Title: The Story of Florence

Author: Edmund G. Gardner

Illustrator: Nelly Erichsen

Release date: October 18, 2011 [eBook #37793]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Melissa McDaniel and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Some illustrations were originally located in the middle of paragraphs. These have been adjusted so as not to interrupt the flow of reading. In some cases this means that the page number of the illustration is not visible.

All rights reserved

First Edition, September 1900.

Second Edition, December 1900.

The Story of Florence

London: J. M. Dent & Co.

Aldine House, 29 and 30 Bedford Street

Covent Garden W.C. * * 1900

To

MY SISTER

MONICA MARY GARDNER

THE present volume is intended to supply a popular history of the Florentine Republic, in such a form that it can also be used as a guide-book. It has been my endeavour, while keeping within the necessary limits of this series of Mediæval Towns, to point out briefly the most salient features in the story of Florence, to tell again the tale of those of her streets and buildings, and indicate those of her artistic treasures, which are either most intimately connected with that story or most beautiful in themselves. Those who know best what an intensely fascinating and many-sided history that of Florence has been, who have studied most closely the work and characters of those strange and wonderful personalities who have lived within (and, in the case of the greatest, died without) her walls, will best appreciate my difficulty in compressing even a portion of all this wealth and profusion into the narrow bounds enjoined by the aim and scope of this book. Much has necessarily been curtailed over which it would have been tempting to linger, much inevitably omitted which the historian could not have passed over, nor the compiler of a guide-book failed to mention. In what I have selected for treatment and what omitted, I have usually let myself be guided by the remembrance of my own needs when I first commenced to visit Florence and to study her arts and history.

It is needless to say that the number of books, old and new, is very considerable indeed, to which anyone[viii] venturing in these days to write yet another book on Florence must have had recourse, and to whose authors he is bound to be indebted–from the earliest Florentine chroniclers down to the most recent biographers of Lorenzo the Magnificent, of Savonarola, of Michelangelo–from Vasari down to our modern scientific art critics–from Richa and Moreni down to the Misses Horner. My obligations can hardly be acknowledged here in detail; but, to mention a few modern works alone, I am most largely indebted to Capponi's Storia della Repubblica di Firenze, to various writings of Professor Pasquale Villari, and to Mr Armstrong's Lorenzo de' Medici; to the works of Ruskin and J. A. Symonds, of M. Reymond and Mr Berenson; and, in the domains of topography, to Baedeker's Hand Book. In judging of the merits and the authorship of individual pictures and statues, I have usually given more weight to the results of modern criticism than to the pleasantness of old tradition.

Carlyle's translation of the Inferno and Mr Wicksteed's of the Paradiso are usually quoted.

If this little book should be found helpful in initiating the English-speaking visitor to the City of Flowers into more of the historical atmosphere of Florence and her monuments than guide-books and catalogues can supply, it will amply have fulfilled its object.

E. G. G.

Roehampton, May 1900.

The Story of Florence

"La bellissima e famosissima figlia di Roma, Fiorenza."

–Dante.

BEFORE the imagination of a thirteenth century poet, one of the sweetest singers of the dolce stil novo, there rose a phantasy of a transfigured city, transformed into a capital of Fairyland, with his lady and himself as fairy queen and king:

"Amor, eo chero mea donna in domino,

l'Arno balsamo fino,

le mura di Fiorenza inargentate,

le rughe di cristallo lastricate,

fortezze alte e merlate,

mio fedel fosse ciaschedun Latino."[2]

But is not the reality even more beautiful than the dreamland Florence of Lapo Gianni's fancy? We stand on the heights of San Miniato, either in front of the Basilica itself or lower down in the Piazzale Michelangelo. Below us, on either bank of the silvery Arno, lies outstretched Dante's "most famous[2] and most beauteous daughter of Rome," once the Queen of Etruria and centre of the most wonderful culture that the world has known since Athens, later the first capital of United Italy, and still, though shorn of much of her former splendour and beauty, one of the loveliest cities of Christendom. Opposite to us, to the north, rises the hill upon which stands Etruscan Fiesole, from which the people of Florence originally came: "that ungrateful and malignant people," Dante once called them, "who of old came down from Fiesole." Behind us stand the fortifications which mark the death of the Republic, thrown up or at least strengthened by Michelangelo in the city's last agony, when she barred her gates and defied the united power of Pope and Emperor to take the State that had once chosen Christ for her king.

"O foster-nurse of man's abandoned glory

Since Athens, its great mother, sunk in splendour;

Thou shadowest forth that mighty shape in story,

As ocean its wrecked fanes, severe yet tender:

The light-invested angel Poesy

Was drawn from the dim world to welcome thee.

"And thou in painting didst transcribe all taught

By loftiest meditations; marble knew

The sculptor's fearless soul–and as he wrought,

The grace of his own power and freedom grew."

Between Fiesole and San Miniato, then, the story of the Florentine Republic may be said to be written.

The beginnings of Florence are lost in cloudy legend, and her early chroniclers on the slenderest foundations have reared for her an unsubstantial, if imposing, fabric of fables–the tales which the women of old Florence, in the Paradiso, told to their house-holds–

"dei Troiani, di Fiesole, e di Roma."

Setting aside the Trojans ("Priam" was mediæval for[5] "Adam," as a modern novelist has remarked), there is no doubt that both Etruscan Fiesole and Imperial Rome united to found the "great city on the banks of the Arno." Fiesole or Faesulae upon its hill was an important Etruscan city, and a place of consequence in the days of the Roman Republic; fallen though it now is, traces of its old greatness remain. Behind the Romanesque cathedral are considerable remains of Etruscan walls and of a Roman theatre. Opposite it to the west we may ascend to enjoy the glorious view from the Convent of the Franciscans, where once the old citadel of Faesulae stood. Faesulae was ever the centre of Italian and democratic discontent against Rome and her Senate (sempre ribelli di Roma, says Villani of its inhabitants); and it was here, in October b.c. 62, that Caius Manlius planted the Eagle of revolt–an eagle which Marius had borne in the war against the Cimbri–and thus commenced the Catilinarian war, which resulted in the annihilation of Catiline's army near Pistoia.

This, according to Villani, was the origin of Florence. According to him, Fiesole, after enduring the stupendous siege, was forced to surrender to the Romans under Julius Cæsar, and utterly razed to the ground. In the second sphere of Paradise, Justinian reminds Dante of how the Roman Eagle "seemed bitter to that hill beneath which thou wast born." Then, in order that Fiesole might never raise its head again, the Senate ordained that the greatest lords of Rome, who had been at the siege, should join with Cæsar in building a new city on the banks of the Arno. Florence, thus founded by Cæsar, was populated by the noblest citizens of Rome, who received into their number those of the inhabitants of fallen Fiesole who wished to live there. "Note then," says the old chronicler, "that it is not wonderful that the[6] Florentines are always at war and in dissensions among themselves, being drawn and born from two peoples, so contrary and hostile and diverse in habits, as were the noble and virtuous Romans, and the savage and contentious folk of Fiesole." Dante similarly, in Canto XV. of the Inferno, ascribes the injustice of the Florentines towards himself to this mingling of the people of Fiesole with the true Roman nobility (with special reference, however, to the union of Florence with conquered Fiesole in the twelfth century):–

"che tra li lazzi sorbi

si disconvien fruttare al dolce fico."[3]

And Brunetto Latini bids him keep himself free from their pollution:–

"Faccian le bestie Fiesolane strame

di lor medesme, e non tocchin la pianta,

s'alcuna surge ancor nel lor letame,

in cui riviva la semente santa

di quei Roman che vi rimaser quando

fu fatto il nido di malizia tanta."[4]

