Title: War in the Garden of Eden

Author: Kermit Roosevelt

Release date: October 11, 2004 [eBook #13665]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/13665

Credits: E-text prepared by Michael Ciesielski and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, War in the Garden of Eden, by Kermit Roosevelt

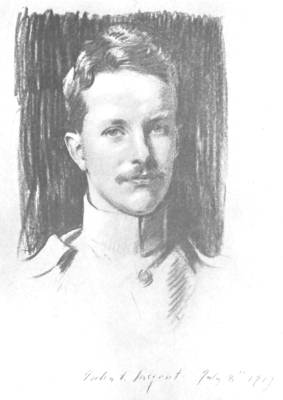

Kermit Roosevelt

From the drawing by John S. Sargent, July 8, 1917

| Kermit Roosevelt | Frontispiece |

| Map of Mesopotamia showing region of the fighting | 8 |

| Ashar Creek at Busra | 14 |

| Golden Dome of Samarra | 34 |

| Rafting down from Tekrit | 34 |

| Captured Turkish camel corps | 50 |

| Towing an armored car across a river | 66 |

| Reconnaissance | 66 |

| The Lion of Babylon | 78 |

| A dragon on the palace wall | 78 |

| Hauling out a badly bogged fighting car | 92 |

| A Mesopotamian garage | 92 |

| A water-wheel on the Euphrates | 106 |

| A "Red Crescent" ambulance | 124 |

| A jeweller's booth in the bazaar | 140 |

| Indian cavalry bringing in prisoners after the charge | 158 |

| The Kurd and his wife | 168 |

| Sheik Muttar and the two Kurds | 168 |

| Kirkuk | 180 |

| A street in Jerusalem | 196 |

| Japanese destroyers passing through the gut at Taranto | 206 |

It was at Taranto that we embarked for Mesopotamia. Reinforcements were sent out from England in one of two ways—either all the way round the Cape of Good Hope, or by train through France and Italy down to the desolate little seaport of Taranto, and thence by transport over to Egypt, through the Suez Canal, and on down the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. The latter method was by far the shorter, but the submarine situation in the Mediterranean was such that convoying troops was a matter of great difficulty. Taranto is an ancient Greek town, situated at the mouth of a landlocked harbor, the entrance to which is a narrow channel, certainly not more than two hundred yards across. The old part of the town is built on a hill, and the alleys and runways winding among the great stone dwellings serve as streets. As is the case with maritime towns, it is along the wharfs that the most interest centres. During one afternoon I wandered through the old town and listened to the fisherfolk singing as they overhauled and mended their nets. Grouped around a stone archway sat six or seven women and girls. They were evidently members of one family—a grandmother, her daughters, and their children. The old woman, wild, dark, and hawk-featured, was blind, and as she knitted she chanted some verses. I could only understand occasional words and phrases, but it was evidently a long epic. At intervals her listeners would break out in comments as they worked, but, like "Othere, the old sea-captain," she "neither paused nor stirred."

There are few things more desolate than even the best situated "rest-camps"—the long lines of tents set out with military precision, the trampled grass, and the board walks; but the one at Taranto where we awaited embarkation was peculiarly dismal even for a rest-camp. So it happened that when Admiral Mark Kerr, the commander of the Mediterranean fleet, invited me to be his guest aboard H.M.S. Queen until the transport should sail, it was in every way an opportunity to be appreciated. In the British Empire the navy is the "senior service," and I soon found that the tradition for the hospitality and cultivation of its officers was more than justified. The admiral had travelled, and read, and written, and no more pleasant evenings could be imagined than those spent in listening to his stories of the famous writers, statesmen, and artists who were numbered among his friends. He had always been a great enthusiast for the development of aerial warfare, and he was recently in Nova Scotia in command of the giant Handley-Page machine which was awaiting favorable weather conditions in order to attempt the nonstop transatlantic flight. Among his poems stands out the "Prayer of Empire," which, oddly enough, the former German Emperor greatly admired, ordering it distributed throughout the imperial navy! The Kaiser's feelings toward the admiral have suffered an abrupt change, but they would have been even more hostile had England profited by his warnings:

After four or five most agreeable days aboard the Queen the word came to embark, and I was duly transferred to the Saxon, an old Union Castle liner that was to run us straight through to Busra.

As we steamed out of the harbor we were joined by two diminutive Japanese destroyers which were to convoy us. The menace of the submarine being particularly felt in the Adriatic, the transports travelled only by night during the first part of the voyage. To a landsman it was incomprehensible how it was possible for us to pursue our zigzag course in the inky blackness and avoid collisions, particularly when it was borne in mind that our ship was English and our convoyers were Japanese. During the afternoon we were drilled in the method of abandoning ship, and I was put in charge of a lifeboat and a certain section of the ropes that were to be used in our descent over the side into the water. Between twelve and one o'clock that night we were awakened by three blasts, the preconcerted danger-signal. Slipping into my life-jacket, I groped my way to my station on deck. The men were filing up in perfect order and with no show of excitement. A ship's officer passed and said he had heard that we had been torpedoed and were taking in water. For fifteen or twenty minutes we knew nothing further. A Scotch captain who had charge of the next boat to me came over and whispered: "It looks as if we'd go down. I have just seen a rat run out along the ropes into my boat!" That particular rat had not been properly brought up, for shortly afterward we were told that we were not sinking. We had been rammed amidships by one of the escorting destroyers, but the breach was above the water-line. We heard later that the destroyer, though badly smashed up, managed to make land in safety.

We laid up two days in a harbor on the Albanian coast, spending the time pleasantly enough in swimming and sailing, while we waited for a new escort. Another night's run put us in Navarino Bay. The grandfather of Lieutenant Finch Hatton, one of the officers on board, commanded the Allied forces in the famous battle fought here in 1827, when the Turkish fleet was vanquished and the independence of Greece assured.

Several days more brought us to Port Said, and after a short delay we pushed on through the canal and into the Red Sea. It was August, and when one talks of the Red Sea in August there is no further need for comment. The Saxon had not been built for the tropics. She had no fans, nor ventilating system such as we have on the United Fruit boats. Some unusually intelligent stokers had deserted at Port Said, and as we were in consequence short-handed, it was suggested that any volunteers would be given a try. Finch Hatton and I felt that our years in the tropics should qualify us, and that the exercise would improve our dispositions. We got the exercise. Never have I felt anything as hot, and I have spent August in Yuma, Arizona, and been in Italian Somaliland and the Amazon Valley. The shovels and the handles of the wheelbarrows blistered our hands.

Map of Mesopotamia showing region of the fighting

Inset, showing relative position of Mesopotamia and other countries

We had a number of cases of heat-stroke, and the hospital facilities on a crowded transport can never be all that might be desired. The first military burial at sea was deeply impressive. There was a lane of Tommies drawn up with their rifles reversed and heads bowed; the short, classic burial service was read, and the body, wrapped in the Union Jack, slid down over the stern of the ship. Then the bugles rang out in the haunting, mournful strains of the "Last Post," and the service ended with all singing "Abide With Me."

We sweltered along down the Red Sea and around into the Indian Ocean. We wished to call at Aden in order to disembark some of our sick, but were ordered to continue on without touching. Our duties were light, and we spent the time playing cards and reading. The Tommies played "house" from dawn till dark. It is a game of the lotto variety. Each man has a paper with numbers written on squares; one of them draws from a bag slips of paper also marked with numbers, calls them out, and those having the number he calls cover it, until all the numbers on their paper have been covered. The first one to finish wins, and collects a penny from each of the losers. The caller drones out the numbers with a monotony only equalled by the brain-fever bird, and quite as disastrous to the nerves. There are certain conventional nicknames: number one is always "Kelley's eye," eleven is "legs eleven," sixty-six is "clickety click," and the highest number is "top o' the 'ouse." There is another game that would be much in vogue were it not for the vigilance of the officers. It is known as "crown and anchor," and the advantage lies so strongly in favor of the banker that he cannot fail to make a good income, and therefore the game is forbidden under the severest penalties.

