[Transcriber's notes]

This text is derived from

http://www.archive.org/details/catholicworld02pauluoft

Page numbers in this book are indicated by numbers enclosed in curly

braces, e.g. {99}. They have been located where page breaks occurred

in the original book.

Footnotes generally appear following the paragraph in which they are

positioned. If the paragraph is exceptionally long they will be

placed within the paragraph immediately following their position.

Between typesetting, inking and scanning there are many illegible

words. I have reviewed the images carefully but some words are

guesses. Question marks replace totally unknown letters.

Although square brackets [] usually designate footnotes or

transcriber's notes, they do appear in the original text.

This text includes Volume II;

Number 7—October 1865

Number 8—November 1865

Number 9—December 1865

Number 10—January 1866

Number 11—February 1866

Number 12—March 1866

[End Transcriber's notes]

THE CATHOLIC WORLD.

A

Monthly Eclectic Magazine

OF

GENERAL LITERATURE AND SCIENCE.

VOL. II.

OCTOBER, 1865, TO MARCH, 1866.

NEW YORK:

LAWRENCE KEHOE, PUBLISHER,

7 Beekman Street.

1866.

CONTENTS.

Adventure, The, 843.

Anglican and Greek Church, Attempt at Union between the, 65.

All-Hallow Eve; or, The Test of Futurity, 71, 199, 377, 507, 697, 816.

Ancient Laws of Ireland, The, 129.

Anglicanism and the Greek Schism, 429.

Ancient Faculty of Paris, The, 496, 681.

Bell Gossip, 32.

Birds, Migration of, 57.

Bruges, The Capuchin of, 237.

Bossuet and Leibnitz, 433.

Catholic Congresses at Malines and Würzburg, 1, 221, 331, 519

Constance Sherwood, 37, 160, 304, 455, 614, 759.

Chinese Characteristics, 102.

Catholic Settlements In Pennsylvania, 145.

Capuchin of Bruges. The, 237.

Christmas Carols, A Bundle of, 349.

Christendom, Formation of, 856.

Calcutta and its Vicinity, A Ride through, 386.

Christmas Eve: or, The Bible, 397.

Charles II. and his Son, Father James Stuart, 577.

Canton, Up and Down, 656.

California and the Church, 790.

Charles II.'s Last Attempt to Emancipate The Catholics, 827.

Duc d'Ayen, The Daughters of the, 252.

Epidemics, Past and Present, 420.

Formation of Christendom, The, 356.

Gallitzin, Rev. Demetrius Augustin, 145.

Gertrude, Saint, Thoughts on, 406.

Genzano, The Inflorata of, 608.

Glastonbury Abbey, Past and Present, 662.

Handwriting, 695.

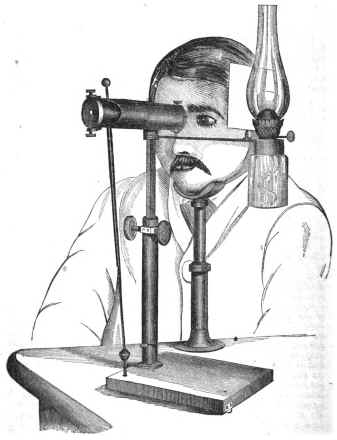

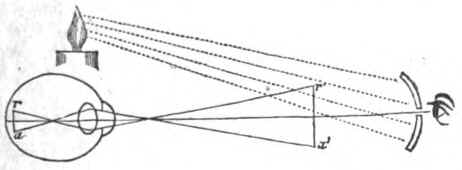

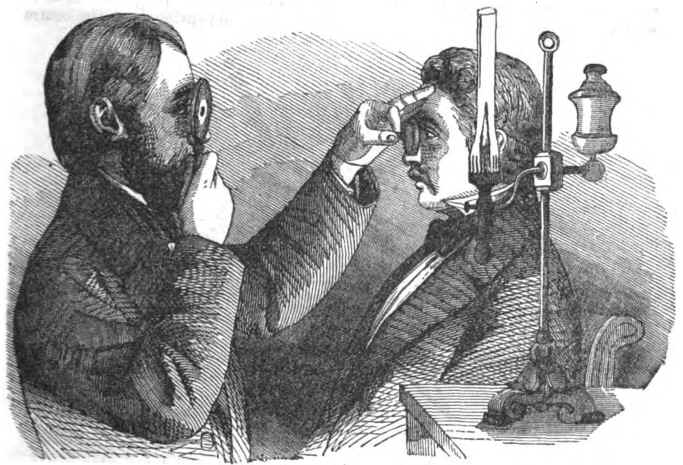

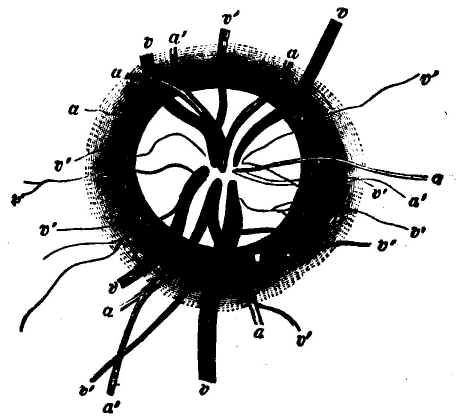

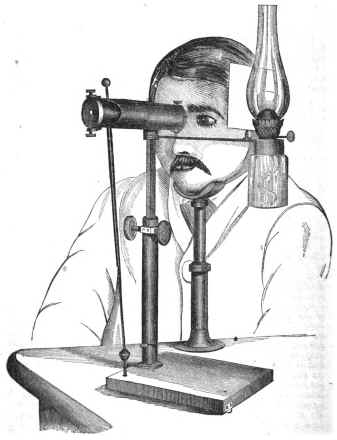

Inside the Eye, 119.

Ireland before Christianity, 541.

Kingdom without a King, 705.

Leibnitz and Bossuet, 433.

Law and Literature, 560.

Malines and Würzburg, Catholic Congresses in, 1, 221, 332, 519.

Marie Louise, Napoleon's Marriage with, 12.

Migrations of European Birds, 57.

Miscellany, 136, 276, 563, 714, 853.

Moricière, General De La, 289.

Malta, Siege of, 483.

Mistaken Identity, 707.

Mary, Queen of Scots, The Two Friends of, 813.

Natural History of the Tropics, Gleanings from, 178

Novel Ticket-of-leave, A, 707.

Pierre Prévost's Story, 110.

Pen, Slips of the, 272.

Paris, The Ancient Faculty of, 496, 681.

Pusey, Dr., on the Church of England, 530.

Positivism, 791.

Plain-Work, 740.

Procter, Adelaide Anne, Poems of, 837.

Récamier, Madame, and her Friends, 79.

Rome, Facts and Fictions about, 325.

Religious Statistics of the World, 491.

Rhodes, The Colossus of, 544.

Steam Engine, The Inventor of, 211.

Saturnine Observations, A Few, 266.

Slips of the Pen, 272.

Saints of the Desert, 274, 453, 655, 835.

Saint Catharine of Siena, Public Life of, 547.

Saint Patrick, The Birth place of, 744.

True to the Last, 110.

The Eye, Inside of, 119.

Tropics, Gleanings from the Natural History of, 178

The Clouds and the Poor, 213

The Bible; or, Christmas Eve, 397.

The Adventure, 848.

World, Religious Statistics of the, 491.

POETRY.

An English Maiden's Love, 27.

Better Late than Never, 454.

Books, 495.

Children, The, 70.

Christmas Carol, A, 419, 559.

City Aspirations, 680.

"Dum Spiro Spero," 159.

Falling Stars, 348.

Inquietus, 704

Kirkstall Abbey, 36.

Keviaar, Pilgrimage to, 127.

Little Things, 836.

Properzia Rossi, 235.

Patience, 812.

Resigned, 654.

Song of the Year, 490.

Saint Elizabeth, 529.

Tender and True and Tried, 385.

The Round of the Waters, 396.

The Better Part, 757.

Unshed Tears, 789.

Winter Signs, 198.

{iv}

NEW PUBLICATIONS.

Archbishop Hughes's Complete Works, 282.

American Republic, The, 714.

Andrew Johnson, Life of, 856.

Banim's Works, 286.

