"THE MAHOGANY TREE."

"THE MAHOGANY TREE."

Title: The History of "Punch"

Author: M. H. Spielmann

Release date: December 17, 2007 [eBook #23881]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Malcolm Farmer, Janet Blenkinship, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Malcolm Farmer, Janet Blenkinship,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

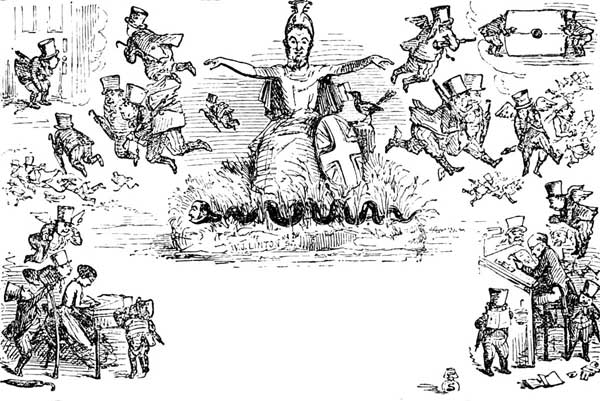

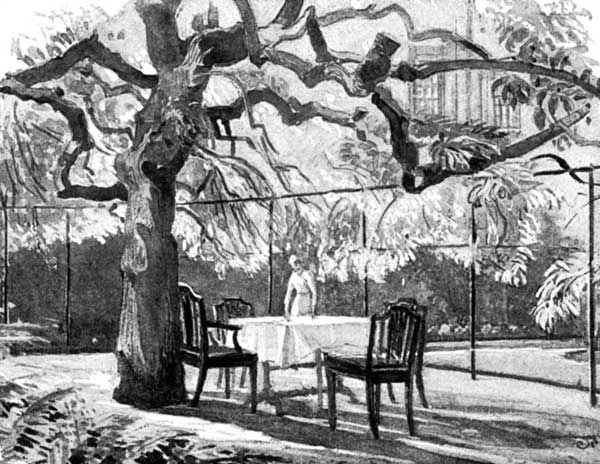

(By Linley Sambourne. From "Punch's" Jubilee Number, by special

permission of Sir William Agnew, Bart., Owner of the original drawing.)

(See page 536.)

CASSELL and COMPANY, Limited

LONDON, PARIS, & MELBOURNE

1895

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The prevailing idea of the origin and history of Punch has hitherto rested mainly on three productions: the "Memories" of George Hodder, "Mr. Punch's Origin and Career," and Mr. Joseph Hatton's delightful but fragmentary papers, entitled "The True Story of Punch." So far as the last-named is based upon the others, it is untrustworthy in its details; but the statements founded on the writer's own knowledge and on the documentary matter in his hands, as well as upon his intimacy with Mark Lemon, possess a distinct and individual value, and I have not failed to avail myself in the following pages of Mr. Hatton's courteous permission to make such use of them as might be desirable.

During the four years in which I have been engaged upon this book, my correspondents have been numbered by hundreds. Hardly a man living whom I suspected of having worked for Punch, but I have communicated with him; scarce one but has afforded all the information within his knowledge in response to my application. Editor and members of the Punch Staff, past and present—"outsiders," equally with those belonging to "the Table"—the relations and friends of such as are dead, all have given their help, and have shown an interest in the work which I hope the result may be thought to justify. All this mass of material—all the evidence, published and unpublished, that was adduced in order to establish certain points and refute others—had to be carefully sifted and collated, contrary testimony weighed, and the truth determined. Especially was this the case in dealing with the valuable reminiscences imparted by Punch's earliest collaborators, still or till lately living. Of undoubted contributors and their work, it may be stated, more than two hundred and fifty are here dealt with. A further number cheerfully submitted to cross-examination on one or other of the many subjects touched upon; and probably as many more were approached with only negative results.

My special thanks are due to Mrs. Chaplin, the daughter of the late Mr. Ebenezer Landells, who unreservedly placed in my hands all the Punch documents, legal and otherwise, accounts, and letters, concerning the origin and early editorships of Punch, which have been preserved in the family; and to Messrs. Bradbury and Agnew, who have supplemented these with similar assistance, as well as with books of the Firm establishing points of literary interest not hitherto suspected, together with the letters of Thackeray which illustrate his early connection with and final secession from the Staff. Apart from their general interest, these documents, taken together, establish the facts of such very vexed questions as the origin and the early editorships of Punch. This is the more satisfactory, perhaps, by reason of the numerous unfounded claims—or founded chiefly on family tradition or filial pride and affection—which are still being made on behalf of supposed originators of the Paper. Even these partisan historians, it is believed, will hardly be able to resist the proofs here set forth; although attested fact does not, with them, necessarily carry conviction. For such services, and for their ready and sympathetic acquiescence in the requests I have made for permission to quote text or reproduce engraving, my hearty thanks to Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew and Co. are due. To them and to all my numerous correspondents I here repeat the assurance of gratitude for their courtesy which I have privately expressed before.

I have reproduced no more pictures from Punch than were rendered necessary by the topics under discussion. I would rather send the reader, for Punch's pictures, to the ever-fresh pages of Punch itself. Nor, I may add, did I seek information and assistance from its Proprietors until this book was well advanced, preferring to make independent research and to test statements on my own account.

My primary inducement to the writing of this book has been the interest surrounding Punch, the study of which has not begotten in me the hero-worship that can see no fault. How far I have succeeded, it rests with the readers of this volume to decide.

September, 1895.

| PAGE | |

| Introductory. | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| PUNCH'S BIRTH AND PARENTAGE. | |

| The Mystery of His Birth—Previous Unsuccessful Attempts at Solution—Proposal for a "London Charivari"—Ebenezer Landells and His Notion—Joseph Last Consults with Henry Mayhew—Whose Imagination is Fired—Staff Formed—Prospectus—Punch is Born and Christened—The First Number | 10 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| PUNCH'S EARLY PROGRESS AND VICISSITUDES. | |

| Reception of Punch—Early Struggles—Financial Help Invoked—The First Almanac—Its Enormous Success—Transfer of Punch to Bradbury and Evans—Terms of Settlement—The New Firm—Punch's Special Efforts—Succession of Covers—"Valentines," "Holidays," "Records of the Great Exhibition," and "At the Paris Exhibition" | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE PUNCH DINNER AND THE PUNCH CLUB. | |

| Origin and Antiquity of the Meal—Place of Celebration—The "Crown"—In Bouverie Street and Elsewhere—The Dining-Hall—The Table—And Plans—Jokes and Amenities—Jerrold and his "Bark"—A Night at the Dinner—From Mr. Henry Silver's Diary—Loyalty and Perseverance of Diners—Charles H. Bennett and the Jeu d'esprit—Keene Holds Aloof—Business—Evolution of the Cartoon—Honours Divided—Guests—Special Dinners, "Jubilee," "Thackeray," "Burnand," and "Tenniel"—Dinners to Punch—The Punch Club—Exit Albert Smith—High Spirits—"The Whistling Oyster"—Baylis as a Prophet—"Two Pins Club" | 53 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| PUNCH AS A POLITICIAN. | |

| Punch's Attitude—His Whiggery—And Sincerity—Catholics and Jews—Home Rule—European Politics—Prince Napoleon—Punch's Mistakes—His Campaign against Sir James Graham—His Relations with Foreign Powers—And Comprehensive Survey of Affairs | 99 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| "CHARIVARIETIES." | |

| Punch's Influence on Dress and Fashion—His Records—As a Prophet—As an Artist—As an Actor and Dramatist—Benefit Performances—Guild of Literature and Art | 122 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| PUNCH'S JOKES—THEIR ORIGIN, PEDIGREE, AND APPROPRIATION. | |

| "The Unknown Man"—Jokes from Scotland—"Bang went Saxpence"—"Advice to Persons about to Marry"—Claimants and True Authorship—Origin of some of Punch's Jokes and Pictures—Contributors of Witty Things—A Grim Coincidence—"I Used Your Soap Two Years Ago"—Charles Keene Offended—The Serjeant-at-Arms and Mr. Furniss's Beetle—Mr. Birket Foster and Mr. Andrew Tuer—Plagiarism and Repetition—The Seamy Side of Joke-editing—Punch Invokes the Law—Rape of Mrs. Caudle—Sturm und Drang— Plagiarism or Coincidence?—Anticipations of the "Puppet-Show" and "The Arrow"—Of Joe Miller—And Others—Punch-baiting—Impossibility of Joke-identification—Repetitions and Improvements | 138 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| CARTOONS—CARTOONISTS AND THEIR WORK. | |

| The Cartoon takes Shape—"The Parish Councils Cockatoo"—Cartoonists and their Relative Achievements—John Leech's First—Rapidity in Design—"General Février turned Traitor"—"The United Service"—Sir John Tenniel's Animal Types—"The British Lion Smells a Rat"—The Indian Mutiny—A Cartoon of Vengeance—Punch and Cousin Jonathan—"Ave Cæsar!"—The Franco-Prussian War—The Russo-Turkish War—"The Political 'Mrs. Gummidge'"—"Dropping the Pilot," its Origin and Present Ownership—"Forlorn Hope"—"The Old Crusaders"—Troubles of the Cartoonist—The Obituary Cartoon | 168 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| CARTOONS AND THEIR EFFECT. | |

| Origin and Growth of the Cartoon—And of its Name—Its Reflection of Popular Opinion—Source of Punch's Power—Punch's Downrightness offends France—Germany—And Russia—Lord Augustus Loftus's Fix—Lord John Russell and "No Popery"—Mr. Gladstone and Professor Ruskin on Punch's Cartoons—Their Effect on Mr. Disraeli—His Advances and Magnanimity—Rough Handling of Lord Brougham—Sir Robert Peel—Lord Palmerston's Straw—Mr. Bright's Eye-glass—Difficulties of Portraiture—John Bull alias Mark Lemon—Sir John Tenniel's Types | 185 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| PUNCH ON THE WAR-PATH: ATTACK. | |

| Punch lays about Him—Assaults the "Morning Post"—The Factitious "Jenkins"—Thackeray's Farewell—Mrs. Gamp (the "Morning Herald") and Mrs. Harris (the "Standard")—Lèse Majesté!—The "Standard" Fulminates a Leader—The Retort—His Loyalty—Banters the Prince Consort—Tribute on the Prince's Death—Punch's Butts: Lord William Lennox—Jullien—Sir Peter Laurie—Harrison Ainsworth—Lytton—Turner—A Fallacy of Hope—Burne-Jones—Charles Kean—S. C. Hall as "Pecksniff"—James Silk Buckingham and the "British and Foreign Destitute"—Alfred Bunn—Punch's Waterloo: "A Word with Punch"—Bunn, Hot and Cross—A Second "Word" Prepared, but never Uttered—Other Points of Attack | 209 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| PUNCH ON THE WAR-PATH: COUNTER-ATTACK. | |

| Satire and Libel—Mrs. Ramsbotham Assaulted—Attacks of "The Man in the Moon" and "The Puppet-Show"—H. S. Leigh's Banter—Malicious Wit—Mr. Pincott—Punch's Purity gives Offence—His Slips of Fact—Quotation—And Dialect are Resented—His Drunkards not Appreciated by the U. K. A.—"Punch is not as good as it was!" | 234 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| ENGRAVING AND PRINTING. | |

| Mr. Joseph Swain supersedes Ebenezer Landells—His Education as Engraver—Head of His Department—Engraving the Big Cut: Then and Now—Printing from the Wood-blocks—Leech's Fastidiousness—Impracticability of Keene—Thackeray's Little Confidence—A Record of Half a Century | 247 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| PUNCH'S WRITERS: 1841. | |

| Mark Lemon—As Others Saw Him—His Duties—His Industry—His Staff and their Apportioned Work—Lemon as an Editor—And Diplomatist—A Testimonial—And a Practical Joke—Henry Mayhew—His Great Powers and Little Weaknesses—Disappointment and Retirement—Stirling Coyne—Gilbert Abbott à Beckett—His Early Career—Tremendous Industry—À Beckett and Robert Seymour—Appointed Magistrate—Locked in—Agnus B. Reach | 254 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| PUNCH'S WRITERS: 1841. | |

