Title: Discoveries Among the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon

Author: Austen Henry Layard

Release date: June 2, 2012 [eBook #39897]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

G P PUTNAM & Co NEW YORK.

NORTH-EASTERN FACADE AND GRAND ENTRANCE OF SENNACHERIBS PALACE KOUYUNJIK

Restored from a Sketch by J Fergusson, Esqre

DISCOVERIES

AMONG THE RUINS OF

NINEVEH AND BABYLON;

WITH

TRAVELS IN ARMENIA, KURDISTAN, AND THE DESERT:

BEING THE RESULT OF A SECOND EXPEDITION

UNDERTAKEN FOR

THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

BY

AUSTEN H. LAYARD, M. P.

AUTHOR OF “NINEVEH AND ITS REMAINS.”

| “For thou hast made of a city an heap; of a defenced city a ruin; a palace of strangers to be no city; it shall never be built.”—Isaiah xxv. 2. |

ABRIDGED FROM THE LARGER WORK.

NEW-YORK:

G. P. PUTNAM & CO., 10 PARK PLACE.

1853.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1853, by

GEORGE P. PUTNAM & CO.,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the Southern District of

New-York.

The present Abridgment of Mr. Layard’s Discoveries among the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon has been prepared with much care and attention; and a studious effort has been made to retain, in the Author’s own language, the more interesting and important portions of the larger work. This has been done by omitting the greater part of the minute details of the descriptions of sculpture and monumental remains, by dispensing with several tables of cuneiform characters, elaborate examinations of various matters by scientific men, &c. At the same time there has been retained every thing relating to the Bible, and illustrating and enforcing its truth and the fulfilment of prophecy; as well as the genial and life-like portraitures of Arab habits and customs, and the pleasant adventures of the Author in regions that to most men seem like fairy land.

[Pg 4]For general use it is confidently hoped and believed that the present volume will be more widely serviceable than the larger work, from its expensiveness and size, could possibly be.

S.

New-York, May 2d, 1853.

Since the publication of my first work on the discoveries at Nineveh much progress has been made in deciphering the cuneiform character, and the contents of many highly interesting and important inscriptions have been given to the public. For these additions to our knowledge we are mainly indebted to the sagacity and learning of two English scholars, Col. Rawlinson and the Rev. Dr. Hincks. In making use of the results of their researches, I have not omitted to own the sources from which my information has been derived. I trust, also, that I have in no instance availed myself of the labors of other writers, or of the help of friends, without due acknowledgments. I have endeavored to assign to every one his proper share in the discoveries recorded in these pages.

I am aware that several distinguished French scholars, amongst whom I may mention my friends, M. Botta and M. de Saulcy, have contributed to the successful deciphering of the Assyrian inscriptions. Unfortunately I have been unable to consult the published results of their investigations. If, therefore, I should have overlooked in any instance their claims to prior discovery, I have to express my regret for an error arising from ignorance, and not from any unworthy national prejudice.

[Pg 6]Doubts appear to be still entertained by many eminent critics as to the progress actually made in deciphering the cuneiform writing. These doubts may have been confirmed by too hasty theories and conclusions, which, on subsequent investigation, their authors have been the first to withdraw. But the unbiased inquirer can scarcely now reject the evidence which can be brought forward to confirm the general accuracy of the interpretations of the inscriptions. Had they rested upon a single word, or an isolated paragraph, their soundness might reasonably have been questioned; when, however, several independent investigators have arrived at the same results, and have not only detected numerous names of persons, nations, and cities in historical and geographical series, but have found them mentioned in proper connection with events recorded by sacred and profane writers, scarcely any stronger evidence could be desired. The reader, I would fain hope, will come to this conclusion when I treat of the contents of the various records discovered in the Assyrian palaces.

To Mr. Thomas Ellis, who has added so much to the value of my work by his translations of inscriptions on Babylonian bowls, now for the first time, through his sagacity, deciphered; to those who have assisted me in my labors, and especially to my friend and companion, Mr. Hormuzd Rassam, to the Rev. Dr. Hincks, to the Rev. S. C. Malan, who has kindly allowed me the use of his masterly sketches, to Mr. Fergusson, Mr. Scharf, and to Mr. Hawkins, Mr. Birch, Mr. Vaux, and the other officers of the British Museum, I beg to express my grateful thanks and acknowledgments.

