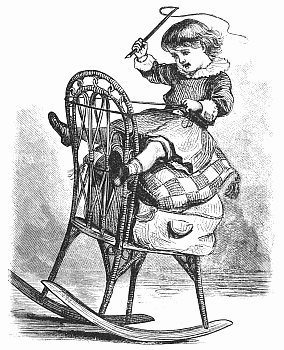

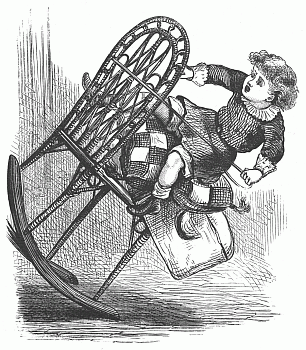

Frank wanted a high horse: so he took the sewing-chair, put the hassock on it, put the sofa-pillow on that, and mounted.

How he got seated up there so nicely I don't know; but I know just how he got down.

Title: The Nursery, December 1877, Vol. XXII. No. 6

Author: Various

Release date: February 20, 2009 [eBook #28140]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. Music

by Linda Cantoni.

| PAGE | |

| The Starlings and the Sparrows | 164 |

| Katie and Waif | 166 |

| Amy and Robert in China | 169 |

| About two old Horses | 171 |

| Baby's Exploit | 173 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 177 |

| Birdie's Pig Story | 180 |

| Our Friend the Robin | 181 |

| Frank's high Horse | 183 |

| Sagacity of a Horse | 185 |

| Phantom | 186 |

| PAGE | |

| The last Guest | 161 |

| For Ethel | 172 |

| The Fox and the Crow | 176 |

| The Swallows and the Robins | 178 |

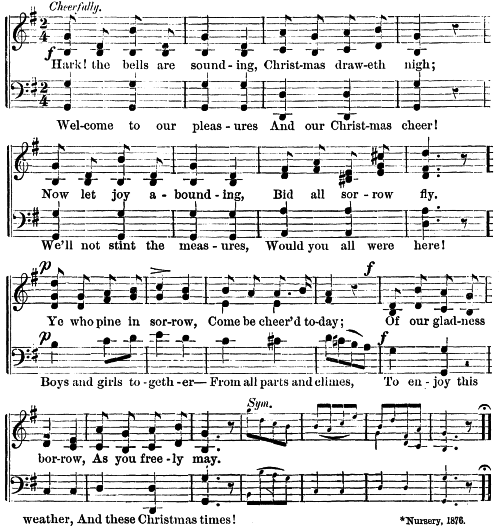

| Christmas (with music) | 188 |

"Look here, my dear," said a starling to her mate: "in our pretty summer-villa a pair of saucy sparrows have taken up their abode. What shall we do?"

"What shall we do?" cried Mr. Starling, who was calmly standing on a fence; "why, rout them out, of course; give them notice to quit."

"That we will do," replied Mrs. Starling. "Here, you beggars, you: out of that house! You've no business there. Be off!"

"What's all that?" piped Mrs. Sparrow, looking out of her little round doorway. "Go away, you impudent tramp! Don't come near our house."

"It is not your house!" said Mr. Starling, springing nimbly to a bough, and confronting Mrs. Sparrow.

"It is ours!" cried Mr. Sparrow, looking down from the roof of the house. "I have the title-deeds. Stand up for your rights, my love!"

"Yes, stand up for your rights. I'll back you," said Mrs. Sparrow's brother-in-law, taking position on a branch just at the foot of the house.[165]

"We'll see about that, you thieves!" cried Mrs. Starling, in a rage, making a dash at Mrs. Sparrow's brother-in-law.

But two of Mrs. Sparrow's cousins came to the rescue just then, and attacked Mrs. Starling in the rear.

Thereupon Mr. Starling flew at Mrs. Sparrow. Mr. Sparrow, without more delay, went at Mr. Starling. Mrs. Sparrow's brother-in-law paid his respects to Mrs. Starling. There was a lively fight.