Baker, Rev. F. A., Memoir and Sermons of, 566.

Brownson's American Republic, 714.

Brincker, Hans, 719.

Catholic Anecdotes, 287.

Cobden, Richard, Career of, 860.

Complete Works of Archbishop Hughes, 282.

Croppy, The, 859.

Darras' History of the Church, 143.

De Guérin, Eugénie, Journal of, 716.

Draper's Civil Policy of America, 858.

England, Froude's History of, 676.

Faith, the Victory, Bishop McGill's, 575.

Hedge's Reason in Religion, 430.

Holmes, Oliver W., Humorous Poems, 576.

Lives of the Popes, 288.

Mother Juliana's Sixteen Revelations, 281.

Metropolites, The, 287.

Memoir and Sermons of Rev. F. A. Baker, 566.

Manning's Temporal Mission of the Holy Ghost, 568.

Merry Christmas, A Cantata, 719.

Monthly, The, 719.

Mozart, Letters of, 856.

Newman's, Rev. Dr., History of Religious Opinions, 139.

Nicholas of the Flue, 718.

Remy St. Remy, 287.

Reason in Religion, 430.

Sixteen Revelations of Mother Juliana, 281.

Sherman's Great March, Story of, 283.

Saint John of the Cross, Works of, 432.

Spelling Book, The Practical Dictation, 576.

Spare Hours, 718.

St. Teresa, Life of, 855.

Thoreau's Cape Cod, 283.

The Old House by the Boyne, 26.

The Christian Examiner, 573, 717.

United States Cavalry, History of, 858.

Vade Mecum, The Catholic's, 859.

THE

CATHOLIC WORLD.

VOL. II., NO. 7.—OCTOBER, 1865.

Translated from the German.

MALINES AND WÜRZBURG.

A SKETCH OF THE CATHOLIC CONGRESSES

HELD AT MALINES AND WÜRZBURG

BY ANDREW NIEDERMASSER.

CHAPTER I.

The Catholic Congresses in Belgium are of more recent date than the

general conventions of all Catholic societies in Germany. The

political commotions of 1848 burst the chains which had fettered the

German Church, and ushered in a period of renewed religious life and

activity. This new and glorious era was inaugurated by the council of

twenty-six German bishops at Würzburg, which lasted from Oct 22 to

Nov. 16, 1848. There it was that our prelates boldly seized the

serpent of German revolution, and in their hands the serpent was

turned into a budding rod, the stay alike of Church and state.

Since then sixteen years have rolled by; sixteen general conventions

have been held, each of which gained for its participants the respect

of the public. Powerful was the influence exerted by these meetings on

the religious life of the laity, as is shown both by the numerous and

active associations that arose everywhere, and by the general spirit

of enterprise which they fostered. By their means, the spirit and

principles of the Church were made known to the Catholic laity, whose

actions they were not slow to influence.

To these meetings may be traced, directly or indirectly, whatever good

was accomplished within the past sixteen years in Catholic Germany;

every part of Germany has felt their beneficial effects; they were

well suited to perform the task allotted them; and have thus far at

least attained the end for which they were called into existence.

These meetings were associations of laymen; of laymen penetrated with

the spirit of faith, devoted to the Church, and fully convinced that

in matters relating to the government of the Church, to the

realization of the liberty and independence due to the Church, their

only duty was to listen to the voice of their pastors, and to follow

devotedly the lead of a {2} hierarchy they respected and revered.

Though for the most part but one third of the members of the annual

conventions were laymen, the lay character of the conventions is still

theoretically asserted, and appears to some extent at least in

practice, inasmuch as the president of the convention is always a

layman, and the principal committee is mainly composed of laymen. The

preference is also given to lay orators. The society of laymen

submitted the constitution drafted and adopted at its first meeting,

held at Mayence in 1848, not only to the Holy Father, but to all the

bishops of Germany, who joyfully approved its sentiment, and expressed

their interest in the welfare of the society. The same course is

pursued to the present day; each of the sixteen general conventions

maintained the most intimate relations with the German bishops and the

Holy See.

In honor of the present pontiff, Pius IX., these associations at first

adopted the name of Piusvereine, thus paying a just tribute of

respect to the Holy Father. For Pius IX., during his long pontificate

of almost twenty years, has become the leading spirit of the age; we

live in the age of Pius IX. It was he who brought into vogue modern

ideas, and he was the first to do justice to the wants of the age. As

the historian now speaks of the age of Gregory VII. and Innocent III.,

so will the future historian write of the age of Pius IX. The true

sons of the nineteenth century are gathered to fight under the banners

of the many Catholic associations which, founded for the purpose of

putting to flight the threatening assaults of infidelity, have spread

during the pontificate of Pius IX. over every portion of the globe. In

Switzerland the original name of these societies is retained; in

Germany, owing to their branching out into numerous similar

associations, it has disappeared, and we now speak of a "general

convention of the Catholic associations in Germany."

The first general convention took place toward the beginning of

October, 1848, in the ancient electoral palace at Mayence. Hundreds of

noble spirits from every quarter of Germany met here, as if by magic;

the Spirit of God had convened them. Meeting for the first time, they

felt at once that they were friends and brothers. There was no

discord, no embarrassment, for on all hearts rested a deep

consciousness of the unity, the power, and the charity of their common

faith. Whoever was present at this first gathering of the Catholics of

Germany, owned to himself that by no scene which he had previously

witnessed had he been so profoundly impressed. Opposite the stand from

which the speakers were to address the meeting sat Bishop Kaiser, of

Mayence, whilst most prominent among the orators of the occasion

appeared his destined successor, Baron Emmanuel von Ketteler, who was

at that time pastor of the poor and insignificant parish of Hopsten.

Writing of him, Beda Weber said: "His determined character is a fresh

and living type of the German nation, of its universality, its

history, and its Catholic spirit. In his heart he bears the great and

brave German race with all its countless virtues, and hence springs

the peculiar boldness of his words, asserting that the revolution is

but a means to rear the edifice of the German Church, an edifice

destined to be far statelier than the cathedral of Cologne. His form

was tall and powerful, his features marked, expressing at once his

fearlessness, his energy, and his Westphalian devotion to God and the

Church, to the emperor and the nation. The words of Baron von Ketteler

acted irresistibly on all present, for they were but the echo of their

own sentiments." Such was the impression then produced by the man who

is now looked upon by the Catholics of Germany as their

standard-bearer.

The voice of Beda Weber too was heard on that occasion. Frankfort had

not as yet become the scene of his {3} labors as pastor, for he was

still professor at Meran. He was a member of the German parliament,

then holding its sessions at Frankfort, and like many other Catholic

fellow members had come to Mayence for the purpose of assisting at the

first general reunion of the Catholic societies. His eloquence

likewise called forth immense enthusiasm. Strong and energetic,

sometimes pointed and unsparing, a vigorous son of the mountains,

manly, noble, and respected, he came forth at a most opportune moment

from the solitude of his mountains and his cell, in order to take part

in the struggles of his age and become their historian. A master at

painting characters, he has written unrivalled sketches of the German

parliament and clergy. Equally successful as an orator, a poet, a

historian, and a contributor to periodical literature, Beda Weber was

distinguished no less by a childlike heart and a nice appreciation of

the beautiful in nature and art, than by manly force and an untiring

zeal for what is true and good. His deep and extensive learning has

proved a useful weapon at all times. His writings were read throughout

Germany, and to the rising generation Beda Weber has been an efficient

instructor and director.

Döllinger of Munich was also present; he spoke for the twenty-three

members of the German parliament, maintaining that the concessions

granted to Catholics by that body would necessarily lead to the entire

independence of the Church and the liberty of education. At a meeting

of the Rhenish-Westphalian societies, held at Cologne in May, 1849,

the learned provost delivered another speech, which was at that time

considered one of the best, most timely, and most telling efforts of

German eloquence. Döllinger's speech at the third general convention,

which took place at Regensburg in October, 1849, was hailed as one of

the few consoling signs of that gloomy period. It was a masterpiece of

oratory, that brought conviction to all minds, and which will prove a

lasting monument of German eloquence. The interest Döllinger displayed

in these conventions should not be forgotten. He is entitled to our

respect and gratitude for his aid in laying the foundations of the

edifice; its completion he might well leave to others.

