Title: Harper's Round Table, October 1, 1895

Author: Various

Release date: July 13, 2010 [eBook #33147]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| PUBLISHED WEEKLY. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 1, 1895. | FIVE CENTS A COPY. |

| VOL. XVI.—NO. 831. | TWO DOLLARS A YEAR. |

"I say, Hal, do you realize that the Ready Rangers will have been in existence a whole year on the 30th?" asked Will Rogers, as he and Hal Bacon walked homeward from school one afternoon of the May following the Rangers' memorable trip to New York. "I remember the exact date, because it was Decoration day, and the first time I was out after my accident."

"That's so," replied Lieutenant Hal, "and I think we ought to do something in the way of a celebration."

"My idea exactly; and at the meeting to-night I want to talk it over. So bring along any suggestions you can pick up, and let's see what can be done."

Never had the Berks boys, who were also Rangers, worked so hard as during the winter just passed. In spite of the allurements of skating, coasting, and all the other fascinating winter sports of country life, they had never lost sight of the coveted bicycles that Tom Burgess's father had promised to let them have at much less than cost, if only they could earn the money to pay for them. At the suggestion of Reddy Cuddeback, their newest member, of whom they were intensely proud, because he held the five-mile racing record of the United States, they had decided to make a common fund of all their earnings, and place it in the hands of honorary member Pop Miller for safe keeping. They did this, because, while it was necessary to the success of their organization that every member should own a bicycle, some of them were possessed of greater advantages or abilities for earning money than others. Also those who already owned machines, and so were not obliged to earn them, could still work with enthusiasm for the fund. Besides these reasons the Rangers proposed to raise some[Pg 978] of the money by giving entertainments, the proceeds from which would necessarily go into a common fund.

So, while several of the boys under direction of "Cracker" Bob Jones, who had a great head for business, gathered nuts in the autumn for shipment to New York, caught fish through the ice during the winter, and sold them in the village, and made maple sugar, to order, in the early spring, others split wood or did similar chores for neighbors. Will Rogers and Hal Bacon organized a mail-and-package delivery service. Beth Barlow, working on behalf of her brother, the naval cadet member, made the caramels and pop-corn balls that little Cal Moody sold to his school-mates at recess, while Reddy Cuddeback, who proved to be possessed of decided dramatic talent, arranged and managed the several entertainments given by the Rangers during the winter.

One of these was a minstrel show, the first ever seen in Berks. Another was a Good Roads talk, given by a distinguished highway engineer, and illustrated by stereopticon views, while the third, which was the crowning success of the season, was a play written by Will Rogers and Beth Barlow. It was called Blue Billows—a title cribbed from Raftmates—or, Fighting for the Old Flag: a nautical drama in two watches, founded on facts more thrilling than fiction. This play was suggested by the story of Reddy Cuddeback's father, as told by Admiral Marlin to his Road-Ranger guests the summer before, and in order that it should present a realistic picture of naval life, its leading scenes and all of its conversation were in closest imitation of Pinafore, which the Rangers had been taken to see in New York, and which was their chief source of knowledge concerning life on the ocean wave. So they had a Little Buttercup, only she was called Pink Clover, a midshipmite represented by little Cal Moody, a Jack Jackstraw, a Bill Bullseye, and a close imitation of Sir Joseph Porter, named Sir Birch Beer. They sang sea-songs, danced what they believed to be hornpipes, hitched their white duck trousers, shivered their timbers, and were altogether so salt and tarry, that had not the dazzled spectators known better they might have believed the Rangers to be regular oakum-pickers who had never trod dry land in their lives. So well was this performance received in Berks that the boys were induced to repeat it in Chester, whereby they added a very tidy sum to their fund.

This was their final effort at money-making, for about this time a letter was received from Mr. Burgess stating that he found it necessary to dispose of his stock of bicycles at once, and asking if the Rangers were not ready to relieve him of them. So the meeting called by Captain Will Rogers, to be held in Range Hall, as the boys termed Pop Miller's house, was for the purpose of learning the amount of the fund and deciding upon its disposal. The speculations as to its size, and what it would purchase, were as numerous as there were members, and as diverse as were the characters of the boys. Little Cal Moody hoped it might reach the magnificent sum of one hundred dollars; while "Cracker" Bob Jones thought one thousand dollars would more nearly represent the amount obtained. "That's what we've got to have," he argued, "for there are ten members without wheels, not counting what I owe Reddy Cuddeback on mine, and I don't believe even Mr. Burgess can afford to sell such beauties as those we rode last fall for less than a hundred apiece. So there you are; and if we haven't got a thousand dollars, some of us will have to go without wheels, or else only own 'em on shares."

This statement from so eminent an authority caused considerable uneasiness among the other boys, and they almost held their breath with anxiety as Mr. Pop Miller wiped his spectacles, and, producing a small blue bank-book, prepared to make the important announcement.

"Mr. President and fellow-members of the most honorable body of Ready Rangers," began the little old gentleman, beaming upon the expectant faces about him. "It is with gratified pride and sincere pleasure that I contemplate the wonderful success now crowning your tireless efforts of the past winter. I must confess that both your perseverance and the result accomplished have exceeded my expectations, and I congratulate you accordingly. As treasurer of the Rangers' bicycle fund, I have the honor to announce that, with all expenses for entertainments, etc., deducted, there is now on deposit in the First National Bank of Berks, and subject to your order, the very creditable sum of three hundred and eighty-five dollars and twelve cents. All of which is respectfully submitted by

"P. Miller, Treasurer."

"Hooray!" shouted little Cal Moody, forgetting his surroundings in the excitement of what he regarded as the vastness of this sum. As no one else echoed his shout, he blushed, looked very sheepish, and wished he had kept his mouth shut.

The Rangers had done well, remarkably well, as any one must acknowledge who has tried to raise money under similar conditions; but in view of "Cracker" Bob's recent statement, most of them felt that their great undertaking had resulted in what was almost equivalent to failure, and were correspondingly cast down.

"It is too bad!" exclaimed Sam Ray, breaking a gloomy silence. "Of course we've got to pay the thirty-five dollars that Bob still owes Reddy, for that is promised, and, besides, I'm certain that 'Cracker' has earned more than that amount himself. After that is done, though, we shall have only three hundred and fifty dollars left, which isn't more than enough to purchase three and a half or four machines at the most, and that will leave six of us with nothing to show for our winter's work."

"I move," said Mif Bowers, who having been a performer in Blue Billows, was fully persuaded that he was cut out for a sailor, "that we don't buy wheels at all, but put our money into a yacht, and go on a cruise down the Sound this summer."

"Second the motion!" cried Alec Cruger, who, having acted the part of Bill Bullseye, was equally anxious to put his recently acquired nautical knowledge to practical use.

"The motion is not in order," announced Will Rogers, firmly. "This money was raised for an especial purpose; and, whether it is much or little, it must be devoted to that purpose."

"That's so," agreed Sam Ray, who wanted a bicycle more than anything else in the world, "and I move that the money be sent to Mr. Burgess, with the request that he return just as many wheels as it will buy. We can take turns at riding them, and work all through long vacation for money to get the rest."

"Second the motion!" cried Si Carew.

"All in favor of Sam Ray's motion say 'aye.'"

"Aye!" responded half a dozen voices, though not very enthusiastically, for most of the boys were greatly disappointed, and did not relish the prospect of several months more of hard work for an object they had believed already attained. Still no one voted against the motion, and so it was pronounced carried.

"If we had got the machines I was going to suggest a grand parade in celebration of our birthday," said Hal Bacon, after the meeting had broken up; "but now I suppose it's no use."

So the three hundred and fifty dollars was forwarded to Mr. Burgess, together with a note from the Captain of the Rangers, stating all the circumstances, and hoping that the owner of the coveted wheels would sell just as many for the sum enclosed as he could possibly afford.

An answer to this momentous communication was awaited with such deep anxiety, that during the next few days the Rangers fairly haunted the railway station as though expecting to see their longed-for bicycles come rolling, of their own accord, up the track.

"Hi-Ho! Hi-ho!" The well-known call of the Rangers summoning them to immediate assembly at the engine-house rang out, clear and shrill up and down the quiet village street. It was early morning, the sun was just rising, and though there was already much activity in kitchen and barn-yard, the long elm-shaded and grass-bordered thoroughfare was almost as deserted as at midnight. Still[Pg 979] there was one team in sight, and one boy. The former was that belonging to Squire Bacon; and, driven by Evert Bangs, it was coming from the direction of the railway station, where it had been to deliver, for the early morning train, the very last russet apples that would be shipped from Berks that year. The boy was little Cal Moody, who was earning twenty-five cents a week towards his bicycle by driving a neighbor's cow to and from pasture every morning and evening. He had just completed his task for that morning, and was on his way home when he noticed the approaching team.

