Title: A history of art in Chaldæa & Assyria, Vol. 1 (of 2)

Author: Georges Perrot

Charles Chipiez

Translator: Sir Walter Armstrong

Release date: February 14, 2009 [eBook #28072]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Paul Dring, Adrian Mastronardi and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

FROM THE FRENCH

OF

GEORGES PERROT,

PROFESSOR IN THE FACULTY OF LETTERS, PARIS; MEMBER OF THE INSTITUTE,

AND

CHARLES CHIPIEZ.

ILLUSTRATED WITH FOUR HUNDRED AND FIFTY-TWO ENGRAVINGS IN THE TEXT

AND FIFTEEN STEEL AND COLOURED PLATES.

IN TWO VOLUMES.—VOL. I.

TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY

WALTER ARMSTRONG, B.A., Oxon.,

AUTHOR OF "ALFRED STEVENS," ETC.

London: CHAPMAN AND HALL, Limited.

New York: A. C. ARMSTRONG AND SON.

1884.

London:

R. Clay, Sons, and Taylor,

BREAD STREET HILL.

[Pg v] In face of the cordial reception given to the first two volumes of MM. Perrot and Chipiez's History of Ancient Art, any words of introduction from me to this second instalment would be presumptuous. On my own part, however, I may be allowed to express my gratitude for the approval vouchsafed to my humble share in the introduction of the History of Art in Ancient Egypt to a new public, and to hope that nothing may be found in the following pages to change that approval into blame.

W. A.

October 10, 1883.

THE GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CHALDÆO-ASSYRIAN CIVILIZATION.

§ 1.—Situation and Boundaries of Chaldæa and Assyria.

[Pg 1] The primitive civilization of Chaldæa, like that of Egypt, was cradled in the lower districts of a great alluvial basin, in which the soil was stolen from the sea by long continued deposits of river mud. In the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, as in that of the Nile, it was in the great plains near the ocean that the inhabitants first emerged from barbarism and organized a civil life. As the ages passed away, this culture slowly mounted the streams, and, as Memphis was older by many centuries than Thebes, in dignity if not in actual existence, so Ur and Larsam were older than Babylon, and Babylon than Nineveh. The manners and beliefs, the arts and the written characters of Egypt were carried into the farthest recesses of Ethiopia, partly by commerce but still more by military invasion; so too Chaldaic civilization made itself felt at vast distances from its birthplace, even in the cold valleys and snowy plateaux of Armenia, in districts which are separated by ten degrees of latitude from the burning shores where the fish god Oannes showed himself to the rude fathers of the race, and taught them "such things as contribute [Pg 2] to the softening of life."[1] In Egypt progressive development took place from north to south, while in Chaldæa its direction was reversed. The apparent contrast is, however, but a resemblance the more. The orientation, if such a term may be used, of the two basins, is in opposite directions, but in each the spread of religion with its rites and symbols, of written characters with their adaptation to different languages, and of all those arts and processes which, when taken together, make up what we call civilization, advanced from the seaboard to the river springs.

In these two countries the conscience of man seems to have been first awakened to his innate power of bettering his own condition by well directed observation, by the elaboration of laws, and by forethought for the future. Between Egypt on the one hand, and Chaldæa with that Assyria which was no more than its offshoot and prolongation, on the other, there are strong analogies, as will be clearly seen in the course of our study, but there are also differences that are not less appreciable. Professor Rawlinson shows this very clearly in a page of descriptive geography which he will allow us to quote as it stands. It will not be the last of our borrowings from his excellent work, The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, a book that has done so much to popularize the discoveries of modern scholars.[2]

"The broad belt of desert which traverses the eastern hemisphere, in a general direction from west to east (or, speaking more exactly, of W.S.W. to N.E.E.) reaching from the Atlantic on the one hand nearly to the Yellow Sea on the other, is interrupted about its centre by a strip of rich vegetation, which at once breaks the continuity of the arid region, and serves also to mark the point where the desert changes its character from that of a plain at a low level to that of an elevated plateau or table-land. West of the favoured district, the Arabian and African wastes are seas of land seldom raised much above, often sinking below the level of the ocean; while east of the same, in Persia, Kerman, Seistan, Chinese Tartary, and Mongolia, the desert consists of a series of plateaux, [Pg 3] having from 3,000 to nearly 10,000 feet of elevation. The green and fertile region which is thus interposed between the 'highland' and 'lowland' deserts,[3] participates, curiously enough, in both characters. Where the belt of sand is intersected by the valley of the Nile, no marked change of elevation occurs; and the continuous low desert is merely interrupted by a few miles of green and cultivable surface, the whole of which is just as smooth and as flat as the waste on either side of it. But it is otherwise at the more eastern interruption. Then the verdant and productive country divides itself into two tracts, running parallel to each other, of which the western presents features, not unlike those that characterize the Nile valley, but on a far larger scale; while the eastern is a lofty mountain region, consisting for the most part of five or six parallel ranges, and mounting in many places far above the level of perpetual snow.

"It is with the western or plain tract that we are here concerned. Between the outer limits of the Syro-Arabian desert and the foot of the great mountain range of Kurdistan and Luristan intervenes a territory long famous in the world's history, and the chief site of three out of the five empires of whose history, geography, and antiquities, it is proposed to treat in the present volumes. Known to the Jews as Aram-Naharaim, or 'Syria of the two rivers'; to the Greeks and Romans as Mesopotamia, or 'the between-river country'; to the Arabs as Al-Jezireh, or 'the island,' this district has always taken its name from the streams which constitute its most striking feature, and to which, in fact, it owes its existence. If it were not for the two great rivers—the Tigris and Euphrates—with their tributaries, the more northern part of the Mesopotamian lowland would in no respect differ from the Syro-Arabian desert on which it adjoins, and which, in latitude, elevation, and general geological character, it exactly resembles. Towards the south the importance of the rivers is still greater; for of Lower Mesopotamia it may be said, with more truth than of Egypt,[4] that it is 'an acquired land,' the actual 'gift' of the two streams which wash it on either side; being as it is, entirely a recent formation—a deposit which the streams have made in the shallow waters of a gulf into which they have flowed for many ages.[5]

[Pg 4] "The division, which has here forced itself upon our notice, between the Upper and the Lower Mesopotamian country, is one very necessary to engage our attention in connection with ancient Chaldæa. There is no reason to think that the term Chaldæa had at any time the extensive signification of Mesopotamia, much less that it applied to the entire flat country between the desert and the mountains. Chaldæa was not the whole, but a part, of the great Mesopotamian plain; which was ample enough to contain within it three or four considerable monarchies. According to the combined testimony of geographers and historians,[6] Chaldæa lay towards the south, for it bordered upon the Persian Gulf, and towards the west, for it adjoined Arabia. If we are called upon to fix more accurately its boundaries, which, like those of most countries without strong natural frontiers, suffered many fluctuations, we are perhaps entitled to say that the Persian Gulf on the south, the Tigris on the east, the Arabian desert on the west, and the limit between Upper and Lower Mesopotamia on the north, formed the natural bounds, which were never greatly exceeded, and never much infringed upon. These boundaries are for the most part tolerably clear, though the northern only is invariable. Natural causes, hereafter to be mentioned more particularly, are perpetually varying the course of the Tigris, the shore of the Persian Gulf and the line of demarcation between the sands of Arabia and the verdure of the Euphrates valley. But nature has set a permanent mark, half way down the Mesopotamian lowland, by a difference of a geological structure, which is very conspicuous. Near Hit on the Euphrates, and a little below Samarah on the Tigris,[7] the traveller who descends the streams, bids adieu to a somewhat waving and slightly elevated plain of secondary formation, and enters on the dead flat and low level of the new alluvium. The line thus formed is marked and invariable; it constitutes the only natural division between the upper and lower portions of the [Pg 5]valley; and both probability and history point to it as the actual boundary between Chaldæa and her northern neighbour."[8]

Whether the two States had independent and separate life, or whether, as in after years, one of the two had, by its political and military superiority reduced the other to the condition of a vassal, the line of demarcation was constant, a line traced in the first instance by nature and rendered more rigid and ineffaceable by historical developments. Even when Chaldæa became nominally a mere province of Assyria, the two nationalities remained distinct. Chaldæa was older than Assyria. The centres of her civil life were the cities built upon the alluvial lands between the thirty-first and thirty-third degree of latitude. The most famous of these cities was Babylon. Those whom we call Assyrians, a people who rose to power and glory at a much more recent date, drew the seeds of their civilization from their more precocious neighbour.

These expressions, Assyria and Chaldæa, are now employed in a sense far more precise than they ever had in antiquity. For Herodotus Babylonia was a mere district of Assyria;[9] in his time both States were comprised in the Persian Empire, and had no distinct existence of their own. Pliny calls the whole of Mesopotamia Assyria.[10] Strabo carries the western frontier of Assyria as far as Syria.[11] To us these variations are of small importance. The geographical and historical nomenclature of the ancients was never clearly defined. It was always more or less of a floating quantity, especially for those countries which to Herodotus or Diodorus, to Pliny or to Tacitus, were dimly perceptible on the extreme limits of their horizon.

It would, however, be easy to show that in assigning a more definite value to the terms in question—a proceeding in which we have the countenance of nearly every modern historian—we do not detach them from their original acceptation; at most we give them more constancy and precision than the colloquial language of the Greeks and Romans demanded.[12] The expressions [Pg 6] Khasdim and Chaldæi were used in the Bible and by classic authors mainly to denote the inhabitants of Babylon and its neighbourhood; and we find Strabo attaching with precision the name Aturia, which is nothing but a variant upon Assyria, to that district watered and bounded by the Tigris in which Nineveh was situated.[13] Our only aim is to adopt, once for all, such terms as may be easily understood by our readers, and may render all confusion impossible between the two kingdoms, between the people of the north and those of the south.

