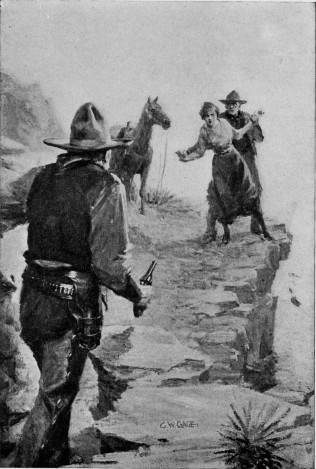

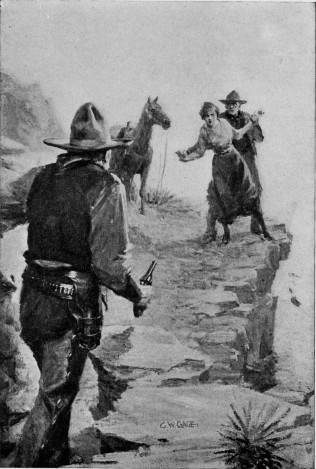

“I can stand here till I get tired,” retorted Lynch.

Title: Shoe-Bar Stratton

Author: Joseph Bushnell Ames

Illustrator: George W. Gage

Release date: November 28, 2008 [eBook #27355]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

“I can stand here till I get tired,” retorted Lynch.

Shoe-Bar Stratton

By JOSEPH B. AMES

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by arrangement with The Century Company

Printed in U. S. A.

Copyright, 1922, by

The Century Co.

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

To

BILL McBRIDE

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Back from the Dead | 3 |

| II | Crooked Work | 13 |

| III | Mistress Mary Quite Contrary | 24 |

| IV | The Branding-Iron | 31 |

| V | Tex Lynch | 41 |

| VI | The Blood-Stained Saddle | 51 |

| VII | Rustlers | 60 |

| VIII | The Hoodoo Outfit | 70 |

| IX | Revelations | 81 |

| X | Buck Finds Out Something | 91 |

| XI | Danger | 106 |

| XII | Thwarted | 119 |

| XIII | Counterplot | 127 |

| XIV | The Lady From the Past | 136 |

| XV | “Blackleg” | 145 |

| XVI | The Unexpected | 153 |

| XVII | The Primeval Instinct | 166 |

| XVIII | A Change of Base | 176 |

| XIX | The Mysterious Motor-Car | 186 |

| XX | Catastrophe | 197 |

| XXI | What Mary Thorne Found | 208 |

| XXII | Nerve | 219 |

| XXIII | Where the Wheel Tracks Led | 230 |

| XXIV | The Secret of North Pasture | 239 |

| XXV | The Trap | 248 |

| XXVI | Sheriff Hardenberg Intervenes | 256 |

| XXVII | An Hour Too Late | 268 |

| XXVIII | Forebodings | 276 |

| XXIX | Creeping Shadows | 284 |

| XXX | Lynch Scores | 291 |

| XXXI | Gone | 301 |

| XXXII | Buck Rides | 309 |

| XXXIII | Carried Away | 319 |

| XXXIV | The Fight on the Ledge | 332 |

| XXXV | The Dead Heart | 339 |

| XXXVI | Two Trails Converge | 345 |

SHOE-BAR STRATTON

Westward the little three-car train chugged its way fussily across the brown prairie toward distant mountains which, in that clear atmosphere, loomed so deceptively near. Standing motionless beside the weather-beaten station shed, the solitary passenger watched it absently, brows drawn into a single dark line above the bridge of his straight nose. Tall, lean, with legs spread apart a bit and shoulders slightly bent, he made a striking figure against that background of brilliant sky and drenching, golden sunlight. For a brief space he did not stir. Then of a sudden, when the train had dwindled to the size of a child’s toy, he turned abruptly and drew a long, deep breath.

It was a curious transformation. A moment before his face—lined, brooding, somber, oddly pale for that country of universal tan—looked almost old. At least one would have felt it the face of a man who 4 had recently endured a great deal of mental or physical suffering. Now, as he turned with an unconscious straightening of broad shoulders and a characteristic uptilt of square, cleft chin, the lines smoothed away miraculously, a touch of red crept into his lean cheeks, an eager, boyish gleam of expectation flashed into the clear gray eyes that rested caressingly on the humdrum, sleepy picture before him.

Humdrum it was, in all conscience. A single street, wide enough, almost, for a plaza, paralleled the railroad tracks, the buildings, such as they were, all strung along the further side in an irregular line. One of these, ramshackle, weather-worn, labeled laconically “The Store,” stood directly opposite the station. The architecture of the “Paloma Springs Hotel,” next door, was very similar. On either side of these two structures a dozen or more discouraged-looking adobe houses were set down at uneven intervals. To the eastward the street ended in the corrals and shipping-pens; in the other direction it merged into a narrow dusty trail that curved northward from the twin steel rails and quickly lost itself in the encompassing prairie.

That was all. Paloma Springs in its entirety lay there in full view, drowsing in the torrid heat of mid-September. Not a human being was in sight. Only a brindled dog slept in a small patch of shade beside the store; and fastened to the hotel hitching-rack, two burros, motionless save for twitching tails and ears, 5 were almost hidden beneath stupendous loads of firewood.

But to Buck Stratton the charm lay deeper than mere externals. As a matter of fact he had seen Paloma Springs only twice in his life, and then very briefly. But it was a typical little cow-town of the Southwest, and to the homesick cattleman the sight of it was like a refreshing draft of water in the desert. Pushing back his hat, Stratton drew another full breath, the beginnings of a smile curving the corners of his mouth.

“It sure is good to get back,” he murmured, picking up his bag. “Someway the very air tastes different. Gosh almighty. It don’t seem like two years, though.”

Abruptly the light went out of his eyes and his face clouded. No wonder the time seemed short when one of those years had vanished from his life as utterly and completely as if it had never been. Whenever Stratton thought of it, which was no oftener than he could help, he cringed mentally. There was something uncanny and even horrible in the realization that for the better part of a twelve-month he had been eating, sleeping, walking about, making friends, even, like any normal person, without retaining a single atom of recollection of the entire period.

Frowning, Buck put up one hand and absently touched a freshly healed scar half-hidden by his thick 6 hair. Even now there were moments when he felt the whole thing must be some wild nightmare. Vividly he remembered the sudden winking out of consciousness in the midst of that panting, uphill dash through Belleau Wood. He could recall perfectly the most trifling event leading up to it—the breaking down of his motor-cycle in a strange sector just before the charge, his sudden determination to take part in it by hook or crook, even the thrill and tingle of that advance against heavy machine-gun fire.

The details of his awakening were equally clear. It was like closing his eyes one minute and opening them the next. He lay on a hospital bed, his head swathed in bandages. That seemed all right. He had been wounded in the charge against the Boche, and they had carried him to a field-hospital. He was darned lucky to have come out of it alive.

But little by little the conviction was forced upon him that it wasn’t as simple as that. At length, when he was well on the way to recovery, he learned to his horror that the interval of mental blankness, instead of being a few hours, or at the most a day or two, had lasted for over a year!

Without fully understanding certain technical portions of the doctor’s explanation, Stratton gathered that the bullet which had laid him low had produced a bone-pressure on the portion of his brain which was the seat of memory. The wound healing, he had 7 recovered perfect physical health, but with a mind blank of anything previous to his awakening in the French hospital over a year ago. The recent operation, which was pronounced entirely successful, had been performed to relieve that pressure, and Stratton was informed that all he needed was a few weeks of convalescence to make him as good a man as he had ever been.

It took Buck all of that time to adjust himself to the situation. He was in America instead of France, without the slightest recollection of getting there. The war was over long ago. A thousand things had happened of which he had not the remotest knowledge. And because he was a very normal, ordinary young man with a horror of anything queer and eccentric, the thought of that mysterious year filled him with dismay and roused in him a passionate longing to escape at once from everything which would remind him of his uncanny lapse of memory. If he were only back where he belonged in the land of wide spaces, of clean, crisp air and blue, blue sky, he felt he would quickly forget this nightmare which haunted so many waking moments.

Unfortunately there were complications. To begin with he found himself in the extraordinary position of a man without identity. The record sent over from the hospital in France stated that he had been brought in from the field minus his tag and every other mark of 8 identification. Buck was not surprised at this, nor at the failure of anyone in the strange sector to recognize him. Only a few hours before the battle the tape of his identification-disk had parted and he had thrust the thing carelessly into his pocket. He had seen too many wounded men brought into field-hospitals not to realize how easy it is to lose a blouse.

Recovering from the bullet-wound and unable to tell anything about himself, he had apparently passed under the name of Robert Green. Stratton wondered with a touch of grim amusement whether this christening was not the result of doughboy humor. He must have been green enough, in all conscience.