The truth appears to be that Florence was originally founded by Etruscans from Fiesole, who came down from their mountain to the plain by the Arno for commercial purposes. This Etruscan colony was probably destroyed during the wars between Marius and Sulla, and a Roman military colony established here–probably in the time of Sulla, and augmented later by Cæsar and by Augustus. It has, indeed, been urged of late that the old Florentine story has some truth in it, and that Cæsar, not only in legend but in fact, may be[7] regarded as the true first founder of Florence. Thus the Roman colony of Florentia gradually grew into a little city–come una altra piccola Roma, declares her patriotic chronicler. It had its capitol and its forum in the centre of the city, where the Mercato Vecchio once stood; it had an amphitheatre outside the walls, somewhere near where the Borgo dei Greci and the Piazza Peruzzi are to-day. It had baths and temples, though doubtless on a small scale. It had the shape and form of a Roman camp, which (together with the Roman walls in which it was inclosed) it may be said to have retained down to the middle of the twelfth century, in spite of legendary demolitions by Attila and Totila, and equally legendary reconstructions by Charlemagne. Above all, it had a grand temple to Mars, which almost certainly occupied the site of the present Baptistery, if not actually identical with it. Giovanni Villani tells us–and we shall have to return to his statement–that the wonderful octagonal building, now known as the Baptistery or the Church of St John, was consecrated as a temple by the Romans in honour of Mars, for their victory over the Fiesolans, and that Mars was the patron of the Florentines as long as paganism lasted. Round the equestrian statue that was supposed to have once stood in the midst of this temple, numberless legends have gathered. Dante refers to it again and again. In Santa Maria Novella you shall see how a great painter of the early Renaissance, Filippino Lippi, conceived of his city's first patron. When Florence changed him for the Baptist, and the people of Mars became the sheepfold of St John, this statue was removed from the temple and set upon a tower by the side of the Arno:–

"The Florentines took up their idol which they called the God Mars, and set him upon a high tower near the river Arno; and they would not break or[8] shatter it, seeing that in their ancient records they found that the said idol of Mars had been consecrated under the ascendency of such a planet, that if it should be broken or put in a dishonourable place, the city would suffer danger and damage and great mutation. And although the Florentines had newly become Christians, they still retained many customs of paganism, and retained them for a long time; and they greatly feared their ancient idol of Mars; so little perfect were they as yet in the Holy Faith."

This tower is said to have been destroyed like the rest of Florence by the Goths, the statue falling into the Arno, where it lurked in hiding all the time that the city lay in ruins. On the legendary rebuilding of Florence by Charlemagne, the statue, too–or rather the mutilated fragment that remained–was restored to light and honour. Thus Villani:–

"It is said that the ancients held the opinion that there was no power to rebuild the city, if that marble image, consecrated by necromancy to Mars by the first Pagan builders, was not first found again and drawn out of the Arno, in which it had been from the destruction of Florence down to that time. And, when found, they set it upon a pillar on the bank of the said river, where is now the head of the Ponte Vecchio. This we neither affirm nor believe, inasmuch as it appeareth to us to be the opinion of augurers and pagans, and not reasonable, but great folly, to hold that a statue so made could work thus; but commonly it was said by the ancients that, if it were changed, our city would needs suffer great mutation."

Thus it became quella pietra scema che guarda il ponte, in Dantesque phrase; and we shall see what terrible sacrifice its clients unconsciously paid to it. Here it remained, much honoured by the Florentines; street boys were solemnly warned of the fearful judgments[9] that fell on all who dared to throw mud or stones at it; until at last, in 1333, a great flood carried away bridge and statue alike, and it was seen no more. It has recently been suggested that the statue was, in reality, an equestrian monument in honour of some barbaric king, belonging to the fifth or sixth century.

Florence, however, seems to have been–in spite of Villani's describing it as the Chamber of the Empire and the like–a place of very slight importance under the Empire. Tacitus mentions that a deputation was sent from Florentia to Tiberius to prevent the Chiana being turned into the Arno. Christianity is said to have been first introduced in the days of Nero; the Decian persecution raged here as elsewhere, and the soil was hallowed with the blood of the martyr, Miniatus. Christian worship is said to have been first offered up on the hill where a stately eleventh century Basilica now bears his name. When the greater peace of the Church was established under Constantine, a church dedicated to the Baptist on the site of the Martian temple and a basilica outside the walls, where now stands San Lorenzo, were among the earliest churches in Tuscany.

In the year 405, the Goth leader Rhadagaisus, omnium antiquorum praesentiumque hostium longe immanissimus, as Orosius calls him, suddenly inundated Italy with more than 200,000 Goths, vowing to sacrifice all the blood of the Romans to his gods. In their terror the Romans seemed about to return to their old paganism, since Christ had failed to protect them. Fervent tota urbe blasphemiae, writes Orosius. They advanced towards Rome through the Tuscan Apennines, and are said to have besieged Florence, though there is no hint of this in Orosius. On the approach of Stilicho, at the head of thirty legions with a large force of barbarian auxiliaries, Rhadagaisus and[10] his hordes–miraculously struck helpless with terror, as Orosius implies–let themselves be hemmed in in the mountains behind Fiesole, and all perished, by famine and exhaustion rather than by the sword. Villani ascribes the salvation of Florence to the prayers of its bishop, Zenobius, and adds that as this victory of "the Romans and Florentines" took place on the feast of the virgin martyr Reparata, her name was given to the church afterwards to become the Cathedral of Florence.

Zenobius, now a somewhat misty figure, is the first great Florentine of history, and an impressive personage in Florentine art. We dimly discern in him an ideal bishop and father of his people; a man of great austerity and boundless charity, almost an earlier Antoninus. Perhaps the fact that some of the intervening Florentine bishops were anything but edifying, has made these two–almost at the beginning and end of the Middle Ages–stand forth in a somewhat ideal light. He appears to have lived a monastic life outside the walls in a small church on the site of the present San Lorenzo, with two young ecclesiastics, trained by him and St Ambrose, Eugenius and Crescentius. They died before him and are commonly united with him by the painters. Here he was frequently visited by St Ambrose–here he dispensed his charities and worked his miracles (according to the legend, he had a special gift of raising children to life)–here at length he died in the odour of sanctity, a.d. 424. The beautiful legend of his translation should be familiar to every student of Italian painting. I give it in the words of a monkish writer of the fourteenth century:–

"About five years after he had been buried, there was made bishop one named Andrew, and this holy bishop summoned a great chapter of bishops and clerics,[11] and said in the chapter that it was meet to bear the body of St Zenobius to the Cathedral Church of San Salvatore; and so it was ordained. Wherefore, on the 26th of January, he caused him to be unburied and borne to the Church of San Salvatore by four bishops; and these bishops bearing the body of St Zenobius were so pressed upon by the people that they fell near an elm, the which was close unto the Church of St John the Baptist; and when they fell, the case where the body of St Zenobius lay was broken, so that the body touched the elm, and gradually, as the elm was touched, it brought forth flowers and leaves, and lasted all that year with the flowers and leaves. The people, seeing the miracle, broke up all the elm, and with devotion carried the branches away. And the Florentines, beholding what was done, made a column of marble with a cross where the elm had been, so that the miracle should ever be remembered by the people."

Like the statue of Mars, this column was destroyed by the flood of 1333, and the one now standing to the north of the Baptistery was set up after that year. It was at one time the custom for the clergy on the feast of the translation to go in procession and fasten a green bough to this column. Zenobius now stands with St Reparata on the cathedral façade. Domenico Ghirlandaio painted him, together with his pupils Eugenius and Crescentius, in the Sala dei Gigli of the Palazzo della Signoria; an unknown follower of Orcagna had painted a similar picture for a pillar in the Duomo. Ghiberti cast his miracles in bronze for the shrine in the Chapel of the Sacrament; Verrocchio and Lorenzo di Credi at Pistoia placed him and the Baptist on either side of Madonna's throne. In a picture by some other follower of Verrocchio's in the Uffizi he is seen offering up a model of his city to the[12] Blessed Virgin. Two of the most famous of his miracles, the raising of a child to life and the flowering of the elm tree at his translation, are superbly rendered in two pictures by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio. On May 25th the people still throng the Duomo with bunches of roses and other flowers, which they press to the reliquary which contains his head, and so obtain the "benedizione di San Zenobio." Thus does his memory live fresh and green among the people to whom he so faithfully ministered.

Another barbarian king, the last Gothic hero Totila, advancing upon Rome in 542, took the same shorter but more difficult route across the Apennines. According to the legend, he utterly destroyed all Florence, with the exception of the Church of San Giovanni, and rebuilt Fiesole to oppose Rome and prevent Florence from being restored. The truth appears to be that he did not personally attack Florence, but sent a portion of his troops under his lieutenants. They were successfully resisted by Justin, who commanded the imperial garrison, and, on the advance of reinforcements from Ravenna, they drew off into the valley of the Mugello, where they turned upon the pursuing "Romans" (whose army consisted of worse barbarians than Goths) and completely routed them. Fiesole, which had apparently recovered from its old destruction, was probably too difficult to be assailed; but it appears to have been gradually growing at the expense of Florence–the citizens of the latter emigrating to it for greater safety. This was especially the case during the Lombard invasion, when the fortunes of Florence were at their lowest, and, indeed, in the second half of the eighth century, Florence almost sank to being a suburb of Fiesole.

