Title: The History of England in Three Volumes, Vol.III.

Author: Edward Farr

E. H. Nolan

Release date: September 8, 2006 [eBook #19218]

Most recently updated: February 25, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

JUDGES MADE INDEPENDENT OF THE CROWN.

CORONATION OF THEIR MAJESTIES.

FRANCE AND SPAIN DECLARE WAR AGAINST PORTUGAL.

THE MEETING OF PARLIAMENT AND THE CONCLUSION OF PEACE.

THE CHARACTER AND IMPEACHMENT OF WILKES.

MEETING OF PARLIAMENT, AND FURTHER PROCEEDINGS AGAINST WILKES.

PROPOSITION TO TAX THE AMERICAN COLONIES.

WAR WITH THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS.

ATTEMPTS TO FORM A NEW ADMINISTRATION.

OPPOSITION TO THE STAMP DUTIES IN AMERICA.

EMBARRASSMENT OF MINISTERS AND MEETING OF PARLIAMENT.

SENTIMENTS OF THE AMERICANS ON THE DECLARATORY ACT.

THE DISSOLUTION OF THE ROCKINGHAM CABINET.

DECLINE OF LORD CHATHAM’S POPULARITY.

DOMESTIC TROUBLES AND COMMOTIONS.

DISCONTENTS IN ENGLAND AND IRELAND.

DISSOLUTION OF THE GRAFTON CABINET.

DEBATES ON THE MIDDLESEX ELECTION, ETC.

THE QUESTION OF CONTROVERTED ELECTIONS, ETC.

THE PROROGATION OF PARLIAMENT.

REMONSTRANCE OF BECKFORD TO THE KING.

PROSECUTION OF WOODFALL AND ALMON.

DISPUTES RESPECTING FALKLAND ISLANDS.

DEBATE CONCERNING THE FALKLAND ISLANDS.

PARLIAMENTARY PROCEEDINGS OF THE LAW OF LIBEL.

QUARRELS BETWEEN THE LORDS AND COMMONS.

RESOLUTIONS RESPECTING THE PUBLICATION OF DEBATES.

COMMITTAL OF THE LORD MAYOR AND ALDERMAN OLIVER TO THE TOWER.

CONTEST BETWEEN THE CITY AND LEGISLATURE.

THE QUESTION OF THE MIDDLESEX ELECTION.

THE QUESTION OF THE DISSOLUTION OF PARLIAMENT.

RELEASE OF THE LORD MAYOR AND ALDERMAN OLIVER.

EDUCATION OF THE PRINCE OF WALES.

DEBATES ON SUBSCRIPTION TO THE THIRTY-NINE ARTICLES.

ECCLESIASTICAL NULLUM TEMPUS BILL.

DEATH OF THE PRINCESS DOWAGER OF WALES.

INVESTIGATION OF THE MIDDLESEX ELECTION.

SUBSCRIPTION TO THE THIRTY-NINE ARTICLES.

DEBATES ON EAST INDIA MEASURES.

DISPUTES WITH THE AMERICAN COLONIES.

EARLY MEASURES IN THIS SESSION.

PARLIAMENTARY PROCEEDINGS AGAINST AMERICA.

BILL FOR THE ADMINISTRATION OF CANADA.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

PACIFIC MEASURE OF LORD NORTH.

PETITION OF THE CITY OF LONDON.

EXPEDITION TO SEIZE STORES AT SALEM.

MEETING OF THE ASSEMBLIES AND OF GENERAL CONGRESS.

EXPEDITIONS AGAINST TICONDEROGA AND CROWN POINT, ETC.

DISPOSITION AND REVOLT OF THE VIRGINIANS.

CONDUCT OF CONGRESS TOWARDS NEW YORK, ETC.

PROSECUTION AND TRIAL OF HORNE TOOKE, ETC.

MOTIONS OF THE DUKE OF GRAFTON.

BURKE’S SECOND CONCILIATORY MOTION.

LORD NORTH’S PROHIBITORY BILL.

SENTIMENTS OF FOREIGN POWERS, ETC.

EVACUATION OF BOSTON BY THE BRITISH.

UNSUCCESSFUL ATTACK ON SULLIVAN’S ISLAND.

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE BY CONGRESS.

DEFEAT OF THE AMERICANS ON LONG ISLAND.

CAPTURE OF FORT LEE, AND RETREAT OF WASHINGTON.

EXPEDITION AGAINST RHODE ISLAND.

SUCCESSES OF GENERAL CARLETON.

DEFECTION OF THE COLONISTS, ETC.

ATTEMPT TO FIRE HIS MAJESTY’S DOCKYARD AT PORTSMOUTH.

BILL FOR DETAINING PERSONS IN PRISON CHARGED WITH HIGH-TREASON.

SPIRITED ADDRESS OF THE SPEAKER TO THE KING.

LORD CHATHAM’S MOTION FOR CONCESSIONS TO AMERICA.

BRITISH EXPEDITION UP THE HUDSON RIVER.

AMERICAN EXPEDITION TO LONG ISLAND.

CAPTURE OF GENERAL PRESCOT, ETC.

BATTLE OF THE BRANDYWINE, ETC.

EXPEDITION AND CAPTURE OF BURGOYNE.

CLINTON’S EXPEDITION UP THE HUDSON.

DUKE OF RICHMOND’S MOTION FOR INQUIRING INTO THE STATE OF THE NATION.

FOX’S MOTION FOR INQUIRING INTO THE STATE OF THE NATION.

INTELLIGENCE OF BURGOYNES DEFEAT

ROYAL ASSENT TO SEVERAL BILLS.

DEMONSTRATION OF PUBLIC SPIRIT IN ENGLAND.

COMMITTEE FOR TAKING THE STATE OF THE NATION INTO CONSIDERATION.

BURKE’S MOTION RELATIVE TO THE EMPLOYMENT OF INDIANS.

COMMITTEE OF EVIDENCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS, ETC.

LORD NORTHS CONCILIATORY BILLS.

INTIMATION OF THE FRENCH TREATY WITH AMERICA.

INVESTIGATION OF THE STATE OF THE NAVY.

MOTION FOR EXCLUDING CONTRACTORS FROM PARLIAMENT.

REVISION OF THE TRADE OF IRELAND.

BILL FOR THE RELIEF OF THE ROMAN CATHOLICS.

MOTION OF CENSURE ON LORD GEORGE GERMAINE, ETC.

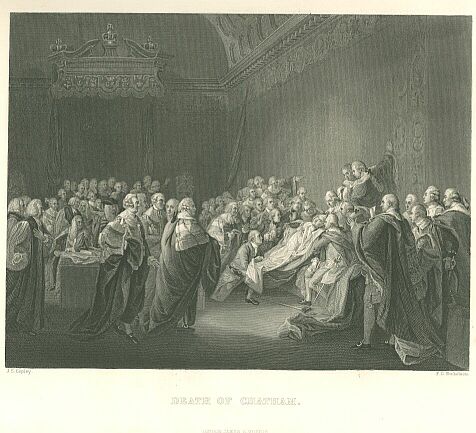

LORD CHATHAM’S LAST APPEARANCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS.

DEATH OF LORD CHATHAM, AND POSTHUMOUS HONOURS TO HIS MEMORY.

THE DUKE OF RICHMOND’S MOTION RESUMED.

NAVAL OPERATIONS IN THE BRITISH CHANNEL.

DISGRACEFUL INFRACTION OF THE CONVENTION OF SARATOGA.

LAFAYETTE’S EXPEDITION TO CANADA.

UNFORTUNATE ACTION UNDER LAFAYETTE.

SIR HENRY CLINTON TAKES THE COMMAND OF THE BRITISH TROOPS.

ARRIVAL OF THE COMMISSIONERS IN AMERICA WITH THE CONCILIATORY BILLS.

EVACUATION OF PHILADELPHIA BY THE BRITISH, ETC.

UNSUCCESSFUL ATTACK BY THE AMERICANS AND FRENCH ON RHODE ISLAND.

OPERATIONS OF THE BRITISH ARMY.

ATTACK OF THE SAVAGES ON THE SETTLEMENT OF WYOMING, ETC.

ARRIVAL OF THE FRENCH ENVOY AT PHILADELPHIA.

MOVEMENTS OF THE BRITISH AND FRENCH FLEETS.

CAPTURE OF DOMINICA BY THE FRENCH.

CAPTURE OF ST. LUCIE BY THE BRITISH.

RE-CAPTURE OF THE ISLANDS OF ST. PIERRE AND MIQUELON.

FRENCH PLANS REGARDING CANADA COUNTERACTED BY WASHINGTON.

CAPTURE OF SAVANNAH BY THE BRITISH.

AFFAIR RESPECTING ADMIRAL KEPPEL AND SIR HUGH PALLISER.

TRIAL OF ADMIRAL KEPPEL AND VICE-ADMIRAL PALLISER.

INVESTIGATION RESPECTING THE CONDUCT OF GENERAL AND LORD HOWE.

RELIEF TO PROTESTANT DISSENTERS.

DEBATES ON THE TRADE OF IRELAND.

BILL FOR THE IMPRESSMENT OF SEAMEN.

THE CAUSES OF THE RUPTURE WITH SPAIN.

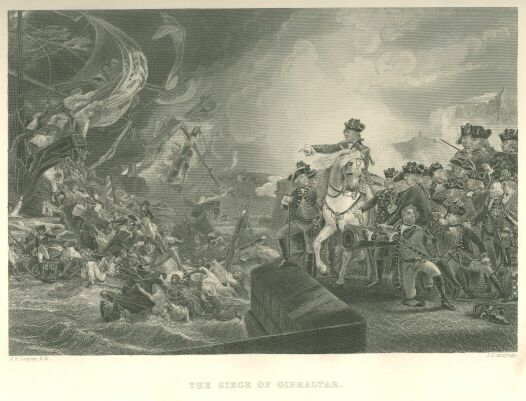

SPANISH ATTEMPT UPON GIBRALTAR.

FRENCH AND ENGLISH FLEETS IN THE CHANNEL, ETC.

INEFFECTUAL ATTEMPT OF THE AMERICANS TO REDUCE SAVANNAH.

BRITISH INCURSIONS INTO VIRGINIA.

CAPTURE OF STONEY-POINT AND VERPLANKS.

BRITISH EXPEDITION AGAINST CONNECTICUT.

STONEY-POINT RE-CAPTURED, BUT DESERTED AT THE APPROACH OF THE BRITISH.

BRITISH GARRISON SURPRISED AT PAULUS-HOOK.

AMERICAN DISASTER AT PENOBSCOT.

AMERICAN RETALIATION ON THE INDIANS, ETC.

ACTION BETWEEN PAUL JONES AND CAPTAIN PEARSON.

LORD SHELBURNE ATTACKS MINISTERS IN THE CASE OF IRELAND.

LORD OSSORY’S ATTACK ON MINISTERS RESPECTING IRELAND.

LORD NORTH’S PROPOSITION FOR THE RELIEF OF IRELAND.

