Title: Mysterious Psychic Forces

Author: Camille Flammarion

Release date: March 27, 2012 [eBook #39279]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.)

MYSTERIOUS

PSYCHIC FORCES

AN ACCOUNT OF THE AUTHOR'S INVESTIGATIONS IN

PSYCHICAL RESEARCH, TOGETHER WITH THOSE

OF OTHER EUROPEAN SAVANTS

BY

CAMILLE FLAMMARION

Director of Observatory of Jovisy,

France. Author of "The Unknown,"

"The Atmosphere," etc.

BOSTON

SMALL, MAYNARD AND COMPANY

1909

Copyright, 1907,

By Small, Maynard & Co.

All rights reserved.

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

He who pronounces anything to be "impossible," outside of the field of pure mathematics, is wanting in prudence.

Francois Arago.

A learned pedant who laughs at the possible comes very near being an idiot. To purposely shun a fact, and turn one's back upon it with a supercilious smile, is to bankrupt Truth.

Victor Hugo.

Science is under bonds, by the eternal principles of honor, to look fearlessly in the face every problem that is presented to her.

Sir William Thompson.

The subject treated in the following pages has made great progress in the course of forty years. Now what we are concerned with in psychical studies is always unknown forces, and these forces must belong to the natural order, for nature embraces the entire universe, and everything is therefore under the sway of her sceptre.

I do not conceal from myself, however, that the present work will excite discussion and bring forth legimate objections, and will only satisfy independent and unbiased investigators. But nothing is rarer upon our planet than an independent and absolutely untrammelled mind, nor is anything rarer than a true scientific spirit of inquiry, freed from all personal interest. Most readers will say: "What is there in these studies, anyway? The lifting of tables, the moving of various pieces of furniture, the displacement of easy-chairs, the rising and falling of pianos, the blowing about of curtains, mysterious rappings, responses to mental questions, dictations of sentences in reverse order, apparitions of hands, of heads, or of spectral figures,—these are only common place trivialities or cheap hoaxes, unworthy to occupy the attention of a scientist or scholar. And what would it all prove even if it were true? That kind of thing does not interest us."

Well, there are people upon whose heads the sky might tumble without causing them any unusual emotion.

But I reply: What! is it nothing to know, to prove, to see with one's own eyes, that there are unknown forces around us? Is it nothing to study our own proper nature and our[Pg vi] own faculties? Are not the mysterious problems of our being such as are worthy to be inscribed on the program of our investigation, and of having devoted to them laborious nights and days? Of course, the independent seeker gets no thanks from anybody for his toil. But what of that? We work for the pleasure of working, of fathoming the secrets of nature, and of instructing ourselves. When, in studying the double stars at the Paris Observatory and cataloguing these celestial twins, I established for the first time a natural classification of those distant orbs; when I discovered stellar systems, composed of several stars, swept onward through immensity by one common impulse; when I studied the planet Mars and compared all the observations made during two hundred years in order to obtain at once an analysis and a synthesis of this next-door neighbor of ours among the planets; when, in examining the effect of solar radiations I created the new branch of physics to which has been given the name "radioculture" and caused variations of the most radical and sweeping nature in the dimensions, the forms, and the colors of certain plants; when I discovered that a grasshopper, eviscerated and kept in straw did not die, and that these insects can live for a fortnight after having had their heads cut off; when I planted in a conservatory of the Museum of Natural History, in Paris, one of the ordinary oaks of our woods (quercus robur), thinking that, if withdrawn from the changes of seasons, it would always have green leaves (a thing which everybody can prove),—when I was doing these things I was working for my own personal pleasure; but that is no reason why these studies have not been useful in the developing work of science, and no reason for their not being admitted within the scope of the practical work of specialists.

It is the same with these psychical studies of ours; only there is a little more passion and prejudice connected with[Pg vii] them. On the one hand, the sceptics cleave fast to their denials, convinced that they know all the forces of nature, that all mediums are humbugs, and all experimenters imbeciles. On the other hand, there are the credulous Spiritualists, who imagine they always have spirits at their beck and call in a centre-table, who evoke, with the utmost sang-froid, the spirits of Plato, Zoroaster, Jesus Christ, St. Augustine, Charlemagne, Shakespeare, Newton, or Napoleon, and who set about stoning me for the tenth or twentieth time, affirming that I am sold to the Institute on account of a deep-seated and obstinate ambition, and that I dare not declare myself in favor of the identity of the spirits for fear of annoying my illustrious friends. The individuals of this class refuse to be satisfied just as much as the first class.

So much the worse for them! I insist on only saying what I know; but I do say this.

And if what I know is displeasing, so much the worse for the prejudices, the general ignorance, and the good breeding of these distinguished gentry, in whose eyes the maximum of happiness consists in an increase of their fortune, the pursuit of lucrative places, sensual pleasures, automobile-racing, a box at the Opéra, or five-o'clock teas at a fashionable restaurant, and whose lives are frittered away along paths that never cross those of the rapt idealist, and who never know the pure satisfaction of his mind and heart, or the pleasures of thought and feeling.

As for me, a humble student of the prodigious problem of the universe, I am only a seeker. What are we? We have scarcely shed a ray more of light on this point than at the time when Socrates laid down, as a principle, the maxim, Know thyself,—notwithstanding we have measured the distances of the stars, analyzed the sun, and weighed the worlds of space. Does it stand to reason that the knowledge of ourselves should interest us less than that of the macrocosm, the[Pg viii] external world? It is not credible. Let us therefore study on, convinced that all sincere research will further the progress of humanity.

Juvisy Observatory, December, 1906.

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| Preface | v | |

| Introduction | xiii | |

| Chapter | ||

| I. | On Certain Unknown Natural Forces | 1 |

| II. | My First Séances In The Allen Kardec Group, And With The Mediums Of That Epoch | 24 |

| III. | My Experiments With Eusapia Paladino | 63 |

| IV. | Other Séances With Eusapia Paladino | 135 |

| V. | Frauds, Tricks, Deceptions, Impostures, Feats Of Legerdemain, Mystifications, Impediments | 194 |

| VI. | The Experiments Of Count De Gasparin | 229 |

| VII. | The Researches Of Professor Thury | 266 |

| VIII. | The Experiments Of The Dialectical Society Of London | 289 |

| IX. | The Experiments Of Sir William Crookes | 306 |

| X. | Sundry Experiments And Observations | 352 |

| XI. | My General Inquiry Respecting Observations Of Unexplained Phenomena | 376 |

| XII. | Explanatory Hypotheses—Theories And Doctrines—Conclusions Of The Author | 406 |

| Index | 455 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

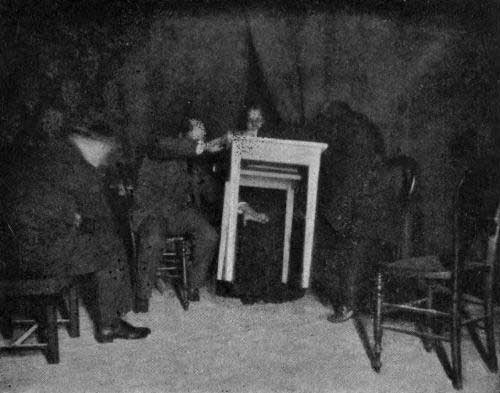

| Plate I. Complete Levitation of a Table in Professor Flammarion's Salon through Mediumship of Eusapia Paladino | Facing page | 8 | |

| Plate II. House of Zoroastre of Jupiter from Somnambulistic Drawing by Victorien Sardou | After page | 26 | |

| Plate III. Animals' Quarters. House of Zoroastre of Jupiter from Somnambulistic Drawing by Victorien Sardou | After page | 26 | |

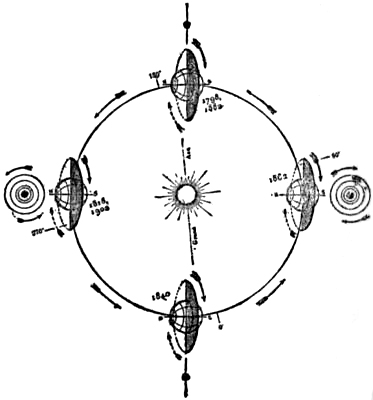

| Figure 1. The Inclination of the System of Uranus | Page | 54 | |

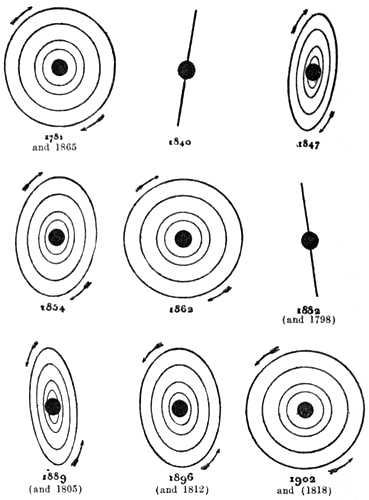

| Figure 1a. Orbits of Satellites of Uranus as Seen from the Earth | Page | 56 | |

| Plate IV. Plaster Cast of Imprint Made in Putty without Contact by the Medium Eusapia Paladino | After page | 76 | |

| Plate V. Eusapia Paladino, Showing Resemblance to the Imprint in Putty | After page | 76 | |

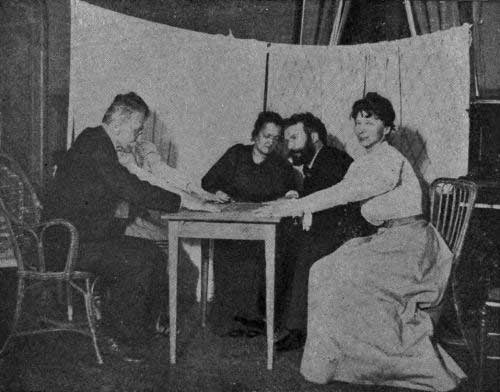

| Plate VI. Photographs Taken by M. G. de Fontenay of an Experiment in Table Levitation | Facing page | 82 | |

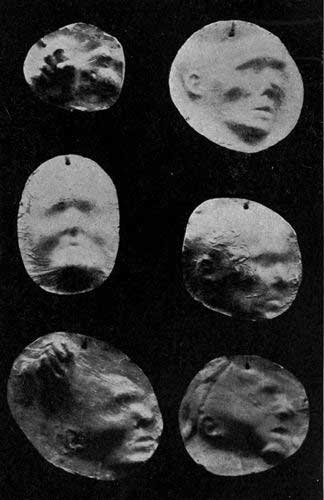

| Plate VII. Plaster Casts of Impressions in Clay Produced by an Unknown Force | Facing page | 138 | |

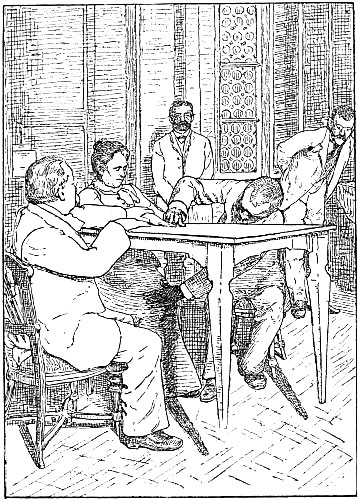

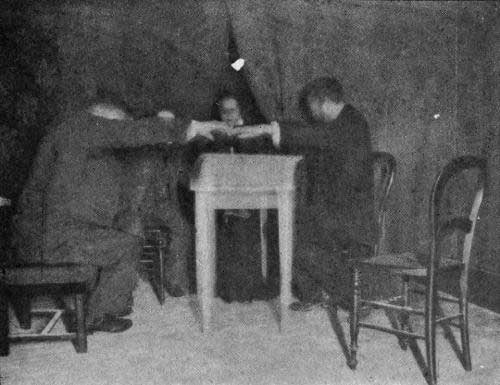

| Plate VIII. Drawing from Photograph, Showing Method of Control by Professors Lombroso and Richet of Eusapia. Table Completely Raised | Facing page | 154 | |

| Plate IX. Photographs of Levitation of Table Accompanying Colonel De Rochas' Report | Facing page | 174 | |

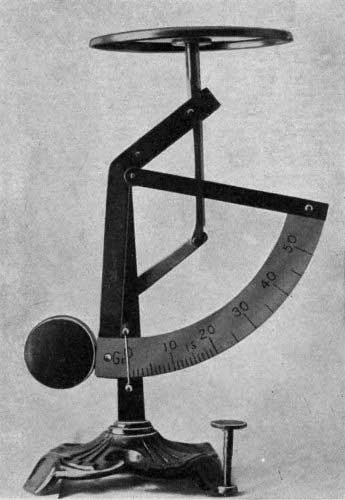

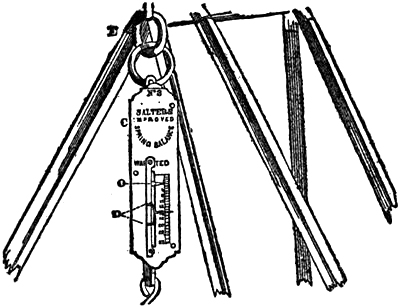

| Plate X. Scales Used in Professor Flammarion's Experiments | Facing page | 200 | |

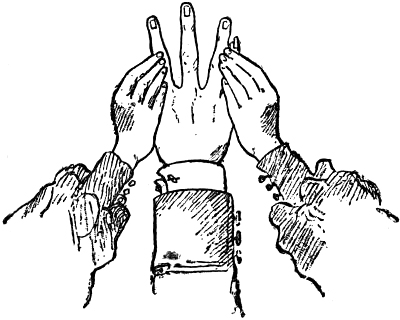

| [Pg xii]Plate XI. Method Used by Eusapia to Surreptitiously Free her Hand | Facing page | 206 | |

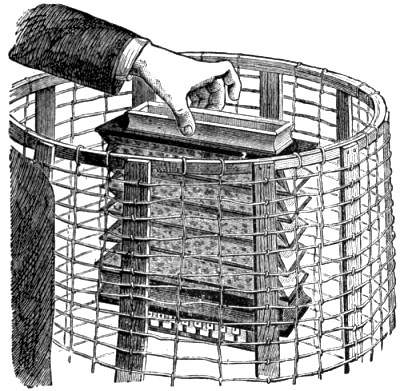

| Plate XII. Cage of Copper Wire, Electrically Charged, Used by Professor Crookes in the Home Accordion Experiment | Facing page | 308 | |

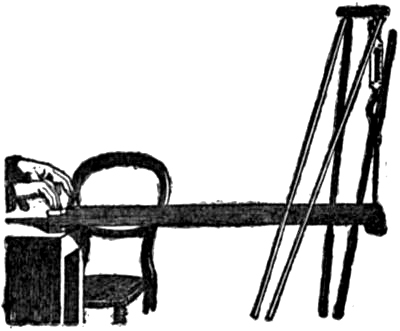

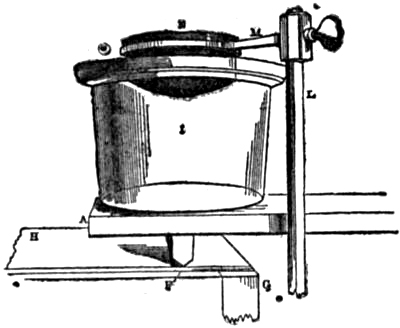

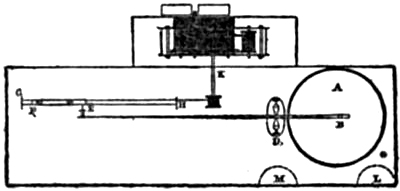

| Figure 3. Board and Scale Experiment of Sir William Crookes | Page | 312 | |

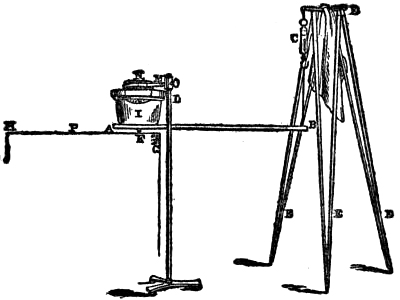

| Figures 4 and 5. Instruments Used in Scale Experiment by Sir William Crookes | Page | 317 | |

| Figure 6. Glass Vessel Used by Home | Page | 318 | |

| Figure 7. Automatically Registered Chart of Unknown Force Generated by Mr. Home | Page | 320 | |

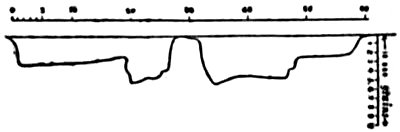

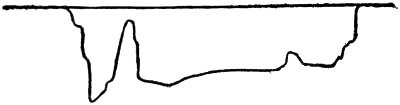

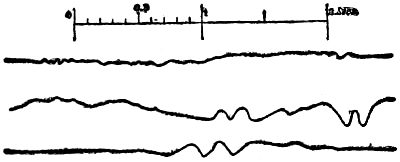

| Figures 8, 9, 10. Charts from Sir William Crookes Instruments Used in Experiments with Mr. Home | Page | 321 | |

| Figures 11 and 12. Third Instrument Devised by Sir William Crookes for Recording Automatically the Unknown Force Generated by Home | Page | 322 | |

| Figure 13. Charts Made by Third Instrument | Page | 323 | |

| Figures 14 and 15. Charts Made by Third Instrument | Page | 324 | |

| Plate XIII. Instantaneous Photograph Taken by M. de Fontenay of Table Levitation Produced by the Medium Auguste Politi | Facing page | 368 |

As long ago as 1865 I published, under the title, Unknown Natural Forces, a little monograph of a hundred and fifty pages which is still occasionally found in the book-shops, but has not been reprinted. I reprint here (pp. xiii-xxiii), what I wrote at that time in this critical study "apropos of the phenomena produced by the Davenport brothers and mediums in general." It was published by Didier & Co., book-sellers to the Academy, who had already issued my first two works, The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds and Imaginary Worlds and Real Worlds.

"France has just been engaged in an exciting debate, where the sound of voices was drowned in a great uproar, and out of which no conclusion has emerged. A disputation more noisy than intelligent has been raging around a whole group of unexplained facts, and so completely muddled the problem that, in place of illuminating it, the debate has only served to shroud it in deeper darkness.

"During the discussion a singular remark was frequently heard, to the effect that those who shouted the loudest in this court of assize were the very ones who were least informed on the subject. It was an amusing spectacle to see these persons in a death-grapple with mere phantoms. Panurge himself would have laughed at it.

"The result of the matter is that less is known to-day upon the subject in dispute than at the opening of the debates.

"In the mean time, seated upon neighboring heights were certain excellent old fellows who observed the writs of arrest[Pg xiv] issued against the more violent combatants, but who remained for the most part grave and silent, though they occasionally smiled, and withal did a deal of hard thinking.

"I am going to state what weight should be given to the opinions of those of us who do not rashly affirm the impossibility of the facts now put under the ban and who do not add their voices to the dominant note of opposition.

"I do not conceal from myself the consequences of such sincerity. It requires a good deal of boldness to insist on affirming, in the name of positive science, the POSSIBILITY of these phenomena (wrongly styled supernatural), and to constitute one's self the champion of a cause apparently ridiculous, absurd, and dangerous, knowing, at the same time, that the avowed adherents of said cause have little standing in science, and that even its eminent partisans only venture to speak of their approval of it with bated breath. However, since the matter has just been treated momentarily in fugitive writings by a group of journalists whose exacting labors wholly forbid a study of the psychic and physical forces; and since, of all this multitude of writers, the greater part have only heaped error upon error, puerility upon extravagance; and since it appears from every page they have written (I hope they will pardon me) that not only are they ignorant of the very a, b, c of the subject they have so fantastically treated, but their opinions upon this class of facts rest upon no basis whatever,—therefore I have thought it would serve a purpose if I should leave, as a souvenir of the long wrangle, a piece of writing better based and buttressed than the lucubrations of the above-mentioned gentlemen. As a lover of truth, I am willing to face a thousand reproaches. Be it distinctly understood that I do not for a moment deem my judgment superior to that of my confrères, some of whom are in other respects highly gifted. The simple fact is that they are not familiar with this [Pg xv]subject, but are straying in it at random, wandering through a strange region. They misunderstand the very terminology, and imagine that facts long ago well authenticated are impossible. By way of contrast, the writer of these lines will state that for several years he has been engaged in discussions and experiments upon the subject. (I am not speaking of historical studies.)

"Moreover, although the old saw would have us believe that 'it is not always desirable to state the truth,' yet, to speak frankly, I am so indignant at the overweening presumption of certain polemical opponents, and at the gall they have injected into the debate, that I do not hesitate to rise and point out to the deceived public that, without a single exception, all the arguments brought up by these writers, and upon which they have boldly planted their banner of victory, prove absolutely nothing, NOTHING, against the possible truth of the things which they, in the fury of their denial, have so perverted. Such a snarl of opinions must be analyzed. In brief, the true must be disentangled from the false. Veritas, veritas!"

"I hasten to anticipate a criticism on the part of my readers by apprising them, on the threshold of this plea, that I am not going to take the Davenport brothers as my subject, but only as the ostensible motive or pretext of the discussion,—as they have been, for that matter, of the majority of the discussions. I shall deal in these pages with the facts brought to the surface again by these two Americans,—facts inexplicable (which they have put on the stage at Herz Hall here in Paris, but which none the less existed before this mise-en-scène, and which none the less will exist even should the Davenport brothers' representations prove to be counterfeit),—things which others had already exhibited, and still exhibit with as much facility and under much better conditions; occurrences, in short, which constitute the[Pg xvi] domain of the unknown forces to which have been given, one after another, five or six names explaining nothing. These forces, mind you, are as real as the attraction of gravitation, and as invisible as that. It is about facts that I here concern myself. Let them be brought to the light by Peter or by Paul, it concerns us little; let them be imitated by Sosie[1] or parodied by Harlequin, still less does it concern us. The question is, Do these facts exist, and do they enter into the category of known physical forces?

"It amazes me, every time I think of it, that the majority of men are so densely ignorant of the psychic phenomena in question, considering the fact that they have been known, studied, valued, and recorded for a good long time now by all who have impartially followed the movement of thought during the last few lustrums.

"I not only do not make common cause with the Davenport brothers, but I ought furthermore to add that I consider them as placed in a very compromising situation. In laying to the account of the supernatural matters in occult natural philosophy which have a tolerable resemblance to feats of prestidigitation, they appear to a curious public to add imposture to insolence. In setting a financial value upon their talents, they seem to the moralist, who is investigating still unexplained phenomena, to place themselves on the level of mountebanks. Whatever way you look at them, they are to blame. Accordingly, I condemn at once both their grave error in assuming to be superior to the forces of which they are only the instruments and the venal profit they draw from powers of which they are not master and which it is no merit of theirs to possess. In my opinion, it is a piece of exaggeration to draw conclusions from[Pg xvii] these unhappy semblances of truth; and it is to abdicate one's right of private judgment to make one's self but the echo of the vulgar herd who hiss and shout themselves hoarse before the curtain rises. No, I am not the advocate of the two brothers, nor of their personal claims. For me, individual men do not exist. That which I defend is the superiority of nature to us: that which I fight against is the conceited silliness of certain persons.

"You satirical gentlemen will have the frankness, I hope, to confess with me that the different reasons pleaded by you in explanation of these problems are not so solid as they appear to be. Since you have discovered nothing, let us admit, between ourselves, that your explanations explain nothing.

"I do not doubt that, at the point in the discussion which we have actually reached, you would like to change rôles with me, and, stopping me here, constitute yourselves in turn my questioners.

"But I hasten to anticipate your proposal. As for me, gentlemen, I am not sufficiently well informed to explain these mysteries. I pass my life in a retired garden belonging to one of the nine Muses, and my attachment to this fair creature is such that I have scarcely ever quitted the approaches to her temple. It is only at intervals, in moments of relaxation or curiosity, that I have allowed my eyes to wander, from time to time, over the landscapes which surround it. Therefore ask me nothing. I am making a sincere confession. I know nothing of the cause of these phenomena.

"You see how modest I am. All I wanted in undertaking this examination was to have the opportunity of saying this:

"You know nothing about it.

"Neither do I.

[Pg xviii]"If you acknowledge this, we can shake hands. And, if you are tractable, I will tell you a little secret.

"In the month of June, 1776 (few among us remember it), a young man twenty-five years old, named Jouffroy, was making a trial trip on the river Doubs of a new steamboat forty feet in length and six feet in breadth. For two years he had been calling the attention of scientific authorities to his invention; for two years he had been stoutly asserting that there is a powerful latent energy in steam,—at that time a neglected asset. All ears were deaf to his words. His only reward was to be completely isolated and neglected. When he passed through the streets of Baume-les-Dames, his appearance was the signal for jests innumerable. He was dubbed 'Jouffroy, the Steam Man' ('Jouffroy-la-Pompe'). Ten years later, having built a pyroscaphe [literally, fireboat] which had ascended the Saône from Lyons to the island of Barbe, he presented a petition to Calonne, the comptroller-general of finance, and to the Academy of Sciences. They would not look at his invention!

"On August 9, 1803, Fulton went up the Seine in a new steamboat at the rate of about four miles an hour. The members of the Academy of Sciences as well as government officials were present on the occasion. The next day they had forgotten all about it, and Fulton went to make the fortunes of Americans.

"In 1791 an Italian at Bologna, named Galvani, having hung on the iron railing outside his window some skinned frogs which had been used in making a bouillon for his wife, noted that they moved automatically, although they had been killed since the evening before. The thing was incredible, so everybody to whom he told it opposed his statement. Men of sense would have thought it beneath their dignity to take the trouble to verify the story, so convinced were they of its impossibility. But Galvani had noted that[Pg xix] the maximum of effect was attained when he joined the lumbar nerves and the ends of the feet of a frog by a metallic arc of tin and copper. The frog's muscles then jerked convulsively. He believed it was due to a nervous fluid, and so lost the fruit of his investigations. It was reserved for Volta to discover electricity.

"And to-day the globe is threaded with a network of trains drawn by flame-breathing dragons. Distances have disappeared, annihilated by improvements in the locomotive. The genius of man has contracted the dimensions of the earth; the longest voyages are but excursions over definite lines (the curved paths of the 'ocean lanes'); the most gigantic tasks are accomplished by the tireless and powerful hand of this unknown force. A telegraphic despatch flies in the twinkling of an eye from one continent to another; a man can talk with a citizen of London or St. Petersburg without getting out of his arm-chair. And these wonders attract no special notice. We little think through what struggles, bitter disappointments and persecutions they came into being! We forget that the impossible of yesterday is the accomplished fact of to-day. So it comes to pass that we still find men who come to us saying: 'Halt there, you little fellows! We don't understand you, therefore you don't know what you're talking about.'

"Very well, gentlemen. However narrow may be your opinions, there is no reason for thinking that your myopia is to spread over the world. You are hereby informed that, in spite of you and in spite of your obscurantism and obstruction tactics, the car of human progress will roll on and continue its triumphal march and conquest of new forces and powers. As in the case of Galvani's frog, the laughable occurrences that you refuse to believe reveal the existence of new unknown forces. There is no effect without a cause. Man is the least known of all beings. We have learned[Pg xx] how to measure the sun, cross the deeps of space, analyze the light of the stars, and yet have not dropped a plummet into our own souls. Man is dual,—homo duplex; and this double nature remains a mystery to him. We think: what is thought? No one can say. We walk: what is that organic act? No one knows. My will is an immaterial force; all the faculties of my soul are immaterial. Nevertheless, if I will to move my arm, my will moves matter. How does it act? What is the mediator between mind and muscle? As yet no one can say. Tell me how the optic nerve transmits to the thinking brain the perception of outward objects. Tell me how thought is born, where it resides, what is the nature of cerebral action. Tell me—but no, gentlemen: I could question you for ten years on a stretch, and the most eminent of you could not answer the least of my interrogatories.

"We have here, as in the preceding cases, the unknown element in a problem. I am far from claiming that the force that comes into play in these phenomena can one day be financially exploited, as in the case of electricity and steam. Such an idea has not the slightest interest for me. But, though differing essentially from these forces, the mysterious psychic force none the less exists.

"In the course of the long and laborious studies to which I have consecrated many a night, as a relief or by-play in more important work, I have always observed in these phenomena the action of a force the properties of which are to us unknown. Sometimes it has seemed to me analogous to that which puts to sleep the magnetized subject under the will of the hypnotizer (a reality this, also slighted even by men of science). Again, in other circumstances, it has seemed to me analogous to the curious freaks of the lightning. Still, I believe I can affirm it to be a force distinct[Pg xxi] from all that we know, and which more than any other resembles intelligence.

"A certain savant with whom I am acquainted, M. Frémy, of the Institute, has recently presented to the Academy of Science, apropos of spontaneous generation, substances which he has called semi-organic. I believe I am not perpetrating a neologism bolder than this when I say that the force of which I am speaking has seemed to me to belong to the semi-intellectual plane.

"Some years ago I gave these forces the name psychic. That name can be justified.

"But words are nothing. They often resemble cuirasses, hiding the real impression that ideas should produce in us. That is the reason why it is perhaps better not to name a thing that we are not yet able to define. If we did, we should find ourselves so shackled afterwards as not to have perfect freedom in our conclusions. It has often been seen in history that a premature hypothesis has arrested the progress of science, says Grove: 'When natural phenomena are observed for the first time, a tendency immediately arises to relate them to something already known. The new phenomenon may be quite remote from the ideas with which one would compare it. It may belong to a different order of analogies. But this distinction cannot be perceived, since the necessary data or co-ordinates are lacking.' Now the theory originally announced is soon accepted by the public; and when it happens that subsequent facts, different from the preceding, fail to fit the mould, it is difficult to enlarge this without breaking it, and people often prefer to abandon a theory now proved erroneous, and silently ignore the intractable facts. As to the special phenomena in question in this little volume, I find them implicitly embodied in three words uttered nearly twenty centuries ago,—MENS AGITAT MOLEM (mind acting on matter gives it life and [Pg xxii]motion); and I leave the phenomena embedded in these words, like fire in the flint. I will not strike with the steel, for the spark is still dangerous. 'Periculosum est credere et non credere' ('It is dangerous to believe and not to believe'), says the ancient fabulist Phædrus. To deny facts a priori is mere conceit and idiocy. To accept them without investigation is weakness and folly. Why seek to press on so eagerly and prematurely into regions to which our poor powers cannot yet attain? The way is full of snares and bottomless pits. The phenomena we are treating in these pages do not perhaps throw new light upon the solution of the great problem of immortality, but they invite us to remember that there are in man elements to study, to determine, to analyze,—elements still unexplained, and which belong to the psychic realm.

"There has been much talk about Spiritualism in connection with these phenomena. Some of its defenders have thought to strengthen it by supporting it on so weak a basis as that. The scoffers have thought they could positively ruin the creed of the psychics, and, hurling it from its base, bury it under a fallen wardrobe (l'éboulement d'une armoire).[2] Now the first-named have rather compromised than assisted the cause: the others have not overturned it after all. Even if it should be proved that Spiritualism consists only of tricks of legerdemain, the belief in the existence of souls separate from the body would not be affected in the slightest degree. Besides, the deceptions of mediums do not prove that they are always tricky. They only put us on our guard, and induce us to keep a stern watch upon them.

"As to the psychological question of the soul and the [Pg xxiii]analysis of spiritual forces, we are just where chemistry was at the time of Albert the Great: we don't know.

"Can we not then keep the golden mean between negation, which denies all, and credulity, which accepts all? Is it rational to deny everything that we cannot understand, or, on the contrary, to believe all the follies that morbid imaginations give birth to, one after another? Can we not possess at once the humility which becomes the weak and the dignity which becomes the strong?

"I end this plea, as I began it, by declaring that it is not for the sake of the brothers Davenport, nor of any sect, nor of any group, nor, in short, of any person whatever, that I have entered the lists of controversy, but solely for the sake of facts the reality of which I ascertained several years ago, without having discovered their cause. However, I have no reason to fear that those who do not know me will take a fancy to misrepresent my thought; and I think that those who are acquainted with me know that I am not accustomed to swing a censer in any one's honor. I repeat for the last time: I am not concerned with individuals. My mind seeks the truth, and recognizes it wherever it finds it. 'Gallus escam quærens margaritam reperit.'"[3]

A certain number of my readers have been for some time kindly expressing a wish for a new edition of this early book. But strictly speaking I could not do this without considerably enlarging my original plan and composing an entirely new work. The daily routine of my astronomical labors has constantly hindered me from devoting myself to that task. The starry heaven is a vast and absorbing field of work, and it is difficult to turn aside (even for a relaxation in itself scientific) from the exacting claims of a science which goes on developing unceasingly at a most prodigious rate.

Still, the present work may be considered as, in a sense,[Pg xxiv] an enlarged edition of the earlier one. The foregoing citation of a little book written for the purpose of proving the existence of unknown forces in nature has seemed to me necessary here; useful in this new volume, brought out for the same purpose after more than forty years of study, since it may serve to show the continuity and consistent development of my thought on the subject.

MYSTERIOUS PSYCHIC FORCES

ON CERTAIN UNKNOWN NATURAL FORCES

I purpose to show in this book what truth there is in the phenomena of table-turnings, table-movings, and table-rappings, in the communications received therefrom, in levitations that contradict the laws of gravity, in the moving of objects without contact, in unexplained noises, in the stories told of haunted houses,—all to be considered from the physical and mechanical point of view. Under all the just mentioned heads we can group material facts produced by causes still unknown to science, and it is with these physical phenomena that we shall specially occupy ourselves here; for the first point is to definitely prove, by sufficient observations, their real existence. Hypotheses, theories, doctrines, will come later.

In the country of Rabelais, of Montaigne, of Voltaire, we are inclined to smile at everything that relates to the marvellous, to tales of enchantment, the extravagances of occultism, the mysteries of magic. This arises from a reasonable prudence. But it does not go far enough. To deny and prejudge a phenomenon has never proved anything. The truth of almost every fact which constitutes the sum of the positive sciences of our day has been denied. What we ought to do is to admit no unverified statement, to apply to every subject of study, no matter what, the experimental method, without any preconceived idea whatever, either for or against.

[Pg 2]We are dealing here with a great problem, which touches on that of the survival of human consciousness. We may study it, in spite of smiles.

When we consecrate our lives to an idea, useful, noble, exalted, we should not hesitate for a moment to sacrifice personalities; above all, our own self, our interest, our self-esteem, our natural vanity. This sacrifice is a criterion by which I have estimated a good many characters. How many men, how many women, put their miserable little personality above everything else!

If the forces of which we are to treat are real, they cannot but be natural forces. We ought to admit, as an absolute principle, that everything is in nature, even God himself, as I have shown in another work. Before any attempt at theory, the first thing to do is to scientifically establish the real existence of these forces.

Mediumistic experiences might form (and doubtless soon will form) a chapter in physics. Only it is a kind of transcendental physics which touches on life and thought, and the forces in play are pre-eminently living forces, psychic forces.

I shall relate in the following chapter the experiments I made between the years 1861 and 1865, previous to the penning of the protest, reprinted in the long citation above given (in the Introduction). But, since in certain respects they are summed up in those I have just had, in 1906, I will begin by describing the latter in this first chapter.

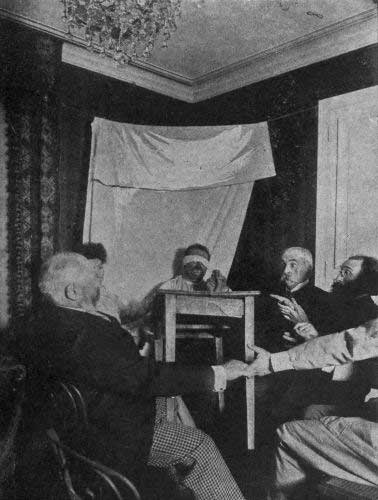

In fact, I have recently renewed these investigations with a celebrated medium,—Mme. Eusapia Paladino, of Naples, who has been several times in Paris; namely, in 1898, 1905, and, very recently, in 1906. The things I am going to speak of happened in the salon of my home in Paris,—the last ones in full light without any preparation, very simply, as if during after-dinner talks.

[Pg 3]Let me add that this medium came to Paris during the first months of the year, 1906, at the invitation of the Psychological Institute, several members of which have been recently engaged in researches begun long ago. Among these savants I will mention the name of the lamented Pierre Curie, the eminent chemist, with whom I had a conversation a few days before his unfortunate and terrible death. My mediumistic experiences with Mme. Paladino formed for him a new chapter in the great book of nature, and he also was convinced that there exist hidden forces to the investigation of which it is not unscientific to consecrate one's self. His subtle and penetrating genius would perhaps have quickly determined the character of these forces.

Those who have given some little attention to these psychological studies are acquainted with the powers of Mme. Paladino. The published works of Count de Rochas, of Professor Richet, of Dr. Dariex, of M. G. de Fontenay, and notably the Annales des sciences psychiques, have pointed them out and described them in such detail that it would be superfluous to recur to them at this point. Farther on we shall find a place for discussing them.

Running underneath all the observations of the above-mentioned writers, one dominant idea can be read as if in palimpsest; namely, the imperious necessity the experimenters are constantly under of suspecting tricks in this medium (Mme. Paladino). But all mediums, men and women, have to be watched. During a period of more than forty years I believe that I have received at my home nearly all of them, men and women of divers nationalities and from every quarter of the globe. One may lay it down as a principle that all professional mediums cheat. But they do not always cheat; and they possess real, undeniable psychic powers.

Their case is nearly that of the hysterical folk under observation at the Salpêtrière or elsewhere. I have seen some[Pg 4] of them outwit with their profound craft not only Dr. Charcot, but especially Dr. Luys, and all the physicians who were making a study of their case. But, because hysteriacs deceive and simulate, it would be a gross error to conclude that hysteria does not exist. And, because mediums frequently descend to the most brazen-faced imposture, it would not be less absurd to conclude that mediumship has no existence. Disreputable somnambulists do not forbid the existence of magnetism, hypnotism, and genuine somnambulism.

This necessity of being constantly on our guard has discouraged more than one investigator, as the illustrious astronomer Schiaparelli, director of the Observatory of Milan, specially wrote me, in a letter which will appear farther on.

Still, we have got to endure this evil.

The words "fraud" (supercherie) and "trickery" (tricherie) have in this connection a sense a little different from their ordinary meaning. Sometimes the mediums deceive purposely, knowing well what they are doing, and enjoying the fun. But oftener they unconsciously deceive, impelled by the desire to produce the phenomena that people are expecting.

They help on the success of the experiment when that success is slow in its appearance. Mediums who deal with objective phenomena are gifted with the power of causing objects at a distance to move, of lifting tables, etc. But they usually appear to apply this power at the ends of their fingers, and the objects to be moved have to be within reach of their hands or feet, a very regrettable thing, and one which furnishes fine sport for the prejudiced sceptics. Sometimes the mediums act like the billiard player, who continues for an instant the gesture of hand and arm, holding his cue pointed at the rolling ivory ball, and leaning forward as if by his will he could push it to a carom. He knows very well that he has no further power over the fate of the ball, which[Pg 5] his initial stroke alone impels; but he guides its course by his thought and his gesture.

It may not be superfluous to caution the reader that the word "medium" is employed in these pages without any preconceived idea, and not in the etymological sense in which it took its rise at the time of the first Spiritualistic theories, which affirmed that the man or the woman endowed with psychic powers is an intermediary between spirits and those who are experimenting. The person who has the power of causing objects to move contrary to the laws of gravity (even sometimes without touching them), of causing sounds to be heard at a distance and without any exertion of muscular force, and of bringing before the eyes various apparitions, has not necessarily, on that account, any bond of union with disembodied minds or souls. We shall keep this word "medium," however, now so long in use. We are concerned here only with facts. I hope to convince the reader that these things really exist, and are neither illusions nor farces, nor feats of prestidigitation. My object is to prove their reality with absolute certainty, to do for them what (in my volume The Unknown and the Psychic Problems) I have done for telepathy, the apparitions of the dying, premonitory dreams, and clairvoyance.

I shall begin, I repeat, with experiments which I have recently renewed; namely, during four séances on March 29, April 5, May 30, and June 7, of 1906.

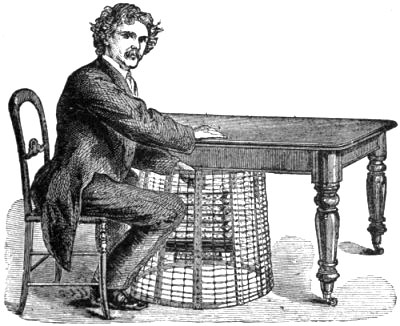

1. Take the case of the levitation of a round table. I have so often seen a rather heavy table lifted to a height of eight, twelve, sixteen inches from the floor, and I have taken such undeniably authentic photographs of these; I have so often proved to myself that the suspension of this article of furniture by the imposition upon it of the hands of four or five persons produces the effect of a floating in a tub full of water or other elastic fluid, that, for me,[Pg 6] the levitation of objects is no more doubtful than that of a pair of scissors lifted by the aid of a magnet. But one evening when I was almost alone with Eusapia, March 29, 1906 (there were four of us altogether), being desirous of examining at leisure how the thing was done, I asked her to place her hands with mine upon the table, the other persons remaining at a distance. The table very soon rose to a height of fifteen or twenty inches while we were both standing. At the moment of the production of the phenomenon the medium placed one of her hands on one of mine, which she pressed energetically, our two other hands resting side by side. Moreover, on her part, as on mine, there was an act of will expressed in words of command addressed to "the spirit": "Come now! Lift the table! Take courage! Come! Try now!" etc.

We ascertained at once that there were two elements or constituents present. On the one hand, the experimenters address an invisible entity. On the other hand, the medium experiences a nervous and muscular fatigue, and her weight increases in proportion to that of the object lifted (but not in exact proportion).

We are obliged to act as if there really were a being present who is listening. This being appears to come into existence, and then become non-existent as soon as the experiment is ended. It seems to be created by the medium. Is it an auto-suggestion of hers or of the dynamic ensemble of the experimenters that creates a special force? Is it a doubling of her personality? Is it the condensation of a psychic milieu in the midst of which we live? If we seek to obtain proofs of actual and permanent individuality, and above all of the identity of a particular soul called up in our memory, we never obtain any satisfaction. There lies the mystery.

[Pg 7]Conclusion: we have here an unknown force of the psychic class, a living force, the life of a moment only.

May it not be possible that, in exerting ourselves, we give rise to a detachment of forces which acts exteriorly to our body? But this is not the place, in these first pages, to make hypotheses.

The experiment of which I have just spoken was repeated three times running, in the full light of a gas chandelier, and under the same conditions of complete proof in each case. A round table weighing about fourteen pounds is lifted by this unknown force. A table of twenty-five or fifty pounds or more requires a greater number of persons. But they will get no result if one at least among them is not gifted with the mediumistic power.

And let me add, on the other hand, that there is in such an experiment so great an expenditure of nervous and muscular energy that such an extraordinary medium as Eusapia, for instance, can obtain scarcely any results six hours, twelve hours, even twenty-four hours, after a séance in which she has so lavishly expended her psychic energy.

I will add that quite often the table continues to rise even after the experimenters have ceased to touch it. This is movement without contact.

This phenomenon of levitation is, to me, absolutely proved, although we cannot explain it. It is like what would happen if one had his hands gloved with loadstone, and, placing them on a table of iron, should lift it from the ground. But the action is not so simple as that: it is a case of psychic activity exterior to ourselves, momentarily in operation.[4]

[Pg 8]Now how are these levitations and movements produced?

How is it that a stick of sealing-wax or a lamp-chimney, when rubbed, attracts bits of paper or elder pith?

How is it that a particle of iron grips so firmly to the loadstone when brought near it?

How is it that electricity accumulates in the vapor of water, in the molecules of a cloud, until it gives rise to the thunder, the thunderbolt, the lightning flash, and all their formidable results?

How is it that the thunderbolt strips the clothes from a man or a woman with its characteristic nonchalance?

And (to take a simple instance), without departing from our common and normal condition of life, how is it that we raise our arm?

2. Take now a specimen of another group of cases. The medium places one of her hands upon that of some person, and with the other beats the air, with one, two, three, or four strokes or raps. The raps are heard in the table, and you feel the vibrations at the same time that you hear them,—sharp blows which make you think of electric shocks. It is superfluous to state that the feet of the medium do not touch those of the table, but are kept at a distance from them.

The medium next places her hands with ours upon the table, and the taps heard in the table are stronger than in the preceding case.

Plate I. Complete Levitation of a Table in Professor

Flammarion's Salon through Mediumship

of Eusapia Paladino.

These taps audible in the table, this "typtology" well[Pg 9] known to Spiritualists, have been frequently attributed to some kind of trickery or another, to a cracking muscle or to various actions of the medium. After the comparative study I have made of these special occurrences I believe I am right in affirming that this fact also is not less certain than the first. Rappings, as is well known, are obtained in all kinds of rhythms, and responses to all questions are obtained through simple conventions, by which it is agreed, for instance, that three taps shall mean "yes" and two mean "no," and that, while the letters of the alphabet are being read, words can be dictated by taps made as each letter is named.

3. During our experiments, while we four persons are seated around a table asking for a communication which does not arrive, an arm-chair, placed about twenty-four inches from the medium's foot (upon which I have placed my foot to make sure that she cannot use hers),—an arm-chair, I say, begins to move, and comes sliding up to us. I push it back; it returns. It is a stuffed affair (pouf), very heavy, but easily capable of gliding over the floor. This thing happened on the 29th of last March, and again on April 5th.

It could have been done by drawing the chair with a string or by the medium putting her foot sufficiently far out. But it happened over and over again (five or six times), automatically moving, and that so violently that the chair jumped about the floor in a topsy-turvy fashion and ended by falling bottom side up without anybody having touched it.

4. Here is a fourth case re-observed this year, after having been several times verified by me, notably in 1898.

Curtains near the medium, but which it is impossible for her to touch, either with the hand or the foot, swell out their whole length, as if inflated by a gusty wind. I have several[Pg 10] times seen them envelop the heads of the spectators as if with cowls of Capuchin monks.

5. Here is a fifth instance, authenticated by me several times, and always with the same care.

While I am holding one hand of Eusapia in mine, and one of my astronomical friends, tutor at the Ecole Polytechnique, is holding the other, we are touched, first one and then the other, upon the side and on the shoulders, as if by an invisible hand.

The medium usually tries to get together her two hands, held separately by each of us, and by a skilful substitution to make us believe we hold both when she has succeeded in disengaging one. This fraud being well known by us, we act the part of forewarned spectators, and are positive that we have each succeeded in holding her hands apart. The touchings in this experiment seem to proceed from an invisible entity and are rather disagreeable. Those which take place in the immediate vicinity of the medium could be due to fraud; but to some of them this explanation is inapplicable.

This is the place to remark that, unfortunately, the extraordinary character of the phenomena is in direct ratio with the absence of light, and we are continually asked by the medium to turn down the gas, almost to the vanishing point: "Meno luce! meno luce!" ("Less light, less light"). This, of course, is advantageous to all kinds of fraud. But it is a condition no more obligatory than the others. There is in it no implication of a threat.

We can get a large number of mediumistic phenomena with a light strong enough for us to distinguish things with certainty. Still, it is a fact that light is unfavorable to the production of phenomena.

This is annoying. Yet we have no right to impose the opposite condition. We have no right to demand of nature[Pg 11] conditions which happen to suit us. It would be just as reasonable to try to get a photographic negative without a dark room, or to draw electricity from a rotating machine in the midst of an atmosphere saturated with moisture. Light is a natural agent capable of producing certain effects and of opposing the production of others.

This aphorism calls to my mind an anecdote in the life of Daguerre, related in the first edition of this book.

One evening this illustrious natural philosopher meets an elegant and fashionable woman in the neighborhood of the Opera House, of which he was at that time the decorator. Enthusiastic over his progress in natural philosophy, he happens to speak of his photogenic studies. He tells her of a marvellous discovery by which the features of the face can be fixed upon a plate of silver. The lady, who is a person of plain common sense, courteously laughs in his face. The savant goes on with his story, without being disconcerted. He even adds that it is possible for the phenomenon to take place instantaneously when the processes become perfected. But he has his pains for his trouble. His charming companion is not credulous enough to accept such an extravagance. Paint without colors and without a brush! design without pen or crayon! as if a portrait could get painted all by itself, etc. But the inventor is not discouraged, and, to convince her, offers to make her portrait by this process. The lady is unwilling to be thought a dupe and refuses. But the skilful artist pleads his cause so well that he overcomes her objections. The blond daughter of Eve consents to pose before the object-glass. But she makes one condition,—only one.

Her beauty is at its best in the evening, and she feels a little faded in the garish light of day.

"If you could take me in the evening—"

"But, madame, it is impossible—"

[Pg 12]"Why? You say that your invention reproduces the face, feature by feature. I prefer my features of the evening over those of the morning."

"Madame, it is the light itself which pencils the image, and without it I can do nothing."

"We will light a chandelier, a lamp, do anything to please you."

"No, madame, the light of day is imperative."

"Will you please tell me why?"

"Because the light of the sun exhibits an intense activity, sufficient to decompose the iodide of silver. So far, I have not been able to take a photograph except in full sunlight."

Both remained obstinate, the lady maintaining that what could be done at ten o'clock in the morning could also easily be done at ten o'clock in the evening. The inventor affirmed the contrary.

So, then, all you have to do, gentlemen, is to forbid the light to blacken iodine, or order it to blacken lime, and condemn the photographer to develop his negative in full light. Ask Electricity why it will pass instantaneously from one end to the other of an iron wire a thousand miles long and why it refuses to traverse a thread of glass half an inch long. Beg the night-blooming flowers to expand in the day, or those that only bloom in the light not to close at dusk. Give me the explanation of the respiration of plants, diurnal and nocturnal, and of the production of chlorophyll and how plants develop a green color in the light; why they breathe in oxygen and exhale carbonic acid gas during the night, and reverse the process during the day. Change the equivalents of simple substances in chemistry, and order combinations to be produced. Forbid azotic acid to boil at the freezing temperature, and command water to boil at zero. You have only to ask these accommodations and nature will obey you, gentlemen, depend upon it.

[Pg 13]A good many phenomena of nature only occur in obscurity. The germs of plants, animals, man, in forming a new being, work their miracle only in the dark.

Here, in a flask, is a mixture of hydrogen and chlorine in equal volumes. If you wish to preserve the mixture, you must keep the flask in the dark, whether you want to or not. Such is the law. As long as it remains in the dark, it will retain its properties. But suppose you take a schoolboy notion to expose the thing to the action of light. Instantly a violent explosion is heard; the hydrogen and the chlorine disappear, and you find in the flask a new substance,—chloridic acid. There is no use in your finding fault: darkness respects the two substances, while light explodes them.

If we should hear a malignant sceptic of some clique or other say, "I will only believe in jack-o'-lanterns when I see them in the light of day," what should we think of his sanity? About what we should think if he should add that the stars are not certainties, since they are only seen at night.

In all the observations and experiments of physics there are conditions to be observed. In those of which we are speaking a too strong light seems to imperil the success of the experiment. But it goes without saying that precautions against deception ought to increase in direct ratio with the decrease of visibility and other means of verification.

Let us return to our experiments.

6. Taps are heard in the table, or it moves, rises, falls back, raps with its leg. A kind of interior movement is produced in the wood, violent enough, sometimes, to break it. The round table I made use of (with others) in my home was dislocated and repaired more than once, and it was by no means the pressure of the hands upon it that could have caused the dislocations. No, there is something more[Pg 14] than that in it: there is in the actions of the table the intervention of mind, of which I have already spoken.

The table is questioned, by means of the conventional signs described a few pages back, and it responds. Phrases are rapped out, usually banal and without any literary, scientific, or philosophical value. But, at any rate, words are rapped out, phrases are dictated. These phrases do not come of their own accord, nor is it the medium who taps them—consciously—either with her foot or her hand, or by the aid of a snapping muscle, for we obtain them in séances held without professional mediums and at scientific reunions where the existence of trickery would be a thing of the greatest absurdity. The mind of the medium and that of the experimenters most assuredly have something to do with the mystery. The replies obtained generally tally the intellectual status of the company, as if the intellectual faculties of the persons present were exterior to their brains and were acting in the table wholly unknown to the experimenters themselves. How can this thing be? How can we compose and dictate phrases without knowing it. Sometimes the ideas broached seem to come from a personality unknown to the company, and the hypothesis of spirits quite naturally presents itself. A word is begun; some one thinks he can divine its ending; to save time, he writes it down; the table parries, is agitated, impatient. It is the wrong word; another was being dictated. There is here, then, a psychic element which we are obliged to recognize, whatever its nature may be when analyzed.

The success of experiments does not always depend on the will of the medium. Of course that is the chief element in it; but certain conditions independent of her are necessary. The psychical atmosphere created by the persons present has an influence that cannot be neglected. So the state of health of the medium is not without its influence. If he is fatigued,[Pg 15] although he may have the best will in the world, the value of the results will be affected. I had a new proof of this thing, so often observed, at my house, with Eusapia Paladino, on May 30, 1906. She had for more than a month been suffering from a rather painful affection of the eyes; and furthermore her legs were considerably swollen. We were seven, of whom two lookers-on were sceptics. The results were almost nil; namely, the lifting, during scarcely two seconds of time, of a round table weighing about four pounds; the tipping up of one side of a four-legged table; and a few rappings. Still, the medium seemed animated by a real wish to obtain some result. She confessed to me, however, that what had chiefly paralyzed her faculties was the sceptical and sarcastic spirit of one of the two incredulous persons. I knew of the absolute scepticism of this man. It had not been manifested in any way; but Eusapia had at once divined it.

The state of mind of the by-standers, sympathetic or antipathetic, has an influence upon the production of the phenomena. This is an incontestable matter of observation. I am not speaking here merely of a tricky medium rendered powerless to act by a too close critical inspection, but also of a hostile force which may more or less neutralize the sincerest volition. Is it not the same, moreover, in assemblies, large or small, in conferences, in salons, etc.? Do we not often see persons of baleful and antipathetic spirit defeat at their very beginning the accomplishment of the noblest purposes.

Here are the results of another sitting of the same medium held a few days afterwards.

On the 7th of June, 1906, I had been informed by my friend Dr. Ostwalt, the skilled oculist, who was at that time treating Eusapia, that she was to be at his house that evening and that perhaps I would be able to try a new [Pg 16]experiment. I accepted with all the more readiness because the mother-in-law of the doctor, Mme. Werner, to whom I had been attached by a friendship of more than thirty years, had been dead a year, and had many a time promised me, in the most formal manner, to appear after her death for the purpose of giving completeness to my psychical researches by a manifestation, if the thing was possible. We had so often conversed on these subjects, and she was so deeply interested in them, that she had renewed her promise very emphatically a few days before her death. And at the same time she made a similar promise to her daughter and to her son-in-law.

Eusapia, also, on her part, grateful for the care she had received at the doctor's hands and for the curing of her eye, wished to be agreeable to him in any way she could.

The conditions, then, were in all respects excellent. I agreed with the doctor that we had before us four possible hypotheses, and that we should seek to fix on the most probable one.

a. What would take place might be due to fraud, conscious or unconscious.

b. The phenomena might be produced by a physical force emanating from the medium.

c. Or by one or several invisible entities making use of this force.

d. Or by Mme. Werner herself.

We had on that evening some movements of the table and a complete lifting of the four feet to a height of about eight inches. Six of us sat around the table,—Eusapia, Madame and Monsieur Ostwalt, their son Pierre, sixteen years old, my wife and myself. Our hands placed above the table scarcely touched it, and were almost wholly detached at the moment it rose from the floor. No fraud possible. Full light.

[Pg 17]The séance then continued in the dark. The two portières of a great double-folding door, against which the medium was seated, her back to the door, were blown about for nearly an hour, sometimes so violently as to form something like a monk's hood on the head of the doctor and that of his wife.

This great door was several times shaken violently, and tremendous blows were struck upon it.

We tried to obtain words by means of the alphabet, but without success. (I will remark in this connection that Eusapia knows neither how to read nor to write.)

Pierre Ostwalt was able to write a word with the pencil. It seemed as if an invisible force was guiding his hand. The word he pencilled down was the first name of Mme. Werner, well known to him.

In spite of all our efforts, we were unable to obtain a single proof of identity. Yet it would have been very easy for Mme. Werner to find one, as she had so solemnly promised us to do.

In spite of the announcement by raps that an apparition would appear which we would be permitted to see, we were only able to perceive a dim white form, devoid of precise outline, even when we manipulated the light so as to get almost complete darkness. From this new sitting the following conclusions are deduced:

a. Fraud cannot explain the phenomena, especially the levitation of the table, the violent blows and shakings given to the door, and the projection of the curtain into the room.

b. These phenomena are certainly produced by a force emanating from the medium, for they all occur in her immediate neighborhood.

c. This force is intelligent. But it is possible that this intelligence which obeys our requests is only that of the medium.

[Pg 18]d. Nothing proves that the spirit evoked had any influence.

These propositions, however, will be examined and developed one by one in the pages that follow.

All the experiments described in this first chapter reveal to us unknown forces in operation. It will be the same in the chapters that follow.

These phenomena are so unexplained, so inexplicable, so incredible, that the simplest plan is to deny them, to attribute them all to fraud or to hallucination, and to believe that all the participators are sand-blind.

Unfortunately for our opponents, this hypothesis is inadmissible.

Let me say here that there are very few men—and above all, women—whose spirit is completely free; that is, in a condition capable of accepting, without any preconceived idea, new or unexplained facts. In general, people are disposed to admit only those facts or things for which they are prepared by the ideas they have received, cherished, and maintained. Perhaps there is not one human being in a hundred who is capable of making a mental record of a new impression, simply, freely, exactly, with the accuracy of a photographic camera. Absolute independence of judgment is a rare thing among men.

A single fact accurately observed, even if it should contradict all science, is worth more than all the hypotheses.

But only the independent minds, free from the classic leading-strings which tie the dogmatists to their chairs, dare to study extra-scientific facts or consider them possible.

I am acquainted with erudite men of genius, members of the Academy of Sciences, professors at the university, masters in our great schools, who reason in the following way: "Such and such phenomena are impossible because[Pg 19] they are in contradiction with the actual state of science. We should only admit what we can explain."

They call that scientific reasoning!

Examples.—Frauenhofer discovers that the solar spectrum is crossed by dark lines. These dark lines could not be explained in his time. Therefore we ought not to believe in them.

Newton discovers that the stars move as if they were governed by an attractive force. This attraction could not be explained in his time. Nor is it explained to-day. Newton himself takes the pains to declare that he does not wish to explain it by an hypothesis. "Hypotheses non fingo" ("I do not make hypotheses"). So, after the reasoning of our pseudo-logicians, we ought not to admit universal gravitation. Oxygen combined with hydrogen forms water. How? We don't know. Hence we ought not to admit the fact.

Stones sometimes fall from the sky. The Academy of Sciences of the eighteenth century, not being able to divine where they came from, simply denied the fact, which had been observed for thousands of years. They denied also that fish and toads can fall from the clouds, because it had not then been observed that waterspouts draw them up by suction and transport them from one place to another. A medium places his hand upon a table and seems actually to transmit to it independent life. It is inexplicable, therefore it is false. Yet that is the predominant method of reasoning of a great number of scholars. They are only willing to admit what is known and explained. They declared that locomotives would not be able to move, or, if they did succeed, railways would introduce no change in social relations; that the transatlantic telegraph would never transmit a despatch; that vaccine would not render immune; and at one time they stoutly maintained (this was long ago) that the earth does[Pg 20] not revolve. It seems that they even condemned Galileo. Everything has been denied.

Apropos of facts somewhat similar to those we are here studying,—I mean the stigmata of Louise Lateau,—a very famous German scholar, Professor Virchow, closed his report to the Berlin Academy with this dilemma: Fraud or Miracle. This conclusion acquired a classic vogue. But it was an error, for it is now known that stigmata are due neither to fraud nor miracle.

Another rather common objection is presented by certain persons apparently scientific. Confounding experience with observation, they imagine that a natural phenomenon, in order to be real, ought to be able to be produced at will, as in a laboratory. After this manner of looking at things, an eclipse of the sun would not be a real thing, nor a stroke of lightning which sets fire to a house, nor an aërolite that falls from the sky. An earthquake, a volcanic eruption, are phenomena of observation, not of experiment. But they none the less exist, often to the great damage of the human race. Now, in the order of facts that we are studying here, we can almost never experiment, but only observe, and this reduces considerably the range of the field of study. And, even when we do experiment, the phenomena are not produced at will: certain elements, several of which we have not yet been able to get hold of, intervene to cross, modify, and thwart them, so that for the most part we can only play the rôle of observers. The difference is analogous to that which separates chemistry from astronomy. In chemistry we experiment: in astronomy we observe. But this does not hinder astronomy from being the most exact of the sciences.

Mediumistic phenomena that come directly under the observation, notably those I have described some pages back, have for me the stamp of absolute certainty and [Pg 21]incontestability, and amply suffice to prove that unknown physical forces exist outside of the ordinary and established domain of natural philosophy. As a principle, moreover, this is an unimpeachable tenet.[5]

I could adduce still other instances, for example the following:

7. During séance experiments, phantoms often appear,—hands, arms, a head, a bust, an entire human figure. I was a witness of this thing, especially on July 27, 1897, at Montfort-l'Amaury (see Chapter III). M. de Fontenay having declared that he perceived an image or spirit over the table, between himself and me (we were sitting face to face, keeping watch over Eusapia, he holding one of her hands, and I the other), and I seeing nothing at all, I asked him to change places with me. And then I, too, perceived this spirit-shadow, the head of a bearded man, rather vaguely outlined, which was moving like a silhouette, advancing and retiring in front of a red lantern placed on a piece of furniture. I had not been able to see at first from where I sat, because the lantern was then behind me, and the spectral appearance was formed between M. de Fontenay and me. As this dark silhouette remained rather vague, I asked if I could not touch its beard. The medium replied, "Stretch out your hand." I then felt upon the back of my hand the brushing of a very soft beard.

This case did not have for me the same absolute certainty as the preceding. There are degrees in the feeling of security we have in observations. In astronomy, even, there are stars at the limit of visibility. And yet in the opinion of all the participators in the séance there was no trick. Besides, on another occasion, at my own home, I saw another figure, that of a young girl, as the reader will see in the third chapter.

[Pg 22]8. That same day, at Montfort, in the course of the conversation, some one recalled the circumstance that the "spirits" have sometimes impressed on paraffin or putty or clay the print of their head or of their hands,—a thing that seems in the last degree absurd. But we bought some putty at a glazier's and fixed up in a wooden box a perfectly soft cake. At the end of the séance there was the imprint of a head, of a face, in this putty. In this case, no more than in the other, am I absolutely certain there was no trickery. We will speak of it farther on.

Other manifestations will be noted in subsequent pages of this book. Stopping right here, for the present, at the special point of view of the proved existence of unknown forces, I will confine myself to the six preceding cases, regarding them as incontestable, in the judgment of any man of good faith or of any observer. If I have considered these particular cases so early in the work, it is in response to readers of my works who have been begging me for a long time to give my personal observations.

The simplest of these manifestations—that of raps, for example—is not a negligible asset. There is no doubt that it is one or another of the experimenters, or their dynamic resultant, that raps in the table without knowing how. So, even if it should be a psychic entity unknown to the mediums, it evidently makes use of them, of their physiological properties. Such a fact is not without scientific interest. The denials of scepticism prove nothing, unless it be that the deniers themselves have not observed the phenomena.

I have no other aim in this first chapter than to give a preliminary summary of the observed facts.

I do not desire to put forth in these first pages any explanatory hypothesis. My readers will themselves form an opinion from the narratives that follow, and the last chapter of the volume will be devoted to theories. Yet I believe it[Pg 23] will be useful to call attention at once to the fact that matter is not, in reality, what it appears to be to our vulgar senses,—to our sense of touch, to our vision,—but that it is identical with energy, and is only a manifestation of the movement of invisible and imponderable elements. The universe is a dynamism. Matter is only an appearance. It will be useful for the reader to bear this truth in mind, as it will help him to comprehend the studies we are about to make.

The mysterious forces we are here studying are themselves manifestations of the universal dynamism with which our five senses put us very imperfectly into relation.

These things belong to the psychical order as well as to the physical. They prove that we are living in the midst of an unexplored world, in which the psychic forces play a rôle as yet very imperfectly studied.

We have here a situation analogous to that in which Christopher Columbus found himself on the evening of the day when he perceived the first hints of land in the New World. We are pushing our prow through an absolutely unknown sea.

MY FIRST SÉANCES IN THE ALLAN KARDEC GROUP AND WITH THE MEDIUMS OF THAT EPOCH

One day in the month of November, 1861, under the Galeries de l'Odéon,[6] I spied a book, the title of which struck me,—Le Livre des Esprits ("The Book of Spirits"), by Allan Kardec. I bought it and read it with avidity, several chapters seeming to me to agree with the scientific bases of the book I was then writing, The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds. I hunted up the author, who proposed that I should enter, as a free associated member, the Parisian Society for Spiritualistic Studies, which he had founded, and of which he was president. I accepted, and by chance have just found the green ticket signed by him on the fifteenth day of November, 1861. This is the date of my début in psychic studies. I was then nineteen, and for three years had been an astronomical pupil at the Paris Observatory. At this time I was putting the last touches to the book I just mentioned, the first edition of which was published some months afterwards by the printer-publisher of the Observatory.

The members came together every Friday evening in the assembly room of the society, in the little passageway of Sainte Anne, which was placed under the protection of Saint Louis. The president opened the séance by an "invocation to the good spirits." It was admitted, as a principle, that invisible spirits were present there and revealed[Pg 25] themselves. After this invocation a certain number of persons, seated at a large table, were besought to abandon themselves to their inspiration and to write. They were called "writing mediums." Their dissertations were afterwards read before an attentive audience. There were no physical experiments of table-turning, or tables moving or speaking. The president, Allan Kardec, said he attached no value to such things. It seemed to him that the instructions communicated by the spirits ought to form the basis of a new doctrine, of a sort of religion.

At the same period, but several years earlier, my illustrious friend Victorien Sardou, who had been an occasional frequenter of the Observatory, had written, as a medium, some curious pages on the inhabitants of the planet Jupiter, and had produced picturesque and surprising designs, having as their aim to represent men and things as they appeared in this giant of worlds. He designed the dwellings of people in Jupiter. One of his sketches showed us the house of Mozart, others the houses of Zoroaster and of Bernard Palissy, who were country neighbors in one of the landscapes of this immense planet. The dwellings are ethereal and of an exquisite lightness. They may be judged of by the two figures here reproduced (Pl. II and III). The first represents a residence of Zoroaster, the second "the animals' quarters" belonging to the same. On the grounds are flowers, hammocks, swings, flying creatures, and, below, intelligent animals playing a special kind of ninepins where the fun is not to knock down the pins, but to put a cap on them, as in the cup and ball toy, etc.

These curious drawings prove indubitably that the signature "Bernard Palissy, of Jupiter," is apocryphal and that the hand of Victorien Sardou was not directed by a spirit from that planet. Nor was it the gifted author himself who planned these sketches and executed them in accordance[Pg 26] with a definite plan. They were made while he was in the condition of mediumship. A person is not magnetized, nor hypnotized, nor put to sleep in any way while in that state. But the brain is not ignorant of what is taking place: its cells perform their functions, and act (doubtless by a reflex movement) upon the motor nerves. At that time we all thought Jupiter was inhabited by a superior race of beings. The spiritistic communications were the reflex of the general ideas in the air. To-day, with our present knowledge of the planets, we should not imagine anything of the kind about that globe. And, moreover, spiritualistic séances have never taught us anything upon the subject of astronomy. Such results as were attained fail utterly to prove the intervention of spirits. Have the writing mediums given any more convincing proofs of it than these? This is what we shall have to examine in as impartial a way as we can.

I myself tried to see if I, too, could not write. By collecting and concentrating my powers and allowing my hand to be passive and unresistant, I soon found that, after it had traced certain dashes, and o's, and sinuous lines more or less interlaced, very much as a four-year-old child learning to write might do, it finally did actually write words and phrases.

In these meetings of the Parisian Society for Spiritualistic Studies, I wrote for my part, some pages on astronomical subjects signed "Galileo." The communications remained in the possession of the society, and in 1867 Allan Kardec published them under the head General Uranography, in his work entitled Genesis. (I have preserved one of the first copies, with his dedication.) These astronomical pages taught me nothing. So I was not slow in concluding that they were only the echo of what I already knew, and that Galileo had no hand in them. When I wrote the pages,[Pg 27] I was in a kind of waking dream. Besides, my hand stopped writing when I began to think of other subjects.

Plate II. House of Zoroastre of Jupiter from

Somnambulistic Drawing by Victorien Sardou.

Plate III. Animals' Quarters. House of Zoroastre of Jupiter from

Somnambulistic Drawing by Victorien Sardou.

I may quote here what I said on this subject in my work, The Worlds of Space (Les Terres du Ciel), in the edition of 1884, p. 181:—

The writing medium is not put to sleep, nor is he magnetized or hypnotized in any way. One is simply received into a circle of determinate ideas. The brain acts (by the mediation of the nervous system) a little differently from what it does in its normal state. The difference is not so great as one might suppose. The chief difference may be described as follows:

In the normal state we think of what we are going to write before the act of writing begins. There is a direct action of the will in causing the pen, the hand, and the fore-arm to move over the paper. In the abnormal state, on the other hand, we do not think before writing; we do not move the hand, but let it remain inert, passive, free; we place it upon the paper, taking care merely that it shall meet with the least possible resistance; we think of a word, a figure, a stroke of the pen, and the hand of its own volition begins to write. But the writing medium must think of what he is doing, not beforehand, but continuously; otherwise the hand stops. For example, try to write the word "ocean," not voluntarily (the ordinary way), but by simply taking a lead-pencil, and letting the hand rest lightly and freely upon the paper, while you think of your word and observe carefully whether the hand will write. Very good; it does begin to move over the paper, writing first an o, then a c, and the rest. At least that was my experience when I was studying the new problems of spiritualism and magnetism.