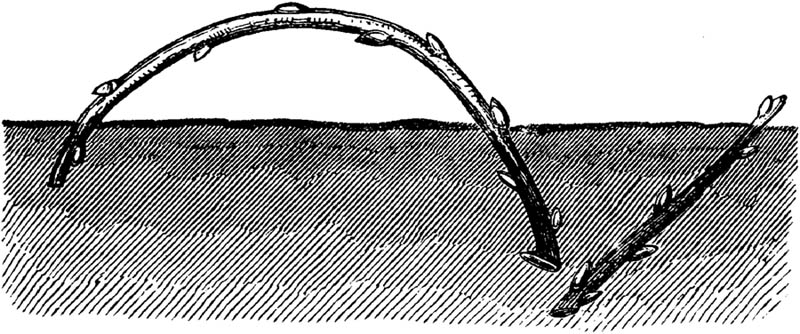

Fig. 1.—FRENCH AND COMMON MODES OF SETTING CUTTINGS.

Title: American Pomology. Apples

Author: J. A. Warder

Release date: October 2, 2011 [eBook #37596]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jeannie Howse, Steven Giacomelli and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images produced by Core Historical

Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell University)

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document has been preserved.

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. For a complete list, please see the end of this document.

A Table of Contents has been added for the reader's convenience. There is no Chapter 13.

In the classification chapter inconsistant illustration placement has been regularized.

Click on the images to see a larger version.

290 ILLUSTRATIONS.

All patriots may realize a sense of pride, when they consider the capabilities of the glorious country in which we are favored to live; and while fostering no sectional feelings, nor pleading any local interests, yet, as Americans and as men, we may be allowed to love our own homes, our own neighborhoods, our States and regions; and we may be permitted to think them the brightest and best portions of the great Republic to which we all belong. Therefore the writer asks to be excused for expressing a preference for his own favored Northwest, and while claiming all praise for this noble expanse, he wishes still to be acknowledged as most devotedly an American Citizen, who feels the deepest interest in the prosperity of the whole country.

His fellow-laborers in the extensive field of Horticulture, who are scattered over the great Northwest, having called upon him for a work on fruits which should be adapted to their wants, the author has for several years devoted himself to the task of collecting materials from which he is preparing a work upon American Pomology, of which this is to be the first volume.

The title has been adopted as the most appropriate, because the book is intended to be truly American in its character, and, though it may be especially adapted to the wants of the Western States, great pains have been taken [iv]to make it a useful companion to the orchardists of all portions of our country.

When examining this volume, his friends are asked to look gently upon the many faults they may find, and they are requested also to observe the peculiarities by which this fruit book is characterized. Much to his regret, the author found that it was considered necessary to the completeness of the volume, that the general subject of fruit-growing should be treated in detail, and, therefore, introductory chapters were prepared; whereas, he had set out simply to describe the fruits of our country. To this necessity, as it was considered by his friends, the author yielded reluctantly, because he felt that this labor had already been thoroughly done by his predecessors, whose volumes were to be seen in the houses of all intelligent fruit-growers. From them he did not wish to borrow other men's ideas and language, and therefore undertook to write the whole anew, without any reference to printed books. But, of course, it is impossible to be original in treating such familiar and hackneyed topics as those which are discussed at every meeting of horticulturists all over the country, and which form the subject of the familiar discourse of the green-house and nursery, the potting-shed and the grafting-room, the garden and the orchard.

After the introductory chapters upon the general or leading topics connected with fruit-culture and orcharding, the reader will find that especial attention has been paid to the classification of the fruits under consideration in this volume. Classification is the great need of our pomology, and, indeed, it is almost a new idea to many American readers. The author has fully realized the [v]difficulties attendant upon the undertaking, but its importance, and its growing necessity, were considered sufficient to warrant the attempted innovation. It is hoped that American students of pomology will appreciate the efforts which have been made in their behalf. The formulæ which have been adopted may not prove to be the best, but it is believed that they will render great assistance to those who desire to identify fruits; and that, at least, they may lead to a more perfect classification in the future.

On the contrary, with these simple formulæ, under which the fruits are arranged, the student has only to decide as to which of the sub-divisions his specimen must be referred, and then seek among a limited number for the description that shall correspond to his fruit, and the identification is made out.

In the systematic descriptions of fruits, the alphabetical succession of the names is used in each sub-division. An earnest endeavor has been made to be minute in the details without becoming prolix. A regular order is adopted for considering the several parts, and some new or unusual characters are brought into requisition to aid in the identification. Some of these characters appear to have been strangely overlooked by previous pomologists, though they are believed to be permanent and of considerable value in the diagnosis.

In deciding upon the selection of the names of fruits, the generally received rules of our Pomological Societies have been departed from in a few instances, where good reasons were thought to justify differing from the authorities. Thus, when a given name has been generally adopted over a large extent of country, though different from that used [vi]by a previous writer, it has been selected as the title of the fruit in this work.

To avoid incumbering the pages, authorities for the nomenclature have not been cited, except in a few instances, nor have numerous synonyms been introduced. Such only as are in common use have been given, and those of foreign origin have been dropped.

The attention of the reader is particularly directed to the catalogue of fruits near the close of the volume, which also answers as the index to those which are described in detail. This portion of the work has cost an immense amount of labor and time, and, though making little display, will, it is hoped, prove very useful to the orchardist. In it the names of fruits are presented in their alphabetical order, followed by information as to the average size, the origin of the variety, its classification, from which are deduced its shape, flavor and modes of coloring; next is noted its season, and then its quality. This last character is, of course, but the result of private judgment, and the estimate may differ widely from that of others; the quality, too, it should be remembered, is here intended to be the result of a consideration of many properties besides that of mere flavor.

This catalogue will furnish a great deal of information respecting the fruits it embraces. Unfortunately, it is not so full nor so complete as it should be, but it is offered as the result of many years' observations, and is submitted for what it is worth.

Acknowledgments.—It is but an act of common justice for an author to acknowledge his indebtedness to those who have aided him in his labors, especially where, from [vii]the nature of the investigations, so much material has to be drawn from extrinsic sources. Upon the present occasion, instead of an extended parade of references to the productions of other writers, which might be looked upon as rather pedantic, it is preferred to make a general acknowledgment of the important assistance derived from many pomological authors of our own country and of Europe. Quotations are credited on the pages where they occur.

But the writer is also under great obligations to a host of co-laborers for the assistance they have kindly rendered him in the collecting, and in the examination and identification of fruits. Such friends he has happily found wherever he has turned in the pursuit of these investigations, and there are others whom it has never been his good fortune to meet face to face. To name them all would be impossible. The contemplation of their favors sadly recalls memories of the departed, but it also revives pleasant associations of the bright spirits that are still usefully engaged in the numerous pomological and horticultural associations of our country, which have become important agencies in the diffusion of valuable information in this branch of study.

To all of his kind friends the author returns his sincere thanks.

With a feeling of hesitation in coming before the public, but satisfied that he has made a contribution to the fund of human knowledge, this volume is presented to the Horticulturists of our country, for whom it was prepared by their friend and fellow-laborer,

JNO. A. WARDER.

