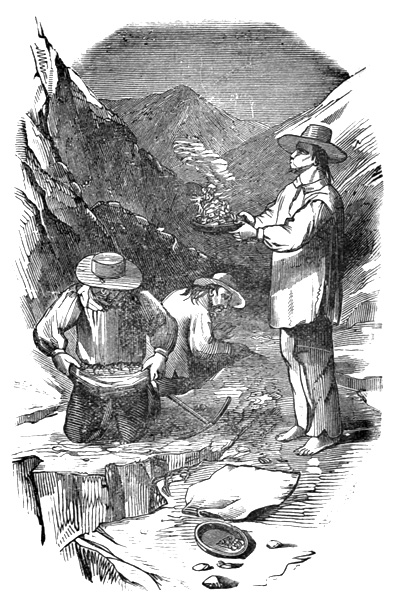

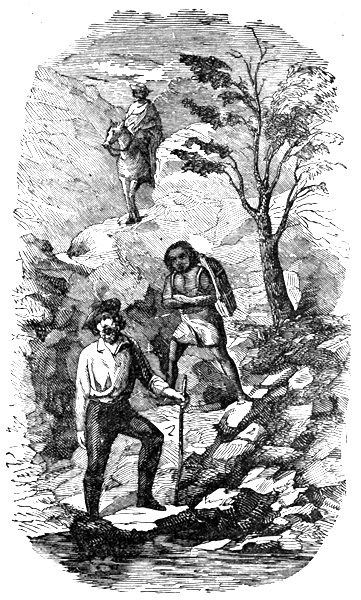

MOUNTAIN SCENERY IN LOWER CALIFORNIA.

Title: History of the State of California

Author: John Frost

Release date: August 14, 2012 [eBook #40503]

Most recently updated: September 27, 2025

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation, spelling, and accents in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. California place names were left as printed, regardless of inconsistencies or apparent misspellings.

Page 17: Aurquoises changed to turquoises

Page 64: "ancle" was the spelling in the quoted text.

Page 376: United Ship Cyane should possibly be United States Ship Cyane.

Page 393: 1st U. Dragoons should possibly be 1st U.S. Dragoons

Appendix C and E not labeled.

Appendix C presumed to be the "MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT"

Appendix E presumed to be the "despatch of General Persifor

F. Smith"

MOUNTAIN SCENERY IN LOWER CALIFORNIA.

HISTORY

— OF THE —

STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

FROM THE PERIOD OF THE CONQUEST BY SPAIN,

TO HER OCCUPATION BY THE UNITED

STATES OF AMERICA.

CONTAINING AN ACCOUNT OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE IMMENSE

GOLD MINES AND PLACERS, A DESCRIPTION OF HER

MINERAL AND AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES, WITH

THRILLING ACCOUNTS OF ADVENTURES

AMONG THE MINERS.

— ALSO, —

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE GOVERNMENT

AND CONSTITUTION OF THE STATE.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS.

By JOHN FROST, LL.D.

NEW YORK:

HURST & CO., PUBLISHERS,

122 NASSAU STREET.

ARGYLE PRESS,

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING

24-26 WOOSTER ST., N.Y.

The occupation of California by the people of the United States, and the discovery of its rich gold mines, form a new era in the history of the world. According to present appearances, these events forebode a complete revolution in monetary and commercial affairs. The receipts of gold from California have already produced a sensible effect on the financial affairs of our country; and far-seeing people predict an entirely new state of things with respect to the relative value of money and property.

Still more important effects are anticipated from the establishment of a new, rich, and enterprising State of the American Union on the shores of the Pacific. Railroads across the continent will soon transport the rich products of Eastern Asia, by a quick transit, to the Atlantic cities and to Europe; and a passage to China or India, which was formerly a serious undertaking, will become a pleasant excursion. 4

To gratify the public curiosity with respect to the history and present state of this new member of the Union, is the purpose of this volume. In preparing it, the author has passed rapidly over the early history, and dwelt chiefly on recent events, and the actual state of the country, as he considered that, by this course, utility would be more effectually consulted.

In the Appendix he has introduced the constitution of California, and some official documents, whose importance demanded their preservation in a permanent form.

| CHAPTER I. | Page |

Geographical Outline of California |

7 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

Discovery of California |

11 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

From the first Settlement to the Revolution in Mexico |

20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

From the Revolution till the War between the United States and Mexico |

24 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

From the Commencement of the War till its Close |

27 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

Discovery of the Gold Placers |

36 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

Adventures of some of the Miners, and Incidents connected with Mining |

56 |

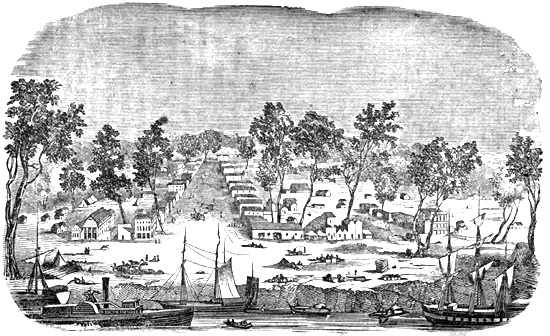

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

Description of some of the Cities and towns of California, before and after the discovery of the Gold Mines |

87 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

The Formation of a State Government |

118 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

Present state of California |

132 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

The different Routes to California, and their respective characters |

181 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

Recent Events connected with, and happening in, California |

218 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

The Mineralogical and other characteristics of Gold, and the mode of distinguishing it when found; together with the assay, reduction, and refinement of Gold |

233 6 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Additional Recent Events | 243 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| A General View of California at the present time | 255 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Natural History of California | 275 |

| Appendix | 287 |

THE

HISTORY OF CALIFORNIA

GEOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE OF CALIFORNIA

The territory called California is that part of North America situated on the Pacific Ocean, and extending from the 42° of north latitude southwardly to 22° 48', and from 107° longitude, west from Greenwich, to 124°. It is bounded on the north by Oregon territory, east by territories belonging to the United States and the Gulf of California, and on the south and west by Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. California is naturally divided into two portions; the peninsula, called Lower California, and the territory extending northward from the peninsula, on the Pacific Ocean, called Upper California. The line of division between Upper and Lower California runs nearly along the 32d parallel of latitude, westward from the head of the Gulf of California.

The peninsula of California is about one hundred and thirty miles in breadth, where it joins the continent. It extends south-eastwardly, generally diminishing in breadth, till it terminates in two points. The point farthest south-west is called Cape San 8 Lucas. The other, sixty miles east by north of San Lucas, is called Cape Palmo. The peninsula is about seven hundred miles long.

Upper California extends, upon the Pacific, from the 32d parallel of latitude, northward to the 42d parallel, a distance of about seven hundred miles. It is separated from Oregon by a range of highlands, called the Snowy Mountains, or, by the Spaniards, the Sierra Nevada. The eastern limit of Upper California is rather uncertain. By some it is considered as including the region watered by the Colorado River, while others limit it by the great mountain range that extends along the western side of the continent.

The Californian peninsula seems to be a prolongation of the great western chain of mountains. It consists entirely of high, stony ridges, separated by sandy valleys, and contains very few tracts of level ground. In a general view, it might be termed an irreclaimable desert. The scarcity of rain and the small number of springs of water, with the intense heat of the sun's rays, uninterrupted in their passage, render the surface of the country almost destitute of vegetation. Yet in the small oases formed by the passage of a rivulet through a sandy defile, where irrigation is possible, the ground may be made to produce all the fruits of tropical climes, of the finest quality, and in great quantity. The southern portion of the peninsula contains several gold mines, which have been worked, though not to any great extent. On the Pacific side, the coast offers many excellent harbors, but the lack of fresh water near them proves an obstacle in the way of their occupation. The principal harbors are the Bay of la Magdalena, separated from the ocean by the long island of Santa 9 Margarita, the Bay of Sebastian Vizcaino, east of the Isle of Cedaro, Port San Bartolomé, sometimes called Turtle Bay, and Port San Quintin, a good harbor, with fresh water in the vicinity, and called by the Spanish navigators the Port of the Eleven Thousand Virgins.

