Title: The Statue

Author: Mari Wolf

Illustrator: Bob Martin

Release date: May 20, 2010 [eBook #32448]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

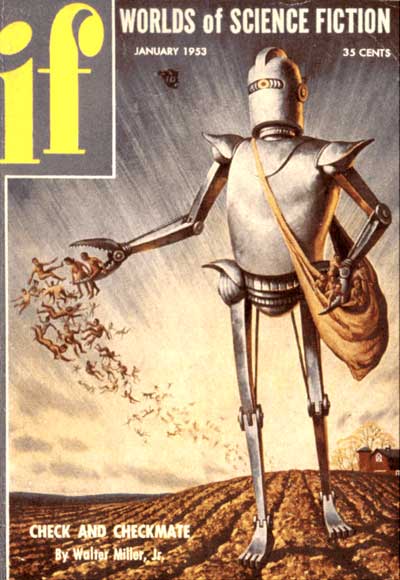

This etext was produced from IF Worlds of Science Fiction January 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

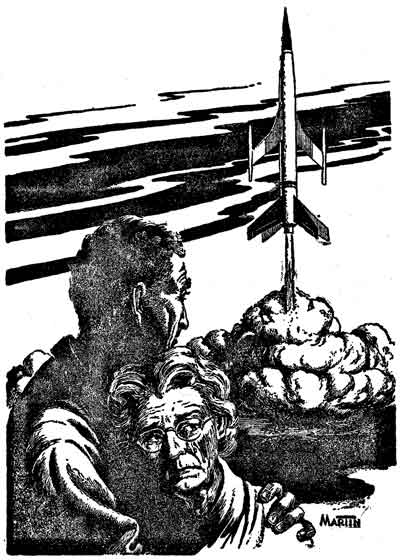

I put my arms around her shoulders but there was no

way I could comfort her.

I put my arms around her shoulders but there was no

way I could comfort her.

There is a time for doing and a time for going home. But where is home in an ever-changing universe?

ewis," Martha said. "I want to go home."

She didn't look at me. I followed her gaze to Earth, rising in the east.

It came up over the desert horizon, a clear, bright star at this distance. Right now it was the Morning Star. It wasn't long before dawn.

I looked back at Martha sitting quietly beside me with her shawl drawn tightly about her knees. She had waited to see it also, of course. It had become almost a ritual with us these last few years, staying up night after night to watch the earthrise.

She didn't say anything more. Even the gentle squeak of her rocking chair had fallen silent. Only her hands moved. I could see them trembling where they lay folded in her lap, trembling with emotion and tiredness and old age. I knew what she was thinking. After seventy years there can be no secrets.

We sat on the glassed-in veranda of our Martian home looking up at the Morning Star. To us it wasn't a point of light. It was the continents and oceans of Earth, the mountains and meadows and laughing streams of our childhood. We saw Earth still, though we had lived on Mars for almost sixty-six years.

"Lewis," Martha whispered softly. "It's very bright tonight, isn't it?"

"Yes," I said.

"It seems so near."

She sighed and drew the shawl higher about her waist.

"Only three months by rocket ship," she said. "We could be back home in three months, Lewis, if we went out on this week's run."

I nodded. For years we'd watched the rocket ships streak upward through the thin Martian atmosphere, and we'd envied the men who so casually travelled from world to world. But it had been a useless envy, something of which we rarely spoke.

Inside our veranda the air was cool and slightly moist. Earth air, perfumed with the scent of Earth roses. Yet we knew it was only illusion. Outside, just beyond the glass, the cold night air of Mars lay thin and alien and smelling of alkali. It seemed to me tonight that I could smell that ever-dry Martian dust, even here. I sighed, fumbling for my pipe.

"Lewis," Martha said, very softly.

"What is it?" I cupped my hands over the match flame.

"Nothing. It's just that I wish—I wish we could go home, right away. Home to Earth. I want to see it again, before we die."

