WHG Kingston

"Arctic Adventures"

Chapter One.

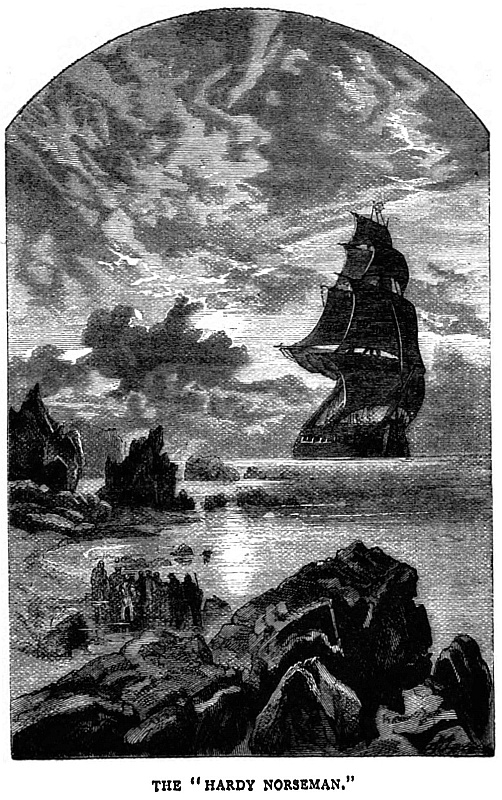

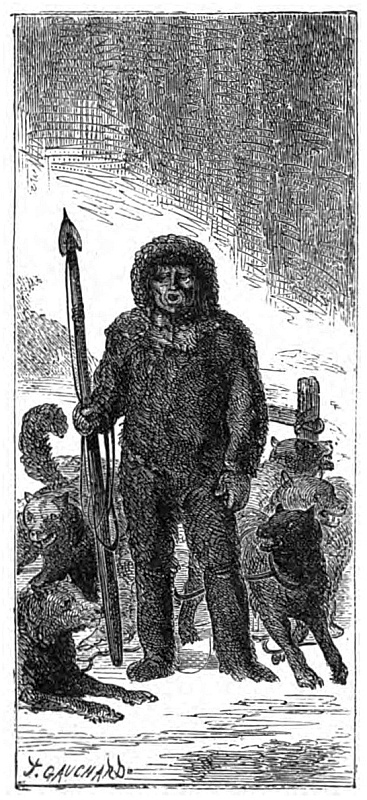

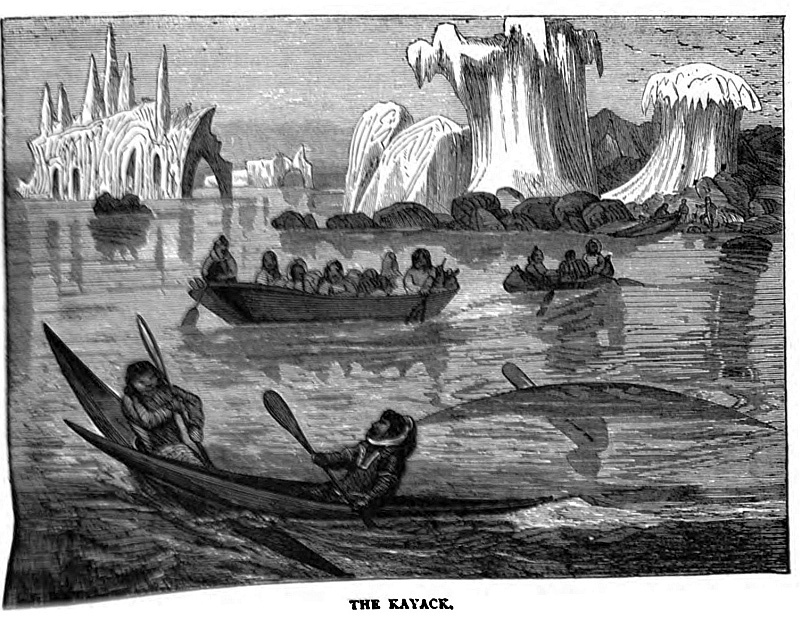

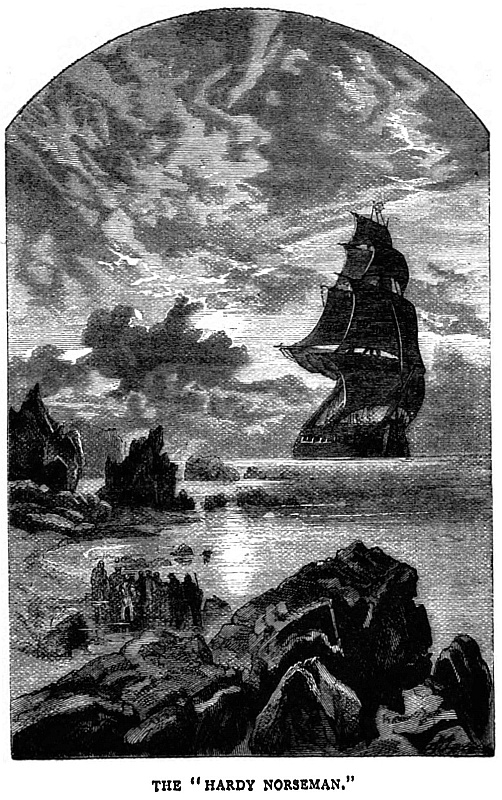

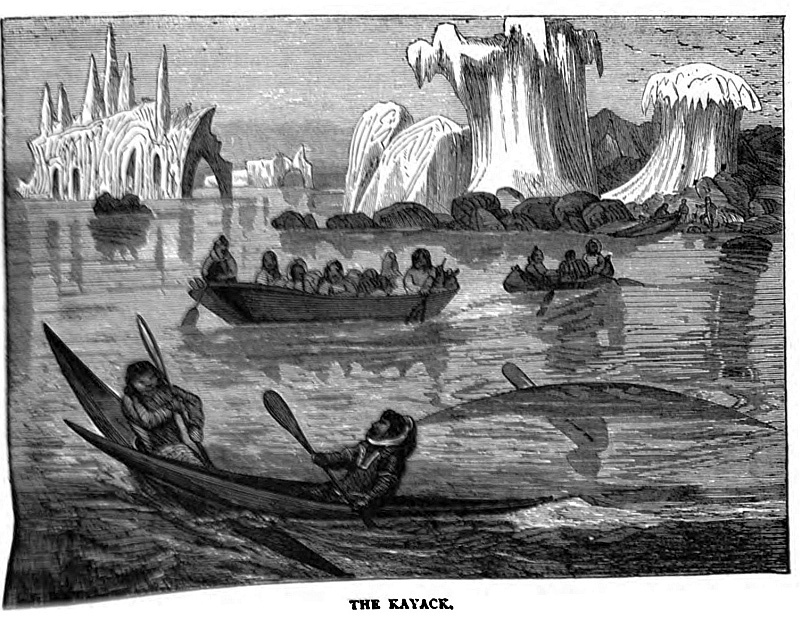

I had often dreamed of icebergs and Polar bears, whales and rorquals, of walruses and seals, of Esquimaux, and Laplanders and kayaks, of the Aurora Borealis and the midnight sun, and numerous other wonders of the arctic regions, and here was I on board the stout ship the Hardy Norseman, of and from Dundee, Captain Hudson, Master, actually on my way to behold them, to engage in the adventures, and perchance to endure the perils and hardships which voyagers in those northern seas must be prepared to encounter.

Born in the Highlands, and brought up by my uncle, the laird of Glenlochy, a keen sportsman, I had been accustomed to roam over my native hills, rifle in hand, often without shoes, the use of which I looked upon as effeminate. I feared neither the biting cold, nor the perils I expected to meet with. I had a motive also for undertaking the trip. My brother Andrew had become surgeon of the Hardy Norseman and we were both anxious to obtain tidings of our second brother David, who had gone in the same capacity on board the Barentz, which had sailed the previous year on a whaling and sealing voyage to Spitzbergen and Nova Zembla, and had not since been heard of. I was younger than either, and had not yet chosen my future profession; though, having always had a fancy for the sea, I was glad of an opportunity of judging how near the reality approached my imaginings, besides the chief motive which had induced me to apply to our old friend Captain Hudson for leave to accompany Andrew.

I had undertaken to make myself generally useful, to act as purser and captain’s clerk, to assist in taking care of the ship when the boats were away, and to help my brother when necessary, so that I was generally known as the “doctor’s mate.”

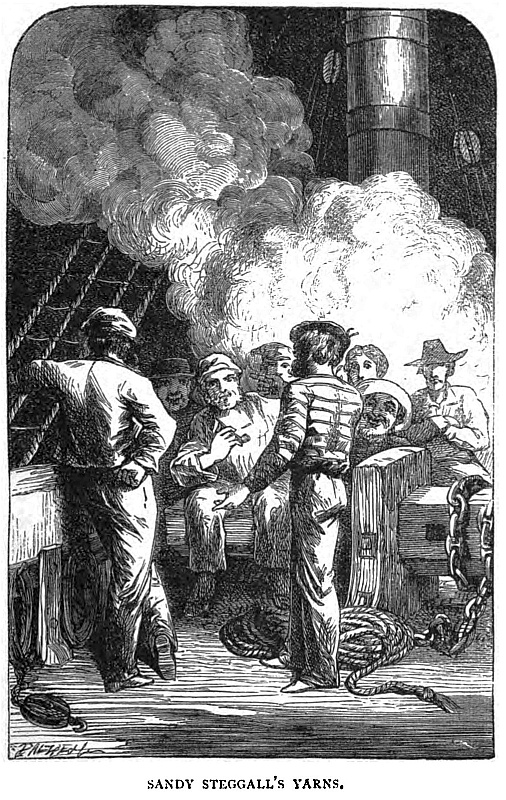

The Hardy Norseman’s crew consisted of Scotchmen, Shetlanders, Orkney men, Norwegians, and Danes. The most notable among them was Sandy Steggall, the boatswain, a bold harpooner, who possessed a tongue—the second mate used to say—as long as a whale spear, which he kept wagging day and night, and I got no little insight into the particulars of our future life by listening to his yarns.

We had not been long at sea, when one night, it having fallen calm, I went forward, where I found the watch on deck assembled, Sandy and two or three others holding forth in succession, though the boatswain, by virtue of his rank, claimed the right of speaking the oftenest. Wonderful were Sandy’s yarns. He told how once he had been surprised by a bear, when, as he was on the point of being carried off, he stuck his long knife into bruin’s heart, and the creature fell dead at his feet. On another occasion, when landing on the coast of Spitzbergen, he and his companions found a hut with three dead men within, and others lying in shallow graves, the former having buried the latter, and then died themselves, without a human soul near to close their eyes. Again, he had come upon the grave of an old shipmate who had been dead twenty years, whose features, frozen into marble, looked as fresh as when first placed there, the only change being that his hair and beard had grown more than half a fathom in length.

Yarn after yarn of shipwreck and disaster was spun, until I began to wish that David had not gone to sea, and that we could have avoided the necessity of going to look for him.

With the bright sun-light of the next morning I had forgotten the more sombre hues of his narratives, and looked forward with as much eagerness as at first to the adventures we might meet with.

That afternoon I had occasion to go into the hold, accompanied by the boatswain and another man carrying a lantern, to search for some stores which ought to have been stowed aft, when, as I was looking about, I fancied I heard a moan. I called the attention of the boatswain to it. We listened.

“Bring the light here, Jack!” he said to the seaman, and he made his way in the direction whence the sound proceeded. Presently, as he stooped down, I heard him exclaim—

“Where do you come from, my lad?”

“From Dundee. I wanted to go to sea, so I got in here,” answered the person to whom he spoke, in a weak voice.

“Come out then and show yourself,” said Sandy.

“But that’s more than I can do!” was the answer.

“I’ll help you then,” returned the boatswain, dragging out a lad about my own age, apparently so weak and cramped as to be utterly unable to help himself.

“We must carry you to the doctor, for we don’t want to let you die, though you have no business to be here,” observed Sandy, with a look of commiseration. He afterwards remarked to me, “I did the same thing myself, and I couldna say anything hard to the puir laddie.”

The boatswain at once carried the young stranger up on deck. The captain had begun to rate him well for coming on board without leave, but seeing that he was ill fit to bear it, he told me to summon the doctor, who was below.

I called Andrew, who returned with me to the deck.

“What’s your name?” asked the captain, while Andrew was feeling his pulse.

“Ewen Muckilligan,” was the answer.

As I heard the name, I looked more particularly than before at the young stowaway’s features, and recognised an old schoolfellow and chum of mine. Both his parents being dead, he had been left under charge of some relatives who cared very little for him.

“He only requires some food to bring him round, but the sooner he has it the better,” observed Andrew.

With the captain’s permission, I got him placed in my berth, where, after swallowing a basin of broth, he fell asleep. By frequent repetition of the same remedy, he was able, after a couple of days, to stand on his feet, when the captain administered a severe lecture, telling him that he must send him back by the first vessel we might fall in with. Ewen, however, begged so hard to remain, that the captain promised to consider the matter.

“I may as well make a virtue of necessity, for we are not at all likely to fall in with any homeward-bound craft,” he afterwards observed to Andrew.

Hearing this, I told Ewen that he might make his mind easy, that if he had determined to be a sailor he had now an opportunity of learning his profession, though he would gain his experience in a very rough school.

As Ewen was in every sense a gentleman, he was allowed to mess with us; for which permission I was very grateful to Captain Hudson, as most captains would have sent him forward to take his chance with the men. He soon proved that he intended to adhere to his resolution. On all occasions he showed his willingness to do whatever he was set to, while he was as active and daring as any one on board.

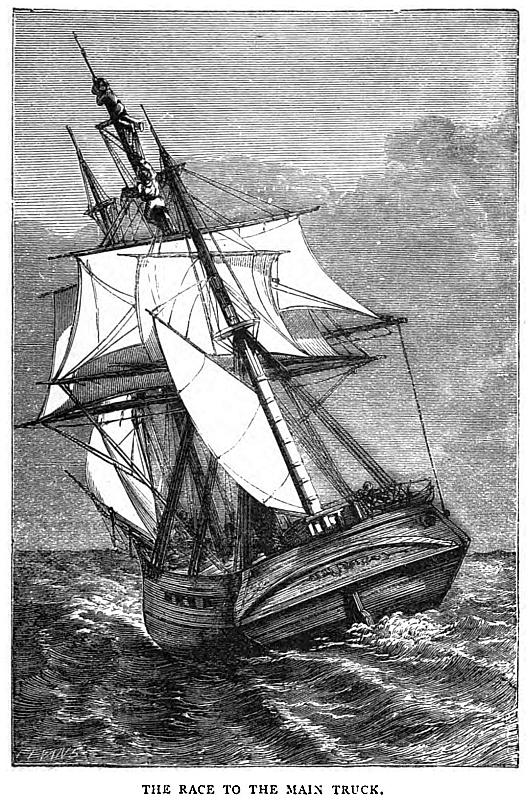

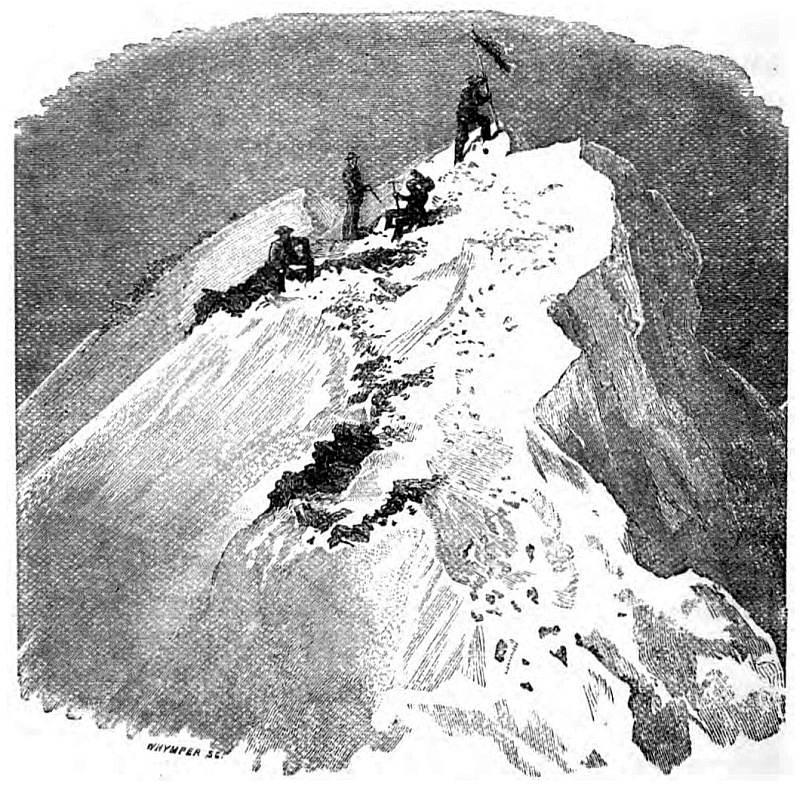

We were forward one evening, talking to the men, after they had knocked off work, the second mate having charge of the deck, the captain, first mate, and Andrew being below, when it was suggested that we two should try who could first reach the main truck. One was to start from the fore-top, the other from the mizen cross-trees. We were to come down on deck and then ascend the mainmast. We cast lots. It was decided that Ewen should start from the fore-top, I from the latter position. The second mate liked the fun, and did not interfere. We took up our positions, waiting for the signal—the wave of a boat-flag from the deck. The moment I saw it, without waiting to ascertain what Ewen was about, I began to run down the mizen shrouds; he in the meantime descended by the back stay and was already half up the main rigging on the port side before I had my feet on the ratlines on the starboard side. When once there I made good play, but he kept ahead of me and had already reached the royal-mast, swarming up it, before I had got on the cross-trees. As he gained the truck he shouted “Won! won!”

I slid down, acknowledging myself defeated, and feeling not a little exhausted by my exertions. Judging by my own sensations, I feared that he might let go and be killed. I dared not, as I made my way down, look up to see what he was doing. Scarcely had I put my foot on deck than he stood by my side, having descended by the back stay.

The crew applauded both of us, and Ewen was greatly raised in their estimation when they found that he had never been before higher than the maintop.

