Title: The Princess Dehra

Author: John Reed Scott

Release date: June 18, 2012 [eBook #40034]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

JOHN REED SCOTT

AUTHOR OF “THE COLONEL OF THE RED HUZZARS,”

“BEATRIX OF CLARE,” ETC.

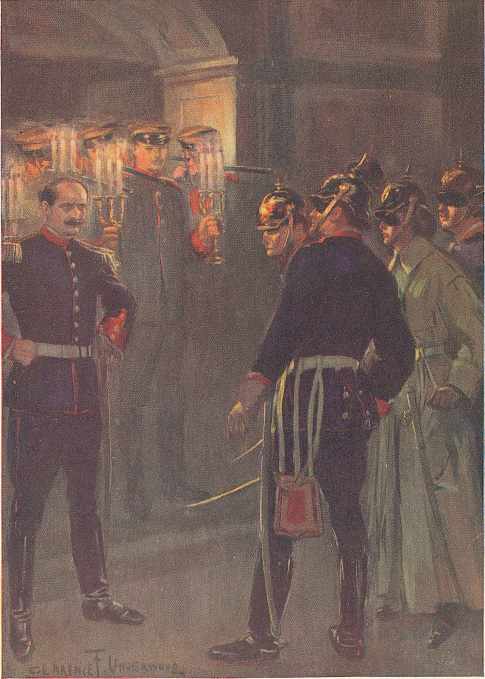

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOR

BY CLARENCE F. UNDERWOOD

PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1908

Copyright, 1908, by John Reed Scott

Published May, 1906

Printed by J. B. Lippincott Company

The Washington Square Press, Philadelphia, U. S. A.

TO

THE REAL PRINCESS

For the first time in a generation the Castle of Lotzen was entertaining its lord. He had come suddenly, a month before, and presently there had followed rumors of strange happenings in Dornlitz, in which the Duke had been too intimately concerned to please the King, and as punishment had been banished to his mountain estates. But Lotzenia was far from the Capital and isolated, and the people cared more for their crops and the amount of the tax levy than for the doings of the Court. And so it concerned them very little why the red banner with the golden cross floated from the highest turret of the old pile of stone, on the spur of the mountain overhanging the foaming Dreer. They knew it meant the Duke himself was in presence; but to them there was but one over-lord: the Dalberg, who reigned in Dornlitz; and in him they had all pride—for was not the Dalberg their hereditary chieftain centuries before he was the King!

True, the Duke of Lotzen had long been the Heir Presumptive, and so, in the prospective, entitled to their loyalty, but lately there had come from across the Sea a new Dalberg, of the blood of the great Henry, who, it was said, had displaced him in the line of Succession, and was to marry the Princess Dehra.

And at her name every woman of them curtsied and every man uncovered; blaming High Heaven the while, that she might not reign over them, when Frederick the King were gone; and well prepared to welcome the new heir if she were to be his queen.

At first the Duke had kept to the seclusion of his own domain, wide and wild enough to let him ride all day without crossing its boundary, but after a time he came at intervals, with a companion or two, into the low-lands, choosing the main highways, and dallying occasionally at some cross-road smithy for a word of gossip with those around the forge.

For Lotzen was not alone in his exile; he might be banished from the Capital, but that was no reason for denying himself all its pleasures; and the lights burned late at the Castle, and when the wind was from the North it strewed the valley with whisps of music and strands of laughter. And the country-side shook its head, and marveled at the turning of night into day, and at people who seemed never to sleep except when others worked; and not much even then, if the tales of such of the servants as belonged to the locality were to be believed.

And the revelry waxed louder and wilder as the days passed, and many times toward evening the whole company would come plunging down the mountain, and, with the great dogs baying before them, go racing through the valleys and back again to the Castle, as though some fiend were hot on their trail or they on his.

And ever beside the Duke, on a great, black horse, went the same woman, slender and sinuous, with raven hair and dead-white cheek; a feather touch on rein, a careless grace in saddle. And as they rode the Duke watched her with glowing eyes; and his cold face warmed with his thoughts, and he would speak to her earnestly and persuasively; and she, swaying toward him, would answer softly and with a tantalizing smile.

Then, one day, she had refused to ride.

“I am tired,” she said, when at the sounding of the horn he had sought her apartments; “let the others go.”

He went over and leaned on the back of her chair.

“Tired—of what?” he asked.

“Of everything—of myself most of all.”

“And of everybody?” smiling down at her.

“One usually tires of self last.”

“And you want to leave me?” he asked.

She shook her head. “No, not you, Ferdinand—the others.”

“Shall I send them away?” he said eagerly.

“And make this lonely place more lonely still!”

“I despise the miserable place,” he exclaimed.

“Then why not to Paris to-night?” she asked.

“Why not, indeed?” he answered, gravely, “for the others and—you.”

“And you, too?” glancing up at him and touching, for an instant, his hand.

He shrugged his shoulders. “You forget, there is a King in Dornlitz!”

“You would go incog. and old Frederick never be the wiser, nor care even if he were.”

He laughed shortly. “Think you so, ma belle,—well, believe me, I want not to be the one to try him.”

The horn rang out again from the court-yard; the Duke crossed to a window.

“Go on,” he called, “we will follow presently;” and with a clatter and a shout, they spurred across the bridge and away.

“Who leads?” she asked, going over and drawing herself up on the casement.

He put his arm around her. “What matters,” he laughed, “since we are here?” and bent his head to her cheek.

“Let us go to Paris, dear,” she whispered, caressingly; “to the boulevards and the music, the life, and the color.”

He shook his head. “You don’t know what you ask, little one—once I might have dared it, but not now—no, not now.”

She drew a bit nearer. “And would the penalty now be so very serious?” she asked.

He looked at her a while uncertainly; and she smiled back persuasively. She knew that he was in disfavor because of his plots against the Archduke Armand’s honor and life; and that he had been sent hither in disgrace; but all along what had puzzled her was his calm acquiescence; his remaining in this desolation, with never a word of anger toward the King, nor disposition to slip away surreptitiously to haunts beyond the border. Why should he be so careful not to transgress even the spirit of the royal order?—he who had not hesitated to play a false wife against the Archduke Armand, to try assassination, and to arrange deliberately to kill him in a duel. She remembered well that evening in her reception room, at the Hotel Metzen in Dornlitz, when Lotzen’s whole scheme had suddenly collapsed like a house of cards. She recalled the King’s very words of sentence when, at last, he had deigned to notice the Duke. “The Court has no present need of plotters and will be the better for your absence,” he had said. “It has been over long since you have visited your titular estates and they doubtless require your immediate attention. You are, therefore, permitted to depart to them forthwith—and to remain indefinitely.” Surely, it was very general and precluded only a return to Dornlitz.

That the question of the succession was behind it all, she was very well persuaded; the family laws of the Dalbergs were secret, undisclosed to any but the ranking members of the House, but the Crown had always descended by male primogeniture. The advent of Armand, the eldest male descendant [16] of Hugo Dalberg (who had been banished by his father, the Great Henry, when he had gone to America and taken service under Washington) had tangled matters, for Armand was senior in line to Lotzen. It was known that Henry, shortly before his death, had revoked the former decree and restored Hugo and his children to their rank and estates; and Frederick had proclaimed this decree to the Nation and had executed it in favor of Armand, making him an Archduke and Colonel of the Red Huzzars. But what no one knew was whether Lotzen had hereby been displaced as Heir Presumptive. How far did the Great Henry’s decree of restoration extend? How far had Frederick made it effective? In short, would the next King be Ferdinand, Duke of Lotzen, or Armand, Archduke of Valeria?

And to Madeline Spencer the answer was of deep concern; and she had been manœuvering to draw it from the Duke ever since she had come to the Castle. But every time she had led up to it, he had led away, and with evident deliberation. Plainly there was something in the Laws that made it well for him to drive the King no further; and what could it be but the power to remove him as Heir Presumptive.

And as Lotzen knew the answer, she would know it, too. If he were not to be king, she had no notion to entangle herself further with him; he was then too small game for her bow; and there would be a very chill welcome for her in Dornlitz from [17] Queen Dehra. But should he get the Crown—well, there are worse positions than a king’s favorite—for a few months—the open-handed months.

So she slipped an arm about his shoulders and let a whisp of perfumed hair flirt across his face.

“Tell me, dear,” she said, “why won’t you go to Paris?”

He laughed and lightly pinched her cheek. “Because I’m surer of you here. Paris breeds too many rivals.”

“Yet I left them all to come here,” she answered.

“But now you would go back.”

She smiled up at him. “Yes, but with you, dear—not alone.” Her hand stole into his. “Tell me, sweetheart, why you will not go—might it cause Frederick to deprive you of the succession?”

