Title: Pet Farm

Author: Roger D. Aycock

Illustrator: Dick Francis

Release date: May 12, 2010 [eBook #32344]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction February 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

They had fled almost to the sheer ambient face of the crater wall when the Falakian girl touched Farrell's arm and pointed back through the scented, pearly mists.

"Someone," she said. Her voice stumbled over the almost forgotten Terran word, but its sound was music.

"No matter," Farrell answered. "They're too late now."

He pushed on, happily certain in his warm euphoric glow of mounting expectancy that what he had done to the ship made him—and his new-found paradise with him—secure.

He had almost forgotten who they were; the pale half-memories that drifted through his mind touched his consciousness lightly and without urgency, arousing neither alarm nor interest.

The dusk grew steadily deeper, but the dimming of vision did not matter.

Nothing mattered but the fulfillment to come.

Far above him, the lacy network of bridging, at one time so baffling, arched and vanished in airy grace into the colored mists. To right and left, other arms of the aerial maze reached out, throwing vague traceries from cliff to cliff across the valley floor. Behind him on the plain he could hear the eternally young people playing about their little blue lake, flitting like gay shadows through the tamarisks and calling to each other in clear elfin voices while they frolicked after the fluttering swarms of great, bright-hued moths.

The crater wall halted him and he stood with the Falakian girl beside him, looking back through the mists and savoring the sweet, quiet mystery of the valley. Motion stirred there; the pair of them laughed like anticipant children when two wide-winged moths swam into sight and floated toward them, eyes glowing like veiled emeralds.

Footsteps followed, disembodied in the dusk.

"It is only Xavier," a voice said. Its mellow uninflection evoked a briefly disturbing memory of a slight gray figure, jointed yet curiously flexible, and a featureless oval of face.

It came out of the mists and halted a dozen yards away, and he saw that it spoke into a metallic box slung over one shoulder.

"He is unharmed," it said. "Directions?"

Xavier? Directions? From whom?

Another voice answered from the shoulder-box, bringing a second mental picture of a face—square and brown, black-browed and taciturnly humorless—that he had known and forgotten.

Whose, and where?

"Hold him there, Xav," it said. "Stryker and I are going to try to reach the ship now."

The moths floated nearer, humming gently.

"You're too late," Farrell called. "Go away. Let me wait in peace."

"If you knew what you're waiting for," a third voice said, "you'd go screaming mad." It was familiar, recalling vaguely a fat, good-natured face and ponderous, laughter-shaken paunch. "If you could see the place as you saw it when we first landed...."

The disturbing implications of the words forced him reluctantly to remember a little of that first sight of Falak.

... The memory was sacrilege, soiling and cheapening the ecstasy of his anticipation.

But it had been different.

His first day on Falak had left Farrell sick with disgust.

He had known from the beginning that the planet was small and arid, non-rotating, with a period of revolution about its primary roughly equal to ten Earth years. The Marco Four's initial sweep of reconnaissance, spiraling from pole to pole, had supplied further information without preparing him at all for what the three-man Reclamations team was to find later.

The weed-choked fields and crumbled desolation of Terran slave barracks had been depressing enough. The inevitable scattering of empty domes abandoned a hundred years before by the Hymenop conquerors had completed a familiar and unpromising pattern, a workaday blueprint that differed from previous experience only in one significant detail: There was no shaggy, disoriented remnant of descendants from the original colonists.

The valley, a mile-wide crater sunk between thousand-foot cliffs, floored with straggling bramble thickets and grass flats pocked with stagnant pools and quaking slime-bogs, had been infinitely worse. The cryptic three-dimensional maze of bridges spanning the pit had made landing there a ticklish undertaking. Stryker and Farrell and Gibson, after a conference, had risked the descent only because the valley offered a last possible refuge for survivors.

Their first real hint of what lay ahead of them came when Xavier, the ship's mechanical, opened the personnel port against the heat and humid stink of the place.