Aston, January 1, 1867.

| INTRODUCTION. | 9 |

| CHAPTER II. | 26 |

| HISTORY OF THE APPLE. | |

| CHAPTER III. | 52 |

| PROPAGATION. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | 144 |

| DWARFING. | |

| CHAPTER V. | 160 |

| DISEASES. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | 198 |

| THE SITE FOR AN ORCHARD. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | 213 |

| PREPARATION OF THE SOIL FOR AN ORCHARD. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 229 |

| SELECTION AND PLANTING. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | 242 |

| CULTURE, ETC. | |

| CHAPTER X. | 251 |

| PHILOSOPHY OF PRUNING. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | 263 |

| THINNING. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | 275 |

| RIPENING AND PRESERVING FRUITS. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | 294 |

| INSECTS. | |

| CHAPTER XV. | 350 |

| CHARACTERS OF FRUITS AND THEIR VALUE. TERMS USED. |

|

| CHAPTER XVI. | 366 |

| CLASSIFICATION. | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | 698 |

| FRUIT LISTS. | |

| CATALOGUE AND INDEX OF APPLES. | 711 |

| INDEX | 738 |

IMPORTANCE OF ORCHARD PRODUCTS—GOVERNMENT STATISTICS—GREAT VALUE OF ORCHARD AND GARDEN PRODUCTS—DELIGHTS OF FRUIT CULTURE—TEMPERATE REGIONS THE PROPER FIELD FOR FRUIT CULTURE, AS FOR MENTAL DEVELOPMENT—PLANTS OF CULTURE, PLANTS OF NATURE—NOMADIC CONDITION UNFAVORABLE FOR TERRA-CULTURE—NECESSITIES OF AN INCREASING POPULATION A SPUR—HIGH CIVILIZATION DEMANDS HIGH CULTURE—HORTICULTURE A FINE ART, THE POETRY OF THE FARMER'S LIFE—MORAL INFLUENCES OF FRUIT-CULTURE—SINGULAR LEGISLATION RESPECTING PROPERTY IN FRUIT—INFLUENCE UPON HEALTH—APPLES IN BREAD-MAKING; AS FOOD FOR STOCK—SOURCES AND ROUTES OF INTRODUCTION—AGENCY OF NURSERYMEN—INDIAN ORCHARDS—FRENCH SETTLERS—JOHNNY APPLE-SEED—VARIETIES OF FRUITS, LIKE MAN, FOLLOW PARALLELS OF LATITUDE—LOCAL VARIETIES OF MERIT TO BE CHERISHED—OHIO PURCHASE—SILAS WHARTON—THE PUTNAM LIST.

Few persons have any idea of the great value and importance of the products of our orchards and fruit-gardens. These are generally considered the small things of agriculture, and are overlooked by all but the statist, whose business it is to deal with these minutiæ, to hunt them up, to collocate them, and when he combines these various details and produces the sum total, we are all astonished at the result.

[10]Our government wisely provides for the gathering of statistics at intervals of ten years, and some of the States also take an account of stock and production at intermediate periods, some of them, like Ohio, have a permanent statistician who reports annually to the Governor of the State.

Our Boards of Trade publish the amounts of the leading articles that arrive at and depart from the principal cities, and thus they furnish us much additional information of value. Besides this, the county assessors are sometimes directed to collect statistics upon certain points of interest, and now that we all contribute toward the extinction of the national debt, the United States Assessors in the several districts are put in possession of data, which should be very correct, in regard to certain productions that are specified by act of Congress as liable to taxation. By these several means we may have an opportunity of learning from time to time what are the productions of the country, and their aggregate amounts are surprising to most of us. When they relate to our special interests, they are often very encouraging. This is particularly the case with those persons who have yielded to the popular prejudice that cotton was the main agricultural production of the United States; to such it will be satisfactory to learn that the crop of corn, as reported in the last census, is of nearly equal value, at the usual market prices of each article. Fruit-growers will be encouraged to find that the value of orchard products, according to the same returns, was nearly twenty millions, that of Ohio being nearly one million; of New York, nearly three and three-quarters millions; that the wine crop of the United States, an [11]interest that is still in its infancy, amounted to nearly three and one-quarter millions; and that the valuation of market garden products sums up to more than sixteen millions of dollars' worth. It is to be regretted that for our present purpose, the data are not sufficiently distinct to enable us to ascertain the relative value of the productions of our orchards of apples, pears, peaches, quinces, and the amount and value of the small fruits, as they are termed, since these are variously grouped in the returns of the census takers, and cannot now be separated. Of their great value, however, we may draw our conclusions from separate records that have been kept and reported by individuals, who assert the products of vineyards in some cases to have been as high as three thousand dollars per acre; of strawberries, at one thousand dollars; of pears, at one hundred dollars per tree, which would be four thousand dollars per acre; of apples, at twenty-five bushels per tree, or one thousand bushels per acre, which, at fifty cents per bushel, would produce five hundred dollars.

But, leaving this matter of dollars and cents, who will portray for us the delights incident to fruit-culture? They are of a quiet nature, though solid and enduring. They carry us back to the early days of the history of our race, when "the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden ... and out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food ... and the Lord God took the man and put him into the garden of Eden, to dress it and to keep it." We are left to infer that this dressing and keeping of the garden was but a light and pleasant occupation, unattended with toil and trouble, and that in their natural condition [12]the trees and plants, unaided by culture, yielded food for man. Those were paradisean times, the days of early innocence, when man, created in the image of his Maker, was still obedient to the divine commands; but, after the great transgression, everything was altered, the very ground was cursed, "thorns and thistles shall it bring forth to thee, and thou shalt eat of the herb of the field. In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread."——From that day to the present hour it has been the lot of man to struggle with difficulties in the cultivation of the soil, and he has been driven to the necessity of constant watchfulness and care to preserve and to improve the various fruits of the earth upon which he subsists. In the tropics, it is true, there are many vegetable productions which are adapted for human food, even in a state of nature, and there we find less necessity for the effort of ingenuity and the application of thought and labor to produce a subsistence. Amid these productive plants of nature, the natives of such regions lead an idle life, and seldom rise above a low scale of advancement; but in the temperate regions of the globe, where the unceasing effort of the inhabitants is required to procure their daily food, we find the greatest development of human energies and ingenuity—there man thinks, and works; there, indeed, he is forced to improve the natural productions of the earth—and there we shall find him progressing. As with everything else, so it is with fruits, some of which were naturally indifferent or even inedible, until subjected to the meliorating influences of high culture, of selection, and of improvement. Here we find our plants of culture, which so well repay the labor and skill bestowed upon them.

[13]In the early periods of the history of our race, while men were nomadic and wandered from place to place, little attention was paid to any department of agricultural improvement, and still less care was bestowed upon horticulture. Indeed, it can scarcely be supposed that, under such conditions, either branch of the art could have existed, any more than they are now found among the wandering hordes of Tartars on the steppes of Asia. So soon, however, as men began to take possession of the soil by a more permanent tenure, agriculture and horticulture also, attracted their chief attention, and were soon developed into arts of life. With advancing civilization, this has been successively more and more the case; the producing art being obliged to keep pace with the increased number of consumers, greater ingenuity was required and was applied to the production of food for the teeming millions of human beings that covered the earth, and, as we find, in China, at the present time, the greatest pains were taken to make the earth yield her increase.

High civilization demands high culture of the soil, and agriculture becomes an honored pursuit, with every department of art and science coming to its assistance. At the same time, and impelled by the same necessities, supported and aided by the same co-adjutors, horticulture also advances in a similar ratio, and, from its very nature, assumes the rank of a fine art, being less essential than pure agriculture, and in some of its branches being rather an ornamental than simply a useful art. It is not admitted, however, that any department of horticulture is to be considered useless, and many of its applications are eminently practical, and result in the production of vast [14]quantities of human food of the most valuable kind. This pursuit always marks the advancement of a community.—As our western pioneers progress in their improvements from the primitive log cabins to the more elegant and substantial dwelling houses, we ever find the garden and the orchard, the vine-arbor and the berry-patch taking their places beside the other evidences of progress. These constitute to them the poetry of common life, of the farmer's life.

