Title: The Pirate

Author: Walter Scott

Editor: Andrew Lang

Release date: March 23, 2013 [eBook #42389]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by sp1nd and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Pirate, by Sir Walter Scott

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/thepirate00scotuoft |

THE PIRATE.

| Nothing in him—— |

| But doth suffer a sea-change. |

| Tempest. |

BIBLIOPHILE EDITION

This Edition of the Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart, is limited to One Thousand Numbered and Signed Sets, of which this is

Number ...

University Library Association

Bibliophile Edition

THE WAVERLEY NOVELS

WITH NEW INTRODUCTIONS, NOTES AND GLOSSARIES

BY ANDREW LANG

ILLUSTRATED

University Library Association

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright, 1893

By Estes & Lauriat

Andrew Lang Edition.

| Volume I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Mordaunt in Yellowley’s Cottage | Frontispiece |

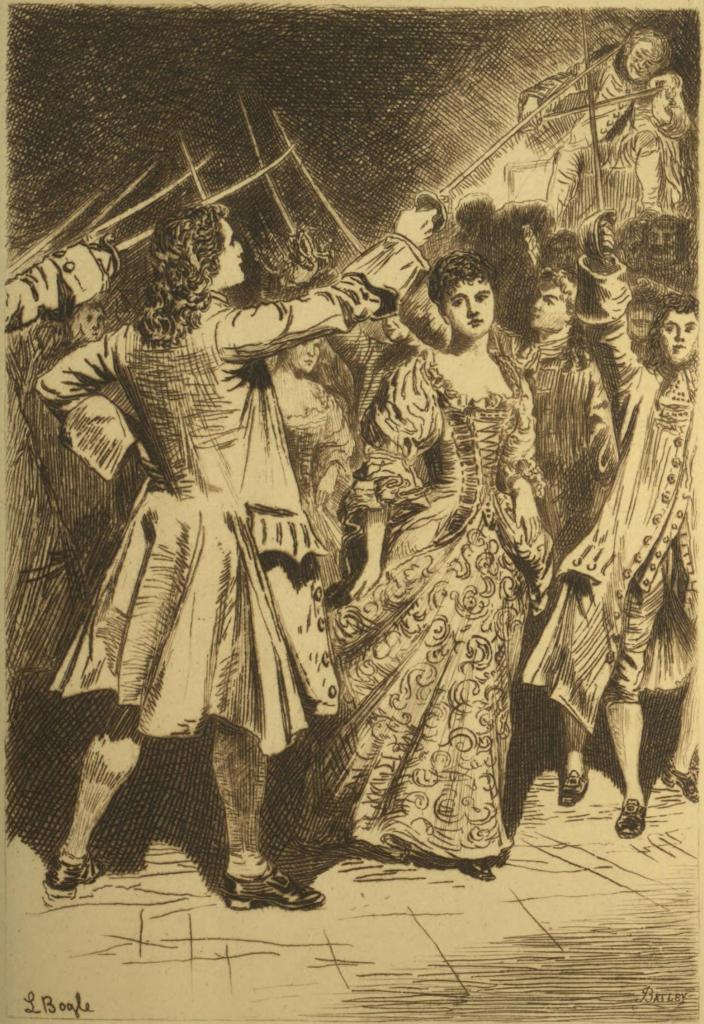

| The Sword Dance | 234 |

Volume II. | |

| Minna on the Cliff | 103 |

| The Pirate’s Council | 208 |

| Minna taking the Pistol | 250 |

The circumstances in which “The Pirate” was composed have for the Editor a peculiar interest. He has many times scribbled at the old bureau in Chiefswood whereon Sir Walter worked at his novel, and sat in summer weather beneath the great tree on the lawn where Erskine used to read the fresh chapters to Lockhart and his wife, while the burn murmured by from the Rhymer’s Glen. So little altered is the cottage of Chiefswood by the addition of a gabled wing in the same red stone as the older portion, so charmed a quiet has the place, in the shelter of Eildon Hill, that there one can readily beget the golden time again, and think oneself back into the day when Mustard and Spice, running down the shady glen, might herald the coming of the Sheriff himself. Happy hours and gone: like that summer of 1821, whereof Lockhart speaks with an emotion the more touching because it is so rare,—

the first of several seasons, which will ever dwell on my memory as the happiest of my life. We were near enough Abbotsford to partake as often as we liked of its brilliant society; yet could do so without being exposed to the worry and exhaustion of spirit which the daily reception of new visitors entailed upon all the society except Sir Walter himself. But, in truth, even he was not always proof against the annoyances connected with such a style of open-house-keeping. Even his temper sank sometimes under the solemn applause of learned dulness, the vapid raptures of painted [Pg x] and periwigged dowagers the horse-leech avidity with which underbred foreigners urged their questions, and the pompous simpers of condescending magnates. When sore beset in this way, he would every now and then discover that he had some very particular business to attend to on an outlying part of his estate, and, craving the indulgence of his guests overnight, appear at the cabin in the glen before its inhabitants were astir in the morning. The clatter of Sibyl Grey’s hoofs, the yelping of Mustard and Spice, and his own joyous shout of reveillée under our window, were the signal that he had burst his bonds, and meant for that day to take his ease in his inn.... After breakfast he would take possession of a dressing-room upstairs, and write a chapter of “The Pirate”; and then, having made up and dispatched his parcel for Mr. Ballantyne, away to join Purdie where the foresters were at work....

The constant and eager delight with which Erskine watched the progress of the tale has left a deep impression on my memory: and indeed I heard so many of its chapters first read from the MS. by him, that I can never open the book now without thinking I hear his voice. Sir Walter used to give him at breakfast the pages he had written that morning, and very commonly, while he was again at work in his study, Erskine would walk over to Chiefswood, that he might have the pleasure of reading them aloud to my wife and me under our favourite tree.[1]

“The tree is living yet!” This long quotation from a book but too little read in general may be excused for its interest, as bearing on the composition of “The Pirate,” in the early autumn of 1821. In “The Pirate” Scott fell back on his recollections of the Orcades, as seen by him in a tour with the Commissioners of Light Houses, in August 1814, immediately after[Pg xi] the publication of “Waverley.” They were accompanied by Mr. Stevenson, the celebrated engineer, “a most gentlemanlike and modest man, and well known by his scientific skill.”[2] It is understood that Mr. Stevenson also kept a diary, and that it is to be published by the care of his distinguished grandson, Mr. Robert Louis Stevenson, author of “Kidnapped,” “The Master of Ballantrae,” and other novels in which Scott would have recognised a not alien genius.

Sir Walter’s Diary, read in company with “The Pirate,” offers a most curious study of his art in composition. It may be said that he scarcely noted a natural feature, a monument, a custom, a superstition, or a legend in Zetland and Orkney which he did not weave into the magic web of his romance. In the Diary all those matters appear as very ordinary; in “The Pirate” they are transfigured in the light of fancy. History gives Scott the career of Gow and his betrothal to an island lady: observation gives him a few headlands, Picts’ houses, ruined towers, and old stone monuments, and his characters gather about these, in rhythmic array, like the dancers in the sword-dance. We may conceive that Cleveland, like Gow, was originally meant to die, and that Minna, like Margaret in the ballad of Clerk Saunders, was to recover her troth from the hand of her dead lover. But, if Scott intended this, he was good-natured, and relented.

Taking the incidents in the Diary in company with the novel, we find, in the very first page of “The Pirate,” mention of the roost, or rost, of Sumburgh, the running current of tidal water, which he hated so, because it made him so sea-sick. “All the landsmen sicker than sick, and our Viceroy, Stevenson, qualmish. It is proposed to have a light on Sumburgh Head.[Pg xii] Fitful Head is higher, but is to the west, from which quarter few vessels come.” As for Sumburgh Head, Scott climbed it, rolled down a rock from the summit, and found it “a fine situation to compose an ode to the Genius of Sumburgh Head, or an Elegy upon a Cormorant—or to have written or spoken madness of any kind in prose or poetry. But I gave vent to my excited feelings in a more simple way, and, sitting gently down on the steep green slope which led to the beach, I e’en slid down a few hundred feet, and found the exercise quite an adequate vent to my enthusiasm.”

Sir Walter was certainly not what he found Mrs. Hemans, “too poetical.”

