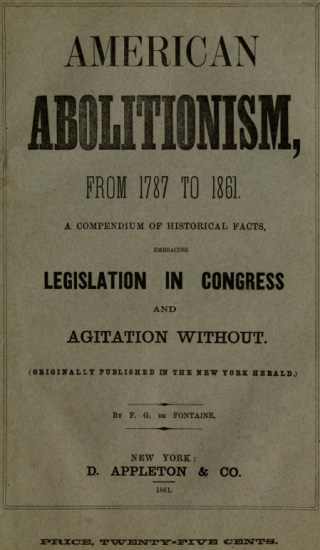

Text of Cover

Title: History of American Abolitionism

Author: F. G. De Fontaine

Release date: March 27, 2011 [eBook #35693]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

HISTORY

OF

AMERICAN ABOLITIONISM;

Its Four Great Epochs,

EMBRACING NARRATIVES OF THE

| ORDINANCE OF 1787, | ABOLITION RIOTS, |

| COMPROMISE OF 1820, | SLAVE RESCUES, |

| ANNEXATION OF TEXAS, | COMPROMISE OF 1850, |

| MEXICAN WAR, | KANSAS BILL OF 1854, |

| WILMOT PROVISO, | JOHN BROWN INSURRECTION, 1859, |

| NEGRO INSURRECTIONS, | VALUABLE STATISTICS, |

| &c., &c., &c. | |

TOGETHER WITH A

HISTORY OF THE SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY.

(ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE NEW YORK HERALD.)

BY F. G. DE FONTAINE.

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON & Co.

1861.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one,

By F. G. de FONTAINE,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States, for the Southern District of New York.

CHAS. CRASKE,

Stereotyper.

BARTON & SON,

Printers,

111 Fulton Street, N. Y.

The following pages originally appeared in the New York Herald, of February 2d, 1861. By request, they have been reproduced in their present shape, with the view of preserving, in a form more compact than that of a newspaper, the valuable facts embraced.

Without an extensive range of research it is almost impossible to acquire the information which is thus compiled, and, at the present time, especially, it is believed that the publication of these facts will be desirable to the reading community.

F. G. de F.

The Spirit of the Age—Two Classes of Abolitionists—Their Objects—The Sources of their Inspiration—Influences upon Church and State—Proposed Invasions upon the Constitution—Effect upon the Slave States, &c., &c.

One of the commanding characteristics of the present age is the spirit of agitation, collision and discord which has broken forth in every department of social and political life. While it has been an era of magnificent enterprises and unrivalled prosperity, it has likewise been an era of convulsion, which has well nigh upturned the foundations of the government. Never was this truth more evident than at the present moment. A single topic occupies the public mind—Union or Disunion—and is one of pre-eminently absorbing interest to every citizen. Upon this issue the entire nation has been involved in a moral distemper, that threatens its utter and irrevocable dissolution. Union—the child of compact, the creature of social and political tolerance—stands face to face with Disunion, the natural off-spring of that anti-slavery sentiment, which has ever warred against the interests of[Pg 4] the people and the elements of true government, and struggles for the maintenance of that sacred pledge by which the United States have heretofore been bound in a common brotherhood. Like the marvellous tent given by the fairy Banou to Prince Achmed, which, when folded up, became an ornament in the delicate hands of women, but, spread out, afforded encampment to mighty armies; so is this question of abolitionism, to which the present overwhelming trouble of our land is to be traced, in its capacity to encompass all things, and its ability to attach itself even to the amenities and refinements of life. It has entered into everything, great and small, high and low, political, theological, social and moral, and in one section has become the standard by which all excellence is to be judged. Under the guise of philanthropic reform, it has pursued its course with energy, boldness and unrelenting bitterness, until it has grown from “a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand” into the dimensions of the tempest which is to-day lowering over the land charged with the elements of destruction. Commencing with a pretended love for the black race, it has arrived at a stage of restless, uncompromising fanaticism which will be satisfied with nothing short of the consummation of its wildest hopes. It has become the grand question of the day—of politics, of ethics, of expediency, of justice, of conscience, and of law, covering the whole field of human society and divine government.

In this view of the subject, and in view also of the surrounding unhappy circumstances of the country which have their origin in this agitation, we give below a history of abolition, from the period it commenced to exist as an active element in the affairs of the nation down to the present moment.

ABOLITIONISTS AND THEIR OBJECTS.

There are two classes of persons opposed to the continued existence of slavery in the United States. The first are those who are actuated by sentiments of philanthropy and humanity, but are at the same time no less opposed to any disturbance of the peace or tranquility of the Union, or to any infringement of the powers of the States composing the confederacy. Among these may be classed the society of “Friends,” one of whose established principles is an abhorrence of war in all its forms, and the cultivation of peace and good will amongst mankind. As far back as 1670, the ancient records of their society refer to the peaceful and exemplary efforts of the sect to prevent the holding of slaves by any of their number; and a quaint incident is related of an eccentric “Friend,” who, at one of their monthly meetings, “seated himself among the audience with a bladder of bullock’s blood secreted under his mantle, and at length broke the quiet stillness of the worship by rising in full view of the congregation, piercing the bladder, spilling the blood upon the floor and seats, and exclaiming with all the solemnity of an inspired prophet, ‘Thus shall the Lord spill the blood of those that traffic in the blood of their fellow men.’”

The second class are the real ultra abolitionists—the “reformers” who, in the language of Henry Clay, are “resolved to persevere at all hazards, and without regard to any consequences, however calamitous they may be. With them the rights of property are nothing; the deficiency of the powers of the general government is nothing; the acknowledged and incontestible powers of the State are nothing; civil war, a dissolution of the Union, and the overthrow of a government in which are concentrated the fondest hopes of the civilized world, are nothing. They are for the immediate abolition of slavery, the prohibition of the [Pg 5]removal of slaves from State to State, and the refusal to admit any new State comprising within its limits the institution of domestic slavery—all these being but so many means conducive to the accomplishment of the ultimate but perilous end at which they avowedly and boldly aim—so many short stages, as it were, in the long and bloody road to the distant goal at which they would ultimately arrive. Their purpose is abolition, ‘peaceably if it can, forcibly if it must.’”

Utterly destitute of Constitutional or other rightful power; living in totally distinct communities, as alien to the communities in which the subject on which they would operate resides, as far as concerns political power over that subject, as if they lived in Asia or Africa, they nevertheless promulgate to the world their purpose to immediately convert without compensation four millions of profitable and contented slaves into four millions of burdensome and discontented negroes.

This idea, which originated and still generally prevails in New England, is the result of that puritanical frenzy which has always characterized that section of the country, and made it the natural breeding ground of the most absurd “isms” ever concocted. The Puritans of to-day are not less fanatical than were the Puritans of two centuries ago. In fact, they have progressed rather than retrograded. Their god then was the angry, wrathful, jealous god of the Jews—the Supreme Being now is the creation of their own intellects, proportioned in dimensions to the depth and fervor of their individual understandings. Then the Old Testament was their rule of faith. Now neither old nor new, except in so far as it accords with their consciences, is worth the paper upon which it is written. Their creeds are begotten of themselves, and their high priests are those who best represent their peculiar “notions.” The same spirit which, in the days of Robespierre and Marat, abolished the Lord’s day and worshipped Reason, in the person of a harlot, yet survives to work other horrors. In this age, however, and in a community like the present, a disguise must be worn; but it is the old threadbare advocacy of human rights, which the enlightenment of the age condemns as impracticable. The decree has gone forth which strikes at God, by striking at all subordination and law, and under the specious cry of reform it is demanded that every pretended evil shall be corrected, or society become a wreck—that the sun must be stricken from the heavens if a spot is found upon his disc.

