Title: Chelsea

Author: G. E. Mitton

Editor: Walter Besant

Release date: November 28, 2008 [eBook #27356]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Susan Skinner and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Susan Skinner

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

THE FASCINATION

OF LONDON

CHELSEA

IN THIS SERIES.

Cloth, price 1s. 6d. net; leather, price 2s. net, each.

CHELSEA.

By G. E. Mitton. Edited by Sir Walter Besant.

WESTMINSTER.

By Sir Walter Besant and G. E. Mitton.

THE STRAND DISTRICT.

By Sir Walter Besant and G. E. Mitton.

HAMPSTEAD.

By G. E. Mitton. Edited by Sir Walter Besant.

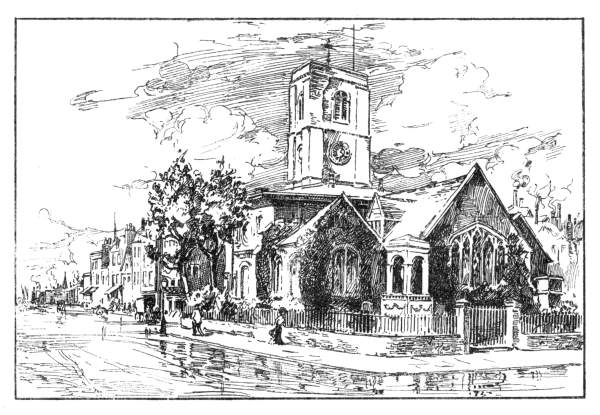

CHELSEA OLD CHURCH.

After an etching by Miss E. Piper.

BY

G. E. MITTON

EDITED BY

SIR WALTER BESANT

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1902

A survey of London, a record of the greatest of all cities, that should preserve her history, her historical and literary associations, her mighty buildings, past and present, a book that should comprise all that Londoners love, all that they ought to know of their heritage from the past—this was the work on which Sir Walter Besant was engaged when he died.

As he himself said of it: “This work fascinates me more than anything else I’ve ever done. Nothing at all like it has ever been attempted before. I’ve been walking about London for the last thirty years, and I find something fresh in it every day.”

He had seen one at least of his dreams realized in the People’s Palace, but he was not destined to see this mighty work on London take form. He died when it was still incomplete. His scheme included several volumes on the history of London as a whole. These he finished up to the end of the eighteenth century, and they form a record of the great city practically unique, and exceptionally viii interesting, compiled by one who had the qualities both of novelist and historian, and who knew how to make the dry bones live. The volume on the eighteenth century, which Sir Walter called a “very big chapter indeed, and particularly interesting,” will shortly be issued by Messrs. A. and C. Black, who had undertaken the publication of the Survey.

Sir Walter’s idea was that the next two volumes should be a regular and systematic perambulation of London by different persons, so that the history of each parish should be complete in itself. This was a very original feature in the great scheme, and one in which he took the keenest interest. Enough has been done of this section to warrant its issue in the form originally intended, but in the meantime it is proposed to select some of the most interesting of the districts and publish them as a series of booklets, attractive alike to the local inhabitant and the student of London, because much of the interest and the history of London lie in these street associations. For this purpose Chelsea, Westminster, the Strand, and Hampstead have been selected for publication first, and have been revised and brought up to date.

The difficulty of finding a general title for the series was very great, for the title desired was one that would express concisely the undying charm ix of London—that is to say, the continuity of her past history with the present times. In streets and stones, in names and palaces, her history is written for those who can read it, and the object of the series is to bring forward these associations, and to make them plain. The solution of the difficulty was found in the words of the man who loved London and planned the great scheme. The work “fascinated” him, and it was because of these associations that it did so. These links between past and present in themselves largely constitute The Fascination of London.

G. E. M.

| PAGE | |

| Prefatory Note | vii |

| PART I | |

| Chelsea South of the King's Road | 1 |

| PART II | |

| Chelsea North of the King's Road | 55 |

| PART III | |

| The Royal Hospital and Ranelagh Gardens | 67 |

| Index | 97 |

| Map at end of Volume. | |

The name Chelsea, according to Faulkner and Lysons, only began to be used in the early part of the eighteenth century. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the place was known as Chelsey, and before that time as Chelceth or Chelchith. The very earliest record is in a charter of King Edward the Confessor, where it is spelt Cealchyth. In Doomsday Book it is noted as Cercehede and Chelched. The word is derived variously. Newcourt ascribes it to the Saxon word ceald, or cele, signifying cold, combined with the Saxon hyth, or hyd, a port or haven. Norden believes it to be due to the word “chesel” (ceosol, or cesol), a bank “which the sea casteth up of sand or pebble-stones, thereof called Cheselsey, briefly Chelsey, as is Chelsey [Winchelsea?] in Sussex.” Skinner agrees with him substantially, deriving the principal part of the word from banks of sand, and the ea or ey from land situated near 2 the water; yet he admits it is written in ancient records Cealchyth—“chalky haven.” Lysons asserts that if local circumstances allowed it he would have derived it from “hills of chalk.” Yet, as there is neither hill nor chalk in the parish, this derivation cannot be regarded as satisfactory. The difficulty of the more generally received interpretation—viz., shelves of gravel near the water—is that the ancient spelling of the name did undoubtedly end in hith or heth, and not in ea or ey.

The dividing line which separated the old parish of Chelsea from the City of Westminster was determined by a brook called the Westbourne, which took its rise near West End in Hampstead. It flowed through Bayswater and into Hyde Park. It supplied the water of the Serpentine, which we owe to the fondness of Queen Caroline for landscape gardening. This well-known piece of water was afterwards supplied from the Chelsea waterworks. The Westbourne stream then crossed Knightsbridge, and from this point formed the eastern boundary of St. Luke’s parish, Chelsea. The only vestige of the rivulet now remaining is to be seen at its southern extremity, where, having become a mere sewer, it empties itself into the Thames about 300 yards above the bridge. The 3 name survives in Westbourne Park and Westbourne Street. The boundary line of the present borough of Chelsea is slightly different; it follows the eastern side of Lowndes Square, and thence goes down Lowndes Street, Chesham Street, and zigzags through Eaton Place and Terrace, Cliveden Place, and Westbourne Street, breaking off from the last-named at Whitaker Street, thence down Holbein Place, a bit of Pimlico, and Bridge Road to the river.

In a map of Chelsea made in 1664 by James Hamilton, the course of the original rivulet is clearly shown. The northern boundary of Chelsea begins at Knightsbridge. The north-western, that between Chelsea and Kensington, runs down Basil and Walton Streets, and turns into the Fulham Road at its junction with the Marlborough Road. It follows the course of the Fulham Road to Stamford Bridge, near Chelsea Station. The western boundary, as well as the eastern, had its origin in a stream which rose to the north-west of Notting Hill. Its site is now occupied by the railway-line (West London extension); the boundary runs on the western side of this until it joins an arm of Chelsea Creek, from which point the Creek forms the dividing line to the river.

The parish of Chelsea, thus defined, is roughly triangular in shape, and is divided by the King’s Road into two nearly equal triangles. 4

An outlying piece of land at Kensal Town belonged to Chelsea parish, but is not included in the borough.

The population in 1801 was 12,079. In the year 1902 (the latest return) it is reckoned at 73,842.

Bowack, in an account of Chelsea in 1705, estimates the inhabited houses at 300; they are now computed at 8,641.

The first recorded instance of the mention of Chelsea is about 785, when Pope Adrian sent legates to England for the purpose of reforming the religion, and they held a synod at Cealchythe.

In the reign of Edward the Confessor Thurstan gave Chilchelle or Chilcheya, which he held of the King, to Westminster Abbey. This gift was confirmed by a charter which is in the Saxon language, and is still preserved in the British Museum. Gervace, Abbot of Westminster, natural son of King Stephen, aliened the Manor of Chelchithe; he bestowed it upon his mother, Dameta, to be held by her in fee, paying annually to the church at Westminster the sum of £4. In Edward III.’s reign one Robert de Heyle leased the Manor of Chelsith to the Abbot and Convent 5 of Westminster during his own lifetime, for which they were to make certain payments: “£20 per annum, to provide him daily with two white loaves, two flagons of convent ale, and once a year a robe of Esquier’s silk.” The manor at that time was valued at £25 16s. 6d. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster hold among their records several court rolls of the Manor of Chelsea during the reigns of Edward III. and Richard II. With the exception that one Simon Bayle seems to have been lessee of the Manor House in 1455, we know nothing definite of it until the reign of Henry VII., after which the records are tolerably clear. It was then held by Sir Reginald Bray, and from him it descended to his niece Margaret, who married Lord Sandys. Lord Sandys gave or sold it to Henry VIII., and it formed part of the jointure of Queen Catherine Parr, who resided there for some time with her fourth husband, Lord Seymour.