With the advent of Charlemagne and the restoration of the Empire, brighter days commenced for Florence,–so[13] much so that the story ran that he had renewed the work of Julius Caesar and founded the city again. In 786 he wintered here with his court on his third visit to Rome; and, according to legend, he was here again in great wealth and pomp in 805, and founded the Church of Santissimi Apostoli–the oldest existing Florentine building after the Baptistery. Upon its façade you may still read a pompous inscription concerning the Emperor's reception in Florence, and how the Church was consecrated by Archbishop Turpin in the presence of Oliver and Roland, the Paladins! Florence was becoming a power in Tuscany, or at least beginning to see more of Popes and Emperors. The Ottos stayed within her walls on their way to be crowned at Rome; Popes, flying from their rebellious subjects, found shelter here. In 1055 Victor II. held a council in Florence. Beautiful Romanesque churches began to rise–notably the SS. Apostoli and San Miniato, both probably dating from the eleventh century. Great churchmen appeared among her sons, as San Giovanni Gualberto–the "merciful knight" of Burne-Jones' unforgettable picture–the reformer of the Benedictines and the founder of Vallombrosa. The early reformers, while Hildebrand was still "Archdeacon of the Roman Church," were specially active in Florence; and one of them, known as Peter Igneus, in 1068 endured the ordeal of fire and is said to have passed unhurt through the flames, to convict the Bishop of Florence of simony. This, with other matters relating to the times of Giovanni Gualberto and the struggles of the reformers of the clergy, you may see in the Bargello in a series of noteworthy marble bas-reliefs (terribly damaged, it is true), from the hand of Benedetto da Rovezzano.

Although we already begin to hear of the "Florentine people" and the "Florentine citizens," Florence was at this time subject to the Margraves of Tuscany. One[14] of them, Hugh the Great, who is said to have acted as vicar of the Emperor Otto III., and who died at the beginning of the eleventh century, lies buried in the Badia which had been founded by his mother, the Countess Willa, in 978. His tomb, one of the most noteworthy monuments of the fifteenth century, by Mino da Fiesole, may still be seen, near Filippino Lippi's Vision of St Bernard.

It was while Florence was nominally under the sway of Hugo's most famous successor, the Countess Matilda of Tuscany, that Dante's ancestor Cacciaguida was born; and, in the fifteenth and sixteenth cantos of the Paradiso, he draws an ideal picture of that austere old Florence, dentro dalla cerchia antica, still within her Roman walls. We can still partly trace and partly conjecture the position of these walls. The city stood a little way back from the river, and had four master gates; the Porta San Piero on the east, the Porta del Duomo on the north, the Porta San Pancrazio on the west, the Porta Santa Maria on the south (towards the Ponte Vecchio). The heart of the city, the Forum or, as it came to be called, the Mercato Vecchio, has indeed been destroyed of late years to make way for the cold and altogether hideous Piazza Vittorio Emanuele; but we can still perceive that at its south-east corner the two main streets of this old Florentia quadrata intersected,–Calimara, running from the Porta Santa Maria to the Porta del Duomo, south to north, and the Corso, running east to west from the Porta San Piero to the Porta San Pancrazio, along the lines of the present Corso, Via degli Speziali, and Via degli Strozzi. The Porta San Piero probably stood about where the Via del Corso joins the Via del Proconsolo, and there was a suburb reaching out to the Church of San Piero Maggiore. Then the walls ran along the lines of the present Via del Proconsolo[15] and Via dei Balestrieri, inclosing Santa Reparata and the Baptistery, to the Duomo Gate beyond the Bishop's palace–probably somewhere near the opening of the modern Borgo San Lorenzo. Then along the Via Cerretani, Piazza Antinori, Via Tornabuoni, to the Gate of San Pancrazio, which was somewhere near the present Palazzo Strozzi; and so on to where the Church of Santa Trinità now stands, near which there was a postern gate called the Porta Rossa. Then they turned east along the present Via delle Terme to the Porta Santa Maria, which was somewhere near the end of the Mercato Nuovo, after which their course back to the Porta San Piero is more uncertain. Outside the walls were churches and ever-increasing suburbs, and Florence was already becoming an important commercial centre. Matilda's beneficent sway left it in practical independence to work out its own destinies; she protected it from imperial aggressions, and curbed the nobles of the contrada, who were of Teutonic descent and who, from their feudal castles round, looked with hostility upon the rich burgher city of pure Latin blood that was gradually reducing their power and territorial sway. At intervals the great Countess entered Florence, and either in person or by her deputies and judges (members of the chief Florentine families) administered justice in the Forum. Indeed she played the part of Dante's ideal Emperor in the De Monarchia; made Roman law obeyed through her dominions; established peace and curbed disorder; and therefore, in spite of her support of papal claims for political empire, when the Divina Commedia came to be written, Dante placed her as guardian of the Earthly Paradise to which the Emperor should guide man, and made her the type of the glorified active life. Her praises, la lauda di Matelda, were long sung in the Florentine churches, as may be gathered from a passage[16] in Boccaccio.

It is from the death of Matilda in 1115 that the history of the Commune dates. During her lifetime she seems to have gradually, especially while engaged in her conflicts with the Emperor Henry, delegated her powers to the chief Florentine citizens themselves; and in her name they made war upon the aggressive nobility in the country round, in the interests of their commerce. For Dante the first half of this twelfth century represents the golden age in which his ancestor lived, when the great citizen nobles–Bellincion Berti, Ubertino Donati, and the heads of the Nerli and Vecchietti and the rest–lived simple and patriotic lives, filled the offices of state and led the troops against the foes of the Commune. In a grand burst of triumph that old Florentine crusader, Cacciaguida, closes the sixteenth canto of the Paradiso:

"Con queste genti, e con altre con esse,

vid'io Fiorenza in sì fatto riposo,

che non avea cagion onde piangesse;

con queste genti vid'io glorioso,

e giusto il popol suo tanto, che'l giglio

non era ad asta mai posto a ritroso,

nè per division fatto vermiglio."[5]

When Matilda died, and the Popes and Emperors prepared to struggle for her legacy (which thus initiated the strifes of Guelfs and Ghibellines), the Florentine Republic asserted its independence: the citizen nobles who had been her delegates and judges now became the Consuls of the Commune and the leaders of the republican forces in war. In 1119 the Florentines assailed the castle of Monte Cascioli, and killed the[17] imperial vicar who defended it; in 1125 they took and destroyed Fiesole, which had always been a refuge for robber nobles and all who hated the Republic. But already signs of division were seen in the city itself, though it was a century before it came to a head; and the great family of the Uberti–who, like the nobles of the contrada, were of Teutonic descent–were prominently to the front, but soon to be disfatti per la lor superbia. Scarcely was Matilda dead than they appear to have attempted to seize on the supreme power, and to have only been defeated with much bloodshed and burning of houses. Still the Republic pursued its victorious course through the twelfth century–putting down the feudal barons, forcing them to enter the city and join the Commune, and extending their commerce and influence as well as their territory on all sides. And already these nobles within and without the city were beginning to build their lofty towers, and to associate themselves into Societies of the Towers; while the people were grouped into associations which afterwards became the Greater and Lesser Arts or Guilds. Villani sees the origin of future contests in the mingling of races, Roman and Fiesolan; modern writers find it in the distinction, mentioned already, between the nobles, of partly Teutonic origin and imperial sympathies, and the burghers, who were the true Italians, the descendants of those over whom successive tides of barbarian conquest had swept, and to whom the ascendency of the nobles would mean an alien yoke. This struggle between a landed military and feudal nobility, waning in power and authority, and a commercial democracy of more purely Latin descent, ever increasing in wealth and importance, is what lies at the bottom of the contest between Florentine Guelfs and Ghibellines; and the rival claims of Pope and Emperor are of secondary importance,[18] as far as Tuscany is concerned.