In the first chapter, his Giffords, Scotts (of Scotstarvet, the Fifeshire house, not of the Border clan), and Mouats are the very gentry who entertained him on his tour. His “plantie cruives,” in the novel, had been noted in the Diary (Lockhart, iv. 193). “Pate Stewart,” the oppressive Earl, is chronicled at length in “the Diary.” “His huge tower remains wild and desolate—its chambers filled with sand, and its rifted walls and dismantled battlements giving unrestrained access to the roaring sea-blast.” So Scott wrote in his last review for the “Quarterly,” a criticism of Pitcairn’s “Scotch Criminal Trials” (1831). The Trows, or Drows, the fairy dwarfs he studied on the spot, and connects the name with Dwerg, though Trolls seem rather to be their spiritual and linguistic ancestors. The affair of the clergyman who was taken for a Pecht, or Pict, actually occurred during the tour, and Mr. Stevenson, who had met the poor Pecht before, was able to clear his character.[3] In the same place the Kraken is mentioned: he had been visible for nearly a fortnight, but no sailor dared go near him.[Pg xiii]

He lay in the offing a fortnight or more,

But the devil a Zetlander put from the shore.

If your Grace thinks I’m writing the thing that is not,

You may ask at a namesake of ours, Mr. Scott,

Sir Walter wrote to the Duke of Buccleugh. He paid a visit to an old lady, who, like Norna, and Æolus in the Odyssey, kept the winds in a bag, and could sell a fair breeze. “She was a miserable figure, upwards of ninety, she told me, and dried up like a mummy. A sort of clay-coloured cloak, folded over her head, corresponded in colour to her corpse-like complexion. Fine light-blue eyes, and nose and chin that almost met, and a ghastly expression of cunning gave her quite the effect of Hecate. She told us she remembered Gow the Pirate, betrothed to a Miss Gordon,”—so here are the germs of Norna, Cleveland, and Minna, all sown in good ground, to bear fruit in seven years (1814-1821). Triptolemus Yellowley is entirely derived from the Diary, and is an anachronism. The Lowland Scots factors and ploughs were only coming in while Scott was in the isles. He himself saw the absurd little mills (vol. i. ch. xi.), and the one stilted plough which needed two women to open the furrows, a feebler plough than the Virgilian specimens which one still remarks in Tuscany. “When this precious machine was in motion, it was dragged by four little bullocks, yoked abreast, and as many ponies harnessed, or rather strung, to the plough by ropes and thongs of raw hide.... An antiquary might be of opinion that this was the very model of the original plough invented by Triptolemus,” son of the Eleusinian king, who sheltered Demeter in her wanderings. The sword-dance was not danced for Scott’s entertainment, but he heard of the Pupa dancers, and got a copy of the accompanying chant, and was presented with examples of the flint and bronze Celts which Norna treasured. All over the[Pg xiv] world, as in Zetland, they were regarded as “thunder stones.” (Diary; Lockhart, iv. 220.) The bridal of Norna, by clasping of hands through Odin’s stone ring, was still practised as a form of betrothal. (Lockhart, iv. 252.) Some island people were despised, as by Magnus Troil, as “poor sneaks” who ate limpets, “the last of human meannesses.” The “wells,” or smooth wave-currents, were also noted, and the Garland of the whalers often alluded to in the tale. The Stones of Stennis were visited, and the Dwarfie Stone of Hoy, where Norna, like some Eskimo Angekok, met her familiar demon. Scott held that the stone “probably was meant as the temple of some northern edition of the dii Manes. They conceive that the dwarf may be seen sometimes sitting at the door of his abode, but he vanishes on a nearer approach.” The dwelling of Norna, a Pict’s house, with an overhanging story, “shaped like a dice-box,” is the ancient Castle of Mousa.[4] The strange incantation of Norna, the dropping of molten lead into water, is also described. Usually the lead was poured through the wards of a key. In affections of the heart, like Minna’s, a triangular stone, probably a neolithic arrow-head, was usually employed as an amulet. (Lockhart, iv. 208.) Even the story of the pirate’s insolent answer to the Provost is adapted from a recent occurrence. Two whalers were accused of stealing a sheep. The first denied the charge, but said he had seen the animal carried off by “a fellow with a red nose and a black wig. Don’t you think he was like his honour, Tom?” “By God, Jack, I believe it was the very man.” (Diary; Lockhart, iv. 222; “The Pirate,” vol. ii. ch. xiv.) The goldless Northern Ophir was also visited—in brief, Scott scarcely made a remark on his tour which he did not manage to[Pg xv] transmute into the rare metal of his romance. It is no wonder that the Orcadians at once detected his authorship. A trifling anecdote of the cruise has recently been published. Scott presented a lady in the isles with a piano, which, it seems, is still capable of producing a melancholy jingling tune.[5]

Lockhart says, as to the reception of “The Pirate” (Dec. 1821): “The wild freshness of the atmosphere of this splendid romance, the beautiful contrast of Minna and Brenda, and the exquisitely drawn character of Captain Cleveland, found the reception which they deserved.” “The wild freshness of the atmosphere” is indeed magically transfused, and breathes across the pages as it blows over the Fitful Head, the skerries, the desolate moors, the plain of the Standing Stones of Stennis. The air is keen and salt and fragrant of the sea. Yet Sydney Smith was greatly disappointed. “I am afraid this novel will depend upon the former reputation of the author, and will add nothing to it. It may sell, and another may half sell, but that is all, unless he comes out with something vigorous, and redeems himself. I do not blame him for writing himself out, if he knows he is doing so, and has done his best, and his all. If the native land of Scotland will supply no more scenes and characters, for he is always best in Scotland, though he was very good in England the (time) he was there; but pray, wherever the scene is laid, no more Meg Merrilies and Dominie Sampsons—very good the first and second times, but now quite worn out, and always recurring.” (“Archibald Constable,” iii. 69.)

It was Smith’s grammar that gave out, and produced no apodosis to his phrase. Scott could not write himself out, before his brain was affected by dis[Pg xvi]ease. Had his age been miraculously prolonged, with health, it could never be said that “all the stories have been told,” and he would have delighted mankind unceasingly.

Scott himself was a little nettled by the criticisms of Norna as a replica of Meg Merrilies. She is, indeed, “something distinct from the Dumfriesshire gipsy”—in truth, she rather resembles the Ulrica of “Ivanhoe.” Like her, she is haunted by the memory of an awful crime, an insane version of a mere accident; like her, she is a votaress of the dead gods of the older world, Thor and Odin, and the spirits of the tempest. Scott’s imagination lived so much in the past that the ancient creeds never ceased to allure him: like Heine, he felt the fascination of the banished deities, not of Greece, but of the North. Thus Norna, crazed by her terrible mischance, dwells among them, worships the Red Beard, as outlying descendants of the Aztecs yet retain some faith in their old monstrous Pantheon. Even Minna keeps, in her girlish enthusiasm, some touch of Freydis in the saga of Eric the Red: for her the old gods and the old years are not wholly exiled and impotent. All this is most characteristic of the antiquary and the poet in Scott, who lingers fondly over what has been, and stirs the last faint embers of fallen fires. It is of a piece with the harmless Jacobitism of his festivals, when they sang

Here’s to the King, boys!

Ye ken wha I mean, boys.

In the singularly feeble and provincial vulgarities which Borrow launches, in the appendix to “Lavengro,” against the memory of Scott, the charge of reviving Catholicism is the most bitter. That rowdy evangelist might as well have charged Scott with a desire to restore the worship of Odin, and to sacrifice human vic[Pg xvii]tims on the stone altar of Stennis. He saw in Orkney the ruined fanes of the Norse deities, as at Melrose of the Virgin, and his loyal heart could feel for all that was old and lost, for all into which men had put their hearts and faiths, had made, and had unmade, in the secular quest for the divine. Like a later poet, he might have said:—

Not as their friend or child I speak,

But as on some far Northern strand,

Thinking of his own gods, a Greek

In pity and mournful awe might stand

Beside some fallen Runic stone,

For both were gods, and both are gone.

And surely no creed is more savage, cruel, and worthy of death than Borrow’s belief in a God who “knew where to strike,” and deliberately struck Scott by inducing Robinson to speculate in hops, and so bring down his Edinburgh associate, Constable, and with him Sir Walter! Such was the religion which Borrow expressed in the style of a writer in a fourth-rate country newspaper. We might prefer the frank Heathenism of the Red Beard to the religion of the author of “The Bible in Spain.”