Afterwards it appears to have been granted to the Duke of Northumberland, who was beheaded in 1553 for his attempt to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne. The Duchess of Northumberland held it for her life, and at her death it was granted to John Caryl, who only held it for a few months before parting with it to John Bassett, “notwithstanding which,” says Lysons, “Lady Anne of Cleves, in the account of her funeral, 6 is said to have died at the King and Quene’s majestys’ Place of Chelsey beside London in the same year.”

Queen Elizabeth gave it to the Earl of Somerset’s widow for life, and at her death it was granted to John Stanhope, afterwards first Lord Stanhope, subject to a yearly rent-charge. It is probable that he soon surrendered it, for we find it shortly after granted by Queen Elizabeth to Katherine, Lady Howard, wife of the Lord Admiral. Then it was held by the Howards for several generations, confirmed by successive grants, firstly to Margaret, Countess of Nottingham, and then to James Howard, son of the Earl of Nottingham, who had the right to hold it for forty years after the decease of his mother. She, however, survived him, and in 1639 James, Duke of Hamilton, purchased her interest in it, and entered into possession. He only held it until the time of the Commonwealth, when it was seized and sold; but it seems that the purchasers, Thomas Smithby and Robert Austin, only bought it to hold in trust for the heirs of Hamilton, for in 1657 Anne, daughter and coheiress of the Duke of Hamilton, and her husband, Lord Douglas, sold it to Charles Cheyne. He bought it with part of the large dower brought him by his wife, Lady Jane Cheyne, as is recorded on her tombstone in Chelsea Church. Sir Hans Sloane in 1712 purchased it from the then Lord 7 Cheyne. He left two daughters, who married respectively Lord Cadogan and George Stanley. As the Stanleys died out in the second generation, their share reverted by will to the Cadogans, in whom it is still vested.

Beginning our account of Chelsea at a point in the eastern boundary in the Pimlico Road, we have on the right-hand side Holbein Place, a modern street so named in honour of the great painter, who was a frequent visitor at Sir Thomas More’s house in Chelsea. Holbein Place curves to the west, and finally enters Sloane Square.

In the Pimlico Road, opposite to the barracks, there stood until 1887-88 a shop bearing the sign of the “Old Chelsea Bun House.” But this was not the original Bun House, which stood further eastward, outside the Chelsea boundary. It had a colonnade projecting over the pavement, and it was fashionable to visit it in the morning. George II., Queen Caroline, and the Princesses frequently came to it, and later George III. and Queen Charlotte. A crowd of some 50,000 people gathered in the neighbourhood on Good Friday, and a record of 240,000 buns being sold on that day is reported. Swift, in his Journal to Stella, 1712, writes: “Pray are not fine buns sold here 8 in our town as the rare Chelsea Buns?” In 1839 the place was pulled down and sold by auction.

The barracks, on the south side of the road, face westwards, and have a frontage of a thousand feet in length. As a matter of fact, they are not included in the borough of Chelsea, though the old parish embraced them; but as they are Chelsea Barracks, and as we are here more concerned with sentiment than surveyor’s limits, it would be inexcusable to omit all mention of them.

The chapel stands behind the drill-yard at the back. It is calculated that it seats 800 people. The organ was built by Hill. The brass lectern was erected in 1888 in memory of Bishop Claughton. The east end is in the form of an apse, with seven deeply-set windows, of which only two are coloured. The walls of the chancel are inlaid with alabaster. Round the walls are glazed tiles to the memory of the men of the Guards who have died. The oak pulpit is modern, and the font, cut from a solid block of dark-veined marble and supported by four pillars, stands on a small platform of tessellated pavement. Passing out of the central gateway of the barracks and turning northward, we come to the junction of Pimlico Road and Queen’s Road. From this point to the corner of Smith Street the road is known as Queen’s Road. Along the first part of its southern side is the ancient burial-ground of the 9 hospital. At the western end of this the tombstones cluster thickly, though many of the inscriptions are now quite illegible. The burial-ground was consecrated in 1691, and the first pensioner, Simon Box, was buried here in 1692. In 1854 the ground was closed by the operation of the Intramural Burials Act, but by special permission General Sir Colin Halkett was buried here two years later. His tomb is a conspicuous object about midway down the centre path. It is said that two female warriors, who dressed in men’s clothes and served as soldiers, Christina Davies and Hannah Snell, rest here, but their names cannot be found. The first Governor of the Royal Hospital, Sir Thomas Ogle, K.T., was buried here in 1702, aged eighty-four, and also the first Commandant of the Royal Military Asylum, Lieutenant-Colonel George Williamson, in 1812. The pensioners are now buried in the Brompton Cemetery. For complete account of the Royal Hospital and the Ranelagh Gardens adjoining, see p. 67.

At the corner between Turks Row and Lower Sloane Street there is a great red-brick mansion rising several stories higher than its neighbours. This is an experiment of the Ladies’ Dwelling Company to provide rooms for ladies obliged to live in London on small means, and has a restaurant below, where meals can be obtained at a reasonable 10 rate. The first block was opened in February, 1889. It is in a very prosperous condition, the applications altogether surpassing the accommodation. The large new flats and houses called Sloane Court and Revelstoke and Mendelssohn Gardens have been built quite recently, and replace very “mean streets.” The little church of St. Jude’s—district church of Holy Trinity—stands on the north side of the Row, and at the back are the National and infant schools attached to it. It was opened for service in 1844. In 1890 it was absorbed into Holy Trinity parish. It seats about 800 persons. From Turks Row we pass into Franklin’s Row. On Hamilton’s map (corrected to 1717) we find marked “Mr. Franklin’s House,” not on the site of the present Row, but opposite the north-western corner of Burton’s Court, at the corner of the present St. Leonard’s Terrace and Smith Street. The name Franklin has been long connected with Chelsea, for in 1790 we find John Franklin and Mary Franklin bequeathing money to the poor of Chelsea. At the south end is an old public-house, with overhanging story and red-tiled roof; it is called the Royal Hospital, and contrasts quaintly with its towering modern red-brick neighbours.

The entrance gates of the Royal Military Asylum, popularly known as the Duke of York’s School, open on to Franklin’s Row just before it 11 runs into Cheltenham Terrace. The building itself stands back behind a great space of green grass. It is of brick faced with Portland stone, and is of very solid construction. Between the great elm-trees on the lawn can be seen the immense portico, with the words “The Royal Military Asylum for the Children of the Soldiers of the Regular Army” running across the frieze.

The building is in three wings, enclosing at the back laundry, hospital, Commandant’s house, etc., and great playgrounds for the boys. Long low dormitories, well ventilated, on the upper floors in the central building contain forty beds apiece, while those in the two wings are smaller, with thirteen beds each. Below the big dormitories are the dining-rooms, the larger one decorated with devices of arms; these were brought from the Tower and arranged by the boys themselves. There are 550 inmates, admitted between the ages of nine and eleven, and kept until they are fourteen or fifteen. The foundation was established by the Duke of York in 1801, and was ready for occupation by 1803. It was designed to receive 700 boys and 300 girls, and there was an infant establishment connected with it in the Isle of Wight. In 1823 the girls were removed elsewhere. There are a number of boys at the sister establishment, the Hibernian Asylum, in Ireland. The Commandant, Colonel G. A. W. 12 Forrest, is allowed 6½d. per diem for the food of each boy, and the bill of fare is extraordinarily good. Cocoa and bread-and-butter, or bread-and-jam, for breakfast and tea; meat, pudding, vegetables, and bread, for dinner. Cake on special fête-days as an extra. The boys do credit to their rations, and show by their bright faces and energy their good health and spirits. They are under strict military discipline, and both by training and heredity have a military bias. There is no compulsion exercised, but fully 90 per cent. of those who are eligible finally enter the army; and the school record shows a long list of commissioned and non-commissioned officers, and even two Major-Generals, who owed their early training to the Chelsea Asylum. The site on which the Asylum stands was bought from Lord Cadogan; it occupies about twelve acres, and part of it was formerly used for market-gardens.