In 1173 (as the most recent historian of Florence has shown, and not in the eleventh century as formerly supposed), the second circle of walls was built, and included a much larger tract of city, though many of the churches which we have been wont to consider the most essential things in Florence stand outside them. A new Porta San Piero, just beyond the present façade of the ruined church of San Piero Maggiore, enclosed the Borgo di San Piero; thence the walls passed round to the Porta di Borgo San Lorenzo, just to the north of the present Piazza, and swept round, with two gates of minor importance, past the chief western Porta San Pancrazio or Porta San Paolo, beyond which the present Piazza di Santa Maria Novella stands, down to the Arno where there was a Porta alla Carraia, at the point where the bridge was built later. Hence a lower wall ran along the Arno, taking in the parts excluded from the older circuit down to the Ponte Vecchio. About half-way between this and the Ponte Rubaconte, the walls turned up from the Arno, with several small gates, until they reached the place where the present Piazza di Santa Croce lies–which was outside. Here, just beyond the old site of the Amphitheatre, there was a gate, after which they ran straight without gate or postern to San Piero, where they had commenced.

Instead of the old Quarters, named from the gates, the city was now divided into six corresponding Sesti or sextaries; the Sesto di Porta San Piero, the Sesto still called from the old Porta del Duomo, the Sesto di Porta Pancrazio, the Sesto di San Piero Scheraggio (a church near the Palazzo Vecchio, but now totally destroyed), and the Sesto di Borgo Santissimi Apostoli–these two replacing the old Quarter of Porta Santa Maria. Across the river lay the Sesto d'Oltrarno–then for the most part unfortified. At that time the[19] inhabitants of Oltrarno were mostly the poor and the lower classes, but not a few noble families settled there later on. The Consuls, the supreme officers of the state, were elected annually, two for each sesto, usually nobles of popular tendencies; there was a council of a hundred, elected every year, its members being mainly chosen from the Guilds as the Consuls from the Towers; and a Parliament of the people could be summoned in the Piazza. Thus the popular government was constituted.

Hardly had the new walls risen when the Uberti in 1177 attempted to overthrow the Consuls and seize the government of the city; they were partially successful, in that they managed to make the administration more aristocratic, after a prolonged civil struggle of two years' duration. In 1185 Frederick Barbarossa took away the privileges of the Republic and deprived it of its contrada; but his son, Henry VI., apparently gave it back. With the beginning of the thirteenth century we find the Consuls replaced by a Podestà, a foreign noble elected by the citizens themselves; and the Florentines, not content with having back their contrada, beginning to make wars of conquest upon their neighbours, especially the Sienese, from whom they exacted a cession of territory in 1208.

In 1215 there was enacted a deed in which poets and chroniclers have seen a turning point in the history of Florence. Buondelmonte dei Buondelmonti, "a right winsome and comely knight," as Villani calls him, had pledged himself for political reasons to marry a maiden of the Amidei family–the kinsmen of the proud Uberti and Fifanti. But, at the instigation of Gualdrada Donati, he deserted his betrothed and married Gualdrada's own daughter, a girl of great beauty. Upon this the nobles of the kindred of the deserted girl held a council together to decide what vengeance[20] to take, in which "Mosca dei Lamberti spoke the evil word: Cosa fatta, capo ha; to wit, that he should be slain; and so it was done." On Easter Sunday the Amidei and their associates assembled, after hearing mass in San Stefano, in a palace of the Amidei, which was on the Lungarno at the opening of the present Via Por Santa Maria; and they watched young Buondelmonte coming from Oltrarno, riding over the Ponte Vecchio "dressed nobly in a new robe all white and on a white palfrey," crowned with a garland, making his way towards the palaces of his kindred in Borgo Santissimi Apostoli. As soon as he had reached this side, at the foot of the pillar on which stood the statue of Mars, they rushed out upon him. Schiatta degli Uberti struck him from his horse with a mace, and Mosca dei Lamberti, Lambertuccio degli Amidei, Oderigo Fifanti, and one of the Gangalandi, stabbed him to death with their daggers at the foot of the statue. "Verily is it shown," writes Villani, "that the enemy of human nature by reason of the sins of the Florentines had power in this idol of Mars, which the pagan Florentines adored of old; for at the foot of his figure was this murder committed, whence such great evil followed to the city of Florence." The body[21] was placed upon a bier, and, with the young bride supporting the dead head of her bridegroom, carried through the streets to urge the people to vengeance. Headed by the Uberti, the older and more aristocratic families took up the cause of the Amidei; the burghers and the democratically inclined nobles supported the Buondelmonti, and from this the chronicler dates the beginning of the Guelfs and Ghibellines in Florence.

But it was only the names that were then introduced, to intensify a struggle which had in reality commenced a century before this, in 1115, on the death of Matilda. As far as Guelf and Ghibelline meant a struggle of the commune of burghers and traders with a military aristocracy of Teutonic descent and feudal imperial tendencies, the thing is already clearly defined in the old contest between the Uberti and the Consuls. This, however, precipitated matters, and initiated fifty years of perpetual conflict. Dante, through Cacciaguida, touches upon the tragedy in his great way in Paradiso XVI., where he calls it the ruin of old Florence.

"La casa di che nacque il vostro fleto,

per lo giusto disdegno che v'ha morti

e posto fine al vostro viver lieto,

era onorata ed essa e suoi consorti.

O Buondelmonte, quanto mal fuggisti

le nozze sue per gli altrui conforti!

Molti sarebbon lieti, che son tristi,

se Dio t'avesse conceduto ad Ema

la prima volta che a città venisti.

Ma conveniasi a quella pietra scema

che guarda il ponte, che Fiorenza fesse

vittima nella sua pace postrema."[6]

And again, in the Hell of the sowers of discord,[22] where they are horribly mutilated by the devil's sword, he meets the miserable Mosca.

"Ed un, ch'avea l'una e l'altra man mozza,

levando i moncherin per l'aura fosca,

sì che il sangue facea la faccia sozza,

gridò: Ricorderaiti anche del Mosca,

che dissi, lasso! 'Capo ha cosa fatta,'

che fu il mal seme per la gente tosca."[7]

For a time the Commune remained Guelf and powerful, in spite of dissensions; it adhered to the Pope against Frederick II., and waged successful wars with its Ghibelline rivals, Pisa and Siena. Of the other Tuscan cities Lucca was Guelf, Pistoia Ghibelline. A religious feud mingled with the political dissensions; heretics, the Paterini, Epicureans and other sects, were multiplying in Italy, favoured by Frederick II. and patronised by the Ghibellines. Fra Pietro of Verona, better known as St Peter Martyr, organised a crusade, and, with his white-robed captains of the Faith, hunted them in arms through the streets of Florence; at the Croce al Trebbio, near Santa Maria Novella, and in the Piazza di Santa Felicità over the Arno, columns still mark the place where he fell furiously upon them, con l'uficio apostolico. But in 1249, at the instigation of Frederick II., the Uberti[23] and Ghibelline nobles rose in arms; and, after a desperate conflict with the Guelf magnates and the people, gained possession of the city, with the aid of the Emperor's German troops. And, on the night of February 2nd, the Guelf leaders with a great following of people armed and bearing torches buried Rustico Marignolli, who had fallen in defending the banner of the Lily, with military honours in San Lorenzo, and then sternly passed into exile. Their palaces and towers were destroyed, while the Uberti and their allies with the Emperor's German troops held the city. This lasted not two years. In 1250, on the death of Frederick II., the Republic threw off the yoke, and the first democratic constitution of Florence was established, the Primo Popolo, in which the People were for the first time regularly organised both for peace and for war under a new officer, the Captain of the People, whose appointment was intended to outweigh the Podestà, the head of the Commune and the leader of the nobles. The Captain was intrusted with the white and red Gonfalon of the People, and associated with the central government of the Ancients of the people, who to some extent corresponded to the Consuls of olden time.

