Title: With Joffre at Verdun: A Story of the Western Front

Author: F. S. Brereton

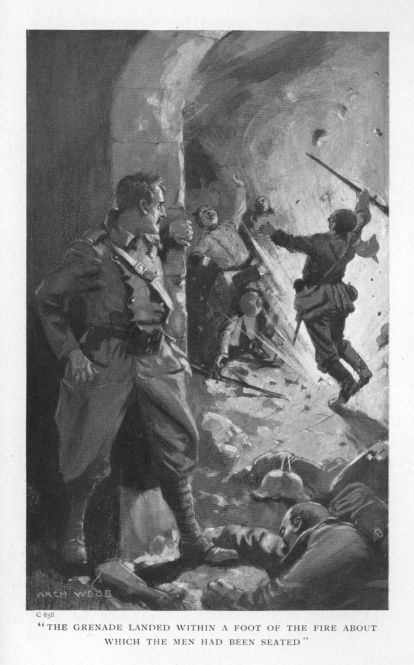

Illustrator: Archibald Webb

Release date: December 28, 2009 [eBook #30791]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

With the Allies to the Rhine: A Story of the Finish of the War.

With Allenby in Palestine: A Story of the latest Crusade.

Under Foch's Command: A Tale of the Americans in France.

The Armoured-Car Scouts: The Campaign in the Caucasus.

On the Road to Bagdad: A Story of the British Expeditionary Force in Mesopotamia.

From the Nile to the Tigris: Campaigning from Western Egypt to Mesopotamia.

Under Haig in Flanders: A Story of Vimy, Messines, and Ypres.

With Joffre at Verdun: A Story of the Western Front.

On the Field of Waterloo.

With Wellington in Spain: A Story of the Peninsula.

Kidnapped by Moors: A Story of Morocco.

The Hero of Panama: A Tale of the Great Canal.

The Great Aeroplane: A Thrilling Tale of Adventure.

A Hero of Sedan: A Tale of the Franco-Prussian War.

Roger the Bold: A Tale of the Conquest of Mexico.

At Grips with the Turk: A Story of the Dardanelles Campaign.

The Great Airship.

A Sturdy Young Canadian.

A Boy of the Dominion: A Tale of Canadian Immigration.

Under the Chinese Dragon: A Tale of Mongolia.

With Roberts to Candahar: Third Afghan War.

A Hero of Lucknow: A Tale of the Indian Mutiny.

Under French's Command: A Story of the Western Front from Neuve Chapelle to Loos.

With French at the Front: A Story of the Great European War down to the Battle of the Aisne.

John Bargreave's Gold: A Search for Sunken Treasure.

Tom Stapleton, the Boy Scout.

A Soldier of Japan: A Tale of the Russo-Japanese War.

A Knight of St. John: A Tale of the Siege of Malta.

Foes of the Red Cockade: The French Revolution.

One of the Fighting Scouts: Guerrilla War in South Africa.

The Dragon of Pekin: A Story of the Boxer Revolt.

A Gallant Grenadier: A Story of the Crimean War.

LONDON: BLACKIE & SON, LTD., 50 OLD BAILEY, E.C.

| CHAP. | |

| I. | THE CAMP AT RUHLEBEN |

| II. | HENRI AND JULES AND STUART |

| III. | THE ROAD TO FREEDOM |

| IV. | THE HEART OF GERMANY |

| V. | ELUDING THE PURSUERS |

| VI. | CHANGING THEIR DIRECTION |

| VII. | A FRIEND IN NEED |

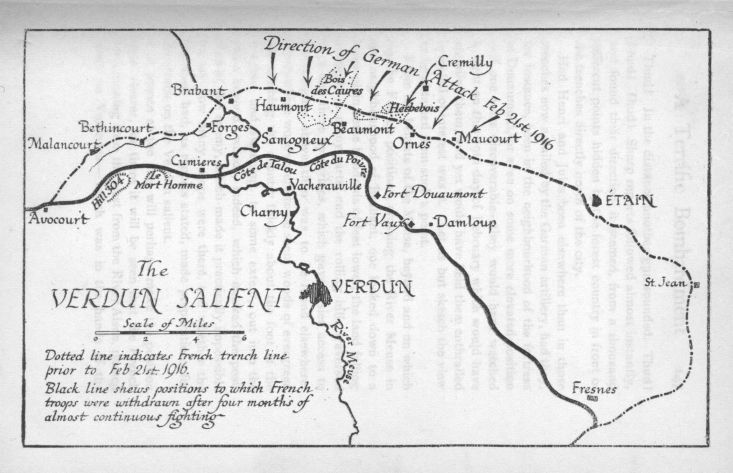

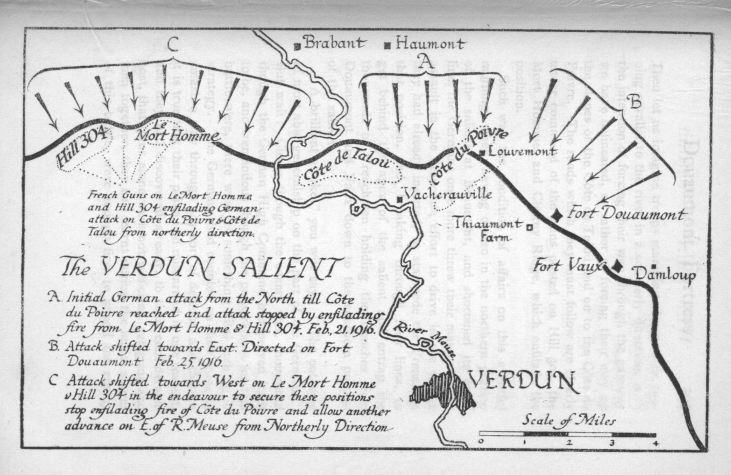

| VIII. | THE VERDUN SALIENT |

| IX. | A TERRIFIC BOMBARDMENT |

| X. | THE THIN LINE OF HEROES |

| XI. | FALLING BACK |

| XII. | A RECONNOITRING-PARTY |

| XIII. | DOUAUMONT FORTRESS |

| XIV. | FRENCHMEN AND BRANDENBURGERS |

| XV. | RATS IN A TRAP |

| XVI. | A FIGHT TO A FINISH |

| XVII. | CHARGE OF THE GALLANT BRETONS |

| XVIII. | A SINISTER GERMAN |

| XIX. | HEROIC "POILUS" |

You'd have said, if you had glanced casually at Henri de Farquissaire, that he was British—British from the well-trimmed head of hair beneath his light-grey Homberg hat to the most elegant socks and tan shoes which adorned his feet. His walk was British, his stride the active, elastic, athletic stride of one of our young fellows; and the poise of his head, the erectness of his lithe figure, a symbol of what one is accustomed to in Britons wherever they are met. That one gathered from a mere casual glance; though a second glance—a more penetrating one, we will say, one with a trifle more curiosity thrown into it—would have discovered other points still bearing out the same assumption as to Henri's nationality, and leaving hardly a suspicion that in point of fact he was French—as French as they make them.

For, putting aside the fact that this young gentleman was dressed in clothes unmistakably British, tailored, in fact, in the heart of fashionable London, his features, as well as his figure and his method of progress, pointed to a British origin. Not, let us add, that there is need to make comparisons between the appearance of young men of France and those of our country, nor need to exploit the one against the other. That there are essential differences between the two nationalities all will admit—differences accentuated, no doubt, in the great majority of cases by dress, by manner, and by environment.

But Henri—what nationality could he have belonged to other than British—with those rosy cheeks, that fresh complexion, and that little perky moustache which adorned his upper lip? His "How do you do?" in the purest English as he met a companion in the street was as devoid of accent as would have been that of a habitué of London. There was nothing exaggerated about his method of raising his hat to a lady whom he passed, no gesticulations, no active nervous movements of his hands, and none of that shrugging of the shoulders which, public opinion has it, is so eminently characteristic of our Gallic neighbours. And yet the young man was French.

Striding down one of Berlin's main streets in that summer of 1914, now so historic, he was chatting amiably with his chum, Jules Epain, a resident, like himself, of Berlin.

"So it's war, eh?" he asked his chum in French.

"War?"

There was silence for a little while, and then from Jules: "And we are here, in Berlin, the Kaiser's city!"

