THE LETTER-BAG OF TOBY, M.P.

From the Minister to Persia.

Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 93, December 17, 1887

Author: Various

Editor: F. C. Burnand

Release date: August 30, 2012 [eBook #40629]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Punch, or the London Charivari, Wayne Hammond,

Malcolm Farmer and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Dear Toby,

I am, as you will understand, so busy in my preparations for departure, that I fear I may not find time to call upon you, p.p.c., and therefore take up my pen to write these few lines, hoping they will find you well, as they leave me at present. It is an odd reflection to one who has reached my time of life, that henceforward sixteen-shilling trousers shall have no more interest for me. Already, in the privacy of my room, I don the flowing robes of the East, and sit by the hour as you see me in a little sketch I have had made, and beg your acceptance herewith. It is all very strange to me yet. As Gr-nd-lph says, it is the oddest thing in the world that the Ark and I, after much tossing about in troublous waters, should finally settle down in the neighbourhood of Ararat. If I had had my choice, I would not have gone so far afield. The wise men, you know, come from the East, they do not go there; at least, not further than Constantinople, which would have suited me admirably. Rome I have eyed askance. I could have dressed the part for St. Petersburg. Berlin would not have been bad; and I feel that I was born for Paris. But the Markiss of course has his way, and he has mapped mine out for Teheran.

It is odd to reflect (and as I sit here trying to grow accustomed to the hookah, I feel in a reflective mood) that if Br-dl-gh had not been elected for Northampton in 1880, I would never have been Her Majesty's Minister at the Court of the Shah. Do you remember the night, nearly eight years gone, when I jumped up from my seat below the Gangway and physically barred Br-dl-gh's passage up the House? In the loose way history is written, Gr-nd-lph gets the credit of incubating the Fourth Party. But if it had not been for me, that remarkable cohort would never have existed, and the history of English politics for the last seven years would have been written differently. Gr-nd-lph was actually not in the House when I created the Br-dl-gh difficulty. Three weeks earlier, on Br-dl-gh's first presenting himself, Freddy C-v-nd-sh had moved for a Select Committee to consider his claim to make affirmation. St-ff-rd N-rthc-te had seconded the hum-drum motion, the Committee was agreed to, and there the matter ended. When Gr-sv-n-r moved to nominate the Committee, I came to the front, was snubbed by H-lk-r at the instance of our respected Leaders, but stuck to it then and after, till presently, the Conservative Party, seeing the advantage, came round to my view and poor St-ff-rd N-rthc-te had to eat his words. Gr-nd-lph came on the field and the ball was set rolling; but it was I who gave it the first kick.

And now behold me solemn, sedate, responsible, the Representative of the greatest of Western Powers at the Court where once Artaxerxes ruled! In quitting Parliamentary life I leave behind me an example which young Members will find it profitable to study. The opportunities I possessed were held in common with hundreds of others whom I leave in obscurity. I had no particular gifts that promised the comfortable pre-eminence I have reached. The coarsest flatterer could not accuse me of oratorical ability. Gr-nd-lph, I confess, excelled me there, and so did G-rst, an abler man than either of us, but lacking in the quality that brought Gr-nd-lphand me to the front and kept us there. What I did, was to keep myself in evidence, and to make myself as disagreeable as possible to people in authority. If the object of attack were Gl-dst-ne, good; if it were N-rthc-te, better, as showing more independence, and as securing the favourable attention of the Opposition. It is a commonplace, ordinary thing to be cheered by your own side. What the young aspirant to Parliamentary distinction should look to, is to gain the applause of the Benches opposite. R-b-ck knew that in old days, and so did H-rsm-n, and in these later times Gr-nd-lph better and more successfully than either.

I quit the House of Commons with unfeigned regret, tempered only by the anticipated pleasure of watching from Teheran the coming cropper of my old friends. The deluge is surely coming for them, whilst I loll landed high and dry upon Ararat. I like to make B-lf-r uneasy by telling him this. But he boasts of an infallible receipt the Government have for keeping up their Parliamentary majority. Here and there a bye-election may reduce it, "but," says B-lf-r, "we can always play next, and win. For every bye-election lost we clap an Irish Member in gaol, or, for the matter of that, a Radical, and thus maintain an even balance. We lose Coventry and they lose O'Br-n's vote. Spalding goes, and T. H-rr-ngt-n's vote is crossed out. Northwich is lost, and the Lord Mayor of Dublin is lagged. We lose a vote in the Exchange Ward, Liverpool, and they are bereft of Sheehy, whilst we have left to the good Cox and E. H-rr-ngt-n, with P-ne safe within the mud walls of his castle."

That is all very well, but evidently it cannot go on indefinitely. I at least am out of the scuffle happily, and in good time, and, political life's fever over, shall live well.

Hasty assumption, by spite inspired,

Spouting in public before you've inquired

Basis of fact or authority's worth;

Wriggles, provoking much cynical mirth,

Roundaboutation, sophistical fudge;

Then retractation, but done with a grudge!—

Gentlemen, gentlemen, is this good form?

Would you political citadels storm

Like Heathen Chinees with (word) "stinkpots"? For shame!

This is not manfully playing the game.

It is not "good business," believe me, but bad,

Whether you're Tory or whether you're Rad.

Young and conceited, or old and grand,

To tell taradiddles—at second-hand!

First of all came The London Savoyards, who, after sending their D'Oyly Carte de visite in advance, showed our cousins-German the way to perform Burlesque Opera of native English growth. Then followed Herr Wyndham, and Fraülein Moore, who have just been instructing the Berliners in the art of playing Comedy, and have achieved an undeniable success in David Garrick. Odd international combination this, English actors playing before a German audience a piece adapted by an English author from a French play translated into German. Our actors and actresses will go in for the study of German, and as we now hear in England that German labour ousts native labour from the market, so we may expect very soon to hear German actors protesting against the influx of English Theatrical Companies who are taking the bread out of their mouths. What will be the next move in this game? Will Sardou adapt The Butler to be played here by Coquelin, in Toole's part, and at his theatre, with Sarah Bernhardt as the Cook, just to strengthen the cast? Herr Wyndham appeared at the Residenz Theatre. We hope he is not going to take up his Residenz there, as we can't spare him.

"Flout 'em and scout 'em, and scout 'em, and flout 'em.

Trade is free."

Sir,—The reason why I have not hitherto contributed to the controversy on the recent unhappy (Police) Divisions is, because I have been laid up in the Hospital. Never mind which Hospital—but I have not been so comfortable since I had the mumps, years and years ago, at school. Being a born economist, I naturally turned out in my myriads to assist at a gratis show in Trafalgar Square; and, Sir, I never came so near realising what a "dead head" was in the whole course of a chequered (not to say chuckered) career. But do I turn round and abuse the Police? Why, ever since that fortunate Sunday, I have enjoyed, at no expense to myself, the most delicate of viands, the tenderest of nursing, and a complete immunity from even the suggestion of getting anything to do; and, in addition to all this, the satisfaction of having employed the services of a force to whose maintenance I have never contributed one farthing. But soft, a nurse approaches, and I must dissemble.

The Woodford tenants

Must have liquor'd

To hear of the penance

Of Lord Clanricarde.

Dear Mr. Punch,

I. It is plain that the soi-disant Shakspeare was poor to the end of his days. This is proved by Milton's sonnet beginning—

"What needs my Shakspeare for his honour'd bones?"

This shows that the person in question was in the habit of selling his kitchen refuse, and more noteworthy still, that Milton was in the habit of buying it. Whether out of respect for the vendor, which would go a long way towards proving the esteem in which he was held, or because Milton was in the marine store line at this period, I leave to Mr. Donnelly to decide.