One of the schoolrooms has still the pulpit, and a raised gallery running round, which mark it as having been the original chapel; but the present chapel stands at the corner of King’s Road and Cheltenham Terrace. On Sunday morning the boys parade on the green in summer and on the large playground in winter before they march in procession to the chapel with their band playing, a scene which has been painted by Mr. Morris, A.R.A., as “The Sons of the Brave.” The chaplain 13 is the Rev. G. H. Andrews. The gallery of the chapel is open to anyone, and is almost always well filled. The annual expenditure of the Asylum is supplied by a Parliamentary grant.

On Hamilton’s Survey the ground now occupied by the Duke of York’s School is marked “Glebe,” and exactly opposite to it, at the corner where what is now Cheltenham Terrace joins King’s Road, is a small house in an enclosure called “Robins’ Garden.” On this spot now stands Whitelands Training College for school-mistresses. “In 1839 the Rev. Wyatt Edgell gave £1,000 to the National Society to be the nucleus for a building fund, whenever the National Society could undertake to build a female training college.” But it was not until 1841 that the college for training school-mistresses was opened at Whitelands. In 1850 grants were made from the Education Department and several of the City Companies, and the necessary enlargements and improvements were set on foot. Some of the earlier students were very young, but in 1858 the age of admission was raised to eighteen. From time to time the buildings have been enlarged. Mr. Ruskin instituted in 1880 a May Day Festival, to be held annually, and as long as he lived, he himself presented to the May Queen a gold cross and chain, and distributed to her 14 comrades some of his volumes. Mr. Ruskin also presented to the college many books, coins, and pictures, and proved himself a good friend. In the chapel there is a beautiful east window erected to the memory of Miss Gillott, one of the former governesses. The present Principal is the Rev. J. P. Faunthorpe, F.R.G.S.

On the west side is Walpole Street, so called from the fact that Sir Robert Walpole is supposed to have lodged in a house on this site before moving into Walpole House, now in the grounds of the Royal Hospital. Walpole Street leads us into St. Leonard’s Terrace, formerly Green’s Row, which runs along the north side of the great court known as Burton’s Court, treated in the account of the Hospital. In this terrace there is nothing calling for remark. Opening out of it, parallel to Walpole Street, runs the Royal Avenue, also connected with the Hospital. To the north, facing King’s Road, lies Wellington Square, named after the famous Wellington, whose brother was Rector of Chelsea (1805). The centre of the square is occupied by a double row of trees. St. Leonard’s Terrace ends in Smith Street, the southern part of which was formerly known as Ormond Row. The southern half is full of interest. Durham House, now occupied by Sir Bruce Maxwell Seton, stands on the site of Old Durham House, about which very little is known. It may have been 15 the town residence of the Bishops of Durham, but tradition records it not. Part of the building was of long, narrow bricks two inches wide, thus differing from the present ones of two and a half inches; some of the same sort are still preserved in the wall of Sir Thomas More’s garden. This points to its having been of the Elizabethan or Jacobean period. Yet in Hamilton’s Survey it is not marked; instead, there is a house called “Ship House,” a tavern which is said to have been resorted to by the workmen building the Hospital. It is possible this is the same house which degenerated into a tavern, and then recovered its ancient name. Connected with this until quite recently there was a narrow passage between the houses in Paradise Row called Ship Alley, and supposed to have led from Gough House to Ship House. This was closed by the owner after a lawsuit about right of way.

A little to the north of Durham House was one of the numerous dwellings in Chelsea known as Manor House. It was the residence of the Steward of the Manor, and had great gardens reaching back as far as Flood Street, then Queen Street. This is marked in a map of 1838. This house was afterwards used as a consumption hospital, and formed the germ from which the Brompton Hospital sprang. On its site stands Durham Place. Below Durham Place is a little row of old houses, or, rather, cottages, with plaster fronts, 16 and at the corner a large public-house known as the Chelsea Pensioner. On the site of this, the corner house, the local historian Faulkner lived. He was born in 1777, and wrote histories of Fulham, Hammersmith, Kensington, Brentford, Chiswick, and Ealing, besides his invaluable work on Chelsea. He is always accurate, always painstaking, and if his style is sometimes dry, his is, at all events, the groundwork and foundation on which all subsequent histories of Chelsea have been reared. Later on he moved into Smith Street, where he died in 1855. He is buried in the Brompton Road Cemetery.

The continuation of St. Leonard’s Terrace is Redesdale Street; we pass down this and up Radnor Street, into which the narrow little Smith Terrace opens out. Smith Street and Smith Terrace are named after their builder. Radnor House stood at the south-eastern corner of Flood Street, but the land owned by the Radnors gave its name to the adjacent street. At the northern corner of Radnor Street stands a small Welsh chapel built of brick. In the King’s Road, between Smith and Radnor Streets, formerly stood another manor-house. Down Shawfield Street we come back into Redesdale Street, out of which opens Tedworth Square. Robinson’s Street is a remnant of Robinson’s Lane, the former name of Flood Street, a corruption of “Robins his street,” from Mr. 17 Robins, whose house is marked on Hamilton’s map. Christ Church is in Christchurch Street, and is built of brick in a modern style. It holds 1,000 people. The organ and the dark oak pulpit came from an old church at Queenhithe, and were presented by the late Bishop of London, and the carving on the latter is attributed to Grinling Gibbons. At the back of the church are National Schools. Christchurch Street, which opens into Queen’s Road West (old Paradise Row), was made by the demolition of some old houses fronting the Apothecaries’ Garden.

At the extreme corner of Flood Street and Queen’s Road West stood Radnor House, called by Hamilton “Lady Radnor’s House.” In 1660, when still only Lord Robartes, the future Earl of Radnor entertained Charles II. here to supper. Pepys, the indefatigable, has left it on record that he “found it to be the prettiest contrived house” that he ever saw. Lord Cheyne (Viscount Newhaven) married the Dowager Duchess of Radnor, who was at that time living in Radnor House. After the death of the first Earl, the family name is recorded as Roberts in the registers, an instance of the etymological carelessness of the time. In Radnor House was one of the pillared arcades fashionable in the Jacobean period, of which a specimen is still to be seen over the doorway of the dining-room in the Queen’s House. On the 18 first floor was a remarkably fine fireplace, which has been transferred bodily to one of the modern houses in Cheyne Walk. At the back of Radnor House were large nursery-gardens known as “Mr. Watt’s gardens” from the time of Hamilton (1717) until far into the present century. An old hostel adjoining Radnor House was called the Duke’s Head, after the Duke of Cumberland, of whom a large oil-painting hung in the principal room.

From this corner to the west gates of the Hospital was formerly Paradise Row. Here lived the Duchess of Mazarin, sister to the famous Cardinal. She was married to the Duke de la Meilleraie, who adopted her name. It is said that Charles II. when in exile had wished to marry her, but was prevented by her brother, who saw at the time no prospect of a Stuart restoration. The Duchess, after four years of unhappy married life with the husband of her brother’s choice, fled to England. Charles, by this time restored to his throne, received her, and settled £4,000 on her from the secret service funds. She lived in Chelsea in Paradise Row. Tradition asserts very positively that the house was at one end of the row, but at which remains a disputed point. L’Estrange and others have inclined to the belief that it was at the east end, the last of a row of low creeper-covered houses still standing, fronted 19 by gardens and high iron gates. The objection to this is that these are not the last houses in the line, but are followed by one or two of a different style.

The end of all, now a public-house, is on the site of Faulkner’s house, and it is probable that if the Duchess had lived there, he, coming after so comparatively short an interval, would have mentioned the fact; as it is, he never alludes to the exact locality. Even £4,000 a year was quite inadequate to keep up this lady’s extravagant style of living. The gaming at her house ran high; it is reported that the guests left money under their plates to pay for what they had eaten. St. Evremond, poet and man of the world, was frequently there, and he seems to have constituted himself “guide, philosopher, and friend” to the wayward lady. She was only fifty-two when she died in 1699, and the chief records of her life are found in St. Evremond’s writings. He, her faithful admirer to the end, was buried in Westminster Abbey.

A near neighbour of the Duchess’s was Mrs. Mary Astell, one of the early pioneers in the movement for the education for women. She published several volumes in defence of her sex, and proposed to found a ladies’ college. She gave up the project, however, when it was condemned by Bishop Burnet. She was ridiculed by 20 the wits of her time—Swift, Steele, and Addison—but she was undoubtedly a very able woman.