BURKE’S PLAN OF ECONOMICAL REFORM.

REJECTION OF LORD SHELBURNE’S MOTION FOR A COMMISSION OF ACCOUNTS.

MINISTERIAL BILL FOR COMMISSION OF ACCOUNTS.

BILL FOR EXCLUDING CONTRACTORS FROM PARLIAMENT REJECTED.

MOTIONS REGARDING PLACES AND PENSIONS.

DEBATES ON THE INCREASE OF CROWN INFLUENCE.

LORD NORTH’S PROPOSAL RESPECTING THE EAST INDIA COMPANY.

GENERAL CONWAY’S PLAN OF RECONCILIATION WITH AMERICA.

POPULAR RAGE AGAINST THE CATHOLICS; RIOTS IN LONDON, ETC.

MEASURES ADOPTED BY PARLIAMENT, ARISING OUT OF THE LONDON RIOTS.

TRIAL OF LORD GEORGE GORDON AND THE RIOTERS.

ADMIRAL RODNEY’S SUCCESS AGAINST THE SPANIARDS.

RODNEY ENGAGES THE FRENCH FLEET.

EXPEDITION AGAINST SOUTH CAROLINA.

TREASON OF ARNOLD, AND FATE OF MAJOR ANDRE.

MARITIME LOSSES SUSTAINED BY THE BRITISH.

NOTICE OF THE RUPTURE WITH HOLLAND.

BURKE RE-INTRODUCES THE SUBJECT OF ECONOMICAL REFORM, ETC.

MOTION ON THE EMPLOYMENT OF THE MILITARY IN THE LATE RIOTS.

PETITION OF THE DELEGATES OF THE COUNTY ASSOCIATIONS.

MOTION OF FOX RESPECTING THE AMERICAN WAR.

THE GARRISON OF GIBRALTAR RELIEVED.

ARNOLD’S EXPEDITION TO VIRGINIA, ETC.

LORD CORNWALLIS’S EXPEDITION TO VIRGINIA.

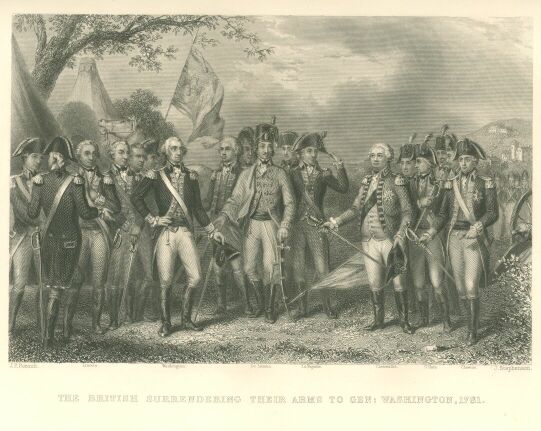

SIEGE OF LORD CORNWALLIS IN YORK-TOWN.

LOSS OF THE BRITISH DOMINION IN FLORIDA.

FRENCH AND SPANISH FLEETS IN THE ENGLISH CHANNEL.

COMMODORE JOHNSTONE ATTACKED BY DE SUFFREIN, ETC.

FURTHER OPERATIONS IN THE WEST INDIES.

SENTIMENTS OF FOREIGN POWERS TOWARD ENGLAND.

CENSURES ON RODNEY AND VAUGHAN.

MOTION OF SIR JAMES LOWTHER FOR PEACE, ETC.

RECENT EVENTS ON THE THEATRE OF WAR.

FOX’S MOTIONS FOR INQUIRY INTO THE NAVY.

MOTIONS OF INQUIRY IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS.

DEBATES ON LORD GEORGE GERMAINE’S ELEVATION TO THE PEERAGE.

RENEWED ATTACKS ON LORD SANDWICH: RESIGNATION OF LORD NORTH.

BILL FOR EXCLUDING CONTRACTORS, ETC.

RESOLUTIONS RESPECTING WILKES EXPUNGED FROM THE JOURNALS.

DISFRANCHISEMENT OF CRICKLADE, ETC.

DEBATES ON PARLIAMENTARY REFORM.

AFFAIRS OF THE WAR IN AMERICA.

STATE OF THE WAR IN THE WEST INDIES, ETC.

SIEGE AND RELIEF OF GIBRALTAR.

PROSPECT OF GENERAL PACIFICATION.

RE-ESTABLISHMENT OF COMMERCIAL INTERCOURSE WITH AMERICA, ETC.

PITT’S PLAN FOR REFORMING THE TREASURY ETC.

PETITION OF THE QUAKERS AGAINST THE SLAVE TRADE.

SETTLEMENT ON THE PRINCE OF WALES.

DISSOLUTION OF THE COALITION MINISTRY—PITT MADE PRIME MINISTER.

EFFORTS OF THE OPPOSITION AGAINST THE NEW MINISTRY.

THE TRIAL OF PARTIES, AND TRIUMPH OF PITT.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

ACTS TO PREVENT SMUGGLING, ETC.

BILL FOR THE RESTORATION OF FORFEITED ESTATES IN SCOTLAND.

BILL FOR THE FORTIFICATION OF THE DOCK-YARDS AT PORTSMOUTH AND PLYMOUTH.

A RETROSPECTIVE VIEW OF INDIAN AFFAIRS.

TREATIES WITH FRANCE AND SPAIN.

AFFAIRS OF THE PRINCE OF WALES.

DEBATE ON THE TREATY OF COMMERCE BETWEEN ENGLAND AND FRANCE.

PITT’S PLAN OF FINANCIAL REFORM.

MOTION FOR THE REPEAL OF THE CORPORATION AND TEST ACTS.

AFFAIRS OF THE PRINCE OF WALES.

MOTION FOR INQUIRY INTO THE ABUSES OF THE POST-OFFICE.

IMPEACHMENT OF WARREN HASTINGS.

DISPUTES BETWEEN GOVERNMENT, AND THE EAST INDIA COMPANY.

ADDITIONS MADE TO THE BILL FOR TRYING CONTROVERTED ELECTIONS.

CLAIMS OF THE AMERICAN ROYALISTS, ETC.

CHARGE AGAINST SIR ELIJAH IMPEY.

IMPEACHMENT OF WARREN HASTINGS.

DERANGEMENT OF HIS MAJESTY: DEBATES ON THE REGENCY.

THE QUESTION OF THE REGENCY RESUMED.

ADOPTION OF A PLAN OF FORTIFYING THE WEST INDIAN ISLANDS.

BILL FOR THE COMMEMORATION OF THE PEOPLE’S RIGHTS, ETC.

MOTION RESPECTING THE CORPORATION AND TEST ACTS, ETC.

IMPEACHMENT OF WARREN HASTINGS.

DEBATES ON THE TEST AND CORPORATION ACTS.

FLOOD’S MOTION FOR REFORM OF PARLIAMENT.

PITT’S FINANCIAL STATEMENT, ETC.

IMPEACHMENT OF WARREN HASTINGS.

PARLIAMENT PROROGUED, AND DISSOLVED.

SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTES WITH SPAIN.

PROGRESS OF REVOLUTIONARY PRINCIPLES IN ENGLAND.

BILL FOR THE REGULATION OF CANADA.

BILL TO AMEND THE LAW ON LIBELS.

IMPEACHMENT OF WARREN HASTINGS.

PROGRESS OF THE REVOLUTION IN FRANCE.

STATE OF PUBLIC OPINION IN ENGLAND, ETC.

DEBATES ON THE RUSSIAN ARMAMENT.

DEBATES ON THE AFFAIRS OF INDIA.

ACT TO RELIEVE THE SCOTCH EPISCOPALIANS, ETC.

SHERIDAN’S MOTION RESPECTING THE ROYAL BURGHS OF SCOTLAND.

DEBATES ON PARLIAMENTARY REFORM, ETC.

BILL RESPECTING THE NEW FOREST AND TIMBER FOR THE NAVY.

PROGRESS OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

STATE OF THE PUBLIC MIND IN ENGLAND.

HOSTILE MESSAGE OF THE KING TO PARLIAMENT.

DECLARATION OF WAR BY THE FRENCH, ETC.

THE TRAITOROUS CORRESPONDENCE BILL.

RELIEF GRANTED TO MERCANTILE MEN.

RENEWAL OF THE EAST INDIA COMPANY’S CHARTER.

RELIEF OF THE ROMAN CATHOLICS OF SCOTLAND, ETC.

DISCUSSION ON A MEMORIAL PRESENTED TO THE STATES-GENERAL.

MR. GREY’S MEASURE OF PARLIAMENTARY REFORM.

PROSPECTS OF THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, &c.

SUSPENSION OF THE HABEAS CORPUS ACT.

AGITATION IN ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND.

INTRODUCTION OF FOREIGN TROOPS.

MOTION ON BEHALF OF LA FAYETTE.

MOTION FOR INQUIRY INTO THE RECENT FAILURES OF OUR ARMIES.

THE PROROGATION OF PARLIAMENT.

CORSICA ANNEXED TO THE CROWN OF ENGLAND.

LORD HOWE’S NAVAL VICTORY, ETC.

BRITISH CONQUESTS IN THE WEST INDIES.

MILITARY OPERATIONS ON THE CONTINENT.

THE INTERNAL CONDITION OF FRANCE.

CONVENTION WITH SWEDEN AND DENMARK.

BILL FOR THE SUSPENSION OF THE HABEAS CORPUS ACT (CONTINUED.)

PITT’S PLAN TO MAN THE NAVY, ETC.

TERMINATION OF THE TRIAL OF WARREN HASTINGS.

MOTION FOR INQUIRY INTO THE STATE OF THE NATION REJECTED.

MARRIAGE OF THE PRINCE OF WALES.

NAVAL AFFAIRS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN, ETC.

FRENCH OPERATIONS IN HOLLAND, ETC.

TREATIES BETWEEN FRANCE AND PRUSSIA, ETC.

TREATY BETWEEN ENGLAND AND RUSSIA, ETC.

BILL TO PREVENT SEDITIOUS MEETINGS, ETC.

MILITARY AFFAIRS ON THE CONTINENT.

SURRENDER OF CORSICA AND THE ISLE OF ELBA.

DUTCH ATTEMPT TO RETAKE THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE.

DISPUTES BETWEEN FRANCE AND AMERICA.

MISSION OF LORD MALMESBURY TO PARIS.

STOPPAGE OF CASH PAYMENTS AT THE BANK.

GREY’S MOTION FOR REFORM, ETC.

REDEMPTION OF THE LAND-TAX, ETC.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE CONSULAR GOVERNMENT IN FRANCE.

COMMENCEMENT OF THE UNION WITH IRELAND.

MOTION FOR AN INQUIRY INTO THE STATE OF THE NATION.

DISSOLUTION OF THE NORTHERN CONFEDERACY.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

ACT TO RELIEVE CATHOLICS, ETC.

THE CAUSES FOR THE RENEWAL OF WAR WITH FRANCE.

LETTER OF THE PRINCE OF WALES.