Sandy Steggall, the boatswain, however, who soon afterwards came on deck, scolded both of us for our folly, and rated the men well for encouraging us.

“What would ye have said if these twa laddies had broken their necks, or fallen overboard and been drowned?” he exclaimed.

We had, I should have said, four dogs on board, all powerful animals; two were Newfoundland dogs, one was a genuine Mount Saint Bernard, and a fourth was a mongrel, a shaggy monster, brought by our captain from Norway. They were known respectively as Bruno, Rob, Alp and Nap.

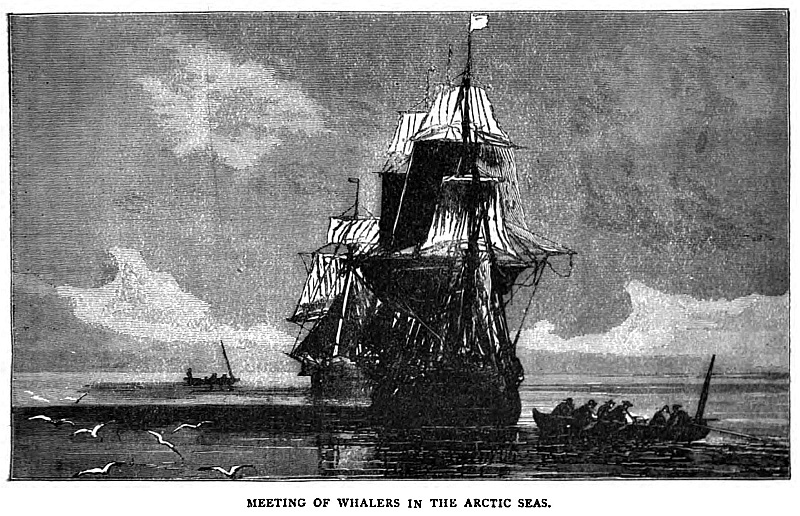

We had crossed the Arctic circle, sighted the coast of Norway; and, with the crow’s nest at the mast head, and the boats all ready, we were approaching the latitude where we might expect at any hour to fall in with ice. We had already seen several rorquals or finners; but those mighty monsters of the deep, the largest species of the whale, it was considered unadvisable to attack, as they afford comparatively little oil and are apt to turn upon the boats and destroy them.

“There she spouts! There she spouts!” shouted the captain from the crow’s nest, which he or one of the mates had occupied continually.

In a few minutes the boats were in the water, and the watch below came tumbling on deck, carrying their clothes with them. As I could pull a good oar, I got a seat in one of the boats. We were in chase of the true whale, which can easily be distinguished from the rorqual by the mode of its spouting. Marking the spot where it sounded, we had hopes of getting up to it the next time it should rise to the surface.

We lay on our oars waiting anxiously for its appearance. Presently up it came half a mile off. We gave way with a will. As we approached the monster, our harpooner, Sandy, throwing in his oar, got his gun ready. He fired, and in a moment we were fast. The sea around us was broken into foam, and we were covered with spray as the creature dived, dragging out the line which flew over the bollard at a rate which would soon have set it on fire had not water been thrown upon it. Immediately a staff, with the Jack at the end, was raised in our boat as a signal that we were fast, and the other two boats came pulling up to our assistance. Two lines were drawn out, and the boat was dragged along at a rapid rate, sending the water flying over her bows. At length the pace slackened and we were able to haul in our line until the whole of one and part of the other was again coiled away in the tubs. By this time the other boats had reached us. First one on one side, then on the other, got close enough to fire two more harpoons into the body of the monster, besides which several lances were darted into it. Again the whale dived, leaving the surface covered with blood and oil, but it was only for a short time. Now again rising, she lay almost motionless, while we pulled up and plied her with our deadly lances, trying to find out the most vital parts. Then there came a cry of “Back! back! all of you!”

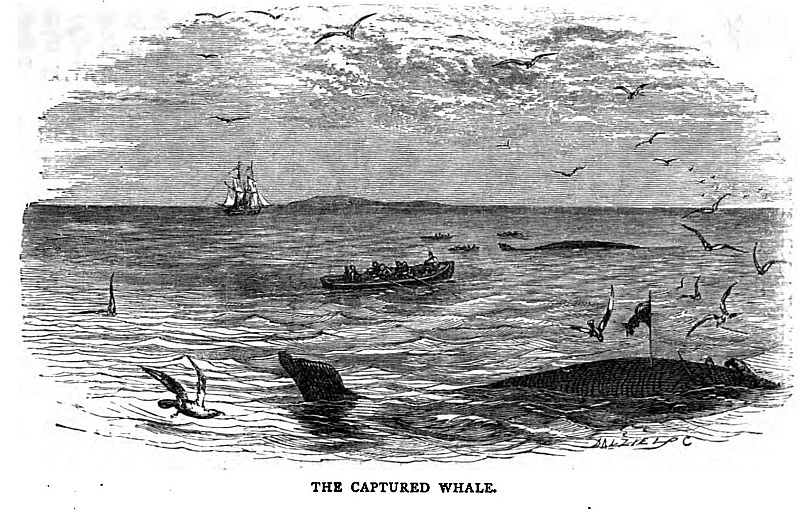

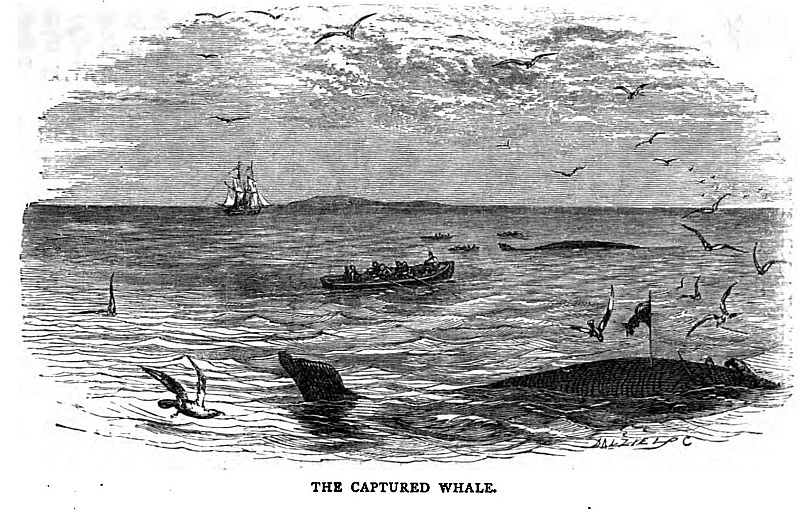

We had barely time to escape from beneath her flukes, with which she furiously lashed the water, until, her strength exhausted, she floated a lifeless mass.

A jack was stuck into her body and we made chase after a second whale which had just before appeared, and after a pretty severe fight we succeeded in killing it. We had now to tow our two prizes alongside the ship, already a considerable distance off, the wind being too light to enable her to beat up to us. As only one of the whales could be brought alongside at a time, the last we killed was taken in tow by the other boats, while we remained with the first which we had struck.

“Come, lads,” said Sandy, “we will take our fish in tow, and get as near the ship as we can. The weather looks a bit threatening, and the sooner we are alongside the better.”

We did as he advised, though we made but little progress. We had not gone far when another whale was seen spouting in an opposite direction to the ship. The temptation to try to kill it was too great to be resisted, and, regardless of the threatening look of the weather, casting off from our prize we made chase. The whale sounded just before we got up to her, but we knew she would rise to the surface again before long, and we lay on our oars waiting for her appearance.

“There she spouts, there she spouts!” cried Sandy, and we saw, not a quarter of a mile off, our chase.

Again we gave way. As we got close to the monster Sandy stood up with his gun ready. He fired, following up his shot with his hand harpoon. The lines ran out at a rapid rate until the ends were reached and we had no others to bend on.

Instead of sounding, the whale swam along the surface, dragging the boat after her right in the wind’s eye, while the foam in thick masses flew over us. The sea was getting up, and soon not only spray but the tops of the waves came washing over the gunwale. Still our only chance of winning the prize was to hold on, and we hoped, from the exertions the whale was making, that its strength would soon be exhausted. I looked astern. The ship was nowhere to be seen, nor could I distinguish the flag of the other whale. Our position was critical, and we had to depend entirely upon ourselves. At length the whale began to slacken its speed, and we began to haul in the lines. Sandy got another gun ready, and had half-a-dozen lances at hand to dart into the back of the monster when we should get up to it. We were within half-a-dozen fathoms when, suddenly raising its huge flukes, down it went again, dragging out the lines.

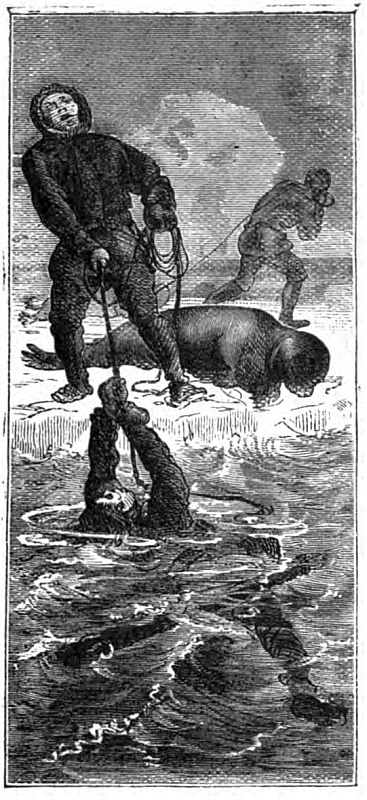

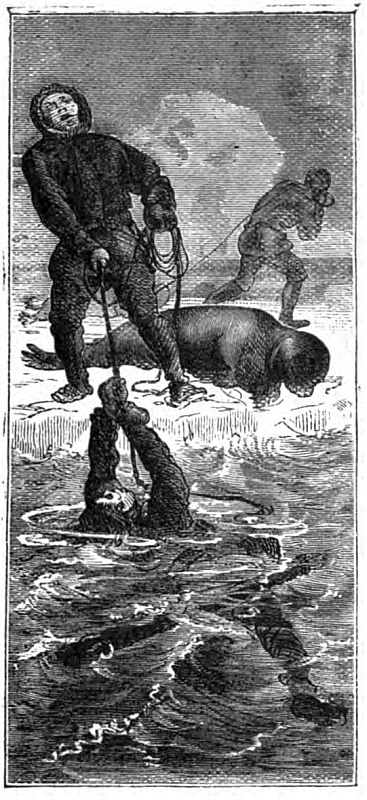

Suddenly the man whose business it was to attend to the coil of the hand harpoon gave a loud cry. Before anyone could stop him he was overboard, disappearing in an instant under the water. It was no use cutting the line, and, unless by a miracle the whale should return to the surface, his fate was sealed. Out ran the lines, but a few fathoms remained in the tubs.

“Get the axe ready, Tom,” said Sandy to the man who had taken the other poor fellow’s place. In vain he attempted to take a turn round the bollard, to check the monster’s descent; each time that he did so the bows dipped, and it seemed as if the boat must inevitably be drawn down, but as he let the line out her bows rose. Still the hope of obtaining the whale made him hold on. We might also recover the body of our shipmate; that he should be alive we knew was impossible. The line ran out, it was near the bitter end. I sprang to the after-part of the boat to assist in counter-balancing the pressure forward. But this did not avail, already the water was rushing over the bows. Two sharp blows were given. The whale was loose. We might yet, however, recover the lines, as the wounds the monster had received must ultimately prove mortal.

Again we took to our oars to keep the boat’s head to the sea, while we watched for the reappearance of the whale which we knew must soon rise to the surface. We had been too eagerly engaged to pay attention to the appearance of the weather. It had now, we found, become very much worse than before. Even should we kill the whale we could not hope to tow it to the ship. With bitter disappointment we had to acknowledge that our shipmate’s life had been uselessly lost and our own labour thrown away, while we could only hope against hope that the weather would again moderate and that we should fall in with the whale we had before killed.

We had now to consider our own safety, and to try to get back to the ship. We knew that she would have beat up to the boats which had the whale in tow. We had the wind in our favour, but to run before the fast rising seas would soon be perilous in the extreme. It must be done, however, for we had come away without food or water, and hunger and thirst made us doubly anxious to get on board.

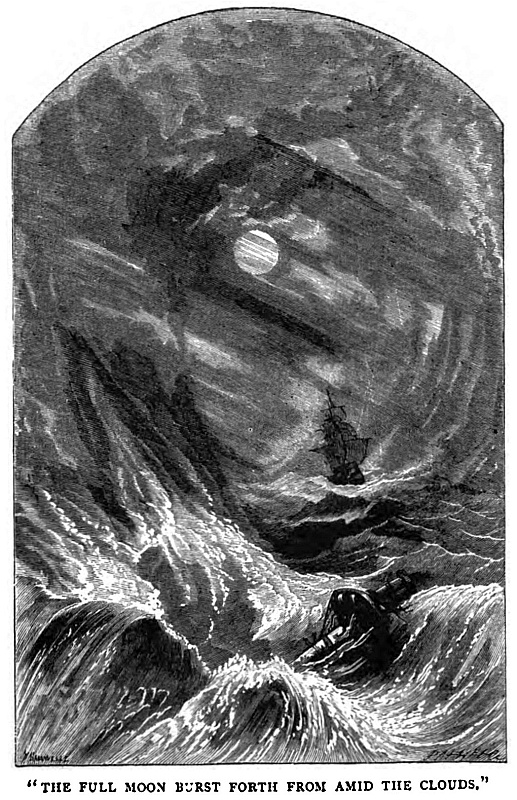

Already the sun had set. We had been a far longer time away than we had supposed. Night came down upon us. The boat’s compass feebly lighted by the lantern would, however, enable us to steer a proper course. We bent to our oars, but, unaccustomed to pull in so heavy a sea, I had great difficulty in keeping mine moving. Every instant it seemed as if we must be overwhelmed by the foaming billows which rolled up astern.

Sandy had taken his place at the steering oar, and with cheering words urged us to continue our exertions; but all hands by this time were pretty well knocked up with what we had previously gone through.

We tugged and tugged away; now a sea roared up on one side, now on the other; now we plunged down into a deep gulf from which it seemed as if we should never rise. I had supposed it impossible that a boat could live in such tumultuous waters. Not a star could be discovered over head, while around we could only dimly discern dark liquid masses capped with hissing foam. How earnestly I longed for daylight and quiet, and to be once more on the deck of our ship! I knew too how anxious my brother would be. Though tumbled and tossed, the boat still continued to float. Hour after hour passed by, they seemed to be days or weeks. We had been pulling I fancied all night, and expected daylight every moment to appear, when Sandy exclaimed—

“Hurrah boys, there’s the ship’s light. We shall get safe on board now.”

Although we could see the ship’s light, we could not be seen from her deck, and she might be standing away from us. Sandy anxiously watched the light, then altered our course more to the eastward, whereby the sea being brought on our beam rendered our condition even more dangerous than before. Sandy assured us, however, that we were getting nearer; and at last, believing that we might be heard, we all shouted together at the top of our voices, forgetting that the rattling of the blocks and dash of the sea against the sides of the ship would have rendered our cries inaudible. I had for long been pulling on mechanically, scarcely knowing what I was about, when I heard Sandy again shout out, “Heave lad, heave,” and looking round I saw the bowman standing up with a rope in his hand. It had been hove to him, but the end must have been slack. We had now to regain the ship which was flying from us, but could that be done, I asked myself.

Again Sandy cheered us up by exclaiming, “She’ll heave to, lads; never doubt it, she’ll heave to.”

Of that I feared there was but little chance, for her dark hull quickly again disappeared, and I could no longer see even the least glimmer of light. Sandy, however, declared that he could, and on we pulled as before. I should have said that we passed another long hour before we once more saw the hull of the ship, and her tall masts swaying to and fro against the sky. It was no easy matter to get alongside, half full of water as was our boat. Thanks to the skill of Sandy, we at length succeeded in hooking on, and the boat was hoisted on board, by which time I was more dead than alive.

My brother and Ewen carried me below, and I was speedily restored by a basin of hot broth. Ewen had begun to tell me what had happened to the other boats and the whale, when, eager as I was to know, I dropped off fast asleep.

In the morning, when I awoke, I found a furious gale raging, and the ship hove to. It was a mercy we had got on board when we did, for if not we should in all probability have been lost. Andrew told me that the whale had been towed up alongside, but that, before half the blubber had been cut off, they had been compelled to cast it adrift. The captain intended to wait where we were in the hopes of again getting hold of it, and of picking up the other whale we had killed, and perhaps also the one we had wounded.

I had now to learn what a down-right gale at sea really is. I had thought it would be good fun, but I found it very much the contrary. The stout ship was tossed about like a shuttle-cock; the masts, yards, bulkheads, and every timber in her, creaked and groaned; the leaden seas capped with foam, now rose high above the bulwarks, now sank down forming a yawning gulf, while the stout ship was tossed from one wave to the other like a shuttle-cock. As my duty did not require me to be on deck, I lay down, fearfully tired, intending to go to sleep; but, before I dropped off, the captain came into his cabin to look at his chart. I asked him to tell me our position. We had been drifting some hours to the northward, and Bear Island, which lies between Spitzbergen and Norway, was not far off.

While he was sitting at the table with his compasses in his hand, I felt a sudden shock, and, though for an instant the ship appeared to be motionless, she trembled throughout every timber. Then came a sound like the roar of thunder, followed by a fearful crashing and rending of planks, while a sudden heave sent me and everything loose in the cabin to leeward.

The captain rushed on deck, and I sprang up after him. My first impression was that the ship was going down, and that the waves were already rolling over her.

A tremendous sea had struck her on the beam and came pouring down on our deck like a cataract sweeping all before it. Wreck and destruction met my view. The quarter-deck was cleared of rails and bulwarks, stanchions, binnacle, and the greater portion of the wheel, while one of the quarter boats, having been torn away from the davits, the wreck hung in two fragments battering against the side.

A piercing shriek reached my ear. It rose from a poor fellow whom I could see floating away to leeward on the binnacle, well knowing that no human power could assist him. Another also who had been on deck was missing, struck probably by fragments of bulwarks, and carried away.

