The Inhabitants of the Philippines

Frontispiece.

Sampson Low, Marston and Company Limited

St. Dunstan’s House

Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C.

1900

London:

Printed by William Clowes and Sons, Limited,

Stamford Street and Charing Cross. [v]

Preface.

The writer feels that no English book does justice to the natives of the Philippines, and this conviction has impelled him to publish his own more favourable estimate of them. He arrived in Manila with a thorough command of the Spanish language, and soon acquired a knowledge of the Tagal dialect. His avocations brought him into contact with all classes of the community—officials, priests, land-owners, mechanics, and peasantry: giving him an unrivalled opportunity to learn their ideas and observe their manners and customs. He resided in Luzon for fourteen years, making trips either on business or for sport all over the Central and Southern Provinces, also visiting Cebú, Iloilo, and other ports in Visayas, as well as Calamianes, Cuyos, and Palawan.

Old Spanish chroniclers praise the good breeding of the natives, and remark the quick intelligence of the young.

Recent writers are less favourable; Cañamaque holds them up to ridicule, Monteverde denies them the possession of any good quality either of body or mind.

Foreman declares that a voluntary concession of justice is regarded by them as a sign of weakness; other writers judge them from a few days’ experience of some of the cross-bred corrupted denizens of Manila.

Mr. Whitelaw Reid denounces them as rebels, savages, and treacherous barbarians.

Mr. McKinley is struck by their ingratitude for American kindness and mercy. [vi]

Senator Beveridge declares that the inhabitants of Mindanao are incapable of civilisation.

It seems to have been left to French and German contemporary writers, such as Dr. Montano and Professor Blumentritt to show a more appreciative, and the author thinks, a fairer spirit, than those who have requited the hospitality of the Filipinos by painting them in the darkest colours. It will be only fair to exempt from this censure two American naval officers, Paymaster Wilcox and Mr. L. S. Sargent, who travelled in North Luzon and drew up a report of what they saw.

As regards the accusation of being savages, the Tagals can claim to have treated their prisoners of war, both Spaniards and Americans with humanity, and to be fairer fighters than the Boers.

The writer has endeavoured to describe the people as he found them. If his estimate of them is more favourable than that of others, it may be that he exercised more care in declining to do business with, or to admit to his service natives of doubtful reputation; for he found his clients punctual in their payments, and his employés, workmen and servants, skilful, industrious, and grateful for benefits bestowed.

If the natives fared badly at the hands of recent authors, the Spanish Administration fared worse, for it has been painted in the darkest tints, and unsparingly condemned.

It was indeed corrupt and defective, and what government is not? More than anything, it was behind the age, yet it was not without its good points.

Until an inept bureaucracy was substituted for the old paternal rule, and the revenue quadrupled by increased taxation, the Filipinos were as happy a community as could be found in any colony. The population greatly multiplied; they lived in competence, if not in affluence; cultivation was extended, and the exports steadily increased.

The natives were secured the perpetual usufruct of the [vii]land they tilled, they were protected against the usurer, that curse of East and West.

In guaranteeing the land to the husbandman, the “Laws of the Indies” compare favourably with the law of the United States regarding Indian land tenure. The Supreme Court in 1823 decided that “discovery gives the dominion of the land discovered to the States of which the discoverers were the subjects.”

It has been almost an axiom with some writers that no advance was made or could be made under Spanish rule.

There were difficulties indeed. The Colonial Minister, importuned on the one hand by doctrinaire liberals, whose crude schemes of reform would have set the Archipelago on fire, and confronted on the other by the serried phalanx of the Friars with their hired literary bravos, was very much in the position of being between the devil and the deep sea, or, as the Spaniards phrase it “entre la espada y la pared.”

Even thus the Administration could boast of some reforms and improvements.

The hateful slavery of the Cagayanes had been abolished; the forced cultivation of tobacco was a thing of the past, and in all the Archipelago the corvée had been reduced.

A telegraph cable connecting Manila with Hong Kong and the world’s telegraph system had been laid and subsidized. Telegraph wires were extended to all the principal towns of Luzon; lines of mail steamers to all the principal ports of the Archipelago were established and subsidized. A railway 120 miles long had been built from Manila to Dagupan under guarantee. A steam tramway had been laid to Malabon, and horse tramways through the suburbs of Manila. The Quay walls of the Pasig had been improved, and the river illuminated from its mouth to the bridge by powerful electric arc lights.

Several lighthouses had been built, others were in progress. A capacious harbour was in construction, although unfortunately defective in design and execution. [viii]The Manila waterworks had been completed and greatly reduced the mortality of the city. The schools were well attended, and a large proportion of the population could read and write. Technical schools had been established in Manila and Iloilo, and were eagerly attended. Credit appears to be due to the Administration for these measures, but it is rare to see any mention of them.

As regards the Religious Orders that have played so important a part scarcely a word has been said in their favour. Worcester declares his conviction that their influence is wholly bad. However they take a lot of killing and seem to have got round the Peace Commission and General Otis.

They are not wholly bad, and they have had a glorious history. They held the islands from 1570 to 1828, without any permanent garrison of Spanish regular troops, and from 1828 to 1883 with about 1500 artillerymen. They did not entirely rely upon brute force. They are certainly no longer suited to the circumstances of the Philippines having survived their utility. They are an anachronism. But they have brought the Philippines a long way on the path of civilisation. Let us be just; what British, French, or Dutch colony, populated by natives, can compare with the Philippines as they were till 1895?

And what about American rule? It has begun unfortunately, and has raised a feeling of hatred in the natives that will take a generation to efface. It will not be enough for the United States to beat down armed resistance. A huge army must be maintained to keep the natives down. As soon as the Americans are at war with one of the Great Powers, the natives will rise; whenever a land-tax is imposed there will be an insurrection.

The great difference between this war and former insurrections is that now for the first time the natives have rifles and ammunition, and have learned to use them. Not all the United States Navy can stop them from bringing in fresh supplies. Unless some arrangement is come to [ix]with the natives, there can be no lasting peace. Such an arrangement I believe quite possible, and that it could be brought about in a manner satisfactory to both parties.

This would not be, however, on the lines suggested in the National Review of September under the heading, “Will the United States withdraw from the Philippines?”

Three centuries of Spanish rule is not a fit preparation for undertaking the government of the Archipelago. But Central and Southern Luzon, with the adjacent islands, might be formed into a State whose inhabitants would be all Tagals and Vicols, and the northern part into another State whose most important peoples would be the Pampangos, the Pangasinanes, the Ilocanos, and the Cagayanes; the Igorrotes and other heathen having a special Protector to look after their interests.

Visayas might form a third State, all the inhabitants being of that race, whilst Mindanao and Southern Palawan should be entirely governed by Americans like a British Crown Colony.

The Sulu Sultanate could be a Protectorate similar to North Borneo or the Malay States. Manila could be a sort of Federal District, and the Consuls would be accredited to the President’s representative, the foreign relations being solely under his direction. There should be one tariff for all the islands, for revenue only, treating all nations alike, the custom houses, telegraphs, post offices, and lighthouse service being administered by United States officials, either native or American. With power thus limited, the Tagals, Pampangos, and Visayas might be entrusted with their own affairs, and no garrisons need be kept, except in certain selected healthy spots, always having transports at hand to convey them wherever they were wanted. If, as seems probable, Mr. McKinley should be re-elected, I hope he will attempt some such arrangement, and I heartily wish him success in pacifying this sorely troubled country, the scene of four years continuous massacre. [x]

The Archipelago is at present in absolute anarchy, the exports have diminished by half, and whereas we used to travel and camp out in absolute security, now no white man dare show his face more than a mile from a garrison.

Notwithstanding this, some supporters of the Administration in the States are advising young men with capital that there is a great opening for them as planters in the Islands.

There may be when the Islands are pacified, but not before.

To all who contemplate proceeding to or doing any business, or taking stock in any company in the Philippines, I recommend a careful study of my book. They cannot fail to benefit by it.

Red Hill, Oct. 15th, 1900. [xi]

Salámat.

The author desires to express his hearty thanks to all those who have assisted him.

To Father Joaquin Sancho, S.J., Procurator of Colonial Missions, Madrid, for the books, maps and photographs relating to Mindanao, with permission to use them.

To Mr. H. W. B. Harrison of the British Embassy, Madrid, for his kindness in taking photographs and obtaining books.

