Title: Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965

Author: Morris J. MacGregor

Release date: February 15, 2007 [eBook #20587]

Most recently updated: January 27, 2020

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20587

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

[Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, author's spelling has been retained.]

|

Alfred Goldberg Office of the Secretary of Defense |

Robert J. Watson Historical Division, Joint Chiefs of Staff |

|

Brig. Gen. James L. Collins, Jr. Chief of Military History |

Maj. Gen. John W. Huston Chief of Air Force History |

|

Maurice Matloff Center of Military History |

Stanley L. Falk Office of Air Force History |

|

Rear Adm. John D. H. Kane, Jr. Director of Naval History |

Brig. Gen. (Ret.) Edwin H. Simmons Director of Marine Corps History and Museums |

|

Dean C. Allard Naval Historical Center |

Henry J. Shaw, Jr. Marine Corps Historical Center |

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

MacGregor, Morris J

Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965.

(Defense studies series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Supt. of Docs. no.: D 114.2:In 8/940-65

1. Afro-American soldiers. 2. United States—

|

Race Relations. UB418.A47M33 |

I. Title. 335.3'3 |

II. Series. 80-607077 |

|

Otis A. Singletary University of Kentucky |

Maj. Gen. Robert C. Hixon U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command |

|

Brig. Gen. Robert Arter U.S. Army Command and General Staff College |

Sara D. Jackson National Historical Publications and Records Commission |

|

Harry L. Coles Ohio State University |

Maj. Gen. Enrique Mendez, Jr. Deputy Surgeon General, USA |

|

Robert H. Ferrell Indiana University |

James O'Neill Deputy Archivist of the United States |

|

Cyrus H. Fraker The Adjutant General Center |

Benjamin Quarles Morgan State College |

|

William H. Goetzmann University of Texas |

Brig. Gen. Alfred L. Sanderson Army War College |

|

Col. Thomas E. Griess U.S. Military Academy |

Russell F. Weigley Temple University |

The integration of the armed forces was a momentous event in our military and national history; it represented a milestone in the development of the armed forces and the fulfillment of the democratic ideal. The existence of integrated rather than segregated armed forces is an important factor in our military establishment today. The experiences in World War II and the postwar pressures generated by the civil rights movement compelled all the services—Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps—to reexamine their traditional practices of segregation. While there were differences in the ways that the services moved toward integration, all were subject to the same demands, fears, and prejudices and had the same need to use their resources in a more rational and economical way. All of them reached the same conclusion: traditional attitudes toward minorities must give way to democratic concepts of civil rights.

If the integration of the armed services now seems to have been inevitable in a democratic society, it nevertheless faced opposition that had to be overcome and problems that had to be solved through the combined efforts of political and civil rights leaders and civil and military officials. In many ways the military services were at the cutting edge in the struggle for racial equality. This volume sets forth the successive measures they and the Office of the Secretary of Defense took to meet the challenges of a new era in a critically important area of human relationships, during a period of transition that saw the advance of blacks in the social and economic order as well as in the military. It is fitting that this story should be told in the first volume of a new Defense Studies Series.

The Defense Historical Studies Program was authorized by the then Deputy Secretary of Defense, Cyrus Vance, in April 1965. It is conducted under the auspices of the Defense Historical Studies Group, an ad hoc body chaired by the Historian of the Office of the Secretary of Defense and consisting of the senior officials in the historical offices of the services and of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Volumes produced under its sponsorship will be interservice histories, covering matters of mutual interest to the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The preparation of each volume is entrusted to one of the service historical sections, in this case the Army's Center of Military History. Although the book was written by an Army historian, he was generously given access to the pertinent records of the other services and the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and this initial volume in the Defense Studies Series covers the experiences of all components of the Department of Defense in achieving integration.

|

Washington, D.C. 14 March 1980 |

James L. Collins, Jr. Brigadier General, USA Chief of Military History |

Morris J. MacGregor, Jr., received the A.B. and M.A. degrees in history from the Catholic University of America. He continued his graduate studies at the Johns Hopkins University and the University of Paris on a Fulbright grant. Before joining the staff of the U.S. Army Center of Military History in 1968 he served for ten years in the Historical Division of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He has written several studies for military publications including "Armed Forces Integration—Forced or Free?" in The Military and Society: Proceedings of the Fifth Military Symposium of the U.S. Air Force Academy. He is the coeditor with Bernard C. Nalty of the thirteen-volume Blacks in the United States Armed Forces: Basic Documents and with Ronald Spector of Voices of History: Interpretations in American Military History. He is currently working on a sequel to Integration of the Armed Forces which will also appear in the Defense Studies Series.

This book describes the fall of the legal, administrative, and social barriers to the black American's full participation in the military service of his country. It follows the changing status of the black serviceman from the eve of World War II, when he was excluded from many military activities and rigidly segregated in the rest, to that period a quarter of a century later when the Department of Defense extended its protection of his rights and privileges even to the civilian community. To round out the story of open housing for members of the military, I briefly overstep the closing date given in the title.

The work is essentially an administrative history that attempts to measure the influence of several forces, most notably the civil rights movement, the tradition of segregated service, and the changing concept of military efficiency, on the development of racial policies in the armed forces. It is not a history of all minorities in the services. Nor is it an account of how the black American responded to discrimination. A study of racial attitudes, both black and white, in the military services would be a valuable addition to human knowledge, but practically impossible of accomplishment in the absence of sufficient autobiographical accounts, oral history interviews, and detailed sociological measurements. How did the serviceman view his condition, how did he convey his desire for redress, and what was his reaction to social change? Even now the answers to these questions are blurred by time and distorted by emotions engendered by the civil rights revolution. Few citizens, black or white, who witnessed it can claim immunity to the influence of that paramount social phenomenon of our times.

At times I do generalize on the attitudes of both black and white servicemen and the black and white communities at large as well. But I have permitted myself to do so only when these attitudes were clearly pertinent to changes in the services' racial policies and only when the written record supported, or at least did not contradict, the memory of those participants who had been interviewed. In any case this study is largely history written from the top down and is based primarily on the written records left by the administrations of five presidents and by civil rights leaders, service officials, and the press.

Many of the attitudes and expressions voiced by the participants in the story are now out of fashion. The reader must be constantly on guard against viewing the beliefs and statements of many civilian and military officials out of context of the times in which they were expressed. Neither bigotry nor stupidity was the monopoly of some of the people quoted; their statements are important for what they tell us about certain attitudes of our society rather than for what they reveal (p. x) about any individual. If the methods or attitudes of some of the black spokesmen appear excessively tame to those who have lived through the 1960's, they too should be gauged in the context of the times. If their statements and actions shunned what now seems the more desirable, albeit radical, course, it should be given them that the style they adopted appeared in those days to be the most promising for racial progress.

The words black and Negro have been used interchangeably in the book, with Negro generally as a noun and black as an adjective. Aware of differing preferences in the black community for usage of these words, the author was interested in comments from early readers of the manuscript. Some of the participants in the story strongly objected to one word or the other. "Do me one favor in return for my help," Lt. Comdr. Dennis D. Nelson said, "never call me a black." Rear Adm. Gerald E. Thomas, on the other hand, suggested that the use of the term Negro might repel readers with much to learn about their recent past. Still others thought that the historian should respect the usage of the various periods covered in the story, a solution that would have left the volume with the term colored for most of the earlier chapters and Negro for much of the rest. With rare exception, the term black does not appear in twentieth century military records before the late 1960's. Fashions in words change, and it is only for the time being perhaps that black and Negro symbolize different attitudes. The author has used the words as synonyms and trusts that the reader will accept them as such. Professor John Hope Franklin, Mrs. Sara Jackson of the National Archives, and the historians and officials that constituted the review panel went along with this approach.

The second question of usage concerns the words integration and desegregation. In recent years many historians have come to distinguish between these like-sounding words. Desegregation they see as a direct action against segregation; that is, it signifies the act of removing legal barriers to the equal treatment of black citizens as guaranteed by the Constitution. The movement toward desegregation, breaking down the nation's Jim Crow system, became increasingly popular in the decade after World War II. Integration, on the other hand, Professor Oscar Handlin maintains, implies several things not yet necessarily accepted in all areas of American society. In one sense it refers to the "leveling of all barriers to association other than those based on ability, taste, and personal preference";[1] in other words, providing equal opportunity. But in another sense integration calls for the random distribution of a minority throughout society. Here, according to Handlin, the emphasis is on racial balance in areas of occupation, education, residency, and the like.

From the beginning the military establishment rightly understood that the breakup of the all-black unit would in a closed society necessarily mean more than mere desegregation. It constantly used the terms integration and equal treatment and opportunity to describe its racial goals. Rarely, if ever, does one find the word desegregation in military files that include much correspondence from (p. xi) the various civil rights organizations. That the military made the right choice, this study seems to demonstrate, for the racial goals of the Defense Department, as they slowly took form over a quarter of a century, fulfilled both of Professor Handlin's definitions of integration.

The mid-1960's saw the end of a long and important era in the racial history of the armed forces. Although the services continued to encounter racial problems, these problems differed radically in several essentials from those of the integration period considered in this volume. Yet there is a continuity to the story of race relations, and one can hope that the story of how an earlier generation struggled so that black men and women might serve their country in freedom inspires those in the services who continue to fight discrimination.

This study benefited greatly from the assistance of a large number of persons during its long years of preparation. Stetson Conn, chief historian of the Army, proposed the book as an interservice project. His successor, Maurice Matloff, forced to deal with the complexities of an interservice project, successfully guided the manuscript through to publication. The work was carried out under the general supervision of Robert R. Smith, chief of the General History Branch. He and Robert W. Coakley, deputy chief historian of the Army, were the primary reviewers of the manuscript, and its final form owes much to their advice and attention. The author also profited greatly from the advice of the official review panel, which, under the chairmanship of Alfred Goldberg, historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense, included Martin Blumenson; General J. Lawton Collins (USA Ret.); Lt. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. (USAF Ret.); Roy K. Davenport, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army; Stanley L. Falk, chief historian of the Air Force; Vice Adm. E. B. Hooper, Chief of Naval History; Professor Benjamin Quarles; Paul J. Scheips, historian, Center of Military History; Henry I. Shaw, chief historian of the U.S. Marine Corps; Loretto C. Stevens, senior editor of the Center of Military History; Robert J. Watson, chief historian of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; and Adam Yarmolinsky, former assistant to the Secretary of Defense.