There is no denying that Scott had in his imagination a certain mould of romance, into which his ideas, when he wrote most naturally, and most for his own pleasure, were apt to run. It is one of the charms of “The Pirate” that here he is manifestly writing for his own pleasure, with a certain boyish eagerness. Had we but the plot of one of the tales which he told, as a lad, to his friend Irving, we might find that it turned on a romantic mystery, a clue in the hands of some witch or wise woman, of some one who was always appearing in the nick of time, was always round the corner when anything was to be heard. This is a[Pg xviii] standing characteristic of the tales: now it is Edie Ochiltree, now Flibbertigibbet, now Meg Merrilies, now Norna, who holds the thread of the plot, but these characters are all well differentiated. Again, he had types, especially the pedantic type, which attracted him, but they vary as much as Yellowley and Dugald Dalgetty, the Antiquary, and Dominie Sampson. Yellowley is rather more repressed than some of Scott’s bores; but then he is not the only bore, for Claud Halcro, with all his merits, is a professed proser. Swift had exactly described the character, the episodical narrator, in a passage parallel to one in Theophrastus. In writing to Morritt, Scott says (November 1818): “I sympathise with you for the dole you are dreeing under the inflictions of your honest proser. Of all the boring machines ever devised, your regular and determined story-teller is the most peremptory and powerful in his operations.”

“With what perfect placidity he submitted to be bored even by bores of the first water!” says Lockhart. The species is one which we all have many opportunities of studying, but it may be admitted that Scott produced his studies of bores with a certain complacency. Yet they are all different bores, and the gay, kind scald Halcro is very unlike Master Mumblasen or Dominie Sampson.

For a hero Mordaunt may be called almost sprightly and individual. His mysterious father occasionally suggests the influence of Byron, occasionally of Mrs. Radcliffe. The Udaller is as individual and genial as Dandie Dinmont himself; or, again, he is the Cedric of Thule, though much more sympathetic than Cedric to most readers. His affection for his daughters is characteristic and deserved. Many a pair of sisters, blonde and brune, have we met in fiction since Minna and Brenda, but none have been their peers, and, like Mor[Pg xix]daunt in early years, we know not to which of them our hearts are given. They are “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso” of the North, and it is probable that all men would fall in love with Minna if they had the chance, and marry Brenda, if they could. Minna is, indeed, the ideal youth of poetry, and Brenda of the practical life. The innocent illusions of Minna, her love of all that is old, her championship of the forlorn cause, her beauty, her tenderness, her truth, her passionate waywardness of sorrow, make her one of Scott’s most original and delightful heroines. She believes and trembles not, like Bertram in “Rokeby.” Brenda trembles, but does not believe in Norna’s magic, and in the spirits of ancient saga. As for Cleveland, Scott managed to avoid Byron’s Lara-like pirates, and produced a freebooter as sympathetic as any hostis humani generis can be, while “Frederick Altamont” (Thackeray borrowed the name for his romantic crossing-sweeper) has a place among the Marischals and Bucklaws of romance. Scott’s minute studies in Dryden come to the aid of his local observations, and so, out of not very promising materials, and out of the contrast of Lowland Scot and Orcadian, the romance is spun. Probably the “psychological analysis” which most interested the author is the double consciousness of Norna, the occasional intrusions of the rational self on her dreams of supernatural powers. That double consciousness, indeed, exists in all of us: occasionally the self in which we believe has a vision of the real underlying self, and shudders from the sight, like the pair “who met themselves” in the celebrated drawing.

“The Pirate” can scarcely be placed in the front rank of Scott’s novels, but it has a high and peculiar place in the second, and probably will always be among the special favourites of those who, being young, are fortunate enough not to be critical.[Pg xx]

Scott’s novels at this time came forth so frequently that the lumbering “Quarterlies” toiled after them in vain. They adopted the plan of reviewing them in batches, and the “Quarterly” may be said to have omitted “The Pirate” altogether. About this time Gifford began to find that the person who spoke of a “dark dialect of Anglified Erse” was not a competent critic, and Mr. Senior noticed several of the tales in a more judicious manner. As to “The Pirate,” the “Edinburgh Review” found “the character and story of Mertoun at once commonplace and extravagant.” Cleveland disappoints “by turning out so much better than we had expected, and yet substantially so ill.” “Nothing can be more beautiful than the description of the sisters.” “Norna is a new incarnation of Meg Merrilies, and palpably the same in the spirit ... but far above the rank of a mere imitated or borrowed character.” “The work, on the whole, opens up a new world to our curiosity, and affords another proof of the extreme pliability, as well as vigour, of the author’s genius.”

Andrew Lang.

August 1893.

[1] Lockhart, vi. 388-393. Erskine died before Scott, slain by a silly piece of gossip, and Mr. Skene says: “I never saw Sir Walter so much affected by any event, and at the funeral, which he attended, he was quite unable to suppress his feelings, but wept like a child.” His correspondence with Scott fell into the hands of a lady, who, seeing that it revealed the secret of Scott’s authorship, most unfortunately burned all the letters. (Journal, i. 416.)

[2] Scott’s Diary, July 29, 1814. Lockhart, vi. 183.

[3] See Author’s Note No. I.

[4] Diary; Lockhart, iv. 223.

[5] “Atalanta,” December 1892.

“Quoth he, there was a ship.”

This brief preface may begin like the tale of the Ancient Mariner, since it was on shipboard that the author acquired the very moderate degree of local knowledge and information, both of people and scenery, which he has endeavoured to embody in the romance of the Pirate.

In the summer and autumn of 1814, the author was invited to join a party of Commissioners for the Northern Light-House Service, who proposed making a voyage round the coast of Scotland, and through its various groups of islands, chiefly for the purpose of seeing the condition of the many lighthouses under their direction,—edifices so important, whether regarding them as benevolent or political institutions. Among the commissioners who manage this important public concern, the sheriff of each county of Scotland which borders on the sea, holds ex-officio a place at the Board. These gentlemen act in every respect gratuitously, but have the use of an armed yacht, well found and fitted up, when they choose to visit the lighthouses. An excellent engineer, Mr. Robert Stevenson, is attached to the Board, to afford the benefit of his professional advice. The author accompanied this expedition as a[Pg xxii] guest; for Selkirkshire, though it calls him Sheriff, has not, like the kingdom of Bohemia in Corporal Trim’s story, a seaport in its circuit, nor its magistrate, of course, any place at the Board of Commissioners,—a circumstance of little consequence where all were old and intimate friends, bred to the same profession, and disposed to accommodate each other in every possible manner.

The nature of the important business which was the principal purpose of the voyage, was connected with the amusement of visiting the leading objects of a traveller’s curiosity; for the wild cape, or formidable shelve, which requires to be marked out by a lighthouse, is generally at no great distance from the most magnificent scenery of rocks, caves, and billows. Our time, too, was at our own disposal, and, as most of us were freshwater sailors, we could at any time make a fair wind out of a foul one, and run before the gale in quest of some object of curiosity which lay under our lee.

With these purposes of public utility and some personal amusement in view, we left the port of Leith on the 26th July, 1814, ran along the east coast of Scotland, viewing its different curiosities, stood over to Zetland and Orkney, where we were some time detained by the wonders of a country which displayed so much that was new to us; and having seen what was curious in the Ultima Thule of the ancients, where the sun hardly thought it worth while to go to bed, since his rising was at this season so early, we doubled the extreme northern termination of Scotland, and took a rapid survey of the Hebrides, where we found many kind friends. There, that our little expedition might not want the dignity of danger, we were favoured with a distant glimpse of what was said to be an American cruiser, and had opportunity to consider what a pretty figure we should have made had the voyage ended in[Pg xxiii] our being carried captive to the United States. After visiting the romantic shores of Morven, and the vicinity of Oban, we made a run to the coast of Ireland, and visited the Giant’s Causeway, that we might compare it with Staffa, which we had surveyed in our course. At length, about the middle of September, we ended our voyage in the Clyde, at the port of Greenock.

And thus terminated our pleasant tour, to which our equipment gave unusual facilities, as the ship’s company could form a strong boat’s crew, independent of those who might be left on board the vessel, which permitted us the freedom to land wherever our curiosity carried us. Let me add, while reviewing for a moment a sunny portion of my life, that among the six or seven friends who performed this voyage together, some of them doubtless of different tastes and pursuits, and remaining for several weeks on board a small vessel, there never occurred the slightest dispute or disagreement, each seeming anxious to submit his own particular wishes to those of his friends. By this mutual accommodation all the purposes of our little expedition were obtained, while for a time we might have adopted the lines of Allan Cunningham’s fine sea-song,

“The world of waters was our home,

And merry men were we!”