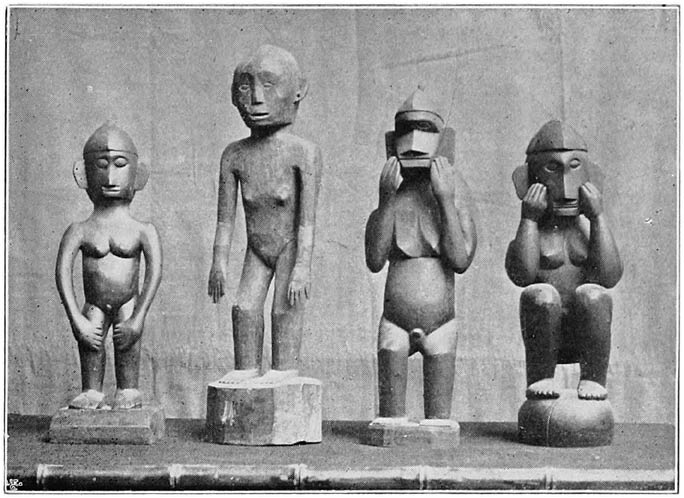

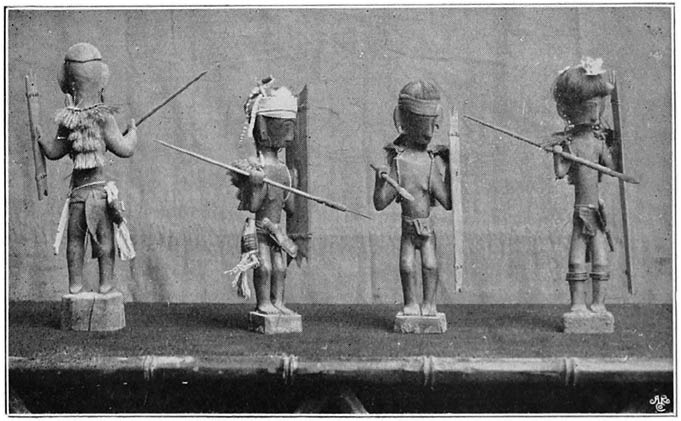

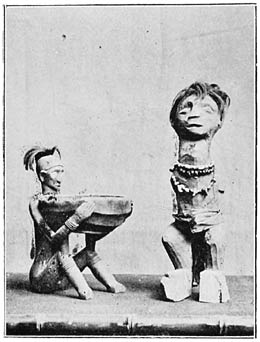

To Don Francisco de P. Vigil, Director of the Colonial Museum, Madrid, for affording special facilities for photographing the Anitos and other curiosities of the Igorrotes.

To Messrs. J. Laurent and Co., Madrid, for permission to reproduce interesting photographs of savage and civilised natives.

To Mr. George Gilchrist of Manila, for photographs, and for the use of his diary with particulars of the Tagal insurrection, and for descriptions of some incidents of which he was an eye-witness.

To Mr. C. E. de Bertodano, C.E., of Victoria Street, Westminster, for the use of books of reference and for information afforded.

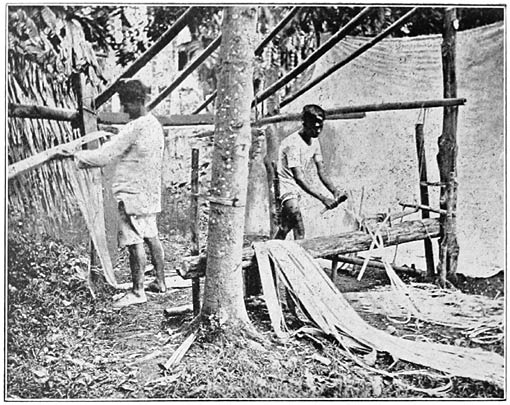

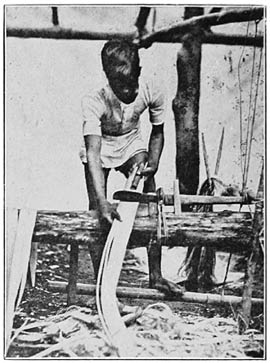

To Mr. William Harrison of Billiter Square, E.C., for the use of photographs of Vicols cleaning hemp.

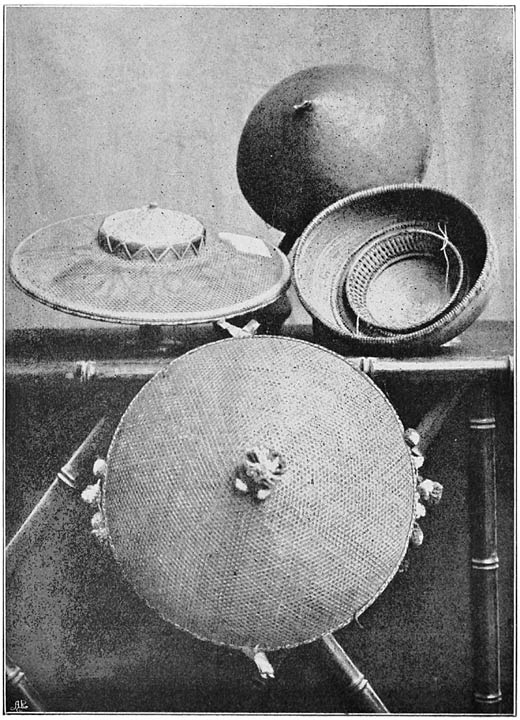

To the late Mr. F. W. Campion of Trumpets Hill, Reigate, for the photograph of Salacot and Bolo taken from very fine specimens in his possession, and for the use of other photographs. [xii]

To Messrs. Smith, Bell and Co. of Manila, for the very complete table of exports which they most kindly supplied.

To Don Sixto Lopez of Balayan, for the loan of the Congressional Record, the Blue Book of the 55th Congress, 3rd Session, and other books.

To the Superintendent of the Reading Room and his Assistants for their courtesy and help when consulting the old Spanish histories in the noble library of the British Museum. [xiii]

Alphabetical List of Works Cited, Referred to, or Studied whilst Preparing this Work.

Abella, Enrique—‘Informes’ (Reports).

Anonymous—‘Catálogo Oficial de la Exposicion de Filipinas’; ‘Filipinas: Problema Fundamental,’ 1887; ‘Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas,’ 1595; ‘Las Filipinas se pierden,’ a scurrilous Spanish pamphlet, Manila, 1841; ‘Aviso al publico,’ account of an attempt by the French to cause Joseph Bonaparte to be acknowledged King of the Philippines.

Barrantes Vicente—‘Guerras piraticas de Filipinas contra Mindanaos y Joloanos,’ Madrid, 1878, and other writings.

Becke, Louis—‘Wild Life in Southern Seas.’

Bent, Mrs. Theodore—‘Southern Arabia.’

Blanco, Padre—‘Flora Filipina.’

Blumentritt, Professor Ferdinand—‘Versuch einer Ethnographie der Philippinen’ (Petermann’s).

Brantôme, Abbé de—(In Motley’s ‘Rise of the Dutch Republic.’)

Cavada, Agustin de la—‘Historia, Geografica, Geologica, y estadistica de Filipinas,’ Manila, 1876, 1877.

Centeno, José—‘Informes’ (Reports).

Clifford, Hugh—‘Studies in Brown Humanity,’ ‘In Court and Kampong.’

Comyn, Tomas de.

Crawford, John—‘History of the Indian Archipelago,’ Edinburgh, 1820; ‘Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands,’ London, 1856.

Cuming, E. D.—‘With the Jungle Folk.’

Dampier, William—(from Pinkerton).

De Guignes—‘Voyage to Pekin, Manila, and Isle of France.’

D’Urville, Dumont.

Foreman, John—‘The Philippine Islands,’ first and second editions.

Garcilasso, Inca de la Vega—‘Comentarios Réales.’

Gironière, Paul de la—‘Vingt ans aux Philippines.’

Jagor, F.—‘Travels in the Philippines.’

Jesuits, Society of—‘Cartas de los P.P. de la Cia de Jesus de la mision de Filipinas,’ Cuads ix y x (1891–95); ‘Estados Generales,’ Manila, 1896, 1897; ‘Mapa Politica Hidrografica’; ‘Plano de los Distritos 2o y 5o de Mindanao’; ‘Mapa de Basilan.’

Mas, Sinibaldo de—‘Informe sobre el estado de las Yslas Filipinas en 1842.’ [xiv]

Montano, Dr. J.—‘Voyage aux Philippines,’ Paris, 1886.

Monteverde, Colonel Federico de—‘La Division Lachambre.’

Morga, Antonio de—‘Sucesos de las Yslas Filipinas,’ Mejico, 1609.

Motley, John Lothrop—‘Rise of the Dutch Republic.’

Navarro, Fr. Eduardo—‘Filipinas. Estudio de Asuntos de momento,’ 1897.

Nieto José—‘Mindanao, su Historia y Geographia,’ 1894.

Palgrave, W. G.—‘Ulysses, or Scenes in Many Lands’; ‘Malay Life in the Philippines.’

Petermann—‘Petermanns Mitth.’, Ergänzungsheft Nr 67, Gotha, 1882.

Pigafetta—‘Voyage Round the World,’ Pinkerton, vol. ii.

Prescott—‘Conquest of Peru.’

Posewitz, Dr. Theodor—‘Borneo, its Geology and Mineral Resources.’

Rathbone—‘Camping and Tramping in Malaya.’

Reyes, Ysabelo de los—Pamphlet.

Rizal—‘Noli me Tangere.’

St. John, Spenser—‘Life in the Forests of the Far East.’

Torquemada, Fray Juan—‘Monarquia Indiana.’

Traill, H. D.—‘Lord Cromer.’

Vila, Francisco—‘Filipinas,’ 1880.

Wallace, Alfred R.—‘The Malay Archipelago.’

Wingfield, Hon. Lewis—‘Wanderings of a Globe-trotter.’

Worcester, Dean C.—‘The Philippine Islands and their People.’

Younghusband, Major—‘The Philippines and Round About.’

Magazine Articles.

Scribner (George F. Becker)—‘Are the Philippines Worth Having?’

Blackwood (Anonymous)—‘The Case of the Philippines.’

Tennie, G. Claflin (Lady Cook)—‘Virtue Defined’ (New York Herald).

Contents.

Extent, Beauty and Fertility. Pages

Extent, beauty and fertility of the Archipelago—Variety of landscape—Vegetation—Mango trees—Bamboos 1–6

Spanish Government.