As we passed through the Strait of Ormuz memories of the early days of European supremacy in the East crowded back, for I had read many a vellum-covered volume in Portuguese about the early struggles for supremacy in the gulf. One in particular interested me. The Portuguese were hemmed in at Ormuz by a greatly superior English force. The expected reinforcements never arrived, and at length their resources sank so low, and they suffered in addition, or in consequence, so greatly from disease that they decided to sail forth and give battle. This they did, but before they joined in fight the ships of the two admirals sailed up near each other—the Portuguese commander sent the British a gorgeous scarlet ceremonial cloak, the British responded by sending him a handsomely embossed sword. The British admiral donned the cloak, the Portuguese grasped the sword; a page brought each a cup of wine; they pledged each other, threw the goblets into the sea, and fell to. The British were victorious. Times indeed have sadly changed in the last three hundred years!

I was much struck with the accuracy of the geographical descriptions in Camoens' letters and odes. He is the greatest of the Portuguese poets and wrote the larger part of his master-epic, "The Lusiad," while exiled in India. For seventeen years he led an adventurous life in the East; and it is easy to recognize many harbors and stretches of coast line from his inimitable portrayal.

Busra, our destination, lies about sixty miles from the mouth of the Shatt el Arab, which is the name given to the combined Tigris and Euphrates after their junction at Kurna, another fifty or sixty miles above. At the entrance to the river lies a sand-bar, effectively blocking access to boats of as great draft as the Saxon. We therefore transshipped to some British India vessels, and exceedingly comfortable we found them, designed as they were for tropic runs. We steamed up past the Island of Abadan, where stand the refineries of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. It is hard to overestimate the important part that company has played in the conduct of the Mesopotamian campaign. Motor transport was nowhere else a greater necessity. There was no possibility of living on the country; at first, at all events. General Dickson, the director of local resources, later set in to so build up and encourage agriculture that the army should eventually be supported, in the staples of life, by local produce. Transportation was ever a hard nut to crack. Railroads were built, but though the nature of the country called for little grading, obtaining rails, except in small quantities, was impossible. The ones brought were chiefly secured by taking up the double track of Indian railways. This process naturally had a limit, and only lines of prime importance could be laid down. Thus you could go by rail from Busra to Amara, and from Kut to Baghdad, but the stretch between Amara and Kut had never been built, up to the time I left the country. General Maude once told me that pressure was being continually brought by the high command in England or India to have that connecting-link built, but that he was convinced that the rails would be far more essential elsewhere, and had no intention of yielding.

I don't know the total number of motor vehicles, but there were more than five thousand Fords alone. On several occasions small columns of infantry were transported in Fords, five men and the driver to a car. Indians of every caste and religion were turned into drivers, and although it seemed sufficiently out of place to come across wizened, khaki-clad Indo-Chinese driving lorries in France, the incongruity was even more marked when one beheld a great bearded Sikh with his turbaned head bent over the steering-wheel of a Ford.

Modern Busra stands on the banks of Ashar Creek. The ancient city whence Sinbad the sailor set forth is now seven or eight miles inland, buried under the shifting sands of the desert. Busra was a seaport not so many hundreds of years ago. Before that again, Kurna was a seaport, and the two rivers probably only joined in the ocean, but they have gradually enlarged the continent and forced back the sea. The present rate of encroachment amounts, I was told, to nearly twelve feet a year.

The modern town has increased many fold with the advent of the Expeditionary Force, and much of the improvement is of a necessarily permanent nature; in particular the wharfs and roads. Indeed, one of the most striking features of the Mesopotamian campaign is the permanency of the improvements made by the British. In order to conquer the country it was necessary to develop it,—build railways and bridges and roads and telegraph systems,—and it has all been done in a substantial manner. It is impossible to contemplate with equanimity the possibility of the country reverting to a rule where all this progress would soon disappear and the former stagnancy and injustice again hold sway.

Ashar Creek at Busra

As soon as we landed I wandered off to the bazaar—"suq" is what the Arab calls it. In Busra there are a number of excellent ones. By that I don't mean that there are art treasures of the East to be found in them, for almost everything could be duplicated at a better price in New York. It is the grouping of wares, the mode of sale, and, above all, the salesmen and buyers that make a bazaar—the old bearded Persian sitting cross-legged in his booth, the motley crowd jostling through the narrow, vaulted passageway, the veiled women, the hawk-featured, turbaned men, the Jews, the Chaldeans, the Arabs, the Armenians, the stalwart Kurds, and through it all a leaven of khaki-clad Indians, purchasing for the regimental mess. All these and an ever-present exotic, intangible something are what the bazaar means. Close by the entrance stood a booth festooned with lamps and lanterns of every sort, with above it scrawled "Aladdin-Ibn-Said." My Arabic was not at that time sufficient to enable me to discover from the owner whether he claimed illustrious ancestry or had merely been named after a patron saint.

A few days after landing at Busra we embarked on a paddle-wheel boat to pursue our way up-stream the five hundred intervening miles to Baghdad. Along the banks of the river stretched endless miles of date-palms. We watched the Arabs at their work of fertilizing them, for in this country these palms have to depend on human agency to transfer the pollen. At Kurna we entered the Garden of Eden, and one could quite appreciate the feelings of the disgusted Tommy who exclaimed: "If this is the Garden, it wouldn't take no bloody angel with a flaming sword to turn me back." The direct descendant of the Tree is pointed out; whether its properties are inherited I never heard, but certainly the native would have little to learn by eating the fruit.

Above Kurna the river is no longer lined with continuous palm-groves; desert and swamps take their place—the abode of the amphibious, nomadic, marsh Arab. An unruly customer he is apt to prove himself, and when he is "wanted" by the officials, he retires to his watery fastnesses, where he can remain in complete safety unless betrayed by his comrades. On the banks of the Tigris stands Ezra's tomb. It is kept in good repair through every vicissitude of rule, for it is a holy place to Moslem and Jew and Christian alike.

The third night brought us to Amara. The evening was cool and pleasant after the scorching heat of the day, and Finch Hatton and I thought that we would go ashore for a stroll through the town. As we proceeded down the bank toward the bridge, I caught sight of a sentry walking his post. His appearance was so very important and efficient that I slipped behind my companion to give him a chance to explain us. "Halt! Who goes there?" "Friend," replied Finch Hatton. "Advance, friend, and give the countersign." F.H. started to advance, followed by a still suspicious me, and rightly so, for the Tommy, evidently member of a recent draft, came forward to meet us with lowered bayonet, remarking in a businesslike manner: "There isn't any countersign."

Except for the gunboats and monitors, all river traffic is controlled by the Inland Water Transport Service. The officers are recruited from all the world over. I firmly believe that no river of any importance could be mentioned but what an officer of the I.W.T. could be found who had navigated it. The great requisite for transports on the Tigris was a very light draft, and to fill the requirements boats were requisitioned ranging from penny steamers of the Thames to river-craft of the Irrawaddy. Now in bringing a penny steamer from London to Busra the submarine is one of the lesser perils, and in supplying the wants of the Expeditionary Force more than eighty vessels were lost at sea, frequently with all aboard.

As was the custom, we had a barge lashed to either side. These barges are laden with troops, or horses, or supplies. In our case we had the first Bengal regiment—a new experiment, undertaken for political reasons. The Bengali is the Indian who most readily takes to European learning. Rabindranath Tagore is probably the most widely known member of the race. They go to Calcutta University and learn a smattering of English and absorb a certain amount of undigested general knowledge and theory. These partially educated Bengalis form the Babu class, and many are employed in the railways. They delight in complicated phraseology, and this coupled with their accent and seesaw manner of speaking supply the English a constant source of caricature. As a race they are inclined to be vain and boastful, and are ever ready to nurse a grievance against the British Government, feeling that they have been provided with an education but no means of support. The government felt that it might help to calm them if a regiment were recruited and sent to Mesopotamia. How they would do in actual fighting had never been demonstrated up to the time I left the country, but they take readily to drill, and it was amusing to hear them ordering each other about in their clipped English. They were used for garrisoning Baghdad.