London, January, 1853.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE | |

| N. E. Façade and Entrance to Sennacherib’s Palace, restored | Frontispiece. |

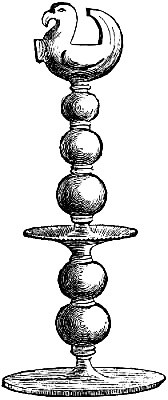

| The Melek Taous or Copper Bird of the Yezidis | 46 |

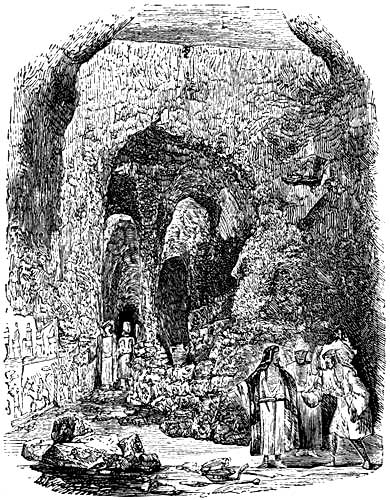

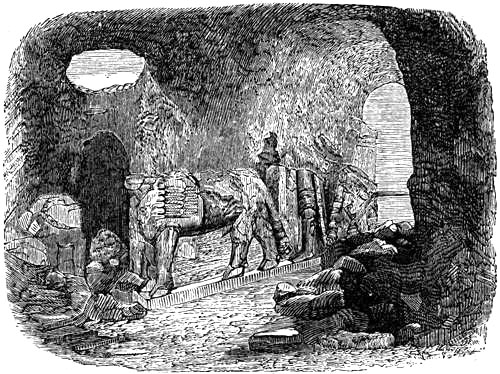

| Subterranean Excavations at Kouyunjik | 61 |

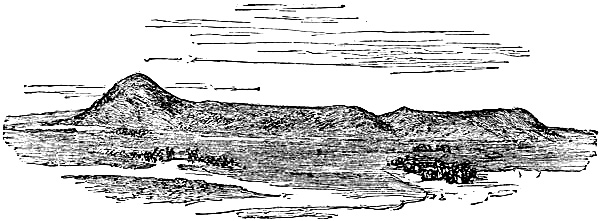

| Mound of Nimroud | 84 |

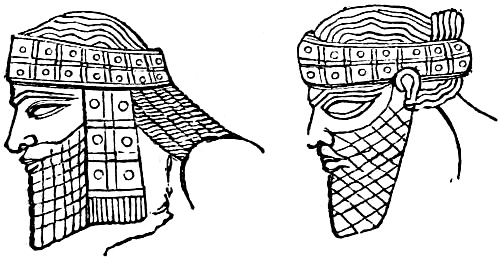

| Head-dress of Captives employed by Assyrians in moving Bull (Kouyunjik) | 92 |

| Village with Conical Roofs near Aleppo | 97 |

| Bulls with Historical Inscriptions of Sennacherib (Kouyunjik) | 113 |

| Sennacherib on his Throne before Lachish | 129 |

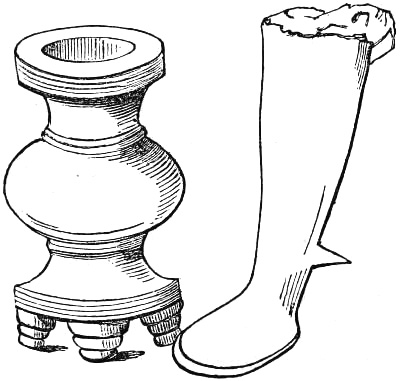

| Feet of Tripods in Bronze and Iron | 151 |

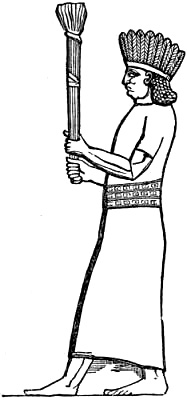

| A Captive (of the Tokkari?) Kouyunjik | 193 |

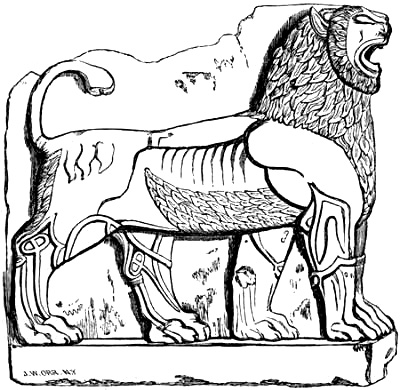

| Lion discovered at Arban | 231 |

| Volcanic Cone of Koukab | 268 |

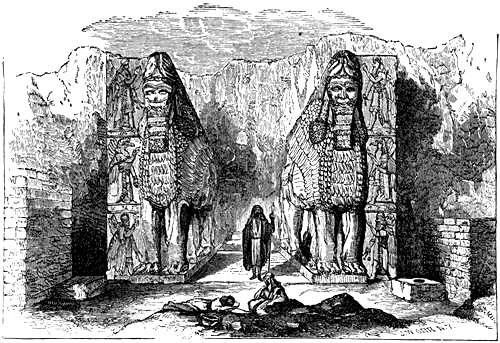

| Entrance to small Temple (Nimroud) | Facing page 288 |

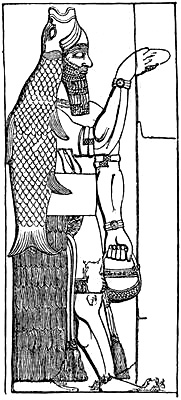

| Fish-God at Entrance to small Temple (Nimroud) | 289 |

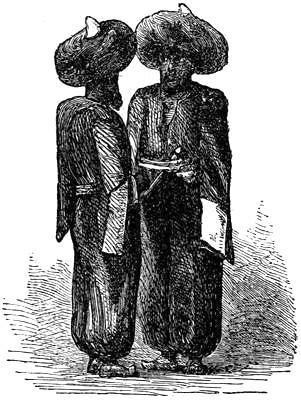

| Kurds of Wan | 320 |

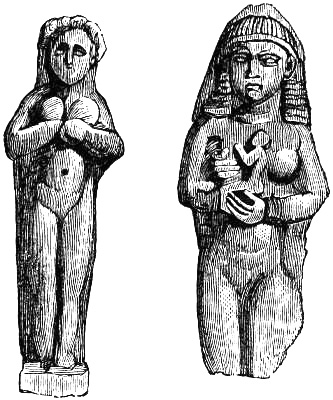

| Figures of Assyrian Venus in baked Clay | 383 |

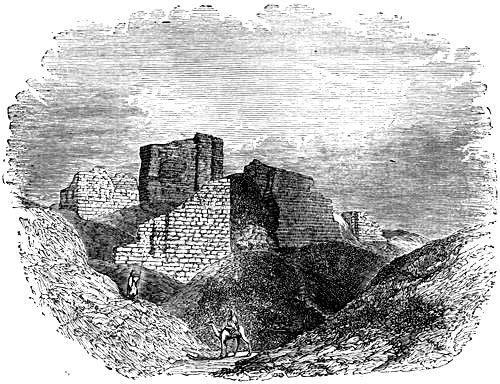

| The Mujelibé or Kasr (from Rich) | 392 |

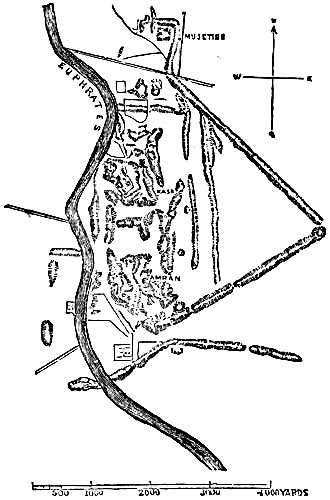

| Plan of part of the Ruins of Babylon on the Eastern Bank of the Euphrates | 396 |

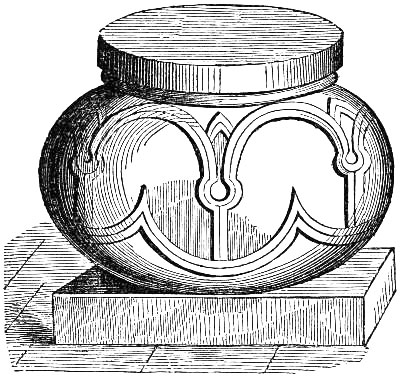

| Jug of Soapstone, from the Mound of Babel | 409 |

| Assyrian Pedestal, from Kouyunjik | 477 |

| Part of Colossal Head, from Kouyunjik | 481 |

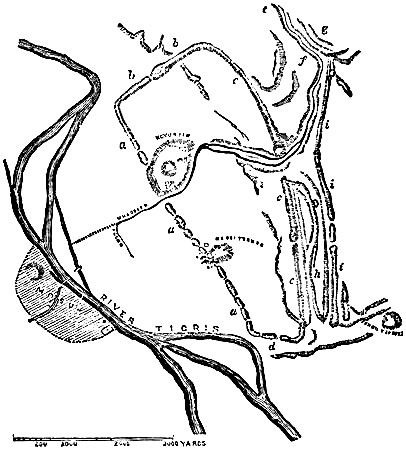

| Plan of the Inclosure Walls and Ditches at Kouyunjik | 536 |

| Map of Assyria, etc. General Map of Mesopotamia |

at the end. |

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Trustees of the British Museum resume Excavations at Nineveh.—Departure from Constantinople.—Description of our Party.—Roads from Trebizond to Erzeroom.—Description of the Country.—Armenian Churches.—Erzeroom.—Reshid Pasha.—The Dudjook Tribes.—Shahan Bey.—Turkish Reform.—Journey through Armenia.—An Armenian Bishop.—The Lakes of Shailu and Nazik | 15 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Lake of Wan.—Akhlat.—Tatar Tombs.—Ancient Remains.—A Dervish.—A Friend.—The Mudir.—Armenian Remains.—An Armenian Convent and Bishop.—Journey to Bitlis.—Nimroud Dagh.—Bitlis.—Journey to Kherzan.—Yezidi Village | 30 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Reception by the Yezidis.—Village of Guzelder.—Triumphal March to Redwan.—Redwan.—Armenian Church.—The Melek Taous, or Brazen Bird.—Tilleh.—Valley of the Tigris.—Bas-reliefs.—Journey to Dereboun.—To Semil.—Abde Agha.—Journey to Mosul.—The Yezidi Chiefs.—Arrival at Mosul.—Xenophon’s March from the Zab to the Black Sea | 42 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| State of the Excavations on my Return to Mosul.—Discoveries at Kouyunjik.—Tunnels in the Mound.—Bas-reliefs representing Assyrian Conquests.—A Well.—Siege of a City.—Nature of Sculptures at Kouyunjik.—Arrangement for Renewal of Excavations.—Description of Mound.—Kiamil Pasha.—Visit to Sheikh Adi.—Yezidi Ceremonies.—Sheikh Jindi.—Yezidi Meeting.—Dress of the Women.—Bavian.—Doctrines of the Yezidi.—Jerraiyah.—Return to Mosul | 61 |

| [Pg 10] | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Renewal of Excavations at Kouyunjik.—First Visit to Nimroud.—State of Ruins.—Renew Excavations in Mound.—Visit of Col. Rawlinson.—Mr. H. Rassam.—The Jebour Workmen at Kouyunjik.—Discoveries at Kouyunjik.—Sculptures representing moving of great Stones and Winged Bulls.—Methods adopted.—Epigraphs on Bas-reliefs of moving Bulls.—Sculptures representing Invasion of Mountainous Country, and Sack of City.—Discovery of Gateway.—Excavation in high conical Mound at Nimroud.—Discovery of Wall of Stone.—Visit to Khorsabad.—Discovery of Slab.—State of the Ruins.—Futhliyah.—Baazani.—Baasheikhah | 84 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Discovery of Grand Entrance to the Palace of Kouyunjik.—Of the Name of Sennacherib in the Inscriptions.—The Records of that King in the Inscriptions on the Bulls.—An Abridged Translation of them.—Name of Hezekiah.—Account of Sennacherib’s Wars with the Jews.—Dr. Hincks and Col. Rawlinson.—The Names of Sargon and Shalmaneser.—Discovery of Sculptures at Kouyunjik, representing the Siege of Lachish.—Description of the Sculptures.—Discovery of Clay Seals.—Of Signets of Egyptian and Assyrian Kings.—Cartouche of Sabaco.—Name of Essarhaddon.—Confirmation of Historical Records of the Bible.—Royal Cylinder of Sennacherib | 113 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Road open for removal of Winged Lions.—Discovery of Vaulted Drain.—Of other Arches.—Of Painted Bricks.—Attack of the Tai on the Village of Nimroud.—Visit to the Howar.—Description of the Encampment of the Tai.—The Plain of Shomamok.—Sheikh Faras.—Wali Bey.—Return to Nimroud | 137 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Contents of newly-discovered Chamber.—A Well.—Large Copper Caldrons.—Bells, Rings, and other Objects in Metal.—Tripods.—Caldrons and large Vessels.—Bronze Bowls, Cups, and Dishes.—Description of the Embossings upon them.—Arms and Armour.—Shields.—Iron Instruments.—Ivory Remains.—Bronze Cubes inlaid with Gold.—Glass Bowls.—Lens.—The Royal Throne | 150 |

| [Pg 11] | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Visit to the Winged Lions by Night.—The Bitumen Springs.—Removal of the Winged Lions to the River.—Floods at Nimroud.—Yezidi Marriage Festival.—Baazani.—Visit to Bavian.—Site of the Battle of Arbela.—Description of Rock-Sculptures.—Inscriptions.—The Shabbaks | 167 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Visit to Kalah Sherghat prevented.—Visit to Shomamok.—Keshaf.—The Howar.—A Bedouin.—His Mission.—Descent of Arab Horses.—Their Pedigree.—Ruins of Mokhamour.—The Mound of the Kasr.—Plain of Shomamok.—The Gla or Kalah.—Xenophon and the Ten Thousand.—A Wolf.—Return to Nimroud and Mosul.—Discoveries at Kouyunjik.—Description of the Bas-reliefs | 182 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Preparations for a Journey to the Khabour.—Sculptures discovered there.—Sheikh Suttum.—His Rediff.—Departure from Mosul.—First Encampment.—Abou Khameera.—A Storm.—Tel Ermah.—A Stranger.—Tel Jemal.—The Chief of Tel Afer.—A Sunset in the Desert.—A Jebour Encampment.—The Belled Sinjar.—The Sinjar Hill.—Mirkan.—Bukra.—The dress of the Yezidis.—The Shomal.—Ossofa.—Aldina.—Return to the Belled.—A Snake-Charmer.—Journey continued in the Desert.—Rishwan.—Encampment of the Boraij.—Dress of Arab Women.—Rathaiyah.—A Deputation from the Yezidis.—Arab Encampments.—The Khabour.—Mohammed Emin.—Arrival at Arban | 195 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Arban.—Our Encampment.—Suttum and Mohammed Emin.—Winged Bulls discovered.—Excavations commenced.—Their Results.—Discovery of Small Objects—of Second Pair of Winged Bulls.—of Lion—of Chinese Bottle—of Vase—of Egyptian Scarabs—of Tombs.—The Scene of the Captivity | 225 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Residence at Arban.—Mohammed Emin’s Tent.—The Agaydat.—our Tents.—Bread-baking.—Food of the Bedouins.—Thin Bread.—The Produce of their Flocks.—Diseases amongst them.—Their Remedies.—The Deloul or Dromedary.—Bedouin Warfare.—Suttum’s First Wife.—A Storm.—Turtles.—Lions.—A Bedouin Robber.—Beavers.—Ride to Ledjmiyat—A Plundering Expedition.—Loss of a Hawk.—Ruins of Shemshani.—Return to Arban.—Visit to Moghamis | 237 |

