Title: Philo Gubb, Correspondence-School Detective

Author: Ellis Parker Butler

Illustrator: Rea Irvin

Release date: August 17, 2009 [eBook #29721]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D Alexander, Joseph Cooper and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1918

COPYRIGHT, 1913, 1914, AND 1915, BY THE RED BOOK CORPORATION

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY ELLIS PARKER BUTLER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published September 1918

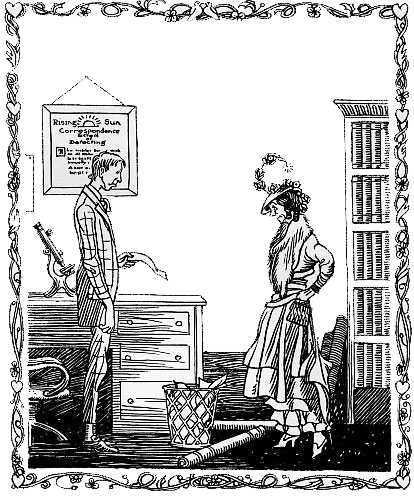

“IN THE DETECKATIVE LINE NOTHING SOUNDS FOOLISH” (page

218)

“IN THE DETECKATIVE LINE NOTHING SOUNDS FOOLISH” (page

218)

| The Hard-Boiled Egg | 3 |

| The Pet | 21 |

| The Eagle’s Claws | 43 |

| The Oubliette | 66 |

| The Un-Burglars | 95 |

| The Two-Cent Stamp | 113 |

| The Chicken | 138 |

| The Dragon’s Eye | 156 |

| The Progressive Murder | 171 |

| The Missing Mr. Master | 185 |

| Waffles and Mustard | 205 |

| The Anonymous Wiggle | 227 |

| The Half of a Thousand | 247 |

| Dietz’s 7462 Bessie John | 266 |

| Henry | 288 |

| Buried Bones | 307 |

| Philo Gubb’s Greatest Case | 329 |

| “In the deteckative line nothing sounds foolish” | Frontispiece |

| “This shell game is easy enough when you know how” |

8 |

| Mr. Winterberry did not seem to be concealed among them |

30 |

| A head silhouetted against one of the glowing windows |

44 |

| “These here is false whiskers and hair” | 86 |

| “Who sent you here, anyway?” | 106 |

| Under his arm he carried a small bundle | 108 |

| She made gestures with her hands | 128 |

| “Deteckating is my aim and my profession” | 138 |

| With another groan Wixy raised his hands | 150 |

| “The ‘ongsomble’ of my costume is ruined” | 162 |

| “There ain’t a day he don’t shoot and hit me” | 178 |

| The Missing Mr. Master | 202 |

| “You are a man, and big and strong and brave-like” | 234 |

| He perspires, and out comes the cruel admission |

252 |

| A man who looked like Napoleon Bonaparte gone to seed |

268 |

| He wore a set of red under-chin whiskers | 280 |

| “She thinks it’s Henry. She’s fixed up the guest bedroom for him” |

304 |

| A deteckative like you are oughtn’t to need twenty-five cents so bad as that” |

320 |

| He was followed by a large and growing group intent on watching a detective detect |

340 |

Walking close along the wall, to avoid the creaking floor boards, Philo Gubb, paper-hanger and student of the Rising Sun Detective Agency’s Correspondence School of Detecting, tiptoed to the door of the bedroom he shared with the mysterious Mr. Critz. In appearance Mr. Gubb was tall and gaunt, reminding one of a modern Don Quixote or a human flamingo; by nature Mr. Gubb was the gentlest and most simple-minded of men. Now, bending his long, angular body almost double, he placed his eye to a crack in the door panel and stared into the room. Within, just out of the limited area of Mr. Gubb’s vision, Roscoe Critz paused in his work and listened carefully. He heard the sharp whistle of Mr. Gubb’s breath as it cut against the sharp edge of the crack in the panel, and he knew he was being spied upon. He placed his chubby hands on his knees and smiled at the door, while a red flush of triumph spread over his face.

Through the crack in the door Mr. Gubb could [Pg 4]see the top of the washstand beside which Mr. Critz was sitting, but he could not see Mr. Critz. As he stared, however, he saw a plump hand appear and pick up, one by one, the articles lying on the washstand. They were: First, seven or eight half shells of English walnuts; second, a rubber shoe heel out of which a piece had been cut; third, a small rubber ball no larger than a pea; fourth, a paper-bound book; and lastly, a large and glittering brick of yellow gold. As the hand withdrew the golden brick, Mr. Gubb pressed his face closer against the door in his effort to see more, and suddenly the door flew open and Mr. Gubb sprawled on his hands and knees on the worn carpet of the bedroom.

“There, now!” said Mr. Critz. “There, now! Serves you right. Hope you hurt chuself!”

Mr. Gubb arose slowly, like a giraffe, and brushed his knees.

“Why?” he asked.

“Snoopin’ an’ sneakin’ like that!” said Mr. Critz crossly. “Scarin’ me to fits, a’most. How’d I know who ’twas? If you want to come in, why don’t you come right in, ’stead of snoopin’ an’ sneakin’ an’ fallin’ in that way?”

As he talked, Mr. Critz replaced the shells and the rubber heel and the rubber pea and the gold-brick on the washstand. He was a plump little man with a shiny bald head and a white goatee. As he talked, he bent his head down, so that he might look above the glasses of his spectacles; and in spite of his pretended [Pg 5]anger he looked like nothing so much as a kindly, benevolent old gentleman—the sort of old gentleman that keeps a small store in a small village and sells writing-paper that smells of soap, and candy sticks out of a glass jar with a glass cover.

“How’d I know but what you was a detective?” he asked, in a gentler tone.

“I am,” said Mr. Gubb soberly, seating himself on one of the two beds. “I’m putty near a deteckative, as you might say.”

“Ding it all!” said Mr. Critz. “Now I got to go and hunt another room. I can’t room with no detective.”

“Well, now, Mr. Critz,” said Mr. Gubb, “I don’t want you should feel that way.”

“Knowin’ you are a detective makes me all nervous,” complained Mr. Critz; “and a man in my business has to have a steady hand, don’t he?”

“You ain’t told me what your business is,” said Mr. Gubb.

“You needn’t pretend you don’t know,” said Mr. Critz. “Any detective that saw that stuff on the washstand would know.”

“Well, of course,” said Mr. Gubb, “I ain’t a full deteckative yet. You can’t look for me to guess things as quick as a full deteckative would. Of course that brick sort of looks like a gold-brick—”

“It is a gold-brick,” said Mr. Critz.

“Yes,” said Mr. Gubb. “But—I don’t mean no offense, Mr. Critz—from the way you look—I [Pg 6]sort of thought—well, that it was a gold-brick you’d bought.”

Mr. Critz turned very red.

“Well, what if I did buy it?” he said. “That ain’t any reason I can’t sell it, is it? Just because a man buys eggs once—or twice—ain’t any reason he shouldn’t go into the business of egg-selling, is it? Just because I’ve bought one or two gold-bricks in my day ain’t any reason I shouldn’t go to sellin’ ’em, is it?”

Mr. Gubb stared at Mr. Critz with unconcealed surprise.

“You ain’t,—you ain’t a con’ man, are you, Mr. Critz?” he asked.

“If I ain’t yet, that’s no sign I ain’t goin’ to be,” said Mr. Critz firmly. “One man has as good a right to try his hand at it as another, especially when a man has had my experience in it. Mr. Gubb, there ain’t hardly a con’ game I ain’t been conned with. I been confidenced long enough; from now on I’m goin’ to confidence other folks. That’s what I’m goin’ to do; and I won’t be bothered by no detective livin’ in the same room with me. Detectives and con’ men don’t mix noways! No, sir!”

“Well, sir,” said Mr. Gubb, “I can see the sense of that. But you don’t need to move right away. I don’t aim to start in deteckating in earnest for a couple of months yet. I got a couple of jobs of paper-hanging and decorating to finish up, and I can’t start in sleuthing until I get my star, anyway. [Pg 7]And I don’t get my star until I get one more lesson, and learn it, and send in the examination paper, and five dollars extra for the diploma. Then I’m goin’ at it as a reg’lar business. It’s a good business. Every day there’s more crooks—excuse me, I didn’t mean to say that.”

“That’s all right,” said Mr. Critz kindly. “Call a spade a spade. If I ain’t a crook yet, I hope to be soon.”

“I didn’t know how you’d feel about it,” explained Mr. Gubb. “Tactfulness is strongly advised into the lessons of the Rising Sun Deteckative Agency Correspondence School of Deteckating—”

“Slocum, Ohio?” asked Mr. Critz quickly. “You didn’t see the ad. in the ‘Hearthstone and Farmside,’ did you?”

“Yes, Slocum, Ohio,” said Mr. Gubb, “and that is the paper I saw the ad. into; ‘Big Money in Deteckating. Be a Sleuth. We can make you the equal of Sherlock Holmes in twelve lessons.’ Why?”

“Well, sir,” said Mr. Critz, “that’s funny. That ad. was right atop of the one I saw, and I studied quite considerable before I could make up my mind whether ’twould be best for me to be a detective and go out and get square with the fellers that sold me gold-bricks and things by putting them in jail, or to even things up by sending for this book that was advertised right under the ‘Rising Sun Correspondence School.’ How come I settled to do as I done was that I had a sort of stock to start with, [Pg 8]with a fust-class gold-brick, and some green goods I’d bought; and this book only cost a quatter of a dollar. And she’s a hummer for a quatter of a dollar! A hummer!”

He pulled the paper-covered book from his pocket and handed it to Mr. Gubb. The title of the book was “The Complete Con’ Man, by the King of the Grafters. Price 25 cents.”