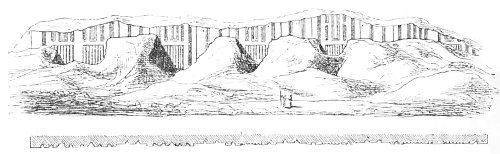

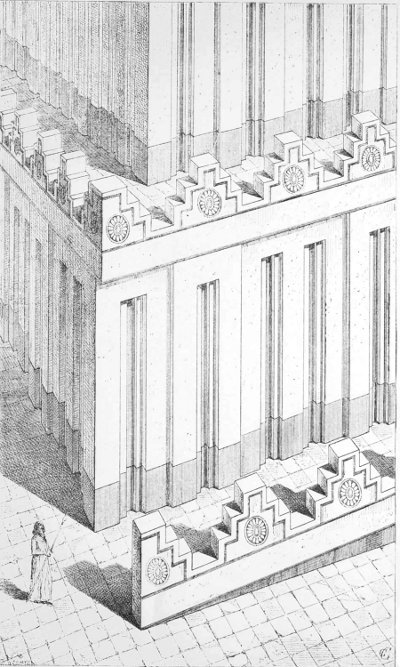

In order to define Assyria exactly we should have to determine its frontiers, and that we can only do approximately. As the nation grew its territory extended in certain directions. To the east, however, where the formidable rampart of the Zagros forbade all progress, no such extension took place. Those lofty and precipitous chains which we now call the mountains of Kurdistan, were only to be crossed in two or three places, and by passes which during their few months of freedom from snow and floods gave access to the high-lying plains of Media. These narrow defiles might well be traversed by an army in a summer campaign, but neither dwellings nor cultivated lands could invade such a district with success; at most they could take possession of the few spots of fertile soil which lay at the mouth of the lateral valleys; such, for example, was the plain of Arbeles which was watered by the great Zab before its junction with the Tigris. Towards the south there was no natural barrier, but in that direction all development was hindered by the density of the Chaldee population which was thickly spread over the country above Babylon and about the numerous towns and villages which looked towards that city as their capital. To the north, on the other hand, the wide terraces which mounted like steps from the plains of Mesopotamia to the mountains of Armenia offered an ample field for expansion. To the west there was still more room. Little by little rural and urban life overflowed the valley of the Tigris into that of the Chaboras or Khabour, the principal affluent of the Euphrates, until at last it reached the banks of the great western river itself. In all Northern Mesopotamia, between the hills of the Sinjar and the last slopes of Mount Masius, the Assyrians encountered only nomad tribes whom they could drive when they chose into the Syrian [Pg 7] desert. Over all that region the remains of artificial mounds have been found which must at one time have been the sites of palaces and cities. In some cases the gullies cut in their flanks by the rain discover broken walls and fragments of sculpture whose style is that of the Ninevitish monuments.[14]

In the course of their victorious career the Assyrians annexed several other states, such as Syria and Chaldæa, Cappadocia and Armenia, but those countries were never more than external dependencies, than conquered provinces. Taking Assyria proper at its greatest development, we may say that it comprised Northern Mesopotamia and the territories which faced it from the other bank of the Tigris and lay between the stream and the lower slopes of the mountains. The heart of the country was the district lying along both sides of the river between the thirty-fifth and thirty-seventh degree of latitude, and the forty-first and forty-second degree of longitude, east. The three or four cities which rose successively to be capitals of Assyria were all in that region, and are now represented by the ruins of Khorsabad, of Kouyundjik with Nebbi-Younas, of Nimroud, and of Kaleh-Shergat. One of these places corresponds to Ninos, as the Greeks call it, or Nineveh, the famous city which classic writers as well as Jewish prophets looked upon as the centre of Assyrian history.

To give some idea of the relative dimensions of these two states Rawlinson compares the surface of Assyria to that of Great Britain, while that of Chaldæa must, he says, have been equal in extent to the kingdom of Denmark.[15] This latter comparison seems below the mark, when, compass in hand, we attempt to verify it upon a modern map. The discrepancy is caused by the continual encroachments upon the sea made by the alluvial deposits from the two great rivers. Careful observations and calculations have shown that the coast line must have been from forty to forty-five leagues farther north than it is at present when the ancestors of the Chaldees first appeared upon the scene.[16] Instead of flowing together as they do now to form what is called the Shat-el-Arab, the Tigris and Euphrates then fell into the sea at points some twenty leagues apart in a gulf which extended [Pg 8] eastwards as far as the last spurs thrown out by the mountains of Iran, and westwards to the foot of the sandy heights which terminate the plateau of Arabia. "The whole lower part of the valley has thus been made, since the commencement of the present geological period, by deposits from the Tigris, the Euphrates, and such minor streams as the Adhem, the Gyndes, the Choaspes, streams which, after having long enjoyed an independent existence and having contributed to drive back the waters into which they fell, have ended by becoming mere feeders of the Tigris."[17] We see, therefore, that when Chaldæa received its first inhabitants it was sensibly smaller than it is to-day, as the district of which Bassorah is now the capital and the whole delta of the Shat-el-Arab were not yet in existence.

NOTES:

[1] Berosus, fragment No. 1, in the Essai de Commentaire sur les Fragments cosmogoniques de Bérose d'après les Textes cunéiformes et les Monuments de l'Art Asiatique of François Lenormant (Maisonneuve, 1871, 8vo.).

[2] The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World; or, The History, Geography, and Antiquities of Chaldæa, Assyria, Babylon, Media, and Persia. Collected and Illustrated from Ancient and Modern Sources, by George Rawlinson. Fourth edition, 3 vols., 8vo., with Maps and Illustrations (Murray, 1879).

[3] Humboldt, Aspects of Nature, vol. i. pp. 77, 78.—R.

[4] Herodotus, ii. 5.

[5] Loftus's Chaldæa and Susiana, p. 282.—R.

[6] See Strabo, xvi. 1, § 6; Pliny, H.N. vi. 28; Ptolemy, v. 20; Berosus, pp. 28, 29.—R.

[7] Ross came to the end of the alluvium and the commencement of the secondary formation in lat. 34°, long. 44° (Journal of Geographical Society, vol. ix. p. 446). Similarly, Captain Lynch found the bed of the Tigris change from pebbles to mere alluvium near Khan Iholigch, a little above its confluence with the Aahun (Ib. p. 472). For the point where the Euphrates enters on the alluvium, see Fraser's Assyria and Mesopotamia, p. 27.—R.

[8] Rawlinson. The Five Great Monarchies, &c., vol. i., pp. 1-4. As to the name and boundaries of Chaldæa, see also Guignaut, La Chaldée et les Chaldéens, in the Encyclopédie Moderne, vol. viii.

[9] Herodotus, i. 106, 192; iii. 92.

[10] Pliny, Nat. Hist. vi. 26.

[11] Strabo, xvi. i. § 1.

[12] Genesis xi. 28 and 31; Isaiah xlvii. 1; xiii. 19, &c.; Diodorus ii. 17; Pliny, Nat. Hist. vi. 26; the Greek translators of the Bible rendered the Hebrew term Khasdim by Χαλδαιοι; both forms seem to be derived from the same primitive word.

[13] Strabo, xvi. i. 1, 2, 3.

[14] Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, vol. i. pp. 312, 315; Discoveries, p. 245.

[15] Rawlinson, Five Great Monarchies, vol. i. pp. 4, 5.

[16] Loftus, in the Journal of the Geographical Society, vol. xxvi. p. 142; Ib., Sir Henry Rawlinson, vol. xxvii. p. 186.

[17] Maspero, Histoire Ancienne des Peuples de l'Orient, p. 137.

§ 2.—Nature in the Basin of the Euphrates and Tigris.

The inundation of the Nile gives renewed life every year to those plains of Egypt which it has slowly formed, and so it is with the Tigris and Euphrates. Lower Mesopotamia is entirely their creation, and if the time were to come when their vivifying streams were no longer to irrigate its surface, it would very soon be changed into a monotonous and melancholy desert. It hardly ever rains in Chaldæa.[18] There are a few showers at the changes of the season, and, in winter, a few days of heavy rain. During the summer, for long months together, the sky remains inexorably blue while the temperature is hot and parching. In winter, clouds are almost as rare; but winds often play violently over the great tracts of unbroken country. When these blow from the south they soon lose their warmth and humidity at the contact of a soil which, but a short while ago, was at the bottom of the sea, and is, therefore, in many places still strongly impregnated with salt which acts as a refrigerant.[19] Again, when the north wind comes down from the snowy summits of Armenia or Kurdistan, it is already cold enough, so that, during the months of December and January, it often happens that the mercury falls below freezing point, even in Babylonia. At daybreak the [Pg 9] waters of the marshes are sometimes covered with a thin layer of ice, and the wind increases the effect of the low temperature. Loftus tells us that he has seen the Arabs of his escort fall benumbed from their saddles in the early morning.[20]

It is, then, upon the streams, and upon them alone, that the soil has to depend for its fertility; all those lands to which they never reach are doomed to barrenness and death. It is fortunate for the prosperity of the country through which they flow, that the Tigris and Euphrates swell and rise annually from their beds, not indeed like the Nile, almost on a stated day, but ever in the same season, about the commencement of spring. Without these periodical floods many parts of the plain of Mesopotamia would be beyond the reach of irrigation, but their regular occurrence allows water to be stored in sufficient quantities for use during the months of drought. To obtain the full advantage of this precious capital, the inhabitants must, however, take more care and expend more labour than is necessary in Egypt. The rise of the Euphrates and of the Tigris is neither so slow nor so regular as that of the Nile. The waters do not spread so gently over the soil, neither do they stay upon it so long;[21] since they have been abandoned to themselves as they are at present, a great part of them are lost, and, far from rendering a service to agriculture, they turn vast regions into dangerous hot-beds of infection.

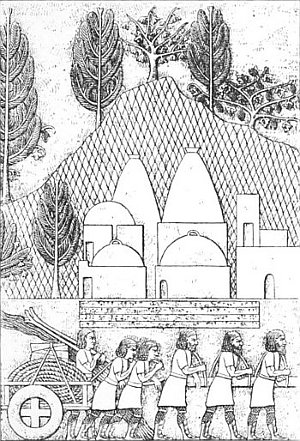

It was to the west of the double basin that the untoward effects of the territorial conformation were chiefly felt. The valley of the Euphrates is not like that of the Nile, a canal hollowed out between two clearly marked banks. From the northern boundary of the alluvial plain to the southern, the slope is very slight, while from east to west, from the plains of Mesopotamia to the foot of the Arabian plateau, there is also an inclination. When the river is in flood the right bank no longer exists. Where it is [Pg 10] not raised and defended by dykes, the waters flow over it at more than one point. They spread through large breaches into a sort of hollow where they form wide marshes, such as those which stretch in these days from the country west of the ruins of Babylon almost to the Persian Gulf. In the parching heat of the summer months the mud blackens, cracks, and exhales miasmic vapours, so that a long acclimatization, like that of the Arabs, is necessary before one can live in the region. Some of these Arabs live in forests of reeds like those represented in the Assyrian bas-reliefs.[22]

Their huts of mud and rushes rise upon a low island in the marshes; and all communication with neighbouring tribes and with the town in which they sell the product of their rice-fields, is carried on by boats. The brakes are more impenetrable than the thickest underwood, but the natives have cut alleys through them, along which they impel their large flat-bottomed teradas with poles.[23] Sometimes a sudden rise of the river will raise the level of these generally stagnant waters by a yard or two, and during the night the huts and their inhabitants, men and animals together, will be sent adrift. Two or three villages have been destroyed in this fashion amid the complete indifference of the authorities. The tithe-farmer may be trusted to see that the survivors pay the taxes due from their less fortunate neighbours.