"We'll go back," I said. "Next year for sure. We'll have enough money then."

She sighed. "Next year may be too late."

I looked over at her, startled. She'd never talked like that before. I started to protest, but the words died away before I could even speak them. She was right. Next year might indeed be too late.

Her work-coarsened hands were thin, too thin, and they never stopped shaking any more. Her body was a frail shadow of what it had once been. Even her voice was frail now.

She was old. We were both old. There wouldn't be many more Martian summers for us, nor many years of missing Earth.

"Why can't we go back this year, Lewis?"

She smiled at me almost apologetically. She knew the reason as well as I did.

"We can't," I said. "There's not enough money."

"There's enough for our tickets."

I'd explained all that to her before, too. Perhaps she'd forgotten. Lately I often had to explain things more than once.

"You can't buy passage unless you have enough extra for insurance, and travelers' checks, and passport tax. The company has to protect itself. Unless you're financially responsible, they won't take you on the ships."

She shook her head. "Sometimes I wonder if we'll ever have enough."

e'd saved our money for years, but it was a pitifully small savings. We weren't rich people who could go down to the spaceport and buy passage on the rocket ships, no questions asked, no bond required. We were only farmers, eking our livelihood from the unproductive Martian soil, only two of the countless little people of the solar system. In all our lifetime we'd never been able to save enough to go home to Earth.

"One more year," I said. "If the crop prices stay up...."

She smiled, a sad little smile that didn't reach her eyes. "Yes, Lewis," she said. "One more year."

But I couldn't stop thinking of what she'd said earlier, nor stop seeing her thin, tired body. Neither of us was strong any more, but of the two I was far stronger than she.

When we'd left Earth she'd been as eager and graceful as a child. We hadn't been much past childhood then, either of us....

"Sometimes I wonder why we ever came here," she said.

"It's been a good life."

She sighed. "I know. But now that it's nearly over, there's nothing to hold us here."

"No," I said. "There's not."

If we had had children it might have been different. As it was, we lived surrounded by the children and grandchildren of our friends. Our friends themselves were dead. One by one they had died, all of those who came with us on the first colonizing ship to Mars. All of those who came later, on the second and third ships. Their children were our neighbors now—and they were Martian born. It wasn't the same.

She leaned over and pressed my hand. "We'd better go in, Lewis," she said. "We need our sleep."

Her eyes were raised again to the green star that was Earth. Watching her, I knew that I loved her now as much as when we had been young together. More, really, for we had added years of shared memories. I wanted so much to give her what she longed for, what we both longed for. But I couldn't think of any way to do it. Not this year.

Once, almost seventy years before, I had smiled at the girl who had just promised to become my wife, and I'd said: "I'll give you the world, darling. All tied up in pink ribbons."

I didn't want to think about that now.

We got up and went into the house and shut the veranda door behind us.

couldn't go to sleep. For hours I lay in bed staring up at the shadowed ceiling, trying to think of some way to raise the money. But there wasn't any way that I could see. It would be at least eight months before enough of the greenhouse crops were harvested.

What would happen, I wondered, if I went to the spaceport and asked for tickets? If I explained that we couldn't buy insurance, that we couldn't put up the bond guaranteeing we wouldn't become public charges back on Earth.... But all the time I wondered I knew the answer. Rules were rules. They wouldn't be broken especially not for two old farmers who had long outlived their usefulness and their time.

Martha sighed in her sleep and turned over. It was light enough now for me to see her face clearly. She was smiling. But a minute ago she had been crying, for the tears were still wet on her cheeks.

Perhaps she was dreaming of Earth again.

Suddenly, watching her, I didn't care if they laughed at me or lectured me on my responsibilities to the government as if I were a senile fool. I was going to the spaceport. I was going to find out if, somehow, we couldn't go back.

I got up and dressed and went out, walking softly so as not to awaken her. But even so she heard me and called out to me.

"Lewis...."

I turned at the head of the stairs and looked back into the room.