The culture of fruits, and gardens also, contributes in no small degree to the improvement of a people by the excellent moral influence it exercises upon them. Everything that makes home attractive must contribute to this desirable end. Beyond the sacred confines of the happy hearthstone, with its dear familiar circle, there can be no more pleasant associations than those of the garden, where, in our tender years, we have aided loved parents, from them taking the first lessons in plant-culture, gathering the luscious fruits of their planting or of our own; nor of the rustic arbor, in whose refreshing shade we have reclined to rest and meditate amid its sheltering canopy of verdure, and where we have gathered the purple berries of the noble vine at a later period of the rolling year; nor of the orchard, with its bounteous supplies of golden and ruddy apples, blushing peaches, and melting pears. With such attractions about our homes, with such ties to be sundered, it is wonderful, and scarcely credible, that youth should ever be induced to wander from them, and to stray into paths of evil. Such happy influences must have a good moral effect upon the young. If it be argued that such luxuries will tend to degrade our morals by making [15]us effeminate and sybaritic, or that such enjoyments may become causes of envy and consequent crime on the part of those who are less highly favored, it may be safely asserted that there is no better cure for fruit-stealing, than to give presents of fruit, and especially of fruit-trees, to your neighbors, particularly to the boys—encourage each to plant and to cherish his own tree, and he will soon learn the meaning of meum and tuum, and will appreciate the beauties of the moral code, which he will be all the more likely to respect in every other particular.

Some of the legislation of our country is a very curious relic of barbarism. According to common law, that which is attached to the soil, may be removed without a breach of propriety, by one who is not an owner of the fee simple; thus, such removal of a vegetable product does not constitute theft or larceny, but simply amounts to a trespass: whereas the taking of fruit from the ground beneath the tree, even though it be defective or decaying, is considered a theft. An unwelcome intruder, or an unbidden guest, may enter our orchard, garden, or vineyard, and help himself at his pleasure to any of our fruits, which we have been most carefully watching and nursing tor months upon trees, for the fruitage of which we may have been laboring and waiting for years, and, forsooth, our only recourse is to sue him at the law, and our only satisfaction, after all the attendant annoyance and expense, is a paltry fine for trespass upon our freehold, which, of course, is not commensurate with our estimate of the value of the articles taken: fruits often possess, in the eyes of the devoted orchardist, a real value much beyond their market price.

[16]Were I asked to describe the location of the fabled fountain of Hygeia, I should decide that it was certainly situated in an orchard; it must have come bubbling from earth that sustained the roots of tree and vine; it must have been shaded by the umbrageous branches of the wide-spreading apple and pear, and it was doubtless approached by alleys that were lined by peach trees laden with their downy fruit, and over-arched by vines bearing rich clusters of the luscious grape, and they were garnished at their sides by the crimson strawberry. Such at least would have been an appropriate setting for so valued a jewel as the fountain of health, and it is certain that the pursuit of fruit-growing is itself conducive to the possession of that priceless blessing. The physical as well as the moral qualities of our nature are wonderfully promoted by these cares. The vigorous exercise they afford us in the open air, the pleasant excitement, the expectation of the results of the first fruits of our plants, tending, training and cultivating them the while, are all so many elements conducive to the highest enjoyment of full health.

The very character of the food furnished by our orchards should be taken into the account, in making up our estimate of their contributions to the health of a community. From them we procure aliment of the most refined character, and it has been urged that the elements of which they are composed are perfected or refined to the highest degree of organization that is possible to occur in vegetable tissues. Such pabulum is not only gratefully refreshing, but it is satisfying—without being gross, it is nutritious. The antiscorbutic effects of ripe fruits, [17]especially those that are acid, are proverbial, and every fever patient has appreciated the relief derived from those that are acidulous. Then as a preventive of the febrile affections peculiar to a miasmatic region, the free use of acid fruits, or even of good sound vinegar made from grapes or apples, is an established fact in medical practice—of which, by the by, prevention is always the better part.

Apples were esteemed an important and valuable article of food in the days of the Romans, for all school boys have read in the ore rotundo of his own flowing measures, what Virgil has said, so much better than his tame translator:

But in more modern times, beside their wonted use as dessert fruit, or evening feast, or cooked in various modes, a French economist "has invented and practiced with great success a method of making bread with common apples, which is said to be very far superior to potato-bread. After having boiled one-third part of peeled apples, he bruised them while quite warm into two-thirds parts of flour, including the proper quantity of yeast, and kneaded the whole without water, the juice of the fruit being quite sufficient; he put the mass into a vessel in which he allowed it to rise for about twelve hours. By this process he obtained a very excellent bread, full of eyes, and extremely light and palatable."[1]

Nor is this class of food desirable for man alone. Fruits of all kinds, but particularly what may be called [18]the large fruits, such as are grown in our orchards, may be profitably cultivated for feeding our domestic animals. Sweet apples have been especially recommended for fattening swine, and when fed to cows they increase the flow of milk, or produce fat according to the condition of these animals. Think of the luxury of eating apple-fed pork! Why, even the strict Rabbi might overcome his prejudices against such swine flesh! And then dream of enjoying the luxury of fresh rich milk, yellow cream, and golden butter, from your winter dairy, instead of the sky-blue fluid, and the pallid, or an anotto-tinted, but insipid butter, resulting from the meager supplies of nutriment contained in dry hay and fibrous, woody cornstalks. Now this is not unreasonable nor ridiculous. Orchards have been planted with a succession of sweet apples that will sustain swine in a state of most perfect health, growing and fattening simultaneously from June to November; and the later varieties may be cheaply preserved for feeding stock of all kinds during the winter, when they will be best prepared by steaming, and may be fed with the greatest advantage. Our farmers do not appreciate the benefits of having green food for their animals during the winter season. Being blessed with that royal grain, the Indian corn, they do not realize the importance of the provision of roots which is so great a feature in British husbandry; but they have yet to learn, and they will learn, that for us, and under our conditions of labor and climate, they can do still better, and produce still greater results with a combination of hay or straw, corn meal and apples, all properly prepared by means of steam or hot water. Besides, such orchards may be advantageously planted in [19]many places where the soil is not adapted to the production of grain.—The reader is referred to the chapter on select lists in another part of this volume, in which an attempt will be made to present the reader with the opinions of the best pomologists of various parts of the country.

It were an interesting and not unprofitable study to trace the various sources and routes by which fruits have been introduced into different parts of our extended country. In some cases we should find that we were indebted for these luxuries to the efforts of very humble individuals, while in other regions the high character of the orchards is owing to the forethought, knowledge, enterprise, and liberality of some prominent citizen of the infant community, who has freely spent his means and bestowed his cares in providing for others as well as for his own necessities or pleasures. But it is to the intelligent nurserymen of our country that we are especially indebted for the universal diffusion of fruits, and for the selection of the best varieties in each different section. While acting separately, these men were laboring under great disadvantages, and frequently cultivated certain varieties under a diversity of names, as they had received them from various sources. This was a difficulty incident to their isolation, but the organization of Pomological Societies in various parts of the country, has enabled them in a great measure to unravel the confusion of an extended synonymy, and also by comparison and consultation with the most intelligent fruit-growers, they have been prepared to advise the planter as to the best and most profitable varieties to be set out in different soils and situations.

Most of our first orchards were planted with imported [20]trees. The colonists brought plants and seeds. Even now, in many parts of the country, we hear many good fruits designated as English, to indicate that they are considered superior to the native; and we are still importing choice varieties from Europe and other quarters of the globe.

The roving tribes of Indians who inhabited this country when discovered and settled by the whites, had no orchards—they lived by the chase, and only gathered such fruits as were native to the soil. Among the earliest attempts to civilize them, however, those that exerted the greatest influence, were efforts to make them an agricultural people, and of these the planting of fruit-trees was one of the most successful. In many parts of the country we find relics of these old Indian orchards still remaining, and it is probable that from the apple seeds sent by the general government for distribution among the Cherokees in Georgia, we are now reaping some of the most valuable fruits of this species. The early French settlers were famous tree-planters, and we find their traces across the continent, from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico. These consist in noble pear and apple trees, grown from seeds planted by them, at their early and scattered posts or settlements. These were made far in advance of the pioneers, who have, at a later period, formed the van of civilization, that soon spread into a solid phalanx in its march throughout the great interior valley of the continent.

