Title: The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 403, December 5, 1829

Author: Various

Release date: March 1, 2004 [eBook #11458]

Most recently updated: October 28, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, Andy Jewell, David Garcia, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 14, Issue 403, December 5, 1829, by Various

| VOL. XIV, NO. 403.] | SATURDAY, DECEMBER 5, 1829. | [PRICE 2d. |

In the poet and the philosopher, the lover of the sublime, and the student of the beautiful in art—the contemplation of such a scene as this must awaken ecstatic feelings of admiration and awe. Its effect upon the mere man of the world, whose mind is clogged up with common-places of life, must be overwhelming as the torrent itself; perchance he soon recovers from the impression; but the lover of Nature, in her wonders, reads lessons of infinite wisdom, combined with all that is most fascinating to the mind of inquiring man. In the school of her philosophy, mountains, rivers, and falls not only astonish and delight him in their vast outlines and surfaces, but in their exhaustless varieties and transformations, he enjoys old and new worlds of knowledge, apart from the proud histories of man, and the comparative insignificance of all that he has laboured to produce on the face of the globe.

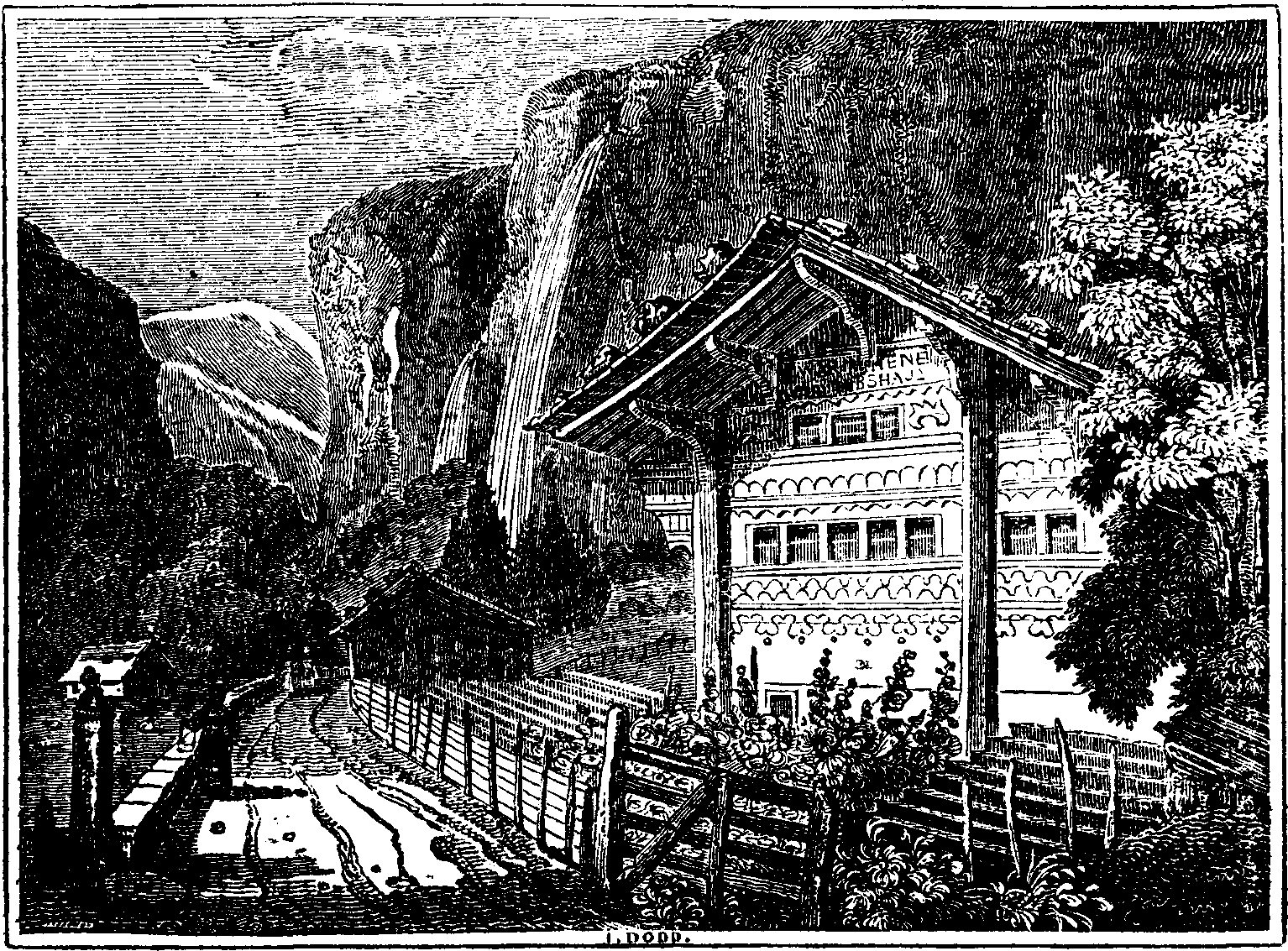

Few have witnessed the Staubbach, or similar wonders without acknowledging the force of their impressions. This Fall is in the valley of Lauterbrun, the most picturesque district of Switzerland. Simond,1 in describing its beauties, says, "we began to ascend the valley of Lauterbrun, by the side of its torrent (the Lutschine) among fragments of rocks, torn from the heights on both sides, and beautiful trees, shooting up with great luxuriance and in infinite variety; smooth pastures of the richest verdure, carpeted over every interval of plain ground; and the harmony of the sonorous cow-bell of the Alps, heard among the precipices above our heads and below us, told us we were not in a desart." "The ruins of the mineral world, apparently so durable, and yet in a state of incessant decomposition, form a striking contrast with the perennial youth of the vegetable world; each individual plant, so frail and perishable, while the species is eternal in the existing economy of nature. Imperceptible forests of timber scarcely tinge their inert masses of gneiss and granite, into which they anchor their roots; grappling with substances which, when [pg 386] struck with steel, tear up the tempered grain, and dash out the spark." This may be an enthusiastic, but is doubtless the faithful, impression of our tourist; and in descriptions of sublime nature, we should

Survey the whole; nor seek slight fault to find,

Where Nature moves, and rapture warms the mind.

Each valley has its appropriate stream, proportioned to its length, and the number of lateral valleys opening into it. The boisterous Lutschine is the stream of Lauterbrun, and it carries to the Lake of Brientz scarcely less water than the Aar itself. About half way between Interlaken and Lauterbrun, is the junction of the two Lutschines, the black and the white, from the different substances with which they have been in contact.