But sorrow mixes her memorials with the purest remembrances of pleasure. On returning from the voyage which had proved so satisfactory, I found that fate had deprived her country most unexpectedly of a lady, qualified to adorn the high rank which she held, and who had long admitted me to a share of her friendship. The subsequent loss of one of those comrades who made up the party, and he the most intimate friend I had in the world, casts also its shade on recollections which,[Pg xxiv] but for these embitterments, would be otherwise so pleasing.

I may here briefly observe, that my business in this voyage, so far as I could be said to have any, was to endeavour to discover some localities which might be useful in the “Lord of the Isles,” a poem with which I was then threatening the public, and was afterwards printed without attaining remarkable success. But as at the same time the anonymous novel of “Waverley” was making its way to popularity, I already augured the possibility of a second effort in this department of literature, and I saw much in the wild islands of the Orkneys and Zetland, which I judged might be made in the highest degree interesting, should these isles ever become the scene of a narrative of fictitious events. I learned the history of Gow the pirate from an old sibyl, (the subject of a note, p. 326 of this volume,) whose principal subsistence was by a trade in favourable winds, which she sold to mariners at Stromness. Nothing could be more interesting than the kindness and hospitality of the gentlemen of Zetland, which was to me the more affecting, as several of them had been friends and correspondents of my father.

I was induced to go a generation or two farther back, to find materials from which I might trace the features of the old Norwegian Udaller, the Scottish gentry having in general occupied the place of that primitive race, and their language and peculiarities of manner having entirely disappeared. The only difference now to be observed betwixt the gentry of these islands, and those of Scotland in general, is, that the wealth and property is more equally divided among our more northern countrymen, and that there exists among the resident proprietors no men of very great wealth, whose display of its luxuries might render the others discontented with their own lot. From the same cause of general equal[Pg xxv]ity of fortunes, and the cheapness of living, which is its natural consequence, I found the officers of a veteran regiment who had maintained the garrison at Fort Charlotte, in Lerwick, discomposed at the idea of being recalled from a country where their pay, however inadequate to the expenses of a capital, was fully adequate to their wants, and it was singular to hear natives of merry England herself regretting their approaching departure from the melancholy isles of the Ultima Thule.

Such are the trivial particulars attending the origin of that publication, which took place several years later than the agreeable journey from which it took its rise.

The state of manners which I have introduced in the romance, was necessarily in a great degree imaginary, though founded in some measure on slight hints, which, showing what was, seemed to give reasonable indication of what must once have been, the tone of the society in these sequestered but interesting islands.

In one respect I was judged somewhat hastily, perhaps, when the character of Norna was pronounced by the critics a mere copy of Meg Merrilees. That I had fallen short of what I wished and desired to express is unquestionable, otherwise my object could not have been so widely mistaken; nor can I yet think that any person who will take the trouble of reading the Pirate with some attention, can fail to trace in Norna,—the victim of remorse and insanity, and the dupe of her own imposture, her mind, too, flooded with all the wild literature and extravagant superstitions of the north,—something distinct from the Dumfries-shire gipsy, whose pretensions to supernatural powers are not beyond those of a Norwood prophetess. The foundations of such a character may be perhaps traced, though it be too true that the necessary superstructure cannot[Pg xxvi] have been raised upon them, otherwise these remarks would have been unnecessary. There is also great improbability in the statement of Norna’s possessing power and opportunity to impress on others that belief in her supernatural gifts which distracted her own mind. Yet, amid a very credulous and ignorant population, it is astonishing what success may be attained by an impostor, who is, at the same time, an enthusiast. It is such as to remind us of the couplet which assures us that

“The pleasure is as great

In being cheated as to cheat.”

Indeed, as I have observed elsewhere, the professed explanation of a tale, where appearances or incidents of a supernatural character are referred to natural causes, has often, in the winding up of the story, a degree of improbability almost equal to an absolute goblin narrative. Even the genius of Mrs. Radcliffe could not always surmount this difficulty.

Abbotsford,

1st May, 1831.

The purpose of the following Narrative is to give a detailed and accurate account of certain remarkable incidents which took place in the Orkney Islands, concerning which the more imperfect traditions and mutilated records of the country only tell us the following erroneous particulars:—

In the month of January, 1724-5, a vessel, called the Revenge, bearing twenty large guns, and six smaller, commanded by John Gow, or Goffe, or Smith, came to the Orkney Islands, and was discovered to be a pirate, by various acts of insolence and villainy committed by the crew. These were for some time submitted to, the inhabitants of these remote islands not possessing arms nor means of resistance; and so bold was the Captain of these banditti, that he not only came ashore, and gave dancing parties in the village of Stromness, but before his real character was discovered, engaged the affections, and received the troth-plight, of a young lady possessed of some property. A patriotic individual, James Fea, younger of Clestron, formed the plan of securing the buccanier, which he effected by a mixture of courage and address, in consequence chiefly of Gow’s vessel having gone on shore near the harbour of Calfsound, on the Island of Eda, not far distant from a house then inhabited by Mr. Fea. In the various stratagems by which Mr. Fea contrived finally, at the peril of his life, (they being well armed and desperate,) to make the whole pirates[Pg xxviii] his prisoners, he was much aided by Mr. James Laing, the grandfather of the late Malcolm Laing, Esq., the acute and ingenious historian of Scotland during the 17th century.

Gow, and others of his crew, suffered, by sentence of the High Court of Admiralty, the punishment their crimes had long deserved. He conducted himself with great audacity when before the Court; and, from an account of the matter by an eye-witness, seems to have been subjected to some unusual severities, in order to compel him to plead. The words are these: “John Gow would not plead, for which he was brought to the bar, and the Judge ordered that his thumbs should be squeezed by two men, with a whip-cord, till it did break; and then it should be doubled, till it did again break, and then laid threefold, and that the executioners should pull with their whole strength; which sentence Gow endured with a great deal of boldness.” The next morning, (27th May, 1725,) when he had seen the terrible preparations for pressing him to death, his courage gave way, and he told the Marshal of Court, that he would not have given so much trouble, had he been assured of not being hanged in chains. He was then tried, condemned, and executed, with others of his crew.

It is said, that the lady whose affections Gow had engaged, went up to London to see him before his death, and that, arriving too late, she had the courage to request a sight of his dead body; and then, touching the hand of the corpse, she formally resumed the troth-plight which she had bestowed. Without going through this ceremony, she could not, according to the superstition of the country, have escaped a visit from the ghost of her departed lover, in the event of her bestowing upon any living suitor the faith which she had plighted to the dead. This part of the legend may serve as a[Pg xxix] curious commentary on the fine Scottish ballad, which begins,

“There came a ghost to Margaret’s door,” &c.(a)[6]

The common account of this incident farther bears, that Mr. Fea, the spirited individual by whose exertions Gow’s career of iniquity was cut short, was so far from receiving any reward from Government, that he could not obtain even countenance enough to protect him against a variety of sham suits, raised against him by Newgate solicitors, who acted in the name of Gow, and others of the pirate crew; and the various expenses, vexatious prosecutions, and other legal consequences, in which his gallant exploit involved him, utterly ruined his fortune, and his family; making his memory a notable example to all who shall in future take pirates on their own authority.

It is to be supposed, for the honour of George the First’s Government, that the last circumstance, as well as the dates, and other particulars of the commonly received story, are inaccurate, since they will be found totally irreconcilable with the following veracious narrative, compiled from materials to which he himself alone has had access, by

The Author of Waverley.

[6] See Editor’s Notes at the end of the Volume. Wherever a similar reference occurs, the reader will understand that the same direction applies.

THE PIRATE.

The storm had ceased its wintry roar,

Hoarse dash the billows of the sea;

But who on Thule’s desert shore,

Cries, Have I burnt my harp for thee?

Macniel.

That long, narrow, and irregular island, usually called the mainland of Zetland, because it is by far the largest of that Archipelago, terminates, as is well known to the mariners who navigate the stormy seas which surround the Thule of the ancients, in a cliff of immense height, entitled Sumburgh-Head, which presents its bare scalp and naked sides to the weight of a tremendous surge, forming the extreme point of the isle to the south-east. This lofty promontory is constantly exposed to the current of a strong and furious tide, which, setting in betwixt the Orkney and Zetland Islands, and running with force only inferior to that of the Pentland Frith, takes its name from the headland we have mentioned, and is called the Roost of Sumburgh; roost being the phrase assigned in those isles to currents of this description.