"Don't get up, Martha," I said. "I'm going into town."

"All right, Lewis."

She relaxed, and a minute later she was asleep again. I tiptoed downstairs and out the front door to where the trike car was parked, and started for the village a mile to the west.

It was desert all the way. Dry, fine red sand that swirled upward in choking clouds, if you stepped off the pavement into it. The narrow road cut straight through it, linking the outlying district farms to the town. The farms themselves were planted in the desert. Small, glassed-in houses and barns, and large greenhouses roofed with even more glass, that sheltered the Earth plants and gave them Earth air to breathe.

hen I came to the second farmhouse John Emery hurried out to meet me.

"Morning, Lewis," he said. "Going to town?"

I shut off the motor and nodded. "I want to catch the early shuttle plane to the spaceport," I said. "I'm going to the city to buy some things...."

I had to lie about it. I didn't want anyone to know we were even thinking of leaving, at least not until we had our tickets in our hands.

"Oh," Emery said. "That's right. I suppose you'll be buying Martha an anniversary present."

I stared at him blankly. I couldn't think what anniversary he meant.

"You'll have been here thirty-five years next week," he said. "That's a long time, Lewis...."

Thirty-five years. It took me a minute to realize what he meant. He was right. That was how long we had been here, in Martian years.

The others, those who had been born here on Mars, always used the Martian seasons. We had too, once. But lately we forgot, and counted in Earth time. It seemed more natural.

"Wait a minute, Lewis," Emery said. "I'll ride into the village with you. There's plenty of time for you to make your plane."

I went up on his veranda and sat down and waited for him to get ready. I leaned back in the swing chair and rocked slowly back and forth, wondering idly how many times I'd sat here.

This was old Tom Emery's house. Or had been, until he died eight years ago. He'd built this swing chair the very first year we'd been on Mars.

Now it was young John's. Young? That showed how old we were getting. John was sixty-three, in Earth years. He'd been born that second winter, the month the parasites got into the greenhouses....

He came back out onto the veranda. "Well, I'm ready, Lewis," he said.

We went down to my trike car and got in.

"You and Martha ought to get out more," he said. "Jenny's been asking me why you don't come to call."

I shrugged. I couldn't tell him we seldom went out because when we did we were always set apart and treated carefully, like children. He probably didn't even realize that it was so.

"Oh," I said. "We like it at home."

He smiled. "I suppose you do, after thirty-five years."

I started the motor quickly, and from then on concentrated on my driving. He didn't say anything more.

t took only a few minutes to get to the village, but even so I was tired. Lately it grew harder and harder to drive, to keep the trike car on the narrow strip of pavement. I was glad when we pulled up in the square and got out.

"I'll walk over to the plane with you," Emery said. "I've got plenty of time."

"All right."

"By the way, Lewis, Jenny and I and some of the neighbors thought we'd drop over on your anniversary."

"That's fine," I said, trying to sound enthusiastic. "Come on over."

"It's a big event," he said. "Deserves a celebration."

The shuttle plane was just landing. I hurried over to the ticket window, with him right beside me.

"I just wanted to be sure you'd be home," he said. "We wouldn't want you to miss your own party."

"Party?" I said. "But John—"

He wouldn't even let me finish protesting.

"Now don't ask any questions, Lewis. You wouldn't want to spoil the surprise, would you?"

He chuckled. "Your plane's loading now. You'd better be going. Thanks for the ride, Lewis."

I went across to the plane and got in. I hoped that somehow we wouldn't have to spend that Martian anniversary being congratulated and petted and babied. I didn't think Martha could stand it. But there wasn't any polite way to say no.

t wasn't a long trip to the spaceport. In less than an hour the plane dropped down to the air strip that flanked the rocket field. But it was like flying from one civilization to another.

The city was big, almost like an Earth city. There was lots of traffic, cars and copters and planes. All the bustle of the spaceways stations.

But although the city looked like Earth, it smelled as dry and alkaline as all the rest of Mars.