"Another damned tropical pesthole," Farrell said, shucking off his comfortable shorts and donning booted coveralls for the preliminary survey. "The sooner we count heads—assuming there are any left to count—and get out of here, the better. The long-term Reorientation boys can have this one and welcome."

Stryker, characteristically, had laughed at his navigator's prompt disgust. Gibson, equally predictable in his way, had gathered his gear with precise efficiency, saying nothing.

"It's a routine soon finished," Stryker said. "There can't be more than a handful of survivors here, and in any case we're not required to do more than gather data from full-scale recolonization. Our main job is to prepare Reorientation if we can for whatever sort of slave-conditioning deviltry the Hymenops practiced on this particular world."

Farrell grunted sourly. "You love these repulsive little puzzles, don't you?"

Stryker grinned at him with good-natured malice. "Why not, Arthur? You can play the accordion and sketch for entertainment, and Gib has his star-maps and his chess sessions with Xavier. But for a fat old man, rejuvenated four times and nearing his fifth and final, what else is left except curiosity?"

He clipped a heat-gun and audicom pack to the belt of his bulging coveralls and clumped to the port to look outside. Roiling gray fog hovered there, diffusing the hot magenta point of Falak's sun to a liverish glare half-eclipsed by the crater's southern rim. Against the light, the spidery metal maze of foot-bridging stood out dimly, tracing a random criss-cross pattern that dwindled to invisibility in the mists.

"That network is a Hymenop experiment of some sort," Stryker said, peering. "It's not only a sample of alien engineering—and a thundering big one at that—but an object lesson on the weird workings of alien logic. If we could figure out what possessed the Bees to build such a maze here—"

"Then we'd be the first to solve the problem of alien psychology," Farrell finished acidly, aping the older man's ponderous enthusiasm. "Lee, you know we'd have to follow those hive-building fiends all the way to 70 Ophiuchi to find out what makes them tick. And twenty thousand light-years is a hell of a way to go out of curiosity, not to mention a dangerous one."

"But we'll go there some day," Stryker said positively. "We'll have to go because we can't ever be sure they won't try to repeat their invasion of two hundred years ago."

He tugged at the owlish tufts of hair over his ears, wrinkling his bald brow up at the enigmatic maze.

"We'll never feel safe again until the Bees are wiped out. I wonder if they know that. They never understood us, you know, just as we never understood them—they always seemed more interested in experimenting with slave ecology than in conquest for itself, and they never killed off their captive cultures when they pulled out for home. I wonder if their system of logic can postulate the idea of a society like ours, which must rule or die."

"We'd better get on with our survey," Gibson put in mildly, "unless we mean to finish by floodlight. We've only about forty-eight hours left before dark."

He moved past Stryker through the port, leaving Farrell to stare blankly after him.

"This is a non-rotating world," Farrell said. "How the devil can it get dark, Lee?"

Stryker chuckled. "I wondered if you'd see that. It can't, except when the planet's axial tilt rolls this latitude into its winter season and sends the sun south of the crater rim. It probably gets dark as pitch here in the valley, since the fog would trap even diffused light." To the patiently waiting mechanical, he said, "The ship is yours, Xav. Call us if anything turns up."

Farrell followed him reluctantly outside into a miasmic desolation more depressing than he could have imagined.

A stunted jungle of thorny brambles and tough, waist-high grasses hampered their passage at first, ripping at coveralls and tangling the feet until they had beaten their way through it to lower ground. There they found a dreary expanse of bogland where scummy pools of stagnant water and festering slime heaved sluggishly with oily bubbles of marsh gas that burst audibly in the hanging silence. The liverish blaze of Falakian sun bore down mercilessly from the crater's rim.

They moved on to skirt a small lead-colored lake in the center of the valley, a stagnant seepage-basin half obscured by floating scum. Its steaming mudflats were littered with rotting yellowed bones and supported the first life they had seen, an unpleasant scurrying of small multipedal crustaceans and water-lizards.