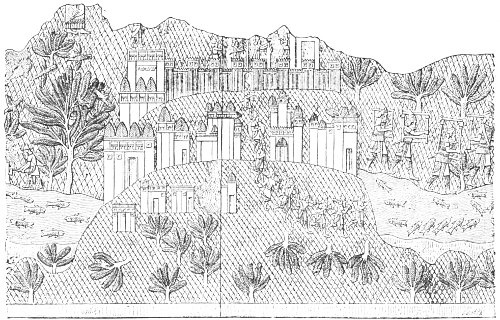

The masters of the country could, if they chose, do much to render the country more healthy, more fertile, more capable of supporting a numerous population. They might direct the course of the annual floods, and save their excess. When the land was managed by a proprietory possessing intelligence, energy, and foresight, it had, especially in minor details, a grace and picturesque beauty of its own. When every foot of land was carefully cultivated, when the two great streams were thoroughly kept in hand, their banks and those of the numerous canals intersecting the plains were overhung with palms. The eye fell with pleasure upon the tall trunks with their waving plumes, upon the bouquets of broad leaves with their centre of yellow dates; upon the cereals and other useful and ornamental plants growing under their gentle shade, and forming a carpet [Pg 11] for the rich and sumptuous vegetation above. Around the villages perched upon their mounds the orchards spread far and wide, carrying the scent of their orange trees into the surrounding country, and presenting, with their masses of sombre foliage studded with golden fruit, a picture of which the eye could never grow weary.

No long series of military disasters was required to destroy all this charm; fifty years, or, at most, a century, of bad administration was enough.[24] Set a score of Turkish pachas to work, one after the other, men such as those whom contemporary travellers have encountered at Mossoul and Bagdad; with the help of their underlings they will soon have done more harm than the marches and conflicts of armies. There is no force more surely and completely destructive than a government which is at once idle, ignorant, and corrupt.

With the exception of the narrow districts around a few towns and villages, where small groups of population have retained something of their former energy and diligence, Mesopotamia is now, during the greater part of the year, given over to sterility and desolation. As it is almost entirely covered with a deep layer of vegetable earth, the spring clothes even its most abandoned solitudes with a luxuriant growth of herbs and flowers. Horses and cattle sink to their bellies in the perfumed leafage,[25] but after the month of May the herbage withers and becomes discoloured; the dried stems split and crack under foot, and all verdure disappears except from the river-banks and marshes. Upon these wave the feathery fronds of the tamarisk, and in the stagnant or slowly moving water which fills all the depressions of the soil, aquatic plants, water-lilies, rushes, papyrus, and gigantic reeds spring up in dense masses, and make the low-lying country look like a vast prairie, whose native freshness even the sun at its zenith has no power to destroy. Everywhere else nature is as [Pg 12] dreary in its monotony as the vast sandy deserts which border the country on the west. In one place the yellow soil is covered with a dried, almost calcined, stubble; in another, with a grey dust which rises in clouds before the slightest breeze; in the neighbourhood of the ancient townships it has received a reddish hue from the quantity of broken and pulverized brick with which it is mixed. These colours vary in different places, but from Mount Masius to the shores of the Persian Gulf, from the Euphrates to the Tigris, the traveller is met almost constantly by the one melancholy sight—of a country spreading out before him to the horizon, in which neglect has gone on until the region which the biblical tradition represents as the cradle of the human race has been rendered incapable of supporting human life.[26]

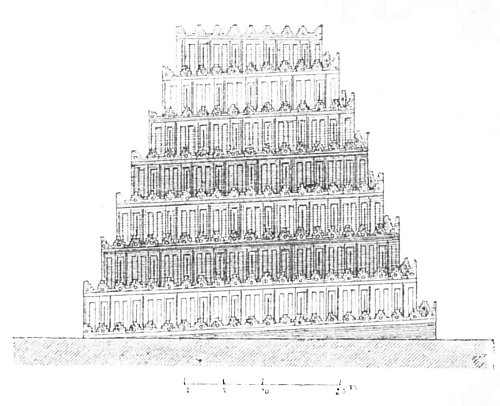

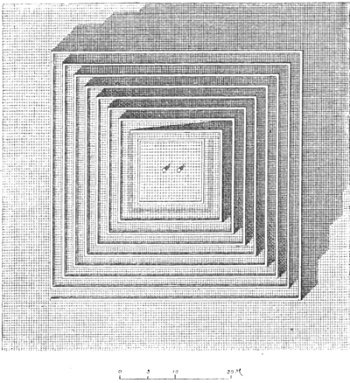

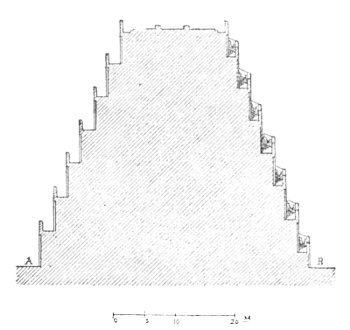

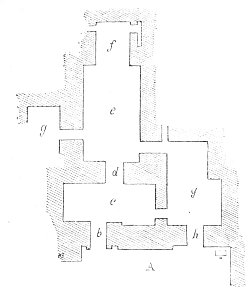

The physiognomy of Mesopotamia has then been profoundly modified since the fall of the ancient civilization. By the indolence of man it has lost its adornments, or rather its vesture, in the ample drapery of waving palms and standing corn that excited the admiration of Herodotus.[27] But the general characteristics and leading contours of the landscape remain what they were. Restore in thought one of those Babylonian structures whose lofty ruins now serve as observatories for the explorer or passing traveller. Suppose yourself, in the days of Nebuchadnezzar, seated upon the summit of the temple of Bel, some hundred or hundred and twenty yards above the level of the plain. At such a height the smiling and picturesque details which were formerly so plentiful and are now so rare, would not be appreciated. The domed surfaces of the woods would seem flat, the varied cultivation, the changing colours of the fields and pastures would hardly be distinguished. You would be struck then, as you are struck to-day, by the extent[Pg 13] and uniformity of the vast plain which stretches away to all the points of the compass.

In Assyria, except towards the south where the two rivers begin to draw in towards each other, the plains are varied by gentle undulations. As the traveller approaches the northern and eastern frontiers, chains of hills, and even snowy peaks, loom before him. In Chaldæa there is nothing of the kind. The only accidents of the ground are those due to human industry; the dead level stretches away as far as the eye can follow it, and, like the sea, melts into the sky at the horizon.

NOTES

[18] Herodotus, i. 193: Ἡ δε γη των Ασσυριων ὑεται μεν ολιγωι

[19] Loftus, Susiana and Chaldæa, i. vol. 8vo. 1857, London, p. 73.

[20] Loftus, Susiana and Chaldæa, p. 73; Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, p. 146 (i. vol. 8vo. 1853).

[21] Herodotus, exaggerates this difference, but it is a real one. "The plant," he says, "is nourished and the ears formed by means of irrigation from the river. For this river does not, as in Egypt, overflow the cornlands of its own accord, but is spread over them by the hand or by the help of engines," i. 193. [Our quotations are from Prof. Rawlinson's Herodotus (4 vols. 8vo. 1875; Murray); Ed.] The inundations of the Tigris and Euphrates do not play so important a rôle in the lives of the inhabitants of Mesopotamia, as that of the Nile in those of the Egyptians.

[22] Layard, A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh, plate 27 (London, oblong folio, 1853).

[23] Layard, Discoveries, pp. 551-556; Loftus, Chaldæa and Susiana, chap. x.

[24] Layard (Discoveries, pp. 467, 468 and 475) tells us what the Turks "have made of two of the finest rivers in the world, one of which is navigable for 850 miles from its mouth, and the other for 600 miles."

[25] Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, vol. i. p. 78 (1849). "Flowers of every hue enamelled the meadows; not thinly scattered over the grass as in northern climes, but in such thick and gathering clusters that the whole plain seemed a patch-work of many colours. The dogs as they returned from hunting, issued from the long grass dyed red, yellow, or blue, according to the flowers through which they had last forced their way."

[26] Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, vol. ii. pp. 68-75.

[27] Herodotus, i. 193. "Of all the countries that we know, there is none which is so fruitful in grain. It makes no pretension indeed, of growing the fig, the olive, the vine, or any other trees of the kind; but in grain it is so fruitful as to yield commonly two hundredfold, and when the production is greatest, even three hundredfold. The blade of the wheat plant and barley is often four fingers in breadth. As for millet and the sesame, I shall not say to what height they grow, though within my own knowledge; for I am not ignorant that what I have already written concerning the fruitfulness of Babylonia, must seem incredible to those who have never visited the country.... Palm trees grow in great numbers over the whole of the flat country, mostly of the kind that bears fruit, and this fruit supplies them with bread, wine, and honey."

§ 3.—The Primitive Elements of the Population.

The two great factors of all life and of all vegetable production are water and warmth, so that of the two great divisions of the country we have just described, the more southern must have been the first inhabited, or at least, the first to invite and aid its inhabitants to make trial of civilization.

In the north the two great rivers are far apart. The vast spaces which separate them include many districts which have always been, and must ever be, very difficult of irrigation, and consequently of cultivation. In the south, on the other hand, below the thirty-fourth degree of latitude, the Tigris and Euphrates approach each other until a day's march will carry the traveller from one to the other; and for a distance of some eighty leagues, ending but little short of the point of junction, their beds are almost parallel. In spite of the heat, which is, of course, greater than in northern Mesopotamia, nothing is easier than to carry the blessings of irrigation over the whole of such a region. When the water in the rivers and canals is low, it can be raised by the aid of simple machines, similar in principle to those we described in speaking of Egypt.[28]

It is here, therefore, that we must look for the scene of the first attempts in Asia to pass from the anxious and uncertain life of the fisherman, the hunter, or the nomad shepherd, to that of the sedentary husbandman, rooted to the soil by the pains he has taken to improve its [Pg 14] capabilities, and by the homestead he has reared at the border of his fields. In the tenth and eleventh chapters of Genesis we have an echo of the earliest traditions preserved by the Semitic race of their distant origin. "And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there."[29] The land of Shinar is the Hebrew name of what we call Chaldæa. There is no room for mistake. When the sacred writer wishes to tell us the origin of human society, he transports us into Lower Mesopotamia. It is there that he causes the posterity of Noah to build the first great city, Babel, the prototype of the Babylon of history; it is there that he tells us the confusion of tongues was accomplished, and that the common centre existed from which men spread themselves over the whole surface of the earth, to become different nations. The oldest cities known to the collector of these traditions were those of Chaldæa, of the region bordering on the Persian Gulf.

