COPYRIGHT, 1921.

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published December, 1921.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PREFACE

This sketch of the History of Rome to 565 A. D. is primarily intended to meet the needs of introductory college courses in Roman History. However, it is hoped that it may also prove of service as a handbook for students of Roman life and literature in general. It is with the latter in mind that I have added the bibliographical note. Naturally, within the brief limits of such a text, it was impossible to defend the point of view adopted on disputed points or to take notice of divergent opinions. Therefore, to show the great debt which I owe to the work of others, and to provide those interested in particular problems with some guide to more detailed study, I have given a list of selected references, which express, I believe, the prevailing views of modern scholarship upon the various phases of Roman History.

I wish to acknowledge my general indebtedness to Professor W. S. Ferguson of Harvard University for his guidance in my approach to the study of Roman History, and also my particular obligations to Professor W. L. Westermann of Cornell, and to my colleagues, Professors A. L. Cross and J. G. Winter, for reading portions of my manuscript and for much helpful criticism.

October, 1921

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION | PAGE | |

| The Sources for the Study of Early Roman History | xiii | |

| PART I THE FORERUNNERS OF ROME IN ITALY |

||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| The Geography of Italy | 3 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Prehistoric Civilization in Italy | 7 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| The Peoples of Historic Italy | 13 | |

| The Etruscans; the Greeks. | ||

| PART II THE EARLY MONARCHY AND THE REPUBLIC, FROM PREHISTORIC TIMES TO 27 B. C. |

||

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Early Rome to the Fall of the Monarchy | 25 | |

| The Latins; the Origins of Rome; the Early Monarchy; Early Roman Society. | ||

| CHAPTER V | ||

| The Expansion of Rome to the Unification of the Italian Peninsula: c. 509–265 b. c. | 33 | |

| To the Conquest of Veii, c. 392 B. C.; the Gallic Invasion; the Disruption of the Latin League and the Alliance of the Romans with the Campanians; Wars with the Samnites, Gauls and Etruscans; the Roman Conquest of South Italy; the Roman Confederacy. | ||

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| The Constitutional Development of Rome to 287 b. c. | 47 | |

| The Early Republic; the Assembly of the Centuries and the Development of the Magistracy; the Plebeian Struggle for Political Equality; the Roman Military System. | ||

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| Religion and Society in Early Rome | 61 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| Roman Domination in the Mediterranean: The First Phase—the Struggle with Carthage, 265–201 b. c. | 67 | |

| The Mediterranean World in 265 B. C.; the First Punic War; the Illyrian and Gallic Wars; the Second Punic War; the Effect of the Second Punic War upon Italy. | ||

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| Roman Domination in the Mediterranean: The Second Phase—Rome and the Greek East | 89 | |

| The Second Macedonian War; the War with Antiochus the Great and the Ætolians; the Third Macedonian War; Campaigns in Italy and Spain. | ||

| CHAPTER X | ||

| Territorial Expansion in Three Continents: 167–133 b. c. | 99 | |

| The Spanish Wars; the Destruction of Carthage; War with Macedonia and the Achæan Confederacy; the Acquisition of Asia. | ||

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| The Roman State and the Empire: 265–133 b. c. | 105 | |

| The Rule of the Senatorial Aristocracy; the Administration of the Provinces; Social and Economic Development; Cultural Progress. | ||

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| The Struggle of the Optimates and the Populares: 133–78 b. c. | 125 | |

| The Agrarian Laws of Tiberius Gracchus; the Tribunate of Caius Gracchus; the War with Jugurtha and the Rise of Marius; the Cimbri and the Teutons; Saturninus and Glaucia; the Tribunate of Marcus Livius Drusus; the Italian or Marsic War; the First Mithridatic War; Sulla’s Dictatorship. | ||

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| The Rise of Pompey the Great: 78–59 b. c. | 151 | |

| Pompey’s Command against Sertorius in Spain; the Command of Lucullus against Mithridates; the Revolt of the Gladiators; the Consulate of Pompey and Crassus; the Commands of Pompey against the Pirates and in the East; the Conspiracy of Cataline; the Coalition of Pompey, Cæsar and Crassus. | ||

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| The Rivalry of Pompey and Caesar: Caesar’s Dictatorship: 59–44 b. c. | 166 | |

| Cæsar, Consul; Cæsar’s Conquest of Gaul; the Civil War between Cæsar and the Senate; the Dictatorship of Julius Cæsar. | ||

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| The Passing of the Republic: 44–27 b. c. | 185 | |

| The Rise of Octavian; the Triumvirate of 43 B. C.; the victory of Octavian over Antony and Cleopatra; Society and Intellectual Life in the Last Century of the Republic. | ||

| PART III THE PRINCIPATE OR EARLY EMPIRE: 27 B. C.–285 A. D. |

||

| CHAPTER XVI | ||

| The Establishment of the Principate: 27 b. c.–14 a. d. | 205 | |

| The Princeps; the Senate, the Equestrians and the Plebs; the Military Establishment; the Revival of Religion and Morality; the Provinces and the Frontiers; the Administration of Rome; the Problem of the Succession; Augustus as a Statesman. | ||

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| The Julio-Claudian Line and the Flavians: 14–96 a. d. | 226 | |

| Tiberius; Caius Caligula; Claudius; Nero; the First War of the Legions or the Year of the Four Emperors; Vespasian and Titus; Domitian. | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| From Nerva to Diocletian: 96–285 a. d. | 244 | |

| Nerva and Trajan; Hadrian; the Antonines; the Second War of the Legions; the Dynasty of the Severi; the Dissolution and Restoration of the Empire. | ||

| CHAPTER XIX | ||

| The Public Administration under the Principate | 264 | |

| The Victory of Autocracy; the Growth of the Civil Service; the Army and the Defence of the Frontiers; the Provinces under the Principate; Municipal Life; the Colonate or Serfdom. | ||

| CHAPTER XX | ||

| Religion and Society | 293 | |

| Society under the Principate; the Intellectual World; the Imperial Cult and the Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism; Christianity and the Roman State. | ||

| PART IV THE AUTOCRACY OR LATE EMPIRE: 285–565 A. D. |

||

| CHAPTER XXI | ||

| From Diocletian to Theodosius the Great: the Integrity of the Empire Maintained: 285–395 a. d. | 317 | |

| Diocletian; Constantine I, the Great; the Dynasty of Constantine; the House of Valentinian and Theodosius the Great. | ||

| CHAPTER XXII | ||

| The Public Administration of the Late Empire | 333 | |

| The Autocrat and his Court; the Military Organization; the Perfection of the Bureaucracy; the Nobility and the Senate; the System of Taxation and the Ruin of the Municipalities. | ||

| CHAPTER XXIII | ||

| The Germanic Occupation of Italy and the Western Provinces: 395–493 a. d. | 351 | |

| General Characteristics of the Period; the Visigothic Migrations; the Vandals; the Burgundians, Franks and Saxons; the Fall of the Empire in the West; the Survival of the Empire in the East. | ||

| CHAPTER XXIV | ||

| The Age of Justinian: 518–565 a. d. | 369 | |

| The Germanic Kingdoms in the West to 533 A. D.; the Restoration of the Imperial Power in the West; Justinian’s Frontier Problems and Internal Administration. | ||

| CHAPTER XXV | ||

| Religious and Intellectual Life in the Late Empire | 385 | |

| The End of Paganism; the Church in the Christian Empire; Sectarian Strife; Monasticism; Literature and Art. | ||

| Epilogue | 403 | |

| Chronological Table | 405 | |

| Bibliographical Note | 415 | |

| Index | 423 |

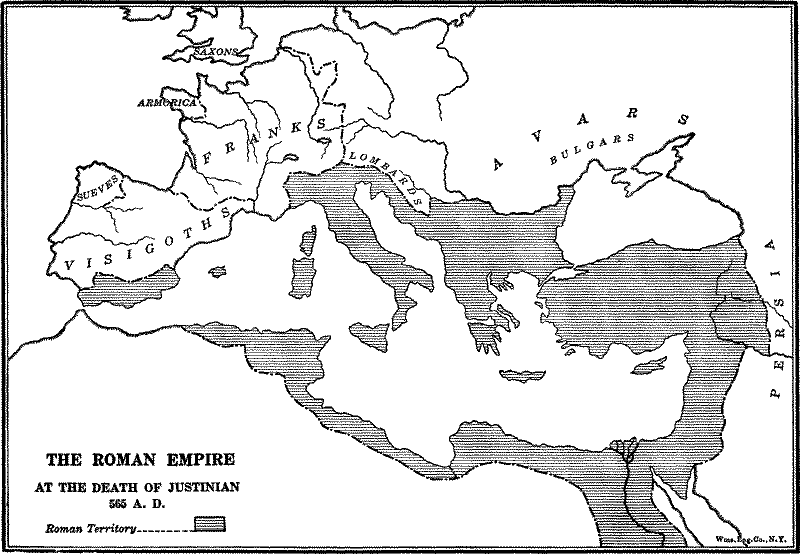

LIST OF MAPS

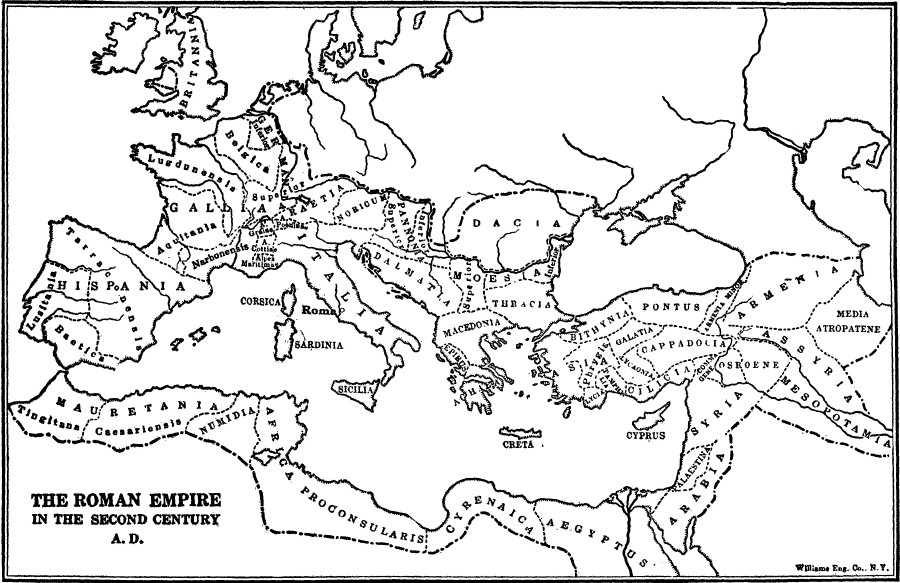

| The Roman Empire in the Second Century A. D. | Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | ||

