Title: Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Author: Robert Armitage Sterndale

Release date: October 16, 2006 [eBook #19550]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ron Swanson

|

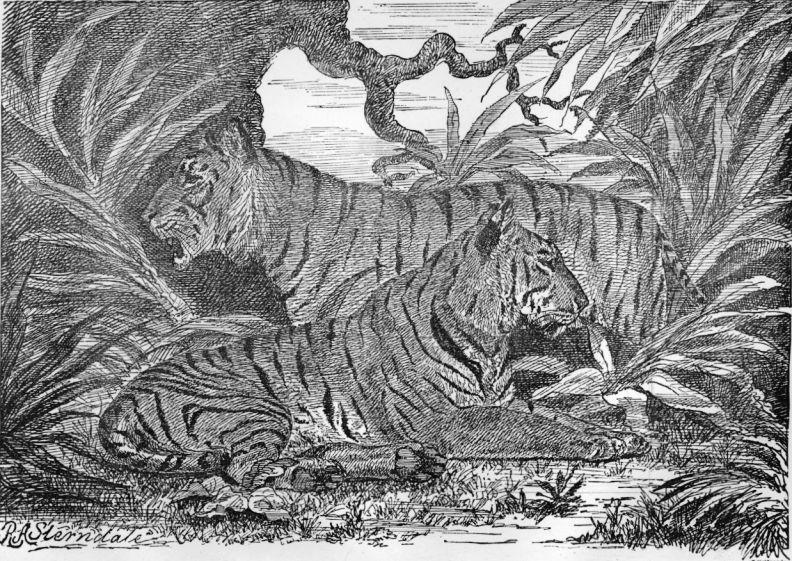

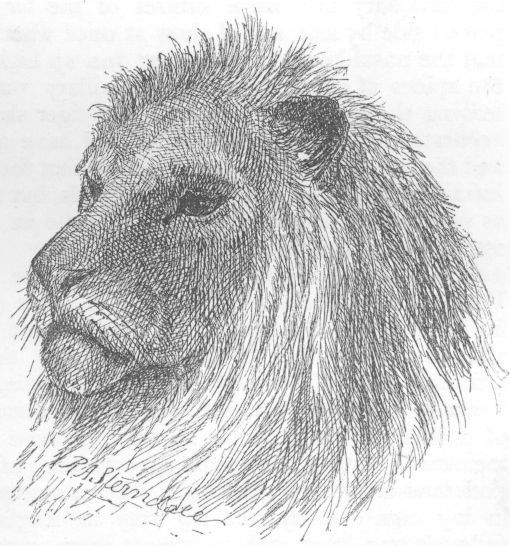

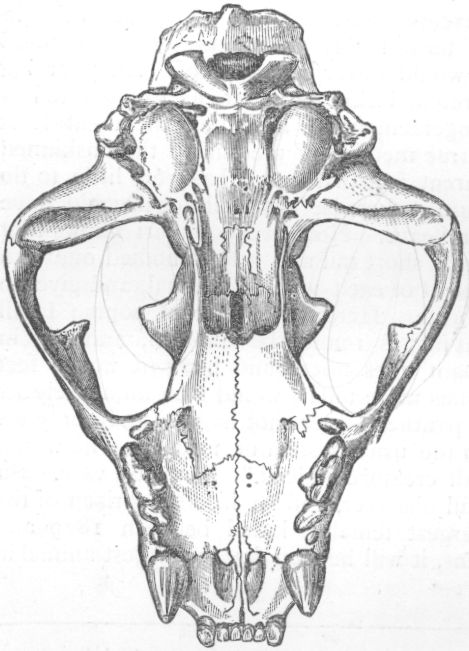

| FELIS TIGRIS. |

This work is designed to meet an existing want, viz.: a popular manual of Indian Mammalia. At present the only work of the kind is one which treats exclusively of the Peninsula of India, and which consequently omits the more interesting types found in Assam, Burmah, and Ceylon, as well as the countries bordering the British Indian Empire on the North. The geographical limits of the present work have been extended to all territories likely to be reached by the sportsman from India, thus greatly enlarging the field of its usefulness.

The stiff formality of the compiled "Natural Histories" has been discarded, and the Author has endeavoured to present, in interesting conversational and often anecdotal style, the results of experience by himself and his personal friends; at the same time freely availing himself of all the known authorities upon the subject.

In laying before the public the following history of the Indian Mammalia, I am actuated by the feeling that a popular work on the subject is needed, and would be appreciated by many who do not care to purchase the expensive books that exist, and who also may be more bothered than enlightened by over-much technical phraseology and those learned anatomical dissertations which are necessary to the scientific zoologist.

Another motive in thus venturing is, that the only complete history of Indian Mammalia is Dr. Jerdon's, which is exhaustive within the boundaries he has assigned to India proper; but as he has excluded Assam, Cachar, Tenasserim, Burmah, Arracan, and Ceylon, his book is incomplete as a Natural History of the Mammals of British India. I shall have to acknowledge much to Jerdon in the following pages, and it is to him I owe much encouragement, whilst we were together in the field during the Indian Mutiny, in the pursuit of the study to which he devoted his life; and the general arrangement of this work will be based on his book, his numbers being preserved, in order that those who possess his 'Mammals of India' may readily refer to the noted species.

But I must also plead indebtedness to many other naturalists who have left their records in the 'Journals of the Asiatic Society' and other publications, or who have brought out books of their own, such as Blyth, Elliott, Hodgson, Sherwill, Sykes, Tickell, Hutton, Kellaart, Emerson Tennent, and others; Col. McMaster's 'Notes on Jerdon,' Dr. Anderson's 'Anatomical and Zoological Researches,' Horsfield's 'Catalogue of the Mammalia in the Museum of the East India Company,' Dr. Dobson's 'Monograph of the Asiatic Chiroptera,' the writings of Professors Martin Duncan, Flowers, Kitchen Parker, Boyd Dawkins, Garrod, Mr. E. R. Alston, Sir Victor Brooke and others; the Proceedings and Journals of the Zoological, Linnean, and Asiatic Societies, and the correspondence in The Asian; so that after all my own share is minimised to a few remarks here and there, based on personal experience during a long period of jungle life, and on observation of the habits of animals in their wild state, and also in captivity, having made a large collection of living specimens from time to time.

As regards classification, Cuvier's system is the most popular, so I shall adopt it to a certain extent, keeping it as a basis, but engrafting on it such modifications as have met with the approval of modern naturalists. For comparison I give below a synopsis of Cuvier's arrangement. I have placed Cetacea after Carnivora, and Edentata at the end. In this I have followed recent authors as well as Jerdon, whose running numbers I have preserved as far as possible for purposes of reference.

Cuvier divides the Mammals into nine orders, as follows. (The examples I give are Indian ones, except where stated otherwise):—

Order I.—BIMANA. Man.

Order II.—QUADRUMANA. Two families—1st, Apes and Monkeys; 2nd, Lemurs.

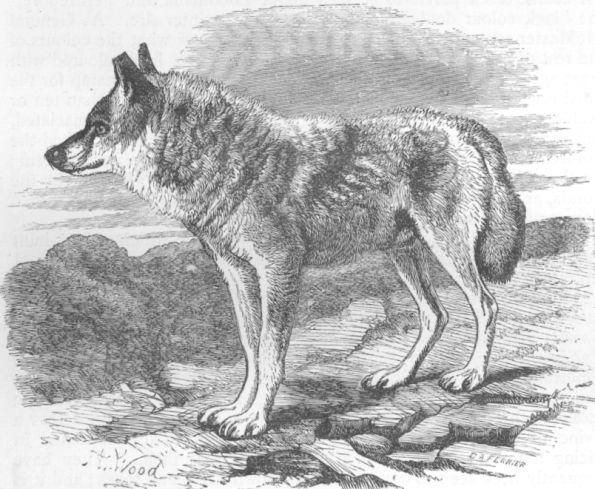

Order III.—CARNARIA. Three families—1st, Cheiroptera, Bats; 2nd, Insectivora, Hedgehogs, Shrews, Moles, Tupaiæ, &c.; 3rd, Carnivora: Tribe 1, Plantigrades, Bears, Ailurus, Badger, Arctonyx; 2, Digitigrades, Martens, Weasels, Otters, Cats, Hyænas, Civets, Musangs, Mongoose, Dogs, Wolves and Foxes.

Order IV.—MARSUPIATA. Implacental Mammals peculiar to America and Australia, such as Opossums, Dasyures, Wombats, and Kangaroos. We have none in India.

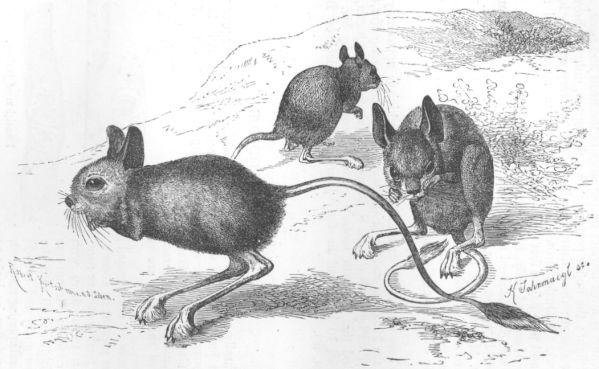

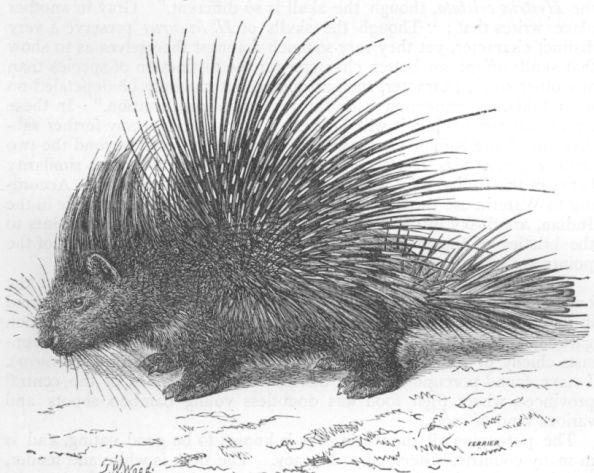

Order V.—RODENTIA. Squirrels, Marmots, Jerboas, Mole-Rats, Rats, Mice, Voles, Porcupines, and Hares.

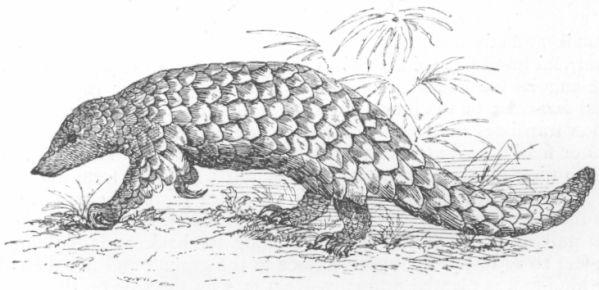

Order VI.—EDENTATA, or toothless Mammals, either partially or totally without teeth. Three families—1st, Tardigrades, the Sloths, peculiar to America; 2nd, Effodientia, or Burrowers, of which the Indian type is the Manis, but which includes in other parts of the world the Armadillos and Anteaters; 3rd, Monotremata, Spiny Anteaters or Echidnas, and the Ornithorynchus.

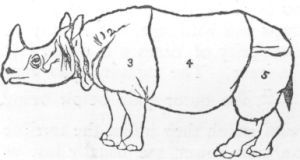

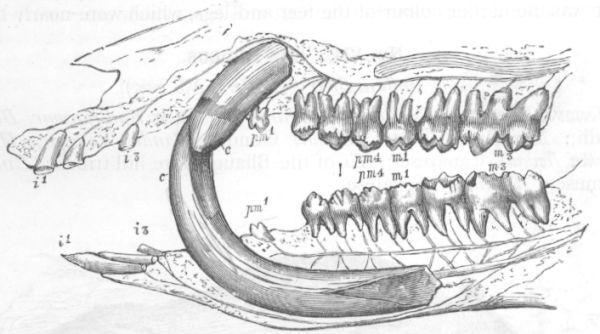

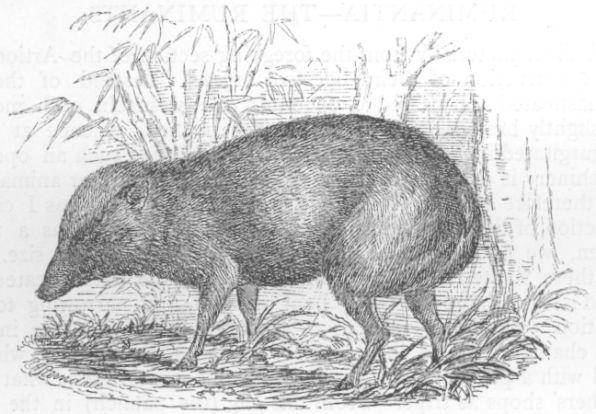

Order VII.—PACHYDERMATA, or thick-skinned Mammals. Three families—1st, Proboscidians, Elephants; 2nd, Ordinary Pachyderms, Rhinoceroses, Hogs; 3rd, Solidungula, Horses.

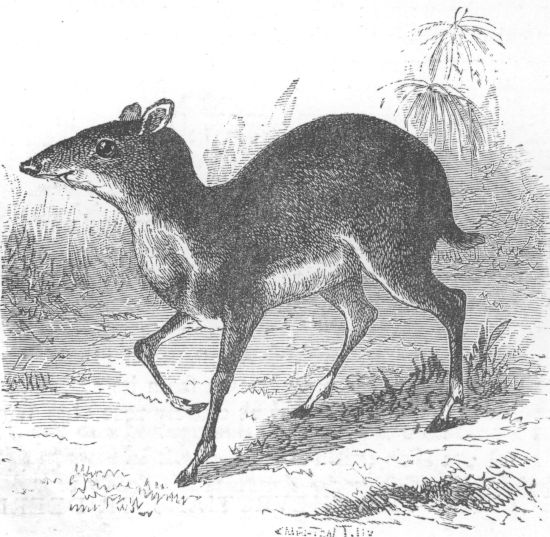

Order VIII.—RUMINANTIA, or cud-chewing Mammals. Four families—1st, Hornless Ruminants, Camels, Musks; 2nd, Cervidæ, true horns shed periodically, Deer; 3rd, Persistent horns, Giraffes; 4th, Hollow-horned Ruminants, Antelopes, Goats, Sheep and Oxen.

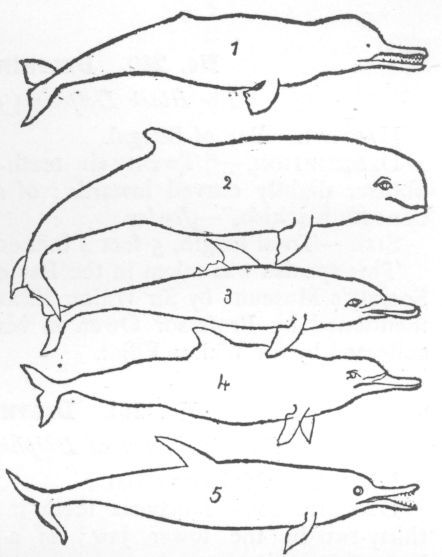

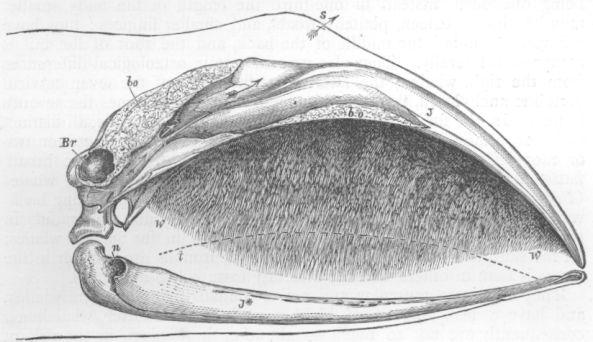

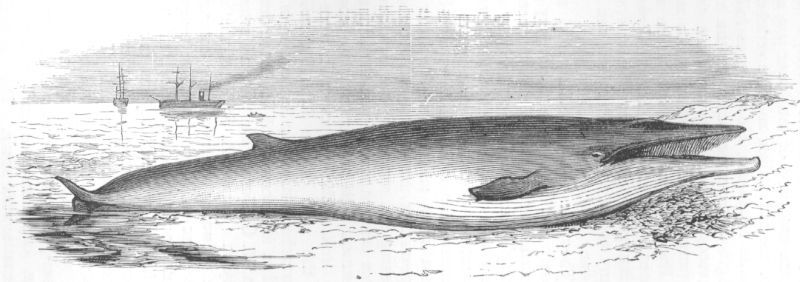

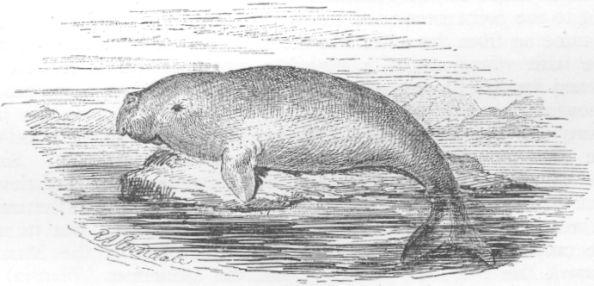

Order IX.—CETACEA. Three families—1st, Herbivorous Cetacea, Manatees, Dugongs; 2nd, Ordinary Cetacea, Porpoises; 3rd, Balænidæ, Whales.