It ended in the defeat of the sparrows. The starlings were too big for them. The sparrows retreated in good order, and left the starlings to enjoy their triumph.

"Now, my dear," said Mr. Starling, "go in, and put the house in order. I'll warrant those vulgar sparrows have made a nice mess in there. Sweep the floors, dust the furniture, and get the beds made. I'll stay here in the garden, and rest myself."

"Just like that husband of mine!" muttered Mrs. Starling: "I must do all the work, while he has all the fun. But I suppose there's no help for it."

So she flew up to the door of the house; but, to her surprise, she could not get through it: the opening was not large enough.

"Well, Mr. Starling," said she, "I do believe we have made a mistake. This is not our house, after all."

"Why did you say it was, then?" said Mr. Starling, in a huff. "Here I have got a black eye, and a lame claw, and[166] a sprained wing, and have lost two feathers out of my tail, all through your blunder. You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Mrs. Starling!"

"I own that I was hasty," said poor Mrs. Starling; "but I meant well."

"Yes, you thought the sparrows were thieves, and so did I. But it turns out, that we are no better than burglars ourselves; and, what's more, we shall have a whole army of sparrows back upon us before long. We had better take ourselves off." And off they flew.

I am Katie Sinclair, and Waif is my dog. Now, as everybody who knows him says he is the nicest dog in the world, I will tell my "Nursery" friends why people think so.

First I must tell you how I got him, and how he came to have such an odd name. One cold, rainy day, about three years ago, I heard a strange noise under the window, and ran to the door to see what it was. There stood a homely little puppy, dripping wet, shivering from the cold, and crying, oh, so mournfully!

I took him in, and held him before the fire till he was dry and warm. Then I got him some nice fresh milk, which he drank eagerly; and he looked up in my face in such a thankful way, that he quite won my heart.

"Poor little dog!" said I. "He hasn't had a very nice time in this world so far; but I will ask mamma to let him stay and be my dog." Mamma consented; and, if that dog has not enjoyed himself since then, it is not my fault.

I was bothered not a little to find a name for him. I[167] wanted one, you see, that would remind me always of the way he came to me,—not a common name, such as other little dogs have. No; I did not want a "Carlo," or a "Rover," or a "Watch." After trying in vain to think of a name fit for him, I asked mamma to help me.

She said, "Call him Waif." I was such a little goose then (that was over three years ago, you know), that I had to ask her what "Waif" meant.

"A waif," said she, "is something found, of which nobody knows the owner. On that account 'Waif' would be a good name for your puppy." So I gave him that name, and he soon got to know and answer to it.

Waif grew fast, and we taught him ever so many tricks. He has learned to be very useful too, as I shall show you.

On a shelf in the kitchen stands a small basket, with his name, in red letters, printed upon it. To this basket he goes every morning, and barks. When Ellen the cook hears him, she takes the basket down, and places the handle in his mouth. Then he goes to mamma, and waits patiently till she is ready, when he goes down town with her, and brings back the meat for dinner.

When papa gets through dinner, he always pushes back his chair, and says, "Now, Waif:" and Waif knows what that means; for he jumps up from where he has been lying,—and, oh! such fun as we have with him then! He walks on his hind-feet, speaks for meat, and catches crumbs.

Last summer I went out to Lafayette to visit grandma. Mamma says, that, while I was away, Waif would go to my room, and sniff at the bed-clothes, and go away whining and crying bitterly. When I came back, he was nearly beside himself with delight.

We never found out where he came from that rainy day. But I don't love him a bit the less because he was a poor, friendless puppy; and when I look into his good, honest brown eyes, and think what a true friend he is, I put my arms around his neck, and whisper in his ear, that I would not change him for the handsomest dog in the country.

