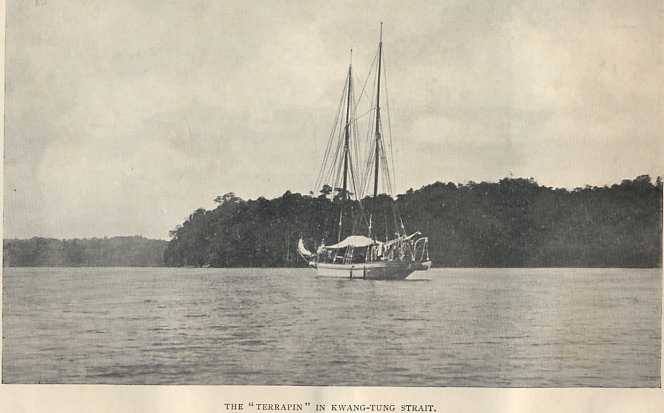

THE "TERRAPIN" IN KWANG-TUNG STRAIT.

THE "TERRAPIN" IN KWANG-TUNG STRAIT.

Title: In the Andamans and Nicobars: The Narrative of a Cruise in the Schooner "Terrapin"

Author: C. Boden Kloss

Release date: June 28, 2011 [eBook #36545]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by StevenGibbs and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| "Where, beneath another sky, |

| Parrot islands anchored lie." |

The following pages are the result of an attempt to record a cruise, in a schooner, to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bengal Sea, the main purpose of which was to obtain good representative collections (now in the National Museum, Washington, U.S.A.) of natural history and ethnological objects from the places visited. Special attention was given to the trapping of small mammals, which, comprising the least known section of the island fauna, were the most interesting subject for investigation. Sixteen new varieties were obtained in the Andamans and Nicobars together, thus raising the known mammalian fauna of those islands from twenty-four to forty individuals, while the collections also included ten hitherto undescribed species of birds. All the collecting and preparation was done by my companion, whose guest I was, and myself, for we were accompanied by no native assistants or hunters. Broadly speaking, one half of the day passed in obtaining specimens, the other in preserving them; and such observations as I have been able to chronicle were, for the greater part, made during the periods of actual collecting and the consequent going to and fro.

In order to give a certain completeness to the account, I have included a more or less general description of the two Archipelagoes, their inhabitants, etc.; the chapters of this nature are partly compiled from the writings of those who had had previous experience of the islands, and for the most part the references have been given.

I cannot but regard the illustrations, which are a selection from my series of photographs, as the most valuable part of this work, but I hope that my written record, in spite of its imper[Pg viii]fections, may stimulate some more competent observer and chronicler than myself to visit the latter islands—for the Andamans have already been described[1] in an admirable monograph by one who dwelt there for many years—before it is too late. Ethnically, much remains to be done, and every day that goes by produces some deterioration of native life and custom. To this end I have added many details about supplies, anchorages, etc., that might otherwise seem superfluous.

Of those who entertained and assisted us during the voyage, thanks are specially due to Mr P. Vaux of Port Blair, for his hospitality to us during our stay in that place;[2] and I am greatly indebted to Messrs O. T. Mason, G. S. Miller, and Dr C. W. Richmond, respectively, for the photographs of the Nicobarese pottery and skirt, for permission to include here much information from the report on the Andaman and Nicobar mammals, and for a list of the new species of birds obtained, which, however, up to the present, have not received specific designations. I have also to gratefully acknowledge the help rendered me by Mr E. H. Man, C.I.E., who, besides volunteering to read through the proof sheets, has given me much information, and corrected a number of inaccuracies. To my sister, for her superintendence of the book since my departure from England, and to my publishers for their kindness and assistance in many ways, I must not omit to offer my thanks.

October, 1902.

| INTRODUCTION | |

| PAGE | |

| The Terrapin—Crew—Itinerary of the Cruise—Daily Routine—Provisions and Supplies—Collecting Apparatus—Guns—Shooting—Path-making—Clothing—Head-dress—A Scene in the Tropics—Native Indolence—Attractive Memories | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Barren Island and the Archipelago | 9 |

| Shipboard Monotony—Edible Sharks—Calm Nights—Squalls—Barren Island—Appearance—Anchorage—Landing-place—Hot Spring—Goats—The Eruptive Cone—Lava—Paths—Interior of the Crater—Volcanic Activity—Fauna—Fish—The Archipelago—Kwang-tung Strait—Path-making—The Jungle—Birds—Coral Reefs—Parrots—Two New Rats—Inhabitants. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Port Blair | 19 |

| We enter the Harbour—Surveillance—Ross Island Pastimes—Visit the Chief Commissioner—The Harbour—Cellular Jail—Lime-kilns—Phœnix Bay—Hopetown—Murder of Lord Mayo—Chatham Island—Haddo and the Andamanese—Tea Gardens—Viper Island and Jail—The Convicts—Occupations—Punishments—Troops—Departure. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Macpherson Strait—South Andaman and Rutland Island | 28 |

| Gunboat Tours—South Andaman—Rutland Island—Navigation—Landing-place—Native Camp—Natives—Jungle—Birds—Appearance of the Natives—Our Guests—Native Women: Decorations and Absurd Appearance—Trials of Photography—The Village—Food—Bows, Arrows, and Utensils—Barter—Coiffure—Fauna—Water—New Species. | [Pg x] |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Cinques and Little Andaman | 36 |

| Position of the Cinques—Anchorage—Clear Water—The Forest—Beach Formation—Native Hut—Little Andaman—Bumila Creek—Natives—Flies—Personal Decoration—Dress and Modesty—Coats of Mud—Coiffure—Absence of Scarification—Elephantiasis—A Visit to the Village—Peculiar Huts—Canoe—Bows and Arrows—The Return Journey—A slight contretemps—Andamanese Pig—We leave the Andamans. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

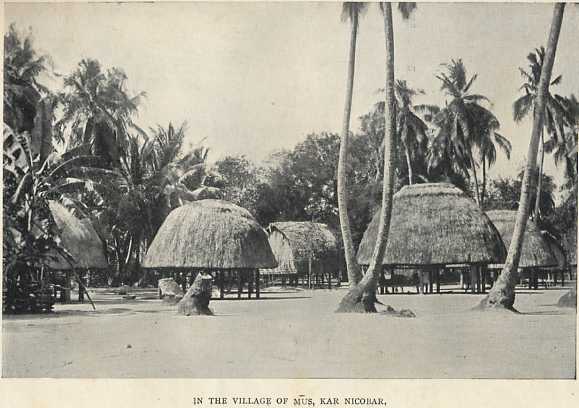

| Kar Nicobar | 44 |

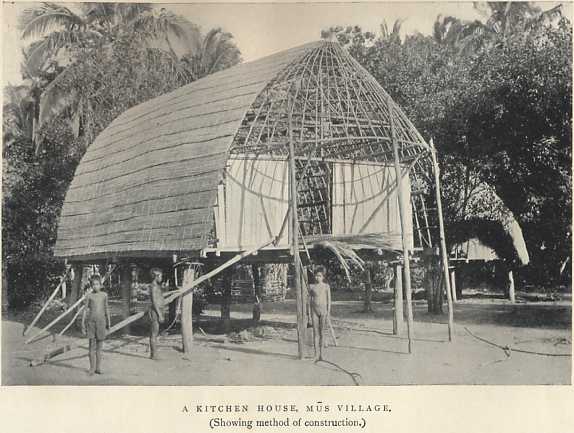

| To the Nicobars—A Tide-race—A Change of Scene—Sáwi Bay—Geological Formation—V. Solomon—Mūs Village—Living-houses—Kitchens—Fruit-trees—The Natives—Headman Offandi—"Town-Halls"—Death-house—Maternity Houses—Hospitals—Floods—"Babies' Houses"—Birds—Oil Press—Canoes—Offandi—"Friend of England"—"Frank Thomson"—"Little John"—Thirst for Information—Natives' Nick-names—Mission School Boys' Work—A Truant—The Advantage of Canoes—A Spill—Our Method of Landing—Collecting Native Birds—A New Bat—Coconuts—V. Solomon—The Nicobarese and Christianity—Water—Area of Kar Nicobar—Geology—Flora—Supplies. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

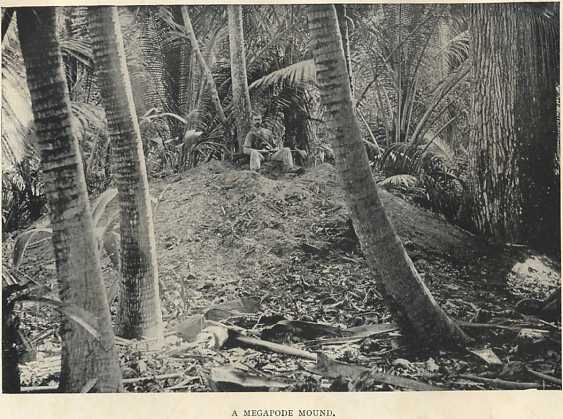

| Tilanchong | 66 |

| Batti Malv—Tilanchong—Novara Bay—Terrapin Bay—Form and Area of Tilanchong—Birds—Megapodes—A Swamp—Crocodile—Megapode Mound—Wreck and Death of Captain Owen, 1708—Leave Tilanchong—Foul Ground—Kamorta. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Trinkat | 73 |

| Beresford Channel—A Deserted Village—Jheel—Bird Life—Wild Cattle—Scenery—Photographs—Port Registers—Tanamara—Population—Customs—The Shom Peṅ—The Sequel to a Death—Interior of the Houses. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

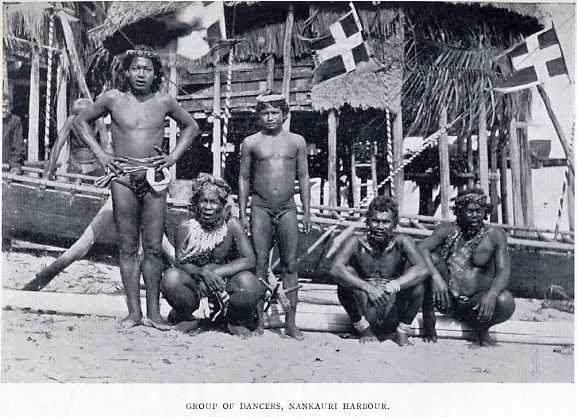

| Nankauri | 78 |

| The Harbour Shores—A Village—Kanaia—Canoe—Feeding the Animals—Collecting-ground—Mangrove Creeks—Preparations for a Festival—Burial Customs—Malacca Village—Houses—Visit Tanamara—Furniture—Talismans and "Scare-devils"—Beliefs—Festivities—A Dance—An Educated Native—Tanamara and his Relations—Cigarettes—Refreshments—The Collections—Geology—Flora—Population—Piracy. | [Pg xi] |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Kamorta | 95 |

| The Old Settlement—The Cemetery—F.H. de Röepstorff—Mortality—Birds—The Harbour—Appearance of Kamorta—Dring Harbour—Olta-möit—Buffalo—Spirit Traffic—Cookery—Ceremonial Dress—A Visit from Tanamara—Geology—Flora—Topography—Population—Hamilton's Description. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Kachal and Other Islands | 103 |

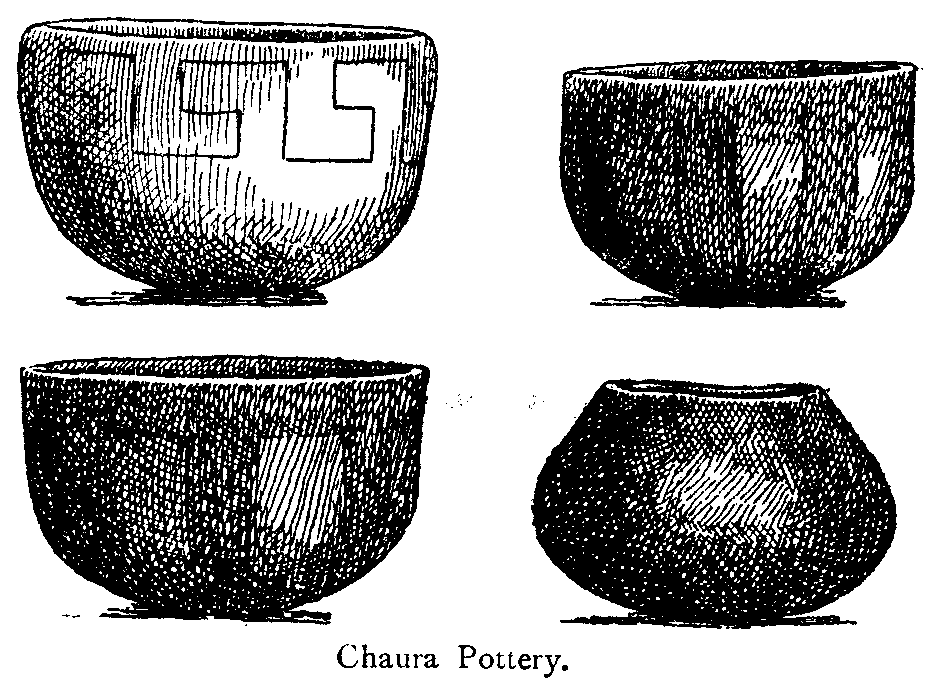

| Heavy Surf—Teressa—Bompoka—A Native Legend—Hamilton—Chaura—Wizardry—Pottery—Kachal typical of the Tropics—Nicobarese Dress—West Bay—Lagoon—Mangroves—Whimbrel—Formation of Kachal—Birds—Visitors to the Schooner—Fever—Chinese Junks—Thatch—Relics—The Reef—Megapodes—Monkeys—Full-dressed Natives—Medicine—A Death Ceremony—Talismans—Fish and Fishing—Geology. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

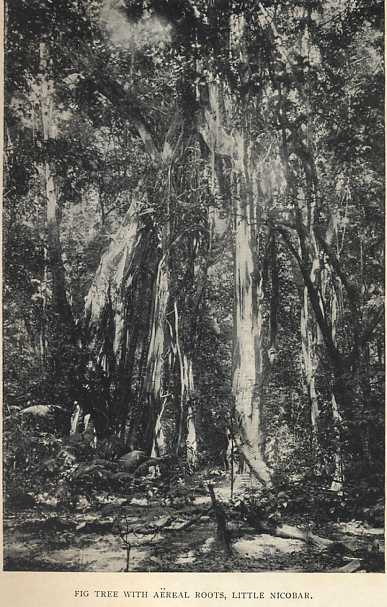

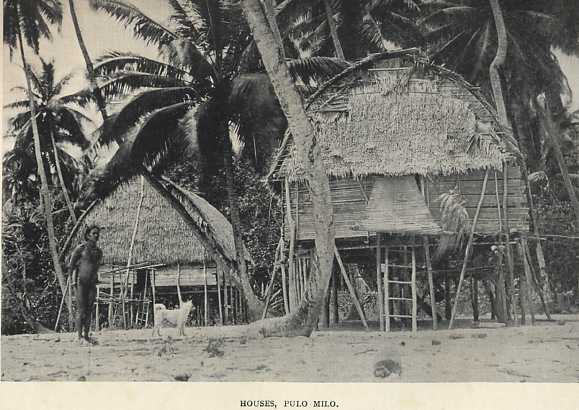

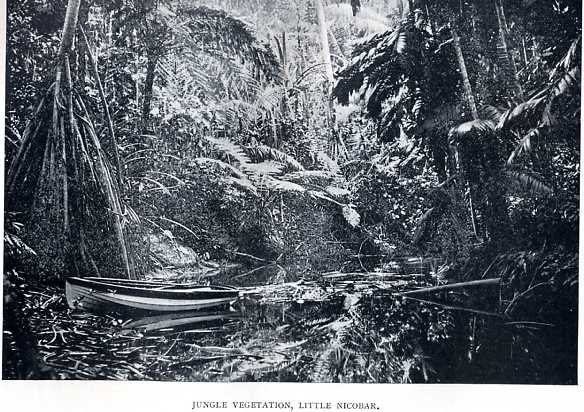

| Little Nicobar and Pulo Milo | 118 |

| A Tide-rip—Islets—A Cetacean—Pulo Milo—Timidity of the Natives—Little Nicobar—Geology—Flora—Population—Site for a Colony—Jungle Life—Banian Trees—The Houses and their Peculiarity—The Natives—Practices and Beliefs—The Shom Peṅ—The Harbour—We ascend a River—Kingfishers—Water—Caves—Bats and Swallows—Nests—A Jungle Path—Menchál Island—Collections—Monkeys—Crabs. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

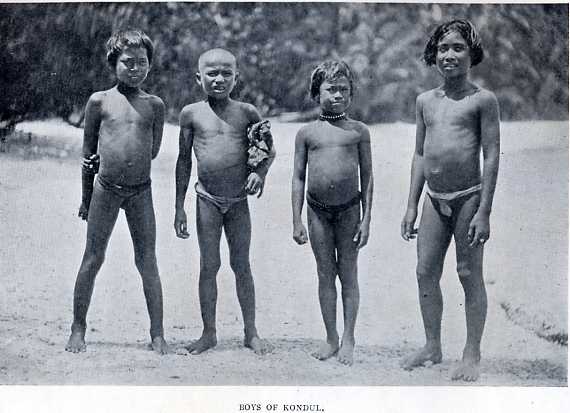

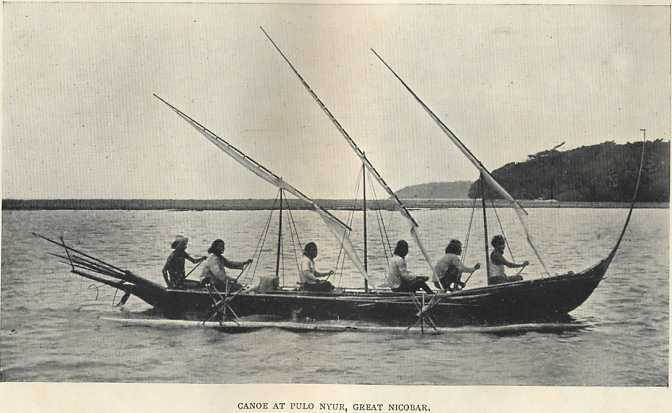

| Kondul and Great Nicobar | 131 |

| The Anchorage—The Island—Villages—We leave Kondul—Great Nicobar—Anchorage—Collecting—Up the Creek—A Bat Camp—Young Bats—Traces of the Shom Peṅ—Bird Life—Fish—Ganges Harbour—Land Subsidence—Tupais—We Explore the Harbour—A Jungle Pig—"Jubilee" River—Chinese Navigation—Rainy Weather—Kondul Boys—Coconuts—Chinese Rowing. | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