Some people have an extreme repugnance to the idea that man should be treated of in connection with other animals. The development theory is shocking to them, and they would deny that man has anything in common with the brute creation. This is of course mere sentiment; no history of nature would be complete without the noblest work of the Creator. The great gulf that separates the human species from the rest of the animals is the impassable one of intellect. Physically, he should be compared with the other mammals, otherwise we should lose our first standpoint of comparison. There is no degradation in this, nor is it an acceptance of the development theory. To argue that man evolved from the monkey is an ingenious joke which will not bear the test of examination, and the Scriptural account may still be accepted. I firmly believe in man as an original creation just as much as I disbelieve in any development of the Flying Lemur (Galeopithecus) from the Bat, or that the habits of an animal would in time materially alter its anatomy, as in the case of the abnormal length of the hind toe and nail of the Jacana. It is not that the habit of running over floating leaves induced the change, but that an all-wise Creator so fashioned it that it might run on those leaves in search of its food. I accept the development theory to the extent of the multiplication of species, or perhaps, more correctly, varieties in genera. We see in the human race how circumstances affect physical appearance. The child of the ploughman or navvy inherits the broad shoulders and thick-set frame of his father; and in India you may see it still more forcibly in the difference between Hindu and Mahomedan races, and those Hindus who have been converted to Mahomedanism. I do not mean isolated converts here and there who intermarry with pure Mahomedan women, but I mean whole communities who have in olden days been forced to accept Islam. In a few generations the face assumes an unmistakable Mahomedan type. It is the difference in living and in thought that effects this change.

It is the same with animals inhabiting mountainous districts as compared with the same living in the plains; constant enforced exercise tells on the former, and induces a more robust and active form.

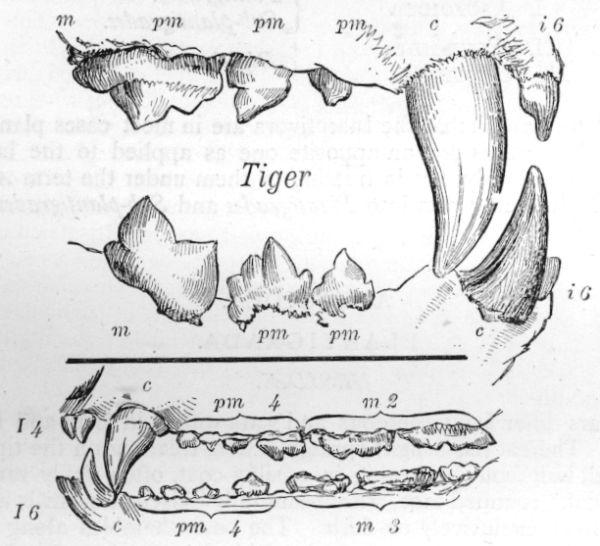

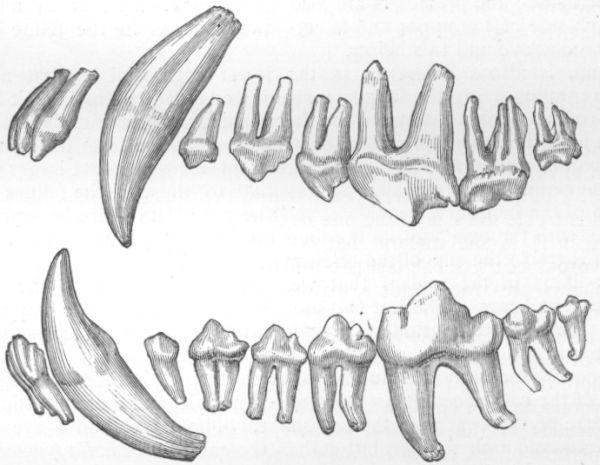

Whether diet operates in the same degree to effect changes I am inclined to doubt. In man there is no dental or intestinal difference, whether he be as carnivorous as an Esquimaux or as vegetarian as a Hindu; whereas in created carnivorous, insectivorous, and herbivorous animals there is a striking difference, instantly to be recognised even in those of the same family. Therefore, if diet has operated in effecting such changes, why has it not in the human race?

"Who shall decide when doctors disagree?" is a quotation that may aptly be applied to the question of the classification of man; Cuvier, Blumenbach, Fischer, Bory St. Vincent, Prichard, Latham, Morton, Agassiz and others have each a system.

Cuvier recognises only three types—the Caucasian, the Mongolian, and the Negro or Ethiopian, including Blumenbach's fourth and fifth classes, American and Malay in Mongolian. But even Cuvier himself could hardly reconcile the American with the Mongol; he had the high cheek-bone and the scanty beard, it is true, but his eyes and his nose were as Caucasian as could be, and his numerous dialects had no affinity with the type to which he was assigned.

Fischer in his classification divided man into seven races:—

1st.—Homo japeticus, divided into three varieties—Caucasicus, Arabicus and Indicus.

2nd.—H. Neptunianus, consisting of—1st, the Malays peopling the coasts of the islands of the Indian Ocean, Madagascar, &c.; 2nd, New Zealanders and Islanders of the Pacific; and, 3rd, the Papuans.

3rd.—H. Scythicus. Three divisions, viz.: 1st, Calmucks and other Tartars; 2nd, Chinese and Japanese; and, 3rd, Esquimaux.

4th.—H. Americanus, and

5th.—H. Columbicus, belong to the American Continent.

6th.—H. Æthiopicus. The Negro.

7th.—H. Polynesius. The inland inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula, of the Islands of the Indian Ocean, of Madagascar, New Guinea, New Holland, &c.

I think this system is the one that most commends itself from its clearness, but there are hardly two writers on ethnology who keep to the same classification.

Agassiz classifies by realms, and has eight divisions.

The Indian races with which we have now to deal are distributed, generally speaking, as follows:—

Caucasian.—(Homo japeticus, Bory and Fischer). Northerly, westerly, and in the Valley of the Ganges in particular, but otherwise generally distributed over the most cultivated parts of the Peninsula, comprising the Afghans (Pathans), Sikhs, Brahmins, Rajputs or Kshatryas of the north-west, the Arabs, Parsees, and Mahrattas of the west coast, the Singhalese of the extreme south, the Tamils of the east, and the Bengalis of the north-east.

Mongolians (H. Scythicus), inhabiting the chain of mountains to the north, from Little Thibet on the west to Bhotan on the east, and then sweeping downwards southerly to where Tenasserim joins the Malay Peninsula. They comprise the Hill Tribes of the N. Himalayas, the Goorkhas of Nepal, and the Hill Tribes of the north-eastern frontier, viz. Khamtis, Singphos, Mishmis, Abors, Nagas, Jynteas, Khasyas, and Garos. Those of the northern borders: Bhotias, Lepchas, Limbus, Murmis and Haioos; of the Assam Valley Kachari, Mech and Koch.

The Malays (H. Neptunianus) Tipperah and Chittagong tribes, the Burmese and Siamese.

Now comes the most difficult group to classify—the aborigines of the interior, and of the hill ranges of Central India, the Kols, Gonds, Bhils, and others which have certain characteristics of the Mongolian, but with skins almost as dark as the Negro, and the full eye of the Caucasian. The main body of these tribes, which I should feel inclined to classify under Fischer's H. Polynesius, have been divided by Indian ethnologists into two large groups—the Kolarians and Dravidians. The former comprise the Juangs, Kharrias, Mundas, Bhumij, Ho or Larka Kols, Santals, Birhors, Korwas, Kurs, Kurkus or Muasis, Bhils, Minas, Kulis. The latter contains the Oraons, Malers, Paharis of Rajamahal, Gonds and Kands.

The Cheroos and Kharwars, Parheyas, Kisans, Bhuikers, Boyars, Nagbansis, Kaurs, Mars, Bhunyiars, Bendkars form another great group apart from the Kolarians and Dravidians, and approximating more to the Indian variety of the Japetic class.

Then there are the extremely low types which one has no hesitation in assigning to the lowest form of the Polynesian group, such as the Andamanese, the jungle tree-men of Chittagong, Tipperah, and the vast forests stretching towards Sambhulpur.

On these I would now more particularly dwell as points of comparison with the rest of the animal kingdom. I have taken but a superficial view of the varieties of the higher types of the human race in India, for the subject, if thoroughly entered into, would require a volume of no ordinary dimensions; and those who wish to pursue the study further should read an able paper by Sir George Campbell in the 'Journal of the Asiatic Society' for June 1866 (vol. xxxv. Part II.), Colonel Dalton's 'Ethnology of Bengal,' the Rev. S. Hislop's 'Memoranda,' and the 'Report of the Central Provinces Ethnological Committee.' There is as yet, however, very little reliable information regarding the wilder forms of humanity inhabiting dense forests, where, enjoying apparently complete immunity from the deadly malaria that proves fatal to all others, they live a life but a few degrees removed from the Quadrumana.

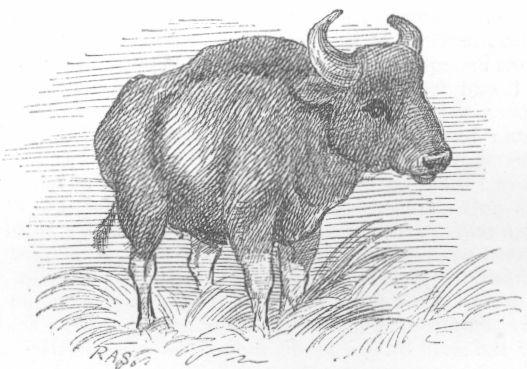

I have in my book on the Seonee District described the little colonies in the heart of the Bison jungles. Clusters of huts imbedded in tangled masses of foliage, surrounded by an atmosphere reeking with the effluvia of decaying vegetation, where, unheedful of the great outer world beyond their sylvan limits, the Gonds pass year after year of uneventful lives.

In some of these hamlets I was looked upon with positive awe, as being the first white man the Baigas had seen. But these simple savages rank high in the scale compared with some others, of whom we have as yet but imperfect descriptions.

Some years ago Mr. Piddington communicated to the Asiatic Society an account of some "Monkey-men" he came across on the borders of the Palamow jungle. He was in the habit of employing the aboriginal tribes to work for him, and on one occasion a party of his men found in the jungle a man and woman in a state of starvation, and brought them in. They were both very short in stature, with disproportionately long arms, which in the man were covered with a reddish-brown hair. They looked almost more like baboons than human beings, and their language was unintelligible, except that words here and there resembled those in one of the Kolarian dialects. By signs, and by the help of these words, one of the Dhangars managed to make out that they lived in the depths of the forest, but had to fly from their people on account of a blood feud. Mr. Piddington was anxious to send them down to Calcutta, but before he could do so, they decamped one night, and fled again to their native wilds. Those jungles are, I believe, still in a great measure unexplored; and, if some day they are opened out, it is to be hoped that the "Monkey-men" will be again discovered.[1]

1 There has been lately exhibited in London a child from Borneo which has several points in common with the monkey—hairy face and arms, the hair on the fore-arm being reversed, as in the apes.

The lowest type with which we are familiar is the Andamanese, and the wilder sort of these will hardly bear comparison with even the degraded Australian or African Bosjesman, and approximate in debasement to the Fuegians.

The Andamanese are small in stature—the men averaging about five feet, the women less. They are very dark, I may say black, but here the resemblance to the Negro ceases. They have not the thick lips and flat nose, nor the peculiar heel of the Negro. In habit they are in small degree above the brutes, architecture and agriculture being unknown. The only arts they are masters of are limited to the manufacture of weapons, such as spears, bows and arrows, and canoes. They wear no kind of dress, but, when flies and mosquitoes are troublesome, plaster themselves with mud. The women are fond of painting themselves with red ochre, which they lay thickly over their heads, after scraping off the hair with a flint-knife. They swim and dive like ducks, and run up trees like monkeys. Though affectionate to their children, they are ruthless to the stranger, killing every one who happens to be cast away on their inhospitable shores. They have been accused of cannibalism, but this is open to doubt. The bodies of those they have killed have been found dreadfully mutilated, almost pounded to a jelly, but no portion had been removed.[2]

2 Since the above was written there has been published in the 'Journal of the Anthropological Institute,' vol. xii., a most interesting and exhaustive paper on these people by Mr. E. H. Man, F.R.G.S., giving them credit for much intelligence.

In the above description I speak of the savage Andamanese in his wild state, and not of the specimens to be seen at Port Blair, who have become in an infinitesimal degree civilised—that is to say, to the extent of holding intercourse with foreigners, making some slight additions to their argillaceous dress-suits, and understanding the principles of exchange and barter—though as regards this last a friend informs me that they have no notion of a token currency, but only understand the argumentum ad hominem in the shape of comestibles, so that your bargains, to be effectual, must be made within reach of a cookshop or grocery. The same friend tells me he learnt at Port Blair that there were marriage restrictions on which great stress was laid. This may be the case on the South Island; there is much testimony on the other side as regards the more savage Andamanese.

The forest tribes of Chittagong are much higher in the scale than the Andamanese, but they are nevertheless savages of a low type. Captain Lewin says: "The men wear scarcely any clothing, and the petticoat of the women is scanty, reaching only to the knee; they worship the terrene elements, and have vague and undefined ideas of some divine power which overshadows all. They were born and they die for ends to them as incomputable as the path of a cannon-shot fired into the darkness. They are cruel, and attach but little value to life. Reverence or respect are emotions unknown to them, they salute neither their chiefs nor their elders, neither have they any expression conveying thanks." There is, however, much that is interesting in these wild people, and to those who wish to know more I recommend Captain Lewin's account of 'The Hill Tracts of Chittagong.'

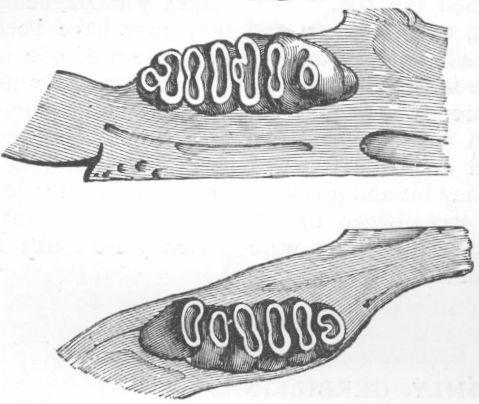

The monkeys of the Indian Peninsula are restricted to a few groups, of which the principal one is that of the Semnopitheci. These monkeys are distinguished not only by their peculiar black faces, with a ridge of long stiff black hair projecting forwards over the eyebrows, thin slim bodies and long tails, but by the absence of cheek pouches, and the possession of a peculiar sacculated stomach, which, as figured in Cuvier, resembles a bunch of grapes. Jerdon says of this group that, out of five species found on the continent there is only one spread through all the plains of Central and Northern India, and one through the Himalayas, whilst there are three well-marked species in the extreme south of the Peninsula; but then he omits at least four species inhabiting Chittagong, Tenasserim, Arracan, which also belong to the continent of India, though perhaps not to the actual Peninsula. Sir Emerson Tennent, in his 'Natural History of Ceylon,' also mentions and figures three species, of which two are not included in Jerdon's 'Mammals,' though incidentally spoken of. I propose to add the Ceylon Mammalia to the Indian, and therefore shall allude to these further on.