II. It is certain that there is a cypher in the Midsummer Night's Dream. Pyramus has the line, "O, dainty duck. O, dear!" Now "duck" stands with cricketers for 0, and 0 is a cypher (or is it figures that are cyphers? but, never mind). Therefore we have here the expression, "O, dainty cypher, O, dear!" which proves conclusively, that the cypher was dainty,—exquisite, elaborated; and also that Bakspeare was heartily tired of it, unless, "dear" refers to the terms he had to pay to Shakon to hold his tongue. But the fact that the supposed author used to sell bones, and inferentially rags, to Milton, rather militates against this hypothesis. And here note what a flood of light is thrown upon the disappearance of the manuscripts. They were indubitably sold, with the honoured rags and bones to Milton, who has certainly more than one suspicious coincidence of thought and phraseology, especially in his earlier poems.

III. My play, Piccoviccius, contains the clue to the whole matter. There is a picture on the title-page of a boy blowing an egg, while an elderly gentlewoman, who is remarkably like the bust of the poet in Stratford Church, looks on with every appearance of interest. Underneath is the legend, "Lyttel Francis teaching his Crypto-gra'mother." I am firmly convinced that Piccoviccius was written by both of them. The style is not the least like that of either, which proves that they didn't want everyone to know. I subjoin a specimen. The scene is the palace of the usurping Duke Jingulus, who is about to wed the Lady Rachel.

Jingulus, Rachel, Philostrate, and others.

Jing. Say, Philostrate, what abridgment have you for

This dull, three-volumed day?

Phil. There is, my lord,

A show of cats and tame canary birds.

The cats, sleek sleepy creatures, well content,

Doze fur in fur, the while the nimble birds

Climb ladders, carry baskets, beg for pence:

Which given, they in bills receive, and take

With hops, well-satisfied unto their keepers,

Then the sleek cats sit up and 'gin to spar,

And get sleek heads in furry chancery.

Jing. That will we not see at our wedding-time,

No sparring, nor no caging. Well, what next?

Phil. A hunch-back'd man, long-nosed, there is, my lord,

Who in a curtained tabernacle dwells,

Himself, his wife, his child, a helpless babe,

His dog, of rare sagacity, though small,

Is full as large as all the family.

The man a cudgel bears, and carries it

As though he lov'd it. Spurning household cares,

To pity dead, he through the window flings

His wailing, helpless babe, nor spares the pæan

Of nasal triumph and the drumming foot.

The mother thus bereav'd, such comfort gets

As in the cudgel lies, and joins too soon

Her infant sped. Again the nasal song

Shrills, and the blood-stained tabernacle shakes

With heels triumphant tapping. All who come—

Many there are who come—learn soon or late

The flavour of the cudgel. At the end

All human powers defied, the hangman trick'd

By childlike wile, and hois'd with his own halter,

A day of reckoning comes. The unseen world

A minister sends forth who terrifies

The heart that knew no terror; turns the song

Of triumph to a long wail of despair;

And this most wicked puppet goes below

The curtain of his booth.

Jing. A moral play!

This we will see. Command it. Lords, away!

[Exit in State.

Hydropathic Art.—"O give me the sweet shady side of Pall-Mall," sang Captain Morris, the Laureate of the Old Beef-steak Club. At the present period of the year we have a greater liking for the sunny side. And the sunniest spot on the sunny side we have discovered during the last week is undoubtedly in the rooms of the Sanatorium presided over by Sir John Gilbert. The Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours is a capital hydropathic establishment at this season of the year.

A Necessary Explanation.—Considerable remark has been excited by the sudden departure from London of Count Corti, the Italian Ambassador. The fact is, Count Corti was compelled to appear at Rome, in person, as an answer to the imperious order of recall which (to translate the legal process exactly) is of the nature of a "County Corti Summons."

[Palmistry is now a fashionable amusement at bazaars and at evening parties.]

The Sibyl in the times of old,

Who dealt in charms unlawful,

Had hair unkempt and eyes that rolled

'Mid conjurations awful.

The prophetess of modern days,

Who dabbles in divining,

A pair of pleasant eyes will raise,

'Neath hair that's soft and shining.

The latest "fad" appears to be

Commingled fact and fancy,

What led of old Leuconöe

To trust to chiromancy.

Which is, the victim understands,

That each vice or perfection

Can be discovered in his hands

By Sibylline inspection.

She'll tell us all the Mounts and Lines

Of Saturn and of Venus;

With man and wife her skill divines

What shadows come between us.

She sees in hands a taste for Art,

For Music, or for Letters,

And knows how often each poor heart

Has yielded to Love's fetters.

It's rather hard to stand and hear

Your character decided,

And imperfections that appear,

By captious friends derided.

Yet if you'll listen to advice,

You'll smile, and looking pleasant,

Trust only prophecies when nice,

Of either past or present.

Dear Charlie,

I'm much obligated for that there St. James's Gazette

As you sent me larst Satterday's post. I 'ave read it with hintrest, you bet;

Leastways, more pertikler the harticle writ on "yours truly," dear boy;

Wich the paper is one as a gent who is reelly a gent can enjoy.

I shall paternize it with much pleasure; it's steep, but it's puffect good form.

Seems smart at the "ground" and the "lofty," and makes it tremenjusly warm

For Willyum the Woodchopper. Scissors! His name's never orf of their lips.

Wy, it's worth a fair six d a week jest to see 'em a slating Old Chips!

Proves as 'Arry is well to the front wen sech higperlite pens pop on him,

Does me proud and no herror, dear pal; shows we're both in the same bloomin' swim.

Still, they don't cop my phiz quite ker-rect; they know Gladstone right down to the ground;

But I ain't quite so easy 'it off, don'tcher see, if you take me all round.

Old Collars is simple as lyin', becos he's all bad, poor old 'ack,

And you can't be fur out in his portrait as long as you slop on the black.

But I'm quite another guess sort; penny plain, tuppence coloured, yer see,

May do all very well for the ruck; but they'll find it won't arnser for me!

I'm a daisy, dear boy, and no 'eeltaps! I wish the St. James's young man

Could drop into my diggings permiskus; he's welcome whenever he can;

For he isn't no J., that's a moral; I don't bear no malice; no fear!

But I'd open 'is hoptics a mossel concernin' my style and my spere.

The essence of 'Arry, he sez, is high sperrits. That ain't so fur out.

I'm "Fiz," not four 'arf, my dear feller. Flare-up is my motter, no doubt.

Carn't set in a corner canoodling, and do the Q. T. day and night.

My mug, mate, was made for a larf, and you don't ketch it pulling a kite.

So fur all serene; but this joker, I tell yer, runs slap orf the track

Wen he says that my togs and my talk are "the fashion of sev'ral years back."

The slang of the past is my patter—mine, Charlie, he sez! Poor young man!

If I carn't keep upsides with the cackle of snide 'uns, dear Charlie, who can?

Wot is slang, my dear boy, that's the question. The mugs and the jugs never joke,

Never gag, never work in a wheeze; no, their talk is all skilly and toke,

'Cos they ain't got no bloomin' hinvention; they keeps to the old line of rails,

With about as much "go" as a Blue Point, about as much rattle as snails.

Mavor's Spellin' and Copybook motters is all they can run to. But slang?

Wy, it's simply smart patter, of wich ony me and my sort 'as the 'ang.

Snappy snideness put pithy, my pippin, the pick of the chick and the hodd,

And it fettles up talk, my dear Charlie, like 'ot hoyster sauce with biled cod.

"Swell vernacular"? Swells don't invent it; they nick it from hus, and no kid.

Did a swell ever start a new wheeze? Would it 'ave any run if he did?

Let the ink-slingers trot out their kibosh, and jest see 'ow flabby it falls.

Bet it won't raise a grin at the bar, bet it won't git a 'and at the 'Alls.

And fancy my slang being stale, Charlie! Gives me the needle, that do.

In course I've been in it for years, mate, and mix up the old and the new;

But if the St. James's young gentleman fancies hisself on this lay,

I'll "slang" him for glasses all round, him whose patter fust fails 'im to pay.