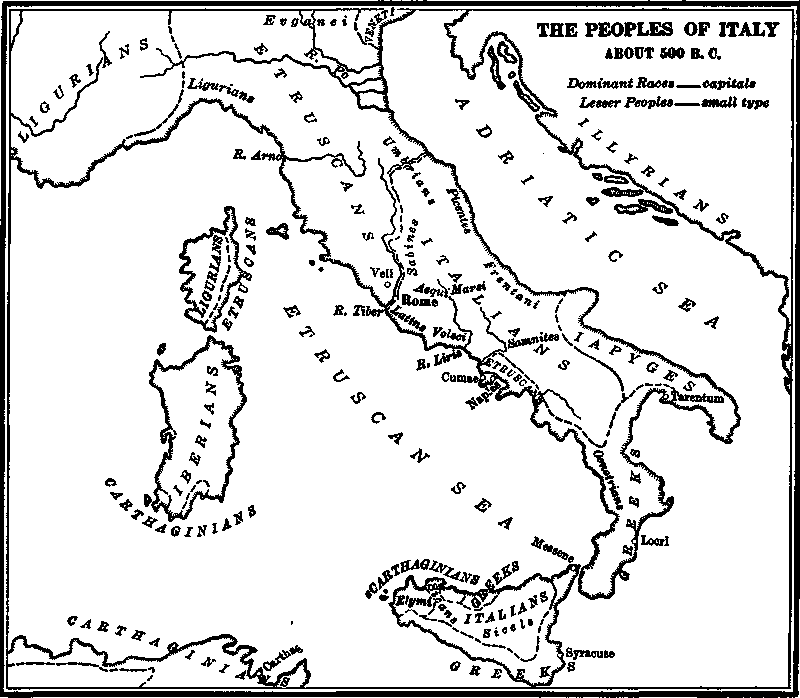

| The Peoples of Italy about 500 B. C. | 14 | |

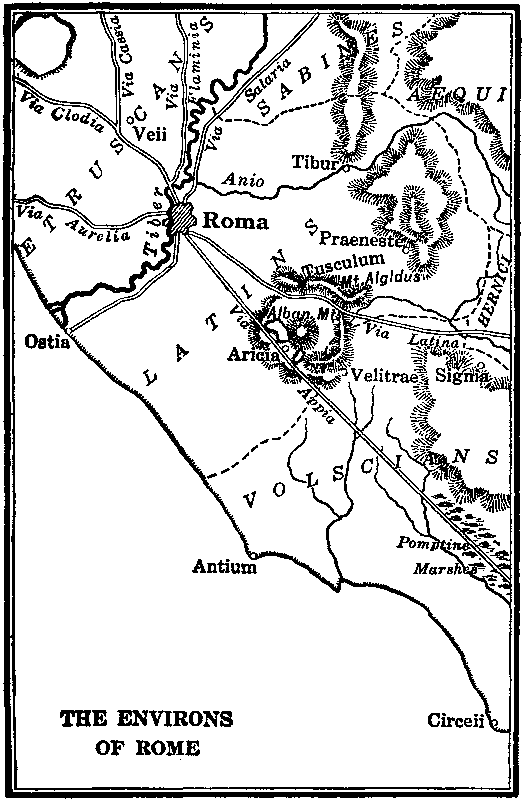

| The Environs of Rome | 24 | |

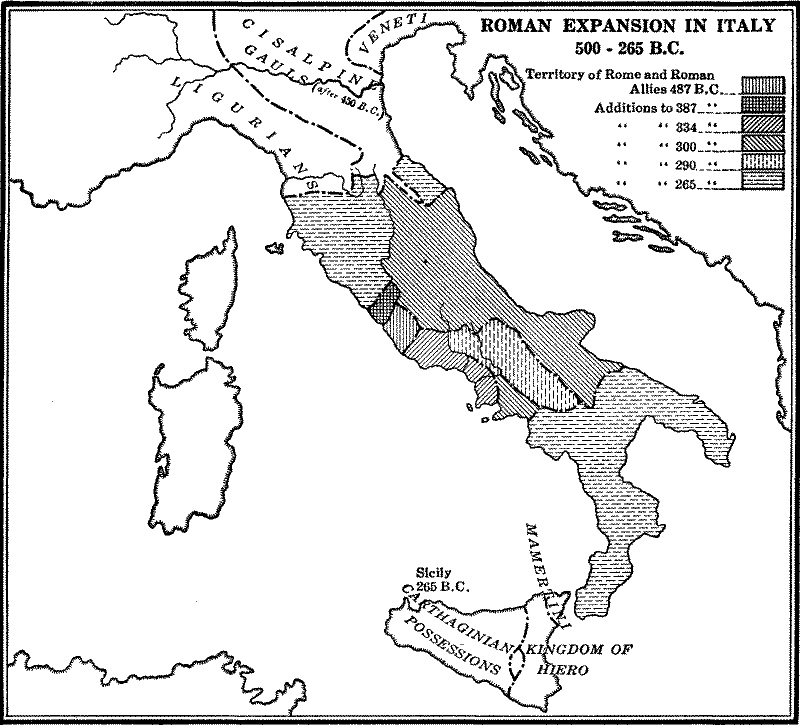

| Roman Expansion in Italy to 265 B. C. | 32 | |

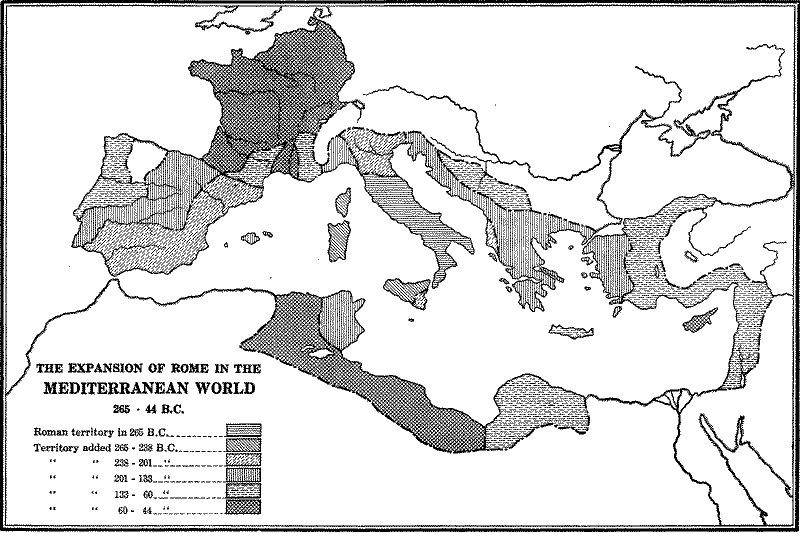

| The Expansion of Rome in the Mediterranean World 265–44 B. C. | 68 | |

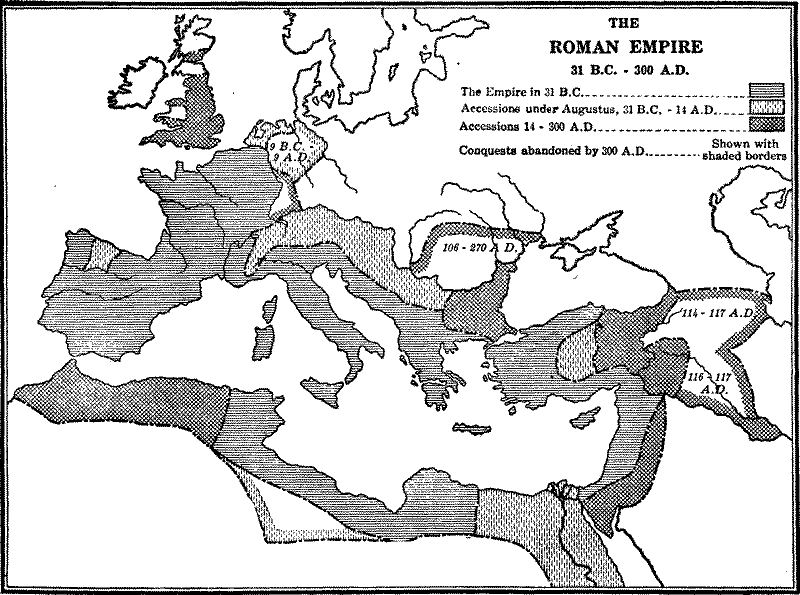

| The Roman Empire from 31 B. C. to 300 A. D. | 204 | |

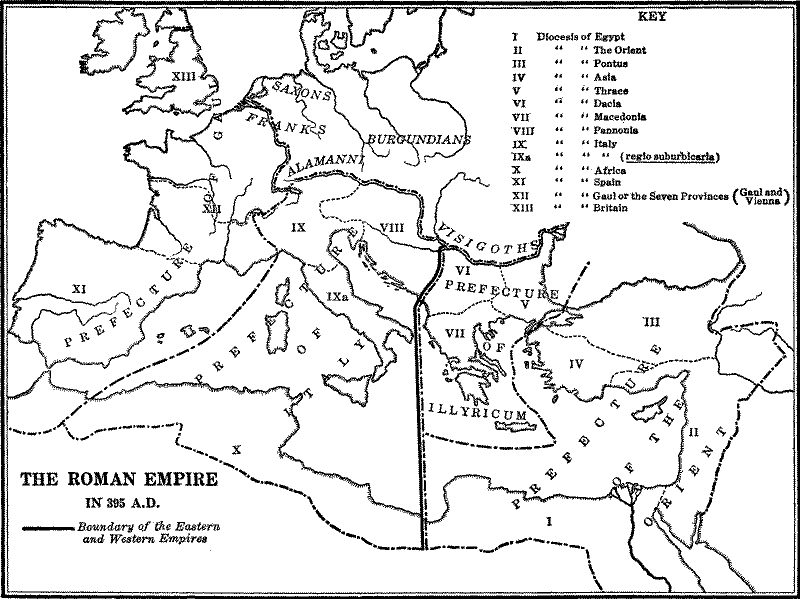

| The Roman Empire in 395 A. D. | 332 | |

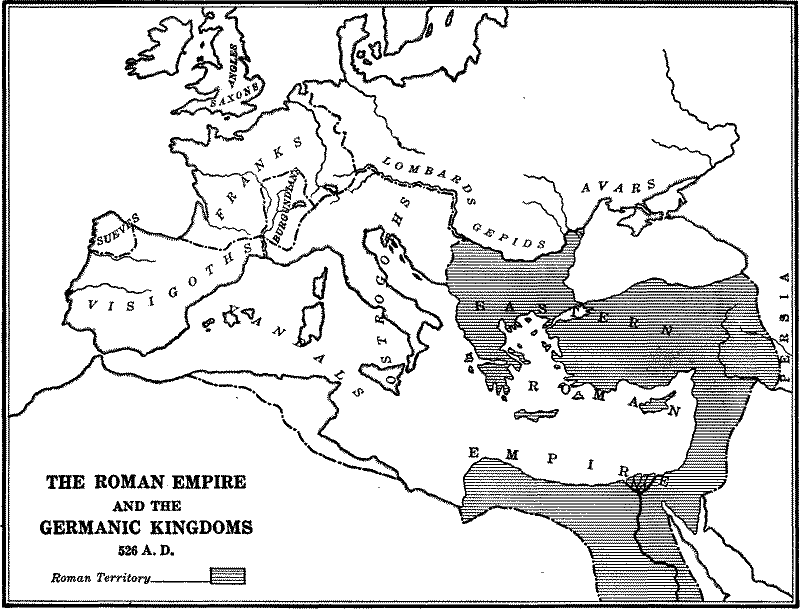

| The Roman Empire and the Germanic Kingdoms in 526 A. D. | 368 | |

| The Roman Empire in 565 A. D. | 380 |

INTRODUCTION

The Sources for the Study of Early Roman History

The student beginning the study of Roman History through the medium of the works of modern writers cannot fail to note wide differences in the treatment accorded by them to the early centuries of the life of the Roman State. These differences are mainly due to differences of opinion among moderns as to the credibility of the ancient accounts of this period. And so it will perhaps prove helpful to give a brief review of these sources, and to indicate the estimate of their value which is reflected in this book.

The earliest Roman historical records were in the form of annals, that is, brief notices of important events in connection with the names of the consuls or other eponymous officials for each year. They may be compared to the early monastic chronicles of the Middle Ages. Writing was practised in Rome as early as the sixth century B. C. and there can be no doubt that the names of consuls or their substitutes were recorded from the early years of the republic, although the form of the record is unknown. It is in the annals that the oldest list of the consuls was preserved, the Capitoline consular and triumphal Fasti or lists being reconstructions of the time of Augustus.

The authorship of the earliest annals is not recorded. However, at the opening of the second century B. C. the Roman pontiffs had in their custody annals which purported to run back to the foundation of the city, including the regal period. We know also that as late as the time of the Gracchi it was customary for the Pontifex Maximus to record on a tablet for public inspection the chief events of each year. When this custom began is uncertain and it can only be proven for the time when the Romans had commenced to undertake maritime wars. From these pontifical records were compiled the so-[pg xiv]called annales Maximi, or chief annals, whose name permits the belief that briefer compilations were also in existence. There were likewise commentaries preserved in the priestly colleges, which contained ritualistic formulæ, as well as attempted explanations of the origins of usages and ceremonies.

Apart from these annals and commentaries there existed but little historical material before the close of the third century B. C. There was no Roman literature; no trace remains of any narrative poetry, nor of family chronicles. Brief funerary inscriptions, like that of Scipio Barbatus, appear in the course of the third century, and laudatory funeral orations giving the records of family achievements seem to have come into vogue about the end of the same century.

However, the knowledge of writing made possible the inscription upon stone or other material of public documents which required to be preserved with exactness. Thus laws and treaties were committed to writing. But the Romans, unlike the Greeks, paid little attention to the careful preservation of other documents and, until a late date, did not even keep a record of the minor magistrates. Votive offerings and other dedications were also inscribed, but as with the laws and treaties, few of these survived into the days of historical writing, owing to neglect and the destruction wrought in the city by the Gauls in 387 B. C.

Nor had the Greeks paid much attention to Roman history prior to the war with Pyrrhus in 281 B. C., although from that time onwards Greek historians devoted themselves to the study of Roman affairs. From this date the course of Roman history is fairly clear. However, as early as the opening of the fourth century B. C. the Greeks had sought to bring the Romans into relation with other civilized peoples of the ancient world by ascribing the foundation of Rome to Aeneas and the exiles from Troy; a tale which had gained acceptance in Rome by the close of the third century.