"There can't be any survivors here," Farrell said, appalled by the thought of his kind perpetuating itself in a place like this. "God, think what the mortality rate would be! They'd die like flies."

"There are bound to be a few," Stryker stated, "even after a hundred years of slavery and another hundred of abandonment. The human animal, Arthur, is the most fantastically adaptable—"

He broke off short when they rounded a clump of reeds and stumbled upon their first Falakian proof of that fantastic adaptability.

The young woman squatting on the mudflat at their feet stared back at them with vacuous light eyes half hidden behind a wild tangle of matted blonde hair. She was gaunt and filthy, plastered with slime from head to foot, and in her hands she held the half-eaten body of a larger crustacean that obviously had died of natural causes and not too recently, at that.

Farrell turned away, swallowing his disgust. Gibson, unmoved, said with an aptness bordering—for him—on irony: "Too damned adaptable, Lee. Sometimes our kind survives when it really shouldn't."

A male child of perhaps four came out of the reeds and stared at them. He was as gaunt and filthy as the woman, but less vapid of face. Farrell, watching the slow spark of curiosity bloom in his eyes, wondered sickly how many years—or how few—must pass before the boy was reduced to the same stupid bovinity as the mother.

Gibson was right, he thought. The compulsion to survive at any cost could be a curse instead of an asset. The degeneracy of these poor devils was a perpetual affront to the race that had put them there.

He was about to say as much when the woman rose and plodded away through the mud, the child at her heels. It startled him momentarily, when he followed their course with his eyes, to see that perhaps a hundred others had gathered to wait incuriously for them in the near distance. All were as filthy as the first two, but with a grotesque uniformity of appearance that left him frowning in uneasy speculation until he found words to identify that similarity.

"They're all young," he said. "The oldest can't be more than twenty—twenty-five at most!"

Stryker scowled, puzzled without sharing Farrell's unease. "You're right. Where are the older ones?"

"Another of your precious little puzzles," Farrell said sourly. "I hope you enjoy unraveling it."

"Oh, we'll get to the bottom of it," Stryker said with assurance. "We'll have to, before we can leave them here."

They made a slow circuit of the lake, and the closer inspection offered a possible solution to the problem Stryker had posed. Chipped and weathered as the bones littering the mudflats were, their grisly shapings were unmistakable.

"I'd say that these are the bones of the older people," Stryker hazarded, "and that they represent the end result of another of these religio-economic control compulsions the Hymenops like to condition into their slaves. Men will go to any lengths to observe a tradition, especially when its origin is forgotten. If these people were once conditioned to look on old age as intolerable—"

"If you're trying to say that they kill each other off at maturity," Farrell interrupted, "the inference is ridiculous. In a hundred years they'd have outgrown a custom so hard to enforce. The balance of power would have rested with the adults, not with the children, and adults are generally fond of living.

Stryker looked to Gibson for support, received none, and found himself saddled with his own contention. "Economic necessity, then, since the valley can support only a limited number. Some of the old North American Indians followed a similar custom, the oldest son throttling the father when he grew too old to hunt."

"But even there infanticide was more popular than patricide," Farrell pointed out. "No group would practice decimation from the top down. It's too difficult to enforce."

Stryker answered him with a quotation from the Colonial Reclamations Handbook, maliciously taking the pontifical classmaster's tone best calculated to irritate Farrell.

"Chapter Four, Subsection One, Paragraph Nineteen: Any custom, fixation or compulsion accepted as the norm by one group of human beings can be understood and evaluated by any other group not influenced by the same ideology, since the basic perceptive abilities of both are necessarily the same through identical heredity. Evaluation of alien motivations, conversely—"

"Oh, hell," Farrell cut in wearily. "Let's get back to the ship, shall we? We'll all feel more like—"

His right foot gave way beneath him without warning, crushing through the soft ground and throwing him heavily. He sat up at once, and swore in incredulous anger when he found the ankle swelling rapidly inside his boot.