CHANGE IN THE MINISTRY—PITT RESUMES OFFICE.

THE BUDGET—PARLIAMENT PROROGUED.

AFFAIRS OF FRANCE: NAPOLEON CREATED EMPEROR.

COALITION BETWEEN PITT AND ADDINGTON.

DEBATE ON THE RUPTURE WITH SPAIN.

NAPOLEON CROWNED KING OF ITALY

CONQUESTS OF NAPOLEON IN BAVARIA.

WAR BETWEEN FRANCE AND PRUSSIA, ETC.

DEBATE ON THE NEGOCIATION WITH FRANCE.

BILL FOR REMOVING THE DISABILITIES OF THE ROMAN CATHOLICS.

TRIAL OF STRENGTH BETWEEN THE TWO PARTIES.

DEBATES ON THE ORDERS IN COUNCIL.

MOTION RESPECTING THE DROITS OF ADMIRALTY, ETC.

RISING OF THE SPANISH NATION, ETC.

AFFAIRS OF PORTUGAL. CONFEDERATION OF FRANCE AND RUSSIA.

NAVAL AFFAIRS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN.

CHARGES AGAINST THE DUKE OF YORK.

CAMPAIGN OF NAPOLEON IN ITALY.

BRITISH EXPEDITION AGAINST NAPLES AND WALCHEREN.

DEBATE ON THE WALCHEREN EXPEDITION.

PROCEEDINGS AGAINST SIR FRANCIS BURDETT.

PETITION OF THE IRISH CATHOLICS, ETC.

THE MARRIAGE OF NAPOLEON, ETC.

ILLNESS OF HIS MAJESTY—OPENING OF PARLIAMENT, ETC.

OPENING OF PARLIAMENT BY THE REGENT

DEBATE ON THE RE-APPOINTMENT OF THE DUKE OF YORK TO THE WAR-OFFICE.

SUBJECT OF MILITARY DISCIPLINE.

LOUD SIDMOUTH’S MOTION RESPECTING DISSENTING PREACHERS.

AFFAIRS OF THE IRISH CATHOLICS.

AFFAIRS OF SPAIN, CAPTURE OF BADAJOZ, ETC.

AUGMENTATION OF THE CIVIL LIST.

BILL FOR PROHIBITING THE GRANT OF OFFICES IN REVERSION, ETC.

ASSASSINATION OF MR. PERCEVAL.

ADMINISTRATION OF LORD LIVERPOOL.

BILL FOR PRESERVATION OF THE PEACE.

BILL TO EXTEND THE PRIVILEGES OF DISSENTERS.

PROROGATION OF PARLIAMENT, ETC.

CAPTURE OF CIUDAD RODRIGO BY THE BRITISH.

WAR BETWEEN FRANCE AND RUSSIA.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

DEBATES ON THE WAR WITH AMERICA.

RENEWAL OF THE EAST INDIA COMPANY’S CHARTER.

APPOINTMENT OF VICE-CHANCELLOR.

DEBATES ON THE TREATY WITH SWEDEN.

BILL FOR ALLOWING THE MILITIA TO VOLUNTEER INTO THE LINE, ETC.

THE ALLIES ENTER PARIS; NAPOLEON DETHRONED, ETC.

HONOURS CONFERRED ON WELLINGTON, ETC.

VISIT OF THE ALLIED SOVEREIGNS.

TREATY OF PEACE WITH AMERICA, ETC.

RETURN OF NAPOLEON FROM. ELBA.

WAR RESOLVED ON; FINANCIAL MEASURES.

CAPTURE OF PARIS.—SURRENDER OF NAPOLEON, ETC.

RETURN OF LOUIS XVIII. TO PARIS.

BRITAIN GAINS POSSESSION OF THE ISLAND OF CEYLON.

RESTRICTIONS ON PUBLIC LIBERTY.

COMMITTEE ON THE POOR-LAWS, ETC.

DEATH OF THE PRINCESS CHARLOTTE.

MOTION FOR SECRET COMMITTEES PREPARATORY TO A BILL OF INDEMNITY.

EXTENSION OF THE BANK RESTRICTION.

STATE OF THE MANUFACTURERS OF LANCASHIRE, ETC.

THE DUKE OF YORK APPOINTED GUARDIAN TO HIS MAJESTY.

COMMITTEE ON THE CRIMINAL CODE.

MEASURES FOR RESUMPTION OF CASH-PAYMENTS.

MOTION FOR INQUIRY INTO THE STATE OF THE NATION.

CESSION OF PARGA TO THE TURKS.

BILLS FOR AMENDING THE CRIMINAL CODE.

MOTION FOR A COMMITTEE ON THE CORN-LAWS.

MOTION FOR A COMMITTEE RESPECTING FREE TRADE.

MOTIONS FOR PARLIAMENTARY REFORM, ETC.

REPORT OF THE AGRICULTURAL COMMITTEE.

MOTION TO RESTORE ROMAN CATHOLIC PEERS TO THEIR SEATS IN PARLIAMENT.

MOTION ON AGRICULTURAL DISTRESS, ETC.

ACTS FOR THE REDUCTION OF EXPENDITURE.

MOTION FOR PARLIAMENTARY REFORM

CAUSE OF THE GREEKS—PROROGATION OF PARLIAMENT.

AFFAIRS OF AGRICULTURE AND COMMERCE.

MOTIONS TO REFORM THE CRIMINAL LAW.

MOTION TO REFORM THE SCOTCH REPRESENTATION.

MOTION RESPECTING THE DUTY ON THE LEEWARD ISLANDS.

IRISH TITHE COMMUTATION BILL, ETC.—PROROGATION OF PARLIAMENT.

ATTACK ON MINISTERS WITH REFERENCE TO SPAIN, ETC.

DISCUSSIONS ON THE REVOLT IN DEMARARA, ETC.

STATE OF THE BRITISH COLONIES.

BILL FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF UNLAWFUL ASSOCIATIONS IN IRELAND.

COMMITTEE OF INQUIRY INTO THE STATE OF IRELAND.

MR. HUME’S MOTION AGAINST THE IRISH CHURCH ESTABLISHMENT, ETC.

STATE OF THE IRISH CHARTER SCHOOLS.

DEBATES ON ALLEGED ABUSES IN CHANCERY.

REGULATION OF THE SALARIES OF THE JUDGES.

REJECTION OF THE UNITARIAN MARRIAGE ACT, ETC.

ACT AGAINST COMBINATIONS AMONG WORKMEN.

SURRENDER, OF THE CHARTER OF THE LEVANT COMPANY.

PROPOSALS FOR THE ABOLITION OF CERTAIN TAXES, ETC.

MEASURES PROPOSED FOR RELIEVING COMMERCIAL DISTRESS.

BILL TO ENABLE PRIVATE BANKS TO HAVE AN UNLIMITED NUMBER OF PARTNERS,

APPOINTMENT OF A COMMITTEE ON EMIGRATION.

MODIFICATION OF THE CORN-LAWS.

BILL TO PREVENT BRIBERY AT ELECTIONS.

ALTERATION OF THE CRIMINAL CODE.

MODE FOR AMENDING THE REPRESENTATION OF EDINBURGH, ETC.

RESOLUTION FOR THE REGULATION OF PRIVATE COMMITTEES.

MOTION TO HOLD PARLIAMENT OCCASIONALLY IN DUBLIN AND EDINBURGH.

RESTORATION OF FORFEITED SCOTCH PEERAGES.

MOTION TO DISJOIN THE PRESIDENCY OF THE BOARD OF TRADE FROM THE

PROROGATION AND DISSOLUTION OF PARLIAMENT.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

MOTION FOR A SELECT COMMITTEE ON JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES, ETC.

KING’S MESSAGE RESPECTING THE CONDUCT OF SPAIN TOWARDS PORTUGAL.

RESOLUTIONS AGAINST BRIBERY AT ELECTIONS.

EXPLANATIONS OF MEMBERS, AND HOSTILITY TO THE MINISTRY.

OPINIONS OF HIS MAJESTY ON THE CATHOLIC QUESTION.

MOTION ON THE CHANCELLOR’S JURISDICTION IN BANKRUPTCY.

MOTIONS REGARDING THE STAMP-DUTY AND CHEAP PUBLICATIONS.

IMPROVEMENT OF THE CRIMINAL CODE.

ADMINISTRATION OF LORD GODERICH.

DUKE OF WELLINGTON’S ADMINISTRATION.

DISCUSSIONS AND EXPLANATIONS CONCERNING THE DISSOLUTION OF THE GODERICH

MOTION FOR A GRANT TO THE FAMILY OF MR. CANNING.

REPEAL OF THE TEST AND CORPORATION ACTS.

MOTION ON THE STATE OF THE LAW.

BILLS CONNECTED WITH ELECTION OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE.

DEATH OF THE EARL OF LIVERPOOL.

SUPPRESSION OF THE CATHOLIC ASSOCIATION.

REJECTION OF MR. PEEL AT OXFORD.

THE TRIUMPH OF CATHOLIC EMANCIPATION.

BILL FOR THE DISFRANCHISEMENT OF THE FORTY-SHILLING FREEHOLDERS.

MOTION FOR PARLIAMENTARY REFORM.

PROROGATION OF PARLIAMENT, ETC.

AGRICULTURAL AND COMMERCIAL DISTRESS.

MOTION FOR A COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE ON THE STATE OF THE NATION.

REDUCTION OF SALARIES OF PUBLIC OFFICERS, ETC.

MOTION FOR REVISING THE WHOLE SYSTEM OF TAXATION.

COMMITTEE ON THE EAST INDIA COMPANY’S CHARTER.

DEBATE ON A PROPOSAL TO ALTER THE CURRENCY.

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS—BILL FOR REPEALING THE DUTY ON BEER, ETC.

MR. O’CONNELL’S BILL FOR REFORM BY UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE, ETC.

MR. O’CONNELL’S BILL FOR REFORM BY UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE AND VOTE BY

BILL FOR REMOVING THE CIVIL DISABILITIES AFFECTING JEWS.

BILL FOR CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN CASES OF FORGERY.

BILL FOR AMENDING THE LAW OF LIBEL.

ALTERATIONS IN COURTS OF JUSTICE.

BILL TO AUTHORISE THE ADHIBITING OF THE SIGN-MANUAL BY STAMP.

DEATH OF THE KING, AND ACCESSION OF THE DUKE OF CLARENCE, WILLIAM IV.

ROYAL MESSAGE TO PARLIAMENT—RUPTURE BETWEEN THE MINISTERS AND

PROROGATION AND DISSOLUTION OF PARLIAMENT.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING THEIR MAJESTIES’ VISIT TO LONDON.

MAJORITY AGAINST MINISTERS FOR A SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE CIVIL LIST.

FORMATION OF EARL GREY’S ADMINISTRATION.

INTRODUCTION OF THE REFORM BILL.

DEBATE ON THE MOTION THAT THE BILL BE READ A SECOND TIME, ETC.