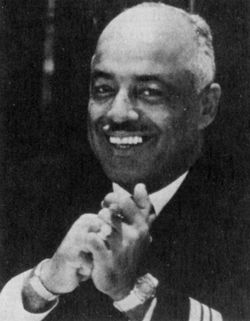

Many of the participants in this story generously shared their knowledge with me and kindly reviewed my efforts. My footnotes acknowledge my debt to them. Nevertheless, two are singled out here for special mention. James C. Evans, former counselor to the Secretary of Defense for racial affairs, has been an endless source of information on race relations in the military. If I sometimes disagreed with his interpretations and assessments, I never doubted his total dedication to the cause of the black serviceman. I owe a similar debt to Lt. Comdr. Dennis D. Nelson (USN Ret.) for sharing his intimate understanding of race relations in the Navy. A resourceful man with a sure social touch, he must have been one hell of a sailor.

I want to note the special contribution of several historians. Martin Blumenson was first assigned to this project, and before leaving the Center of Military History he assembled research material that proved most helpful. My former colleague John Bernard Corr prepared a study on the National Guard upon which my account of the guard is based. In addition, he patiently reviewed many pages of (p. xii) the draft manuscript. His keen insights and sensitive understanding were invaluable to me. Professors Jack D. Foner and Marie Carolyn Klinkhammer provided particularly helpful suggestions in conjunction with their reviews of the manuscript. Samuel B. Warner, who before his untimely death was a historian in the Joint Chiefs of Staff as well as a colleague of Lee Nichols on some of that reporter's civil rights investigations, also contributed generously of his talents and lent his support in the early days of my work. Finally, I am grateful for the advice of my colleague Ronald H. Spector at several key points in the preparation of this history.

I have received much help from archivists and librarians, especially the resourceful William H. Cunliffe and Lois Aldridge (now retired) of the National Archives and Dean C. Allard of the Naval Historical Center. Although the fruits of their scholarship appear often in my footnotes, three fellow researchers in the field deserve special mention: Maj. Alan M. Osur and Lt. Col. Alan L. Gropman of the U.S. Air Force and Ralph W. Donnelly, former member of the U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center. I have benefited from our exchange of ideas and have had the advantage of their reviews of the manuscript.

I am especially grateful for the generous assistance of my editors, Loretto C. Stevens and Barbara H. Gilbert. They have been both friends and teachers. In the same vein, I wish to thank John Elsberg for his editorial counsel. I also appreciate the help given by William G. Bell in the selection of the illustrations, including the loan of two rare items from his personal collection, and Arthur S. Hardyman for preparing the pictures for publication. I would like to thank Mary Lee Treadway and Wyvetra B. Yeldell for preparing the manuscript for panel review and Terrence J. Gough for his helpful pre-publication review.

Finally, while no friend or relative was spared in the long years I worked on this book, three colleagues especially bore with me through days of doubts and frustrations and shared my small triumphs: Alfred M. Beck, Ernest F. Fisher, Jr., and Paul J. Scheips. I also want particularly to thank Col. James W. Dunn. I only hope that some of their good sense and sunny optimism show through these pages.

|

Washington, D.C. 14 March 1980 |

Morris J. MacGregor, Jr. |

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION

The Armed forces Before 1940

Civil Rights and the Law in 1940

To Segregate Is To Discriminate

2. WORLD WAR II: THE ARMY

A War Policy: Reaffirming Segregation

Segregation and Efficiency

The Need for Change

Internal Reform: Amending Racial Practices

Two Exceptions

3. WORLD WAR II: THE NAVY

Development of a Wartime Policy

A Segregated Navy

Progressive Experiments

Forrestal Takes the Helm

4. WORLD WAR II: THE MARINE CORPS AND THE COAST GUARD

The First Black Marines

New Roles for Black Coast Guardsmen

5. A POSTWAR SEARCH

Black Demands

The Army's Grand Review

The Navy's Informal Inspection

6. NEW DIRECTIONS

The Gillem Board Report

Integration of the General Service

The Marine Corps

7. A PROBLEM OF QUOTAS

The Quota in Practice

Broader Opportunities

Assignments

A New Approach

The Quota System: An Assessment

8. SEGREGATION'S CONSEQUENCES

Discipline and Morale Among Black Troops

Improving the Status of the Segregated Soldier

(p. xiv)

Discrimination and the Postwar Army

Segregation in Theory and Practice

Segregation: An Assessment

9. THE POSTWAR NAVY

The Steward's Branch

Black Officers

Public Image and the Problem of Numbers

10. THE POSTWAR MARINE CORPS

Racial Quotas and Assignments

Recruitment

Segregation and Efficiency

Toward Integration

11. THE POSTWAR AIR FORCE

Segregation and Efficiency

Impulse for Change

12. THE PRESIDENT INTERVENES

The Truman Administration and Civil Rights

Civil Rights and the Department of Defense

Executive Order 9981

13. SERVICE INTERESTS VERSUS PRESIDENTIAL INTENT

Public Reaction to Executive Order 9981

The Army: Segregation on the Defensive

A Different Approach

The Navy: Business as Usual

Adjustments in the Marine Corps

The Air Force Plans for Limited Integration

14. THE FAHY COMMITTEE VERSUS THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

The Committee's Recommendations

A Summer of Discontent

Assignments

Quotas

An Assessment

15. THE ROLE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE, 1949-1951

Overseas Restrictions

Congressional Concerns

16. INTEGRATION IN THE AIR FORCE AND THE NAVY

The Air Force, 1949-1951

The Navy and Executive Order 9981

17. THE ARMY INTEGRATES

Race and Efficiency: 1950

Training

Performance of Segregated Units

Final Arguments

Integration of the Eighth Army

(p. xv)

Integration of the European and Continental Commands

18. INTEGRATION OF THE MARINE CORPS

Impetus for Change

Assignments

19. A NEW ERA BEGINS

The Civil Rights Revolution

Limitations on Executive Order 9981

Integration of Navy Shipyards

Dependent Children and Integrated Schools

20. LIMITED RESPONSE TO DISCRIMINATION

The Kennedy Administration and Civil Rights

The Department of Defense, 1961-1963

Discrimination Off the Military Reservation

Reserves and Regulars: A Comparison

21. EQUAL TREATMENT AND OPPORTUNITY REDEFINED

The Secretary Makes a Decision

The Gesell Committee

Reaction to a New Commitment

The Gesell Committee: Final Report

22. EQUAL OPPORTUNITY IN THE MILITARY COMMUNITY

Creating a Civil Rights Apparatus

Fighting Discrimination Within the Services

23. FROM VOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE TO SANCTIONS

Development of Voluntary Action Programs

Civil Rights, 1964-1966

The Civil Rights Act and Voluntary Compliance

The Limits of Voluntary Compliance

24. CONCLUSION

Why the Services Integrated

How the Services Integrated, 1946-1954

Equal Treatment and Opportunity

NOTE ON SOURCES

INDEX

Crewmen of the USS Miami During the Civil War

Buffalo Soldiers

Integration in the Army of 1888

(p. xvi)

Gunner's Gang on the USS Maine

General John J. (Black Jack) Pershing Inspects Troops

Heroes of the 369th Infantry, February 1919

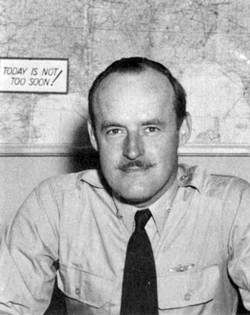

Judge William H. Hastie

General George C. Marshall and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson

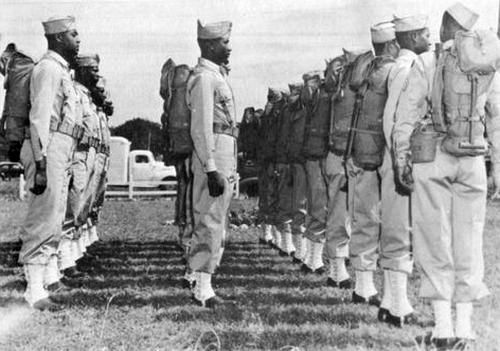

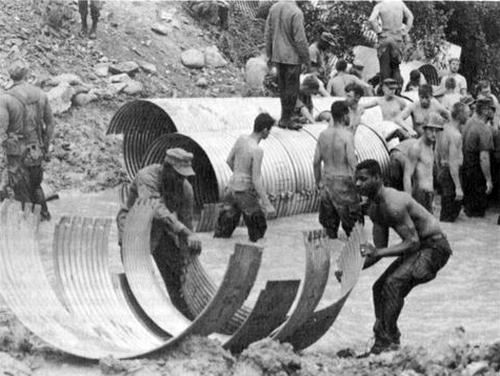

Engineer Construction Troops in Liberia, July 1942

Labor Battalion Troops in the Aleutian Islands, May 1943

Sergeant Addressing the Line

Pilots of the 332d Fighter Group

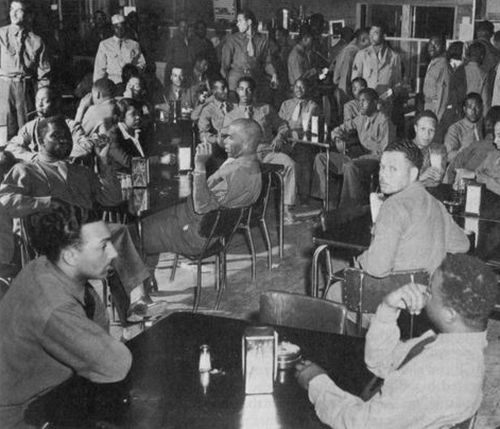

Service Club, Fort Huachuca

93d Division Troops in Bougainville, April 1944

Gun Crew of Battery B, 598th Field Artillery, September 1944

Tankers of the 761st Medium Tank Battalion Prepare for Action

WAAC Replacements

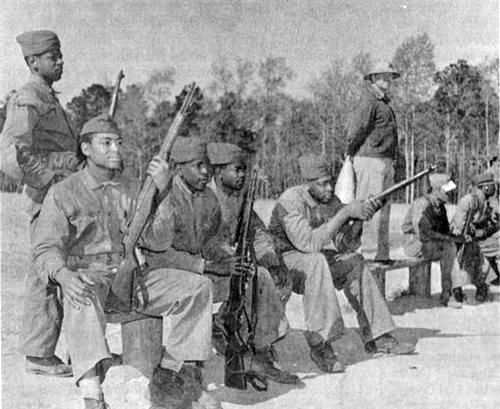

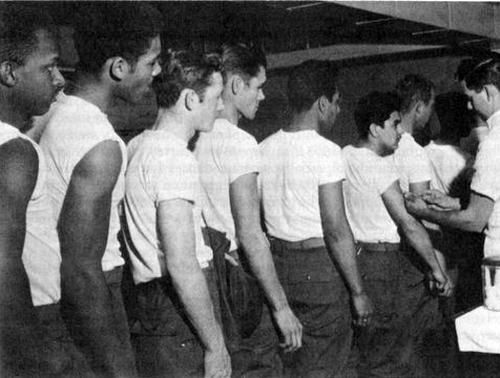

Volunteers for Combat in Training

Road Repairmen

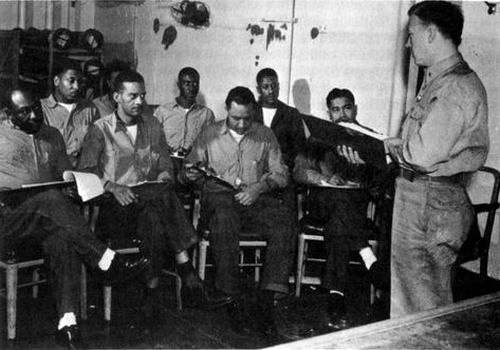

Mess Attendant, First Class, Dorie Miller Addressing Recruits at Camp Smalls

Admiral Ernest J. King and Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox

Crew Members of USS Argonaut, Pearl Harbor, 1942

Messmen Volunteer as Gunners, July 1942

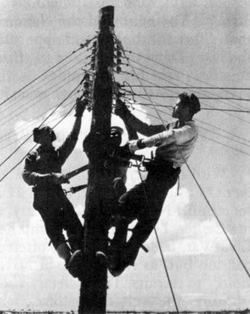

Electrician Mates String Power Lines

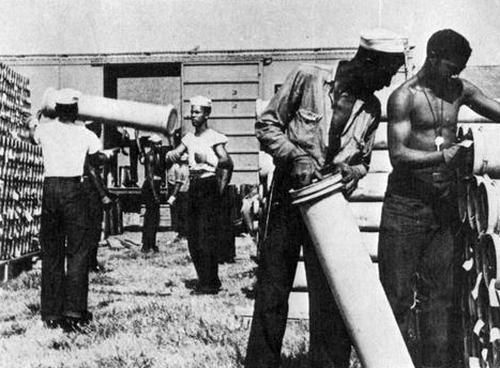

Laborers at Naval Ammunition Depot

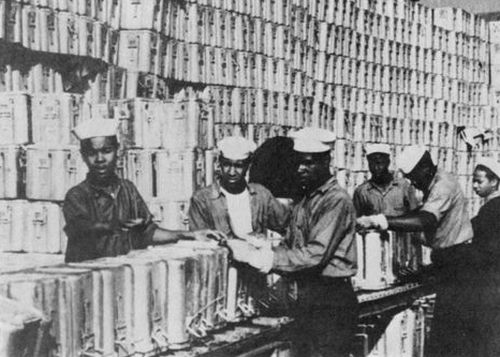

Seabees in the South Pacific

Lt. Comdr. Christopher S. Sargent

USS Mason

First Black Officers in the Navy

Lt. (jg.) Harriet Ida Pickens and Ens. Frances Wills

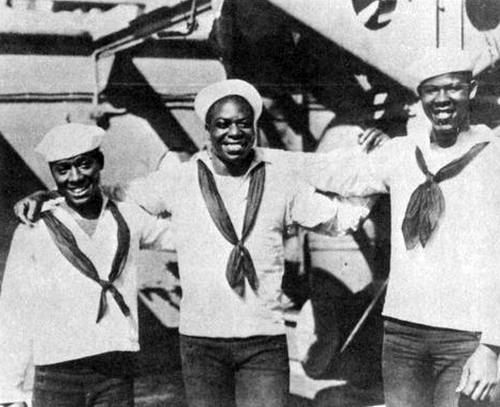

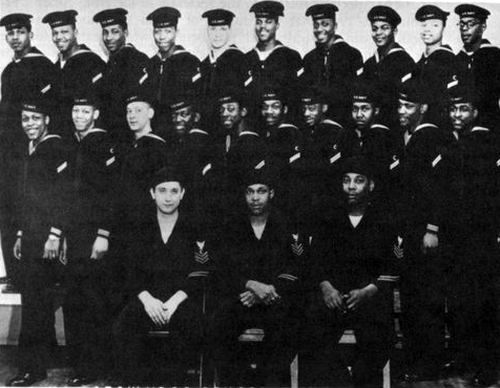

Sailors in the General Service

Security Watch in the Marianas

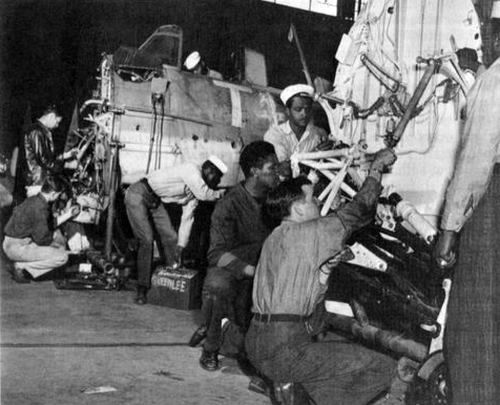

Specialists Repair Aircraft

The 22d Special Construction Battalion Celebrates V-J Day

Marines of the 51st Defense Battalion, Montford Point, 1942

Shore Party in Training, Camp Lejeune, 1942

D-day on Peleliu

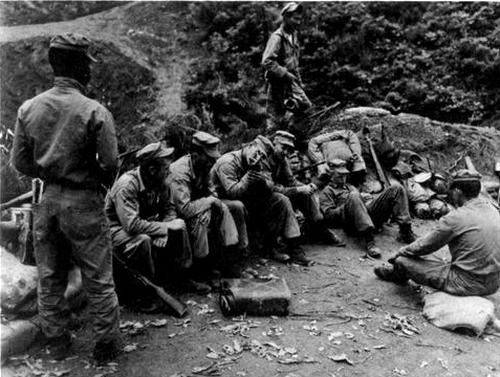

Medical Attendants at Rest, Peleliu, October 1944

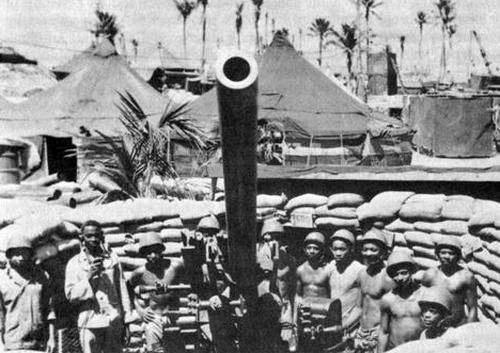

Gun Crew of the 52d Defense Battalion

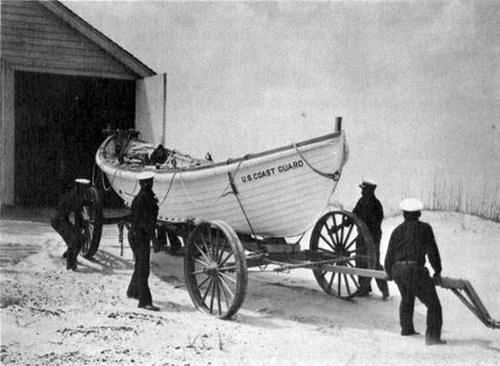

Crewmen of USCG Lifeboat Station, Pea Island, North Carolina

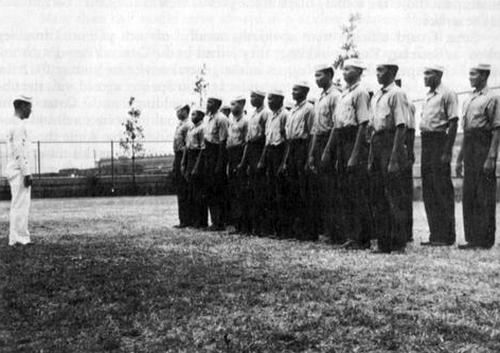

Coast Guard Recruits at Manhattan Beach Training Station, New York

Stewards at Battle Station on the Cutter Campbell

Shore Leave in Scotland

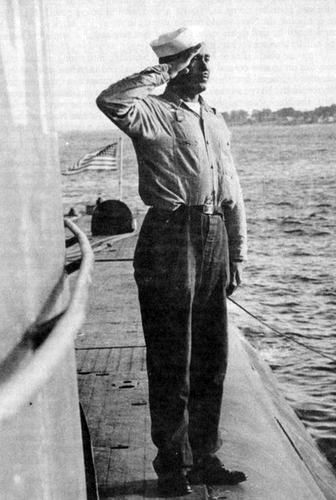

Lt. Comdr. Carlton Skinner and Crew of the USS Sea Cloud

Ens. Joseph J. Jenkins and Lt. (jg.) Clarence Samuels

President Harry S. Truman Addressing the NAACP Convention

Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy

(p. xvii)

Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War Truman K. Gibson

Company I, 370th Infantry, 92d Division, Advances Through Cascina, Italy

92d Division Engineers Prepare a Ford for Arno River Traffic

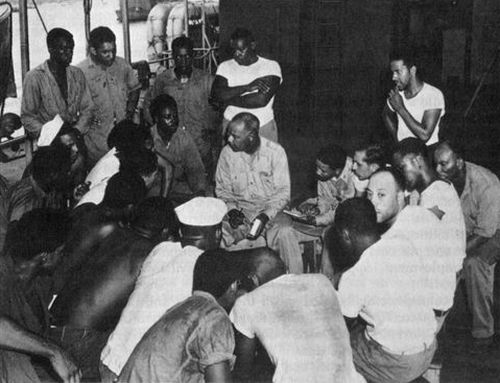

Lester Granger Interviewing Sailors

Granger With Crewmen of a Naval Yard Craft

Lt. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem, U.S. Army

Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson

Admiral Louis E. Denfeld, U.S. Navy

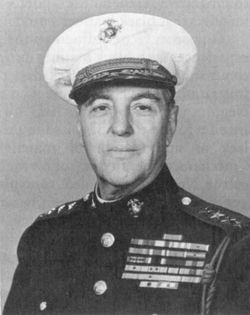

General Gerald C. Thomas, U.S. Marine Corps

Lt. Gen. Willard S. Paul

Adviser to the Secretary of War Marcus Ray

Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger Inspects 24th Infantry Troops

Army Specialists Report for Airborne Training

Bridge Players, Seaview Service Club, Tokyo, Japan, 1948

24th Infantry Band, Gifu, Japan, 1947

Lt. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner Inspects the 529th Military Police Company

Reporting to Kitzingen

Inspection by the Chief of Staff

Brig. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis, Sr.

Shore Leave in Korea

Mess Attendants, USS Bushnell, 1918

Mess Attendants, USS Wisconsin, 1953

Lt. Comdr. Dennis D. Nelson II

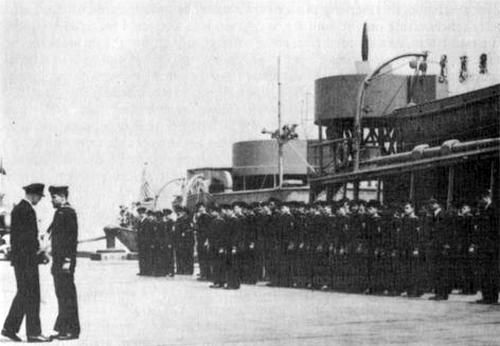

Naval Unit Passes in Review, Naval Advanced Base, Bremerhaven, Germany

Submariner

Marine Artillery Team

2d Lt. and Mrs. Frederick C. Branch

Training Exercises

Damage Inspection

Col. Noel F. Parrish

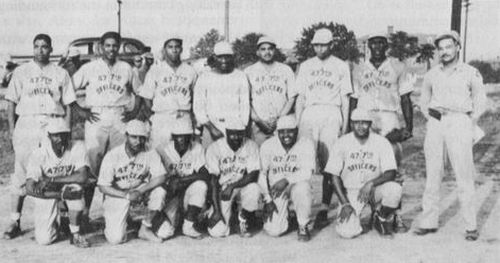

Officers' Softball Team

Checking Ammunition

Squadron F, 318th AAF Battalion, in Review

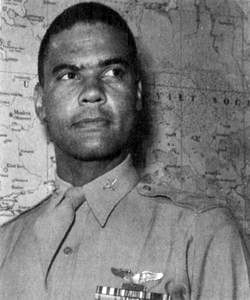

Col. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., Commander, 477th Composite Group, 1945

Lt. Gen. Idwal H. Edwards

Col. Jack F. Marr

Walter F. White

Truman's Civil Rights Campaign

A. Philip Randolph

National Defense Conference on Negro Affairs, 26 April 1948

MP's Hitch a Ride

Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall Reviews Military Police Battalion

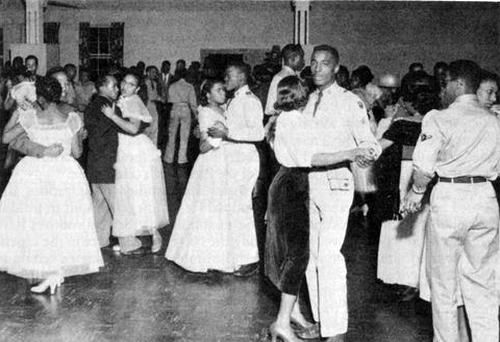

Spring Formal Dance, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, 1952

Secretary of Defense James V. Forrestal

(p. xviii)

General Clifton B. Cates

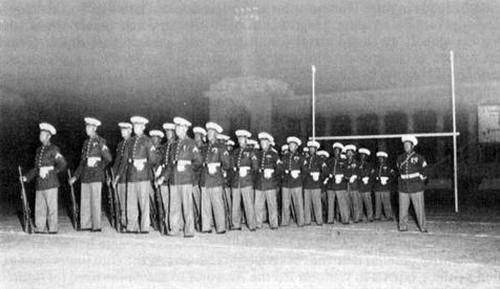

1st Marine Division Drill Team on Exhibition

Secretary of the Air Force W. Stuart Symington

Secretary of Defense Louis C. Johnson

Fahy Committee With President Truman and Armed Services Secretaries

E. W. Kenworthy

Charles Fahy

Roy K. Davenport

Press Notice

Secretary of the Army Gordon Gray

Chief of Staff of the Army J. Lawton Collins

"No Longer a Dream"

Navy Corpsman in Korea

25th Division Troops in Japan

Assistant Secretary of Defense Anna M. Rosenberg

Assistant Secretary of the Air Force Eugene M. Zuckert

Music Makers

Maintenance Crew, 462d Strategic Fighter Squadron

Jet Mechanics

Christmas in Korea, 1950

Rearming at Sea

Broadening Skills

Integrated Stewards Class Graduates, Great Lakes, 1953

WAVE Recruits, Naval Training Center, Bainbridge, Maryland, 1953

Rear Adm. Samuel L. Gravely, Jr.

Moving Up

Men of Battery A, 159th Field Artillery Battalion

Survivors of an Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, 24th Infantry

General Matthew B. Ridgway, Far East Commander

Machine Gunners of Company L, 14th Infantry, Hill 931, Korea

Color Guard, 160th Infantry, Korea, 1952

Visit With the Commander

Brothers Under the Skin

Marines on the Kansas Line, Korea

Marine Reinforcements

Training Exercises on Iwo Jima, March 1954

Marines From Camp Lejeune

Lt. Col. Frank E. Petersen, Jr.

Sergeant Major Edgar R. Huff

Clarence Mitchell

Congressman Adam Clayton Powell

Secretary of the Navy Robert B. Anderson

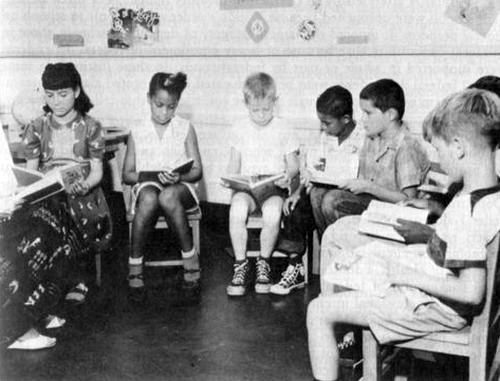

Reading Class in the Military Dependents School, Yokohama

Civil Rights Leaders at the White House

(p. xix)

President John F. Kennedy and President Jorge Allessandri

Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara

Adam Yarmolinsky

James C. Evans

The Gesell Committee Meets With the President

Alfred B. Fitt

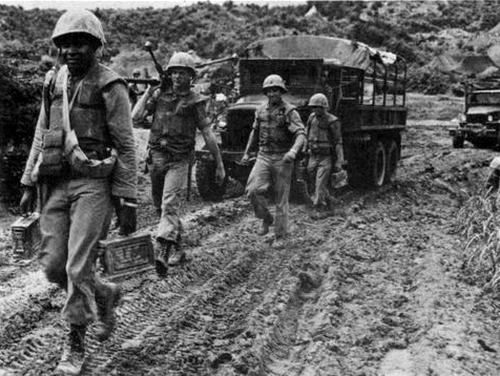

Arriving in Vietnam

Digging In

Listening to the Squad Leader

Supplying the Seventh Fleet

USAF Ground Crew, Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Vietnam

Fighter Pilots on the Line

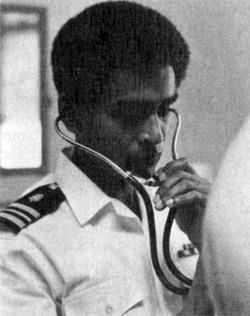

Medical Examination

Auto Pilot Shop

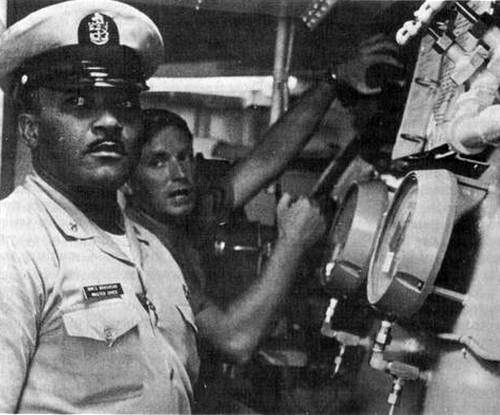

Submarine Tender Duty

First Aid

Vietnam Patrol

Marine Engineers in Vietnam

Loading a Rocket Launcher

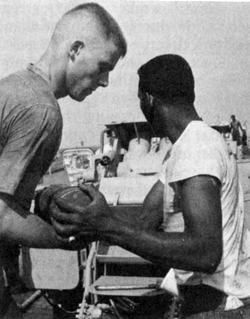

American Sailors Help Evacuate a Vietnamese Child

Booby Trap Victim from Company B, 47th Infantry

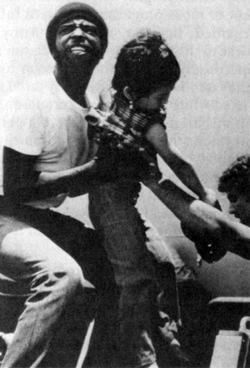

Camaraderie

All illustrations are from the files of the Department of Defense and the National Archives and Records Service with the exception of the pictures on pages 6 and 10, courtesy of William G. Bell; on page 20, by Fabian Bachrach, courtesy of Judge William H. Hastie; on page 120, courtesy of Carlton Skinner; on page 297, courtesy of the Washington Star, on page 361, courtesy of the Afro-American Newspapers; on page 377, courtesy of the Sengstacke Newspapers; and on page 475, courtesy of the Washington Bureau of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

No.