“That there book,” said Mr. Critz proudly, as if he himself had written it, “tells everything a man need to know to work every con’ game there is. Once I get it by heart, I won’t be afraid to try any of them. Of course, I got to start in small. I can’t hope to pull off a wire-tapping game right at the start, because that has to have a gang. You don’t know anybody you could recommend for a gang, do you?”

“Not right offhand,” said Mr. Gubb thoughtfully.

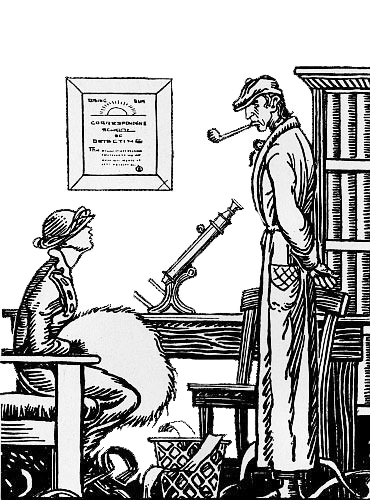

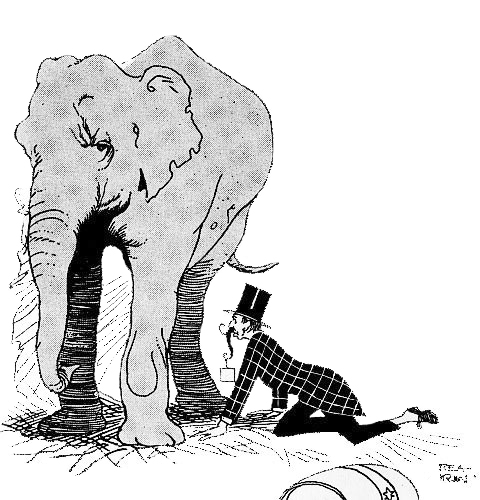

“THIS SHELL GAME IS EASY ENOUGH WHEN YOU KNOW HOW”

“THIS SHELL GAME IS EASY ENOUGH WHEN YOU KNOW HOW”

“If you wasn’t goin’ into the detective business,” said Mr. Critz, “you’d be just the feller for me. You look sort of honest and not as if you was too bright, and that counts a lot. Even in this here simple little shell game I got to have a podner. I got to have a podner I can trust, so I can let him look like he was winnin’ money off of me. You see,” he explained, moving to the washstand, “this shell game is easy enough when you know how. I put three shells down like this, on a stand, and I put the little rubber pea on the stand, and then I take up the three shells like this, two in one hand and [Pg 9]one in the other, and I wave ’em around over the pea, and maybe push the pea around a little, and I say, ‘Come on! Come on! The hand is quicker than the eye!’ And all of a suddent I put the shells down, and you think the pea is under one of them, like that—”

“I don’t think the pea is under one of ’em,” said Mr. Gubb. “I seen it roll onto the floor.”

“It did roll onto the floor that time,” said Mr. Critz apologetically. “It most generally does for me, yet. I ain’t got it down to perfection yet. This is the way it ought to work—oh, pshaw! there she goes onto the floor again! Went under the bed that time. Here she is! Now, the way she ought to work is—there she goes again!”

“You got to practice that game a lot before you try it onto folks in public, Mr. Critz,” said Mr. Gubb seriously.

“Don’t I know that?” said Mr. Critz rather impatiently. “Same as you’ve got to practice snoopin’, Mr. Gubb. Maybe you thought I didn’t know you was snoopin’ after me wherever I went last night.”

“Did you?” asked Mr. Gubb, with surprise plainly written on his face.

“I seen you every moment from nine p.m. till eleven!” said Mr. Critz. “I didn’t like it, neither.”

“I didn’t think to annoy you,” apologized Mr. Gubb. “I was practicin’ Lesson Four. You wasn’t supposed to know I was there at all.”

“Well, I don’t like it,” said Mr. Critz. “’Twas all right last night, for I didn’t have nothin’ important on hand, but if I’d been workin’ up a con’ game, the feller I was after would have thought it mighty strange to see a man follerin’ me everywhere like that. If you went about it quiet and unobtrusive, I wouldn’t mind; but if I’d had a customer on hand and he’d seen you it would make him nervous. He’d think there was a—a crazy man follerin’ us.”

“I was just practicin’,” apologized Mr. Gubb. “It won’t be so bad when I get the hang of it. We all got to be beginners sometime.”

“I guess so,” said Mr. Critz, rearranging the shells and the little rubber pea. “Well, I put the pea down like this, and I dare you to bet which shell she’s goin’ to be under, and you don’t bet, see? So I put the shells down, and you’re willin’ to bet you see me put the first shell over the pea like this. So you keep your eye on that shell, and I move the shells around like this—”

“She’s under the same shell,” said Mr. Gubb.

“Well, yes, she is,” said Mr. Critz placidly, “but she hadn’t ought to be. By rights she ought to sort of ooze out from under whilst I’m movin’ the shells around, and I’d ought to sort of catch her in between my fingers and hold her there so you don’t see her. Then when you say which shell she’s under, she ain’t under any shell; she’s between my fingers. So when you put down your money I tell you to pick [Pg 11]up that shell and there ain’t anything under it. And before you can pick up the other shells I pick one up, and let the pea fall on the stand like it had been under that shell all the time. That’s the game, only up to now I ain’t got the hang of it. She won’t ooze out from under, and she won’t stick between my fingers, and when she does stick, she won’t drop at the right time.”

“Except for that, you’ve got her all right, have you?” asked Mr. Gubb.

“Except for that,” said Mr. Critz; “and I’d have that, only my fingers are stubby.”

“What was it you thought of having me do if I wasn’t a deteckative?” asked Mr. Gubb.

“The work you’d have to do would be capping work,” said Mr. Critz. “Capper—that’s the professional name for it. You’d guess which shell the ball was under—”

“That would be easy, the way you do it now,” said Mr. Gubb.

“I told you I’d got to learn it better, didn’t I?” asked Mr. Critz impatiently. “You’d be capper, and you’d guess which shell the pea was under. No matter which you guessed, I’d leave it under that one, so’d you’d win, and you’d win ten dollars every time you bet—but not for keeps. That’s why I’ve got to have an honest capper.”

“I can see that,” said Mr. Gubb; “but what’s the use lettin’ me win it if I’ve got to bring it back?”

“That starts the boobs bettin’,” said Mr. Critz. [Pg 12]“The boobs see how you look to be winnin’, and they want to win too. But they don’t. When they bet, I win.”

“That ain’t a square game,” said Mr. Gubb seriously, “is it?”

“A crook ain’t expected to be square,” said Mr. Critz. “It stands to reason, if a crook wants to be a crook, he’s got to be crooked, ain’t he?”

“Yes, of course,” said Mr. Gubb. “I hadn’t looked at it that way.”

“As far as I can see,” said Mr. Critz, “the more I know how a detective acts, the better off I’ll be when I start in doin’ real business. Ain’t that so? I guess, till I get the hang of things better, I’ll stay right here.”

“I’m glad to hear you say so, Mr. Critz,” said Mr. Gubb with relief. “I like you, and I like your looks, and there’s no tellin’ who I might get for a roommate next time. I might get some one that wasn’t honest.”

So it was agreed, and Mr. Critz stood over the washstand and manipulated the little rubber pea and the three shells, while Mr. Gubb sat on the edge of the bed and studied Lesson Eleven of the “Rising Sun Detective Agency’s Correspondence School of Detecting.”

When, presently, Mr. Critz learned to work the little pea neatly, he urged Mr. Gubb to take the part of capper, and each time Mr. Gubb won he gave him a five-dollar bill. Then Mr. Gubb posed [Pg 13]as a “boob” and Mr. Critz won all the money back again, beaming over his spectacle rims, and chuckling again and again until he burst into a fit of coughing that made him red in the face, and did not cease until he had taken a big drink of water out of the wash-pitcher. Never had he seemed more like a kindly old gentleman from behind the candy counter of a small village. He hung over the washstand, manipulating the little rubber pea as if fascinated.

“Ain’t it curyus how a feller catches onto a thing like that all to once?” he said after a while. “If it hadn’t been that I was so anxious, I might have fooled with that for weeks and weeks and not got anywheres with it. I do wisht you could be my capper a while anyway, until I could get one.”

“I need all my time to study,” said Mr. Gubb. “It ain’t easy to learn deteckating by mail.”

“Pshaw, now!” said Mr. Critz. “I’m real sorry! Maybe if I was to pay you for your time and trouble five dollars a night? How say?”

Mr. Gubb considered. “Well, I dunno!” he said slowly. “I sort of hate to take money for doin’ a favor like that.”

“Now, there ain’t no need to feel that way,” said Mr. Critz. “Your time’s wuth somethin’ to me—it’s wuth a lot to me to get the hang of this gold-brick game. Once I get the hang of it, it won’t be no trouble for me to sell gold-bricks like this one for all the way from a thousand dollars up. I paid fifteen hundred for this one myself, and got it cheap. [Pg 14]That’s a good profit, for this brick ain’t wuth a cent over one hundred dollars, and I know, for I took it to the bank after I bought it, and that’s what they was willin’ to pay me for it. So it’s easy wuth a few dollars for me to have help whilst I’m learnin’. I can easy afford to pay you a few dollars, and to pay a friend of yours the same.”

“Well, now,” said Mr. Gubb, “I don’t know but what I might as well make a little that way as any other. I got a friend—” He stopped short. “You don’t aim to sell the gold-brick to him, do you?”

Mr. Critz’s eyes opened wide behind their spectacles.

“Land’s sakes, no!” he said.

“Well, I got a friend may be willing to help out,” said Mr. Gubb. “What’d he have to do?”

