E-text prepared by Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, Linda Cantoni,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Transcriber's Notes: The original book cites Holland's

Herωologia in several places, but consistently misspells

it Heroωlogia. This has been corrected based on the image of

the original title page of Herωologia at the Library of

Congress, www.loc.gov.

The original book contains a number of full-page illustrations.

In this e-book, these illustrations have been moved to the nearest

paragraph break so as not to disturb the flow of the text. The page

numbers for these illustrations have been omitted, and page references

in the text are linked to the pages on which the illustrations actually appear.

Page numbers for blank and unnumbered pages are also omitted.

Contents

Shakespearean

Playhouses

A HISTORY OF ENGLISH

THEATRES from the BEGINNINGS

to the

RESTORATION

By JOSEPH QUINCY ADAMS

Cornell University

Gloucester, Mass.

PETER SMITH

1960

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY

JOSEPH QUINCY ADAMS

REPRINTED, 1960,

BY PERMISSION OF

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN CO.

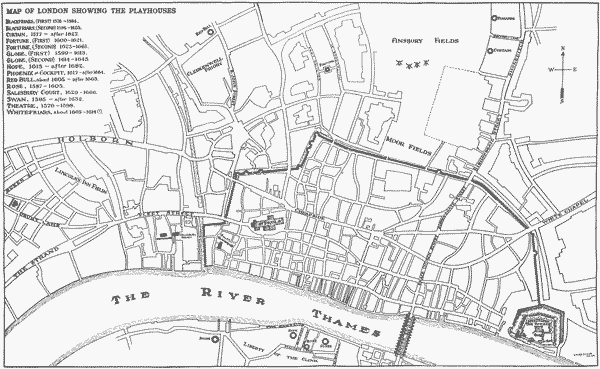

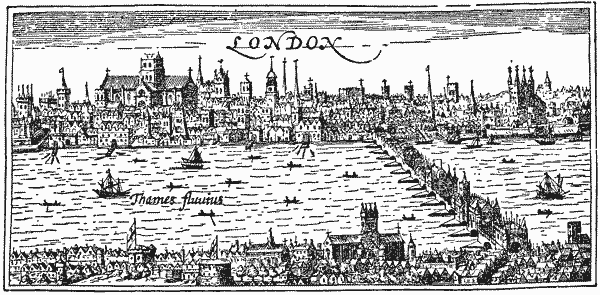

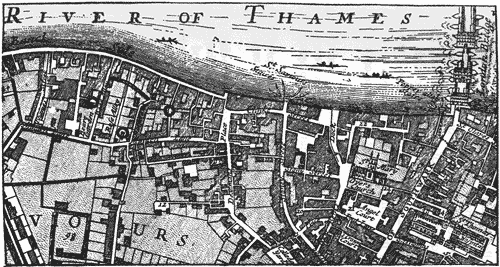

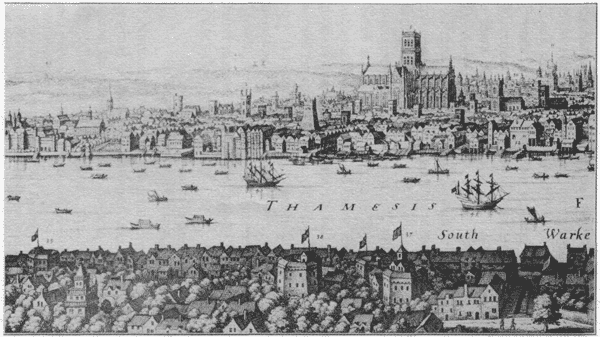

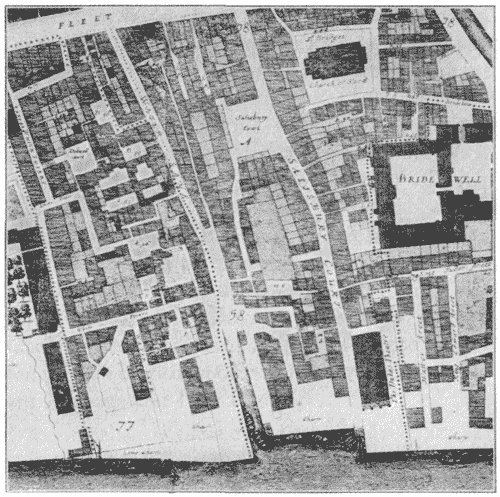

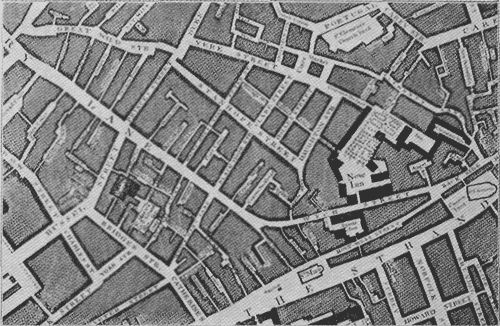

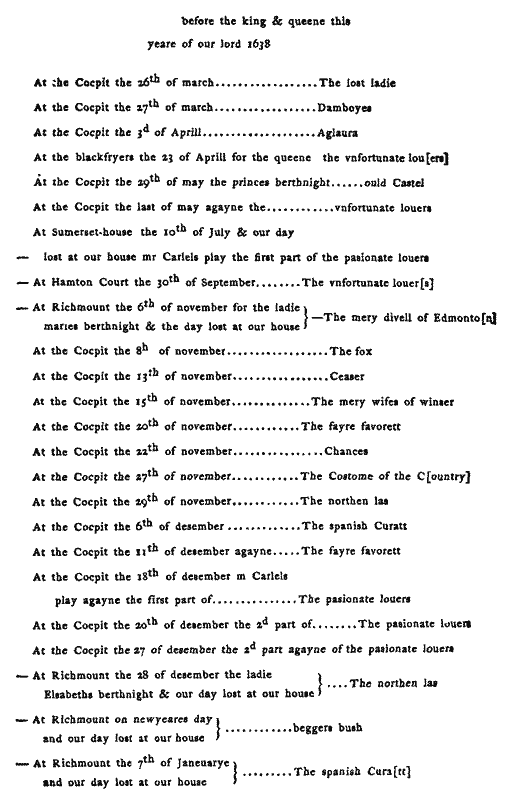

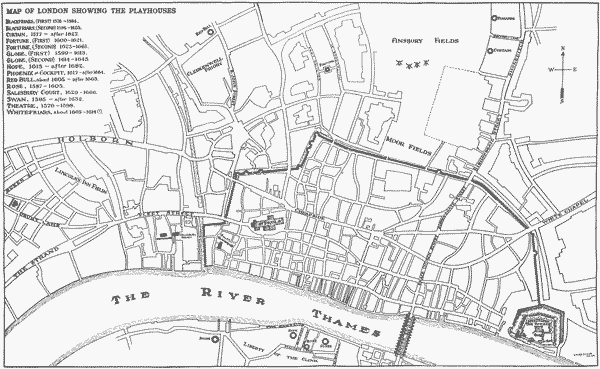

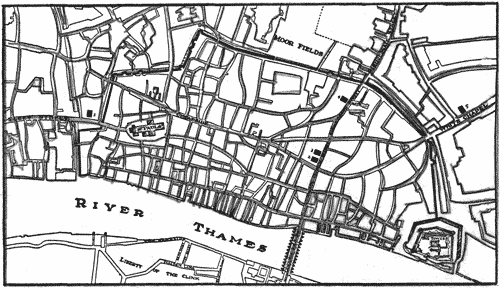

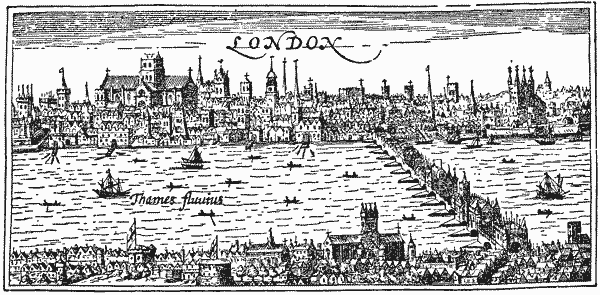

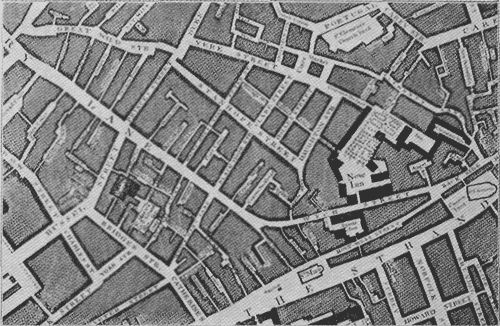

MAP OF LONDON SHOWING THE PLAYHOUSES

[Enlarge]

Blackfriars, (first) 1576-1584.

Blackfriars, (second) 1596-1655.

Curtain, 1577-after 1627.

Fortune, (first) 1600-1621.

Fortune, (second) 1623-1661.

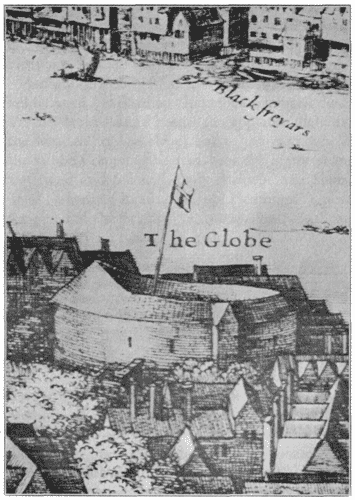

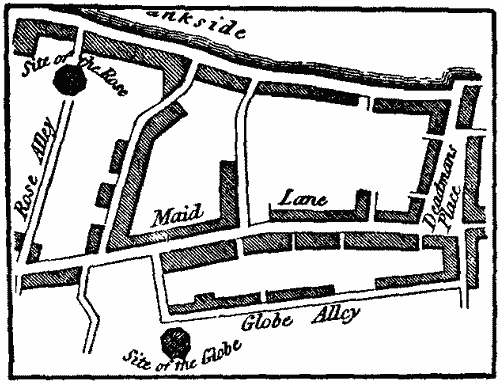

Globe, (first) 1599-1613.

Globe, (second) 1614-1645.

Hope, 1613-after 1682.

Phoenix or Cockpit, 1617-after 1664.

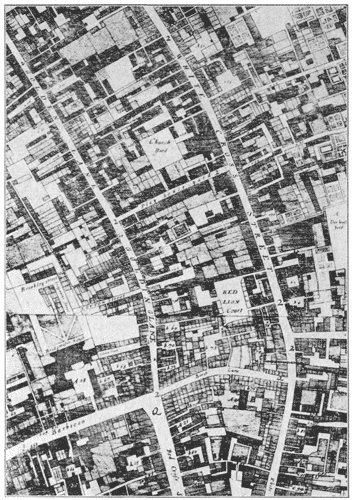

Red Bull, about 1605-after 1663.

Rose, 1587-1605.

Salisbury Court, 1629-1666.

Swan, 1595-after 1632.

Theatre, 1576-1598.

Whitefriars, about 1605-1614(?).

TO

LANE COOPER

IN GRATITUDE AND ESTEEM

vii

PREFACE

THE method of dramatic representation in the time of Shakespeare has

long received close study. Among those who have more recently devoted

their energies to the subject may be mentioned W.J. Lawrence, T.S.

Graves, G.F. Reynolds, V.E. Albright, A.H. Thorndike, and B.

Neuendorff, each of whom has embodied the results of his

investigations in one or more noteworthy volumes. But the history of

the playhouses themselves, a topic equally important, has not hitherto

been attempted. If we omit the brief notices of the theatres in Edmond

Malone's The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare (1790) and John

Payne Collier's The History of English Dramatic Poetry (1831), the

sole book dealing even in part with the topic is T.F. Ordish's The

Early London Theatres in the Fields. This book, however, though good

for its time, was written a quarter of a century ago, before most of

the documents relating to early theatrical history were discovered,

and it discusses only six playhouses. The present volume takes

advantage of all the materials made available by the industry of later

scholars, and records the history of seventeen regular, and five

temporary or projected, theatres. The book is throughout the result of

a first-hand examination of originalviii sources, and represents an

independent interpretation of the historical evidences. As a

consequence of this, as well as of a comparison (now for the first

time possible) of the detailed records of the several playhouses, many

conclusions long held by scholars have been set aside. I have made no

systematic attempt to point out the cases in which I depart from

previously accepted opinions, for the scholar will discover them for

himself; but I believe I have never thus departed without being aware

of it, and without having carefully weighed the entire evidence.

Sometimes the evidence has been too voluminous or complex for detailed

presentation; in these instances I have had to content myself with

reference by footnotes to the more significant documents bearing on

the point.

In a task involving so many details I cannot hope to have escaped

errors—errors due not only to oversight, but also to the limitations

of my knowledge or to mistaken interpretation. For such I can offer no

excuse, though I may request from my readers the same degree of

tolerance which I have tried to show other laborers in the field. In

reproducing old documents I have as a rule modernized the spelling and

the punctuation, for in a work of this character there seems to be no

advantage in preserving the accidents and perversities of early

scribes and printers. I have also consistently altered the dates when

the Old Style conflicted with our present usage.ix

I desire especially to record my indebtedness to the researches of

Professor C.W. Wallace, the extent of whose services to the study of

the Tudor-Stuart drama has not yet been generally realized, and has

sometimes been grudgingly acknowledged; and to the labors of Mr. E.K.

Chambers and Mr. W.W. Greg, who, in the Collections of The Malone

Society, and elsewhere, have rendered accessible a wealth of important

material dealing with the early history of the stage.