The first step in Roman historical writing was taken at the close of the Second Punic War by Quintus Fabius Pictor, who wrote in Greek a history of Rome from its foundation to his own times. A similar work, also in Greek, was composed by his contemporary, Lucius Cincius Alimentus. The oldest traditions were thus wrought into a connected version, which has been preserved in some passages of Polybius, but to a larger extent in the fragments of the Library of Universal History compiled by Diodorus the Sicilian about 30 B. C. [pg xv]Existing portions of his work (books 11 to 20) cover the period from 480 to 302 B. C.; and as his library is little more than a series of excerpts his selections dealing with Roman history reflect his sources with little contamination.

Other Roman chroniclers of the second century B. C. also wrote in Greek and, although early in that century Ennius wrote his epic relating the story of Rome from the settlement of Aeneas, it was not until about 168 that the first historical work in Latin prose appeared. This was the Origins of Marcus Porcius Cato, which contained an account of the mythical origins of Rome and other Italian cities, and was subsequently expanded to cover the period from the opening of the Punic Wars to 149 B. C.

Contemporary history soon attracted the attention of the Romans but they did not neglect the earlier period. In their treatment of the latter new tendencies appear about the time of Sulla under patriotic and rhetorical stimuli. The aim of historians now became to provide the public with an account of the early days of Rome that would be commeasurate with her later greatness, and to adorn this narrative, in Greek fashion, with anecdotes, speeches, and detailed descriptions, which would enliven their pages and fascinate their readers. Their material they obtained by invention, by falsification, and by the incorporation into Roman history of incidents from the history of other peoples. These writers were not strictly historians, but writers of historical romance. Their chief representative was Valerius Antias.

The Ciceronian age saw great vigor displayed in antiquarian research, with the object of explaining the origin of ancient Roman customs, ceremonies, institutions, monuments, and legal formulæ, and of establishing early Roman chronology. In this field the greatest activity was shown by Marcus Terentius Varro, whose Antiquities deeply influenced his contemporaries and successors.

In the age of Augustus, between 27 B. C. and 19 A. D., Livy wrote his great history of Rome from its beginnings. His work summed up the efforts of his predecessors and gave to the history of Rome down to his own times the form which it preserved for the rest of antiquity. Although it is lacking in critical acumen in the handling of sources, and in an understanding for political and military history, the dramatic and literary qualities of his work have ensured its popularity. Of it there have been preserved the first ten books (to [pg xvi]293 B. C.), and books 21 to 45 (from 218 to 167 B. C.). A contemporary of Livy was the Greek writer Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who wrote a work called Roman Antiquities, which covered the history of Rome down to 265 B. C. The earlier part of his work has also been preserved. In general he depended upon Varro and Livy, and gives substantially the same view of early Roman history as the latter.

What these later writers added to the meagre annalistic narrative preserved in Diodorus is of little historical value, except in so far as it shows what the Romans came to believe with regard to their own past. The problem which faced the later Roman historians was the one which faces writers of Roman history today, namely, to explain the origins and early development of the Roman state. And their explanation does not deserve more credence than a modern reconstruction simply because they were nearer in point of time to the period in question, for they had no wealth of historical materials which have since been lost, and they were not animated by a desire to reach the truth at all costs nor guided by rational principles of historical criticism. Accordingly we must regard as mythical the traditional narrative of the founding of Rome and of the regal period, and for the history of the republic to the time of the war with Pyrrhus we should rely upon the list of eponymous magistrates, whose variations indicate political crises, supplemented by the account in Diodorus, with the admission that this itself is not infallible. All that supplements or deviates from this we should frankly acknowledge to be of a hypothetical nature. Therefore we should concede the impossibility of giving a complete and adequate account of the history of these centuries and refrain from doing ourselves what we criticize in the Roman historians.

PART I

THE FORERUNNERS OF ROME IN ITALY

[pg 2] [pg 3]A HISTORY OF ROME TO 565 A. D.