"Sprained! Damn it all!"

Gibson and Stryker, on their knees beside the broken crust of soil, ignored him. Gibson took up a broken length of stick and prodded intently in the cavity, prying out after a moment a glistening two-foot ellipsoid that struggled feebly on the ground.

"A chrysalid," Stryker said, bending to gauge the damage Farrell's heavy boot had done. "In a very close pre-eclosion stage. Look, the protective sheathing has begun to split already."

The thing lay twitching aimlessly, prisoned legs pushing against its shining transparent integument in an instinctive attempt at premature freedom. The movement was purely reflexive; its head, huge-eyed and as large as a man's clenched fist, had been thoroughly crushed under Farrell's heel.

Oddly, its injury touched Farrell even through the pain of his injured foot.

"It's the first passably handsome thing we've seen in this pesthole," he said, "and I've maimed it. Finish it off, will you?"

Stryker grunted, feeling the texture of the imprisoning sheath with curious fingers. "What would it have been in imago, Gib? A giant butterfly?"

"A moth," Gibson said tersely. "Lepidoptera, anyway."

He stood up and ended the chrysalid's strugglings with a bolt from his heat-gun before extending a hand to help Farrell up. "I'd like to examine it closer, but there'll be others. Let's get Arthur out of here."

They went back to the ship by slow stages, pausing now and then while Gibson gathered a small packet of bone fragments from the mudflats and underbrush.

"Some of these are older than others," he explained when Stryker remarked on his selection. "But none are recent. It should help to know their exact age."

An hour later, they were bathed and dressed, sealed off comfortably in the ship against the humid heat and stink of the swamp. Farrell lay on a chart room acceleration couch, resting, while Stryker taped his swollen ankle. Gibson and Xavier, the one disdaining rest and the other needing none, used the time to run a test analysis on the bones brought in from the lakeside.

The results of that analysis were more astonishing than illuminating.

A majority of the fragments had been exposed to climatic action for some ten years. A smaller lot averaged twenty years; and a few odd chips, preserved by long burial under alluvial silt, thirty.

"The older natives died at ten-year intervals, then," Stryker said. "And in considerable numbers; the tribe must have been cut to half strength each time. But why?" He frowned unhappily, fishing for opinion. "Gib, can it really be a perversion of religious custom dreamed up by the Hymenops to keep their slaves under control? A sort of festival of sacrifice every decade, climaxing in tribal decimation?"

"Maybe they combine godliness with gluttony," Farrell put in, unasked. "Maybe their orgy runs more to long pig than to piety."

He stood up, wincing at the pain, and was hobbling toward his sleeping cubicle when Gibson's answer to Stryker's question stopped him with a cold prickle along his spine.

"We'll know within twenty-four hours," Gibson said. "Since both the decimations and the winter darkness periods seem to follow the same cycle, I'd say there's a definite relationship."

For once Farrell's cubicle, soundproofed and comfortable, brought him only a fitful imitation of sleep, an intermittent dozing that wavered endlessly between nightmare and wakefulness. When he crawled out again, hours later, he found Xavier waiting for him alone with a thermo-bulb of hot coffee. Stryker and Gibson, the mechanical said blandly, had seen no need of waking him, and had gone out alone on a more extensive tour of investigation.

The hours dragged interminably. Farrell uncased his beloved accordion, but could not bear the sound of it; he tried his sketch-book, and could summon to mind no better subjects than drab miasmic bogs and steaming mudflats. He discarded the idea of chess with Xavier without even weighing it—he would not have lasted past the fourth move, and both he and the mechanical knew it.

He was reduced finally to limping about the ship on his bandaged foot, searching for some routine task left undone and finding nothing. He even went so far as to make a below-decks check on the ship's matter-synthesizer, an indispensable unit designed for the conversion of waste to any chemical compound, and gave it up in annoyance when he found that all such operational details were filed with infallible exactness in Xavier's plastoid head.

The return of Stryker and Gibson only aggravated his impatience. He had expected them to discover concealed approaches to the maze of bridging overhead, tunnelings in the cliff-face to hidden caverns complete with bloodstained altars and caches of sacrificial weapons, or at least some ominous sign of preparation among the natives. But there was nothing.

"No more than yesterday," Stryker said. Failure had cost him a share of his congenital good-humor, leaving him restless and uneasy. "There's nothing to find, Arthur. We've seen it all."

Surprisingly, Gibson disagreed.

"We'll know what we're after when darkness falls," he said. "But that's a good twelve hours away. In the meantime, there's a possibility that our missing key is outside the crater, rather than here inside it."

They turned on him together, both baffled and apprehensive.

"What do you mean, outside?" Farrell demanded. "There's nothing there but grassland. We made sure of that at planetfall."

"We mapped four Hymenop domes on reconnaissance," Gibson reminded him. "But we only examined three to satisfy ourselves that they were empty. The fourth one—"

Farrell interrupted derisively. "That ancient bogey again? Gib, the domes are always empty. The Bees pulled out a hundred years ago."

Gibson said nothing, but his black-browed regard made Farrell flush uncomfortably.

"Gib is right," Stryker intervened. "You're too young in Colonial Reclamations to appreciate the difficulty of recognizing an alien logic, Arthur, let alone the impossibility of outguessing it. I've knocked about these ecological madhouses for the better part of a century, and the more I see of Hymenop work, the more convinced I am that we'll never equate human and Hymenop ideologies. It's like trying to add quantities of dissimilar objects and expressing the result in a single symbol; it can't be done, because there's no possible common denominator for reducing the disparate elements to similarity."

When Farrell kept silent, he went on, "Our own reactions, and consequently our motivations, are based on broad attributes of love, hate, fear, greed and curiosity. We might empathize with another species that reacts as we do to those same stimuli—but what if that other species recognizes only one or two of them, or none at all? What if their motivations stem from a set of responses entirely different from any we know?"

"There aren't any," Farrell said promptly. "What do you think they would be?"

"There you have it," Stryker said triumphantly. He chuckled, his good-nature restored. "We can't imagine what those emotions would be like because we aren't equipped to understand. Could a race depending entirely on extra-sensory perception appreciate a Mozart quintet or a Botticelli altar piece or a performance of Hamlet? You know it couldn't—the esthetic nuances that make those works great would escape it completely, because the motives that inspired their creation are based on a set of values entirely foreign to its comprehension.

"There's a digger wasp on Earth whose female singles out a particular species of tarantula to feed her larvae—and the spider stands patiently by, held by some compulsion whose nature we can't even guess, while the wasp digs a grave, paralyzes the spider and shoves it into the hole with an egg attached. The spider could kill the wasp, and will kill one of any other species, but it submits to that particular kind without a flicker of protest. And if we can't understand the mechanics of such a relationship between reflexive species, then what chance have we of understanding the logic of an intelligent race of aliens? The results of its activities can be assessed, but not the motivations behind those activities."

"All right," Farrell conceded. "You and Gib are right, as usual, and I'm wrong. We'll check that fourth dome."

"You'll stay here with Xav," Stryker said firmly, "while Gib and I check. You'd only punish yourself, using that foot."

After another eight-hour period of waiting, Farrell was nearing the end of his patience. He tried to rationalize his uneasiness and came finally to the conclusion that his failing hinged on a matter of conditioning. He was too accustomed to the stable unity of their team to feel comfortable without Gibson and Stryker. Isolated from their perpetual bickering and the pleasant unspoken warmth of their regard, he was lonesome and tense.

It would have been different, he knew, if either of the others had been left behind. Stryker had his beloved Reclamations texts and his microfilm albums of problems solved on other worlds; Gibson had his complicated galactic charts and his interminable chess bouts with Xavier....

Farrell gave it up and limped outside, to stand scowling unhappily at the dreary expanse of swampland. Far down under the reasoning levels of his consciousness a primal uneasiness nagged at him, whispering in wordless warning that there was more to his mounting restlessness than simple impatience. Something inside him was changing, burgeoning in strange and disturbing growth.

A pale suggestion of movement, wavering and uncertain in the eddying fog, caught his eye. A moment of puzzled watching told him that it was the bedraggled young woman they had seen earlier by the lake, and that she was approaching the ship timorously and under cover.

"But why?" he wondered aloud, recalling her bovine lack of curiosity. "What the devil can she want here?"

A shadow fell across the valley. Farrell, startled, looked up sharply to see the last of the Falakian sun's magenta glare vanishing below the crater's southern rim. A dusky forerunner of darkness settled like a tangible cloud, softening the drab outlines of bramble thickets and slime pools. The change that followed was not seen but felt, a swelling rush of glad arousal like the joy of a child opening its eyes from sleep.

To Farrell, the valley seemed to stir, waking in sympathy to his own restlessness and banishing his unease.

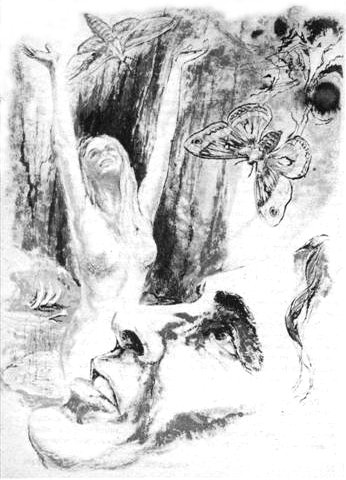

The girl ran to him through the dusk on quick, light feet, timidity forgotten, and he saw with a pleasant shock of astonishment that she was no longer the filthy creature he had first seen by the lakeside. She was pretty and nubile, eyes and soft mouth smiling together in a childlike eagerness that made her at once infinitely desirable and untouchably innocent.

"Who are you?" he asked shakily.

Her hesitant voice was music, rousing in Farrell a warm and expectant euphoria that glowed like old wine in his veins.

"Koaele," she said. "Look—"

Behind her, the valley lay wrapped like a minor paradise in soft pearly mists and luminous shadows, murmurous with the far sound of running water and the faint chiming of voices that drifted up from the little blue lake to whisper back in cadenced echo from the fairy maze of bridging overhead. Over it all, like a deep, sustained cello note, rose the muted humming of great flame-winged moths dipping and swaying over bright tropical flowers.

"Moths?" he thought. And then, "Of course."

The chrysalids under the sod, their eclosion time completed, were coming into their own—bringing perfection with them. Born in gorgeous iridescent imago, they were beautiful in a way that hurt with the yearning pain of perfection, the sorrow that imperfection existed at all—the joy of finally experiencing flawlessness.

An imperative buzzing from the ship behind him made a rude intrusion. A familiar voice, polite but without inflection, called from an open port: "Captain Stryker in the scoutboat, requesting answer."

Farrell hesitated. To the girl, who followed him with puzzled, eager eyes, he begged, "Don't run away, please. I'll be back."

In the ship, Stryker's moon-face peered wryly at him from the main control screen.

"Drew another blank," it said. "You were right after all, Arthur—the fourth dome was empty. Gib and I are coming in now. We can't risk staying out longer if we're going to be on hand when the curtain rises on our little mystery."

"Mystery?" Farrell echoed blankly. Earlier discussions came back slowly, posing a forgotten problem so ridiculous that he laughed. "We were wrong about all that. It's wonderful here."

Stryker's face on the screen went long with astonishment. "Arthur, have you lost your mind? What's wrong there?"

"Nothing is wrong," Farrell said. "It's right." Memory prodded him again, disturbingly. "Wait—I remember now what it was we came here for. But we're not going through with it."

He thought of the festival to come, of the young men and girls running lithe in the dusk, splashing in the lake and calling joyously to each other across the pale sands. The joyous innocence of their play brought an appalling realization of what would happen if the fat outsider on the screen should have his way:

The quiet paradise would be shattered and refashioned in smoky facsimile of Earth, the happy people herded together and set to work in dusty fields and whirring factories, multiplying tensions and frustrations as they multiplied their numbers.

For what? For whom?

"You've got no right to go back and report all this," Farrell said plaintively. "You'd ruin everything."

The alternative came to him and with it resolution. "But you won't go back. I'll see to that."

He left the screen and turned on the control panel with fingers that remembered from long habit the settings required. Stryker's voice bellowed frantically after him, unheeded, while he fed into the ship's autopilot a command that would send her plunging skyward bare minutes later.

Then, ignoring the waiting mechanical's passive stare, he went outside.

The valley beckoned. The elfin laughter of the people by the lake touched a fey, responsive chord in him that blurred his eyes with ecstatic tears and sent him running down the slope, the Falakian girl keeping pace beside him.

Before he reached the lake, he had dismissed from his mind the ship and the men who had brought it there.

But they would not let him forget. The little gray jointed one followed him through the dancing and the laughter and cornered him finally against the sheer cliffside. With the chase over, it held him there, waiting with metal patience in the growing dusk.

The audicom box slung over its shoulder boomed out in Gibson's voice, the sound a noisy desecration of the scented quiet.

"Don't let him get away, Xav," it said. "We're going to try for the ship now."

The light dimmed, the soft shadows deepened. The two great-winged moths floated nearer, humming gently, their eyes glowing luminous and intent in the near-darkness. Mist currents from their approach brushed Farrell's face, and he held out his arms in an ecstasy of anticipation that was a consummation of all human longing.

"Now," he whispered.

The moths dipped nearer.

The mechanical sent out a searing beam of orange light that tore the gloom, blinding him briefly. The humming ceased; when he could see again, the moths lay scorched and blackened at his feet. Their dead eyes looked up at him dully, charred and empty; their bright gauzy wings smoked in ruins of ugly, whiplike ribs.

He flinched when the girl touched his shoulder, pointing. A moth dipped toward them out of the mists, eyes glowing like round emerald lanterns. Another followed.

The mechanical flicked out its orange beam and cut them down.

A roar like sustained thunder rose across the valley, shaking the ground underfoot. A column of white-hot fire tore the night.

"The ship," Farrell said aloud, remembering.

He had a briefly troubled vision of the sleek metal shell lancing up toward a black void of space powdered with cold star-points whose names he had forgotten, marooning them all in Paradise.

The audicom boomed in Gibson's voice, though oddly shaken and strained. "Made it. Is he still safe, Xav?"

"Safe," the mechanical answered tersely. "The natives, too, so far."

"No thanks to him," Gibson said. "If you hadn't canceled the blastoff order he fed into the autopilot...." But after a moment of ragged silence: "No, that's hardly fair. Those damned moths beat down Lee's resistance in the few minutes it took us to reach the ship, and nearly got me as well. Arthur was exposed to their influence from the moment they started coming out."

Stryker's voice cut in, sounding more shaken than Gibson's. "Stand fast down there. I'm setting off the first flare now."

A silent explosion of light, searing and unendurable, blasted the night. Farrell cried out and shielded his eyes with his hands, his ecstasy of anticipation draining out of him like heady wine from a broken urn. Full memory returned numbingly.

When he opened his eyes again, the Falakian girl had run away. Under the merciless glare of light, the valley was as he had first seen it—a nauseous charnel place of bogs and brambles and mudflats littered with yellowed bones.

In the near distance, a haggard mob of natives cowered like gaping, witless caricatures of humanity, faces turned from the descending blaze of the parachute flare. There was no more music or laughter. The great moths fluttered in silent frenzy, stunned by the flood of light.

"So that's it," Farrell thought dully. "They come out with the winter darkness to breed and lay their eggs, and they hold over men the same sort of compulsion that Terran wasps hold over their host tarantulas. But they're nocturnal. They lose their control in the light."