The captain took in at a glance the state of things, and then issuing his orders in a firm tone, raised confidence in the men. A long tiller was shipped to replace the shattered wheel. The wreck was cleared. Spars were lashed to the stanchions to serve as bulwarks, and in a wonderfully short time comparative order was restored.

Chapter Two.

The gales of those northern regions during the summer though sharp are generally short. As soon as the weather moderated we made sail, to try and pick up the whales we had killed, or if unable to find them to attack others.

The carpenter and his crew meantime were busily employed in repairing damages and building another boat in lieu of the one which had been lost. A sharp look-out was kept from the crow’s nest for the dead whales, or for any fresh whales which might be seen spouting.

“I am afraid it is like looking for a needle in a haystack,” observed Sandy to me. “Still there is nothing like trying; one or two may be seen, to be sure, but as to falling in with many, it’s more than I expect we shall do, for they are mostly, do ye see, gone northward among the ice.”

Just as Sandy had delivered himself of this opinion, the second mate from the crow’s nest shouted:—

“There she spouts! There she spouts!” and pointed to the north-east.

The loud stamping of the men on deck soon summoned those who were below. The first mate took charge of one boat, and the boatswain, with whom I went, of the other. Away we pulled as fast as we could lay our backs to the oars, hoping to get up to the whale before she sounded, but we were disappointed; down she went, and we had to wait for her reappearance. It was uncertain where she would next come up. We saw the mate’s boat paddling to the northward.

“She’ll not come up there,” observed Sandy, steering to the west.

We kept our oars slowly moving, ready to give way at an instant’s notice. The result proved that neither was right, for the whale appeared between the two points.

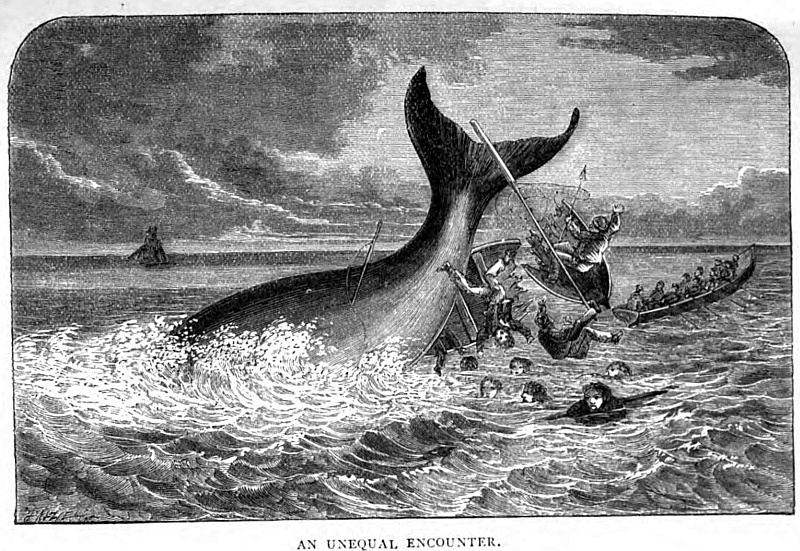

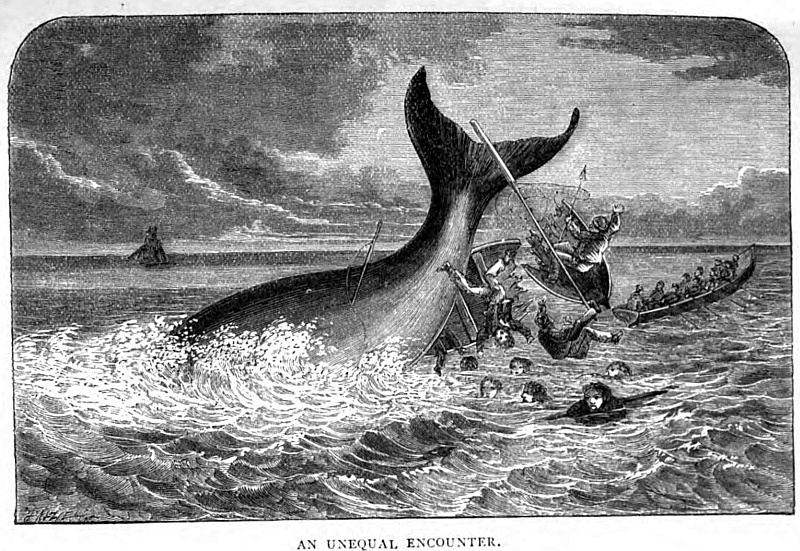

“There she spouts!” shouted Sandy, and away we pulled as if our lives depended upon our exertions. Our boat was somewhat nearer the whale than was the other, and Sandy was eager to have the honour of winning the prize. The whale was evidently one of the largest size. It had discovered our approach and seemed prepared for the encounter. Notwithstanding this we pulled on, Sandy standing in the bows with his gun ready to send his harpoon into the monster’s side. He fired and, as the line ran out, seizing his spear, he was in the act of thrusting it not far from where he had planted his harpoon, when he shouted:—

“Back of all! Back of all!”

It was indeed time, for Sandy had observed by the movements of the whale that it was about to throw itself out of the water. Before we had pulled a couple of strokes it rose completely above the surface, and, rapidly turning, down came its enormous flukes on the very centre of our boat, cutting it in two, as if a giant’s hatchet had descended upon it. Those who were able sprang overboard and swam in all directions for our lives. Two poor fellows in the centre of the boat had been struck by those ponderous flukes, and, without uttering a cry, sank immediately. While Sandy, with a spear in his hand, still clung to the bows until jerked off by a second blow, which sent that part of the boat flying into the air.

As I swam away I looked round with a horrible dread of seeing the whale open-mouthed following me; but, instead, I caught sight of its flukes raised high in the air, and down it dived, carrying out the line still fast.

Sandy shouted out to us to swim back to the wreck to try and secure the end, that the mate’s boat might get hold of it when she came up; but just then the tub itself floated away and, as may be supposed, we were all eager to get hold of whatever would assist to float us. Some clung to the fragments of the wreck, others to the oars, until rescued by the mate’s boat, which quickly reached the scene of the disaster. Had not our two shipmates lost their lives, this accident was too common an occurrence to make us think much about the matter. No sooner were we on board than we pulled away in the direction we thought the whale would reappear, knowing that it must soon come to the surface again to breathe.

As I lay exhausted in the bottom of the boat I heard the cry of “There she spouts!” and I saw the crew rowing lustily away. I soon recovered sufficiently to look about me. The mate approached cautiously, to be prepared for any vicious trick the whale might play. He fired, and I heard the men shout:—

“A fall, a fall!”

Several lances were also stuck into it. The creature dived. A second line was bent on, but before it ran to the end it slackened, and we hauled up ready to attack the whale with our lances.

By this time a third boat had come up, and when the whale appeared it was attacked on both sides. After some violent struggles it turned over on its side. It was dead.

Recollecting the loss of our two shipmates the shout of triumph was subdued, and the crews refrained from singing as usual as we towed the prize towards the ship, which was beating up to meet us.

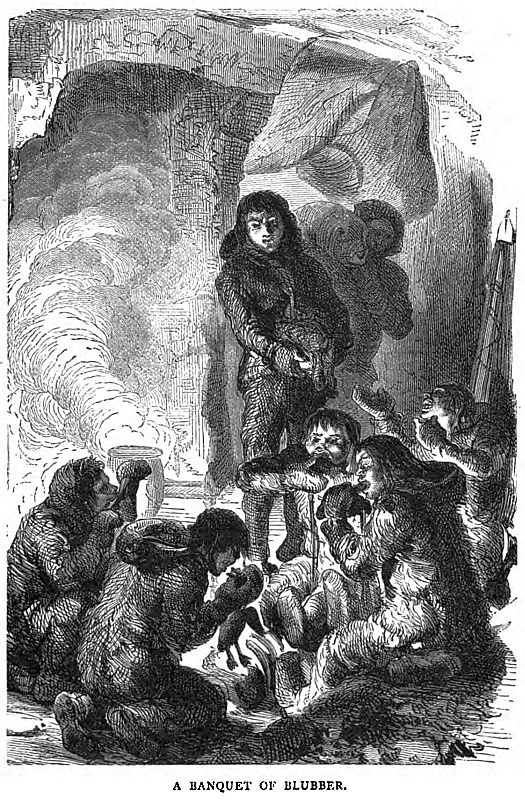

I now saw the whole operation of “flensing,” or cutting off the blubber. A band was first formed round the animal, between the head and fins, called the “kent.” To this a series of tackles, called the “kent-purchase,” was fixed, by which means, with the aid of the windlass, the body of the whale could be turned round and round. The blubber was then cut off by spades and large knives, parallel cuts being made from end to end, and then divided by cross cuts into pieces about half a ton each. These being hoisted up on deck were cut into smaller portions and stowed below in casks. The whole part of the blubber above water being cut off, the body was further turned round, so as to expose a new portion; and, this being stripped off, another turn to the body was given. The kent was then unrolled, and, the whalebone from the head being extracted, the remainder of the mass, called the “kreng,” was allowed to go adrift, affording a fine feast to the mollies, which in countless numbers had been flying round us, ready to take possession of their prize. From its power of wing and its general habits, the fulmar of the north may be likened to the albatross of the southern hemisphere. Why the fulmar is called molly I could not learn. Sandy assured me that many sailors believe the birds to be animated by the spirits of the ancient Greenland skippers.

“For because, do ye see,” he remarked, “the mollies have as great a liking for blubber as those old fellows had.”

The fulmars having gorged themselves flew away towards the nearest ice to the northward, in which direction we now steered, the captain having abandoned all hope of recovering the lost whales. Scarcely had we got the blubber stowed away than it again began to blow hard, but we were still able to steer northward, a constant look out being kept for the ice.

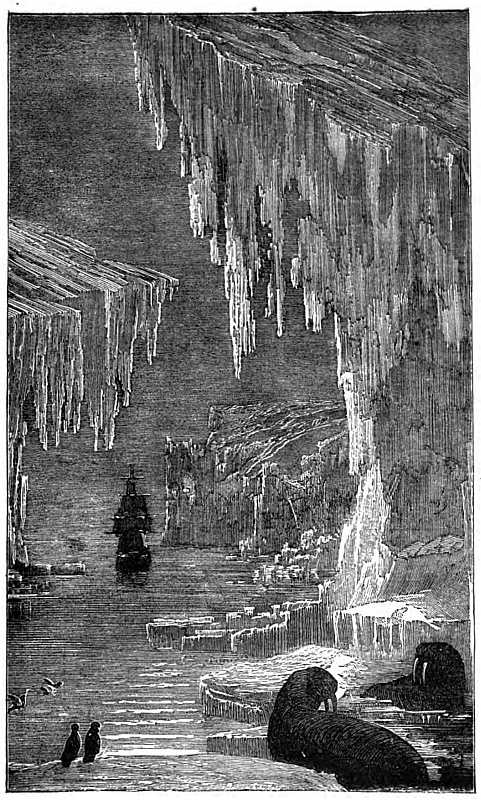

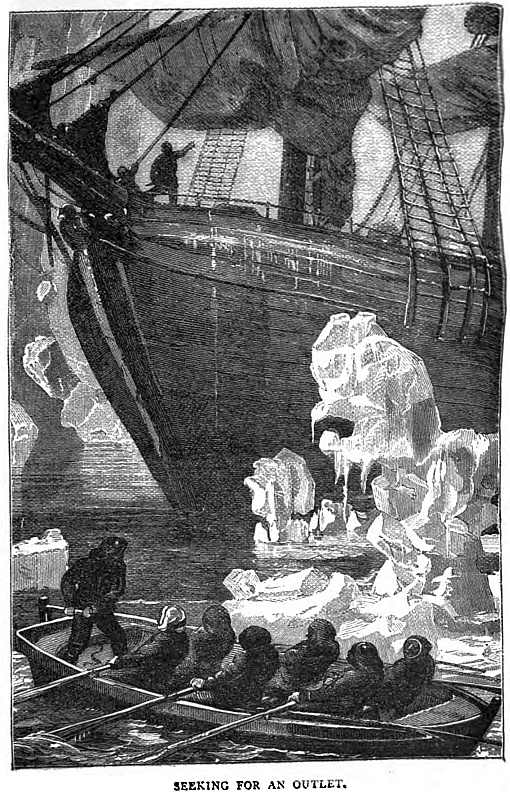

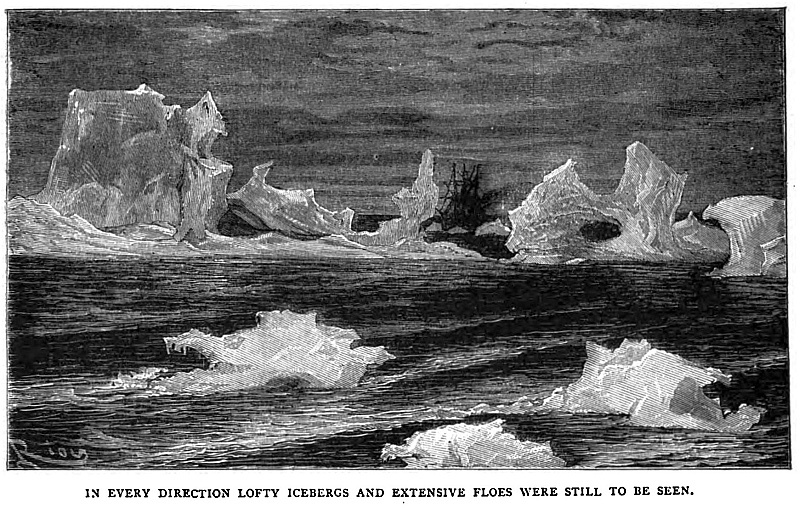

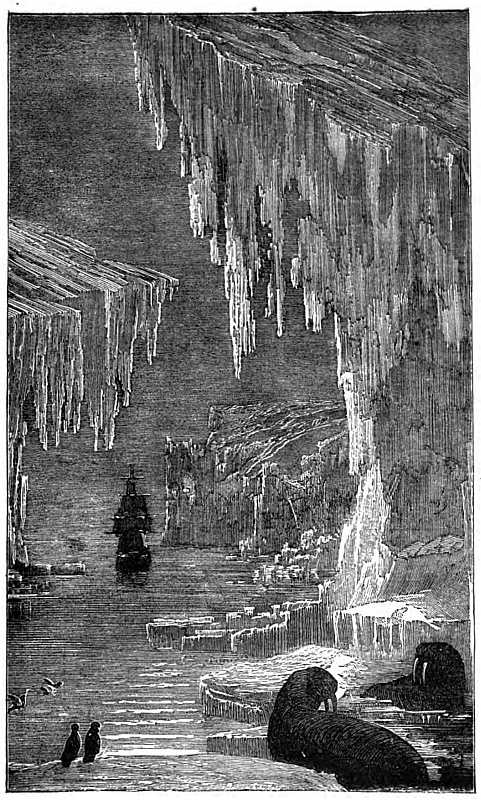

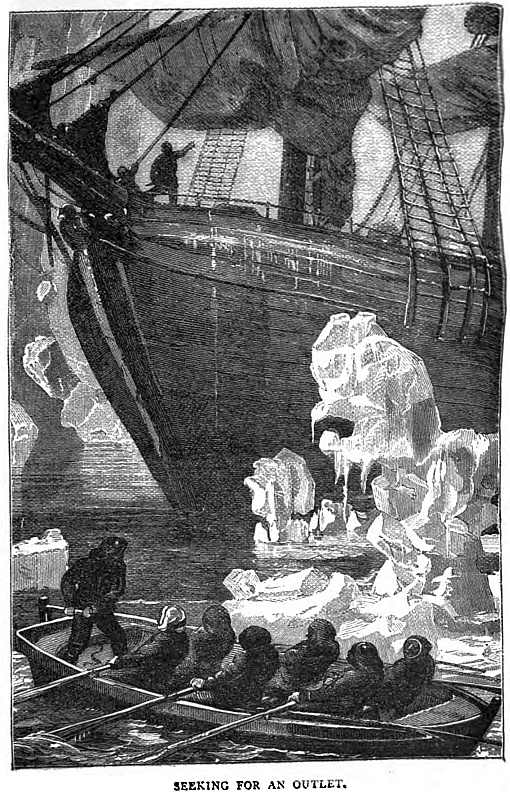

We were standing on when I heard “Hard to starboard,” shouted, and on looking ahead I saw a huge mass of ice, of fantastic shape, rising out of the water, of sufficient size, had we touched it and caused it to overturn, to have crushed the ship. Scraping by we found ourselves almost immediately afterwards surrounded by countless masses, differing greatly in size, most of them being loose drift-ice. Our stout ship, however, still continued her course, avoiding some masses and turning off other pieces from her well-protected bows. Every mile we advanced, the ice was becoming thicker. Still on we went, threading our way through the heaving masses. At length, above the ceaseless splashing sound, a roar increasing in loudness struck our ears. It was the ocean beating on the still fixed ice, and ever and anon hurling fragments against it with the force of battering rams.

“The sea is doing us good service,” observed the mate, “for it will break up the floes.”

It seemed to me much more likely that the ship would be dashed to pieces. When, however, the fixed ice could be seen from the crow’s nest, we hove to, to wait for calmer weather. There we lay, tossed about with the huge slabs and masses of ice grinding together or rolling over each other around us, and threatening every moment to come crashing down on our deck, while reiterated blows came thundering against our sides.