| [Pg 12] | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Leave Arban.—The Banks of the Khabour.—Artificial Mounds.—Mijwell.—The Cadi of the Bedouins.—The Thar or Blood-Revenge.—Caution of Arabs.—A natural Cavern.—An extinct volcano.—The Confluents of the Khabour.—Bedouin Marks.—Suleiman Agha.—Encampment at Um-Jerjeh.—The Turkish Irregular Cavalry.—Mound of Mijdel.—Ruins on the Khabour.—Mohammed Emin leaves us.—Visit to Kurdish Tents and Harem.—The Milli Kurds.—The Family of Rishwan.—Arab Love-making.—The Dakheel.—Bedouin Poets and Poetry.—Turkish Cavalry Horses | 252 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Departure from the Khabour.—Arab Sagacity.—The Hol.—The Lake of Khatouniyah.—Return of Suttum.—Encampment of the Shammar.—Arab Horses—their Breeds—their Value—their Speed.—Sheikh Ferhan.—Yezidi Villages.—Falcons.—An Alarm.—Abou Maria.—Eski Mosul.—Arrival at Mosul.—Return of Suttum to the Desert | 268 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Discoveries at Kouyunjik.—Procession of Figures bearing Fruit and Game.—Locusts.—Led Horses.—An Assyrian Campaign.—Dagon, or the Fish-God.—The Chambers of Records.—Inscribed Clay Tablets.—Return to Nimroud.—Effects of the Flood.—Discoveries.—Small Temple under high Mound.—The Evil Spirit.—Fish-God.—Fine Bas-relief of the King.—Extracts from the Inscription.—Great inscribed Monolith.—Extracts from the Inscription.—Cedar Beams.—Small Objects.—Second Temple.—Marble Figure and other Objects | 280 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Summer.—Encampment at Kouyunjik.—Visitors.—Mode of Life.—Departure for the Mountains.—Akra.—Rock-Tablets at Gunduk.—District of Zibari.—Namet Agha.—District of Shirwan—of Baradost—of Gherdi—of Shemdina.—Mousa Bey.—Nestorian Bishop.—Convent of Mar Hananisho.—Dizza.—An Albanian Friend.—Bash-Kalah.—Izzet Pasha.—A Jewish Encampment.—High Mountain Pass.—Mahmoudiyah.—First View of Wan | 300 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Mehemet Pasha.—Description of Wan.—Its History.—Improvement in its Condition.—The Armenian Bishop.—The Cuneiform Inscriptions.—The [Pg 13]Caves of Khorkhor.—The Meher Kapousi.—A Tradition.—Observations on the Inscriptions.—The Bairam.—An American School.—The American Missions.—Protestant Movement in Turkey.—Amikh.—The Convent of Yedi Klissia | 320 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Leave Wan.—The Armenian Patriarch.—The Island of Akhtamar.—An Armenian Church.—History of the Convent.—Pass into Mukus.—The District of Mukus—of Shattak—of Nourdooz.—A Nestorian Village.—Encampments.—Mount Ararat.—Mar Shamoun.—Julamerik.—Valley of Diz.—Pass into Jelu.—Nestorian District of Jelu.—An ancient Church.—The Bishop.—District of Baz—of Tkhoma.—Return to Mosul | 337 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Discoveries at Kouyunjik during the Summer.—Description of the Sculptures.—Capture of Cities on a great River.—Pomp of Assyrian King.—Alabaster Pavement.—Conquest of Tribes inhabiting a Marsh.—Their Wealth.—Chambers with Sculptures belonging to a new King.—Description of the Sculptures.—Conquest of the People of Susiana.—Portrait of the King.—His guards and Attendants.—The City of Shushan.—Captive Prince.—Musicians.—Captives put to the Torture.—Artistic Character of the Sculptures.—An Inclined Passage.—Two small Chambers.—Colossal Figures.—More Sculptures | 356 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Preparations for leaving Nineveh.—Departure for Babylon.—Descent of the River.—Tekrit.—The State of the Rivers of Mesopotamia.—Commerce upon them.—Turkish Roads.—The Plain of Dura.—The Naharwan.—Samarrah.—Kadesia.—Palm Groves.—Kathimain.—Approach to Baghdad.—The City.—Arrival.—Dr. Ross.—A British Steamer.—Modern Baghdad.—Tel Mohammed.—Departure for Babylon.—A Persian Prince.—Abde Pasha’s Camp.—Eastern Falconry.—Hawking the Gazelle.—Approach to Babylon.—The Ruins.—Arrival at Hillah | 372 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| The Chiefs of Hillah.—Present of Lions.—The Son of the Governor.—Description of the Town.—Zaid.—The Ruins of Babylon.—Changes in the Course of the Euphrates.—The Walls.—Visit to the Birs Nimroud.—Description of the Ruin.—View from it.—Excavations and Discoveries in the Mound of Babel.—In the Mujelibé or Kasr.—The Tree Athelé.—Excavations in the Ruin of Amran.—Bowls, with Inscriptions in Hebrew and Syriac Characters.—The Jews of Babylonia | 392 |

| [Pg 14] | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| State of the Ruins of Babylon.—Cause of the Disappearance of Buildings.—Nature of original Edifices.—Babylonian Bricks.—The History of Babylon.—Its Fall.—Its Remarkable Position.—Commerce.—Canals and Roads.—Skill of Babylonians in the Arts.—Engraved Gems.—Corruption of Manners, and consequent Fall of the City.—The Mecca Pilgrimage.—Sheikh Ibn Reshid.—The Gebel Shammar.—The Mounds of El Hymer—of Anana | 419 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Ruins in Southern Mesopotamia.—Departure from Hillah.—Sand-Hills.—Villages in the Jezireh.—Sheikh Karboul.—Ruins.—First View of Niffer.—The Marshes.—Arab Boats.—Arrive at Souk-el-Afaij.—Sheikh Agab.—Town of the Afaij.—Description of the Ruins of Niffer.—Excavations in the Mounds.—Discovery of Coffins—of various Relics.—Mr. Loftus’ Discoveries at Wurka.—The Arab Tribes.—Wild Beasts.—Lions.—Customs of the Afaij.—Leave the Marshes.—Return to Baghdad.—A Mirage | 437 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Preparations for Departure.—Sahiman.—Plunder of his Camels.—Leave Baghdad.—Journey through Mesopotamia.—Early Arab Remains.—The Median Wall.—Tekrit.—Horses stolen.—Instances of Bedouin Honesty.—Excavations at Kalah Sherghat.—Reach Mosul.—Discoveries during Absence.—New Chambers at Kouyunjik.—Description of Bas-reliefs.—Extent of the Ruins explored.—Bases of Pillars.—Small objects.—Roman Coins struck at Nineveh.—Hoard of Denarii.—Greek Relics.—Absence of Assyrian Tombs.—Fragment with Egyptian Characters.—Assyrian Relics.—Remains beneath the Tomb of Jonah.—Discoveries at Shereef-Khan—at Nimroud.—Assyrian Weights.—Engraved Cylinders | 463 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Results of the Discoveries to Chronology and History.—Names of Assyrian Kings in the Inscriptions.—A Date fixed.—The Name of Jehu.—The Obelisk King.—The earlier Kings—Sardanapalus.—His Successors.—Pul, or Tiglath Pileser.—Sargon.—Sennacherib.—Essarhaddon.—The last Assyrian Kings.—Tables of proper Names in the Assyrian Inscriptions.—Antiquity of Nineveh.—Of the Name of Assyria.—Illustrations of Scripture.—State of Judæa and Assyria compared.—Political Condition of the Empire.—Assyrian Colonies.—Prosperity of the Country.—Religion.—Extent of Nineveh.—Assyrian Architecture—Compared with Jewish.—Palace of Kouyunjik restored.—Platform at Nimroud restored.—The Assyrian fortified Inclosures.—Description of Kouyunjik.—Conclusion | 491 |

NINEVEH AND BABYLON.

THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM RESUME EXCAVATIONS AT NINEVEH.—DEPARTURE FROM CONSTANTINOPLE.—DESCRIPTION OF OUR PARTY.—ROADS FROM TREBIZOND TO ERZEROOM.—DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY.—ARMENIAN CHURCHES.—ERZEROOM.—RESHID PASHA.—THE DUDJOOK TRIBES.—SHAHAN BEY.—TURKISH REFORM.—JOURNEY THROUGH ARMENIA.—AN ARMENIAN BISHOP.—THE LAKES OF SHAILU AND NAZIK.

After a few months’ residence in England during the year 1848, to recruit a constitution worn by long exposure to the extremes of an Eastern climate, I received orders to proceed to my post at Her Majesty’s Embassy in Turkey. The Trustees of the British Museum did not, at that time, contemplate further excavations on the site of ancient Nineveh. Ill health and limited time had prevented me from placing before the public, previous to my return from the East, the results of my first researches, with the illustrations of the monuments and copies of the inscriptions recovered from the ruins of Assyria. They were not published until some time after my departure, and did not consequently receive that careful superintendence and revision necessary to works of this nature. It was at [Pg 16]Constantinople that I first learnt the general interest felt in England in the discoveries, and that they had been universally received as fresh illustrations of Scripture and prophecy, as well as of ancient history sacred and profane.