CHAPTER I

THE GEOGRAPHY OF ITALY

Italy, ribbed by the Apennines, girdled by the Alps and the sea, juts out like a “long pier-head” from Europe towards the northern coast of Africa. It includes two regions of widely differing physical characteristics: the northern, continental; the southern, peninsular. The peninsula is slightly larger than the continental portion: together their area is about 91,200 square miles.

Continental Italy. The continental portion of Italy consists of the southern watershed of the Alps and the northern watershed of the Apennines, with the intervening lowland plain, drained, for the most part, by the river Po and its numerous tributaries. On the north, the Alps extend in an irregular crescent of over 1200 miles from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic. They rise abruptly on the Italian side, but their northern slope is gradual, with easy passes leading over the divide to the southern plain. Thus they invite rather than deter immigration from central Europe. East and west continental Italy measures around 320 miles; its width from north to south does not exceed seventy miles.

The peninsula. The southern portion of Italy consists of a long, narrow peninsula, running northwest and southeast between the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas, and terminating in two promontories, which form the toe and heel of the “Italian boot.” The length of the peninsula is 650 miles; its breadth is nowhere more than 125 miles. In striking contrast to the plains of the Po, southern Italy is traversed throughout by the parallel ridges of the Apennines, which give it an endless diversity of hill and valley. The average height of these mountains, which form a sort of vertebrate system for the peninsula (Apennino dorso Italia dividitur, Livy xxxvi, 15), is about 4,000 feet, and even their highest peaks (9,500 feet) are [pg 4]below the line of perpetual snow. The Apennine chain is highest on its eastern side where it approaches closely to the Adriatic, leaving only a narrow strip of coast land, intersected by numerous short mountain torrents. On the west the mountains are lower and recede further from the sea, leaving the wide lowland areas of Etruria, Latium and Campania. On this side, too, are rivers of considerable length, navigable for small craft; the Volturnus and Liris, the Tiber and the Arno, whose valleys link the coast with the highlands of the interior.

The coast-line. In comparison with Greece, Italy presents a striking regularity of coast-line. Throughout its length of over 2000 miles it has remarkably few deep bays or good harbors, and these few are almost all on the southern and western shores. Thus the character of the Mediterranean coast of Italy, with its fertile lowlands, its rivers, its harbors, and its general southerly aspect, rendered it more inviting and accessible to approach from the sea than the eastern coast, and determined its leadership in the cultural and material advancement of the peninsula.

Climate. The climate of Italy as a whole, like that of other Mediterranean lands, is characterized by a high average temperature, and an absence of extremes of heat or cold. Nevertheless, it varies greatly in different localities, according to their northern or southern situation, their elevation, and their proximity to the sea. In the Po valley there is a close approach to the continental climate of central Europe, with a marked difference between summer and winter temperatures and clearly marked transitional periods of spring and autumn. On the other hand, in the south of the peninsula the climate becomes more tropical, with its periods of winter rain and summer drought, and a rapid transition between the moist and the dry seasons.

Malaria. Both in antiquity and in modern times the disease from which Italy has suffered most has been the dreaded malaria. The explanation is to be found in the presence of extensive marshy areas in the river valleys and along the coast. The ravages of this disease have varied according as the progress of civilization has brought about the cultivation and drainage of the affected areas or its decline has wrought the undoing of this beneficial work.

Forests. In striking contrast to their present baldness, the slopes of the Apennines were once heavily wooded, and the well-tilled [pg 5]fields of the Po valley were also covered with tall forests. Timber for houses and ships was to be had in abundance, and as late as the time of Augustus Italy was held to be a well-forested country.

Minerals. The mineral wealth of Italy has never been very great at any time. In antiquity the most important deposits were the iron ores of the island of Elba, and the copper mines of Etruria and Liguria. For a time, the gold washings in the valleys of the Graian Alps were worked with profit.

Agriculture. The true wealth of Italy lay in the richness of her soil, which generously repaid the labor of agriculturist or horticulturist. The lowland areas yielded large crops of grain of all sorts—millet, maize, wheat, oats and barley—while legumes were raised in abundance everywhere. Campania was especially fertile and is reported to have yielded three successive crops annually. The vine and the olive flourished, and their cultivation eventually became even more profitable than the raising of grain.

The valleys and mountain sides afforded excellent pasturage at all seasons, and the raising of cattle and sheep ranked next in importance to agricultural pursuits among the country’s industries.

The islands: Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica. The geographical location of the three large islands, Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, links their history closely with that of the Italian peninsula. The large triangle of Sicily (11,290 sq. mi.) is separated from the southwest extremity of Italy by the narrow straits of Rhegium, and lies like a stepping-stone between Europe and Africa. Its situation, and the richness of its soil, which caused it to become one of the granaries of Rome, made it of far greater historical importance than the other two islands. Sardinia (9,400 sq. mi.) and Corsica (3,376 sq. mi.), owing to their rugged, mountainous character and their greater remoteness from the coast of Italy, have been always, from both the economic and the cultural standpoint, far behind the more favored Sicily.

The historical significance of Italy’s configuration and location. The configuration of the Italian peninsula, long, narrow, and traversed by mountain ridges, hindered rather than helped its political unification. Yet the Apennine chain, running parallel to the length of the peninsula, offered no such serious barriers to that unification as did the network of mountains and the long inlets that intersect the peninsula of Greece. And when once Italy had been welded [pg 6]into a single state by the power of Rome, its central position greatly facilitated the extension of the Roman dominion over the whole Mediterranean basin.

The name Italia. The name Italy is the ancient Italia, derived from the people known as the Itali, whose name had its origin in the word vitulus (calf). It was applied by the Greeks as early as the fifth century B. C. to the southwestern extremity of the peninsula, adjacent to the island of Sicily. It rapidly acquired a much wider significance, until, from the opening of the second century, Italia in a geographical sense denoted the whole country as far north as the Alps. Politically, as we shall see, the name for a long time had a much more restricted significance.

CHAPTER II

PREHISTORIC CIVILIZATION IN ITALY

Accessibility of Italy to external influences. The long coast-line of the Italian peninsula rendered it peculiarly accessible to influences from overseas, for the sea united rather than divided the peoples of antiquity. Thus Italy was constantly subjected to immigration by sea, and much more so to cultural stimuli from the lands whose shores bordered the same seas as her own. Nor did the Alps and the forests and swamps of the Po valley oppose any effectual barrier to migrations and cultural influences from central Europe. Consequently we have in Italy the meeting ground of peoples coming by sea from east and south and coming over land from the north, each bringing a new racial, linguistic, and cultural element to enrich the life of the peninsula. These movements had been going on since remote antiquity, until, at the beginning of the period of recorded history, Italy was occupied by peoples of different races, speaking different languages, and living under widely different political and cultural conditions.

As yet many problems connected with the origin and migrations of the historic peoples of Italy remain unsolved; but the sciences of archaeology and philology have done much toward enabling us to present a reasonably clear and connected picture of the development of civilization and the movements of these peoples in prehistoric times.

The Old Stone Age. From all over Italy come proofs of the presence of man in the earliest stage of human development—the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. The chipped flint instruments of this epoch have been found in considerable abundance, and are chiefly of the Moustérien and Chelléen types. With these have been unearthed the bones of the cave bear, cave lion, cave hyena, giant stag, and early types of the rhinoceros, hippopotamus, and elephant, which Paleolithic man fought and hunted. In the Balzi Rossi caves, near Ventimiglia in Liguria, there have been found human skeletons, some of which, at least, are agreed to be of the Paleolithic Age. But the [pg 8]caves in Liguria and elsewhere, then the only habitations which men knew, do not reveal the lifelike and vigorous mural drawings and carvings on bone, which the Old Stone Age has left in the caves of France and Spain.

The New Stone Age. With the Neolithic or New Stone Age there appears in Italy a civilization characterized by the use of instruments of polished stone. Axes, adzes, and chisels, of various shapes and sizes, as well as other utensils, were shaped by polishing and grinding from sandstone, limestone, jade, nephrite, diorite, and other stones. Along with these, however, articles of chipped flint and obsidian, for which the workshops have been found, and also instruments of bone, were in common use. The Neolithic people were also acquainted with the art of making pottery, an art unknown to the Paleolithic Age.

Like the men of the preceding epoch, those of the Neolithic Age readily took up their abode in natural caves. However, they also built for themselves villages of circular huts of wicker-work and clay, at times erected over pits excavated in the ground. Such village sites, the so-called fonde di capanne, are widely distributed throughout Italy.

They buried their dead in caves, or in pits dug in the ground, sometimes lining the pit with stones. The corpse was regularly placed in a contracted position, accompanied by weapons, vases, clothing, and food. Second burials and the practice of coloring the bones of the skeletons with red pigment were in vogue.

Climatic change. The climate of Italy had changed considerably from that of the preceding age, and a new fauna had appeared. In place of the primitive elephant and his associates, Neolithic men hunted the stag, beaver, bear, fox, wolf and wild boar. Remains of such domestic animals as the ox, horse, sheep, goat, pig, dog, and ass, show that they were a pastoral although not an agricultural people.

A new racial element. The use of polished stone weapons, the manufacture of pottery, the hut villages and a uniform system of burial rites distinguished the Neolithic from the Paleolithic civilization. And, because of these differences, especially because of the introduction of this system of burial which argues a distinctive set of religious beliefs, in addition to the fact that the development of this civilization from that which preceded cannot be traced on Italian [pg 9]soil, it is held with reason that at the opening of the Neolithic Age a new race entered Italy, bringing with it the Neolithic culture. Here and there men of the former age may have survived and copied the arts of the newcomers, but throughout the whole peninsula the racial unity of the population is shown by the uniformity of their burial customs. The inhabitants of Sicily and Sardinia in this age had a civilization of the same type as that on the mainland.