The great westernmost range of mountains runs northward from the peninsula, nearly parallel with the Pacific coast, to the 34th parallel of latitude, below which is Mount San Bernardin, one of the highest peaks in California, about forty miles from the ocean. Farther northward, the space between the mountains and the coast becomes wider, and, in a few places, reaches eighty miles. The intermediate region is traversed by lines of hills, or smaller mountains joined with the great range. The most considerable of the inferior ridges extends from Mount San Bernardin to the south side of the entrance of the Bay of San Francisco, where it is called the San Bruno Mountains. Between this range and the coast runs the Santa Barbara range, terminating at the Cape of Pines, on the south-west side of the Bay of Monterey. Bordering on the Bay of San Francisco, on the east side, is the Bolbona ridge. Beyond these are lines of highlands which stretch from the great chain and terminate in capes on the Pacific.

There are many streams among the valleys of Upper California, some of which, in the rainy season, swell to a considerable size. But no river, except the Sacramento, falling into the Bay of San Francisco, is known to flow through the maritime range of mountains, from the interior to the Pacific. The valleys thus watered offer abundant pasturage for cattle.

The principal harbors of Upper California are those 10 offered by the Bays of San Francisco, Monterey, San Pedro, Santa Barbara, and San Diego. The Bay of San Francisco is one of the finest harbors in the world. The combined fleets of all the naval powers of Europe might there find safe shelter. It is surrounded by ranges of high hills, and joins the Pacific by a passage two miles wide and three in length. The other harbors can only be frequented in the fine season, and afford a very insecure shelter for vessels. San Diego is the farthest south. The bay at that place runs ten miles eastward into the land, and is separated from the ocean by a ridge of sand. Proceeding northward, about seventy miles, the Bay of San Pedro is next met. It is open to the south-west winds, but sheltered from the north-west. About a hundred miles north-west of San Pedro, is the harbor of Santa Barbara. It is an open roadstead sheltered from the north and west winds, but exposed to the violence of the south-westerly storms, which prevail during the greater part of the year. A hundred miles farther north is the Bay of Monterey. It is extensive, and lies in an indentation of the coast, somewhat semicircular. The southernmost portion is separated from the ocean by the point of land ending at the Cape of Pines. In the cove thus formed, stands the town of Monterey, for some time the capital of California. The harbor affords but a poor shelter from storms.

The Sacramento and San Joachim are the principal rivers of California, but the Sacramento alone is navigable to any extent worthy of mention. There are numerous small streams and lakes in the interior, the principal outlet of which is the Colorado River. The valleys through which these streams flow are 11 fertile, and afford good pasture for cattle; but the remainder of the region between the maritime and the Colorado ranges of mountains is a barren waste of sand.

DISCOVERY OF CALIFORNIA.

The first exploration of the Pacific coasts of North America was made by the Spaniards, in the sixteenth century. After Hernando Cortes had completed the conquest of Mexico, he commenced exploring the adjoining seas and countries; no doubt, with the hope of discovering lands richer than those which he had conquered, and which would afford new fields for the exercise of his daring enterprise and undaunted perseverance. He employed vessels in surveying the coasts of the Mexican Gulf, and of the Atlantic more northerly. Vessels were built upon the Pacific coast for like purposes, two of which as early as 1526, were sent to the East Indies.

The first expedition of the Spaniards, sent along the western coast of Mexico, was conducted by Pedro Nunez de Maldonado, an officer under Cortes. He sailed from the mouth of the Zacatula River, in July, 1528, and was six months engaged in surveying the shores from his starting-place to the mouth of the Santiago River, a hundred leagues farther north-west. The territory he visited was then called Xalisco, and inhabited by fierce tribes of men who had never been 12 conquered by the Mexicans. Flattering accounts of the fertility of the country and of the abundance of the precious metals in it were brought back by the expedition, and these served to excite the attention of the Spaniards. When the expedition returned Cortes was in Spain, whither he had gone to have his title and powers more clearly defined. He returned in 1530 with full power to make discoveries and conquests upon the western coast of Mexico. From the opposition of his enemies, he was prevented from fitting out an expedition before 1532. The most northern post upon the Pacific coast, occupied by the Spaniards, was Aguatlan, beyond which the coast was little known.

The expedition sent by Cortes to the north-western coast of Mexico was commanded by his kinsman, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza. It sailed from Tehuantepec in July, 1532, and consisted of two vessels; one commanded by Diego Hurtado de Mendoza in person, and the other by Juan de Mazuela. Mendoza proceeded slowly along the shore of the continent as far as the 27° of latitude, where, his crew being mutinous, he sent back one of his vessels with the greater part of his men, and continued the voyage with the remaining vessel. Vague reports were afterwards received that Mendoza's vessel was thrown ashore somewhere to the northward, and that all on board had perished. The vessel which was sent back, was stranded near the mouth of the River Vanderas, and after the murder of the greater part of the crew, she was plundered by Nuno de Guzman, Governor of Xalisco. About the middle of the next year, Cortes received the news of the return of the vessel which Mendoza had sent back, and he immediately despatched two ships under 13 the command of Hernando Grijalva and Diego Becerra, in search of the other. These ships sailed on the 30th of September, 1533, but were soon separated. Grijalva discovered the islands of St. Thomas, as he called them—a group of islands about fifty leagues from the coast. He remained there till the following spring, and then returned home. Becerra proceeded north-westward; but his crew mutinied, and he was murdered by Fortuno Ximenes. The mutineers, under Ximenes, then steered directly west from the main land, and soon reached a coast not known to them before. They landed, and soon after Ximenes and nineteen men were killed by the natives. The rest of the men carried the vessel over to Xalisco, where she was seized by Nuno de Guzman.

Soon after these unlucky expeditions, Nuno de Guzman sent out several exploring parties in a northerly direction, one of which traced the western shore as far as the mouth of the Colorado, and brought back accounts of a rich and populous country and splendid cities in the interior. When Cortes became acquainted with the seizure of his vessels, a dispute arose between him and Nuno de Guzman, which almost led to a battle between their forces. But no action occurred, and Cortes, having heard of the newly discovered country, which was said to abound in the finest pearls, embarked at Chiametla, with a portion of his men, and set sail for the new land of promise. On the 3d of May, 1535, the day of the Invention of the Holy Cross, according to the Roman Catholic Calendar, Cortes arrived in the bay where Ximenes and his fellow-mutineers had met their fate in the previous year. In honor of the day, the place was called 14 Santa Cruz, and possession of it was taken in the name of the Spanish sovereign.

The country claimed by Cortes for Spain, was the south-east portion of the peninsula, which was afterwards called California. The bay, called by Cortes, Santa Cruz, was, perhaps, the same now known as Port La Paz, about a hundred miles from the Pacific, near the 24th parallel of latitude. Cortes landed on the shore of this bay, rocky and forbidding as it appeared, with a hundred and thirty men, and forty horses. He then sent back two of his ships to Chiametla, to bring over the rest of his troops. The vessels soon returned with a portion of the troops, and being again despatched to the Mexican coast, only one of them returned. The other was wrecked on her way. Cortes then took seventy men and embarked for Xalisco, from which he returned just in time to save his troops from death by famine. A year was spent in these operations, and the troops began to grow discontented. A few pearls had been found on the coast, but the country was found to be barren, and without attractions for Spaniards.

In the mean time, the wife of Cortes hearing reports of his ill success, sent a vessel to Santa Cruz, and entreated him to return. He then learned that he had been superseded in the government of New Spain by Don Antonio de Mendoza, who had already entered the capital as viceroy. Cortes returned to Mexico, and soon after, recalled the vessels and troops from Santa Cruz.

The viceroy, Mendoza, had received some information concerning the country north-west of Mexico, from de Cabeza-Vaca and two other Spaniards, who had wandered nine years, through forests and deserts, 15 from Tampa Bay, Florida, until they reached Culiacan. They had received from the natives, accounts of rich and populous countries situated to the north-west. Mendoza, wishing to ascertain the truth of the reports, sent two friars, according to the advice of Las Casas, to make an exploration. They were accompanied by a Moor who had crossed the continent with Cabeza-Vaca and his friends, and they set out from Culiacan on the 7th of March, 1539.