On the borders of civilization we sometimes meet with a singular being, more savage than polished, and yet useful in his way. Such an one in the early settlement of the northwestern territory was Johnny Apple-seed—a [21]simple-hearted being, who loved to roam through the forests in advance of his fellows, consorting, now with the red man, now with the white, a sort of connecting link—by his white brethren he was, no doubt, considered rather a vagabond, for we do not learn that he had the industry to open farms in the wilderness, the energy to be a great hunter, nor the knowledge and devotion to have made him a useful missionary among the red men. But Johnny had his use in the world. It was his universal custom, when among the whites, to save the seeds of all the best apples he met with. These he carefully preserved and carried with him, and when far away from his white friends, he would select an open spot of ground, prepare the soil, and plant these seeds, upon the principle of the old Spanish custom, that he owed so much to posterity, so that some day, the future traveler or inhabitant of those fertile valleys, might enjoy the fruits of his early efforts. Such was Johnny Apple-seed—did he not erect for himself monuments more worthy, if not more enduring, than piles of marble or statues of brass?

In tracing the progress of fruits through different portions of our country, we should very naturally expect to find the law that governs the movements of men, applying with equal force to the fruits they carry with them. The former have been observed to migrate very nearly on parallels of latitude, so have, in a great degree, the latter; and whenever we find a departure from this order, we may expect to discover a change, and sometimes a deterioration in the characters of the fruits thus removed to a new locality. It is true, much of this alteration, whether improvement or otherwise, may be owing to the difference of [22]soil. Western New York received her early fruits from Connecticut, and Massachusetts; Michigan, Northern Illinois, and later, Wisconsin and Iowa received theirs in a great degree from New York. Ohio and Indiana received their fruits mainly from New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, and we may yet trace this in the prevalence of certain leading varieties that are scarcely known, and very little grown on different parallels. The early settlement at the mouth of the Muskingum river, was made by New England-men, and into the "Ohio-purchase," they introduced the leading varieties of the apples of Massachusetts. Among these, the Boston or Roxbury Russet was a prominent favorite, but it was so changed in its appearance as scarcely to be recognized by its old admirers, and it was christened with a new name, the Putnam Russet, under the impression that it was a different variety. Most of the original Putnam varieties have disappeared from the orchards. Kentucky received her fruits in great measure from Virginia; Tennessee from the same source and from North Carolina, and these younger States sent them forward on the great western march with their hardy sons to southern Indiana, southern Illinois, to Missouri, and to Arkansas, in all which regions we find evident traces in the orchards, of the origin of the people who planted them.

Of course, we shall find many deflections from the precise parallel of latitude, some inclining to the south, and many turning to the northward. To the latter we of the West are looking with the greatest interest, since we so often find that the northern fruits do not maintain their high characters in their southern or southwestern migrations, and all winter kinds are apt to become autumnal in [23]their period of ripening, which makes them less valuable; and because, among those from a southern origin, we have discovered many of high merit as to beauty, flavor, and productiveness—and, especially where they are able to mature sufficiently, they prove to be long keepers, thus supplying a want which was not filled by fruits of a northern origin. There may be limits beyond which we cannot transport some sorts to advantage in either direction, but this too will depend very much upon the adaptability of our soils to particular varieties.

In every region where fruit has been cultivated we find local varieties grown from seed, many of these are of sufficient merit to warrant their propagation, and it behooves us to be constantly on the look out for them; for though our lists are already sufficiently large to puzzle the young orchardist in making his selections, we may well reduce the number by weeding out more of the indifferent fruit, at the same time that we are introducing those of a superior character. It has been estimated that there may be as many as one in ten of our seedling orchard trees that would be ranked as "good," but not one in a hundred that could be styled "best."[2] Certain individuals have devoted themselves to the troublesome though thankless office of collecting these scattered varieties of decided merit, and from their collections our pomological societies will, from time to time, select and recommend the best for more extended cultivation. Such devoted men as H.N. Gillett, Lewis Jones, Reuben Ragan, A.H. Ernst, who have been industriously engaged in this good work for a quarter of a century, are entitled to the highest [24]commendation; but there are many others who have contributed their full share of benefits by their labors in the same field, to whom also we owe a debt of gratitude. Two of the chief foci in the Ohio valley from which valuable fruits have been distributed most largely, were the settlement at the mouth of the Muskingum, with its Putnam list given below; and a later, but very important introduction of choice fruits, brought into the Miami country by Silas Wharton, a nurseryman from Pennsylvania, who settled among a large body of the religious Society of Friends, in Warren Co., Ohio. The impress of this importation is very manifest in all the country, within a radius of one hundred miles, and some of his fruits are found doing well in the northwestern part of the State of Ohio, in northern Indiana, and in an extended region westward.

There are, no doubt, many other local foci, whence good fruits have radiated to bless regions more or less extensive, and in every neighborhood we find the name of some early pomologist attached to the good fruits that he had introduced, thus adding another synonym to the numerous list of those belonging to so many of our good varieties.

A.W. Putnam commenced an apple nursery in 1794, a few years after the first white settlement at Marietta, Ohio, the first grafts were set in the spring of 1796; they were obtained from Connecticut by Israel Putnam, and were the first set in the State, and grafted by W. Rufus Putnam. Most of the early orchards of the region were planted from this nursery. These grafts were taken from the [25]orchard of Israel Putnam (of wolf-killing memory) in Pomfret, Connecticut. In the Ohio Cultivator for August 1st, 1846, may be found the following authentic list of the varieties propagated:—

"1. Putnam Russet, (Roxbury.)

2. Seek-no-further, (Westfield.)

3. Early Chandler.

4. Gilliflower.

5. Pound Royal, (Lowell).

6. Natural, (a seedling).

7. Rhode Island Greening.

8. Yellow Greening.

9. Golden Pippin.

10. Long Island Pippin.

11. Tallman Sweeting.

12. Striped Sweeting.

13. Honey Greening.

14. Kent Pippin.

15. Cooper.

16. Striped Gilliflower.

17. Black, do.

18. Prolific Beauty.

19. Queening, (Summer Queen?)

20. English Pearmain.

21. Green Pippin.

22. Spitzenberg, (Esopus?)

Many of these have disappeared from the orchards and from the nurserymen's catalogues."

[1] Companion for the Orchard.—Phillips.

[2] Elliott—Western Fruits.

DIFFICULTIES IN THE OUTSET—APPLE A GENERIC TERM, AS CORN IS FOR DIFFERENT GRAINS; BIBLE AND HISTORIC USE OF THE WORD THEREFORE UNCERTAIN—ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD—BOTANICAL CHARACTERS—IMPROVABILITY OF THE APPLE—NATIVE COUNTRY—CRUDE NOTIONS OF EARLY VARIETIES—PLINY'S ACCOUNT EXPLAINED—CHARLATAN GRAFTING—INTRODUCTION INTO BRITAIN—ORIGINAL SORTS THERE—GERARD'S LIST OF SEVEN—HE URGES ORCHARD PLANTING—RECIPE FOR POMATUM—DERIVATION OF THE WORD—VIRGIL'S ADVICE AS TO GRAFTING—PLINY'S EULOGY OF THE APPLE: WILL OURS SURVIVE AS LONG?—PLINY'S LIST OF 29—ACCIDENTAL ORIGIN OF OUR FRUITS—CROSSING—LORD BACON'S GUESS—BRADLEY'S ACCOUNT—SUCCESS IN THE NETHERLANDS—MR. KNIGHT'S EXPERIMENTS—HYBRIDS INFERTILE—LIMITS, NONE NATURAL—LIMITS OF SPECIES—HERBERT'S VIEWS—DIFFICULTIES ATTEND CROSSING ALSO—NO MULES—KIRTLAND'S EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS OF—VAN MONS' THEORY—ILLINOIS RESULTS—RUNNING OUT OF VARIETIES.

