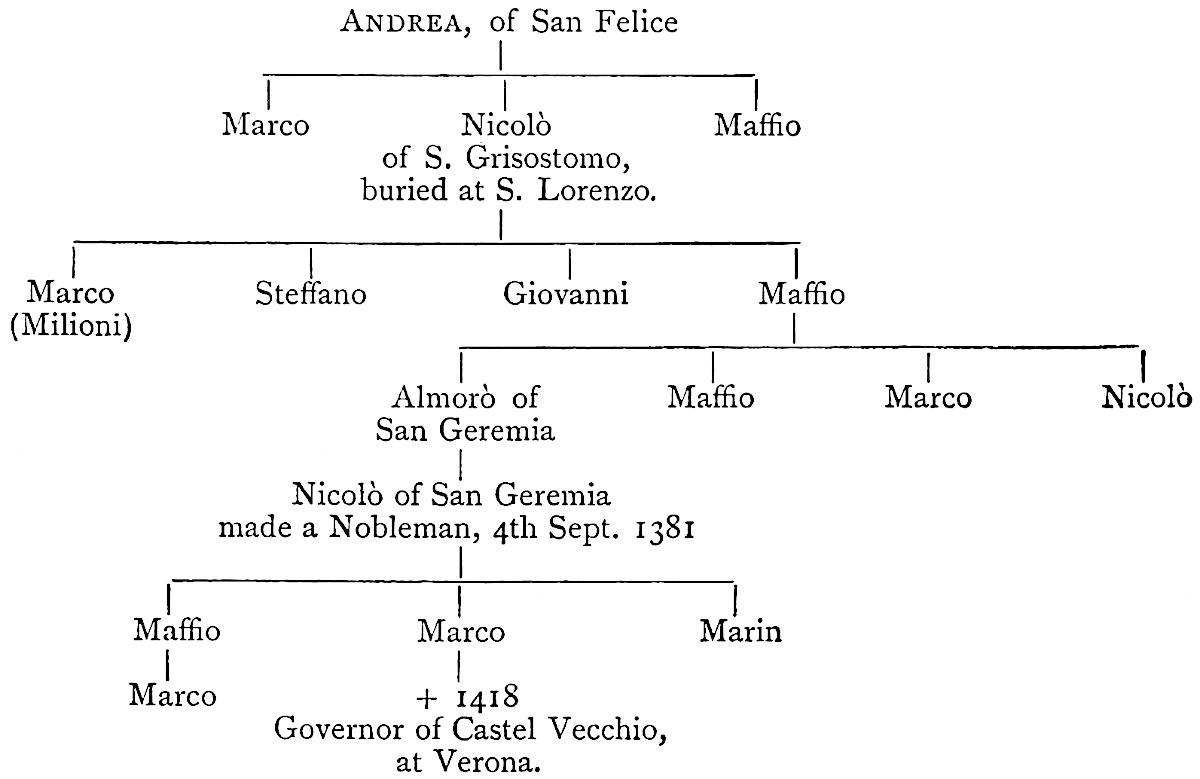

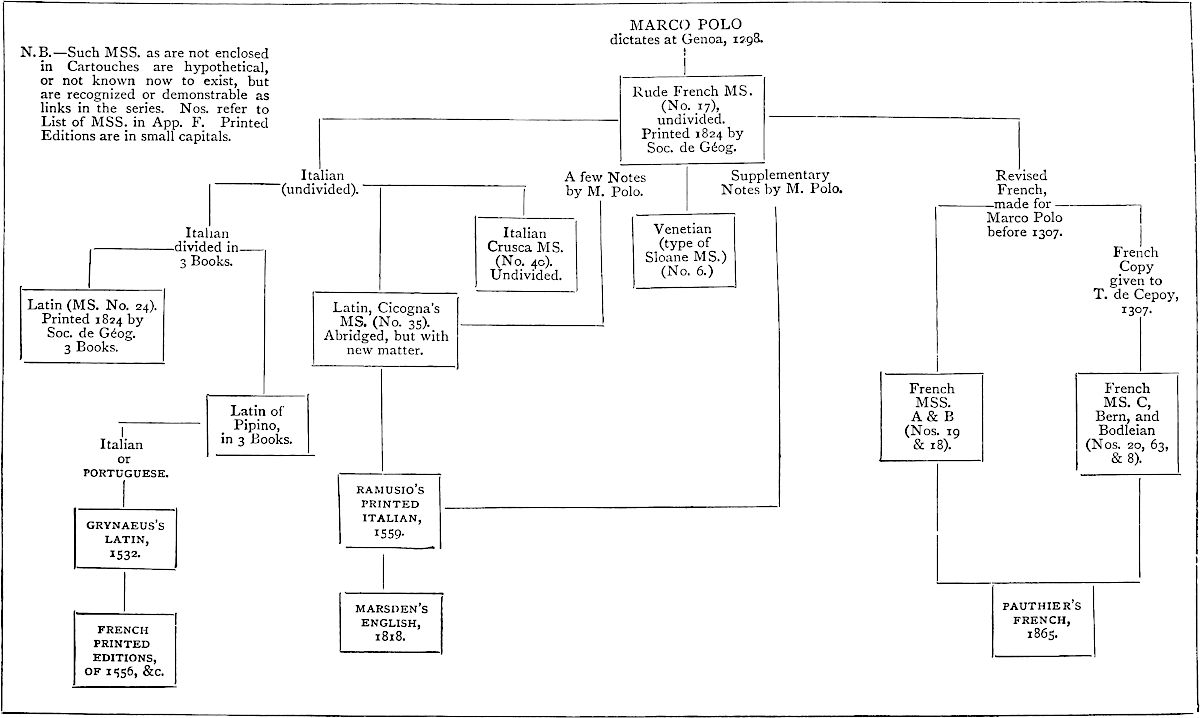

Title: The Travels of Marco Polo — Volume 2

Author: Marco Polo

da Pisa Rusticiano

Editor: Henri Cordier

Translator: Sir Henry Yule

Release date: May 1, 2004 [eBook #12410]

Most recently updated: July 1, 2025

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12410

Credits: Charles Franks, Robert Connal, John Williams and PG Distributed Proofreaders, updated and HTML created by Robert Tonsing

Page |

|

|---|---|

| Synopsis of Contents | iii |

| Explanatory List of Illustrations | xvi |

| The Book of Marco Polo | |

| Appendices | 503 |

| Index | 607 |

Chap. |

Page |

|

|---|---|---|

| —Here begins the Description of the Interior of Cathay; and first of the River Pulisanghin | 3 |

|

| Notes.—1. Marco’s Route. 2. The Bridge Pul-i-sangin, or Lu-ku-k’iao. | ||

| —Account of the City of Juju | 10 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Silks called Sendals. 2. Chochau. 3. Bifurcation of Two Great Roads at this point. | ||

| —The Kingdom of Taianfu | 12 |

|

| Notes.—1. Acbaluc. 2. T’ai-yuan fu. 3. Grape-wine of that place. 4. P’ing-yang fu. | ||

| —Concerning the Castle of Caichu. the Golden King and Prester John | 17 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Story and Portrait of the Roi d’Or. 2. Effeminacy reviving in every Chinese Dynasty. | ||

| —How Prester John treated the Golden King his Prisoner | 21 |

|

| —Concerning the Great River Caramoran and the City of Cachanfu | 22 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Kará Muren. 2. Former growth of silk in Shan-si and Shen-si. 3. The akché or asper. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Kenjanfu | 24 |

|

| Notes.—1. Morus alba. 2. Geography of the Route since Chapter XXXVIII. 3. Kenjanfu or Si-ngan fu; the Christian monument there. 4. Prince Mangala. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Cuncun, which is right wearisome to travel through | 31 |

|

| Note.—The Mountain Road to Southern Shen-si. | ||

| iv | —Concerning the Province of Acbalec Manzi | 33 |

| Notes.—1. Geography, and doubts about Acbalec. 2. Further Journey into Sze-ch’wan. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Sindafu | 36 |

|

| Notes.—1. Ch’êng-tu fu. 2. The Great River or Kiang. 3. The word Comercque. 4. The Bridge-Tolls. 5. Correction of Text. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Tebet | 42 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Part of Tibet and events referred to. 2. Noise of burning bamboos. 3. Road retains its desolate character. 4. Persistence of eccentric manners illustrated. 5. Name of the Musk animal. | ||

| —Further Discourse concerning Tebet | 49 |

|

| Notes.—1. Explanatory. 2. “Or de Paliolle.” 3. Cinnamon. 4. 5. Great Dogs, and Beyamini oxen. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Caindu | 53 |

|

| Notes.—1. Explanation from Ramusio. 2. Pearls of Inland Waters. 3. Lax manners. 4. Exchange of Salt for Gold. 5. Salt currency. 6. Spiced Wine. 7. Plant like the Clove, spoken of by Polo. Tribes of this Tract. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Carajan | 64 |

|

| Notes.—1. Geography of the Route between Sindafu or Ch’êng-tu fu, and Carajan or Yun-nan. 2. Christians and Mahomedans in Yun-nan. 3. Wheat. 4. Cowries. 5. Brine-spring. 6. Parallel. | ||

| —Concerning a further part of the Province of Carajan | 76 |

|

| Notes.—1. City of Talifu. 2. Gold. 3. Crocodiles. 4. Yun-nan horses and riders. Arms of the Aboriginal Tribes. 5. Strange superstition and parallels. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Zardandan | 84 |

|

| Notes.—1. Carajan and Zardandan. 2. The Gold-Teeth. 3. Male Indolence. 4. The Couvade. (See App. L. 8.) 5. Abundance of Gold. Relation of Gold to Silver. 6. Worship of the Ancestor. 7. Unhealthiness of the climate. 8. Tallies. 9.–12. Medicine-men or Devil-dancers; extraordinary identity of practice in various regions. | ||

| —Wherein is related how the King of Mien and Bangala vowed vengeance against the Great Kaan | 98 |

|

| Notes.—1. Chronology. 2. Mien or Burma. Why the King may have been called King of Bengal also. 3. Numbers alleged to have been carried on elephants. | ||

| —Of the Battle that was fought by the Great Kaan’s Host and his Seneschal against the King of Mien | 101 |

|

| Notes.—1. Nasruddin. 2. Cyrus’s Camels. 3. Chinese Account of the Action. General Correspondence of the Chinese and Burmese Chronologies. | ||

| v | —Of the Great Descent that leads towards the Kingdom of Mien | 106 |

| Notes.—1. Market-days. 2. Geographical difficulties. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Mien, and the Two Towers that are therein, one of Gold, and the other of Silver | 109 |

|

| Notes.—1. Amien. 2. Chinese Account of the Invasion of Burma. Comparison with Burmese Annals. The City intended. The Pagodas. 3. Wild Oxen. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Bangala | 114 |

|

| Notes.—1. Polo’s view of Bengal; and details of his account illustrated. 2. Great Cattle. | ||

| —Discourses of the Province of Caugigu | 116 |

|

| Note.—A Part of Laos. Papesifu. Chinese Geographical Etymologies. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Anin | 119 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Name. Probable identification of territory. 2. Textual. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Coloman | 122 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Name. The Kolo-man. 2. Natural defences of Kwei-chau. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Cuiju | 124 |

|

| Notes.—1. Kwei-chau. Phungan-lu. 2. Grass-cloth. 3. Tigers. 4. Great Dogs. 5. Silk. 6. Geographical Review of the Route since Chapter LV. 7. Return to Juju. |

| —Concerning the Cities of Cacanfu and Changlu | 132 |

|

| Notes.—1. Pauthier’s Identifications. 2. Changlu. The Burning of the Dead ascribed to the Chinese. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Chinangli, and that of Tadinfu, and the Rebellion of Litan | 135 |

|

| Notes.—1. T’si-nan fu. 2. Silk of Shan-tung. 3. Title Sangon. 4. Agul and Mangkutai. 5. History of Litan’s Revolt. | ||

| vi | —Concerning the Noble City of Sinjumatu | 138 |

| Note.—The City intended. The Great Canal. | ||

| —Concerning the Cities of Linju and Piju | 140 |

|

| Notes.—1. Linju. 2. Piju. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Siju, and the Great River Caramoran | 141 |

|

| Notes.—1. Siju. 2. The Hwang-Ho and its changes. 3. Entrance to Manzi; that name for Southern China. | ||

| —How the Great Kaan conquered the Province of Manzi | 144 |

|

| Notes.—1. Meaning and application of the title Faghfur. 2. Chinese self-devotion. 3. Bayan the Great Captain. 4. His lines of Operation. 5. The Juggling Prophecy. 6. The Fall of the Sung Dynasty. 7. Exposure of Infants, and Foundling Hospitals. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Coiganju | 151 |

|

| Note.—Hwai-ngan fu. | ||

| —Of the Cities of Paukin and Cayu | 152 |

|

| Note.—Pao-yng and Kao-yu. | ||

| —Of the Cities of Tiju, Tinju, and Yanju | 153 |

|

| Notes.—1. Cities between the Canal and the Sea. 2. Yang-chau. 3. Marco Polo’s Employment at this City. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Nanghin | 157 |

|

| Note.—Ngan-king. | ||

| —Concerning the very Noble City of Saianfu, and how its Capture was effected | 158 |

|

| Notes.—1. and 2. Various Readings. 3. Digression on the Military Engines of the Middle Ages. 4. Mangonels of Cœur de Lion. 5. Difficulties connected with Polo’s Account of this Siege. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Sinju and the Great River Kian | 170 |

|

| Notes.—1. I-chin hien. 2. The Great Kiang. 3. Vast amount of tonnage on Chinese Waters. 4. Size of River Vessels. 5. Bamboo Tow-lines. 6. Picturesque Island Monasteries. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Caiju | 174 |

|

| Notes.—1. Kwa-chau. 2. The Grand Canal and Rice-Transport. 3. The Golden Island. | ||

| —Of the City of Chinghianfu | 176 |

|

| Note.—Chin-kiang fu. Mar Sarghis, the Christian Governor. | ||

| —Of the City of Chinginju and the Slaughter of certain Alans there | 178 |

|

| Notes.—1. Chang-chau. 2. Employment of Alans in the Mongol Service. 3. The Chang-chau Massacre. Mongol Cruelties. | ||

| vii | —Of the Noble City of Suju | 181 |

| Notes.—1. Su-chau. 2. Bridges of that part of China. 3. Rhubarb; its mention here seems erroneous. 4. The Cities of Heaven and Earth. Ancient incised Plan of Su-chau. 5. Hu-chau, Wu-kiang, and Kya-hing. | ||

| —Description of the Great City of Kinsay, which is the Capital of the whole Country of Manzi | 185 |

|

| Notes.—1. King-szé now Hang-chau. 2. The circuit ascribed to the City; the Bridges. 3. Hereditary Trades. 4. The Si-hu or Western Lake. 5. Dressiness of the People. 6. Charitable Establishments. 7. Paved roads. 8. Hot and Cold Baths. 9. Kanp’u, and the Hang-chau Estuary. 10. The Nine Provinces of Manzi. 11. The Kaan’s Garrisons in Manzi. 12. Mourning costume. 13. 14. Tickets recording inmates of houses. | ||

| —[Further Particulars concerning the Great City of Kinsay.] | 200 |

|

(From Ramusio only.) |

||

| Notes.—1. Remarks on these supplementary details. 2. Tides in the Hang-chau Estuary. 3. Want of a good Survey of Hang-chau. The Squares. 4. Marco ignores pork. 5. Great Pears: Peaches. 6. Textual. 7. Chinese use of Pepper. 8. Chinese claims to a character for Good Faith. 9. Pleasure-parties on the Lake. 10. Chinese Carriages. 11. The Sung Emperor. 12. The Sung Palace. Extracts regarding this Great City from other mediæval writers, European and Asiatic. Martini’s Description. | ||

| —Treating of the Yearly Revenue that the Great Kaan hath from Kinsay | 215 |

|

| Notes.—1. Textual. 2. Calculations as to the values spoken of. | ||

| —Of the City of Tanpiju and others | 218 |

|

| Notes.—1. Route from Hang-chau southward. 2. Bamboos. 3. Identification of places. Chang-shan the key to the route. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Fuju | 224 |

|

| Notes.—1. “Fruit like Saffron.” 2. 3. Cannibalism ascribed to Mountain Tribes on this route. 4. Kien-ning fu. 5. Galingale. 6. Fleecy Fowls. 7. Details of the Journey in Fo-kien and various readings. 8. Unken. Introduction of Sugar-refining into China. | ||

| —Concerning the Greatness of the City of Fuju | 231 |

|

| Notes.—1. The name Chonka, applied to Fo-kien here. Cayton or Zayton. 2. Objections that have been made to identity of Fuju and Fu-chau. 3. The Min River. | ||

| —Of the City and Great Haven of Zayton | 234 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Camphor Laurel. 2. The Port of Zayton or T’swan-chau; Recent objections to this identity. Probable viiiorigin of the word Satin. 3. Chinese Consumption of Pepper. 4. Artists in Tattooing. 5. Position of the Porcelain manufacture spoken of. Notions regarding the Great River of China. 6. Fo-kien dialects and variety of spoken language in China. 7. From Ramusio. |

Chap. |

Page |

|

|---|---|---|

| —Of the Merchant Ships of Manzi that sail upon the Indian Seas | 249 |

|

| Notes.—1. Pine Timber. 2. Rudder and Masts. 3. Watertight Compartments. 4. Chinese substitute for Pitch. 5. Oars used by Junks. 6. Descriptions of Chinese Junks from other Mediæval Writers. | ||

| —Description of the Island of Chipangu, and the Great Kaan’s Despatch of a Host against it | 253 |

|

| Notes.—1. Chipangu or Japan. 2. Abundance of Gold. 3. The Golden Palace. 4. Japanese Pearls. Red Pearls. | ||

| —What Further came of the Great Kaan’s Expedition against Chipangu | 258 |

|

| Notes.—1. Kúblái’s attempts against Japan. Japanese Narrative of the Expedition here spoken of. (See App. L. 9.) 2. Species of Torture. 3. Devices to procure Invulnerability. | ||

| —Concerning the Fashion of the Idols | 263 |

|

| Notes.—1. Many-limbed Idols. 2. The Philippines and Moluccas. 3. The name Chin or China. 4. The Gulf of Cheinan. | ||

| —Of the Great Country called Chamba | 266 |

|

| Notes.—1. Champa, and Kúblái’s dealings with it. (See App. L. 10). 2. Chronology. 3. Eagle-wood and Ebony. Polo’s use of Persian words. | ||

| —Concerning the Great Island of Java | 272 |

|

| Note.—Java; its supposed vast extent. Kúblái’s expedition against it and failure. | ||

| —Wherein the Isles of Sondur and Condur are spoken of; and the Kingdom of Locac | 276 |

|

| Notes.—1. Textual. 2. Pulo Condore. 3. The Kingdom of Locac, Southern Siam. | ||

| —Of the Island called Pentam, and the City Malaiur | 280 |

|

| Notes.—1. Bintang. 2. The Straits of Singapore. 3. Remarks on the Malay Chronology. Malaiur probably Palembang. | ||

| ix | —Concerning the Island of Java the Less. the Kingdoms of Ferlec and Basma | 284 |

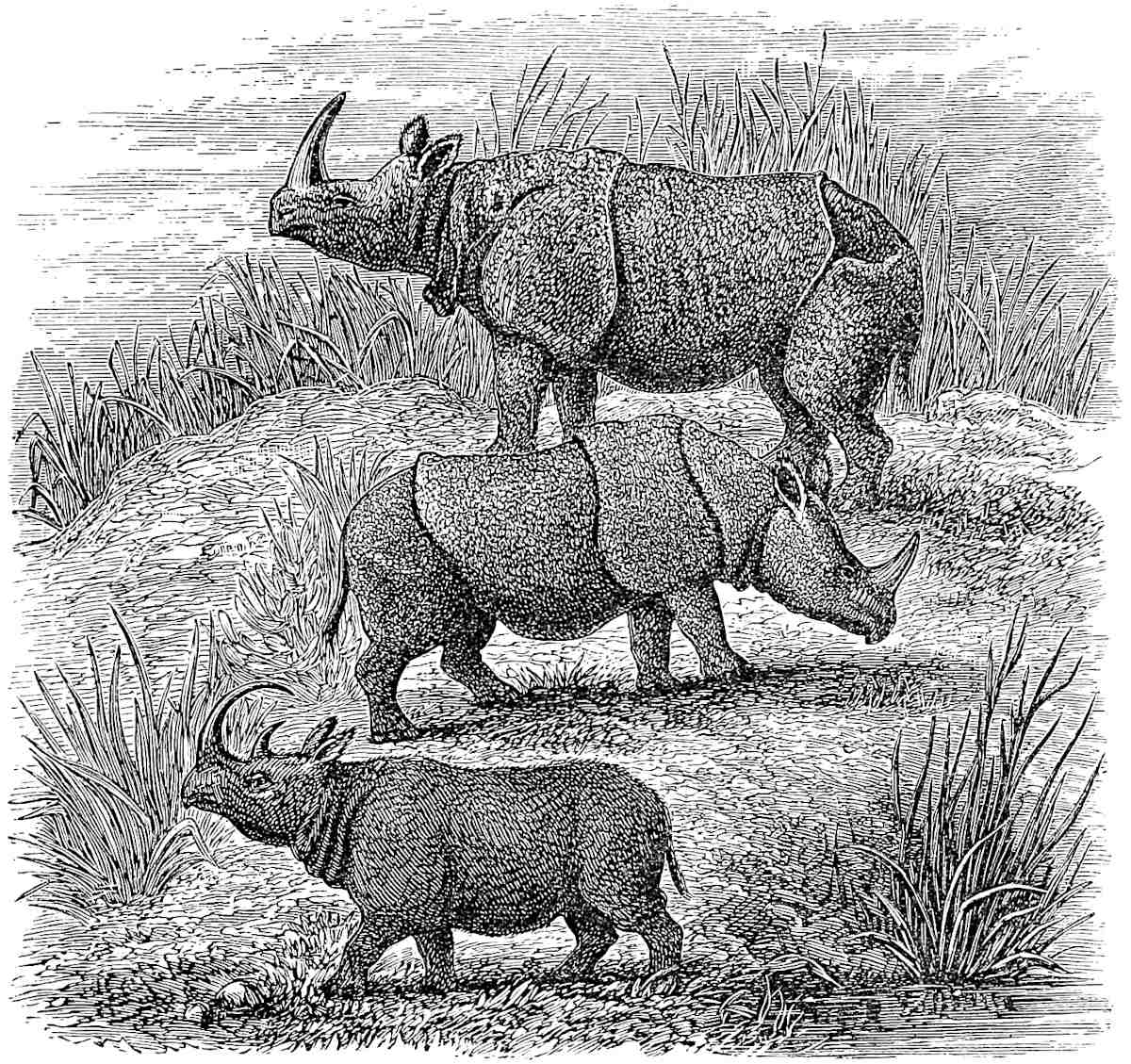

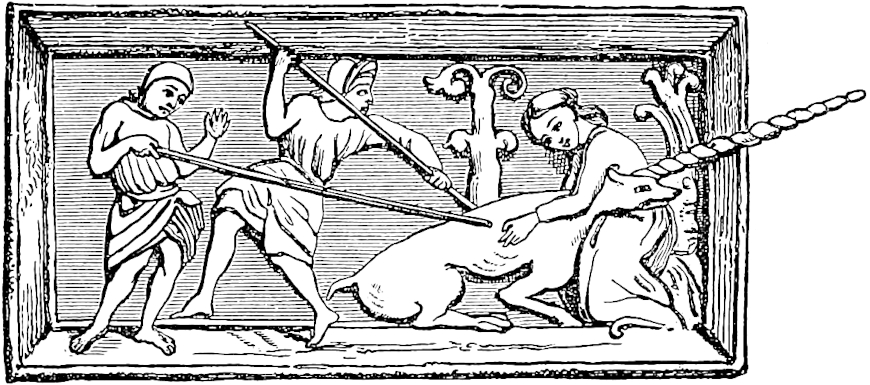

| Notes.—1. The Island of Sumatra: application of the term Java. 2. Products of Sumatra. The six kingdoms. 3. Ferlec or Parlák. The Battas. 4. Basma, Pacem, or Pasei. 5. The Elephant and the Rhinoceros. The Legend of Monoceros and the Virgin. 6. Black Falcon. | ||

| —The Kingdoms of Samara and Dagroian | 292 |

|

| Notes.—1. Samara, Sumatra Proper. 2. The Tramontaine and the Mestre. 3. The Malay Toddy-Palm. 4. Dagroian. 5. Alleged custom of eating dead relatives. | ||

| —Of the Kingdoms of Lambri and Fansur | 299 |

|

| Notes.—1. Lambri. 2. Hairy and Tailed Men. 3. Fansur and Camphor Fansuri. Sumatran Camphor. 4. The Sago-Palm. 5. Remarks on Polo’s Sumatran Kingdoms. | ||

| —Concerning the Island of Necuveran | 306 |

|

| Note.—Gauenispola, and the Nicobar Islands. | ||

| —Concerning the Island of Angamanain | 309 |

|

| Note.—The Andaman Islands. | ||

| —Concerning the Island of Seilan | 312 |

|

| Notes.—1. Chinese Chart. 2. Exaggeration of Dimensions. The Name. 3. Sovereigns then ruling Ceylon. 4. Brazil Wood and Cinnamon. 5. The Great Ruby. | ||

| —The Same Continued. The History of Sagamoni Borcan and the beginning of Idolatry | 316 |

|

| Notes.—1. Adam’s Peak, and the Foot thereon. 2. The Story of Sakya-Muni Buddha. The History of Saints Barlaam and Josaphat; a Christianised version thereof. 3. High Estimate of Buddha’s Character. 4. Curious Parallel Passages. 5. Pilgrimages to the Peak. 6. The Pâtra of Buddha, and the Tooth-Relic. 7. Miraculous endowments of the Pâtra; it is the Holy Grail of Buddhism. | ||

| —Concerning the Great Province of Maabar, which is called India the Greater, and is on the Mainland | 331 |

|

| Notes.—1. Ma’bar, its definition, and notes on its Mediæval History. 2. The Pearl Fishery. | ||

| —Continues to speak of the Province of Maabar | 338 |

|

| Notes.—1. Costume. 2. Hindu Royal Necklace. 3. Hindu use of the Rosary. 4. The Saggio. 5. Companions in Death; the word Amok. 6. Accumulated Wealth of Southern India at this time. 7. Horse Importation from the Persian Gulf. 8. Religious Suicides. 9. Suttees. 10. Worship of the Ox. The Govis. 11. Verbal. 12. The Thomacides. 13. Ill-success of Horse-breeding in S. India. 14. Curious Mode of xArrest for Debt. 15. The Rainy Seasons. 16. Omens of the Hindus. 17. Strange treatment of Horses. 18. The Devadásis. 19. Textual. | ||

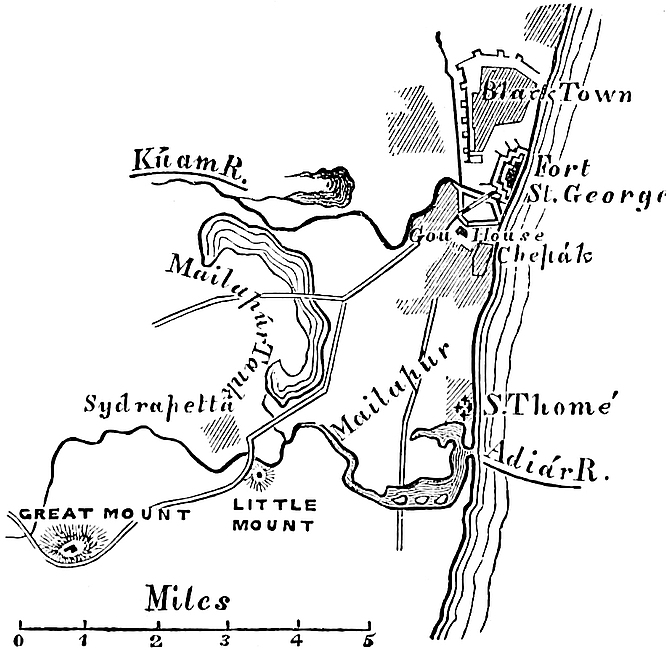

| —Discoursing of the Place where lieth the Body of St. Thomas the Apostle; and of the Miracles thereof | 353 |

|

| Notes.—1. Mailapúr. 2. The word Avarian. 3. Miraculous Earth. 4. The Traditions of St. Thomas in India. The ancient Church at his Tomb; the ancient Cross preserved on St. Thomas’s Mount. 5. White Devils. 6. The Yak’s Tail. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Mutfili | 359 |

|

| Notes.—1. Motapallé. The Widow Queen of Telingana. 2. The Diamond Mines, and the Legend of the Diamond Gathering. 3. Buckram. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Lar whence the Brahmans come | 363 |

|

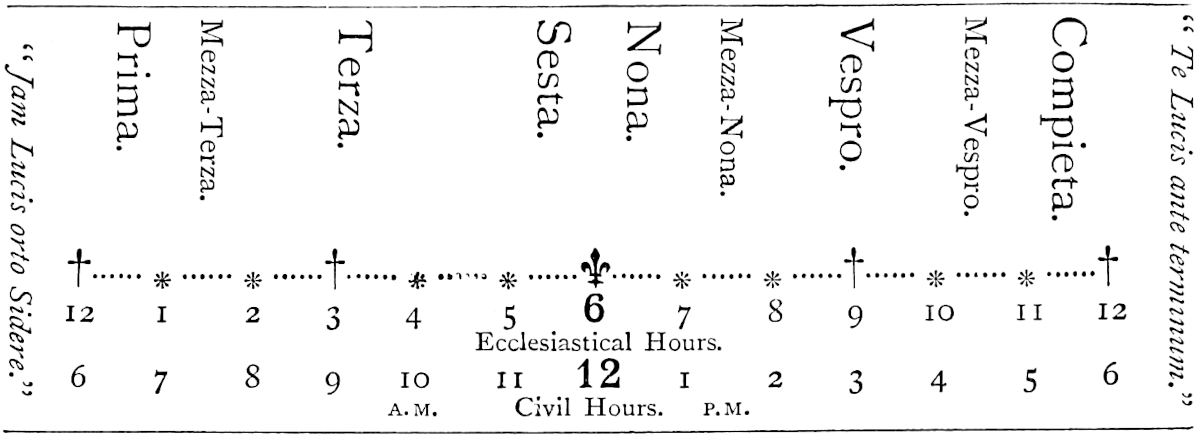

| Notes.—1. Abraiaman. The Country of Lar. Hindu Character. 2. The Kingdom of Soli or Chola. 3. Lucky and Unlucky Days and Hours. The Canonical Hours of the Church. 4. Omens. 5. Jogis. The Ox-emblem. 6. Verbal. 7. Recurrence of Human Eccentricities. | ||

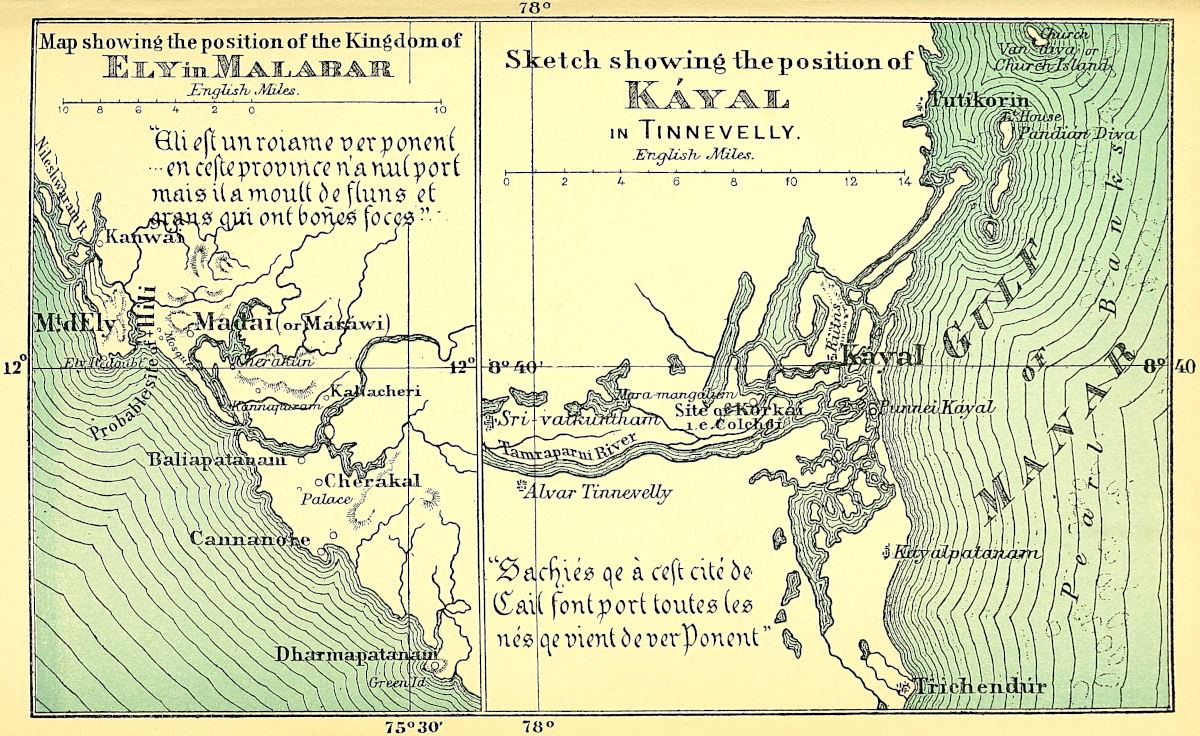

| —Concerning the City of Cail | 370 |

|

| Notes.—1. Káyal; its true position. Kolkhoi identified. 2. The King Ashar or As-char. 3. Correa, Note. 4. Betel-chewing. 5. Duels. | ||