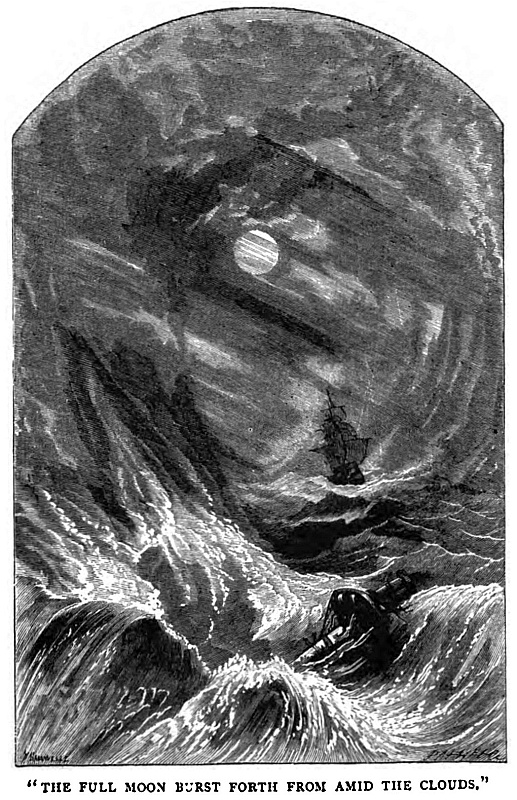

Night came on, and shortly afterwards the snow began to fall thickly, covering our deck, while from one side of the heavens the full moon burst forth from amid the clouds, lighting up the scene, increasing rather than diminishing its horrors. The snow circled in thick eddies round us, the sea foamed and raged, and masses of ice in the wildest motion were swept by; the timbers strained and creaked, while the ship shook under the reiterated shocks, sufficient it seemed to rend her into fragments, but the ice which had collected round her prevented her destruction.

Ewen and I occasionally went on deck, for to sleep was impossible. “Are you sorry you came to sea?” I asked.

“No,” he answered, “I wanted to know what a storm was like, and now I shall be satisfied, but I shall be glad when it’s calm again.”

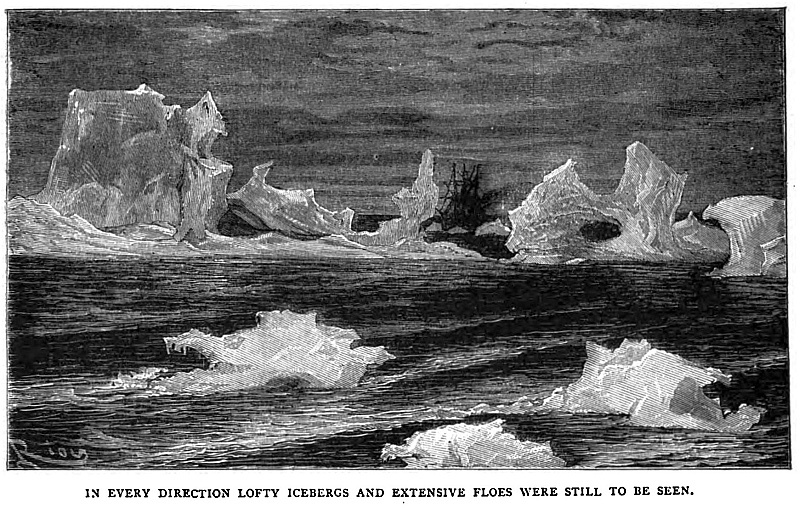

When I awoke a change had come over the scene. I went on deck, a perfect calm prevailed. All round us were piles of ice. The blocks and masses which stood out against the sky were cast into shades, while the level floes sparkled like silver in the rising sun. Far away to the southward we could still see the ocean heaving slowly. In a short time, however, leads between the bergs and floes opened out, the water being of the colour of lead. All hands were called up to make sail, and we stood on forcing our way between the floes, until open water was reached, though in every direction lofty icebergs and extensive floes were still to be seen. Many of the bergs were of the most fantastic form and brilliant colours. Some had arches of vast size, others caverns worn in them within which the ice appeared of the brightest blue and green, curtained with glittering icicles, all without being of stainless white.

I should fill up the whole of my journal were I to attempt to describe all the wonders and beauties of the Arctic regions.

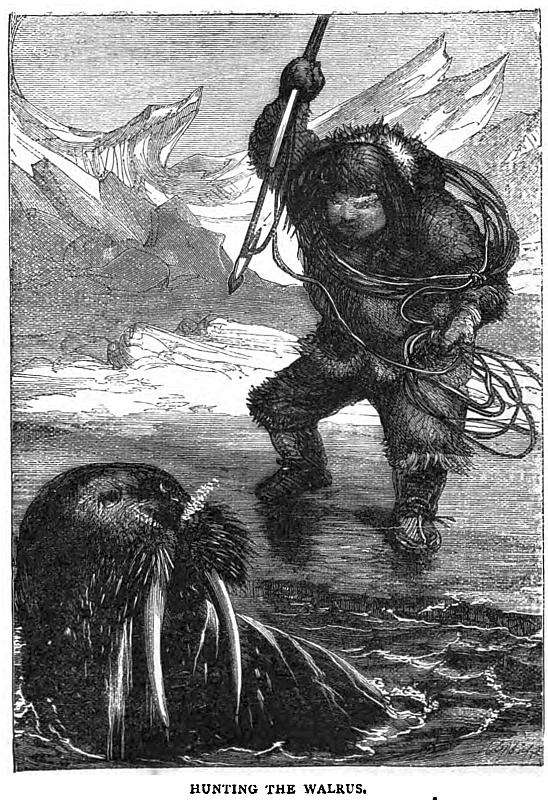

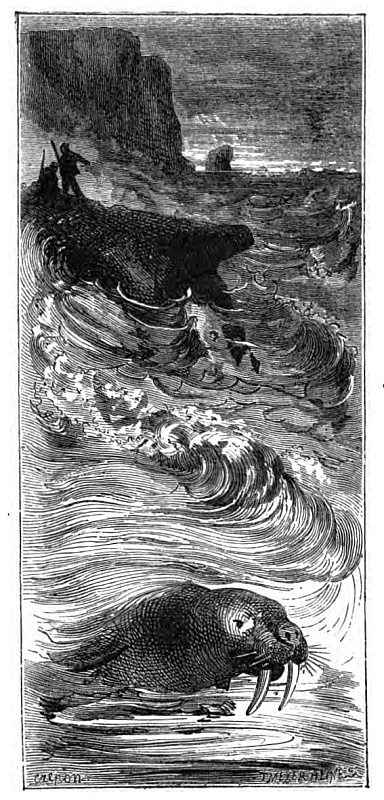

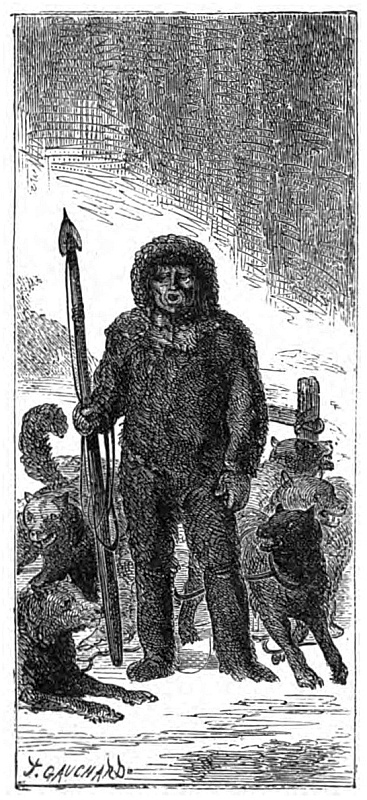

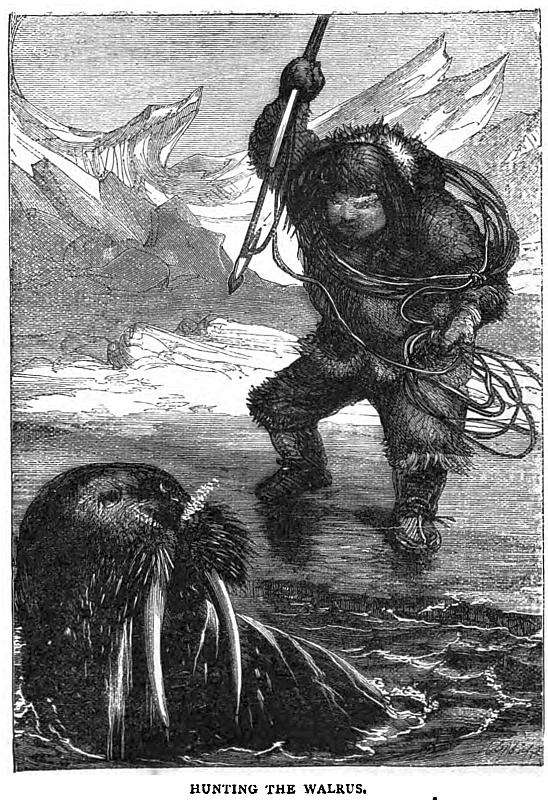

Our object, when whales were not to be met with, was to kill walruses, and for this purpose our boats were provided with the necessary gear. We had in each boat six harpoon-heads, and four shafts of white pine. Each harpoon had fastened to its neck one end of a line, twelve or fifteen fathoms long, the line being coiled away in its proper box. It is not necessary to have longer lines, because the walrus does not frequent water more than fifteen fathoms deep, and even should the water exceed that depth, owing to the pressure above him he is unable to exert his full strength.

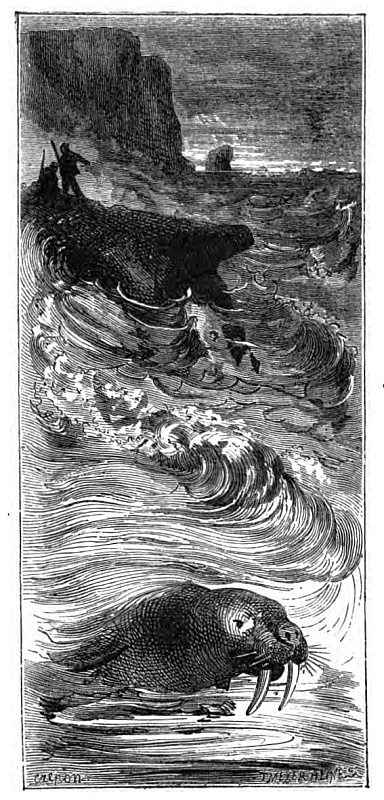

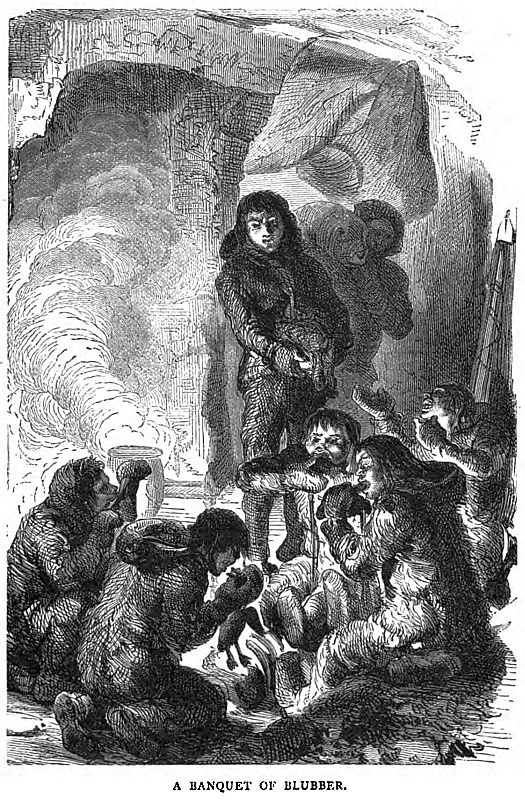

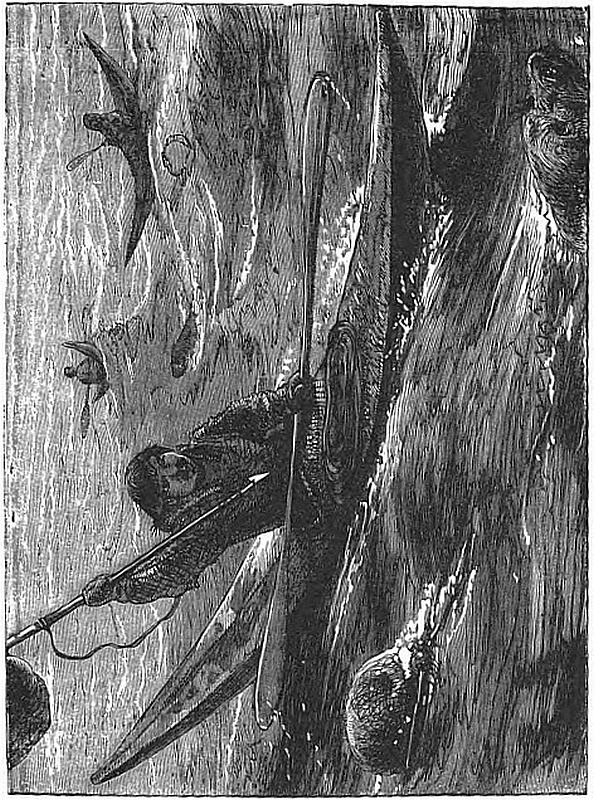

Besides these harpoons, we had four lances nine feet in length, to which the iron barbed heads were strongly fixed. As we were approaching the ice, we caught sight of two hundred black heads, at least, swimming rapidly along. They were morse, or walruses, and Andrew declared had got young with them who would retard their progress. Three boats were instantly lowered with their proper gear. I went with Sandy, who was an experienced walrus-hunter, and at once took the lead. We made the boat fly through the water, while ahead was the herd of walruses bellowing, snorting, blowing, and splashing. The herd kept close together, now diving, now reappearing simultaneously. One moment we saw their grizzly heads and long gleaming white tusks above the water, then they gave a spout and took a breath of fresh air, and the next moment their brown backs and huge flippers were to be seen and the whole herd were down. Sandy stood up in the bows with his harpoon ready for a dart. In a few seconds up again came the walruses, and we were in their midst. The harpoon flew from Sandy’s hand deep into the body of the nearest walrus. He then seized another harpoon and darted it into a “junger” which came swimming incautiously by. Its mother, hearing its plaintive cry, rushed towards us with her formidable tusks, endeavouring to recover it; but before she had time to dig them in the side of the boat a shot from one of our guns and a plunge from Sandy’s spear had terminated her existence. The “junger,” which was only slightly wounded, uttered a whimpering bark, when a score or more of walruses swam fiercely towards us, rearing their heads out of the water, snorting and blowing, ready to tear the boat to fragments. Several were killed before the calf had ceased its cries, when they prudently retired to a distance to escape our bullets and the thrusts from our spears. We had secured six walruses; for, though others were wounded they sank.

So well satisfied was the captain with the result of our chase, that, soon after the blubber and skins had been stowed away, he ordered the two boats to be prepared for another chase. Andrew, who wished to see the sport, went in the boatswain’s boat, and Ewen got leave to accompany us, he being now able to pull an oar well.

We could see the land to the westward, and, by keeping as close to it as the ice would allow, we hoped to fall in with plenty of game. We accordingly pulled away to the west where the sea was tolerably open. Our wish was to find the animals asleep on the ice where they could be more easily attacked and secured than in the water in which they have the means of exerting their great strength to the uttermost, whereas on the ice they were at our mercy.

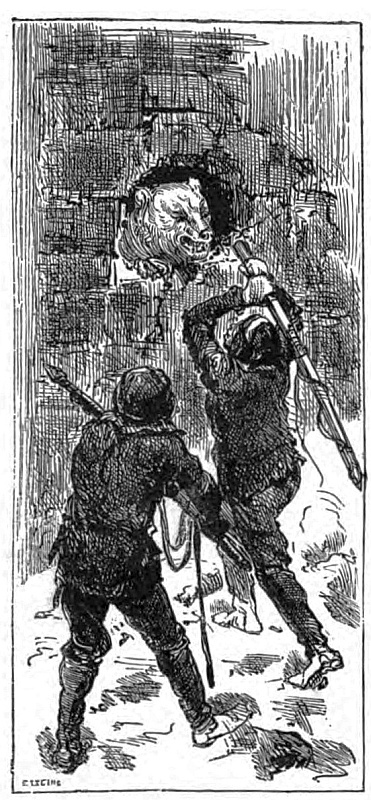

The days were now increasing in length so much that we often forgot how many hours we had been out. Though the Arctic summer was approaching the weather continued uncertain. We had killed two ordinary-sized walruses, when a third, an enormous fellow, was seen sleeping not far from the edge of the floe. We approached cautiously, hoping to kill him, or at all events to get a harpoon well secured in his body. Once he lifted up his head and winked an eye, but did not appear to apprehend danger. With bated breaths we urged the boat slowly forward. My brother fired and the bullet went crashing into the animal’s head. Next instant Sandy, leaping out, drove his harpoon into its body. It was fortunate that he succeeded in doing this, as the walrus by a violent effort rolled itself over into the water rapidly carrying out the line, the end of which was secured to the bollard.

Sandy had barely time to leap back into the boat, when away we went, towed by the walrus, the bow pressed down in a way which threatened to drag it under water. Sandy stood ready, axe in hand, to cut the line to save us from such a catastrophe. Suddenly the line slackened. The walrus dived and shortly afterwards came up again.

My brother fired and missed. The animal disappeared. We felt far from easy, for we knew that there was a great chance of its rising directly under the boat which it might too possibly capsize, or it might tear out a plank with its formidable tusks, when it would follow up the proceeding by attacking us as we struggled in the water. Happily, however, exhausted by the wounds it had received, it rose a short distance ahead, when a thrust from Andrew’s spear finished its career. We hauled it up on the ice by means of the tackles we carried for the purpose, to denude the huge body of the skin and blubber.

We were so busily engaged in the operation, that we did not perceive the approach of a thick fog which quickly enveloped us, while the wind began to blow directly on the ice. It became important therefore to get a good offing to avoid the risk of the boat being dashed to pieces. We now steered in the direction we supposed the ship to lie, but as we could not see fifty fathoms ahead we knew well that we were very likely to miss her. The wind increased and the sea, getting up, threatened every instant to swamp the boat.

“It must be done,” cried Sandy; “heave overboard the blubber and skins, better get back to the ship with an empty boat than not get back at all.”

His directions were obeyed and everything not absolutely required in the boat was thrown out of her. Notwithstanding this there was still the danger of being cast on a mass of floating ice, or of having one come toppling down on us, when our destruction would have been certain. We did our utmost to keep the boat’s head to the sea, as the only hope we had of saving her from going down.

What had become of the other boat we could not tell. We looked out for her, but she was nowhere visible. Our ship, too, was in no small peril, for she might—should she be unable to beat off the solid ice—be dashed against it and knocked to pieces.