It does not take much to arouse curiosity in a quiet little place like Berks, and the boy's attention was instantly attracted to the fact that Squire Bacon's wagon bore a very queer-looking load. As it passed through occasional level shafts of sunlight that were darting between the trees it seemed to be full of flashes and bright gleamings. What could it be? Cal stopped to find out.

The nearer it approached the more he was puzzled, and it was not until the team was actually passing him, when the good-natured driver sang out: "Here they are, Cal! Came at last on the night freight, and I thought I might as well bring 'em along up," that the mystery was solved.

With a great tingling wave of joyful excitement sweeping over him, Cal knew that Squire Bacon's wagon held a load of bicycles in crates, and that they were being taken to the engine-house on the village green. He tried to give a shout of delight, but at first could only gasp without uttering a sound. Then, as he recovered his voice, the Ranger rallying cry of "Hi-ho! Hi-ho!" rang shrilly out on the morning air with a distinctness that instantly roused the sleepy village into full activity. The meaning of the cry was well understood by this time, and believing that it now indicated the breaking out of a fire, every one within hearing instantly repeated it, at the same time running toward the place whence it first issued. So within two minutes the exciting cry was sounding from end to end of the village, and even far beyond its limits. Sam Ray heard it in the new house up on the hill, and Reddy Cuddeback heard it in the mill settlement down by the river. Will Rogers heard it while he was dressing, and rushed out without stopping to complete his toilet. Thus the echoes of Cal's first summons had hardly died away before every Ranger in the village was tearing up or down the long street toward the engine-house, and yelling at the top of his voice.

The first to arrive got there even ahead of Evert Bangs, and were already running out the natty little red-and-gold engine as he drove up.

"Hold on!" he shouted. "I ruther guess your engine won't be wanted just yet. Seems to me you boys get het up terrible easy. No, your 'Hi-ho!' don't mean fire this time, nor nothing like it. What it means is bicycles, and here they be. I was calculating to have 'em all unloaded before any of you fellers showed up, as a sort of surprise, you understand; but seeing as you're on hand, I guess you'd better help."

Better help! Wouldn't they, though? and weren't they just glad of the chance? So many and so eager were the hands upraised to grasp the precious crates, that, even while some of the later arrivals were still asking, "where was the fire?" the last one was lifted out, carried into the engine-house, and there carefully deposited.

"How many are there?" asked "Cracker" Bob Jones, anxiously, as Evert Bangs drove off with his empty wagon, and the engine-house doors were closed to all except Rangers.

"I don't know," replied Will Rogers. "Let's count them."

As all began to count aloud at the same moment, it is not surprising that several different results were announced. "Fifteen!" shouted Si Carew. "Eight!" called little Cal Woody.

"Oh, pshaw!" laughed Will Rogers. "You fellows are so excited that I don't believe any one of you could say his A B C's straight through. Keep quiet for a moment and let me count them. One, two, three, four, fi— There! I believe I've missed one already. One, two, three—"

"Here's a letter for you, Will," shouted Hal Bacon, who had been to the post-office, and came running breathlessly in at that moment. "What's all this I hear about bicycles? Oh, my eye! What a lot! How did they get here?"

"Just wheeled themselves up from New York," laughed Will, at the same time tearing open his letter, which was postmarked at that city. After a hasty glance at its contents, he called for silence, and read the following:

William Rogers, Esq., Captain Berks Ready Rangers:

Dear Sir,—Your favor of 10th inst. with check for three hundred and fifty dollars enclosed, is at hand, and contents noted. As per request I forward by freight, charges prepaid, three hundred and fifty dollars' worth of bicycles, or ten (10) in all.

I am greatly pleased at the energy and perseverance shown by the Rangers in earning this sum of money, which I may as well admit is larger than I believed they would raise, and I congratulate them most heartily upon their success.

Tom does not expect to spend this summer in Berks, but is making arrangements for a most delightful outing elsewhere. In it he hopes his fellow Rangers will be able to join him. It is nothing more nor less than a— But I must not anticipate, nor rob him of the pleasure of telling you his plans himself.

With best wishes for the continued prosperity and happiness of the Ready Rangers, I remain,

Sincerely their friend,

L. A. Burgess.

"Ten bicycles for three hundred and fifty dollars!" cried "Cracker" Bob Jones. "And all of 'em first-class, A No. 1 machines. That beats anything I ever heard of. If Mr. Burgess has got any more to sell at the same price I'd like to take them off his hands, that's all."

"But he hasn't," declared Will Rogers. "Don't you remember that ten was the exact number he happened to have?"

"And it's the exact number that happens to make just one apiece for us," commented Abe Cruger. "Seems to me that's about as big a piece of luck as I ever ran across."

"If it is luck," added Hal Bacon, shrewdly.

"Let's open 'em right away," cried Cal Moody, jumping up and down in his excitement. "It doesn't seem as if I could wait another minute."

"Yes. Let's open 'em!" shouted half a dozen voices.

"Hold on," commanded Will Rogers. "We haven't time to open all the crates and put the machines together now. Besides, Pop Miller isn't here, nor lots of people who have helped us get these bicycles, and who would be awfully interested in seeing them opened. So I propose that we leave them just as they are until after school, and then hold what you might call an opening reception."

Although the Rangers agreed to this proposition, it was with reluctance; and that their thoughts remained with those precious crates all day was shown in more ways than one. In school, for instance, when little Cal Moody was asked to spell and define the word biennial, he promptly replied, with "Bi—bi, cy—cy, cle—cle—bicycle—a machine having two wheels;" and when "Cracker" Bob Jones was requested to favor the arithmetic class with an example in percentage he complied by stating, "that if ten bicycles, listed at $125 each, could be bought for $350, and sold at their listed price, the percentage of profit would be—" Just here he was interrupted by a shout of laughter, in which even the teacher, who thoroughly understood and sympathized with the situation, was forced to join.

When the hour for the opening of the crates at length arrived, half the village was there to see, and when the ten glittering bicycles, each of which bore a small silver plate inscribed with the name of its new owner, were finally put together and displayed to the admiring public of Berks, there were no happier nor prouder boys in the United States than the young Rangers who had earned them.

From that time on, they rode their bicycles during every leisure moment, and on the 30th of May they celebrated their birthday by giving an exhibition parade as bicycle fire scouts, that was pronounced the very finest thing of its kind ever seen in that section of country. In this parade each machine carried a fire bucket, and while some also bore axes, others were equipped with the rope-ladder[Pg 980] that Will Rogers and Sam Ray had used so effectively, a fire-net, blankets, spades, and other articles to be used in an emergency.

The Chester Wheel Club came over to join in the parade, and with them came the bicycle-supply man, who was so impressed with the fact that Berks was becoming a bicycling centre that he at once established a branch of his business there, and appointed Pop Miller his agent.

Best of all was a visit from Tom Burgess, who came on from New York, not only to take part in the parade, but to unfold the gorgeous plan he had evolved for the summer vacation, and in which he wished his fellow Rangers to join. He first confided it privately to Will Rogers, and when he concluded, the latter exclaimed:

"Tom Burgess, it seems almost too good to be true, but with the experience we've already gained in Blue Billows I believe we can carry it through. If we only can, it will be the biggest thing the Rangers have undertaken yet."

Many years ago had you been, let us say, a tinker travelling with your wares or a knight riding by, you might have passed, upon a small arched bridge that spanned a little river in the heart of "Merrie England," a small boy, hanging over the railing, now watching the rippling water, or with eager eyes looking along the roadway that ran between green meadows toward that distant London, from which, perhaps, you were tramping or riding.

"HAVE YOU SEEN MY FATHER AS YOU CAME ALONG?"

"HAVE YOU SEEN MY FATHER AS YOU CAME ALONG?"

I think, as you passed, you would have looked twice at that small boy on the bridge, whether you were low-down tinker or high-born knight. For he was a bright, sweet-faced little ten-year-old in his quaint sixteenth-century costume, and the look of expectancy in his eyes might, as it fell upon your face, have shaped itself into the spoken question, "Have you seen my father as you came along?"

Whereupon, had you been the lordly knight you might have said, "And who might your father be, little one?" Or had you been the low-down tramping tinker you would probably have grunted out: "Hoi, zurs! An' who be'est yure feythur, lad?"

To either of which questions that small boy on the bridge would have answered in some surprise—for he supposed that, surely, all men knew his father—"Why, Master William Shakespeare, the player in London."

For that little river is the Avon; that small bridge of arches is Clopton's mill-bridge, that small boy is Hamnet, the only son of Master William Shakespeare, of Henley Street, in Stratford-on-Avon. And in the year 1595 the name of William Shakespeare was already known in London as one of the Lord Chamberlain's company of actors, and a writer of masterly poems and plays.