MOTION OF ADJOURNMENT PENDING THE ORDNANCE ESTIMATES CARRIED AGAINST

THE BUDGET—PROPOSED CHANGES IN TAXES, ETC.—ARRANGEMENT OF THE CIVIL

MEETING OF PARLIAMENT—THE REFORM QUESTION RENEWED IN PARLIAMENT.

REJECTION OF THE REFORM BILL BY THE LORDS.

CONSEQUENCES OF THE REJECTION OF THE REFORM BILL.

OPENING OF NEW LONDON BRIDGE, ETC.

REFORM BILL PASSED BY THE COMMONS.

DEBATES ON THE REFORM BILL IN THE LORDS.

DISTURBED STATE OF THE NATION.

FAILURE OF THE ATTEMPTS TO FORM A NEW ADMINISTRATION—MINISTERS

IRISH AND SCOTCH REFORM BILLS PASSED.

BILL TO PREVENT BRIBERY AT ELECTIONS, ETC.

COMMITTEE ON THE CHARTER OF THE EAST INDIA COMPANY, ETC.

THE AFFAIRS OF THE WEST INDIES.

MEETING OF PARLIAMENT—RE-ELECTION OF MR. MANNERS SUTTON AS SPEAKER.

OPENING OF THE REFORMED PARLIAMENT BY THE KING IN PERSON.

BANK OF ENGLAND CHARTER RENEWED.

ABOLITION OF SLAVERY IN THE COLONIES.

RESOLUTIONS AGAINST BRIBERY, ETC.

BILL TO REMOVE THE CIVIL DISABILITIES OF JEWS.—PROROGATION OF

MR. O’CONNELL’S MOTION FOR THE REPEAL OF THE UNION.

COMMISSION ISSUED TO INQUIRE INTO THE STATE OF THE IRISH CHURCH.

RENEWAL OF THE IRISH COERCION BILL.

RESIGNATION OF EARL GREY, ETC.

REJECTION OF THE IRISH TITHE QUESTION BY THE PEERS.

STATE OF ECCLESIASTICAL QUESTIONS AND THE CLAIMS OF DISSENTERS.

BILL FOR THE REMOVAL OF THE CIVIL DISABILITIES OF THE JEWS, ETC.

SIR ROBERT PEEL APPOINTED PRIME-MINISTER.

THE ACT ABOLISHING SLAVERY IN THE WEST INDIES CARRIED INTO EFFECT.

MEETING OF PARLIAMENT.—CONTEST FOR THE ELECTION OF SPEAKER.

DISCUSSION IN THE LORDS RESPECTING THE SLAVERY ABOLITION ACT.

MOTION OF THE MARQUIS OF CHANDOS TO REPEAL THE MALT-TAX.

REPORT OF COMMISSION REGARDING THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND, ETC.

REPEATED DEFEATS OF THE MINISTRY IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS.

THE QUESTION OF THE APPROPRIATION OF THE SURPLUS OF THE REVENUES OF THE

RESIGNATION OF MINISTERS, AND RESTORATION OF LORD MELBOURNE’S CABINET.

MUNICIPAL REFORM AND THE IRISH CHURCH.

DISCUSSION REGARDING ORANGE SOCIETIES IN IRELAND.

THE QUESTION OF ORANGE LODGES.

BILL TO REFORM THE IRISH MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS.

COMMUTATION OF TITHES IN ENGLAND.

BILL FOR REGISTRATION OF BIRTHS, DEATHS, AND MARRIAGES, ETC.

BILL TO ALTER THE REVENUES AND TERRITORIES OF THE DIFFERENT SEES, ETC.

BILL TO ABOLISH THE SECULAR JURISDICTION OF BISHOPS, ETC.

BILL TO AMEND THE ENGLISH MUNICIPAL CORPORATION ACT.

BILL TO ALLOW FELONS’ COUNSEL TO ADDRESS THE JURY, ETC.

ABOLITION OF IMPRISONMENT FOR DEBT, ETC.

MOTION FOR THE REDUCTION OF TAXATION ON BEHALF OF THE AGRICULTURISTS.

DISCUSSIONS ON THE COLONIES, AND ON OUR FOREIGN RELATIONS.

CONSIDERATION OF THE STATE OF IRELAND.

QUESTION OF ESTABLISHING A SYSTEM OF POOR-LAWS IN IRELAND.

NOTICES OF MOTIONS FOR CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGES.

OPERATION OF THE NEW POOR-LAWS.

STATE OF THE BANKING SYSTEM, ETC.

CONSIDERATION OF THE FOREIGN POLICY OF ENGLAND UNDER THE WHIG

MOTION ON THE STATE OF THE NATION.

ILLNESS AND DEATH OF THE KING—REMARKS ON HIS CHARACTER.

THE ACCESSION OF QUEEN VICTORIA.

THE QUEEN’S MESSAGE TO BOTH HOUSES—EULOGIES OF THE LATE SOVEREIGN IN

BILL FOR PROVIDING THE SUCCESSION TO THE CROWN.

ALTERATIONS IN THE CRIMINAL LAW, ETC.

STATE OF PARTIES AND ELECTIONS.

OPENING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

THE SUBJECT OF THE CIVIL LIST DEBATED.

THE SUBJECT OF THE PENSION LIST.

INTELLIGENCE FROM CANADA—DISCUSSION ON THE SUBJECT—ADJOURNMENT OF THE

PARLIAMENT REASSEMBLES—DEBATES ON CANADA—ADDRESS TO THE THRONE

THE QUESTION OF ELECTION COMMITTEES, ETC.

PARLIAMENTARY QUALIFICATION BILL.

REVIVAL OF ANTI-SLAVERY AGITATION, ETC.

DEBATES ON THE IRISH POOR-LAW BILL—THE BILL CARRIED.

MOTION FOR THE REPEAL OF THE APPROPRIATION CLAUSE—MINISTERIAL PLAN FOR

COMMITTEE OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS UPON THE IRISH MUNICIPAL BILL—THE

DEBATES IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS ON THE IRISH TITHE QUESTION.

THE IRISH POOR-LAW BILL CARRIED IN THE LORDS.

PROJECTED FORMATION OF A COLONY IN NEW ZEALAND, ETC.

MOTION FOR THE REPEAL OF THE CORN-LAWS.

VARIOUS IMPROVEMENTS IN THE LAW.

A SELECT COMMITTEE TO INQUIRE INTO THE OPERATION OF THE POOR-LAWS.

COMBINATIONS IN ENGLAND AND IRELAND.

JOHN THOM. ALIAS SIR WILLIAM COURTENAY.

ACT FOR ABOLISHING PLURALITIES, ETC.

THE SUBJECT OF EDUCATION DISCUSSED IN PARLIAMENT.

THE QUESTION OF CANADA RENEWED.

DISAFFECTION AMONG THE WORKING CLASSES.

PROPOSED REDUCTION OF THE RATES OF POSTAGE.

THE AFFAIRS OF IRELAND DISCUSSED IN PARLIAMENT.

IRISH MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS BILL.

PROCEEDINGS IN PARLIAMENT RESPECTING JAMAICA.

RESIGNATION OF MINISTERS, AND FAILURE OF SIR ROBERT PEEL TO FORM A NEW

BILL FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF THE PORTUGUESE SLAVE-TRADE, ETC.

ACT FOR THE BETTER ORDERING OF PRISONS.

MOTION FOR A COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE TO CONSIDER THE NATIONAL

THE BUDGET—PROPOSED REDUCTION OF POSTAGE DUTIES, ETC.

MEETING OF PARLIAMENT.—ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE QUEEN’S MARRIAGE.

BILL FOR THE NATURALIZATION OF PRINCE ALBERT.

QUESTION OF PRIVILEGE—HANSARD AND STOCKDALE.

THE IRISH MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS BILL, ETC.

ECCLESIASTICAL DUTIES AND REVENUES BILL.

JEWS’ CIVIL DISABILITIES REMOVAL BILL.

CHURCH OF SCOTLAND: NON-INTRUSION QUESTION, ETC.

RESOLUTION OF WANT OF CONFIDENCE IN THE GOVERNMENT.

PROROGATION AND DISSOLUTION OF PARLIAMENT.

MEETING OF THE NEW HOUSE OF COMMONS, ETC.

RESIGNATION OF MINISTERS.—SIR ROBERT PEEL’S ADMINISTRATION.

STATEMENT OF SIR ROBERT PEEL AS TO HIS INTENDED COURSE OF PROCEEDING,

DEBATE ON THE CORN-LAWS—PROPOSITION OF MINISTERS ON THE SUBJECT.

FINANCIAL MEASURES—INCOME-TAX BILL, ETC.

MR. VILLIERS’S MOTION ON THE CORN-LAWS.

BILL FOR RESTRAINING THE EMPLOYMENT OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN MINES AND

BILL FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ROYAL PERSON.

ADDRESS TO THE CROWN ON THE SUBJECT OF EDUCATION.

THE CORN-LAW QUESTION RESUMED.

AGITATION IN IRELAND, FORMATION OF THE FREE CHURCH IN SCOTLAND, ETC.

MOTION FOR THE STOPPAGE OF SUPPLIES.

RESTRICTIONS ON LABOUR IN FACTORIES, ETC.

THE CORN-LAWS AND FREE-TRADE QUESTION.

BANK CHARTER AND BANKING REGULATIONS.

MISCELLANEOUS MEASURES OF THE SESSION.

PROCEEDINGS AGAINST MR. O’CONNELL.

FINANCIAL AND COMMERCIAL POLICY—RETENTION OF THE INCOME-TAX, ETC.

AFFAIRS OF IRELAND—MAYNOOTH IMPROVEMENT BILL.

ACADEMICAL EDUCATION IN IRELAND.

QUESTION OF THE OREGON TERRITORY.

MISCELLANEOUS MEASURES OF THE SESSION.

STATE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS AT THE COMMENCEMENT OF THIS YEAR, ETC.

SETTLEMENT OF THE CORN-LAW QUESTION.

POSITION OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY ON THE DEFECTION OF SIR ROBERT PEEL.

THE CONDITION OF IRELAND.—DISTURBED STATE OF THE COUNTRY.—DISAFFECTION

POLITICAL AGITATION.—YOUNG IRELAND.

AFFAIRS OF INDIA.—BATTLE OF ALIWAL.—TOTAL EXPULSION OF THE SIKHS

STATE OF AFFAIRS AT THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE.—SUCCESSES OF THE

STATE OF NEW ZEALAND.—SUPPRESSION OF THE NATIVE REVOLT.

RELATIONS WITH CONTINENTAL EUROPE.

STATE OF IRELAND.—PROGRESS OF FAMINE AND DISEASE.

CONTINUED POLITICAL AGITATION.—DREADFUL PREVALENCE OF CRIME.

MR. JOHN O’CONNELL ASSUMES THE PRESIDENCY OF THE REPEAL

BITTER DISPUTES BETWEEN “OLD IRELAND” AND “YOUNG IRELAND.”