"And Cush begat Nimrod: he began to be a mighty one in the earth.

"He was a mighty hunter before the Lord: wherefore it is said, 'Even as Nimrod, the mighty hunter before the Lord.'

"And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.

"Out of that land went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh, and the city Rehoboth, and Calah,

"And Resen between Nineveh and Calah: the same is a great city."[30]

These statements have been confirmed by the architectural and other remains found in Mesopotamia. Inscriptions from which fresh secrets are wrested day by day; ruins of buildings whose dates are to be approximately divined from their plans, their structure, and their decorations; statues, statuettes, bas-reliefs, and all the various débris of a great civilization, when studied with the industrious ardour which distinguishes modern science, enable the critic to realize the vast antiquity of those Chaldæan cities, in which legend and history are so curiously mingled.

Even before they could decipher their meaning Assyriologists had compared, from the palæographic point of view, the different varieties of the written character known as cuneiform—a character which lent itself for some two thousand years, to the notation of the five or six successive languages, [Pg 15] at least, in which the inhabitants of Western Asia expressed their thoughts. These wedge-shaped characters are found in their most primitive and undeveloped forms in the mounds dotted over the southern districts of Mesopotamia, in company with the earliest signs of those types which are especially characteristic of the architecture, ornamentation, and plastic figuration of Assyria.

There is another particular in which the monumental records and the biblical tradition are in accord. During those obscure centuries that saw the work sketched out from which the civilization of the Tigris and Euphrates basin was, in time, to be developed, the Chaldæan population was not homogeneous; the country was inhabited by tribes who had neither a common origin nor a common language. This we are told in Genesis. The earliest chiefs to build cities in Shinar are there personified in the person of Nimrod, who is the son of Cush, and the grandson of Ham. He and his people must be placed, therefore, in the same family as the Ethiopians, the Egyptians, and the Libyans, the Canaanites and the Phœnicians.[31]

A little lower down in the same genealogical table we find attached to the posterity of Shem that Asshur who, as we are told in the verses quoted above, left the plains of Shinar in order to found Nineveh in the upper country.[32] So, too, it was from Ur of the Chaldees that Terah, another descendant of Shem, and, through Abraham, the ancestor of the Jewish people, came up into Canaan.[33]

The world has, unhappily, lost the work of Berosus, the Babylonish priest, who, under the Seleucidæ, did for Chaldæa what Manetho was doing almost at the same moment for Egypt. [Pg 16][34] Berosus compiled the history of Chaldæa from the national chronicles and traditions. The loss of his work is still more to be lamented than that of Manetho. The wedges may never, perhaps, be read with as much certainty as the hieroglyphs; the remains of Chaldæo-Assyrian antiquity are much less copious and well preserved than those of the Egyptian civilization, while the gap in the existing documents are more frequent and of a different character. And yet much precious information, especially in these latter days, has been drawn from those fragments of his work which have come down to us. In one of these we find the following evidence as to the mixture of races: "At first there were at Babylon a great number of men belonging to the different nationalities that colonized Chaldæa."[35]

How far did that diversity go? The terms used by Berosus are vague enough, while the Hebraic tradition seems to have preserved the memory of only two races who lived one after the other in Chaldæa, namely, the Kushites and the Shemites. And may not these groups, though distinct, have been more closely connected than the Jews were willing to admit? We know how bitterly the Jews hated those Canaanitish races against whom they waged their long and destructive wars; and it is possible that, in order to mark the separation between themselves and their abhorred enemies, they may have shut their eyes to the exaggeration of the distance between the two peoples. More than one historian is inclined to believe that the Kushites and Shemites were less distantly related than the Hebrew writers pretend. Almost every day criticism discovers new points of resemblance between the Jews before the captivity and certain of their neighbours, such as the Phœnicians. Almost the same language was spoken by each; each had the same arts and the same symbols, while many rites and customs were common to both. Baal and Moloch were adored in Judah and Israel as well as in Tyre and Sidon. This is not the proper place to discuss such a question, but, whatever view we may take of it, it seems that the researches of Assyriologists have led to the following conclusion: That primitive Chaldæa received and retained various ethnic elements upon its fertile soil; that those elements in time became fused together, and that, even in the [Pg 17] beginning, the diversities that distinguished them one from another were less marked than a literal acceptance of the tenth chapter of Genesis might lead us to believe.

We cannot here undertake to explain all the conjectures to which this point has given rise. We are without some, at least, of the qualifications necessary for the due appreciation of the proofs, or rather of the probabilities, which are relied on by the exponents of this or that hypothesis. We must refer curious readers to the works of contemporary Assyriologists; or they may, if they will, find all the chief facts brought together in the writings of MM. Maspero and François Lenormant, whom we shall often have occasion to quote.[36] We shall be content with giving, in as few words as possible, the theory which appears at present to be generally admitted.

There is no doubt as to the presence in Chaldæa of the Kushite tribes. It is the Kushites, as represented by Nimrod, who are mentioned in Genesis before any of the others; a piece of evidence which is indirectly confirmed by the nomenclature of the Greek writers. They often employed the terms Κισσαιοι and Κισσιοι to denote the peoples who belonged to this very part of Asia,[37] terms under which it is easy to recognize imperfect transliterations of a name that began its last syllable in the Semitic tongues with the sound we render by sh. As the Greeks had no letters corresponding to our h and j, they had to do the best they could with breathings. Their descendants had to make the same shifts when they became subject to the Turks, and had to express every word of their conqueror's language without possessing any signs for those sounds of sh and j in which it abounded.

The same vocable is preserved to our day in the name borne by one of the provinces of Persia, Khouzistan. The objection that the Κισσαιοι or Κισσιοι of the classic writers and poets were placed in Susiana rather than in Chaldæa will no longer be made. Susiana borders upon Chaldæa and belongs, like it, to the basin of the Tigris. There is no natural frontier between the two countries, which were closely connected both in peace and war. On the [Pg 18] other hand, the name of Ethiopians, often applied by the same authors to the dwellers upon the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman, recalls the relationship which attached the Kushites of Asia to those of Africa in the Hebrew genealogies.

We have still stronger reasons of the same kind for affirming that the Shemites or Semites occupied an important place in Chaldæa from the very beginning. Linguistic knowledge here comes to the aid of the biblical narrative and confirms its ethnographical data. The language in which most of our cuneiform inscriptions are written, the language, that is, that we call Assyrian, is closely allied to the Hebrew. Towards the period of the second Chaldee Empire, another dialect of the same family, the Aramaic, seems to have been in common use from one end of Mesopotamia to the other. A comparative study of the rites and religious beliefs of the Semitic races would lead us to the same result. Finally, there is something very significant in the facility with which classic writers confuse such terms as Chaldæans, Assyrians, and Syrians; it would seem that they recognized but one people between the Isthmus of Suez on the south and the Taurus on the north, between the seaboard of Phœnicia on the west and the table lands of Iran in the east. In our day the dominant language over the whole of the vast extent of territory which is inclosed by those boundaries is Arabic, as it was Syriac during the early centuries of our era, and Aramaic under the Persians and the successors of Alexander. From the commencement of historic times the Semitic element has never ceased to play the chief rôle from one end of that region to the other. For Syria proper, its pre-eminence is attested by a number of facts which leave no room for doubt. Travellers and historians classed the inhabitants of Mesopotamia with those of Phœnicia and Palestine, because, to their unaccustomed ears, the differences between their languages were hardly perceptible, while their personal characteristics were practically identical. Such affinities and resemblances are only to be explained by a common origin, though the point of junction may have been distant.

It has also been asserted that an Aryan element helped to compose the population of primitive Chaldæa, that sister tribes to those of India and Persia, Armenia and Asia Minor furnished their contingents to the mixed population of Shinar. Some have even declared that a time came when those tribes obtained the chief power. It may have been so, but the evidence upon which the [Pg 19] hypothesis rests is very slight. Granting that the Aryans did settle in Chaldæa, they were certainly far less numerous than the other colonists, and were so rapidly absorbed into the ranks of the majority that neither history nor language has preserved any sensible trace of their existence. We may therefore leave them out of the argument until fresh evidence is forthcoming.

But the students of the inscriptions had another, and, if we accept the theories of MM. Oppert and François Lenormant, a better-founded, surprise in store for us. It seemed improbable that science would ever succeed in mounting beyond those remote tribes, the immediate descendants of Kush and Shem, who occupied Chaldæa at the dawn of history; they formed, to all appearance, the most distant background, the deepest stratum, to which the historian could hope to penetrate; and yet, when the most ancient epigraphic texts began to yield up their secrets, the interpreters were confronted, as they assure us, with this startling fact: the earliest language spoken, or, at least, written, in that country, belonged neither to the Aryan nor to the Semitic family, nor even to those African languages among which the ancient idiom of Egypt has sometimes been placed; it was, in an extreme degree, what we now call an agglutinative language. By its grammatical system and by some elements of its vocabulary it suggests a comparison with Finnish, Turkish, and kindred tongues.

Other indications, such as the social and religious conditions revealed by the texts, have combined with these characteristics to convince our Assyriologists that the first dwellers in Chaldæa—the first, that is, who made any attempt at civilization—were Turanians, were part of that great family of peoples who still inhabit the north of Europe and Asia, from the marshes of the Baltic to the banks of the Amoor and the shores of the Pacific Ocean.[38] The [Pg 20] languages of all those peoples, though various enough, had certain features in common. No one of them reached the delicate and complex mechanism of internal and terminal inflexion; they were guiltless of the subtle processes by which Aryans and Semites expressed the finest shades of thought, and, by declining the substantive and conjugating the verb, subordinated the secondary to the principal idea; they did not understand how to unite, in an intimate and organic fashion, the root to its qualifications and determinatives, to the adjectives and phrases which give colour to a word, and indicate the precise rôle it has to play in the sentence in which it is used. These languages resemble each other chiefly in their lacunæ. Compare them in the dictionaries and they seem very different, especially if we take two, such as Finnish and Chinese, that are separated by the whole width of a continent.