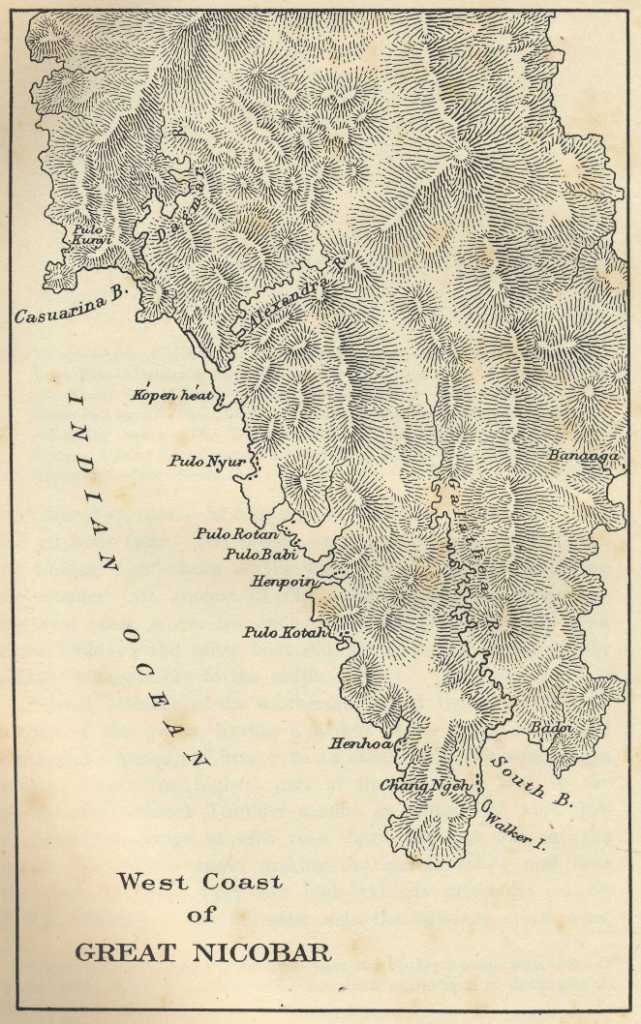

| Great Nicobar—West Coast | 141 |

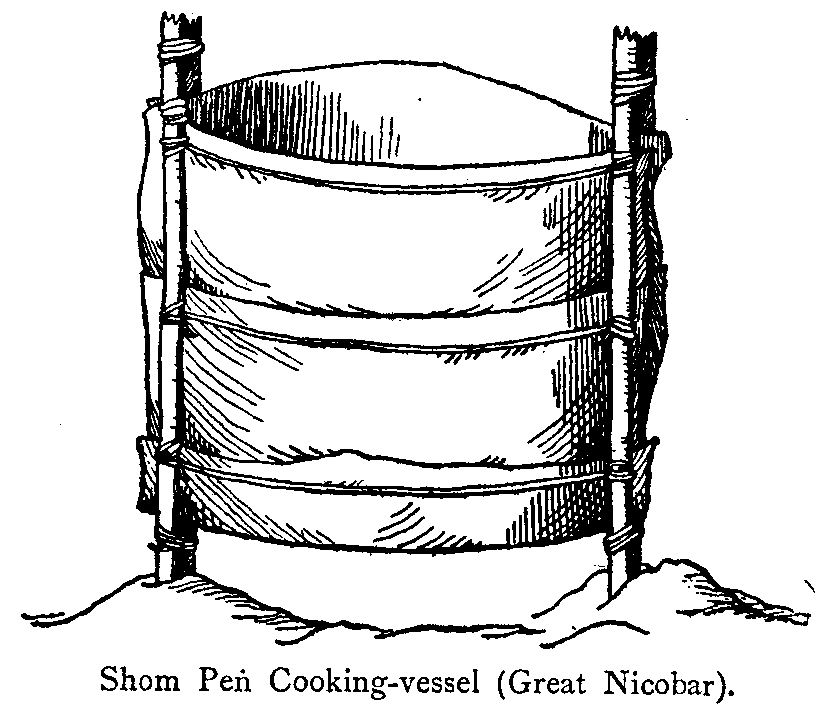

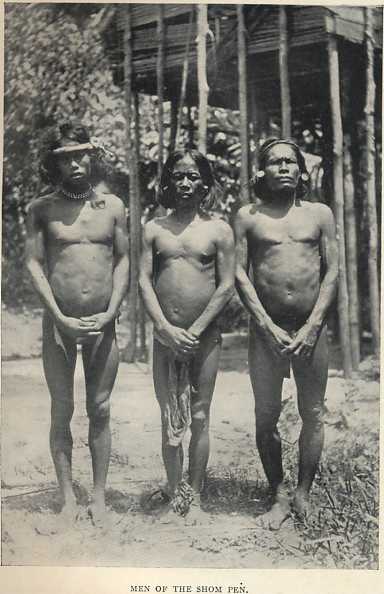

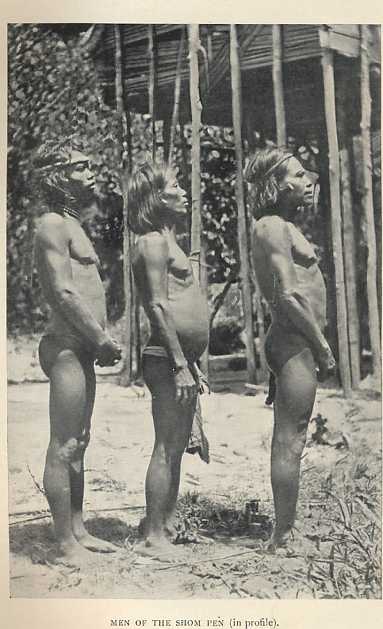

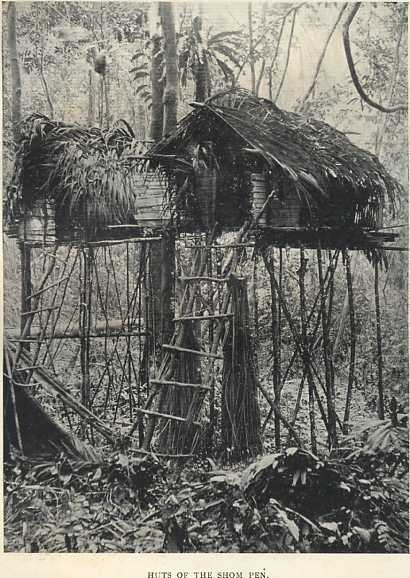

| Pulo Kunyi—Area of Great Nicobar—Mountains—Rivers—The Village—The Shom Peṅ—Casuarina Bay—An Ingenious "Dog-hobble"—In the Jungle—A Shom Peṅ Village—Men of the Shom Peṅ-A Lazy Morning—The Shom Peṅ again—Their Similarity to the Nicobarese—Food—Implements—Cooking-vessel—The Dagmar River—Casuarina Bay—Pulo Nyur—Water—A Boat Expedition—The Alexandra River—Shom Peṅ Villages—Kópenhéat—More Shom Peṅ—Elephantiasis—Pet Monkeys—Anchorage. | [Pg xii] |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Great Nicobar—West and South Coasts | 154 |

| "Domeat"—Malay Traders—Trade Prices—The Shom Peṅ Language—Place Names—Pulo Bábi—The Growth of Land—Climbing a Palm Tree—Servitude—Population—Views on Marriage with the Aborigines—Towards the Interior—A Shom Peṅ Village—The Inhabitants—Canoe-building—Barter—The West Coast—South Bay—Walker Island—Chang-ngeh—Up the Galathea River—Water—We leave the Nicobars and sail to Sumatra. | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Andaman Islands and their Inhabitants | 167 |

| Position—Soundings—Relationship—Islands—Area—Great Andaman Mountains—Little Andaman—Rivers—Coral Banks—Scenery—Harbours—Timber—Flora—Climate—Cyclones—Geology—Minerals—Subsidence—Earthquakes—History—Aborigines—Convicts and the Penal System—Growth and Resources of the Settlement—Products and Manufactures. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Nicobar Islands and their Aborigines | 201 |

| The Nicobar Islands and their Aborigines—The Islands—Coral Banks—Nankauri Harbour—Population—Geology—Earthquakes—Climate—Flora—History—The Shom Peṅ: their Derivation, Appearance, Houses, Gardens, Cooking-vessel, Domestic Animals, Manufactures, Trade, Clothing, Headmen, Position of Women, Disposition, Diseases. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Nicobarese | 221 |

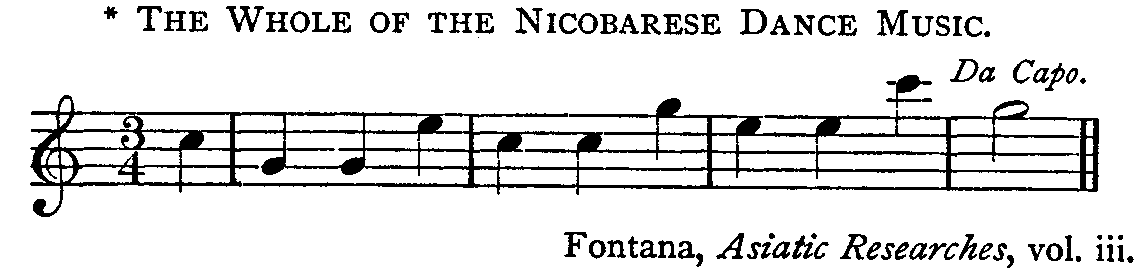

| The Evolution of the Nicobarese—Description—Character—Language—Legends of Origin—Origin of Coco Palms—Invention of Punishments—Superstitious Beliefs—Diseases—Medicines—Marriage—Matriarchal System—Divorce—Polygamy—Courtship—Property—Takoia—Headmen—Social State—Position of Women and Children—Domestic Animals—Weapons—Tools—Fishing—Turtle—Food—Beverages—Narcotics and Stimulants—Cleanliness—Clothing—Ornaments—Coiffure—Amusements—Arts and Industries—Cultivation—Produce—Traders and Commerce. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Dampier's Sojourn in Great Nicobar, and Voyage thence to Acheen in a Canoe | 254 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| An Old Account of Kar Nicobar | 276 |

| [Pg xiii] | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Some Customs of the Kar Nicobarese | 285 |

| The Feast of Exhumation—A Scene in the Graveyard—"Katap-hang"—"Kiala"—"Enwan-n'gi"—Fish Charms—Canoe Offerings—"Ramal"—"Gnunota"—Converse with the Dead—"Kewi-apa"—"Maya"—"Yintovná Síya"—Exorcism—"Tanangla"—Other Ceremonies—The "Sano-kuv"—The "Mafai"—The "Tamiluana"—Mafai Ceremonies—Burial—Mourning—Burial Scenes—The Origin of Village Gardens—Destruction of Gardens—Eclipses—Canoe-buying—Dances—Quarrels—"Amok"—Wizardry—Wizard Murders—-Suicides—Land Sale and Tenure—Dislike to Strangers—Cross-bow Accidents—Canoe Voyages—Commercial Occupations—Tallies. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Fauna of the Andamans and Nicobars | 320 |

| A.—Average Wind and Weather in the Andamans | 335 |

| B.—Principal Forest Trees of the Andamans | 336 |

| C.—Notes on the Produce of the Andaman Forests | 339 |

| D.—Census, Andaman Islands, 1901 | 342 |

| E.—Government Schools at Port Blair | 343 |

| F.—Measurements of some Andamanese met at Rutland Island | 344 |

| G.—Principal Flora of the Nicobars | 345 |

| H.—Census, Nicobar Islands, 1901 and 1886 | 350 |

| I.—Trade Articles and their Value in the Nicobars | 351 |

| J.—Presents and Barter in Demand during the Cruise of the Terrapin | 352 |

| K.—Measurements of some Nicobarese and Shom Peṅ | 353 |

| Index | 359 |

| The "Terrapin" in Kwang-tung Strait | Frontispiece | ||

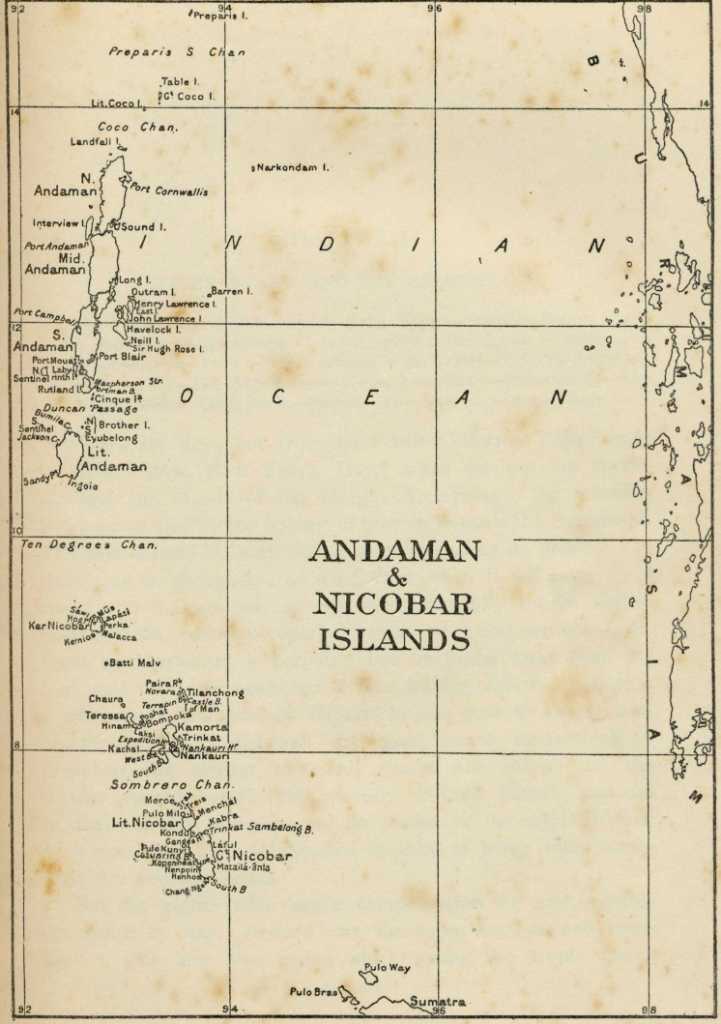

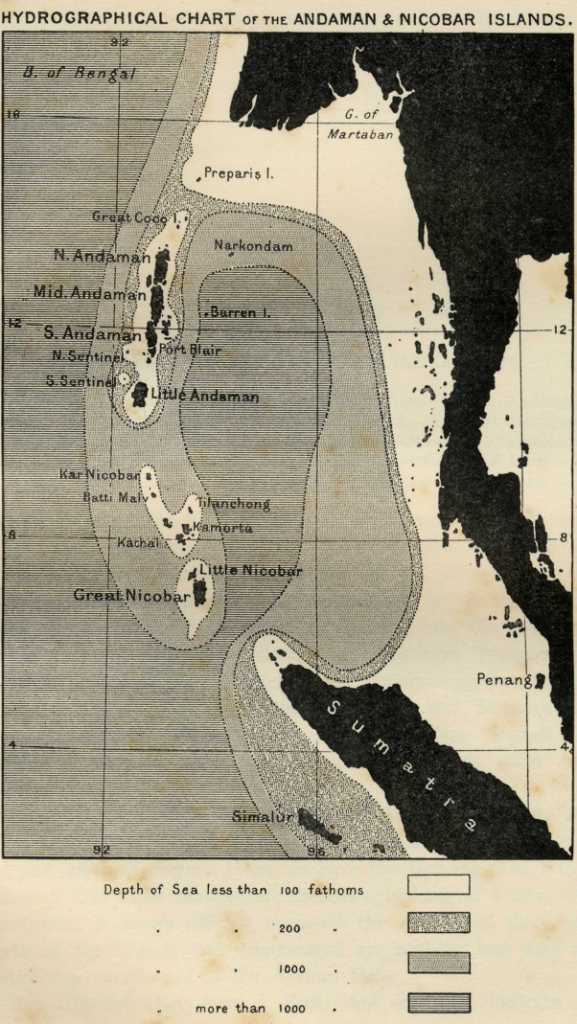

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | To face page | 8 | |

| The Landing-place, Barren Island | " | " | 10 |

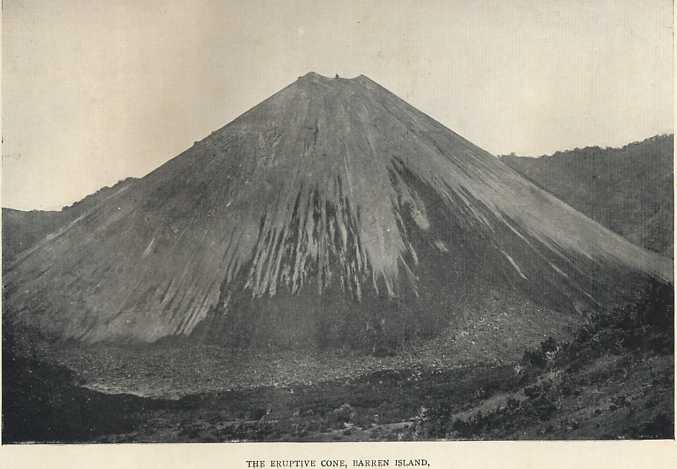

| The Eruptive Cone, Barren Island | " | " | 12 |

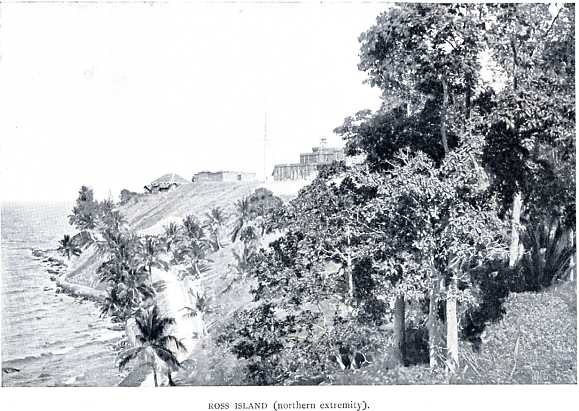

| Ross Island (northern extremity) | " | " | 20 |

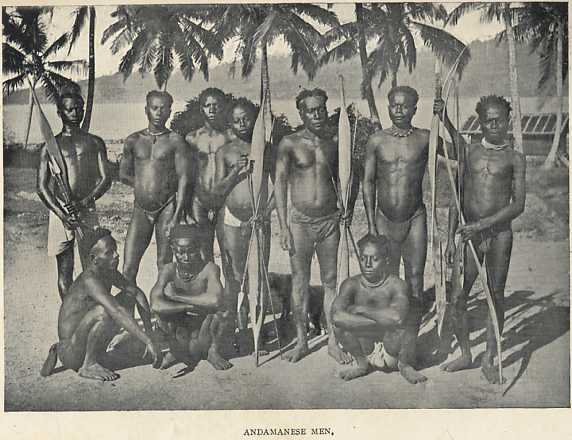

| Andamanese Men | " | " | 22 |

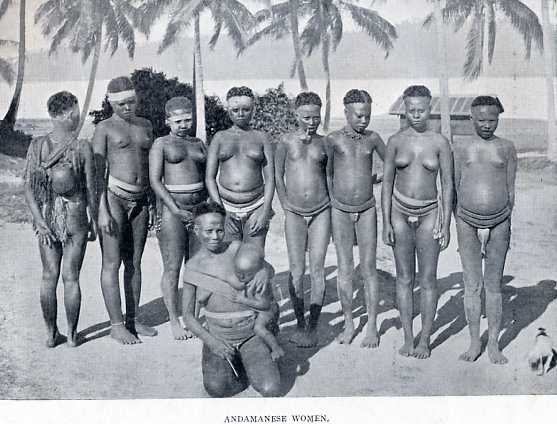

| Andamanese Women | " | " | 24 |

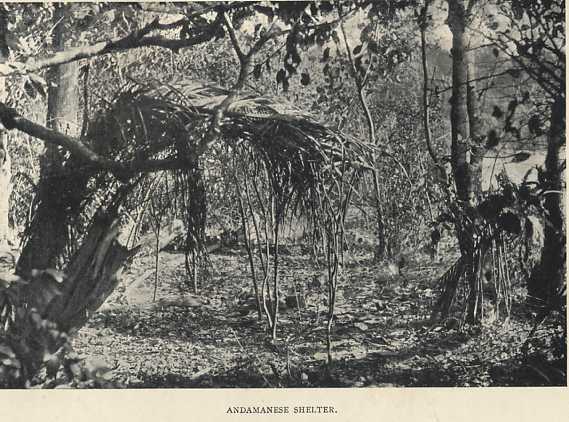

| Andamanese Shelter | " | " | 28 |

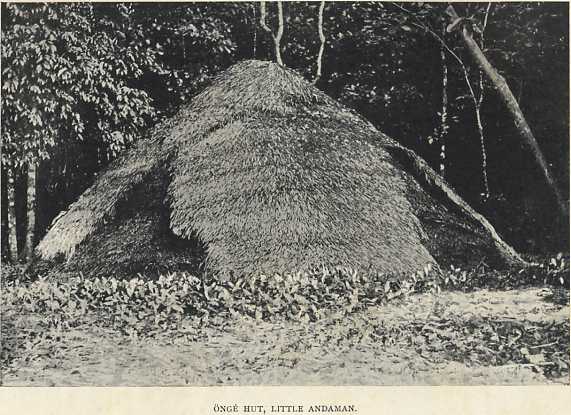

| Öngé Hut, Little Andaman | " | " | 40 |

| In the Village of Mūs, Kar Nicobar | " | " | 44 |

| Kar Nicobarese Family and Dwelling-house, with Lounge beneath | " | " | 46 |

| A Kitchen House, Mūs Village (showing method of construction) | " | " | 48 |

| Death House, Hospitals, Maternity Houses, and Burial-grod, Mūs Village | " | " | 50 |

| "Talik N'gi" (The Place of the Baby), Mūs Village | " | " | 52 |

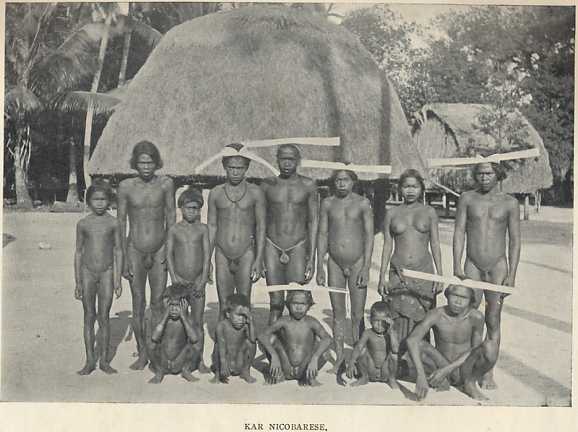

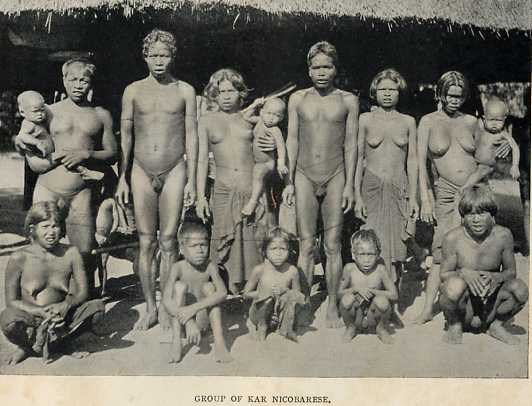

| Kar Nicobarese | " | " | 54 |

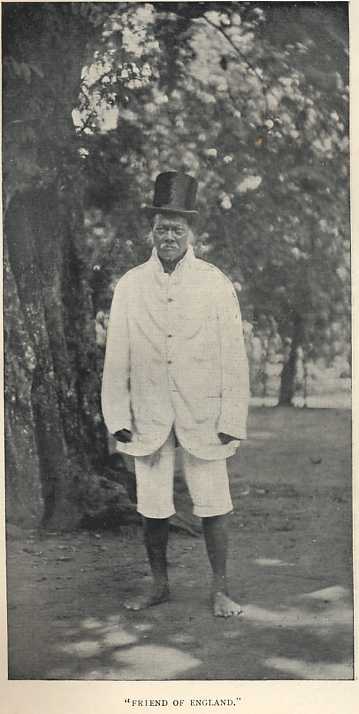

| "Friend of England" | " | " | 56 |

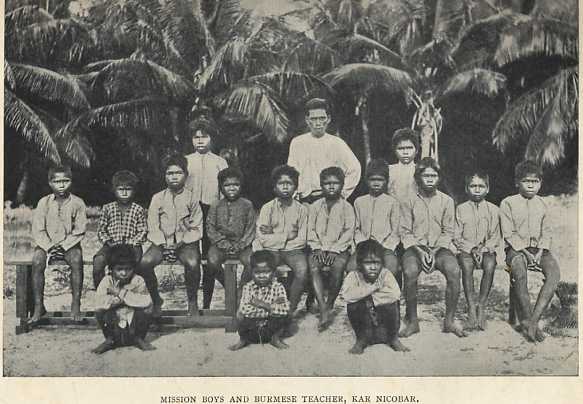

| Mission Boys and Burmese Teacher, Kar Nicobar | " | " | 60 |

| Women and Children, Kar Nicobar | " | " | 64 |

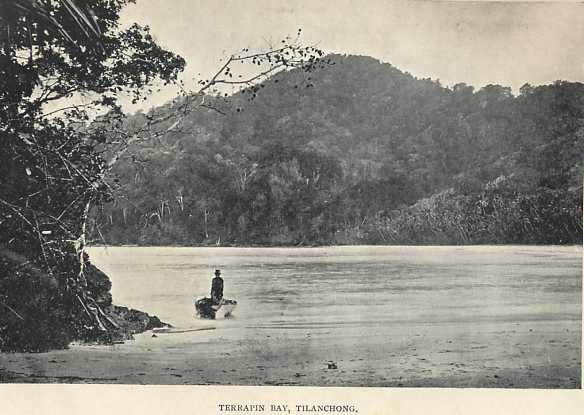

| Terrapin Bay, Tilanchong | " | " | 66 |

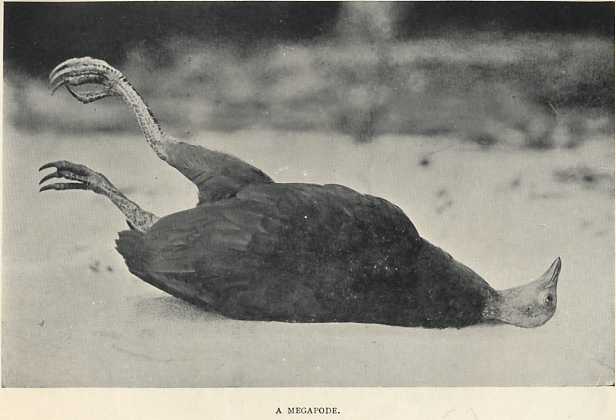

| A Megapode | " | " | 68 |

| A Megapode Mound | " | " | 70 |

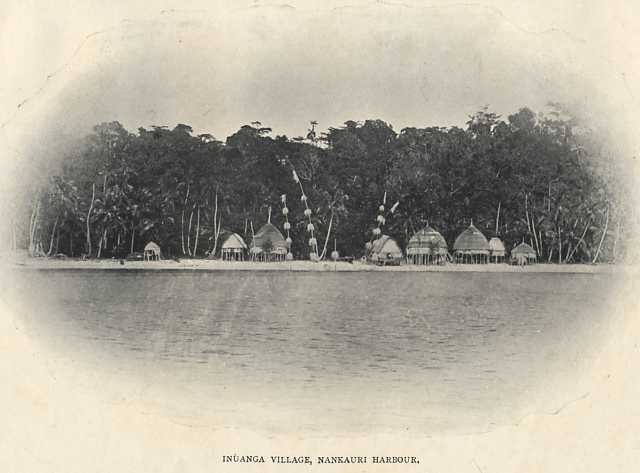

| Inúanga Village, Nankauri Harbour | " | " | 78 |

| Nankauri Canoe, with Festival Decorations | " | " | 80 |

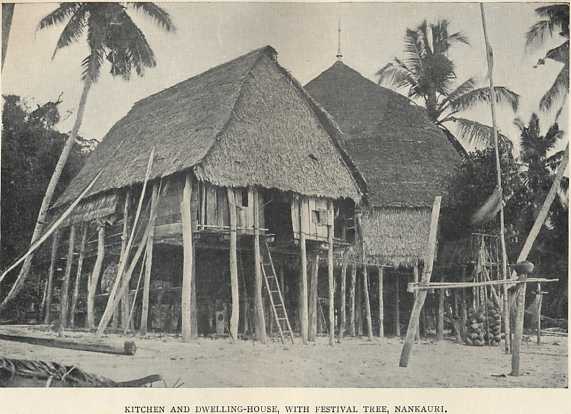

| Kitchen and Dwelling-house, with Festival Tree, Nankauri | " | " | 82 |

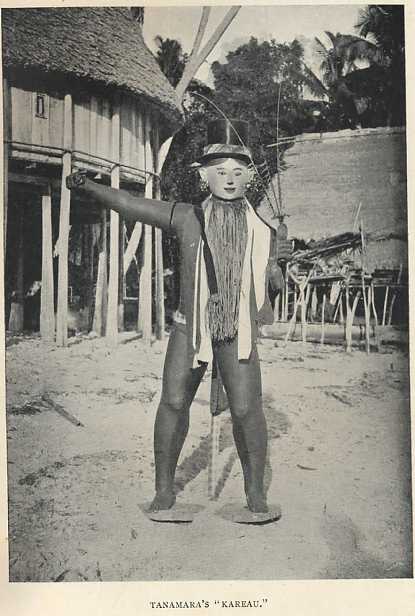

| Tanamara's "Kareau" | " | " | 84 |

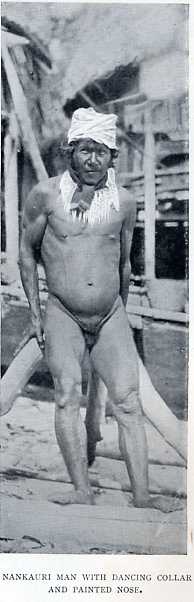

| Nankauri Man with Dancing Collar and Painted Nose | " | " | 86 |

| Group of Dancers, Nankauri Harbour | " | " | 88 |

| Nankauri Man with Silver Necklace | " | " | 90 |

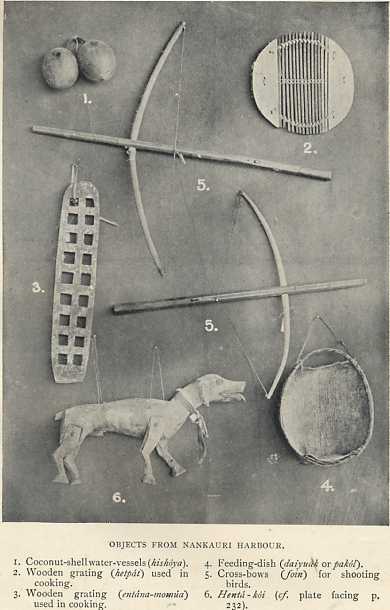

| Objects from Nankauri Harbour | " | " | 94 |

| Dwelling-houses, Dring Harbour, Kamorta (partially constructed, and complete) | " | " | 98[Pg xv] |