GENERAL STATE OF AFFAIRS IN GREAT BRITAIN.

POLITICAL AGITATION IN ENGLAND.

HOME NAVAL AND MILITARY AFFAIRS.

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY OF THE YEAR.

BILL FOR CREATING A NEW DIOCESS OF MANCHESTER.

DEBATE ON THE ANNEXATION OF CRACOW.

PROROGATION AND DISSOLUTION OF PARLIAMENT.

ASSEMBLING OF A NEW PARLIAMENT.

DEBATE ON THE DISTRESS OF THE NATION.

MEASURES FOR THE REPRESSION OF HOMICIDE AND OUTRAGE IN IRELAND.

MOTION FOR THE REPEAL OF JEWISH DISABILITIES.

ADJOURNMENT OF THE HOUSE.—CLOSE OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LABOURS OF 1847.

MUTINY OF SIKH TROOPS IN THE PUNJAUB. AND REVOLT OF CHUTTUR SINGH.

CAMPAIGN IN THE PUNJAUB UNDER LORD GOUGH.

SPAIN: DIPLOMATIC DISAGREEMENT WITH THAT COUNTRY; DISMISSION OF THE

VISIT OF FRENCH NATIONAL GUARDS TO LONDON.

AGITATION CONCERNING THE NAVIGATION LAWS.

REFORM OF THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY.

PROSECUTION OF THE WAR IN INDIA, AND ANNEXATION OF THE PUNJAUB.

CANADA.—POLICY OF THE GOVERNMENT.—OPPOSITION AND INSOLENT PROCEEDINGS

AUSTRALIA.—DISCONTENTS CREATED BY THE TRANSPORTATION QUESTION.

THE ARCTIC EXPEDITION UNDER SIR J. ROSS.

DEMANDS OF THE RUSSIAN AND AUSTRIAN EMPERORS UPON THE SULTAN OF TURKEY.

CONTINUED DISTRESS IN IRELAND—CRIME AND OUTRAGE—POLITICAL

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY OF 1849—OPENING OF THE SESSION.

REPEAL OF THE NAVIGATION LAWS.

AGRICULTURAL DISTRESS—MOTION FOR GOVERNMENTAL RELIEF.

VOTE OF THANKS TO THE ARMY IN INDIA.

MR. COBDEN’S MOTION FOR REDUCING THE ARMY AND NAVY.

MOTION ON THE STATE OF THE NATION

HOME EVENTS.—PROPOSAL FOR AN EXHIBITION OF THE INDUSTRY OF ALL NATIONS.

COMPLIMENT TO LORD PALMERSTON.

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY.—OPENING OF THE SESSION.

CONSTITUTIONS FOR THE COLONIES.

BILL FOR THE ABOLITION OF THE LORD-LIEUTENANCY OF IRELAND.

MISCELLANEOUS TOPICS OF DEBATE.

GENERAL PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY OF 1851.

EXHIBITION OF THE INDUSTRY OF ALL NATIONS.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS—EUROPEAN RELATIONS.

DISCUSSIONS IN THE ENGLISH PARLIAMENT CONCERNING THE STATE OF AFFAIRS AT

DIPLOMATIC DISPUTE WITH AUSTRIA AND TUSCANY, ARISING FROM AN OUTRAGE

STATEMENT OF MR. ERSKINE MATHER TO M. SALVAGNOLI.*

DEATHS OF EMINENT PERSONS DURING THE YEAR 1851.

DEATH OF THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON.

PARLIAMENTARY PROCEEDINGS AND PARTY CONFLICTS DURING 1852.

THE MILITIA BILL.—DEFEAT AND RESIGNATION OF THE CABINET.

THE EARL OF DERBY’S ADMINISTRATION.

FOREIGN POLICY OF THE GOVERNMENT.—OUTRAGE ON MR. MATHER AT FLORENCE.

PROROGATION AND DISSOLUTION OF PARLIAMENT.—GENERAL ELECTION.

MEETING OF THE NEW PARLIAMENT.

BOTH HOUSES CARRY RESOLUTIONS PLEDGING THEM TO THE FREE-TRADE POLICY.

THE GOVERNMENT SCHEME OF FINANCE.—DEFEAT AND RESIGNATION OF THE

EFFORTS AGAINST THE SLAVE TRADE, AND TO SUPPRESS PIRACY.

GENERAL STATE OF GREAT BRITAIN.

GENERAL CONDITION OF THE COLONIES.

DISCUSSIONS ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS.—RUSSIA AND TURKEY.

HOME AFFAIRS.—GENERAL PROSPECTS.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS.—THE ALLIANCE WITH FRANCE, THE WAR WITH RUSSIA.

HOME AFFAIRS—PUBLIC OPINION, AGITATION OF PEOPLE AND PARLIAMENT.

DEPARTURE OF THE BALTIC FLEET.

FINANCIAL OPERATIONS FOR THE YEAR.

VISIT OF THE EMPEROR OF THE FRENCH.

DISTRIBUTION OF MEDALS BY THE QUEEN.

VISIT OF THE KING OF THE BELGIANS.

HER MAJESTY VISITS THE FRENCH EMPEROR.

VISIT OF THE KING OF SARDINIA TO THE ENGLISH COURT.

PARLIAMENTARY PROCEEDINGS, MINISTERIAL CHANGES, AND DIPLOMATIC

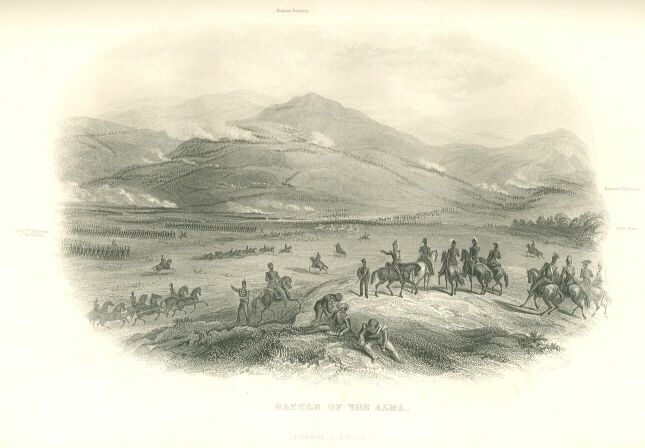

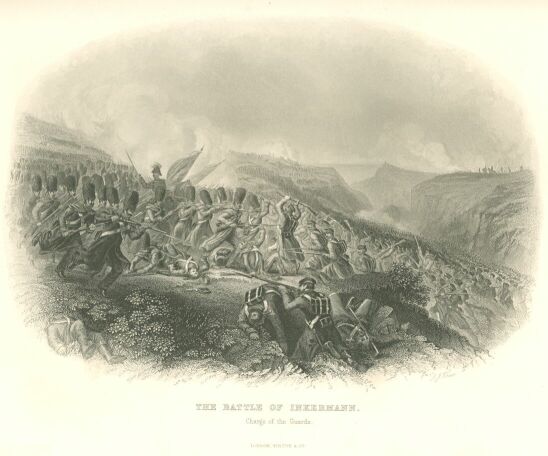

THE CONDUCT OF THE WAR—OPERATIONS IN THE CRIMEA AND BLACK SEA.

OPERATIONS IN THE SEA OF AZOFF.

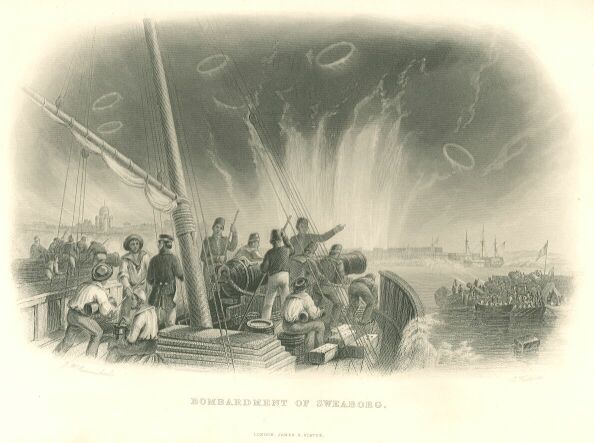

OPERATIONS OF THE ALLIES IN THE BALTIC.

OPERATIONS IN THE PACIFIC, AND AGAINST THE RUSSIAN SETTLEMENTS IN

CONCLUSION OF THE RUSSIAN WAR.

GENERAL CONDITION OF THE FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM.

DISPUTES WITH THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

HOME—GENERAL CONDITION OF GREAT BRITAIN.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS: RELATIONS WITH FRANCE, AND WITH OTHER EUROPEAN POWERS

DIFFERENCE WITH THE UNITED STATES.

DEBATES ON THE CHINESE WAR-DEFEAT OF THE MINISTRY.

SUDDEN CONVENTION OF PARLIAMENT IN DECEMBER.

Illustrations

General Burgoyne Addressing the Indians

1760

Few monarchs ever ascended a throne under more auspicious circumstances than George III. The sources of national wealth and prosperity were daily becoming developed, and the British arms were everywhere victorious. So extensive were their conquests, indeed, that it may be said, the sun rose and set, at this date, within the limits of the British dominions.

Prince George, who was the eldest son of the late Frederick, Prince of Wales, was riding on horseback in the neighbourhood of Kew palace, with his groom of the stole, Lord Bute, when news was brought him that his grandfather was dead. This intelligence was confirmed soon after by the arrival of Mr. Pitt, the head of the government, and they repaired together to Kew. On the next morning George went up to St. James’s, where Pitt waited upon him, and presented the sketch of an address to be pronounced at the meeting of the privy council. Pitt, however, was doomed to find a rival where he thought to have found a friend. He was told by his majesty, that an address had already been prepared, which convinced him that Bute, on whose favour he had reckoned, would not be contented with a subordinate place in the new government, but would aspire to the highest offices in the state. In the course of the day, October 26th, George was proclaimed king with the usual solemnities.

The accession of George, notwithstanding, did not involve any immediate change in the existing administration. The Earl of Bute, together with Prince Edward, Duke of York, were admitted into the privy council, but it was given out that his majesty was satisfied, and even charmed, with the existing cabinet, and that he would make no changes, with the exception of a few in the household and in the minor offices. One of the first acts of George III., was a proclamation “for the encouragement of piety and virtue, and for preventing and punishing of vice, profaneness, and immorality.” This was naturally looked upon as a token of his majesty’s virtue and devotion, which view was borne out by his after character; for although the proclamation may be considered in the light of a dead letter as regards actual operation, it was enforced, or recommended, by his example; and example hath a louder tongue either than precept, proclamations, or laws. From the beginning to the close of his long reign, George III. manifested a decent, moral, and religious life, which doubtless had very beneficial effects upon society at large.

