Title: Garden and Forest Weekly, Volume 1 No. 1, February 29, 1888

Author: Various

Editor: Charles Sprague Sargent

Release date: April 26, 2010 [eBook #32141]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by the Library of Congress)

A

PRIL HOPES. A Novel. By William Dean Howells.

12mo, Cloth, $1 50.

Mr. Howells never wrote a more bewitching book. It is useless to deny the rarity and worth of the skill that can report so perfectly and with such exquisite humor the manifold emotions of the modern maiden and her lover.—Philadelphia Press.

M

ODERN ITALIAN POETS. Essays and Versions. By

William Dean Howells.

Author of “April Hopes,” &c. With Portraits.

12mo, Half Cloth, Uncut Edges and Gilt Tops, $2 00.

A portfolio of delightsome studies.... No acute and penetrating critic surpasses Mr. Howells in true insight, in polished irony, in effective and yet graceful treatment of his theme, in that light and indescribable touch that fixes your eye on the true heart and soul of the theme.—Critic, N. Y.

K

INGLAKE’S CRIMEAN WAR. The Invasion of the Crimea:

its Origin, and an account of its Progress down to the Death of Lord Raglan.

By Alexander William Kinglake. With Maps and Plans. Five Volumes

now ready. 12mo, Cloth, $2 00 per vol.

Vol. V. From the Morrow of Inkerman to the Fall of Canrobert; just published.—Vol. VI. From the Rise of Pelissier to the Death of Lord Raglan—completing the work—nearly ready.

The charm of Mr. Kinglake’s style, the wonderful beauty of his pictures, the subtle irony of his reflections, have made him so long a favorite and companion, that it is with unfeigned regret we read the word “farewell” with which these volumes close.—Pall Mall Gazette, London.

W

HAT I REMEMBER. By T. Adolphus Trollope.

With Portrait. 12mo, Cloth, $1 75.

The most delightful pot-pourri that we could desire of the time just anterior to our own.... Mr. Trollope preserves for us delightful, racy stories of his youth and the youth of his century, and gives us glimpses of loved or worshipped faces banished before our time. Hence the success of these written remembrances.—Academy, London.

L

IFE AND LABOR; or, Characteristics of Men of Industry,

Culture, and Genius. By Samuel Smiles, LL.D.,

Author of “Self-Help,” &c. 12mo, Cloth, $1 00.

Commends itself to the entire confidence of readers. Dr. Smiles writes nothing that is not fresh, strong, and magnetically bracing. He is one of the most helpful authors of the Victorian era.... This is just the book for young men.—N. Y. Journal of Commerce.

W

OMEN AND MEN. By Thomas W. Higginson,

Author of “A Larger History of the United States,” &c. 16mo, Cloth, $1 00.

These essays are replete with common-sense ideas, expressed in well-chosen language, and reflect on every page the humor, wit, wisdom of the author.—N. Y. Sun.

B

IG WAGES, AND HOW TO EARN THEM. By A Foreman.

16mo, Cloth, 75 cents.

The views of an intelligent observer upon some of the foremost social topics of the day. The style is simple, the logic cogent, and the tone moderate and sensible.—N. Y. Commercial Advertiser.

H

ISTORY OF THE INQUISITION OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

By Henry Charles Lea. To be completed in Three Volumes. 8vo,

Cloth,

Uncut Edges and Gilt Tops, $3 00 per volume. Vols. I. and II. now ready.

Vol. III. nearly ready.

Characterized by the same astounding reach of historical scholarship as made Mr. Lea’s “Sacerdotal Celibacy” the wonder of European scholars. But it seems even to surpass his former works in judicial repose and in the mastery of materials.... Of Mr. Lea’s predecessors no one is so like him as Gibbon.—Sunday-School Times, Philadelphia.

M

ODERN SHIPS OF WAR. By Sir Edward J. Reed, M.P.,

late Chief Constructor of the British Navy, and Edward Simpson,

Rear-Admiral

U.S.N., late President of the U.S. Naval Advisory Board. With

Supplementary Chapters and Notes by J. D. Jerrold Kelley, Lieutenant

U.S.N. Illustrated. Square 8vo, Cloth, Ornamental, $2 50.

This is the most valuable contribution yet made to the popular literature of modern navies.... The whole country is indebted to the authors and to the publishers for a book on men-of-war that both in matter and make-up is without an equal.—N. Y. Herald.

M

Y AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND REMINISCENCES.

By W. P. Frith, R.A. Portrait. 12mo, Cloth, $1 50.

The whole round of English autobiography does not comprise a work more full of character, more rich in anecdote, or more fruitful in entertainment for the general reader. A delightful volume.—London Daily News.

H

ISTORY OF THE NEGRO TROOPS IN THE WAR OF THE REBELLION. 1861-1865.

By G. W. Williams, LL.D. Portrait. 8vo,

Cloth, Ornamental, $1 75.

Mr. Williams has written an excellent book. He was one of the gallant men whose patriotic deeds he commemorates, and he has made a careful study of all the best accessible records of their achievements. His people may well be proud of the showing.—N. Y. Tribune.

F

AMILY LIVING ON $500 A YEAR. A Daily Reference

Book for Young and Inexperienced Housewives. By Juliet Corson. 16mo,

Cloth, Extra, $1 25.

Miss Corson has rendered a valuable service by this book, in which she shows conclusively how for five hundred dollars a plentiful, appetizing and varied diet can be furnished throughout the year to a family.—N. Y. Sun.

C

APTAIN MACDONALD’S DAUGHTER. By Archibald Campbell.

16mo, Cloth, $1 00.

N

ARKA, THE NIHILIST. By Kathleen O’Meara.

16mo, Cloth, Extra, $1 00.

M

R. ABSALOM BILLINGSLEA, AND OTHER GEORGIAN FOLK.

By R. M. Johnston. Illustrated. 16mo, Cloth, Extra, $1 25.

A

MAGNIFICENT PLEBEIAN. By Julia Magruder.

16mo, Cloth, Extra, $1 00.

A

PRINCE OF THE BLOOD. By James Payn.

16mo, Cloth, 75 cents.

The above works are for sale by all booksellers, or will be sent by Harper & Brothers, postpaid, to any part of the United States and Canada on receipt of price. Catalogue sent on receipt of Ten Cents in postage stamps.

GARDEN AND FOREST will be devoted to Horticulture in all its branches, Garden Botany, Dendrology and Landscape Gardening, and will discuss Plant Diseases and Insects injurious to vegetation.

Professor C. S. Sargent, of Harvard College, will have general editorial control of GARDEN AND FOREST.

Professor Wm. G. Farlow, of Harvard College, will have editorial charge of the Department of Cryptogamic Botany and Plant Diseases.

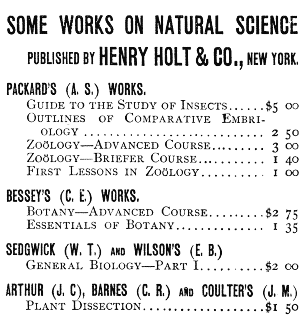

Professor A. S. Packard, of Brown University, will have editorial charge of the Department of Entomology.

Mr. Wm. A. Stiles will be the Managing Editor.

GARDEN AND FOREST will record all noteworthy discoveries and all progress in science and practice within its field at home and abroad. It will place scientific information clearly and simply before the public, and make available for the instruction of all persons interested in garden plants the conclusions reached by the most trustworthy investigators. Arrangements have been made to figure and describe new and little-known plants (especially North American) of horticultural promise. A department will be devoted to the history and description of ornamental trees and shrubs. New florists’ flowers, fruits and vegetables will be made known, and experienced gardeners will describe practical methods of cultivation.

GARDEN AND FOREST will report the proceedings of the principal Horticultural Societies of the United States and the condition of the horticultural trade in the chief commercial centres of the country.

GARDEN AND FOREST, in view of the growing taste for rural life, and of the multiplication of country residences in all parts of the United States, especially in the vicinity of the cities and of the larger towns, will make a special feature of discussing the planning and planting of private gardens and grounds, small and large, and will endeavor to assist all who desire to make their home surroundings attractive and artistic. It will be a medium of instruction for all persons interested in preserving and developing the beauty of natural scenery. It will co-operate with Village Improvement Societies and every other organized effort to secure the proper ordering and maintenance of parks and squares, cemeteries, railroad stations, school grounds and roadsides. It will treat of Landscape Gardening in all its phases; reviewing its history and discussing its connection with architecture.