I found the ticket office easily enough and went in. The young clerk barely glanced up at me. "Yes?" he said.

"I want to inquire about tickets to Earth," I said.

My hands were sweating, and I could feel my heart pounding too fast against my ribs. But my voice sounded casual, just the way I wanted it to sound.

"Tickets?" the clerk said. "How many?"

"Two. How much would they cost? Everything included."

"Forty-two eighty," he said. His voice was still bored. "I could give them to you for the flight after next. Tourist class, of course...."

We didn't have that much. We were at least three hundred short.

"Isn't there any way," I said hesitantly, "that I could get them for less? I mean, we wouldn't need insurance, would we?"

He looked up at me for the first time, startled. "You don't mean you want them for yourself, do you?"

"Why yes. For me and my wife."

He shook his head. "I'm sorry," he said flatly. "But that would be impossible in any case. You're too old."

He turned away from me and bent over his desk work again.

The words hung in the air. Too old ... too old ... I clutched the edge of the desk and steadied myself and forced down the panic I could feel rising.

"Do you mean," I said slowly, "that you wouldn't sell us tickets even if we had the money?"

He glanced up again, obviously annoyed at my persistence. "That's right. No passengers over seventy carried without special visas. Medical precaution."

I just stood there. This couldn't be happening. Not after all our years of working and saving and planning for the future. Not go back. Not even next year. Stay here, because we were old and frail and the ships wouldn't be bothered with us anyway.

Martha.... How could I tell her? How could I say, "We can't go home, Martha. They won't let us."

I couldn't say it. There had to be some other way.

"Pardon me," I said to the clerk, "but who should I see about getting a visa?"

He swept the stack of papers away with an impatient gesture and frowned up at me.

"Over at the colonial office, I suppose," he said. "But it won't do you any good."

I could read in his eyes what he thought of me. Of me and all the other farmers who lived in the outlying districts and raised crops and seldom came to the city. My clothes were old and provincial and out of style, and so was I, to him.

"I'll try it anyway," I said.

He started to say something, then bit it back and looked away from me again. I was keeping him from his work. I was just a rude old man interfering with the operation of the spaceways.

Slowly I let go of the desk and turned to leave. It was hard to walk. My knees were trembling, and my whole body shook. It was all I could do not to cry. It angered me, the quavering in my voice and the weakness in my legs.

I went out into the hall and looked for the directory that would point the way to the colonial office. It wasn't far off.

I walked out onto the edge of the field and past the Earth rocket, its silver nose pointed up at the sky. I couldn't bear to look at it for longer than a minute.

It was only a few hundred yards to the colonial office, but it seemed like miles.

his office was larger than the other, and much more comfortable. The man seated behind the desk seemed friendlier too.

"May I help you?" he asked.

"Yes," I said slowly. "The man at the ticket office told me to come here. I wanted to see about getting a permit to go back to Earth...."

His smile faded. "For yourself?"

"Yes," I said woodenly. "For myself and my wife."

"Well, Mr...."

"Farwell. Lewis Farwell."

"My name's Duane. Please sit down, won't you?... How old are you, Mr. Farwell?"

"Eighty-seven," I said. "In Earth years."

He frowned. "The regulations say no space travel for people past seventy, except in certain special cases...."

I looked down at my hands. They were shaking badly. I knew he could see them shake, and was judging me as old and weak and unable to stand the trip. He couldn't know why I was trembling.

"Please," I whispered. "It wouldn't matter if it hurt us. It's just that we want to see Earth again. It's been so long...."

"How long have you been here, Mr. Farwell?" It was merely politeness. There wasn't any promise in his voice.

"Sixty-five years." I looked up at him. "Isn't there some way—"

"Sixty-five years? But that means you must have come here on the first colonizing ship."

"Yes," I said. "We did."

"I can't believe it," he said slowly. "I can't believe I'm actually looking at one of the pioneers." He shook his head. "I didn't even know any of them were still on Mars."