Then he sez, "'Arry's always a Londoner." Shows 'Arry ain't no bad judge.

"Wot the crockerdile is to the Nile 'Arry is to the Thames." Well, that's fudge.

That's a ink-slinger's try-on at patter. Might jest as well call me a moke.

Try another, young man; this is kibosh purtending to pass for a joke.

Wen he sez my god's "go,"—well he's 'it it. Great Scott! wot is life without "go"?

But "loud, slangy, vulgar"? No, 'ang it, young man, this is—well, there, it's low.

Me vulgar! a Primroser, Charlie, a true "Anti-Radical" pot!

No, excuse me, St. J., I admire you; but this is all dashed tommy-rot.

Stale, too, orful stale, my young josser. It's wot all the soap-crawlers say,

If a party 'as "go" and "high sperrits"—percise wot you praise me for, hay?—

If he "can laugh aloud," as you say I can, better than much finer folk,

Will you ticket 'im "vulgar," for doin' it? Oh, you go 'ome and eat coke!

Leastways I don't mean that exackly; I like you too well; you're my sort;

But you ain't took my measure kerrect, I'm a Tory, a patriot, a "sport."

So wy should you round on me thusly? I call it a little mite mean.

If I took and turned Radical now; but oh! no, 'Arry isn't so green.

'Owsomever in one thing you've nicked me. No marriage

for 'Arry, sez you.

O, right you are, chummie! I'm single, you bet, though I'm turned twenty-two,

And I've 'ad lots o' chances, I tell yer; fair 'ot 'uns, old man, and no kid.

But I'll 'ave a free run for my money, as long as I'm good for a quid.

Yah! Marriage is orful queer paper; it's fatal, dear boy, as you say,

It damps down the rortiest dasher, it spiles yer for every prime lay.

No; gals is good fun, wives wet blankets, that's wot my egsperience tells,

And the swells foller me on that track, though you say as I follers the swells.

Wot odds arter all? We're jest dittos! I'm not bad at bottom, sez you.

Well, thankye for nothink, my joker. As long as I've bullion to blue,

I mean to romp round a rare buster, lark, lap, take the pick of the fun,

And, bottom or top, good or bad, keep my heye on one mark—Number One!

There, Charlie, that's 'ow I should answer my criticks. They ain't nicked me yet,

Not even the pick o' the basket, 'im of the St. James's Gazette.

He's not a bad sort though, I reckon. Laugh, lark, cut a dash, never marry!

Yus, it only want's my fillin' in to make that a fair photo, of

A Demonstration was held yesterday afternoon at St. Giles's Hall, in connection with the Imperial Association, for the raising of Agricultural and other Prices, "to protest still further against the late unrestricted ability to live on their means enjoyed by the British Middle Classes," and "to take ulterior measures for rendering it more impossible." A large number of members of the Association were assembled, among whom were the Duke of Glutland, the Right Hon. James Mowther, Mr. Gruntz, Mr. C. W. Bray, M.P., and others.

Mr. Flowerd Mispent, M.P., said he was proud to take the chair on such an occasion, and to congratulate the assembly on the immense progress made in the country of the principles they were met to advocate. ("Hear, hear!") Their great object had been, by forcing the Government to put a prohibitive tax on all foreign imports whatever, to so stimulate home industries, that while the producer flourished at the expense of the consumer, the latter, representing four-fifths of the nation, was driven to the verge of desperation by a general rise of prices, that he was powerless either to stave off or meet. (Loud cheers.) He thought that the great bulk of the Middle Classes of the country must, if not already hopelessly ruined, at least have got it pretty hot. (Laughter.) Take his own case. Owing to the new import duties levied on foreign wool and silk, the tweed suit in which he stood up before them on that platform had been charged to him by his tailor at £37 15s. (laughter), while his hat, for the appearance of which he could not say much, had cost him £5 18s. 6d. (Renewed laughter.) Such prices as these must tell in the long run on the pocket of that great enemy of national industry, the "Consumer." (Cheers.)

The Chairman then read letters of apology from the Duke of Twickenham, Lord Starch, and Baron Dimock, M.P., who declared their readiness to favour any motion calculated to stimulate a still further rise of prices. Mr. Jollis, M.P., wrote in a similar sense, and in a letter expressing regret that he was unable to be present, Lord Hapence said:—The brilliant future that is now dawning on the prospects of the British Agricultural Interests must be patent to all. Only yesterday I was charged 18s. 6d. in a local hotel bill for a small omelette, and, on asking for some explanation, was informed by the waiter that since the importation of French eggs had ceased, the market price of those procurable from English poultry had risen to 4s. 6d. (cheers), and they were not to be relied on at that. This is as it should be. Need I say I paid my bill, not only without a murmur, but with positive satisfaction. (Loud cheers.)

Sir Edward Mulligan, M.P., wrote:—"Your meeting is a very important one, and has my cordial support. But with British-made ladies' gloves at £1 3s. 6d. a pair, British-made chocolate at 17s. 6d. a pound, and British-made silver watches at £38 a piece, it cannot be denied that the absence of foreign competition has favourably affected home prices. May this encouraging catalogue be continued. I hear, too, that since prohibitive duty has been imposed on the importation of petroleum the coarsest kinds of composite candles have been selling at 9s. 6d. a pound. Living for the Middle Classes must be getting unendurable. I hail the prospect as a hopeful sign of the times." (Cheers.)

Mr. Joynter, the Chairman of the Association, then rose to move the first Resolution:—"That in consideration of the fact that, though the threepenny halfpenny loaf was now at 3s. 9d., and that though the agricultural labourer was paying 4s. 7d. a pound for bacon, £3 17s. for a smock, and £1 15s. 6d. for a second-hand spade, and that yet, notwithstanding these fiscal advantages, he did not seem entirely satisfied with his improved condition, the meeting should urge upon the State, the necessity of imposing still further prohibitive duties on foreign imports in the hope of introducing even greater complications into the vexed question of how to make the British Consumer entirely support the British Producer."

Mr. Waitland seconded the motion. He added, however, that notwithstanding the undeniably flourishing condition of British trade at home, he could not regard its prospects as equally satisfactory abroad. Owing to the retaliatory action of Foreign Governments, our Exports appeared somehow entirely to have disappeared. (Laughter.)

Mr. Gruntz, said that was so. Still there could be no doubt as to its healthy progress in our midst, and that reflection ought to quiet the misgivings and comfort the heart of the ardent Imperial Associationist. He had in his pocket at that moment a British-made cigar. (Cheers.) It hadn't a nice flavour, it wouldn't draw, and it cost him 12s. 6d.—(laughter)—still, it was made of British-grown tobacco, and that was everything. (Hear, hear!) Perhaps it was in their wine that people of his class suffered most. In the old days he used to drink Dry Monopole; but since a Government duty of £20 a dozen was imposed on all imported Champagne, he had had to have his from the "British Home-manufactured Wine Company;" and, though they charged him eleven guineas a dozen for it, and he believed it frequently made his guests seriously ill, still he felt he was supporting a "home industry," and did not scruple to put it freely before them. (Roars of laughter.)

After the enthusiastic singing of "Rule Britannia" by the whole meeting, a vote of thanks to the Chairman brought the proceedings, which were of a very animated character, to a conclusion.

"Fiscal Reform"? A pretty phrase

To mark the old exploded craze;

But, Gothamites, you're surely blind!

Think you to reach "Protection's" goal

By squatting in that leaky bowl,

And whistling for a (Fair Trade) Wind?

New Work by Mr. O'Brien.—Under the general heading of Tullamore Tales, we are to expect a good story, entitled, Reverses on the other side of the Tweed.

"King Diddle," by H. Davidson, deals with the wondrous sight,

Seen by two little children in a lumber-room one night.