It is the same with their physical types. Certain tribes whom we place in the Turanian group have all the distinctive characteristics of the white races. Others are hardly to be distinguished from the yellow nations. Between these two extremes there are numerous varieties which carry us, without any abrupt transition, from the most perfect European to the most complete Chinese type.[39] In the Aryan family the ties of blood are perceptible even between the most divergent branches. By a comparative study of their languages, traditions, and religious conceptions, it has been proved that the Hindoos upon the Ganges, the Germans on the Rhine, and the Celts upon the Loire, are all offshoots of a single stem. Among the Turanians the connections between one race and another are only perceptible in the case of tribes living in close neighbourhood to one another, who have had mutual relations over a long course of years. In such a case the natural affinities are easily seen, and a family of peoples can be established with certainty. The classification is less definitely marked and clearly [Pg 21] divided than that of the Aryan and Semitic families; but, nevertheless, it has a real value for the historian.[40]

According to the doctrine which now seems most widely accepted, it was from the crowded ranks of the immense army which peopled the north that the tribes who first attempted a civilized life in the plains of Shinar and the fertile slopes between the mountains and the left bank of the Tigris, were thrown off. It is thought that these tribes already possessed a national constitution, a religion, and a system of legislation, the art of writing and the most essential industries, when they first took possession of the lands in question.[41] A tradition still current among the eastern Turks puts the cradle of the race in the valleys of the Altaï, north of the plateau of Pamir.[42] Whether the emigrants into Chaldæa brought the rudiments of their civilization with them, or whether their inventive faculties were only stirred to action after their settlement in that fertile land, is of slight importance. In any case we may say that they were the first to put the soil into cultivation, and to found industrious and stationary communities along the banks of its two great rivers. Once settled in Chaldæa, they called themselves, according to M. Oppert, the people of Sumer, a title which is continually associated with that of "the people of Accad" in the inscriptions.[43]

NOTES

[28] History of Art in Ancient Egypt, vol. i. p. 15 (London, 1883, Chapman and Hall). Upon the Chaldæan chadoufs see Layard, Discoveries, pp. 109, 110.

[29] Genesis xi. 2.

[30] Genesis x. 8-12.

[31] Genesis x. 6-20.

[32] Genesis x. 22: "The children of Shem."

[33] Genesis xi. 27-32.

[34] In his paper upon the Date des Écrits qui portent les Noms de Bérose et de Manéthou (Hachette, 8vo. 1873), M. Ernest Havet has attempted to show that neither of those writers, at least as they are presented in the fragments which have come down to us, deserve the credence which is generally accorded to them. The paper is the production of a vigorous and independent intellect, and there are many observations which should be carefully weighed, but we do not believe that, as a whole, its hypercritical conclusions have any chance of being adopted. All recent progress in Egyptology and Assyriology goes to prove that the fragments in question contain much authentic and precious information, in spite of the carelessness with which they were transcribed, often at second and third hand, by abbreviators of the basse époque.

[35] See § 2 of Fragment 1. of Berosus, in the Fragmenta Historicorum Græcorum of Ch. Müller (Bibliothèque Grecque-Latine of Didot), vol. ii. p. 496; Εν δε τη Βαβυλωνι πολυ πληθος ανθρωπων γενεσθαι αλλοεθνων κατοικησαντων την Χαλδαιαν.

[36] Gaston Maspero, Histoire ancienne des Peuples de l'Orient, liv. ii. ch. iv. La Chaldée. François Lenormant, Manuel d'Histoire ancienne de l'Orient, liv. iv. ch. i. (3rd edition).

[37] The principal texts in which these terms are to be met with are brought together in the Wörterbuch der griechischen Eigennamen of Pape (3rd edition), under the words Κισσια, Κισσιοι, Κοσσαιοι.

[38] A single voice, that of M. Halévy, is now raised to combat this opinion. He denies that there is need to search for any language but a Semitic one in the oldest of the Chaldæan inscriptions. According to him, the writing under which a Turanian idiom is said to lurk, is no more than a variation upon the Assyrian fashion of noting words, than an early form of writing which owed its preservation to the quasi-sacred character imparted by its extreme antiquity. We have no intention of discussing his thesis in these pages; we must refer those who are interested in the problem to M. Halévy's dissertation in the Journal Asiatique for June 1874: Observations critiques sur les prétendus Touraniens de la Babylonie. M. Stanislas Guyard shares the ideas of M. Halévy, to whom his accurate knowledge and fine critical powers afford no little support.

[39] Maspero, Histoire ancienne, p. 134. Upon the etymology of Turanians see Max Müller's Science of Language, 2nd edition, p. 300, et seq. Upon the constituent characteristics of the Turanian group of races and languages other pages of the same work may be consulted.... The distinction between Turan and Iran is to be found in the literature of ancient Persia, but its importance became greater in the Middle Ages, as may be seen by reference to the great epic of Firdusi, the Shah-Nameh. The kings of Iran and Turan are there represented as implacable enemies. It was from the Persian tradition that Professor Müller borrowed the term which is now generally used to denote those northern races of Asia that are neither Aryans nor Semites.

[40] This family is sometimes called Ural-Altaïc, a term formed in similar fashion to that of Indo-Germanic, which has now been deposed by the term Aryan. It is made up of the names of two mountain chains which seem to mark out the space over which its tribes were spread. Like the word Indo-Germanic, it made pretensions to exactitude which were only partially justified.

[41] This is the opinion of M. Oppert. He was led to the conclusion that their writing was invented in a more northern climate than that of Chaldæa, by a close study of its characters. There is one sign representing a bear, an animal which does not exist in Chaldæa, while the lions which were to be found there in such numbers had to be denoted by paraphrase, they were called great dogs. The palm tree had no sign of its own. See in the Journal Asiatique for 1875, p. 466, a note to an answer to M. Halévy entitled Summérien ou rien.

[42] Maspero, Histoire ancienne, p. 135.

[43] These much disputed terms, Sumer and Accad, are, according to MM. Halévy and Guyard, nothing but the geographical titles of two districts of Lower Chaldæa.

The writing of Chaldæa, like that of Egypt, was, in the beginning, no more than the abridged and conventionalized representation of familiar objects. The principle was identical with that of [Pg 22] the Egyptian hieroglyphs and of the oldest Chinese characters. There are no texts extant in which images are exclusively used,[44] but we can point to a few where the ideograms have preserved their primitive forms sufficiently to enable us to recognize their origin with certainty. Among those Assyrian syllabaries which have been so helpful in the decipherment of the wedges, there is one tablet where the primitive form of each symbol is placed opposite the group of strokes which had the same value in after ages.[45]

This tablet is, however, quite exceptional, and, as a rule, the cuneiform characters cannot thus be traced to their primitive form. But well-ascertained and independent facts allow us to come to certain conclusions which even this scanty evidence is enough to confirm.

In inventing the process of writing and bringing it to perfection, the human intellect worked on the same lines among the Turanians of Chaldæa as it did everywhere else. The point of departure and the early stages have been the same for all peoples, although some have stopped half-way and others when three-fourths of the journey were complete. The supreme discovery which should crown the effort is the attribution of a special sign to each of the elementary articulations of the human voice. This final object, an object towards which the most gifted nations of antiquity were working for so many centuries, was just missed by the Egyptians. They were, we may say, wrecked in port, and the glory of creating [Pg 23] the alphabet that men will use as long as they think and write was reserved for the Phœnicians.

Even when their civilization was at its height the Babylonians never came so near to alphabetism as the Egyptians. This is not the place for an inquiry into the reasons of their failure, nor even for an explanation how signs with a phonetic value forced themselves in among the ideograms, and became gradually more and more important. Our interest in the two kinds of writing is of a different nature; we have to learn and explain their influence upon the plastic arts in the countries where they were used.

In our attempt to define the style of Egyptian sculpture and to give reasons for its peculiar characteristics, we felt obliged to attribute great importance to the habits of eye and hand suggested and confirmed by the cutting and painting of the hieroglyphs. In their monumental inscriptions, if nowhere else, the symbols of the Egyptian system retained their concrete imagery to the end; and the images, though abridged and simplified, never lost their resemblance;[46] and if it is necessary to know something more than the particular animal or thing which they represent before we can get at their meaning, that is only because in most cases they had a metaphorical or even a purely phonetic signification as well as their ideographic one. For the most part, however, it is easy to recognize their origin, and in this they differ greatly from the symbols of the first Chaldæan alphabet. In the very oldest documents there are certain ideograms that, when we are warned, remind us of the natural objects from which their forms have been taken, but the connection is slight and difficult of apprehension. Even in the case of those characters whose forms most clearly suggest their true figurative origin, it would have been impossible to assign its prototype to each without the help of later texts, where, with more or less modification, they formed parts of sentences whose general significance was known. Finally, the Assyrian syllabaries have preserved the meaning of signs, that, so far as we can judge, would otherwise have been stumbling-blocks even to the wise men of Nineveh when they were confronted with such ancient inscriptions as those whose fragments are still found among the ruins of Lower Chaldæa.

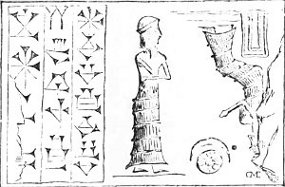

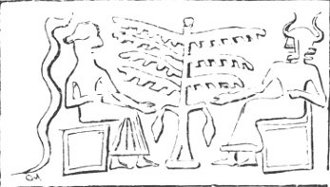

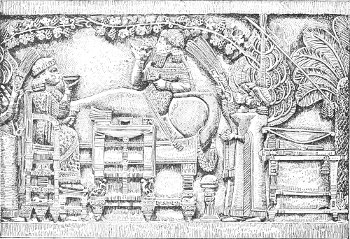

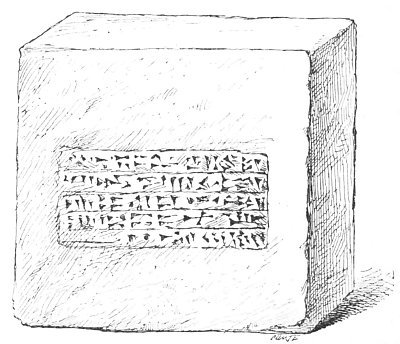

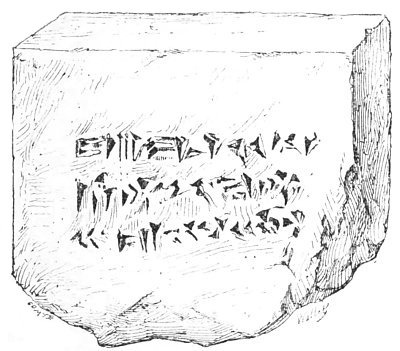

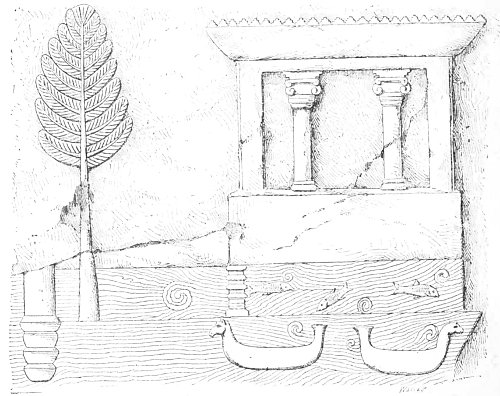

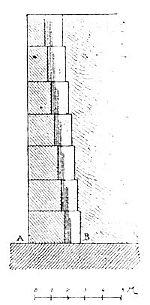

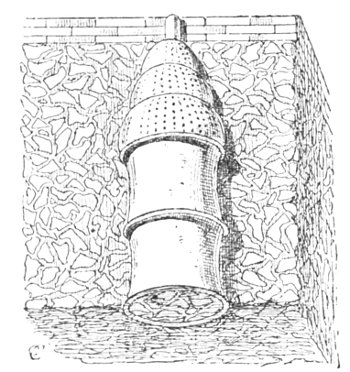

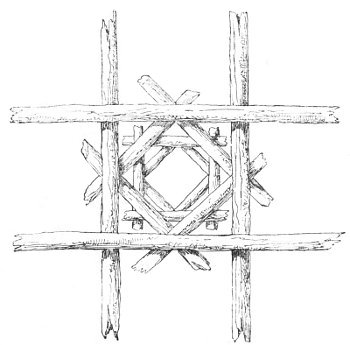

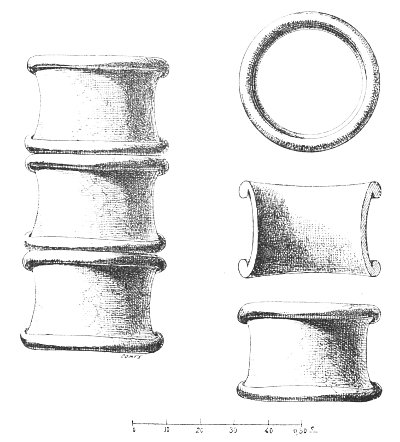

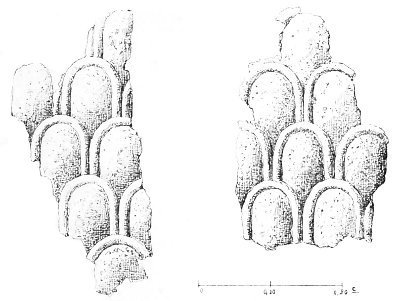

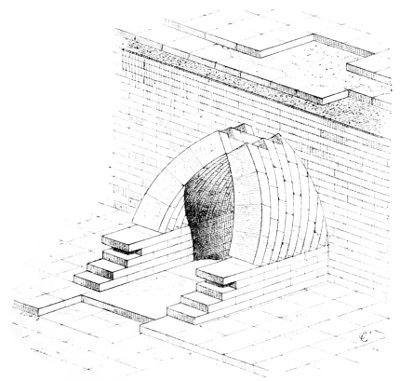

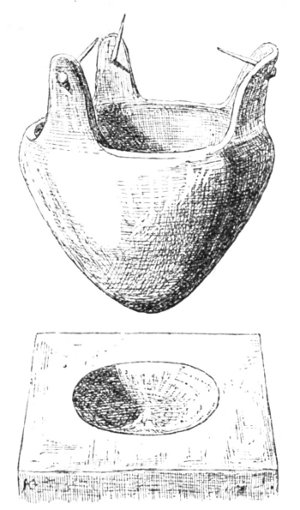

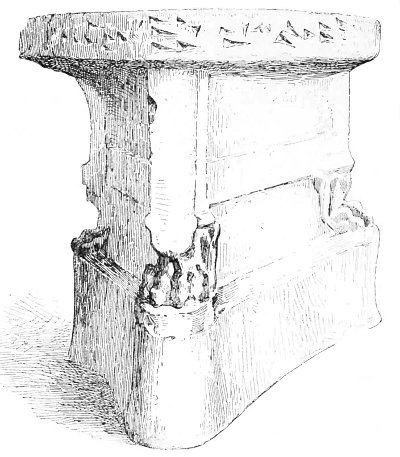

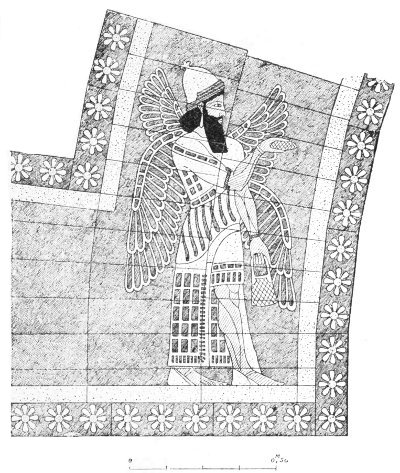

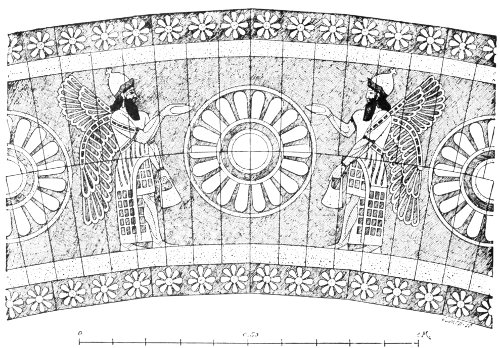

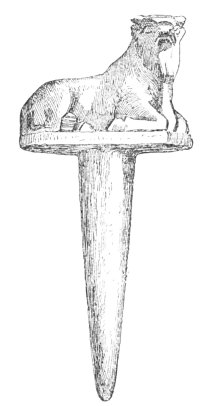

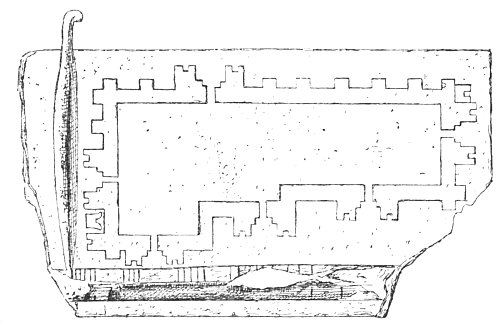

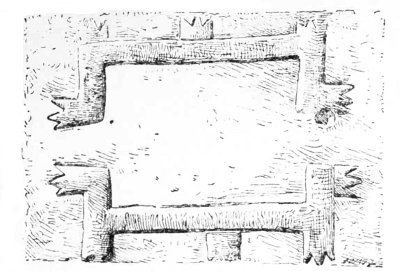

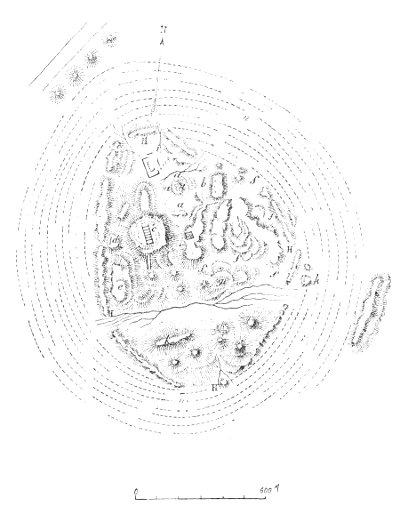

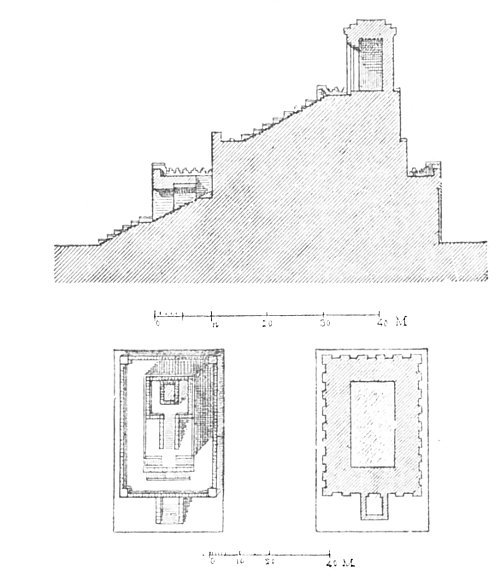

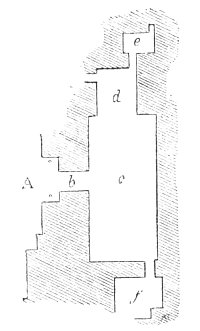

Even in the remote days that saw the most venerable of these inscriptions cut, the images upon which their forms were based [Pg 24] had been rendered almost unrecognizable by a curious habit, or caprice, which is unique in history. Writing had not yet become entirely cuneiform, it had not yet adopted those triangular strokes which are called sometimes nails, sometimes arrow-heads, and sometimes wedges, as the exclusive constituents of its character. If we examine the tablets recovered by Mr. Loftus from the ruins of Warka, the ancient Erech (Fig. 1), or the inscriptions upon the diorite statues found at Tello by M. de Sarzec (Fig. 2), we shall find that in the distant period from which those writings date, most of the characters had what we may call an unbroken trace.[47] This trace, like that of the hieroglyphs, would have been well fitted for the succinct imitation of natural objects but for a rigid exclusion of those curves of which nature is so fond. This exclusion is complete, all the lines are straight, and cut one another at various angles. The horror of a curve is pushed so far that even the sun, which is represented by a circle in Egyptian and other ideographic systems, is here a lozenge.

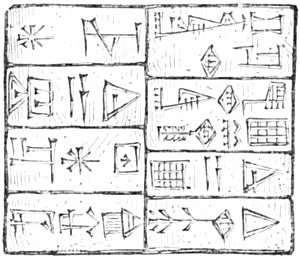

Fig. 1.—Brick from Erech.

Fig. 1.—Brick from Erech.

It is very unlikely that even the oldest of these texts show us Chaldæan writing in its earliest stage. Analogy would lead us to think that these figures must at one time have been more directly imitative. However that may have been, the image must have been very imperfect from the day that the rectilinear trace came into general use. Figures must then have rapidly degenerated into conventional signs. Those who used them could no longer [Pg 27] pretend to actually represent the objects they wished to denote. They must have been content to suggest their ideas by means of a character whose value had been determined by usage. This transformation would be accelerated by certain habits which forced themselves upon the people as soon as they were finally established in the land of Shinar.