For a space the Duke made no answer, gazing the while steadily into the distance, with eyebrows slightly drawn. And she, having dared so far, dared further.

“Surely, dear, he would not wrong you by making Armand king!” she exclaimed, as though the thought had but that moment come.

He turned to her with quick sympathy, a look of warm appreciation in his eyes. The answer she had played for trembled on his lips—then died unspoken.

He bent down and kissed her forehead.

“We of the Dalbergs still believe, my dear, that the King can do no wrong,” he said, and swung her to the floor. “Come, let us walk on the wall, and forget everything except that we are together, and that I love you.”

She closed her eyes to hide the flash of angry disappointment, though her voice was calm and easy.

“Love!” she laughed; “love! what is it? The infatuation of the moment—the pleasure of an hour.”

“And hence this eagerness for Paris?”

She gave him a quick glance. “May be, my lord, to prolong our moment; to extend our hour.” He paused, his hand upon the door.

“And otherwise are they ended?” he asked quietly.

She let her eyes seek the door. “No—not yet.” He slowly closed the door and leaned against it.

“My dear Madeline,” he said, “let us deal frankly with each other. I am not so silly as to think you love me, though I’m willing to admit I wish you did. You have fascinated me—ever since that evening in the Hanging Garden when you made the play of being the Archduke Armand’s wife. Love may be what you style it: ‘the infatuation of the moment; the pleasure of an hour.’ If so, for you, my moment and my hour still linger. But with you, I know, there is a different motive; you may like me passing well—I believe you do—yet it was not that which brought you here, away from Paris—‘the boulevards and the music.’ You came because—well, what matters the because: you came; and for that I am very grateful; they have been pleasant days for me——“

She had been gazing through the window; now she looked him in the eyes.

“And for me as well,” she said.

“I am glad,” he answered gravely—”and it shall not be I that ends them. You wish to know if I am still the Heir Presumptive. You shall have your answer: I do not know. It rests with the King. He has the power to displace me in favor of Armand.”

She smiled comprehendingly. It was as she had feared.

“And the Princess Royal is betrothed to Armand,” she commented.

Lotzen shrugged his shoulders. “Just so,” he said. “Do you wonder I may not go to Paris?”

She went over to the fireplace, and sitting on the arm of a chair rested her slender feet on the fender, her silk clad ankles glistening in the fire-light.

“I don’t quite understand,” she said, “why, when the American was restored to Hugo’s rank, he did not, by that very fact, become also Heir Presumptive—his line is senior to yours.”

There was room on the chair arm for another and he took it.

“You have touched the very point,” he said. “Henry the Third himself restored Hugo and his heirs to rank and estate; but it needs Frederick’s decree to make him eligible to the Crown.”

“And has he made it?”

He shook his head. “I do not know——”

“But, surely, it would be promulgated, if he had.”

“Very probably; but not necessarily. All that is required is a line in the big book which for centuries has contained the Laws of the Dalbergs.”

She studied the tip of her shoe, tapping it the while on the fender rod.

“When will this marriage be solemnized?” she asked.

He laughed rather curtly. “Never, I hope.”

She gave him a quick look. “So—the wound still hurts. I beg your pardon; I did not mean to be unkind. I was only thinking that, if the decree were not yet made, the wedding would be sure to bring it.”

He put his arm around her waist and drew her over until the black hair pressed his shoulder.

“Nay, Madeline, you are quite wrong,” he said. “The Princess is nothing to me now—nothing but the King’s daughter and the American’s chief advocate. I meant what you did:—that the marriage will lose me the Crown.”

For a moment she suffered his embrace, watching him the while through half closed eyes; then she drew away.

“I suppose there is no way to prevent the marriage,” she remarked, her gaze upon the fire.

He arose and, crossing to the table, found a cigarette.

“Can you suggest a way?” he asked, his back toward her, the match aflame, poised before his face.

She had turned and was watching him with sharp interest, but she did not answer, and when he glanced around, in question, she was looking at the fire.

“Want a cigarette?” he said.

She nodded, and he took it to her and held the match for its lighting.

“I asked you if you could suggest a way,” he remarked.

She blew a smoke ring toward the ceiling. “Yes, go back to Dornlitz and kill the American.”

“Will you go with me?” banteringly.

“Indeed I won’t,” with a reminiscent smile; “I have quite too vivid a memory of my recent visit there.”

“And the killing—shall I do it by proxy or in person?”

“Any way—so it is done—though one’s best servant is one’s self, you know.”

He had thought her jesting, but now he leaned forward to see her face.

“Surely, you do not mean it,” he said uncertainly.

“Why not?” she asked. “It’s true you have already tried both ways—and failed; but that is no assurance of the future. The second, or some other try may win.”

A tolerant smile crossed his lips. “And meanwhile, of course, the American would wait patiently to be killed.”

She shrugged her shoulders. “You seem to have forgot that steel vests do not protect the head; and that several swords might penetrate a guard which one could not.”

“Surely,” he exclaimed, “surely, you must have loved this man!”

She put his words aside with a wave of her hand.

“My advice is quite impersonal,” she said—“and it is only trite advice at that, as you know. You have yourself considered it already scores of times, and have been deterred only by the danger to yourself.”

He laughed. “I’m glad you cannot go over to my enemies. You read my mind too accurately.”

“Nonsense,” she retorted; “Armand knows it quite as well as I, though possibly he may not yet have realized how timid you have grown.”

“Timid!”

She nodded. “Yes, timid; you had plenty of nerve at first, when the American came; but it seems to have run to water.”

“And I shall lose, you think?”

She tossed the cigarette among the red ashes and arose.

“Why should you win, Ferdinand?” she asked—then a sly smile touched her lips—“so far as I have observed, you haven’t troubled even so much as to pray for success.”

He leaned forward and drew her back to the place beside him.

“Patience, Madeline, patience,” said he; “some day I’m going back to Dornlitz.”

“To see the Archduke Armand crowned?” she scoffed.

He bent his head close to her ear. “I trust so—with the diadem that never fades.”

She laughed. “Trust and hope are the weapons of the apathetic. Why don’t you, at least, deal in predictions; sometimes they inspire deeds.”

“Very good,” he said smilingly. “I predict that there is another little game for you and me to play in Dornlitz, and that we shall be there before many days.”

“You are an absent-minded prophet,” she said; “I told you I would not go to Dornlitz.”

“But if I need you, Madeline?”

She shook her head. “Transfer the game to Paris, or any place outside Valeria, and I will gladly be your partner.”

He took her hand. “Will nothing persuade you?”

She faced him instantly. “Nothing, my lord, nothing, so long as Frederick is king.”

The Duke lifted her hand and tapped it softly against his cheek.

“Tres bien ma chère, tres bien,” he said; then frowned, as Mrs. Spencer’s maid entered.

“Pour Monsieur le Duc,” she curtsied.

Lotzen took the card from the salver and turned it over.

“I will see him at once,” he said; “have him shown to my private cabinet.... It is Bigler,” he explained.

“Why not have him here?”

He hesitated.

“Oh, very well; I thought you trusted me.”

He struck the bell. “Show Count Bigler here,” he ordered. Then when the maid had gone: “There, Madeline, that should satisfy you, for I have no idea what brings him.”

She went quickly to him, and leaning over his shoulder lightly kissed his cheek.

“I knew you trusted me, dear,” she said, “but a woman likes to have it demonstrated, now and then.”

He turned to catch her; but she sprang away.

“No, Ferdinand, no,” as he pursued her; “the Count is coming—go and sit down.”—She tried to reach her boudoir, but with a laugh he headed her off, and slowly drove her into a corner.

“Surrender,” he said; “I’ll be merciful.”

For answer there came the swish of high-held skirts, a vision of black silk stockings and white lace, and she was across a huge sofa, and, with flushed face and merry eyes, had turned and faced him.

And as they stood so, Count Bigler was announced.

“Welcome, my dear Bigler, welcome!” the Duke exclaimed, hurrying over to greet him; “you are surely Heaven sent.... Madame Spencer, I think you know the Count.”

She saw the look of sharp surprise that Bigler tried to hide by bowing very low, and she laughed gayly.

“Indeed, you do come in good time, my lord,” she said; “we were so put to for amusement we were reduced to playing tag around the room—don’t be shocked; you will be playing it too, if you are here for long.”

“If it carry the usual penalty,” he answered, joining in her laugh, “I am very ready to play it now.”

“Doubtless,” said the Duke dryly, motioning him to a chair. “But first, tell us the gossip of the Capital; we have heard nothing for weeks. What’s my dear cousin Armand up to—not dying, I fear?”