This Primo Popolo ran a victorious course of ten years, years of internal prosperity and almost continuous external victory. It was under it that the banner of the Commune was changed from a white lily on a red field to a red lily on a white field–per division fatto vermiglio, as Dante puts it–after the Uberti and Lamberti with the turbulent Ghibellines had been expelled. Pisa was humbled; Pistoia and Volterra forced to submit. But it came to a terrible end, illuminated only by the heroism of one of its conquerors. A conspiracy on the part of the Uberti to take the government from the people and subject the[24] city to the great Ghibelline prince, Manfredi, King of Apulia and Sicily, son of Frederick II., was discovered and severely punished. Headed by Farinata degli Uberti and aided by King Manfredi's German mercenaries, the exiles gathered at Siena, against which the Florentine Republic declared war. In 1260 the Florentine army approached Siena. A preliminary skirmish, in which a band of German horsemen was cut to pieces and the royal banner captured, only led a few months later to the disastrous defeat of Montaperti, che fece l'Arbia colorata in rosso; in which, after enormous slaughter and loss of the Carroccio, or battle car of the Republic, "the ancient people of Florence was broken and annihilated" on September 4th, 1260. Without waiting for the armies of the conqueror, the Guelf nobles with their families and many of the burghers fled the city, mainly to Lucca; and, on the 16th of September, the Germans under Count Giordano, Manfredi's vicar, with Farinata and the exiles, entered Florence as conquerors. All liberty was destroyed, the houses of Guelfs razed to the ground, the Count Guido Novello–the lord of Poppi and a ruthless Ghibelline–made Podestà. The Via Ghibellina is his record. It was finally proposed in a great Ghibelline council at Empoli to raze Florence to the ground; but the fiery eloquence of Farinata degli Uberti, who declared that, even if he stood alone, he would defend her sword in hand as long as life lasted, saved his city. Marked out with all his house for the relentless hate of the Florentine people, Dante has secured to him a lurid crown of glory even in Hell. Out of the burning tombs of the heretics he rises, come avesse l'inferno in gran dispitto, still the unvanquished hero who, when all consented to destroy Florence, "alone with open face defended her."

For nearly six years the life of the Florentine people[25] was suspended, and lay crushed beneath an oppressive despotism of Ghibelline nobles and German soldiery under Guido Novello, the vicar of King Manfredi. Excluded from all political interests, the people imperceptibly organised their greater and lesser guilds, and waited the event. During this gloom Farinata degli Uberti died in 1264, and in the following year, 1265, Dante Alighieri was born. That same year, 1265, Charles of Anjou, the champion of the Church, invited by Clement IV. to take the crown of the kingdom of Naples and Sicily, entered Italy, and in February 1266 annihilated the army of Manfredi at the battle of Benevento. Foremost in the ranks of the crusaders–for as such the French were regarded–fought the Guelf exiles from Florence, under the Papal banner specially granted them by Pope Clement–a red eagle clutching a green dragon on a white field. This, with the addition of a red lily over the eagle's head, became the arms of the society known as the Parte Guelfa; you may see it on the Porta San Niccolò and in other parts of the city between the cross of the People and the red lily of the Commune. Many of the noble Florentines were knighted by the hand of King Charles before the battle, and did great deeds of valour upon the field. "These men cannot lose to-day," exclaimed Manfredi, as he watched their advance; and when the silver eagle of the house of Suabia fell from Manfredi's helmet and he died in the melée crying Hoc est signum Dei, the triumph of the Guelfs was complete and German rule at an end in Italy. Of Manfredi's heroic death and the dishonour done by the Pope's legate to his body, Dante has sung in the Purgatorio.

When the news reached Florence, the Ghibellines trembled for their safety, and the people prepared to win back their own. An attempt at compromise was[26] first made, under the auspices of Pope Clement. Two Frati Gaudenti or "Cavalieri di Maria," members of an order of warrior monks from Bologna, were made Podestàs, one a Guelf and one a Ghibelline, to come to terms with the burghers. You may still trace the place where the Bottega and court of the Calimala stood in Mercato Nuovo (the Calimala being the Guild of dressers of foreign cloth–panni franceschi, as Villani calls it), near where the Via Porta Rossa now enters the present Via Calzaioli. Here the new council of thirty-six of the best citizens, burghers and artizans, with a few trusted members of the nobility, met every day to settle the affairs of the State. Dante has branded these two warrior monks as hypocrites, but, as Capponi says, from this Bottega issued at once and almost spontaneously the Republic of Florence. Their great achievement was the thorough organisation of the seven greater Guilds, of which more presently, to each of which were given consuls and rectors, and a gonfalon or ensign of its own, around which its followers might assemble in arms in defence of People and Commune. To counteract this, Guido Novello brought in more troops from the Ghibelline cities of Tuscany, and increased the taxes to pay his Germans; until he had fifteen hundred horsemen in the city under his command. With their aid the nobles, headed by the Lamberti, rushed to arms. The people rose en masse and, headed by a Ghibelline noble, Gianni dei Soldanieri, who apparently had deserted his party in order to get control of the State (and who is placed by Dante in the Hell of traitors), raised barricades in the Piazza di Santa Trinità and in the Borgo SS. Apostoli, at the foot of the Tower of the Girolami, which still stands. The Ghibellines and Germans gathered in the Piazza di San Giovanni, held all the north-east of the town, and swept down upon the[27] people's barricades under a heavy fire of darts and stones from towers and windows. But the street fighting put the horsemen at a hopeless disadvantage, and, repulsed in the assault, the Count and his followers evacuated the town. This was on St Martin's day, November 11th, 1266. The next day a half-hearted attempt to re-enter the city at the gate near the Ponte alla Carraia was made, but easily driven off; and for two centuries and more no foreigner set foot as conqueror in Florence.

Not that Florence either obtained or desired absolute independence. The first step was to choose Charles of Anjou, the new King of Naples and Sicily, for their suzerain for ten years; but, cruel tyrant as he was elsewhere, he showed himself a true friend to the Florentines, and his suzerainty seldom weighed upon them oppressively. The Uberti and others were expelled, and some, who held out among the castles, were put to death at his orders. But the government became truly democratic. There was a central administration of twelve Ancients, elected annually, two for each sesto; with a council of one hundred "good men of the People, without whose deliberation no great thing or expense could be done"; and, nominally at least, a parliament. Next came the Captain of the People (usually an alien noble of democratic sympathies), with a special council or credenza, called the Council of the Captain and Capetudini (the Capetudini composed of the consuls of the Guilds), of 80 members; and a general council of 300 (including the 80), all popolani and Guelfs. Next came the Podestà, always an alien noble (appointed at first by King Charles), with the Council of the Podestà of 90 members, and the general Council of the Commune of 300–in both of which nobles could sit as well as popolani. Measures presented by the 12 to the 100 were then submitted[28] successively to the two councils of the Captain, and then, on the next day, to the councils of the Podestà and the Commune. Occasionally measures were concerted between the magistrates and a specially summoned council of richiesti, without the formalities and delays of these various councils. Each of the seven greater Arts[8] was further organised with its own officers and councils and banners, like a miniature republic, and its consuls (forming the Capetudini) always sat in the Captain's council and usually in that of the Podestà likewise.

There was one dark spot. A new organisation was set on foot, under the auspices of Pope Clement and King Charles, known as the Parte Guelfa–another miniature republic within the republic–with six captains (three nobles and three popolani) and two councils, mainly to persecute the Ghibellines, to manage confiscated goods, and uphold Guelf principles in the State. In later days these Captains of the Guelf Party became exceedingly powerful and oppressive, and were the cause of much dissension. They met at first in the Church of S. Maria sopra la Porta (now the Church of S. Biagio), and later had a special palace of their own–which still stands, partly in the Via delle Terme, as you pass up it from the Via Por Santa Maria on the right, and partly in the Piazza di San Biagio. It is an imposing and somewhat threatening mass, partly of the fourteenth and partly of the early fifteenth century.[31] The church, which retains in part its structure of the thirteenth century, had been a place of secret meeting for the Guelfs during Guido Novello's rule; it still stands, but converted into a barracks for the firemen of Florence.

Thus was the greatest and most triumphant Republic of the Middle Ages organised–the constitution under which the most glorious culture and art of the modern world was to flourish. The great Guilds were henceforth a power in the State, and the Secondo Popolo had arisen–the democracy that Dante and Boccaccio were to know.

"Godi, Fiorenza, poi che sei sì grande

che per mare e per terra batti l'ali,

e per l'inferno il tuo nome si spande."

–Dante.