Simond says, "after passing several falls of water, each of which we mistook for the Staubbach, we came at last to the house where we were to sleep. It had taken us three hours to come thus far; in twenty minutes more we reached the heap of rubbish accumulated by degrees at the foot of the Staubbach; its waters descending from the height of the Pletschberg, form in their course several mighty cataracts, and the last but one is said to be the finest; but is not readily accessible, nor seen at all from the valley. The fall of the Staubbach, about eight hundred feet in height, wholly detached from the rock, is reduced into vapour long before it reaches the ground; the water and the vapour undulating through the air with more grace and elegance than sublimity. While amusing ourselves with watching the singular appearance of rockets of water shooting down into the dense cloud of vapour below, we were joined by some country girls, who gave us a concert of three voices, pitched excessively high, and more like the vibrations of metal or glass than the human voice, but in perfect harmony, and although painful in some degree, yet very fine. In winter an immense accumulation of ice takes place at the foot of the Fall, sometimes as much as three hundred feet broad, with two enormous icy stalactites hanging down over it. When heat returns, the falling waters hollow out cavernous channels through the mass, the effect of which is said to be very fine; this, no doubt, is the proper season to see the Staubbach to most advantage." Six or eight miles further, the valley ends in glaciers scarcely practicable for chamois hunters. About forty years since some miners who belonged to the Valais, and were at work at Lauterbrun, undertook to cross over to their own country, simply to hear mass on a Sunday. They traversed the level top of the glacier in three hours; then descended, amidst the greatest dangers, its broken slope into the Valais, and returned the day after by the same way; but no one else has since ventured on the dangerous enterprise.

Apart from the romantic attraction of the Fall, the broad-eaved chalet and its accessaries form a truly interesting picture of village simplicity and repose. Here you are deemed rich with a capital of three hundred pounds. All that is not made in the country, or of its growth, is deemed luxury: a silver chain here as at Berne, is transmitted from mother to daughter. Dwellings and barns covered with tiles, and windows with large panes of glass, give to the owner a reputation of wealth; and if the outside walls are adorned with paintings, and passages of Scripture are inscribed on the front of the house, the owner ranks at once among the aristocracy of the country. What an association of primitive happiness do these humble attributes and characteristics of Swiss scenery convey to the unambitious mind. Think of this, ye who regard palaces as symbols of true enjoyment! and ye who imprison yourselves in overgrown cities, and wear the silken fetters of wealth and pride!—an aristocrat of Lauterbrun eclipses all your splendour, and a poor Swiss cottager in his humble chalet, is richer than the wealthiest of you—for he is content.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

In my paper of the 22nd of August, on this subject, I promised to resume it on my next coming to London, which has been retarded by several causes.

In visiting the Churches of All Souls, and Trinity, the psalmody is by no means to be praised. It is chiefly by the charity children, the singing (or rather noise) is in their usual way, and which will go on to the end of time, unless by the permission of the clergy, some intelligent instructors are allowed to lead as in the Chapel of St. James, near Mornington Place, in the Hampstead Road. The author of the paper on Music, in your publication of the 6th of September, very fairly puts the question, "Why are not the English a musical people?" and he shows many of [pg 387] the interrupting causes. It may happen, however, that by cultivating psalmody in our churches and chapels, considerable progress may be made. The young will be instructed, and the more advanced will attend, and we know the power of attention (the only quality in which Sir Isaac Newton could be persuaded to believe he had any one advantage in intellect over his fellow men.)

It is much to be regretted that the poetry in which our Episcopal Psalms and Hymns are sung, is confined to the versions of Sternhold and Hopkins, and of Tate and Brady. The poetry of Sternhold and Hopkins is in general uncouth with some few exceptions. Tate and Brady have made their versification somewhat more congenial with the modern improvements of our language; but each confines himself to the very literal language of the Old Testament; Sternhold and Hopkins in this respect have the advantage of their successors, Tate and Brady; for the translations of Sternhold and Hopkins are nearer to the original Hebrew.

The main object of my hope is, that the version of the Psalms now in use may be altered, or rather improved, in such a manner as to manifest their prophetic and typical relation to Christianity, to which in their present form so little reference is to be perceived by those "who should read as they run." A change or improvement in this respect would give a more enlivening interest in Psalmody. Dr. Watts has done this with great truth and effect, and the singing in the churches and chapels in which his version is in whole or in part introduced, proceeds with a more Christian spirit: and a vast improvement has sprung from this source, in the sacred music of those churches and chapels.

To illustrate this part of my paper, let me refer to the version employed in several of the new churches, and to the version of Dr. Watts, in the spiritual interpretation of the 4th Psalm. In the version first referred to, the words are—

The place of ancient sacrifice

Let righteousness supply,

And let your hope securely fix'd

On Him alone rely.

Now in this version it naturally occurs to inquire what righteousness? The high churchman will content himself that it is a literal translation; but the way-faring man sees nothing of the atoning righteousness of Christ in this translation; but which according to the 11th article of the Church of England, he reasonably looks for. Even the Unitarians refer to this and other parts of our translation of the Hebrew Psalms, as a justification of THEIR main principle of the unity alone in the godhead.

Dr. Watts, a genuine Christian, believing in the union of the Father, Son, and Spirit, and manifesting this pure faith to the end of a well-spent life, gives the Christian meaning of this righteousness, in his version of the 4th Psalm:

Know that the Lord divides his Saints

From all the tribes of men beside,

He hears the cry of penitents

For the dear sake of Christ who died.

Here the true typical and prophetic meaning of the Old Testament is given.

The version used by the English church in the 5th Psalm is subject to the same observation as on the 4th.

The church version is

Thou in the morn shall hear my voice

And with the dawn of day,

To thee devoutly I look up,

To thee devoutly pray.

Dr. Watts, who gives the Christian meaning of this Psalm, translates or paraphrases thus truly:—

Lord in the morning thou shall hear

My voice ascending high,

To thee will I direct my pray'r,

To thee lift up mine eye.

Up to the hills where Christ is gone

To plead for all his Saints,

Presenting at his father's throne,

Our songs and our complaints.

Psalmody, or the singing of sacred music, conducted by such a gracious and animated sense of the revealed word of God, must naturally be performed, as it must be ardently felt, in a different spirit—and this truth we perceive daily verified; but while a considerable portion of our clergy not only are strict in confining the singing to the last version, or to parts of Sternhold, and even prescribe the very dull old tunes to be made use of, improvement in church music is not to be expected. I have before me a list of tunes, to which the organists of our churches and episcopal chapels are limited in their playing; and, what is singular, three of the chief clergymen of the churches confess they literally have no ear for music, and are utter strangers to what an octave means, and yet their authority decides.

It is not intended to enter into any polemical discussion, as controversy is not necessary to the improvement of psalmody; but less than has been stated would not have shown the advantage to be acquired by the use of a more Christian sense to those who rely on Christ as their Redeemer. We know, from experience, how agreeable it is to the [pg 388] mind and senses to hear the praises to the Almighty sung by the proper rules of harmony, and with what spiritual animation the upright and sincere youth of both sexes unite in this delightful service.