The Ligurians probably a Neolithic people. It is highly probable that one of the historic peoples of Italy was a direct survival from the Neolithic period. This was the people called the Ligures (Ligurians), who to a late date maintained themselves in the mountainous district around the Gulf of Genoa. In support of this view it may be urged (1) that tradition regarded them as one of the oldest peoples of Italy, (2) that even when Rome was the dominant state in Italy they occupied the whole western portion of the Po valley and extended southward almost to Pisa, while they were believed to have held at one time a much wider territory, (3) that at the opening of our own era they were still in a comparatively barbarous state, living in caves and rude huts, and (4) that the Neolithic culture survived longest in this region, which was unaffected by the migrations of subsequent ages.

The Aeneolithic Age. The introduction of the use of copper marks the transition from the Neolithic period to that called the Aeneolithic, or Stone and Copper Age. This itself is but a prelude to the true Bronze Age. Apparently copper first found its way into Italy along the trade routes from the Danube valley and from the eastern Mediterranean, while the local deposits were as yet unworked. In other respects there is no great difference between the Neolithic civilization and the Aeneolithic, and there is no evidence to place the entrance of a new race into Italy at this time.

The Bronze Age. The Bronze Age proper in Italy is marked by the appearance of a new type of civilization—that of the builders of the pile villages. There are two distinct forms of pile village. The one, called palafitte, is a true lake village, raised on a pile structure above the waters of the surrounding lake or marsh. The other, called terramare, is a pile village constructed on solid ground and surrounded by an artificial moat.

The palafitte. The traces of the palafitte are fairly closely confined to the Alpine lake region of Italy from Lake Maggiore to Lake [pg 10]Garda. In general, these lake villages date from an early stage of Bronze Age culture, for later on, in most cases, their inhabitants seem to have abandoned them for sites on dry land further to the south. The lake-dwellers were hunters and herdsmen, but they practised agriculture as well, raising corn and millet. In addition to their bronze implements, they continued to use those of more primitive materials—bone and stone. They, too, manufactured a characteristic sort of pottery, of rather rude workmanship, which differs strikingly from that of the Neolithic Age. In the late Bronze Age, at any rate, they cremated their dead and buried the ashes in funerary urns. For their earlier practice evidence is lacking.

The terramare. The terramare settlements are found chiefly in the Po valley; to the north of that river around Mantua, and to the south between Piacenza and Bologna. Scattered villages have been found throughout the peninsula; one as far south as Taranto. The terramare village was regularly constructed in the form of a trapezoid, with a north and south orientation. It was surrounded by an earthen wall, around the base of which ran a wide moat, supplied with running water from a neighboring stream. Access to the settlement was had by a single wooden bridge, easy to destroy in time of danger. The space within the wall was divided in the center by a main road running north and south the whole length of the settlement. It was paralleled by some narrower roads and intersected at right angles by others. On one side of this main highway was a space surrounded by an inner moat, crossed by a bridge. This area was uninhabited and probably devoted to religious purposes. The dwellings were built on pile foundations along the roadways. Outside the moat was placed the cemetery. The dead were cremated and the ashes deposited in ossuary urns, which were laid side by side in the burial places. The remains were rarely accompanied by anything but some smaller vases placed in the ossuary.

The terramare civilization. With the terramare people bronze had almost completely supplanted stone instruments. Bronze daggers, swords, axes, arrowheads, spearheads, razors, and pins have been preserved in abundance. However, articles of bone and of horn were also in general use. The terramare civilization had likewise its special type of hand-made pottery of peculiar shapes and ornamentation. A characteristic form of ornamentation was the crescent-shaped handle (ansa lunata). The terramare peoples were both agricultural and [pg 11]pastoral, cultivating wheat and flax and raising the better known domestic animals; while they also hunted the stag and the wild boar.

The peoples of the palafitte and the terramare. Owing to their custom of dwelling in pile villages, their practice of cremating their dead, and other characteristics peculiar to their type of civilization, the peoples of the palafitte and the terramare are believed to have introduced a new racial element into Italy. The former probably descended from the Swiss lake region, while the latter probably came from the valley of the Danube. These peoples, abandoning the lakes and marshes of the Po valley, spread southward over the peninsula. Because of this expansion and because of the striking similarity between the design of the terramare settlements and that of the Roman fortified camps, it has been suggested that they were the forerunners of the Italian peoples of historic times.

Other types of Bronze Age culture in Italy. The Neolithic population of northern Italy developed a Bronze Age civilization under the stimulus of contact with the terramare people and the lake-dwellers. In the southern part of the peninsula and in Sicily, however, the Bronze Age developed more independently, although showing decided traces of influences from the eastern Mediterranean. Only in its later stages does it show the effect of the southward migration of the builders of the pile villages.

The Iron Age. The prehistoric Iron Age in Italy has left extensive remains in the northern and central regions, but such is by no means the case in the south. The most important center of this civilization was at Villanova, near Bologna. Here, again, we have to do with a new type of civilization, which is not a development of the terramare culture. In addition to the use of iron, this age is marked by the practice of cremation, with the employment of burial urns of a distinctive type, placed in well tombs (tombe a pozzo). In Etruria, to the south of the Apennines, the Early Iron Age is of the Villanova type. It seems fairly certain that both in Umbria and in Etruria this civilization is the work of the Umbrians, who at one time occupied the territory on both sides of the Apennines. Regarding the migration of the Umbrians into Italy we know nothing, but it seems probable that their civilization had its rise in central Europe. The later Iron Age civilization both in Etruria and northward of the Apennines has been identified as that of the Etruscans.

Latium. In Latium the Iron Age civilization is a development un[pg 12]der Villanovan influences. Here a distinctive feature is the use of a hut-shaped urn to receive the ashes of the dead. This urn was itself deposited in a larger burial urn. This civilization is that of the historic Latins, to whom belong also the hill villages of Latium and the walled towns, constructed between the eighth and the sixth centuries B. C.

Elsewhere in the northern part of Italy in the Iron Age we have to do with a culture developing out of that of the terramare period. Likewise in the east and south of the peninsula the Iron Age is a local development under outside stimulus.

The preceding sketch of the rise of civilization in Italy has brought us down to the point where we have to do with the peoples who occupied Italian soil at the beginning of the historic period, for from the sixth century it is possible to attempt a connected historical record of the movements of these Italian races.

CHAPTER III

THE PEOPLES OF HISTORIC ITALY: THE ETRUSCANS; THE GREEKS

I. The Peoples of Italy

At the close of the sixth century B. C., the soil of Italy was occupied by many peoples of diverse language and origin.

The Ligurians. The northwest corner of Italy, including the Po valley as far east as the river Ticinus and the coast as far south as the Arno, was occupied by the Ligurians.

The Veneti. On the opposite side of the continental part of Italy, in the lowlands to the north of the Po between the Alps and the Adriatic, dwelt the Veneti, whose name is perpetuated in modern Venice. They are generally believed to have been a people of Illyrian origin.

The Euganei. In the mountain valleys, to the east and west of Lake Garda, lived the Euganei, a people of little historical importance, whose racial connections are as yet unknown.

The Etruscans. The central plain of the Po, between the Ligurians to the west and the Veneti to the east, was controlled by the Etruscans. Their territory stretched northwards to the Alps and eastwards to the Adriatic coast. They likewise occupied the district called after them, Etruria, to the south of the Apennines, between the Arno and the Tiber. Throughout all this area the Etruscans were the dominant element, although it was partly peopled by subject Ligurians and Italians. Etruscan colonies were also established in Campania.

The Italians. Over the central and southwestern portion of the peninsula were spread a number of peoples speaking more or less closely related dialects of a common, Indo-germanic, tongue. Of these, the Latini, the Aurunci (Ausones), the Osci (Opici), the Oenotri, and the Itali occupied, in the order named, the western coast from the Tiber to the Straits of Rhegium. Between the valley of the upper Tiber and the Adriatic were the Umbri, while to the south of these, in the valleys of the central Apennines and along the [pg 15]Adriatic coast, were settled the so-called Sabellian peoples, chief of whom were the Sabini, the Picentes, the Vestini, the Frentani, the Marsi, the Aequi, the Hernici, the Volsci, and the Samnites. As we have noted, one of these peoples, the Itali, gave their name to the whole country to the south of the Alps, and eventually to this group of peoples in general, whom we call Italians, as distinct from the other races who inhabited Italy in antiquity.

The Iapygians. Along the eastern coast from the promontory of Mt. Garganus southwards were located the Iapygians; most probably, like the Veneti, an Illyrian folk.

The Greeks. The western and southern shores of Italy, from the Bay of Naples to Tarentum, were fringed with a chain of Hellenic settlements.

The peoples of Sicily. The Greeks had likewise colonized the eastern and southern part of the island of Sicily. The central portion of the island was still occupied by the Sicans and the Sicels, peoples who were in possession of Sicily prior to the coming of the Greeks, and whom some regard as an Italian, others as a Ligurian, or Iberian, element. In the extreme west of Sicily were wedged in the small people of the Elymians, another ethnographic puzzle. Here too the Phoenicians from Carthage had firmly established themselves.

Iberians in Sardinia and Corsica. The inhabitants of Sardinia and Corsica, islands which were unaffected by the migrations subsequent to the Neolithic Age, are believed to have been of the same stock as the Iberians of the Spanish peninsula. The Etruscans had their colonies in eastern Corsica and the Carthaginians had obtained a footing on the southern and western coasts of Sardinia.

From this survey of the peoples of Italy at the close of the sixth century B. C., we can see that to the topographical obstacles placed by nature in the path of the political unification of Italy there was added a still more serious difficulty—that of racial and cultural antagonism.