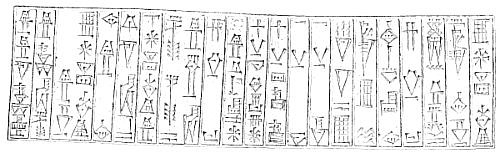

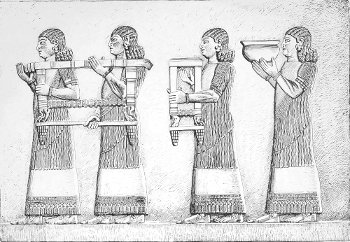

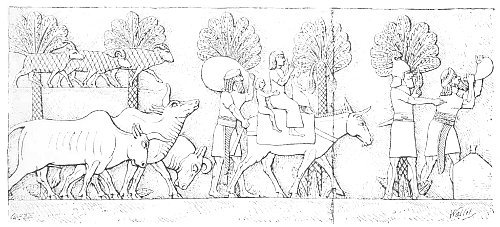

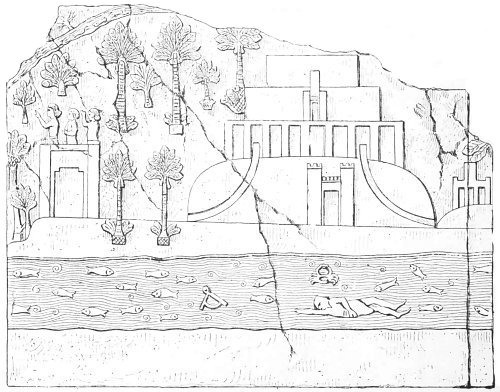

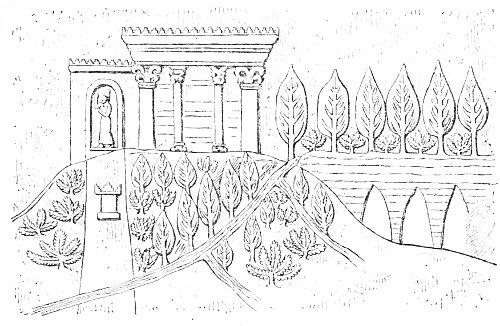

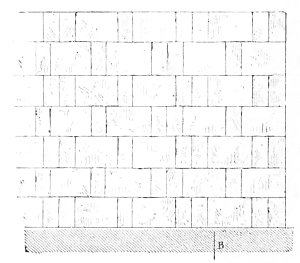

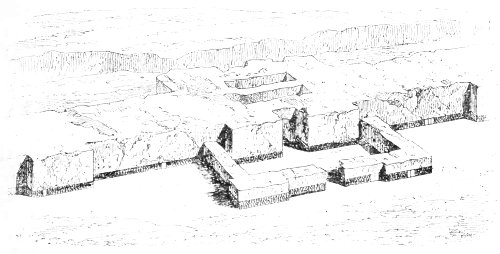

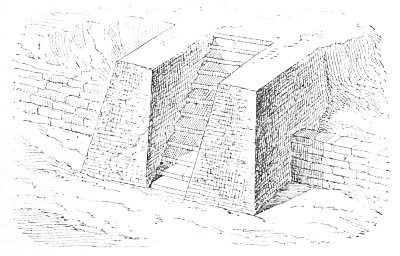

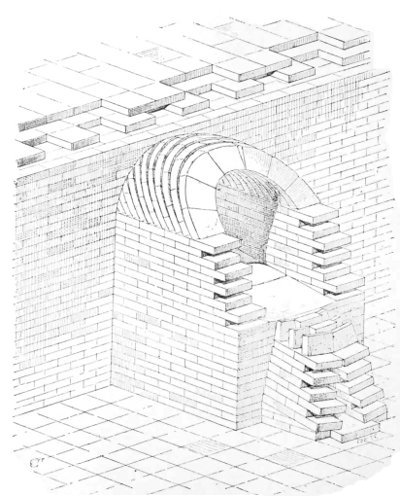

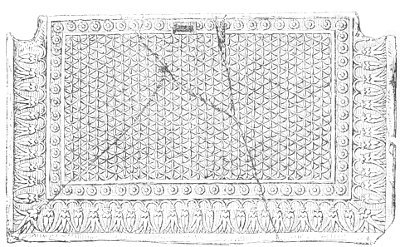

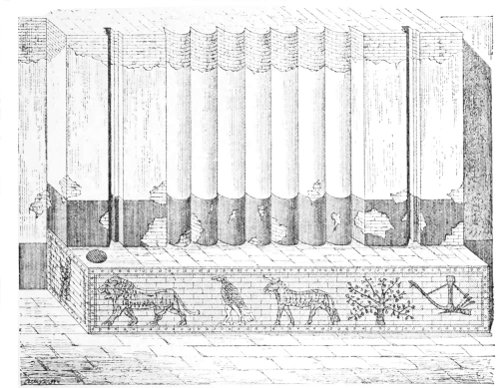

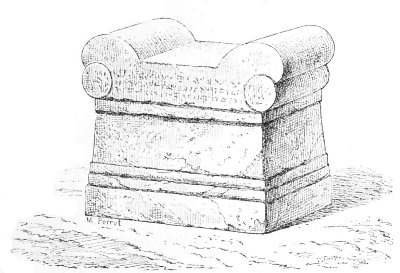

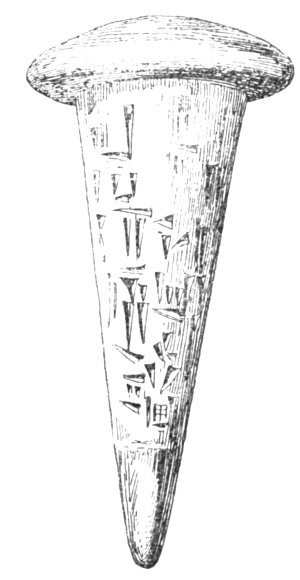

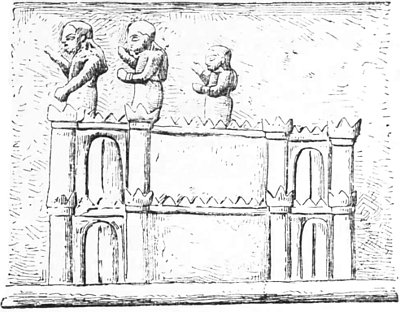

Fig. 2.—Fragment of an inscription engraved upon the back

of a statue from Tello. Louvre. (Length 10¼ inches.)

Fig. 2.—Fragment of an inscription engraved upon the back

of a statue from Tello. Louvre. (Length 10¼ inches.)

We are told that there are certain expressions in the Assyrian language which lead to the belief that the earliest writing was on the bark of trees, that it offered the first surface to the scribe in those distant northern regions from which the early inhabitants of Chaldæa were emigrants. It is certain that the dwellers in that vast alluvial plain were compelled by the very nature of the soil to use clay for many purposes to which no other civilization has put it. In Mesopotamia, as in the valley of the Nile, the inhabitants had but to stoop to pick up an excellent modelling clay, fine in texture and close grained—a clay which had been detached from the mountain sides by the two great rivers, and deposited in inexhaustible quantities over the whole width of the double valley. We shall see hereafter what an important part bricks, crude, fired, and enamelled, played in the construction and decoration of Chaldæan buildings. It was the same material that received most of their writing.

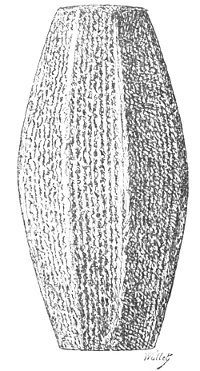

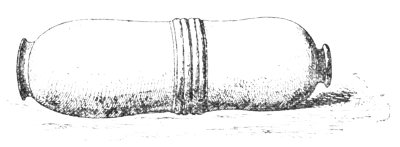

Clay offered a combination of facility with durability which no other material could equal. While soft and wet it readily took the shape of any figure impressed upon it. The deftly-handled tool could engrave characters upon its yielding surface almost as fast as the reed could trace them upon papyrus, and much more rapidly than the chisel could cut them in wood. Again, in its final condition as solid terra-cotta, it offered a chance of duration far beyond that of either wood or papyrus. Once safely through the kiln it had nothing to fear short of deliberate destruction. The message intrusted to a terra-cotta slab or cylinder could only be finally lost by the reduction of the latter to powder. At Hillah, the town which now occupies a corner of the vast space once covered by the streets of Babylon, bricks are found built into the walls to this day, upon which the Assyrian scholar may read as he runs the royal style and titles of Nebuchadnezzar.[48]

As civilization progressed, the dwellers upon the Persian Gulf felt an ever-increasing attraction towards the art of writing. It afforded a medium of communication with distant points, and a bond of connection [Pg 28] between one generation and another; by its means the son could profit by the accumulated experience of the father. The slab of terra-cotta was the most obvious material for its reception. It cost almost nothing, while such an elaborate substance as the papyrus of Egypt can never have been very cheap. It lent itself kindly to the service demanded of it, and the writer who had confided his thoughts to its surface had only to fire it for an hour or two to secure them a kind of eternity. This latter precaution did not require any very lengthy journey; brick kilns must have blazed day and night from one end of Chaldæa to another.

If we consider for a moment the properties of the material, and examine the remains which have come down to us, we shall understand at once what writing was certain to become under the triple impulse of a desire to write much, to write fast, and to use clay as we moderns use paper. Suppose oneself compelled to trace upon clay figures whose lines necessitated continual changes of direction; at each angle or curve it would be necessary to turn the hand, and with it the tool, because the clay surface, however tender it might be, would still afford a certain amount of resistance. Such resistance would hardly be an obstacle, but it would in some degree diminish the speed with which the tool could be driven. Now, as soon as writing comes into common use, most of those who employ it in the ordinary matters of life have no time to waste. It is important that all hindrances to rapid work should be avoided. The designs of the old writing with their strokes sometimes broken, sometimes continuous, sometimes thick, and sometimes thin, wearied the writer and took much time, and at last it came about that the clay was attacked in a number of short, clear-cut triangular strokes each similar in form to its fellow. As these little depressions had all the same depth and the same shape, and as the hand had neither to change its pressure nor to shift its position, it arrived with practice at an extreme rapidity of execution.

Some have asserted that the instrument with which these marks were made has

been found among the Mesopotamian ruins. It is, we are told, a small style

in bone or ivory with a bevelled triangular point.[49] And yet when we look

with attention at these

[Pg 29]

terra-cotta inscriptions, we fall to doubting

whether the hollow marks of which they are composed could have been made by

such a point. There is no sign of those scratches which we should expect to

find left by a sharp instrument in its process of cutting out and removing

part of the clay. The general appearance of the surface leads us rather to

think that the strokes were made by thrusting some instrument with a sharp

ridge like the corner of a flat rule, into the clay, and that nothing was

taken away as in the case of wood or marble, but an impression made by

driving back the earth into itself.[50] However this may be, the first

element of the cuneiform writing was a hollow incision made by a single

movement of the hand, and of a form which may be compared to a greatly

elongated triangle. These triangles were sometimes horizontal, sometimes

vertical, sometimes oblique, and when arranged in more or less complex

groups, could easily furnish all the necessary symbols. In early ages, the

elements of some of these ideographic or phonetic signs—signs which

afterwards became mere complex groups of wedges—were so arranged as to

suggest the primitive forms—that is, the more or less roughly blocked out

images—from which they had originally sprung. The fish may easily be

recognized in the following group

![]() : while the character that

stands for the sun,

: while the character that

stands for the sun,

![]() , reminds us of the lozenge which was the

primitive sign for that luminary. In the two symbols

, reminds us of the lozenge which was the

primitive sign for that luminary. In the two symbols

![]() and

and

![]() , we may, with a little good will, recognize a shovel with its

handle, and an ear. But even in the oldest texts the instances in which

the primitive types are still recognizable are very few; the wedge has in

nearly every case completely transfigured, and, so to speak, decomposed,

their original features.