With these views, I respectfully submit to the clergymen of the new churches to pursue the course which receives such universal approbation in St. James's Chapel, Mornington-place, Hampstead-road. The simplicity and effect must be strong motives to excite their attention, and I hope to witness its adoption.

CHRISTIANUS.

(For the Mirror.)

I tell with equal truth and grief,

That little C—'s an arrant thief,

Before the urchin well could go,

She stole the whiteness of the snow.

And more—that whiteness to adorn,

She snatch'd the blushes of the morn;

Stole all the softness aether pours

On primrose buds in vernal show'rs.

There's no repeating all her wiles,

She stole the Graces' winning smiles;

'Twas quickly seen she robb'd the sky,

To plant a star in either eye;

She pilfer'd orient pearl for teeth,

And suck'd the cow's ambrosial breath;

The cherry steep'd in morning dew

Gave moisture to her lips and hue.

These were her infant spoils, a store

To which in time she added more;

At twelve she stole from Cyprus' Queen

Her air and love-commanding mien;

Stole Juno's dignity, and stole

From Pallas sense, to charm the soul;

She sung—amaz'd the Sirens heard

And to assert their voice appear'd.

She play'd, the Muses from their hill,

Marvell'd who thus had stole their skill;

Apollo's wit was next her prey,

Her next the beam that lights the day;

While Jove her pilferings to crown,

Pronounc'd these beauties all her own;

Pardon'd her crimes, and prais'd her art,

And t'other day she stole—my heart.

Cupid, if lovers are thy care,

Revenge thy vot'ry on this fair;

Do justice on her stolen charms,

And let her prison be—my arms.

W.H.H.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

In the Drama entitled Shakspeare's Early Days, the compliment which the poet is made to pay the queen: "That as at her birth she wept when all around was joy, so at her death she will smile while all around is grief," has been admired by the critics. In this jewel-stealing age, it is but just to restore the little brilliant to its owner. The following lines are in Sir William Jones's Life, translated by him from one of the Eastern poets, and are so exquisitely beautiful that I think they will be acceptable to some of your fair readers for their albums.

T.B.

On parent's knees, a naked new-born child,

Weeping thou sat'st, while all around thee smil'd.

So live, that sinking to thy last long sleep,

Calm thou may'st smile, while all around thee—weep.

(For the Mirror.)

The form of ages long gone by

Crowd thick on Fancy's wondering eye,

And wake the soul to musings high!

J.T. WALTER.

Where are the lights that shone of yore

Around this haunted spring?

Do they upon some distant shore

Their holy lustre fling?

It was not thus when pilgrims came

To hymn beneath the night,

And dimly gleam'd the censor's flame

When stars and streams were bright.

What art thou—since five hundred years

Have o'er thy waters roll'd;

Since clouds have wept their crystal tears

From skies of beaming gold?

Thy rills receive the tint of heaven,

Which erst illum'd thy shrine;

And sweetest birds their songs have given,

For music more divine.

Beside thee hath the maiden kept

Her vigils pale and lone;

While darkly have her ringlets swept

The chapel's sculptur'd stone;

And when the vesper-hymn was sung

Around the warrior's bier,

With cross and banner o'er him hung,

What splendour crown'd thee here!

But a cloud has fall'n upon thy fame!

The woodman laves his brow,

Where shrouded monks and vestals came

With many a sacred vow;

And bluely gleams thy sainted spring

Beneath the sunny tree;

Then let no heart its sadness bring,

When Nature is with thee.

REGINALD AUGUSTINE.

A Siamese Chief hearing an Englishman expatiate upon the magnitude of our navy, and afterwards that England was at peace, cooly observed, "If you are at peace with all the world, why do you keep up so great a navy?"

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

I take the liberty of transmitting you an authentic, though somewhat concise, narrative of the loss of the Hon. Company's regular ship, "Cabalva," (on the Cargados, Carajos, in the Indian Seas, in latitude 16° 45 s.) in July, 1818, no detailed account having hitherto appeared. The following was written by one of the surviving officers, in a letter to a friend.

A CONSTANT READER.

The Hon. Company's ship, Cabalva, having struck on the Owers, in the English Channel, and from that circumstance, proving leaky, and manifesting great weakness in her frame, it was thought advisable to bear up for Bombay in order to dock the ship. Meeting with a severe gale of wind off the Cape, (in which we made twenty inches of water per hour,) we parted from our consort, and shaped a course for Bombay; but on the 7th of July, between four and five A.M. (the weather dark and cloudy) the ship going seven or eight knots, an alarm was given of breakers on the larboard bow; the helm was instantly put hard-a-port, and the head sheets let go; but before it could have the desired effect, she struck; the shock was so violent, that every person was instantly on deck, with horror and amazement depicted on their countenances. An effort was made to get the ship off, but it was immediately seen that all endeavours to save her must be useless; she soon became fixed, and the sea broke over her with tremendous force; stove in her weather side, making a clear passage—washed through the hatchways, tearing up the decks, and all that opposed its violence.

We were now uncertain of our distance from a place of safety; the surf burst over the vessel in a dreadful cascade, the crew despairing and clinging to her sides to avoid its violence, while the ship was breaking up with a rapidity and crashing noise, which added to the roaring of the breakers, drowned the voices of the officers. The masts were cut away to ease the ship, and the cutter cleared from the booms and launched from the lee-gunwale. When the long wished-for dawn at last broke on us, instead of alleviating, it rather added to, our distress. We found the ship had run on the south-easternmost extremity of a coral reef, surrounding on the eastern side those sand-banks or islands in the Indian ocean, called Cargados, Carajos: the nearest of these was about three miles distant, but not the least appearance of verdure could be discovered, or the slightest trace of anything on which we might hope to subsist. In two or three places some pyramidical rocks appeared above the rest like distant sails, and were repeatedly cheered as such by the crew, till it was soon perceived they had no motion, and the delusion vanished. The masts had fallen towards the reef, the ship having fortunately canted in that direction, and the boat was thereby protected in some measure from the surf. Our commander, whom a strong sense of misfortune had entirely deprived of mind so necessary on these occasions, was earnestly requested to get into the boat, but he would not, thinking her unsafe. He maintained his station on the mizen top-mast that lay among the wreck to leeward; the surf which was rushing round the bow and stern continually overwhelming him. I was myself close to him on the same spar, and in this situation we saw many of our shipmates meet an untimely end, being either dashed against the rocks or swept over by the breakers. The large cutter, full of officers and men, now cleared a passage through the mass of wreck, and being furnished with oars, watched the proper moment and pushed off for the reef, which she fortunately gained in safety; they were all washed out of her in an instant by a tremendous surf, yet out of more than sixty which it contained, only one man was drowned. Our captain seeing this, wished he had taken advice, which was now of no use. Finding I could not longer maintain myself on the same spar, and seeing the captain in a very exhausted state, I solicited him to return to the wreck, but he replied, that since we must all eventually perish, I should not think of his, but rather of my own, preservation. An enormous breaker now burst on us with irresistible force, so that I scarcely noticed what occurred to him afterwards, being buried by successive seas. At length, after the most desperate efforts, I was thrown on the reef, half drowned and severely cut by the sharp coral, when I silently offered up thanks for my preservation, and crawling up the reef, waved my hand to encourage those who remained behind.

