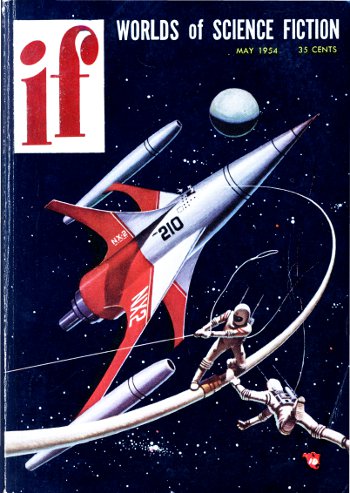

Title: Perchance to Dream

Author: Richard Stockham

Illustrator: Kelly Freas

Release date: June 17, 2010 [eBook #32859]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/32859

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from IF Worlds of Science Fiction May 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

All along the line of machines, the men's hands and arms worked like the legs of spiders spinning a web. They wound wire and hammered bolts, tied knots and welded pieces of steel and fitted gears. They did not look at each other or sing or whistle or talk or laugh.

And then—he made a mistake.

Instantly he stepped back and a trouble shooter moved into his place. The trouble shooter's hands flew over the controls.

The trouble shooter finished and the workman took his place. His arms moved ceaselessly again.

He was a tall man, slim and wiry, his dress identical to that of the others—grey coveralls that fit like tights.

Suddenly a red light flashed in his eyes and he began to tremble. He took two steps backward. The trouble shooter moved into the empty space.

The man stood for a moment, like a soldier at attention, turned and walked smartly toward the mouth of a corridor.

The silence was like a motion picture with a dead sound track. There was only motion—and him walking down the line of machines where the hands reached out, working, working.

In the corridor now, he looked straight ahead, marching. The walls glowed like water beneath a shallow sea.

He raised his arm, felt the door strike and the heel of his hand; felt it swing open; saw the desk suspended from the ceiling by luminous, silver chains.

A man with a massive, white-maned head and a pink, smiling face rose from behind the desk. His suit was like that of a general.

"Well, Twenty-three." The Superfather stared down at the dossier on his desk. "Two mistakes in three months. Too bad. Just when you were on your way to the head of the machine room."

"I don't know what's the matter with me," said Twenty-three.

"I'm afraid we'll have to drop you back to a less responsible position."

"Of course."

The Superfather looked up quickly. "You accept this? No depression? No threat of suicide?... You are in bad shape." He handed a packet of cards to Twenty-three. "Put these in your dream machine tonight. Go to your new job tomorrow."

Twenty-three stood motionless, staring over the other man's shoulder.

The Superfather sat down. "Tell me about the dreams you have when you don't use the machine."

Twenty-three made a quick decision. He couldn't tell him he didn't use the standard dream cards anymore. And he certainly couldn't tell about the other dream cards he'd been getting from the little man he'd met on the street. He'd simply answer the factual truth to the question that had been asked.

"Well," he said, as though he were confessing a crime. "I dream I'm walking in the city. It's dark. I feel like I've got to find something. I don't know what. But the feeling's very strong. All of a sudden I notice the city's empty. There're just buildings and streets and a faint glow of light. And it comes to me that everybody's dead and buried. Then I know what I'm looking for. I've got to find something alive or I'll die too. So I start running around, in and out buildings, up and down streets. But there's nothing. I'm breathing so hard I think my heart's going to burst. Finally I fall down. I feel myself beginning to die. I try to get up but I can't! I try to yell! I've got no voice! I'm so afraid, I can't stand it! Then I wake up."

The Superfather frowned. "Incredible. Several other cases like yours have turned up in the last month. We're working on them. But yours is the worst yet. You had such high capabilities. Your tests showed, when you first began to work, ten years ago, that you were capable of going to the head of your production line. But you're not doing it. Also your normal dreams should correspond to the ones on the cards. And they don't.... Are you using the standard cards every other night?"

Twenty-three lied. "Yes."

"And the nights you don't use them, you have a dream like the one you just told me."

"That's right."

"Incredible." The Superfather shook his head. "It just doesn't add up. As you know, you get the prescribed dreams every other night and that's supposed to condition your mind to dreaming those same dreams, by itself, on the nights you don't use the machine. The prescribed dreams merely show you the true way of life. And when you're on your own you're supposed to follow that way of life whether you're asleep or awake. That's what the dream machine is for. I'm sure you're aware of all this?"

"Yes," said Twenty-three. "Yes."