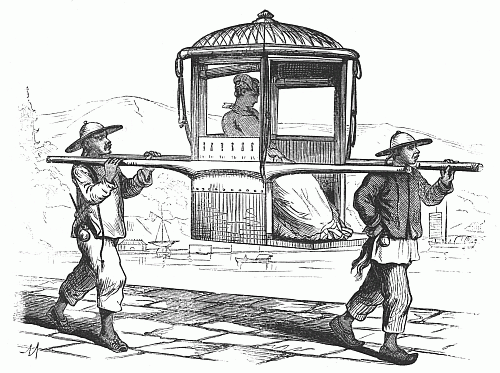

Amy and Robert, with their papa and mamma, live in China, in a place called Foochow. They came here last January, when Amy was just three years old, and Robert a little over one year. They came all the way from Boston by water.

They have a good grandma at home, who sends Amy "The Nursery" every month, and she is never tired of hearing the nice stories.

Out here, the children see many things that you little folks in America know nothing about. When they go to ride, they do not go in a carriage drawn by horses, but in a chair resting on two long poles, carried by some Chinamen called coolies. When it is pleasant, and the sun is not too hot, the chair is open; but, if it rains, there is a close cover to fit over it.[170]

It is so warm here, that flowers blossom in the garden all winter; and Amy is very fond of picking them, and putting them into vases. When it is too warm to go into the garden, she has a pot of earth on the shady piazza, and the cooly picks her flowers, to plant in it.

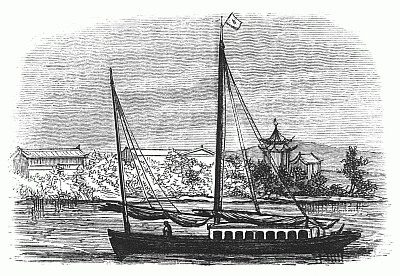

Foochow is on a large river; and the children like much to go out in the sail-boats, called "house-boats." These boats are fitted up just like a house, with a dining-room, sleeping-room, bath-room, and pantry.

The night before Fourth of July, Amy and Robert started with their papa, mamma, and Amah (their colored nurse), and went to Sharp Peak, on the seashore, twenty-five miles from here. They found the boat very nice to sleep in, but were glad enough to get into their own beds the next night.

I am afraid you would not know what these little children say, if you should hear them talk; for they pick up words from their Amah, and do not speak like little American girls and boys.

By and by I shall have more to tell you about them.

In my great-great-grandfather's barn-yard stood an old-fashioned well, with a long sweep or pole, by which the bucket was pulled up. This well was used entirely for the horses and cattle.

Grandfather had a horse named Pete, who would walk out of his stall every morning, go to the well, take the pole, by which the bucket was attached to the well-sweep, between his teeth, and thus pull up the bucket until it rested on the shelf made for it. Then old Pete would drink the water which he had taken so much pains to get.

But one of my uncles had a horse even more knowing than old Pete. This horse was named Whitey. Every Sunday morning, when the church-bell rang, Uncle George would lead Whitey out of his stall, harness him, drive him to church, and tie him in a certain shed, where he would stand quietly till church was done.

After a while, Whitey grew so used to this weekly performance, that, when the bells rang, he would walk out of his stall, and wait to be harnessed. One Sunday morning, Old Whitey, on hearing the bells, walked out of his stall as usual, and patiently waited for Uncle George. But it happened that uncle was sick that morning, and none of the family felt like going to church.

I do not really know what Whitey's thoughts were; but I have no doubt that they were something like this: "Well, well! I guess my master is not going to church this morning; but that is no reason why I should not go. I must go now, or I shall be late."

Whitey had waited so long, that he was rather late; but he jogged steadily along to his post in the shed, and there took his stand, as usual.[172]

As soon as old Mr. Lane, who sat in one of the back-pews and always came out of church before anybody else, appeared at the door, Whitey started for home. At the door of the house he was greeted by several members of the family, who had just discovered his absence, and who learned the next day, from Mr. Lane, that old Whitey had merely been attending strictly to his church-duties.

In the first place baby had her bath. Such a time! Mamma talked as fast and as funny as could be; and the baby crowed and kicked as if she understood every word.