Slight sketch of organization—Distribution of population—Collection of taxes—The stick 7–13

Six Governors-General.

Moriones—Primo de Rivera—Jovellar—Terreros—Weyler—Despujols 14–23

Courts of Justice.

Alcaldes—The Audiencia—The Guardia Civil—Do not hesitate to shoot—Talas 24–30

Tagal Crime and Spanish Justice.

The murder of a Spaniard—Promptitude of the Courts—The case of Juan de la Cruz—Twelve years in prison waiting trial—Piratical outrage in Luzon—Culprits never tried; several die in prison 31–47 [xvi]

Historical.

Causes of Tagal Revolt.

Corrupt officials—“Laws of the Indies”—Philippines a dependency of Mexico, up to 1800—The opening of the Suez Canal—Hordes of useless officials—The Asimilistas—Discontent, but no disturbance—Absence of crime—Natives petition for the expulsion of the Friars—Many signatories of the petition punished 48–56

The Religious Orders.

The Augustinians—Their glorious founder—Austin Friars in England—Scotland—Mexico—They sail with Villalobos for the Islands of the Setting Sun—Their disastrous voyage—Fray Andres Urdaneta and his companions—Foundation of Cebú and Manila with two hundred and forty other towns—Missions to Japan and China—The Flora Filipina—The Franciscans—The Jesuits—The Dominicans—The Recollets—Statistics of the religious orders in the islands—Turbulence of the friars—Always ready to fight for their country—Furnish a war ship and command it—Refuse to exhibit the titles of their estates in 1689—The Augustinians take up arms against the British—Ten of them fall on the field of battle—Their rectories sacked and burnt—Bravery of the archbishop and friars in 1820—Father Ibañez raises a battalion—Leads it to the assault of a Moro Cotta—Execution of native priests in 1872—Small garrison in the islands—Influence of the friars—Their behaviour—Herr Jagor—Foreman—Worcester—Younghusband—Opinion of Pope Clement X.—Tennie C. Claflin—Equality of opportunity—Statesque figures of the girls—The author’s experience of the Friars—The Philippine clergy—Who shall cast the first stone!—Constitution of the orders—Life of a friar—May become an Archbishop—The Chapter 57–70

Their Estates.

Malinta and Piedad—Mandaloyan—San Francisco de Malabon—Irrigation works—Imus—Calamba—Cabuyao—Santa Rosa Biñan—San Pedro Tunasan—Naic—Santa Cruz—[xvii]Estates a bone of contention for centuries—Principal cause of revolt of Tagals—But the Peace Commission guarantee the Orders in possession—Pacification retarded—Summary—The Orders must go!—And be replaced by natives 71–78

Secret Societies.

Masonic Lodges—Execution or exile of Masons in 1872—The “Asociacion Hispano Filipina”—The “Liga Filipina”—The Katipunan—Its programme 79–83

The Insurrection of 1896–97.

Combat at San Juan del Monte—Insurrection spreading—Arrival of reinforcements from Spain—Rebel entrenchments—Rebel arms and artillery—Spaniards repulsed from Binacáyan—and from Noveleta—Mutiny of Carabineros—Prisoners at Cavite attempt to escape—Iniquities of the Spanish War Office—Lachambre’s division—Rebel organization—Rank and badges—Lachambre advances—He captures Silang—Perez Dasmariñas—Salitran—Anabo II. 84–96

The Insurrection of 1896–97—continued.

The Division encamps at San Nicolas—Work of the native Engineer soldiers—The division marches to Salitran—Second action at Anabo II.—Crispulo Aguinaldo killed—Storming the entrenchments of Anabo I.—Burning of Imus by the rebels—Proclamation by General Polavieja—Occupation of Bacoor—Difficult march of the division—San Antonio taken by assault—Division in action with all its artillery—Capture of Noveleta—San Francisco taken by assault—Heavy loss of the Tagals—Losses of the division—The division broken up—Monteverde’s book—Polaveija returns to Spain—Primo de Rivera arrives to take his place—General Monet’s butcheries—The pact of Biak-na-Bato—The 74th Regiment joins the insurgents—The massacre of the Calle Camba—Amnesty for torturers—Torture in other countries 97–108

The Americans in the Philippines.

Manila Bay—The naval battle of Cavite—General Aguinaldo—Progress of the Tagals—The Tagal Republic—Who were the aggressors?—Requisites for a settlement—Scenes of drunkenness—The estates of the religious orders to be [xviii]restored—Slow progress of the campaign—Colonel Funston’s gallant exploits—Colonel Stotsenburg’s heroic death—General Antonio Luna’s gallant rally of his troops at Macabebe—Reports manipulated—Imaginary hills and jungles—Want of co-operation between Army and Navy—Advice of Sir Andrew Clarke—Naval officers as administrators—Mr. Whitelaw Reid’s denunciations—Senator Hoar’s opinion—Mr. McKinley’s speech at Pittsburgh—The false prophets of the Philippines—Tagal opinion of American Rule—Señor Mabini’s manifesto—Don Macario Adriatico’s letter—Foreman’s prophecy—The administration misled—Racial antipathy—The curse of the Redskins—The recall of General Otis—McArthur calls for reinforcements—Sixty-five thousand men and forty ships of war—State of the islands—Aguinaldo on the Taft Commission 109–123

Native Admiration for America.

Their fears of a corrupt government—The islands might be an earthly paradise—Wanted, the man—Rajah Brooke—Sir Andrew Clarke—Hugh Clifford—John Nicholson—Charles Gordon—Evelyn Baring—Mistakes of the Peace Commission—Government should be a Protectorate—Fighting men should be made governors—What might have been—The Malay race—Senator Hoar’s speech—Four years’ slaughter of the Tagals 124–128

Resources of the Philippines.

Resources of the Philippines.

At the Spanish conquest—Rice—the lowest use the land can be put to—How the Americans are misled—Substitutes for rice—Wheat formerly grown—Tobacco—Compañia General de Tabacos—Abacá—Practically a monopoly of the Philippines—Sugar—Coffee—Cacao—Indigo—Cocoa-nut oil—Rafts of nuts—Copra—True localities for cocoa palm groves Summary—More sanguine forecasts—Common-sense view 129–138

Forestal.

Value exaggerated—Difficulties of labour and transport—Special sawing machinery required—Market for timber in the islands—Teak not found—Jungle produce—Warning to investors in companies—Gutta percha 139–142 [xix]

The Minerals.

Gold: Dampier—Pigafetta—De Comyn—Placers in Luzon—Gapan—River Agno—The Igorrotes—Auriferous quartz from Antaniac—Capunga—Pangutantan—Goldpits at Suyuc—Atimonan—Paracale—Mambulao—Mount Labo—Surigao River Siga—Gigaquil, Caninon-Binutong, and Cansostral Mountains—Misamis—Pighoulugan—Iponan—Pigtao—Dendritic gold from Misamis—Placer gold traded away surreptitiously—Cannot be taxed—Spanish mining laws—Pettifogging lawyers—Prospects for gold seekers. Copper: Native copper at Surigao and Torrijos (Mindoro)—Copper deposits at Mancayan worked by the Igorrotes—Spanish company—Insufficient data—Caution required. Iron: Rich ores found in the Cordillera of Luzon—Worked by natives—Some Europeans have attempted but failed—Red hematite in Cebú—Brown hematite in Paracale—Both red and brown in Capiz—Oxydised iron in Misamis—Magnetic iron in San Miguel de Mayumo—Possibilities. Coal (so called): Beds of lignite upheaved—Vertical seams at Sugud—Reason of failure—Analysis of Masbate lignite. Various minerals: Galena—Red lead—Graphite—Quicksilver—Sulphur Asbestos—Yellow ochre—Kaolin, Marble—Plastic clays—Mineral waters 143–157

Manufactures and Industries.

Cigars and cigarettes—Textiles—Cotton—Abacá—Júsi—Rengue—Nipis—Saguran—Sinamáy—Guingon—Silk handkerchiefs—Piña—Cordage—Bayones—Esteras—Baskets—Lager beer—Alcohol—Wood oils and resins—Essence of Ylang-ilang—Salt—Bricks—Tiles—Cooking-pots—Pilones—Ollas—Embroidery—Goldsmiths’ and silversmiths’ work—Salacots—Cocoa-nut oil—Saddles and harness—Carromatas—Carriages—Schooners—Launches—Lorchas—Cascos—Pontines—Bangcas—Engines and boilers—Furniture—Fireworks—Lanterns—Brass Castings—Fish breeding—Drying sugar—Baling hemp—Repacking wet sugar—Oppressive tax on industries—Great future for manufactures—Abundant labour—Exceptional intelligence 158–163

Commercial and Industrial Prospects.

Philippines not a poor man’s country—Oscar F. Williams’ letter—No occupation for white mechanics—American merchants unsuccessful in the East—Difficulties of living [xx]amongst Malays—Inevitable quarrels—Unsuitable climate—The Mali-mali or Sakit-latah—The Traspaso de hambre—Chiflados—Wreck of the nervous system—Effects of abuse of alcohol—Capital the necessity—Banks—Advances to cultivators—To timber cutters—To gold miners—Central sugar factories—Paper-mills—Rice-mills—Cotton-mills—Saw-mills—Coasting steamers—Railway from Manila to Batangas—From Siniloan to the Pacific—Survey for ship canal—Bishop Gainzas’ project—Tramways for Luzon and Panay—Small steamers for Mindanao—Chief prospect is agriculture 164–172

Social.