"We're the last ones," I said. "That's the main reason we want to go back. It's awfully hard staying on when your friends are dead."

uane got up and crossed the room to the window and looked out over the rocket field.

"But what good would it do to go back, Mr. Farwell?" he asked. "Earth has changed very much in the last sixty-five years."

He was trying to soften the disappointment. But nothing could. If only I could make him realize that.

"I know it's changed," I said. "But it's home. Don't you see? We're Earthmen still. I guess that never changes. And now that we're old, we're aliens here."

"We're all aliens here, Mr. Farwell."

"No," I said desperately. "Maybe you are. Maybe a lot of the city people are. But our neighbors were born on Mars. To them Earth is a legend. A place where their ancestors once lived. It's not real to them...."

He turned and crossed the room and came back to me. His smile was pitying. "If you went back," he said, "you'd find you were a Martian, too."

I couldn't reach him. He was friendly and pleasant and he was trying to make things easier, and it wasn't any use talking. I bent my head and choked back the sobs I could feel rising in my throat.

"You've lived a full life," Duane said. "You were one of the pioneers. I remember reading about your ship when I was a boy, and wishing I'd been born sooner so that I could have been on it."

Slowly I raised my head and looked up at him.

"Please," I said. "I know that. I'm glad we came here. If we had our lives to live over, we'd come again. We'd go through all the hardships of those first few years, and enjoy them just as much. We'd be just as thrilled over proving that it's possible to farm a world like this, where it's always freezing and the air is thin and nothing will grow outside the greenhouses. You don't need to tell me what we've done, or what we've gotten out of it. We know. We've had a wonderful life here."

"But you still want to go back?"

"Yes," I said. "We still want to go back. We're tired of living in the past, with our friends dead and nothing to do except remember."

He looked at me for a long moment. Then he said slowly, "You realize, don't you, that if you went back to Earth you'd have to stay there? You couldn't return to Mars...."

"I realize that," I said. "That's what we want. We want to die at home. On Earth."

or a long, long moment his eyes never left mine. Then, slowly, he sat down at his desk and reached for a pen.

"All right, Mr. Farwell," he said. "I'll give you a visa."

I couldn't believe it. I stared at him, sure that I'd misunderstood.

"Sixty-five years...." He shook his head. "I only hope I'm doing the right thing. I hope you won't regret this."

"We won't," I whispered.

Then I remembered that we were still short of money. That that was why I'd come to the spaceport originally. I was almost afraid to mention it, for fear I'd lose everything.

"Is there—is there some way we could be excused from the insurance?" I said. "So we could go back this year? We're three hundred short."

He smiled. It was a very reassuring smile. "You don't need to worry about the money," he said. "The colonial office can take care of that. After all, we owe your generation a great debt, Mr. Farwell. A passport tax and the fare to Earth are little enough to pay for a planet."

I didn't quite understand him, but that didn't matter. The only thing that mattered was that we were going home. Back to Earth. I could see Martha's face when I told her. I could see her tears of happiness....

There were tears on my own cheeks, but I wasn't ashamed of them now.

"Mr. Farwell," Duane said. "You go back home. The shuttle ship will be leaving in a few minutes."

"You mean that—" I started.

He nodded. "I'll get your tickets for you. On the first ship I can. Just leave it to me."

"It's too much trouble," I protested.

"No it's not." He smiled. "Besides, I'd like to bring them out to you. I'd like to see your farm, if I may."

Then I remembered what John Emery had said this morning about our anniversary. It would be a wonderful celebration, now that there was something to celebrate. We could even save our announcement that we were going home until then.

"Mr. Duane," I said. "Next week, on the tenth, we'll have been here thirty-five Martian years. Maybe you'd like to come out then. I guess our neighbors will be giving us a sort of party."

He laid the pen down and looked at me very intently. "They don't know you're planning to leave yet, do they?"

"No. We'll wait and tell them then."