The Duke of St. Albans, Nell Gwynne’s son, also had a house in Paradise Row. The Duke of Ormond lived in Ormond House, two or three doors from the east corner. In 1805 the comedian Suett died in this row. Further down towards the river are enormous new red-brick mansions. Tite Street runs right through from Tedworth Square to the Embankment, being cut almost in half by Queen’s Road West. It is named after Sir W. Tite, M.P. The houses are modern, built in the Queen Anne style, and are mostly of red brick. To this the white house built for Mr. Whistler is an exception; it is a square, unpretentious building faced with white bricks.

At different times the names of many artists have been associated with this street, which is still a favourite one with men of the brush. The great block of studios—the Tower House—rises up to an immense height on the right, almost opposite to the Victoria Hospital for Children. The nucleus of this hospital is ancient Gough House, one of the few old houses still remaining in Chelsea. John Vaughan, third and last Earl of Carbery, built it in the beginning of the eighteenth century. He had been Governor of Jamaica under Charles II., and had left behind him a bad reputation. He did not live long to enjoy his Chelsea 21 home, for Faulkner tells us he died in his coach going to it in 1713. Sir Robert Walpole, whose land adjoined, bought some of the grounds to add to his own.

In 1866 the Victoria Hospital for Children was founded by a number of medical men, chief of whom were Edward Ellis, M.D., and Sydney Hayward, M.D. There was a dispute about the site, which ended in the foundation of two hospitals—this and the Belgrave one. This one was opened first, and consequently earned the distinction of being the first children’s hospital opened after that in Ormond Street. At first only six beds were provided; but there are now seventy-five, and an additional fifty at the convalescent home at Broadstairs, where a branch was established in 1875. The establishment is without any endowment, and is entirely dependent on voluntary subscriptions. From time to time the building has been added to and adapted, so that there is little left to tell that it was once an old house. Only the thickness of the walls between the wards and the old-fashioned contrivances of some of the windows betray the fact that the building is not modern. Children are received at any age up to sixteen; some are mere babies. Across Tite Street, exactly opposite, is a building containing six beds for paying patients in connection with the Victoria Hospital. 22

Paradise Walk, a very dirty, narrow little passage, runs parallel to Tite Street. In it is a theatre built by the poet Shelley, and now closed. At one time private theatricals were held here, but when money was taken at the door, even though it was in behalf of a charity, the performances were suppressed. Paradise Row opens into Dilke Street, behind the pseudo-ancient block of houses on the Embankment. Some of these are extremely fine. Shelley House is said to have been designed by Lady Shelley. Wentworth House is the last before Swan Walk, in which the name of the Swan Tavern is kept alive. This tavern was well known as a resort by all the gay and thoughtless men who visited Chelsea in the seventeenth century. It is mentioned by Pepys and Dibdin, and is described as standing close to the water’s edge and having overhanging wooden balconies. In 1715 Thomas Doggett, a comedian, instituted a yearly festival, in which the great feature was a race by watermen on the river from “the old Swan near London Bridge to the White Swan at Chelsea.” The prize was a coat, in every pocket of which was a guinea, and also a badge. This race is still rowed annually, Doggett’s Coat and Badge being a well-known river institution.

Adjoining Swan Walk is the Apothecaries’ Garden, the oldest garden of its kind in London. Sir Hans Sloane, whose name is revered in Chelsea 23 and perpetuated in one of the principal streets, is so intimately associated with this garden that it is necessary at this point to give a short account of him. Sir Hans Sloane was born in Ireland, 1660. He began his career undistinguished by any title and without any special advantages. Very early he evinced an ardent love of natural history, and he came over while still a youth to study in London. From this time his career was one long success. When he was only twenty-seven he was selected by the Duke of Albemarle, who had been appointed Governor of Jamaica, to accompany him as his physician. About a year and a half later he returned, bringing with him a wonderful collection of dried plants.

Mr. Sloane was appointed Court physician, and after the accession of George I. he was created a Baronet. He was appointed President of the Royal Society on the death of Sir Isaac Newton in 1727. He will be remembered, however, more especially as being the founder of the British Museum. During the course of a long life he had collected a very valuable assortment of curiosities, and this he left to the nation on the payment by the executors of a sum of £20,000—less than half of what it had cost him. In 1712 he purchased the Manor of Chelsea, and when the lease of the Apothecaries’ Garden ran out in 1734, he granted it to the Society perpetually on certain conditions, 24 one of which was that they should deliver fifty dried samples of plants every year to the Royal Society until the number reached 2,000. This condition was fulfilled in 1774. Sir Hans Sloane died in 1753.

A marble statue by Rysbach in the centre of the garden commemorates him. It was erected in 1737 at a cost of nearly £300. Mr. Miller, son of a gardener employed by the Apothecaries, wrote a valuable horticultural dictionary, and a new genus of plants was named after him.

Linnæus visited the garden in 1736. Of the four cedars—the first ever brought to England—planted here in 1683, one alone survives.

Returning to the Embankment, we see a few more fine houses in the pseudo-ancient style. Clock House and Old Swan House were built from designs by Norman Shaw, R.A. Standing near is a large monument, with an inscription to the effect: “Chelsea Embankment, opened 1874 by Lt.-Col. Sir J. Macnaghten Hogg, K.C.B. Sir Joseph W. Bazalgette, C.B., engineer.” The Embankment is a magnificent piece of work, extending for nearly a mile, and made of Portland cement concrete, faced with dressed blocks of granite. Somewhere on the site of the row of houses in Cheyne Walk stood what was known as the New Manor House, built by King Henry VIII. as part of the jointure of Queen Catherine Parr, 25 who afterwards lived here with her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour, Lord High Admiral. Here the young Princess Elizabeth came to stay with her stepmother, and also poor little Lady Jane Grey at the age of eleven. The history of the Manor House, of course, coincides with the history of the manor, which has been given at length elsewhere. Lysons, writing in 1795, states that the building was pulled down “many years ago.” It was built in 1536, and thus was probably in existence about 250 years. More than a century after, some time prior to 1663, James, Duke of Hamilton, had built a house adjoining the Manor House on the western side. The palace of the Bishops of Winchester at Southwark had become dilapidated, and the Bishop of that time, George Morley, purchased Hamilton’s new house for £4,250 to be the episcopal residence. From that time until the investment of Bishop Tomline, 1820, eight Bishops lived in the house successively. Of these, Bishop Hoadley, one of the best-known names among them, was the sixth. He was born in 1676, the son of a master of Norwich Grammar School. He was a Fellow of Catherine’s Hall at Cambridge, and wrote several political works which brought him into notice. He passed successively through the sees of Bangor, Hereford, Salisbury, and Winchester. He was succeeded by the Hon. Brownlow North, to whom Faulkner dedicated his first 26 edition of “Chelsea.” Lady Tomline, the wife of the Bishop of that name, took a dislike to the house at Chelsea and refused to live there. The great hall was forty feet long by twenty wide, and the three drawing-rooms extended the whole length of the south front. The front stood rather further back than the Manor House, not on a line with it. The palace stood just where Oakley Street now opens into Cheyne Walk. The houses standing on the sites of these palaces are mostly modern. No. 1 has a fine doorway which came from an old house at the other end of the row. In the next Mr. Beerbohm Tree and his wife lived for a short time after their marriage.