And "Rider's Leap," by Langbridge,—no, not by Rider Haggard,

Shows how a brave and noble youth, can never be a blaggard.

The Christmas Number of London Society—Society!

With Strange Winter, Griffith, and Fenn,

Gives us all a most pleasing variety—Variety!

There's a tale from the Cameron pen.

If sly Francis Bacon was Shakspeare incog.

His publisher nowadays ought to be Hogg,

Whose books for the Season, the "Stories and Yarns,"

Must prove to us all that "one lives and one larns."

But "Cocky and Clucky and Cackle," I fear,

Which is from the German, is not very clear.

Griffiths and Farren, farren-aceous food

For children's taste provide—all very good.

In his story of the "Willoughby" two "Captains," T. B. Reed

Shows how a public school-boy's life both pride and courage need.

In your "Walks in the Ardennes," which some may prefer to Surrey—

Percy Lindley's is a Guide-book—to be re-named "Lindley-Murray."

Here's "Bo-Peep" and also "Little Folks," with prose and verse combined,

Wherein the smallest readers may find something to their mind.

The charming "Rosebud Annual,", with pictures, we confess

Is a book all little gardeners should certainly possess.

The Sporting Cards of Harding, funny.

Hazelberg's "Diadem" worth the money.

For toys that pop up with a spring,

Tra la!

Or toys not at all in that line,

To Cremer's you'll go, and you'll sing

Tra la!

I want to lay out a shil-ling,

Tra la!

For which you will get something fine

That cheapness and taste will combine.

For "Modes et robes pour les dames et les enfants,"

And toy model series amusing and strong,

To Cremer, tra la!

To Cremer, tra la!

Junior Cremer, go!

Paintings on leather, satin, whence this show?

We reply, "Walker"—meaning John & Co.

You're searching out for something very new

These diaries, all shapes and sizes, view, Sir.

Instead of "En revenant de la Revue,"

With "date cards" reviendrez De la Rue, Sir.

Wirths Brothers' cards we like, and for this reason—

They are in keeping with the Christmas season.

Of Christmas Cards you ask well where on earth's

Their point? Quite so: but here's your money's wirths.

Do you ken Tom Smith

As you ought to do,

He is coming with

Some Crackers new,

Crackers and costumes not a few,

To make merry a Christmas ev'ning.

Oh, did you ne'er hear of the name Arthur Ackermann,

Who imports Christmas Cards called after Prang,

They are American, 'tis safe to back a man,

Who holds for landscape cards premier rang.

The Marion Album intended for photos,

Three-quarter pictures with scant legs and no toes.

Cards neat and droll, not too elaborated,

Come from card-houses, which are Castell-ated.

"Take a Card," says Bennett, "do,"

And a satin card-case too.

The Sockl Court Card much delighted the Bard.

And Faulkner's are charming. I "speak by the Card."

Joy! Joy! my task I've done! and I, sweet Sire,

Vainly, Macbeth-like, strike the slavish lyre.[1]I'll sing no more. Books! cards! go on the shelf.

Sooner than strike my harp, I'll "strike" myself!

My holiday's begun. Accept my benison!

Signed Morris-Browning-Austin-Swinburne-Tennyson.

[1] "Lyre and slave! (strikes him.)"—Macbeth, Act v., sc. 5.

"Dancing Dolls in Chancery.—The solicitors' table was cleared of papers, and the ballet-girl doll, having been wound up, commenced to dance on the table, to the amusement of a crowded court. Mr. Justice Kay watched the performance with evident interest, and when the dance was concluded the doll was handed up to him and carefully examined. He then handed it to the Registrar of the Court, with an injunction 'not to hurt it.'"

Sing a song of Justice

Kay up in his place,

Four-and-twenty dancing dolls

All in a case;

When the case was opened

The dolls were made to play,

Wasn't that a pretty sight

For Mr. Justice Kay?

The Judge sat in the Court-house

Thinking it so funny,

The dolls were on the table

Worth a lot of money,

His Lordship said, "The ballet-

Girly-dolly I'll inspect,"

Which he did, and then pronounced it

"Quite O Kay," or "Orl Kayrect."

Occasionally our Mrs. Ram likes to display her perfect knowledge of the French language. "I've just been reading," she said, "a most interesting work, the life of Monsignor Dupanloup, who was the Bishop—or, as they call it in French—the Equivoque d'Orléans."

Delacruche (the rising young Tragedian at the Parthenon). "Oh, the Fickleness of Woman! Look at that Idiot they're all swarming over now! Ugh! I should like to Kick him, if ever I get an opportunity!"

Brown, F. R. S., &c., &c. (who is fond of Tragedies, but dislikes Popular Tragedians). "Oh, Do, my dear Fellow, Do! And, I say, let Me be there to see the Result."

Delacruche. "Humph! Who is the Beast?"

Brown. "Slogg, the Pugilist from California, Champion of the World!"

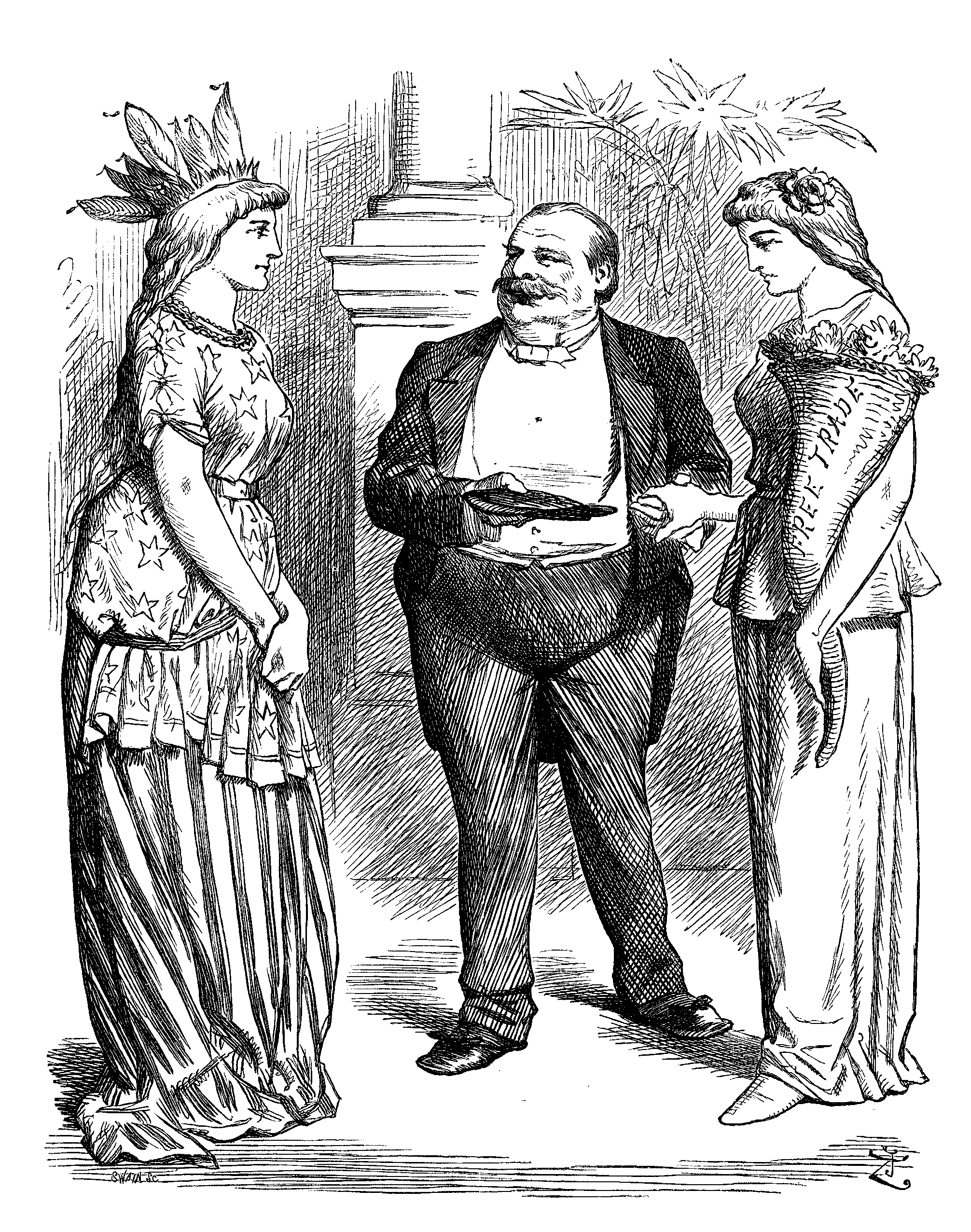

May I ask you, Columbia, this lady to note?