Perhaps if you were the tinker, you might be tired enough with your tramping to throw off your pack, and, sitting upon it, to talk with the little lad; or, if you were the knight, it might please your worship to breathe your horse upon the bridge and hold a moment's converse with the child.

Were you tinker or knight the time would not be misspent, for you would find young Hamnet Shakespeare most entertaining.

He would tell you of his twin sister Judith—something of a "tomboy," I fear, but a pretty and lovable little girl, nevertheless. And as Hamnet told you about Judith, you would remember—no, you would not, though, for neither tinker nor knight nor any other Englishman of 1595 knew what we do to-day of Shakespeare's plays; but if you should happen to have a dream of the little fellow now, you might remember that Shakespeare's twins must have been often in the great writer's mind; for they stole into his work repeatedly in such shapes as that charming brother and sister of his Twelfth Night—Sebastian and Viola—

"An apple cleft in two is not more twin

Than these two creatures,"

or the twin brothers Antipholus of Ephesus and Syracuse, and those very, very funny twin brothers of the Comedy of Errors, forever famous as the Two Dromios.

And if young Hamnet told you of his sister he would tell you, doubtless, of his grandfather who was once the bailiff or head man of Stratford town, and who lived with them in the little house in Henley Street; and especially would he tell you of his own dear father, Master William Shakespeare, who wrote poems and plays, and had even acted, at the last Christmas-time, before her Majesty the Queen in her palace at Greenwich. For you may be sure boy Hamnet was very proud of this—thinking more of it, no doubt, than of all the poems and plays his father had written.

Then, perhaps, you could lead the boy to tell you about himself. He might tell you how he liked his school—if he did like it; for perhaps, like his father's schoolboy, he did sometimes go

"with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school."

He would, however, be more interested to tell you that he went to school in the chapel of the Holy Cross, because the old school-house next door, to which his father had gone as a boy, was being repaired that year, and he liked going to school in the chapel because it gave him more holidays.

Ah, he would tell you, he did enjoy those holidays. For the little house in Henley Street was a bit crowded, and he liked to be out of doors, being, I suspect, rather a boy of the woods and the fields than of the Horn-Book, the Queen's Grammar, and Cato's Maxims. He and Judith had jolly times abroad, for Judith was a good comrade, and really had it easier than he did—so he would tell you—for Judith never went to school. In fact, to her dying day, Judith Shakespeare—think of that, you Shakespeare scholars!—a daughter of the greatest man in English literature could neither read nor write!

So the Shakespeare twins would roam the fields, and knew, blindfold, all that bright country-side about beautiful Stratford. Their father was a great lover of nature. You know that from reading his plays, and his twins took after him in this. Young Hamnet Shakespeare loved to hang over Clopton Bridge, as we found him to-day, watching the rippling Avon as it wound through the Stratford meadows and past the little town. He knew all the turns and twists of that storied river with which his great father's name is now so closely linked. He knew where to find and how to catch the perch and pike that swam beneath its surface. He and Judith had punted on it above and below Clopton Bridge, and on many a warm summer day he had stripped for a swim in its cooling water.

He knew Stratford from the Guild Pits to the Worcester road, and from the Salmon Tail to the Cross-on-the-Hill. He could tell you how big a jump it was across the streamlet in front of the Rother Market, and how much higher the roof of the Bell was than of the Wool-Shop, next door—for he had climbed them both.

He knew where, in Stratford meadows, the violets grew thickest and bluest in the spring, where the tall cowslips fairly "smothered" the fields, as the boys and girls of Stratford affirmed, and where, in the wood by the weir-brakes just below the town the fairies sometimes came from the Long Compton quarries to dance and sing on a midsummer night.

He had time and time again wandered along the Avon from Luddington to Charlecote. He had been many a time to his mother's home cottage at Shottery, and to his grandfather's orchards at Snitterfield for leather-coats and wardens. He knew how to snare rabbits and "conies" in Ilmington woods, and he had learned how to tell, by their horns, the age of the deer in Charlecote Park—descendants, perhaps, of that very deer because of which his father once got into trouble with testy old Sir Thomas Lucy, the lord of Charlecote Manor.

The birds were his pets and playfellows. And what quantities there were all about Stratford town! Hamnet[Pg 981] knew their ways and their traditions. He could tell you why the lark was hanged for treason; how the swan celebrated its own death; how the wren came to be king of the birds; and how the cuckoo swallowed its stepfather. He could tell you where the nightingale and the lark sang their sweetest "tirra-lirra" in the weir-brake below Stratford Church, and just how many thievish jackdaws made their nests in Stratford spire. He could show you the very fallow in which he had caught a baby lapwing scudding away with its shell on its head, and in just what field the crow-boys had rigged up the best kind of a "mammet" or scarecrow to frighten the hungry birds.

So, you see, little Hamnet Shakespeare could keep you interested with his talk until it was time—if you were the tramping tinker—to toss once more your heavy pack on your shoulders, or, if you were lordly knight, to cry "get on" to your now rested horse. And by this time you would have discovered that here was a boy who, with eyes to see and ears to hear all the sights and sounds of that beautiful country about Stratford and along the Avon's banks, had learned to find, as his father, later on, described it:

"tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything."

A clatter of hoofs rings upon the London highway. The boy springs to his feet; he scarcely waits to give you his hasty good-day, but with a hop, skip, and jump, flies across the bridge and along the road. And, as he is lifted to the saddle by the well-built, handsome man with scarlet doublet, loose riding-cloak, white ruff, auburn hair and beard, who sits his horse so well, you know that father and son are riding home together, and that there will be joy in the little house in Henley Street. For Master William Shakespeare, the London player, has come from town to spend a day at home in the Stratford village he loved so dearly.

Perhaps, two or three years later, you may be led again to tramp or ride through Stratford town. As you loiter awhile at the Bear Tavern, near the Clopton Bridge, you recognize the arches and the pleasant river that flows beneath them, and then you remember the little boy with whom you talked on the bridge.

To your inquiries the landlord of the Bear says, with a sigh and a shake of the head,

"A gentle lad, sir, and a sad loss to his father."

"What—dead?" you ask.

"Yes, two years ago," the landlord replies. "Little Hamnet was never very strong, to be sure, but he sickened and died almost before we knew aught was wrong with him. A sad loss to his father. Master Shakespeare dearly loved the lad, and while he was gathering fame and wealth he thought most, I doubt not, of that boy to whom he was to pass them on."

"So Master William Shakespeare has grown rich as well as famous, has he?" you say, for all England knows by that time of his wonderful plays.

"Indeed yes," the landlord answers you. "See, across the trees, that big house yonder? It is New Place, bought in the spring of this very year of 1597, by Master Shakespeare, and put into fine repair. And there all his family live now—his old father, Master John, his wife, Mistress Ann, and all the children. But little Hamnet is not there, and I doubt not Master Shakespeare would gladly give all New Place and his theatre in London too, for that son of his back again, alive and well, and as happy of face as he used to be in the old house in Henley Street."

The landlord of the Bear is right. Hamnet Shakespeare ended his short life on the 11th of August, 1596, being then but eleven years old.

We know but little of his famous father's life; we know even less of the son he so dearly loved. Nor can any one say, had the boy but lived, whether he would have inherited anything of his father's genius.

The play of Hamlet may have been called in memory of the boy Hamnet, so nearly are the names alike; even more is it possible that the lovely boy, Prince Arthur, whose tragic story is a part of Shakespeare's play of King John, may have been drawn in memory of the writer's dead boy. For King John was written in the year of young Hamnet Shakespeare's death, and with the loss of the boy he so dearly loved weighing upon his soul, the great writer, whose name and fame the years only make yet more great, may thus have put into words a tender memory of the short-lived little Hamnet, the gentle son of Shakespeare.[Pg 982]

here were weeping and wailing within the Saunders' modest "one-story-and-a-jump" cottage. Monongahela's eyes were red from crying; the twins, Dallas Lee and Jemima Calline, had for once lost their appetite, even for corn-pone and molasses; and Washington Beauregard, the eldest of the brood of youngsters, frowned gloomily, and ground his teeth in deep if silent rage as he polished up his antiquated old rifle and thought upon vengeance. Only the baby crowed and gurgled as lustily as ever, shaking his gourd rattle in blissful infantile ignorance of the loss that had befallen the family—a loss most keenly felt by the children, for it was that of the bonny ewe-lamb, their pet and plaything by day, and almost their bedfellow by night; while the manner of its disappearance was shrouded in profound mystery.

"Mebbe 'twas Butcher Killem who tuck him," suddenly suggested the lugubrious boy twin. "Tuck him to make roasts 'n' chops of; 'n' if it was, we may be eatin' Cotton Ball for dinner some of these fine days."