The captain, however, was not to be seen, and most of the others had returned to the wreck and were employed in getting the small cutter into the [pg 390] water, which they accomplished, and safely reached the shore. About noon, when we had all left the ship, she was a perfect wreck. The whole of the upper works, from the after part of the forecastle to the break of the poop deck, had separated from her bottom about the upper futtock-heads, and was driving in towards the reef. Most of the lighter cargo had floated out of her. Bales of company's cloth, cases of wine, puncheons of spirits, barrels of gunpowder, hogsheads of beer, &c. lay strewed on the shore, together with a chest of tools. Finding the men beginning to commit the usual excesses, we stove in the heads of the spirit casks, to prevent mischief, and endeavoured to direct their attention to the general benefit. The tide was flowing fast, and we saw that the reef must soon be covered; we therefore conveyed the boats to a place of safety, and filling them with all the provisions that could be collected, proceeded to the highest sand-bank as the only place which held out the remotest chance of security. Our progress was attended with the most excruciating pain I ever endured, with feet cut to the bones by the rocks, and back blistered by the sun—exhausted with fatigue—up to the waist—sometimes to the neck in the water, and frequently obliged to swim. Seeing, however, that several had reached the highest sand-bank, lighted a fire, and were employed in erecting a tent from the cloth and small spars which had floated up, I felt my spirits revive, and had strength sufficient to reach the desired spot, when I was invited to partake of a shark which had just been caught by the people. Having set a watch to announce the approach of the sea, lest it should cover us unawares, I sunk exhausted on the sand, and fell into a sound sleep. I awoke in the morning stiff with the exertions of the former day, yet feeling grateful to Providence that I was still alive.

The people now collected together to ascertain who had perished, when sixteen were missing: the captain, surgeon's assistant, and fourteen of the crew. We divided the crew into parties, each headed by an officer; some were sent to the wreck and along the beach in search of provisions, others to roll up the hogsheads of beer, and butts of water that had floated on shore; but the greater number were employed in hauling the two cutters up, when the carpenters were directed to repair them.

By the time it was dark, we had collected about eighty pieces of salt pork, ten hogsheads of beer, three butts of water, several bottles of wine, and many articles of use and value; particularly three sextants and a quadrant, Floresburg's Directory, and Hamilton Moore; the latter were deemed inestimable. In course of time four live pigs, and five live sheep, came on shore through the surf.

We first began upon the dead stock, serving out two ounces to each, and half a pint of beer for the day. Nothing but brackish water could be obtained by digging in the sand. We collected all the provisions together near the tent, and formed a kind of storehouse, setting an officer to guard them from plunder, to which indeed some of the evil characters were disposed; but as they were threatened with instant death if detected, they were soon deterred. The second night was passed like the first, all being huddled together under one large tent; the more robust, however, soon began to build separate tents for themselves, and divided into messes, as on board. A staff was next erected, on which we hoisted a red flag, as a signal to any vessel which might be passing. Every morning, to each mess, was distributed the allowance of two ounces per man, and half a pint of beer; if they got any thing else, it was what they could catch by fishing, &c. Of fish, indeed, there was a great variety, but we had few facilities for catching them, so that upon the whole, we were no better than half-starved. The bank on which we lived, was in latitude 16° 45 s. and about two miles in circumference at low water; the high tides would sometimes leave us scarcely half a mile of sand, and often approached close to the tents; and if the wind had blown from the westward, or shifted only a few points, we must inevitably have been swept away, as an encampment of fishermen had been, a short time previous from the same spot; however, Providence was pleased to preserve us, one hundred and twenty in number, to return to our native country.

On the 13th the largest boat was repaired, and the officers thought it advisable to despatch her for relief to the Isle of France, distant about four hundred miles. The superior officers finding it impossible to leave the crew, dedicated the charge of her to the purser. We furnished him with two sextants, a navigation book, sails, oars, and log line. Six officers and eight men, who perfectly understood the management of the boat, joined him. He was directed to run [pg 391] first into the latitude, and then bear up for the land. On the 17th he arrived at the Mauritius, and on the 20th returned by his Majesty's vessels, Magician and Challenger. On the 21st we were taken on board, after being sixteen days on this barren reef, suffering great distress in mind and body. We all received the most humane attention from the captains of his Majesty's vessels, and on the 28th, we reached the Mauritius whence I returned to England.

This has been a very ancient custom both among the Jews and Christians. St. Paul mentions this practice, which has continued in all succeeding ages, with some variations as to mode and circumstance; for so long as immediate inspiration lasted, the preacher, &c. frequently gave out a hymn; and when this ceased, proper portions of scripture were selected, or agreeable hymns thereto composed; but by the council of Laodicea, it was ordered that no private composition should be used in church; the council also ordered that the psalms should no longer be one continued service, but that proper lessons should be interposed to prevent the people being tired. At first the whole congregation bore a part, singing all together; afterwards the manner was altered, and they sung alternately, some repeating one verse, and some another. After the emperors became Christians, and persecution ceased, singing grew much more into use, so that not only in the churches but also in private houses, the ancient music not being quite lost, they diversified into various sorts of harmony, and altered into soft, strong, gay, sad, grave, or passionate, &c. Choice was always made of that which agreed with the majesty and purity of religion, avoiding soft and effeminate airs; in some churches they ordered the psalms to be pronounced with so small an alteration of voice, that it was little more than plain speaking, like the reading of psalms in our cathedrals, &c. at this day; but in process of time, instrumental music was introduced first amongst the Greeks.

Pope Gregory the Great refined upon the church music and made it more exact and harmonious; and that it might be general, he established singing schools at Rome, wherein persons were educated to be sent to the distant churches, and where it has remained ever since; only among the reformed there are various ways of performing, and even in the same church, particularly that of England, in which parish churches differ much from cathedrals; but most dissenters comply with this part of worship in some form or other.

HALBERT H.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

Having noticed a description of an exhibition called "Skimington Riding," in the present volume of the MIRROR, and your correspondent being at a loss for the origin of such a title, allow me to observe, that it appears to me that it originated from a skimmer being always used (as I have heard from very good authority it is) as the leading instrument towards making the various sounds usual on such occasions. I think it, therefore, very probable it took its rise from the utensil skimmer, and would be more properly called Skimmerting Riding.