All night long we pulled on, amid the heaving waves and tossing floes, sometimes narrowly escaping being thrown on one of them. We could hear them crashing and grinding together as one was driven against the other. I, for one, did not expect to see another sun rise, nor did probably any of my companions. Few words were exchanged between us. Sandy sat at the steering oar, keeping an anxious look out for dangers ahead and occasionally cheering us up to continue our exertions.

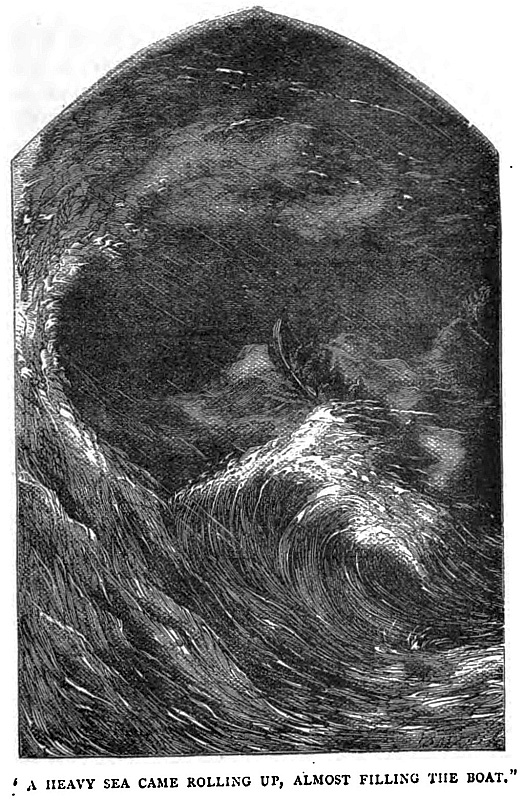

“Pull away, lads, pull away; as the boat has kept afloat so long, there’s no reason why she shouldn’t swim till the gale is over,” he cried out. Just then, however, a heavy sea came rolling up, and down it came right over our bows, almost filling the boat.

“Never fear, bale it out, doctor,” cried Sandy; and my brother and Ewen set to work, and, happily, before another sea struck us, got the boat free. None of the rowers, however, could venture to cease pulling for an instant; not that we made much progress, but it was all-important to keep the boat’s head to the sea. Looking up some few minutes after this, I fancied that I saw a peculiar light away to leeward. I was just going to draw Sandy’s attention to it, when I discovered, close under our lee, a huge iceberg towering up towards the sky. Had we been on the opposite side, it would have afforded us some shelter from the gale, provided it did not topple over. As, however, we were to windward, we had the greatest difficulty in escaping from being thrown upon it. Sandy’s voice sounded almost like a shriek as he urged us to pull away, while he kept the boat off from the furious surf, which, with a sound of thunder, beat upon the lower portion of the berg. We did not need urging, for we all saw our danger. Though the sea tumbled about much as before, we felt in comparative safety when the berg was passed. Still, other bergs or floes might have to be encountered, and we knew not at what moment we might come upon them. How anxiously we all wished for daylight I need not say. At length it came, presenting a wild scene of confusion around us, the ocean as turbulent as ever. We had been mercifully preserved through it, and we trusted that our buoyant craft would carry us back to the ship. She, however, was not to be seen, but we made out, far off, a speck, now on the top of a wave, now disappearing in the trough, which Sandy declared was the other boat. Our spirits rose somewhat, but we were getting exhausted from hunger and thirst, for we had no food nor water with us, nor if we had could we have spared time to eat and drink.

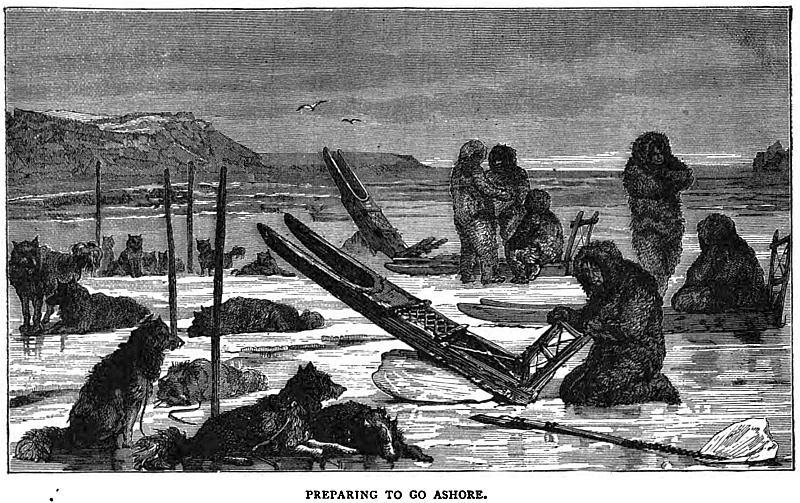

As daylight increased we made out the land, for which Sandy steered, as the other boat was apparently doing. The thought of setting foot on shore, and obtaining a short rest, encouraged us to renew our exertions. The ice had been driven away from us, and formed a barrier some distance off from the land. We were thus able to make better progress than during the night. We could now distinguish the other boat clearly over the starboard quarter.

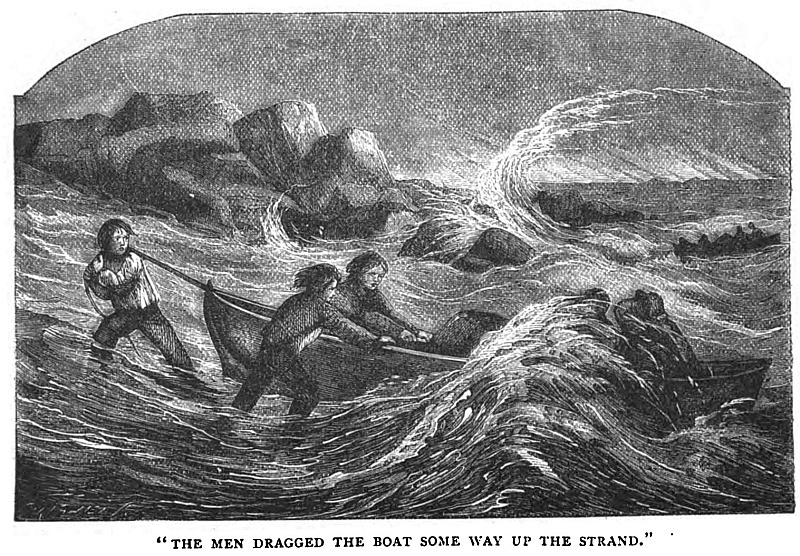

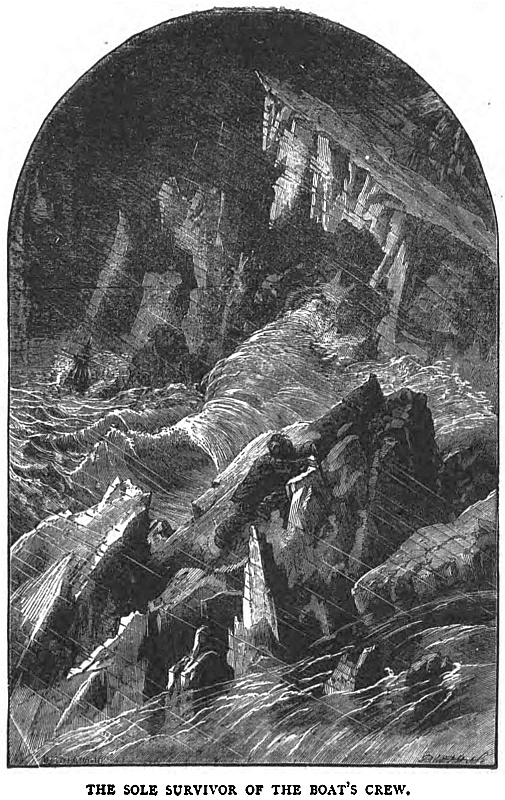

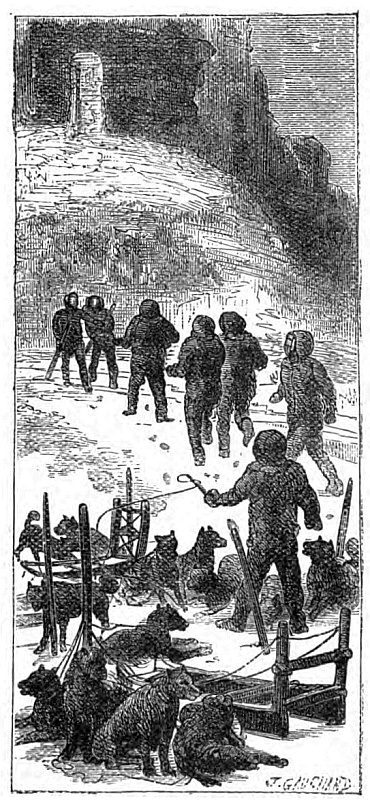

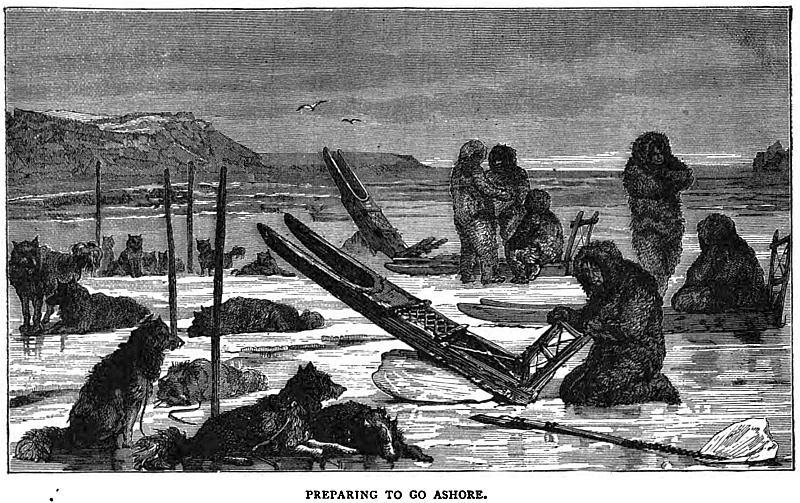

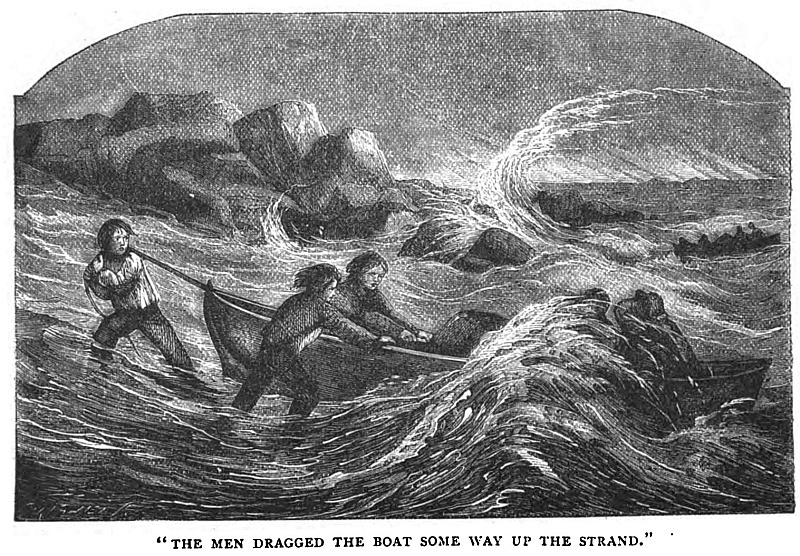

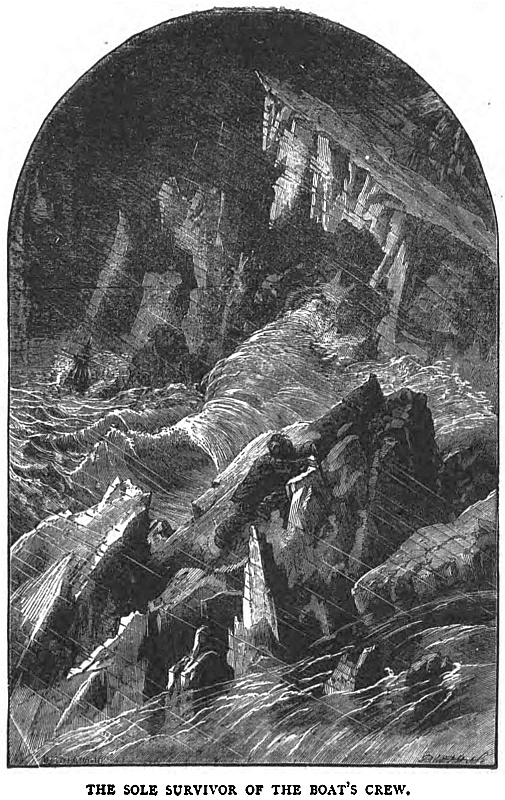

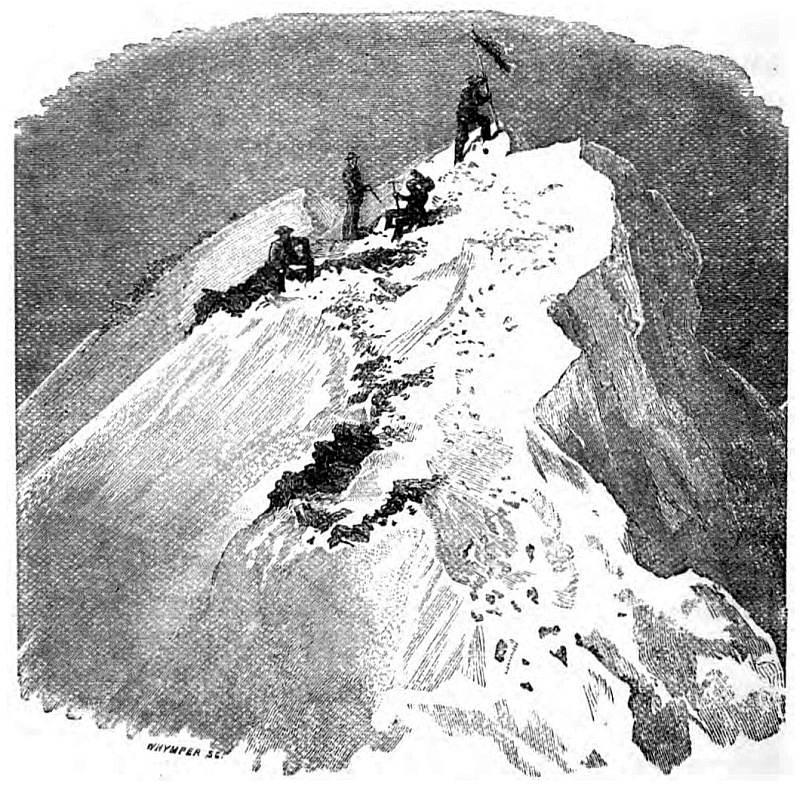

Mr Patterson, the second mate, evidently considered—as did Sandy—that it would be hopeless to try and get on board the ship until the gale was over. Perhaps he feared, as we did, that she had been knocked to pieces on a floe or against one of the icebergs floating about. As we approached the land we saw that it was fringed with rocks and masses of ice, between which it would be perilous in the extreme to make our way. Still, unless we could get round to the lee side, it must be done. Sandy stood up to look for the shore. A bay presented itself where the sea broke with less force. We stood on rocks and ice rising up amidst the seething waters, now on one side, now on the other. Sandy steered between them with consummate skill. Mr Patterson’s boat followed at some distance. A foaming wave came sweeping up, on the summit of which we were carried forward until we could hear the boat’s keel grate on the beach.

“Jump out, jump out!” cried Sandy to the men forward, who obeyed, and, carrying the painter, dragged the boat some way up the strand. We all followed, and, putting our shoulders to the gunwale, had her safe out of the power of the waves. We then ran to assist our shipmates, whose boat had suffered more than ours, and was almost knocked to pieces; indeed, on examining her, we found, to our dismay, that to make her fit for sea she would require more repairs than, without tools, we were able to give. We had thus only one boat in which to make our escape from the island, and she was insufficient to carry the whole of the party. Should the ship not appear, therefore, we should be compelled to remain, and perhaps have to endure the hardships of an arctic winter with very inadequate means for our support. We were, however, on shore, and at all events safe for the present; but we were without food, fuel, or shelter, except such as our boat would afford us. Water we could procure from the fragments of icebergs driven on the beach, but we were unlikely to obtain either walruses or seals, as they would have sought the shelter of the lee side of the island; even the birds had deserted the shore on which we were driven. We determined, therefore, to make an excursion across the island, hoping, either to reach the other side, or fall in with reindeer or other animals.

Several of the men, overcome with fatigue, preferred remaining under the boats, waiting for the food we might obtain. My brother, Sandy, Ewen, and I, with the second mate and Charley Croil, a fine young lad of whom I have not yet spoken, set off; the mate, my brother, and I having our rifles, and Sandy his harpoon and lines, while the others carried lances. Though feeling somewhat weak from our long fast, hunger urged us on; and in spite of the roughness of the ground, making our way to the westward, we soon lost sight of our companions on the beach.

Chapter Three.

We found tramping across the rough ground very fatiguing, for in most places it was soft and spongy, except where we crossed more level ridges of bare rock. Already the grass was beginning to grow, and flowers were opening their petals, although most of the streams were partially frozen and we could only cross them by wading halfway up to our knees in slush. As yet we had not got sufficiently near to any deer to give us a chance of obtaining some venison, for which we were longing with the appetites of half-starved men, nor had we been able to catch any birds.

“We shall have to get over to where the walruses are, and it will be hard if we don’t get enough then to fill us up to the throats,” observed Sandy, “though we may chance to find fowl rather scarce.”