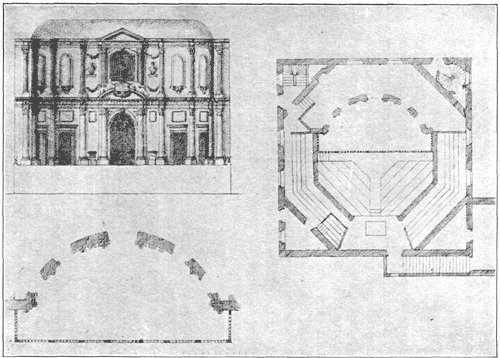

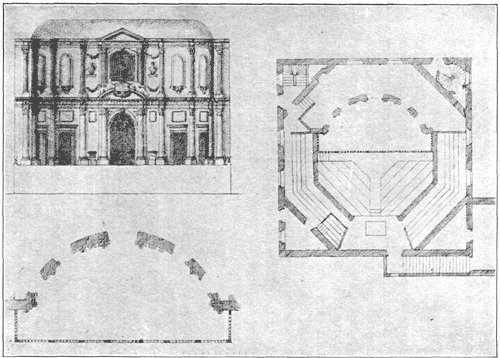

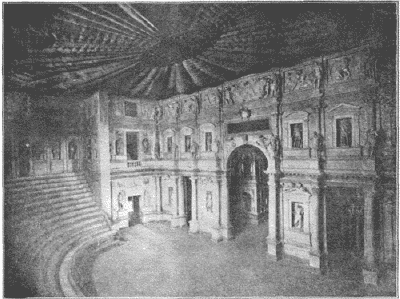

Finally, I desire to express my gratitude to Mr. Hamilton Bell and the

editor of The Architectural Record for permission to reproduce the

illustration and description of Inigo Jones's plan of the Cockpit; to

the Governors of Dulwich College for permission to reproduce three

portraits from the Dulwich Picture Gallery, one of which, that of Joan

Alleyn, has not previously been reproduced; to Mr. C.W. Redwood,

formerly technical artist at Cornell University, for expert assistance

in making the large map of London showing the sites of the playhouses,

and for other help generously rendered; and to my colleagues,

Professor Lane Cooper and Professor Clark S. Northup, for their

kindness in reading the proofs.

Joseph Quincy Adams

Ithaca, New York

xi

CONTENTS

xiii

ILLUSTRATIONS

1

Shakespearean Playhouses

CHAPTER I

THE INN-YARDS

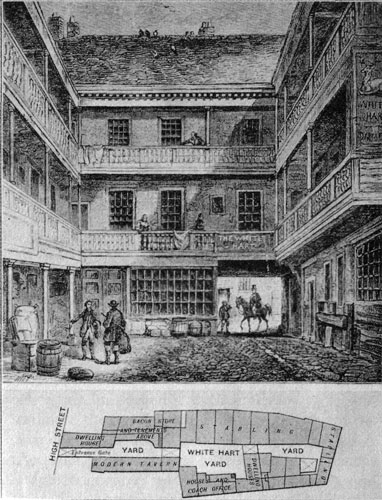

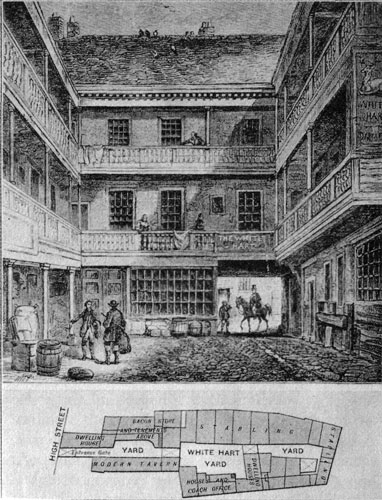

BEFORE the building of regular playhouses the itinerant troupes of

actors were accustomed, except when received into private homes, to

give their performances in any place that chance provided, such as

open street-squares, barns, town-halls, moot-courts, schoolhouses,

churches, and—most frequently of all, perhaps—the yards of inns.

These yards, especially those of carriers' inns, were admirably suited

to dramatic representations, consisting as they did of a large open

court surrounded by two or more galleries. Many examples of such

inn-yards are still to be seen in various parts of England; a picture

of the famous White Hart, in Southwark, is given opposite page 4 by

way of illustration. In the yard a temporary platform—a few boards,

it may be, set on barrel-heads[1]—could be erected for a stage; in

the adjacent stables a dressing-room could be provided for the actors;

the rabble—always the larger and2 more enthusiastic part of the

audience—could be accommodated with standing-room about the stage;

while the more aristocratic members of the audience could be

comfortably seated in the galleries overhead. Thus a ready-made and

very serviceable theatre was always at the command of the players; and

it seems to have been frequently made use of from the very beginning

of professionalism in acting.

One of the earliest extant moralities, Mankind, acted by strollers

in the latter half of the fifteenth century, gives us an interesting

glimpse of an inn-yard performance. The opening speech makes distinct

reference to the two classes of the audience described above as

occupying the galleries and the yard:

O ye sovereigns that sit, and ye brothers that stand right

up.

The "brothers," indeed, seem to have stood up so closely about the

stage that the actors had great difficulty in passing to and from

their dressing-room. Thus, Nowadays leaves the stage with the request:

Make space, sirs, let me go out!

New Gyse enters with the threat:

Out of my way, sirs, for dread of a beating!

While Nought, with even less respect, shouts:

Avaunt, knaves! Let me go by!

3

Language such as this would hardly be appropriate if addressed to the

"sovereigns" who sat in the galleries above; but, as addressed to the

"brothers," it probably served to create a general feeling of good

nature. And a feeling of good nature was desirable, for the actors

were facing the difficult problem of inducing the audience to pay for

its entertainment.

This problem they met by taking advantage of the most thrilling moment

of the plot. The Vice and his wicked though jolly companions, having

wholly failed to overcome the hero, Mankind, decide to call to their

assistance no less a person than the great Devil himself; and

accordingly they summon him with a "Walsingham wystyle." Immediately

he roars in the dressing-room, and shouts:

I come, with my legs under me!

There is a flash of powder, and an explosion of fireworks, while the

eager spectators crane their necks to view the entrance of this

"abhomynabull" personage. But nothing appears; and in the expectant

silence that follows the actors calmly announce a collection of money,

facetiously making the appearance of the Devil dependent on the

liberality of the audience:

New Gyse. Now ghostly to our purpose, worshipful sovereigns,

We intend to gather money, if it please your negligence.

4For a man with a head that of great omnipotence—

Nowadays [interrupting]. Keep your tale, in goodness, I

pray you, good brother!

[Addressing the audience, and pointing towards the

dressing-room, where the Devil roars again.]

He is a worshipful man, sirs, saving your reverence.

He loveth no groats, nor pence, or two-pence;

Give us red royals, if ye will see his abominable presence.

New Gyse. Not so! Ye that may not pay the one, pay the other.

And with such phrases as "God bless you, master," "Ye will not say

nay," "Let us go by," "Do them all pay," "Well mote ye fare," they

pass through the audience gathering their groats, pence, and twopence;

after which they remount the stage, fetch in the Devil, and continue

their play without further interruption.

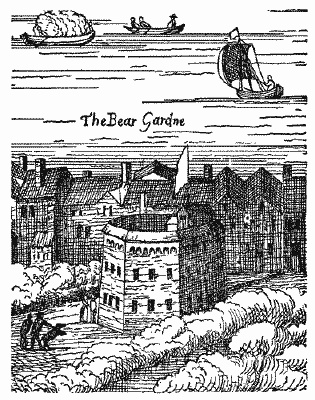

AN INN-YARD

The famous White Hart, in Southwark. The

ground-plan shows the

arrangement of a carriers' inn with the stabling below; the guest

rooms were on the upper floors.

In the smaller towns the itinerant players might, through a letter of

recommendation from their noble patron, or through the good-will of

some local dignitary, secure the use of the town-hall, of the

schoolhouse, or even of the village church. In such buildings, of

course, they could give their performances more advantageously, for

they could place money-takers at the doors, and exact adequate payment

from all who entered. In the great city of London, however, the

players were necessarily forced to make use almost entirely of public

inn-yards—an arrangement which, we may well believe, they found far

from satisfactory. Not being masters of the inns, they were merely

tolerated; they had to content themselves with has5tily provided and

inadequate stage facilities; and, worst of all, for their recompense

they had to trust to a hat collection, at best a poor means of

securing money. Often too, no doubt, they could not get the use of a

given inn-yard when they most needed it, as on holidays and festive

occasions; and at all times they had to leave the public in

uncertainty as to where or when plays were to be seen. Their street

parade, with the noise of trumpets and drums, might gather a motley

crowd for the yard, but in so large a place as London it was

inadequate for advertisement among the better classes. And as the

troupes of the city increased in wealth and dignity, and as the

playgoing public grew in size and importance, the old makeshift

arrangement became more and more unsatisfactory.

At last the unsatisfactory situation was relieved by the specific

dedication of certain large inns to dramatic purposes; that is, the

proprietors of certain inns found it to their advantage to subordinate

their ordinary business to the urgent demands of the actors and the

playgoing public. Accordingly they erected in their yards permanent

stages adequately equipped for dramatic representations, constructed

in their galleries wooden benches to accommodate as many spectators as

possible, and were ready to let the use of their buildings to the

actors on an agreement by which the proprietor shared with the troupe

in the "tak6ings" at the door. Thus there came into existence a number

of inn-playhouses, where the actors, as masters of the place, could

make themselves quite at home, and where the public without special

notification could be sure of always finding dramatic entertainment.

Richard Flecknoe, in his Discourse of the English Stage (1664), goes

so far as to dignify these reconstructed inns with the name

"theatres." At first, says he, the players acted "without any certain

theatres or set companions, till about the beginning of Queen

Elizabeth's reign they began here to assemble into companies, and set

up theatres, first in the city (as in the inn-yards of the Cross Keys

and Bull in Grace and Bishop's Gate Street at this day to be seen),

till that fanatic spirit [i.e., Puritanism], which then began with the

stage and after ended with the throne, banished them thence into the

suburbs"—that is, into Shoreditch and the Bankside, where, outside

the jurisdiction of the puritanical city fathers, they erected their

first regular playhouses.

The "banishment" referred to by Flecknoe was the Order of the Common

Council issued on December 6, 1574. This famous document described

public acting as then taking place "in great inns, having chambers and

secret places adjoining to their open stages and galleries"; and it

ordered that henceforth "no inn-keeper, tavern-keeper, nor other

person whatsoever within the liberties7 of this city shall openly

show, or play, nor cause or suffer to be openly showed or played

within the house yard or any other place within the liberties of this

city, any play," etc.

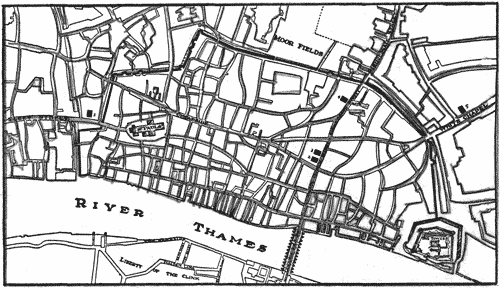

How many inns were let on special occasions for dramatic purposes we

cannot say; but there were five "great inns," more famous than the

rest, which were regularly used by the best London troupes. Thus

Howes, in his continuation of Stow's Annals (p. 1004), in attempting

to give a list of the playhouses which had been erected "within London

and the suburbs," begins with the statement, "Five inns, or common

osteryes, turned to playhouses." These five were the Bell and the

Cross Keys, hard by each other in Gracechurch Street, the Bull, in

Bishopsgate Street, the Bell Savage, on Ludgate Hill, and the Boar's

Head, in Whitechapel Street without Aldgate.[2]

Although Flecknoe referred to the Order of the Common Council as a

"banishment," it did not actually drive the players from the city.

They were able, through the intervention of the Privy Council, and on

the old excuse of rehearsing plays8 for the Queen's entertainment, to

occupy the inns for a large part of each year.[3] John Stockwood, in a

sermon preached at Paul's Cross, August 24, 1578, bitterly complains

of the "eight ordinary places" used regularly for plays, referring, it

seems, to the five inns and the three playhouses—the Theatre,

Curtain, and Blackfriars—recently opened to the public.

Richard Reulidge, in A Monster Lately Found Out and Discovered

(1628), writes that "soon after 1580" the authorities of London

received permission from Queen Elizabeth and her Privy Council "to

thrust the players out of the city, and to pull down all playhouses

and dicing-houses within their liberties: which accordingly was

effected; and the playhouses in Gracious Street [i.e., the Bell and

the Cross Keys], Bishopsgate Street [i.e., the Bull], that nigh Paul's

[i.e., Paul's singing school?], that on Ludgate Hill [i.e., the Bell

Savage], and the Whitefriars[4] were quite put down and suppressed by

the care of these religious senators."