Duane nodded slowly. "I'll be there," he promised.

artha was out on the veranda again, looking down the road toward the village. All afternoon at least one of us had been out there watching for our guests, waiting for our anniversary celebration to begin.

"Do you see anyone yet?" I called.

"No," she said. "Not yet...."

I looked around the room hoping I'd find something left undone that I could work on, so I wouldn't have to sit and worry about the possibility of Duane's having forgotten us. But everything was ready. The extra chairs were out and the furniture all dusted, and Martha's cakes and cookies arranged on the table.

I couldn't sit still. Not today. I got up out of the chair and joined her on the veranda.

"I wonder what their surprise is...." she said. "Didn't John give you any hint at all?"

"No," I said. "But whatever it is, it can't be half as wonderful as ours."

She reached for my hand. "Lewis," she whispered. "I can hardly believe it, can you?"

"No," I said. "But it's true. We're really going."

I put my arm around her, and she rested her head against me.

"I'm so happy, Lewis."

Her cheeks were full of color once again, and her step had a spring to it that I hadn't seen for years. It was as if the years of waiting were falling away from both of us now.

"I wish they'd come," she said. "I can hardly wait to see their faces when we tell them."

It was getting late in the afternoon. Already the sun was dipping down toward the desert horizon. It was hard to wait. In some ways it was harder to be patient these last few hours than it had been during all those years we'd wanted to go back.

"Look," Martha said suddenly. "There's a car now."

Then I saw the car too, coming quickly toward us. It pulled up in front of the house and stopped and Duane stepped out.

"Well, hello there, Mr. Farwell," he called. "All ready for the trip?"

I nodded. Suddenly, now that he was here, I couldn't say anything at all.

He must have seen how excited we were. By the time he was inside the veranda door he'd reached into his wallet and pulled out a long envelope.

"Here's your schedule," he said. "Your tickets are all made out for next week's flight."

Martha's hand crept into mine. "You've been so kind," she whispered.

e went into the house and smiled at each other while Duane admired the furniture and the farming district in general and our place in particular. We hardly heard what he was saying.

When the doorbell rang we stared at each other. For a minute I couldn't think who it might be. I'd forgotten our guests and their surprise party, even the anniversary itself had slipped my mind.

"Hello in there," John Emery called. "Come on out, you two."

Martha pressed my hand once more. Then she stepped to the door and opened it.

"Happy anniversary!"

We stood frozen. We'd expected only a few visitors, some of our nearest neighbors. But the yard was full of people. They crowded up our walk and in the road and more of them were still piling out of cars. It looked as if everyone in the district was along.

"Come on out," Emery called. "You too, Duane."

The two men smiled at each other knowingly, and for just a moment I had time to wonder why.

Then Martha clutched my arm. "You tell him, Lewis."

"John," I said. "We have a surprise for you too—"

He wouldn't let me finish. He took hold of my arm with one hand and Martha's with the other and drew us outside where everyone could see us.

"You can tell us later, Lewis," he said, "First we have a surprise for you!"

"But wait—"

They crowded in around us, laughing and waving and calling "Happy anniversary". We couldn't resist them. They swept us along with them down the walk and into one of the cars.

I looked around for Duane. He was in the back seat, smiling somewhat nervously. Perhaps he thought that this was normal farm life.

"Lewis," Martha said, "where are they taking us?"

"I don't know...."

The cars started, ours leading the way. It was a regular procession back to the village, with everyone laughing and calling to us and telling us how happy we were going to be with our surprise. Every time we tried to ask questions, John Emery interrupted.

"Just wait and see," he kept saying. "Wait and see...."

t the end of the village square they'd put up a platform. It wasn't very big, nor very well made, but it was strung with yards of bunting and a huge sign that said, "Happy Anniversary, Lewis and Martha."

We were pushed toward it, carried along by the swarm of people. There wasn't any way to resist. Martha clung to my arm, pressing close against me. She was trembling again.

"What does it mean, Lewis?"

"I wish I knew."