Life in Manila.

(A Chapter for the Ladies.)

Climate—Seasons—Terrible Month of May—Hot winds—Longing for rain—Burst of the monsoon—The Alimóom—Never sleep on the ground floor—Dress—Manila houses—Furniture—Mosquitoes—Baths—Gogo—Servants—Wages in 1892—The Maestro cook—The guild of cooks—The Mayordomo—Household budget, 1892—Diet—Drinks—Ponies—Carriage a necessity for a lady—The garden—Flowers—Shops—Pedlars—Amusements—Necessity of access to the hills—Good Friday in Manila 173–187

Sport.

(A Chapter for Men.)

The Jockey Club—Training—The races—An Archbishop presiding—The Totalisator or Pari Mutuel—The Manila Club—Boating club—Rifle clubs—Shooting—Snipe—Wild duck—Plover—Quail—Pigeons—Tabon—Labuyao, or jungle cock—Pheasants—Deer—Wild pig—No sport in fishing 188–191 [xxi]

Geographical.

Brief Geographical Description of Luzon.

Irregular shape—Harbours—Bays—Mountain ranges—Blank spaces on maps—North-east coast unexplored—River and valley of Cagayan—Central valley from Bay of Lingayen to Bay of Manila—Rivers Agno, Chico, Grande—The Pinag of Candaba—Project for draining—River Pasig—Laguna de Bay—Lake of Taal—Scene of a cataclysm—Collapse of a volcanic cone 8000 feet high—Black and frowning island of Mindoro—Worcester’s pluck and endurance—Placers of Camarines—River Vicol—The wondrous purple cone of Mayon—Luxuriant vegetation 192–200

The Inhabitants of the Philippines.

Description of their appearance, dress, arms, religion, manners and customs, and the localities they inhabit, their agriculture, industries and pursuits, with suggestions as to how they can be utilised, commercially and politically. With many unpublished photographs of natives, their arms, ornaments, sepulchres and idols.

Aboriginal Inhabitants.

Scattered over the Islands.

Aetas or Negritos.

Including Balúgas, Dumágas, Mamanúas, and Manguiánes 201–207 [xxii]

Part I.

Inhabitants of Luzon and Adjacent Islands.

Tagals (1) 208–221

Tagals as Soldiers and Sailors 222–237

Pampangos (2) 238–245

Zambales (3)—Pangasinanes (4)—Ilocanos (5)—Ibanags or Cagayanes (6) 246–253

Igorrotes (7) 254–267

Isinays (11)—Abacas (12)—Italones (13)—Ibilaos (14)—Ilongotes (15)—Mayoyaos and Silipanes (16)—Ifugaos (17)—Gaddanes (18)—Itetapanes (19)—Guinanes (20) 268–273

Caláuas or Itaves (21)—Camuangas and Bayabonanes (22)—Dadayags (23)—Nabayuganes (24)—Aripas (25)—Calingas (26)—Tinguianes (27)—Adangs (28)—Apayaos (29)—Catalanganes and Irayas (30–31) 274–282

Catubanganes (32)—Vicols (33) 283–287

The Chinese in Luzon.

Mestizos or half-breeds 288–294 [xxiii]

Part II.

The Visayas and Palawan.

The Visayas Islands.

Area and population—Panay—Negros—Cebú—Bohol—Leyte—Samar 295–299

The Visayas Race.

Appearance—Dress—Look upon Tagals as foreigners—Favourable opinion of Tomas de Comyn—Old Christians—Constant wars with the Moro pirates and Sea Dayaks—Secret heathen rites—Accusation of indolence unfounded—Exports of hemp and sugar—Ilo-ilo sugar—Cebú sugar—Textiles—A promising race 300–306

The Island of Palawan, or Paragua.

The Tagbanúas—Tandulanos—Manguianes—Negritos—Moros of southern Palawan—Tagbanúa alphabet 307–320

Part III.

Mindanao, Including Basilan.

Brief Geographical Description.

Configuration—Mountains—Rivers—Lakes—Division into districts—Administration—Productions—Basilan 321–330 [xxiv]

The Tribes of Mindanao.

Visayas (1) [Old Christians]—Mamanúas (2)—Manobos (3)—Mandayas (4)—Manguángas (5)—Montéses or Buquidnónes(6)—Atás or Ata-as (7)—Guiangas (8)—Bagobos (9) 331–351

The Tribes of Mindanao—continued.

Calaganes (10)—Tagacaolos (11)—Dulanganes (12)—Tirurayes (13)—Tagabelies (14)—Samales (15)—Vilanes (16)—Subanos (17) 352–360

The Moros, or Mahometan Malays (18 to 23).

Illanos (18)—Sanguiles (19)—Lutangas (20)—Calibuganes (21) Yacanes (22)—Samales (23) 361–373

Tagabáuas (24) 374–375

The Chinese in Mindanao.

N.B.—The territory occupied by each tribe is shown on the general map of Mindanao by the number on this list.

The Political Condition of Mindanao, 1899.

Relapse into savagery—Moros the great danger—Visayas the mainstay—Confederation of Lake Lanao—Recall of the Missionaries—Murder and pillage in Davao—Eastern Mindanao—Western Mindanao—The three courses—Orphanage of Tamontaca—Fugitive slaves—Polygamy an impediment to conversion—Labours of the Jesuits—American Roman Catholics should send them help 376–388 [xxv]

Chronological Table 389

Table of Exports for twelve Years 411

Estimate of Population 415

Philippine Budget of 1897 compared with Revenue of 1887 416, 417

Value of Land in several Provinces of Luzon 418

List of Spanish and Filipino Words used in the Work 419

Cardinal Numbers in Seven Malay Dialects 422 [xxvii]

List of Illustrations.