A dire prediction, which immediately sent Jemima Calline off into a wild paroxysm of grief, flinging herself flat upon the floor, and drumming a funereal tattoo with her best Sunday shoes on the gay rag carpet of domestic manufacture. "I'll never taste mutton again; never, never, the longest day I live," she howled.

"Now, Dallas Lee, see what you've done!" scolded Monongahela, usually called Monny for short. "You've set her off agin, and we'll have her in 'sterics direckly. Thar ain't no need of any sech fool talk either, and slanderin' your neighbor into the bargain. Mr. Killem is an honest man, who buys 'n' pays for all the critters he cuts up. Besides, I caught the lamb myself, and shet her up in the wood-shed before ever we started for the bush-meetin'. I locked the door 'n' took the key in my pocket. The door was still locked when we came back."

"Ya—as; but ye couldn't lock the hole in the roof," drawled Wash, looking up from his polishing. "The hole pap 'n' I hev been calculatin' to mend for some time back, but 'ain't got at yit, more's the pity. Thar's where the thief come in. For thar on the shingles is where the locks of wool are a-hangin'."

"But I can't see how anybody could clamber up thar, drop through a hole, and git back agin with a big kickin' beast in his arms; for if he'd killed it on the spot ther'd be blood spattered 'round."

"Mebbe nobody could, but mebbe something might."

"Some thing! What sort of a thing? A fox or any other animal?"

"P'r'aps so," but Wash would say no more. He was famous for holding his own counsel, and did so now, until the yellow moon had risen from behind the glorious mountain peaks surrounding their little primitive West Virginia home, and he and his favorite sister wandered out together into the soft, pine-scented night. Then, however, their thoughts naturally reverted to the mysterious disappearance, and the girl asked somewhat curiously, "So, Washington Beauregard, you won't allow that the 'ornery' thief what stole our pet come on two legs?"

"No, Monny, nor on four legs nuther," answered her brother. "Though I didn't want to say much afore the chillen. But I've been a-studyin' over this matter, and I begin to fear that he comes on wings."

"On wings! Law, then, he must be a bird! But I never saw a hawk or even an eagle big and strong enough to tote off a half-grown sheep like Cotton Ball. Strikes me it's dumb foolishness you're talkin', Wash."

"Waal, I dunno about that. Hevn't you heard the old hunters, on winter nights, tell of a curisome-winged thing that once made its nest over yonder on Snaggle Tooth?" and the youth pointed to a high, dark, jagged crag silhouetted against the purplish-blue sky. "It did a power of mischief in this neighborhood, totin' off chickens 'n' dogs 'n' sheep, and some say even tacklin' a calf. 'Twas a cute old fowl, so nobody could git a crack at it; but was up to so much devilment, that they called it the Demon of Snaggle-Tooth Rock."

"Oh, yaas, I've heard o' that often; but it was years ago, before you or I were born, an' the critter hasn't been raound here since."

"That's so; but what has been kin be; and the other day Tim Harkins tole me a yarn about jest sech a bird havin' been seen lately over Stonycliff way. A monstrous chap, something like a golden eagle, only bigger an' wickeder-lookin', with a more crooked beak, an' feathers of a dirty brownish-gray. At the time I thought Tim was jest a-humbuggin', but after the little beast disappeared so unaccountable like, I begun to reckon it must be true, sure enough."

"Oh, Wash, I can't bear to think of it!" and Monny's face looked quite pale in the moonlight. "Poor, dear little Cotton Ball! Fancy that demon and his mate tearing her limb from limb. It 'most breaks my heart." And long after the girl had climbed the ladder leading to the low attic under the clapboard roof, which she had shared with the younger children ever since their mother's death one year before, she lingered at the tiny two-paned window gazing off at the peaceful-seeming hills, but in imagination following the lost lambkin to the eagle's grim eyrie on wild, inaccessible Snaggle-Tooth Rock.

"It is dreadful, dreadful; but I won't tell Jemima Calline," was her last thought as she crept into bed beside her sister.

For Monongahela was old beyond her fourteen years, and bravely strove to fill the place of their lost parent to the motherless little ones, sending them trim and tidy to school and "Methody meetin'," feeding them on plenty of bacon, corn-dodgers, and apple-butter, and every morning, in spite of grimaces, dosing them all round with "whiskey and burdock" as an antidote against dyspepsia, the curse of that hog-eating, excessive coffee-drinking community.

Within a few days Washington's fears were painfully confirmed. Our young mountain folk were out one afternoon on the hill-side gathering ginseng and other herbs, when they met the circuit-rider who visited in turn the churches of their vicinity, and whom Mr. Saunders had frequently entertained. He paused for a chat, and informed them of the consternation created in a neighboring valley by the appearance of the terrible bird to prey upon any poultry or small animals left out over night; while one man had been severely wounded in an almost hand-to-claw tussle in order to save his dog.

The following morning, then, when Monny, with the baby toddling by her side, went out early to milk the cow, she heard a continuous firing, and came upon her brother armed with the old flint-lock rifle which he had inherited from his grandfather, popping away at the brown and purple cones on the top of a tall pine-tree, and deftly snapping off the one at which he aimed nine times out of ten.

"Well, Washington Beauregard, I'll allow you are a pretty fair marksman," she remarked, after a moment of admiring watching. "Not many private hunters kin wing a bird as well as you, kin they?"

"Reckon I could hold my own agin most of they-uns if I only had a new-fangled gun," returned the boy. "This old fowlin'-piece ain't wurth much, and I do hope I kin sell enough 'sang'[1] this year to buy another. 'Tain't much fun to git a fine aim at a buck and lose him 'cause your gun misses fire. As it is, though, I believe I could snip a curl off the baby's head an' hardly scare the darlin'. Jest hold him up, honey, an' let me hev a try." But to this William Tell arrangement Monny objected in horror, and scurried off with the infant, followed by Wash's roar of laughter and shout of "Ho, scare rabbit! But anyhow I[Pg 983] mean to keep in practice,'n' hev a cold-lead welcome ready for that air eagle if he ever shows hisself this way agin."

The bird did not come; but about noon Tim Harkins did, ambling along on a rawboned sorrel nag, and reined up at the gate with a long-drawn-out "Whoa, thar'!"

"Wash Saunders! Oh, Wash!" he called, and that youth, rising from the dinner-table, appeared in the ramshackle porch.

"Hello, Tim, is that you? Step in an' hev a bite, won't yer?"

"No, thankee. I'm jest on my way to a gander-pull over nigh the Springs, 'n' on'y stopped to fotch you a message. Ye wouldn't keer, naow, to hire out for a few weeks, at a dollar a day, would yer?"

"What to do?"

"Oh, jest to show a gentleman through the mountings, an' pint out the hants o' the wild birds. 'Pears this Perfessor, as they call him, is stoppin' over to the Spring Hotel, an' the landlord, Poke Dickson, axed me ef I knowed any o' the neighborhood boys who would like the job. Somenn what wuz a first-rate shot, an' 'quainted with all the trails. Yaas, I tole him Wash Saunders am the very chap, ef you kin git him. But, I added, the Saunders air pooty ticky, an' Wash, mebbe, won't relish playin' pinter-dorg to any one. For, sez I, his pappy am a forehanded man, who keeps his fambly comf'ble. He hez a good corn 'n' tobaccy field, 'n' the gyurls hez a kyarpet on the best room, 'n' curtings to the windys, 'n' everything mighty slick. Still, sez I, 'twon't do no harm to ax, so here I be."

"Sho, Tim, you know I ain't so ticky as that. Dunno but I'd like it first rate, for I'm strivin' to get a new rifle. Granddaddy's old 'Sally Blazer,' as he used to name it, is about played out."

"Waal, naow, then, here's your chance, 'n' I'm real tickled. But I must be ajoggin'. G'lang, Juniper! Shall I tell Poke you will go over 'n' see the Perfessor?"

"Yes, I will, this very evenin'"; which the boy did, and returned jubilant. "It's a snap, a reg'lar snap," he declared to the group of brothers and sisters who ran to meet him. "Professor Stuart is real quality, an' no mistake. He's an orni—orni—waal, I don't rightly remember the name, but he's plumb crazy about birds, 'n' comed here a purpose to see those what live in West Virginia. It's a curous notion, but he's nice, 'n' so is Mis' Stuart, though she lies on a sofy most of the time, and looks drefful white 'n' pindlin'."

"Air there any chilluns?" inquired Jemima Calline.

"Yaas, two. An awful pooty gyurl, with eyes like brown stars, an' all rigged out in white, same as an angel, with big, puffy sleeves; an' the jolliest small boy you ever see. He's a downright little man, though he's only five year old, an' he's curls down to his waist."