They pushed us right up onto the platform and John Emery followed us up and held out his hand to quiet the crowd. I put my arm around Martha and looked down at them. Hundreds of people. All in their best clothes. Our friends's children and grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren.

"I won't make a speech," John Emery said when they were finally quiet. "You know why we're here today—all of you except Lewis and Martha know. It's an anniversary. A big anniversary. Thirty-five years today since our fathers—and you two—landed here on Mars...."

He paused. He didn't seem to know what to say next. Finally he turned and swept his arm past the platform to where a big canvas-covered object stood on the ground.

"Unveil it," he said.

The crowd grew absolutely quiet. A couple of boys stepped up and pulled the canvas off.

"There's your surprise," John Emery said softly.

It was a statue. A life-size statue carved from the dull red stone of Mars. Two figures, a man and a woman, dressed in farm clothes, standing side by side and looking out across the square toward the open desert.

They were very real, those figures. Real, and somehow familiar.

"Lewis," Martha whispered. "They're—they're us!"

She was right. It was a statue of us. Neither old nor young, but ageless. Two farmers, looking out forever across the endless Martian desert....

There was an inscription on the base, but I couldn't quite make it out. Martha could. She read it, slowly, while everyone in the crowd stood silent, listening.

"Lewis and Martha Farwell," she read. "The last of the pioneers—" Her voice broke. "Underneath," she whispered, "it says—the first Martians. And then it lists them—us...."

She read the list, all the names of our friends who had come out on that first ship. The names of men and women who had died, one by one, and left their farms to their children—to the same children who now crowded close about the platform and listened to her read, and smiled up at us.

She came to the end of the list and looked out at the crowd. "Thank you," she whispered.

They shouted then. They called out to us and pressed forward and held their babies up to see us.

looked out past the people, across the flat red desert to the horizon, toward the spot in the east where the Earth would rise, much later. The dry smell of Mars had never been stronger.

The first Martians....

They were so real, those carved figures. Lewis and Martha Farwell....

"Look at them, Lewis," Martha said softly. "They're cheering us. Us!"

She was smiling. There were tears in her eyes, but her smile was bright and proud and shining. Slowly she turned away from me and straightened, staring out over the heads of the crowd across the desert to the east. She stood with her head thrown back and her mouth smiling, and she was as proudly erect as the statue that was her likeness.

"Martha," I whispered. "How can we tell them goodbye?"

Then she turned to face me, and I could see the tears glistening in her eyes. "We can't leave, Lewis. Not after this."

She was right, of course. We couldn't leave. We were symbols. The last of the pioneers. The first Martians. And they had carved their symbol in our image and made us a part of Mars forever.

I glanced down, along the rows of upturned, laughing faces, searching for Duane. He was easy to find. He was the only one who wasn't shouting. His eyes met mine, and I didn't have to say anything. He knew. He climbed up beside me on the platform.

I tried to speak, but I couldn't.

"Tell him, Lewis," Martha whispered. "Tell him we can't go."

Then she was crying. Her smile was gone and her proud look was gone and her hand crept into mine and trembled there. I put my arm around her shoulders, but there was no way I could comfort her.

"Now we'll never go," she sobbed. "We'll never get home...."

I don't think I had ever realized, until that moment, just how much it meant to her—getting home. Much more, perhaps, than it had ever meant to me.

The statues were only statues. They were carved from the stone of Mars. And Martha wanted Earth. We both wanted Earth. Home....

I looked away from her then, back to Duane. "No," I said. "We're still going. Only—" I broke off, hearing the shouting and the cheers and the children's laughter. "Only, how can we tell them?"

Duane smiled. "Don't try to, Mr. Farwell," he said softly. "Just wait and see."

He turned, nodded to where John Emery still stood at the edge of the platform. "All right, John."

Emery nodded too, and then he raised his hand. As he did so, the shouting stopped and the people stood suddenly quiet, still looking up at us.