The other members of the parliament that spoke at Mayence were

Osterrath, of Dantzic; von Bally, a Silesian; A. Reichensperger,

of Cologne; Prof. Sepp, of Munich; and Prof. Knoodt, of Bonn. One of

the most impressive speakers was Forster of Breslau, at that time

canon of the Metropolitan church of Silesia, now prince-bishop of one

of the seven principal sees in the world. Germany looks upon him as

her best pulpit orator. Listen to the words of one who heard Forster

at Mayence: "The chords of his soul are so delicate that every breath

calls forth a sound, and as he must frequently encounter the storms of

the world, we may readily pardon the deep melancholy which tinges his

words. As he spoke, his heart was weighed down by the troubles of the

times, and grief was pictured in his countenance, for he saw no

prospect of reconciliation between the conflicting elements. He has no

faith in a speedy settlement of the relations between Church and

state, such a settlement as will allow freedom of action to the

former. To him the revolution appears to be a divine judgment,

punishing the clergy for their negligence, and chastising the laity

for their crimes. His voice possesses a rich melody, which speaks in

powerful accents to the heart. It sounds like the solemn chimes of a

bell, waking every mind to the convictions which burst forth from the

depth of his soul. He is an orator whose words seem like drops of

honey, and whose faith and devotion call forth our love and our

gratitude."

The best known of the Frankfort representatives were, Arndts, of

Munich; Aulicke, of Berlin; Flir, of {4} Landeck; Kutzen, of Breslau;

von Linde, of Darmstadt; Herman Müller, of Würtzburg; Stülz of St.

Florian; Thinnes, of Eichstädt; and Vogel, of Dillingen.

The noble Baron Henry von Andlaw also assisted at the convention in

Mayence. For sixteen years this chivalric and devoted defender of the

Church has furthered by every means in his power the success of the

Catholic conventions, and his name will often appear in these pages.

Chevalier Francis Joseph von Buss, of Freiburg, was president of the

meeting at Mayence. Buss is the founder of the Catholic associations

in Germany; to him above all others was due the success of the

convention at Mayence, and he it was who laid down the principles on

which are based the Catholic societies throughout Germany, and which

are the chief source of their efficacy. In 1848 Buss was in the flower

of his age, fresh and vigorous in body and mind. All Germany was

acquainted with his writings, his exertions, his sufferings, and his

struggles. He was no novice on the battle-field, for he had passed

through a fiery ordeal, and bore the marks of wounds inflicted both by

his own passions and by the broken lances of his enemies. Naturally an

agitator, and an enthusiast for ideas, bold, quick, and intrepid, he

united restless activity and unquenchable ardor with the most

self-sacrificing devotion. He is distinguished for extensive learning,

a powerful imagination, and for the force and flow of his language. So

constant and untiring have been his exertions for the liberty and

independence of the Church, that one who is no mean painter of men and

character has lately styled him the Bayard of the Church in the

nineteenth century. The last time I saw and heard the Chevalier von

Buss was in the convention held at Frankfort in 1862. His imposing

figure, his bold commanding eye, his fiery patriotic heart, his

glowing fancy, his powerful ringing voice, all were unchanged. His

speeches exert the magic influence which belongs to an enthusiastic,

powerful, and penetrating mind. Age has whitened his hair, wrinkles

furrow his noble features, his life is on the wane. A glance at

Catholic Germany and the growth of the Church during the past sixteen

years, will reflect a bright consoling radiance on the evening of his

life.

We must still mention one of the founders and chief stays of the

Catholic general conventions, and one who, alas, is no more. I refer

to Dr. Maurice Lieber, attorney and counsellor at Camberg in Nassau,

one of the most active members at Mayence in 1848; he was elected

president of the second general convention at Breslau in 1849. He was

present at the first seven general meetings, and at Salzburg in 1857

filled the chair a second time. At Cologne, in 1858, this honor would

again have been conferred on him had he not declined. Maurice Lieber

seems by nature to have been designed to preside at these assemblies.

Of a noble appearance, he combined dignity with gentleness, force and

decision with moderation; his remarks were always to the point. An

able and spirited writer and journalist, he contributed in a great

measure to make the public acquainted with the aim and object of the

newly founded association. He never grew weary of scattering good and

fruitful seed, and his writings as well as his speeches were

life-inspiring, strengthening, purifying productions. The name of

Maurice Lieber will ever be honored.

Beside the eminent men above mentioned, those whose exertions aided in

calling into existence the Catholic general conventions in Germany are

Lennig, vicar-general at Mayence, Prof. Riffel, Himioben, now dead,

and lastly, Heinrich and Moufang, who have been present at almost

every meeting.

So many illustrious names are connected with the foundation of the {5}

Catholic congress in Belgium that to do all justice will be extremely

difficult.

The political and religions status of Belgium is sufficiently well

known. In Belgium there are but two parties; the one espouses the

cause of God, the other supports that of Antichrist. These parties are

on the point of laying aside entirely their political character and of

opposing each other on religious grounds. War is inevitable, war to

the knife; either party must perish. "To be or not to be, that is the

question."

Outnumbering the Catholics in parliament, the followers of Antichrist

eagerly use their superiority to trample their opponents in the dust

and, if possible, annihilate them. The people is the stronghold of the

latter; for the great majority of the Belgians are Catholics, sincere,

fervent, self-sacrificing Catholics. They yield support neither to the

rationalists nor to the solidaires and affranchis. Day by day the

influence of the Catholic leaders increases; they are whetting their

swords, and gathering recruits to fight for Christ and his Church. The

congress at Malines is their rendezvous, as it were. Even the first

congress, that of 1863, exerted a magic influence; the drowsy were

aroused from their lethargy, and the faint-hearted were inspired with

confidence; they saw their strength and felt it. In that congress we

see the beginning of a new epoch in the religious history of Belgium.

The Belgium congresses are imitations of the Catholic conventions in

Germany. A number of men used their best endeavors to bring about the

congress of 1863, and for this they deserve our respect and gratitude.

We shall mention but a few of the many.

Dumortier will head our list. He is one of the most powerful

speakers in Belgium, a ready debater, a valiant champion of the

Catholic cause, whose delight it is to fight for his principles.

Dumortier has the power of kindling in his hearers his own enthusiasm,

as he proved in 1863 at Aix-la-chapelle. He has all the qualities of

an agitator, and these qualities were the cause of his success in

bringing about the congress of 1863. When indignant, Dumortier

inspires awe; his brow is clouded, and like a hurricane he sweeps

everything before him. It is the anger of none but noble spirits that

increases our affection for them. Once only I saw Dumortier swell with

just indignation, and I seldom witnessed a spectacle more sublime.

Ducpetiaux was the soul of the congresses at Malines. To singular

talent for organization he joins a burning zeal for the interests of

Catholicity, and to them he devotes every day and hour of his life. No

sacrifice is too great, no labor too exhausting, if it is needed to

further the Catholic cause. As general secretary, he is in

communication with the leading men of Catholic Europe. At his call

Catholics from every country flocked to Malines. Ducpetiaux was the

ruling mind of the congress, for the president had intrusted him, to a

great extent, with its management. Cautious, subtle, and quick, he is

prompt in action, though no great speaker. The most numerous assembly

would be obedient to his nod. Ducpetiaux is no stranger to Germany,

for he was among us at Aix-la-chapelle in 1862, and at Würzburg in

1864, and the whole-souled remarks made by him on the latter occasion

will long ring in our memory. He is an international character, a type

of the nineteenth century. By the interest a man takes in the

movements and ideas of his age, and by his intercourse with prominent

characters, we may easily estimate his influence. To Germany a general

secretary like Ducpetiaux would be of inestimable advantage.

Viscount de Kuckhove must not be passed over in silence. A thorough

well bred gentleman, he is familiar with the nations and languages of

{6} Europe. He is a man of mind, energy, and prudence, and of a

dazzling appearance. He seems the embodiment of elegance. His speeches

sparkle with delicate touches and are distinguished for refinement.