On the land side, the promontory is covered with short grass, and slopes steeply down to a little isthmus, upon which the sea has encroached in creeks,[Pg 2] which, advancing from either side of the island, gradually work their way forward, and seem as if in a short time they would form a junction, and altogether insulate Sumburgh-Head, when what is now a cape, will become a lonely mountain islet, severed from the mainland, of which it is at present the terminating extremity.

Man, however, had in former days considered this as a remote or unlikely event; for a Norwegian chief of other times, or, as other accounts said, and as the name of Jarlshof seemed to imply, an ancient Earl of the Orkneys had selected this neck of land as the place for establishing a mansion-house. It has been long entirely deserted, and the vestiges only can be discerned with difficulty; for the loose sand, borne on the tempestuous gales of those stormy regions, has overblown, and almost buried, the ruins of the buildings; but in the end of the seventeenth century, a part of the Earl’s mansion was still entire and habitable. It was a rude building of rough stone, with nothing about it to gratify the eye, or to excite the imagination; a large old-fashioned narrow house, with a very steep roof, covered with flags composed of grey sandstone, would perhaps convey the best idea of the place to a modern reader. The windows were few, very small in size, and distributed up and down the building with utter contempt of regularity. Against the main structure had rested, in former times, certain smaller co-partments of the mansion-house, containing offices, or subordinate apartments, necessary for the accommodation of the Earl’s retainers and menials. But these had become ruinous; and the rafters had been taken down for fire-wood, or for other purposes; the walls had given way in many places;[Pg 3] and, to complete the devastation, the sand had already drifted amongst the ruins, and filled up what had been once the chambers they contained, to the depth of two or three feet.

Amid this desolation, the inhabitants of Jarlshof had contrived, by constant labour and attention, to keep in order a few roods of land, which had been enclosed as a garden, and which, sheltered by the walls of the house itself, from the relentless sea-blast, produced such vegetables as the climate could bring forth, or rather as the sea-gale would permit to grow; for these islands experience even less of the rigour of cold than is encountered on the mainland of Scotland; but, unsheltered by a wall of some sort or other, it is scarce possible to raise even the most ordinary culinary vegetables; and as for shrubs or trees, they are entirely out of the question, such is the force of the sweeping sea-blast.

At a short distance from the mansion, and near to the sea-beach, just where the creek forms a sort of imperfect harbour, in which lay three or four fishing-boats, there were a few most wretched cottages for the inhabitants and tenants of the township of Jarlshof, who held the whole district of the landlord upon such terms as were in those days usually granted to persons of this description, and which, of course, were hard enough. The landlord himself resided upon an estate which he possessed in a more eligible situation, in a different part of the island, and seldom visited his possessions at Sumburgh-Head. He was an honest, plain Zetland gentleman, somewhat passionate, the necessary result of being surrounded by dependents; and somewhat over-convivial in his habits, the consequence, per[Pg 4]haps, of having too much time at his disposal; but frank-tempered and generous to his people, and kind and hospitable to strangers. He was descended also of an old and noble Norwegian family; a circumstance which rendered him dearer to the lower orders, most of whom are of the same race; while the lairds, or proprietors, are generally of Scottish extraction, who, at that early period, were still considered as strangers and intruders. Magnus Troil, who deduced his descent from the very Earl who was supposed to have founded Jarlshof, was peculiarly of this opinion.

The present inhabitants of Jarlshof had experienced, on several occasions, the kindness and good will of the proprietor of the territory. When Mr. Mertoun—such was the name of the present inhabitant of the old mansion—first arrived in Zetland, some years before the story commences, he had been received at the house of Mr. Troil with that warm and cordial hospitality for which the islands are distinguished. No one asked him whence he came, where he was going, what was his purpose in visiting so remote a corner of the empire, or what was likely to be the term of his stay. He arrived a perfect stranger, yet was instantly overpowered by a succession of invitations; and in each house which he visited, he found a home as long as he chose to accept it, and lived as one of the family, unnoticed and unnoticing, until he thought proper to remove to some other dwelling. This apparent indifference to the rank, character, and qualities of their guest, did not arise from apathy on the part of his kind hosts, for the islanders had their full share of natural curiosity; but their delicacy deemed it would be an infringement upon the laws of hospi[Pg 5]tality, to ask questions which their guest might have found it difficult or unpleasing to answer; and instead of endeavouring, as is usual in other countries, to wring out of Mr. Mertoun such communications as he might find it agreeable to withhold, the considerate Zetlanders contented themselves with eagerly gathering up such scraps of information as could be collected in the course of conversation.

But the rock in an Arabian desert is not more reluctant to afford water, than Mr. Basil Mertoun was niggard in imparting his confidence, even incidentally; and certainly the politeness of the gentry of Thule was never put to a more severe test than when they felt that good-breeding enjoined them to abstain from enquiring into the situation of so mysterious a personage.

All that was actually known of him was easily summed up. Mr. Mertoun had come to Lerwick, then rising into some importance, but not yet acknowledged as the principal town of the island, in a Dutch vessel, accompanied only by his son, a handsome boy of about fourteen years old. His own age might exceed forty. The Dutch skipper introduced him to some of the very good friends with whom he used to barter gin and gingerbread for little Zetland bullocks, smoked geese, and stockings of lambs-wool; and although Meinheer could only say, that “Meinheer Mertoun hab bay his bassage like one gentlemans, and hab given a Kreitz-dollar beside to the crew,” this introduction served to establish the Dutchman’s passenger in a respectable circle of acquaintances, which gradually enlarged, as it appeared that the stranger was a man of considerable acquirements.[Pg 6]

This discovery was made almost per force; for Mertoun was as unwilling to speak upon general subjects, as upon his own affairs. But he was sometimes led into discussions, which showed, as it were in spite of himself, the scholar and the man of the world; and, at other times, as if in requital of the hospitality which he experienced, he seemed to compel himself, against his fixed nature, to enter into the society of those around him, especially when it assumed the grave, melancholy, or satirical cast, which best suited the temper of his own mind. Upon such occasions, the Zetlanders were universally of opinion that he must have had an excellent education, neglected only in one striking particular, namely, that Mr. Mertoun scarce knew the stem of a ship from the stern; and in the management of a boat, a cow could not be more ignorant. It seemed astonishing such gross ignorance of the most necessary art of life (in the Zetland Isles at least) should subsist along with his accomplishments in other respects; but so it was.

Unless called forth in the manner we have mentioned, the habits of Basil Mertoun were retired and gloomy. From loud mirth he instantly fled; and even the moderated cheerfulness of a friendly party, had the invariable effect of throwing him into deeper dejection than even his usual demeanour indicated.

Women are always particularly desirous of investigating mystery, and of alleviating melancholy, especially when these circumstances are united in a handsome man about the prime of life. It is possible, therefore, that amongst the fair-haired and blue-eyed daughters of Thule, this mysterious and pensive stranger might have found some one to take upon[Pg 7] herself the task of consolation, had he shown any willingness to accept such kindly offices; but, far from doing so, he seemed even to shun the presence of the sex, to which in our distresses, whether of mind or body, we generally apply for pity and comfort.

To these peculiarities Mr. Mertoun added another, which was particularly disagreeable to his host and principal patron, Magnus Troil. This magnate of Zetland, descended by the father’s side, as we have already said, from an ancient Norwegian family, by the marriage of its representative with a Danish lady, held the devout opinion that a cup of Geneva or Nantz was specific against all cares and afflictions whatever. These were remedies to which Mr. Mertoun never applied; his drink was water, and water alone, and no persuasion or entreaties could induce him to taste any stronger beverage than was afforded by the pure spring. Now this Magnus Troil could not tolerate; it was a defiance to the ancient northern laws of conviviality, which, for his own part, he had so rigidly observed, that although he was wont to assert that he had never in his life gone to bed drunk, (that is, in his own sense of the word,) it would have been impossible to prove that he had ever resigned himself to slumber in a state of actual and absolute sobriety. It may be therefore asked, What did this stranger bring into society to compensate the displeasure given by his austere and abstemious habits? He had, in the first place, that manner and self-importance which mark a person of some consequence: and although it was conjectured that he could not be rich, yet it was certainly known by his expenditure that neither was he absolutely poor. He had, besides, some powers of con[Pg 8]versation, when, as we have already hinted, he chose to exert them, and his misanthropy or aversion to the business and intercourse of ordinary life, was often expressed in an antithetical manner, which passed for wit, when better was not to be had. Above all, Mr. Mertoun’s secret seemed impenetrable, and his presence had all the interest of a riddle, which men love to read over and over, because they cannot find out the meaning of it.