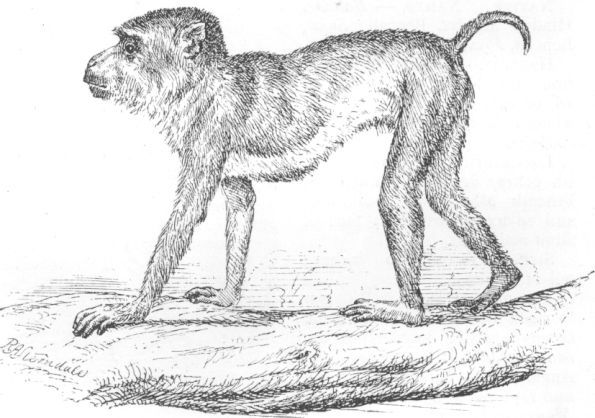

The next group of Indian monkeys is that of the Macaques or Magots, or Monkey Baboons of India, the Lal Bundar of the natives. They have simple stomachs and cheek pouches, which last, I dare say, most of us have noticed who have happened to give two plantains in succession to one of them.

Although numerically the Langurs or Entellus Monkeys form the most important group of the Quadrumana in India, yet the Gibbons (which are not included by Jerdon) rank highest in the scale, though the species are restricted to but three—Hylobates hooluck, H. lar and H. syndactylus. They are superior in formation (that is taking man as the highest development of the form, to which some people take objection, though to my way of thinking there is not much to choose between the highest type of monkey and the lowest of humanity, if we would but look facts straight in the face), and they are also vastly superior in intellect to either the Langurs or the Macaques, though inferior perhaps to the Ourangs.

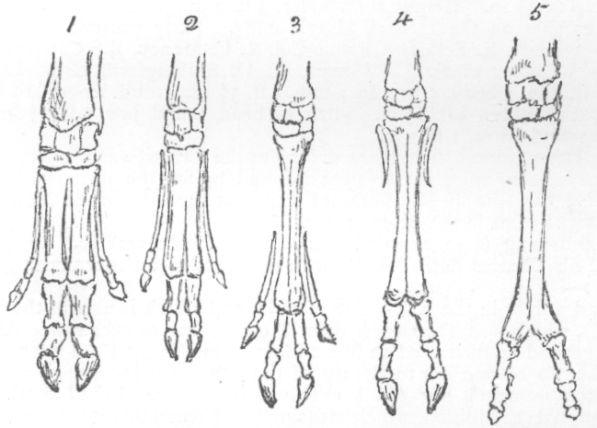

Which, with the long arms of the Ourangs and the receding forehead of the Chimpanzee, possess the callosities of the true monkeys, but differ from them in having neither tail nor cheek pouches. They are true bipeds on the ground, applying the sole of the foot flatly, not, as Cuvier and others have remarked of the Ourangs, with the outer edge of the sole only, but flat down, as Blyth, who first mentions it, noticed it, with the thumb or big toe widely separated.

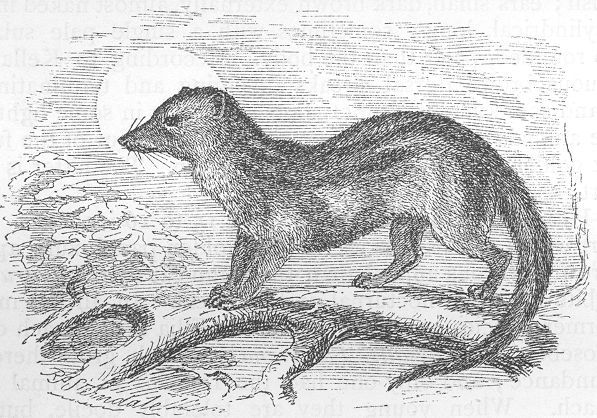

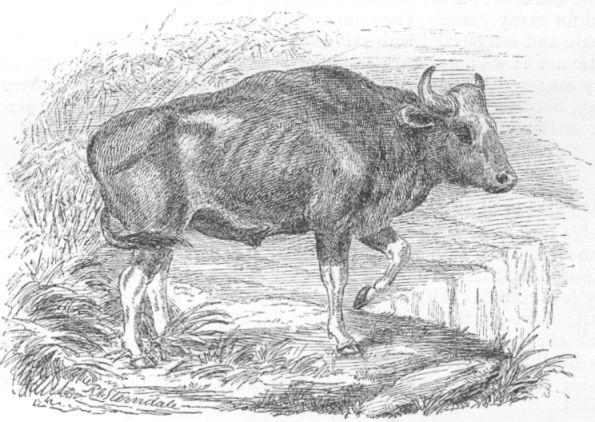

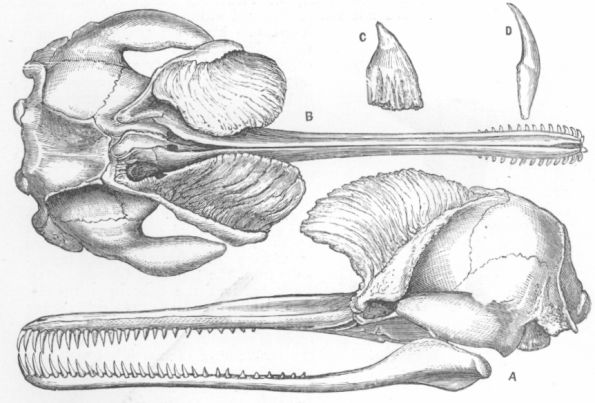

NATIVE NAMES.—Hooluck, Hookoo.

HABITAT.—Garo and Khasia Hills, Valley of Assam, and Arracan.

DESCRIPTION.—Males deep black, marked with white across the forehead. Females vary from brownish black to whitish-brown, without, however, the fulvous tint observable in pale specimens of the next species.

"In general they are paler on the crown, back, and outside of limbs, darker in front, and much darker on the cheeks and chin."—Blyth.

SIZE.—About two feet.

|

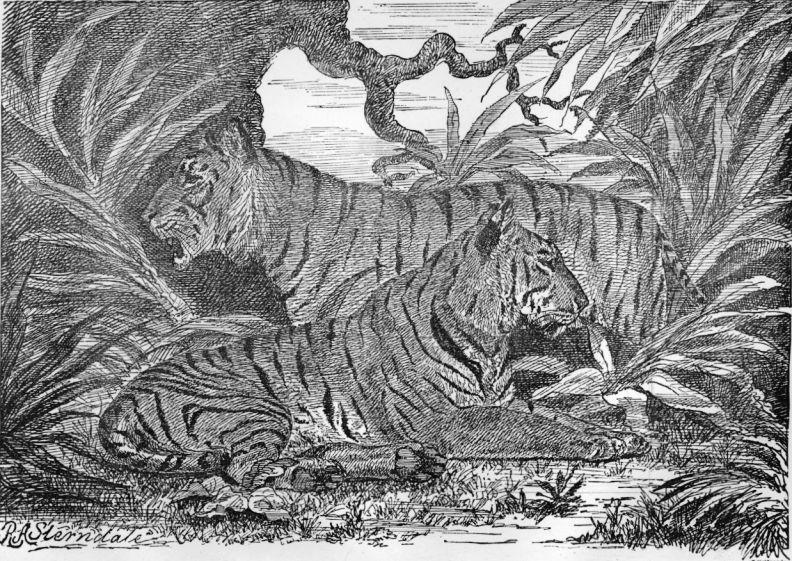

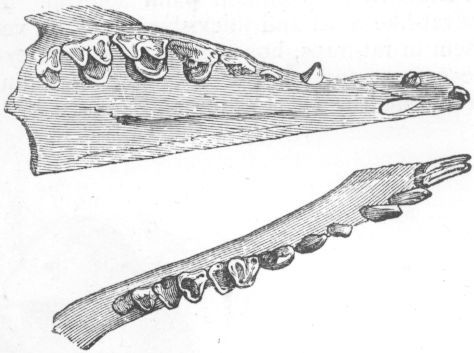

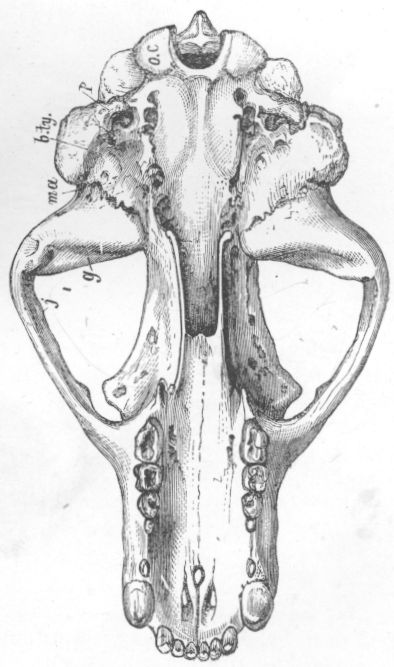

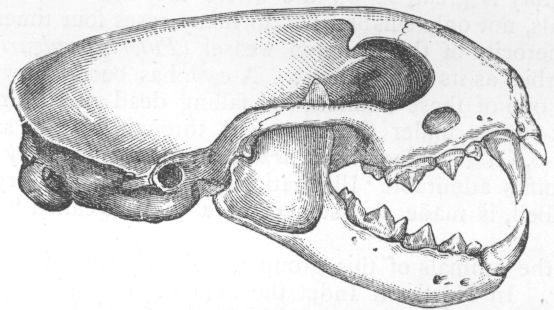

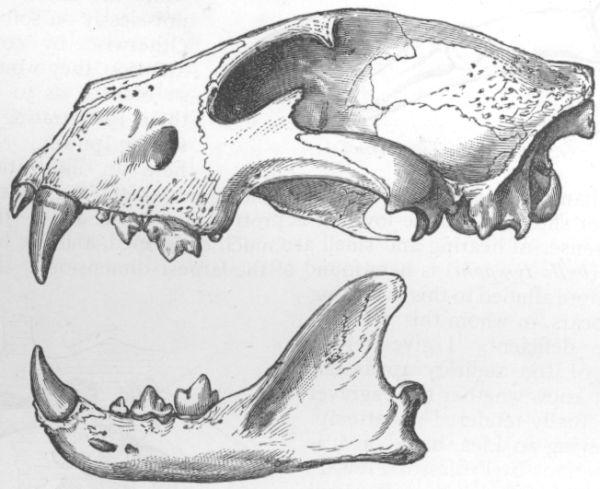

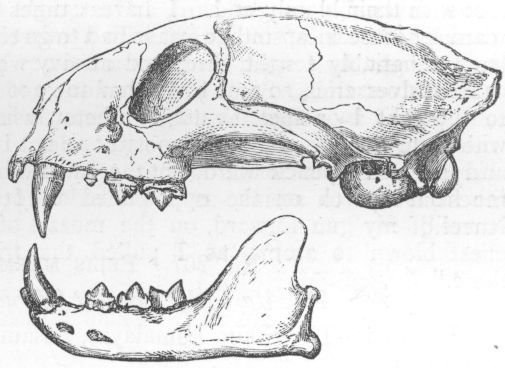

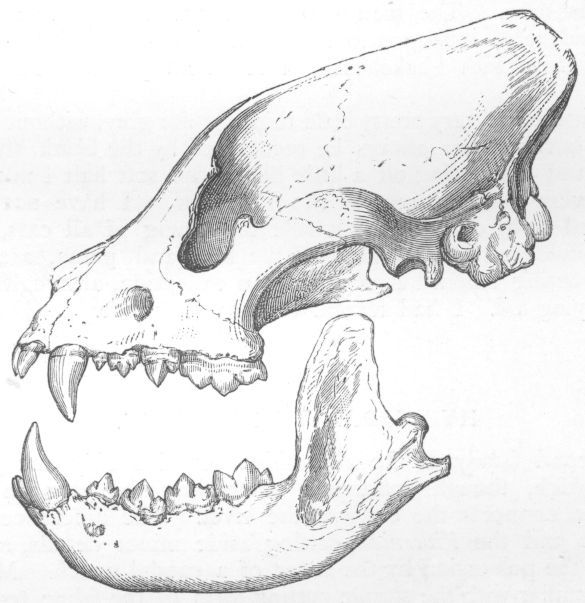

| Skull of Hylobates hooluck. |

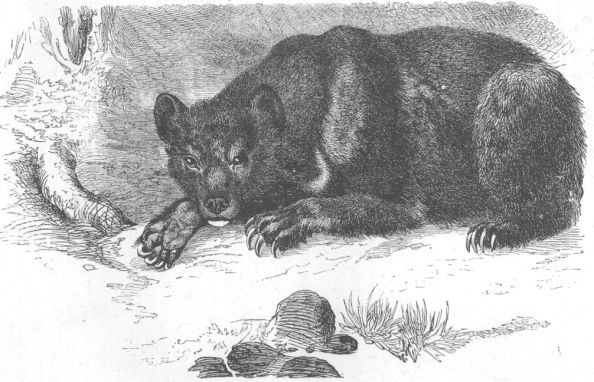

I think of all the monkey family this Gibbon makes one of the most interesting pets. It is mild and most docile, and capable of great attachment. Even the adult male has been caught, and within the short space of a month so completely tamed that he would follow and come to a call. One I had for a time, some years ago, was a most engaging little creature. Nothing contented him so much as being allowed to sit by my side with his arm linked through mine, and he would resist any attempt I made to go away. He was extremely clean in his habits, which cannot be said of all the monkey tribe. Soon after he came to me I gave him a piece of blanket to sleep on in his box, but the next morning I found he had rolled it up and made a sort of pillow for his head, so a second piece was given him. He was destined for the Queen's Gardens at Delhi, but unfortunately on his way up he got a chill, and contracted a disease akin to consumption. During his illness he was most carefully tended by my brother, who had a little bed made for him, and the doctor came daily to see the little patient, who gratefully accepted his attentions; but, to their disappointment, he died. The only objection to these monkeys as pets is the power they have of howling, or rather whooping, a piercing and somewhat hysterical "Whoop-poo! whoop-poo! whoop-poo!" for several minutes, till fairly exhausted.

They are very fond of swinging by their long arms, and walk something like a tipsy sailor. A friend, resident on the frontiers of Assam, tells me that the full-grown adult pines and dies in confinement. I think it probable that it may miss a certain amount of insect diet, and would recommend those who cannot let their pets run loose in a garden to give them raw eggs and a little minced meat, and a spider or two occasionally.

In its wild state this Gibbon feeds on leaves, insects, eggs and small birds. Dr. Anderson notices the following as favourite leaves: Moringa pterygosperma (horse-radish tree), Spondias mangifera (amra), Ficus religiosa (the pipal), also Beta vulgaris; and it is specially partial to the Ipomoea reptans (the water convolvulus) and the bright-coloured flowers of the Indian shot (Canna Indica). Of insects it prefers spiders and the Orthoptera; eggs and small birds are also eagerly devoured.