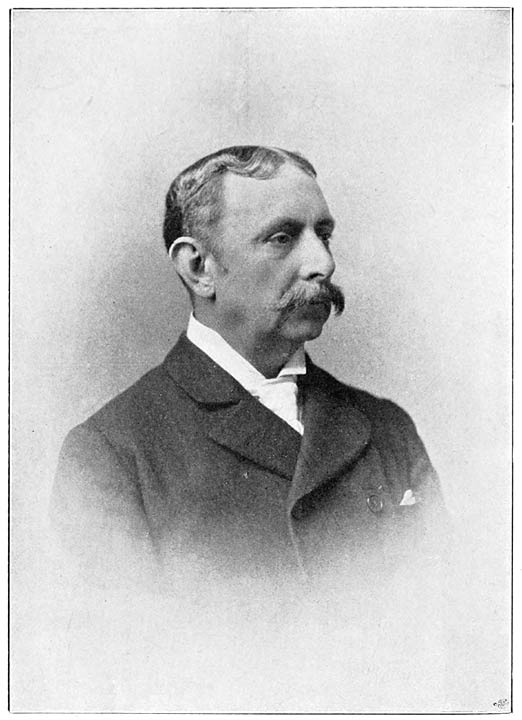

- Portrait of the Author Frontispiece

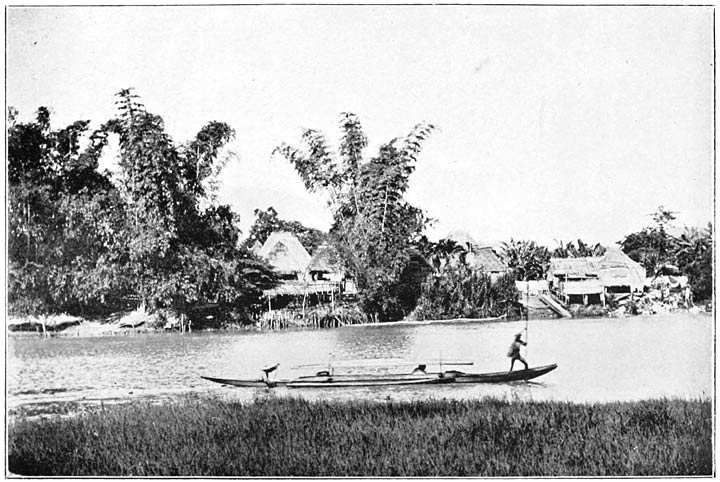

- View on the Pasig with Bamboos and Canoe To face p. 6

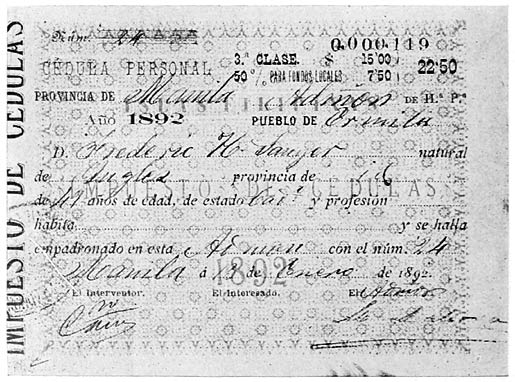

- Facsimile of Cédula Personal To face p. 53

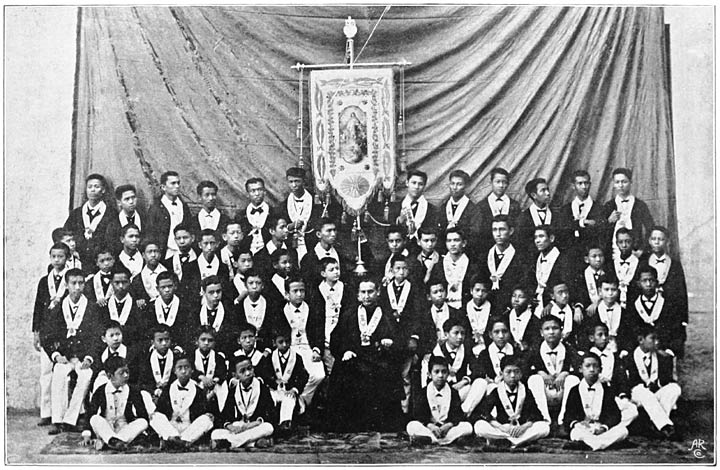

- Some of the rising generation in the Philippines To face p. 75

- Map of the Philippine Islands To face p. 150

- Group of women making Cigars To face p. 158

- Salacots and Women’s Hats To face p. 160

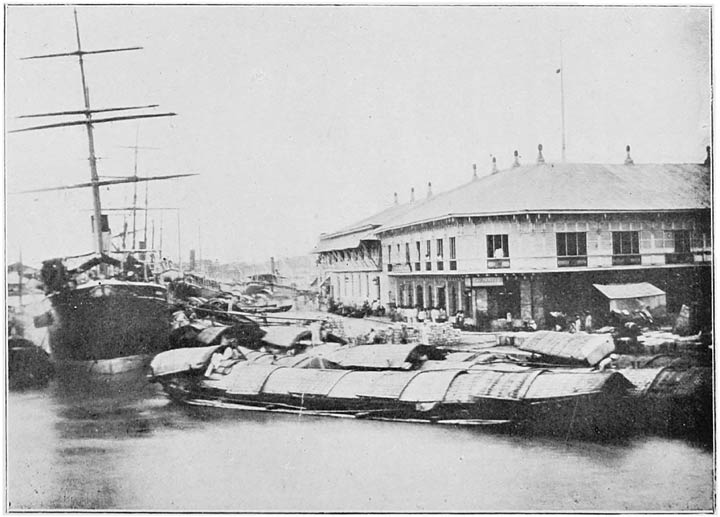

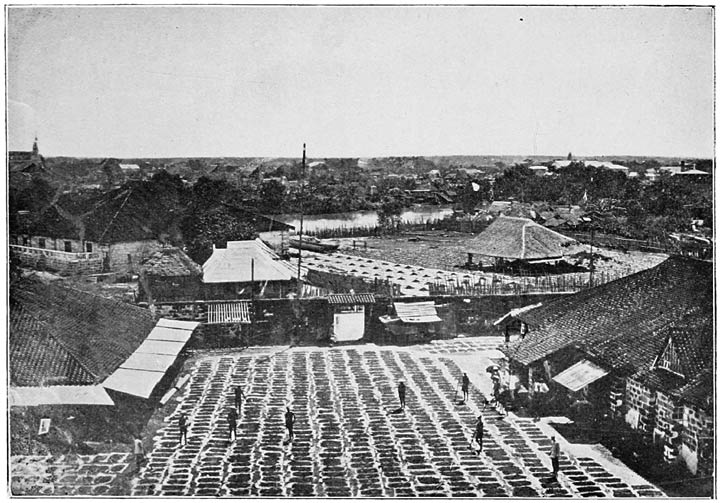

- Author’s office, Muelle Del Rey, ss. Salvadora, and Lighters called “Cascos” To face p. 161

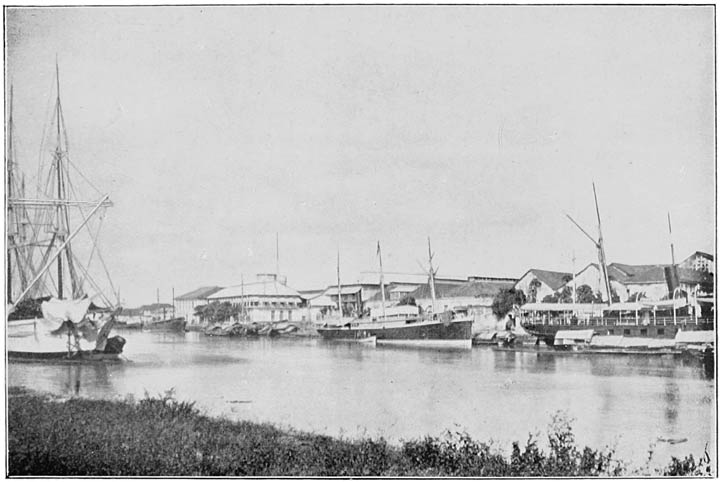

- River Pasio showing Russell and Sturgis’s former office To face p. 166

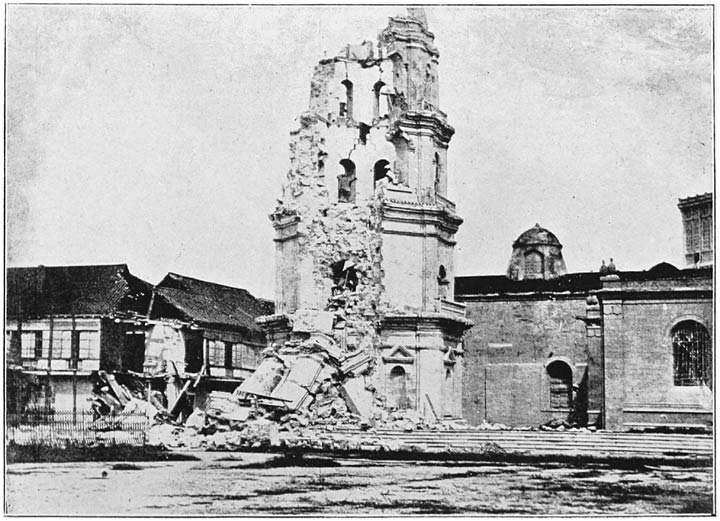

- Tower of Manila Cathedral after the Earthquakes, 1880 Between pp. 168–9

- Suburb of Malate after a typhoon, October 1882, When thirteen ships were driven ashore