No. 4 has had a series of notable inmates. William Dyce, R.A., was the occupant in 1846, and later on Daniel Maclise, R.A. Then came George Eliot, with Mr. Cross, intending to stay in Chelsea for the winter, but three weeks after she caught cold and died in this house. Local historians have mentioned a strange shoot which ran from the top to the bottom of this house; this has disappeared, but on the front-staircase still remain some fresco paintings executed by Sir J. Thornhill, and altered by Maclise. In 1792 a retired jeweller named Neild came to No. 5. The condition of prisoners incarcerated for small debts occupied his thoughts and energies, and he worked to ameliorate it. He left his son 27 James Neild an immense fortune. This eccentric individual, however, was a miser, who scrimped and scraped all his life, and at his death left all his money to Queen Victoria. The gate-piers before this house are very fine, tall, and square, of mellowed red brick, surmounted by vases. These vases superseded the stone balls in fashion at the end of the Jacobean period. Hogarth is said to have been a frequent visitor to this house. In the sixth house Dr. Weedon Butler, father of the Headmaster of Harrow, kept a school, which was very well known for about thirty years. In the next block we have the famous Queen’s House, marked by the little statuette of Mercury on the parapet. It is supposed to have been named after Catherine of Braganza, but beyond some initials—C. R. (Catherine Regina)—in the ironwork of the gate, there seems no fact in support of this. The two Rossettis, Meredith, and Swinburne came here in 1862, but soon parted company, and D. G. Rossetti alone remained. He decorated some of the fireplaces with tiles himself; that in the drawing-room is still inlaid with glazed blue and white Persian tiles of old design. In his time it was called Tudor House, but when the Rev. H. R. Haweis (d. 1901) came to live here, he resumed the older name of Queen’s House. It is supposed to have been built by Wren, and the rooms are beautifully proportioned, panelled, and of great height. 28

The next house to this on the eastern side was occupied for many years by the artistic family of the Lawsons. Thomas Attwood, a pupil of Mozart and himself a great composer, died there in 1838. The house had formerly a magnificent garden, to the mulberries of which Hazlitt makes allusion in one of his essays. No. 18 was the home of the famous Don Saltero’s museum. This man, correctly Salter, was a servant of Sir Hans Sloane, and his collection was formed from the overflowings of his master’s. Some of the curiosities dispersed by the sale in 1799 are still to be seen in the houses of Chelsea families in the form of petrified seaweed and shells. The museum was to attract people to the building, which was also a coffee-house; this was at that time something of a novelty. It was first opened in 1695. Sir Richard Steele, in the Tatler, says: “When I came into the coffee-house I had not time to salute the company before my eye was diverted by ten thousand gimcracks round the room and on the ceiling.” Catalogues of the curiosities are still extant, and one of them is preserved in the Chelsea Public Library.

Of the remaining houses none have associations. The originals were too small for the requirements of those who wished to live in such an expensive situation, and within the last score of years they have been pulled down and others built on their 29 sites. One of these so destroyed was called the Gothic House; in it lived Count D’Orsay, and it was most beautifully finished both inside and out. The decorative work was executed by Pugin, and has been described by those who remember it as gorgeous. In another there was a beautiful Chippendale staircase, which, it is to be feared, was ruthlessly chopped up. In the last house of all was an elaborate ceiling after the style of Wedgwood. The doorway of this house is now at No. 1.

The garden which lies in front of these houses adds much to their picturesqueness in summer by showing the glimpses of old walls and red brick through curtains of green leaves. In it, opposite to the house where he used to live, there is a gray granite fountain to the memory of Rossetti. It is surmounted by a bronze alto-relievo bust modelled by Mr. F. Madox Brown.

A district old enough to be squalid, but not old enough to be interesting, is enclosed by Smith and Manor Streets, running at right angles to the Embankment. New red-brick mansions at the end of Flood Street indicate that the miserable plaster-fronted houses will not be allowed to have their own way much longer. No street has changed its name so frequently as Flood Street. It was first called Pound Lane, from the parish pound that stood at the south end; it then became Robinson’s 30 Lane; in 1838 it is marked as Queen Street; and in 1865 it was finally turned into Flood Street, from L. T. Flood, a parish benefactor, in whose memory a service is still held every year in St. Luke’s Church.

Oakley Street is very modern. In a map of 1838 there is no trace of it, but only a great open space where Winchester House formerly stood. In No. 32 lives Dr. Phené, who was the first to plant trees in the streets of London. Phené Street, leading into Oakley Crescent, is named after him. The line of houses on the west side of Oakley Street is broken by a garden thickly set with trees. This belongs to Cheyne House, the property of Dr. Phené; the house cannot be seen from the street in summer-time. The oldest part is perhaps Tudor, and the latest in the style of Wren. One wall is decorated with fleurs-de-lys. In the garden was grown the original moss-rose, a freak of Nature, from which all other moss-roses have sprung. In the grounds was discovered a subterranean passage, which Dr. Phené claims fixes the site of Shrewsbury or Alston House. It runs due south, and indicates the site as adjacent to Winchester House on the west side. Faulkner, writing in 1810, says: “The most ancient house now remaining in this parish is situated on the banks of the river, not far from the site of the Manor House built by King Henry VIII., and 31 appears to have been erected about that period. It was for many years the residence of the Shrewsbury family, but little of its ancient splendour now remains.” He describes it as an irregular brick building, forming three sides of a quadrangle. The principal room, which was wainscotted with oak, was 120 feet long, and one of the rooms, supposed to have been an oratory, was painted in imitation of marble. Faulkner mentions the subterranean passage “leading towards Kensington,” which Dr. Phené has opened out.

Shrewsbury House was built in the reign of Henry VIII. by George, Earl of Shrewsbury, who was succeeded in 1538 by his son Francis. The son of Francis, George, sixth Earl of Shrewsbury, who succeeded in his turn, was a very wealthy and powerful nobleman. He was high in Queen Elizabeth’s favour, and it was to his care that the captive Mary, Queen of Scots, was entrusted. Though Elizabeth considered he treated the royal prisoner with too much consideration, she afterwards forgave him, and appointed him to see the execution of the death-warrant. He married for his second wife a lady who had already had three husbands, each more wealthy than the last. By the second of these, Sir William Cavendish, she had a large family. Her husband left his house at Chelsea wholly to her. She outlived him 32 seventeen years, and with her immense wealth built the three magnificent mansions of Chatsworth, Oldcotes, and Hardwick, and all these she left to her son William Cavendish, afterwards created Baron Cavendish and Earl of Devonshire. A son of a younger brother was created Marquis of Newcastle, and his daughter and coheiress was Lady Jane, who brought her husband, Charles Cheyne, such a large dower that he was enabled to buy the Manor of Chelsea.

After the death of the Earl of Devonshire, Shrewsbury House became the residence of his widow until her death in 1643. It then was held by the Alstons, from whom it took its secondary name, and was finally in the possession of the Tates, and was the seat of a celebrated wall-paper manufactory. “The manufacture of porcelain acquired great celebrity. It was established near the water-side.... Upon the same premises was afterwards established a manufactory of stained paper.” This seems to point to Shrewsbury House as the original home of the celebrated Chelsea china. But, on the other hand, all later writers point authoritatively to Lawrence Street, at the corner of Justice Walk, as the seat of the china manufacture. There seems to be some confusion as to the exact site of the original works, for in “Nollekens and his Times” it is indicated as being at Cremorne House, further 33 westward. One Martin Lister mentions a china manufactory in Chelsea as early as 1698, but the renowned manufactory seems to have been started about fifty years later. The great Dr. Johnson was fired with ambition to try his hand at this delicate art, and he went again and again to the place to master the secret; but he failed, and one can hardly imagine anyone less likely to have succeeded. The china service in the possession of Lord Holland, known as Johnson’s service, was not made by him, but presented to him by the proprietors as a testimony to his painstaking effort. The first proprietor was a Mr. Nicholas Sprimont, and a jug in the British Museum, bearing date “1745 Chelsea,” is supposed to be one of the earliest productions.

The first sale by auction took place in the Haymarket in 1754, when table sets and services, dishes, plates, tureens, and épergnes were sold. These annual sales continued for many years. In 1763 Sprimont attempted to dispose of the business and retire owing to lameness, but it was not until 1769 that he sold out to one Duesbury, who already owned the Derby China Works, and eventually acquired those at Bow also.

The Chelsea china was very beautiful and costly. An old tradition is mentioned in the “Life of Nollekens” that the clay was at first brought as ballast in ships from China, and when 34 the Orientals discovered what use was being made of it, they forbade its exportation, and the Englishmen had to be content with their own native clay. Nollekens says that his father worked at the pottery, and that Sir James Thornhill had furnished designs. The distinctive mark on the china was an anchor, which was slightly varied, and at times entwined with one or two swords. Walpole in 1763 says that he saw a service which was to be given to the Duke of Mecklenburg by the King and Queen, and that it was very beautiful and cost £1,200.

From the corner of Oakley Street to the church, Cheyne Walk faces a second garden, in which there is a statue of Carlyle in bronze, executed by the late Sir Edgar Boehm and unveiled in 1882. This locality is associated with many famous men, though the exact sites of their houses are not known. Here lived Sir Richard Steele and Sir James Northcote, R.A. Somewhere near the spot Woodfall, the printer of the famous “Letters of Junius,” lived and died. A stone at the north-east corner of the church (exterior) commemorates him. In the Chelsea Public Library is preserved the original ledger of the Public Advertiser, showing how immensely the sales increased with the publication of these famous letters.

In this part there was a very old inn bearing the name The Magpie and Stump. It was a 35 quaint old structure, and the court-leet and court-baron held sittings in it. In 1886 it was destroyed by a fire, and is now replaced by a very modern structure of the same name. Further on there are immense red-brick mansions called Carlyle Mansions, and then, at right angles, there is Cheyne Row, the home for many years of one of England’s deepest and sincerest thinkers. Carlyle was the loadstar who drew men of renown from all quarters of the civilized globe to this somewhat narrow, dark little street in Chelsea. The houses are extraordinarily dull, of dark brick, monotonously alike; they face a row of small trees on the west side, and Carlyle’s house is about the middle, numbered 24 (formerly 5). A medallion portrait was put up by his admirers on the wall; inscribed beneath it is: “Thomas Carlyle lived at 24, Cheyne Row, 1834-81.” The house has been acquired by trustees, and is open to anyone on the payment of a shilling. It contains various Carlylean relics: letters, scraps of manuscript, furniture, pictures, etc., and attracts visitors from all parts of the world. There is no need to expatiate on the life of the philosopher; it belongs not to Chelsea, but to the English-speaking peoples of all countries. Here came to see him Leigh Hunt, who lived only in the next street, and Emerson from across the Atlantic; such diverse natures as Harriet 36 Martineau and Tennyson, Ruskin and Tyndall, found pleasure in his society.

At the north end of Cheyne Row is a large Roman Catholic church, built 1896. Upper Cheyne Row was for many years the home of Leigh Hunt. A small passage from this leads into Bramerton Street. This was built in 1870 upon part of what were formerly the Rectory grounds, which by a special Act the Rector was empowered to let for the purpose. Parallel to Cheyne Row is Lawrence Street, and at the corner, facing the river, stands the Hospital for Incurable Children. It is a large brick building, with four fluted and carved pilasters running up the front. The house is four stories high and picturesquely built. In 1889 it was ready for use. The charity was established by Mr. and Mrs. Wickham Flower, and had been previously carried on a few doors lower down in Cheyne Walk. Voluntary subscriptions and donations form a large part of the income, and besides this a small payment is required from the parents and friends of the little patients. The hospital inside is bright and airy. The great wide windows run down to the ground, and over one of the cots hangs a large print of Holman Hunt’s “Light of the World,” a gift from the artist himself, who formerly lived in a house on this site and in it painted the original. The ages at which patients are received 37 are between three and ten, and the cases are frequently paralysis, spinal or hip disease.

Lawrence or Monmouth House stood on the north side of Lordship Yard. Here Dr. Smollett once lived and wrote many of his works; one of the scenes of “Humphrey Clinker” is actually laid in Monmouth House. The old parish church stands at the corner of Church Street. The exterior is very quaint, with the ancient brick turned almost purple by age; and the monuments on the walls are exposed to all the winds that sweep up the river. The square tower was formerly surmounted by a cupola, which was taken down in 1808 because it had become unsafe. The different parts of the church have been built and rebuilt at different dates, which makes it difficult to give an idea of its age. Faulkner says: “The upper chancel appears to have been rebuilt in the fifteenth century; the chapel of the Lawrence family at the end of the north aisle appears to have been built early in the fourteenth century, if we may judge from the form of the Gothic windows, now nearly stopped up. The chapel at the west end of the south aisle was built by Sir T. More about the year 1522, soon after he came to reside in Chelsea. The tower was built between the years 1667 and 1679.”

The interior is so filled up with tombs and a great gallery, that the effect is most strange, and 38 the ghosts of the past seem to be whispering from every corner. There are few churches remaining so untouched and containing so miscellaneous a record of the flying centuries as Chelsea Old Church. A great gallery which hid Sir Thomas More’s monument was removed in 1824. Soon after the church was finished it was enlarged by the addition of what is now known as the Lawrence Chapel on the north side. This was built by Robert Hyde, called by Faulkner ‘Robert de Heyle,’ who then owned the manor-house. In 1536 the manor was sold to King Henry VIII., who parted with the old manor-house and the chapel to the family of Lawrence. There are three monuments of the family still existing in the chapel. The best known of these is that against the north wall, representing Thomas Lawrence, the father of Sir John, kneeling with folded hands face to face with his wife in the same attitude. Behind them are respectively their three sons and six daughters. This is the monument which Henry Kingsley refers to through the mouth of Joe Burton in his novel “The Hillyars and the Burtons.”

Not far from this is a large and striking monument to the memory of Sarah Colvile, daughter of Thomas Lawrence. She is represented as springing from the tomb clothed in a winding-sheet. The figure is larger than life and of white marble, 39 which is discoloured and stained by time. Overhead there was once a dove, of which only the wings remain, and the canopy is carved to represent clouds. The third Lawrence monument is a large tablet of black marble set in a frame of white marble, exquisitely and richly carved. This hangs against the eastern wall, and is inscribed to the memory of Sir John Lawrence. A hagioscope opens from this chapel into the chancel, and was discovered accidentally when an arch was being cut on the north wall of the chancel to contain the tomb of Lord Bray. This tomb formerly stood in the “myddest of the hyghe channcel,” but being both inconvenient and unsightly, it was removed to its present position in 1857. It possessed formerly two or three brasses, which have now disappeared. This is the oldest tomb in the church, dated 1539.

The Lawrence Chapel was private property, and could be sold or given away independently of the church. Between it and the nave—or, more accurately, over the north aisle, at its entrance into the nave—is a great arch which breaks the continuity of line in the arch of the pillars. This is the Gervoise monument, and may have originally enclosed a tomb. Of this, however, there is no evidence. In the chancel opposite to the Bray tomb stands the monument of Sir Thomas More, prepared by himself before his death, and 40 memorable for the connection of the word “heretics” with thieves and murderers, which word Erasmus afterwards omitted from the inscription. More’s crest, a Moor’s head, is in the centre of the upper cornice, and the coats-of-arms of himself and his two wives are below. The inscription is on a slab of black marble, and is very fresh, as it was restored in 1833. The question whether the body of Sir Thomas More lies in the family vault will probably never be definitely answered. Weever in his “Funeral Monuments” strongly inclines to the belief that it is so. “Yet it is certain,” he says, “that Margaret, wife of Master Roper and daughter of the said Sir Thomas More, removed her father’s corpse not long after to Chelsea.”

Sir Thomas More’s chapel is on the south side of the chancel. It was to his seat here that More himself came after service, in place of his manservant, on the day when the King had taken his high office from him, and, bowing to his wife, remarked with double meaning, “Madam, the Chancellor has gone.” The chapel contains the monuments and tombs of the Duchess of Northumberland and Sir Robert Stanley. The latter is at the east end, and stands up against a window. It is surmounted by three urns standing on pedestals. The centre one of these has an eagle on the summit, and is flanked by two female 41 figures representing Justice and Solitude in flowing draperies. The one holds a shield and crown, the other a shield. In the centre pedestal is a man’s head in alto-relievo, with Puritan collar and habit. On the side-pedestals are carved the heads of children. The whole stands on a tomb of veined marble with carved edges, and slabs of black marble bear the inscriptions of Sir Robert Stanley and two of his children. The tomb of the Duchess of Northumberland which stands next, against the south wall, has been compared to that of Chaucer in Westminster Abbey. This has a Gothic canopy, and formerly contained two brasses, representing her eight sons and five daughters kneeling, one behind the other, in the favourite style of the time. The brass commemorating the sons has disappeared.

A little further south, in the aisle, formerly stood the tomb of A. Gorges, son of Sir A. Gorges, who was possessor of the chapel for many years. This blocked up the aisle and was taken to pieces. The black slab which was on the top is set in the floor, and the brasses containing an epitaph in doggerel rhyme, attributing all the merits in the universe to the deceased, hang on the wall on the north side. The date of the chapel, 1528, is on the capital of one of the pillars supporting the arch which divides the chapel from the nave. The capitals are beautifully executed, though the 42 design is grotesque. In one of them the rough end of stone is left unfinished, as if the builder had been called hastily away and had never been able to complete his task. The chapel was recently bought by the church on the death of its owner, and is now inalienably possessed by the parish.