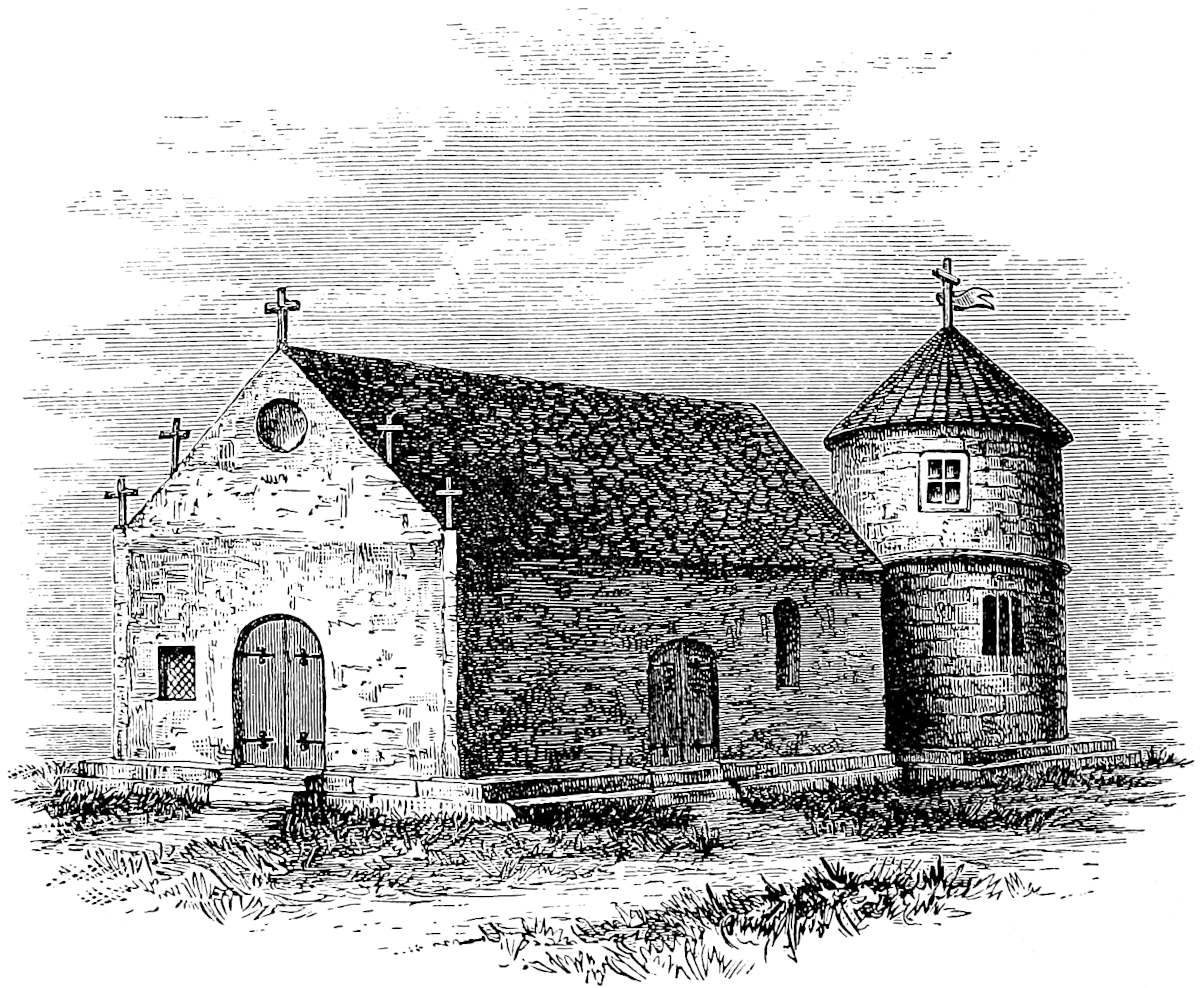

| —Of the Kingdom of Coilum | 375 |

|

| Notes.—1. Coilum, Coilon, Kaulam, Columbum, Quilon. Ancient Christian Churches. 2. Brazil Wood: notes on the name. 3. Columbine Ginger and other kinds. 4. Indigo. 5. Black Lions. 6. Marriage Customs. | ||

| —Of the Country called Comari | 382 |

|

| Notes.—1. Cape Comorin. 2. The word Gat-paul. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom Eli | 385 |

|

| Notes.—1. Mount D’Ely, and the City of Hili-Máráwi. 2. Textual. 3. Produce. 4. Piratical custom. 5. Wooden Anchors. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Melibar | 389 |

|

| Notes.—1. Dislocation of Polo’s Indian Geography. The name of Malabar. 2. Verbal. 3. Pirates. 4. Cassia: Turbit: Cubebs. 5. Cessation of direct Chinese trade with Malabar. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Gozurat | 392 |

|

| Notes.—1. Topographical Confusion. 2. Tamarina. 3. Tall Cotton Trees. 4. Embroidered Leather-work. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Tana | 395 |

|

| Notes.—1. Tana, and the Konkan. 2. Incense of Western India. | ||

| xi | —Concerning the Kingdom of Cambaet | 397 |

| Note.—Cambay. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Semenat | 398 |

|

| Note.—Somnath, and the so-called Gates of Somnath. | ||

| —Concerning the Kingdom of Kesmacoran | 401 |

|

| Notes.—1. Kij-Mekrán. Limit of India. 2. Recapitulation of Polo’s Indian Kingdoms. | ||

| —Discourseth of the Two Islands called Male and Female, and why they are so called | 404 |

|

| Note.—The Legend and its diffusion. | ||

| —Concerning the Island of Scotra | 406 |

|

| Notes.—1. Whales of the Indian Seas. 2. Socotra and its former Christianity. 3. Piracy at Socotra. 4. Sorcerers. | ||

| —Concerning the Island of Madeigascar | 411 |

|

| Notes.—1. Madagascar; some confusion here with Magadoxo. 2. Sandalwood. 3. Whale-killing. The Capidoglio or Sperm-Whale. 4. The Currents towards the South. 5. The Rukh (and see Appendix L. 11). 6. More on the dimensions assigned thereto. 7. Hippopotamus Teeth. | ||

| —Concerning the Island of Zanghibar. A Word on India in General | 422 |

|

| Notes.—1. Zangibar; Negroes. 2. Ethiopian Sheep. 3. Giraffes. 4. Ivory trade. 5. Error about Elephant-taming. 6. Number of Islands assigned to the Indian Sea. 7. The Three Indies, and various distributions thereof. Polo’s Indian Geography. | ||

| —Treating of the Great Province of Abash, which is Middle India, and is on the Mainland | 427 |

|

| Notes.—1. Ḥabash or Abyssinia. Application of the name India to it. 2. Fire Baptism ascribed to the Abyssinian Christians. 3. Polo’s idea of the position of Aden. 4. Taming of the African Elephant for War. 5. Marco’s Story of the Abyssinian Invasion of the Mahomedan Low-Country, and Review of Abyssinian Chronology in connection therewith. 6. Textual. | ||

| —Concerning the Province of Aden | 438 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Trade to Alexandria from India viâ Aden. 2. “Roncins à deux selles.” 3. The Sultan of Aden. The City and its Great Tanks. 4. The Loss of Acre. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Esher | 442 |

|

| Notes.—1. Shihr. 2. Frankincense. 3. Four-horned Sheep. 4. Cattle fed on Fish. 5. Parallel passage. | ||

| —Concerning the City of Dufar | 444 |

|

| Notes.—1. Dhofar. 2. Notes on Frankincense. | ||

| xii | —Concerning the Gulf of Calatu, and the City so called | 449 |

| Notes.—1. Kalhát. 2. “En fra terre.” 3. Maskat. | ||

| —Returns to the City of Hormos whereof we spoke formerly | 451 |

|

| Notes.—1. Polo’s distances and bearings in these latter chapters. 2. Persian Bád-gírs or wind-catching chimneys. 3. Island of Kish. |

Chap. |

Page |

|

|---|---|---|

| —Concerning Great Turkey | 457 |

|

| Notes.—1. Kaidu Khan. 2. His frontier towards the Great Kaan. | ||

| —Of certain Battles that were fought by King Caidu against the Armies of his Uncle the Great Kaan | 459 |

|

| Notes.—1. Textual. 2. “Araines.” 3. Chronology in connection with the events described. | ||

| —†What the Great Kaan said to the Mischief done by Caidu his nephew | 463 |

|

| —Of the Exploits of King Caidu’s valiant Daughter | 463 |

|

| Note.—Her name explained. Remarks on the story. | ||

| —How Abaga sent his Son Argon in command against King Caidu | 466 |

|

(Extract and Substance.) |

||

| Notes.—1. Government of the Khorasan frontier. 2. The Historical Events. | ||

| —How Argon after the Battle heard that his Father was dead and Went to assume the Sovereignty as was his right | 467 |

|

| Notes.—1. Death of Ábáká. 2. Textual. 3. Ahmad Tigudar. | ||

| —†How Acomat Soldan set out with his Host against his Nephew who was coming to claim the throne that belonged to him | 468 |

|

| xiii | —†How Argon took Counsel with his Followers about attacking his Uncle Acomat Soldan | 468 |

| —†How the Barons of Argon answered his Address | 469 |

|

| —†The Message sent by Argon to Acomat | 469 |

|

| —How Acomat replied to Argon’s Message | 469 |

|

| —Of the Battle between Argon and Acomat, and the Captivity of Argon | 470 |

|

| Notes.—1. Verbal. 2. Historical. | ||

| —How Argon was delivered from Prison | 471 |

|

| —How Argon got the Sovereignty at last | 472 |

|

| —†How Acomat was taken Prisoner | 473 |

|

| —How Acomat was slain by Order of his Nephew | 473 |

|

| —How Argon was recognised as Sovereign | 473 |

|

| Notes.—1. The historical circumstances and persons named in these chapters. 2. Arghún’s accession and death. | ||

| —How Kiacatu seized the Sovereignty after Argon’s Death | 475 |

|

| Note.—The reign and character of Kaikhátú. | ||

| —How Baidu seized the Sovereignty after the Death of Kiacatu | 476 |

|

| Notes.—1. Baidu’s alleged Christianity. 2. Gházán Khan. | ||

| —Concerning King Conchi who rules the Far North | 479 |

|

| Notes.—1. Kaunchi Khan. 2. Siberia. 3. Dog-sledges. 4. The animal here styled Erculin. The Vair. 5. Yugria. | ||

| —Concerning the Land of Darkness | 484 |

|

| Notes.—1. The Land of Darkness. 2. The Legend of the Mares and their Foals. 3. Dumb Trade with the People of the Darkness. | ||

| —Description of Rosia and its People. Province of Lac | 486 |

|

| Notes.—1. Old Accounts of Russia. Russian Silver and Rubles. 2. Lac, or Wallachia. 3. Oroech, Norway (?) or the Waraeg Country (?) | ||

| —He begins to speak of the Straits of Constantinople, but decides to leave that matter | 490 |

|

| xiv | —Concerning the Tartars of the Ponent and their Lords | 490 |

| Notes.—1. The Comanians; the Alans; Majar; Zic; the Goths of the Crimea; Gazaria. 2. The Khans of Kipchak or the Golden Horde; errors in Polo’s list. Extent of their Empire. | ||

| —Of the War that arose between Alau and Barca, and the Battles that they fought | 494 |

|

(Extracts and Substance.) |

||

| Notes.—1. Verbal. 2. The Sea of Sarai. 3. The War here spoken of. Wassáf’s rigmarole. | ||

| —†How Barca and his Army advanced to meet Alau | 495 |

|

| —†How Alau addressed his followers | 495 |

|

| —†Of the Great Battle between Alau and Barca | 496 |

|

| —How Totamangu was Lord of the Tartars of the Ponent; and after him Toctai | 496 |

|

| Note.—Confusions in the Text. Historical circumstances connected with the Persons spoken of. Toctai and Noghai Khan. Symbolic Messages. | ||

| —†Of the Second Message that Toctai sent to Nogai | 498 |

|

| —†How Toctai marched against Nogai | 499 |

|

| —†How Toctai and Nogai address their People, and the next Day join Battle | 499 |

|

| —†The Valiant Feats and Victory of King Nogai | 499 |

|

| —and Last. Conclusion | 500 |

| To face page | |

|---|---|

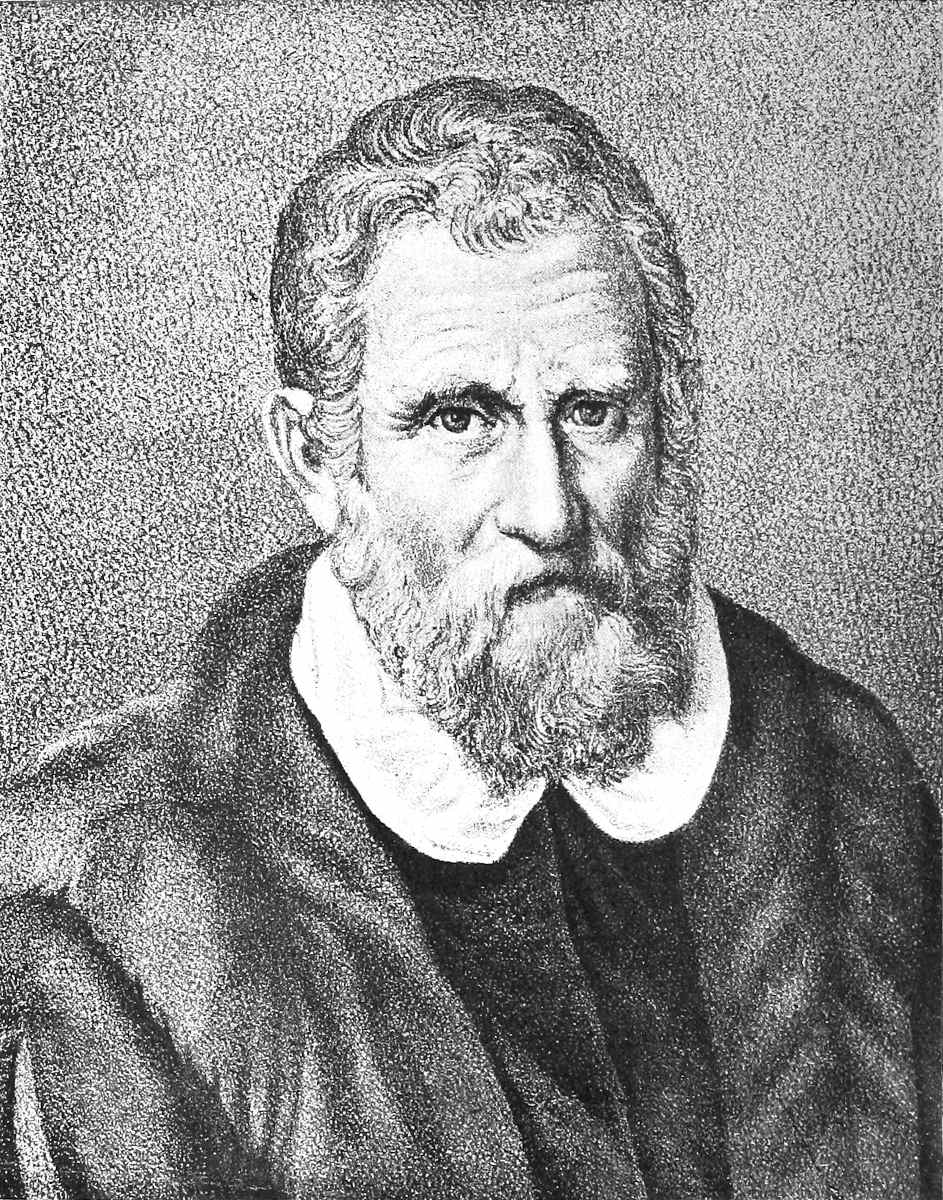

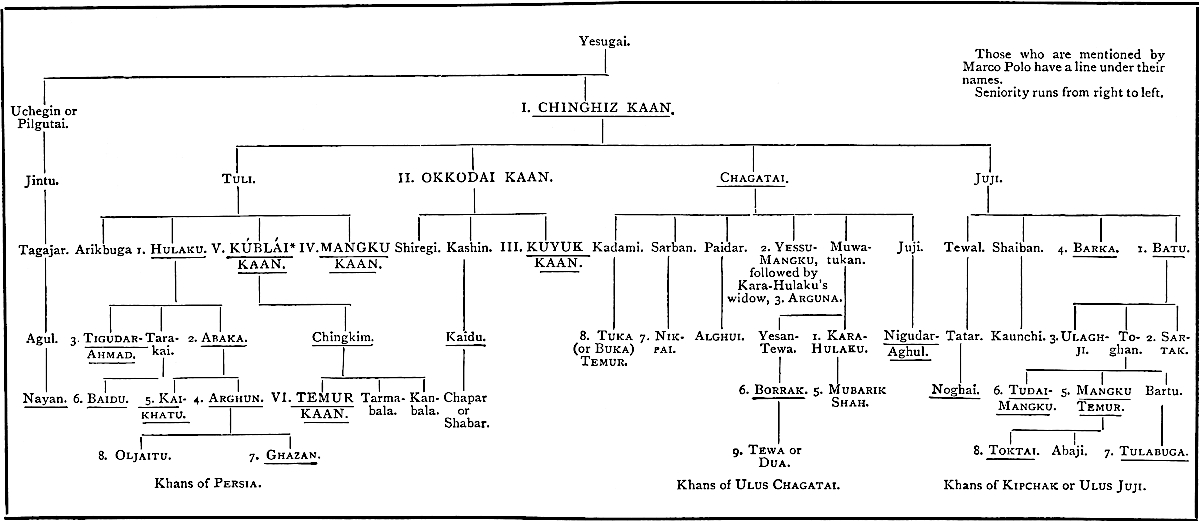

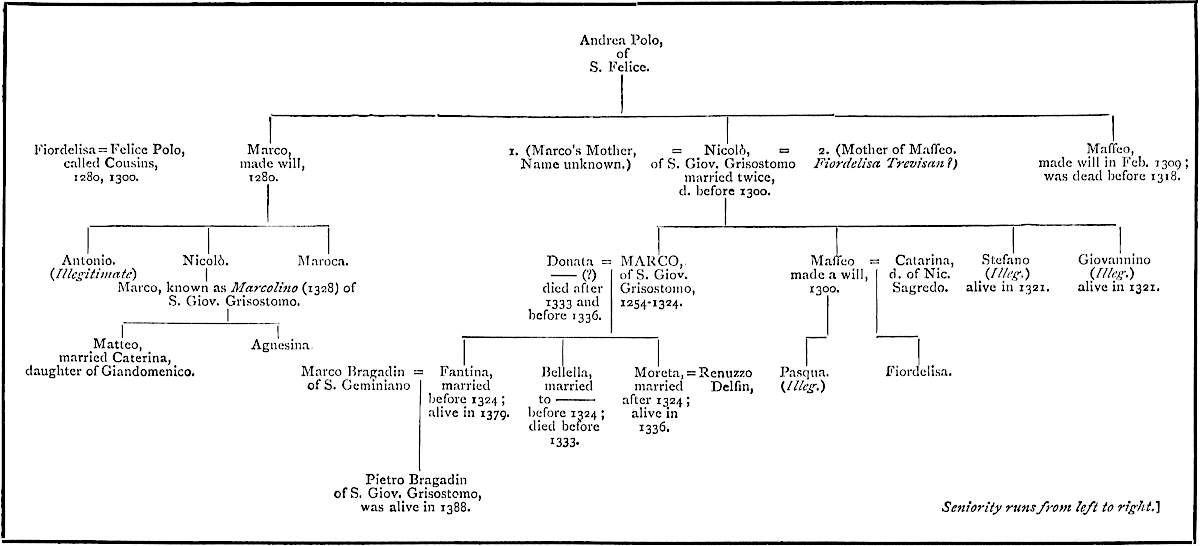

| Portrait bearing the inscription “Marcus Polvs Venetvs Totivs Orbis et Indie Peregrator Primvs.” In the Gallery of Monsignor Badia at Rome; copied by Sign. Giuseppe Gnoli, Rome. | |

| Medallion, representing Marco Polo in the Prison of Genoa, dictating his story to Master Rustician of Pisa, drawn by Signor Quinto Cenni from a rough design by Sir Henry Yule. | |

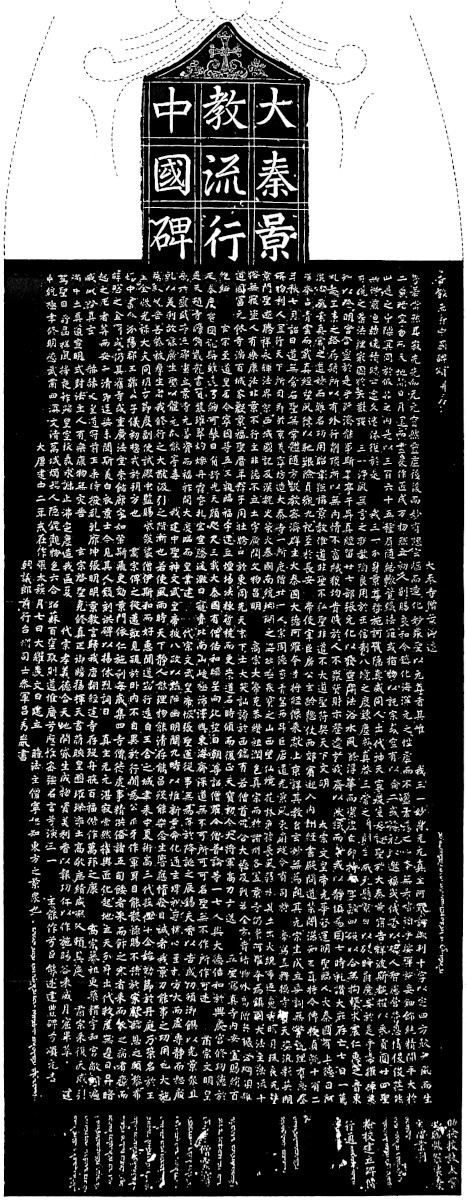

| The celebrated Christian Inscription of Si-ngan fu.

Photolithographed by Mr. W. Grigg, from a Rubbing of the

original monument, given to the Editor by the Baron F. von

Richthofen.

This rubbing is more complete than that used in the first edition, for which the Editor was indebted to the kindness of William Lockhart, Esq. |

|

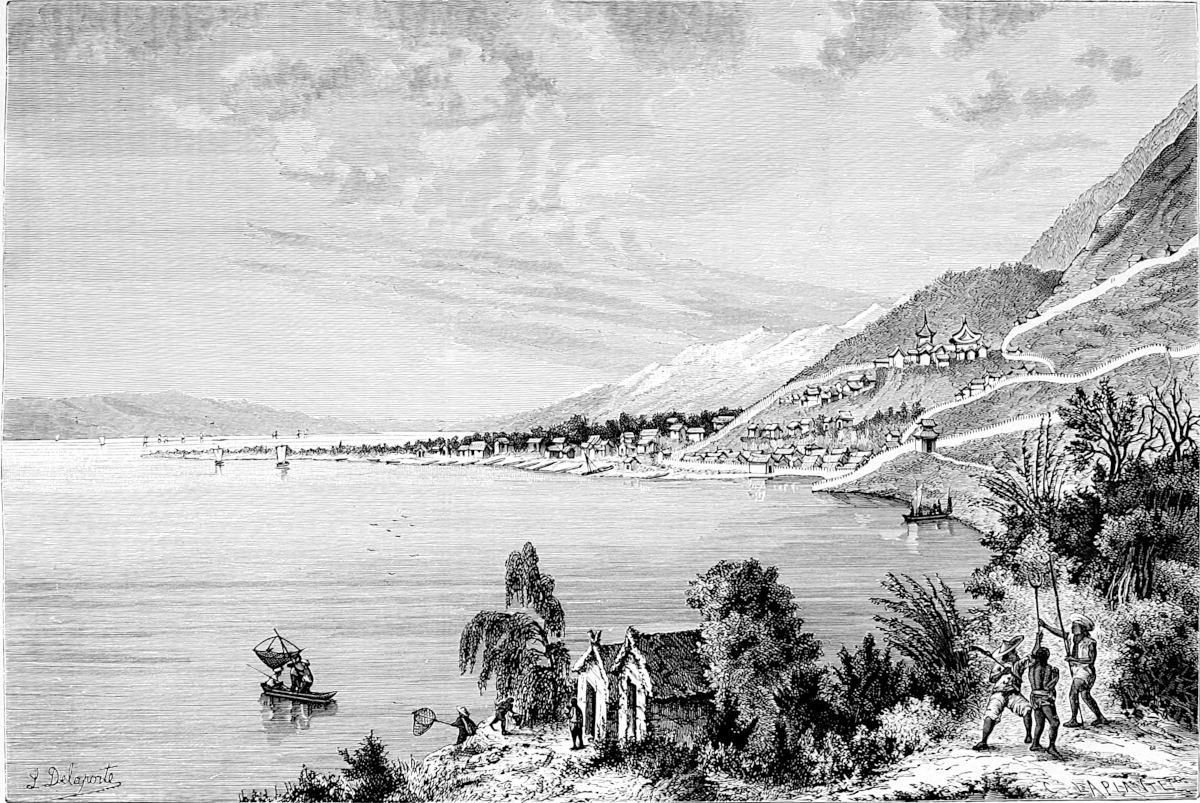

| The Lake of Tali (Carajan of Polo) from the Northern End. Woodcut after Lieut. Delaporte, borrowed from Lieut. Garnier’s Narrative in the Tour du Monde. | |

| Suspension Bridge, neighbourhood of Tali. From a photograph by M. Tannant. | |

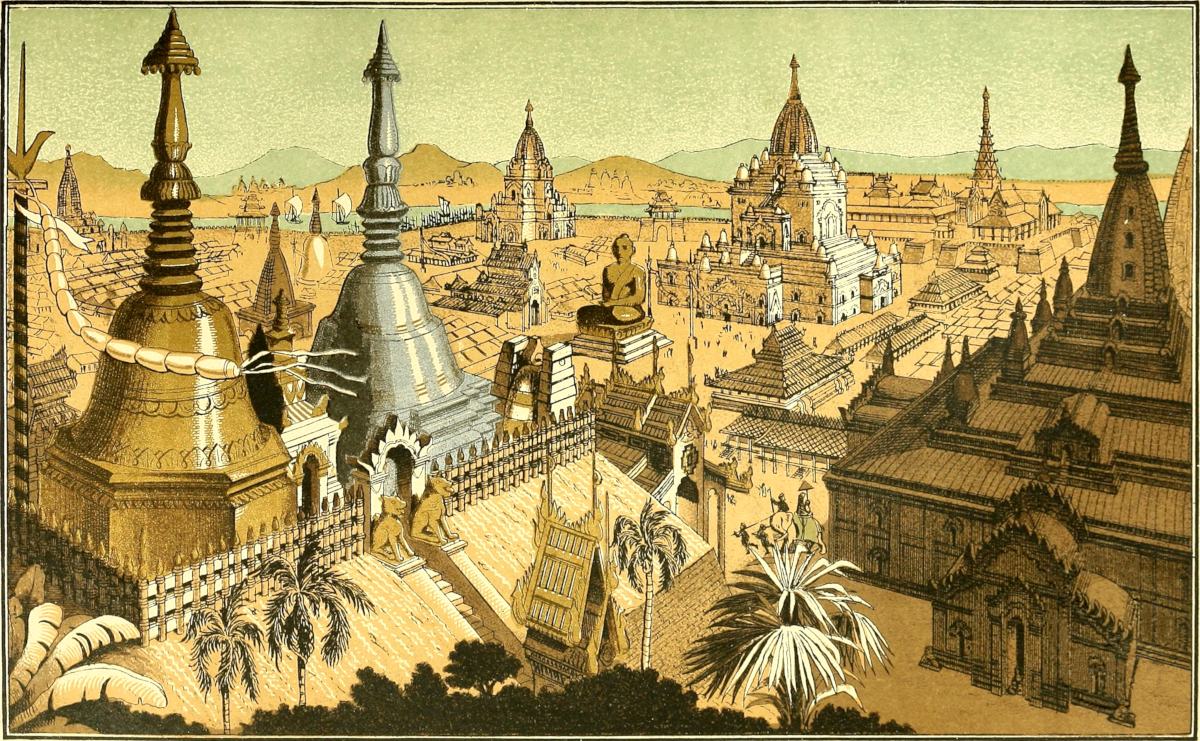

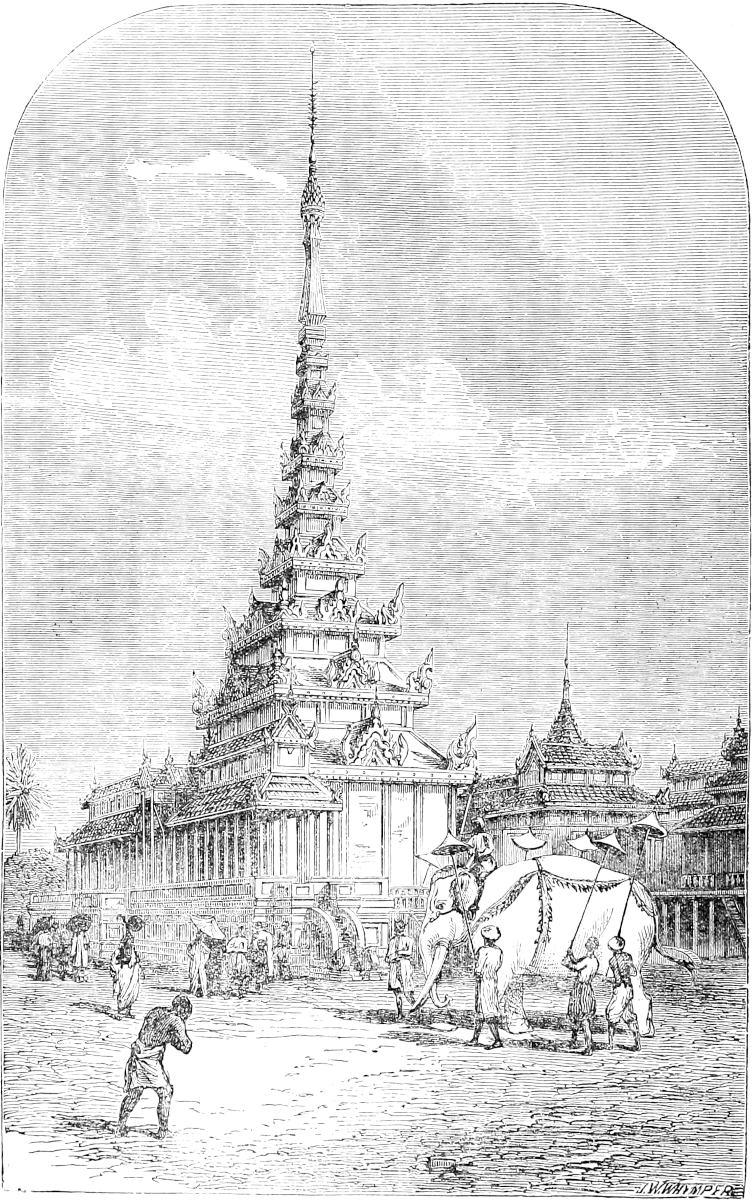

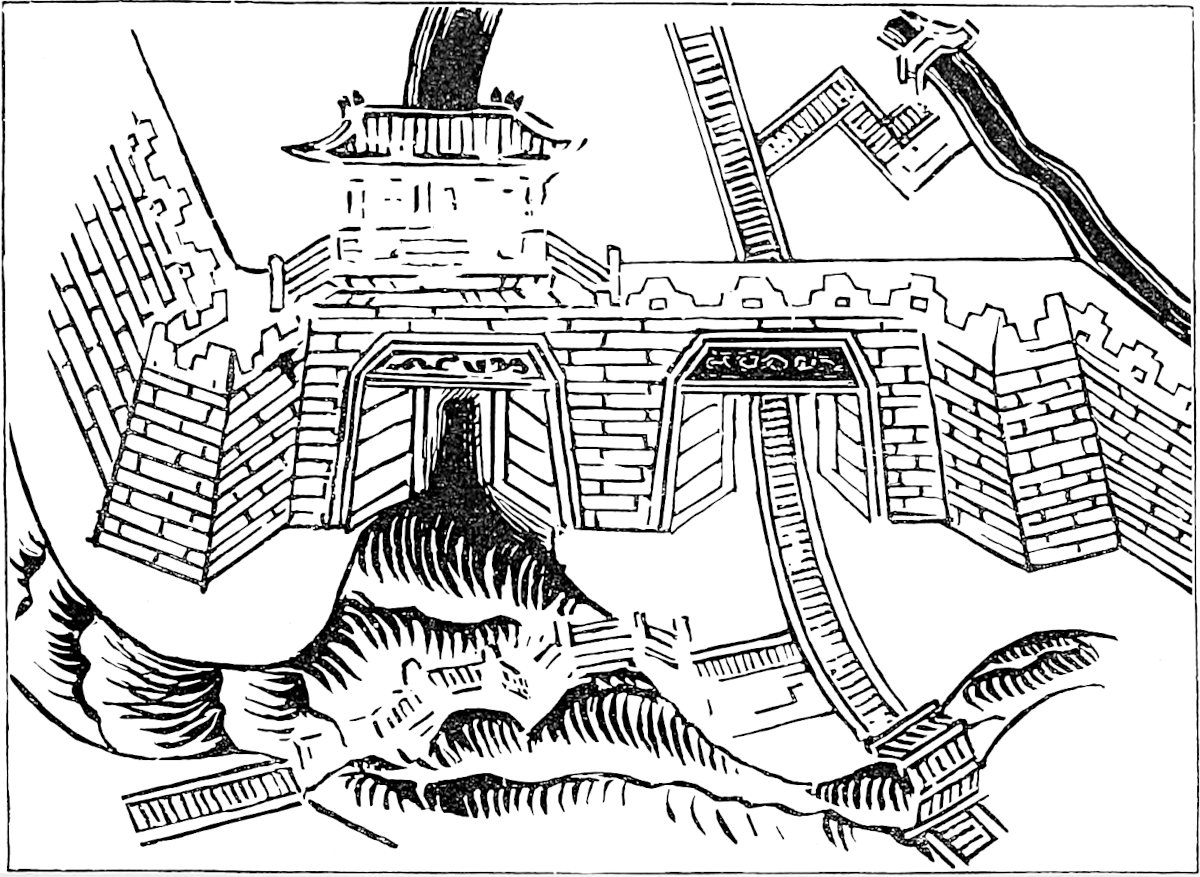

| The City of Mien, with the Gold and Silver Towers. From a drawing by the Editor, based upon his sketches of the remains of the City so called by Marco Polo, viz., Pagán, the mediæval capital of Burma. | |