"Waal, then, sence they were so friendly, I s'pose you came to some bargain?" said Monongahela.

"Sartain; an' I'm to meet Mr. Stuart to-morrer mornin' at the cross-roads an' show-him a red-bird's nest. He wants to collect eggs an' live specimens."

When, then, the Professor rode up to the appointed rendezvous on the following day, he found Wash awaiting him, "Sally Blazer" in hand, and a powder-horn and shot-pouch slung from his neck by a leather strap. His feet, too, were encased in moccasins that his footfall might not startle the shy creatures of the wildwood.

"Ah, my lad, I see you understand the business," remarked the ornithologist, with an approving nod, "and I predict we shall be fine friends."

Thus, too, it proved and for both. That was the beginning of a month of happy, halcyon days spent in the open; a perpetual picnic, scaling the rough but ever-enchanting hills, wandering through the beautiful solemn pine forests, following Nature's most winsome things to their chosen haunts, and always breathing in the resinous health-giving mountain air. Sometimes, when the tramp was not to be too long a one, small Royal accompanied his father, gay and joyous as a dancing grig, and looking like a little Highland princeling in his outing costume of Scotch plaid, proudly flourishing a tiny wooden gun.

"We are good chums, ain't we, Wash?" he would say, in his precocious friendly little way—"good chums, going hunting together. But we mustn't kill things just for fun. That is naughty. Papa says food or science is the only excuse. He never takes but one egg from a nest, and would rather snare birds than shoot them."

Occasionally, too, pretty Jean would join the party at a given point, driving over with a dainty lunch from the hotel, and then there would be a merry out-door meal in some cozy green nook, near to one of the cold clear mountain springs which furnished the purest and most refreshing beverage.

And what a revelation this experience was to poor little Washington Beauregard! Not only the bits of knowledge he picked up from the ornithologist's learned discourses on the gorgeous Virginia-cardinals and orioles, the red-capped woodpeckers and flitting humming-birds, but in a different style of girlhood and more refined mode of life than he had ever known. Day by day, too, he became fonder of and more devoted to his new friends, and looked forward with dread to the time when they must part. All too speedily, then, that date drew on apace, until the morning set for their last pleasant tramp dawned. The Professor and Washington started early, while at noon Jean and Royal met them on the hills above Stonycliff, climbing the last rough incline, that being too steep for the horses and carriage, which were left with the driver at a small clearing part way down the mountain.

"And just think, papa," cried Jean, "we found the squatter's wife at the log house below in sore trouble. Yesterday that horrible eagle, of which we have heard so much, swooped down and carried off her milch-goat almost before her very eyes, and now what she is going to do for milk for her baby she does not know."

"Well, that is a misfortune truly," said the Professor, "and we must see what we can do to help her, but I wish I had been here to have a peep at that abnormal bird. I imagine the stories regarding it are much exaggerated, but if not, it cannot be an eagle, must belong to the semi-vulturine family, though those are rarer than white black-birds in this part of the world. I really am curious to get a glimpse of the creature." And as it chanced, he was destined to have his curiosity satisfied in a way he little dreamed of.

The collation eaten that day under the trees was an unusually bountiful one, reflecting credit on mine host of the Spring House, and after it the ornithologist stretched himself out to enjoy an afternoon cigar, while Jean, followed by her small brother, wandered off to sketch a charming view that had taken her fancy. Meanwhile Wash cleared away the remains of the feast, packing the dishes in the hamper, and carefully saving any fragments of good things for the little ones at home.

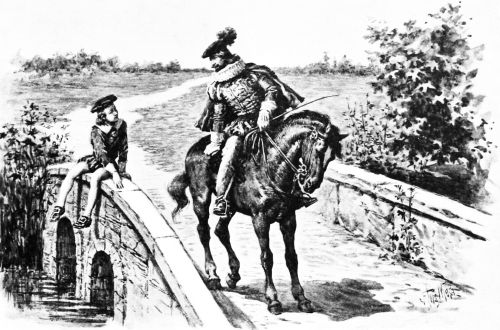

He had just completed his task, when a frightened cry of "Sister, oh, sister!" and a blood-curdling shriek from the girl made him snatch up his fowling-piece and fly in the direction the young Stuarts had taken. The Professor also sprang to his feet and followed suit, while, as they emerged from the shadow of the wood, both were almost paralyzed by the sight they beheld. For there stood Jean, white to the very lips, but bravely endeavoring with her climbing-staff to beat off an enormous bird, in whose great cruel talons struggled little Royal, upon whom had been made a sudden and fierce attack.

"My goodness! it's the demon!" gasped Wash, while the father, overcome by a sickening horror, fell back against a tree. Even too, as they approached, the huge, repulsive creature spread its big dusky wings and began slowly to rise, bearing off in its claws the poor child, who stretched out his tiny hand, sobbing piteously, "Oh, papa, save me!" There was one terrible nightmarish second, when nobody had power to move, and then the Professor, with a wild lunge forward, caught at his vanishing boy. But the gay kilt slipped through his fingers, and still the bird of prey soared relentlessly upward and onward.

But at that moment Granddaddy Saunders's old rifle was raised and levelled at the monster.

"Oh, Wash, pray be careful: you may hit the wee laddie," cried Jean, sinking down and covering her face.[Pg 984]

"MAY OLD 'SALLY BLAZERS' NOT MISS FIRE THIS TIME!"

"MAY OLD 'SALLY BLAZERS' NOT MISS FIRE THIS TIME!"

No one knew the danger better than the mountain-bred youth, but he held himself well in hand and kept cool. "I must only maim, not kill, the critter outright," he thought, "and may old 'Sally Blazers' not miss fire this time!"

Then he took careful aim, a bullet whistled through the air, and the "demon's" left wing dropped powerless at his side. They could see the wrathful red gleam in the creature's eyes as it paused, wavered, and careened to one side, but the right pinion still flapped vigorously, and kept it up, while it still retained its clutch on the little fellow, who no longer screamed, but now appeared ominously quiet and white.

"Ef he gits over the precipice all is lost," murmured the young sportsman, with a glance toward the edge of the cliff upon which they stood, and he wasted no time in reloading and firing again. And oh, joy! again he winged his victim, which, uttering an unearthly, discordant cry, began to flutter slowly downward. But now a fresh danger threatened Royal, for the bird, maddened by pain, suddenly released its hold, and the fair little head must surely have been crushed on the jagged rocks beneath, had not Wash been prepared for this, and, springing forward, caught him in his strong young arms, although the precipitancy with which the child came almost flung both to the ground. There was just an instant, too, in which to stagger to one side, before, with a whirl and a whir, the mighty fowl was upon them, striking the stony ledge with a dull, sickening thud. Wounded, but by no means dead, was the Snaggle-Tooth demon, and he fought desperately with beak and claws, and beat himself against the granite, until a third shot from old "Sally Blazers" finally ended his career forever.

Meanwhile poor little Royal lay stretched on a bed of moss, pale and unconscious, his garments torn to tatters, and blood streaming from his chubby legs and arms.

"He is dead; my bonny wee laddie is dead, and how ever shall I tell his mother?" sobbed the Professor, completely unnerved; but Jeanie never stopped chafing the dimpled hands, and bathing the white forehead with cold water; until, after what seemed an eternity, a low sigh issued from between the child's pale lips.

"No, papa dear, he is breathing, and it is Wash, good brave Wash, who has saved him"; and when the young girl turned and thanked him, and her eyes filled with grateful tears, the uncouth backwoods boy, though he could only stammer and blush, felt it to be the proudest moment in all his fifteen years of life.

Soon Royal regained consciousness, but seemed so dazed and frightened, clinging to his sister and imploring her to "hide him from the awful, scratching claws," both father and daughter looked worried. "For it will kill mamma to see him in this condition," groaned Jean.

"Oh, then," put in Wash, eagerly, "jest tote him down to our house. Monny would admire to hev yer, 'n' she's a fust-rate nuss."

"Do you think so? Would your sister really not object?"

"'Deed no; she will be plumb right glad."

So it was decided, and so the young Stuarts made the acquaintance of Monongahela, Jemima Calline, Dallas Lee, and the baby, and slept in the room with the "rag kyarpet and the curtings," which was hastily prepared for the unexpected guests, while by the fitful light of six pine knots the killing of the Snaggle-Rock demon was rehearsed again and again. Monny lost her heart to gentle, ladylike Jean, and concocted such a bowl of "yarb tea" for Royal that he slept soundly all night, and awoke his own bright, bonny, little self.

"It has been a strange conclusion to a most satisfactory summer," said Mr. Stuart, when he appeared at the cottage the next day. "And but for you, Washington, would have been a very tragic one."