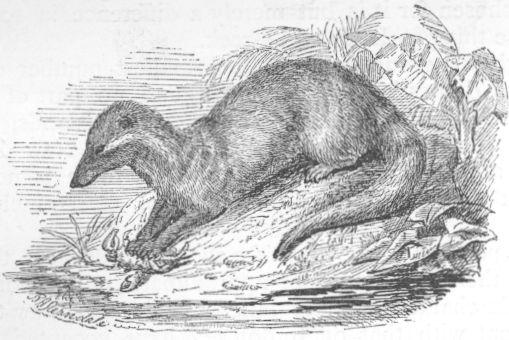

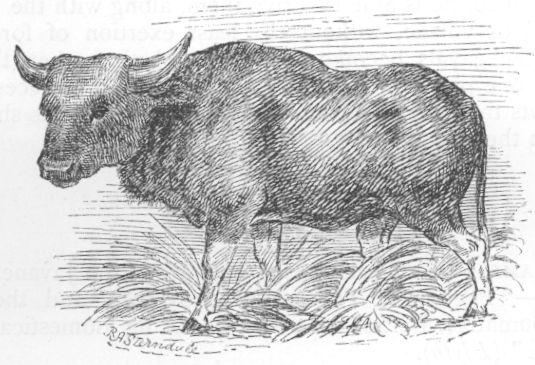

HABITAT.—Arracan, Lower Pegu, Tenasserim, and the Malayan Peninsula.

|

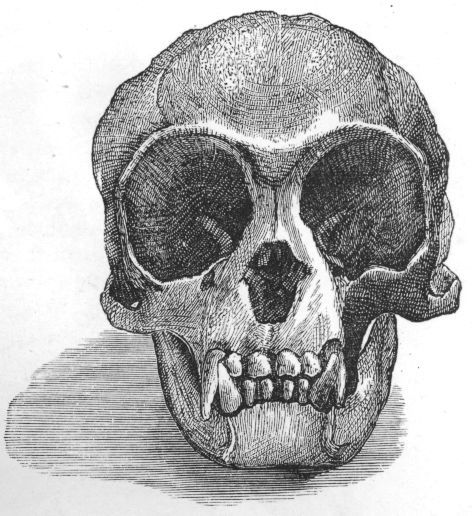

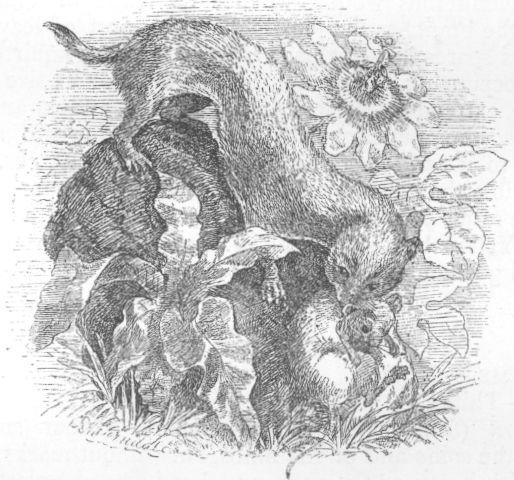

| HYLOBATES LAR. HYLOBATES HOOLUCK. |

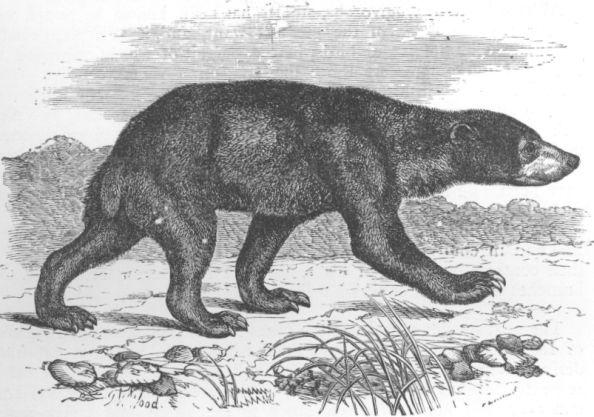

DESCRIPTION.—"This species is generally recognisable by its pale yellowish, almost white hands and feet, by the grey, almost white, supercilium, whiskers and beard, and by the deep black of the rest of the pelage."—Anderson.

SIZE.—About same as H. hooluck.

It is, however, found in every variety of colour, from black to brownish, and variegated with light-coloured patches, and occasionally of a fulvous white. For a long time I supposed it to be synonymous with H. agilis of Cuvier, or H. variegatus of Temminck, but both Mr. Blyth and Dr. Anderson separate it. Blyth mentions a significant fact in distinguishing the two Indian Gibbons, whatever be their variations of colour, viz.: "H. hooluck has constantly a broad white frontal band either continuous or divided in the middle, while H. lar has invariably white hands and feet, less brightly so in some, and a white ring encircling the visage, which is seldom incomplete."[3]

3 There is an excellent coloured drawing by Wolf of these two Gibbons in the 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society,' 1870, page 86, from which I have partly adapted the accompanying sketch.

H. lar has sometimes the index and middle fingers connected by a web, as in the case of H. syndactylus (a Sumatran species very distinct in other respects). The very closely allied H. agilis has also this peculiarity in occasional specimens. This Gibbon was called "agilis" by Cuvier from its extreme rapidity in springing from branch to branch. Duvaucel says: "The velocity of its movements is wonderful; it escapes like a bird on the wing. Ascending rapidly to the top of a tree, it then seizes a flexible branch, swings itself two or three times to gain the necessary impetus, and then launches itself forward, repeatedly clearing in succession, without effort and without fatigue, spaces of forty feet."

Sir Stamford Raffles writes that it is believed in Sumatra that it is so jealous that if in captivity preference be given to one over another, the neglected one will die of grief; and he found that one he had sickened under similar circumstances and did not recover till his rival (a Siamang, H. syndactylus) was removed.

HABITAT.—Tenasserim Province, Sumatra, Malayan Peninsula.

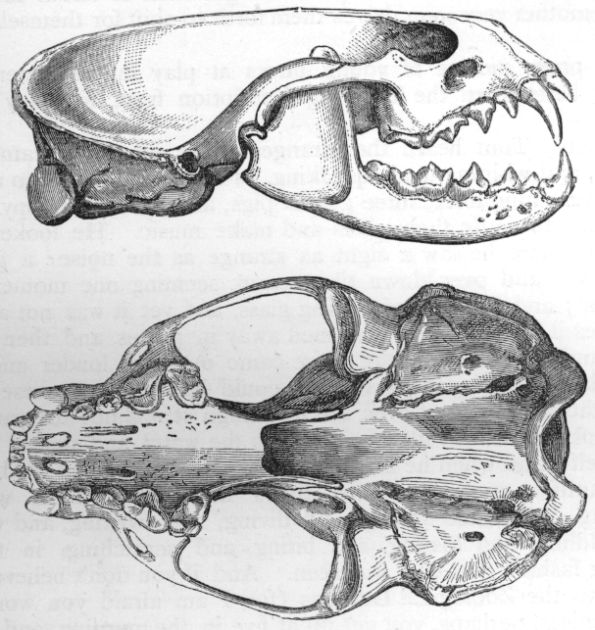

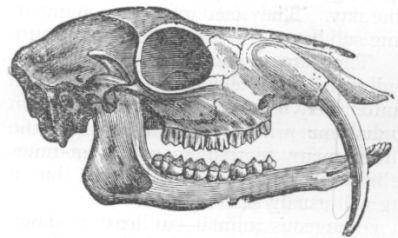

DESCRIPTION.—A more robust and thick-set animal than the two last; deep, woolly, black fur; no white supercilium nor white round the face. The skull is distinguished from the skull of the other Gibbons, according to Dr. Anderson, by the greater forward projection of the supraorbital ridges, and by its much deeper face, and the occipital region more abruptly truncated than in the other species. The index and middle toes of the foot are united to the last phalange.

SIZE.—About three feet.

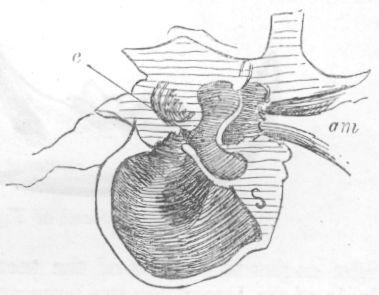

This Gibbon is included in the Indian group on the authority of Helfer, who stated it to be found in the southern parts of the Tenasserim province. Blyth mentions another distinguishing characteristic—it is not only larger than the other Gibbons, but it possesses an inflatable laryngeal sac. Its arms are immense—five feet across in an adult of three feet high.

The other species of this genus inhabiting adjacent and other countries are H. Pileatus and H. leucogenys in Siam; H. leuciscus, Java; H. Mulleri and H. concolor, Borneo.

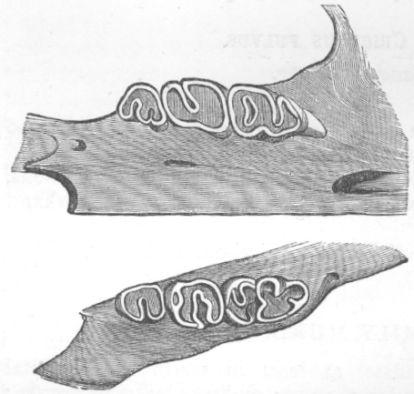

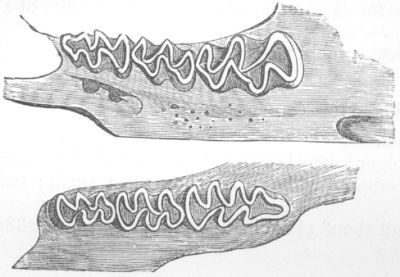

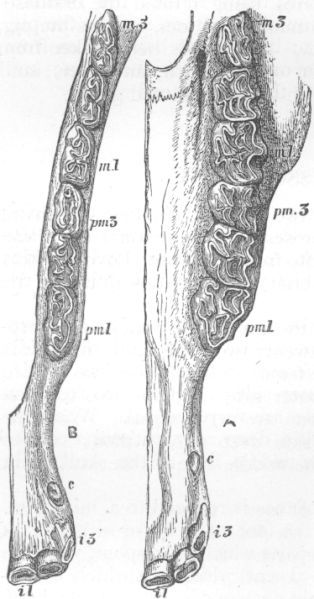

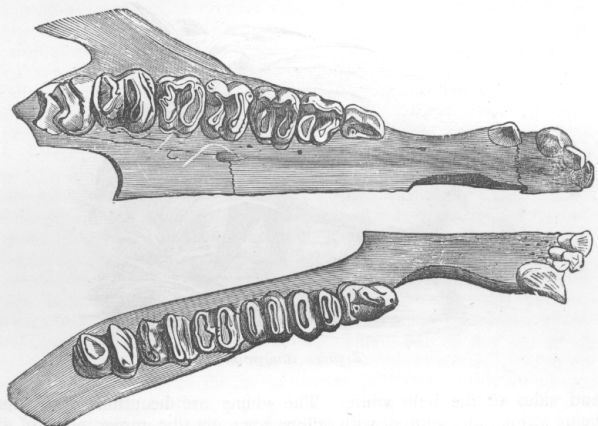

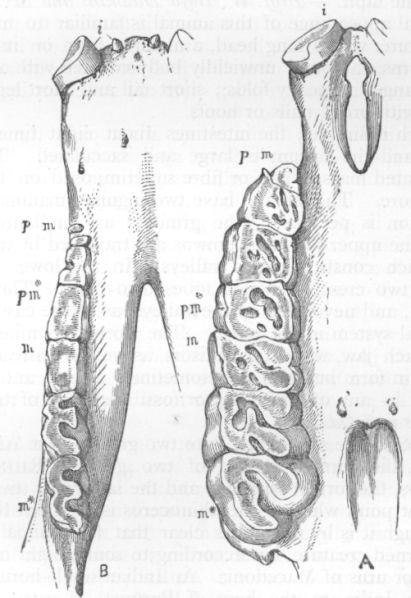

These monkeys are characterised by their slender bodies and long limbs and tails. Jerdon says the Germans call them Slim-apes. Other striking peculiarities are the absence of cheek pouches, which, if present, are but rudimentary. Then they differ from the true monkeys (Cercopithecus) by the form of the last molar tooth in the lower jaw, which has five tubercles instead of four; and, finally, they are to be distinguished by the peculiar structure of the stomach, which is singularly complicated, almost as much so as in the case of Ruminants, which have four divisions. The stomach of this genus of monkey consists of three divisions: 1st, a simple cardiac pouch with smooth parietes; 2nd, a wide sacculated middle portion; 3rd, a narrow elongated canal, sacculated at first, and of simple structure towards the termination. Cuvier from this supposes it to be more herbivorous than other genera, and considers this conclusion justified by the blunter tubercles of the molars and greater length of intestines and cæcum, all of which point to a vegetable diet. "The head is round, the face but little produced, having a high facial angle."—Jerdon.

But the tout ensemble of the Langur is so peculiar that no one who has once been told of a long, loosed-limbed, slender monkey with a prodigious tail, black face, with overhanging brows of long stiff black hair, projecting like a pent-house, would fail to recognise the animal.

The Hanuman monkey is reverenced by the Hindus. Hanuman was the son of Pavana, god of the winds; his strength was enormous, but in attempting to seize the sun he was struck by Indra with a thunderbolt which broke his jaw (hanu), whereupon his father shut himself up in a cave, and would not let a breeze cool the earth till the gods had promised his son immortality. Hanuman aided Rama in his attack upon Ceylon, and by his superhuman strength mountains were torn up and cast into the sea, so as to form a bridge of rocks across the Straits of Manar.[4]

4 The legend, with native picture, is given in Wilkin's 'Hindoo Mythology.'

The species of this genus of monkey abound throughout the Peninsula. All Indian sportsmen are familiar with their habits, and have often been assisted by them in tracking a tiger. Their loud whoops and immense bounds from tree to tree when excited, or the flashing of their white teeth as they gibber at their lurking foe, have often told the shikari of the whereabouts of the object of his search. The Langurs take enormous leaps, twenty-five feet in width, with thirty to forty in a drop, and never miss a branch. I have watched them often in the Central Indian jungles. Emerson Tennent graphically describes this: "When disturbed their leaps are prodigious, but generally speaking their progress is not made so much by leaping as by swinging from branch to branch, using their powerful arms alternately, and, when baffled by distance, flinging themselves obliquely so as to catch the lower boughs of an opposite tree, the momentum acquired by their descent being sufficient to cause a rebound of the branch that carries them upwards again till they can grasp a higher and more distant one, and thus continue their headlong flight."

Jerdon's statement that they can run with great rapidity on all-fours is qualified by McMaster, who easily ran down a large male on horseback on getting him out on a plain.

A correspondent of the Asian, quoting from the Indian Medical Gazette for 1870, states that experiments with one of this genus (Presbytes entellus) showed that strychnine has no effect on Langurs—as much as five grains were given within an hour without effect. "From a quarter to half of a grain will kill a dog in from five to ten minutes, and even one twenty-fourth of a grain will have a decided tetanic effect in human beings of delicate temperament."—Cooley's Cycl. Two days after ten grains of strychnine were dissolved in spirits of wine, and mixed with rum and water, cold but sweet, which the animal drank with relish, and remained unhurt.

The same experiment was tried with one of another genus (Inuus rhesus), who rejected the poisoned fruit at once, and on having strychnine in solution poured down his throat, died.

The Langur was then tried with cyanide of potassium, which he rejected at once, but on being forced to take a few grains, was dead in a few seconds.

Although we may not sympathize with those who practise such cruel experiments as these above alluded to, the facts elucidated are worth recording, and tend to prove the peculiar herbivorous nature of this genus, which, in common with other strictly herbivorous animals, instinctively knows what to choose and what to avoid, and can partake, without danger, of some of the most virulent vegetable poisons. It is possible that in the forests they eat the fruit of the Strychnos nux-vomica, which is also the favourite food of the pied hornbill (Hydrocissa coronata).

NATIVE NAMES.—Langur, Hanuman, Hindi; Wanur and Makur, Mahratti; Musya, Canarese.

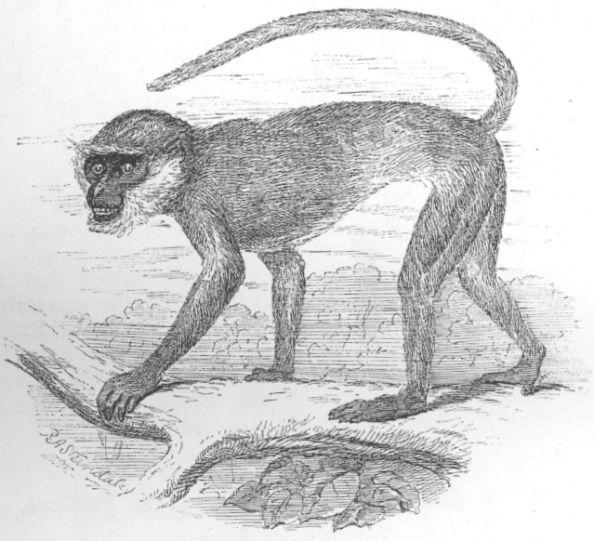

HABITAT.—Bengal and Central India.

|

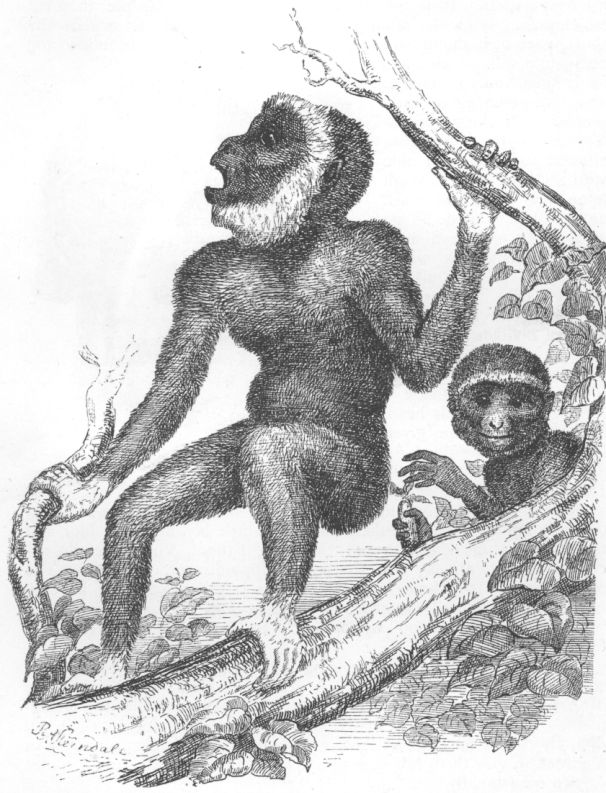

| Presbytes entellus. |

DESCRIPTION.—Pale dirty or ashy grey; darker on the shoulders and rump; greyish-brown on the tail; paler on the head and lower parts; hands and feet black.

