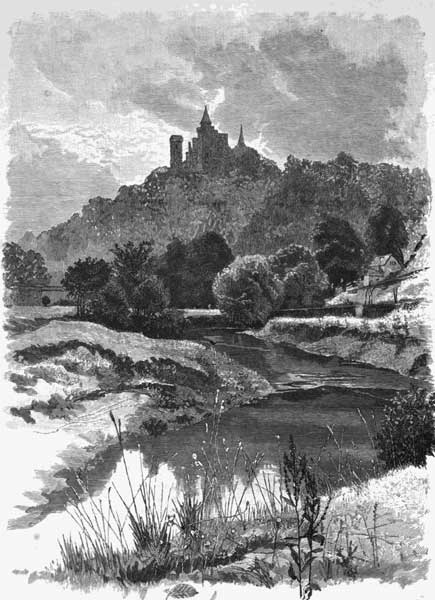

ALTON TOWERS.

ALTON TOWERS.

Title: England, Picturesque and Descriptive: A Reminiscence of Foreign Travel

Author: Joel Cook

Release date: August 24, 2009 [eBook #29787]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sigal Alon, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

PHILADELPHIA;

PORTER AND COATES.

[Pg 2]

Copyright

By PORTER & COATES,

1882.

Press of Henry B. Ashmead, Philada.

Electrotyped by Westcott & Thomson, Philada.

[Pg 3]

No land possesses greater attractions for the American tourist than England. It was the home of his forefathers; its history is to a great extent the history of his own country; and he is bound to it by the powerful ties of consanguinity, language, laws, and customs. When the American treads the busy London streets, threads the intricacies of the Liverpool docks and shipping, wanders along the green lanes of Devonshire, climbs Alnwick's castellated walls, or floats upon the placid bosom of the picturesque Wye, he seems almost as much at home as in his native land. But, apart from these considerations of common Anglo-Saxon paternity, no country in the world is more interesting to the intelligent traveller than England. The British system of entail, whatever may be our opinion of its political and economic merits, has built up vast estates and preserved the stately homes, renowned castles, and ivy-clad ruins of ancient and celebrated structures, to an extent and variety that no other land can show. The remains of the abbeys, castles, churches, and ancient fortresses in England and Wales that war and time together have crumbled and scarred tell the history of centuries, while countless legends of the olden time are revived as the tourist passes them in review. England, too, has other charms than these. British scenery, though not always equal in sublimity and grandeur to that displayed in many parts of our own country, is exceedingly beautiful, and has always been a fruitful theme of song and story.

"The splendor falls on castle-walls

And snowy summits old in story:

The long light shakes across the lakes.

And the wild cataract leaps in glory."

Yet there are few satisfactory and comprehensive books about this land[Pg 6] that is so full of renowned memorials of the past and so generously gifted by Nature. Such books as there are either cover a few counties or are devoted only to local description, or else are merely guide-books. The present work is believed to be the first attempt to give in attractive form a book which will serve not only as a guide to those about visiting England and Wales, but also as an agreeable reminiscence to others, who will find that its pages treat of familiar scenes. It would be impossible to describe everything within the brief compass of a single book, but it is believed that nearly all the more prominent places in England and Wales are included, with enough of their history and legend to make the description interesting. The artist's pencil has also been called into requisition, and the four hundred and eighty-seven illustrations will give an idea, such as no words can convey, of the attractions England presents to the tourist.

The work has been arranged in eight tours, with Liverpool and London as the two starting-points, and each route following the lines upon which the sightseer generally advances in the respective directions taken. Such is probably the most convenient form for the travelling reader, as the author has found from experience, while a comprehensive index will make reference easy to different localities and persons. Without further introduction it is presented to the public, in the confident belief that the interest developed in its subject will excuse any shortcomings that may be found in its pages.

Philadelphia, July, 1882.[Pg 7]

| I | ||

|---|---|---|

| LIVERPOOL, WESTWARD TO THE WELSH COAST. | ||

| Liverpool—Birkenhead—Knowsley Hall—Chester—Cheshire—Eaton Hall—Hawarden Castle—Bidston—Congleton—Beeston Castle—The river Dee—Llangollen—Valle-Crucis Abbey—Dinas Bran—Wynnstay—Pont Cysylltau—Chirk Castle—Bangor-ys-Coed—Holt—Wrexham—The Sands o' Dee—North Wales—Flint Castle—Rhuddlan Castle—Mold—Denbigh—St. Asaph—Holywell—Powys Castle—The Menai Strait—Anglesea—Beaumaris Castle—Bangor—Penrhyn Castle—Plas Newydd—Caernarvon Castle—Ancient Segontium—Conway Castle—Bettws-y-Coed—Mount Snowdon—Port Madoc—Coast of Merioneth—Barmouth—St. Patrick's Causeway—Mawddach Vale—Cader Idris—Dolgelly—Bala Lake—Aberystwith—Harlech Castle—Holyhead | 17 | |

| II | ||

| LIVERPOOL, NORTHWARD TO THE SCOTTISH BORDER. | ||

| Lancashire—Warrington—Manchester—Furness Abbey—The Ribble—Stonyhurst—Lancaster Castle—Isle of Man—Castletown—Rusben Castle—Peele Castle—The Lake Country—Windermere—Lodore Fall—Derwentwater—Keswick—Greta Hall—Southey, Wordsworth, and Coleridge—Skiddaw—-The Border Castles—Kendal Castle—Brougham Hall—The Solway—Carlisle Castle—Scaleby Castle—Naworth—Lord William Howard | 51 | |

| III | ||

| LIVERPOOL, THROUGH THE MIDLAND COUNTIES, TO LONDON. | ||

| The Peak of Derbyshire—Castleton—Bess of Hardwicke—Hardwicke Hall—Bolsover Castle—The Wye and the Derwent—Buxton—Bakewell—Haddon Hall—The King of the Peak—Dorothy Vernon—Rowsley—The Peacock Inn—Chatsworth—The Victoria Regia—Matlock—Dovedale—Beauchief Abbey—Stafford Castle—Trentham Hall—Tamworth—Tutbury Castle—Chartley Castle—Alton Towers—Shrewsbury Castle—Bridgenorth—Wenlock Abbey—Ludlow Castle—The Feathers Inn—Lichfield Cathedral—Dr. Samuel Johnson—Coventry—Lady Godiva and Peeping Tom—Belvoir Castle—Charnwood Forest—Groby and Bradgate—Elizabeth Widvile and Lady Jane Grey—Ulverscroft Priory—Grace Dien Abbey—Ashby de la Zouche—Langley Priory—Leicester Abbey and Castle—Bosworth Field—Edgehill—Naseby—The Land of Shakespeare—Stratford-on-Avon—Warwick—Kenilworth—Birmingham—Boulton and Watt—Fotheringhay Castle—Holmby House—Bedford Castle—John Bunyan—Woburn Abbey and the Russells—Stowe—Whaddon Hall—Great Hampden—Creslow House | 70 | |

| IV | ||

| THE RIVER THAMES AND LONDON. | ||

| The Thames Head—Cotswold Hills—Seven Springs—Cirencester—Cheltenham—Sudeley Castle—Chavenage—Shifford—Lechlade—Stanton Harcourt—Cumnor Hall—Fair Rosamond—Godstow Nunnery—Oxford—Oxford Colleges—Christ Church—Corpus Christi—Merton—Oriel—All Souls—University—Queen's—Magdalen—Brasenose—New College—Radcliffe Library—Bodleian Library—Lincoln—Exeter—Wadham—Keble—Trinity—Balliol—St. John's—Pembroke—Oxford Churches—Oxford Castle—Carfax Conduit—Banbury—Broughton Castle—Woodstock—Marlborough—Blenheim—Minster Lovel—Bicester—Eynsham—Abingdon—Radley—Bacon, Rich, and Holt—Clifton-Hampden—Caversham—Reading—Maidenhead—Bisham Abbey—Vicar of Bray—Eton College—Windsor Castle—Magna Charta Island—Cowey Stakes—Ditton—Twickenham—London—Fire Monument—St. Paul's Cathedral—Westminster Abbey—The Tower—Lollards and Lambeth—Bow Church—St. Bride's—Whitehall—Horse Guards—St. James Palace—Buckingham Palace—Kensington Palace—Houses of Parliament—Hyde Park—Marble Arch—Albert Memorial—South Kensington Museum—Royal Exchange—Bank of England—Mansion House—Inns of Court—British Museum—Some London Scenes—The Underground Railway—Holland House—Greenwich—Tilbury Fort—The Thames Mouth | 137 | |

| V | ||

| LONDON, NORTHWARD TO THE TWEED. | ||

| Harrow—St. Albans—Verulam—Hatfield House—Lord Burleigh—Cassiobury—Knebworth—Great Bed of Ware—The River Cam—Audley End—Saffron Walden—Newport—Nell Gwynne—Littlebury—Winstanley—Harwich—Cambridge—Trinity and St. John's Colleges—Caius College—Trinity Hall—The Senate House—University Library—Clare College—Great St. Mary's Church—King's College—Corpus Christi College—St. Catharine's College—Queens' College—The Pitt Press—Pembroke College—Peterhouse—Fitzwilliam Museum—Hobson's Conduit—Downing College—Emmanuel College—Christ's College—Sidney-Sussex College—The Round Church—Magdalene College—Jesus College—Trumpington—The Fenland—Bury St. Edmunds—Hengrave Hall—Ely—Peterborough—Crowland Abbey—Guthlac—Norwich Castle and Cathedral—Stamford—Burghley House—George Inn—Grantham—Lincoln—Nottingham—Southwell—Sherwood Forest—Robin Hood—The Dukeries—Thoresby Hall—Clumber Park—Welbeck Abbey—Newstead Abbey—Newark—Hull—Wilberforce—Beverley—Sheffield—Wakefield—Leeds—Bolton Abbey—The Strid—Ripon Cathedral—Fountains Abbey—Studley Royal—Fountains Hall—York—Eboracum—York Minster—Clifford's Tower—Castle Howard—Kirkham Priory—Flamborough Head—Scarborough—Whitby Abbey—Durham Cathedral and Castle—St. Cuthbert—The Venerable Bede—Battle of Neville's Cross—Chester-le-Street—Lumley Castle—Newcastle-upon-Tyne—Hexham—Alnwick Castle—Hotspur and the Percies—St. Michael's Church—Hulne Priory—Ford Castle—Flodden Field—The Tweed—Berwick—Holy Isle—Lindisfarne—Bamborough—Grace Darling | 224 | |

| VI | ||

| LONDON, WESTWARD TO MILFORD HAVEN. | ||

| The Cotswolds—The River Severn—Gloucester—Berkeley Castle—New Inn—Gloucester Cathedral—Lampreys—Tewkesbury; its Mustard, Abbey, and Battle—Worcester; its Battle—Charles II.'s Escape—Worcester Cathedral—The Malvern Hills—Worcestershire Beacon—Herefordshire Beacon—Great Malvern—St. Anne's Well—The River Wye—Clifford Castle—Hereford—Old Butcher's Row—Nell Gwynne's Birthplace—Ross—The Man of Ross—Ross Church and its Trees—Walton Castle—Goodrich Castle—Forest of Dean—Coldwell—Symond's Vat—The Dowards—Monmouth—Kymin Hill—Raglan Castle—Redbrook—St. Briard Castle—Tintern Abbey—The Wyncliff—Wyntour's Leap—Chepstow Castle—The River Monnow—The Golden Valley—The Black Mountains—Pontrilas Court—Ewias Harold—Abbey Dore—The Scyrrid Vawr—Wormridge—Kilpeck—Oldcastle—Kentchurch—Grosmont—The Vale of Usk—Abergavenny—Llanthony Priory—Walter Savage Landor—Capel-y-Ffyn—Newport—Penarth Roads—Cardiff—The Rocking-Stone—Llandaff—Caerphilly Castle and its Leaning Tower—Swansea—The Mumbles—Oystermouth Castle—Neath Abbey—Caermarthen—Tenby—Manorbeer Castle—Golden Grove—Pembroke—Milford—Haverfordwest—Milford Haven—Pictou Castle—Carew Castle | 337 | |

| VII | ||

| LONDON, SOUTH-WEST TO LAND'S END. | ||

| Virginia Water—Sunninghill—Ascot—Wokingham—Bearwood—The London Times—White Horse Hill—Box Tunnel—Salisbury—Salisbury Plain—Old Sarum—Stonehenge—Amesbury—Wilton House—The Earls of Pembroke—Carpet-making—Bath—William Beckford—Fonthill—Bristol—William Canynge—Chatterton—Clifton—Brandon Hill—Well—The Mendips—Jocelyn—Beckington—Ralph of Shrewsbury—Thomas Ken—The Cheddar Cliffs—The Wookey Hole—The Black Down—The Isle of Avelon—Glastonbury—Weary-all Hill—Sedgemoor—The Isle of Athelney—Bridgewater—Oldmixon—Monmouth's Rebellion—Weston Zoyland—King Alfred—Sherborne—Sir Walter Raleigh—The Coast of Dorset—Poole—Wareham—Isle of Purbeck—Corfe Castle—The Foreland—Swanage—St. Aldhelm's Head—Weymouth—Portland Isle and Bill—The Channel Islands—Jersey—Corbière Promontory—Mount Orgueil—Alderney—Guernsey—Castle Comet—The Southern Coast of Devon—Abbotsbury—Lyme Regis—Axminster—Sidmouth—Exmouth—Exeter—William, Prince of Orange—Exeter Cathedral—Bishop Trelawney—Dawlish—Teignmouth—Hope's Nose—Babbicombe Bay—Anstis Cove—Torbay—Torquay—Brixham—Dartmoor—The River Dart—Totnes—Berry Pomeroy Castle—Dartmouth—The River Plym—The Dewerstone—Plympton Priory—Sir Joshua Reynolds—Catwater Haven—Plymouth—Stonehouse—Devonport—Eddystone Lighthouse—Tavistock Abbey—Buckland Abbey—Lydford Castle—The Northern Coast of Devon—Exmoor—Minehead—Dunster—Dunkery Beacon—Porlock Bay—The River Lyn—Oare—Lorna Doone—Jan Ridd—Lynton—Lynmouth—Castle Rock—The Devil's Cheese-Ring—Combe Martin—Ilfracombe—Norte Point—Morthoe—Barnstable—Bideford—Clovelly—Lundy Island—Cornwall—Tintagel—Launceston—Liskeard—Fowey—Lizard Peninsula—Falmouth—Pendennis Castle—Helston—Mullyon Cove—Smuggling—Kynance Cove—The Post-Office—Old Lizard Head—Polpeor—St. Michael's Mount—Penzance—Pilchard Fishery—Penwith—Land's End | 384 | |

| VIII | ||

| LONDON, TO THE SOUTH COAST. | ||

| The Surrey Side—The Chalk Downs—Guildford—The Hog's Back—Albury Down—Archbishop Abbot—St. Catharine's Chapel—St. Martha's Chapel—Albury Park—John Evelyn—Henry Drummond—Aldershot Camp—Leith Hill—Redland's Wood—Holmwood Park—Dorking—Weller and the Marquis of Granby Inn—Deepdene—Betchworth Castle—The River Mole—Boxhill—The Fox and Hounds—The Denbies—Ranmore Common—Battle of Dorking—Wotton Church—Epsom—Reigate—Pierrepoint House—Longfield—The Weald of Kent—Goudhurst—Bedgebury Park—Kilndown—Cranbrook—Bloody Baker's Prison—Sissinghurst—Bayham Abbey—Tunbridge Castle—Tunbridge Wells—Penshurst—Sir Philip Sidney—Hever Castle—Anne Boleyn—Knole—Leeds Castle—Tenterden Steeple and the Goodwin Sands—Rochester—Gad's Hill—Chatham—Canterbury Cathedral—St. Thomas à Becket—Falstaff Inn—Isle of Thanet—Ramsgate—Margate—North Foreland—The Cinque Ports—Sandwich—Rutupiæ—Ebbsfleet—Goodwin Sands—Walmer Castle—South Foreland—Dover—Shakespeare's Cliff—Folkestone—Hythe—Romney—Dungeness—Rye—Winchelsea—Hastings—Pevensey—Hailsham—Hurstmonceux Castle—Beachy Head—Brighton—The Aquarium—The South Downs—Dichling Beacon—Newhaven—Steyning—Wiston Manor—Chanctonbury Ring—Arundel Castle—Chichester—Selsey Bill—Goodwood—Bignor—Midhurst—Cowdray—Dunford House—Selborne—Gilbert White; his book; his house, sun-dial, and church—Greatham Church—Winchester—The New Forest—Lyndhurst—Minstead Manor—Castle Malwood—Death of William Rufus—Rufus's Stone—Beaulieu Abbey—Brockenhurst—Ringwood—Lydington—Christchurch—Southampton—Netley Abbey—Calshot Castle—The Solent—Portsea Island—Portsmouth—Gosport—Spithead—The Isle of Wight—High Down—Alum Bay—Yarmouth—Cowes—Osborne House—Ryde—Bratling—Sandown—Shanklin Chine—Bonchurch—The Undercliff—Ventnor—Niton—St. Lawrence Church—St. Catharine's Down—Blackgang Chine—Carisbrooke Castle—Newport—Freshwater—Brixton—The Needles | 463 | |

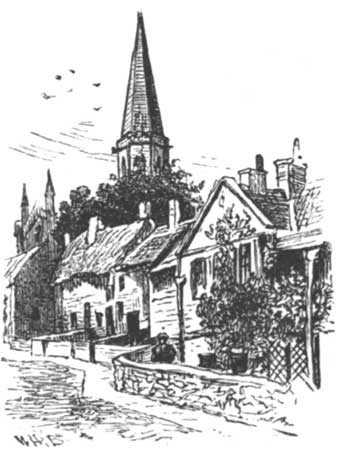

MARKET-PLACE, PETERBOROUGH.