But when he attempted to reward the boy with money, he stiffened in a moment. "No, thankee, sir," he said. "I can't take it. Why, I love that leetle R'yal most as much as I do Dallas Lee, 'n' I won't be paid for rescuin' him. Besides, I had a grudge agin that air eagle, on my own account, all along of Cotton Ball."

"That vulture, you mean; for I was not mistaken. It belongs to the vulture family, though sometimes erroneously called the 'golden eagle.' Well, I am not sure but you will get a nice little sum for that specimen, as it is a rare and unusually large one. Suppose I take it to the city, and see what I can do for you?"

To this Wash agreed, and the huge bird of prey, which was found to measure fourteen feet from tip to tip of its broad wings, after lying in state, and being visited by half the county, was shipped to New York, while the amount returned by the Professor for the great carcass seemed a veritable fortune to the Saunders, whom the neighbors say are more "ticky" than ever.

Certainly St. George never won more local fame by his dragon slaying than did Washington Beauregard by his lucky feat, and he is proud of the handsome silver-mounted Winchester rifle, the gift of "his grateful friend Royal Stuart," that hangs side by side with the ancient gun which shot the voracious bird of prey now adorning a city museum, labelled "The Lammergeir, or Bearded Vulture," but which in the West Virginia mountains will go down to history as the Demon of Snaggle-Tooth Rock.

The drive to Blue Hill had been delightful and the view from the top exceptionally fine, it being one of those clear, still days when distant objects are brought near. It seemed almost possible to lay one's finger upon the spires of Boston and the glistening dome of the State-house miles away.

Bronson had exerted himself to the utmost. He wished to stand well with all men, and particularly with the Franklin family. From a worldly point of view it would have a most excellent effect for him to be seen driving with pretty Edith Franklin, of Oakleigh. He was glad whenever they passed a handsome turnout from Milton, and he was obliged to take off his hat to its occupants. He felt that he had really gone up in the world during the last year or two. It was a lucky thing for him, he thought, that he had fallen in with Tom Morgan at St. Asaph's. By the time he left college, which he was entering this year, he would have made quite a number of desirable acquaintances.

His talk was clever, but every now and then he said something that made Edith wince. He spoke of Neal, and was sorry he had gone to the bad altogether. Had he really disappeared?

Edith hesitated; she had not the ready wit with which Cynthia would have parried the question.

"We think he is in Philadelphia," she said, finally.

Bronson laughed.

"Hardly," he said; "I saw him in Boston a day or two ago. He looked rather seedy, I thought, and I felt sorry for him, but I didn't stop and speak. Thought it wouldn't do, don't you know; and I'm glad I didn't, as you feel this way."

"I hardly know what you mean," said Edith, somewhat distantly; "we are sorry Neal went away, that is all."

Though she thought he must have taken the money, Edith felt obliged to defend Neal for the sake of the family honor. She had suffered extremely from the talk that there had been in Brenton: she did so dislike to be talked about, and this affair had given rise to much gossip.

"You are very good to say that," said Bronson. "How generous you are not to acknowledge that Gordon stole the money to pay me."

"Stole!" repeated Edith, shuddering.

"I beg pardon, I shouldn't have stated it so broadly; but I'm so mixed up in it, don't you know. It was really my fault, you see, that he felt obliged to—er—to take it. But, of course, I'd no idea it would lead to any such thing as this. I fancied Gordon could get hold of as much money as he wanted by perfectly fair means. Will you believe me, Miss Edith, when I tell you how awfully sorry I am that I should have indirectly caused you any annoyance?"

He looked very handsome, and Edith could not see the expression of triumph in his steely eyes. It was nice of him, perhaps, to say this, even though there was something "out" in his way of doing it.

What was it about Bronson that always affected her thus, even though she liked him, and was flattered by his attentions? She said to herself that it was merely the effect of Cynthia's outspoken dislike. Unreasonable though it was, it influenced her.

But now it came over Edith with overwhelming force[Pg 986] that she had done very wrong to come with Tony Bronson this afternoon. She was disobeying her step-mother, besides acting most deceitfully. Yes; she had deliberately deceived Mrs. Franklin when she wrote the note the day before; for had she not had it in her mind then to allow herself to be over-persuaded in regard to the drive? These thoughts made Edith very silent.

And then they had driven through Brenton. Unfortunately an electric car reached the corner just as they did. The gay little mare from the livery-stable, which had been rather resentful of control all the afternoon, bolted and ran. A heavy ice-cart barred the way. There was a crash, and Bronson and Edith were both thrown out.

It was all over in a moment; but Edith had time to realize what was about to happen, and again there flashed through her mind the conviction of how wrongly she had behaved. What would mamma say?

It was significant that she thought of Mrs. Franklin then for the first time as "mamma."

Bronson escaped with a few bruises, but Edith was very much hurt—just how much the doctor could not tell. She was unconscious for several hours.

Cynthia never forgot that night; her father away; her mother, with tense, strained face, watching by the bedside; and, above all, the awful stillness in Edith's room while they waited for her to open her eyes. Perhaps she would never open them. What then? Beyond that Cynthia's imagination refused to go.

She was sorry that she had been so cross with Edith about Bronson. Suppose she never were able to speak to her sister again! Her last words would have been angry ones. She would not remember that Edith had done wrong to go; all that was forgotten in the vivid terror of the present moment.

The tall clock in the hall struck twelve. It was midnight again, just as it had been on New Year's Eve when she and Neal stood by the window and looked out on the snow. The clock had struck and Neal had not promised.

Reminded of Neal, she put her hand in her pocket and drew out the crumpled note. It had quite escaped her mind that she was to meet him to-morrow. To-morrow? It was to-day! She was to see Neal to-day, and bring him back to her mother. Poor mamma! And Cynthia looked lovingly at the silent watcher by the bed.

Edith did not die. The doctor, who spent the night at Oakleigh, spoke more hopefully in the morning. She was very seriously hurt, but he thought that in time she would recover. She was conscious when he left.

The morning dawned fair, but by nine o'clock the sun was obscured. It was one of those warm spring days when the clouds hang low and showers are imminent. Mrs. Franklin was surprised when Cynthia told her that she was going on the river.

"To-day, Cynthia? It looks like rain, and you must be tired, for you had little sleep last night. Besides, your father may arrive at any moment if he got my telegram promptly, and then, dear Edith!"

"I know, mamma," faltered Cynthia. It was hard to explain away her apparent thoughtlessness. "But I sha'n't be gone long. It always does me good to paddle, and Jack will be at home and the nurse has come. Do you really need me, mamma?"

"Oh no, not if you want to go so much. I thought perhaps Edith would like to have you near. But I must go back to her now. Don't stay away too long, Cynthia. I like to have you within call."

Cynthia would have preferred to stay close by Edith's side, but there was no help for it: she must go to Neal. Afterwards, when she came back and brought Neal with her, her mother would understand.

She was soon in the canoe, paddling rapidly down-stream. A year had not made great alteration in Cynthia's appearance. As she was fifteen years old now her gowns were a few inches longer, and her hair was braided and looped up at the neck, instead of hanging in curly disorder as it once did; and this was done only out of regard for Edith. Cynthia herself cared no more about the way she looked than she ever did. She did not want to grow up, she said. She preferred to remain a little girl, and have a good time just as long as she possibly could.

It was quite a warm morning for the time of year, and the low-hanging clouds made exercise irksome, but Cynthia did not heed the weather. Her one idea was to reach Neal as quickly as possible and bring him home. How happy her mother would be! She wondered why he had not returned to the house at once, instead of sending for her in this mysterious fashion; it would have been so much nicer. However, she was glad he had come, even this way. It was far better than not coming at all.

Her destination lay several miles from Oakleigh; but the current and what breeze there was were both in Cynthia's favor, and it was not long before she had passed under the stone bridge which stood about half-way between. She met no one; the river was little frequented at this hour of the morning so far from the town, for the numerous curves in the Charles made it a much longer trip by water than by road from Oakleigh to Brenton. A farmer's boy or two watched her pass, and criticised loudly, though amiably, the long free sweep of her paddle.

Cynthia did not notice them. Her mind was fully occupied, and her eyes were fixed upon the distance. As each bend in the river was rounded she hoped that she might see Neal's familiar figure waiting for her.

And at last she did see him. He was sitting on the bank, leaning against the trunk of a tree, and when she came in sight he ran down to the little beach that made a good landing-place just at this point.

"Cynthia, you're a brick!" he exclaimed. "I was afraid you were not coming."

"Oh, Neal, I'm so glad to see you! Get in quickly, and we'll go back as fast as we can. Of course I came, but we mustn't lose a minute on account of Edith. Hurry!"

"What do you mean? I'm not going back with you."