1. Classification of All Men Tested From March 1941 Through December 1942

2. AGCT Percentages in Selected World War II Divisions

3. Percentage of Black Enlisted Men and Women

4. Disposition of Black Personnel at Eight Air Force Bases, 1949

5. Racial Composition of Air Force Units

6. Black Strength in the Air Force

7. Racial Composition of the Training Command, December 1949

(p. xx)

8. Black Manpower, U.S. Navy

9. Worldwide Distribution of Enlisted Personnel by Race, October 1952

10. Distribution of Black Enlisted Personnel by Branch and Rank, 31 October

1952

11. Black Marines, 1949-1955

12. Defense Installations With Segregated Public Schools

13. Black Strength in the Armed Forces for Selected Years

14. Estimated Percentage Distribution of Draft-Age Males in U.S.

Population by AFQT Groups

15. Rate of Men Disqualified for Service in 1962

16. Rejection Rates for Failure To Pass Armed Forces Mental Test, 1962

17. Nonwhite Inductions and First Enlistments, Fiscal Years 1953-1962

18. Distribution of Enlisted Personnel in Each Major Occupation, 1956

19. Occupational Group Distribution by Race, All DOD, 1962

20. Occupational Group Distribution of Enlisted Personnel by Length of Service,

and Race

21. Percentage Distribution of Navy Enlisted Personnel by Race, AFQT

Groups and Occupational Areas, and Length of Service, 1962

22. Percentage Distribution of Blacks and Whites by Pay Grade, All

DOD, 1962

23. Percentage Distribution of Navy Enlisted Personnel by Race, AFQT

Groups, Pay Grade, and Length of Service, 1962

24. Black Percentages, 1962-1968

25. Rates for First Reenlistments, 1964-1967

26. Black Attendance at the Military Academies, July 1968

27. Army and Air Force Commissions Granted at Predominately Black

Schools

28. Percentage of Negroes in Certain Military Ranks, 1964-1966

29. Distribution of Servicemen in Occupational Groups by Race, 1967

In the quarter century that followed American entry into World War II, the nation's armed forces moved from the reluctant inclusion of a few segregated Negroes to their routine acceptance in a racially integrated military establishment. Nor was this change confined to military installations. By the time it was over, the armed forces had redefined their traditional obligation for the welfare of their members to include a promise of equal treatment for black servicemen wherever they might be. In the name of equality of treatment and opportunity, the Department of Defense began to challenge racial injustices deeply rooted in American society.

For all its sweeping implications, equality in the armed forces obviously had its pragmatic aspects. In one sense it was a practical answer to pressing political problems that had plagued several national administrations. In another, it was the services' expression of those liberalizing tendencies that were permeating American society during the era of civil rights activism. But to a considerable extent the policy of racial equality that evolved in this quarter century was also a response to the need for military efficiency. So easy did it become to demonstrate the connection between inefficiency and discrimination that, even when other reasons existed, military efficiency was the one most often evoked by defense officials to justify a change in racial policy.

Progress toward equal treatment and opportunity in the armed forces was an uneven process, the result of sporadic and sometimes conflicting pressures derived from such constants in American society as prejudice and idealism and spurred by a chronic shortage of military manpower. In his pioneering study of race relations, Gunnar Myrdal observes that ideals have always played a dominant role in the social dynamics of America.[1-1] By extension, the ideals that helped involve the nation in many of its wars also helped produce important changes in the treatment of Negroes by the armed forces. The democratic spirit embodied in the Declaration of Independence, for example, opened the Continental Army to many Negroes, holding out to them the promise of eventual freedom.[1-2]

Yet (p. 004) the fact that the British themselves were taking large numbers of Negroes into their ranks proved more important than revolutionary idealism in creating a place for Negroes in the American forces. Above all, the participation of both slaves and freedmen in the Continental Army and the Navy was a pragmatic response to a pressing need for fighting men and laborers. Despite the fear of slave insurrection shared by many colonists, some 5,000 Negroes, the majority from New England, served with the American forces in the Revolution, often in integrated units, some as artillerymen and musicians, the majority as infantrymen or as unarmed pioneers detailed to repair roads and bridges.

Again, General Jackson's need for manpower at New Orleans explains the presence of the Louisiana Free Men of Color in the last great battle of the War of 1812. In the Civil War the practical needs of the Union Army overcame the Lincoln administration's fear of alienating the border states. When the call for volunteers failed to produce the necessary men, Negroes were recruited, generally as laborers at first but later for combat. In all, 186,000 Negroes served in the Union Army. In addition to those in the sixteen segregated combat regiments and the labor units, thousands also served unofficially as laborers, teamsters, and cooks. Some 30,000 Negroes served in the Navy, about 25 percent of its total Civil War strength.

The influence of the idealism fostered by the abolitionist crusade should not be overlooked. It made itself felt during the early months of the war in the demands of Radical Republicans and some Union generals for black enrollment, and it brought about the postwar establishment of black units in the Regular Army. In 1866 Congress authorized the creation of permanent, all-black units, which in 1869 were designated the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry.

Crewmen of the USS Miami During the Civil War

Military needs and idealistic impulses were not enough to guarantee uninterrupted racial progress; in fact, the status of black servicemen tended to reflect the changing patterns in American race relations. During most of the nineteenth century, for example, Negroes served in an integrated U.S. Navy, in the latter half of the century averaging between 20 and 30 percent of the enlisted strength.[1-3] But the employment of Negroes in the Navy was abruptly curtailed after (p. 005) 1900. Paralleling the rise of Jim Crow and legalized segregation in much of America was the cutback in the number of black sailors, who by 1909 were mostly in the galley and the engine room. In contrast to their high percentage of the ranks in the Civil War and Spanish-American War, only 6,750 black sailors, including twenty-four women reservists (yeomanettes), served in World War I; they constituted 1.2 percent of the Navy's total enlistment.[1-4] Their service was limited chiefly to mess duty and coal passing, the latter becoming increasingly rare as the fleet changed from coal to oil.

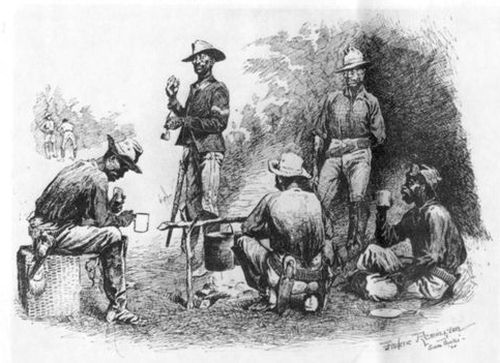

Buffalo Soldiers.

(Frederick Remington's 1888 sketch.)]

When postwar enlistment was resumed in 1923, the Navy recruited Filipino stewards instead of Negroes, although a decade later it reopened the branch to black enlistment. Negroes quickly took advantage of this limited opportunity, their numbers rising from 441 in 1932 to 4,007 in June 1940, when they constituted 2.3 percent of the Navy's 170,000 total.[1-5] Curiously enough, because black (p. 006) reenlistment in combat or technical specialties had never been barred, a few black gunner's mates, torpedomen, machinist mates, and the like continued to serve in the 1930's.

Although the Army's racial policy differed from the Navy's, the resulting limited, separate service for Negroes proved similar. The laws of 1866 and 1869 that guaranteed the existence of four black Regular Army regiments also institutionalized segregation, granting federal recognition to a system racially separate and theoretically equal in treatment and opportunity a generation before the Supreme Court sanctioned such a distinction in Plessy v. Ferguson.[1-6] So important to many in the black community was this guaranteed existence of the four regiments that had served with distinction against the frontier Indians that few complained about segregation. In fact, as historian Jack Foner has pointed out, black leaders sometimes interpreted demands for integration as attempts to eliminate black soldiers altogether.[1-7]

The Spanish-American War marked a break with the post-Civil War tradition of limited recruitment. Besides the 3,339 black regulars, approximately 10,000 (p. 007) black volunteers served in the Army during the conflict. World War I was another exception, for Negroes made up nearly 11 percent of the Army's total strength, some 404,000 officers and men.[1-8] The acceptance of Negroes during wartime stemmed from the Army's pressing need for additional manpower. Yet it was no means certain in the early months of World War I that this need for men would prevail over the reluctance of many leaders to arm large groups of Negroes. Still remembered were the 1906 Brownsville affair, in which men of the 25th Infantry had fired on Texan civilians, and the August 1917 riot involving members of the 24th Infantry at Houston, Texas.[1-9] Ironically, those idealistic impulses that had operated in earlier wars were operating again in this most Jim Crow of administrations.[1-10] Woodrow Wilson's promise to make the world safe for democracy was forcing his administration to admit Negroes to the Army. Although it carefully maintained racially separate draft calls, the National Army conscripted some 368,000 Negroes, 13.08 percent of all those drafted in World War I.[1-11]

Black assignments reflected the opinion, expressed repeatedly in Army staff studies throughout the war, that when properly led by whites, blacks could perform reasonably well in segregated units. Once again Negroes were called on to perform a number of vital though unskilled jobs, such as construction work, most notably in sixteen specially formed pioneer infantry regiments. But they also served as frontline combat troops in the all-black 92d and 93d Infantry Divisions, the latter serving with distinction among the French forces.