THE century that passed from the birth of Dante in 1265 to the deaths of Petrarch and Boccaccio, in 1374 and 1375 respectively, may be styled the Trecento, although it includes the last quarter of the thirteenth century and excludes the closing years of the fourteenth. In general Italian history, it runs from the downfall of the German Imperial power at the battle of Benevento, in 1266, to the return of the Popes from Avignon in 1377. In art, it is the epoch of the completion of Italian Gothic in architecture, of the followers and successors of Niccolò and Giovanni Pisano in sculpture, of the school of Giotto in painting. In letters, it is the great period of pure Tuscan prose and verse. Dante and Giovanni Villani, Dino Compagni, Petrarch, Boccaccio and Sacchetti, paint the age for us in all its aspects; and a note of mysticism is heard at the close (though not from a Florentine) in the Epistles of St. Catherine of Siena, of whom a living Italian poet has written–Nel Giardino del conoscimento di sè ella è come una rosa di fuoco. But at the same time it is a century full of civil war and sanguinary factions, in which every Italian city was divided against itself; and nowhere were these divisions more notable or more[35] bitterly fought out than in Florence. Yet, in spite of it all, the Republic proceeded majestically on its triumphant course. Machiavelli lays much stress upon this in the Proem to his Istorie Fiorentine. "In Florence," he says, "at first the nobles were divided against each other, then the people against the nobles, and lastly the people against the populace; and it ofttimes happened that when one of these parties got the upper hand, it split into two. And from these divisions there resulted so many deaths, so many banishments, so many destructions of families, as never befell in any other city of which we have record. Verily, in my opinion, nothing manifests more clearly the power of our city than the result of these divisions, which would have been able to destroy every great and most potent city. Nevertheless ours seemed thereby to grow ever greater; such was the virtue of those citizens, and the power of their genius and disposition to make themselves and their country great, that those who remained free from these evils could exalt her with their virtue more than the malignity of those accidents, which had diminished them, had been able to cast her down. And without doubt, if only Florence, after her liberation from the Empire, had had the felicity of adopting a form of government which would have kept her united, I know not what republic, whether modern or ancient, would have surpassed her–with such great virtue in war and in peace would she have been filled."

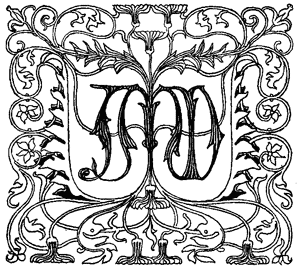

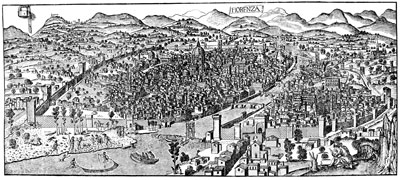

FLORENTINE FAMILIES, EARLY THIRTEENTH CENTURY,

WITH

A PORTION OF THE SECOND WALLS INDICATED

(Temple

Classics: Paradiso).

(The representation is approximate

only: the Cerchi Palace near the Corso degli

Adimari should be more to the right.)

The first thirty-four years of this epoch are among the brightest in Florentine history, the years that ran from the triumph of the Guelfs to the sequel to the Jubilee of 1300, from the establishment of the Secondo Popolo to its split into Neri and Bianchi, into Black Guelfs and White Guelfs. Externally Florence became the chief power of Tuscany, and all the neighbouring towns gradually, to a greater or less extent,[36] acknowledged her sway; internally, in spite of growing friction between the burghers and the new Guelf nobility, between popolani and grandi or magnates, she was daily advancing in wealth and prosperity, in beauty and artistic power. The exquisite poetry of the dolce stil novo was heard. Guido Cavalcanti, a noble Guelf who had married the daughter of Farinata degli Uberti, and, later, the notary Lapo Gianni and Dante Alighieri, showed the Italians what true lyric song was; philosophers like Brunetto Latini served the state; modern history was born with Giovanni Villani. Great palaces were built for the officers of the Republic; vast Gothic churches arose. Women of rare beauty, eternalised as Beatrice, Giovanna, Lagia and the like, passed through the streets and adorned the social gatherings in the open loggias of the palaces. Splendid pageants and processions hailed the Calends of May and the Nativity of the Baptist, and marked the civil and ecclesiastical festivities and state solemnities. The people advanced more and more in power and patriotism; while the magnates, in their towers and palace-fortresses, were partly forced to enter the life of the guilds, partly held aloof and plotted to recover their lost authority, but were always ready to officer the burgher forces in time of war, or to extend Florentine influence by serving as Podestàs and Captains in other Italian cities.

Dante was born in the Sesto di San Piero Maggiore in May 1265, some eighteen months before the liberation of the city. He lost his mother in his infancy, and his father while he was still a boy. This father appears to have been a notary, and came from a noble but decadent family, who were probably connected with the Elisei, an aristocratic house of supposed Roman descent, who had by this time almost entirely disappeared. The Alighieri, who were Guelfs, do not seem to have ranked officially as grandi or magnates;[37] one of Dante's uncles had fought heroically at Montaperti. Almost all the families connected with the story of Dante's life had their houses in the Sesto di San Piero Maggiore, and their sites may in some instances still be traced. Here were the Cerchi, with whom he was to be politically associated in after years; the Donati, from whom sprung one of his dearest friends, Forese, with one of his deadliest foes, Messer Corso, and Dante's own wife, Gemma; and the Portinari, the house according to tradition of Beatrice, the "giver of blessing" of Dante's Vita Nuova, the mystical lady of the Paradiso. Guido Cavalcanti, the first and best of all his friends, lived a little apart from this Sesto di Scandali–as St Peter's section of the town came to be called–between the Mercato Nuovo and San Michele in Orto. Unlike the Alighieri, though not of such ancient birth as theirs, the Cavalcanti were exceedingly rich and powerful, and ranked officially among the grandi, the Guelf magnates. At this epoch, as Signor Carocci observes in his Firenze scomparsa, Florence must have presented the aspect of a vast forest of towers. These towers rose over the houses of powerful and wealthy families, to be used for offence or defence, when the faction fights raged, or to be dismantled and cut down when the people gained the upper hand. The best idea of such a mediæval city, on a smaller scale, can still be got at San Gemignano, "the fair town called of the Fair Towers," where dozens of these torri still stand; and also, though to a less extent, at Gubbio. A few have been preserved here in Florence, and there are a number of narrow streets, on both sides of the Arno, which still retain some of their mediæval characteristics. In the Borgo Santissimi Apostoli, for instance, and in the Via Lambertesca, there are several striking towers of this kind, with remnants of palaces of the grandi;[38] and, on the other side of the river, especially in the Via dei Bardi and the Borgo San Jacopo. When one family, or several associated families, had palaces on either side of a narrow street defended by such towers, and could throw chains and barricades across at a moment's notice, it will readily be understood that in times of popular tumult Florence bristled with fortresses in every direction.

In 1282, the year before that in which Dante received the "most sweet salutation," dolcissimo salutare, of "the glorious lady of my mind who was called by many Beatrice, that knew not how she was called," and saw the vision of the Lord of terrible aspect in the mist of the colour of fire (the vision which inspired the first of his sonnets which has been preserved to us), the democratic government of the Secondo Popolo was confirmed by being placed entirely in the hands of the Arti Maggiori or Greater Guilds. The Signoria was henceforth to be composed of the Priors of the Arts, chosen from the chief members of the Greater Guilds, who now became the supreme magistrates of the State. They were, at this epoch of Florentine history, six in number, one to represent each Sesto, and held office for two months only; on leaving office, they joined with the Capetudini, and other citizens summoned for the purpose, to elect their successors. At a later period this was done, ostensibly at least, by lot instead of election. The glorious Palazzo Vecchio had not yet been built, and the Priors met at first in a house belonging to the monks of the Badia, defended by the Torre della Castagna; and afterwards in a palace belonging to the Cerchi (both tower and palace are still standing). Of the seven Greater Arts–the Calimala, the Money-changers, the Wool-merchants, the Silk-merchants, the Physicians and Apothecaries, the traders in furs and skins, the Judges and Notaries–the latter[39] alone do not seem at first to have been represented in the Priorate; but to a certain extent they exercised control over all the Guilds, sat in all their tribunals, and had a Proconsul, who came next to the Signoria in all state processions, and had a certain jurisdiction over all the Arts. It was thus essentially a government of those who were actually engaged in industry and commerce. "Henceforth," writes Pasquale Villari, "the Republic is properly a republic of merchants, and only he who is ascribed to the Arts can govern it: every grade of nobility, ancient or new, is more a loss than a privilege." The double organisation of the People under the Captain with his two councils, and the Commune under the Podestà with his special council and the general council (in these two latter alone, it will be remembered, could nobles sit and vote) still remained; but the authority of the Podestà was naturally diminished.

Florence was now the predominant power in central Italy; the cities of Tuscany looked to her as the head of the Guelfic League, although, says Dino Compagni, "they love her more in discord than in peace, and obey her more for fear than for love." A protracted war against Pisa and Arezzo, carried on from 1287 to 1292, drew even Dante from his poetry and his study; it is believed that he took part in the great battle of Campaldino in 1289, in which the last efforts of the old Tuscan Ghibellinism were shattered by the Florentines and their allies, fighting under the royal banner of the House of Anjou. Amerigo di Narbona, one of the captains of King Charles II. of Naples, was in command of the Guelfic forces. From many points of view, this is one of the more interesting battles of the Middle Ages. It is said to have been almost the last Italian battle in which the burgher forces, and not the mercenary soldiery of the Condottieri, carried the day.[40] Corso Donati and Vieri dei Cerchi, soon to be in deadly feud in the political arena, were among the captains of the Florentine host; and Dante himself is said to have served in the front rank of the cavalry. In a fragment of a letter ascribed to him by one of his earlier biographers, Dante speaks of this battle of Campaldino; "wherein I had much dread, and at the end the greatest gladness, by reason of the varying chances of that battle." One of the Ghibelline leaders, Buonconte da Montefeltro, who was mortally wounded and died in the rout, meets the divine poet on the shores of the Mountain of Purgation, and, in lines of almost ineffable pathos, tells him the whole story of his last moments. Villani, ever mindful of Florence being the daughter of Rome, assures us that the news of the great victory was miraculously brought to the Priors in the Cerchi Palace, in much the same way as the tidings of Lake Regillus to the expectant Fathers at the gate of Rome. Several of the exiled Uberti had fallen in the ranks of the enemy, fighting against their own country. In the cloisters of the Annunziata you will find a contemporary monument of the battle, let into the west wall of the church near the ground;[41] the marble figure of an armed knight on horseback, with the golden lilies of France over his surcoat, charging down upon the foe. It is the tomb of the French cavalier, Guglielmo Berardi, "balius" of Amerigo di Narbona, who fell upon the field.

The eleven years that follow Campaldino, culminating in the Jubilee of Pope Boniface VIII. and the opening of the fourteenth century, are the years of Dante's political life. They witnessed the great political reforms which confirmed the democratic character of the government, and the marvellous artistic embellishment of the city under Arnolfo di Cambio and his contemporaries. During these years the Palazzo Vecchio, the Duomo, and the grandest churches of Florence were founded; and the Third Walls, whose gates and some scanty remnants are with us to-day, were begun. Favoured by the Popes and the Angevin sovereigns of Naples, now that the old Ghibelline nobility, save in a few valleys and mountain fortresses, was almost extinct, the new nobles, the grandi or Guelf magnates, proud of their exploits at Campaldino, and chafing against the burgher rule, began to adopt an overbearing line of conduct towards the people, and to be more factious than ever among themselves. Strong measures were adopted against them, such as the complete enfranchisement of the peasants of the contrada in 1289–measures which culminated in the famous Ordinances of Justice, passed in 1293, by which the magnates were completely excluded from the administration, severe laws made to restrain their rough usage of the people, and a special magistrate, the Gonfaloniere or "Standard-bearer of Justice," added to the Priors, to hold office like them for two months in rotation from each sesto of the city, and to rigidly enforce the laws against the magnates. This Gonfaloniere became practically the[42] head of the Signoria, and was destined to become the supreme head of the State in the latter days of the Florentine Republic; to him was publicly assigned the great Gonfalon of the People, with its red cross on a white field; and he had a large force of armed popolani under his command to execute these ordinances, against which there was no appeal allowed.[9] These Ordinances also fixed the number of the Guilds at twenty-one–seven Arti Maggiori, mainly engaged in wholesale commerce, exportation and importation, fourteen Arti Minori, which carried on the retail traffic and internal trade of the city–and renewed their statutes.

The hero of this Magna Charta of Florence is a certain Giano della Bella, a noble who had fought at Campaldino and had now joined the people; a man of untractable temper, who knew not how to make concessions; somewhat anti-clerical and obnoxious to the Pope, but consumed by an intense and savage thirst for justice, upon which the craftier politicians of both sides played. "Let the State perish, rather than such things be tolerated," was his constant political formula: Perisca innanzi la città, che tante opere rie si sostengano. But the magnates, from whom he was endeavouring to snatch their last political refuge, the Parte Guelfa, muttered, "Let us smite the shepherd, and the sheep shall be scattered"; and at length, after an ineffectual conspiracy against his life, Giano was driven out of the[43] city, on March 5th, 1295, by a temporary alliance of the burghers and magnates against him. The popolo minuto and artizans, upon whom he had mainly relied and whose interests he had sustained, deserted him; and the government remained henceforth in the hands of the wealthy burghers, the popolo grosso. Already a cleavage was becoming visible between these Arti Maggiori, who ruled the State, and the Arti Minori whose gains lay in local merchandise and traffic, partly dependent upon the magnates. And a butcher, nicknamed Pecora, or, as we may call him, Lambkin, appears prominently as a would-be politician; he cuts a quaintly fierce figure in Dino Compagni's chronicle. In this same year, 1295, Dante Alighieri entered public life, and, on July 6th, he spoke in the General Council of the Commune in support of certain modifications in the Ordinances of Justice, whereby nobles, by leaving their order and matriculating in one or other of the Arts, even without exercising it, could be free from their disabilities, and could share in the government of the State, and hold office in the Signoria. He himself, in this same year, matriculated in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, the great guild which included the painters and the book-sellers.

The growing dissensions in the Guelf Republic came to a head in 1300, the famous year of jubilee in which the Pope was said to have declared that the Florentines were the "fifth element." The rival factions of Bianchi and Neri, White Guelfs and Black Guelfs, which were now to divide the whole city, arose partly from the deadly hostility of two families each with a large following, the Cerchi and the Donati, headed respectively by Vieri dei Cerchi and Corso Donati, the two heroes of Campaldino; partly from an analogous feud in Pistoia, which was governed from Florence; partly from the political discord between that party in the State that[44] clung to the (modified) Ordinances of Justice and supported the Signoria, and another party that hated the Ordinances and loved the tyrannical Parte Guelfa. They were further complicated by the intrigues of the "black" magnates with Pope Boniface VIII., who apparently hoped by their means to repress the burgher government and unite the city in obedience to himself. With this end in view, he had been endeavouring to obtain from Albert of Austria the renunciation, in favour of the Holy See, of all rights claimed by the Emperors over Tuscany. Dante himself, Guido Cavalcanti, and most of the best men in Florence either directly adhered to, or at least favoured, the Cerchi and the Whites; the populace, on the other hand, was taken with the dash and display of the more aristocratic Blacks, and would gladly have seen Messer Corso–"il Barone," as they called him–lord of the city. Rioting, in which Guido Cavalcanti played a wild and fantastic part, was of daily occurrence, especially in the Sesto di San Piero. The adherents of the Signoria had their head-quarters in the Cerchi Palace, in the Via della Condotta; the Blacks found their legal fortress in that of the Captains of the Parte Guelfa in the Via delle Terme. At last, on May 1st, the two factions "came to blood" in the Piazza di Santa Trinità on the occasion of a dance of girls to usher in the May. On June 15th Dante was elected one of the six Priors, to hold office till August 15th, and he at once took a strong line in resisting all interference from Rome, and in maintaining order within the city. In consequence of an assault upon the officers of the Guilds on St. John's Eve, the Signoria, probably on Dante's initiative, put under bounds a certain number of factious magnates, chosen impartially from both parties, including Corso Donati and Guido Cavalcanti. From his place of banishment at Sarzana, Guido, sick to death,[45] wrote the most pathetic of all his lyrics:–

"Because I think not ever to return,

Ballad, to Tuscany,–

Go therefore thou for me

Straight to my lady's face,

Who, of her noble grace,

Shall show thee courtesy.

* * * * *

"Surely thou knowest, Ballad, how that Death

Assails me, till my life is almost sped:

Thou knowest how my heart still travaileth

Through the sore pangs which in my soul are bred:–

My body being now so nearly dead,

It cannot suffer more.