| H. P. Grattan—W. H. Wills—R. B. Postans—Bread-Tax and Tooth-Tax—G. Hodder—G. H. B. Rodwell—Douglas Jerrold—His Caustic Wit—The "Q Papers"—A Statesman pour rire—His Sympathy with the Poor and Oppressed—Wins for Punch his Political Influence—Ill-health—"Punch's Letters"—The "Jenkins" and "Pecksniff" Papers—"Mrs. Caudle"—Jerrold's Love of Children, common to the Staff—He Silences his Fellow-wits—And is Routed by a Barmaid—He sends his Love to the Staff—And they prove theirs | 282 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| PUNCH'S WRITERS: 1841-2. | |

| Percival Leigh—His Medical Shrewdness—Unsuspected Wealth—His Ability and Work—His Decay—Kindness of the Proprietors to the Old Pensioner—Albert Smith—Inspires varied Sentiments—Jerrold's Hostility—"Lord Smith"—Parts Company—H. A. Kennedy—Dr. Maginn—John Oxenford—W. M. Thackeray—His First Contribution—"Miss Tickletoby" Fails to Please—He Withdraws—And Resumes—Rivalry with Jerrold—As an Illustrator—A Mysterious Picture—Thackeray's Contributions—And Pseudonyms—-Quaint Orthography—"The Snobs of England"—He Tires of Punch— His Motives for Resignation—The Letter—Death of "Dear Old Thack"—Punch's Tribute to his Memory | 299 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| PUNCH'S WRITERS: 1843-51. | |

| Horace Mayhew—"The Wicked Old Marquis"—A Birthday Ode—R. B. Peake—Thomas Hood—"The Song of the Shirt"—Its Origin—Its Effect in the Country—Its Authorship Claimed by Others—Translated throughout Europe—A Missing Verse—Hood Compared with Jerrold—"Reflections on New Year's Day"—Dr. E. V. Kenealy—J. W. Ferguson—Charles Lever—Laman Blanchard—Tom Taylor—Passed over by Shirley Brooks—Taylor's Critics—Mr. Coventry Patmore—"Jacob Omnium"—Tennyson v. Bulwer Lytton—Horace Smith—"Rob Roy" Macgregor—Mr. Henry Silver—Introduces Charles Keene—His Literary Work—Service to Leech—Retirement—Mr. Sutherland Edwards—Charles Dickens and Punch—Sothern Earns his Dinner—Reconciliation of Dickens and Mark Lemon—J. L. Hannay—Cuthbert Bede | 327 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| PUNCH'S WRITERS: 1852-78. | |

| Shirley Brooks—His Wit and Humour—Training—Lays Siege to Punch—And Carries him by Assault—"Essence of Parliament"—William Brough—Mr. Beatty Kingston—F. I. Scudamore—M. J. Barry—Dean Hole—Mr. Charles L. Eastlake—Mr. Francis Cowley Burnand—His Little Joke with Cardinal Manning—"Fun"—"Mokeanna"—Its Success—Thackeray's Congratulations to Punch—"Happy Thoughts"—And Other Happy Thoughts—Mr. Burnand as a Ground-Swell—Promoted to the Editorship—The Apotheosis of the Pun—Mr. J. Priestman Atkinson—Mr. John Hollingshead—Mr. R. F. Sketchley—"Artemus Ward"—A Death-bed Ambition—H. Savile Clarke—Locker-Lampson and C. S. Calverley—Miss Betham-Edwards—Mr. du Maurier's "Vers Nonsensiques"—Mr. A. P. Graves—Rev. Stainton Moses—Mr. Arthur W. à Beckett—"A. Briefless, Junior"—Mortimer Collins—Mr. E. J. Milliken—"The 'Arry Papers"—Gilbert à Beckett—"How we Advertise Now"—Mr. H. F. Lester—Mr. Burnand and the Corporal | 356 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| PUNCH'S WRITERS: 1880-94. | |

| "Robert"—Mr. Deputy Bedford—Mr. Ashby-Sterry—Reginald Shirley Brooks—Mr. George Augustus Sala—Mr. Clement Scott—The "Times" Approves—Mr. H. W. Lucy—"Toby, M.P."—Martin Tupper and Edmund Yates—Mr. George Grossmith—Mr. Weedon Grossmith—Mr. Andrew Lang's "Confessions of a Duffer"—Miss May Kendall—Miss Burnand—Lady Humorists—Mr. Brandon Thomas and Mr. Gladstone—Mr. Warham St. Leger—Mr. Anstey—"Modern Music-hall Songs"—"Voces Populi"—Mr. R. C. Lehmann—Mr. Barry Pain—Mr. H. P. Stephens—Mr. Charles Geake—Mr. Gerald Campbell—R. F. Murray—Mr. George Davis—Mr. Arthur A. Sykes—Rev. A. C. Deane—Mr. Owen Seaman—Lady Campbell—Mr. James Payn—Mr. H. D. Traill—Mr. A. Armitage—Mr. Hosack—"Arthur Sketchley"—Henry J. Byron—Punch's Literature Considered | 385 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| PUNCH'S ARTISTS: 1841. | |

| Punch's Primitive Art—A. S. Henning—Brine—A Strange Doctrine—John Phillips—W. Newman—Pictorial Puns—H. G. Hine—John Leech—His Early Life—Friendship with Albert Smith—Leech Helps Punch up the Social Ladder—His Political Work—Leech Follows the "Movements"—"Servantgalism"—"The Brook Green Volunteer"—The Great Beard Movement—Sothern's Indebtedness to Leech for Lord Dundreary—Crazes and Fancies—Leech's Types—"Mr. Briggs"—Leech the Hunter—Leech as a Reformer—Leech as an Artist—His "Legend" Writing—His Prejudices—His Death—And Funeral | 409 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| PUNCH'S ARTISTS: 1841-50. | |

| William Harvey—Mr. Birket Foster—Kenny Meadows—His Joviality—Alfred "Crowquill"—Sir John Gilbert—Exit "Rubens"—Hablôt Knight Browne ("Phiz")—Henry Heath—Mr. R. J. Hamerton—W. Brown—Richard Doyle—Desires Pseudonymity—His Protest against Punch's "Papal Aggression" Campaign—Withdraws—His Art—Epitaph by Punch—Henry Doyle—T. Onwhyn—"Rob Roy" Macgregor—William McConnell—Sir John Tenniel—His Career—And Technique—His Early Work—Cartoons—His Art—His Memory and its Lapses—"Jackīdēs"—Knighthood | 444 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| PUNCH'S ARTISTS: 1850-60. | |

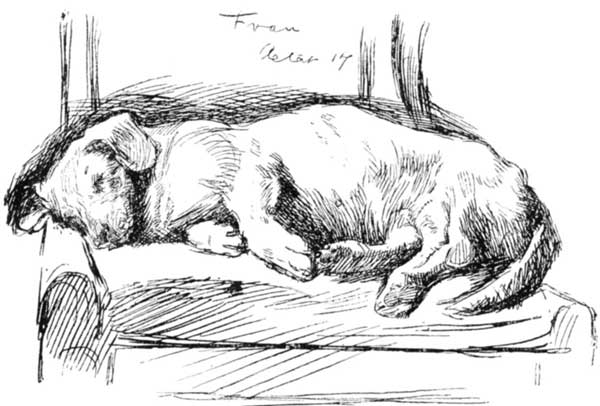

| Captain Howard—Receipt for Landscape Drawing—Earnings, Real and Ideal—George H. Thomas—Charles Keene—His Training—Introduction to Punch—Called to the Table—Uselessness in Council—A Strong Politician—Inherits Leech's Position—Keene as an Artist—Where He Failed—His Joke-Primers—Torturing the Bagpipes—Good Stories, Used, Spoiled, and Rejected—"Toby" as a Dachshund—Death of "Frau"—Keene's Technique—His Inventions and Creations—And what He Earned by Them—Charles Martin—Harry Hall—Rev. Edward Bradley ("Cuthbert Bede")—"Verdant Green" or "Blanco White"?—Double Acrostics—George Cruikshank Defies Punch—Mr. T. Harrington Wilson—Mr. Harrison Weir—Mr. Ashby-Sterry—Alfred Thompson—Frank Bellew—Julian Portch—"Cham"—G. H. Haydon—J. M. Lawless | 475 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| PUNCH'S ARTISTS: 1860-67. | |

| Mr. G. du Maurier's First Drawing—The "Romantic Tenor"—Polite Satire—His Types and Creations—His Pretty Women—And Fair American—"Chang," "Don," and "Punch"—Mr. du Maurier as a Punch Writer—Mr. Gordon Thompson—Mr. Stacy Marks, R.A.—Paul Gray—Sir John Millais, Bart., R.A.—Mr. Fred Barnard—First Joke Refused as "Painful"—Mr. R. T. Pritchett—Initiation by Sir John Tenniel—Fritz Eltze—His Amiable Jocularity—Mr. A. R. Fairfield—Colonel Seccombe—Fred Walker, A.R.A.—Mr. J. Priestman Atkinson ("Dumb Crambo")—C. H. Bennett—Mr. W. S. Gilbert ("Bab")—His Classic Joke—G. B. Goddard—Miss Georgina Bowers—Mr. Walter Crane | 503 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| PUNCH'S ARTISTS: 1867-82. | |

| Mr. Linley Sambourne—His Work—His Photographs—And Enterprise—Strasynski—Mr. Wilfrid Lawson—Mr. E. J. Ellis—Mr. Ernest Griset—Mr. A. Chasemore—Mr. Walter Browne—Mr. Briton Riviere, R.A.—An Undergraduate Humorist—A Punch Initial Converted into an Academy Picture—Mrs.—Jopling Rowe—Mr. Wallis Mackay—Mr. J. Sands—Mr. W. Ralston—Mr. A. Chantrey Corbould—Charles Keene's Advice—Randolph Caldecott—Major-General Robley—R. B. Wallace—Colonel Ward Bennitt—Mr. Montagu Blatchford—Mr. Harry Furniss—Origin of Mr. Gladstone's Collars—A Favourite Ruse—How It's Done—Mr. Furniss and the Irish Members—The Lobby Incident—Clever Retaliation—Mr. Furniss's Withdrawal—Mr. Lillie—Mr. Storey, A.R.A.—Mr. Alfred Bryan. | 531 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| PUNCH'S ARTISTS: 1882-95. | |

| Mr. William Padgett—Mr. E. M. Cox—Mr. J. P. Mellor—Sir F. Leighton, Bart., P.R.A.—Mr. G. H. Jalland—Monsieur Darré—Mr. E. T. Reed—His Original Humour—"Contrasts" and "Prehistoric Peeps"—Approved by Sports Committees and School Classes—Mr. Maud—A Useful Drain—Mr. Bernard Partridge—Fine Qualities of his Art—Mr. Everard Hopkins—Mr. Reginald Cleaver—Mr. W. J. Hodgson—Excites the Countryside—Miss Sambourne—Sir Frank Lockwood, Q.C., M.P.—Mr. Arthur Hopkins—Mr. J. F. Sullivan—Mr. J. A. Shepherd—Mr. A. S. Boyd—Mr. Phil May—A Test of Drunkenness—Mr. Stafford—"Caran d'Ache"—Conclusion | 558 |