"Just so!" from Henri; "and, Jules, my boy, the sooner we take steps to move along the better. I have taken tickets for England already, and don't forget we are English."

There again, without a doubt, the appearance of Henri's friend would assist the suggestion which he had just mentioned. English? Yes, if Henri looked a British subject, and indeed spoke and behaved essentially as one of our people, then Jules, too, was not behind him. Perhaps more elegant, of darker features, spruce, neat, and well-groomed like his chum, he too had the distinguished air, that quiet and unassuming demeanour which stamp the Englishman throughout the world.

"You've the tickets, eh?" he asked Henri as they strode along. "For England too?"

"For England. And a tremendous job it was to get them. You see, Germany has declared war on France and Russia, and to attempt to return to France would have been out of the question. It had to be England, or Holland, or some such place, and England's quite good enough for me if I can get there."

"Bah!" Someone exploded near them; a huge, stout, helmeted individual gave vent to an exclamation of disgust, anger, hatred. The man spluttered as he suddenly pounced upon the two and ordered them to halt abruptly.

"So, French canaille!"

This huge Berlin constable positively foamed as he looked down upon the two young fellows, positively gnashed his teeth as he clenched his fists and regarded them angrily. In his super-arrogance this huge bully towered over the couple, and treated them to a stare, a derisive, angry, contemptuous inspection, which humbled them exceedingly. Indeed, Henri and Jules might have been simply noxious animals, mere beetles to be trodden underfoot, so contemptuous was this bullying constable of them.

"Bah! So, French at large, and not yet imprisoned! You are arrested."

"But arrested? But we're not soldiers," Henri told him in the best of German; "and in any case you will allow us to go to our lodging and get our baggage?"

Allow them to go to their lodgings! Permit any sort of privilege! Did any German since the commencement of this war allow any sort of a kindly sentiment to guide his actions when dealing with so-called enemies? The constable exploded, and, opening his heavily moustached mouth, roared an order at them.

"You will come with me at once! Hi, you! My Fritz! You will assist me, lest these men make an attack upon my person."

He called to his help a constable even bigger than himself, stouter by far, a man who looked as though he had lived on the fat of the earth, and had derived intense enjoyment from it. One would have imagined from his proportions, from the beefiness of his face, from his girth, that this second individual might have proved—as is the case with so many men of size—of a genial and gentle disposition. Yet Henri and Jules knew well enough that no such thing was to be expected; indeed, to speak only the truth, the people of Berlin knew this Fritz as a sardonic, brutal, overbearing individual. He bore down upon the trio like a huge, overgrown bull, and, making no bones of the matter, seized Henri in a grip from which there was no escaping.

"Get on with you to the station. A spy, eh?" he asked the cheerful constable who had called for his assistance.

"Who knows?" the man grunted. "But it's more than likely, for all Frenchmen in these parts are spies. Drag him along, while I see to this other whipper-snapper."

They were followed by a growing crowd of citizens of Berlin, a curious crowd which ran beside the two mountains of the law, so as to get a clear view of the prisoners, a crowd composed of elderly, white-bearded gentlemen, of middle-aged ladies of almost aristocratic appearance, and of youths and young girls, and gutter urchins—people who, you would have thought, once they had obtained a view of the captives and ascertained the reason for their arrest, would have been satisfied to leave the matter and to go on their way forgetting the subject. Perhaps in other days that crowd might have so behaved itself, and might have vanished long before the constables and their captives had reached the station; but crowds in the city of Berlin of other days, and the mob as it was in the latter part of July and the early days of August of 1914, were essentially and unmistakably different. War had been declared by the Fatherland, that war expected by the nation, eagerly awaited by all Teutons, longed for, oh how much and how eagerly, by all the subjects of the Kaiser! And now that it had come, now that the Emperor had thrown down the gauntlet before France and Russia, you would have imagined that the people of Berlin would have been overjoyed, would have been delighted, too happy and too contented to be angry. And yet, it so happened that there was disappointment, anger, rage, in the hearts of almost all these Germans. True, they had obtained, after all those years of training, a declaration for which they had so eagerly waited. France was in their power, conquered already, they told themselves, for was she not utterly unprepared for war? And as for Russia, Russia the Colossus, the steam-roller, inefficiency reigned in her ranks, and she, too, in her turn, would be most unquestionably conquered.

Then what, what had occurred to make this Berlin crowd—the swarm of people who hurried along the streets elsewhere, the mobs which gathered in front of embassies—so violent, so intensely hostile to France, so suspicious of the presence of spies, so furiously disappointed and angry?

"Spies! British spies!" a young man in the ranks of that crowd bellowed, catching a full view of Jules and Henri; "spies from the King of England! Kill them!"

And the mob took up the shout: "British! Down with Britain!"

Was that then the explanation of the hatred, of the intense animosity, shown by these people? Was that then the reason why these two Berlin constables, for one of them at least knew Jules and Henri to be French—why they too should grit their teeth, should scowl and mutter at the name of Britain? Yes, indeed, that was the reason why all the subjects of the Kaiser, deliriously happy but a few hours ago, were now snarling with anger, less contented with what was occurring, furiously indignant at something beyond their conception. For within half an hour of Henri's successful purchase of tickets, which were to take himself and his chum to safety in England, there had come news of importance from London. Already German troops had invaded Belgium, had fired upon the people, were engaged with King Albert's soldiers, and Britain—that arrogant Britain, ever an eyesore and a thorn in the flesh for Germans—had protested, had declared her detestation of that Germanic act, and her decision to oppose it. Indeed, she had answered the deeds of the Kaiser and his soldiers by declaring war, by announcing her determination to fight the Germans, and her decision to support France and Belgium and Russia to her utmost.

That, then, was the reason why that mob, gathering weight at every moment, howled with rage when, seeing Jules and Henri so distinctly British in appearance, they recalled to their minds the engrossing fact that all Britons were now their enemies.

"Hang them to the nearest lamp-post! Strangle the spies!" they bellowed; "why take them to the police station?"

In his excessive zeal to deal a blow for his country, with an extremity of valour which he would hardly have displayed had Jules and Henri been free to defend themselves, one youth, possessed of coal-black, flashing eyes, of raven locks, and of pallid and bloated features, darted in between the two constables and struck a blow at Jules which, if it had taken effect, would most decidedly have damaged his personal appearance.

"Himmel! But not that!" shouted the stoutest of the constables. "What! You would strike and damage a prisoner of ours who may be valuable to the authorities! You would!"

In a moment he had gripped the scabbard of his sword, and, swinging it round, dealt this malefactor a blow across the head which stretched him on the pavement. Then, jostling their prisoners between them, hurrying them on, and smiling triumphantly at the crowd still massed around them, encouraging them almost to repeat the attempt of that young fellow so drastically punished, and so to torture their prisoners, and yet keeping the most valiant of these angry individuals at arm's length, the two men of law dragged Jules and Henri swiftly onwards.

And at last the doors of the police station closed behind them, leaving outside a great mass of men and women, of gutter-snipes, and of every sort and class of individual—a mob which howled like hungry wolves as the prisoners were lost to sight to them.

Inside that station Jules and Henri at once underwent a most thorough and rigorous search.

"Ha! Tickets for England! Then you were bound for that country? And letters from France, from Paris—suspicious!"

It was useless to point out to these police officials that it was natural enough for two Frenchmen caught in Berlin at a time of declaration of war between Germany and their own people to attempt to reach some other place; and hopeless to draw their attention to the fact that, being French, letters from France in their possession were to be expected, while the contents alone could prove whether Jules and Henri were of necessity suspects.

We need hardly follow the course of events after the capture of these two unfortunate, if lively, young fellows. They were clapped into prison as a natural course, into a dark, noisome cell, which would have been but indifferent accommodation for some malefactor. They were half-starved, bullied, browbeaten, and even beaten by their jailers, they were threatened with death as spies—though there was not an atom of evidence against them—and, finally, after many months of anguish, of short commons, of brutal treatment, they found themselves interned in Ruhleben race-course, to which so many unfortunate civilians were sent, there to mope and fret and rot while the war was in progress.

"And here we'll stay, I suppose," grumbled Henri, when some weeks had passed, and they had, as it were, settled down to the routine of camp life in Ruhleben, and had become inured—as far as young men of active dispositions and healthy appetites can become inured, to the scantily short rations with which the Germans supplied them. "It's awfully hard luck to be prisoners in a place like this when our people are fighting."