After we left Amara we continued our winding course up-stream. A boat several hours ahead may be seen only a few hundred yards distant across the desert. The banks are so flat and level that it looks as if the other vessels were steaming along on land. The Arab river-craft was most picturesque. At sunset a mahela, bearing down with filled sail, might have been the model for Maxfield Parrish's Pirate Ship. The Arab women ran along the bank beside us, carrying baskets of eggs and chickens, and occasionally melons. They were possessed of surprising endurance, and would accompany us indefinitely, heavily laden as they were. Their robes trailed in the wind as they jumped ditches, screaming out their wares without a moment's pause. An Indian of the boat's crew was haggling with a woman about a chicken. He threw her an eight-anna piece. She picked up the money but would not hand him the chicken, holding out for her original price. He jumped ashore, intending to take the chicken. She had a few yards' start and made the most of it. In and out they chased, over hedge and ditch, down the bank and up again. Several times he almost had her. She never for a moment ceased screeching—an operation which seemed to affect her wind not a particle. At the end of fifteen minutes the Indian gave up amid the delighted jeers of his comrades, and returned shamefaced and breathless to jump aboard the boat as we bumped against the bank on rounding a curve.

One evening we halted where, not many months before, the last of the battles of Sunnaiyat had been fought. There for months the British had been held back, while their beleaguered comrades in Kut could hear the roar of the artillery and hope against hope for the relief that never reached them. It was one phase of the campaign that closely approximated the gruelling trench warfare in France. The last unsuccessful attack was launched a week before the capitulation of the garrison, and it was almost a year later before the position was eventually taken. The front-line trenches were but a short distance apart, and each side had developed a strong and elaborate system of defense. One flank was protected by an impassable marsh and the other by the river. When we passed, the field presented an unusually gruesome appearance even for a battle-field, for the wandering desert Arabs had been at work, and they do not clean up as thoroughly as the African hyena. A number had paid the penalty through tampering with unexploded grenades and "dud" shells, and left their own bones to be scattered around among the dead they had been looting. The trenches were a veritable Golgotha with skulls everywhere and dismembered legs still clad with puttees and boots.

At Kut we disembarked to do the remaining hundred miles to Baghdad by rail instead of winding along for double the distance by river, with a good chance of being hung up for hours, or even days, on some shifting sand-bar. At first sight Kut is as unpromising a spot as can well be imagined, with its scorching heat and its sand and the desolate mud-houses, but in spite of appearances it is an important and thriving little town, and daily becoming of more consequence.

The railroad runs across the desert, following approximately the old caravan route to Baghdad. A little over half-way the line passes the remaining arch of the great hall of Ctesiphon. This hall is one hundred and forty-eight feet long by seventy-six broad. The arch stands eighty-five feet high. Around it, beneath the mounds of desert sand, lies all that remains of the ancient city. As a matter of fact the city is by no means ancient as such things go in Mesopotamia, dating as it does from the third century B.C., when it was founded by the successors of Alexander the Great.

My first night in Baghdad I spent in General Maude's house, on the river-bank. The general was a striking soldierly figure of a man, standing well over six feet. His military career was long and brilliant. His first service was in the Coldstream Guards. He distinguished himself in South Africa. Early in the present war he was severely wounded in France. Upon recovering he took over the Thirteenth Division, which he commanded in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, and later brought out to Mesopotamia. When he reached the East the situation was by no means a happy one for the British. General Townshend was surrounded in Kut, and the morale of the Turk was excellent after the successes he had met with in Gallipoli. In the end of August, 1916, four months after the fall of Kut, General Maude took over the command of the Mesopotamian forces. On the 11th of March of the following year he occupied Baghdad, thereby re-establishing completely the British prestige in the Orient. One of Germany's most serious miscalculations was with regard to the Indian situation. She felt confident that, working through Persia and Afghanistan, she could stir up sufficient trouble, possibly to completely overthrow British rule, but certainly to keep the English so occupied with uprisings as to force them to send troops to India rather than withdraw them thence for use elsewhere. The utter miscarriage of Germany's plans is, indeed, a fine tribute to Great Britain. The Emir of Afghanistan did probably more than any single native to thwart German treachery and intrigue, and every friend of the Allied cause must have read of his recent assassination with a very real regret.

When General Maude took over the command, the effect of the Holy War that, at the Kaiser's instigation, was being preached in the mosques had not as yet been determined. This jehad, as it was called, proposed to unite all "True Believers" against the invading Christians, and give the war a strongly religious aspect. The Germans hoped by this means to spread mutiny among the Mohammedan troops, which formed such an appreciable element of the British forces, as well as to fire the fury of the Turks and win as many of the Arabs to their side as possible. The Arab thoroughly disliked both sides. The Turk oppressed him, but did so in an Oriental, and hence more or less comprehensible, manner. The English gave him justice, but it was an Occidental justice that he couldn't at first understand or appreciate, and he was distinctly inclined to mistrust it. In course of time he would come to realize its advantages. Under Turkish rule the Arab was oppressed by the Turk, but then he in turn could oppress the Jew, the Chaldean, and Nestorian Christians, and the wretched Armenian. Under British rule he suddenly found these latter on an equal footing with him, and he felt that this did not compensate the lifting from his shoulders of the Turkish burden. Then, too, when a race has been long oppressed and downtrodden, and suddenly finds itself on an equality with its oppressor, it is apt to become arrogant and overbearing. This is exactly what happened, and there was bad feeling on all sides in consequence. However, real fundamental justice is appreciated the world over, once the native has been educated up to it, and can trust in its continuity.

The complex nature of the problems facing the army commander can be readily seen. He was an indefatigable worker and an unsurpassed organizer. The only criticism I ever heard was that he attended too much to the details himself and did not take his subordinates sufficiently into his confidence. A brilliant leader, beloved by his troops, his loss was a severe blow to the Allied cause.

Baghdad is often referred to as the great example of the shattered illusion. We most of us have read the Arabian Nights at an early age, and think of the abode of the caliphs as a dream city, steeped in what we have been brought up to think of as the luxury, romance, and glamour of the East. Now glamour is a delicate substance. In the all-searching glare of the Mesopotamian sun it is apt to appear merely tawdry. Still, a goodly number of years spent in wandering about in foreign lands had prepared me for a depreciation of the "stuff that dreams are made of," and I was not disappointed. It is unfortunate that the normal way to approach is from the south, and that that view of the city is flat and uninteresting. Coming, as I several times had occasion to, from the north, one first catches sight of great groves of date-palms, with the tall minarets of the Mosque of Kazimain towering above them; then a forest of minarets and blue domes, with here and there some graceful palm rising above the flat roofs of Baghdad. In the evening when the setting sun strikes the towers and the tiled roofs, and the harsh lights are softened, one is again in the land of Haroun-el-Raschid.

The great covered bazaars are at all times capable of "eating the hours," as the natives say. One could sit indefinitely in a coffee-house and watch the throngs go by—the stalwart Kurdish porter with his impossible loads, the veiled women, the unveiled Christian or lower-class Arab women, the native police, the British Tommy, the kilted Scot, the desert Arab, all these and many more types wandered past. Then there was the gold and silver market, where the Jewish and Armenian artificers squatted beside their charcoal fires and haggled endlessly with their customers. These latter were almost entirely women, and they came both to buy and sell, bringing old bracelets and anklets, and probably spending the proceeds on something newer that had taken their fancy. The workmanship was almost invariably poor and rough. Most of the women had their babies with them, little mites decked out in cheap finery and with their eyelids thickly painted. The red dye from their caps streaked their faces, the flies settled on them at will, and they had never been washed. When one thought of the way one's own children were cared for, it seemed impossible that a sufficient number of these little ones could survive to carry on the race. The infant mortality must be great, though the children one sees look fat and thriving.