The abolitionist is a practical atheist. In the language of one of their congregational ministers—Rev. Henry Wright, of Massachusetts:—

“The God of humanity is not the God of slavery. If so, shame upon such a God. I scorn him. I will never bow to his shrine; my head shall go off with my hat when I take it off to such a God as that. If the Bible sanctions slavery, the Bible is a self-evident falsehood. And, if God should declare it to be right, I would fasten the chain upon the heel of such a God, and let the man go free. Such a God is a phantom.”

The religion of the people of New England is a peculiar morality, around which the minor matters of society arrange themselves like ferruginous particles around a loadstone. All the elements obey this general law. Accustomed to doing as it pleases, New England “morality” has usually accomplished what it has undertaken. It has attacked the Sunday mails, assaulted Free Masonry, triumphed over the intemperate use of ardent spirits, and finally engaged in an onslaught upon the slavery of the South. Its channels have been societies, meetings, papers, lectures, sermons, resolutions, memorials, protests, legislation, private discussion, public addresses; in a word, every conceivable method whereby appeal may be brought to mind. Its spirit has been agitation!—and its language, fruits and measures have partaken throughout of a character that is thoroughly warlike.

[Pg 6]“In language no element ever flung out more defiance of authority, contempt of religion, or authority to man. As to agency, no element on earth has broken up more friendships and families, societies and parties, churches and denominations, or ruptured more organizations, political, social or domestic. And as to measures! What spirit of man ever stood upon earth with bolder front and wielded fiercer weapons? Stirring harangues! Stern resolutions! Fretful memorials! Angry protests! Incendiary pamphlets at the South! Hostile legislation at the North! Underground railroads at the West! Resistance to the Constitution! Division of the Union! Military contribution! Sharpe’s rifles! Higher law! If this is not belligerence enough, Mohammed’s work and the old Crusades were an appeal to argument and not to arms.”

What was philanthrophy in our forefathers has become misanthrophy in their descendants, and compassion for the slave has given way to malignity against the master. Consequences are nothing. The one idea preeminent above all others is abolition!

It is worthy of notice in this connection that most abolitionists know little or nothing of slavery and slaveholders beyond what they have learned from excited, caressed and tempted fugitives, or from a superficial, accidental or prejudiced observation. From distorted facts, gross misrepresentations, and frequently malicious caricatures, they have come to regard Southern slaveholders as the most unprincipled men in the Universe, with no incentive but avarice, no feeling but selfishness, and no sentiment but cruelty.

Their information is acquired from discharged seamen, runaway slaves, agents who have been tarred and feathered, factious politicians, and scurrilous tourists; and no matter how exaggerated may be the facts, they never fail to find willing believers among this class of people.

In the Church, the missionary spirit with which the men of other times and nobler hearts intended to embrace all, both bond and free, has been crushed out. New methods of Scriptural interpretation have been discovered, under which the Bible brings to light things of which Jesus Christ and his disciples had no conception. Assemblings for divine worship have been converted into occasions for the secret dissemination of incendiary doctrines, and thus a common suspicion has been generated of all Northern agency in the diffusion of religious instruction among the slaves. Of the five broad beautiful bands of Christianity thrown around the North and the South—Presbyterian, old school and new, Episcopalian, Methodist and Baptist, to say nothing of the divisions of Bible, tract and missionary societies—three are already ruptured—and whenever an anniversary brings together the various delegates of these organizations, the sad spectacle is presented of division, wrangling, vituperation and reproach, that gives to religion and its professors anything but that meekness of spirit with which it is wont to be invested.

Politically, the course of abolition has been one of constant aggression upon the South.

At the time of the Old Confederation, the amount of territory owned by the Southern States was 647,202 square miles; and the amount owned, by the Northern States, 164,081. In 1783, Virginia ceded to the United States, for the common benefit, all her immense territory northwest of the river Ohio. In 1787, the Northern States appropriated it to their own exclusive use by passing the celebrated ordinance of that year, whereby Virginia and all her sister States were excluded from the benefits of the territory. This was the first in the series of aggressions.

Again, in April, 1803, the United States purchased from France, for fifteen millions of dollars, the territory of Louisiana, comprising an area of 1,189,112 square miles, the whole of which was slaveholding territory. In 1821, by the[Pg 7] passage of the Missouri Compromise, 964,667 square miles of this was converted into free territory.

Again, by the treaty with Spain, of February, 1819, the United States gained the territory from which the present State of Florida was formed, with an area of 59,268 square miles, and also the Spanish title of Oregon, from which they acquired an area of 341,463 square miles. Of this cession, Florida only has been allowed to the Southern States, while the balance—nearly six-sevenths of the whole—was appropriated by the North.

Again, by the Mexican cession, was acquired 526,078 square miles, which the North attempted to appropriate under the pretence of the Mexican laws, but which was prevented by the measures of the Compromise of 1850. Of slave territory cut off from Texas, there have been 44,662 square miles.

To sum this up, the total amount of territory acquired under the Constitution has been, by the

| Northwest cession | 286,681 | square miles. | |

| Louisiana cession | 1,189,112 | do. | |

| Florida and Oregon cession | 400,731 | do. | |

| Mexican cession | 526,078 | do. | |

| Total | 2,377,602 | do. |

Of all this territory the Southern States have been permitted to enjoy only 283,713 square miles, while the Northern States have been allowed 2,083,889 square miles, or between seven and eight times more than has been allowed to the South.

The following are some of the invasions that have been from time to time proposed upon the Constitution in the halls of Congress by these agitators:

1. That the clause allowing the representation of three-fifths of the slaves shall be obliterated from the Constitution; or, in other words, that the South, already in a vast and increasing minority, shall be still further reduced in the scale of insignificance, and thus, on every attempted usurpation of her rights, be far below the protection of even a Presidential veto.

Next has been demanded the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, in the forts, arsenals, navy yards and other public establishments of the United States. What object have the abolitionists had for raising all this clamor about a little patch of soil ten miles square, and a few inconsiderable places thinly scattered over the land—a mere grain of sand upon the beach—unless it be to establish the precedent of Congressional interference, which would enable them to make a wholesale incursion upon the constitutional rights of the South, and to drain from the vast ocean of alleged national guilt its last drop? Does any one suppose that a mere microscopic concession like this would alone appease a conscience wounded and lacerated by the “sin of slavery?”

Another of these aggressions is that which was proposed under the pretext of regulating commerce between the States—namely, that no slave, for any purpose and under any circumstances whatever, shall be carried by his lawful owner from one slaveholding State to another; or, in other words, that where slavery now is there it shall remain forever, until by its own increase the slave population shall outnumber the white race, and thus by a united combination of causes—the fears of the master, the diminution in value of his property and the exhausted condition of the soil—the final purposes of fanaticism may be accomplished.

Still another in the series of aggressions was that attempted by the Wilmot Proviso, by which Congress was called upon to prohibit every slaveholder from[Pg 8] removing with his slaves into the territory acquired from Mexico—a territory as large as the old thirteen States originally composing the Union. It appears to have been forgotten that whether slavery be admitted upon one foot of territory or not, it cannot affect the question of its sinfulness in the slightest degree, and that if every nook and corner of the national fabric were open to the institution, not a single slave would be added to the present number, or that, if excluded, their number would not be a single one the less.

We might also refer to the armed and bloody opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law, to the passage of Personal Liberty Bills, to political schemes in Congress and out, and to systematic agitation everywhere, with a view to stay the progress of the South, contract her political power, and eventually lead, at her expense, if not of the Union itself, to the utter expurgation of this “tremendous national sin.”

In short, the abolitionists have contributed nothing to the welfare of the slave or of the South. While over one hundred and fifty millions have been expended by slaveholders in emancipation, except in those sporadic cases where the amount was capital invested in self-glorification, the abolitionists have not expended one cent.

