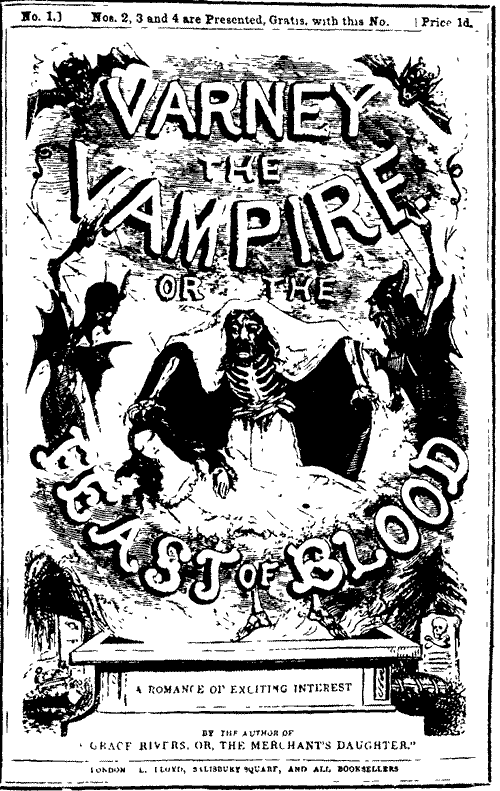

Title: Varney the Vampire; Or, the Feast of Blood

Author: Thomas Peckett Prest

James Malcolm Rymer

Release date: January 29, 2005 [eBook #14833]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charles Franks, Debra Storr, Sandra Brown and the PG

Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

Transcriber's Note: This book was originally published in "penny dreadful" form. This edition does not include the entire 109 episodes, which were published in three volumes. Authorship has also been ascribed to James Malcolm Rymer.

The Table of Contents was added by the transcriber.

CHAPTER I.—MIDNIGHT.—THE HAIL-STORM.—THE DREADFUL VISITOR.—THE VAMPYRE.

CHAPTER II.—THE ALARM.—THE PISTOL SHOT.—THE PURSUIT AND ITS CONSEQUENCES.

CHAPTER IV.—THE MORNING.—THE CONSULTATION.—THE FEARFUL SUGGESTION.

CHAPTER V.—THE NIGHT WATCH.—THE PROPOSAL.—THE MOONLIGHT.—THE FEARFUL ADVENTURE.

CHAPTER VII.—THE VISIT TO THE VAULT OF THE BANNERWORTHS, AND ITS UNPLEASANT RESULT.—THE MYSTERY.

CHAPTER X.—THE RETURN FROM THE VAULT.—THE ALARM, AND THE SEARCH AROUND THE HALL.

CHAPTER XI.—THE COMMUNICATIONS TO THE LOVER.—THE HEART'S DESPAIR.

CHAPTER XII.—CHARLES HOLLAND'S SAD FEELINGS.—THE PORTRAIT.—THE OCCURRENCE OF THE NIGHT AT THE HALL.

CHAPTER XVIII.—THE ADMIRAL'S ADVICE.—THE CHALLENGE TO THE VAMPYRE.—THE NEW SERVANT AT THE HALL.

CHAPTER XIX.—FLORA IN HER CHAMBER.—HER FEARS.—THE MANUSCRIPT.—AN ADVENTURE.

CHAPTER XX.—THE DREADFUL MISTAKE.—THE TERRIFIC INTERVIEW IN THE CHAMBER.—THE ATTACK OF THE VAMPYRE.

CHAPTER XXI.—THE CONFERENCE BETWEEN THE UNCLE AND NEPHEW, AND THE ALARM.

CHAPTER XXII.—THE CONSULTATION.—THE DETERMINATION TO LEAVE THE HALL.

CHAPTER XXIII.—THE ADMIRAL'S ADVICE TO CHARLES HOLLAND.—THE CHALLENGE TO THE VAMPYRE.

CHAPTER XXIV.—THE LETTER TO CHARLES.—THE QUARREL.—THE ADMIRAL'S NARRATIVE.—THE MIDNIGHT MEETING.

CHAPTER XXV.—THE ADMIRAL'S OPINION.—THE REQUEST OF CHARLES.

CHAPTER XXVI.—THE MEETING BY MOONLIGHT IN THE PARK.—THE TURRET WINDOW IN THE HALL.—THE LETTERS.

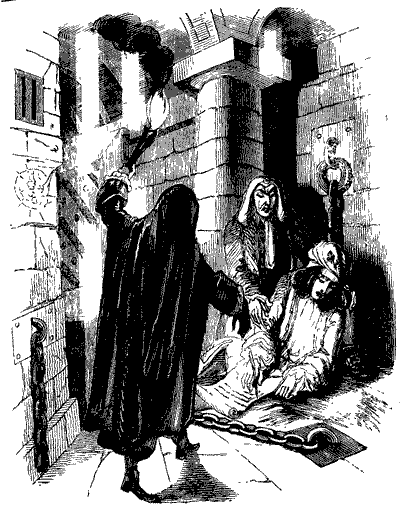

CHAPTER XXIX.—A PEEP THROUGH AN IRON GRATING.—THE LONELY PRISONER IN HIS DUNGEON.—THE MYSTERY.

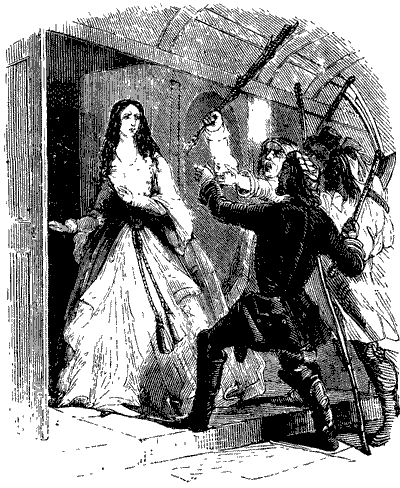

CHAPTER XXX.—THE VISIT OF FLORA TO THE VAMPYRE.—THE OFFER.—THE SOLEMN ASSEVERATION.

CHAPTER XXXI.—SIR FRANCIS VARNEY AND HIS MYSTERIOUS VISITOR.—THE STRANGE CONFERENCE.

CHAPTER XXXII.—THE THOUSAND POUNDS.—THE STRANGER'S PRECAUTIONS.

CHAPTER XXXIII.—THE STRANGE INTERVIEW.—THE CHASE THROUGH THE HALL.

CHAPTER XXXIV.—THE THREAT.—ITS CONSEQUENCES.—THE RESCUE, AND SIR FRANCIS VARNEY'S DANGER.

CHAPTER XXXV.—THE EXPLANATION.—MARCHDALE'S ADVICE.—THE PROJECTED REMOVAL, AND THE ADMIRAL'S ANGER.

CHAPTER XXXVI.—THE CONSULTATION.—THE DUEL AND ITS RESULTS.

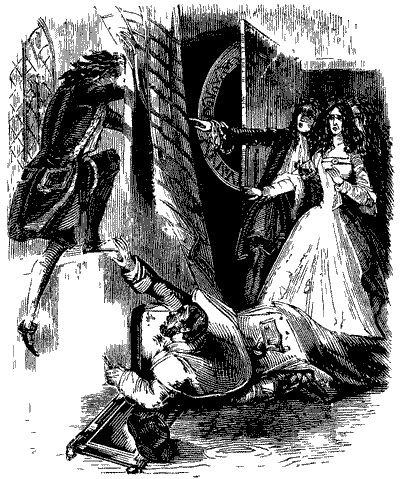

CHAPTER XXXVII.—SIR FRANCIS VARNEY'S SEPARATE OPPONENTS.—THE INTERPOSITION OF FLORA.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.—MARCHDALE'S OFFER.—THE CONSULTATION AT BANNERWORTH HALL.—THE MORNING OF THE DUEL.

CHAPTER XXXIX.—THE STORM AND THE FIGHT.-THE ADMIRAL'S REPUDIATION OF HIS PRINCIPAL.

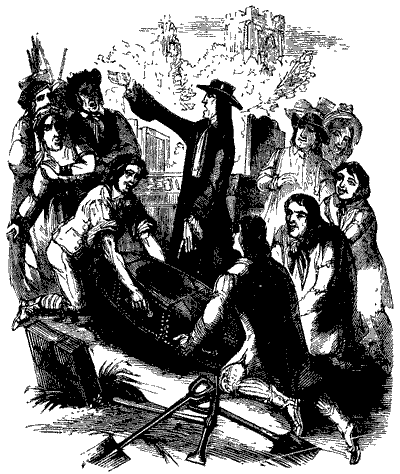

CHAPTER XL.—THE POPULAR RIOT.—SIR FRANCIS VARNEY'S DANGER.—THE SUGGESTION AND ITS RESULTS.

CHAPTER XLIV.—VARNEY'S DANGER, AND HIS RESCUE.—THE PRISONER AGAIN, AND THE SUBTERRANEAN VAULT.

CHAPTER XLV.—THE OPEN GRAVES.—THE DEAD BODIES.—A SCENE OF TERROR.

CHAPTER XLVII.—THE REMOVAL FROM THE HALL.—THE NIGHT WATCH, AND THE ALARM.

CHAPTER XLVIII—THE STAKE AND THE DEAD BODY.

CHAPTER XLIX—THE MOB'S ARRIVAL AT SIR FRANCIS VARNEY'S.—THE ATTEMPT TO GAIN ADMISSION.

CHAPTER L.—THE MOB'S ARRIVAL AT SIR FRANCIS VARNEY'S.—THE ATTEMPT TO GAIN ADMISSION.

CHAPTER LIV.—THE BURNING OF VARNEY'S HOUSE.—A NIGHT SCENE.—POPULAR SUPERSTITION.

CHAPTER LVI.—THE DEPARTURE OF THE BANNERWORTHS FROM THE HALL.—THE NEW ABODE.—JACK PRINGLE, PILOT.

CHAPTER LVII.—THE LONELY WATCH, AND THE ADVENTURE IN THE DESERTED HOUSE.

CHAPTER LVIII.—THE ARRIVAL OF JACK PRINGLE.—MIDNIGHT AND THE VAMPYRE.—THE MYSTERIOUS HAT.

CHAPTER LIX.—THE WARNING.—THE NEW PLAN OF OPERATION.—THE INSULTING MESSAGE FROM VARNEY.

CHAPTER LX.—THE INTERRUPTED BREAKFAST AT SIR FRANCIS VARNEY'S.

CHAPTER LXI.—THE MYSTERIOUS STRANGER.—THE PARTICULARS OF THE SUICIDE AT BANNERWORTH HALL.

CHAPTER LXII.—THE MYSTERIOUS MEETING IN THE RUIN AGAIN.—THE VAMPYRE'S ATTACK UPON THE CONSTABLE.

CHAPTER LXIII.—THE GUESTS AT THE INN, AND THE STORY OF THE DEAD UNCLE.

CHAPTER LXIV.—THE VAMPIRE IN THE MOONLIGHT.—THE FALSE FRIEND.

CHAPTER LXV.—VARNEY'S VISIT TO THE DUNGEON OF THE LONELY PRISONER IN THE RUINS.

