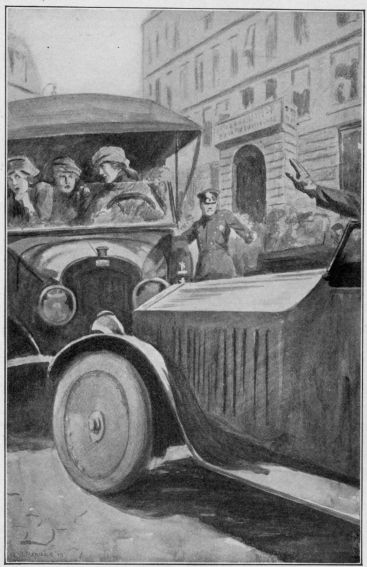

THE TWO CARS COLLIDED.

Polly’s Business Venture. Frontispiece—(Page 99)

Title: Polly's Business Venture

Author: Lillian Elizabeth Roy

Release date: June 13, 2008 [eBook #25778]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

POLLY’S BUSINESS VENTURE

POLLY’S

BUSINESS VENTURE

BY

LILLIAN ELIZABETH ROY

Author of

POLLY OF PEBBLY PIT, POLLY AND ELEANOR,

POLLY IN NEW YORK, POLLY AND

HER FRIENDS ABROAD

ILLUSTRATED BY

H. S. BARBOUR

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1922, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Polly Returns To America | 1 |

| II | A Disappointing Evening | 18 |

| III | The Accident | 34 |

| IV | A Reunion and a Visitor | 47 |

| V | The Raid on Choko’s Find Mine | 58 |

| VI | Polly and Eleanor Begin Collecting | 74 |

| VII | A Revolutionary Relic Hunt | 94 |

| VIII | Another Attempt at Collecting | 109 |

| IX | Polly’s Hunt in ’Jersey | 127 |

| X | Unexpected News From Pebbly Pit | 151 |

| XI | Polly’S First Contract | 167 |

| XII | The Parsippany Vendue | 182 |

| XIII | Tom Means Business | 199 |

| XIV | Necessary Explanations | 213 |

| XV | Mutual Consolation | 231 |

| XVI | Beaux or Business | 250 |

| XVII | Business | 269 |

POLLY’S BUSINESS VENTURE

Five girls were promenading the deck of one of our great Atlantic liners, on the last day of the trip. The report had gone out that they might expect to reach quarantine before five o’clock, but it would be too late to dock that night, therefore the captain had planned an evening’s entertainment for all on board.

“Miss Brewster! Miss Polly Brewster! Polly Brewster!” came a call from one of the young boys of the crew who was acting as messenger for the wireless operator.

“Polly, he is calling you! I wonder what it is?” cried Eleanor Maynard, Polly’s dearest friend.

“Here, boy! I am Polly Brewster,” called Polly, waving her hand to call his attention to herself. 2

“Miss Polly Brewster?” asked the uniformed attendant politely, lifting his cap.

“Yes.”

He handed her an envelope such as the wireless messages are delivered in, and bowed to take his leave of the group of girls. Polly gazed at the outside of the envelope but did not open it. Her friends laughed and Nancy Fabian, the oldest girl of the five, said teasingly:

“Isn’t it delicious to worry one’s self over who could have sent us a welcome, when we might know for certain, if we would but act prosaically and open the seal.”

The girls laughed, and Eleanor remarked, knowingly: “Oh, Polly knows who it is from! She just wants to enjoy a few extra thrills before she reads the message.”

“Nolla, I do not know, and you know it! You always make ‘a mountain from a mole-hill.’ I declare, you are actually growing to be childish in your old age!” retorted Polly, sarcastically.

Her latter remark drew forth a peal of laughter from the girls, Eleanor included. But Polly failed to join in the laugh. She cast a withering glance at Eleanor, and walked aside to open the envelope. The four interested girls watched 3 her eagerly as she read the short message.

Polly would have given half of her mine on Grizzly Slide, to have controlled her expression. But the very knowledge that the four friends were critically eyeing her, made her flush uncomfortably as she folded up the paper again, and slipped it in her pocket.

“Ha! What did I tell you! It is from HIM!” declared Eleanor, laughingly.

Dorothy Alexander was duly impressed, for she had firmly believed, hitherto, that Polly was a man-hater. The manner in which she had scorned Jimmy Osgood on that tour of England would have led anyone to believe that such was the case. Now the tell-tale blush and Eleanor’s innuendo, caused Dorothy to reconsider her earlier judgment.

Polly curled her full red lip at Eleanor’s remark, and was about to speak of something of general interest, when Dorothy unexpectedly asked a (to her) pertinent question.

“Polly, has anyone ever proposed to you?”

Eleanor laughed softly to herself, and Polly sent poor Dodo a pitying glance. “Is that little head of yours entirely void of memory, Dodo?” said she.

Then, without waiting for a reply, Polly continued: 4 “Did not Jimmy propose to me, as well as to every one of you girls?”

“Oh, but I didn’t mean that sort of an affair,” explained Dorothy. “I mean—were you ever in love with anyone who thought he loved you?”

“Oh, isn’t this a delightful conversation? I wouldn’t have missed it for anything in the world!” laughed Eleanor.

“Nolla,” rebuked Polly, seriously, “your head has been so turned since all those poor fortune-hunters in Europe flattered you, that I fear you will never succeed in business with me. I shall have to find someone else who will prove trustworthy and work.”

Polly’s threat did not appear to disturb Eleanor very much, for she laughed merrily and retorted: “Dodo, if I answer your question for Polly, what will you do for me, some day?”

“Nolla, you mind your own affairs!” exclaimed Polly, flushing again. “Dodo is such a tactless child that she never stops to consider whether her questions are too personal, or not. But you—well, you know better, and I forbid you to discuss me any further.”

“Come, come, girls! This little joke is really going too far, if Polly feels hurt about it. Let us drop the subject and talk about the dance the 5 Captain is going to give us tonight,” suggested Nancy.

“I’m going to wear the new gown mother got in Paris,” announced Dorothy. “Ma says we can save duty on it if I wear it before it reaches shore.”

The other girls laughed, and Eleanor added: “That’s a good plan, Dodo. I guess I will follow your example. I’ve got so many dutiable things in my trunks, that I really ought to economise on something.”

“Well, I won’t wear one of my new dresses tonight for just that reason. If I want them badly enough, to bring them all the way from Paris where we get them so much cheaper than on this side, then I’m willing to pay Uncle Sam his revenue on them,” said Polly, loftily.

“Ho! I don’t believe it is duty you are saving, as much as indulging in perverseness by not donning one of your most fetching gowns,” declared Eleanor.

“Maybe it is,” said Polly, smiling tantalizingly at her chum. “Perhaps I want to keep the freshness of them for someone in New York, eh?”

“Certainly! He will be there to meet you, sure thing!” laughed Eleanor.

At that, Dorothy drew Eleanor aside and, when 6 Polly was not looking, whispered eagerly: “Do tell me who he is?”

But Eleanor laughingly shook her head and whispered back: “I dare not! That is Polly’s secret!”

But she did not add for Dorothy’s edification, that try as she would, she (Eleanor) had never been able to make Polly confess whether she preferred one swain to another. As Eleanor considered this a weakness in her own powers of persuasion, she never allowed anyone to question her that far.

Had anyone of the four girls dreamed of who the sender of the wireless was, what a buzzing there would have been! Eleanor Maynard would have been so pleased at the possibility of a romance, that she would have acted even more tantalizing, in Polly’s opinion, than she had been of late months.

Perhaps you are not as well acquainted with Polly and her friends, however, as I am, and it would be unkind to continue their experiences for your entertainment, until after you are duly informed of how Polly happened to leave her home in Oak Creek and also what had passed during the Summer in Europe.

Polly Brewster was born and reared on a 7 Rocky Mountain ranch, in Colorado, and had until her fourteenth year, never been farther from her home than Oak Creek, which was the railroad station and post office of the many ranchers of that section.

Eleanor Maynard, the younger daughter of Mr. Maynard who was a prosperous banker of Chicago, accompanied her sister Barbara and Anne Stewart, the teacher, when they spent a summer on the ranch. Their thrilling adventures during the first half of that summer are told in the book called “Polly of Pebbly Pit,” the first volume of this series.

After the discovery of the gold mine on Grizzly Slide, and the subsequent troubles with the claim-jumpers, Polly and her friends sent for John Brewster who was engaged to Anne Stewart, and Tom Latimer, John’s best friend, to leave their engineering work on some mines, for the time being, and hasten to Pebbly Pit to advise about the gold mine, and to take action to protect the girls. These experiences are told in the second volume of this series.

Success being assured in the mining plans of the gold vein on Grizzly Slide, and the valuable lava cliffs located on Pebbly Pit ranch also finding a market as brilliant gems for use in jewelry, Polly 8 and Eleanor decided to accompany Anne Stewart to New York, where she was going to teach in an exclusive school for young ladies.

In the third book, Polly and Eleanor’s adventures in New York are told. Their school experiences; the amateur theatricals at which Polly saved a girl from the fire, and thus found some splendid friends; and the new acquaintance, Ruth Ashby, who was the only child of the Ashbys. They also met Mr. Fabian in a most unusual manner, and through him, they became interested in Interior Decorating, to study it as a profession. When the school-year ended, all these friends invited the two girls to join their party that was planned to tour Europe and visit noted places where antiques are exhibited.

The following fourth book describes the amusing incidents of the three girls on board the steamer, after they meet the Alexanders. Mrs. Alexander, the gorgeously-plumed ranch-woman; Dorothy, always known as “Dodo,” the restive girl of Polly’s own age; and little Ebeneezer Alexander, too meek and self-effacing to deny his spouse anything, but always providing the funds for her caprices. This present caprice, of rushing to Europe to find a “title” for Dodo to marry, 9 was the latest and hardest of all for him to agree to.

Because of Mrs. Alexander’s whim, the ludicrous experiences that came upon the innocent heads of Polly and her friends, in the tour of England in two motor cars, decided them to escape from that lady, and run away to Paris. Before they could sigh in relief at their freedom, however, the Alexanders loomed again on their horizon.

Plan as they would, the badgered tourists found that Mrs. Alexander had annexed herself permanently to them. They resigned themselves to the inevitable. But that carried with it more ridiculous affairs, when Mrs. Alexander plotted for the titles found dangling before her, in various places on the Continent.

One good result came from this association with the Alexanders: Dodo found how fascinating the work of collecting really was, and decided to study decorating as an art. Hence she spurned her mother’s ambitions for her, and announced her plan of remaining in New York with the girls, upon their return to America, to follow in their line of study.

Mrs. Alexander felt quite satisfied to live in 10 New York for a season, as she fancied it an easy matter to forge a way into good society there. But her spouse detested large cities and longed for his mining life once more, but agreed to it because Dodo was delighted with the opportunity opened before her, in the profession of decorator.

Polly’s party on board the steamer consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Ashby and Ruth; Mr. and Mrs. Fabian and Nancy; Mr. and Mrs. Alexander and Dodo; and lastly, Polly Brewster and Eleanor Maynard.

Just a word about the last two girls: Polly knew that Eleanor was fond of Paul Stewart since she met him a few years before. And Eleanor wondered if Polly preferred Tom Latimer to any other young man she knew; but Polly always declared that she was married to her profession and had no time to spare for beaus. Hence Tom Latimer sighed and hoped that she might change her mind some day.

Meantime, Tom lost no good opportunity to show how he appreciated Polly and, whenever possible, he managed to perform the little deeds that mean so much to a woman—especially if that woman is young and impressionable. Thus he actually made better headway in his silent campaign 11 for Polly, by never broaching the subject of love—from which she would have fled instantly and then barred the doors of her heart.

The wireless received by Polly was from Tom who had been anxiously awaiting the time when he could communicate with the vessel. The contents of the message could have been read to all the world without exciting comment—it was so brotherly. But Polly felt that it was a private welcome to her and so it was not to be shared with others.

The wireless said that Tom and Polly’s dear friends who were in New York, had been invited on board Mr. Dalken’s yacht, to visit the quarantined steamer that evening. That they would arrive about eight o’clock, having secured passes from the Inspector at Quarantine.

Although this explanation about Polly and her associates took time for us, it did not interrupt the lively banter between the five girls. Dorothy was now certain that Polly had a real beau, somewhere, and being so very candid and talkative herself, she admired the reticence displayed by Polly in keeping the affairs of her heart to herself.

Dodo whispered back to Eleanor: “Dear me! I hope he is worthy of her. She ought to have the finest husband in the world.” 12

Eleanor laughed. “Don’t worry, Dodo. She will. If he was not meant for Polly, I’d try and get him for myself—that is how much I admire him.”

“Oh my! Won’t you tell me something about him, Nolla?” asked Dorothy, eagerly.

“I really don’t dare, Dodo,” returned Eleanor, assuming a wise expression. “Polly would drop me forever, if she thought I confided in anyone about her love-affairs. Besides, you can find out everything for yourself, now that you are going to remain with us, this winter. Still, I would love to know just who that wireless came from.” Eleanor added the latter remark after a moment’s deep consideration.

“I’ll tell you what we can do,” ventured Dorothy, in a whisper. “We have often visited the wireless room; let’s you and I go there again, and start a friendly chat with the operator. Maybe he will speak of the message.”

Without stopping to think whether this method would be principled or not, Eleanor eagerly agreed to Dorothy’s plan. While Polly and Nancy were discussing the beautiful hazy picture made by New York’s sky-line as seen from the Harbor at Quarantine, Dorothy and Eleanor hurried to the wireless room. 13

The young man had often been entertained by the girls during the trip from Europe, so this visit was not suspected of having a secret motive back of it. He chatted pleasantly with his callers and, after a time, spoke of the very topic they wished to hear about.

“I suppose you girls will all be on the qui vive this evening?”

“Yes, it is awfully nice of the captain, isn’t it?” said Eleanor, referring to the dance and thinking that the operator also meant that event.

“Oh, I do not think the captain had as much to do with the invitation as had the Inspector General of the Quarantine. Of course we have a clean bill for the ship or no one would have been allowed to step on board tonight; but at the same time your friends must have had a good hard time to get the invitation from the authorities. Only a New Yorker who understands the ropes, could have managed the matter so quickly.”

Dorothy was about to ask what he was talking about, when Eleanor pinched her arm for silence. Then the latter spoke: “Oh yes! He is a wonder—we think!”

Dorothy gasped at Eleanor, and the smiling girl winked secretly at her. The operator had not seen the pinch nor the wink, but he continued 14 guilelessly: “Well, from what I’ve seen of Miss Polly, only a ‘wonder’ would cause her to notice him at all!”

He laughed at his own words and Eleanor joined him, even though she failed to see a joke. Then she said: “Polly could have so many admirers, but she never looks at a man. Perhaps that is why all you males sigh so broken-heartedly at her heels.”

The young man laughed softly to himself. “Maybe! But this ‘Tom’ seems to feel assured of a ‘look’ from her.”

Now it was Dorothy’s turn to pinch Eleanor, and she did so with great gusto. Eleanor winced but dared not express herself in any other manner, just then. She was too keen on the trail of learning what she could, to signify any sense of having felt that pinch.

“Oh—Tom! He is an old family friend, you know. He was Polly’s brother’s college-chum for four years while both boys studied at the University of Chicago. I am from Chicago, and I knew those boys when they used to come to my home with my brother, who also attended the engineering classes. There was a fourth boy—Paul Stewart, who was from Denver. Anne Stewart was his sister and she married John 15 Brewster, this Spring. So you see, we are all old friends together. I suppose the whole family crowd will come out on the yacht, tonight.”

Dorothy listened in sheer amazement, as Eleanor spoke with all the assurance possible. But Dorothy was not aware of Eleanor’s lifelong training in the home of a social leader of Chicago’s exclusive set. That such a home-training made a girl precocious and subtle, was not strange, and Eleanor had had fourteen years of such a life before she went to Pebbly Pit and met Polly. Habits so well-engrounded are not easily broken, or forgotten.

“Then the sender ought to have sent his message to one of the adults of the party. Even I misjudged the matter, because I thought this ‘Tom’ must be a faithful admirer of Miss Polly’s to get through to visit the steamer tonight,” explained the operator.

“But he isn’t coming alone—didn’t you stop to consider that?” asked Eleanor, eagerly. “Seeing that most of the friends are Polly’s personal ones, the wire was sent to her, you know.”

“I see.”

“The only thing that hurt me, was that no one sent me a message. Tom is as dear to me as to Polly, and I wonder he did not wire me.” 16

“Perhaps this Tom thought you would have scores of eager messages the moment your beaus knew you were near enough to get them,” laughed the young officer.

“Well, they didn’t! But I want you to do something for me—will you?” asked Eleanor, quite unexpectedly.

“I will if I can,” agreed the officer.

“Write off a fake message for me and sign some make-believe name to it, so I can hold my head up with Polly. She will never let me rest if she thinks she got a line, and I didn’t!”

“Oh, that is easy to do. As long as we know it will never come out, and that I wrote a line to you, it will be a good joke.”

“All right!” laughed Eleanor, delightedly. “Now write:——” She stopped suddenly, then thought for a moment before she said: “Why not copy the exact words sent to Polly, but sign another name?”

“I’ll write one, as much like the original as possible without actually duplicating that information,” chuckled the officer.

Then he took up a slip of paper and wrote: “Miss Eleanor Maynard. We will join you this evening, on steamer. Yacht will arrive about 17 eight.” He looked up laughingly and asked: “Now what name shall we sign to this?”

“Oh—let me see! Sign ‘Paul.’ I know he is in New York, now, so I am not taking chances of making a mistake,” laughed Eleanor.

The name “Paul” was added to the message and the paper placed in an envelope. This was addressed to Eleanor Maynard and her stateroom number written down upon it. Then it was handed to the gratified girl.

The young man was thanked with unwarranted warmth, and the two girls hastened away.

Eleanor and Dorothy did not join their friends at once, after leaving the wireless room. Eleanor explained wisely: “We must promenade along the deck and let them see us reading and talking over the message, you know, to make them believe we just got it from the boy.”

So this little act was carried out, and when the two girls felt sure that Polly and her companions had noticed them reading the wireless message, Eleanor whispered: “Now we can stroll over and join them. Leave it to me.”

Just before she joined her friends, Eleanor thrust the paper into her sweater pocket, and seemed not to remember it. But Nancy spoke of it, immediately.

“I see you received a billet-doux, too. Is there any reason why I should not say to you exactly what you said to Polly, when she got hers?” laughed the young lady. 19

“Oh, not at all! I am not so bashful about my affair,” retorted Eleanor, taking the paper from her pocket and handing it to Nancy. “You may read it aloud, if you choose.”

So Nancy read, and the fact that the words conveyed the same information as Polly’s had done, but the sender had signed himself “Paul,” made Polly feel relieved. Then she said:

“It is evident that someone secured a yacht to carry our friends out to see us this evening. My message said about the same thing, so now, you see, it was ridiculous in Eleanor to tease about it being a love-note. Had she been sensible I would have read it aloud to all, but because of her silliness, I made up my mind to keep her guessing.”

Nancy and Ruth laughed, but Eleanor and Dorothy exchanged glances with each other. Then Nancy said anxiously: “We ought to start and dress most fetchingly for tonight, if everyone you know is coming out.”

Before anyone could reply to this suggestion, Mr. Fabian was seen hurrying across the deck to join them. “Girls, our old friend Dalken has a yacht, I hear, and he has invited everyone we know to come out here this evening to welcome us home. We are to be ready to return with him, as he has secured the necessary bill-of-health for 20 us. Now get down to your rooms quickly and pack.”

“Oh—aren’t we going to remain to the dance?” asked Eleanor, with disappointment in her tones.

“You can do as you please about that, but we will go back on the yacht when she returns to the city.”

In the bustle of packing the stateroom trunks, and then dressing for the evening, the girls forgot about the wireless messages. Then during the dinner that was like a party affair because of the passengers’ exuberant spirits at being so near home again, Mr. Fabian smiled approvingly at the five young girls in his charge. They looked so charming in their Paris gowns, and their youthful forms and faces expressed such joy and pleasure in living, that he felt gratified to think the old friends would see them as he did that evening.

Shortly after leaving the dining-salon, the attention of the Fabian party was drawn to a graceful white yacht that sailed swiftly down the Bay and soon came alongside the steamer. The spotless looking sailors instantly lowered the boat and a party of young people got in. The Fabian group leaned over the rail of the steamer and watched breathlessly as the boat was rowed across 21 the intervening space and, finally, was made fast to the steamer.

“Poll, did you recognize your future Fate?” giggled Eleanor, nudging her companion, knowingly.

“I saw yours!” retorted Polly. “And now I comprehend why you can speak of nothing else than beaus and Fate! You are so obsessed by your own dreams that you think everyone you know must be dreaming the same stuff!”

Polly turned quickly and hurried to the spot where the visitors were being greeted by Mr. Fabian, and the other girls, laughing at the repartee, followed. In the first group to arrive were Tom Latimer and his younger brother Jim; Kenneth Evans, Jim’s chum; Paul Stewart; and John Brewster with Anne, his bride.

Happy welcomes were exchanged between everyone, but Polly purposely avoided any extra favor being shown Tom Latimer, although he looked as if he deserved it more than Jim and his friend Kenneth. Eleanor quite openly showed her preference for Paul, when they separated from the others for the evening.

“Where is Mr. Dalken and the others?” asked Polly, gazing around at the small group that had arrived on board. 22

“The boat is going back for the second installment,” explained Anne, keeping an arm about Polly’s waist. “We-all were too impatient to see you to accept the suggestion of waiting for the second trip, so the older ones sent us off first.”

To Polly’s surprise and joy, the second boat-load brought her father and mother, Mrs. Stewart, the Latimers, the Evans, and Mr. Dalken, the owner of the yacht. When the family circle was complete, on board the steamer, they proved to be a happy party, and many of the passengers wished they were included in that merry group.

The steamer rolled gently with the swells from the ocean, while the full moon shone mistily through a fog that veiled its brightness enough to add romance to the meeting of the various young people on deck. Eleanor and Paul had been genuinely delighted to see each other again, and neither cared who knew just how much they liked each other.

Polly watched them for a time, then smiled as they walked away to discover a cozy retreat behind one of the giant smoke-stacks, where they could enjoy a tête-à-tête without interruption. When she turned to hear what her brother John 23 was saying, she found Tom Latimer just at her elbow.

“Suppose we find a nice sheltered spot where you can tell me all about your trip abroad?” suggested Tom, his eyes speaking too plainly how anxious he was to get Polly away from the others.

“Oh, I’d far rather be with the crowd and hear all that is being said,” said Polly, nervously.

“Very well, then,” said Tom, moodily. “I only thought you’d like to hear all about Grizzly Slide and how it’s been cutting up this summer. The gold mine has had several adventurers trying to jump the claim, too; and Rainbow Cliffs has had an injunction served on it so that we are tied up by law, this year.”

“So mother wrote to me. But I don’t want to hear about troubles and business tonight. I just want to enjoy myself after coming home to all the dear folks,” said Polly.

Tom was too unsophisticated with girls, although he was so popular with men, to make allowance for the contrary spirit that often sways a girl when she wishes to make a good impression; so he sulked and followed at Polly’s heels when she hurried after her friends.

Mr. Dalken turned just now, and saw the girl 24 running as if to get away from Tom, and he understood, fairly well, just how matters were. So he endeavored to calm Polly’s perturbed spirit and encourage Tom’s “faint heart” at the same time.

“Well, Polly dear,” said he, placing an arm about her shoulders, “now that you have seen many of the wonder-spots of Europe, and know more about antiques and art than any of us, I suppose you are quite decided that business is not your forte, eh? The next thing I’ll hear from you, you’ll have dropped your ambitions and be sailing down a love-stream to a snug harbor.”

“Indeed not! You ought to know me better than that, Mr. Dalken,” declared Polly, vehemently, causing her companions to laugh. “I am more determined than ever, since seeing such wonderful things in Europe, to devote my life to my chosen profession. Why, the marvellous objects I saw in Europe, used in interior decorating in centuries past, enthuse me anew. I wonder that anyone can keep from studying this fascinating art where there is such a broad field of work and interest.”

Polly’s mother and father listened to their daughter, with adoration plainly expressed on 25 their faces, and Tom had to grit his teeth to keep from swearing, because of what he considered their influence over Polly in this, her foolish infatuation for a business when she ought to be in love with him.

When Mr. Dalken saw that he had launched a dangerous subject for Polly and Tom, he had a bright idea. So he acted upon it instantly. He excused himself from his friends’ circle, and sought the Captain. In a short time thereafter, the passengers heard the band playing dance music, and immediately, most of the younger set hurried to the Grand Salon.

It was second nature with Polly to dance, and she did so with as much grace as she rode her father’s thoroughbred horses on the ranch; or hiked the Rockies, over boulders and down-timber like a fawn. Kenneth Evans, the youngest man in the party from the city, was by far the handsomest one in the group; and when he guided Polly through the maze of dancers, they both attracted much attention.

Tom stood and sulked while he watched Polly dance, but he refused to dance himself, although he was considered a most desirable partner by any one who had ever danced with him. Eleanor 26 was having such a thoroughly good time while dancing with Paul, that she forgot about the romances and lovers’ quarrels of others.

The moment Kenneth escorted Polly to a chair and stood fanning her, Tom pushed a way over to them and said, quite assuredly: “The next dance is mine, Polly.”

“Why, I never told you so, at all!” exclaimed Polly, annoyed at Tom’s tone and manner. “How do you know there will be another one?”

Tom flushed and sent Kenneth an angry glance, although poor Ken was innocent of any guile in this case.

“If you do not care to dance with me, Polly, say so, and I’ll go to the smoking-room and enjoy the companionship of men who appreciate me,” retorted Tom, impatiently.

The imp of resistance took instant possession of Polly, and she said: “Tom, there’s where you belong—with men who want to talk about work and money. You are too old to enjoy youthful follies as I do.”

Tom had been dreaming of this meeting with Polly again, for so long, that now everything seemed shattered for him. He felt so injured at her mention of his age in comparison with her own, that he said nothing more, but turned on 27 his heel and marched away without a backward glance. His very foot-falls spoke of his feelings.

Polly turned to Kenneth and resumed her laughing banter, and he thought she was glad to rid herself of Tom’s company. He felt puzzled, too, because Tom Latimer, in his estimation, was everything noble and manly. But Kenneth was inexperienced with girls’ subtleties. Had Eleanor been present she would have understood perfectly how matters were.

After this incident, Polly danced every dance with a gayety of manner that she did not truly feel. Some of the joy of that party was lacking, but she would not question the cause of it.

Tom went directly to the smoking-room where he sat down to brood over his misery. He never filled his pipe, but sat lost in thought until a friendly voice at his elbow said: “Well, old pard! Anne says you are to come with me. She has a word to say. She is a wizard, too, so you’d best obey without question.”

Tom looked up and saw John. “Can Anne help me in the planning of the legal defence of those lava-cliffs at Pebbly Pit?” Tom demanded of his friend.

John smiled knowingly. “I’ll admit you’re not smoking, even though you rushed to a sanctum 28 protected from girls’ invasion; and you are not thinking of lava or injunctions, just now. You’re pitying yourself for what you consider shabby treatment, while all the time Anne can see that your evening’s disappointment is your own fault.”

Tom weakened. “For goodness’ sake, tell Anne to advise me what to do, if she knows every cure.”

“Come on and have a talk with her. She is just outside, waiting for us,” coaxed John, placing his arm in that of his friend’s, and gently forcing him out of the room.

When Tom met Anne’s sympathetic eyes, he confessed. “Anne, what’s the matter with Polly? She doesn’t seem to know I am on earth. Did you watch her enjoy that dance with a kid like Ken, and then snub me outright when I asked her to dance the next one with me?”

“I don’t know what she did, Tom, but let me give you a bit of sensible advice about Polly. John thinks I am right in this, too, don’t you, dear?” Wise Anne Brewster turned anxiously to John for his opinion.

“Yes, Tom, Anne is a wonder in such things. You listen to her, old man,” agreed John.

Tom sighed heavily and signified his willingness 29 to listen to anything that would end his heartache. Both his companions smiled as if they deemed this case an everyday matter.

“Tom, you are morbid from over-work at the mines,” began Anne. “Remember this, Polly has been on the go in Europe all summer, seeing first one interesting thing after another, and not giving a single thought to you, or anyone, on this side the water. She sneered at anyone who tried to flatter her, or pretended to make love to her, while in Europe, and only cared for art during that tour which meant so much to her.

“You ought to be thankful that she took this attitude, and returned home heart-whole. What would you have done, had she fallen in love with an attractive young man with a title? But she was too sensible for that. She returns home with her mind still filled with the wonderful things she saw abroad, and eager to tell everyone she knows all about her trip. Naturally, she never gives a thought to a lover, or a future husband. She is too young for that sort of thing, anyway, and her family would discourage anyone who suggested such ideas to her. We want her to continue her studies and find joy and satisfaction in her work, until she is twenty-one, at least, and then she can consider matrimony. 30

“You know, Tom, that we all favor you immensely, as a future husband for Polly, but we certainly would discountenance any advances you might make right now, to turn Polly’s thoughts from sensible work and endeavor, to a state of discontent caused by the dreams of young love. If you are not willing to be a good friend to the girl, now, and wait until she is older, before you show your intentions, then I will certainly do my utmost to keep Polly out of your way. But if, on the other hand, you promise to guard your expression and behavior, and only treat Polly as a good brother might, then we will do everything in our power to protect Polly from any other admirers and to further your interests as best we can. Do you understand, now?”

Tom had listened thoughtfully, and when Anne concluded, he said: “If I thought I had a chance in the end, I would gladly wait a thousand years for Polly!”

“Well, you won’t have to do that,” laughed Anne. “In a few years, at the most, Polly will want to get out of business, and settle down like other girls—to a slave of a husband and a lovely home of her own that she can decorate and enjoy to her heart’s content.”

Tom brightened up visibly at such alluring pictures, 31 and promised to do exactly as Anne advised him to.

“If Polly pays no attention to you now, remember it is because she is different from most girls you have known. She was brought up at Pebbly Pit ranch without any young companions, until we went there that summer. She had a yearning for the beautiful in art and other things, but never had the slightest opportunity in the Rocky Mountains, to further her ideals. The only education she had had in the great and beautiful, was when she was riding the peaks and could study Nature in her grandest works.

“Can you blame her, then, because she revels in her studies and has no other desire, at present, than that of reaching a plane where she can indulge her talent and ideals? Can’t you see that a youthful marriage to Polly, now seems like a sacrifice of all she considers worth while in life?”

Tom nodded understandingly as he listened to Anne. And John added: “I told you Anne had the right idea of this affair! Polly’s absolutely safe, for a few years, from all love-tangles. And when she begins to weary of hard work and disappointments in business, then is your chance to show her a different life.”

“But, Tom,” quickly added Anne, “do not give 32 Polly the opportunity, again, to suspect you of lover-like intentions. Be a first-class brother to her, and let her wonder if she has any further interest in you. Never show your trump card to a girl.”

Both men laughed at this sage advice, and John nodded smilingly: “Anne ought to know, Tom. That was the way she got me.”

Anne was about to answer teasingly, when Mr. Dalken came up and said: “I’ve been hunting you three everywhere. Hurry and get your wraps, as the yacht is waiting to return to the City.”

The trio then learned that passes had been granted the members in Mr. Fabian’s party, to leave the steamer that night and go back with their friends, on the yacht. So the cabin baggage had been brought up to the gang-way, and when Mr. Dalken summoned John and his companions to come and help the girls get away, the boats were already on their way to the yacht with the luggage.

Many of their fellow-passengers crowded about the party when they were ready to go. Good-bys were exchanged and the happy bevy of young folks left. Then the boat returned for the older members in the party, and soon the yacht was 33 ready to fly back to her dock, up the River, near 72nd street. But the thick haze that had made the moon look so romantic, developed into an impenetrable fog. And anyone who has ever experienced such a fog hanging over New York Harbor, knows what it is to try to go through it.

So the vessel had not traveled past the Statue of Liberty, before the heavy pall of fog suddenly dropped silently over the Bay, and anything farther than a few feet away from the radius of the electric lights on the boat, was completely hidden.

The Captain bawled forth orders to the crew and instantly the uniformed men were running back and forth to carry out the instructions. Before all impetus to the yacht was closed down, however, the engines had driven her into the route generally used by the pilots of the boats running to Staten Island.

Captain Johnson anxiously studied his chart but could not gauge his position exactly, because of the dense fog and the lack of signals. In a few minutes more, every fog-horn in the Bay and all the great reflectors from guiding lights from bell-buoys would be in full operation. But at the time, there was nothing to tell him that he was in a dangerous zone.

When the party reached the yacht, Mr. Dalken said that chairs had been placed on the forward deck where they could sit and watch the scenes at night, as they sailed up to the City. So all but Tom and Polly went forward and found comfortable seats. Tom had asked Polly to stroll about with him, and she, feeling guilty of neglecting such an old friend when on the steamer, consented.

Thus it happened that Tom led her to the side of the craft where they had climbed the ladder to the deck, as this side was in shadow and farthest from the group of friends who were seated on the forward deck.

But they had not promenaded up and down many times, before the Captain gave anxious commands to his crew. Every man jumped to obey, instantly, while Tom and Polly halted in 35 their walk just at the gap in the rail, where the adjustable ladder had been lowered to the boat when the passengers arrived from the steamer. The steps had been hauled in but the sailor had forgotten to replace the sliding rail. In the dense fog this neglect had been overlooked.

Immediately following the Captain’s shouts, a great hulk loomed up right beside the yacht, and a fearful blow to the rear end of the pleasure craft sent her flying diagonally out of her path, across the water. The collision made her nose dip down dangerously while the stern rose up clear of the waves.

The group seated forwards slid together, and some were thrown from their chairs, but managed to catch hold of the ropes and rail to prevent being thrown overboard.

Polly and Tom, standing, unaware, so near the open gap in the rail, still arm in arm as they had been walking, were thrown violently side-ways and there being nothing at hand to hold to, or to prevent their going over the side, they fell into the dark sea.

Feeling as if the earth had dropped from under her, Polly screamed in terror before her voice was choked with water. Tom instinctively held on to her arm, as he had been doing when the impact 36 of a larger vessel came upon the yacht, and he maintained this grip as they both sank.

Polly had always dreaded water, because it seemed so unfamiliar to her. After living in the mountains with only narrow roaring streams, or the glacial lakes found in the Rockies, she had never tried to swim in the ocean, but preferred swimming in a pool. Consequently, this sudden dive into the awesome black abyss so frightened her, that she fainted before she could fight or struggle.

But Tom Latimer was an expert swimmer, having won several medals while at College for his continued swimming under water. At one time during his first college days, he had saved the lives of some young folks when their canoe capsized a long distance from shore. In this supreme test of ability and presence of mind, with the girl he loved in his arms to save, Tom was as self-possessed as if on deck with Polly.

In less time than it takes to tell, both victims of the collision sank until the natural fight between the weight of the water and the force of the air in their lungs, sent them up again to the surface. In that short time, Tom used every muscle and physical power to swim far enough under the water to clear away from the boats 37 which might do them more harm than the water.

Fortunately he found the surface free when he rose for breath, and finding no resistance from the unconscious form he held, he managed to change his grip from her arm to a firm hold under the shoulders. In this position he could manage to keep Polly’s head above water, and at the same time, could swim backwards, by using his feet as propellers.

The only handicap he now had, was his clothing and shoes; these interfered with his free action in swimming so he managed to kick off his dancing pumps. The greatest danger he feared, was the sudden coming of some craft that would compel him to dive again, or might even run them down, unseen in the dark.

But the very fog that had caused this accident, also befriended them now, as no wary seaman would recklessly go on his way in such a bewildering mist, and the majority preferred waiting for a temporary lifting of the blanket, before continuing their journeys.

Tom felt no concern over the fact that Polly had fainted or had been in the water for a time, for he knew she was so healthy that no ill would occur to her from such causes. All he feared now, was his power of endurance to keep floating 38 until some craft might pick them up, or he could reach a temporary rest.

Suddenly he felt a sweeping current whirl him about and in another moment, he was swimming rapidly with instead of against the tide in the Bay. He realized that in that short time the tide had turned, either about some point of land, or in the River. He began to tread water while he tried to lift his head and gaze across the waves. Then a broad shaft of dazzling light shot across the Bay from a nearby reflector. At the same time Tom heard the tolling of a bell-buoy, not very far distant.

He changed his course that the outgoing tide would assist him in reaching this light that might be coming from a ship, or maybe, from an island in the Bay. As his powerful strokes carried him along, the sound of the bell-buoy seemed to come so plainly that he felt sure it was not far away. If he could but hang on to it for a time, in order to gain second wind!

Suddenly there was a momentary lift of the heavy fog, and he discovered he was quite near Bedloe’s Island. The powerful search light had reflected from the arc held aloft in the hand of the Goddess of Liberty; and the light that danced upon the waves all about him came from the 39 smaller arcs which were placed along the sea-wall of the Island.

The current now carried him helplessly past the pier where the boats from the Battery land, but just as he tried to lift his head once more and yell for help, a motor boat was heard chugging through the fog. His cry was heard by those in the boat, and in a few moments the flash-light in its prow was blinding Tom because of its proximity.

A chorus of amazed voices now mingled with the noise of the water dashing against the wall and the ringing of the buoy, and Tom began to feel faint and dazed. But almost before he knew what was happening, a powerful grip caught him on his thick hair, and he was dragged partly out of the water.

A commanding voice shouted: “Help grab the girl—we’ll take care of the man!”

Then Tom heard no more, nor indeed, knew more until he indistinctly heard a far-off call of “Guard! Guard!” Then he opened his eyes to find he was on the solid earth, once more. Polly was stretched out on the sand. The Guards tumbled out of the barracks and rushed for the spot where the officer stood calling.

While a few of the boys lifted and half carried 40 Tom to the general assembly room, others ran to assist the boatman with the girl. She was carefully conveyed to the barracks and the doctor sent for. Meantime the men applied the Schaefer Method to both the strangers; Tom instantly recovered himself fully but Polly’s faint lasted longer.

When the doctor hurried in, his kindly wife followed. Tom was able to sit up and tell the story of how the accident happened; then he begged someone to notify the Wharf Police to keep a lookout in the Harbor as there might be a yacht in distress after that collision. Also, if inquiry was made at Police Headquarters, the news was to be given that both Polly and he were safe on Liberty Island.

A Corporal of the Guard was sent to attend to these messages, and Tom was taken to a cot in the ward of the Barracks. His wet clothing was removed and he was rolled in a hot blanket and given hot lemonade. In a few moments he was sound asleep.

Polly was taken to the doctor’s cottage where his wife attended the patient as well as any trained nurse could have done. The girl also was rolled in warm blankets with hot-water bottles placed about her cold body. Slowly she began to show more animation, and when she could speak, she asked if Tom was saved.

“Yes, dear; you both are safe now,” replied Mrs. Hall.

“And can we get word——” began she.

“We have taken care of that, too, dear. Now try to drink this nice hot lemonade and then go to sleep.”

Polly obediently drank the hot drink and sighed in relief. Then she sank back and, almost instantly, Nature claimed her rights to make up for the unwonted interference with her customary routine.

Mrs. Hall sat beside the cot for some time after Polly was asleep, but she finally succumbed to weariness, and finding her patient fully recovered and warm, she threw herself upon a nearby cot.

Both young people slept late in the morning, and when Tom finally opened his eyes, feeling a bit stiff in his joints, he had to collect his thoughts to remember where he was. Like a flash, everything came back, and he jumped up to dress and find out how Polly was.

His suit had been dried and pressed and hung over a chair beside the cot. His dress-coat seemed ridiculously out of order after that swim 42 and, now, for the morning’s work. But he smiled as he donned the clothes, and started for the door of the long room.

Just as Tom reached the door one of the men entered and greeted him warmly. “I see you’re all right again!”

“Yes, thank you. I hope the little girl is feeling as well,” ventured Tom, anxiously.

“Doctor Hall just left her and says she is right as a fiddle. I’m the young fellow that telephoned the Police for you. I got back word, early this morning, that your folks finally got home, without any harm to anyone. And say! Maybe there wasn’t some joy when they heard you two were safe with us!”

Tom felt a strange gripping at his throat, and his voice quavered as he replied: “I know there was!”

The young man glanced at the evening dress and then said, “I’m going to loan you one of my long coats to cover those togs.”

Tom responded gratefully, and said: “If I can only do as much for you boys some time!”

“Say,” laughed the soldier, “don’t wish such an experience on any of us!”

Then both laughed. As they reached the house 43 where Polly had spent the night, the doctor opened the door and smiled. When he saw that Tom was feeling as good as ever, he said: “I just hung up the ’phone. A gentleman called ‘Dalken’ told me that they were all coming over to take you away. But I warned him that the entire party would be arrested if they landed on Government Ground without a permit.

“Then I remembered that he might secure a permit, so I said: ‘Anyway, before you people can get here, my patients will be on their way to the Battery.’ I said that, because the young lady ought to be kept perfectly quiet all morning, after such a fearful experience, you know.”

“Yes, I know,” admitted Tom. “And I am glad you said what you did.”

“Now we had her dress dried and pressed, and the little miss will be up and ready to thank you for your courageous deed, in an hour or so,” explained the doctor, significantly.

“Thank you, ever so much!” said Tom, grasping his hand.

“Let Ted, here, show you about the place and entertain you until it’s time to call again,” suggested the doctor.

So Tom went away with his companion, not to 44 explore the Island, but to go to the telephone and have a long talk with his friends in the city, who were anxious to hear about the accident.

Just before noon, an orderly came to Tom to say that Mrs. Hall said, “Mr. Latimer could call, if he liked.” Tom laughed at the message—“if he liked.”

As he entered the little sitting-room of the doctor’s house, Tom tiptoed as if he felt he had to tread softly. But Polly sat in an arm-chair by the window and saw him coming. She jumped up and ran to the door to greet him, and Mrs. Hall went out of the room by the kitchen-door.

Tom was unable to speak a word when he finally came into Polly’s presence. She caught hold of his hands and shook them gladly, as she cried: “Oh, Tom! What do I not owe you after last night!”

Tom wanted to demand payment, but he knew that would ruin his chances forever, so he held a tight leash on his feelings and smiled wanly. Then he said in an unnatural tone: “Lucky for us both that I knew how to swim, eh, Polly?”

Polly was relieved to hear him speak in such a way, but her next act was the outgrowth of spontaneous gratitude. She flung both arms about his neck and being too short to reach his cheek, kissed 45 him on the chin as she would have done had he been John. Tom trembled, but realized at the same time, that Polly’s kiss meant nothing. Still he was humbly grateful for even that token of gratitude from the reserved girl.

“Now tell me, Tom dear, what did the folks say about our sudden elopement?” Polly laughed as she used the term.

“Oh, Polly! I’d swim from here to China for you if only it could be an elopement!”

The girl instantly took alarm, and looked about for Mrs. Hall. But Tom forced a laugh and tried to make her believe he was joking. “Do you think that any man would do that for a girl?” he added.

Then he hurried on to say that no one on the yacht had been injured by the collision, but they were hours in reaching their dock. He said that they (Polly and Tom) were not missed at first, and not until conditions had calmed down somewhat, did Eleanor call for Polly. Then it was found that neither Tom nor Polly were to be found.

“It was Eleanor who remembered seeing us promenade along the side where the rail was detachable, and it was Eleanor who said we must have been thrown out where the steps came up. 46 So the captain was taken to task for having such a careless man on board, and both the man and the captain were discharged.”

“Poor man—it wasn’t his fault!” sighed Polly.

“Well, if you hadn’t recovered, I’d have sent him to jail for life, because it was criminal negligence to leave that rail open as it was!” was Tom’s threatening reply.

“I’m glad there is no cause for such harsh treatment,” responded Polly.

Tom gazed, with his soul in his eyes, as he breathed fervently: “You’re not half as glad as I am, darling!”

Polly sprang away at that, and ran to the window, saying: “Don’t you think we might start for the City? Mrs. Hall went to fetch a hat and wrap for me and she ought to be back by this time.”

Never was maiden welcomed so enthusiastically and so fervently, as Polly Brewster, that morning when she stepped from the launch to the sea-wall at Battery Park. Her father and mother vied with each other in embracing and kissing her, while the tears of happiness streamed from their eyes; John and Anne hovered beside them, watching every dear feature of Polly’s face. Eleanor stood holding fast to her best friend’s skirt, as if that could keep her forever near her.

The members in the “Delegation of Welcome,” acted as if they had been imbibing some intoxicating stimulant. Such happy laughter, and vehement demonstrations of joy and love because Polly was with them again, spoke louder than words that they had all thought she was drowned. Tom found that little fuss was made over him in the first exuberant greetings, but he came in for his share after the doctor had concluded his story about the valiant young rescuer. 48

“Now, Mr. Brewster, you pay attention to me,” remarked the physician, when he was ready to depart on the launch: “You take your daughter home, at once, and put her to bed for the rest of the day, to spare her any nervous reaction. Then, if she is all right tomorrow, you may allow her to receive a caller, or two—no more for the time being, or you will have her break down.”

Mr. Brewster promised to obey the orders faithfully, and soon afterwards, Polly’s friends followed her and her parents to the automobiles which were waiting near the curb of the Park. Tom was surrounded, on both sides and fore and aft, by his family and John and Mr. Dalken, all of whom wished to hear the thrilling story of the rescue again.

“I’d rather hear how you folks kept afloat after that boat rammed the yacht,” said he, shunning a subject that still made him shudder.

Mr. Dalken insisted that Tom with his father and mother get into his luxurious limousine and let him drive them home. On the way uptown, Mr. Dalken told the story of their narrow escape from being lost in the Bay after the collision.

“Immediately after the yacht was rammed and we could collect our senses to comprehend what had happened, and what to do, the old tub of a 49 ferry-boat kept on her course. But there were some worried citizens on board, for they shouted and, finally, the captain stopped his engines and blew the whistles to see if we needed help.

“Fortunately for us, a river tug was quite close at hand when the accident occurred, and its captain called through a megaphone to say that he would assist us in any way we commanded.

“Our Captain then ascertained that part of our gear had been shaken out of place, and it would be dangerous for him to try to run the vessel under her own power, and trust our steering gear. So the good old man on the tug took us in tow and landed us, towards dawn, at our dock.

“The moment we were on land, I rushed to the telephone at the Yacht Club house, and notified Police Headquarters. Ken Evans was an eye-witness to the dive that we feared had cost Polly and you your lives; so we told the Sergeant at the Station just about where you went down.

“The Bureau at Battery Park was ’phoned but they said the tide was running out at that time, so you both would be carried past Bedloe’s Island; if you both were good swimmers there was a slight hope of your being rescued.

“I tell you, Tom, we were almost frantic with joy and relief when word came from Liberty Island 50 that you both were safe in bed, there, without injury or other hurt, excepting the shock. Polly’s mother swooned and we thought she was gone because it was so long before we could revive her.”

Tom’s mother sat holding her boy’s hand within her own, and his father smiled at him so often that Tom began to feel fussed. But Mr. Dalken laughed at his apparent self-consciousness.

“Tom, my boy, grin and bear this ordeal for the time, as you may never in your life, have another experience like it. It shows you what we all think of you, to sit and idolize you in this fashion.”

They laughed at the banter, but Tom felt more at ease after Mr. Dalken’s little speech.

Having arrived at his home, Tom rebelled against being kept quiet that day. “Goodness’ sakes, mother! any one would think I was an invalid. Why, I feel better than I have in months!” and his happy gayety attested to his spirits. But no one knew that he was joyous because Polly had kissed him that morning. And he was sure that that something he had detected in her eyes, was the awakening of love, instead of the fervent gratitude it really was.

Tom could not settle down to do anything that 51 day, but he called John up on the ’phone several times to ask about Polly. John patiently replied each time, that Polly was fast asleep and would probably remain so, for several hours more, because she required it. When Tom asked if he had better come down that evening and call, John was most emphatic in his refusal.

But the following day, Tom kept telephoning the Brewsters every little while and Anne finally capitulated and invited him to call that evening.

Polly was fully recovered again, with no signs of the shock or soaking she had received; so, when Tom was announced by the telephone girl in the hotel office, she felt no undue nervousness.

“Anne, you are going to help entertain Tom, aren’t you?” said she, casually patting her hair down neatly.

Anne looked at her sister-in-law with an amused smile. “If you think you will need a chaperone when such an old friend calls. Tom always seems more like a brother than a young man who might turn out to be a beau, some day.”

Polly pondered this sentence for a time, then said: “Well, there’s no telling what he may think after that ducking, you know, so it will be more comfortable to have you about.”

Tom fully expected a warm welcome from 52 Polly, and perhaps, another flash of something akin to love that he thought he had detected in her deep blue eyes, when he met her in the hospital. So he was more than chagrined to find Polly smile friendily upon him as she took his hand in the same manner that she would have taken Mr. Dalken’s.

“I just thought I would bring in a little glow with me, Polly,” remarked Tom, when he recovered self-possession again. “A few roses, such as I know you like.”

He handed a long box to Polly and watched eagerly as she cut the string and opened the lid of the box.

“Oh, Tom! American Beauties again! How lovely!” and she buried her face in the fragrant red petals that filled the one end of the box.

Anne held out her hand for the box when Polly went to place it on a chair. “I’ll hand them to mother, Polly, for her to arrange in a jar. The others that came yesterday, can be placed in another glass.”

“Oh, did Polly receive other roses?” asked Tom, trying to appear unconcerned, but flushing as he spoke.

“Why, didn’t you send them to me? There was no card in the box, but you always send American 53 Beauties, Tom,” exclaimed Polly, in surprise.

Tom laughed sheepishly. “Well, I did send them, Polly, but I thought I would make you guess who it could have been. I never dreamed you would give me credit for the roses.”

“Why shouldn’t I? It would have seemed queer if you hadn’t sent flowers, when everyone within a thousand miles, sent boxes and bouquets to me, all yesterday and all day today.”

“They did! What for?” asked Tom, wonderingly.

“What for? Why, goodness me! Don’t you suppose my friends were glad that I wasn’t drowned,” retorted Polly, in amazement. “Everyone that ever knew me, sent love and flowers, so I never thought it strange that you sent me some, too.”

This was a hard slap for Tom, and he winced under the words which denoted that Polly considered him only as one of many friends. Even the roses presented that night, with a little heart-shaped card tied in the center of the group of stems, now seemed useless in his eyes.

But Polly had not removed the roses from the box so she failed to find the heart-shaped card that Tom had spent the whole afternoon in inditing. Anne gave the box to Mrs. Brewster, and when 54 that sensible mother took the roses out, one by one, and found the card, she put it away with the cards that had come with other flowers. She also forgot to mention the card to Polly, so the girl never knew that Tom had written her of his undying love. As Anne replied, for Polly, to all the cards, Tom received the same sort of polite little note as others did, with Polly’s name and a “per A.B.” signed to it.

Finding Polly so self-possessed that evening, Tom pulled himself together with an effort, and tried to converse on various topics of general interest. Anne eagerly assisted in the conversation, so Polly listened without having much to say.

Tom tried to make Polly talk, too, but without success, so he became silent and left most of the entertaining for Anne to do. But even she found the task of finding subjects to interest two dumb people rather irksome, and she decided on a coup.

“Excuse me for a moment, please, while I see if John has returned with his father.” So saying, Anne ran from the room.

Polly sat up and watched her go as if her protector had turned traitor. She glanced at Tom in a half doubtful manner as if to ask what he would do now with the chaperone out of the way? 55

But Anne’s absence gave Tom’s morbid senses an inspiration that he acted upon without second thought. It was the best thing he could have done with Polly in this baffling mood.

“I’m returning to Pebbly Pit, in a few days, Polly. I am actually homesick for a sight of the dear old mountains.”

Polly gasped. “Oh, no one told me you were leaving us. Jim told me that he thought you might remain here for several months.”

“Jim? What does that kid know about my affairs?” said Tom, impatiently. “Besides, when did you see Jim?”

“Oh, Jim just dropped in for a minute this afternoon.”

Tom felt the pangs of jealousy because his younger brother had been able to see Polly before she would allow him to call. Then he remembered his rôle to act the part of a platonic brother and friend.

Polly continued: “I think Jim is a dear boy. He is so fond and proud of you, too. Why, when he was here he sat and talked of nothing else but you and your loyalty to family, friends, and your work.”

As Polly spoke, Tom felt ashamed of his momentary jealousy of his brother. When she had 56 finished speaking, he laughed and said: “What a pity Jim sees me through such fine magnifying glasses. The undesirable qualities in my character he never detects.”

“I think it is great to have your family think you are all that is wonderful! I think my family regard me as a saint, and I like it, too,” declared Polly.

“That’s because you are one, Polly dear,” retorted Tom, and the fervor he expressed in his eyes and voice, caused his companion to gasp.

Before Tom could follow up his sudden declaration and make Polly understand his sentiments for her, she broached another subject of conversation.

“Tom, what has been accomplished at the mine and at Rainbow Cliffs while I was in Europe?”

Tom frowned, but he realized that Polly was more sensible than he. He remembered, once more, what Anne had advised, so he choked the despondent sigh and replied instead, with seeming interest:

“Oh, John and I had another queer bout with some thieves. They were not after the land this time, but they planned to get at the ore and carry off as much of the gold as they could lay hands on. Our old friend, Rattlesnake Mike, caught 57 them red-handed, and now they are serving a term in prison at hard labor.”

“Oh, Tom! I never heard a word of this!” cried Polly, eagerly. “Do tell me about it.”

“You remember when we all came East last June to attend John’s wedding and see you off for Europe?” asked Tom.

Polly nodded eagerly but said nothing to interrupt him.

“Well, we remained longer than we had planned when we left Pebbly Pit. The friends in New York were so eager to entertain us before we went back home, that the days passed swiftly before we realized we had stayed on ten days longer than we should have done at that time.

“Now to go back to the time when those two rascals tried to jump your claim, the time your father and Mike guided the party when you-all climbed the Indian Trail to Grizzly Slide.

“It seems that crafty clerk who had copied the rough map of the claim you staked on Flat Top and filed in Oak Creek, never gave up hope of some day getting his hands on enough of that gold 59 to help him get away and live comfortably, ever after, on the proceeds.

“When he learned that everyone of the family at Pebbly Pit, would be East for a few weeks, and the mine would be left in charge of Mike and the other employees, he immediately called a few cut-throats together and laid his plans accordingly.

“After the discovery of his perfidy in copying the claim papers and then trying to jump the staked claim, he had been discharged from the office in Oak Creek and, thereafter, no one respectable would employ him. So he hung about the saloon and spent his time in gambling with the miners from Up-Crest, back of Oak Creek station. He found willing confederates in this group of Slavs who hailed the invitation to steal enough gold to enable them to go back to Europe and pose as rich men.

“The whole plot had been kept unusually secret for that species of foreigner, so no one at Oak Creek knew of the proposed raid. But Mike rode into Oak Creek the morning before the night these rascals planned to act, and with his unusual gift of intuition, he felt that something was working quietly in the minds of the evil-looking men he found whispering over a small table in one corner of the saloon. 60

“Mike hung around for several hours to try and learn if any plot was hatching against Rainbow Cliffs while the owners were absent; or perhaps these men planned a rush on the mine while he and but few men were on guard. But nothing could be discovered. Feeling assured because of the sly and malicious expressions of the men at the table when they glanced at Mike, as he sat in another corner and pretended to doze, that Hank had some move under way to trouble him and his assistants, made the Indian use splendid judgment and action that day.

“He borrowed the Sheriff’s thoroughbred bloodhound, and asked for a few extra men to accompany him to the cave and stay there until the owners returned, promising them better wages than they could earn at any work in Oak Creek, or on the ranches nearby. To allay suspicion he rode out of town, alone, but he had agreed to wait at Pine Tree Blaze for the extra men.

“The men rode away from town each at a different time, to avoid talk or notice by the loungers at the saloon, and all met at the rendezvous that afternoon. Mike then led the way up the steep trail, and by dark they were in camp.

“This was the second day after we left Pebbly 61 Pit. Mike had warned Jeb of his suspicions, too, and that wary little man had instantly taken steps to protect the Cliffs, by ordering all hands working there to keep away from Oak Creek until the Boss got home. He said that unusual care must be used for a time, to watch during the nights, and keep trespassers out during the day, for fear of raiders.

“The first night in camp on the mountains, Mike never rested a minute, but moved silently from one place to another, with senses keyed for some sign of the rascals. However, that first night passed quietly away. His extra men spent the evening in smoking and playing cards, then they rolled up in their blankets and snored peacefully the night through.

