Lieut. Paul Jones.

(From a Photograph by his Brother.)

Title: War Letters of a Public-School Boy

Author: Henry Paul Mainwaring Jones

Release date: July 6, 2009 [eBook #29333]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Geetu Melwani, Sigal Alon, Christine P. Travers

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected. Hyphenation and accentuation have been standardised, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Lieut. Paul Jones.

(From a Photograph by his Brother.)

Lieutenant of the Tank Corps

Scholar-Elect of Balliol College, Oxford: Head of the Modern Side and Captain of Football, Dulwich College, 1914

WITH A MEMOIR BY HIS FATHER

HARRY JONES

He was the very embodiment in himself of all that is best in the public-school spirit, the very incarnation of self-sacrifice and devotion.

A Dulwich Master.

WITH EIGHT PLATES

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1918

PART I. MEMOIR

Chapter

PART II. WAR LETTERS

PART III

These laid the world away; poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be

Of work and joy ...

And those who would have been,

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.

Rupert Brooke.

In deciding to publish some of the letters written by the late Lieutenant H. P. M. Jones during his twenty-seven months' service with the British Army, accompanying them with a memoir, I was actuated by a desire, first, to enshrine the memory of a singularly noble and attractive personality; secondly, to describe a career which, though tragically cut short, was yet rich in honourable achievement; thirdly, to show the influence of the Great War on the mind of a public-school boy of high intellectual gifts and sensitive honour, who had shone with equal lustre as a scholar and as an athlete.

My choice of the title of this book was determined by the frequent allusions made by my son in his war letters to his old school. He spent six and a half years at Dulwich College. His career there was gloriously happy and very distinguished. On the scholastic side, it culminated in December, 1914, in the winning of a scholarship in History and Modern Languages at Balliol College, Oxford; on the athletic side, in his carrying off four silver cups at the Athletic Sports in (p. 002) March, 1915, and tieing for the "Victor Ludorum" shield.

As a merry, light-hearted boy in his early years at Dulwich, his love for the College was marked. It waxed with every term he spent within its walls. After he left it, that love became a passion, sustained, coloured and glorified by happy memories. Everybody and everything connected with it shared in his glowing affection. Its welfare and reputation were infinitely precious to him. Like a leitmotif in a musical composition, this love of Dulwich College recurs again and again in his war letters. Every honour won by a Dulwich boy on the battlefield, in scholarship or in athletics gave him exquisite pleasure. The very last letter he wrote is irradiated with love of the old school. When he joined the Tank Corps, stripping, as it were, for the deadly combat, he sent to the depôt at Boulogne all his impedimenta. But among the few cherished personal possessions that he took with him into the zone of death were two photographs—one of the College buildings, the other of the Playing Fields, this latter depicting the cricket matches on Founder's Day. In death as in life Dulwich was close to his heart.

Paul Jones was a young man of herculean strength—tall, muscular, deep-chested and broad-shouldered. But he had one grave physical defect. He was extremely short-sighted, had worn spectacles habitually from his sixth year and was almost helpless without them. In fact, his vision was not one-twelfth of normal. Much to his chagrin, his myopia excluded him from the Infantry which he tried to enter in the spring of 1915, and he had to put up with a Commission as a subaltern in the Army Service Corps. His first three months in the Army were spent at a home port, one of the chief depôts of supply for the British Army in the field. Eagerly embracing the first chance to go abroad, he left Southampton (p. 003) for Havre in the last week of July, 1915. A few days after his arrival in France, he was appointed requisitioning officer to the 9th Cavalry Brigade—a post for the duties of which he was specially qualified by his excellent knowledge of the French language. After 11 months in this employment, he was appointed to a Supply Column, and subsequently, during the protracted battles on the Somme, was in command of an ammunition working party. In October, 1916, he was again appointed requisitioning officer, this time to the 2nd Cavalry Brigade.

Though his duties were often laborious and exacting, his relative freedom from peril and hardship while other men were facing death every day in the trenches sorely troubled his conscience. Feeling that he was not pulling his weight in the war and seeing no prospect of the Cavalry going into action he resolved, at all hazards, to get into the fighting line. After two abortive efforts to transfer from the A.S.C., he succeeded on the third attempt, and was appointed Lieutenant in the Tank Corps, which he joined on 13th February, 1917. His elation at the change was unbounded, and thenceforth his letters home sang with joy. He took part as a Tank officer in the battle of Arras in April, and when the great offensive was planned in Flanders he was shifted to that sector. In the battle of 31st July, when advancing with his tank north-east of Ypres, he was killed by a sniper's bullet. He seemed to have had a premonition some days before that death might soon claim him. In a letter to his brother, a Dulwich school boy, dated 27th July, he wrote:

Have you ever reflected on the fact that, despite the horrors of the war, it is at least a big thing? I mean to say that in it one is brought face to face with realities. The follies, selfishness, luxury and general pettiness of the vile (p. 004) commercial sort of existence led by nine-tenths of the people of the world in peace time are replaced in war by a savagery that is at least more honest and outspoken. Look at it this way: in peace time one just lives one's own little life, engaged in trivialities, worrying about one's own comfort, about money matters, and all that sort of thing—just living for one's own self. What a sordid life it is! In war, on the other hand, even if you do get killed, you only anticipate the inevitable by a few years in any case, and you have the satisfaction of knowing that you have "pegged out" in the attempt to help your country. You have, in fact, realised an ideal, which, as far as I can see, you very rarely do in ordinary life. The reason is that ordinary life runs on a commercial and selfish basis; if you want to "get on," as the saying is, you can't keep your hands clean.

Personally, I often rejoice that the war has come my way. It has made me realise what a petty thing life is. I think that the war has given to everyone a chance to "get out of himself," as I might say. Of course, the other side of the picture is bound to occur to the imagination. But there! I have never been one to take the more melancholy point of view when there's a silver lining to the cloud.

The eagerness to subordinate self displayed in this letter was very characteristic of its author. He was by nature altruistic, and this propensity was intensified by his career at Dulwich and his experience of athletics, both influences tending to merge the individual in the whole and to subordinate self to the side. Death he had never feared, and he dreaded it less than ever after his experience of campaigning. His last letter shows with what serenity of mind he faced the ultimate realities. He greeted the Unseen with a cheer.

His Commanding Officer, in a letter to us after Paul's death, wrote:

"No officer of mine was more popular. He was efficient, very keen, and a most gallant gentleman. His crew loved him and would follow him anywhere. He did not know what fear was."

(p. 005) From the crew of his Tank we received a very sympathetic letter which among other things said:

"We all loved your son. He was the best officer in our company and never will be replaced by one like him."

A gunner who served in the same Tank company testified his love and admiration for our son and said that all the men would do anything for him; even the roughest came under his spell.

A brother officer who served with Paul in the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, in paying homage to his character, wrote: "He was a most interesting and lovable companion and friend. He never seemed to think of himself at all."

Among the many tributes that reached us were several from the masters, old boys, and present boys at Dulwich College. Several of the writers express the opinion that Paul Jones would, if he had lived, have done great things. Mr. Gilkes, late headmaster of Dulwich, in a touching letter, spoke of the nobility of his character and his high gifts; Mr. Smith, the present headmaster, testified to his intellectual power, energy and keenness; Mr. Joerg, master of the Modern Sixth, to his sense of justice, loyalty and truth; Mr. Hope, master of the Classical Sixth, to his high conception of duty, "his sterling qualities and great ability." From the young man who was captain of the school when Paul was head of the Modern Side came this testimony: "He was one of the finest characters of my time at school; in me he inspired all the highest feelings." One of his contemporaries in the Modern Sixth wrote: "I owe more than I can express to your son's influence over me. As long as I live I shall never forget him. His spirit is with me always; for it is to him that I owe my first real insight into life." A well-known Professor wrote: "I felt sure he was destined to do great things; (p. 006) but he has done greater things; he has done the greatest thing of all." Some of these letters are set forth in full in the Epilogue.