| Appendix. | 573 |

| Index. | 581 |

| PAGE | |

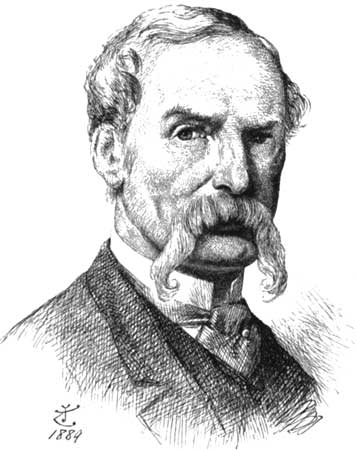

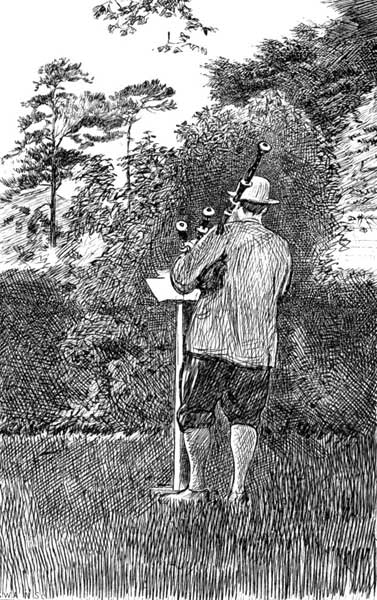

| "The Mahogany Tree." By Linley Sambourne | Frontis. |

| Headpiece to Preface. By G. du Maurier | vii |

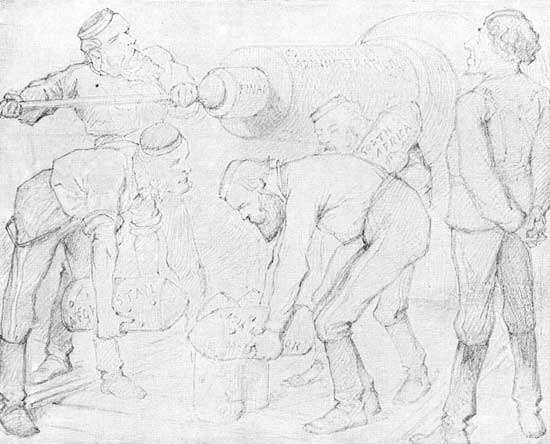

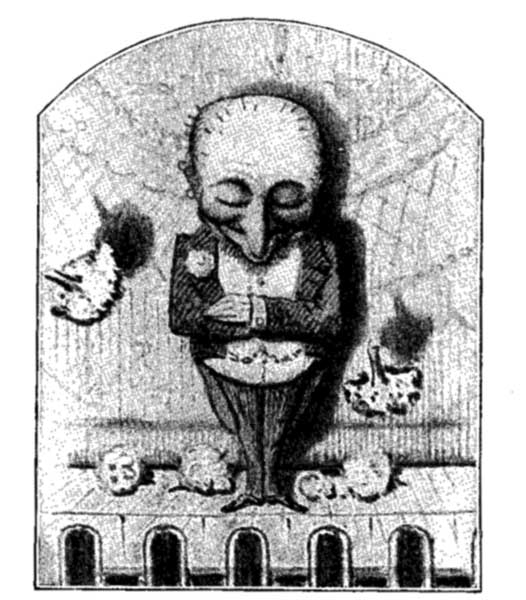

| An Introduction. From First Sketch by C. H. Bennett | x |

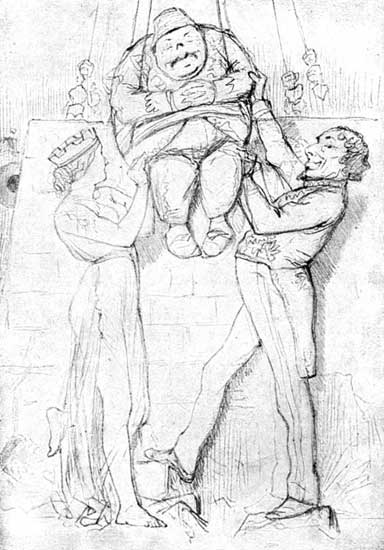

| Mr. Punch. By Harry Furniss | xiv |

| Mr. Punch portrayed by Different Hands | 7 |

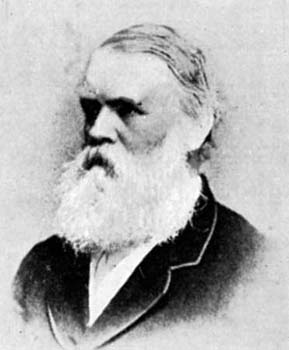

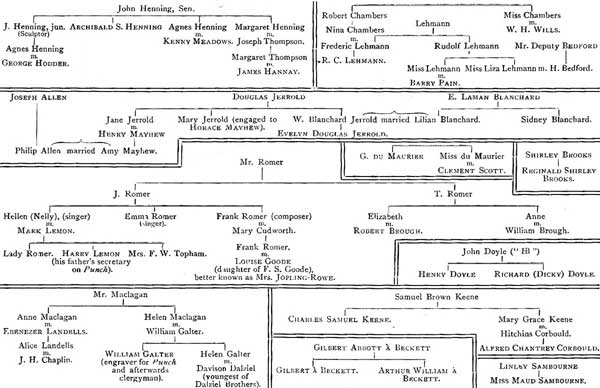

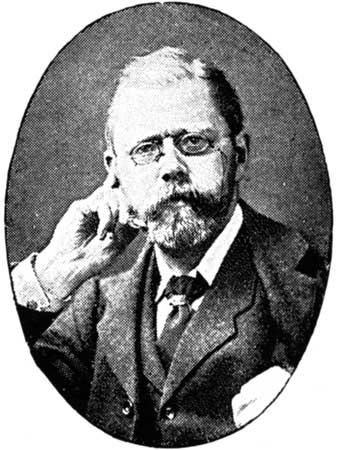

| Ebenezer Landells | 15 |

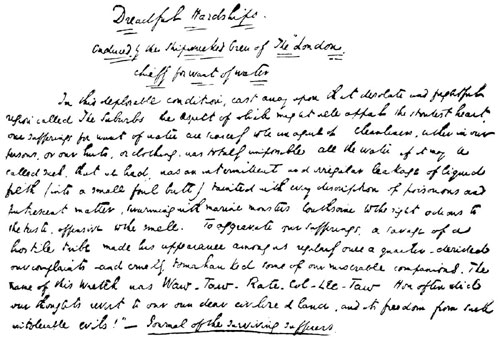

| Prospectus of Punch, Facsimile of Mark Lemon's MS. | 20-22 |

| Preliminary Leaflet | 23 |

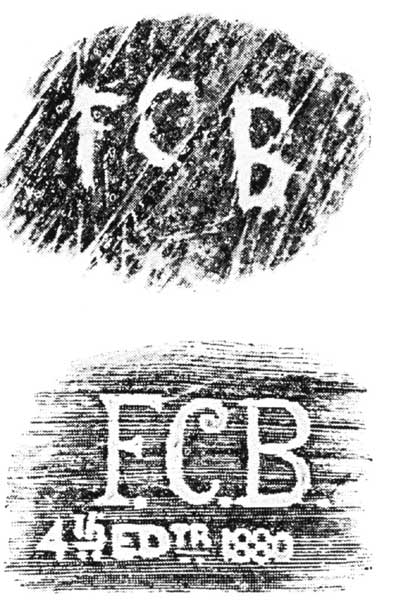

| Signatures to the Original Agreement | 25 |

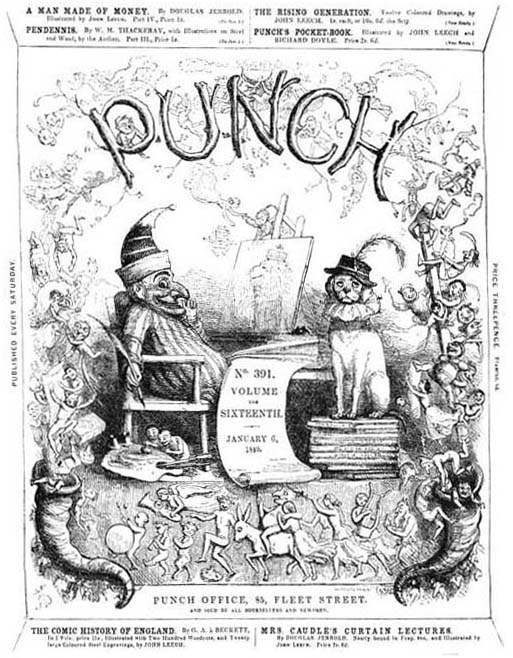

| First Cover of Punch. By A. S. Henning. | 27 |

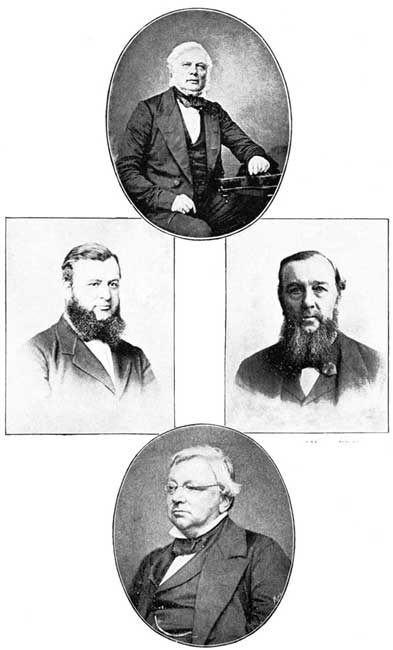

| The Four Earlier Proprietors | 37 |

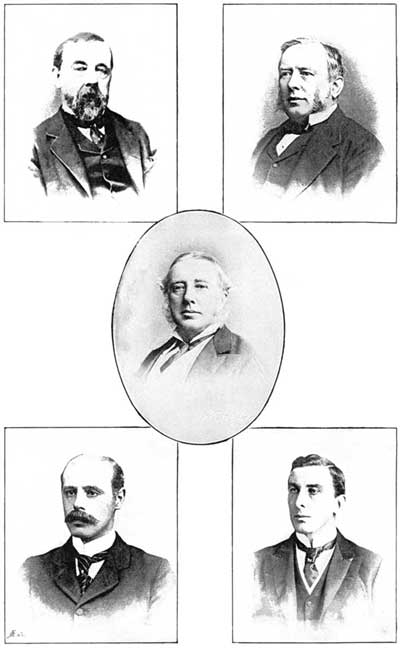

| The Five Later Proprietors | 39 |

| Second Cover. By "Phiz" | 42 |

| Third Proposed Cover. By H. G. Hine | 43 |

| Third Cover. By W. Harvey | 44 |

| Fourth Cover. By Sir John Gilbert, R.A. | 45 |

| Fifth Cover. By Kenny Meadows | 46 |

| Sixth Cover. First Design. By Richard Doyle | 47 |

| Sixth Cover. Second Design. By Richard Doyle | 48 |

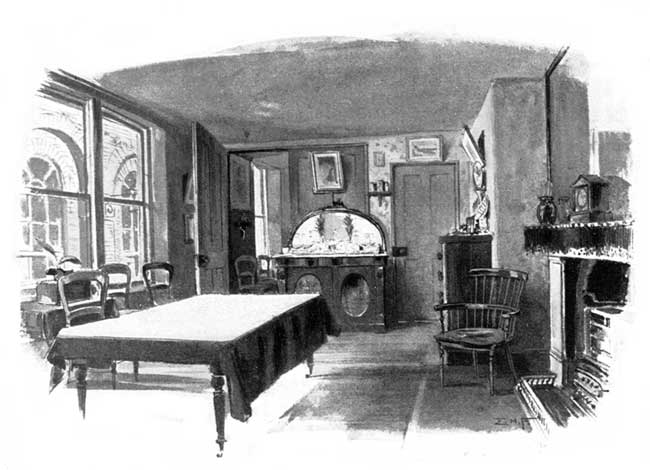

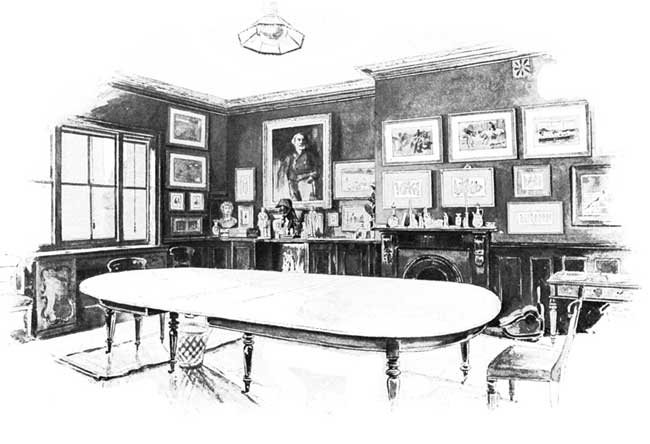

| The First Punch Table: "Crown Inn" | 57 |

| The Present Punch Table: Bouverie Street | 59 |

| Twenty-six Initials Carved upon the Table | 60-75 |

| The Dinner Card | 69 |

| "Peel's Dirty Boy": Leech's First Sketch | 112 |

| "Peel's Dirty Boy": The Cartoon | 113 |

| The Anti-Graham Envelope | 115 |

| Punch's Anti-Graham Wafers | 117 |

| The Draughtsman's Revenge | 127 |

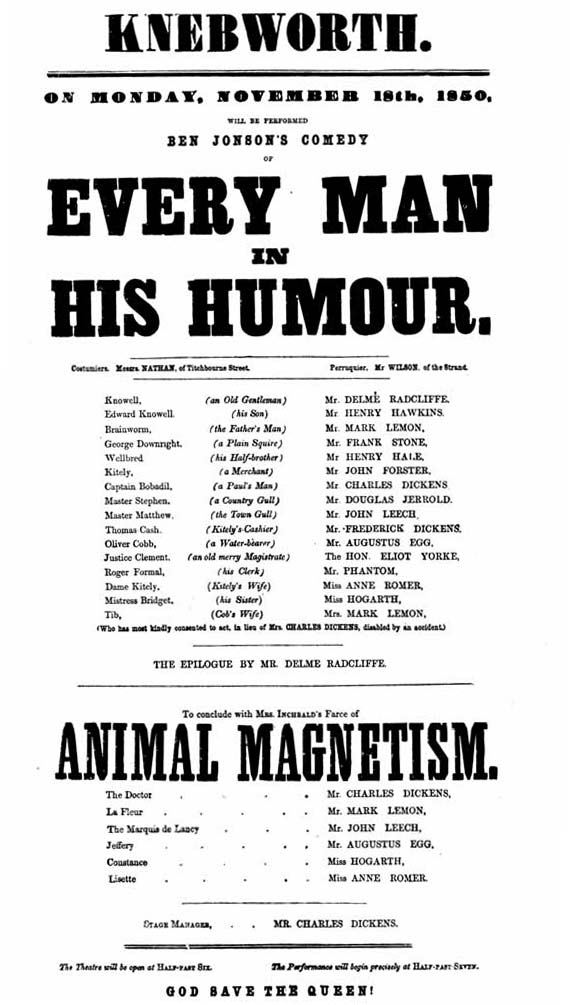

| Bennett's Benefit—The Cast | 133 |

| Playbill of the Guild of Literature and Art | 137 |

| Musical: First Sketch. By Henry Walker | 148 |

| Musical: Drawing. By G. du Maurier | 149 |

| The Political "Pas de Quatre." By A. S. Henning | 154 |

| The Political "Pas de Quatre." By J. Leech | 155 |

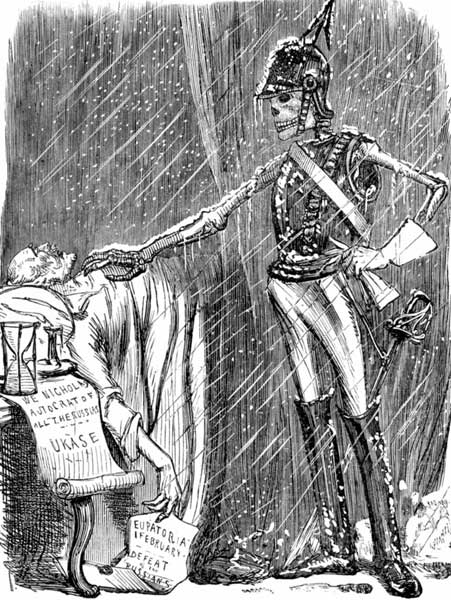

| General Février. By J. Leech | 175 |

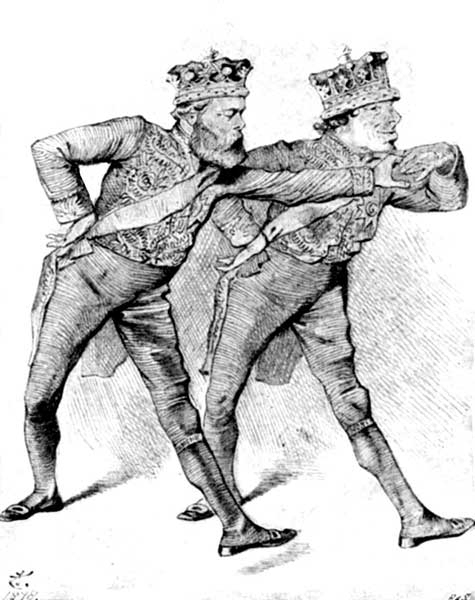

| The "Pas de Deux:" Original Drawing. By Sir John Tenniel | 178 |

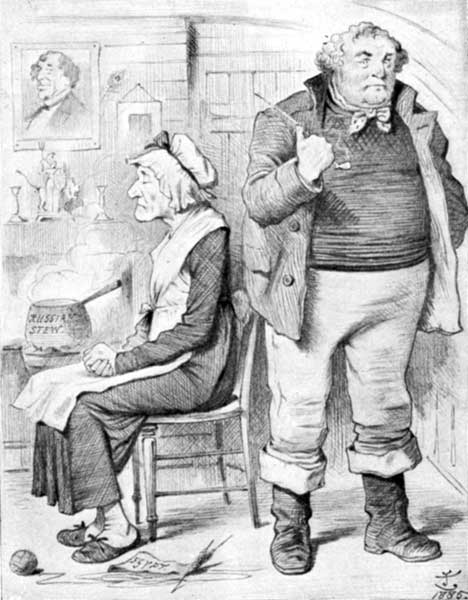

| "The Political Mrs. Gummidge." By Sir John Tenniel | 181 |