"Not going back? Why, Neal, of course you are."

"Not by a long shot. Did you think I would ever go back there?"

"Neal!"

Cynthia's voice trembled. The color rose in her face and her eyes filled with tears.

"Neal, you can't really mean it?"

"Of course I do."

"Then why did you send for me?"

"Because I wanted to see you. There, don't look as if you were going to cry, Cynthia. I hate girls that cry, and you never were that sort. I'll be sorry I sent for you if you do."

Cynthia struggled to regain her composure. This was a bitter disappointment, but she must make every effort to prevail upon Neal to yield.

"I'm not crying," she said, blinking her eyes very hard. "Tell me what you mean."

"I don't mean anything in particular, except that I wanted to see you again, perhaps for the last time." This with a rather tragic air.

"The last time?"

"Yes. I've made up my mind to cut loose from everybody, and just look out for myself after this. If my only sister suspects me of stealing, I don't care to have anything more to do with her. I can easily get along until I'm twenty-five. I'll just knock round and take things easy, and if I go to the bad no one will care particularly."

"Neal, I had no idea you were such a coward!" exclaimed Cynthia, indignantly.

"Coward! You had better look out, Cynthia. I won't stand much of that sort of thing."

"YOU WERE AFRAID TO BRAVE IT OUT. AFRAID!"

"YOU WERE AFRAID TO BRAVE IT OUT. AFRAID!"

"You've got to stand it. I call you a coward. You ran away like a boy in a dime novel, just because you couldn't stand having anything go wrong. You were afraid to brave it out. Afraid!"

There was no suspicion of tears now in Cynthia's voice. She knelt in the canoe very erect and very angry. Her cheeks were crimson, and her blue eyes had grown very dark.

"I tell you again to take care," said Neal, restraining his anger with difficulty. "I did not send for you to come down here and rave this way."[Pg 987]

"And I never would have come if I'd thought you were going to behave this way. I'm dreadfully, dreadfully disappointed in you, Neal. I always thought you were a very nice boy, and I was awfully fond of you—almost as fond of you as I am of Jack, and now—"

She broke off abruptly and looked away across the river.

If Neal was touched by this speech he did not show it at the moment. He stood with his hands in his pockets, kicking the toe of his boot against a rock.

"Of course I couldn't stay there," he said, presently. "Your father as good as called me a thief."

"He didn't at all. He didn't really believe you had taken the money until you ran away. Then, of course, every one thought it strange that you went, and I don't wonder. And I couldn't tell how it really was, because I had promised you; but I'm not going to keep the promise any longer, Neal. I am going to tell."

"No, you can't. You've promised, and I won't release you. I am not going to demean myself by explaining; they ought to have believed in me. But I wish you would stop scolding, Cynthia, and come up here on the bank. I can't talk while you are swinging round there with the current."

After a moment's hesitation Cynthia complied with his request. It occurred to her that perhaps she could accomplish more by persuasion than by wrath. Neal drew up the boat and they sat down under the tree.

"Where have you been all this time?" asked Cynthia.

"In Boston, first. I've been staying with several fellows. I gave out that I was going to Philadelphia, for I thought you would be looking for me, and it is true, for I am going, some time soon. Then I went to Roxbury, and yesterday I walked out from there and found that little shaver to take the note to you."

"Have you told your friends that you ran away?"

"No. Why should I? Fortunately I took enough clothes, though these are beginning to look a little shabby. I spent last night in a shed. I've only got a little money left, but it will answer until I get something to do."

"Neal, do you know you are just breaking mamma's heart?"

Neal said nothing.

"She has looked so awfully ever since you left, and she wrote to you in Philadelphia, and papa went on, but we had to send for him to come back on account of Edith."

"What about Edith?"

"Oh, didn't I tell you? Edith had a fearful accident yesterday. She was driving with—she went to drive, and was thrown out and was terribly hurt."

"I'm awfully sorry," said Neal, with real concern in his voice. "How did it happen? Was it one of your horses?"

"No," said Cynthia, hurrying over that part of it, for she did not want Neal to know that Edith had been with Bronson; "but she was very much hurt, Neal. She was unconscious nearly all night, and the doctor thought perhaps she—she would die. Oh, Neal, won't you come back? Won't you please come back?"

Neal rose abruptly, and began to walk up and down the little clearing.

"I wish you wouldn't, Cynthia," he remonstrated; "I've told you I couldn't, and you ought not to ask me. I'm awfully sorry about Edith, and I'm sorry Hessie feels so badly about me. I'll give in about one thing. You can tell her you have seen me and that I am well. You needn't say I'm going to the bad, but very likely I shall. You mustn't say a word about having lent me the money, I will not have that explained. There, it has begun to rain."

A few big drops came pattering down, falling with loud splashes into the river.

"Oh, I must hurry back!" exclaimed Cynthia, hastily drying her eyes.

"It's only going to be a shower. Come up here where the trees are thicker, and wait till it is over. See, it's all bright over there."

Cynthia looked in the direction indicated, and seeing a streak of cloud that was somewhat lighter than the rest, concluded to wait. Perhaps she could yet prevail upon Neal to come.

They went into the woods a short distance, and though there were not many leaves upon the trees as yet, they were more protected than in the open. It was raining hard now.

"Neal," said Cynthia, in her gentlest tones, "when you have thought it over a little more I'm sure you will agree with me. Indeed, you ought to come."

"I have done nothing else but think it over, and I tell you I am not coming, Cynthia. I wish you wouldn't say any more. I sent for you because I wanted to see you once more, and now you're spoiling it all. I don't believe you care a bit about me."

"Oh, Neal, how can you say so? You know I do care, very much. I'm awfully disappointed in you, that's all. I always thought you were brave and good, and would do things you ought to do, even when you didn't want to. It does seem selfish to stay away and make mamma feel so badly, when it would only be necessary to come home and say you had borrowed the money of me, to make everything all right. It seems very selfish indeed, but perhaps I am mistaken. I dare say I'm very selfish myself, and have no right to preach to you, but if you could see mamma I'm sure you would feel as I do."

Neal remained silent.

"But I still have faith in you," continued Cynthia. "I think some day you will see it as I do. I am sure you will. Oh, dear, how wet it is getting."

The rain was coming down in torrents. The ground was wet and soggy, and their feet sank in the drenched leaves. The canoe, drawn up on the bank, was full of water.

"I ought to have gone home. It is going to rain all day, and mamma will be so worried."

The clouds had settled down heavily, and there was no prospect whatever of the rain stopping.

"I must go right away; I am wet through now. Oh, Neal, if you would only go with me! Won't you go, Neal?"

But Neal shook his head.

"Very well; then it is good-by. But remember what I said, Neal. It's your own fault that the family think you took it. And if mamma or any one ever asks me any questions about what I am going to do with Aunt Betsey's present, I'm not going to pretend anything. If they choose to find out I lent it to you, they can. You won't say I can tell them; so, of course, I can't do it, as I promised, but I sha'n't prevent them finding it out. Oh, Neal, do, do come!"

"I'm a brute, Cynth, I know, but I can't give in. You don't know how hard it is for me ever to give in. I'll remember what you said. Please shake hands for good-by to me, if you don't think I'm too mean and selfish and heartless and a coward, and everything else you've said."

"Oh, Neal!" cried Cynthia, as she grasped his hand with both of hers, "some day I'm sure you will come. Good-by, Neal."

They turned over the canoe, which was full of rain-water, and then Cynthia embarked. Suddenly an idea occurred to her—she would make one more effort.

"Neal, you will have to go part way with me. I'm really afraid to go alone. It is raining so hard the boat will fill up, and it will take me so long to go alone."

Neal could not resist this very feminine appeal. He hesitated, and then got in and took the extra paddle.

"I'll go part way. Cynthia, but I won't go home. Of course I can't let you go off alone if you're afraid. I never knew you to be so before."

With long, vigorous strokes they were soon pulling up-stream. Occasionally one of them would stop and bail with the big sponge kept in the boat for emergencies.

The rain splashed into the river, and the dull gray stream seemed to run more swiftly than usual. It looked very different from its wont. Cynthia and Neal, many times as they had been together on the Charles, had never before been there in a storm.

"Everything is changed," thought Cynthia: "even my own river is different. Will things ever be the same again? Oh, if Neal will only give in when we get near home!"

SIGNALLING FROM THE FLAG-SHIP.

SIGNALLING FROM THE FLAG-SHIP.