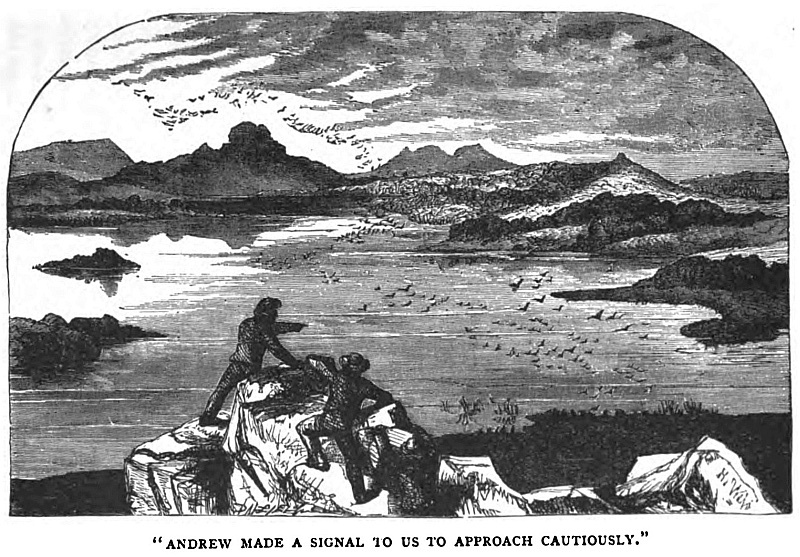

On we trudged, mile after mile, drawing in our belts and keeping up our spirits, urged forward by hope. At last my brother Andrew, who was leading, reached the top of a high rocky ledge, which lay directly across our course, when he turned round and made a signal to us with his hand to approach cautiously. I followed, Sandy came next. We soon climbed up the rock, when we saw before us a low shore and lofty hills in the distance. The ice was in great part melted. Near the shore were countless wild fowl, assembled in large flocks,—swans, geese, ducks, snipes, terns, and many others. Scrambling down the rock, we were soon blazing away right and left. In a few minutes we killed a sufficient number of birds to afford us an ample feast. The question was how to cook them, as the stems of the largest trees were less in circumference than our small fingers. We managed, however, to collect a sufficient quantity of moss and twigs to make up a diminutive fire, at which we browned, though we could not thoroughly cook, our fishy-tasting fowl. We were, indeed, too hungry to be particular.

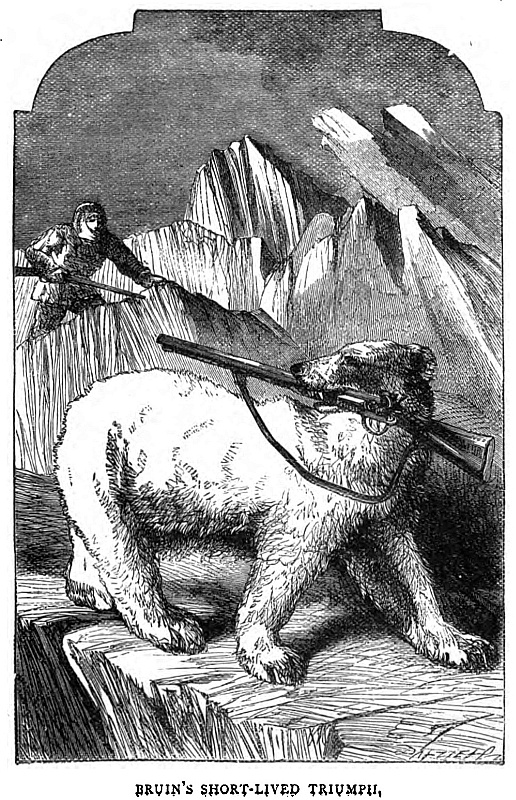

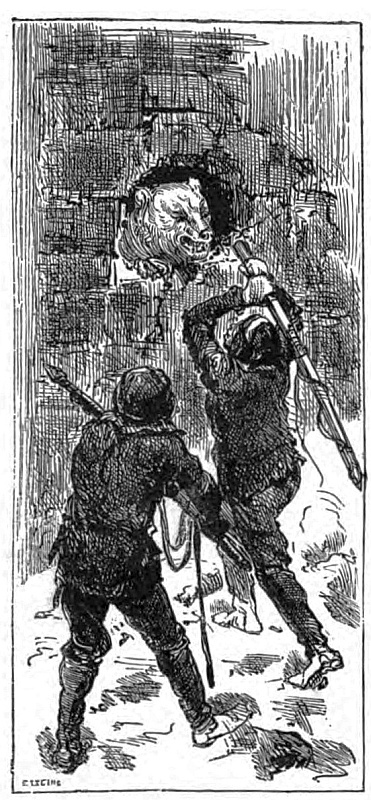

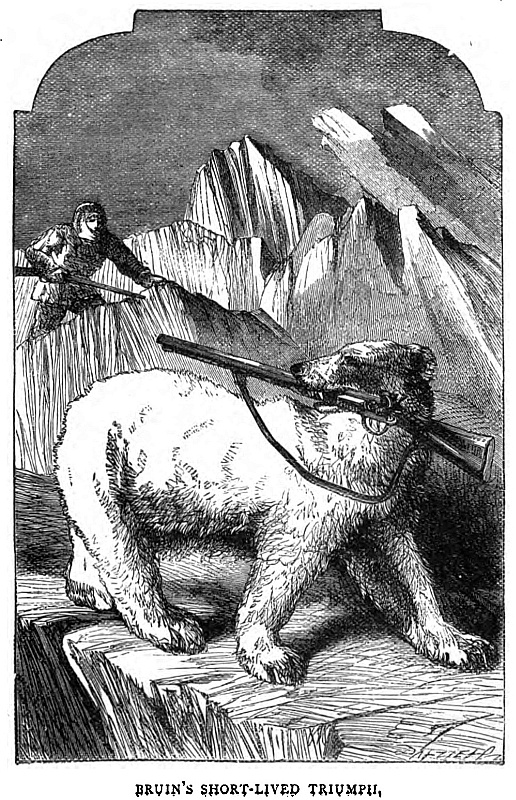

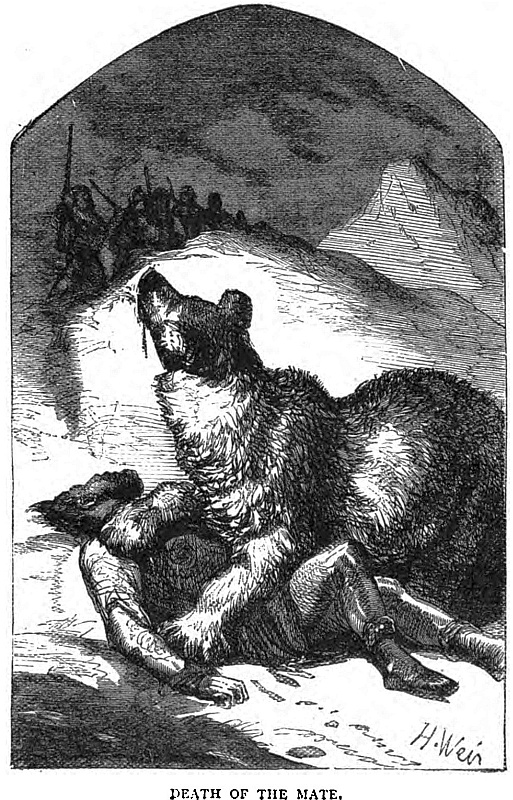

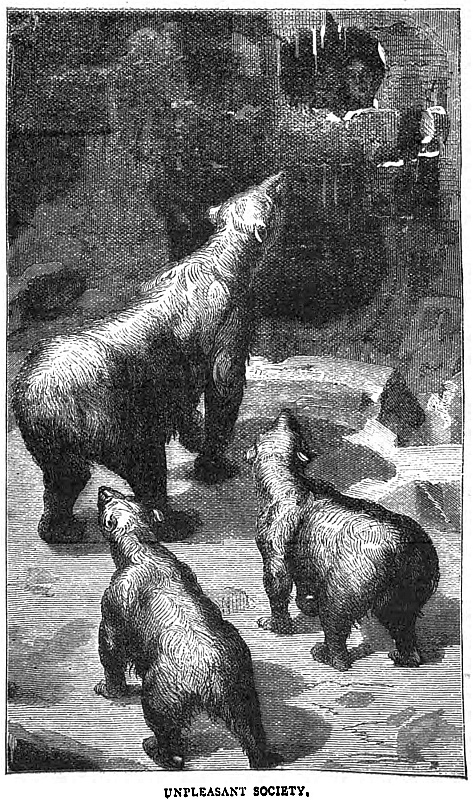

After we had satisfied our own hunger, we began to think of our companions. Two of the men volunteered to return with a supply of the birds sufficient for the crew, while the remainder of us continued our route to the west. We had to make a wide circuit round the end of a lake. As may be supposed, we kept a bright look-out for deer. We had gone some distance, when we observed a couple in a small valley where the snow had melted. To have a better chance of securing the reindeer, we divided; Mr Patterson, Sandy, and Ewen making their way along the side of the hill, while my brother and I proceeded up the valley, concealing ourselves among the rocks or in the gullies, hoping thus to get within shot of the deer. The wind came down the valley, so that we were to leeward, and had some prospect of getting close to the game without being perceived. Greatly to our satisfaction we saw that the animals were coming towards us, browsing on their way. We, therefore, knelt down behind a rock, waiting until the deer should approach. At length we could hear the sound they made, munching the herbage as they tore off the moss and grass. At this Andrew rose and fired at one, and I, imitating his example, aimed at the other. Greatly to our disappointment, as the smoke cleared away, we could see both the deer scampering off up the valley, but one soon fell behind the other. It had been hit in the shoulder. Slower and slower it went; we made chase, but it still kept a long way ahead of us. We both reloaded as we ran, hoping to overtake it and get another shot, should it not in the meantime come to the ground. Greatly to my delight, I saw the deer which I had shot suddenly stop, when presently over it fell. The other held on for some time longer, when that too rolled over. We had a long chase, though we scarcely knew how far we had gone. On looking round we could nowhere see our companions. I fired off my rifle to attract their attention, as we wanted them to assist us in cutting up the deer and to carry back the venison. Scarcely had I fired than I saw, coming out of a hollow in the side of the hill, a huge white monster, followed by two smaller creatures, which I at once knew must be a bear and her cubs. Her intention was evidently to appropriate our venison, an object which we were anxious to defeat. Andrew had seen her, and stood with his rifle ready for an encounter. I reloaded as rapidly as I could. We had neither of us shown ourselves first-rate shots, and I was afraid that my brother might miss the bear, and that she might seize him before I could go to his rescue. The animal sat upon her haunches sniffing the air; then, once more dropping down, she approached, resolved to carry off the deer or attack us should we attempt to prevent her. Andrew allowed her to get within twelve paces or so, when he fired at her head. The bear, instead of dropping as I expected, to my horror rushed towards my brother.

“Leap out of the way,” I shouted, for I dared not fire as he then stood, lest I might hit him.

He followed my advice, when I levelled my rifle, knowing that his life, and probably my own, might depend upon the accuracy of my aim. The bear, growling terrifically, came on, and when about three yards from me rose on her hind legs, stretching out her formidable paws, about to spring and grasp me in her deadly embrace. I pulled the trigger, and as I did so jumped back with all the agility I possessed, knowing that should my shot fail to take effect, I might—even though she were mortally wounded—be torn to pieces by her teeth and claws before another minute was over. Great was my thankfulness when I saw her huge body sink slowly to the ground, where she lay without moving a limb; still, as I thought it possible that she might not be dead, I joined Andrew, who was reloading a few paces off.

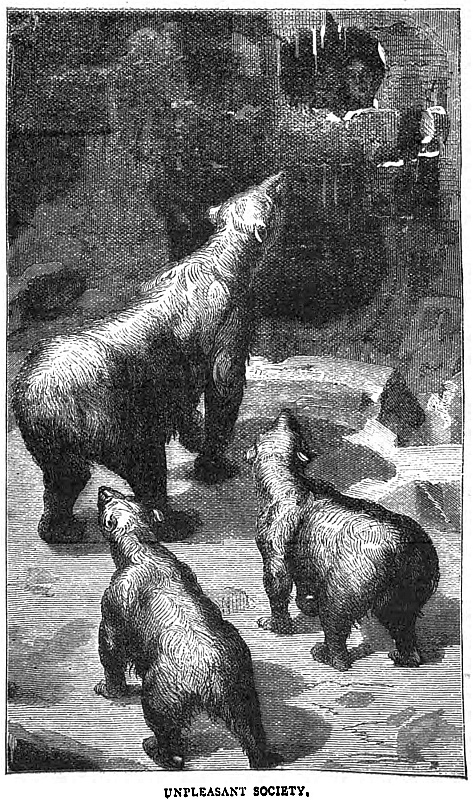

The bear cubs, who had followed her a short distance behind, now came up, and began pulling away at her body, not understanding why she did not move. We were soon convinced that she was perfectly dead. What was now to be done with the little animals? When they found that she would not move, they began biting at her savagely. However, they soon scented out the deer, and, while we were employed in cutting them up, came to us and eagerly devoured the pieces we threw to them, they not showing the slightest fear of us, nor anger at the way we treated their mother.

We had now more meat than we could carry away, even with the assistance of the rest of the party; and, as they did not appear, we each took a heavy load and prepared to set off.

Andrew, who was anxious to take the little creatures on board, suggested fastening some lines we had in our pockets round their necks to lead them with us, but no force would compel them to budge. I tried, however, to get them to move by putting a small piece of meat a short distance from their noses, when they both darted forward to catch it. I then gradually increased the distance between the pieces of meat, and got them out of sight of their mother.

Following the traces left by the wounded deer, we were enabled to make our way with more certainty than we should otherwise have done. At last we caught sight of our shipmates, who were not a little astonished at seeing our two small shaggy companions, and highly delighted at finding that we had brought so fine a supply of meat.

On hearing of the abundance we had left behind, they wanted us to return with them; but we, having done our duty, preferred resting in a sheltered spot on the side of the hill, while they followed our tracks to bring away some more venison and bear’s flesh. In the meantime the little cubs gambolled together at our feet, occasionally coming up to get a suck at a piece of venison.

The party at length arrived, each man staggering under as much meat as he could carry. They all sat down that we might consult in what, direction we should proceed. Mr Patterson wished, as we had gone thus far, to continue on to the lee side, where he believed that a harbour would be found into which the ship might possibly have put, for he was certain she would not, if she could help it, approach the other side of the island. Should such be the case, we hoped to be able to get the boats round, either by the shore or by the ice. We had still three men who had accompanied us, and the boats’ crews would by this time be in want of food. Mr Patterson accordingly sent back Sandy and two of them, each carrying a load of venison and bear’s flesh. He directed the boatswain, after provisioning the men, to search along the shore, and ascertain if there was any possibility of getting the boat over it.

“We had better take the little bears with us,” said Sandy; “they’ll amuse the men, and, if the worst comes to the worst, we can eat them.” Saying this, and adopting our plan, he threw a small piece of meat before the noses of the little animals, who at once rushed forward to seize it, not aware that it was part of the flesh of their parent.

“You’ll be gorging yourselves, ye little gluttons,” observed Sandy, and, fastening a piece of meat to the line, he dragged it after him, whisking it away the moment the creatures got up to it. Thus enticed, they parted from us, their first friends, without the slightest sign of regret, eagerly following Sandy and the men. As it was important not to expend more powder and shot than we could help, we carried a larger supply of meat than we should otherwise have done, so that we might have food enough to last us for several days if necessary. Our progress was therefore somewhat slow, and it was not until the sun had set that we caught sight of the ocean, or rather of the fields of ice and bergs which covered it, with here and there a line of open water, showing that it was breaking up and being driven away from the coast. Descending from some high ground which we had been traversing, we found ourselves on the shores of a deep bay, on the northern side bordered by cliffs and rocks, but with a sandy beach at the inner end. It was already partially open, and although small floes floated about, some remained attached to the shore.

“This is just the place I hoped to find,” observed Mr Patterson. “If we are compelled to remain here we shall be able to obtain a supply of fish, while it is the sort of spot walruses and seals are likely to frequent.”

We had now to look out for a sheltered nook in which we could pass the night.

“We shall be able to have a fire too,” I remarked, as I pointed to a quantity of drift-wood, which lay above high water-mark.

“You and Ewen and Croil collect it then,” he answered, “while the doctor and I search for a sheltered spot.”

While picking up the wood I was separated from my companions, and found myself going in the direction Mr Patterson and my brother had taken.