II. The Etruscans

Etruria. About the opening of the eighth century, the region to the north of the Tiber, west and south of the Apennines, was occupied by the people whom the Greeks called Tyrseni or Tyrreni, the Romans Etrusci or Tusci, but who styled themselves Rasenna. Their [pg 16]name still clings to this section of Italy (la Toscana), which to the Romans was known as Etruria.

The origin of the Etruscans. Racially and linguistically the Etruscans differed from both Italians and Hellenes, and their presence in Italy was long a problem to historians. Now, however, it is generally agreed that their own ancient tradition, according to which they were immigrants from the shores of the Aegean Sea, is correct. They were probably one of the pre-Hellenic races of the Aegean basin, where a people called Tyrreni were found as late as the fifth century B. C., and it has been suggested that they are to be identified with the Tursha, who appear among the Aegean invaders of Egypt in the thirteenth century. Leaving their former abode during the disturbances caused by the Hellenic occupation of the Aegean islands and the west coast of Asia Minor, they eventually found a new home on the western shore of Italy. Here they imposed their rule and their civilization upon the previous inhabitants. The subsequent presence of the two elements in the population of Etruria is well attested by archaeological evidence.

Walled towns. The Etruscans regularly built their towns on hill-tops which admitted of easy defence, but, in addition, they fortified these towns with strong walls of stone, sometimes constructed of rude polygonal blocks and at other times of dressed stone laid in regular courses.

Tombs. However, the most striking memorials of the presence of the Etruscans are their elaborate tombs. Their cemeteries contain sepulchres of two types—trench tombs (tombe a fossa) and chamber tombs (tombe a camera). The latter, a development of the former type, are hewn in the rocky hillsides. The Etruscans practised inhumation, depositing the dead in a stone sarcophagus. However, under the influence of the Italian peoples with whom they came into contact, they also employed cremation to a considerable extent. Their larger chamber tombs were evidently family burial vaults, and were decorated with reliefs cut on their rocky walls or with painted friezes, from which we derive most of our information regarding the Etruscan appearance, dress, and customs. Objects of Phoenician and Greek manufacture found in these tombs show that the Etruscans traded with Carthage and the Greeks as early as the seventh century.

Etruscan industries. The Etruscans worked the iron mines of Elba and the copper deposits on the mainland. Their bronzes, espe[pg 17]cially their mirrors and candelabra, enjoyed high repute even in fifth-century Athens. Their goldsmiths, too, fashioned elaborate ornaments of great technical excellence. Etruria also produced the type of black pottery with a high polish known as bucchero nero.

Etruscan art. In general, Etruscan art as revealed in wall paintings and in the decorations of vases and mirrors displays little originality in choice of subjects or manner of treatment. In most cases it is a direct and not too successful imitation of Greek models, rarely attaining the grace and freedom of the originals.

Architecture. In their architecture, however, although even here affected by foreign influences, the Etruscans displayed more originality and were the teachers of the Romans and other Italians. They made great use of the arch and vault, they created distinctive types of column and atrium (both later called Etruscan) and they developed a form of temple architecture, marked by square structures with a high podium and a portico as deep as the cella. Their mural architecture has been referred to already.

Writing. Knowledge of the art of writing reached the Etruscans from the Greek colony of Cyme, whence they adopted the Chalcidian form of the Greek alphabet. Several thousand inscriptions in Etruscan have been preserved, but so far all attempts to translate their language have failed.

Religion. The religion of the Etruscans was characterized by the great stress laid upon the art of divination and augury. Certain features of this art, especially the use of the liver for divination, appear to strengthen the evidence that connects the Etruscans with the eastern Mediterranean. For them the after-world was peopled by powerful, malicious spirits: a belief which gives a gloomy aspect to their religion. Their circle of native gods was enlarged by the addition of Hellenic and Italian divinities and their mythology was greatly influenced by that of Greece.

Commerce. The Etruscans were mariners before they settled on Italian soil and long continued to be a powerful maritime people. They early established commercial relations with the Carthaginians and the Greeks, as is evidenced by the contents of their tombs and the influence of Greece upon their civilization in general. But they, as well as the Carthaginians, were jealous of Greek expansion in the western Mediterranean, and in 536 a combined fleet of these two peoples forced the Phoceans to abandon their settlement on the island [pg 18]of Corsica. For the Greeks their name came to be synonymous with pirates, on account of their depredations which extended even as far as the Aegean.

Government. In Etruria there existed a league of twelve Etruscan cities. However, as we know of as many as seventeen towns in this region, it is probable that several cities were not independent members of the league. This league was a very loose organization, religious rather than political in its character, which did not impair the sovereignty of its individual members. Only occasionally do several cities seem to have joined forces for the conduct of military enterprises. The cities at an early period were ruled by kings, but later were under the control of powerful aristocratic families, each backed by numerous retainers.

Expansion north of the Apennines, in Latium and in Campania. In the course of the sixth century the Etruscans crossed the Apennines and occupied territory in the Po valley northwards to the Alps and eastwards to the Adriatic. Somewhat earlier, towards the end of the seventh century, they forced their way through Latium, established themselves in Campania, where they founded the cities of Capua and Nola, and gradually completed the subjugation of Latium itself. This marks the extreme limits of their expansion in Italy, and before the opening of the fifth century their power was already on the wane.

The decline of the Etruscan power. It was about this time that Rome freed itself from Etruscan domination, while the other Latins, aided by Aristodemus, the Greek tyrant of Cyme, inflicted a severe defeat upon the Etruscans at Aricia (505 B. C.). A land and sea attack upon Cyme itself, in 474, resulted in the destruction of the Etruscan fleet by Hieron, tyrant of Syracuse. The year 438 B. C. saw the end of the Etruscan power in Campania with the fall of Capua before a Samnite invasion. Not long afterwards, as we shall see, a Celtic invasion drove them from the valley of the Po. The explanation of this rapid collapse of the Etruscan power outside Etruria proper is that, owing to the lack of political unity, these conquests were not national efforts but were made by independent bands of adventurers. These failed to assimilate the conquered populations and after a few generations were overthrown by native revolutions or outside invasions, especially since there was no Etruscan nation to protect them in time of need. Thus failure to develop a strong [pg 19]national state was the chief reason why the Etruscans did not unite Italy under their dominion, as they gave promise of doing in the course of the sixth century.

The significance of the Etruscans in the history of Italy. Our general impression of the Etruscans is that they were a wealthy, luxury-loving people, quick to appreciate and adopt the achievements of others, but somewhat lacking in originality themselves. Cruel, they took delight in gladiatorial combats, especially in Campania, where the Romans learned this custom. Bold and energetic warriors, as their conquests show, they lacked the spirit of discipline and coöperation, and were incapable of developing a stable political organization. Nevertheless, they played an important part in the cultural development of Italy, even though here their chief mission was the bringing of the Italian peoples into contact with Hellenic civilization.

III. The Greeks

Greek colonization. As early as the eighth century the Greeks had begun their colonizing activity in the western Mediterranean, and, in the course of the next two centuries, they had settled the eastern and southern shores of Sicily, stretched a chain of settlements on the Italian coast from Tarentum to the Bay of Naples, and established themselves at the mouth of the Rhone and on the Riviera. The opposition of Carthage shut them out from the western end of Sicily, and from Spain; the Etruscans closed to them Italy north of the Tiber; while the joint action of these two peoples excluded them from Sardinia and Corsica.

In the fifth century these Greek cities in Sicily and Italy were at the height of their power and prosperity. In Sicily they had penetrated from the coast far into the interior where they had brought the Sicels under their domination. By the victory of Himera, in 480 B. C., Gelon of Syracuse secured the Sicilian Greeks in the possession of the greater part of the island and freed them from all danger of Carthaginian invasion for over seventy years. Six years later, his brother and successor, Hieron, in a naval battle off Cyme, struck a crushing blow at the Etruscan naval power and delivered the mainland Greeks from all fear of Etruscan aggression. The extreme southwestern projection of the Italian peninsula had passed com[pg 20]pletely under Greek control, but north as far as Posidonia and east to Tarentum their territory did not extend far from the seaboard. In these areas they had occupied the territory of the Itali and Oenotrians, while on the north of the Bay of Naples Cyme, Dicaearchia, and Neapolis (Naples) were established in the land of the Opici (Osci). The name Great Greece, given by the Hellenes to South Italy, shows how firmly they were established there.

Lack of political unity. However, the Greeks possessed even less political cohesion than did the Etruscans. Each colony was itself a city-state, a sovereign independent community, owning no political allegiance to its mother city. Thus New Greece reproduced all the political characteristics of the Old. Only occasionally, in times of extreme peril, did even a part of the Greek cities lay aside their mutual jealousies and unite their forces in the common cause. Such larger political structures as the tyrants of Syracuse built up by the subjugation of other cities were purely ephemeral, barely outliving their founders. The individual cities also were greatly weakened by incessant factional strife within their walls. The result of this disunion was to restrict the Greek expansion and, eventually, to pave the way for the conquest of the western Greeks by the Italian “barbarians.”

The decline of the Greek power in Italy and Sicily. Even before the close of the fifth century, the decline of the Western Greeks had begun. In Italy their cities were subjected to repeated assaults from the expanding Samnite peoples of the central Apennines. In 421, Cyme fell into the hands of a Samnite horde, and from that time onwards the Greek cities further south were engaged in a struggle for existence with the Lucanians and the Bruttians, peoples of Samnite stock. In Sicily the Carthaginians renewed their assault upon the Greeks in 408 B. C. For a time (404–367) the genius and energy of Dionysius I, tyrant of Syracuse, welded the cities of the island and the mainland into an empire which enabled them to make head against their foes. But his empire had only been created by breaking the power of the free cities, and after his death they were left more disunited and weaker than ever. After further warfare, by 339, Carthage remained in permanent occupation of the western half of the island of Sicily, while in Italy only a few Greek towns, such as Tarentum, Thurii, and Rhegium, were able to maintain themselves, and that with ever increasing difficulty, against the rising tide of the [pg 21]Italians. Even by the middle of the fourth century an observant Greek predicted the speedy disappearance of the Greek language in the west before that of the Carthaginians or Oscans. However, their final struggles must be postponed for later consideration.