And let me here, at the very outset, gratefully acknowledge that generous spirit of English criticism which overlooks the incapacity and shortcomings of the laborer when his object is worthy of praise, and that object is sought with sincerity and singleness of purpose. The gratitude, which I deeply felt for encouragement rarely equalled, could be best shown by cheerfully consenting, without hesitation, to the request made to me by the Trustees of the British Museum, urged by public opinion, to undertake the superintendence of a second expedition into Assyria. Being asked to furnish a plan of operations, I stated what appeared to me to be the course best calculated to produce interesting and important results, and to enable us to obtain the most accurate information on the ancient history, language, and arts, not only of Assyria, but of its sister kingdom, Babylonia. Perhaps my plan was too vast and general to admit of performance or warrant adoption. I was merely directed to return to the site of Nineveh, and to continue the researches commenced amongst its ruins.

Arrangements were hastily, and of course inadequately, made in England. The assistance of a competent artist was most desirable, to portray with fidelity those monuments which injury and decay had rendered unfit for removal. Mr. F. Cooper was selected by the Trustees of the British Museum to accompany the expedition in this capacity. Mr. Hormuzd Rassam, already well known to many of my readers for the share he had taken in my first discoveries, quitted England with him. They both joined me at Constantinople. Dr. Sandwith, an English [Pg 17]physician on a visit to the East, was induced to form one of our party. One Abd-el-Messiah, a Catholic Syrian of Mardin, an active and trustworthy servant during my former residence in Assyria, was fortunately at this time in the capital, and again entered my service: my other attendants were Mohammed Agha, a cawass, and an Armenian named Serkis. The faithful Bairakdar, who had so well served me during my previous journey, had accompanied the English commission for the settlement of the boundaries between Turkey and Persia; with the understanding, however, that he was to meet me at Mosul, in case I should return. Cawal Yusuf, the head of the Preachers of the Yezidis, with four chiefs of the districts in the neighbourhood of Diarbekir, who had been for some months in Constantinople, completed my party.

In consequence of the severe and unjust treatment of the Yezidis, in compelling them to serve in the Turkish army, Hussein Bey and Sheikh Nasr, the chiefs of the whole community, hearing that I was at Constantinople, sent a deputation to the Sultan. Through Sir Stratford Canning’s friendly interference, a firman was obtained, and they were freed from all illegal impositions for the future.

Our arrangements were complete by the 28th of August (1849), and on that day we left the Bosphorus by an English steamer bound for Trebizond. The size of my party and its consequent incumbrances rendering a caravan journey absolutely necessary, I determined to avoid the usual tracks, and to cross eastern Armenia and Kurdistan, both on account of the novelty of part of the country in a geographical point of view, and its political interest as having only recently been brought under the immediate control of the Turkish government.

We disembarked at Trebizond on the 31st, and on the[Pg 18] following day commenced our land journey. The country between this port and Erzeroom has been frequently traversed and described. Through it pass the caravan routes connecting Persia with the Black Sea, the great lines of intercourse and commerce between Europe and central Asia. The roads usually frequented are three in number. The summer, or upper, road is the shortest, but is most precipitous, and, crossing very lofty mountains, is closed after the snows commence; it is called Tchaïrler, from its fine upland pastures, on which the horses are usually fed when caravans take this route. The middle road has few advantages over the upper, and is rarely followed by merchants, who prefer the lower, although making a considerable detour by Gumish Khaneh, or the Silver Mines. The three unite at the town of Baiburt, midway between the sea and Erzeroom. Although an active and daily increasing trade is carried on by these roads, no means whatever have until recently been taken to improve them. They consist of mere mountain tracks, deep in mud or dust according to the season of the year. The bridges have been long permitted to fall into decay, and commerce is frequently stopped for days by the swollen torrent or fordless stream. This has been one of the many evil results of the system of centralization so vigorously commenced by Sultan Mahmoud, and so steadily carried out during the present reign.

Since my visit to Trebizond a road for carts has been commenced, which is to lead from that port to the Persian frontiers; but it will, probably, like other undertakings of the kind be abandoned long before completed, or if ever completed will be permitted at once to fall to ruin from the want of common repair. And yet the Persian trade is one of the chief sources of revenue of the Turkish empire, and unless conveniences are afforded for its [Pg 19]prosecution, will speedily pass into other hands. The southern shores of the Black Sea, twelve years ago rarely visited by a foreign vessel, are now coasted by steamers belonging to three companies, which touch nearly weekly at the principal ports; and there is commerce and traffic enough for more. The want of proper harbors is a considerable drawback in the navigation of a sea so unstable and dangerous as the Euxine. Trebizond has a mere roadstead, and from its position is otherwise little calculated for a great commercial port, which, like many other places, it has become rather from its hereditary claims as the representative of a city once famous, than from any local advantages. The only harbour on the southern coast is that of Batoun, nor is there any retreat for vessels on the Circassian shores. This place is therefore probably destined to become the emporium of trade, both from its safe and spacious port, and from the facility it affords of internal communication with Persia, Georgia, and Armenia.

At the back of Trebizond, as indeed along the whole of this singularly bold and beautiful coast, the mountains rise in lofty peaks, and are wooded with trees of enormous growth and admirable quality, furnishing an unlimited supply of timber for commerce or war. Innumerable streams force their way to the sea through deep and rocky ravines. The more sheltered spots are occupied by villages and hamlets, chiefly inhabited by a hardy and industrious race of Greeks. In spring the choicest flowers perfume the air, and luxuriant creepers clothe the limbs of gigantic trees. In summer the richest pastures enamel the uplands, and the inhabitants of the coasts drive their flocks and herds to the higher regions of the hills.

Our journey to Erzeroom was performed without incident. A heavy and uninterrupted rain for two days tried the patience and temper of those who for the first time[Pg 20] encountered the difficulties and incidents of Eastern travel. The only place of any interest, passed during our ride, was a small Armenian village, the remains of a larger, with the ruins of three early Christian churches, or baptisteries. These remarkable buildings, of which many examples exist, belong to an order of architecture peculiar to the most eastern districts of Asia Minor and to the ruins of ancient Armenian cities, on the borders of Turkey and Persia. There are many interesting questions connected with this Armenian architecture which will deserve elucidation. From it was probably derived much that passed into the Gothic, whilst the Tatar conquerors of Asia Minor adopted it, as will be hereafter seen, for their mausoleums and places of worship. It is peculiarly elegant both in its decorations, its proportions, and the general arrangement of the masses, and might with advantage be studied by the modern architect. Indeed, Asia Minor contains a mine of similar materials unexplored and almost unknown.

We reached Erzeroom on the 8th, and were most hospitably received by the British consul, Mr. Brant, a gentleman who has long, well, and honorably sustained our influence in this part of Turkey, and who was the first to open an important field for our commerce in Asia Minor. With him I visited the commander-in-chief of the Turkish forces in Anatolia, who had recently returned from a successful expedition against the wild mountain tribes of central Armenia. Reshid Pasha, known as the “Guzlu,” or the “Wearer of Spectacles,” enjoyed the advantages of an European education, and had already distinguished himself in the military career. With a knowledge of the French language he united a taste for European literature, which, during his numerous expeditions into districts unknown to western travellers, had led him to examine their[Pg 21] geographical features, and to make inquiries into the manners and religion of their inhabitants. His last exploit had been the subjugation of the tribes inhabiting the Dudjook Mountains, to the south-west of Erzeroom, long in open rebellion against the Sultan. The account he gave me of the country and its occupants, though curious and interesting, is not perhaps to be strictly relied on, but a district hitherto inaccessible may possibly contain the remains of ancient races, monuments of antiquity, and natural productions of sufficient importance to merit the attention of the traveller in Asia Minor.

The city of Erzeroom is rapidly declining in importance, and is almost solely supported by the Persian transit trade. It would be nearly deserted if that traffic were to be thrown into a new channel by the construction of the direct road from Batoun to the Persian frontiers. It contains no buildings of any interest, with the exception of a few ruins of monuments of early Mussulman domination; and the modern Turkish edifices, dignified with the names of palaces and barracks, are meeting the fate of neglected mud.

The districts of Armenia and Kurdistan, through which lay our road from Erzeroom to Mosul, are sufficiently unknown and interesting to merit more than a casual mention. Our route by the lake of Wan, Bitlis, and Jezirah was nearly a direct one. It had been but recently opened to caravans. The haunts of the last of the Kurdish rebels were on the shores of this lake. After the fall of the most powerful of their chiefs, Beder Khan Bey, they had one by one been subdued and carried away into captivity. Only a few months had, however, elapsed since the Beys of Bitlis, who had longest resisted the Turkish arms, had been captured. With them rebellion was extinguished for the time in Kurdistan.

[Pg 22]Our caravan consisted of my own party, with the addition of a muleteer and his two assistants, natives of Bitlis, who furnished me with seventeen horses and mules from Erzeroom to Mosul. The first day’s ride, as is customary in the East, where friends accompany the traveller far beyond the city gates, and where the preparations for a journey are so numerous that everything cannot well be remembered, scarcely exceeded nine miles. We rested for the night in the village of Guli, whose owner, one Shahan Bey, had been apprised of my intended visit. He had rendered his newly-built house as comfortable as his means would permit for our accommodation, and, after providing us with an excellent supper, passed the evening with me. Descended from an ancient family of Dereh-Beys, he had inherited the hospitality and polished manners of a class now almost extinct, in consequence of the policy pursued by the Turkish sultans, Mahmoud and Abdul-Medjid, to break down the great families and men of middle rank, who were more or less independent, and to consolidate and centralize the vast Ottoman empire.