| Portraits of Beaconsfield. Re-drawn by Harry Furniss | 201 |

| "The Mrs. Caudle of the House of Lords:" Original Sketch. By J. Leech | 203 |

| Portraits of Gladstone. Re-drawn by Harry Furniss | 207 |

| Maternal Solicitude. By J. Leech | 212 |

| "A Word with Punch" | 229 |

| Joseph Swain | 247 |

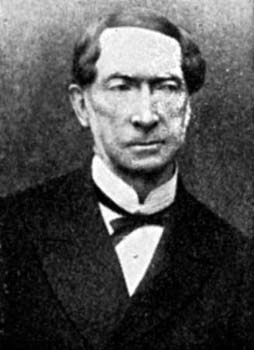

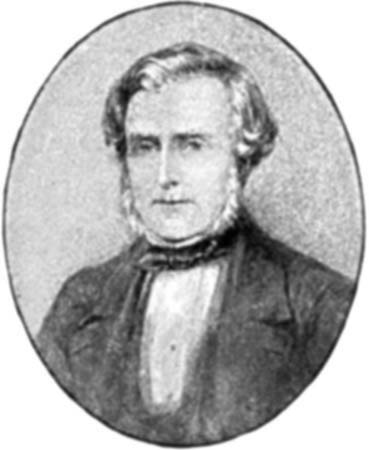

| Mark Lemon | 254 |

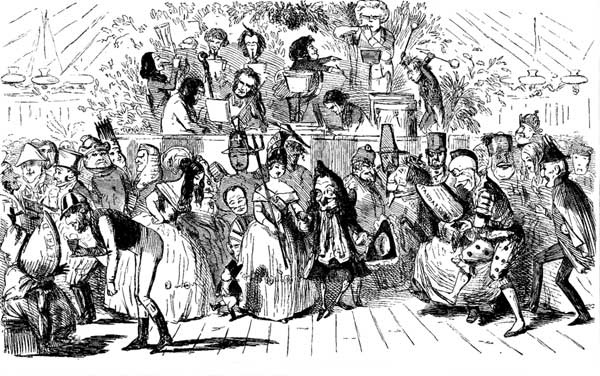

| "Mr. Punch's Fancy Ball" | 261 |

| Portraits of Punch Staff | 262 |

| Lemon's Presentation Inkstand | 264 |

| Henry Mayhew | 268 |

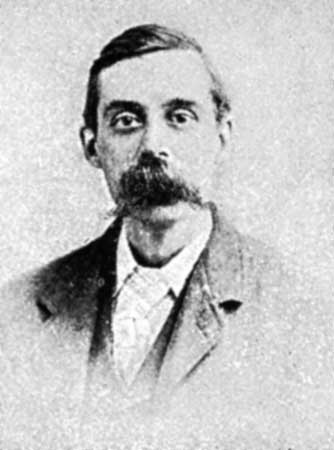

| J. Stirling Coyne | 271 |

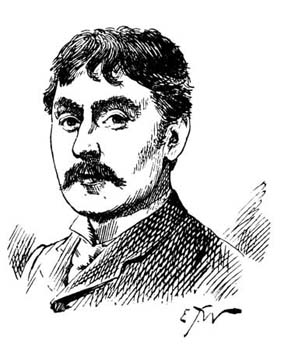

| Gilbert Abbott à Beckett | 272 |

| Douglas Jerrold | 284 |

| Albert Smith | 303 |

| John Oxenford | 308 |

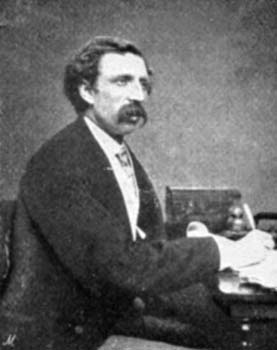

| W. M. Thackeray | 309 |

| Thackeray and Jerrold ("Authors' Miseries") | 312 |

| Thackeray's Presentation Inkstand | 321 |

| Thackeray at Work. By E. M. Ward, R.A. | 325 |

| Horace Mayhew | 327 |

| Thomas Hood | 330 |

| Tom Taylor | 338 |

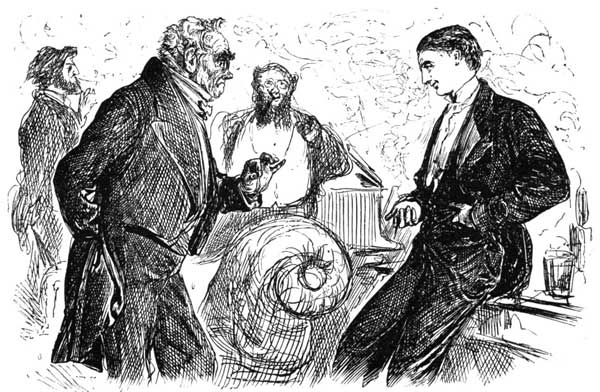

| Leech, Tom Taylor, and part of Horace Mayhew. By R. Doyle | 339 |

| Henry Silver | 347 |

| Dickens' Sole (and Rejected) Contribution | 350 |

| J. Hannay | 354 |

| Shirley Brooks | 356 |

| F. C. Burnand | 363 |

| R. F. Sketchley | 369 |

| "Artemus Ward" | 370 |

| H. Savile Clarke | 371 |

| Arthur W. à Beckett | 375 |

| E. J. Milliken | 378 |

| Gilbert à Beckett | 381 |

| Punch's Family Trees | 382 |

| John T. Bedford | 385 |

| J. Ashby-Sterry | 386 |

| H. W. Lucy | 390 |

| F. Anstey | 396 |

| R. C. Lehmann | 401 |

| A. S. Henning | 411 |

| H. G. Hine | 414 |

| Punch's Seal. By H. G. Hine | 415 |

| John Leech. By Sir J. E. Millais, Bart., R.A. | 418 |

| "How long have you been gay?" By J. Leech | 428 |

| "Leech's 'Pretty Girl'": A Skit. By Sir J. E. Millais, Bart., R.A. | 431 |

| Leech's House in Kensington. By J. Fulleylove, R. I. | 438 |

| The Historical Ash-tree in Leech's Garden. By J. Fulleylove, R. I. | 439 |

| "Two Roses": Sketch by John Leech | 440 |

| A Page from Leech's Sketch-Book: My Lord Brougham | 441 |

| Kenny Meadows | 447 |

| Alfred "Crowquill" | 450 |

| Hablôt K. Browne ("Phiz") | 451 |

| R. J. Hamerton | 453 |

| W. McConnell | 461 |

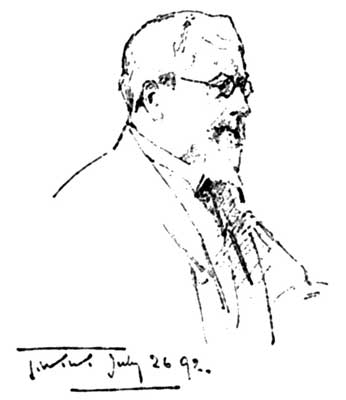

| Sir J. Tenniel. By Himself | 462 |

| Sketch for the Pocket-Book, "Arthur and Guinevere." By Sir John Tenniel | 464 |