The rôle of the Greeks in Italian history. It was the coming of the Greeks that brought Italy into the light of history, and into contact with the more advanced civilization of the eastern Mediterranean. From the Greek geographers and historians we derive our earliest information regarding the Italian peoples, and they, too, shaped the legends that long passed for early Italian history. The presence of the Greek towns in Italy gave a tremendous stimulus to the cultural development of the Italians, both by direct intercourse and indirectly through the agency of the Etruscans. In this spreading of Greek influences, Cyme, the most northerly of the Greek colonies and one of the earliest, played a very important part. It was from Cyme that the Romans as well as the Etruscans took their alphabet. The more highly developed Greek political institutions, Greek art, Greek literature, and Greek mythology found a ready reception among the Italian peoples and profoundly affected their political and intellectual progress. Traces of this Greek influence are nowhere more noticeable than in the case of Rome itself, and the cultural ascendancy which Greece thus early established over Rome was destined to last until the fall of the Roman Empire.

[pg 22]PART II

THE PRIMITIVE MONARCHY AND THE REPUBLIC:

FROM PREHISTORIC TIMES TO 27 B. C.

[pg 24]

CHAPTER IV

EARLY ROME TO THE FALL OF THE MONARCHY

I. The Latins

Latium and the Latins. The district to the south of the Tiber, extending along the coast to the promontory of Circeii and from the coast inland to the slopes of the Apennines, was called in antiquity Latium. Its inhabitants, at the opening of the historic period, were the Latins (Latini), a branch of the Italian stock, perhaps mingled with the remnants of an older population.

They were mainly an agricultural and pastoral people, who had settled on the land in pagi, or cantons, naturally or artificially defined rural districts. The pagus constituted a rude political and religious unit. Its population lived scattered in their homesteads. If some few of the homesteads happened to be grouped together, they constituted a vicus, which, however, had neither a political nor a religious organization.

At one or more points within the cantons there soon developed small towns (oppida), usually located on hilltops and fortified, at first with earthen, later with stone, walls. These towns served as market-places and as points of refuge in time of danger for the people of the pagus. There developed an artisan and mercantile element, and there the aristocratic element of the population early took up their abode, i. e., the wealthier landholders, who could leave to others the immediate oversight of their estates. And so these oppida became the centers of government for the surrounding pagi. It is very doubtful if the Latins as a whole were ever united in a single state. But even if that had once been the case, this loosely organized state must early have been broken up into a number of smaller units. These were the various populi; that is, the cantons with their oppida. The names of some sixty-five of these towns are known, but before the close of the sixth century many of the smaller of them had been merged with their more powerful neighbors.

The Latin League. The realization of the racial unity of the [pg 26]Latins was expressed in the annual festival of Jupiter Latiaris celebrated on the Alban Mount. For a long time also the Latin cities formed a league, of which there were thirty members according to tradition. Actually, about the middle of the fifth century there were only some eight cities participating in the association upon an independent footing. The central point of the league was the grove and temple of Diana at Aricia, and it was in the neighborhood of Aricia that the meetings of the assembly of the league were held. The league possessed a very loose organization, but we know of a common executive head—the Latin dictator.

II. The Origins of Rome

The site of Rome. Rome, the Latin Roma, is situated on the Tiber about fifteen miles from the sea. The Rome of the later Republic and the Empire, the City of the Seven Hills, included the three isolated eminences of the Capitoline, Palatine and Aventine, and the spurs of the adjoining plateau, called the Quirinal, Viminal, Esquiline, and Caelian. Other ground, also on the left bank of the river, and likewise part of Mount Janiculum, across the Tiber, were included in the city. But this extent was only attained after a long period of growth, and early Rome was a town of much smaller area.

The growth of the city. Late Roman historians placed the founding of Rome about the year 753 B. C., and used this date as a basis for Roman chronology. However, it is absolutely impossible to assign anything like a definite date for the establishment of the city. Excavations have revealed that in the early Iron Age several distinct settlements were perched upon the Roman hills, separated from one another by low, marshy ground, flooded by the Tiber at high water. These were probably typical Latin walled villages (oppida).

At a very early date some of these villages formed a religious union commemorated in the festival of the Septimontium or Seven Mounts. These montes were crests of the Palatine, Esquiline and Caelian hills, perhaps each the site of a separate settlement.

But the earliest city to which we can with certainty give the name of Rome is of later date than the establishment of the Septimontium. It is the Rome of the Four Regions—the Palatina, Esquilina, Col[pg 27]lina and Sucusana (later Suburana)—which included the Quirinal, Viminal, Esquiline, Caelian and Palatine hills, as well as the intervening low ground. Within the boundary of this city, but not included in the four regions, was the Capitoline, which had separate fortifications and served as the citadel (arx). It may be that the organization of this city of the Four Regions was effected by Etruscan conquerors, for the name Roma seems to be of Etruscan origin, and, for the Romans, an urbs, as they called Rome, was merely an oppidum of which the limits had been marked out according to Etruscan ritual. The consecrated boundary line drawn in this manner was called the pomerium.

The Aventine Hill, as well as the part of the plateau back of the Esquiline, was only brought within the city walls in the fourth century, and remained outside the pomerium until the time of Claudius.

The location of Rome, on the Tiber at a point where navigation for sea-going vessels terminated and where an island made easy the passage from bank to bank, marked it as a place of commercial importance. It was at the same time the gateway between Latium and Etruria and the natural outlet for the trade of the Tiber valley. Furthermore, its central position in the Italian peninsula gave it a strategic advantage in its wars for the conquest of Italy. But the greatness of Rome was not the result of its geographic advantages: it was the outgrowth of the energy and political capacity of its people, qualities which became a national heritage because of the character of the early struggles of the Roman state.

Although it is very probable that the historic population of Rome was the result of a fusion of several racial elements—Latin, Sabine, Etruscan, and even pre-Italian, nevertheless the Romans were essentially a Latin people. In language, in religion, in political institutions, they were characteristically Latin, and their history is inseparably connected with that of the Latins as a whole.

III. The Early Monarchy

The tradition. The traditional story of the founding of Rome is mainly the work of Greek writers of the third century B. C., who desired to find a link between the new world-power Rome and the older centers of civilization: while the account of the reign of the [pg 28]Seven Kings is a reconstruction on the part of Roman annalists and antiquarians, intended to explain the origins of Roman political and religious institutions. And, in fact, owing to the absence of any even relatively contemporaneous records (a lack from which the Roman historians suffered as well as ourselves) it is impossible to attempt an historical account of the period of kingly rule. We can improve but little on the brief statement of Tacitus (i, 1 Ann.)—“At first kings ruled the city Rome.”

The kingship. The existence of the kingship itself is beyond dispute, owing to the strength of the Roman tradition on this point and the survival of the title rex or king in the priestly office of rex sacrorum. It seems certain, too, that the last of the Roman kings were Etruscans and belong to the period of Etruscan domination in Rome and Latium. As far as can be judged, the Roman monarchy was not purely hereditary but elective within the royal family, like that of the primitive Greek states, where the king was the head of one of a group of noble families, chosen by the nobles and approved by the people as a whole. About the end of the sixth century the kingship was deprived of its political functions, and remained at Rome solely as a lifelong priestly office. It is possible that there had been a gradual decline of the royal authority before the growing power of the nobles as had been the case at Athens, but it is very probable that the final step in this change coincided with the fall of an Etruscan dynasty and the passing of the control of the state into the hands of the Latin nobility (about 508 B. C.).

Institutions of the regal period. The royal power was not absolute, for the exercise thereof was tempered by custom, by the lack of any elaborate machinery of government, and by the practical necessity for the king to avoid alienating the good will of the community. The views of the aristocracy were voiced in the Senate (senatus) or Council of Elders, which developed into a council of nobles, a body whose functions were primarily advisory in character. From a very early date the Roman people were divided into thirty groups called curiae, and these curiae served as the units in the organization of the oldest popular assembly—the comitia curiata. Membership in the curiae was probably hereditary, and each curia had its special cult, which was maintained long after the curiae had lost their political importance. The primitive assembly of the curiae was convoked at the pleasure of the king to hear matters of interest [pg 29]to the whole community. It did not have legislative power, but such important steps as the declaration of war or the appointment of a new rex required its formal sanction.

Expansion under the kings. Under the kings Rome grew to be the chief city in Latium, having absorbed several smaller Latin communities in the immediate neighborhood, extended her territory on the left bank of the Tiber to the seacoast, where the seaport of Ostia was founded, and even conquered Alba Longa, the former religious center of the Latins. It is possible that by the end of the regal period Rome exercised a general suzerainty over the cities of the Latin plain. The period of Etruscan domination failed to alter the Latin character of the Roman people and left its traces chiefly in official paraphernalia, religious practices (such as the employment of haruspices), military organization, and in Etruscan influences in Roman art.

IV. Early Roman Society

The Populus Romanus. The oldest name of the Romans was Quirites, a name which long survived in official phraseology, but which was superseded by the name Romani, derived from that of the city itself. The whole body of those who were eligible to render military service, to participate in the public religious rites and to attend the meetings of the popular assembly, with their families, constituted the Roman state—the populus Romanus.

Patricians and Plebeians. At the close of the regal period the populus Romanus comprised two distinct social and political classes. These were the Patricians and the Plebeians. A very considerable element of the latter class was formed by the Clients. These class distinctions had grown up gradually under the economic and social influences of the early state; and, in antiquity, were not confined to Rome but appeared in many of the Greek communities also at a similar stage of their development.

The Patricians were the aristocracy. Their influence rested upon their wealth as great landholders, their superiority in military equipment and training, their clan organization, and the support of their clients. Their position in the community assured to them political control, and they had early monopolized the right to sit in the Senate. The members of the Senate were called collectively patres, whence the name patricii (patricians) was given to all the members of their [pg 30]class. The patricians formed a group of many gentes, or clans, each an association of households (familiae) who claimed descent from a common ancestor. Each member of a gens bore the gentile name and had a right to participate in its religious practices (sacra).

Patrons and clients. Apparently, the clients were tenants who tilled the estates of the patricians, to whom they stood for a long time in a condition of economic and political dependence. Each head of a patrician household was the patron of the clients who resided on his lands. The clients were obliged to follow their patrons to war and to the political arena, to render them respectful attention, and, on occasion, pecuniary support. The patron, in his turn, was obliged to protect the life and interests of his client. For either patron or client to fail in his obligations was held to be sacrilege. This relationship, called patronatus on the side of the patron, clientela on that of the client, was hereditary on both sides. The origin of this form of clientage is uncertain and it is impossible for us to form a very exact idea of position of the clients in the early Roman state, for the like-named institution of the historic republican period is by no means the one that prevailed at the end of the monarchy. The older, serf-like, conditions had disappeared; the relationship was voluntarily assumed, and its obligations, now of a much less serious nature, depended for their observance solely upon the interest of both parties.

The patrician aristocracy formed a social caste, the product of a long period of social development, and this caste was enlarged in early times by the recognition of new gentes as possessing the qualifications of the older clans (patres maiorum and minorum gentium). But eventually it became a closed order, jealous of its prerogatives and refusing to intermarry with the non-patrician element.

The Plebs. This latter constituted the plebeians or plebs. They were free citizens—the less wealthy landholders, tradesmen, craftsmen, and laborers—who lacked the right to sit in the Senate and so had no direct share in the administration. Beyond question, however, they were included in the curiae and had the right to vote in the comitia curiata. Nor is there any proof of a racial difference between plebeians and patricians. It is not easy to determine to what degree the clients participated in the political life of the community, yet, in the general use of the term, the plebs included the clients, who later, under the republic, shared in all the privileges won by the [pg 31]plebeians and who, consequently, must have had the status of plebeians in the eye of the state.

The sharp social and political distinction between nobles and commons, between patricians and plebeians, is the outstanding feature of early Roman society, and affords the clue to the political development of the early republican period.

[pg 32]

CHAPTER V

THE EXPANSION OF ROME TO THE UNIFICATION OF THE ITALIAN PENINSULA: c. 509–265 B. C.

I. To the Conquest of Veii—392 b. c.

The alliance of Rome and the Latin League, about 486 B. C. At the close of the regal period Rome appears as the chief city in Latium, controlling a territory of some 350 sq. miles to the south of the Tiber. But the fall of the monarchy somewhat weakened the position of Rome, for it brought on hostilities with the Etruscan prince Lars Porsena of Clusium, which resulted in a defeat for Rome and the forced acceptance of humiliating conditions.

This defeat naturally broke down whatever suzerainty Rome may have exercised over Latium and necessitated a readjustment of the relations between Rome and the Latin cities. A treaty attributed by tradition to Spurius Cassius was finally concluded between Rome on the one hand and the Latin league on the other, which fixed the relations of the two parties for nearly one hundred and fifty years. By this agreement the Romans and the Latin league formed an offensive and defensive military alliance, each party contributing equal contingents for joint military enterprises and dividing the spoils of war, while the Latins at Rome and the Romans in the Latin cities enjoyed the private rights of citizenship. The small people called the Hernici, situated to the east of Latium, were early included in this alliance. This union was cemented largely through the common dangers which threatened the dwellers in the Latin plain from the Etruscans on the north and the highland Italian peoples to the east and south. For Rome it was of importance that the Latin cities interposed a barrier between the territory of Rome and her most aggressive foes, the Aequi and the Volsci.

Wars with the Aequi and Volsci. Of the details of these early wars we know practically nothing. However, archæological evidence seems to show that about the beginning of the fifth century B. C. the [pg 34]Latins sought an outlet for their surplus population in the Volscian land to the south east. Here they founded the settlements of Signia, Norba and Satricum. But this expansion came to a halt, and about the middle of the fifth century the Volsci still held their own as far north as the vicinity of Antium, while the Aequi were in occupation of the Latin plain as far west as Tusculum and Mt. Algidus. Towards the end of the century, however, under Roman leadership the Latins resumed their expansion at the expense of both these peoples.

Veii. In addition to these frequent but not continuous wars, the Romans had to sustain a serious conflict with the powerful Etruscan city of Veii, situated about 12 miles to the north of Rome, across the Tiber. The causes of the struggle are uncertain, but war broke out in 402, shortly after the Romans had gained possession of Fidenae, a town which controlled a crossing of the Tiber above the city of Rome. According to tradition the Romans maintained a blockade of Veii for eleven years before it fell into their hands. It was in the course of this war that the Romans introduced the custom of paying their troops, a practice which enabled them to keep a force under arms throughout the entire year if necessary. Veii was destroyed, its population sold into slavery, and its territory incorporated in the public land of Rome. By this annexation the area of the Roman state was nearly doubled.

Recent excavations have shown that Veii was a place of importance from the tenth to the end of the fifth century B. C., that Etruscan influence became predominant there in the course of the eighth century, and that, at the time of its destruction, it was a flourishing town, which, like Rome itself, was in contact with the Greek cultural influences then so powerful throughout the Italian peninsula.

II. The Gallic Invasion

The Gauls in the Po Valley. But scarcely had the Romans emerged victorious from the contest with Veii when a sudden disaster overtook them from an unexpected quarter. Towards the close of the fifth century various Celtic tribes crossed the Alpine passes and swarmed down into the Po valley. These Gauls overcame and drove out the Etruscans, and occupied the land from the Ticinus and Lake Maggiore southeastwards to the Adriatic between the mouth of the Po and Ancona. This district was subsequently known as Gallia [pg 35]Cisalpina. The Gauls formed a group of eight tribes, which were often at enmity with one another. Each tribe was divided into many clans, and there was continual strife between the factions of the various chieftains. They were a barbarous people, living in rude villages and supporting themselves by cattle-raising and agriculture of a primitive sort. Drunkenness and love of strife were their characteristic vices: war and oratory their passions. In stature they were very tall; their eyes were blue and their hair blond. Brave to recklessness, they rushed naked into battle, and the ferocity of their first assault inspired terror even in the ranks of veteran armies. Their weapons were long, two-edged swords of soft iron, which frequently bent and were easily blunted, and small wicker shields. Their armies were undisciplined mobs, greedy for plunder, but disinclined to prolonged, strenuous effort, and utterly unskilled in siege operations. These weaknesses nullified the effects of their victories in the field and prevented their occupation of Italy south of the Apennines.

The sack of Rome. In 387 B. C., a horde of these marauders crossed the Apennines and besieged Clusium. Thence, angered, as was said, by the hostile actions of Roman ambassadors, they marched directly upon Rome. The Romans marched out with all their forces and met the Gauls near the Allia, a small tributary of the Tiber above Fidenae. The fierce onset of the Gauls drove the Roman army in disorder from the field. Many were slain in the rout and the majority of the survivors were forced to take refuge within the ruined fortifications of Veii. Deprived of their help and lacking confidence in the weak and ill-planned walls, the citizen body evacuated Rome itself and fled to the neighboring towns. The Capitol, however, with its separate fortifications, was left with a small garrison. The Gauls entered Rome and sacked the city, but failed to storm the citadel. Apparently they had no intention of settling in Latium and therefore, after a delay of seven months, upon information that the Veneti were attacking their new settlements in the Po valley, they accepted a ransom of 1000 pounds of gold (about $225,000) for the city and marched off home. The Romans at once reoccupied and rebuilt their city, and soon after provided it with more adequate defences in the new wall of stone later known as the Servian wall.

Later Gallic invasions. For some years the Gauls ceased their inroads, but in 368 another raid brought them as far as Alba in the land of the Aequi, and the Romans feared to attack the invaders. [pg 36]However, when a fresh horde appeared in 348 the Romans were prepared. They and their allies blocked the foe’s path, and the Gauls retreated, fearing to risk a battle. Rome thus became the successful champion of the Italian peoples, their bulwark against the barbarian invaders from the north. In 334 the Gauls and the Romans concluded peace and entered upon a period of friendly relations which lasted for the rest of the fourth century.

III. The Disruption of the Latin League and the Roman Alliance with the Campanians: 387–334 b. c.

Wars with the Aequi, Volsci, and Etruscans. The disaster that overtook Rome created a profound impression throughout the civilized world and was noted by contemporary Greek writers. But the blow left no permanent traces, for only the city, not the state, had been destroyed. It is true that, encouraged by their enemy’s defeat, the Aequi, Volsci and the Etruscan cities previously conquered by Rome took up arms, but each met defeat in turn. Rome retained and consolidated her conquests in southern Etruria. Part of the land was allotted to Romans for settlement and four tribal districts were organized there. On the remainder, two Latin colonies, Sutrium (383) and Nepete (372), were founded. The territory won from the Volsci was treated in like manner.

In 354 the Romans concluded an alliance with the Samnite peoples of the south central Apennines. Probably this agreement was reached in view of the common fear of Gallic invasions and because both parties were at war with the smaller peoples dwelling between Latium and Campania, so that a delimitation of their respective spheres of action was deemed advisable. At any rate, it was in the course of the next few years that Rome completely subdued the Volsci and Aurunci, while the Samnites overran the land of the Sidicini.