"Now we Superfathers never have to use the dream machines. We're so filled with the way of life they advocate and it's become such an integral part of us, we simply are what our prescribed dreams are. And the more successful a person is in the city, the less he has to use the dream machine. Now you have to use it every other night. That's entirely too much for a man of your potential. You realize this, of course.

"Oh I do," said Twenty-three shaking his head sadly.

"Well now," said the Superfather, "that means something's wrong. Very wrong." He rubbed his chin, thinking. "Your prescribed dreams show you working faster and faster on the machines, going on month after month year after year, with one hundred percent accuracy. They show you happy in your work, driven by ambition on up to the end of your capabilities. They show you contented there to the end of your working life." He paused. "And you're doing just the opposite ... I suppose your wife is—concerned?"

Twenty-three nodded.

"After all, the marriage center assured her your index was right for her. Her sleep cards were coordinated with yours. The normal dreams of both of you, without the machine, should be identical.... Yet you come up with this horror—running through the city, alone, falling, dying."

Twenty-three's mouth twitched.

"Well." The Superfather stood. "If you can't adjust to normal, we'll simply have to send you to the pre-frontal lobotomy men. You wouldn't want that."

"Oh no!"

"Good!" The Superfather held out another packet of cards. "Use these tomorrow night. It's a concentration pattern which should be dense enough to make you dream of being, well—perhaps even President, eh?"

"Yes." Twenty-three hesitated.

"Well?" said the Superfather.

"I'd—like to ask a question."

The Superfather nodded.

"What—what use," went on Twenty-three, "is all this—work being put to—that we do—along the machine lines—every day? We don't, seem to really be making anything. Just working."

The Superfather's eyes narrowed. "You're kept busy. You get paid. You live. The city is here. That's all. That's enough."

"Yes, sir. Thank you, sir." Twenty-three turned abruptly, marched to the door and stepped into the empty, silent corridor.

Twenty-three looked up at the glowing dome of the city that curved away to the horizon. He wondered if there really was a white ball beyond it sometimes and tiny dots of light, set in blue black. And at other times did a ball of fire flame up there, giving light and heat and life? And if there was this life and light up there, why the great dome over the city? Why the factories and machine lines replacing it section after section, generation after generation? The slabs that the workers fused together this year and the next and the next, pushing back this life and light and heat. Why not let it pour down into the city and warm all the people? Why not go to the space out there and the depth and freedom? Why this great shell that closed them away? For the sake of the Superfathers maybe? And the Superfathers-plus? For the sake of the ones, like himself maybe who worked and built? For the sake of them, so they wouldn't become dangerous maybe and tear the great wall down and rush out into whatever was beyond? Why else?

But it could be all a farce. They could all be working in the great dome because they didn't know what was beyond. Who could know if they'd never been beyond?

And so they were held under the domes with the buildings and the machines that carried them all around in the city; held with the plumbing and the theatres and all the intricate mechanisms that spoke to them and fed them, that washed them and poured thoughts into their minds, that healed them when they were sick and rested them when they were tired. The same as they were held with the great dome. Held and shackeled with the replacing of parts that didn't need replacing; the making over and over again of the tiny and large pieces of the mechanisms and the taking of the old mechanisms and the melting of them or smashing of them to powder so that this dust or molten metal could be fashioned again and again into the same pieces that they had been for so many thousands of years. All this to keep them busy? All this to keep something outside that was supposed to be destructive because once it had been so five thousand years ago or ten or fifty? All this because that was the way it had been for as long as the hundreds and the thousands of years that history had been recorded?

He walked on through the silence, dimly aware now of the people moving about him, of the automobiles rolling past, as though moved by some invisible force. He passed row upon row of movie theatres that called to him with invisible vibrations. He turned away.

Where was the little man?

He stopped, moving only his eyes. After a moment, he saw the little man step out of a shop-front and stand waiting. Twenty-three, a cigarette in his mouth, walked over and asked for a light. The little man touched a lighter to the cigarette, at the same time dropping a packet of cards into Twenty-three's pocket.

Twenty-three moved on. He felt the pounding of his heart. If only his wife were asleep so he would not have to wait to look at these new cards.