More than this: They have defeated the very objects at which they have aimed. When Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, or some other border State has come so near to the passage of gradual emancipation laws that the hopes of the real friends of the movement seemed about to be realized, abolitionism has stepped in, and, with frantic appeals to the passions of the negroes, through incendiary publications, dashed them to the ground, tightening the fetters of the slave, sharpening authority, and producing a reaction throughout the entire community that has crushed out every incipient thought of future manumission.

Such have been the obvious fruits of abolition. Church, state and society! Nothing has escaped it. Nowhere pure, nor peaceable, nor gentle, nor easily entreated, nor full of mercy and good fruits; but everywhere forward, scowling, uncompromising, and fierce, breaking peace, order and structure at every step, crushing with its foot what would not bow to its will; defying government, despising the Church, dividing the country, and striking Heaven itself if it dared to obstruct its progress; purifying, pacifying, promising nothing, but marking its entire pathway by disquiet, schism and ruin.

We come now to the train of historical facts upon which we rely in proof of the foregoing assertions.

From 1787 to 1820.

CHAPTER II.

The Ordinance of 1787—The Slave Population of 1790—Abolitionism at that time—The Importation of Slaves the Work of Northerners—Statistics of the Port of Charleston, S. C., from 1804 to 1808—Anecdote of a Rhode Island Senator, &c., &c.

The first great epoch in the history of our country at which the spirit of abolitionism displayed itself was immediately preceding the formation of the present government. From the close of the Revolutionary War, in 1783, to the sitting of the Constitutional Convention, was a space of only four years. Two years more brings us to the adoption of the Constitution, in 1789. It was in the summer of 1787, and at the very time the Convention in Philadelphia was framing that instrument, that the Congress in New York was framing the ordinance which was passed on the 13th of July, 1787, by which slavery was forever excluded from all the territory northwest of the river Ohio, which, three years before, had been generously ceded to the United States by Virginia, and out of which have since been organised the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa.

According to the first census, taken in 1790, under the Constitution, when every State in the Union, with one exception, was a slave State, the number of slaves was as follows:—

| States. | No. of Slaves. | ||

| 1 | Massachusetts | ||

| 2 | New Hampshire | 158 | |

| 3 | Rhode Island | 948 | |

| 4 | Connecticut | 2,764 | |

| 5 | New York | 21,340 | |

| 6 | New Jersey | 11,423 | |

| 7 | Pennsylvania | 3,737 | |

| 8 | Delaware | 8,887 | |

| 9 | Maryland | 103,036 | |

| 10 | Virginia | 305,057 | |

| 11 | North Carolina | 100,571 | |

| 12 | South Carolina | 107,094 | |

| 13 | Georgia | 29,264 | |

| Territory of Ohio | 3,417 | ||

| Total | 697,696 | ||

In 1820, New York had 10,088 slaves. In 1827, however, by virtue of an Act, passed in 1817, they were declared free, and emancipated, without compensation to their owners. Even in 1830, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania had slaves: New Jersey containing 2,254. Since 1790, the increase of slaves has been at the rate of thirty per cent. each decade.

At this period numerous emancipation societies were formed, comprised principally of the Society of Friends, and petitions were presented to Congress, praying for the abolition of slavery. These were received with but little comment, referred, and reported upon by a committee. The reports stated that the general government had no power to abolish slavery as it existed in the several States, and that the States themselves had exclusive jurisdiction over the subject.[Pg 10] This sentiment was generally acquiesced in, and satisfaction and tranquility ensued, the abolition societies thereafter limiting their exertions, in respect to the black population, to offices of humanity within the scope of existing laws.

In fact, if we carry ourselves by historical research back to that day, and ascertain men’s opinions by authentic records still existing among us, it will be found that there was no great diversity of opinion between the North and the South upon the subject of slavery. The great ground of objection to it then was political; that it weakened the social fabric; that, taking the place of free labor, society was less strong and labor less productive; and both sections, with an exhibition of no little acerbity of temper and violence of language, ascribed the evil to the injurious and aggrandizing policy of Great Britain, by whom it was first entailed upon the Colonies. The terms of reprobation were then more severe in the South than the North. It is a notorious fact that some of our Northern forefathers were then the most aggravated slave dealers. They transported the miserable captives from Africa, sold them at the South, and were well paid for their work; and, when emancipation laws forbade the prolongation of slavery at the North, there are living witnesses who saw the crowds of negroes assembled along the shores of the New England and the Middle States to be shipped to latitudes where their bondage would be perpetual. Their posterity toil to-day in the fields of the Southern planter.

It is a remarkable fact, also, that of the slaves imported into the United States during a period of eighteen years, from 1790 to 1808, not less than nine-tenths were imported for and by account of citizens of the Northern States and subjects of Great Britain—imported in Northern and British vessels, by Northern and British men, and delivered to Northern born and British born consignees.

The trade was thus carried on, with all its historic inhumanity, by the sires and grandsires of the very men and women, who, for thirty years, have been denouncing slavery as a sin against God, and slaveholders as the vilest class of men and tyrants who ever disgraced a civilised community; and the very wealth in which, in a large degree, these agitators now revel, has descended to them as the fruit of the slave trade in which their fathers grew fat.

The following statistics of the port of Charleston, S. C., from the year 1804 to 1808, will more plainly illustrate this remark:—

| Imported | into Charleston from Jan. 1, 1804, to Jan. 1, 1808, slaves | 39,075 | |

| By | British subjects | 19,649 | |

| " | French subjects | 1,078 | |

| " | Foreigners in Charleston | 5,107 | |

| " | Rhode Islanders | 8,238 | |

| " | Bostonians | 200 | |

| " | Philadelphians | 200 | |

| " | Hartford, citizens of | 250 | |

| " | Charlestonians | 2,006 | |

| " | Baltimoreans | 750 | |

| " | Savannah, citizens of | 300 | |

| " | Norfolk, citizens of | 587 | |

| " | New Orleans, citizens of | 100 | |

| 39,075 | |||

| " | British, French and Northern people | 35,532 | |

| " | Southern people | 3,543 | |

| 39,075 | |||

| CONSIGNEES OF THESE SLAVES. | |||

| Natives of Charleston | 13 | ||

| Natives of Rhode Island | 88 | ||

| Natives of Great Britain | 91 | ||

| Natives of France | 10 | ||

| Total | 202 | ||

[Pg 11]It is related, that during the debate on the Missouri question, a Senator from South Carolina introduced in the Senate of the United States a document from the Custom House of Charleston, exhibiting the names and owners of vessels engaged in the African slave trade. In reading the document the name of De Wolfe was repeatedly called. De Wolfe, who was the Senator elect from Rhode Island, was present, but had not been qualified. The Carolina Senator was called to order. “Order!” “Order!” echoed through the Senate Chamber. “It is contrary to order to call the name of a Senator,” said a distinguished gentleman. The Senator contended he was not out of order, for the Senator from Rhode Island had not been qualified, and consequently was not entitled to a seat. He appealed to the Chair. The Chair replied, “You are correct, sir; proceed;” and proceed he did, calling the name of De Wolfe so often, that before he had finished the document, he had proved the honorable gentleman the importer of three-fourths of the “poor Africans” brought to the Charleston market, and the Rhode Island abolitionist bolted, amid the sympathies of his comrades and the sneers of the auditors.