“Dying! Not he—not while there are any honors handy, with a doting King to shower them on him, and a Princess waiting for wife.”

The Duke’s face, cold at best, went yet colder.

“Has the wedding date been announced?” he asked.

“Not formally, but I understand it has been fixed for the twenty-seventh.”

Lotzen glanced at a calendar. “Three weeks from to-morrow—well, much may happen in that time. Come,” he said good-naturedly, shaking off [26] the irritation, “tell us all you know—everything—from the newest dance at the opera to the tattle of the Clubs. I said you were Heaven sent—now prove it. But first—was it wise for you to come here? What will Frederick say?”

The Count laughed. “Oh, I’m not here; I’m in Paris, on two weeks leave.”

“Paris!” the Duke exclaimed. “Surely, this Paris fever is the very devil; are you off to-night or in the morning?”

Bigler shot a quick glance at Mrs. Spencer, and understood.

“I’m not to Paris at all,” he said, “unless you send me.”

“He won’t do that, Monsieur le Comte,” the lady laughed; and Lotzen, who had quite missed the hidden meaning in their words, nodded in affirmance.

“Come,” he said, “your budget—out with it. I’m athirst for news.”

The Count drew out a cigar and, at Mrs. Spencer’s smile of permission, he lighted it, and began his tale. And it took time in the telling, for the Duke was constant in his questions, and a month is very long for such as he to be torn from his usual life and haunts.

And, through it all, Mrs. Spencer lay back in sinuous indolence among the cushions on the couch before the fire, one hand behind her shapely head, her eyes, languidly indifferent, upon the two men, [27] her thoughts seemingly far away. And while he talked, Count Bigler watched her curiously, but discreetly. This was the first time he had seen the famous “Woman in Black” so closely, and her striking beauty fairly stunned him. He knew his Paris and Vienna well, but her equal was not there—no, nor elsewhere, he would swear. Truly, he had wasted his sympathy on Lotzen—he needed none of it with such a companion for his exile.

And she, unseeing, yet seeing all, read much of his thoughts; and presently, from behind her heavy lashes, she flashed a smile upon him—half challenge, half rebuke—then turned her face from him, nor shifted it until the fading daylight wrapped her in its shadow.

“There, my tale is told,” the Count ended. “I’m empty as a broken bottle—and as dry,” and he poured himself a glass of wine from the decanter on a side table.

“You are a rare gossip, truly,” said the Duke; “but you have most carefully avoided the one matter that interests me most:—what do they say of me in Dornlitz?”

Bigler shrugged his shoulders. “Why ask?” he said. “You know quite well the Capital does not love you.”

“And, therefore, no reason for me to be sensitive. Come, out with it. What do they say?”

“Very well,” said Bigler, “if you want it, here it is:—they have the notion that you are no longer [28] the Heir Presumptive, and it seems to give them vast delight.”

The Duke nodded. “And on what is the notion based?”

“Originally, on hope, I fancy; but lately it has become accepted that the King not only has the power to displace you, but has actually signed the decree.”

“And Frederick—does he encourage the idea?”

The Count shook his head. “No, except by his open fondness for the American.”

“I’ve been urged to go to Dornlitz and kill the American,” Lotzen remarked, with a smile and a nod toward Mrs. Spencer.

“If you can kill him,” said Bigler instantly, “the advice is excellent.”

“Exactly. And if I can’t, it’s the end of me—and my friends.”

“I think your friends would gladly try the hazard,” the Count answered. “It is dull prospect and small hope for them, even now. And candidly, my lord, to my mind, it’s your only chance, if you wish the Crown; for, believe me, the Archduke Armand is fixed for the succession, and the day he weds the Princess Royal will see him formally proclaimed.”

The Duke strode to the far end of the room and back again.

“Is that your honest advice—to go to Dornlitz?” he asked.

The other arose and raised his hand in salute. “It is, sir; and not mine alone, but Gimels’ and Rosen’s and Whippen’s, and all the others’—that is what brought me here.”

“And have you any plan arranged?”

The Count nodded ever so slightly, then looked the Duke steadily in the face—and the latter understood.

He turned to Madeline Spencer. “Come nearer, my dear,” he said, “we may need your quick wit—there is plotting afoot.”

She gave him a smile of appreciation, and came and took the chair he offered, and he motioned for Bigler to proceed.

“But, first, tell me,” he interjected, “am I to go to Dornlitz openly or in disguise? I don’t fancy the latter.”

“Openly,” said the Count. “Having been in exile a month, you can venture to return and throw yourself on Frederick’s mercy. We think he will receive you and permit you to remain—but, at least, it will give you two days in Dornlitz, and, if our plan does not miscarry, that will be quite ample.”

“Very good,” the Duke commented; “but my going will depend upon how I like your plot; let us have it—and in it, I trust you have not overlooked my fiasco at the Vierle Masque and so hung it all on my single sword.”

“Your sword may be very necessary, but, if so, it won’t be alone. We have several plans—the one we hope to——”

A light tap on the door interrupted him, and a servant entered, with the bright pink envelope that, in Valeria, always contained a telegram.

“My recall to Court,” laughed the Duke, and drawing out the message glanced at it indifferently.

But it seemed to take him unduly long to read it; and when, at length, he folded it, his face was very grave; and he sat silent, staring at the floor, creasing and recreasing the sheet with nervous fingers, and quite oblivious to the two who were watching him, and the servant standing stiffly at attention at his side.

Suddenly, from without, arose a mad din of horses’ hoofs and human voices, as the returning cavalcade dashed into the courtyard, women and men yelling like fiends possessed. And it roused the Duke.

“You may go,” to the footman; “there is no answer now.” He waited until the door closed; then held up the telegram. “His Majesty died, suddenly, this afternoon,” he said.

Count Bigler sprang half out of his chair.

“Frederick dead! the King dead!” he cried—“then, in God’s name, who now is king—you or the American?”

The Duke arose. “That is what we are about to find out,” he said, very quietly. “Come, we will go to Dornlitz.”

Frederick of Valeria had died as every strong man wants to die: suddenly and in the midst of his affairs, with the full vigor of life still upon him and no premonition of the end. It had been a sharp straightening in saddle, a catch of breath, a lift of hand toward heart, and then, with the great band of the Foot Guards thundering before him, and the regiment swinging by in review, he had sunk slowly over and into the arms of the Archduke Armand. And as he held him, there was a quick touch of surgeon’s fingers to pulse and breast, a shake of head, a word; and then, sorrowfully and in silence, they bore him away; while the regiment, wheeling sharply into line, spread across the parade and held back the populace. And presently, as the people lingered, wondering and fearful, and the Guards stood stolid in their ranks, the royal standard on the great tower of the Castle dropped slowly to half staff, and the mellow bell of the Cathedral began to toll, to all Valeria, the mournful message that her King was dead.

And far out in the country the Princess Dehra heard it, but faintly; and drawing rein, she listened in growing trepidation for a louder note. Was it [32] the Cathedral bell?—the bell that tolled only when a Dalberg died! For a while she caught no stroke, and the fear was passing, when down the wind it came, clear and strong—and again—and yet again.

And with blanched cheek and fluttering heart she was racing at top speed toward Dornlitz, staying neither for man nor beast, nor hill nor stream, the solemn clang smiting her ever harder and harder in the face. There were but two for whom it could be speaking, her father and her lover—for she gave no thought to Lotzen or his brother, Charles. And now, which?—which?—which? Mile after mile went behind her in dust and flying stones, until six were passed, and then the outer guard post rose in front.

“The bell!” she cried, as the sentry sprang to attention, “the bell, man, the bell?”

The soldier grounded arms.

“For the King,” he said.

But as the word was spoken she was gone—joy and sorrow now fighting strangely in her heart—and as she dashed up the wide Avenue, the men uncovered and the women breathed a prayer; but she, herself, saw only the big, gray building with the drooping flag, and toward it she sped, the echo of the now silent bell still ringing in her ears.

The Castle gates were closed, and before them with drawn swords, stern and impassive, sat two huge Cuirassiers of the Guard; they heard the nearing hoof beats, and, over the heads of the crowd that hung about the entrance, they saw and understood.

“Stand back!” they cried; “stand back—the Princess comes!”

And the gates swung open, and the big sorrel horse, reeking with sweat and flecked with foam and dust, flashed by, and on across the courtyard. And Colonel Moore, who was about to ride away, sprang down and swung her out of saddle.

“Take me to him,” she said quietly, as he stood aside to let her pass.

She swayed slightly at the first step, and her legs seemed strangely stiff and heavy, but she slipped her hand through his arm and drove herself along. And so he led her, calm and dry-eyed, down the long corridor and through the ante-room to the King’s chamber, and all who met them bowed head and drew back. At the threshold she halted.