CHAPTER LXVII.—THE ADMIRAL'S STORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL BELINDA.

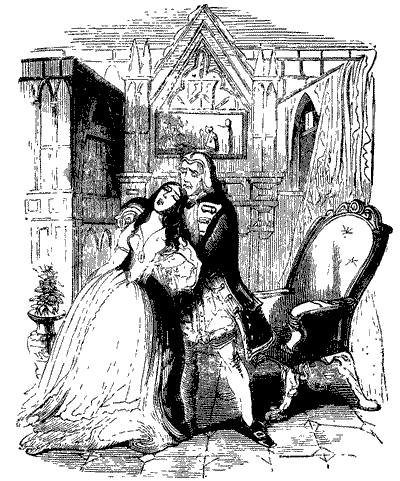

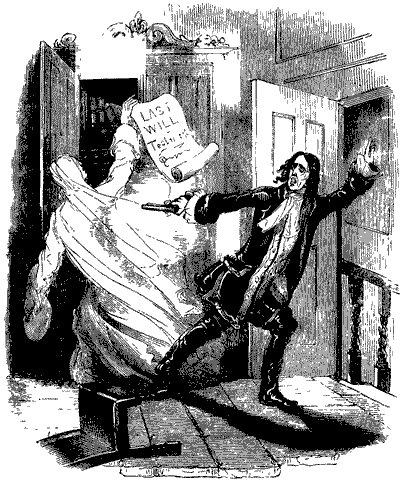

CHAPTER LXVIII.—MARCHDALE'S ATTEMPTED VILLANY, AND THE RESULT.

CHAPTER LXIX.—FLORA BANNERWORTH AND HER MOTHER.—THE EPISODE OF CHIVALRY.

CHAPTER LXXII.—THE STRANGE STORY.—THE ARRIVAL OF THE MOB AT THE HALL, AND THEIR DISPERSION.

CHAPTER LXXIII.—THE VISIT OF THE VAMPIRE.—THE GENERAL MEETING.

CHAPTER LXXIV.—THE MEETING OF CHARLES AND FLORA.

CHAPTER LXXV.—MUTUAL EXPLANATIONS, AND THE VISIT TO THE RUINS.

CHAPTER LXXVI.—THE SECOND NIGHT-WATCH OF MR. CHILLINGWORTH AT THE HALL.

CHAPTER LXXIX.—THE VAMPYRE'S DANGER.—THE LAST REFUGE.—THE RUSE OF HENRY BANNERWORTH.

CHAPTER LXXXI.—THE VAMPYRE'S FLIGHT.—HIS DANGER, AND THE LAST PLACE OF REFUGE.

CHAPTER LXXXII.—CHARLES HOLLAND'S PURSUIT OF THE VAMPYRE.—THE DANGEROUS INTERVIEW.

CHAPTER LXXXIII.—THE MYSTERIOUS ARRIVAL AT THE INN.—THE HUNGARIAN NOBLEMAN.—THE LETTER TO VARNEY.

CHAPTER LXXXIV.—THE EXCITED POPULACE.—VARNEY HUNTED.—THE PLACE OF REFUGE.

CHAPTER LXXXVI.—THE DISCOVERY OF THE POCKET BOOK OF MARMADUKE BANNERWORTH.—ITS MYSTERIOUS CONTENTS.

CHAPTER LXXXVIII.—THE RECEPTION OF THE VAMPYRE BY FLORA.—VARNEY SUBDUED.

CHAPTER LXXXIX.—TELLS WHAT BECAME OF THE SECOND VAMPYRE WHO SOUGHT VARNEY.

CHAPTER XCII.—THE MISADVENTURE OF THE DOCTOR WITH THE PICTURE.

CHAPTER XCIV.—THE VISITOR, AND THE DEATH IN THE SUBTERRANEAN PASSAGE.

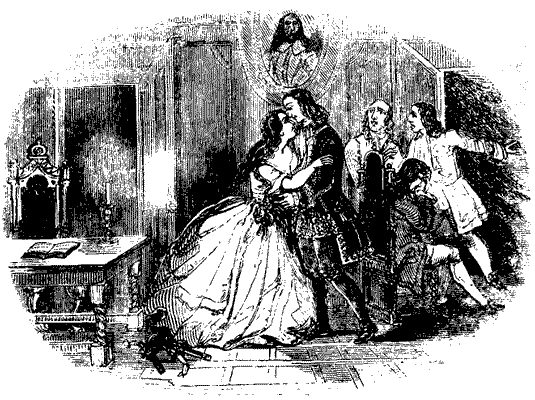

CHAPTER XCV.—THE MARRIAGE IN THE BANNERWORTH FAMILY ARRANGED.

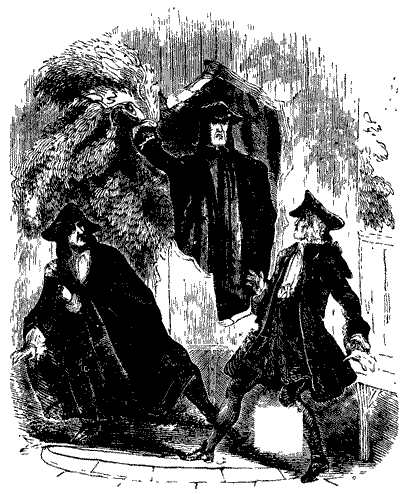

CHAPTER XCVI.—THE BARON TAKES ANDERBURY HOUSE, AND DECIDES UPON GIVING A GRAND ENTERTAINMENT.

The unprecedented success of the romance of "Varney the Vampyre," leaves the Author but little to say further, than that he accepts that success and its results as gratefully as it is possible for any one to do popular favours.

A belief in the existence of Vampyres first took its rise in Norway and Sweden, from whence it rapidly spread to more southern regions, taking a firm hold of the imaginations of the more credulous portion of mankind.

The following romance is collected from seemingly the most authentic sources, and the Author must leave the question of credibility entirely to his readers, not even thinking that he is peculiarly called upon to express his own opinion upon the subject.

Nothing has been omitted in the life of the unhappy Varney, which could tend to throw a light upon his most extraordinary career, and the fact of his death just as it is here related, made a great noise at the time through Europe and is to be found in the public prints for the year 1713.

With these few observations, the Author and Publisher, are well content to leave the work in the hands of a public, which has stamped it with an approbation far exceeding their most sanguine expectations, and which is calculated to act as the strongest possible incentive to the production of other works, which in a like, or perchance a still further degree may be deserving of public patronage and support.

To the whole of the Metropolitan Press for their laudatory notices, the Author is peculiarly obliged.

London Sep. 1847

——"How graves give up their dead.

And how the night air hideous grows

With shrieks!"

The solemn tones of an old cathedral clock have announced midnight—the air is thick and heavy—a strange, death like stillness pervades all nature. Like the ominous calm which precedes some more than usually terrific outbreak of the elements, they seem to have paused even in their ordinary fluctuations, to gather a terrific strength for the great effort. A faint peal of thunder now comes from far off. Like a signal gun for the battle of the winds to begin, it appeared to awaken them from their lethargy, and one awful, warring hurricane swept over a whole city, producing more devastation in the four or five minutes it lasted, than would a half century of ordinary phenomena.

It was as if some giant had blown upon some toy town, and scattered many of the buildings before the hot blast of his terrific breath; for as suddenly as that blast of wind had come did it cease, and all was as still and calm as before.

Sleepers awakened, and thought that what they had heard must be the confused chimera of a dream. They trembled and turned to sleep again.

All is still—still as the very grave. Not a sound breaks the magic of repose. What is that—a strange, pattering noise, as of a million of fairy feet? It is hail—yes, a hail-storm has burst over the city. Leaves are dashed from the trees, mingled with small boughs; windows that lie most opposed to the direct fury of the pelting particles of ice are broken, and the rapt repose that before was so remarkable in its intensity, is exchanged for a noise which, in its accumulation, drowns every cry of surprise or consternation which here and there arose from persons who found their houses invaded by the storm.

Now and then, too, there would come a sudden gust of wind that in its strength, as it blew laterally, would, for a moment, hold millions of the hailstones suspended in mid air, but it was only to dash them with redoubled force in some new direction, where more mischief was to be done.

Oh, how the storm raged! Hail—rain—wind. It was, in very truth, an awful night.

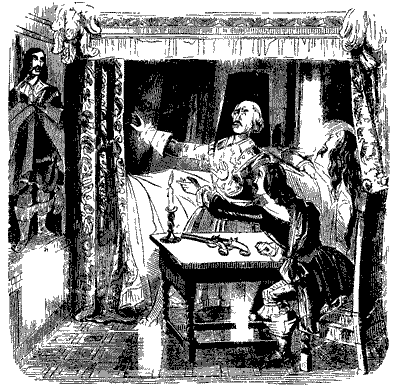

There is an antique chamber in an ancient house. Curious and quaint carvings adorn the walls, and the large chimney-piece is a curiosity of itself. The ceiling is low, and a large bay window, from roof to floor, looks to the west. The window is latticed, and filled with curiously painted glass and rich stained pieces, which send in a strange, yet beautiful light, when sun or moon shines into the apartment. There is but one portrait in that room, although the walls seem panelled for the express purpose of containing a series of pictures. That portrait is of a young man, with a pale face, a stately brow, and a strange expression about the eyes, which no one cared to look on twice.

There is a stately bed in that chamber, of carved walnut-wood is it made, rich in design and elaborate in execution; one of those works of art which owe their existence to the Elizabethan era. It is hung with heavy silken and damask furnishing; nodding feathers are at its corners—covered with dust are they, and they lend a funereal aspect to the room. The floor is of polished oak.

God! how the hail dashes on the old bay window! Like an occasional discharge of mimic musketry, it comes clashing, beating, and cracking upon the small panes; but they resist it—their small size saves them; the wind, the hail, the rain, expend their fury in vain.

The bed in that old chamber is occupied. A creature formed in all fashions of loveliness lies in a half sleep upon that ancient couch—a girl young and beautiful as a spring morning. Her long hair has escaped from its confinement and streams over the blackened coverings of the bedstead; she has been restless in her sleep, for the clothing of the bed is in much confusion. One arm is over her head, the other hangs nearly off the side of the bed near to which she lies. A neck and bosom that would have formed a study for the rarest sculptor that ever Providence gave genius to, were half disclosed. She moaned slightly in her sleep, and once or twice the lips moved as if in prayer—at least one might judge so, for the name of Him who suffered for all came once faintly from them.

She has endured much fatigue, and the storm does not awaken her; but it can disturb the slumbers it does not possess the power to destroy entirely. The turmoil of the elements wakes the senses, although it cannot entirely break the repose they have lapsed into.

Oh, what a world of witchery was in that mouth, slightly parted, and exhibiting within the pearly teeth that glistened even in the faint light that came from that bay window. How sweetly the long silken eyelashes lay upon the cheek. Now she moves, and one shoulder is entirely visible—whiter, fairer than the spotless clothing of the bed on which she lies, is the smooth skin of that fair creature, just budding into womanhood, and in that transition state which presents to us all the charms of the girl—almost of the child, with the more matured beauty and gentleness of advancing years.