His voice is somewhat shrill and sharp, but melodious withal. In

Belgium the viscount ranks as an orator equal to Dechamps and

Dumortier. His favorite scheme, to the promotion of which he gives his

entire energies, is the closest union among Catholics of all

countries. At times he expresses this idea so forcibly that he is

misunderstood, but in itself the scheme is praiseworthy, and has been

more or less realized in the age of Pius IX.

Baron von Gerlache now demands our attention. He was president of

the congress both in 1863 and in 1864. If I were writing his

biography, how eventful a life would it be my lot to portray! Baron

Gerlache is identified with Belgian history since 1830; for more than

forty years he has been acknowledged by the Catholics in Belgium as

their head. In 1831 he had no mean share in forming the Belgian

constitution, a constitution based on political eclecticism, which at

that time satisfied all parties, and which promised even-handed

justice to all. Gerlache has ever been the loyal defender of this

constitution; Belgium has not a more devoted son. He is a historian

and a statesman. But the Church too claims his affection, the great

and holy Catholic Church. All Belgium listens to his voice, and his

words sometimes become decrees. He speaks with dignity and moderation,

with caution and prudence; he is always guided by reason, and never

loses sight of facts. His energies spent in the course of a life of

seventy-two years, he is no longer understood as well as formerly; his

voice has become too weak to address an assemblage of six thousand

persons; but there is in it something so solemn, so moving, that his

hearers seem spell-bound. His language is appropriate, and at times

approaches sublimity. Baron Gerlache is as much the idol of the

Catholics of Belgium as O'Connell was of the Irish; he is as respected

as Joseph von Grörres was in Germany; he is the Godfrey de Bouillon of

the great Belgian crusade of the nineteenth century. Great men seldom

appear alone; around them are grouped many minor characters, well

worthy of a niche in the temple of fame. The most prominent of those

who have fought side by side with Baron von Gerlache are the Count de

Theux, a veteran in political warfare, generous, able, and experienced

in the art of governing; the Baron della Faille, a man distinguished

for the dignity of his demeanor and the nobility of his character; his

manners are captivating, and his features bear the impress of

calmness, moderation, and judgment; the Viscount Bethune of Ghent, a

venerable old man, whose countenance beams with piety, and who in the

course of a long career has gathered a store of wisdom and experience;

General Capiaumont, a man immovable as a rock, and full of chivalrous

sentiments. These venerable men were seated on each side of the

President von Gerlache. But the other members are no less worthy of

notice. To hear and see such men produces a profound impression.

Dechamps, the mighty Dechamps, the lion of Flanders and Brabant,

must not be forgotten. He stands at the head of the Belgian statesmen,

brave as Achilles, the terror of the so-called liberals. Dechamps was

one of the pearls of the last congress; his mere appearance had a

magic effect; the few words he addressed to the assembly before its

organization called forth a storm of applause; he electrifies his

hearers by his bold and sparkling ideas.

We must next call attention to Joseph de Hemptinne. The owner of

immense factories, he employs thousands of laborers, and freely

devotes his fortune to the cause of the Church. He also contributed

to the success of {7} the congress of Malines. His employés owe him a

debt of gratitude. Like a father, he cares for their corporal and

spiritual welfare, accompanies them when going to assist at mass, and

with them he says the beads and receives the sacrament. De Hemptinne

is entirely devoted to his country and his faith; his countenance is a

mirror that reflects a pure and guileless soul, deeply imbued with

religious feeling. It has seldom been my good fortune to meet as

amiable a man as Joseph de Hemptinne.

Perin next demands our notice. He fills a professorship at Louvain,

and is well known to the public by his writings. In the congress be

was noted as an adroit business man. Possessing a refined mind, stored

with manifold attainments, he exerts a peculiar, I might almost say

magic, influence on those with whom he deals. His fine piercing eye

beams with knowledge, not mere book learning, but the knowledge of

men, whilst his noble forehead is stamped with the seal of uncommon

intellectual power. In his language as well as in his actions Perin is

extremely graceful; he might not inaptly be styled the doctor

elegantissimus. Count Villermont of Brussels is well known in

Germany, and respected for his historical researches. At Malines he

displayed extraordinarily activity. True, he seems to be no favorite

of the graces—the warrior appears in all his actions. On seeing him,

I imagined I beheld the colonel of one of Tilly's Walloon regiments.

This circumstance must surprise us all the more, as the count is not

only a diligent student of history and a generous supporter of the

Catholic press in Belgium, but also a man who takes a lively interest

in every charitable undertaking and in the social amelioration of his

country. Would to God that Germany had many Counts Villermont!

Monsignor de Ram the rector magnificus of the university of Louvain,

was the representative of Belgian science at Malines. Ever since its

establishment, he has been at the head of that institution, which he

has governed with a firm and steady hand. He is the pride of Belgium,

eminent, perhaps the most eminent, among all her sons. His authority

is most ample, and to it we must probably trace the majestic calmness

that distinguishes his whole being, for to me de Ram appears to be the

personification of dignity. At the proper moment, however, he knows

how to display the volubility and affable manners of the Roman

prelate.

Many illustrious Belgian names might still be mentioned, but we will

speak of them in a more appropriate place.

The Belgian congresses differ in some respects from the Catholic

conventions in Germany, for the latter are by no means so well

attended as the former. At the German meetings, the number of members

never exceeded fifteen hundred; only six hundred representatives were

present at the convention of Frankfort in 1863, whilst that of Breslau

in 1849 mustered scarcely two hundred members. In 1863 four thousand,

and in 1864 no less than five thousand, were present at the Malines

congress. The sight of this army, full of fervor and of zeal to do

battle for the faith, involuntarily reminds us of the warriors who

were marshalled under the banners of Godfrey for the purpose of

achieving the conquest of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Or it recalls

to our mind the great council of Clermont (Nov., 1095), at which the

entire assembly, hurried away by the eloquent appeals of Urban II.,

shouted with one accord "Deus lo volt," "God wills it," and swore to

deliver Jerusalem from the tyranny of the Moslems. The members of the

Catholic congresses are the crusaders of the nineteenth century, for

in their own way they too battle for Christendom against its enemies,

falsehood and malice.

Belgium is a small kingdom, Malines the central point where all its

railroads converge; it is a Catholic {8} country, boasting of a

numerous clergy both secular and regular; it is an international

country, the Lombardy of the north. Its position has made it the

connecting link between the Romanic and Teutonic races, between the

continent and England. Thus situated, Belgium is a rendezvous equally

convenient for the German, the Frenchman, and the Briton. Moreover,

Belgium has ever been the battle ground of Germany and France: where

can be found a more suitable spot on which to decide the great

struggle for the freedom of the Church? This explains sufficiently the

numerous attendance of the Belgium congress. In addition to the

foreign element, the congress at Malines calls forth the entire

intellectual strength of Belgium, both lay and clerical No one remains

at home; all are brethren fighting for the same cause; all wish to

imbibe new vigor, to gather new courage for the struggle, for the

congress acts like the spiritual exercises of a mission.

Very different is the situation of Germany. Much larger than Belgium,

its most central point is at a considerable distance from its

extremities. Beside, the conventions do not even meet at the most

convenient point, but change their place of meeting every year.

Suppose, therefore, the convention is held in some city on the French

border, say Freiburg, or Treves, or Aix-la-chapelle, this arrangement

will render it very difficult for the delegates from the opposite

extremity of the empire to attend, the more so since it is not likely

that the German railroad companies will reduce their fares to half

price, as was done by the Belgium government roads. Lastly, our

language, difficult in itself, and especially so to the Romanic races,

who are not distinguished for extensive philological learning, will

prevent many from attending our meetings.

For these reasons, the German reunions are hardly an adequate

representation of the Church militant; comparatively few can attend,

the majority must remain at home. For the most part, our conventions

are chiefly composed of delegates from the district or diocese in

which they are held. Nevertheless, every German tribe has its

representative, and Germany, with its many tribes and states, is by no

means an inappropriate emblem of the European family of nations.