It is customary to regard these old Turkish lords as inexorable tyrants—robber chiefs, who lived on the plunder of travellers and of their subjects. That there were many who answered to this description cannot be denied; but they were, I believe, exceptions. Amongst them were some rich in virtues and high and noble feeling. It has been frequently my lot to find a representative of this nearly extinct class in some remote and almost unknown spot in Asia Minor or Albania. I have been received with affectionate warmth at the end of a day’s journey by a venerable Bey or Agha in his spacious mansion, now fast crumbling to ruin, but still bright with the remains of rich, yet tasteful, oriental decoration; his long beard, white as snow, falling low on his breast; his many-folded[Pg 23] turban shadowing his benevolent yet manly countenance, and his limbs enveloped in the noble garments rejected by the new generation; his hall open to all comers, the guest neither asked from whence he came or whither he was going, dipping his hands with him in the same dish; his servants, standing with reverence before him, rather his children than his servants; his revenues spent in raising fountains[1] on the wayside for the weary traveller, or in building caravanserais on the dreary plain; not only professing, but practising all the duties and virtues enjoined by the Koran, which are Christian duties and virtues too; in his manners, his appearance, his hospitality, and his faithfulness, a perfect model for a Christian gentleman. The race is fast passing away, and I feel grateful in being able to testify, with a few others, to its existence once, against prejudice, intolerance, and so-called reform.

Our host at Guli, Shahan Bey, although not an old man, was a very favorable specimen of the class I have described. He was truly, in the noble and expressive phraseology of the East, an “Ojiak Zadeh,” “a child of the hearth,” a gentleman born. His family had originally migrated from Daghistan, and his father, a pasha, had distinguished himself in the wars with Russia. He entertained me with animated accounts of feuds between his ancestors and the neighbouring chiefs; and steadily refused to allow any recompense to himself or his servants for his hospitality.

From Guli we crossed a high range of mountains, [Pg 24]running nearly east and west, by a pass called Ali-Baba, or Ala-Baba, enjoying from the summit an extensive view of the plain of Pasvin, once one of the most thickly peopled and best cultivated districts in Armenia. The Christian inhabitants were partly induced by promises of land and protection, and partly compelled by force, to accompany the Russian army into Georgia after the end of the last war with Turkey. By similar means, that part of the Pashalic of Erzeroom adjoining the Russian territories was almost stripped of its most industrious Armenian population. To the south of us rose the snow-capped mountains of the Bin-Ghiul, or the “Thousand Lakes,” in which the Araxes and several confluents of the Euphrates have their source. We descended from the pass into undulating and barren downs. The villages, thinly scattered over the low hills, were deserted by their inhabitants, who, at this season of the year, pitch their tents and seek pasture for their flocks in the uplands.

Next day we continued our journey amongst undulating hills, abounding in flocks of the great and lesser bustard. Innumerable sheep-walks branched from the beaten path, a sign that villages were near; but, like those we had passed the day before, they had been deserted for the yilaks, or summer pastures. These villages are still such as they were when Xenophon traversed Armenia. “Their houses,” says he, “were under ground; the mouth resembling that of a well, but spacious below: there was an entrance dug for the cattle, but the inhabitants descended by ladders. In these houses were goats, sheep, cows, and fowls, with their young.”[2] The low hovels, mere holes in the hill-side, and the common refuge of man, poultry, and cattle, cannot be seen from any [Pg 25]distance, and they are purposely built away from the road, to escape the unwelcome visits of travelling government officers and marching troops. It is not uncommon for a traveller to receive the first intimation of his approach to a village by finding his horse’s fore feet down a chimney, and himself taking his place unexpectedly in the family circle through the roof. Numerous small streams wind among the valleys, marking by meandering lines of perpetual green their course to the Arras, or Araxes. We crossed that river about mid-day by a ford not more than three feet deep, but the bed of the stream is wide, and after rains, and during the spring, is completely filled by an impassable torrent.

During the afternoon we crossed the western spur of the Tiektab Mountains, a high and bold range with three well defined peaks, which had been visible from the summit of the Ala-Baba pass. From the crest we had the first view of Subhan, or Sipan, Dagh, a magnificent conical peak, covered with eternal snow, and rising abruptly from the plain to the north of Lake Wan. It is a conspicuous and beautiful object from every part of the surrounding country. We descended into the wide and fertile plain of Hinnis. The town was just visible in the distance, but we left it to the right, and halted for the night in the large Armenian village of Kosli, after a ride of more than nine hours. I was received at the guesthouse (a house reserved for travellers, and supported by joint contributions), with great hospitality by one Misrab Agha, a Turk, to whom the village formerly belonged as Spahilik or military tenure, and who, deprived of his hereditary rights, had now farmed its revenues. He hurried with a long stick among the low houses, and heaps of dry dung, piled up in every open space for winter fuel, collecting fowls, curds, bread, and barley, abusing at the[Pg 26] same time the tanzimat, which compelled such exalted travellers as ourselves, he said, “to pay for the provisions we condescended to accept.” The inhabitants were not, however, backward in furnishing us with all we wanted, and the flourish of Misrab Agha’s stick was only the remains of an old habit. I invited him to supper with me, an invitation he gladly accepted, having himself contributed a tender lamb roasted whole towards our entertainment.

The inhabitants of Kosli could scarcely be distinguished either by their dress or by their general appearance from the Kurds. They seemed prosperous and were on the best terms with the Mussulman farmer of their tithes. The village stands at the foot of the hills forming the southern boundary of the plain of Hinnis, through which flows a branch of the Murad Su, or Lower Euphrates. We forded this river near the ruins of a bridge at Kara Kupri. The plain is generally well cultivated, the principal produce being corn and hemp. The villages, which are thickly scattered over it, have the appearance of extreme wretchedness, and, with their low houses and heaps of dried manure piled upon the roofs and in the open spaces around, look more like gigantic dunghills than human habitations. The Kurds and Armenian Christians, both hardy and industrious races, are pretty equally divided in numbers, and live sociably in the same filth and misery.

We left the plain of Hinnis by a pass through the mountain range of Zernak. On reaching the top of the pass we had an interrupted view of the Subhan Dagh. From the village of Karagol, where we halted for the night, it rose abruptly before us. This magnificent peak, with the rugged mountains of Kurdistan, the river Euphrates winding through the plain, the peasants driving[Pg 27] the oxen over the corn on the threshing-floor, and the groups of Kurdish horsemen with their long spears and flowing garments, formed one of those scenes of Eastern travel which leave an indelible impression on the imagination, and bring back in after years indescribable feelings of pleasure and repose.

We crossed the principal branch of the Euphrates soon after leaving Karagol. Although the river is fordable at this time of year, during the spring it is nearly a mile in breadth, overflowing its banks, and converting the entire plain into one great marsh. We had now to pick our way through a swamp, scaring, as we advanced, myriads of wild-fowl. I have rarely seen game in such abundance and such variety in one spot; the water swarmed with geese, duck, and teal, the marshy ground with herons and snipe, and the stubble with bustards and cranes. After the rains the lower road is impassable, and caravans are obliged to make a considerable circuit along the foot of the hills.

We were not sorry to escape the fever-breeding swamp and mud of the plain, and to enter a line of low hills, separating us from the lake of Gula Shailu. I stopped for a few minutes at an Armenian monastery, situated on a small platform overlooking the plain. The bishop was at his breakfast, his fare frugal and episcopal enough, consisting of nothing more than boiled beans and sour milk. He insisted that I should partake of his repast, and I did so, in a small room scarcely large enough to admit the round tray containing the dishes, into which I dipped my hand with him and his chaplain. I found him profoundly ignorant, like the rest of his class, grumbling about taxes, and abusing the Turkish government.

After a pleasant ride of five hours we reached a deep clear lake, embedded in the mountains, two or three [Pg 28]pelicans, “swan and shadow double,” and myriads of waterfowl, lazily floating on its blue waters. Piron, the village where we halted for the night, stands at the further end of the Gula Shailu, and is inhabited by Kurds of the tribe of Hasananlu, and by Armenians, all living in good fellowship amidst the dirt and wretchedness of their eternal dung-heaps. Ophthalmia had made sad havoc amongst them, and the doctor was soon surrounded by a crowd of the blind and diseased clamoring for relief. The villagers said that a Persian, professing to be a Hakim, had passed through the place some time before, and had offered to cure all bad eyes on payment of a certain sum in advance. These terms being agreed to, he gave his patients a powder which left the sore eyes as they were, and destroyed the good ones. He then went his way: “And with the money in his pocket too,” added a ferocious-looking Kurd, whose appearance certainly threw considerable doubt on the assertion; “but what can one do in these days of accursed Tanzimat (reform)?”

The lake of Shailu is separated from the larger lake of Nazik, by a range of low hills about six miles in breadth. We reached the small village of Khers, built on its western extremity, in about two hours and a half, and found the chief, surrounded by the principal inhabitants, seated on a raised platform near a well-built stone house. He assured me, stroking a beard of spotless white to confirm his words, that he was above ninety years of age, and had never seen an European before the day of my visit. Half blind, he peered at me through his blear eyes until he had fully satisfied his curiosity; then spoke contemptuously of the Franks, and abused the Tanzimat. The old gentleman, notwithstanding his rough exterior, was hospitable after his fashion, and would not suffer us to[Pg 29] depart until we had eaten of every delicacy the village could afford.

Leaving the Nazik Gul, we entered an undulating country traversed by very deep ravines, mere channels cut into the sandstone by mountain torrents. The villages are built at the bottom of these gulleys, amidst fruit-trees and gardens, sheltered by perpendicular rocks and watered by running streams. They are undiscovered until the traveller reaches the very edge of the precipice, when a pleasant and cheerful scene opens suddenly beneath his feet. He would have believed the upper country a mere desert had he not spied here and there in the distance a peasant slowly driving his plough through the rich soil. The inhabitants of this district are more industrious and ingenious than their neighbours. They carry the produce of their harvest not on the backs of animals, as in most parts of Asia Minor, but in carts entirely made of wood, no iron being used even in the wheels, which are ingeniously built of walnut, oak, and kara agatch (literally, black tree—? thorn), the stronger woods being used for rough spokes let into the nave. The plough also differs from that in general use in Asia. To the share are attached two parallel boards, about four feet long and a foot broad, which separate the soil and leave a deep and well defined furrow.