Notwithstanding these recommendations, Mertoun differed in so many material points from his host, that after he had been for some time a guest at his principal residence, Magnus Troil was agreeably surprised when, one evening after they had sat two hours in absolute silence, drinking brandy and water,—that is, Magnus drinking the alcohol, and Mertoun the element,—the guest asked his host’s permission to occupy, as his tenant, this deserted mansion of Jarlshof, at the extremity of the territory called Dunrossness, and situated just beneath Sumburgh-Head. “I shall be handsomely rid of him,” quoth Magnus to himself, “and his kill-joy visage will never again stop the bottle in its round. His departure will ruin me in lemons, however, for his mere look was quite sufficient to sour a whole ocean of punch.”

Yet the kind-hearted Zetlander generously and disinterestedly remonstrated with Mr. Mertoun on the solitude and inconveniences to which he was about to subject himself. “There were scarcely,” he said, “even the most necessary articles of furniture in the old house—there was no society within many miles—for provisions, the principal article of food would be sour sillocks, and his only company gulls and gannets.[Pg 9]”

“My good friend,” replied Mertoun, “if you could have named a circumstance which would render the residence more eligible to me than any other, it is that there would be neither human luxury nor human society near the place of my retreat; a shelter from the weather for my own head, and for the boy’s, is all I seek for. So name your rent, Mr. Troil, and let me be your tenant at Jarlshof.”

“Rent?” answered the Zetlander; “why, no great rent for an old house which no one has lived in since my mother’s time—God rest her!—and as for shelter, the old walls are thick enough, and will bear many a bang yet. But, Heaven love you, Mr. Mertoun, think what you are purposing. For one of us to live at Jarlshof, were a wild scheme enough; but you, who are from another country, whether English, Scotch, or Irish, no one can tell”——

“Nor does it greatly matter,” said Mertoun, somewhat abruptly.

“Not a herring’s scale,” answered the Laird; “only that I like you the better for being no Scot, as I trust you are not one. Hither they have come like the clack-geese—every chamberlain has brought over a flock of his own name, and his own hatching, for what I know, and here they roost for ever—catch them returning to their own barren Highlands or Lowlands, when once they have tasted our Zetland beef, and seen our bonny voes and lochs. No, sir,” (here Magnus proceeded with great animation, sipping from time to time the half-diluted spirit, which at the same time animated his resentment against the intruders, and enabled him to endure the mortifying reflection which it suggested,)—“No, sir, the ancient days and the genuine manners of these Islands are no more; for our ancient possessors,[Pg 10]—our Patersons, our Feas, our Schlagbrenners, our Thorbiorns, have given place to Giffords, Scotts, Mouats, men whose names bespeak them or their ancestors strangers to the soil which we the Troils have inhabited long before the days of Turf-Einar, who first taught these Isles the mystery of burning peat for fuel, and who has been handed down to a grateful posterity by a name which records the discovery.”

This was a subject upon which the potentate of Jarlshof was usually very diffuse, and Mertoun saw him enter upon it with pleasure, because he knew he should not be called upon to contribute any aid to the conversation, and might therefore indulge his own saturnine humour while the Norwegian Zetlander declaimed on the change of times and inhabitants. But just as Magnus had arrived at the melancholy conclusion, “how probable it was, that in another century scarce a merk—scarce even an ure of land, would be in the possession of the Norse inhabitants, the true Udallers[7] of Zetland,” he recollected the circumstances of his guest, and stopped suddenly short. “I do not say all this,” he added, interrupting himself, “as if I were unwilling that you should settle on my estate, Mr. Mertoun—But for Jarlshof—the place is a wild one—Come from where you will, I warrant you will say, like other travellers, you came from a better climate than ours, for so say you all. And yet you think of a retreat, which the very natives run away from. Will you not take your glass?”—(This was to be considered as interjectional,)—“then here’s to you.[Pg 11]”

“My good sir,” answered Mertoun, “I am indifferent to climate; if there is but air enough to fill my lungs, I care not if it be the breath of Arabia or of Lapland.”

“Air enough you may have,” answered Magnus, “no lack of that—somewhat damp, strangers allege it to be, but we know a corrective for that—Here’s to you, Mr. Mertoun—You must learn to do so, and to smoke a pipe; and then, as you say, you will find the air of Zetland equal to that of Arabia. But have you seen Jarlshof?”

The stranger intimated that he had not.

“Then,” replied Magnus, “you have no idea of your undertaking. If you think it a comfortable roadstead like this, with the house situated on the side of an inland voe,[8] that brings the herrings up to your door, you are mistaken, my heart. At Jarlshof you will see nought but the wild waves tumbling on the bare rocks, and the Roost of Sumburgh running at the rate of fifteen knots an-hour.”

“I shall see nothing at least of the current of human passions,” replied Mertoun.

“You will hear nothing but the clanging and screaming of scarts, sheer-waters, and seagulls, from daybreak till sunset.”

“I will compound, my friend,” replied the stranger, “so that I do not hear the chattering of women’s tongues.”

“Ah,” said the Norman, “that is because you hear just now my little Minna and Brenda singing in the garden with your Mordaunt. Now, I would rather listen to their little voices, than the skylark which I once heard in Caithness, or the nightingale that I[Pg 12] have read of.—What will the girls do for want of their playmate Mordaunt?”

“They will shift for themselves,” answered Mertoun; “younger or elder they will find playmates or dupes.—But the question is, Mr. Troil, will you let to me, as your tenant, this old mansion of Jarlshof?”

“Gladly, since you make it your option to live in a spot so desolate.”

“And as for the rent?” continued Mertoun.

“The rent?” replied Magnus; “hum—why, you must have the bit of plantie cruive,[9] which they once called a garden, and a right in the scathold, and a sixpenny merk of land, that the tenants may fish for you;—eight lispunds[10] of butter, and eight shillings sterling yearly, is not too much?”

Mr. Mertoun agreed to terms so moderate, and from thenceforward resided chiefly at the solitary mansion which we have described in the beginning of this chapter, conforming not only without complaint, but, as it seemed, with a sullen pleasure, to all the privations which so wild and desolate a situation necessarily imposed on its inhabitant.

[7] The Udallers are the allodial possessors of Zetland, who hold their possessions under the old Norwegian law, instead of the feudal tenures introduced among them from Scotland.

[8] Salt-water lake.

[9] Patch of ground for vegetables. The liberal custom of the country permits any person, who has occasion for such a convenience, to select out of the unenclosed moorland a small patch, which he surrounds with a drystone wall, and cultivates as a kailyard, till he exhausts the soil with cropping, and then he deserts it, and encloses another. This liberty is so far from inferring an invasion of the right of proprietor and tenant, that the last degree of contempt is inferred of an avaricious man, when a Zetlander says he would not hold a plantie cruive of him.

[10] A lispund is about thirty pounds English, and the value is averaged by Dr. Edmonston at ten shillings sterling.

’Tis not alone the scene—the man, Anselmo,

The man finds sympathies in these wild wastes,

And roughly tumbling seas, which fairer views

And smoother waves deny him.

Ancient Arama.

The few inhabitants of the township of Jarlshof had at first heard with alarm, that a person of rank superior to their own was come to reside in the ruinous tenement, which they still called the Castle. In those days (for the present times are greatly altered for the better) the presence of a superior, in such a situation, was almost certain to be attended with additional burdens and exactions, for which, under one pretext or another, feudal customs furnished a thousand apologies. By each of these, a part of the tenants’ hard-won and precarious profits was diverted for the use of their powerful neighbour and superior, the tacksman, as he was called. But the sub-tenants speedily found that no oppression of this kind was to be apprehended at the hands of Basil Mertoun. His own means, whether large or small, were at least fully adequate to his expenses, which, so far as regarded his habits of life, were of the most frugal description. The luxuries of a few books, and some philosophical instruments, with which he was supplied from London as occasion offered, seemed to indicate a degree of wealth unusual in those islands; but, on the other hand, the table and the accommodations at Jarlshof, did not[Pg 14] exceed what was maintained by a Zetland proprietor of the most inferior description.

The tenants of the hamlet troubled themselves very little about the quality of their superior, as soon as they found that their situation was rather to be mended than rendered worse by his presence; and, once relieved from the apprehension of his tyrannizing over them, they laid their heads together to make the most of him by various petty tricks of overcharge and extortion, which for a while the stranger submitted to with the most philosophic indifference. An incident, however, occurred, which put his character in a new light, and effectually checked all future efforts at extravagant imposition.