The hall of the Petit Seminaire at Malines, where the Belgian

congress meets, is spacious and well fitted for its purpose; it will

seat six thousand persons. Nevertheless, only such as have admission

tickets, which cannot be obtained except at extravagant prices, can

assist at the sessions. The public in general are excluded, and but

few seats are reserved for ladies. On the other hand, the German

convention, which meets now in one city, then in another, desires and

encourages, above all things, the attendance of the inhabitants of the

city where it meets. In every city it has scattered fruit-producing

seed. At one place, the convention called into existence a society for

the promotion of Christian art; at another, an altar society, a

conference of St. Vincent de Paul, or a social club; and in many

cities it inspired new religious life and activity. In fact, if the

city for some reason cannot assist at the meetings, as was the case in

Würzburg, one of the most important ends of the convention is

defeated. The congress at Malines is too numerous to travel from place

to place; moreover, its meetings are not annual, as are those of the

German conventions.

The congress of Malines, like the German convention, claims to be a

congress of laymen. But though here, too, the principal committee is

mainly composed of laymen, the assembly has almost lost its lay

character. Among the laymen, however, who attend the Belgian congress,

there are many excellent speakers, in fact these are more numerous

than in Germany.

All the Belgian bishops were present at Malines. Whilst in Germany but

one or two bishops assist at the convention, the daily meetings of the

Malines congress were attended by the primate of Belgium, Cardinal

Sterex, and the bishops of Bruges, Namur, Ghent, Liege, and Doornik.

The bishops took part in the debates, and in 1864 the speech of

Monseigneur Dupanloup was the event of the day, whilst the congress of

1863 had been distinguished by the presence of the illustrious

archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Wiseman. Whenever the bishops

appeared, they were welcomed with bursts of enthusiasm. For a full

week might be witnessed the most friendly intercourse between the

bishops and the other members of the congress, and thus the bonds of

affectionate love already existing between the hierarchy, the clergy,

and the laity were drawn still closer.

The nobility too of Flanders and Brabant, nay of all Belgium, was well

and worthily represented. On the rolls of the Malines congress we meet

the most illustrious Belgian names, names pregnant with historic

interest. The German nobles, on the contrary, have thus far paid

little attention to what is nearest and dearest to mankind, the

interests of humanity and religion. True, the Rhenish-Westphalian

nobility appeared in considerable numbers and displayed praiseworthy

zeal at the conventions of Aix-la-chapelle, Frankfort, and Würzburg,

nevertheless there is still room for improvement. Thus far the

Bavarian and Franconian nobles have taken no part in furthering the

restoration of the Church in Germany, and of the same indifference the

Austrian nobility were accused by Count Frederick von Thun, of Vienna.

Still, what a blessing for the nobility if they devoted their

influence to the service of the Church! The consequence would be the

regeneration of the German nobility. May God grant that the German

nobles, like those of Belgium, will join in cordially promoting our

great and sacred cause. Leaders are not wanting, men of talent,

energy, and devotion, such as the Prince Charles of Löwenstein,

Werthheim, and Prince Charles of Isenburg-Birstein.

The professors of the university at Louvain were not only present at

Malines, but worked with their usual energy and ability in the

different sections of the congress. They presented to the world the

noble spectacle of laymen uniting learning with zeal for religion and

devotion to the Church, a spectacle seldom witnessed in Germany. Of

the two thousand professors and fellows of the twenty-two German

universities, how many are there who, untainted by pride and

self-sufficiency, call the Church their mother? It is the union of

knowledge and piety that produces genuine men, worthy of admiration,

and at Malines such men were not scarce.

At Malines the foreigners were well represented; in the German

conventions but few make their appearance. Twice did France send her

chosen warriors to the congress—the first time in 1863, led by

Montalembert, at present the most brilliant defender of the Church,

and again in 1864, under the Bishop of Orleans, called by some the

Bossuet of our day. In August, 1863, the Tuileries were anxiously

occupied with the speeches held in the Petit Seminaire at Malines, for

in France despotism has gagged free speech, and there a congress of

Catholic Europe is an impossibility; the Caesar's minions would

tolerate no such assembly.

Next to the French delegation, the German, led by A. Reichensperger,

of Cologne, was the most numerous. There might also be seen a noble

band of Englishmen, and their speaker, Father Herman the convert,

seemed another St Bernard preaching the crusade. Spain, Italy,

Ireland, Hungary, Poland, Brazil, the United States, Palestine, the

Cape of Good Hope, almost every country on the globe, were represented

at Malines. True, the assembly was by no means {10} as large as the

multitude that met in Rome on June 8, 1862, when Pius IX. saw gathered

around him in St. Peter's church three hundred prelates, thousands of

priests, and forty to fifty thousand laymen, representing every nation

of the earth. Still, the congress at Malines brings to recollection

those immense gatherings of bygone times, where princes and bishops,

nobles and priests, met to provide for the welfare of the nations

committed to their charge.

The Malines congress is in its infancy, still the general committee

has displayed rare ability. All business matters are intrusted to a

few, whilst in Germany there is a great want of order, owing partly to

the inexperience of the local committees, and partly to the scarcity

of men versed in parliamentary proceedings. At the Mayence convention

in 1848, want of preparation might be excused; the subsequent meeting

had not the same claims on our indulgence. The Frankfort reunion in

1863 attempted to remedy the evil and partly succeeded, but until an

efficient general committee be established, many irregularities must

be expected. At Malines the delegates are furnished with a programme

of the questions to be discussed in the different sections; at

Würzburg, on the contrary, the convention seemed at first scarcely to

know the purpose for which it had been convened. In Germany, the

bureau of direction is composed of three presidents and sundry

honorary members and secretaries; at Malines it consists of fifty to

sixty officers of the congress, and the list of honorary

vice-presidents is at times very formidable. In Belgium secret

sessions are unknown, whilst in Germany it often happens that the most

important proceedings are decided upon in secret session, whereas the

public meetings are mainly devoted to the delivery of brilliant

speeches. At Malines the resolutions adopted by the different sections

are passed upon in a short session, seldom attended by more than

one-fifth of all the delegates. One evil at the Belgium congress is

the imperfect knowledge of the German character and of the religious

status of Germany. As the Romanic nations will never learn our

language, it remains for us to supply the deficiency. We must go to

Malines, and expound our views in French both in the sections and

before the full congress. A. Reichensperger pursued the proper course

in the section of Christian art. With surpassing ability he defended

the principles of the Church, triumphantly he came forth from the

contest, and many were prevailed upon to adopt his views. No doubt men

like Reichensperger are not found every day, nevertheless we might

easily send one or two able representatives to every section of the

congress. If some one were to do for Germany what Cardinal Wiseman did

for England in 1863, when he set forth in clear and forcible language

the state of Catholicity in that country, he would deserve the

everlasting gratitude of the Romanic races.

Leaving these considerations aside for the present, one thing is

certain, we must profit by each other's wisdom and experience.

Whatever may be the defects of the Belgian congresses or of the German

conventions, they mark the beginning of a new era for Belgium and

Germany. For when in the spring of 1848 the storm of revolution swept

away dynasties built on diplomacy and police regulations, the

Catholics, quick to take advantage of the liberty granted them, made

use of the freedom of assembly, of speech, and of the press to defend

the interests of religion and of the Church. To Germany the liberty

thus acquired for the Church has proved a blessing. This liberty,

attained after so many years of Babylonian captivity, acted so

forcibly, that many called the day on which the first general

convention met a "second Pentecost, revealing the spirit, the force,

and the charity of Catholicism." We Catholics have learned the

language of freedom, we {11} know the power of free speech. Next to

the liberty of speech, it is their publicity that gives a charm to

these conventions. Whoever addresses these assemblies speaks before

the whole Church, and his words are re-echoed in every country. There

the prince and the mechanic, the master and the journeyman, the

refined gentleman and the child of nature, all alike have the right to

express their opinions. They afford a general insight into the social

and religions condition of our times, disclosing at once their defects

and their fair side. How inspiring it is to see men, thorough men,

with sound principles, full of vital energy, and of experience

acquired in public life, men of intellectual vigor and mental

refinement! Hence arise great and manifold activity, unity of

sentiment, and zeal for the weal of all, in short, feelings of true

brotherly love. Great events arouse deep feelings, and the glory of

one casts its radiance over many. There is something beautiful and

grand in these Catholic reunions. They tend to awaken society to a

consciousness of its nobler feelings and to spread Catholic ideas;

they give strength and unity to the exertions of all who endeavor

seriously to promote the interests of Catholicity; they are, as it

were, a mirror that reflects an exact image of the life of the Church.