Soon after the departure of the friars, Cortes sent out his last expedition. It was commanded by Francisco de Ulloa, and consisted of three vessels, well equipped. Sailing from Acapulco, on the 8th of July 1539, Ulloa reached the Bay of Santa Cruz, after losing one of his vessels in a storm. From Santa Cruz he started to survey the coast towards the north-west. He completely examined both shores of the Gulf of California, and discovered the fact of the connection of the peninsula with the main land, near the 32° of latitude. This gulf Ulloa named the Sea of Cortes. On the 18th of October, he returned to Santa Cruz, and on the 29th again sailed with the object of exploring the coasts farther west. He rounded the point now called Cape San Lucas, the southern extremity of California, and sailed along the coast towards the north. The Spaniards proceeded slowly, as they were opposed by north-western storms, and often landed and fought with the natives. In January, 1540, Ulloa reached the island under the 28th parallel of latitude, near the coast, which they named the Isle of Cedars. There he remained till April, when one of the ships, bearing the sick and accounts of the discoveries, was sent back to Mexico. The returning vessel was seized at Santiago by the 16 officers of the viceroy. The fate of the remaining vessel is uncertain. Some of the writers of that day asserting that he continued his voyage as far north as the 30° of latitude, and returned safely to Mexico; while one asserts that nothing more was heard of him after the return of the vessel he sent back.

In the mean time, the two friars and the Moor penetrated a considerable distance into the interior of the continent, and sent home glowing accounts of rich and delightful countries which they said they had discovered. The inhabitants had, at first, been hostile, and had killed the Moor; but in the end submitted to the authority of the King of Spain. Mendoza, believing the accounts of the friars to be strictly true, prepared an expedition for the conquest of the countries they described. Disputes with the different Spanish chieftains occupied some months, at the end of which Cortes returned to Spain, in disgust. Mendoza despatched two bodies of troops, one by land, the other by sea, to reconnoitre the newly discovered land, and clear the way for conquest. The marine expedition was undertaken by two ships, under the command of Fernando de Alarcon, who sailed from Santiago on the 9th of May, 1540, and proceeding north-west along the coast, he reached the head of the California Gulf, in August of the same year. There he discovered the river now called the Colorado. The stream was ascended to the distance of eighty leagues, by Alarcon and some of his men, in boats; but all their inquiries were unsatisfactorily answered, and it was determined to return to Mexico. The vessels returned safely before the end of the year.

The land forces sent, at the same time, to the north-west, were composed of infantry and cavalry, and 17 commanded by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, who had been appointed governor of New Gallicia, in place of Nuno de Guzman. The party left Culiacan on the 22d of April, 1540, and took their way north, following the course described by the friars. They found the route which had been represented as easy, almost impassable. They made their way over mountains, and deserts, and rivers, and, in July, they reached the country called Cibola by the natives, but found it a half cultivated region, thinly inhabited by a people destitute of the wealth and civilization they had been represented as possessing. What had been represented as seven great cities, were seven small towns, rudely built. A few turquoises and some gold and silver supposed to be good, constituted the amount of what had been termed immense quantities of jewels, gold and silver. The Spaniards took possession of the country and wanted to remain and settle there. But Vasquez refused to acquiesce; and after naming one of the towns he visited, Granada, he started for the north-west, in search of other countries. The region called Cibola by the inhabitants, which Vasquez visited, is the territory now called Sonora, and is situated about the head waters of the Rivers Yaqui and Gila, east of the upper portion of the Gulf of California. The movements of the Spaniards after leaving Cibola, in August, 1540, have been the subject of very vague and contradictory accounts. All that is certain is, that the greater part of the force soon returned to Mexico, and that Vasquez, with the remainder, wandered through the interior for nearly two years longer, when, being disappointed in his expectations, he returned to Mexico in 1542.

In the spring of 1542, two vessels were placed under 18 the command of Juan Roderiguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese navigator of great reputation. The two vessels sailed from Navidad, a small port in Xalisco, in June, 1542. They rounded Cape San Lucas, and proceeded north-west, along the coast, as far as the 38th degree of latitude, when he was driven back, and took refuge in a harbor of one of the San Barbara islands. There Cabrillo died and the command devolved on Bartolome Ferrelo. Ferrelo was a zealous and determined man, and he resolved to proceed with the expedition. He sailed towards the north, and on the 26th of February, reached a promontory near the 41st parallel of latitude, which he named Stormy Cape. On the 1st of March, the ships reached the 44th parallel, but they were again driven south; and the men being almost worn out, Ferrelo resolved to go back to Mexico. He arrived at Navidad on the 14th of April, 1543. The promontory called Stormy Cape by Ferrelo, was the most northern portion of California visited by that navigator, and it is probably the same which is now called Cape Mendocino.

From all accounts that they had been able to collect, the Spaniards concluded that neither rich and populous countries existed beneath the 40th parallel of latitude, nor was there any navigable passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to be found in the same region. They, therefore, ceased to explore the north-western territory for some time after the return of Ferrelo in 1543.

Having thus given a somewhat detailed account of the discovery and explorations of the territory now called California, it will be sufficient to merely mention the various expeditions that visited it prior to the first regular settlement. In the spring of 1579, California 19 was visited by Sir Francis Drake, the English navigator, who landed on the shores of a bay supposed to be that of San Francisco. He formally took possession of the country in the name of Queen Elizabeth, and called it New Albion. He left California on the 22d of July, 1579. In the spring of 1596, Sebastian Viscaino, under orders from the viceroy of Mexico, attempted to plant colonies on the peninsula of California, but the country was soon abandoned on account of the barrenness of the soil and the ferocity of the natives. Viscaino visited the coast of Upper California in 1602, and discovered and named some of the places Cabrillo had discovered and named long before. The Port San Miguel of Cabrillo was named Port San Diego; Cape Galera was named Cape Conception, the name now borne by it; the Port of Pines was named Port Monterey. This was the last expedition made by the Spaniards along the coast of California for more than a hundred and sixty years.

Various attempts were made to establish colonies, garrisons, and fishing or trading ports, on the eastern side of the peninsula of California, during the seventeenth century, but all failed, either from the want of funds, the sterility of the country, or the hostility of the natives. The pearl fishery in the gulf was the principal bait that attracted the Spaniards, and they succeeded in obtaining a considerable quantity, some of which were very valuable. 20

FROM THE FIRST SETTLEMENT TO THE REVOLUTION IN MEXICO.

The first establishment of the Spaniards in California, was made by the Jesuits, in November, 1697. The settlement was called Loreto, and founded on the eastern side of the peninsula, about two hundred miles from the Pacific. On entering California, the Jesuits encountered the same obstacles which had before prevented a settlement of the country. The land was so sterile, that it scarcely yielded sustenance to the most industrious tiller, and as the settlements were all located near the sea, fishing was the resource of the settlers to make up the deficiency of food. The natives continued hostile, and killed several of the Jesuit fathers. By perseverance and kindness, the Jesuits overcame all the obstacles with which they met, and within sixty years after their entrance into California, they had established sixteen missions, extending along the eastern side of the peninsula, from Cape San Lucas to the head of the gulf. Each of these establishments consisted of a church, a fort, garrisoned by a few soldiers, and some stores and dwelling-houses, all under the control of the resident Jesuit father. Each of the missions formed the centre of a district containing several villages of converted Indians. None of the Jesuits visited the western coast of the peninsula except on one occasion, in 1716.

Great exertions were made by the settlers to acquire 21 a knowledge of the geography, natural history and languages of the peninsula, and they appear to have been generally successful. The result of their researches were published in Madrid, in 1757, and the work was entitled a "History of California." They surveyed the whole coast of the Gulf of California, and, in 1709, Father Kuhn, one of the Jesuit fathers, ascertained beyond doubt the connection of the peninsula with the continent, which had been denied for a century. But all the labors of the Jesuits were brought to an end in 1767. In that year, Charles III. of Spain, issued a decree, banishing members of that order from the Spanish territories; and a strong military force, under command of Don Gasper de Portola, was despatched to California, and soon put an end to the rule of the Jesuits by tearing them from their converts.

The Spanish government did not intend to abandon California. The peninsula immediately became a province of Mexico, and was provided with a civil and military government, subordinate to the viceroy of that country. The mission fell under the rule of the Dominicans, and from their mode of treatment, most of the converts soon returned to their former state of barbarism. The Spaniards soon formed establishments on the western side of the peninsula. In the spring of 1769, a number of settlers, with some soldiers and Franciscan friars, marched through the peninsula towards San Diego. They reached the bay of San Diego after a toilsome journey, and the settlement on the shore of the bay was begun in the middle of May, 1769. An attempt was made, soon after, to establish a colony at Port Monterey; but the party under Portola that went in search of the place, passed further 22 on to the bay of San Francisco, and could not retrace their steps before the cold weather set in, and they then returned to San Diego. The people left at San Diego had been several times attacked by the natives, and after the return of Portola's party they almost perished for want of food. But a supply arrived on the very day upon which they had agreed to abandon the place and return to Mexico. Portola again set out for Monterey, and there effected a settlement. Parties of emigrants from Mexico came to the western shore of California during the year 1770, and establishments were made on the coast between San Diego and Monterey. The multiplication of their cattle, independent of the fruits of agricultural labor, before 1775, made the settlers of Upper California able to resist the perils to which their situation exposed them.