"You all know that this is an anniversary," John Emery said. "And you all know something else that Lewis and Martha thought they'd kept as a surprise—that this is more than an anniversary. It's goodbye."

I stared at him. He knew. All of them knew. And then I looked at Duane and saw that he was smiling more than ever.

"They've lived here on Mars for thirty-five years," John Emery said. "And now they're going back to Earth."

Martha's hand tightened on mine. "Look, Lewis," she cried. "Look at them. They're not angry. They're—they're happy for us!"

John Emery turned to face us. "Surprised?" he said.

I nodded. Martha nodded too. Behind him, the people cheered again.

"I thought you would be," Emery said. Then, "I'm not very good at speeches, but I just wanted you to know how much we've enjoyed being your neighbors. Don't forget us when you get back to Earth."

t was a long, long trip from Mars to Earth. Three months on the ship, thirty-five million miles. A trip we had dreamed about for so long, without any real hope of ever making it. But now it was over. We were back on Earth. Back where we had started from.

"It's good to be alone, isn't it, Lewis?" Martha leaned back in her chair and smiled up at me.

I nodded. It did feel good to be here in the apartment, just the two of us, away from the crowds and the speeches and the official welcomes and the flashbulbs popping.

"I wish they wouldn't make such a fuss over us," she said. "I wish they'd leave us alone."

"You can't blame them," I said, although I couldn't help wishing the same thing. "We're celebrities. What was it that reporter said about us? That we're part of history...."

She sighed. She turned away from me and looked out the window again, past the buildings and the lighted traffic ramps and the throngs of people bustling by outside, people who couldn't see in through the one-way glass, people whom we couldn't hear because the room was soundproofed.

"Mars should be up by now," she said.

"It probably is." I looked out again, although I knew that we would see nothing. No stars. No planets. Not even the moon, except as a pale half disc peering through the haze. The lights from the city were too bright. The air held the light and reflected it down again, and the sky was a deep, dark blue with the buildings about us towering into it, outlined blackly against it. And we couldn't see the stars....

"Lewis," Martha said slowly. "I never thought it would have changed this much, did you?"

"No." I couldn't tell from her voice whether she liked the changes or not. Lately I couldn't tell much of anything from her voice. And nothing was the same as we had remembered it.

Even the Earth farms were mechanized now. Factory production lines for food, as well as for everything else. It was necessary, of course. We had heard all the reasons, all the theories, all the latest statistics.

"I guess I'll go to bed soon," Martha said. "I'm tired."

"It's the higher gravity." We'd both been tired since we got back to Earth. We had forgotten, over the years, what Earth gravity was like.

She hesitated. She smiled at me, but her eyes were worried. "Lewis—are you really glad we came back?"

It was the first time she had asked me that. And there was only one answer I could give her. The one she expected.

"Of course, Martha...."

She sighed again. She got up out of the chair and turned toward the bedroom door, and then she paused there by the window looking out at the deep blue sky.

"Are you really glad, Lewis?"

Then I knew. Or, at least, I hoped. "Why, Martha? Aren't you?"

For one long minute she stood beside me, looking up at the Mars we couldn't see. And then she turned to face me once again, and I could see the tears.

"Oh, Lewis, I want to go home!"

Full circle. We had both come full circle these last few hectic weeks on Earth.

"So do I, Martha."

"Do you, Lewis?" And then the tiredness came back to her eyes and she looked away again. "But of course we can't."

Slowly I crossed over to the desk and opened the top drawer and took out the folder that Duane had given me, that last day at the spaceport, just before our ship to Earth had blasted off. Slowly I unfolded the paper that Duane had told me to keep in case we ever wanted it.

"Yes, we can, Martha. We can go back."

"What's that, Lewis?" And then she saw what it was. Her face came alive again, and her eyes were shining. "We're going home?" she whispered. "We're really going home?"

I looked down at the Earth-Mars half of the round trip ticket that Duane had given me, and I knew that this time she was right.

This time we'd really be going home.