Baghdad is not an old city. Although there was probably a village on the site time out of mind, it does not come into any prominence until the eighth century of our era. As the residence of the Abasside caliphs it rapidly assumed an important position. The culmination of its magnificence was reached in the end of the eighth century, under the rule of the world-famous Haroun-el-Raschid. It long continued to be a centre of commerce and industry, though suffering fearfully from the various sieges and conquests which it underwent. In 1258 the Mongols, under a grandson of the great Genghis Khan, captured the city and held it for a hundred years, until ousted by the Tartars under Tamberlane. It was plundered in turn by one Mongol horde after another until the Turks, under Murad the Fourth, eventually secured it. Naturally, after being the scene of so much looting and such massacres, there is little left of the original city of the caliphs. Then, too, in Mesopotamia there is practically no stone, and everything was built of brick, which readily lapses back to its original state. For this reason the invaders easily razed a conquered town, and Mesopotamia, so often called the "cradle of the world," retains but little trace of the races and civilizations that have succeeded each other in ruling the land. When the Tigris was low at the end of the summer season, we used to dig out from its bank great bricks eighteen inches square, on which was still distinctly traced the seal of Nebuchadnezzar. These, possibly the remnants of a quay, were all that remained of the times before the advent of the caliphs.

A few days after reaching Baghdad I left for Samarra, which was at that time the Tigris front. I was attached to the Royal Engineers, and my immediate commander was Major Morin, D.S.O., an able officer with an enviable record in France and Mesopotamia. The advance army of the Tigris was the Third Indian Army Corps, under the command of General Cobbe, a possessor of the coveted, and invariably merited, Victoria Cross. The Engineers were efficiently commanded by General Swiney. The seventy miles of railroad from Baghdad to Samarra were built by the Germans, being the only Mesopotamian portion of the much-talked-of Berlin-to-Baghdad Railway, completed before the war. It was admirably constructed, with an excellent road-bed, heavy rails and steel cross-ties made by Krupp. In their retreat the Turks had been too hurried to accomplish much in the way of destruction other than burning down a few stations and blowing up the water-towers. The rolling-stock had been left largely intact. There were no passenger-coaches, and you travelled either by flat or box car. Every one followed the Indian custom of carrying with them their bedding-rolls, and leather-covered wash-basin containing their washing-kit, as well as one of the comfortable rhoorkhee chairs. In consequence, although for travel by boat or train nothing was provided, there was no discomfort entailed. The trains were fitted out with anti-aircraft guns, for the Turkish aeroplanes occasionally tried to "lay eggs," a by no means easy affair with a moving train as a target. Whatever the reason was, and I never succeeded in discovering it, the trains invariably left Baghdad in the wee small hours, and as the station was on the right bank across the river from the main town, and the boat bridges were cut during the night, we used generally, when returning to the front, to spend the first part of the night sleeping on the station platform. Generals or exalted staff officers could usually succeed in having a car assigned to them, and hauled up from the yard in time for them to go straight to bed in it. Frequently their trip was postponed, and an omniscient sergeant-major would indicate the car to the judiciously friendly, who could then enjoy a solid night's sleep. The run took anywhere from eight to twelve hours; but when sitting among the grain-bags on an open car, or comfortably ensconced in a chair in a "covered goods," with Vingt Ans Après, the time passed pleasantly enough in spite of the withering heat.

While still a good number of miles away from Samarra we would catch sight of the sun glinting on the golden dome of the mosque, built over the cleft where the twelfth Imam, the Imam Mahdi, is supposed to have disappeared, and from which he is one day to reappear to establish the true faith upon earth. Many Arabs have appeared claiming to be the Mahdi, and caused trouble in a greater or less degree according to the extent of their following. The most troublous one in our day was the man who besieged Kharthoum and captured General "Chinese" Gordon and his men. Twenty-five years later, when I passed through the Sudan, there were scarcely any men of middle age left, for they had been wiped out almost to a man under the fearful rule of the Mahdi, a rule which might have served as prototype to the Germans in Belgium.

Golden Dome of Samarra

Rafting down from Tekrit

Samarra is very ancient, and has passed through periods of great depression and equally great expansion. It was here in A.D. 363 that the Roman Emperor Julian died from wounds received in the defeat of his forces at Ctesiphon. The golden age lasted about forty years, beginning in 836, when the Caliph Hutasim transferred his capital thither from Baghdad. During that time the city extended for twenty-one miles along the river-bank, with glorious palaces, the ruins of some of which still stand. The present-day town has sadly shrunk from its former grandeur, but still has an impressive look with its great walls and massive gateways. The houses nearest the walls are in ruins or uninhabited; but in peacetime the great reputation that the climate of Samarra possesses for salubrity draws to it many Baghdad families who come to pass the summer months. A good percentage of the inhabitants are Persians, for the eleventh and twelfth Shiah Imams are buried on the site of the largest mosque. The two main sects of Moslems are the Sunnis and the Shiahs; the former regard the three caliphs who followed Mohammed as his legitimate successors, whereas the latter hold them to be usurpers, and believe that his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, husband of Fatimah, together with their sons Husein and Hasan, are the prophet's true inheritors. Ali was assassinated near Nejef, which city is sacred to his memory, and his son Husein was killed at Kerbela; so these two cities are the greatest of the Shiah shrines. The Turks belong almost without exception to the Sunni sect, whereas the Persians and a large percentage of the Arabs inhabiting Mesopotamia are Shiahs.

The country around Samarra is not unlike in character the southern part of Arizona and northern Sonora. There are the same barren hills and the same glaring heat. The soil is not sand, but a fine dust which permeates everything, even the steel uniform-cases which I had always regarded as proof against all conditions. The parching effect was so great that it was not only necessary to keep all leather objects thoroughly oiled but the covers of my books cracked and curled up until I hit upon the plan of greasing them well also. In the alluvial lowlands trench-digging was a simple affair, but along the hills we found a pebbly conglomerate that gave much trouble.

Opinion was divided as to whether the Turk would attempt to advance down the Tigris. Things had gone badly with our forces in Palestine at the first battle of Gaza; but here we had an exceedingly strong position, and the consensus of opinion seemed to be that the enemy would think twice before he stormed it. Their base was at Tekrit, almost thirty miles away. However, about ten miles distant stood a small village called Daur, which the Turks held in considerable force. Between Daur and Samarra there was nothing but desert, with gazelles and jackals the only permanent inhabitants. Into this no man's land both sides sent patrols, who met in occasional skirmishes. For reconnaissance work we used light-armored motor-cars, known throughout the army as Lam cars, a name formed by the initial letters of their titles. These cars were Rolls-Royces, and with their armor-plate weighed between three and three-quarters and four tons. They were proof against the ordinary bullet but not against the armor-piercing. When I came out to Mesopotamia I intended to lay my plans for a transfer to the cavalry, but after I had seen the cars at work I changed about and asked to be seconded to that branch of the service.

A short while after my arrival our aeroplanes brought in word that the Turks were massing at Daur, and General Cobbe decided that when they launched forth he would go and meet them. Accordingly, we all moved out one night, expecting to give "Abdul," as the Tommies called him, a surprise. Whether it was that we started too early and their aeroplanes saw us, or whether they were only making a feint, we never found out; but at all events the enemy fell back, and save for some advance-guard skirmishing and a few prisoners, we drew a blank. We were not prepared to attack the Daur position, and so returned to Samarra to await developments.