As he walked, his thoughts cried out against the silence. He glanced suspiciously from side to side. If only he could hear the sounds of the city. But except for human voices and music, the city had always been silent. The human voices spoke only words written by the Superfathers, and the music came from records that had been composed by them—all this back when the city had first come into being. Other than these sounds there could be only the quiet all around. No chugging motors or scraping footsteps. No crashing engines in the sky, or pounding of steel on stone. No shrieking of factory whistles or clanging steeple bells or honking automobile horns. None of this to pluck and pound at nerves, to suggest that this place was not the most soothing and gentle of all places to be in. There were no winds to swirl and moan away into the distance. The chirp of birds had long since been stilled, and so had the patter of rain and the crash of thunder. There must not be any of these sounds either to lure the imagination into some distance where danger and excitement might be waiting.

Now he was walking toward the door of his apartment house. It swung open. Thirty seconds later he stopped before another door. It too swung open.

His wife stood in the middle of the room, between two traveling bags. He moved slowly toward her and stopped just out of arm's reach.

"What's this?" He gestured toward the bags. "Where're you going?"

She stared at him for a long moment, her face set. She was of his height and build and wore a suit the same light grey as his. Their hair cuts were identical, their faces sharp featured and pale. They might have been brother and sister—or two brothers, or two sisters.

"I'm going to the marriage center."

"What for?" He had tried to inject surprise into his voice. But the tone was listless.

"The Superfather called about your dream."

Twenty-three turned away, lighted a cigarette. He should beg her to stay, should promise to change. But the silence was in him, like a sickness.

"A terrible thing's happening to you. I don't want any part of it." She picked up the bags. "When you come to your senses, you know where to reach me.... If I haven't already made another contract, I might come back to you."

She hesitated at the door.

"There's one thing I don't understand. You haven't begged me to stay. You haven't broken down. You haven't threatened suicide." She paused. "It's standard procedure, you know. It might even make me decide to wait awhile."

"I don't want you to stay," he said. He felt a shock of surprise. It was as though a voice had spoken from behind him.

He watched the door shut between them.

Dressed in his pajamas, he stood beside the metal tube, in which for so many years he had slept his regulation sleep and dreamed his regulation dreams. There was something of the finely made casket about this tube—the six foot length and three foot diameter; the lid along its top and the dull shine of the metal and the quiet of it, as though it were asleep and lying in wait for a tired body to bring it awake so that it could put the body to sleep and live in the dreams it would give to the sleeper.

Beside his own tube stood its twin, where his wife had also slept and dreamed through the years.

Leaning slightly forward, he felt the press of metal against his hip bones, felt the tube roll an inch with his weight. He rested one hand on the metal top, felt its warmth and smoothness, was aware of its cleanness, like that of a surgical instrument.

Now he glanced at the glistening black panel that stood two feet high at the tube's head; quickly checked its four illuminated dials and three gleaming arrows and at the same time raised his hand to drop the cards into the softly glowing slot at the panel's top.

Suddenly his hand stopped.

He bent forward.

What was this? A feeling of strangeness. Vague. Like sensing some subtle change in a picture that has hung for twenty years above the fireplace in one's home.

He drew closer, squinting. The dials and meters seemed to be the same as they had yesterday and the day before and the year before.

And yet?

The dials. Larger? By a fraction? And the tiny gleaming arrows of the meters. Barely longer? And the marks on the dials and meters? One extra each, very faintly, like a piece of hair.

He was very still for a long moment. Then he moved around the foot of his own sleeping tube, pushed between the two and stood at the head of the other one.

He checked its dials and meters. They were as they had been for many years. He stepped back to the panel of his own and pressed a button. As the glistening metal top rose, silently, he ran his hand around the yawning interior, felt the downy softness and the body-like warmth. Then his hand touched a pliable metal plate. That should not be there. He stood back, remembering the workmen who had come into the house that morning for the routine checkup of the tubes. His wife had already left for work and he had just stepped through the door when they had met him in the corridor. They had gone on into the rooms and he had sensed vaguely that something was wrong. Then he had put the feeling out of his mind and gone to his work.

Now suddenly, he turned to the illuminated four inch square panel above the door, read April 15, 2563. The workmen had checked a day early. He frowned. Either the Superfather had ordered the machine changed, which was highly improbable, because every object in the city was standardized and any change would upset the established order, or the workmen were tied up with the man who had given him the different dream cards.... In any event he had to sleep in the tube that night and he definitely wanted to dream the dreams on the cards he had just gotten from the man on the corner.

He dropped the cards into the slot at the top of the panel, climbed into the tube and pressed a button. The top closed over him, like a hand. He lay still, feeling the warm clasp wash over his body. There was darkness and silence and a cool motion of antiseptic air. He could try the first dream. If it wasn't right, he could shut it off and sleep without dreams.

He pressed another button.

Silence.