Dorset

FELIX.

At Lynn Regis, Norfolk, on every first Monday of the month, the mayor, aldermen, magistrates, and preachers, meet to hear and determine controversies between the inhabitants in an amicable manner, to prevent lawsuits. This custom was first established in 1583, and is called the Feast of Reconciliation.

HALBERT H.

In the Magna Britannia, the author in his Account of the Hundred of Croydon, says, "Our historians take notice of two things in this parish, which may not be convenient to us to omit, viz. a great wood called Norwood, belonging to the archbishops, wherein was anciently a tree called the vicar's oak, where four parishes met, as it were in a point. It is said to have consisted wholly of oaks, and among them was one that bore mistletoe, which some persons were so hardy as to cut for the gain of selling it to the apothecaries of London, leaving a branch of it to sprout out; but they proved unfortunate after it, for one of them fell lame, and others lost an eye. At length in the year 1678, a certain man, notwithstanding he was warned against it, upon the account of what the others had suffered, adventured to cut the tree down, and he soon after broke his leg. To fell oaks hath [pg 392] long been counted fatal, and such as believe it produce the instance of the Earl of Winchelsea, who having felled a curious grove of oaks, soon after found his countess dead in her bed suddenly, and his eldest son, the Lord Maidstone, was killed at sea by a cannon ball."

P.T.W.

Have preserved dances in honour of Flora. The wives and maidens of the village gather and scatter flowers, and bedeck themselves from head to foot. She who leads the dance, more ornamented than the others, represents Flora and the Spring, whose return the hymn they sing announces; one of them sings—

"Welcome sweet nymph,

Goddess of the month of May."

In the Grecian villages, and among the Bulgarians, they still observe the feast of Ceres. When harvest is almost ripe, they go dancing to the sound of the lyre, and visit the fields, whence they return with their heads ornamented with wheat ears, interwoven with the hair. Embroidering is the occupation of the Grecian women; to the Greeks we owe this art, which is exceedingly ancient among them, and has been carried to the highest degree of perfection. Enter the chamber of a Grecian girl, and you will see blinds at the window, and no other furniture than a sofa, and a chest inlaid with ivory, in which are kept silk, needles, and articles for embroidery. Apologues, tales, and romances, owe their origin to Greece. The modern Greeks love tales and fables, and have received them from the Orientals and Arabs, with as much eagerness as they formerly adopted them from the Egyptians. The old women love always to relate, and the young pique themselves on repeating those they have learnt, or can make, from such incidents as happen within their knowledge. The Greeks at present have no fixed time for the celebration of marriages, like the ancients; among whom the ceremony was performed in the month of January. Formerly the bride was bought by real services done to the father; which was afterwards reduced to presents, and to this time the custom is continued, though the presents are arbitrary. The man is not obliged to purchase the woman he marries, but, on the contrary, receives a portion with her equal to her condition. It is on the famous shield of Achilles that Homer has described a marriage procession—

Here sacred pomp and genial feast delight,

And solemn dance and hymeneal rite.

Along the streets the new made bride is led,

With torches flaming to the nuptial bed;

The youthful dancers in a circle bound

To the saft lute and cittern's silver sound,

Through the fair streets the matrons in a row,

Stand in their porches, and enjoy the show.

POPE.

The same pomp, procession, and music, are still in use. Dancers, musicians, and singers, who chant the Epithalamium, go before the bride; loaded with ornaments, her eyes downcast, and herself sustained by women, or two near relations, she walks extremely slow. Formerly the bride wore a red or yellow veil. The Arminians do so still; this was to hide the blush of modesty, the embarrassment, and the tears of the young virgin. The bright torch of Hymen is not forgotten among the modern Greeks. It is carried before the new married couple into the nuptial chamber, where it burns till it is consumed, and it would be an ill omen were it by any accident extinguished, wherefore it is watched with as much care as of old was the sacred fire of the vestals. Arrived at the church, the bride and bridegroom each wear a crown, which, during the ceremony, the priest changes, by giving the crown of the bridegroom to the bride, and that of the bride to the bridegroom, which custom is also derived from the ancients.

I must not forget an essential ceremony which the Greeks have preserved, which is the cup of wine given to the bridegroom as a token of adoption; it was the symbol of contract and alliance. The bride drank from the same cup, which afterwards passed round to the relations and guests. They dance and sing all night, but the companions of the bride are excluded—they feast among themselves in separate apartments, far from the tumult of the nuptials. The modern Greeks, like the ancient, on the nuptial day, decorate their doors with green branches and garlands of flowers.

W.G.C.

Among the customs which formerly prevailed in this country during the season of Lent, was the following:—An officer denominated the King's Cock Crower, crowed the hour each night, within the precincts of the palace, instead of proclaiming it in the manner of the late watchmen. This absurd ceremony did not fall into disuse till the reign of George I.

C.J.T.

Yarmouth is bound by its charter, to send to the Sheriffs of Norwich a tribute of one hundred herrings, baked in twenty-four pasties, which they ought to deliver to the Lord of the Manor of East Charlton, and he is obliged to present them to the King wherever he is. Is not this a dainty dish to set before the King?

Newcastle-Under-Line was once famous for a peculiar method of taming shrews: this was by putting a bridle into the scold's mouth, in such a manner as quite to deprive her of speech for the time, and so leading her about the town till she made signs of her intention to keep her tongue in better discipline for the future.

HALBERT H.

Our extracts from the previous portion of this work, have forcibly illustrated the striking originality of its style, and the interesting character of its information.

The present Part concludes Newstead, and includes Mansfield, Chesterfield, Dronfield, Sheffield, Rotherham, and Barnsley; and from it we extract the following facts, which almost form a picture of Sheffield.2

"The drive from Dronfield to Sheffield is pleasant and picturesque. It is the dawn of a region of high hills, a fine range of which stretch westward into Derbyshire, while on every side there are lofty eminences and deep valleys. Sheffield opens magnificently on the right, and its villas and ornamented suburbs stretch full two miles on the eminences to the left. At two or three miles from Sheffield, the western suburbs display a rich and pleasing variety of villas and country-houses. On the left, the Dore-moors, a ridge of barren hills, stretch to an indefinite distance: and on the right, some high hills skreen from sight the town of Sheffield. At a mile distant, the view to the right opens, and from a rise in the road is beheld the fine amphitheatre of Sheffield; the sun displaying its entire extent, and the town being surmounted by fine hills in the rear. The wind carried the smoke to the east of the town, and the sun in the meridian presented as fine a coup d'oeil as can be conceived. The approach was by a broad and well-built street, the population were in activity, and I entered a celebrated place with many agreeable expectations.