In attempting to trace out the history of any plant that has long been subjected to the dominion of man, we are beset with difficulties growing out of the uncertainty of language, and arising also from the absence of precise terms of science in the descriptions or allusions which we meet [27]respecting them. As he who would investigate the history of our great national grain crop, the noble Indian maize, which, in our language, claims the generic term corn, will at once meet with terms apt to mislead him in the English translation of the Bible, and in the writings of Europeans, who use the word corn in a generic sense, as applying to all the edible grains, and especially to wheat—so in this investigation we may easily be misled by meeting the word apple in the Bible and in the translations of Latin and Greek authors, and we may be permitted to question whether the original words translated apple may not have been applied to quite different fruits, or perhaps we may ask whether our word may not originally have had a more general sense, meaning as it does, according to its derivation, any round body.

The etymology of the word apple is referred by the lexicographers to abhall, Celtic; avall, Welsh; afall or avall, Armoric; aval or avel, Cornish; and these are all traceable to the Celtic word ball, meaning simply a round body.

Worcester traces the origin of apple directly to the German apfel, which he derives from æpl, apel, or appel.

Webster cites the Saxon appl or appel; Dutch, appel; German, apfel; Danish, æble; Swedish, aple; Welsh, aval; Irish, abhal or ubhal; Armoric, aval; Russian, yabloko.

Its meaning being fruit in general, with a round form. Thus the Persian word ubhul means Juniper berries, and in Welsh the word used means other fruits, and needs a qualifying term to specify the variety or kind.

[28]Hogg, in his British Pomology, quoting Owen, says, the ancient Glastonbury was called by the Britons Ynys avallac or avallon, meaning an apple orchard, and from this came the Roman word avallonia, from this he infers that the apple was known to the Britons before the advent of the Romans. We are told, that in 973, King Edgar, when fatigued with the labors of the chase, laid himself down under a wild apple tree, so that it becomes a question whether this plant was not a native of England as of other parts of Europe, where in many places it is found growing wild and apparently indigenous. Thornton informs us in his history of Turkey, that apples are common in Wallachia, and he cites among the varieties one, the domniasca, "which is perhaps the finest in Europe, both for its size, color, and flavor." It were hard to say what variety this is, and whether it be known to us.

The introduction of this word apple in the Bible is attributable to the translators, and some commentators suggest that they have used it in its general sense, and that in the following passages where it occurs, it refers to the citron, orange, or some other subtropical fruit.

"Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples."—Songs of Solomon ii, 5.

"As the apple-tree (citron) among the trees of the wood, * * * I sat me down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste."—Sol. ii, 2.

* * * "I raised thee up under the apple-tree."—Solomon viii, 5.

"A word fitly spoken, is like apples of gold in pictures of silver."—Prov. xxv, 11.

[29]The botanical position of the cultivated apple may be stated as follows:—Order, Rosaceæ; sub-order, Pomeæ; or the apple family and genus, Pyrus. The species under our consideration is the Pyrus Malus, or apple. It has been introduced into this country from Europe, and is now found in a half-wild state, springing up in old fields, hedge-rows, and roadsides; but, even in such situations, by their eatable fruit and broad foliage, and by the absence of spiny or thorny twigs, the trees generally give evidence of a civilized origin. It is not that the plant has changed any of its true specific characters, but that it has been affected by the meliorating influences of culture, which it has not been able entirely to shake off in its neglected condition. Sometimes, indeed, trees are found in these neglected and out-of-the-way situations, which produce fruits of superior quality—and the sorts have been gladly introduced into our nurseries and orchards.

Very early in the history of horticulture the apple attracted attention by its improvability, showing that it belonged to the class of culture-plants. Indeed it is a very remarkable fact in the study of botany, and the pivot upon which the science and art of horticulture turns, that while there are plants which show no tendency to change from their normal type, even when brought under the highest culture, and subjected to every treatment which human ingenuity can suggest, there are others which are prone to variations or sports, even in their natural condition, but more so when they are carefully nursed by the prudent farmer or gardener. These may be called respectively the plants of nature and the plants of culture. Some of the former furnish human food, and are otherwise useful to [30]man; but the latter class embraces by far the larger number of food-plants, and we are indebted to this pliancy, aided by human skill, for our varieties of fruits, our esculent vegetables, and the floral ornaments of our gardens.

The native country of the apple, though not definitively settled, is generally conceded to be Europe, particularly its southern portions, and perhaps Western Asia: that is, the plant known and designated by botanists as Pyrus Malus, for there are other and distinct species in America and Asia which have no claims to having been the source of our favorite orchard fruits. Our own native crab is the Pyrus coronaria, which, though showing some slight tendency to variation, has never departed from the strongly marked normal type. The P. baccata, or Siberian crab, is so distinctly marked as to be admitted as a species. It has wonderfully improved under culture, and has produced some quite distinct varieties; it has even been hybridized by Mr. Knight, with the cultivated sorts of the common Wilding or Crab of Europe, the P. Malus. Pallas, who found it wild near Lake Baikal and in Daouria, says, it grows only 3 or 4 feet high, with a trunk of as many inches diameter, and yields pear-shaped berries as large as peas.

The P. rivularis, according to Nuttall, is common in the maritime portions of Oregon, in alluvial forests. The tree attains a height of 15 to 25 feet. It resembles the Siberian Crab, to which it has a close affinity. The fruit grows in clusters, is purple, scarcely the size of a cherry, and of an agreeable flavor; sweetish and sub-acid when ripe, not at all acid and acerb as the P. coronaria.[3]

[31]Among the early writers upon the subject of pomology, we find some very crude notions, particularly in regard to the wonderful powers of the grafter, for this art of improving the Wilding by inserting buds or scions of better sorts, and thus multiplying trees of good kinds, was a very ancient invention. Pliny, the naturalist, certainly deserves our praise for his wonderful and comprehensive industry in all branches of natural history. In regard to grafting, which seems to have been well understood in his day, he says, that he had seen near Thuliæ a tree bearing all manner of fruits, nuts and berries, figs and grapes, pears and pomegranates; no kind of apple or other fruit that was not to be found on this tree. It is quaintly noted, however, that "this tree did not live long,"—is it to be wondered that such should have been the case? Now some persons may object to the testimony of this remarkable man, and feel disposed to discredit the statement of what appears so incredible to those who are at all acquainted with the well-known necessity for a congenial stock into which the graft should be inserted. But a more extended knowledge of the subject, would explain what Pliny has recorded as a marvel of the art. The same thing has been done in our own times, it is a trick, and one which would very soon be detected now-a-days by the merest tyro in horticulture, though it may have escaped the scrutiny of Pliny, whose business it was to note and record the results of his observations, rather than to examine the modus of the experiment. By the French, the method is called Charlatan grafting, and is done by taking a stock of suitable size, hollowing it out, and introducing through its cavity several stocks of [32]different kinds, upon each of which may be produced a different sort of fruit, as reported by Pliny. The needed affinity of the scion and stock, and the possible range that may be successfully taken in this mode of propagation, with the whole consideration of the influence of the stock upon the graft, will be more fully discussed in another chapter.

Though it be claimed and even admitted that the wild apple or crab was originally a native of Britain, and though it be well known that many varieties have originated from seed in that country, still it appears from their own historians that the people introduced valuable varieties from abroad. Thus we find in Fuller's account, that in the 16th year of the reign of Henry VIII, Pippins were introduced into England by Lord Maschal, who planted them at Plumstead, in Sussex.

After this, the celebrated Golden Pippin was originated at Perham Park, in Sussex, and this variety has attained a high meed of praise in that country and in Europe, though it has never been considered so fine in this country as some of our own seedlings. Evelyn says, in 1685, at Lord Clarendon's seat, at Swallowfield, Berks, there is an orchard of one thousand golden and other cider Pippins.[4] The Ribston Pippin, which every Englishman will tell you is the best apple in the world, was a native of Ribston Park, Yorkshire. Hargrave says: "This place is remarkable for the produce of a delicious apple, called the Ribston Park Pippin." The original tree was raised from a Pippin brought from France.[5] This apple is well-known in this country, but not a favorite.