The sound of his regular breathing.

Then a sighing came into his mind, and a green haze. The sighing became a soft breeze; the green, tree-covered hills rolling off to the horizon. He relaxed, aware in a fading, sinking part of his consciousness that the machine worked as usual. He would dream and wait and hope....

And so the wind was breathing across the land from off a vast stretch of blue water, which broke along a sandy beach in foamy white breakers. The surf thundered all through his body. The wind brushed against him like a great, purring cat. He looked up at the blue sky and seemed to feel himself rising and sinking, both at the same time, up into its depths. As his sight touched the sun there was an explosion of brightness which blinded him. He turned away then to the rolling green sea of hills, saw the trees bending from the surge of wind and heard the rustling of leaves.

And then a deep voice moved through his mind.

"Outside the city," it said, "all this exists. During the terrible burning of the Earth back in the wars of its antiquity, the city was built as a place of life for those who yet lived. But those people were not aware that the Earth would come alive again and they made the city so that no death could enter it from without and no life could escape from within. And they turned away from the Earth and lived only with the city so that it became their universe—to all but a very few of us. We still held a faint awareness of what the Earth had been—this passed down to us for many generations, in whisperings, by the wise ones of our people, back in the beginning of the city. And in those times, we had been in the city too long, for thousands of years. We knew that there must be freedom beyond the walls, if we could get through. But the walls were thick and high and without a flaw, making a sky over us. We worked for five hundred years on a machine to get us through the wall. Now a few of us have succeeded and more will follow us to the freedom out here in the good land. There is room for everyone here, there are no boundaries and no ceilings and no walls anywhere. And you may join us some time in the near future, if you wish."

Twenty-three sighed in his sleep.

Now a great city faded into his mind. There were long, tree lined streets and buildings, some built in rising spirals, some in spreading squares, others in ovals, domes and curved half circles. The wind wandered among the buildings and the bursts of green. People, dressed in white, flowing robes or black tights, walked the streets. He could hear their footsteps on the stone or grassy walk, could hear the hum of vehicles rolling along the streets or flying through the air. They were long and streamlined or short and round, or they were curved like gondolas or squat like saucers. And they were moving at many speeds. Yet there was order. And the air was sweet and clean. A black line of clouds was rising across the horizon. Soon there would be lightning and thunder and cool rain.

The deep voice touched him again. "This is the city that can be. A city of life, open to the sky and the earth, a city in which people can find and follow their own lives. After the wars, the cities were built to shut out the death of Earth. But the Earth has come to life again. And so can the cities."

The silence came while the picture changed and Twenty-three stirred, waiting.

A figure grew in his mind, wavered, and became a woman. Twenty-three saw the long body and the softness; saw the flowing hair and the smile as she watched him. He saw the gentleness in her face; saw a strength under the softness, like the storm that lies below the charged quiet of a summer evening. Her lips moved.

"Paul. Dream your dreams for us." The words seemed to fall on him. He trembled and cried out. And he felt a violent stirring in his body and a breaking away as though he had flung himself through the walls of a tomb.

The picture blew away while the voice continued: "She is a woman, not a woman who half resembles a man." A pause. "When you wish to leave the city, ask for the final card. You are welcome."

There was silence and darkness. Twenty-three stirred. He opened his eyes. The glow from the city outside filtered into the room through the translucent walls. He lay motionless. Paul. He was Paul. Not Twenty-three. A man with a name. Wonder came into him, and a sense of strength, and a willingness to remember without fear.

His mind ran back to the first mistake, almost a year past. He remembered the horror of failure then and the terror at his being subjected to a mistake. He remembered the inference from the Superfather that there might be a bad strain in his blood line. He remembered taking the dream cards that were to have set him straight, that were to have shown him working over the machines with super speed, moving up along the production line to its pinnacle and on up to the position of Superfather and on up to Superfather-plus and on up to the place of Father of The City. But the cards had been sabotaged, so that from them into his mind had come the dreams of the trees and the oceans and the green earth spreading off to the horizon and the expanse of blue sky.

And then the words had directed him to the little man who had given him the cards on the street corner. They had known him, the words had said, through what was called telepathetic screening, for ones suitable to leave the city. He was one of those chosen, because he, like a few others, had been unable to adjust completely to the demands of the city. He was one of those in whom a rebellious nature had been passed down from generation to generation, by attitudes and acts of his ancestors, by a word spoken here and one there, by an intangible reaching out toward the sky and the green growing things and the need to understand who and what he was. But in him now this feeling was weak and close to death and would die in him if it were not brought out into life of the Earth.