In order to give efficiency to the operations on the western coast of North America, the Spanish government selected the port of San Blas, in Mexico, at the entrance of the Gulf of California, for the establishment of arsenals, ship-yards and warehouses, and made it the centre of all operations undertaken in that quarter. A marine department was created for the special purpose of advancing the interests of the Spaniards in the settlement of the western shore of California. By the energy displayed in managing this department the Spaniards succeeded in making eight establishments on the Pacific coast between the California peninsula and Cape Mendocino, before 1779. The most southern post was San Diego, and the most northern, San Francisco, on the great bay of the same name. The establishments were almost entirely military and missionary, the object of the Spaniards being solely the occupation of the country. 23 The missions were under the control of the Franciscans, who, unlike the Jesuits, took little care to exert themselves in procuring information concerning the country in which they were established.

Various expeditions for exploring the coast of Upper California above Cape Mendocino, were made by the Spaniards. One of these proceeded as far north as the latitude of 41 degrees, and some men were landed on the shores of a small bay, just beyond Cape Mendocino, and gave the harbor the name of Port Trinidad. The small river which flows into the Pacific near the place where they landed was called Pigeon River, from the great number of those birds in the neighborhood of it. The Indians appeared to be a peaceable and industrious race, and conducted themselves towards the Spaniards in the most inoffensive manner. In the same year, 1775, Bodega, a Spanish commander, returning from a voyage extended as far north as the 58th degree of latitude, discovered a small bay which had not previously been described, and he accordingly gave it his own name, which it still retains. This Bay of Bodega is situated a little north of the 38th degree of latitude.

Few events worth recording occurred in California, during the whole period of fifty years, from the first establishment of the Spaniards on the western coast till the termination of the Mexican war of independence. An attempt of the Russians to form a settlement on the shores of the Bay of Bodega, in 1815, was met with a remonstrance from the governor of California. The remonstrance of the governor was disregarded, and his commands to quit the place disobeyed. The Russian agent, Kushof, denied the right of the Spaniards to the territory, and the governor being unable to 24 enforce his commands, the intruders kept possession of the ground until 1840, when they left of their own accord.

FROM THE REVOLUTION TILL THE WAR BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICO.

Before the commencement of the struggle for independence in Mexico, the missions in California were, to some extent, fostered by the Spanish government, and supplies were sent to them regularly. But when the war began, the remittances were reduced, and the establishments soon began to decay. After the overthrow of the Spanish rule, in 1822, the territory of California was divided into two portions. The peninsula was then called Lower California, and the whole of the continental territory called Upper California. When the Mexicans adopted a constitution, in 1824, each of these territories became entitled to send one representative to the National Congress. At the same time, the adult Indians who could be considered civilized, were declared citizens of the republic, and had lands given to them. This, of course, freed them from submission to the missionaries, who, thus deprived of their authority, either returned to Spain or Mexico, or took refuge in other lands. The Indians being free from restraint, soon sank to a low depth of barbarism and vice.

Immediately after the overthrow of the Spanish 25 authorities, the ports of California began to be the resort of foreigners, principally whalers and traders from the United States. The trade in which they engaged, that of exchanging manufactured goods for the provisions, hide and tallow furnished by the natives, was at first irregular, but as it increased, it became more systematic, and mercantile houses were established in the principal ports. The Mexican government became dissatisfied with this state of things, and ordered the governor of Upper California to enforce the laws which prohibited foreigners from entering or residing in the territories of Mexico without a special permission from the authorities. Accordingly, in 1828, a number of American citizens were seized at San Diego, and kept in confinement until 1830. In that year, an insurrection broke out, headed by General Solis, and the captured Americans were of some assistance in suppressing it, and, in consideration of their services, they were permitted to leave the territory.

The Mexican government strove to prevent the evils expected to flow from the presence of numbers of foreigners in California, by establishing colonies of their own citizens in the territory. A number of persons were sent out from Mexico, to settle on the lands of the missions, but they never reached their destination. The administration which originated the scheme was overthrown, and the new authorities ordered the settlers to be driven back to Mexico. In 1836, the federal system was abolished by the Mexican government, and a new constitution adopted, which destroyed all state rights, and established a central power. This was strenuously resisted in California. The people rose, and drove the Mexican 26 officers from the country, declaring that they would remain independent until the federal constitution was restored. The general government issued strong proclamations against the Californians, and sent an expedition to re-establish its authority. But General Urrea, by whom the expedition was commanded, declared in favor of the federalists, and the inhabitants governed themselves until July, 1837, when they swore allegiance to the new constitution.

Things went on quietly in California until 1842. In that year, Commodore Jones, while cruising in the Pacific, received information which led him to believe that Mexico had declared war against the United States. He determined to strike a blow at the supposed enemy, and, accordingly, he appeared before Monterey, on the 19th of October, 1842, with the frigate United States and the sloop-of-war Cyane. He demanded the surrender of all the castles, posts, and military places, on penalty, if refused, of the visitation of the horrors of war. The people were astonished. A council decided that no defence could be made, and every thing was surrendered at once to the unexpected Americans. The flag of the United States was hoisted, and the commodore issued a proclamation to the Californians, inviting them to submit to the government of the United States, which would protect them in the exercise of their rights. The proclamation was scarcely issued, before the commodore became aware of the peaceable relations existing between the United States and Mexico, and he accordingly restored the possession of Monterey to the authorities, and retired with his forces to his ships, just twenty-four hours after the surrender. This affair irritated the inhabitants considerably, and, no 27 doubt, tended to increase the ill-feeling before existing between Mexico and the people of the United States.

FROM THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE WAR TILL ITS CLOSE.

War was declared by Mexico against the United States, in May, 1846. The same month, orders were transmitted to Commodore Sloat, commanding the Pacific squadron, instructing him to protect the interests of the citizens of the United States near his station, and to employ his forces to the best advantage in operations directed against the Mexican territory on the Pacific. The fleet under Commodore Sloat was the largest the Americans ever sent to that quarter, and the men were anxious to commence active operations. Soon after receiving his first orders, the commodore was again instructed to take and keep possession of Upper California; or, at least, of the principal ports.

On the 8th of June, Commodore Sloat left Mazatlan, in the flag-ship Savannah, and on the 2d of July, reached Monterey, in Upper California. There he found the Cyane and Levant, and learned that the Portsmouth was at San Francisco, as previously arranged. On the morning of the 7th, Captain Mervine was sent to demand the surrender of Monterey. The Mexican commandant replied that he was not authorized to surrender the place, but referred Commodore 28 Sloat to the commanding-general of California. A force of two hundred and fifty marines and seamen was immediately landed, under Captain Mervine, and they marched to the custom-house. There they hoisted the American flag amid cheers and a salute of twenty-one guns. The proclamation of Commodore Sloat was then read and posted about the town.

After taking possession of Monterey, Commodore Sloat despatched a courier to the commanding-general of California, summoning him to surrender every thing under his control in the country, and assuring him of protection if he should comply. The general refused, and said he would defend the country as long as he could reckon on a single person to join his cause. A summons to surrender was also sent to the governor of Santa Barbara, but no answer was returned. Orders were despatched to Commander Montgomery, in the Portsmouth, at San Francisco, directing him to take possession of the Bay of San Francisco, and hoist the flag of the United States at Yerba Buena.

On the 9th of July, the day after the receipt of his orders, Montgomery landed at Yerba Buena with seventy seamen and marines, and hoisted the American flag in the public square, amid the cheers of the people. A proclamation was then posted to the flag staff, and Montgomery addressed the people. The greater part of the seamen and marines then returned to the ship, leaving Lieutenant H. B. Watson with a small guard, formally installed as military occupant of the post. Thirty-two of the male residents of Yerba Buena were enrolled as a volunteer corps, choosing their own officers. Lieutenant Missroon was despatched with a small party of these volunteers to reconnoitre the Presidio and fort. He returned the 29 same day, and reported that the Presidio had been abandoned, and that the fort, seven miles from the town, was dilapidated and mounted only a few old pieces of cannon. The flag of the United States had been displayed from its ramparts. On the 11th, Montgomery informed Commodore Sloat that the flag of the United States was then flying at Yerba Buena, Sutter's Fort, on the Sacramento, Bodega, on the coast, and Sonoma. The inhabitants of these places appeared to be satisfied with the protection afforded them by the Americans.