Before their influence narrow-mindedness withers; we take an interest

in men and things that had never before come within the scope of our

mental vision, and on our return from the congress to the ordinary

pursuits of life, we forget fossil notions and take up new ideas. As

we feel the heat of the sun after it has set, so long after the

adjournment of each convention do we feel its influence. The eloquent

words of the champion of their faith kindle in the hearts of Catholic

youth a glowing ardor which promises a bright and glorious future. All

are impressed with the conviction that it is only by unflinching

bravery that victories are won.

"As in nature," says Hergenröther, "individuals are subordinate to

species, species to genera, and these again to a general unity of

design, thus in the Catholic Church all submit freely to the triple

unity of faith, of the sacraments, and of government. Whether they

come from the north or the south, from beyond the Channel or from

the banks of the Rhine, from the Scheldt or the Danube, from the

March or the Leitha, all Catholics of every country and every clime

are brethren, members of the same family, all speak but one

language, the lips of all pronounce the same Catholic prayer, and

all offer to their Heavenly Father the same august sacrifice. Every

Catholic convention is a symbol of this great, this universal

society. And as in nature we admire the most astonishing variety,

and the wonderful display of thousands of hues and tints, so in the

Church we behold a gathering of countless tribes and nations,

differing in their institutions, their customs, and in their

application of the arts and sciences."

Some of my readers, perhaps, are impatient of the praise here lavished

on contemporaries. Fame, it is true, has ever dazzled mortal eyes, but

I am not now dealing with the miserable characters who consider fame

as merchandise that can be bought and sold, who are always panting for

honied words, and who never lose sight of themselves. No; I am in the

presence of Catholic men, purified by Catholic doctrine and

discipline, who hold fame to be vain trumpery. Claiming to be no

infallible judge of men, my aim has been to note down what I have seen

and heard, for I have been at no special pains to study the characters

of those here mentioned.

[TO BE CONTINUED.]

From The Month.

NAPOLEON'S MARRIAGE WITH MARIE-LOUISE.

There are many circumstances where even an excess of caution may not

be injudicious, and few things can be more important than to ascertain

the veracity of historical facts. Therefore we would fain preface this

second episode drawn from the memoirs of Cardinal Consalvi, by

pointing out the grounds on which their authenticity rests. We pass

over the editor himself, Monsieur Crétineau-Joly, to arrive at the

account he gives of the manner in which these papers fell into his

possession. Written for the most part by the cardinal during his exile

at Rheims, they were hastily penned, and carefully concealed from the

French officials that surrounded him. When dying, Cardinal Consalvi

intrusted these important documents to friends on whom he could rely.

They have since been transmitted as a sacred deposit from one

fiduciary executor to another. The last clause of his will relates to

this matter, and runs thus:

"My fiduciary heir (and those who shall succeed him in the

administration of my property) will take particular care of my

writings: on the conclave held at Venice in 1799 and 1800; on the

concordat of 1801; on the marriage of the Emperor Napoleon with the

Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria; on the different epochs of my

life and ministry. These five papers (of which some are far

advanced, and I shall set about the others) are not to be published

till after the death of the principal personages named therein. As

the memoirs upon the conclave, the concordat, the marriage, and my

ministry relate more especially to the Holy See and the pontifical

government, my fiduciary heir will be solicitous to present them to

the reigning pontiff; and he will beg the Holy Father to have these

writings carefully preserved in the archives of the Vatican. They

may serve the Holy See more than once; especially if the history of

events therein related comes to be written, or if there were some

false account to refute. As to the memoirs concerning the different

epochs of my life, the extinction of my family leaving no one whom

they may interest, these writings can remain in the hands of my

fiduciary heir and his successors in the administration of my

property (or they might go with the others to the archives of the

Vatican if they are thought worth preserving). My only desire is,

that if hereafter, as will probably be the case, the lives of the

cardinals are continued, these pages written by me may then be made

known. For I wish that nothing contrary to truth should be published

concerning me; being desirous to preserve a good reputation, as is

recommended by holy Scripture. With regard to the truth of the facts

contained in my writings, it suffices me to say: 'Deus scit quia

non mentior.'

"(Signed) E. Card. Consalvi."

"Rome, 1st August, 1822."

In 1858 it was deemed that the time for publication had come. Monsieur

Crétineau-Joly was then staying at Rome; and the papers were confided

to him for that purpose by "those eminent personages who, through

gratitude or respect, had accepted the deposit of Consalvi's

manuscripts." Accordingly, a part did come out the following year, and

the remainder is now before the public. The part which appeared first,

embodied in "L'Eglise Romaine en face de la Révolution," won for M.

Crétineau-Joly in 1861 a flattering brief from Pope Pius IX., which

heads the third edition of the work.

Nine years had rolled on since the concordat. Ten months after the

Pope's presence had given solemnity to his coronation, Napoleon caused

the French troops to occupy Ancona; Pius VII., having refused to

become virtually a French prefect, was deprived of his temporal

sovereignty, and then at last dragged from his capital to be

transferred a prisoner to Florence, Grenoble, and finally Savona.

Excommunication had been pronounced against those who perpetrated

these deeds of violence. Meanwhile, Napoleon, at the summit of earthly

grandeur, longed for an heir to whom he might transmit his vast

dominions. The repudiation of Josephine offered some difficulty to his

heart, we believe; but his strong will soon triumphed over that and

every other obstacle. Proud Austria stooped to court his preference.

Napoleon, disappointed in his wish for a Russian alliance, but in too

much haste to wait negotiations, let his choice fall with equal

pleasure on a daughter of the house of Hapsburg; Marie-Louise, just

then eighteen, came a willing bride to share the splendors of the

imperial throne. To prepare for her reception, a state comedy had been

enacted at the Tuileries, when Napoleon, holding his good and

well-beloved Josephine by the hand, read from a written paper his

heroic determination to renounce her for the public weal. Poor

Josephine could not get on so well; sobs choked her utterance when she

essayed to read her paper in turn. Convulsive fainting-fits had

followed when Napoleon first broached in private the resolve he had

taken, and called upon her to aid it by consenting to become, instead

of his wife, his best and dearest friend. But all that was over now.

One only difficulty had arisen, which even the imperious will of

Napoleon failed wholly to break. It was the same that had ever

thwarted him. He could destroy all temporal barriers to his ambition;

but the spiritual element would rise up and protest. How cut asunder

the religious tie that linked him to Josephine? For the Church's

blessing had been given to their union ere the Pope would consent to

perform the ceremony of the coronation. Full well Napoleon knew that

he could with an iron hand put down clamor for the present; but would

that dispel the feeling in men's consciences? would that suffice to

establish the legitimacy of a future heir to the throne?

M. Thiers gives a curious account of the whole transaction. Cardinal

Fesch, usually so pliant to all his nephew's wishes, appears to have

been the first to start the difficulty; M. Cambaérès, the chancellor,

transmitted his observations to Napoleon. The latter was highly

indignant, declaring that a ceremony which had taken place privately,

in the chapel of the Tuileries, without any witnesses, and with the

sole view of quieting Josephine's scruples and those of the Pope,

could not be binding. Finally, however, it was agreed to look at the

marriage religiously as well as civilly, and to dissolve both ties.

For both, annulment was preferred to the ordinary form of divorce, as

more honorable for Josephine; and a defect in procedure or a great

state reason were to constitute the grounds of dissolution. It was

resolved that no reference should be made to the Pope in any way, as

his feelings toward Napoleon under present circumstances could not be

friendly. The civil marriage had been easily dissolved by mutual

consent of the parties and for public reasons, as seen above, when

Napoleon and Josephine read their respective papers before the

assembled council. With the views just stated, a committee of seven

bishops was formed to pronounce on the religious tie. They declared

the marriage irregular; as having taken place without witnesses, and

without sufficient consent of the parties concerned. With regard to

the absence of witnesses, M. Thiers puts in a note: "It was through a

false indication given {14} by a contemporary manuscript that I before

mentioned MM. de Talleyrand and Berthier as having been present at the

religious marriage privately celebrated at the Tuileries on the eve of

Napoleon's coronation. The author of this manuscript held the facts

from the lips of the Empress Josephine, and had been led into error.