"Sheffield is within the bounds of Yorkshire, but on the verge of Derbyshire, and was the most remarkable place and society of human beings which I had yet seen. It stands in one of the most picturesque situations that can be imagined, originally at the south end of a valley surrounded by high hills, but now extended around the western hill; the first as a compact town, and the latter as scattered villas and houses on the same hill, to the distance of two miles from the ancient site. It is connected with London by Nottingham and Derby, and distant from Leeds 33 miles, and York 54 miles. Its foundation was at the junction of two rivers, the Sheaf and the Don; in the angle formed by which once stood the Castle, built by the, Barons Furnival, Lords of Hallamshire; but subsequently in the tenure of the Talbots, Earls of Shrewsbury. Three or four miles from this Castle, on the western hill, stood the Saxon town of Hallam, said to have been destroyed by the Norman invaders, on account of their gallant opposition.

"The town was originally a mere village, dependant on the Castle; but its mineral and subterranean wealth led the early inhabitants to become manufacturers of edged tools, of which arrow heads, spear heads, &c. are presumed to have been a considerable part; a bundle of arrows being at this day in the town arms, and cross arrows the badge of the ancient Cutlers' Company of Sheffield.

"The exhaustless coal seams and iron-stone beds in the vicinity, combined with the ingenuity of the people, conferred early fame on their products; for Chaucer, in alluding to a knife, calls it 'a Sheffield thwittel,'—whittle being among the manufacturers at this day the name of a common kind of knife. [pg 394] The increasing demand for articles of cutlery, and their multiplied variety have gradually enlarged the population of Sheffield to 42,157 in 1821; since which it has considerably increased, and may, in 1829, be estimated at 50,000. In 1821, it contained 8,726 houses, and perhaps 500 have been built since, chiefly villas to the westward, while the compact town is about one mile by half a mile. The principal streets are well built, and there are three old churches, and two new ones lately finished, besides another now building.

"Sheffield presents at this time the extraordinary spectacle of an immense town expanded from a village, without any additional arrangements for its government beyond what it originally possessed as a village. There is no corporation, not even a resident magistrate, and yet all live in peace, decorum, and advantageous mutual intercourse."

"Order is a moral result of religion in Sheffield. No town in the kingdom more universally exhibits the external forms of devotion, and in none are there perhaps a greater number of serious devotees. The largest erections in Sheffield are those for the service of religion, and they are numerous. Besides six old and new churches, adapted to accommodate from 10,000 to 12,000 persons, there are seventeen chapels for the various denominations of Dissenters, capable of affording sitting room for 12,000 or 15,000 more. Except the Unitarian Chapel, and perhaps the Catholic one, the doctrines preached in all the others, are what, in London, and at Oxford and Cambridge, would generally be called Ultra.

"A spectacle highly characteristic of Sheffield, and exemplifying, at the same time the harmony of the several sects, is the juxtaposition of four several chapels, observable on one side of a main street; while nearly adjoining is the church of St. Paul. There are thus every Sunday, in simultaneous local devotion, the ceremonial Catholics, the moral Unitarians, the metaphysical Calvinists, the serious disciples of John Wesley, and the spiritual members of the establishment.

"The whole of the places of worship afford accommodation for about 12,000 Methodists and Dissenters, and about 9,500 of the Church Establishment. So that, if half go twice a day, and half once, 30,000 of the 50,000 inhabitants attend places of worship every Sunday."

"There are the following institutions for the promotion of knowledge and science:—

"1. A Permanent Library supported by the subscriptions of 270 members at one guinea each, and four guineas admission. The books are numerous; but, contrary to the practice of other similar institutions, books of Theology, and the trash of modern Novels, are introduced.

"2. A Literary and Philosophical Society for lectures, and the purchase of apparatus, now very complete, supported by 80 proprietors, at two guineas, besides a still greater number of subscribers at one guinea per annum.

"3. Two News-rooms, in which the London and Provincial papers may be read.

"4. A Public Concert, supported by subscriptions, which amount to £700 per annum, and of which Mr. Fritch, from Derby, is the present leader.

"5. A Subscription Assembly held through the winter, but ill supported.

"6. A Shakspeare Club, for sustaining the drama, consisting of 80 members, who subscribe a guinea per annum, once a-year bespeak a play, and partake of a dinner, to which the sons of Thespis are invited.

"7. An Infirmary on a large scale, and munificently supported.

"8. Two Schools, in which sixty boys and sixty girls are clothed, fed, and educated.

"9. A Lancasterian and a National School well supported, and numerously attended.

"10. Sunday Schools attached to the twenty-three congregations, besides others.

"11. A Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor, in much activity.

"12. Dorcas' Societies, connected with the churches and chapels, to assist poor married women during child-birth.

"13. A Bible Society on the usual plan.

"14. Two Medical and Anatomical Schools.

"15. A thriving Mechanics' Library.

"Several of these institutions rendezvous in a spacious building called the Music Hall. The concerts are given in the upper room, a suitable saloon; and beneath are the Subscription Library, the Commercial News-room, and the Museum of the Literary and Philosophical Society."

"The staple manufactures of Sheffield embrace the metallic arts in all their varieties. The chief articles are sharp instruments, as knives, scissors, razors, saws, and edge-tools of various kinds, and to these may be added, files and plated goods to a great extent, besides stove-grates and fenders of exquisite beauty. It is altogether performed by hand, therefore the fabrication may always be rendered correspondent with the demand, and may be arrested when the demand ceases. This confers a definite advantage on the manufactory, not enjoyed by other trades which operate in the large way. The result is mediocrity of wealth, and little ruinous speculation. At the same time, the sanguine expectations of manufacturers often lead them to overstock themselves, and as the demand has been, so they expect it always to be.

"Sheffield employs about 15,000 persons in its various branches, and of these full one-third are engaged on knives and forks, pocket-knives, razors, and scissors. The rest are engaged in the plated trades, in saws, files, and some fancy trades. The following is an exact enumeration of the hands employed in the various departments two or three years since:—

"On table-knives 2,240

On spring-knives 2,190

On razors 478

On scissors 806

On files 1,284

On saws 400

On edge-tools 541

On forks 480

In the country 130

In the plated trade nearly 2,000

______

"About 10,549

"Besides those who are employed in Britannia-metal ware, smelting, optical instruments, grinding, polishing, &c. &c., making full 5,000 more.

"There are full 1,700 forges engaged in the various branches of the trades, and of course as many fires, fixing oxygen to make their heat, and evolving the undecomposed carbon in active volumes of steam and smoke.

"The place is usually described as smoky, but I thought it less so than the central parts of London. The manufactures, for the most part, are carried on in an unostentatious way, in small scattered shops, and no where make the noise and bustle of a single great iron works. Compared with them Sheffield is a seat of elegant arts, nevertheless compared with the cotton and silk trades, it must be regarded as dirty and smoky.

"The steel and plated manufactures require much taste, and in some cases make a great display. Hence there were exhibitions of elegant products, not exceeded in the Palais Royal, or any other place abroad, and superior to any of the cutlers' shops in London. All that the lustre of steel ware and silver plate can produce, is, in Sheffield, exhibited in splendid arrangement, in the warerooms of some of the principal manufacturers. In particular Messrs. J. Rodgers and Sons, cutlers to his Majesty, display in a magnificent saloon, all the multiplied elegant products of their own most ingenious manufactory.

"As proofs of their power of manufacturing, Messrs. Rodgers have, in their show-rooms the most extraordinary products of highly finished manufacture which are to be seen in the world. Among them are the following:—

"1. An arrangement in a Maltese cross about 18 inches high, and 10 inches broad, which developes 1,821 blades and different instruments; worthy of a royal cabinet, but in the best situation in the place which produced it.

"2. A knife which unfolds 200 blades for various purposes, matchless in workmanship, and a wonderful display of ingenuity. Its counterpart was presented to the King; and that in possession of Messrs. Rodgers, is offered at 200 guineas, and is worthy of some imperial cabinet.

"3. A knife containing 75 blades, not a mere curiosity, but a package of instruments of real utility in the compass of a knife 4 inches long, 3 inches high, and 1-1/4 inches broad. It is valued at 50 guineas.

"4. A miniature knife, enfolding 75 articles, which weigh but 7 dwts., exquisitely wrought and valued at 50 guineas.

"5. A common quill, containing 24 dozen of scissors, perfect in form, and made of polished steel.

"These are kept as trophies of skill, in the perfect execution of which, the manufacturer considers that he displays his power of producing any useful articles of which the Sheffield manufacture consists. Mr. Rodgers obligingly conducted me through his various workshops, and I discovered that the perfection of the Sheffield manufacture arises from the judicious division of labour. I saw knives, razors, &c. &c., produced in a few minutes from the raw material. [pg 396] I saw dinner knives made from the steel bar and all the process of hammering it into form, welding the tang of the handle to the steel of the blade, hardening the metal by cooling it in water and tempering it by de-carbonizing it in the fire with a rapidity and facility that were astonishing.

"The number of hands through which a common table knife passes in its formation is worthy of being known to all who use them. The bar steel is heated in the forge by the maker, and he and the striker reduce it in a few minutes into the shape of a knife. He then heats a bar of iron and welds it to the steel so as to form the tang of the blade which goes into the handle. All this is done with the simplest tools and contrivances. A few strokes of the hammer in connexion with some trifling moulds and measures, attached to the anvil, perfect, in two or three minutes the blade and its tang or shank. Two men, the maker and striker, produce about nine blades in an hour, or seven dozen and a half per day.

"The rough blade thus produced then passes through the hands of the filer, who files the blade into form by means of a pattern in hard steel. It then goes to the halters to be hafted in ivory, horn, &c. as may be required; it next proceeds to the finisher, to Mr. Rodgers for examination, and is then packed for sale or exportation. In this progression every table-knife, pocket-knife, or pen-knife, passes step by step, through no less than sixteen hands, involving in the language of Mr. Rodgers, at least 144 separate stages of workmanship in the production of a single pen-knife. The prices vary from 2s. 6d. per dozen knives and forks, to £10."

(To be concluded in our next.)

Monosyllables are always expressive, but seldom more comprehensive than in this instance. A thousand recollections of urchin waggeries spring up at its repetition. Our present example is "Skying a Copper," from Mr. Hood's Comic Annual, of which a copious notice will be found in the SUPPLEMENT published with the present number.

As Mister B. and Mrs. B.

One night were sitting down to tea,

With toast and muffins hot—

They heard a loud and sudden bounce,

That made the very china flounce,

They could not for a time pronounce

If they were safe or shot—

For memory brought a deed to match

At Deptford done by night—

Before one eye appear'd a Patch

In t'other eye a Blight!

To be belabour'd out of life,

Without some small attempt at strife,

Our nature will not grovel;

One impulse mov'd both man and dame,

He seized the tongs—she did the same,

Leaving the ruffian, if he came,

The poker and the shovel.

Suppose the couple standing so,

When rushing footsteps from below

Made pulses fast and fervent;

And first burst in the frantic cat,

All steaming like a brewer's rat,

And then—as white as my cravat—

Poor Mary May, the servant!

Lord how the couple's teeth did chatter,

Master and Mistress both flew at her,

"Speak! Fire? or Murder? What's the matter?"

Till Mary getting breath,

Upon her tale began to touch

With rapid tongue, full trotting, such

As if she thought she had too much

To tell before her death:—

"We was both, Ma'am, in the wash-house, Ma'am, a-standing at our tubs,

And Mrs. Round was seconding what little things I rubs;

'Mary,' says she to me, 'I say'—and there she stops for coughin,

'That dratted copper flue has took to smokin very often,

But please the pigs,'—for that's her way of swearing in a passion,

'I'll blow it up, and not be set a coughin in this fashion!'

Well down she takes my master's horn—I mean his horn for loading.

And empties every grain alive for to set the flue exploding.

'Lawk, Mrs. Round?' says I, and stares, 'that quantum is unproper,

I'm sartin sure it can't not take a pound to sky a copper;

You'll powder both our heads off, so I tells you, with its puff,

But she only dried her fingers, and she takes a pinch of snuff.'

Well, when the pinch is over—'Teach your Grandmother to suck

A powder horn,' says she—Well, says I, I wish you luck.

Them words sets up her back, so with her hands upon her hips,

'Come,' says she, quite in a huff, 'come keep your tongue inside your lips;

Afore ever you was born, I was well used to things like these;

I shall put it in the grate, and let it burn up by degrees.'

So in it goes, and Bounce—O Lord! it gives us such a rattle,

I thought we both were cannonized, like Sogers in a battle!

Up goes the copper like a squib, and us on both our backs,

And bless the tubs, they bundled off, and split all into cracks

Well, there I fainted dead away, and might have been cut shorter,

But Providence was kind, and brought me to with scalding water

I first looks round for Mrs. Round, and sees her at a distance,

As stiff as starch, and looked as dead as any thing in existence;

All scorched and grimed, and more than that, I sees the copper slap

Right on her head, for all the world like a percussion copper cap.

Well, I crooks her little fingers, and crumps them well up together,

As humanity pints out, and burnt her nostrums with a feather;

[pg 397]But for all as I can do, to restore her to her mortality,

She never gives a sign of a return to sensuality.

Thinks I, well there she lies, as dead as my own late departed mother,

Well, she'll wash no more in this world, whatever she does in t'other.