On the 13th of July, Commodore Sloat sent a flag to the foreigners of the pueblo of San Jose, about seventy miles from Monterey, in the interior, and appointed a justice of the peace in place of the alcaldes. On the 15th, Commodore Stockton arrived at Monterey, in the frigate Congress; and Commodore Sloat being in bad health, the command devolved upon Stockton, and Sloat returned home. The operations of Commodore Stockton, from the 23d of July to the 28th of August, 1846, have been rapidly sketched by himself in his despatches to the secretary of the navy. From these we condense a short account.

On the 23d of July, the commodore organized the "California Battalion of Mounted Riflemen." Captain Fremont was appointed major, and Lieutenant Gillespie captain of the battalion. The next day, they were embarked on board the sloop-of-war Cyane, Commander Dupont, and sailed from Monterey for San Diego, in order to land south of the Mexican force, consisting of 500 men, under General Castro, well fortified at a place three miles from the city. A few days afterwards, Commodore Stockton sailed in the Congress for San Pedro, thirty miles from Monterey, 30 and having landed, marched for the Mexican camp. When he arrived within twelve miles of the Mexicans, they fled in small parties, in different directions. Most of the principal officers were afterwards taken, but the mounted riflemen not getting up in time, most of the men escaped. On the 13th of August, Commodore Stockton being joined by eighty riflemen, under Major Fremont, entered the capital of California, Ciudad de los Angeles, or the "City of the Angels." Thus, in less than a month after Stockton's assuming command, the American flag was flying from every commanding position in California, conquered by three hundred and sixty men, mostly sailors.

The form of government established in California, after the conquest, was as follows: The executive power was vested in a governor, holding office for four years unless sooner removed by the President of the United States. The governor was to reside in the territory, be commander-in-chief of the army thereof, perform all the duties of a superintendent of Indian affairs, have a pardoning and reprieving power, commission all persons appointed to office under the laws of said territory, and approve all laws passed by the legislature before they took effect. There was the office of the Secretary of the Territory established, whose principal duty was to preserve all the laws and proceedings of the legislative council, and all the acts and proceedings of the governor. The legislative power was vested in the governor and a council of seven persons, who were to be appointed by the governor at first, and hold their office for two years; afterwards they were to be elected by the people. All the laws of Mexico, and the municipal officers existing in the 31 territory before the conquest, were continued until altered by the governor and council.

On the 15th of August, 1846, Commodore Stockton adopted a tariff of duties on all goods imported from foreign parts, of fifteen per cent. ad valorem, and a tonnage duty of fifty cents per ton on all foreign vessels. On the 15th of September, when the elections were held, Walter Colton, the chaplain of the frigate Congress, was elected Alcalde of Monterey. In the mean time, a newspaper called the "Californian," had been established by Messrs. Colton and Semple. This was the first newspaper issued in California.

Early in September, Commodore Stockton withdrew his forces from Los Angeles, and proceeded with his squadron to San Francisco. Scarcely had he arrived when he received intelligence that all the country below Monterey was in arms and the Mexican flag again hoisted. The Californians invested the "City of the Angels," on the 23d of September. That place was guarded by thirty riflemen under Captain Gillespie, and the Californians investing it numbered 300. Finding himself overpowered, Captain Gillespie capitulated on the 30th, and thence retired with all the foreigners aboard of a sloop-of-war, and sailed for Monterey. Lieutenant Talbot, who commanded only nine men at Santa Barbara, refused to surrender, and marched out with his men, arms in hand. The frigate Savannah was sent to relieve Los Angeles, but she did not arrive till after the above events had occurred. Her crew, numbering 320 men, landed at San Pedro and marched to meet the Californians. About half way between San Pedro and Los Angeles, about fifteen miles from their ship, the sailors found the enemy drawn up on a plain. The Californians were 32 mounted on fine horses, and with artillery, had every advantage. The sailors were forced to retreat with a loss of five killed and six wounded.

Commodore Stockton came down in the Congress to San Pedro, and then marched for the "City of the Angels," the men dragging six of the ship's guns. At the Rancho Sepulvida, a large force of the Californians was posted. Commodore Stockton sent one hundred men forward to receive the fire of the enemy and then fall back upon the main body without returning it. The main body was formed in a triangle, with the guns hid by the men. By the retreat of the advance party, the enemy were decoyed close to the main force, when the wings were extended and a deadly fire opened upon the astonished Californians. More than a hundred were killed, the same number wounded, and their whole force routed. About a hundred prisoners were taken, many of whom were at the time on parole and had signed an obligation not to take up arms during the war.

Commodore Stockton soon mounted his men and prepared for operations on shore. Skirmishes followed, and were continually occurring until January, 1847, when a decisive action occurred. General Kearny had arrived in California, after a long and painful march overland, and his co-operation was of great service to Stockton. The Americans left San Diego on the 29th of December, to march to Los Angeles. The Californians determined to meet them on their route, and decide the fate of the country in a general battle. The American force amounted to six hundred men, and was composed of detachments from the ships Congress, Savannah, Portsmouth and Cyane, aided by General Kearny, with sixty men on foot, from the 33 first regiment of United States dragoons, and Captain Gillespie with sixty mounted riflemen. The troops marched one hundred and ten miles in ten days, and, on the 8th of January, they found the Californians in a strong position on the high bank of the San Gabriel river, with six hundred mounted men and four pieces of artillery, prepared to dispute the passage of the river. The Americans waded through the water, dragging their guns with them, exposed to a galling fire from the enemy, without returning a shot. When they reached the opposite shore, the Californians charged upon them, but were driven back. They then charged up the bank and succeeded in driving the Californians from their post. Stockton, with his force, continued his march, and the next day, in crossing the plains of Mesa, the enemy made another attempt to save their capital. They were concealed with their artillery in a ravine, until the Americans came within gun-shot, when they opened a brisk fire upon their right flank, and at the same time charged both their front and rear. But the guns of the Californians were soon silenced, and the charge repelled. The Californians then fled, and the next morning the Americans entered Los Angeles without opposition. The loss of the Americans in killed and wounded did not exceed twenty, while that of their opponents reached between seventy and eighty.

These two battles decided the contest in California. General Flores, governor and commandant-general of the Californians, as he styled himself, immediately after the Americans entered Los Angeles, made his escape and his troops dispersed. The territory became again tranquil, and the civil government was soon in operation again in the places where it had 34 been interrupted by the revolt. Commodore Stockton and General Kearny having a misunderstanding about their respective powers, Colonel Fremont exercised the duties of governor and commander-in-chief of California, declining to obey the orders of General Kearny.

The account of the adventures and skirmishes with which the small force of United States troops under General Kearny met, while on their march to San Diego, in Upper California, is one of the most interesting to which the contest gave birth. The party, which consisted of one hundred men when it started from Santa Fé, reached Warner's rancho, the frontier settlement in California, on the Sonoma route, on the 2d of December, 1846. They continued their march, and on the 5th were met by a small party of volunteers, under Captain Gillespie, sent out by Commodore Stockton to meet them, and inform them of the revolt of the Californians. The party encamped for the night at Stokes's rancho, about forty miles from San Diego. Information was received that an armed party of Californians was at San Pasqual, three leagues from Stokes's rancho. A party of dragoons was sent out to reconnoitre, and they returned by two o'clock on the morning of the 6th. Their information determined General Kearny to attack the Californians before daylight, and arrangements were accordingly made. Captain Johnson was given the command of an advance party of twelve dragoons, mounted upon the best horses in possession of the party. Then followed fifty dragoons, under Captain Moore, mounted mostly on the tired mules they had ridden from Santa Fé—a distance of 1050 miles. Next came about twenty volunteers, under 35 Captain Gibson. Then followed two mountain howitzers, with dragoons to manage them, under charge of Lieutenant Davidson. The remainder of the dragoons and volunteers were placed under command of Major Swords, with orders to follow on the trail with the baggage.