Presently came the clean clothes,—a nice, dainty pile, fresh from yesterday's ironing. Baby Lila was seven months old that very May morning; but not a sign had she given yet of trying to creep: so the long white dresses still went on, though mamma said every day, "I must make some short dresses for this child. She's too old to wear these dragging things any longer."[174]

When baby had been dressed and kissed, she was set down in the middle of the clean kitchen-floor, on her own rug, hedged in by soft white pillows. There she sat, serene and happy, surveying her playthings with quizzical eyes; while her mamma gathered up bath-tub, towel, and cast-off clothes, and went up stairs to put them away.

Left to herself, Lila first made a careful review of her treasures. The feather duster was certainly present. So was the old rattle. Was the door-knob there? and the string of spools? Yes; and so was the little red pincushion, dear to baby's color-loving eyes.

She was slowly poking over the things in her lap, when mamma came back, bringing a pot of yeast to set by the open fire-place, where a small fire burned leisurely on this cool May morning. She put a little tin plate on the top of the pot, kissed the precious baby, and then went out again. Baby Lila was used to being left alone, though seldom out of mamma's hearing. At such times she would sit among the pillows, tossing her trinkets all about, and crowing at her own performances. Sometimes she would drop over against a pillow, and go to sleep.

But this morning Lila had no intention of going to sleep. She flourished the duster, and laughed at the pincushion; then gazed meditatively at the bright window, and reflected gravely on the broad belt of sunshine lying across the floor. That speculation over, she fell to hugging the cherished duster, rocking back and forth as if it were another baby.

A smart little snap of the fire,—a "How-do-you-do?" from the fire-place,—made the baby twist her little body[175] to look at it. She watched the small flames dancing in and out, as long as her neck could bear the twist.

As she turned back again, her eyes fell on the pot of yeast. Oh! wasn't that her own tin plate shining in the sunlight? Didn't she make music on it with a spoon every meal-time? and hadn't her little gums felt of every A, B, C, around its edge? Didn't she want it now? And wouldn't she have it too?

How she ever did it, nobody knows. How she ever got over the pillows, and made her way across to the fire-place in her long, hindering skirts, nobody can tell.

Mamma was busy in another room, when she heard the little plate clatter on the kitchen-floor. Not a thought of the real mischief-maker entered her head. She only said to herself,—

"I didn't know the cat was in there. Well, she'll find out her mistake. I'm not going in till I get this pie done, any way. The baby's all right, and that's enough."

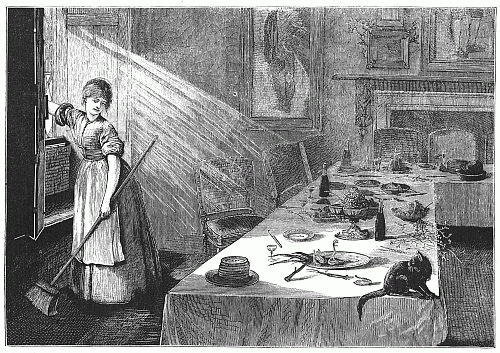

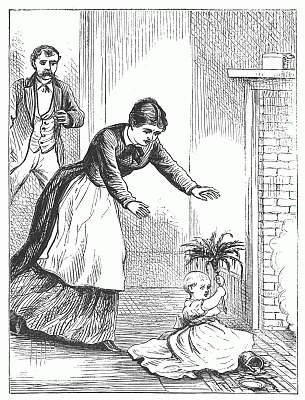

As soon as mamma's hands were at liberty, she thought she would just look in and see what kept the darling so quiet. "All right," indeed! What a spectacle she beheld!

On the bricks before the fire, her pretty white skirts much too near the ashes, sat Baby Lila, having a glorious time. She had found her dear little plate empty; but the brown pitcher was full enough. She had dropped the plate, dipped the feather-duster into the yeast, and proceeded to spread it about, on her clean clothes, on the bricks, on the floor, everywhere.

So, when mamma opened the door, she saw this wee[176] daughter besmeared from head to foot, the yeast dripping over her head and face as she held the duster aloft in both hands.

Just then papa came in by another door. "O John! do you see this child! What if she had put the duster into the fire instead of the yeast!" Mamma shuddered as she took little Lila into her lap for another bath and change of clothes. Papa standing by said,—

"You don't seem to mind having all that to do again."