“You or him,” said Mr. Critz, “would be the ‘come-on,’ and pretend to buy the brick. And you or him would pretend to help me to sell it. Maybe you better have the brick, because you can look stupid, and the feller that’s got the brick has got to look that.”

“I can look anyway a’most,” said Mr. Gubb with pride.

“Do tell!” said Mr. Critz, and so it was arranged that the first rehearsal of the gold-brick game should take place the next evening, but as Mr. Gubb turned away Mr. Critz deftly slipped something into the student detective’s coat pocket.

It was toward noon the next day that Mr. Critz, [Pg 15]peering over his spectacles and avoiding as best he could the pails of paste, entered the parlor of the vacant house where Mr. Gubb was at work.

“I just come around,” said Mr. Critz, rather reluctantly, “to say you better not say nothing to your friend. I guess that deal’s off.”

“Pshaw, now!” said Mr. Gubb. “You don’t mean so!”

“I don’t mean nothing in the way of aspersions, you mind,” said Mr. Critz with reluctance, “but I guess we better call it off. Of course, so far as I know, you are all right—”

“I don’t know what you’re gettin’ at,” said Mr. Gubb. “Why don’t you say it?”

“Well, I been buncoed so often,” said Mr. Critz. “Seem’s like any one can get money from me any time and any way, and I got to thinkin’ it over. I don’t know anything about you, do I? And here I am, going to give you a gold-brick that cost me fifteen hundred dollars, and let you go out and wait until I come for it with your friend, and—well, what’s to stop you from just goin’ away with that brick and never comin’ back?”

Mr. Gubb looked at Mr. Critz blankly.

“I’ve went and told my friend,” he said. “He’s all ready to start in.”

“I hate it, to have to say it,” said Mr. Critz, “but when I come to count over them bills I lent you to cap the shell game with, there was a five-dollar one short.”

“I know,” said Gubb, turning red. “And if you [Pg 16]go over there to my coat, you’ll find it in my pocket, all ready to hand back to you. I don’t know how I come to keep it in my pocket. Must ha’ missed it, when I handed you back the rest.”

“Well, I had a notion it was that way,” said Mr. Critz kindly. “You look like you was honest, Mr. Gubb. But a thousand-dollar gold-brick, that any bank will pay a hundred dollars for—I got to get out of this way of trustin’ everybody—”

Mr. Critz was evidently distressed.

“If ’twas anybody else but you,” he said with an effort, “I’d make him put up a hundred dollars to cover the cost of a brick like that whilst he had it. There! I’ve said it, and I guess you’re mad!”

“I ain’t mad,” protested Mr. Gubb, “’long as you’re goin’ to pay me and Pete, and it’s business; I ain’t so set against puttin’ up what the brick is worth.”

Mr. Critz heaved a deep sigh of relief.

“You don’t know how good that makes me feel,” he said. “I was almost losin’ what faith in mankind I had left.”

Mr. Gubb ate his frugal evening meals at the Pie Wagon, on Willow Street, just off Main, where, by day, Pie-Wagon Pete dispensed light viands; and Pie-Wagon Pete was the friend he had invited to share Mr. Critz’s generosity. The seal of secrecy had been put on Pie-Wagon Pete’s lips before Mr. Gubb offered him the opportunity to accept or decline; and when Mr. Gubb stopped for his evening [Pg 17]meal, Pie-Wagon Pete—now off duty—was waiting for him. The story of Mr. Critz and his amateur con’ business had amused Pie-Wagon Pete. He could hardly believe such utter innocence existed. Perhaps he did not believe it existed, for he had come from the city, and he had had shady companions before he landed in Riverbank. He was a sharp-eyed, red-headed fellow, with a hard fist, and a scar across his face, and when Mr. Gubb had told him of Mr. Critz and his affairs, he had seen an opportunity to shear a country lamb.

“How goes it for to-night, Philo?” he asked Mr. Gubb, taking the stool next to Mr. Gubb, while the night man drew a cup of coffee.

“Quite well,” said Mr. Gubb. “Everything is arranged satisfactory. I’m to be on the old house-boat by the wharf-house on the levee at nine, with it.” He glanced at the night man’s back and lowered his voice. “And Mr. Critz will bring you there.”

“Nine, eh?” said Pie-Wagon. “I meet him at your room, do I?”

“You meet him at the Riverbank Hotel at eight-forty-five,” said Mr. Gubb. “Like it was the real thing. I’m goin’ over to my room now, and give him the money—”

“What money?” asked Pie-Wagon Pete quickly.

“Well, you see,” said Mr. Gubb, “he sort of hated to trust the—trust it out of his hands without a deposit. It’s the only one he has. So I thought I’d put up a hundred dollars. He’s all right—”

“Oh, sure!” said Pie-Wagon. “A hundred dollars, eh?”

He looked at Mr. Gubb, who was eating a piece of apple pie hand-to-mouth fashion, and studied him in a new light.

“One hundred dollars, eh?” he repeated thoughtfully. “You give him a hundred-dollar deposit now and he meets you at nine, and me at eight-forty-five, and the train leaves for Chicago at eight-forty-three, halfway between the house-boat and the hotel! Say, Gubby, what does this old guy look like?”

Mr. Gubb, albeit with a tongue unused to description, delineated Mr. Critz as best he could, and as he proceeded, Pie-Wagon Pete became interested.

“Pinkish, and bald? Top of his head like a hard-boiled egg? He ain’t got a scar across his face? The dickens he has! Short and plump, and a reg’lar old nice grandpa? Blue eyes? Say, did he have a coughin’ spell and choke red in the face? Well, sir, for a brand-new detective, you’ve done well. Listen, Jim: Gubby’s got the Hard-Boiled Egg!”

The night man almost dropped his cup of coffee.

“Go ’way!” he said. “Old Hard-Boiled? Himself?”

“That’s right! And caught him with the goods. Say, listen, Gubby!”

For five minutes Pie-Wagon Pete talked, while Mr. Gubb sat with his mouth wide open.

“See?” said Pie-Wagon at last. “And don’t you [Pg 19]mention me at all. Don’t mention no one. Just say to the Chief: ‘And havin’ trailed him this far, Mr. Wittaker, and arranged to have him took with the goods, it’s up to you?’ See? And as soon as you say that, have him send a couple of bulls with you, and if they can do it, they’ll nab Old Hard-Boiled just as he takes your cash. And Old Sleuth and Sherlock Holmes won’t be in it with you when to-morrow mornin’s papers come out. Get it?”

Mr. Gubb got it. When he entered his bedroom, Mr. Critz was waiting for him. It was slightly after eight o’clock; perhaps eight-fifteen. Mr. Critz had what appeared to be the gold-brick neatly wrapped in newspaper, and he looked up with his kindly blue eyes. He had been reading the “Complete Con’ Man,” and had pushed his spectacles up on his forehead as Mr. Gubb entered.

“I done that brick up for you,” he said, indicating it with his hand, “so’s it wouldn’t glitter whilst you was goin’ through the street. If word got passed around there was a gold-brick in town, folks might sort of get suspicious-like. Nice night for goin’ out, ain’t it? Got a letter from my wife this aft’noon,” he chuckled. “She says she hopes I’m doin’ well. Sally’d have a fit if she knew what business I was goin’ into. Well, time’s gettin’ along—”

“I brung the money,” said Mr. Gubb, drawing it from his pocket.

“Don’t seem hardly necess’ry, does it?” said Mr. Critz mildly. “But I s’pose it’s just as well. [Pg 20]Thankee, Mister Gubb. I’ll just pile into my coat—”

Mr. Gubb had picked up the gold-brick, and now he let it fall. Once more the door flew open, but this time it opened for three stalwart policemen, whose revolvers pointed unwaveringly at Mr. Critz. The plump little man gave one glance, and put up his hands.

“All right, boys, you’ve got me,” he said in quite another voice, and allowed them to seize his arms. He paid no attention to the police, but at Mr. Gubb, who was tearing the wrapper from what proved to be but a common vitrified paving-brick, he looked long and hard.

“Say,” said Mr. Critz to Mr. Gubb, “I’m the goat. You stung me all right. You worked me to a finish. I thought I knew all of you from Burns down, but you’re a new one to me. Who are you, anyway?”

Mr. Gubb looked up.

“Me?” he said with pride. “Why—why—I’m Gubb, the foremost deteckative of Riverbank, Iowa.”

On the morning following his capture of the Hard-Boiled Egg, the “Riverbank Eagle” printed two full columns in praise of Detective Gubb and complimented Riverbank on having a superior to Sherlock Holmes in its midst.

“Mr. Philo Gubb,” said the “Eagle,” “has thus far received only eleven of the twelve lessons from the Rising Sun Detective Agency’s Correspondence School of Detecting, and we look for great things from him when he finally receives his diploma and badge. He informed us to-day that he hopes to begin work on the dynamite case soon. With the money he will receive for capturing the Hard-Boiled Egg, Mr. Gubb intends to purchase eighteen complete disguises from the Supply Department of the Rising Sun Detective Agency, Slocum, Ohio. Mr. Gubb wishes us to announce that until the disguises arrive he will continue to do paper-hanging, decorating, and interior painting at reasonable rates.”

Unfortunately there were no calls for Mr. Gubb’s detective services for some time after he received his disguises and diploma, but while waiting he devoted his spare time to the dynamite mystery, a remarkable case on which many detectives had been working for many weeks. This led only to his being [Pg 22]beaten up twice by Joseph Henry, one of the men he shadowed.

The arrival in Riverbank of the World’s Monster Combined Shows the day after Mr. Gubb received his diploma seemed to offer an opportunity for his detective talents, as a circus is usually accompanied by crooks, and early in the morning Mr. Gubb donned disguise Number Sixteen, which was catalogued as “Negro Hack-Driver, Complete, $22.00”; but, while looking for crooks while watching the circus unload, his eyes alighted on Syrilla, known as “Half a Ton of Beauty,” the Fat Lady of the Side-Show.