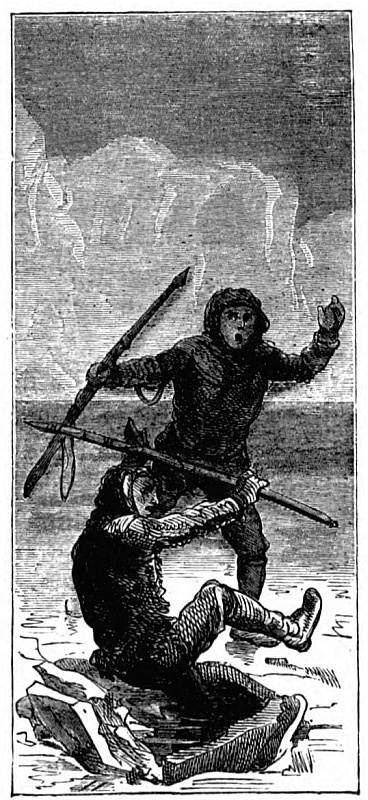

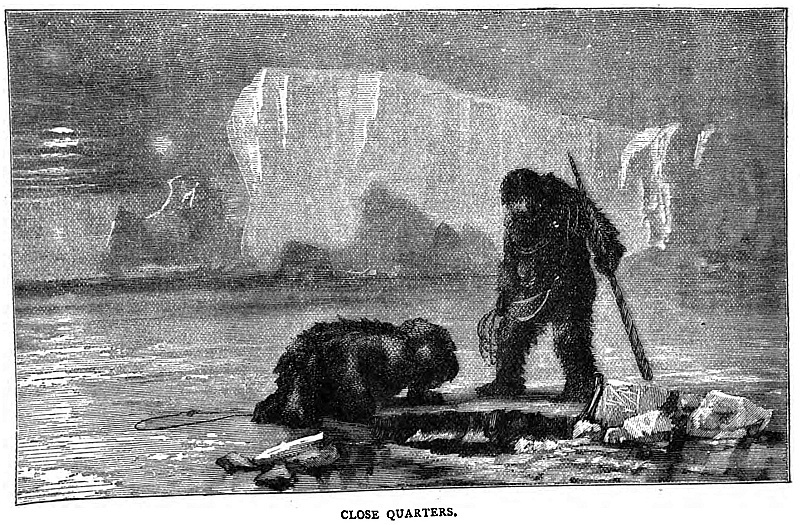

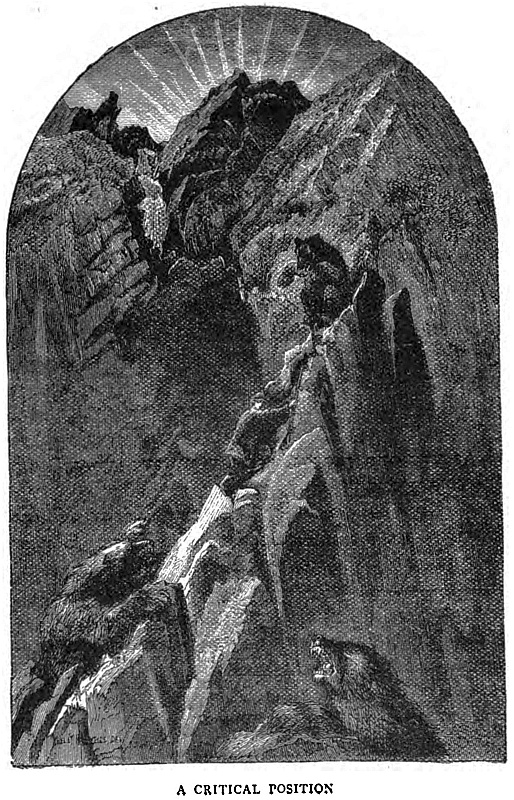

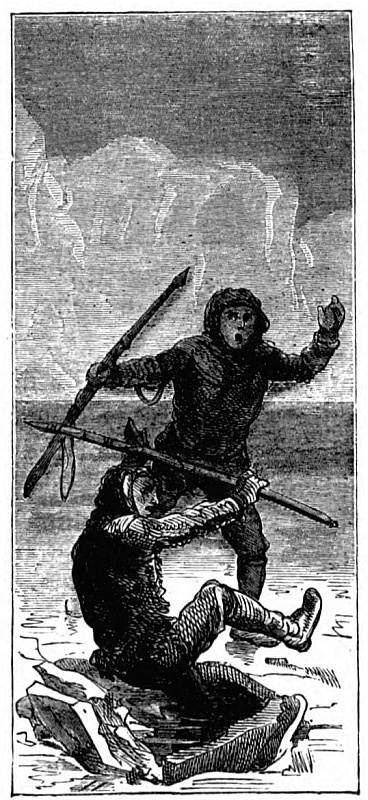

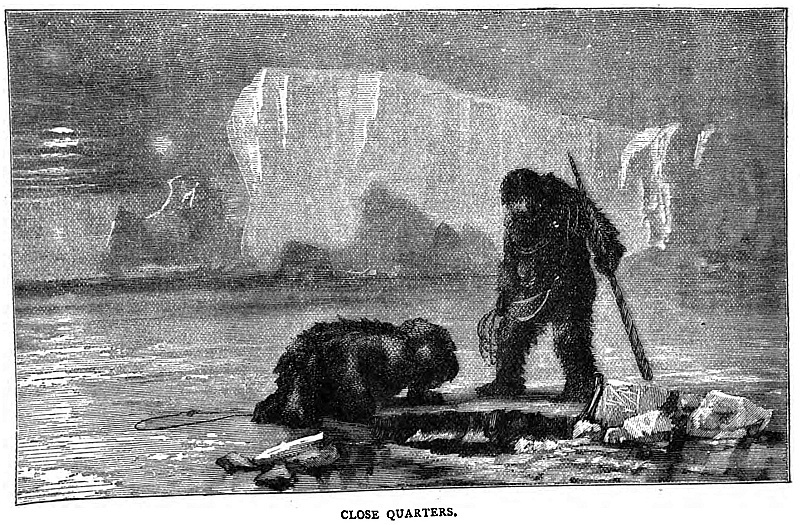

Passing round some rocks, I saw several dark heads in the water, which I at once recognised as walruses. As I felt sure they would not land to attack me, I went on without hesitation. Presently I heard a shout. Looking round the rock I saw Mr Patterson, with his rifle clubbed, engaged in what seemed to me a desperate conflict with a huge walrus. Though he was retreating, the creature, working its way on with its flappers, pressed him so hard that it was impossible for him to turn and fly. I immediately unslung my rifle, which I had hitherto carried at my back, but dared not fire for fear of wounding him. I hurried on, endeavouring to get to one side of the walrus so that I might take sure aim, when, to my horror, the mate’s foot slipped, and down he came with great force. The next instant the huge monster was upon him, and was about to dig its formidable tusks into his body. In another moment he might be killed. I was still nearly twenty paces off, but there was not a moment to be lost. Praying that my bullet might take effect, I lifted my rifle and fired. Then, without stopping to see the result of my shot, I dashed forward in the hopes of still being in time to drag the mate out of the way of the monster’s terrific tusks. Thankful I was to see that the walrus was not moving, but still it might with one blow of its tusks have killed the mate.

Shouting to Andrew, who was, I supposed, not far off, I sprang forward. The walrus was dead, and so I feared was the mate. Not a sound did he utter, and his eyes were closed. It was with the greatest difficulty that I could drag him from under the body of the walrus. Again and again I shouted, and at last Andrew appeared, his countenance expressing no little dismay at what he beheld.

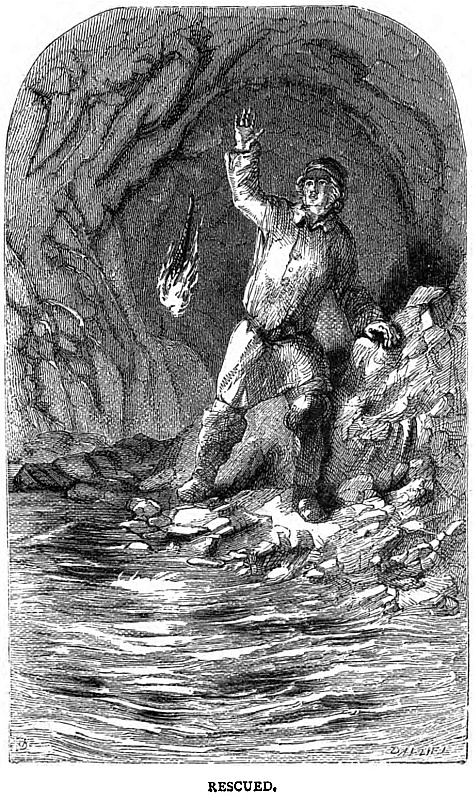

“He is still alive,” he said, after he had examined the mate. “The walrus has not wounded him with its tusks, but has well-nigh pressed the breath out of his body, and may possibly have broken some of his ribs. We’ll carry him to a dry cave I have just found, in which we can light a fire, and I hope he’ll soon come round. Get Ewen and Croil to assist us.” I hurried along the shore and summoned them. We all four managed to carry the mate to the cavern. While Andrew attended to him, Ewen, Croil and I brought the drift-wood we had collected, and getting some dry moss from the rocks to kindle a flame, we soon had a fire blazing.

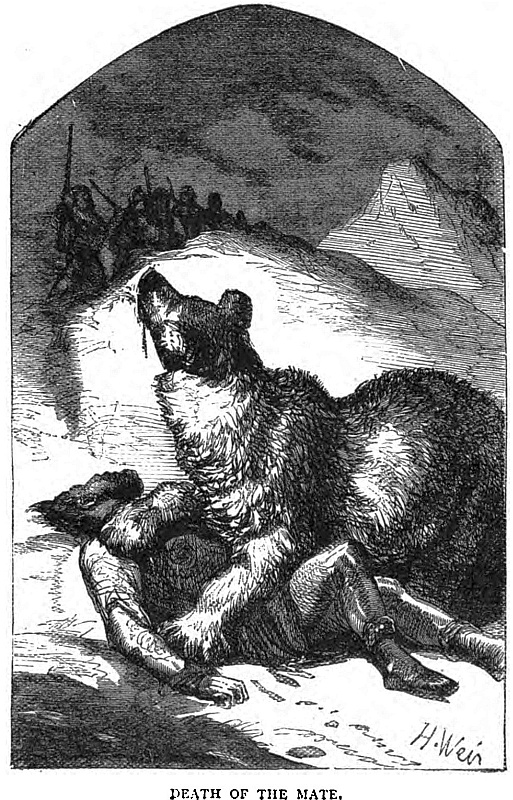

Andrew reported unfavourably of the mate. Two of his ribs were broken, and his legs fearfully crushed.

“Much turns upon his having a good constitution to enable him to get over it,” observed my brother. “He has been a temperate man, and that’s in his favour, but I wish that he was safe on board, as he requires careful nursing, and that’s more than he can obtain in this wild region.”

A restorative which the doctor always carried, at length brought the mate somewhat round, and he was able to speak.

“Have you seen anything of the ship?” was the first question he asked.

“No, we did not expect her so soon,” answered Andrew; “she will come here in good time, I dare say!”

“Then where are the boats?” inquired the mate.

“One is very much damaged,” said Andrew; “we must wait for a favourable opportunity for bringing the other to this side of the island. In the meantime you must try and go to sleep. In the morning we will see what is best to be done.”

The poor mate asked no further questions, but lay back in an almost unconscious state, while Andrew sat by his side, endeavouring to alleviate his sufferings.

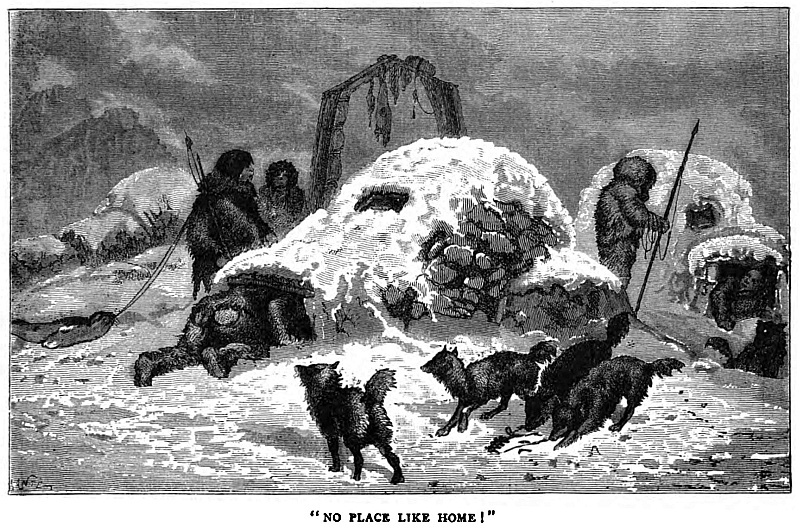

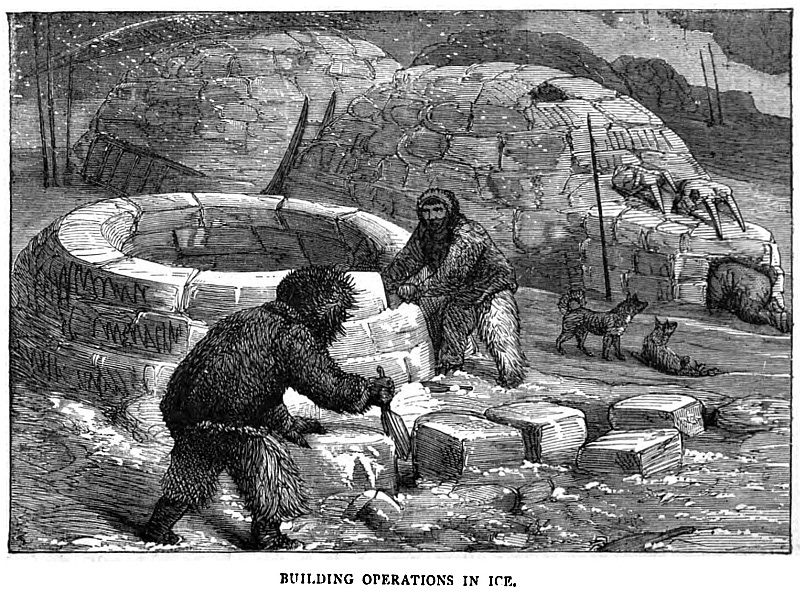

The rest of us, having cooked some venison, made a hearty supper, but the mate was unable to eat a morsel. Andrew decided on sending Ewen and me back the next morning to obtain a cooking pot, in which he might make some broth for the mate, as well as to bring the sail of the damaged boat, which might assist to shelter him from the cold. Should it be found impossible to get the boat round to the bay, he thought it would be best to leave her there, and to let all the men come across, bringing the gear of the two boats, and as much of the wood of the wrecked one as they could carry. His idea was to build a hut, or to make the cavern habitable. It was agreed that we should catch as many bears and walruses as we could, so that we might have materials for constructing the hut as well as for covering ourselves.

“It will be wise at once to make preparations for the winter. We must provide shelter, food, clothing, and fuel, and this will fully occupy all hands until the cold weather sets in,” said Andrew. “Had we been cast on shore here at the end of the summer, we should in all probability have perished; but now I hope that we shall be able to support existence until another spring, when we may expect the appearance of a ship to take us off.”

Our plans being arranged, Andrew told us to lie down and try and get some sleep, saying that he would keep watch in case any prowling bear should pay us a visit, besides which he wished to attend to the mate. I begged him, however, to let me sit up for a couple of hours, promising to call him, should I fancy that our injured companion required his assistance. He at last consented. In a few minutes he and the rest of the party were fast asleep. I carefully made up the fire, then, after some time, feeling drowsy, I took my rifle, and went outside the cavern. The night was tolerably light, indeed the darkness in that latitude was of short duration. As I looked in the direction where the body of the walrus lay, I fancied I saw two or three white objects on the rocks. At first I thought that they were piles of snow or ice; but, watching them attentively, I observed that they were moving, and I had no doubt they were bears attracted by the body of the dead walrus, on which they expected to banquet. I now regretted that we had not had time to carry off the skin, which would of course be torn to pieces and rendered valueless. I was much tempted to try and shoot the bears, which I might easily have done while they were feasting, but I considered that I ought not to leave my post, and I did not like to awake Andrew, who required all the rest he could obtain, I therefore returned to the cave and sat down by the fire, thankful for the warmth it afforded. When I judged I had been on watch a couple of hours, I aroused my brother.

“You were right in not trying to shoot the bears, for even had you killed one the others might have set upon you, and we cannot afford to lose another of our party,” he said. “Lie down now, as you have a long journey before you; and I shall be glad if you can bring the men over here before another night sets in.” It was broad daylight when my brother awoke me and the rest. The mate appeared somewhat better, and, as he had no feverish symptoms, Andrew expressed his belief that he would recover. Having breakfasted and done up a portion of the cooked venison for provisions during our journey, Ewen and I set off, leaving Croil to assist my brother in taking care of the mate. Andrew charged us not to expend our powder on birds, or we might have shot as many as we required. Every hour they were arriving in large flocks on their way to still more northern regions, where they might enjoy the long summer day without interruption. I will not describe the journey, which we managed to accomplish in about six hours. Sandy, who came to meet us, reported that the men were behaving well, thankful for the food we had sent them; but, as far as he could judge, it would be impossible to get the boat round for the present, either over the ice or across the land. All hands therefore were ready to obey the directions Andrew had sent them. While Ewen and I rested, they made up the loads each man was to carry. As to launching the boat among the rocks which fringed that side of the island, it was clearly impossible unless in the calmest weather, without the risk of her being knocked to pieces; for the sea continually rolled in huge masses of ice, which with thundering sound were shivered into fragments. It seemed surprising that we had escaped, when we looked at the spot where we had landed.

“We are all ready, and if you and Ewen think you can trudge back by the way you have come, we’ll set out at once,” said Sandy.

“All right,” we answered, springing to our feet and taking our rifles, with a few articles—all the men would let us carry—we led the way.

The men, however, had not taken any of the shattered boat, or oars, or spars, and it would, therefore, be necessary to make another journey to bring them across. The other boat was turned bottom upmost, out of the reach of the highest tide, with the things we had to leave placed under her. We took longer to perform the journey back than we had occupied in coming, as the men, with their heavy loads, could not proceed as fast as Ewen and I had done. On approaching the bay we looked out for Croil, whom we expected to see on the watch for us. He was nowhere visible. We shouted to give notice that we were near, but no reply reached us.

“He is probably in the cave assisting the doctor,” observed Ewen. “I hope the mate is not worse.”

On getting near the shore, however, we saw my brother, who had just come out of the cave. He waved to us to hasten on.

“Thank heaven you are come!” he said. “I am very anxious about young Croil. He went away a couple of hours ago to collect drift-wood, and has not returned. I could not leave the mate, who still continues in a very precarious condition, to look for him, and I fear that some accident has happened; probably he has been attacked either by a walrus or a bear, and, if so, I fear that he will be added to our list of casualties.”

“We must find him at all events,” I answered. “Should he have been attacked by a bear, we shall discover some traces which will show what has happened to him.”

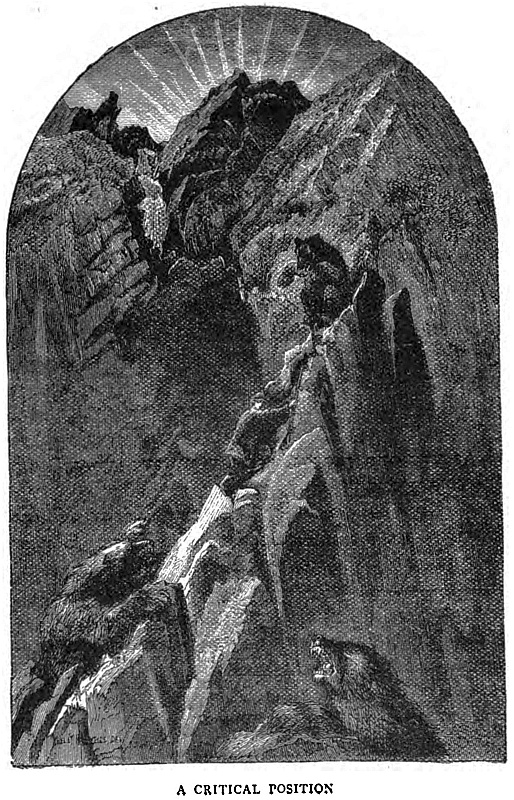

The men, having deposited their loads, tired as they were, dispersed in all directions. Sandy, Ewen, and I went to the northward under the cliffs. Every moment I expected to see the mangled remains of the poor lad, or traces of his blood, should a bear have carried him off. Of one thing we felt sure, that he would have kept as close as he could to the beach, where he might hope to meet with drift-wood. Before long, however, our progress was stopped by cliffs which jutted out into the sea, though we saw that there was a continuation of the beach farther on. We had, therefore, to climb up and try to find a way down again to the level of the water. It was no easy task to climb the cliff, but we accomplished it at last. We went on for some distance, but so precipitous were the cliffs that it seemed impossible that we should be able to descend with any safety. Every now and then we peered over them, and as I was doing so I thought I saw an object lying close to the base some way on. I felt almost sure that it was a human being, while not far from it was what looked like the wreck of a boat. That it was poor Croil we could have little doubt, and that he had been killed by a fall from above appeared too probable.