“Do you please bid all retire,” she said. “I would see my father alone.”

And when he had done her will, he came and held open the door for her a little way, then stood at attention and raised his hand in salute; and the Princess went in to her dead.

Meanwhile, the Archduke Armand was searching for the Princess. The moment he had seen the King at rest in the Castle, declining all escort, he had galloped away for the Summer Palace, first ordering that no information should be conveyed there by telephone. It was a message for him to deliver in [34] person, though he shrank from it, as only a man can shrink from such a duty. But he knew nothing of the Cathedral bell and its tolling, and when, as he neared the Park, the first note broke upon him, he listened in surprise; then he grasped its meaning, and with an imprecation, spurred the faster, racing now with a brazen clapper as to which should tell the Princess first. And the sentry at the gate stared in wonder; but the officer on duty at the main entrance ran out to meet him, knowing instantly for whom the bell was tolling and for whom the Archduke came.

“Her Highness is not here,” he cried. “She rode away alone by the North Avenue a short while ago.”

“Make report to the Castle the instant she returns,” Armand called, and was gone—to follow her, as he thought, on the old forge road.

“Ye Gods!” the officer exclaimed, “that was the King—the new King!” and mechanically he clicked his heels together and saluted.

Nor did he imagine that all unwittingly he had sent his master far astray; for the Princess had gone but a little way by the North Avenue, and then had circled over to the South gate.

And so Armand searched vainly, until at last, bearing around toward Dornlitz, he struck the main highway and learned that she had passed long since, making for the Capital as fast as horse could run. And he knew that the Bell had been the messenger, and that there was now naught for him to do but to [35] return with all speed and give such comfort as he might. Though what to do or to say he had no idea—for never before had he been called upon to minister to a woman’s grief; and he pondered upon it with a misgiving that was at its deepest when, at length, he stood outside her door and heard her bid the servant to admit him.

But if he looked for tears and trembling he was disappointed, for she met him as she had met those in the corridor and the ante-room, dry-eyed and calmly. And in silence he took her in his arms, and held her close, and stroked her shining hair.

And presently she put his arms aside, and stepping back, she curtsied low and very gravely.

“Life to Your Majesty!” she said; “long live the King!” and kissed his hand.

He raised her quickly. “Never bend knee to me, Dehra,” he said. “And believe me, I had quite forgot everything except that you had lost your father.”

She went back to him. “And so had I, dear, until you came; but now, since he is gone, you are all I have—is it very selfish, then, for me to think of you so soon?”

He drew her to a chair and stood looking down at her.

“If it is,” he said, “I am surely not the one to judge you.”

She shook her head sadly. “There is no one to judge but—him,” she answered; “and he, I know, would give me full approval.” She was silent for a while, her thoughts in the darkened room across the court, where the tapers burned dimly, and a Captain of the Guard kept watch. And her heart sobbed afresh, though her lips were mute and her eyes undimmed. At last she spoke.

“Is the Book of Laws at the Summer Palace or here?” she asked.

“I do not know,” said Armand, “I have never seen it except the day that the King read old Henry’s decree and offered me Hugo’s titles and estates.”

“Well, at least, he spoke of it to you to-day.”

Armand shook his head. “Never a word; neither to-day nor for many days.”

A faint frown showed between her eyes. “Didn’t he mention to you, this afternoon, the matter of the Succession?”

“No.”

She sat up sharply. “It can’t be he didn’t——”

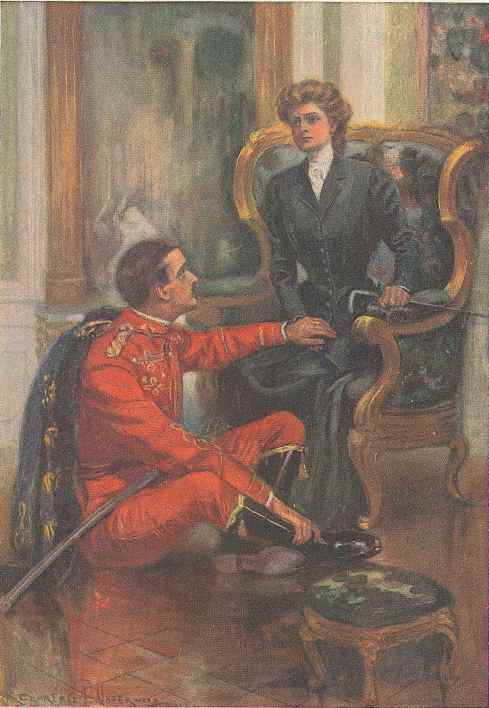

The Archduke dropped on the floor at her feet and took her hand. “I assure you, Dehra, the King didn’t speak a single word to me on such a matter.”

“THE KING DIDN’T SPEAK A SINGLE WORD TO ME ON SUCH A MATTER.”

“No, no,” she said, “you don’t understand. I mean it can not be he didn’t make the decree.”

“The decree!” Armand exclaimed, though he knew well there was but one she would refer to; and his pulse bounded fiercely and his face grew very hot.

“Yes, dear—the decree—that would have made you Heir Presumptive—and now King.”

“And you think it was drawn?”

“I am sure of it.”

“The King told you so?”

“Not directly, but by inference. I came upon him late last night in his library, with the Laws open before him and a pen in his hand; and when I ventured to voice my curiosity, he smiled and closed the book, saying, ‘You may see it to-morrow, child; after I have told Armand.’”

“Doubtless he intended to tell me after the review.”

The Princess leaned over and put her arm around his neck.

“And now you are the King, dear; as he had always intended you should be,” she whispered. “Thank God, the decree was made in time.”

For a while Armand toyed with her slender fingers, and did not answer. Of course, she was right:—it was the decree they both had been hoping for so earnestly, but which neither had dared mention to the King. And now, when it had come, and in such fashion, was it really worth the while. Worth the turmoil and the trouble, and, may be, the fighting, that was sure to follow his assumption of the royal dignity. Had Frederick lived to proclaim the decree and to school the Nation into accepting him as his successor, the way would have been easy and well assured. But it was vastly different now—with [38] Frederick dead, the decree yet to be announced, and few, doubtless, of those in authority around him, to be depended on to aid him hold the throne. Dalberg though he was, and now, by birth, the Head of the House, yet he was a foreigner, and no people take kindly to a foreign King. Frederick had died too soon—another year——

And Dehra, bending down questioning his abstraction, read his face and understood his thoughts.

“Come, dear,” she said, “the crisis is here, and we must face it. Dismiss the idea that you’re a foreigner. Only you and Lotzen and I are familiar with our Laws. You forget that the people do not know it required a special decree to make you eligible for the Crown; and to them you have been the next King ever since you were proclaimed as Hugo’s heir. And surely they have shown you a rare good will, and an amazing preference over the Duke. He has spent his whole life in cultivating their dislike; do you fancy it won’t bring its harvest now?”

He had turned and was watching her with an indulgent smile. It was sweet to hear her argue so; to see her intense devotion to his cause; her passionate desire that he should sit in her father’s place and rule the ancient monarchy. And at her first words, and the sight of her loving eyes and flushed cheeks, his doubts had vanished, and his decision had been made. Yet, because he liked to see her so, he led her on.

“But what of the Nobility,” he objected; “in Valeria they still lead the people.”

“True,” she answered instantly, “true; but you forget again that the Nobles are sworn to maintain the Laws of the Dalbergs; and that for centuries none has ever broken faith. No, no, Armand, they will be true to their oaths; they will uphold the decree.”

“Don’t you think, dear,” he smiled, “you are making it rather too assured? If the people are for me (or at least are not for Lotzen) and the Nobles will abide by the Laws, nothing remains but to mount the Throne and seize the sceptre.”

“Just about that, I fancy,” she replied.

“And, meanwhile, what will Lotzen be doing?”

She frowned. “Whatever the Head of his House orders him to do. As a Dalberg he is bound to obey.”

“And you think he will obey?”

“I surely do. I cannot imagine a Dalberg dishonoring the Book of Laws.”

“I fear you do not know Ferdinand of Lotzen,” said Armand seriously. “He intends to dispute the Succession. I have never told you how, long ago, he warned me what to expect if I undertook to ‘filch the Crown,’ as he put it. It was the afternoon he insulted me at headquarters—the Vierle Masque was in the evening.”

The Princess nodded eagerly. “Yes,” said she, “yes—I know—the time he wanted you to toss up a coin for me. What did he say?”