Such was the aspect of affairs with reference to this question at the time of the adoption of the Constitution. The spirit of affection created and fostered by the revolution—the cords binding together a common country in a common struggle and a common destiny—were too strong in the breasts of our revolutionary fathers for them to countenance the feeble efforts even of those prompted by motives of humanity for the immediate emancipation of the slaves, and by almost the entire North of that period they were regarded with general disfavor, as an unwarrantable interference with an already established institution of the country. The consequence was that they sank into disrepute, and the country was blessed with and prospered under their comparative cessation for a number of years. This hostile feeling long lay dormant, and it was not until the year 1818, when Missouri applied for admission into the Union as a State, that the period of quiet was interrupted, and the little streams of abolitionism that had been quietly forming, merged into the foul and noisome current which is now devastating the land, has undermined and destroyed the Union, and is exerting its blighting influence upon every department of the political and social fabric.

CHAPTER III.

History of the Missouri Compromise, 1820—Benjamin Lundy and the “Genius of Universal Emancipation”—Insurrection at Charleston, S. C.—The result of agitation in Congress—British Influence and Interference—Abolition in the East and West Indies—Remarkable opinion of Sir Robert Peel—Letter from Lord Brougham on the Harper’s Ferry Insurrection.

Probably there has never been in the history of the United States, except at the present time, a more critical moment, arising from the violence of domestic excitement, than the agitation of the Missouri question from 1818 to 1821. On the 18th day of December, 1818, the Speaker of the House of Representatives of the United States presented before that body a memorial of the Legislature of the Territory of Missouri, praying that they might be admitted to form a Constitution and State government upon “an equal footing with the original States.” Here originated the difficulty. Slavery existed in the Territory proposed to be erected into an independent State. The proposition was therefore to admit Missouri as a slave State, which involved three very essential and important features. These were:—

1. The recognition of slavery therein as a State institution by the national sovereignty.

2. The guarantee of protection to the ownership of her slave property by the laws of the United States, as in the original States under the Constitution.

3. That the right of representation in the National Legislature should be apportioned on her slave population, as in the original States. This was a recognition of slavery, which at once aroused the interest of the people in every section of the Union.

The petition was received, read and reported upon, and in February, 1819, Mr. Tallmadge, of New York, proposed an amendment “prohibiting slavery except for the punishment of crimes, and that all children born in the said State after the admission thereof into the Union, shall be free at the age of twenty-five years.”

This passed the House, but was lost in the Senate. The excitement, not only in Congress, but throughout the Union, soon became intense, and for eighteen months the country was agitated from one extreme to the other. In many of the Northern States meetings were called, resolutions were passed instructing members how to vote, prayers ascended from the churches, and the pulpit began to be the medium of the incendiary diatribes for which it has since become so famous.

In both branches of Congress amendments were passed and rejected without number, while the arguments on both sides brought out the strongest views of the respective champions.

On one hand it was maintained that the compromise of the federal constitution regarding slavery respected only its existing limits at the time; that it was remote from the views of the framers of the Constitution to have the domain of slavery extended on that basis; that the fundamental principles of the American Revolution and of the government and institutions erected upon it were hostile to slavery; that the compromise of the Constitution was simply a toleration of things that[Pg 13] were, and not a basis of things that were to be; that these securities of slavery, as it existed, would be forfeited by an extension of the system; that the honor of the republic before the world, and its moral influence with mankind in favor of freedom, were identified with the advocacy of principles of universal emancipation; that the act of 1787, which established the Territorial government north and west of the river Ohio, prohibiting slavery forever therefrom, was a public recognition and avowal of the principles and designs of the people of the United States in regard to new States and Territories north and west; and that the proposal to establish slavery in Missouri was a violation of all these great and fundamental principles.

On the other hand, it was urged that slavery was incorporated in the system of society as established in Louisiana, which comprehended the Territory of Missouri, when purchased from France in 1803; that the faith of the United States was pledged by treaty to all the inhabitants of that wide domain to maintain their rights and privileges on the same footing with the people of the rest of the country; and consequently, that slavery, being a part of their state of society, it would be a violation of engagements to abolish it without their consent. Nor could the government, as they maintained, prescribe the abolition of slavery to any part of said Territory as a condition of being erected into a State, if they were otherwise entitled to it. It might as well, as they said, be required of them to abolish any other municipal regulation, or to annihilate any other attribute of sovereignty. If the government had made an ill-advised treaty in the purchase of Louisiana, they maintained it would be manifest injustice to make its citizens suffer on that account. They claimed that they were received as a slaveholding community on the same footing with the slave States, and that the existence or non-existence of slavery could not be made a question when they presented themselves at the door of the Capitol of the republic for a State charter.

After much bitter and acrimonious discussion, the question was finally, through the exertions of Henry Clay, settled by a compromise, and a bill was passed for the admission of Missouri without any restriction as to slavery, but prohibiting it throughout the United States north of latitude thirty-six degrees and thirty minutes.

Missouri was not declared independent until August, 1821. Previous to the passage of the bill for its admission, the people had formed a State constitution, a provision of which required the Legislature to pass a law “To prevent free negroes from coming to and settling in the State.” When the constitution was presented to Congress, this provision was strenuously opposed. The contest occupied a greater part of the session; but Missouri was finally admitted on condition that no laws should be passed by which any free citizen of the United States should be prevented from enjoying those rights within the State to which he was entitled by the Constitution of the United States.

Such was the Missouri Compromise, and though its settlement once more brought repose to the country and strengthened the bonds of fraternity and union between the States, its agitation in Congress was like the opening of a foul ulcer—the beginning of that domineering, impertinent, ill-timed, vociferous and vituperative opposition which has ever since been the leading characteristic of the abolition movement.

The “settlement” of the question in Congress seemed to be merely the signal[Pg 14] for its agitation among the non-slaveholding States. Fanatics sprang up like mushrooms, and, “in the name of God,” proclaimed the enormity of slavery and eternal damnation to all who indulged in the wicked luxury.

Among the earliest and most notable of these philanthropic reformers was one Benjamin Lundy, who, in the year 1821, commenced the publication of a monthly periodical called the “Genius of Universal Emancipation,” which was successively published at Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington City, and frequently en route during his travels wherever he could find a press. It is related of him that at one time he traversed the free States lecturing, collecting, obtaining subscribers, stirring up the people, writing for his paper, getting it printed where he could, stopping to read the “proof” on the road, and directing and mailing his papers at the nearest post-office. Then, packing up in his trunk his column-rules, type, “heading” and “direction book,” he pushed along like a thorough-going pioneer. What this solitary “Friend”—for such he was—in this manner accomplished, he himself states in an appeal to the public in 1830. He says:—

“I have within the period above mentioned (ten years) sacrificed several thousands of dollars of my own hard earnings; I have travelled upwards of five thousand miles on foot and more than twenty thousand in other ways; have visited nineteen States of this Union, and held more than two hundred public meetings—have performed two voyages to the West Indies, by which means the emancipation of a considerable number of slaves has been effected, and I hope the way paved for the enfranchisement of many more.”

INSURRECTION AT CHARLESTON, S. C.

The year 1822 was marked by one of the most nefarious negro plots ever developed in the history of the country. The first revelation was made to the Mayor of the city of Charleston on the 30th of May, 1822, by a gentleman who had on the morning of the same day returned from the country, and obtained on his arrival an inkling of what was going on from a confidential slave, to whom the secret had been imparted.

Investigations were immediately set on foot, and one of the slaves who was apprehended, fearing a summary execution, confessed all he knew. He said he had known of the plot for some time; that it was very extensive, embracing an indiscrimate massacre of the whites, and that the blacks were to be headed by an individual who carried about him a charm which rendered him invulnerable. The period fixed for the rising was on Sunday, the 16th of June, at twelve o’clock at night.