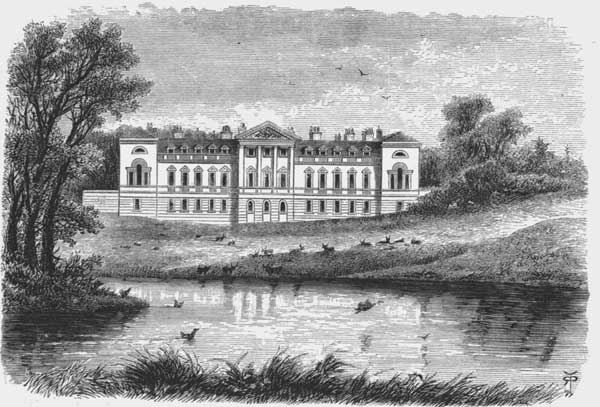

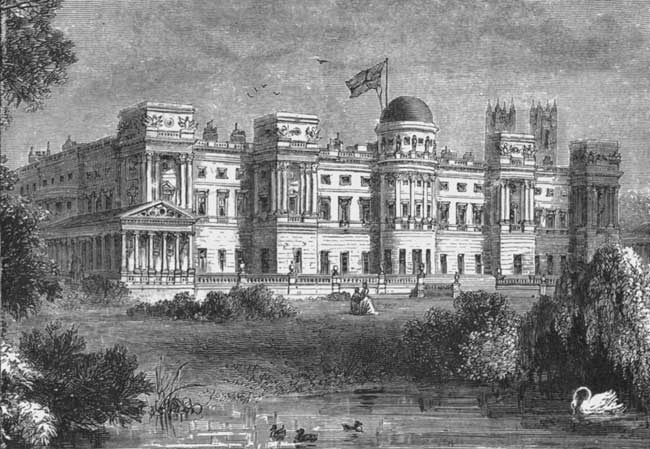

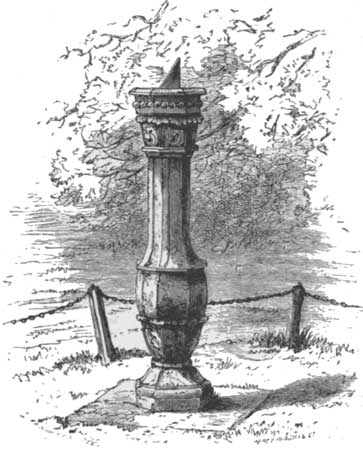

MARKET-PLACE, PETERBOROUGH.| Alton Towers | Frontispiece. |

| The Old Mill, Selborne | Title-Page. |

| Market-place, Peterborough | After Contents. |

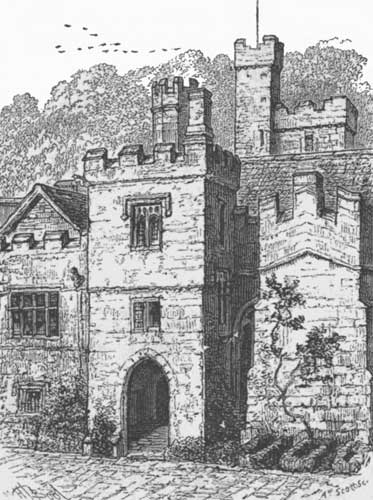

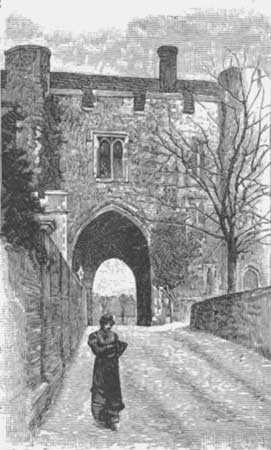

| The Pottergate, Alnwick | 16 |

| Perch Rock Light | 17 |

| St. George's Hall, Liverpool | 19 |

| Chester Cathedral, Exterior | 21 |

| Chester Cathedral, Interior | 21 |

| Julius Cæsar's Tower, Chester | 22 |

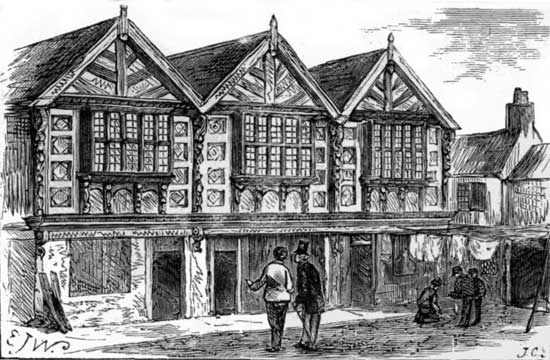

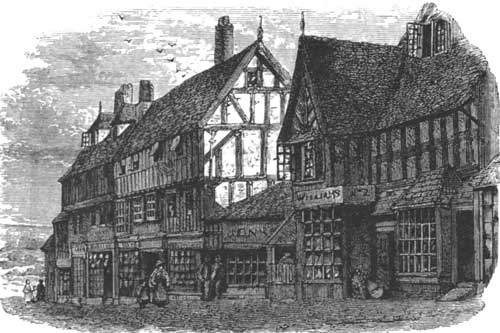

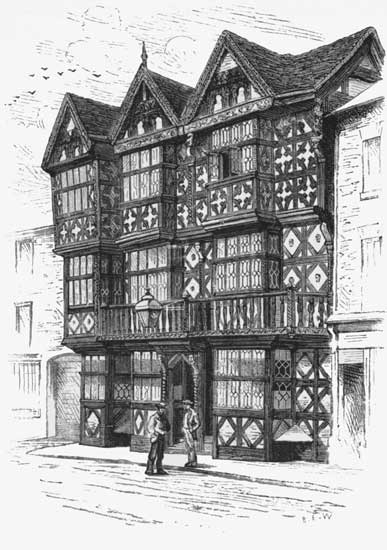

| Ancient Front, Chester | 22 |

| God's Providence House, Chester | 23 |

| Bishop Lloyd's Palace, Chester | 23 |

| Old Lamb Row, Chester | 23 |

| Stanley House, Front, Chester | 24 |

| Stanley House, Rear, Chester | 24 |

| Phœnix Tower, Chester | 25 |

| Water Tower, Chester | 25 |

| Abbey Gale, Chester | 26 |

| Ruins of St. John's Chapel, Chester | 26 |

| Plas Newydd, Llangollen | 28 |

| Ruins of Valle-Crucis Abbey | 29 |

| Wynnstay | 30 |

| Pont Cysylltau | 30 |

| Wrexham Tower | 31 |

| The Roodee, from the Railway-bridge, Chester | 32 |

| The "Sands o' Dee" | 33 |

| Menai Strait | 36 |

| Beaumaris Castle | 37 |

| Bangor Cathedral | 37 |

| Caernarvon Castle | 39 |

| Conway Castle, from the Road to Llanrwst | 40 |

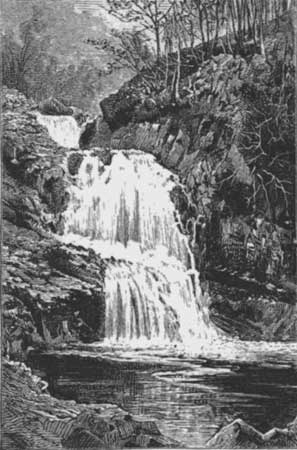

| Falls of the Conway | 41 |

| Swallow Falls | 42 |

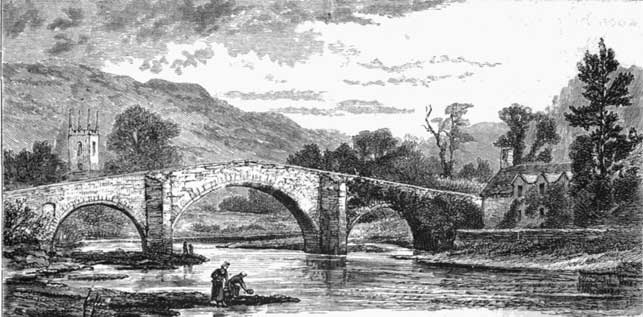

| Llanrwst Bridge | 43 |

| Barmouth | 44 |

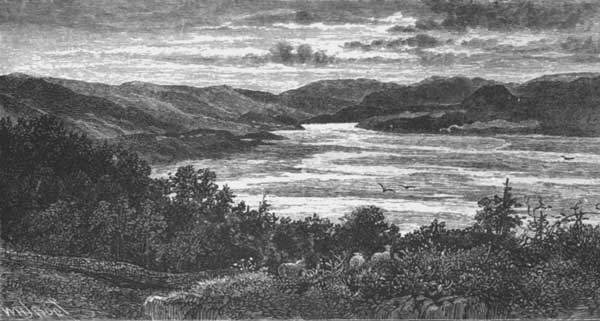

| Barmouth Estuary | 45 |

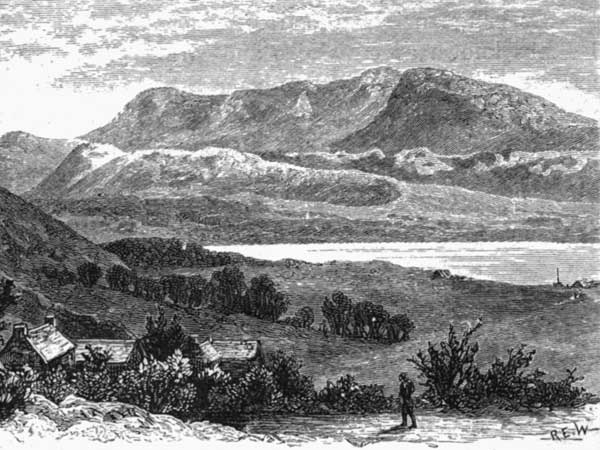

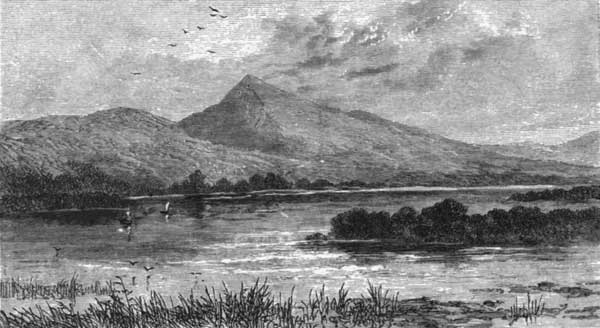

| Cader Idris, on the Taly-slyn Ascent | 46 |

| Rhayadr-y-Mawddach | 46 |

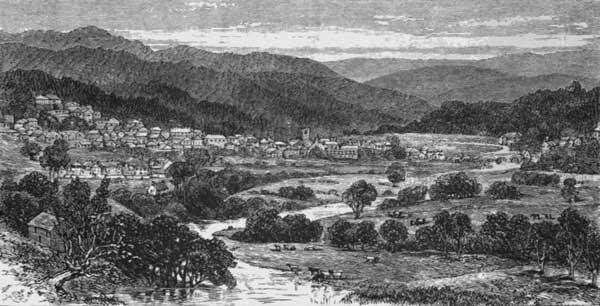

| Dolgelly | 47 |

| Owen Glendower's Parliament House, Dolgelly | 47 |

| Lower Bridge, Torrent Walk, Dolgelly | 48 |

| Bala Lake | 48 |

| Aberystwith | 49 |

| Harlech Castle | 50 |

| Old Market, Warrington | 51 |

| Manchester Cathedral, from the South-east | 53 |

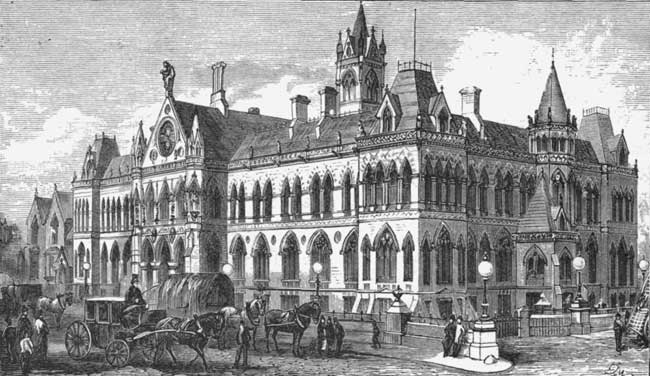

| Assize Courts, Manchester | 54 |

| Royal Exchange, Manchester | 55 |

| Furness Abbey | 56 |

| Castle Square, Lancaster | 58 |

| Bradda Head, Isle of Man | 59 |

| Kirk Bradden, Isle of Man | 59 |

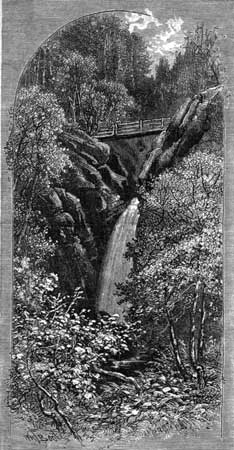

| Rhenass Waterfall, Isle of Man | 60 |

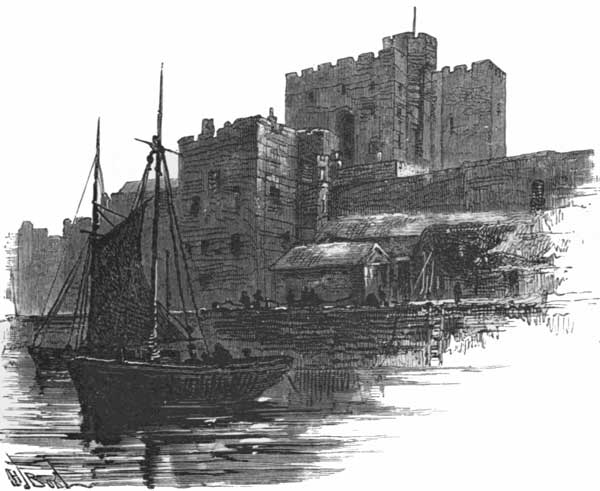

| Castle Rushen, Isle of Man | 61 |

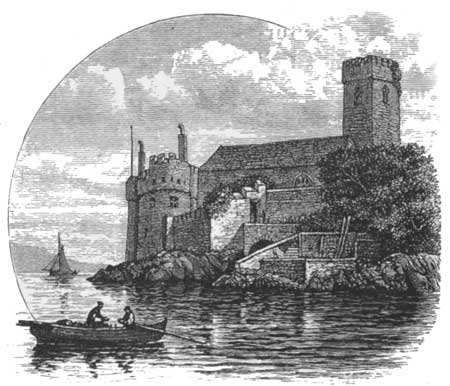

| Peele Castle, Isle of Man | 63 |

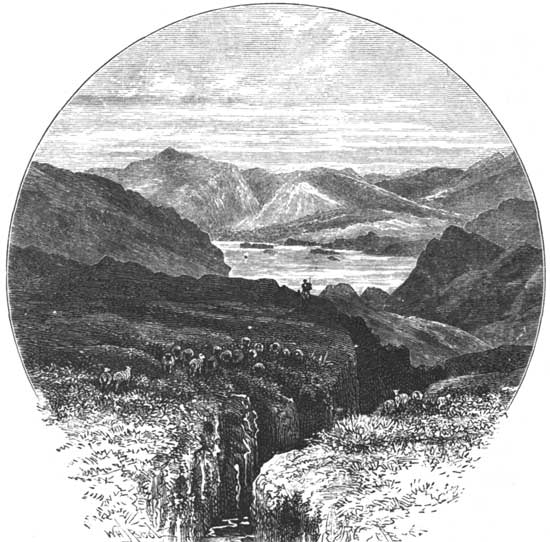

| Glimpse of Derwentwater, from Scafell | 64 |

| Falls of Lodore, Derwentwater | 65 |

| Road through the Cathedral Close, Carlisle | 68 |

| View on the Torrent Walk, Dolgelly | 69 |

| Peveril Castle, Castleton | 71 |

| Hardwicke Hall | 72 |

| Hardwicke Hall, Elizabethan Staircase | 73 |

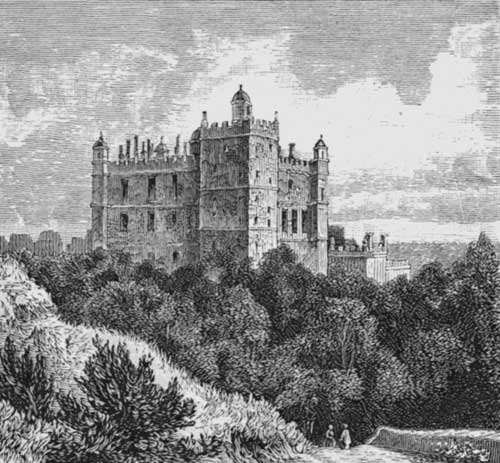

| Bolsover Castle | 74 |

| The Crescent, Buxton | 75 |

| Bakewell Church | 76 |

| Haddon Hall, from the Wye | 77 |

| Haddon Hall, Entrance to Banquet-hall | 78 |

| Haddon Hall, the Terrace | 79 |

| The Peacock Inn from the Road | 81 |

| Chatsworth House, from the South-west | 81 |

| Chatsworth House, Door to State Drawing-room | 82 |

| Chatsworth House, State Drawing-room | 82 |

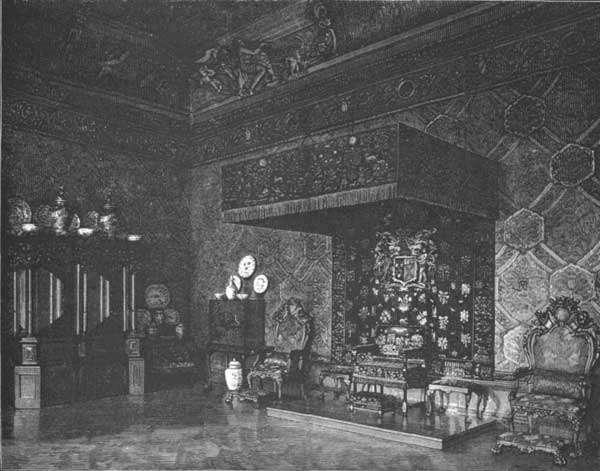

| Chatsworth House, State Bedroom | 83 |

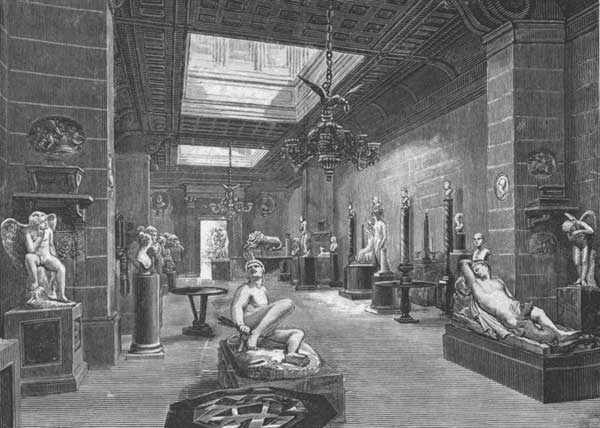

| Chatsworth House, the Sculpture-gallery | 84 |

| Chatsworth House, Gateway to Stable | 85 |

| High Tor, Matlock | 85 |

| The Straits, Dovedale | 86 |

| Banks of the Dove | 86 |

| Tissington Spires, Dovedale | 87 |

| Trentham Hall | 89 |

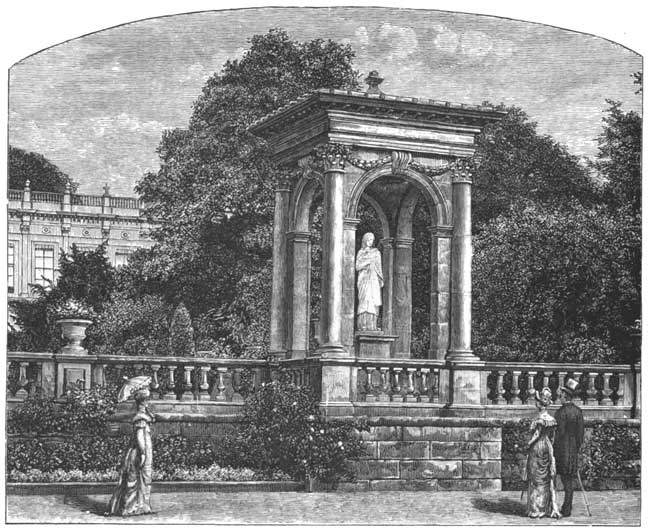

| Trentham Hall—on the Terrace | 90 |

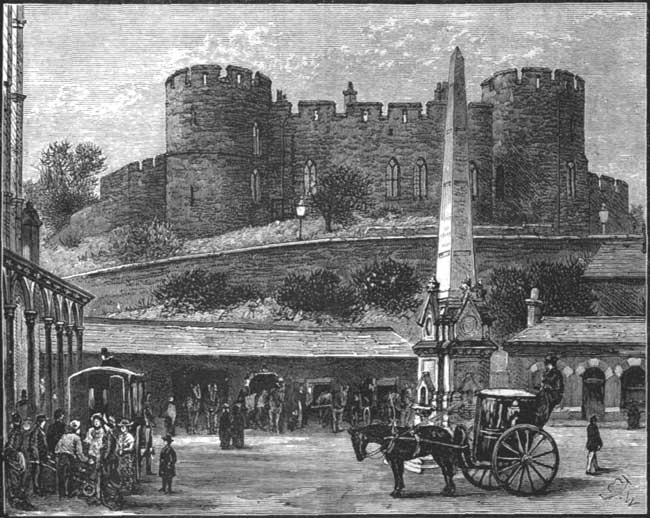

| Shrewsbury Castle, from the Railway-station | 93 |

| Head-quarters of Henry VII. on his Way to Bosworth Field, Shrewsbury | 94 |

| On Battlefield Road, Shrewsbury | 94 |

| Bridgenorth, from near Oldbury | 95 |

| Bridgenorth, Keep of the Castle | 95 |

| Bridgenorth, House where Bishop Percy was born | 96 |

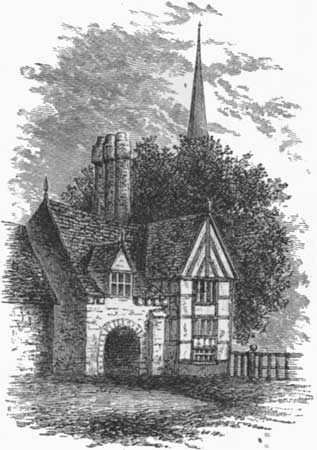

| Lodge of Much Wenlock Abbey | 96 |

| Wenlock | 97 |

| Ludlow Castle[Pg 12] | 98 |

| Ludlow Castle, Entrance to the Council-chamber | 99 |

| The Feathers Hotel, Ludlow | 100 |

| Lichfield Cathedral, West Front | 101 |

| Lichfield Cathedral, Interior, looking West | 101 |

| Lichfield Cathedral, Rear View | 102 |