Sandy, who was of this opinion, told Ewen and me to wait while he hurried back to obtain a coil of rope which he had brought from the boat, as also the assistance of some of the other men should they have returned. Ewen and I accordingly went on, and, carefully looking over the cliff, to our sorrow discovered that it was indeed our poor shipmate. That he had fallen from such a height without being killed seemed impossible.

“Take care that we do not share his fate,” I observed to Ewen, as I got up to ascertain if there was any less precipitous part near at hand, by which we could descend without waiting for the rope.

As far as I could discover there were no marks on the edge of the cliffs to show from whence he had fallen. Going on a little further I found a narrow ledge, which apparently sloped downwards. Very likely he had attempted to make his way by this ledge to the shore. From its extreme narrowness I felt that it would be folly to trust myself to it, and that I should probably fall as he had done.

While looking about I heard Ewen exclaim—

“He is moving, I saw him lift his hand!” He then shouted out: “Hullo! Croil, we are coming to help you.”

It was a great relief to know that the lad was alive, though it made us still more anxious for the return of Sandy. At last he appeared. Now came the question, Who should descend? It was a hazardous task. Sandy insisted on going down, but I felt that I would much rather descend than have to hold the rope.

“No, no,” said Sandy, “I’ll trust you. I’ll stick this stake into the ground, and if you hold on to the upper end the rope will be firm enough.”

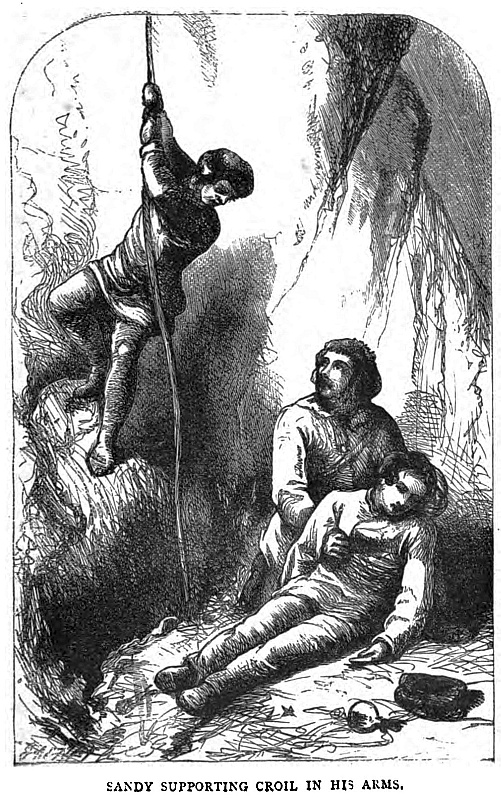

While we were securing the rope as Sandy proposed, a man with another length of rope came running towards us. It was fortunate he brought it, for the first was not sufficiently long to reach the bottom. Our preparations were speedily made, and Sandy, with the activity of a sailor, sliding over the edge of the cliff, glided down by the rope until he reached the spot where Croil lay. I fancied that I heard him shout out for help, so I told Ewen to hold on to the stake, and, taking hold of the rope, slid down as Sandy had done. I saw him, as I reached the bottom, supporting Croil in his arms.

“I did not want you to come, Hugh, but as you are here, you can help me in getting up the laddie. There is still life in him, but he has had a shaking which might have broken every bone in his body, though I cannot discover that any are broken. We must hoist him up gently, for he cannot bear any rough handling, that’s certain.”

I suggested that we should make a cradle from the wreck of the boat which had tempted Croil to try to reach the beach.

Sandy had some small line in his pocket; I also had another piece, and Dick Black—the man who had come to our assistance—had brought a whole coil, which he threw down to us. We soon formed a cradle, in which we placed the lad, securing it to the end of the rope. We had, besides this, lines sufficient to enable me to stand below and assist to guide it in its ascent. Sandy then swarmed up to the top, and he and our two companions began to hoist away while I guided the cradle from below. I was thankful to see Croil at length safely placed on the top of the cliff. The rope was then let down, and making a bow-line in which I could sit, I shouted to the rest to haul away. I felt rather uncomfortable as I found myself dangling in mid-air, for fear the rope should get cut by the rocks, but I reached the top without accident. I was thankful to find that Croil had come to himself, though unable to describe how he had fallen.

“We must mark this spot, to come back for that wood; it will be a perfect god-send to us, for we shall want every scrap of fuel we can find,” I observed.

The cradle enabled us to carry Croil without difficulty to the cave, where my brother at once attended to him.

Wonderful as it seemed, not a bone in his body was broken, nor had his spine received any injury, which Andrew at first thought might be the case. He thus hoped that the lad might get round and in a short time be as well as ever. He was far more anxious about the mate, who still remained in a precarious condition.

Supper over and a watch being set, we all lay down inside the cave, with our feet to the fire which blazed in front of it. And thus passed the third night of our residence on the island.

Chapter Four.

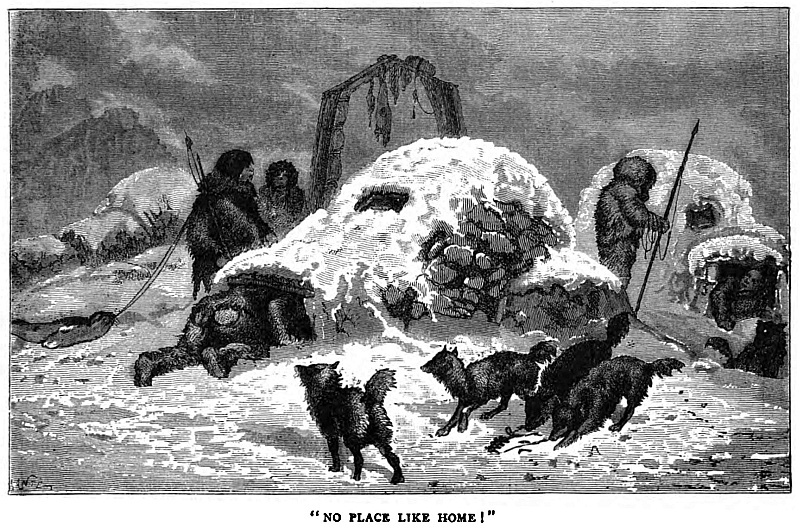

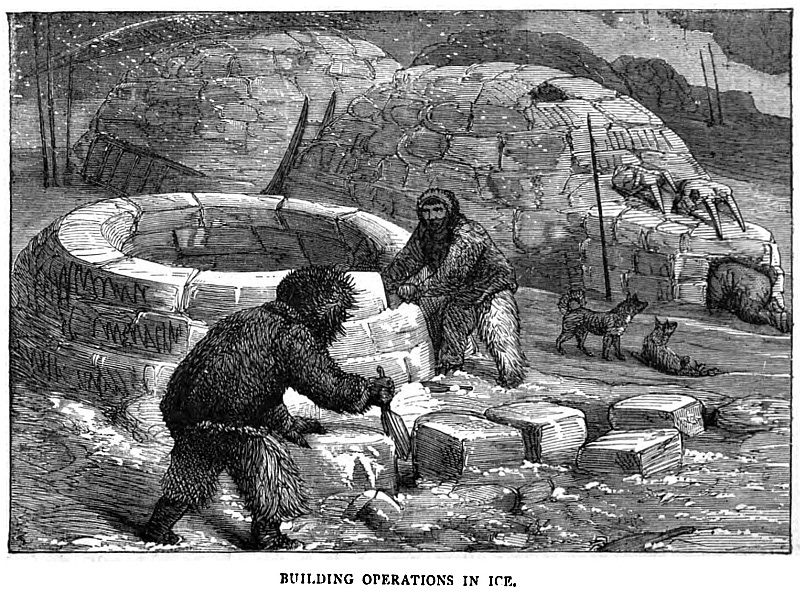

Sandy and my brother had now become the real leaders of the party, as the mate was too ill to issue orders. We speedily built a hut with sods and stones, and roofed it with the boat’s sails. It proved a far more comfortable abode than the cavern. We also collected all the drift-wood we could find, including that of the wrecked boat which had so nearly cost Croil his life. On examining the quantity, however, we saw that it was utterly insufficient to last us through a winter. My brother, therefore, proposed that we should cut turf and dry it during the summer, and advised that the hut should be much increased in size, with two outer chambers, by which the inner room could be approached and but a small quantity of cold air admitted. A lamp of walrus’ blubber or bear’s grease would be sufficient to warm it at night, provided that the walls were thick enough to keep out the cold. Our stock of powder being small it was necessary to husband it with the greatest care, and we therefore agreed to shoot only such animals as were necessary to supply ourselves with food.

I killed three deer and a bear which one night paid us a visit, and Sandy killed two walruses which he found asleep on the rocks. From the appearance of the ice Sandy hoped at length that he would be able to bring round the boat. For several days a huge mass had been seen floating by, carried on apparently by a strong current, while that in the bay had either melted or had been blown out by the wind. He accordingly set off with the boat’s crew, carrying provisions for several days’ consumption. Ewen and I meantime made our way northward to explore the part of the island we had not yet visited. We saw that it was of far greater extent than we had supposed, and that we should perhaps have to camp out two or three nights if we persevered in our attempt.

As Andrew had charged us to return before nightfall we were about to direct our steps homewards, when Ewen’s sharp eyes discovered a peculiar looking mound at the top of a headland some distance to the northward. As it would not delay us more than an hour we hurried on. Below the headland was a bay, on the shores of which we saw a hut. Could it be inhabited? If so we might meet with some one whose experience of the country would be of the greatest use. We were considerably disappointed on entering the hut to find it empty. It had apparently been for a long time deserted. Without delay we climbed up the top of the headland. We examined the cairn carefully, and found that it was built round and contained a bottle, on opening which I discovered a paper having a few lines apparently written with the burnt end of a stick. They were in English, but so nearly illegible that it was with difficulty I could read them. What was my surprise when I made out the words—

“Left here by the whaler Barentz. Saw her drift out to sea, beset by ice. Fear that she was overwhelmed, and all on board perished. Spent the winter here. A sloop coming into the bay, hope to be taken off by her.

“David Ogilvy.”

Here was a trace of my long-lost brother; what had since become of him? Had he got off in the sloop and returned to Europe, or had she been lost? Had the former been the case, we should have heard of him before we sailed. We hurried eagerly back to discuss the subject with Andrew. It was dark before we reached the hut. We talked and talked, but could arrive at no conclusion. Andrew feared for the worst. The boat had not arrived, indeed we scarcely expected to see her that day. Next day passed by and she did not appear. Two more days elapsed. We were constantly on the look out for her. I proposed going over to try to ascertain what had happened. The mate was getting somewhat better, and I took Andrew’s place that he might go out and take some exercise while in search of a deer. I was talking with Mr Patterson, who spoke hopefully of getting away before the winter commenced, when Ewen rushed into the hut exclaiming—

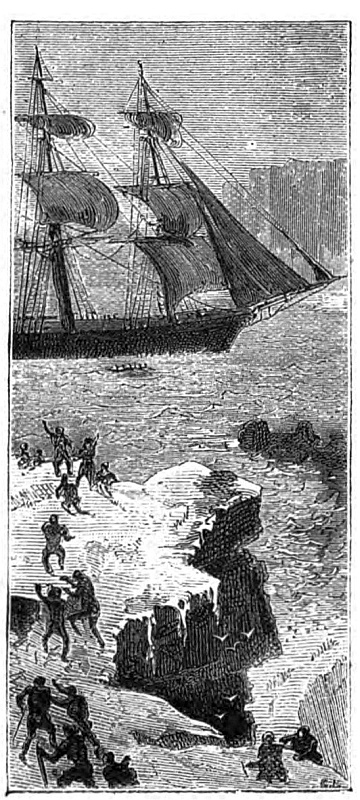

“A sail, a sail! She’s standing for the bay.”

“Go and have a look at her,” said Mr Patterson; “I was sure we should get off before long.”

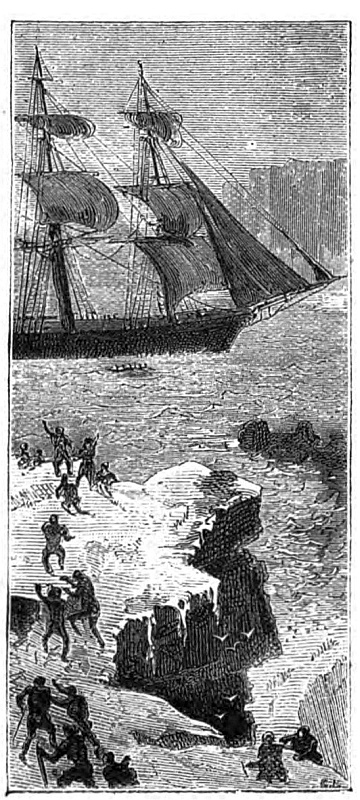

I rushed down to the beach, where I found the rest of the party collected, gazing at the approaching vessel.

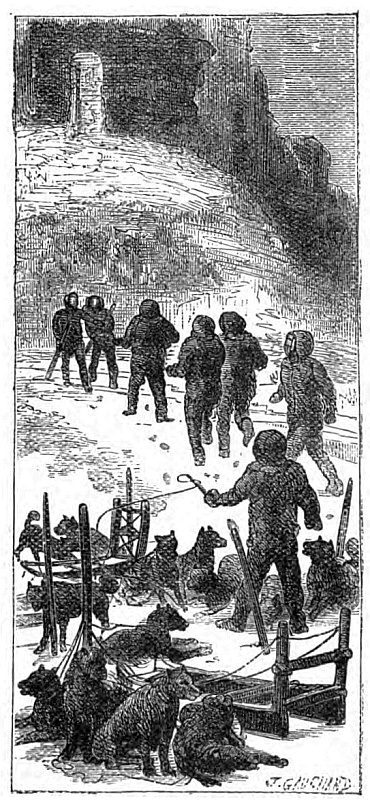

She was the Hardy Norseman, trim and taut. There was no doubt about the matter. On she came, gliding over the now smooth ocean. A shout of joy burst from our throats. All our troubles were over, as we thought. She stood fearlessly on, evidently piloted by one who knew the harbour, and at length came to an anchor. Her sails were furled immediately, and a boat approached the shore.

As she got nearer we saw that the boatswain was steering. His boat had then got off and fallen in with the ship. Such, indeed, he told us, as he sprang on the beach, had been the case. Had he not done so she would have passed on, supposing that we had all been lost; for, although short-handed, the captain had determined on prosecuting the fishery until the weather compelled him to return.

Carrying the mate and Croil, who—as Andrew said—had turned the corner, we were soon on board, heartily welcomed by all hands. Our hut and store of fuel were left for the benefit of any other unfortunate people who might be cast on the island, but the meat and skins were, of course, carried with us.

As the sea was now open to the northward, we sailed slowly on, the boats frequently being sent in to shoot walruses or seals, of which vast quantities were seen on the rocks and floating ice. We were now off the coast of Spitzbergen. Passing some islands, we pulled on shore in expectation of obtaining some walruses. We had killed several, when we saw among the rocks a number of eider ducks which had just laid their eggs. The first mate and boatswain, who were in command of the boats, ordered us to land with the boat-stretchers in our hands, when we rushed in among the birds, knocking them over right and left. While they lay stunned, we were directed to pull off the down from their breasts. We were thus employed for several hours, during which we collected an enormous quantity of eider down, as well as a vast number of eggs. On returning on board, the skipper sent us back for a further supply. As we obtained nearly four hundred pounds of down, and as each pound is worth a guinea in England, the skipper was well pleased with our day’s work, more so than were the poor ducks, deprived of their warm waistcoats and eggs at the same time. Happily the stern ice saves them from frequent visits of the same description.

As we were pulling along we caught sight of a walrus asleep on a rock. Without disturbing the animal, Sandy and two other men landed. His harpoon was soon plunged into the side of the walrus, while the end of the line still remained in the boat. A fierce struggle commenced. The walrus, rolling into the water with head erect and tusks upraised, came swimming towards the boat, regardless of the spears thrust at it, and had almost gained the victory, when a shot through its head put an end to its existence. The next day, having again landed, we killed a number of seals by concealing ourselves behind the rocks on the shore, while they lay enjoying the warm sun on the ice. Andrew, Ewen, and I were some what ahead of the rest of the party, when we caught sight of a bear lying down under the shelter of a hummock. We were intending to stalk him, when we saw a seal sunning itself upon the ice, some distance off. The bear crept from behind his place of shelter, and began to roll about as if also to enjoy the sun. The seal lifted up its head, when Bruin stopped, lying almost on his back, with his legs in the air, and his eyes directed towards his expected prey. The seal dropped its head, and the bear began once more to move forward, again to stop and remain perfectly motionless until the seal’s eyes were closed. Again Bruin advanced, when the seal, which must have been somewhat suspicious of the hairy creature, looked about it. For yet another time Bruin stopped, until, the seal’s suspicions once more lulled, the bear got near enough with one leap to bound upon his prey, when, before the seal was dead, he began tearing away at its flesh. We determined to put a stop to his supper. While he was thus employed and less on the watch than usual, we crept up to him and a shot through his head prevented him from gaining the water. We thus got both bear and seal.