As the day of December 6th dawned, the enemy at San Pasqual were seen to be already in the saddle, and Captain Johnson, with his advance guard, made a furious charge upon them; he being supported by the dragoons, the Californians at length gave way. They had kept up a continual fire from the first appearance of the dragoons, and had done considerable execution. Captain Johnson was shot dead in his first charge. The enemy were pursued by Captain Moore and his dragoons, and they retreated about half a mile, when seeing an interval between the small advance party of Captain Moore and the main force coming to his support, they rallied their whole force, and charged with their lances. For five minutes they held the ground, doing considerable execution, until the arrival of the rest of the American party, when they broke and fled. The troops of Kearny lost two captains, a lieutenant, two sergeants, two corporals, and twelve privates. Among the wounded were General Kearny, Lieutenant Warner, Captains Gillespie and Gibson, one sergeant, one bugleman, and nine privates. The Californians carried off all their wounded and dead except six.

On the 7th the march was resumed, and, near San Bernardo, Kearny's advance encountered and defeated a small party of the Californians who had taken post on a hill. At San Bernardo, the troops remained till the morning of the 11th, when they were joined by a 36 party of sailors and marines, under Lieutenant Gray. They then proceeded upon their march, and on the 12th, arrived at San Diego; having thus completed a march of eleven hundred miles through an enemy's country, with but one hundred men. The force of General Kearny having joined that of Commodore Stockton, the expedition against Los Angeles, of which we have given an account in this chapter, was successfully consummated, and tranquillity restored in California. General Kearny and Commodore Stockton returned to the United States in January, 1847, leaving Colonel Fremont to exercise the office of governor and military commandant of California. No further events of an importance worth recording occurred till the treaty of peace between the United States and Mexico.

DISCOVERY OF THE GOLD PLACERS.

By the treaty concluded between the United States and Mexico, in 1847, the territory of Upper California became the property of the United States. Little thought the Mexican government of the value of the land they were ceding, further than its commercial importance; and, doubtless, little thought the buyers of the territory, that its soil was pregnant with a wealth untold, and that its rivers flowed over golden beds.

This territory, now belonging to the American 37 Union, embraces an area of 448,961 square miles. It extends along the Pacific coast, from about the thirty-second parallel of north latitude, a distance of near seven hundred miles, to the forty-second parallel, the southern boundary of Oregon. On the east, it is bounded by New Mexico. During the long period which transpired between its discovery and its cession to the United States, this vast tract of country was frequently visited by men of science, from all parts of the world. Repeated examinations were made by learned and enterprising officers and civilians; but none of them discovered the important fact, that the mountain torrents of the Sierra Nevada were constantly pouring down their golden sands into the valleys of the Sacramento and San Joaquin. The glittering particles twinkled beneath their feet, in the ravines which they explored, or glistened in the watercourses which they forded, yet they passed them by unheeded. Not a legend or tradition was heard among the white settlers, or the aborigines, that attracted their curiosity. A nation's ransom lay within their grasp, but, strange to say, it escaped their notice—it flashed and sparkled all in vain.[1]

The Russian American Company had a large establishment at Ross and Bodega, ninety miles north of San Francisco, founded in the year 1812; and factories were also established in the territory by the Hudson Bay Company. Their agents and employes ransacked the whole country west of the Sierra Nevada, or Snowy Mountain, in search of game. In 1838, Captain Sutter, formerly an officer in the Swiss 38 Guards of Charles X., King of France, emigrated from the state of Missouri to Upper California, and obtained from the Mexican government a conditional grant of thirty leagues square of land, bounded on the west by the Sacramento river. Having purchased the stock, arms, and ammunition of the Russian establishment, he erected a dwelling and fortification on the left bank of the Sacramento, about fifty miles from its mouth, and near what was termed, in allusion to the new settlers, the American Fork. This formed the nucleus of a thriving settlement, to which Captain Sutter gave the name of New Helvetia. It is situated at the head of navigation for vessels on the Sacramento, in latitude 38° 33' 45" north, and longitude 121° 20' 05" west. During a residence of ten years in the immediate vicinity of the recently discovered placéras, or gold regions, Captain Sutter was neither the wiser nor the richer for the brilliant treasures that lay scattered around him.[2]

In the year 1841, careful examinations of the Bay of San Francisco, and of the Sacramento River and its tributaries, were made by Lieutenant Wilkes, the commander of the Exploring Expedition; and a party under Lieutenant Emmons, of the navy, proceeded up the valley of the Willamette, crossed the intervening highlands, and descended the Sacramento. In 1843-4, similar examinations were made by Captain, afterwards Lieutenant-Colonel Fremont, of the Topographical Engineers, and in 1846, by Major Emory, of the same corps. None of these officers made any discoveries of minerals, although they were led to conjecture, as private individuals who had visited the 39 country had done, from its volcanic formation and peculiar geological features, that they might be found to exist in considerable quantities.[3]

As is often the case, chance at length accomplished what science had failed to do. In the winter of 1847-8, a Mr. Marshall commenced the construction of a saw-mill for Captain Sutter, on the north branch of the American Fork, and about fifty miles above New Helvetia, in a region abounding with pine timber. The dam and race were completed, but on attempting to put the mill in motion, it was ascertained that the tail-race was too narrow to permit the water to escape with perfect freedom. A strong current was then passed in, to wash it wider and deeper, by which a large bed of mud and gravel was thrown up at the foot of the race. Some days after this occurrence, Mr. Marshall observed a number of brilliant particles on this deposit of mud, which attracted his attention. On examining them, he became satisfied that they were gold, and communicated the fact to Captain Sutter. It was agreed between them, that the circumstance should not be made public for the present; but, like the secret of Midas, it could not be concealed. The Mormon emigrants, of whom Mr. Marshall was one, were soon made acquainted with the discovery, and in a few weeks all California was agitated with the startling information.

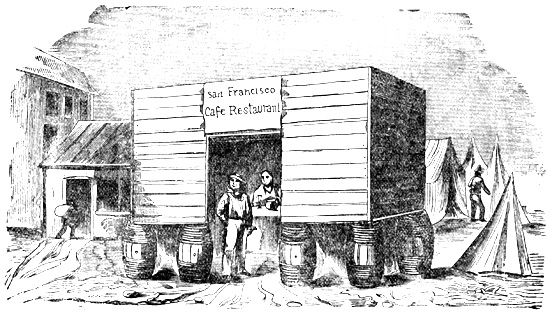

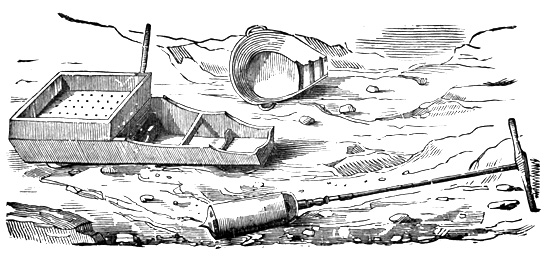

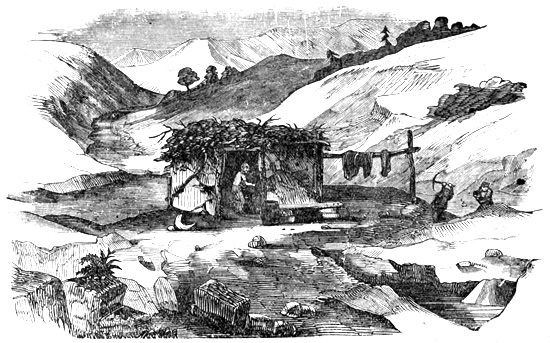

Business of every kind was neglected, and the ripened grain was left in the fields unharvested. Nearly the whole population of Upper California became infected with the mania, and flocked to the mines. Whalers and merchant vessels entering the ports were abandoned by their crews, and the American soldiers and sailors deserted in scores. Upon the disbandment of Colonel Stevenson's regiment, most of the men made their way to the mineral regions. Within three months after the discovery, it was computed that there were near four thousand persons, including Indians, who were mostly employed by the whites, engaged in washing for gold. Various modes were adopted to separate the metal from the sand and gravel—some making use of tin pans, others of close-woven Indian baskets, and others still, of a rude machine called the cradle, six or eight feet long, and mounted on rockers, with a coarse grate, or sieve, at one end, but open at the other. The washings were mainly confined to the low wet grounds, and the margins of the streams—the earth being rarely disturbed more than eighteen inches below the surface. The value of the gold dust obtained by each man, per day, is said to have ranged from ten to fifty dollars, and sometimes even to have far exceeded that. The natural consequence of this state of things was, that the price of labor, and, indeed, of every thing, rose immediately from ten to twenty fold.[4]

As may readily be conjectured, every stream and ravine in the valley of the Sacramento was soon explored. Gold was found on every one of its tributaries; 41 but the richest earth was discovered near the Rio de los Plumas, or Feather River,[5] and its branches, the Yuba and Bear rivers, and on Weber's creek, a tributary of the American Fork. Explorations were also made in the valley of the San Joaquin, which resulted in the discovery of gold on the Cosumnes and other streams, and in the ravines of the Coast Range, west of the valley, as far down as Ciudad de los Angeles.