GARDEN AND FOREST will give special attention to scientific and practical Forestry in their various departments, including Forest Conservation and economic Tree Planting, and to all the important questions which grow out of the intimate relation of the forests of the country to its climate, soil, water supply and material development.

Original information on all these subjects will be furnished by numerous American and foreign correspondents.

Among those who have promised contributions to GARDEN AND FOREST are:

Mr. Sereno Watson, Curator of the Herbarium, Harvard College.

Prof. Geo. L. Goodale, Harvard College.

“ Wolcott Gibbs, “

“ Wm. H. Brewer, Yale College.

“ D. G. Eaton, “

“ Wm. J. Beal, Agricultural College of Michigan.

“ L. H. Bailey, Jr., “ “ “

“ J. L. Budd, Agricultural College of Iowa.

“ B. D. Halsted, “ “ “

“ E. W. Hilgard, University of California.

“ J. T. Rothrock, University of Pennsylvania.

“ Chas. E. Bessey, University of Nebraska.

“ Wm. Trelease, Shaw School of Botany, St. Louis.

“ T. J. Burrill, University of Illinois.

“ W. W. Bailey, Brown University.

“ E. A. Popenoe, Agricultural College, Kansas.

“ Raphael Pumpelly. United States Geological Survey.

“ James H. Gardiner, Director New York State Survey.

“ Wm. R. Lazenby, Director of the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station.

“ W. W. Tracy, Detroit, Mich.

“ C. V. Riley, Washington, D. C.

Mr. Donald G. Mitchell, New Haven, Conn.

“ Frank J. Scott, Toledo, O.

Hon. Adolphe Leué, Secretary of the Ohio Forestry Bureau.

“ B. G. Northrop, Clinton, Conn.

Mr. G. W. Hotchkiss, Secretary of the Lumber Manufacturers’ Association.

Dr. C. L. Anderson, Santa Cruz, Cal.

Mr. Frederick Law Olmsted, Brookline, Mass.

“ Francis Parkman, Boston.

Dr. C. C. Parry, San Francisco.

Mr. Prosper J. Berckmans, President of the American Pomological Society.

“ Charles A. Dana, New York.

“ Burnet Landreth, Philadelphia.

“ Robert Ridgeway, Washington, D. C.

“ Calvert Vaux, New York.

“ J. B. Harrison, Franklin Falls, N. H.

Dr. Henry P. Walcott, President of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

Mr. C. G. Pringle, Charlotte, Vt.

“ Robert Douglas, Waukegan, Ill.

“ H. W. S. Cleveland, Minneapolis, Minn.

“ Chas. W. Garfield, Secretary of the American Pomological Society.

“ C. R. Orcutt, San Diego, Cal.

“ B. E. Fernow, Chief of the Forestry Division, Washington, D. C.

“ John Birkenbine, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Forestry Association.

“ Josiah Hoopes, West Chester, Pa.

“ Peter Henderson, New York.

“ Wm. Falconer, Glen Cove, N. Y.

“ Jackson Dawson, Jamaica Plain, Mass.

“ Wm. H. Hall, State Engineer, Sacramento, Cal.

“ C. C. Crozier, Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C.

The Rev. E. P. Roe, Cornwall, N. Y.

Dr. C. C. Abbott, Trenton, N. J.

Mrs. Schuyler van Rensselaer, New York.

“ Mary Treat, Vineland, N. J.

Dr. Karl Mohr, Mobile, Ala.

Hon. J. B. Walker, Forest Commissioner of New Hampshire.

Mr. Wm. Hamilton Gibson, Brooklyn, N. Y.

“ Edgar T. Ensign, Forest Commissioner of Colorado.

“ E. S. Carman, Editor of the Rural New Yorker.

“ Wm. M. Canby. Wilmington, Del.

“ John Robinson, Salem, Mass.

“ J. D. Lyman, Exeter, N. H.

“ Samuel Parsons, Jr., Superintendent of Central Park, N. Y.

“ Wm. McMillan, Superintendent of Parks, Buffalo. N. Y.

“ Sylvester Baxter, Boston.

“ Charles Eliot, Boston.

“ John Thorpe, Secretary of the New York Horticultural Society.

“ Edwin Lonsdale, Secretary of the Philadelphia Horticultural Society.

“ Robert Craig, President of the Philadelphia Florists’ Club.

“ Samuel B. Parsons, Flushing, N. Y.

“ George Ellwanger, Rochester.

“ P. H. Barry, Rochester.

“ W. J. Stewart, Boston, Mass.

“ W. A. Manda, Botanic Gardens, Cambridge, Mass.

“ David Allan, Mount Vernon, Mass.

“ Wm. Robinson, North Easton, Mass.

“ A. H. Fewkes, Newton Highlands, Mass.

“ F. Goldring, Kenwood, N. Y.

“ C. M. Atkinson, Brookline, Mass.

Dr. Maxwell T. Masters, Editor of the Gardener’s Chronicle.

Mr. Geo. Nicholson, Curator of the Royal Gardens, Kew.

“ W. B. Hemsley, Herbarium, Royal Gardens, Kew.

“ Wm. Goldring, London.

Mr. Max Leichtlin, Baden Baden.

M. Edouard André, Editor of the Revue Horticole, Paris, France.

Dr. G. M. Dawson, Geological Survey of Canada.

Prof. John Macoun, “ “ “

M. Charles Naudin, Director of the Gardens of The Villa Thuret, Antibes.

Dr. Chas. Bolle, Berlin.

M. J. Allard, Angers, Maine & Loire, France.

Dr. H. Maye, University of Tokio, Japan.

Prof. D. P. Penhallow, Director of the Botanical Gardens, Montreal.

Mr. Wm. Saunders, Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station, Ontario.

“ Wm. Little, Montreal.

Single numbers, 10 cents. Subscription price, Four Dollars a year, in advance.

THE GARDEN AND FOREST PUBLISHING CO., Limited,

D. A. MUNRO, Manager. Tribune Building, New York

| PAGE. | |

| Editorial Articles:—Asa Gray. The Gardener’s Monthly. The White Pine in Europe |

1 |

| The Forests of the White Mountain | Francis Parkman. 2 |

| Landscape Gardening.—A Definition | Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer. 2 |

| Floriculture in the United States | Peter Henderson. 2 |

| How to Make a Lawn | Professor W. J. Beal. 3 |

| Letter from London | W. Goldring. 4 |

| A New Departure in Chrysanthemums | A. H. Fewkes. 5 |

| New Plants from Afghanistan | Max Leichtlin. 6 |

| Iris Tenuis, with figure | Sereno Watson. 6 |

| Hardy Shrubs for Forcing | Wm. Falconer. 6 |

| Plant Notes | C. C. Pringle; Professor W. Trelease. 7 |

| Wire Netting for Tree Guards | A. A. Crozier. 7 |

| Artificial Water, with Illustration | 8 |

| Some New Roses | Edwin Lonsdale. 8 |

| Two Ferns and Their Treatment | F. Goldring. 9 |

| Timely Hints about Bulbs | John Thorpe. 9 |

| Entomology: | |

| Arsenical Poisons in the Orchard | Professor A. S. Packard. 9 |

| The Forest: | |

| The White Pine in Europe | Professor H. Mayr. 10 |

| European Larch in Massachusetts | 11 |

| Thinning Pine Plantations | B. E. Fernow. 11 |

| Book Reviews: | |

| Gray’s Elements of Botany | Professor G. L. Goodale. 11 |

| Kansas Forest Trees | Professor G. L. Goodale. 12 |

| Public Works:—The Falls of Minnehaha—A Park for Wilmington | 12 |

| Flower Markets:—New York—Philadelphia—Boston | 12 |

T HE whole civilized world is mourning the death of Asa Gray with a depth of feeling and appreciation perhaps never accorded before to a scholar and man of science.

To the editors of this Journal the loss at the very outset of their labors is serious indeed. They lose a wise and sympathetic adviser of great experience and mature judgment to whom they could always have turned with entire freedom and in perfect confidence; and they lose a contributor whose vast stores of knowledge and graceful pen might, it was reasonable to hope, have long enriched their columns.