Incredulously, he recalled the expectant euphoria that had blinded him, and he wondered sickly: "Is that what the spider feels while it watches its grave being dug?"

A second flare bloomed far up in the fog, outlining the criss-cross network of bridging in stark, alien clarity. A smooth minnow-shape dipped past and below it, weaving skilfully through the maze. The mechanical's voice box spoke again.

"Give us a guide beam, Xav. We're bringing the Marco down."

The ship settled a dozen yards away, its port open. Farrell, with Xavier at his heels, went inside hastily, not looking back.

Gibson crouched motionless over his control panel, too intent on his readings to look up. Beside him, Stryker said urgently: "Hang on. We've got to get up and set another flare, quickly."

The ship surged upward.

Hours later, they watched the last of the flares glare below in a steaming geyser of mud and scum. The ship hovered motionless, its only sound a busy droning from the engine room where her mass-synthesizer discharged a deadly cloud of insecticide into the crater.

"There'll be some nasty coughing among the natives for a few days after this," Gibson said. "But it's better than being food for larvae.... Reorientation will pull them out of that pesthole in a couple of months, and another decade will see them raising cattle and wheat again outside. The young adapt fast."

"The young, yes," Stryker agreed uncomfortably. "Personally, I'm getting too old and fat for this business."

He shuddered, his paunch quaking. Farrell guessed that he was thinking of what would have happened to them if Gibson had been as susceptible as they to the overpowering fascination of the moths. A few more chrysalids to open in the spring, an extra litter of bones to puzzle the next Reclamations crew....

"That should do it," Gibson said. He shut off the flow of insecticide and the mass-converter grew silent in the engine room below. "Exit another Hymenop experiment in bastard synecology."

"I can understand how they might find, or breed, a nocturnal moth with breeding-season control over human beings," Farrell said. "And how they'd balance the relationship to a time-cycle that kept the host species alive, yet never let it reach maturity. But what sort of principle would give an instinctive species compulsive control over an intelligent one, Gib? And what did the Bees get out of the arrangement in the first place?"

Gibson shrugged. "We'll understand the principle when—or if—we learn how the wasp holds its spider helpless. Until then, we can only guess. As for identifying the motive that prompted the Hymenops to set up such a balance, I doubt that we ever will. Could a termite understand why men build theaters?"

"There's a possible parallel in that," Stryker suggested. "Maybe this was the Hymenop idea of entertainment. They might have built the bridge as balconies, where they could see the show."

"It could have been a business venture," Farrell suggested. "Maybe they raised the moth larvae or pupae for the same reason we raise poultry. A sort of insectile chicken ranch."

"Or a kennel," Gibson said dryly. "Maybe they bred moths for pets, as we breed dogs."

Farrell grimaced sickly, revolted by the thought. "A pet farm? God, what a diet to feed them!"

Xavier came up from the galley, carrying a tray with three steaming coffee-bulbs. Farrell, still pondering the problem of balance between dominant and dominated species, found himself wondering for the thousandth time what went on in the alert positronic brain behind the mechanical's featureless face.

"What do you think, Xav?" he demanded. "What sort of motive would you say prompted the Hymenops to set up such a balance?"

"Evaluation of alien motivations, conversely," the mechanical said, finishing the Reclamations Handbook quotation which Stryker had begun much earlier, "is essentially impossible because there can be no common ground of comprehension."

It centered the tray neatly on the charting table and stood back in polite but unmenial deference while they sucked at their coffee-bulbs.

"A greater mystery to me," Xavier went on, "is the congenital restlessness that drives men from their own comfortable worlds to such dangers as you have met with here. How can I understand the motivations of an alien people? I do not even understand those of the race that built me."

The three men looked at each other blankly, disconcerted by the ancient problem so unexpectedly posed.

It was Stryker who sheepishly answered it.

"That's nothing for you to worry about, Xav," he said wryly. "Neither do we."