, we may, with a little good will, recognize a shovel with its

handle, and an ear. But even in the oldest texts the instances in which

the primitive types are still recognizable are very few; the wedge has in

nearly every case completely transfigured, and, so to speak, decomposed,

their original features.

This is the case even in what is called the Sumerian system itself, and when its signs and processes were borrowed by other nations, the tendency to abandon figuration was of course still more marked. It has now been clearly proved that the wedges have served the turn of at least four languages beside that of the people who devised them, and that in passing from one people to another their groups never lost the phonetic value [Pg 30] assigned to them by their first inventors.[51]

In the absence of this extended employment all attempts to decipher the wedges would have been condemned to almost certain failure from the first, but as soon as its existence had been placed beyond doubt, there was every reason to count upon success. It allowed the words of a text to be transliterated into phonetic characters, and that being done, to discover their meaning was but an affair of time, patience, and method.

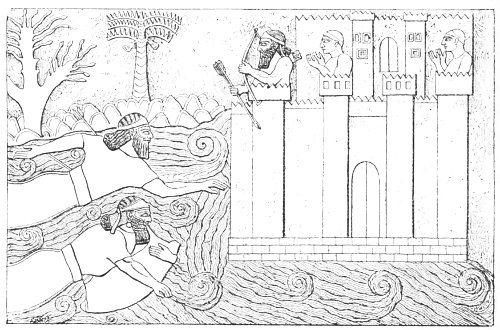

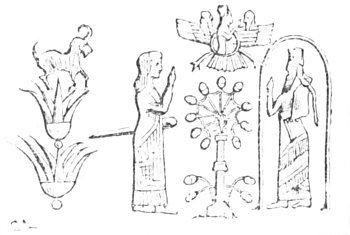

We see then, that the system of signs invented by the first inhabitants of Chaldæa had a vogue similar to that which attended the alphabet of the Phœnicians in the Mediterranean basin. For all the peoples of Western Asia it was a powerful agent of progress and civilization. We can understand, therefore, how it was that the wedge, the essential element of all those groups which make up cuneiform writing, became for the Assyrian one of the holy symbols of the divine intelligence. Upon the stone called the Caillou Michaud, from the name of its discoverer, it is shown standing upon an altar and receiving the prayers and homage of a priest.[52] It deserved all the respect it received; thanks to it the Babylonian genius was able to rough out and hand down to posterity the science from which Greece was to profit so largely.

And yet, in spite of all the services it had rendered, this form of writing fell into disuse towards the commencement of our era; it was supplanted even in the country of its origin by alphabets derived from that of the Phœnicians.[53] It had one grave defect: its phonetic signs always [Pg 31] represented syllables. No one of the wedge-using communities made that decisive step in advance of which the honour belongs to the Phœnicians alone. No one of them carried the analysis of language so far as to reduce the syllable to its elements, and to distinguish the consonant, mute by itself, from the vowel upon which it depends, if we may say so, for an active life.

All those races who have not borrowed their alphabet en bloc from their neighbours or predecessors but have invented it for themselves, began with the imitation of objects. At first we have a mere outline, made to gratify some special want.[54] The more these figures were repeated, the more they tended towards a single stereotyped form, and that an epitomized and conventional one. They were only signs, so that it was not in the least necessary to painfully reproduce every feature of the original model, as if the latter were copied for its plastic beauty. As time passed on, writing and drawing won separate existences; but at first they were not to be distinguished one from the other, the latter was but a use of the former, and, in a sense, we may even say that writing was the first and simplest of the plastic arts.

In Egypt this art remained more faithful to its origin than elsewhere. Even when it had attained the highest development it ever reached in that country, and was on the point of crowning its achievements by the invention of a true alphabet, it continued to reproduce the general shapes and contours of objects. The hieroglyphs were truly a system of writing by which all the sounds of the language could be noted and almost reduced to their final elements; but they were also, up to their last day, a system of design in which the characteristic features of genera and species, if not of individuals, were carefully distinguished.

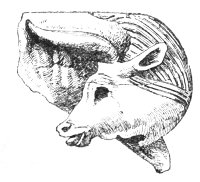

Was it the same in Chaldæa? Had the methods, and what we may call the style of the national writing, any appreciable influence upon the plastic arts, upon the fashion in which living nature was understood and reproduced? We do not think it had, and the reason of the difference is not far to seek. The very oldest of the ideographic signs of Chaldæa are much farther removed from the objects upon which they were based than the Egyptian hieroglyphs; [Pg 32] and when the wedge became the primary element of all the characters, the scribe ceased to give even the most distant hint of the real forms of the things signified. Throughout the period which saw those powerful empires flourishing in Mesopotamia whose creations were admired and copied by all the peoples of Western Asia, the more or less complex groups and arrangements of the cuneiform writing, to whatever language applied, had no aim but to represent sometimes whole words, sometimes the syllables of which those words were composed. Under such conditions it seems unlikely that the forms of the written characters can have contributed much to form the style of artists who dealt with the figures of men and animals. We may say that the sculptors and painters of Chaldæa were not, like those of Egypt, the scholars of the scribes.

And yet there is a certain analogy between the handling of the inscriptions and that of the bas-reliefs. It is doubtless in the nature of the materials employed that we must look for the final explanation of this similarity, but it is none the less true that writing was a much earlier and a much more general art than sculpture. The Chaldæan artist must have carried out his modelling with a play of hand and tool learnt in cutting texts upon clay, and still more, upon stone. The same chisel-stroke is found in both; very sure, very deep, and a little harsh.

However this may be, we cannot embark upon the history of Art in Chaldæa without saying a word upon her graphic system. If there be one proof more important than another of the great part played by the Chaldæans in the ancient world, it is the success of their writing, and its diffusion as far as the shores of the Euxine and the eastern islands of the Mediterranean. Some cuneiform texts have lately been discovered in Cappadocia, the language of which is that of the country,[55] and the most recent discoveries point to the conclusion that the Cypriots borrowed from Babylonia the symbols by which the words of the Greek dialect spoken in their island were noted.[56]

[Pg 33] We have yet to visit more than one famous country. In our voyage across the plains where antique civilization was sketched out and started on its long journey to maturity, we shall, whenever we cross the frontiers of a new people, begin by turning our attention for a space to their inscriptions; and wherever we are met by those characters which are found in their oldest shapes in the texts from Lower Chaldæa, there we shall surely find plastic forms and motives whose primitive types are to be traced in the remains of Chaldæan art. A man's writing will often tell us where his early days were passed and under what masters his youthful intellect received the bent that only death can take away.

NOTES

[44] We are told that there is an inscription at Susa of this character. It has been examined but not as yet reproduced. We can, therefore, make no use of it. See François Lenormant, Manuel d'Histoire ancienne, vol. ii. p. 156.

[45] M. Lenormant reproduces this tablet in his Histoire ancienne de l'Orient (9th edition, vol. i. p. 420). The whole of the last chapter in this volume should be carefully studied. It is well illustrated, and written with admirable clearness. The same theories and discoveries are explained at greater length in the introduction to M. Lenormant's great work entitled Essai sur la Propagation de l'Alphabet phenicien, of which but one volume has as yet appeared (Maisonneuve, 8vo., 1872). At the very commencement of his investigations M. Oppert had called attention to the curious forms presented by certain characters in the oldest inscriptions. See Expédition scientifique de Mésopotamie, vol. ii. pp. 62, 3, notably the paragraph entitled Origine Hiéroglyphique de l'Écriture anarienne. The texts upon which the remarks of MM. Oppert and Lenormant were mainly founded were published under the title of Early Inscriptions from Chaldæa in the invaluable work of Sir Henry Rawlinson (A Selection from the Historical Inscriptions of Chaldæa, Assyria, and Babylonia, prepared for publication by Major-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, assisted by Edwin Norris, British Museum, folio, 1861).

[46] See the History of Art in Ancient Egypt, vol. ii. pp. 350-3 (?).

[47] This peculiarity is still more conspicuous in the engraved limestone pavement which was discovered in the same place, but the fragments are so mutilated as to be unfit for reproduction here.

[48] Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, p. 506.

[49] Oppert, Expédition scientifique de Mésopotamie, vol. ii. pp. 62, 3.

[50] Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, vol. ii. p. 180.

[51] A list of these languages, and a condensed but lucid explanation of the researches which have led to the more or less complete decipherment of the different groups of texts will be found in the Manuel de l'Histoire ancienne de l'Orient of Lenormant, 3rd edition, vol. ii. pp. 153, &c.—"Several languages—we know of five up to the present moment—have given the same phonetic value to these symbols. It is clear, however, that a single nation must have invented the system," Oppert, Journal Asiatique, 1875, p. 474. M. Oppert has given an interesting account of the mode of decipherment in the Introduction and in Chapter 1. of the first volume of his Expédition scientifique de Mésopotamie.

[52] A reproduction of this stone will be found farther on. The detail in question is engraved in Layard's Nineveh and its Remains, vol. ii. p. 181.

[53] The latest cuneiform inscription we possess dates from the time of Domitian. It has been published by M. Oppert, Mélanges d'Archéologie égyptienne et assyrienne, vol. i. p. 23 (Vieweg, 1873, 4to.). Some very long ones, from the time of the Seleucidæ and the early Arsacidæ, have been discovered.

[54] Hence the name pictography which some scholars apply to this primitive form of writing. The term is clear enough, but unluckily it is ill composed: it is a hybrid of Greek and Latin, which is sufficient to prevent its acceptance by us.

[55] See the Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archæology, twelfth session, 1881-2.

[56] See Michel Bréal, Le Déchiffrement des Inscriptions cypriotes (Journal des Savants, August and September, 1877). In the last page of his article, M. Bréal, while fully admitting the objections, asserts that it is "difficult to avoid recognizing the general resemblance (difficile de méconnaître la ressemblance générale)." He refers us to the paper of Herr Deecke, entitled Der Ursprung der Kyprischen Sylbenschrift, eine palæographische Untersuchung, Strasbourg, 1877. Another hypothesis has been lately started, and an attempt made to affiliate the Cypriot syllabary to the as yet little understood hieroglyphic system of the Hittites. See a paper by Professor A. H. Sayce, A Forgotten Empire in Asia Minor, in No. 608 of Fraser's Magazine.

§ 5.—The History of Chaldæa and Assyria.