The Archduke reflected a moment. “I can give you his exact words: ‘Do you think,’ he said, ‘that I, who have been the Heir Presumptive since the instant of my birth, almost, will calmly step aside and permit you to take my place? Do you fancy for an instant that the people of Valeria would have a foreigner for King? And even if old Frederick were to become so infatuated with you that he would restore you to Hugo’s place in the line of Succession, do you imagine that the House of Nobles would hesitate to annul it the instant he died?’”

When he had finished, Dehra’s fingers were beating a tattoo on the chair’s arm, and her eyes were snapping—as once or twice he had seen Frederick’s snap.

“And I suppose you never told the King?” she exclaimed.

“Naturally not.”

“Of course, of course,” with a toss of the handsome head. “That’s a man’s way—his silly, senseless way—never tell tales about a rival. And as a result, see what a mess you have made. Had you informed the King, he instantly would have proclaimed you as his heir, and then disgraced Lotzen publicly and sent him into exile. And you would now be his successor, without a shadow of opposition.”

Armand subdued a smile. “You don’t understand, Dehra——” he began.

“Quite right,” she cut in; “quite right; I don’t. Why didn’t you tell me? I would have told the King, you may be sure.”

“Of course you would, little woman; that’s just the reason I didn’t tell you.”

She shrugged her shoulders, and the tattoo began afresh.

“I’ve no patience with such nonsense,” she declared; “Lotzen deserved no gentlemanly consideration; he would have shown none to you; and besides, it was your duty to your King and your House to uphold the Laws of the Dalbergs and to prevent any attempt to violate them.”

“I am very much afraid that lately, between Lotzen and myself, the Laws of the Dalbergs have been sadly slighted.”

His bantering jarred upon her. “To me, Armand,” she answered gravely, “our Laws are holy. For almost a thousand years they have been our unchallenged rule of governance. I can understand why, to you, they have no sacredness and no sentiment; but Lotzen has been born and bred under them, and should honor them with his life—and more especially as they alone made him the Heir Presumptive. But for the decree of the first Dalberg King, four hundred years ago, I would be the Queen-Regent of Valeria.”

“It’s a pity, a crying pity!” he exclaimed.

She looked down at him with shining eyes. “No, dear, it isn’t; once I thought it was; but now I’m quite content to be Queen-consort.”

He took both her hands and held them between his own. “That, dear, is what makes it possible, and worth the struggle; and if Valeria does accept me as its King, it will be solely for love of you, and to get you for its Queen.”

A smile of satisfaction crossed her face. “I hope the people do love me,” she said. “I would like to feel I may have helped you, even a little.”

“A little! but for you, my princess, I’d go back to America and leave the way clear for Lotzen.”

She laughed softly. “No, no, Armand, you would do nothing of the sort. A Dalberg never ran from duty—and least of all the Dalberg whom God has made in the image of the greatest of them all.”

He glanced in the tall mirror across the room. He was wearing the dress uniform of the Red Huzzars (who had been inspected immediately before the Foot Guards; and he, as titular Colonel, had led them in the march by), and there was no denying he made a handsome figure, in the brilliant tunic and black, fur-bound dohlman, his Orders sparkling, his sword across his knees.

She put her head close beside his and smiled at him in the mirror.

“Henry the Great was not at all bad looking,” she said.

He smiled back at her. “But with a beastly bad temper, at times, I’m told.”

“I’m not afraid—I mean his wife wasn’t afraid; tradition is, she managed him very skilfully.”

“Doubtless,” he agreed; “any clever woman can manage a man if she take the trouble to try.”

“And shall I try, Armand?”

“Try!” he chuckled; “you couldn’t help trying; man taming is your natural avocation. By all means, manage me—only, don’t let me know it.”

“I’ll not,” she laughed—“the King never——” and she straightened sharply. “I forgot, dear, I forgot!” And she got up suddenly, and went over to the window. Nor did he follow her; but waited silently, knowing well it was no time for him even to intrude.

After a while she came slowly back to him, a wistfully sad look in her eyes. And as he met her she gave him both her hands.

“I shall never be anything but a thoughtless child, Armand,” she said, with a wan, little smile. “So be kind to me, dear—and don’t forget.”

He drew her arms about his neck. “Let us always be children to each other,” he answered, “forgetting, when together, everything but the joy of living, the pleasures of to-day, the anticipations of to-morrow.”

She shook her head. “A woman is always a child in love,” she said; “it’s the man who grows into maturity, and sobers with age.”

He knew quite well she was right, and for the moment he had no words to answer; and she understood and helped him.

“But this is no time for either of us to be children,” she went on; “there is work to do and plans to be arranged.” She drew a chair close to the table and, resting both arms upon it, looked up at the Archduke expectantly. “What is first?”

He hesitated.

“Come, dear,” she said; “Frederick was my father and my dearest friend, but there remains for him now only the last sad offices the living do the dead; we will do them; but we will also do what he has decreed. We will seat you in his place, and confound Lotzen and his satellites.”

He took her hand and gravely raised it to his lips.

“You are a rare woman, Dehra,” he said, “a rare woman. No man can reach your level, nor understand the beauty of your faith, the meaning of your love. Yet, at least, will I try to do you honor and to give you truth.”

She drew him down and kissed him lightly on the cheek.

“You do not know the Dalberg women, dear,” she said—“to them the King is next to God—and the line that separates is very narrow.”

“But I’m not yet the King,” he protested.

“You’ve been king, in fact, since the moment—Frederick died. With us, the tenet still obtains in all its ancient strength; the throne is never vacant.”

“So it’s Lotzen or I, and to-morrow the Book will decide.”

“Yes,” she agreed; “to-morrow the Book will decide for the Nation; but we know it will be you.”

“Not exactly,” he smiled; “we think we know; we can’t be sure until we see the decree.”

“I have no doubt,” she averred, “my father’s words can bear but one construction.”

“It would seem so—yet I’ve long learned that, in this life, it’s the certain things that usually are lost.”

She sprang up. “Why not settle it at once—let us send for the Book; of course it is at the Palace—it was there last night.”

He shook his head decisively. “No, dear, no; believe me it is not wise now for either of us to touch the Book. It were best that it be opened only by the Prime Minister in presence of the Royal Council. We must give Lotzen no reason to cry forgery.”

She shrugged her shoulders. “Small good would it do him, as against Frederick’s writing and my testimony. However, we can wait—the Council meets in the morning, I assume?”

“Yes; at ten o’clock, at the Palace.”

She looked up quickly. “The key?” she asked; “it was always on his watch chain—have you got it?”

“No,” said he; “I never thought of it.”

She rang the bell and sent for the Chamberlain.

“Bring me King Frederick’s watch, and the Orders he was wearing,” she said. When they came she handed the Orders to Armand.

“They are yours now, dear,” she said. She took the watch and held up the chain, from the end of which hung the small, antique key of the brass bound box, in which the Book of Laws had been kept for centuries that now reached back to tradition. She contemplated, for a moment, the swaying bit of gold and bronze, then loosed it from the ring.

“This also is yours, Sire,” she said, and proffered it to him.

But he declined. “To-morrow,” he said.

“And in the meantime?”

“If Count Epping is still in the Castle, we will let him hold it.”

The Princess nodded in approval. “Doubtless that is wiser,” she said, “though quite unprecedented; none but the King ever holds that key, save when he rides to war.”

“We are dealing with a situation that has no precedents,” he smiled; “we must make some.”

As he went toward the bell, a servant entered with a card.

“Admit him,” he said.... “It is Epping,” he explained.

The Prime Minister of Valeria was one of those extraordinary exceptions that occasionally occur in public officials; he had no purpose in life but to serve his King. Without regard to his own private ends or personal ambition, he had administered his [47] office for a generation, and Frederick trusted him as few monarchs ever trusted a powerful subject. To the Nation, he was honesty and justice incarnate, and only the King and the Princess Royal excelled him in popularity and respect. Seventy years had passed over the tall and slender figure, leaving a crown of silver above the pale, lean face, with its tight-shut mouth, high cheek bones and faded blue eyes; but they had brought no stoop to the shoulders, nor feebleness to the step, nor dullness to the brain.

He saluted Armand with formal dignity; then bent over Dehra’s hand, silently and long—and when he rose a tear was trembling on his lashes. He dashed it away impatiently and turned to the Archduke.

“Sire,” he said—and Armand, in sheer surprise, made no objection—“I have brought the proclamation announcing His late Majesty’s death and your accession. It should be published in the morning. Will it please you to sign it now?”