On the accession of the new king, parliament was prorogued, first to the thirteenth, and afterwards to the eighteenth, of November. In the meantime, public attention was engaged by the equipment of a large squadron of men-of-war and transports at Portsmouth, and speculations were rife as to the policy of the monarch—whether it would be favourable to war or to peace. All classes of society, however, agreed in anticipating the happiest results from his rule, since he had been born and bred among them, and was well acquainted with the language, manners, laws, and institutions of the people over whom he presided. Loyal and dutiful addresses, expressing such sentiments, were presented to the young monarch by the city of London, the two universities, and from various bodies of people, to all which he returned sententious but suitable replies, declaring his fixed resolve to respect their rights and conciliate their esteem. A letter was addressed to him by the venerable Bishop of London, Dr. Sherlock, as a parting benediction, in which he gave him the following wise council:—“You, sir,” he writes, “are the person whom the people ardently desire; which affection of theirs is happily returned by your majesty’s declared concern for their prosperity: and let nothing disturb this mutual consent; let there be but one contest, whether the king loves the people best, or the people him; and may it be a long, a very long, contest; may it never be decided, but let it remain doubtful; and may the paternal affection on the one side, and the filial obedience on the other, he had in perpetual remembrance.”

The new king met parliament for the first time on the eighteenth of November. He opened the session with a speech, announcing not only the state of public and domestic affairs, but also the general principles by which he intended to rule. One clause in his speech was very gratifying to the people: “Born and educated in this country,” he observed, “I glory in the name of Briton.” Having uttered this memorable sentence, he said it would be the happiness of his life to promote the happiness and interests of his loyal and affectionate people; and that their civil and religious rights were equally as dear to him as the valuable prerogatives of his crown. He then declared, that on his accession to the throne of his ancestors he found the kingdom in a flourishing and glorious state; victorious and happy; although engaged in a necessary war, which, in the language of the late reign, he designated, “a war for the Protestant interest.” In this speech he neither spoke of peace nor negociation, but asked the assistance of parliament to prosecute this war with vigour. Finally, addressing the Commons on the subject of supplies, he concluded his speech thus:—“The eyes of all Europe are on you; from your resolutions the Protestant interest hopes for protection, as well as all our friends for the preservation of their independency; and our enemies fear the final disappointment of their ambitious and destructive views: let these hopes and fears be confirmed and augmented, by the vigour, unanimity, and despatch of our proceedings. In this expectation I am the more encouraged, by a pleasing circumstance, which I consider one of the most auspicious omens of my reign—that happy extinction of divisions, and that union and good harmony, which continue to prevail amongst my subjects, afford me the most agreeable prospects; the natural disposition and wish of my heart are to cement and promote them; and I promise myself, that nothing will arise on your part to interrupt or disturb a situation so essential to the true and lasting felicity of this great people.” This speech was warmly responded to by addresses from both houses of parliament; and the supplies for the ensuing year, amounting to £19,616,119, were cheerfully voted, while the civil list was fixed at £809,000; the king, on his part, consenting to such a disposition of the hereditary revenues of the crown, as might best promote the interests of the nation.

War, therefore, was to be continued, and Mr. Pitt and his colleagues seemed to be confirmed in office: yet at this very moment the train was laying for their expulsion. Earl Bute was anxious to become secretary of state, and he was busily engaged in a correspondence with the noted intriguer, Bubb Doddington. A few days after the meeting of parliament his lordship declared to Doddington, that Lord Holderness “was ready at his desire to quarrel with his fellow ministers, and go to the king and throw up with seeming-anger, and then he (Bute) might come in without seeming to displace anybody.” This expedient, however, did not please Doddington, and Bute paid deference to his opinion. Still the two friends took counsel together on this important affair. In a letter from Doddington to Bute, which was written in December, he advises “that nothing be done that can be justly imputed to precipitation; nothing delayed that can be imputed to fear.” He adds: “Remember, my noble and generous friend, that to recover monarchy from the inveterate usurpation of oligarchy, is a point too arduous and important to be achieved without much difficulty, and some degree of danger; though none but what attentive moderation and unalterable firmness will certainly surmount.”

In his career of ambition, Bute, who was “better fitted to perform Lothario on the stage,” than to act as secretary of state, paid small regard to danger, but kept his eye fixed steadily on the point he had in view. In January, he told Doddington that “Mr. Pitt meditated a retreat;” and in the same month Doddington writes to him—“If the intelligence they bring me be true, Mr. Pitt goes down fast in the city, and faster at this end of the town: they add, you rise daily. This may not be true; but if he sinks, you will observe that his system sinks with him, and that there is nothing to replace it but recalling the troops and leaving Hanover in deposit.” Again, on the 6th of February, Lord Bute declared, that it was easy to make the Duke of Newcastle resign, but at the same time he expressed a doubt as to the expediency of beginning in that quarter. Doddington replied, that he saw no objection to this step; and that if Bute thought there was, he might put it into hands that would resign it to him when he thought proper to take it. But Bute was not disposed to try the duke too much, nor to risk too bold a leap at once: so all ill humours were concealed under a fair surface.

Had Earl Bute taken any decisive step thus early in the reign of the new king, it would probably have exposed him to public derision and scorn. At this time the old system seemed to please everybody; and among the supplies voted by the House of Commons, none were more freely granted than the continental subsidies, and especially that of £670,000 to the King of Prussia. His victory at Torgau, which subjected all Saxony—Dresden excepted—to his power, was made known in England just before the meeting of parliament, and it had the effect of raising him high in the public favour of the people of England. Nor was it less advantageous to him on the Continent. His victory, with its results, indeed, were a full compensation to him for the previous losses he had sustained during the campaign. Laudohn raised the siege of Cosel, and evacuated Silesia; the Russians raised that of Colburg, and retreated into Poland; and the Swedes were driven out of Western Pomerania. In the same spirit of gratitude, the parliament granted £200,000 to our colonies in America, for the expenses they had incurred, and the efforts they had made in the present war—a war which laid some of the groundworks of the independence which a few years later was claimed by those colonies.

By an act passed in the year 1701, under the reign of William III., the commissions of the judges were continued quamdiu bené se gesserint; or the power of displacing them was taken from the crown, and their continuance in office was made solely dependent on the faithful discharge of their duties, so that it might be lawful to remove them on the address of both houses to the king. Still, at the demise of the crown, their offices were vacated, and George II. had even refused to renew the commission of a judge who had given him personal offence. Towards the close of this session, his present majesty, in a speech from the throne, recommended an important improvement in this matter, which greatly increased his popularity. He declared his wish to render the bench still more independent of the crown, and the administration of justice still more impartial; and he recommended that provisions should be made for the continuance of their commissions and salaries, without any reference to the death of one king, or the accession of his successor. In compliance with this expressed wish, a bill was framed for rendering the judges thus independent, which was carried through both houses. It received the royal assent on the 19th of March, on which day his majesty put an end to the session.

Before this event took place, a certain party in the state began to think that circumstances would authorise them to commence a gradual change of ministers, and of the policy of the nation. In this his majesty seems to have coincided, for on the same day that he closed the session, Mr. Legge, who was co-partner with Mr. Pitt in popularity, was unceremoniously dismissed from the office of chancellor of the exchequer, and Sir Francis Dashwood nominated his successor. On the same day, also, Lord Holderness having secured a pecuniary indemnification, with the reversion of the wardenship of the cinque ports, resigned the office of secretary of state in favour of Lord Bute. It was said that the king “was tired of having two secretaries, of which one (Pitt) would do nothing, and the other (Holderness) could do nothing; and that he would have a secretary who both could and would act.” At the same time, Lord Halifax was advanced from the board of trade to be Lord-lieutenant of Ireland, and was replaced by Lord Barrington; and the Duke of Richmond, displeased by a military promotion injurious to his brother, resigned his post as lord of the bed-chamber. Other changes, of minor importance, took place—such as the introduction of several Tories into the offices of the court, and there was a considerable addition made to the peerage. These changes were, doubtless, unpalatable to Mr. Pitt; but Horace Walpole says that he was somewhat softened by the offer of the place of cofferer for his brother-in-law, James Grenville. At all events Mr. Pitt continued in office, and Earl Bute consented to leave the management of foreign affairs in his hands; but at the same time, both Bute and his majesty gave him to understand that an end must be put to the war.

Since the accession of George III., the events of the war had been various. Although Frederick the Great had driven the Russians and Austrians from his capital, they were still within his own territory; while the French were on the side of the Rhine, and the Swedes continued to threaten invasions. Such was his situation when he heard that George II, was dead; that his successor was desirous of peace; that some of his advisers were projecting a separate treaty with France; and that it was probable that the English subsidies would soon be discontinued. This intelligence in some degree was confirmed by the tardiness with which the subsidy, so readily granted by the parliament in December, was paid into his treasury. Nothing daunted, however, Frederick planned fresh campaigns, and remonstrated with England; and, as an effect of the bold front he put upon his affairs, he had the satisfaction of learning, before he went into winter-quarters, that the Russians had retired beyond the Vistula, and that the Austrians and Swedes had departed out of Brandenburg, Silesia, and Pomerania. Still his situation was a critical one. His losses in men had been great, his coffers were empty, and his recruiting was therefore difficult: he looked forward to the campaign of 1761 with doubt and anxiety.

Contrary to the general rules of war, this campaign opened in the very depth of the winter. Contrasting the strong constitutions of his troops with the less hardy character of his opponents, Prince Ferdinand resolved to take them thus by surprise. Accordingly, early in February, by a sudden attack, he drove the French out of their quarters near Cassel, and they were only saved from utter destruction, by the defiles, and other difficulties of the country, which favoured their retreat. Almost simultaneously with this achievement, the Prussian general, Sybourg, effected a junction with the Hanoverian general, Sporken, and took three thousand French prisoners. Subsequently, these generals defeated the troops of the empire under General Clefeld; and Prince Ferdinand followed up these advantages by laying siege to Cassel, Marbourg, and Ziegenhayn. He was ably seconded in his operations by the Marquis of Granby, but he failed in capturing these places, and was compelled to retire into the electorate of Hanover. The retreat of Ferdinand took place in April, and in the same month the hereditary Prince of Brunswick was defeated by the French under Broglie, near Frankfort.

At this time, Frederick had certain information that the English were negociating with the French. This information appears to have paralysed his efforts, for preparations were not recommenced before June. On their part the French, also, were inactive till that time, when Broglie, being joined by the Prince of Soubise with large reinforcements, endeavoured to drive Prince Ferdinand and the combined army of English and Hanoverians from their entrenchments at Hohenower. On two several days Broglie made a fierce attack upon his posts, chiefly directing his murderous fire against that commanded by Lord Granby; but on the second day the French gave way, and made a precipitate retreat, leaving behind them several pieces of cannon, with five thousand of their comrades sleeping the sleep of death. Their non-success produced mutual recriminations between Broglie and Soubise, who had never perfectly agreed, and they resolved to separate: Broglie crossed the Weser, and threatened to fall upon Hanover, while Soubise crossed the Lippe, as if with the intention of laying siege to Munster.