Now the memories receded; he lay motionless, listening to his breathing and his heartbeat, feeling his body press against the softness that held him.

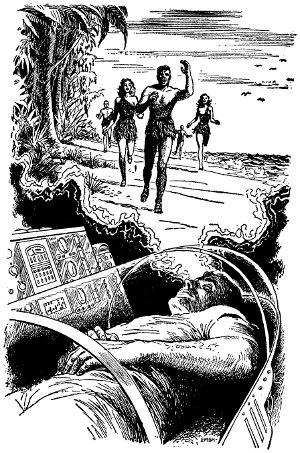

Suddenly a shaft of light fell on him through the transparent square. Opening his eyes, he saw his wife's face staring down at him.

She moved her hand. The lid of the tube raised. He lay watching her, feeling naked and, for a moment, helpless.

"I talked for a long while with your Superfather," she said. "I feel better. He told me you'd promised to take the prescribed dreams tonight."

Twenty-three turned his face away from her.

She began to undress.

"I'm going out for a walk." He stepped from the machine.

She watched him dress, her look a mixture of curiosity and fright.

When he left it was as though he were leaving an empty room and she watched him as though he were not quite human.

The glow of the city was all around him as he walked toward the corner where the little man stood. The telepathic advertisers reached out from the places of entertainment, pulling at him. The voices enveloped him for a moment so that he almost turned back to them. But then he saw, in his mind, his arms working over the machines, saw them make a wrong motion that smashed a gear, saw the flashing red light and the heavy, expressionless face of the Superfather. He was aware that his memory would be erased and the skies, and the ocean, and the green hills. His name would be gone. Paul would die. And the city would be his tomb.

Quickly he turned down a side street, saw the small figure leaning against the corner of the building.

Walking rapidly toward him, as though he were being chased, he saw the lean, ruddy face smile and the deep, blue eyes look at him; heard the voice gently say:

"Welcome, Paul."

"The last card," said Twenty-three.

The little man handed it to him, quickly. "Good luck. Turn the dials one extra point on the control panel. Our men have made the machine ready. It's time now."

Twenty-three thrust the card into the inner pocket of his jacket. So that was it. They had changed the machine.

"One extra point," he repeated, glancing up and down the street.

"And remember," said the little man. "Destroy all the cards you've used before. They were designed particularly for you. If you don't make it across to us, the Superfathers will use the cards against you."

Twenty-three whirled around. The little man had gone. Twenty-three suddenly felt weak. My God! The other cards! Left in the machine! If his wife—!

He stood very still for a long moment, then he ran!

The door to his apartment swung open. The room beyond was empty. A light shown faintly. He stood for a moment, listening. Silence. He stepped to the bedroom. The top of his wife's sleeping tube was closed. He could see her face through the transparent square, could hear her quiet breathing.

In one quick, silent motion, he stepped to the side of his own tube, pulling the last card from his pocket, and dropped it into the glowing slot at the top of the black control panel. Then he turned the dials to the extra point.

Several minutes later he pressed the button at the bottom of the control panel. The top opened. At the same moment, he heard a step behind him. He whirled around. The Superfather stood in the doorway. At his back hovered the dark bulks of two other men. Twenty-three felt his muscles lock. He saw the Superfather's dead smile and then his wife stepping down to the floor and hurrying to the side of the Superfather.

"Those pictures," she said, shuddering. "They were so—strange."

The Superfather held his eyes on Twenty-three but spoke to the woman. "Thank God you were strong. It was commendable of you to call us."

"I don't know what made me look at his dreams," she cried. "Maybe it was when I asked him if he'd taken the prescribed dreams and he didn't answer.... Anyway, I tested his machine. It was insane!"

"Dreams made by some twisted mind," the Superfather said. "Remember. They've no real existence. Nothing lives or moves outside the city. There were old myths but they've been dead for countless generations." He paused. "Where are the pictures?"

"I burned them."

"Good." He motioned to the men behind him. They came forward and stood on each side of Twenty-three.

"Twenty-three," said the Superfather, "we may have to erase your memories and your present individuality." He cleared his throat. "Our records show that some two thousand people have disappeared in the last five years. Your case has much to do with it.... Where'd you get the new cards?"

Twenty-three was silent.