"Indeed I don't. To think how near she was to that fire! I can never be thankful enough that she dusted the yeast instead of the coals. But how do you suppose she ever got over there?"

DRAWING-LESSON.

DRAWING-LESSON.

THE SWALLOWS AND THE ROBIN.

The woods were showing autumn tints Of crimson and of gold; The sunny days were growing short, The evenings long and cold: So the swallows held a parliament, And voted it was time To bid farewell to northern skies, And seek a warmer clime. Southward with glad and rapid flight They flew for many a mile, Till in a quiet woodland glen They stopped to rest a while: A streamlet rippled in the dell; And on a hawthorn-tree A robin-redbreast sat alone, [179]And carolled merrily. The wandering swallows listened, And eagerly said they, "O pretty bird! your notes are sweet: Come, fly with us away. We're following the sunshine, For it is bright and warm: We're leaving winter far behind With all its cold and storm. "The iron ground will yield no food, The berries will be few; Half-starved with hunger and with cold, Poor bird, what will you do?" "Nay, nay," said he, "when frost is hard, And all the leaves are dead, I know that kindly little hands Will give me crumbs of bread." |

The English Robin.

The English Robin.

I told my story first, as mammas usually do; and it was all about a naughty little pig, who did not mind his mother when she bade him stay in the sty, but crawled through a hole in the wall.

Of course this pig got into the garden, and was whipped by the farmer, and bitten by the dog, and had all sorts of unpleasant things happen to him, till he was glad to get back again to the sty.

"Now I'll tell you a pig story," said Birdie, with a very wise look.

"Once there was a big mother-pig, and she had lots of children-pigs. One was spotted, and his name was Spotty; one's tail curled, and he was Curly; another was white, and he was Whitey; another was Browny; and another was Greeny."

"Oh, dear! the idea of a green pig!" said I.

But Birdie's eyes were fixed on the floor. He was too busy thinking of his story to notice my remark. He went on,—

"One day the pigs found a hole in the wall, and they crawled through,—all of 'em, the mother-pig and all; and, when they got out, they ran off, grunting with—with joy. And when the farmer saw them, he went after them on a horse; but he couldn't catch them, for they all ran down under a bridge where there had been a brook; but the water was all dried up.

"Then the farmer got a long pole, and poked under the bridge; but he couldn't reach them. He put some potatoes down there too, but the pigs weren't going to be coaxed out. And when they had staid as long as they wanted to, they came out themselves, and got home before the farmer did."

That was the story, and I forgot to ask how they got home before the farmer did unless he drove them; but I think they must have gone home across the field, because it is plain that Birdie's pigs did just as they liked all[181] through. What I did ask was, "Well, what was the good of it all?" for I thought nobody ought to tell a story without meaning some good by it.

"Why, they got some fresh air!" cried Birdie, triumphantly; and considering that most farmers keep their pig-sties in a filthy condition, which can't be healthy for the pigs, nor for those who eat them, I thought Birdie's story had a very good moral, which is only another way of saying that it had a good lesson in it.

One very hard winter, a robin came, day after day, to our window-sill. He was fed with crumbs, and soon became tame enough not to fly away when we opened the window. One cold day we found the little thing hopping about the kitchen. He had flown in at the window, and did not attempt to fly out again when we came near.[182]

We did not like to drive him out in the bitter cold: so we put him in a cage, in which he soon made himself quite at home. Sometimes we would let him out in the room, and he would perch on our finger, and eat from our hand without the least sign of fear.

When the spring came on, we opened the cage-door and let him go. At first he was not at all inclined to leave us; but after a while he flew off, and we thought we should never see him again.

All through the summer and autumn, the cage stood on a table in a corner of the kitchen. We often thought of the little robin, and were rather sorry that the cage was empty.

When the winter set in, we fancied we saw our old friend again hopping about outside the window. We were by no means sure that it was the same robin; but, just to see what he would do, we opened the window, and set the cage in its old place.

Then we all left the room for a few minutes. When we returned, we found, to our great delight, that the bird was in the cage. He seemed to know us as we petted him and chirruped to him; and we felt certain that it was our dear old friend.

Chiswick, London.

Frank wanted a high horse: so he took the sewing-chair, put the hassock on it, put the sofa-pillow on that, and mounted.

How he got seated up there so nicely I don't know; but I know just how he got down.

The horse did not mind the bridle, but he would not stand the whip. He reared, lost his balance, and fell over.

Down came Frank with sofa-pillow, hassock, and all. By good luck, he was not hurt; but he will not try to ride that horse again.

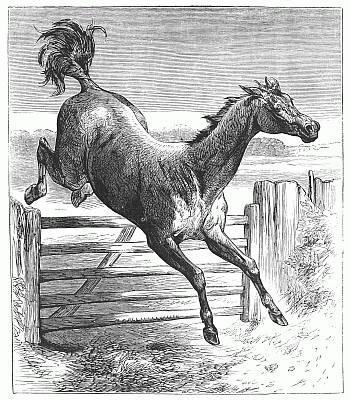

A Young gentleman bought a hunting-mare from a farmer at Malton in England, and took her with him to Whitby, a distance of nearly sixty miles. One Wednesday morning the mare was missing from the field where her owner had placed her. A search was made for her, but with no success.

The next day the search was renewed. The owner and[186] his groom went some ten miles, and were told that the mare had crossed the railway the morning before. At this point the trail was easy. The mare had taken the high road to her old home at Malton.

Six men had tried, but in vain, to stop her. At a place called Pickering, she jumped a load of wood and the railway gates, and then, finding herself in her old hunting country, made a bee-line for home. In doing this, she had to swim two rivers, and cross a railway.

She was found at her old home, rather lame, and with one shoe off, but otherwise no worse for her gallop of nearly sixty miles across the country,—all done in one day; for her old owner found her on Wednesday night, standing at the gate of the field where she had grazed for two previous years. Was she not a pretty clever horse?

We have a little white dog whose name is Phantom. This is his portrait. I hope you are glad to meet him. Ask him to shake hands. He would do so at once if you could only see him in reality.

When he was only a few months old, he followed us all to church without our knowing it; nor did we see him, till, in the most solemn part of the service, we heard a patter, patter, patter, coming up the aisle, and there stood Phantom at the door of our pew. In his mouth was a long-handled feather duster, which he had found in some obscure corner of the building, and where it had been put (as it was supposed) carefully out of everybody's way.

Phantom is very intelligent, and has learned a number of[187] tricks. He can understand what is said to him better than any dog I ever knew; but he is best known among the children here for his love of music and singing.

He has only learned one song yet; but he knows that as soon as he hears it. Wherever he may be,—up stairs, or down stairs, or out of doors,—if he hears that song, he will sit up, throw his head back, and you will hear his voice taking part in the music.

You may sing a dozen songs, all in about the same tone; but he will take no notice till he hears the tune he has learned, and then he will sing with you—not in a bark or a yelp, but in a pure, clear voice, as if he enjoyed it.

If you could see him sitting up, with his nose in the air, his mouth open, and his fore-paws moving as if playing the piano, and could hear his music, I am sure you would laugh till the tears came into your eyes.

Carondelet, Mo.

| Hark! the bells are sounding, | Welcome to our pleasures |

| Christmas draweth nigh; | And our Christmas cheer! |

| Now let joy abounding, | We'll not stint the measures, |

| Bid all sorrow fly. | Would you all were here! |

Ye who pine in sorrow, | Boys and girls together— |

| Come be cheer'd to-day; | From all parts and climes, |

| Of our gladness borrow, | To enjoy this weather, |

| As you freely may. | And these Christmas times! |

[A] Nursery, 1876.

The July edition of the Nursery had a table of contents for the next six issues of the year. This table was divided to cover each specific issue. A title page copied from this same July edition was also used for this number and the issue number added after the Volume number.

Page 176, period added to end of paragraph (in both hands.)