Through the instrumentality of a colored class-leader in one of the churches, this information was corroborated, and it was ascertained that enlistment for the insurrection was being actively carried on in the colored community of the church. It appeared that three months before that time, a slave named Rolla, belonging to Governor Bennett, had communicated intelligence of the intended rising, saying that when this event occurred they would be aided in obtaining their liberty by people from St. Domingo and Africa, and that if they would make the first movement at the time above named, a force would cross from James Island and land at South Bay, march up and seize the arsenal and guardhouse; that another body would at the same time seize the arsenal on the Neck, and a third would rendezvous in the vicinity of his master’s mill. They would then sweep the town with fire and sword, not permitting a single white soul to escape.

[Pg 15]Startled by this terrible intelligence, the military were immediately ordered out and preparations made to suppress the first signs of an outbreak. Finding the city encompassed with patrols and a strict watch kept upon every movement, the negroes feared to carry out their designs, and when the period had passed for the explosion of the plot, the authorities proceeded with vigor to arrest all against whom they possessed information.

The first prisoner tried was Rolla, a commander of one of the contemplated forces. On being asked whether he intended to kill the women and children, he remarked, “When we have done with the men we know what to do with the women.” On this testimony he was found guilty, and sentenced to be executed on the 2d of July.

Another was Denmark Vesey, the father of the plot, and a free black man. It was proved that he had spoken of this conspiracy upwards of four years previously. His house was the rendezvous of the conspirators, where he always presided, encouraging the timid by the hopes of success, removing the scruples of the religious by the grossest perversion of Scripture, and influencing the bold by all the savage fascinations of blood, beauty and booty. It was afterwards proved, though not on his trial, that he had been carrying on a correspondence with certain persons in St. Domingo—the massacre and rebellion in that island having suggested to him the conspiracy in which he embarked at Charleston. His design was to set the mills on fire, and as soon as the bells began to ring the alarm, to kill every man as he came out of his door, and afterwards murder the women and children, “for so God had commanded in the Scriptures.” At the same time, the country negroes were to rise in arms, attack the forts, take the ships, kill every man on board except the captains, rob the banks and stores, and then sail for St. Domingo. English and French assistance was also expected.

Six thousand were ascertained to have been enlisted in the enterprise, their names being enrolled on the books of “The Society,” as the organization was called.

When the first rising failed, the leaders, who still escaped arrest, meditated a second one, but found the blacks cowed by the execution of their associates and by the vigilance of the whites. The leaders waited, they said, “for the head man, who was a white man,” but they would not reveal his name.

The whole number of persons executed was thirty-five; sentenced to transportation, twenty-one; the whole number arrested, one hundred and thirty-one.

Among the conspirators brought to trial and conviction, the cases of Glen, Billy Palmer and Jack Purcell were distinguished for the sanctimonious hypocrisy they blended with their crime. Glen was a preacher, Palmer exceedingly pious, and Purcell no less devout. The latter made the following important confession:—

“If it had not been for the cunning of that old villain Vesey I should not now be in my present situation. He employed every stratagem to induce me to join him. He was in the habit of reading to me all the passages in the newspapers that related to St. Domingo, and apparently every pamphlet he could lay his hands on that had any connection with slavery. He one day brought in a speech which he told me had been delivered in Congress by a Mr. King on the subject of slavery. He told me this Mr. King was the black man’s friend; that he (Mr. King) had declared he would continue to speak, write and publish pamphlets against slavery to the latest day he lived, until the Southern States consented to emancipate their slaves, for that slavery was a great disgrace to the country.”

The Mr. King here spoken of was Rufus King, Senator from New York. This confession shows that the evil which was foretold would arise from the discussion of the Missouri question had been in some degree realized in the course of two or three years.

[Pg 16]Religious fanaticism also had its share in the conspiracy at Charleston, as well as politics. The secession of a large body of blacks from the white Methodist church formed a hot-bed, in which the germ of insurrection was nursed into life. A majority of the conspirators belonged to the “African church,” an appellation which the seceders assumed after leaving the white Methodist church, and among those executed were several who had been class-leaders. Thus was religion made a cloak for the most diabolical crimes on record. It is the same at this day. The tirades of the North are calculated to drive the negro population of the South to bloody massacres and insurrections.

BRITISH INFLUENCE AND INTERFERENCE.

During all this time, British abolition sentiments and designs were industriously infused into the minds of the people of the North. Looking over their own homeless, unfed, ragged millions, their filthy hovels and mud floors, worse than the common abode of pigs and poultry, crowded cellars, hungry paupers, children at work under ground—a community of wretchedness such as the American slave never dreamed of—British philanthropists wrote, declaimed, and expended untold sums upon a supposed abuse three thousand miles off, with which they have no connection, civil, social or political, and of which they know comparatively nothing. They passed their fellow-subjects by who were dying of hunger upon their very door-sills, to make long prayers in the market-place for the imaginary sufferings of negroes to whose well-fed and happy condition their own wretched paupers might aspire in vain.

Before they indulged in this invective, it would have been wise to have inquired who were the authors of the evil. In the language of an English statesman—

“If slavery is the misfortune of America, it is the crime of Great Britain. We poured the foul infection into her veins, and fed and cherished the leprosy which now deforms that otherwise prosperous country.”

Having filled their purses as traders in slaves, they have become traders in philanthropy, and manage to earn a character for helping slavery out of the very plantations of the South they helped to stock. They resemble their own beau ideal of a fine gentleman—George IV.—who, it is said, drove his wife into imprudences by his brutality and neglect, and then persecuted her to death for having fallen into them; or one of those fashionable philosophers who seduce women and then upbraid them for a want of virtue. Like the Roman emperor, they find no unsavory smell in the gold derived from the filthiest source.

The first abolition society in Great Britain was established in 1823, and it is a fact worthy of note that the first public advocate in England of the doctrine of immediate and unconditional abolition was a woman—Elizabeth Herrick. In 1825, the Anti-Slavery Society commenced the circulation of the Monthly Anti-Slavery Reporter, which was edited by Zacharay Macaulay, Esq., the father of the late Thomas B. Macaulay, the essayist, historian and lord. Petitions began to be circulated, public meetings were held, and the Methodist Conferences took an active part in the movement, exhorting their brethren, “for the love of Christ,” to vote for no candidates not known to be pledged to the cause of abolition. Rectors, curates, doctors of divinity, members of Parliament and peers engaged in the work, and converts rapidly increased. Riots and disturbances resulted. In 1832, an [Pg 17]insurrection, fomented by abolition missionaries, broke out in the island of Jamaica, which was only terminated by a resort to the musket and gibbet—the usual fruit of these incendiary doctrines, wherever they have been circulated. In 1833, a bill was passed by the British government, by which, for a compensation of one hundred millions of dollars, eight hundred thousand slaves in the British West Indies received their liberation. This was followed, in 1843, by the abolition of slavery throughout the British dominions, which emancipated twelve millions more in the East Indies. The cause thus received a new impetus; societies sprang into life all over the United Kingdom; a correspondence was opened in every part of the world where negroes were held in bondage; lecturers were sent abroad, especially to the United States, to disseminate their doctrines and stir up rebellion, both among the people and the slaves; earnest endeavors were made to influence the policy of the non-slaveholding States of the North, and create a hatred for the South; and, in short, the abolition movement settled down in a determined warfare against the institution of slavery wherever it existed.

It has been a war in which newspapers, pamphlets, periodicals, tracts, books, novels, essays—in a word, the entire moral forces of the human mind—have been the weapons. England became the champion of anti-slavery, and the United States became the theatre of a crusade, which seemed as if intended to carry out the spirit of the remark of Sir Robert Peel, that “the one hundred millions of dollars paid for the abolition of slavery in the West Indies was the best investment ever made for the overthrow of American institutions.”