He was not even grimly amused by the ultimate discovery that the name of Roth Stratton had appeared months and months ago on one of the official lists of “killed or missing.” It increased his discomfort over the whole hateful business and made him thankful for the first time that he was alone in the world. At least no mother or sister had been tortured by this strange prank of fate.

But at last the miles of red tape had been untied or cut, and the moment his discharge came Stratton took the first possible train out of New York. He did not even wire Bloss, his ranch-foreman, that he was coming. As a matter of fact he felt that doing so would only further complicate an already sufficiently difficult situation. 9

The Shoe-Bar outfit, in western Arizona, had been his property barely a week before he left it for the recruiting-office. Born and bred in the Texas Panhandle, he inherited his father’s ranch when barely twenty-one. Even then many of the big outfits were being cut up into farms, public range-land had virtually ceased to exist, and one by one the cattlemen were driven westward before the slowly encroaching wave of civilization.

Two years later Stratton decided to give up the fight and follow them. During the winter before the war he sold out for a handsome figure, spent several months looking over new ground, and finally located and bought the Shoe-Bar outfit.

The deal was hurried through because of his determination to enlist. Indeed, he would probably not have purchased at all had not the new outfit, even to his hasty inspection, seemed to be so unusual a bargain and so exactly what he wanted. But buy he did, placed Joe Bloss, a reliable and experienced cattleman who had been with him for years, in charge, and departed.

From that moment he had never once set eyes on the Shoe-Bar. Bloss wrote frequent and painstaking reports which seemed to indicate that everything was going well. But all through the long and tedious journey ending at the little Arizona way-station, Stratton fumed and fretted and wondered. Even if Joe had 10 failed to see his name amongst the missing, what must he have thought of his interminable silence? All through Buck’s brief training and the longer interval overseas, the foreman’s letters had come with fair regularity and been answered promptly and in detail. What had Bloss done when the break came? What had he been doing ever since?

A fresh wave of troubled curiosity sent Stratton swinging briskly across the street. Keeping inside the long hitching-rack, he crossed the sagging porch and stepped through the open door into the store. For a moment he thought it empty. Then a chair scraped, and over in one corner a short, stout, grizzled man dropped his feet from the window-sill and shuffled forward, yawning.

“Wal! Wal!” he mumbled, his faded, sleep-dazed eyes taking in Buck’s bag. “Train come in? Reckon I must of been dozin’ a mite.”

“Looks to me like the whole place was taking an afternoon nap,” smiled Stratton. “Not much doing this time of day, I expect.”

“You said it,” yawned the stout man, supporting himself against the rough pine counter. “Things is liable to brisk up in a hour or two, though, when the boys begin to drift in. Stranger around these parts, ain’t yuh?” he added curiously.

For a tiny space Buck hesitated. Then, moved by 11 an involuntary impulse he did not even pause to analyze, he shrugged his shoulders slightly.

“I was out at the Shoe-Bar a couple of times about two years ago,” he answered. “Haven’t been around here since.”

“The Shoe-Bar? Huh?” Pop Daggett looked interested. “You don’t say so! Funny I don’t recollect yore face.”

“Not so very. I only passed through here to take the train.”

“That was it, eh? Two years ago must of been about the time the outfit was bought by that Stratton feller from Texas. Yuh know him well?”

“Joe Bloss, the foreman, was a friend of mine,” evaded Stratton. “He’s the one I stopped off now to see.”

Pop Daggett’s jaw sagged, betraying a cavernous expanse of sparsely-toothed gums. “Joe Bloss!” he ejaculated. “My land! I hope you ain’t traveled far fur that. If so, yuh sure got yore trouble for yore pains. Why, man alive! Joe Bloss ain’t been nigh the Shoe-Bar for close on to a year.”

Stratton’s eyes narrowed. “A year?” he repeated curtly. “Where’s he gone?”

“You got me. I did hear he’d signed up with the Flying-V’s over to New Mexico, but that might have been jest talk.” He sniffed disapprovingly. “There 12 ain’t no doubt about it; the old Shoe-Bar’s changed powerful these two years. I dunno what we’re comin’ to with wimmin buttin’ into the cattle business.”

Buck stared at him in frank amazement. “Women?” he repeated. “What the dickens are you talking about, anyway?”

“I sh’d think I was plain enough,” retorted Pop Daggett with some asperity. “Mebbe female ranchers ain’t no novelty to yuh, but this is the first time I ever run up ag’in one m’self, an’ I ain’t much in love with the idear.”

Stratton’s teeth dug into his under lip, and one hand gripped the edge of the counter with a force that brought out a row of white dots across the knuckles.

“You mean to tell me there’s a—a—woman at the Shoe-Bar?” he asked incredulously.

“At it?” snorted the old man. “Why, by cripes, she owns it! Not only that, but folks say she’s goin’ to run the outfit herself like as if she was a man.” He paused to spit accurately and with volume into the empty stove. “Her name’s Thorne,” he added curtly. “Mary Thorne.”

Stratton suddenly turned his back and stared blankly through the open door. With the same unconscious instinct which had moved him to conceal his face from the old man, he fumbled in one pocket and drew forth papers and tobacco sack. It spoke well for his self-control that his fingers were almost steady as he deliberately fashioned a cigarette and thrust it between his lips. When he had lighted it and inhaled a puff or two, he turned slowly to Pop Daggett again.

“You sure know how to shoot a surprise into a fellow, old-timer,” he drawled. “A woman rancher, eh? That’s going some around this country, I’ll say. How long has she—er—owned the Shoe-Bar?”

“Only since her pa died about four months back.” Pop Daggett assumed an easier pose; his tone had softened to one of garrulous satisfaction at having a new listener to a tale he had worn threadbare. “It’s consid’able of a story, but if yuh ain’t pressed for time—” 14

“Go to it,” invited Buck, leaning back against the counter. “I’ve got all the time there is.”

Daggett’s small, faded blue eyes regarded him curiously.

“Did yuh ever meet up with this here Stratton?” he asked abruptly.

“I—a—know what he looks like.”

“It’s more’n I do,” grumbled Pop regretfully. “The only two times he was here I was laid up with a mean attack of rheumatiz, an’ never sot eyes on him. Still an’ all, there ain’t hardly anybody else around Paloma that more ’n glimpsed him passin’ through. He bought the outfit in a terrible hurry, an’ I thinks to m’self at the time he must be awful trustin’, or else a mighty right smart jedge uh land an’ cattle. He couldn’t of hardly rid over it even once real thorough before he plunks down his money, gets him a proper title, an’ hikes off to the war, leavin’ Joe Bloss in charge.”

He paused, fished in his pocket, and, producing a plug, carefully bit off one corner. Stratton watched him impatiently, a faint flush staining his clear, curiously white skin.

“Well?” he prodded presently. “What happened then? From what I know of Joe, I’ll say he made good all right.”

“Sure he did.” Pop spoke with emphasis, though somewhat thickly. “There ain’t nobody can tell Joe 15 Bloss much about cattle. He whirled in right capable and got things runnin’ good. For a while he was so danged busy he’d hardly ever get to town, but come winter the work eased up an’ I used to see him right frequent. He’d set there alongside the stove evenings an’ tell me what he was doin’, or how he’d jest had a letter from Stratton, who was by now in France, an’ all the rest of it. Wal, to make a long story short, a year last month the letters stopped comin’. Joe begun to get worried, but I told him likely Stratton was too busy fightin’ to write, or he might even of got wounded. Yuh could have knocked me down with a wisp uh bunch-grass when one uh the boys come in one night with a Phoenix paper, an’ showed me Stratton’s name on a list uh killed or missin’!”

“When was that?” asked Buck briefly, seeing that Daggett evidently expected some comment. If only the man would get on!

“’Round the middle of September. Joe was jest naturally shot to pieces, him knowin’ young Stratton from a kid an’ likin’ him fine, besides bein’ consid’able worried about what was goin’ to happen to the ranch an’ him. Still an’ all, there wasn’t nothin’ he could do but go on holdin’ down his job, which he done until the big bust along the end of October.”

He paused again expectantly. Buck ground the butt of his cigarette under one heel and reached for the makings. He had an almost irresistible desire 16 to take the garrulous old man by the shoulders and shake him till his teeth rattled.

“It was this here Thorne from Chicago,” resumed Daggett, a trifle disappointed. Usually at this point of the story, his listener broke in with exclamation or interested question. “He showed up one morning with the sheriff an’ claimed the ranch was his. Said Stratton had sold it to him an’ produced the deed, signed, sealed, an’ witnessed all right an’ proper.”

Match in one hand and cigarette in the other, Buck stared at him, the picture of arrested motion. For a moment or two his brain whirled. Could he possibly have done such a thing and not remember? With a ghastly sinking of his heart he realized that anything might have been possible during that hateful vanished year. Mechanically he lit his cigarette and of a sudden he grew calmer. According to the hospital records he had not left France until well into November of the preceding year. Tossing the match into the stove, he met Pop Daggett’s glance.

“How could that be?” he asked briefly. “Didn’t you say this Stratton was in France for months before he was killed?”

Pop nodded hearty agreement. “That’s jest what I said, an’ so did Bloss. But according to Thorne this here transfer was made a couple uh weeks before Stratton went over to France.” 17

“But that’s impossible!” exclaimed Buck hotly. “How could he have——”

He ceased abruptly and bit his lip. Daggett chuckled.

“Gettin’ kinda interested, ain’t yuh?” he remarked in a satisfied tone. “I thought you would ’fore I was done. I don’t say as it’s impossible, but it shore looked queer to me. As Joe says, why would he go an’ sell the outfit jest after buyin’ it without a word to him. Not only that but he kept on writin’ about how Joe was to do this an’ that an’ the other thing like he was mighty interested in havin’ it run good. Joe, he even got suspicions uh somethin’ crooked an’ hired a lawyer to look into it, Stratton not havin’ any folks. But that’s all the good it done him. He couldn’t pick no flaw in it at all. Seems Stratton was in Chicago on one of these here furloughs jest before he took ship. One uh the witnesses had gone to war, but they hunted out the other one an’ he swore he’d seen the deed signed.”

“Did this Thorne— What did you say his name was?”

“I don’t recolleck sayin’, but it was Andrew J.”

Buck’s lids narrowed; a curious gleam flashed for an instant in his gray eyes and was gone.

“Well, did Thorne explain why he let it go so long before making his claim?” 18

“Oh, shore! He was right there when it come to explainin’. Seems he had some important war business on his hands an’ wanted to get shed uh that before he took up ranchin’. Knowed it was in good hands, ’count uh Bloss bein’ on the job, an’ Stratton havin’ promised to write frequent an’ keep Joe toein’ the mark. Stratton, it seems, had sold out because he didn’t know what might happen to him across the water. Oh, Andrew J. was a right smooth talker, believe me, but still an’ all he didn’t make no great hit with folks around the country even after he settled down on the Shoe-Bar and brung his daughter there to live. There weren’t no tears shed, neither, when an ornery paint horse throwed him last May an’ broke his neck.”

“What about Bloss?” Stratton asked briefly.

“Oh, he got his time along with all the other cow-men. There shore was a clean sweep when Thorne whirled in an’ took hold. Joe hung around here a week or two an’ then drifted down to Phoenix. Last I heard he was goin’ to try the Flyin’-V’s, but that was six months or more ago.”

Buck’s shoulders straightened and his chin went up with a sudden touch of swift decision.

“Got a horse I can hire?” he asked abruptly.

Pop hesitated, his shrewd gaze traveling swiftly over Stratton’s straight, tall figure to rest reflectively on the lean, square-jawed, level-eyed young face. 19

“I dunno but I have,” he answered slowly. “Uh course I don’t know yore name even, an’ a man’s got to be careful how he—”

“Oh, that’ll be all right,” interrupted Stratton, his white teeth showing briefly in a smile. “I’ll leave you a deposit. My name’s Bob Green, though folks mostly call me Buck. I’ve got a notion to ride over to the Shoe-Bar and see if they know anything about—Joe.”

“’T ain’t likely they will,” shrugged Daggett. “Still, it won’t do no harm to try. Yuh can’t ride in them things, though,” he added, surveying Stratton’s well-cut suit of gray.

“I don’t specially want to, but they’re all I’ve got,” smiled Buck. “When I quit ranching to show ’em how to run the war, I left my outfit behind, and I haven’t been back yet to get it.”

“Cow-man eh?” Pop nodded approvingly. “I thought so; yuh got the look, someway. Wal, yore welcome to some duds I bought off ’n Dick Sanders about a month ago. He quit the Rockin’-R to go railroadin’ or somethin’, an’ sold his outfit, saddle an’ all. I reckon they’ll suit.”

Stepping behind the counter, he poked around amongst a mass of miscellaneous merchandise and finally drew forth a pair of much-worn leather chaps, high-heeled boots almost new, and a cartridge-belt from which dangled an empty holster. 20

“There yuh are,” he said triumphantly, spreading them out on the counter. “Gun’s the only thing missin’. He kep’ that, but likely yuh got one of yore own. Saddle’s hangin’ out in the stable.”

Without delay Stratton took off his coat and vest and sat down on an empty box to try the boots, which proved a trifle large but still wearable. He already had on a dark flannel shirt and a new Stetson, which he had bought in New York; and when he pulled on the chaps and buckled the cartridge-belt around his slim waist Pop Daggett surveyed him with distinct approval.

“All yuh need is a good coat uh tan to look like the genuine article,” he remarked. “How come yuh to be so white?”

“Haven’t been out of the hospital long enough to get browned up.” Buck opened his bag and, fumbling for a moment, produced a forty-five army automatic. “This don’t go very well with the outfit,” he shrugged. “Happen to have a regular six-gun around the place you’ll sell me?”

Pop had, this being part of his stock in trade. Buck looked the lot over carefully, finally picking out a thirty-eight Colt with a good heft. When he had paid for this and a supply of ammunition, Pop led the way out to a shed back of the store and pointed out a Fraser saddle, worn but in excellent condition, hanging from a hook. 21

“It’s a wonder to me any cow-man is ever fool enough to sell his saddle,” commented Stratton as he took it down. “They never get much for ’em, and new ones are so darn ornery to break in.”

“Yuh said it,” agreed Daggett. “I’d ruther buy one second-hand than new any day. There’s the bridle. Yuh take that roan in the near stall. He ain’t much to look at, but he’ll travel all day.”

Fifteen minutes later the roan, saddled and bridled, pawed the dust beside the hitching rack in front of the store, while Buck Stratton made a small bundle of his coat, vest, and a few necessaries from his bag and fastened it behind the saddle. The remainder of his belongings had been left with Pop Daggett, who lounged in the doorway fingering a roll of bills in his trousers pocket and watching his new acquaintance with smiling amiability.

“Well, I’ll be going,” said Stratton, tying the last knot securely. “I’ll bring your cayuse back to-morrow or the day after at the latest.”

Pop looked surprised. “The day after?” he repeated. “What’s goin’ to keep yuh that long?”

“Will you be needing the horse sooner?”

“No, I dunno’s I will. But seems like yuh ought to be back by noon to-morrow. It ain’t more ’n eighteen miles.” He straightened abruptly and his blue eyes widened. “Say, young feller! Yuh ain’t thinkin’ of gettin a job out there, are yuh?” 22

Stratton hesitated for an instant. “Well, I don’t know,” he shrugged presently. “I’ve got to get to work right soon at something.”

Daggett took a swift step or two across the sagging porch, his face grown oddly serious. “Wal, I wouldn’t try the Shoe-Bar, nohow. There’s the Rockin’-R. They’re short a man or two. Yuh go see Jim Tenny an’ tell him—”

“What’s the matter with the Shoe-Bar?” persisted Buck.

Pop’s glance avoided Stratton’s. “Yuh—wouldn’t like it,” he mumbled, glancing down the trail. “It—it ain’t like it was in Joe’s time. That there Tex Lynch—he—he don’t get on with the boys.”

“Who’s he? The foreman?”

“Yeah. Beauty Lynch, some calls him ’count uh his looks. I ain’t denyin’ he’s han’some, with them black eyes an’ red cheeks uh his, but somethin’ queer—Like I said, there ain’t nobody stays long at the Shoe-Bar. Yuh take my advice, Buck, an’ try the Rockin’-R. They’s a nice bunch there.”

Buck swung himself easily into the saddle; “I’ll think about it,” he smiled, gathering up the reins. “Well, so-long; see you in a day or so, anyway. Thanks for helping me out, old-timer.”

He loosened the reins, and the roan took the trail at a canter. Well beyond the last adobe house, Stratton glanced back to see old Pop Daggett still standing on 23 the store porch and staring after him. Buck flung up one arm in a careless gesture of farewell; then a gentle downward slope in the prairie carried him out of sight of the little settlement.

“Acts to me like he was holding back something,” he thought as he rode briskly on through the wide, rolling solitudes. “Now, I wonder what sort of a guy is this Tex Lynch, and what’s going on at the Shoe-Bar that an old he-gossip like Pop Daggett is afraid to talk about?”

But Stratton’s mind was too full of the amazing information he had gleaned from the old storekeeper to leave much room for minor reflections. He had been stunned at first—so completely floored that anyone save the garrulous old man intent on making the most of his shop-worn story could not have helped seeing that something was seriously wrong. Then anger came—a hot, raging fury against the authors of this barefaced, impudent attempt at swindle. From motives of policy he had done his best to conceal that, too, from Pop Daggett; but now that he was alone it surged up again within him, dyeing his face a deep crimson and etching hard lines on his forehead and about his straight-lipped mouth.

“Thought they’d put it over easy,” he growled behind set teeth, one clenched, gloved hand thumping the saddle-horn. “Saw the notice in the papers, of course, and decided it would be a cinch to rob a dead man. Well, there’s a surprise coming to somebody that’ll make mine look like thirty cents.”

His lips relaxed in a grim smile, which presently 25 merged into an expression of puzzled wonder. Thorne, of all people, to try and put across a crooked deal like this! Stratton had never known the man really intimately, but during the several years of their business relationship the Chicago lawyer struck him as being scrupulously honest and upright. Indeed, when Buck came to enlist, it seemed a perfectly safe and natural thing to leave his deeds and other important papers in Andrew Thorne’s keeping.

“Shows how you can be fooled in a man,” murmured Stratton, as he followed the trail down into a shallow draw. “I sure played into his hands nice. He had the deeds and everything, and it would be simple enough to fake a transfer when he thought I was dead and knew I hadn’t any kin to make trouble. I wonder what the daughter’s like. A holy terror, I’ll bet, and tarred with the same brush. Well, she’ll get hers in about two hours’ time, and get it good.”

The grim smile flickered again on his lips for a moment, to vanish as he saw the head and shoulders of a horseman appear over the further edge of the draw. An instant later the bulk of a big sorrel flashed into view and thudded toward him.

On the open range men usually stop for a word or two when they meet, but this one did not. As he approached Stratton at a rapid speed there was a brief, involuntary movement as if he meant to pull up and then changed his mind. The next moment he had 26 whirled past with a careless, negligent gesture of one hand and a keen, penetrating, questioning stare from a pair of hard black eyes.

Buck glanced over one shoulder at the flying dust-cloud and pursed his lips.

“Wonder if that’s the mysterious Tex?” he pondered, urging his horse forward. “Black eyes and red cheeks, all right. He’s a good looking scoundrel—too darn good looking for a man. All the same, I can’t say it was a case of love at first sight.”

Unconsciously his right hand dropped to the holster at his side, the fingers caressing for an instant the butt of his Colt. He had set out on his errand of exposure with an angry impulsiveness which gave no thought to details or possibilities. But in some subtle fashion that searching glance from the passing stranger brought him up with a little mental jerk. For the first time he remembered that he was playing a lone hand, that the very nature of his business was likely to rouse the most desperate and unscrupulous opposition. Considering the value of the stake and the penalties involved, the present occupant of the Shoe-Bar was likely to use every means in her power to prevent his accusations from becoming public. If the fellow who had just passed really was Tex Lynch, Buck had a strong intuition that he was the sort of a man who could be counted on to take a prominent hand in the 27 game, and also that he wouldn’t be any too particular as to how he played it.

A mile beyond the draw the trail forked, and Stratton took the left-hand branch. The grazing hereabouts was poor, and at this time of year particularly the Shoe-Bar cattle were more likely to be confined to the richer fenced-in pastures belonging to the ranch. The scenery thus presenting no points of interest, Buck’s thoughts turned to the interview ahead of him. Marshaling his facts, he planned briefly how he would make use of them, and finally began to draw scrappy mental pen-pictures of the usurping Mary Thorne.

She would be tall, probably, and raw-boned—that domineering, “bossy” type he always associated with women who assumed men’s jobs—harsh-voiced and more than a trifle hard. He dwelt particularly on her hardness, for surely no other sort of woman could possibly have helped to engineer the crooked deal which Andrew Thorne and his daughter had so successfully put across. She would be painfully plain, of course, and doubtless also would wear knickerbockers like a certain woman farmer he had once met in Texas, smoke cigarettes constantly, and pack a gun. Having endowed the lady with a few other disagreeable qualities which pleased him mightily, Buck awoke to the realization that he was approaching the eastern extremity of the Shoe-Bar ranch. His eyes brightened, and, 28 dismissing all thoughts of Miss Thorne, he began to cast interested, appraising glances to right and left as he rode.

There is little that escapes the eye of the professional ranchman, especially when he has been absent from his property for more than two years. Buck Stratton observed quite as much as the average man, and it presently became evident that what he saw did not please him. His keen eyes sought out sagging fence-wire where staples, drawn or fallen out, had never been replaced. Here and there a rotting post leaned at a precarious angle, or gates between pastures needed repairing badly. What cattle were in sight seemed in good condition but their number was much less than he expected. Only once did he observe any signs of human activity, and then the loafing attitude of the two punchers riding leisurely through a field half a mile away was but too apparent. By the time he came within sight of the ranch-house, nestling pleasantly in a little grove of cottonwoods beyond the creek, his face was set in a hard scowl.

“Looks to me like they were letting the whole outfit go to pot,” he muttered angrily. “It sure is time I whirled in and took a hand.”

Urging the roan forward, he rode splashing through the shallow stream, up the gentle slope, and swung out of his saddle close to the kitchen door. This stood open, and striding up to it Buck met the languid gaze 29 of a swarthy middle-aged Mexican who lounged just within the portal.

“Miss Thorne around?” he asked curtly.

“Sure,” shrugged the Mexican. “I t’ink she in fron’ house. Yoh try aroun’ other door, mebbe fin’ her.”

In the old days the kitchen entrance had been the one most used, but Buck remembered that there was another at the opposite end of the building which opened directly into the ranch living-room. He sought it now, observing with preoccupied surprise that a small covered veranda had been built out from the house, found it ajar like the other, and knocked.

“Come in,” said a voice.

Stratton crossed the threshold, instinctively removing his hat. As he remembered it, the room, though of good size and comfortable enough, had been a clutter of purely masculine belongings. He was quite unprepared for the colorful gleam of Navajo rugs, the curtained windows, the general air of swept and garnished tidiness which seemed almost luxury. Briefly his sweeping glance took in a bowl of flowers on the center-table and then came to rest abruptly on a slight, girlish figure just risen from a chair beside it.

“I’d like to see Miss Thorne, please,” he said, stifling his momentary surprise.

The girl took a step forward, her slim, tanned, ringless fingers clasped loosely about a book she held. 30

“I’m Miss Thorne,” she answered in a low, pleasant voice.

Buck gasped and his eyes widened. Then he recovered himself swiftly.

“I mean Miss Mary Thorne,” he explained; “the—er—owner of this outfit.”

The girl smiled faintly, a touch of veiled wistfulness in her eyes.

“I’m Mary Thorne,” she said quietly. “There’s only one, you know.”

Stratton was never sure just how long he stood staring at her in dumb, dazed bewilderment. After those mental pictures of the Mary Thorne he had expected to find, it was small wonder that the sight of this slip of a black-frocked girl, with her soft voice, her tawny-golden hair and wistful eyes, should stun him into temporary speechlessness. Even when he finally pulled himself together to feel a hot flush flaming in his face and find one gloved hand recklessly crumpling his new Stetson, he could not quite credit the evidence of his hearing.

“I—I beg pardon,” he said stiffly. “But it doesn’t seem possible that—”

He hesitated. The girl’s smile deepened whimsically.

“I know,” she said ruefully. “It never does. Nobody seems to think a girl can seriously attempt to run a cattle-ranch—even the way I’m trying to run it, with a capable foreman to look after things. Sometimes I wonder if—”

She paused, her glance falling on the book she held. 32 Stratton saw that it was a shabby account-book, a stubby pencil thrust between the leaves.

“Yes?” he prompted, scarcely aware what made him ask the question.

She looked up at him, her eyes a little wider than before. They were a warm hazel, and for an instant in their depths Stratton glimpsed a troubled expression, so veiled and swiftly passing that a moment later he could not be sure he had read aright.

“It’s nothing,” she shrugged. “You probably know what a lot of nagging little worries a ranchman has, and sometimes it seems to me they all have to come at once. I suppose even a man gets a bit discouraged, now and then.”

“He sure does,” agreed Buck. “What—er—particular sort of worry do you mean?”

He asked the question impulsively without realizing how it might sound, coming from a total stranger. The girl’s slim figure stiffened and her chin went up. Then—perhaps something in his expression told her he had not meant to be impertinent—her face cleared.

“The principal one is lack of help,” she explained readily enough, and yet Stratton got a curious impression, somehow, that this wasn’t really the worst of her troubles. “We’re awfully short-handed.” She hesitated an instant and then went on frankly, “To tell the truth, when you first came in I was hoping you might be looking for a job.” 33

For an instant Buck had all he could do to conceal his amazement at this extraordinary turn of events.

“You mean I’d stand a chance of being taken on?” he countered, sparring for time.

“Of course! That is—You are a cow-puncher, aren’t you?”

Stratton’s lips twitched slightly.