| Sketch for the Cartoon "Will it Burst?" By Sir John Tenniel | 465 |

| Sketch for the Pocket-Book: "Thor." By Sir John Tenniel | 468 |

| Sketch for the Cartoon "Humpty-Dumpty." By Sir John Tenniel | 469 |

| Captain H. R. Howard | 475 |

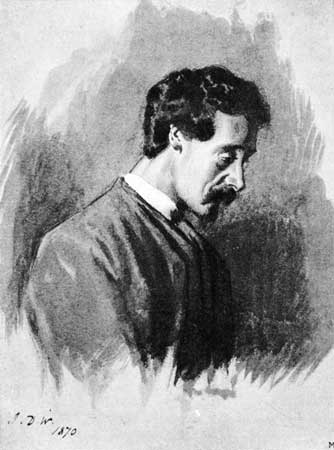

| Charles S. Keene. By J. D. Watson | 478 |

| Keene torturing the Bagpipes. By Himself | 485 |

| From Keene to his Editor | 486 |

| "Frau," alias "Toby"—Keene's last Drawing | 488 |

| "Cuthbert Bede" | 492 |

| T. Harrington Wilson. By T. Walter Wilson | 497 |

| George du Maurier | 503 |

| "My Pretty Woman." By G. du Maurier | 508 |

| Pencil Study. By G. du Maurier | 509 |

| "Chang." By G. du Maurier | 514 |

| "Don." By G. du Maurier | 515 |

| Pencil Study. By G. du Maurier | 516 |

| Pencil Study. By G. du Maurier | 517 |

| Fred Barnard. A Libel on Himself | 518 |

| R. T. Pritchett | 520 |

| J. Priestman Atkinson | 524 |

| In a Hansom with Mark Lemon. By J. Priestman Atkinson | 524 |

| C. H. Bennett. By Himself | 526 |

| Mrs. Bowers-Edwards (Miss G. Bowers) | 529 |

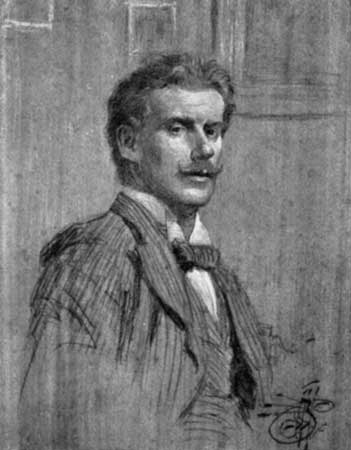

| Linley Sambourne. By Himself | 531 |

| Ernest Griset | 538 |

| Mr. Griset introduces himself to Mark Lemon | 538 |

| J. Moyr Smith | 541 |

| J. Sands | 542 |

| W. Ralston | 543 |

| A. Chantrey Corbould | 544 |

| M. Blatchford | 548 |

| E. J. Wheeler | 549 |

| Harry Furniss | 549 |

| Punch as the Bishop of Lincoln. By Harry Furniss | 550 |

| Mr. Gladstone Collared. By Harry Furniss | 552 |

| Two Friends. By Harry Furniss | 554 |

| "A Happy Release:" A Rejected Trifle. By C. J. Lillie | 556 |

| E. T. Reed. By Himself | 560 |

| J. Bernard Partridge. By Himself | 564 |

| Phil May at Work. By Himself | 568 |

| Phil May as Punch. By Himself | 570 |

| The Punch Staff at Table, 1895 | 571 |

| "Finale." By Linley Sambourne | 572 |

| Index. Original Sketch. By Charles Keene. | 581 |

The engravings here borrowed from Punch are reproduced (in all cases in smaller sizes) by special permission of the Proprietors, Messrs. Bradbury, Agnew & Co. The Portrait of Charles Keene by J. D. Watson, and of Himself with the Bagpipes, were first published in Black and White, through whose courtesy they appear here. To all who have accorded the various permissions for reproductions, or who have lent drawings for the better illustration of this volume, the acknowledgments of the writer are gratefully recorded. The Copyright of the illustrations is in every case strictly reserved.[Pg 1]

"If humour only meant laughter," said Thackeray, in his essay on the English humorists, "you would scarcely feel more interest about humorous writers than the life of poor Harlequin, who possesses with these the power of making you laugh. But the men regarding whose lives and stories you have curiosity and sympathy appeal to a great number of our other faculties, besides our mere sense of ridicule. The humorous writer professes to awaken and direct your love, your pity, your kindness; your scorn of untruth, pretension, imposture; your tenderness for the weak, the poor, the oppressed, the unhappy. To the best of his means and ability he comments on all the ordinary actions and passions of life almost."

It may surely be claimed that these words, consecrated to his mighty predecessors by the Great Humorist of Punch, may be applied without undue exaggeration to his colleagues on the paper. Though posing at first only as the puppet who waded knee-deep in comic vice, Punch has worked as a teacher as well as a jester—a leader, and a preacher of kindness. Nor was it simple humour that was Punch's profession at the beginning; he always had a more serious and, so to say, a worthier object in view. This may be gathered from the very first article in the very first number,[Pg 2] the manifesto of the band of men who started it, contributed by Mark Lemon, under the title of—

"As we hope, gentle public, to pass many happy hours in your society, we think it right that you should know something of our character and intentions. Our title, at a first glance, may have misled you into a belief that we have no other intention than the amusement of a thoughtless crowd, and the collection of pence. We have a higher object. Few of the admirers of our prototype, merry Master Punch, have looked upon his vagaries but as the practical outpourings of a rude and boisterous mirth. We have considered him as a teacher of no mean pretensions, and have, therefore, adopted him as the sponsor for our weekly sheet of pleasant instruction. When we have seen him parading in the glories of his motley, flourishing his bâton in time with his own unrivalled discord, by which he seeks to win the attention and admiration of the crowd, what visions of graver puppetry have passed before our eyes!... Our ears have rung with the noisy frothiness of those who have bought their fellow-men as beasts in the market-place, and found their reward in the sycophancy of a degraded constituency, or the patronage of a venal ministry—no matter of what creed, for party must destroy patriotism....

"There is one portion of Punch's drama we wish was omitted, for it always saddens us—we allude to the prison scene. Punch, it is true, sings in durance, but we hear the ring of the bars mingling with the song. We are advocates for the correction of offenders; but how many generous and kindly beings are there pining within the walls of a prison whose only crimes are poverty and misfortune!...

"We now come to the last great lesson of our motley teacher—the gallows; that accursed tree which has its root in injuries. How clearly Punch exposes the fallacy of that dreadful law which authorises the destruction of life! Punch sometimes destroys the hangman, and why not? Where is the divine injunction against the shedder of man's blood to rest? None can answer! To us there is but One disposer of life. At other times Punch hangs the devil: this is as it should be. Destroy the principle of evil by increasing the means of cultivating the good, and the gallows will then become as much a wonder as it is now a jest....

"As on the stage of Punch's theatre many characters appear[Pg 3] to fill up the interstices of the more important story, so our pages will be interspersed with trifles that have no other object than the moment's approbation—an end which will never be sought for at the expense of others, beyond the evanescent smile of a harmless satire."

A portion of this programme was duly eliminated by the abolition of the Fleet and the Marshalsea; and it must be admitted that Punch has long since forgotten his declared crusade against capital punishment. But he has been otherwise busy. His sympathy for the poor, the starving, the ill-housed, and the oppressed; for the ill-paid curate and the worse-paid clerk; for the sempstress, the governess, the shop-girl, has been with him not only a religion, but a passion. Professor Ruskin, judging only by Punch's pictures, and that a little narrowly, has thought otherwise. Punch "has never in a single instance," says he in his "Art of England," "endeavoured to represent the beauty of the poor. On the contrary, his witness to their degradation, as inevitable consequences of their London life, is constant and, for the most part, contemptuous."

Truth to tell, Punch has been kindly from the first; and a man of mettle, too. None has been too exalted or too powerful for attack; withal, his assaults, in comparison with those of his scurrilous contemporaries, have been moderate and gentlemanly in tone. He has attacked abuses from the highest to the lowest. Sham gentility, vulgar ostentation, crazes and fads, linked æstheticism long drawn out, foolish costume, silly affectations of fashion in compliment and language—all have been set up as targets for his shafts of ridicule or scorn. He has been a moral reformer and a disinterested critic. A liberal-minded patriot, he has ever opposed the advocacy of "Little Peddlington" in Imperial politics; and municipal maladministration is a perennial subject for his denunciations. He has been a kindly cauteriser of social sores; caustic, but rarely vindictive. Spiritualism, Socialism, Ibsenism, Walt Whitmania—all the movements and sensations of the day, social, political, and artistic, in so far as they are follies—have been shot at as they rose. And having[Pg 4] conquered his position, Punch has known how to retain it. "The clown," says Oliver Wendell Holmes, "knows his place to be at the tail of the procession." It is to Punch's honour that with conscious dignity—and, of course, with conscious impudence—he took his place at its head. And there he has stayed; and transforming his pages into the Royal Academy of pictorial satire, his alone among all the comic papers has forced its way into the library and taken up its position in the boudoir. His workers are the best available in the land; and when in course of time one contributor falls away, another is ready to step quickly into his place—uno avulso non deficit alter.

So Punch—who for many years past has set up as the incarnation of all that is best in wit and virtue—is a scholar and a gentleman. He is, moreover, on his own showing, a perfect combination of humour, wisdom, and honour; and yet, in spite of it all, not a bit of a prig. It is true that when he donned the dress-coat, and "Punch" and "Toby" put on airs as "Mr. Punch" and "Toby, M.P.," he became milder at the expense of some of his political influence. Yet what he lost in power he gained in respectability, as well as in the affection of his countrymen. He appealed to a higher class, to the greater constituency of the whole nation; and remembering that a jest's prosperity lies in the ear that hears it, he transferred some of his allegiance from pit to stalls, and was content with the well-bred smile where before he had been eager for noisy laughter and loud applause.

People say—among them Mr. du Maurier himself—that there does not seem quite as much fun and jollity in the world as when John Leech was alive; but that surely is only the wail of the middle-aged. Englishmen never were uproarious in their mirth, as Froissart once reminded us. But it is true that Punch does not indulge so much as once he did in caricature—which after all, as Carlyle has pointed out, is not Humour at all, but Drollery. Caricature, one must remember, has two mortal enemies—a small and a great: artistic excellence of draughtsmanship, and national prosperity with its consequent contentment.[Pg 5] Good harvests beget good-humour. They stifle all motive for genuine caricature, for "satire thrives only on the wrath of the multitude." A joke may be only a joke—or a comedy, or a tragedy; but the greatest caricature (which need by no means display the greatest art) is necessarily that which goes straightest to the heart and mind. No drawing is true caricature which does not make the beholder think, whether it springs simply from good-humour or has its source in the passion of contempt, hatred, or revenge, of hope or despair. Mere amusement, said Swift, "is the happiness of those who cannot think," while Humour, to quote Carlyle again, "is properly the exponent of low things; that which first renders them poetical to the mind." Through this truth we may see how Punch has so continually dealt with vulgarity without being vulgar; while many of his so-called rivals, touching the self-same subjects, have so tainted themselves as to render them fitter for the kitchen than the drawing-room, through lack of this saving grace. Fun may have been in their jokes, but not true humour. Punch thus became to London much what the Old Comedy was to Athens; and, whatever individual critics may say, he is recognised as the Nation's Jester, though he has always sought to do what Swift declared was futile—to work upon the feelings of the vulgar with fine sense, which "is like endeavouring to hew blocks with a razor."

If there is one thing more than another on which Punch prides himself—on which, nevertheless, he is constantly reproached by those who would see his pages a remorseless mirror of human weakness and vice—it is his purity and cleanness; his abstention from the unsavoury subjects which form the principal stock-in-trade of the French humorist. This trait was Thackeray's delight. "As for your morality, sir," he wrote to Mr. Punch, "it does not become me to compliment you on it before your venerable face; but permit me to say that there never was before published in this world so many volumes that contained so much cause for laughing, and so little for blushing; so many jokes, and so little harm. Why, sir, say even that your modesty, which[Pg 6] astonishes me more and more every time I regard you, is calculated, and not a virtue naturally inherent in you, that very fact would argue for the high sense of the public morality among us. We will laugh in the company of our wives and children; we will tolerate no indecorum; we like that our matrons and girls should be pure."

It was not till the great occasion of his Jubilee that the Merry Old Gentleman of Fleet Street, who "hath no Party save Mankind; no Leader—but Himself," discovered the full measure of his popularity. The day broke for him amid a chorus of greeting—a perfect pæan of triumph, in which his own trumpet was not the softest blown. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Press of the world welcomed the fiftieth anniversary of his birth, and that with a cordiality and unanimity never before accorded to any paper. Hardly a journal in the English-speaking world but commented on the event with kindly sympathy; hardly one that marred the celebration with an ill-humoured reflection. Pencil as well as pen was put to it to do honour to the greatest comic paper in the world, and demonstrate in touching friendliness the confraternity of the Press.

For the public, Punch issued his "Jubilee number" and, in accordance with the promise given in the first volume fifty years before, he produced in his hundredth a brief history of his career and the names of the men who made it, modestly advising his readers to secure a set of his back volumes as the real "Hundred Best Books." For himself, he dined with the Staff at the "Ship Hotel" at Greenwich, when the Editor, who occupied the chair, was fêted by the proprietors of the paper and received a suitable memento of the glorious event.