SIZE.—Length of male thirty inches to root of tail; tail forty-three inches.

The Entellus monkey is in some parts of India deemed sacred, and is permitted by the Hindus to plunder their grain-shops with impunity; but I think that with increasing hard times the Hanumans are not allowed such freedom as they used to have, and in most parts of India I have been in they are considered an unmitigated nuisance, and the people have implored the aid of Europeans to get rid of their tormentors. In the forest the Langur lives on grain, fruit, the pods of leguminous trees, and young buds and leaves. Sir Emerson Tennent notices the fondness of an allied species for the flowers of the red hibiscus (H. rosa sinensis). The female has usually only one young one, though sometimes twins. The very young babies have not black but light-coloured faces, which darken afterwards. I have always found them most difficult to rear, requiring almost as much attention as a human baby. Their diet and hours of feeding must be as systematically arranged; and if cow's milk be given it must be freely diluted with water—two-thirds to one-third milk when very young, and afterwards decreased to one-half. They are extremely susceptible to cold. In confinement they are quiet and gentle whilst young, but the old males are generally sullen and treacherous. Jerdon says, on the authority of the Bengal Sporting Magazine (August 1836), that the males live apart from the females, who have only one or two old males with each colony, and that they have fights at certain seasons, when the vanquished males receive charge of all the young ones of their own sex, with whom they retire to some neighbouring jungle. Blyth notices that in one locality he found only males of all ages, and in another chiefly females. I have found these monkeys mostly on the banks of streams in the forests of the Central Provinces; in fact, the presence of them anywhere in arid jungles is a sign that water is somewhere in the vicinity. They are timid creatures, and I have never seen the slightest disposition about them to show fight, whereas I was once most deliberately charged by the old males of a party of Rhesus monkeys. I was at the time on field service during the Mutiny, and, seeing several nursing mothers in the party, tried to run them down in the open and secure a baby; but they were too quick for me, and, on being attacked by the old males, I had to pistol the leader.

5 Mr. J. Cockburn, of the Imperial Museum, has, since I wrote about the preceding species, given me some interesting information regarding the geographical distribution of Presbytes entellus and Hylobates hooluck. He says: "The latter has never been known to occur on the north bank of the Brahmaputra, though swarming in the forests at the very water's edge on the south bank. The entellus monkey is also not found on the north bank of the Ganges, and attempts at its introduction have repeatedly failed." P. schistaceus replaces it in the Sub-Himalayan forests.

NATIVE NAMES.—Langur, Hindi; Kamba Suhú, Lepcha; Kubup, Bhotia.

HABITAT.—The whole range of the Himalayas from Nepal to beyond Simla.

DESCRIPTION (after Hodgson).—Dark slaty above; head and lower parts pale yellowish; hands concolorous with body, or only a little darker; tail slightly tufted; hair on the crown of the head short and radiated; on the cheeks long, directed backwards, and covering the ears. Hutton's description is, dark greyish, with pale hands and feet, white head, dark face, white throat and breast, and white tip to the tail.

SIZE.—About thirty inches; tail, thirty-six inches.

Captain Hutton, writing from Mussoorie, says: "On the Simla side I observed them also, leaping and playing about, while the fir-trees, among which they sported, were loaded with snow-wreaths, at an elevation of 11,000 feet."—'Jour. As. Soc. Beng.' xiii. p. 471.

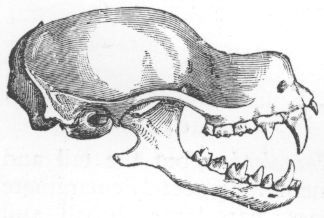

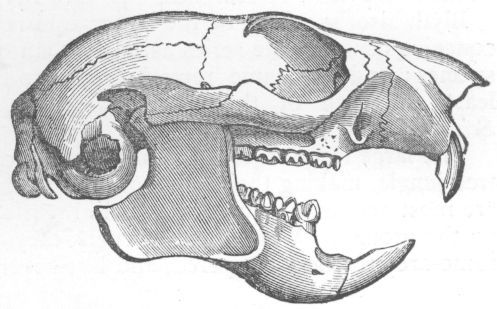

Dr. Anderson remarks on the skull of this species, that it can be easily distinguished from entellus by its larger size, the supraorbital ridge being less forwardly projected, and not forming so thick and wide a pent roof, but the most marked difference lies in the much longer facial portion of schistaceus; the teeth are also larger; the symphysis or junction of the lower jaw is considerably longer and broader, and the lower jaw itself is generally more massive and deep.

NATIVE NAME.—Gandangi, Telugu.

HABITAT.—The Coromandel Coast and Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—Ashy grey, with a pale reddish or chocolat-au-lait tint overlying the whole back and head; sides of the head, chin, throat, and beneath pale yellowish; hands and feet whitish; face, palms and fingers, and soles of feet and toes black; hair long and straight, not wavy; tail of the colour of the darker portion of the back, ending in a whitish tuft.—Jerdon.

SIZE.—About the same as P. entellus.

Blyth, who is followed by Jerdon, describes this monkey as having a compressed high vertical crest, but Dr. Anderson found that the specimens in the Indian Museum owed these crests to bad stuffing. Kellaart, however, mentions it, and calls the animal "the Crested Monkey." In Sir Emerson Tennent's figure of P. priamus a slight crest is noticeable; but Kellaart is very positive on this point, saying: "P. priamus is easily distinguished from all other known species of monkeys in Ceylon by its high compressed vertical crest."

Jerdon says this species is not found on the Malabar Coast, but neither he nor McMaster give much information regarding it. Emerson Tennent writes: "At Jaffna, and in other parts of the island where the population is comparatively numerous, these monkeys become so familiarised with the presence of man as to exhibit the utmost daring and indifference. A flock of them will take possession of a palmyra palm, and so effectually can they crouch and conceal themselves among the leaves that, on the slightest alarm, the whole party becomes invisible in an instant. The presence of a dog, however, excites such irrepressible curiosity that, in order to watch his movements, they never fail to betray themselves. They may be frequently seen congregated on the roof of a native hut; and, some years ago, the child of a European clergyman, stationed near Jaffna, having been left on the ground by the nurse, was so teased and bitten by them as to cause its death."

In these particulars this species resembles P. entellus.

HABITAT.—The Malabar Coast, from N. Lat. 14° or 15° to Cape Comorin.

DESCRIPTION.—Above dusky brown, slightly paling on the sides; crown, occiput, sides of head and beard fulvous, darkest on the crown; limbs and tail dark brown, almost black; beneath yellowish white.—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Not quite so large as P. entellus.

This monkey was named after a member of the Danish factory at Tranquebar, M. John, who first described it. It abounds in forests, and does not frequent villages, though it will visit gardens and fields, where, however, it shuns observation.

The young are of a sooty brown, or nearly black, without any indication of the light-coloured hood of the adult.

HABITAT.—The Nilgheri Hills, the Animallies, Pulneys, the Wynaad, and all the higher parts of the range of the Ghâts as low as Travancore.

DESCRIPTION.—Dark glossy black throughout, except head and nape, which are reddish brown; hair very long; in old individuals a greyish patch on the rump.—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Length of head and body, 26 inches; tail, 30.

This monkey does not, as a rule, descend lower than 2,500 to 3,000 feet; it is shy and wary. The fur is fine and glossy, and is much prized (Jerdon). Its flesh is excellent food for dogs (McMaster).

Dr. Anderson makes this synonymous with the last.

HABITAT.—Assam, Chittagong, Tipperah.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour dark ashy grey, with a slight ferruginous tint; darker near head and on shoulders; underneath and on the inside of the limbs pale yellowish, with a darker shade of orange or golden yellow on the breast and belly. The crown of the head is densely covered with bristly hairs, regularly disposed and somewhat elongated on the vertex so as to resemble a cap, whence the name. Along the forehead is a superciliary crest of long black bristles, directed outwardly; whiskers full and down to the chin: behind the ears is a small tuft of white hairs; the tail is long, one third longer than the body, darker near the end, and tufted; fingers and toes black.

SIZE.—A little smaller than P. entellus.

This monkey is found in Northern Assam, Tipperah and southwards to Tenasserim; in Blyth's 'Catalogue of the Mammals of Burmah' it is mentioned as P. chrysogaster (Semnopithecus potenziani of Bonaparte and Peters). He writes of it: "Females and young have the lower parts white, or but faintly tinted with ferruginous, and the rest of the coat is of a pure grey; the face black, and there is no crest, but the hairs of the crown are so disposed as to appear like a small flat cap laid upon the top of the head. The old males seem always to be of a deep rust-colour on the cheeks, lower parts, and more or less on the outer side of the limbs; while in old females this rust colour is diluted or little more than indicated."

Dr. Anderson says that a young one he had was of a mild disposition, which however is not the character of the adult animal, which is uncertain, and the males when irritated are fierce, and determined in attack. No rule, however, is without its exception, for one adult male, possessed by Blyth, is reported as having been an exceeding gentle animal.

HABITAT.—Tipperah, Tenasserim.

DESCRIPTION.—No vertical crest of hair on the head, nor is the occipital hair directed downwards, as in the next species. Shoulders and outside of arm silvered; tail slightly paler than body, "which is of a blackish fuliginous hue."

More information is required about this monkey, which was named by Blyth after its donor to the Asiatic Society, the Rev. J. Barbe. Blyth considered it as distinct from P. Phayrei and P. obscurus, which last is from Malacca.

Dr. Anderson noticed it in the valley of the Tapeng in the centre of the Kakhyen Hills, in troops of thirty to fifty, in high forest trees overhanging the mountain streams. Being seldom disturbed, they permitted a near approach.

HABITAT.—Arracan, Malayan Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo.

DESCRIPTION.-Colour dusky grey-brown above, more or less dark, with black hands and feet; a conspicuous crest on the vertex; under parts white, scarcely extending to the inside of the limbs; sides grey like the back; whiskers dark, very long, concealing the ears in front; lips and eyelids conspicuously white, with white moustachial hairs above and similar hairs below.

SIZE.—Two feet; tail, 2 feet 6 inches.

This monkey was named by Blyth after Captain (now Sir Arthur) Phayre, who first brought it to his notice; but he afterwards reconciled it as being synonymous with Semnopithecus cristatus. The colouring, according to different authors, seems to vary considerably, which causes some confusion in description. It differs from an allied species, S. maurus, in selecting low marshy situations near the banks of streams. Its favourite food is the fruit of the Nibong palm (Oncosperma filamentosa).

HABITAT.—Mergui and the Malayan Peninsula.

DESCRIPTION.—Adults ashy or brownish black, darker on forehead, sides of face, shoulder, and sides of body; the hair on the nape is lengthened and whitish. The newly-born young are of a golden ferruginous colour, which afterward changes to dusky-ash colour, the terminal half of the tail being last to change; the mouth and eyelids are whitish, but the rest of the face black.

SIZE.—Body, 1 foot 9 inches; tail, 2 feet 8 inches.

This monkey is most common in the Malayan Peninsula, but has been found to extend to Mergui, where Blyth states it was procured by the late Major Berdmore. Dr. Anderson says it is not unfrequently offered for sale in the Singapore market.

NATIVE NAME.—Kallu Wanderu.

HABITAT.—The low lands of Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour cinereous black; croup and inside of thighs whitish; head rufescent brown; hair on crown short, semi-erect; occipital hairs long, albescent; whiskers white, thick and long, terminating at the chin in a short beard, and laterally angularly pointed; upper lip thinly fringed with white hairs; superciliary hairs black, long, stiff and standing erect; tail albescent and terminating in a beard tuft; face, palms, soles, fingers, toes and callosities black; irides brown.—Kellaart.

SIZE.—Length, 20 inches; tail 24 inches.

Sir E. Tennent says of this monkey that it is never found at a higher elevation than 1,300 feet (when it is replaced by the next species).

"It is an active and intelligent creature, little larger than the common bonneted macaque, and far from being so mischievous as others of the monkeys in the island. In captivity it is remarkable for the gravity of its demeanour and for an air of melancholy in its expression and movements, which are completely in character with its snowy beard and venerable aspect. In disposition it is gentle and confiding, sensible in the highest degree of kindness, and eager for endearing attention, uttering a low plaintive cry when its sympathies are excited. It is particularly cleanly in its habits when domesticated, and spends much of its time in trimming its fur and carefully divesting its hair of particles of dust. Those which I kept at my house near Colombo were chiefly fed upon plantains and bananas, but for nothing did they evince a greater partiality than the rose-coloured flowers of the red hibiscus (H. rosa sinensis). These they devoured with unequivocal gusto; they likewise relished the leaves of many other trees, and even the bark of a few of the more succulent ones."

NATIVE NAME.—Maha Wanderu.

HABITAT.—The mountainous district of Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—Fur long, almost uniformly greyish black; whiskers full and white; occiput and croup in old specimens paler coloured; hands and feet blackish; tail long, getting lighter towards the lower half. The young and adults under middle age have a rufous tint, corresponding with that of the head of all ages.

SIZE.—Body about 22 inches; tail, 26 inches.

The name Wanderu is a corruption of the Singhalese generic word for monkey, Ouandura, or Wandura, which bears a striking resemblance to the Hindi Bandra, commonly called Bandar—b and v being interchangeable—and is evidently derived from the Sanscrit Banur, which in the south again becomes Wanur, and further south, in Ceylon, Wandura. There has been a certain amount of confusion between this animal and Inuus silenus, the lion monkey, which had the name Wanderu applied to it by Buffon, and it is so figured in Cuvier. They are both large monkeys, with great beards of light coloured hair, but in no other respect do they resemble. Sir Emerson Tennent says: "It is rarely seen by Europeans, this portion of the country having till very recently been but partially opened; and even now it is difficult to observe its habits, as it seldom approaches the few roads which wind through these deep solitudes. At early morning, ere the day begins to dawn, its loud and peculiar howl, which consists of quick repetition of the sound how-how! may be frequently heard in the mountain jungles, and forms one of the characteristic noises of these lofty situations." This was written in 1861; since then much of the mountainous forest land has been cleared for coffee-planting, and the Wanderu either driven into corners or become more familiarised with man. More therefore must be known of its habits by this time, and information regarding it is desirable.

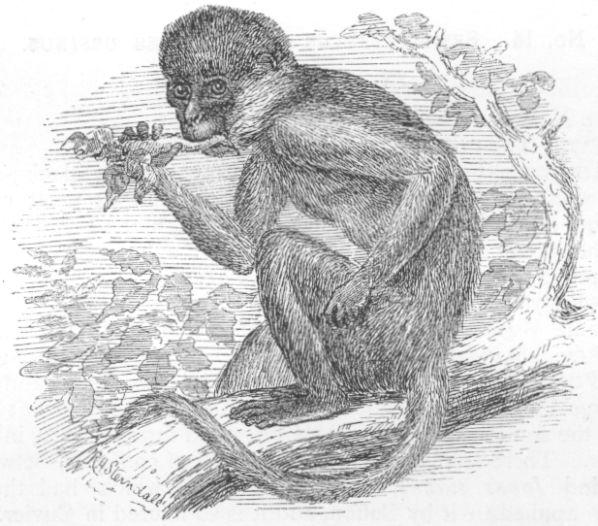

NATIVE NAME.—Ellee Wanderu (Kellaart).

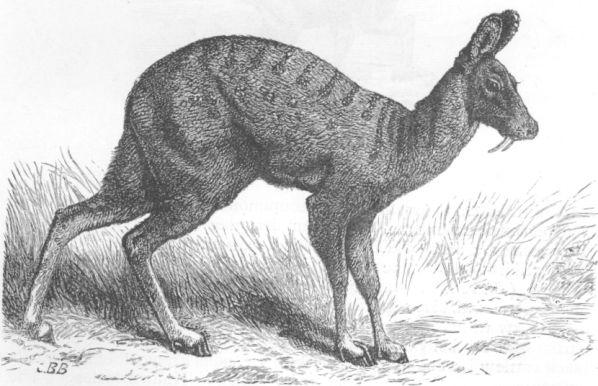

HABITAT.—Ceylon.

|

| Presbytes thersites. |

DESCRIPTION.—Chiefly distinguished from the others by wanting the head tuft; uniform dusky grey, darker on crown and fore-limbs; slaty brown on wrists and hands; hair on toes whitish; whiskers and beard largely developed and conspicuously white.