Official documents which I have since procured enable me to rectify

this assertion."

What more likely than that Josephine told the simple truth, and that

official papers were made to meet future contingencies? If it had not

been intended to annul the marriage by any means, why was the

certificate of it wrested from Josephine?

Agreeably to the decision of the bishops, it was resolved to pursue

the annulment of the marriage as defective in form before the diocesan

officialty in the first instance, and afterward before the

metropolitan authority. Canonical proceedings were quietly instituted,

and witnesses summoned. These witnesses were Cardinal Fesch, MM. de

Talleyrand, Berthier, and Duroc. The first was to testify as to the

forms observed; and the three others as to the nature of the consent

given by both parties concerned. Cardinal Fesch declared he had

received dispensations from the Pope authorizing the omission of

certain forms, and thus justified the absence of witnesses and of the

parish curé. MM. de Talleyrand, Berthier, and Duroc affirmed having

heard from Napoleon several times that he only intended to allow a

mere ceremony for the purpose of reassuring the Pope's conscience and

that of Josephine; but that his formal determination had ever been not

to complete his union with the empress, being unhappily convinced that

he must one day renounce her for the good of his empire.

A strange conscience is here manifested by Napoleon. Josephine does

not appear to have been summoned to tell her tale.

After this inquiry, the ecclesiastical authority recognized that there

had not been sufficient consent; but out of respect to the parties

this ground of nullity was not specially insisted on. The causes

assigned for dissolving the marriage rested on the absence of all

witnesses, and of the parish curé. The general dispensations granted

to Cardinal Fesch were not considered to have superseded these

necessities. M. Thiers says on this point, "En conséquence, le mariage

fut cassé devant les deux jurisdictions diocésaine et métropolitaine,

c'est à dire, en première et en seconde instances, avec le décence

convenable, et la pleine observance du droit canonique! Napoleon

était donc` libre."

M. Thiers makes no reference to the Pope, who surely must be supposed

to have known whether the ceremony performed for the sole purpose of

allaying his and Josephine's scruples were perfectly valid by canon

law. It is not possible to admit that he could have insisted on the

same, and being present on the spot could yet have failed to ascertain

beyond doubt the religious legality of the marriage; more especially

as he could have at once removed the obstacle by a dispensation.

This topic must have been mentioned between the Pope and Cardinal

Consalvi; it is evident from the conduct of the latter that he and

many other cardinals considered the marriage with Josephine as binding

in a religious point of view. The character of Consalvi precludes the

possibility of supposing any petty motives for his opposition;

conscience alone could have dictated it. Evidently he yielded as far

as he could; and what he withheld from duty was with manifest peril to

himself, and, humanly speaking, even to the Church, whose interests

were so dear to him. As to the number of cardinals holding opposite

views, or at least acting as if they did, the weakness of human

nature, alas, and the selfishness of human interests, too well explain

that {15} circumstance. Grave historians and writers of genius do not

always take sufficient account of conscience in their estimate of

men and things, and thence flow many errors. Those who are politicians

also, from their wide knowledge of human vices, fall still more

readily into this mistake. Thus Napoleon probably never believed the

Pope to be in earnest, of at least his mind could not hold such an

idea long together. To himself state policy was all, or nearly all.

His negotiations with the Holy See, his appreciations of Consalvi, all

bear the stamp of that starting-point; to him it was a trial of

strength in will, or of skill in diplomacy: he ignored conscience. In

the same way, a mind eminently lucid as that of M. Thiers judges facts

in a very different manner than he would do if he could see that with

some minds conscience is the spring of action. If this were not the

case, he could not, while speaking of the Pope with due respect, pass

over his motives so slightly; nor would he construe as he does

Consalvi's conduct with regard to the marriage and that of the other

black cardinals. The opinions of such men deserved to raise a doubt

in the mind of the historian, and to lead to investigation that might

have had other results. We purposely lay stress on this matter because

M. Thiers is popular with a large class of readers, who justly admire

his talent, but who erroneously consider him a fair exponent on

ecclesiastical affairs. He does respect religion; but evidently fails

to apprehend the idea of men constantly swayed by duty and conscience;

whose judgments may err, as all things human do, but whose

supernatural principle of action ever lives.

Toward the close of January, 1810, the conclusion of a matrimonial

alliance to take place between Napoleon and the Archduchess

Marie-Louise was made public in Paris. The ceremony was to be

performed by proxy at Vienna in the early part of March; the Archduke

Charles being chosen to represent Napoleon on this occasion, and

Berthier was the ambassador extraordinary named to ask formally the

hand of the princess. The subsequent fêtes at Paris were to vie in

splendor with those given at Vienna. Napoleon wished to surround

himself with all the members of the Sacred College; a large number had

already been summoned to Paris soon after the Pope's captivity; they

had been ordered to partake in the festivities of the capital, and we

regret to say that they complied. Rome, it must not be forgotten, was

now called a French provincial town; Napoleon was progressing on to

become the emperor of the West, with the Pope, the spiritual father of

Christendom, as his satellite. The other cardinals in Rome were called

to Paris. Some found pretexts for delaying obedience; Cardinals

Consalvi and di Pietro replied that they could not think of leaving

without the Pope's permission, but would immediately refer to him, at

the same time declining the pension offered in Paris. After the lapse

of a few days an express order enjoined them to quit Rome within

twenty-four hours. They alleged that no answer had yet arrived from

the Pope. But at the expiration of the period fixed, French soldiers

visited their houses to carry them off by force. Yielding to violence

they departed, and reached Paris together on the 20th January, 1810.

Twenty-nine cardinals, including Fesch, were then assembled in the

French capital. How they should act with regard to the new marriage

became soon a subject of grave consultation for them. Consalvi and di

Pietro had not long arrived when it was publicly announced. Napoleon

seemed disposed to treat them with courtesy. Consalvi had his audience

six days after his arrival. Five other cardinals, new comers also,

were presented at the same time. They were ranged together on one

side, while the other cardinals remained opposite. Further on were the

nobles, ministers, kings. {16} queens, princes, and princesses. When

the emperor appeared, Cardinal Fesch stepped forward and began

presenting the five. "Cardinal Pignatelli," said he. "Neapolitan,"

replied the emperor, and passed on. "Cardinal di Pietro," continued

Fesch. The emperor stopped a moment, and said, "You have grown fat; I

remember having seen you here with the Pope at my coronation."

"Cardinal Saluzzo," said Fesch, presenting the third. "Neapolitan,"

replied the emperor, and walked on. "Cardinal Desping," said Fesch, as

the fourth saluted. "Spanish," replied the emperor. "From Majorca,"

cried Desping, in alarm. But Napoleon had already reached Consalvi,

and ere Cardinal Fesch could say the name, he exclaimed, in the

kindest tone, and standing still, "Oh, Cardinal Consalvi; how thin you

have become! I should hardly have recognized you." "Sire," replied

Consalvi, "years accumulate. Ten have passed since I had the honor of

saluting your majesty." "That is true," resumed Napoleon; "it is now

almost ten years since you came for the concordat. We made that treaty

in this very hall; but what purpose has it served? All has vanished in

smoke. Rome would lose all. It must be owned, I was wrong to displace

you from the ministry. If you had continued in that post, things would

not have been carried so far."

Listening only to the fear of having his actions misconstrued by the

public, Consalvi instantly replied with energy, "Sire, if I had

remained in that post, I should have done my duty." Napoleon looked at

him fixedly, made no answer, and then going backward and forward

through the half-circle formed by the cardinals, began a long

monologue, enumerating a number of grievances against the Pope and

against Rome for not having adhered to his will by refusing to adopt

the system offered. At length, being near Consalvi, he stopped, and

said a second time, "No, if you had remained at your post, things

would not have gone so far." Again Consalvi replied, "Your majesty may

believe that I should have done my duty." Napoleon gave the cardinal

another fixed glance, and then without reply recommenced his walks,

continuing his former discourse. At last he stopped near Cardinal di

Pietro, and said for the third time, "If Cardinal Consalvi had

remained secretary of state, things would not have gone so far."