Meanwhile I busied myself searching for an Arab servant. Seven or eight years previous, when with my father in Africa, I had learned Swahili, and although I had forgotten a great deal of it, still I found it a help in taking up Arabic. Most of the officers had either British or Indian servants; in the former case they were known as batmen, and in the latter as bearers; but I decided to follow suit with the minority and get an Arab, and therefore learn Arabic instead of Hindustanee, for the former would be of vastly more general use. The town commandant, Captain Grieve of the Black Watch, after many attempts at length produced a native who seemed, at any rate, more promising than the others that offered themselves. Yusuf was a sturdy, rather surly-looking youth of about eighteen. Evidently not a pure Arab, he claimed various admixtures as the fancy took him, the general preference being Kurd. I always felt that there was almost certainly a good percentage of Turk. His father had been a non-commissioned officer in the Turkish army, and at first I was loath to take him along on advances and attacks, for he would have been shown little mercy had he fallen into enemy hands. He was, however, insistent on asking to go with me, and I never saw him show any concern under fire. He spoke, in varying degrees of fluency, Kurdish, Persian, and Turkish, and was of great use to me for that reason. He became by degrees a very faithful and trustworthy follower, his great weakness being that he was a one-man's man, and although he would do anything for me, he was of little general use in an officers' mess.

I had two horses, one a black mare that I called Soda, which means black in Arabic, and the other a hard-headed bay gelding that was game to go all day, totally unaffected by shell-fire, but exceedingly stubborn about choosing the direction in which he went. After numerous changes I came across an excellent syce to look after them. He was a wild, unkempt figure, with a long black beard—a dervish by profession, and certainly gave no one any reason to believe that he was more than half-witted. Indeed, almost all dervishes are in a greater or less degree insane; it is probably due to that that they have become dervishes, for the native regards the insane as under the protection of God. Dervishes go around practically naked, usually wearing only a few skins flung over the shoulder, and carrying a large begging-bowl. In addition they carry a long, sharp, iron bodkin, with a wooden ball at the end, having very much the appearance of a fool's bauble. They lead an easy life. When they take a fancy to a house, they settle down near the gate, and the owner has to support them as long as the whim takes them to stay there. To use force against a dervish would be looked upon as an exceedingly unpropitious affair to the true believer. Then, too, I have little doubt but that they are capable of making good use of their steel bodkins. Why my dervish wished to give up his easy-going profession and take over the charge of my horses I never fully determined, but it must have been because he really loved horses and found that as a dervish pure and simple he had very little to do with them. When he arrived he was dressed in a very ancient gunny-sack, and it was not without much regret at the desecration that I provided him with an outfit of the regulation khaki.

My duties took me on long rides about the country. Here, and throughout Mesopotamia, the great antiquity of this "cradle of the world" kept ever impressing itself upon one, consciously or subconsciously. Everywhere were ruins; occasionally a wall still reared itself clear of the all-enveloping dust, but generally all that remained were great mounds, where the desert had crept in and claimed its own, covering palace, house, and market, temple, synagogue, mosque, or church with its everlasting mantle. Often the streets could still be traced, but oftener not. The weight of ages was ever present as one rode among the ruins of these once busy, prosperous cities, now long dead and buried, how long no one knew, for frequently their very names were forgotten. Babylon, Ur of the Chaldees, Istabulat, Nineveh, and many more great cities of history are now nothing but names given to desert mounds.

Close by Samarra stands a strange corkscrew tower, known by the natives as the Malwiyah. It is about a hundred and sixty feet high, built of brick, with a path of varying width winding up around the outside. No one knew its purpose, and estimates of its antiquity varied by several thousand years. One fairly well-substantiated story told that it had been the custom to kill prisoners by hurling them off its top. We found it exceedingly useful as an observation-post. In the same manner we used Julian's tomb, a great mound rising up in the desert some five or six miles up-stream of the town. The legend is that when the Roman Emperor died of his wounds his soldiers, impressing the natives, built this as a mausoleum; but there is no ground whatever for this belief, for it would have been physically impossible for a harassed or retreating army to have performed a task of such magnitude. The natives call it "The Granary," and claim that that was its original use. Before the war the Germans had started in excavating, and discovered shafts leading deep down, and on top the foundations of a palace. Around its foot may be traced roadways and circular plots, and especially when seen from an aeroplane it looks as if there had at one time been an elaborate system of gardens.

We were continually getting false rumors about the movements of the Turks. We had believed that it would be impossible for them to execute a flank movement, at any rate in sufficient strength to be a serious menace, for from all the reports we could get, the wells were few and far between. Nevertheless, there was a great deal of excitement and some concern when one afternoon our aeroplanes came in with the report that they had seen a body of Turks that they estimated at from six to eight thousand marching round our right flank. The plane was sent straight back with instructions to verify most carefully the statement, and be sure that it was really men they had seen. They returned at dark with no alteration of their original report. As can well be imagined, that night was a crowded one for us, and the feeling ran high when next morning the enemy turned out to be several enormous herds of sheep.

As part consequence of this we were ordered to make a thorough water reconnaissance, with a view of ascertaining how large a force could be watered on a march around our flank. I went off in an armored car with Captain Marshall of the Intelligence Service. Marshall had spent many years in Mesopotamia shipping liquorice to the American Tobacco Company, and he was known and trusted by the Arabs all along the Tigris from Kurna to Mosul. He spoke the language most fluently, but with an accent that left no doubt of his Caledonian home. We had with us a couple of old sheiks, and it was their first ride in an automobile. It was easy to see that one of them was having difficulty in maintaining his dignity, but I was not quite sure of the reason until we stopped a moment and he fairly flew out of the car. It didn't seem possible that a man able to ride ninety miles at a stretch on a camel, could be made ill by the motion of an automobile. However, such was the case, and we had great difficulty in getting him back into the car. We discovered far more wells than we had been led to believe existed, but not enough to make a flank attack a very serious menace.

The mirage played all sorts of tricks, and the balloon observers grew to be very cautious in their assertions. In the early days of the campaign, at the battle of Shaiba Bund, a friendly mirage saved the British forces from what would have proved a very serious defeat. Suleiman Askari was commanding the Turkish forces, and things were faring badly with the British, when of a sudden to their amazement they found that the Turks were in full retreat. Their commanders had caught sight of the mirage of what was merely an ambulance and supply train, but it was so magnified that they believed it to be a very large body of reinforcements. The report ran that when Suleiman was told of his mistake, his chagrin was so great that he committed suicide.

It was at length decided to advance on the Turkish forces at Daur. General Brooking had just made a most successful attack on the Euphrates front, capturing the town of Ramadie, with almost five thousand prisoners. It was believed to be the intention of the army commander to try to relieve the pressure against General Allenby's forces in Palestine by attacking the enemy on all three of their Mesopotamian fronts. Accordingly, we were ordered to march out after sunset one night, prepared to attack the enemy position at daybreak. During a short halt by the last rays of the setting sun I caught sight of a number of Mohammedan soldiers prostrating themselves toward Mecca in their evening prayers, while their Christian or pagan comrades looked stolidly on. It was late October, and although the days were still very hot and oppressive, the nights were almost bitterly cold. A night-march is always a disagreeable business. The head of the column checks and halts, and those in the rear have no idea whether it is an involuntary stop for a few minutes, or whether they are to halt for an hour or more, owing to some complication of orders. So we stood shivering, and longed for a smoke, but of course that was strictly forbidden, for the cigarettes of an army would form a very good indication of its whereabouts on a dark night. All night we marched and halted, and started on again; the dust choked us, and the hours seemed interminable, until at last at two in the morning word was passed along that we could have an hour's sleep. The greater part of the year in Mesopotamia the regulation army dress consisted of a tunic and "shorts." These are long trousers cut off just above the knee, and the wearer may either use wrap puttees, or leather leggings, or golf stockings. They are a great help in the heat, as may easily be understood, and they allow, of course, much freer knee action, particularly when your clothes are wet. The reverse side of the medal reads that when you try to sleep without a blanket on a cold night, you find that your knees are uncomfortably exposed. Still we were, most of us, so drunk with sleep that it would have taken more than that to keep us awake. At three we resumed our march, and attacked just at dawn. The enemy had abandoned the first-line positions, and we met with but little resistance in the second. Our cavalry, which was concentrated at several points in nullahs (dry river-beds), suffered at the hands of the hostile aircraft. The Turk had evidently determined to fall back to Tekrit without putting up a serious defense. They certainly could have given us a much worse time than they did, for they had dug in well and scientifically. Among the prisoners we took there were some that proved to be very worth while. These Turkish officers were, as a whole a good lot—well dressed and well educated. Many spoke French. There is an excellent gunnery school at Constantinople, and one of the officers we captured had been a senior instructor there for many years. We had with us among our intelligence officers a Captain Bettelheim, born in Constantinople of Belgian parentage. He had served with the Turks against the Italians and with the British against the Boers. This gunnery officer turned out to be an old comrade of his in the Italian War. Many of the officers we got knew him, for he had been chief of police in Constantinople. Apparently none of them bore him the slightest ill-will when they found him serving against them.

Among the supplies we captured at Daur were a lot of our own rifles and ammunition that the Arabs had stolen and sold to the Turks. It was impossible to entirely stop this, guard our dumps as best we could. On dark nights they would creep right into camp, and it was never safe to have the hospital barges tie up to the banks for the night on their way down the river. On many occasions the Arabs crawled aboard and finished off the wounded. There was only one thing to be said for the Arab, and that was that he played no favorite, but attacked, as a rule, whichever side came handier. We were told, and I believe it to be true, that during the fighting at Sunnaiyat the Turks sent over to know if we would agree to a three days' truce, during which time we should join forces against the Arabs, who were watching on the flank to pick off stragglers or ration convoys.

That night we bivouacked at Daur, and were unmolested except for the enemy aircraft that came over and "laid eggs." Next morning we advanced on Tekrit. Our orders were to make a feint, and if we found that the Turk meant to stay and fight it out seriously, we were to fall back. Some gazelles got into the no man's land between us and the Turk, and in the midst of the firing ran gracefully up the line, stopping every now and then to stare about in amazement. Later on in the Argonne forest in France we had the same thing happen with some wild boars. The enemy seemed in no way inclined to evacuate Tekrit, so in accordance with instructions we returned to our previous night's encampment at Daur. On the way back we passed an old "arabana," a Turkish coupé, standing abandoned in the desert, with a couple of dead horses by it. It may have been used by some Turkish general in the retreat of two days before. It was the sort of coupé one associates entirely with well-kept parks and crowded city streets, and the incongruity of its lonely isolation amid the sand-dunes caused an amused ripple of comment.

Our instructions were to march back to Samarra early next morning, but shortly before midnight orders came through from General Maude for us to advance again upon Tekrit and take it. Next day we halted and took stock in view of the new orders. The cavalry again suffered at the hands of the Turkish aircraft. I went to corps headquarters in the afternoon, and a crowd of "red tabs," as the staff-officers were called, were seated around a little table having the inevitable tea. A number of the generals had come in to discuss the plan of attack for the following day. Suddenly a Turk aeroplane made its appearance, flying quite low, and dropping bombs at regular intervals. It dropped two, and then a third on a little hill in a straight line from the staff conclave. It looked as if the next would be a direct hit, and the staff did the only wise thing, and took cover as flat on the ground as nature would allow; but the Hun's spacing was bad, and the next bomb fell some little way beyond. I remember our glee at what we regarded as a capital joke on the staff. The line-officer's humor becomes a trifle robust where the "gilded staff" is concerned, notwithstanding the fact that most staff-officers have seen active and distinguished service in the line.

Our anti-aircraft guns—"Archies" we called them—were mounted on trucks, and on account of their weight had some difficulty getting up. I shall not soon forget our delight when they lumbered into view, for although I never happened personally to see an aeroplane brought down by an "Archie," there was no doubt about it but that they did not bomb us with the same equanimity when our anti-aircrafts were at hand.

Captured Turkish camel corps

That night we marched out on Tekrit, and as dawn was breaking were ready to attack. As the mist cleared, an alarming but ludicrous sight met our eyes. On the extreme right some caterpillar tractors hauling our "heavies" were advancing straight on Tekrit, as if they had taken themselves for tanks. They were not long in discovering their mistake, and amid a mixed salvo they clumsily turned and made off at their best pace, which was not more than three miles an hour. Luckily, they soon got under some excellent defilade, but not until they had suffered heavily.

Our artillery did some good work, but while we were waiting to attack we suffered rather heavily. We had to advance over a wide stretch of open country to reach the Turkish first lines. By nightfall the second line of trenches was practically all in our hands. Meanwhile the cavalry had circled way around the flank up-stream of Tekrit to cut the enemy off if he attempted to retreat. The town is on the right bank of the Tigris, and we had a small force that had come up from Samarra on the left bank, for we had no means of ferrying troops across. Our casualties during the day had amounted to about two thousand. The Seaforths had suffered heavily, but no more so than some of the native regiments. In Mesopotamia there were many changes in the standing of the Indian battalions. The Maharattas, for instance, had never previously been regarded as anything at all unusual, but they have now a very distinguished record to take pride in. The general feeling was that the Gurkhas did not quite live up to their reputation. But the Indian troops as a whole did so exceedingly well that there is little purpose in making comparisons amongst them. At this time, so I was informed, the Expeditionary Force, counting all branches, totalled about a million, and a very large percentage of this came from India. We drew our supplies from India and Australia, and it is interesting to note that we preferred the Australian canned beef and mutton (bully beef and bully mutton, as it was called) to the American.

At dusk the fighting died down, and we were told to hold on and go over at daybreak. As I was making my way back to headquarters a general pounced upon me and told me to get quickly into a car and go as rapidly as possible to Daur to bring up a motor ration-convoy with fodder for the cavalry horses and food for the riders. A Ford car happened to pass by, and he stopped it and shoved me in, with some last hurried injunction. It was quite fifteen miles back, and the country was so cut up by nullahs or ravines that in most places it was inadvisable to leave the road, which was, of course, jammed with a double stream of transport of every description. When we were three or four miles from Daur a tire blew out. The driver had used his last spare, so there was nothing to do but keep going on the rim. The car was of the delivery-wagon type—"pill-boxes" were what they were known as—and while we were stopped taking stock I happened to catch sight of a good-sized bedding-roll behind. "Some one's out of luck," said I to the driver; "whose roll is it?" "The corps commander's, sir," was his reply. After exhausting my limited vocabulary, I realized that it was far too late to stop another motor and send this one back, so I just kept going. Across the bed of one more ravine, the sand up to the hubs, and we were in the Daur camp. I managed to rank some one out of a spare tire and started back again. My driver proved unable to drive at night, at all events at a pace that would put us anywhere before dawn, so I was forced to take the wheel. By the time I had the convoy properly located I was rather despondent of the corps commander's temper, even should I eventually reach him that night, which seemed a remote chance, for the best any one could do was give me the rough location on a map. Still, taking my luminous compass, I set out to steer a cross-country course. I ran into five or six small groups of ambulances filled with wounded, trying to find their way to Daur, and completely lost. Most had given up—some were unknowingly headed back for Tekrit. I could do no more than give them the right direction, which I knew they had no chance of holding. Of course I could have no headlights, and the ditches were many, but in some miraculous way, more through good luck than good management, I did find corps headquarters, and what was better still, the general's reprimand took the form of bread and ham and a stiff peg of whiskey—the first food I had had since before daylight.

During the night the Turks evacuated the town. Their forces were certainly mobile. They could cover the most surprising distances, and live on almost nothing. We marched in and occupied. White flags were flying from all the houses, which were not nearly so much damaged from the bombardment as one would have supposed. This was invariably the case; indeed, it is surprising to see how much shelling a town can undergo without noticeable effect. It takes a long time to level a town in the way it has been done in northern France. In this region the banks of the river average about one hundred and fifty feet in height, and Tekrit is built at the junction of two ravines. No two streets are on the same level; sometimes the roofs of the houses on a lower level serve as the streets for the houses above. Many of the booths in the bazaar were open and transacting business when we arrived, an excellent proof of how firmly the Arabs believed in British fair dealing. Our men bought cigarettes, matches, and vegetables. Yusuf had lived here three or four years, so I despatched him to get chickens and eggs for the mess. I ran into Marshall, who was on his way to dine with the mayor, who had turned out to be an old friend of his. He asked me to join him, and we climbed up to a very comfortable house, built around a large courtyard. It was the best meal we had either of us had in days—great pilaus of rice, excellent chicken, and fresh unleavened bread. This bread looks like a very large and thin griddle-cake. The Arab uses it as a plate. Eating with your hands is at first rather difficult. Before falling to, a ewer is brought around to you, and you are supplied with soap—a servant pours water from the ewer over your hands, and then gives you a towel. After eating, the same process is gone through with. There are certain formalities that must be regarded—one of them being that you must not eat or drink with your left hand.

In Tekrit we did not find as much in the way of supplies and ammunition as we had hoped. The Turk had destroyed the greater part of his store. We did find great quantities of wood, and in that barren, treeless country it was worth a lot. Most of the inhabitants of Tekrit are raftsmen by profession. Their rafts have been made in the same manner since before the days of Xerxes and Darius. Inflated goatskins are used as a basis for a platform of poles, cut in the up-stream forests. On these, starting from Diarbekr or Mosul, they float down all their goods. When they reach Tekrit they leave the poles there, and start up-stream on foot, carrying their deflated goatskins. The Turks used this method a great deal bringing down their supplies. In pre-war days the rafts, keleks as they are called, would often come straight through to Baghdad, but many were always broken up at Tekrit, for there is a desert route running across to Hit on the Euphrates, and the supplies from up-river were taken across this in camel caravans.

The aerodrome lay six or seven miles above the town, and I was anxious to see it and the comfortable billets the Germans had built themselves. I found a friend whose duties required motor transportation, and we set off in his car. A dust-storm was raging, and we had some difficulty in finding our way through the network of trenches. Once outside, the storm became worse, and we could only see a few yards in front of us. We got completely lost, and after nearly running over the edge of the bluff, gave up the attempt, and slowly worked our way back.

When we started off on the advance I was reading Xenophon's Anabasis. On the day when we were ordered to march on Tekrit a captain of the Royal Flying Corps, an ex-master at Eton, was in the mess, and when I told him that I was nearly out of reading matter, he said that next time he came over he would drop me Plutarch's Lives. I asked him to drop it at corps headquarters, and that a friend of mine there would see that I got it. The next day in the heat of the fighting a plane came over low, signalling that it was dropping a message. As the streamer fell close by, there was a rush to pick it up and learn how the attack was progressing. Fortunately, I was far away when the packet was opened and found to contain the book that the pilot had promised to drop for me.

After we had been occupying the town for a few days, orders came through to prepare to fall back on Samarra. The line of communication was so long that it was impossible to maintain us, except at too great a cost to the transportation facilities possessed by the Expeditionary Forces. Eight or ten months later, when we had more rails in hand, a line was laid to Tekrit, which had been abandoned by the Turks under the threat of our advance to Kirkuk, in the Persian hills. It was difficult to explain to the men, particularly to the Indians, the necessity for falling back. All they could understand was that we had taken the town at no small cost, and now we were about to give it up.

For several days I was busy helping to prepare rafts to take down the timber and such other captured supplies as were worth removing. The river was low, leaving a broad stretch of beach below the town, and to this we brought down the poles. Several camels had died near the water, probably from the results of our shelling, and the hot weather soon made them very unpleasant companions. The first day was bad enough; the second was worse. The natives were not in the least affected. They brought their washing and worked among them—they came down and drew their drinking-water from the river, either beside the camels or down-stream of them, with complete indifference. It is true this water percolates drop by drop through large, porous clay pots before it is drunk, but even so, it would have seemed that they would have preferred its coming from up-stream of the derelict "ships of the desert." On the third day, to their mild surprise, we managed with infinite difficulty to tow the camels out through the shallow water into the main stream.

We finally got our rafts built, over eighty in number, and arranged for enough Arab pilots to take care of half of them. On the remainder we put Indian sepoys. They made quite a fleet when we finally got them all started down-stream. Two were broken up in the rapids near Daur, the rest reached Samarra in safety on the second day.

We had a pleasant camp on the bluffs below Tekrit—high-enough above the plain to be free of the ordinary dust-storms, and the prospect of returning to Samarra was scarcely more pleasant to us than to the men. Five days after we had taken the town, we turned our backs on it and marched slowly back to rail-head.

We returned to find Samarra buried in dust and more desolate than ever. A few days later came the first rain-storm. After a night's downpour the air was radiantly clear, and it was joy to ride off on the rounds, no longer like Zeus, enveloped in a cloud.

It was a relief to see the heat-stroke camps broken up. During the summer months our ranks were fearfully thinned through the sun. Although it was the British troops that suffered most, the Indians were by no means immune. Before the camps were properly organized the percentage of mortality was exceedingly large, for the only effective treatment necessitates the use of much ice. The patient runs a temperature which it was impossible to control until the ice-making machines were installed. The camps were situated in the coolest and most comfortable places, but in spite of everything, death was a frequent result, and recoveries were apt to be only partial. Men who had had a bad stroke were rarely of any further use in the country.

Another sickness of the hot season which now began to claim less victims was sand-fly fever. This fever, which, as its name indicates, was contracted from the bites of sand-flies, varied widely in virulence. Sometimes it was so severe that the victim had to be evacuated to India; as a rule he went no farther than a base hospital at Baghdad or Amara.

One of the things about which the Tommy felt most keenly in the Mesopotamian campaign was that there was no such thing as a "Cushy Blighty." To take you to "Blighty" a wound must mean permanent disablement, otherwise you either convalesced in the country or, at best, were sent to India. In the same manner there were no short leaves, for there was nowhere to go. At the most rapid rate of travelling it took two weeks to get to India, and once there, although the people did everything possible in the way of entertaining, the enlisted man found little to make him less homesick than he had been in Mesopotamia. Transportation was so difficult and the trip so long that only under very exceptional circumstances was leave to England given. One spring it was announced that officers wishing to get either married or divorced could apply for leave with good hopes of success. Many applied, but a number returned without having fulfilled either condition, so that the following year no leaves were given upon those grounds. The army commander put all divorce cases into the hands of an officer whose civil occupation had been the law, and who arranged them without the necessity of granting home leave.

A week after our return to Samarra a rumor started that General Maude was down with cholera. For some time past there had been sporadic cases, though not enough to be counted an epidemic. The sepoys had suffered chiefly, but not exclusively, for the British ranks also supplied a quota of victims. An officer on the staff of the military governor of Baghdad had recently died. We heard that the army commander had the virulent form, and knew there could be no chance of his recovery. The announcement of his death was a heavy blow to all, and many were the gloomy forebodings. The whole army had implicit confidence in their leader, and deeply mourned his loss. The usual rumors of foul play and poison went the rounds, but I soon after heard Colonel Wilcox—in pre-war days an able and renowned practitioner of Harley Street—say that it was an undoubted case of cholera. The colonel had attended General Maude throughout the illness. The general had never taken the cholera prophylactic, although Colonel Wilcox had on many occasions urged him to do so, the last time being only a few days before the disease developed.