Appended is a list of events in this rich and strenuous, albeit brief life:

All that was mortal of Paul Jones is buried at a point west of Zonnebeke, north-east of Ypres.[Back to Contents]

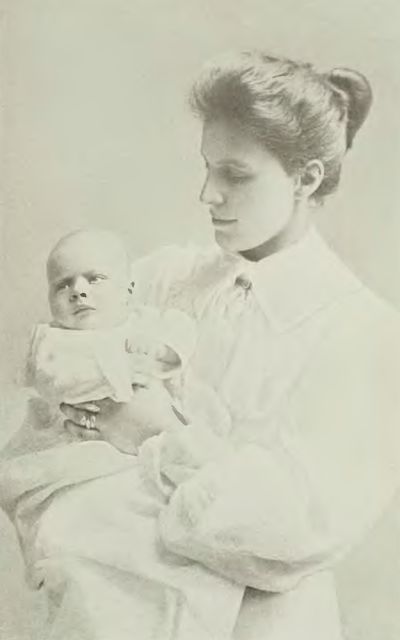

Paul Jones as an Infant.

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life's Star

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar;

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness.

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, Who is our home.

Wordsworth: "Intimations of Immortality."

Henry Paul Mainwaring Jones, born in London on May 18, 1896, was the first child of Henry and Emily Margaret Jones. His grandfather, the late Thomas Mainwaring, was in his day a leading figure in literary and political circles in Carmarthenshire. My own people have been associated with that county for centuries. For our son's christening a vessel containing water drawn from the Pool of Bethesda was sent to us by my old friend Sir John Foster Fraser, who in the spring of that year passed through Palestine on his journey by bicycle round the world.

At this time I was acting editor of The Weekly Sun, a journal then in high repute. Later, at Mr. T. P. O'Connor's request, I took charge of his evening newspaper, The Sun. After the purchase of The Sun by a Conservative proprietary I severed my connection with it, and in January, 1897, went to reside in Plymouth, having undertaken the managing editorship of the Western Daily Mercury.

We remained at Plymouth more than seven years. Paul received his early education at the Hoe Preparatory (p. 010) School in that town. He was a lively and vigorous child overflowing with health. When he was in his sixth year we discovered that he was shortsighted—a physical defect inherited from me. The discovery caused us acute distress. I knew from personal experience what a handicap and an embarrassment it is to be afflicted with myopia. Regularly thenceforward his eyes had to be examined by oculists. For several years, in fact until he was 16, the myopia increased in degree, but we were comforted by successive reports of different oculists that though myopic his eyes were very strong, and that there was not a trace of disease in them, the defect being solely one of structure which glasses would correct.

To Paul as a boy the habitual wearing of spectacles was at first very irksome, but in time he adapted himself to them. Even defects have their compensations. He was naturally rash and daring, and his short sight undoubtedly acted as a check on an impetuous temperament. He early gave signs of unusual intelligence. His activity of body was as remarkable as his quickness of mind. At play and at work, with his toys as with his books, he displayed the same intensity; he could do nothing by halves. There never was a merrier boy. His vivacity and energy and the gaiety of his spirit brightened everybody around him. When he bounded or raced into a room he seemed to bring with him a flood of sunshine.

From his childhood he gave evidences of an unselfish nature and a desire to avoid giving trouble. He had his share of childish ailments, but always made light of them and bore discomfort with a sunny cheerfulness; his invariable reply, if he were ill and one asked how he fared, was "Much better; I'm all right, thanks." Marked traits in him as a small boy were truthfulness, generosity and sensitiveness. In a varied experience of (p. 011) the world I have never met anyone in whom love of truth was more deeply ingrained. On one occasion in his twelfth year, when he was wrestling with an arithmetical problem—the only branch of learning that ever gave him trouble was mathematics—and I offered to help in its solution, he rejected my proffered aid with the indignant remark: "Dad, how could I hand this prep. in as my own if you had helped me to do it?" His generosity of spirit was displayed in his eagerness to share his toys and books with other children; his sensitiveness by his acute self-reproaches if he had been unkind to anyone or had caused pain to his mother or his nurse.

Plymouth is a fine old city, beautifully situated and steeped in historic memories. Our home was in Carlisle Avenue, just off the Hoe, and on that spacious front Paul spent many happy hours as a small boy. His young eyes gazed with fascination on the warships passing in and out of Plymouth Sound, on the great passenger steamers lying at anchor inside the Breakwater, or steaming up or down the Channel; on the fishing fleet, with its brown sails, setting out to reap the harvest of the sea; and when daylight faded in the short winter days he would watch the Eddystone light—that diamond set in the forehead of England—flashing its warning and greeting to "those who go down to the sea in ships and do business in great waters." Always from the Hoe there is something to captivate the eye—the wonder and beauty of the unresting ocean; on the Cornish side the wooded slopes and green sward of Mount Edgcumbe; on the Devon side Staddon Height, rising bold and sheer from the water; looking landward the picturesque mass of houses, towers, spires, turrets that is Plymouth, and far behind the outline of the Dartmoor Hills. On the Hoe itself one's historic memories are stirred by the Armada memorial and the (p. 012) Drake statue; close at hand is the Citadel, the snout of guns showing through its embrasures; and near by is Sutton Pool, whence the Pilgrim Fathers set forth in the little Mayflower, carrying the English language and the principles of civil and religious liberty across the stormy Atlantic.

All these sights and scenes and historical associations had their influence on a bright and ardent boy in these impressionable years. He soon got to be keenly interested in the Navy, amassed a surprising amount of information about the types, engine strength and gun-power of the principal warships, and found delight in making models of cruisers and torpedo-boats. The Army in those days made no appeal to him, though he was familiar with military sights and sounds—the ceremonious displays that take place from time to time in a garrison town, bugles blowing, the crunch of feet on the gravel in the barrack square, and the tramp, tramp of marching men. It was to the Navy that his heart went out. The natural set of his mind to the Navy was encouraged by the accident that his first school prize was Southey's "Life of Nelson"—a book that inspired him with hero-worship for the illustrious admiral.

Paul in his 6th Year.

On Saturday afternoons, whenever weather permitted, it was my custom to roam with Paul over the pleasant environs of Plymouth. We would visit Plympton or Plym Bridge, Roborough Down or Ivybridge, Tavistock or Princetown, for a tramp on Dartmoor. Or we would go by water to Newton, Yealmpton, Salcombe, or Calstock, or cross by the ferry to Mount Edgcumbe for Penlee Point, with its marvellous seaward view. He was an excellent walker and a most delightful little companion, keenly interested in all he saw, and absorbing eagerly the beauty of earth and sea and sky. No wonder he had happy memories of the West country and that his mind retained (p. 013) clear images of Plymouth, the sea, and gracious, beautiful Devon!

In the summer of 1904 I returned to London, having accepted an appointment on the editorial staff of the Daily Chronicle. Paul, who had left his first school with high commendation, was entered in September at Brightlands Preparatory School, Dulwich Common. There he remained four years, during which he made rapid strides in knowledge. His first report said: "Is very keen and has brains above the average; conduct and work excellent; extremely quick and a splendid worker. Doing very well in Classics, and making marvellous progress in French." From later reports the following expressions are taken: "Keen in the extreme, and a hard worker; a marvellously retentive memory." "His work has been superlatively good; conduct excellent; drawing poor; written work marred by blots and smudges." "Developing very much; thoroughly deserves his prizes; his work is neater; composition and geography excellent; and even in mathematics no boy has improved more; now plays very keenly in games." "He is making splendid progress with his Greek; gets flustered in Mathematics when difficulties appear." Paul won numerous prizes at Brightlands for Classics, English, French, General Knowledge, Reading, Athletics, and was almost invariably top of his form. He left the Preparatory School after the summer term, 1908.[Back to Contents]

Ah! happy years! once more who would not be a boy?

Byron: "Childe Harold."

Our son entered Dulwich College in September, 1908, when he was twelve years of age, and remained a member of it until March, 1915. These six and a half years had a powerful influence on the development of his character, which flowered beautifully in this congenial atmosphere. The most famous school in South London, Dulwich College has a notable history. It was founded through the munificence of Edward Alleyn, theatre-proprietor and actor, a contemporary, an acquaintance, and probably a friend of Shakespeare. At the inaugural dinner in September, 1619, to celebrate the foundation of Alleyn's "College of God's gift," an illustrious company was present, including the Lord Chancellor, Francis Bacon, "the greatest and the meanest of mankind," then at the summit of his fame but soon to fall in disgrace from his high eminence; Inigo Jones, the famous architect, who in that year was superintending the erection of the new Banqueting Hall in Whitehall; and other distinguished men.

Since its foundation the College has passed through many vicissitudes. With the development of building on the estate the income rapidly expanded in the nineteenth century. In 1857 the charity was reorganised and the trust varied by Act of Parliament. The present school buildings were opened in 1870. The old college—including the chapel (containing the pious founder's (p. 015) tomb), almshouses and the offices of the estate governors—remains in Dulwich Village, a very picturesque and well-preserved structure embowered in trees. At its rear is the celebrated Picture Gallery, the nucleus of which was a collection of pictures originally intended to grace the palace of Stanislaus, the last King of Poland. The new college buildings have a delightful situation. All around them are wide stretches of green fields; here and there pleasant hedgerows; on the slopes of Sydenham Hill charming woodlands, some of them a veritable sanctuary for bird-life. In the spring-time the whole neighbourhood is musical with the song of birds, and one is often thrilled by the rich haunting note of the cuckoo. On the fringes of the playing-fields and round about the boarding-houses are magnificent trees—chiefly elm, beech, birch and chestnut, more rarely oak. In short, the surroundings of the college have a thoroughly rural aspect. It is an ideal environment for the training of boys. There is nothing in this sylvan and pastoral beauty to suggest that we are in a great city.

Dulwich College is both a boarding school and a day school, the boarders numbering about 120 and the day-boys about 550. When Paul Jones entered the college as a day-boy in 1908 the Headmaster was Mr. A. H. Gilkes, who retired after the summer term of 1914. Our son, therefore, had the good fortune to come under the influence for six years of one of the greatest public-school masters of our generation. A former colleague of mine, Mr. Henry W. Nevinson, used to speak to me in glowing terms of Mr. Gilkes, who was a master at Shrewsbury School when he was a boy there, and I note that the Rev. Dr. Horton in his "Autobiography" alludes to him as "the master at Shrewsbury to whom I owed most." Undoubtedly Mr. Gilkes's best work was done as Headmaster of Dulwich. (p. 016) The College has never known a greater head. Under him the whole place was revivified. During his reign not only did a fine moral tone characterise the school, but there was equal enthusiasm for work and games. Thanks to a commanding personality, in which strength, dignity and graciousness were subtly mingled, the influence of Mr. Gilkes pervaded the whole school from the highest to the lowest forms. Paul quickly recognised the nobility of the "Old Man," as he was universally known to the boys. His affection for him amounted to veneration, and however brief the leave he had from the Army he always found time to pay his old headmaster a visit. On his part Mr. Gilkes had a great regard for our son, whom with sure perception he described as "fearless, strong and capable, with a heart as soft and kind as a heart can be."

A new boy's early days in a public school are often trying. He is in a strange world with its own laws and customs; and at the outset he has to endure the scrutiny of curious and often hostile eyes. Our son's marked idiosyncrasies, sturdy independence, fastidious refinement and passion for work, singled him out from his fellows as an original. As boys resent any deviation from the normal, he had a rough time until he found his feet, and the experience was repeated as he moved up to new forms. Not a word about all this escaped his lips at home; I have ascertained it from others. Stories reached me of personal combats from which he usually emerged the victor, and of one prolonged fight with an older boy that had at last to be drawn. In the end Paul won through; his pluck and strength compelled a respect that would have been refused to his intellectual gifts. His tormentors realised that he was not a mere "swot," that he had fists and knew how to use them. Animosity was also disarmed by his chivalric spirit. He began his career at Dulwich in the Classical Lower (p. 017) IV. In June, 1909, he won a Junior Scholarship, which freed him from school fees for three years, and in 1912 a Senior Scholarship of the same nature. When he was in the Classical Lower Fifth (1909), his form master, Mr. H. V. Doulton reported:

"He is a boy of great promise and will make an excellent scholar. He has marked aptitude for classical work, and success in the great public examinations may be predicted for him with absolute confidence." "Painstaking and anxious to do well, but rather slow," was the verdict of his mathematical teacher.

In the summer term, 1910, Paul changed over from the Classical to the Modern side of the school. I was averse to the change, and his Classical form-master dissuaded him against it. But once Paul's mind was made up nothing would break his resolution: he had a strong and tenacious will. His main desire in transferring to the Modern side was to study English literature and modern languages thoroughly. He never regretted the change. As he grew older the firmer became his conviction that Classics were overdone in the public schools. Even in a school responsive to the spirit of the age like Dulwich, which has Modern, Science, and Engineering sides, the primacy still belongs to Classics, and the captaincy of the school is rigidly confined to boys on the Classical side. My son believed that this bias for Classics was bad educationally. He thought the prestige given to Greek and Latin as compared with English Literature, Science, Modern Languages and History was simply the outcome of a pedantic scholastic tradition, which made for narrowness not for broad culture. With him it was not a case of making a virtue of necessity, as he had real aptitude for Greek and Latin. But he wanted the windows of our public schools to be cleared of mediæval cobwebs and flung wide open to the fresh breezes of the modern world.

(p. 018) In the report for the last term of 1910, when he was in the Modern Upper V, he was described as "a very capable boy with great abilities." The next report, when he was in the Remove, complained of his "frivolous attitude" in the Physics classes, but "otherwise he has worked well and made good progress." In June, 1911, he passed the Senior School Examination with honours, winning distinction in English, French and Latin—a remarkable achievement for a boy who had only just turned fifteen. Owing to his being under age, the London Matriculation certificate in respect of this examination was not forwarded until he had reached sixteen. "Considering that he is only fifteen," wrote Mr. J. A. Joerg, his form-master, "it should be deemed a great honour for him to have passed in the First Division; it does him much credit." Mr. Boon, who prepared him in mathematics, testified that Paul had "worked with interest and energy" at what was for him an uncongenial subject. He entered the Sixth Form in September, 1911, being then fifteen and a half years old; the form average was seventeen years. In 1912 his reports showed that he was making all-round progress, and was applying himself with zest to a new subject, Logic. In the summer term, 1913, he was first in form order—1st in English, 2nd in Latin, 3rd in French, 4th in German. Though specialising in History, he retained his position as head of the Modern side until he left school, with one interval in the summer term of 1914, when he had to take second place, recovering the headship next term. In order to have a clear road to Oxford University, he qualified in Greek at the London Matriculation Examination, January, 1914. During his Dulwich career he won many prizes, most of which took the form of historical works. As will appear later, he played as whole-heartedly in games as he worked at his books.

(p. 019) History was a subject to which he was instinctively drawn, and in 1913 he began preparing definitely for an Oxford University scholarship. He read thoroughly and covered a wide field. In addition to the systematic study of History, he touched the fringes of philosophy and political economy. He was helped in his studies by a very retentive memory. One of his schoolfellows said to me, "Paul has only to read a book once and it is for ever imprinted on his mind." Among the historical writers whom he read during his eighteen months' preparation were: Gibbon, Carlyle, Macaulay, Hallam, Guizot, Michelet, Thiers, Bluntschli, Maine, Froude, Bagehot, Seeley, Maitland, Stubbs, Gardiner, Acton, John Morley, Bryce, Dicey, Tout, Mahan, Holland Rose, G. M. Trevelyan, Hilaire Belloc and H. W. C. Davis. Two recent books that gave him special pleasure were Mr. G. P. Gooch's masterly "History of Historians" and Mr. F. S. Marvin's entrancing little work "The Living Past."

His hard reading was crowned in December, 1914, by a considerable achievement, for he won the coveted Brakenbury Scholarship in History and Modern Languages at Balliol College, Oxford. This scholarship, worth £80 per annum, is tenable for four years; to it subsequently Dulwich College added an exhibition of the annual value of £20. He was the first Balliol scholar in history from Dulwich. Not at all confident that he had won the Brakenbury, he went up to Oxford a second time, while the result of the Balliol examination was still unknown, to try for a less exacting scholarship. Happily there was no necessity for him to undergo this second test, as he found on his arrival at Oxford that his name had just been posted as a Brakenbury scholar.

When he went up, in the last week in November, 1914, for examination at Balliol College, it was his first (p. 020) visit to Oxford. Short as was his stay within its precincts, it was long enough for the glamour and beauty of the venerable university to steal into his soul; and the spell of it remained with him as a permanent possession. In spite of examination anxieties he had a pleasant time at Oxford, as the following letter shows:

The Old Parsonage,

Oxford,

December 1st, 1914.

Everything going as well as could be anticipated. But I don't expect to win the Brakenbury, so there can't be much of a disappointment. I have done one paper already, the essay—subject, "A Nation's character as expressed in its Art and Literature." I think I got on fairly well. The papers end by Thursday afternoon. I was round with all the Dulwich fellows in Wetenhall's rooms at Worcester College last night, and had a great time. Cartwright came across, and a lot of other O.A.'s. To-night I am dining with Gover, an old friend of mine, in hall at Balliol, and going on to his rooms afterwards. I am booked for brekker and dinner to-morrow. Dulwich is a magic name here; if you add "captain of football" all doors fly open to you. Altogether I don't feel I am up for a scholarship at all—a good thing, for it prevents my getting nervous.

Of the many congratulations on his success in winning a Balliol scholarship, none granted him more than a letter from an "Old Alleynian," who wrote:

My very best congratters on the fresh laurel with which you have adorned your crown of victory. A Balliol scholarship for four years, and this to have been secured by the captain of a public school 1st XV that has won four out of its five great school matches! My dear Paul, you have done splendidly. I don't remember during my time such a happy combination of work and play.

Mr. Llewelyn Williams, K.C., M.P., himself an Oxford history scholar, wrote: "Paul's brilliant success warmed even my old heart. Tell him from me I (p. 021) hope when he is a Don he will write the History of Wales."

Paul was appointed a prefect at Dulwich in 1912. He participated in every phase of school life and was devoted to athletics. In cricket he was quick and adroit as a fielder, but he had no skill either as a batsman—doubtless owing to his visual defect—or as a bowler. Very fond of swimming, he was a regular visitor to the college swimming bath. He had great endurance in the water, but lacked speed, and much to his disappointment failed to get his swimming colours. His love of swimming never waned, and in the sea he would swim long distances. Swimming brought him an ecstasy of physical and moral exhilaration. He could say with Byron:

I have loved thee, Ocean! and my joy

Of youthful sports was on thy breast to be

Borne, like thy bubbles, onward.

Lawn tennis is discouraged at Dulwich, but Paul became adept in this pastime, thanks to games on the lawn attached to our house. In the whole range of athletics nothing gave him so much pleasure and satisfaction as Rugby football. Too massive in build to be a swift runner, and unable owing to his defective vision to give or take "passes" with quick precision, he was not suited to the three-quarter line; but as a forward he made a reputation second to none of his contemporaries in public-school football. He played for the College 1st XV in three successive seasons, during which he was not once "crocked," nor did he miss a single match. His success in football was an illustration of how a resolute will can triumph over a hampering physical defect.

In the autumn of 1913 he was offered a house scholarship, which would have meant residence in one of the (p. 022) boarding-houses. Without hesitation he declined what was at once an honour and a privilege, preferring to remain a day-boy. He dearly loved his home, and his opinion was that the advantages of public-school training were much enhanced when combined with home life. His custom was to ride to the College on his bicycle in the morning, stay there for dinner and return home in the evening between 6 and 7 o'clock, the hours following afternoon school being devoted to games, the gymnasium, or some other form of physical training.

In 1914 he was elected Captain of the 1st XV. No distinction he ever won—and there were many—gratified him more. In a great public school the duties that devolve on a captain of football are laborious and responsible. They entail many hours of work weekly, the careful compilation of lists of players for the numerous school teams, a vigilant oversight of training and a watchful eye for budding talent. But Paul loved the work, and love lightens labour. He threw himself into the duties with all the enthusiasm of his nature. The amount of time he was devoting to football in September and October made me doubtful of his ability to carry off a Balliol scholarship in December. Accordingly I suggested that he might relinquish the captaincy temporarily, say for a month, so as to allow him freedom to concentrate on his history reading before the examination. He would not listen to the suggestion. He said he meant to fulfil the duties of captain to the uttermost. If this jeopardised his chances for a scholarship he would be sorry, but whatever the cost he was not going to fall short in his work as captain of football. In the result he brought off the double event, winning the scholarship and leading his team with shining success.

Winning the Mile, March 27, 1915.

His athletic career culminated at the school sports on March 27, 1915, when he won the mile flat race, the (p. 023) half-mile, and the steeplechase, and was awarded the silver cup for the best forward in the 1st XV. He tied for the "Victor Ludorum" shield with his friend S. J. Hannaford (a versatile athlete reported missing in France, September, 1917). These successes at the sports were a dazzling finish to Paul's school days. He bore them, like his scholastic triumphs, very modestly, but in his heart he was proud and happy. It was not his nature to plume himself on any achievement. Only once do I remember his betraying pride in what he had accomplished. It is the custom in Dulwich to inscribe on the walls of the great hall the names of boys who distinguish themselves on entering or leaving the Universities and the Army. In due time the ten Oxford scholars of 1914 were walled. During his first leave from the Army Paul revisited the old school, and I recollect his telling me that the names of those who had won scholarships at Oxford had been duly painted in hall. "My name is placed first," he said with a smile; adding with emphasis, "and so it ought to be."

It was his hope that his own success would give a stimulus to the study of history at Dulwich. In 1916, when he learnt that another Dulwich boy was thinking of preparing for a Balliol scholarship in history, he wrote to me from France, requesting that his notes, memoranda, essays and books should be placed at the student's disposal. He added in reference to a matter on which I had asked his opinion:

The education you get from a correspondence course is of a kind which, while useful for acquiring a knowledge of facts, is of very little value in the development of that culture which is the first and essential element in obtaining a 'Varsity—above all, a Balliol—scholarship. If a boy decides to go in for a history scholarship, the Dulwich authorities ought to provide him with adequate tutorship as part of his school training. Were the boy to go to an outside institution, the school would lose part of the (p. 024) honour gained by the winning of the scholarship. But remember that no one would have the ghost of a chance for an Oxford scholarship on the knowledge gained from a correspondence course taken by itself. Finally, any honour gained by a Dulwich boy ought to redound to the credit of Dulwich; the school alone should have the credit of the achievements of its members.

From masters and boys I learnt that my son's influence was specially marked in his last two years at the College. It was an influence that was always thrown on the side of what was lovely, pure and of good report. Frank, free-spirited, open-hearted, his buoyancy and his rich capacity for laughter diffused an atmosphere of cheerfulness; his unflagging enthusiasm stimulated interest in athletics; his love of learning and passion for work were contagious; his high ideals of conduct helped to set the tone in morals and manners. The qualities he most prized in boys were courage, purity, veracity. No one loved books more, but book-learning by itself he placed low on the list. To use his own words: "It is character and personality that tell." Purity in deed and thought was with him a constant aspiration. He reverenced the body as the temple of the Holy Spirit. From the ordeal of the difficult years between 14 and 16 he emerged like refined gold. A boy he was

With rosy cheeks

Angelical, keen eye, courageous look,

And conscious step of purity and pride.

His serene and radiant air was witness to a soul at peace with itself. Things coarse and impure fled from his presence. It was the union in him of moral elevation with physical courage that explained the secret of his remarkable influence in school.

At Dulwich the school year is full and various. In addition to the acquisition of knowledge there is much (p. 025) else to engage a boy's interest—cricket, football, fives, swimming, the gymnasium, athletic competitions, the choir; and then those red-letter days—Founder's Day, with its Greek, French or German play, the Prize Distribution and the Concerts. Our son bore his share in every phase of this varied life. He had a warm corner in his heart for the College Mission, which maintains a home in Walworth for boys without friends or relatives and enables them to be trained as skilled artisans. The home has accommodation for twenty-one boys; a married couple look after the house work, and two old Alleynians are in residence. He never failed after he left the College to send an annual subscription anonymously to the Mission funds. An enthusiastic lover of music, he was for years in the College Choir, singing latterly with the basses.

At the 1913 Founder's Day celebration Paul took a subsidiary part, that of Fitzwater, in a scene from Shakespeare's Richard II, on which occasion the King was brilliantly impersonated by E. F. Clarke (killed in action, April, 1917). On the same occasion Paul was one of the voyageurs in the scenes from Le Voyage de Monsieur Perrichon, his amusing by-play in that modest rôle sending the junior school into roars of laughter. At the 1914 celebration of Founder's Day he took the part of Fluellen in a scene from Henry V, and sustained a very different rôle, that of Karl der Sieberite, in a scene from Schiller's Jungfrau von Orleans. Reviewing the performances, The Alleynian said of the former: "In this piece Jones was the comedian. He was clumsy and not quite at home on the boards, but his Welsh was delightful."

Of his performances as Charles VII in Schiller's play the critic wrote:

The scene chosen is one of the most powerful scenes in the play. It is that in which the King, sceptical of the (p. 026) divine inspiration of the Maid, determines to test her by substituting a courtier upon his throne.... When she is not only not deceived, but proceeds also to interpret many of the King's innermost thoughts, the surprise of the monarch, passing into hushed reverence, calls for a studied piece of careful acting. H. P. M. Jones sustained this part, and sustained it well. He gave it the dignity which it needed, and if his natural gift of physical stature helped him somewhat, so also did the smooth diction and easy repose which he had evidently been at pains to acquire.

Of the performance as a whole: "It says a very great deal for the German in the upper part of the school, that a scene can be enacted in which both accent and acting can reach so high a level."

The school year at Dulwich always closes with a concert at which the music, thanks to the competent leadership of Mr. H. V. Doulton, is of a high order. The solos of the two school songs on 19th December, 1914, were sung by H. P. M. Jones and H. Edkins, both of them Oxford scholars who have since been killed in action. Edkins, who had a rich baritone voice, sang the song in praise of Edward Alleyn, the pious founder. My son, as captain of football, sang the football song, the first and last verses of which are appended:

Rain and wind and hidden sun,

Wild November weather,

Muddy field and leafless tree

Bare of fur or feather.

Sweeps there be who scorn the game,

On them tons of soot fall!

All Alleynians here declare

Nought like Rugby football.

.....

Broken heads and bleeding shins!

What's the cause for sorrow?

Shut your mouth and grin the more,

Plaster-time to-morrow.

(p. 027) Young or old this shall remain

Still your favourite story:

Fifteen fellows fighting-full,

Out for death or glory.

After each stanza the choir and the whole school rolled in with the chorus, proclaiming in stentorian voices that "the Blue and Black" (these being the Dulwich football colours) shall win the day. My wife and I were present at this concert, and there is a vivid image before us of our son, a tall, powerful figure in evening dress, standing on the platform in front of the choir, his eager face now following the conductor's bâton, now glancing at the music-score, now looking in his forthright way at the audience. The reception that greeted him when he stepped on to the platform must have thrilled every fibre of his being; another rapturous outburst of cheers acclaimed him as he retired to his place in the choir. Those cheers, loud, shrill and clear, with that poignant note that there often is in boyish voices, still resound in our ears. We had heard that Paul was popular at Dulwich: we had ocular and audible testimony of it on this unforgettable night. Those had not exaggerated who told us that he was the hero of the school.[Back to Contents]

Play it long and play it hard

Till the game is ended.

Dulwich Football Song.

The earliest reference to Paul as a footballer appears in The Alleynian's report of a match, "Boarders v. School," played on September 25, 1912, when the School won by 32 points to 21. "Jones," says the reporter, "presented an awesome sight." His first appearance in the 1st XV was against London Hospitals "A" in October. Singling him out for honourable mention, the critic says: "Jones displayed any amount of go." He was awarded his 1st XV colours after the match against Bedford School at Bedford in November. In this hard-fought game Bedford led at half-time by 15 points to 5, and 25 minutes before the close of play the score was in Bedford's favour by 28 to 5. Then, by a wonderful rally, Dulwich scored 23 points in almost as many minutes, the match finally being drawn 28-28. In The Alleynian for February, 1913, Paul is thus described in the article, "First XV Characters":

A young, heavy and extremely energetic forward. Puts all he knows into his play, and is a great worker in the scrum. In the loose, however, a lot of his energy is somewhat misdirected, and he has an alarming tendency for getting off-side.

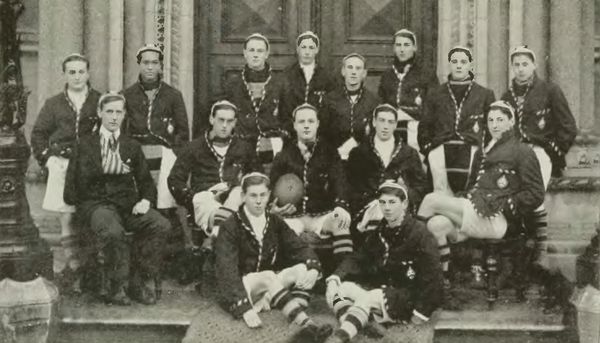

DULWICH COLLEGE 1st XV, 1914-15, OF WHICH PAUL JONES WAS CAPTAIN.

From left to right, top Row: H. C. Jensen, M. Z. Ariffin, E. A. F. Hawke, R. L. Paton, J. Paget, J. F. G. Schlund, J. M. Cat, G. H. Gilkes. Middle Row: A. H. H. Gilligan, L. W. Franklin, H. P. M. Jones, L. Minot, R. S. Hellier. On Ground: C. A. R. Hoggan, S. H. Killick.

In the 1913-14 season, a daily newspaper, describing the hard-fought Sherborne v. Dulwich match, said: "H. P. M. Jones worked like a Trojan for the losers, (p. 029) his Pillmanesque hair being seen in the thick of everything." That season Paul had charge of the Junior games. He had a way with small boys, and soon fired them with his own zeal. In an article in The Alleynian for December, 1913, giving counsel to the juniors, he wrote:

You must not gas so much on the field, but play the game as hard as it can be played. Except in rare circumstances, the only players who are to shout are the captain, the scrum-half, and the leader of the forwards. Forwards must learn to pack low and shove straight and hard. Three-quarters must remember not to run across too much, and never to pass the ball when standing still.

There are other useful hints. Looking upon the junior games as the seed-bed for future crops of 1st XV players, he devoted a great deal of time and patience to teaching the youngsters how to play. In addition to matches with other schools and clubs, a feature of the football season at Dulwich are the side-games. Paul played in three seasons for the Modern Sixth and Remove, and was captain of the victorious team in the side-contests, 1914-15. House matches of which he was only a spectator he often reported for The Alleynian.

It was at a meeting of the Field Sports Board on July 28, 1914, that Paul Jones was elected captain of the 1st XV, being proposed by A. W. Fischer and seconded by A. E. R. Gilligan. At the same meeting R. B. B. Jones was elected captain of the gymnasium. Fischer, Basil Jones and my son have been killed in the War. In a report of a meeting of the Field Sports Board held on September 29 appears the following: "H. P. M. Jones then submitted a code of rules to regulate the management of the school games. These were unanimously approved." In a survey of the prospects of the 1914-15 football season which appeared in the October Alleynian, Paul paid tribute to the magnificent (p. 030) work done for football in Dulwich by one of the masters, Mr. W. D. Gibbon, an old International, who joined the Army shortly after the outbreak of war and is now Lieutenant-Colonel. Paul wrote:

The loss of Mr. Gibbon is a staggering-blow. He it is who, more than anyone, has given us the very high place we hold among Rugby-playing schools. To lose his services is disastrous. Still, it would be shameful to grouse over his departure considering that he goes to serve his country. Rather let us congratulate him on his captaincy in the Worcestershires.

A reformer by temperament, my son was determined to improve the forward play during his captaincy, as he believed that not enough attention had been given to the forwards for several seasons at Dulwich. It was inevitable that the War would derange the football programme, but though there would be few club matches, the new captain thought that the "school games" might benefit from this very lack. Anyhow it was "a unique chance to build them up on a sound basis." He believed in doing everything to encourage in-school football, meaning by that the half-holiday games, the side-matches, cup matches, and such games as Prefects v. School, Boarders v. School, the House matches, etc. He realised that the first three XV's only include 45 boys, and that there were 600 others whose claims to consideration were equally great. Moreover, good in-school football would produce a succession of players for the first XV. Having all this in mind, in his article in The Alleynian he exhorted the game captains to instil "a general keenness" and to do their duty unselfishly and enthusiastically. His survey then proceeds:

Now as to the teams. In the first place, let it be said at once that the outsides are going to be fine this year. Franklin and A. H. H. Gilligan, the "star" wings of (p. 031) last year's team, and Minôt, undoubtedly the best of the centres, remain to us. Franklin is faster than of yore, and still goes down the right touch-line like a miniature thunderbolt, brushing aside the opposition like so many flies. If he is the thunderbolt, Gilligan, on the other wing, is undoubtedly the "greased lightning"; we have not seen so fast a school wing for years, and his newly acquired swerve makes him all the more dangerous. Minôt has quite mastered the art of passing; we have rarely seen "transfers" made so accurately and so artistically. He can cut through when required, and altogether should make Gilligan a splendid partner. All these three defend stoutly. We are also fortunate in retaining the services of Paton (2nd XV) for the other centre position; he only wants a little more judgment to be quite first-class.

At half, Evans and A. E. R. Gilligan have left a terrible gap. But again fortune is on our side, as we have in Killick (2nd XV) a worthy successor to the latter—very quick off the mark, and an excellent giver and taker of passes; while Jensen (2nd XV) shows promise of becoming a really "class" scrum worker. At present his chief fault is inaccuracy of direction, but that will soon vanish. Both these halves are excellent in defence. Again, Hooker (3rd XV) is a very useful scrum half, but slow in attack. For the full-back position we have that wily old veteran Ariffin (2nd XV), whose kicking has distinctly improved since last year. He tackles as well as ever. Sellick (3rd XV) is a useful back, but weak in defence.

So, gentlemen, outside the scrum all is well. But what of the scrum itself? This, we don't deny, is going to be a difficult problem. It is not that there isn't plenty of good stuff. Hellier and Gilkes (2nd XV), Hoggan, Schlund, Cat and Fischer (all 3rd XV)—here is the nucleus of a fine pack, not to mention a host of hefty and keen fellows as yet without colours. But the difficulty lies in the traditions of the past. Since 1912, our forwards have steadily deteriorated as our backs have got better and better. It was always the way last year that, if we had a ground wet to any degree, we were as good as beaten—look at the Easter term, for example. Also, the helplessness of the forwards threw a lot too much work on the outsides. This has got to be stopped. You can't always get weather to suit your team's outsides. We must learn how to play a forward game when it's necessary. We must (p. 032) learn to screw, to wheel, to shove and to rush. We repeat, the individuals are there, but they have to be trained into a combination. The outsides are so brilliant that they can be trusted faithfully to fulfil the work of passing and open-side attack.

Our chief efforts this year must be directed to the training of the forwards: (1) to play a truer forward game; (2) and not to forget how to attack and adopt open-side tactics when necessary. Once the teams have re-learnt these lessons, the games will automatically do so. In the days of Jordan, Mackinnon and Green we won as many matches by our forwards as by our outsides. It is fatuous to develop one division at the expense of the other. The outsides are going this season to receive all possible attention, but so are the forwards.

Paul carried out thoroughly the policy here foreshadowed. As a consequence forward play at Dulwich was absolutely transformed, and the impulse he gave to it survives to this day. Under his captaincy the 1st XV had a brilliantly successful season, winning four out of five of the great school matches, viz.:

With the exception of 1909-10, when Dulwich won all its school matches, this 1914-15 record during Paul's captaincy was the best for a dozen years. Of the football in the school generally the captain, writing in the December Alleynian, said: "Such a uniform standard of keenness has rarely been witnessed. For this I have to thank the Games Captains most sincerely. They have done their part most loyally and unselfishly. The next few years will prove the value of their work."

DULWICH MODERN SIDE XV, 1914-15, CAPTAINED BY PAUL JONES.

From left to right, Top Row: C. F. N. Ambrose, W. B. Jellett, B. A. J. Mills, G. Walker, C. R. Mountain. Second Row, J. C. Corrie, R. W. Mills, G. Roederwald, L. Paton, H. V. Morlock. Seated: R. L. Paton, A. H. H. Gilligan, H. P. M. Jones, C. A. R. Hoggan, J. F. G. Schlund. On Ground: L. A. Hotchkiss, R. A. Mayne.

In a review of the 1st XV characters in The Alleynian for February, 1915, appeared the following:

(p. 033) H. P. M. Jones (captain) (1912-13-14-15) (12 st. 6 lb.). Forward.—One of the keenest captains Dulwich has ever produced. An untiring and zealous worker both in the game and organisation, from which he has produced one of the finest packs Dulwich has seen in recent years. He uses every ounce of his weight to advantage, and his knowledge of the game is beyond reproach. He is sound in defence, and in the open wherever the ball is you will find him. We shall all greatly miss him, but will remember that his valuable work for the forwards will mean much to the school in the future. (Forward Challenge Cup.)

On February 6 he had the gratification of avenging the defeat by St. Paul's in the previous November, Dulwich this time being victorious over the Paulines by 39 to nil. With this victory he regarded his work as captain of football finished, though he played in the side-games until March. In spite of the difficulties caused by the war, the season had been a triumphant one. An old member of the 1st XV, Lieut. A. E. R. Gilligan, writing from his regiment, congratulated Paul on "the magnificent record of the team—a record which reflects the utmost credit on its captain. Without your keenness and energy the side would have been a poor one." Lieut. Gilligan added: "To have beaten St. Paul's was absolutely a crowning effort. All the 'O.A.'s' here are overjoyed at our victory. It is simply splendid, and makes up for the defeat of last term. Best congratulations to all the gallant team and to its victorious captain."

Paul's football enthusiasm inspired him on one occasion to attempt a metrical description of a match between Bedford and Dulwich. The nature of this poetical effusion may be gauged by the following quotations:

In November, month of drabness,

Month of mud and month of wetness,

Came the red-shirted Bedfordians,

Came the lusty Midland schoolmen,

(p. 034) Skilled in every wile of football,

Swift to run, adept to collar,

'Gainst the Blue-and-Blacks to battle.

Know ye that this famous contest

Has from age to age endured:

Thirty years and more it's lasted

'Twixt Bedfordians and Dulwich,

'Twixt the Midlanders and Southrons.

.....

Behold the game now well in progress;

See the dashing Dulwich outsides,

Swift as leopards, brave as lions,

Down the field come running strongly—

See the fleet right-wing three-quarter

Darting through the ranks of Bedford,

Handing off his fierce opponents,

Scoring now 'mid deaf'ning uproar,

'Mid wild shouts of "Well played, Dulwich!"

'Mid the sweetest of confusion.

He followed with close attention the exploits of the chief Rugby clubs, especially those hailing from South Wales. His sympathies were with Wales in the international games. These international matches enthralled him, and he was a spectator whenever possible of those that were played in the vicinity of London. One of his ambitions was some day to don the scarlet jersey with the Prince of Wales's plume and play for Wales in international contests. To achieve that distinction and to win his football "blue" for Oxford—these were cherished ambitions which but for the War would doubtless have been realised.

In the spring of 1915, interviewed by a London football editor, he explained how Dulwich had built up its great football reputation. Much of the success he attributed to the system of training.

We do not divide the school into so many "houses," as they do elsewhere, but into "games." We have no fewer (p. 035) than eight senior games, which means eight groups of players, about thirty in each group; and these are selected so that boys of about the same age and weight will meet each other. When we have arranged our games, one of the Colours—1st XV men—is told off to coach. Sometimes we play as many as nine XV's in one day. With the first team we practise what are called "set-pieces." One day we will take the forwards, get the scrum properly formed, practise hooking, heeling and screwing. We have devoted a lot of attention to wheeling. We also practise hand-to-hand passing among the forwards.

My son held that brain as well as muscle was needed in athletics. "Rugby football," he wrote, "tends more and more to become an ideal combination of scientific actions. Haphazard, clumsy battering is useless. Your footballer has to be a thinking and a reasoning factor." He believed that games properly played are invaluable as a training in character. "They make," he wrote, "not only for courage and unselfishness, but also for clean living: a sportsman dare not indulge in excesses."

Nobody could have found greater happiness in a game of football than did Paul Jones. He revelled in a hard-fought match and seemed impervious to knocks and bruises. One of his merits as a captain was that he never lost heart; he would fight doggedly to the last, even against adverse conditions. He knew, too, how to adapt his tactics skilfully to varying conditions of play. It was an intoxicating moment after a victory, for the boys would sweep into the field of play and carry the captain in triumph shoulder-high from the arena. In public-school football no animosities are left, no matter how keenly contested the game. Victor and vanquished dine together after the match, the best of friends, and the home team escort their visitors to the railway station. How well I recollect Paul coming home on Saturday evenings about eight o'clock after a victorious match; his firm, quick step, and the eager joy that shone in his (p. 036) face! His mother and I often watched the games at Dulwich, and he would go over every phase of the play with us, inviting comments and contributing his own. He was always severe in his condemnation of anything in the shape of "gallery play," his constant maxim being that the player should subordinate himself entirely to the side. It was his conviction that unselfishness was stimulated by football. The amateur athlete, who forgot himself in the team of which he was a part, and who played and worked hard for the honour of the game, and without thought of personal advantage or reward, was the god of his idolatry. Fond as he was of sport, and highly as he appreciated it as a discipline for character, he held that the cult of athletics could be overdone, and that to make a business of what should only be a pastime was a grave blunder. In an essay which he wrote on "Sport," he characterises the professional athlete as a man who is engaged "in the vilest of trades." "Life," he wrote, "is made up of varied interests, and man has serious work to do in the world. Excess in sport—or in anything else—puts the notes of the great common chord of life out of harmony."[Back to Contents]

Your cricketer, right English to the core,

Still loves the man best he has licked before.

Tom Taylor in Punch.

Though, as has been said, Paul had no skill in cricket, he was jealous of the cricket reputation of the College. He knew the game thoroughly. His cricket "Bible," if I may use the expression, was Prince Ranjitsinhji's excellent "Jubilee Book of Cricket." He often accompanied the 1st XI for out-of-town matches, to act as scorer or reporter. His cricket reports in The Alleynian make racy reading. The following is taken from a picturesquely-written account of a victory over Brighton at Brighton in May, 1914:

When A. E. R. Gilligan appeared at the wicket things became more than merry. He was in fine fettle, and from the first made light of the bowling, hitting all round the wicket with immense vigour. The gem of the day was his treatment of D. S. Johnson's fifth over. We seem to recollect reading in our childhood a work of P. G. Wodehouse's, in which he remarks that "when a slow bowler begins to bowl fast, it is as well to be batting if you can manage it." Well, Johnson was—we think—originally a slow bowler, and he tried to bowl fast. The result was that traffic had to be suspended on the road running past the school. First Franklin—who had replaced Shirley, brilliantly caught at point—smote Johnson for a three. This brought Gilligan to the batting end, and a horse passing outside the ground nearly had its life cut short. The next ball just missed the railings, and the next almost smashed the fanlight in a house across the road. It was then that the police suspended the traffic. Gilligan finally (p. 038) played inside a good length ball, and was most unfortunately bowled when within two of his century. Hard luck! He had been missed twice—once, we admit, badly—but on the whole his smiting was admirably timed and placed. He hit three sixes and fifteen fours. Franklin had meanwhile been busy, and scored 22, with three fours. Finally, Brown and Wood put on some 30 runs, the former being not out for a useful 16, and the latter getting 13. Our score was 326 for eight when Gilligan declared.

Appended is a passage from his account of the match with Bedford on June 6 (in which Dulwich were victorious by 81 runs), describing a record achievement by A. H. H. Gilligan, one of three brothers who distinguished themselves in athletics in Dulwich:

A. H. H. Gilligan was now well over the 170 mark, and had therefore beaten the previous school record for the highest score. At 190, however, he just touched a short fast ball from Cameron, and put the ball into the hands of Dix at second slip: 283-9-190. The innings closed for 284 in the next over, Paton being run out. To score 190 out of 284 is an almost superhuman performance. For a man who was only playing his second match this season it was a positively marvellous achievement. Gilligan's innings was a masterpiece, and at no time did he seem to be in the slightest degree troubled by the bowlers, yet the latter were distinctly good, as they proved by the fact that they got nine men out for 94 runs or less. Gilligan's innings included a six and thirty-two fours. The previous best score—against a weak scratch side in 1911—was 171 by C. V. Arnold. Gilligan was at the wickets in all only two and a quarter hours or so.

The following is from his report of the Sherborne match, which Dulwich won handsomely:

Had not the last few wickets been able to put on a few more runs all earlier efforts might have been wasted, and certainly all would have been altered had it not been for the amazing bowling of Paton. His analysis was five for 6—a wonderful achievement. The wicket was, indeed, to a certain extent favourable to him, but he was (p. 039) able to make the ball swing with his arm and break back in a fashion that was quite astounding. A. E. R. Gilligan worked with his usual energy and bore the brunt of the bowling. While he did not have the success of Paton, he bowled extremely well, taking four for 30. All our team fielded so well that to specify individuals would be unnecessary. The Sherborne team brought off some excellent catches, though their ground-fielding was not quite so good. Wheeler bowled very well, and Westlake was in splendid form behind the wicket. After the match there were the usual handshakings and so forth, and we started back for London at five-thirty, getting to Waterloo at about eight o'clock. Our visit was quite delightful, and we send our very best thanks to our Sherborne friends for their kindness and hospitality.

Of the match with St. Paul's School in July, 1914, in which Dulwich were badly beaten, he wrote:

We would have given much to win this match, in particular, but at least there is the consolation that we lost to a really great side which could hardly have been beaten by any school in the country. The St. Paul's batting was so splendidly balanced that every man could be sure of a 10 or 20, while Skeet and Gibb were always certain of really good knocks; and in bowling the wizardry of Pearson was in itself enough to conjure any team out.

St. Paul's knocked up 188 in their first innings. Dulwich were disposed of for 67, largely owing to the bowling of Pearson.

The Pauline "demon" had now got all our men into a terrible "funk," and the result was that wickets began to fall at both ends like ninepins: 44-9-3. Then came the best batting of the game. Gilkes joined Brown, and quickly showed that he was not the man to hide his head before foes, however strong. After smiting Roberts to the leg boundary, he did the same to the off, and with Brown playing his usually steady game—being particularly smart in short runs—the 50 and 60 soon went up. But it could not go on, for at 67 Brown, avoiding Scylla, fell into the jaws of Charybdis—in other words, keeping (p. 040) Pearson out, was bowled by Skeet: 67-10-11. His 11 was a most valuable piece of batting. Gilkes, with 12 not out, was top scorer on our side—except for Mr. Extras. He had really done extremely well, and played with a straight bat at everything—therefore he did not get out. A most plucky and useful bit of work this.

But what of our innings as a whole? Let the heavens fall in confusion on us! We decline to discuss the matter. Pearson took five wickets for 17, Skeet three for 21, Roberts two for 13. St. Paul's fielded well, especially Skeet, Hayne and Gibb. It was Pearson's cakewalk-tango bowling that undid us. Note, however, that in a second innings we quite redeemed ourselves, Rowbotham (31 not out), Paton (29), and Brown (29 not out) playing really excellently. Why, oh, why! didn't we do it in the first innings?

His detailed and graphic reports were greatly appreciated by the members of the 1st XI, and read with relish by the whole school. Whenever opportunity offered Paul would visit the Oval for a great cricket match. Lord's not being so accessible, he seldom went to the M.C.C. ground. Though a poor cricketer himself, he loved the great summer game and admired those who excelled in it.[Back to Contents]

True ease in writing comes from art, not chance.

Pope: "Essay on Criticism."

To the school magazine, The Alleynian, which is published monthly, Paul began contributing in 1912. His success in essays having shown that he had facility in writing, he was asked by those in authority to report the lectures for the magazine and help to liven up its contents. His first contribution deals with a lantern lecture on the "Soudan," delivered before the Science and Photographic Society by Major Perceval on November 23, 1912. A summary of the lecture is enlivened by such observations as these:

A large and very distinguished audience was present. On the back benches in particular was a great array of Dulwich "knuts." The lecturer was, however, undaunted, though there can be no doubt that he felt much awe at the number of mighty men in his audience.

From the report of a lecture delivered on January 31, 1913, "The Land of the Maori," the following quotation is made because of its allusions to then topical events:

The lecturer said that in New Zealand the interests of labour were so well safeguarded that the country is called "the working-man's paradise" (loud cheers), while the women there had votes. At this an unparalleled uproar broke out. Cheers and hisses were commingled in one tremendous cataclysm of sound. Certainly we heard shouts of "Bravo" countered by shrieks of "Shame." The lecturer seemed dazed by the dreadful din.

(p. 042) A report of the "Servants' Concert" (28th July, 1913) is in rollicking vein:

Success was in the air from the very start. The crush at the doors was like Twickenham on the day of the England v. Scotland match—we had almost said the Crystal Palace on Cup Final Day. It is evident that there is a tremendous amount of talent for the stage and the music-halls in the school. To hear Gill give the tragic history of "Tommy's Little Tube of Seccotine," or the duet on the touching story of "Two Little Sausages," by Savage and Livock, would have brought tears to the eyes of a prison warder. Then there were F. W. Gilligan to relate his horticultural, and brother A. E. R. his zoological reminiscences—works of great value to scientists and others. To hear Killick dilate upon the dangers of the new disease, the "Epidemic Rag" (which seems to be quite as catching as the mumps), Gill upon the risks of the piscatorial art, or Savage upon an original Polynesian theme, "Zulu Lulu," was to feel like Keats's watcher of the skies, "when a new planet swims into his ken." For the admirer of Spanish customs there was A. E. J. Inglis (O.A.) to sing, as only he can, the Toreador's song; while for the Cockney there was Killick to give, in his own inimitable fashion, that really touching little ballad "My Old Dutch," Ould Oireland being well catered for by Livock in "A Little Irish Girl." The pianoforte solos by Nalder, Jacob and Shirley were all excellent and thoroughly well appreciated, as was our old friend, "Let's have a Peal," by the First XI.

And now for the "star" performance of the evening. Positively for one night only, the Dulwich College Dramatic Society were down to give us W. G. O. Gill's one-act farce, "The Lottery Ticket." This fairly brought down the house. It went "with a bang," as actors say, from the very start. The great point about it was that all the performers forgot that they were acting, and were so perfectly natural. There was not a hitch. Killick, as a withered old Shylock, gave a really masterly representation of ancient villainy. Evans was admirably suited with the rôle of a dashing young man-about-town. The way he took his gloves off was worth a fortune in itself. We felt that there must be many degrees of blue blood in his veins. His back-chat repartee was far better than that of Mr. F. E. Smith, K.C. If Gill and Waite are in the (p. 043) future ever in need of a berth they should, judging by their performances in this play, apply to Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree for parts as a dilapidated charwoman and unwashed office-boy respectively. The topical allusions in the play were all thoroughly well made and appreciated. We might suggest that it is not the custom "in polite circles" to open and read other people's telegrams, but for a hardened old reprobate like Mr. Grabbit we can feel no pity, while we can forgive anything to a Principal Boy like Mr. Knowall.

It is an open secret that the concert was organised by Killick. We take this opportunity of congratulating him heartily. From what rumour says, we take it that the Powers-that-be are very pleased with the concert. So are we. It was a complete success from start to finish. It is to be hoped that it will become a regular institution, especially considering the object it has in view—to give pleasure to those who have not often the chance of it.

In 1913 he was appointed secretary and treasurer of the magazine, and a few months later he became one of the editors. Throughout 1913 and 1914 he was the chief contributor to its pages. Reporting a lady's lecture on Tibet (October 17, 1913), he wrote:

But, at least, the Tibetans can teach us something—simplicity in ceremonies. For when Miss Kemp went to see the palace of the King all the decoration she saw there was a simple table and chair. A Tibetan kitchen was a very popular slide. In that country they apparently use a golf-bag to brew tea in, and cast-off bicycle wheels for plates. There prevails in Tibet some element of democracy, for Miss Kemp's cook was also a J.P., a Civil Servant, and held other such offices of fame. One of her assistants was a positive marvel—a human carpet-sweeper. If the floor was to be brushed he would simply roll over and over on it and clean it with his clothes! The Tibetans have no motor-bikes and no S. F. Edges, their fastest conveyance being a yâk, a species of ox, which moves at an average speed of two miles an hour (with the high gear in), and can slow down to an infinite extent. However, the nature of the country would make high speeds rather dangerous, as constantly you find yourself in danger (p. 044) of falling over precipices, down crevasses, or of being overwhelmed by falling boulders, for the mountain lands are covered with great glaciers. It was these mountain views that were especially magnificent. They were, for the most part, taken with tele-photographic lenses at a distance of fifty or sixty miles.

To the November Alleynian he contributed a racy and rattling parody of the modern sensational drama entitled Red Blood: a Western Drama in Two Acts, in which the dramatis personæ are an English cowboy (heir to a million dollars without knowing it), an Indian chief (his friend), a wicked uncle, a murderer, and a New York detective. His historical tastes peep out in his report of a lecture delivered 7th November, 1913, on the famous mediæval doctor, Pareil (1510-1590). From this report the following is extracted:

Much interest attaches to the historic associations of Pareil's life. As a famous surgeon he was in constant attendance on figures renowned in history, personages like Coligny (who was murdered by the mob of Paris while recovering from an amputation of Pareil's), Erasmus, Servetus, Leonardo da Vinci, and Catherine de Medici. Like Chaucer's doctour of physik, Pareil knew well the works of "Olde Ypocras," Galen, Avycen, etc., the famous physicians whose names have come down from history, but he was no pedantic scholar, preferring to do his own thinking. A stout Protestant, his last act was to beseech the Catholic Archbishop of Lyons, who was holding Paris against the assaults of Henry of Navarre (with the result that the population of the city was perishing by thousands), to open the gates and save the inhabitants, but he beseeched in vain.

Altogether a remarkable figure, this old Pareil. Looked at in perspective, and in his era, it is clear how great a man he was. For he, first of all men in medicine, freed the world from the influence of pedantic tradition, and paved the way for modern medical science. Then all honour to his name, for, as the Master put it in proposing the vote of thanks to Mr. Paget, the art of healing is the greatest boon which man can give to the world.

(p. 045) The last lecture he reported was delivered by Mr. F. M. Oldham, chief Science Master at the College, on "Primitive Man," on 3rd April, 1914. From this report the following extract is taken:

Our main knowledge of man in the earliest stages of his existence comes from the examination of river mud. Mr. Oldham showed how different strata are built up by the river on its bed, and how in the lowest of these strata there will be found the oldest relics of man. In this way we are able to declare that the difference between the earliest man and his immediate followers lay in the question of polishing his flint instruments. That is to say, the earliest or palæolithic man had his implements unpolished; his successors polished them, often to a beautifully smooth surface. This Mr. Oldham illustrated with a series of films—your pardon, slides—of the arrow-heads made by palæolithic and neolithic man. It was a natural step, once man had learned to polish his instruments, and when he was advanced enough to try to form conceptions of beauty for himself, that he should draw or scratch pictures on stone. Several of these Mr. Oldham showed on the screen; some of them are extraordinarily well executed and show real artistic feeling. We would particularly mention one such representation of a reindeer, and another of a man stalking a bison.

After the cave-dwellers' epoch comes that of huts, wood and bronze. Man in this stage is really but little different from what he is to-day. He has even the wit to construct himself lake-dwellings, consisting of huts placed on rafts and secured temporarily with large stones sunk in the lake-bed. Characteristic of this period are the great tolmens and monoliths found all over the world. Neolithic man had, indeed, sometimes constructed for himself a hut of stone, as Dartmoor will testify, but the tolmens are of quite different origin, and indicate a distinctly greater mental development, in that they are usually put up as monuments to great men or events. Of the same nature are the great mounds or "barrows" that abound in Ireland; inside there was a sort of crypt in which chiefs were buried. The monoliths were constructed, as doubtless the Pyramids also were, by rolling the great stones up an inclined bank of earth previously built up.

(p. 046) Throughout 1914 Paul was the mainstay of the magazine. The May number contains from his pen exhaustive reports of two house matches (football), a shrewd commentary on the Junior School Cup matches, and a long report of a lecture. For the July number he wrote ten pages of cricket reports, and an account of the swimming competition. He was also responsible for the finances of the magazine, continuing to act as secretary and treasurer. All this time he was preparing for his Oxford scholarship. If he owed much to Dulwich, the College also owed something to him. No boy ever worked harder for it, or consecrated himself with more entire devotion to its welfare.[Back to Contents]

Now all the youth of England are on fire.

Shakespeare: "Henry V."

To The Alleynian for October, 1914, Paul contributed an editorial article on the War that had then begun to rage in its destructive fury. Taking the view that "this war had to come sooner or later," he wrote: