A MESSAGE FROM OUR CHIEF

In this initial number of THE STARS AND STRIPES, published by the men of the Overseas Command, the Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces extends his greetings through the editing staff to the readers from the first line trenches to the base ports.

These readers are mainly the men who have been honored by being the first contingent of Americans to fight on European soil for the honor of their country. It is an honor and privilege which makes them fortunate above the millions of their fellow citizens at home. Commensurate with their privilege in being here, is the duty which is laid before them, and this duty will be performed by them as by Americans of the past, eager, determined, and unyielding to the last.

The paper, written by the men in the service, should speak the thoughts of the new American Army and the American people from whom the Army has been drawn. It is your paper. Good luck to it.

(Signed) JOHN J. PERSHING,

Commander-in-Chief, A. E. F.

MEN ON LEAVE

NOT TO BE LED

ROUND BY HAND

——

Impression That They Will

Be Chaperoned Wholly

Erroneous.

——

SAVOY FOR FIRST GROUP

——

Zone System to Be Instituted and

Rotated to Give All Possible

Variety.

——

"PINK TICKETS" FOR PARIS.

——

Special Trains to Convey Soldiers

to Destinations—Rules Are

Explicit.

——

As a great deal of misapprehension regarding leaves, the conditions under which they are to be granted, etc., has existed in the A.E.F. for some time past, the complete and authoritative rulings on the subject are given below.

A.E.F. men whose leaves fall due on or about February 15 will be allowed to visit the department of Savoy, in the south-east of France, during their week of leisure. That department constitutes their "leave zone" for the present. When their next leaves come around four months hence it is planned to give them a different leave zone, and to rotate such zones in future, in order to give all an equal chance to see as much of France as possible.

While the Y.M.C.A. has worked hard and perfected arrangements for soldiers' accommodations and provided amusements at Aix-les-Baines, one of the famous watering-places in Savoy, no man is bound in any way to avail himself of those accommodations and amusements if he does not so desire. In other words, there are no strings attached to a man's leave time, provided he does not violate the obvious rules of military deportment. The widespread idea that there will be official or semi-official chaperonage of men on leave by the Y.M.C.A. or other organizations is, therefore, incorrect.

Leaves Every Four Months.

The general order from Headquarters, A. E. F., on the subject of leaves is both complete and explicit. Leaves will be available for soldiers only after four months' service in France, and will be granted to officers and men in good standing. The plan is to give every soldier one leave of seven days every four months, excluding the time taken in traveling to and from the place in France where he may spend his holiday. As far as practicable, special trains will be run for men on leave.

A man may not save up his seven days leave with the idea of taking one of longer duration at a later date. He must take his leaves as they come. Regular leave will not be granted within one month after return from sick or convalescent leave.

In principle, leaves will be granted by roster, based on length of time since last leave or furlough; length of service in France; length of service as a whole lot. Officers authorized to grant leaves are required to make the necessary adjustments of leave rosters so as to avoid absence of too many non-coms, or specially qualified soldiers at any time. Not more than ten per cent. of the soldiers of any command are to be allowed away at the same time, nor, it is stipulated, is any organization to be crippled for lack of officers.

Leave areas, as stated above, will be allotted to divisions, corps, or other units or territorial commands, and rotated as far as practicable. Allotments covering Paris, however, will be made separately from all other areas, so as to limit the number of American soldiers visiting Paris on leave. For this reason the leave tickets will be of different color, those consigning a man to his unit's regular leave area being white, and those permitting a visit to Paris being pink, dividing the American permissionaires into white ticket men and pink ticket men.

Exceptional Cases.

In case a man has relatives in France, it is provided that he may, for that reason or some other exceptional one, be granted leave for another area than that allotted to his unit with the stipulation that the number of men authorized to visit Paris shall not be increased in that way. For the present, officers will not be restricted as to points to be visited on leave, other than Paris. Any leaves which may be granted by Headquarters to go to allied or neutral countries will be counted as beginning on leaving France and terminating on arrival back in France. The French Zone of the Armies, and the departments of Doubs, Jura, Ain, Haute-Savoie, Seine Inférieure and Pyrénées Orientales, and the arrondissements of Basses-Pyrénées touching on the Spanish frontier may not, however, be visited without the concurrence of the Chief French Military Mission.

Leave papers will specify the date of departure and the number of days' leave authorized. The leave will begin to run at 12.01 a. m. (night) following the man's arrival at the destination authorized in his leave papers, and will end at midnight after the passing of the number of days' leave granted him. After that, the next leave train must be taken by that man back to his unit. Or if he is not near a railroad line over which leave trains pass, he must take the quickest available transportation back to connect with a leave train. Each man on leave will carry his ticket as well as the identity card prescribed in G. O. 63, A. E. F.; and he will be required to wear his identification tag.

Travel Regulations.

Before going on leave, a man must register his address, in his own handwriting. He must satisfy his company or detachment commander that he is neat and tidy in appearance. He must prove to that officer's satisfaction that he has the required leave ticket, and so forth, and sufficient funds for the trip.

——

OFF FOR THE TRENCHES.

——

When a certain regiment of American doughboys departed from its billets in a little town back of the front and marched away to our trenches in Lorraine, this poem was found tacked up on a billet door:—

By the rifle on my back,

By my old and well-worn pack,

By the bayonets we sharpened in the billets down below,

When we're holding to a sector,

By the howling, jumping hector,

Colonel, we'll be Gott-Strafed if the Blank-teenth lets it go.

And the Boches big and small,

Runty ones and Boches tall,

Won't keep your boys a-squatting in the ditches very long;

For we'll soon be busting through, sir,

God help Fritzie when we do, sir—

Let's get going, Colonel Blank, because we're feeling mighty strong.

TOOTH YANKING CAR

IS TOURING FRANCE

——

Red Cross Dentist's Office

——

Lacks Nothing but the

Lady Assistant

——

The latest American atrocity—a dentist's office on wheels!

Gwan, you say? Gwan, yourself! We've seen it; most of the chauffeurs have seen it; the Colonel and everybody else who gets about at all has seen it. That's what it is, a portable dentist's office—chair, wall-buzzer and all, with meat-axes, bung-starters, pinwheels, spittoons, gobs of cotton batting, tear gas, laughing gas, chloroform, ether, eau de vie, gold, platinum and cement to match. Everything is there but the lady assistant, and even she may be added in time.

If you wanted to be funny about the thing, you might call this motorized dentist's parlor the crowning achievement of the Red Cross; for, strange to say, it is the Red Cross, commonly supposed to be on the job of alleviating human misery, that has put the movable torture chamber on the road, to play one-tooth stands all along the countryside. But no one wants to be funny about a dentist's office that, instead of lying in wait for you, comes out on the road and chases you. It's too darn serious a matter; you might almost say that it flies in the teeth of all the conventions, Hague and otherwise.

It looks part like an ambulance, but it isn't. An ambulance carries you somewhere so that you can get some rest; a traveling tooth-yankery doesn't give you a chance to rest. It's white, is the outside of the car, just like a baby's hearse, and just about as cheerful to contemplate. On its side it says, "Dental Traveling Ambulance No. 1"—the No. 1 part gleefully promising, no doubt, that this isn't the end of them by any means, but that there may be more to follow.

Useful As a Tank?

Somebody had a nerve to invent it, all right, as if we didn't have troubles enough as it is, dodging the regimental dentist, and ducking shells, and clapping on gas masks, and all the rest. It is designed, according to one who professes to know about it, to kill the nerves of anything that gets in front of it; so we one and all move that it, instead of the tanks, be sent "over the top" and tried on the Boches. The minute they see a fully-lighted, white-painted car, with the dentist, arrayed with all his instruments of maltreatment, standing ready for action by his electric chair, those Boches will just turn around and run, and run, and run, and won't stop running till they get smack up against their own old barbed wire on the Eastern front. The crowned heads of Europe tremble before the advance of the crowned teeth of America, as you might say if you were inclined to joke about it; which we aren't.

For French Patients First

One of the Red Cross people, who was standing by ready for the command "Clear guns for action!" told THE STARS AND STRIPES that the peripatetic pain producer wasn't to be used so much for the American troops' discomfort as to fix up the cavities and what-not of the civil population of France. That was encouraging news, for while we don't bear our allies any ill-will, we think they ought to have the honor of trying out the experiment first "Après vous, mon chere Gaston," as the saying goes.

After all the French people in need of dental treatment have been treated, however, the Red Cross person went on to say that it might be tried out on the Americans—yanks for the Yanks, as you might say, if you were inclined to be funny about it, as you ought not to be; but we prefer to think that the war will be over by that time. Anyhow, who ever heard of an American who would own up to having anything the matter with his jaw.

Be that as it may, when you see the cussed thing on the road, jump into the ditch and lie low. It's real, and it means business.

——

ANZAC MAKES SAFE GUESS.

——

A company commander received an order from battalion headquarters to send in a return giving the number of dead Huns in the front of his sector of trench. He sent in the number as 2,001.

H. Q. rung up and asked him how he arrived at this unusual figure.

"Well," he replied. "I'm certain about the one, because I counted him myself. He's hanging on the wire just in front of me. I estimated the 2000. I worked it out all by myself in my own head that it was healthier to estimate 'em than to walk about in No Man's Land and count 'em!"—Aussie, the Australian Soldiers' Magazine.

HUNS STARVE

AND RIDICULE

U.S. CAPTIVES

——

A.E.F. Soldiers Compelled

to Clean Latrines of

Crown Prince.

——

GIVEN UNEATABLE BREAD.

——

Photographed Sandwiched Between

Negroes Wearing

Tall Hats.

——

EMBASSY HEARS THE FACTS.

——

Repatriate Smuggles Addresses of

Prisoners' Relatives Into

France.

——

Ridicule, degrading labor, insufficient food and inhumane treatment generally are the lot of American soldiers taken prisoner by the Huns. This is the experience of three Americans captured last Autumn by the German Army at the Canal de la Marne au Rhin, in the forest of Parcy, near Luneville. The deposition of M. L. Rollett, a repatriated Frenchman who was quartered in the same town with the American prisoners, made before First Secretary Arthur Hugh Frazier of the United States Embassy in Paris, throws ample light on the methods of the Boche dealing with his captives.

"How were the Americans treated?" M. Rollett was asked.

"They were obliged to clean the streets, and the latrines of the Crown Prince [The heir to the German throne had his headquarters at that time in Charleville, the captured French town to which the Americans were taken.] This was done in order to make them appear ridiculous. They were photographed standing between six negroes from Martinique; and when the photograph was taken the negroes were ordered to wear tall hats."

"Did the Americans have sufficient food?" Secretary Frazier inquired.

"No," replied M. Rollett. "Their food was insufficient. They received a loaf of bread every five days, which was as hard as leather and almost uneatable. Occasionally they received a few dried vegetables."

Fed by French People.

"Could they subsist on this food?"

"No, but the inhabitants of Charleville formed a little committee to supply the prisoners with food and with linen. The food had to be given to them clandestinely."

M. Rollett, who left Charleville on December 19, 1917, to come into France by way of Switzerland, visited the Embassy to forward to the relatives of the three American prisoners messages saying that they were still alive. The addresses they gave him were: Mrs. James Mulhull, 177 Fifth street, Jersey City, N. J.; Mrs. R. L. Dougal, 822 East First street, Maryville, Miss.; and Mrs. O. M. Haines, Wood Ward, Oklahoma. On the day the Americans were captured, he added, the American communique (published later on by the Germans) had reported five men killed and seven wounded.

"They were written," he replied, "on a piece of linen which a young girl who speaks English had sewed under the lining of a cloak belonging to one of my daughters."

"Black Misery" In Germany.

In conclusion, M. Rollett was asked if, from his journey from Charleville through Germany to Switzerland, he could form any idea as to conditions in Germany.

"No," he answered, "because we traveled through Alsace-Lorraine at night; but the German soldiers talked very freely about conditions in Germany, and they said that life in all parts of the Empire is black misery. They all long for peace; and the soldiers are in dread of the British and French heavy artillery."

M. Rollett's disposition was subscribed and sworn to before Secretary Frazier on January 9, 1918, and a copy of it is in the archives of the American Embassy.

——

MARINES ADVISE SWIGGING.

——

For Hikers They Say, It Is Better

Than Sipping.

——

Quantico, Va.—The drinking of water at frequent intervals while on long hikes is not recommended by U. S. Marines, stationed here.

While the average man should consume, according to medical authorities, from two to three quarts a day, troops on the march should drink this amount at regular periods and not sip a mouthful at a time, say the Marine officers.

In Haiti, the Philippines and other countries where the Marines have been compelled to hike long and hard, men who constantly sipped at their canteens were the first to become exhausted. On the contrary, the men who drank their fill every two or three hours, and not between times, proved to be the best hikers.

FREE SEEDS FOR

SOLDIER FARMERS

——

Congress Votes Us Packets

but Overlooks

Hoes and Spades

——

PRIZES FOR BIG PUMPKINS

——

A.E.F. Garden Enthusiasts Speculate

Upon Probability of Flower

Pots in Tin Derbies.

——

Sergeant Carey, quite contrary,

How does your garden grow?

Tomato buds, and Kerry spuds,

And string beans all in a row?

That's the song some of us will be singing when the ground gets a little softer—oh yes, it will be much muddied before long—and the grass, what there is left of it, gets a little greener, and the dickey-birds begin to sing sweet "Oui, oui," in the tree-tops.

For be it known that by and with the consent of the Congress of the United States, that ancient and venerable and highly profitable body which votes the money to buy us our grub has, out of the kindness of its large and collective heart, extended its privilege of free seed distribution to the United States Quartermaster Corps. So, if you haven't received your little package of bean seed, pea seed, anise seed, tomato seed, lettuce seed, pansy seed, begonia seed, and what not, trot right up to the supply sergeant's diggings and ask him when it's coming in.

Oui, Oui—Spuds and Beans!

No kidding; you know yourself you're grumbling now because all you get in the line of vegetables is spuds, and beans, and tomatoes and beans, and spuds, and spuds, and beans, and beans, and spuds and beans, and beans, and beans, and beans, and beans, and beans and—what was that other vegetable you gave us last night, Mess-Sergeant?—oh, yes, beans; all of them canned, with now and then, on Christmas, St. Patrick's Day, Yom Kippur and Hallowe'en, a few grains of canned corn. If you want fresh vegetables, therefore, it's up to you to grow them. Unfortunate people who live in big cities are able to grow them in cute little window boxes, and thus cut down the high cost of living. Why shouldn't you, with a steel helmet for a flower pot, be able to do the same?

Go to the French thou sluggard

ARMY MEN BUILD AN

OVER-SEAS PITTSBURGH

——

Mammoth Warehouses and the World's Largest

Cold Storage Plant Spring Up in

Three Months.

——

FORESTERS AND ENGINEERS DOING THE WORK.

——

"Winter of Our Discontent" Sees Big Job of Preparation

Speeded "Somewhere" in France.

——

You, Mr. Infantryman, out there for heaven knows how many hours a day jabbing at a straw-filled burlap bag and pretending it's old Rat-Face, the Crown Prince—been doing that ever since you came over here, haven't you?

You, Mr. Artilleryman, loading, unloading, standing clear, and all the rest of it until your back aches and your ear-drums wellnigh cave in—

You, Mr. Machine-Gunner, going out every day and lugging about a ton of assorted hardware and cutlery around a vacant lot—

You, Mr. Marine, land-logged, land-sick, trying out your web feet in wading through the muddy depths of Europe instead of wading ashore through the roaring surr-yip! hi-ho, and a bottla grape juice!—

You, all of you, own up now! Doesn't seem as though you weren't getting anywhere at times, now does it? Doesn't seem as though you had made any particular progress, eh, what? Doesn't seem to have made the beef any tenderer, the supplies come up any quicker, the Q.M.'s clothing get issued any quicker? As far as you can see, things have been pretty much at a standstill, on account of the weather and what-not, for some time, haven't they?

With Speed and Drive.

But that, Mr. Infantryman, Cannoneer, Machine-Gunner or whoever and whatever you are, is where you are, for one, dead wrong. The old U. S. is making all sorts of progress here in France—progress towards your comfort, and upkeep, and safety, and toward that of the millions who are coming along to play your game with you. Not in your particular section, perhaps, but, in a certain spot in inland France, the old U. S. has been engaged in big doings this winter, doing big things as only Americans can do 'em and putting them through with the speed and drive that, as we like to think, only the Yanks can put into an undertaking. And the work which the old U. S. has been doing at that particular place in France, has excited the outspoken admiration and surprise of every officer of the Allied armies who has watched it grow.

In three months this spot in France has been transformed from an insignificant railroad station—such as White River Junction, New Hampshire, or Princeton Junction, in New Jersey, say—surrounded by wild woodland and rolling plains, into a regular young Pittsburgh of industry. Fact! Not only a young Pittsburgh of industry, but a young St. Louis of railway tracks, a young Chicago of meat refrigerators, a young Boston of bean stowawayeries, a young New York water front of warehouses. Just for example, the warehouses already put up at this place will hold more stuff than the new Pennsylvania Railroad freight terminal in Chicago, which is some monster of its kind.

Cold Storage Plants.

Wait! That's only a sample. The foundations are already on the ground for—now, get this; it's straight dope, no bull—for what will be the largest refrigerating cold storage plant in the world. Its construction, by the time this article sees the light of print, will be well under way. It will have a manufacturing capacity of 500 tons of ice, and will be capable of handling 2,000 tons of fresh beef daily, besides having storage space for 5,000 tons of beef additional, to say nothing of other fresh food supplies whenever they may be awaiting shipment up forward to the men in the Amexforce. Every detail of it is absodarnlutely the last word in uptodateness.

Along with a refrigerating plant of that magnitude, there have also been going up—going up all during the time you thought there was "nothing doing" over here, too—a number of monster storage houses for ammunition and other inflammable supplies. These are built of real old honest-to-goodness hollow fireproof brick, brought all the way from the United States. And if that were not enough to safeguard the bonbons for the Boche contained in them, the storage depot has a waterworks system all its own; to construct it, a pipe line had to be laid half a mile—the distance of the plant from the nearest body of water. Hundreds of miles of auxiliary piping have already been laid, and the water supply will be more than adequate for mechanical purposes and for protection against fire.

Regulars Lend a Hand.

The warehouses themselves are one story buildings, 50 by 30 feet in dimension, constructed in rows of fours, with loading and unloading tracks between them and with big doors in their sides, making easy the quick handling of the supplies to be stowed therein. Goods for four branches of the service are to be stored in them—machinery, ordinance supplies, medical necessaries, and all the varied articles handled by the Quartermaster's Corps. The construction of the buildings has been in the hands of a regiment of railroad engineers and a forestry regiment, assisted by companies detailed from regular regiments.

As if that were not enough in the line of construction, over in a corner of the mammoth reservation is a gas plant, and buster, too. This plant is already in operation and other plants of like size are busy in repairing machinery and in other work. Everywhere about the place there is incessant activity—regular "Hurry up Yost" speed-upativeness—in road building, well driving (some deep ones have been plugged down, too), in track laying, in hundreds of other ways.

Some plant, isn't it, to have been put up in the short time, comparatively, that we have been over here in France? It even puts into the shade the overnight growth of, say Hopewell, Va., the famous munitions city that, unlike Rome, seemed almost to have been built in a day.

Of course it has taken a tremendous force of workers to do all this, and it is going to take more and more and more as time goes on, and as more and more and more troops from the States keep pouring into the French seaports. The size of the plant, with the provisions for making it larger, prove, for one thing, that our Uncle Sam expects to send a lot more troops—and, what is more, intends to keep them well supplied with everything they need as long as they are here.

No Delay About Moving In.

Our Uncle Samuel, be it remembered, is a cautious old gent, and looks well on both sides before getting into a scrap; but once he gets in—and the canny old customer always picks the right side—he's in to stay until the whole job is cleaned up, and he's in right up to his shoulderblades. No more convincing proof of America's determination to see the thing through could be had than a sight of Uncle Sam's big storage depot and all-around tool shop. And, to clinch the argument even further, as fast as the shops on the big reservation have been put up, the machinery has been shoved into them and the work in them started as soon as the machinery was in place and oiled up.

No, Mr. Infantryman, Mr. Artilleryman, Mr. Machine-Gun-toter, Mr. Aviator, Mr. Wireless-buzzer, this has not been "the winter of our discontent"—as footless and no-use-at-all as your own work may have seemed to you sometimes. It has been the winter during which your old uncle has been laying a firm foundation for your comfort and safety and for that of the men who will follow you over—and believe us, he's done an almighty big, an almightily far-sighted, an all-around almightily creditable and thoroughly American, workmanlike job.

——

A NEWS STORY IN VERSE

——

(The incident this poem describes was told by a

British sergeant in a dug-out to the author—an

American serving at the time in the British

Army, but now fighting under the Stars and Stripes.)

——

Joe was me pal, and a likely lad, as gay

as gay could be;

The worst I expected to happen was the

leave that would set him free

To visit the wife and the kiddies; but

they're waiting for him in vain.

All along of a Boche wot peppered our

water and ration train.—

You see, w'd been pals from childhood;

him and me chummed through school,

And when we growed up and got married

we put our spare kale in a pool,

And both made a comfortable living;

'twas just for our mates and the

kids,—

Now the Hun—damn his soul—has

taken his toll, and me pal had to

cash in his bids.

That night when we left the ration

dump to face the dark ahead,

I can never forget the look on his face

when he picked up his kit and said

"Another trip to the front, old lad;

we'll take 'em their bully and tea;

We'll catch hell to-night, but we'll get

there all right; take that little tip

from me."

And Joe swung up in his saddle; I

crawled in the trailer behind;

The train moved off with a groan and a

squeak, for the midnight work and

the grind

Then Joe looked 'round as we started

off, I could see his face all alight;

"I got a letter from home," he said;

"I'll read it to you to-night."

We pulled along through Dick Busch,

through Fairy Court and Dell.

When word came back from the blokes

ahead to give the nags a spell.

Joe slid outen his saddle, with a chuckle

deep down in his throat,

An' he walked back to me, as gay as

could be, and pulled the kid's note

from his coat.

Says he, "Listen, lad, for a kid it ain't

bad—it's her birthday—she's

five to-night—

It's a ripping note this—she sends

you a kiss—" and Joe, poor old pal,

struck a light.

He held up the kiddie's letter—we were

laughin' a bit at the scrawl,

All warm inside with a feeling—well,

you know what I mean, damn it

all!

When along come a German bullet, and Joe,

he wavered a mite,

Then without a word he wilted down.

They carried him West that night:

A bullet hole in his temple, by God, but

clutching that letter tight.

I've forgot all me bloomin' duties, for

me blood is boilin' with hate;

And I'll get that sniping rotter what

drilled me pal through the pate.

I'll teach the dirty beggar how an

Englishman sticks to his friend:

I'm saving a foot of cold steel for the

rat—so help me God to the end.

——

HE OUGHT TO BE GOOD.

——

"Jim, I see that old Bill Boozum, from home, has been drafted."

"Well, Hank, he ought to pass out some nifty hand salutes, all right."

"How's that?"

"Why, look at the practice he's had in bending his elbow!"

Don't Forget that War-Risk

Insurance. February 12 is

Your last chance at it.

ARMY'S MOTOR ARMADA

TO BE 50,000 STRONG

——

Uncle Sam's Garages and Assembling Shops Demand

the Services of 150,000 Chauffeurs

and Repair Men

——

FIRST AID AMBULANCES FOR BREAKDOWNS

——

Experts from American Factories to Take Charge of

Efficiency Problems

——

Uncle Samuel has gone into the garage business here in France. He has gone into it feet first. He knows the importance of the automobile game in modern warfare; he realizes that if Napoleon the Great had only had one "Henry" at the battle of Waterloo, Marshal Blucher's famous advance through the mud would have been in vain. So he is determined, by aid of all the up-to-date motors, all the up-to-date mechanics and chauffeurs and technical experts he can muster, to prevent any of Marshal Blucher's Prussian successors from stealing a march on him.

Fifty thousand motor vehicles, roughly speaking, represent Uncle Samuel's immediate needs for his charges in France. Of these, some 38,000 will be trucks, some 2,500 ambulances, some 3,000 "plain darn autos," and some 6,500 motorcycles. To take care of this vast motor fleet, to run it, keep it in repair, and so forth, our Uncle will need about 150,000 men—a young army in itself.

When one stops to consider the factories, repair shops, rebuilding stations and what not that will be required, one can see that Uncle Sam's garage is going to be no five-and-ten affair. It is going to be a real infant industry all by its lonesome; and already it is a pretty husky infant, with a loud honk-honk instead of a teething cry. In fact, in the few months since our collective arrival in France Uncle Sam has built up such an organization to keep his cars on the roads as to stagger the imagination of the men of big business, both of our own country and of our allies who have come to look it over.

These Are Real Experts

The A. E. F.—and this is news to many of its members—has, right here in France, a fully equipped automobile factory which is able not only to rebuild from the ground up any of a dozen or more makes of motors, but to turn out parts, tools, anything required from the vast stores of raw materials which has been shipped overseas for the purpose, with the special machinery which has been torn up in the States and replanted here. The factory is going to employ thousands of expert mechanics, and is going to have a capacity for general repair work unequalled by any similar plant back home.

People who dwell within the desolate region bounded by the Rhine on the west and the Russian frontier on the east have been in the habit of considering our national Uncle as a superficial sort of an old geezer; but the way he has taken hold of his automobile business proves that they have another good think coming. He hasn't overlooked a thing. Hard by his big new factory there is an "organization ground," a "salvage ground," a supply depot, and what is perhaps most important of all, the headquarters of a highly trained technical staff.

This is a staff of experts; not self-styled experts, but the real thing—big men in the automobile business representing all the important motor factories in the United States. Some of these experts inspect the broken down machines and pieces of machines in the salvage grounds, and report whether the wearing out process was due to a chauffeur's mishandling of the car, to the use of poor material in its construction, or to something wrong in its original designing.

Working "On the Ground"

If it is the chauffeur or mechanic who was responsible, he, wherever he is, is hauled up on the carpet. If the fault is found to lie with the factory in the States that turned out the machine, the representative of that company on the board of experts reports the facts to the home office himself, with recommendations for future betterment. In making out his recommendations for a car of a new design, peculiarly fitted to traffic and combat conditions in France, his co-workers on the board lend him their assistance. In this way defects in cars are detected "on the ground" and the responsibility placed at once, so that future errors of the same sort will be avoided.

This is, in brief, the journey that lies before an American made auto shipper, say "F.O.B. Detroit." Knocked down, or unassembled, it is packed and put aboard a transport at "an American port." It makes the same voyage that we all made to "a French port," gracefully thumbing its nose at any passing submarines. At the port it is assembled, painted, duly catalogued and numbered, and given a severe once-over and several finishing touches by the experts of the technical staff and their assistants.

For Emergency Calls

Having passed this examination, it is loaded with supplies—for even a car has to carry a pack while traveling—and headed towards the interior under charge of a picked crew of mechanics, who try it out under actual traffic conditions and adjust it. On the way it is held over at the "organization grounds," where it is given its supplementary equipment of tools, water cask, and the necessary picks, shovels and tow cables to get it out of the mud. This done, it is turned over to a new crew of men, and, as one of the component parts of a train of cars in charge of a truck company, it is sent "up front" if the need is urgent, or, in case there are cars aplenty in that interesting locality, it is run to a reserve station to await call.

When the car, after days or months at the front, begins to show, by its coughing or wheezing or other signs, that it is about due for a new lease of life, the journey is reversed. If the car is able to get back under its own power, it goes back that way; if it is not, a hurry call is sent for the auto-doctoring-train, which is nothing more nor less than a repair shop on wheels. There the blue-jeaned doctors of the train do their best for the car, and if it doesn't come around in a day or so, it is towed back to be overhauled from A to Izzard.

For the supplying of this auto armada, Uncle Sam, who seems to have overlooked nothing, has dotted the main routes from the Atlantic coast of France up to the fighting lines with gasoline stations. At the ports of entry themselves he has erected immense storage tanks, each capable of holding 25,000 barrels of the precious juice. At a number of inland bases on the way up are other tanks with a capacity of 5,000 gallons each. Near the front are many smaller tanks, while at the front itself the regular gas drums, small in size and readily transported, are available for the cars that have run out.

Just to make sure, Uncle Sam has brought over a flying squadron of some five hundred tank cars, which again has caused the natives to sit up and take notice. These cars are loaded from the tank ships at the ports of entry, and then sent inland to fill up the various depots. All in all, this same Uncle Sam who, by the way, is now supplying his allies with practically all their gasoline and lubricants, is doing a pretty good and speedy job as a distributing agent.

One more sample of how this lean and canny old unk of ours uses his head, and this story will be over. All the motor trucks are being distributed about France in definite areas, according to their make; for example, a certain area will be served by Packard trucks exclusively, while another will have G.M.C.'s, and G.M.C.'s only. This system does away with the need for repair men carrying many kinds of parts, and makes it possible for one trouble-expert knowing all about one kind of car, to serve a whole district. In that way harmony of operation and speed in mending broken-down cars is secured.

MEN ON LEAVE

NOT TO BE LED

ROUND BY HAND

——

Continued from Page 1

——

All travel on leave by men of units situated within the French Zone of the Armies will, as far as possible, be on the special leave trains. Transportation on these trains will be furnished by the Government, and rations will be provided for both going and returning journeys. Commutation and rations while on leave will not be paid in any case. Travel on regular trains will be at the expense of the officer or soldier so traveling, at one-fourth the regular rate. Commissioned officers and army nurses will be entitled to first class, field clerks and non-commissioned officers to second class, and all others to third class accommodations on regular trains.

Except on special leave trains, soldiers will be allowed to purchase second-class seats, but if a shortage of such seats should occur, they will not displace regular passengers.

Lodgings In Leave Zone

On their arrival at destination, all men will have their leave papers stamped with the date of arrival, and will have noted on them the date and hour of the train to be taken on expiration of their leave, by the American Provost Marshal at the railroad station, or by the French railroad officials. They will report to the Provost Marshal for information, for the looking over of leave papers, and for the selection of an assignment to lodgings and registry of address. If there is no Provost Marshal in the place to which they go, they will register their addresses and submit their leave papers for O. K.ing at the French Bureau de la Place of a garrisoned town, or else at the Gendarmerie, or police station. They will exhibit their leave papers to the French authorities at any time upon request.

Lodgings will be paid for in advance. If they prove unsatisfactory, a man may apply to the Provost Marshal for a change. Men who are unable to pay, or who commit any serious breach of discipline, will be promptly returned to their units. Misconduct will be reported by American Provost Marshals direct to the man's regimental or other Commander for disciplinary action—and for consideration at the next turn of leave.

In case of groups of men on leave traveling, the senior non-commissioned officer will be responsible for the conduct of the men. No liquor and no fire-arms or explosives of any sort may be carried by any soldier going to or returning from leave.

——

THE SUPREME SACRIFICE.

——

(Corset makers all over the United States are

forsaking that line of business in order to devote

their factories to the turning out of gas

masks for the Army.—News item from the States.)

——

Heaven bless the women! They are giving up their corsets

So that we, in snowy France, may 'scape the Teuton's ire;

Sacrificing form divine so factories may more sets

Make of gas protectors and of shields 'gainst liquid fire!

Heaven bless the women! They are losing lines each minute

So that we may hold the line from Belfort to the sea;

Giving up their whalebones so that, after we get in it,

We may whale the daylightes outer men from Germanee!

Heaven bless the women! They are wearing middy blouses

As a sort of camouflage, the while we spite the Hun;

Donning Mother Hubbards, too, and keeping to the houses

While we Yanks gas-helmeted, put Fritzie on the run!

Heaven bless the women and their perfect thirty-sixes!

Waists we clasped a-waltzing they some other way now drape.

Disregarding fashion so that every Yank may fix his

Breathing tube at "Gas—alert!" and thus preserve his shape!

Heaven bless the women! They are doing without dancing,

Knitting, packing, helping in a hundred thousand ways;

But they help the most by this while the foe's advancing—

Giving us the staying power by going without their stays!

——

THE ANZAC DICTIONARY.

——

ARCHIE.—A person who aims high and is not discouraged by daily failures.

A.W.L.—An expensive form of amusement entailing loss to the Commonwealth and extra work for one's pals.

BARRAGE.—That which shelters or protects, often in an offensive sense, i.e., loud music forms a barrage against the activity of a bore; a barrage of young brothers and sisters interfere with the object of a visit; and an orchard is said to be barraged by a large dog or an active owner.

BEER.—A much appreciated form of nectar now replaced by a colored liquor of a light yellow taste.

CAMOUFLAGE.—A thin screen disguising or concealing the main thing, i.e., a camouflage of sauce covers the iniquity of stale fish; a suitor camouflages his true love by paying attention to another girl; ladies in evening dress may or may not adequately camouflage their charms; and men resort to a light camouflage of drink to conceal a sorrow or joy.

CIVILIAN.—A male person of tender or great age, or else of weak intellect and faint heart.

COMMUNIQUE.—An amusing game played by two or more people with paper and pencil in which the other side is always losing and your own side is always winning.

DIGGER.—A friend, pal, or comrade, synonymous with cobber; a white man who runs straight.

DUD.—A negative term signifying useless, ineffective or worthless, e.g., a "dud" egg; a "dud of a girl" is one who is unattractive; and a dud joke falls flat.

DUGOUT.—A deep recess in the earth usually too small. As an adjective it is used to denote that such a one avoids hopping over the bags, or, indeed, venturing out into the open air in a trench. At times the word is used to denote antiquated relics employed temporarily.

HOME.—The place or places where Billzac would fain be when the job is done. Also known as "Our Land" and "Happyland."

HOPOVER.—A departure from a fixed point into the Unknown, also the first step in a serious undertaking.

IMSHI.—Means "go," "get out quickly." Used by the speaker, the word implies quick and noiseless movement in the opposite direction to the advance.

LEAVE.—A state or condition of ease, comfort and pleasure, involving the cessation of work: not to be confounded with sick leave. Time is measured by leaves denoting intervals of from three months to three years. Leave on the other hand is measured by time, usually too short.

MUD.—Unpleasantness, generally connected with delay, danger or extreme discomfort. Hence a special meaning of baseness in "his name is mud."

OVER THE BAGS.—The intensive form of danger: denoting a test of fitness and experience for Billzac and his brethren.

RELIEF.—A slow process of changing places; occurs in Shakespeare: "for this relief many thanks."

REST.—A mythical period between being relieved and relieving in the trenches, which is usually spent in walking away from the line and returning straight back in poor weather and at short notice.

SALVAGE.—To rescue unused property and make use of it. The word is also used of the property rescued. Property salvaged in the presence of the owner leads to trouble and is not done by an expert.

SOUVENIR.—Is generally used in the same sense as salvage but of small, easily portable articles. Coal or firewood for instance, is salvaged at night, but an electric torch would be souvenired.

STUNT.—A successful enterprise or undertaking usually involving surprise. A large scale stunt lacks the latter and is termed a "push", and the element of success is not essential.

TRENCHES.—Long narrow excavations in earth or chalk, sometimes filled with mud containing soldiers, bits of soldiers, salvage and alleged shelters.

WIND UP.—An aerated condition of mind due to apprehension as to what may happen next, in some cases amounting to an incurable disease closely allied to "cold feet."

ZERO.—A convenient way of expressing an indefinite time or date, i.e., will meet you at zero; call me at zero plus 30; or, to a debt collector, pay day at zero.—Aussie, the Australian Soldiers' Magazine.

FREE SEEDS FOR

SOLDIER FARMERS

——

Continued from Page 1

——

doughboy. Consider their ways. Get wise.

They're hard up for food, as you know; and at that, to judge from the reports from back home, they're no blooming curiosities. But look at what they do about it. Instead of folding their hands, saying, "C'est la guerre," they go out and dig, and then plant, and then hoe, and finally they have fresh vegetables—and backaches—to show for it. You can't go anywhere along the roadsides or up the hillsides these days without stumbling over their neat and well-kept-up little garden patches. And, with butter selling at what it is, and eggs selling for what they do, and everything else in the eats line skybooting in price, those little garden patches come in mighty handy. It's worth trying.

No Favors for Lemon Squads

Although no official announcement has been made as yet, it is safe to surmise that some company commanders will offer prizes for the squads producing the biggest pumpkins, the best summer squashes, and the most luscious watermelons. (Texas troops please heed.) Company commanders, you know, have never been in the habit of awarding prizes for the squads producing the most lemons, but, then, war changes every thing.

So keep your old campaign list for garden wear (if the Q.M. will let you); make a pair of overalls out of the burlap the meat comes done up in; use your trench pick and shovel, plus your bayonet, to do the plowing, and scatter the tender seedlets. If a few acorns come along with the rest of the plantables, plant them, too, for if we're going to be over here a good long time the shade from these oaks will come in mighty handy when we're old men and have time to sit down.

——

OUR OWN HORSE MARINES.

——

Horace Lovett, U. S. Marine Corps, on duty "somewhere over here," has just been appointed a horseshoer of Marines with the rank of corporal. In the same company Sergeant John Ochsner is stable sergeant and Corporal Stanley A. Smith is saddler. No, you have guessed wrong. The captain's name is not Jinks but Drum—Captain Drum of the horse and other marines.

HIS MORNING'S MAIL

IS 8,000 LETTERS

——

Base Censor Reads Them

All, Including 600 Not

in English

——

"Now, how the devil did he pick mine out of the pile?"

Shuddering, a young American in France gazed at the envelope before him, addressed in his own handwriting, to be sure, but with its end cut open and a stout sticker partially closing the cut. Stamped upon the face of the envelope were the fatal words "Examined by Base Censor." And the words, because of the gloom they brought the young man, were properly framed within a deep black border.

It was this way: The young man in question had been carrying on, for some time, a more or less hectic correspondence with a mademoiselle tres charmante in a not far distant town. That in itself would be harmless enough if he had sent his letters through the regular military channels—that is, submitted them to his own company officers to be censored. But dreading the "kidding" he might receive at the hands of his platoon commander—which he needn't have dreaded at all, for American officers are gentlemen and gentlemen respect confidence—he had been using the French postal service for his intimate and clandestine lovemaking. That, as everyone knows or ought to know, is strictly forbidden but the young man being "wise," thought he could put one over on the army. Result: That much dreaded bogey-man, the Base Censor knew just how many crosses he had made at the bottom of his note to Mlle. X.

But he needn't have worried a bit, for the bogey-man isn't a likely rival of any one. In fact, he isn't a man at all, but a System—just as impersonal as if he wrote his name, "Base Censor, Inc." Also, he is pretty well-nigh fool-proof and puncture-proof—which again removes him from consideration as "a human."

Remembers No Secrets

All delusions to the contrary, the censorship, though it learns an awful lot, doesn't care a tinker's hoot about nine-tenths of the stuff it learns. It isn't concerned with Private Jones's morals, with Corporal Brown's unpaid grocery bills, with Sergeant Smith's mother-in-law, with Lieutenant Johnson's fraternity symbols. It is, however, actively concerned in keeping out of correspondence all matters relating to the location and movement of troops, all items which pieced together might furnish the common enemy with information which would be valuable to him in the conduct of his nefarious enterprises.

In addition to keeping such damaging information out of soldiers' and officers' correspondence, the base censorship is lying in wait for everything and anything in the mail line which the senders hope to slip through uncensored. It regularly goes over a large proportion of the mail which has already been vised by company officers. It sifts through all mail for the army from neutral countries; and finally it censors all letters in foreign languages, written by men in the A. E. F.—letters which company officers are forbidden to O. K.

In the exercise of this last-named function lies perhaps the greatest task allotted to the base censorship. Our army is probably the most "international" in history, and it sends letters to the base written in forty-six different languages, excluding English. Out of 600 such letters—a typical day's grist—the chances are but half will be written in Italian, followed in the order of their numerousness, by those inscribed in Polish, French and Scandinavian. The censor's staff handles mail couched in twenty-five European languages, many tongues and dialects of the Balkan States and a scattering few in Yiddish, Chinese, Japanese, Hindu, Tahitian, Hawaiian, Persian and Greek, to say nothing of a number in Philippine dialects.

A Few Are in German

An interesting by-product of the censors' work is the discovery of foreign language interpreters within the ranks of the army. One soldier, for example, wrote in Turkish and wrote so well that the censor handling the letters in that tangled tongue passed on his name to those higher up. As a result, the man was detailed to the interpreters' corps where he is now serving his adopted country ably and well.

Seldom, say the members of the censor's staff, is anything forbidden found in the foreign language letters. The only striking feature about them as a whole is the small number that are written in German. In fact the Chinese letters as a rule outnumber those expressed in the language of the Kaiser.

Besides all this thousands of letters are sent direct to the base censors every day, in cases where soldiers are unwilling that their own immediate superiors should become acquainted with the contents. To humor, therefore, the enlisted man in a former National Guard unit whose censoring officer he suspects of trying to cut him out with The Girl Back Home, the base censor takes the responsibility off the company officer's shoulders; and the enlisted man feels oh! so much relieved.

Those clever chaps who devise all sorts of codes to tell the home folks just where they are in France, meet short shrift at the censor's hands. For example, one of them was anxious to describe a certain city in this fair land. "You know grandmother's first name," he wrote naively, thinking it would get by. But the particular censor it came before, having a New England grandmother of his own, promptly sent the letter back with the added comment, "Yes, and so do I! Can it!"

Another man was so bold as to write: "The name of the town where I am located is the same as that of the dance hall on Umptumpus avenue in ——" well, a certain well-known American city. He was also caught up; for the censor, being himself somewhat of a man of the world, shot the letter back with the tart comment: "I've been there, too."

Those two men, however, were more fortunate than the average in having their letters sent back to them for revision. The usual scheme is for the censor to clip out completely the portion of the letter carrying the damaging information. In case, therefore, a man has written something innocuous—but interesting none the less to his correspondent—on the other side, he is simply "out of luck." One can see it pays to be careful.

On the whole—aside from the mania which seems to have possessed some men to give away the location of their units in France—the censoring officials declare that the army deserves a great deal of credit for living up to both the letter and the spirit of the censor's code. They do, however, find fault with the men who continually "over-address" their letters—that is, who persist in tacking on the number of their divisions to the company and regimental designations. This, for military reasons, is forbidden, but many men seem as yet unaware of the fact.

Many Thank-you Letters

During the first half of January the base censor's office alone handled more than 8,000 letters a day—two thousand a day increase over December, due, no doubt, to the thank-you letters which our dutiful soldier-men felt compelled to write in return for those bounteous Christmas boxes. In the spring, though more transports will be coming over, more men will be writing letters, but still the work will go on. The abuse of the letter-writing privilege by one man might mean the loss of many of his comrades, so the long and tough job of censoring must be "seen through."

So, you smarty with the private code to transmit all sorts of dope to the folks, have a care! No matter how the letters pile up, old Base Censor, Inc., is always on the job! Like the roulette wheel at Monte Carlo, he'll get you in the end, no matter how lucky and clever you think yourself. Or, as Indiana's favorite poet might put it,

"The censor-man 'ull git you ef you

don't

watch

out!"

MIRABELLE

One striking feature of the war is the number of women and girls engaged in various kinds of work back of the lines. The British Army has thousands of them doing clerical work or driving ambulances, while in the A.E.F. their activities so far have been limited to canteen work with the Red Cross or Y. M. C. A.

Most of them are practical individuals doing a lot of good, but occasionally one slips over imbued with the idea that soldiers are sort of overgrown bacteriological specimens to be studied and handled only with sterilized gloves.

Possibly one of the latter inspired a certain A.E.F. private to lapse into poetry after he had stowed her baggage away and heard her dissertation on what the camp needed. His verses were:

The ether ethered,

The cosmos coughed,

Mirabelle whispered—

The words were soft:

"I shall go," Mirabelle said—

And her voice, how it bled!—

"I shall go to be hurt

By the dead, dead, dead.

To be hurt, hurt, hurt"—

Oh, the sad, sweet mien,

And the dreepy droop

Of that all-nut bean!

"One must grow," Mirabelle wailed,

"And one grows by the knife.

I shall grow in my soul

In that awful strife.

Let me go, let me grow,"

Was the theme of her dirge;

"Let the sobbiest of sobs

Through my bosom surge."

The sergeant took a lean

On the canteen door

The captain ran away:

"What a bore! What a bore!"

WAR RISK

INSURANCE

February 12 is the

last day to take out

war risk insurance.

DO IT NOW!

——

THE MACHINE-GUN SONG.

——

(As rendered by a certain battalion of Amex

mitrailleurs, to the tune of "Lord Geoffrey

Amherst.")

——

We've come from old New England for to blast the bloomin' Huns,

We have sailed from afar across the sea;

We will drive the Boche before us with our baby-beauty guns

To the heart of the Rhine countree!

And to his German majesty we will not do a thing

But to spray his carcass with our hail;

And when we're through with pepp'ring him, we'll make the lobster sing

As we ride him into Berlin on a rail!

CHORUS.

Oh, machine guns, machine guns!

They're the things to rake the Kaiser aft and fore!

May they never jam on us

Till we've gone and won this gosh-darn war!

Oh, machine guns are the handy things to drive the Fritzy out

When he hides back of bags of sand;

And machine guns are the dandy things to put the Hun to rout

If he tries to regain his land.

So just keep the clips a-comin', and we'll give her all the juice

As we speed along our glorious way:

And Von Hindenburg and Ludendorff will beat it like the deuce

When the little old rat-rattlers start to play!

CHORUS.

Oh, machine guns, machine guns!

They're the things to rake the Kaiser aft and fore!

May they never jam on us

Till we've gone and won this gosh-darn war!

——

CAN'T DO WITHOUT 'EM

——

Scene: An A.E.F. cookshack, during sanitary inspection.

Enter, to the cook standing at attention, one major, U.S.M.C., accompanied by one major, British Army Medical Corps.

U.S. Major: "Well cook, how's everything going?"

Cook: "Rotten, sir; men are either all sick or away on D.S., and there's only the mess sergeant and myself to look out for things. You can't get along without K.P.'s."

U.S. Major (to his British friend): "Major, you told me you knew a good deal of American Army slang; what would you say our friend the cook meant by 'K.P.'s'?"

British Major: "K.P.'s? Why, ah-er, I should say that cook was undoubtedly referring to the Knights of Pythias!"

FAMILY HOTEL, 7, Ave. du Trocadéro.

Full board from 10 francs.

HOTEL D'ALBE, Av. Champs-Elysées &

Avenue de l'Alma, Paris.

PATRONISED BY AMERICANS.

——

ONE EYE IS NOT TRUE BLUE.

——

So a Hoosier Patriot Tries to

Return It to Berlin.

——

Paul Gary of Anderson, Indiana, is all American, with the exception of a glass eye. The substitute optic is alien. Gary tried to enlist in the U. S. Marine Corps at their recruiting station in Louisville, Ky., but was rejected when his infirmity was discovered by Sergeant G. C. Wright.

"Didn't you know that the loss of an eye would prevent your enlisting?" asked the sergeant.

"I thought it might," explained Gary, "but this glass blinker is the only part of me that was made in Germany, and I want to take it back."

He was advised to mail it.

——

QUITE RIGHT.

——

"Do you suffer from headaches?" queried the M. O.

"Certainly I do," rejoined the hurried infantry officer. "If I enjoyed them as I do whisky and soda, I wouldn't have consulted you!"—Aussie, the Australian Soldiers' Magazine.

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE

READING ROOM

194 Rue de Rivoli.

Open daily 2.30 to 5 p.m.

ALBERTI'S Grand Café

KNICKERBOCKER

14, Bd des Capucines, 1, Rue Scribe, PARIS.

LUNCH 7 francs DINNER 8 francs

(wine included)

OFFICERS & SOLDIERS

Equip yourself at

A.A. TUNMER & CO.

1-3 Place Saint-Augustin,

PARIS.

SPORTING OUTFITTER

MEURICE HOTEL

AND

RESTAURANT

228 Rue de Rivoli

Opposite Tuileries Gardens

Restaurant Open to Non-Residents

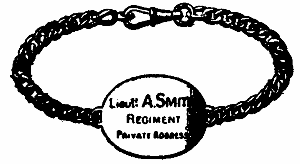

Solid Silver

IDENTITY

DISCS

AND

BRACELETS

KIRBY, BEARD & Co. Ld.

(Established 1743)

5, RUE AUBER (OPÉRA), PARIS

PERRIN LIFE-SAVING BELT

THE ONLY INSTANTANEOUS Patented S.G.D.G.

AND AUTOMATIC APPARATUS

Offers every guarantee.

BARCLAY, 18 & 20, Avenue de l'Opéra, PARIS.

Furnishers of Governments of America, England

and France and of all Centers of Aviation.

Description and Catalogue free on application.

Guaranty Trust Company of New York

Paris: 1 & 3 Rue des Italiens.

UNITED STATES DEPOSITARY OF PUBLIC MONEYS

Places its banking facilities at the disposal of the

officers and men of the

AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES

Special facilities afforded officers with accounts

with this institution to negotiate their personal

checks anywhere in France. Money transferred to

all parts of the United States by draft or cable.

Capital and Surplus : : : $50,000,000

Resources more than : : : $600,000,000

AN AMERICAN BANK WITH AMERICAN METHODS

ADAMS EXPRESS CO.

===== PARIS OFFICE =====

28, Rue du Quatre-Septembre.

Every Banking Facility for American Expeditionary Forces

MONEY TRANSFERRED BY CABLE AND MAIL

TO ALL PARTS OF AMERICA AND CANADA

Mail us your Pay Checks endorsed to our order.

WE OPEN DEPOSIT ACCOUNTS WITH YOU FREE OF CHARGE, SUPPLYING CHECK-BOOKS.

GERMAN BRANDS

YOUNG MOTHER

WITH AN IRON.

——

Victim of a Violation

Officially Labeled by

Army Authorities.

——

PAINT BADGE FOR OTHERS

——

Children of German Fathers

Catalogued as the Government's

Property.

——

FORCED INTO MENIAL SERVICE

——

An Officer Formerly in British

Army Tells How Kultur

Repopulates Itself.

A new and startling story of German atrocities is told by an American formerly in the service of the British Army, but now attending one of the A.E.F. schools in preparation for a commission in the American Army. It is in accordance with other stories of the prostitution of womanhood which the Kaiser is forcing in order to repopulate the German Empire.

The rapid British advance at Cambria, in November, when towns which the Germans had occupied for three years were captured before the latter could deport the civilian population into Germany as is their custom, disclosed the latest effort of the German army. French women and girls had been made the victims.

"Among the refugees who passed along the roads making their way southward farther into France after we made our first big advance were scores of women and girls, each marked on her breast by a cross in red paint," said the officer. "These were disclosed when the refugees passed in front of our medical officers who were inspecting them. All of them were about to become mothers, and the French interpreter who was assisting the medicos explained that the cross indicated that German soldiers were the fathers. The crosses had been painted on them, the women explained, to show that their children would belong to the German Government.

This Iron Cross Red Hot.

"One of these unfortunates, apparently not more than seventeen years of age, had not only been painted but branded with a hot iron so that she would be marked for life with the sign of the cross. She said that a German officer would be the father of her child. This officer, the girl said, had been quartered in her parents' home and she had been forced to accede to his desires.

"After her health became such that he had no further use for her, she said, he ordered her to act as his personal servant, doing the menial work in his chamber. It was not long until she was unable to continue this and then, angered at her weakness, he ordered soldiers to scour the paint from her breast and burn the cross into her flesh. When this was done, she was forced to leave her home and taken to a maternity hospital which the army had established for other girls and women of the town in the same condition.

An Eye-Witness on "Kultur."

"I myself saw the girl who had been branded and the others who had been painted like sheep and heard their stories, as I had been detailed to supervise the return of the refugees. Thank God, America, by coming into the war, will help to stamp out this beastly 'kultur' from the world and make it a safe, clean place to live in for your womenfolk and mine—our mothers, our sweethearts, our wives, and our daughters. I have a daughter just seventeen years old," concluded the American grimly.

——

WHEN THE FRENCH BAND PLAYS.

——

There's a military band that plays, on Sunday afternoons,

In a certain nameless city's quaint old square.

It can rouse the blood to battle with its patriotic tunes,

And still render hymns as gentle as a prayer.

When it starts "Ave Maria" there is no one in the throng

But would doff his cap, his heart to heaven raise;

And who would shrink from combat when, with brasses sounding strong,

There is flung out on the breeze "La Marseillaise"?

When it starts to render "Sambre et Meuse," the march that won the day

At the battle of the Marne, one sees again

The grey-green hosts of Hundom melt before the stern array

Of our gallant sister-ally's blue-clad men.

And when it plays our Anthem, with rendition bold and clear—

While the khaki lads stand steady—then we feel

That, though tongues and ways may vary, we've found brothers over here,

Tried in war, and in allegiance true as steel.

For it's olive-drab, horizon-blue, packed closely side by side,

Till their color sets ablaze the grey old square;

And it's olive-drab, horizon-blue, whatever may betide,

That will blaze the path to victory "up there."

So, while standing thus together, let us pledge anew our troth

To the Cause—the world set free!—for which we fight.

As the evening twilight gilds the ranks of blue and khaki both,

And the bugles die away into the night.

WHEN PACKS ARE LIGHTEST

BY CHAPLAIN MOODY.

Probably the cow is the least complaining and discriminating of all animals, yet it is worthy of note that the wise farmer who understands his cows does everything to make them as happy as possible and studies their comfort and convenience as far as possible. This is not because he is a sentimentalist, but for the very opposite reason. He knows his cows will give more milk and he will get more money therefrom if they are contented in their bovine minds and not worried by the high cost of living and other problems.

The expert poultry man will tell you that the frame of mind of his feathered employes has a very direct bearing on the egg output, and so he tries to study their happiness.

Recently experiments have been carried on in some factories with phonographs, and it has been proven that if the fingers of the employes are stimulated by some music they enjoy, it is possible to get more work out of them. In some Cuban cigar factories it is the customary thing to employ a man to read to the cigar makers some story which they like, as, under these conditions, they work better and faster.

All this is not done out of sentiment, again, but because it contributes to efficiency. The cow, the hen, the factory girl and the cigar wrapper do better work for being in a pleasant frame of mind.

While we of the American Expeditionary Forces do not fall into any of these classes, the same is nevertheless probably true of us. We can be better soldiers if we are cheerful than we can if we are not. It may be difficult to see how you can sight a gun any better for smiling or bayonet a man more effectively when you are cheerful. But if we believe what we are told, this is so, and, hence, since we all want to be good soldiers, it becomes a duty toward this end to be happy, just as it is a duty to wash your face or police your bunk, or to keep your rifle clean. It is a duty to be happy.

That is all very well and good to say, some one interrupts at this point, but you cannot be happy when your feet are sore or you do not have all you want to eat. Or, it would be easy to be happy if the mail would come, or they would "bust" the Mess Sergeant, or take some other great step forward in the improvement of the army. But we all know better.

Our happiness is not dependent on conditions outside of us, but on our hearts within us, and some of the happiest men have been the victims of extraordinary misfortune and some of the unhappiest people have been possessors of great wealth who could have all they wanted. The most joyous book in the world was written by an old man in prison who had come to the conclusion that when they let him out they would chop his head off. Many a man has just grinned himself out of worse fixes than you or I are ever apt to get into.

There are very few things we cannot laugh at. By laughing, we do not actually shorten the hike, but we make it seem shorter; we do not in reality lighten the pack, but we make it seem lighter, and it all comes to the same thing, for we would rather carry a heavy load and have it seem light than carry a light load and have it seem heavy. If we laugh at the cooties when they come, and hunt them with the same merriment that the French hunt the wild boar, the joke will be on them after all, for they do not laugh back. And then they won't seem half so bad. Laughter is a good insecticide.

We American soldiers in France are in for a big thing. Just how big it is and how long it will last we do not know and no one can tell us. But we are determined that America shall do her part and that we as individuals shall do ours and be the best soldiers possible, and this is some task when we remember how gallantly our Allies have fought. It will be, in our own language, "some job," and for this reason we must use every means within our power to accomplish it. So we must not forget happiness as an asset to efficient soldiering. We will all smile where the coward would whimper, and laugh where the weakling would whine, and buckle down to what Robert Louis Stevenson called "The great task of happiness."

VOLUNTEER VIC'S BIG IDEA BY LEMEN IN THE

ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH

——

THERE'S A REASON.

——

No more ham or eggs or grapefruit when the bugle blows for chow. No more apple pie or dumplings, for we're in the army now; and they feed us beans for breakfast, and at noon we have 'em, too; while at night they fill our tummies with a good old army stew.

No more shirts of silk and linen. We all wear the O. D. stuff. No more night shirts or pyjamas, for our pants are good enough. No more feather ticks or pillows, but we're glad to thank the Lord we've got a cot and blanket when we might just have a board.

For they feed us beans for breakfast, and at noon we have 'em, too; while at night they fill our stomachs with a good old army stew. By, by gum, we'll lick the kaiser when the sergeants teach us how, for, dad burn it, he's the reason that we're in the army now!—Pittsburgh Post.

——

A DOUGHBOY'S DICTIONARY.

——

Camouflage—Wearing an overcoat to reveille.

Military Road—A large body of land, without beginning or end, entirely covered by water.

Camion—1. A large, immovable body which one is expected to carry on one's shoulders through the mud. 2. The thing that brings the mail out.

Army Rifle—Something eternally dirty which must be kept eternally clean.

Bayonet—A long, sharp, pointed object whose only satisfactory resting place is the midriff of a Hun.

Pay-day—1. A "movable feast." 2. A time for cancellation of debts. 3. The date of the return of the laundry one sent away a month and a half before.

——

THIS REALLY HAPPENED.

——

End of letter: "Goodbye, my dear, for the present. Yours, Jack." Then—"x—x—x—x—x—x—x—x. P. S. I hope the censor doesn't object to those crosses."

Added by Friend Censor: "Certainly not! x—x—x—x—x—x—x—x!"

KISS FOR RESCUER

OF PIG FROM BLAZE

——

A Beantown Fire-Fighter

Hero of Epoch-Making

Conflagration.

——

"Weee-ah-eeeeeee-ah-eeeeeee!"

Private John Doe, late of the Boston fire department, knew something was up when, on a certain Sunday morning not long ago, he heard that sound issuing from the second story of the house-barn in which his command was billeted. Also he saw a thin streamer of smoke, no bigger than Rhode Island, winding its way out of the house-barn door. He sniffed, then hollered "Fire!"

"Fire?" echoed some of his bunk mates, coming up the road. Fire? How could there be fire in a country where not even sulphurous language served to start the kitchen kindlings? How could there be fire in a country where only every other match will light at all, at all?

Nevertheless, up they hustled, to see a bit of blaze lapping the edge of the house-barn door, and to hear, from within, the plaintive cry of "Weee-ah-eeeeee-ah-eeeeeee!"

"Steady, piggy darlint!" came Private Doe's soothing accents, from the second story. "Sure an' it's meeself will resthcue yeze from this burnin' ould shack! You below there! Climb on up an' lind a hand at pullin' out the hay that's up here, or ilse the whole place will be burnted down intoirely!"

Enter the Reserves.

Into the barn rushed half of Private Doe's squad. The other half, calling down the road, summoned a good two companies, which came up on the double.

At this point entered, front and centre, M. le Maire of the commune, who, being the owner of the pig in distress, had more than a casual interest in the proceedings. "The fire engine! The fire engine!" he shouted, in accents both wild and French. But, since there had been no fire in the town in fifty years, nobody seemed to know just what he meant.

Fact! No fire in the town in fifty years! 'Way back in the days of Napoleon III. there had been a fire, a little blaze, in the town. Think of that, you insurance men who used to write policies for clothing dealers on New York's East Side!

When he had sufficiently recovered his avoirdupois, M. le Maire dragged out of the Hotel de Ville, with the aid of the embattled infantrymen, some fire apparatus, of early Bourbon vintage. One private who helped handle it swears that he spotted the date "1748" on the leather hose which led from a water tank, about twelve by eight by four, toward the general direction of the fire. The tank, in turn, had to be filled by a bucket brigade strung along from the scene of action to the village fountain, about a quarter of a mile away.

Fire a Social Success.

It's a shame to spoil a good story, but Private Doe did not throw down the pig into an army blanket held out to receive it. He clambered down a smouldering flight of ladder stairs, with His Pigship under his arm, quite unharmed, save for a severe nervous shock. Aside from a few scorched kit bags, the loss of the top sergeant's cherished pipe, and a few lungfuls of smoke acquired by Private Doe, the fire was not a success—that is, from a historical standpoint. But as a social event, in bringing the Americans—and Private Doe, kissed by the lady mayoress for his pains, in particular—closer to the hearts of the villagers, it was decidedly there.

——

JIM.

——

Honest, but Jim was the sourest man in

all o' Comp'ny G;

You could sing and tell stories the whole

night long, but never a cuss gave he.

You could feed him turkey at Christmastime—and

Tony the cook's no slouch—

But Jim wouldn't join in "Three cheers

for the cook!" Gosh, but he had a

grouch!

He wouldn't go up to the hill cafay when

our daily hike was done,

And sip his beer, and chin with the lads,

the crabby son-of-a-gun;

He'd growl if you asked him to hold the

light, he'd snarl if you asked for a butt,

Till at last the gang was 'most ready to

put Jim down for a mutt.

About the first time that our mail came

in, we all felt as high as a king;

"What luck?" somebody hollers to Jim:

he says, "Not a dad-blamed thing."

And then he goes off in his end o' the

shack, and Tom Breed swears 'at he

cried;

But when somebody went and repeated it,

Jim swore, by gad, Tom lied.

We were gettin' our mail, irregular-like,

for about a month or two;

But Jim? He never drew anything, and

blooey! but he was blue!

Not only blue, but surly; he was off'n

the whole darn shop,

And once he was put onto "heavy" for

talkin' back to the Top.

'Twas a day or two before New Year's,

when the postal truck came in;

The orderly fishes one out for Jim; he

takes it, without a grin,

And then, as he opens the envelope—eeyow!

How that man did yell:

"A letter from James J., Junior, boys!

the youngster has learnt to spell!"

So nothin' would do but the bunch of us

had to read the letter through;

'Twas all writ out by that kid of his,

and a mighty smart kid, too,

For it isn't every six-year-old at school

as can take a prize,

(Like the boy wrote Jim as he had done):

and you oughter seen Jim's eyes!

Well, Jim had a mighty good New

Year's; he stood the squad a treat,

And now, 'stead o' turnin' out sloppy,

he's always trim and neat;

Fact is, the lieutenant passed the word

that if Jim keeps on that way

He'll be wearing little stripes on his

arm and drawin' a bit more pay.

Don't it beat hell how a little thing will

change a man like that?

Now Jim's as cheerful as anything instead

o' mum as a bat.

An' the reason? Why, it's easy! A

guy is bound to fail

Of bein' a proper soldier if he don't get

no fambly mail!

If all of those post office birds was wise

to the change they made in Jim,

They'd hustle a bit on our letters, for

they's lots that's just like him;

It may be a kid, or it may be a girl;

a mother, a pal, a wife,—

And believe me, this hearin' from 'em—why,

it's half o' the joy o' life!

Chartered 1822

The Farmers' Loan and Trust Company

NEW YORK

PARIS BORDEAUX

41, Boulevard Haussmann 8, Cours du Chapeau-Rouge

AND

TWO ARMY ZONE OFFICES

Specially designated

United States Depositary of Public Moneys.

LONDON: 26, Old Broad Street, E.C.2 and 16, Pall Mall East. S.W.1.

The Société Générale pour favoriser etc., & its Branches throughout France will

act as our correspondents for the cashing of Officers' cheques & transfer of funds for

MEMBERS of the AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES.

BIG GUNS ON FLAT CARS

TO BATTER HUNS' LINES.

——

A. E. F. Operates Railroad Artillery that will Hurl

Tons of Steel Twenty Miles into

Enemy's Territory.

——

LONG-BARRELLED 155s ARE ALSO DEADLY.

——

Fortresses and Mountains Crumble like Sandhills

Before Blasts from the Busters.

——