Just below the south aisle is the Dacre tomb, the richest and most striking in the church. It contains two life-size effigies of Lord and Lady Dacre lying under a canopy which is supported by two pillars with gilded capitals; above is a semicircular arch. The whole interior of the arch and the background is most richly carved and gilded. Above the arch are the Dacre coat-of-arms and two shields, while two smaller pillars, wedge-shaped like Cleopatra’s Needles, rise at each corner. At the feet of the figures lie two dogs, and the effigy of a small child lies on a marble slab below the level of its parents. By Lady Dacre’s will certain presentations to some almshouses in Westminster are left to the parish on condition of the tombs being kept in good repair. The tomb was redecorated and restored in 1868.

The south and west walls are covered with monuments, and careless feet tread on inscribed stones in the aisle. On the northern wall below the north aisle is a monument which immediately attracts attention from its great size and striking 43 design. It is that of Lady Jane Cheyne, daughter of William, Duke of Newcastle. It is an effigy of Lady Jane in white marble, larger than life-size; she lies in a half-raised position. Below is a black marble tomb with lighter marble pillars. Overhead is a canopy supported by two Corinthian columns. The inscription, which states it was with her money her husband bought the Manor of Chelsea, is on a black marble slab at the back. The monument is by Bernini.

All these tombs, with their wealth of carving and bold design, give a rich and furnished look to the dark old church, an effect enhanced by the tattered colours hanging overhead. The principal one of these colours was executed by Queen Victoria and her daughters for the volunteers at Chelsea when an invasion was expected. The shelf of chained books by a southern window is interesting. These formerly stood against the west wall, but were removed here for better preservation. They include a “Vinegar” Bible, date 1717, a desk Prayer-Book, and Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs.” The Communion-rails and pulpit are of oak, and the font of white marble of a peculiarly graceful design. Outside in the south-east corner of the churchyard is Sir Hans Sloane’s monument. It is a funeral urn of white marble, standing under a canopy supported by pillars of Portland stone. Four serpents twine round the urn, and the 44 whole forms a striking, though not a beautiful, group.

The church has been the scene of some magnificent ceremonies, of which the funeral of Lord Bray was notable. It was in this church that Henry VIII. married Jane Seymour the day after the execution of Anne Boleyn.

Church Lane, near at hand, is very narrow. Dean Swift, who lodged here, is perhaps one of the best-known names, and his friend Atterbury, who first had a house facing the Embankment, afterwards came and lived opposite to him. Thomas Shadwell, Poet Laureate, was associated with the place, and also Bowack, whose “Antiquities of Middlesex,” incomplete though it is, remains a valuable book of reference. Bowack lived near the Rectory, and not far from him was the Old White Horse Inn, famous for the beauty of its decorative carving.

Petyt’s school was next to the church. The name was derived from its founder, who built it at his own expense for the education of poor children in the beginning of the eighteenth century. William Petyt was a Bencher of the Inner Temple, Keeper of the Records in the Tower, and a prolific author. A tablet inscribed with quaint English, recording Petyt’s charity, still stands on the dull little block building of the present century, which replaced the old school. 45

Dr. Chamberlayne was another famous inhabitant of Church Street. His epitaph is on the exterior church wall beside those of his wife, three sons, and daughter, the latter of whom fought on board ship against the French disguised in male attire. Chamberlayne wrote and translated many historical tracts, and his best-known work is the “Present State of England” (1669). He was tutor to the Duke of Grafton, and later to Prince George of Denmark, and was one of the original members of the Royal Society.

The Rectory was built by the Marquis of Winchester. It was first used as a Rectory in 1566. It is picturesque, having been added to from time to time, and has a large old garden. The list of Rectors includes many well-known men. Dr. Littleton, author of a Latin dictionary, was presented to the living in 1669, and held it for twenty-five years. He was succeeded by Dr. John King, whose manuscript account of Chelsea is still extant. Reginald Heber, the father of the celebrated Bishop Heber, came in 1766. Later on the Hon. and Rev. Dr. Wellesley, brother to the first Duke of Wellington, was Rector from 1805, and still more recently the Rev. Charles Kingsley, father of the two brothers who have made the name of Kingsley a household word by the power of their literary talent.

The next turning out of the Embankment after 46 Church Street is Danvers Street, and an inscribed stone on the corner house tells that it was begun in 1696. Danvers House, occupied, (some authorities say built,) by Sir John Danvers in the first half of the seventeenth century, seems, with its grounds, to have occupied almost the whole space from the King’s Road to the Embankment. Thus Paulton’s Square and Danvers Street must both be partly on its site. The gardens were laid out in the Italian style, and attracted much notice. Sir John Danvers was knighted by James I. After he had been left a widower twice and was past middle age, he began to take an active part in the affairs of his time. He several times protested against Stuart exactions, and during the Civil War took the side of the Parliament. He was one of those who signed Charles I.’s death-warrant. He married a third time at Chelsea, and died there in April, 1655. His house was demolished in 1696. The house has gained some additional celebrity from its having been one of the four supposed by different writers to have been the dwelling of Sir Thomas More. This idea, however, has been repeatedly shown to be erroneous. More’s house was near Beaufort Street.

The next opening from the Embankment to the King’s Road is Beaufort Street. There is no view of More’s house known to be in existence, and, as stated above, four houses have contended for the 47 honour—Danvers, Beaufort, Alston, and that once belonging to Sir Reginald Bray. Dr. King went very carefully into the subject, and one of his manuscripts preserved at the British Museum is “A letter designed for Mr. Hearn respecting Sir Thos. More’s House at Chelsea.” His reasons cannot be given better than in his own words:

“First, his grandson, Mr. Thomas More, who wrote his life ... says that Sir Thomas More’s house in Chelsea was the same which my lord of Lincoln bought of Sir Robert Cecil. Now, it appears pretty plainly that Sir Robert Cecil’s house was the same which is now the Duke of Beaufort’s, for in divers places [are] these letters R.C., and also R.c.E., with the date of the year, viz., 1597, which letters were the initials of his name and his lady’s, and the year 1597, when he new built, or at least new fronted, it. From the Earl of Lincoln that house was conveyed to Sir Arthur Gorges; from him to Lionel Cranford, Earl of Middlesex; from him to King Charles I.; from the King to the Duke of Buckingham; from his son, since the Restoration, to Plummer, a citizen, for debts; from the said Plummer to the Earl of Bristol; and from his heirs to the Duke of Beaufort, so that we can trace all the Mesne assignments from Sir Robert Cecil to the present possessor.”

He goes on to add that More built the south 48 chancel (otherwise the chapel) in the church, and that this belonged to Beaufort House until Sir Arthur Gorges sold the house but retained the chapel. When Sir Thomas More came to Chelsea he was already a famous man, high in the King’s favour. The house he lived in is supposed to have stood right across the site of Beaufort Street, not very far from the river. It is unnecessary here to sketch that life, already so well known and so often written, but we can picture that numerous and united household which even the second Lady More’s mean and acrid temper was unable to disturb. Here royal and notable visitors frequently came. The King himself, strolling in the well-kept garden with his arm round his Chancellor’s neck, would jest pleasantly, and Holbein, in the dawn of his fame, would work for his patron, unfolding day by day the promise of his genius. Bishops from Canterbury, London, and Rochester came to confer with More. Dukes and Lords were honoured by Sir Thomas’s friendship before his fall. The barge which so often carried its owner to pleasure or business lay moored on the river ready to carry him that last sad journey to the Tower; and sadder still, to bring back the devoted daughter when the execution was accomplished, and later also when she bore her gruesome burden of a father’s head, said to have been buried with her in Chelsea Church. 49

After his death, More’s estates were confiscated and granted to Sir William Paulet, who with his wife occupied the house for about fifty years. It then passed through the possession of the Winchesters and the Dacres, the same whose tomb is such an ornament in the church, and by will Lady Dacre bequeathed it to Sir Robert Cecil, who sold it (1597) to the Earl of Lincoln, from which time we have the pedigree quoted from Dr. King. On the death of the Duke of Beaufort, Sir Hans Sloane bought it for £2,500 and pulled it down (1740).