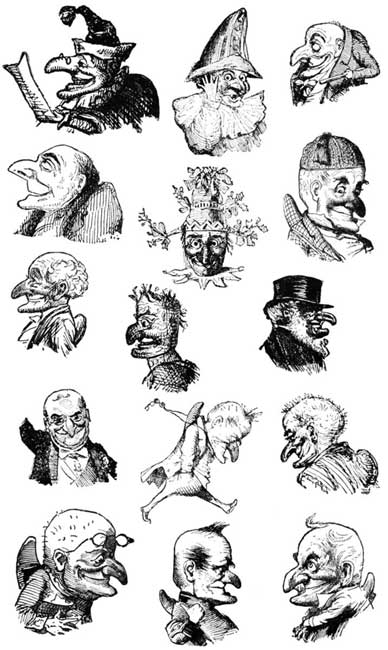

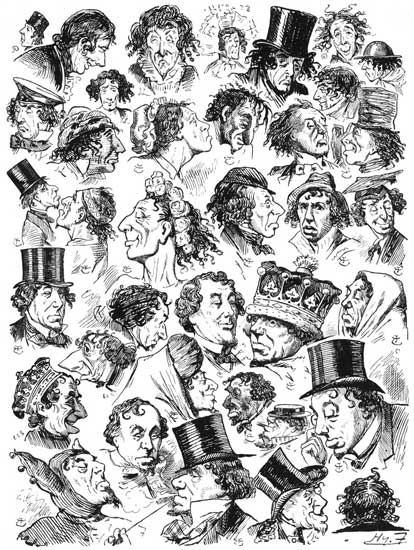

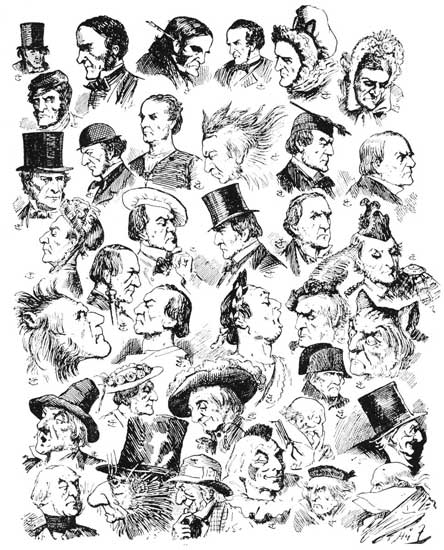

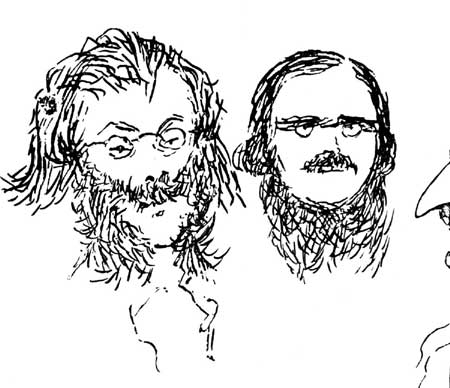

MR. PUNCH PORTRAYED BY DIFFERENT HANDS.

MR. PUNCH PORTRAYED BY DIFFERENT HANDS.

See p.9.

And what may appear to some as the most curious celebration of all was a solemn religious celebration—nothing less than a Te Deum—in honour of the occasion. It sounds at first, perhaps, a little like a joke—though not in good enough taste to be one of Mr. Punch's own; but the service was held; and when regarded in the light shed upon it by the Rev. J. de Kewer Williams, the incongruity of it almost disappears. "I led my people yesterday," he wrote, "in giving[Pg 8] thanks on the occasion of your Jubilee, praying that you might ever be as discreet and as kindly as you have always been." The prayer spoken in the pulpit appropriately ended as follows: "For it is so easy to be witty and wicked, and so hard to be witty and wise. May its satire ever be as good and genial, and the other papers follow its excellent example!"

The public tribute was not less cordial and sincere, and poetic effusions flowed in a gushing stream. But none of these verses, doggerel and otherwise, expressed more felicitously the general feeling than those which had been written some years before by Henry J. Byron—(who had himself attempted to establish a rival to Punch, but had been crushed by the greater weight)—one of his verses running:—

But greater far than the public esteem is the affection of the Staff, who naturally enough regard the personality of Punch with a good deal more than ordinary loyal sentiment and esprit de corps. It is interesting to observe the different views the artists have severally taken of it, for most of them in turn have attempted his portrayal. Brine regarded him as a mere buffoon, devoid of either dignity or breeding; Crowquill, as a grinning, drum-beating Showman; Doyle, Thackeray, and others adhered to the idea of the Merry, but certainly not uproarious, Hunchback; Sir John Tenniel showed him as a vivified puppet, all that was earnest, responsible, and wise, laughing and high-minded; Keene looked on him generally as a youngish, bright-eyed, but apparently brainless gentleman, afflicted with a pitiable deformity of chin, and sometimes of spine; Sir John Gilbert as a rollicking Polichinelle, and Kenny Meadows as Punchinello; John Leech's conception,[Pg 9] originally inspired, no doubt, by George Cruikshank's celebrated etchings, was the embodiment of everything that was jolly and all that was just, on occasion terribly severe, half flesh, half wood—the father, manifestly, of Sir John Tenniel's improved figure of more recent times. Every artist—Mr. du Maurier, Mr. Sambourne, Mr. Furniss, and the rest—has had his own ideal; and it is curious to observe that in his realisation of it, each has illustrated or betrayed in just measure the strength or weakness of his own imagination.

Some of these portraits, characteristic examples of Punch's leading artists, are reproduced on page 7, arranged according to authorship, thus:—

| W. Newman | Kenny Meadows | R. Doyle |

| W. M. Thackeray | J. Leech (1) | J. Tenniel (1) |

| C. Keene | J. Leech(2) | G. du Maurier |

| L. Sambourne (1) | J. Tenniel(2) | F. Eltze |

| L. Sambourne (2) | J. Tenniel (3) | H. Furniss |

The Mystery of His Birth—Previous Unsuccessful Attempts at Solution—Proposal for a "London Charivari"—Ebenezer Landells and His Notion—Joseph Last Consults with Henry Mayhew—Whose Imagination is Fired—Staff Formed—Prospectus—Punch is Born and Christened—The First Number.

It should be counted against neither the fair fame nor the reputation of Punch that the facts of his birth have never yet been definitely and honourably established. It is not that his parentage has been lost to history in a discreet and charitable silence; on the contrary, it is rather that that honour has been claimed by over-many, covetous of the distinction. He seems to come within the category of Defoe's true-born Englishman, "whose parents were the Lord knows who," not because there should be any doubt upon the subject, but because none suspected at the time the latent importance of the bantling and the circumstances of his birth until it seemed too late to decide by demonstration or simple affirmation who was father and who the sponsors. Had it then been known that Punch was born for immortality, I should not now be at the pains of setting forth, at greater length than would otherwise be necessary or justifiable, the proofs of his parentage and of his natal place.

Rubens was born both at Antwerp and Cologne. One knows it to be so, when one has visited both houses. Hans Memling, again, was native of Bruges and Mömelingen too. It is hardly surprising, then, that several roof-trees claim the honour of having sheltered the new-born Punch, and that many men have contended for his paternity.[Pg 11]

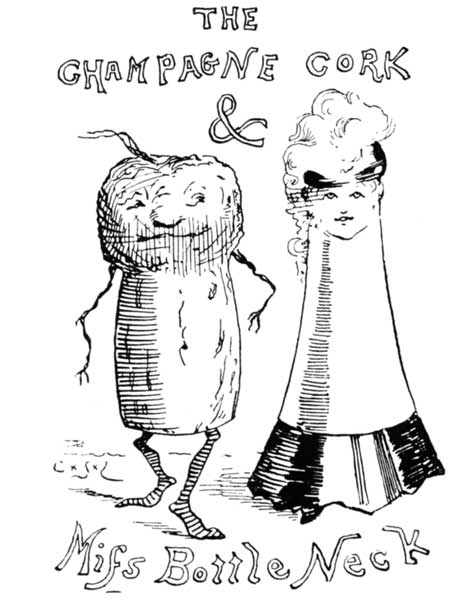

I say "his" paternity; for the absolute personality of Punch has long been recognised. It has been the usual custom of comic papers to indulge in a similar fiction, mildly humorous and conveniently anonymous—"Figaro in London," "Pasquin," "The Puppet Show"-man, "The Man in the Moon," and the rest. But Punch was not only a personality himself, but at the outset began by introducing the rest of his family to the public. Nowadays he ignores his wife, especially since a contemporary has appropriated her name. But this was not always so. In his prospectus he announces that his department of "Fashion" will be conducted by Mrs. J. Punch, whose portrait, drawn by Leech's pencil, appeared in 1844 (p. 19, Vol. VI.), and who was seen again, under the name of Judina, in honourable companionship with her husband, in the preface to Vol. XLVII., for 1864, and once more in "Mrs. Punch's Letters to Her Daughter." His daughter Julia, too, being then, in 1841, "in service," wrote a letter to the journal in that style of damaged orthography afterwards adopted by the immortal Jeames and his American cousin, Artemus Ward. But it was not long before Punch took a rise in the social scale, and many men of distinction in literature have claimed him for their child with all the emphasis of groundless assertion.

According to the "City Press" (June 27th, 1892), Mr. C. Mitchell frequently declared that Punch originated with him, Shirley Brooks, Henry Mayhew, and Ebenezer Landells, in his office in Red Lion Court, the latter drawing the original sketch of the pink monthly cover of Punch. But as Shirley Brooks did not come on the scene till thirteen years later, and as the cover in question is the one designed, and signed, by Sir John Gilbert in 1842, the claim may be dismissed, except in so far as it may support Landells' statement that he prepared the scheme of such a paper and submitted it to several publishers before he and his associates determined upon carrying it themselves into execution. And soon after it was started, as will be seen, the services of a speculative printer were anxiously sought.

Mr. Hatton declares that Mark Lemon "always spoke of it to me as a project of himself and Henry Mayhew," wherein[Pg 12] he is followed by the "Dictionary of National Biography;" and the Hon. T. T. à Beckett gives the exclusive honour to Henry Mayhew (wherein he is followed by the same authority in the notice of the latter writer), but admits the further founder's claim of Stirling Coyne.

The writer of the well-known, but sadly inaccurate, pamphlet entitled "Mr. Punch, His Origin and Career," which was published in 1882 as a memorial of Mark Lemon, explains circumstantially that it was Mr. Last, the printer, who proposed the idea to Henry Mayhew, who "readily accepted it." The book is generally accredited to Sidney Blanchard; but when I explain that the printer of it, now deceased, informed me that it was written and brought to him by Last's son, the transfer of the central interest from Landells and Henry Mayhew becomes intelligible.

The late Mr. R. B. Postans, the house-chum of Henry Mayhew, "his companion from morning to night," and George Hodder, in his oft-quoted "Memories of My Time," agree in according undivided credit to Henry Mayhew; but they unfortunately disagree in essentials, and contradict each other, and indirectly confirm my own conclusions. Hodder further declares that Mayhew invented the paper and its name simultaneously, which sprang Minerva-like, full-titled, from his brain—which we know to be untrue, as the name was not decided upon until a subsequent meeting. Indeed, on the final prospectus, written with Mark Lemon's hand, as may be seen on p. 20, the present title was only inserted as an after-thought.

Then comes the version of Henry Mayhew's son, Mr. Athol Mayhew, who claims everything for his father in a statement of some length, in some respects authentic, but in many details entirely erroneous. He carries back Mayhew's idea of a "London Charivari" to the year 1835; but, as will be seen a little further on, Orrin Smith, Jerrold, Thackeray, and several more of the wags of the day afterwards combined in a stillborn effort to start a similar paper based on the same model. The writer bases his case far too much on Hodder's "Memories," which, entertaining though they are, do not[Pg 13] universally command the trust and respect with which Mr. Athol Mayhew regards them. "A more sanguine man than my father," he says, "never breathed, and in his arrangement with Hodder appears to have taken everything for granted, although the scheme had not as yet been even breathed to Messrs. Landells and Last [the engraver and printer]; for when the latter gentleman agreed to enter into the speculation, Mayhew had removed to Clement's Inn." But the writer, who would appear to have inherited the paternal characteristic of "taking everything for granted," has not considered that Hodder declared that his visit to Hemming's Row, by which occasion it is alleged that the new Punch had sprung to Mayhew's brain, was "in the summer". As Punch appeared in the middle of July, and, according to the draft prospectus, was first arranged to appear on June 10th (though this may possibly have been a lapsus calami), it requires more than ordinary sanguineness to accept the statement that not a word had been breathed to persons so paramount in such a newspaper enterprise as the printer and engraver—especially when the paper was to make its appearance in a few days' time. And yet Mr. Mayhew adds that matters did not progress even so rapidly as his authority, George Hodder, narrates.