She's English, you know; quite English, you know.

(What effect will this have on the Democrat Vote?

She's English, I know; quite English, I know.)

She comes from a country that's cursed with a throne;

Yet I think, in your interest, she ought to be known.

She may help you to deal with your Surplus o'ergrown.

(That's not English, you know; not English, you know.)

I'll ask you, Columbia, this lady to hear;

She's English, you know; quite English, you know.

Her form, which is slim, and her eyes, which are clear,

Are English; quite English, you know.

Just now, Ma'am, our Surplus has reached such a size,

(Not English, you know; not English, you know,)

The difficulty I can no more disguise.

(Plain English, you know; plain English, you know.)

Why, every year,—it reads like a romance—

That Surplus, by millions, fails not to advance.

If at this young lady you'd give just a glance!

(She's English, you know; quite English, you know.)

Her words, Ma'am, may please, if you'll deign but to hear;

They're English, you know; quite English, you know.

If you banish her now, she must soon reappear.

Still English, quite English, you know.

What Columbia has done she of course can undo

(That's English, you know; quite English, you know);

Our old fiscal system has gone all askew.

(Like the English, you know; say some English, you know.)

Protection has got to the street that's called Queer;

Free Trade!—well, her advent may distant appear;

Anyhow, do just glance at this lady, my dear.

She's English, you know; quite English, you know.

Mark the things she will say which 'twere prudent to hear,

They're English, you know; quite English, you know.

Our system's not solid or stable, I fear.

Not English, not English, you know.

Protection and you very long have been friends

(That's Yankee, you know; quite Yankee, you know);

But sure such a Surplus serves no useful ends.

To Yankees, you know, robbed Yankees, you know.

Humph! Yes, English "Chambers of Commerce" do pule

Just now for Protection; they're playing the fool.

But they'll hardly score much off the old Free Trade School.

That's English, you know; quite English, you know.

Heed not all the Vincents and Bartletts you hear,

Though English, you know; mad English, you know.

Economists know they are very small beer,

Though English, half English, you know.

For Salisbury, Gladstone and Bright all agree

(They're English, you know; all English, you know,)

That this new Fair Trade fad is pure fiddle-de-dee.

(Not English, you know; not English, you know.)

The Farmers and Landlords want prices to rise,

So they look on Fair Trade with encouraging eyes;

But they'll hardly get Statesmen to be their allies,

Who're English, you know; true English, you know.

President Cleveland (to Columbia). "WILL YOU ALLOW ME TO INTRODUCE THIS YOUNG LADY?"

Trade Chambers may vote, Tory delegates cheer

(They're sure to, you know; quite sure to, you know);

But "Fiscal Reform" won't fool many, I fear,

Who're English; wise English, you know.

Columbia, may I present my young friend?

She's English, I know; quite English, I know.

I don't say adopt her; I do say—attend,

Though she's English, you know; quite English, you know.

At any rate deign to vouchsafe her a smile,

I fear my Republican friends she will rile;

But she may prove a friend, though she comes from the Isle

That's English, you know; quite English, you know.

The things I have said 'tis high time you should hear,

In English, you know; plain English, you know.

So let me present this young lady, my dear,

Though she's English, quite English, you know!

By Britt Part.

There was commotion in Gggrrandddolllmann's Camp. It could not have been a fight, for in those days, just when gold had been discovered on Welsh soil, such things as fights were unknown. And yet the entire settlement were assembled. The schools and libraries were not only deserted, but Jones's Coffee Palace had contributed its tea-drinkers, who, it will be remembered, had calmly continued their meal when even such an exciting paper as the Grocers' Journal had arrived. The whole Camp was collected before a rude cabin on the outer edge of the clearing. Conversation was carried on in a low tone, but the name of a man was frequently repeated. It was a name familiar enough in the Camp—"W. E. G.—a first-rate feller." Perhaps the less said of him the better. He was a strong, but, it is to be feared, a very unstable person. However, he had sent them a message, when messages were exceptional. Hence the excitement.

"You go in there, Taffy," said a prominent citizen, addressing one of the loungers; "go in there, and see if you can make it out. You've had experience in them things."

Perhaps there was a fitness in the selection. Taffy had once been the collector for a Trades Union Society, and it had been from some informality in performing his duty that Gggrrandddolllmann's Camp was indebted for his company. The crowd approved the choice, and Taffy was wise enough to bow to the majority.

The assemblage numbered about a hundred men. Physically they exhibited no indication of their past lives and character. They were ordinary Britons, and there was nothing to show they had been less contented than their neighbours; and yet these men, in spite of their loneliness, had never wanted for a single reform. Until now they had been absolutely satisfied with their lot.

There was a solemn hush as Taffy entered the Post Office. It was known that he was reading the despatch. Then there was a sharp querulous cry—a cry unlike anything heard before in the Camp. It was muttered by Taffy. He told them that the document called upon the whole community to ask for Disestablishment and Home Rule. The Camp rose to its feet as one man. It was proposed to explode a barrel of dynamite in imitation of the Irish Nationalists, but in consideration of the position of the Camp, which would certainly have been blown to pieces, better counsels prevailed, and there was merely a cutting of bludgeons from the trees the levelling of which W. E. G. was known to love so well.

Then the door was opened, and the anxious crowd of men, who had already formed themselves into a queue, entered in single file. On a table lay the document they had come to read.

"Gentlemen," said Taffy, with a singular mixture of authority and ex officio complacency; "gentlemen will please pass in at the front door and out of the back. Them as wishes to contribute anything towards the carrying out of the written wishes of the document will find a hat handy."

The first man entered with his hat on; he uncovered, however, as he looked at the writing, and so unconsciously set an example to the next. In such communities good and bad actions are catching. As the procession filed in, comments were audible. "A lot for the money!" "Just like him!" "Gets a deal into three lines!" And so on. The contributions were as characteristic. A life assurance policy, a pledge to abstain from intoxicating drinks, several volumes on political economy.