"Awfully hard," Jules echoed despondently, for he was not gifted with quite the allowance of high spirits possessed of Henri.

"But it needn't necessarily last for ever, this imprisonment," his friend told him; and perhaps he had said the same a hundred times already. "Little news comes to us in this hole, but yet tales have reached us of men who have escaped, who have got out of Germany and have joined their French regiments."

Yes, there had been news of such escapes, and no doubt there would be others; and perhaps even Henri and Jules might themselves contrive to get out of their predicament. Yet, how? Look round the camp and see those rolls of barbed wire which encircled them, see the armed sentries who moved along their beats, and the jailers and men appointed to watch and spy amongst the prisoners, who strode here and there, hectoring the weak, browbeating the strong, and fawning, perhaps, upon those fortunate enough to be possessed of a store of money. Bitterly did the two young fellows regret the chances which had brought them to Berlin, and had found them there at the outbreak of war; for, indeed, it was but a chance which had taken them to the Kaiser's city.

Let us explain how it happened that these two young men were of such distinctly British appearance. After all, there was nothing extraordinary about that fact, nothing particularly unusual, for in Paris, for years past, there has been a sufficiency of British tailors to turn out every young man after the latest British fashion. But it was more than clothes in the case of these two young men, more than mere dress, that made them so conspicuously British; it was environment, in fact, training and education; it was the result of the intuition of their parents.

"France is all right, my boy," Monsieur de Farquissaire had told Henri when he was quite a lad, "France is a splendid country, and, if you are but like your fellows when you reach man's age, neither you nor I will have anything to complain of. But there is good in other nationalities, and there is great advantage to one among our people who both speaks the language, say, of England, and, better even than that, understands her people and has inside knowledge of them. So you will go to an English university once you have left your school in Paris."

As a matter of strict fact, Henri had left his school in Paris when only fifteen years of age, and had crossed the Channel to become one of the inmates of a public school famous throughout Great Britain. It was there that he had learned to speak like a native, and, better still, it was there that he had learned, unconsciously, quite easily in fact, to behave just as did his fellows, to speak as they did, quietly, without undue or exaggerated action, to play their games, to understand and practise their codes of honour; and so faithful and diligent a student was he, so heartily did he enter into the work and games of that public school, that, when in due course he went to a university, he was mistaken, just as he had been at the moment of the opening of this story, for a British subject, an essentially insular individual.

As for Jules, when one has described the appearance and the life-history, though only a short one so far, of the energetic Henri, one has practically described that of his companion. For Jules and Henri were born next-door to one another, were chums from their earliest boyhood, and, thanks to the intimate friendship of their parents, had the same course marked out for them. Jules, then, followed Henri to that public school in England, followed him to the university, was like him in his fancy for British ways and British customs, and followed him yet again, indeed went in his company, on that journey to Berlin which immersed them in this misfortune.

And there they were, interned in Ruhleben, impounded, corralled if you like, separated from their countrymen by ghastly fences of barbed wire, and by a nation composed of men and women who, almost without exception, would, if they were to discover them outside their prison, most eagerly tear them to pieces.

"But it's got to be done!" Jules said, as he and Henri sat outside the stable, the wooden hovel, indeed, in which they lived, in which they bedded down at night in stalls once occupied by horses, and now merely strewed with straw, cruelly cold and unfit for human habitation.

"And the sooner we set about it the better. We'll have to harden our hearts," said Henri, looking very determined and attempting to twist the ends of his miniature moustache; "we'll have to save our food for the journey."

Jules shivered. He wasn't a greedy young man, nor could his appetite be described as unusually large, but he was hungry. Hungry then, at the moment when Henri spoke of saving rations, hungry at night, hungry when he had had his food, hungry always. He was like every member of the unfortunate crowd now inhabiting the race-course at Ruhleben, he was short of food—for the Germans were the harshest of captors. And how could a man save sufficient from a mere crust of bread? How could he put away from rations, already and for so long insufficient, even a crumb per diem to carry him on during some coming journey?

"Yes, it's got to be done," said Henri, with determination; "and, what's more, we shall have to save money. We are getting a little already: I had a few marks sent through from Paris only last week, while we have both got a few notes tucked away in our clothing. But it's not money, however, which will help us; not even food. It will be our wits, which will have to be brisk, I can tell you."

Looking about them as they sat near their hovel, both knew that the words were abundantly true, for where was there a loophole in those barbed-wire fences? Where was there an opportunity to break out of this prison? Yet the chance came, came unexpectedly, came after some weeks of waiting and despondency, came at a moment, in fact, when it found Jules and Henri almost unready, unprepared to seize a golden opportunity.

There was a hue and cry in the camp of Ruhleben which caused heads to be thrust out of doors and out of windows, made prisoners who had been languishing in the place for months start to their feet and look enquiringly about them, and set a German official turning round and round like a teetotum—his moustaches bristling, his hair on end, amazed at the din and fearful for the cause of it. It all commenced with a sudden shout, and then was emphasized by the explosion of a rifle. A dull thud followed as a bullet struck one of the huts and perforated it, and then a dozen weapons went off, the somewhat aged guardians of the camp losing their heads and blazing away without aim and without authority.

"What's up? What's happened? Why is there firing?"

"Shooting a prisoner, eh? Brutes—they'd do anything! Mon Dieu! What will happen next?"

The first speaker was a delicate, pale-faced, spectacled Breton; the second, a vivacious individual from Paris, who, like Henri and Jules, had had the misfortune to be in Germany when the war broke out. Their eager questions were followed by the somewhat phlegmatic and casual words of an Englishman—a red-headed, red-cheeked, healthy-looking individual, who, in spite of short commons, still looked bulky.

"Someone's lost his head," he said caustically, with a growl, sitting up and looking about him. "I'll get the reason in two guesses: someone's trying to escape, or someone has escaped."

Something very dreadful might really have happened, judging by the commotion in the camp, by the shouts of the sentries, and by the firing. The Governor himself—living aloof from the individuals interned in the place and under his administration—heard the racket and came out, buttoning up his tunic, alarmed, his thoughts in a whirl, eager to discover what had given rise to the commotion; and Henri and Jules, like the rest of their companions, were, as one may imagine, just as curious and just as eager.

"Whatever the ruction is, whatever the cause, the point where it commenced is over there, behind those huts in the far corner," said the former, watching the German guards race across the place and listening to their shouts and to the loud commands of the non-commissioned officers amongst them. "Let's saunter in that direction. Come along."

And saunter they did, being joined in a little while by a number of people interned in the camp; and amongst them by the red-headed, red-cheeked, and healthy-looking individual who boasted, somewhat loudly it is to be feared at times, of his English nationality. Not that such boastings disgusted the unhappy people interned at Ruhleben, for it did them good in those days of depression to hear a man—a robust man such as this individual—proud of his birth, and still possessed of sufficient spirit to glory in it, to draw comparisons between himself, his French, his Belgian, and his Japanese fellow-prisoners, and Germans in general, The man's swagger, in fact, delighted them, and helped to bolster up the fading spirits of many an unfortunate captive in the camp—of many a man, who, but for the jibes and uncomplimentary remarks of this robust prisoner, would long since have given up hope and have subsided into melancholy.

"What a row!" he scoffed, as side by side with Jules and Henri he sauntered across the compound. "No, don't you hurry, you fellows, for there's never any knowing what will happen in these days. Those German guards have lost their heads, and the chances are that, if in your curiosity you happen to step along too quickly or to run, they'd imagine that a mutiny had broken out, and would blaze away at you. Lor' what a commotion!"

By now some twenty of the German guards—those Landsturm men of perhaps fifty years of age—had collected in the opposite corner, at the point where the alarm had first been given, and could be seen, grouped together, gesticulating, shouting at one another, peering into the corner of the compound, and carrying on in a manner which accentuated, if anything, the curiosity of the prisoners.

"One could imagine anything," laughed Henri as they got nearer. "For instance, you could imagine that one of the fellows interned here, goaded to rashness by these bullies who look after us, had struck one of them."

"Yes, that's not at all unlikely. Goaded to madness, one of the poor chaps may have put his fist into the face of a German guard, and that shot would have been the result; of course, the poor beggar would be killed instantly, for your German is nothing if not ruthless. He's armed, you see, and is the stronger party, and knows that the authorities won't look too harshly on any drastic action."