Was that lightning? Yes—an awful, vivid, terrifying flash—then a roaring peal of thunder, as if a thousand mountains were rolling one over the other in the blue vault of Heaven! Who sleeps now in that ancient city? Not one living soul. The dread trumpet of eternity could not more effectually have awakened any one.

The hail continues. The wind continues. The uproar of the elements seems at its height. Now she awakens—that beautiful girl on the antique bed; she opens those eyes of celestial blue, and a faint cry of alarm bursts from her lips. At least it is a cry which, amid the noise and turmoil without, sounds but faint and weak. She sits upon the bed and presses her hands upon her eyes. Heavens! what a wild torrent of wind, and rain, and hail! The thunder likewise seems intent upon awakening sufficient echoes to last until the next flash of forked lightning should again produce the wild concussion of the air. She murmurs a prayer—a prayer for those she loves best; the names of those dear to her gentle heart come from her lips; she weeps and prays; she thinks then of what devastation the storm must surely produce, and to the great God of Heaven she prays for all living things. Another flash—a wild, blue, bewildering flash of lightning streams across that bay window, for an instant bringing out every colour in it with terrible distinctness. A shriek bursts from the lips of the young girl, and then, with eyes fixed upon that window, which, in another moment, is all darkness, and with such an expression of terror upon her face as it had never before known, she trembled, and the perspiration of intense fear stood upon her brow.

"What—what was it?" she gasped; "real, or a delusion? Oh, God, what was it? A figure tall and gaunt, endeavouring from the outside to unclasp the window. I saw it. That flash of lightning revealed it to me. It stood the whole length of the window."

There was a lull of the wind. The hail was not falling so thickly—moreover, it now fell, what there was of it, straight, and yet a strange clattering sound came upon the glass of that long window. It could not be a delusion—she is awake, and she hears it. What can produce it? Another flash of lightning—another shriek—there could be now no delusion.

A tall figure is standing on the ledge immediately outside the long window. It is its finger-nails upon the glass that produces the sound so like the hail, now that the hail has ceased. Intense fear paralysed the limbs of that beautiful girl. That one shriek is all she can utter—with hands clasped, a face of marble, a heart beating so wildly in her bosom, that each moment it seems as if it would break its confines, eyes distended and fixed upon the window, she waits, froze with horror. The pattering and clattering of the nails continue. No word is spoken, and now she fancies she can trace the darker form of that figure against the window, and she can see the long arms moving to and fro, feeling for some mode of entrance. What strange light is that which now gradually creeps up into the air? red and terrible—brighter and brighter it grows. The lightning has set fire to a mill, and the reflection of the rapidly consuming building falls upon that long window. There can be no mistake. The figure is there, still feeling for an entrance, and clattering against the glass with its long nails, that appear as if the growth of many years had been untouched. She tries to scream again but a choking sensation comes over her, and she cannot. It is too dreadful—she tries to move—each limb seems weighed down by tons of lead—she can but in a hoarse faint whisper cry,—

"Help—help—help—help!"

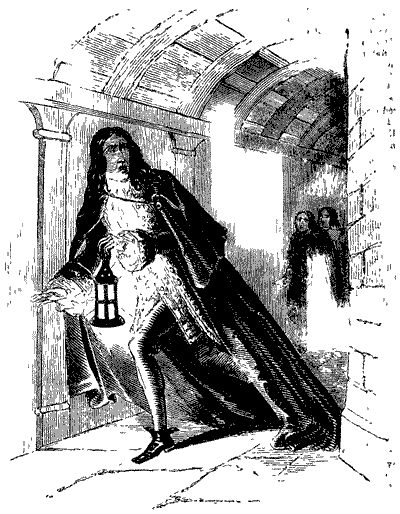

And that one word she repeats like a person in a dream. The red glare of the fire continues. It throws up the tall gaunt figure in hideous relief against the long window. It shows, too, upon the one portrait that is in the chamber, and that portrait appears to fix its eyes upon the attempting intruder, while the flickering light from the fire makes it look fearfully lifelike. A small pane of glass is broken, and the form from without introduces a long gaunt hand, which seems utterly destitute of flesh. The fastening is removed, and one-half of the window, which opens like folding doors, is swung wide open upon its hinges.

And yet now she could not scream—she could not move. "Help!—help!—help!" was all she could say. But, oh, that look of terror that sat upon her face, it was dreadful—a look to haunt the memory for a lifetime—a look to obtrude itself upon the happiest moments, and turn them to bitterness.

The figure turns half round, and the light falls upon the face. It is perfectly white—perfectly bloodless. The eyes look like polished tin; the lips are drawn back, and the principal feature next to those dreadful eyes is the teeth—the fearful looking teeth—projecting like those of some wild animal, hideously, glaringly white, and fang-like. It approaches the bed with a strange, gliding movement. It clashes together the long nails that literally appear to hang from the finger ends. No sound comes from its lips. Is she going mad—that young and beautiful girl exposed to so much terror? she has drawn up all her limbs; she cannot even now say help. The power of articulation is gone, but the power of movement has returned to her; she can draw herself slowly along to the other side of the bed from that towards which the hideous appearance is coming.

But her eyes are fascinated. The glance of a serpent could not have produced a greater effect upon her than did the fixed gaze of those awful, metallic-looking eyes that were bent on her face. Crouching down so that the gigantic height was lost, and the horrible, protruding, white face was the most prominent object, came on the figure. What was it?—what did it want there?—what made it look so hideous—so unlike an inhabitant of the earth, and yet to be on it?

Now she has got to the verge of the bed, and the figure pauses. It seemed as if when it paused she lost the power to proceed. The clothing of the bed was now clutched in her hands with unconscious power. She drew her breath short and thick. Her bosom heaves, and her limbs tremble, yet she cannot withdraw her eyes from that marble-looking face. He holds her with his glittering eye.

The storm has ceased—all is still. The winds are hushed; the church clock proclaims the hour of one: a hissing sound comes from the throat of the hideous being, and he raises his long, gaunt arms—the lips move. He advances. The girl places one small foot from the bed on to the floor. She is unconsciously dragging the clothing with her. The door of the room is in that direction—can she reach it? Has she power to walk?—can she withdraw her eyes from the face of the intruder, and so break the hideous charm? God of Heaven! is it real, or some dream so like reality as to nearly overturn the judgment for ever?

The figure has paused again, and half on the bed and half out of it that young girl lies trembling. Her long hair streams across the entire width of the bed. As she has slowly moved along she has left it streaming across the pillows. The pause lasted about a minute—oh, what an age of agony. That minute was, indeed, enough for madness to do its full work in.

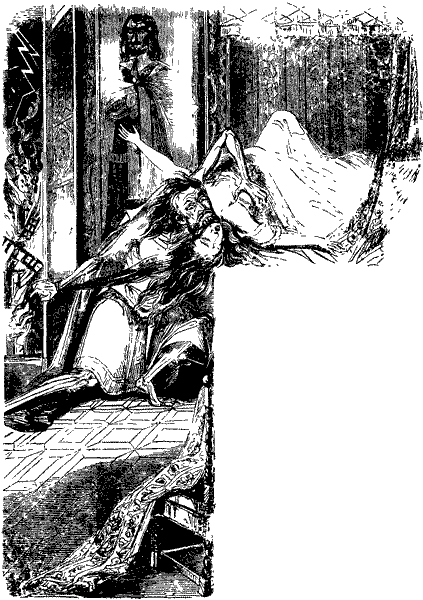

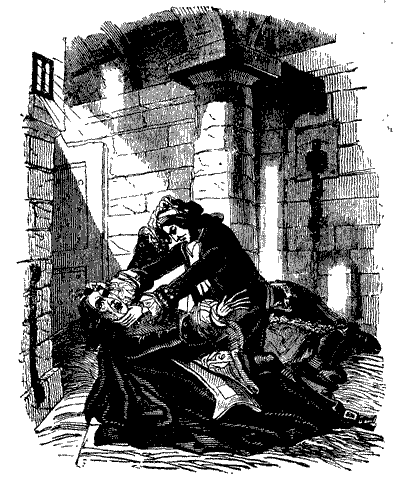

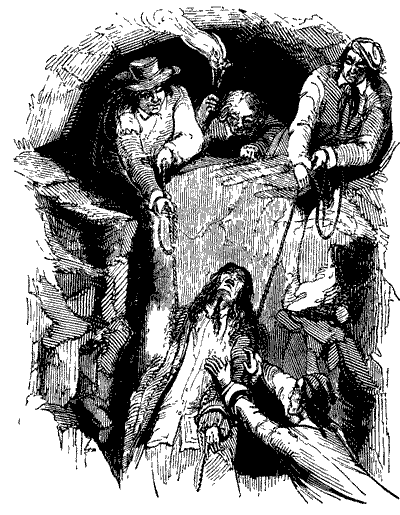

With a sudden rush that could not be foreseen—with a strange howling cry that was enough to awaken terror in every breast, the figure seized the long tresses of her hair, and twining them round his bony hands he held her to the bed. Then she screamed—Heaven granted her then power to scream. Shriek followed shriek in rapid succession. The bed-clothes fell in a heap by the side of the bed—she was dragged by her long silken hair completely on to it again. Her beautifully rounded limbs quivered with the agony of her soul. The glassy, horrible eyes of the figure ran over that angelic form with a hideous satisfaction—horrible profanation. He drags her head to the bed's edge. He forces it back by the long hair still entwined in his grasp. With a plunge he seizes her neck in his fang-like teeth—a gush of blood, and a hideous sucking noise follows. The girl has swooned, and the vampyre is at his hideous repast!

Lights flashed about the building, and various room doors opened; voices called one to the other. There was an universal stir and commotion among the inhabitants.

"Did you hear a scream, Harry?" asked a young man, half-dressed, as he walked into the chamber of another about his own age.

"I did—where was it?"

"God knows. I dressed myself directly."

"All is still now."

"Yes; but unless I was dreaming there was a scream."

"We could not both dream there was. Where did you think it came from?"

"It burst so suddenly upon my ears that I cannot say."

There was a tap now at the door of the room where these young men were, and a female voice said,—

"For God's sake, get up!"

"We are up," said both the young men, appearing.

"Did you hear anything?"

"Yes, a scream."

"Oh, search the house—search the house; where did it come from—can you tell?"

"Indeed we cannot, mother."

Another person now joined the party. He was a man of middle age, and, as he came up to them, he said,—

"Good God! what is the matter?"

Scarcely had the words passed his lips, than such a rapid succession of shrieks came upon their ears, that they felt absolutely stunned by them. The elderly lady, whom one of the young men had called mother, fainted, and would have fallen to the floor of the corridor in which they all stood, had she not been promptly supported by the last comer, who himself staggered, as those piercing cries came upon the night air. He, however, was the first to recover, for the young men seemed paralysed.

"Henry," he cried, "for God's sake support your mother. Can you doubt that these cries come from Flora's room?"