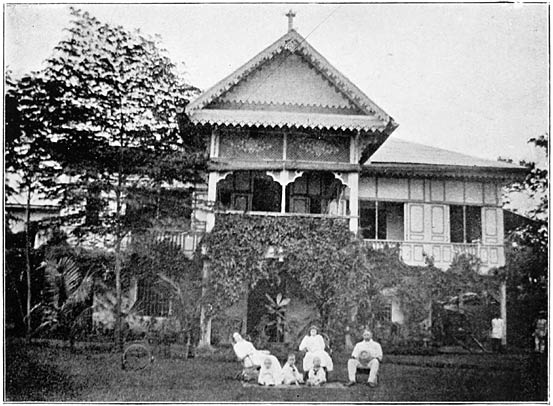

- Author’s house at Ermita To face p. 177

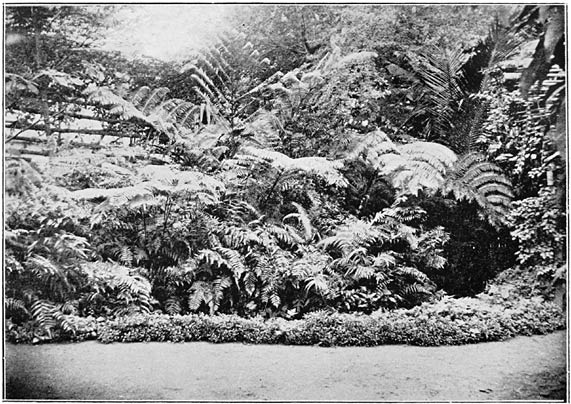

- Fernery at Ermita To face p. 185

- A Negrito from Negros Island To face p. 207

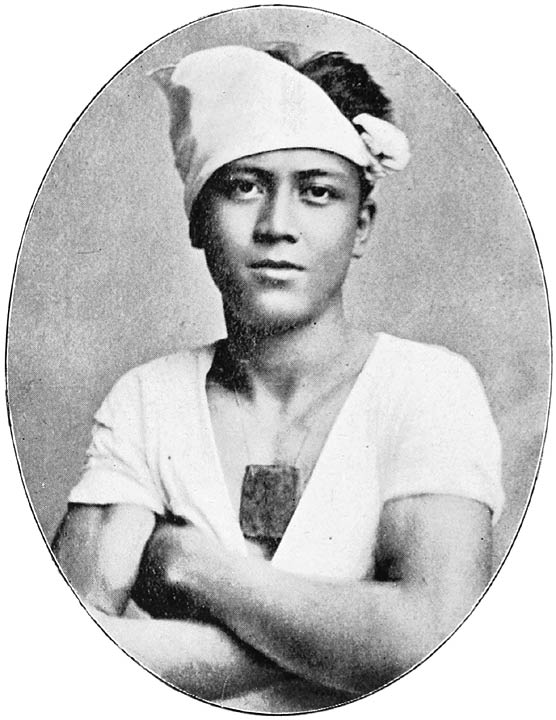

- A Manila Man Between pp. 208–9

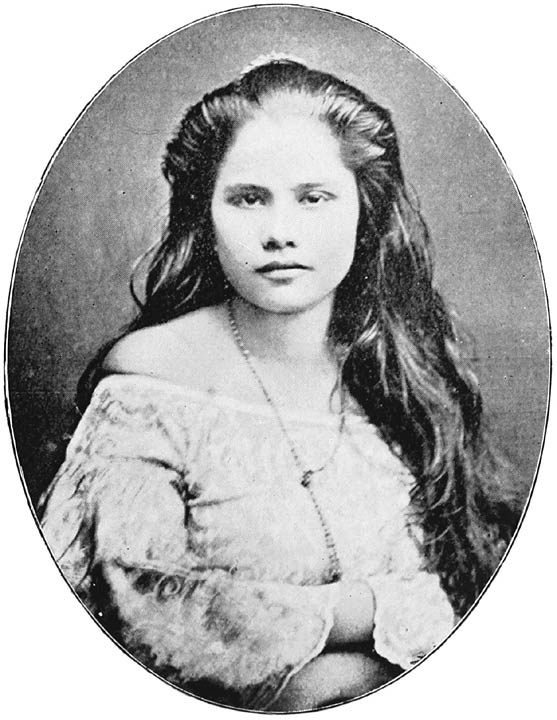

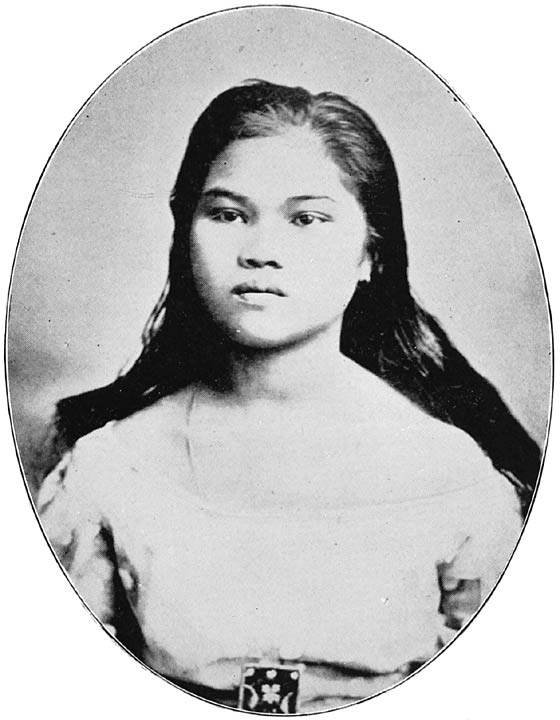

- A Manila Girl

- Tagal Girl wearing Scapulary To face p. 216

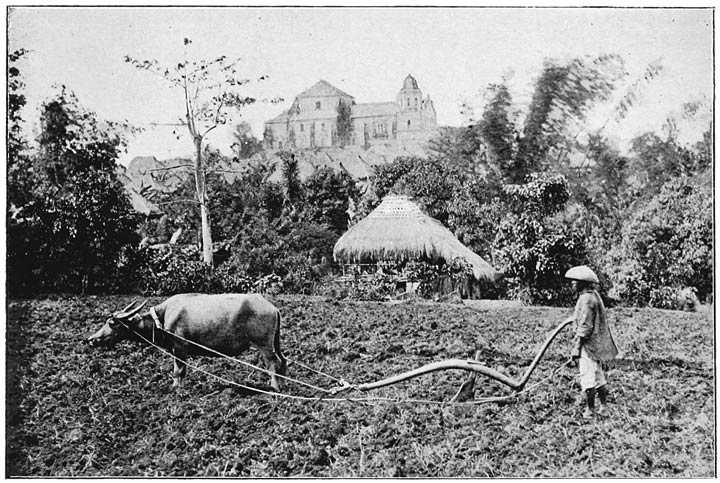

- Carabao harnessed to native Plough; Ploughman, Village, and Church Between pp. 226–7

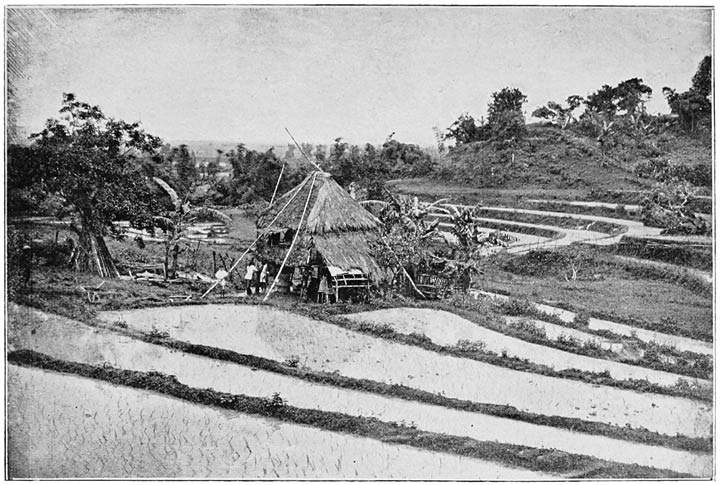

- Paddy Field recently planted

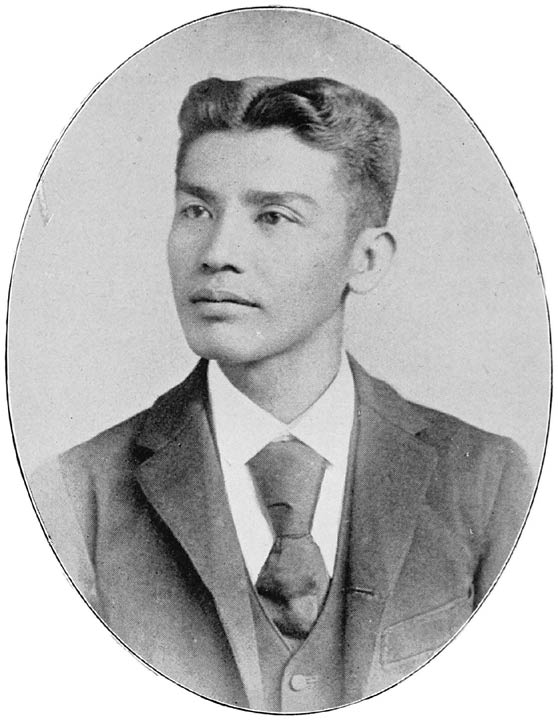

- Paulino Marillo, a Tagal of Laguna, Butler to the author To face p. 229

- A Farderia, or Sugar Drying and Packing Place To face p. 240[xxviii]

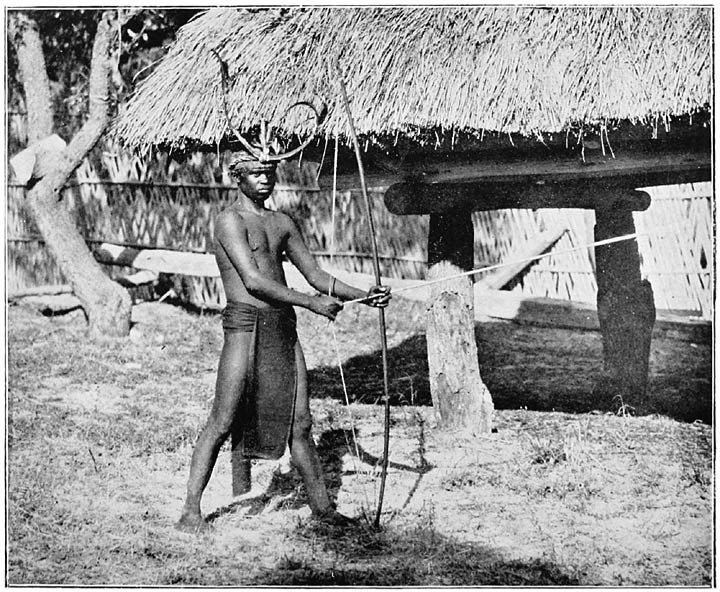

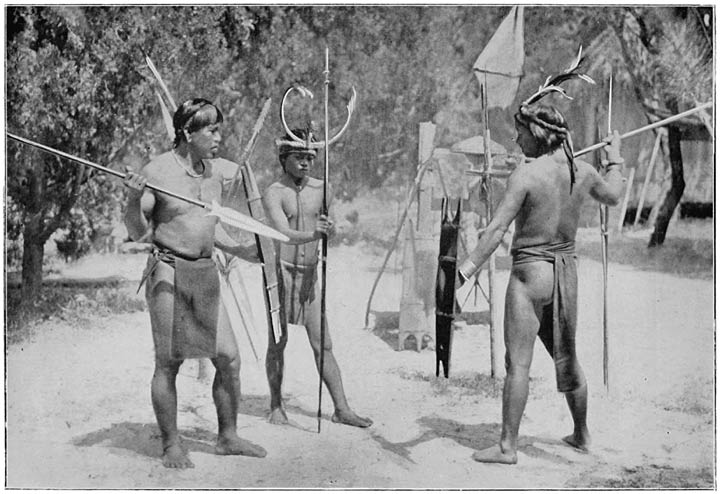

- Igorrote Spearmen and Negriot Archer To face p. 254

- Anitos of Northern Tribes To face p. 258

- Aitos of the Igorrotes To face p. 258

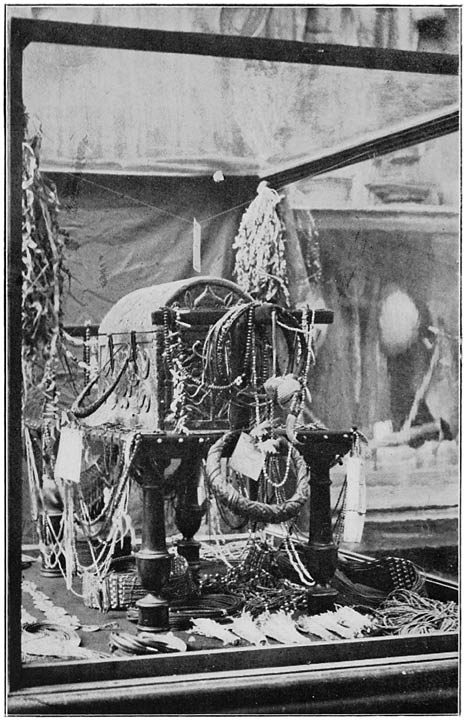

- Coffin of an Igorrote Noble, with his Coronets and other Ornaments To face p. 259