“The next day Mike smiled to himself when the men laughed at his suspicions. They were so far from any settlement and the mountains were so great and silent, that it gave them confidence in the peace and good will with all men.

“The second night the men were again playing cards near the camp-fire. Mike sat on the ledge in front of the cave with the hound stretched out on a slab of rock at his feet. The giant wooden flume could be faintly discerned, through the smoke of the fire and from the pipes of the men, 62 not twenty feet away from the engines that worked it.

“Suddenly the hound lifted his head and pointed his ears. Mike leaned forward with face turned towards the flume, listening. Then he laid his pipe down on the rock and crawled away upon his hands and knees, followed closely by the hound.

“Do you remember the giant flume we planned to carry off the water of the river that flowed underground; the one into which Nolla and you dropped the torch the day you found the cave?”

Polly silently signified that she remembered, and Tom continued: “Well, we used that flume during the work of mining and washing trash from the ore, but at night, when there was no need for the water to pour through it, we turned the current down the other way on the opposite side of the mountain.

“Mike crept silently across the ledge and peered far down into the black chasm below, to ascertain if the suspicious sounds came from that pit. But the dog crawled noiselessly across the ledge to the flume and there he stood with tense nerves. His ears were erect and his tail was standing out straight behind him, as he stood and glared at the wooden flume. 63

“As the dog was so well-trained, Mike did not doubt his instinct, but crept over to his side and there waited and listened.

“Had he not been absolutely quiet, the faint sound of something moving inside that flume would have been lost on the outside. But Mike was as keen a hunter as his dog, and they both sensed that something very foreign to water was passing through that flume.

“Accompanying the strange muffled sound inside the flume every few moments, there came a different sound, as if something sharp was being driven into the wood for a hold. Mike figured out that the inside of the flume had been worn so slippery with the flood of waters and sand or pebbles passing through it in torrents, that it was necessary to use steel-pointed staffs and creepers to help anyone in the dangerous ascent.

“As soon as Mike felt convinced that someone was trying a new trick to gain possession of the mine, he crept back to the camp-fire and told the men of the sounds inside the flume. They laughed immoderately at Mike, and declared that he was going mad because of his prohibition since his employers left him in charge.

“But Mike ordered a few of his most trustworthy 64 miners to guard the cave in front, while the others were sent over the top of the range to keep watch at the opposite entrance to the mine. You’ll remember, Polly, that that was the side where the pit cut the cave in half. We bridged that chasm, you know, and used the short-cut entrance quite often, although the ore was brought out through Choko’s Find.

“Mike then selected several of his brawniest fighters and very quietly led the way to the opening of the flume where the water-gate was located. As they could travel faster on the ground than the men creeping up inside the slippery wooden tube, Mike and his companions reached the water-gate before they heard the suspicious sounds from within the flume.

“He signalled his men to keep absolutely quiet, and then crept out on the lintel of the gate and got a firm purchase on the lever. No one dreamed of his purpose at the moment, and he suddenly seemed to reconsider his plan, for he crept back again and had just reached the trio of curious men, when a sigh of relief was distinctly heard from inside the flume.

“Then a whispering was heard, but not understood. In a few moments a grating sound as if some sharp tool was being used. Mike surmised 65 that they were trying to break a way through the wooden door by which to get out.

“Without further delay, then, Mike threw open the lid in the top of the flume and commanded the trespassers to come forth.

“There was no reply from within, and not a sound was heard after Mike opened the lid. So he called again: ‘Ef yoh no come us wash riber fru dis pipe.’

“Still no reply or sound was heard, so Mike winked at his companions, and gave a fictitious order: ‘Frow water gate open!’

“‘Stop! Wait a minute!’ shouted a frightened voice from the flume.

“Another voice cursed in the most dreadful way, but soon after Mike’s order to turn in the water, four men managed to emerge from the tube and sit astride it.

“Seeing but four opponents there to fight, the leader of the gang gave a sign, and the daring raiders tried to over-power Mike and his three men. But they had not seen the wolf-hound in the shadows. As they dropped upon the men to fight them, the dog sprang out and drove his fangs deep into one rascal’s throat. He will carry those marks to his last day. It was a wonder he was not killed outright. 66

“That released Mike and he turned his attention to help his companions free themselves. The dog fought mightily, and after a short but fierce battle, the trespassers were bound and laid on the ground for the night.

“‘What’cha goin’ to do wid’dem, Mike?’ asked one of his men.

“‘Ship ’em down th’ flume, Mike, th’ way they come up,’ laughed another of his men.

“‘So me say, but Mike go jail fer kill man,’ replied the Indian.

“The other men strongly approved of that course of justice, however, and Mike had all he could do to keep them from following their inclination to wash the guilty men down the flume and out into Bear Forks River at the foot of the mountain.

“The next day Mike and his men drove the raiders down the steep trail and left them in the hands of the constable of Oak Creek, to await trial in the County Court. But the captured rascals had boon companions in Oak Creek, and when they learned that four of their group were in prison they started a regular riot.

“They tarred and feathered poor little Jeb the next time he drove in to Oak Creek for mail and 67 supplies, and a few days before we got back home, they made a well-planned raid on the lava mines at Rainbow Cliffs. Not a piece of machinery was left intact, and the great bags of jewels we had waiting for shipment were scattered far and wide by the vandals.

“But the sheriff heard of the proposed visit to Pebbly Pit, and took a possé of men to follow the drunken miners to the Cliffs. Such a battle as ensued, beggars my weak description. The sheriff told us about it when we got home, but his language is not very graphic, nor is it thrilling, so we only heard the bare facts of the fight.

“But, Polly, you must supply with your own vivid imagination, the details that may be missing from my account. When I tell you that the vandals were slowly backed away from the Cliffs and were, eventually, driven to the gully back of the Devil’s Causeway where those two men were engulfed in the slide, the day they came to cajole your father into signing papers for the Cliffs, you can picture their horror when the edge of the great cliff began to crumble in. They could not turn to right or left, as they were hemmed in by the pursuers, and they dared not remain where they were for fear of being swallowed in the quicksand 68 that was already sliding downwards. So they gave up to the sheriff and surrendered their guns.

“That was a bad case, as one of the sheriff’s men had been dangerously wounded and it was feared he would die. All our valuable machinery was ruined and all orders for the delivery of the lava jewels had to be cancelled, or postponed for a year. So the culprits each got twenty years and Oak Creek is quieter, by far, because more than a score of its worst citizens are safely housed in jail.”

As Tom ended his story, Polly unclasped her hands which she had nervously clenched during the recital of the raids on her precious property.

“Oh, Tom! I never dreamed of all the trouble everyone would have because of those precious mines, the day Nolla and I filed our papers at Oak Creek,” gasped Polly.

“No one does dream of these things—they only see the future in rosy hues,” retorted Tom.

“And to think of the work and worry John and you have had in establishing this great undertaking, while I was in Europe taking life easy, and spending money without a thought of how it was being produced at home!” sighed Polly.

“That is as it should be, Polly. You were not 69 squandering the money, but using it in ways to profit yourself for the future. John and I knew, when we started in on this mining venture, that the line would not lay in flower-strewn paths, but that it might force us over all sorts of snags, before we reached success.”

“Well, it is fine of you to talk like this, Tom,” admitted Polly, gratefully. “If it were not for you boys taking an interest in the work, I might as well say ‘good-by’ to the gold.”

Tom laughed. “Polly, this is so insignificant a work to do for you—just taking an interest in your mine. Some day I hope to prove in some greater way, just what I want to, and can, do for you.”

Tom’s manner and looks again alarmed Polly and she changed the subject adroitly. “Tom, do you like the home in Pebbly Pit? Isn’t it different from living in the city, in these apartments?”

Tom smiled, for he understood. “Yes, it is fine, Polly. It is a real home—with your blessed mother at the ranch-house. I have lived in adobe huts in Arizona, and out on sand wastes in New Mexico, you know, so that Pebbly Pit is great, in comparison.”

“Mother told me how good it was to have Anne and you with her all summer, while I was 70 abroad,” said Polly, after a short interval of silence. “I feel that it was not so heartless of me to enjoy myself in Europe as I did, so long as mother and father were not lonely and homesick for me.”

“But your mother often said to me, that were it not for Anne’s being with her, she would have cabled you to come home. She had looked forward so anxiously to your spending this vacation at Pebbly Pit,” remarked Tom.