There are moments in life so sharp with emotion that they cut into one’s memory like a sculptor’s tool, and, ever after, stand clear-lined and cameoed against the blurred background of commonplace existence. Such was the moment at the Palace when Frederick had handed him the patents of an Archduke, and such now was this. “Sire!” the word was pounding in his brain. “Sire!” he, who, [48] less than a year ago, was but a Major in the American Army; “Sire!” he—he—King of Valeria!

Then, through the mirage, he saw Dehra’s smiling face, and he awoke suddenly to consciousness and the need for speech, and for immediate decision. Should he sign the proclamation on the chance that the decree was in his favor, and that he was, in truth, the King? He hesitated just an instant—tempted by his own desires and by the eager eyes of the fair woman before him; then he straightened his shoulders and chose the way of prudence.

He waved the Prime Minister to a chair.

“Your pardon, my lord,” he said; “your form of address was so new and unexpected, it for the moment bound my tongue.”

The old man bowed. “I think I understand, Sire,” he said, with a smile that, for an instant, softened amazingly his stern face. “Yet, believe me, one says it to you very naturally”—and his glance strayed deliberately to the wall opposite, where hung a small copy of the Great Henry’s portrait in the uniform of the Red Huzzars. “It is very wonderful,” he commented;—“and I fancy it won you instant favor and, even now, may be, makes us willing to accept you as our King. Sometimes, Your Majesty, sentiment dominates even a nation.”

“Then I trust sentiment will be content with the physical resemblance and not examine the idol too closely.”

The Count smiled again; this time rather coldly.

“The first duty of a king is to look like one,” he said; “and sentiment demands nothing else;” and, with placid insistence, he laid the proclamation on the table beside Armand.

The latter picked it up and read it—and put it down.

“My lord,” he said, “I prefer not to exercise any prerogative of kingship until the Royal Council has examined the Book of Laws and confirmed my title under the decrees.”

The faded blue eyes looked at him contemplatively.

“I assumed there was no question as to the Succession,” he remarked.

“Nor did I mean to intimate there was,” Armand answered.

“Then, with all respect, Sire, I see no reason why you should not sign the proclamation.”

Armand shook his head. “May be I am foolish,” he said; “but I will not assume the government until after the Council to-morrow—it will do no harm to delay the proclamation for a few hours. And, in the interim, you will oblige Her Royal Highness and me by keeping this key, which she removed from King Frederick’s watch chain, but a moment before you came.”

The Count nodded and took the key.

“I recognize it,” he replied. “I know the lock it opens.”

“Good,” said Armand; “the box is at the Palace, and doubtless you also know what it contains. For reasons you may easily appreciate, I desire to avoid any imputation that the Book has been touched since His Majesty’s demise. You will produce this key at the meeting to-morrow, explaining how and where you got it; and then, in the presence of the Council, I shall open the box and if, by the Laws of the Dalbergs, I am Head of the House, I will enter into my heritage and try to keep it.”

The Prime Minister got up; gladness in his heart, though his face was quite impassive. He had come in doubt and misgiving; he was easy now—here was a man who led, a man to be served; he asked no more—he was content.

“I understand,” he said; “the proclamation can wait;” then he drew himself to his full height. “God save Your Majesty!” he ended.

Count Epping was the last of the five Ministers to arrive at the Council, the following morning. He came in, a few minutes before the hour, acknowledged with grave courtesy, but brief words, the greetings of the others, and when his secretary had put his dispatch box on the table he immediately opened it and busied himself with his papers. It was his way—and none of them had ever seen him otherwise; but now there seemed to be a special significance in his silence and preoccupation.

The failure of the Court Journal to appear that morning had broken a custom that ante-dated the memory of man, and the information which was promptly conveyed to the Ministers that it was delayed until evening, and by the personal order of the Prime Minister, had provoked both amazement and expectancy. It could mean only that the paper was being held for something that must be in that day’s issue, and as they had promptly disclaimed to one another all responsibility, the inference was not difficult that it had to do with the new King’s first proclamation.

“The Count was at the Castle last evening,” Duval, the War Minister, had remarked, “and I assumed it was to submit the proclamation and have it signed.”

Baron Retz, the Minister of Justice, shrugged his shoulders.

“May be you assumed correctly,” he remarked.

The others looked at him with quick interest, but got only a smile and another shrug.

“Then why didn’t he sign it?” Duval demanded.

The Baron leaned back in his chair and studied the ceiling. “When you say ‘he,’ you mean——?”

“The King, of course,” the other snapped. “Who the devil else would I mean?”

“And by ‘the King,’” drawled Retz, “you mean——?”

There was a sudden silence—then General Duval brought his fist down on the table with a bang.

“Monsieur le Baron,” he exclaimed, “you understand perfectly whom I meant by the King—the Archduke Armand. If he is not the King, and you know it, it is your duty as a member of the Council to disclose the fact to us forthwith; this is no time nor place to indulge in innuendoes.”

The Baron’s small grey eyes turned slowly and, for a brief instant, lingered, with a dull glitter, on the War Minister’s face.

“My dear General,” he laughed, “you are so precipitate. If you ever lead an army you will deal only in frontal attacks—and defeats. I assure you I know nothing; but to restate your own question: if the Archduke Armand be the King, why didn’t he sign the proclamation?”

Steuben, the grey-bearded Minister of the Interior, cut in with a growl.

“What is the profit of all these wonderful theories?” he demanded, eyeing Retz. “The ordinary and reasonable explanation is that the proclamation is to be submitted to us this morning.”

“In which event,” said the Baron, “we shall have the explanation in a very few minutes,” and resumed his study of the ceiling.

“And in the meantime,” remarked Admiral Marquand, “I am moved to inquire, where is the Duke of Lotzen?”

Steuben gave a gruff laugh. “Doubtless the Department of Justice can also offer a violent presumption on that subject.”

“On the contrary, my friend,” said Retz, “it will offer the very natural presumption that the Duke of Lotzen is hastening to Dornlitz; to the funeral—and the coronation.”

“Whose coronation?” Duval asked quickly.

“My dear General,” said the Baron, “there can’t be two Kings of Valeria, and it would seem that the Army has spoken for the Archduke Armand.”

“And the Department of Justice for whom?” the General exclaimed.

A faint sneer played over Retz’s lips. “Monsieur le General forgets that when the Army speaks, Justice is bound and gagged.”

It was at that moment that Count Epping had entered.

When the clock on the mantel chimed the hour the Count sat down and motioned the others to attend.

“Will not the King be present?” Retz asked casually, as he took his place.

The Prime Minister looked at him in studious comprehension.

“Patience, monsieur, patience,” he said softly, “His Majesty will doubtless join us in proper time. Have you any business that requires his personal attention?”

The Baron shook his head. “No—nothing. I was only curious as to what uniform he would wear.”

A faint smile touched the Count’s thin lips.

“But more particularly curious as to who would wear it,” he remarked dryly.

Retz swung around and faced him.

“My lord,” he said, “I would ask you, who is King in Valeria: the Archduke Armand or Ferdinand of Lotzen?”

The old Minister’s smile chilled to a sneer.

“That is a most astonishing question from the chief law officer of the kingdom,” he said.

“But not so astonishing as that he should be compelled to ask it,” was the quick answer.

“Is there, then, monsieur, any doubt in your mind as to the eldest male of the House of Dalberg?”

“None whatever; but can you assure us that he is king?”

“What has my assurance to do with the matter?” the Count asked. “By the laws of the Dalbergs the Crown has always passed to the eldest male.”

The Baron laughed quietly. “At last we near the point—the Laws. There is no doubt that, by birth, the Archduke Armand is the eldest male; yet what of the decree of the Great Henry as to Hugo? As I remember, Frederick explained enough of it to the Council to cover Armand’s assumption of his ancestor’s rank and estates, but said no word as to the Crown.” He leaned forward and looked the old Count in the eyes. “And I ask you now, my lord, if, under the decree, Armand became the Heir Presumptive, why was it that, at all our sessions, the Duke of Lotzen, until his banishment, retained his place on the King’s right, and Armand sat on the left? Is it not a fair inference, from the actions of the three men who know the exact words of the decree, that, though it restored Hugo’s heir to archducal rank, it specifically barred him from the Crown?”

The Prime Minister had listened with an impassive face and now he nodded curtly.

“There might be some weight to your argument, Monsieur le Baron,” he said, “if you displayed a more judicial spirit in its presentation—and if you did not know otherwise.”

“I shall not permit even you——” Retz broke in.

The Count silenced him with a wave of his hand. “You have sat at this board with us, and since the Duke of Lotzen’s absence, at least, you have seen our dead master treat the Archduke Armand, in every way, as his successor; and on one occasion, in your hearing and to your knowledge—for I saw you slyly note the exact words, on your cuff—he referred to him as the one who would ‘come after.’ Hence, I say, you are not honest with the Council.”