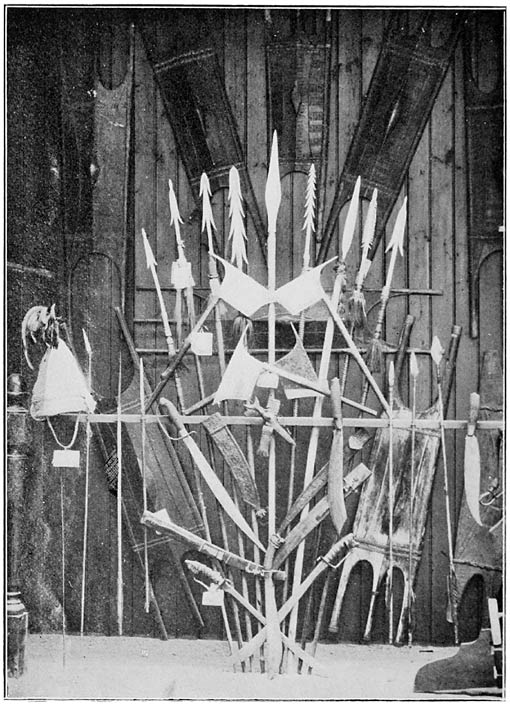

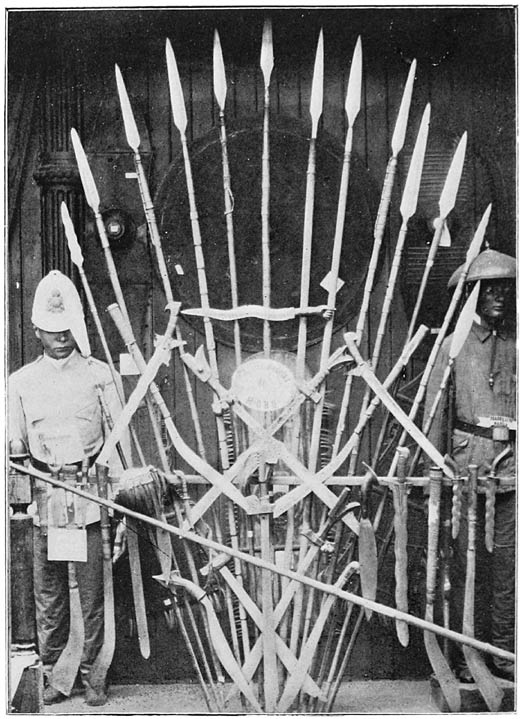

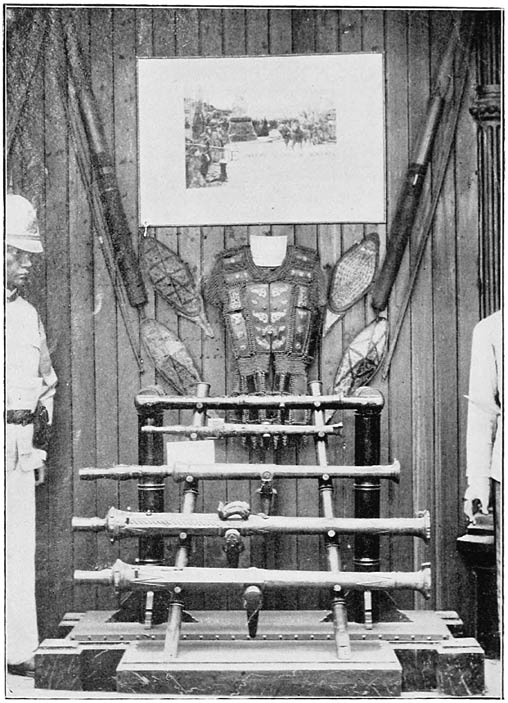

- Weapons of the Highlands of Luzon To face p. 261

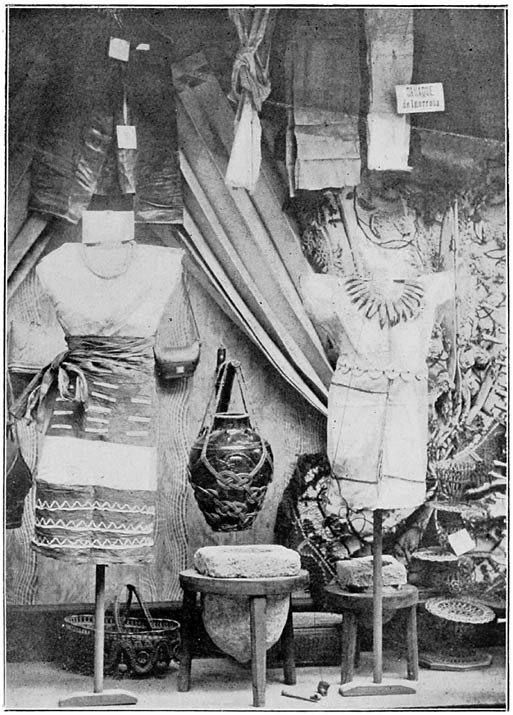

- Igorrote Dresses and Ornaments, Water-Jar, Dripstones, Pipes, and Baskets To face p. 264

- Anitos, Highlands To face p. 266

- Anito of the Igorrotes To face p. 266

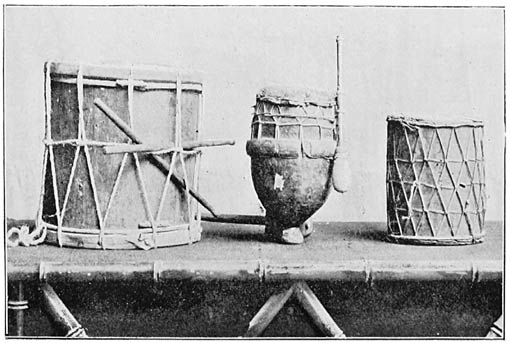

- Igorrote Drums To face p. 266

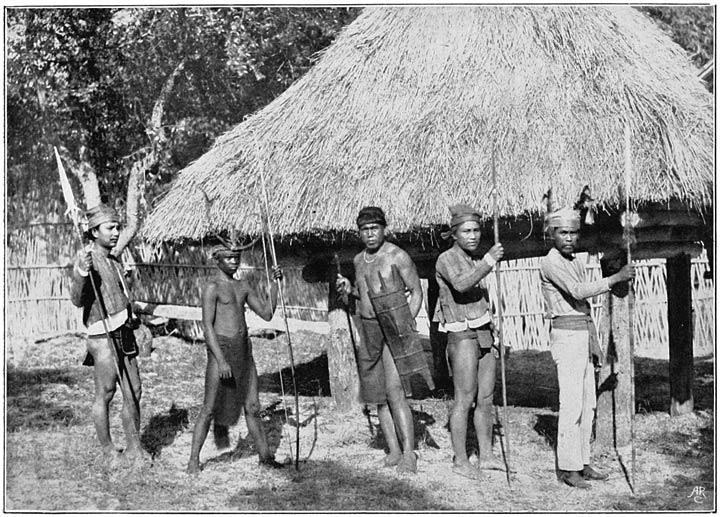

- Tinguianes, Aeta, and Igorrotes To face p. 276

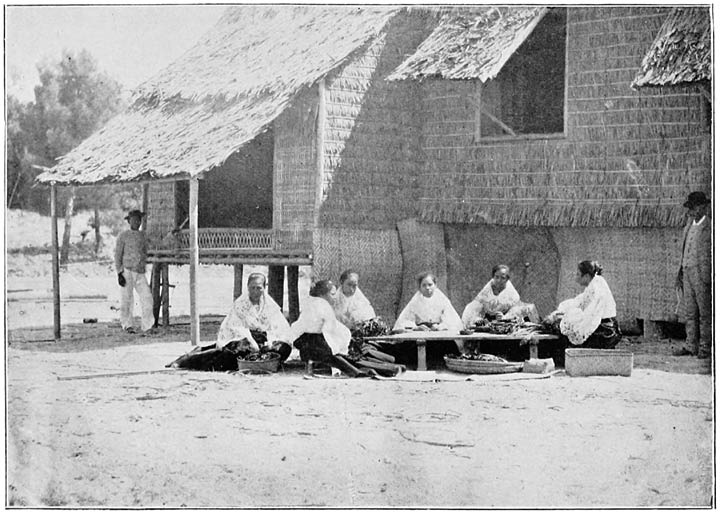

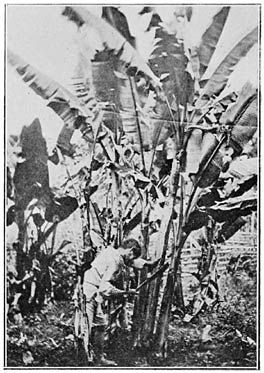

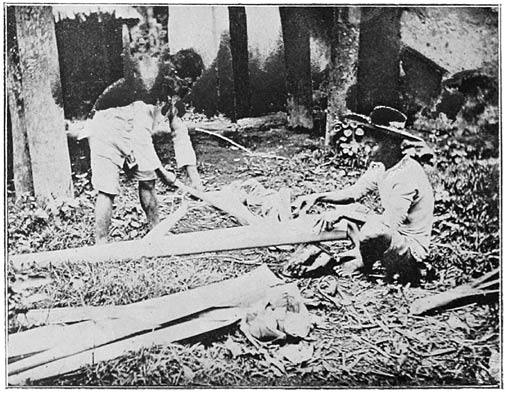

- Vicols Preparing Hemp:— To face p. 287

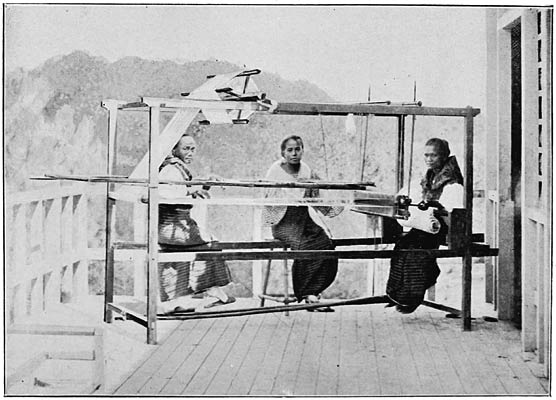

- Visayas Women at a Loom To face p. 305

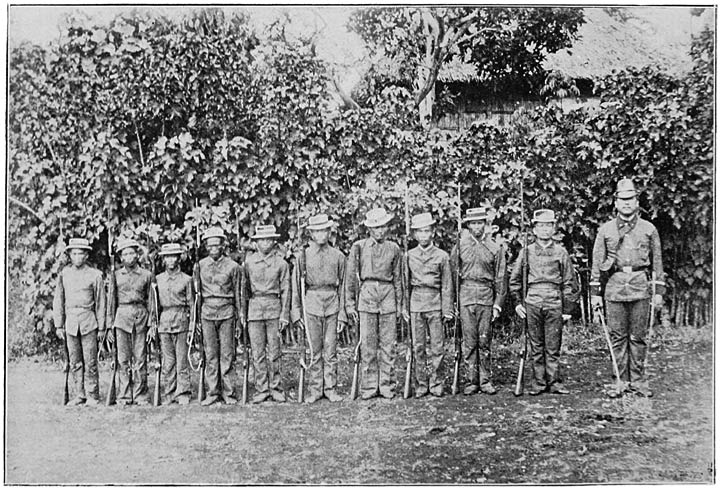

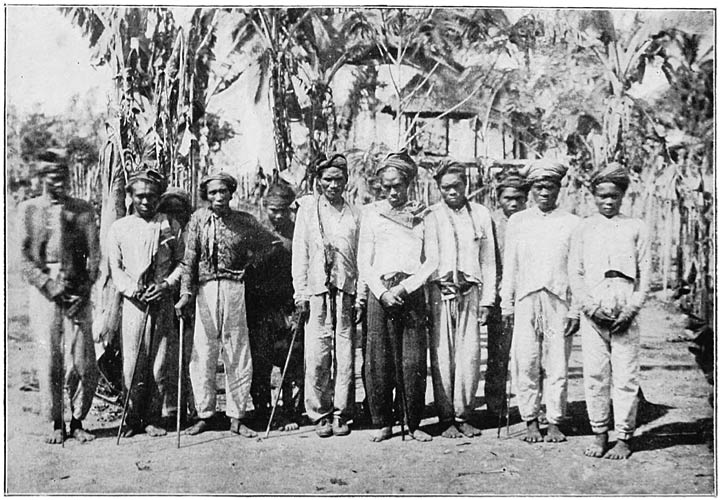

- Lieut. P. Garcia and Local Militia of Baganga, Caraga (East Coast) To face p. 333

- Atás from the Back Slopes of the Apo To face p. 347

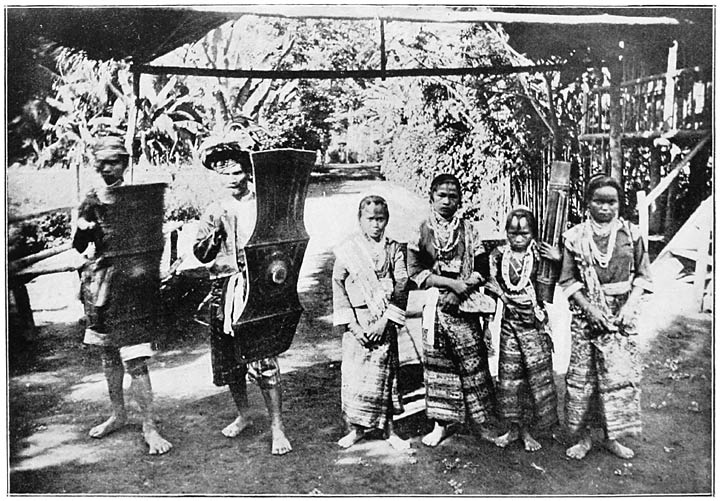

- Heathen Guiangas, from the Slopes of the Apo To face p. 349

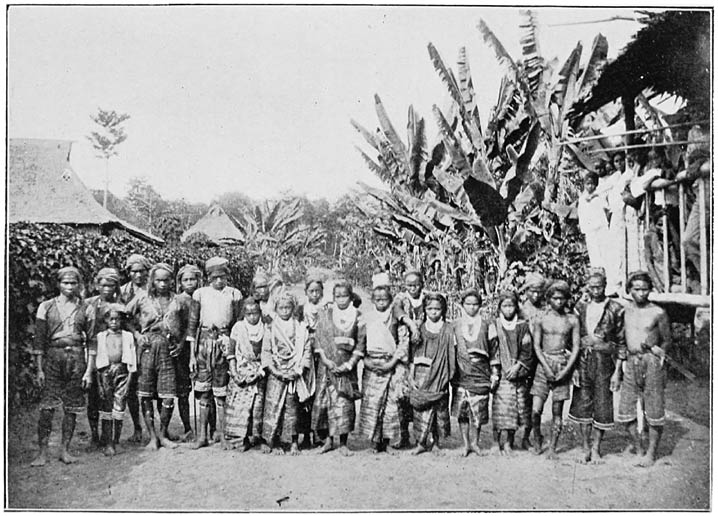

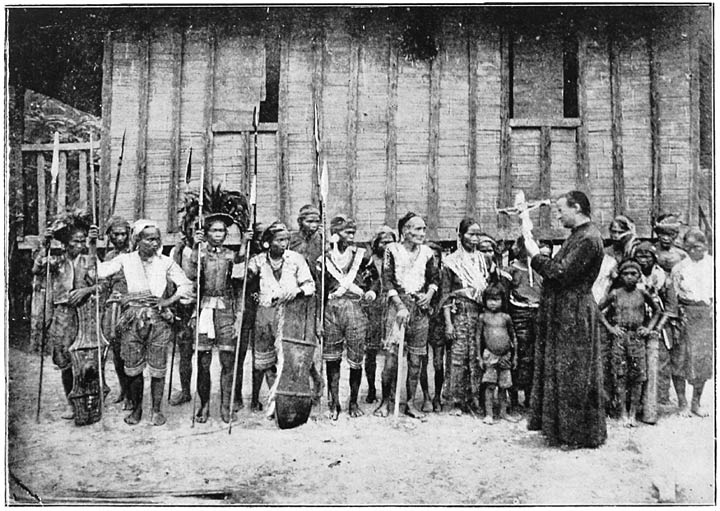

- Father Gisbert, S.J. exhorting a Bagobo Datto and his Followers to Abandon their custom of making Human Sacrifices Between pp. 350–1

- The Datto Manib, Principal Bagani of the Bagabos, with some Wives and Followers and Two Missionaries Between pp. 350–1

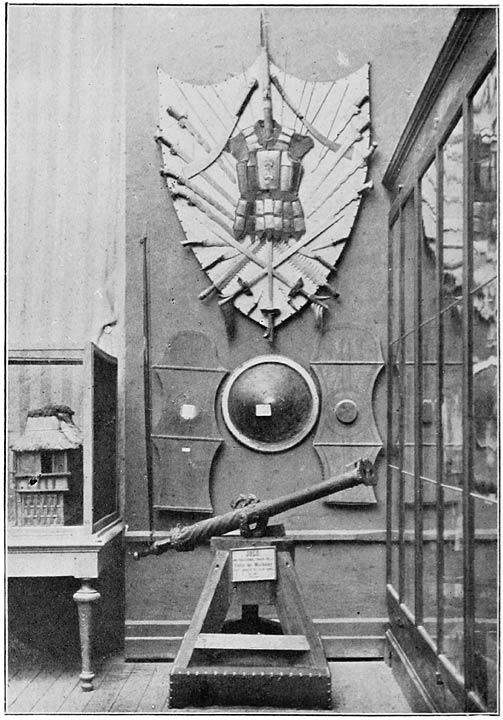

- The Moro Sword and Spear To face p. 363

- Moros of the Bay of Mayo To face p. 367

- Moro Lantacas and Coat of Mail To face p. 373

- Seat of the Moro Power, Lake Lanao To face p. 377

- Double-barrelled Lantaca of Artistic Design and Moro Arms To face p. 387

[1]