The career of Asa Gray is interesting from many points of view. It is the story of the life of a man born in humble circumstances, without the advantages of early education, without inherited genius—for there is no trace in his yeoman ancestry of any germ of intellectual greatness—who succeeded in gaining through native intelligence, industry and force of character, a position in the very front rank of the scientific men of his age. Among the naturalists who, since Linnæus, have devoted their lives to the description and classification of plants, four or five stand out prominently in the character and importance of their work. In this little group Asa Gray has fairly won for himself a lasting position. But he was something more than a mere systematist. He showed himself capable of drawing broad philosophical conclusions from the dry facts he collected and elaborated with such untiring industry and zeal. This power of comprehensive generalization he showed in his paper upon the “Characters of Certain New Species of Plants Collected in Japan” by Charles Wright, published nearly thirty years ago. Here he first pointed out the extraordinary similarity between the Floras of Eastern North America and Japan, and then explained the peculiar distribution of plants through the northern hemisphere by tracing their direct descent through geological eras from ancestors which flourished in the arctic regions down to the latest tertiary period. This paper was Professor Gray’s most remarkable and interesting contribution to science. It at once raised him to high rank among philosophical naturalists and drew the attention of the whole scientific world to the Cambridge botanist.

Asa Gray did not devote himself to abstract science alone; he wrote as successfully for the student as for the professional naturalist. His long list of educational works have no equals in accuracy and in beauty and compactness of expression. They have had a remarkable influence upon the study of botany in this country during the half century which has elapsed since the first of the series appeared.

Botany, moreover, did not satisfy that wonderful intellect, which hard work only stimulated but did not weary, and one of Asa Gray’s chief claims to distinction is the prominent and commanding position he took in the great intellectual and scientific struggle of modern times, in which, almost alone and single handed he bore in America the brunt of the disbelief in the Darwinian theory shared by most of the leading naturalists of the time.

But the crowning labor of Asa Gray’s life was the preparation of a descriptive work upon the plants of North America. This great undertaking occupied his attention and much of his time during the last forty years of his life. Less fortunate than his greatest botanical contemporary, George Bentham, who turned from the last page of corrected proof of his work upon the genera of plants to the bed from which he was never to rise again, Asa Gray’s great work is left unfinished. The two volumes of the “Synoptical Flora of North America” will keep his memory green, however, as long as the human race is interested in the study of plants.

But his botanical writings and his scientific fame are not the most valuable legacy which Asa Gray has left to the American people. More precious to us is the example of his life in this age of grasping materialism. It is a life that teaches how industry and unselfish devotion to learning can attain to the highest distinction and the most enduring fame. Great as were his intellectual gifts, Asa Gray was greatest in the simplicity of his character and in the beauty of his pure and stainless life.

It is with genuine regret that we read the announcement of the discontinuance of the Gardener’s Monthly. It is like reading of the death of an old friend. Ever since we have been interested in the cultivation of flowers we have looked to the Monthly for inspiration and advice, and its pages have rarely been turned without finding the assistance we stood in need of. But, fortunately, the Gardener’s Monthly, and its modest and accomplished editor, Mr. Thomas Meehan, were one and the same thing. It is Mr. Meehan’s long editorial experience, high character, great learning and varied practical knowledge, which made the Gardener’s Monthly what it was. These, we are happy to know, are not to be lost to us, as Mr. Meehan will, in a somewhat different field and with new associates, continue to delight and instruct the horticultural public.

Americans who visit Europe cannot fail to remark that in the parks and pleasure grounds of the Continent no coniferous tree is more graceful when young or more dignified at maturity than our White Pine. The notes of Dr. Mayr, of the Bavarian Forest Academy, in another column, testify that it holds a position of equal importance as a forest tree for economic planting. It thrives from Northern Germany to Lombardy, corresponding with a range of climate in this country from New England to Northern Georgia. It needs bright sunshine, however, and perhaps it is for lack of this that so few good specimens are seen in England. It was among the first of our trees to be introduced there, but it has been universally pronounced an indifferent grower.

N EW Hampshire is not a peculiarly wealthy State, but it has some resources scarcely equaled by those of any of its sisters. The White Mountains, though worth little to the farmer, are a piece of real estate which yields a sure and abundant income by attracting tourists and their money; and this revenue is certain to increase, unless blind mismanagement interposes. The White Mountains are at present unique objects of attraction; but they may easily be spoiled, and the yearly tide of tourists will thus be turned towards other points of interest whose owners have had more sense and foresight.

These mountains owe three-fourths of their charms to the primeval forest that still covers them. Speculators have their eyes on it, and if they are permitted to work their will the State will find a most productive piece of property sadly fallen in value. If the mountains are robbed of their forests they will become like some parts of the Pyrenees, which, though much higher, are without interest, because they have been stripped bare.

The forests of the White Mountains have a considerable commercial value, and this value need not be sacrificed. When lumber speculators get possession of forests they generally cut down all the trees and strip the land at once, with an eye to immediate profit. The more conservative, and, in the end, the more profitable management, consists in selecting and cutting out the valuable timber when it has matured, leaving the younger growth for future use. This process is not very harmful to the landscape. It is practiced extensively in Maine, where the art of managing forests with a view to profit is better understood than elsewhere in this country. A fair amount of good timber may thus be drawn from the White Mountains, without impairing their value as the permanent source of a vastly greater income from the attraction they will offer to an increasing influx of tourists. At the same time the streams flowing from them, and especially the Pemigewasset, a main source of the Merrimac, will be saved from the alternate droughts and freshets to which all streams are exposed that take their rise in mountains denuded of forests. The subject is one of the last importance to the mill owners along these rivers.

S OME of the Fine Arts appeal to the ear, others to the eye. The latter are the Arts of Design, and they are usually named as three—Architecture, Sculpture and Painting. A man who practices one of these in any of its branches is an artist; other men who work with forms and colors are at the best but artisans. This is the popular belief. But in fact there is a fourth art which has a right to be rated with the others, which is as fine as the finest, and which demands as much of its professors in the way of creative power and executive skill as the most difficult. This is the art whose purpose it is to create beautiful compositions upon the surface of the ground.

The mere statement of its purpose is sufficient to establish its rank. It is the effort to produce organic beauty—to compose a beautiful whole with a number of related parts—which makes a man an artist; neither the production of a merely useful organism nor of a single beautiful detail suffices. A clearly told story or a single beautiful word is not a work of art—only a story told in beautifully connected words. A solidly and conveniently built house, if it is nothing more, is not a work of architecture, nor is an isolated stone, however lovely in shape and surface. A delightful tint, a graceful line, does not make a picture; and though the painter may reproduce ugly models he must put some kind of beauty into the reproduction if it is to be esteemed above any other manufactured article—if not beauty of form, then beauty of color or of meaning or at least of execution. Similarly, when a man disposes the surface of the soil with an eye to crops alone he is an agriculturist; when he grows plants for their beauty as isolated objects he is a horticulturist; but when he disposes ground and plants together to produce organic beauty of effect, he is an artist with the best.

Yet though all the fine arts are thus akin in general purpose they differ each from each in many ways. And in the radical differences which exist between the landscape-gardener’s and all the others we find some reasons why its affinity with them is so commonly ignored. One difference is that it uses the same materials as nature herself. In what is called “natural” gardening it uses them to produce effects which under fortunate conditions nature might produce without man’s aid. Then, the better the result, the less likely it is to be recognized as an artificial—artistic—result. The more perfectly the artist attains his aim, the more likely we are to forget that he has been at work. In “formal” gardening, on the other hand, nature’s materials are disposed and treated in frankly unnatural ways; and then—as a more or less intelligent love for natural beauty is very common to-day, and an intelligent eye for art is rare—the artist’s work is apt to be resented as an impertinence, denied its right to its name, called a mere contorting and disfiguring of his materials.

Again, the landscape-gardener’s art differs from all others in the unstable character of its productions. When surfaces are modeled and plants arranged, nature and the artist must work a long time together before the true result appears; and when once it has revealed itself, day to day attention will be forever needed to preserve it from the deforming effects of time. It is easy to see how often neglect or interference must work havoc with the best intentions, how often the passage of years must travesty or destroy the best results, how rare must be the cases in which a work of landscape art really does justice to its creator.

Still another thing which affects popular recognition of the art as such is our lack of clearly understood terms by which to speak of it and of those who practice it. “Gardens” once meant pleasure-grounds of every kind and “gardener” then had an adequately artistic sound. But as the significance of the one term has been gradually specialized, so the other has gradually come to denote a mere grower of plants. “Landscape gardener” was a title first used by the artists of the eighteenth century to mark the new tendency which they represented—the search for “natural” as opposed to “formal” beauty; and it seemed to them to need an apology as savoring, perhaps, of grandiloquence or conceit. But as taste declined in England it was assumed by men who had not the slightest right, judged either by their aims or by their results, to be considered artists; and to-day it is fallen into such disesteem that it is often replaced by “landscape architect.” This title has French usage to support it and is in many respects a good one. But its correlative—“landscape architecture”—is unsatisfactory; and so, on the other hand, is “landscape artist,” though “landscape art” is an excellent generic term. Perhaps the best we can do is to keep to “landscape gardener,” and try to remember that it ought always to mean an artist and an artist only.

A T the beginning of the present century, it is not probable that there were 100 florists in the United States, and their combined green-house structures could not have exceeded 50,000 square feet of glass. There are now more than 10,000 florists distributed through every State and Territory in the Union and estimating 5,000 square feet of glass to each, the total area would be 50,000,000 feet, or about 1,000 acres of green-houses. The value of the bare structures, with heating apparatus, at 60 cents per square foot would be $30,000,000, while the stock of plants grown in them would not be less than [page 3] twice that sum. The present rate of growth in the business is about 25% per annum, which proves that it is keeping well abreast of our most flourishing industries.

The business, too, is conducted by a better class of men. No longer than thirty years ago it was rare to find any other than a foreigner engaged in commercial floriculture. These men had usually been private gardeners, who were mostly uneducated, and without business habits. But to-day, the men of this calling compare favorably in intelligence and business capacity with any mercantile class.

Floriculture has attained such importance that it has taken its place as a regular branch of study in some of our agricultural colleges. Of late years, too, scores of young men in all parts of the country have been apprenticing themselves to the large establishments near the cities, and already some of these have achieved a high standing; for the training so received by a lad from sixteen to twenty, better fits him for the business here than ten years of European experience, because much of what is learned there would prove worse than useless here. The English or German florist has here to contend with unfamiliar conditions of climate and a manner of doing business that is novel to him. Again he has been trained to more deliberate methods of working, and when I told the story a few years ago of a workman who had potted 10,000 cuttings in two inch pots in ten consecutive hours, it was stigmatized in nearly every horticultural magazine in Europe as a piece of American bragging. As a matter of fact this same workman two years later, potted 11,500 plants in ten hours, and since then several other workmen have potted plants at the rate of a thousand per hour all day long.

Old world conservatism is slow to adopt improvements. The practice of heating by low pressure steam will save in labor, coal and construction one-fifth of the expense by old methods, and nearly all the large green-house establishments in this country, whether private or commercial, have been for some years furnished with the best apparatus. But when visiting London, Edinburgh and Paris in 1885, I neither saw nor heard of a single case where steam had been used for green-house heating. The stress of competition here has developed enterprise, encouraged invention and driven us to rapid and prudent practice, so that while labor costs at least twice as much as it does in Europe, our prices both at wholesale and retail, are lower. And yet I am not aware that American florists complain that their profits compare unfavorably with those of their brethren over the sea.

Commercial floriculture includes two distinct branches, one for the production of flowers and the other for the production of plants. During the past twenty years the growth in the flower department of the business has outstripped the growth of the plant department. The increase in the sale of Rosebuds in winter is especially noteworthy. At the present time it is safe to say that one-third of the entire glass structures in the United States are used for this purpose; many large growers having from two to three acres in houses devoted to Roses alone, such erections costing from $50,000 to $100,000 each, according to the style in which they are built.

More cut flowers are used for decoration in the United States than in any other country, and it is probable that there are more flowers sold in New York than in London with a population four times as great. In London and Paris, however, nearly every door-yard and window of city and suburb show the householder’s love for plants, while with us, particularly in the vicinity of New York (Philadelphia and Boston are better), the use of living plants for home decoration is far less general.

There are fashions in flowers, and they continually change. Thirty years ago thousands of Camellia flowers were retailed in the holiday season for $1 each, while Rosebuds would not bring a dime. Now, many of the fancy Roses sell at $1 each, while Camellia flowers go begging at ten cents. The Chrysanthemum is now rivaling the Rose, as well it may, and no doubt every decade will see the rise and fall of some floral favorite. But beneath these flitting fancies is the substantial and unchanging love of flowers that seems to be an original instinct in man, and one that grows in strength with growing refinement. Fashion may now and again condemn one flower or another, but the fashion of neglecting flowers altogether will never prevail, and we may safely look forward in the expectation of an ever increasing interest and demand, steady improvement in methods of cultivation, and to new and attractive developments in form, color and fragrance.

"A SMOOTH, closely shaven surface of grass is by far the most essential element of beauty on the grounds of a suburban home.” This is the language of Mr. F. J. Scott, and it is equally true of other than suburban grounds. A good lawn then is worth working for, and if it have a substantial foundation, it will endure for generations, and improve with age.

We take it for granted that the drainage is thorough, for no one would build a dwelling on water soaked land. No labor should be spared in making the soil deep, rich and fine in the full import of the words, as this is the stock from which future dividends of joy and satisfaction are to be drawn. Before grading, one should read that chapter of Downing’s on “The Beauty in Ground.” This will warn against terracing or leveling the whole surface, and insure a contour with “gentle curves and undulations,” which is essential to the best effects.

If the novice has read much of the conflicting advice in books and catalogues, he is probably in a state of bewilderment as to the kind of seed to sow. And when that point is settled it is really a difficult task to secure pure and living seeds of just such species as one orders. Rarely does either seller or buyer know the grasses called for, especially the finer and rarer sorts; and more rarely still does either know their seeds. The only safe way is to have the seeds tested by an expert. Mr. J. B. Olcott, in a racy article in the “Report of the Connecticut Board of Agriculture for 1886,” says, “Fifteen years ago nice people were often sowing timothy, red top and clover for door-yards, and failing wretchedly with lawn-making, while seedsmen and gardeners even disputed the identity of our June grass and Kentucky blue-grass.”

We have passed beyond that stage of ignorance, however; and to the question what shall we sow, Mr. Olcott replies: “Rhode Island bent and Kentucky blue-grass are their foolish trade names, for they belong no more to Kentucky or Rhode Island than to other Northern States. Two sorts of fine Agrostis are honestly sold under the trade name of Rhode Island bent, and, as trade goes, we may consider ourselves lucky if we get even the coarser one. The finest—a little the finest—Agrostis canina—is a rather rare, valuable, and elegant grass, which should be much better known by grass farmers, as well as gardeners, than it is. These are both good lawn as well as pasture grasses.” The grass usually sold as Rhode Island bent is Agrostis vulgaris, the smaller red top of the East and of Europe. This makes an excellent lawn. Agrostis canina has a short, slender, projecting awn from one of the glumes; Agrostis vulgaris lacks this projecting awn. In neither case have we in mind what Michigan and New York people call red top. This is a tall, coarse native grass often quite abundant on low lands, botanically Agrostis alba.

Sow small red top or Rhode Island bent, and June grass (Kentucky blue grass, if you prefer that name), Poa pratensis. If in the chaff, sow in any proportion you fancy, and in any quantity up to four bushels per acre. If evenly sown, less will answer, but the thicker it is sown the sooner the ground will be covered with fine green grass. We can add nothing else that will improve this mixture, and either alone is about as good as both. A little white clover or sweet vernal grass or sheep’s fescue may be added, if you fancy them, but they will not improve the appearance of the lawn. Roll the ground after seeding. Sow the seeds in September or in March or April, and under no circumstance yield to the advice to sow a little oats or rye to “protect the young grass.” Instead of protecting, they will rob the slender grasses of what they most need.

Now wait a little. Do not be discouraged if some ugly weeds get the start of the numerous green hairs which slowly follow. As soon as there is any thing to be cut, of weeds or grass, mow closely, and mow often, so that nothing need be raked from the ground. As Olcott puts it, “Leave one crop where it belongs [page 4] for home consumption. The rains will wash the soluble substance of the wilted grass into the earth to feed the growing roots.” During succeeding summers as the years roll on, the lawn should be perpetually enriched by the leaching of the short leaves as they are often mown. Neither leave a very short growth nor a very heavy growth for winter. Experience alone must guide the owner. If cut too closely, some of it may be killed or start too late in spring; if left too high during winter, the dead long grass will be hard to cut in spring and leave the stubble unsightly. After passing through one winter the annual weeds will have perished and leave the grass to take the lead. Perennial weeds should be faithfully dug out or destroyed in some way.

Every year, add a top dressing of some commercial fertilizer or a little finely pulverized compost which may be brushed in. No one will disfigure his front yard with coarse manure spread on the lawn for five months of the year.

If well made, a lawn will be a perpetual delight as long as the proprietor lives, but if the soil is thin and poor, or if the coarser grasses and clovers are sown instead of those named, he will be much perplexed, and will very likely try some expensive experiments, and at last plow up, properly fit the land and begin over again. This will make the cost and annoyance much greater than at first, because the trees and shrubs have already filled many portions of the soil. A small piece, well made and well kept, will give more satisfaction than a larger plot of inferior turf.

At a late meeting of the floral committee of the Royal Horticultural Society at South Kensington among many novelties was a group of seedling bulbous Calanthes from the garden of Sir Trevor Lawrence, who has devoted much attention to these plants and has raised some interesting hybrids. About twenty kinds were shown, ranging in color from pure white to deep crimson. The only one selected for a first-class certificate was C. sanguinaria, with flowers similar in size and shape to those of C. Veitchii, but of an intensely deep crimson. It is the finest yet raised, surpassing C. Sedeni, hitherto unequaled for richness of color. The pick of all these seedlings would be C. sanguinaria, C. Veitchii splendens, C. lactea, C. nivea, and C. porphyrea. The adjectives well describe the different tints of each, and they will be universally popular when once they find their way into commerce.

Cypripedium Leeanum maculatum, also shown by Sir Trevor Lawrence, is a novelty of sterling merit. The original C. Leeanum, which is a cross between C. Spicerianum and C. insigne Maulei, is very handsome, but this variety eclipses it, the dorsal sepal of the flower being quite two and one-half inches broad, almost entirely white, heavily and copiously spotted with purple. It surpasses also C. Leeanum superbum, which commands such high prices. I saw a small plant sold at auction lately for fifteen guineas and the nursery price is much higher.

Lælia anceps Schrœderæ, is the latest addition to the now very numerous list of varieties of the popular L. anceps. This new form, to which the committee with one accord gave a first class certificate, surpasses in my opinion all the colored varieties, with the possible exception of the true old Barkeri. The flowers are of the average size and ordinary form. The sepals are rose pink, the broad sepals very light, almost white in fact, while the labellum is of the deepest and richest velvety crimson imaginable. The golden tipped crest is a veritable beauty spot, and the pale petals act like a foil to show off the splendor of the lip.

Two new Ferns of much promise received first class certificates. One named Pteris Claphamensis is a chance seedling and was found growing among a lot of other sporelings in the garden of a London amateur. As it partakes of the characters of both P. tremula and P. serrulata, old and well known ferns, it is supposed to be a natural cross between these. The new plant is of tufted growth, with a dense mass of fronds about six inches long, elegantly cut and gracefully recurved on all sides of the pot. It is looked upon by specialists as just the sort of plant that will take in the market. The other certificated fern, Adiantum Reginæ, is a good deal like A. Victoriæ and is supposed to be a sport from it. But A. Reginæ, while it has broad pinnæ of a rich emerald green like A. Victoriæ, has fronds from nine to twelve inches long, giving it a lighter and more elegant appearance. I don’t know that the Victoria Maidenhair is grown in America yet, but I am sure those who do floral decorating will welcome it as well as the newer A. Reginæ. A third Maidenhair of a similar character is A. rhodophyllum and these form a trio that will become the standard kinds for decorating. The young fronds of all three are of a beautiful coppery red tint, the contrast of which with the emerald green of the mature fronds is quite charming. They are warm green-house ferns and of easy culture, and are supposed to be hybrid forms of the old A. scutum.

Nerine Mansellii, a new variety of the Guernsey Lily, was one of the loveliest flowers at the show. From the common Guernsey Lily it differs only in color of the flowers. These have crimpled-edged petals of clear rose tints; and the umbel of flowers is fully six inches across, borne on a stalk eighteen inches high. These Guernsey Lilies have of recent years come into prominence in English gardens since so many beautiful varieties have been raised, and as they flower from September onward to Christmas they are found to be indispensable for the green-house, and indoor decoration. The old N. Fothergillii major, with vivid scarlet-crimson flowers and crystalline cells in the petals which sparkle in the sunlight like myriads of tiny rubies, remains a favorite among amateurs. Baron Schroeder, who has the finest collection in Europe, grows this one only in quantity. An entire house is filled with them, and when hundreds of spikes are in bloom at once, the display is singularly brilliant.

A New Vegetable, a Japanese plant called Choro-Gi, belonging to the Sage family, was exhibited. Its botanical name is Stachys tuberifera and it was introduced first to Europe by the Vilmorins of Paris under the name of Crosnes du Japon. The edible part of the plant is the tubers, which are produced in abundance on the tips of the wiry fibrous roots. These are one and a half inches long, pointed at both ends, and have prominent raised rings. When washed they are as white as celery and when eaten raw taste somewhat like Jerusalem artichokes, but when cooked are quite soft and possess the distinct flavor of boiled chestnuts. A dish of these tubers when cooked look like a mass of large caterpillars, but the Committee pronounced them excellent, and no doubt this vegetable will now receive attention from some of our enterprising seedsmen and may become a fashionable vegetable because new and unlike any common kind. The tubers were shown now for the first time in this country by Sir Henry Thompson, the eminent surgeon. The plant is herbaceous, dying down annually leaving the tubers, which multiply very rapidly. They can be dug at any time of the year, which is an advantage. The plant is perfectly hardy here and would no doubt be so in the United States, as it remains underground in winter. [A figure of this plant with the tubers appeared in the Gardener’s Chronicle, January 7th, 1888.—Ed.]

Phalænopsis F. L. Ames, a hybrid moth orchid, the result of intercrossing P. grandiflora of Lindley with P. intermedia Portei (itself a natural hybrid between the little P. rosea and P. amabilis), was shown at a later exhibition. The new hybrid is very beautiful. It has the same purplish green leaves as P. amabalis, but much narrower. The flower spikes are produced in the same way as those of P. grandiflora, and the flowers in form and size resemble those of that species, but the coloring of the labellum is more like that of its other parent. The sepals and petals are pure white, the latter being broadest at the lips. The labellum resembles that of P. intermedia, being three-lobed, the lateral lobes are erect, magenta purple in color and freckled. The middle or triangular lobe is of the same color as the lateral lobes, but pencilled with longitudinal lines of crimson, flushed with orange, and with the terminal cirrhi of a clear magenta. The column is pink, and the crest is adorned with rosy speckles. The Floral Committee unanimously awarded a first-class certificate of merit to the plant.

A New Lælia named L. Gouldiana has had an eventful history. The representative of Messrs. Sander, of St. Albans, the great orchid importers, while traveling in America saw it blooming in New York, in the collection of Messrs. Siebrecht & Wadley, and noting its distinctness and beauty bought the stock of it. The same week another new Lælia flowered in England and was sent up to one of the London auction rooms for sale. As it so answered the description of the American novelty which Messrs. Sander had just secured it was bought for the St. Albans collection, and now it turns out that the English novelty and the American novelty are one and the same thing, and a comparison of dates shows that they flowered on the same day, although in different hemispheres. As, however, it was first discovered in the United States, it is intended to call it an American orchid, and that is why Mr. Jay Gould has his name attached to it, In bulb and leaf the novelty closely resembles L. albida, and in flower both L. anceps and L. autumnalis. The flowers are as large as those of an average form of L. anceps, the sepals are rather narrow, the petals as broad as those of L. [page 5] anceps Dawsoni, and both petals and sepals are of a deep rose pink, intensified at the tips as if the color had collected there and was dripping out. The tip is in form between that of L. anceps and L. autumnalis and has the prominent ridges of the latter, while the color is a rich purple crimson. The black viscid pubescence, always seen on the ovary of L. autumnalis, is present on that of L. Gouldiana. The plants I saw in the orchid nursery at St. Albans lately, bore several spikes, some having three or four flowers. Those who have seen it are puzzled about its origin, some considering it a hybrid between L. anceps and L. autumnalis, others consider it a distinct species and to the latter opinion I am inclined. Whatever its origin may be, it is certain we have a charming addition to midwinter flowering orchids.

London, February 1st.

T HE Chrysanthemum of which the figure gives a good representation is one of a collection of some thirty varieties lately sent from Japan to the lady for whom it has been named, Mrs. Alpheus Hardy of Boston, by a young Japanese once a protégé of hers, but now returned as a teacher to his native country. As may be seen, it is quite distinct from any variety known in this country or Europe, and the Japanese botanist Miyabe, who saw it at Cambridge, pronounces it a radical departure from any with which he is acquainted.

The photograph from which the engraving was made was taken just as the petals had begun to fall back from the centre, showing to good advantage the peculiarities of the variety.

The flower is of pure white, with the firm, long and broad petals strongly incurved at the extremities. Upon the back or [page 6] outer surface of this incurved portion will be found, in the form of quite prominent hairs, the peculiarity which makes this variety unique.

These hairs upon close examination are found to be a glandular outgrowth of the epidermis of the petals, multi-cellular in structure and with a minute drop of a yellow resinous substance at the tip. The cells at first conform to the wavy character of those of the epidermis, but gradually become prismatic with straight walls, as shown in the engraving of one of the hairs, which was made from a drawing furnished by Miss Grace Cooley, of the Department of Botany at Wellesley College, who made a microscopic investigation of them.

This is one of those surprises that occasionally make their appearance from Japan. Possibly it is a chance seedling; but since one or two other specimens in the collection are striking in form, and others are distinguished for depth and purity of color, it is more probable that the best of them have been developed by careful selection.

This Chrysanthemum was exhibited at the Boston Chrysanthemum Show last December by Edwin Fewkes & Son of Newton Highlands, Mass.

Arnebia cornuta.—This is a charming novelty, an annual, native of Afghanistan. The little seedling with lancet-like hairy, dark green leaves, becomes presently a widely branching plant two feet in diameter and one and one-half feet high. Each branch and branchlet is terminated by a lengthening raceme of flowers. These are in form somewhat like those of an autumnal Phlox, of a beautiful deep golden yellow color, adorned and brightened up by five velvety black blotches. These blotches soon become coffee brown and lose more and more their color, until after three days they have entirely disappeared. During several months the plant is very showy, the fading flowers being constantly replaced by fresh expanding ones. Sown in April in the open border, it needs no care but to be thinned out and kept free from weeds. It must, however, have some soil which does not contain fresh manure.

Delphinium Zalil.—This, also, is a native of Afghanistan, but its character, whether a biennial or perennial, is not yet ascertained. The Afghans call it Zalil and the plant or root is used for dyeing purposes. Some years ago we only knew blue, white and purple larkspurs, and then California added two species with scarlet flowers. The above is of a beautiful sulphur yellow, and, all in all, it is a plant of remarkable beauty. From a rosette of much and deeply divided leaves, rises a branched flower stem to about two feet; each branch and branchlet ending in a beautiful spike of flowers each of about an inch across and the whole spike showing all its flowers open at once. It is likely to become a first rate standard plant of our gardens. To have it in flower the very first year it must be sown very early, say in January, in seed pans, and transplanted later, when it will flower from the end of May until the end of July. Moreover, it can be sown during spring and summer in the open air to flower the following year. It is quite hardy here.

Baden-Baden.

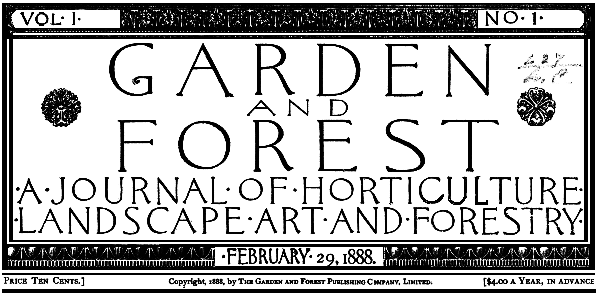

T HIS pretty delicate species of Iris, Fig. 3, is a native of the Cascade Mountains of Northern Oregon. Its long branching rootstocks are scarcely more than a line in thickness, sending up sterile leafy shoots and slender stems about a foot high. The leaves are thin and pale green, rather taller than the stems, sword-shaped and half an inch broad or more. The leaves of the stem are bract-like and distant, the upper one or two subtending slender peduncles. The spathes are short, very thin and scarious, and enclose the bases of their rather small solitary flowers, which are “white, lightly striped and blotched with yellow and purple.” The sepals and petals are oblong-spatulate, from a short tube, the sepals spreading, the shorter petals erect and notched.

The peculiar habitat of this species doubtless accounts in good measure for its slender habit and mode of growth. Mr. L. F. Henderson, of Portland, Oregon, who discovered it in 1881, near a branch of the Clackamas River called Eagle Creek, about thirty miles from Portland, reports it as growing in the fir forests in broad mats, its very long rootstocks running along near the surface of the ground, just covered by moss or partly decayed fir-needles, with a light addition of soil. This also would indicate the need of special care and treatment in its cultivation. In May, 1884, Mr. Henderson took great pains to procure roots for the Botanic Garden at Cambridge, which were received in good order, but which did not survive the next winter. If taken up, however, later in the season or very early in the spring, it is probable that with due attention to soil and shade there would be little trouble in cultivating it successfully. The accompanying figure is from a drawing by Mr. C. E. Faxon.

* TENUIS. Watson, Proc. Amer. Acad., xvii, 380. Rootstock elongated, very slender (a line thick); leaves thin, ensiform, about equaling the stems, four to eight lines broad; stems scarcely a foot high, 2 or 3-flowered, with two or three bract-like leaves two or three inches long; lateral peduncles very slender, as long as the bracts; spathes scarious, an inch long; pedicels solitary, very short; flowers small, white marked with yellow and purple; tube two or three lines long; segments oblong-spatulate, the sepals spreading, one and one-half inches long, the petals shorter and emarginate; anthers as long as the filaments; styles with narrow entire crests; capsule oblong-ovate, obtuse, nine lines long.]

S HRUBS for forcing should consist of early blooming kinds only. The plants should be stocky, young and healthy, well-budded and well-ripened, and in order to have first-class stock they should be grown expressly for forcing. For cut flower purposes only, we can lift large plants of Lilacs, Snowballs, Deutzias, Mock oranges and the like with all the ball of roots we can get to them and plant at once in forcing-houses. But this should not be done before New Year’s. We should prepare for smaller plants some months ahead of forcing time. say in the preceding April or August, by lifting them and planting in small pots, tubs or boxes as can conveniently contain their roots, and we should encourage them to root well before winter sets in. Keep them out of doors and plunged till after the leaves drop off; then either mulch them where they are or bring them into a pit, shed or cool cellar, where there shall be no fear of their getting dry, or of having the roots fastened in by frost. Introduce them into the green-house in succession; into a cool green-house at first for a few weeks, then as they begin to start, into a warmer one. From the time they are brought into the green-house till the flowers begin to open give a sprinkling overhead twice a day with tepid water. When they have done blooming, if worth keeping over for another time, remove them to a cool house and thus gradually harden them off, then plant them out in the garden in May, and give them two years’ rest.

Shrubs to be forced for their cut flowers only should consist of such kinds as have flowers that look well and keep well after being cut. Among these are Deutzia gracilis, common Lilacs of various colors, Staphyllea Colchica, Spiræa Cantonensis (Reevesii) single and double, the Guelder Rose, the Japanese Snowball and Azalea mollis. To these may be added some of the lovely double-flowering and Chinese apples, whose snowy or crimson-tinted buds and leafy twigs are very pretty. The several double-flowered forms of Prunus triloba are also desirable, but a healthy stock is hard to get. Andromeda floribunda and A. Japonica set their flower buds the previous summer for the next year’s flowers, and are, therefore, like the Laurestinus, easily forced into bloom after New Year’s. Hardy and half-hardy Rhododendrons with very little forcing may be had in bloom from March.

In addition to the above, for conservatory decoration we may introduce all manner of hardy shrubs. Double flowering peach and cherry trees are easily forced and showy while they last. Clumps of Pyrus arbutifolia can easily be had in bloom in March, when their abundance of deep green leaves is an additional charm to their profusion of hawthorn-like flowers. The Chinese Xanthoceras is extremely copious and showy, but of brief duration and ill-fitted for cutting. Bushes of yellow Broom and double-flowering golden Furze can easily be had after January. Jasminum nudiflorum may be had in bloom from November till April, and Forsythia from January. They look well when trained up to pillars. The early-flowering Clematises may be used to capital advantage in the same way, from February onward. Although the Mahonias flower well, their foliage at blooming time is not always comely. Out-of-doors the American Red-bud makes a handsomer tree than does the Japanese one; but the latter is preferable for green-house work, as the flowers are bright and the smallest plants bloom. The Chinese Wistaria blooms as well in the [page 7] green-house as it does outside; indeed, if we introduce some branches of an out-door plant into the green-house, we can have it in bloom two months ahead of the balance of the vine still left out-of-doors. Hereabout we grow Wistarias as standards, and they bloom magnificently. What a sight a big standard wistaria in the green-house in February would be! Among other shrubs may be mentioned Shadbush, African Tamarix, Daphne of sorts and Exochorda. We have also a good many barely hardy plants that may be wintered well in a cellar or cold pit, and forced into bloom in early spring. Among these are Japanese Privet, Pittosporum, Raphiolepis, Hydrangeas and the like.

And for conservatory decoration we can also use with excellent advantage some of our fine-leaved shrubs, for instance our lovely Japanese Maples and variegated Box Elder.

Glen Cove, N. Y.

A Half-hardy Begonia.—When botanizing last September upon the Cordilleras of North Mexico some two hundred miles south of the United States Boundary, I found growing in black mould of shaded ledges—even in the thin humus of mossy rocks—at an elevation of 7,000 to 8,000 feet, a plant of striking beauty, which Mr. Sereno Watson identifies as Begonia gracilis, HBK., var. Martiana, A. DC. From a small tuberous root it sends up to a height of one to two feet a single crimson-tinted stem, which terminates in a long raceme of scarlet flowers, large for the genus and long enduring. The plant is still further embellished by clusters of Scarlet gemmæ in the axils of its leaves. Mr. Watson writes: “It was in cultivation fifty years and more ago, but has probably been long ago lost. It appears to be the most northern species of the genus, and should be the most hardy.” Certainly the earth freezes and snows fall in the high region, where it is at home.

Northern Limit of the Dahlia.—In the same district, and at the same elevation, I met with a purple flowered variety of Dahlia coccinea, Cav. It was growing in patches under oaks and pines in thin dry soil of summits of hills. In such exposed situations the roots must be subjected to some frost, as much certainly as under a light covering of leaves in a northern garden. The Dahlia has not before been reported, as I believe, from a latitude nearly so high.

Ceanothus is a North American genus, represented in the Eastern States by New Jersey Tea, and Red Root (C. Americanus and C. ovalus), and in the West and South-west by some thirty additional species. Several of these Pacific Coast species are quite handsome and well worthy of cultivation where they will thrive. Some of the more interesting of them are figured in different volumes of the Botanical Magazine, from plants grown at Kew, and I believe that the genus is held in considerable repute by French gardeners.

In a collection of plants made in Southern Oregon, last spring, by Mr. Thomas Howell, several specimens of Ceanothus occur which are pretty clearly hybrids between C. cuneatus and C. prostratus, two common species of the region. Some have the spreading habit of the latter, their flowers are of the bright blue color characteristic of that species, and borne on slender blue pedicels, in an umbel-like cluster. But while many of their leaves have the abrupt three-toothed apex of C. prostratus, all gradations can be found from this form to the spatulate, toothless leaves of C. cuneatus. Other specimens have the more rigid habit of the latter species, and their flowers are white or nearly so, on shorter pale pedicels, in usually smaller and denser clusters. On these plants the leaves are commonly those of C. cuneatus, but they pass into the truncated and toothed form proper to C. prostratus.

According to Focke (Pflanzenmischlinge, 1881, p. 99), the French cross one or more of the blue-flowered Pacific Coast species on the hardier New Jersey Tea, a practice that may perhaps be worthy of trial by American gardeners. Have any of the readers of Garden And Forest ever met with spontaneous hybrids?

Wire Netting for Tree Guards.—On some of the street trees of Washington heavy galvanized wire netting is used to protect the bark from injury by horses. It is the same material that is used for enclosing poultry yards. It comes in strips five or six feet wide, and may be cut to any length required by the size of the tree. The edges are held in place by bending together the cut ends of the wires, and the whole is sustained by staples over the heavy wires at the top and bottom. This guard appears to be an effective protection and is less unsightly than any other of which I know, in fact it can hardly be distinguished at the distance of a few rods. It is certainly an improvement on the plan of white-washing the trunks, which has been extensively practiced here since the old guards were removed.

O NE of the most difficult parts of a landscape gardener’s work is the treatment of what our grandfathers called “pieces of water” in scenes where a purely natural effect is desired. The task is especially hard when the stream, pond or lake has been artificially formed; for then Nature’s processes must be simulated not only in the planting but in the shaping of the shores. Our illustration partially reveals a successful effort of this sort—a pond on a country-seat near Boston.

It was formed by excavating a piece of swamp and damming a small stream which flowed through it. In the distance towards the right the land lies low by the water and gradually rises as it recedes. Opposite us it forms little wooded promontories with grassy stretches between. Where we stand it is higher, and beyond the limits of the picture to the left it forms a high, steep bank rising to the lawn, on the further side of which stands the house. The base of these elevated banks and the promontories opposite are planted with thick masses of rhododendrons, which flourish superbly in the moist, peaty soil, protected, as they are, from drying winds by the trees and high ground. Near the low meadow a long stretch of shore is occupied by thickets of hardy azaleas. Beautiful at all seasons, the pond is most beautiful in June, when the rhododendrons are ablaze with crimson and purple and white, and when the yellow of the azalea-beds—discreetly separated from the rhododendrons by a great clump of low-growing willows—finds delicate continuation in the buttercups which fringe the daisied meadow. The lifted banks then afford particularly fortunate points of view; for as we look down upon the rhododendrons, we see the opposite shore and the water with its rich reflected colors as over the edge of a splendid frame. No accent of artificiality disturbs the eye despite the unwonted profusion of bloom and variety of color. All the plants are suited to their place and in harmony with each other; and all the contours of the shore are gently modulated and softly connected with the water by luxuriant growths of water plants. The witness of the eye alone would persuade us that Nature unassisted had achieved the whole result. But beauty of so suave and perfect a sort as this is never a natural product. Nature’s beauty is wilder if only because it includes traces of mutation and decay which here are carefully effaced. Nature suggests the ideal beauty, and the artist realizes it by faithfully working out her suggestions.

T HE following list comprises most of the newer Roses that have been on trial to any extent in and about Philadelphia during the present winter:

Puritan (H. T.) is one of Mr. Henry Bennett’s seedlings, and perhaps excites more interest than any other. It is a cross between Mabel Morrison and Devoniensis, creamy white in color and a perpetual bloomer. Its flowers have not opened satisfactorily this winter. The general opinion seems to be that it requires more heat than is needed for other forcing varieties. Further trial will be required to establish its merit.

Meteor (H. T., Bennett.)—Some cultivators will not agree with me in classing this among hybrid Teas. In its manner of growth it resembles some Tea Roses, but its coloring and scanty production of buds in winter are indications that there is Hybrid Remontant blood in it. It retains its crimson color after being cut longer than any Rose we have, and rarely shows a tendency to become purple with age, as other varieties of this color are apt to do. For summer blooming under glass it will prove satisfactory. In winter its coloring is a rich velvety crimson, but as the sun gets stronger it assumes a more lively shade.

Mrs. John Laing (H. R., Bennett,) is a seedling from Francois Michelon, which it somewhat resembles in habit of growth and color of flower. It is a free bloomer out-of-doors in summer and forces readily in winter. Blooms of it have been offered for sale in the stores here since the first week in December. It is a soft shade of pink in color, with a delicate lilac tint. It promises to become a general favorite, as in addition to the qualities referred to, it is a free autumnal bloomer outside. For forcing it will be tried extensively next winter.

Princess Beatrice (T., Bennett,) was distributed for the first time in this country last autumn, but has so far been a disappointment in this city. But some lots arrived from Europe too late and misfortunes befell others, so that the trial can hardly be counted decisive, and we should not hastily condemn it. Some have admired it for its resemblance, in form of flower, to a Madame Cuisin, but its color is not just what we need. In shade it somewhat resembles Sunset, but is not so effective. It may, however, improve under cultivation, as some other Roses have done; so far as I know it has not been tried out-of-doors.

Papa Gontier (H. B., Nabonnaud.)—This, though not properly a new rose, is on trial for the first time in this city. It has become a great favorite with growers, retailers and purchasers. In habit it is robust and free blooming, and in coloring, though similar to Bon Silene, is much deeper or darker. There seems to be a doubt in some quarters as to whether it blooms as freely as Bon Silene; personally, I think there is not much difference between the two. Gontier is a good Rose for outdoor planting.

Adiantum Farleyense.—This beautiful Maidenhair is supposed to be a subfertile, plumose form of A. tenerum, which much resembles it, especially in a young state. For decorative purposes it is almost unrivaled, whether used in pots or for trimming baskets of flowers or bouquets. It prefers a warm, moist house and delights in abundant water. We find it does best when potted firmly in a compost of two parts loam to one of peat, and with a good sprinkling of sifted coal ashes. In this compost it grows very strong, the fronds attaining a deeper green and lasting longer than when grown in peat. When the pots are filled with roots give weak liquid manure occasionally. This fern is propagated by dividing the roots and potting in small pots, which should be placed in the warmest house, where they soon make fine plants. Where it is grown expressly for cut fronds the best plan is to plant it out on a bench in about six inches of soil, taking care to give it plenty of water and heat, and it will grow like a weed.

Actiniopteris radiata.—A charming little fern standing in a genus by itself. In form it resembles a miniature fan palm, growing about six inches in height. It is generally distributed throughout the East Indies. In cultivation it is generally looked upon as poor grower, but with us it grows as freely as any fern we have. We grow a lot to mix in with Orchids, as they do not crowd at all. We pot in a compost of equal parts loam and peat with a few ashes to keep it open, and grow in the warmest house, giving at all times abundance of water both at root and overhead. It grows very freely from spores, and will make good specimens in less than a year. It is an excellent Fern for small baskets.

S PRING flowering bulbs in-doors, such as the Dutch Hyacinths, Tulips and the many varieties of Narcissus, should now be coming rapidly into bloom. Some care is required to get well developed specimens. When first brought in from cold frames or wherever they have been stored to make roots, do not expose them either to direct sunlight or excessive heat.

A temperature of not more than fifty-five degrees at night is warm enough for the first ten days, and afterwards, if they show signs of vigorous growth and are required for any particular occasion, they may be kept ten degrees warmer. It is more important that they be not exposed to too much light than to too much heat.

Half the short stemmed Tulips, dumpy Hyacinths and blind Narcissus we see in the green-houses and windows of amateurs are the result of excessive light when first brought into warm quarters. Where it is not possible to shade bulbs without interfering with other plants a simple and effective plan is to make funnels of paper large enough to stand inside each pot and six inches high. These may be left on the pots night and day from the time the plants are brought in until the flower spike has grown above the foliage; indeed, some of the very finest Hyacinths cannot be had in perfection without some such treatment. Bulbous plants should never suffer for water when growing rapidly, yet on the other hand, they are easily ruined if allowed to become sodden.

When in flower a rather dry and cool temperature will preserve them the longest.

Of bulbs which flower in the summer and fall, Gloxinias and tuberous rooted Begonias are great favorites and easily managed. For early summer a few of each should be started at once—using sandy, friable soil. Six-inch pots, well drained, are large enough for the very largest bulbs, while for smaller even three-inch pots will answer. In a green-house there is no difficulty in finding just the place to start them. It must be snug, rather shady and not too warm. They can be well cared for, however, in a hot-bed or even a window, but some experience is necessary to make a success.

Lilies, in pots, whether L. candidum or L. longiflorum that are desired to be in flower by Easter, should now receive every attention—their condition should be that the flower buds can be easily felt in the leaf heads. A temperature of fifty-five to sixty-five at night should be maintained, giving abundance of air on bright sunny days to keep them stocky. Green fly is very troublesome at this stage, and nothing is more certain to destroy this pest than to dip the plants in tobacco water which, to be effective, should be the color of strong tea. Occasional waterings of weak liquid manure will be of considerable help if the pots are full of roots.

A S is well known, about fifty per cent. of the possible apple crop in the Western states is sacrificed each year to the codling moth, except in sections where orchardists combine to apply bands of straw around the trunks. But as is equally well known this is rather a troublesome remedy. At all events, in Illinois, Professor Forbes, in a bulletin lately issued from the office of the State Entomologist of Illinois, claims that the farmers of that state suffer an annual loss from the attacks of this single kind of insect of some two and three-quarters millions of dollars.

As the results of two years’ experiments in spraying the trees with a solution of Paris green, only once or twice in early spring, before the young apples had drooped upon their stems, there was a saving of about seventy-five per cent. of the apples.

The Paris green mixture consisted of three-fourths of an ounce of the powder by weight, of a strength to contain 15.4 per cent. of metallic arsenic, simply stirred up in two and a half gallons of water. The tree was thoroughly sprayed with a hand force-pump, and with the deflector spray and solid jet-hose nozzle, manufactured in Lowell, Mass. The fluid was thrown in a fine mist-like spray, applied until the leaves began to drip.

The trees were sprayed in May and early in June while the apples were still very small. It seems to be of little use to employ this remedy later in the season, when later broods of the moth appear, since the poison takes effect only in case it reaches the surface of the apple between the lobes of the calyx, and it can only reach this place when the apple is very small and stands upright on its stem, It should be added that spraying “after the apples have begun to hang downward is unquestionably dangerous,” since even heavy winds and violent rains are not sufficient to remove the poison from the fruit at this season.

At the New York Experimental station last year a certain number of trees were sprayed three times with Paris green with the result that sixty-nine per cent. of the apples were saved.

It also seems that last year about half the damage that might have been done by the Plum weevil or curculio was prevented by the use of Paris green, which should be sprayed on the trees both early in the season, while the fruit is small, as well as later.

The cost of this Paris green application, when made on a large scale, with suitable apparatus, only once or twice a year, must, says Mr. Forbes, fall below an average of ten cents a tree.

The use of solutions of Paris green or of London purple in water, applied by spraying machines such as were invented and described in the reports of the national Department of Agriculture by the U. S. Entomologist and his assistants, have effected a revolution in remedies against orchard and forest insects. We expect to see them, in careful hands, tried with equal success in shrubberies, lawns and flower gardens.

T HE White Pine was among the very first American trees which came to Europe, being planted in the year 1705 by Lord Weymouth on his grounds in Chelsea. From that date, the tree has been cultivated in Europe under the name of Weymouth Pine; in some mountain districts of northern Bavaria, where it has become a real forest tree, it is called Strobe, after the Latin name Pinus strobus. After general cultivation as an ornamental tree in parks this Pine began to be used in the forests on account of its hardiness and rapid growth, and it is now not only scattered through most of the forests of Europe, but covers in Germany alone an area of some 300 acres in a dense, pure forest. Some of these are groves 120 years old, and they yield a large proportion of the seed demanded by the increasing cultivation of the tree in Europe.

The White Pine has proved so valuable as a forest tree that it has partly overcome the prejudices which every foreign tree has to fight against. The tree is perfectly hardy, is not injured by long and severe freezing in winter, nor by untimely frosts in spring or autumn, which sometimes do great harm to native trees in Europe. On account of the softness of the leaves and the bark, it is much damaged by the nibbling of deer, but it heals quickly and throws up a new leader.

The young plant can endure being partly shaded by other trees far better than any other Pine tree, and even seems to enjoy being closely surrounded, a quality that makes it valuable for filling up in young forests where the native trees, on account of their slow growth, could not be brought up at all.

The White Pine is not so easily broken by heavy snowfall as the Scotch Pine, on account of the greater elasticity of its wood. The great abundance of soft needles falling from it every year better fits it for improving a worn-out soil than any European Pine, therefore the tree has been tried with success as a nurse for the ground in forest plantations of Oak, when the latter begin to be thinned out by nature, and grass is growing underneath them.

And finally, all observations agree that the White Pine is a faster growing tree than any native Conifer in Europe, except, perhaps, the Larch. The exact facts about that point, taken from investigations on good soil in various parts of Germany, are as follows:

| Years. | Height. | Annual Growth During Last Decade. | |

| The White Pine at | 20 reaches | 7.5 meters. | 37 centimeters |

| “ | 30 “ | 12.5 “ | 50 “ |

| “ | 40 “ | 18.5 “ | 60 “ |

| “ | 50 “ | 22.5 “ | 40 “ |

| “ | 60 “ | 26.5 “ | 40 “ |

| “ | 70 “ | 28.5 “ | 20 “ |

| “ | 80 “ | 30.0 “ | 15 “ |

| “ | 90 “ | 32.0 “ | 20 “ |

For comparison I add here the average growth on good soil, of the Scotch Pine, one of the most valuable and widely distributed timber trees of Europe.

| Years. | Height. | Annual Growth During Last Decade. | |

| The Scotch Pine at | 20 reaches | 7.3 meters. | 36.5 centimeters |

| “ | 30 “ | 11.6 “ | 43.0 “ |

| “ | 40 “ | 15.7 “ | 41.0 “ |

| “ | 50 “ | 19.4 “ | 37.0 “ |

| “ | 60 “ | 22.1 “ | 27.0 “ |

| “ | 70 “ | 24.0 “ | 22.0 “ |

| “ | 80 “ | 26.0 “ | 17.0 “ |

| “ | 90 “ | 27.5 “ | 15.0 “ |

| “ | 100 “ | 28.5 “ | 10.0 “ |