The fleet cruiser Minneapolis lies straining at her arched cable off Tompkinsville, Staten Island. The last of the flood tide is singing around the outward curve of her powerful ram, and a gentle southerly breeze is floating to leeward from her massive yellow smoke-stacks, two columns of oily-brown smoke, for the signal "spread fires" flew from the flag-ship hours ago, and the fleet is in readiness to get under way. Down in the fire-room the coal-passers feed the giant furnaces that roar for more. Water-tenders and machinists glide hither and thither watching the boilers and the machinery. On the platforms beside the twin engines stand engineer officers waiting for the signal to start the propellers. Brass-work and steel-work glitter with the splendor of a new polish, and under all rumbles the dull monotone of the dynamo.

On the bridge stand the Captain, the Executive Officer, the navigator, the officer of the watch, the cadet whose duty it is to watch for signals, and a signal boy. A seaman stands by the wheel, and a quartermaster stands beside him. On the after-bridge stand the junior-officer of the watch, a quartermaster, and two signal boys. About the decks are hundreds of seamen ready to jump to their allotted stations. All are silent, eager, alert.

"Signal, sir," says the cadet, referring to his fleet signal-book; "137—get under way."

A word from the Executive Officer, and the steam-winch rolls in the cable. A touch upon an electric button, a rattle of jangling bells below, and the mighty engines turn slowly over, taking the strain off the cable, and sending the ship up to her anchor. Another string of flags runs to the signal-yard of the flag-ship.

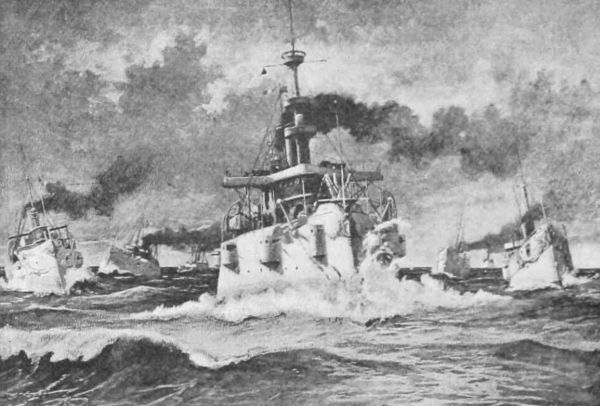

"Form column of vessels," reads the cadet from the signal-book, "natural order." A minute later the North Atlantic Squadron, Admiral Bunce commanding, is steaming in single file out toward the Narrows, the flag-ship New York leading, followed by the Minneapolis, Columbia, Raleigh, Montgomery, Cushing, Ericsson, and Stiletto. A triangular shape swings point up half-way between the Deck and the signal-yard of the New York. It means half-cruising speed—five knots an hour—and the other ships repeat the signal. Silently, majestically, keeping their distances like soldiers on parade, the powerful steel cruisers and the agile torpedo-boats move down the Conover Channel, around the Southwest Spit, past the Hook bell-buoy, out the Gedney Channel, and past the old red light-ship to the open sea. Another string of signals rises on the flag-ship, and the answering pennants flutter on the other ships while the signal-book says,

"Form double column."

"FORM DOUBLE COLUMN!"

"FORM DOUBLE COLUMN!"

Every ship knows her place, and in a few minutes the right wing is made of the Minneapolis, Montgomery, Cushing, and Stiletto, and the left of the others, the flag-ship at the head and in the centre. The speed is now up to the full cruising limit—ten knots an hour—and as the ships go rolling and bowing over the Atlantic swells, their keen prows send up fountains of silvery foam that spread away on either bow in streamers of snow on the living blue. The flag-ship signals the course, and again the others answer with the pennant of perpendicular red and white stripes. The quiet of an orderly sea-march settles down over the fleet, yet never for one instant, night or day, does vigilance relax, for at any moment signals may break out on the flag-ship, though they be nothing more than some vessel's number to warn her that she is out of position.

"All HANDS CLEAR SHIP FOR ACTION!"

"All HANDS CLEAR SHIP FOR ACTION!"

But other signals do appear, for this is no holiday cruise, but one of practice and ceaseless drill. Fleet tactics are executed almost without rest. "Form line of battle, wings right and left front into line;" "By vessels from the right front into echelon," "Front into line," "Squadrons right turn," "Form line, left wing left oblique," "Form column, vessels right turn," and dozens of other orders are given by the flag-ship, and executed with precision and accuracy which would amaze a landsman, but which probably fall far short of the high ideal in the Admiral's mind. Empty, paradelike manœuvres these would seem to the ignorant, but it was the skill of his captains in the execution of such movements, combined with their knowledge of his plans, that enabled Nelson to hurl his fleet upon that of Villeneuve at Trafalgar with such fatal accuracy after hoisting only three signals to the yard-arm of the Victory.

In the darkness of a cloudy night one of the ships is detached with secret orders. She is to indicate an enemy's force, and to fall upon the fleet at some unexpected hour the next day. From the moment of her departure the lookouts on the remaining ships doubly strain their eyes, and not a spar rises above the horizon that is not studied with all a seaman's skill. In the first dog-watch of the next afternoon, when the sailors forward are amusing themselves with pipe and song, the lookout in the foretop cries,

"Steamer ho!"[Pg 989]

In answer to the questions of the officer of the watch, he says the smoke looks like that of a cruiser. The New York has seen her too, and the next minute signals fly at her yard-arm. The Captain nods, and the hollows of the ship are filled with the sharp beating of a drum, the shrill screeching of boatswains' pipes, and the sound of heavy voices bawling, "All hands clear ship for action!" That is a thrilling cry, even in time of peace, and half-slumbering sailors spring to their feet with staring eyes and panting breath. Marines rush to the arm-racks to get their rifles, belts, and bayonets. Officers buckle on swords and revolvers, and spring to their stations.

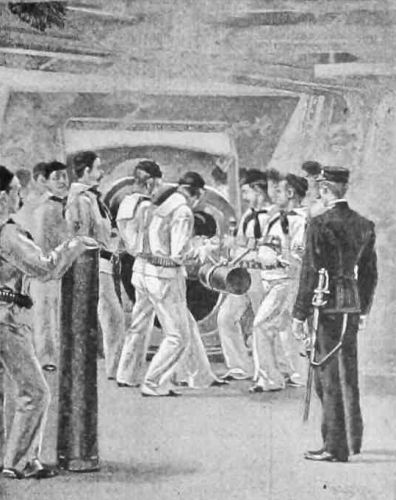

LOADING A BIG GUN.

LOADING A BIG GUN.

And now begins a brief period of bustling activity, which to a landsman would seem like confusion itself confounded. Boats are lashed around with canvas to keep splinters from flying, extra slings are rigged on yards and gaffs to keep them from falling to the deck if struck by shot, breastworks of hammocks are made on bridges, forecastle, and poops, stanchions and rails are sent below, and everything that can be removed is taken from the deck so that the guns may have a clear sweep. The magazines and fixed ammunition-rooms are thrown open, and the men of the powder division take the stations allotted to them for keeping up a continuous supply of ammunition to the whole battery. Hatch-covers are lifted, shell-whips are rigged for hoisting away the heavy charges for the big guns, and chutes are placed for sending empty cartridge-cases below. The men belonging to the lighting-tops go aloft and hoist ammunition for their guns. The crews of the main battery open the breeches of their great weapons, sponge out the chambers, insert the big steel shells and powder cartridges, and stand waiting for orders.

At last all is ready, and the division officers report to the Executive Officer, who in turn reports to the Captain.

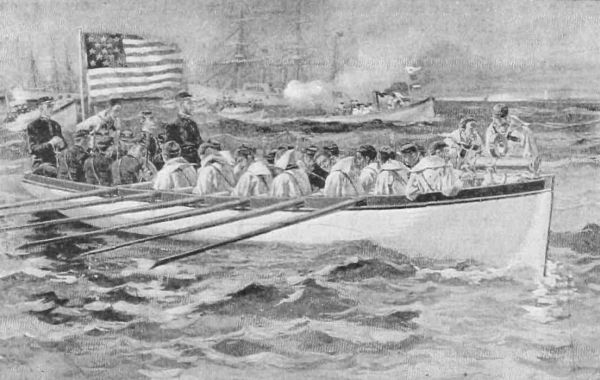

The flag-ship signals the order for the formation for attack, and then at full speed the vessels dash forward. Signals follow signals, and the ships go through swift and graceful evolutions, until the Admiral's programme has been fully carried out. Then the vessel that was detached to represent the enemy lowers over her side a pyramidal target of white canvas with a black spot painted in the centre. She steams back to her position in line. Now the vessels in turn glide slowly along at a distance of 1600 or 1800 yards from the target, and the thunder of great guns fairly shakes the heavens, while the massive steel projectiles strike the water around the target, and thrash it into glaring geysers of milk-white foam. It would be a sad time for any hostile ship if she lay where that target is.

FIRING FROM THE MILITARY TOPS.

FIRING FROM THE MILITARY TOPS.