| Dr. Johnson's Birthplace, Lichfield | 103 |

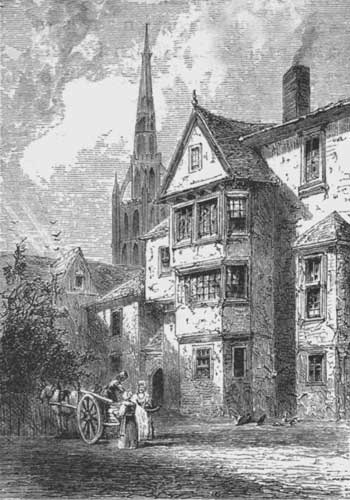

| Coventry Gateway | 105 |

| Coventry | 106 |

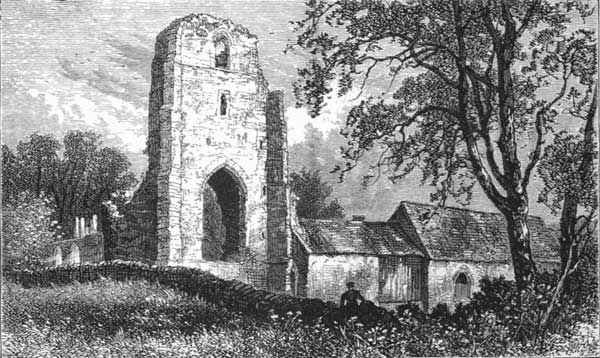

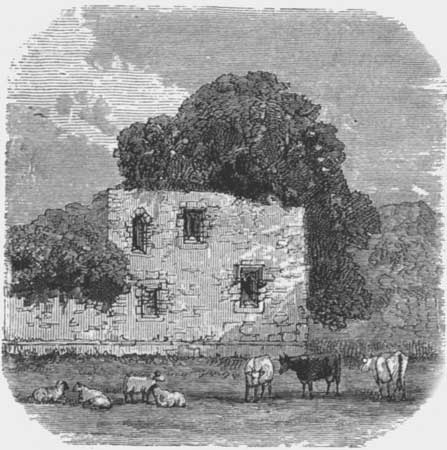

| Ruins of Bradgate House | 108 |

| Ruins of Ulverscroft Priory | 109 |

| Ruins of Grace Dieu Abbey | 110 |

| Leicester Abbey | 111 |

| Gateway, Newgate Street, Leicester | 112 |

| Edgehill | 113 |

| Edgehill, Mill at | 115 |

| Church and Market-hall, Market Harborough | 117 |

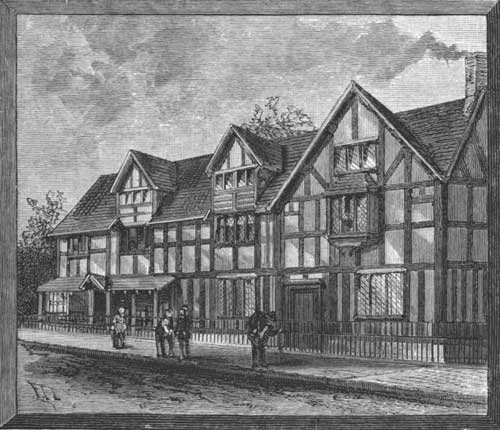

| Shakespeare's House, Stratford | 118 |

| Anne Hathaway's Cottage, Shottery | 119 |

| Warwick Castle | 120 |

| Leicester's Hospital, Warwick | 122 |

| Oblique Gables in Warwick | 122 |

| Kenilworth Castle | 123 |

| St. Martin's Church, Birmingham | 124 |

| Aston Hall, Birmingham | 125 |

| Aston Hall, the "Gallery of the Presence" | 126 |

| The Town-hall, Birmingham | 127 |

| Elstow, Bedford | 130 |

| Elstow Church | 130 |

| Elstow Church, North Door | 131 |

| Woburn Abbey, West Front | 132 |

| Woburn Abbey, the Sculpture-gallery | 133 |

| Woburn Abbey, Entrance to the Puzzle garden | 134 |

| Thames Head | 138 |

| Dovecote, Stanton Harcourt | 140 |

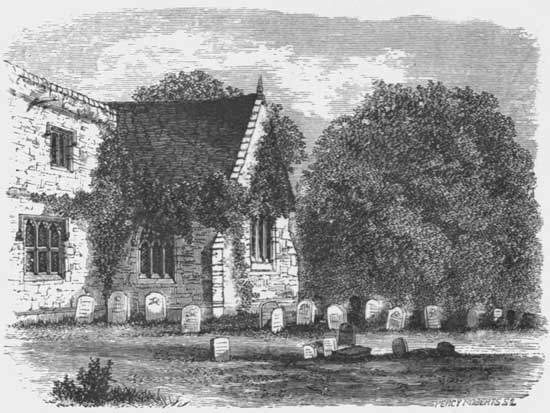

| Cumnor Churchyard | 141 |

| Godstow Nunnery | 142 |

| Magdalen College, Oxford, from the Cherwell | 143 |

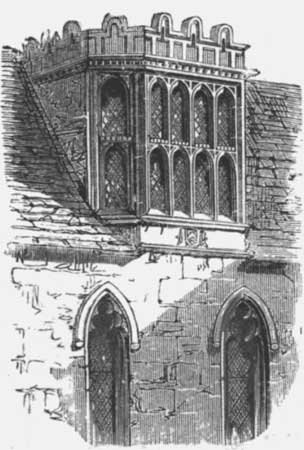

| Magdalen College, Stone Pulpit | 144 |

| Magdalen College, Bow Window | 144 |

| Gable at St. Aldate's College, Oxford | 144 |

| Dormer Window, Merton College, Oxford | 144 |

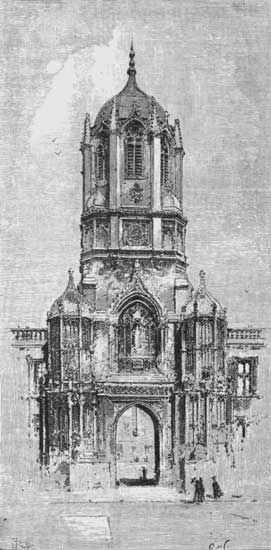

| Gateway of Christ Church College, Oxford | 145 |

| Merton College Chapel, Oxford | 146 |

| Merton College Gateway | 146 |

| Oriel College, Oxford | 147 |

| Magdalen College Cloisters, Oxford | 148 |

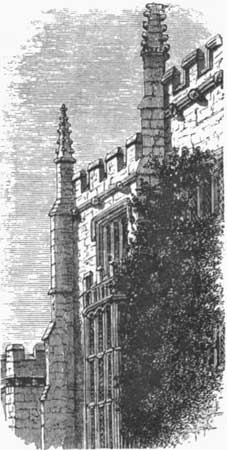

| Magdalen College, Founders' Tower | 149 |

| Magdalen College | 150 |

| New College, Oxford, from the Garden | 151 |

| New College | 152 |

| The Radcliffe Library, from the Quadrangle of Brasenose, Oxford | 152 |

| Dining-hall, Exeter College, Oxford | 153 |

| Trinity College Chapel, Oxford | 153 |

| Window in St. John's College, Garden Front, Oxford | 154 |

| Tower St. John's College, Oxford | 154 |

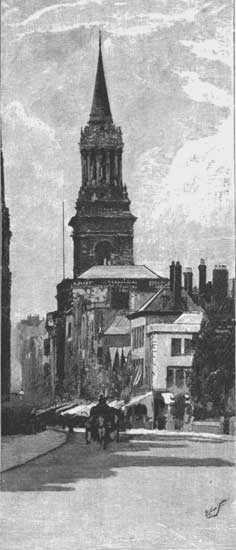

| St. Mary the Virgin, from High Street, Oxford | 155 |

| All Saints, from High Street, Oxford | 156 |

| Carfax Conduit | 157 |

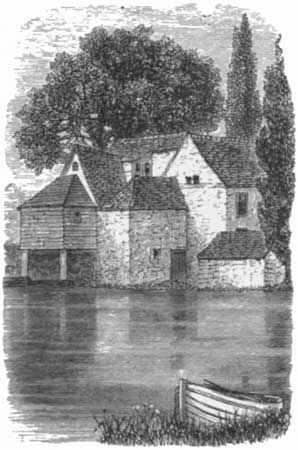

| Iffley Mill | 157 |

| Iffley Church | 158 |

| Cromwell's Parliament-house, Banbury | 159 |

| Berks and Wilts Canal | 160 |

| Chaucer's House, Woodstock | 161 |

| Old Remains at Woodstock | 162 |

| Blenheim Palace, from the Lake | 163 |

| Bicester Priory | 165 |

| Bicester Market | 166 |

| Cross at Eynsham | 166 |

| Entrance to Abingdon Abbey | 167 |

| Radley Church | 168 |

| The Thames at Clifton-Hampden | 170 |

| Bray Church | 171 |

| Eton College, from the Playing Fields | 173 |

| Eton College, from the Cricket-ground | 173 |

| Windsor Castle, from the Brocas | 174 |

| Windsor Castle Round Tower, West End | 175 |

| Windsor Castle, Queen's Rooms in South-east Tower | 176 |

| Windsor Castle, Interior of St. George's Chapel | 177 |

| Magna Charta Island | 178 |

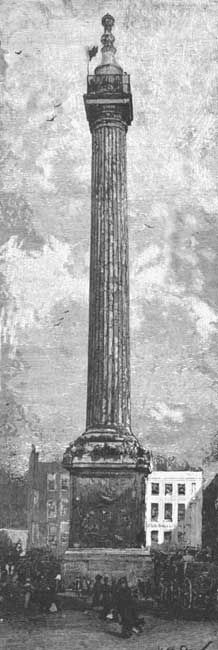

| The Monument, London | 180 |

| St. Paul's Cathedral, London | 182 |

| St. Paul's Cathedral, South Side | 183 |

| St. Paul's Cathedral, the Choir | 183 |

| St. Paul's Cathedral, Wellington Monument | 184 |

| Westminster Abbey, London | 185 |

| Westminster Abbey, Cloisters of | 186 |

| Westminster Abbey, Interior of Choir | 187 |

| Westminster Abbey, King Henry VII.'s Chapel | 188 |

| The Tower of London, Views in | 191 |

| The Church of St. Peter, on Tower Green | 193 |

| The Lollards' Tower, Lambeth Palace, London | 194 |

| St. Mary-le-Bow, London | 195 |

| St. Bride's, Fleet Street, London. | 195 |

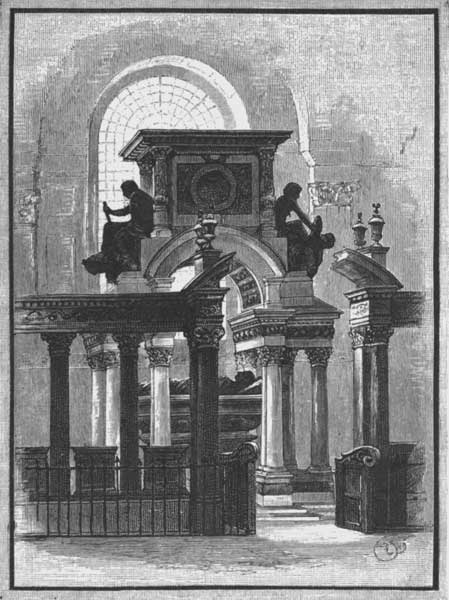

| Chapel Royal, Whitehall, London | 196 |

| Chapel Royal, Interior of (Banqueting-hall) | 197 |

| The Horse Guards, from the Parade-ground, London | 198 |

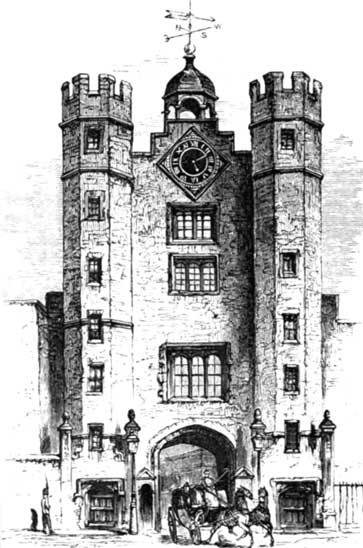

| Gateway of St. James Palace, London | 199 |

| Buckingham Palace, Garden Front, London | 200 |

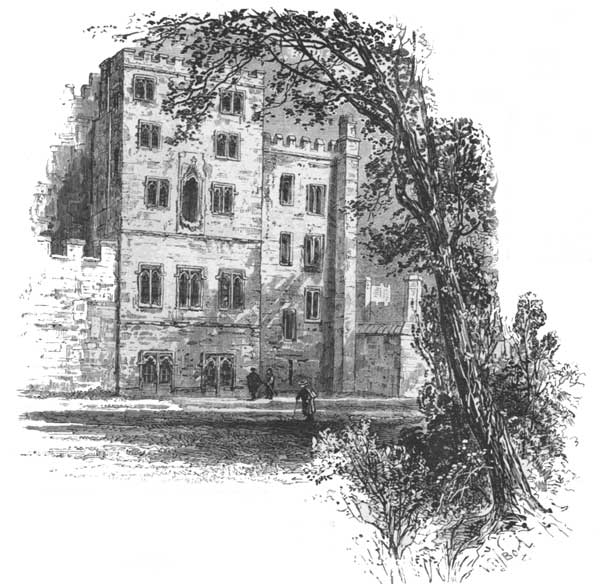

| Kensington Palace, West Front, London | 201 |

| Victoria Tower, Houses of Parliament, London | 203 |

| Interior of the House of Commons | 204 |

| The Marble Arch, Hyde Park, London Principal Entrance New Museum of Natural History, | 205 |