As Syrilla descended from the car, aided by the Living Skeleton and the Strong Man, the fair creature wore a low-neck evening gown. Her arms and shoulders were snowy white (except for a peculiar mark on one arm). Not only had Mr. Gubb never seen such white arms and shoulders, but he had never seen so much arm and shoulder on one woman, and from that moment he was deeply and hopelessly in love. Like one hypnotized he followed her to the side-show tent, paid his admission, and stood all day before her platform. He was still there when the tent was taken down that night.

Mr. Gubb was not the only man in Riverbank to fall in love with Syrilla. When the ladies of the Riverbank Social Service League heard that the circus was coming to town they were distressed to think how narrow the intellectual life of the side-show [Pg 23]freaks must be and they instructed their Field Secretary, Mr. Horace Winterberry, to go to the side-show and organize the freaks into an Ibsen Literary and Debating Society. This Mr. Winterberry did and the Tasmanian Wild Man was made President, but so deeply did Mr. Winterberry fall in love with Syrilla that he begged Mr. Dorgan, the manager of the side-show, to let him join the side-show, and this Mr. Dorgan did, putting him in a cage as Waw-Waw, the Mexican Hairless Dog-Man, as Mr. Winterberry was exceedingly bald.

At the very next stop made by the circus a strong, heavy-fisted woman entered the side-show and dragged Mr. Winterberry away. This was his wife. Of this the ladies of the Riverbank Social Service League knew nothing, however. They believed Mr. Winterberry had been stolen by the circus and that he was doubtless being forced to learn to swing on a trapeze or ride a bareback horse, and they decided to hire Detective Gubb to find and return him.

At the very moment when the ladies were deciding to retain Mr. Gubb’s services the paper-hanger detective was on his way to do a job of paper-hanging, thinking of the fair Syrilla he might never see again, when suddenly he put down the pail of paste he was carrying and grasped the handle of his paste-brush more firmly. He stared with amazement and fright at a remarkable creature that came toward him from a small thicket near the railway tracks. [Pg 24]Mr. Gubb’s first and correct impression was that this was some remarkable creature escaped from the circus. The horrid thing loping toward him was, indeed, the Tasmanian Wild Man!

As the Wild Man approached, Philo Gubb prepared to defend himself. He was prepared to defend himself to his last drop of blood.

When halfway across the field, the Tasmanian Wild Man glanced back over his shoulder and, as if fearing pursuit, increased his speed and came toward Philo Gubb in great leaps and bounds. The Correspondence School detective waved his paste-brush more frantically than ever. The Tasmanian Wild Man stopped short within six feet of him.

Viewed thus closely, the Wild Man was a sight to curdle the blood. Remnants of chains hung from his wrists and ankles; his long hair was matted about his face; and his finger nails were long and claw-like. His face was daubed with ochre and red, with black rings around the eyes, and the circles within the rings were painted white, giving him an air of wildness possessed by but few wild men. His only garments were a pair of very short trunks and the skin of some wild animal, bound about his body with ropes of horse-hair.

Philo Gubb bent to receive the leap he felt the Tasmanian Wild Man was about to make, but to his surprise the Wild Man held up one hand in token of amity, and with the other removed the matted hair from his head, revealing an under-crop of taffy [Pg 25]yellow, neatly parted in the middle and smoothed back carefully.

“I say, old chap,” he said in a pleasant and well-bred tone, “stop waving that dangerous-looking weapon at me, will you? My intentions are most kindly, I assure you. Can you inform me where a chap can get a pair of trousers hereabout?”

Philo Gubb’s experienced eye saw at once that this creature was less wild than he was painted. He lowered the paste-brush.

“Come into this house,” said Philo Gubb. “Inside the house we can discuss pants in calmness.”

The Tasmanian Wild Man accepted.

“Now, then,” said Philo Gubb, when they were safe in the kitchen. He seated himself on a roll of wall-paper, and the Tasmanian Wild Man, whose real name was Waldo Emerson Snooks, told his brief story.

Upon graduating from Harvard, he had sought employment, offering to furnish entertainment by the evening, reading an essay entitled, “The Comparative Mentality of Ibsen and Emerson, with Sidelights on the Effect of Turnip Diet at Brook Farm,” but the agency was unable to get him any engagements. They happened, however, to receive a request from Mr. Dorgan, manager of the side-show, asking for a Tasmanian Wild Man, and Mr. Snooks had taken that job. To his own surprise, he made an excellent Wild Man. He was able to rattle his chains, dash up and down the cage, gnaw the iron [Pg 26]bars of the cage, eat raw meat, and howl as no other Tasmanian Wild Man had ever done those things, and all would have been well if an interloper had not entered the side-show.

The interloper was Mr. Winterberry, who had introduced the subject of Ibsen’s plays, and in a discussion of them the Tasmanian Wild Man and Mr. Hoxie, the Strong Man, had quarreled, and Mr. Hoxie had threatened to tear Mr. Snooks limb from limb.

“And he would have done so,” said the Tasmanian Wild Man with emotion, “if I had not fled. I dare not return. I mean to work my way back to Boston and give up Tasmanian Wild Man-ing as a profession. But I cannot without pants.”

“I guess you can’t,” said Philo Gubb. “In any station of Boston life, pants is expected to be worn.”

“So the question is, old chap, where am I to be panted?” said Waldo Emerson Snooks.

“I can’t pant you,” said Philo Gubb, “but I can overall you.”

The late Tasmanian Wild Man was most grateful. When he was dressed in the overalls and had wiped the grease-paint from his face on an old rag, no one would have recognized him.

“And as for thanks,” said Philo Gubb, “don’t mention it. A deteckative gent is obliged to keep up a set of disguises hitherto unsuspected by the mortal world. This Tasmanian Wild Man outfit will [Pg 27]do for a hermit disguise. So you don’t owe me no thanks.”

As Philo Gubb watched Waldo Emerson Snooks start in the direction of Boston—only some thirteen hundred miles away—he had no idea how soon he would have occasion to use the Tasmanian Wild Man disguise, but hardly had the Wild Man departed than a small boy came to summon Mr. Gubb, and it was with a sense of elation and importance that he appeared before the meeting of the Riverbank Ladies’ Social Service League.

“And so,” said Mrs. Garthwaite, at the close of the interview, “you understand us, Mr. Gubb?”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Philo Gubb. “What you want me to do, is to find Mr. Winterberry, ain’t it?”

“Exactly,” agreed Mrs. Garthwaite.

“And, when found,” said Mr. Gubb, “the said stolen goods is to be returned to you?”

“Just so.”

“And the fiends in human form that stole him are to be given the full limit of the law?”

“They certainly deserve it, abducting a nice little gentleman like Mr. Winterberry,” said Mrs. Garthwaite.

“They do, indeed,” said Philo Gubb, “and they shall be. I would only ask how far you want me to arrest. If the manager of the side-show stole him, my natural and professional deteckative instincts would tell me to arrest the manager; and if the whole side-show stole him I would make bold to arrest the [Pg 28]whole side-show; but if the whole circus stole him, am I to arrest the whole circus, and if so ought I to include the menagerie? Ought I to arrest the elephants and the camels?”

“Arrest only those in human form,” said Mrs. Garthwaite.

Philo Gubb sat straight and put his hands on his knees.

“In referring to human form, ma’am,” he asked, “do you include them oorangootangs and apes?”

“I do,” said Mrs. Garthwaite. “Association with criminals has probably inclined their poor minds to criminality.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Philo Gubb, rising. “I leave on this case by the first train.”

Mr. Gubb hastily packed the Tasmanian garment and six other disguises in a suitcase, put the fourteen dollars given him by Mrs. Garthwaite in his pocket, and hurried to catch the train for Bardville, where the World’s Monster Combined Shows were to show the next day. With true detective caution Philo Gubb disguised even this simple act.

Having packed his suitcase, Mr. Gubb wrapped it carefully in manila paper and inserted a laundry ticket under the twine. Thus, any one seeing him might well suppose he was returning from the laundry and not going to Bardville. To make this seem the more likely, he donned his Chinese disguise, Number Seventeen, consisting of a pink, skull-like wig with a long pigtail, a blue jumper, and a yellow complexion. [Pg 29]Mr. Gubb rubbed his face with crude ochre powder, and his complexion was a little high, being more the hue of a pumpkin than the true Oriental skin tint. Those he met on his way to the station imagined he was in the last stages of yellow fever, and fled from him hastily.

He reached the station just as the train’s wheels began to move; and he was springing up the steps onto the platform of the last car when a hand grasped his arm. He turned his head and saw that the man grasping him was Jonas Medderbrook, one of Riverbank’s wealthiest men.

“Gubb! I want you!” shouted Mr. Medderbrook energetically, but Philo Gubb shook off the detaining arm.

“Me no savvy Melican talkee,” he jabbered, bunting Mr. Medderbrook off the car step.

Bright and early next morning, Philo Gubb gave himself a healthy coat of tan, with rather high color on his cheek-bones. From his collection of beards and mustaches—carefully tagged from “Number One” to “Number Eighteen” in harmony with the types of disguise mentioned in the twelve lessons of the Rising Sun Detective Agency’s Correspondence School of Detecting—he selected mustache Number Eight and inserted the spring wires in his nostrils.

Mustache Number Eight was a long, deadly black mustache with up-curled ends, and when Philo Gubb had donned it he had a most sinister appearance, [Pg 30]particularly as he failed to remove the string tag which bore the legend, “Number Eight. Gambler or Card Sharp. Manufactured and Sold by the Rising Sun Detective Agency’s Correspondence School of Detecting Supply Bureau.” Having put on this mustache, Mr. Gubb took a common splint market-basket from under the bed and placed in it the matted hair of the Tasmanian Wild Man, his make-up materials, a small mirror, two towels, a cake of soap, the Tasmanian Wild Man’s animal skin robe, the hair rope, and the abbreviated trunks. He covered these with a newspaper.

The sun was just rising when he reached the railway siding, and hardly had Mr. Gubb arrived when the work of unloading the circus began.

MR. WINTERBERRY DID NOT SEEM TO BE CONCEALED AMONG

THEM

MR. WINTERBERRY DID NOT SEEM TO BE CONCEALED AMONG

THEMMr. Gubb—searching for the abducted Mr. Winterberry—sped rapidly from place to place, the string tag on his mustache napping over his shoulder, but he saw no one answering Mrs. Garthwaite’s description of Mr. Winterberry. When the tent wagons had departed, the elephants and camels were unloaded, but Mr. Winterberry did not seem to be concealed among them, and the animal cages—which came next—were all tightly closed. There were four or five cars, however, that attracted Philo Gubb’s attention, and one in particular made his heart beat rapidly. This car bore the words, “World’s Monster Combined Shows Freak Car.” And as Mr. Winterberry had gone as a social reform agent to the side-show, Mr. Gubb rightly felt that here if anywhere [Pg 31]he would find a clue, and he was doubly agitated since he knew the beautiful Syrilla was doubtless in that car.

Walking around the car, he heard the door at one end open. He crouched under the platform, his ears and eyes on edge. Hardly was he concealed before the head ruffian of the unloading gang approached.

“Mister Dorgan,” he said, in quite another tone than he had used to his laborers, “should I fetch that wild man cage to the grounds for you to-day?”

“No,” said Dorgan. “What’s the use? I don’t like an empty cage standing around. Leave it on the car, Jake. Or—hold on! I’ll use it. Take it up to the grounds and put it in the side-show as usual. I’ll put the Pet in it.”

“Are ye foolin’?” asked the loading boss with a grin. “The cage won’t know itself, Mister Dorgan, afther holdin’ that rip-snortin’ Wild Man to be holdin’ a cold corpse like the Pet is.”

“Never you mind,” said Dorgan shortly. “I know my business, Jake. You and I know the Pet is a dead one, but these country yaps don’t know it. I might as well make some use of the remains as long as I’ve got ’em on hand.”

“Who you goin’ to fool, sweety?” asked a voice, and Mr. Dorgan looked around to see Syrilla, the Fat Lady, standing in the car door.

“Oh, just folks!” said Dorgan, laughing.

“You’re goin’ to use the Pet,” said the Fat Lady [Pg 32]reproachfully, “and I don’t think it is nice of you. Say what you will, Mr. Dorgan, a corpse is a corpse, and a respectable side-show ain’t no place for it. I wish you would take it out in the lot and bury it, like I wanted you to, or throw it in the river and get rid of it. Won’t you, dearie?”

“I will not,” said Mr. Dorgan firmly. “A corpse may be a corpse, Syrilla, any place but in a circus, but in a circus it is a feature. He’s goin’ to be one of the Seven Sleepers.”

“One of what?” asked Syrilla.

“One of the Seven Sleepers,” said Dorgan. “I’m goin’ to put him in the cage the Wild Man was in, and I’m goin’ to tell the audiences he’s asleep. ‘He looks dead,’ I’ll say, ‘but I give my word he’s only asleep. We offer five thousand dollars,’ I’ll say, ‘to any man, woman, or child that proves contrary than that we have documents provin’ that this human bein’ in this cage fell asleep in the year 1837 and has been sleepin’ ever since. The longest nap on record,’ I’ll say. That’ll fetch a laugh.”

“And you don’t care, dearie, that I’ll be creepy all through the show, do you?” said Syrilla.

“I won’t care a hang,” said Dorgan.

Mr. Gubb glided noiselessly from under the car and sped away. He had heard enough to know that deviltry was afoot. There was no doubt in his mind that the Pet was the late Mr. Winterberry, for if ever a man deserved to be called “Pet,” Mr. Winterberry—according to Mrs. Garthwaite’s description—was [Pg 33]that man. There was no doubt that Mr. Winterberry had been murdered, and that these heartless wretches meant to make capital of his body. The inference was logical. It was a strong clue, and Mr. Gubb hurried to the circus grounds to study the situation.

“No,” said Syrilla tearfully, “you don’t care a hang for the nerves of the lady and gent freaks under your care, Mr. Dorgan. It’s nothin’ to you if repulsion from that corpse-like Pet drags seventy or eighty pounds of fat off of me, for you well know what my contract is—so much a week and so much for each additional pound of fat, and the less fat I am the less you have to add onto your pay-roll. The day the Pet come to the show first I fainted outright and busted down the platform, but little do you care, Mr. Dorgan.”

“Don’t you worry; you didn’t murder him,” said Mr. Dorgan.

“He looks so lifelike!” sobbed Syrilla.

“Oh, Hoxie!” shouted Mr. Dorgan.

“Yes, sir?” said the Strong Man, coming to the car door.

“Take Syrilla in and tell the girls to put ice on her head. She’s gettin’ hysterics again. And when you’ve told ’em, you go up to the grounds and tell Blake and Skinny to unpack the Petrified Man. Tell ’em I’m goin’ to use him again to-day, and if he’s lookin’ shop-worn, have one of the men go over his complexion and make him look nice and lifelike.”

Mr. Dorgan swung off from the car step and walked away.

The Petrified Man had been one of his mistakes. In days past petrified men had been important side-show features and Mr. Dorgan had supposed the time had come to re-introduce them, and he had had an excellent petrified man made of concrete, with steel reinforcements in the legs and arms and a body of hollow tile so that it could stand rough travel.

Unfortunately, the features of the Petrified Man had been entrusted to an artist devoted to the making of clothing dummies. Instead of an Aztec or Cave Dweller cast of countenance, he had given the Petrified Man the simpering features of the wax figures seen in cheap clothing stores. The result was that, instead of gazing at the Petrified Man with awe as a wonder of nature, the audiences laughed at him, and the living freaks dubbed him “the Pet,” or, still more rudely, “the Corpse,” and when the glass case broke at the end of the week, Mr. Dorgan ordered the Pet packed in a box.

Just now, however, the flight of the Tasmanian Wild Man, and the involuntary departure of Mr. Winterberry at the command of his wife after his short appearance as Waw-Waw, the Mexican Hairless Dog-Man, suggested the new use for the Petrified Man.

When Detective Gubb reached the circus grounds the glaring banners had not yet been erected before [Pg 35]the side-show tent, but all the tents except the “big top” were up and all hands were at work on that one, or supposed to be. Two were not. Two of the roughest-looking roustabouts, after glancing here and there, glided into the property tent and concealed themselves behind a pile of blue cases, hampers, and canvas bags. One of them immediately drew from under his coat a small but heavy parcel wrapped in an old rag.

“Say, cul,” he said in a coarse voice, “you sure have got a head on you. This here stuff will be just as safe in there as in a bank, see? Gimme the screw-driver.”

“‘Not to be opened until Chicago,’” said the other gleefully, pointing to the words daubed on one of the blue cases. “But I guess it will be—hey, old pal? I guess so!”

Together they removed the lid of the box, and Detective Gubb, seeking the side-show, crawled under the wall of the property tent just in time to see the two ruffians hurriedly jam their parcel into the case and screw the lid in place again. Mr. Gubb’s mustache was now in a diagonal position, but little he cared for that. His eyes were fastened on the countenances of the two roustabouts. The men were easy to remember. One was red-headed and pockmarked and the other was dark and the lobes of his ears were slit, as if some one had at some time forcibly removed a pair of rings from them. Very quietly Philo Gubb wiggled backward out of the [Pg 36]tent, but as he did so his eyes caught a word painted on the side of the blue case. It was “Pet”!

Mr. Gubb proceeded to the next tent. Stooping, he peered inside, and what he saw satisfied him that he had found the side-show. Around the inside of the tent men were erecting a blue platform, and on the far side four men were wheeling a tongueless cage into place. A door at the back of the cage swung open and shut as the men moved the cage, but another in front was securely bolted and barred. Mr. Gubb lowered the tent wall and backed away. It was into this cage that the body of Mr. Winterberry was to be put to make a public holiday for yokels! And the murderer was still at large!

Murderer? Murderers! For who were the two rough characters he had seen tampering with the case containing the remains of the Pet? What had they been putting in the case? If not the murderers, they were surely accomplices. Walking like a wary flamingo, Mr. Gubb circled the tent. He saw Mr. Dorgan and Syrilla enter it. Himself hidden in a clump of bushes, he saw Mr. Lonergan, the Living Skeleton; Mr. Hoxie, the Strong Man; Major Ching, the Chinese Giant; General Thumb, the Dwarf; Princess Zozo, the Serpent Charmer; Maggie, the Circassian Girl; and the rest of the side-show employees enter the tent. Then he removed his Number Eight mustache and put it in his pocket, and balanced his mirror against a twig. Mr. Gubb was changing his disguise.

For a while the lady and gentleman freaks stood talking, casting reproachful glances at Mr. Dorgan. Syrilla, with traces of tears on her face, was complaining of the cruel man who insisted that the Pet become part of the show once more and Mr. Dorgan was resisting their reproaches.

“I’m the boss of the show,” he said firmly. “I’m goin’ to use that cage, and I’m goin’ to use the Pet.”

“Couldn’t you put Orlando in it, and get up a spiel about him?” asked Princess Zozo, whose largest serpent was called Orlando. “If you got him a bottle of cold cream from the make-up tent he’d lie for hours with his dear little nose sniffin’ it. He’s pashnutly fond of cold cream.”

“Well, the public ain’t pashnutly fond of seein’ a snake smell it,” said Mr. Dorgan. “The Pet is goin’ into that cage—see?”

“Couldn’t you borry an ape from the menagerie?” asked Mr. Lonergan, the Living Skeleton, who was as passionately fond of Syrilla as Orlando was of cold cream. “And have him be the first man-monkey to speak the human language, only he’s got a cold and can’t talk to-day? You did that once.”

“And got roasted by the whole crowd! No, sir, Mr. Lonergan. I can’t, and I won’t. Bring that case right over here,” he added, turning to the four roustabouts who were carrying the blue case into the tent. “Got it open? Good! Now—”

He looked toward the cage and stopped short, his mouth open and his eyes staring. Sitting on his [Pg 38]haunches, his fore paws, or hands, hanging down like those of a “begging” dog, a Tasmanian Wild Man stared from between the bars of the cage. The matted hair, the bare legs, the animal skin blanket, the streaks of ochre and red on the face, the black circles around the eyes with the white inside the circles, were those of a real Tasmanian Wild Man, but this Tasmanian Wild Man was tall and thin, almost rivaling Mr. Lonergan in that respect. The thin Roman nose and the blinky eyes, together with the manner of holding the head on one side, suggested a bird—a large and dissipated flamingo, for instance.

Mr. Dorgan stared with his mouth open. He stared so steadily that he even took a telegram from the messenger boy who entered the tent, and signed for it without looking at the address. The messenger boy, too, stopped to stare at the Tasmanian flamingo. The men who had brought the blue case set it down and stared. The freaks gathered in front of the cage and stared.

“What is it?” asked Syrilla in a voice trembling with emotion.

“Say! Where in the U.S.A. did you come from?” asked Mr. Dorgan suddenly. “What in the dickens are you, anyway?”

“I’m a Tasmanian Wild Man,” said Mr. Gubb mildly.

“You a Tasmanian Wild Man?” said Mr. Dorgan. “You don’t think you look like a Tasmanian [Pg 39]Wild Man, do you? Why, you look like—you look like—you look—”

“He looks like an intoxicated pterodactyl,” said Mr. Lonergan, who had some knowledge of prehistoric animals,—“only hairier.”

“He looks like a human turkey with a piebald face,” suggested General Thumb.

“He don’t look like nothin’!” said Mr. Dorgan at last. “That’s what he looks like. You get out of that cage!” he added sternly to Mr. Gubb. “I don’t want nothin’ that looks like you nowhere near this show.”

“But, Mr. Dorgan, dearie, think how he’d draw crowds,” said Syrilla.

“Crowds? Of course he’d draw crowds,” said Mr. Dorgan. “But what would I say when I lectured about him? What would I call him? No, he’s got to go. Boys,” he said to the four roustabouts, two of whom were those Mr. Gubb had seen in the property tent, “throw this feller out of the tent.”

“Stop!” said Mr. Gubb, raising one hand. “I will admit I have tried to deceive you: I am not a Tasmanian Wild Man. I am a deteckative!”

“Detective?” said Mr. Dorgan.

“In disguise,” said Mr. Gubb modestly. “In the deteckative profession the assuming of disguises is often necessary to the completion of the clarification of a mystery plot.”

He pointed down at the Pet, whose newly rouged [Pg 40]and powdered face rested smirkingly in the box below the cage.

“I arrest you all,” he said, but before he could complete the sentence, the red-headed man and the black-headed man turned and bolted from the tent. Mr. Gubb beat and jerked at the bars of his cage as frantically as Mr. Waldo Emerson Snooks had ever beaten and jerked, but he could not rend them apart.

“Get those two fellers,” Mr. Gubb shouted to Mr. Hoxie, and the strong man ran from the tent.

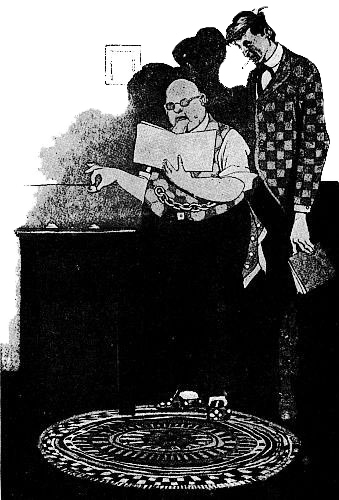

“What’s this about arrest?” asked Mr. Dorgan.

“I arrest this whole side-show,” said Mr. Gubb, pressing his face between the bars of the cage, “for the murder of that poor, gentle, harmless man now a dead corpse into that blue box there—Mr. Winterberry by name, but called by you by the alias of the ‘Pet.’”

“Winterberry?” exclaimed Mr. Dorgan. “That Winterberry? That ain’t Winterberry! That’s a stone man, a made-to-order concrete man, with hollow tile stomach and reinforced concrete arms and legs. I had him made to order.”

“The criminal mind is well equipped with explanations for use in time of stress,” said Mr. Gubb. “Lesson Six of the Correspondence School of Deteckating warns the deteckative against explanations of murderers when confronted by the victim. I demand an autopsy onto Mr. Winterberry.”

“Autopsy!” exclaimed Mr. Dorgan. “I’ll autopsy him for you!”

He grasped one of the Pet’s hands and wrenched off one concrete arm. He struck the head with a tent stake and shattered it into crumbling concrete. He jerked the Roman tunic from the body and disclosed the hollow tile stomach.

“Hello!” he said, lifting a rag-wrapped parcel from the interior of the Pet. “What’s this?”

When unwrapped it proved to be two dozen silver forks and spoons and a good-sized silver trophy cup.

“‘Riverbank Country Club, Duffers’ Golf Trophy, 1909?’” Mr. Dorgan read. “‘Won by Jonas Medderbrook.’ How did that get there?”

“Jonas Medderbrook,” said Mr. Gubb, “is a man of my own local town.”

“He is, is he?” said Mr. Dorgan. “And what’s your name?”

“Gubb,” said the detective. “Philo Gubb, Esquire, deteckative and paper-hanger, Riverbank, Iowa.”

“Then this is for you,” said Mr. Dorgan, and he handed the telegram to Mr. Gubb. The detective opened it and read:—

Gubb,

Care of Circus,

Bardville, Ia.

My house robbed circus night. Golf cup gone. Game now rotten: never win another. Five hundred dollars reward for return to me.

Jonas Medderbrook

“You didn’t actually come here to find Mr. Winterberry, did you?” asked Syrilla.

Mr. Gubb folded the telegram, raised his matted hair, and tucked the telegram between it and his own hair for safe-keeping.

“When a deteckative starts out to detect,” he said calmly, “sometimes he detects one thing and sometimes he detects another. That cup is one of the things I deteckated to-day. And now, if all are willing, I’ll step outside and get my pants on. I’ll feel better.”

“And you’ll look better,” said Mr. Dorgan. “You couldn’t look worse.”

“In the course of the deteckative career,” said Mr. Gubb, “a gent has to look a lot of different ways, and I thank you for the compliment. The art of disguising the human physiology is difficult. This disguise is but one of many I am frequently called upon to assume.”

“Well, if any more are like this one,” said Mr. Dorgan with sincerity, “I’m glad I’m not a detective.”

Syrilla, however, heaved her several hundred pounds of bosom and cast her eyes toward Mr. Gubb.

“I think detectives are lovely in any disguise,” she said, and Mr. Gubb’s heart beat wildly.

As Philo Gubb boarded the train for Riverbank after recovering the silver loving-cup from the interior of the petrified man, he cast a regretful glance backward. It was for Syrilla. There was half a ton of her pinky-white beauty, and her placid, cow-like expression touched an echoing chord in Philo Gubb’s heart.

Philo felt, however, that his admiration must be hopeless, for Syrilla must earn a salary in keeping with her size, and his income was too irregular and small to keep even a thin wife.

Five hundred dollars was a large reward for a loving-cup that cost not over thirty dollars, it is true, but Mr. Jonas Medderbrook could afford to pay what he chose, and as he was passionately fond of golf and passionately poor at the game, and as this was probably the only golf prize he would ever win, he was justified in paying liberally, especially as this cup was not merely a tankard, but almost large enough to be called a tank.

Detective Gubb hastened to the home of Mr. Medderbrook, but when the door of that palatial house opened, the colored butler told Mr. Gubb that Mr. Medderbrook was at the Golf Club, attending the annual banquet of the Fifty Worst Duffers. [Pg 44]Mr. Gubb started for the Golf Club. As he walked he thought of Syrilla, and he was at the gate of the Golf Club before he knew it.

He walked up the path toward the club-house, but when halfway, he stopped short, all his detective instincts aroused. The windows of the club-house glowed with light, and sounds of merriment issued from them, but the cause of Philo Gubb’s sudden pause was a head silhouetted against one of the glowing windows. As Mr. Gubb watched, he saw the head disappear in the gloom below the window only to reappear at another window. Mr. Gubb, following the directions as laid down in Lesson Four of the Correspondence Lessons, dropped to his hands and knees and crept silently toward the “Paul Pry.” When within a few feet of him, Mr. Gubb seated himself tailor-fashion on the grass.

As Philo sat on the damp grass, the man at the window turned his head, and Mr. Gubb noted with surprise that the stranger had none of the marks of a sodden criminal. The face was that of a respectably benevolent old German-American gentleman. Kindliness and good-nature beamed from its lines; but at the moment the plump little man seemed in trouble.

“Good-evening,” said Mr. Gubb. “I presume you are taking an observation of the dinner-party within the inside of the club.”

The old gentleman turned sharply.

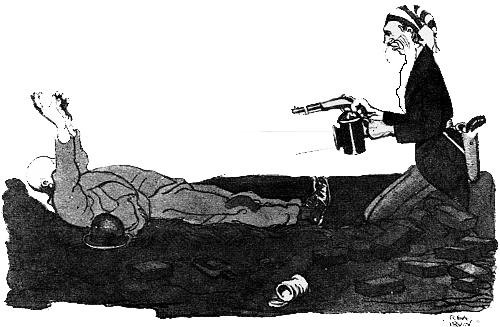

A HEAD SILHOUETTED AGAINST ONE OF THE GLOWING WINDOWS

A HEAD SILHOUETTED AGAINST ONE OF THE GLOWING WINDOWS

“Shess!” he said. “I look at der peoples eading and drinking. Alvays I like to see dot. Und sooch [Pg 45]goot eaders! Dot man mit der black beard, he vos a schplendid eader!”

Mr. Gubb raised himself to his knees and looked into the dining-room.

“That,” he said, “is the Honorable Mr. Jonas Medderbrook, the wealthiest rich man in Riverbank.”

“Metterbrook? Mettercrook?” said the old German-American. “Not Chones, eh?”

“Not Jones, to my present personal knowledge at this time,” said Philo Gubb.

“Not Chones!” repeated the plumply benevolent-looking German-American. “Dot vos stranche! You vos sure he vos not Chones?”

“I’m quite almost positive upon that point of knowledge,” said Philo Gubb, “for I have under my arm a golf cup I am returning back to Mr. Medderbrook to receive five hundred dollars reward from him for.”

“So?” queried the stranger. “Fife hunderdt dollars? Und it is his cup?”

“It is,” said Philo Gubb. He raised the cup in his hand that the stranger might read the inscription stating that the cup was Jonas Medderbrook’s.

The light of the window made the engraving easy to read, but the old German-American first drew from his pocket a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles and adjusted them carefully on his nose. He then took the cup and moved closer to the window and read the inscription.

“Shess! Shess!” he agreed, nodding his head several times, and then he smiled at Mr. Gubb a broadly benevolent smile. “Oxcoose me!” he added, and with gentle deliberation he removed Mr. Gubb’s hat. “Shoost a minute, please!” he continued, and with his free hand he felt gently of the top of Mr. Gubb’s head. He turned Mr. Gubb’s head gently to the right. “So!” he exclaimed: “Dot vos goot!” He raised the cup above his head and brought it down on top of Mr. Gubb’s head in the exact spot he had selected. For two moments Mr. Gubb made motions with his hands resembling those of a swimmer, and then he collapsed in a heap. The kindly looking old German-American gentleman, seeing he was quite unconscious, tucked the golf cup under his own arm, and waddled slowly down the path to the club gates.

Ten minutes later a small automobile drove up and young Dr. Anson Briggs hopped out. Mr. Gubb was just getting to his feet, feeling the top of his head with his hand as he did so.

“Here!” said Dr. Briggs. “You must not do that!”

“Why can’t I do it?” Mr. Gubb asked crossly. “It is my own personal head, and if I wish to desire to rub it, you are not concerned in the occasion whatever.”

“Oh, rub your head if you want to!” exclaimed the doctor. “I say you must not stand up. A man that has just had a fit must not stand up.”

“Who had a fit?” asked Philo Gubb.

“You did,” said Dr. Briggs. “I am told you had a very bad fit, and fell and knocked your head against the building. You’re dazed. Lie down!”

“I prefer to wish to stand erect on my feet,” said Mr. Gubb firmly. “Where’s my cup?”

“What cup?”

“Who told you I was suffering from the symptom of a fit?” demanded Philo Gubb.

“Why, a short, plump little German did,” said the doctor. “He sent me here. And he gave me this to give to you.”

The doctor held an envelope toward Mr. Gubb, and the detective took it and tore it open. By the light of the window he read:—

Rec’d of J. Jones, golluf cup worth $500.P. H. Schreckenheim.

Philo Gubb turned to Dr. Briggs.

“I am much obliged for the hastiness with which you came to relieve one you considered to think in trouble, doctor,” he said, “but fits are not in my line of sickness, which mainly is dyspeptic to date.”

“Now, what is all this?” asked the doctor suspiciously. “What is that letter, anyway?”

“It is a clue,” said Philo Gubb, “which, connected with the bump on the top of the cranium of my skull, will, no doubt, land somebody into jail. So good-evening, doctor.”

He picked his hat from the lawn, and in his most [Pg 48]stately manner walked around the club-house and in at the door.

Inside the club-house, Mr. Gubb asked one of the waiters to call Mr. Medderbrook, and Mr. Medderbrook immediately appeared.

As he came from the dining-room rapidly, the napkin he had had tucked in his neck fell over his shoulder behind him, and Mr. Medderbrook, instead of turning around bent backward until he could pick up the napkin with his teeth, after which he resumed his normal upright position.

“Excuse me, Gubb,” he said; “I didn’t think what I was doing. Where is the cup?”

The detective explained. He handed Mr. Medderbrook the receipt that had been sent by Mr. Schreckenheim, and the moment Mr. Medderbrook’s eyes fell upon it he turned red.

“That infernal Dutchman!” he cried, although Mr. Schreckenheim was not a Dutchman at all, but a German-American. “I’ll jail him for this!”

He stopped short.

“Gubb,” he said, “did that fellow tell you what his business was?”

“He did not,” said Philo Gubb. “He failed to express any mention of it.”

“That man,” said Mr. Medderbrook bitterly, “is Schreckenheim, the greatest tattoo artist in the world. He is the king of them all. A connoisseur in tattooish art can tell a Schreckenheim as easily as a picture-dealer can tell a Corot. But no matter! [Pg 49]Mr. Gubb, you are a detective and I believe what is told detectives is held inviolable. Yes. You—and all Riverbank—see in me an ordinary citizen, wealthy, perhaps, but ordinary. As a matter of fact, I was once”—he looked cautiously around—“I was once a contortionist. I was once the contortionist. And now I am a wealthy man. My wife left me because she said I was stingy, and she took my child—my only daughter. I have never seen either of them since. I have searched high and low, but I cannot find them. Mr. Gubb, I would give the man that finds my daughter—if she is alive—a thousand dollars.”

“You don’t object to my attempting to try?” said Philo Gubb.

“No,” said Mr. Jonas Medderbrook, “but that is not what I wish to explain. In my contortion act, Mr. Gubb, I was obliged to wear the most expensive silk tights. Wiggling on the floor destroys them rapidly. I had a happy thought. I was known as the Man-Serpent. Could I not save all expense of tights by having myself tattooed so that my skin would represent scales? Look.”

Mr. Medderbrook pulled up his cuff and showed Mr. Gubb his arm. It was beautifully tattooed in red and blue, like the scales of a cobra.

“The cost,” continued Mr. Medderbrook, “was great. Herr Schreckenheim worked continuously on me, and when he reached my manly chest I had a brilliant thought. I would have tattooed upon it [Pg 50]an American eagle. Imagine the enthusiasm of an audience when I stood straight, spread my arms and showed that noble emblem of our nation’s strength and freedom! I told Herr Schreckenheim and he set to work. When—and the contract price, by the way, for doing that eagle was five hundred dollars—when the eagle was about completed, I said to Herr Schreckenheim, ‘Of course you will do no more eagles?’

“‘More eagles?’ he said questioningly.

“‘On other men,’ I said. ‘I want to be the only man with an eagle on my chest.’

“‘I am doing an eagle on another man now,’ he said.

“I was angry at once. I jumped from the table and threw on my clothes. ‘Cheater!’ I cried. ‘Not another spot or dot shall you make on me! Go! I will never pay you a cent!’

“He was very angry. ‘It is a contract!’ he cried. ‘Five hundred dollars you owe me!’

“‘I owe it to you when the job is complete,’ I declared. ‘That was the contract. Is this job complete? Where are the eagle’s claws? I’ll never pay you a cent!’

“We had a lot of angry words. He demanded that I give him a chance to put the claws on the eagle. I refused. I said I would never pay. He said he would follow me to the end of the world and collect. He said he would do those eagle claws if he had to do them on my infant daughter. I dared him [Pg 51]to touch the child. And now,” said Mr. Medderbrook, “he has taken the golf cup I value at five hundred dollars. He has won.”

At the mention of the threat regarding the child, Philo Gubb’s eyes opened wide, but he kept silence.

“Gubb,” said Mr. Medderbrook suddenly, “I’ll give you a thousand dollars if you can recover my poor child.”

“The deteckative profession is full of complicity of detail,” said Mr. Gubb, “and the impossible is quite possible when put in the right hands. The cup—”

“Bother the cup!” said Mr. Medderbrook carelessly. “I want my child—I’ll give ten thousand dollars for my child, Gubb.”

With difficulty could Philo Gubb restrain his eagerness to depart. He had a clue!

Ordinarily Mr. Gubb would have taken any disguise that seemed to him best suited for the work in hand; but now he was going to see and be seen by Syrilla!

Mr. Gubb ran down the list—Number Seven, Card Sharp; Number Nine, Minister of the Gospel; Number Twelve, Butcher; Number Sixteen, Negro Hack-Driver; Number Seventeen, Chinese Laundryman; Number Twenty, Cowboy.... Philo Gubb paused there. He would be a cowboy, for it was a jaunty disguise—“chaps,” sombrero, spurs, buckskin gloves, holsters and pistols, blue shirt, yellow hair, stubby mustache. He donned the complete [Pg 52]disguise, put his street garments in a suitcase and viewed himself in his small mirror. He highly approved of the disguise. He touched his cheeks with red to give himself a healthy, outdoor appearance.

Early the next morning, before the earliest merchants had opened their shops, Philo Gubb boarded the train for West Higgins, for it was there the World’s Greatest Combined Shows were to appear. The few sleepy passengers did not open their eyes; the conductor, as he took Mr. Gubb’s ticket, merely remarked, “Joining the show at West Higgins?” and passed on. Boys were already gathering on the West Higgins station platform when the train pulled in, and they cheered Mr. Gubb, thinking him part of the show. This greatly increased the difficulty of Mr. Gubb’s detective work. He had hoped to steal unobserved to the circus grounds, but a dozen small boys immediately attached themselves to him, running before him and whooping with joy.

“Boys,” said Mr. Gubb sternly, “I wish you to run away and play elsewhere than in front of me continuously and all the time,”—and they cheered because he had spoken. Only the glad news that the circus trains had reached town finally dragged them reluctantly away. Detective Gubb hurried to the circus grounds. The cook tent was already up, and the grub tent was being put up. Presently the side-show tent was up and the “big top” rising. It was not until nine o’clock, however, that the side-show ladies and gentlemen began to appear, and [Pg 53]when they arrived they went at once to the grub tent and seated themselves at the table. From a corner of the “big top’s” side wall, Detective Gubb watched them.

“Look there, dearie,” said Syrilla suddenly to Princess Zozo, “don’t that cowboy look like Mr. Gubb that was at Bardville and got the golf cup?”

“It don’t look like him,” said Princess Zozo; “it is him. Why don’t you ask him to come over and help at the eats? You seemed to like him yesterday.”

“I thought he was a real gentlem’nly gentlemun, dearie, if that’s what you mean,” said Syrilla; and raising her voice she called to Mr. Gubb. For a moment he hesitated, and then he came forward. “We knowed you the minute we seen you, Mr. Gubb. Come and sit in beside me and have some breakfast if you ain’t dined. I thought you went home last night. You ain’t after no more crim’nals, are you?”

“There are variously many ends to the deteckative business,” said Mr. Gubb, as he seated himself beside Syrilla. “I’m upon a most important case at the present time.”

Syrilla reached for her fifth boiled potato, and as her arm passed Mr. Gubb’s face he thrilled. He had not been mistaken. Upon that arm was a pair of eagle’s claws, tattooed in red and blue! How little these had meant to him before, and how much they meant now!

“I presume you don’t hardly ever long for a home in one place, Miss Syrilla,” he began, with his eye fixed on her arm just above the elbow.

“Well, believe me, dearie,” said Syrilla, “you don’t want to think that just because I travel with a side-show I don’t long for the refinements of a true home just like other folks. Some folks think I’m easy to see through and that I ain’t nothin’ but fat and appetite, but they’ve got me down wrong, Mr. Gubb. I was unfortunate in gettin’ lost from my father and mother when a babe, but many is the time I’ve said to Zozo, ‘I got a refined strain in my nature.’ Haven’t I, Zozo?”

“You say it every time we begin to rag you about fallin’ in love with every new thin man you see,” said Princess Zozo. “You said it last night when we was joshin’ you about Mr. Gubb here.”

Syrilla colored, but Mr. Gubb thrilled joyously.

“Just the same, dearie,” Syrilla said to Princess Zozo, “I’ve got myself listed right when I say I got a refined nature. I’ve got all the instincts of a real society lady and sometimes it irks me awful not to be able to let myself loose and bant like—”

“Pant?” asked Mr. Gubb.

“Bant was the word I used, Mr. Gubb,” Syrilla replied. “Maybe you wouldn’t guess it, lookin’ at me shovelin’ in the eatables this way, but eatin’ food is the croolest thing I have to do. It jars me somethin’ terrible. Yes, dearie, what I long for day and night is a chance to take my place in the social [Pg 55]stratums I was born for and bant off the fat like other social ladies is doin’ right along. I don’t eat food because I like it, Mr. Gubb, but because a lady in a profession like mine has got to keep fatted up. My outside may be fat, Mr. Gubb, but I got a soul inside of me as skinny as any fash’nable lady would care to have, and as soon as possible I’m goin’ to quit the road and bant off six or seven hundred pounds. Would you believe it possible that I ain’t dared to eat a pickle for over seven years, because it might start me on the thinward road?”

“I presume to suppose,” said Mr. Gubb politely, “that if you was to be offered a home that was rich with wealth and I was to take you there and place you beside your parental father, you wouldn’t refuse?”

Mr. Gubb awaited the reply with eagerness. He tried to remain calm, but in spite of himself he was nervous.

“Watch me!” said Syrilla. “If you could show me a nook like that, you couldn’t hold me in this show business with a tent-stake and bull tackle. But that’s a rosy dream!”

“You ain’t got a locket with the photo’ of your mother’s picture into it?” asked Mr. Gubb.

“No,” said Syrilla. “My pa and ma was unknown to me. I dare say they got sick of hearin’ me bawl and left me on a doorstep. The first I knew of things was that I was travelin’ with a show, representin’ a newborn babe in an incubator machine. [Pg 56]I was incubated up to the time I was five years old, and got too long to go in the glass case.”

“But some one was your guardian in charge of you, no doubt?” asked Gubb.

“I had forty of them, dearie,” said Syrilla. “Whenever money run low, they quit because they couldn’t get paid on Saturday night.”

“Hah!” said Mr. Gubb. “And does the name Jones bring back the memory of any rememberance to you?”

“No, Mr. Gubb,” said Syrilla regretfully, seeing how eager he was. “It don’t.”

“In that state of the case of things,” said Mr. Gubb, “I’ve got to go over to that wagon-pole and sit down and think awhile. I’ve got a certain clue I’ve got to think over and make sure it leads right, and if it does I’ll have something important to say to you.”

The wagon-pole in question was attached to a canvas wagon near by, and Detective Gubb seated himself on it and thought. The side-show ladies and gentlemen, having finished, entered the side-show tent—with the exception of Syrilla, who remained to finish her meal. She ate a great deal at meals, before meals, and after meals. Mr. Gubb, from his seat on the wagon-pole, looked at Syrilla thoughtfully. He had not the least doubt that Syrilla was the lost daughter of Mr. Jones (or Medderbrook as he now called himself). The German-American tattoo artist had sworn to complete the eagle by [Pg 57]putting its claws on Mr. Jones’s daughter, if need be, and here were the claws on Syrilla’s arm. But, just as it is desirable at times to have a handwriting expert identify a bit of writing, Mr. Gubb felt that if he could prove that the claws tattooed on Syrilla’s arm were the work of Mr. Schreckenheim, his case would be complete. He longed for Mr. Schreckenheim’s presence, but, lacking that, he had a happy idea. Mr. Enderbury, the tattooed man of the side-show, should be a connoisseur and would perhaps be able to identify the eagle’s claws. Leaving Syrilla still eating, Mr. Gubb entered the side-show tent.

Mr. Enderbury, seated on a blue property case, was engaged in biting the entire row of finger nails on his right hand, and a frown creased his brow. He was enwrapped by a long purple bathrobe which tied closely about his neck. As he caught sight of Mr. Gubb, he started slightly and doubled his hand into a fist, but he immediately calmed himself and assumed a nonchalant air. As a matter of fact, Mr. Enderbury led a dog’s life. For years he had loved Syrilla devotedly, but he was so bashful he had never dared to confess his love to her, and year after year he saw her smile upon one thin man after another. Now it was Mr. Lonergan; again it was Mr. Winterberry—or it was Mr. Gubb, or Smith, or Jones, or Doe; but for Mr. Enderbury she seemed to have nothing but contempt. Mr. Enderbury had first seen her when she was posing in the infant incubator, and had loved her even then, for he was [Pg 58]twenty when she was but five. The coming of a new rival always affected him as the coming of Mr. Gubb had, but for good reason he hated Mr. Gubb worse than any of the others.

“Excuse me for begging your pardon,” said Mr. Gubb, “but in the deteckative business questions have to be asked. Have you ever chanced to happen to notice some tattoo work upon the arm of Miss Syrilla of this side-show?”

“I have,” said Mr. Enderbury shortly.

“A pair of eagle’s claws,” said Mr. Gubb. “Can you tell me, from your knowledge and belief, if the work there done was the work of a Mr. Herr Schreckenheim?”

“I can tell you if I want to,” said Mr. Enderbury. “What do you want to know for?”

“If those claws are the work of Mr. Herr Schreckenheim,” said Mr. Gubb, “I am prepared to offer to Miss Syrilla her daughterly place in a home of wealth at Riverbank, Iowa. If those claws are Schreckenheim claws, Miss Syrilla is the daughter of Mr. Jonas Medderbrook of the said burg, beyond the question of a particle of doubt.”

Mr. Enderbury looked at Mr. Gubb with surprise.

“That’s non—” he began. “And if Schreckenheim did those claws, you’ll take Syrilla away from this show? Forever?” he asked.

“I will,” said Philo Gubb, “if she desires to wish to go.”

“Then I have nothing whatever to say,” said [Pg 59]Mr. Enderbury, and he shut his mouth firmly; nor would he say more.

“Do you desire to wish me to understand that they are not the work of Mr. Herr Schreckenheim?” persisted Mr. Gubb.

“I have nothing to say!” said Mr. Enderbury.

“I consider that conclusive circumstantial evidence that they are,” said Detective Gubb, and he clanked out of the side-show.

Syrilla was still seated at the grub table, finishing her meal, and Mr. Gubb seated himself opposite her. As delicately as he could, he told of Jonas Medderbrook and his lost daughter, of the home of wealth that awaited that daughter, and finally, of his belief that Syrilla was that daughter. It was clear that Syrilla was quite willing to take up a life of refinement and dieting if she was given an opportunity such as Mr. Gubb was able to offer in the name of Jonas Medderbrook; and, this being so, he questioned her regarding the eagle’s claws.