We rode for two or three hours on these uplands, until, suddenly reaching the edge of a ravine, a beautiful prospect of a lake, woodland, and mountain opened before us.

THE LAKE OF WAN.—AKHLAT.-TATAR TOMBS.—ANCIENT REMAINS.—A DERVISH.—A FRIEND.—THE MUDIR.—ARMENIAN REMAINS.—AN ARMENIAN CONVENT AND BISHOP.—JOURNEY TO BITLIS.—NIMROUD DAGH.—BITLIS.—JOURNEY TO KHERZAN.—YEZIDI VILLAGE.

The first view the traveller obtains of the Lake of Wan, on descending towards it from the hills above Akhlat, is singularly beautiful. This great inland sea, of the deepest blue, is bounded to the east by ranges of serrated snow-capped mountains, peering one above the other, and springing here and there into the highest peaks of Tiyari and Kurdistan; beneath them lies the sacred island of Akhtamar, just visible in the distance, like a dark shadow on the water. At the further end rises the one sublime cone of the Subhan, and along the lower part of the eastern shores stretches the Nimroud Dagh, varied in shape, and rich in local traditions.

At our feet, as we drew nigh to the lake, were the gardens of the ancient city of Akhlat, leaning minarets and pointed Mausoleums peeping above the trees. We rode through vast burying-grounds, a perfect forest of upright stones seven or eight feet high of the richest red colour, most delicately and tastefully carved with arabesque ornaments and inscriptions in the massive character of the early Mussulman age. In the midst of them rose here and there a conical turbeh[3] of beautiful shape, covered with exquisite tracery. The monuments of the dead still[Pg 31] stand, and have become the monuments of a city, itself long crumbled into dust. Amidst orchards and gardens are scattered here and there low houses rudely built out of the remains of the earlier habitations, and fragments of cornice and sculpture are piled up into the walls around the cultivated plots.

Beyond the turbeh, said to be that of Sultan Baiandour through a deep ravine such as I have already described, runs a brawling stream, crossed by an old bridge; orchards and gardens make the bottom of the narrow valley, and the cultivated ledges as seen from above, a bed of foliage. The lofty perpendicular rocks rising on both sides are literally honeycombed with entrances to artificial caves, ancient tombs, or dwelling-places. On a high isolated mass of sandstone stand the walls and towers of a castle, the remains of the ancient city of Khelath, celebrated in Armenian history, and one of the seats of Armenian power. I ascended to the crumbling ruins, and examined the excavations in the rocks. The latter are now used as habitations, and as stables for herds and flocks.

Many of the tombs are approached by flights of steps, also cut in the rock. An entrance, generally square, unless subsequently widened, and either perfectly plain or decorated with a simple cornice, opens into a spacious chamber, which frequently leads into others on the same level, or by narrow flights of steps into upper rooms. There are no traces of the means by which these entrances were closed: they probably were so by stones, turning on rude hinges, or rolling on rollers.

Leaving the valley and winding through a forest of fruit trees, here and there interspersed with a few primitive dwellings, I came to the old Turkish castle, standing on the very edge of the lake. It is a pure Ottoman [Pg 32]edifice, less ancient than the turbehs, or the old walls towering above the ravine. Inscriptions over the gateways state that it was partly built by Sultan Selim, and partly by Sultan Suleiman, and over the northern entrance occurs the date of 975 of the Hejira. In the fort there dwelt, until very recently, a notorious Kurdish freebooter, of the name of Mehemet Bey, who, secure in this stronghold, ravaged the surrounding country, and sorely vexed its Christian inhabitants. He fled on the approach of the Turkish troops, after their successful expedition against Nur-Ullah Bey, and is supposed to be wandering in the mountains of southern Kurdistan.

The ancient city of Khelath was the capital of the Armenian province of Peznouni. It came under the Mohammedan power as early as the ninth century, but was conquered by the Greeks of the Lower Empire at the end of the tenth. The Seljuks took it from them, and it then again became a Mussulman principality. It was long a place of contention for the early Arab and Tartar conquerors. Shah Armen[4] reduced it towards the end of the twelfth century. It was besieged, without result, by the celebrated Saleh-ed-din, and was finally captured by his nephew, the son of Melek Adel, in A. D. 1207.

The sun was setting as I returned to the tents. The whole scene was lighted up with its golden tints, and Claude never composed a subject more beautiful than was here furnished by nature herself. I was seated outside my tent gazing listlessly on the scene, when I was roused by a well-remembered cry, but one which I had not heard for years. I turned about and saw standing before me a[Pg 33] Persian Dervish, clothed in the fawn-colored gazelle skin, and wearing the conical red cap, edged with fur, and embroidered in black braid with verses from the Koran and invocations to Ali, the patron of his sect. He was no less surprised than I had been at his greeting, when I gave him the answer peculiar to men of his order. He was my devoted friend and servant from that moment, and sent his boy to fetch a dish of pears, for which he actually refused a present ten times their value.

Whilst we were seated chatting in the soft moonlight, Hormuzd was suddenly embraced by a young man resplendent with silk and gold embroidery and armed to the teeth. He was a chief from the district of Mosul, and well known to us. Hearing of our arrival he had hastened from his village at some distance to welcome us, and to endeavour to persuade me to move the encampment and partake of his hospitality. Failing of course, in prevailing upon me to change my quarters for the night, he sent his servant to his wife, who was a lady of Mosul, and formerly a friend of my companion’s, for a sheep. We found ourselves thus unexpectedly amongst friends. Our circle was further increased by Christians and Mussulmans of Akhlat, and the night was far spent before we retired to rest.

In the morning, soon after sunrise, I renewed my wanderings amongst the ruins, first calling upon the Mudir, or governor, who received me seated under his own fig-tree. He was an old greybeard, a native of the place, and of a straightforward, honest bearing. I had to listen to the usual complaints of poverty and over-taxation, although, after all, the village, with its extensive gardens, only contributed yearly ten purses, or less than forty-five pounds, to the public revenue. This sum seems small enough, but without trade, and distant from any high[Pg 34] road, there was not a para of ready money, according to the Mudir, in the place.

From the Mudir’s house I rode to the more ancient part of the city and to the rock-tombs. I entered many of these; and found all of them to be of the same character, though varying in size. Amongst them there are galleries and passages in the cliffs without apparent use, and flights of steps, cut out of the rock, which seem to lead nowhere. I searched and inquired in vain for inscriptions and remains of sculpture, and yet the place is of undoubted antiquity, and in the immediate vicinity of cotemporary sites where cuneiform inscriptions do exist.

During my wanderings I entered an Armenian church and convent standing on a ledge of rock overhanging the stream, about four miles up the southern ravine. The convent was tenanted by a bishop and two priests. They dwelt in a small low room, scarcely lighted by a hole carefully blocked up with a sheet of oiled paper to shut out the cold; dark, musty, and damp, a very parish clerk in England would have shuddered at the sight of such a residence. Their bed, a carpet worn to threads, spread on the rotten boards; their diet, the coarsest sandy bread and a little sour curds, with beans and mangy meat for a jubilee. A miserable old woman sat in a kind of vault under the staircase preparing their food, and passing her days in pushing to and fro with her skinny hands the goat’s skin containing the milk to be shaken into butter. She was the housekeeper and handmaiden of the episcopal establishment. The church was somewhat higher, though even darker than the dwelling-room, and was partly used to store a heap of mouldy corn and some primitive agricultural implements. The whole was well and strongly built, and had the evident marks of [Pg 35]antiquity. The bishop showed me a rude cross carved on a rock outside the convent, which, he declared, had been cut by one of the disciples of the Saviour himself. It is, at any rate, considered a relic of very great sanctity, and is an object of pilgrimage for the surrounding Christian population.

On my return to our encampment the tents were struck, and the caravan had already begun its march. Time would not permit me to delay, and with a deep longing to linger on this favored spot, I slowly followed the road leading along the margin of the lake to Bitlis. I have seldom seen a fairer scene, one richer in natural beauties. The artist and the lover of nature may equally find at Akhlat objects of study and delight. The architect, or the traveller, interested in the history of that graceful and highly original branch of art, which attained its full perfection under the Arab rulers of Egypt and Spain, should extend his journey to the remains of ancient Armenian cities, far from high roads and mostly unexplored. He would then trace how that architecture, deriving its name from Byzantium, had taken the same development in the East as it did in the West, and how its subsequent combination with the elaborate decoration, the varied outline, and tasteful coloring of Persia had produced the style termed Saracenic, Arabic, and Moresque. He would discover almost daily, details, ornaments, and forms, recalling to his mind the various orders of architecture, which, at an early period, succeeded to each other in Western Europe and in England; modifications of style for which we are mainly indebted to the East during its close union with the West by the bond of Christianity. The Crusaders, too, brought back into Christendom, on their return from Asia, a taste for that rich and harmonious union of color and architecture[Pg 36] which had already been so successfully introduced by the Arabs into the countries they had conquered.