Yet although it was not, as will appear, Henry Mayhew who was the actual initiator of Punch, it was unquestionably he to whom the whole credit belongs of having developed Landells' specific idea of a "Charivari," and of its conception in the form it took. Though not the absolute author of its existence, he was certainly the author of its literary and artistic being, and to that degree, as he was wont to claim, he was its founder.

From all these versions (which, after all, vary hardly more than the accounts of other incidents of Punch life[1]) it is[Pg 14] not very easy at first sight to sift the truth. There is a story of the tutor of an Heir-Apparent who asked his pupil, by way of examination, what was the date of the battle of Agincourt. "1560," promptly replied the Prince. "The date which your Royal Highness has mentioned," said the tutor, "is perfectly correct, but I would venture to point out that it has no application to the subject under discussion." A like criticism might fairly be passed on each existing reading of the genesis of Punch. It has been worth while, for the first time, and it is to be hoped the last, to collate and compare these statements, and ascertain the facts as far as possible. Claims have been set up, variously and severally, for Henry Mayhew, Mark Lemon, Joseph Last, Ebenezer Landells, and Stirling Coyne; even Douglas Jerrold and Gilbert à Beckett have been declared originators, though no such pretentions came directly from them. Otherwise than in the spirit of the Scottish minister who exclaimed, "Brethren, let us look our difficulties boldly and fairly in the face—and pass on," I propose to take those portions of the stories which tally with the facts I have ascertained and verified beyond all doubt, and, disentangling the general confusion as briefly as may be, to present one consistent version, which must stand untainted by claims of friendship, by pride of kinship, or filial respect.

It had occurred to many of the wits, literary and artistic, who well understood the cause of mortality in the so-called comic press that had gone before, that a paper might succeed which was decently and cleanly conducted. It might be as slashing in its wit and as fearless in its opinions as it pleased,[Pg 15] so long as those opinions were honest and their expression restrained. Their idea was founded rather on Philipon's Paris "Charivari" than on anything that had appeared in England; but they plainly saw that to attract and hold the public the paper which they imagined must be a weekly and not a daily one. The Staff which was brought together consisted of Douglas Jerrold, Thackeray, Laman Blanchard, Percival Leigh, and Poole, author of "Paul Pry"—authors; and Kenny Meadows, Leech, and perhaps Crowquill—artists; with Orrin Smith as engraver. The whole scheme of this new "London Charivari" was in a forward state of preparation, even to pages of text being set up, when it suddenly collapsed through a mistaken notion of Thackeray's that each co-partner—there being no "capitalist" thought of—would be liable for the private debts of his colleagues. The suggestion was too much for the faith of the schemers in one another's discretion, and "The London Charivari" was incontinently dropped; yet unquestionably it had some indirect influence on the subsequent constitution and career of Mr. Punch.

EBENEZER LANDELLS.

EBENEZER LANDELLS.

For some years the success of the Paris "Charivari" had attracted the attention of Mr. Ebenezer Landells, wood-engraver, draughtsman, and newspaper projector. He had been a favourite pupil of the great Bewick himself, and had come up to London, where he soon made his mark as John Jackson's and Harvey's chief lieutenant and obtained an entrance into literary and artistic circles. A man of great originality and initiative ability, of unflagging energy and industry, of considerable artistic taste, and of great amiability, he also had the defect of the creative quality of his mind, so that, owing to that lack of business talent which the public generally associates with the artistic temperament, he did not ultimately prove himself more than a moderate financial success. As Jerrold,[Pg 16] Thackeray, and the rest had done before him, he believed in a "Charivari" for England, and pondered how the Parisian success might be emulated and achieved. In his house at 22, Bidborough Street, St. Pancras (where most of the early Punch blocks were cut), he had a ready-made staff of engravers that included some names destined to become better known—Mr. Birket Foster; Mr. Edmund Evans, best known nowadays in connection with Miss Kate Greenaway's delightful children's books; J. Greenaway, her father, who became a master engraver himself; and William Gaiter, who afterwards took Orders; while "outside" were Edward and George Dalziel, T. Armstrong, and Charles Gorway. With these young men the handsome, tall engraver was extremely popular; they called him "the Skipper," or "Old Tooch-it-oop" behind his back, in token of his Northumbrian accent, but to his friends he was generally known as "Daddy Longlegs," or "Daddy Landells."

So Landells took the idea, which he determined upon carrying out, to one or two well-established publishers, Wright of Fleet Street amongst them, but none could see the germ of a first-rate property in it. It was objected that the temperament of the English people so differed from that of the French that they certainly would neither appreciate nor encourage the requisite style of writing, even supposing—which they did not believe—that the necessary talent were forthcoming. Moreover, they would not credit that a comic paper could succeed without the scurrility, and often enough the indecencies, that had distinguished earlier satirical prints; and although the popularity of Hood's "Comic Annual" and Cruikshank's "Comic Almanac" was pointed to, they would have nothing to do with a weekly, however much it professed to supersede previous ribaldry with clean wit and healthy humour.

As it happened, early in 1841 Landells was concerned, with his friend Joseph Last, printer, of 3, Crane Court, Fleet Street, in projecting a periodical known as "The Cosmorama," an illustrated journal of life and manners of the day, and to him Landells imparted his conviction that such a journal as he imagined[Pg 17] would certainly succeed. The enterprising printer lent a readier ear than others had done (perhaps, in view of his limited capital and still more limited ideas of speculation, altogether too ready an ear), and agreed with Landells to take up so excellent a notion. Now, in the little world of comic writing a brilliant humorist was at work—Henry Mayhew, one of several brothers of ability, a man whose resource was equal to his wit. He was already known to Last as the son of the leading member of the firm of Mayhew, Johnston, and Mayhew, of Carey Street, his legal advisers. He was residing at the time at Hemming's Row, over a haberdasher's shop, and, with F. W. N. Bayley and others, he had been secured as writer on "The Cosmorama." Landells, introduced to him by Last, approached him on the subject of the "Charivari." Mayhew grasped the conception at once, and, as the sequel proved, saw it more completely, and perhaps appreciated its literary and artistic possibilities more clearly, than either its material originator or his ambassador had done. He immediately advised dropping "The Cosmorama," and directing on to the new comic all the energy and resources that were to have been put into the more commonplace publication. In due course he imparted the new idea to his friend Postans, who shared his room, and to other visitors; but he forgot to mention how the idea had been brought to him, so that his friends not unnaturally counted it as another of Harry's many happy, but usually impracticable, thoughts. But in this instance Mayhew made his personality felt, for the character of the paper, instead of partaking of that acidulated, sardonic satire which was distinctive of Philipon's journal, on which it was to have been modelled, took its tone from Mayhew's genial temperament, and from the first became, or aimed at becoming, a budget of wit, fun, and kindly humour, and of honest opposition based upon fairness and justice.

As for the Staff of such a paper as he imagined, Mayhew urged that he could secure the services of Douglas Jerrold, Gilbert à Beckett, Mark Lemon, Stirling Coyne, and others, in addition to those already engaged; and then adjournment was proposed to Mark Lemon's rooms in Newcastle Street,[Pg 18] Strand. "The Shakespeare's Head," in Wych Street, had previously been Lemon's place of business. It was the meeting-place of the little "quoting, quipping, quaffing" club of fellow-workers in Bohemia; and Lemon, it was explained, had dabbled both in verse and the lighter drama, efforts which were "not half bad." Little did the writer dream that his modest Muse had marked him out for the editorship of the greatest comic journal the world has seen! To the duties of tavern-keeper Lemon, who was enamoured of literature and the drama, had been condemned by a fate more than usually unkind. He had found himself nearly penniless when Mr. Very, his stepfather, offered him a clerical position in his brewery in Kentish Town. But the brewery failed, and with it Lemon's livelihood, and he was only rescued by a jovial tavern-keeper named Roper, one of his stepfather's customers, and by him put into charge—disastrously for both—of the Wych Street public-house. Then he married, having borrowed five pounds to do it with, and by his wife's advice kept in touch with his literary acquaintance; and by the acceptance of a five-act comedy by Charles Mathews at Covent Garden—which was to be played by a cast including the great comedian's self, Mme. Vestris, and "Old" Farren—he received a hundred pounds down, and was tided over his difficulties until the starting of Punch gave him permanent employment.

So to Mark Lemon they went, and a full list was quickly drawn up. Mayhew undertook to communicate with Douglas Jerrold, who, then better known to the public as the successful dramatist than as the great satirist, was staying at Boulogne for the sake of his young family's education; and a charming picture has been drawn by his son of how, on the visit of à Beckett, Charles Dickens, and the rest, he would throw off his clothes and swim with them in the sea, or challenge them to a game of leap-frog on the sands—a curious contrast to his own declaration that the only exercise he cared for was cribbage.[2][Pg 19]

Stirling Coyne, Daily, W. H. Wills, H. P. Grattan (H. Plunkett, otherwise "Fusbos"), Henning, Henry Baylis, and "Paul Prendergast"—whose "Comic Latin Grammar" had been attracting much attention—were proposed, and Hodder was told off to wait upon the latter. At the adjourned meeting at the "Edinburgh Castle" tavern in the Strand, Somerset House, Postans, William Newman, Baylis (afterwards president of the "Punch Club"), Stirling Coyne, Henning, Mayhew, Landells, and Hodder were present. The latter then explained that "Prendergast" was a young medical man, Percival Leigh by name, who preferred to wait before giving his adhesion until he was satisfied as to the character of the publication; and "Phiz" had returned a similar reply to Mark Lemon—though later on he was glad enough to accept little commissions in the way of drawing initial letters for the paper.

Henning was then nominated cartoonist; Brine, Phillips, and Newman, artists-in-ordinary; and Lemon, Coyne, Mayhew, à Beckett, and Wills, the literary Staff, until the advent of the others, whose adhesion was anxiously awaited. Henry Mayhew, Mark Lemon, and Stirling Coyne were to be joint editors; Last, of course, was to be printer, and Landells engraver; and W. Bryant publisher. Several more meetings were held—at the "Crown" in Vinegar Yard, at Landells' house, and elsewhere—and in due course Mark Lemon produced the draft prospectus, consisting of three folios of blue paper, which probably contains a good deal more of Mayhew and Coyne than of Mark Lemon. Edmund Yates estimated its chemical composition thus:—

| Henry Mayhew | 95 |

| Stirling Coyne | 3 |

| W. H. Wills | 1.5 |

| Mark Lemon | .5 |

| —— | |

| 100 |

And his estimate was probably correct. This interesting document is here shown in reduced facsimile:[Pg 20]—

(Original size of page 5¼ x 3¾ inches.)

At the head of this announcement there was a woodcut of Lord Morpeth, Lord Melbourne (Prime Minister), and Lord John Russell, who were then in[Pg 23] office, but were popularly, and correctly, supposed to be in imminent danger of defeat. The price originally proposed was twopence—the usual price of similar papers of the day—but it was altered to "the irresistibly comic charge of threepence!!" and the title was being[Pg 24] given as "The Fun——," when the writer stopped short and erased it. It is generally believed that the intention was to call the paper "The Funny Dog—with Comic Tales," as appears in the final line of the prospectus; a title, moreover, that was employed in 1857 for a book in which more than one Punch man co-operated. A reduced copy of the now rare leaflet as it was printed and circulated by tens of thousands is given on the previous page. "Vates," it should be explained, was the nom de plume of the notorious sporting tipster then attached to "Bell's Life in London."

As to the origin of Punch's name, there are as many versions as of the origin of Punch itself. Hodder declares that it was Mayhew's sudden inspiration. Last asserted that when "somebody" at the "Edinburgh Castle" meeting spoke of the paper, like a good mixture of punch, being nothing without Lemon, Mayhew caught at the idea and cried, "A capital idea! We'll call it Punch!" Jovial Hal Baylis it was, says another, who, when refreshment time came round (it was always coming round with him), gave the hint so readily taken. Mrs. Brezzi, wife of the sculptor, lays the scene of the first meeting in the "Wrekin Tavern," Broad Street, Longacre, and writes that the founders were only prevented from calling the paper "Cupid," with Lord Brougham in that character on the title-page [presumably a mistake for Lord Palmerston, who subsequently was so shown in Punch by Brine, picking his teeth with his arrow] by the sight from Joseph Allen's window of a Punch and Judy show in the north-eastern corner of Trafalgar Square. Mrs. Bacon, Mark Lemon's niece, informs me that she distinctly remembers being seated among the gentlemen who met at his rooms in Newcastle Street, and hearing Henry Mayhew suddenly exclaim, "Let the name be 'Punch'!"—a fact engraven on her memory through her childish passion for the reprobate old puppet. Mr. E. Stirling Coyne claims that it was his father who suggested the title at the memorable meeting at Allen's. This, at least, in Lemon's words, is certain: "It was called Punch because it was short and sweet. And Punch is an English institution. Everyone loves Punch, and will be[Pg 25] drawn aside to listen to it. All our ideas connected with Punch are happy ones." The decision was not set aside when it was found that Jerrold had edited a "Punch in London" years before, proposed to him a few months earlier by Mr. Mills (of Mills, Jowett, and Mills). But the favour with which the title was received was not universal. "I remember," Mr. Birket Foster tells me, "Landells coming into the workshop and saying, 'Well, boys, the title for the new work is to be Punch.' When he was gone, we said it was a very stupid one, little thinking what a great thing it was to become."

The business plan was to be a co-operative one. Mayhew, Lemon, and Coyne, it was finally agreed, were to be co-editors and own one-third share as payment.[3] Last was to find the[Pg 26] printing and own one share, and Landells was to find drawings and engraving, and own one share. The claims of outside contributors (among whom were Jerrold and à Beckett) and the paper-maker's bill were to be the first charge on the proceeds; and if these were not enough, Landells and Last were to make up the deficiency. So, on the same plan as the first abortive attempt of a "London Charivari," the new paper was embarked on, by men who with but little capital ("it was started with £25—which I found!" says Landells) yet threw themselves into it, and became their own publishers. Advertising to the extent of £111 12s. was ventured on, including "billing in 6 Mags.," "page in 'Master Humphrey's Clock' twice," 100,000 of the prospectuses reproduced on p. 23,[4] and 2,000 window-bills that bore the design which Henning drew for Punch's cover, after a rough sketch by Landells.

It was a busy fortnight; and it may well be doubted if any other journal of such great eventual popularity has ever been launched with so little preparation. Every technical detail identical with what was employed up to recent years was settled; Henning drew his ill-composed cartoon of "Parliamentary Candidates under Different Heads," roughly done, but not ill-cut; and Mark Lemon, Henry Mayhew, Henry Grattan, Joseph Allen, F. G. Tomlins, Gilbert à Beckett, and W. H. Wills (the biting epigram "To the Black-balled of the United Service Club," i.e. Lord Cardigan, was his), all contributed to the first number. It is an axiom of newspaper conductors that "the first number is always the worst number," and Punch did nothing to disprove the rule. Nevertheless, it was a great success. The tone and quality were far higher in dignity and excellence than was common to an avowedly smart and comic paper—far different from what is suggested by the word "Charivari;" and the public admitted that here was a novel school of comic writing, by a motley moralist and punning philosopher, and hailed with pleasure the advent of a "New Humour."

(Designed by A. S. Henning.)

"Out came the first number," wrote Landells. "I shall never forget the excitement of that first number! It was so great that Mr. Mayhew, Mr. Lemon, and myself, sat up all night at the printer's, waiting to see it printed." When "our Mr. Bryant," as the publisher was called, opened the publishing[Pg 28] office on that memorable 17th of July, at 13, Wellington Street, Strand, the unexpected demand for the paper raised the expectations and enthusiasm of the confederates to the highest pitch. Mayhew, with Hodder and Landells, walked up and down outside the office and in the neighbouring Strand, discussing the paper and its prospects, and constantly calling to hear from Bryant how things were progressing. At news of each fresh thousand sold, their spirits rose, and their anxiety became satisfaction when the whole edition of five thousand had been taken up by the trade, and another like edition was called for, and, on the following day, was sold out. Ten thousand copies! Ten thousand proofs, they took it, of public sympathy and encouragement.

Such is the outline of Punch's conception and birth, based on many original documents and a mass of evidence, as well as on the independent testimony collected from survivors. In the words of Mr. Jabez Hogg, "Landells and Henry Mayhew were certainly the founders"—the former conceiving the idea of the paper which was presently established, and the latter developing it, as set forth, according to his original views—founding the tradition and personality of "Mr. Punch," and converting him from a mere strolling puppet, an irresponsible jester, into the laughing philosopher and man of letters, the essence of all wit, the concentration of all wisdom, the soul of honour, the fountain of goodness, and the paragon of every virtue.[Pg 29]

Reception of Punch—Early Struggles—Financial Help Invoked—The First Almanac—Its Enormous Success—Transfer of Punch to Bradbury and Evans—Terms of Settlement—The New Firm—Punch's Special Efforts—Succession of Covers—"Valentines," "Holidays," "Records of the Great Exhibition," and "At the Paris Exhibition."

The public reception of the first number of Punch was varied in character. Mr. Watts, R.A., once told me that the paper was regarded with but little encouragement by the occupants of an omnibus in which he was riding, one gentleman, after looking gravely through its pages, tossing it aside with the remark, "One of those ephemeral things they bring out; won't last a fortnight!" Dr. Thompson, Master of Trinity, informed Professor Herkomer that he, too, was riding in an omnibus on the famous 17th of July, when he bought a copy from a paper-boy, and began to look at it with curiosity. When he chuckled at the quaint wit of the thing, "Do you find it amusing, sir?" asked a lady, who was observing him narrowly. "Oh, yes." "I'm so glad," she replied; "my husband has been appointed editor; he gets twenty pounds a week!" One may well wonder who was this sanguine and trustful lady. Mr. Frith describes how, having overheard Joe Allen tell a friend, in the gallery of the Society of British Artists, to "look out for our first number; we shall take the town by storm!" he duly looked out, but was disappointed at finding nothing in it by Leech; and how when he went to a shop for the second number, to see if his idol had drawn anything for it, the newsman replied, "'What paper, sir? Oh, Punch! Yes, I took a few of the first number; but it's no go. You see, they billed it about a good deal' (how well I recollect that expression!), 'so I wanted to see what it was like. It won't do; it's no go.'"[Pg 30]

The reception by the press was more encouraging—that is to say, by the provincial press, for the London papers took mighty little notice of the newcomer. The "Morning Advertiser," it is true, quaintly declared in praise of the "exquisite woodcuts, serious and comic," that they were "executed in the first style of art, at a price so low that we really blush to name it;" while the "Sunday Times" and a number of provincial papers of some slight account in their day professed astonishment at the absence of grossness, partisanship, profanity, indelicacy, and malice from its pages. "It is the first comic we ever saw," said the "Somerset County Gazette," "which was not vulgar. It will provoke many a hearty laugh, but never call a blush to the most delicate cheek." They vied with each other in their vocabulary of praise; and as to Punch's quips and sallies, his puns, his propriety, his "pencillings," and his cuts—they simply defied description; you just cracked your sides with laughter at the jokes, and that was all about it.

Yet, notwithstanding all this praise, the paper did not prosper; but whether it was that the price did not suit the public, although the "Advertiser" really blushed to name it, or that Punch had not yet educated his Party, cannot be decided. The support of the public did not lift it above a circulation of from five to six thousand, and on the appearance of the fifth number Jerrold muttered with a snort, "I wonder if there will ever be a tenth!" Everything that could be done to command attention, with the limited funds at disposal, was done. No sooner was Lord Melbourne's Administration defeated and discredited (for the Premier was angrily denounced for hanging on to office), than Punch displayed a huge placard across the front of his offices inscribed, "Why is Punch like the late Government? Because it is Just Out!!" And no device of the sort, or other artifice that could be suggested to the resourceful minds in Punch's cabinet, was left untried. Things were against Punch. It was not only that the public was neglectful, unappreciative. There was prejudice to live down; there were stamp duty, advertisement duty, and paper duty to stand up to; and there were no Smiths or Willings, or other great distributing agencies, to assist.[Pg 31]

While Bryant was playing his uphill game, Punch, written by educated men, was doing his best not only to attract politicians and lovers of humour and satire, but to enlist also the support of scholars, to whom at that time no comic paper had avowedly appealed; and it is doubtless due to the assumption that his readers, like his writers, were gentlemen of education, that he quickly gained the reputation of being entitled to a place in the library and drawing-room, diffusing, so to speak, an odour of culture even in those early days of his first democratic fervour. We had a German "Punchlied," Greek Anakreontics, and plenty of Latin—not merely Leigh's mock-classic verses, but efforts of a higher humour and a purer kind, such, among many more, as the "Petronius," and the clever interlinear burlesque translations of Horace which came from the pen of H. A. Kennedy. Then "Answers to Correspondents" were maintained for a while inside the wrapper, which were witty enough to justify their existence. But it was felt that something more was wanted to make the paper "move;" and the first "Almanac" was decided upon.

The circulation meanwhile had not risen above six thousand, and ten thousand were required to make the paper pay. Stationer and contributors had all been paid, and "stock" was now valued at £250. That there was a constant demand for these back numbers (on September 27th, 1841, for example, £1 3s. 4½d.-worth were sold "over the counter"), was held to prove that the work was worth pushing; but it seemed that for want of capital it would go the way of many another promising concern. The difficulties into which Punch had fallen soon got noised abroad, and offers of assistance, not by any means disinterested, were not wanting to remind the stragglers of their position. Helping hands were certainly put out, but only that money might be dropped in. Then Last declined to go on. He had neither the patience nor the speculative courage of the Northumbrian engraver, and money had, not without great difficulty and delay, been found to pay him for his share—which had hitherto been a share only of loss. The firm of Bradbury and Evans had been looked to as a deus ex machinâ to take over the printing,[Pg 32] and lift Punch out of the quagmire by acquiring Last's share and interest for £150. The offer was entertained, and an agreement drafted on September 25th, when, on the very same day, Bradbury and Evans wrote to withdraw, on the ground that they found the proposed acquisition "would involve them in the probable loss of one of their most valuable connections." Landells, who always regarded this action—without any definite grounds that I can discover—as a diplomatic move to involve him and his friends still more, so that more advantageous salvage terms might be made, hurriedly cast about for other succour, and alighted on one William Wood, printer, who lent money, but whose agreement as a whole was not executed, as it was considered "either usurious or exorbitant" by their solicitors, who characteristically concluded their bill thus:—"Afterwards attending at the office in Wellington Street to see as to making the tender, and to advise you on the sufficiency thereof, but you were not there; afterwards attending at Mr. H. Mayhew's lodging, but he was out; afterwards attending at Mr. Lemon's, and he was out; and we were given to understand you had all gone to Gravesend"—showing the one touch of nature which made all Punch-men kin.

In due course Landells acquired Last's share, and the printing was executed successively by Mr. Mitchell and by Mills, Jowett, and Mills, until it slid by a sort of natural gravitation into the hands of Bradbury and Evans. Landells had endeavoured to interest his friends in the paper, but soon discovered the fatal truth that one's closest friends are never so close as when it is a question of money.

Then came the Almanac, upon which were based many hopes that were destined to be more than realised. It has hitherto been considered as the work of Dr. Maginn, at that time, as at many others, an unwilling sojourner in a debtor's prison. But H. P. Grattan has since claimed the distinction of being, like the doctor, an inmate of the retreat known as Her Majesty's Fleet, where he was visited by Henry Mayhew. Mayhew, he said, lived surreptitiously with him for a week, and during that time, without any assistance from Dr. Maginn, they brought the whole work to a brilliant termination. Thirty-five jokes a day[Pg 33] to each man's credit for seven consecutive days in the melancholy privacy of a prison cell is certainly a very remarkable feat—hardly less so than the alleged fact that Mayhew, who proposed the Almanac, as he proposed so many other good things for Punch, should have gone to the incarcerated Grattan for sole assistance, when he and his co-editors had so many capable colleagues at large. The claim does not deserve full credence, especially in face of Landells' declaration that "everyone engaged on it worked so admirably together, and it was done so well, that the town was taken by surprise, and the circulation went up in that one week from 6,000 to 90,000—an increase, I believe, unprecedented in the annals of publishing." The Almanac became at once the talk of the day; everybody had read it, and a contemporary critic declared that its cuts "would elicit laughter from toothache, and render gout oblivious of his toe."