The name was given by Blyth to a single specimen forwarded by Dr. Templeton, and it was for a time doubtful whether it was really a native, till Dr. Kellaart procured a second. Dr. Templeton's specimen was partial to fresh vegetables, plantains, and fruit, but he ate freely boiled rice, beans, and gram. He was fond of being noticed and petted, stretching out his limbs in succession to be scratched, drawing himself up so that his ribs might be reached by the finger, closing his eyes during the operation, and evincing his satisfaction by grimaces irresistibly ludicrous.—Emerson Tennent.

Dr. Anderson considers this monkey as identical with Semnopithecus priamus, but Kellaart, as I have before stated, is very positive on the point of difference, calling S. priamus emphatically the crested monkey, and alleging that thersites has no crest, and it is probable he had opportunities of observing the two animals in life; he says he had a young specimen of priamus, which distinctly showed the crest, and a young thersites of the same age which showed no sign of it.

In Emerson Tennent's 'Natural History of Ceylon,' (1861) page 5, there is a plate of a group in which are included priamus and thersites; in the original they are wrongly numbered—the former should be 2 and not 3, and the latter 3 and not 2. If these be correct (and Wolf's name should be a voucher for their being so) there is a decided difference. There is no crest in the latter, and the white whiskers terminate abruptly on a level with the eyebrow, and the superciliary ridge of hair is wanting.

HABITAT.—Ceylon, in the hills beyond Matelle.

DESCRIPTION.—Fur dense, sinuous, nearly of uniform white colour, with only a slight dash of grey on the head; face and ears black; palm, soles, fingers and toes flesh-coloured; limbs and body the shape of P. ursinus; long white hairs prolonged over the toes and claws, giving the appearance of a white spaniel dog to this monkey; irides brown; whiskers white, full, and pointed laterally.—Kellaart.

The above description was taken by Dr. Kellaart from a living specimen. He considered it to be a distinct species, and not an Albino, from the black face and ears and brown eyes.

The Kandyans assured him that they were to be seen (rarely however) in small parties of three and four over the hills beyond Matelle, but never in company with the dark kind.

Emerson Tennent also mentions one that was brought to him taken between Ambepasse and Kornegalle, where they were said to be numerous; except in colour it had all the characteristics of P. cephalopterus. So striking was its whiteness that it might have been conjectured to be an Albino, but for the circumstance that its eyes and face were black. An old writer of the seventeenth century, Knox, says of the monkeys of Ceylon (where he was captive for some time) that there are some "milk-white in body and face, but of this sort there is not such plenty."—Tennent's 'Natural History of Ceylon,' page 8.

NOTE.—Since the above was in type I have found in the List of Animals in the Zoological Society's Gardens, a species entered as Semnopithecus leucoprymnus, the Purple-faced Monkey from Ceylon—see P.Z.S.

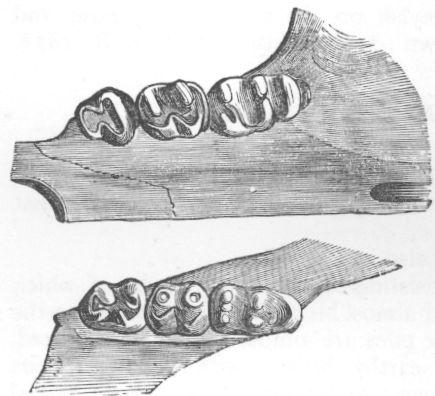

This sub-family comprises the true baboons of Africa and the monkey-like baboons of India. They have the stomach simple, and cheek-pouches are always present. According to Cuvier they possess, like the last family, a fifth tubercle on their last molars. They produce early, but are not completely adult for four or five years; the period of gestation is seven months.

The third sub-family of Simiadæ consists of the genera Cercopithicus, Macacus, and Cynocephalus, as generally accepted by modern zoologists, but Jerdon seems to have followed Ogilby in his classification, which merges the long-tailed Macaques into Cercopithecus, and substituting Papio for the others.

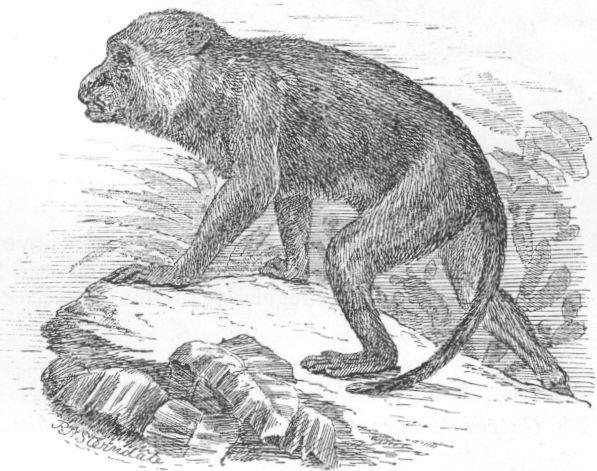

Cuvier applies this term to the Magots or rudimentary-tailed Macaques. The monkeys of this genus are more compactly built than those of the last. They are also less herbivorous in their diet, eating frogs, lizards, crabs and insects, as well as vegetables and fruit. Their callosities and cheek-pouches are large, and they have a sac which communicates with the larynx under the thyroid cartilage, which fills with air when they cry out.

Some naturalists of the day, however, place all under the generic name Macacus.

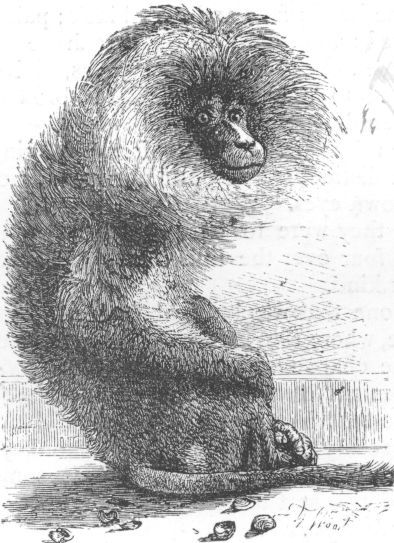

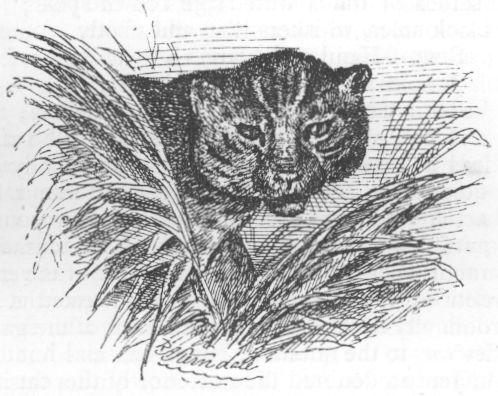

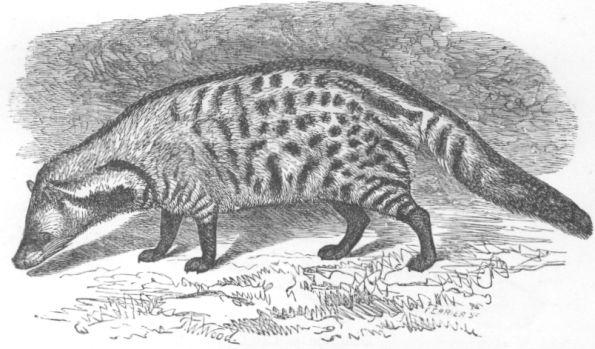

|

| Macacus silenus. |

NATIVE NAMES.—Nil bandar, Bengali; Shia bandar, Hindi; Nella manthi, Malabari.

HABITAT.—The Western Ghâts of India from North Lat. 14° to the extreme south, but most abundant in Cochin and Travancore (Jerdon), also Ceylon (Cuvier and Horsfield), though not confirmed by Emerson Tennent, who states that the silenus is not found in the island except as introduced by Arab horse-dealers occasionally, and that it certainly is not indigenous. Blyth was also assured by Dr. Templeton of Colombo that the only specimens there were imported.

DESCRIPTION.—Black, with a reddish-white hood or beard surrounding the face and neck; tail with a tuft of whitish hair at the tip; a little greyish on the chest.

SIZE.—About 24 inches; tail, 10 inches.

There is a plate of this monkey in Carpenter and Westwood's edition of Cuvier, under the mistaken name of Wanderoo.

It is somewhat sulky and savage, and is difficult to get near in a wild state. Jerdon states that he met with it only in dense unfrequented forest, and sometimes at a considerable elevation. It occurs in troops of from twelve to twenty.

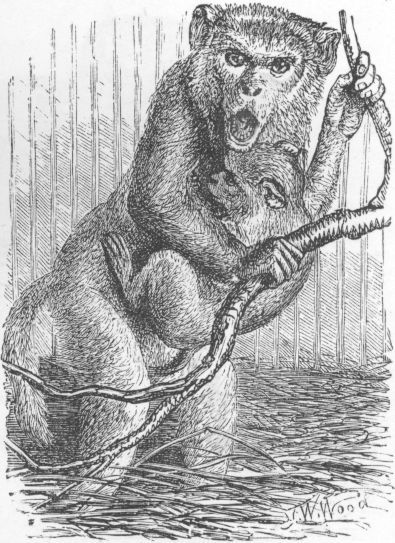

|

| Macacus rhesus. |

NATIVE NAMES.—Bandar, Hindi; Markot, Bengali; Suhu, Lepcha, Piyu, Bhotia.

HABITAT.—India generally from the North to about Lat. 18° or 19°; but not in the South, where it is replaced by Macacus radiatus.

DESCRIPTION.—Above brownish ochrey or rufous; limbs and beneath ashy-brown; callosities and adjacent parts red; face of adult males red.

SIZE.—Twenty-two inches; tail 11 inches.

This monkey is too well-known to need description. It is the common acting monkey of the bandar-wallas, the delight of all Anglo-Indian children, who go into raptures over the romance of Munsur-ram and Chameli, their quarrels, parting, and reconciliation, so admirably acted by these miniature comedians.

NOTE.—For Macacus rheso-similis, Sclater, see P.Z.S. 1872, p. 495, pl. xxv., also P.Z.S. 1875, p. 418.

HABITAT.—The Himalayan ranges and Assam.

DESCRIPTION.—Brownish grey, somewhat mixed with slaty, and rusty brownish on the shoulders in some; beneath light ashy brown; fur fuller and more wavy than in rhesus; canine teeth long; of stout habit; callosities and face less red than in the last species (Jerdon). Face flesh-coloured, but interspersed with a few black hairs (McClelland).

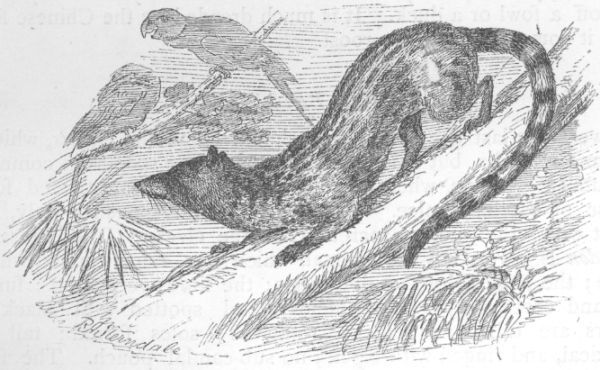

HABITAT.—Tenasserim and the Malay Archipelago.

|

| Macacus nemestrinus. |

DESCRIPTION.—General colour grizzled brown; the piles annulated with dusky and fulvous; crown darker, and the middle of the back also darker; the hair lengthened on the fore-quarters; the back stripe extends along the tail, becoming almost black; the tail terminates in a bright ferruginous tuft. This monkey is noted for its docility, and in Bencoolen is trained to be useful as well as amusing. According to Sir Stamford Raffles it is taught to climb the cocoa palms for the fruit for its master, and to select only those that are ripe.

HABITAT.—Arracan.

DESCRIPTION.—A thick-set powerful animal, with a broad, rather flattened head above, and a moderately short, well clad, up-turned tail, about one-third the length of the body and head; the female smaller.—Anderson.

Face fleshy brown; whitish round the eyes and on the forehead; eyebrows brownish, a narrow reddish line running out from the external angle of the eye. The upper surface of the head is densely covered with short dark fur, yellowish brown, broadly tipped with black; the hair radiating from the vertex; on and around the ear the hair is pale grey; above the external orbital angle and on the sides of the face the hair is dense and directed backwards, pale greyish, obscurely annulated with dusky brown, and this is prolonged downwards to the middle of the throat. On the shoulders, back of the neck, and upper part of the thighs, the hairs are very long, fully three inches in the first-mentioned localities; the basal halves greyish; and the remainder ringed with eleven bands of dark brown and orange; the tips being dark. The middle and small of the back is almost black, the shorter hair there being wholly dark; and this colour is prolonged on the tail, which is tufted. The hair on the chest is annulated, but paler than on the shoulders, and it is especially dense on the lower part. The lower halves of the limbs are also well clad with annulated fur, like their outsides, but their upper halves internally and the belly are only sparsely covered with long brownish grey plain hairs, not ringed.

The female differs from the male in the absence of the black on the head and back, and in the hair of the under parts being brownish grey, without annulations. The shoulders somewhat brighter than the rest of the fur, which is yellowish olive; greyish olive on outside of limbs; dusky on upper surface of hands and feet; and black on upper surface of tail.

SIZE.—Length of male, head and body 23 inches; tail, without hair, 8 inches; with hair 10 inches.

The above description is taken from Dr. Anderson's account, 'Anat. and Zool. Res.,' where at page 54 will be found a plate of the skull showing the powerful canine teeth. Blyth mentions a fine male with hair on the shoulders four to five inches long.

HABITAT.—Cachar, Kakhyen Hills, east of Bhamo.

DESCRIPTION.—Upper surface of head and along the back dark brown, almost blackish; sides and limbs dark brown; the hair, which is very long, is ringed with light yellowish and dark brown, darker still at the tips; face red; tail short and stumpy, little over an inch long.

This monkey is one over which many naturalists have argued; it is synonymous with Macacus speciosus, M. maurus, M. melanotus, and was thought to be with M. brunneus till Dr. Anderson placed the latter in a separate species on account of the non-annulation of its hair. It is essentially a denizen of the hills; it has been obtained in Cachar and in Upper Assam. Dr. Anderson got it in the Kakhyen Hills on the frontier of Yunnan, beyond which, he says, it spreads to the southeast to Cochin-China.

DESCRIPTION.—Head large and whiskered; form robust; tail stumpy and clad; general colour of the animal brown; whiskers greyish; face nude and flesh-coloured, with a deep crimson flush round the eyes.

SIZE.—Two feet 9 inches; tail about 3 inches.

This large monkey, though not belonging to British India, inhabiting, it is said, "the coldest and least accessible forests of Eastern Thibet," is mentioned here, as the exploration of that country by travellers from India is attracting attention.

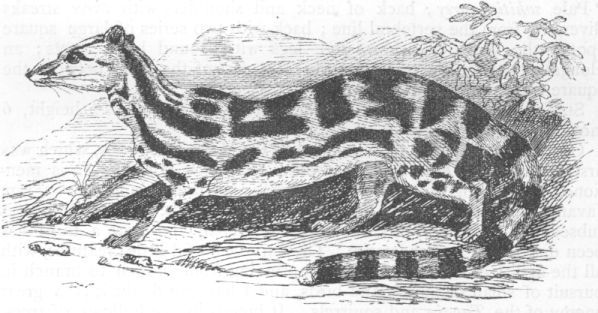

Tail longer than in Inuus, and face not so lengthened; otherwise as in that genus.—Jerdon.

NATIVE NAMES.—Bandar, Hindi; Makadu or Wanur, Mahratti; Kerda mahr of the Ghâts; Munga, Canarese; Koti, Telegu; Vella munthi, Malabar.

HABITAT.—All over the southern parts of India, as far north as lat. 18°.