The Superfather pulled out a pack of cards. "Before we leave this room, you'll be a different man. If you tell us,"—he waggled the cards in his right hand—"this'll be your new life. You'll have dreams of outdoing every man on the machine lines and fix your body so you'll have the capacity to do it. You will do it. You'll become a Superfather. You'll burn to excel them. You'll push on up, become a Superfather-plus. You'll work with ideas, ways of increasing efficiency, pushing the workmen faster and faster. And you'll find ways of conditioning them to meet the greater and greater demands for speed. The city and people'll be at your fingertips. There'll be rooms of marble and gold for you. Soft carpets and buttons to push that'll give you any desire instantly. You'll have everything and be everything!" He paused and took a deep breath. "All this'll be yours if you'll tell us where you got the cards, without forcing us to probe your mind with the electric-scalpel...."

With an effort, Twenty-three raised his eyes to the Superfather's face.

"And if I don't tell you?"

"Moving a lever back and forth twice a minute hour after hour, year after year. Living in a bare cubicle. No entertainment. No desires." He paused. "And no memories."

Twenty-three looked over the Superfather's shoulder. The last card, he thought, is in the machine. Escape from the city. They said that, from outside. I've got to know. No matter what they put in the machine, that card will show first. Even if it's only for ten seconds or thirty or sixty, or however long—I'll know.

"No," he said, "I won't tell you...."

The woman gasped and hid her face. The Superfather, scowling, made a motion.

The two dark men took hold of Twenty-three. They lifted him into the tube.

The Superfather dropped the second pack of cards into the panel and pressed the button. The top closed silently, like a mouth.

Twenty-three's eyes closed; his body waited.

For an instant—blackness, and silence, like a moment after death, or a moment before birth. Then twilight, or dusk, over an ocean. A sky of pale blue. A shine on the gently surging waters. A scent of clean air. Sea spray. The cool sound of wind.

Then a man's voice, deep and flowing: "You know that there is no entrance or exit to this city. It is sealed off and will always be so. But the dream machine in which you lie has been changed by our agents inside the city. The last card you dropped into it is different from the others. These changes have been made so your dream will become a reality. Your mind will be transmitted to us here among the hills and under the trees and by the ocean. And a new body, that we have grown, artificially, from all the elements, a body like the one you will leave behind, will be waiting for you. You need not be afraid."

Twenty-three felt himself moving forward. Sight and hearing and sensation, without a body. Time dropping away, like a forgetting of yesterday and tomorrow. There was only this moment. And then he felt the great humming surging power of the machine, like an ocean rushing him toward some unseen shore. He was caught in a gigantic tingling shock wave, and felt like a tremendously outsized torch, lit and flaming, and carried, still burning, in the green tide of sizzling electricity. The machine screamed. The machine chanted. The machine raved. Dimly, he heard his wife cry, and above him felt the Superfather scrabbling at the machine, the guards shouting. The machine shrieked and the great tidal wave of power jolted and flung him, white-hot kindling, through air, through sky, up and down! Down upon a white shore, upon creaming sands, leaving him to quiet, to silence, to a pulling away of the tide....

Now the scent of sea came strong into him. He heard the crash and roar of surf and the rustling of leaves and the sweep of wind. There were bird songs and the cries of animals. He saw the spread of rolling hills, saw a stream searching its way among great rocks and swelling and rolling full into a river and the river flowing and sinking into the sea. He felt the earth upon his feet and the touch of grass. Breezes, heavy with green from the land eddied all around him and filled his body and washed him. He heard his name—saw people coming toward him saying, "Welcome." He felt their arms, embracing him. He saw an open city growing among the hills. Its buildings rolled away with the hills of the Earth and became a part of the Earth. The people took him by the hand and led him toward it speaking to him of no one hurting the other, and no one locked in a cell and all the walls of this world outside, tumbled down....

He was happy and repeated the name they spoke to him.

"Paul."

Back in the city, in the room, the wife cried out.

The Superfather, too, seeing the strange look on the face of the man inside the chrysalis of the dream-maker, quickly touched the button that raised the lid. He bent down and took the wrist of the cold man lying there.

"Dead."

"Are you sure?"

The Superfather bent still further down and listened to the chest, and the wife came close, and they both stood there, half-bent. The mouth of the dead man was open and the Superfather listened for any faint whisper of breath. The wife listened. They both looked at each other for a long time.

Because, from the open mouth of the cold man lying there, faintly, far away, and fading slowly into silence, they heard quiet laughter, and the sound of many birds and voices, and trees rustling in the late afternoon. Then it was gone and no matter how the two people bending there waited and listened, it was like putting their ear to a white stone.