Exeter Hall and the Stafford House became the centre of this new system, around which revolved all the lights of British abolitionism. The ground of immediate and unconditional emancipation, however, was not taken by the English abolitionists until subsequent years, but these views, when presented, found ready concurrence from Clarkson, Wilberforce and other well known advocates of the cause. Among the English statesmen pledged upon the subject, were Grey, Lansdowne, Holland, Brougham, Melbourne, Palmerston, Graham, Stanley and Buxton, and in the hands of these fervent leaders the cause speedily progressed towards its fruition.

From this time forward the coalesced efforts of British and Northern influence to disturb the institution of slavery in the South, to render slave labor less valuable and incite the negroes to rebellion, have been continued with more or less system, occasionally threatening the stability of the Union; the whole object of Great Britain being, not the welfare of the slave, but the destruction of slave labor, whereby, through a system of conquest and forced labor, she would be able to supplant the United States, by producing her cotton from the fields of the Eastern world. With this end in view, and coupled perhaps with the idea that the abolition of slavery would break down our republican form of government, she resorted to every species of intrigue that promised success. Dissensions have been sown between the North and South; the “underground railroad” system has been established leading to her Canadian possessions; agitation and assault have been perseveringly maintained; the country has been flooded with tirades of every hue and kind against the institution; the Northern pulpit has been desecrated in its dedication to the work of stirring up strife; churches have been severed in twain, and Southern Christians denied fellowship with their Northern brethren, until the grand political climax has been reached of secession and revolution. It is safe to[Pg 18] say that from the time this plan of operation was digested in England, thirty years ago, there is scarcely a movement that has taken place on the chess-board of American abolitionism, which, under the guise of philanthropy, has not been dictated at Exeter Hall for the purpose of destroying the production of cotton and breaking down the free government of this country.

Among the more far-seeing and practical statesmen of Great Britain, however—men who have ever dissented from the ultra views of abolitionists—there is an evident alarm that this headlong policy that has been pursued will rebound upon the interests of the mother country. Already the subject has become a source of anxious consideration, and the people of England are beginning to look around for some relief from that dependence upon American institutions which has heretofore been the reliance and support of millions of their workers. They find that the example they have set, and the policy they have urged, does not promise to be altogether so beneficial to them as they supposed. In this connection it will be interesting, as a matter of history, to preserve the master rebuke of Lord Brougham to the unconditional abolitionists of Boston, who invited him to be present at the John Brown anniversary of the past year. He says:—

“Brougham, Nov. 20, 1860.

“Sir—I feel honored by the invitation to attend the Boston Convention, and to give my opinion upon the question “How can American Slavery be abolished?” I consider the application is made to me as conceiving me to represent the anti-slavery body in this country; and I believe that I speak their sentiments as well as my own in expressing the widest difference of opinion with you upon the merits of those who prompted the Harper’s Ferry expedition, and upon the fate of those who suffered for their conduct in it. No one will doubt my earnest desire to see slavery extinguished, but that desire can only be gratified by lawful means, a strict regard to the rights of property, or what the law declares property, and a constant repugnance to the shedding of blood. No man can be considered a martyr unless he not only suffers but is witness to the truth; and he does not bear this testimony who seeks a lawful object by illegal means. Any other course taken for the abolition of slavery can only delay the consummation we so devoutly wish, besides exposing the community to the hazard of an insurrection perhaps less hurtful to the master than the slave.”

Progress of Abolition in America—An Era of Reforms—Southern Efforts for Manumission—Various Plans of Emancipation that have been suggested—The first Abolition journal—New York “Journal of Commerce”—William Lloyd Garrison, his Early Life and Associations—The Nat. Turner Insurrection in 1832, &c., &c.

Probably no period in the history of the country has been more characterized by the spirit of reform and innovation than that embraced between the years 1825 and 1830. It then seemed as if all the social, moral and religious influences of the community had been gathered in a focus that was destined to annihilate the wickedness of man. Missionary enterprises, though in their youth, were full of vigor. Anniversaries were the occasion of an almost crazy excitement; religion assumed the shape of fanaticism; the churches were thrilled with the sudden idea that the millennium was at hand—the “evangelization of the world” never was blessed with fairer prospects—the “awakenings to grace” were on the most tremendous scale. Peace societies were formed—temperance societies flourished more than ever—Free Masonry was attacked, socially and politically—the Sabbath mail question became one of the absorbing topics of the day—theatres, lotteries, the treatment of the “poor Indian” by the general government—all came under the most rigorous religious review—the Colonization Society, established in 1816, enlarged its [Pg 19]operations, and, in short, the spirit of reform became epidemic, and the period one of unprecedented moral and political inquiry.

It was a period, too, when in many of the States of the South, and especially those upon the Northern border, the subject was freely discussed of a gradual and healthy emancipation of the slaves, and various plans for this object were presented and entertained. The most valuable agencies were set at work—not by abolitionists, but by Southerners themselves, in whose hearts there had sprung up an embryo reformatory principle simultaneously with the landing upon their shores of the first slaves of their Northern brethren; which would have gone on increasing and fructifying had not the bitterest of denunciation been launched against them and driven the assaulted into an attitude of self-defence, whose defiant spirit now speaks out to the assailant in a bold justification of the institution attacked, as natural and necessary, and which it shall be their purpose to perpetuate forever.

As early as 1816 a manumission society was formed in Tennessee, whose object was the gradual emancipation of the slaves under a system of healthy and judicious State legislation. At a later day, Virginia, Maryland and Kentucky were the theatres of discussion on the same subject, and in all of them the question was agitated, socially and politically, with a freedom and liberty that indicated a general desire to effect the philanthropic object.

Various plans having the same end in view were likewise proposed, some of them evincing a remarkable ingenuity. One of these, in 1817, was to encourage, by all proper means, emancipation in the South; then to make arrangements with the non-slaveholding States to receive the freed negroes, and compel the latter, by law, if necessary, to reside in those States. By this means it was thought that a gradual change of “complexion” could be effected from natural causes, which would not take place unless the blacks were scattered, and that thus, from simple association and adventitious mixtures, the sable color would retire by degrees, and after a few generations a black person would be a rarity in the community.

Another plan proposed in 1819 was to remove the females to the Northern States, where they should be bound out in respectable families; those unmarried, of ten years and upwards, to be immediately free, and all the rest of the stock then existing to become so at ten years of age; the proceeds of the males sold to be appropriated by the party making the purchase to the removal and education of these females. In furtherance of this scheme, it was argued that while negro women would still bear children, though settled among white persons, they would not do so half so rapidly, and thus their posterity would in three or four generations lose the offensive color and have a tint not more disagreeable than the millions who are called white men in Southern Europe and the West Indies, and finally be lost in the common mass of humanity. While it is true that very few people, after fifty or sixty years, could under this rule boast of their fathers and mothers, the grand object would be attained, and the world be satisfied.

Another proposition, which emanated from a distinguished gentleman in one of the Southern States, and filling one of the highest offices in the government of the United States, was that a grade of color should be fixed in all the slaveholding States at which a person should be declared free and entitled to all the rights of a citizen, even if born of a slave. He contended that this act would separate all such[Pg 20] persons from the negro race, and present a very considerable check to the progress of the black population, giving them at the same time new interests and feelings. The children thus emancipated, even if the parents should not be wholly fitted for it, would come into society with advantages nearly equal to those of the poorer classes of white people, and might work their way to independence as well, without any counteracting detriment to the public good.

In Virginia, in 1821, it was suggested through the columns of the Richmond Enquirer, that an act should be passed declaring that all involuntary servitude should cease to exist in that State from and after the year 2000; thus, without reducing for one or two generations the value of slave property one cent, affording ample time and opportunity to dispose of or exchange that dead property for a more useful and profitable kind.

In 1825, Hon. Mr. King, of New York, introduced into the Senate of the United States the annexed resolution:—

“That as soon as the portion of the existing funded debt of the United States, for the payment of which the public land is pledged, shall have been paid off, thenceforth the whole of the public lands of the United States, with the net proceeds of all future sales thereof, shall constitute and form a fund which is hereby appropriated to aid the emancipation of such slaves and the removal of any free persons of color in any of the said States, as by the laws of the several States respectively may be allowed to be emancipated, or to be removed to any territory or country without the limits of the United States of America.”

This resolution, however, was not called up by the mover, or otherwise acted upon.

Still another plan was to raise money by contribution throughout the Union and elsewhere, and buy all the slaves at $250 each. The value of four million negroes at $500 each, their average market value, would be $2,000,000,000. It is unnecessary to say that none of these propositions were ever adopted in practice. In fact, while abolitionism has pretended to feel for the supposed sufferings of slaves, it has never felt much in its pockets to aid them.

At such a period—when the rampant spirit of reform was attacking every imaginary evil of the times—it is not a matter of wonder that northern abolitionists, yielding to their fanatical prejudices and to the British intrigue that was urging them onward, commenced that acrimonious agitation of the question which has since been its leading characteristic. The negro was pronounced “a man and a brother,” and that was the beginning and end of the argument. Tracts, speeches, pamphlets and essays were scattered, “without money and without price.” The pulpit vied with the press, and every imaginable form of argument was used to hold up slavery as the most horrible of all atrocities, and the “sum of all villanies.” Newspapers began to be an acknowledged element in the land, and, falling in the train of the young revolution, or rather growing out of it, wielded immense power among the masses. Among those then devoted to the subject of reform were the National Philanthropist, commenced in 1826; the Investigator, published at Providence, R. I., by William Goodell, in 1827; the Liberator, by William Lloyd Garrison, at Boston, in 1831, and the Emancipator, in New York.

The first abolition journal ever published in this city was the present Journal of Commerce, which was commenced September 1, 1827, by a company of stockholders, the principal of whom was the famous Arthur Tappan. The following extracts from its prospectus, issued March 24, 1827, will sufficiently indicate the puritanical character of its authors, and the general tone of the paper:—

“In proposing to add another daily paper to the number already published in this city, the projectors deem it proper to state that the measure has been neither hasty nor unadvisedly undertaken.[Pg 21] Men of wisdom, intelligence and character have been consulted, and with one voice have recommended its establishment.

“Believing, as we do, that the theatre is an institution which all experience proves to be inimical to morality, and consequently tending to the destruction of our republican form of government, it is a part of our design to exclude from the columns of the journal all theatrical advertisements.

“The pernicious influence of lotteries being admitted by the majority of intelligent men, and this opinion coinciding with our own, all lottery advertisements will also be excluded.

“In order to avoid a violation of the Sabbath, by the setting of types, collecting of ship news, &c., on that day, the paper on Monday will be issued at a later hour than usual, but as early as possible after the arrival of the mails. In this way the Journal will anticipate by several hours a considerable part of the news contained in the evening papers of Monday and the morning papers of Tuesday, and will also give the ship news collected after the publication of the other morning papers. With these views we ask all who are friendly to the cause of morality in encouraging our undertaking.”

Extract from the Minutes of a Meeting of Merchants and others at the

American Tract Society’s House, March 24, 1827:

“Resolved, That the prospectus of a new daily commercial paper, to be called the ‘New York Journal of Commerce,’ having been laid before this meeting, we approve of the plan upon which it is conducted, and cordially recommend it to the patronage of all friends to good morals and to the stability of our republican institutions.”

“ARTHUR TAPPAN, Chairman.”

“Roe Lockwood, Secretary.”

In its issue of October 30, 1828, we find the following:—

“It appears from an article in the Journal of the Times, a newspaper of some promise just established in Bennington, Vt., that a petition to Congress for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia is about to be put in circulation in that State.

“The idea is an excellent one, and we hope it will meet with success. That Congress has a right to abolish slavery in that District seems reasonable, though we fear it will meet with some opposition, so very sensitive are the slaveholding community to every movement relating to the abolition of slavery. At the same time, it would furnish to the world a beautiful pledge of their sincerity if they would unite with the non-slaveholding States, and by a unanimous vote proclaim freedom to every soul within sight of the capital of this free government. We could then say, and the world would then admit our pretence, that the voice of the nation is against slavery, and throw back upon Great Britain that disgrace which is of right and justice her exclusive property.”

Another of its editorials on November, 15, 1828:—

“We are all equally interested in demolishing the fabric (of slavery) and we may as well go to work peaceably and reduce it brick by brick as to make it a matter of warfare, and throw our enterprise and industry into the opposite scale.”

In the course of time changes were made in the ownership of the paper, but one of its original proprietors is still its senior editor.

About this period William Lloyd Garrison made his appearance upon the stage, and he has been probably one of the most intensely hated, as well as one of the most sternly, severely and vociferously enthusiastic men in the Union. He is a native of Massachusetts, and at a very early age was placed in a printing office in Newburyport by his mother. Shortly after he was twenty-one years of age he set up a paper which he called the Free Press, which was read chiefly by a class of very advanced readers at the North. After this he removed to Vermont, and edited the Journal of the Times. This was as early as 1828. In September, 1829, he removed to Baltimore for the purpose of editing the Genius of Universal Emancipation, in company with Benjamin Lundy. While performing these duties, a Newburyport merchant, named Francis Todd, fitted out a small vessel, and filled it in Baltimore with slaves for the New Orleans market. Mr. Garrison noticed this fact in his paper, and commented upon it in terms so severe that Mr. Todd directed a suit to be brought against him for libel. He was thereupon tried, convicted and thrown in jail for non-payment of the fine (one hundred dollars and costs.) After an incarceration of fifty days, he was released on the payment of his fine, by Mr. Arthur Tappan, of this city, who, and his brother Lewis, before and since that time, have been chiefly celebrated for their efforts in the cause of abolition. In 1831, he[Pg 22] wrote a few paragraphs that bear out the idea we have advanced—that there was then more real philanthropy in the South than at the North. He says:—

“I issued proposals for the publication of the “Liberator” in Washington City, during my recent tour, for the purpose of exciting the minds of the people on the subject of slavery. Every place I visited gave fresh evidences of the fact that a greater revolution in public sentiment was to be effected in the free States, and particularly in New England, than at the South. I found contempt more bitter, opposition more active, detraction more relentless, prejudice more stubborn and apathy more frozen, than among the slaveowners themselves. I determined at every hazard to lift up the standard of emancipation in the eyes of the nation, within sight of Bunker Hill, and in the birthplace of liberty. I am in earnest; I will not equivocate, I will not excuse, I will not retreat a single inch. I will be heard. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue lift from its pedestal, and to hasten the resurrection of the dead.”

From this time it may be said that the anti-slavery cause took its place among the moral enterprises of the day. It assumed a definite shape, and commenced that system of warfare which has since been unremittingly waged against the South.

During this year—1830—Mr. Tappan, Rev. S. S. Jocelyn, and others, projected the establishment of a seminary of learning at New Haven for the benefit of colored students; but, opposition manifesting itself, it was abandoned.

The first regularly organized convention of colored men ever assembled in the United States for a similar purpose also held a meeting this year, and aided and abetted by the Tappans, Jocelyns and other agitators of the period, attempted to devise ways and means for bettering their condition and that of their race. They reasoned that all distinctive differences made among men on account of their origin was wicked, unrighteous and cruel, and solemnly protested against every unjust measure and policy in the country having for its object the proscription of the colored people, whether state, national, municipal, social, civil or religious. In fact, white men and black seem to have started in the race together, consorting like brothers and sisters together in their aims and projects to accomplish the same end.

About this time publications began to be scattered through the South, whose direct tendency was to stir up insurrection among the slaves. The Liberator found its way mysteriously into the hands of the negroes, and individuals, under the garb of religion, were discovered in private consultation with the slaves. Suddenly, in August, 1831, the whole Union was startled by the announcement of an outbreak among the slaves of Southampton County, Va; and now commences the history of a career of violence and bloodshed that has marked every footstep of the abolition movement.

THE NAT TURNER INSURRECTION.

The leader of this outbreak was a slave named Nat Turner, and from him its name has been derived. Impelled by the belief that he was divinely called to be the deliverer of his oppressed countrymen, he succeeded in fixing the impression upon the minds of two or three others, his fellow slaves. Turner could read and write, and these acquirements gave him an influence over his associates. He was possessed, however, of little information, and, is represented to have been cowardly, cruel, and as he afterwards confessed, “a little credulous.” It was a matter of notoriety that “secret agents of abolition had corrupted and betrayed him.” However that may be, Nat declared that “he was advised” only to read[Pg 23] to the slaves, that “Jesus came not to bring peace, but a sword!” Such a tree produced fitting fruits.

About midnight on the Sabbath of the 21st of August, 1831, Turner, with his confederates, burst into his master’s house, and murdered every one of the white inmates. They were armed with knives and axes, and, in order to strike terror into the whites, most shockingly mangled the bodies of their victims. Neither helpless infancy nor female loveliness were spared. They then, by threats of death, compelled all the slaves to join them who would not do it voluntarily, and, exciting themselves to fury by ardent spirits, they proceeded to the next plantation. The happy family were reposing in the sound and quiet slumbers which precede the break of day, as the shouts of the raving insurgents fell upon their ears. It was the work of a moment, and they were all weltering in their gore. Not a white individual was spared to carry the tidings. The blow which dashed the infant left its brains upon the hearth. The head of the youthful maiden was in one part of the room and her mangled body was in another. Here again the number of insurgents was increased by those who voluntarily joined them, and by others who did it through compulsion. Stimulating their passions still more by intoxication, and arming themselves with such guns as they could obtain, some on horseback and others on foot, they rushed along to the next plantation. The morning now began to dawn, and the shrieks of those who fell under the sword and the axe of the negro were heard at a distance, and thus the alarm was soon spread from plantation to plantation, carrying inconceivable terror to every heart. The whites supposed it was a plot deeply laid and widely spread, and that the day had come for indiscriminate massacre. One gentleman who heard the appalling tidings hurried to a neighboring plantation, and arrived there just in time to hear the dying shrieks of the family and triumphant shouts of the negroes. He hastened in terror to his own home, but the negroes were there before him, and his wife and daughter had already fallen victims to their fury. Thus the infuriated slaves went on from plantation to plantation, gathering strength at every step, and leaving not a living white behind. They passed the day, until late in the afternoon, in this work of carnage, and numberless were the victims of their rage.

The population in this country is not dense, and, rapidly as the alarm spread, it was impossible for some time to collect a sufficient number to make a defence. Every family was entirely at the mercy of its own slaves. It is impossible to conceive of more distressing circumstances of apprehension. It is said that most of the insurgent slaves belonged to kind and indulgent masters, and consequently no one felt secure.

Late in the afternoon, a small party of whites, well armed, collected at a plantation for defence. The slaves came on in large numbers, and, emboldened by success, they at first drove back the whites. The slaves pressed on, thirsting for blood, and shouting with triumphant fury as the whites slowly retreated, apparently destined to be butchered, with their wives and children. Just at this awful moment a reinforcement of troops arrived, which turned the tide of victory and dispersed the slaves.

Exhausted with the horrible labors of the day, the insurgents retired to the woods and marshes to pass the night.

[Pg 24]Early the next morning they commenced their work again. But the first plantation they attacked—that of Dr. Blount—they were driven from by the slaves, who rallied around their master, and fearlessly hazarded their lives in his defence. By this time the whites were collected in sufficient force to bar their further progress. The fugitives were scattered over the country in small parties, but every point was defended, and wherever they appeared they were routed, shot, taken prisoners, and the insurrection quelled. The leader, Nat Turner, for a few weeks succeeded in concealing himself in a cave in Southampton county, near the theatre of his bloody exploits; but was finally taken, and suffered the extreme penalty of the law.

To describe the state of alarm to which this outbreak gave rise is impossible. Whole States were agitated; every plantation was the object of fear and suspicion; free negroes and slaves underwent the most rigid examination; armed bodies of men were held in constant readiness for any emergency which might arise; every slave who had participated in the insurrection was either shot or hung, and for months the entire South remained in a fever of excitement.

All this time the abolition journals of the North were singing their hallelujahs over the event. They circulated through the South then much more freely than at present, and the following extract was read from one of these by a gentleman to his terrified family, in the presence of the gentleman from whom the above particulars were derived:—

“The news from the South is glorious. General Nat is a benefactor of his race. The Southampton massacre is an auspicious era for the African. The blood of the men, women and children shed by the sword and the axe in the hand of the negro is a just return for the drops which have followed the master’s lash.”

Another extract, of similar rhetoric, from the record of that day, is from a speech by the “Reverend” Mr. Bayley, then of Sheffield, Mass.:—

“It is time that the ice was broken—time that the blacks considered they have the same right to regain their liberties, and even the present property of their owners, as the Hebrews had in despoiling the heathen round about them. The blacks should also know that it is their duty to destroy, if no other means offer conveniently, the monstrous incubuses and tyrants, yclept planters; and I, for one, would gladly lend a helping hand to lay them in one common grave! The country would be all the better for ridding the world of such a nest of vampyres.”

Whether the abolitionists of the present time have modified the ideas they promulgated then, we shall see hereafter from a few among the ten thousand specimens that might be adduced.

The effect of these tirades upon the South cannot be well conceived.

Public opinion, just then opening to a free discussion of the question, drew back and shut itself within its castle. The bonds of slavery were bound tighter, the rivets were more strongly fastened, and a reactionary movement commenced that has never yet terminated.

The New England Anti-Slavery Society, 1832—More Newspapers and Tracts—New York City Anti-Slavery Society and the Incidents of Its Organization—The American Anti-Slavery Society and its Creed—The Extent and System of their operations—Abolition Riots in New York—An Era of Excitement—Negro Conspiracy in Mississippi—George Thompson, the English Abolitionist—Riot at Alton, Ill., and Death of the Rev. E. P. Lovejoy.

In the year 1832, January 30, the New England or Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society went into operation, but with limited means. From this society have sprung the American Anti-Slavery Society and all its numerous auxiliaries. It was the first organized body that attacked slavery on the principle of its inherent sinfulness, and enforced the consequent duty of “immediate emancipation.” All the events of a historical character which have marked the annals of the last thirty years, may be traced directly to the agitation which this society first set on foot in this country. Men have been forced to throw aside their disguises and stand forth either as the open defenders of slavery or as propagators of the abolition movement. The two great antagonistic parties of the present day are the children of its vile creation. It has excited the very fury of antagonism; it has shaken the pulpit with excommunicating thunders; it has indulged in the most bitter invective, deluged the country with invented instances of Southern barbarity, denounced the Constitution as a “league with hell,” and scattered its venom in every household of the free States, until men, women and children have become imbued with its contaminating infection. Their discourses have all been tirades; their exordium, argument and peroration have turned on epithets, slanders, inuendoes; Southerners have been reviled as “tyrants,” “thieves,” “murderers,” “atrocious monsters,” “violators of the laws of nature, God and man,” while their homes have been designated as “the abodes of iniquity,” and their land “one vast brothel.”