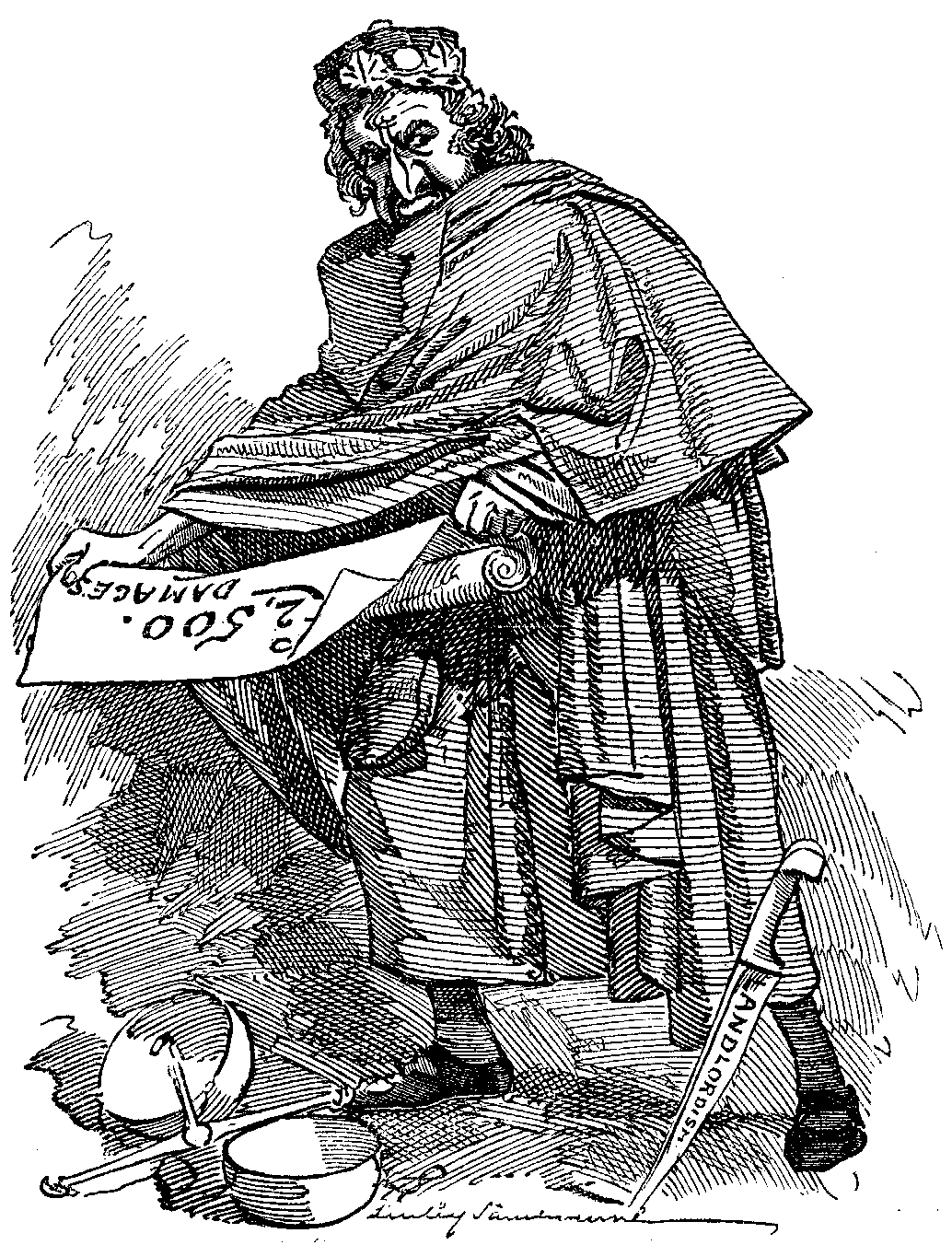

From a Portrait sketched by the Great McDermott, Q.C., during a recent Irish Trial.

So the despatch was read and re-read a score of times, and it was found necessary to give it a name. The natives of Wales are generally sagacious, and so they gave it the name of the Pluck. For the sake of the Pluck they did everything. It was certain, of late, they had not been very successful. They had certainly not paid their rents, and refused to patronise the Parson, and so the work of degeneration began in Gggrrandddolllmann's Camp. Instead of working as of old, the inhabitants gave up labour and shouted to one another. They repeated the phrases of the despatch crying, "Be worthy of yourself, gallant little Wales," "Remember Michelstown!" and went to sleep. Before the arrival of the despatch they had been a clean, hard-working, thrifty race. Latterly, however, there had been a rude attempt to let things go from bad to worse. The newly discovered mines were deserted and all industry was at a discount. "It is the Pluck of Gggrrandddolllmann's Camp that's doing it," said Taffy, as he gazed at the document as it lay on the table before him.

But at length things came to a crisis. The converted miners, as it has been explained, refused to work, and then neglected to pay their rents. Then came evictions, supported by the law. There was a confusion of staves and bayonets, buck-shot and black-thorn sticks. The Camp disappeared amidst much excitement. Some of the Campers emigrated, and others were sent to gaol. Taffy was missing. At length he was found in a ditch, holding a postcard bearing some warlike words, and signed "W. E. G."

"I have got the Pluck with me now," he said, as he was arrested; and the strong man, clinging to the thin document so full of wild advice, as a drowning man is said to cling to a straw, was marched off to prison!

The times have been

When German brains no bout with us would try;

We ruled the roast. Now Teuton scribblers come,

With twenty languages upon their tongues,

And push us from our stools!

A Sound Opinion.—Our Own French-Pronouncing Impressionist says that the new Cabinet in Paris cannot possibly be a success, as it commences with a Fallière.

Husband. "Didn't I tell you not to invite your Mother back in my——"

Wife. "Dear, that's the very Thing she's come about! She read your Letter!"

As Madame Patti would have said, if she had thought of quoting Bacon last Tuesday week, and as somebody probably will say after reading this, and then send it, a few months hence, to Mr. Punch as quite new and original, "When my Kuhe comes, call me." And when her Kuhe (English pronunciation) did come, she came up to time and tune, and came up smiling. Of course with such names as Mmes. Patti, Trebelli, Messrs. Lloyd and Santley with Miss Eissler on the violin, Mr. Leo Stern ("Leo the Terrible") on the 'cello (sounds uncomfortable this), Miss Kuhe on the pianoforte (unpleasant position), Mr. Ganz as "accompanyist," (what an ugly word!) and the Great Panjandrum himself, Mr. W. G. Cusins (Sir W. G. Cusins as is to be,—which was our Jubilee Midsummer Knight's Dream) as Conductor, what could the result be, but success? Every seat taken; up gets the Conductor, "Full inside, all right!" and on we goes again! And after this, off goes Madame Patti to America to earn any amount of dollars by singing her well-known répertoire, which, with one or two exceptions, she may leave t'other side of the Atlantic, and return to tell us of "The songs I left behind me," and to chant with feeling "I cannot sing the old Songs." Au plaisir! Adelina, and all good Engels guard thee! I beg to sign myself, re-signing myself to the absence of the Diva,

Before the applauding British P.

The fistic crack, Smith, stands,

Jem Smith a mighty man is he,

With smart and smiting hands;

And the muscles of his legs and arms

Stand out like steely bands.

His hair is fair, and closely cropped,

His pink face bears no tan;

His brow is low, his wits seem slow,

He "gates" whate'er he can!

But he gets more cheers than Salisbury's self,

Or e'en the Grand Old Man.

Whene'er their Champion spars at night

Excited Britons go,

To see him swing his left and right

With slogging force though slow;

And the guests are scarce a pretty sight,

They're loud and rather low.

Green youngsters scarce released from school

Flock in at the open door.

They love to see him "kid" and feint,

And pay their bobs therefor;

And if his right he does let fly

Great Cæsar, how they roar!

At length he into training goes,

Attended by "the bhoys,"

Punches the ball, pickles his hands,

With other training joys,

Which in the penny sporting prints

Abroad his backers noise,

To read the which boys about town

Esteem it Paradise;

They buy the accounts and o'er them pore,

Though probably all lies,

And to each other whisper them

With wonder-rounded eyes.

Bouncing, belauding, gammoning,

Onward the game still goes;

But whether in the fistic ring

The Champions will close,

Why, that is quite another thing,

Which nobody quite knows.

Thanks, thanks to thee, my fistic friend,

For the lesson thou hast taught.

If pugs can get a barney up,

Whereby the crowd is caught,

What matters it whether they'll fight

Or whether they have fought?

Toying with Truth.—The Annual Truth Toy Exhibition, which shows the toys provided for any number of Children in our hospitals, workhouses, and infirmaries at Christmas time, will be held at Willis's Rooms, December 19 and 20. No further intimation is necessary. When there a Will is, there a Way is.