[33]At a later period, 1597, John Gerard issued in an extensive folio his History of Plants, in which he mentions seven kinds of Pippins. The following is given as a sample of the pomology of that day:—

"The fruit of apples do differ in greatnesse, forme, colour, and taste, some covered with red skin, others yellow or greene, varying infinitely according to soil and climate; some very greate, some very little, and many of middle sort; some are sweet of taste, or something soure, most be of middle taste between sweet and soure; the which to distinguish, I think it impossible, notwithstanding I heare of one who intendeth to write a peculiar volume of apples and the use of them." He further says: "The tame and grafted apple trees are planted and set in gardens and orchards made for that purpose; they delight to growe in good fertile grounds. Kent doth abounde with apples of most sortes; but I have seen pastures and hedge-rows about the grounds of a worshipful gentleman dwelling two miles from Hereford, so many trees of all sortes, that the seruantes drinke for the moste parte no other drinke but that which is made of apples. * * * Like as there be divers manured apples, so is there sundry wilde apples or crabs, not husbanded, that is, not grafted." He also speaks of the Paradise, which is probably the same we now use as a dwarfing stock.

Dr. Gerard fully appreciated the value of fruits, and thus vehemently urges his countrymen to plant orchards: "Gentlemen, that have land and living, put forward, * * * * * graft, set, plant, and nourish up trees in every corner of your grounds; the labor is small, the cost is nothing, the commoditie is great, yourselves shall have plentie, [34]the poor shall have somewhat in time of want to relieve their necessitie, and God shall reward your good minde and diligence." The same author gives us a peculiar use of the apple which may be interesting to some who never before associated pomatum with the products of the orchard. He recommends apples as a cosmetic. "There is made an ointment with the pulp of apples, and swine's grease and rose water, which is used to beautify the face and to take away the roughness of the skin; it is called in shops pomatum, of the apples whereof it is made."[6] When speaking of the importance of grafting to increase the number of trees of any good variety, Virgil advises to

So high an estimate did Pliny have of this fruit, that he asserted that "there are apples that have ennobled the countries from whence they came, and many apples have immortalized their first founders and inventors. Our best apples will immortalize their first grafters forever; such as took their names from Manlius, Cestius, Matius, and Claudius."—Of the Quince apple, he says, that came of a quince being grafted upon the apple stock, which "smell like the quince, and were called Appiana, after Appius, who was the first that practiced this mode of grafting. Some are so red that they resemble blood, which is caused by their being grafted upon the mulberry stock. Of all the apples, the one which took its name from Petisius, was the most excellent for eating, both on account of its [35]sweetness and its agreeable flavor." Pliny mentions twenty-nine kinds of apples cultivated in Italy, about the commencement of the Christian Era.[7]

Alas! for human vanity and apple glory! Where are now these boasted sorts, upon whose merits the immortality of their inventors and first grafters was to depend? They have disappeared from our lists to give place to new favorites, to some of which, perhaps, we are disposed to award an equally high meed of praise, that will again be ignored in a few fleeting years, when higher skill and more scientific applications of knowledge shall have produced superior fruit to any of those we now prize so highly; and this is a consummation to which we may all look forward with pleasure.

In this country the large majority of our favorite fruits, of whatever species or kind, seem to have originated by accident, that is, they have been discovered in seedling orchards, or even in hedge-rows. These have no doubt, however, been produced by accidental crosses of good kinds, and this may occur through the intervention of insects in any orchard of good fruit, where there may chance to be some varieties that have the tendency to progress. The discoveries of Linnæus, and his doctrine of the sexual characters of plants, created quite a revolution in botany, and no doubt attracted the attention of Lord Bacon, who was a close observer of nature, for he ventured to guess that there might be such a thing as crossing the breeds of plants, when he says:—"The compounding or mixture of kinds in plants is not found out, [36]which, nevertheless, if it be possible, is more at command than that of living creatures; wherefore it were one of the most noteable experiments touching plants to find it out, for so you may have great variety of new fruits and flowers yet unknown. Grafting does it not, that mendeth the fruit or doubleth the flowers, etc., but hath not the power to make a new kind, for the scion ever overruleth the stock." In which last observation he shows more knowledge and a deeper insight into the hidden mysteries of plant-life than many a man in our day, whose special business it is to watch, nurse, and care for these humble forms of existence.

Bradley, about a century later, in 1718, is believed to have been the first author who speaks of the accomplishment of cross-breeding, which he describes as having been effected by bringing together the branches of different trees when in blossom. But the gardeners of Holland and the Netherlands were the first to put it into practice.[8]

The following extract is given to explain the manner in which Mr. Knight conducted his celebrated experiments on fruits, which rewarded him with some varieties that were highly esteemed:—"Many varieties of the apple were collected which had been proved to afford, in mixtures with each other, the finest cider. A tree of each was then obtained by grafting upon a Paradise stock, and these trees were trained to a south wall, or if grafted on Siberian crab, to a west wall, till they afforded blossoms, and the soil in which they were planted was made of the most rich and favorable kind. Each [37]blossom of this species of fruit contains about twenty chives or males (stamens,) and generally five pointals or females (pistils,) which spring from the center of the cup or cavity of the blossom. The males stand in a circle just within the bases of the petals, and are formed of slender threads, each of which terminates in an anther. It is necessary in these experiments that both the fruit and seed should attain as large a size and as much perfection as possible, and therefore a few blossoms only were suffered to remain on each tree. As soon as the blossoms were nearly full-grown, every male in each was carefully extracted, proper care being taken not to injure the pointals; and the blossoms, thus prepared, were closed again, and suffered to remain till they opened spontaneously. The blossoms of the tree which it was proposed to make the male parent of the future variety, were accelerated by being brought into contact with the wall, or retarded by being detached from it, so that they were made to unfold at the required period; and a portion of their pollen, when ready to fall from the mature anthers, was during three or four successive mornings deposited upon the pointals of the blossoms, which consequently afforded seeds. It is necessary in this experiment that one variety of apple only should bear unmutilated blossoms; for, where other varieties are in flower at the same time, the pollen of these will often be conveyed by bees to the prepared blossoms, and the result of the experiment will in consequence be uncertain and unsatisfactory." * * *

In his Pomona Herefordiensis, he says:—"It is necessary to contrive that the two trees from which you intend to raise the new kind, shall blossom at the same time; [38]therefore, if one is an earlier sort than the other, it must be retarded by shading or brought into a cooler situation, and the latest forwarded by a warm wall or a sunny position, so as to procure the desired result."

We must distinguish between hybrids proper and crosses, as it were between races or between what may have been erroneously designated species, for there has been a great deal of looseness in the manner of using these terms by some writers. A true hybrid[9] is produced only when the pollen of one species has been used to fertilize the ovules of another, and as a general rule these can only be produced between plants which are very nearly allied, as between species of the same genus. Even such as these, however, cannot always be hybridized, for we have never found a mule or hybrid between the apple and pear, the currant and gooseberry, nor between the raspberry and blackberry, though each of these, respectively, appear to be very nearly related, and they are all of the order Rosaceæ.

In hybrids there appears to be a mixture of the elements of each, and the characters of the mule or cross will depend upon one or the other, which it will more nearly resemble. True hybrids are mules or infertile, and cannot be continued by seed, but must be propagated by cuttings, or layers, or grafting. If not absolutely sterile at first, they become so in the course of the second or third generation. This is proved by several of our flowering plants that have been wonderfully varied by ingenious crossing of different species. But it has been found [39]that the hybrid may be fertilized by pollen taken from one of its parents, and that then the offspring assumes the characters of that parent.[10]

Natural hybrids do not often occur, though in diœcious plants, this seems to have been the case with willows that present such an intricate puzzle to botanists in their classification, so that it has become almost impossible to say what are the limits and bounds of some of the species. Hybrids are, however, very frequently produced by art, and particularly among our flowering plants, under the hands of ingenious gardeners. Herbert thinks, from his observations, "that the flowers and organs of reproduction partake of the characters of the female parent, while the foliage and habit, or the organs of vegetation, resemble the male."