Our road skirted the foot of the Nimroud Dagh, which stretches from Akhlat to the southern extremity of the lake. We crossed several dykes of lava and scoria, and wide mud-torrents now dry, the outpourings of a volcano long since extinct. Our road gradually led away from the lake. With Cawal Yusuf and my companions I left the caravan far behind. The night came on, and we were shrouded in darkness. We sought in vain for the village which was to afford us a resting-place, and soon lost our uncertain track. The Cawal took the opportunity of relating tales collected during former journeys on this spot, of robber Kurds and murdered travellers, which did not tend to remove the anxiety felt by some of my party. At length, after wandering to and fro for above an hour, we heard the distant jingle of the caravan bells. We rode in the direction of the welcome sound, and soon found ourselves at the Armenian village of Keswak, standing in a small bay, and sheltered by a rocky promontory jutting boldly into the lake.

Next morning we rode along the margin of the lake, still crossing the spurs of the Nimroud Dagh, furrowed by numerous streams of lava and mud. In one of the deep gulleys, opening from the mountain to the water’s edge, are a number of isolated masses of sandstone, worn into fantastic shapes by the winter torrents, which sweep down from the hills. The people of the country call them “the Camels of Nimrod.” Tradition says that the rebellious patriarch, endeavoring to build an inaccessible castle, strong enough to defy both God and man, the Almighty, to punish his arrogance, turned the workmen, as they were working, into stone. The rocks on the border of the lake are the camels, who, with their burdens, were[Pg 37] petrified into a perpetual memorial of the Divine vengeance. The unfinished walls of the castle are still to be seen on the top of the mountain; and the surrounding country, the seat of a primeæval race, abounds in similar traditions.

We left the southern end of the lake, near the Armenian village of Tadwan, once a place of some importance, and soon entered a rugged ravine, worn by the mountain rills, collected into a large stream. This was one of the many head-waters of the Tigris. It was flowing tumultuously to our own bourne, and, as we gazed upon the troubled waters, they seemed to carry us nearer to our journey’s end. The ravine was at first wild and rocky; cultivated spots next appeared, scattered in the dry bed of the torrent; then a few gigantic trees; gardens and orchards followed, and at length the narrow valley opened on the long, straggling town of Bitlis. The governor had here provided quarters for us in a large house belonging to an Armenian, who had been tailor to Beder Khan Bey.

My party was now, for the first time during the journey, visited with that curse of Eastern travel, fever and ague. The doctor was prostrate, and having then no experience of the malady, at once had dreams of typhus and malignant fever. A day’s rest was necessary, and our jaded horses needed it as well as we, for there were bad mountain roads and long marches before us. I had a further object in remaining:—this was, to obtain indemnity for the robbery committed on some relations of Cawal Yusuf two years before. The official order of Reshid Pasha, and the governor’s intervention, speedily effected the desired arrangement.

The governor ordered cawasses to accompany me through the town. I had been told that ancient inscriptions existed in the castle, or on the rock, but I searched[Pg 38] in vain for them: those pointed out to me were early Mohammedan. Bitlis contains many picturesque remains of mosques, baths, and bridges, and was once a place of considerable size and importance. It is built in the very bottom of a deep valley, and on the sides of ravines, worn by small tributaries of the Tigris. The export trade is chiefly supplied by the produce of the mountains; galls, honey, wax, wool, and carpets and stuffs, woven and dyed in the tents. The dyes of Kurdistan, and particularly those from the districts around Bitlis, Sert, and Jezireh, are celebrated for their brilliancy. They are made from herbs gathered in the mountains, and from indigo, yellow berries, and other materials, imported into the country. The carpets are of a rich soft texture, the patterns displaying considerable elegance and taste: they are much esteemed in Turkey. There was a fair show of Manchester goods and coarse English cutlery in the shops. The sale of arms, once extensively carried on, had been prohibited.

Having examined the town, I visited the Armenian bishop, who dwells in a large convent in one of the ravines branching off from the main valley. On my way I passed several hot springs, some gurgling up in the very bed of the torrent. The bishop was maudlin, old, and decrepit; he cried over his own personal woes, and over those of his community, abused the Turks, and the American missionaries, whispering confidentially in my ear as if the Kurds were at his door. He insisted in the most endearing terms, and occasionally throwing his arms round my neck, that I should drink a couple of glasses of fiery raki, although it was still early morning, pledging me himself in each glass. He showed me his church, an ancient building, well hung with miserable daubs of saints and miracles.

[Pg 39]There are three roads from Bitlis to Jezireh; two over the mountains through Sert, generally frequented by caravans, but very difficult and precipitous; a third more circuitous, and winding through the valleys of the eastern branch of the Tigris. I chose the last, as it enabled me to visit the Yezidi villages of the district of Kherzan. We left Bitlis on the 20th.

About five miles from Bitlis the road is carried by a tunnel, about twenty feet in length, through a mass of calcareous rock, projecting like a huge rib from the mountain’s side. The mineral stream, which in the lapse of ages has formed this deposit, is still at work, projecting great stalactites from its sides, and threatening to close ere long the tunnel itself. There is no inscription to record by whom and at what period this passage was cut.

We continued during the following day in the same ravine, crossing by ancient bridges the stream, which was gradually gathering strength as it advanced towards the low country. About noon we passed a large Kurdish village, called Goeena, belonging to Sheikh Kassim, one of those religious fanatics who are the curse of Kurdistan. He was notorious for his hatred of the Yezidis, on whose districts he had committed numerous depredations, murdering those who came within his reach. His last expedition had not proved successful; he was repulsed, with the loss of many of his followers. We encamped in the afternoon on the bank of the torrent, near a cluster of Kurdish tents, concealed from view by the brushwood and high reeds. The owners were poor but hospitable, bringing us a lamb, yahgourt, and milk. Late in the evening a party of horsemen rode to our encampment. They were a young Kurdish chief, with his retainers, carrying off a girl with whom he had fallen in love,—not an uncommon occurrence in Kurdistan. They [Pg 40]dismounted, eat bread, and then hastened on their journey to escape pursuit.

Starting next morning soon after dawn we rode for two hours along the banks of the stream, and then, turning from the valley, entered a country of low undulating hills. We halted for a few minutes in the village of Omais-el-Koran, belonging to one of the innumerable saints of the Kurdish mountains. The Sheikh himself was on his terrace superintending the repair of his house, gratuitously undertaken by the neighbouring villagers, who came eagerly to engage in a good and pious work. Leaving a small plain, we ascended a low range of hills by a precipitous pathway, and halted on the summit at a Kurdish village named Khokhi. It was filled with Bashi-Bozuks, or irregular troops, collecting the revenue, and there was such a general confusion, quarrelling of men and screaming of women, that we could scarcely get bread to eat. Yet the officer assured me that the whole sum to be raised amounted to no more than seventy piastres (about thirteen shillings.) The poverty of the village must indeed have been extreme, or the bad will of the inhabitants outrageous.

It was evening before we descended into the plain country of the district of Kherzan. The Yezidi village of Hamki had been visible for some time from the heights, and we turned towards it. As the sun was fast sinking, the peasants were leaving the threshing-floor, and gathering together their implements of husbandry. They saw the large company of horsemen drawing nigh, and took us for irregular troops,—the terror of an Eastern village. Cawal Yusuf, concealing all but his eyes with the Arab kefieh, which he then wore, rode into the midst of them, and demanded in a peremptory voice provisions and quarters for the night. The poor creatures huddled together,[Pg 41] unwilling to grant, yet fearing to refuse. The Cawal, having enjoyed their alarm for a moment, threw his kerchief from his face, exclaiming, “O evil ones, will you refuse bread to your priest, and turn him hungry from your door?” There was surely then no unwillingness to receive us. Casting aside their shovels and forks, the men threw themselves upon the Cawal, each struggling to kiss his hand. The news spread rapidly, and the rejoicing was so great that the village was alive with merriment and feasting.

Yusuf was soon seated in the midst of a circle of the elders. He told his whole history, with such details and illustrations as an Eastern alone can introduce, to bring every fact vividly before his listeners. Nothing was omitted: his arrival at Constantinople, his reception by me, his introduction to the ambassador, his interview with the great ministers of state, the firman of future protection for the Yezidis, prospects of peace and happiness for the tribe, our departure from the capital, the nature of steamboats, the tossing of the waves, the pains of sea-sickness, and our journey to Kherzan. Not the smallest particular was forgotten; and, when he had finished, it was my turn to be the object of unbounded welcomes and salutations.

As the Cawal sat on the ground, with his noble features and flowing robes, surrounded by the elders of the village, eager listeners to every word which dropped from their priest, and looking towards him with looks of profound veneration, the picture brought vividly to my mind many scenes described in the sacred volumes. Let the painter who would throw off the conventionalities of the age, who would feel as well as portray the incidents of Holy Writ, wander in the East, and mix, not as the ordinary traveller, but as a student of men and of nature,[Pg 42] with its people. He will daily meet with customs which he will otherwise be at a loss to understand, and be brought face to face with those who have retained with little change the manners, language, and dress of a patriarchal race.

RECEPTION BY THE YEZIDIS.—VILLAGE OF GUZELDER.—TRIUMPHAL MARCH TO REDWAN.—REDWAN.—ARMENIAN CHURCH.—THE MELEK TAOUS, OR BRAZEN BIRD.—TILLEH.—VALLEY OF THE TIGRIS.—BAS RELIEFS.—JOURNEY TO DEREBOUN—TO SEMIL—ABDE AGHA—JOURNEY TO MOSUL.—THE YEZIDI CHIEFS.—ARRIVAL AT MOSUL.—XENOPHON’S MARCH FROM THE ZAB TO THE BLACK SEA.

I was awoke on the following morning by the tread of horses and the noise of many voices. The good people of Hamki having sent messengers in the night to the surrounding villages to spread the news of our arrival, a large body of Yezidis on horse and on foot had already assembled, although it was not yet dawn, to greet us and to escort us on our journey. They were dressed in their gayest garments, and had adorned their turbans with flowers and green leaves. Their chief was Akko, a warrior well known in the Yezidi wars, still active and daring, although his beard had long turned grey. The head of the village of Guzelder, with the principal inhabitants, had come to invite me to eat bread in his house, and we followed him. As we rode along we were joined by parties of horsemen and footmen, each man kissing my hand as he arrived, the horsemen alighting for that purpose. Before we reached Guzelder the procession had swollen to many hundreds. The men had assembled at some distance from[Pg 43] the village, the women and children, dressed in their holiday attire, and carrying boughs of trees, congregated on the housetops.