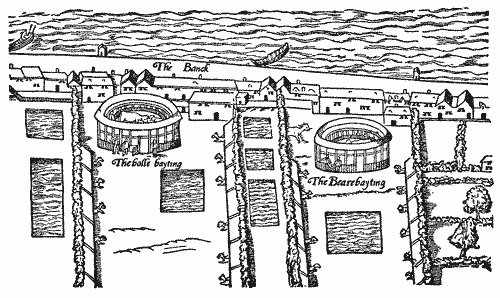

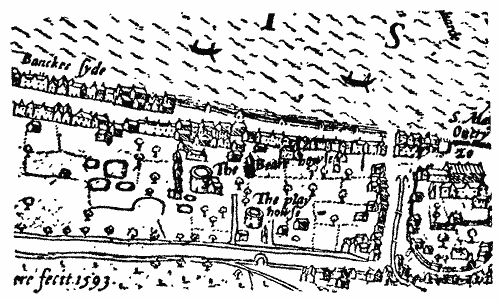

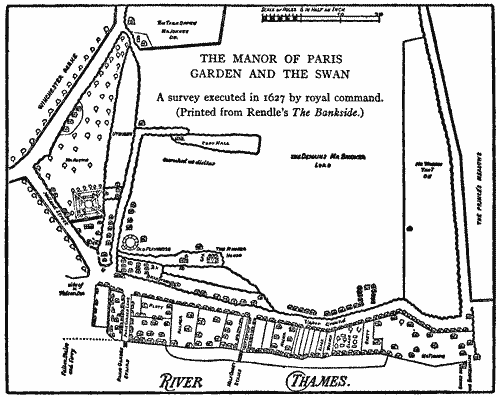

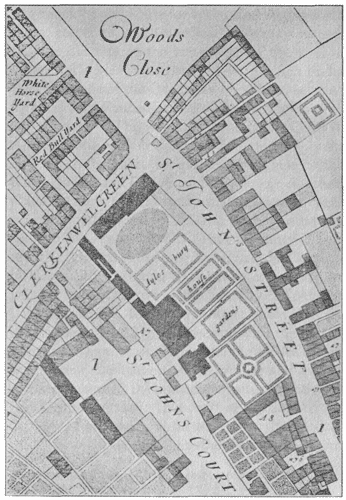

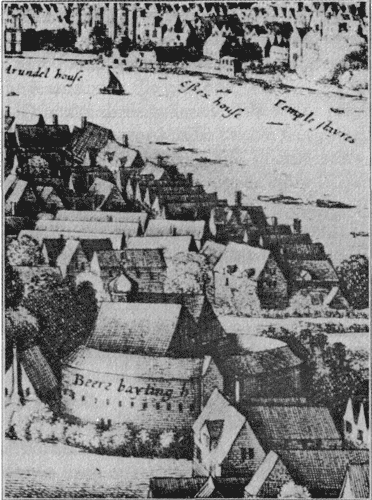

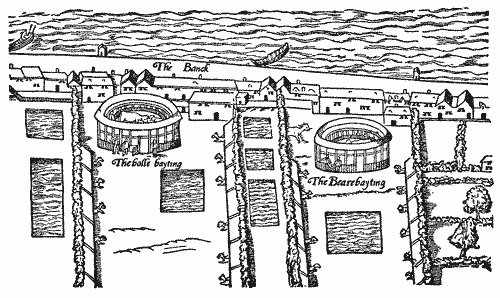

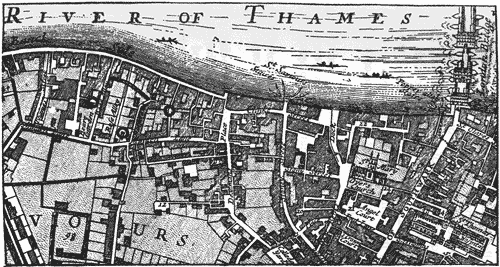

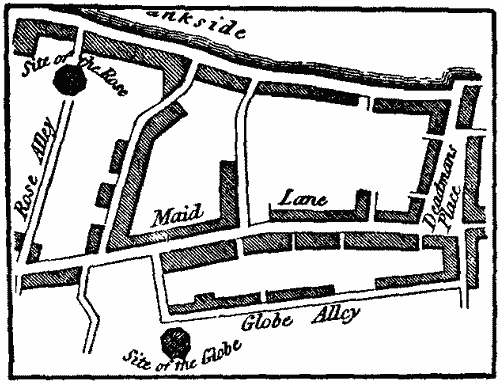

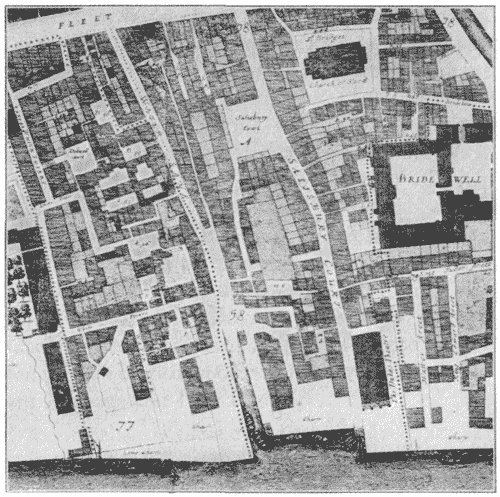

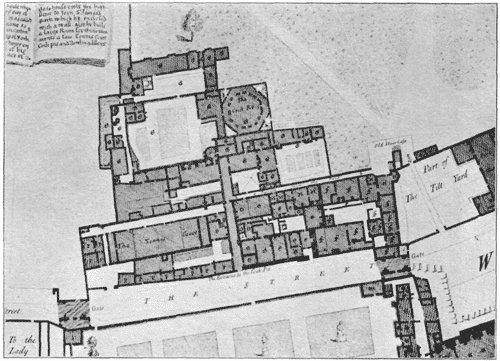

MAP OF LONDON SHOWING THE INN-PLAYHOUSES

1. The Bell Savage; 2. The Cross Keys; 3. The Bell; 4. The

Bull; 5. The Boar's Head.

[Enlarge]

Yet, in spite of what Reulidge says, these five inns continued to be

used by the players for many10 years.[5] No doubt they were often used

surreptitiously. In Martin's Month's Mind (1589), we read that a

person "for a penie may have farre better [entertainment] by oddes at

the Theatre and Curtaine, and any blind playing house everie

day."[6] But the more important troupes were commonly able, through

the interference of the Privy Council, to get official permission to

use the inns during a large part of each year.

There is not enough material about these early inn-playhouses to

enable one to write their separate histories. Below, however, I have

recorded in chronological order the more important references to them

which have come under my observation.

1557. On September 5 the Privy Council instructed the Lord Mayor of

London "that some of his officers do forthwith repair to the Boar's

Head without Aldgate, where, the Lords are informed, a lewd play

called A Sackful of News shall be played this day," to arrest the

players, and send their playbook to the Council.[7]

1573. During this year there were various fencing contests held at the

Bull in Bishopsgate.[8]

1577. In February the Office of the Revels made a payment of 10d.

"ffor the cariadge of the11 parts of ye well counterfeit from the Bell

in gracious strete to St. Johns, to be performed for the play of

Cutwell."[9]

1579. On June 23 James Burbage was arrested for the sum of £5 13d.

"as he came down Gracious Street towards the Cross Keys there to a

play." The name of the proprietor of this inn-playhouse is preserved

in one of the interrogatories connected with the case: "Item. Whether

did you, John Hynde, about xiii years past, in anno 1579, the xxiii

of June, about two of the clock in the afternoon, send the sheriff's

officer unto the Cross Keys in Gratious Street, being then the

dwelling house of Richard Ibotson, citizen and brewer of London,"

etc.[10] Nothing more, I believe, is known of this person.

1579. Stephen Gosson, in The Schoole of Abuse, writes favorably of

"the two prose books played at the Bell Savage, where you shall find

never a word without wit, never a line without pith, never a letter

placed in vain; the Jew and Ptolome, shown at the Bull ... neither

with amorous gesture wounding the eye, nor with slovenly talk hurting

the ears of the chast hearers."[11]

12

1582. On July 1 the Earl of Warwick wrote to the Lord Mayor requesting

the city authorities to "give license to my servant, John David, this

bearer, to play his profest prizes in his science and profession of

defence at the Bull in Bishopsgate, or some other convenient place to

be assigned within the liberties of London." The Lord Mayor refused to

allow David to give his fencing contest "in an inn, which was somewhat

too close for infection, and appointed him to play in an open place of

the Leaden Hall," which, it may be added, was near the Bull.[12]

1583. William Rendle, in The Inns of Old Southwark, p. 235, states

that in this year "Tarleton, Wilson, and others note the stay of the

plague, and ask leave to play at the Bull in Bishopsgate, or the Bell

in Gracechurch Street," citing as his authority merely "City MS." The

Privy Council on November 26, 1583, addressed to the Lord Mayor a

letter requesting "that Her Majesty's Players [i.e., Tarleton, Wilson,

etc.] may be suffered to play within the liberties as heretofore they

have done."[13] And on November 28 the Lord Mayor issued to them a

license to play "at the sign of the Bull in Bishopsgate Street, and

the sign of the Bell in Gracious Street, and nowhere else within this

City."[14]

13

1587. "James Cranydge played his master's prize the 21 of November,

1587, at the Bellsavage without Ludgate, at iiij sundry kinds of

weapons.... There played with him nine masters."[15]

Before 1588. In Tarlton's Jests[16] we find a number of references

to that famous actor's pleasantries in the London inns used by the

Queen's Players. It is impossible to date these exactly, but Tarleton

became a member of the Queen's Players in 1583, and he died in 1588.

At the Bull in Bishops-gate-street, where the Queen's

Players oftentimes played, Tarleton coming on the stage, one

from the gallery threw a pippin at him.

There was one Banks, in the time of Tarleton, who served the

Earl of Essex, and had a horse of strange qualities; and

being at the Cross Keys in Gracious Street getting money

with him, as he was mightily resorted to. Tarleton then,

with his fellows playing at the Bell by, came into the Cross

Keys, amongst many people, to see fashions.

At the Bull at Bishops-gate was a play of Henry the Fifth.

14

The several "jests" which follow these introductory sentences indicate

that the inn-yards differed in no essential way from the early public

playhouses.

1588. "John Mathews played his master's prize the 31 day of January,

1588, at the Bell Savage without Ludgate."[17]

1589. In November Lord Burghley directed the Lord Mayor to "give order

for the stay of all plays within the city." In reply the Lord Mayor

wrote:

According to which your Lordship's good pleasure, I

presently sent for such players as I could hear of; so as

there appeared yesterday before me the Lord Strange's

Players, to whom I specially gave in charge and required

them in Her Majesty's name to forbear playing until further

order might be given for their allowance in that respect.

Whereupon the Lord Admiral's Players very dutifully obeyed;

but the others, in very contemptuous manner departing from

me, went to the Cross Keys and played that afternoon.[18]

1594. On October 8, Henry, Lord Hunsdon, the Lord Chamberlain and the

patron of Shakespeare's company, wrote to the Lord Mayor:15

After my hearty commendations. Where my now company of

players have been accustomed for the better exercise of

their quality, and for the service of Her Majesty if need so

require, to play this winter time within the city at the

Cross Keys in Gracious Street, these are to require and pray

your Lordship (the time being such as, thanks to God, there

is now no danger of the sickness) to permit and suffer them

so to do.[19]

By such devices as this the players were usually able to secure

permission to act "within the city" during the disagreeable months of

the winter when the large playhouses in the suburbs were difficult of

access.

1594. Anthony Bacon, the elder brother of Francis, came to lodge in

Bishopsgate Street. This fact very much disturbed his good mother, who

feared lest his servants might be corrupted by the plays to be seen at

the Bull near by.[20]

1596. William Lambarde, in his Perambulation of Kent,[21] observes

that none of those who go "to Paris Garden, the Bell Savage, or

Theatre, to behold bear-baiting, interludes, or fence play, can

account of any pleasant spectacle unless they first pay one penny at

the gate, another at the entry of the scaffold, and the third for a

quiet standing."

16

1602. On March 31 the Privy Council wrote to the Lord Mayor that the

players of the Earl of Oxford and of the Earl of Worcester had been

"joined by agreement together in one company, to whom, upon notice of

Her Majesty's pleasure, at the suit of the Earl of Oxford, toleration

hath been thought meet to be granted." The letter concludes:

And as the other companies that are allowed, namely of me

the Lord Admiral, and the Lord Chamberlain, be appointed

their certain houses, and one and no more to each company,

so we do straightly require that this third company be

likewise [appointed] to one place. And because we are

informed the house called the Boar's Head is the place they

have especially used and do best like of, we do pray and

require you that the said house, namely the Boar's Head, may

be assigned unto them.[22]

That the strong Oxford-Worcester combination should prefer the Boar's

Head to the Curtain or the Rose Playhouse,[23] indicates that the

inn-yard was not only large, but also well-equipped for acting.

1604. In a draft of a license to be issued to Queen Anne's Company,

those players are allowed to act "as well within their now usual

houses, called the Curtain and the Boar's Head, within our County of

Middlesex, as in any other playhouse not used by others."[24]

17

In 1608 the Boar's Head seems to have been occupied by the newly

organized Prince Charles's Company. In William Kelly's extracts from

the payments of the city of Leicester we find the entry: "Itm. Given

to the Prince's Players, of Whitechapel, London, xx s."

In 1664, as Flecknoe tells us, the Cross Keys and the Bull still gave

evidence of their former use as playhouses; perhaps even then they

were occasionally let for fencing and other contests. In 1666 the

great fire completely destroyed the Bell, the Cross Keys, and the Bell

Savage; the Bull, however, escaped, and enjoyed a prosperous career

for many years after. Samuel Pepys was numbered among its patrons, and

writers of the Restoration make frequent reference to it. What became

of the Boar's Head without Aldgate I am unable to learn; its memory,

however, is perpetuated to-day in Boar's Head Yard, between Middlesex

Street and Goulston Street, Whitechapel.