Simply crossing different members of the same species, like the crossing of races in animal life, is not always easily accomplished; but we here find much less difficulty, and we do not produce a mule progeny. In these experiments the same precautions must be taken to avoid the interference of natural agents in the transportation of pollen from flower to flower; but this process is now so familiar to horticulturists, that it scarcely needs a mention. In our efforts with the strawberry, some very curious results have occurred, and we have learned that some of the recognized species appear under this severe test to be well founded, as the results have been infertile. Where the perfection of the fruit depends upon the development of the seed, this is a very important matter to the fruit-grower; but fortunately this is not always the case, for [40]certain fruits swell and ripen perfectly, though containing not a single well developed seed. It would be an interesting study to trace out those plants which do furnish a well developed fleshy substance or sarcocarp, without the true seeds. Such may be found occasionally in the native persimmon, in certain grapes, and in many apples; but in the strawberry, blackberry, and raspberry, the berry which constitutes our desirable fruit, never swells unless the germs have been impregnated and the seeds perfect. In the stone-fruits the stone or pit is always developed, but the enclosed seed is often imperfect from want of impregnation or other cause—and yet the fleshy covering will sometimes swell and ripen.

One of the most successful experimenters in this country is Doctor J.P. Kirtland, near Cleveland, Ohio, whose efforts at crossing certain favorite cherries, were crowned with the most happy results, and all are familiar with the fruits that have been derived from his crosses. The details of his applying the pollen of one flower to the pistils of another are familiar to all intelligent readers, and have been so often set forth, that they need not be repeated in this case—great care is necessary to secure the desired object, and to guard against interference from causes that would endanger or impair the value of the results.

Van Mons' theory was based upon certain assumptions and observations, some of which are well founded, others are not so firmly established. He claimed correctly that all our best fruits were artificial products, because the essential elements for the preservation of the species in their natural condition, are vigor of the plant and perfect seeds for the perpetuation of the race. It has been the [41]object of culture to diminish the extreme vigor of the tree so as to produce early fruitage, and at the same time to enlarge and to refine the pulpy portion of the fruit. He claimed, as a principle, that our plants of culture had always a tendency to run back toward the original or wild type, when they were grown from seeds. This tendency is admitted to exist in many cases, but it is also claimed, that when a break is once made from the normal type, the tendency to improve may be established. Van Mons asserted that the seeds from old trees would be still more apt to run back toward the original type, and that "the older the tree, the nearer will the seedlings raised from it approach the wild state," though he says they will not quite reach it. But the seeds from a young tree, having itself the tendency to melioration, are more likely to produce improved sorts.

He thinks there is a limit to perfection, and that, when this is reached, the next generation will more probably produce bad fruit than those grown from an inferior sort, which is on the upward road of progression. He claims that the seeds of the oldest varieties of good fruit yield inferior kinds, whereas those taken from new varieties of bad fruit, and reproduced for several generations, will certainly give satisfactory results in good fruit.

He began with seeds from a young seedling tree, not grafted upon another stock; he cared nothing for the quality of the fruit, but preferred that the variety was showing a tendency to improvement or variation. These were sowed, and from the plants produced, he selected such as appeared to him to have evidence of improvement, (it is supposed by their less wild appearance), and [42]transplanted them to stations where they could develop themselves. When they fruited, even if indifferent, if they continued to give evidence of variation, the first seeds were saved and planted and treated in the same way. These came earlier into fruit than the first, and showed a greater promise. Successive generations were thus produced to the fourth and fifth, each came into bearing earlier than its predecessor, and produced a greater number of good varieties, and he says that in the fifth generation they were nearly all of great excellence. He found pears required the longest time, five generations; while the apple was perfected in four, and stone fruits in three.

Starting upon the theory that we must subdue the vigor of the wilding to produce the best fruits, he cut off the tap roots when transplanting and shortened the leaders, and crowded the plants in the orchard or fruiting grounds, so as to stand but a few feet apart. He urged the "regenerating in a direct line of descent as rapidly as possible an improving variety, taking care that there be no interval between the generations. To sow, re-sow, to sow again, to sow perpetually, in short to do nothing but sow, is the practice to be pursued, and which cannot be departed from; and, in short, this is the whole secret of the art I have employed." (Arbres Fruitiers.)

Who else would have the needed patience and perseverance to pursue such a course? Very few, indeed—especially if they were not very fully convinced of the correctness of the premises upon which this theory is founded. Mr. Downing thinks that the great numbers of fine varieties of apples that have been produced in this country, go to sustain the Van Mons doctrine, because, as he [43]assumes, the first apples that were produced from seeds brought over by the early emigrants, yielded inferior fruit which had run back toward the wild state, and the people were forced to begin again with them, and that they most naturally pursued this very plan, taking seeds from the improving varieties for the next generations and so on. This may have been so, but it is mere assumption—we have no proof, and, on the contrary, our choice varieties have so generally been conceded to have been chance seedlings, that there appears little evidence to support it—on the contrary, some very fine varieties have been produced by selecting the seeds of good sorts promiscuously, and without regarding the age of the trees from which the fruit was taken. Mr. Downing himself, after telling us that we have much encouragement to experiment upon this plan of perfecting fruits, by taking seeds from such as are not quite ripe, gathered from a seedling of promising quality, from a healthy young tree (quite young,) on its own root, not grafted, and that we "must avoid 1st, the seeds of old trees; 2d, those of grafted trees; 3d, that we must have the best grounds for good results"—still admits what we all know, that "in this country, new varieties of rare excellence are sometimes obtained at once by planting the seeds of old grafted varieties; thus the Lawrence Favorite and the Columbia Plums were raised from seeds of the Green Gage, one of the oldest European varieties."

Let us now look at an absolute experiment conducted avowedly upon the Van Mons plan in our own country, upon the fertile soil of the State of Illinois, and see to what results it led:—

[44]The following facts have been elicited from correspondence with H.P. Brayshaw, of Du Quoin, Illinois. The experiments were instituted by his father many years ago, to test the truth of the Van Mons' theory of the improvement of fruits by using only the first seeds.

Thirty-five years ago, in 1827, his father procured twenty-five seedling trees from a nursery, which may be supposed to have been an average lot, grown from promiscuous seed. These were planted, and when they came into bearing, six of them furnished fruit that might be called "good" and of these, "four were considered fine." One of the six is still in cultivation, and known as the Illinois Greening. Of the remainder of the trees, some of the fruits were fair, and the rest were worthless, and have disappeared.

Second Generation.—The first fruits of these trees were selected, and the seeds were sown. Of the resulting crop, some furnished fruit that was "good," but they do not appear to have merited much attention.

Third Generation.—From first seeds of the above, one hundred trees were produced, some of which were good fruit, and some "even fine," while some were very poor, "four or five only merited attention." So that we see a retrogression from the random seedlings, furnishing twenty-five per cent, of good fruit, to only four or five per cent. in the third generation, that were worthy of note.

Fourth Generation.—A crop of the first seed was again sown, producing a fourth generation; of these many were "good culinary fruits," none, or very few being of the "poorest class of seedlings," none of them, however, were fine enough "for the dessert."

[45]Fifth Generation.—This crop of seedlings was destroyed by the cut-worms, so that only one tree now remains, but has not yet fruited. But Mr. Brayshaw appears to feel hopeful of the results, and promises to continue the experiment.

Crops have also been sown from some of these trees, but a smaller proportion of the seedlings thus produced were good fruits, than when the first seeds were used—this Mr. Brayshaw considers confirmatory evidence of the theory, though he appears to feel confidence in the varieties already in use, most of which had almost an accidental origin.