In addition to the gold mines, other important discoveries were made in Upper California. A rich vein of quicksilver was opened at New Almaden, near Santa Clara, which, with imperfect machinery,—the heat by which the metal is made to exude from the rock being applied by a very rude process,—yielded over thirty per cent. This mine—one of the principal advantages to be derived from which will be, that the working of the silver mines scattered through the territory must now become profitable—is superior to those of Almaden, in Old Spain, and second only to those of Idria, near Trieste, the richest in the world.

Lead mines were likewise discovered in the neighborhood of Sonoma, and vast beds of iron ore near the American Fork, yielding from eighty-five to ninety per cent. Copper, platina, tin, sulphur, zinc, and cobalt, were discovered every where; coal was found to exist in large quantities in the Cascade range of Oregon, of which the Sierra Nevada is a continuation; and in the vicinity of all this mineral wealth, there 42 are immense quarries of marble and granite, for building purposes.

Colonel Mason had succeeded Colonel Fremont in the post of governor of California and military commandant. A regiment of New York troops, under the command of Colonel Stevenson, had been ordered to California before the conclusion of the treaty of peace, and formed the principal part of the military force in the territory.

Colonel Mason expressed the opinion, in his official despatch, that "there is more gold in the country drained by the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, than will pay the cost of the [late] war with Mexico a hundred times over." Should this even prove to be an exaggeration, there can be little reason to doubt, when we take into consideration all the mineral resources of the country, that the territory of California is by far the richest acquisition made by this government since its organization.

The appearance of the mines, at the period of Governor Mason's visit, three months after the discovery, he thus graphically describes:

"At the urgent solicitation of many gentlemen, I delayed there [at Sutter's Fort] to participate in the first public celebration of our national anniversary at that fort, but on the 5th resumed the journey, and proceeded twenty-five miles up the American Fork to a point on it now known as the Lower Mines, or Mormon Diggins. The hill-sides were thickly strewn with canvas tents and bush arbors; a store was erected, and several boarding shanties in operation. The day was intensely hot, yet about two hundred men were at work in the full glare of the sun, washing for gold—some with tin pans, some with close-woven Indian 43 baskets, but the greater part had a rude machine, known as the cradle. This is on rockers, six or eight feet long, open at the foot, and at its head has a coarse grate, or sieve; the bottom is rounded, with small cleats nailed across. Four men are required to work this machine; one digs the ground in the bank close by the stream; another carries it to the cradle and empties it on the grate; a third gives a violent rocking motion to the machine; while a fourth dashes on water from the stream itself.

"The sieve keeps the coarse stones from entering the cradle, the current of water washes off the earthy matter, and the gravel is gradually carried out at the foot of the machine, leaving the gold mixed with a heavy, fine black sand above the first cleats. The sand and gold, mixed together, are then drawn off through auger holes into a pan below, are dried in the sun, and afterward separated by blowing off the sand. A party of four men thus employed at the lower mines, averaged $100 a day. The Indians, and those who have nothing but pans or willow baskets, gradually wash out the earth and separate the gravel by hand, leaving nothing but the gold mixed with sand, which is separated in the manner before described. The gold in the lower mines is in fine bright scales, of which I send several specimens.

"From the mill [where the gold was first discovered], Mr. Marshall guided me up the mountain on the opposite or north bank of the south fork, where, in the bed of small streams or ravines, now dry, a great deal of coarse gold has been found. I there saw several parties at work, all of whom were doing very well; a great many specimens were shown me, some as heavy as four or five ounces in weight, and I send 44 three pieces, labeled No. 5, presented by a Mr. Spence. You will perceive that some of the specimens accompanying this, hold mechanically pieces of quartz; that the surface is rough, and evidently moulded in the crevice of a rock. This gold cannot have been carried far by water, but must have remained near where it was first deposited from the rock that once bound it. I inquired of many people if they had encountered the metal in its matrix, but in every instance they said they had not; but that the gold was invariably mixed with washed gravel, or lodged in the crevices of other rocks. All bore testimony that they had found gold in greater or less quantities in the numerous small gullies or ravines that occur in that mountainous region.

"On the 7th of July I left the mill, and crossed to a stream emptying into the American Fork, three or four miles below the saw-mill. I struck this stream (now known as Weber's creek) at the washings of Sunol and Co. They had about thirty Indians employed, whom they payed in merchandise. They were getting gold of a character similar to that found in the main fork, and doubtless in sufficient quantities to satisfy them. I send you a small specimen, presented by this company, of their gold. From this point, we proceeded up the stream about eight miles, where we found a great many people and Indians—some engaged in the bed of the stream, and others in the small side valleys that put into it. These latter are exceedingly rich, and two ounces were considered an ordinary yield for a day's work. A small gutter not more than a hundred yards long, by four feet wide and two or three feet deep, was pointed out to me as the one where two men—William Daly and Parry McCoon—had, a short 45 time before, obtained $17,000 worth of gold. Captain Weber informed me that he knew that these two men had employed four white men and about a hundred Indians, and that, at the end of one week's work, they paid off their party, and had left $10,000 worth of this gold. Another small ravine was shown me, from which had been taken upward of $12,000 worth of gold. Hundreds of similar ravines, to all appearances, are as yet untouched. I could not have credited these reports, had I not seen, in the abundance of the precious metal, evidence of their truth.

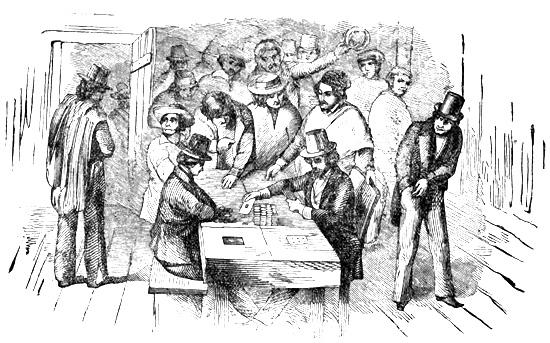

"Mr. Neligh, an agent of Commodore Stockton, had been at work about three weeks in the neighborhood, and showed me, in bags and bottles, over $2000 worth of gold; and Mr. Lyman, a gentleman of education, and worthy of every credit, said he had been engaged, with four others, with a machine, on the American Fork, just below Sutter's mill; that they worked eight days, and that his share was at the rate of fifty dollars a day; but hearing that others were doing better at Weber's place, they had removed there, and were then on the point of resuming operations. I might tell of hundreds of similar instances; but, to illustrate how plentiful the gold was in the pockets of common laborers, I will mention a single occurrence which took place in my presence when I was at Weber's store. This store was nothing but an arbor of bushes, under which he had exposed for sale goods and groceries suited to his customers. A man came in, picked up a box of Seidlitz powders, and asked the price. Captain Weber told him it was not for sale. The man offered an ounce of gold, but Captain Weber told him it only cost fifty cents, and he did not wish to sell it. The man then offered an ounce and a half, 46 when Captain Weber had to take it. The prices of all things are high, and yet Indians, who before hardly knew what a breech cloth was, can now afford to buy the most gaudy dresses.

"The country on either side of Weber's creek is much broken up by hills, and is intersected in every direction by small streams or ravines, which contain more or less gold. Those that have been worked are barely scratched; and although thousands of ounces have been carried away, I do not consider that a serious impression has been made upon the whole. Every day was developing new and richer deposits; and the only impression seemed to be, that the metal would be found in such abundance as seriously to depreciate in value.