The division of the French army caused a corresponding division in that of Prince Ferdinand; for whilst he marched with one half to watch the operations of Broglie, the hereditary Prince of Brunswick marched with the other half to check the career of Soubise. The skill and vigour of Ferdinand prevented Broglie from making any important conquests, though he could not protect the country from his ravages. Perceiving, indeed, that he could not check the onward march of his enemy, Ferdinand turned aside into Hesse, and cut off all the communications of the French in that country, destroying their magazines and menacing their forts, which, as he foresaw, had the effect of alarming Broglie, and causing him to retreat out of Hanover. In the meantime, the hereditary Prince of Brunswick had checked the career of Soubise, and destroyed many of his magazines; and soon after the French went into winter quarters—Soubise on the Lower Rhine, and Broglie at Cassel.

Frederick had taken the field in the month of April, and had marched into Silesia, where the fortress of Schweidnitz was threatened by the Austrian general, Laudon. On his approach, Laudon retreated into Bohemia, where he was joined by fresh columns of Russians under Marshal Butterlin. At the same time another Russian horde, under Romanzow, re-occupied Pomerania. The Austrian and Russian generals conceived that they could hem in Frederick, and prevent his escape; but aware of his danger, the skilful monarch threw himself into his fortified camp of Buntzelwitz, from behind the strong ramparts of which he laughed his enemies to scorn. A blockade was attempted, but the country, wasted by long wars, had become like a wilderness, and afforded no food either for man or horse; while their provision-waggons, 5000 in number, had all been taken by a flying column of Prussians, under General Platen, who had also destroyed three of the largest magazines which the Russians had established on the confines of Poland. Famine stared them in the face, and breaking up their blockade, Butterlin marched into Pomerania, and Laudon to an entrenched camp, near Fribourg. Thus relieved, Frederick marched towards Upper Silesia, which proved to be an unfortunate movement; for Laudon, taking advantage of it, rushed from his entrenched camp, made an assault by night upon Schweidnitz, which lie took by storm, and then took up his winter-quarters in Silesia. About the same time the Russians, assisted by the Swedes, took Colberg, which enabled them to winter in Pomerania and Brandenburg.

In the meantime the arms of the English had, for the most part, been successfully employed. Pondicherry, the capital settlement of the French in, the East Indies, and their last stronghold in that country, surrendered at discretion to Colonel Coote, after the garrison and inhabitants had been reduced to the necessity of feeding on the flesh of camels and elephants, and even upon dogs and vermin. In the West Indies, also, Lord Rollo and Sir James Douglas reduced the island of Dominica, which, contrary to treaty, had been fortified by the French. A less important conquest was made on the coast of Brittany. A secret expedition, which had been for some time in preparation, suddenly sailed from Spithead, and under the command of Commodore Kepple, with troops on board under General Hodgson, took its course across the Channel. Great things were expected as the result of this expedition, but it only enacted the old story of “The mountain in labour.” The point against which this force was directed was the sterile rock of Bellisle, which, at the expense of two thousand lives, was captured. Thus disappointed, the people complained of the obstinacy of Pitt, and asked, sarcastically, what could be done with it? Nevertheless, if it was no use to England, it was a place of importance to France, as commanding a large extent of coast, and affording a convenient receptacle to privateers, whence it was insisted on as a valuable article of exchange, when peace was concluded between the two nations.

At this time France was rapidly sinking under the efforts made to sustain war. Many of her colonies were conquered, her navy was ruined, and her finances exhausted, while the people were impoverished and discontented. Under these circumstances the king wished for repose and peace, and in this wish, Sweden, Poland, and even Russia were ready to join. Austria alone, whose empress-queen was bent on the recovery of Silesia, and the overthrow of its conqueror Frederick, was desirous of prolonging hostilities.

This wish of the king of France—which was also the wish of his people—seemed to be favoured by circumstances in England. The influence of Pitt was daily growing weaker, and Bute was fast gaining paramount ascendancy. The French ministers, therefore, flattered themselves that there would be no great difficulty in negociating; especially as they were ready and willing to make some sacrifices, in order to obtain peace. Accordingly an interchange of memorials was commenced, and in the month of July Mr. Stanley was dispatched to Paris, while the Count de Bussy came over to London, for the purpose of negociating. Preliminaries were mutually proposed and examined. On their part the French offered to cede Canada; to restore Minorca in exchange for Guadaloupe and Marigalante; to give up Senegal and Goree for Anamaboo and Acra; to renounce all claim to Cape Breton, on which no fortification was to be erected; and to consent that Dunkirk should be demolished. But one demand made by the French was fatal to the success of the negociations. They demanded the restitution of all the captures made at sea by the English before the declaration of war, on the ground that such captures were contrary to all international law, which restitution was sternly and absolutely refused, the English ministers arguing, that the right of all hostile operations results not from a formal declaration of war, but from the original hostilities of the aggressor. Another obstacle in the way of peace, was the refusal of the French to restore Cassel, Gueldres, and other places which they had taken from his Prussian majesty, although they were ready to evacuate what they occupied in Hanover. And as if these obstacles were not sufficient, the French preliminaries were accompanied by a private memorial, demanding from England the satisfaction of certain claims advanced by Spain, a country with which, though differences existed, England was at peace. The French ambassador was given to understand on this point, that the king of England would never suffer his disputes with Spain to be thus mixed up with the negociations carrying on with his country, and the cabinet called upon the Spanish ambassador to disavow all participation in such a procedure, and to state that his court was neither cognizant of it, nor wished to blend its trifling differences with the weighty quarrels of France. But this demand produced an unlooked-for budget, The Spanish ambassador at first returned an evasive reply, but he was soon authorized by the court of Spain to declare, that the proceedings of the French envoy had the entire sanction of his Catholic majesty; and that, while his master was anxious for peace, he was united as much by mutual interest as by the ties of blood with the king of France. The fact is, Charles III., who now occupied the throne of Spain, had privately agreed, before this date, with the King of France, to consider every power as their common enemy who might become the enemy of either, and to afford mutual succours by sea and land. It had been also stipulated between them, that no proposal of peace to their common enemies was to be made except by common consent; that the two monarchs were to act as if they formed one and the same power; that they should maintain for each other all the possessions which they might possess at the conclusion of peace; and finally, that the King of Naples might be allowed to participate in their treaty, though no other family, except a prince of the house of Bourbon, was to be admitted into this family compact.

Negociations for peace, therefore, proved abortive. Even Bute considered many of the proposals of the French if not insulting to the majesty of the British nation, at least inadmissible. Yet these négociations resulted in the downfall of Pitt. At the council-table, that great minister represented that Spain was only waiting for the arrival of her annual plate-fleet from America, and then she would declare war. He proposed, therefore, that her declaration should be anticipated by England: that war should be forthwith proclaimed against Spain, and a fleet sent out to intercept her ships and treasures from the western world. He likewise proposed an immediate attack upon her colonies; recommending the capture of the Havannah and the occupation of the Isthmus of Panama, from whence an expedition might be sent against Manilla and the Philippine Isles, to intercept the communication between the continent of South America and the rich regions of the East. It suited the purpose of Bute, however, to raise the laugh of incredulity as to the declaration of war by Spain, questioning, at the same time, the real meaning of the treaty entered into between the two Bourbons. The other members of the cabinet also—Lord Temple excepted—pronounced the measures proposed by Pitt too precipitate, and he had no alternative but to resign; especially as he found, also, that the king was adverse to his schemes. Accordingly, on the 6th of October, Pitt delivered up his seals to the king, which his majesty received with ease and firmness, but without requesting him to resume them. The monarch, notwithstanding, lamented to him the loss of so valuable a servant, while he declared that even if his cabinet had been unanimous for war with Spain, he should have found great difficulty in consenting to such a measure. Pitt was affected by the kind, yet dignified, behaviour of the young king. “I confess, sire,” said he, with emotion, “I had but too much reason to expect your majesty’s displeasure: I did not come prepared for this exceeding goodness: pardon me, sir; it overpowers,—it oppresses me.”

Pitt retired with a pension of £3,000 per annum, which was to be continued for three lives. The peerage was offered him, but he declined it personally, accepting it only for his wife and her issue. He was succeeded in office by Lord Egremont, son of the great Tory, Sir William Wyndam. At the same time Lord Temple retired from office, and the privy seal was given to the Duke of Bedford. The resignation of Mr. Pitt, with his honours and rewards, were published in the Gazette on the following day, and in the same paper a letter was published from the English ambassador at Madrid, which was replete with assurances of the pacific intentions of Spain. On this circumstance, combined with the resignation of Mr. Pitt, Burke remarks:—“It must be owned that this manouvre was very skilfully executed: for it at once gave the people to understand the true motive to the resignation, the insufficiency of that motive, and the gracious-ness of the king, notwithstanding the abrupt departure of his minister. If after this the late minister should choose to enter into opposition, he must go into it loaded and oppressed with the imputation of the blackest ingratitude; if, on the other hand, he should retire from business, or should concur in support of that administration which he had left, because he disapproved its measures, his acquiescence would be attributed by the multitude to a bargain for his forsaking the public, and that the title and his pension were the considerations. These were the barriers that opposed against that torrent of popular rage which it was apprehended would proceed from this resignation. And the truth is, they answered their end perfectly.”

This reasoning of Mr. Burke was strictly correct. The friends and partisans of Mr. Pitt raised violent clamours against Bute, for displacing a man who had raised the nation from its once abject state to the pinnacle of glory; and addresses, resolutions, and condolences were set on foot in London and the greater corporations, with a view of exciting the smaller cities and boroughs in England to follow the example. The press, also, was active in vilifying Bute for the part he had taken in this affair. But Bute had his friends as well as his enemies, and Pitt had his enemies as well as his friends. The press worked on both sides of the question; while it vilified Bute, it animadverted on Pitt’s pensions and honours. At the same time the people were only partially in the favour of the ex-minister. The progress of addresses, resolutions, and condolences was languid, and in some instances the people were disposed to cast odium upon, and to blacken the character of, the retired secretary. The popularity of Pitt was, in truth, obscured with mists and clouds for a time, and it was not till after he had raised a few thunder-storms of opposition, that his political atmosphere once again became radiant with the sunshine of prosperity. For the mind of Pitt was not to be long borne down by its heavy weight of gratitude to royalty, or by public accusations: he soon shook off the one, and resolutely braved the other.

On the 8th of July the young king having called an extraordinary council, made the following declaration to its members:—“Having nothing so much at heart as to procure the welfare and happiness of my people, and to render the same stable and permanent to posterity, I have, ever since my accession to the throne, turned my thoughts towards the choice of a princess for my consort; and I now with great satisfaction acquaint you, that after the fullest information, and mature deliberation, I am come to a resolution to demand in marriage the Princess Charlotte of Mecklenberg Strelitz; a princess distinguished by every eminent virtue and amiable endowment; whose illustrious line has constantly shown the firmest zeal for the Protestant religion, and a particular attachment to my family. I have judged it proper to communicate to you these my intentions, in order that you may be fully apprised of a matter so highly important to me and to my kingdoms, and which I persuade myself will be most acceptable to my loving subjects.”