He thinks the result would have been more successful had the blossoms been protected from impregnation by other trees, and recommends that those to be experimented with should be planted at a distance from orchards, so as to avoid this cross-breeding, and to allow of what is called breeding in-and-in. If this were done, he feels confident that "the seedlings would more nearly resemble the parent, and to a certain extent would manifest the tendency to improvement, and that from the earliest ripened fruits, some earlier varieties would be produced, from those latest ripening, later varieties, from those that were inferior and insipid, poor sorts would spring, and that from the very best and most perfect fruits we might expect one in one thousand, or one-tenth of one per cent., to be better than the parent." This diminishes the chance for improvement to a beautifully fine point upon which to hang our hopes of the result of many generations of seedlings occupying more than a lifetime of experiments.

Mr. Brayshaw, citing some of the generally adopted [46]axioms of breeders of animals, assumes that crosses, as of distinct races, will not be so likely to produce good results, as a system of breeding in-and-in, persistently carried out. This plan he recommends, and alludes to the quince and mulberry as suitable species to operate upon, because in them there are fewer varieties, and therefore less liability to cross-breeding, and a better opportunity for breeding in-and-in. He also reminds us of the happy results which follow the careful selection of the best specimens in garden flowers and vegetables, combined with the rejection of all inferior plants, when we desire to improve the character of our garden products, and he adopts the views of certain physiologists, which, however, are questioned by other authorities, to the effect that violent or decided crosses are always followed by depreciation and deterioration of the offspring.

The whole communication referring to these experiments, which are almost the only ones, so far as I know, which have been conducted in this country to any extent, to verify or controvert the Van Mons' theory, is very interesting, but it is easy to perceive that the experimenter, though apparently very fair, and entirely honest, has been fully imbued with the truth and correctness of the proposition of Van Mons, that the first ripened seed of a natural plant was more likely to produce an improved variety, and that this tendency to improvement would ever increase, and be most prominent in the first ripened seeds of successive generations grown from it.

The theory of Van Mons I shall not attempt in this place to controvert, but will simply say that nothing which has yet come under my observation has had a [47]tendency to make me a convert to the avowed views of that great Belgian Pomologist, while, on the contrary, the rumors of his opponents, that he was really attempting to produce crosses from some of the best fruits, as our gardeners have most successfully done in numerous instances, in the beautiful flowers and delicious vegetables of modern horticulture, have always impressed me with a color of probability, and if he were not actually and intentionally impregnating the blossoms with pollen of the better varieties, natural causes, such as the moving currents of air, and the ever active insects, whose special function in many instances appears to be the conveyance of pollen, would necessarily cause an admixture, which, in a promiscuous and crowded collection, like the "school of Van Mons," would at least have an equal chance of producing an improvement in some of the resulting seeds.

The whole subject of variation in species, the existence of varieties, and also of those partial sports, which may perhaps be considered as still more temporary variations from the originals, than those which come through the seeds, is one of deep interest, well worthy of our study, but concerning which we must confess ourselves as yet quite ignorant, and our best botanists do not agree even as to the specific distinctions that have been set up as characters of some of our familiar plants, for the most eminent differ with regard to the species of some of our common trees and plants.

It has been a very generally received opinion among intelligent fruit-growers, that any given variety of fruit can [48]have but a limited period of existence, be that longer or shorter. Reasoning from the analogies of animal life this would appear very probable, for it is well known that individuals of different species all have a definite period of life, some quite brief, others quite extended, beyond which they do not survive. But with our modern views of vegetation, though we know that all perennial plants do eventually die and molder away to the dust from whence they were created, and that many trees of our own planting come to an untimely end, while we yet survive to observe their decay, still, we can see no reason why a tree or parts of a tree taken from it, and placed under circumstances favorable to its growth from time to time, may not be sempiternal. Harvey has placed this matter in a correct light, by showing that the true life and history of a tree is in the buds, which are annual, while the tree itself is the connecting link between them and the ground. Any portion of such a compound existence, grafted upon another stock, or planted immediately in the ground itself and established upon its own roots, will produce a new tree like the first, being furnished with supplies of nourishment it may grow indefinitely while retaining all the qualities of the parent stock—if that be healthy and vigorous so will this—indeed new life and vigor often seem to be imparted by a congenial thrifty stock, and a fertile soil, so that there does not appear to be any reason why the variety should ever run out and disappear.

The distinguished Thomas Andrew Knight, President of the London Horticultural Society, was one of the leading advocates of the theory that varieties would necessarily run out and disappear as it were by exhaustion.

[49]In his Pomona Herefordiensis, he tells us that "those apples, which have been long in cultivation, are on the decay. The Redstreak and Golden Pippin can no longer be propagated with advantage. The fruit, like the parent tree, is affected by the debilitated old age of the variety." And in his treatise on the culture of the apple and pear, he says: "The Moil and its successful rival, the Redstreak, with the Must and Golden Pippin, are in the last stage of decay, and the Stire and Foxwhelp are hastening rapidly after them." In noticing the decay of apple trees, Pliny probably refers to particular trees, rather than the whole of any variety, when he says that "apples become old sooner than any other tree, and the fruit becomes smaller and is subject to be cankered and worm-eaten, even while on the trees."—Lib. XVI, Chap. 27.

Speechly combated the views of Mr. Knight, and says: "It is much to be regretted that this apparently visionary notion of the extinction of certain kinds of apples should have been promulgated by authors of respectability, since the mistake will, for a time at least, be productive of several ill consequences."

Some of the old English varieties that were supposed to be worn out or exhausted, appear to have taken a new lease of life in this country, but we have not yet had a long enough experience to decide this question. Many of the earlier native favorites of the orchard have, for some reason, disappeared from cultivation—whether they have run out, were originally deficient in vigor, or have merely been superseded by more acceptable varieties, does not appear.

Mr. Phillips, in his Companion, states "that in 1819, he [50]observed a great quantity of the Golden Pippin in Covent Garden Market, which were in perfect condition, and was induced to make inquiries respecting the health of the variety, which resulted in satisfactory replies from all quarters, that the trees were recovering from disease, which he thought had been induced by a succession of unpropitious seasons. He cites Mr. Ronald's opinion, that there was then no fear of losing this variety; and Mr. Lee, who thought that the apparent decay of some trees was owing to unfavorable seasons. Mr. Harrison informed him that this variety was very successfully grown on the mountains of the island of Madeira, at an elevation of 3000 feet, and produced abundantly. Also that the variety was quite satisfactory in many parts of England, and concludes that the Golden Pippin only requires the most genial situation, to render it as prolific is formerly."

It is quite probable, as Phillips suggests, that Mr. Knight had watched the trees during unfavorable seasons which prevailed at that period, and as he found the disease increase, he referred it to the old age of the variety, and based his theory to that effect upon partial data.

Mr. Knight's views, though they have taken a strong hold upon the popular mind, have not been confirmed by physiologists. For though the seed would appear to be the proper source whence to derive our new plants, and certainly our new varieties of fruits, many plants have, for an indefinite period, been propagated by layers, shoots or scions, buds, tubers, etc., and that the variety has thus been extended much beyond the period of the life of the parent or original seedling. Strawberries are propagated and multiplied by the runners, potatoes by tubers, the [51]Tiger Lily by bulblets, some onions by proliferous bulbs, sugarcane by planting pieces of the stalk, many grapes by horizontal stems, and many plants by cuttings, for a very great length of time. The grape vine has been continued in this way from the days of the Romans. A slip taken from a willow in Mr. Knight's garden pronounced by him to be dying from old age, was planted in the Edinburgh Botanic Garden many years ago, and is now a vigorous tree, though the original stock has long since gone to decay.[11]

[3] North American Sylva, Nuttall II, p. 25.

[4] Diary.

[5] History of Knaresborough, p. 216.—Companion of the Orchard, p. 34.

[6] Our lexicographers give it a similar origin, but refer it to the shape in which it was put up. Others derive it from poma, Spanish, a box of perfume.

[7] Phillips' Companion, p. 32.

[8] Phillips' Companion, p. 41.