18

CHAPTER II

THE HOSTILITY OF THE CITY

AS the actors rapidly increased in number and importance, and as

Londoners flocked in ever larger crowds to witness plays, the

animosity of two forces was aroused, Puritanism and Civic

Government,—forces which opposed the drama for different reasons, but

with almost equal fervor. And when in the course of time the Governors

of the city themselves became Puritans, the combined animosity thus

produced was sufficient to drive the players out of London into the

suburbs.

The Puritans attacked the drama as contrary to Holy Writ, as

destructive of religion, and as a menace to public morality. Against

plays, players, and playgoers they waged in pulpit and pamphlet a

warfare characterized by the most intense fanaticism. The charges they

made—of ungodliness, idolatrousness, lewdness, profanity, evil

practices, enormities, and "abuses" of all kinds—are far too numerous

to be noted here; they are interesting chiefly for their

unreasonableness and for the violence with which they were urged.

And, after all, however much the Puritans might rage, they were

helpless; authority to restrain acting was vested in the Lord Mayor,

his brethren19 the Aldermen, and the Common Council. The attitude of

these city officials towards the drama was unmistakable: they had no

more love for the actors than had the Puritans. They found that "plays

and players" gave them more trouble than anything else in the entire

administration of municipal affairs. The dedication of certain "great

inns" to the use of actors and to the entertainment of the

pleasure-loving element of the city created new and serious problems

for those charged with the preservation of civic law and order. The

presence in these inns of private rooms adjoining the yard and

balconies gave opportunity for immorality, gambling, fleecing, and

various other "evil practices"—an opportunity which, if we may

believe the Common Council, was not wasted. Moreover, the proprietors

of these inns made a large share of their profits from the beer, ale,

and other drinks dispensed to the crowds before, during, and after

performances (the proprietor of the Cross Keys, it will be recalled,

was described as "citizen and brewer of London"); and the resultant

intemperance among "such as frequented the said plays, being the

ordinary place of meeting for all vagrant persons, and masterless men

that hang about the city, theeves, horse-stealers, whoremongers,

cozeners, cony-catching persons, practicers of treason, and such other

like,"[25] led20 to drunkenness, frays, bloodshed, and often to general

disorder. Sometimes, as we know, turbulent apprentices and other

factions met by appointment at plays for the sole purpose of starting

riots or breaking open jails. "Upon Whitsunday," writes the Recorder

to Lord Burghley, "by reason no plays were the same day, all the city

was quiet."[26]

Trouble of an entirely different kind arose when in the hot months of

the summer the plague was threatening. The meeting together at plays

of "great multitudes of the basest sort of people" served to spread

the infection throughout the city more quickly and effectively than

could anything else. On such occasions it was exceedingly difficult

for the municipal authorities to control the actors, who were at best

a stubborn and unruly lot; and often the pestilence had secured a full

start before acting could be suppressed.

These troubles, and others which cannot here be mentioned, made one of

the Lord Mayors exclaim in despair: "The Politique State and

Government of this City by no one thing is so greatly annoyed and

disquieted as by players and plays, and the disorders which follow

thereupon."[27]

This annoyance, serious enough in itself, was aggravated by the fact

that most of the troupes21 were under the patronage of great noblemen,

and some were even high in favor with the Queen. As a result, the

attempts on the part of the Lord Mayor and his Aldermen to regulate

the players were often interfered with by other or higher authority.

Sometimes it was a particular nobleman, whose request was not to be

ignored, who intervened in behalf of his troupe; most often, however,

it was the Privy Council, representing the Queen and the nobility in

general, which championed the cause of the actors and countermanded

the decrees of the Lord Mayor and his brethren. One of the most

notable things in the City's Remembrancia is this long conflict of

authority between the Common Council and the Privy Council over actors

and acting.

In 1573 the situation seems to have approached a crisis. The Lord

Mayor had become strongly puritanical, and in his efforts to suppress

"stage-plays" was placing more and more obstacles in the way of the

actors. The temper of the Mayor is revealed in two entries in the

records of the Privy Council. On July 13, 1573, the Lords of the

Council sent a letter to him requesting him "to permit liberty to

certain Italian players"; six days later they sent a second letter,

repeating the request, and "marveling that he did it not at their

first request."[28] His continued efforts to suppress the drama

finally led the troupes to appeal for re22lief to the Privy Council. On

March 22, 1574, the Lords of the Council dispatched "a letter to the

Lord Mayor to advertise their Lordships what causes he hath to

restrain plays." His answer has not been preserved, but that he

persisted in his hostility to the drama is indicated by the fact that

in May the Queen openly took sides with the players. To the Earl of

Leicester's troupe she issued a special royal license, authorizing

them to act "as well within our city of London and liberties of the

same, as also within the liberties and freedoms of any our cities,

towns, boroughs, etc., whatsoever"; and to the mayors and other

officers she gave strict orders not to interfere with such

performances: "Willing and commanding you, and every of you, as ye

tender our pleasure, to permit and suffer them herein without any your

lets, hindrances, or molestation during the term aforesaid, any act,

statute, proclamation, or commandment heretofore made, or hereafter to

be made, to the contrary notwithstanding."

This license was a direct challenge to the authority of the Lord

Mayor. He dared not answer it as directly; but on December 6, 1574, he

secured from the Common Council the passage of an ordinance which

placed such heavy restrictions upon acting as virtually to nullify the

license issued by the Queen, and to regain for the Mayor complete

control of the drama within the city. The Preamble of this remarkable

ordinance23 clearly reveals the puritanical character of the City

Government:

Whereas heretofore sundry great disorders and inconveniences

have been found to ensue to this city by the inordinate

haunting of great multitudes of people, specially youths, to

plays, interludes, and shews: namely, occasion of frays and

quarrels; evil practises of incontinency in great inns

having chambers and secret places adjoining to their open

stages and galleries; inveigling and alluring of maids,

specially orphans and good citizens' children under age, to

privy and unmeet contracts; the publishing of unchaste,

uncomly, and unshamefaced speeches and doings; withdrawing

of the Queen's Majesty's subjects from divine service on

Sundays and holy days, at which times such plays were

chiefly used; unthrifty waste of the money of the poor and

fond persons; sundry robberies by picking and cutting of

purses; uttering of popular, busy, and seditious matters;

and many other corruptions of youth, and other enormities;

besides that also sundry slaughters and maimings of the

Queen's subjects have happened by ruins of scaffolds,

frames, and stages, and by engines, weapons, and powder used

in plays. And whereas in time of God's visitation by the

plague such assemblies of the people in throng and press

have been very dangerous for spreading of infection.... And

for that the Lord Mayor and his brethren the Aldermen,

together with the grave and discreet citizens in the Common

Council assembled, do doubt and fear lest upon God's

merciful withdrawing his hand of sickness from us (which God

grant), the people, specially the meaner and most unruly

sort, should with sudden forgetting of His visitation,

without24 fear of God's wrath, and without due respect of the

good and politique means that He hath ordained for the

preservation of common weals and peoples in health and good

order, return to the undue use of such enormities, to the

great offense of God....[29]

The restrictions on playing imposed by the ordinance may be briefly

summarized:

1. Only such plays should be acted as were free from all unchastity,

seditiousness, and "uncomely matter."

2. Before being acted all plays should be "first perused and allowed

in such order and form, and by such persons as by the Lord Mayor and

Court of Aldermen for the time being shall be appointed."

3. Inns or other buildings used for acting, and their proprietors,

should both be licensed by the Lord Mayor and the Aldermen.

4. The proprietors of such buildings should be "bound to the

Chamberlain of London" by a sufficient bond to guarantee "the keeping

of good order, and avoiding of" the inconveniences noted in the

Preamble.

5. No plays should be given during the time of sickness, or during any

inhibition ordered at any time by the city authorities.

6. No plays should be given during "any usual time of divine service,"

and no persons should be25 admitted into playing places until after

divine services were over.

7. The proprietors of such places should pay towards the support of

the poor a sum to be agreed upon by the city authorities.

In order, however, to avoid trouble with the Queen, or those noblemen

who were accustomed to have plays given in their homes for the private

entertainment of themselves and their guests, the Common Council

added, rather grudgingly, the following proviso:

Provided alway that this act (otherwise than touching the

publishing of unchaste, seditious, and unmeet matters) shall

not extend to any plays, interludes, comedies, tragedies, or

shews to be played or shewed in the private house, dwelling,

or lodging of any nobleman, citizen, or gentleman, which

shall or will then have the same there so played or shewed

in his presence for the festivity of any marriage, assembly

of friends, or other like cause, without public or common

collections of money of the auditory or beholders thereof.

Such regulations if strictly enforced would prove very annoying to the

players. But, as the Common Council itself informs us, "these orders

were not then observed." The troupes continued to play in the city,

protected against any violent action on the part of the municipal

authorities by the known favor of the Queen and the frequent

interference of the Privy Council. This state of affairs was not, of

course, comfortable for the actors;26 but it was by no means desperate,

and for several years after the passage of the ordinance of 1574 they

continued without serious interruption to occupy their inn-playhouses.

The long-continued hostility of the city authorities, however, of

which the ordinance of 1574 was an ominous expression, led more or

less directly to the construction of special buildings devoted to

plays and situated beyond the jurisdiction of the Common Council. As

the Reverend John Stockwood, in A Sermon Preached at Paules Crosse,

1578, indignantly puts it:

Have we not houses of purpose, built with great charges

for the maintenance of plays, and that without the

liberties, as who would say "There, let them say what they

will say, we will play!"

Thus came into existence playhouses; and with them dawned a new era in

the history of the English drama.

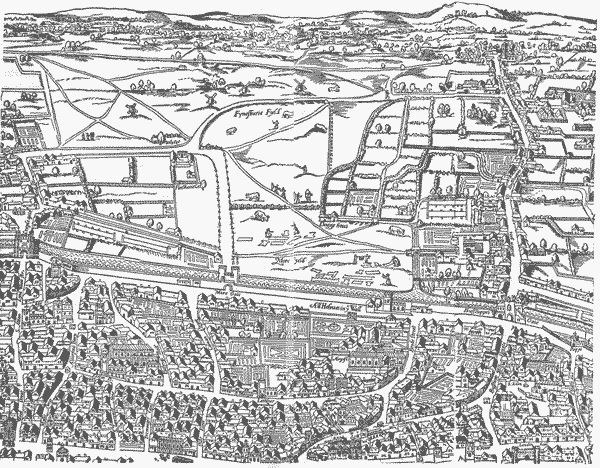

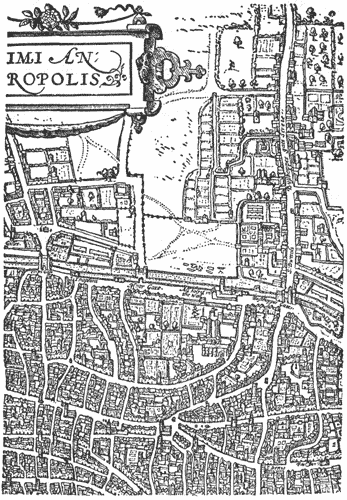

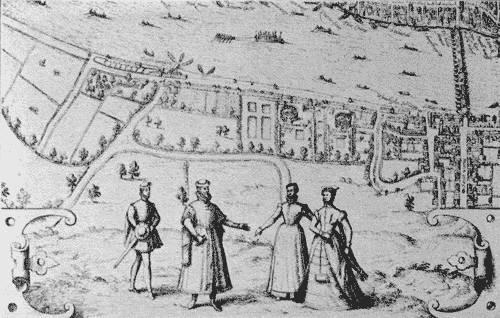

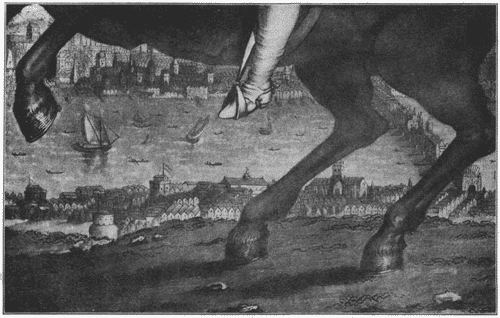

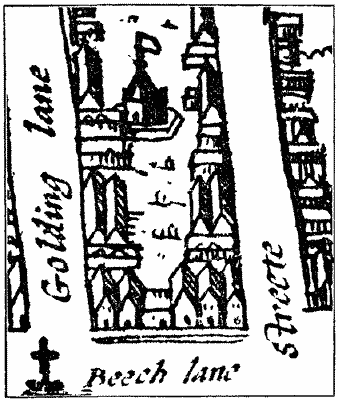

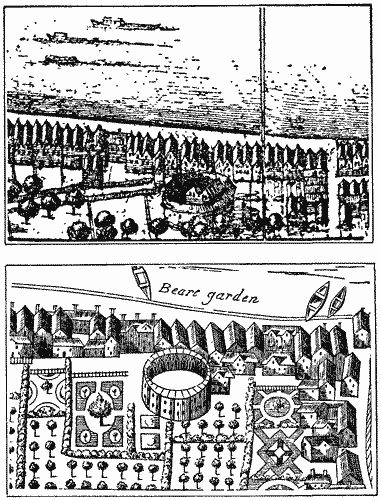

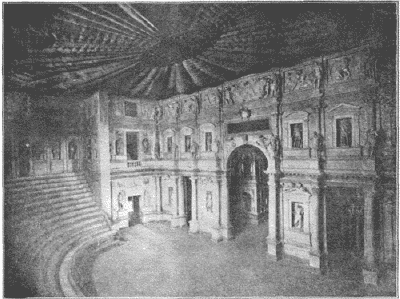

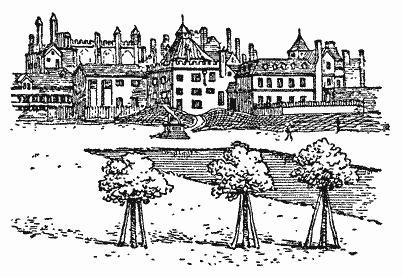

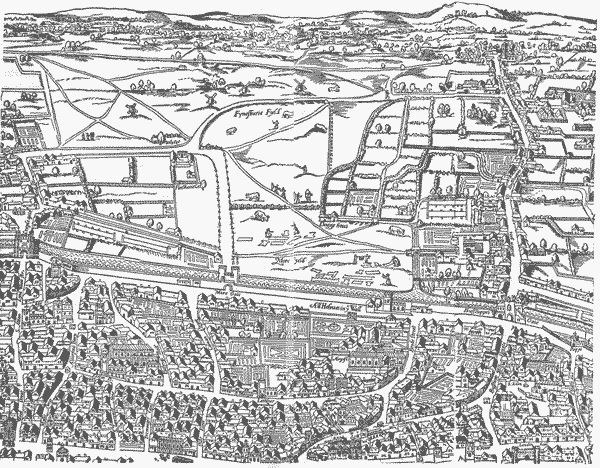

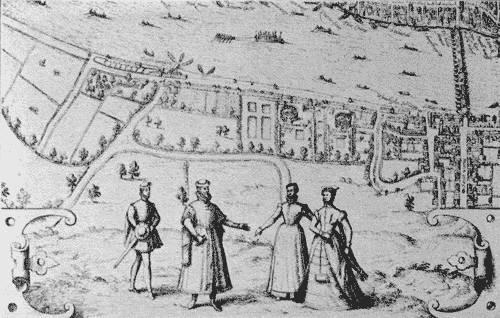

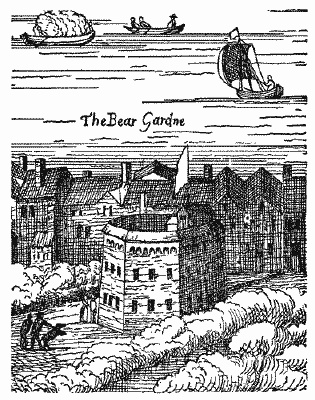

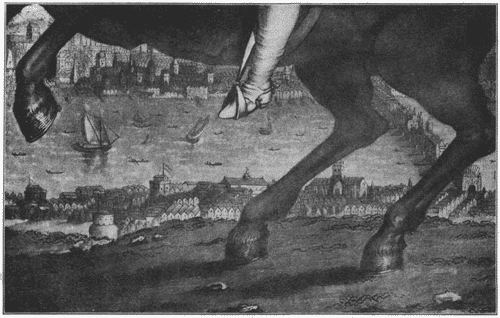

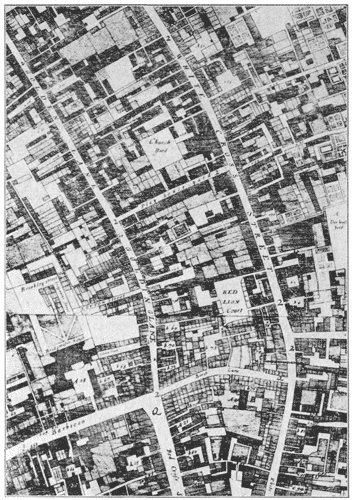

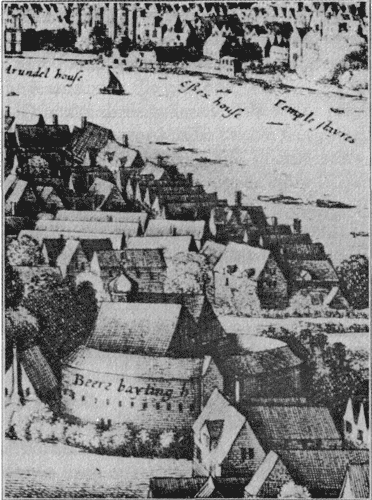

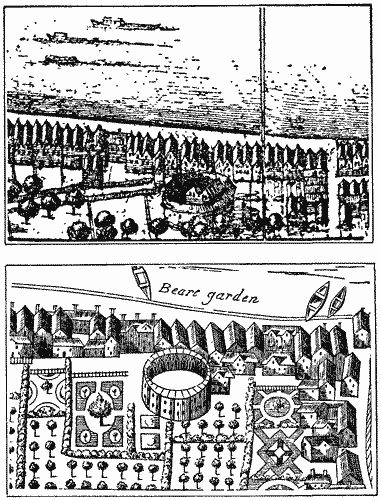

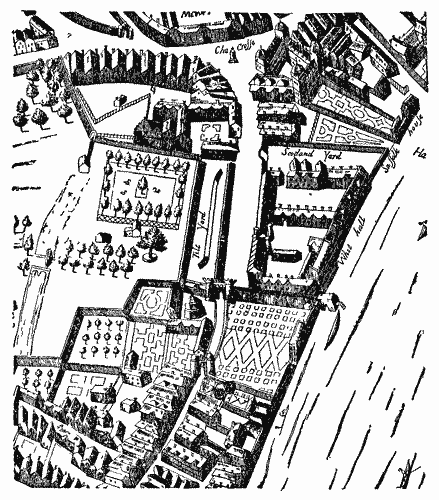

THE SITE OF THE FIRST PLAYHOUSES

Finsbury Field and Holywell. The man walking from the Field towards

Shoreditch is just entering Holywell Lane.

(From Agas's Map of London, representing the city

as it was about 1560.)

[Enlarge]

27

CHAPTER III

THE THEATRE

THE hostility of the city to the drama was unquestionably the main

cause of the erection of the first playhouse; yet combined with this

were two other important causes, usually overlooked. The first was the

need of a building specially designed to meet the requirements of the

players and of the public, a need yearly growing more urgent as plays

became more complex, acting developed into a finer art, and audiences

increased in dignity as well as in size. The second and the more

immediate cause was the appearance of a man with business insight

enough to see that such a building would pay. The first playhouse, we

should remember, was not erected by a troupe of actors, but by a

money-seeking individual.[30] Although he was himself an actor, and

the manager of a troupe, he did not, it seems, take the troupe into

his confidence. In complete independence of any theatrical

organization he pro28ceeded with the erection of his building as a

private speculation; and, we are told, he dreamed of the "continual

great profit and commodity through plays that should be used there

every week."

This man, "the first builder of playhouses,"—and, it might have been

added, the pioneer in a new field of business,—was James Burbage,

originally, as we are told by one who knew him well, "by occupation a

joiner; and reaping but a small living by the same, gave it over and

became a common player in plays."[31] As an actor he was more

successful, for as early as 1572 we find him at the head of

Leicester's excellent troupe.

Having in 1575 conceived the notion of erecting a building specially

designed for dramatic entertainments, he was at once confronted with

the problem of a suitable location. Two conditions narrowed his

choice: first, the site had to be outside the jurisdiction of the

Common Council; secondly, it had to be as near as possible to the

city.

No doubt he at once thought of the two suburbs that were specially

devoted to recreation, the Bankside to the south, and Finsbury Field

to the north of the city. The Bankside had for many years been

associated in the minds of Londoners with "sports and pastimes."

Thither the citizens were accustomed to go to witness bear-baiting29

and bull-baiting, to practice archery, and to engage in various

athletic sports. Thither, too, for many years the actors had gone to

present their plays. In 1545 King Henry VIII had issued a proclamation

against vagabonds, ruffians, idle persons, and common players,[32] in

which he referred to their "fashions commonly used at the Bank." The

Bankside, however, was associated with the lowest and most vicious

pleasures of London, for here were situated the stews, bordering the

river's edge. Since the players were at this time subject to the

bitterest attacks from the London preachers, Burbage wisely decided

not to erect the first permanent home of the drama in a locality

already a common target for puritan invective.

The second locality, Finsbury Field, had nearly all the advantages,

and none of the disadvantages, of the Bankside. Since 1315 the Field

had been in the possession of the city,[33] and had been used as a

public playground, where families could hold picnics, falconers could

fly their hawks, archers could exercise their sport, and the militia

on holidays could drill with all "the pomp and circumstance of

glorious war." In short, the Field was eminently respectable, was

accessible to the city, and was definitely associated with the idea of

en30tertainment. The locality, therefore, was almost ideal for the

purpose Burbage had in mind.[34]

The new playhouse, of course, could not be erected in the Field

itself, which was under the control of the city; but just to the east

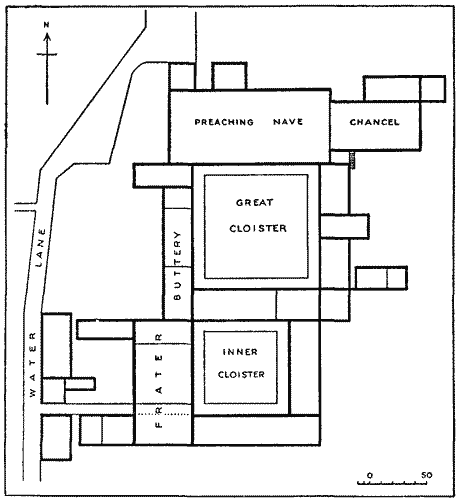

of the Field certain vacant land, part of the dissolved Priory of

Holywell, offered a site in every way suitable to the purpose. The

Holywell property, at the dissolution of the Priory, had passed under

the jurisdiction of the Crown, and hence the Lord Mayor and the

Aldermen could not enforce municipal ordinances there. Moreover, it

was distant from the city wall not much more than half a mile. The old

conventual church had been demolished, the Priory buildings had been

converted into residences, and the land near the Shoreditch highway

had been built up with numerous houses. The land next to the Field,

however, was for the most part undeveloped. It contained some

dilapidated tenements, a few old barns formerly belonging to the

Priory, and small garden plots, conspicuous objects in the early maps.

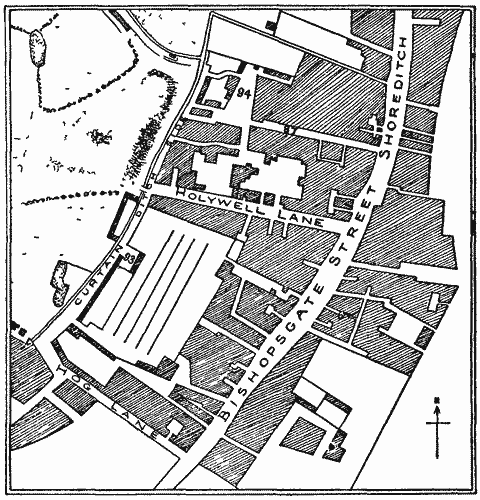

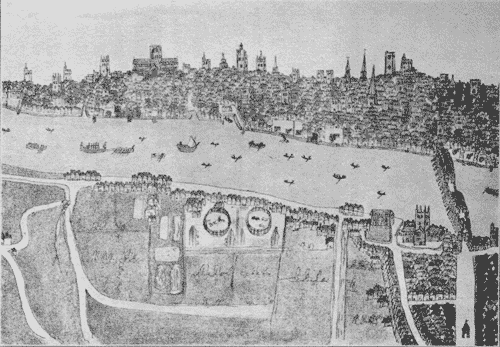

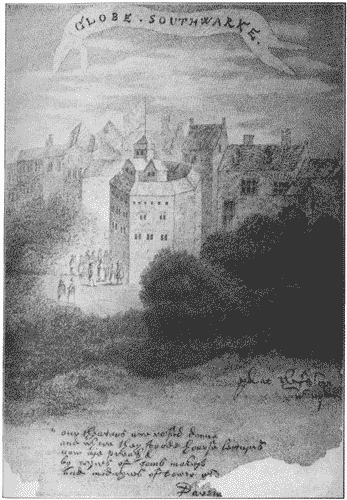

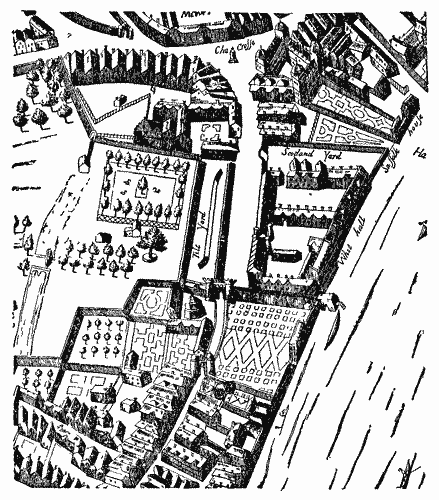

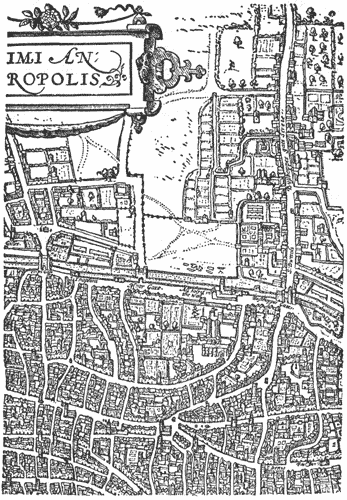

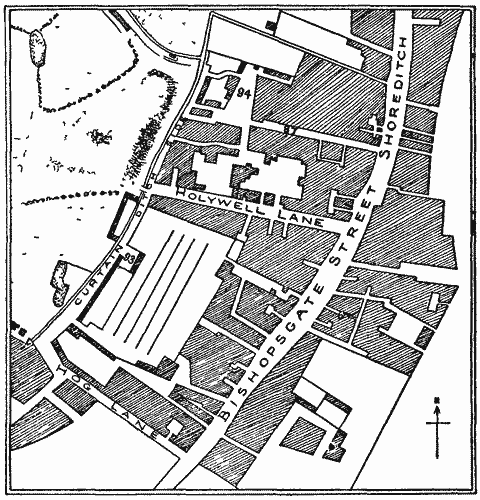

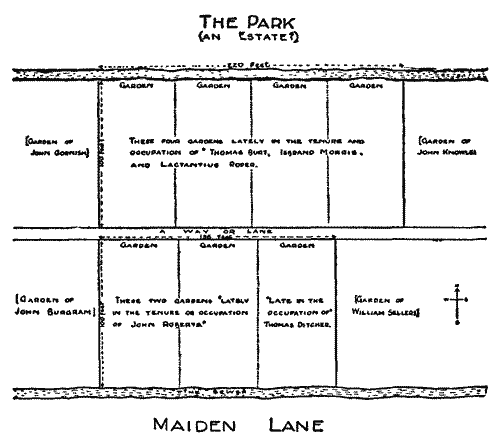

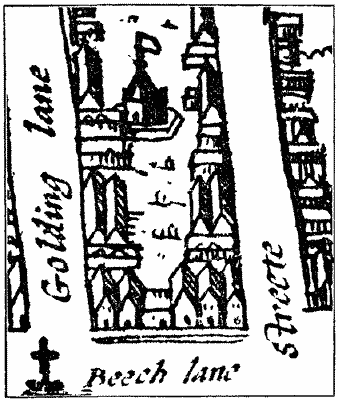

THE SITE OF THE FIRST PLAYHOUSES

Finsbury Field lies to the north (beyond Moor Field, the small

rectangular space next to the city wall), and the Holywell Property

lies to the right of Finsbury Field, between the Field and the

highway. Holywell Lane divides the garden plots; the Theatre was

erected just to the north, and the Curtain just to the south of this

lane, facing the Field. (From the Map of London by Braun and Hogenbergius

representing the city as it was in 1554-1558.)

[Enlarge]

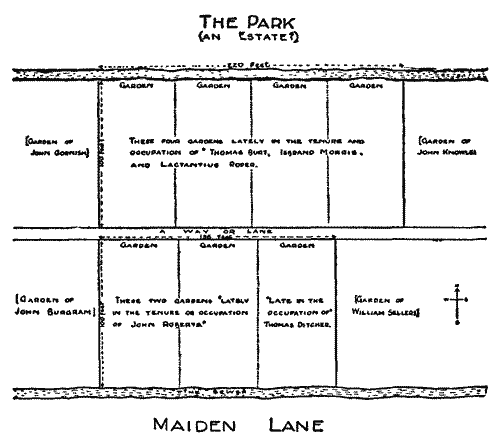

Burbage learned that a large portion of this land lying next to the

Field was in the possession of a well-to-do gentleman named Gyles

Alleyn,[35] and32 that Alleyn was willing to lease a part of his

holding on the conditions of development customary in this section of

London. These conditions are clearly revealed in a chancery suit of

1591:

The ground there was for the most part converted first into

garden plots, and then leasing the same to diverse tenants

caused them to covenant or promise to build upon the same,

by occasion whereof the buildings which are there were for

the most part erected and the rents increased.[36]

The part of Alleyn's property on which Burbage had his eye was in sore

need of improvement. It consisted of five "paltry tenements,"

described as "old, decayed, and ruinated for want of reparation, and

the best of them was but of two stories high," and a long barn "very

ruinous and decayed and ready to have fallen down," one half of which

was used as a storage-room, the other half as a slaughter-house. Three

of the tenements had small gardens extending back to the Field, and

just north of the barn was a bit of "void ground," also adjoining the

Field. It was this bit of "void ground" that Burbage had selected as a

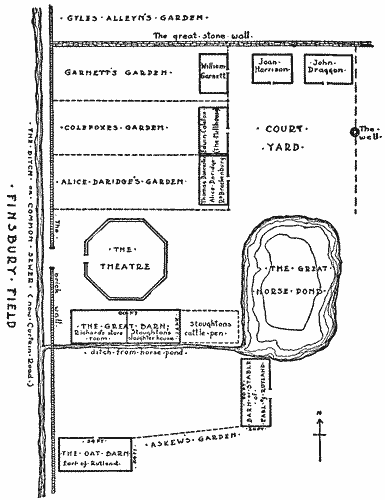

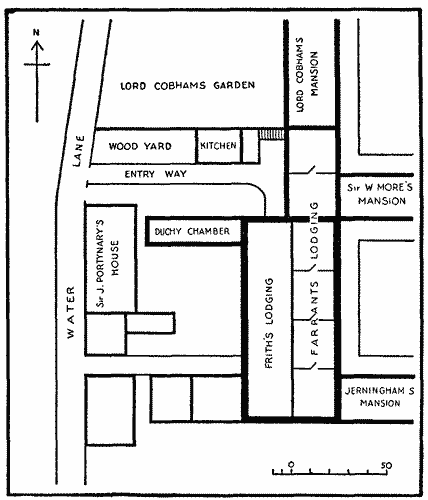

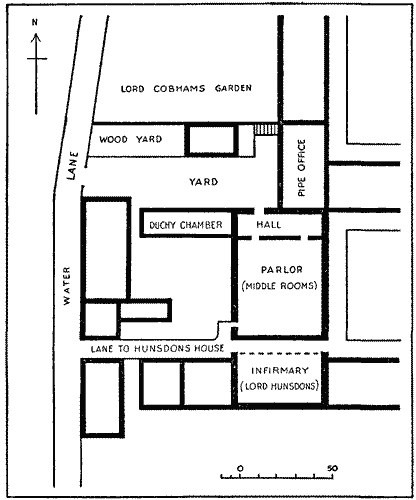

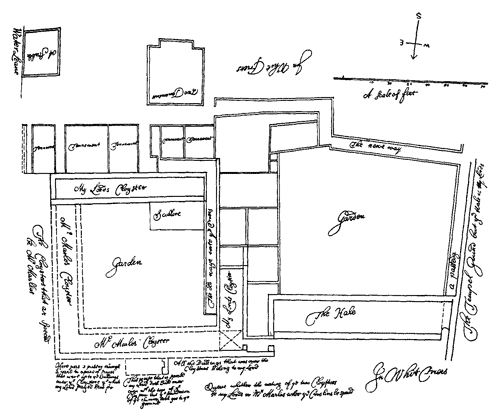

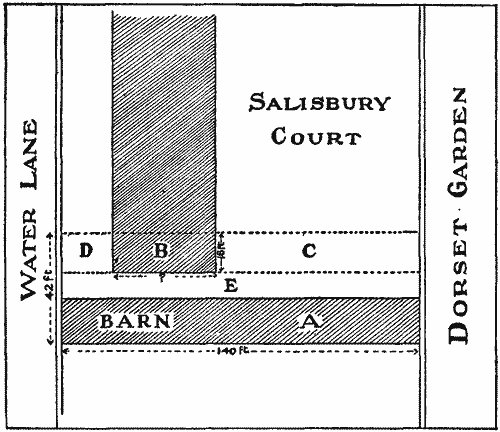

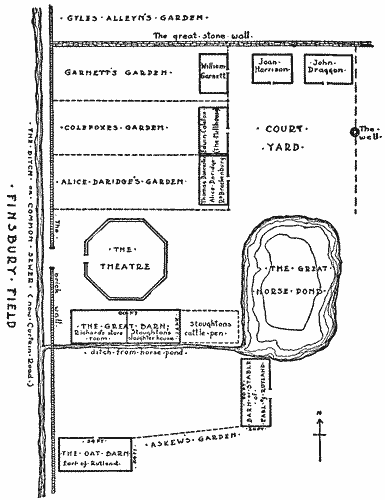

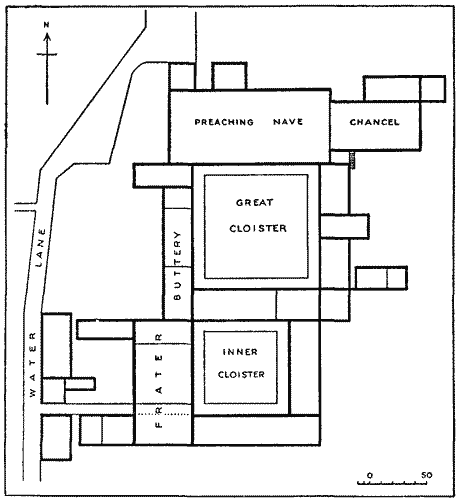

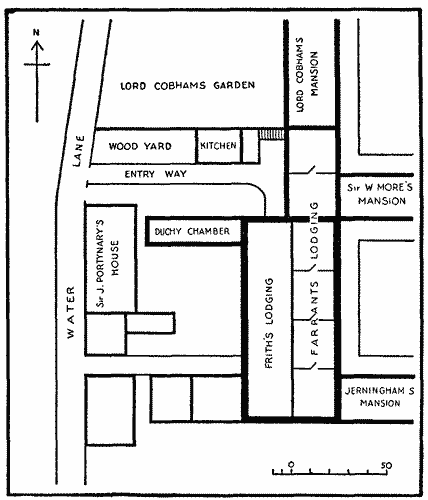

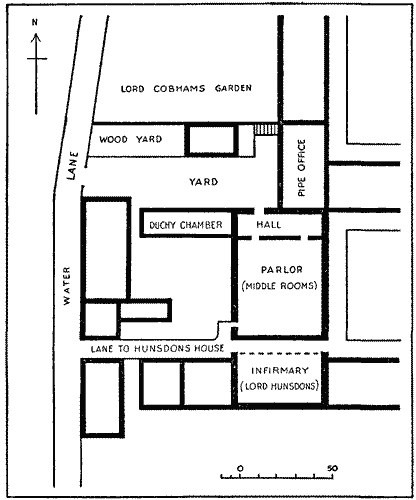

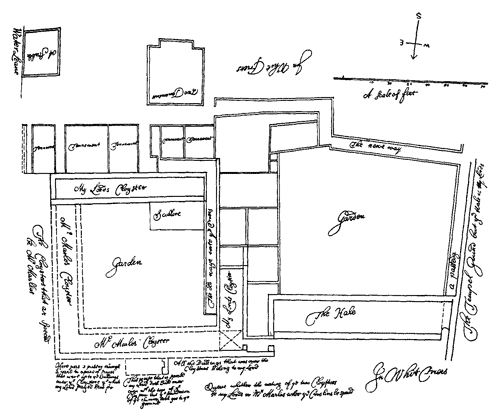

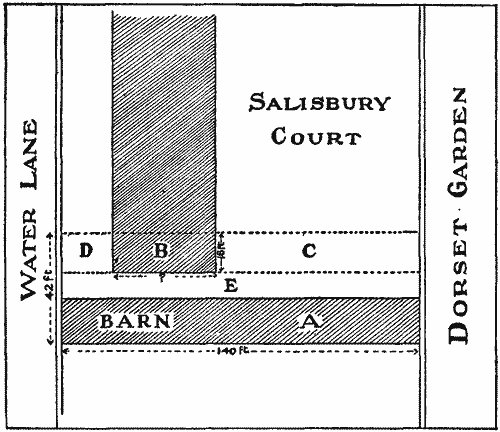

suitable location for his proposed playhouse. The accompanying map of

the property[37] will make clear the position of this "void ground"

and of the barns and34 tenements about it. Moreover, it will serve to

indicate the exact site of the Theatre. If one will bear in mind the

fact that in the London of to-day Curtain Road marks the eastern

boundary of Finsbury Field, and New Inn Yard cuts off the lower half

of the Great Barn, he will be able to place Burbage's structure within

a few yards.[38]

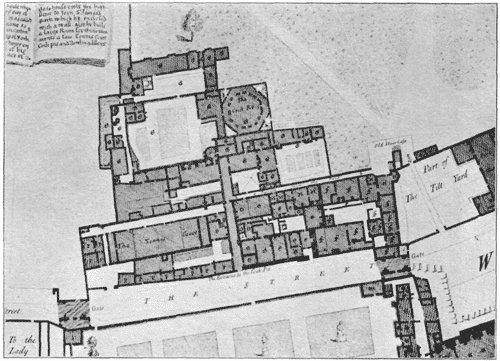

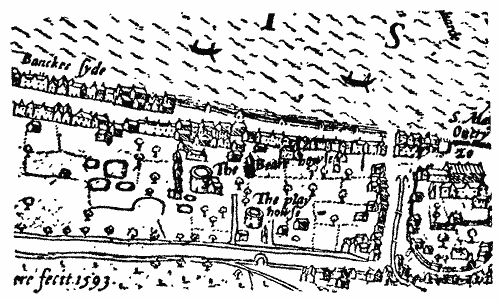

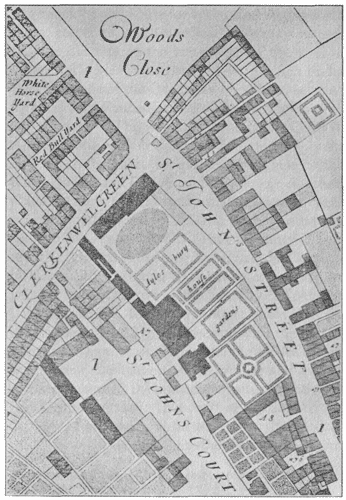

A PLAN OF BURBAGE'S HOLYWELL PROPERTY

Based on the lease, and on the miscellaneous documents

printed by Halliwell-Phillipps and by Braines. The "common sewer" is now marked

by Curtain Road, and the "ditch from the horse-pond" by New Inn Yard.

[Enlarge]

The property is carefully described in the lease—quoted below—which

Burbage secured from Alleyn, but the reader will need to refer to the

map in order to follow with ease the several paragraphs of

description:[39]

All those two houses or tenements, with appurtenances, which

at the time of the said former demise made were in the

several tenures or occupations of Joan Harrison, widow, and

John Dragon.

And also all that house or tenement with the appurtenances,

together with the garden ground lying behind part of the

same, being then likewise in the occupation of William

Gardiner; which said garden plot doth extend in breadth from

a great stone wall there which doth enclose part of the

garden then or lately being in the occupation of the said

Gyles, unto the garden there then in the occupation of Edwin

Colefox, weaver, and in length from the same35 house or

tenement unto a brick wall there next unto the fields

commonly called Finsbury Fields.

And also all that house or tenement, with the appurtenances,

at the time of the said former demise made called or known

by the name of the Mill-house; together with the garden

ground lying behind part of the same, also at the time of

the said former demise made being in the tenure or

occupation of the aforesaid Edwin Colefox, or of his

assigns; which said garden ground doth extend in length from

the same house or tenement unto the aforesaid brick wall

next unto the aforesaid Fields.

And also all those three upper rooms, with the

appurtenances, next adjoining to the aforesaid Mill-house,

also being at the time of the said former demise made in the

occupation of Thomas Dancaster, shoemaker, or of his

assigns; and also all the nether rooms, with the

appurtenances, lying under the same three upper rooms, and

next adjoining also to the aforesaid house or tenement

called the Mill-house, then also being in the several

tenures or occupations of Alice Dotridge, widow, and Richard

Brockenbury, or of their assigns; together with the garden

ground lying behind the same, extending in length from the

same nether rooms down unto the aforesaid brick wall next

unto the aforesaid Fields, and then or late being also in

the tenure or occupation of the aforesaid Alice Dotridge.

And also so much of the ground and soil lying and being

afore all the tenements or houses before granted, as

extendeth in length from the outward part of the aforesaid

tenements being at the time of the making of the said former

demise in the occupation of the aforesaid Joan Harrison and

John Dragon, unto a pond there being next unto the barn or

stable then36 in the occupation of the right honorable the

Earl of Rutland or of his assigns, and in breadth from the

aforesaid tenement or Mill-house to the midst of the well

being afore the same tenements.

And also all that Great Barn, with the appurtenances, at the

time of the making of the said former demise made being in

the several occupations of Hugh Richards, innholder, and

Robert Stoughton, butcher; and also a little piece of ground

then inclosed with a pale and next adjoining to the

aforesaid barn, and then or late before that in the

occupation of the said Robert Stoughton; together also with

all the ground and soil lying and being between the said

nether rooms last before expressed, and the aforesaid Great

Barn, and the aforesaid pond; that is to say, extending in

length from the aforesaid pond unto a ditch beyond the brick

wall next the aforesaid Fields.

And also the said Gyles Alleyn and Sara his wife do by these

presents demise, grant, and to farm lett unto the said James

Burbage all the right, title, and interest which the said

Gyles and Sara have or ought to have in or to all the

grounds and soil lying between the aforesaid Great Barn and

the barn being at the time of the said former demise in the

occupation of the Earl of Rutland or of his assigns,

extending in length from the aforesaid pond and from the

aforesaid stable or barn then in the occupation of the

aforesaid Earl of Rutland or of his assigns, down to the

aforesaid brick wall next the aforesaid Fields.[40]37

And also the said Gyles and Sara do by these presents

demise, grant, and to farm lett to the said James all the

said void ground lying and being betwixt the aforesaid ditch

and the aforesaid brick wall, extending in length from the

aforesaid [great stone] wall[41] which encloseth part of the

aforesaid garden being at the time of the making of the said

former demise or late before that in the occupation of the

said Gyles Allen, unto the aforesaid barn then in the

occupation of the aforesaid Earl or of his assigns.

The lease was formally signed on April 13, 1576, and Burbage entered

into the possession of his property. Since the terms of the lease are

important for an understanding of the subsequent history of the

playhouse, I shall set these forth briefly:

First, the lease was to run for twenty-one years from April 13, 1576,

at an annual rental of £14.

Secondly, Burbage was to spend before the expiration of ten years the

sum of £200 in rebuilding and improving the decayed tenements.

Thirdly, in view of this expenditure of £200, Burbage was to have at

the end of the ten years the right to renew the lease at the same

rental of £14 a year for twenty-one years, thus making the lease good

in all for thirty-one years:

And the said Gyles Alleyn and Sara his wife did thereby

covenant with the said James Burbage that they should and

would at any time within the ten38 years next ensuing at or

upon the lawful request or demand of the said James Burbage

make or cause to be made to the said James Burbage a new

lease or grant like to the same presents for the term of one

and twenty years more, to begin from the date of making the

same lease, yielding therefor the rent reserved in the

former indenture.[42]

Fourthly, it was agreed that at any time before the expiration of the

lease, Burbage might take down and carry away to his own use any

building that in the mean time he might have erected on the vacant

ground for the purpose of a playhouse:

And farther, the said Gyles Alleyn and Sara his wife did

covenant and grant to the said James Burbage that it should

and might be lawful to the said James Burbage (in

consideration of the imploying and bestowing the foresaid

two hundred pounds in forme aforesaid) at any time or times

before the end of the said term of one and twenty years, to

have, take down, and carry away to his own proper use for

ever all such buildings and other things as should be

builded, erected, or set up in or upon the gardens and void

grounds by the said James, either for a theatre or playing

place, or for any other lawful use, without any stop, claim,

let, trouble, or interruption of the said Gyles Alleyn and

Sara his wife.[43]

Protected by these specific terms, Burbage proceeded to the erection

of his playhouse. He must39 have had faith and abundant courage, for he

was a poor man, quite unequal to the large expenditures called for by

his plans. A person who had known him for many years, deposed in 1592

that "James Burbage was not at the time of the first beginning of the

building of the premises worth above one hundred marks[44] in all his

substance, for he and this deponent were familiarly acquainted long

before that time and ever since."[45] We are not surprised to learn,

therefore, that he was "constrained to borrow diverse sums of money,"

and that he actually pawned the lease itself to a money-lender.[46]

Even so, without assistance, we are told, he "should never be able to

build it, for it would cost five times as much as he was worth."

Fortunately he had a wealthy brother-in-law, John Brayne,[47] a London

grocer, described as "worth five hundred pounds at the least, and by

common fame worth a thousand marks."[48] In some way Brayne became

interested in the new venture. Like Burbage, he believed that large

profits would flow from such a novel undertaking; and as a result he

readily agreed to share the expense of erecting and maintaining the

building.40 Years later members of the Brayne faction asserted that

James Burbage "induced" his brother-in-law to venture upon the

enterprise by unfairly representing the great profits to ensue;[49]

but the evidence, I think, shows that Brayne eagerly sought the

partnership. Burbage himself asserted in 1588 that Brayne "practiced

to obtain some interest therein," and presumed "that he might easily

compass the same by reason that he was natural brother"; and that he

voluntarily offered to "bear and pay half the charges of the said

building then bestowed and thereafter to be bestowed" in order "that

he might have the moiety[50] of the above named Theatre."[51] As a

further inducement, so the Burbages asserted, he promised that "for

that he had no children," the moiety at his death should go to the

children of James Burbage, "whose advancement he then seemed greatly

to tender."

Whatever caused Brayne to interest himself in the venture, he quickly

became fired with such hopes of great gain that he not only spent upon

the building all the money he could gather or borrow, but sold his

stock of groceries for £146, disposed of his house for £100, even

pawned his clothes, and put his all into the new structure. The spirit

in which he worked to make the venture a success, and the personal

sacrifices that he41 and his wife made, fully deserve the quotation

here of two legal depositions bearing on the subject:

This deponent, being servant, in Bucklersbury, aforesaid, to

one Robert Kenningham, grocer, in which street the said John

Brayne dwelled also, and of the same trade, he, the said

Brayne, at the time he joined with the said James Burbage in

the aforesaid lease, was reputed among his neighbors to be

worth one thousand pounds at the least, and that after he

had joined with the said Burbage in the matter of the

building of the said Theatre, he began to slack his own

trade, and gave himself to the building thereof, and the

chief care thereof he took upon him, and hired workmen of

all sorts for that purpose, bought timber and all other

things belonging thereunto, and paid all. So as, in this

deponent's conscience, he bestowed thereupon for his owne

part the sum of one thousand marks at the least, in so much

as his affection was given so greatly to the finishing

thereof, in hope of great wealth and profit during their

lease, that at the last he was driven to sell to this

deponent's father his lease of the house wherein he dwelled

for £100, and to this deponent all such wares as he had left

and all that belonged thereunto remaining in the same, for

the sum of £146 and odd money, whereof this deponent did pay

for him to one Kymbre, an ironmonger in London, for iron

work which the said Brayne bestowed upon the said Theatre,

the sum of £40. And afterwards the said Brayne took the

matter of the said building so upon him as he was driven to

borrow money to supply the same, saying to this deponent

that his brother Burbage was not able to help the same, and

that he found42 not towards it above the value of fifty

pounds, some part in mony and the rest in stuff.[52]

In reading the next deposition, one should bear in mind the fact that

the deponent, Robert Myles, was closely identified with the Brayne

faction, and was, therefore, a bitter enemy to the Burbages. Yet his

testimony, though prejudiced, gives us a vivid picture of Brayne's

activity in the building of the Theatre:

So the said John Brayne made a great sum of money of purpose

and intent to go to the building of the said playhouse, and

thereupon did provide timber and other stuff needful for the

building thereof, and hired carpenters and plasterers for

the same purpose, and paid the workmen continually. So as he

for his part laid out of his own purse and what upon credit

about the same to the sum of £600 or £700 at the least. And

in the same time, seeing the said James Burbage nothing able

either of himself or by his credit to contribute any like

sum towards the building thereof, being then to be finished

or else to be lost that had been bestowed upon it already,

the said Brayne was driven to sell his house he dwelled in

in Bucklersbury, and all his stock that was left, and give

up his trade, yea in the end to pawn and sell both his own

garments and his wife's, and to run in debt to many for

money, to finish the said playhouse, and so to employ

himself only upon that matter, and all whatsoever he could

make, to his utter undoing, for he saieth that in the latter

end of the finishing thereof, the said Brayne and his wife,

the now complainants, were driven to labor in43 the said work

for saving of some of the charge in place of two laborers,

whereas the said James Burbage went about his own business,

and at sometimes when he did take upon him to do some thing

in the said work, he would be and was allowed a workman's

hire as other the workman there had.[53]

The last fling at Burbage is quite gratuitous; yet it is probably true

that the main costs of erecting the playhouse fell upon the shoulders

of Brayne. The evidence is contradictory; some persons assert that

Burbage paid half the cost of the building,[54] others that Brayne

paid nearly all,[55] and still others content themselves with saying

that Brayne paid considerably more than half. The last statement may

be accepted as true. The assertion of Gyles Alleyn in 1601, that the

Theatre was "erected at the costs and charges of one Brayne and not of

the said James Burbage, to the value of one thousand marks,"[56] is

doubtless incorrect; more correct is the assertion of Robert Myles,

executor of the Widow Brayne's will, in 1597: "The said John Brayne

did join with the said James [Burbage] in the building aforesaid, and

did expend thereupon greater sums than the said James, that is to say,

at least five or six hundred44 pounds."[57] Since there is evidence

that the playhouse ultimately cost about £700,[58] we might hazard the

guess that of this sum Brayne furnished about £500,[59] and Burbage

about £200. To equalize the expenditure it was later agreed that "the

said Brayne should take and receive all the rents and profits of the

said Theatre to his own use until he should be answered such sums of

money which he had laid out for and upon the same Theatre more than

the said Burbage had done."[60]

But if Burbage at the outset was "nothing able to contribute any"

great sum of ready money towards the building of the first playhouse,

he did contribute other things equally if not more important. In the

first place, he conceived the idea, and he carried it as far towards

realization as his means allowed. In the second place, he planned the

building—its stage as well as its auditorium—to meet the special

demands of the actors and the comfort of the audience. This called for

bold originality and for ingenuity of a high order, for, it must be

remembered, he had no model to study—he was designing the first

structure of its kind in England.[61] For this task45 he was well

prepared. In the first place, he was an actor of experience; in the

second place, he was the manager of one of the most important troupes

in England; and, in the third place, he was by training and early

practice a carpenter and builder. In other words, he had exact

knowledge of what was needed, and the practical skill to meet those

needs.

The building that he designed and erected he named—as by virtue of

priority he had a right to do—"The Theatre."

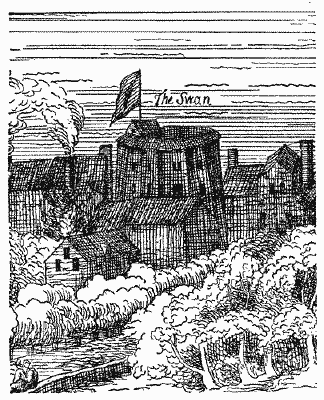

Of the Theatre, unfortunately, we have no pictorial representation,

and no formal description, so that our knowledge of its size, shape,

and general arrangement must be derived from scattered and

miscellaneous sources. That the building was large we may feel sure;

the cost of its erection indicates as much. The Fortune, one of46 the

largest and handsomest of the later playhouses, cost only £520, and

the Hope, also very large, cost £360. The Theatre, therefore, built at

a cost of £700, could not have been small. It is commonly referred to,

even so late as 1601, as "the great house called the Theatre," and the

author of Skialetheia (1598) applied to it the significant adjective

"vast." Burbage, no doubt, had learned from his experience as manager

of a troupe the pecuniary advantage of having an auditorium large

enough to receive all who might come. Exactly how many people his

building could accommodate we cannot say. The Reverend John Stockwood,

in 1578, exclaims bitterly: "Will not a filthy play, with the blast of

a trumpet, sooner call thither a thousand than an hour's tolling of

the bell bring to the sermon a hundred?"[62] And Fleetwood, the City

Recorder, in describing a quarrel which took place in 1584 "at Theatre

door," states that "near a thousand people" quickly assembled when the

quarrel began.

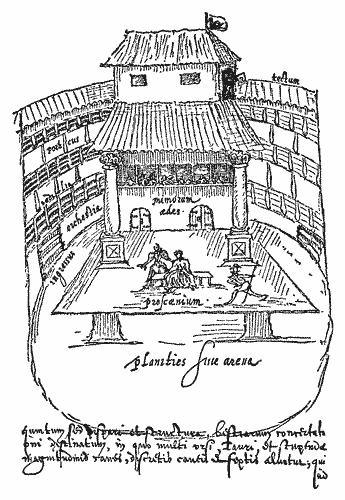

In shape the building was probably polygonal, or circular. I see no

good reason for supposing that it was square; Johannes de Witt

referred to it as an "amphitheatre," and the Curtain, erected the

following year in imitation, was probably polygonal.[63] It was built

of timber, and its exterior,47 no doubt, was—as in the case of

subsequent playhouses—of lime and plaster. The interior consisted of

three galleries surrounding an open space called the "yard." The

German traveler, Samuel Kiechel, who visited London in the autumn of

1585, described the playhouses—i.e., the Theatre and the Curtain—as

"singular [sonderbare] houses, which are so constructed that they

have about three galleries, one above the other."[64] And Stephen

Gosson, in Plays Confuted (c. 1581) writes: "In the playhouses at

London, it is the fashion for youths to go first into the yard, and to

carry their eye through every gallery; then, like unto ravens, where

they spy the carrion, thither they fly, and press as near to the

fairest as they can." The "yard" was unroofed, and all persons there

had to stand during the entire performance. The galleries, however,

were protected by a roof, were divided into "rooms," and were provided

for the most part with seats. Gyles Alleyn inserted in the lease he

granted to Burbage the following condition:

And further, that it shall or may [be] lawful for the said

Gyles and for his wife and family, upon lawful request

therefor made to the said James Burbage, his executors or

assigns, to enter or come into48 the premises, and there in

some one of the upper rooms to have such convenient place to

sit or stand to see such plays as shall be there played,

freely without anything therefor paying.[65]

The stage was a platform, projecting into the yard, with a

tiring-house at the rear, and a balcony overhead. The details of the

stage, no doubt, were subject to alteration as experience suggested,

for its materials were of wood, and histrionic and dramatic art were

both undergoing rapid development.[66] The furnishings and

decorations, as in the case of modern playhouses, seem to have been

ornate. Thus T[homas] W[hite], in A Sermon Preached at Pawles Crosse,

on Sunday the Thirde of November, 1577, exclaims: "Behold the

sumptuous Theatre houses, a continual monument of London's

prodigality"; John Stockwood, in A Sermon Preached at Paules Cross,

1578, refers to it as "the gorgeous playing place erected in the

Fields"; and Gabriel Harvey could think of no more appropriate epithet

for it than "painted"—"painted theatres," "painted stage."

The building was doubtless used for dramatic performances in the

autumn of 1576, although it was not completed until later; John

Grigges, one of the carpenters, deposed that Burbage and49 Brayne

"finished the same with the help of the profits that grew by plays

used there before it was fully finished."[67] Access to the playhouse

was had chiefly by way of Finsbury Field and a passage made by Burbage

through the brick wall mentioned in the lease.[68]

The terms under which the owners let it to the actors were simple: the

actors retained as their share the pennies paid at the outer doors for

general admission, and the proprietors received as their share the

money paid for seats or standings in the galleries.[69] Cuthbert

Burbage states in 1635: "The players that lived in those first times

had only the profits arising from the doors, but now the players

receive all the comings in at the doors to themselves, and half the

galleries."[70]

Before the expiration of two years, or in the early summer of 1578,

Burbage and Brayne began to quarrel about the division of the money

which fell to their share. Brayne apparently thought that he should at

once be indemnified for all the money he had expended on the playhouse

in excess of Burbage; and he accused Burbage of "indirect

dealing"—there were even whispers of "a secret key" to the "common

box" in which the50 money was kept.[71] Finally they agreed to "submit

themselves to the order and arbitrament of certain persons for the

pacification thereof," and together they went to the shop of a notary

public to sign a bond agreeing to abide by the decision of the

arbitrators. There they "fell a reasoning together," in the course of

which Brayne asserted that he had disbursed in the Theatre "three

times at the least as much more as the sum then disbursed by the said

James Burbage." In the end Brayne unwisely hinted at "ill dealing" on

the part of Burbage, whereupon "Burbage did there strike him with his

fist, and so they went together by the ears, in so much," says the

notary, "that this deponent could hardly part them." After they were

parted, they signed a bond of £200 to abide by the decision of the

arbitrators. The arbitrators, John Hill and Richard Turnor, "men of

great honesty and credit," held their sessions "in the Temple church,"

whither they summoned witnesses. Finally, on July 12, 1578, after

"having thoroughly heard" both sides, they awarded that the profits

from the Theatre should be used first to pay the debts upon the

building, then to pay Brayne the money he had expended in excess of

Burbage, and thereafter to be shared "in divident equally between

them."[72] These conditions,51 however, were not observed, and the

failure to observe them led to much subsequent discord.

The arbitrators also decided that "if occasion should move them

[Burbage and Brayne] to borrow any sum of money for the payment of

their debts owing for any necessary use and thing concerning the said

Theatre, that then the said James Burbage and the said John Brayne

should join in pawning or mortgageing of their estate and interest

of and in the same."[73] An occasion for borrowing money soon arose.

So on September 26, 1579, the two partners mortgaged the Theatre to

John Hide for the sum of £125 8s. 11d. At the end of a year, by

non-payment, they forfeited the mortgage, and the legal title to the

property passed to Hide. It seems, however, that because of some

special clause in the mortgage Hide was unable to expel Burbage and

Brayne, or to dispose of the property to others. Hence he took no

steps to seize the Theatre; but he constantly annoyed the occupants by

arrest and otherwise. This unfortunate transference of the title to

Hide was the cause of serious quarreling between the Burbages and the

Braynes, and finally led to much litigation.

In 1582 a more immediate disaster threatened the owners of the

Theatre. One Edmund Peckham laid claim to the land on which the

playhouse had been built, and brought suit against Alleyn for

recovery. More than that, Peckham tried to52 take actual possession of

the playhouse, so that Burbage "was fain to find men at his own charge

to keep the possession thereof from the said Peckham and his

servants," and was even "once in danger of his own life by keeping

possession thereof." As a result of this state of affairs, Burbage

"was much disturbed and troubled in his possession of the Theatre, and

could not quietly and peaceably enjoy the same. And therefore the

players forsook the said Theatre, to his great loss."[74] In order to

reimburse himself in some measure for this loss Burbage retained £30

of the rental due to Alleyn. The act led to a bitter quarrel with

Alleyn, and figured conspicuously in the subsequent litigation that

came near overwhelming the Theatre.

In 1585 Burbage, having spent the stipulated £200 in repairing and

rebuilding the tenements on the premises, sought to renew the lease,

according to the original agreement, for the extended period of

twenty-one years. On November 20, 1585, he engaged three skilled

workmen to view the buildings and estimate the sum he had disbursed in

improvements. They signed a formal statement to the effect that in

their opinion at least £220 had been thus expended on the premises.

Burbage then "tendered unto the said Alleyn a new lease devised by his

counsel, ready written and engrossed, with labels and wax thereunto

affixed, agreeable to the covenant." But Alleyn53 refused to sign the

document. He maintained that the new lease was not a verbatim copy of

the old lease, that £200 had not been expended on the buildings, and

that Burbage was a bad tenant and owed him rent. In reality, Alleyn

wanted to extort a larger rental than £14 for the property, which had

greatly increased in value.

On July 18, 1586, Burbage engaged six men, all expert laborers, to

view the buildings again and estimate the cost of the improvements.

They expressed the opinion in writing that Burbage had expended at

least £240 in developing the property.[75] Still Alleyn refused to

sign an extension of the lease. His conduct must have been very

exasperating to the owner of the Theatre. Cuthbert Burbage tells us

that his father "did often in gentle manner solicit and require the

said Gyles Alleyn for making a new lease of the said premises

according to the purporte and effect of the said covenant." But

invariably Alleyn found some excuse for delay.

The death of Brayne, in August, 1586, led John Hide, who by reason of

the defaulted mortgage was legally the owner of the Theatre, to

redouble his efforts to collect his debt. He "gave it out in speech

that he had set over and assigned the said lease and bonds to one

George Clough, his ... father-in-law (but in truth he did not so),"

and "the said Clough, his father-in-law, did go about54 to put the said

defendant [Burbage] out of the Theatre, or at least did threaten to

put him out." As we have seen, there was a clause in the mortgage

which prevented Hide from ejecting Burbage;[76] yet Clough was able to

make so much trouble, "divers and sundry times" visiting the Theatre,

that at last Burbage undertook to settle the debt out of the profits

of the playhouse. As Robert Myles deposed in 1592, Burbage allowed the

widow of Brayne for "a certain time to take and receive the one-half

of the profits of the galleries of the said Theatre ... then on a

sudden he would not suffer her to receive any more of the profits

there, saying that he must take and receive all till he had paid the

debts. And then she was constrained, as his servant, to gather the

money and to deliver it unto him."[77]

For some reason, however, the debt was not settled, and Hide continued

his futile demands. Several times Burbage offered to pay the sum in

full if the title of the Theatre were made over to his son Cuthbert

Burbage; and Brayne's widow made similar offers in an endeavor to gain

the entire property for herself. But Hide, who seems to have been an

honest man, always declared that since Burbage and Brayne "did jointly

mortgage it unto him" he was honor-bound to assign the property back

to Burbage and the widow of Brayne jointly. So matters stood for a

while.55

At last, however, in 1589, Hide declared that "since he had forborne

his money so long, he could do it no more, so as they that came first

should have it of him." Thereupon Cuthbert Burbage came bringing not

only the money in hand, but also a letter from his master and patron,

Walter Cape, gentleman usher to the Lord High Treasurer, requesting

Hide to make over the Theatre to Cuthbert, and promising in return to

assist Hide with the Lord Treasurer when occasion arose. Under this

pressure, Hide accepted full payment of his mortgage, and made over

the title of the property to Cuthbert Burbage. Thus Brayne's widow was

legally excluded from any share in the ownership of the Theatre. Myles

deposed, in 1592, that henceforth Burbage "would not suffer her to

meddle in the premises, but thrust her out of all."

This led at once to a suit, in which Robert Myles acted for the widow.

He received an order from the Court of Chancery in her favor, and

armed with this, and accompanied by two other persons, he came on

November 16, 1590, to Burbage's "dwelling house near the Theatre,"

called to the door Cuthbert Burbage, and in "rude and exclamable sort"

demanded "the moiety of the said Theatre." James Burbage "being within

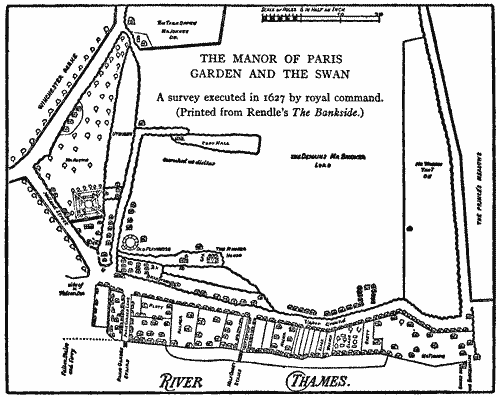

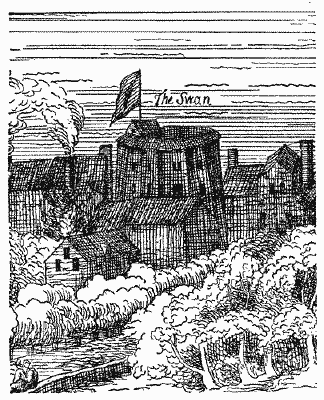

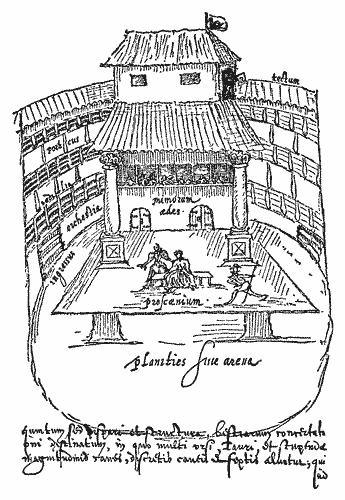

the house, hearing a noise at the door, went to the door, and there