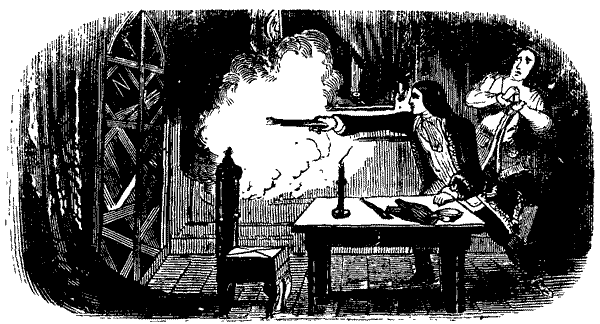

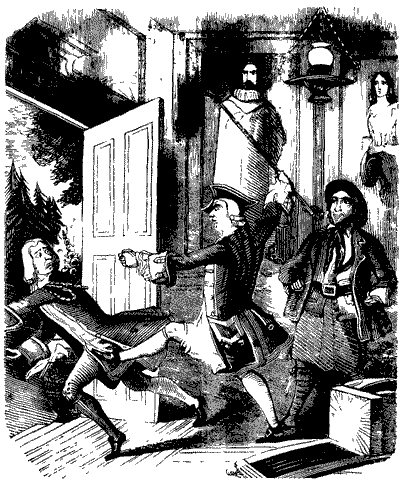

The young man mechanically supported his mother, and then the man who had just spoken darted back to his own bed-room, from whence he returned in a moment with a pair of pistols, and shouting,—

"Follow me, who can!" he bounded across the corridor in the direction of the antique apartment, from whence the cries proceeded, but which were now hushed.

That house was built for strength, and the doors were all of oak, and of considerable thickness. Unhappily, they had fastenings within, so that when the man reached the chamber of her who so much required help, he was helpless, for the door was fast.

"Flora! Flora!" he cried; "Flora, speak!"

All was still.

"Good God!" he added; "we must force the door."

"I hear a strange noise within," said the young man, who trembled violently.

"And so do I. What does it sound like?"

"I scarcely know; but it nearest resembles some animal eating, or sucking some liquid."

"What on earth can it be? Have you no weapon that will force the door? I shall go mad if I am kept here."

"I have," said the young man. "Wait here a moment."

He ran down the staircase, and presently returned with a small, but powerful, iron crow-bar.

"This will do," he said.

"It will, it will.—Give it to me."

"Has she not spoken?"

"Not a word. My mind misgives me that something very dreadful must have happened to her."

"And that odd noise!"

"Still goes on. Somehow, it curdles the very blood in my veins to hear it."

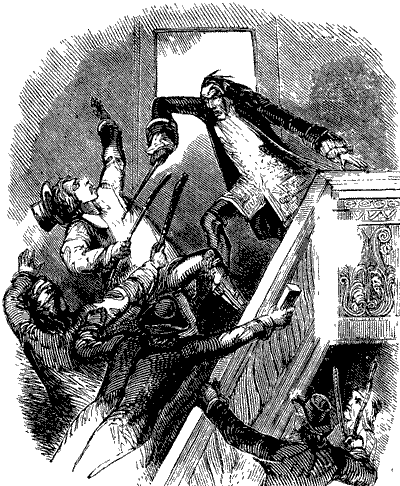

The man took the crow-bar, and with some difficulty succeeded in introducing it between the door and the side of the wall—still it required great strength to move it, but it did move, with a harsh, crackling sound.

"Push it!" cried he who was using the bar, "push the door at the same time."

The younger man did so. For a few moments the massive door resisted. Then, suddenly, something gave way with a loud snap—it was a part of the lock,—and the door at once swung wide open.

How true it is that we measure time by the events which happen within a given space of it, rather than by its actual duration.

To those who were engaged in forcing open the door of the antique chamber, where slept the young girl whom they named Flora, each moment was swelled into an hour of agony; but, in reality, from the first moment of the alarm to that when the loud cracking noise heralded the destruction of the fastenings of the door, there had elapsed but very few minutes indeed.

"It opens—it opens," cried the young man.

"Another moment," said the stranger, as he still plied the crowbar—"another moment, and we shall have free ingress to the chamber. Be patient."

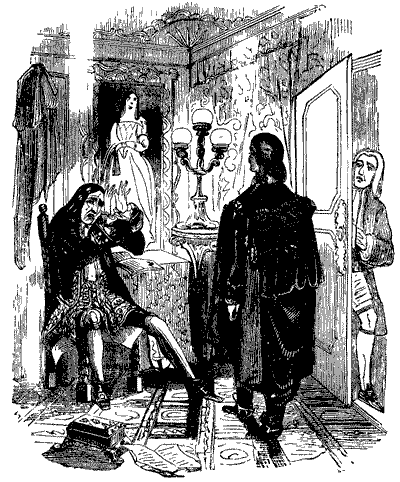

This stranger's name was Marchdale; and even as he spoke, he succeeded in throwing the massive door wide open, and clearing the passage to the chamber.

To rush in with a light in his hand was the work of a moment to the young man named Henry; but the very rapid progress he made into the apartment prevented him from observing accurately what it contained, for the wind that came in from the open window caught the flame of the candle, and although it did not actually extinguish it, it blew it so much on one side, that it was comparatively useless as a light.

"Flora—Flora!" he cried.

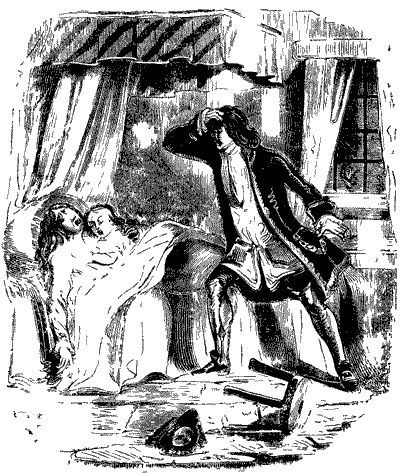

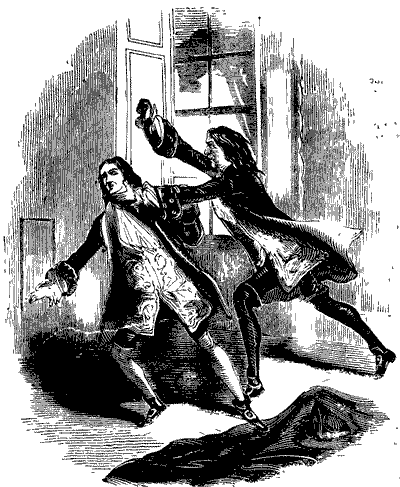

Then with a sudden bound something dashed from off the bed. The concussion against him was so sudden and so utterly unexpected, as well as so tremendously violent, that he was thrown down, and, in his fall, the light was fairly extinguished.

All was darkness, save a dull, reddish kind of light that now and then, from the nearly consumed mill in the immediate vicinity, came into the room. But by that light, dim, uncertain, and flickering as it was, some one was seen to make for the window.

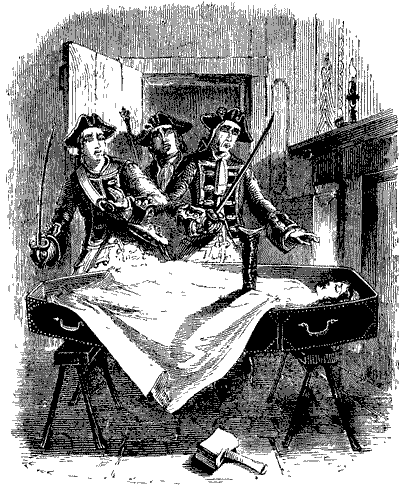

Henry, although nearly stunned by his fall, saw a figure, gigantic in height, which nearly reached from the floor to the ceiling. The other young man, George, saw it, and Mr. Marchdale likewise saw it, as did the lady who had spoken to the two young men in the corridor when first the screams of the young girl awakened alarm in the breasts of all the inhabitants of that house.

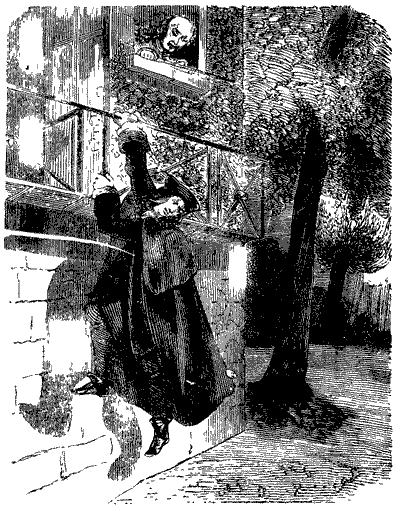

The figure was about to pass out at the window which led to a kind of balcony, from whence there was an easy descent to a garden.

Before it passed out they each and all caught a glance of the side-face, and they saw that the lower part of it and the lips were dabbled in blood. They saw, too, one of those fearful-looking, shining, metallic eyes which presented so terrible an appearance of unearthly ferocity.

No wonder that for a moment a panic seized them all, which paralysed any exertions they might otherwise have made to detain that hideous form.

But Mr. Marchdale was a man of mature years; he had seen much of life, both in this and in foreign lands; and he, although astonished to the extent of being frightened, was much more likely to recover sooner than his younger companions, which, indeed, he did, and acted promptly enough.

"Don't rise, Henry," he cried. "Lie still."

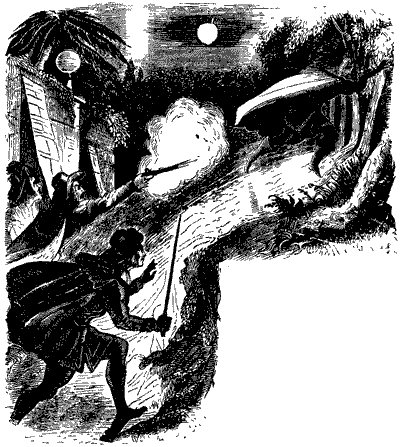

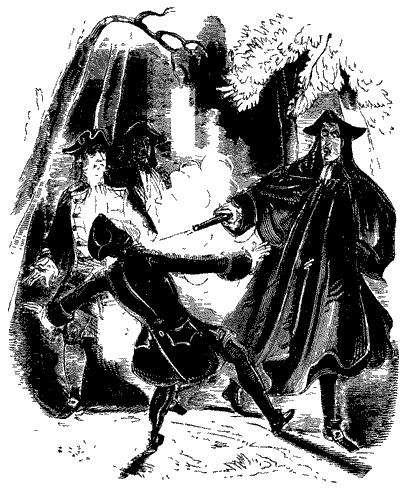

Almost at the moment he uttered these words, he fired at the figure, which then occupied the window, as if it were a gigantic figure set in a frame.

The report was tremendous in that chamber, for the pistol was no toy weapon, but one made for actual service, and of sufficient length and bore of barrel to carry destruction along with the bullets that came from it.

"If that has missed its aim," said Mr. Marchdale, "I'll never pull a trigger again."

As he spoke he dashed forward, and made a clutch at the figure he felt convinced he had shot.