Consalvi was at the other end of the little group of five, and need

not have answered; but earnest to exonerate himself from all

suspicion, he advanced toward Napoleon, and seizing his arm,

exclaimed, "Sire, I have already assured your majesty that had I

remained in that post, I should certainly have done my duty." The

emperor no longer containing himself, and with eyes steadily bent on

Consalvi, burst forth into these words, "Oh! I repeat it, your duty

would not have allowed you to sacrifice spiritual to temporal things."

After this he turned his back on Consalvi, and going over to the

cardinals opposite, asked if they had heard his words. Then returning

to the five, he observed that the College of Cardinals was now nearly

complete in Paris, and that they would do well to see among themselves

if there was anything to propose or regulate concerning Church

affairs. "Let Cardinal Consalvi be of the committee," added Napoleon;

"for if, as I suppose, he is ignorant of theology, he knows well the

science of politics."

At a second and third audience, Napoleon showed similar kindness to

Consalvi, always asking after his health, and remarking that he was

getting fatter now. The cardinal only answered by deep salutations.

Principally through Consalvi's influence, the cardinals, in a

collective letter addressed to the emperor, declined acting in any way

while separated from their head, the Pope. Napoleon had angrily torn

their letter to pieces; but even this opposition to his will had not

changed his courtesy {17} toward Consalvi, as seen above. He was bent

on creating a schism between them and the Pope. Fesch, his ready

instrument, proposed several steps as beneficial to religion, but the

majority of cardinals refused to do anything. Unlike many of his

colleagues, Consalvi held aloof from all society. Beside the

prohibition of the Pope, who at Rome had forbidden the members of the

Sacred College to assist at festivities while the Church was in

mourning, he considered it unworthy conduct for them to take part in

amusements while their head remained in captivity, or to seem to court

one who had brought such calamities on the Holy See.

While invited to discuss ecclesiastical matters in committee for

presentation to the emperor, the cardinals were not by any means

requested to give an opinion on the new marriage. But it became very

necessary that they should have one as the time approached for the

arrival of Marie-Louise, and for the celebration of the marriage

ceremonies in Paris.

She reached Compiègne on the 27th of March. Napoleon, to spare her the

embarrassment of a public meeting, had surprised her on the road, and

they entered the little town together. A few days after they proceeded

to St. Cloud. Four ceremonies were to take place. First there was to

be a grand presentation on the 31st of March, at St. Cloud, of all the

bodies in the state, the nobles and other dignitaries. The next

morning the civil marriage was to be celebrated also at St Cloud. The

2d of April was fixed for the grand entrance of the sovereigns into

Paris, and for the solemnity of the religious marriage in the chapel

of the Tuileries; the following morning another presentation of the

state bodies and the court was to take place before the emperor and

the new empress seated on their thrones.

Twenty-seven cardinals had taken counsel together; for Fesch, as

grand-almoner to the emperor, was out of the question, and Caprara was

dying. They had decided, after deliberate research, that matrimonial

cases between sovereigns belong exclusively to the cognizance of the

Holy See, which either itself pronounces sentence at Rome, or else

through the medium of the legates names local judges for instituting

the affair.

According to Consalvi's account, the diocesan officialty of Paris on

this occasion refused at first to intervene, on the ground of

incompetency; but the emperor caused competency to be declared by a

committee of bishops assembled at Paris, and presided over by Cardinal

Fesch. The words, however, "declared competent," were not eventually

inserted in the documents drawn up of the meeting; it was pretended

instead that access could not be had to the Pope. But this pretended

impossibility could of course arise only from the will of Napoleon.

Consalvi assures us that the preamble used by the committee in the

first instance ran thus:

"The officialty, being declared competent, and without derogating from

the right of the sovereign pontiff, to whom access is for the moment

forbidden, proclaims null and void the marriage contracted with the

Empress Josephine, the reasons for such decision being stated in the

sentence." But when it was remarked how prejudicial this avowal would

be, the government made it disappear from among the acts of the

ecclesiastical curia. For it had been previously arranged that all

papers relative to this affair should be submitted to government.

According to general report in Paris, some of the papers were burnt,

and others changed. A person belonging to the officialty succeeded,

however, in secretly saving a part, and especially the beginning of

the sentence, which was as given above.

Consalvi does not so much as name the validity or invalidity of the

marriage; the point to establish for him was that the right of

cognizance {18} belonged solely to the Holy See. The incident he

mentions of the papers destroyed has no other importance than as

showing how conscience at first pronounced and how a strong hand

silenced its expression.

Thirteen cardinals resolved to brave any consequences rather than

consent to a dereliction of duty; for their oath, when raised to the

purple, binds them to maintain at all hazards the rights of the

Church. The names of these thirteen were: Cardinals Mattei,

Pignatelli, della Somaglia, di Pietro, Litta, Saluzzo, Ruffo Scilla,

Brancadoro, Galeffi, Scotti, Gabrielli, Opizzoni, and Consalvi. The

other fourteen held different shades of opinion, and only agreed in

deciding not to oppose the emperor.

The sole means by which the thirteen could protest, under the

circumstances, was not to sanction the new marriage by appearing at

the ceremonies. This resolve was accordingly taken, and the fourteen

were apprised. Mattei, the oldest cardinal among the thirteen, called

upon most of the fourteen to acquaint them with the resolution; other

members of the thirteen likewise spoke of it to their colleagues; but

no result was produced on the minds of the fourteen. To the shame of

the latter it must be said that they afterward untruly declared

themselves ignorant of the line of conduct which the thirteen had

intended to adopt. Consalvi positively asserts that such was not the

case. The thirteen spoke with the caution commanded by prudence on so

delicate a matter, not seeking ostensibly to prevent the others from

following their own opinions, and anxious to avoid giving any pretext

for the accusation of exciting a feeling against the government. But

this reserve did not prevent them from clearly expressing their

intention to uphold the rights of the Pope and of the Holy See by

abstaining from all participation in the marriage ceremonies.

Though called upon by duty to act in the way mentioned, the thirteen

cardinals naturally wished to avoid, as much as possible, wounding

Napoleon. With this view Mattei was deputed to seek an interview with

Fesch, for the purpose of informing him what course they felt obliged

to pursue. At the same time Mattei gave him to understand that all

publicity might be avoided, or any bad effect on the public obviated,

by addressing partial, instead of general, invitations to the

cardinals. This was to be done with regard to the senate and the

legislative body, and, indeed, the smallness of the enceinte offered a

plausible pretext; for it was impossible that all entitled to appear

on the occasion could be present. Cardinal Fesch evinced great

surprise and anger, endeavoring to reason Mattei out of this view; but

finding it was of no use, he promised to speak to the emperor, who was

then at Compiègne.

According to Fesch's account, Napoleon flew into a violent passion on

learning the decision come to by the thirteen; but he declared that

they would never dare to carry out their plot, and utterly rejected

the idea of not inviting all the members of the Sacred College.

At the proper time a special invitation reached each cardinal. There

was no possibility of escape. To feign illness or invent a pretext

they rightly deemed would be unworthy.

Nevertheless, anxious as they were to avoid offence, when they came to

consider more closely the nature of the different ceremonies, it was

considered by some that they might, without failing in duty, assist at

the two presentations that were to take place before and after the

marriages. Consalvi was among those opposed to this view on grounds of

honor at least; but, not to provoke any further schism in their ranks,

the minority yielded, and this mode of proceeding was decided on. Both

marriages were to be eschewed; but they would assist at both

presentations. The cardinals hoped thus to prove that they did all

{19} they possibly could to please Napoleon consistently with their

sense of duty. It was also considered highly desirable to shield the

fourteen from remark as much as could be, for it was a grievous matter

to right-minded men to see the honor and dignity of the Sacred College

thus abased.

Accordingly, on the evening fixed, all the cardinals went to St Cloud.

Together with the other dignitaries, they were in the grand gallery

waiting the arrival of Napoleon and his new empress, when Fouché, the

minister of police, came up. Consalvi had been very intimate with him,

but having paid scarcely any visits since his return to Paris, from

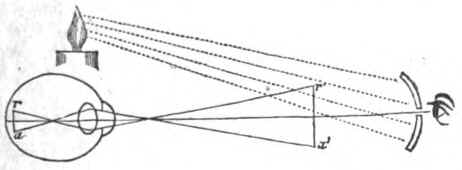

the motives stated above, they had not hitherto met. Fouché drew him