"On the 8th of July, I returned to the lower mines, and on the following day to Sutter's, where, on the 19th, I was making preparations for a visit to the Feather, Yuba, and Bear Rivers, when I received a letter from Commander A. R. Long, United States Navy, who had just arrived at San Francisco from Mazatlan with a crew for the sloop-of-war Warren, with orders to take that vessel to the squadron at La Paz. Captain Long wrote to me that the Mexican Congress had adjourned without ratifying the treaty of peace, that he had letters from Commodore Jones, and that his orders were to sail with the Warren on or before the 20th of July. In consequence of these, I determined to return to Monterey, and accordingly arrived here on the 17th of July. Before leaving Sutter's, I satisfied myself that gold existed in the bed of the Feather River, in the Yuba and Bear, and in many of the smaller streams that lie between the latter and the American Fork; also, that it had been 47 found in the Cosumnes to the south of the American Fork. In each of these streams the gold is found in small scales, whereas in the intervening mountains it occurs in coarser lumps.

"Mr. Sinclair, whose rancho is three miles above Sutter's, on the north side of the American, employs about fifty Indians on the north fork, not far from its junction with the main stream. He had been engaged about five weeks when I saw him, and up to that time his Indians had used simply closely woven willow baskets. His net proceeds (which I saw) were about $16,000 worth of gold. He showed me the proceeds of his last week's work—fourteen pounds avoirdupois of clean-washed gold.

"The principal store at Sutter's Fort, that of Brannan and Co., had received in payment for goods $36,000 (worth of this gold) from the 1st of May to the 10th of July. Other merchants had also made extensive sales. Large quantities of goods were daily sent forward to the mines, as the Indians, heretofore so poor and degraded, have suddenly become consumers of the luxuries of life. I before mentioned that the greater part of the farmers and rancheros had abandoned their fields to go to the mines. This is not the case with Captain Sutter, who was carefully gathering his wheat, estimated at 40,000 bushels. Flour is already worth at Sutter's thirty-six dollars a barrel, and soon will be fifty. Unless large quantities of breadstuffs reach the country, much suffering will occur; but as each man is now able to pay a large price, it is believed the merchants will bring from Chili and Oregon a plentiful supply for the coming winter.

"The most moderate estimate I could obtain from men acquainted with the subject, was, that upward of 48 four thousand men were working in the gold district, of whom more than one-half were Indians; and that from $30,000 to $50,000 worth of gold, if not more, was daily obtained. The entire gold district, with very few exceptions of grants made some years ago by the Mexican authorities, is on land belonging to the United States. It was a matter of serious reflection with me, how I could secure to the government certain rents or fees for the privilege of procuring this gold; but upon considering the large extent of country, the character of the people engaged, and the small scattered force at my command, I resolved not to interfere, but to permit all to work freely, unless broils and crimes should call for interference. I was surprised to hear that crime of any kind was very unfrequent, and that no thefts or robberies had been committed in the gold district.

"All live in tents, in bush arbors, or in the open air; and men have frequently about their persons thousands of dollars worth of this gold, and it was to me a matter of surprise that so peaceful and quiet state of things should continue to exist. Conflicting claims to particular spots of ground may cause collisions, but they will be rare, as the extent of country is so great, and the gold so abundant, that for the present there is room enough for all. Still the government is entitled to rents for this land, and immediate steps should be devised to collect them, for the longer it is delayed the more difficult it will become. One plan I would suggest is, to send out from the United States surveyors with high salaries, bound to serve specified periods.

"The discovery of these vast deposits of gold has entirely changed the character of Upper California. Its people, before engaged in cultivating their small 49 patches of ground, and guarding their herds of cattle and horses, have all gone to the mines, or are on their way thither. Laborers of every trade have left their work benches, and tradesmen their shops. Sailors desert their ships as fast as they arrive on the coast, and several vessels have gone to sea with hardly enough hands to spread a sail. Two or three are now at anchor in San Francisco with no crew on board. Many desertions, too, have taken place from the garrisons within the influence of these mines; twenty-six soldiers have deserted from the post of Sonoma, twenty-four from that of San Francisco, and twenty-four from Monterey. For a few days the evil appeared so threatening, that great danger existed that the garrisons would leave in a body; and I refer you to my orders of the 25th of July, to show the steps adopted to meet this contingency. I shall spare no exertions to apprehend and punish deserters, but I believe no time in the history of our country has presented such temptations to desert as now exist in California.

"The danger of apprehension is small, and the prospect of high wages certain; pay and bounties are trifles, as laboring men at the mines can now earn in one day more than double a soldier's pay and allowances for a month, and even the pay of a lieutenant or captain cannot hire a servant. A carpenter or mechanic would not listen to an offer of less than fifteen or twenty dollars a day. Could any combination of affairs try a man's fidelity more than this? I really think some extraordinary mark of favor should be given to those soldiers who remain faithful to their flag throughout this tempting crisis.

"Many private letters have gone to the United States, giving accounts of the vast quantity of gold 50 recently discovered, and it may be a matter of surprise why I have made no report on this subject at an earlier date. The reason is, that I could not bring myself to believe the reports that I heard of the wealth of the gold district until I visited it myself. I have no hesitation now in saying that there is more gold in the country drained by the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers than will pay the cost of the present war with Mexico a hundred times over. No capital is required to obtain this gold, as the laboring man wants nothing but his pick and shovel and tin pan, with which to dig and wash the gravel; and many frequently pick gold out of the crevices of the rocks with their butcher knives, in pieces of from one to six ounces.

"Mr. Dye, a gentleman residing in Monterey, and worthy of every credit, has just returned from Feather River. He tells me that the company to which he belonged worked seven weeks and two days, with an average of fifty Indians (washers,) and that their gross product was two hundred and seventy-three pounds of gold. His share (one seventh,) after paying all expenses, is about thirty-seven pounds, which he brought with him and exhibited in Monterey. I see no laboring man from the mines who does not show his two, three, or four pounds of gold. A soldier of the artillery company returned here a few days ago from the mines, having been absent on furlough twenty days. He made by trading and working, during that time, $1500. During these twenty days he was travelling ten or eleven days, leaving but a week in which he made a sum of money greater than he receives in pay, clothes, and rations, during a whole enlistment of five years. These statements appear incredible, but they are true. 51

"Gold is also believed to exist on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada; and when at the mines, I was informed by an intelligent Mormon that it had been found near the Great Salt Lake by some of his fraternity. Nearly all the Mormons are leaving California to go to the Salt Lake, and this they surely would not do unless they were sure of finding gold there in the same abundance as they now do on the Sacramento.

"The gold 'placer' near the mission of San Fernando has long been known, but has been little wrought for want of water. This is a spur which puts off from the Sierra Nevada (see Fremont's map,) the same in which the present mines occur. There is, therefore, every reason to believe, that in the intervening spaces, of five hundred miles (entirely unexplored) there must be many hidden and rich deposits. The 'placer' gold is now substituted as the currency of this country; in trade it passes freely at $16 per ounce; as an article of commerce its value is not yet fixed. The only purchase I made was of the specimen No. 7, which I got of Mr. Neligh at $12 the ounce. That is about the present cash value in the country, although it has been sold for less. The great demand for goods and provisions, made by this sudden development of wealth, has increased the amount of commerce at San Francisco very much, and it will continue to increase."

The Californian, published at San Francisco on the 14th of August, furnishes the following interesting account of the Gold Region:

"It was our intention to present our readers with a description of the extensive gold, silver, and iron mines, recently discovered in the Sierra Nevada, together with some other important items, for the good of the people, but we are compelled to defer it for a future 52 number. Our prices current, many valuable communications, our marine journal, and other important matters, have also been crowded out. But to enable our distant readers to draw some idea of the extent of the gold mine, we will confine our remarks to a few facts. The country from the Ajuba to the San Joaquin rivers, a distance of about one hundred and twenty miles, and from the base toward the summit of the mountains, as far as Snow Hill, about seventy miles, has been explored, and gold found on every part. There are now probably 3000 people, including Indians, engaged collecting gold. The amount collected by each man who works, ranges from $10 to $350 per day. The publisher of this paper, while on a tour alone to the mining district, collected, with the aid of a shovel, pick and tin pan, about twenty inches in diameter, from $44 to $128 a day—averaging $100. The gross amount collected will probably exceed $600,000, of which amount our merchants have received about $250,000 worth for goods sold; all within the short space of eight weeks. The largest piece of gold known to be found weighed four pounds.