The preliminary negociations concerning this union had been conducted with great secresy, whence this announcement occasioned some surprise to most of the members of the extraordinary council. It met, however, with the warmest approbation of them all, and the treaty was concluded on the 15th of August. The Earl of Harcourt, with the Duchesses of Ancaster and Hamilton, were selected to escort the young bride to England, and Lord Anson was the commander of the fleet destined to convoy the royal yacht. Princess Charlotte arrived in England on the 7th of September, and on the following day she was escorted to St. James’s, where she was met by his majesty.

Before the arrival of the future Queen of England, in a letter to one of his correspondents, Lord Harcourt had given this description of her:—“Our queen, that is to be, has seen very little of the world; but her very good sense, vivacity, and cheerfulness, I dare say will recommend her to the king, and make her the darling of the British nation. She is no regular beauty; but she is of a pretty size, has a charming complexion, with very pretty eyes, and is finely made.” Lord Harcourt was right in his conjectures concerning the views which the king would take of his young bride. It is said, that in the first interview, although he saluted her tenderly, the king was disappointed in not finding in the princess those personal charms which he had expected. But this was only a momentary feeling. The king soon became interested in her artlessness, cheerful manners, and obliging disposition, while the whole court was loud in their praises of her affability, and even of her beauty. “In half an hour,” says Horace Walpole, “one heard of nothing but proclamations of her beauty: everybody was content; everybody was pleased.” So the marriage took place in the midst of good-humour and rejoicings: the nuptial benediction was given by Dr. Seeker, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Duke of Cumberland gave away the bride.

Extraordinary preparations were made for the coronation of their majesties. It took place on the 22nd of September, and though described as solemn and magnificent, it did not materially differ from preceding coronations. The crown was placed on the head of the monarch by Archbishop Seeker, and before his majesty partook of the holy sacrament, he exhibited a very pleasing instance of piety before the assembled court. As he approached the altar, he asked if he might lay aside his crown; and when the archbishop, after consulting with Bishop Pearce, replied, that no order existed on the subject in the service, he rejoined, “Then it ought to be done;” at the same time taking the diadem from his head, he placed it, reverentially, on the altar. His majesty wished the queen to manifest the same reverence to the Almighty, but being informed that her crown was fastened to her hair, he did not press the subject. On the return of the procession, an incident occurred, which, had it happened among the nations of antiquity, would have been considered an omen of evil portent, which could only have been averted by a whole hecatomb of sacrifices. The most valuable diamond in his majesty’s diadem fell from it, and was for some time lost, but it was afterwards found, and restored to his crown. The coronation of George III. could boast of one very extraordinary spectator among the many thousands present. This was Charles Edward Stuart, the young Pretender, who had come over in disguise, and who obtained admission into the abbey, and witnessed all the ceremonies consecrating a king on that throne which he considered legitimately belonged to his father or himself! It is said that George knew that he was in London, and that he would not allow him to be molested; feeling, no doubt, secure in the affections of a loyal people. And that he was secure, the éclat with which the great festival of his coronation passed off, fully manifested. All combined to testify that their majesties were very popular, and that they had good reasons for anticipating a happy and prosperous reign.

The new parliament met on the 3rd of November, when Sir John Cust was elected speaker of the commons. He was presented to his majesty on the 6th, on which day the king, having first approved of the choice, thus addressed both houses:—“At the opening of the first parliament summoned and elected under my authority, I with pleasure notice an event which has made me completely happy, and given universal joy to my loving subjects. My marriage with a princess, eminently distinguished by every virtue and amiable endowment, while it affords me all possible domestic comfort, cannot but highly contribute to the happiness of my kingdoms, which has been, and always shall be, the first object in every action of my life.

“It has been my earnest wish that this first period of my reign might be marked with another felicity; the restoring of the blessings of peace to my people, and putting an end to the calamities of war, under which so great a part of Europe suffers: but though overtures were made to me, and my good brother and ally, the King of Prussia, by the several belligerent powers, in order to a general pacification, for which purpose a congress was appointed, and propositions were made to me by France for a particular peace with that crown, which were followed by an actual négociation; yet that congress has not hitherto taken place, and the negociation with France is entirely broken off.

“The sincerity of my disposition to effectuate this good work has been manifested in the progress of it: and I have the consolation to reflect, that the continuance of the war, and the further effusion of Christian blood, to which it was the desire of my heart to put a stop, cannot, with justice, be imputed to me.

“Our military operations have been in no degree suspended or delayed; and it has pleased God to grant us further important success, by the conquest of the islands of Belleisle and Dominica: and by the reduction of Pondicherry, which has in a manner annihilated the French power in the East Indies. In other parts, where the enemy’s numbers were greatly superior, their principal designs and projects have been generally disappointed, by a conduct which does the highest honour to the distinguished capacity of my general, Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick, and by the valour of my troops. The magnanimity and ability of the King of Prussia have eminently appeared in resisting such numerous armies, and surmounting so great difficulties.

“In this situation I am glad to have an opportunity of receiving the truest information of the sense of my people by a new choice of their representatives: I am fully persuaded you will agree with me in opinion, that the steady exertion of our most vigorous efforts, in every part where the enemy may still be attacked with advantage, is the only means that can be productive of such a peace as may with reason be expected from our successes. It is therefore my fixed resolution, with your concurrence and support, to carry on the war in the most effectual manner, for the interest and advantage of my kingdoms; and to maintain to the utmost of my power the good faith and honour of my crown, by adhering firmly to the engagements entered into with my allies. In this I will persevere until my enemies, moved by their own losses and distresses, and touched with the miseries of so many nations, shall yield to the equitable conditions of an honourable peace: in which case, as well as in the prosecution of the war, I do assure you, no consideration whatever shall make me depart from the true interests of these my kingdoms, and the honour and dignity of my crown.”

His majesty concluded his speech by calling upon the commons for adequate supplies to enable him to prosecute the war with vigour, and by asking for a provision for the queen in case she should survive him. The commons, besides the usual address, sent a message of congratulation to the queen, and they proved the sincerity of their professions by making her a grant of £100,000 per annum, with Somerset House and the Lodge in Richmond Park annexed: a patent also passed the privy seal, granting her majesty the yearly sum of £40,000 for the support of her dignity. On the subject of the supplies for the ensuing year, however, a long and stormy debate took place; and a month elapsed before they were finally adjusted. Opposition to them chiefly arose from the circumstance that the sentiments of the people, and likewise of the court, were beginning to change respecting the German war. But Lord Egremont found himself compelled to walk in the very steps which Pitt had marked out, at least for some time, and the large demands made were pressed upon the parliament, and finally received its sanction. Seventy thousand seamen were voted, and it was agreed to maintain 67,676 effective men, beside the militia of England, two regiments of fencibles in Scotland, the provincial troops in America, and 67,167 German auxiliaries. Some new taxes, also, were imposed, including an additional one on windows, and an increased duty on spirituous liquors, in order to pay the interest of £12,000,000, which it was found necessary to borrow, to make good the deficiences of last session. In the whole the supplies for the year 1762, voted by the parliament, amounted to more than £18,000,000: two millions of which were required for the defence of Portugal.

GEORGE III. 1760-1765

In the month of October, Lord Halifax, the new Lord-lieutenant of Ireland met his Majesty’s first parliament in that country. The Irish parliament responded to the sentiments of the English parliament respecting the accession of the young monarch. Addresses replete with loyalty were voted by both houses; and the greatest confidence was expressed in the rule of Lord Halifax, auguring the happiest results from his administration, and promising cordial co-operation. That ill-fated country, however, was restless as the waves of the ocean. During the viceroyalty of the Duke of Bedford, it had been totally under the dominion of the lord’s justices, and they had recently made an attempt to gain popularity, by expressing doubts in the privy council concerning the propriety of sending over a money bill, lest the rejection of it should occasion the dissolution of the new parliament, and thereby endanger the peace of the country. They were opposed in their views by Lord Chancellor Bowes and his party, and party violence was inflamed to the highest pitch. The popular coalition prevailed so far as to alter the established custom, by sending a bill not for the actual supplies, but relating to a vote of credit for Ireland, whence all ferment on this subject subsided. In such a contest it is not likely that the people would have joined, but they had grievances of their own, which endangered the public tranquillity. In his speech to the new parliament, Lord Halifax had recommended that the linen trade, which had been confined to the southern parts of the kingdom, should be extended throughout the country, inasmuch as there was a large demand for it, and it might thereby be made a source of wealth to the whole country. True patriots would have observed the wisdom of, and have acquiesced in, this measure; but self-interest in Ireland, as in all countries under the face of the sun, prevailed over the feelings of patriotism. The people in the southern parts of the kingdom murmured at such a project, as it would affect their personal interests, and their discontents were increased by the conversion of considerable quantities of land from a state of tillage to that of pasturage, for the purpose of feeding more cattle. By this measure, great numbers of the peasantry were deprived at once, not only of employment, but of their cottages. Many small farms were indeed still let to some cottagers at rack-rent, which cottages had the right of commonage, guaranteed to them in their leases; but afterwards the commons were enclosed, and no recompense was made to the tenants by the landlords. Thus provoked, and being joined by the idle and dissolute, these unhappy people sought to redress their own wrongs by acts of violence. Fences were destroyed, horses and arms were seized, cattle were maltreated, and obnoxious persons, especially tithe-proctors, were exposed to their vengeance. Many were stripped naked, and made to ride on horses with saddles formed of the skins of hedgehogs, or buried up to their chins in holes lined with thorns that were trodden down closely to their bodies. From their outrageous violence these people obtained the name of “Levellers,” but afterwards, from the circumstance of their wearing white shirts over their clothes for the purpose of disguise, they were termed “White Boys.” Their outrages demanded the strong arm of the law, and the royal troops were employed in their suppression. Many suffered the extreme penalty of the law, though many more were permitted to escape through the lenity of the judges, whence the disorders long prevailed. As the rioters were all Romanists, a popish plot was suspected, and the Romish clergy were charged with promoting their outrages. A motion was made in parliament to investigate this matter, but there not being sufficient evidence to inculpate any parties, it was dropped, and no efficient remedy was therefore applied to heal the disorder.

The year had not closed before the ministers found that a rupture with Spain was inevitable. The first intimation of it was detected in the menacing conduct of the court of Versailles; and Lord Bristol, the English ambassador at Madrid, was instructed to demand the real intentions of Charles III., and the real purport of the family compact. General Wall, the Spanish minister replied more insolently than before; but an open rupture was avoided till the plate-ships had arrived at Cadiz with all the wealth expected from Spanish America. Then it was seen that the political vision of Pitt could penetrate much deeper than that of Bute and his colleagues. Complaining of the haughty spirit and the discord which prevailed in the British cabinet, and of the insults offered to his sovereign, Wall informed Bristol that he might leave Spain as soon as he pleased, and at the same time issued orders to detain all English ships then in the ports of Spain. Lord Bristol returned; the Count of Fuentes, the Spanish ambassador, quitted London, and war was mutually declared by both countries.