“I’ve worked around cattle all my life.”

“Then naturally it would be all right. I should be very glad to hire you. Tex Lynch usually looks after all that, but he’s away this afternoon and there’s no reason why I shouldn’t—” Her quaint air of dignity was marred by a sudden, amused twitch of the lips. “I’m really awfully pleased you did come to me,” she smiled. “He’s been telling me for over two weeks that he couldn’t hire a man for love or money; it’ll be amusing to show him what I’ve done, sitting quietly here at home.”

“That’s all settled, then?” Stratton had been doing some rapid thinking. “You’d like me to start in right away, I suppose? That’ll suit me fine. My name’s Bob Green. If you’ll just explain to Lynch that I’m hired, I’ll go down to the bunk-house and he can put me to work when he comes back.”

With a slight bow, he was moving away when Miss Thorne stopped him.

“Wait!” she cried. “Why, you haven’t said a word about wages.” 34

Buck turned back, biting his lip and inwardly cursing himself for his carelessness.

“I s’posed it would be the usual forty dollars,” he explained.

“We pay that for new hands,” the girl informed him in some surprise. She sat down beside the table and opened her book. “I can put you down for forty, I suppose, and then Tex will tell me what it ought to be after he’s seen you work. Green, did you say?”

“Robert Green.”

“And the address?”

Buck scratched his head.

“I don’t guess I’ve got any,” he returned. “I used to punch cows in Texas, but I’ve been away two years and a half, and the last outfit I was with has sold out to farmers.”

“Oh!” She looked up swiftly and her gaze leaped unerringly to the scar which showed below his tumbled hair. “Oh! I see. You—you’ve been through the war.”

Her voice broke a little, and to Buck’s astonishment she turned quite white as her eyes sought the book again. A sudden fear smote him that she had guessed his real identity, but he dismissed the notion quickly. Such a thing was next to impossible when she had never set eyes upon him before to-day.

“That’s all, I think,” she said presently in a low 35 voice. “You’ll find the bunk-house, at the foot of the slope beside the creek. I’ll speak to Tex as soon as he comes back.”

Outside the ranch house, Buck paused for a moment or two, ostensibly to stare admiringly at a carefully tended flower-bed, but in reality to adjust his mind to the new and extraordinary situation. During the last two hours he had speculated a good deal on this interview, but not even his wildest imaginings had pictured the turn it had actually taken.

“Hired as a puncher on my own ranch by the girl whose father stole it from me!” he murmured under his breath. “It’s a scream! Darned if it wouldn’t make a good vaudeville turn.”

But as he walked slowly back to where he had left his horse, Stratton’s face grew thoughtful. He was trying to analyze the motives which had prompted him to accept such a position and found them a trifle mixed. Undeniably the girl’s unexpected personality influenced him considerably. She did not strike him, even remotely, as the sort who would deliberately do anything dishonest. And though Buck knew there were women who might be able to assume that air of almost childlike innocence, he did not believe, somehow, that in her case it was assumed. At any rate a little delay would do no harm. By accepting the proffered job he would be able to study the lady and the situation at his leisure. Also—and this he told himself was 36 even more important—he would have a chance of quietly investigating conditions on the ranch. Pop Daggett’s vague hints, his own observations, and the intuition he had that Miss Thorne was worrying about something much more vital than the mere lack of hands, all combined to make him feel that things were not going right at the Shoe-Bar. Of course it might be simply a case of rotten management. But in the back of Buck’s mind there lurked a curious notion that something deeper and more far-reaching was going on beneath the surface, though of what nature he could not even guess.

Leading the roan into a corral which ranged beyond the kitchen, Stratton unsaddled him and turned him loose. Having hung the saddle and bridle in the adjacent shed, he tucked his bundle under one arm and headed for the bunk-house. He was within a few yards of the entrance to the long, adobe structure when the door was suddenly flung open and a slim, slight figure, hatless and stripped to the waist, plunged out, closely pursued by three other men.

He ran blindly with head down, and Buck had just time to drop his bundle and extend both arms to prevent a collision. An instant later his tense muscles quivered under the impact of some hundred and thirty pounds of solid bone and muscle; the runner staggered and flung up his head, a gasp of terror jolted from his lips. 37

“Oh!” he said more quietly, his tone an equal blend of astonishment and relief. “I thought—Don’t let ’em—”

He broke off, flushing. He was a pleasant-faced youngster of not more than eighteen or nineteen, with a tangled mop of blonde hair and blue eyes, the pupils of which were curiously dilated. Stratton, whose extended arms had caught the boy just under the armpits, could feel his heart pounding furiously.

“What’s the matter, kid?” he asked briefly.

“They were going to brand me—on the back,” the boy muttered.

Over the fellow’s bare, muscular shoulders Buck’s glance swept the trio who had pulled up just outside the bunk-house door. They seemed typical cow-punchers in dress and manner. Two of them were tall and well set up; the third was short and stocky and held a branding iron in one hand. Meeting Stratton’s gaze, he laughed loudly.

“By cripes, Bud! Yuh shore are easy. I thought yuh had more guts than to be scared of an iron that’s hardly had the chill took off.”

He guffawed again, the other two joining in. A flush crept up into the boy’s face, but his lips were firm now, and as he turned to face the others his eyes narrowed slightly.

“If it’s so cold as that mebbe you’d like me to try it on yuh,” he suggested significantly. 38

The short man haw-hawed again, but not quite so boisterously. Buck noticed that he held the branding iron carefully away from his leg.

“I shore wouldn’t hollar like you done ’fore I was touched,” he retorted. “Wal, we got his goat good that time, didn’t we, Butch? Better come in an’ git yore shirt on ’fore the boss sees yuh half naked.”

He turned and disappeared into the bunk-house, followed by the two other punchers. Buck picked up his bundle and glanced at the boy.

“Seems like you’ve got a right sociable, amusing bunch around here,” he drawled.

The youngster’s lips parted impulsively, to close as swiftly over his white teeth.

“Oh, they’re a great lot of jokers,” he returned non-committally, moving toward the door. “Coming in?”

The room they entered was long and rather narrow, with built-in bunks occupying most of the wall space, while the usual assemblage of bridles, ropes, old hats, and garments, hanging from pegs, crowded the remainder. Opposite the door stood a rusty, pot-bellied stove which gave forth a heat that seemed rather superfluous on such a warm evening. The stocky fellow, having leaned his branding-iron against the adobe chimney, was occupied in closing the drafts. His two companions, both rolling cigarettes, stood beside him, while lounging at a rough table to the left 39 of the door sat two other men, one of them idly shuffling a pack of dirty cards. As he entered, Stratton was conscious of the intent scrutiny of all five, and an easy, careless smile curved his lips.

“Reckon this is the bunk-house, all right,” he drawled. “The lady told me it was down this way. My name’s Bob Green—Buck for short. I’ve just been hired to show you guys how to punch cows proper.”

There was a barely perceptible silence, broken by one of the men at the table.

“Hired?” he repeated curtly. “Why, I thought Tex went to town.”

“Tex?” queried Stratton. “Oh, you mean the foreman. The lady did say something about that when she signed me up. Said she’d tell him about it when he came back.”

He was aware of a swift exchange of glances between several of the men. The stocky fellow suddenly abandoned his manipulation of the stove-dampers and came forward.

“Oh, that’s it?” he remarked with an amiable grin. “Tex most always does the hirin’, yuh see. Glad to know yuh. My name’s McCabe—Slim, they calls me, ’count uh my sylph-like figger. These here guys is Bill Joyce an’ his side-kick, Butch Siegrist; likewise Flint Kreeger an’ Doc Peters over to the table. Bud Jessup yuh already met.” 40

He chuckled, and Buck glancing toward the corner where the youngster was tucking in the tails of his flannel shirt, smiled slightly.

“Got acquainted kinda sudden, didn’t we?” he grinned. “Glad to meet you gents. Whereabouts is a bunk I can stake my claim to?”

“This here’s vacant,” spoke up Bud Jessup quickly, indicating one next to his own.

Buck stepped over and tossed his bundle into it. As he did so the raucous clanging of a bell sounded from the direction of the ranch-house, accompanied by a stentorian shout: “Grub-pile!” which galvanized the punchers into action.

Stratton and the boy were the last to leave the room, and as he reached the door Buck noticed a tiny wisp of smoke curling up from the floor to one side of the stove. Looking closer he saw that it was caused by the branding-iron, one corner of which rested on the end of a board where the rough flooring came in contact with the square of hard-packed earth beneath the stove. Bud Jessup saw it, too, and without comment he stepped over and moved the iron to a safer position.

Still without words, the two left the bunk-house. But as they headed for the kitchen Buck’s eyes narrowed slightly and he flashed a momentary glance at his companion which was full of curiosity and thoughtful speculation.

Supper, which was served in the ranch-house kitchen by Pedro, the Mexican cook, was not enlivened by much conversation. The food was plentiful and of good quality, and the punchers addressed themselves to its consumption with the single-hearted purpose of hungry men whose appetites have been sharpened by a long day in the saddle. Now and then someone mumbled a request to “pass the sugar,” or desired more steak or coffee from the shuffling Pedro; but for the most part the serious business of eating occupied them exclusively.

There was no sign of Miss Thorne. Buck decided that she took her meals elsewhere and approved the isolation. It must be pretty hard, he thought, for a girl like that to be living her young life in this out-of-the-way corner of the world with no women companions to keep her company. Then he remembered that for all he knew she might not be the only one of her sex on the Shoe-Bar, and when the meal was over and the men were straggling back toward the 42 bunk-house, he put the question to Bud Jessup, who walked beside him.

“Huh?” grunted the youngster, with a sharp, inquiring glance at his face. “What d’yuh want to know that for?”

Stratton shrugged his shoulders. “No particular reason,” he smiled. “I only thought she’d find it mighty dull alone on the ranch with a bunch of punchers.”

Bud continued to eye him intently. “Well, she ain’t alone,” he said briefly. “Mrs. Archer lives with her; an’ uh course there’s Pedro’s Maria.”

“Who’s Mrs. Archer?”

“Her aunt. Kinda nice old lady, but she ain’t got much pep. Maria’s jest the other way. When she’s got a grouch on she’s some cat, believe me!”

For some reason the subject appeared to be distasteful to Jessup, and Buck asked no more questions. Instead of following the others into the bunk-house they strolled on along the bank of the creek, which was lined with fair-sized cottonwoods. The sun had set, but the glow of it still lingered in the west. Glinting like a flame on the windows of the ranch-house, it even dappled the placid waters of the little stream with red-gold splotches, which mingled effectively with the mirrored reflections of the overhanging trees. From the kitchen chimney a wisp of smoke rose straight into the still clear air. In a corner of the 43 corral half a dozen horses were bunched, lazily switching their tails at intervals. Through one of the pastures across the stream some cattle drifted, idly feeding their way to water.

It was a peaceful picture, yet Stratton could not rid his mind of the curious feeling that the peacefulness was all on the surface. He had not missed that swift exchange of glances that heralded his first appearance in the bunk-house; and though Slim McCabe particularly had been almost effusively affable, Buck was none the less convinced that his presence here was unwelcome. That business of the branding-iron, too, was puzzling. Was it merely a bit of rough but harmless horse-play or had it a deeper meaning? Bud did not look like a fellow to lose his nerve easily, and the iron had certainly been hot enough to brand even the tough hide of a three-year-old steer.

Buck glanced sidewise at his companion to find the blue eyes studying his face with a keen, questioning scrutiny. They were hastily withdrawn, and a faint color crept up, darkening the youngster’s tan.

“Trying to size me up,” thought Stratton interestedly. “He’s got something on his chest, too.”

But he gave no sign of what was in his mind. A moment or two later he paused and, leaning indolently against a tree, let his gaze sweep idly over the cattle in the near-by pasture. 44

“Looks to me like a pretty good bunch of steers,” he commented, and then added carelessly: “What sort of a guy is this Tex Lynch, anyhow?”

Bud hesitated briefly, sending a swift, momentary glance toward the bunk-house.

“Oh, he’s all right, I guess,” he answered slowly.

Stratton grinned. “If you don’t look out you’ll be overpraising him, kid,” he chuckled.

Jessup shrugged his shoulders. “I didn’t say I liked him,” he defended. “He knows his business all right.”

“Oh, sure. Otherwise, I s’pose he wouldn’t hold down his job. But what I want to know is the kind of boss he is. Does he treat the fellows white, or is he a sneak?”

Bud’s face darkened. “He treats some of ’em white enough,” he snapped.

“That so? Favorites, eh? I’ve met up with that kind before. Is he hard to get on the right side of?”

“Dunno,” growled the youngster. “I never tried.”

Buck chuckled again. “Well, kid, so long as you don’t seem to think it’s worth while, I dunno why I should take the trouble. Who else is on the outs with him?”

Jessup flashed a startled glance at him. “How in blazes do you know—”

“Oh, gosh! That’s easy. That open-faced countenance of yours would give you away even if your 45 tongue didn’t. I’d say you weren’t a bit in love with Lynch, or any of the rest of the bunch, either. Likely you got a good reason, an’ of course it ain’t any of my business; but if that stunt with the red-hot branding-iron is a sample of their playfulness, I should think you’d drift. There must be plenty of peaceful jobs open in the neighborhood.”

“But that’s just what they want me to do,” snapped Jessup hotly. “They’re doin’ their best to drive me——”

His jaws clamped shut and a sudden suspicion flashed into his eyes, which caused Buck promptly to relinquish all hope of getting any further information from the boy. Evidently he had said the wrong thing and got the fellow’s back up, though he could not imagine how. And so, when Jessup curtly proposed that they return to the bunk-house, Stratton readily acquiesced.

They found the five punchers gathered around the table playing draw-poker under the light of a flaring oil lamp. McCabe extended a breezy invitation to Buck to join them, which he accepted promptly, drawing up an empty box to a space made for him between Slim and Butch Siegrist. With scarcely a glance at the group, Jessup selected a tattered magazine from a pile in one corner and sprawled out on his bunk, first lighting a small hand lamp and placing it on the floor beside him. 46

Stratton liked poker and played a good game, but he soon discovered that he was up against a pretty stiff proposition. The limit was the sky, and Kreeger and McCabe especially seemed to have a run of phenomenal luck. Buck didn’t believe there was anything crooked about their playing; at least he could detect no sign of it, though he kept a sharp lookout as he always did when sitting in with strangers. But he was rather uncomfortably in a hole and was just beginning to realize rather whimsically that for a while at least he had only a cow-man’s pay to depend on for spending-money, when the door was suddenly jerked open and a tall, broad-shouldered figure loomed in the opening.

“Well, it’s all right, fellows,” said the new-comer, blinking a little at the light. “I saw—”

He caught himself up abruptly and glowered at Stratton.

“Who the devil are yuh?” he inquired harshly, stepping into the room.

Buck met his hard glance with smiling amiability.

“Name of Buck Green,” he drawled. “Passed you on the trail this afternoon, didn’t I? You must be Tex Lynch.”

With a scarcely perceptible movement he shifted his cards to his left hand. His right, the palm half open, rested on the edge of the table just above his thigh. He didn’t really believe the foreman would 47 start anything, but one never knew, especially with a man of such evidently uncertain temper.

“Huh!” grunted Lynch. “Why didn’t yuh stop me then? Yuh might have saved yourself a ride.” He continued to stare at Stratton, a veiled speculation in his smoldering eyes. “Well?” he went on impatiently. “What can I do for yuh now I’m here?”

Buck raised his eyebrows. “Do for me? Why, I don’t know as there’s anything right this minute. I s’pose you’ll be wanting to put me to work in the morning.”

“You’ve sure got nerve a-plenty,” rasped the foreman. “I ain’t hirin’ anybody that comes along just because he wears chaps.”

“That so?” drawled Buck. “Funny the lady didn’t mention that when she signed me up this afternoon.”

Lynch’s face darkened. “Yuh mean to say—”

He paused abruptly, his angry eyes sweeping past Stratton, to rest for an instant on Flint Kreeger, who sat just beyond McCabe. What he saw there Buck did not know, but it must have been something of warning or information. When his eyes returned to Stratton their expression was veiled under drooping lids; his lithe figure relaxed into an easier position against the door-casing, both hands resting lightly on slim hips.

“Miss Thorne hired yuh, then?” he remarked in a non-committal voice which yet held no touch of 48 friendliness. “Well, that’s different. Where’ve yuh worked?”

“The last outfit was the Three-Circles in Texas.” Buck named at random an outfit in the southern part of the state with which he was slightly acquainted. “Been in the army over two years, and just got my discharge.”

“Texas?” repeated Lynch curtly. “How the devil do yuh happen to be lookin’ for work here?”

“I’d heard Joe Bloss was foreman,” explained Buck calmly. “We used to work together on the Three-Circles, and I knew he’d give me a job. When I found out in Paloma he’d gone, I took a chance an’ rode out anyhow.”

He bore the foreman’s searching scrutiny very well, without a change of color or the quiver of an eyelash. Nevertheless he was not a little relieved when Lynch, with a brief comment about trying him out in the morning, moved around the table and sat down on a bunk to pull off his chaps. That sudden and complete bottling up of emotion had shown Buck how much more dangerous the man was than he had supposed, and he was pleased enough to come out of their first encounter so well.