"Hold on! Perhaps it's not a case of an assault on one of the guards," chimed in the healthy Englishman, Stuart by name. "I've said already that I'd guess the reason in two guesses—someone trying to escape, or someone already escaped—and I stick to that opinion. Let's hope it's someone escaped—lucky beggar! Here have I been kicking my heels about this infernal camp for months past, looking round for a chance to get out, ready to 'do in' a German guard if the opportunity came. But, bless you, there's never been the remotest chance, for these Germans keep their eyes so precious wide open. As for 'doing in' a guard, why, I'd do in half a dozen; for, believe me, it'd want a good half-dozen Germans to stop me, once I saw the hole open through which I could get out."

It wasn't altogether undiluted brag on the part of this sturdy fellow—mere boasting of what he would do under particular conditions which were never likely to arise. A glance at him, indeed, rather helped to support his statements, for Stuart, though somewhat attenuated after those months of internment at Ruhleben, after months of short commons and indifferent accommodation, was still a big bony fellow of some twenty-five years of age, with broad shoulders, long arms and legs, and a chest which would have fitted a Hercules. True, there were hollows in his cheeks, and his eyes were gaunt and sunken, yet what man in that camp of suffering, what man amongst all the unfortunate fellows caught in Germany at the outbreak of war and hustled to Ruhleben, did not, long since, show signs of suffering and anxiety and of want, often of destitution. As a matter of fact, the robust Stuart had stood the privations of the place better than the majority of his fellows; and perhaps his very jauntiness of spirit, the courage which sustained him and helped also to sustain his comrades, kept him from feeling his position so acutely, and helped also to assist him in surviving a state of affairs which to some had long since become intolerable, which indeed was killing not a few by inches.

By now the trio had crossed the compound, and were within a few feet of their guards, who, absorbed in whatever had caused the alarm and had sent them rushing to that corner, seemed to overlook the prisoners—all the men about them—seemed to be unaware of the crowd collecting in that quarter. They were gathered in the far corner, just outside one of the many huts erected there—a sorry affair, which at one time had done duty on the race-course as a tool-shed. In those days it would not have been considered good enough even for the dogs of the owners of German race-horses; but now, yes, it was good enough—too good—for these enemy prisoners, for these individuals snatched from amongst the civil population of Germany. Young men, some of them, hale men in those days before the war; elderly men, invalids from some of Germany's health resorts—harmless individuals in numerous cases, who, had they been Germans and in England, would have been left alone, able to live their lives in peace and security, provided they obeyed certain rules and regulations of a not too drastic nature; but in Germany German "frightfulness" allowed of no leniency even to sick men. And here they were, the hale, the young, the sick, and the old, hustled to Ruhleben, and herded there together in such an old shed as the one in this far corner. Many men brought up in luxury in France or in England, needing care and comfort because of the state of their health, and undoubtedly quite harmless individuals, were forced to find such accommodation during those dreary months of later 1914 and the months which followed as this World War went on.

It happened, too, that amongst the people interned at this place were a number of jockeys and racing people, employed up to the date of the war by German masters, and detained in the country. These—perhaps a dozen of them—had been posted to the very hut round which the German guards were then standing, and, as Henri and Jules came upon the scene, could be observed within the ring of guards, cowering, looking askance at the Germans, and evidently in sore trouble.

"One of our jockey friends then is the culprit," said Jules; "it's one of the racing-men who has been goaded to madness."

"And has been shot by a German guard?" asked Henri.

"Not a bit of it, not a bit of it!" exclaimed Stuart; "there has been no shooting here. Just listen to the questions being asked. I know German sufficiently to be able to tell what's passing, and those German guards are asking how the work commenced, who thought of the idea, and who was the ring-leader? If that isn't connected with an attempt at escape, call me a Dutchman. No, no; don't call me a German," he said sotto voce in Henri's ear, grimacing as he did so; "don't call me that, my boy, or you will be in trouble."

Certainly the German guards were asking many questions; they were firing them off by the hundred almost, they were shouting them at their prisoners and at one another, till there was such a babel that no one could answer and few could understand. It was not, indeed, until a non-commissioned officer of burly form and bullying appearance came upon the scene that the commotion ended, and some sort of order was introduced.

"Stop this brawling," he bellowed, thrusting his way in amongst the guards and pushing them unceremoniously to either side. "What's this racket? Who fired the shot? Quick, answer!"

A somewhat startled-looking individual, a man with grey beard and rotund body, who before the onset of the war may have anticipated well enough that he would never again be called to the colours, advanced somewhat timidly from behind his comrades and drew himself up stiffly at attention. Yet not stiffly enough, not with that snap which is characteristic of the younger German. The non-commissioned officer coughed and snorted, and looked the man over with a threatening eye which set the fellow trembling.

"Ha! Ho! It is you, eh? You fired the shot—you?" and there was a note of contempt in his voice. "Then why? On whose orders? Here are the orders of the day as to the duties of a sentry, and as to the occasions on which he shall use a rifle. Listen, I will read them."

It was a sample of German militarism which the Sergeant was reproducing to the full, a sample of the preciseness of the Teuton. Keeping this elderly guard at attention till the poor fellow looked as though he would explode, he groped in the pocket in the tail of his tunic, and, producing a notebook, proceeded to extricate from it a sheet of paper on which were some typewritten lines; and then in a ponderous and somewhat menacing voice he read the orders—orders which set forth exactly and minutely when a guard should come on duty and when he should be relieved, what reports he should prepare, and what he was to observe amongst the prisoners. Finally, having elaborated a number of minor points, it set forth the orders as to using firearms.

"And shall not fire upon the prisoners unless there be occasion," coughed the Sergeant; "that is to say, unless there is insubordination amongst them, mutiny, a threat to strike, or an endeavour to escape. That is the gist of the orders. Now, my friend, you have either obeyed or you have disobeyed your orders. Your report! You fired a shot. Why? Under what heading?"

No wonder the unfortunate and rotund guard who had set the camp in an uproar flushed till he became quite scarlet, till his face swelled to the point of bursting, and until his eyes looked as though they would fall out of his astonished head. He stuttered and coughed, and stood at ease, for the effort to remain at attention was beyond him.

"Halt! Stand to attention!" thundered the non-commissioned officer. "Now, your report. There was incipient mutiny amongst the prisoners, eh?"

The guard shook his head and spluttered; even now he was unable to command so much as a single word.

"No! Then there was insubordination amongst a number, or in the case of a single individual, eh?"

"Not so," the guard managed to stutter; "not so, Sergeant."

"Ah! Then we get nearer to it. A man struck you, or threatened to do so?"

"No, it was not that," the German standing to attention managed to answer; "not that, Sergeant."

"What, then? Then it was someone attempting an escape? Someone trying to break out of Ruhleben!" shouted the Sergeant—bellowed it, in fact—when he saw that the guard was nodding his head emphatically. "You mean to tell me that you have stood there all these minutes, and allowed me to read the orders of the day, and to cross-examine you, without giving so much as a hint as to the real cause of the firing of your rifle? You mean to say that you have allowed all this delay, well knowing that a prisoner is attempting or had made an escape, and thereby have assisted him to make clean away from this prison?"

It was the non-commissioned officer's turn almost to explode with indignation and anger; he towered above the trembling guard as he thundered at him, and might still have been abusing him and threatening him had it not been that at that moment another individual came upon the scene—a short, spare, dried-up fellow, a lieutenant, one risen from the ranks not long ago, and still retaining all the bullying ways of a non-commissioned officer. If the burly sergeant had jostled the guards unceremoniously to either side, had stamped on their feet, had threatened and browbeaten them, the new-comer was tenfold more violent and domineering. If looks could have slaughtered individuals, the glance he cast at the sergeant would have slain that perspiring and angry person in an instant, while the scathing glances cast at the group of guards would have decimated the whole party. Yet, if this under-officer's looks were terrible, if he were still more threatening than the non-commissioned officer, he was at least practical, and quick to get to the bottom of matters.

"Stop this racket!" he commanded abruptly, snapping the words like pistol-shots at those round him. "There was an alarm; it started with a rifle-shot—I know all that, so you needn't report it. Stop!" he commanded, seeing the non-commissioned officer open his mouth as if to describe what had happened. "A rifle-shot gave the alarm—something caused one of the guards to fire. This man here undoubtedly is the man who did so. Sergeant, you have called for his report? You have been here a good five minutes—what's the report?"

"A prisoner escaping. This fool here has kept the knowledge from me until this very moment, and I have only just managed to drag the information from him. I have——"

"Hold!" snapped the officer. "I am not asking what you did; I am asking what caused the sentry to fire. A prisoner escaping, you tell me—he's gone then; you've ascertained that fact?"

"I—I—he—you——"

The non-commissioned officer was utterly taken aback, and it was his turn now to look askance at this dried-up, sinister-looking under-officer. If the unfortunate and aged guard who had fired that shot had been remiss in making a rapid report—remissness excusable enough considering the violence of the Sergeant—the latter had been more remiss in not pursuing the matter more rapidly. He knew it, and knew that the under-officer already condemned him. Moreover, with that under-officer, he was well aware, excuses would not avail him.

"I was going to——"

"That will do," the officer told him. "Whatever you were going to do was not your duty. You have been delaying a report; I will deal with you later in the Commandant's office. Now, my friend," he began, turning upon the trembling guard, "a prisoner was escaping; I will ask the question that should have been asked at the very commencement: you fired a shot—you killed the man, eh?—so that he did not escape, or you stopped him?"

There was the dawn of a smile actually on the face of the rotund guard who had been so odiously browbeaten by the Sergeant. It was his turn, he felt, his turn to be jubilant, and at the expense of the man who had bullied him so abominably. He was, in fact, helping to turn the tables on the Sergeant, and hastened to assist the officer.

"I was about to report the matter, sir," he said. "A prisoner was escaping, but failed. I did not shoot him, because it was not possible, seeing that he was out of sight and underground. I therefore fired my rifle to give an alarm and to call assistance. Meanwhile I stood guard over the opening, which I discovered by mere accident. In the hut, there, sir, there is a hole beneath the boards laid on the floor, and a tunnel leading from it. It is not my duty to enter the huts, and, in fact, the orders of sentries are emphatic on that point; we are to patrol outside though, and not to venture farther unless there is a commotion. But it is the duty of the non-commissioned officer in whose charge a hut may be to see that the prisoners keep the place tidy, to watch them carefully, and to observe if they show signs of an attempted escape."

"Hah!" The fierce little dried-up under-officer actually smiled—smiled at this stout sentry, smiled at him, and, indeed, almost winked. For, in an instant, he had realized what was happening, how by this last statement the guard was implicating the Sergeant, who had been so recently upbraiding him. To speak the truth, he was no lover of the non-commissioned officer either; and in days gone by—not so very long ago either—when he, too, had been of the non-commissioned officers' ranks, and had enjoyed but little seniority over the Sergeant, he had had occasion to complain of his bullying, of his arrogance, and of his unpleasant gibes and innuendoes. It was an opportunity then to be snatched at, both for the sake of himself and of this somewhat ancient sentry, who, whatever he might be, however stupid, was essentially harmless.

"So," he began, "that is as you say, my friend; it is not your duty to enter any of the enclosures, but to march to and fro and to keep an eye on the prisoners. It is for the sergeant in charge of each of the huts to carry out his duties, and to detect any and every effort to escape. Then who is the sergeant in charge of this place outside which we are standing?"

There was silence amongst the group, a deathly silence, during which the aged Landsturm sentry pulled himself up stiffly at attention, or into the nearest approach to that position to which he could attain, and smiled covertly in the direction of the sergeant who had browbeaten him. Others of those somewhat senile guards, who at the sound of their officer's voice had assumed that position of respect demanded of all German soldiers, also cast swift glances in the same direction, and even went so far—seeing that the snappy little officer's back was turned and his attention otherwise engaged—as to grin quite openly, and smirk, as they watched the flaming face of the Sergeant. As for the latter, perspiration was pouring from beneath his helmet, the man's hands were twitching, while his eyes were rolling in the most horrible manner. He was cornered, he knew, and guessed thoroughly that the opportunity thus discovered, thanks to the sentry and to his own bullying manner, would be taken advantage of.

"Who, then, is the sergeant responsible?" asked the officer in cold, unsympathetic tones, looking the unfortunate sergeant over from the spike of his Pickelhaube to the thick soles of his regulation boots. "Surely not this sergeant? Surely not the non-commissioned officer before me—the one so quick to find fault with a sentry who seems to have been doing only his duty? Surely not!"

And yet a glance at his face showed well enough that he knew that the culprit stood before him; moreover, that he was determined to make the most of the opportunity.

"I—we—this fool here——" began the Sergeant, spluttering, confused, and now just as thoroughly frightened as had been the victim he had pounced upon such a little time before.

"Stop!" snapped the officer; "you are under arrest; go back to your quarters. Now, my man, you fired your rifle to stop a man from escaping. Narrate the circumstances, and quickly, for, for all I know, the rascal may be even now continuing the attempt."

At that the sentry smiled—smiled boldly too, when he saw the discomfiture of the Sergeant. Turning half-right abruptly, till he faced the entrance of the hut, he pointed towards it, and shook his grizzly head knowingly.

"It was like this, sir," he said, with an air of triumph, "I was passing to and fro on my beat, noting nothing out of the ordinary, until there came a moment when I was opposite this hut, almost on the precise spot on which I am now standing, when I heard sounds which attracted my notice—heavy sounds, the noise of men digging. There was no sergeant in sight, no one responsible for the hut to whom I could appeal, yet a glance within showed me an opening in the floor, covered as a rule by boards, which were now removed. There was a man in the hole, deep down and beyond it, in a tunnel, a man whose figure I could only just discern—a ruffian who was attempting to dig his way from the hut out beyond the wire entanglements. It was then, seeing there was no one here to support me, that I fired my rifle."

"Ha! And the fellow is there still?" demanded the officer quickly.

"Still, your honour, unless he has escaped during the time the Sergeant cross-questioned me; of a truth, he is still there, unless, perhaps, he should have in the meantime, while I was delayed in executing my duty, contrived to clamber out of the opening."

"Close in, you men," bellowed the officer; "half a dozen of you come along with me, and hold your rifles ready. Now, into the hut and let us capture these fellows."

Closing round the entrance to the hovel—termed a hut—in which the unfortunate interned aliens had been forced to live for months, the sentries watched the officer and a few of their comrades push their way into the interior, heard them stamping on the boards, and listened to the peremptory orders of the former.

"Come out, you ruffian, or ruffians," he bellowed. "We have you securely, and any further attempt at escape will be met with instant execution. Ah! I can see a man down below. Go in, two of you men, and haul him up to the surface."

With no great show of enthusiasm, stiffly, and with a lack of energy and that activity to be expected of younger men, two of the guards at once lowered themselves into the pit dug beneath the boards which did duty as a flooring to this hovel, and, disappearing from sight in the tunnel excavated from the bottom of it, were presently heard giving expression to gruff commands, while the sound of scuffling followed. Then they reappeared, dragging a couple of dishevelled and exceedingly dirty prisoners with them. Others of the guards then stepped forward, and in a trice the wretched men who had been detected in the act of escaping were dragged from the hole, were placed between sentries, and were marched out of the hut.

Meanwhile, as may be imagined, the excitement in the camp had not tended to decrease, for curiosity had been added to it. There was a throng of prisoners round the hut long since, watching at first the altercation between the Sergeant and the sentry, and then observing and listening to all that followed.

"A pretty kettle of fish—eh?" sneered Stuart, the healthy Britisher. "Sorry for those poor beggars; for their rations have been short enough already, and now, if they are not shot, they will get close confinement and bread and water only for a couple of weeks or more. Bad luck! Horribly bad luck! Just at the last, too, for it looks as though they were well on the way to safety."

"Now, report," suddenly came the voice of the little officer, as he glowered upon the prisoners. "You two who went into the tunnel report on its length, its depth. Bah! You didn't look! You didn't ascertain that! Wait while I investigate the matter."

Seizing an electric torch from one of the hapless prisoners, the officer dropped into the pit immediately and was gone for some few minutes, only to emerge again, dirty like the prisoners, but triumphant instead of crestfallen, his face beaming, his eyes sparkling with happiness. So pleased was he that he even went to the length of patting that stout, rotund sentry on the shoulder as soon as he had emerged into the open.

"A fine catch," he told him, "bravely done, my friend! See, you detected them just at the very right moment, for the dusk is already growing, and in five minutes or less they would have been in the open. Let me tell you, that tunnel was not prepared in a day or two, or even in a week, I am certain. It is the work of days and days, grim, hard work, and has been carried right up beyond the hut and under the wire entanglements. There it stops, though already it was rising to the surface, and to-morrow morning, when we investigate the place, I feel sure that a thrust with a bar will break a way into the open. March the prisoners across to the guard-room; and you, my friend, come along and make your report to the Commandant. Ha! What are all these rascals doing here? Curious, eh? Get back to your stables!"

There was an instant move on the part of the prisoners interned in the camp, who had collected in this corner to see what was passing. Turning about promptly—for to disobey an order when under the thumb of Germans was to court a shot from a rifle—they went off briskly in the dusk to their own particular huts, while behind them was heard the sharp command of the sergeant in charge of the sentries, the tramp of heavy feet, and the passage of the sentries and prisoners in the direction of the guard-room.

"Come along," said Stuart, his hands deep in his pockets, his head held forward, his chin on his breast. "I'm frightfully sorry for those poor fellows. Just fancy! To be within, say, a foot of freedom and then to fall, and then to be detected by the merest mischance."

"Within a foot of freedom! That's what that officer said," Henri was muttering to himself. "Just a foot, just a thrust of an iron bar, and then to safety, freedom—freedom from this prison. Why not!"

"Why not?" he asked suddenly, clutching Jules's coat.

"What? Why not?" the latter asked. "Don't understand."

"Why not complete the work? Those fellows have done precisely what we should have done—they've dug a hole and have run a tunnel from the bottom of it out below the open and below the entanglements. It's there—ready for anyone who wants to get out of this place. Anyone, Jules! Don't you understand?"

Stuart grabbed at Henri, and thrust his big, healthy face close up to his. He was breathing deeply, in heavy gusts, and, but for the gathering darkness, it would have been seen that his eyes were shining, while he showed every sign of excitement.

"Why not? You fellows were thinking of making an escape?" he asked.

"Certainly," Henri told him; "we've been saving our grub, and what money we could get. We were ready but for the method, and now it's there—there in that hut—quite close to us, and it's dark enough, and—and—and there's no one about—why not?"

"Come on," said Stuart abruptly, in that resolute way he had. "I'm with you fellows, if you'll have me."

Without another word the trio turned promptly, and, looking round to make sure that no one had observed them, they bolted back to the hut from which those unfortunate prisoners had been dragged, and, closing the door behind them, leapt into the pit and made their way into the tunnel. Freedom lay before them—freedom for which they pined—freedom to be had if only they could break their way into the open.

"What's this? An old shovel, by the feel of it—the thing they've dug the tunnel with," Henri told his comrades as they stood at the entrance of the tunnel in the dense darkness, and felt all about them. "My fingers dropped upon it as I bent at the entrance, and, yes—here's a basket with a rope attached to it, into which, no doubt, one of them shovelled the earth at the far end of the tunnel, while his comrade dragged it to the bottom of the pit by means of the rope. Poor chaps! How hard they must have worked, and what a disappointment it must have been to have failed just at the last moment."

"That's just what we have got to look to," Stuart told them in a hoarse whisper. "They've done the work and have failed; let's look to it that we get out promptly. Come along now. Give me the spade, Henri, for I'm bigger and stronger than you, and, if there's only a foot of earth above our heads when we get to the far end of the tunnel, I'll bash a way through it without difficulty. George! What a narrow space it is! It hardly lets my shoulders through."

That tunnel, indeed, was hardly better than a rabbit burrow. Perhaps four to five feet in height, it was scarcely two in breadth, cold and dark and winding. Let us admit at once that it required no small stock of courage on the part of Stuart and his friends to force their way along it, particularly so in the case of the Englishman, whose frame was such a close fit to the damp earthen sides, that failure to break a way out at the far end would have left him in a difficult position—one from which he would undoubtedly have found it hard to extricate himself. Yet there was liberty beyond, escape from this dreary Ruhleben with its monotonous routine, with its bullying Commandant and guards, with its sordid surroundings, and its sorry accommodation and short commons. Thrusting on, therefore, pushing his way along the tunnel, squeezing himself into as small a compass as possible, Stuart forced a passage deeper into it, one hand feeling his way, while the other gripped the implement which Henri had discovered. Ten yards, twenty, perhaps thirty were covered before a growl came from the leader.

"The end!" they heard him say. "I'm up against the far end of the tunnel, and that officer was quite right when he stated that it rose toward this end. Now, hold your breath for a moment and listen while I thump the roof. There—hollow—eh? Not much earth above us. Then stand back a little whilst I make a stroke for the open."

They heard the thuds as the shovel was dashed against the roof, and listened to clods of earth and debris falling. It was precisely at the fifth stroke that a grunt escaped Stuart, while an instant later Henri felt a breath of fresh air, a cold gust sweeping past him.

"The open!" he exclaimed. "Go easy, Stuart, for it might not be dark enough yet, and impatience on our part might lead to our instant discovery. Put your head up quietly as soon as you've made room."

There were more grunts in front, while from behind came a low, warning exclamation from Jules.

"S—s—sh!" he said. "I can hear someone in the hut behind us, for the sounds are travelling down the tunnel. Push on into the open as fast as you can go, while I turn back and see what's happening."

There were more sounds then, as Jules, less bulky than Stuart, yet of formidable size when it came to free movement in this narrow tunnel, contrived by some acrobatic feat to turn himself about and face the pit from which they had started this adventure. Then he crawled back towards the hut on all fours, listening to the suspicious sounds which he had heard, wondering who caused them, fearing that the German guards had come to make a nearer investigation of the pit and tunnel. Yes, it was that, without a doubt; for there came to his ears now the sound of a man's two feet alighting at the bottom of the pit, a heavy thud, and the fall of earth as it tumbled from the sides of the pit to the bottom. Then rays of light reached him as the person who had dropped into the pit switched on an electric torch and surveyed his surroundings. Once more then Jules performed that acrobatic feat, and, twisting himself round with furious energy, hastened back to warn his comrades.

"There's a fellow at the bottom of the pit already, and no doubt he'll be coming into the tunnel," he told them in a whisper. "He's got an electric torch, and that will be far worse than the light outside, for it'll show us up directly. Shove on into the open. Push your way through. Hang the sentries! We'll have to chance their seeing us."

More blows came from Stuart, lusty blows, and the sound of heavy breathing, then an exclamation, an exclamation of delight, of triumph, and later the sound of more earth falling. That fresh breath of air which had swept into the tunnel became almost keen, while intuitively, for they could not see, Henri and Jules both realized that Stuart had already clambered from the place into the open.

"Come now," they heard a voice. "Come up, quick, and lie down flat as soon as you are beside me."

Henri stumbled on till he was right at the end of the tunnel, and, standing upright, felt a hand stretched down towards him. Gripping it, digging his toes into the sides of the tunnel, and seizing the edge above with his other hand, he was half dragged, and half forced his way upward, then, flinging himself on the ground beside Stuart, he leant over the ragged hole and helped to extricate his comrade.

They were free! They were in the open! They were beyond the wire entanglements! And Germany lay before them—Germany, an enemy country, where every man's hand, aye, and every woman's too, would be against them. Yet they were free, and what did it matter how many enemies they had to face, how many difficulties were before them? For freedom, however much it might be embarrassed, however adventurous it might become, was freedom after all—a godsend compared with the privations, the gibes, the cruel treatment they had suffered in their prison. If anyone had ever a doubt as to this, if, when this ghastly war which is now in progress is finished, a reader happen to think that there has been exaggeration in these statements, let him but look to facts, let him but consult the known history of the treatment of interned aliens and prisoners of war in the Kaiser's country. Though war itself, and this one in particular with its long and terrible tale of casualties, is a ghastly business, the deliberate ill-treatment, the calculated starvation, and the wilful abandonment to misery and death from preventable disease of prisoners of war is a still more ghastly affair—an episode frequently repeated in the case of Germany.

"Out! Hurrah! Mon Dieu! Out of that awful hole," coughed Henri, shaking the dirt out of his hair and brushing it from behind his ears. "Out, my boys! Away from those German guards, and away from that Commandant and the whole breed of 'em."

Jules giggled. He was possessed of a lighter nature altogether, was perhaps of more flippant disposition than his chum, and had less stamina about him. Not that he was lacking in courage, or in dash, or in that élan which the French generally have displayed so magnificently in this conflict, only Jules was, perhaps, just a trifle effeminate, and giggles seemed to come almost naturally from him. Now, as he lay close to the ragged edge of the opening through which he had been forcibly dragged by Stuart and Henri, and as he spluttered and blew dirt which had introduced itself into his mouth from his discoloured lips, he gave vent to a laugh, a smothered sound of merriment, perhaps a semi-hysterical giggle, in any case to a sound which grated on the senses of the Englishman terribly.

"Burr! Stop that!" he commanded, and somehow, for some unascertained reason, Henri and Jules, who would have resented such tones from him on any other occasion, accepted them now without a murmur. "Shut up!" growled Stuart. "Hist! There's one of those beastly sentries coming near the entanglements—and what's that?"

There were other sounds than those of steps within Ruhleben camp, that odious place of misery out of which they had broken, other noises than the heavy tramp of a ponderous Landsturm guard as he strode from behind the hut till the barbed-wire entanglements stopped his progress and he rattled his bayonet upon it, sounds which came from another quarter from beneath the ground, from the tunnel in fact from which Henri and his friends had so recently emerged.

"Hist!" exclaimed Stuart in warning tones. "Keep as low and as flat as you can. Thank goodness! That sentry fellow, after making enough noise to drown the sound of our voices, has turned away without seeing us; but—but—what's that?"

Henri stretched out a hand and gripped him by the sleeve.

"Down there," he whispered, "down there in the tunnel from which we have just come, there's someone stumbling along. And cast your eye into the opening; isn't that the gleam of a torch? Isn't that light being thrown in this direction?"

It was, without the shadow of doubt. For, as all three peered over the edge of the hole they had made so rapidly, thanks to the strength of Stuart, the depths below were illuminated for just a few seconds, and then were hidden in pitch-black darkness, which within a few moments was again lit up by a brilliant beam of light coming from a distance up the tunnel—that long path which they had followed, which had fitted the burly Stuart's shoulders so narrowly, and had made turning in his case an impossibility. It acted now as a tube, and sent sounds along towards them, accentuated them, indeed, until there was no difficulty in deciding that a man was struggling and pushing his way towards them—a man armed with an electric torch, a fellow who breathed heavily, who swore beneath his breath and then out loud, and who set masses of earth tumbling down about him.

"Better go," whispered Henri, when the cause of the sounds was quite certain, "better slip away at once before the fellow finds the opening and shouts an alarm."

"Wait!" Stuart stretched a hand out and gripped him with a grip of iron, a grip which held the vivacious Frenchman to the ground. "Not yet, for that bounder of a sentry is again coming towards us. Lie low!" he cautioned them; "lie low, or he will see us."

"But the man below with the light—he is nearer, far nearer," said Jules, who lay with his head well over the opening. "He'll be here in next to no time—then what?"

Stuart dragged himself a little closer to that opening, and, keeping one eye on the sentry, glanced down to the bottom of the tunnel.

"Leave the beggar to me," he said. "Look here, Henri, grope about for a stone—a brick—anything that's hard and will hurt, and can be thrown easily. Ah! here's one—a big 'un too; you try the same, Jules, and get ready to heave at that sentry. When I bash my fist against the fellow below, you throw your stones as hard as you can at the German inside the entanglements, and so put out his aim; not that there's much to be feared, seeing how dark it is at this moment."

Quick as thought, Henri grabbed the big stone which Stuart thrust into his hand, and, groping about, quickly secured another. Then he slowly raised himself into a kneeling position, ready to spring to his feet and carry out the duty Stuart had given him. Nor was it likely to be a very difficult matter to strike the sentry at that moment hammering again on the barbed wire which formed the fences about the camp at Ruhleben, for though without doubt Henri and his friends lay invisible, close to the ground, the burly figure of the German stood out, huge and broad and solid, silhouetted faintly in the darkness by lights flickering from the range of shelters on the far side of the camp. As for Jules, he, too, quickly secured missiles with which to bombard the sentry, and, as if to show how ready he was for the work in hand, gave vent again to one of those subdued giggles; whereat Stuart growled—a fierce growl—and nudged him violently. Then, of a sudden, the attention of all three was fixed on the hole through which they had emerged, and upon the depths below it. The rough sides of the tunnel, the debris and earth which they themselves had dragged down to the foot of it as they cut their path upward, every stone, every clod, was visible, as the torch—now closer at hand—lit up every crevice. Then the torch itself came into view, the hand which gripped it, the sleeve about the wrist, and finally the shoulders and the head of the individual stumbling and forcing his way towards them.

"Ach, Himmel! What a find! The wretches were almost escaping. What perseverance, though; what hard work; and, yes, what hard luck to have been discovered just on the eve of breaking out of their prison!"

It was the small, snappy under-officer who had appeared on the scene outside the hut but a few minutes earlier, and who, discovering the Sergeant there browbeating the unfortunate sentry, had turned upon him like a dog, had snapped at his heels as it were, had changed the aspect of affairs entirely, and had ended in putting the non-commissioned officer under arrest, and in himself capturing those unlucky prisoners who were hiding in the tunnel.

Doubtless it was a brilliant evening's work for him—work which might even bring him reward—who knows?—might even, in the end, bring him that Iron Cross which the Kaiser has been so fond of distributing. Men in the ranks of the German army had received that reward for lesser acts than that of the under-officer this evening; there are heroes in the armies of the All-Highest Kaiser who have been decorated with that Iron Cross for valour, and others who wear the emblem for deeds which make the rest of civilization shudder. Yes, indeed, the under-officer might well earn such reward, for he had shown acuteness, promptitude, and dispatch in carrying out his duties.

"But what's this?" Henri and Stuart and Jules heard him say, a second later, as his other hand came into view, groping along the floor of the tunnel and plunging deep into the loose soil so recently pulled from the roof above. "The tunnel ends abruptly, and above—what's this?—above, the ruffians were making a hole. But this is strange, for when I entered before there was no sign of such a thing. The tunnel ended just here, as it does now, and the earth at its foot was hard and beaten, while above it was hard as well, but shook and gave out a hollow sound. What's this? Ah! A hole."

It was with amazement that his eyes fell upon the ragged edge of the opening above, as the beams from his electric torch fell upon it. He stumbled and struggled forward, and, rising to his feet, shot his hands upward to grip the edge above him. He would, perhaps, have given vent to a shout had not Stuart, lying immediately over the tunnel, in fact right above the figure of the German, leaned down, and, stretching his hands below him, gripped the German by the nape of the neck with one hand, and the electric torch with the other, jerking the latter back into the tunnel, where it lay with its beams flashing in the opposite direction. He then proceeded to draw the German up towards him as one draws the cork out of the neck of a bottle, to extricate him in spite of his kicks and struggles; while that other hand, set free from the torch, was clapped over his mouth, smothering any sounds of which the under-officer was capable. Not that it was an easy matter to give vent to a shout of alarm in such a position, for Stuart's huge fingers and thumb gripped the German so fiercely and firmly about the neck, just below his jaws, that movement of the latter was impossible, and the very attempt to make a sound was excessively painful. Up then he came slowly, struggling, his hands beating the earth and reaching up in the endeavour to grip his assailant, his heavily shod feet lashing to and fro and kicking clods of earth from the sides of the tunnel; up till his head was clear of the opening, till almost half his body had been extricated; and then, when Stuart, now on his feet and half upright, had placed himself in a favourable position, suddenly the German was shot back into the place from which he had just been dragged, shot back with unexpectedness and violence, till he came with a crash against the bottom of the tunnel, and, collapsing there, rolled backwards into it.

As one can imagine, though the under-officer had given vent to no sound—no shout of warning—the noise of his coming through the tunnel, the flash of his torch and its beams sweeping through the opening above, had attracted the attention of the sentry. The man faced that direction promptly, and brought his rifle to the ready. Then for a while he waited, while Stuart was dragging the German upward, and, indeed, until there came the heavy thud which told of the under-officer's arrival at the bottom of the tunnel.

"What's that?" challenged the sentry. "Who goes there? Halt, and declare yourself!"

"Fire!" whispered Henri, and, standing up, he cast first one stone and then the other at the sentry, while Jules followed suit without waiting, a loud cry of pain and the dull sound of a blow telling that one of the missiles at least had hit the German.

"Now come!" said Stuart. "We're lucky in the fact that the fellow hasn't fired his rifle, though he's shouting hard enough to rouse every man in the camp, and will soon have them all about him. Which way, you fellows? You know more about the business and the place than I do, for I'm a stranger in these parts, and, bad luck to it, know precious little of Germany and the Germans. Bad luck, did I say? when I've seen far too much of them in these months past since I came to Ruhleben. But what's the move? Which way do we turn? Where do we go? And how are we going to get on for victuals?"

That was the worst of this sudden escape, this movement out of the camp without calm thought and contemplation of the future. They had no plans—not a single one—and they had no idea whither to go, or which way to turn, nor where they might seek safety. True, Henri and Jules had discussed the matter on many an occasion, and had, indeed, as we know, been diligently, and with much self-sacrifice, hoarding up what food they could—and in all conscience they had little enough of it—and what money they could gather. But as to their course when once in the open—that had seemed something so far in the distance, so difficult to contemplate, so very unlikely, that they had given it but the smallest consideration. And now they were face to face with the difficulty and must act promptly.

"Of course the town's out of the question," said Henri, taking upon himself to guide the party, for, indeed, as we have mentioned already, he knew his Germany well, just as well almost as he could speak the language, and both he and Jules were fluent. We have described them earlier as typical Englishmen when taking a first glance at them; and we have to declare that they were just as typically French when one had the pleasure of making their acquaintance; but in the darkness, when no one could see their spruce and dapper appearance—and how many German youths can boast of being spruce and dapper?—when the voice alone could give an indication of the nationality of the speaker, then both Henri and Jules could pass muster as Germans with the greatest ease and security. But Stuart, this big, raw-boned, healthy, red-faced individual, was typically British in build, in gesture, and in action, and when he spoke just as typically an offspring of the British peoples. Blunt, direct, uncouth almost at times in his speech, he couldn't, had he attempted to speak German—which he did at times, and could make himself understood—have aped the guttural accents of the Teuton. He despised the German thoroughly, detested him most cordially, and perhaps it was characteristic of his bluntness that he thoroughly detested his language. Thus, while in the darkness Henri and Jules might hope to pass muster, in the case of Stuart there was not the smallest prospect of this.

"We have got to keep clear of the towns, that's the first thing to be remembered," continued Henri; "and my advice is that we stay in the open, right in the country, hiding up in woods in the daytime and marching during the night. For food we shall have to do just as best we can; beg it if possible, steal it if necessary. As to our course, it's not the time now, nor the place, in which to discuss the matter, for the first thing to do is to put as great a distance as possible between us and the camp. To-morrow, when the light comes, our guards will send out a report broadcast, and it may be that they'll put bloodhounds on our track and endeavour to follow us. So let's put the best foot forward and march on. Any direction's good enough, so long as it takes us away from Ruhleben."

Certainly any direction was good enough which would take them away from the babel of shouts and noise which had now broken out in the camp outside which they were lying, and which told plainly enough that another alarm had been given. Indeed, if the noise created by the discovery of the two prisoners in the depths of their tunnel had upset Ruhleben, had broken in a moment, as it were, the monotony of the existence of the unlucky individuals interned there now for so many months, the commotion at that time, which had drawn Henri and Jules and Stuart and many another to that hovel, termed a hut, in the corner beneath which was the entrance to the tunnel, was nothing to the uproar which now arose, to the shouts which echoed across the dreary camp, to the reports of rifles which men, almost too aged to work, and employed as guards, let off in every direction. There was the twang of bullets in the air, while the darkness was punctuated by many a spot of flame, which showed where the sentries were doing duty. That commotion brought the Commandant flaring out of his quarters again, stamping his feet with anger, bellowing with passion. It would also have brought every one of the interned people out of his hut had not exit from them after darkness been strictly prohibited, and almost certain to be rewarded by a bullet. But guards were free to move about—those on duty and their reliefs waiting in their barracks—and fifty or more Germans can create quite a pandemonium when sufficiently excited.

As for sounds nearer to hand, they came in plenty from the corner of the camp just within the barbed-wire fencing; for there the sentry who had challenged, and who had been heavily struck by the missiles flung by Jules and Henri, screamed with pain and terror. Indeed, he was rather more frightened than hurt, though being hurt he made that an excuse for his outcry. But it was from the depths of the tunnel that the most ominous sounds were emitted. Shaken by the manner in which the lusty Stuart had thrown him through the opening, half-stunned, and not a little sick from the violent thump with which he had struck the ground, yet clinging to his senses, stung to action by fierce resentment of the treatment accorded him, and more still by the knowledge that he had been outwitted, the under-officer—that short, spare, dried-up individual who had snapped so vixenishly at the sergeant—was spluttering with wrath, was mingling his shouts with those of the sentry, and, as if that were not enough, had drawn his revolver and was blazing away at nothing.

"Time to be going," said Henri, tapping Stuart on the back; for that huge individual was leaning over the ragged opening leading into the tunnel, ready to make another attack upon the German if need be. "Time to be going, for in a little while men will be sent all round, and may cut us off. Come along."

"Which way? Where? You'll lead, eh?" asked Stuart.

"Certainly! This way—any way—straight in front of us—follow our noses," whispered Henri. "Certainly! Catch hold of my coat; Jules, take hold of Stuart, and let's push on."

One doesn't live in a camp like Ruhleben, or, indeed, in any other camp, without taking stock of one's immediate surroundings, without spending whole hours in contemplating the scenery outside, in watching things usually of little or no interest, and in finding relaxation in beholding perhaps some figure in the distance, and wondering for minutes together who it might be, where he or she had come from, and whither the same individual was going. Thus it happened that without any special effort Henri had noticed that a road passed near the camp at the very corner where they had made their escape, and ran right across the open into the distance. Where precisely it went, why individuals made their way along it, and what was the destination of those who traversed the route he was unable even to guess, and questions to the sentry had received the usual gruff, if not emphatic, refusals to answer.

"Bang straight on! We get on to the road in a little while," Henri told his friends, speaking over his shoulder; "we should, of course, keep to the open fields and make our way right across country, but it would be precious difficult during the darkness, and we should get along very much faster if we follow the road."

"Half a mo'—just wait a second," said Stuart, now that they had gained the road. "Of course I am quite ready to trust myself to you, Henri, for you and Jules are sensible sort of chaps, and we know each other now thoroughly; besides, you've backed me up splendidly in this little business. But put yourselves in the position of the Camp Commandant and of his men. A bolt-hole has been discovered in the corner of the camp, and there's a road near; now put two and two together, and it isn't very difficult—even a German can do that," he added satirically, contemptuously, if you like, for, as we have said before, the lusty Stuart had but the lowest opinion of most Teutons. "What follows? Just this: prisoners escaping find a road, and, knowing themselves to be pursued, follow it. First moral, keep off the road; second moral, find another; better still—make our escape in the very opposite direction."

It was only solid sense, British sense, horse sense as they term it in America, and, hearing him speak, Henri realized that fact immediately.

"Splendid!" he exclaimed enthusiastically, for he had a great opinion of the Englishman; "of course that's the thing to do. Well then, I've noticed that there's a road which turns away from this one a little distance ahead, and no doubt there'll be another one breaking away from that one. Let's sprint. A good fast run after life in a camp will be no disadvantage."

As a matter of fact, they were not in such soft condition as one might have anticipated, seeing that they had been confined within the barbed-wire entanglements about Ruhleben for many months past. The keenness and energy of youth, the fact that they had many companions, had helped them to keep their muscles in tolerable order, for games had been possible and football was quite a favourite. Hence a sprint along that road was not beyond them, and, doubling their arms and setting off at a good steady pace, they had soon contrived to put a mile between them and their late prison; then, slowing down a little till they discovered the other road, they turned into it and continued to run, and in a little while were well away from Ruhleben. Half an hour later they turned sharply to their left again, and, alternately running and walking, covered some fifteen miles before the morning dawned. Waiting till they had gained the top of a wooded hill, they plunged into a thick copse which offered cover, and there, as the light came, they lay down on its edge, able to survey the country all about them, feeling tolerably secure, and, let us add, amazingly hungry.

"A farm, I think, and a big one by the look of it. There should be food, and plenty of it, down there," said Jules, moistening his lips and springing eagerly out from the cover into the open.