Soon after our arrival several Fakirs[5], in their dark coarse dresses and red and black turbans, came to us from the neighbouring villages. Other chiefs and horsemen also flocked in, and were invited to join in the feast, which was not, however, served up until Cawal Yusuf had related his whole history once more, without omitting a single detail. After we had eaten of stuffed lambs, pillaws, and savory dishes and most luscious grapes, the produce of the district, our entertainer placed a present of home-made carpets at my feet, and we rose to depart. The horsemen, the Fakirs, and the principal inhabitants of Guzelder on foot accompanied me. At a short distance from the village we were met by another large body of Yezidis, and by many Jacobites. A bishop and several priests were with him. Two hours’ ride, with this great company, the horsemen galloping to and fro, the footmen discharging their firearms, brought us to the large village of Koshana. The whole of the population, mostly dressed in pure white, and wearing leaves and flowers in their turbans, had turned out to meet us; women stood on the road-side with jars of fresh water and bowls of sour milk, whilst others with the children were assembled on the housetops making the tahlel. Resisting an invitation to alight and eat bread, and having merely stopped to exchange salutations with those assembled, I continued on the road to Redwan, our party swollen by a fresh accession of followers from the village. As we passed through the defile leading into the plain of Redwan, we had the appearance of a triumphal procession, but as we approached the small town a still more enthusiastic reception awaited us. First[Pg 44] came a large body of horsemen, collected from the place itself, and the neighbouring villages. They were followed by Yezidis on foot, carrying flowers and branches of trees, and preceded by musicians playing on the tubbul and zernai.[6] Next were the Armenian community headed by their clergy, and then the Jacobite and other Christian sects, also with their respective priests; the women and children lined the entrance to the place and thronged the housetops. I alighted amidst the din of music and the “tahlel” at the house of Nazi, the chief of the whole Yezidi district, two sheep being slain before me as I took my feet from the stirrups.

I took up my quarters in the Armenian church, dining in the evening with the chiefs to witness the festivities.

The change was indeed grateful to me, and I found at length a little repose and leisure to reflect upon the gratifying scene to which I had that day been witness. I have, perhaps, been too minute in the account of my reception at Redwan, but I record with pleasure this instance of a sincere and spontaneous display of gratitude on the part of a much maligned and oppressed race. To those, unfortunately too many, who believe that Easterns can only be managed by violence and swayed by fear, let this record be a proof that there are high and generous feelings which may not only be relied and acted upon without interfering with their authority, or compromising their dignity, but with every hope of laying the foundation of real attachment and mutual esteem.

The church stands on the slope of a mound, on the summit of which are the ruins of a castle belonging to the former chiefs of Redwan. It was built expressly for the Christians of the Armenian sect by Mirza Agha, the last semi-independent Yezidi chief, a pleasing example[Pg 45] of toleration and liberality well worthy of imitation by more civilised men. Service was performed in the open iwan, or large vaulted chamber, during the afternoon, the congregation kneeling uncovered in the yard. The priests of the different communities called upon me as soon as I was ready to receive their visits. The most intelligent amongst them was a Roman Catholic Chaldæan, a good humoured, tolerant fellow, who with a very small congregation of his own did not bear any ill-will to his neighbours. With the principal Yezidi chiefs, too, I had a long and interesting conversation on the state of their people and on their prospects.

Redwan is called a town, because it has a bazar, and is the chief place of a considerable district. It may contain about eight hundred rudely-built huts, and stands on a large stream, which joins the Diarbekir branch of the Tigris, about five or six miles below. The inhabitants are Yezidis, with the exception of about one hundred Armenian, and forty or fifty Jacobite and Chaldæan families. A Turkish Mudir, or petty governor, generally resides in the place, but was absent at the time of my visit.

We slept in a long room opening on the courtyard, and were awoke long before daybreak by the jingling of small bells and the mumbling of priests. It was Sunday, and the Armenians commence their church services betimes. I gazed half dozing, and without rising from my bed, upon the ceremonies, the bowing, raising of crosses, and shaking of bells, which continued for above three hours, until priests and congregation must have been well nigh exhausted. The people, as during the previous afternoon’s service, stood and knelt uncovered in the courtyard.

The Melek Taous,

or Copper Bird of the Yezidis.

The Cawals, who are sent yearly by Hussein Bey and Sheikh Nasr to instruct the Yezidis in their faith, and to[Pg 46] collect the contributions forming the revenues of the great chief, and of the tomb of Sheikh Adi, were now in Redwan. The same Cawals do not take the same rounds every year. The Yezidis are parcelled out into four divisions for the purpose of these annual visitations, those of the Sinjar, of Kherzan, of the pashalic of Aleppo, and of the villages in northern Armenia, and within the Russian frontiers. The Yezidis of the Mosul districts have the Cawals always amongst them. I was aware that on the occasion of these journeys the priests carry with them the celebrated Melek Taous, or brazen peacock, as a warrant for their mission. As this was a favorable opportunity, I asked and obtained a sight of this mysterious figure. A stand of bright copper or brass, in shape like the candlesticks generally used in Mosul and Baghdad, was surmounted by the rude image of a bird in the same metal, and more like an Indian or Mexican idol than a cock or peacock. Its peculiar workmanship indicated some antiquity, but I could see no traces of inscription upon it. Before it stood a copper bowl to receive contributions, and a bag to contain the bird and stand, which takes to pieces when carried from place to place. There are four such images, one for each district visited by the Cawals. The Yezidis declare that, notwithstanding the frequent wars and massacres to which the sect has been exposed, and the plunder and murder of the priests during their journeys, no Melek Taous has ever fallen into the hands of the [Pg 47]Mussulmans. Mr. Hormuzd Rassam was alone permitted to visit the image with me. As I have elsewhere observed,[7] it is not looked upon as an idol, but as a symbol or banner, as Sheikh Nasr termed it, of the house of Hussein Bey.

Having breakfasted at Nazi’s house we left Redwan, followed by a large company of Yezidis, whom I had great difficulty in persuading to turn back about three or four miles from the town. My party was increased by a very handsome black and tan greyhound with long silky hair, a present from old Akko, the Yezidi chief. Touar, for such was the dog’s name, soon forgot his old masters, and formed an equal attachment for his new.

Cawal Yusuf, and the Yezidi chiefs, had sent messengers even to Hussein Bey to apprise him of our coming. As they travelled along they scattered the news through the country, and I was received outside every village by its inhabitants. At Tilleh, the united waters of Bitlis, Sert, and the upper districts of Bohtan, join the western branch of the Tigris. The two streams are about equal in size, and at this time of the year both fordable in certain places. We crossed the lower, or eastern, which we found wide and exceedingly rapid, the water, however, not reaching above the saddle-girths.

The spot at which we crossed was one of peculiar interest. It was here that the Ten Thousand in their memorable retreat forded this river, called, by Xenophon, the Centritis. The Greeks having fought their way over the lofty mountains of the Carduchians, found their further progress towards Armenia arrested by a rapid stream. The ford was deep, and its passage disputed by a formidable force of Armenians, Mygdonians, and [Pg 48]Chaldæans, drawn up on an eminence 300 or 400 feet from the river. In this strait Xenophon dreamt that he was in chains, and that suddenly his fetters burst asunder of their own accord. His dream was fulfilled when two youths casually found a more practicable ford, by which the army, after a skilful stratagem on the part of their commander, safely reached the opposite bank.[8]

The sun had set before our baggage had been crossed, and we sought, by the light of the moon, the difficult track along the Tigris, where the river forces its way to the low country of Assyria, through a long, narrow, and deep gorge. Huge rocks rose perpendicularly on either side, broken into many fantastic shapes, and throwing their dark shadows over the water. In some places they scarcely left room for the river to pursue its course; and then a footpath, hardly wide enough to admit the loaded mules, was carried along a mere ledge overhanging the gurgling stream. The gradual deepening of this outlet during countless centuries is strikingly shown by the ledges which jutt out like a succession of cornices from the sides of the cliffs. The last ledge left by the retiring waters formed our pathway.

We found no village until we reached Chellek. The place had been deserted by its inhabitants for the Yilaks, or mountain pastures.

For three hours during the following morning we followed the bold and majestic ravine of the Tigris, scenes rivalling each other in grandeur and beauty opening at every turn. Leaving the river, where it makes a sudden bend to the northward, we commenced a steep ascent, and in an hour and a half reached the Christian village of Khouara. We rested during the heat of the day under the[Pg 49] grateful shade of a grove of trees, and in the afternoon we stood on the brink of the great platform of Central Asia. Beneath us were the vast plains of Mesopotamia, lost in the hazy distance, the undulating land between them and the Taurus confounded, from so great a height, with the plains themselves; the hills of the Sinjar and of Zakko, like ridges on an embossed map; the Tigris and the Khabour, winding through the low country to their place of junction at Dereboun; to the right, facing the setting sun, and catching its last rays, the high cone of Mardin; behind, a confused mass of peaks, some snow-capped, all rugged and broken, of the lofty mountains of Bohtan and Malataiyah; between them and the northern range of Taurus, the deep ravine of the river and the valley of Redwan. I watched the shadows as they lengthened over the plain, melting one by one into the general gloom, and then descended to the large Kurdish village of Funduk, whose inhabitants, during the rule of Beder Khan Bey, were notorious amongst even the savage tribes of Bohtan for their hatred and insolence to Christians.