Then, going, I implore

That this my soul thou take

(Nay, do so for my sake),

When my heart sets it free."[10]

And at the end of August, when Dante had left office, Guido returned to Florence with the rest of the Bianchi, only to die. For more than a year the "white" burghers were supreme, not only in Florence, but throughout a greater part of Tuscany; and in the following May they procured the expulsion of the Blacks from Pistoia. But Corso Donati at Rome was biding his time; and, on November 1st, 1301, Charles of Valois, brother of King Philip of France, entered Florence with some 1200 horsemen, partly French and partly Italian,–ostensibly as papal peacemaker, but preparing to "joust with the lance of Judas." In Santa Maria Novella he solemnly swore, as the son of a king, to preserve the peace and well-being of the city; and at once armed his followers. Magnates and burghers alike, seeing themselves betrayed, began to barricade their houses and streets. On the same day[46] (November 5th) Corso Donati, acting in unison with the French, appeared in the suburbs, entered the city by a postern gate in the second walls, near S. Piero Maggiore, and swept through the streets with an armed force, burst open the prisons, and drove the Priors out of their new Palace. For days the French and the Neri sacked the city and the contrada at their will, Charles being only intent upon securing a large share of the spoils for himself. But even he did not dare to alter the popular constitution, and was forced to content himself with substituting "black" for "white" burghers in the Signoria, and establishing a Podestà of his own following, Cante de' Gabbrielli of Gubbio, in the Palace of the Commune. An apparently genuine attempt on the part of the Pope, by a second "peacemaker," to undo the harm that his first had done, came to nothing; and the work of proscription commenced, under the direction of the new Podestà. Dante was one of the first victims. The two sentences against him (in each case with a few other names) are dated January 27th, 1302, and March 10th–and there were to be others later. It is the second decree that contains the famous clause, condemning him to be burned to death, if ever he fall into the power of the Commune. At the beginning of April all the leaders of the "white" faction, who had not already fled or turned "black," with their chief followers, magnates and burghers alike, were hounded into exile; and Charles left Florence to enter upon an almost equally shameful campaign in Sicily.

Dante is believed to have been absent from Florence on an embassy to the Pope when Charles of Valois came, and to have heard the news of his ruin at Siena as he hurried homewards–though both embassy and absence have been questioned by Dante scholars of repute. His ancestor, Cacciaguida, tells him in the[49] Paradiso:–

"Tu lascerai ogni cosa diletta

più caramente, e questo è quello strale

che l'arco dello esilio pria saetta.

Tu proverai sì come sa di sale

lo pane altrui, e com'è duro calle

lo scendere e il salir per l'altrui scale."[11]

The rest of Dante's life was passed in exile, and only touches the story of Florence indirectly at certain points. "Since it was the pleasure of the citizens of the most beautiful and most famous daughter of Rome, Florence," he tells us in his Convivio, "to cast me forth from her most sweet bosom (in which I was born and nourished up to the summit of my life, and in which, with her good will, I desire with all my heart to rest my weary soul and end the time given me), I have gone through almost all the parts to which this language extends, a pilgrim, almost a beggar, showing against my will the wound of fortune, which is wont unjustly to be ofttimes reputed to the wounded."

Attempts of the exiles to win their return to Florence by force of arms, with aid from the Ubaldini and the Tuscan Ghibellines, were easily repressed. But the victorious Neri themselves now split into two factions; the one, headed by Corso Donati and composed mainly of magnates, had a kind of doubtful support in the favour of the populace; the other, led by Rosso della Tosa, inclined to the Signoria and the popolo grosso. It was something like the old contest between Messer Corso and Vieri dei Cerchi, but with more entirely selfish ends; and there was evidently going to be a[50] hard tussle between Messer Corso and Messer Rosso for the possession of the State. Civil war was renewed in the city, and the confusion was heightened by the restoration of a certain number of Bianchi, who were reconciled to the Government. The new Pope, Benedict XI., was ardently striving to pacify Florence and all Italy; and his legate, the Cardinal Niccolò da Prato, took up the cause of the exiles. Pompous peace-meetings were held in the Piazza di Santa Maria Novella, for the friars of St Dominic–to which order the new Pope belonged–had the welfare of the city deeply at heart; and at one of these meetings the exiled lawyer, Ser Petracco dall'Ancisa (in a few days to be the father of Italy's second poet), acted as the representative of his party. Attempts were made to revive the May-day pageants of brighter days–but they only resulted in a horrible disaster on the Ponte alla Carraia, of which more presently. The fiends of faction broke loose again; and in order to annihilate the Cavalcanti, who were still rich and powerful round about the Mercato Nuovo, the leaders of the Neri deliberately burned a large portion of the city. On July 20th, 1304, an attempt by the now allied Bianchi and Ghibellines to surprise the city proved a disastrous failure; and, on that very day (Dante being now far away at Verona, forming a party by himself), Francesco di Petracco–who was to call himself Petrarca and is called by us Petrarch–was born in exile at Arezzo.

This miserable chapter of Florentine history ended tragically in 1308, with the death of Corso Donati. In his old age he had married a daughter of Florence's deadliest foe, the great Ghibelline champion, Uguccione della Faggiuola; and, in secret understanding with Uguccione and the Cardinal Napoleone degli Orsini (Pope Clement V. had already transferred the papal chair to Avignon and commenced the Babylonian captivity),[53] he was preparing to overthrow the Signoria, abolish the Ordinances, and make himself Lord of Florence. But the people anticipated him. On Sunday morning, October 16th, the Priors ordered their great bell to be sounded; Corso was accused, condemned as a traitor and rebel, and sentence pronounced in less than an hour; and with the great Gonfalon of the People displayed, the forces of the Commune, supported by the swordsmen of the Della Tosa and a band of Catalan mercenaries in the service of the King of Naples, marched upon the Piazza di San Piero Maggiore. Over the Corbizzi tower floated the banner of the Donati, but only a handful of men gathered round the fierce old noble who, himself unable by reason of his gout to bear arms, encouraged them by his fiery words to hold out to the last. But the soldiery of Uguccione never came, and not a single magnate in the city stirred to aid him. Corso, forced at last to abandon his position, broke through his enemies, and, hotly pursued, fled through the Porta alla Croce. He was overtaken, captured, and barbarously slain by the lances of the hireling soldiery, near the Badia di San Salvi, at the instigation, as it was whispered, of Rosso della Tosa and Pazzino dei Pazzi. The monks carried him, as he lay dying, into the Abbey, where they gave him humble sepulchre for fear of the people. With all his crimes, there was nothing small in anything that Messer Corso did; he was a great spirit, one who could have accomplished mighty things in other circumstances, but who could not breathe freely in the atmosphere of a mercantile republic. "His life was perilous," says Dino Compagni sententiously, "and his death was blame-worthy."

A brief but glorious chapter follows, though denounced in Dante's bitterest words. Hardly was Corso dead when, after their long silence, the imperial[54] trumpets were again heard in the Garden of the Empire. Henry of Luxemburg, the last hero of the Middle Ages, elected Emperor as Henry VII., crossed the Alps in September 1310, resolved to heal the wounds of Italy, and to revive the fading mediæval dream of the Holy Roman Empire. In three wild and terrible letters, Dante announced to the princes and peoples of Italy the advent of this "peaceful king," this "new Moses"; threatened the Florentines with the vengeance of the Imperial Eagle; urged Cæsar on against the city–"the sick sheep that infecteth all the flock of the Lord with her contagion." But the Florentines rose to the occasion, and with the aid of their ally, the King of Naples, formed what was practically an Italian confederation to oppose the imperial invader. "It was at this moment," writes Professor Villari, "that the small merchant republic initiated a truly national policy, and became a great power in Italy." From the middle of September till the end of October, 1312, the imperial army lay round Florence. The Emperor, sick with fever, had his head-quarters in San Salvi. But he dared not venture upon an attack, although the fortifications were unfinished; and, in the following August, the Signoria of Florence could write exultantly to their allies, and announce "the blessed tidings" that "the most savage tyrant, Henry, late Count of Luxemburg, whom the rebellious persecutors of the Church, and treacherous foes of ourselves and you, called King of the Romans and Emperor of Germany," had died at Buonconvento.

But in the Empyrean Heaven of Heavens, in the mystical convent of white stoles, Beatrice shows Dante the throne of glory prepared for the soul of the noble-hearted Cæsar:–[55]

"In quel gran seggio, a che tu gli occhi tieni

per la corona che già v'è su posta,

prima che tu a queste nozze ceni,

sederà l'alma, che fia giù agosta,

dell'alto Enrico, ch'a drizzare Italia

verrà in prima che ella sia disposta."[12]