A dispute arose in the kitchen of the Castle betwixt an old governante, who acted as housekeeper to Mr. Mertoun, and Sweyn Erickson, as good a Zetlander as ever rowed a boat to the haaf fishing;[11] which dispute, as is usual in such cases, was maintained with such increasing heat and vociferation as to reach the ears of the master, (as he was called,) who, secluded in a solitary turret, was deeply employed in examining the contents of a new package of books from London, which, after long expectation, had found its way to Hull, from thence by a whaling vessel to Lerwick, and so to Jarlshof. With more than the usual thrill of indignation which indolent people always feel when roused into action on some unpleasant occasion, Mertoun descended to the scene of contest, and so suddenly, peremptorily, and strictly, enquired into the cause of dispute, that the parties, notwithstanding every evasion which they attempted, became unable to disguise[Pg 15] from him, that their difference respected the several interests to which the honest governante, and no less honest fisherman, were respectively entitled, in an overcharge of about one hundred per cent on a bargain of rock-cod, purchased by the former from the latter, for the use of the family at Jarlshof.

When this was fairly ascertained and confessed, Mr. Mertoun stood looking upon the culprits with eyes in which the utmost scorn seemed to contend with awakening passion. “Hark you, ye old hag,” said he at length to the housekeeper, “avoid my house this instant! and know that I dismiss you, not for being a liar, a thief, and an ungrateful quean,—for these are qualities as proper to you as your name of woman,—but for daring, in my house, to scold above your breath.—And for you, you rascal, who suppose you may cheat a stranger as you would flinch[12] a whale, know that I am well acquainted with the rights which, by delegation from your master, Magnus Troil, I can exercise over you, if I will. Provoke me to a certain pitch, and you shall learn, to your cost, I can break your rest as easily as you can interrupt my leisure. I know the meaning of scat, and wattle, and hawkhen, and hagalef,(b) and every other exaction, by which your lords, in ancient and modern days, have wrung your withers; nor is there one of you that shall not rue the day that you could not be content with robbing me of my money, but must also break in on my leisure with your atrocious northern clamour, that rivals in discord the screaming of a flight of Arctic gulls.”

Nothing better occurred to Sweyn, in answer to this objurgation, than the preferring a humble re[Pg 16]quest that his honour would be pleased to keep the cod-fish without payment, and say no more about the matter; but by this time Mr. Mertoun had worked up his passions into an ungovernable rage, and with one hand he threw the money at the fisherman’s head, while with the other he pelted him out of the apartment with his own fish, which he finally flung out of doors after him.

There was so much of appalling and tyrannic fury in the stranger’s manner on this occasion, that Sweyn neither stopped to collect the money nor take back his commodity, but fled at a precipitate rate to the small hamlet, to tell his comrades that if they provoked Master Mertoun any farther, he would turn an absolute Pate Stewart[13] on their hand, and head and hang without either judgment or mercy.

Hither also came the discarded housekeeper, to consult with her neighbours and kindred (for she too was a native of the village) what she should do to regain the desirable situation from which she had been so suddenly expelled. The old Ranzellaar of the village, who had the voice most potential in the deliberations of the township, after hearing what had happened, pronounced that Sweyn Erickson had gone too far in raising the market upon Mr. Mertoun; and that whatever pretext the tacksman might assume for thus giving way to his anger, the real grievance must have been the charging the rock cod-fish at a penny instead of a half-penny a-pound; he therefore exhorted all the community never to raise their exactions in future beyond the[Pg 17] proportion of threepence upon the shilling, at which rate their master at the Castle could not reasonably be expected to grumble, since, as he was disposed to do them no harm, it was reasonable to think that, in a moderate way, he had no objection to do them good. “And three upon twelve,” said the experienced Ranzellaar, “is a decent and moderate profit, and will bring with it God’s blessing and Saint Ronald’s.”

Proceeding upon the tariff thus judiciously recommended to them, the inhabitants of Jarlshof cheated Mertoun in future only to the moderate extent of twenty-five per cent; a rate to which all nabobs, army-contractors, speculators in the funds, and others, whom recent and rapid success has enabled to settle in the country upon a great scale, ought to submit, as very reasonable treatment at the hand of their rustic neighbours. Mertoun at least seemed of that opinion, for he gave himself no farther trouble upon the subject of his household expenses.

The conscript fathers of Jarlshof, having settled their own matters, took next under their consideration the case of Swertha, the banished matron who had been expelled from the Castle, whom, as an experienced and useful ally, they were highly desirous to restore to her office of housekeeper, should that be found possible. But as their wisdom here failed them, Swertha, in despair, had recourse to the good offices of Mordaunt Mertoun, with whom she had acquired some favour by her knowledge in old Norwegian ballads, and dismal tales concerning the Trows or Drows, (the dwarfs of the Scalds,) with whom superstitious eld had peopled many a lonely cavern and brown dale in Dunrossness, as in every other district of Zetland. “Swertha,” said the[Pg 18] youth, “I can do but little for you, but you may do something for yourself. My father’s passion resembles the fury of those ancient champions, those Berserkars, you sing songs about.”

“Ay, ay, fish of my heart,” replied the old woman, with a pathetic whine; “the Berserkars(c) were champions who lived before the blessed days of Saint Olave, and who used to run like madmen on swords, and spears, and harpoons, and muskets, and snap them all into pieces, as a finner[14] would go through a herring-net, and then, when the fury went off, they were as weak and unstable as water.”[15]

“That’s the very thing, Swertha,” said Mordaunt. “Now, my father never likes to think of his passion after it is over, and is so much of a Berserkar, that, let him be desperate as he will to-day, he will not care about it to-morrow. Therefore, he has not filled up your place in the household at the Castle, and not a mouthful of warm food has been dressed there since you went away, and not a morsel of bread baked, but we have lived just upon whatever cold thing came to hand. Now, Swertha, I will be your warrant, that if you go boldly up to the Castle, and enter upon the discharge of your duties as usual, you will never hear a single word from him.”

Swertha hesitated at first to obey this bold counsel. She said, “to her thinking, Mr. Mertoun, when he was angry, looked more like a fiend than any Berserkar of them all; that the fire flashed from[Pg 19] his eyes, and the foam flew from his lips; and that it would be a plain tempting of Providence to put herself again in such a venture.”

But, on the encouragement which she received from the son, she determined at length once more to face the parent; and, dressing herself in her ordinary household attire, for so Mordaunt particularly recommended, she slipped into the Castle, and presently resuming the various and numerous occupations which devolved on her, seemed as deeply engaged in household cares as if she had never been out of office.

The first day of her return to her duty, Swertha made no appearance in presence of her master, but trusted that after his three days’ diet on cold meat, a hot dish, dressed with the best of her simple skill, might introduce her favourably to his recollection. When Mordaunt had reported that his father had taken no notice of this change of diet, and when she herself observed that in passing and repassing him occasionally, her appearance produced no effect upon her singular master, she began to imagine that the whole affair had escaped Mr. Mertoun’s memory, and was active in her duty as usual. Neither was she convinced of the contrary until one day, when, happening somewhat to elevate her tone in a dispute with the other maid-servant, her master, who at that time passed the place of contest, eyed her with a strong glance, and pronounced the single word, Remember! in a tone which taught Swertha the government of her tongue for many weeks after.

If Mertoun was whimsical in his mode of governing his household, he seemed no less so in his plan of educating his son. He showed the youth but few symptoms of parental affection; yet, in his ordinary[Pg 20] state of mind, the improvement of Mordaunt’s education seemed to be the utmost object of his life. He had both books and information sufficient to discharge the task of tutor in the ordinary branches of knowledge; and in this capacity was regular, calm, and strict, not to say severe, in exacting from his pupil the attention necessary for his profiting. But in the perusal of history, to which their attention was frequently turned, as well as in the study of classic authors, there often occurred facts or sentiments which produced an instant effect upon Mertoun’s mind, and brought on him suddenly what Swertha, Sweyn, and even Mordaunt, came to distinguish by the name of his dark hour. He was aware, in the usual case, of its approach, and retreated to an inner apartment, into which he never permitted even Mordaunt to enter. Here he would abide in seclusion for days, and even weeks, only coming out at uncertain times, to take such food as they had taken care to leave within his reach, which he used in wonderfully small quantities. At other times, and especially during the winter solstice, when almost every person spends the gloomy time within doors in feasting and merriment, this unhappy man would wrap himself in a dark-coloured sea-cloak, and wander out along the stormy beach, or upon the desolate heath, indulging his own gloomy and wayward reveries under the inclement sky, the rather that he was then most sure to wander unencountered and unobserved.