The tall form turned upon him, and when he got a full view of the face, which he did at that moment, from the opportune circumstance of the lady returning at the instant with a light she had been to her own chamber to procure, even he, Marchdale, with all his courage, and that was great, and all his nervous energy, recoiled a step or two, and uttered the exclamation of, "Great God!"

That face was one never to be forgotten. It was hideously flushed with colour—the colour of fresh blood; the eyes had a savage and remarkable lustre; whereas, before, they had looked like polished tin—they now wore a ten times brighter aspect, and flashes of light seemed to dart from them. The mouth was open, as if, from the natural formation of the countenance, the lips receded much from the large canine looking teeth.

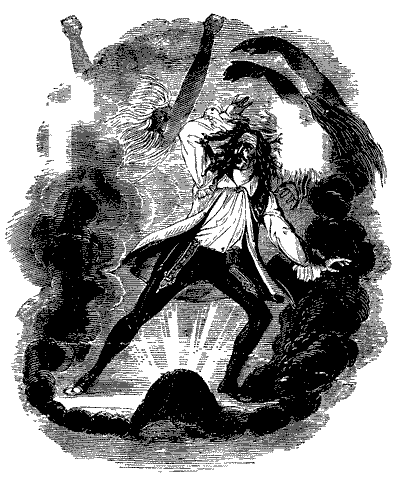

A strange howling noise came from the throat of this monstrous figure, and it seemed upon the point of rushing upon Mr. Marchdale. Suddenly, then, as if some impulse had seized upon it, it uttered a wild and terrible shrieking kind of laugh; and then turning, dashed through the window, and in one instant disappeared from before the eyes of those who felt nearly annihilated by its fearful presence.

"God help us!" ejaculated Henry.

Mr. Marchdale drew a long breath, and then, giving a stamp on the floor, as if to recover himself from the state of agitation into which even he was thrown, he cried,—

"Be it what or who it may, I'll follow it"

"No—no—do not," cried the lady.

"I must, I will. Let who will come with me—I follow that dreadful form."

As he spoke, he took the road it took, and dashed through the window into the balcony.

"And we, too, George," exclaimed Henry; "we will follow Mr. Marchdale. This dreadful affair concerns us more nearly than it does him."

The lady who was the mother of these young men, and of the beautiful girl who had been so awfully visited, screamed aloud, and implored of them to stay. But the voice of Mr. Marchdale was heard exclaiming aloud,—

"I see it—I see it; it makes for the wall."

They hesitated no longer, but at once rushed into the balcony, and from thence dropped into the garden.

The mother approached the bed-side of the insensible, perhaps the murdered girl; she saw her, to all appearance, weltering in blood, and, overcome by her emotions, she fainted on the floor of the room.

When the two young men reached the garden, they found it much lighter than might have been fairly expected; for not only was the morning rapidly approaching, but the mill was still burning, and those mingled lights made almost every object plainly visible, except when deep shadows were thrown from some gigantic trees that had stood for centuries in that sweetly wooded spot. They heard the voice of Mr. Marchdale, as he cried,—

"There—there—towards the wall. There—there—God! how it bounds along."

The young men hastily dashed through a thicket in the direction from whence his voice sounded, and then they found him looking wild and terrified, and with something in his hand which looked like a portion of clothing.

"Which way, which way?" they both cried in a breath.

He leant heavily on the arm of George, as he pointed along a vista of trees, and said in a low voice,—

"God help us all. It is not human. Look there—look there—do you not see it?"

They looked in the direction he indicated. At the end of this vista was the wall of the garden. At that point it was full twelve feet in height, and as they looked, they saw the hideous, monstrous form they had traced from the chamber of their sister, making frantic efforts to clear the obstacle.

Then they saw it bound from the ground to the top of the wall, which it very nearly reached, and then each time it fell back again into the garden with such a dull, heavy sound, that the earth seemed to shake again with the concussion. They trembled—well indeed they might, and for some minutes they watched the figure making its fruitless efforts to leave the place.

"What—what is it?" whispered Henry, in hoarse accents. "God, what can it possibly be?"

"I know not," replied Mr. Marchdale. "I did seize it. It was cold and clammy like a corpse. It cannot be human."

"Not human?"

"Look at it now. It will surely escape now."

"No, no—we will not be terrified thus—there is Heaven above us. Come on, and, for dear Flora's sake, let us make an effort yet to seize this bold intruder."

"Take this pistol," said Marchdale. "It is the fellow of the one I fired. Try its efficacy."

"He will be gone," exclaimed Henry, as at this moment, after many repeated attempts and fearful falls, the figure reached the top of the wall, and then hung by its long arms a moment or two, previous to dragging itself completely up.

The idea of the appearance, be it what it might, entirely escaping, seemed to nerve again Mr. Marchdale, and he, as well as the two young men, ran forward towards the wall. They got so close to the figure before it sprang down on the outer side of the wall, that to miss killing it with the bullet from the pistol was a matter of utter impossibility, unless wilfully.

Henry had the weapon, and he pointed it full at the tall form with a steady aim. He pulled the trigger—the explosion followed, and that the bullet did its office there could be no manner of doubt, for the figure gave a howling shriek, and fell headlong from the wall on the outside.

"I have shot him," cried Henry, "I have shot him."

"He is human!" cried Henry; "I have surely killed him."

"It would seem so," said Mr. Marchdale. "Let us now hurry round to the outside of the wall, and see where he lies."

This was at once agreed to, and the whole three of them made what expedition they could towards a gate which led into a paddock, across which they hurried, and soon found themselves clear of the garden wall, so that they could make way towards where they fully expected to find the body of him who had worn so unearthly an aspect, but who it would be an excessive relief to find was human.

So hurried was the progress they made, that it was scarcely possible to exchange many words as they went; a kind of breathless anxiety was upon them, and in the speed they disregarded every obstacle, which would, at any other time, have probably prevented them from taking the direct road they sought.

It was difficult on the outside of the wall to say exactly which was the precise spot which it might be supposed the body had fallen on; but, by following the wall in its entire length, surely they would come upon it.

They did so; but, to their surprise, they got from its commencement to its further extremity without finding any dead body, or even any symptoms of one having lain there.

At some parts close to the wall there grew a kind of heath, and, consequently, the traces of blood would be lost among it, if it so happened that at the precise spot at which the strange being had seemed to topple over, such vegetation had existed. This was to be ascertained; but now, after traversing the whole length of the wall twice, they came to a halt, and looked wonderingly in each other's faces.

"There is nothing here," said Harry.

"Nothing," added his brother.

"It could not have been a delusion," at length said Mr. Marchdale, with a shudder.

"A delusion?" exclaimed the brother! "That is not possible; we all saw it."

"Then what terrible explanation can we give?"

"By heavens! I know not," exclaimed Henry. "This adventure surpasses all belief, and but for the great interest we have in it, I should regard it with a world of curiosity."

"It is too dreadful," said George; "for God's sake, Henry, let us return to ascertain if poor Flora is killed."

"My senses," said Henry, "were all so much absorbed in gazing at that horrible form, that I never once looked towards her further than to see that she was, to appearance, dead. God help her! poor—poor, beautiful Flora. This is, indeed, a sad, sad fate for you to come to. Flora—Flora—"

"Do not weep, Henry," said George. "Rather let us now hasten home, where we may find that tears are premature. She may yet be living and restored to us."

"And," said Mr. Marchdale, "she may be able to give us some account of this dreadful visitation."

"True—true," exclaimed Henry; "we will hasten home."

They now turned their steps homeward, and as they went they much blamed themselves for all leaving home together, and with terror pictured what might occur in their absence to those who were now totally unprotected.

"It was a rash impulse of us all to come in pursuit of this dreadful figure," remarked Mr. Marchdale; "but do not torment yourself, Henry. There may be no reason for your fears."

At the pace they went, they very soon reached the ancient house, and when they came in sight of it, they saw lights flashing from the windows, and the shadows of faces moving to and fro, indicating that the whole household was up, and in a state of alarm.

Henry, after some trouble, got the hall door opened by a terrified servant, who was trembling so much that she could scarcely hold the light she had with her.

"Speak at once, Martha," said Henry. "Is Flora living?"

"Yes; but—"

"Enough—enough! Thank God she lives; where is she now?"

"In her own room, Master Henry. Oh, dear—oh, dear, what will become of us all?"

Henry rushed up the staircase, followed by George and Mr. Marchdale, nor paused he once until he reached the room of his sister.

"Mother," he said, before he crossed the threshold, "are you here?"

"I am, my dear—I am. Come in, pray come in, and speak to poor Flora."

"Come in, Mr. Marchdale," said Henry—"come in; we make no stranger of you."

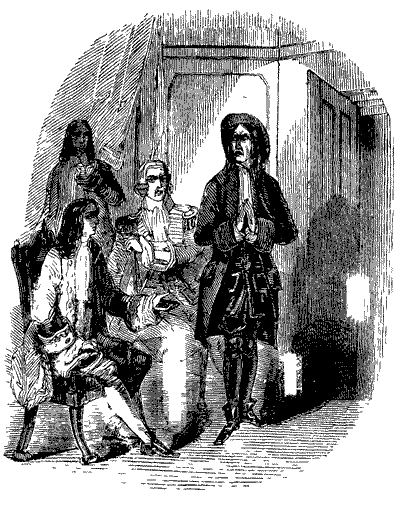

They all then entered the room.

Several lights had been now brought into that antique chamber, and, in addition to the mother of the beautiful girl who had been so fearfully visited, there were two female domestics, who appeared to be in the greatest possible fright, for they could render no assistance whatever to anybody.

The tears were streaming down the mother's face, and the moment she saw Mr. Marchdale, she clung to his arm, evidently unconscious of what she was about, and exclaimed,—

"Oh, what is this that has happened—what is this? Tell me, Marchdale! Robert Marchdale, you whom I have known even from my childhood, you will not deceive me. Tell me the meaning of all this?"

"I cannot," he said, in a tone of much emotion. "As God is my judge, I am as much puzzled and amazed at the scene that has taken place here to-night as you can be."

The mother wrung her hands and wept.

"It was the storm that first awakened me," added Marchdale; "and then I heard a scream."

The brothers tremblingly approached the bed. Flora was placed in a sitting, half-reclining posture, propped up by pillows. She was quite insensible, and her face was fearfully pale; while that she breathed at all could be but very faintly seen. On some of her clothing, about the neck, were spots of blood, and she looked more like one who had suffered some long and grievous illness, than a young girl in the prime of life and in the most robust health, as she had been on the day previous to the strange scene we have recorded.

"Does she sleep?" said Henry, as a tear fell from his eyes upon her pallid cheek.

"No," replied Mr. Marchdale. "This is a swoon, from which we must recover her."

Active measures were now adopted to restore the languid circulation, and, after persevering in them for some time, they had the satisfaction of seeing her open her eyes.

Her first act upon consciousness returning, however, was to utter a loud shriek, and it was not until Henry implored her to look around her, and see that she was surrounded by none but friendly faces, that she would venture again to open her eyes, and look timidly from one to the other. Then she shuddered, and burst into tears as she said,—

"Oh, Heaven, have mercy upon me—Heaven, have mercy upon me, and save me from that dreadful form."