Established by law and tradition and reinforced by the Army staff's conviction that black troops had not performed well in combat, segregation survived to flourish in the postwar era.[1-12] The familiar practice of maintaining a few black units was resumed in the Regular Army, with the added restriction that Negroes were totally excluded from the Air Corps. The postwar manpower retrenchments common to all Regular Army units further reduced the size of the remaining black units. By June 1940 the number of Negroes on active duty stood at approximately 4,000 men, 1.5 percent of the Army's total, about the same proportion as Negroes in the Navy.[1-13]

The same constants in American society that helped decide the status of black servicemen in the nineteenth century remained influential between the world wars, but with a significant change.[1-14] Where once the advancing fortunes of Negroes in the services depended almost exclusively on the good will of white progressives, their welfare now became the concern of a new generation of black leaders and emerging civil rights organizations. Skilled journalists in the black press and counselors and lobbyists presenting such groups as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, and the National Negro Congress took the lead in the fight for racial justice in the United States. They represented a black community that for the most part lacked the cohesion, political awareness, and economic strength which would characterize it in the decades to come. Nevertheless, Negroes had already become a recognizable political force in some parts of the country. Both the New Deal politicians and their opponents openly courted the black vote in the 1940 presidential election.

These politicians realized that the United States was beginning to outgrow its old racial relationships over which Jim Crow had reigned, either by law or custom, for more than fifty years. In large areas of the country where lynchings and beatings were commonplace, white supremacy had existed as a literal fact of life and death.[1-15] More insidious than the Jim Crow laws were the economic deprivation and dearth of educational opportunity associated with racial discrimination. Traditionally the last hired, first fired, Negroes suffered all the handicaps that came from unemployment and poor jobs, a condition further aggravated by the Great Depression. The "separate but equal" educational system dictated by law and the realities of black life in both urban and rural areas, north and south, had proved anything but equal and thus closed to Negroes a traditional avenue to advancement in American society.

In these circumstances, the economic and humanitarian programs of the New Deal had a special appeal for black America. Encouraged by these programs and heartened by Eleanor Roosevelt's public support of civil rights, black voters defected from their traditional allegiance to the Republican Party in overwhelming numbers. But the civil rights leaders were already aware, if the average black citizen was not, that despite having made some considerable improvements Franklin Roosevelt never, in one biographer's words, "sufficiently challenged (p. 009) Southern traditions of white supremacy to create problems for himself."[1-16] Negroes, in short, might benefit materially from the New Deal, but they would have to look elsewhere for advancement of their civil rights.

Men like Walter F. White of the NAACP and the National Urban League's T. Arnold Hill sought to use World War II to expand opportunities for the black American. From the start they tried to translate the idealistic sentiment for democracy stimulated by the war and expressed in the Atlantic Charter into widespread support for civil rights in the United States. At the same time, in sharp contrast to many of their World War I predecessors, they placed a price on black support for the war effort: no longer could the White House expect this sizable minority to submit to injustice and yet close ranks with other Americans to defeat a common enemy. It was readily apparent to the Negro, if not to his white supporter or his enemy, that winning equality at home was just as important as advancing the cause of freedom abroad. As George S. Schuyler, a widely quoted black columnist, put it: "If nothing more comes out of this emergency than the widespread understanding among white leaders that the Negro's loyalty is conditional, we shall not have suffered in vain."[1-17] The NAACP spelled out the challenge even more clearly in its monthly publication, The Crisis, which declared itself "sorry for brutality, blood, and death among the peoples of Europe, just as we were sorry for China and Ethiopia. But the hysterical cries of the preachers of democracy for Europe leave us cold. We want democracy in Alabama, Arkansas, in Mississippi and Michigan, in the District of Columbia—in the Senate of the United States."[1-18]

This sentiment crystallized in the black press's Double V campaign, a call for simultaneous victories over Jim Crow at home and fascism abroad. Nor was the Double V campaign limited to a small group of civil rights spokesmen; rather, it reflected a new mood that, as Myrdal pointed out, was permeating all classes of black society.[1-19] The quickening of the black masses in the cause of equal treatment and opportunity in the pre-World War II period and the willingness of Negroes to adopt a more militant course to achieve this end might well mark the beginning of the modern civil rights movement.

Integration in the Army of 1888.

The Army Band at Fort

Duchesne, Utah, composed of soldiers from the black 9th Cavalry and

the white 21st Infantry.

Historian Lee Finkle has suggested that the militancy advocated by most of the civil rights leaders in the World War II era was merely a rhetorical device; that for the most part they sought to avoid violence over segregation, concentrating as before on traditional methods of protest.[1-20] This reliance on traditional methods was apparent when the leaders tried to focus the new sentiment among Negroes on two war-related goals: equality of treatment in the armed forces and equality of job opportunity in the expanding defense industries. In 1938 the Pittsburgh (p. 010) Courier, the largest and one of the most influential of the nation's black papers, called upon the President to open the services to Negroes and organized the Committee for Negro Participation in the National Defense Program. These moves led to an extensive lobbying effort that in time spread to many other newspapers and local civil rights groups. The black press and its satellites also attracted the support of several national organizations that were promoting preparedness for war, and these groups, in turn, began to demand equal treatment and opportunity in the armed forces.[1-21]

The government began to respond to these pressures before the United States entered World War II. At the urging of the White House the Army announced plans for the mobilization of Negroes, and Congress amended several mobilization measures to define and increase the military training opportunities for Negroes.[1-22] The most important of these legislative amendments in terms of influence on future race relations in the United States were made to the Selective Service Act of 1940. The matter of race played only a small part in the debate on this highly controversial legislation, but during congressional hearings on the bill black spokesmen testified on discrimination against Negroes in the services.[1-23] These witnesses concluded that if the draft law did not provide specific guarantees against it, discrimination would prevail.

Gunner's Gang on the USS Maine.

A (p. 011) majority in both houses of Congress seemed to agree. During floor debate on the Selective Service Act, Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York proposed an amendment to guarantee to Negroes and other racial minorities the privilege of voluntary enlistment in the armed forces. He sought in this fashion to correct evils described some ten days earlier by Rayford W. Logan, chairman of the Committee for Negro Participation in the National Defense, in testimony before the House Committee on Military Affairs. The Wagner proposal triggered critical comments and questions. Senators John H. Overton and Allen J. Ellender of Louisiana viewed the Wagner amendment as a step toward "mixed" units. Overton, Ellender, and Senator Lister Hill of Alabama proposed that the matter should be "left to the Army." Hill also attacked the amendment because it would allow the enlistment of Japanese-Americans, some of whom he claimed were not loyal to the United States.[1-24]

General Pershing, AEF Commander, Inspects Troops

of the 802d (Colored) Pioneer Regiment in France, 1918.

No filibuster was attempted, and the Wagner amendment passed the Senate easily, 53 to 21. It provided

that any person between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five regardless of race or color shall be afforded an opportunity voluntarily to enlist and be inducted into the land and naval forces (including aviation units) of the United States for the training and service prescribed in subsection (b), if he is acceptable to the land or naval forces for such training and service.[1-25]

The Wagner amendment was aimed at volunteers for military service. Congressman Hamilton Fish, also of New York, later introduced a similar measure in (p. 012) the House aimed at draftees. The Fish amendment passed the House by a margin of 121 to 99 and emerged intact from the House-Senate conference. The law finally read that in the selection and training of men and execution of the law "there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race or color."[1-26]

Heroes of the 369th Infantry.

Winners of the Croix de

Guerre arrive in New York Harbor, February 1919.

The Fish amendment had little immediate impact upon the services' racial patterns. As long as official policy permitted separate draft calls for blacks and whites and the officially held definition of discrimination neatly excluded segregation—and both went unchallenged in the courts—segregation would remain entrenched in the armed forces. Indeed, the rigidly segregated services, their ranks swollen by the draft, were a particular frustration to the civil rights forces because they were introducing some black citizens to racial discrimination more pervasive than any they had ever endured in civilian life. Moreover, as the services continued to open bases throughout the country, they actually spread federally sponsored segregation into areas where it had never before existed with the force of law. In the long run, however, the 1940 draft law and subsequent draft legislation had a strong influence on the armed forces' racial policies. They created a climate in which progress could be made toward integration within the services. Although not apparent in 1940, the pressure of a draft-induced flood of (p. 013) black conscripts was to be a principal factor in the separate decisions of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps to integrate their units.

As with all the administration's prewar efforts to increase opportunities for Negroes in the armed forces, the Selective Service Act failed to excite black enthusiasm because it missed the point of black demands. Guarantees of black participation were no longer enough. By 1940 most responsible black leaders shared the goal of an integrated armed forces as a step toward full participation in the benefits and responsibilities of American citizenship.

The White House may well have thought that Walter White of the NAACP singlehandedly organized the demand for integration in 1939, but he was merely applying a concept of race relations that had been evolving since World War I. In the face of ever-worsening discrimination, White's generation of civil rights advocates had rejected the idea of the preeminent black leader Booker T. Washington that hope for the future lay in the development of a separate and strong (p. 014) black community. Instead, they gradually came to accept the argument of one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, William E. B. DuBois, that progress was possible only when Negroes abandoned their segregated community to work toward a society open to both black and white. By the end of the 1930's this concept had produced a fundamental change in civil rights tactics and created the new mood of assertiveness that Myrdal found in the black community. The work of White and others marked the beginning of a systematic attack against Jim Crow. As the most obvious practitioner of Jim Crow in the federal government, the services were the logical target for the first battle in a conflict that would last some thirty years.

This evolution in black attitudes was clearly demonstrated in correspondence in the 1930's between officials of the NAACP and the Roosevelt administration over equal treatment in the armed forces. The discussion began in 1934 with a series of exchanges between Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur and NAACP Counsel Charles H. Houston and continued through the correspondence between White and the administration in 1937. The NAACP representatives rejected MacArthur's defense of Army policy and held out for a quota guaranteeing that Negroes would form at least 10 percent of the nation's military strength. Their emphasis throughout was on numbers; during these first exchanges, at least, they fought against disbandment of the existing black regiments and argued for similar units throughout the service.[1-27]

Yet the idea of integration was already strongly implied in Houston's 1934 call for "a more united nation of free citizens,"[1-28] and in February 1937 the organization emphasized the idea in an editorial in The Crisis, asking why black and white men could not fight side by side as they had in the Continental Army.[1-29] And when the Army informed the NAACP in September 1939 that more black units were projected for mobilization, White found this solution unsatisfactory because the proposed units would be segregated.[1-30] If democracy was to be defended, he told the President, discrimination must be eliminated from the armed forces. To this end, the NAACP urged Roosevelt to appoint a commission of black and white citizens to investigate discrimination in the Army and Navy and to recommend the removal of racial barriers.[1-31]

The White House ignored these demands, and on 17 October the secretary to the President, Col. Edwin M. Watson, referred White to a War Department report outlining the new black units being created under presidential authorization. But the NAACP leaders were not to be diverted from the main chance. Thurgood (p. 015) Marshall, then the head of the organization's legal department, recommended that White tell the President "that the NAACP is opposed to the separate units existing in the armed forces at the present time."[1-32]

When his associates failed to agree on a reply to the administration, White decided on a face-to-face meeting with the President.[1-33] Roosevelt agreed to confer with White, Hill of the Urban League, and A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the session finally taking place on 27 September 1940. At that time the civil rights officials outlined for the President and his defense assistants what they called the "important phases of the integration of the Negro into military aspects of the national defense program." Central to their argument was the view that the Army and Navy should accept men without regard to race. According to White, the President had apparently never considered the use of integrated units, but after some discussion he seemed to accept the suggestion that the Army could assign black regiments or batteries alongside white units and from there "the Army could 'back into' the formation of units without segregation."[1-34]

Nothing came of these suggestions. Although the policy announced by the White House subsequent to the meeting contained concessions regarding the employment and distribution of Negroes in the services, it did not provide for integrated units. The wording of the press release on the conference implied, moreover, that the administration's entire program had been approved by White and the others. To have their names associated with any endorsement of segregation was particularly infuriating to these civil rights leaders, who immediately protested to the President.[1-35] The White House later publicly absolved the leaders of any such endorsement, and Press Secretary Early was forced to retract the "damaging impression" that the leaders had in any way endorsed segregation. The President later assured White, Randolph, and Hill that further policy changes would be made to insure fair treatment for Negroes.[1-36]

Presidential promises notwithstanding, the NAACP set out to make integration of the services a matter of overriding interest to the black community during the war. The organization encountered opposition at first when some black leaders were willing to accept segregated units as the price for obtaining the formation of more all-black divisions. The NAACP stood firm, however, and demanded at its annual convention in 1941 an immediate end to segregation.

In a related move symbolizing the growing unity behind the campaign to integrate the military, the leaders of the March on Washington Movement, a group (p. 016) of black activists under A. Philip Randolph, specifically demanded the end of segregation in the Army and Navy. The movement was the first since the days of Marcus Garvey to involve the black masses; in fact Negroes from every social and economic class rallied behind Randolph, ready to demonstrate for equal treatment and opportunity. Although some black papers objected to the movement's militancy, the major civil rights organization showed no such hesitancy. Roy Wilkins, a leader of the NAACP, later claimed that Randolph could supply only about 9,000 potential demonstrators and that the NAACP had provided the bulk of the movement's participants.[1-37]

Although Randolph was primarily interested in fair employment practices, the NAACP had been concerned with the status of black servicemen since World War I. Reflecting the degree of NAACP support, march organizers included a discussion of segregation in the services when they talked with President Roosevelt in June 1941. Randolph and the others proposed ways to abolish the separate racial units in each service, charging that integration was being frustrated by prejudiced senior military officials.[1-38]

The President's meeting with the march leaders won the administration a reprieve from the threat of a mass civil rights demonstration in the nation's capital, but at the price of promising substantial reform in minority hiring for defense industries and the creation of a federal body, the Fair Employment Practices Committee, to coordinate the reform. While it prompted no similar reform in the racial policies of the armed forces, the March on Washington Movement was nevertheless a significant milestone in the services' racial history.[1-39] It signaled the beginning of a popularly based campaign against segregation in the armed forces in which all the major civil rights organizations, their allies in Congress and the press, and many in the black community would hammer away on a single theme: segregation is unacceptable in a democratic society and hypocritical during a war fought in defense of the four freedoms.

Civil rights leaders adopted the "Double V" slogan as their rallying cry during World War II. Demanding victory against fascism abroad and discrimination at home, they exhorted black citizens to support the war effort and to fight for equal treatment and opportunity for Negroes everywhere. Although segregation was their main target, their campaign was directed against all forms of discrimination, especially in the armed forces. They flooded the services with appeals for a redress of black grievances and levied similar demands on the White House, Congress, and the courts.

Black leaders concentrated on the services because they were public institutions, their officials sworn to uphold the Constitution. The leaders understood, too, that disciplinary powers peculiar to the services enabled them to make changes that might not be possible for other organizations; the armed forces could command where others could only persuade. The Army bore the brunt of this attention, but not because its policies were so benighted. In 1941 the Army was a fairly progressive organization, and few institutions in America could match its record. Rather, the civil rights leaders concentrated on the Army because the draft law had made it the nation's largest employer of minority groups.

For its part, the Army resisted the demands, its spokesmen contending that the service's enormous size and power should not be used for social experiment, especially during a war. Further justifying their position, Army officials pointed out that their service had to avoid conflict with prevailing social attitudes, particularly when such attitudes were jealously guarded by Congress. In this period of continuous demand and response, the Army developed a racial policy that remained in effect throughout the war with only superficial modifications sporadically adopted to meet changing conditions.

The experience of World War I cast a shadow over the formation of the Army's racial policy in World War II.[2-1] The chief architects of the new policy, and many of its opponents, were veterans of the first war and reflected in their judgments the passions and prejudices of that era.[2-2] Civil rights activists were determined (p. 018) to eliminate the segregationist practices of the 1917 mobilization and to win a fair representation for Negroes in the Army. The traditionalists of the Army staff, on the other hand, were determined to resist any radical change in policy. Basing their arguments on their evaluation of the performance of the 92d Division and some other black units in World War I, they had made, but not publicized, mobilization plans that recognized the Army's obligation to employ black soldiers yet rigidly maintained the segregationist policy of World War I.[2-3] These plans increased the number of types of black units to be formed and even provided for a wide distribution of the units among all the arms and services except the Army Air Forces and Signal Corps, but they did not explain how the skilled Negro, whose numbers had greatly increased since World War I, could be efficiently used within the limitations of black units. In the name of military efficiency the Army staff had, in effect, devised a social rather than a military policy for the employment of black troops.

The White House tried to adjust the conflicting demands of the civil rights leaders and the Army traditionalists. Eager to placate and willing to compromise, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought an accommodation by directing the War Department to provide jobs for Negroes in all parts of the Army. The controversy over integration soon became more public, the opponents less reconcilable; in the weeks following the President's meeting with black representatives on 27 September 1940 the Army countered black demands for integration with a statement released by the White House on 9 October. To provide "a fair and equitable basis" for the use of Negroes in its expansion program, the Army planned to accept Negroes in numbers approximate to their proportion in the national population, about 10 percent. Black officers and enlisted men were to serve, as was then customary, only in black units that were to be formed in each major branch, both combatant and noncombatant, including air units to be created as soon as pilots, mechanics, and technical specialists were trained. There would be no racial intermingling in regimental organizations because the practice of separating white and black troops had, the Army staff said, proved satisfactory over a long period of time. To change would destroy morale and impair preparations for national defense. Since black units in the Army were already "going concerns, accustomed through many years to the present system" of segregation, "no experiments should be tried ... at this critical time."[2-4]

The (p. 019) President's "OK, F.D.R." on the War Department statement transformed what had been a routine prewar mobilization plan into a racial policy that would remain in effect throughout the war. In fact, quickly elevated in importance by War Department spokesmen who made constant reference to the "Presidential Directive," the statement would be used by some Army officials as a presidential sanction for introducing segregation in new situations, as, for example, in the pilot training of black officers in the Army Air Corps. Just as quickly, the civil rights leaders, who had expected more from the tone of the President's own comments and more also from the egalitarian implications of the new draft law, bitterly attacked the Army's policy.

Black criticism came at an awkward moment for President Roosevelt, who was entering a heated campaign for an unprecedented third term and whose New Deal coalition included the urban black vote. His opponent, the articulate Wendell L. Willkie, was an unabashed champion of civil rights and was reportedly attracting a wide following among black voters. In the weeks preceding the election the President tried to soften the effect of the Army's announcement. He promoted Col. Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., to brigadier general, thereby making Davis the first Negro to hold this rank in the Regular Army. He appointed the commander of reserve officers' training at Howard University, Col. Campbell C. Johnson, Special Aide to the Director of Selective Service. And, finally, he named Judge William H. Hastie, dean of the Howard University Law School, Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War.