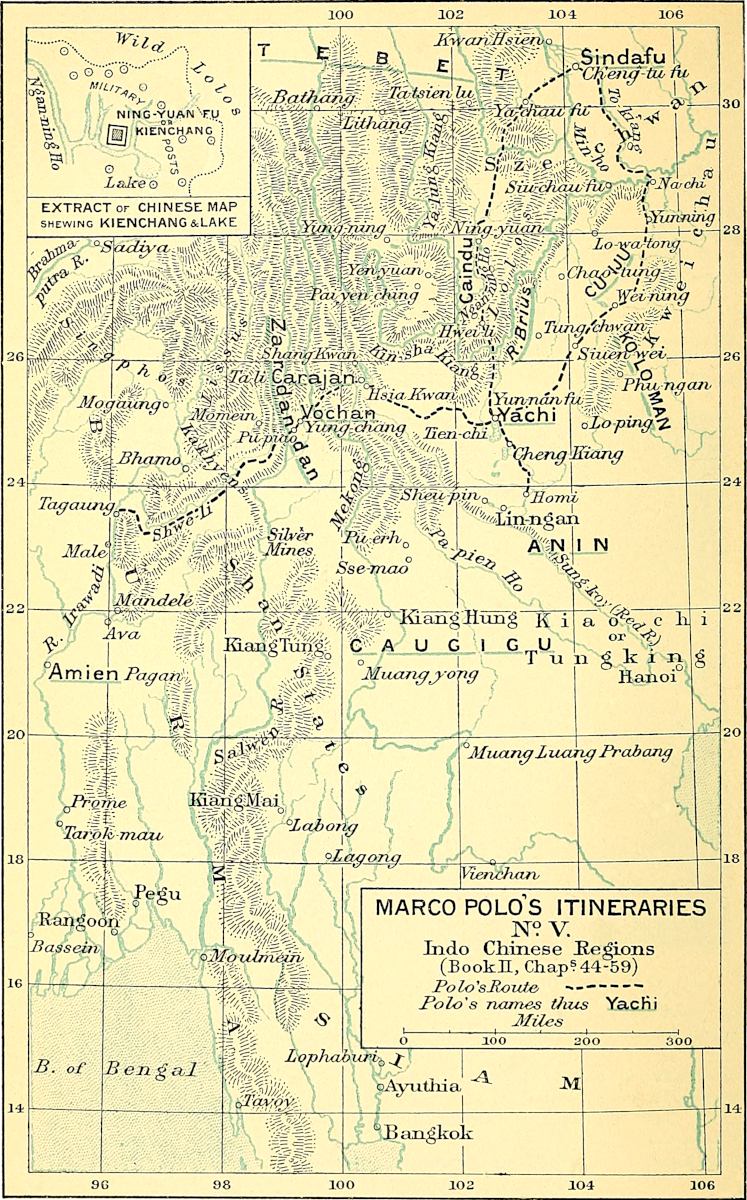

| Itineraries of Marco Polo. No. V. The Indo-Chinese Countries. With a small sketch extracted from a Chinese Map in the possession of Baron von Richthofen, showing the position of Kien-ch’ang, the Caindu of Marco Polo. | |

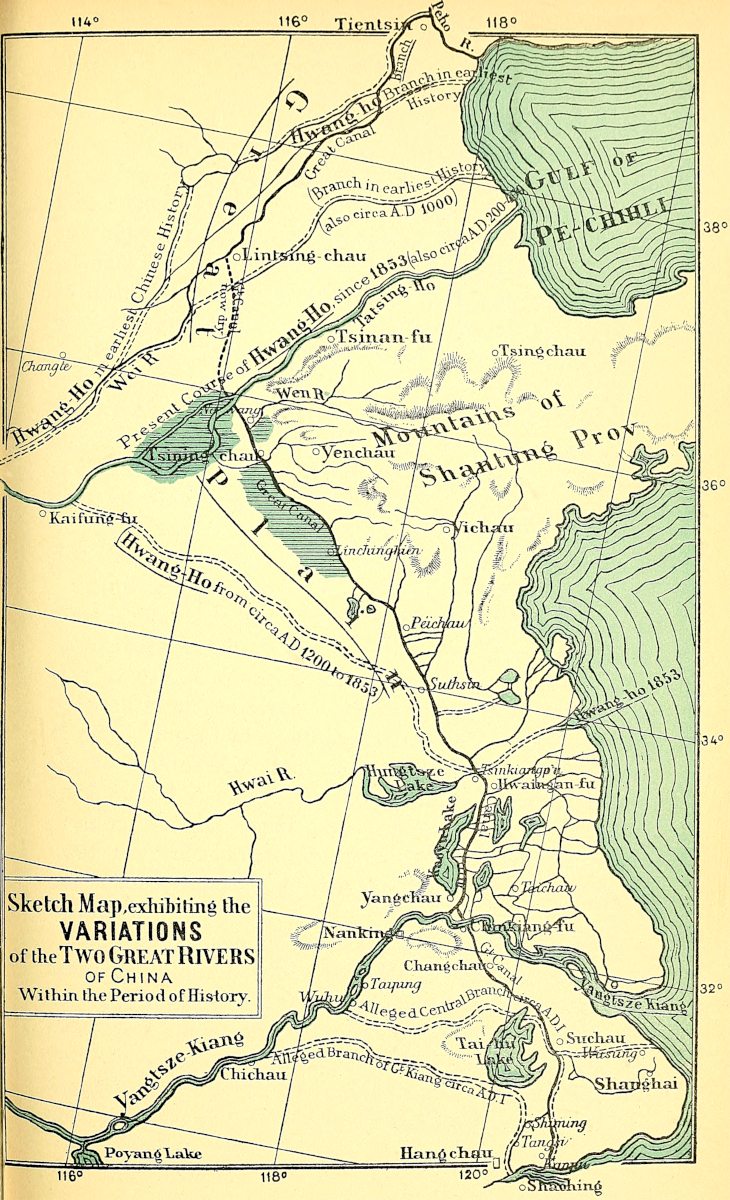

| Sketch Map exhibiting the Variations of the Two Great Rivers of China, within the Period of History. | |

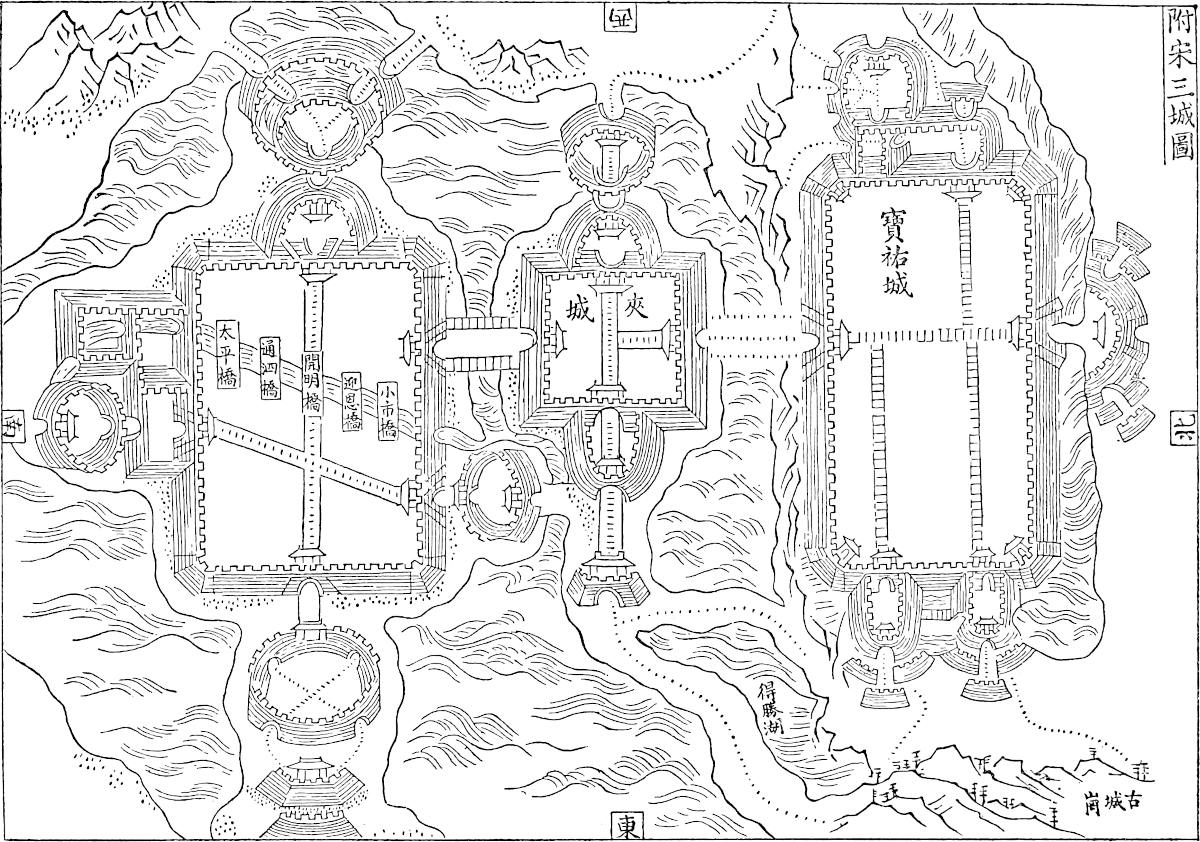

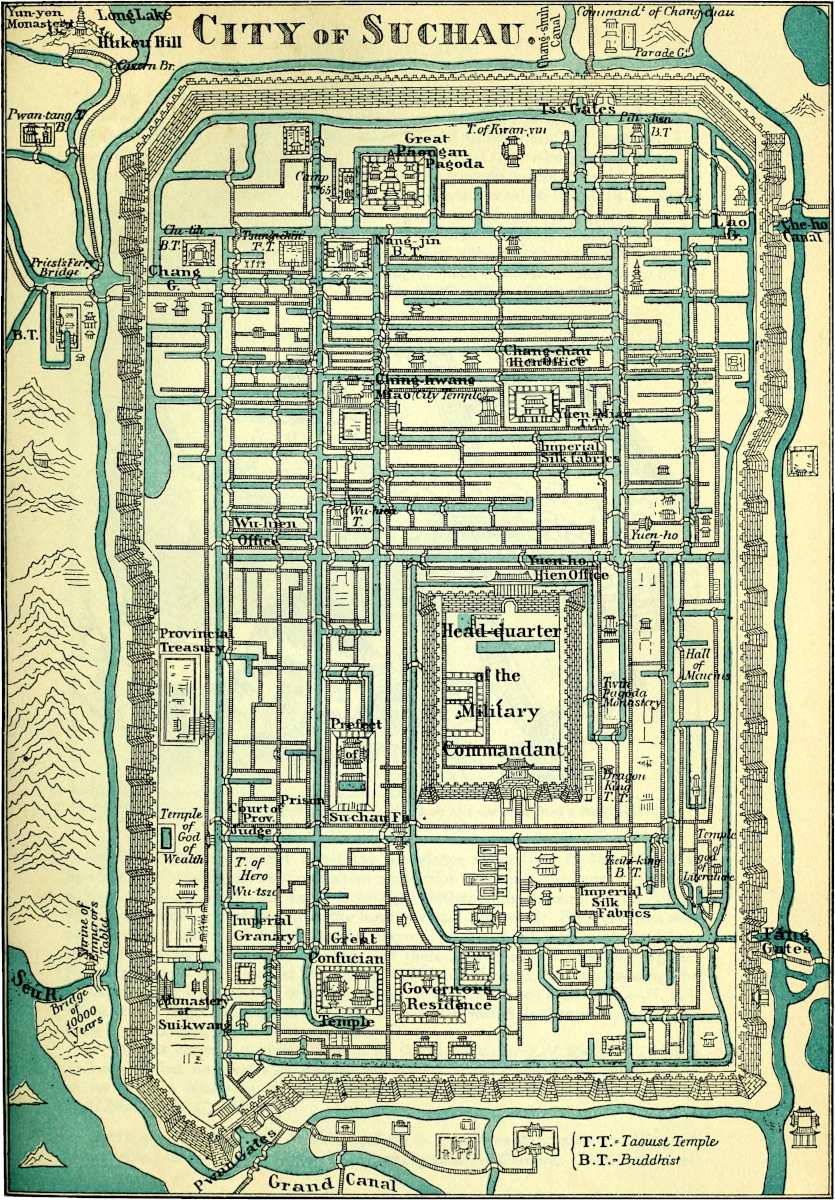

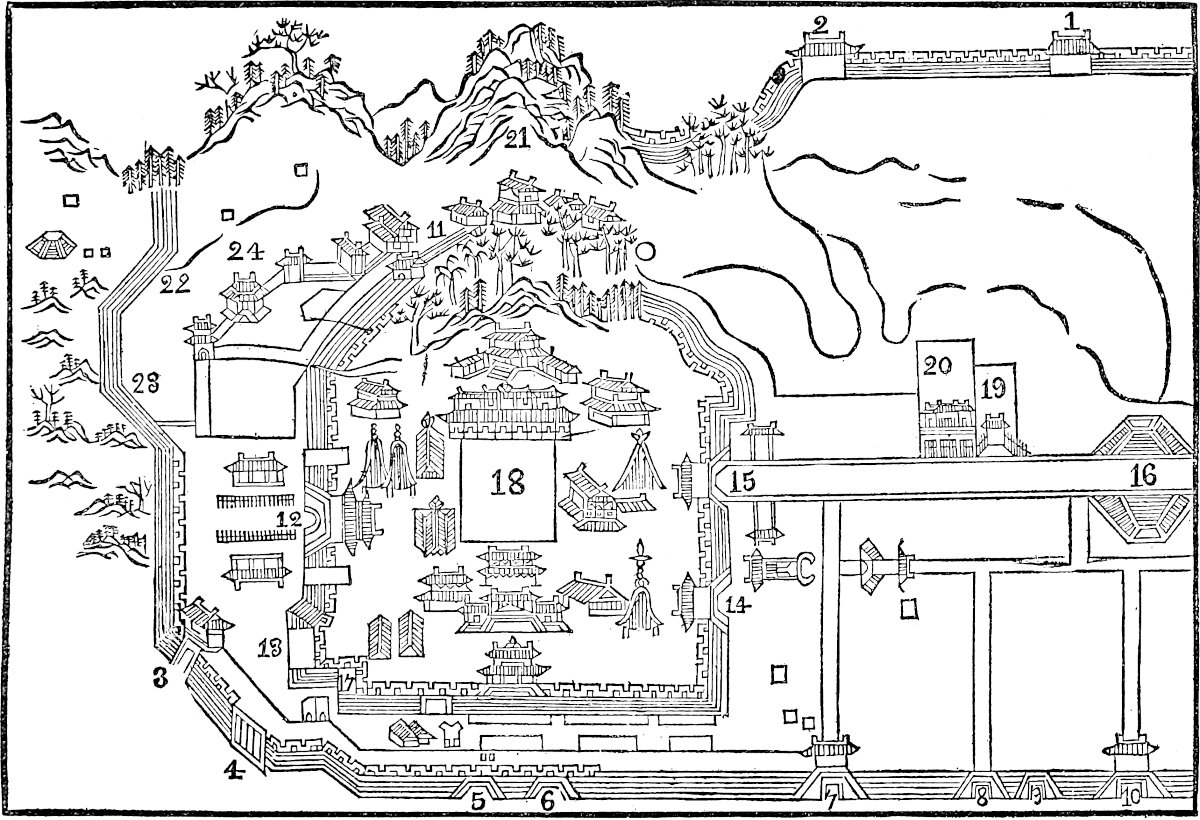

| The City of Su-chau. Reduced by the Editor from a Rubbing

of a Plan incised on Marble, and preserved in the Great

Confucian Temple in the City.

The date of the original set of Maps, of which this was one, is uncertain, owing to the partial illegibility of the Inscription; but it is subsequent to A.D. 1000. They were engraved on the Marble A.D. 1247. Many of the names have been obliterated, and a few of those given in the copy are filled up from modern information, as the Editor learns from Mr. Wylie, to whom he owes this valuable illustration. |

|

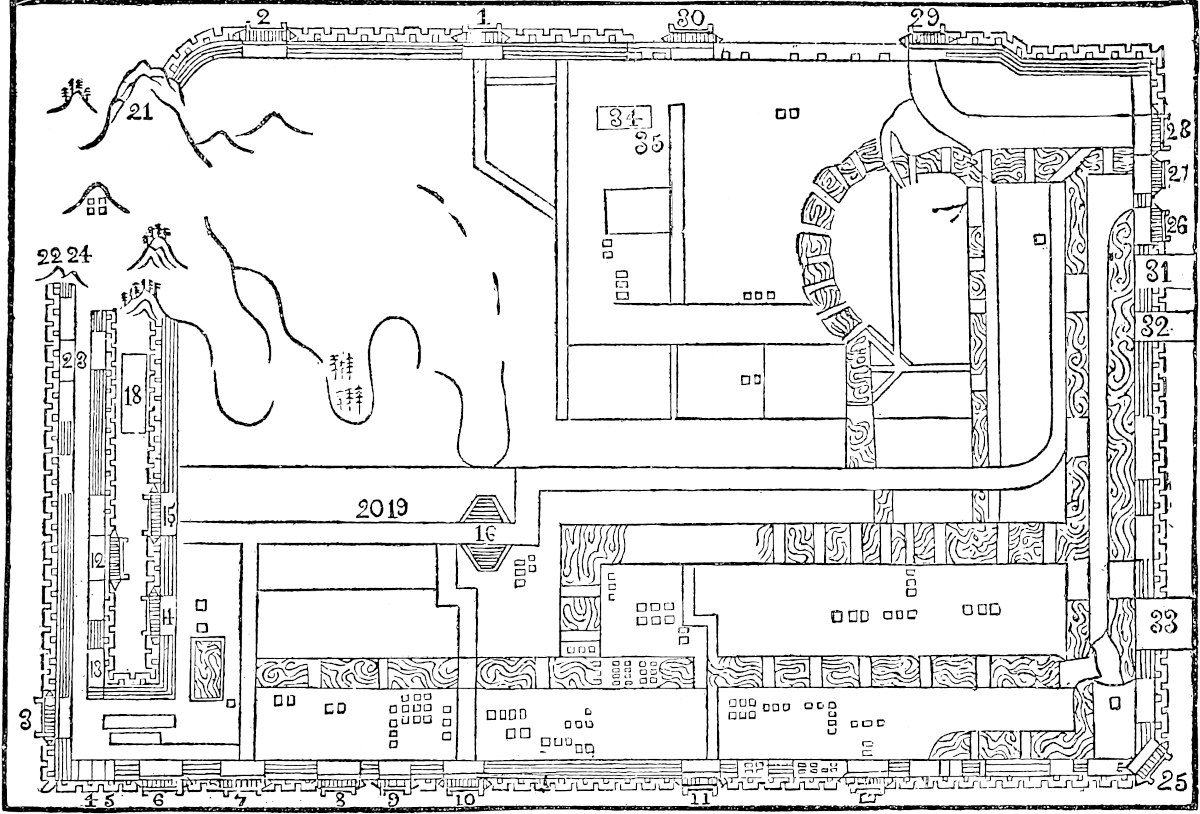

Map of Hang-chau fu and its Lake,

from Chinese Sources.

The Map as published in the former edition was based on a Chinese Map in the possession of Dr. W. Lockhart, with xviisome particulars from Maps in a copy of the Local Topography, Hang-Chau-fu-chi, in the B. Museum Library. In the second edition the Map has been entirely redrawn by the Editor, with many corrections, and with the aid of new materials, supplied by the kindness of the Rev. G. Moule of the Church Mission at Hang-chau. These materials embrace a Paper read by Mr. Moule before the N. China Branch of the R. As. Soc. at Shang-hai; a modern engraved Map of the City on a large scale; and a large MS. Map of the City and Lake, compiled by John Shing, Tailor, a Chinese Christian and Catechist; The small Side-plan is the City of Si-ngan fu, from a plan published during the Mongol rule, in the 14th century, a tracing of which was sent by Mr. Wylie. The following references could not be introduced in lettering for want of space:—

N.B.—The shaded spaces are marked in the original Min-Keu “Dwellings of the People.” |

|

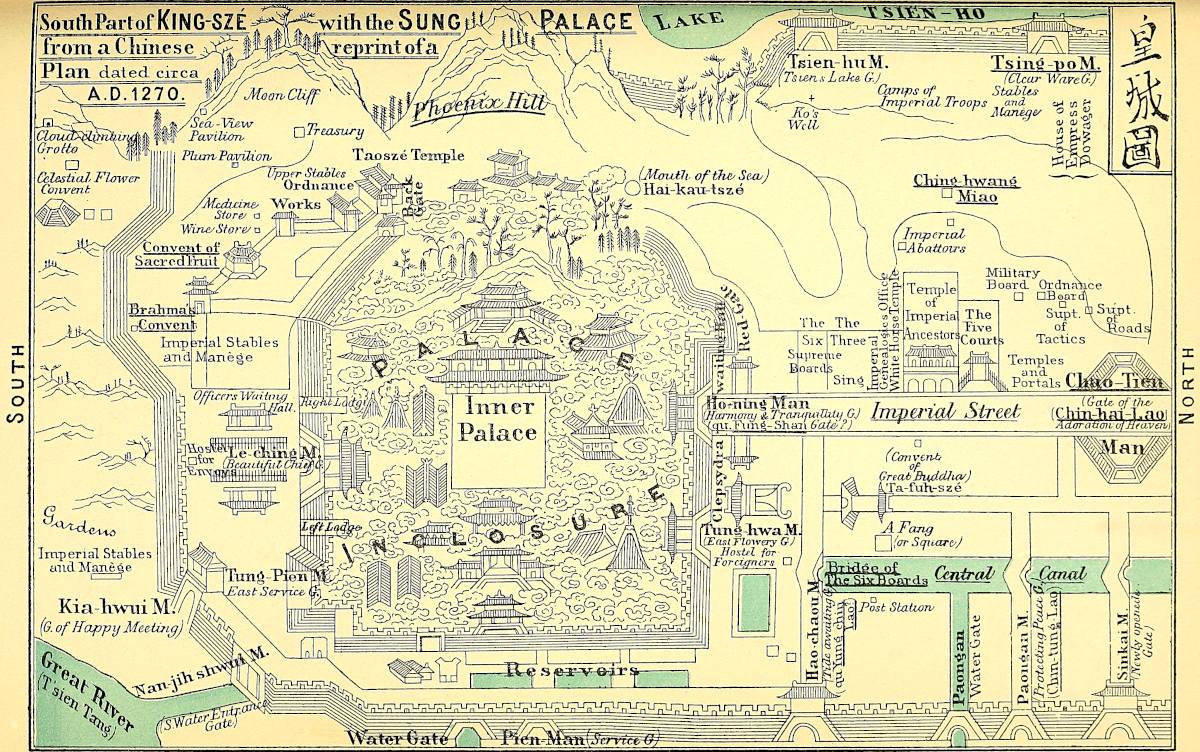

| Plan of Southern Part of the City of King-szé (or Hang-chau), with the Palace of the Sung Emperors. From a Chinese Plan forming part of a Reprint of the official Topography of the City during the period Hien-Shun (1265–1274) of the Sung Dynasty, i.e. the period terminated by the Mongol conquest of the City and Empire. Mr. Moule, who possesses the Chinese plan (with others of the same set), has come to the conclusion that it is a copy at second-hand. Names that are underlined are such as are preserved in the modern Map of Hang-chau. I am indebted for the use of the original plan to Mr. Moule; for the photographic copy and rendering of the names to Mr. Wylie. | |

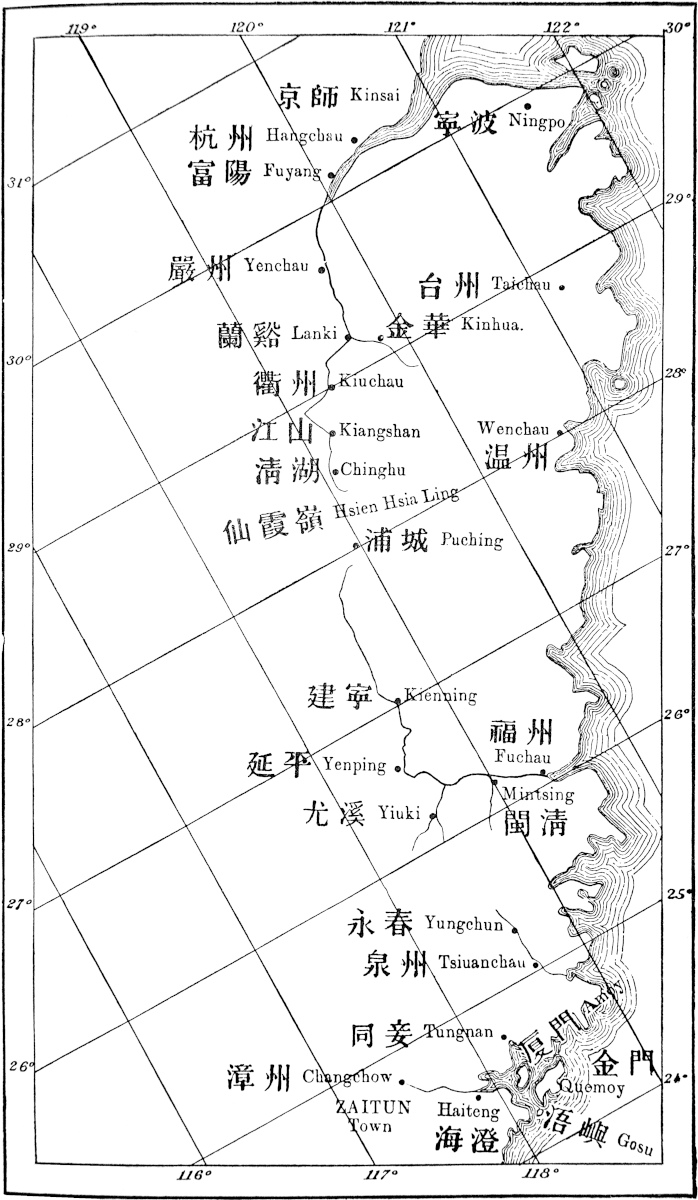

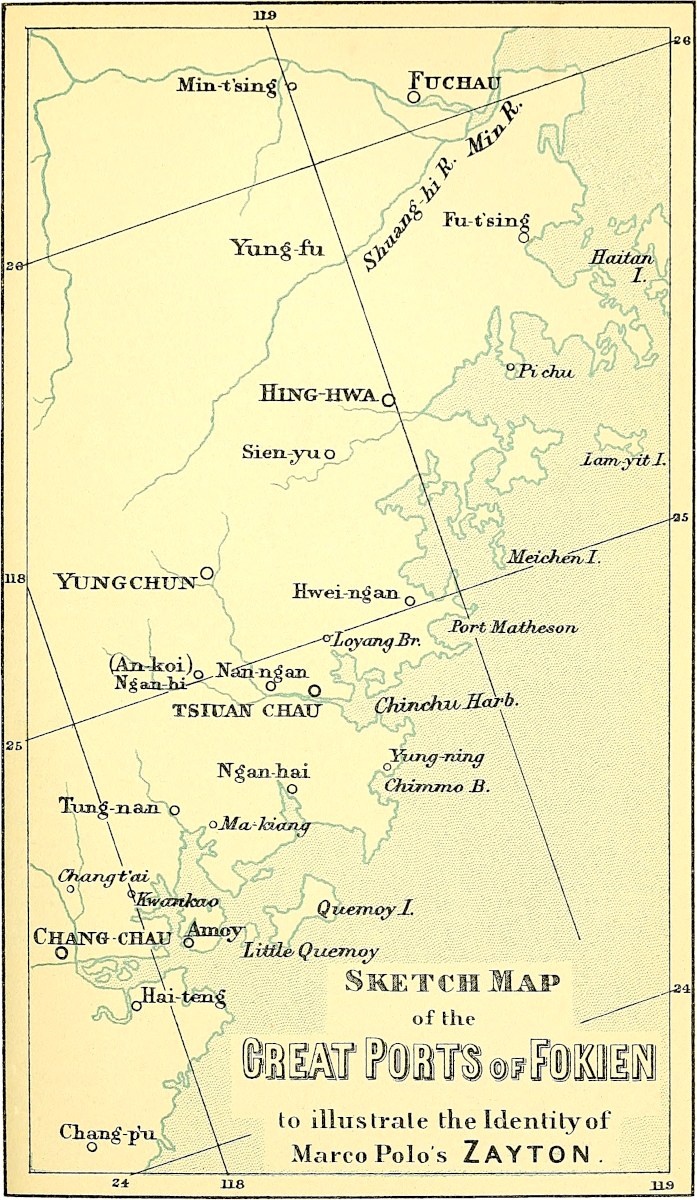

| Sketch Map of the Great Ports of Fo-kien, to illustrate the identity of Marco Polo’s Zayton. Besides the Admiralty Charts and other well-known sources the Editor has used in forming this a “Missionary Map of Amoy and the Neighbouring Country,” on a large scale, sent him by the Rev. Carstairs Douglas, LL.D., of Amoy. This contains some points not to be found in the others. | |

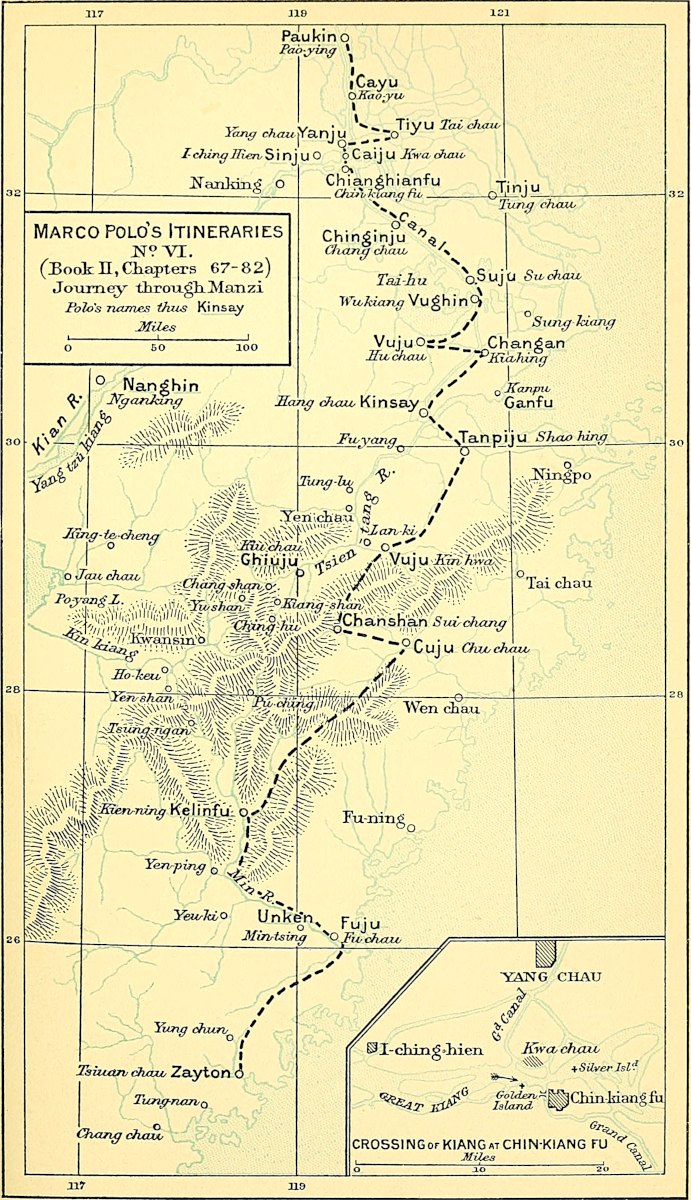

| xviii | Itineraries of Marco Polo, No. VI. The Journey through Kiang-Nan, Che-kiang, and Fo-kien. |