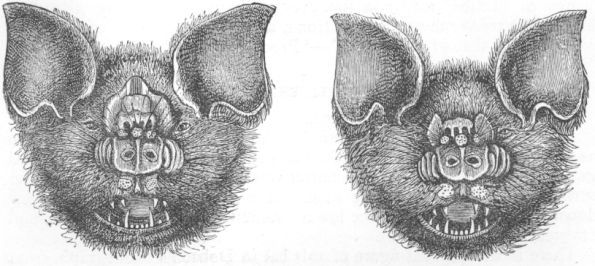

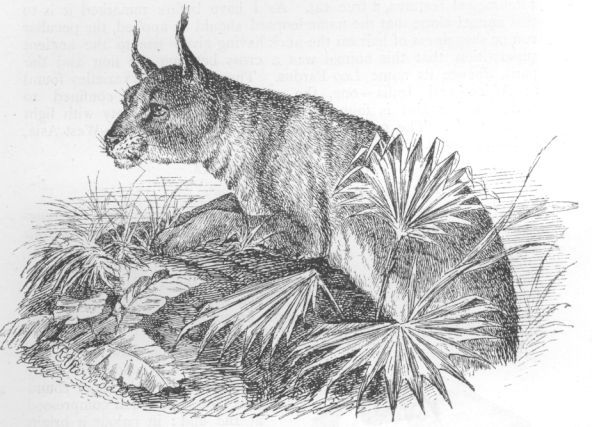

|

| Macacus radiatus and Macacus pileatus. |

DESCRIPTION.—Of a dusky olive brown, paler and whitish underneath, ashy on outer sides of limbs; tail dusky brown above, whitish beneath; hairs on the crown of the head radiated.

SIZE.—Twenty inches; tail 15 inches.

Elliott remarks of this monkey that it inhabits not only the wildest jungles, but the most populous towns, and it is noted for its audacity in stealing fruit and grain from shops. Jerdon says: "It is the monkey most commonly found in menageries, and led about to show various tricks and feats of agility. It is certainly the most inquisitive and mischievous of its tribe, and its powers of mimicry are surpassed by none." It may be taught to turn a wheel regularly; it smokes tobacco without inconvenience.—Horsfield.

NATIVE NAME.—Rilawa, Singhalese.

HABITAT.—Ceylon and China.

DESCRIPTION.—Yellowish brown, with a slight shade of green in old specimens; in some the back is light chestnut brown; yellowish brown hairs on the crown of the head, radiating from the centre to the circumference; face flesh-coloured and beardless; ears, palms, soles, fingers, and toes blackish; irides reddish brown; callosities flesh-coloured; tail longish, terminating in short tuft.—Kellaart.

SIZE.—Head and body about 20 inches; tail 18 inches.

This is the Macacus sinicus of Cuvier, and is very similar to the last species. In Ceylon it takes the place of our rhesus monkey with the conjurors, who, according to Sir Emerson Tennent, "teach it to dance, and in their wanderings carry it from village to village, clad in a grotesque dress, to exhibit its lively performances." It also, like the last, smokes tobacco; and one that belonged to the captain of a tug steamer, in which I once went down from Calcutta to the Sandheads, not only smoked, but chewed tobacco. Kellaart says of it: "This monkey is a lively, spirited animal, but easily tamed; particularly fond of making grimaces, with which it invariably welcomes its master and friends. It is truly astonishing to see the large quantity of food it will cram down its cheek pouches for future mastication."

NATIVE NAME.—Kra, Malay.

HABITAT.—Tenasserim, Nicobars, Malay Archipelago.

|

| Macacus cynomolgus. |

DESCRIPTION.—"The leading features of this animal are its massive form, its large head closely set on the shoulders, its stout and rather short legs, its slender loins and heavy buttocks, its tail thick at the base" (Anderson). The general colour is similar to that of the Bengal rhesus monkey, but the skin of the chest and belly is bluish, the face livid, with a white area between the eyes and white eyelids. Hands and feet blackish.

SIZE.—About that of the Bengal rhesus.

According to Captain (now Sir Arthur) Phayre "these monkeys frequent the banks of salt-water creeks and devour shell-fish. In the cheek-pouch of the female were found the claws and body of a crab. There is not much on record concerning the habits of this monkey in its wild state beyond what is stated concerning its partiality for crabs, which can also, I believe, be said of the rhesus in the Bengal Sunderbunds."

HABITAT.—Burmah.

DESCRIPTION.—In all respects the same as the last, except that its face is blackish, with conspicuously white eyelids.

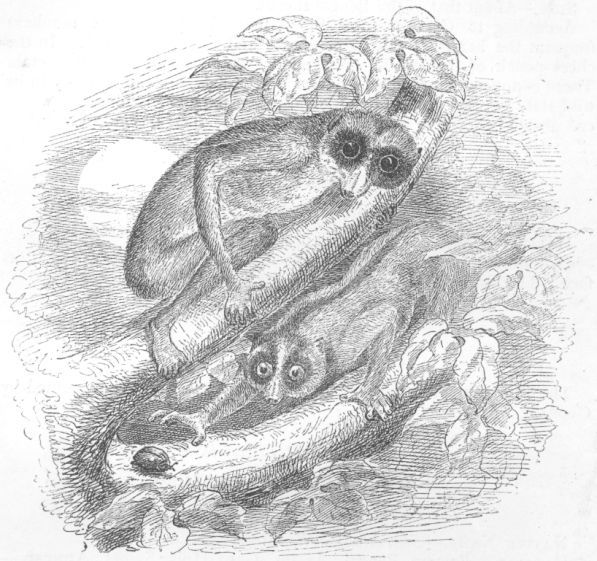

The Indian members of this family belong to the sub-family named by Geoffroy Nycticebinæ.

NATIVE NAME.—Sharmindi billi, Hindi.

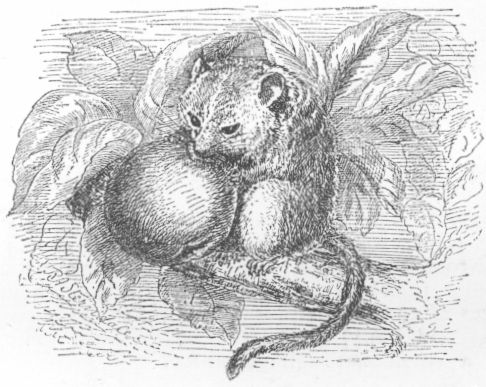

HABITAT.—Eastern Bengal, Assam, Garo Hills, Sylhet, Arracan.—Horsfield.

|

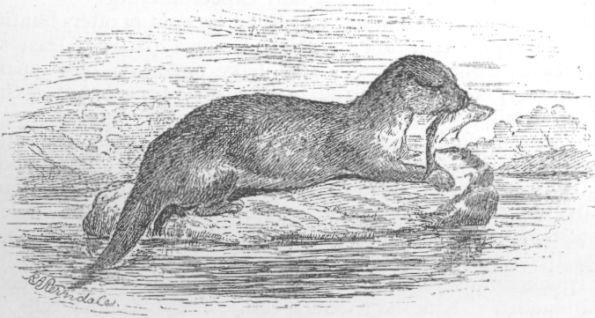

| Loris gracilis and Nycticebus tardigradus. |

DESCRIPTION.—Dark ashy grey, with a darker band down middle of back, beneath lighter grey; forehead in some dark, with a narrow white stripe between the eyes, disappearing above them; ears and round the eye dark; tail very short.—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Length about 14 to 15 inches; tail 5/8 of an inch.

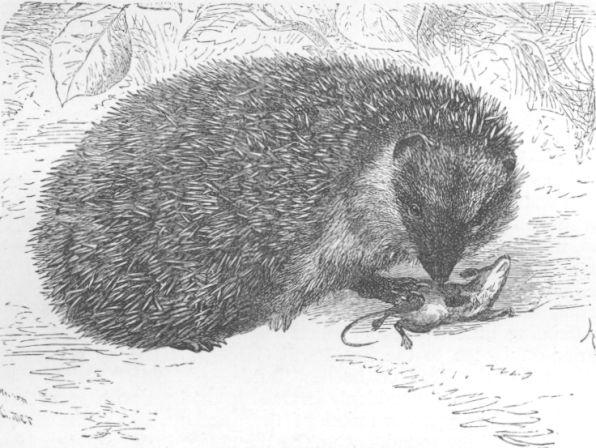

Nocturnal in its habits; sleeping during the day in holes of trees, and coming out to feed at night. Sir William Jones describes one kept by him for some time; it appeared to have been gentle, though at times petulant when disturbed; susceptible of cold; slept from sunrise to sunset rolled up like a hedgehog. Its food was chiefly plantains, and mangoes when in season. Peaches, mulberries, and guavas, it did not so much care for, but it was most eager after grasshoppers, which it devoured voraciously. It was very particular in the performance of its toilet, cleaning and licking its fur. Cuvier also notices this last peculiarity, and with regard to its diet says it eats small birds as well as insects. These animals are occasionally to be bought in the Calcutta market. A friend of mine had a pair which were a source of great amusement to his guests after dinner. (See Appendix C.)

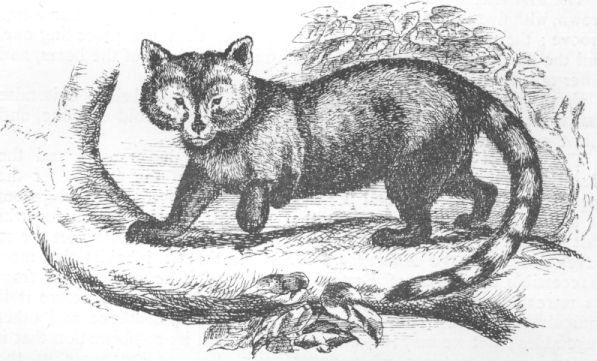

Body and limbs slender; no tail; eyes very large, almost contiguous; nose acute.

NATIVE NAMES.—Tevangar, Tamil; Dewantsipilli, Telegu. (Oona happslava, Singhalese.—Kellaart.)

HABITAT.—Southern India and Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—Above greyish rufescent (tawny snuff brown: Kellaart); beneath a paler shade; a white triangular spot on forehead, extending down the nose; fur short, dense, and soft; ears thin, rounded (Jerdon). A hooped claw on inner toes; nails of other toes flat; posterior third of palms and soles hairy (Kellaart).

SIZE.—About 8 inches; arm, 5; leg, 5½.

This, like the last, is also nocturnal in its habits, and from the extreme slowness of its movements is called in Ceylon "the Ceylon sloth." Its diet is varied—fruit, flower, and leaf buds, insects, eggs, and young birds. Sir Emerson Tennent says the Singhalese assert that it has been known to strangle pea-fowl at night and feast on the brain, but this I doubt. Smaller birds it might overcome. Jerdon states that in confinement it will eat boiled rice, plantains, honey or syrup and raw meat. McMaster, at page 6 of his 'Notes on Jerdon,' gives an interesting extract from an old account of 'Dr. John Fryer's Voyage to East India and Bombain,' in which he describes this little animal as "Men of the Woods, or more truly Satyrs;" asleep during the day; but at "Night they Sport and Eat." "They had Heads like an owl. Bodied like a monkey without Tails. Only the first finger of the Right Hand was armed with a claw like a bird, otherwise they had hands and feet which they walk upright on, not pronely, as other Beasts do."

These little creatures double themselves up when they sleep, bending the head down between their legs. Although so sluggish generally, Jerdon says they can move with considerable agility when they choose.

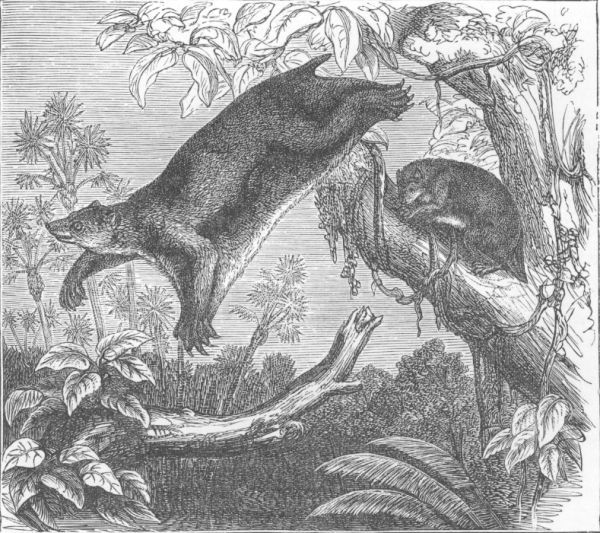

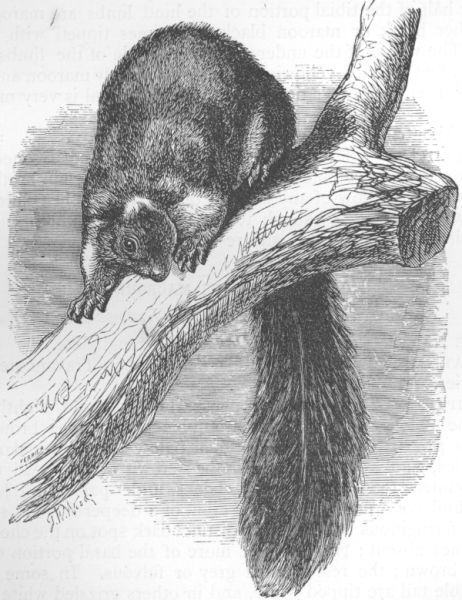

There is a curious link between the Lemurs and the Bats in the Colugos. (Galæopithecus): their limbs are connected with a membrane as in the Flying Squirrels, by which they can leap and float for a hundred yards on an inclined plane. They are mild, inoffensive animals, subsisting on fruits and leaves. Cuvier places them after the Bats, but they seem properly to link the Lemurs and the frugivorous Bats. As yet they have not been found in India proper, but are common in the Malayan Peninsula, and have been found in Burmah.

NATIVE NAME.—Myook-hloung-pyan, Burmese.

HABITAT.—Mergui; the Malayan Peninsula.

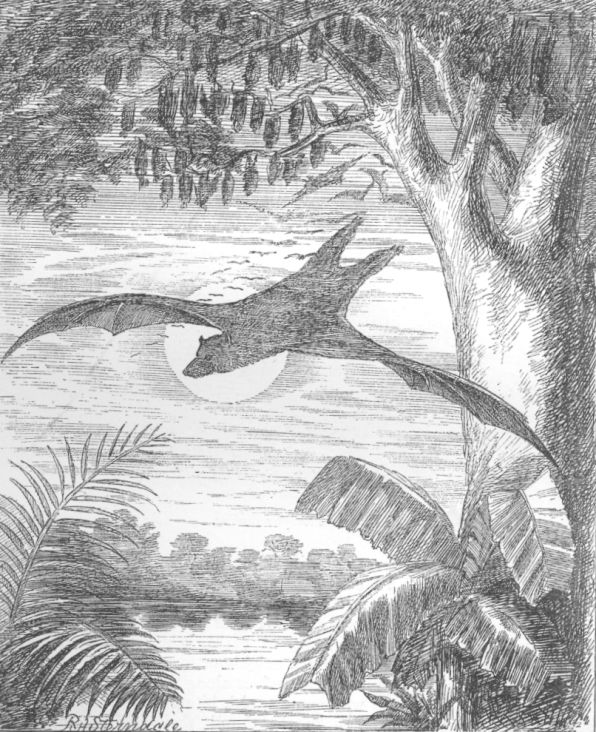

|

| Galæopithecus volans. |

DESCRIPTION.—Fur olive brown, mottled with irregular whitish spots and blotches; the pile is short, but exquisitely soft; head and brain very small; tail long and prehensile. The membrane is continued from each side of the neck to the fore feet; thence to the hind feet, again to the tip of the tail. This animal is also nocturnal in its habits, and very sluggish in its motions by day, at which time it usually hangs from a branch suspended by its fore hands, its mottled back assimilating closely with the rugged bark of the tree; it is exclusively herbivorous, possessing a very voluminous stomach, and long convoluted intestines. Wallace says of it, that its brain is very small, and it possesses such tenacity of life that it is very difficult to kill; he adds that it is said to have only one at a birth, and one he shot had a very small blind naked little creature clinging closely to its breast, which was quite bare and much wrinkled. Raffles, however, gives two as the number produced at each birth. Dr. Cantor says that in confinement plantains constitute the favourite food, but deprived of liberty it soon dies. In its wild state it "lives entirely on young fruits and leaves; those of the cocoanut and Bombax pentandrum are its favourite food, and it commits great injury to the plantations of these."—Horsfield's 'Cat. Mam.' Regarding its powers of flight, Wallace, in his 'Travels in the Malay Archipelago,' says: "I saw one of these animals run up a tree in a rather open space, and then glide obliquely through the air to another tree on which it alighted near its base, and immediately began to ascend. I paced the distance from one tree to the other, and found it to be seventy yards, and the amount of descent not more than thirty-five or forty feet, or less than one in five. This, I think, proves that the animal must have some power of guiding itself through the air, otherwise in so long a distance it would have little chance of alighting exactly upon the trunk."

There is a carefully prepared skeleton of this animal in the Indian Museum in Calcutta.

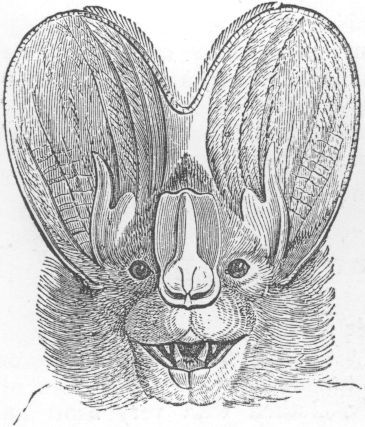

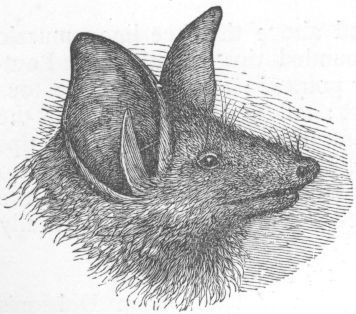

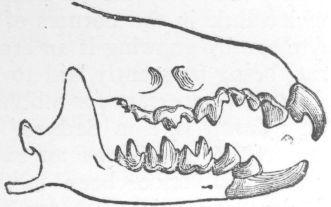

It may seem strange to many that such an insignificant, weird little creature as a bat should rank so high in the animal kingdom as to be but a few removes from man. It has, however, some striking anatomical affinities with the last Order, Quadrumana, sufficient to justify its being placed in the next link of the great chain of creation.

|

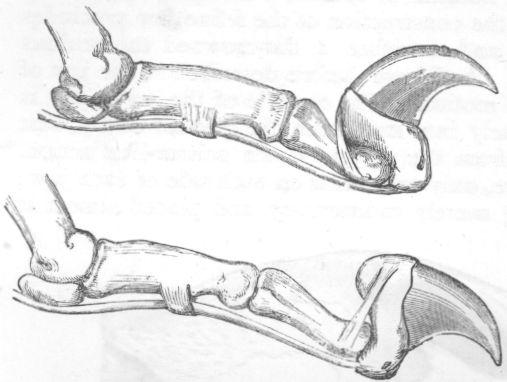

| Sternum of Pteropus. |

"Bats have the arms, fore-arms and fingers excessively elongated, so as to form with the membrane that occupies their intervals, real wings, the surface of which is equally or more extended than in those of birds. Hence they fly high and with great rapidity."—Cuvier. They suckle their young at the breast, but some of them have pubic warts resembling mammæ. The muscles of the chest are developed in proportion, and the sternum has a medial ridge something like that of a bird. They are all nocturnal, with small eyes (except in the case of the frugivorous bats), large ears, and in some cases membranous appendages to the nostrils, which may possibly be for the purpose of guiding themselves in the dark, for it is proved by experiment that bats are not dependent on eyesight for guidance, and one naturalist has remarked that, in a certain species of bat which has no facial membrane, this delicacy of perception was absent. I have noticed this in one species, Cynopterus marginatus, one of which flew into my room not long ago, and which repeatedly dashed itself against a glass door in its efforts to escape. I had all the other doors closed.

Bats are mostly insectivorous; a few are fruit-eaters, such as our common flying-fox. They produce from one to two at a birth, which are carried about by the mother and suckled at the breast, this peculiarity being one of the anatomical details alluded to as claiming for the bats so high a place.

Bats are divided into four sub-families—Pteropodidæ, Vampyridæ, Noctilionidæ, and Vespertilionidæ.

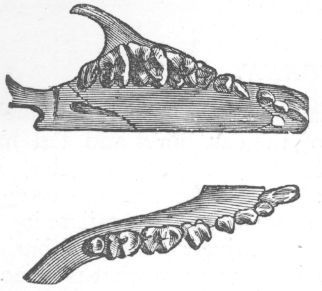

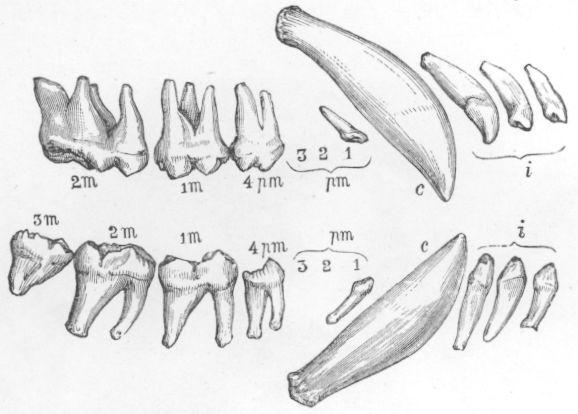

These are frugivorous bats of large size, differing, as remarked by Jerdon, so much in their dentition from the insectivorous species that they seem to lead through the flying Lemurs (Colugos) directly to the Quadrumana. The dentition is more adapted to their diet; they have cutting incisors to each jaw, and grinders with flat crowns, and their intestines are longer than those of the insectivorous bats. They produce but one at birth, and the young ones leave their parents as soon as they can provide for themselves. The tongue is covered with rough papillæ. They have no tail. These bats and some of the following genus, which are also frugivorous, are distinguished from the rest of the bats by a claw on the first or index finger, which is short.

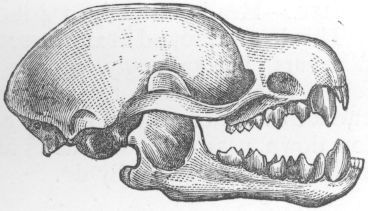

Dental formula: Inc., 4/4; can., 1—1/1—1; premolars, 2—2/3—3; molars, 3—3/3—3.

NATIVE NAMES.—Badul, Bengali and Mahratti; Wurbagul, Hindi; Toggul bawali, Canarese; Sikurayi, Telegu.

HABITAT.—All through India, Ceylon, and Burmah.

|

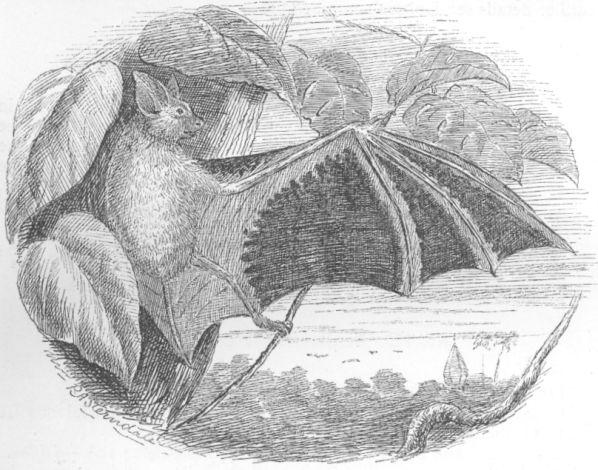

| The Flying Fox at Home. |

DESCRIPTION.—Head and nape rufous black; neck and shoulders golden yellow (the hair longer); back dark brown; chin dark; rest of body beneath fulvous or rusty brown; interfemoral membrane brownish black.—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Length, 12 to 14 inches; extent of wings, 46 to 52 inches.

These bats roost on trees in vast numbers. I have generally found them to prefer tamarinds of large size. Some idea of the extent of these colonies may be gathered from observations by McMaster, who attempted to calculate the number in a colony. He says: "In five minutes a friend and I counted upwards of six hundred as they passed over head, en route to their feeding grounds; supposing their nightly exodus to continue for twenty minutes, this would give upwards of two thousand in one roosting place, exclusive of those who took a different direction."

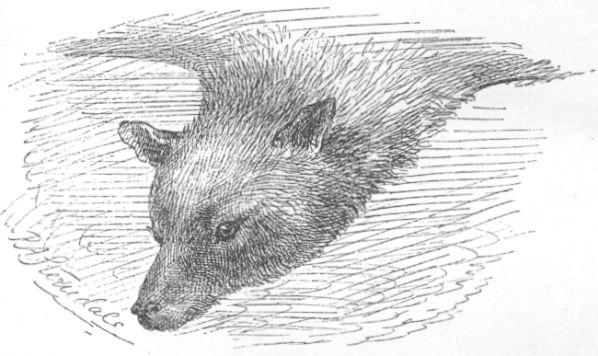

|

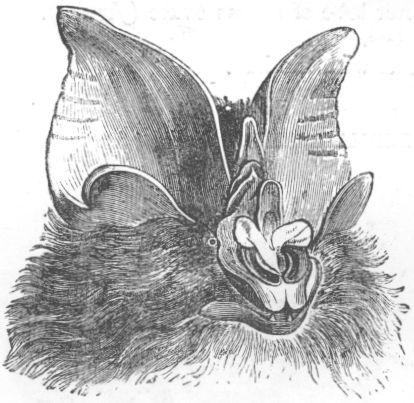

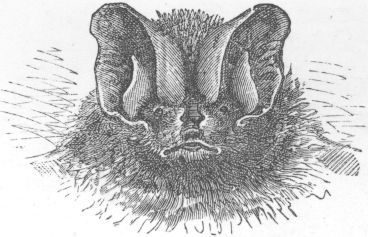

| Head of Pteropus medius. |

Tickell's account of these colonies is most graphic, though Emerson Tennent has also given a most interesting and correct account of their habits. The former writes:—"From the arrival of the first comer until the sun is high above the horizon, a scene of incessant wrangling and contention is enacted among them, as each endeavours to secure a higher and better place, or to eject a neighbour from too close vicinage. In these struggles the bats hook themselves along the branches, scrambling about hand over hand with some speed, biting each other severely, striking out with the long claw of the thumb, shrieking and cackling without intermission. Each new arrival is compelled to fly several times round the tree, being threatened from all points, and, when he eventually hooks on, he has to go through a series of combats, and be probably ejected two or three times before he makes good his tenure." For faithful portraying, no one could improve on this description. These bats are exceeding strong on the wing. I was aware that they went long distances in search of food, but I was not aware of the power they had for sustained flight till the year 1869, when, on my way to England on furlough, I discovered a large flying fox winging his way towards our vessel, which was at that time more than two hundred miles from land. Exhausted, it clung on to the fore-yard arm; and a present of a rupee induced a Lascar to go aloft and seize it, which he did after several attempts. The voracity with which it attacked some plantains showed that it had been for some time deprived of food, probably having been blown off shore by high winds. Hanging head-downwards from its cage, it stuffed the fruit into its cheeks, monkey-fashion, and then seemed to chew it at leisure. When I left the steamer at Suez it remained in the captain's possession, and seemed to be tame and reconciled to its imprisonment, tempered by a surfeit of plantains. In flying over water they frequently dip down to touch the surface. Jerdon was in doubt whether they did this to drink or not, but McMaster feels sure that they do this in order to drink, and that the habit is not peculiar to the Pteropodidæ, as he has noticed other bats doing the same. Colonel Sykes states that he "can personally testify that their flesh is delicate and without disagreeable flavour;" and another colonel of my acquaintance once regaled his friends on some flying fox cutlets, which were pronounced "not bad." Dr. Day accuses these bats of intemperate habits; drinking the toddy from the earthen pots on the cocoanut trees, and flying home intoxicated. The wild almond is a favourite fruit.

Mr. Rainey, who has been a careful observer of animals for years, states that in Bengal these bats prefer clumps of bamboos for a resting place, and feed much on the fruit of the betel-nut palm when ripe. Another naturalist, Mr. G. Vidal, writes that in Southern India the P. medius feeds chiefly on the green drupe or nut of the Alexandrian laurel (Calophyllum inophyllum), the kernels of which contain a strong-smelling green oil on which the bats fatten amazingly; and then they in turn yield, when boiled down, an oil which is recommended as an excellent stimulative application for the hair. I noticed in Seonee a curious superstition to the effect that a bone of this bat tied on to the ankle by a cord of black cowhair is a sovereign remedy, according to the natives, for rheumatism in the leg. Tickell states that these bats produce one at a time in March or April, and they continue a fixture on the mother till the end of May or beginning of June.

Dobson places this bat in the sub-group Cynonycteris. It seems to differ from Pteropus only, as far as I can see, in having a small distinct tail, though the above-quoted author considers it closely allied to the next genus.

HABITAT.—The Carnatic, Madras and Trichinopoly; stated also procurable at Calcutta and Pondicherry (Jerdon); Ceylon (Kellaart).

DESCRIPTION.—Fur short and downy; fulvous ashy, or dull light ashy brown colour, denser and paler beneath; the hairs whitish at the base; membranes dark brown.

SIZE.—Length, 5 to 5½ inches; extent of wing, 18 to 20 inches.

More information is required regarding the habits of this bat.

This genus has four molars less than the last, a shorter muzzle; the cheek-bones or zygomatic arch more projecting; tongue rather longer and more tapering, and slightly extensile.

Dental formula: Inc., 4/4 or 4/2; can., 1—1/1—1; premolars, 2—2/3—3; molars, 2—2/2—2.

NATIVE NAME.—Chamgadili, Hindi; Coteekan voulha, Singhalese.

|

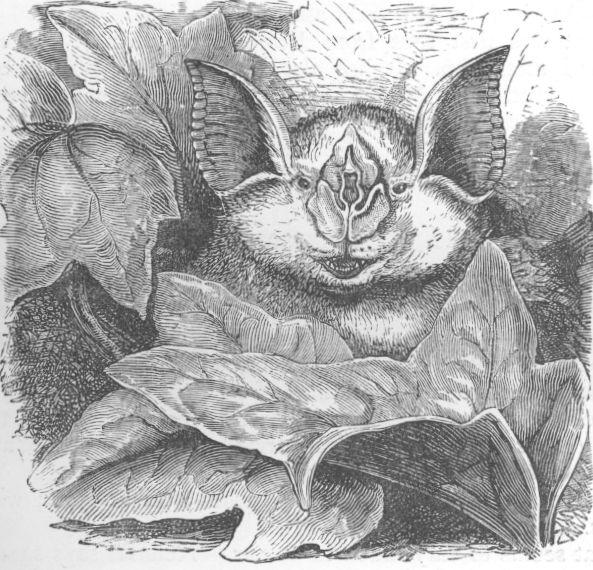

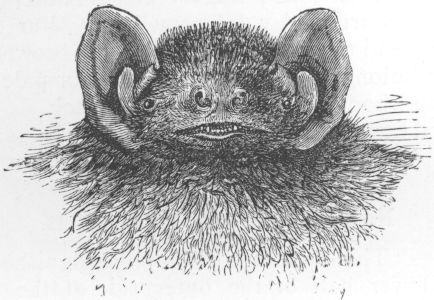

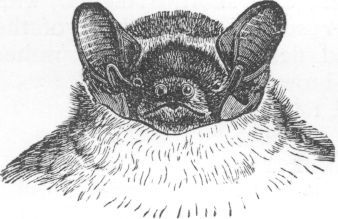

| Cynopterus marginatus. |

HABITAT.—India generally, and Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour fulvous olivaceous, paler beneath and with an ashy tinge; ears with a narrow margin of white (Jerdon.) A reddish smear on neck and shoulders of most specimens; membranes dusky brown. Females paler (Kellaart).

SIZE.—Length, 4½ to 5½ inches; extent of wing, 17 to 20 inches.

This bat is found all over India; it is frugivorous exclusively, though some of this sub-order are insectivorous. Blyth says he kept some for several weeks; they would take no notice of the buzz of an insect held to them, but are ravenous eaters of fruit, each devouring its own weight at a meal, voiding its food but little changed whilst slowly munching away; of guava it swallows the juice only. Blyth's prisoners were females, and after a time they attracted a male which hovered about them for some days, roosting near them in a dark staircase; he was also caught, with one of the females who had escaped and joined him. Dr. Dobson writes that in three hours one of these bats devoured twice its own weight. This species usually roosts in trees.

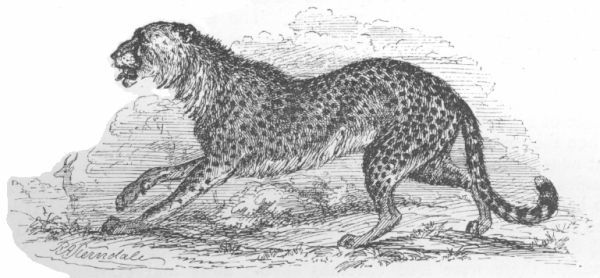

NATIVE NAME.—Lowo-assu (dog-bat), Javanese.

HABITAT.—The Himalayas, Burmah, Tenasserim, and the Indian Archipelago.