"There is no one here, Flora," said Mr. Marchdale, "but those who love you, and who, in defence of you, if needs were would lay down their lives."

"Oh, God! Oh, God!"

"You have been terrified. But tell us distinctly what has happened? You are quite safe now."

She trembled so violently that Mr. Marchdale recommended that some stimulant should be given to her, and she was persuaded, although not without considerable difficulty, to swallow a small portion of some wine from a cup. There could be no doubt but that the stimulating effect of the wine was beneficial, for a slight accession of colour visited her cheeks, and she spoke in a firmer tone as she said,—

"Do not leave me. Oh, do not leave me, any of you. I shall die if left alone now. Oh, save me—save me. That horrible form! That fearful face!"

"Tell us how it happened, dear Flora?" said Henry.

"Or would you rather endeavour to get some sleep first?" suggested Mr. Marchdale.

"No—no—no," she said, "I do not think I shall ever sleep again."

"Say not so; you will be more composed in a few hours, and then you can tell us what has occurred."

"I will tell you now. I will tell you now."

She placed her hands over her face for a moment, as if to collect her scattered, thoughts, and then she added,—

"I was awakened by the storm, and I saw that terrible apparition at the window. I think I screamed, but I could not fly. Oh, God! I could not fly. It came—it seized me by the hair. I know no more. I know no more."

She passed her hand across her neck several times, and Mr. Marchdale said, in an anxious voice,—

"You seem, Flora, to have hurt your neck—there is a wound."

"A wound!" said the mother, and she brought a light close to the bed, where all saw on the side of Flora's neck a small punctured wound; or, rather two, for there was one a little distance from the other.

It was from these wounds the blood had come which was observable upon her night clothing.

"How came these wounds?" said Henry.

"I do not know," she replied. "I feel very faint and weak, as if I had almost bled to death."

"You cannot have done so, dear Flora, for there are not above half-a-dozen spots of blood to be seen at all."

Mr. Marchdale leaned against the carved head of the bed for support, and he uttered a deep groan. All eyes were turned upon him, and Henry said, in a voice of the most anxious inquiry,—

"You have something to say, Mr. Marchdale, which will throw some light upon this affair."

"No, no, no, nothing!" cried Mr. Marchdale, rousing himself at once from the appearance of depression that had come over him. "I have nothing to say, but that I think Flora had better get some sleep if she can."

"No sleep-no sleep for me," again screamed Flora. "Dare I be alone to sleep?"

"But you shall not be alone, dear Flora," said Henry. "I will sit by your bedside and watch you."

She took his hand in both hers, and while the tears chased each other down her cheeks, she said,—

"Promise me, Henry, by all your hopes of Heaven, you will not leave me."

"I promise!"

She gently laid herself down, with a deep sigh, and closed her eyes.

"She is weak, and will sleep long," said Mr. Marchdale.

"You sigh," said Henry. "Some fearful thoughts, I feel certain, oppress your heart."

"Hush-hush!" said Mr. Marchdale, as he pointed to Flora. "Hush! not here—not here."

"I understand," said Henry.

"Let her sleep."

There was a silence of some few minutes duration. Flora had dropped into a deep slumber. That silence was first broken by George, who said,—

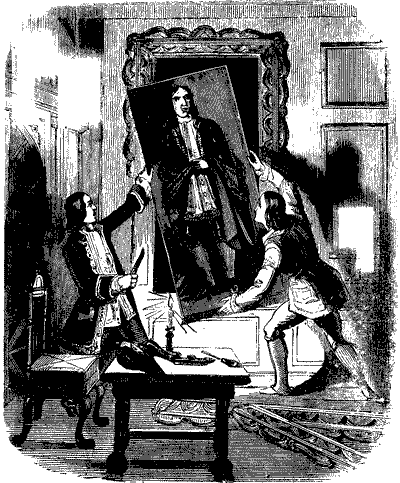

"Mr. Marchdale, look at that portrait."

He pointed to the portrait in the frame to which we have alluded, and the moment Marchdale looked at it he sunk into a chair as he exclaimed,—

"Gracious Heaven, how like!"

"It is—it is," said Henry. "Those eyes—"

"And see the contour of the countenance, and the strange shape of the mouth."

"Exact—exact."

"That picture shall be moved from here. The sight of it is at once sufficient to awaken all her former terrors in poor Flora's brain if she should chance to awaken and cast her eyes suddenly upon it."

"And is it so like him who came here?" said the mother.

"It is the very man himself," said Mr. Marchdale. "I have not been in this house long enough to ask any of you whose portrait that may be?"

"It is," said Henry, "the portrait of Sir Runnagate Bannerworth, an ancestor of ours, who first, by his vices, gave the great blow to the family prosperity."

"Indeed. How long ago?"

"About ninety years."

"Ninety years. 'Tis a long while—ninety years."

"You muse upon it."

"No, no. I do wish, and yet I dread—"

"What?"

"To say something to you all. But not here—not here. We will hold a consultation on this matter to-morrow. Not now—not now."

"The daylight is coming quickly on," said Henry; "I shall keep my sacred promise of not moving from this room until Flora awakens; but there can be no occasion for the detention of any of you. One is sufficient here. Go all of you, and endeavour to procure what rest you can."

"I will fetch you my powder-flask and bullets," said Mr. Marchdale; "and you can, if you please, reload the pistols. In about two hours more it will be broad daylight."

This arrangement was adopted. Henry did reload the pistols, and placed them on a table by the side of the bed, ready for immediate action, and then, as Flora was sleeping soundly, all left the room but himself.

Mrs. Bannerworth was the last to do so. She would have remained, but for the earnest solicitation of Henry, that she would endeavour to get some sleep to make up for her broken night's repose, and she was indeed so broken down by her alarm on Flora's account, that she had not power to resist, but with tears flowing from her eyes, she sought her own chamber.

And now the calmness of the night resumed its sway in that evil-fated mansion; and although no one really slept but Flora, all were still. Busy thought kept every one else wakeful. It was a mockery to lie down at all, and Henry, full of strange and painful feelings as he was, preferred his present position to the anxiety and apprehension on Flora's account which he knew he should feel if she were not within the sphere of his own observation, and she slept as soundly as some gentle infant tired of its playmates and its sports.

What wonderfully different impressions and feelings, with regard to the same circumstances, come across the mind in the broad, clear, and beautiful light of day to what haunt the imagination, and often render the judgment almost incapable of action, when the heavy shadow of night is upon all things.

There must be a downright physical reason for this effect—it is so remarkable and so universal. It seems that the sun's rays so completely alter and modify the constitution of the atmosphere, that it produces, as we inhale it, a wonderfully different effect upon the nerves of the human subject.

We can account for this phenomenon in no other way. Perhaps never in his life had he, Henry Bannerworth, felt so strongly this transition of feeling as he now felt it, when the beautiful daylight gradually dawned upon him, as he kept his lonely watch by the bedside of his slumbering sister.

That watch had been a perfectly undisturbed one. Not the least sight or sound of any intrusion had reached his senses. All had been as still as the very grave.

And yet while the night lasted, and he was more indebted to the rays of the candle, which he had placed upon a shelf, for the power to distinguish objects than to the light of the morning, a thousand uneasy and strange sensations had found a home in his agitated bosom.

He looked so many times at the portrait which was in the panel that at length he felt an undefined sensation of terror creep over him whenever he took his eyes off it.

He tried to keep himself from looking at it, but he found it vain, so he adopted what, perhaps, was certainly the wisest, best plan, namely, to look at it continually.

He shifted his chair so that he could gaze upon it without any effort, and he placed the candle so that a faint light was thrown upon it, and there he sat, a prey to many conflicting and uncomfortable feelings, until the daylight began to make the candle flame look dull and sickly.

Solution for the events of the night he could find none. He racked his imagination in vain to find some means, however vague, of endeavouring to account for what occurred, and still he was at fault. All was to him wrapped in the gloom of the most profound mystery.

And how strangely, too, the eyes of that portrait appeared to look upon him—as if instinct with life, and as if the head to which they belonged was busy in endeavouring to find out the secret communings of his soul. It was wonderfully well executed that portrait; so life-like, that the very features seemed to move as you gazed upon them.

"It shall be removed," said Henry. "I would remove it now, but that it seems absolutely painted on the panel, and I should awake Flora in any attempt to do so."

He arose and ascertained that such was the case, and that it would require a workman, with proper tools adapted to the job, to remove the portrait.

"True," he said, "I might now destroy it, but it is a pity to obscure a work of such rare art as this is; I should blame myself if I were. It shall be removed to some other room of the house, however."

Then, all of a sudden, it struck Henry how foolish it would be to remove the portrait from the wall of a room which, in all likelihood, after that night, would be uninhabited; for it was not probable that Flora would choose again to inhabit a chamber in which she had gone through so much terror.

"It can be left where it is," he said, "and we can fasten up, if we please, even the very door of this room, so that no one need trouble themselves any further about it."

The morning was now coming fast, and just as Henry thought he would partially draw a blind across the window, in order to shield from the direct rays of the sun the eyes of Flora, she awoke.

"Help—help!" she cried, and Henry was by her side in a moment.

"You are safe, Flora—you are safe," he said.

"Where is it now?" she said.

"What—what, dear Flora?"

"The dreadful apparition. Oh, what have I done to be made thus perpetually miserable?"

"Think no more of it, Flora."

"I must think. My brain is on fire! A million of strange eyes seem gazing on me."

"Great Heaven! she raves," said Henry.

"Hark—hark—hark! He comes on the wings of the storm. Oh, it is most horrible—horrible!"

Henry rang the bell, but not sufficiently loudly to create any alarm. The sound reached the waking ear of the mother, who in a few moments was in the room.

"She has awakened," said Henry, "and has spoken, but she seems to me to wander in her discourse. For God's sake, soothe her, and try to bring her mind round to its usual state."

"I will, Henry—I will."

"And I think, mother, if you were to get her out of this room, and into some other chamber as far removed from this one as possible, it would tend to withdraw her mind from what has occurred."

"Yes; it shall be done. Oh, Henry, what was it—what do you think it was?"

"I am lost in a sea of wild conjecture. I can form no conclusion; where is Mr. Marchdale?"

"I believe in his chamber."

"Then I will go and consult with him."

Henry proceeded at once to the chamber, which was, as he knew, occupied by Mr. Marchdale; and as he crossed the corridor, he could not but pause a moment to glance from a window at the face of nature.

As is often the case, the terrific storm of the preceding evening had cleared the air, and rendered it deliciously invigorating and lifelike. The weather had been dull, and there had been for some days a certain heaviness in the atmosphere, which was now entirely removed.

The morning sun was shining with uncommon brilliancy, birds were singing in every tree and on every bush; so pleasant, so spirit-stirring, health-giving a morning, seldom had he seen. And the effect upon his spirits was great, although not altogether what it might have been, had all gone on as it usually was in the habit of doing at that house. The ordinary little casualties of evil fortune had certainly from time to time, in the shape of illness, and one thing or another, attacked the family of the Bannerworths in common with every other family, but here suddenly had arisen a something at once terrible and inexplicable.