As Mordaunt grew older, he learned to note the particular signs which preceded these fits of gloomy despondency, and to direct such precautions as might ensure his unfortunate parent from ill-timed interruption, (which had always the effect of driving him[Pg 21] to fury,) while, at the same time, full provision was made for his subsistence. Mordaunt perceived that at such periods the melancholy fit of his father was greatly prolonged, if he chanced to present himself to his eyes while the dark hour was upon him. Out of respect, therefore, to his parent, as well as to indulge the love of active exercise and of amusement natural to his period of life, Mordaunt used often to absent himself altogether from the mansion of Jarlshof, and even from the district, secure that his father, if the dark hour passed away in his absence, would be little inclined to enquire how his son had disposed of his leisure, so that he was sure he had not watched his own weak moments; that being the subject on which he entertained the utmost jealousy.

At such times, therefore, all the sources of amusement which the country afforded, were open to the younger Mertoun, who, in these intervals of his education, had an opportunity to give full scope to the energies of a bold, active, and daring character. He was often engaged with the youth of the hamlet in those desperate sports, to which the “dreadful trade of the samphire-gatherer” is like a walk upon level ground—often joined those midnight excursions upon the face of the giddy cliffs, to secure the eggs or the young of the sea-fowl; and in these daring adventures displayed an address, presence of mind, and activity, which, in one so young, and not a native of the country, astonished the oldest fowlers.[16][Pg 22]

At other times, Mordaunt accompanied Sweyn and other fishermen in their long and perilous expeditions to the distant and deep sea, learning under their direction the management of the boat, in which they equal, or exceed, perhaps, any natives of the British empire. This exercise had charms for Mordaunt, independently of the fishing alone.

At this time, the old Norwegian sagas were much remembered, and often rehearsed, by the fishermen, who still preserved among themselves the ancient Norse tongue, which was the speech of their forefathers. In the dark romance of those Scandinavian tales, lay much that was captivating to a youthful ear; and the classic fables of antiquity were rivalled at least, if not excelled, in Mordaunt’s opinion, by the strange legends of Berserkars, of Sea-kings, of dwarfs, giants, and sorcerers, which he heard from the native Zetlanders. Often the scenes around him were assigned as the localities of the wild poems, which, half recited, half chanted by voices as hoarse, if not so loud, as the waves over which they floated, pointed out the very bay on which they sailed as the scene of a bloody sea-fight; the scarce-seen heap of stones that bristled over the projecting cape, as the dun, or castle, of some potent earl or noted pirate; the distant and solitary grey stone on the lonely moor, as marking the grave of a hero; the wild cavern, up which the sea rolled in heavy, broad, and unbroken billows, as the dwelling of some noted sorceress.[17]

The ocean also had its mysteries, the effect of which was aided by the dim twilight, through[Pg 23] which it was imperfectly seen for more than half the year. Its bottomless depths and secret caves contained, according to the account of Sweyn and others, skilled in legendary lore, such wonders as modern navigators reject with disdain. In the quiet moonlight bay, where the waves came rippling to the shore, upon a bed of smooth sand intermingled with shells, the mermaid was still seen to glide along the waters, and, mingling her voice with the sighing breeze, was often heard to sing of subterranean wonders, or to chant prophecies of future events. The kraken, that hugest of living things, was still supposed to cumber the recesses of the Northern Ocean; and often, when some fog-bank covered the sea at a distance, the eye of the experienced boatman saw the horns of the monstrous leviathan welking and waving amidst the wreaths of mist, and bore away with all press of oar and sail, lest the sudden suction, occasioned by the sinking of the monstrous mass to the bottom, should drag within the grasp of its multifarious feelers his own frail skiff. The sea-snake was also known, which, arising out of the depths of ocean, stretches to the skies his enormous neck, covered with a mane like that of a war-horse, and with its broad glittering eyes, raised mast-head high, looks out, as it seems, for plunder or for victims.

Many prodigious stories of these marine monsters, and of many others less known, were then universally received among the Zetlanders, whose descendants have not as yet by any means abandoned faith in them.[18]

Such legends are, indeed, everywhere current[Pg 24] amongst the vulgar; but the imagination is far more powerfully affected by them on the deep and dangerous seas of the north, amidst precipices and headlands, many hundred feet in height,—amid perilous straits, and currents, and eddies,—long sunken reefs of rock, over which the vivid ocean foams and boils,—dark caverns, to whose extremities neither man nor skiff has ever ventured,—lonely, and often uninhabited isles,—and occasionally the ruins of ancient northern fastnesses, dimly seen by the feeble light of the Arctic winter. To Mordaunt, who had much of romance in his disposition, these superstitions formed a pleasing and interesting exercise of the imagination, while, half doubting, half inclined to believe, he listened to the tales chanted concerning these wonders of nature, and creatures of credulous belief, told in the rude but energetic language of the ancient Scalds.

But there wanted not softer and lighter amusement, that might seem better suited to Mordaunt’s age, than the wild tales and rude exercises which we have already mentioned. The season of winter, when, from the shortness of the daylight, labour becomes impossible, is in Zetland the time of revel, feasting, and merriment. Whatever the fisherman has been able to acquire during summer, was expended, and often wasted, in maintaining the mirth and hospitality of his hearth during this period; while the landholders and gentlemen of the island gave double loose to their convivial and hospitable dispositions, thronged their houses with guests, and drove away the rigour of the season with jest, glee, and song, the dance, and the wine-cup.

Amid the revels of this merry, though rigorous[Pg 25] season, no youth added more spirit to the dance, or glee to the revel, than the young stranger, Mordaunt Mertoun. When his father’s state of mind permitted, or indeed required, his absence, he wandered from house to house a welcome guest whereever he came, and lent his willing voice to the song, and his foot to the dance. A boat, or, if the weather, as was often the case, permitted not that convenience, one of the numerous ponies, which, straying in hordes about the extensive moors, may be said to be at any man’s command who can catch them, conveyed him from the mansion of one hospitable Zetlander to that of another. None excelled him in performing the warlike sword-dance, a species of amusement which had been derived from the habits of the ancient Norsemen. He could play upon the gue, and upon the common violin, the melancholy and pathetic tunes peculiar to the country; and with great spirit and execution could relieve their monotony with the livelier airs of the North of Scotland. When a party set forth as maskers, or, as they are called in Scotland, guizards, to visit some neighbouring Laird, or rich Udaller, it augured well of the expedition if Mordaunt Mertoun could be prevailed upon to undertake the office of skudler, or leader of the band. Upon these occasions, full of fun and frolic, he led his retinue from house to house, bringing mirth where he went, and leaving regret when he departed. Mordaunt became thus generally known and beloved as generally, through most of the houses composing the patriarchal community of the Main Isle; but his visits were most frequently and most willingly paid at the mansion of his father’s landlord and protector, Magnus Troil.[Pg 26]

It was not entirely the hearty and sincere welcome of the worthy old Magnate, nor the sense that he was in effect his father’s patron, which occasioned these frequent visits. The hand of welcome was indeed received as eagerly as it was sincerely given, while the ancient Udaller, raising himself in his huge chair, whereof the inside was lined with well-dressed sealskins, and the outside composed of massive oak, carved by the rude graving-tool of some Hamburgh carpenter, shouted forth his welcome in a tone, which might, in ancient times, have hailed the return of Ioul, the highest festival of the Goths. There was metal yet more attractive, and younger hearts, whose welcome, if less loud, was as sincere as that of the jolly Udaller. But this is matter which ought not to be discussed at the conclusion of a chapter.

[11] i. e. The deep-sea fishing, in distinction to that which is practised along shore.

[12] The operation of slicing the blubber from the bones of the whale, is called, technically, flinching.

[13] Meaning, probably, Patrick Stewart, Earl of Orkney, executed for tyranny and oppression practised on the inhabitants of those remote islands, in the beginning of the seventeenth century.

[14] Finner, small whale.

[15] The sagas of the Scalds are full of descriptions of these champions, and do not permit us to doubt that the Berserkars, so called from fighting without armour, used some physical means of working themselves into a frenzy, during which they possessed the strength and energy of madness. The Indian warriors are well known to do the same by dint of opium and bang.