Towing an armored car across a river

Reconnaissance

General Marshall, who had commanded General Maude's old division, the Thirteenth, took over. The Seventeenth lost General Gillman, who thereupon became chief of staff. This was a great loss to his division, for he was the idol of the men, but the interest of the Expeditionary Force was naturally and justly given precedence.

In due course my transfer to the Motor Machine-Gun Corps came through approved, and I was assigned to the Fourteenth battery of light-armored motor-cars, commanded by Captain Nigel Somerset, whose grandfather, Lord Raglan, had died, nursed by Florence Nightingale, while in command of the British forces in the Crimean War. Somerset himself was in the infantry at the outbreak of the war and had been twice wounded in France. He was an excellent leader, possessing as he did dash, judgment, and personal magnetism. A battery was composed of eight armored cars, subdivided into four sections. There was a continually varying number of tenders and workshop lorries. The fighting cars were Rolls-Royces, the others Napiers and Fords.

At that time there were only four batteries in the country. We were army troops—that is to say, we were not attached to any individual brigade, or division, or corps, but were temporarily assigned first here and then there, as the need arose.

In attacks we worked in co-operation with the cavalry. Although on occasions they tried to use us as tanks, it was not successful, for our armor-plate was too light. We were also employed in raiding, and in quelling Arab uprisings. This latter use threw us into close touch with the political officers. These were a most interesting lot of men. They were recruited in part from the army, but largely from civil life. They took over the civil administration of the conquered territory and judiciously upheld native justice. Many remarkable characters were numbered among them—men who had devoted a lifetime to the study of the intricacies of Oriental diplomacy. They were distinguished by the white tabs on the collars of their regulation uniforms; but white was by no means invariably the sign of peace, for many of the political officers were killed, and more than once in isolated towns in unsettled districts they sustained sieges that lasted for several days. We often took a political officer out with us on a raid or reconnaissance, finding his knowledge of the language and customs of great assistance. Sir Percy Cox was at the head, with the title "Chief Political Officer" and the rank of general. His career in the Persian Gulf has been as distinguished as it is long, and his handling of the very delicate situations arising in Mesopotamia has called forth the unstinted praise of soldier and civilian alike.

Ably assisting him, and head of the Arab bureau, was Miss Gertrude Bell, the only woman, other than the nursing sisters, officially connected with the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Forces. Miss Bell speaks Arabic fluently and correctly. She first became interested in the East when visiting her uncle at Teheran, where he was British minister. She has made noteworthy expeditions in Syria and Mesopotamia, and has written a number of admirable books, among which are Armurath to Armurath and The Desert and the Sown. The undeniable position which she holds must appear doubly remarkable when the Mohammedan official attitude toward women is borne in mind. Miss Bell has worked steadily and without a leave in this trying climate, and her tact and judgment have contributed to the British success to a degree that can scarcely be overestimated.

The headquarters of the various batteries were in Baghdad. There we had our permanent billets, and stores. We would often be ordered out in sections to be away varying lengths of time, though rarely more than a couple of months. The workshops' officer stayed in permanent charge and had the difficult task of keeping all the cars in repair. The supply of spare parts was so uncertain that much skill and ingenuity were called for, and possessed to a full degree by Lieutenant Linnell of the Fourteenth.

A few days after I joined I set off with Somerset and one of the battery officers, Lieutenant Smith, formerly of the Black Watch. We were ordered to do some patrolling near the ruins of Babylon. Kerbela and Nejef, in the quality of great Shiah shrines, had never been particularly friendly to the Turks, who were Sunnis—but the desert tribes are almost invariably Sunnis, and this coupled with their natural instinct for raiding and plundering made them eager to take advantage of any interregnum of authority. We organized a sort of native mounted police, but they were more picturesque than effective. They were armed with weapons of varying age and origin—not one was more recent than the middle of the last century. Now the Budus, the wild desert folk, were frequently equipped with rifles they had stolen from us, so in a contest the odds were anything but even.

We took up our quarters at Museyib, a small town on the banks of the Euphrates, six or eight miles above the Hindiyah Barrage, a dam finished a few years before, and designed to irrigate a large tract of potentially rich country. We patrolled out to Mohamediyah, a village on the caravan desert route to Baghdad, and thence down to Hilleh, around which stand the ruins of ancient Babylon. The rainy season was just beginning, and it was obvious that the patrolling could not be continuous, for a twelve-hour rain would make the country impassable to our heavy cars for two or three days. We were fortunate in having pleasant company in the officers of a Punjabi infantry battalion and an Indian cavalry regiment. Having commandeered an ancient caravan-serai for garage and billets, we set to work to clean it out and make it as waterproof as circumstances would permit. An oil-drum with a length of iron telegraph-pole stuck in its top provided a serviceable stove, and when it rained we played bridge or read.

I was ever ready to reduce my kit to any extent in order to have space for some books, and Voltaire's Charles XII was the first called upon to carry me to another part of the world from that in which I at the moment found myself. I always kept a volume of some sort in my pocket, and during halts I would read in the shade cast by the turret of my car. The two volumes of Layard's Early Adventures proved a great success. The writer, the great Assyriologist, is better known as the author of Nineveh and Babylon. The book I was reading had been written when he was in his early twenties, but published for the first time forty years later. Layard started life as a solicitor's clerk in London, but upon being offered a post in India he had accepted and proceeded thither overland. On reaching Baghdad he made a side-trip into Kurdistan, and became so enamored of the life of the tribesmen that he lived there with them on and off for two years—years filled with adventure of the most thrilling sort.

I had finished a translation of Xenophon shortly before and found it a very different book than when I was plodding drearily through it in the original at school. Here it was all vivid and real before my eyes, with the scene of the great battle of Cunaxa only a few miles from Museyib. Babylon was in sight of the valiant Greeks, but all through the loss of a leader it was never to be theirs. On the ground itself one could appreciate how great a masterpiece the retreat really was, and the hardiness of the soldiers which caused Xenophon to regard as a "snow sickness" the starvation and utter weariness which made the numbed men lie down and die in the snow of the Anatolian highlands. He remarks naïvely that if you could build a fire and give them something hot to eat, the sickness was dispelled!

The rain continued to fall and the mud became deeper and deeper. It was all the Arabs could do to get their produce into market. The bazaar was not large, but was always thronged. I used to sit in one of the coffee-houses and drink coffee or tea and smoke the long-stemmed water-pipe, the narghile. My Arabic was now sufficiently fluent for ordinary conversation, and in these clubs of the Arab I could hear all the gossip. Bazaar rumors always told of our advances long before they were officially given out. Once in Baghdad I heard of an attack we had launched. On going around to G.H.Q. I mentioned the rumor, and found that it was not yet known there, but shortly after was confirmed. I had already in Africa met with the "native wireless," and it will be remembered how in the Civil War the plantation negroes were often the first to get news of the battles. It is something that I have never heard satisfactorily explained.

In the coffee-houses, besides smoking and gossiping, we also played games, either chess or backgammon or munkula. This last is an exceedingly primitive and ancient game—it must date almost as far back as jackstones or knucklebones. I have seen the natives in Central Africa and the Indians in the far interior of Brazil playing it in almost identical form. In Mesopotamia the board was a log of wood sliced in two and hinged together. In either half five or six holes were scooped out, and the game consisted in dropping cowrie shells or pebbles into the holes. When the number in a particular hollow came to a certain amount with the addition of the one dropped in, you won the contents.

In most places the coffee was served in Arab fashion, not Turkish. In the latter case it is sweet and thick and the tiny cup is half full of grounds; in the former the coffee is clear and bitter and of unsurpassable flavor. The diminutive cup is filled several times, but each time there is only a mouthful poured in. Tea is served in small glasses, without milk, but with lots of sugar. The spoons in the glasses are pierced with holes like tea-strainers so that the tea may be stirred without spilling it.