Says Misther Donelly,

Who writes so funnily,

"Sure, Bacon's side I am on."

"The side of Bacon,"

Says Punch, "you've taken

Against our Will, is—gammon."

(With some allowance made for taking a false quantity.—Ed.)

American-Irish Donelly,

You're cunning as Micky O'Velly,

As you've undertaken

To prove Shakspeare Bacon.

Howld your whisht! "Porker verba,"

I tell 'ee.

Song for Mr. Pritchard-Morgan, of Mawddach Valley, near Dolgelly.—"Darling Mine!"

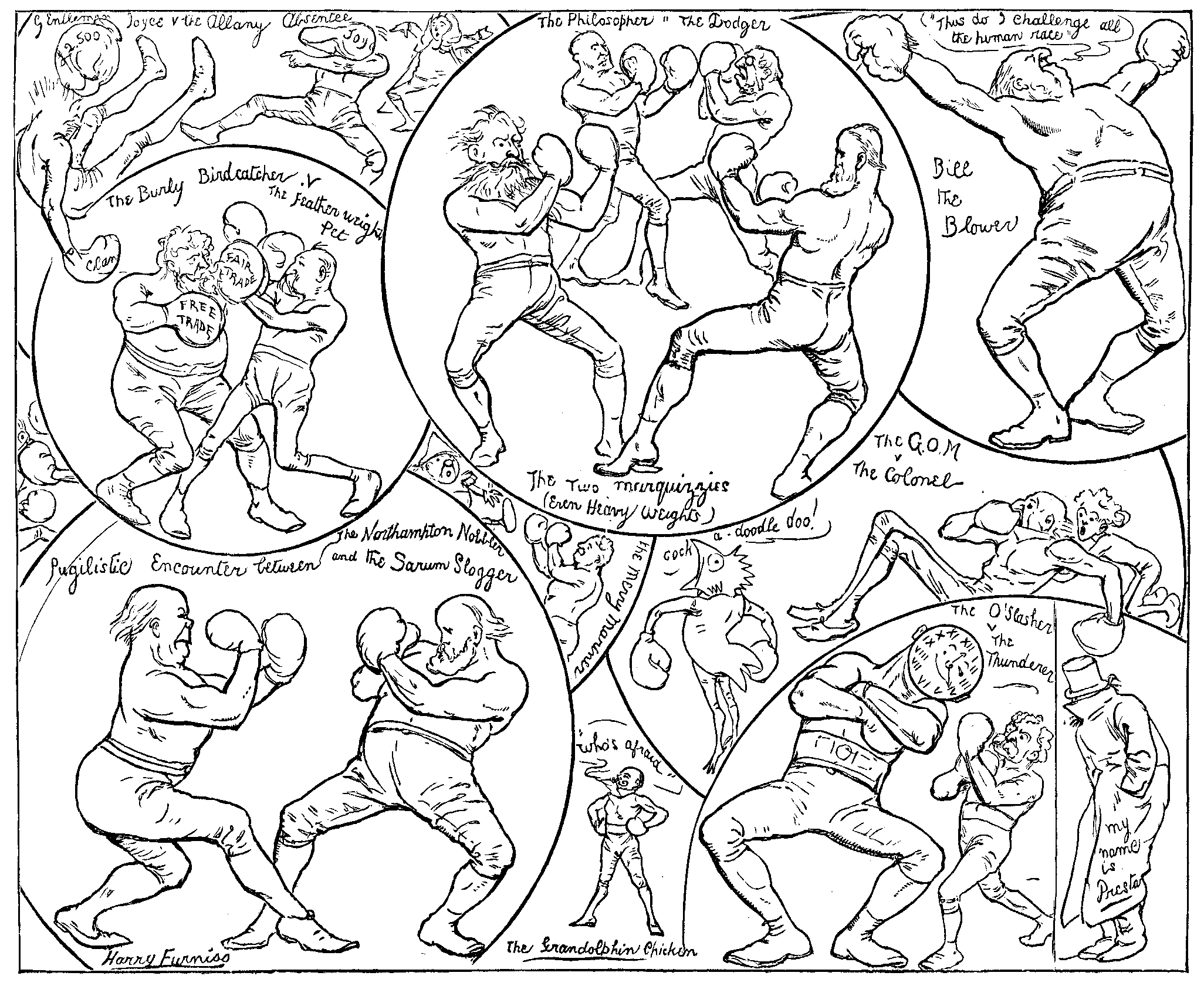

[Prize-Fighting having once again come into fashion, the above Pugilistic Encounters must be recorded as anticipations of "Boxing-Day."]

Professor Mahaffy's book on The Art of Conversation, seems witty, and (in parts) wise. People who want to learn to talk well in society had better consult the genial Professor, who declares that the art can be acquired. In fact he hands to each of his readers, across the visionary "walnuts and the wine," the pinch of Attic Salt which seasons dinner-parties. The theory must, of course, be taken cum grano. A few hints (strangely omitted in Mahaffy's "Haffy Thoughts,") are here appended:—

Should you happen to be in company with a number of eminent Statesmen belonging to one Party (say, at a dinner, when they can't get away from you,) mind and point out in a loud voice what you conceive to have been the chief errors of policy which they committed in their last Ministry, and what would have been your line in their place. If they are smarting under recent defeat, and have just been turned out of Office, they will be sure to thank you heartily for your kind advice.

Supposing politicians of every shade of opinion to be present, your best course will be to at once introduce some "burning" subject of the day—say, Home Rule, or the personal character of Mr. Gladstone or Lord Salisbury. Your host will be delighted, and you will be surprised to find what a brisk conversation you have initiated.

Always talk "shop." It gives local colour to your style. For instance, if you are a lawyer, and you see another legal gentleman at table, engage him in a conversation as to "that curious Equity point in the case of The Queen v. the Executors of Muggins, deceased, before the V.-C." Make your comments as technical as possible. If you don't soon "get the table in a roar," it will be astonishing. By the way, there are two kinds of "roar."

Avoid the least appearance of shyness. This is a pushing age. If you are really bashful by nature, assume a haughty and forbidding demeanour to cover it. This will make you universally liked.

Spice your talk with jokes. Invent at least six good puns for use at any dinner to which you may be invited, and bring them out,—naturally, if you can, but at any rate bring them out! E.g. If you are in Dublin, in a company consisting of fervid Nationalists, who bitterly resent the imprisonment of their Chief Magistrate, remark jocosely that "you hope his Lordship is not suffering much from mal de Mayor!" Conversely, when present at a dinner of Loyalists, refer to the eminent Liberal-Unionist Leader as "Half-Hartington." In either case your host is sure to ask you to come again.

Monopolise the conversation. Carlyle did this, and so did Macaulay, so why shouldn't you? You may be a Macaulay without knowing the fact.

Remember that people like anecdotes. This is how Hayward got his reputation. Don't hesitate because somebody has said that "all the good stories have been told." If so, tell them again without flinching.

Practise allusive and apparently unconscious swagger in private. When you are sure that you can refer to "my friend the Duke of St. David's," at a dinner-party without the slightest change of inflexion in your voice and in a perfectly natural manner, you are fitted to adorn any society—even the lowest.

Never humour women who try to talk learnedly. Bring the conversation down to feeding-bottles and keep it there. They will in reality appreciate your kindness and knowledge of female nature, even if they appear at the moment to resent it deeply.

Scene—An Italian Restaurant—anywhere in the Metropolis. Only a few of the small dining-tables are occupied as Scene opens. Near the buffet is a small lift communicating with the kitchen, and by the lift a speaking-tube.

Enter an Adorer with his Adored; he leads the way down the centre of the room, flushed and jubilant—he has not been long engaged, and this is the very first time he has dined with Her like this.

Adorer (beaming). Where would you like to sit, Pussy?

Pussy (a fine young woman—but past the kitten stage). Oh, it's all the same to me!

Adorer (catching an aggrieved note in her tone). Why, you don't really think I'd have kept you waiting if I could help it? There's always extra work on Foreign Post nights! (Pussy turns away and arranges hat before mirror). Waiter! (A Waiter who has been reading the "Globe" in the corner, presents himself with Menu.) What shall we have to begin with, eh, Pussy?

[The Waiter, conceiving himself appealed to, disclaims the responsibility with a shrug, and privately reflects that these stiff Englishmen can be strangely familiar at times.

Pussy. Oh, I don't feel as if I cared much about anything—now.

Adorer. Well, I've ordered Vermicelli Soup, and Sole au gratin. Now, you must try and think what you'd like to follow. (Tentatively.) A Cutlet?

Pussy (with infinite contempt for such want of originality). A Cutlet—the idea!

Adorer (abashed). I thought perhaps—but look down the list. (Pussy glances down it with eyes which she tries to render uninterested.) "Vol au vent à l' Herbaliste,"—that looks as if it would be rather good. Shall we try that?

Pussy. You may if you like—I shan't touch it myself.

Adorer. Well, look here, then, "Rognons sautés Venézienne,"—Kidneys, you know—you like kidneys.

Pussy (icily). Do I? I was not aware of it.

Adorer. Come—it's for you to say. (Reads from list.) "Châteaubriand Bordelaise," "Jugged Hare and Jelly," "Salmi of Partridge." (Pussy, who is still suffering from offended dignity, repudiates all these suggestions with scorn and contumely.) Don't like any of them? Well, (helplessly) can't you think of anything you would like?

Pussy. Nothing—except—(with decision)—a Cutlet.

Adorer (relieved by this condescension). The very thing! (Tenderly.) We will both have Cutlets.

Waiter (who has been waiting in dignified submission). Two Porzion Cutlet, verri well—enni Pottidoes?

Pussy (sharply). Potted what?

Adorer (to Waiter). Yes. (To Pussy, aside, in same breath.) Potatoes, darling. (The Waiter suspects he is being trifled with.) Do you prefer them sautés, fried, or in chips,—or what?

Pussy (with the lofty indifference of an ethereal nature). I'm sure I don't care how they're done!

Adorer. Then—Potato-chips, Waiter.

Pussy (as Waiter departs). Not for me—I'll have mine sautés!

Adorer (when they are alone, leaning across table). I've been looking forward to this all day!

Pussy (unsympathetically). Didn't you have any lunch then?

Adorer. I don't mean to the dinner—but to having you to talk with, quite alone by our two selves.

Pussy (who has her dignity to consider). Oh, I daresay. I wish you'd do something for me, Joshua.

Adorer (fervently). Only tell me what it is, darling!

Pussy. It's only to get me that Graphic—I'm sure that gentleman over there has done with it.

[The Adorer fetches it with a lengthening face: Pussy retires behind the "Graphic," leaving him outside in solitude. At length he asserts himself by fetching "Punch," (which he happens to have seen) from an adjoining table. A Bachelor dining lonely and unloved on the opposite side of the room, watches them with growing sense of consolation.

Waiter. Una voce poco fa maccaroni! (At least, it sounds something like this. A little cupboard arrives by the lift containing a dish which the Waiter hastens to receive. The new arrival is apparently of a disappointing nature,—he returns it indignantly, and rushes back to tube.) La ci darem la mano curri rabbito Gorgonzola!

A Voice (from bottom of lift—argumentatively). Batti, batti; la donna é mobile risotto Milanaise.

Waiter (losing his temper). Altro! Sul campo della gloria vermicelli!

The Voice (ironically). Parla tele d'amor o cari fior mulligatawni?

Waiter (scathingly). Salve di mora casta e pura entrecote sauce piquante crême à l'orange cotelettes pommes sautés basta-presto!

[Corks up tube with the air of a man who has had the best of it.

Two Brothers are seated here, who may be distinguished for the purposes of dialogue as the Good Brother and the Bad Brother respectively. The Good B. appears (somewhat against his will) to be acting as host, though he restricts his own refreshment to an orange, which he eats with an air of severe reproof. The Bad B. who has a shifty sullen look and a sodden appearance generally, is devouring cold meat with the intense solemnity of a person conscious of being more than three parts drunk. Both attempt to give their remarks an ordinary conversational tone.

The Bad B. (suddenly, with his mouth full). Will you lend me five shillings?

The Good B. No, I won't. I see no reason why I should.

The B. B. (in a low passionate voice). Will you lend me five shillings?

The G. B. (endeavouring to maintain a virtuous calm). I don't think I will.

B. B. You've been giving money away all the afternoon to people after I asked you for some!

G. B. (roused). I was not. It's dashed impertinence of you to say such a thing as that. I'm sick of this dashed nonsense—sick and tired of it! If I hadn't some principle left still, I should have gone to the East long ago!

B. B. I'm glad you didn't. I want five shillings.

G. B. Want five shillings! You keep on saying that, and never say what you want it for. You must have some object. Do you want it to go and get drunk on?

B. B. (with a beery persistence). Lend me five shillings.

G. B. (reflectively). I don't intend to.

B. B. (in a tone of compromise). Then lend me a sovereign.

G. B. (changing the subject with a chilling hospitality). Would you like anything after that beef?

B. B. (doggedly). I should like five shillings.

G. B. (irrelevantly). Look here! I at once admit you've got more brain than I have.

B. B. (handsomely). Not at all—it's you that have got more brain than me.

G. B. (rejecting this overture suspiciously). I've more principle at any rate, and, to tell you the truth, I'm not going to put up with this dashed impertinent treatment any longer!

B. B. You're not, eh? Then lend me five shillings.

G. B. (desperately). Here, Waiter—bill. I pay for this gentleman.

Waiter (after adding up the items). One and four, if you please.

[The G. B. pays.

B. B. And dashed cheap too!

[A small Cook-boy in white comes up to Waiter and whispers.

Waiter. Ze boy say zat gentilman (pointing to B. B.) tell him to give twopence for him to ze Cook.

G. B. (austerely). I have nothing to do with that—he must settle it with him.

B. B. (with fierce indignation). It's a lie! I gave the boy the money. It was a penny!

Waiter (impassively). Ze boy say you did not give nosing.

B. B. (to G. B.). Be d——d! Don't you pay it—it's a rascally imposition! See, Garcong, I'll tell you in French. J'ai donné l'homme, le chef, doo soo (holding up two fingers) pour lui-même-à servir.

G. B. I'm sorry to have to say it—but I don't believe your story.

[To the B. B.

B. B. (rising). I'm going to have it out with Cook. (Lurches up to door leading to kitchen and exit. Sounds of altercation below. Re-enter B. B. pursued by Voice. B. B. turning at door.) What did you say?

Voice. I say you are dronken Ingelis pig, cochon, va!

B. B. Well,—it's just as well you didn't say any more. (Goes up to Waiter, confidentially). That man down there was mos' insultin'—mos' insultin'. But, there, I'll give you the penny—there it is. (Presses that coin into Waiter's hand and closes his fingers over it.) Put it in your pocket, quick—say no more 'bout it, Goo' ni'. Only—remember (pausing on threshold à la Charles the First) if anyone wantsh row—(with recollection of Duke's motto)—I'm here! That 'sh all. (To G. B.) I shall say goo' ni' to you outside.

[Exit B. B. unsteadily.

The G. B. (solemnly to Waiter). I tell you what it is—I'm ashamed of him. There, I am. I'm ashamed of him!

[He stalks after his Brother; sounds of renewed argument without, as Scene closes in.

Bacon Again.—An erudite student informs us that "the crest of Shakspeare's mother's family was a boar," so that there is something Baconian about the Immortal Bard.

À propos of the Welsh Gold Find.—Advice Gratis:—Beware of Welshers.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

Alternative spellings retained.

Punctuation normalized without comment.