With a barely perceptible sense of relaxing tension, the poker game was resumed, for which Buck was devoutly thankful. Throughout the interruption he had not forgotten his hand, which was by far the best 49 he had held that evening. He played it and the succeeding ones so well that when the game ended he had managed to break even.

Ten minutes later the lights were out, and the silence of the bunk-house was broken only by the regular breathing of eight men, or the occasional creak of some one shifting his position in the narrow bunk. Having no blankets—a deficiency he meant to remedy if he could get off long enough to-morrow to ride to Paloma Springs—Buck removed merely chaps and boots and stretched his long form on the corn-husk tick with a little sigh of weariness. Until this moment he had not realized how tired he was. But he had slept poorly on the train, and this, coupled with the heady air and the somewhat stirring events of the last few hours, dragged his eyelids shut almost as soon as his head struck the improvised pillow.

It seemed as if scarcely a moment had passed before he opened them again. But he knew that it must be several hours later, for it had been pitch-dark when he went to sleep, and now a square of moonlight lay across the floor under the southern window, bringing into faint relief the outlines of the long room.

Just what had roused him he did not know; some noise, no doubt, either inside the bunk-house or without. Nerves attuned to battle-front conditions are likely to become sharp as razor-edges, and Buck, starting from deep slumber to complete wakefulness, was 50 almost instantly aware of a sense of strangeness in his surroundings.

In a moment he knew what it was. Even though they may not snore, the breathing of seven sleeping men is unmistakable. Buck did not have to strain his ears to realize that not a sound came from any of the other bunks, and swiftly the utter, unnatural stillness became oppressive.

Quietly he swung his stockinged feet to the floor and was reaching for the holster and cartridge-belt he had laid beside him, when, from the adjoining bunk, Bud Jessup’s voice came in a cautious whisper.

“They’re gone. The whole bunch of ’em just rode off.”

“Hello, kid!” said Stratton quietly. “You awake? What’s up, anyhow?”

There was a rustle in the adjoining bunk, the thud of bare feet on the floor, and Jessup’s face loomed, wedge-shaped and oddly white, through the shadows.

“They’re gone,” he repeated, with a curious, nervous hesitancy of manner.

“I know. You said that before. What the devil are they doing out this time of night?”

In drawing his weapon to him, Buck’s eyes had fallen on his wrist-watch, the radiolite hands of which indicated twenty minutes after twelve. He awaited Jessup’s reply with interest, and it struck him as unnaturally long in coming.

“I don’t rightly know,” the youngster said at length. “I s’pose they must have gone out after—the rustlers.”

Buck straightened abruptly. “What!” he exclaimed. “You mean to say there’s been rustling on the Shoe-Bar?”

Again Jessup hesitated, but more briefly. “I don’t know why I shouldn’t tell yuh. Everybody’s wise 52 to it, or suspects somethin’. They’ve got away with quite a bunch—mostly from the pastures around Las Vegas, over near the hills. Tex says they’re greasers, but I think—” He broke off to add a moment later in a troubled tone, “I wish to thunder he hadn’t gone an’ left Rick out there all alone.”

Stratton remembered Las Vegas as the name of a camp down at the southwesterly extremity of the ranch. It consisted of a one-room adobe shack, which was occupied at certain seasons of the year by one or two punchers, who from there could more easily look after the near-by cattle, or ride fence, than by going back and forth every day from the ranch headquarters.

“Who’s Rick?” he asked briefly.

“Rick Bemis. He—he’s one dandy fellow. We’ve worked together over two years.”

“H’m. How long’s this rustling been going on?”

“Three or four months.”

“Lost many head, have they?”

“Quite a bunch, I’d say, but I don’t know. They never tell me or Rick anythin’.”

Bud’s tone was bitter, and Stratton noticed it in spite of his preoccupation. Rustling! That would account for several of the things that had puzzled him. Rustling was possible, too, with the border-line comparatively near, and that stretch of rough, hilly country which touched the lower extremity of the ranch. But 53 for the stealing to go on for three or four months, without something drastic being done to stop it, seemed peculiar, to say the least.

“What’s been done about it?” Buck asked briefly.

“Oh, they’ve gone out at night a few times, but they never caught anybody that I heard. Seems like the thieves were too slick, or else—”

He paused; Buck regarded him curiously through the faintly luminous shadows.

“Well?” he prodded

Bud moved uneasily. “It ain’t anythin’ special,” he returned evasively. “All this time they never left anybody down to Las Vegas till Rick was sent day before yesterday. I up an’ told Tex straight out there’d oughta be another fellow with him, but all he done was to bawl me out an’ tell me to mind my own business. It ain’t safe, an’ now they’ve gone out—”

Again he broke off, his voice a trifle husky with emotion. He was evidently growing more and more worked up and alarmed for the safety of his friend. It was plain, too, that the recent departure of the punchers for the scene of action, instead of reassuring Bud, had greatly increased his anxiety. Buck decided that the situation wasn’t as simple as it looked, and promptly determined on a little action.

“Would it ease your mind any if we saddled up an’ followed the bunch?” he asked. 54

Jessup drew a quick breath and half rose from the bunk. “By cripes, yes!” he exclaimed. “Yuh mean you’d—”

“Sure,” said Stratton, reaching for his boots. “Why not? If there’s going to be any excitement I’d like to be on hand. Pile into your clothes, kid, and let’s go.”

Jessup began to dress rapidly. “I don’t s’pose Tex’ll be awful pleased,” he murmured, dragging on his shirt.

“I don’t see he’ll have any kick coming,” returned Buck easily. “If he’s laying for rustlers, seems like he’d ought to have routed out the two of us in the beginning to have as big a crowd as possible. You never know what you’re up against with those slippery cusses.”

Bud made no further comment, and a few minutes later they left the bunk-house and went up to the corral. The bright moonlight illumined everything clearly and made it easy to rope and saddle two of the three horses remaining in the enclosure. Then, swinging into the saddle, they rode down the slope, splashed through the creek, and entering the further pasture by a gate, headed south at a brisk lope.

The land comprising the Shoe-Bar ranch was a roughly rectangular strip, much longer than it was wide, which skirted the foothills of the Escalante Mountains. As the crow flies it was roughly seven 55 miles from the ranch-house to Las Vegas camp, and for the better part of that distance there was little conversation between the two riders. Buck would have liked to question his companion about a number of things that puzzled him, but having sized up Jessup and come to the conclusion that the youngster was the sort whose confidence must be given uninvited or not at all, he held his peace. Apparently Bud had not yet made up his mind whether to class Stratton as an enemy or a friend, and Buck felt he could not do better than endeavor unobtrusively to impress the latter fact upon him. That done, he was sure the boy would open up freely.

The wisdom of this policy became evident sooner than he expected. From time to time as they rode, Stratton commented casually, as a new hand would be likely to do, on some feature or other connected with the ranch or their fellow-punchers. To these remarks Jessup replied readily enough, but in a preoccupied manner, until all at once, moved either by something Buck had said, or possibly by a mind burdened to the point where self-restraint was no longer possible, he burst into sudden surprising speech.

“That wasn’t no foolin’ with that iron this afternoon. If yuh hadn’t come along jest then they’d of branded me on the back.”

Astonished, Buck glanced at him sharply. They had traveled more than two-thirds of the distance to Las 56 Vegas camp, and he had quite given up hope of Jessup’s opening up during the ride.

“Oh, say!” he protested. “Are you trying to throw a load into me? Why would they want to do that?”

Jessup gave a short brittle laugh.

“They want me to quit,” he retorted curtly.

“Quit?” repeated Stratton, his eyes widening. “But—”

“Tex don’t want me here,” broke in the youngster. “For the last three months he’s tried all kinds of ways to make me an’ Rick take our time; but it won’t work.” His lips pressed together firmly. “I promised Miss—”

His words clipped off abruptly, as a single shot, sharp and distinct, shattered the still serenity of the night. It came from the south, from the direction of Las Vegas. Buck flung up his head and pulled instinctively on the reins. Jessup caught his breath with an odd, whistling intake.

“There!” he gasped unevenly.

For a moment or two they sat motionless, listening intently, Buck’s face a curious mixture of alertness and surprise. Up to this moment he had taken the whole business rather casually, with small expectation that anything would come of it, but the sound of that shot changed everything. Something was happening, then, after all—something sinister, perhaps, and certainly not far away. His eyes narrowed, and when 57 no other sound followed that single report, he loosed his reins and urged the roan to a gallop.

For perhaps half a mile the two plunged forward amidst a silence that was broken only by the dull thudding of their horses’ hoofs and their own rapid breathing. Then all at once Buck jerked his roan to a standstill.

“Some one’s coming,” he warned briefly.

Straight ahead of them the moonlight lay across the flat, rolling prairie almost like a pathway of molten silver. On either side of the brilliant stretch the light merged gradually and imperceptibly into shadows—shadows which yet held a curious, half-luminous quality, giving a sense of shifting horizons and lending a touch of mystery to the vague distances which seemed to be revealed.