| Fig Tree with Aëreal Roots, Little Nicobar | " | " | 122 |

| Houses, Pulo Milo | " | " | 124 |

| Jungle Vegetation, Little Nicobar | " | " | 126 |

| Man with Pandanus Fruit, Kondul | " | " | 132 |

| Boys of Kondul | " | " | 138 |

| West Coast of Great Nicobar | " | " | 140 |

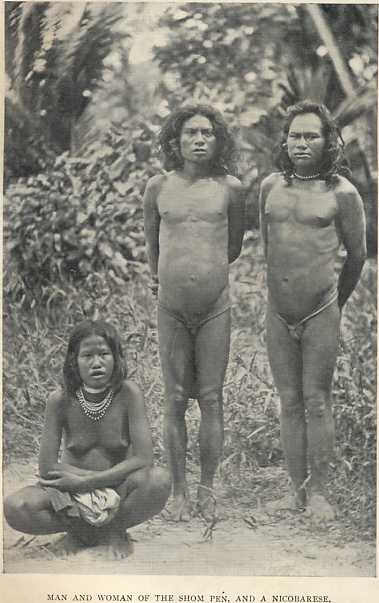

| Man and Woman of the Shom Peṅ, and a Nicobarese | " | " | 142 |

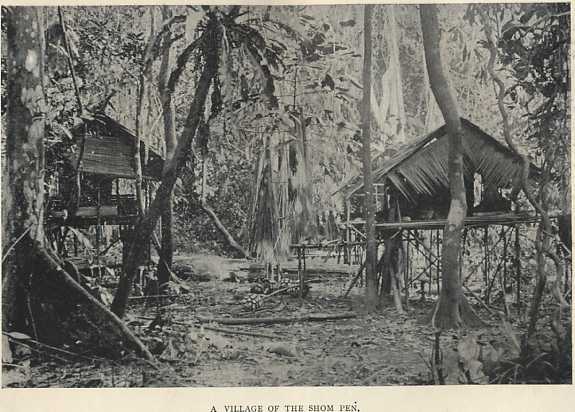

| A Village of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 144 |

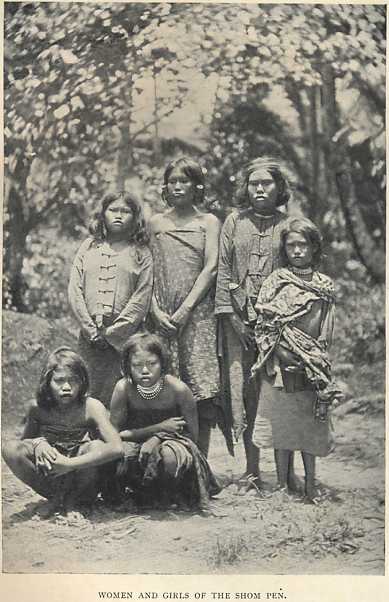

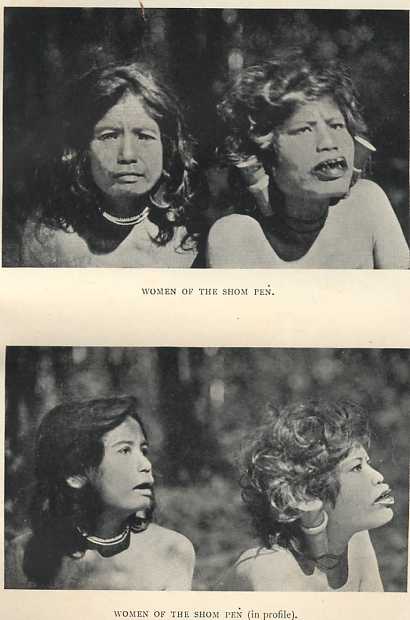

| Women and Girls of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 146 |

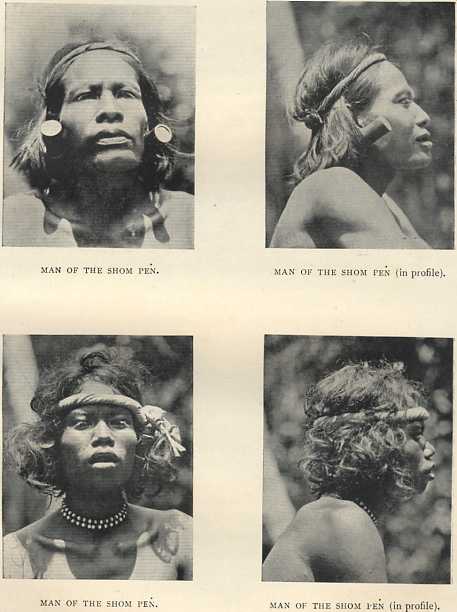

| Men of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 148 |

| Men of the Shom Peṅ (in profile) | " | " | 150 |

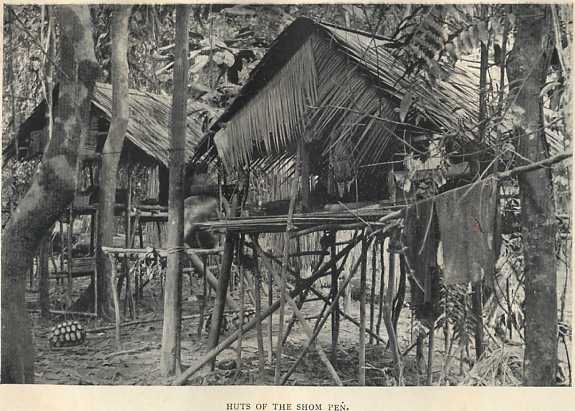

| Hut of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 152 |

| Canoe at Pulo Nyur, Great Nicobar | " | " | 154 |

| Huts of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 158 |

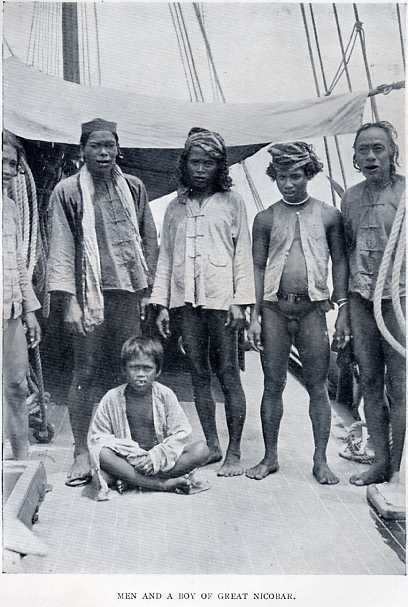

| Men and a Boy of Great Nicobar | " | " | 160 |

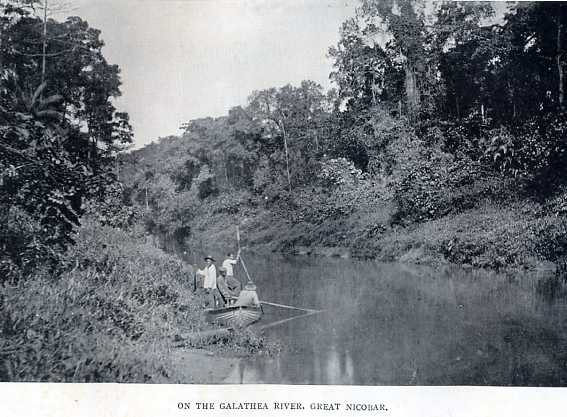

| On the Galathea River, Great Nicobar | " | " | 162 |

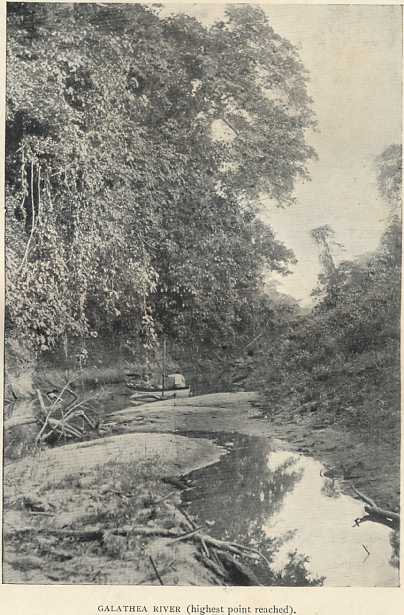

| Galathea River (highest point reached) | " | " | 164 |

| Hydrographical Chart of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands | " | " | 166 |

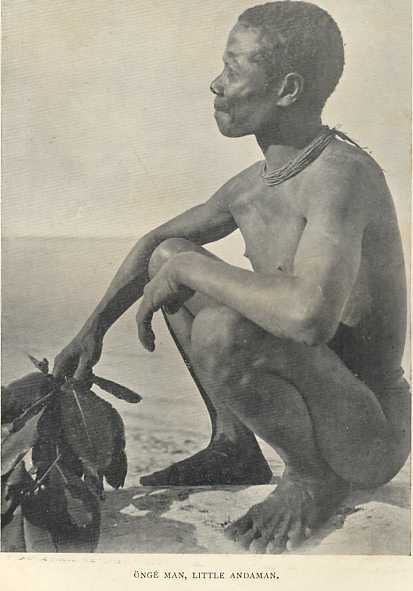

| Öngé Man, Little Andaman | " | " | 186 |

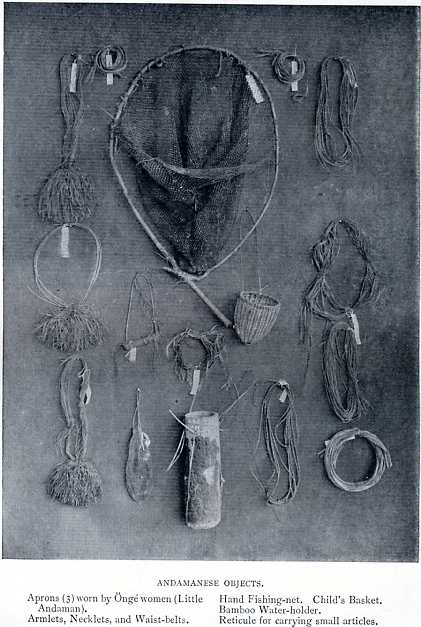

| Andamanese Objects | " | " | 188 |

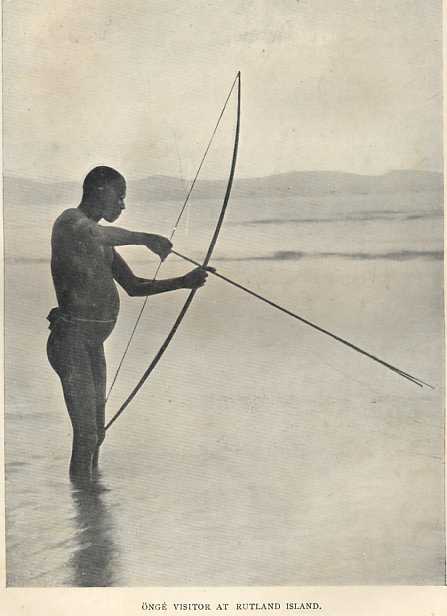

| Öngé Visitor at Rutland Island | " | " | 190 |

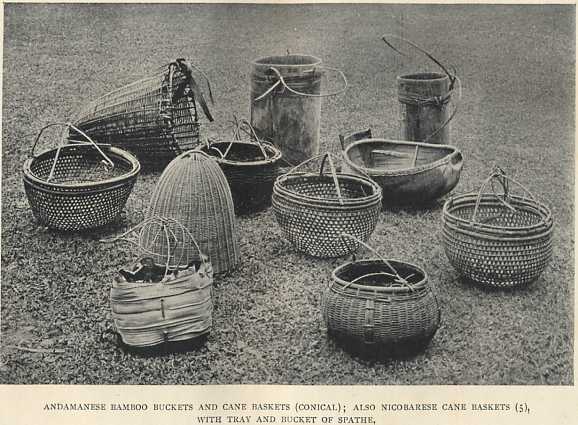

| Andamanese Bamboo Buckets and Cane Baskets (conical); also Nicobarese Cane Baskets (5), with Tray and Bucket of Spathe | " | " | 200 |

| Men of the Shom Peṅ; Men of the Shom Peṅ (in profile) | " | " | 214 |

| Women of the Shom Peṅ; Women of the Shom Peṅ (in profile) | " | " | 216 |

| Women of the Shom Peṅ; Women of the Shom Peṅ (in profile) | " | " | 218 |

| Huts of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 220 |

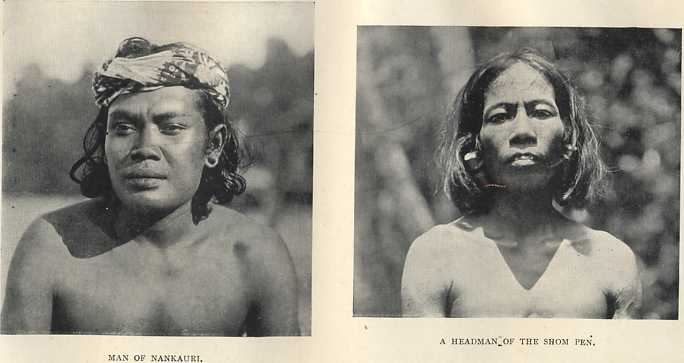

| Man of Nankauri; A Headman of the Shom Peṅ | " | " | 222 |

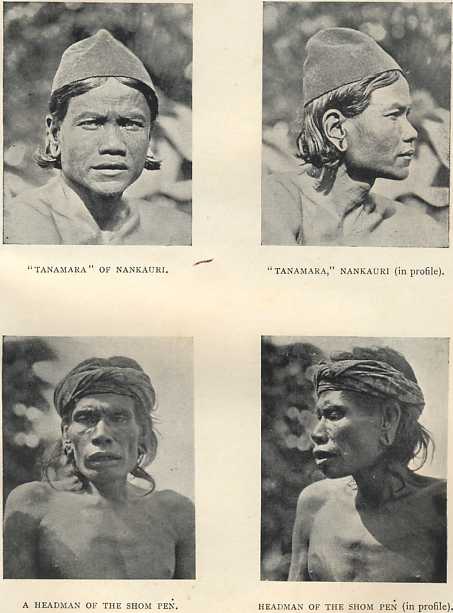

| "Tanamara" of Nankauri; "Tanamara" of Nankauri (in profile); A Headman of the Shom Peṅ; Headman of the Shom Peṅ (in profile) | " | " | 224 |

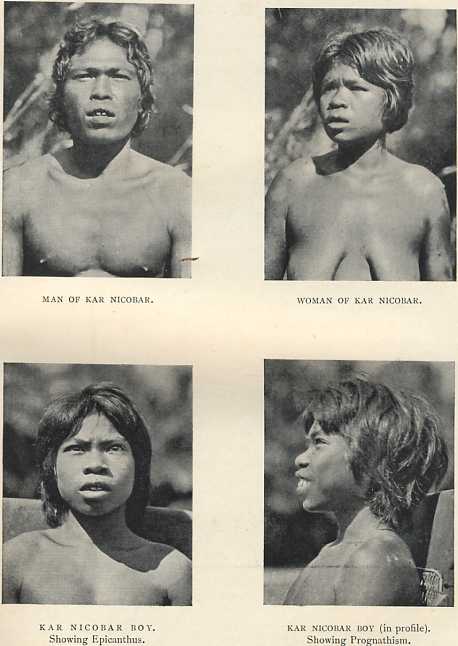

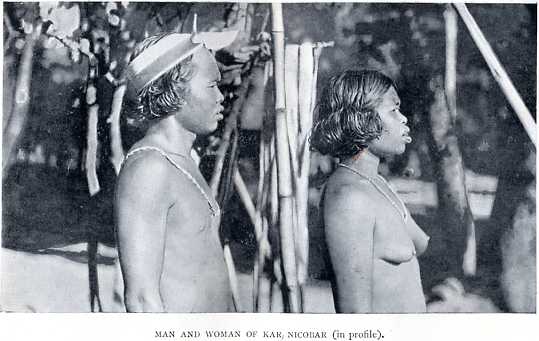

| Man of Kar Nicobar; Woman of Kar Nicobar; Kar Nicobar Boy (showing Epicanthus); Kar Nicobar Boy (in profile, showing Prognathism) | " | " | 226 |

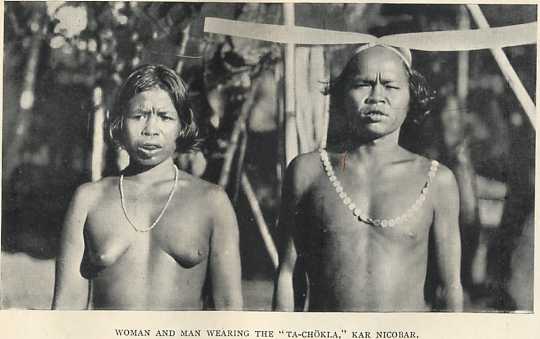

| Woman and Man Wearing the "Tá-Chökla," Kar Nicobar | " | " | 228 |

| Man and Woman of Kar Nicobar (in profile) | " | " | 230 |

| Specimens of "Hentá-kói," made and first used in times of sickness to frighten away the offending evil spirits | " | " | 232 |

| A "Hentá," painted and first suspended inside hut in time of sickness, to gratify good spirits and scare away demons. (Specimen from Nankauri) | " | " | 234[Pg xvi] |

| Old Nicobarese Skirt, "Ngong" | " | " | 248 |

| Baskets, Troughs, and Areca Spathe Feeding-dish, Nicobar Islands | " | " | 252 |

| Group of Kar Nicobarese | " | " | 284 |

| PAGE | |

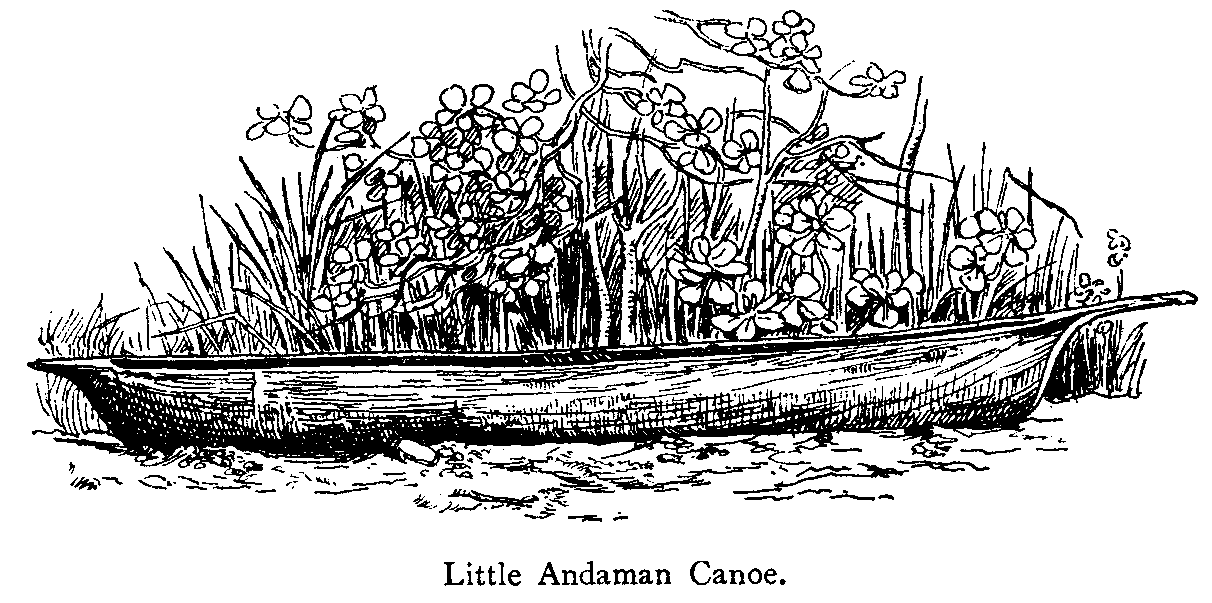

| Little Andaman Canoe | 41 |

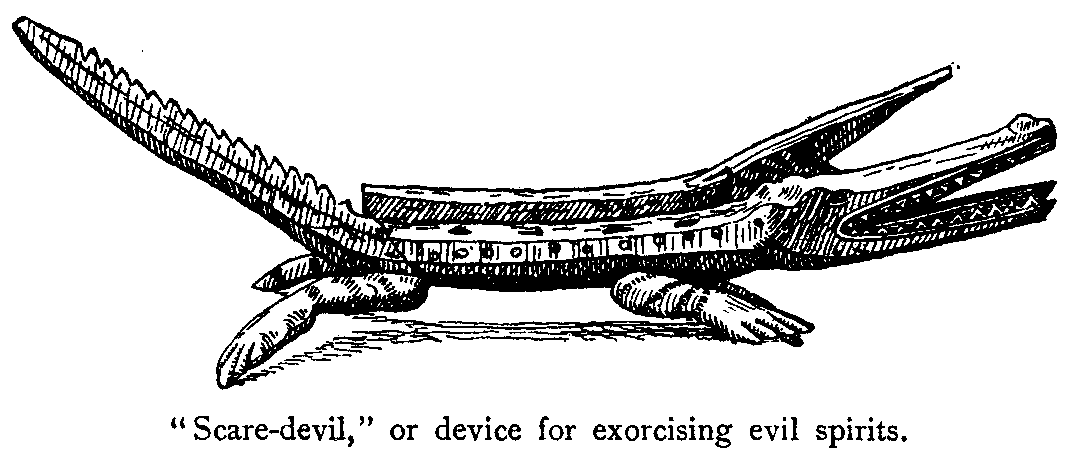

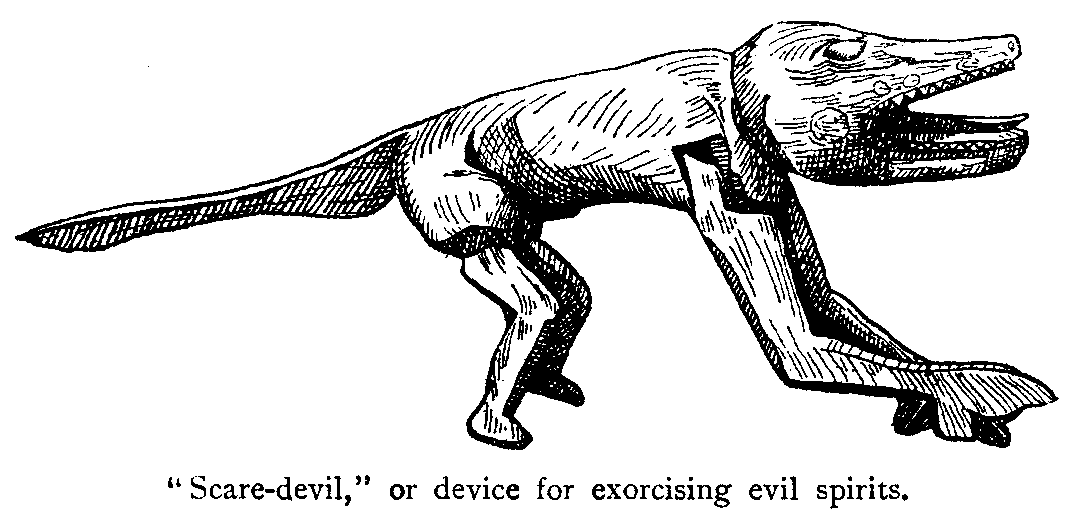

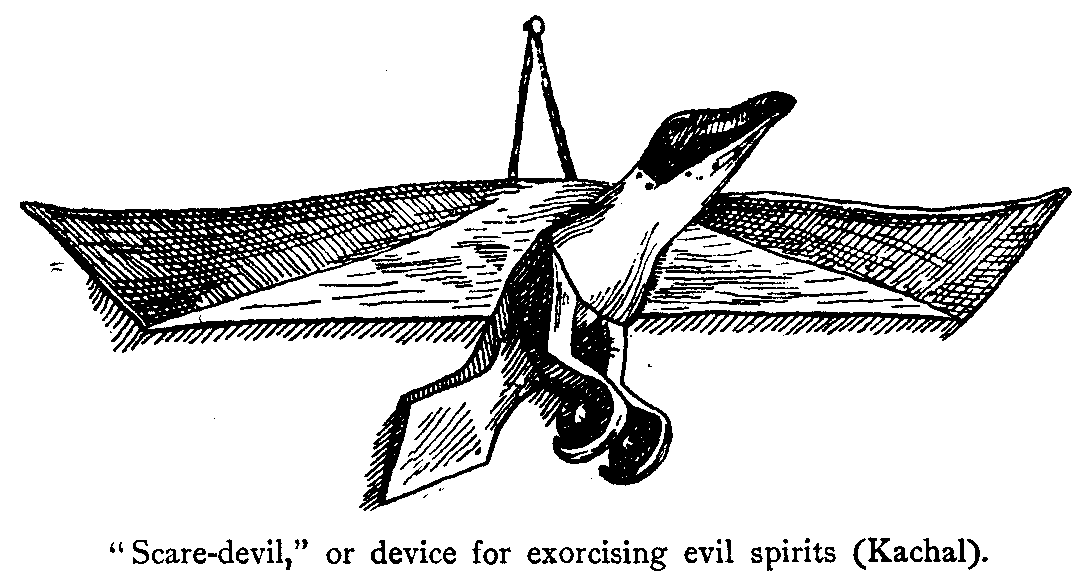

| "Scare-devil," or device for exorcising evil spirits | 44 |

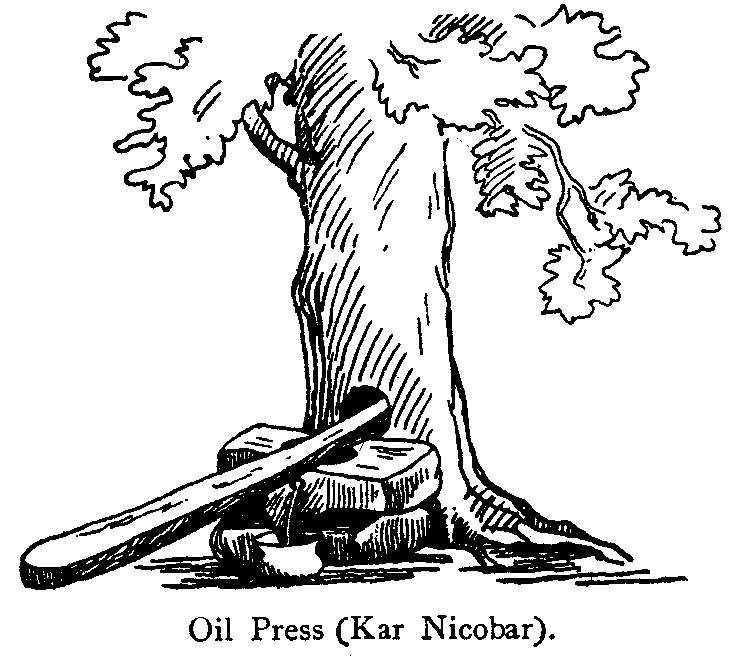

| Oil Press (Kar Nicobar) | 53 |

| "Scare-devil," or device for exorcising evil spirits | 78 |

| Chaura Pottery | 108 |

| Shom Peṅ Cooking-vessel (Great Nicobar) | 148 |

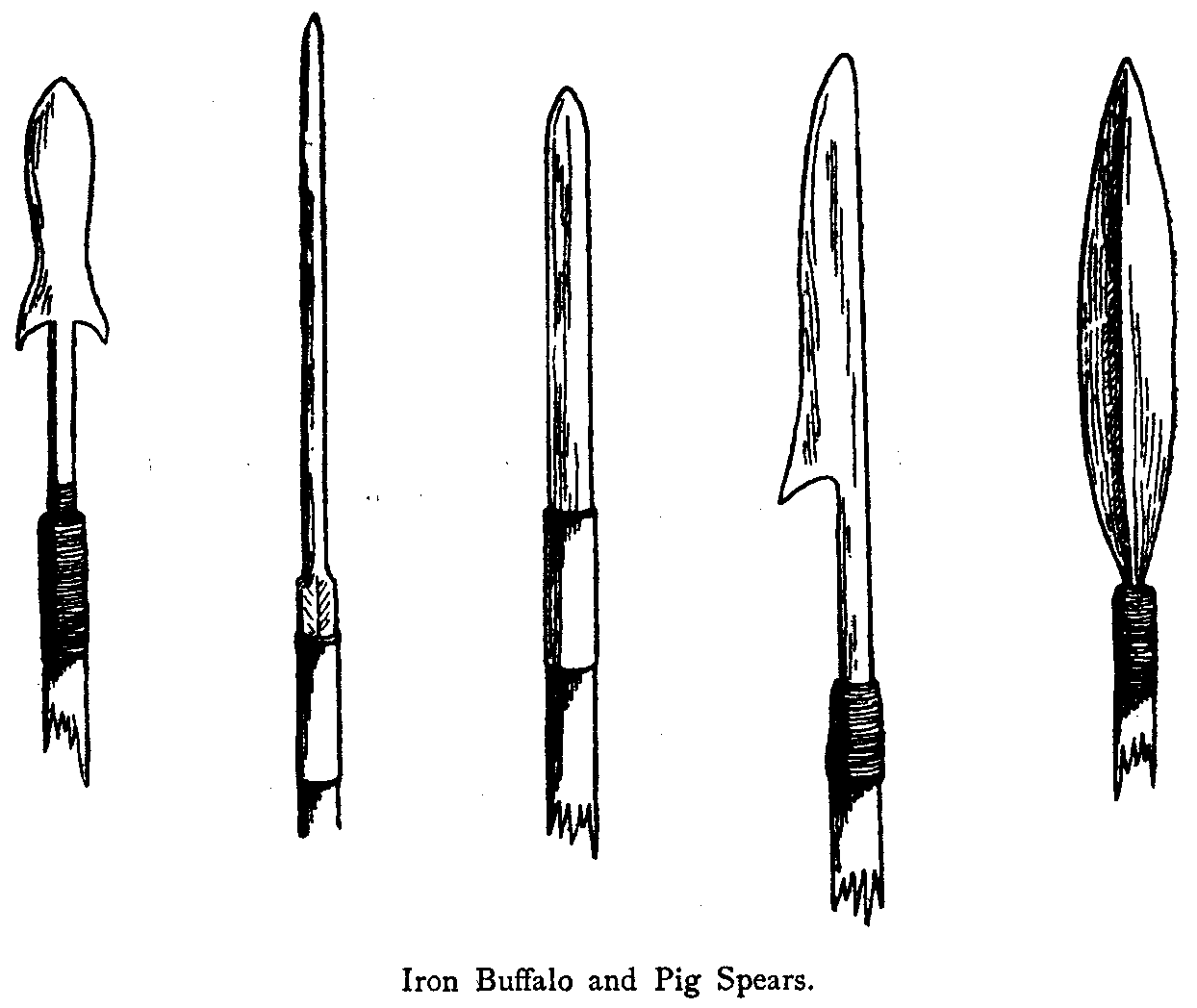

| Iron Buffalo and Pig Spears | 221 |

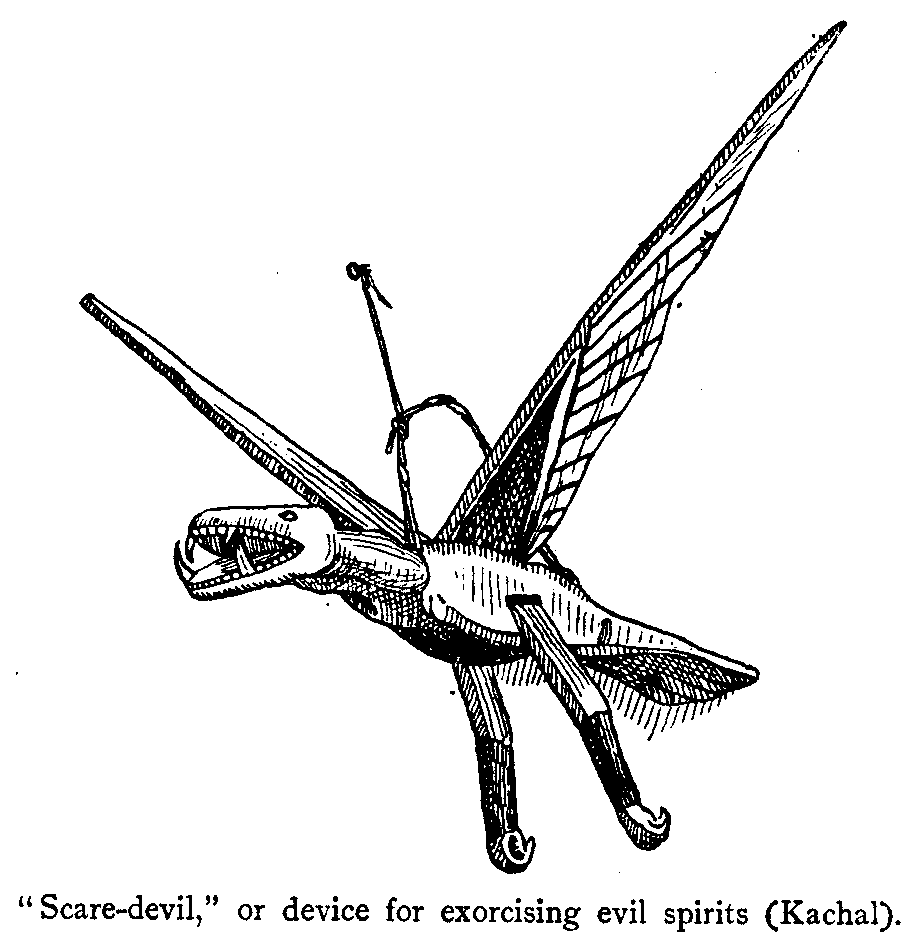

| "Scare-devil," or device for exorcising evil spirits (Kachal) | 231 |

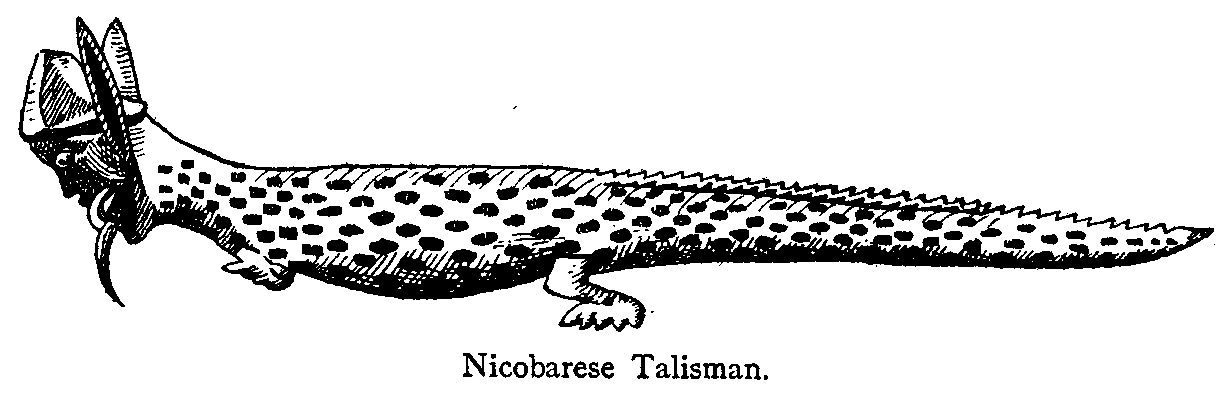

| Nicobarese Talisman | 232 |

| "Scare-devil," or device for exorcising evil spirits (Kachal) | 232 |

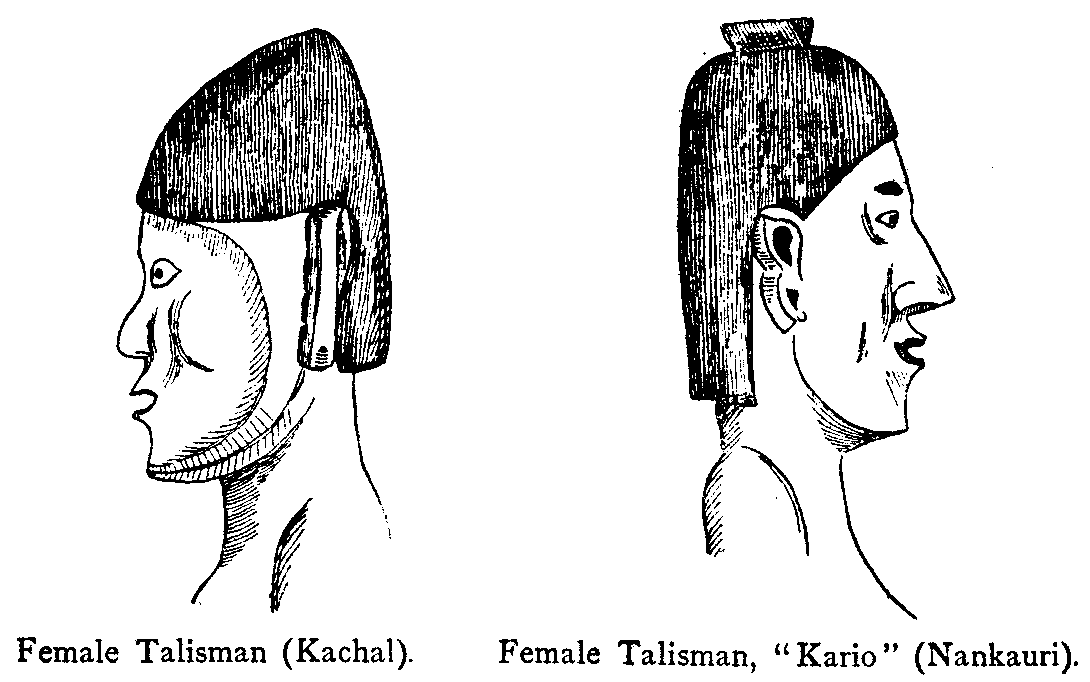

| Female Talisman (Kachal); Female Talisman, "Kario" (Nankauri) | 234 |

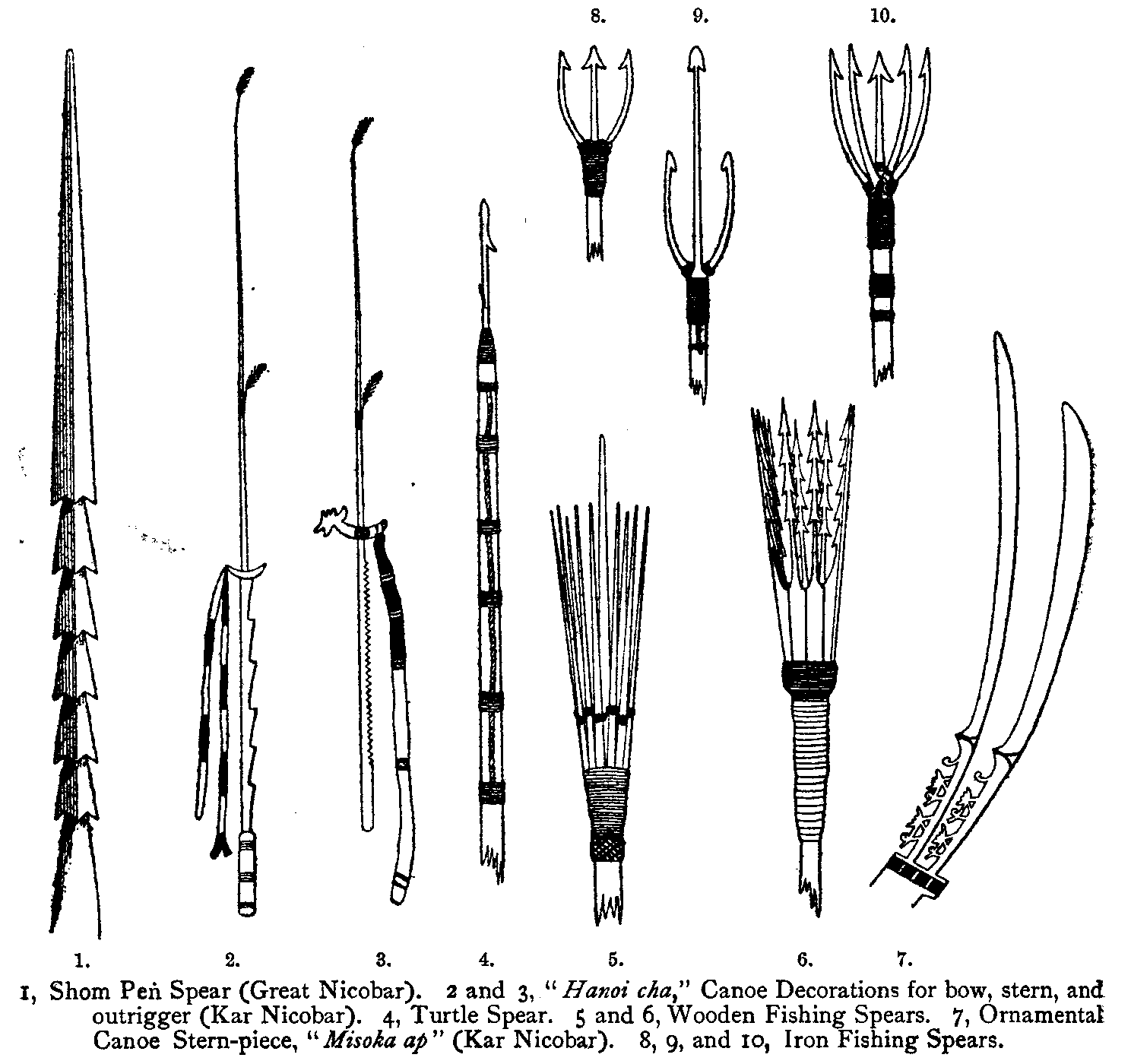

| 1, Shom Peṅ Spear (Great Nicobar). 2 and 3, "Hanoi cha," Canoe Decorations for bow, stern, and outrigger (Kar Nicobar). 4, Turtle Spear. 5 and 6, Wooden Fishing Spears. 7, Ornamental Canoe Stern-piece, "Misoka ap" (Kar Nicobar). 8, 9, and 10, Iron Fishing Spears | 244 |

The Terrapin—Crew—Itinerary of the Cruise—Daily Routine—Provisions and Supplies—Collecting Apparatus—Guns—Shooting—Path-making—Clothing—Head-dress—A Scene in the Tropics—Native Indolence—Attractive Memories.

The Terrapin, captain and owner Dr W. L. Abbott, is a Singapore-built teak schooner of 40 tons register and 67 tons yacht measurement. She is 65 feet long on the water-line, and 16 feet broad, and has been given an almost box-shaped midship section, partly to afford sufficient inside space for the ballast (iron), but principally with the idea that when she takes the ground she may not heel to any uncomfortable extent. The draught is 7½ feet, but two years' experience has proved that this is too much for the class of cruising she is engaged in. The crew are berthed forward, and aft is a large hold where tanks containing about 3 tons of water, supplies, cables, etc., are stored. A large raised trunk hatch about 2½ feet high covers the central third of the boat, leaving 3-feet gangways on either side. This structure affords ample head-room below, and gives coolness and abundant ventilation by means of windows which open all round it. Sailing in the tropics, with the thermometer constantly standing at 84° or so in the shade, necessitates for any comfort a very different arrangement from what would be fitting at home. Whenever possible, the boat, while anchored, is covered with awnings from stem to stern. Under the hatch are a large saloon, two cabins, pantry, etc.

[Pg 2]The crew—five ordinary seamen, a serang (boatswain), and sailing-master—are Malays; for natives are far more satisfactory in nearly every way on a small boat in the tropics than white men, even if the latter could be obtained. They can put up with more restricted quarters, are less inclined to grumble under the peculiar circumstances, or be disobedient, are more at home in every way in the surroundings and with the people one meets, are little trouble to cater for, and, most important of all, keep in good health and can stand the sun. A Chinese "boy" and cook are also carried.

Forward on deck there is a small iron galley for the preparation of meals, and aft repose two boats—an 18-feet double-ender for four oars, and a beamy 10-feet dinghy that best carries a crew of three. The schooner steers with a wheel.

The Terrapin left Singapore in October 1900 and, subsequent to calling at Penang, cruised off the coast of Tenasserim and among the islands of the Mergui Archipelago until I joined her late in December. A few days were then spent in the peninsula, where several deer and wild pig were obtained; then visiting High Island—where an unsuccessful search was made for Sellung[3] skeletons, and a number of birds and small mammals added to the collection—she left for the Andamans.

On the return voyage from the Nicobars we called at Olehleh, the port for Kota Rajah, Dutch capital of Acheen. Even a dissociation from them of only three months made the pink-white skins of the Europeans—sun-avoiding Dutch—seem strange and unhealthy.

Having spent a day or two at this place, where we first heard of the accession of King Edward VII., we skirted the north coast of Sumatra, with its park-like stretches of grass and forest, drifting[Pg 3] along almost in the shadow of its great volcanic mountains, and then, crossing the northern entrance of the Malacca Straits, anchored once more in the harbour of Penang.

At Klang, in Selangor, we stopped a night to visit the museum at Kwala Lumpor, and were passed by the Ophir and her consorts as they steamed to Singapore; which place we ourselves reached, after a slow passage down the coast, on the 27th of April 1901, thus bringing the cruise to an end.

The day's programme during the voyage was simple. We rose before 5 A.M.; and after a hurried chota hazri, rowed ashore the moment it grew at all light. The next five hours were passed collecting in the jungle; and then returning on board, after a bath, change, and breakfast, the preservation of specimens went on until two o'clock; next came tea, then more work until about 3 P.M., when we once more rowed ashore and sought for fresh material until darkness set in. Then after another bath and change came dinner, and by the time the second batch of specimens was disposed of, we were quite ready for mattress and pillow on deck; for unless it rained we never slept below. The development of photographs often kept me up till midnight, since they had to be manipulated in a small pantry which could only be thoroughly darkened after sunset. I have seldom been in a warmer place.

Some consideration should be given to the provisioning of a boat when cruising away from regular supplies for health is largely dependent on this point.

For so long as flour will keep good it is pleasant to have fresh bread, but experience on this and other cruises is that it gets full of weevils after three months in a small boat. While tinned provisions and bottled fruits are very well for a time, one rapidly tires of them, and then there is nothing like the old stand-bys of salt beef and pork, ship's biscuits, rice, etc. Potatoes and onions will keep well for six months, and "sauerkraut," or Chinese preserved greens, are useful articles. Many of the birds shot for specimens—on this cruise, megapodes, pigeons, and whimbrel—form welcome additions to the table, and one gets occasionally wild pig and deer; while even of such unorthodox animals as[Pg 4] squirrels, the larger kinds—Sciurus bicolor attains almost the size of a hare, which it much resembles in flavour—are by no means despicable. When we were under sail, there were always lines towing astern of the vessel, which often produced bonito, dolphin, barracouta, edible shark, and other varieties, and we carried a seine, which, when stretched across the mouth of a tidal creek, was nearly always certain to entangle some kind of fish in its meshes, while with a casting-net catches of what one might call "whitebait" were often made.

One is rarely able to obtain much else than fowls from natives, and except in towns and large villages, where there are regular bazaars and markets, even fruit other than coconuts and bananas is scarce. Tinned and bottled preserves soon become insipid to the palate, but dried fruit, such as apples, apricots and prunes, we found far more attractive, and they should always be carried when native supplies are uncertain. In fact, beyond a few necessaries such as milk, butter, jam, tea, coffee, sugar, cheese and curry stuffs, and a few more luxurious articles, like soups, pickles—but those who have tried a well-seasoned piece of salt junk will admit that these and mustard are almost absolute necessities—sauces, etc., the fewer tinned provisions there are the better, so far as health in the tropics is concerned. When one can keep the hen-coop well stocked, and there is plenty of rice on board, one never feels like grumbling while there is any amount of work to be done.

In the matter of collecting apparatus, the newer powders are preferable, as with them there is less chance, through absence of smoke, of losing sight of the specimen as it falls, which is often the case otherwise. It is well to have cartridge cases of different colours for ease in selection, and the sizes of shot most useful seem to be:—SSG for pigs, deer, and large monkeys; AA and II for monkeys, eagles, and other large birds; V for pigeons, and others of similar size in high tree tops; VIII for the same at moderate range, and for smaller birds and squirrels, etc., when distant; while 2 drams of powder and ½ ounce of XI shot—the cartridge filled out by several wads between the two—is most useful for small[Pg 5] birds and animals up to 20 yards, and for others at proportionate distances. For such little things as sunbirds, and for snakes, lizards, or for point-blank shots, we carried auxiliary barrels, about 9 inches long, that can be slipped in and out of the gun like an ordinary cartridge, and which fired an extra long .32 calibre brass cartridge loaded with a pinch of dust shot (No. XIII). These were invaluable for obtaining the smaller specimens without smashing, and had a killing range of about 12 yards.

There is no more perfect weapon for the collecting naturalist than the three-barrelled guns that we used—shot barrels fully choked, and the third, placed beneath the others, rifled for long .380 cartridges. With one of these, the auxiliary barrel, and a proper selection of cartridges, one is ready for anything that may turn up other than the larger "big game," for the equipment is so portable that there is no temptation ever to leave part of it behind.

The only drawback to such an outfit lies in the time lost in selecting a suitable cartridge for each shot, but the perfect specimens obtained by this method are ample compensation for the extra trouble involved. Even in this way accidents sometimes happen however, as when on one occasion, while walking through some grass, a tiny button-quail sprang up, and was knocked over at close range with what was thought to be a small charge of No. XI shot. The specimen was not found at once, but as it was the first of the kind obtained (and has since proved to be of a new species), the search was persisted in until after a quarter of an hour a little purple pulp attached to a wing was discovered. The collector had forgotten which barrel contained the smaller cartridge, and, pulling the wrong trigger, had fired a full charge of No. VIII from about that distance in yards, at a wretched little bird about the size of a sparrow!

To fire at flying birds in the jungle is both wasteful and unprofitable, for while a bird is only to be seen for a moment as it flashes between the branches, even if hit, it infallibly becomes lost in the dense luxuriance of vegetation. The chances in the favour of the quarry are, however, largely increased by a careful[Pg 6] selection of the smallest cartridge possible on each occasion, often a tiresome stalk, and a large amount of dodging about to get a clean shot through the leaves and branches, so that the event is by no means a more foregone conclusion than sport in the open.

Besides bags for cartridges and specimens, with extractor, knife, string, cotton-wool, and wrapping paper, it is absolutely essential, if it is intended to penetrate the jungle at all, that one should carry some sort of implement—cutlass, parang, or macheté—to hew a way through the tangled undergrowth.

It is far the best plan, when shooting in the tropics, not to indulge in a too elaborate outfit. The most suitable and common-sense clothing consists of a stout cotton suit of pyjamas, grey or brown in colour for preference, with pockets; the ends of the trousers should be tied round the ankles with string, to keep out the ants and leeches, and only when these and thorns are very bad need stronger trousers and puttees be worn. Such clothes are easily put on and off, are comfortable, and are not heavy when soaked with water, rain, and perspiration.

On board ship, when away from civilisation, we invariably wore a similar dress, or the national garment of Malaya, the sarong, than which nothing is more comfortable in a hot climate, unless it be the exceedingly sensible dress of the tropic-dwelling Chinese.

For head-dress there is no better gear than an old felt hat (terai), which can be rolled up and put away in the game-bag when one is in the shade of the forest. In one of the most delightful books that has been written about the East, the following lines occur:[4] "Given a thick jungle, trees 200 feet high, and a mushroom-helmeted sportsman, it will be seen that comfort and a large bag are incompatible. A long training in the Sistine Chapel is necessary for this work. Absurd as it may seem, my spine in the region of the neck eventually became so sore that I was on more than one occasion compelled to give myself a rest." With the latter part of the passage I perfectly concur, for one often stands[Pg 7] for minutes at a time staring vainly upwards, to where, right overhead, the specimen that one knows is there, is vocally proclaiming its presence, and the effect on the back of the neck is, after a time, often one of excruciating agony. Strangely enough, large birds like parrots and pigeons are often the most difficult to see.

But why the helmet in the shade of the forest? We ourselves never wore hats except when out in the open or going to and fro between the schooner and the shore, while the sun was high, and experienced no ill effects from being without them at other times, although one of us made it a practice to keep his head shaved for the sake of coolness. Though they perhaps lay me open to an accusation of thick-headedness, I mention these facts to show that it is not necessary to burden oneself with an awkward sola topee with the idea of evading danger from the sun in such circumstances.

A cloudless sky and a blazing sun; a long stretch of yellow beach lapped by a calm sea of brilliant green above the reef, verging into an intense sapphire in the distance. Inland, swelling hills clothed in densest jungle—the topmost ridge capped by a delicate tracery of foliage that stands out clear cut in the pure atmosphere. Adjoining the sandy shore a grass-grown level expanse, with a grove of stately palm trees, through which runs a rippling brook, and lastly, two or three native huts and their occupants, so that one can lie, pyjama-clad, in the shade, and consume young coconuts without first having to climb for them.

"Only to hear and see the far-off brine,

Only to hear were sweet, stretched out beneath the pine."

Is it fair that we should call the native of the tropics lazy because in some parts of his domain the labour of an hour supplies his daily wants? The working man of colder climates, by eight and even twelve hours' occupation, obtains no more, and often less. The others are the true lotos-eaters, and when one is[Pg 8] amongst them one often feels, as doubtless they do themselves, could they formulate their sensations:

"... Why should we toil alone,

We only toil who are the first of things,

And make perpetual moan,

Still from one sorrow to another thrown:

. . . . . .

'There is no joy but calm!'

Why should we only toil, the roof and crown of things?"

These are one's thoughts, while captivated by the charm of the islands, and if feelings change when analysed in more virile countries, the transformation of ideas only goes to show how relative to circumstances are such things as industry and idleness.

The foregoing are a few prosaic items about a form of life which, although when indulged in too long, it perhaps causes now and again a desire for the amenities of civilisation and a shirt-front, yet when it is over, always leaves a longing for further experiences whenever one is haunted by thoughts of the palms, the sunlight, and the sea; wanderings in the jungle; strange birds, animals, and vegetation, and pleasant memories of easy-going islanders.

ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

Shipboard Monotony—Edible Sharks—Calm Nights—Squalls—Barren Island—Appearance—Anchorage—Landing-place—Hot Spring—Goats—The Eruptive Cone—Lava—Paths—Interior of the Crater—Volcanic Activity—Fauna—Fish—The Archipelago—Kwang-tung Strait—Path-making—The Jungle—Birds—Coral Reefs—Parrots—Two New Rats—Inhabitants.

We were six days out from land before Barren Island hove in sight. Since New Year's Day,[5] when we got up anchor amongst the islands of the Mergui Archipelago, the schooner had been carried by the lightest of breezes towards the Andamans. The days slipped by, each one as monotonous as its predecessor; there was no change in the wind, save when it fell calm for a space, and the sun was so hot that we gladly sought shelter in the cabin, where occupation might be found with a book. Once we harpooned a porpoise, but he broke away from the iron, and now and again, on a line trailing astern, we caught a small shark, immediately claimed by the cook, to appear later on the table; for although the name seems instinctively to prejudice one against them, all sharks are edible, and the smaller species, which can scarcely include human material in their dietary scale, are by no means to be despised when fresh provisions are unobtainable, in spite of being often somewhat dry and flavourless.

But the nights were ample compensation for any possible discomfort by day. Around was the calm flat sea, and overhead a pale blue sky, across which swung the tropic moon,[Pg 10] so bright that all but the larger stars were drowned in light. Then, when the heat of day was over, we would take our pillows on deck and—in a perfect silence but for the creaking booms and the water gurgling in the scupper-pipes—watch mast and stars swing slowly to and fro until sleep brought unconsciousness of the night and its beauty.

But it is not always so even in the tropics, and the contrary, and not infrequent, experience, without going to extremes, is the squall of a moonless night.

As the dense clouds rapidly advance from the horizon and blot out the stars, one is left in inky darkness broken only by the glimmer of the lamps in the binnacle. Soon the wind comes tearing down and whistles loudly in the rigging, while with lowered sail, the vessel seems to fly through the water—judging by the rolling wings of foam that stream from her shoulders and gleam weirdly in the green and red rays of the sidelights. Presently the rain falls in a stinging chilly torrent, killing the breeze and leaving the boat rolling uncomfortably on the surface; and when the furious downpour is over, and the night is quiet once more, all that remains to show the past disturbance is sodden canvas, stiffened cordage, and the uneasy heave of the wind-whipped sea.

So the squall passes—generally leaving a calm behind it—having in a little space squandered enough unavailing breeze to have helped the vessel on her course for hours to come.

At last, one evening, we saw Narkondam from the masthead, about sixty miles away; and next morning Barren Island had risen above the horizon. These two little islands, eastern outliers of the Andamans, and connecting links between the eruptive regions of Burma and Sumatra, are both of volcanic origin, though the former is now extinct.

Barren Island, about two miles in diameter, is merely the crater of a volcano rising abruptly from the sea, which, a quarter of a mile from shore, is nearly everywhere 150 fathoms or more in depth.

THE LANDING-PLACE, BARREN ISLAND.

THE LANDING-PLACE, BARREN ISLAND.

Approaching from the east, we caught a glimpse, while still[Pg 11] some distance off, of the black tip of an eruptive cone, showing above the rim of the crater, which at a nearer view proved to be of igneous basalt, clothed on the outer slopes with a growth of creepers, bushes, and of trees 50 to 60 feet high, frequented by numbers of fruit pigeons.

On the north-west side of the island the wall of the old crater has been broken down, and a large gap about a hundred yards wide at the base affords an easy means of access to the interior. It is through this opening that the best view of the cone is obtained from seawards.

As we sailed past the gap that afternoon the scene was one of striking beauty. Against a background of bright blue sky the little island rose from a sea of lapis-lazuli, which ceaselessly dashed white breakers on the rocky shores. The steep brown slopes, part clothed in brilliant green, framed in the cone—a black and solid mass, round which a pair of eagles circled slowly.

Fortunately for those vessels which may visit the island, there is one place off-shore where soundings can be obtained with the handline, and there we came to anchor in 15 fathoms, a little beach and clump of coconut palms bearing N.N.E., a quarter of a mile away.

Sails were soon stowed and we rowed off to reconnoitre the gap, which is the only practicable landing-place; everywhere else the land slopes steeply to the sea. To the south a heavy swell was breaking on the shore, but in the little cove formed here the sea was perfectly calm, and so clear that as we passed into shallower water the coral bottom, 10 fathoms down, was plainly visible.

A rough wall of lava about a dozen feet high stretches across the opening, and to the left of this, among the stones and boulders of the shore, we found, below high-water mark, a little stream of fresh water trickling to the sea; it is the only water on the island, and at that time was at a temperature of 97.5° F.[6]

[Pg 12]The only inhabitants of any size that the island can boast of are a large herd of goats, whose well-worn tracks show plainly on every slope and cliff. A score of these animals, left in 1891 by the station steamer from Port Blair, have so thriven that their descendants must now be numbered in hundreds, and are so free from fear, and unsuspicious, that had we needed them we could have butchered any quantity.

From the landing-place the ground slopes gently upward to the floor of the crater, which is about 50 feet above sea level. In the centre of this rises the little cone of slightly truncated form. Symmetrical in outline, 1000 feet high and perhaps 2000 feet in diameter at the base, there is nothing it reminds one of more closely than a huge heap of purplish-black coal-dust, with patches and streaks of brown on the top.

To right and left of the base, and thence towards the sea, flows a broad black stream of clinkery lava, the masses of which it is composed varying in dimensions from rugged blocks of scoriæ a ton or more in weight to pieces the size of one's fist. The journey across it would be one of some difficulty, were it not that the goats, coming from all parts of the island in their need for water, by constantly travelling to and fro in the same line, have worn a smooth and deep path from side to side, some 200 yards distant from the sea.

THE ERUPTIVE CONE, BARREN ISLAND.

THE ERUPTIVE CONE, BARREN ISLAND.

The level ground at the base of the cone, widest on the southern side, is covered with tall bamboo grass and various kinds of low bushes. On the inner slopes of the crater, the south and east sides, which are of rocky formation, support a certain amount of small forest, in which we quickly noticed the absence of such tropical forms as palms, rattans and lianas, and of trees more than 60 or 70 feet high and 4 or 5 feet in diameter;[7] [Pg 13] the remaining sides, composed mainly of volcanic ash, afford foothold only to a coarse tussocky plant growing in clumps on the loose black dust. We found these latter slopes not at all an attractive scene of operations, for the feet sank and slipped at every step, and raised at the same time clouds of fine black dust.

During the day the heat in the interior was extreme, for the sun's rays beat down upon, and were reflected from, the dark slopes, while the wall of the crater completely cut off any sea breeze. We did not ascend the cone, for our stay was to be short, and we wished to investigate the fauna as fully as possible; but from reports of the visits paid to the island once every three or four years from Port Blair, it would seem that the slight signs of activity still existent consist of an issue of steam and the continued sublimation of sulphur; while of the two cones which form the top, one is cold, and already bamboo grass and ferns are beginning to clothe the entire summit. There is ample proof in those details which have been recorded of the island during the last century that the volcano is rapidly becoming quiescent, and is indeed, perhaps verging on a condition of extinction, as has long been the case with Narkondam.

Captain Blair, who passed near in 1795, writes of enormous volumes of smoke and frequent showers of red-hot stones. "Some were of a size to weigh three or four tons, and had been thrown some hundred yards past the foot of the cone. There were two or three eruptions while we were close to it; several of the red-hot stones rolled down the sides of the cone and bounded a considerable way beyond us.... Those parts of the island that are distant from the volcano are thinly covered with withered shrubs and blasted trees."

A few years later Horsburgh records an explosion every ten minutes, and a fire of considerable extent burning on the eastern side of the crater. In the next thirty years, the[Pg 14] subterranean forces had considerably diminished in activity, and at the end of that period only volumes of white smoke with no flame were to be seen. Drs Mouat and Liebig, who visited the island within a few months of each other in 1857, write respectively of volumes of dark smoke, and clouds of hot, watery vapour. In 1866, a whitish vapour was emitted from several deep fissures, and about 1890, steam was seen to be issuing at the top from a sulphur-bed, which was liquid and pasty, and a new jet was coming from a lump on the sloping side of the cone; while the sole evidence of activity now to be observed is the deposition of sulphur, and an escape of steam that often condenses on the surface rocks.

Concerning the fauna of the island, birds—inside the crater—were not numerous: commonest were a little white-eye (Zosterops palpebrosa), and the Indian cuckoo, which swarmed everywhere, its loud cries, "ko-el, ko-el," resounding in all directions. The only mammals other than the goats were rats, which, while of one species (Mus atratus, sp. nov.), afford a rather curious example of range of colouring, for while many were of the usual brown shade, a great number were of a glossy coal-black, much resembling in tint the lava and volcanic dust in which they made their homes. The island is everywhere riddled with their holes, but though so numerous, the land-crabs may fairly claim to divide the place with them. Trapping for rats was a failure, for no sooner was one caught than it would be torn to pieces by the crabs, who in other instances would spring the trap long before the others were attracted by the bait.

Altogether we landed four times, but soon found that very little variety was to be obtained: the sea, however, swarmed with fish, and many fine catches of rock-cod, trigger-fish, and mullet, 20 to 70 lbs. in weight, were made by the crew.

Late one evening we left Barren Island, and with a fair though moderate breeze, which, however, soon drew round against us, covered the 36 miles to the Andamans proper,[Pg 15] and anchored before noon next day in the Kwang-tung Juru.

From a distance, all the islands of the Archipelago appear to rise to about the same height,—between 500 and 600 feet—presenting a fairly level sky-line from north to south, and with the exception of East Island, which shows a white sandy beach, all seem fringed with thickets of mangroves.

The strait, which is about a mile wide, separates the islands of John and Henry Lawrence, and with its smooth water and low banks, on which the veil of mangrove and jungle, extending to the water's edge, is broken at short intervals by small bluffs of pale clay shale, might easily, but for its brilliant blue colour, be mistaken for a quiet river.

We landed in the afternoon on the eastern shore, and at once set to work cutting a path, for here was the densest kind of Andaman jungle, and although within it one comes across little patches where the bush is fairly open, it is, on the whole, a wild tangled mass of trunks and branches, bound together by countless ropes of creeping bamboo and thorny rattan.

Cutting right and left, avoiding a thick bush here and a hanging screen of creepers there, perspiring at every step, we forced a sinuous way in from the beach, until, coming upon a well-trodden pig-track, we found progress so much easier, that, with a little chopping now and again, we were able to move about with some degree of freedom, and along the path so slowly made, a long line of traps was set and baited in readiness for night.

Such a performance is one that regularly occurs during the first visit to each fresh locality in which one collects, and on these occasions the noise caused by chopping away branches and crashing through the bushes very naturally makes the denizens of the jungle conspicuous by their absence.

Afterwards, however, as you move quietly along the path, with all the faculties freely given to the detection of those various objects to the desire for possession of which your presence is due, the jungle seems a much less lonely place, and after days spent in wandering in its shade, during which a bit more path[Pg 16] has been cut here, and a few more yards of open space added there, you find that you can take quite a long walk, entirely uninterrupted by use of the parang hanging at your side.

Among the few birds shot that first afternoon were the beautiful Andamanese oriole, with gorgeous plumage of black and yellow, and a peculiar cuckoo—Centropus andamanensis—soberly clad in brown and grey. This bird was a source of much disappointment on one occasion. There are no squirrels known to the Andamans, and seeing what I took for one, without waiting, in the momentary excitement of an apparently fresh discovery, to look more closely, I made a rapid snap-shot, and down tumbled a cuckoo; my consequent disgust may be imagined. The bird, however, can easily be mistaken for a small mammal, for besides resembling one, with its dark brown plumage and fairly long tail, its habit is to spring from bough to bough and creep along the branches in a very rodent-like manner.

Warned by the fading daylight, we returned to the shore, and found a quarter of a mile of dry coral between ourselves and the water, with the dinghy high and dry, so, after making it fast to the mangroves, we picked a way across the reef and hailed the schooner for another boat.

These coral-reefs, although their beauty of form and colour—an endless change of myriad shapes and tints—when seen through the clear water from a boat above is quite beyond description, awaken far less admiration when they have to be crossed on foot while the tide is low. It is impossible for even natives to cross them barefooted. Nearest the shore comes first a belt of mud and coral débris that is easily traversed; next lies a broad strip of sharp and brittle madrepores which break and crumble beneath one's weight; while, seaward, rise from deep water the Astræas—great solid masses of which the reefs are mostly built; and as one jumps from mound to mound, one vaguely wonders at which of those in front a slip may occur, and as the least result plunge one head over heels into the pools around. With a small boat, however, shallow and quick-turning, it is generally possible to pass through these latter and reach a point, where, protected by boots,[Pg 17] the shore may be attained at the slight expense of a wetting below the knees.

To escape this unpleasant little journey, we moved a day or two later farther up the strait to where the shore was free from coral, and therefore more accessible, although having reached it, we were confronted by a precipitous cliff of crumbling earth, but when the top was gained, after a zigzag climb, we moved on level ground covered with heavy jungle.

The smaller species of birds were very rare here, but we got almost immediately the first specimen of the island parrots—the brilliant green Palæornis magnirostris. This bird is the local representative of a continental form, from which it differs only in the enormous size of the bill, which in the male is of bright scarlet.

It is a somewhat callous thing to attempt to do, but should one succeed in only severely wounding a parrot, others of the species are sure to be obtained. The cries of the injured bird so attract its companions that they will gather near from all parts within hearing, and seem so possessed with curiosity to know what is wrong, as to be, for the time, perfectly oblivious of the collector and his gun, while they sit around or fly nearer and nearer to their wounded companion and answer its loud croaking notes with others equally harsh.

Parrots of three species were very numerous, and perhaps the most frequent noise in the jungle was their shrill scream, uttered as they flew from tree to tree. Many big black crows, too, flopped—a word which exactly describes their movement—noisily about, and, when hidden by a screen of leaves, we mimicked their cawing notes, more bewildered birds it would be difficult to find. In these woods the larger birds were fairly common, and the traps obtained for us numerous rats of two varieties, one of which squealed pitifully when approached (Mus stoicus, sp. nov., and M. flebilis, sp. nov.).

The Archipelago is inhabited by a tribe known as Aka-Balawa, now on the verge of extinction, as it numbers only[Pg 18] twenty individuals; but the sole traces of occupation we came across were the decayed remains of a canoe, lying up one of the mangrove creeks that branch off from the strait.

We remained here three days, all that could be spared from the time given to the cruise, and early on January 11th left for Port Blair.

We enter the Harbour—Surveillance—Ross Island Pastimes—Visit the Chief Commissioner—The Harbour—Cellular Jail—Lime Kilns—Phœnix Bay—Hopetown—Murder of Lord Mayo—Chatham Island—Haddo and the Andamanese—Tea Gardens—Viper Island and Jail—The Convicts—Occupations—Punishments—Troops—Departure.

A fresh breeze from the north raised an army of dancing white-caps on the sea, as, rolling along with the wind astern, we made the run to Port Blair in about seven hours.

Easily picking up the Settlement while some distance off, on account of its proximity to Mount Harriet—a pointed hill rising about 1200 feet—we came to anchor to the south of the jetty inside Ross Island, and were immediately boarded by one of the native police—a representative of which body was always on board during the day throughout our stay. This measure is taken to see that the crews of vessels in the harbour hold no communication with the convicts, and also for the prevention of smuggling.

Soon afterwards the doctor and port officer came aboard: both these gentlemen seemed at first to regard us with some suspicion, and indeed by this time, more than two months out from port, we were certainly a rather ruffianly looking party.

The island of Ross is situated at the mouth of the harbour, and tends greatly towards its protection. It is hilly, about 200 acres in area, and is divided into two almost equal parts by a wall running east and west across it; the southern portion is occupied by the barracks of the convicts, and the other contains the headquarters of the Settlement.[Pg 20]

On the summit stands the pleasant-looking residence of the Chief Commissioner; the church, and the barracks (architecturally modelled on Windsor Castle) for European troops; both the latter built of a handsome brown stone quarried on the mainland. Below these come the mess, containing a fine library and some beautiful examples of wood-carving executed by Burmese convicts; then the brown-roofed bungalows of the Settlement officers, all bowered in tropic foliage, amongst which graceful palms and traveller's trees stand prominently forth; and lower still, near the sea, are the treasury, commissariat stores, and other Government buildings. The whole place—in itself of much natural beauty—is kept in most perfect condition by a practically unlimited supply of convict labour.

At first sight, it seemed an altogether delightful spot to find in such an isolated corner of the earth; but its melancholy aspect is quickly and forcibly brought home to one by a visit to the jail on Viper Island, and by the continuous presence of the convicts, who are rendered conspicuous by their fetters, or neck-rings, supporting the numbered badges by which the wearers are distinguished.

As usual with our countrymen, "when two or three are gathered together" in distant portions of the world, plentiful facilities for outdoor amusements have come into being. There are cricket and tennis grounds—the latter both concrete and grass—near which a band of convicts discourses very fair music several times a week. There is a sailing club too, and nearly every Saturday throughout the year races for a challenge cup are held in the breezy harbour, at which a score of various craft are often found competing; and the Volunteer Rifle Corps has some thirty members, who compete with gun and revolver for a numerous list of prizes and trophies. Good salt-water fishing is to be had with the rod, for fish in great variety are everywhere abundant; and on the mainland, near Aberdeen, golf and hockey are played.

ROSS ISLAND (northern extremity).

ROSS ISLAND (northern extremity).

With all this, it is probable that the gentler sex find things somewhat dull at times, for shopping, in the feminine sense of[Pg 21] the word, is impossible. There are no shops, and the wants of the community are supplied by a co-operative store, at which, it is reported, in more than one year recently, articles have been sold at a price considerably under cost. Besides this, there is only the native bazaar, which is, of course, ubiquitous in the East.

Before visiting the Nicobars, it is necessary for all vessels to obtain a permit, so, in duty bound, we called one morning on the Chief Commissioner, and to him we are indebted for much information that became valuable in the next few months.

Colonel Temple, who takes much interest in the natives of his district, particularly from a philological standpoint, possesses a very complete ethnological collection of Andamanese and Nicobarese articles, and an aviary containing a great number of the birds inhabiting the two groups of islands. All these objects we were fortunate enough to see, and so gained at the outset a very good idea of those things we were so anxious to obtain specimens of for ourselves.

One morning, in the company of Mr P. Vaux, acting port officer, we made a delightful tour round the harbour in one of the Government launches.

Port Blair is a long, ragged indentation, about seven miles from head to mouth, broken and diversified by numerous little bays and promontories. The shores—intersected by numerous roads—are almost entirely cleared from jungle, and since they have been in this condition, fever has been practically unknown amongst the European community.

Passing first close by the suburb of Aberdeen, which is on the mainland just opposite Ross, we obtained a good view of the Cellular Jail, a huge building of red-brown bricks, with long arms—three storeys in height—stretching from a common centre like the rays of a starfish. It has been built almost entirely from local resources, and with local establishment and labour, and holds 663 cells and the accompanying jail buildings. Here each newcomer is incarcerated in solitude for six months, with the double intention of such confinement acting both as a[Pg 22] moral sedative and a warning of what may happen again if his behaviour is not satisfactory in future.

We steamed along past the brickfields; the kilns, where, from the raw coral, lime is manufactured; but as the salt cannot be thoroughly washed out, and subsequently effloresces from the mortar, the result is a rather inferior quality.

At Phœnix Bay, a little farther up the harbour, where we landed to inspect the shipyard and workshops, are sheds fitted up with apparatus for blacksmiths and latheworkers, carpenters and woodcarvers, where occupation is provided for more than 600 skilled workmen. The numerous boats one sees passing to and fro in the harbour are built here, for the shipyard can undertake anything from a 250-ton lighter or 70-feet steam-launch down to a half—rater or the smallest dinghy. The materials for construction are close to hand, since the woods used (padouk for the planking and pyimma for frames) are obtained from the neighbouring forests.

Some years ago Phœnix Bay was a swamp, but now large, brick, steam workshops and wooden sheds of the marine yard, in which the lighters and launches are constructed and repaired, stand on the land reclaimed; and connected with these is a slipway, one of the largest in India, that is entirely of local construction—the whole of the ironwork of the carriage, rails, wheels, and ratchet, having been cast on the spot.

Almost opposite Phœnix Bay, the station of Hopetown, conspicuous by its aqueduct, stands on the northern shore. It was here that in 1872 Lord Mayo, the most popular of Indian Viceroys, was murdered by a fanatical prisoner.

ANDAMANESE MEN.

ANDAMANESE MEN.

The Viceroy had visited Mount Harriet in order to judge of its suitability as a sanatorium, and had just finished the descent. "... The ships' bells had just rung seven; the launch, with steam up, was whizzing at the jetty stairs; a group of her seamen were chatting on the pierhead. It was now quite dark, and the black line of the jungle seemed to touch the water's edge. The party passed some large loose stones to the left of the head of the pier, and advanced along the jetty,[Pg 23] two torchbearers in front ... and the Viceroy stepped quickly forward before the rest to descend the stairs to the launch. The next moment the people in the rear heard a noise, as of 'the rush of some animal,' from behind the loose stones; one or two saw a hand and a knife suddenly descend in the torch-light. The private secretary heard a thud, and instantly turning round, found a man 'fastened like a tiger' on the back of the Viceroy. In a second, twelve men were on the assassin; an English officer was pulling them off, and with his sword hilt keeping back the native guards, who would have killed the assailant on the spot. The torches had gone out; but the Viceroy, who had staggered over the pier side, was dimly seen rising up in the knee-deep water and clearing the hair off his brow with his hand, as if recovering himself. His private secretary was instantly by his side in the surf, helping him up the bank. 'Burne,' he said quietly, 'they've hit me.' Then in a louder voice, which was heard on the pier—'I'm all right, I don't think I'm much hurt,' or words to that effect. In another minute he was sitting under the smoky glare of the re-lit torches, on a rude native cart at the side of the jetty, his legs hanging loosely down. Then they lifted him bodily out of the cart, and saw a great dark patch on the back of his light coat. The blood came streaming out, and the men tried to stanch it with their handkerchiefs. For a moment or two he sat up in the cart, then he fell heavily backwards. 'Lift up my head,' he said faintly; and said no more."[8]

Leaving Phœnix Bay, we steamed past Chatham Island, where the sawmills are situated, and where a number of hospital convalescents are kept busy with the easy task of manufacturing rope and mats from the coir prepared in Viper Jail. On the approach of a hurricane, vessels in port proceed up harbour and anchor above this island, where they are secure from all danger.

Our next stopping-place was at Haddo, where we visited the Andamanese in their Homes, and out on the water saw a number of natives fishing from canoes.[Pg 24]

The sheds in which the aborigines are domiciled are substantial structures of attap, standing near the sea in the shade of coco palms. We found present eight or nine women, and twice that number of men and boys, who, on catching sight of our advance, ran out of doors to meet us. Two or three babies present were carried by the mothers in a broad band suspended from forehead or shoulder. The first thought that flashed into one's mind on perceiving them, with their small stature, sooty skins, and frizzly hair, was that here were a number of juvenile negroes ("niggers"): they are, however, far better-looking than that people, and some of the women might almost be called pretty, even when judged from a European standpoint.

For clothing, the men wore breech-clouts of red cotton, and strings of beads or small shells about the neck: the ornaments of the women consisted of similar necklaces, and several girdles of beads or bark, in the lowest of which a green leaf was inserted, by way of apron. The hair of the women was slightly shorter than the men's, but worn in a similar fashion—all but a circular patch on the top of the head, like a skull-cap, was shaved away, and this was often divided by a broad band of bare skin running from back to front. Chest and back were covered with skin decoration of the cicatrice type, which, healing without any tendency to keloid, left a smooth mark, distinguished by its lustre only from the normal surface. Many had smeared themselves with fat, which gave the skin a very shiny appearance.

ANDAMANESE WOMEN.

ANDAMANESE WOMEN.

The bows carried were of the recurved paddle type that attains its greatest development in the Andamans,[9] and the arrows were armed with formidable iron points and barbs: the heads of these are detachable, and are connected with a shaft by a short cord of fibre, which is wound about the arrow by twisting the head in its[Pg 25] socket. These arrows are used in shooting pig, and of course much impede the escape of any animal, by the shaft disengaging from the head and catching in the undergrowth of the jungle. The bows were constructed of white wood, and handled with the recurved end downward.

The foreheads of some of the women were daubed with white clay, and one, in addition to a quantity of coral ornaments, wore suspended from her neck a human skull daubed with red earth. This, however, is not, as was long supposed, a sign of conjugal mourning, for any of the relatives or intimate friends of a deceased person are qualified to wear his disinterred bones, and the skull often passes round amongst a considerable number of people.

We were agreeably surprised at the appearance of the natives, as they were clean, pleasant-looking, and merry, apparently somewhat childish in disposition, and much given to chatter and laughter.

On leaving, we flung a number of small coins amongst them, and these were scrambled for with great noise and excitement.

The Homes are occupied from time to time only by the natives, who are allowed to go and come as they please, and while dwelling in them are supplied with provisions. Love of the jungle, and the life to which they are born, is so deeply rooted in the aborigines, that although they occupy the sheds intermittently for varying periods, few have been found who are sufficiently attracted by the neighbouring civilisation to become permanent residents.

As we proceeded up the harbour we caught a glimpse, at the head of Navy Bay, of the tea gardens which have for some time been established there. The product is very coarse and strong, and finds favour with the European troops in India, and with the Madras Army.

Lastly we came to Viper Island, which has been not inappropriately christened "Hell," for in Viper Jail are kept the very worst of the prisoners in the Settlement, and it must not be forgotten that here are collected the scum of the whole immense Indian Empire and of Burma as well. No one is[Pg 26] sent to the islands who has less than seven years to serve, and many here, perhaps, are those, who, but for some flaw in the evidence which convicted them, might long ago have paid the last penalty for their crimes.

Viper Island is elevated in parts with a somewhat broken surface, and the Jail, with its grey-and-white walls, standing among a group of trees, shows picturesquely from the summit of a hill. A number of convicts are confined to the island, besides those in the prison, and to accommodate them barracks have been erected in various spots.

We landed on a jetty, and, passing by the guardhouse at its foot, soon climbed the little hill, on the top of which the prison is situated. First, and grimmest sight of all, came the condemned cells and the gallows, and then we passed—accompanied by a guard of police—through room after room full of men reclining on slabs of masonry. The shackled inmates of these wards, who rose unwillingly with clanking irons at the word of command, are under the control of promoted convicts made responsible for their behaviour. The effect of our entrance varied with different individuals; some, apparently apathetic and sullen, took no notice whatever, while others seemed to evince the liveliest curiosity.

As the day of our visit was a Sunday, no work was being done: all the inmates were undisturbed, save a few whose heads were being cropped, and some convalescents receiving their midday ration—a chapátí, and an ample portion of coarse boiled rice.

The scope allowed for employment in the prison is somewhat limited, for, while the work must be of sufficient severity to act as a punishment, it must of necessity be of such a nature that the tools accessory to it are not of a kind that can be used by those handling them in an attack on jailers or fellow-prisoners. Among the tasks set are coir-pounding, in which a certain quantity must be produced and made into bundles every day: the heavy mallets used are fastened, for safety, by a short lanyard to the beam on which the husk is broken up. Again,[Pg 27] oil has to be expressed from a given weight of copra by pounding the material in iron mortars with unwieldy wooden pestles. Wool-teasing is yet another form of occupation.

Besides the wards, there are a number of cells for solitary confinement; some of these were occupied by prisoners suspected of malingering, others by those awaiting punishment.

This last, of course, takes various forms, from—for instance—the dark cell, where an offender may be incarcerated for twenty-four hours, to castigation with a rattan, in which, it is said, the maximum sentence of thirty strokes can be applied so severely as to be fatal to the recipient. Lastly, of course, comes execution by hanging, which is inflicted in the case of those prisoners, who, being already under severe sentence, attempt the lives of their fellows, their warders, or the officials of the Settlement.

The transportation of European offenders is now discontinued, but a large number of female convicts are engaged mainly in turning the wool prepared in Viper Jail into blankets.

Caste—a most important point in connection with people of India—is carefully respected, and the Brahmin prisoners are nearly all employed as cooks.

The majority of the convicts are from the Indian Peninsula, and are resident for life. Of the Burmese, however, the greater part are serving sentences of ten years, for engaging too recklessly in the national pastime of dacoity, and many of them are employed in the jungle and as boatmen.

To maintain discipline, and for the protection of the Settlement, a military force of about 440 men is stationed at Aberdeen, Ross, and Viper—two companies of European and four of native troops—and a battalion of military police.

After leaving Viper Island we returned to the headquarters of the Settlement, where next day we left behind the last post of civilisation met with, until three months later we reached Olehleh, the most northerly of the Dutch colonies in Acheen.

Gunboat Tours—South Andaman—Rutland Island—Navigation—Landing-place—Native Camp—Natives—Jungle—Birds—Appearance of the Natives—Our Guests—Native Women: Decorations and Absurd Appearance—Trials of Photography—The Village—Food—Bows, Arrows, and Utensils—Barter—Coiffure—Fauna—Water—New Species.

After leaving Port Blair, where we got up anchor at half-past three in the morning to make the most of a light breeze, we sailed slowly along the coast of South Andaman, until, rounding the point of the south-east corner, we came to anchor in Macpherson Strait.

Just outside the port we met the R.I.M.S. Elphinstone returning from a census-taking visit to the Nicobars; three or four times a year she makes a ten days' trip round the group, stopping at a few of the more important places; and these cruises are almost the only thing that brings home to the natives the fact that they are under the British raj.

For some distance south of the Settlement the land consists of undulating grassy hills, dotted with coco palms, and streaked by gullies, in which dark clumps of jungle still remain. It is an ideal country for game, and some years ago hog-deer were introduced; but, although they have multiplied, they are very rarely seen, and have afforded but little sport.

Nearer the strait, the hills by the coast are still covered with forest; and between the stretches of sandy shore at their feet grow luxuriant thickets of mangroves.

ANDAMANESE SHELTER.

ANDAMANESE SHELTER.

Rutland Island, rising on the east in tall precipitous cliffs, on the north slopes gently to the strait, which on both sides is bordered by alternate tracts of yellow beach and bright green mangrove.

We hauled round Bird's Nest Cape—a bare rocky headland of serpentine, still producing those edible delicacies which are responsible for the name—and, with a man aloft to con a passage along the coral-reef, carefully avoided a rock near mid-channel, and took up a berth in quiet waters about a mile from the entrance of the strait.

When sailing along little known shores, especially in the tropics, a look-out man should always be stationed at the masthead, for from that place dangers of reef and rock unnoticed from the deck are plainly visible. Year by year coral-reefs increase, and banks alter so greatly that entire reliance cannot be placed on the chart, even though it be of comparatively recent date.

We landed on South Andaman in a little bay, whose waters lapped a beach of golden sand. It was, as usual, nearly filled with coral, but fortunately the tide was never so low that we could not land directly on the shore. To left and right the land rose in gentle hills, on the one hand forest, and on the other grass-clothed, but beyond the centre, where it was flat, lay an expanse of tangled swamp.

Although their tracks, made since the last high tide, ran all along the beach, we saw no natives then or later; but just within the bush we found an old camping-place—cold ashes, heaps of broken shells, and a dilapidated hut about 6 feet square and high, made of light branches stuck in the ground, with tops drawn together and covered with a few palm leaves laid stem downwards.

That night a fire shone brightly on the beach of Rutland Island; and so next morning, while Abbott in the dinghy went north to make the round of the traps, I, with a crew in the whaleboat, rowed across the strait, and when we were within two or three hundred yards of the shore, a tall native ran down the[Pg 30] beach and commenced waving a flag on the end of a long pole.

As the sea was pounding heavily on the reef, a couple of men were left in the boat to keep it off shore, and the rest of us, jumping overboard, waded to the beach. Two or three other natives now arrived, and we showed our good intentions by slapping them on their backs, with broad grins, to the latter part of which process they responded most heartily.

It was too early in the day to get to work with the camera, so, after fetching my gun from the boat, I struck into the jungle and spent an hour with the more clothed of its inhabitants.

The jungle was of the kind that may perhaps be best described as forest: that is to say, it was fairly free from the usual superabundance of rattans, lianas, and all those creeping growths which close the intervals among the trees with a thorny network of vegetation, and compel the intruder to go where he can and not where he will. Mighty trees towered upwards, branches interlacing and shutting out the sun, while down below, in the aisles of tree-trunks, stood the smaller brethren and the saplings, waiting the fall of some neighbouring giant to give them in turn room to lift their branches towards the light.

Little blue fly-catchers, utterly fearless, flitted about in the lower bushes, and, higher up, golden-billed grackles hopped or flew from branch to branch, their loud clear whistles resounding through the forest, whilst from the tops of the biggest trees came the deep "boom, boom," of the great fruit-pigeons. However, although birds were fairly numerous, I got but few prizes—best among them, perhaps, a pretty little olive-green and yellow minivet (Pericrocrotus andamanensis), and a black racquet-tailed drongo (Dissemuroides andamanensis), a bird whose flight, as its long tail feathers stretch out behind, is extremely graceful, and who possessed one of the sweetest combination of notes heard in the jungle.

With such specimens in my bag, I presently came on a[Pg 31] little stream, and after following its course to the sea, tramped along the shore, and so came back once more to the boat.

A large fire had been made on the beach, and near it, in spite of the hot sun, the men sat fraternising with the members of the native party—five men and boys, three women, and three children.

In this little company there proved to be the three biggest men we saw among the Andamanese; in height, they stood 5 feet 4¾ inches, 5 feet 3¼ inches, and 5 feet 2 inches respectively.[10] Although possibly a little weak proportionately in the legs, where the skin covering the knee was so thickened and corrugated as to almost resemble callosities, the members of the party were well built and not ungraceful, but spoilt in most cases by a varying degree of distension of the abdomen: this state of things is caused by the immense amount of food they will, when possible, consume at a sitting; but the striking appearance of the eldest matron of the tribe was a more or less temporary feature, principally due to the interesting condition in which she was.

It was a pleasure to photograph these people, for they submitted to the operation most docilely; and when, after taking a series of pictures, I gave a graphic invitation to breakfast—pointing to my mouth, and rubbing that portion of the figure situated in the middle front—the men of the party all accepted the offer, and, reinforced by them, we returned to the Terrapin.

Arrived on board, they were at first rather inquisitive, but after inspecting the schooner and spending a little time below watching us at work, they went forward, and seemed quite comfortable amongst the men. As soon as it could be prepared, a large pailful of boiled rice was placed before them, and this was finished without any sign of flagging being shown. What a convenience the absence of tight clothing must be at such times!

The next few hours were passed by them lying on deck in the sun, where, out of regard for their feelings, we left them[Pg 32] undisturbed, except for the few moments during which they were measured. To a second bucket of rice, offered before they left, they failed to do proper justice, but took what remained ashore, where the women probably had their share.

We ran across the strait under canvas, before a light breeze, and the sail was a source of huge amusement to all but the youngest of the party, who was intermittently busied in returning to daylight all the food he had previously consumed.

Following what seems a wide-spread custom, the ladies ashore, had, to some extent, got themselves up for the reception of visitors. Although the previous dress—a small bunch of grass slung from the waist by a cord—fulfilled all requirements, they were now further decorated with an almost complete coating of ochreous clay, through which black eyes, nose, and lips showed below a bald pate with ludicrous effect. The babies, too, had been glorified in the same manner, and we felt quite bashful and shabby in our old pyjamas.

So absurdly comical did they appear, that it was only by much perseverance I was able to photograph them again, for whenever I attempted to adjust the focus, the picture on the screen gave rise to such fits of laughter that the camera was in danger of being upset. Even the boat's crew, unemotional Malays as they were, lay about, doubled up in paroxysms of laughter, which, increased by the looks of wonder and the ingenuous smiles with which my subjects persisted in regarding us, continued until the point of sheer exhaustion was reached. The old lady of the party and myself became great friends, and when on our departure I presented her with my handkerchief (all that I then had left) as a souvenir of our visit—as I gravely tied it about her head, I am sure we made an impressive picture.

The huts, or cháng, were four in number, and stood side by side just within the jungle, with the fronts facing inland. On a sloping framework of thin branches, raised about 4 feet at the upper edge, and covering a piece of ground 6 feet square,[Pg 33] were laid sufficient palm leaves to make a rain-proof shelter. The front and sides were left completely unprotected, the earth below was covered with more palm leaves, and a small fire was burning on the ground below an upper corner of each roof.

The only food they appeared to be supplied with was obtained from the large trees beneath which the camp stood—a small round fruit with a green skin, and a pleasantly-flavoured pulpy flesh; a large quantity of dark-coloured beeswax was lying about, so honey was probably plentiful and easily obtained.