“I felicitate your lordship on your powers of observation and recollection,” said Retz suavely; “they are vastly more effective and timely than mine, which, I confess, hesitate at miracles. But with due modesty, I submit there is a very simple way to settle this question quickly and finally. Let us have the exact words of Henry’s decree. I am well aware it is unprecedented for any but a Dalberg to see the Dalberg Laws; but we are facing an unprecedented condition. Never before has a Dalberg king failed to have a son to follow him. Now, we hearken back for generations, with a mysterious juggle intervening; and it is for him who claims the Throne to prove his title. Before the coming of the American there was no question that Lotzen was the Heir Presumptive. Did he lose the place when Armand became an Archduke? The decree alone can determine; let it be submitted to the Royal Council for inspection.”

“The Minister of Justice is overdoing his part,” said the old Count, addressing the other Ministers. “It is not for him nor his Department to dictate the method by which the Dalbergs shall decide their kingship, nor does it lie in the mouth of any of us to demand an inspection of the Book of Laws. So much for principle and ancient custom. It may be the pleasure of the Archduke to confirm his right by exhibiting to us the Laws; or the Duke of Lotzen may challenge his title, and so force their submission to us or to the House of Nobles for decision. But, as the matter stands now, the Council has no discretion. We must accept the eldest male Dalberg as King of Valeria; and, as you very well know” (looking directly at Retz) “none but a Dalberg may dispute his claim—do you, Monsieur le Baron, wish to be understood as speaking for the Duke of Lotzen?”

Retz leaned back in his chair and laughed.

“No, no, my lord, no, no!” he said. “I speak no more for Lotzen than you do for Armand.”

“So it would seem—though not with the same motives,” the Count sneered—then arose hastily. “The King, my lords, the King!” he exclaimed, as the door in the far corner opened and Armand entered, unattended, and behind him came a manservant bearing a brass-bound, black-oak box, inlaid with silver.

Never had any of the Council seen it, yet instantly all surmised what it contained; and, courtiers though they were, they (save the old Count) stared at it so curiously that the Archduke, with an amused glance at the latter, turned and motioned the servant to precede him.

“Place it before His Excellency, the Prime Minister,” he said; and now the stares shifted, in unfeigned astonishment to Armand—while the Count’s thin lips twitched ever so slightly, and, for an instant, his faded blue eyes actually sparkled, as they lingered in calm derision on the Baron’s face.

And Retz, turning suddenly, caught the look and straightway realized he had been outplayed. He understood, now, that the Count had been aware, all along, of the Archduke’s purpose to produce the Laws to the Council, this morning, and that he, by his very persistence, had given the grim old diplomat an opportunity to demonstrate, in the most effective fashion, the unprecedented honor Armand was now doing them. It was irritating enough to be out-manœuvered, but to have his own ammunition seized and used to enhance another’s triumph was searing to his pride; and, in truth, this was not the first time that the Prime Minister had left his scar and a score to settle between them.

“Be seated, my lords,” said Armand, “and accept my apologies for my tardiness,” and he took the chair at the head of the table.

Count Epping drew his sword and raised it high.

“Valeria hails the Head of the House of Dalberg as the King!” he cried.

And back from the others, as their blades rang together above the table, came the echo:

“We hail the Dalberg King!”

It was the ancient formula, which had always been used to welcome the new ruler upon his first entrance to the Royal Council.

And it had come as yet another scar to Retz, for it put him to the choice—whether to play the fool now, or the dastard later—and that with every eye upon him, even the Archduke’s, whose glance had instinctively followed the others’. Yet he had made it instantly, smiling mockingly at the Count; and his voice rang loud and his sword was the last to fall.

But Armand knew nothing of this old ceremony, and the surprise of it brought him sharply to his feet, with his hand at the salute, while his face and brow went ruddy and his fingers chill. It was for him to speak, he knew, yet speak he could not. But when led by Count Epping, they crowded close about him and bent knee and would have kissed his hand, he drew back and waved them up.

“I thank you, my lords, I thank you from my heart,” he said gravely, “though not yet will I assume to accept either the homage or the greeting. They belong to him who is King of Valeria, and whether I be he I do not know. As the eldest male, the presumption is with me; yet as the monarch has full power to choose his successor from any of the Dalbergs, it may have been his pleasure, under the peculiar conditions now existing, to name another as his heir. Hence it is my purpose to submit to you the Book of Laws, that you may inspect the decrees [60] and ascertain to whom the Crown descends. I am informed this is a proceeding utterly unknown; that the Dalberg Laws are seen only by Dalberg eyes. Yet, as I apprehend there will be another claimant, who will have a hearty following, and as, in the end, it is the Laws that will decide between us, it is best they should decide now. If, by them, I am King of Valeria I will assume the Crown and its prerogatives; and if I am not King, then I will do homage to him who is, and join with you in his service.”

He paused, and instantly General Duval flashed up his sword.

“God save Your Royal Highness!” he cried. “God grant that you be King.”

And as the others gave it back for answer, their blades locked above the Archduke’s head, the corridor door behind them swung open, and Ferdinand of Lotzen entered and, unnoticed, came slowly down the room.

All night, with a clear track and a special train, he had been speeding to the Capital, anxious and fearful, for in an inter-regnum hours count as days against the absent claimant to a throne. But when, at the station, he learned from Baron Rosen that the Proclamation had not yet been issued and the Council had been called for ten o’clock, the prospect brightened, and he hurried to the Palace.

Yet there was small encouragement in the scene before him, though the words of the acclaim and the black box on the table puzzled him. Why, with the Laws at their disposal, should there be any doubt as to who was King! So he leaned upon a chair and waited, a contemptuous smile on his lips, a storm of hate and anger in his heart. Those shouts, those swords, those ardent faces should all have been his; would all have been his, but for this foreigner, this American, this usurper, this thief. And his fingers closed about his sword’s hilt and, for the shadow of an instant, he was tempted to spring in and drive the blade through his rival’s throat. But instead he laughed—and when at the sound they whirled around, he laughed again, searching the while every face with his crafty eyes, and, save in Retz’s, finding no trace of confusion nor regret.

“A pretty picture, messieurs,” he jeered, “truly, a pretty picture—pray don’t let me disturb it; though I might inquire, since when has the Royal Council of Valeria gone in for private theatricals!”

And Armand promptly gave him back his laugh.

“Our cousin of Lotzen appears in good time,” he said very softly. “Will he not come into the picture?”

Ferdinand shook his head. “In pictures of that sort, there can be but one central figure,” he answered.

The Archduke swung his hand toward the Ministers.

“True, quite true,” said he; “but there is ample space for Your Royal Highness in the background.”

Lotzen’s face went white, and he measured Armand with the steady stare of implacable hate, though on his lips the sneering smile still lingered.

And presently he answered: “I trust, monsieur, you will not mistake my meaning, when I assure you that there isn’t space enough in such a picture to contain us both.”

“It is a positive pleasure, Monsieur le Duc,” returned Armand quickly, “to find, at last, one matter in which our minds can meet.”

And so, for a time, they stood at gaze, while the others watched them, wondering and in silence. Then the Archduke spoke again:

“And now, my dear cousin, since we understand each other, I suggest we permit the Royal Council to continue its session. Be seated, messieurs;” and with a nod to the Ministers, he resumed his place at the head of the table.

Instantly Lotzen stepped forward.

“My lords,” he cried, “as Heir Presumptive I claim the Throne of Valeria. I call upon you, in the name of the House of Dalberg, to acknowledge me and to proclaim my accession.”

“Upon what does Your Royal Highness rest your claim?” Count Epping asked formally.

The Duke pointed to the box; he saw now it was shut tight and the key not in the lock—and this, with what had occurred as he entered, undoubtedly indicated either that the Book had not yet been examined or that it contained no decree fixing the Succession. In either event, he stood a chance to win; and, at least, he had need for time.

“Upon the Laws of the Dalbergs,” he replied, raising his hand in salute; “and under which, as you all well know, I have been the Heir Presumptive since my father’s death.”

“And you will accept them as final arbiter between us?” asked Armand quickly.

Ferdinand turned and looked at him fixedly.

“For the Crown, yes,” he said very softly; and not a man but understood the limitation and the challenge.

And the Archduke smiled, and answered in a voice even softer and more suave.

“So be it—I will chance the rest.” Then he addressed the Council. “His Excellency, the Prime Minister, has the key to the box; with your permission I will ask him to explain when and under what circumstances he got it.”

And the Count took care that Armand should lose nothing in the telling, and when he had finished, he drew out the queer little key, and holding it so all could see looked at the two Dalbergs inquiringly.

“Shall I unlock the box?” he asked; and both nodded.

But the key would enter only a little way; and while the Count worked with it, Armand remembered suddenly the unusual motion Frederick had used the day he showed him the Laws.

“Turn the bit sidewise and push down and in,” he said. And at once the key slipped into place and the lock snapped open.

At the sound, the Ministers eagerly craned forward; but the Count did not offer to lift the lid until he received the Archduke’s nod; then he slowly laid it back, and leaning over peered inside. And he peered so long, that Lotzen grew impatient.

“The Laws, Epping, the Laws,” he said sharply; “let us have them, man.”

The Count looked at him and then at Armand.

“The box is empty,” he said.

Into the silence of amazement that ensued, came the Duke’s sneering laugh.

“Surely, surely, you didn’t think to find it otherwise!” he said.

His insinuation was so apparent that the Archduke turned upon him instantly.

“Don’t be a coward, Ferdinand of Lotzen,” he said. “Speak plainly; do you mean to charge me with having removed the Book from the box?”

The Duke bowed. “Just that, Your Royal Highness,” he said; “just that, since you must have it—you Americans are so blunt of speech.”

Armand leaned forward. “The only way to deal with a liar,” he answered, “is to put him where he can’t lie out.”

Ferdinand shrugged his shoulders deprecatingly. “You play it very cleverly, cousin mine, but the logic of elimination is against you. I assume you will not accuse our dear dead master of having hid the Laws; and since his decease, the key, you admit, has been with only you and His Excellency, the Prime Minister. I assume also you will acquit Count Epping—I am quite sure I will—and so we come back to—you.”

The Archduke had long ago learned that in an encounter with Lotzen it was the smiling face that served him best; so he controlled his anger and turned to the Ministers.

“His Highness overlooks the logic of opportunity,” he said. “I was not in the Summer Palace, since the King’s death, until this morning.”

Ferdinand laughed again. “Naturally not; you’re not such a bungler.”

Baron Steuben, who had been pulling thoughtfully at his beard, eyeing first one and then another, here broke in, addressing Armand.

“Would Your Highness care to tell us when you last saw the Book of Laws?” he inquired.

“I shall gladly answer any question the Council may ask. The only time I ever saw either Book or box was the day the King offered me my inheritance as the heir of Hugo.”

And once again came Lotzen’s sneering interruption.

“And yet you could instruct Count Epping just how to manipulate the key:—‘turn the bit sidewise and push down and in.’”

Retz half closed his eyes and smiled; Epping’s lips grew tighter; Duval and Marquand frowned; Steuben, with a last fierce tug at his beard, relapsed into silence.

But Armand met the issue squarely.

“It is my word against your inference,” he said. “I am quite content to let the Council choose. They, too, have seen that key used but once, and yet I venture that a year hence they also will remember the peculiar motion it requires.”

“They are much more likely to remember your ready wit and clever tongue,” Lotzen retorted.

The Archduke turned from him to the Council.

“My lords,” he said, “there is small profit to you in these personal recriminations. The question is, who is King of Valeria, Ferdinand of Lotzen or myself—and as only the Book of Laws can answer, I ask that you, yourselves, search King Frederick’s apartments and interrogate his particular attendants.”

Count Epping arose. “Will the Minister of Justice aid in the search,” he said—“and also Your Royal Highness?” addressing Lotzen.

The latter smiled. “No; I thank you—what is the good in searching for something that isn’t there!”—then he turned upon Armand. “I assume you brought the box here,” pointing to the table, “and that you found it in the vault, where it is always kept—may I inquire how you got into the vault?”

“Through the door,” said the Archduke dryly.

“Then you know the combination—something the King never told even me. Observe, my lords, the logic of opportunity!”

But Armand shook his head. “No,” said he, “I do not know the combination.”

And Lotzen, seeing suddenly the pit that yawned for him if he pursued farther, simply smiled incredulously and turned away.

The old Count, however, saw it too, and had no mind to let the opportunity slip.

“Who opened the door?” he asked bluntly.

“Her Royal Highness the Princess,” said the Archduke.

And Epping nodded in undisguised satisfaction; while Ferdinand of Lotzen, sauntering nonchalantly over to the nearest window, cursed him under his breath for a meddler and a fool.

As the Duke had predicted, the search of the King’s apartments and the vault proved barren; and then, his particular servants and such attendants as were in the Palace were summoned and examined, and also without result; indeed none of them remembered having seen either box or Book—save one: Adolph, Frederick’s valet. He said that, recently, his master had spent many hours in the evenings studying the Laws, going through them with great care, making notations and marking certain pages with slips of paper; that no one else was ever present at such times, and once, when he had unthinkingly approached the desk, the King had angrily bade him leave the room. Asked when he had last seen the Book, he answered the fourth day before His Majesty’s demise; which, he added, he felt sure was also the last time it had been used; but admitting, frankly, when pressed by the Archduke, that his only reason for so thinking was that he had not seen it in that interval.

“Oh, as to that, my dear cousin,” said Lotzen from the window, the instant the valet had gone, “I am altogether willing to admit, and for the Council to assume, that the Book was safely in the box and the box safely in the vault when Frederick died. Don’t try to obscure the point at issue—what we want to know is what you have—I beg your pardon—what has happened to it since that time.”

Armand waited with polite condescension until the Duke had finished, then he ignored him and addressed the Council.

“My lords,” he said, “you are confronted by a most unpleasant duty: Valeria must have a King, and you must choose him, either Ferdinand of Lotzen or myself. We cannot wait until the Laws are found. I claim the throne by presumptive right; he, by a right admitted to be subordinate to mine. In the absence of the decrees my title is paramount, and the royal dignity falls on me. If the Laws be recovered, and under them I am not King, I will abdicate, instantly.”

Lotzen had come back to the table and resumed his favorite attitude of leaning over the back of a chair.

“Charming, indeed, charming!” he chuckled. “Make me King, and if the Laws unmake me I will abdicate when they are recovered—when—they—are—recovered! Do you fancy, messieurs, they would ever be recovered?”

Count Epping saved the Archduke the necessity of answer.

“Your Highness’ argument,” he observed, “is predicated on the hypothesis that the Archduke Armand has possession of the Book of Laws and is concealing it because it would, if exhibited, prove him ineligible to the Throne.”

“Admirably stated!” said Lotzen.

“But,” Epping went on, “you cannot expect the Council to accept any such hypothesis”—and all the Ministers nodded—“we must assume that neither you nor the Archduke knows aught of the Book, and whatever action we do take must be, upon the distinct condition, agreed to, here and now, by you both, that when the Laws are found—as found they surely will be—the Succession shall be determined instantly by them. Are you willing,”—addressing Lotzen—“that the Council, of which you are one, shall settle it, pending the recovery of the Laws?”

“No, I am not,” said the Duke abruptly; “but pending election by the House of Nobles, I am content.”

The Prime Minister watched the Duke meditatively for a moment, then turned to the Archduke inquiringly.

“I am content, even as His Highness of Lotzen,” said Armand; he saw where the play was leading, and the other’s next move, and he was not minded to balk him; there was likely to be a surprise at the end.

The Count faced the Council.

“The matter is before you,” he said. “Having in view the Laws and circumstances, as we know them, to whom shall we confide the government?” and with a bland smile, he looked at the Minister of Justice—who, as the junior member, would have to vote first.

Retz stirred uneasily and glanced furtively at Lotzen. He was not inclined to go so rapidly, or, at least, so openly. Had he apprehended any such proceeding he would have remained at home, ill, and let his dear colleagues bear the unpleasant burdens. It was an appalling dilemma. He wanted to vote for Lotzen—yet he was sure that Armand would be chosen. If he voted for Armand, he would bear the Duke’s everlasting enmity, and, in the end, the Laws or the Nobles might give him the Crown. If he voted for Lotzen, and Armand were chosen, he lifted himself out of the Council, and ended his career if eventually the American won. He ran his eye around the table and caught the smile on every face, and mentally he consigned them all to death and perdition. Then he heard Epping’s voice again:

“We are waiting, Monsieur le Baron.”

But Lotzen came to his relief—quite unintentionally; he alone had not noted Retz’s embarrassment, having been reading a paper he had taken from his pocket-book.

“One moment, if you please,” he said. “I take it, that what may give the Archduke Armand preference over me in his claim for the Crown, is the presumptive right of the eldest male. If, however, by the Laws, he is specifically deprived of that right and made ineligible to the Crown, save under two conditions, I assume the presumption would be reversed, and he would be disqualified for the Succession until he had proved, by the Laws themselves, his rehabilitation?”

The words were addressed to Epping, and the answer was prompt and to the point: