[Illustration: "These Are My Dearest Children."]

THE

CRYPTOGRAM.

A Novel.

By James De Mille,

Author of

"The Dodge Club," "Cord and Creese," "The American Baron," etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

New York:

Harper & Brothers, Publishers,

Franklin Square.

1872

CHAPTER I.

TWO OLD FRIENDS.

Chetwynde Castle was a large baronial mansion, belonging to the

Plantagenet period, and situated in Monmouthshire. It was a grand old

place, with dark towers, and turrets, and gloomy walls surmounted

with battlements, half of which had long since tumbled down, while

the other half seemed tottering to ruin. That menacing ruin was on

one side of the structure concealed beneath a growth of ivy, which

contrasted the dark green of its leaves with the sombre hue of the

ancient stones. Time with its defacing fingers had only lent

additional grandeur to this venerable pile. As it rose there

--"standing with half its battlements alone, and with five hundred

years of ivy grown"--its picturesque magnificence and its air of hoar

antiquity made it one of the noblest monuments of the past which

England could show.

All its surroundings were in keeping with the central object. Here

were no neat paths, no well-kept avenues, no trim lawns. On the

contrary, every thing bore the unmistakable marks of neglect and

decay; the walks were overgrown, the terraces dilapidated, and the

rose pleasaunce had degenerated into a tangled mass of bushes and

briers. It seemed as though the whole domain were about to revert

into its original state of nature; and every thing spoke either of

the absence of a master, or else of something more important

still--the absence of money.

The castle stood on slightly elevated ground; and from its gray stone

ivy-covered portal so magnificent was the view that the most careless

observer would be attracted by it, and stand wonder-struck at the

beauty of the scene, till he forgot in the glories of nature the

deficiencies of art. Below, and not far away, flowed the silvery Wye,

most charming of English streams, winding tortuously through fertile

meadows and wooded copses; farther off lay fruitful vales and rolling

hills; while in the distance the prospect was bounded by the giant

forms of the Welsh mountains.

At the moment when this story opens these beauties were but faintly

visible through the fast-fading twilight of a summer evening; the

shadows were rapidly deepening; and the only signs of life about the

place appeared where from some of the windows at the eastern end

faint rays of light stole out into the gloom.

The interior of the castle corresponded with the exterior in

magnificence and in ruin--in its picturesque commingling of splendor

and decay. The hall was hung with arms and armor of past generations,

and ornamented with stags' heads, antlers, and other trophies of the

chase; but rust, and mould, and dust covered them all. Throughout the

house a large number of rooms were empty, and the whole western end

was unfurnished. In the furnished rooms at the eastern end every

thing belonged to a past generation, and all the massive and

antiquated furniture bore painful marks of poverty and neglect. Time

was every where asserting his power, and nowhere was any resistance

made to his ravages. Some comfort, however, was still to be found in

the old place. There were rooms which were as yet free from the

general touch of desolation. Among these was the dining-room, where

at this time the heavy curtains were drawn, the lamps shone out

cheerily, and, early June though it was, a bright wood-fire blazed on

the ample hearth, lighting up with a ruddy glow the heavy panelings

and the time-worn tapestries. Dinner was just over, the dessert was

on the table, and two gentlemen were sitting over their wine--though

this is to be taken rather in a figurative sense, for their

conversation was so engrossing as to make them oblivious of even the

charms of the old ancestral port of rare vintage which Lord Chetwynde

had produced to do honor to his guest. Nor is this to be wondered at.

Friends of boyhood and early manhood, sharers long ago in each

other's hopes and aspirations, they had parted last when youth and

ambition were both at their height. Now, after the lapse of years,

wayworn and weary from the strife, they had met again to recount how

those hopes had been fulfilled.

The two men were of distinguished appearance. Lord Chetwynde was of

about the medium size, with slight figure, and pale, aristocratic

face. His hair was silver-white, his features were delicately

chiseled, but wore habitually a sad and anxious expression. His whole

physique betokened a nature of extreme refinement and sensibility,

rather than force or strength of character. His companion, General

Pomeroy, was a man of different stamp. He was tall, with a high

receding brow, hair longer than is common with soldiers; thin lips,

which spoke of resolution, around which, however, there always dwelt

as he spoke a smile of inexpressible sweetness. He had a long nose,

and large eyes that lighted up with every varying feeling. There was

in his face both resolution and kindliness, each in extreme, as

though he could remorselessly take vengeance on an enemy or lay down

his life for a friend.

As long as the servants were present the conversation, animated

though it was, referred to topics of a general character; but as soon

as they had left the room the two friends began to refer more

confidentially to the past.

"You have lived so very secluded a life," said General Pomeroy, "that

it is only at rare intervals that I have heard any thing of you, and

that was hardly more than the fact that you were alive. You were

always rather reserved and secluded, you know; you hated, like

Horace, the _profanum vulgus_, and held yourself aloof from them, and

so I suppose you would not go into political life. Well, I don't know

but that, after all, you were right."

"My dear Pomeroy," said Lord Chetwynde, leaning back in his chair,

"my circumstances have been such that entrance into political life

has scarcely ever depended on my own choice. My position has been so

peculiar that it has hardly ever been possible for me to obtain

advancement in the common ways, even if I had desired it. I dare say,

If I had been inordinately ambitious, I might have done something;

but, as it was, I have done nothing. You see me just about where I

was when we parted, I don't know how many years ago."

"Well, at any rate," said the General, "you have been spared the

trouble of a career of ambition. You have lived here quietly on your

own place, and I dare say you have had far more real happiness than

you would otherwise have had."

"Happiness!" repeated Lord Chetwynde, in a mournful tone. He leaned

his head on his hand for a few moments, and said nothing. At last he

looked up and said, with a bitter smile:

"The story of my life is soon told. Two words will embody it

all--disappointment and failure."

General Pomeroy regarded his friend earnestly for a few moments, and

then looked away without speaking.

"My troubles began from the very first," continued Lord Chetwynde, in

a musing tone, which seemed more like a soliloquy than any thing

else. "There was the estate, saddled with debt handed down from my

grandfather to my father. It would have required years of economy and

good management to free it from encumbrance. But my father's motto

was always _Dum vivimus vivamus_ and his only idea was to get what

money he could for himself, and let his heirs look out for

themselves. In consequence, heavier mortgages were added. He lived in

Paris, enjoying himself, and left Chetwynde in charge of a factor,

whose chief idea was to feather his own nest. So he let every thing

go to decay, and oppressed the tenants in order to collect money for

my father, and prevent his coming home to see the ruin that was going

on. You may not have known this before. I did not until after our

separation, when it all came upon me at once. My father wanted me to

join him in breaking the entail. Overwhelmed by such a calamity, and

indignant with him, I refused to comply with his wishes. We

quarreled. He went back to Paris, and I never saw him again.

"After his death my only idea was to clear away the debt, improve the

condition of the tenants, and restore Chetwynde to its former

condition. How that hope has been realized you have only to look

around you and see. But at that time my hope was strong. I went up to

London, where my name and the influence of my friends enabled me to

enter into public life. You were somewhere in England then, and I

often used to wonder why I never saw you. You must have been in

London. I once saw your name in an army list among the officers of a

regiment stationed there. At any rate I worked hard, and at first all

my prospects were bright, and I felt confident in my future.

"Well, about that time I got married, trusting to my prospects. She

was of as good a family as mine, but had no money."

Lord Chetwynde's tone as he spoke about his marriage had suddenly

changed. It seemed as though he spoke with an effort. He stopped for

a time, and slowly drank a glass of wine. "She married me," he

continued, in an icy tone, "for my prospects. Sometimes you know it

is very safe to marry on prospects. A rising young statesman is often

a far better match than a dissipated man of fortune. Some mothers

know this; my wife's mother thought me a good match, and my wife

thought so too. I loved her very dearly, or I would not have

married--though I don't know, either: people often marry in a whim."

General Pomeroy had thus far been gazing fixedly at the opposite

wall, but now he looked earnestly at his friend, whose eyes were

downcast while he spoke, and showed a deeper attention.

"My office," said Lord Chetwynde, "was a lucrative one, so that I was

able to surround my bride with every comfort; and the bright

prospects which lay before me made me certain about my future. After

a time, however, difficulties arose. You are aware that the chief

point in my religion is Honor. It is my nature, and was taught me by

my mother. Our family motto is, _Noblesse oblige_, and the full

meaning of this great maxim my mother had instilled into every fibre

of my being. But on going into the world I found it ridiculed among

my own class as obsolete and exploded. Every where it seemed to have

given way to the mean doctrine of expediency. My sentiments were

gayly ridiculed, and I soon began to fear that I was not suited for

political life.

"At length a crisis arrived. I had either to sacrifice my conscience

or resign my position. I chose the latter alternative, and in doing

so I gave up my political life forever. I need not tell the

bitterness of my disappointment. But the loss of worldly prospects

and of hope was as nothing compared with other things. The worst of

all was the reception which I met at home. My young, and as I

supposed loving wife, to whom I went at once with my story, and from

whom I expected the warmest sympathy, greeted me with nothing but

tears and reproaches. She could only look upon my act with the

world's eyes. She called it ridiculous Quixotism. She charged me with

want of affection; denounced me for beguiling her to marry a pauper;

and after a painful interview we parted in coldness."

Lord Chetwynde, whose agitation was now evident, here paused and

drank another glass of wine. After some time he went on:

"After all, it was not so bad. I soon found employment. I had made

many powerful friends, who, though they laughed at my scruples, still

seemed to respect my consistency, and had confidence in my ability.

Through them I obtained a new appointment where I could be more

independent, though the prospects were poor. Here I might have been

happy, had it not been for the continued alienation between my wife

and me. She had been ambitions. She had relied on my future. She was

now angry because I had thrown that future away. It was a death-blow

to her hopes, and she could not forgive me. We lived in the same

house, but I knew nothing of her occupations and amusements. She went

much into society, where she was greatly admired, and seemed to be

neglectful of her home and of her child. I bore my misery as best I

could in silence, and never so much as dreamed of the tremendous

catastrophe in which it was about to terminate."

Lord Chetwynde paused, and seemed overcome by his recollections.

"You have heard of it, I suppose?" he asked at length, in a scarce

audible voice.

The General looked at him, and for a moment their eyes met; then he

looked away. Then he shaded his eyes with his hand and sat as though

awaiting further revelations.

Lord Chetwynde did not seem to notice him at all. Intent upon his own

thoughts, he went on in that strange soliloquizing tone with which he

had begun.

"She fled--" he said, in a voice which was little more than a

whisper.

"Heavens!" said General Pomeroy.

There was a long silence.

"It was about three years after our marriage," continued Lord

Chetwynde, with an effort. "She fled. She left no word of farewell.

She fled. She forsook me. She forsook her child. My God! Why?"

He was silent again.

"Who was the man?" asked the General, in a strange voice, and with an

effort.

"He was known as Redfield Lyttoun. He had been devoted for a long

time to my wretched wife. Their flight was so secret and so

skillfully managed that I could gain no clew whatever to it--and,

indeed, it was better so--perhaps--yes--better so." Lord Chetwynde

drew a long breath. "Yes, better so," he continued--"for if I had

been able to track the scoundrel and take his life, my vengeance

would have been gained, but my dishonor would have been proclaimed.

To me that dishonor would have brought no additional pang. I had

suffered all that I could. More were impossible; but as it was my

shame was not made public--and so, above all--above all--my boy was

saved. The frightful scandal did not arise to crush my darling boy."

The agitation of Lord Chetwynde overpowered him. His face grew more

pallid, his eyes were fixed, and his clenched hands testified to the

struggle that raged within him. A long silence followed, during which

neither spoke a word.

At length Lord Chetwynde went on. "I left London forever," said he,

with a deep sigh.

"After that my one desire was to hide myself from the world. I wished

that if it were possible my very name might be forgotten. And so I

came back to Chetwynde, where I have lived ever since, in the utmost

seclusion, devoting myself entirely to the education and training of

my boy.

"Ah, my old friend, that boy has proved the one solace of my life.

Well has he repaid me for my care. Never was there a nobler or

a more devoted nature than his. Forgive a father's emotion, my

friend. If you but knew my noble, my brave, my chivalrous boy, you

would excuse me. That boy would lay down his life for me. In all his

life his one thought has been to spare me all trouble and to brighten

my dark life. Poor Guy! He knows nothing of the horror of shame that

hangs over him--he has found out nothing as yet. To him his mother is

a holy thought--the thought of one who died long ago, whose memory he

thinks so sacred to me that I dare not speak of her. Poor Guy! Poor

Guy!"

Lord Chetwynde again paused, overcome by deep emotion. "God only

knows," he resumed, "how I feel for him and for his future. It's a

dark future for him, my friend. For in addition to this grief which I

have told you of there is another which weighs me down. Chetwynde is

not yet redeemed. I lost my life and my chance to save the estate.

Chetwynde is overwhelmed with debt. The time is daily drawing near

when I will have to give up the inheritance which has come down

through so long a line of ancestors. All is lost. Hope itself has

departed. How can I bear to see the place pass into alien hands?"

"Pass into alien hands?" interrupted the General, in surprise. "Give

up Chetwynde? Impossible! It can not be thought of."

"Sad as it is," replied Lord Chetwynde, mournfully, "it must be so.

Sixty thousand pounds are due within two years. Unless I can raise

that amount all must go. When Guy comes of age he must break the

entail and sell the estate. It is just beginning to pay again, too,"

he added, regretfully. "When I came into it it was utterly

impoverished, and every available stick of timber had been cut down;

but my expenses have been very small, and if I have fulfilled no

other hope of my life, I have at least done something for my

ground-down tenantry; for every which I have saved, after paying

the interest, I have spent on improving their homes and farms, so

that the place is now in very good condition, though I have been

obliged to leave the pleasure-grounds utterly neglected."

"What are you going to do with your son?" asked the General.

"I have just got him a commission in the army," said Lord Chetwynde.

"Some old friends, who had actually remembered me all these years,

offered to do something for me in the diplomacy line; but if he

entered that life I should feel that all the world was pointing the

finger of scorn at him for his mother's sake; besides, my boy is too

honest for a diplomat. No--he must go and make his own fortune. A

viscount with neither money, land, nor position--the only place for

him is the army."

A long silence followed. Lord Chetwynde seemed to lose himself among

those painful recollections which he had raised, while the General,

falling into a profound abstraction, sat with his head on one hand,

while the other drummed mechanically on the table. As much as half an

hour passed away in this manner. The General was first to rouse

himself.

"I arrived in England only a few months ago," he began, in a quiet,

thoughtful tone. "My life has been one of strange vicissitudes. My

own country is almost like a foreign land to me. As soon as I could

get Pomeroy Court in order I determined to visit you. This visit was

partly for the sake of seeing you, and partly for the sake of asking

a great favor. What you have just been saying has suggested a new

idea, which I think may be carried out for the benefit of both of us.

You must know, in the first place, I have brought my little daughter

home with me. In fact, it was for her sake that I came home--"

"You were married, then?"

"Yes, in India. You lost sight of me early in life, and so perhaps

you do not know that I exchanged from the Queen's service to that of

the East India Company. This step I never regretted. My promotion was

rapid, and after a year or two I obtained a civil appointment. From

this I rose to a higher office; and after ten or twelve years the

Company recommended me as Governor in one of the provinces of the

Bengal Presidency. It was here that I found my sweet wife.

"It is a strange story," said the General, with a long sigh. "She

came suddenly upon me, and changed all my life. Thus far I had so

devoted myself to business that no idea of love or sentiment ever

entered my head, except when I was a boy. I had reached the age of

forty-five without having hardly ever met with any woman who had

touched my heart, or even my head, for that matter.

"My first sight of her was most sudden and most strange," continued

the General, in the tone of one who loved to linger upon even the

smallest details of the story which he was telling--"strange and

sudden. I had been busy all day in the audience chamber, and when at

length the cases were all disposed of, I retired thoroughly

exhausted, and gave orders that no one should be admitted on any

pretext whatever. On passing through the halls to my private

apartment I heard an altercation at the door. My orderly was speaking

in a very decided tone to some one.

"'It is impossible,' I heard him say. 'His Excellency has given

positive orders to admit no one to-day.'

"I walked on, paying but little heed to this. Applications were

common after hours, and my rules on this point were stringent. But

suddenly my attention was arrested by the sound of a woman's voice.

It affected me strangely, Chetwynde. The tones were sweet and low,

and there was an agony of supplication in them which lent additional

earnestness to her words.

"'Oh, do not refuse me!' the voice said. 'They say the Resident is

just and merciful. Let me see him, I entreat, if only for one

moment.'

"At these words I turned, and at once hastened to the door. A young

girl stood there, with her hands clasped, and in an attitude of

earnest entreaty. She had evidently come closely veiled, but in her

excitement her veil had been thrown back, and her upturned face lent

an unspeakable earnestness to her pleading. At the sight of her I was

filled with the deepest sympathy.

"'I am the Resident,' said I. 'What can I do for you?'

"She looked at me earnestly, and for a time said nothing. A change

came over her face. Her troubles seemed to have overwhelmed her. She

tottered, and would have fallen, had I not supported her. I led her

into the house, and sent for some wine. This restored her.

"She was the most beautiful creature that I ever beheld," continued

the General, in a pensive tone, after some silence. "She was tall and

slight, with all that litheness and grace of movement which is

peculiar to Indian women, and yet she seemed more European than

Indian. Her face was small and oval, her hair hung round it in rich

masses, and her eyes were large, deep, and liquid, and, in addition

to their natural beauty, they bore that sad expression which, it is

said, is the sure precursor of an early death. Thank God!" continued

the General, in a musing tone, "I at least did something to brighten

that short life of hers.

"As soon as she was sufficiently recovered she told her story. It was

a strange one. She was the daughter of an English officer, who having

fallen in love with an Indian Begum gave up home, country, and

friends, and married her. Their daughter Arauna had been brought up

in the European manner, and to the warm, passionate, Indian nature

she added the refined intelligence of the English lady. When she was

fourteen her father died. Her mother followed in a few years. Of her

father's friends she knew nothing, and her mother's brother, who was

the Rajah of a distant province, was the only one on whom she could

rely. Her mother while dying charged her always to remember that she

was the daughter of a British officer, and that if she were ever in

need of protection she should demand it of the English authorities.

After her mother's death the Rajah took her away, and assumed the

control of all her inheritance. At the age of eighteen she was to

come into possession, and as the time drew near the Rajah informed

her that he wished her to marry his son. But this son was detestable

to her, and to her English ideas the proposal was abhorrent. She

refused to marry him. The Rajah swore that she should. At this she

threatened that she would claim the protection of the British

government. Fearful of this, and enraged at her firmness, he confined

her in her rooms for several months, and at length threatened that if

she did not consent he would use force. This threat reduced her to

despair. She determined to escape and appeal to the British

authorities. She bribed her attendants, escaped, and by good fortune

reached my Residency.

"On hearing her story I promised that full justice should be done

her, and succeeded in quieting her fears. I obtained a suitable home

for her, and found the widow of an English officer who consented to

live with her.

"Ah, Chetwynde, how I loved her! A year passed away, and she became

my wife. Never before had I known such happiness as I enjoyed with

her. Never since have I known any happiness whatever. She loved me

with such devotion that she would have laid down her life for me. She

looked on me as her savior as well as her husband. My happiness was

too great to last.

"I felt it--I knew it," he continued, in a broken voice. "Two years

my darling lived with me, and then--she was taken away.

"I was ill for a long time," continued the General, in a gentle

voice. "I prayed for death, but God spared me for my child's sake. I

recovered sufficiently to attend to the duties of my office, but it

was with difficulty that I did so. I never regained my former

strength. My child grew older, and at length I determined to return

to England. I have come here to find all my relatives dead, and you,

the old friend of my boyhood, are the only survivor. One thing there

is, however, that imbitters my situation now. My health is still very

precarious, and I may at any moment leave my child unprotected. She

is the one concern of my life. I said that I had come here to ask a

favor of you. It was this, that you would allow me to nominate you as

her guardian in case of my death, and assist me also in finding any

other guardian to succeed you in case you should pass away before she

reached maturity. This was my purpose. But after what you have told

me other things have occurred to my mind. I have been thinking of a

plan which seems to me to be the best thing for both of us.

"Listen now to my proposal," he said, with greater earnestness. "That

you should give up Chetwynde is not to be thought of for one moment.

In addition to my own patrimony and my wife's inheritance I have

amassed a fortune during my residence in India, and I can think of no

better use for it than in helping my old friend in his time of need."

Lord Chetwynde raised his hand deprecatingly.

"Wait--no remonstrance. Hear me out," said the General. "I do not ask

you to take this as a loan, or any thing of the kind. I only ask you

to be a protector to my child. I could not rest in my grave if I

thought that I had left her unprotected."

"What!" cried Lord Chetwynde, hastily interrupting him, "can you

imagine that it is necessary to buy my good offices?"

"You don't understand me yet, Chetwynde; I want more than that. I

want to secure a protector for her all her life. Since you have told

me about your affairs I have formed a strong desire to see her

betrothed to your son. True, I have never seen him, but I know very

well the stock he comes from. I know his father," he went on, laying

his hand on his friend's arm; "and I trust the son is like the

father. In this way you see there will be no gift, no loan, no

obligation. The Chetwynde debts will be all paid off, but it is for

my daughter; and where could I get a better dowry?"

"But she must be very young," said Lord Chetwynde, "if you were not

married until forty-five."

"She is only a child yet," said the General. "She is ten years old.

That need not signify, however. The engagement can be made just as

well. I free the estate from all its encumbrances; and as she will

eventually be a Chetwynde, it will be for her sake as well as your

son's. There is no obligation."

Lord Chetwynde wrung his friend's hand.

"I do not know what to say," said he. "It would add years to my life

to know that my son is not to lose the inheritance of his ancestors.

But of course I can make no definite arrangements until I have seen

him. He is the one chiefly interested; and besides," he added,

smilingly, "I can not expect you to take a father's estimate of an

only son. You must judge him for yourself, and see whether my account

has been too partial."

"Of course, of course. I must see him at once," broke in the General.

"Where is he?"

"In Ireland. I will telegraph to him tonight, and he will be here in

a couple of days."

"He could not come sooner, I suppose?" said the General, anxiously.

Lord Chetwynde laughed. "I hardly think so--from Ulster. But why such

haste? It positively alarms me, for I'm an idle man, and have had my

time on my hands for half a lifetime."

"The old story, Chetwynde," said the General, with a smile;

"petticoat government. I promised my little girl that I would be back

tomorrow. She will be sadly disappointed at a day's delay. I shall be

almost afraid to meet her. I fear she has been a little spoiled, poor

child; but you can scarcely wonder, under the circumstances. After

all, she is a good child though; she has the strongest possible

affection for me, and I can guide her as I please through her

affections."

After some further conversation Lord Chetwynde sent off a telegram to

his son to come home without delay.

CHAPTER II.

THE WEIRD WOMAN.

The morning-room at Chetwynde Castle was about the pleasantest one

there, and the air of poverty which prevailed elsewhere was here lost

in the general appearance of comfort. It was a large apartment,

commensurate with the size of the castle, and the deep bay-windows

commanded an extensive view.

On the morning following the conversation already mentioned General

Pomeroy arose early, and it was toward this room that he turned his

steps. Throughout the castle there was that air of neglect already

alluded to, so that the morning-room afforded a pleasant contrast.

Here all the comfort that remained at Chetwynde seemed to have

centred. It was with a feeling of intense satisfaction that the

General seated himself in an arm-chair which stood within the deep

recess of the bay-window, and surveyed the apartment.

The room was about forty feet long and thirty feet wide. The ceiling

was covered with quaint figures in fresco, the walls were paneled

with oak, and high-backed, stolid-looking chairs stood around. On one

side was the fire-place, so vast and so high that it seemed itself

another room. It was the fine old fire-place of the Tudor or

Plantagenet period--the unequaled, the unsurpassed--whose day has

long since been done, and which in departing from the world has left

nothing to compensate for it. Still, the fireplace lingers in a few

old mansions; and here at Chetwynde Castle was one without a peer.

It was lofty, it was broad, it was deep, it was well-paved, it was

ornamented not carelessly, but lovingly, as though the hearth was the

holy place, the altar of the castle and of the family. There was room

in its wide expanse for the gathering of a household about the fire;

its embrace was the embrace of love; and it was the type and model of

those venerable and hallowed places which have given to the English

language a word holier even than "Home," since that word is "Hearth."

It was with some such thoughts as these that General Pomeroy sat

looking at the fire-place, where a few fagots sent up a ruddy blaze,

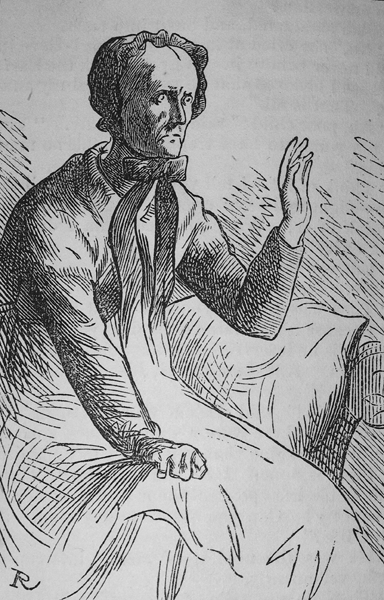

when suddenly his attention was arrested by a figure which entered

the room. So quiet and noiseless was the entrance that he did not

notice it until the figure stood between him and the fire. It was a

woman; and certainly, of all the women whom he had ever seen, no one

had possessed so weird and mystical an aspect. She was a little over

the middle height, but exceedingly thin and emaciated. She wore a cap

and a gown of black serge, and looked more like a Sister of Charity

than any thing else. Her features were thin and shrunken, her cheeks

hollow, her chin peaked, and her hair was as white as snow. Yet the

hair was very thick, and the cap could not conceal its heavy white

masses. Her side-face was turned toward him, and he could not see

her fully at first, until at length she turned toward a picture which

hung over the fire-place, and stood regarding it fixedly.

It was the portrait of a young man in the dress of a British officer.

The General knew that it was the only son of Lord Chetwynde, for whom

he had written, and whom he was expecting; and now, as he sat there

with his eyes riveted on this singular figure, he was amazed at the

expression of her face.

Her eyes were large and dark and mysterious. Her face bore

unmistakable traces of sorrow. Deep lines were graven on her pale

forehead, and on her wan, thin cheeks. Her hair was white as snow,

and her complexion was of an unearthly grayish hue. It was a

memorable face--a face which, once seen, might haunt one long

afterward. In the eyes there was tenderness and softness, yet the

fashion of the mouth and chin seemed to speak of resolution and

force, in spite of the ravages which age or sorrow had made. She

stood quite unconscious of the General's presence, looking at the

portrait with a fixed and rapt expression. As she gazed her face

changed in its aspect. In the eyes there arose unutterable longing

and tenderness; love so deep that the sight of it thus unconsciously

expressed might have softened the hardest and sternest nature; while

over all her features the same yearning expression was spread.

Gradually, as she stood, she raised her thin white hands and clasped

them together, and so stood, intent upon the portrait, as though she

found some spell there whose power was overmastering.

At the sight of so weird and ghostly a figure the General was

strangely moved. There was something startling in such an apparition.

At first there came involuntarily half-superstitious thoughts. He

recalled all those mysterious beings of whom he had ever heard whose

occupation was to haunt the seats of old families. He thought of the

White Lady of Avenel, the Black Lady of Scarborough, the Goblin Woman

of Hurst, and the Bleeding Nun. A second glance served to show him,

however, that she could by no possibility fill the important post of

Family Ghost, but was real flesh and blood. Yet even thus she was

scarcely less impressive. Most of all was he moved by the sorrow of

her face. She might serve for Niobe with her children dead; she might

serve for Hecuba over the bodies of Polyxena and Polydore. The

sorrows of woman have ever been greater than those of man. The widow

suffers more than the widower; the bereaved mother than the bereaved

father. The ideals of grief are found in the faces of women, and

reach their intensity in the woe that meets our eyes in the Mater

Dolorosa. This woman was one of the great community of sufferers, and

anguish both past and present still left its traces on her face.

Besides all this there was something more; and while the General was

awed by the majesty of sorrow, he was at the same time perplexed by

an inexplicable familiarity which he felt with that face of woe.

Where, in the years, had he seen it before? Or had he seen it before

at all; or had he only known it in dreams? In vain he tried to

recollect. Nothing from out his past life recurred to his mind which

bore any resemblance to this face before him. The endeavor to recall

this past grew painful, and at length he returned to himself. Then he

dismissed the idea as fanciful, and began to feel uncomfortable, as

though he were witnessing something which he had no business to see.

She was evidently unconscious of his presence, and to be a witness of

her emotion under such circumstances seemed to him as bad as

eaves-dropping. The moment, therefore, that he had overcome his

surprise he turned his head away, looked out of the window, and

coughed several times. Then he rose from his chair, and after

standing for a moment he turned once more.

As he turned he found himself face to face with the woman. She had

heard him, and turned with a start, and turning thus their eyes met.

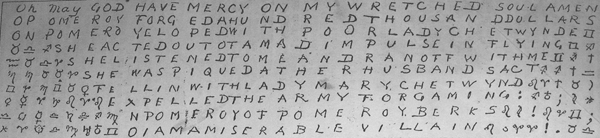

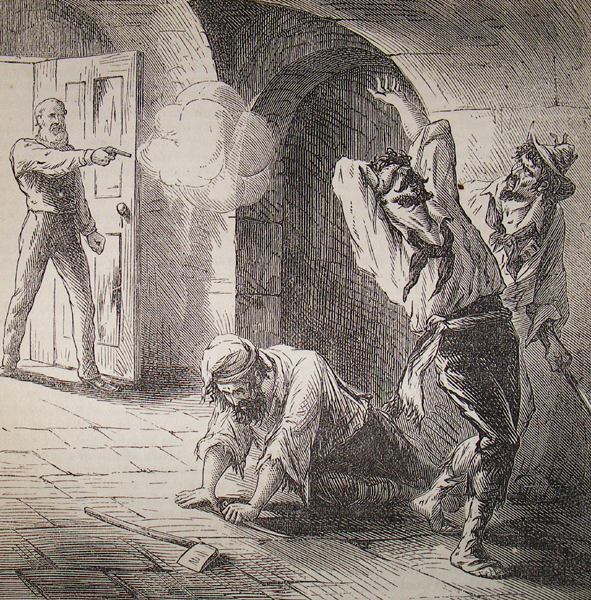

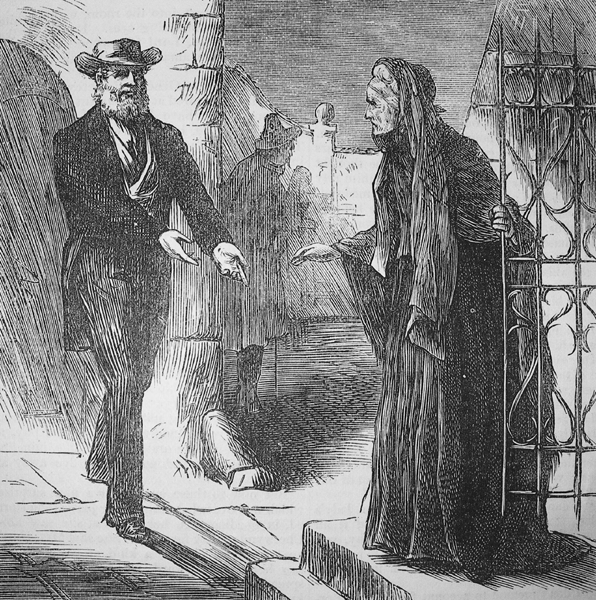

[Illustration: "She Turned Toward A Picture Which Hung Over The

Fire-Place, And Stood Regarding It Fixedly."]

If the General had been surprised before, he was now still more so at

the emotion which she evinced at the sight of himself. She started

back as though recoiling from him; her eyes were fixed and staring,

her lips moved, her hands clutched one another convulsively. Then, by

a sudden effort, she seemed to recover herself, and the wild stare of

astonishment gave place to a swift glance of keen, sharp, and eager

scrutiny. All this was the work of an instant. Then her eyes dropped,

and with a low courtesy she turned away, and after arranging some

chairs she left the room.

The General drew a long breath, and stood looking at the doorway in

utter bewilderment. The whole incident had been most perplexing.

There was first her stealthy entry, and the suddenness with which she

had appeared before him; then those mystic surroundings of her

strange, weird figure which had excited his superstitious fancies;

then the idea which had arisen, that somehow he had known her before;

and, finally, the woman's own strong and unconcealed emotion at the

sight of himself. What did it all mean? Had he ever seen her? Not

that he knew. Had she ever known him? If so, when and where? If so,

why such emotion? Who could this be that thus recoiled from him at

encountering his glance? And he found all these questions utterly

unanswerable.

In the General's eventful life there were many things which he could

recall. He had wandered over many lands in all parts of the world,

and had known his share of sorrow and of joy. Seating himself once

more in his chair he tried to summon up before his memory the figures

of the past, one by one, and compare them with this woman whom he had

seen. Out of the gloom of that past the ghostly figures came, and

passed on, and vanished, till at last from among them all two or

three stood forth distinctly and vividly; the forms of those who had

been associated with him in one event of his life; that life's first

great tragedy; forms well remembered--never to be forgotten. He saw

the form of one who had been betrayed and forsaken, bowed and crushed

by grief, and staring with white face and haggard eyes; he saw the

form of the false friend and foul traitor slinking away with averted

face; he saw the form of the true friend, true as steel, standing

up solidly in his loyalty between those whom he loved and the Ruin

that was before them; and, lastly, he saw the central figure of

all--a fair young woman with a face of dazzling beauty; high-born,

haughty, with an air of high-bred grace and inborn delicacy; but the

beauty was fading, and the charm of all that grace and delicacy

was veiled under a cloud of shame and sin. The face bore all that

agony of woe which looks at us now from the eyes of Guido's Beatrice

Cenci--eyes which disclose a grief deeper than tears; eyes whose

glance is never forgotten.

Suddenly there came to the General a Thought like lightning, which

seemed to pierce to the inmost depths of his being. He started back

as he sat, and for a moment looked like one transformed to stone. At

the horror of that Thought his face changed to a deathly pallor, his

features grew rigid, his hands clenched, his eyes fixed and staring

with an awful look. For a few moments he sat thus, and then with a

deep groan he sprang to his feet and paced the apartment.

The exercise seemed to bring relief.

"I'm a cursed fool!" he muttered. "The thing's impossible--yes,

absolutely impossible."

Again and again he paced the apartment, and gradually he recovered

himself.

"Pooh!" he said at length, as he resumed his seat, "she's insane, or,

more probably, _I_ am insane for having had such wild thoughts as I

have had this morning."

Then with a heavy sigh he looked out of the window abstractedly.

An hour passed and Lord Chetwynde came down, and the two took their

seats at the breakfast-table.

"By-the-way," said the General at length, after some conversation,

and with an effort at indifference, "who is that very

singular-looking woman whom you have here? She seems to be about

sixty, dresses in black, has very white hair, and looks like a Sister

of Charity."

"That?" said Lord Chetwynde, carelessly. "Oh, that must be the

housekeeper, Mrs. Hart."

"Mrs. Hart--the housekeeper?" repeated the General, thoughtfully.

"Yes; she is an invaluable woman to one in my position."

"I suppose she is some old family servant."

"No. She came here about ten years ago. I wanted a housekeeper, she

heard of it, and applied. She brought excellent recommendations, and

I took her. She has done very well."

"Have you ever noticed how very singular her appearance is?"

"Well, no. Is it? I suppose it strikes you so as a stranger. I never

noticed her particularly."

"She seems to have had some great sorrow," said the General, slowly.

"Yes, I think she must have had some troubles. She has a melancholy

way, I think. I feel sorry for the poor creature, and do what I can

for her. As I said, she is invaluable to me, and I owe her positive

gratitude."

"Is she fond of Guy?" asked the General, thinking of her face as he

saw it upturned toward the portrait.

"Exceedingly," said Lord Chetwynde. "Guy was about eight years old

when she came. From the very first she showed the greatest fondness

for him, and attached herself to him with a devotion which surprised

me. I accounted for it on the ground that she had lost a son of her

own, and perhaps Guy reminded her in some way of him. At any rate she

has always been exceedingly fond of him. Yes," pursued Lord

Chetwynde, in a musing tone, "I owe every thing to her, for she once

saved Guy's life."

"Saved his life? How?"

"Once, when I was away, the place caught fire in the wing where Guy

was sleeping. Mrs. Hart rushed through the flames and saved him. She

nearly killed herself too--poor old thing! In addition to this she

has nursed him through three different attacks of disease that seemed

fatal. Why, she seems to love Guy as fondly as I do."

"And does Guy love her?"

"Exceedingly. The boy is most affectionate by nature, and of course

she is prominent in his affections. Next to me he loves her."

The General now turned away the conversation to other subjects; but

from his abstracted manner it was evident that Mrs. Hart was still

foremost in his thoughts.

CHAPTER III.

THE BARTER OF A LIFE.

Two evenings afterward a carriage drove up to the door of Chetwynde

Castle, and a young man alighted. The door was opened by the old

butler, who, with a cry of delight, exclaimed:

"Master Guy! Master Guy! It's welcome ye are. They've been lookin'

for you these two hours back."

"Any thing wrong?" was Guy's first exclamation, uttered with some

haste and anxiety.

"Lord love ye, there's naught amiss; but ye're welcome home, right

welcome, Master Guy," said the butler, who still looked upon his

young master as the little boy who used to ride upon his back, and

whose tricks were at once the torment and delight of his life.

The old butler himself was one of the heirlooms of the family, and

partook to the full of the air of antiquity which pervaded the place.

He looked like the relic of a by-gone generation. His queue,

carefully powdered and plaited, stood out stiff from the back of his

head, as if in perpetual protest against any new-fangled notions of

hair-dressing; his livery, scrupulously neat and well brushed, was

threadbare and of an antediluvian cut, and his whole appearance was

that of highly respectable antediluvianism. As he stood there with

his antique and venerable figure his whole face fairly beamed with

delight at seeing his young master.

"I was afraid my father might be ill," said Guy, "from his sending

for me in such a hurry."

"Ill?" said the other, radiant. "My lord be better and cheerfuler

like than ever I have seen him since he came back from Lunnon--the

time as you was a small chap, Master Guy. There be a gentleman

stopping here. He and my lord have been sittin' up half the night

a-talkin'. I think there be summut up, Master Guy, and that he be

connected with it; for when my lord told me to send you the telegram

he said as it were on business he wanted you, but," he added, looking

perplexed, "it's the first time as ever I heard of business makin' a

man look cheerful."

Guy made a jocular observation and hurried past him into the hall. As

he entered he saw a figure standing at the foot of the great

staircase. It was Mrs. Hart. She was trembling from head

to foot and clinging to the railing for support. Her face was pale as

usual; on each cheek there was a hectic flush, and her eyes were

fastened on him.

"My darling nurse!" cried Guy with the warm enthusiastic tone of a

boy, and hurrying toward her he embraced her and kissed her.

The poor old creature trembled and did not say a single word.

"Now you didn't know I was coming, did you, you dear old thing?" said

Guy. "But what is the matter? Why do you tremble so? Of course you're

glad to see your boy. Are you not?"

Mrs. Hart looked up to him with an expression of mute affection,

deep, fervent, unspeakable; and then seizing his warm young hand in

her own wan and tremulous ones, she pressed it to her thin white lips

and covered it with kisses.

"Oh, come now," said Guy, "you always break down this way when I come

home; but you must not--you really must not. If you do I won't come

home at all any more. I really won't. Come, cheer up. I don't want to

make you cry when I come home."

"But I'm crying for joy," said Mrs. Hart, in a faint voice. "Don't be

angry."

"You dear old thing! Angry?" exclaimed Guy, affectionately. "Angry

with my darling old nurse? Have you lost your senses, old woman? But

where is my father? Why has he sent for me? There's no bad news, I

hear, so that I suppose all is right."

"Yes, all is well," said Mrs. Hart, in a low voice. "I don't know why

you were sent for, but there is nothing bad. I think your father sent

for you to see an old friend of his."

"An old friend?"

"Yes. General Pomeroy," replied Mrs. Hart, in a constrained voice.

"He has been here two or three days."

"General Pomeroy! Is it possible?" said Guy. "Has he come to England?

I didn't know that he had left India. I must hurry up. Good-by, old

woman," he added, affectionately, and kissing her again he hurried up

stairs to his father's room.

Lord Chetwynde was there, and General Pomeroy also. The greeting

between father and son was affectionate and tender, and after a few

loving words Guy was introduced to the General. He shook him heartily

by the hand.

"I'm sure," said he, "the sight of you has done my father a world of

good. He looks ten years younger than he did when I last saw him. You

really ought to take up your abode here, or live somewhere near him.

He mopes dreadfully, and needs nothing so much as the society of an

old friend. You could rouse him from his blue fits and ennui, and

give him new life."

Guy then went on in a rattling way to narrate some events which had

befallen him on the road. As he spoke in his animated and

enthusiastic way General Pomeroy scanned him earnestly and narrowly.

To the most casual observer Guy Molyneux must have been singularly

prepossessing. Tall and slight, with a remarkably well-shaped head

covered with dark curling hair, hazel eyes, and regular features, his

whole appearance was eminently patrician, and bore the marks of

high-breeding and refinement; but there was something more than this.

Those eyes looked forth frankly and fearlessly; there was a joyous

light in them which awakened sympathy; while the open expression of

his face, and the clear and ringing accent of his fresh young voice,

all tended to inspire confidence and trust. General Pomeroy noted all

this with delight, for in his anxiety for his daughter's future he

saw that Guy was one to whom he might safely intrust the dearest idol

of his heart.

"Come, Guy," said Lord Chetwynde at last, after his son had rattled

on for half an hour or more, "if you are above all considerations of

dinner, we are not. I have already had it put off two hours for you,

and we should like to see some signs of preparation on your part."

"All right, Sir. I shall be on hand by the time it is announced,"

said Guy, cheerily; "you don't generally have to complain of me in

that particular, I think."

So saying, Guy nodded gayly to them and left the room, and they

presently heard him whistling through the passages gems from the last

new opera.

"A splendid fellow," said the General, as the door closed, in a tone

of hearty admiration. "I see his father over again in him. I only

hope he will come into our views."

"I can answer for his being only too ready to do so," said Lord

Chetwynde, confidently.

"He exceeds the utmost hopes that I had formed of him," said the

General. "I did not expect to see so frank and open a face, and such

freshness of innocence and purity."

Lord Chetwynde's face showed all the delight which a fond father

feels at hearing the praises of an only son.

Dinner came and passed. The General retired, and Lord Chetwynde then

explained to his son the whole plan which had been made about him. It

was a plan which was to affect his whole life most profoundly in its

most tender part; but Guy was a thoughtless boy, and received the

proposal like such. He showed nothing but delight. He never dreamed

of objecting to any thing. He declared that it seemed to him too good

to be true. His thoughts did not appear to dwell at all upon his own

share in this transaction, though surely to him that share was of

infinite importance, but only on the fact that Chetwynde was saved.

"And is Chetwynde really to be ours, after all?" he cried, at the end

of a burst of delight, repeating the words, boy-like, over and over

again, as though he could never tire of hearing the words repeated.

After all, one can not wonder at his thoughtlessness and enthusiasm.

Around Chetwynde all the associations of his life were twined. Until

he had joined the regiment he had known no other home; and beyond

this, to this high-spirited youth, in whom pride of birth and name

rose very high, there had been from his earliest childhood a bitter

humiliation in the thought that the inheritance of his ancestors,

which had never known any other than a Chetwynde for its master, must

pass from him forever into alien hands. Hitherto his love for his

father had compelled him to refrain from all expression of his

feelings about this, for he well knew that, bitter as it would be for

him to give up Chetwynde, to his father it would be still worse--it

would be like rending his very heartstrings. Often had he feared that

this sacrifice to honor on his father's part would be more than could

be endured. He had, for his father's sake, put a restraint upon

himself; but this concealment of his feelings had only increased the

intensity of those feelings; the shadow had been gradually deepening

over his whole life, throwing gloom over the sunlight of his joyous

youth; and now, for the first time in many years, that shadow seemed

to be dispelled. Surely there is no wonder that a mere boy should be

reckless of the future in the sunshine of such a golden present.

When General Pomeroy appeared again, Guy seized his hand in a burst

of generous emotion, with his eyes glistening with tears of joy.

"How can I ever thank you," he cried, impetuously, "for what you have

done for us! As you have done by us, so will I do by your

daughter--to my life's end--so help me God!"

And all this time did it never suggest itself to the young man that

there might be a reverse to the brilliant picture which his fancy was

so busily sketching--that there was required from him something more

than money or estate; something, indeed, in comparison with which

even Chetwynde itself was as nothing? No. In his inexperience and

thoughtlessness he would have looked with amazement upon any one who

would have suggested that there might be a drawback to the happiness

which he was portraying before his mind. Yet surely this thing came

most severely upon him. He gave up the most, for he gave himself. To

save Chetwynde, he was unconsciously selling his own soul. He was

bartering his life. All his future depended upon this hasty act of a

moment. The happiness of the mature man was risked by the thoughtless

act of a boy. If in after-life this truth came home to him, it was

only that he might see that the act was irrevocable, and that he must

bear the consequences. But so it is in life.

That evening, after the General had retired, Guy and his father sat

up far into the night, discussing the future which lay before them.

To each of them the future marriage seemed but a secondary event, an

accident, an episode. The first thing, and almost the only thing, was

the salvation of Chetwynde. Those day-dreams which they had cherished

for so many years seemed now about to be realized, and Chetwynde

would be restored to all its former glory. Now, for the first time,

each let the other see, to the full, how grievous the loss would have

been to him.

It was not until after all the future of Chetwynde had been

discussed, that the thoughts of Guy's engagement occurred to his

father.

"But, Guy," said he, "you are forgetting one thing. You must not in

your joy lose sight of the important pledge which has been demanded

of you. You have entered upon a very solemn obligation, which we both

are inclined to treat rather lightly."

"Of course I remember it, Sir; and I only wish it were something

twenty times as hard that I could do for the dear old General,"

answered Guy, enthusiastically.

"But, my boy, this may prove a severe sacrifice in the future,"

said Lord Chetwynde, thoughtfully.

"What? To marry, father? Of course I shall marry some time; and as to

the question of whom, why, so long as she is a lady (and General

Pomeroy's daughter must be this), and is not a fright (I own I hate

ugly women), I don't care who she is. But the daughter of such a man

as that ought to be a little angel, and as beautiful as I could

desire. I am all impatience to see her. By-the-way, how old is she?"

"Ten years old."

"Ten years!" echoed Guy, laughing boisterously. "I need not distress

myself, then, about her personnel for a good many years at any rate.

But, I say, father, isn't the General a little premature in getting

his daughter settled? Talk of match-making mothers after this!"

The young man's flippant tone jarred upon his father. "He had good

reasons for the haste to which you object, Guy," said Lord Chetwynde.

"One was the friendlessness of his daughter in the event of any thing

happening to him; and the other, and a stronger motive (for under any

circumstances I should have been her guardian), was to assist your

father upon the only terms upon which he could have accepted

assistance with honor. By this arrangement his daughter reaps the

full benefit of his money, and he has his own mind at ease. And,

remember, Guy," continued Lord Chetwynde, solemnly, "from this time

you must consider yourself as a married man; for, although no altar

vow or priestly benediction binds you, yet by every law of that Honor

by which you profess to be guided, you are bound _irrevocably_."

"I know that," answered Guy, lightly. "I think you will never find me

unmindful of that tie."

"I trust you, my boy," said Lord Chetwynde, "as I would trust

myself."

CHAPTER IV.

A STARTLING VISITOR.

After dinner the General had retired to his room, supposing that Guy

and the Earl would wish to be together. He had much to think of.

First of all there was his daughter Zillah, in whom all his being was

bound up. Her miniature was on the mantle-piece of the room, and to

this he went first, and taking it up in his hands he sat down in an

arm-chair by the window, and feasted his eyes upon it. His face bore

an expression of the same delight which a lover shows when looking at

the likeness of his mistress. At times a smile lighted it up, and so

wrapt up was he in this that more than an hour passed before he put

the picture away. Then he resumed his seat by the window and looked

out. It was dusk; but the moon was shining brightly, and threw a

silvery gleam over the dark trees of Chetwynde, over the grassy

slopes, and over the distant hills. That scene turned his attention

in a new direction. The shadows of the trees seemed to suggest the

shadows of the past. Back over that past his mind went wandering,

encountering the scenes, the forms, and the faces of long ago--the

lost, the never-to-be-forgotten. It was not that more recent past of

which he had spoken to the Earl, but one more distant--one which

intermingled with the Earl's past, and which the Earl's story had

suggested.

It brought back old loves and old hates; it suggested memories which

had lain dormant for years, but now rose before him clothed in fresh

power, as vivid as the events from which they flowed. There was

trouble in these memories, and the General's mind was agitated, and

in his agitation he left the chair and paced the room. He rang for

lights, and after they came he seated himself at the table, took

paper and pens, and began to lose himself in calculations.

Some time passed, when at length ten o'clock came, and the General

heard a faint tap at the door. It was so faint that he could barely

hear it, and at first supposed it to be either his fancy or else one

of the death-watches making a somewhat louder noise than usual. He

took no further notice of it, but went on with his occupation, when

he was again interrupted by a louder knock. This time there was no

mistake. He rose and opened the door, thinking that it was the Earl

who had brought him some information as to his son's views.

Opening the door, he saw a slight, frail figure, dressed in a

nun-like garb, and recognized the housekeeper. If possible she seemed

paler than usual, and her eyes were fixed upon him with a strange

wistful earnestness. Her appearance was so unexpected, and her

expression so peculiar, that the General involuntarily started back.

For a moment he stood looking at her, and then, recovering with an

effort his self-possession, he asked:

"Did you wish to see me about any thing, Mrs. Hart?"

"If I could speak a few words to you I should be grateful," was the

answer, in a low, supplicating tone.

"Won't you walk in, then?" said the General, in a kindly voice,

feeling a strange commiseration for the poor creature, whose face,

manner, and voice exhibited so much wretchedness.

The General held the door open, and waited for her to enter. Then

closing the door he offered her a chair, and resumed his former seat.

But the housekeeper declined sitting. She stood looking strangely

confused and troubled, and for some time did not speak a word. The

General waited patiently, and regarded her earnestly. In spite of

himself he found that feeling arising within him which had occurred

in the morning-room--a feeling as if he had somewhere known this

woman before. Who was she? What did it mean? Was he a precious old

fool, or was there really some important mystery connected with Mrs.

Hart? Such were his thoughts.

Perhaps if he had seen nothing more of Mrs. Hart the Earl's account

of her would have been accepted by him, and no thoughts of her would

have perplexed his brain. But her arrival now, her entrance into his

room, and her whole manner, brought back the thoughts which he had

before with tenfold force, in such a way that it was useless to

struggle against them. He felt that there was a mystery, and that the

Earl himself not only knew nothing about it, but could not even

suspect it. But _what_ was the mystery? That he could not, or perhaps

dared not, conjecture. The vague thought which darted across his mind

was one which was madness to entertain. He dismissed it and waited.

At last Mrs. Hart spoke.

"Pardon me, Sir," she said, in a faint, low voice, "for troubling

you. I wished to apologize for intruding upon you in the

morning-room. I did not know you were there."

She spoke abstractedly and wearily. The General felt that it was not

for this that she had thus visited him, but that something more lay

behind. Still he answered her remark as if he took it in good faith.

He hastened to reassure her. It was no intrusion. Was she not the

housekeeper, and was it not her duty to go there? What could she

mean?

At this she looked at him, with a kind of solemn yet eager scrutiny.

"I was afraid," she said, after some hesitation, speaking still in a

dull monotone, whose strangely sorrowful accents were marked and

impressive, and in a voice whose tone was constrained and stiff, but

yet had something in it which deepened the General's perplexity--"I

was afraid that perhaps you might have witnessed some marks of

agitation in me. Pardon me for supposing that you could have troubled

yourself so far as to notice one like me; but--but--I--that is, I am

a little--eccentric; and when I suppose that I am alone that

eccentricity is marked. I did not know that you were in the room, and

so I was thrown off my guard."

Every word of this singular being thrilled through the General. He

looked at her steadily without speaking for some time. He tried to

force his memory to reveal what it was that this woman suggested to

him, or who it was that she had been associated with in that dim and

shadowy past which but lately he had been calling up. Her voice,

too--what was it that it suggested? That voice, in spite of its

constraint, was woeful and sad beyond all description. It was the

voice of suffering and sorrow too deep for tears--that changeless

monotone which makes one think that the words which are spoken are

uttered by some machine.

Her manner also by this time evinced a greater and a deeper

agitation. Her hands mechanically clasped each other in a tight,

convulsive grasp, and her slight frame trembled with irrepressible

emotion. There was something in her appearance, her attitude, her

manner, and her voice, which enchained the General's attention, and

was nothing less than fascination. There was something yet to come,

to tell which had led her there, and these were only preliminaries.

This the General felt. Every word that she spoke seemed to be a mere

formality, the precursor of the real words which she wished to utter.

What was it? Was it her affection for Guy? Had she come to ask about

the betrothal? Had she come to look at Zillah's portrait? Had she

come to remonstrate with him for arranging a marriage between those

who were as yet little more than children? But what reason had she

for interfering in such an affair? It was utterly out of place in one

like her. No; there was something else, he could not conjecture what.

All these thoughts swept with lightning speed through his mind, and

still the poor stricken creature stood before him with her eyes

lowered and her hands clasped, waiting for his answer. He roused

himself, and sought once more to reassure her. He told her that he

had noticed nothing, that he had been looking out of the window, and

that in any case, if he had, he should have thought nothing about it.

This he said in as careless a tone as possible, willfully misstating

facts, from a generous desire to spare her uneasiness and set her

mind at rest.

"Will you pardon me, Sir, if I intrude upon your kindness so far as

to ask one more question?" said the housekeeper, after listening

dreamily to the General's words. "You are going away, and I shall not

have another opportunity."

"Certainly," said the General, looking at her with unfeigned

sympathy. "If there is any thing that I can tell you I shall be happy

to do so. Ask me, by all means, any thing you wish."

"You had a private interview with the Earl," said she, with more

animation than she had yet shown.

"Yes."

"Pardon me, but will you consider it impertinence if I ask you

whether it was about your past life? I know it is impertinent; but

oh, Sir, I have my reasons." Her voice changed suddenly to the

humblest and most apologetic accent.

The General's interest was, if possible, increased; and, if there

were impertinence in such a question from a housekeeper, he was too

excited to be conscious of it. To him this woman seemed more than

this.

"We were talking about the past," said he, kindly. "We are very old

friends. We were telling each other the events of our lives. We

parted early in life, and have not seen one another for many years.

We also were arranging some business matters."

Mrs. Hart listened eagerly, and then remained silent for a long time.

"His old friend," she murmured at last; "his old friend! Did you find

him much altered?"

"Not more than I expected," replied the General, wonderingly. "His

secluded life here has kept him from the wear and tear of the world.

It has not made him at all misanthropical or even cynical. His heart

is as warm as ever. He spoke very kindly of you."

Mrs. Hart started, and her hands involuntarily clutched each other

more convulsively. Her head fell forward and her eyes dropped.

"What did he say of me?" she asked, in a scarce audible voice, and

trembling visibly as she spoke.

The General noticed her agitation, but it caused no surprise, for

already his whole power of wondering was exhausted. He had a vague

idea that the poor old thing was troubled for fear she might from

some cause lose her place, and wished to know whether the Earl had

made any remarks which might affect her position. So with this

feeling he answered in as cheering a tone as possible:

"Oh, I assure you, he spoke of you in the highest terms. He told me

that you were exceedingly kind to Guy, and that you were quite

indispensable to himself."

"'Kind to Guy'--'indispensable to him,'" she repeated in low tones,

while tears started to her eyes. She kept murmuring the words

abstractedly to herself, and for a few moments seemed quite

unconscious of the General's presence. He still watched her, on his

part, and gradually the thought arose within him that the easiest

solution for all this was possible insanity. Insanity, he saw, would

account for every thing, and would also give some reason for his own

strange feelings at the sight of her. It was, he thought, because he

had seen this dread sign of insanity in her face--that sign only less

terrible than that dread mark which is made by the hand of the King

of Terrors. And was she not herself conscious to some extent of this?

he thought. She had herself alluded to her eccentricity. Was she not

disturbed by a fear that he had noticed this, and, dreading a

disclosure, had come to him to explain? To her a stranger would be an

object of suspicion, against whom she would feel it necessary to be

on her guard. The people of the house were doubtless accustomed to

her ways, and would think nothing of any freak, however whimsical;

but a stranger would look with different eyes. Few, indeed, were the

strangers or visitors who ever came to Chetwynde Castle; but when one

did come he would naturally be an object of suspicion to this poor

soul, conscious of her infirmity, and struggling desperately against

it. Such thoughts as these succeeded to the others which had been

passing through the General's mind, and he was just beginning to

think of some plan by which he could soothe this poor creature, when

he was aware of a movement on her part which made him look up

hastily. Her eyes were fastened on his. They were large, luminous,

and earnest in their gaze, though dimmed by the grief of years. Tears

were in them, and the look which they threw toward him was full of

agony and earnest supplication. That emaciated face, that snow-white

hair, that brow marked by the lines of suffering, that slight figure

with its sombre vestments, all formed a sight which would have

impressed any man. The General was so astonished that he sat

motionless, wondering what it was now that the diseased fancy of one

whom he still believed to be insane would suggest. It was to him that

she was looking; it was to him that her shriveled hands were

outstretched. What could she want with him?

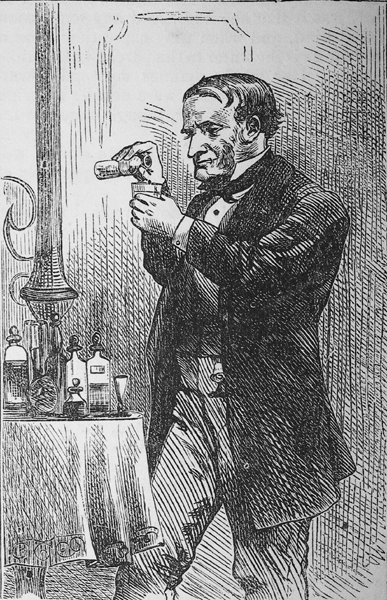

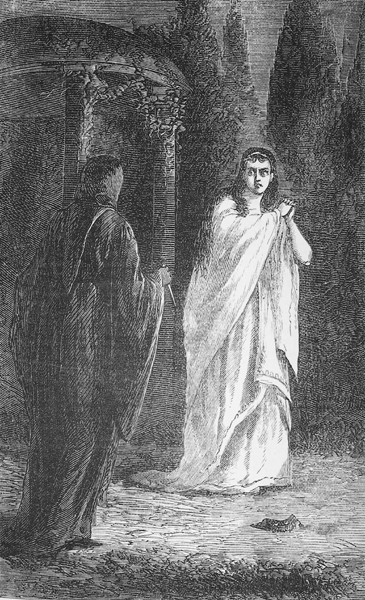

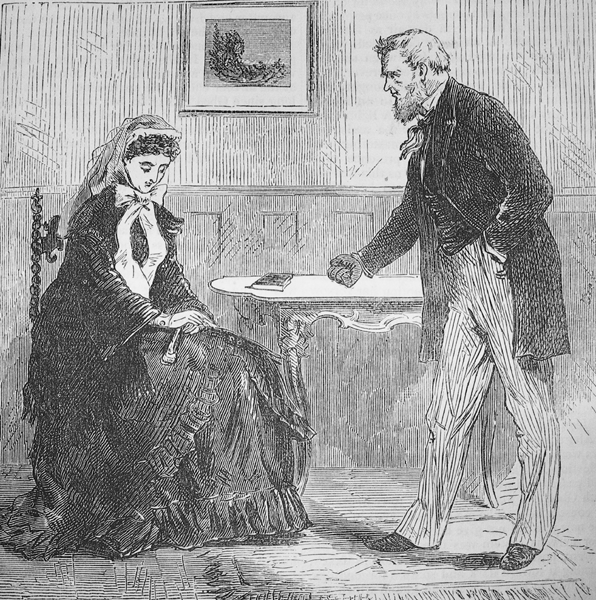

[Illustration: "But The Woman, With A Low Moan, Flung Herself On The

Floor Before Him."]

She drew nearer to him while he sat thus wondering. She stooped

forward and downward, with her eyes still fixed on his. He did not

move, but watched her in amazement. Again that thought which the

sight of her had at first suggested came to him. Again he thrust it

away. But the woman, with a low moan, suddenly flung herself on the

floor before him, and reaching out her hands clasped his feet, and he

felt her feeble frame all shaken by sobs and shudders. He sat

spell-bound. He looked at her for a moment aghast. Then he reached

forth his hands, and without speaking a word took hers, and tried to

lift her up. She let herself be raised till she was on her knees, and

then raised her head once more. She gave him an indescribable look,

and in a low voice, which was little above a whisper, but which

penetrated to the very depths of his soul, pronounced one single

solitary word,---.

The General heard it. His face grew as pale and as rigid as the face

of a corpse; the blood seemed to leave his heart; his lips grew

white; he dropped her hands, and sat regarding her with eyes in which

there was nothing less than horror. The woman saw it, and once more

fell with a low moan to the floor.

"My God!" groaned the General at last, and said not another word, but

sat rigid and mute while the woman lay on the floor at his feet. The

horror which that word had caused for some time overmastered him, and

he sat staring vacantly. But the horror was not against the woman who

had called it up, and who lay prostrate before him. She could not

have been personally abhorrent, for in a few minutes, with a start,

he noticed her once more, and his face was overspread by an anguish

of pity and sympathy. He raised her up, he led her to a couch, and

made her sit down, and then sat in silence before her with his face

buried in his hands. She reclined on the couch with her countenance

turned toward him, trembling still, and panting for breath, with her

right hand under her face, and her left pressed tightly against her

heart. At times she looked at the General with mournful inquiry, and

seemed to be patiently waiting for him to speak. An hour passed in

silence. The General seemed to be struggling with recollections that

overwhelmed him. At last he raised his head, and regarded her in

solemn silence, and still his face and his eyes bore that expression

of unutterable pity and sympathy which dwelt there when he raised her

from the floor.

After a time he addressed her in a low voice, the tones of which were

tender and full of sadness. She replied, and a conversation followed

which lasted for hours. It involved things of fearful moment--crime,

sin, shame, the perfidy of traitors, the devotion of faithful ones,

the sharp pang of injured love, the long anguish of despair, the

deathless fidelity of devoted affection. But the report of this

conversation and the recital of these things do not belong to this

place. It is enough to say that when at last Mrs. Hart arose it was

with a serener face and a steadier step than had been seen in her for

years.

That night the General did not close his eyes. His friend, his

business, even his daughter, all were forgotten, as though his soul

were overwhelmed and crushed by the weight of some tremendous

revelation.

[Illustration.]

CHAPTER V.

THE FUTURE BRIDE.

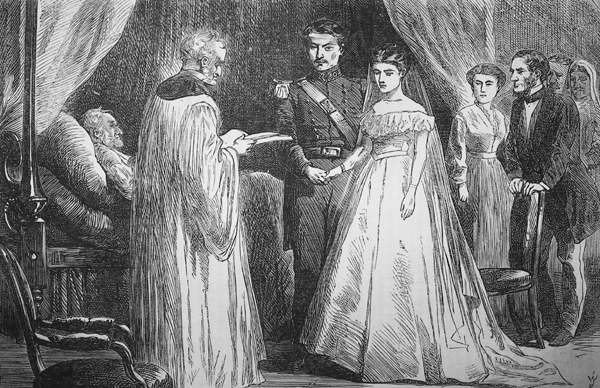

It had been arranged that Guy should accompany General Pomeroy up to

London, partly for the sake of arranging about the matters relating

to the Chetwynde estates, and partly for the purpose of seeing the

one who was some day to be his wife. Lord Chetwynde was unable to

undergo the fatigue of traveling, and had to leave every thing to his

lawyers and Guy.

At the close of a wearisome day in the train they reached London, and

drove at once to the General's lodgings in Great James Street. The

door was opened by a tall, swarthy woman, whose Indian nationality

was made manifest by the gay-colored turban which surmounted her

head, as well as by her face and figure. At the sight of the General

she burst out into exclamations of joy.

"Welcome home, sahib; welcome home!" she cried. "Little missy, her

fret much after you."

"I am sorry for that, nurse," said the General, kindly. As he was

speaking they were startled by a piercing scream from an adjoining

apartment, followed by a shrill voice uttering some words which ended

in a shriek. The General entered the house, and hastened to the room

from which the sounds proceeded, and Guy followed him. The uproar was

speedily accounted for by the tableau which presented itself on

opening the door. It was a tableau extremely vivant, and represented

a small girl, with violent gesticulations, in the act of rejecting a

dainty little meal which a maid, who stood by her with a tray, was

vainly endeavoring to induce her to accept. The young lady's

arguments were too forcible to admit of gainsaying, for the servant

did not dare to venture within reach of either the hands or feet of

her small but vigorous opponent. The presence of the tray prevented

her from defending herself in any way, and she was about retiring,

worsted, from the encounter, when the entrance of the gentlemen gave

a new turn to the position of affairs. The child saw them at once;

her screams of rage changed into a cry of joy, and the face which had

been distorted with passion suddenly became radiant with delight.

"Papa! papa!" she cried, and, springing forward, she darted to his

embrace, and twined her arms about his neck with a sob which her joy

had wrung from her.

"Darling papa!" she cried; "I thought you were never coming back. How

could you leave me so long alone?" and, saying this, she burst into a

passion of tears, while her father in vain tried to soothe her.

At this strange revelation of the General's daughter Guy stood

perplexed and wondering. Certainly he had not been prepared for this.