He found Mr. Marchdale up and dressed, and apparently in deep and anxious thought. The moment he saw Henry, he said,—

"Flora is awake, I presume."

"Yes, but her mind appears to be much disturbed."

"From bodily weakness, I dare say."

"But why should she be bodily weak? she was strong and well, ay, as well as she could ever be in all her life. The glow of youth and health was on her cheeks. Is it possible that, in the course of one night, she should become bodily weak to such an extent?"

"Henry," said Mr. Marchdale, sadly, "sit down. I am not, as you know, a superstitious man."

"You certainly are not."

"And yet, I never in all my life was so absolutely staggered as I have been by the occurrences of to-night."

"Say on."

"There is a frightful, a hideous solution of them; one which every consideration will tend to add strength to, one which I tremble to name now, although, yesterday, at this hour, I should have laughed it to scorn."

"Indeed!"

"Yes, it is so. Tell no one that which I am about to say to you. Let the dreadful suggestion remain with ourselves alone, Henry Bannerworth."

"I—I am lost in wonder."

"You promise me?"

"What—what?"

"That you will not repeat my opinion to any one."

"I do."

"On your honour."

"On my honour, I promise."

Mr. Marchdale rose, and proceeding to the door, he looked out to see that there were no listeners near. Having ascertained then that they were quite alone, he returned, and drawing a chair close to that on which Henry sat, he said,—

"Henry, have you never heard of a strange and dreadful superstition which, in some countries, is extremely rife, by which it is supposed that there are beings who never die."

"Never die!"

"Never. In a word, Henry, have you never heard of—of—I dread to pronounce the word."

"Speak it. God of Heaven! let me hear it."

"A vampyre!"

Henry sprung to his feet. His whole frame quivered with emotion; the drops of perspiration stood upon his brow, as, in, a strange, hoarse voice, he repeated the words,—

"A vampyre!"

"Even so; one who has to renew a dreadful existence by human blood—one who lives on for ever, and must keep up such a fearful existence upon human gore—one who eats not and drinks not as other men—a vampyre."

Henry dropped into his seat, and uttered a deep groan of the most exquisite anguish.

"I could echo that groan," said Marchdale, "but that I am so thoroughly bewildered I know not what to think."

"Good God—good God!"

"Do not too readily yield belief in so dreadful a supposition, I pray you."

"Yield belief!" exclaimed Henry, as he rose, and lifted up one of his hands above his head. "No; by Heaven, and the great God of all, who there rules, I will not easily believe aught so awful and so monstrous."

"I applaud your sentiment, Henry; not willingly would I deliver up myself to so frightful a belief—it is too horrible. I merely have told you of that which you saw was on my mind. You have surely before heard of such things."

"I have—I have."

"I much marvel, then, that the supposition did not occur to you, Henry."

"It did not—it did not, Marchdale. It—it was too dreadful, I suppose, to find a home in my heart. Oh! Flora, Flora, if this horrible idea should once occur to you, reason cannot, I am quite sure, uphold you against it."

"Let no one presume to insinuate it to her, Henry. I would not have it mentioned to her for worlds."

"Nor I—nor I. Good God! I shudder at the very thought—the mere possibility; but there is no possibility, there can be none. I will not believe it."

"Nor I."

"No; by Heaven's justice, goodness, grace, and mercy, I will not believe it."

"Tis well sworn, Henry; and now, discarding the supposition that Flora has been visited by a vampyre, let us seriously set about endeavouring, if we can, to account for what has happened in this house."

"I—I cannot now."

"Nay, let us examine the matter; if we can find any natural explanation, let us cling to it, Henry, as the sheet-anchor of our very souls."

"Do you think. You are fertile in expedients. Do you think, Marchdale; and, for Heaven's sake, and for the sake of our own peace, find out some other way of accounting for what has happened, than the hideous one you have suggested."

"And yet my pistol bullets hurt him not; he has left the tokens of his presence on the neck of Flora."

"Peace, oh! peace. Do not, I pray you, accumulate reasons why I should receive such a dismal, awful superstition. Oh, do not, Marchdale, as you love me!"

"You know that my attachment to you," said Marchdale, "is sincere; and yet, Heaven help us!"

His voice was broken by grief as he spoke, and he turned aside his head to hide the bursting tears that would, despite all his efforts, show themselves in his eyes.

"Marchdale," added Henry, after a pause of some moments' duration, "I will sit up to-night with my sister."

"Do—do!"

"Think you there is a chance it may come again?"

"I cannot—I dare not speculate upon the coming of so dreadful a visitor, Henry; but I will hold watch with you most willingly."

"You will, Marchdale?"

"My hand upon it. Come what dangers may, I will share them with you, Henry."

"A thousand thanks. Say nothing, then, to George of what we have been talking about. He is of a highly susceptible nature, and the very idea of such a thing would kill him."

"I will; be mute. Remove your sister to some other chamber, let me beg of you, Henry; the one she now inhabits will always be suggestive of horrible thoughts."

"I will; and that dreadful-looking portrait, with its perfect likeness to him who came last night."

"Perfect indeed. Do you intend to remove it?"

"I do not. I thought of doing so; but it is actually on the panel in the wall, and I would not willingly destroy it, and it may as well remain where it is in that chamber, which I can readily now believe will become henceforward a deserted one in this house."

"It may well become such."

"Who comes here? I hear a step."

There was a tip at the door at this moment, and George made his appearance in answer to the summons to come in. He looked pale and ill; his face betrayed how much he had mentally suffered during that night, and almost directly he got into the bed-chamber he said,—

"I shall, I am sure, be censured by you both for what I am going to say; but I cannot help saying it, nevertheless, for to keep it to myself would destroy me."

"Good God, George! what is it?" said Mr. Marchdale.

"Speak it out!" said Henry.

"I have been thinking of what has occurred here, and the result of that thought has been one of the wildest suppositions that ever I thought I should have to entertain. Have you never heard of a vampyre?"

Henry sighed deeply, and Marchdale was silent.

"I say a vampyre," added George, with much excitement in his manner. "It is a fearful, a horrible supposition; but our poor, dear Flora has been visited by a vampyre, and I shall go completely mad!"

He sat down, and covering his face with his hands, he wept bitterly and abundantly.

"George," said Henry, when he saw that the frantic grief had in some measure abated—"be calm, George, and endeavour to listen to me."

"I hear, Henry."

"Well, then, do not suppose that you are the only one in this house to whom so dreadful a superstition has occurred."

"Not the only one?"

"No; it has occurred to Mr. Marchdale also."

"Gracious Heaven!"

"He mentioned it to me; but we have both agreed to repudiate it with horror."

"To—repudiate—it?"

"Yes, George."

"And yet—and yet—"

"Hush, hush! I know what you would say. You would tell us that our repudiation of it cannot affect the fact. Of that we are aware; but yet will we disbelieve that which a belief in would be enough to drive us mad."

"What do you intend to do?"

"To keep this supposition to ourselves, in the first place; to guard it most zealously from the ears of Flora."

"Do you think she has ever heard of vampyres?"

"I never heard her mention that in all her reading she had gathered even a hint of such a fearful superstition. If she has, we must be guided by circumstances, and do the best we can."

"Pray Heaven she may not!"

"Amen to that prayer, George," said Henry. "Mr. Marchdale and I intend to keep watch over Flora to-night."

"May not I join you?"

"Your health, dear George, will not permit you to engage in such matters. Do you seek your natural repose, and leave it to us to do the best we can in this most fearful and terrible emergency."

"As you please, brother, and as you please, Mr. Marchdale. I know I am a frail reed, and my belief is that this affair will kill me quite. The truth is, I am horrified—utterly and frightfully horrified. Like my poor, dear sister, I do not believe I shall ever sleep again."

"Do not fancy that, George," said Marchdale. "You very much add to the uneasiness which must be your poor mother's portion, by allowing this circumstance to so much affect you. You well know her affection for you all, and let me therefore, as a very old friend of hers, entreat you to wear as cheerful an aspect as you can in her presence."

"For once in my life," said George, sadly, "I will; to my dear mother, endeavour to play the hypocrite."

"Do so," said Henry. "The motive will sanction any such deceit as that, George, be assured."

The day wore on, and Poor Flora remained in a very precarious situation. It was not until mid-day that Henry made up his mind he would call in a medical gentleman to her, and then he rode to the neighbouring market-town, where he knew an extremely intelligent practitioner resided. This gentleman Henry resolved upon, under a promise of secrecy, makings confidant of; but, long before he reached him, he found he might well dispense with the promise of secrecy.

He had never thought, so engaged had he been with other matters, that the servants were cognizant of the whole affair, and that from them he had no expectation of being able to keep the whole story in all its details. Of course such an opportunity for tale-bearing and gossiping was not likely to be lost; and while Henry was thinking over how he had better act in the matter, the news that Flora Bannerworth had been visited in the night by a vampyre—for the servants named the visitation such at once—was spreading all over the county.

As he rode along, Henry met a gentleman on horseback who belonged to the county, and who, reining in his steed, said to him,

"Good morning, Mr. Bannerworth."

"Good morning," responded Henry, and he would have ridden on, but the gentleman added,—

"Excuse me for interrupting you, sir; but what is the strange story that is in everybody's mouth about a vampyre?"

Henry nearly fell off his horse, he was so much astonished, and, wheeling the animal around, he said,—

"In everybody's mouth!"

"Yes; I have heard it from at least a dozen persons."

"You surprise me."

"It is untrue? Of course I am not so absurd as really to believe about the vampyre; but is there no foundation at all for it? We generally find that at the bottom of these common reports there is a something around which, as a nucleus, the whole has formed."

"My sister is unwell."

"Ah, and that's all. It really is too bad, now."

"We had a visitor last night."

"A thief, I suppose?"

"Yes, yes—I believe a thief. I do believe it was a thief, and she was terrified."

"Of course, and upon such a thing is grafted a story of a vampyre, and the marks of his teeth being in her neck, and all the circumstantial particulars."

"Yes, yes."

"Good morning, Mr. Bannerworth."

Henry bade the gentleman good morning, and much vexed at the publicity which the affair had already obtained, he set spurs to his horse, determined that he would speak to no one else upon so uncomfortable a theme. Several attempts were made to stop him, but he only waved his hand and trotted on, nor did he pause in his speed till he reached the door of Mr. Chillingworth, the medical man whom he intended to consult.

Henry knew that at such a time he would be at home, which was the case, and he was soon closeted with the man of drugs. Henry begged his patient hearing, which being accorded, he related to him at full length what had happened, not omitting, to the best of his remembrance, any one particular. When he had concluded his narration, the doctor shifted his position several times, and then said,—

"That's all?"

"Yes—and enough too."

"More than enough, I should say, my young friend. You astonish me."

"Can you form any supposition, sir, on the subject?"

"Not just now. What is your own idea?"

"I cannot be said to have one about it. It is too absurd to tell you that my brother George is impressed with a belief a vampyre has visited the house."

"I never in all my life heard a more circumstantial narrative in favour of so hideous a superstition."