A successful lawyer, Judge Hastie entered upon his new assignment with several handicaps. Because of his long association with black causes, some civil rights organizations assumed that Hastie would be their man in Washington and regarded his duties as an extension of their crusade against discrimination. Hastie's War Department superiors, on the other hand, assumed that his was a public relations job and expected him to handle all complaints and mobilization problems as had his World War I predecessor, Emmett J. Scott. Both assumptions proved false. Hastie was evidently determined to break the racial logjam in the War Department, yet unlike many civil rights advocates he seemed willing to pay the price of slow progress to obtain lasting improvement. According to those who knew him, Hastie was confident that he could demonstrate to War Department officials that the Army's racial policies were both inefficient and unpatriotic.[2-5]

Judge Hastie spent his first ten months in office observing what was happening to the Negro in the Army. He did not like what he saw. To him, separating black soldiers from white soldiers was a fundamental error. First, the effect on black morale was devastating. "Beneath the surface," he wrote, "is widespread discontent. Most white persons are unable to appreciate the rancor and bitterness which the Negro, as a matter of self-preservation, has learned to hide beneath a smile, a joke, or merely an impassive face." The inherent paradox of trying to inculcate pride, dignity, and aggressiveness in a black soldier while inflicting (p. 020) on him the segregationist's concept of the Negro's place in society created in him an insupportable tension. Second, segregation wasted black manpower, a valuable military asset. It was impossible, Hastie charged, to employ skilled Negroes at maximum efficiency within the traditionally narrow limitations of black units. Third, to insist on an inflexible separation of white and black soldiers was "the most dramatic evidence of hypocrisy" in America's professed concern for preserving democracy.

Although he appreciated the impossibility of making drastic changes overnight, Judge Hastie was disturbed because he found "no apparent disposition to make a beginning or a trial of any different plan." He looked for some form of progressive integration by which qualified Negroes could be classified and assigned, not by race, but as individuals, according to their capacities and abilities.[2-6]

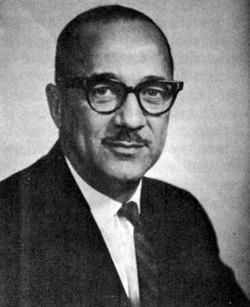

Judge Hastie

Judge Hastie gained little support from the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, or the Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, when he called for progressive integration. Both considered the Army's segregated units to be in accord with prevailing public sentiment against mixing the races in the intimate association of military life. More to the point, both Stimson and Marshall were sensitive to military tradition, and segregated units had been a part of the Army since 1863. Stimson embraced segregation readily. While conveying to the President that he was "sensitive to the individual tragedy which went with it to the colored man himself," he nevertheless urged Roosevelt not to place "too much responsibility on a race which was not showing initiative in battle."[2-7] Stimson's attitude was not unusual for the times. He professed to believe in civil rights for every citizen, but he opposed social integration. He never tried to reconcile these seemingly inconsistent views; in fact, he probably did not consider them inconsistent. Stimson blamed what he termed Eleanor Roosevelt's "intrusive and impulsive folly" for some of the criticism visited upon the Army's racial policy, just as he inveighed against the "foolish leaders of the colored race" (p. 021) who were seeking "at bottom social equality," which, he concluded, was out of the question "because of the impossibility of race mixture by marriage."[2-8] Influenced by Under Secretary Robert P. Patterson, Assistant Secretary John J. McCloy, and Truman K. Gibson, Jr., who was Judge Hastie's successor, but most of all impressed by the performance of black soldiers themselves, Stimson belatedly modified his defense of segregation. But throughout the war he adhered to the traditional arguments of the Army's professional staff.

General Marshall and Secretary Stimson

General Marshall was a powerful advocate of the views of the Army staff. He lived up to the letter of the Army's regulations, consistently supporting measures to eliminate overt discrimination in the wartime Army. At the same time, he rejected the idea that the Army should take the lead in altering the racial mores of the nation. Asked for his views on Hastie's "carefully prepared memo,"[2-9] General Marshall admitted that many of the recommendations were sound but said that Judge Hastie's proposals

would be tantamount to solving a social problem which has perplexed the American people throughout the history of this nation. The Army cannot accomplish such a solution and (p. 022) should not be charged with the undertaking. The settlement of vexing racial problems cannot be permitted to complicate the tremendous task of the War Department and thereby jeopardize discipline and morale.[2-10]

As Chief of Staff, Marshall faced the tremendous task of creating in haste a large Army to deal with the Axis menace. Since for several practical reasons the bulk of that Army would be trained in the south where its conscripts would be subject to southern laws, Marshall saw no alternative but to postpone reform. The War Department, he said, could not ignore the social relationship between blacks and whites, established by custom and habit. Nor could it ignore the fact that the "level of intelligence and occupational skill" of the black population was considerably below that of whites. Though he agreed that the Army would reach maximum strength only if individuals were placed according to their abilities, he concluded that experiments to solve social problems would be "fraught with danger to efficiency, discipline, and morale." In sum, Marshall saw no reason to change the policy approved by the President less than a year before.[2-11]

The Army's leaders and the secretary's civilian aide had reached an impasse on the question of policy even before the country entered the war. And though the use of black troops in World War I was not entirely satisfactory even to its defenders,[2-12] there appeared to be no time now, in view of the larger urgency of winning the war, to plan other approaches, try other solutions, or tamper with an institution that had won victory in the past. Further ordering the thoughts of some senior Army officials was their conviction that wide-scale mixing of the races in the services might, as Under Secretary Patterson phrased it, foment social revolution.[2-13]

These opinions were clearly evident on 8 December 1941, the day the United States entered World War II, when the Army's leaders met with a group of black publishers and editors. Although General Marshall admitted that he was not satisfied with the department's progress in racial matters and promised further changes, the conference concluded with a speech by a representative of The Adjutant General who delivered what many considered the final word on integration during the war.

The Army is made up of individual citizens of the United States who have pronounced views with respect to the Negro just as they have individual ideas with respect to other matters in their daily walk of life. Military orders, fiat, or dicta, will not change their viewpoints. (p. 023) The Army then cannot be made the means of engendering conflict among the mass of people because of a stand with respect to Negroes which is not compatible with the position attained by the Negro in civil life.... The Army is not a sociological laboratory; to be effective it must be organized and trained according to the principles which will insure success. Experiments to meet the wishes and demands of the champions of every race and creed for the solution of their problems are a danger to efficiency, discipline and morale and would result in ultimate defeat.[2-14]

The civil rights advocates refused to concede that the discussion was over. Judge Hastie, along with a sizable segment of the black press, believed that the beginning of a world war was the time to improve military effectiveness by increasing black participation in that war.[2-15] They argued that eliminating segregation was part of the struggle to preserve democracy, the transcendent issue of the war, and they viewed the unvarying pattern of separate black units as consonant with the racial theories of Nazi Germany.[2-16] Their continuing efforts to eliminate segregation and discrimination eventually brought Hastie a sharp reminder from John J. McCloy. "Frankly, I do not think that the basic issues of this war are involved in the question of whether colored troops serve in segregated units or in mixed units and I doubt whether you can convince people of the United States that the basic issues of freedom are involved in such a question." For Negroes, he warned sternly, the basic issue was that if the United States lost the war, the lot of the black community would be far worse off, and some Negroes "do not seem to be vitally concerned about winning the war." What all Negroes ought to do, he counseled, was to give unstinting support to the war effort in anticipation of benefits certain to come after victory.[2-17]

Thus very early in World War II, even before the United States was actively engaged, the issues surrounding the use of Negroes in the Army were well defined and the lines sharply drawn. Was segregation, a practice in conflict with the democratic aims of the country, also a wasteful use of manpower? How would modifications of policy come—through external pressure or internal reform? Could traditional organizational and social patterns in the military services be changed during a war without disrupting combat readiness?

In the years before World War II, Army planners never had to consider segregation in terms of manpower efficiency. Conditioned by the experiences of World War I, when the nation had enjoyed a surplus of untapped manpower even at the height of the war, and aware of the overwhelming manpower surplus of (p. 024) the depression years, the staff formulated its mobilization plans with little regard for the economical use of the nation's black manpower. Its decision to use Negroes in proportion to their percentage of the population was the result of political pressures rather than military necessity. Black combat units were considered a luxury that existed to indulge black demands. When the Army began to mobilize in 1940 it proceeded to honor its pledge, and one year after Pearl Harbor there were 399,454 Negroes in the Army, 7.4 percent of the total and 7.95 percent of all enlisted troops.[2-18]

The effect of segregation on manpower efficiency became apparent only as the Army tried to translate policy into practice. In the face of rising black protest and with direct orders from the White House, the Army had announced that Negroes would be assigned to all arms and branches in the same ratio as whites. Several forces, however, worked against this equitable distribution. During the early months of mobilization the chiefs of those arms and services that had traditionally been all white accepted less than their share of black recruits and thus obliged some organizations, the Quartermaster Corps and the Engineer Corps in particular, to absorb a large percentage of black inductees. The imbalance worsened in 1941. In December of that year Negroes accounted for 5 percent of the Infantry and less than 2 percent each of the Air Corps, Medical Corps, and Signal Corps. The Quartermaster Corps was 15 percent black, the Engineer Corps 25 percent, and unassigned and miscellaneous detachments were 27 percent black.

The rejection of black units could not always be ascribed to racism alone. With some justification the arms and services tried to restrict the number and distribution of Negroes because black units measured far below their white counterparts in educational achievement and ability to absorb training, according to the Army General Classification Test (AGCT). The Army had introduced this test system in March 1941 as its principal instrument for the measurement of a soldier's learning ability. Five categories, with the most gifted in category I, were used in classifying the scores made by the soldiers taking the test (Table 1). The Army planned to take officers and enlisted specialists from the top three categories and the semiskilled soldiers and laborers from the two lowest.

Table 1—Classification of All Men Tested

From March 1941 Through December 1942

| AGCT Category | White | Black | ||

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| I | 273,626 | 6.6 | 1,580 | 0.4 |

| II | 1,154,700 | 28.0 | 14,891 | 3.4 |

| III | 1,327,164 | 32.1 | 54,302 | 12.3 |

| IV | 1,021,818 | 24.8 | 152,725 | 34.7 |

| V | 351,951 | 8.5 | 216,664 | 49.2 |

| Total | 4,129,259 | 100.0 | 440,162 | 100.0 |

Source: Tab A, Memo, G-3 for CofS, 10 Apr 43, AG 201.2 (19 Mar 43) (1).