Beaufort Street has not the width of Oakley Street, but it is by no means narrow, and many of the houses, which are irregularly built, have gardens and trees in front. A few yards further westward is Milman Street, so called after Sir W. Milman, who died in 1713. The site of his house is not definitely known, but the street marks it with sufficient accuracy. It is interesting to reflect that these great houses, described in detail, stood in their own grounds, which reached down to the water’s edge, whence their owners could go to that great London, of which Chelsea was by no means an integral part, to transact their business or pleasure. The water highway was by far the safest and most convenient in those days of robbery and bad roads. “The Village of Palaces,” as Chelsea has been called by Mr. L’Estrange, is no purely fanciful title. 50

Milman Street at present does not look very imposing. The houses and shops are squalid and mean. Near the King’s Road end is the Moravian burial-ground, which is cut off from the street by a door, over which are the words “Park Chapel National School, Church of England.” The burial-ground is small in extent, and is a square enclosure surrounded by wooden palings, and cut into four equal divisions by two bisecting paths. One of its walls is supposed to be the identical one bounding Sir T. More’s garden. At one end it is overshadowed by a row of fine elms, but in the plot itself there are no trees. What was formerly the chapel, at the north end, is now used as a school-house. Now and then the Moravians hold meetings there. The gravestones, laid horizontally in regular rows, are very small, and almost hidden by the long grass. The married men are in one quarter, and the bachelors in another, and the married and single women are separated in the same way. On the side of the chapel is a slab to the memory of Count Zinzendorf, who died in 1760.

Not far from the corner (eastward), as we turn on to the Embankment, is the famous Lindsey House, which claims to be the second oldest house in Chelsea, the first being Stanley House (see p. 55). The original house was built by Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, some time before the middle 51 of the seventeenth century. De Mayerne was Court physician to Henry IV. and Louis XIII. of France. About twenty years later it was bought by Montague Bertie, second Earl of Lindsey, whose son rebuilt or altered it largely. It remained in the Lindsey family until 1750. The family of the Windsors leased it for some time, and one of them was married in the parish church to the widow of the unjust Judge Jeffreys. In 1750 the Earl of Lindsey, created Duke of Ancaster, sold it to the Count Zinzendorf mentioned above, who intended to make it the nucleus for a Moravian settlement in Chelsea. Ten years later he died, and some time after his death the Moravians sold Lindsey House. It is now divided into five houses, and the different portions have been so much altered, by the renovations of various owners, that it is difficult to see the unity of design, but one of the divisions retains the old name on its gateway. It is supposed that Wren was the architect. Amongst other notable residents who lived here were Isambard Brunel, the engineer; Bramah, of lock fame; Martin, the painter, who was visited by Prince Albert; and Whistler, the artist. Close by Lindsey Row the river takes an abrupt turn, making a little bay, and here, below the level of the street, is a little creeper-covered house where the great colourist Turner lived for many years, gaining gorgeous sky effects from the red sunsets 52 reflected in the water. The house is numbered 118, and has high green wooden pailings. It is next to a public-house named The Aquatic, and so will be easily seen. The turning beyond is Blantyre Street. Turner’s real house was in Queen Anne Street, and he used to slip away to Chelsea on the sly, keeping his whereabouts private, even from his nearest friends. He was found here, under the assumed name of Admiral Booth, the day before his death, December 19, 1851. The World’s End Passage is a remembrance of the time when the western end of Chelsea was indeed the end of the world to the folks of London. Beyond World’s End Passage were formerly two houses of note—Chelsea Farm, afterwards Cremorne Villa, and Ashburnham House. The first of these lay near what is now Seaton Street. If we pass down Blantyre Street, which for part of the distance runs parallel to World’s End Passage, we find three streets running into it at an obtuse angle. The first of these, from the King’s Road end, is Seaton Street. It was just beyond this that the Earl of Huntingdon, about the middle of the eighteenth century, built Chelsea Farm. His widow, who lived there after his death, was connected with the Methodist movement, and built many chapels. She left the farm in 1748. It was then sold, and passed through various hands, until it came into the possession of Baron 53 Dartrey, afterwards Viscount Cremorne, from whom it gained its later name. Lady Cremorne was frequently visited by Queen Charlotte. This Lady Cremorne was a descendant of William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania. After her death the villa and grounds were sold. In 1845 the place was opened as Cremorne pleasure-gardens. These gardens, though famous, never rivalled successfully those of Ranelagh, at the eastern extremity of Chelsea. They were only open for thirty-two years, but during that time acquired the reputation for being the resort of all the rowdies in the neighbourhood. The noise made by the rabble passing along the river side after the closing at nights caused great annoyance to the respectable inhabitants, and finally led to the suppression of the gardens. L’Estrange says that the site extended over the grounds of Ashburnham as well as Cremorne House.

Cremorne Road is an offshoot of Ashburnham Road. Ashburnham House was built in 1747 by Dr. Benjamin Hoadley, son of the Bishop of that name, and author of “The Suspicious Husband.” However, the house is remembered, not by his name, but by that of its second purchaser, the Earl of Ashburnham, who had here a collection of costly paintings. The grounds were very well laid out, and adorned with statues.

Lots Road, running parallel to the river, retains 54 in its name a memory of the “lots” of ground belonging to the manor, over which the parishioners had Lammas rights.

Burnaby Street, running out of it, is named after a brother of Admiral Sir William Burnaby, who lived for some time in the neighbourhood. Beyond is Stadium Street, named after Cremorne House when it was used as a national club, and bore the alternative name of The Stadium. To the south of Lots Road are the wharves of Chelsea and Kensington. Chelsea Creek runs in here, cutting past the angle of Lots Road and turning northward to the King’s Road, where it is crossed by Stanley Bridge. The West London railway-line has its Chelsea station just above the bridge.

Even this remote corner of Chelsea is not without its historical associations. Just across the bridge, on the Fulham side, but usually spoken of as belonging to Chelsea, is the old Sandford Manor House, supposed to have been the home of Nell Gwynne. This house is connected with Addison, who wrote from here many beautiful letters to little Lord Warwick, who became his stepson on his marriage with the Dowager Countess in 1716. In one of these he says: “The business of this is to invite you to a concert of music, which I have found in a neighbouring wood. It begins precisely at six in the evening, and consists of a blackbird, 55 a thrush, a robin redbreast and a bullfinch. There is a lark that, by way of overture, sings and mounts until she is almost out of hearing ... and the whole is concluded by a nightingale.”

It would be difficult to find a wood affording such a concert in the vicinity of Chelsea Creek now.

Chelsea may be roughly divided into two great triangles, having a common side in the King’s Road. Allusion has now been made to all the southern half, and there remains the northern, which is not nearly so interesting. Beginning at the west end where the last part finished, we find, bordering the railway, St. Mark’s College and Schools. The house of the Principal is Stanley House, the oldest remaining in the parish. There has been some confusion between this and Milman House, as both were the property of Sir Robert Stanley, the former coming into his possession by his marriage with the daughter of Sir Arthur Gorges. The Stanley monument in More’s chapel will be also recalled in this connection. Stanley House as it now stands was built in 1691, and is not at all picturesque. The original building, 56 which preceded it, was known as Brickills, and was leased by Lady Stanley from her mother, Lady Elizabeth Gorges. In 1637, when Lady Gorges died, she left the house and grounds to her daughter by will, and the Stanleys lived there until 1691, when the last male descendant died. At this time the present house was built. The Arundels occupied it first, and after them Admiral Sir Charles Wager, and then the Countess of Strathmore. It was purchased from her by a Mr. Lochee, who kept a military academy here. Among the later residents were Sir William Hamilton, who built a large hall to contain the original casts of the Elgin Marbles. These casts form a frieze round the room, and detached fragments are hung separately. This room alone in the house is not panelled. The panelling of the others was for many years covered with paper, which has been gradually removed. The drawing-room door, which faces the entrance in the hall, is very finely carved. The house and grounds were bought from Sir W. Hamilton in 1840 by the National Society, at the instigation of Mr. G. F. Mathison, whose untiring efforts resulted in the foundation of St. Mark’s College for the training of school-masters. The first Principal was the Rev. Derwent Coleridge, son of S. T. Coleridge. His daughter Christabel has given a charming account of the early days of St. Mark’s 57 in a little book published in the Jubilee year. In the early part of 1841 ten students were residents in the college. The chapel was opened two years later, in May, 1843.

The Chapel has always been famous for its music and singing. It was among the first of the London churches to have a choral service. The students now number 120, and a large majority of these take Holy Orders. The grounds are kept in beautiful order, and the great elms which overshadow the green lawns must be contemporary with the house.

The King’s Road was so named in honour of Charles II., and it was notorious in its early days for footpads and robbers. In the eighteenth century the Earl of Peterborough was stopped in it by highwaymen, one of whom was discovered to be a student of the Temple, who lived “by play, sharping, and a little on the highway.” There was an attempt made at first to keep the road for the use of the Royal Family, and later on, those who had the privilege of using it had metal tickets given to them, and it was not opened for public traffic until 1830.