"Well, but you cannot believe—"

"Believe what?"

"That the dead can come to life again, and by such a process keep up vitality."

"Do you take me for a fool?"

"Certainly not."

"Then why do you ask me such questions?"

"But the glaring facts of the case."

"I don't care if they were ten times more glaring, I won't believe it. I would rather believe you were all mad, the whole family of you—that at the full of the moon you all were a little cracked."

"And so would I."

"You go home now, and I will call and see your sister in the course of two hours. Something may turn up yet, to throw some new light upon this strange subject."

With this understanding Henry went home, and he took care to ride as fast as before, in order to avoid questions, so that he got back to his old ancestral home without going through the disagreeable ordeal of having to explain to any one what had disturbed the peace of it.

When Henry reached his home, he found that the evening was rapidly coming on, and before he could permit himself to think upon any other subject, he inquired how his terrified sister had passed the hours during his absence.

He found that but little improvement had taken place in her, and that she had occasionally slept, but to awaken and speak incoherently, as if the shock she had received had had some serious affect upon her nerves. He repaired at once to her room, and, finding that she was awake, he leaned over her, and spoke tenderly to her.

"Flora," he said, "dear Flora, you are better now?"

"Harry, is that you?"

"Yes, dear."

"Oh, tell me what has happened?"

"Have you not a recollection, Flora?"

"Yes, yes, Henry; but what was it? They none of them will tell me what it was, Henry."

"Be calm, dear. No doubt some attempt to rob the house."

"Think you so?"

"Yes; the bay window was peculiarly adapted for such a purpose; but now that you are removed here to this room, you will be able to rest in peace."

"I shall die of terror, Henry. Even now those eyes are glaring on me so hidiously. Oh, it is fearful—it is very fearful, Henry. Do you not pity me, and no one will promise to remain with me at night."

"Indeed, Flora, you are mistaken, for I intend to sit by your bedside armed, and so preserve you from all harm."

She clutched his hand eagerly, as she said,—

"You will, Henry. You will, and not think it too much trouble, dear Henry."

"It can be no trouble, Flora."

"Then I shall rest in peace, for I know that the dreadful vampyre cannot come to me when you are by-"

"The what, Flora!"

"The vampyre, Henry. It was a vampyre."

"Good God, who told you so?"

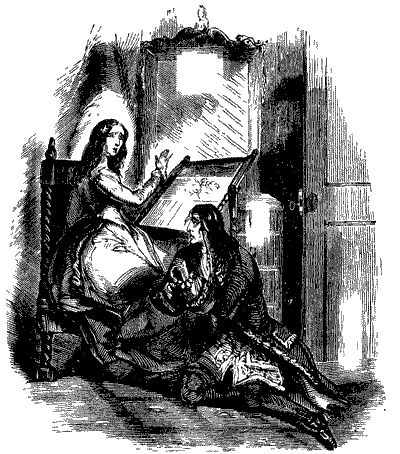

"No one. I have read of them in the book of travels in Norway, which Mr. Marchdale lent us all."

"Alas, alas!" groaned Henry. "Discard, I pray you, such a thought from your mind."

"Can we discard thoughts. What power have we but from that mind, which is ourselves?"

"True, true."

"Hark, what noise is that? I thought I heard a noise. Henry, when you go, ring for some one first. Was there not a noise?"

"The accidental shutting of some door, dear."

"Was it that?"

"It was."

"Then I am relieved. Henry, I sometimes fancy I am in the tomb, and that some one is feasting on my flesh. They do say, too, that those who in life have been bled by a vampyre, become themselves vampyres, and have the same horrible taste for blood as those before them. Is it not horrible?"

"You only vex yourself by such thoughts, Flora. Mr. Chillingworth is coming to see you."

"Can he minister to a mind diseased?"

"But yours is not, Flora. Your mind is healthful, and so, although his power extends not so far, we will thank Heaven, dear Flora, that you need it not."

She sighed deeply, as she said,—

"Heaven help me! I know not, Henry. The dreadful being held on by my hair. I must have it all taken off. I tried to get away, but it dragged me back—a brutal thing it was. Oh, then at that moment, Henry, I felt as if something strange took place in my brain, and that I was going mad! I saw those glazed eyes close to, mine—I felt a hot, pestiferous breath upon my face—help—help!"

"Hush! my Flora, hush! Look at me."

"I am calm again. It fixed its teeth in my throat. Did I faint away?"

"You did, dear; but let me pray you to refer all this to imagination; or at least the greater part of it."

"But you saw it."

"Yes—"

"All saw it."

"We all saw some man—a housebreaker—It must have been some housebreaker. What more easy, you know, dear Flora, than to assume some such disguise?"

"Was anything stolen?"

"Not that I know of; but there was an alarm, you know."

Flora shook her head, as she said, in a low voice,—

"That which came here was more than mortal. Oh, Henry, if it had but killed me, now I had been happy; but I cannot live—I hear it breathing now."

"Talk of something else, dear Flora," said the much distressed Henry; "you will make yourself much worse, if you indulge yourself in these strange fancies."

"Oh, that they were but fancies!"

"They are, believe me."

"There is a strange confusion in my brain, and sleep comes over me suddenly, when I least expect it. Henry, Henry, what I was, I shall never, never be again."

"Say not so. All this will pass away like a dream, and leave so faint a trace upon your memory, that the time will come when you will wonder it ever made so deep an impression on your mind."

"You utter these words, Henry," she said, "but they do not come from your heart. Ah, no, no, no! Who comes?"

The door was opened by Mrs. Bannerworth, who said,—

"It is only me, my dear. Henry, here is Dr. Chillingworth in the dining-room."

Henry turned to Flora, saying,—

"You will see him, dear Flora? You know Mr. Chillingworth well."

"Yes, Henry, yes, I will see him, or whoever you please."

"Shew Mr. Chillingworth up," said Henry to the servant.

In a few moments the medical man was in the room, and he at once approached the bedside to speak to Flora, upon whose pale countenance he looked with evident interest, while at the same time it seemed mingled with a painful feeling—at least so his own face indicated.

"Well, Miss Bannerworth," he said, "what is all this I hear about an ugly dream you have had?"

"A dream?" said Flora, as she fixed her beautiful eyes on his face.

"Yes, as I understand."

She shuddered, and was silent.

"Was it not a dream, then?" added Mr. Chillingworth.

She wrung her hands, and in a voice of extreme anguish and pathos, said,—

"Would it were a dream—would it were a dream! Oh, if any one could but convince me it was a dream!"

"Well, will you tell me what it was?"

"Yes, sir, it was a vampyre."

Mr. Chillingworth glanced at Henry, as he said, in reply to Flora's words,—

"I suppose that is, after all, another name, Flora, for the nightmare?"

"No—no—no!"

"Do you really, then, persist in believing anything so absurd, Miss Bannerworth?"

"What can I say to the evidence of my own senses?" she replied. "I saw it, Henry saw it, George saw, Mr. Marchdale, my mother—all saw it. We could not all be at the same time the victims of the same delusion."

"How faintly you speak."

"I am very faint and ill."

"Indeed. What wound is that on your neck?"

A wild expression came over the face of Flora; a spasmodic action of the muscles, accompanied with a shuddering, as if a sudden chill had come over the whole mass of blood took place, and she said,—

"It is the mark left by the teeth of the vampyre."

The smile was a forced one upon the face of Mr. Chillingworth.

"Draw up the blind of the window, Mr. Henry," he said, "and let me examine this puncture to which your sister attaches so extraordinary a meaning."

The blind was drawn up, and a strong light was thrown into the room. For full two minutes Mr. Chillingworth attentively examined the two small wounds in the neck of Flora. He took a powerful magnifying glass from his pocket, and looked at them through it, and after his examination was concluded, he said,—

"They are very trifling wounds, indeed."

"But how inflicted?" said Henry.

"By some insect, I should say, which probably—it being the season for many insects—has flown in at the window."

"I know the motive," said Flora "which prompts all these suggestions it is a kind one, and I ought to be the last to quarrel with it; but what I have seen, nothing can make me believe I saw not, unless I am, as once or twice I have thought myself, really mad."

"How do you now feel in general health?"

"Far from well; and a strange drowsiness at times creeps over me. Even now I feel it."

She sunk back on the pillows as she spoke and closed her eyes with a deep sigh.

Mr. Chillingworth beckoned Henry to come with him from the room, but the latter had promised that he would remain with Flora; and as Mrs. Bannerworth had left the chamber because she was unable to control her feelings, he rang the bell, and requested that his mother would come.

She did so, and then Henry went down stairs along with the medical man, whose opinion he was certainly eager to be now made acquainted with.

As soon as they were alone in an old-fashioned room which was called the oak closet, Henry turned to Mr. Chillingworth, and said,—

"What, now, is your candid opinion, sir? You have seen my sister, and those strange indubitable evidences of something wrong."

"I have; and to tell you candidly the truth, Mr. Henry, I am sorely perplexed."

"I thought you would be."

"It is not often that a medical man likes to say so much, nor is it, indeed, often prudent that he should do so, but in this case I own I am much puzzled. It is contrary to all my notions upon all such subjects."

"Those wounds, what do you think of them?"

"I know not what to think. I am completely puzzled as regards them."

"But, but do they not really bear the appearance of being bites?"

"They really do."

"And so far, then, they are actually in favour of the dreadful supposition which poor Flora entertains."

"So far they certainly are. I have no doubt in the world of their being bites; but we not must jump to a conclusion that the teeth which inflicted them were human. It is a strange case, and one which I feel assured must give you all much uneasiness, as, indeed, it gave me; but, as I said before, I will not let my judgment give in to the fearful and degrading superstition which all the circumstances connected with this strange story would seem to justify."

"It is a degrading superstition."

"To my mind your sister seems to be labouring under the effect of some narcotic."

"Indeed!"

"Yes; unless she really has lost a quantity of blood, which loss has decreased the heart's action sufficiently to produce the languor under which she now evidently labours."

"Oh, that I could believe the former supposition, but I am confident she has taken no narcotic; she could not even do so by mistake, for there is no drug of the sort in the house. Besides, she is not heedless by any means. I am quite convinced she has not done so."

"Then I am fairly puzzled, my young friend, and I can only say that I would freely have given half of what I am worth to see that figure you saw last night."

"What would you have done?"

"I would not have lost sight of it for the world's wealth."

"You would have felt your blood freeze with horror. The face was terrible."

"And yet let it lead me where it liked I would have followed it."

"I wish you had been here."

"I wish to Heaven I had. If I though there was the least chance of another visit I would come and wait with patience every night for a month."

"I cannot say," replied Henry. "I am going to sit up to-night with my sister, and I believe, our friend Mr. Marchdale will share my watch with me."

Mr. Chillingworth appeared to be for a few moments lost in thought, and then suddenly rousing himself, as if he found it either impossible to come to any rational conclusion upon the subject, or had arrived at one which he chose to keep to himself, he said,—

"Well, well, we must leave the matter at present as it stands. Time may accomplish something towards its development, but at present so palpable a mystery I never came across, or a matter in which human calculation was so completely foiled."

"Nor I—nor I."