From somewhere in that illusive shadow land came the faint beat of a horse’s hoofs, growing steadily louder. Eyes narrowed to mere slits, Stratton stared ahead intently until of a sudden his gaze focused on a faintly visible moving shape.

He straightened, his right hand falling to the butt of his Colt. But presently his grip relaxed and he reached out slowly for his rope.

“There’s no one on him,” he murmured in surprise.

Without turning his head, Jessup made an odd, throaty sound of acquiescence. 58

“He’s saddled, though,” he muttered a moment later, and also began taking down his rope.

Straight toward them along that moonlit pathway came the flying horse, head down, stirrups of the empty saddle flapping. Buck held his rope ready, and when the animal was about a hundred feet away he spurred suddenly to the right, whirling the widening loop above his head. As it fell accurately about the horse’s neck the animal stopped short with the mechanical abruptness of the well-trained range mount and stood still, panting.

Slipping to the ground, Bud ran toward him, with Stratton close behind. The strange cayuse, a sorrel of medium size, was covered with foam and lather, and as Jessup came close to him he rolled his eyes in a frightened manner.

“It’s Rick’s saddle,” said Bud in an agitated tone, after he had made a hasty examination. “I’d know it anywhere from—that—cut—in—”

His voice trailed off into silence and he gazed with wide-eyed, growing horror at the hand that had rested on the saddle-skirt. It was stained bright crimson, and Buck, staring over his shoulder, noticed that the leather surface glistened darkly ominous in the bright moonlight.

Slowly the boy turned his head and looked at Stratton. His face was lint-white, and the pupils of his eyes were curiously dilated. 59

“It’s Rick’s saddle,” he repeated dully, and shuddered as he stared again at his blood-stained hand.

Buck’s own fingers caught the youngster’s shoulder in a reassuring grip, and his lips parted. But before he had time to speak a sudden volley of shots rang out ahead of them, so crisp and distinct and clear that instinctively he stiffened, his ears attuned for the familiar, vibrant hum of flying bullets.

Swiftly the echoes of the shots died away, leaving the still serenity of the night again unruffled. For a moment or two Stratton waited expectantly; then his shoulders squared decisively.

“I reckon it’s up to us to find out what’s going on down there,” he said, turning toward his horse.

Jessup nodded curt agreement. “Better take the sorrel along, hadn’t we?” he asked.

“Sure.” Buck swung himself lightly into the saddle, shortening the lead rope and fastening it to the horn. “I was thinking of that.”

Five minutes later they pulled up in front of a small adobe shack nestling against a background of cottonwoods that told of the near presence of the creek. The door stood open, framing a black rectangle which proclaimed the emptiness of the hut, and with scarcely a pause the two rode slowly on, searching the moonlit vistas with keen alertness.

On their right the country had grown noticeably rougher. Here and there low spurs from the near-by western hills thrust out into the flat prairie, and deep 61 shadows which marked the opening of draw or gully loomed up frequently. It was from one of these, about half a mile south of the hut, that a voice issued suddenly, halting the two riders abruptly by the curtness of its snarling menace.

“Hands up!”

Buck obeyed promptly, having learned from experience the futility of trying to draw on a person whose very outlines are invisible. Jessup’s hands went up, too, and then dropped quickly to his sides again.

“Why, it’s Slim!” he cried, and spurred swiftly toward the mouth of the gully. “What the deuce is the matter?” he asked anxiously. “What’s happened to Rick?”

There was a momentary pause, and then McCabe stepped out of the shadows, six-gun in one hand.

“What the devil are yuh doin’ here?” he demanded with a harshness which struck Buck in curious contrast to his usual air of good humor. “Who’s that with yuh?”

“Only Green. We—we got worried, an’ saddled up an’—followed yuh. When we heard the shots—What did happen to Rick, Slim? We caught his horse out there, the saddle all—”

“Since yuh gotta know,” snapped the puncher, “he got a hole drilled through one leg. He’s right here behind me.”

As Bud flung himself out of the saddle and hurried 62 over to the man lying just inside the gully, McCabe stepped swiftly to the side of Stratton’s horse. There was a mingling of doubt and sharp suspicion in the upturned face.

“Yuh sure are up an’ doin’ for a new hand,” he commented swiftly. “Was it yuh put it into his head to come out here?”

“I reckon maybe it was,” returned Buck easily. “When we woke up an’ found you all gone, the kid got fretting considerable about his friend here, and I didn’t see why we shouldn’t ride out and join you. According to my mind, when you’re out after rustlers, the more the merrier.”

“Huh! He told yuh we was after rustlers?”

“Sure. Why not? It ain’t any secret, is it? Leastwise, I didn’t gather that from Bud.”

McCabe’s face relaxed. “Wal, I dunno as ’t is,” he shrugged. “Tex likes to run things his own way, though. Still, I dunno as there’s any harm done. Truth is, we didn’t get started soon enough. We was half a mile off when we heard the shot, an’ rid up to find Rick drilled through the leg an’ the thieves beatin’ it for the mountains. The rest of the bunch lit out after ’em while I stayed with Rick. I dunno as they caught any of ’em, but I reckon they didn’t have time to run off no cattle.”

Stratton slid out of the saddle and threw the reins 63 over the roan’s head. He had not failed to notice the slight discrepancy in McCabe’s statement as to the length of time it took the punchers to ride from the bunk-house to this spot, but he made no comment.

“Bemis hurt bad?” he asked.

“Not serious. It’s a clean wound in his thigh. I got it tied up with his neckerchief.”

Buck nodded and walked over to where Bud was squatting beside the wounded cow-puncher. By this time his eyes were accustomed to the half-darkness, and he could easily distinguish the long length of the fellow, and even noted that the dark eyes were regarding him questioningly out of a white, rather strained face.

“Want me to look you over?” he asked, bending down. “I’ve had considerable experience with this sort of thing, and maybe I can make you easier.”

“Go to it,” nodded the young chap briefly. “It ain’t bleedin’ like it was, but it could be a whole lot more comfortable.”

With the aid of Jessup and McCabe, Bemis was moved out into the moonlight, where Stratton made a careful examination of his wound. He found that the bullet had plowed through the fleshy part of the thigh, just missing the bone, and, barring chances of infection, it was not likely to be dangerous. He was readjusting Slim’s crude bandaging when he heard 64 the beat of hoofs and out of the corner of one eye saw McCabe walk swiftly out to meet the returning punchers.

These halted about fifty feet away, and there was a brief exchange of words of which Buck could distinguish nothing. Presently two of the men dashed off in the direction of the ranch-house, while Lynch rode slowly forward and dismounted.

“How yuh feelin’?” he asked Bemis, adding with a touch of sarcasm in his voice, “I hear yuh got a reg’lar professional sawbones to look after yuh.”

“He acts like he knew what he was about,” returned Bemis briefly. “How yuh goin’ to get me home?”

“I’ve sent Butch an’ Flint after the wagon,” explained Lynch. “They’ll hustle all they can.”

“Did you catch sight of the rustlers?” asked Stratton suddenly.

The foreman flashed him a sudden not overfriendly glance.

“No,” he returned curtly, and turning on his heel led his horse over to where the others had gathered in the shadow of a rocky butte.

It was nearly an hour before the lumbering farm-wagon appeared. During the interval Buck sat beside the wounded man, smoking and exchanging occasional brief comments with Bud, who stayed close by. One or two of the others strolled up to ask about Bemis, but for the most part they remained in their 65 little group, the intermittent glow of their cigarettes flickering in the darkness and the constant low murmur of their conversation wafted indistinguishably across the intervening space.

Their behavior piqued Buck’s curiosity tremendously. What were they talking about so continually? Where had the outlaws gone, and why hadn’t they been pursued further? Had the whole pursuit been merely in the nature of a bluff? And if so, whom had it been intended to deceive? These and a score of other questions passed through his mind as he sat there waiting, but when the dull rumble of the wagon started them all into activity, he had not succeeded in finding any really plausible answers.

The return trip was necessarily slow, and dawn was just breaking as they forded the creek and drove up to the bunk-house. They had barely come to a standstill when, to Buck’s surprise, the slim figure of Mary Thorne, bare-headed and clad in riding-clothes, appeared suddenly around the corner of the ranch-house and came swiftly toward them.

“Pedro told me,” she said briefly, pausing beside the wagon. “How is he?”

“Doin’ fine,” responded Lynch promptly. “It’s a clean wound an’ ought to heal in no time. Our new hand Green tied him up like a regular professional.”

His manner was almost fulsomely pleasant; Miss Thorne’s expression of anxiety relaxed. 66

“I’m so glad. You’d better bring him right up to the house; he’ll be more comfortable there.”