| The Albert Memorial, Hyde Park | 206 |

| South Kensington, London | 207 |

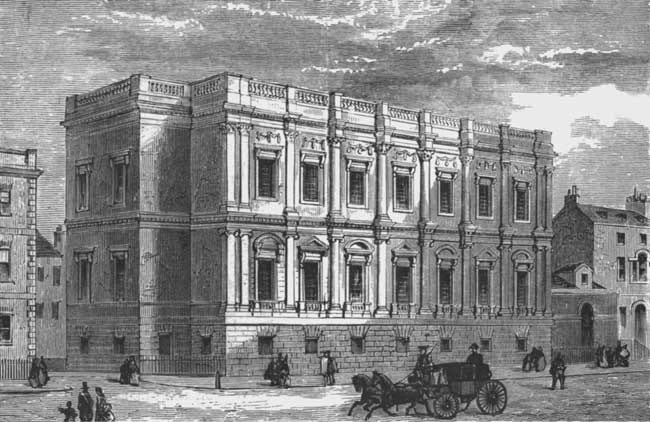

| Royal Exchange, London | 208 |

| Bank of England, London | 208 |

| Mansion House, London | 209 |

| The Law Courts, London[Pg 13] | 210 |

| Sir Paul Finder's House, London | 211 |

| Waterloo Bridge, London | 212 |

| Schomberg House, London | 213 |

| Statue of Sidney Herbert, Pall Mall, London | 213 |

| Doorway, Beaconsfield Club, London | 214 |

| Cavendish Square, London | 214 |

| The "Bell Inn" at Edmonton | 215 |

| The "Old Tabard Inn," London. | 216 |

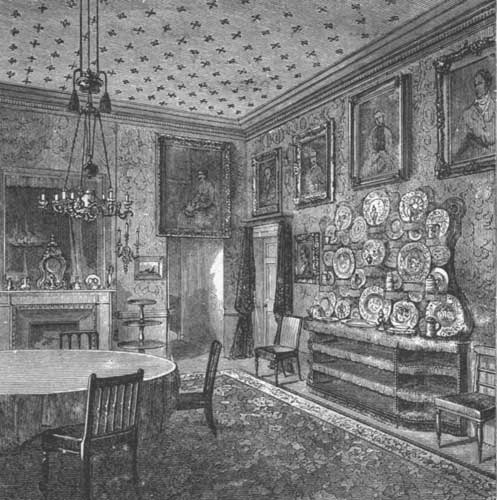

| Holland House, South Side | 217 |

| Holland House, Dining-Room | 218 |

| Holland House, the Dutch Garden | 218 |

| Holland House, the Library | 219 |

| Holland House, Rogers's Seat in the Dutch Garden | 219 |

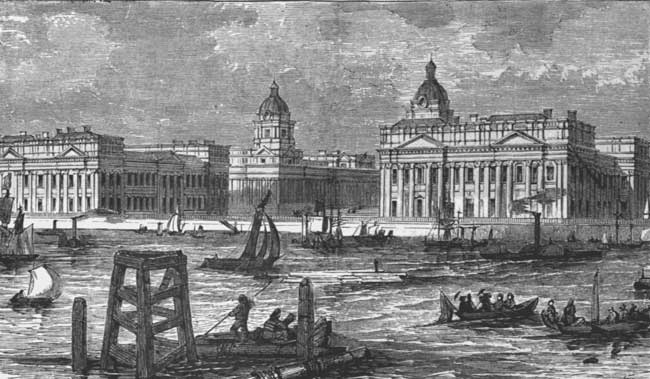

| Greenwich Hospital, from the River | 221 |

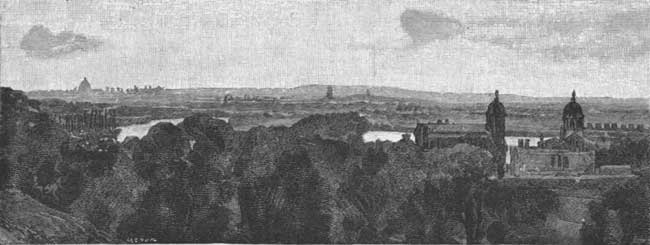

| London, from Greenwich Park | 222 |

| St. Albans, from Verulam | 225 |

| Old Wall at Verulam | 226 |

| Monastery Gate, St. Albans | 226 |

| The Tower of the Abbey, St. Albans | 227 |

| Staircase to Watching Gallery, St. Albans | 227 |

| Shrine and Watching Gallery, St. Albans | 228 |

| Clock Tower, St. Albans | 229 |

| Barnard's Heath | 229 |

| St. Michael's, Verulam | 230 |

| Queen Elizabeth's Oak, Hatfield | 231 |

| Hatfield House | 232 |

| Hatfield House, the Corridor | 233 |

| View through Old Gateway, Hatfield | 234 |

| Audley End, Western Front | 235 |

| Views in Saffron Walden | 237 |

| Town-hall. | |

| Church. | |

| Entrance to the Town. | |

| Jetties at Harwich | 238 |

| Bridge, St. John's College, Cambridge | 239 |

| Hall of Trinity College, Cambridge | 241 |

| St. John's Chapel, Cambridge | 242 |

| Back of Clare College, Cambridge | 244 |

| King's College Chapel—Interior—Cambridge | 245 |

| King's College Chapel, Doorway of | 246 |

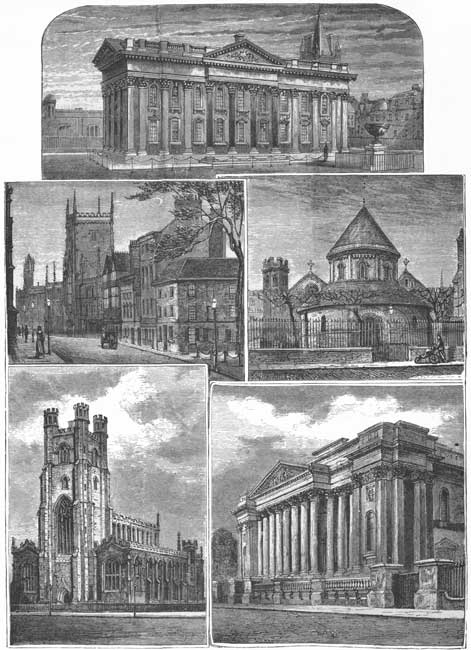

| Scenes in Cambridge | 247 |

| The Senate House. | |

| The Pitt Press. | |

| Great St. Mary's. | |

| The Fitzwilliam Museum. | |

| The Round Church. | |

| Gateway, Jesus College, Cambridge | 249 |

| Hengrave Hall | 250 |

| Road leading to Ely Close | 250 |

| Ely Cathedral, from the Railway Bridge | 251 |

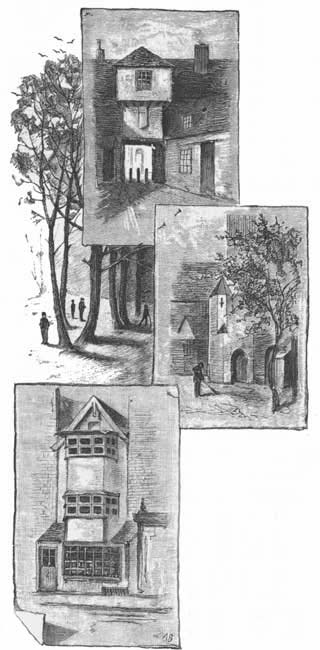

| Old Bits in Ely | 252 |

| Old Passage from Ely Street to Cathedral Ford. | |

| Entrance to Prior Crawdon's Chapel. | |

| Old Houses In High Street. | |

| Peterborough Cathedral | 253 |

| Peterborough Cathedral, Aisle and Choir | 254 |

| East End of Crowland Abbey | 255 |

| Norwich Castle | 257 |

| Norwich Cathedral | 258 |

| Norwich Cathedral—the Choir, looking East | 259 |

| Norwich Market-place | 260 |

| Burghley House | 261 |

| Lincoln Cathedral, from the South-west | 264 |

| "Bits" from Lincoln | 265 |

| The Cloisters. | |

| The Angel Choir. | |

| The High Bridge. | |

| Nottingham Castle | 267 |

| Southwell Minster and Ruins of the Archbishop's Palace | 268 |

| Southwell Minster, the Nave | 269 |

| Clumber Hall | 271 |

| Welbeck Abbey | 272 |

| Newark Castle, Front | 274 |

| Newark Castle and Dungeon | 275 |

| Newark Market-square | 276 |

| Newark Church, looking from the North | 276 |

| The Humber at Hull | 277 |

| House where Wilberforce was born, Hull | 278 |

| Beverley, Entrance-Gate | 278 |

| Beverley, Market-square | 279 |

| Manor House, Sheffield | 280 |

| Entrance to the Cutlers' Hall, Sheffield | 281 |

| Edward IV.'s Chapel, Wakefield Bridge | 282 |

| Wakefield | 283 |

| Briggate, Leeds, looking North | 283 |

| St. John's Church, Leeds | 284 |

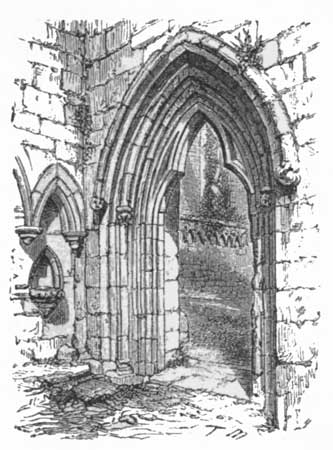

| Bolton Abbey, Gateway in the Priory | 286 |

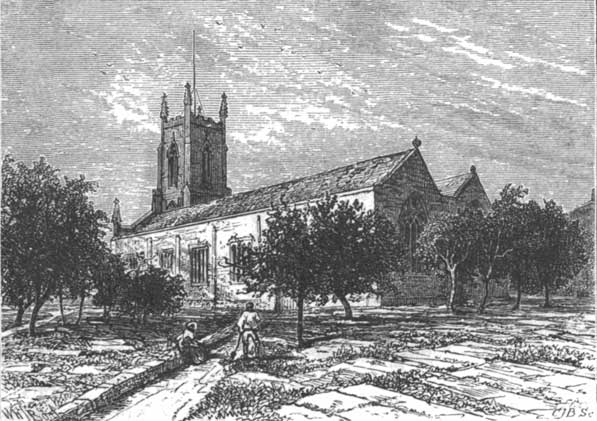

| Bolton Abbey, the Churchyard | 286 |

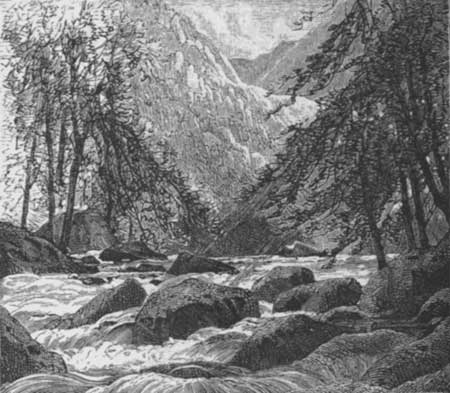

| The Strid | 287 |

| Ripon Minster | 288 |

| Studley Royal Park | 289 |

| Fountains Abbey, the Transept | 290 |

| Fountains Abbey, Tower and Crypt | 291 |

| Fountains Hall | 292 |

| Richmond Castle | 293 |

| The Multangular Tower and Ruins of St. Mary's Abbey, York | 294 |

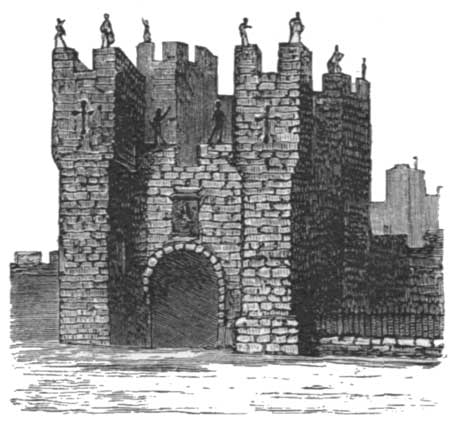

| Micklegate Bar and the Red Tower, York | 297 |

| York Minster | 298 |

| York Minster, the Choir | 299 |

| York Minster, Tomb of Archbishop DeGrey | 300 |

| Clifford's Tower, York | 301 |

| The Shambles, York | 302 |

| Castle Howard, South Front | 303 |

| Castle Howard, the Obelisk | 304 |

| Castle Howard, the Temple, with the Mausoleum in the distance | 305 |

| Gateway, Kirkham Priory | 306 |

| Scarborough Spa and Esplanade | 308 |

| Scarborough, from the Sea | 309 |

| Whitby Abbey | 311 |

| Durham, General View of the Cathedral and Castle | 312 |

| Durham Castle, Norman Doorway | 313 |

| Durham Cathedral, from an old Homestead on the Wear | 315 |

| Durham Cathedral, the Nave | 316 |

| Durham Cathedral, the Choir, looking West | 317 |

| Durham Cathedral, the Galilee and Tomb of Bede | 318 |

| Lumley Castle | 320 |

| Lumley Castle, Gateway from the Walk[Pg 14] | 321 |

| Hexham | 322 |

| Alnwick Castle, from the Lion bridge | 323 |

| Alnwick Castle, the Barbican Gate | 323 |

| Alnwick Castle, the Barbican | 324 |

| Alnwick Castle, the Barbican, Eastern Angle | 325 |

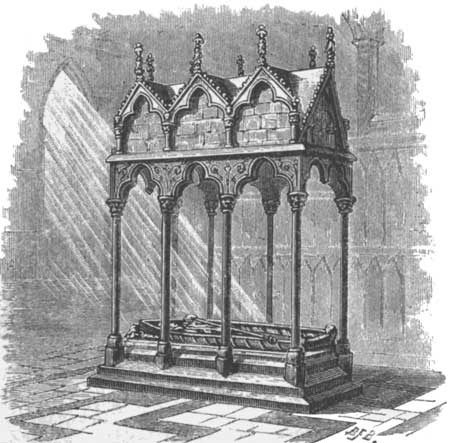

| Alnwick Castle, the Percy Bedstead | 326 |

| Alnwick Castle, the Percy Cross | 326 |

| Alnwick Castle, Constable's Tower | 327 |

| Alnwick Castle, Earl Hugh's Tower | 328 |

| Alnwick Castle, Draw-Well and Norman Gateway | 329 |

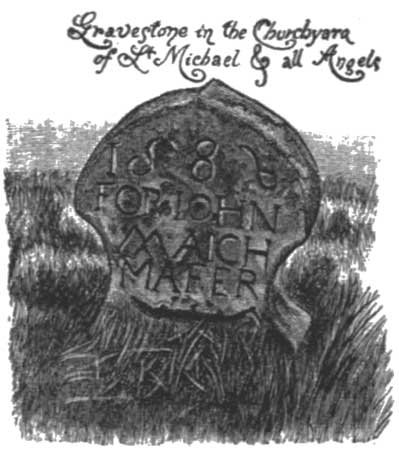

| Alnwick Castle, Gravestone in the Churchyard of St. Michael's and All Angels | 329 |

| Alnwick Castle, Font Lectern, St. Michael's Church | 330 |

| Hulne Priory, Porter's Lodge | 330 |

| Ford Tower, overlooking Flodden | 331 |

| The Cheviots, from Ford Castle | 332 |

| Flodden, from the King's Bedchamber, Ford Castle | 333 |

| Ford Castle, the Crypt | 335 |

| Grace Darling's Monument, Bamborough | 336 |

| Gloucester Cathedral, from the South-east | 338 |

| Gloucester, the New Inn | 340 |

| Gloucester Cathedral, the Monks' Lavatory | 342 |

| Tewkesbury | 343 |

| Tewkesbury Abbey | 344 |

| Tewkesbury Abbey, Choir | 345 |

| Worcester Cathedral, from the Severn | 346 |

| Worcester Cathedral, Choir | 348 |

| Ruins of the Guesten Hall, Worcester | 349 |

| Close in Worcester | 350 |

| St. Anne's Well, Malvern | 352 |

| Butchers' Row, Hereford | 353 |

| Out-house where Nell Gwynne was born, Hereford | 353 |

| Hereford Cathedral | 354 |

| Hereford Cathedral, Old Nave | 355 |

| Ross, House of the "Man of Ross" | 356 |

| Ross Market-place | 357 |

| Ross Church | 358 |

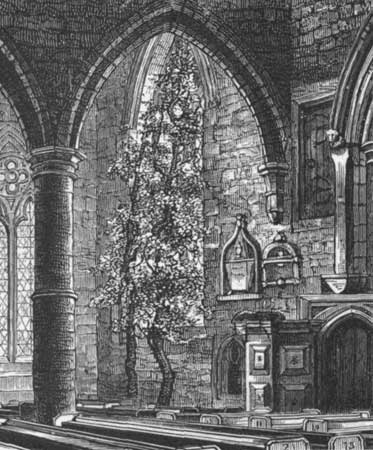

| Ross Church, the Tree, in | 358 |

| Ruins of Goodrich Castle | 359 |

| Bend in the Wye | 360 |

| Symond's Yat, the Wye | 361 |

| Monmouth Bridge | 363 |

| Monmouth Bridge, Gate on | 363 |

| Raglan Castle | 364 |

| Tintern Abbey, from the Highroad | 365 |

| Chepstow Castle | 368 |

| Pontrilas Court | 370 |

| The Scyrrid Vawr | 371 |

| Llanthony Priory, looking down the Nave | 373 |

| Llanthony Priory, the South Transept | 374 |

| Swansea, North Dock | 377 |

| Swansea Castle | 378 |

| The Mumbles | 379 |

| Oystermouth Castle | 380 |

| Neath Abbey, ruins | 381 |

| Bearwood, Berkshire, Residence of John Walter, Esq., proprietor of London Times | 385 |

| Salisbury Cathedral | 387 |

| Salisbury Market | 388 |

| Stonehenge | 390 |

| Wilton House | 392 |

| Wilton House, Fireplace in Double Cube Room | 393 |

| Wilton House, the Library | 393 |

| Wilton House, the Library Window | 394 |

| Bristol Cathedral | 398 |

| Norman Doorway, College Green, Bristol | 399 |

| Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol | 400 |

| Wells Cathedral, from the Bishop's Garden | 401 |

| Wells Cathedral, from the Swan Pool | 402 |

| Wells Cathedral, View under Central Tower | 403 |

| Wells, Ruins of the Old Banquet-Hall | 404 |

| Entrance to the Cheddar Cliffs, Wells | 405 |

| High Rocks at Cheddar, Wells | 406 |

| Glastonbury Tribunal | 408 |

| Sedgemoor, from Cock Hill | 409 |

| Weston Zoyland Church | 410 |

| The Isle of Athelney | 412 |

| Sherbourne | 413 |

| Corfe Castle | 416 |

| Studland Church | 418 |

| Ruins of Old Cross in the Churchyard | 418 |

| St. Aldhelm's Head | 419 |

| Portland Isle | 420 |

| Corbière Lighthouse, Jersey | 422 |

| View from Devil's Hole, Jersey | 423 |

| Exeter Cathedral, West Front | 425 |

| Exeter, Ruins of Rougemont Castle | 426 |

| Exeter, Old Houses in Cathedral Close | 426 |

| Exeter Cathedral, from the North-west | 427 |

| Exeter Cathedral, Bishop's Throne | 428 |

| Exeter Cathedral, Minstrel Gallery | 429 |

| Exeter, Guildhall | 429 |

| Babbicombe Bay | 430 |

| Austis Cove | 431 |

| Totnes, from the river | 432 |

| Berry Pomeroy Castle | 433 |

| A Bend of the Dart | 434 |

| Dartmouth Castle | 434 |

| The Dewerstone | 435 |

| Vale of Bickleigh | 436 |

| Plympton Priory, Old Doorway[Pg 15] | 437 |

| Minehead | 440 |

| Dunster | 441 |

| On Porlock Moor | 442 |

| Doone Valley | 443 |

| Bagworthy Water | 444 |

| Jan Ridd's Tree | 444 |

| View on the East Lyn | 445 |

| Castle Rock, Lynton | 445 |

| Devil's Cheese-Ring, Lynton | 446 |

| Tower on Beach, Lynmouth | 447 |

| Ilfracombe | 447 |

| Morte Point | 449 |

| Bideford Bridge | 450 |

| Clovelly, Main Street | 450 |

| Clovelly, Old Houses on Beach | 451 |

| Fowey Pier | 452 |

| Pendennis Castle | 454 |

| Mullyon Cove | 455 |

| Lion Rock, with Mullyon in the distance | 456 |

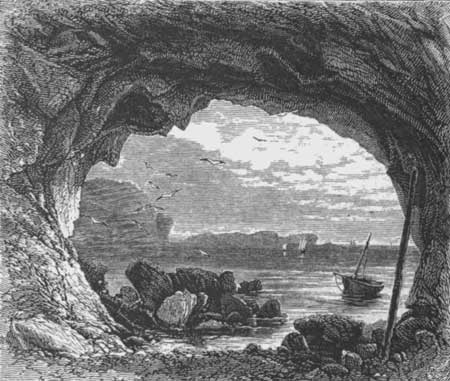

| Cave at Mullyon | 456 |

| Pradenack Point | 457 |

| Kynance Cove | 457 |

| The Post-Office, Kynance | 458 |

| Polpeor | 459 |

| Rocks near the Lizard | 459 |

| St. Michael's Mount | 460 |

| Old Market, Penzance | 461 |

| Land's End | 462 |

| High Street, Guildford | 464 |

| Ruins of St. Catharine's Chapel | 466 |

| Leith Hill | 467 |

| Old Dovecote, Holmwood Park | 468 |

| White Horse Inn, Dorking | 469 |

| Pierrepoint House | 472 |

| Longfield, East Sheen | 473 |

| Ruins of Sissinghurst | 475 |

| Tunbridge Castle | 476 |

| Penshurst Place | 476 |

| Penshurst Church | 477 |

| Hever Castle | 478 |

| Leeds Castle, Gateway | 478 |

| Rochester Castle | 480 |

| Canterbury | 481 |

| Canterbury, Falstaff Inn | 483 |

| Sandwich, the Barbican | 485 |

| Dover Castle, the Pharos | 487 |

| Dover Cattle, Saluting-Battery Gate | 487 |

| Rye, Old Houses | 488 |

| Hurstmonceux Castle | 490 |

| Arundel Castle | 494 |

| Ruins of Cowdray | 494 |

| Selborne, Gilbert White's House | 495 |

| Selborne, Gilbert White's Sun-Dial | 496 |

| Selborne Church | 496 |

| Selborne, Rocky Lane to Alton | 497 |

| Selborne, Wishing-Stone | 498 |

| Greatham Church | 499 |

| Winchester, Cardinal Beaufort's Gate and Brewery | 500 |

| New Forest, from Bramble Hill | 502 |

| New Forest, Rufus's Stone | 503 |

| New Forest, Brockenhurst Church | 505 |

| Christchurch, the Priory from the Quay and Place Mills | 506 |

| Christchurch | 507 |

| Christchurch, Old Norman House and View from Priory | 508 |

| Portsmouth Point | 510 |

| Portsmouth, H.M.S. "Victory" | 511 |

| Cowes Harbor, Isle of Wight | 512 |

| The Needles, from Alum Bay, Isle of Wight | 513 |

| Yarmouth, Isle of Wight | 513 |

| Osborne House, from the Sea, Isle of Wight | 514 |

| Shanklin Chine, Isle of Wight | 516 |

| The Undercliff, Isle of Wight | 517 |

| Carisbrooke Castle, looking from Isle of Wight | 519 |

| Tennyson's House, Isle of Wight | 521 |

| The Needles, Isle of Wight | 522 |

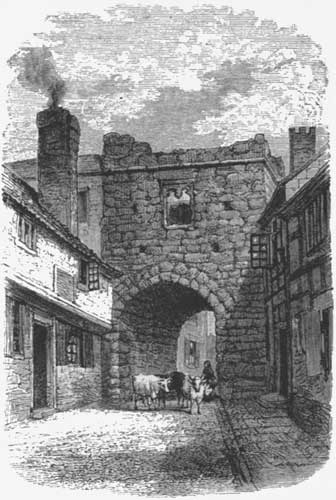

THE POTTERGATE, ALNWICK.

THE POTTERGATE, ALNWICK.

Liverpool—Birkenhead—Knowsley Hall—Chester—Cheshire—Eaton Hall—Hawarden Castle—Bidston—Congleton—Beeston Castle—The river Dee—Llangollen—Valle-Crucis Abbey—Dinas Bran—Wynnstay—Pont Cysylltau—Chirk Castle—Bangor-ys-Coed—Holt—Wrexham—The Sands o' Dee—North Wales—Flint Castle—Rhuddlan Castle—Mold—Denbigh—St. Asaph—Holywell—Powys Castle—The Menai Strait—Anglesea—Beaumaris Castle—Bangor—Penrhyn Castle—Plas Newydd—Caernarvon Castle—Ancient Segontium—Conway Castle—Bettws-y-Coed—Mount Snowdon—Port Madoc—Coast of Merioneth—Barmouth—St. Patrick's Causeway—Mawddach Vale—Cader Idris—Dolgelly—Bala Lake—Aberystwith—Harlech Castle—Holyhead.

THE PERCH ROCK LIGHT.

THE PERCH ROCK LIGHT.

The American transatlantic tourist, after a week or more spent upon the ocean, is usually glad to again see the land. After skirting the bold Irish coast, and peeping into the pretty cove of Cork, with Queenstown in the background, and passing the rocky headlands of Wales, the steamer that brings him from America carefully enters the Mersey River. The shores are low but picturesque as the tourist moves along the estuary between the coasts of Lancashire and Cheshire, and passes the great beacon standing up solitary and alone amid the waste of waters, the Perch Rock Light off New Brighton on the Cheshire side. Thus he comes to the world's greatest seaport—Liverpool—and the steamer finally drops her anchor between the miles of docks that front the two cities, Liverpool on the left and Birkenhead on the right. Forests of masts loom up behind the great dock-[Pg 18]walls, stretching far away on either bank, while a fleet of arriving or departing steamers is anchored in a long line in mid-channel. Odd-looking, low, black tugs, pouring out thick smoke from double funnels, move over the water, and one of them takes the passengers alongside the capacious structure a half mile long, built on pontoons, so it can rise and fall with the tides, and known as the Prince's Landing-Stage, where the customs officers perform their brief formalities and quickly let the visitor go ashore over the fine floating bridge into the city.

At Liverpool most American travellers begin their view of England. It is the great city of ships and sailors and all that appertains to the sea, and its 550,000 population are mainly employed in mercantile life and the myriad trades that serve the ship or deal in its cargo, for fifteen thousand to twenty thousand of the largest vessels of modern commerce will enter the Liverpool docks in a year, and its merchants own 7,000,000 tonnage. Fronting these docks on the Liverpool side of the Mersey is the great sea-wall, over five miles long, behind which are enclosed 400 acres of water-surface in the various docks, that are bordered by sixteen miles' length of quays. On the Birkenhead side of the river there are ten miles of quays in the docks that extend for over two miles along the bank. These docks, which are made necessary to accommodate the enormous commerce, have cost over $50,000,000, and are the crowning glory of Liverpool. They are filled with the ships of all nations, and huge storehouses line the quays, containing products from all parts of the globe, yet chiefly the grain and cotton, provisions, tobacco, and lumber of America. Railways run along the inner border of the docks on a street between them and the town, and along their tracks horses draw the freight-cars, while double-decked passenger-cars also run upon them with broad wheels fitting the rails, yet capable of being run off whenever the driver wishes to get ahead of the slowly-moving freight-cars. Ordinary wagons move upon Strand street alongside, with horses of the largest size drawing them, the huge growth of the Liverpool horses being commensurate with the immense trucks and vans to which these magnificent animals are harnessed.

Liverpool is of great antiquity, but in the time of William the Conqueror was only a fishing-village. Liverpool Castle, long since demolished, was a fortress eight hundred years ago, and afterward the rival families of Molineux and Stanley contended for the mastery of the place. It was a town of slow growth, however, and did not attain full civic dignity till the time of Charles I. It was within two hundred years that it became a seaport of any note. The first dock was opened in 1699, and strangely enough it was the African slave-trade that gave the Liverpool merchants their original start. The port[Pg 19] sent out its first slave-ship in 1709, and in 1753 had eighty-eight ships engaged in the slave-trade, which carried over twenty-five thousand slaves from Africa to the New World that year. Slave-auctions were frequent in Liverpool, and one of the streets where these sales were effected was nicknamed "Negro street." The agitation for the abolition of the trade was carried on a long time before Liverpool submitted, and then privateering came prominently out as the lucrative business a hundred years ago during the French wars, that brought Liverpool great wealth. Next followed the development of trade with the East Indies, and finally the trade with America has grown to such enormous proportions in the present century as to eclipse all other special branches of Liverpool commerce, large as some of them are. This has made many princely fortunes for the merchants and shipowners, and their wealth has been liberally expended in beautifying their city. It has in recent years had very rapid growth, and has greatly increased its architectural adornments. Most amazing has been this advancement since the time in the last century when the mayor and corporation entertained Prince William of Gloucester at dinner, and, pleased at the appetite he developed, one of them called out, "Eat away, Your Royal Highness; there's plenty more in the kitchen!" The mayor was Jonas Bold, and afterwards, taking the prince to church, they were astonished to find that the preacher had taken for his text the words, "Behold, a greater than Jonas is here."

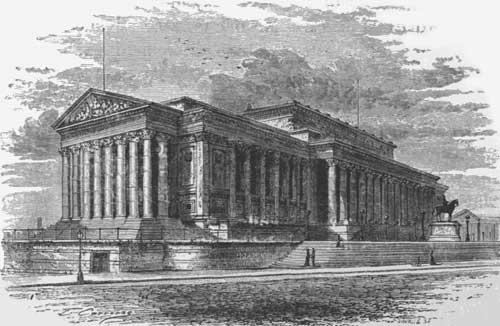

ST. GEORGE'S HALL.

ST. GEORGE'S HALL.

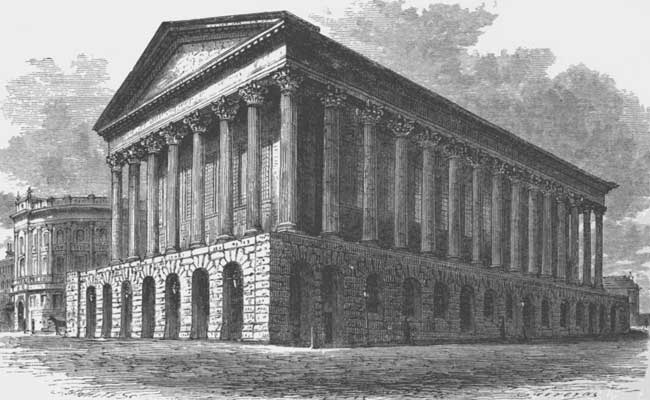

Liverpool has several fine buildings. Its Custom House is a large Ionic structure of chaste design, with a tall dome that can be seen from afar, and richly decorated within. The Town Hall and the Exchange buildings make up the four sides of an enclosed quadrangle paved with broad flagstones. Here, around the attractive Nelson monument in the centre, the merchants meet and transact their business. The chief public building is St. George's Hall, an imposing edifice, surrounded with columns and raised high above one[Pg 20] side of an open square, and costing $2,000,000 to build. It is a Corinthian building, having at one end the Great Hall, one hundred and sixty-nine feet long, where public meetings are held, and court-rooms at the other end. Statues of Robert Peel, Gladstone, and Stephenson, with other great men, adorn the Hall. Sir William Brown, who amassed a princely fortune in Liverpool, has presented the city with a splendid free library and museum, which stands in a magnificent position on Shaw's Brow. Many of the streets are lined with stately edifices, public and private, and most of these avenues diverge from the square fronting St. George's Hall, opposite which is the fine station of the London and North-western Railway, which, as is the railroad custom in England, is also a large hotel. The suburbs of Liverpool are filled for a wide circuit with elegant rural homes and surrounding ornamental grounds, where the opulent merchants live. They are generally bordered with high stone walls, interfering with the view, and impressing the visitor strongly with the idea that an Englishman's house is his castle. Several pretty parks with ornamental lakes among their hills are also in the suburbs. Yet it is the vast trade that is the glory of Liverpool, for it is but an epitome of England's commercial greatness, and is of comparatively modern growth. "All this," not long ago said Lord Erskine, speaking of the rapid advancement of Liverpool, "has been created by the industry and well-disciplined management of a handful of men since I was a boy."

A few miles out of Liverpool is the village of Prescot, where Kemble the tragedian was born, and where the people at the present time are largely engaged in watchmaking. Not far from Prescot is one of the famous homes of England—Knowsley Hall, the seat of the Stanleys and of the Earls of Derby for five hundred years. The park covers two thousand acres and is almost ten miles in circumference. The greater portion of the famous house was built in the time of George II. It is an extensive and magnificent structure, and contains many art-treasures in its picture-gallery by Rembrandt, Rubens, Correggio, Teniers, Vandyke, Salvator Rosa, and others. The Stanleys are one of the governing families of England, the last Earl of Derby having been premier in 1866, and the present earl having also been a cabinet minister. The crest of the Stanleys represents the Eagle and the Child, and is derived from the story of a remote ancestor who, cherishing an ardent desire for a male heir, and having only a daughter, contrived to have an infant conveyed to the foot of a tree in the park frequented by an eagle. Here he and his lady, taking a walk, found the child as if by accident, and the lady, consider[Pg 21]ing it a gift from Heaven brought by the eagle and miraculously preserved, adopted the boy as her heir. From this time the crest was assumed, but we are told that the old knight's conscience smote him at the trick, and on his deathbed he bequeathed the chief part of his fortune to the daughter, from whom are descended the present family.

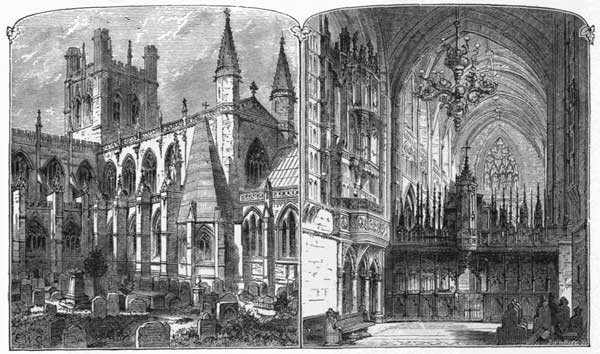

EXTERIOR.—CHESTER CATHEDRAL.—INTERIOR.

EXTERIOR.—CHESTER CATHEDRAL.—INTERIOR.

Not far from Liverpool, and in the heart of Cheshire, we come to the small but famous river Dee and the old and very interesting city of Chester. It is built in the form of a quadrant, its four walls enclosing a plot about a half mile square. The walls, which form a promenade two miles around, over which every visitor should tramp; the quaint gates and towers; the "Rows," or arcades along the streets, which enable the sidewalks to pass under the upper stories of the houses by cutting away the first-floor front rooms; and the many ancient buildings,—are all attractive. The Chester Cathedral is a venerable building of red sandstone, which comes down to us from the twelfth century, though it has recently been restored. It is constructed in the Perpendicular style of architecture, with a square and turret-surmounted central tower. This is the Cathedral of St. Werburgh, and besides other merits of the attractive interior, the southern transept is most striking from its exceeding length.[Pg 22] The choir is richly ornamented with carvings and fine woodwork, the Bishop's Throne having originally been a pedestal for the shrine of St. Werburgh. The cathedral contains several ancient tombs of much interest, and the elaborate Chapter Room, with its Early English windows and pillars, is much admired. In this gorgeous structure the word of God is preached from a Bible whose magnificently-bound cover is inlaid with precious stones and its markers adorned with pearls. The book is the Duke of Westminster's gift, that nobleman being the landlord of much of Chester. In the nave of the cathedral are two English battle-flags that were at Bunker Hill. Chester Castle, now used as a barrack for troops, has only one part of the ancient edifice left, called Julius Cæsar's Tower, near which the Dee is spanned by a fine single-arch bridge.

JULIUS CÆSAR'S TOWER.

JULIUS CÆSAR'S TOWER.

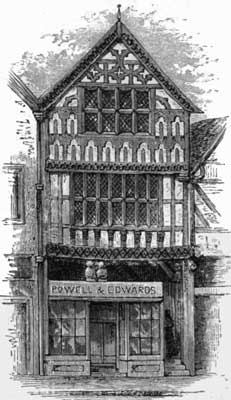

ANCIENT FRONT.

ANCIENT FRONT.

The quaintest part of this curious old city of Chester is no doubt the "Rows," above referred to. These arcades, which certainly form a capital shelter from the hot sun or rain, were, according to one authority, originally built as a refuge for the people in case of sudden attack by the Welsh; but according to others they originated with the Romans, and were used as the vestibules of the houses; and this seems to be the more popular theory with the townsfolk. Under the "Rows" are shops of all sizes, and some of the buildings are grotesquely attractive, especially the curious one bearing the motto of safety from the plague, "God's providence is mine inheritance," standing on Watergate street, and known as "God's Providence House;" and "Bishop Lloyd's Palace," which is ornamented with quaint wood-carvings. The "Old Lamb Row," where Randall Holme,[Pg 23] the Chester antiquary, lived, stood by itself, obeying no rule of regularity, and was regarded as a nuisance two hundred years ago, though later it was highly prized. The city corporation in 1670 ordered that "the nuisance erected by Randall Holme in his new building in Bridge street be taken down, as it annoys his neighbors, and hinders their prospect from their houses." But this law seems to have been enforced no more than many others are on either side of the ocean, for the "nuisance" stood till 1821, when the greater part of it, the timbers having rotted, fell of its own accord. The "Dark Row" is the only one of these strange arcades that is closed from the light, for it forms a kind of tunnel through which the footwalk goes. Not far from this is the famous old "Stanley House," where one unfortunate Earl of Derby spent the last day before his execution in 1657 at Bolton. The carvings on the front of this house are very fine, and there is told in reference to the mournful event that marks its history the following story: Lieutenant Smith came from the governor of Chester to notify the condemned earl to be ready for the journey to Bolton. The earl asked, "When would you have me go?" "To-morrow, about six in the morning," said Smith. "Well," replied the earl, "commend me to the governor, and tell him I shall[Pg 24] be ready by that time." Then said Smith, "Doth your lordship know any friend or servant that would do the thing your lordship knows of? It would do well if you had a friend." The earl replied, "What do you mean? to cut off my head?" Smith said, "Yes, my lord, if you could have a friend." The earl answered, "Nay, sir, if those men that would have my head will not find one to cut it off, let it stand where it is."

THE STANLEY HOUSE, FRONT.

THE STANLEY HOUSE, FRONT.

It is easy in this strange old city to carry back the imagination for centuries, for it preserves its connection with the past better perhaps than any other English town. The city holds the keys of the outlet of the Dee, which winds around it on two sides, and is practically one of the gates into Wales. Naturally, the Romans established a fortress here more than a thousand years ago, and made it the head-quarters of their twentieth legion, who impressed upon the town the formation of a Roman camp, which it bears to this day. The very name of Chester is derived from the Latin word for a camp. Many Roman fragments still remain, the most notable being the Hyptocaust. This was found in Watergate street about a century ago, together with a tessellated pavement. There have also been exhumed Roman altars, tombs, mosaics, pottery and other similar relics. The city is built upon a sandstone rock, and this furnishes much of the building material, so that most of the edifices have their exteriors disintegrated by the elements, particularly the churches—a peculiarity that may have probably partly justified[Pg 25] Dean Swift's epigram, written when his bile was stirred because a rainstorm had prevented some of the Chester clergy from dining with him:

"Churches and clergy of this city

Are very much akin:

They're weather-beaten all without,

And empty all within."

The modernized suburbs of Chester, filled with busy factories, are extending beyond the walls over a larger surface than the ancient town itself. At the angles of the old walls stand the famous towers—the Phœnix Tower, Bonwaldesthorne's Tower, Morgan's Mount, the Goblin Tower, and the Water Tower, while the gates in the walls are almost equally famous—the Eastgate, Northgate, Watergate, Bridgegate, Newgate, and Peppergate. The ancient Abbey of St. Mary had its site near the castle, and not far away are the picturesque ruins of St. John's Chapel, outside the walls. According to a local legend, its neighborhood had the honor of sheltering an illustrious fugitive. Harold, the Saxon king, we are told, did not fall at Hastings, but, escaping, spent the remainder of his life as a hermit, dwelling in a cell near this chapel and on a cliff alongside the Dee. The four streets leading from the gates at the middle of each side of the town come together in the centre at a place formerly known as the "Pentise," where was located the bull-ring at[Pg 26] which was anciently carried on the refining sport of "bull-baiting" while the mayor and corporation, clad in their gowns of office, looked on approvingly. Prior to this sport beginning, we are told that solemn proclamation was made for "the safety of the king and the mayor of Chester"—that "if any man stands within twenty yards of the bull-ring, let him take what comes." Here stood also the stocks and pillory. Amid so much that is ancient and quaint, the new Town Hall, a beautiful structure recently erected, is naturally most attractive, its dedication to civic uses having been made by the present Prince of Wales, who bears among many titles that of Earl of Chester. But this is about the only modern attraction this interesting city possesses. At an angle of the walls are the "Dee Mills," as old as the Norman Conquest, and famous in song as the place where the "jolly miller once lived on the Dee." Full of attractions within and without, it is difficult to tear one's self away from this quaint city, and therefore we will agree, at least in one sense, with Dr. Johnson's blunt remark to a lady friend: "I have come to Chester, madam, I cannot tell how, and far less can I tell how to get away from it."

The county of Cheshire has other attractions. But a short distance from Chester, in the valley of the Dee, is Eaton Hall, the elaborate palace of the Duke of Westminster and one of the finest seats in England, situated in a park of eight hundred acres that extends to the walls of Chester. This palace has recently been almost entirely rebuilt and modernized, and is now the most spacious and splendid example of Revived Gothic architecture in England. The house contains many works of art—statues by Gibson, paintings by Rubens and others—and is full of the most costly and beautiful decorations and furniture, being essentially one of the show-houses of Britain. In the extensive gardens are a Roman altar found in Chester and a Greek altar brought from Delphi.[Pg 27] At Hawarden Castle, seven miles from Chester, is the home of William E. Gladstone, and in its picturesque park are the ruins of the ancient castle, dating from the time of the Tudors, and from the keep of which there is a fine view of the Valley of the Dee. The ruins of Ewloe Castle, six hundred years old, are not far away, but so buried in foliage that they are difficult to find. Two miles from Chester is Hoole House, formerly Lady Broughton's, famous for its rockwork, a lawn of less than an acre exquisitely planted with clipped yews and other trees being surrounded by a rockery over forty feet high. In the Wirral or Western Cheshire are several attractive villages. At Bidston, west of Birkenhead and on the sea-coast, is the ancient house that was once the home of the unfortunate Earl of Derby, whose execution is mentioned above. Congleton, in Eastern Cheshire, stands on the Dane, in a lovely country, and is a good example of an old English country-town. Its Lion Inn is a fine specimen of the ancient black-and-white gabled hostelrie which novelists love so well to describe. At Nantwich is a curious old house with a heavy octagonal bow-window in the upper story overhanging a smaller lower one, telescope-fashion. The noble tower of Nantwich church rises above, and the building is in excellent preservation.

Nearly in the centre of Cheshire is the stately fortress of Beeston Castle, standing on a sandstone rock rising some three hundred and sixty feet from the flat country. It was built nearly seven hundred years ago by an Earl of Cheshire, then just returned from the Crusades. Standing in an irregular court covering about five acres, its thick walls and deep ditch made it a place of much strength. It was ruined prior to the time of Henry VIII., having been long contended for and finally dismantled in the Wars of the Roses. Being then rebuilt, it became a famous fortress in the Civil Wars, having been seized by the Roundheads, then surprised and taken by the Royalists, alternately besieged and defended afterward, and finally starved into surrender by the Parliamentary troops in 1645. This was King Charles's final struggle, though the castle did not succumb till after eighteen weeks' siege, and its defenders were forced to eat cats and rats to satisfy hunger, and were reduced to only sixty. Beeston Castle was then finally dismantled, and its ruins are now an attraction to the tourist. Lea Hall, an ancient and famous timbered mansion, surrounded by a moat, was situated about six miles from Chester, but the moat alone remains to show where it stood. Here lived Sir Hugh Calveley, one of Froissart's heroes, who was governor of Calais when it was held by the English, and is buried under a sumptuous tomb in the church of the neighboring college of Bunbury, which he founded. His armed effigy surmounts the tomb, and the inscription says he died on St. George's Day, 1394.[Pg 28]

PLAS NEWYDD, LLANGOLLEN.

PLAS NEWYDD, LLANGOLLEN.

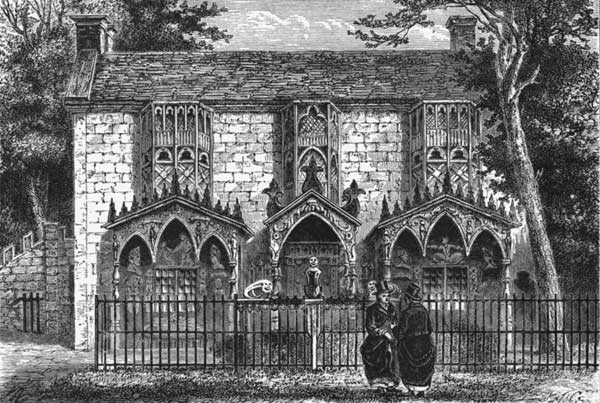

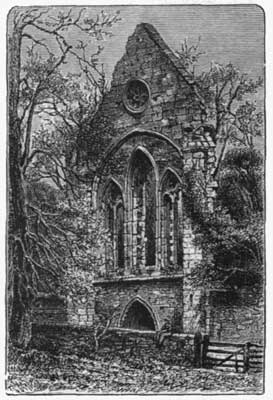

RUINS OF VALLE-CRUCIS ABBEY.

RUINS OF VALLE-CRUCIS ABBEY.

Frequent reference has been made to the river Dee, the Deva of the

Welsh, which is unquestionably one of the finest streams of Britain. It

rises in the Arran Fowddwy, one of the chief Welsh mountains, nearly

three thousand feet high, and after a winding course of about seventy

miles falls into the Irish Sea. This renowned stream has been the theme

of many a poet, and after expanding near its source into the beautiful

Bala Lake, whose bewitching surroundings are nearly all described in

polysyllabic and unpronounceable Welsh names, and are popular among

artists and anglers, it flows through Edeirnim Vale, past Corwen. Here a

pathway ascends to the eminence known as Glendower's Seat, with which

tradition has closely knit the name of the Welsh hero, the close of

whose marvellous career marked the termination of Welsh independence.

Then the romantic Dee enters the far-famed Valley of Llangollen, where

tourists love to roam, and where lived the "Ladies of Llangollen." We

are told that these two high-born dames had many lovers, but, rejecting

all and enamored only of each other, Lady Butler and Miss Ponsonby, the

latter sixteen years the junior of the former, determined on a life of

celibacy. They eloped together from Ireland, were overtaken and brought

back, and then a second time decamped—on this occasion in masquerade,

the elder dressed as a peasant[Pg 29] and the younger as a smart groom in

top-boots. Escaping pursuit, they settled in Llangollen in 1778 at the

quaint little house called Plas Newydd, and lived there together for a

half century. Their costume was extraordinary, for they appeared in

public in blue riding-habits, men's neckcloths, and high hats, with

their hair cropped short. They had antiquarian tastes, which led to the

accumulation of a vast lot of old wood-carvings and stained glass,

gathered from all parts of the world and worked into the fittings and

adornment of their home. They were on excellent terms with all the

neighbors, and the elder died in 1829, aged ninety, and the younger two

years afterward, aged seventy-six. Their remains lie in Llangollen

churchyard.

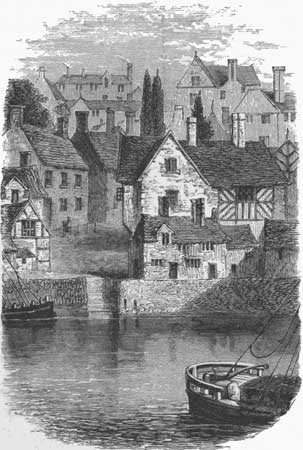

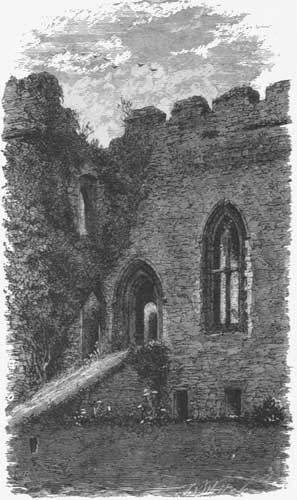

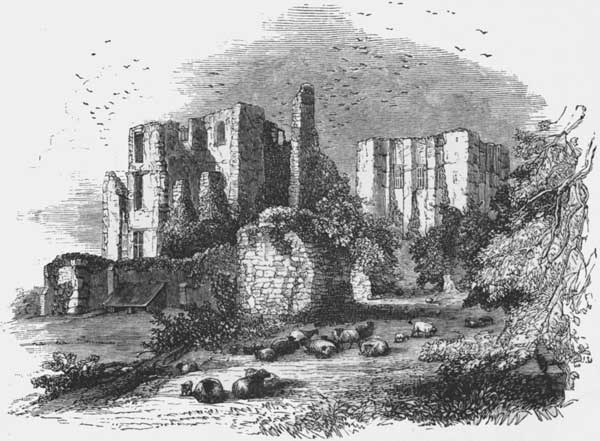

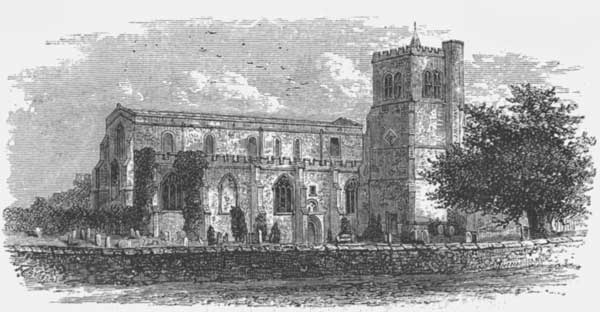

Within this famous valley are the ruins of Valle-Crucis Abbey, the most picturesque abbey ruin in North Wales. An adjacent stone cross gave it the name six hundred years ago, when it was built by the great Madoc for the Cistercian monks. The ruins in some parts are now availed of for farm-houses. Fine ash trees bend over the ruined arches, ivy climbs the clustered columns, and the lancet windows with their delicate tracery are much admired. The remains consist of the church, abbot's lodgings, refectory, and dormitory. The church was cruciform, and is now nearly roofless, though the east and west ends and the southern transept are tolerably perfect, so that much of the abbey remains. It was occupied by the Cistercians, and was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The ancient cross, of which the remains are still standing near by, is Eliseg's Pillar, erected in the seventh century as a memorial of that Welsh prince. It was one of the earliest lettered stones in Britain, standing originally about twelve feet high. From this cross came the name of Valle Crucis, which in the thirteenth century was given to the famous abbey. The great Madoc, who lived in the neighboring castle of Dinas Bran, built this abbey to atone for a life of violence. The ruins of his castle stand on a hill elevated about one thousand feet above the Dee. Bran in Welsh means crow, so that the English know it as Crow Castle. From its ruins there is a beautiful view over the Valley of Llangollen. Farther down the valley is the mansion of Wynnstay, in the midst of a large and richly wooded park, a circle of eight miles enclosing the superb domain, within which are herds of fallow-deer and many noble trees. The old mansion was burnt in 1858, and an imposing struc[Pg 30]ture in Renaissance now occupies the site. Fine paintings adorn the walls by renowned artists, and the Dee foams over its rocky bed in a sequestered dell near the mansion. Memorial columns and tablets in the park mark notable men and events in the Wynn family, the chief being the Waterloo Tower, ninety feet high. Far away down the valley a noble aqueduct by Telford carries the Ellesmere Canal over the Dee—the Pont Cysylltau—supported on eighteen piers of masonry at an elevation of one hundred and twenty-one feet, while a mile below is the still more imposing viaduct carrying the Great Western Railway across.[Pg 31]

Not far distant is Chirk Castle, now the home of Mr. R. Myddelton Biddulph, a combination of a feudal fortress and a modern mansion. The ancient portion, still preserved, was built by Roger Mortimer, to whom Edward I. granted the lordship of Chirk. It was a bone of contention during the Civil Wars, and when they were over, $150,000 were spent in repairing the great quadrangular fortress. It stands in a noble situation, and on a clear day portions of seventeen counties can be seen from the summit. Still following down the picturesque river, we come to Bangor-ys-Coed, or "Bangor-in-the-Wood," in Flintshire, once the seat of a famous monastery that disappeared twelve hundred years ago. Here a pretty bridge crosses the river, and a modern church is the most prominent structure in the village. The old monastery is said to have been the home of twenty-four hundred monks, one half of whom were slain in a battle near Chester by the heathen king Ethelfrith, who afterwards sacked the monastery, but the Welsh soon gathered their forces again and took terrible vengeance. Many ancient coffins and Roman remains have been found here. The Dee now runs with swift current past Overton to the ancient town of Holt, whose charter is nearly five hundred years old, but whose importance is now much less than of yore. Holt belongs to the debatable Powisland, the strip of territory over which the English and Welsh fought for centuries. Holt was formerly known as Lyons, and was a Roman outpost of Chester. Edward[Pg 32] I. granted it to Earl Warren, who built Holt Castle, of which only a few quaint pictures now exist, though it was a renowned stronghold in its day. It was a five-sided structure with a tower on each corner, enclosing an ample courtyard. After standing several sieges in the Civil Wars of Cromwell's time, the battered castle was dismantled.

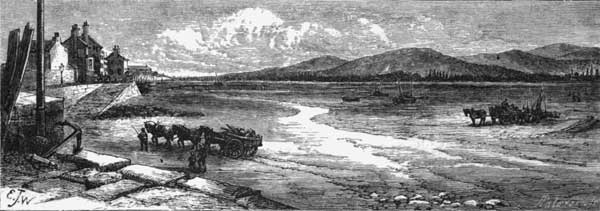

The famous Wrexham Church, whose tower is regarded as one of the "seven wonders of Wales," is three miles from Holt, and is four hundred years old. Few churches built as early as the reign of Henry VIII. can compare with this. It is dedicated to St. Giles, and statues of him and of twenty-nine other saints embellish niches in the tower. Alongside of St. Giles is the hind that nourished him in the desert. The bells of Wrexham peal melodiously over the valley, and in the vicarage the good Bishop Heber wrote the favorite hymn, "From Greenland's Icy Mountains." Then the Dee flows on past the ducal palace of Eaton Hall, and encircles Chester, which has its race-course, "The Roodee"—where they hold an annual contest in May for the "Chester Cup"—enclosed by[Pg 33] a beautiful semicircle of the river. Then the Dee flows on through a straight channel for six miles to its estuary, which broadens among treacherous sands and flats between Flintshire and Cheshire, till it falls into the Irish Sea. Many are the tales of woe that are told of the "Sands o' Dee," along which the railway from Chester to Holyhead skirts the edge in Flintshire. Many a poor girl, sent for the cattle wandering on these sands, has been lost in the mist that rises from the sea, and drowned by the quickly rushing waters. Kingsley has plaintively told the story in his mournful poem:

THE "SANDS O' DEE."

THE "SANDS O' DEE."

"They rowed her in across the rolling foam—

The cruel, crawling foam,

The cruel, hungry foam—

To her grave beside the sea;

But still the boatmen hear her call her cattle home

Across the Sands o' Dee."

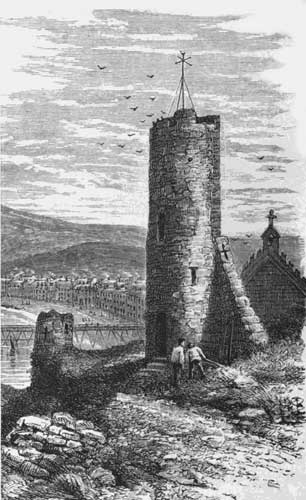

Let us now journey westward from the Dee into Wales, coming first into Flintshire. The town of Flint, it is conjectured, was originally a Roman camp, from the design and the antiquities found there. Edward I., six hundred years ago, built Flint Castle upon an isolated rock in a marsh near the river, and after a checquered history it was dismantled in the seventeenth century. From the railway between Chester and Holyhead the ruins of this castle are visible on its low freestone rock; it is a square, with round towers at three of the corners, and a massive keep at the other, formed like a double tower and detached from the main castle. This was the "dolorous castle" into which Richard II. was inveigled at the beginning of his imprisonment, which ended with abdication, and finally his death at Pomfret. The story is told that Richard[Pg 34] had a fine greyhound at Flint Castle that often caressed him, but when the Duke of Lancaster came there the greyhound suddenly left Richard and caressed the duke, who, not knowing the dog, asked Richard what it meant. "Cousin," replied the king, "it means a great deal for you and very little for me. I understand by it that this greyhound pays his court to you as King of England, which you will surely be, and I shall be deposed, for the natural instinct of the dog shows it to him; keep him, therefore, by your side." Lancaster treasured this, and paid attention to the dog, which would nevermore follow Richard, but kept by the side of the Duke of Lancaster, "as was witnessed," says the chronicler Froissart, "by thirty thousand men."

Rhuddlan Castle, also in Flintshire, is a red sandstone ruin of striking appearance, standing on the Clwyd River. When it was founded no one knows accurately, but it was rebuilt seven hundred years ago, and was dismantled, like many other Welsh castles, in 1646. It was at Rhuddlan that Edward I. promised the Welsh "a native prince who never spoke a word of English, and whose life and conversation no man could impugn;" and this promise he fulfilled to the letter by naming as the first English Prince of Wales his infant son, then just born at Caernarvon Castle. Six massive towers flank the walls of this famous castle, and are in tolerably fair preservation. Not far to the southward is the eminence known by the Welsh as "Yr-Wyddgrug," or "a lofty hill," and which the English call Mold. On this hill was a castle of which little remains now but tracings of the ditches, larches and other trees peacefully growing on the site of the ancient stronghold. Off toward Wrexham are the ruins of another castle, known as Caergwrle, or "the camp of the giant legion." This was of Welsh origin, and commanded the entrance to the Vale of Alen; the English called it Hope Castle.

Adjoining Flintshire is Denbigh, with the quiet watering-place of Abergele out on the Irish Sea. About two miles away is St. Asaph, with its famous cathedral, having portions dating from the thirteenth century. The great castle of Denbigh, when in its full glory, had fortifications one and a half miles in circumference. It stood on a steep hill at the county-town, where scanty ruins now remain, consisting chiefly of an immense gateway with remains of flanking towers. Above the entrance is a statue of the Earl of Lincoln, its founder in the thirteenth century. His only son was drowned in the castle-well, which so affected the father that he did not finish the castle. Edward II. gave Denbigh to Despenser; Leicester owned it in Elizabeth's time; Charles II. dismantled it. The ruins impress the visitor with the stupendous strength of the immense walls of this stronghold, while extensive passages and dungeons have been explored beneath the surface for long dis[Pg 35]tances. In one chamber near the entrance-tower, which had been walled up, a large amount of gunpowder was found. At Holywell, now the second town in North Wales, is the shrine to which pilgrims have been going for many centuries. At the foot of a steep hill, from an aperture in the rock, there rushes forth a torrent of water at the rate of eighty-four hogsheads a minute; whether the season be wet or be dry, the sacred stream gushing forth from St. Winifrede's Well varies but little, and around it grows the fragrant moss known as St. Winifrede's Hair. The spring has valuable medicinal virtues, and an elegant dome covering it supports a chapel. The little building is an exquisite Gothic structure built by Henry VII. A second basin is provided, into which bathers may descend. The pilgrims to this holy well have of late years decreased in numbers; James II., who, we are told, "lost three kingdoms for a mass," visited this well in 1686, and "received as a reward the undergarment worn by his great-grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, on the day of her execution." This miraculous spring gets its name from the pious virgin Winifrede. She having been seen by the Prince of Wales, Caradoc, he was struck by her great beauty and attempted to carry her off; she fled to the church, the prince pursuing, and, overtaking her, he in rage drew his sword and struck off her head; the severed head bounded through the church-door and rolled to the foot of the altar. On the spot where it rested a spring of uncommon size burst forth. The pious priest took up the head, and at his prayer it was united to the body, and the virgin, restored to life, lived in sanctity for fifteen years afterwards: miracles were wrought at her tomb; the spring proved another Pool of Bethesda, and to this day we are told that the votive crutches and chairs left by the cured remain hanging over St. Winifrede's Well.

South of Denbigh, in Montgomeryshire, are the ruins of Montgomery Castle, long a frontier fortress of Wales, around which many hot contests have raged: a fragment of a tower and portions of the walls are all that remain. Powys Castle is at Welsh Pool, and is still preserved—a red sandstone structure on a rocky elevation in a spacious and well-wooded park; Sir Robert Smirke has restored it.

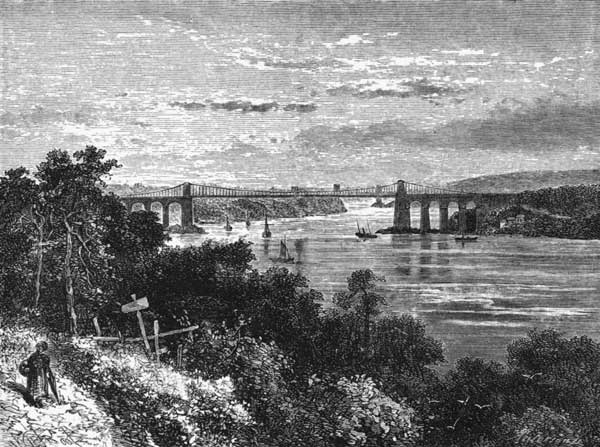

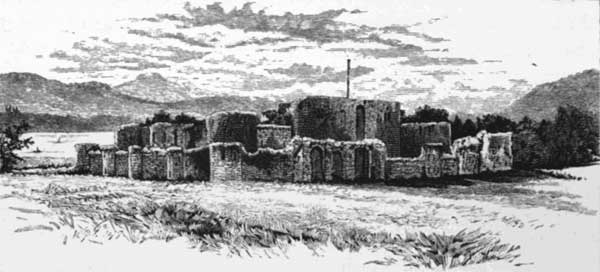

Still journeying westward, we come to Caernarvonshire, and reach the remarkable estuary dividing the mainland from the island of Anglesea, and known as the Menai Strait. This narrow stream, with its steeply-sloping banks and winding shores, looks more like a river than a strait, and it everywhere discloses evidence of the residence of an almost pre-historic people in relics of nations that inhabited its banks before the invasion of the Romans.[Pg 36] There are hill-forts, sepulchral mounds, pillars of stone, rude pottery, weapons of stone and bronze; and in that early day Mona itself, as Anglesea was called, was a sacred island. Here were fierce struggles between Roman and Briton, and Tacitus tells of the invasion of Mona by the Romans and the desperate conflicts that ensued as early as A.D. 60. The history of the strait is a story of almost unending war for centuries, and renowned castles bearing the scars of these conflicts keep watch and ward to this day. Beaumaris, Bangor, Caernarvon, and Conway castles still remain in partial ruin to remind us of the Welsh wars of centuries ago. On the Anglesea shore, at the northern entrance to the strait, is the picturesque ruin of Beaumaris Castle, built by Edward I. at a point where vessels could conveniently land. It stands on the lowlands, and a canal connects its ditch with the sea. It consists of a hexagonal line of outer defences surrounding an inner square. Round towers flanked the outer walls, and the chapel within is quite well preserved. It has not had much place in history, and the neighboring town is now a peaceful watering-place.

THE MENAI STRAIT.

THE MENAI STRAIT.

BEAUMARIS CASTLE.

BEAUMARIS CASTLE.

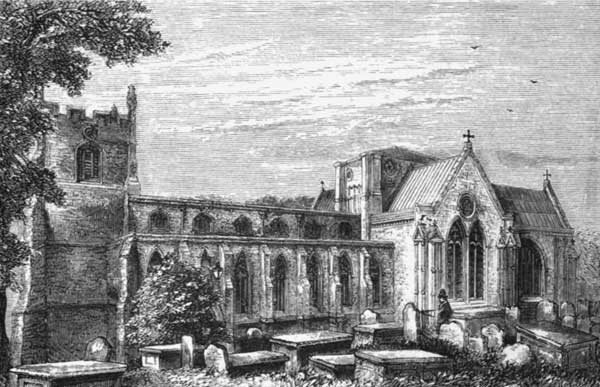

BANGOR CATHEDRAL.

BANGOR CATHEDRAL.

Across the strait is Bangor, a rather straggling town, with a cathedral that is not very old. We are told that its bishop once sold its peal of bells, and, going down to the shore to see them shipped away, was stricken blind as a punishment for the sacrilege. Of Bangor Castle, as it originally stood, but insignificant traces remain, but Lord Penrhyn has recently erected in the neighborhood the imposing castle of Penryhn, a massive pile of dark limestone, in which the endeavor is made to combine a Norman feudal castle with a modern dwelling, though with only indifferent success, excepting in the expenditure involved. The[Pg 38] roads from the great suspension-bridge across the strait lead on either hand to Bangor and Beaumaris, although the route is rather circuitous. This bridge, crossing at the narrowest and most beautiful part of the strait, was long regarded as the greatest triumph of bridge-engineering. It carried the Holyhead high-road across the strait, and was built by Telford. The bridge is five hundred and seventy-nine feet long, and stands one hundred feet above high-water mark; it cost $600,000. Above the bridge the strait widens, and here, amid the swift-flowing currents, the famous whitebait are caught for the London epicures. Three-quarters of a mile below, at another narrow place, the railway crosses the strait through Stephenson's Britannia tubular bridge, which is more useful than ornamental, the railway passing through two long rectangular iron tubes, supported on plain massive pillars. From a rock in the strait the central tower rises to a height of two hundred and thirty feet, and other towers are built on each shore at a distance of four hundred and sixty feet from the central one. Couchant lions carved in stone guard the bridge-portals at each end, and this famous viaduct cost over $2,500,000. A short distance below the Anglesea Column towers above a dark rock on the northern shore of the strait. It was erected in honor of the first Marquis of Anglesea, the gallant commander of the British light cavalry at Waterloo, where his leg was carried away by one of the last French cannon-shots. For many years after the great victory he lived here, literally with "one foot in the grave." Plas Newydd, one and a half miles below, the Anglesea family residence, where the marquis lived, is a large and unattractive mansion, beautifully situated on the sloping shore. It has in the park two ancient sepulchral monuments of great interest to the antiquarian.

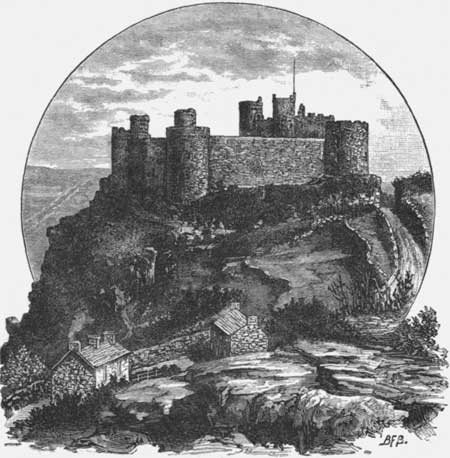

As the famous strait widens below the bridges the shores are tamer, and we come to the famous Caernarvon Castle, the scene of many stirring military events, as it held the key to the valleys of Snowdon, and behind it towers that famous peak, the highest mountain in Britain, whose summit rises to a height of 3590 feet. This great castle also commanded the south-western entrance to the strait, and near it the rapid little Sciont River flows into the sea. The ancient Britons had a fort here, and afterwards it was a Roman fortified camp, which gradually developed into the city of Segontium. The British name, from which the present one comes, was Caer-yn-Arvon—"the castle opposite to Mona." Segontium had the honor of being the birthplace of the Emperor Constantine, and many Roman remains still exist there. It was in 1284, however, that Edward I. began building the present castle, and it took thirty-nine[Pg 39] years to complete. The castle plan is an irregular oval, with one side overlooking the strait. At the end nearest the sea, where the works come to a blunt point, is the famous Eagle Tower, which has eagles sculptured on the battlements. There are twelve towers altogether, and these, with the light-and dark-hued stone in the walls, give the castle a massive yet graceful aspect as it stands on the low ground at the mouth of the Sciont. Externally, the castle is in good preservation, but the inner buildings are partly destroyed, as is also the Queen's Gate, where Queen Eleanor is said to have entered before the first English Prince of Wales was born. A corridor, with loopholes contrived in the thickness of the walls, runs entirely around the castle, and from this archers could fight an approaching enemy. This great fortress has been called the "boast of North Wales" from its size and excellent position. It was last used for defence during the Civil Wars, having been a military stronghold for nearly four centuries. Although Charles II. issued a warrant for its demolition, this was to a great extent disregarded. Prynne, the sturdy Puritan, was confined here in Charles I.'s time, and the first English Prince of Wales, afterwards the unfortunate Edward II., is said to have been born in a little dark room, only twelve by eight feet, in the Eagle Tower: when seventeen years of age the prince received the homage of the Welsh barons at Chester. The town of Caernarvon, notwithstanding its famous history and the possession of[Pg 40] the greatest ruin in Wales, now derives its chief satisfaction from the lucrative but prosaic occupation of trading in slates.

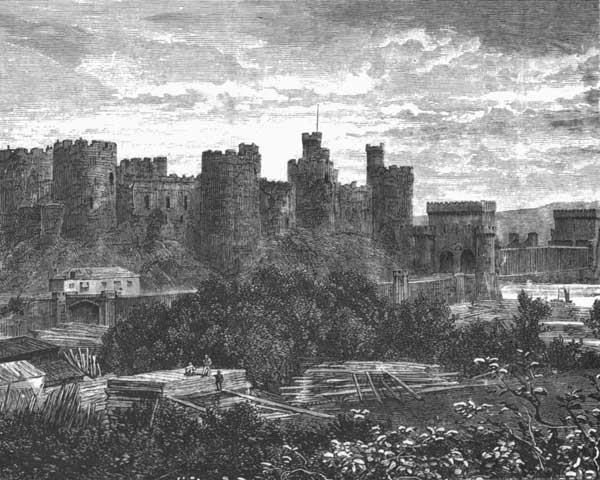

CONWAY CASTLE, FROM THE ROAD TO LLANRWST.

CONWAY CASTLE, FROM THE ROAD TO LLANRWST.

At the northern extremity of Caernarvon county, and projecting into the Irish Sea, is the promontory known as Great Orme's Head, and near it is the mouth of the Conway River. The railway to Holyhead crosses this river on a tubular bridge four hundred feet long, and runs almost under the ruins of Conway Castle, another Welsh stronghold erected by Edward I. We are told that this despotic king, when he had completed the conquest of Wales, came to Conway, the shape of the town being something like a Welsh harp, and he ordered all the native bards to be put to death. Gray founded upon this his ode, "The Bard," beginning—

"On a rock whose lofty brow

Frowns o'er old Conway's foaming flood,

Robed in a sable garb of woe.

With haggard eyes the poet stood."

[Pg 41]