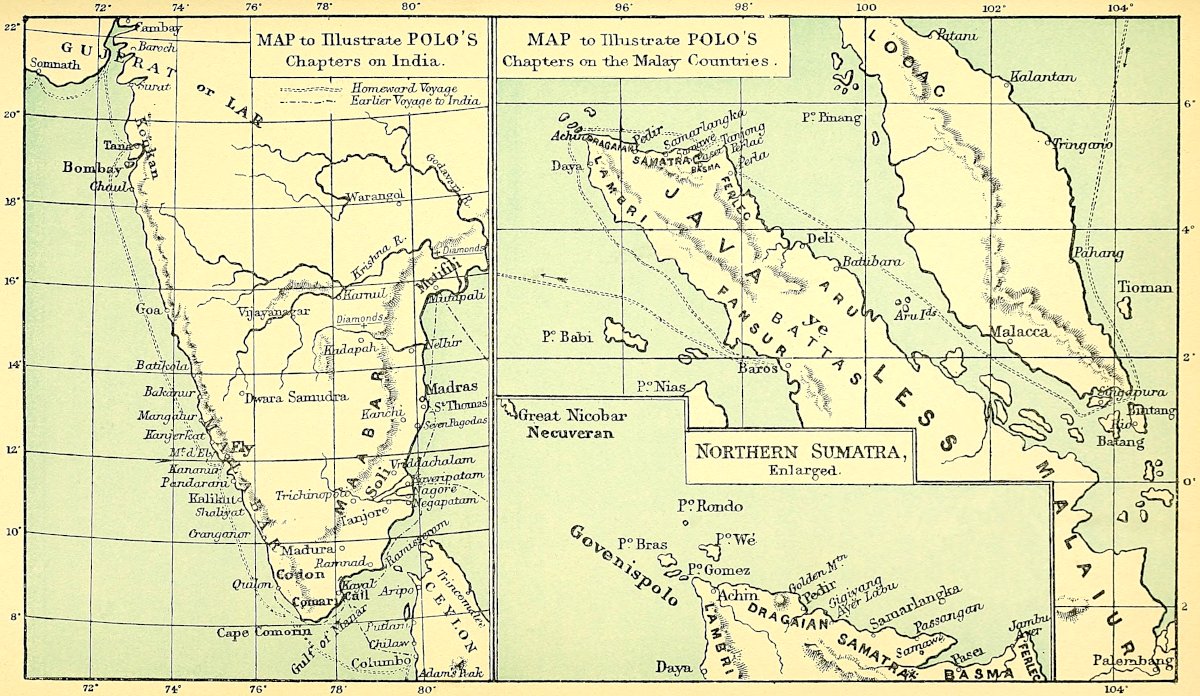

| 1. Map to illustrate Marco Polo’s Chapters on the Malay Countries. 2. Map to illustrate his Chapters on Southern India. |

|

| 1. Sketch showing the Position of Káyal in Tinnevelly. 2. Map showing the Position of the Kingdom of Ely in Malabar. |

|

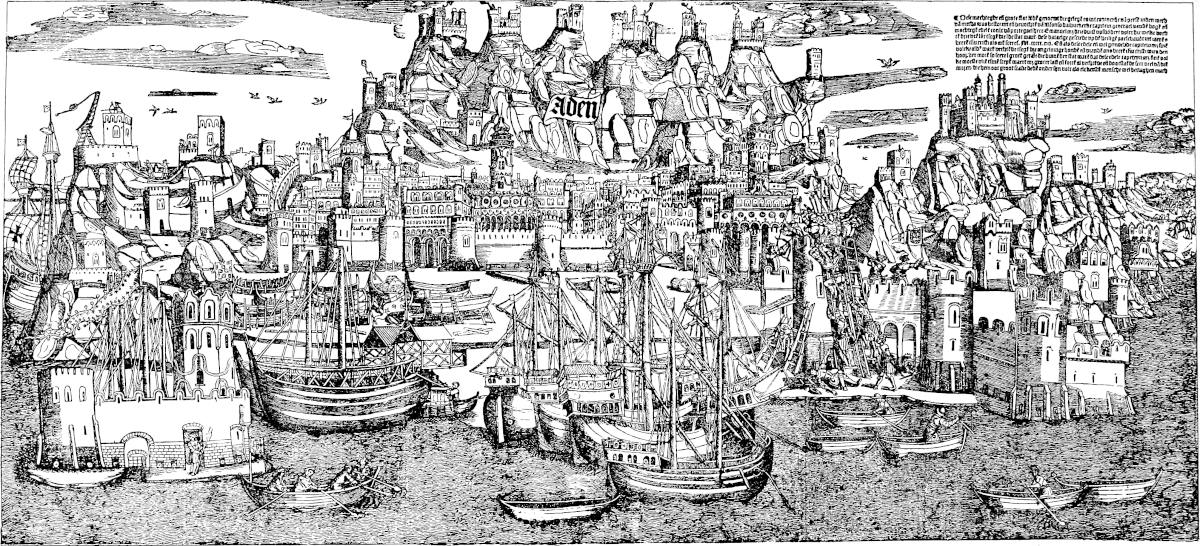

| Aden, with the attempted Escalade under Alboquerque in 1513, being the Reduced Facsimile of a large contemporary Wood Engraving in the Map Department of the British Museum. (Size of the original 42½ inches by 19⅛ inches.) Photolithographic Reduction by Mr. G. B. Praetorius, through the assistance of R. H. Major, Esq. | |

| Facsimile of the Letters sent to Philip the Fair, King of France, by Arghún Khan, in A.D. 1289, and by Oljaïtu, in A.D. 1305, preserved in the Archives of France, and reproduced from the Recueil des Documents de l’Époque Mongole by kind permission of H.H. Prince Roland Bonaparte. | |

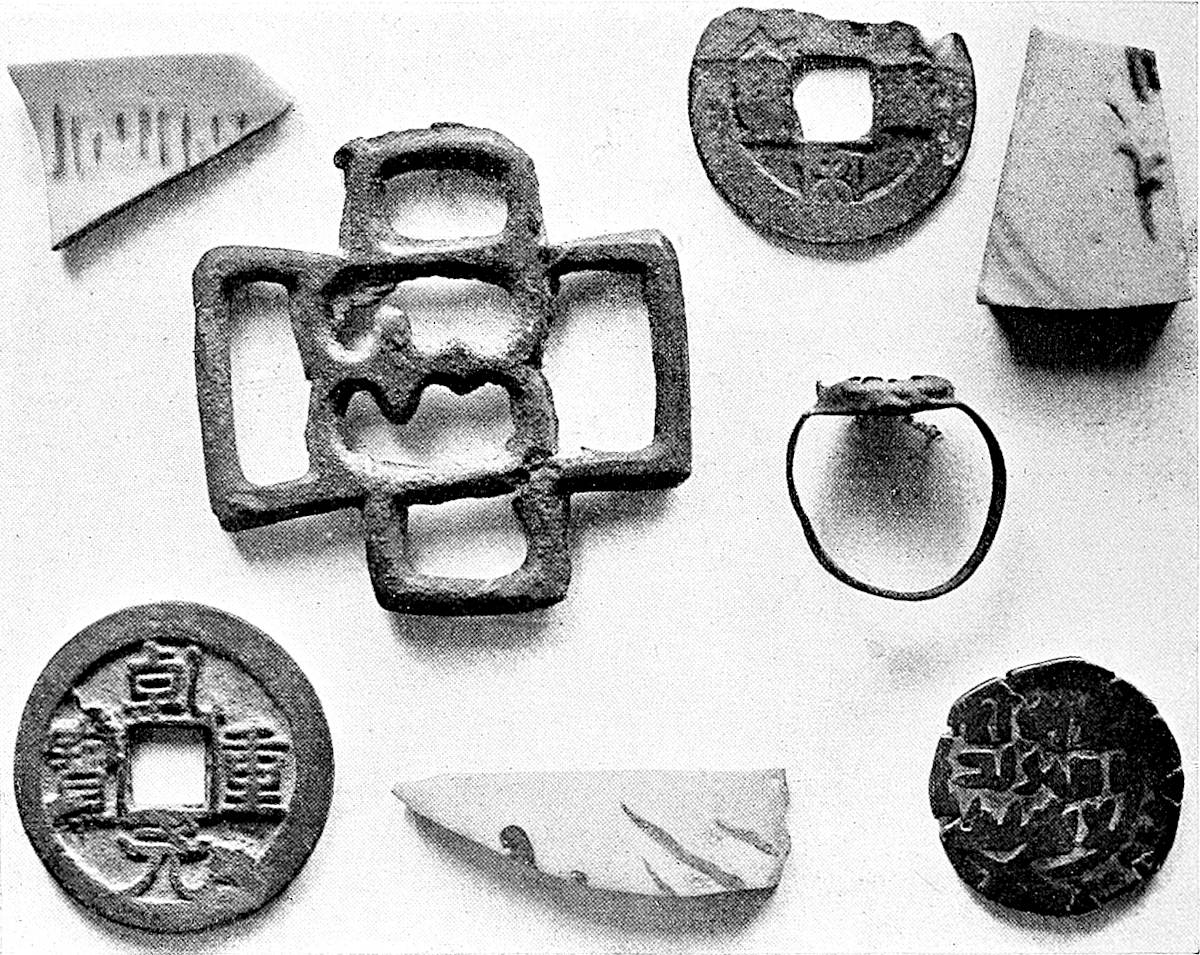

| Some of the objects found by Dr. M. A. Stein, in Central Asia. From a photograph kindly lent by the Traveller. |

Page |

|

|---|---|

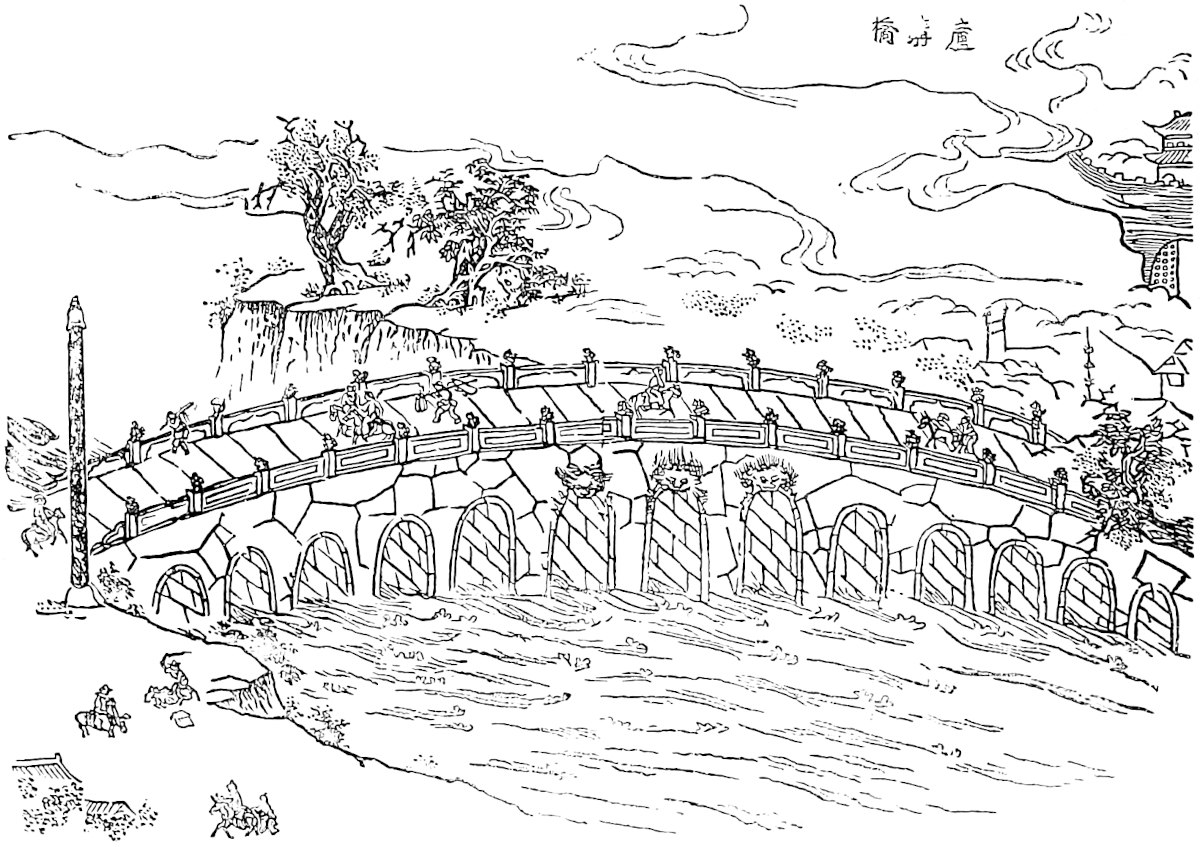

| The Bridge of Pulisanghin, the Lu-ku-k’iao of the Chinese, reduced from a large Chinese Engraving in the Geographical work called Ki-fu-thung-chi in the Paris Library. I owe the indication of this, and of the Portrait of Kúblái Kaan in vol. i. to notes in M. Pauthier’s edition. | |

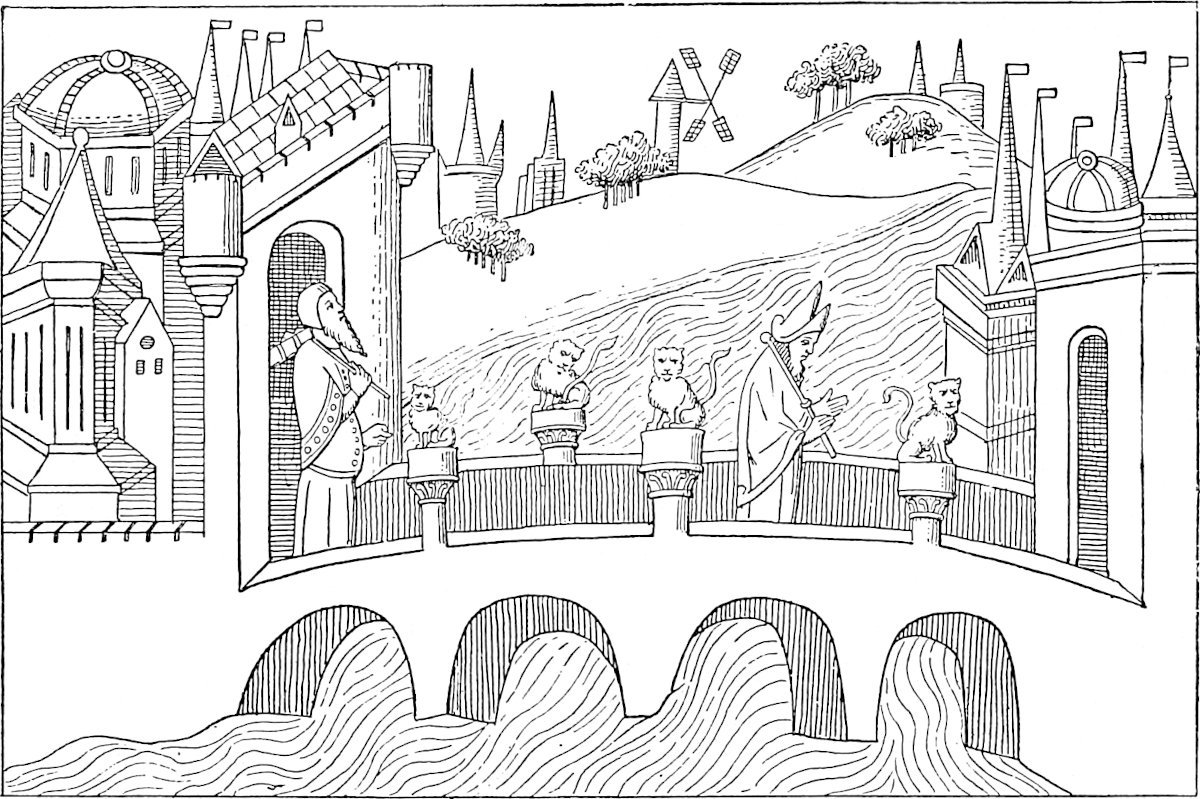

| The Bridge of Pulisanghin. From the Livre des Merveilles. | |

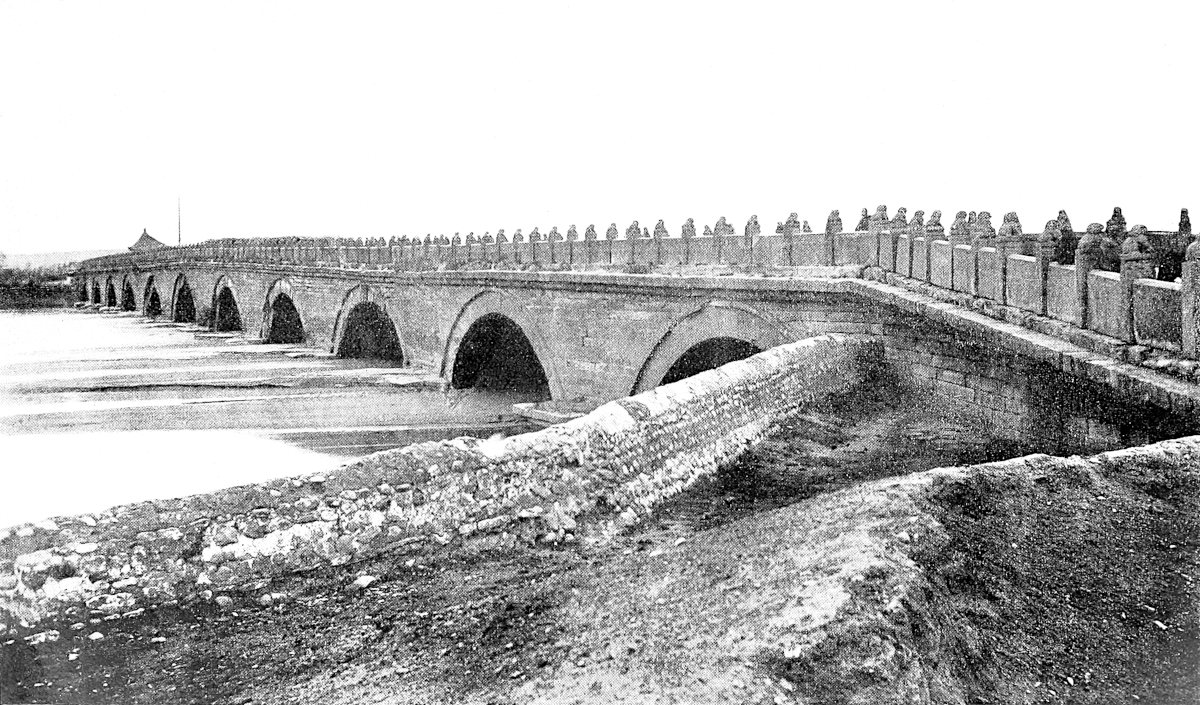

| Bridge of Lu-ku-k’iao. From a photograph by Count de Semallé. | |

| Bridge of Lu-ku-k’iao. From a photograph by Count de Semallé. | |

| The Roi d’Or. Professed Portrait of the Last of the Altun Khans or Kin Emperors of Cathay, from the (fragmentary) Arabic Manuscript of Rashiduddin’s History in the Library of the Royal Asiatic Society. This Manuscript is supposed to have been transcribed under the eye of Rashiduddin, and the drawings were probably derived from Chinese originals. | |

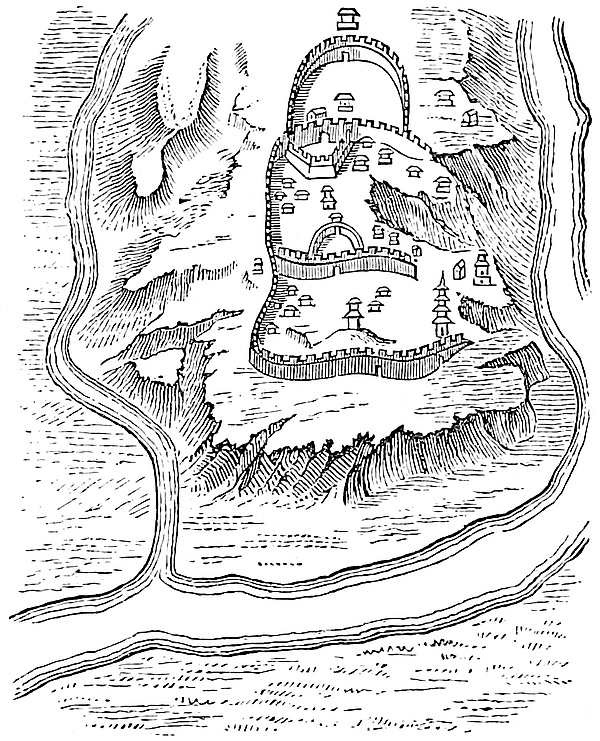

| Plan of Ki-chau, after Duhalde. | |

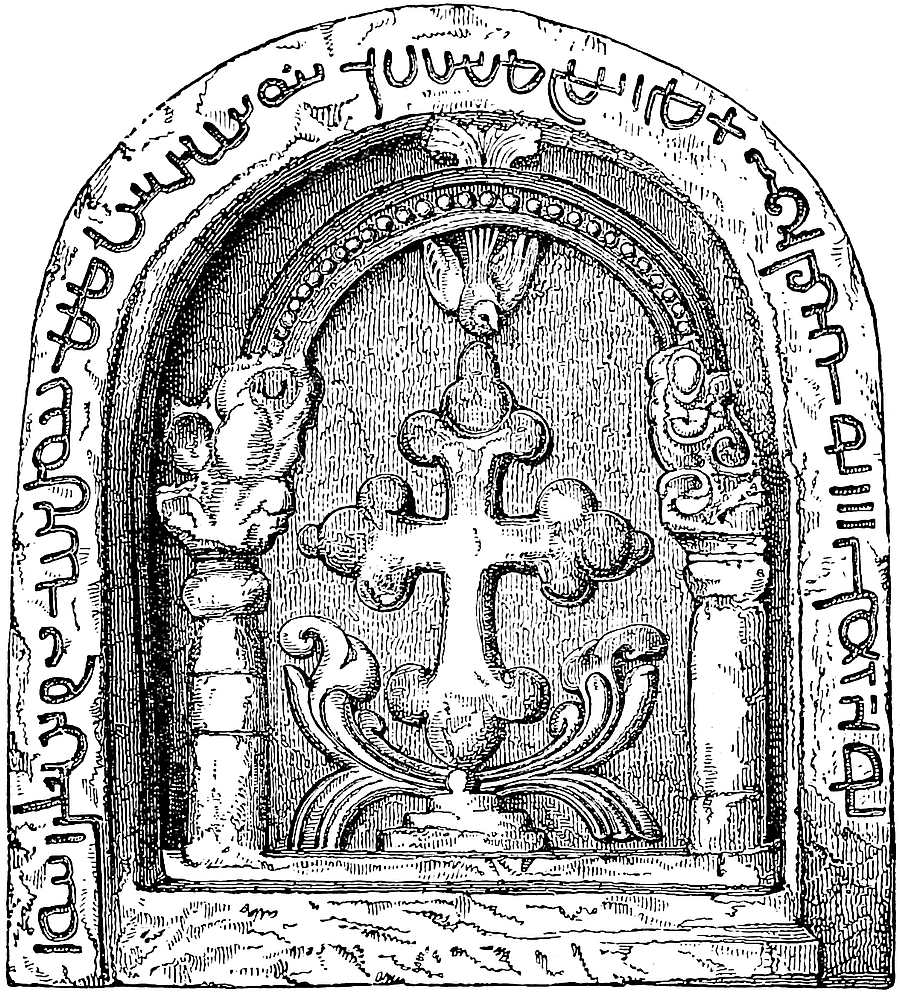

| The Cross incised at the head of the Great Christian Inscription of Si-ngan fu (A.D. 781); actual size, from copy of a pencil rubbing made on the original by the Rev. J. Lees. Received from Mr. A. Wylie. | |

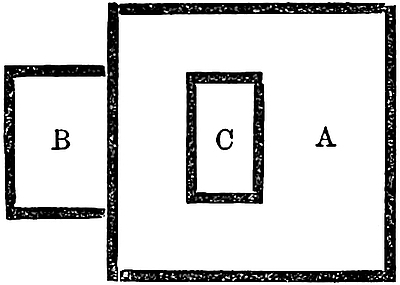

| Diagram to elucidate the cities of Ch’êng-tu fu. | |

| Plan of Ch’êng-tu. From Marcel Monnier’s Tour d’Asie, by kind permission of M. Plon. | |

| Bridge near Kwan-hsien (Ch’êng-tu). From Marcel Monnier’s Tour d’Asie, by kind permission of M. Plon. | |

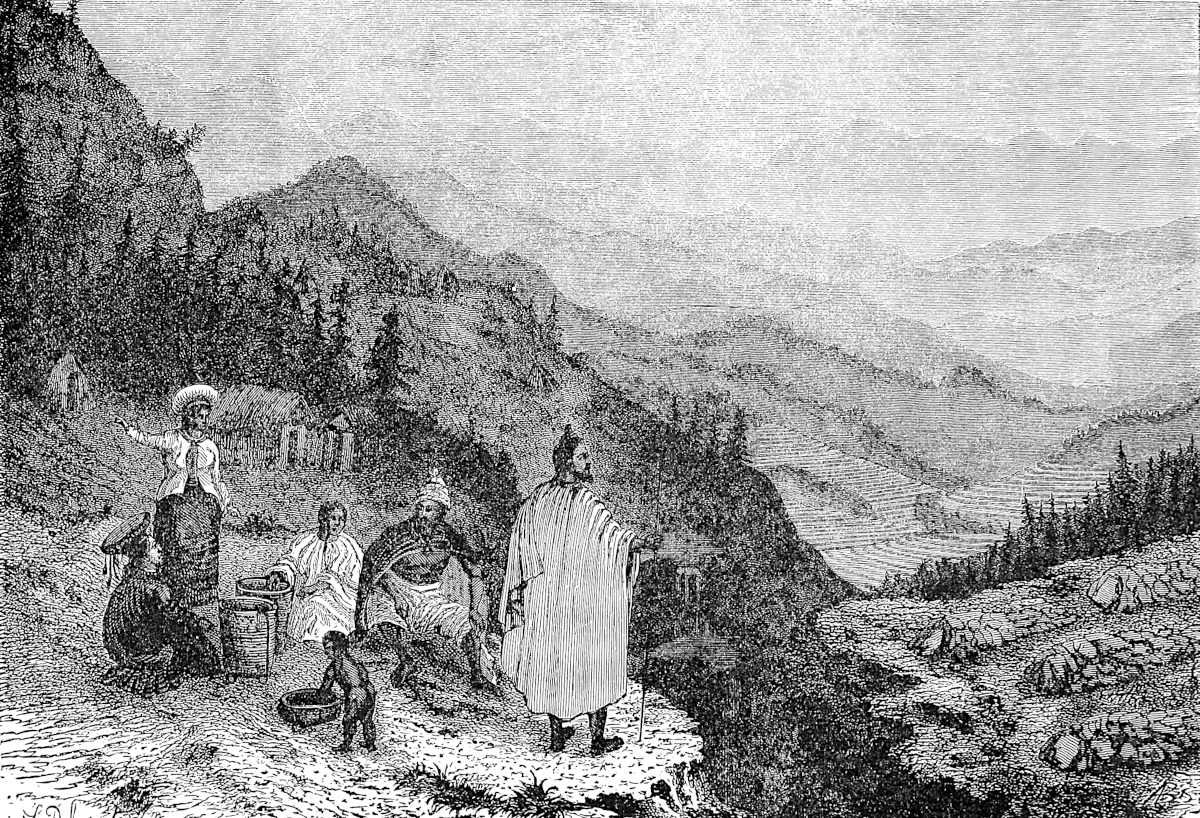

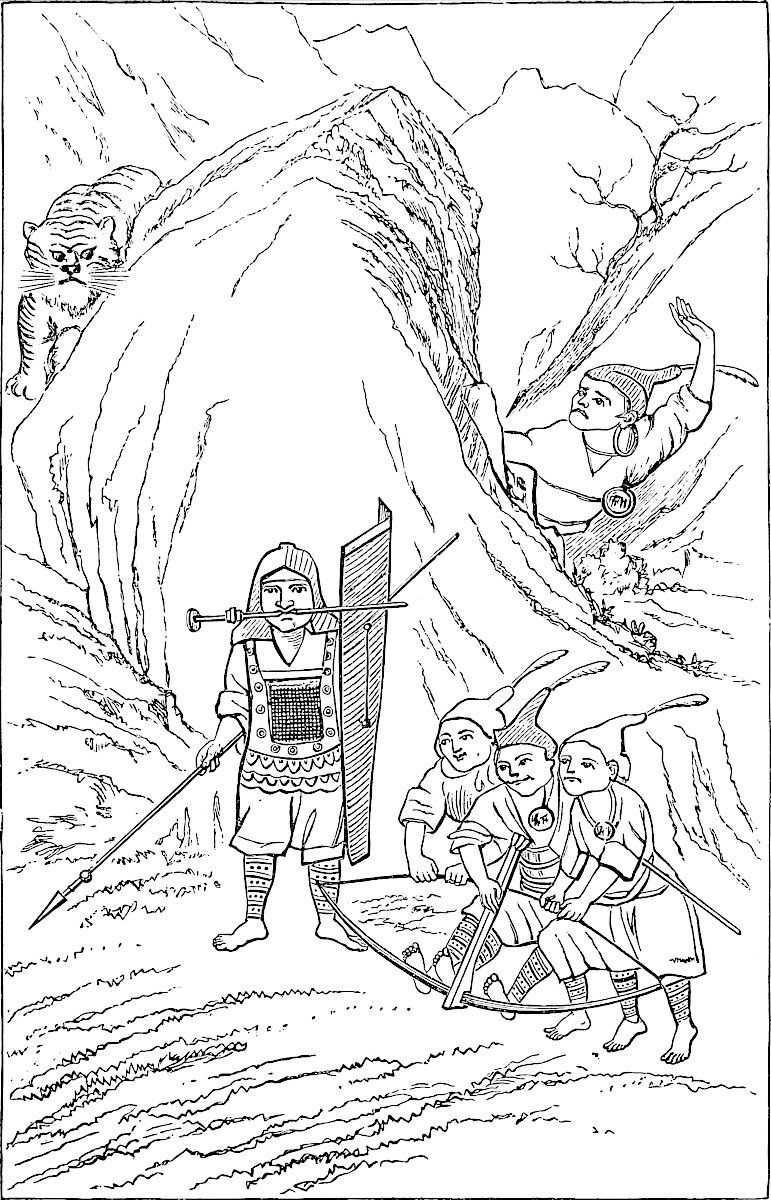

| Mountaineers on the Borders of Sze-ch’wan and Tibet, from one of the illustrations to Lieut. Garnier’s Narrative (see p. 48). From Tour du Monde. | |

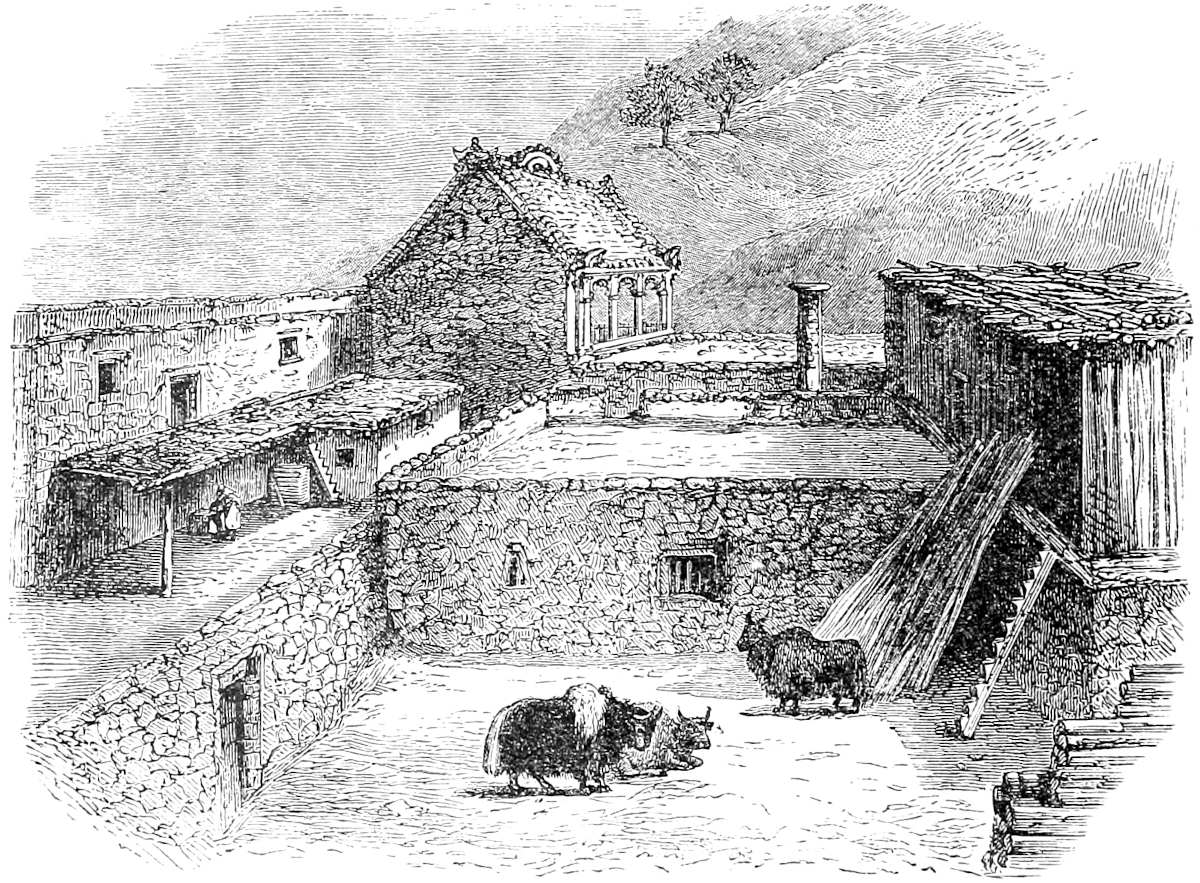

| Village of Eastern Tibet on Sze-ch’wan Frontier. From Mr. Cooper’s Travels of a Pioneer of Commerce. | |

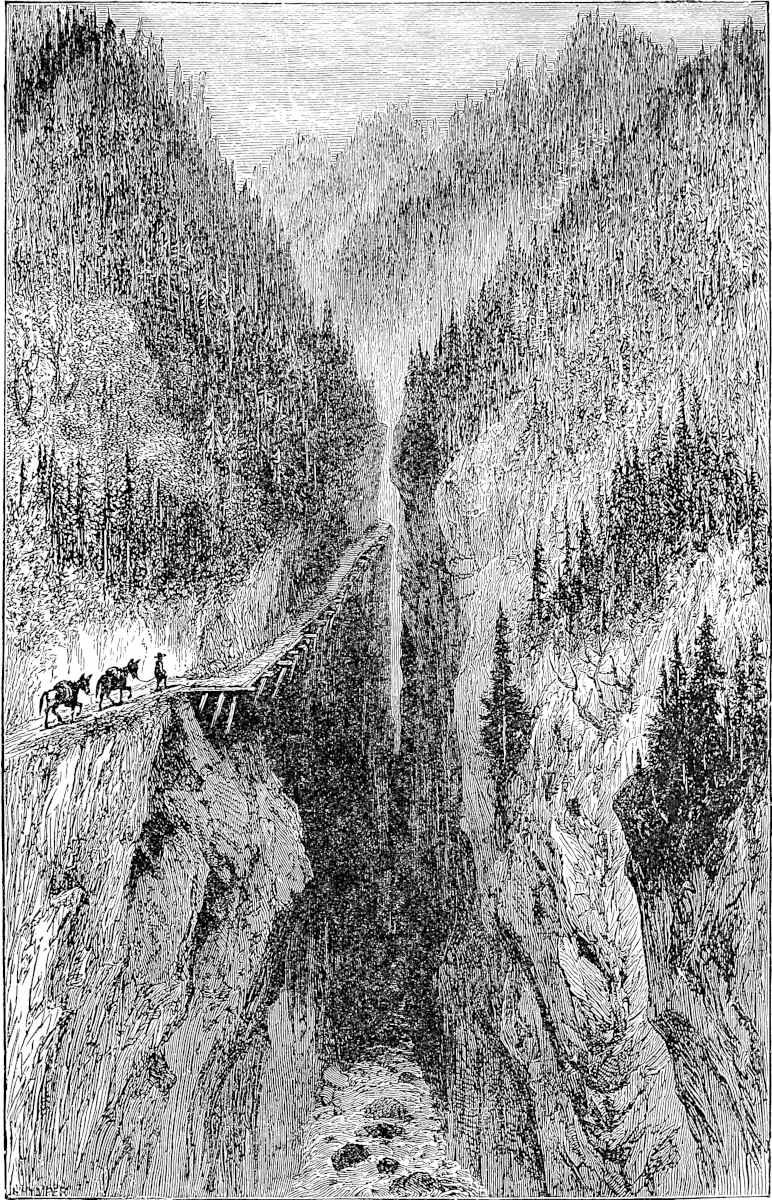

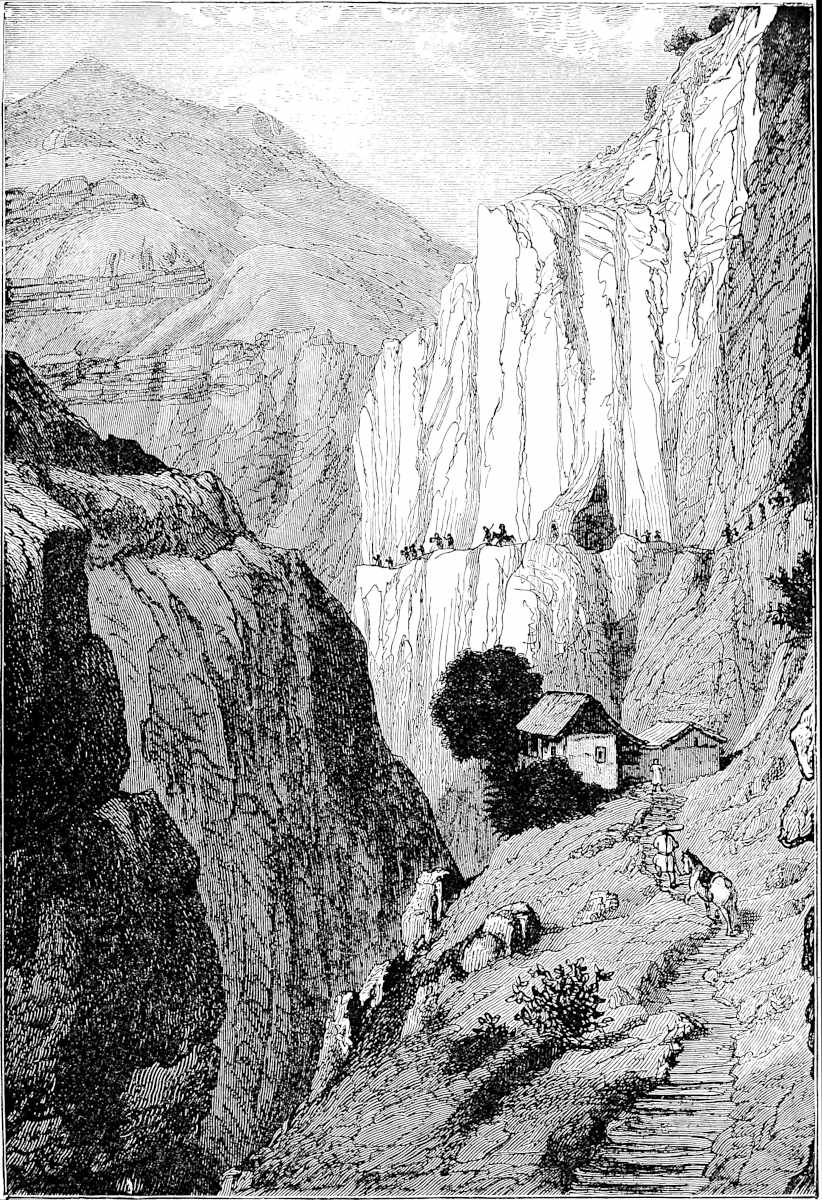

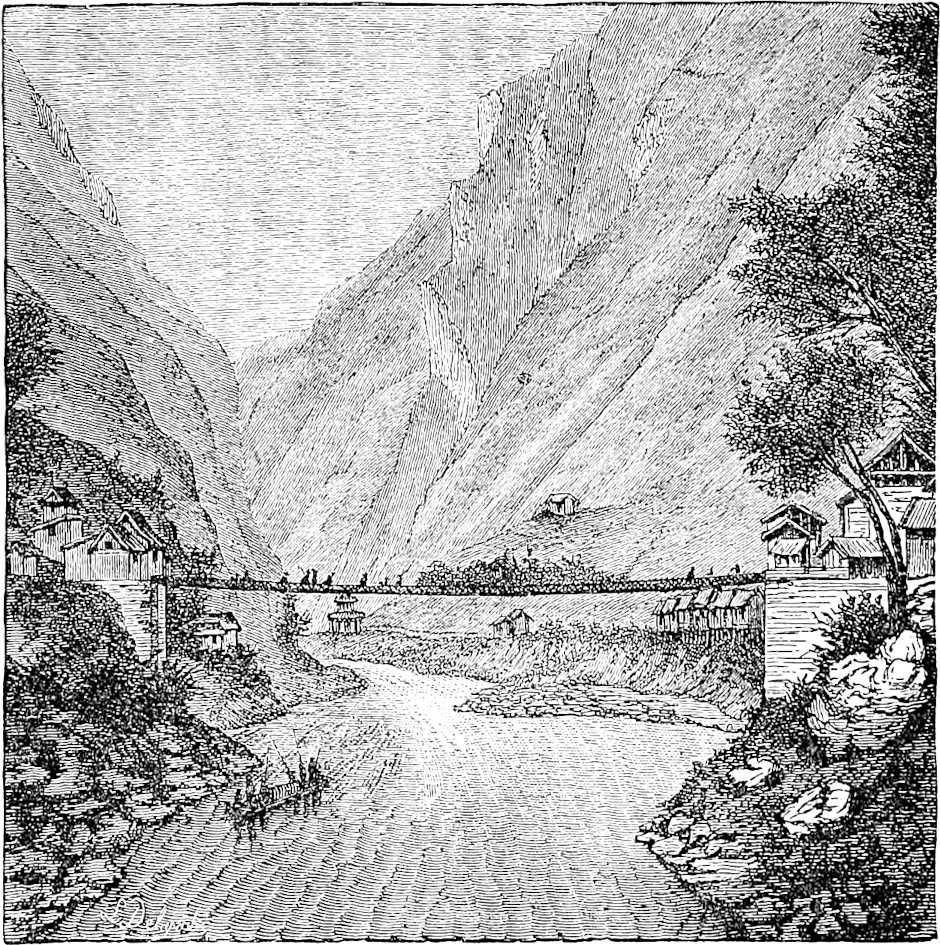

| xix | Example of Roads on the Tibetan Frontier of China (being actually a view of the Gorge of the Lan t’sang Kiang). From Mr. Cooper’s Travels of a Pioneer of Commerce. |

| The Valley of the Kin-sha Kiang, near the lower end of the Caindu of Marco Polo. From Lieut. Garnier in the Tour du Monde. | |

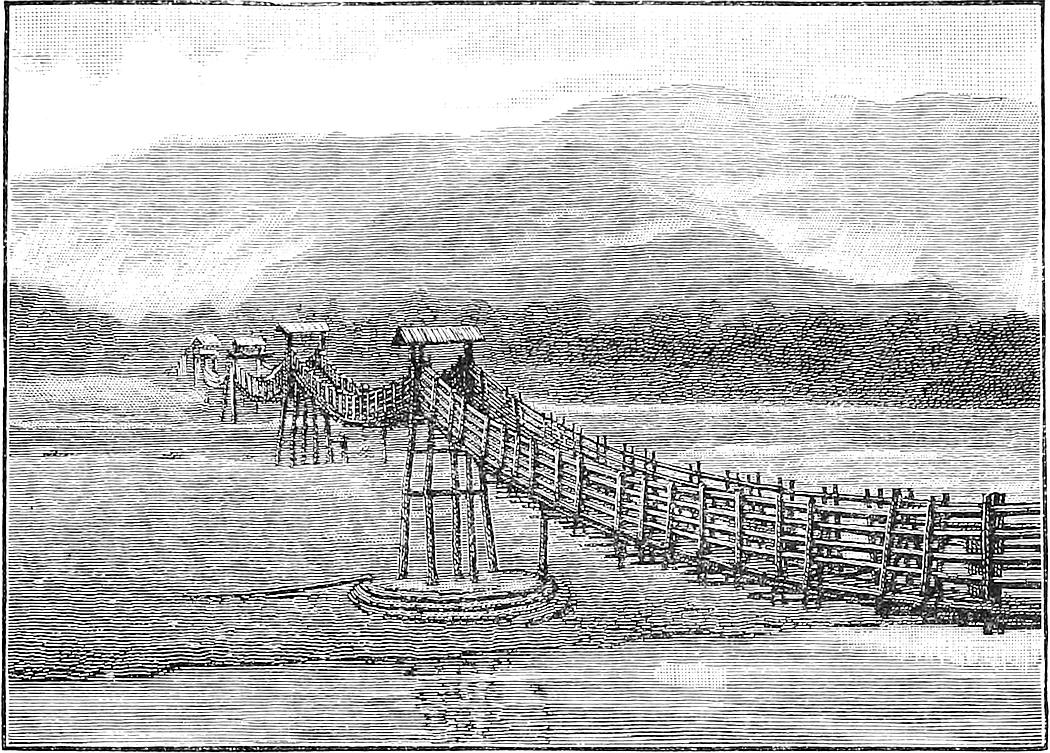

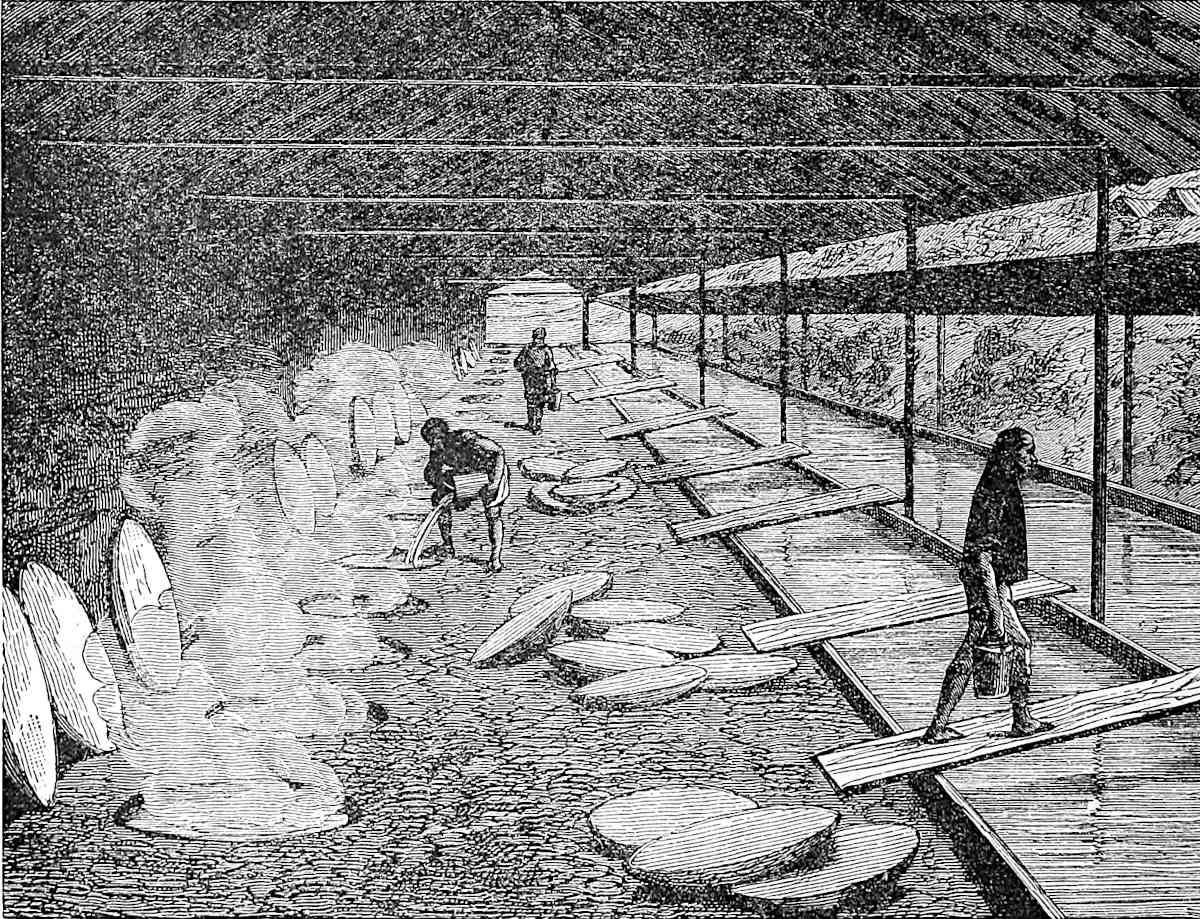

| Salt Pans in Yun-nan. From the same. | |

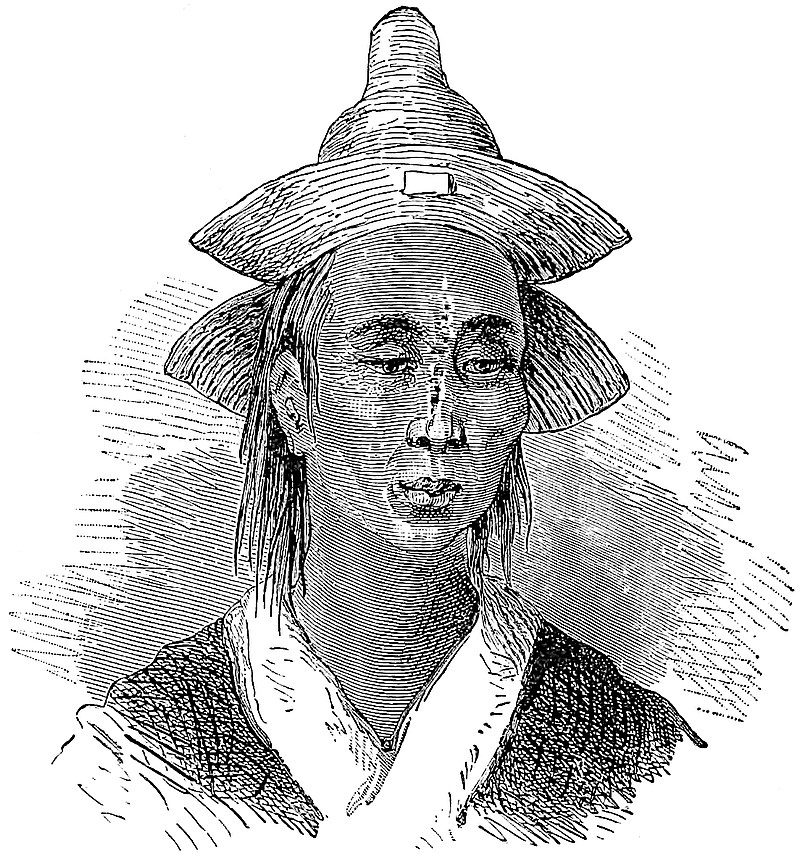

| Black Lolo. | |

| White Lolo. From Devéria’s Frontière Sino-annamite. | |

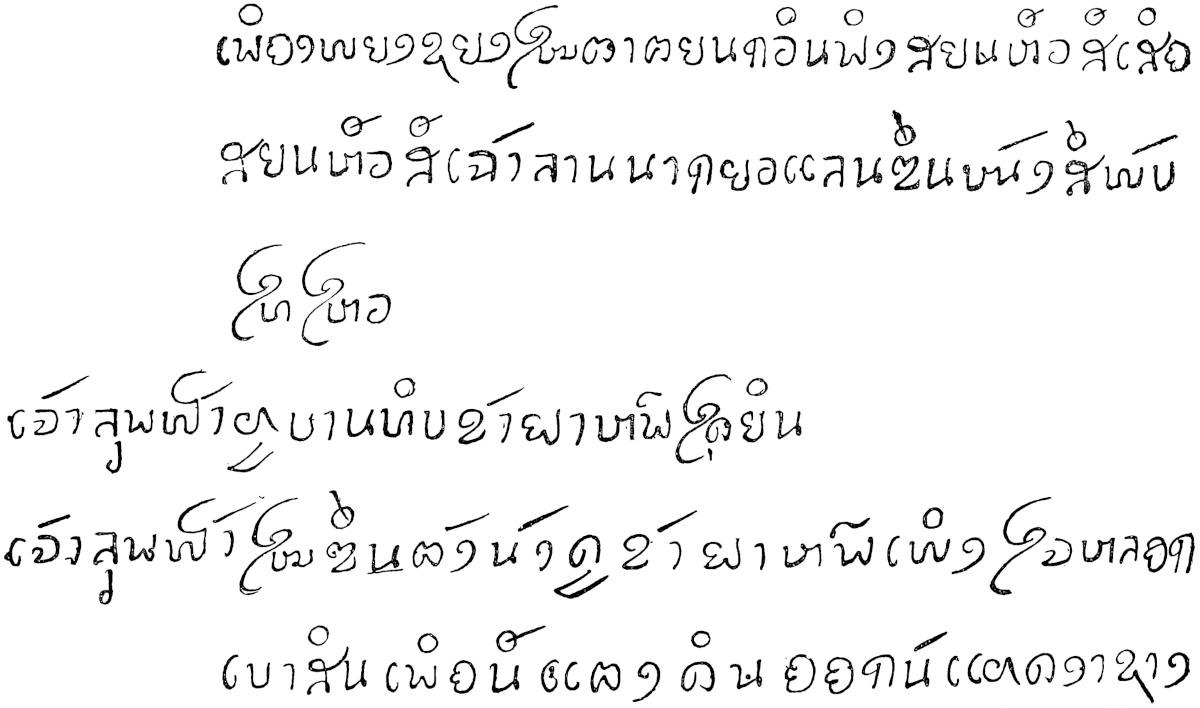

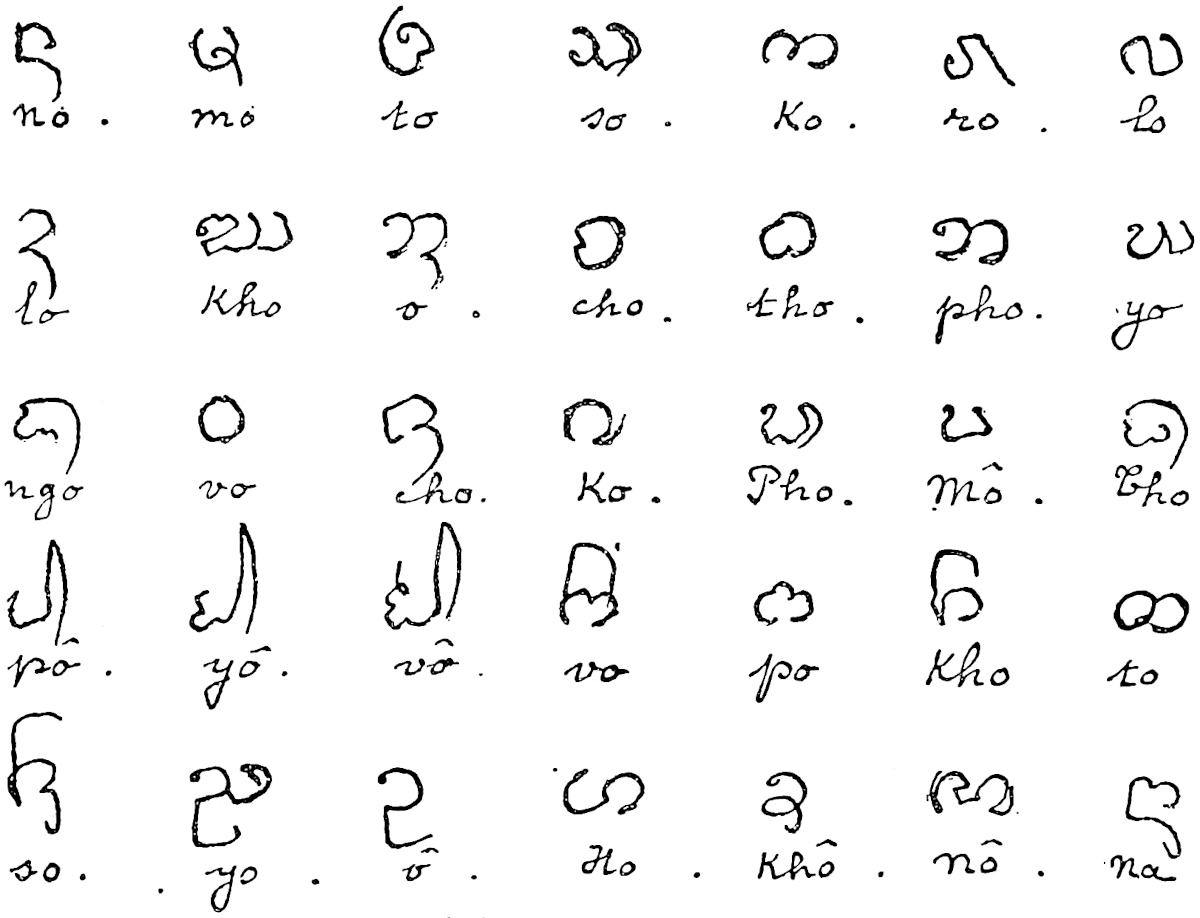

| Pa-y Script. From the T’oung-Pao. | |

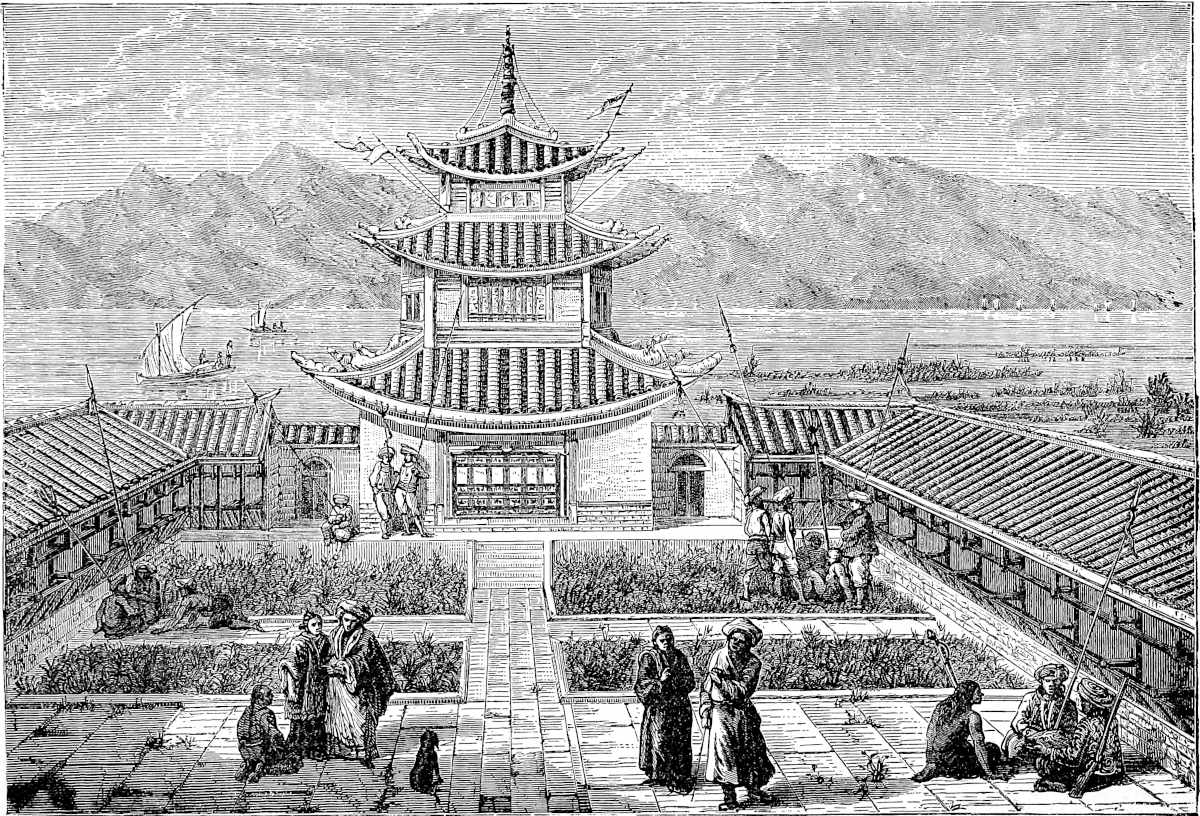

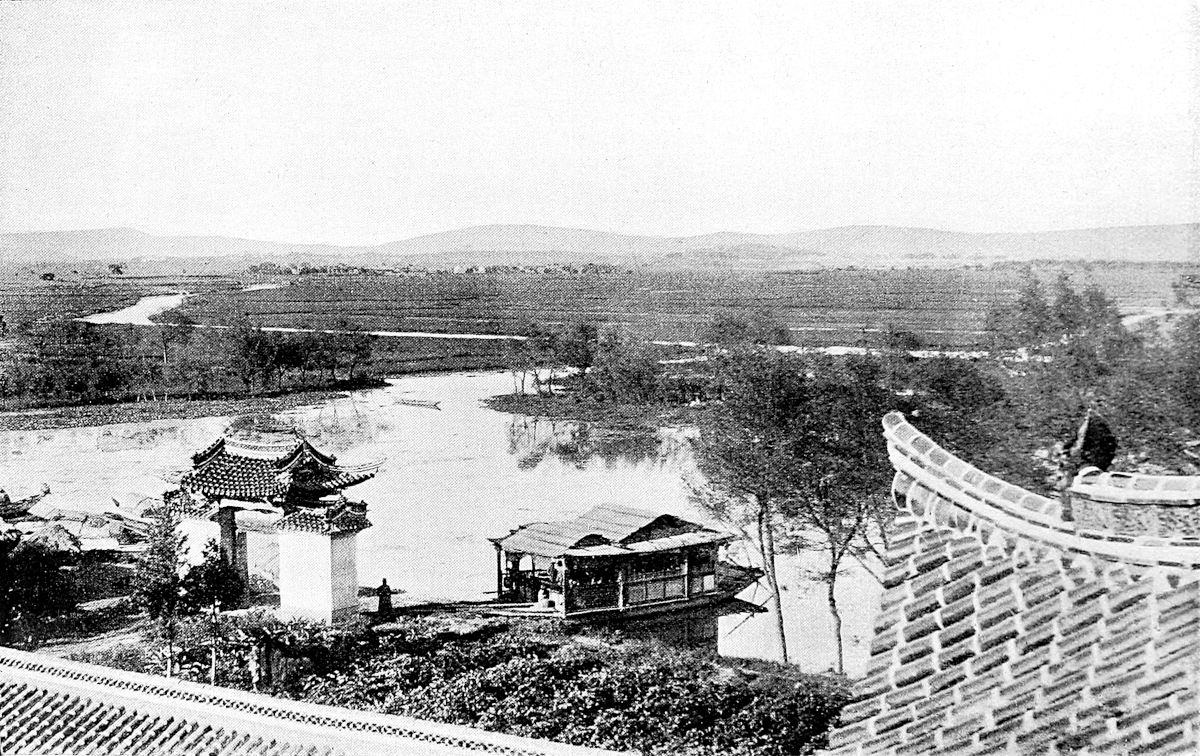

| Garden-House on the Lake of Yun-nan-fu, Yachi of Polo. From Lieut. Garnier in the Tour du Monde. | |

| Road descending from the Table-Land of Yun-nan into the Valley of the Kin-sha Kiang (the Brius of Polo). From the same. | |

| “A Saracen of Carajan,” being the portrait of a Mahomedan Mullah in Western Yun-nan. From the same. | |

| The Canal at Yun-nan fu. From a photograph by M. Tannant. | |

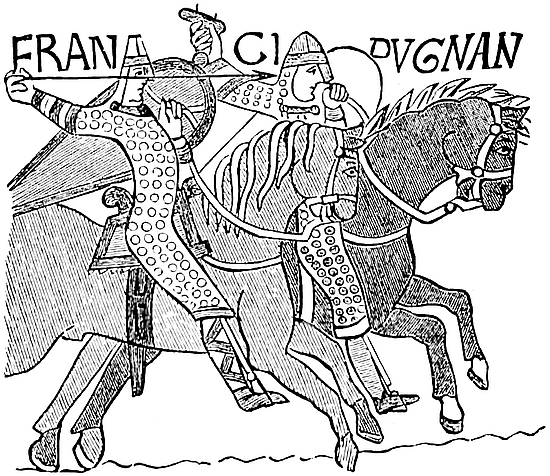

| “Riding long like Frenchmen,” exemplified from the Bayeux Tapestry. After Lacroix, Vie Militaire du Moyen Age. | |

| The Sang-miau tribe of Kwei-chau, with the Cross-bow. From a coloured drawing in a Chinese work on the Aboriginal Tribes, belonging to W. Lockhart, Esq. | |

| Portraits of a Kakhyen man and woman. Drawn by Q. Cenni from a photograph (anonymous). | |

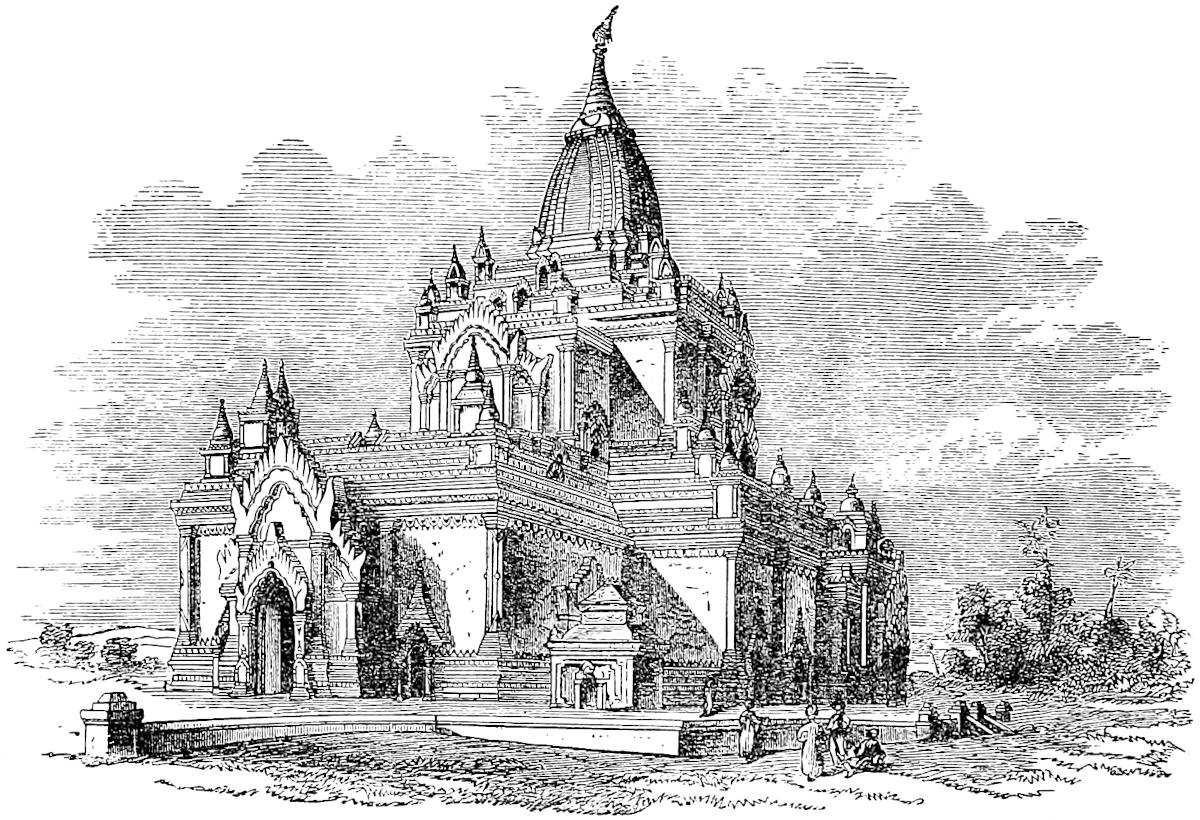

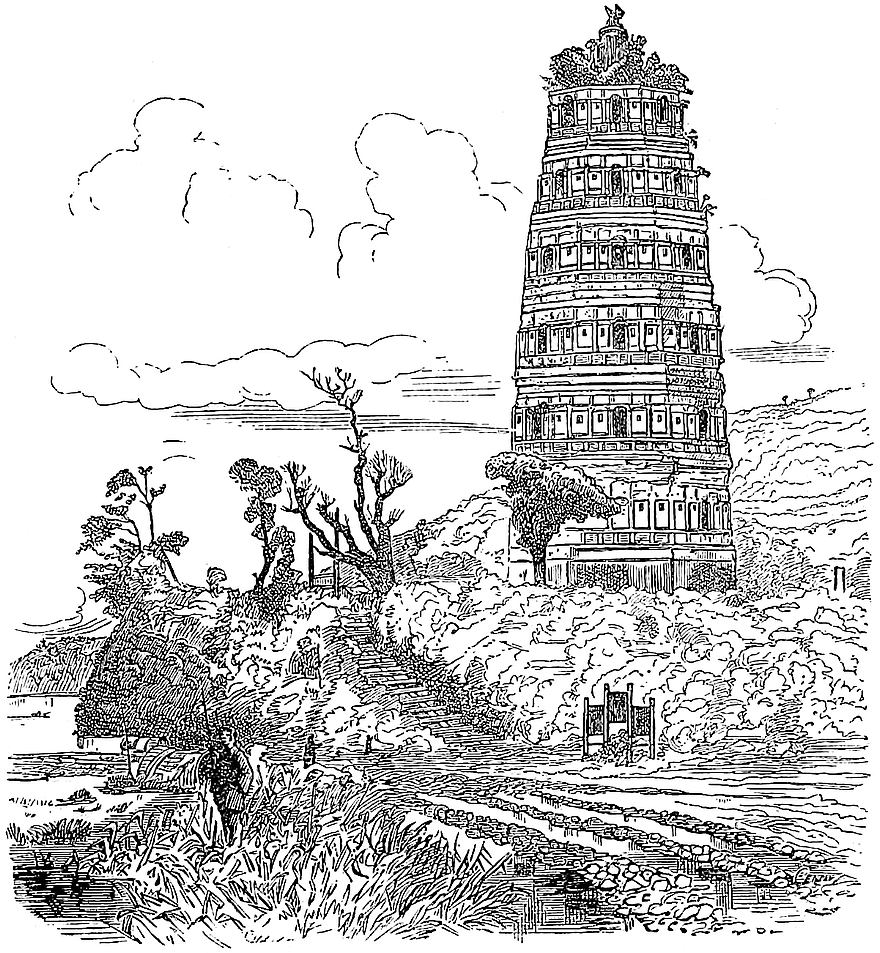

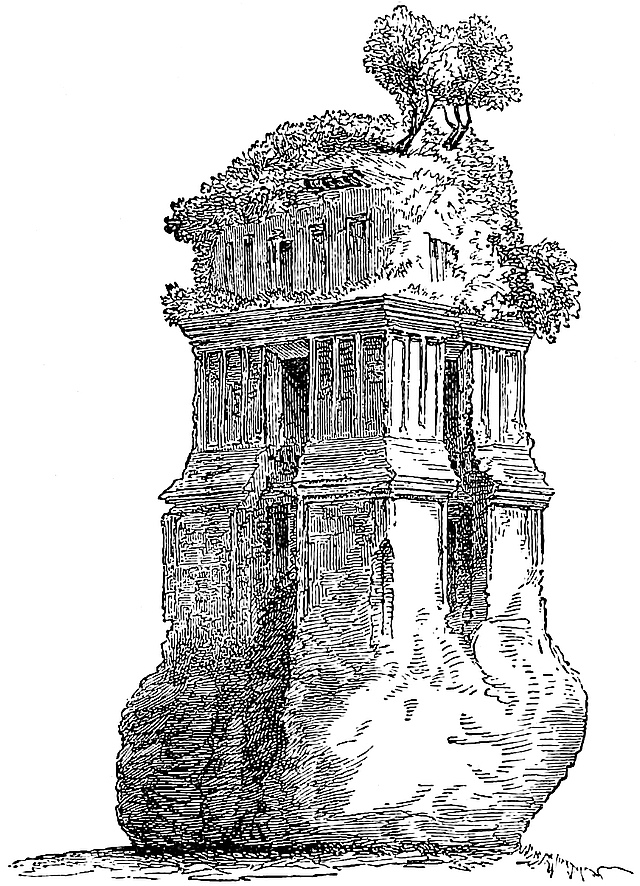

| Temple called Gaudapalén in the city of Mien (i.e. Pagán in Burma), erected circa A.D. 1160. Engraving after a sketch by the first Editor, from Fergusson’s History of Architecture. | |

| The Palace of the King of Mien in modern times (viz., the Palace at Amarapura). From the same, being partly from a sketch by the first Editor. | |

| Script Pa-pe. From the T’oung-Pao. | |

| Ho-nhi and other Tribes in the Department of Lin-ngan in S. Yun-nan, supposed to be the Anin country of Marco Polo. From Garnier in the Tour du Monde. | |

| The Koloman tribe, on borders of Kwei-chau and Yun-nan. From coloured drawing in Mr. Lockhart’s book as above (under p. 83). | |

| Script thaï of Xieng-hung. From the T’oung-Pao. | |

| Iron Suspension Bridge at Lowatong. From Garnier in Tour du Monde. | |

| Fortified Villages on Western Frontier of Kwei-chau. From the same. |

Page |

|

|---|---|

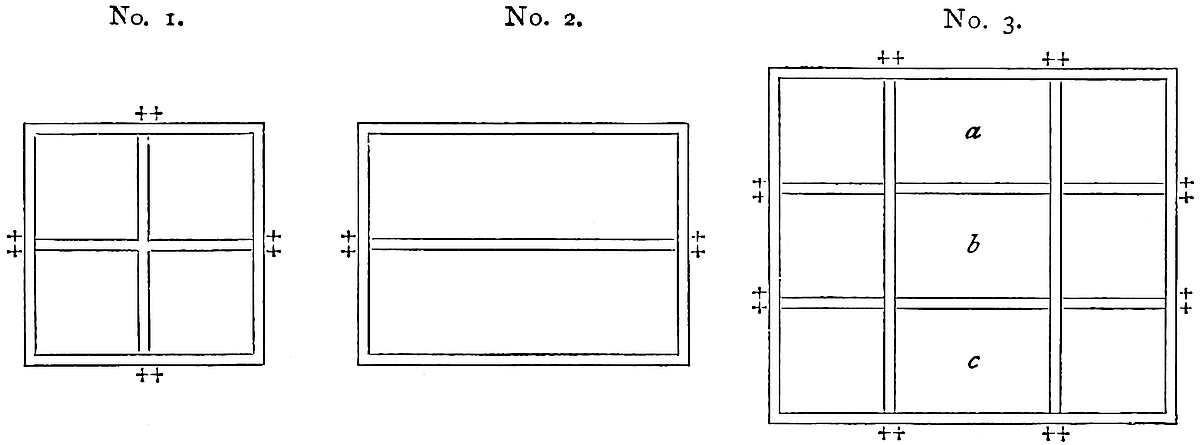

| Yang-chau: the three Cities under the Sung. | |

| Yang-chau: the Great City under the Sung. From Chinese Plans kindly sent to the present Editor by the late Father H. Havret, S.J., Zi-ka-wei. | |

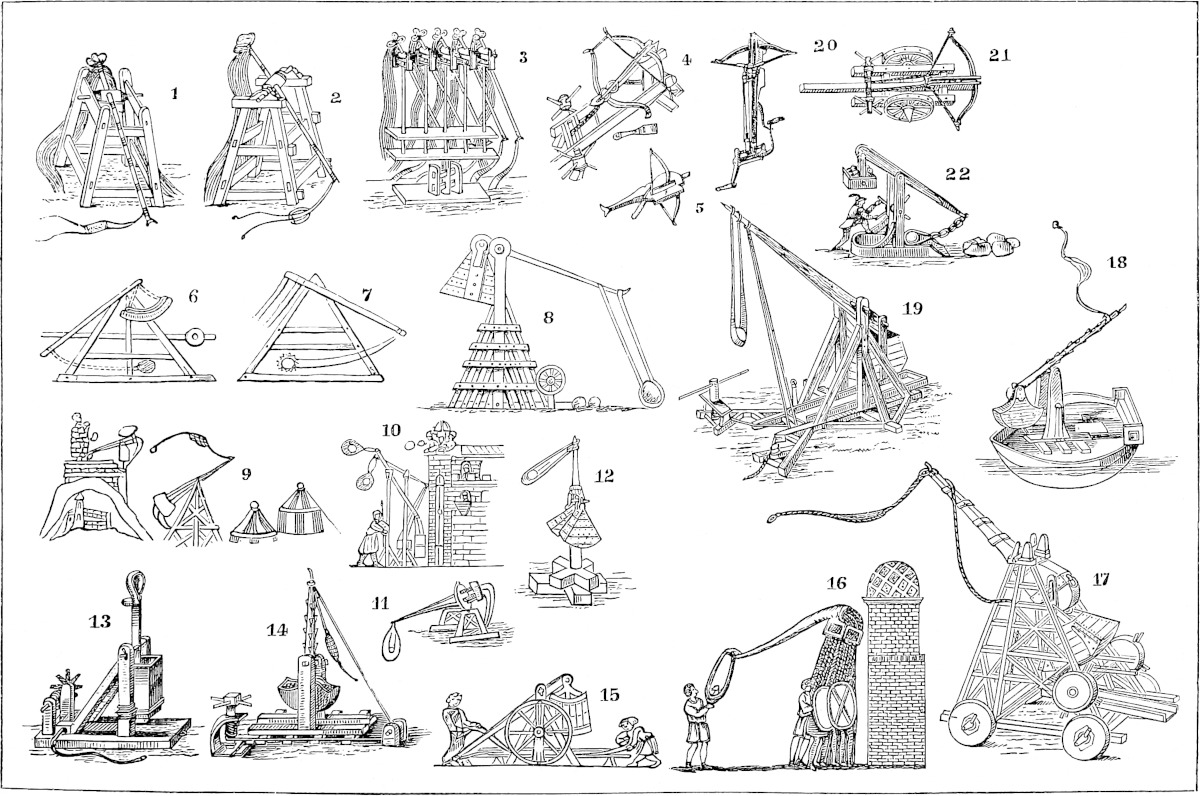

| Mediæval Artillery Engines. Figs, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, are

Chinese. The first four are from the Encyclopædia

San-Thsai-Thou-hoei (Paris Library), the last from

Amyot, vol. viii.

Figs. 6, 7, 8 are Saracen, 6 and 7 are taken from the work of Reinaud and Favé, Du Feu Grégeois, and by them from the Arabic MS. of Hassan al Raumah (Arab Anc. Fonds, No. 1127). Fig. 8 is from Lord Munster’s Arabic Catalogue of Military Works, and by him from a MS. of Rashiduddin’s History. xxThe remainder are European. Fig. 9 is from Pertz, Scriptores, vol. xviii., and by him from a figure of the Siege of Arbicella, 1227, in a MS. of Genoese Annals (No. 773, Supp. Lat. of Bib. Imp.). Fig. 10 from Shaw’s Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages, vol. i., No. 21, after B. Mus. MS. Reg. 16, G. vi. Fig. 11 from Pertz as above, under A.D. 1182. Fig. 12, from Valturius de Re Militari, Verona, 1483. Figs. 13 and 14 from the Poliorceticon of Justus Lipsius. Fig. 15 is after the Bodleian MS. of the Romance of Alexander (A.D. 1338), but is taken from the Gentleman’s Magazine, 3rd ser. vol. vii. p. 467. Fig. 16 from Lacroix’s Art au Moyen Age, after a miniature of 13th cent. in the Paris Library. Figs. 17 and 18 from the Emperor Napoleon’s Études de l’Artillerie, and by him taken from the MS. of Paulus Santinus (Lat. MS. 7329 in Paris Library). Fig. 19 from Professor Moseley’s restoration of a Trebuchet, after the data in the Mediæval Note-book of Villars de Honcourt, in Gentleman’s Magazine as above. Figs. 20 and 21 from the Emperor’s Book. Fig. 22 from a German MS. in the Bern Library, the Chronicle of Justinger and Schilling. |

|

| Coin from a treasure hidden during the siege of Siang-yang in 1268–73, and lately discovered in that city. | |

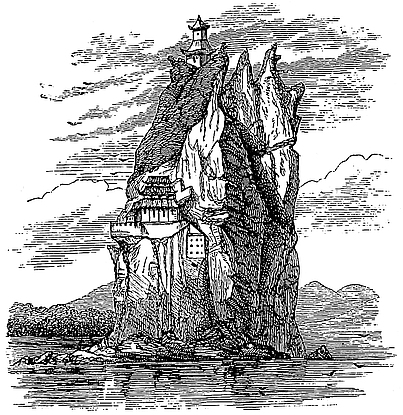

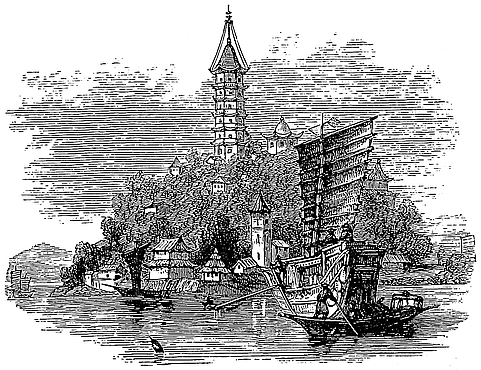

Island Monasteries on the Yang-tzŭ kiang; viz.:—

1. Uppermost. The “Little Orphan Rock,” after a cut in Oliphant’s Narrative. 2. Middle. The “Golden Island” near Chin-kiang fu, after Fisher’s China. (This has been accidentally reversed in the drawing.) 3. Lower. The “Silver Island,” below the last, after Mr. Lindley’s book on the T’ai-P’ings. |

|

| The West Gate of Chin-kiang fu. From an engraving in Fisher’s China after a sketch made by Admiral Stoddart, R.N., in 1842. | |

| South-West Gate and Water Gate of Su-chau; facsimile on half scale from the incised Map of 1247. (See List of Inserted Plates preceding, under p. 182.) | |

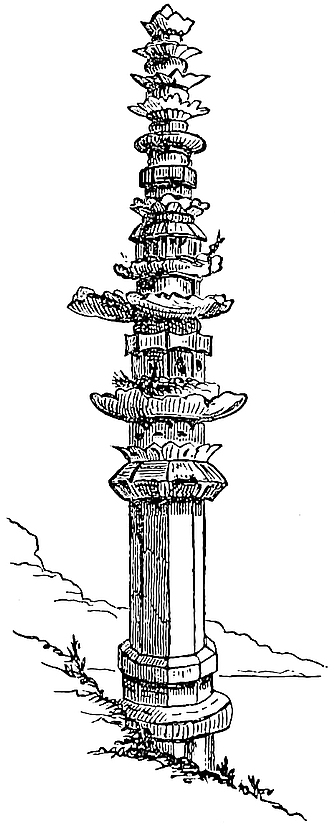

| The old Luh-ho-ta or Pagoda of Six Harmonies near Hang-chau, and anciently marking the extreme S.W. angle of the city. Drawn by Q. Cenni from an anonymous photograph received from the Rev. G. Moule. | |

| Imperial City of Hang-chau in the 13th Century. | |

| Metropolitan City of Hang-chau in the 13th Century. From the Notes of the Right Rev. G. E. Moule. | |

| Fang of Si-ngan Fu. Communicated by A. Wylie. | |

| Stone Chwang or Umbrella Column, one of two which still mark the site of the ancient Buddhist Monastery called Fan-T’ien-Sze or “Brahma’s Temple” at Hang-chau. Reduced from a pen-and-ink sketch by Mr. Moule. | |

| Mr. Phillips’ Theory of Marco Polo’s Route through Fo-Kien. | |

| Scene in the Bohea Mountains, on Polo’s route between Kiang-Si and Fo-Kien. From Fortune’s Three Years’ Wanderings. | |

| Scene on the Min River below Fu-chau. From the same. | |

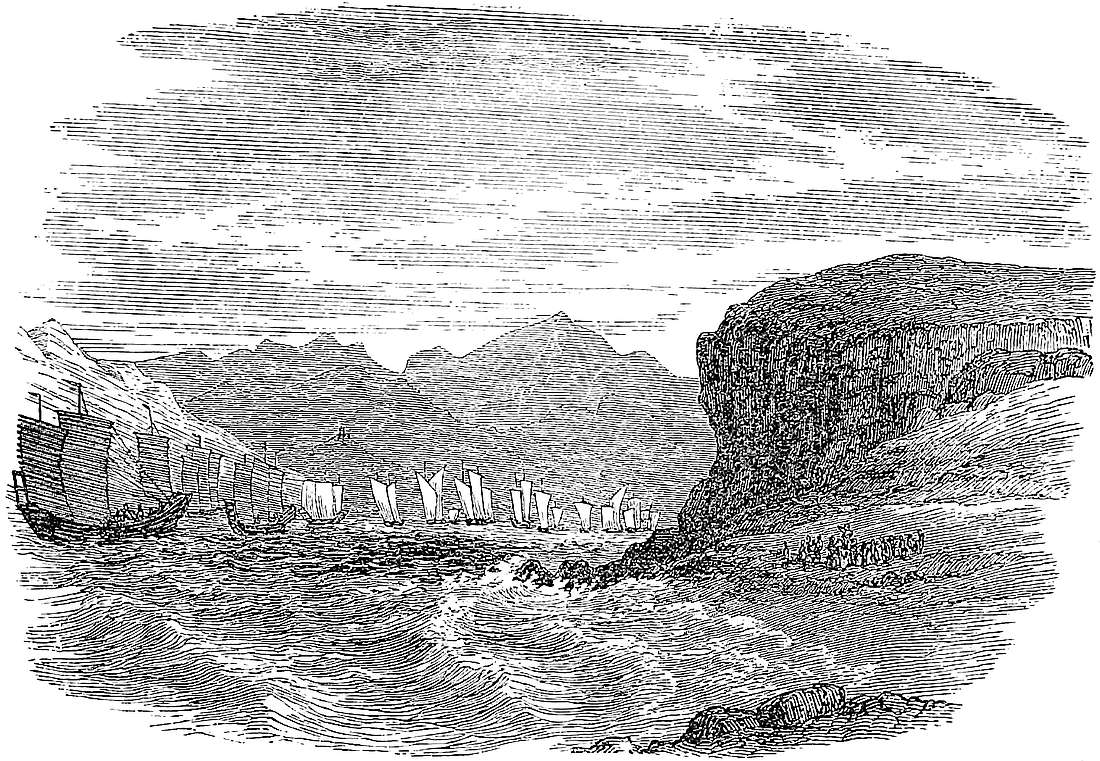

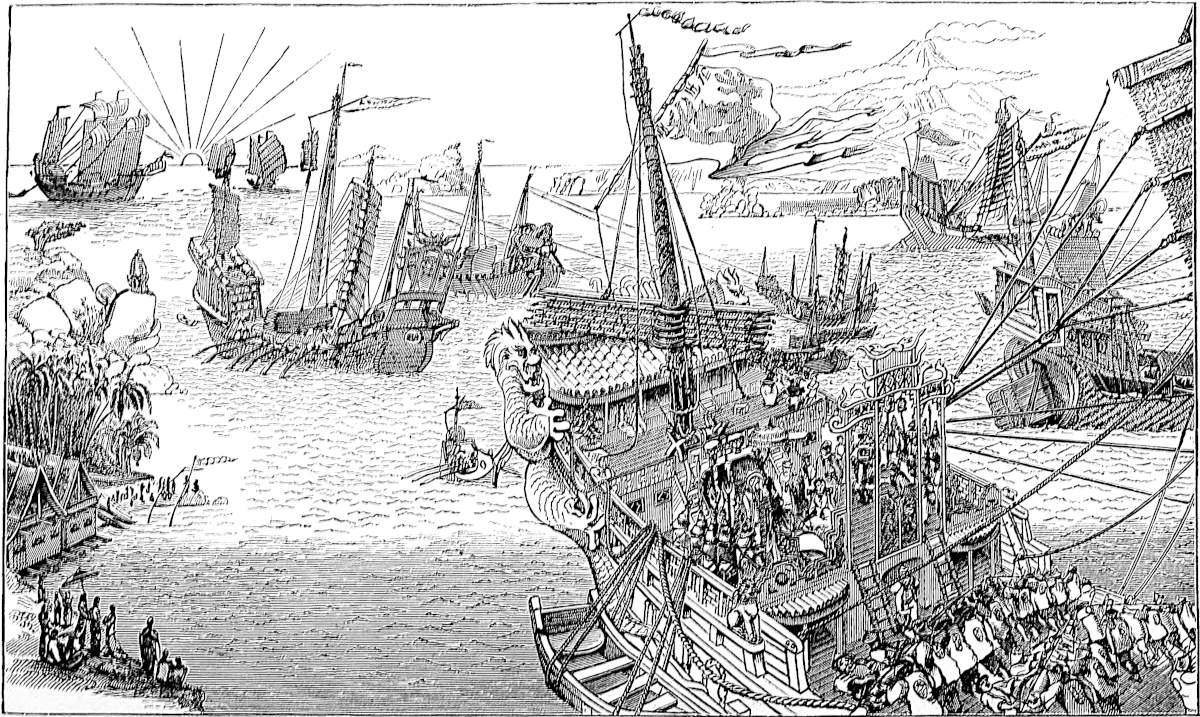

| The Kaan’s Fleet leaving the Port of Zayton. The scenery is taken from an engraving in Fisher’s China, purporting to represent the mouth of the Chinchew River (or River of Tswan-chau), after a sketch by Capt. (now Adm.) Stoddart. But the Rev. Dr. Douglas, having pointed out that this cut really supported his view of the identity of Zayton, being a view of the Chang-chau River, reference was made to Admiral Stoddart, and Dr. Douglas proves to be quite right. The View was really one of the Chang-chau River; but the Editor has not been able to procure material for one of the Tswan-chau River, and so he leaves it. |

xxi

Page |

|

|---|---|

| The Kaan’s Fleet passing through the Indian Archipelago. From a drawing by the Editor. | |

| Ancient Japanese Emperor, after a Native Drawing. From the Tour du Monde. | |

| Ancient Japanese Archer, after a native drawing. From the same. | |

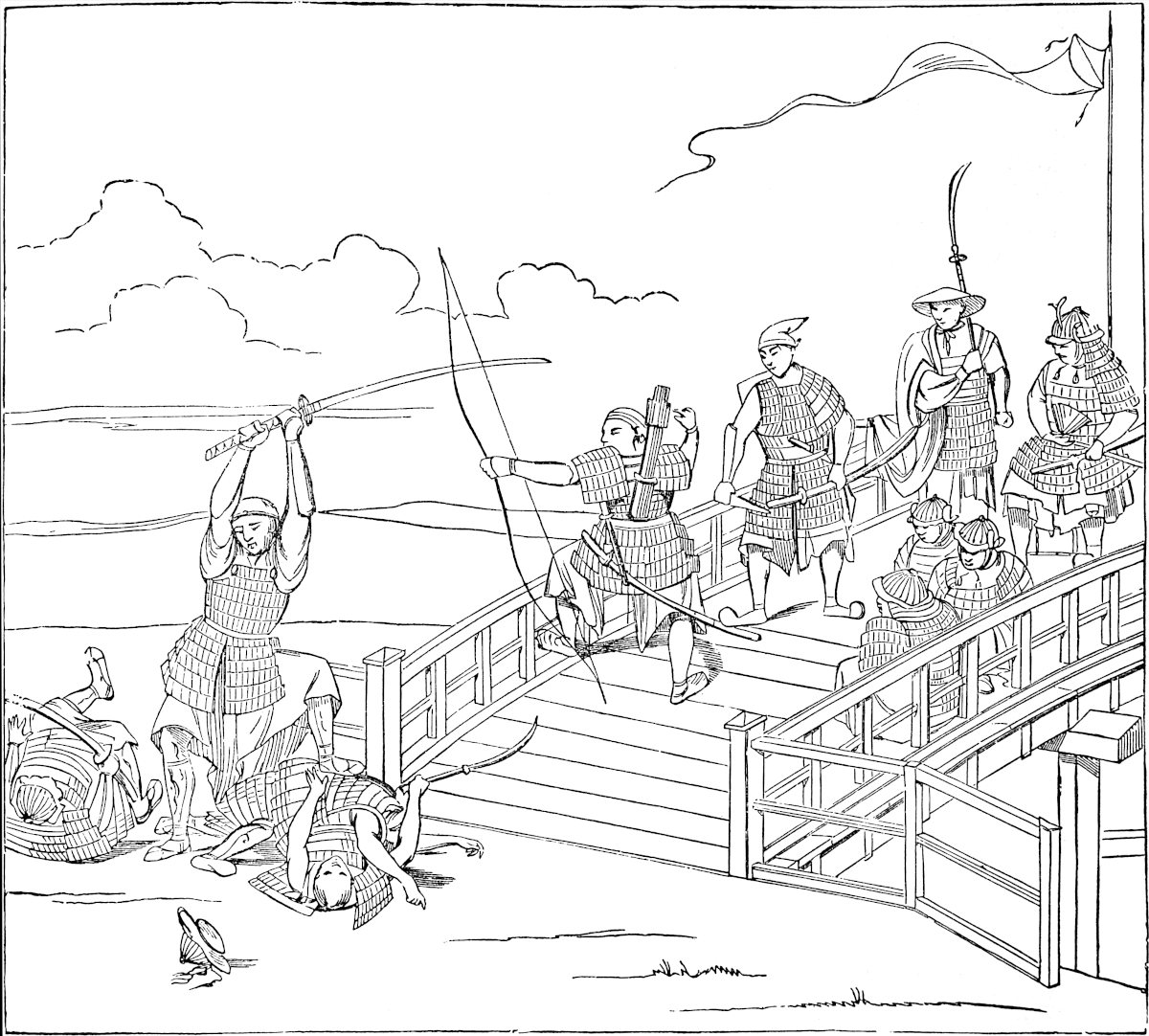

| The Japanese engaged in combat with the Chinese, after an ancient native drawing. From Charton, Voyageurs Anciens et Modernes. | |

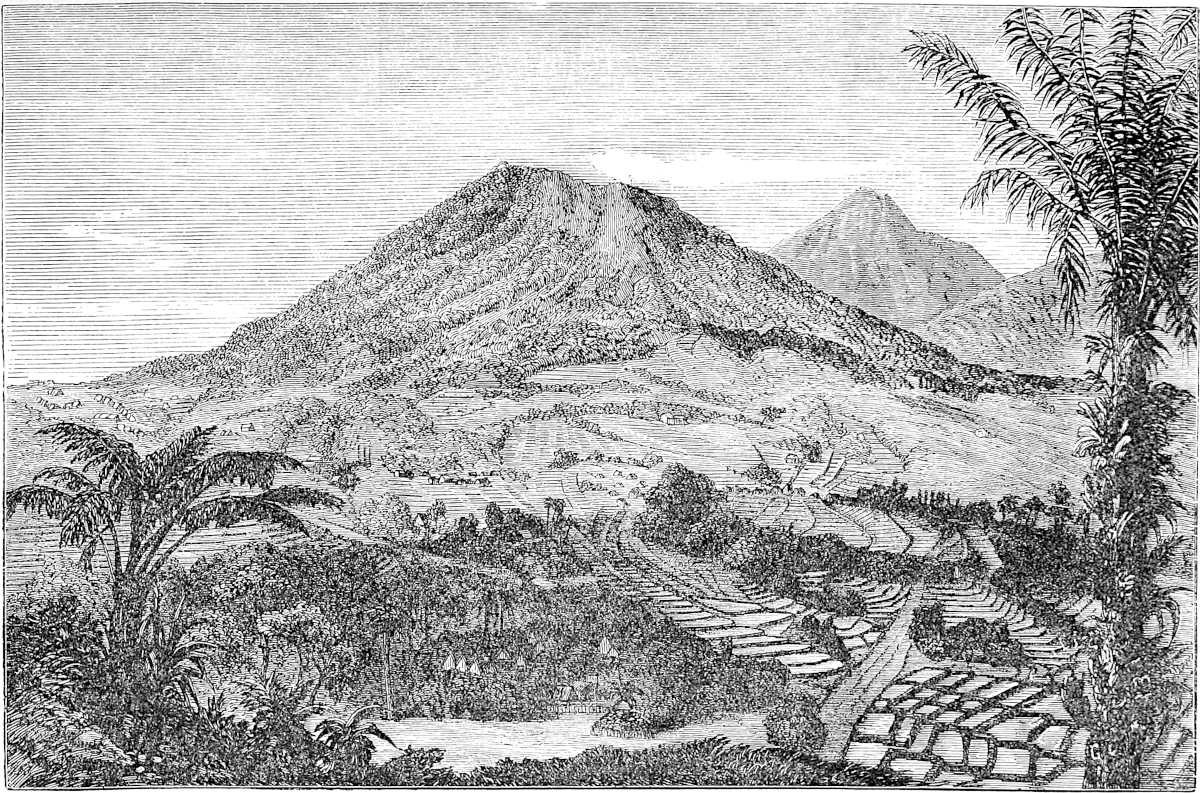

| Java. A view in the interior. From a sketch of the slopes of the Gedéh Volcano, taken by the Editor in 1860. | |

| Bas Relief of one of the Vessels frequenting the Ports of Java in the Middle Ages. From one of the sculptures of the Boro Bodor, after a photograph. | |

| The three Asiatic Rhinoceroses. Adapted from a proof of a woodcut given to the Editor for the purpose by the late eminent zoologist, Edward Blyth. It is not known to the Editor whether the cut appeared in any other publication. | |

| Monoceros and the Maiden. From a mediæval drawing engraved in Cahier et Martin, Mélanges d’Archéologie, II. Pl. 30. | |

| The Borús. From a manuscript belonging to the late Charles Schefer, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. | |

| The Cynocephali. From the Livre des Merveilles. | |

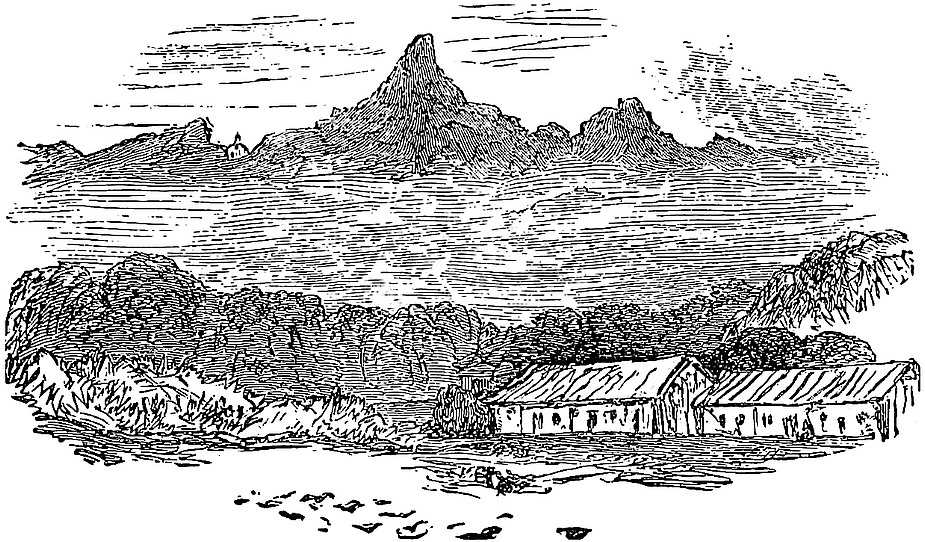

| Adam’s Peak from the Sea. | |

| Sakya Muni as a Saint of the Roman Martyrology. Facsimile from an old German version of the story of Barlaam and Josaphat (circa 1477), printed by Zainer at Augsburg, in the British Museum. | |

| Tooth Reliques of Buddha. 1. At Kandy, after Emerson Tennent. 2. At Fu-chau, after Fortune. | |

| “Chinese Pagoda” (so called) at Negapatam. From a sketch taken by Sir Walter Elliot, K.C.S.I., in 1846. | |

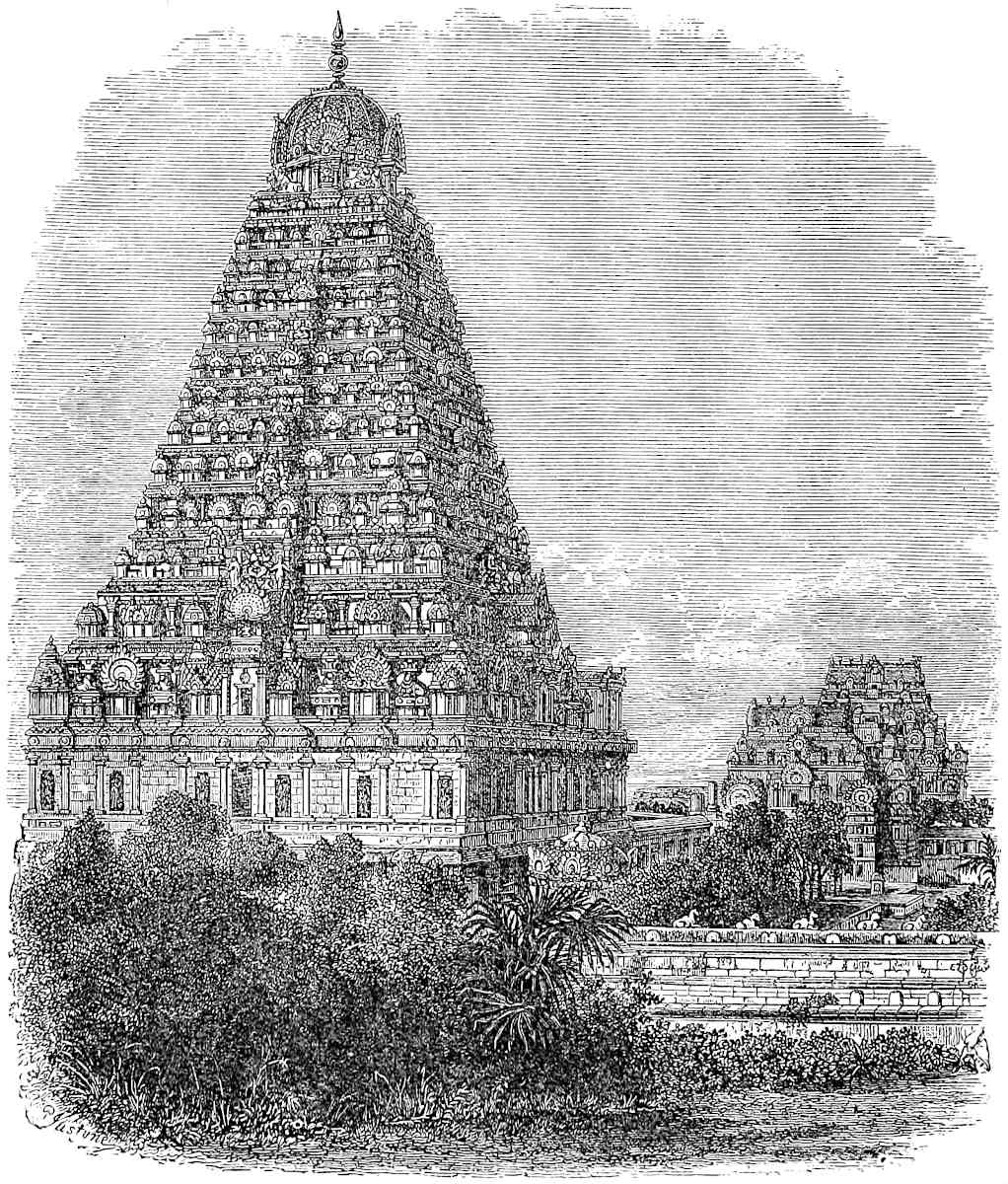

| Pagoda at Tanjore. From Fergusson’s History of Architecture. | |

| Ancient Cross with Pehlvi Inscription, preserved in the church on St. Thomas’s Mount near Madras. From a photograph, the gift of A. Burnell, Esq., of the Madras Civil Service, assisted by a lithographic drawing in his unpublished pamphlet on Pehlvi Crosses in South India. N.B.—The lithograph has now appeared in the Indian Antiquary, November, 1874. | |

| The Little Mount of St. Thomas, near Madras. After Daniel. | |

| Small Map of the St. Thomas localities at Madras. | |

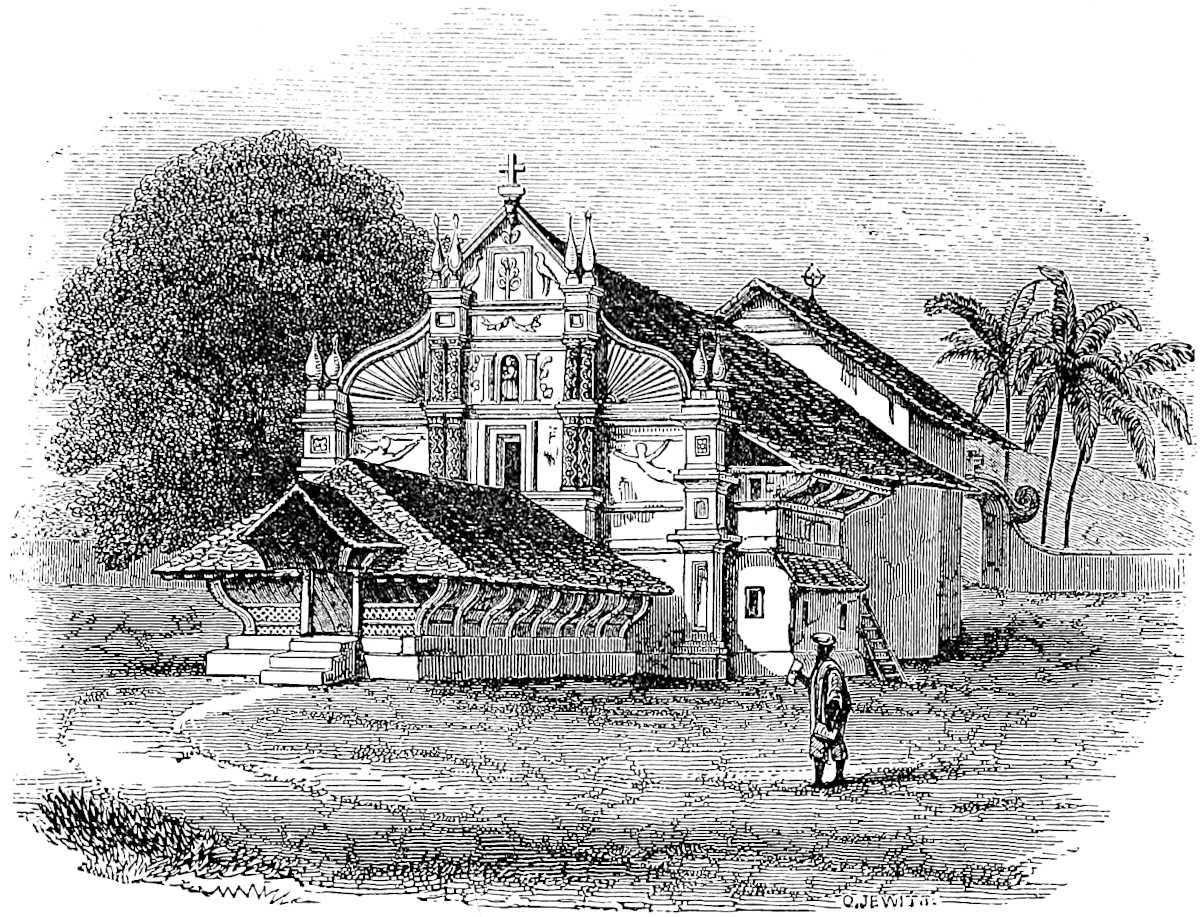

| Ancient Christian Church at Parúr or Palúr, on the Malabar Coast; from an engraving in Pearson’s Life of Claudius Buchanan, after a sketch by the latter. | |

| Syrian Church at Caranyachirra, showing the quasi-Jesuit Façade generally adopted in modern times. From the Life of Bishop Daniel Wilson. | |

| Interior of Syrian Church at Kötteiyam. From the same. | |

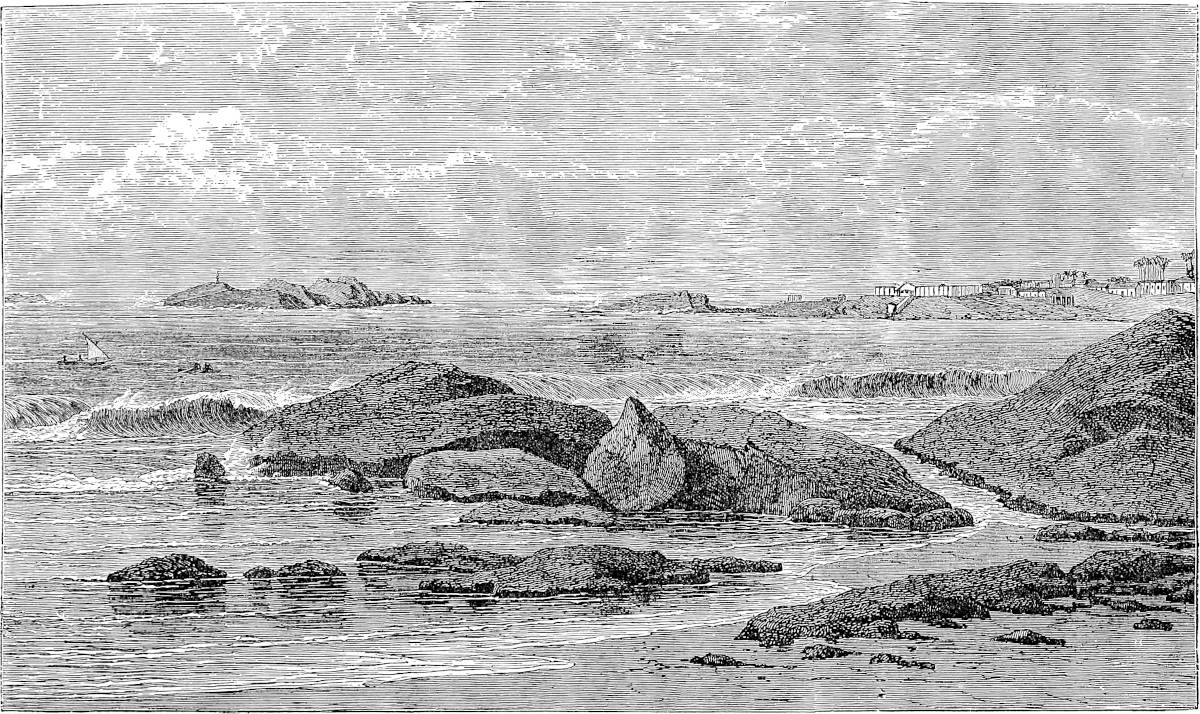

| Cape Comorin. From an original sketch by Mr. Foote of the Geological Survey of India. | |

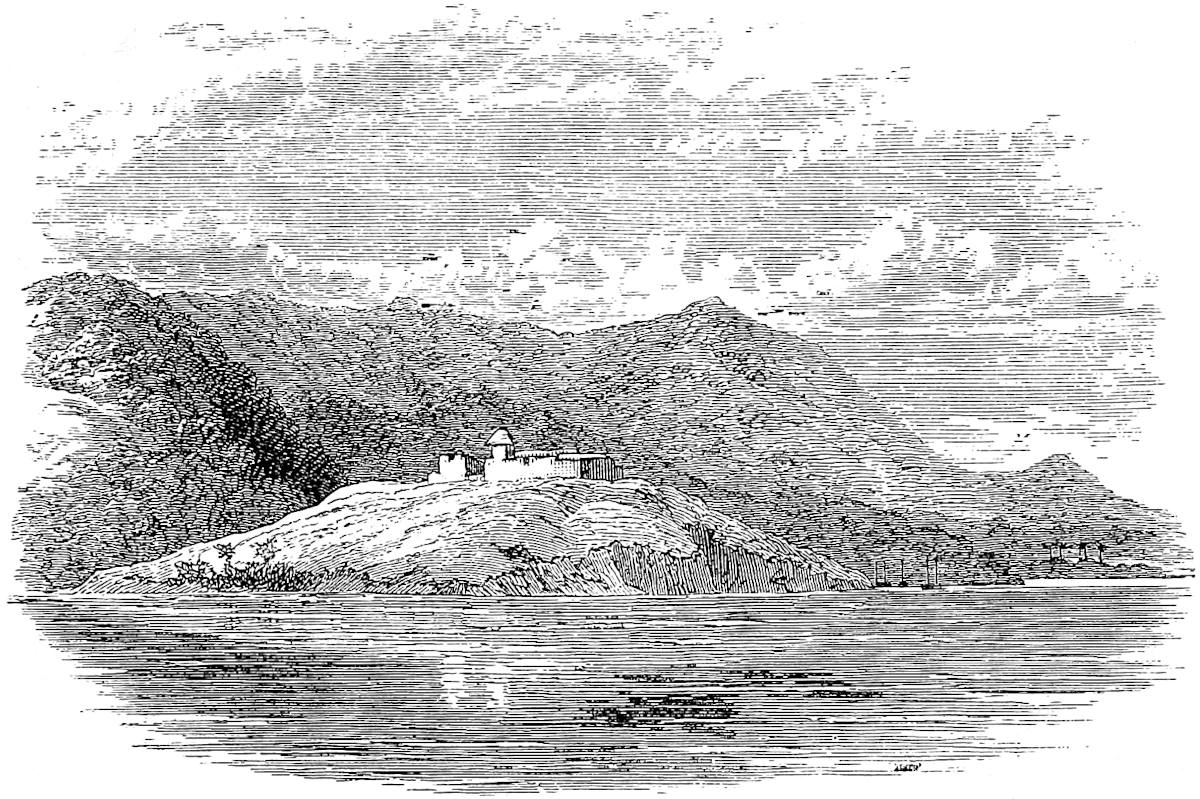

| Mount d’Ely. From a nautical sketch of last century. | |

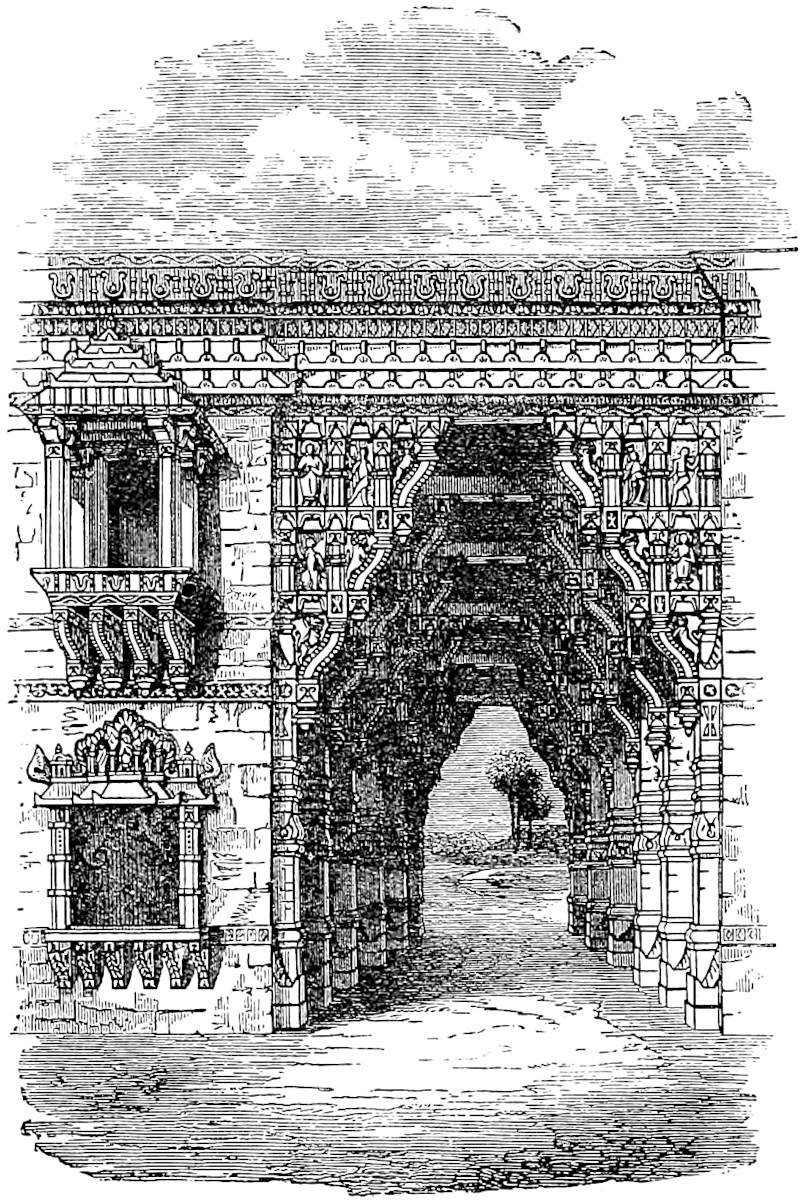

| Mediæval Architecture in Guzerat, being a view of Gateway at Jinjawára, given in Forbes’s Ras Mala. From Fergusson’s History of Architecture. | |

| xxii | The Gates of Somnath (so called), as preserved in the British Arsenal at Agra. From a photograph by Messrs. Shepherd and Bourne, converted into an elevation. |

| The Rukh, after a Persian drawing. From Lane’s Arabian Nights. | |

| Frontispiece of A. Müller’s Marco Polo, showing the Bird Rukh. | |

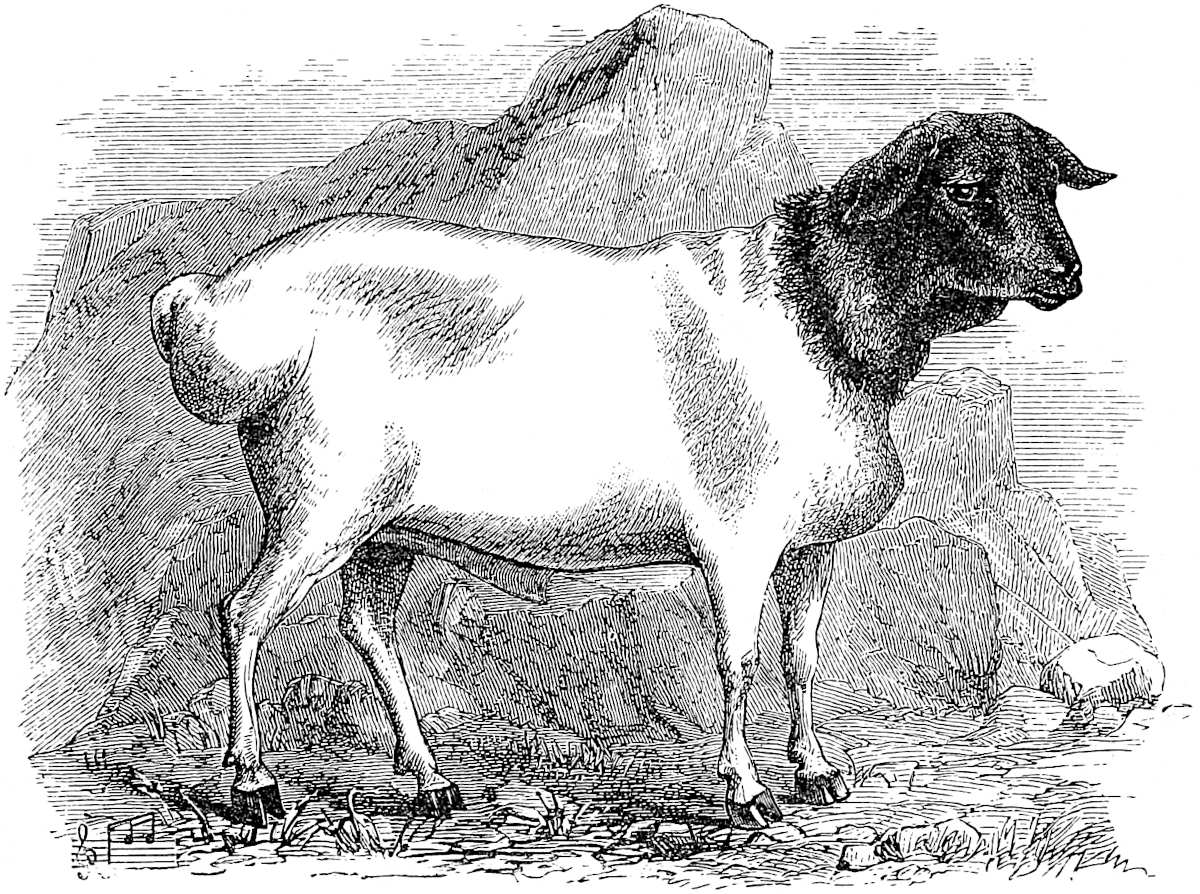

| The Ethiopian Sheep. From a sketch by Miss Catherine Frere. | |

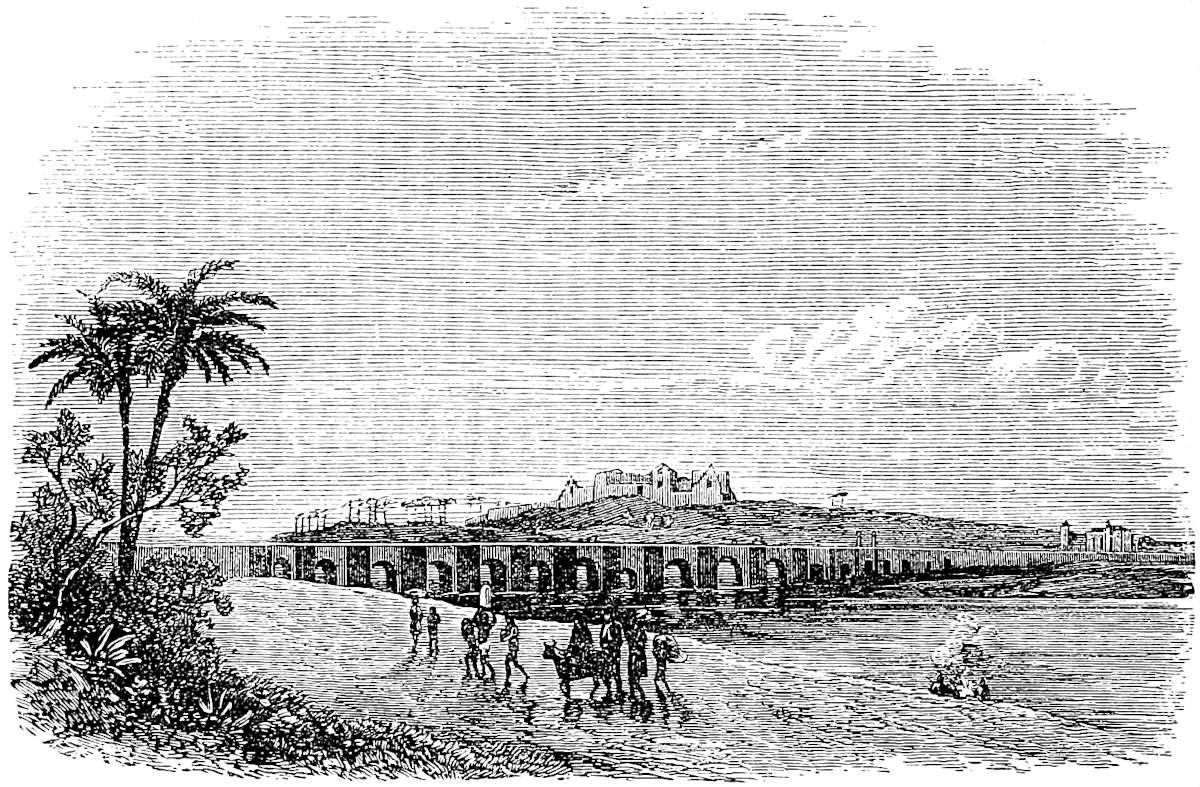

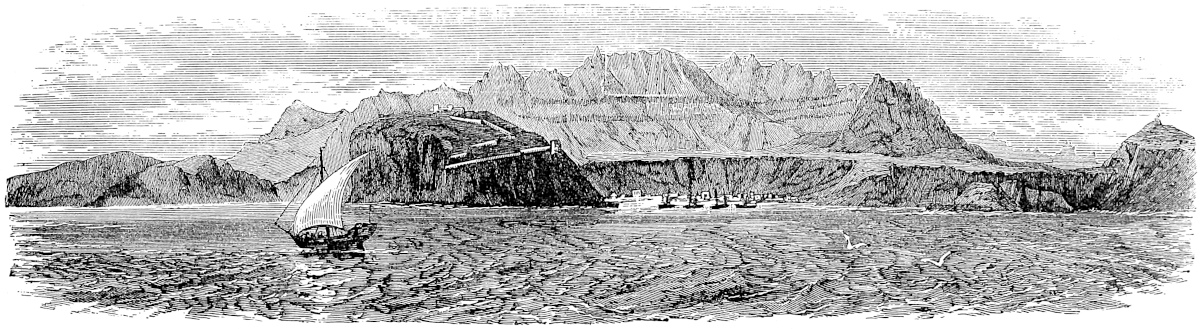

| View of Aden in 1840. From a sketch by Dr. R. Kirk in the Map-room of the Royal Geographical Society. | |

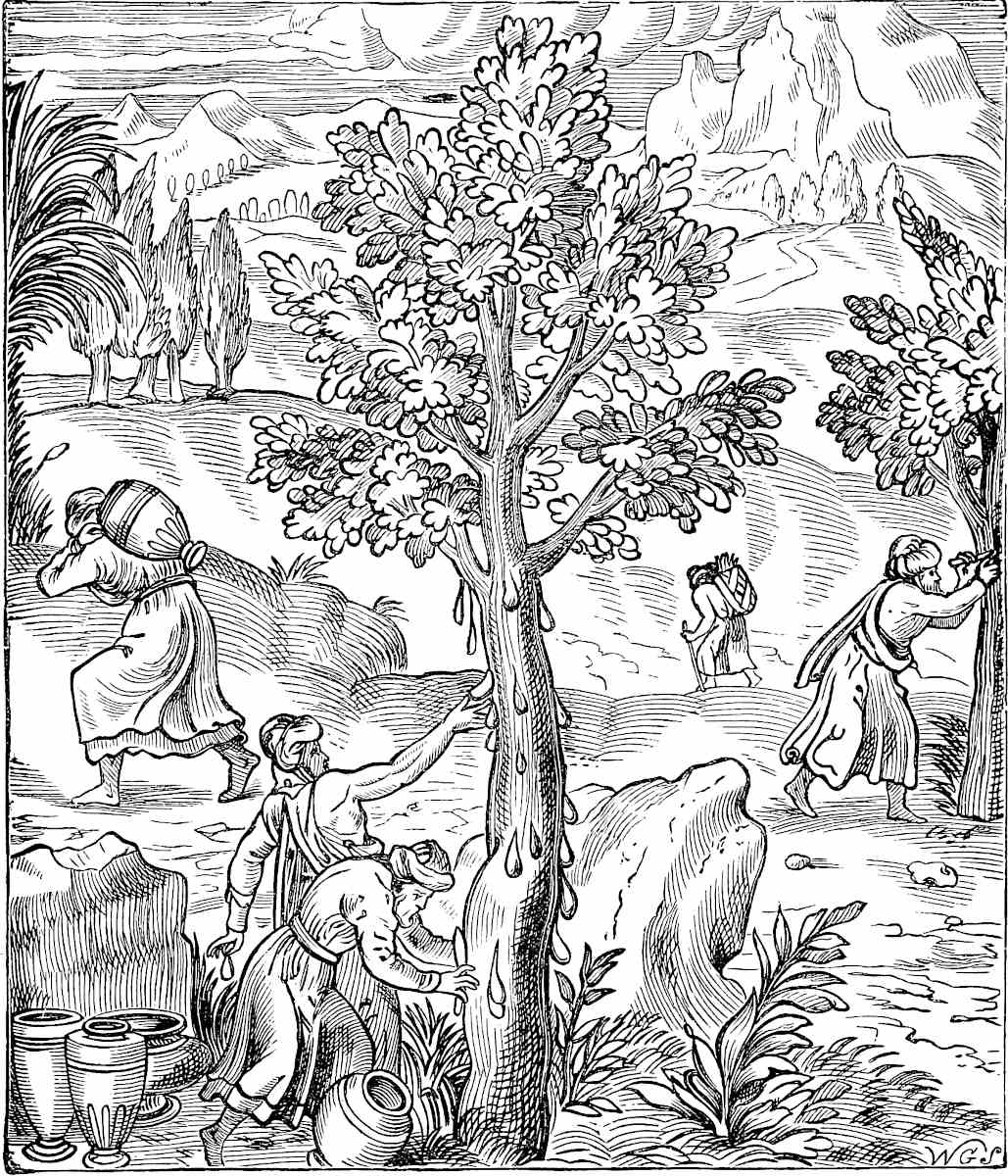

| The Harvest of Frankincense in Arabia. Facsimile of an engraving in Thevet’s Cosmographie Universelle (1575). Reproduced from Cassell’s Bible Educator, by the courtesy of the publishers. | |

| Boswellia Frereana, from a drawing by Mr. W. H. Fitch. The use of this engraving is granted by the India Museum through the kindness of Sir George Birdwood. | |

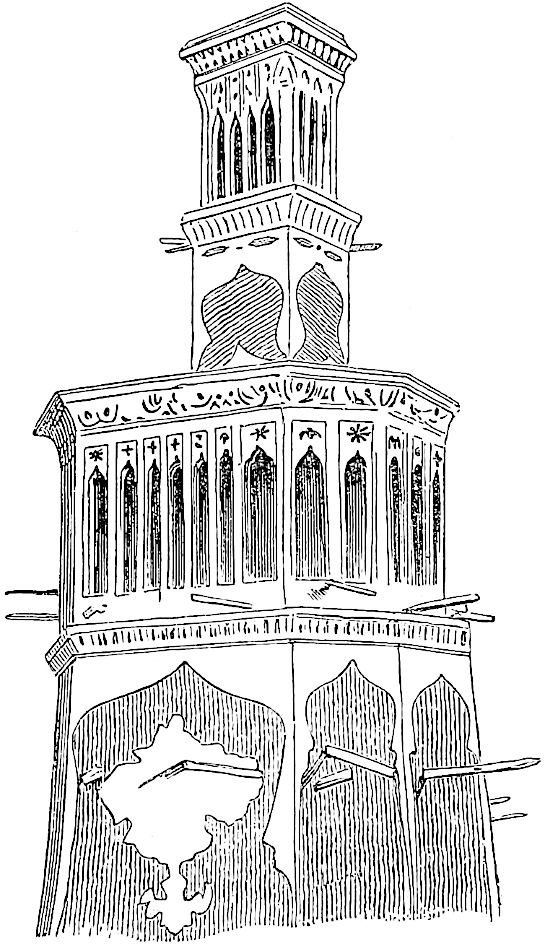

| A Persian Bád-gír, or Wind-Catcher. From a drawing in the Atlas to Hommaire de Hell’s Persia. Engraved by Adeney. |

Page |

|

|---|---|

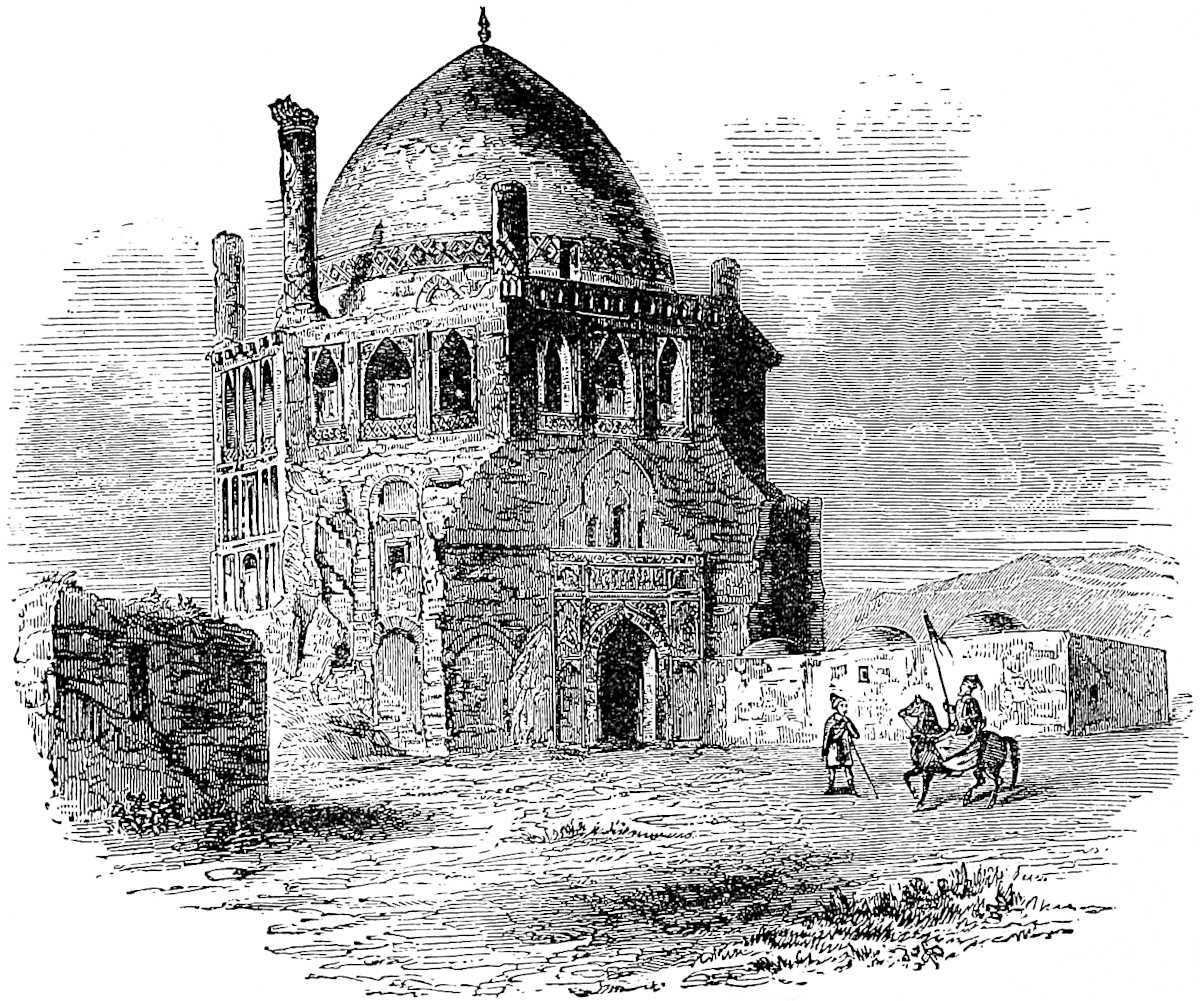

| Tomb of Oljaitu Khan, the brother of Polo’s Casan, at Sultaniah. From Fergusson’s History of Architecture. | |

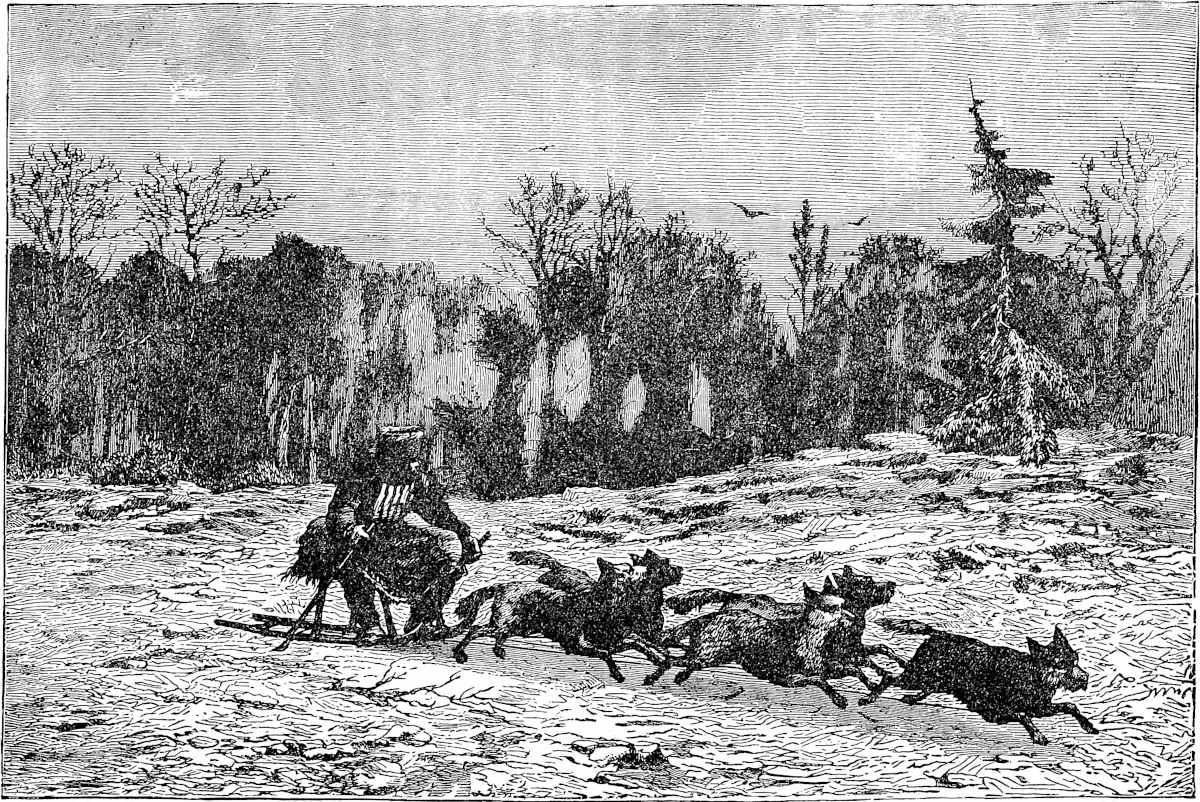

| The Siberian Dog-Sledge. From the Tour du Monde. | |

| Mediæval Russian Church. From Fergusson’s History of Architecture. | |

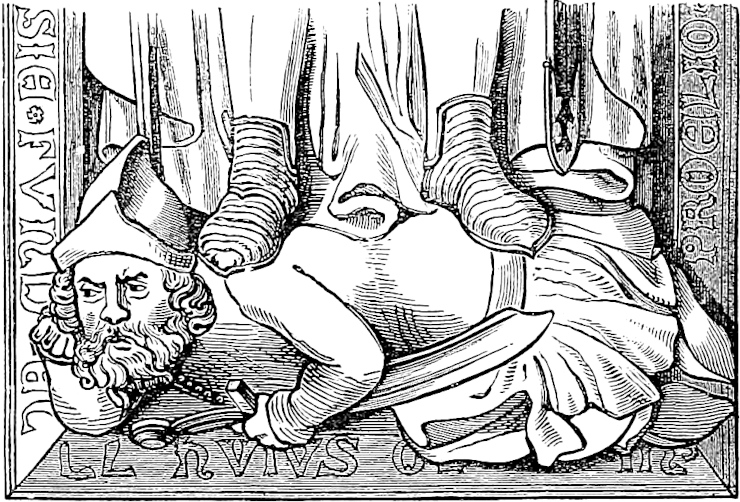

| Figure of a Tartar under the Feet of Henry Duke of Silesia, Cracow, and Poland, from the tomb at Breslau of that Prince, killed in battle with the Tartar host, 9th April, 1241. After a plate in Schlesische Fürstenbilder des Mittelalters, Breslau, 1868. | |

| Asiatic Warriors of Polo’s Age. From the MS. of Rashiduddin’s History, noticed under cut at p. 19. Engraved by Adeney. |

Page |

|

|---|---|

| Figure of Marco Polo, from the first printed edition of his Book, published in German at Nuremberg 1477. Traced from a copy in the Berlin Library. (This tracing was the gift of Mr. Samuel D. Horton, of Cincinnati, through Mr. Marsh.) | |

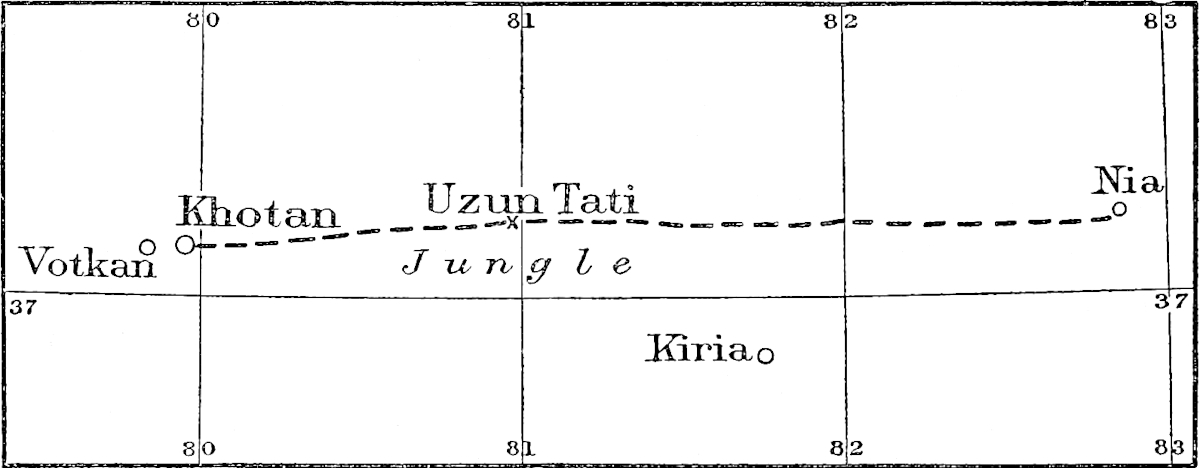

| Marco Polo’s rectified Itinerary from Khotan to Nia. |

Now you must know that the Emperor sent the aforesaid Messer Marco Polo, who is the author of this whole story, on business of his into the Western Provinces. On that occasion he travelled from Cambaluc a good four months’ journey towards the west.{1} And so now I will tell you all that he saw on his travels as he went and returned.

When you leave the City of Cambaluc and have ridden ten miles, you come to a very large river which is called Pulisanghin, and flows into the ocean, so that merchants with their merchandise ascend it from the sea. Over this River there is a very fine stone bridge, so fine indeed, that it has very few equals. The fashion of it is this: it is 300 paces in length, and it must have a good eight paces of width, for ten mounted men can ride across it abreast. It has 24 arches and 4as many water-mills, and ’tis all of very fine marble, well built and firmly founded. Along the top of the bridge there is on either side a parapet of marble slabs and columns, made in this way. At the beginning of the bridge there is a marble column, and under it a marble lion, so that the column stands upon the lion’s loins, whilst on the top of the column there is a second marble lion, both being of great size and beautifully executed sculpture. At the distance of a pace from this column there is another precisely the same, also with its two lions, and the space between them is closed with slabs of grey marble to prevent people from falling over into the water. And thus the columns run from space to space along either side of the bridge, so that altogether it is a beautiful object.{2}

Note 1.—[When Marco leaves the capital, he takes the main road, the “Imperial Highway,” from Peking to Si-ngan fu, viâ Pao-ting, Cheng-ting, Hwai-luh, Taï-yuan, Ping-yang, and T’ung-kwan, on the Yellow River. Mr. G. F. Eaton, writing from 5Han-chung (Jour. China Br. R. As. Soc. XXVIII. No. 1) says it is a cart-road, except for six days between Taï-yuan and Hwai-luh, and that it takes twenty-nine days to go from Peking to Si-ngan, a figure which agrees well with Polo’s distances; it is also the time which Dr. Forke’s journey lasted; he left Peking on the 1st May, 1892, reached Taï-yuan on the 12th, and arrived at Si-ngan on the 30th (Von Peking nach Ch’ang-an). Mr. Rockhill left Peking on the 17th December, 1888, reached T’aï-yuan on the 26th, crossed the Yellow River on the 5th January, and arrived at Si-ngan fu on the 8th January, 1889, in twenty-two days, a distance of 916 miles. (Land of the Lamas, pp. 372–374.) M. Grenard left Si-ngan on the 10th November and reached Peking on the 16th December, 1894 = thirty-six days; he reckons 1389 kilometres = 863 miles. (See Rev. C. Holcombe, Tour through Shan-hsi and Shen-hsi in Jour. North China Br. R. A. S. N. S. X. pp. 54–70.)—H. C.]

Note 2.—Pul-i-Sangín, the name which Marco gives the River, means in Persian simply (as Marsden noticed) “The Stone Bridge.” In a very different region the same name often occurs in the history of Timur applied to a certain bridge, in the country north of Badakhshan, over the Wakhsh branch of the Oxus. And the Turkish admiral Sidi ’Ali, travelling that way from India in the 16th century, applies the name, as it is applied here, to the river; for his journal tells us that beyond Kuláb he crossed “the River Pulisangin.”

A Housselin d.The Bridge of Pulisanghin. (From the Livre des Merveilles.)

A Housselin d.The Bridge of Pulisanghin. (From the Livre des Merveilles.)We may easily suppose, therefore, that near Cambaluc also, the Bridge, first, and then the River, came to be known to the Persian-speaking foreigners of the court and city by this name. This supposition is however a little perplexed by the circumstance that Rashiduddin calls the River the Sangín, and that Sangkan-Ho appears from the maps or citations of Martini, Klaproth, Neumann, and Pauthier to have been one of the Chinese names of the river, and indeed, Sankang is still the name of one of the confluents forming the Hwan Ho.

[“By Sanghin, Polo renders the Chinese Sang-kan, by which name the River Hun-ho is already mentioned, in the 6th century of our era. Hun-ho is also an ancient name; and the same river in ancient books is often called Lu-Kou River also. All 6these names are in use up to the present time; but on modern Chinese maps, only the upper part of the river is termed Sang-Kan ho, whilst south of the inner Great Wall, and in the plain, the name of Hun-ho is applied to it. Hun ho means “Muddy River,” and the term is quite suitable. In the last century, the Emperor K’ien-lung ordered the Hun-ho to be named Yung-ting ho, a name found on modern maps, but the people always call it Hun ho.” (Bretschneider, Peking, p. 54.)—H. C.]

The River is that which appears in the maps as the Hwan Ho, Hun-ho, or Yongting Ho, flowing about 7 miles west of Peking towards the south-east and joining the Pe-Ho at Tientsin; and the Bridge is that which has been known for ages as the Lu-kou-K’iao or Bridge of Lukou, adjoining the town which is called in the Russian map of Peking Feuchen, but in the official Chinese Atlas Kung-Keih-cheng. (See Map at ch. xi. of Bk. II. in the first Volume.) [“Before arriving at the bridge the small walled city of Kung-ki cheng is passed. This was founded in the first half of the 17th century. The people generally call it Fei-ch’eng.” (Bretschneider, Peking, p. 50.)—H. C.] It is described both by Magaillans and Lecomte, with some curious discrepancies, whilst each affords particulars corroborative of Polo’s account of the character of the bridge. The former calls it the finest bridge in China. Lecomte’s account says the bridge was the finest he had yet seen. “It is above 170 geometrical paces (850 feet) in length. The arches are small, but the rails or side-walls are made of a hard whitish stone resembling marble. These stones are more than 5 feet long, 3 feet high, and 7 or 8 inches thick; supported at each end by pilasters adorned with mouldings and bearing the figures of lions.... The bridge is paved with great flat stones, so well joined that it is even as a floor.”

Magaillans thinks Polo’s memory partially misled him, and that his description applies more correctly to another bridge on the same road, but some distance further west, over the Lieu-li Ho. For the bridge over the Hwan Ho had really but thirteen arches, whereas that on the Lieu-li had, as Polo specifies, twenty-four. The engraving which we give of the Lu-kou K’iao from a Chinese work confirms this statement, for it shows but thirteen arches. And what Polo says of the navigation of the river is almost conclusive proof that Magaillans is right, and that our traveller’s memory confounded the two bridges. For the navigation of the Hwan Ho, even when its channel is full, is said to be impracticable on account of rapids, whilst the Lieu-li Ho, or “Glass River,” is, as its name implies, smooth, and navigable, and it is largely navigated by boats from the coal-mines of Fang-shan. The road crosses the latter about two leagues from Cho-chau. (See next chapter.)

7

[The Rev. W. S. Ament (M. Polo in Cambaluc, p. 116–117) remarks regarding Yule’s quotation from Magaillans that “a glance at Chinese history would have explained to these gentlemen that there was no stone bridge over the Liu Li river till the days of Kia Tsing, the Ming Emperor, 1522 A.D., or more than one hundred and fifty years after Polo was dead. Hence he could not have confounded bridges, one of which he never saw. The Lu Kou Bridge was first constructed of stone by She Tsung, fourth Emperor of the Kin, in the period Ta Ting 1189 A.D., and was finished by Chang Tsung 1194 A.D. Before that time it had been constructed of wood, and had been sometimes a stationary and often a floating bridge. The oldest account [end of 16th century] states that the bridge was pu 200 in length, and specifically states that each pu was 5 feet, thus making the bridge 1000 feet long. It was called the Kuan Li Bridge. The Emperor, Kia Tsing of the Ming, was a great bridge builder. He reconstructed this bridge, adding strong embankments to prevent injury by floods. He also built the fine bridge over the Liu Li Ho, the Cho Chou Bridge over the Chü Ma Ho. What cannot be explained is Polo’s statement that the bridge had twenty-four arches, when the oldest accounts give no more than thirteen, there being eleven at the present time. The columns which supported the balustrade in Polo’s time rested upon the loins of sculptured lions. The account of the lions after the bridge was repaired by Kia Tsing says that there are so many that it is impossible to count them correctly, and gossip about the bridge says that several persons have lost their minds in making the attempt. The little walled city on the 8east end of the bridge, rightly called Kung Chi, popularly called Fei Ch’eng, is a monument to Ts’ung Chêng, the last of the Ming, who built it, hoping to check the advance of Li Tzu ch’eng, the great robber chief who finally proved too strong for him.”—H. C.]

Bridge of Lu-ku k’iao.

Bridge of Lu-ku k’iao.The Bridge of Lu-kou is mentioned more than once in the history of the conquest of North China by Chinghiz. It was the scene of a notable mutiny of the troops of the Kin Dynasty in 1215, which induced Chinghiz to break a treaty just concluded, and led to his capture of Peking.

This bridge was begun, according to Klaproth, in 1189, and was five years a-building. On the 17th August, 1688, as Magaillans tells us, a great flood carried away two arches of the bridge, and the remainder soon fell. [Father Intorcetta, quoted by Bretschneider (Peking, p. 53), gives the 25th of July, 1668, as the date of the destruction of the bridge, which agrees well with the Chinese accounts.—H. C.] The bridge was renewed, but with only nine arches instead of thirteen, as appears from the following note of personal observation with which Dr. Lockhart has favoured me:

“At 27 li from Peking, by the western road leaving the gate of the Chinese city called Kwang-’an-măn, after passing the old walled town of Feuchen, you reach the bridge of Lo-Ku-Kiao. As it now stands it is a very long bridge of nine arches (real arches) spanning the valley of the Hwan Ho, and surrounded by beautiful scenery. The bridge is built of green sandstone, and has a good balustrade with short square pilasters crowned by small lions. It is in very good repair, and has a ceaseless traffic, being on the road to the coal-mines which supply the city. There is a pavilion at each end of the bridge with inscriptions, the one recording that K’ang-hi (1662–1723) built the bridge, and the other that Kienlung (1736–1796) repaired it.” These circumstances are strictly consistent with Magaillans’ account of the destruction of the mediæval bridge. Williamson describes the present bridge as about 700 feet long, and 12 feet wide in the middle part.

[Dr. Bretschneider saw the bridge, and gives the following description of it: “The bridge is 350 ordinary paces long and 18 broad. It is built of sandstone, and has on either side a stone balustrade of square columns, about 4 feet high, 140 on each side, each crowned by a sculptured lion over a foot high. Beside these there are a number of smaller lions placed irregularly on the necks, behind the legs, under the feet, or on the back of the larger ones. The space between the columns is closed by stone slabs. Four sculptured stone elephants lean with their foreheads against the edge of the balustrades. The bridge is supported by eleven arches. At each end of the bridge two pavilions with yellow roofs have been built, all with large marble tablets in them; two with inscriptions made by order of the Emperor K’ang-hi (1662–1723); and two with inscriptions of the time of K’ien-lung (1736–1796). On these tablets the history of the bridge is recorded.” Dr. Bretschneider adds that Dr. Lockhart is also right in counting nine arches, for he counts only the waterways, not the arches resting upon the banks of the river. Dr. Forke (p. 5) counts 11 arches and 280 stone lions.—H. C.]

(P. de la Croix, II. 11, etc.; Erskine’s Baber, p. xxxiii.; Timour’s Institutes, 70; J. As. IX. 205; Cathay, 260; Magaillans, 14–18, 35; Lecomte in Astley, III. 529; J. As. sér. II. tom. i. 97–98; D’Ohsson, I. 144.)

9

10

When you leave the Bridge, and ride towards the west, finding all the way excellent hostelries for travellers, with fine vineyards, fields, and gardens, and springs of water, you come after 30 miles to a fine large city called Juju, where there are many abbeys of idolaters, and the people live by trade and manufactures. They weave cloths of silk and gold, and very fine taffetas.{1} Here too there are many hostelries for travellers.{2}

After riding a mile beyond this city you find two roads, one of which goes west and the other south-east. The westerly road is that through Cathay, and the south-easterly one goes towards the province of Manzi.{3}

Taking the westerly one through Cathay, and travelling by it for ten days, you find a constant succession of cities and boroughs, with numerous thriving villages, all abounding with trade and manufactures, besides the fine fields and vineyards and dwellings of civilized people; but nothing occurs worthy of special mention; and so I will only speak of a kingdom called Taianfu.

Note 1.—The word is sendaus (Pauthier), pl. of sendal, and in G. T. sandal. It does not seem perfectly known what this silk texture was, but as banners were made of it, and linings for richer stuffs, it appears to have been a light material, and is generally rendered taffetas. In Richard Cœur de Lion we find

“Many a pencel of sykelatounAnd of sendel of grene and broun,”and also pavilions of sendel; and in the Anglo-French ballad of the death of William Earl of Salisbury in St. Lewis’s battle on the Nile—

“Le Meister du Temple brace les chivauxEt le Count Long-Espée depli les sandaux.”11

The oriflamme of France was made of cendal. Chaucer couples taffetas and sendal. His “Doctor of Physic”

“In sanguin and in persë clad was allë,Linëd with taffata and with sendallë.”[La Curne, Dict., s.v. Sendaus has: Silk stuff: “Somme de la delivrance des sendaus.” (Nouv. Compt. de l’Arg. p. 19).—Godefroy, Dict., gives: “Sendain, adj., made with the stuff called cendal: Drap d’or sendains (1392, Test. de Blanche, duch d’Orl., Ste-Croix, Arch. Loiret).” He says s.v. Cendal, “cendau, cendral, cendel, ... sendail, ... étoffe légère de soie unie qui paraît avoir été analogue au taffetas.” “‘On faisait des cendaux forts ou faibles, et on leur donnait toute sorte de couleurs. On s’en servait surtout pour vêtements et corsets, pour doublures de draps, de fourrures et d’autres étoffes de soie plus précieuses, enfin pour tenture d’appartements.’ (Bourquelot, Foir. de Champ. I. 261).”

“J’ay de toilles de mainte guise,De sidonnes et de cendaulx.Soyes, satins blancs et vermaulx.”—Greban, Mist. de la Pass., 26826, G. Paris.—H. C.]The origin of the word seems also somewhat doubtful. The word Σενδἑς occurs in Constant. Porphyrog. de Ceremoniis (Bonn, ed. I. 468), and this looks like a transfer of the Arabic Săndăs or Sundus, which is applied by Bakui to the silk fabrics of Yezd. (Not. et Ext. II. 469.) Reiske thinks this is the origin of the Frank word, and connects its etymology with Sind. Others think that sendal and the other forms are modifications of the ancient Sindon, and this is Mr. Marsh’s view. (See also Fr.-Michel, Recherches, etc. I. 212; Dict. des Tissus, II. 171 seqq.)

Note 2.—Jújú is precisely the name given to this city by Rashiduddin, who notices the vineyards. Juju is Cho-chau, just at the distance specified from Peking, viz. 40 miles, and nearly 30 from Pulisanghin or Lu-kou K’iao. The name of the town is printed Tsochow by Mr. Williamson, and Chechow in a late Report of a journey by Consul Oxenham. He calls it “a large town of the second order, situated on the banks of a small river flowing towards the south-east, viz. the Kiu-ma-Ho, a navigable stream. It had the appearance of being a place of considerable trade, and the streets were crowded with people.” (Reports of Journeys in China and Japan, etc. Presented to Parliament, 1869, p. 9.) The place is called Jújú also in the Persian itinerary given by ’Izzat Ullah in J. R. A. S. VII. 308; and in one procured by Mr. Shaw. (Proc. R. G. S. XVI. p. 253.)

[The Rev. W. S. Ament (Marco Polo, 119–120) writes, “the historian of the city of Cho-chau sounds the praises of the people for their religious spirit. He says:—‘It was the custom of the ancients to worship those who were before them. Thus students worshipped their instructors, farmers worshipped the first husbandman, workers in silk, the original silk-worker. Thus when calamities come upon the land, the virtuous among the people make offerings to the spirits of earth and heaven, the mountains, rivers, streams, etc. All these things are profitable. These customs should never be forgotten.’ After such instruction, we are prepared to find fifty-eight temples of every variety in this little city of about 20,000 inhabitants. There is a temple to the spirits of Wind, Clouds, Thunder, and Rain, to the god of silk-workers, to the Horse-god, to the god of locusts, and the eight destructive insects, to the Five Dragons, to the King who quiets the waves. Besides these, there are all the orthodox temples to the ancient worthies, and some modern heroes. Liu Pei and Chang Fei, two of the three great heroes of the San Kuo Chih, being natives of Cho Chou, are each honoured with two temples, one in the native village, and one in the city. It is not often that one locality can give to a great empire two of its three most popular heroes: Liu Pei, Chang Fei, Kuan Yu.”

“Judging from the condition of the country,” writes the Rev. W. S. Ament 12(p. 120), “one could hardly believe that this general region was the original home of the silk-worm, and doubtless the people who once lived here are the only people who ever saw the silk-worm in his wild state. The historian of Cho-Chou honestly remarks that he knows of no reason why the production of silk should have ceased there, except the fact that the worms refused to live there.... The palmy days of the silk industry were in the T’ang dynasty.”—H. C.]

Note 3.—“About a li from the southern suburbs of this town, the great road to Shantung and the south-east diverged, causing an immediate diminution in the number of carts and travellers” (Oxenham). [From Peking “to Cheng-ting fu”, says Colonel Bell (Proc. R. G. S., XII. 1890, p. 58), “the route followed is the Great Southern highway; here the Great Central Asian highway leaves it.” The Rev. W. S. Ament says (l.c., 121) about the bifurcation of the road, one branch going on south-west to Pao-Ting fu and Shan-si, and one branch to Shantung and Ho-nan: “The union of the two roads at this point, bringing the travel and traffic of ten provinces, makes Cho Chou one of the most important cities in the Empire. The magistrate of this district is the only one, so far as we know, in the Empire who is relieved of the duty of welcoming and escorting transient officers. It was the multiplicity of such duties, so harassing, that persuaded Fang Kuan-ch’eng to write the couplet on one of the city gateways: Jih pien ch’ung yao, wu shuang ti: T’ien hsia fan nan, ti yi Chou. ‘In all the world, there is no place so public as this: for multiplied cares and trials, this is the first Chou.’ The people of Cho-Chou, of old celebrated for their religious spirit, are now well known for their literary enterprise.”—H. C.] This bifurcation of the roads is a notable point in Polo’s book. For after following the western road through Cathay, i.e. the northern provinces of China, to the borders of Tibet and the Indo-Chinese regions, our traveller will return, whimsically enough, not to the capital to take a fresh departure, but to this bifurcation outside of Chochau, and thence carry us south with him to Manzi, or China south of the Yellow River.

Of a part of the road of which Polo speaks in the latter part of the chapter Williamson says: “The drive was a very beautiful one. Not only were the many villages almost hidden by foliage, but the road itself hereabouts is lined with trees.... The effect was to make the journey like a ramble through the avenues of some English park.” Beyond Tingchau however the country becomes more barren. (I. 268.)

After riding then those ten days from the city of Juju, you find yourself in a kingdom called Taianfu, and the city at which you arrive, which is the capital, is also called Taianfu, a very great and fine city. [But at the end of five days’ journey out of those ten, they say there is a city unusually large and handsome called 13Acbaluc, whereat terminate in this direction the hunting preserves of the Emperor, within which no one dares to sport except the Emperor and his family, and those who are on the books of the Grand Falconer. Beyond this limit any one is at liberty to sport, if he be a gentleman. The Great Kaan, however, scarcely ever went hunting in this direction, and hence the game, particularly the hares, had increased and multiplied to such an extent that all the crops of the Province were destroyed. The Great Kaan being informed of this, proceeded thither with all his Court, and the game that was taken was past counting.]{1}

Taianfu{2} is a place of great trade and great industry, for here they manufacture a large quantity of the most necessary equipments for the army of the Emperor. There grow here many excellent vines, supplying great plenty of wine; and in all Cathay this is the only place where wine is produced. It is carried hence all over the country.{3} There is also a great deal of silk here, for the people have great quantities of mulberry-trees and silk-worms.

From this city of Taianfu you ride westward again for seven days, through fine districts with plenty of towns and boroughs, all enjoying much trade and practising various kinds of industry. Out of these districts go forth not a few great merchants, who travel to India and other foreign regions, buying and selling and getting gain. After those seven days’ journey you arrive at a city called Pianfu, a large and important place, with a number of traders living by commerce and industry. It is a place too where silk is largely produced.{4}

So we will leave it and tell you of a great city called Cachanfu. But stay—first let us tell you about the noble castle called Caichu.

14

Note 1.—Marsden translates the commencement of this passage, which is peculiar to Ramusio, and runs “E in capo di cinque giornate delle predette dieci,” by the words “At the end of five days’ journey beyond the ten,” but this is clearly wrong.[1] The place best suiting in position, as halfway between Cho-chau and T’ai-yuan fu, would be Cheng-ting fu, and I have little doubt that this is the place intended. The title of Ak-Báligh in Turki,[2] or Chaghán Balghásun in Mongol, meaning “White City,” was applied by the Tartars to Royal Residences; and possibly Cheng-ting fu may have had such a claim, for I observe in the Annales de la Prop. de la Foi (xxxiii. 387) that in 1862 the Chinese Government granted to the R. C. Vicar-Apostolic of Chihli the ruined Imperial Palace at Cheng-ting fu for his cathedral and other mission establishments. Moreover, as a matter of fact, Rashiduddin’s account of Chinghiz’s campaign in northern China in 1214, speaks of the city of “Chaghan Balghasun which the Chinese call Jintzinfu.” This is almost exactly the way in which the name of Cheng-ting fu is represented in ’Izzat Ullah’s Persian Itinerary (Jigdzinfu, evidently a clerical error for Jingdzinfu), so I think there can be little doubt that Cheng-ting fu is the place intended. The name of Hwai-luh’ien (see Note 2), which is the first stage beyond Cheng-ting fu, is said to mean the “Deer-lair,” pointing apparently to the old character of the tract as a game-preserve. The city of Cheng-ting is described by Consul Oxenham as being now in a decayed and dilapidated condition, consisting only of two long streets crossing at right angles. It is noted for the manufacture of images of Buddha from Shan-si iron. (Consular Reports, p. 10; Erdmann, 331.)

[The main road turns due west at Cheng-ting fu, and enters Shan-si through what is known among Chinese travellers as the Ku-kwan, Customs’ Barrier.—H. C.]

Between Cheng-ting fu and T’ai-yuan fu the traveller first crosses a high and rugged range of mountains, and then ascends by narrow defiles to the plateau of Shan-si. But of these features Polo’s excessive condensation takes no notice.

The traveller who quits the great plain of Chihli [which terminates at Fu-ch’eng-i, a small market-town, two days from Pao-ting.—H. C.] for “the kingdom of Taianfu,” i.e. Northern Shan-si, enters a tract in which predominates that very remarkable formation called by the Chinese Hwang-tu, and to which the German name Löss has been attached. With this formation are bound up the distinguishing characters of Northern Interior China, not merely in scenery but in agricultural products, dwellings, and means of transport. This Löss is a brownish-yellow loam, highly porous, spreading over low and high ground alike, smoothing over irregularities of surface, and often more than 1000 feet in thickness. It has no stratification, but tends to cleave vertically, and is traversed in every direction by sudden crevices, almost glacier-like, narrow, with vertical walls of great depth, and infinite ramification. Smooth as the löss basin looks in a bird’s-eye view, it is thus one of the most impracticable countries conceivable for military movements, and secures extraordinary value to fortresses in well-chosen sites, such as that of Tung-kwan mentioned in Note 2 to chap. xli.

Agriculture may be said in N. China to be confined to the alluvial plains and the löss; as in S. China to the alluvial plains and the terraced hill-sides. The löss has some peculiar quality which renders its productive power self-renewing without manure (unless it be in the form of a surface coat of fresh löss), and unfailing in returns if there be sufficient rain. This singular formation is supposed by Baron Richthofen, who has studied it more extensively than any one, to be no subaqueous deposit, but to be the accumulated residue of countless generations of herbaceous plants combined with a large amount of material spread over the face of the ground by the winds and surface waters.

[I do not agree with the theory of Baron von Richthofen, of the almost exclusive Eolian formation of loess; water has something to do with it as well as wind, and I think it is more exact to say that loess in China is due to a double action, Neptunian as well as Eolian. The climate was different in former ages from what it is now, and 15rain was plentiful and to its great quantity was due the fertility of this yellow soil. (Cf. A. de Lapparent, Leçons de Géographie Physique, 2e éd. 1898, p. 566.)—H. C.]

Though we do not expect to find Polo taking note of geological features, we are surprised to find no mention of a characteristic of Shan-si and the adjoining districts, which is due to the löss; viz. the practice of forming cave dwellings in it; these in fact form the habitations of a majority of the people in the löss country. Polo has noticed a similar usage in Badakhshan (I. p. 161), and it will be curious if a better acquaintance with that region should disclose a surface formation analogous to the löss. (Richthofen’s Letters, VII. 13 et passim.)

Note 2.—Taianfu is, as Magaillans pointed out, T’ai-yuan fu, the capital of the Province of Shan-si, and Shan-si is the “Kingdom.” The city was, however, the capital of the great T’ang Dynasty for a time in the 8th century, and is probably the Tájah or Taiyúnah of old Arab writers. Mr. Williamson speaks of it as a very pleasant city at the north end of a most fertile and beautiful plain, between two noble ranges of mountains. It was a residence, he says, also of the Ming princes, and is laid out in Peking fashion, even to mimicking the Coal-Hill and Lake of the Imperial Gardens. It stands about 3000 feet above the sea [on the left bank of the Fen-ho.—H. C.]. There is still an Imperial factory of artillery, matchlocks, etc., as well as a powder mill; and fine carpets like those of Turkey are also manufactured. The city is not, however, now, according to Baron Richthofen, very populous, and conveys no impression of wealth or commercial importance. [In an interesting article on this city, the Rev. G. B. Farthing writes (North China Herald, 7th September, 1894): “The configuration of the ground enclosed by T’ai-yuan fu city is that of a ‘three times to stretch recumbent cow.’ The site was chosen and described by Li Chun-feng, a celebrated professor of geomancy in the days of the T’angs, who lived during the reign of the Emperor T’ai Tsung of that ilk. The city having been then founded, its history reaches back to that date. Since that time the cow has stretched twice.... T’ai-yuan city is square, and surrounded by a wall of earth, of which the outer face is bricked. The height of the wall varies from thirty to fifty feet, and it is so broad that two carriages could easily pass one another upon it. The natives would tell you that each of the sides is three miles, thirteen paces in length, but this, possibly, includes what it will be when the cow shall have stretched for the third and last time. Two miles is the length of each side; eight miles to tramp if you wish to go round the four of them.”—H. C.] The district used to be much noted for cutlery and hardware, iron as well as coal being abundantly produced in Shan-si. Apparently the present Birmingham of this region is a town called Hwai-lu, or Hwo-luh’ien, about 20 miles west of Cheng-ting fu, and just on the western verge of the great plain of Chihli. [Regarding Hwai-lu, the Rev. C. Holcombe calls it “a miserable town lying among the foot hills, and at the mouth of the valley, up which the road into Shan-si lies.” He writes (p. 59) that Ping-ting chau, after the Customs’ barrier (Ku Kwan) between Chih-li and Shan-si, would, under any proper system of management, at no distant day become the Pittsburg, or Birmingham, of China.—H. C.] (Richthofen’s Letters, No. VII. 20; Cathay, xcvii. cxiii. cxciv.; Rennie, II. 265; Williamson’s Journeys in North China; Oxenham, u.s. 11; Klaproth in J. As. sér. II. tom. i. 100; Izzat Ullah’s Pers. Itin. in J. R. A. S. VII. 307; Forke, Von Peking nach Ch’ang-an, p. 23.)

[“From Khavailu (Hwo-luh’ien), an important commercial centre supplying Shansi, for 130 miles to Sze-tien, the road traverses the loess hills, which extend from the Peking-Kalgan road in a south-west direction to the Yellow River, and which are passable throughout this length only by the Great Central Asian trade route to T’ai-yuan fu and by the Tung-Kwan, Ho-nan, i.e. the Yellow River route.” (Colonel Bell, Proc. R. G. S. XII. 1890, p. 59.) Colonel Bell reckons seven days (218 miles) from Peking to Hwo-lu-h’ien and five days from this place to T’ai-yuan fu.—H. C.]

Note 3.—Martini observes that the grapes in Shan-si were very abundant and the 16best in China. The Chinese used them only as raisins, but wine was made there for the use of the early Jesuit Missions, and their successors continue to make it. Klaproth, however, tells us that the wine of T’ai-yuan fu was celebrated in the days of the T’ang Dynasty, and used to be sent in tribute to the Emperors. Under the Mongols the use of this wine spread greatly. The founder of the Ming accepted the offering of wine of the vine from T’ai-yuan in 1373, but prohibited its being presented again. The finest grapes are produced in the district of Yukau-hien, where hills shield the plain from north winds, and convert it into a garden many square miles in extent. In the vintage season the best grapes sell for less than a farthing a pound. [Mr. Theos. Sampson, in an article on “Grapes in China,” writes (Notes and Queries on China and Japan, April, 1869, p. 50): “The earliest mention of the grape in Chinese literature appears to be contained in the chapter on the nations of Central Asia, entitled Ta Yuan Chwan, or description of Fergana, which forms part of the historical records (Sze-Ki) of Sze-ma Tsien, dating from B.C. 100. Writing of the political relations instituted shortly before this date by the Emperor Wu Ti with the nations beyond the Western frontiers of China, the historian dwells at considerable length, but unluckily with much obscurity, on the various missions despatched westward under the leadership of Chang K’ien and others, and mentions the grape vine in the following passage:—‘Throughout the country of Fergana, wine is made from grapes, and the wealthy lay up stores of wine, many tens of thousands of shih in amount, which may be kept for scores of years without spoiling. Wine is the common beverage, and for horses the mu-su is the ordinary pasture. The envoys from China brought back seeds with them, and hereupon the Emperor for the first time cultivated the grape and the mu-su in the most productive soils.’ In the Description of Western regions, forming part of the History of the Han Dynasty, it is stated that grapes are abundantly produced in the country of K’i-pin (identified with Cophene, part of modern Afghanistan) and other adjacent countries, and referring, if I mistake not, to the journeys of Chang K’ien, the same work says, that the Emperor Wu-Ti despatched upwards of ten envoys to the various countries westward of Fergana, to search for novelties, and that they returned with grape and mu-su seeds. These references appear beyond question to determine the fact that grapes were introduced from Western—or, as we term it, Central—Asia, by Chang K’ien.”

Dr. Bretschneider (Botanicon Sinicum, I. p. 25), relating the mission of Chang K’ien (139 B.C. Emperor Wu-Ti), who died about B.C. 103, writes:—“He is said to have introduced many useful plants from Western Asia into China. Ancient Chinese authors ascribe to him the introduction of the Vine, the Pomegranate, Safflower, the Common Bean, the Cucumber, Lucerne, Coriander, the Walnut-tree, and other plants.”—H. C.] The river that flows down from Shan-si by Cheng-ting-fu is called “Putu-ho, or the Grape River.” (J. As. u.s.; Richthofen, u.s.)

[Regarding the name of this river, the Rev. C. Holcombe (l.c. p. 56) writes: “Williamson states in his Journeys in North China that the name of this stream is, properly Poo-too Ho—‘Grape River,’ but is sometimes written Hu-t’ou River incorrectly. The above named author, however, is himself in error, the name given above [Hu-t’o] being invariably found in all Chinese authorities, as well as being the name by which the stream is known all along its course.”

West of the Fan River, along the western border of the Central Plain of Shan-si, in the extreme northern point of which lies T’aï-yuan fu, the Rev. C. Holcombe says (p. 61), “is a large area, close under the hills, almost exclusively given up to the cultivation of the grape. The grapes are unusually large, and of delicious flavour.”—H. C.]