi[64].’—‘The priest and 24 villani have 13 teams ... there are 12 bordarii, 16 cotarii and 11 servi[65].’ A division is in this instance made between the people who have oxen and the people who have none; villani have oxen, cotarii and servi have none; sometimes the bordarii stand above this line, sometimes below it.

Legal position of the serf.

Of the legal position of the servus Domesday Book tells us little or nothing; but earlier and later documents oblige us to think of him as a slave, one who in the main has no legal rights. He is the theów of the Anglo-Saxon dooms, the servus of the ecclesiastical canons. But though we do right in calling him a slave, still we might well be mistaken were we to think of the line which divides him from other men as being as sharp as the line which a mature jurisprudence will draw between thing and person. We may well doubt whether this principle—‘The slave is a thing, not a person’—can be fully understood by a grossly barbarous age. It implies the idea of a person, and in the world of sense we find not persons but men.

Degrees of serfdom.