So I gives myself to scramble up the linens for a minute,

Lawk, sich a shirt! thinks I, it's well my master wasn't in it;

Oh! I never, never, never, never, never, see a sight so shockin;

Here lays a leg, and there a leg—I mean, you know, a stockin—

Bodies all slit and torn to rags, and many a tattered skirt,

And arms burnt off and sides and backs all scotched and black with dirt;

But as nobody was in 'em—none but—nobody was hurt!

Well, there I am, a scrambling up the things, all in a lump.

When, mercy on us! such a groan as makes my heart to jump.

And there she is, a-lying with a crazy sort of eye,

A staring at the wash-house roof, laid open to the sky:

Then she beckons with a finger, and so down to her I reaches,

And puts my ear agin her mouth to hear her dying speeches,

For, poor soul! she has a husband and young orphans, as I knew;

Well, Ma'am, you won't believe it, but it's Gospel fact and true,

But these words is all she whispered—'Why, where is the powder blew'"

In those parts of the Highlands of Scotland where eagles are numerous, and where they commit great ravages among the young lambs, the following methods are used for destroying them:—When the nest happens to be in a place situated in the direction of a perpendicular from the edge of a cliff above, a bundle of dry heath or grass inclosing a burning peat is let down into it. In other cases, a person is let down by means of a rope, which is held above by four or five men, and contrives to destroy the eggs or young. The person who thus descends takes a large stick with him, to beat off or intimidate the old eagles. The latter, however, always keep at a respectable distance, for powerful as they are, they possess little of the courage which has in all ages been attributed to them, being in this respect much inferior to the domestic cock, the raven, the sea-swallow, and a hundred other birds. Sometimes eagles have their nests in places accessible without a rope, and instances are known of persons frequenting these nests, for the purpose of carrying off the prey which the eagles carry to their young. A very prevalent method by which eagles are destroyed, is the following:—In a place not far from a nest, or a rock in which eagles repose at night, or on the face of a hill which they are frequently observed to scour in search of prey, a pit is dug to the depth of a few feet, of sufficient size to admit a man with ease. The pit is then covered over with sticks, and pieces of turf, the latter not cut from the vicinity, eagles, like other cowards, being extremely wary and suspicious. A small hole is formed at one end of this pit, through which projects the muzzle of a gun, while at the other is left an opening large enough to admit a featherless biped, who on getting in pulls after him a bundle of heath of sufficient size to close it. A carcass of a sheep or dog, or a fish or fowl, being previously without at the distance of from twelve to twenty yards, the lyer-in-wait watches patiently for the descent of the eagle, and, the moment it has fairly settled upon the carrion, fires. In this manner, multitudes of eagles are yearly destroyed in Scotland. The head, claws, and quills, are kept by the shepherds, to be presented to the factor at Martinmas or Whitsunday, for the premium of from half-a-crown to five shillings which is usually awarded on-such occasions.—Edinburgh Literary Gazette.

This separate and single genus of birds is seldom seen amongst the numerous descriptions of wild fowl, which, in the winter seasons, wing their flight to our marshes. The most striking part of the Oyster-catcher is its bill, the colour of which is scarlet, measuring in length nearly four inches, wide at the nostrils, and grooved beyond them nearly half its length: thence to the tip it is vertically compressed on the sides, and ends obtusely. With this instrument, which in its shape and structure is peculiar to this bird, it easily disengages the limpets from the rocks, and plucks out the oysters from their half-opened shells, on which it feeds, as well as on other shell-fish, sea-worms, and insects.

W.G.C.

The splendid appearance of the plumage of tropical birds is not superior to what the curious observer may discover in a variety of Lepidóptera; and those many-coloured eyes, which deck so gorgeously the peacock's tail, are imitated with success in Vanéssa Io, one of our most common butterflies. "See," exclaims the illustrious Linnaeus, "the large, elegant, painted wings of the butterfly, [pg 398] four in number, covered with small imbricated scales; with these it sustains itself in the air the whole day, rivalling the flight of birds, and the brilliancy of the peacock. Consider this insect through the wonderful progress of its life, how different is the first period of its being from the second, and both from the parent insect. Its changes are an inexplicable enigma to us: we see a green caterpillar, furnished with sixteen feet, creeping, hairy, and feeding upon the leaves of a plant; this is changed into chrysalis, smooth, of a golden lustre, hanging suspended to a fixed point, without feet, and subsisting without food; this insect again undergoes another transformation, acquires wings and six feet, and becomes a variegated white butterfly, living by suction upon the honey of plants. What has nature produced more worthy of our admiration? Such an animal coming upon the stage of the world, and playing its part there under so many different masks! In the egg of the Papilio, the epidermis or external integument falling off, a caterpillar is disclosed; the second epidermis drying, and being detached, it is a chrysalis; and the third, a butterfly. It should seem that the ancients were so struck with the transformations of the butterfly, and its revival from a seeming temporary death, as to have considered it an emblem of the soul, the Greek word psyche signifying both the soul and a butterfly. This is also confirmed by their allegorical sculptures, in which the butterfly occurs as an emblem of immortality." Swammerdam, speaking of the metamorphosis of insects, uses these strong words: "This process is formed in so remarkable a manner in butterflies, that we see therein the resurrection painted before our eyes, and exemplified so as to be examined by our hands." "There is no one," says Paley, "who does not possess some particular train of thought, to which the mind naturally directs itself, when left entirely to its own operations. It is certain too, that the choice of this train of thinking may be directed to different ends, and may appear to be more or less judiciously fixed, but in a moral view, if one train of thinking be more desirable than another, it is that which regards phenomena of nature with a constant reference to a supreme intelligent Author. The works of nature want only to be contemplated. In every portion of them which we can decry, we find attention bestowed upon the minuter objects. Every organized natural body, in the provisions which it contains for its sustentation and propagation, testifies a care, on the part of the Creator, expressly directed to these purposes. We are on all sides surrounded by bodies wonderfully curious, and no less wonderfully diversified." Trifling, therefore, and, perhaps, contemptible, as to the unthinking may seem the study of a butterfly, yet, when we consider the art and mechanism displayed in so minute a structure, the fluids circulating in vessels so small as almost to escape the sight, the beauty of the wings and covering, and the manner in which each part is adapted for its peculiar functions, we cannot but be struck with wonder and admiration, and must feel convinced that the maker of all has bestowed equal skill in every class of animated beings; and also allow with Paley, that "the production of beauty was as much in the Creator's mind in painting a butterfly, as in giving symmetry to the human form."

We know, and posterity will say the same, that there was never such a paragon as her ladyship; that her house in Kildare-street, Dublin, will be to future ages, what Shakspeare's house in Henley-street, Stratford-upon-Avon, is now; that pilgrims from all corners of the civilized globe will pay their devotions at her shrine; and that the name of Morgan will be remembered long after the language in which she has immortalized it has ceased to be a living tongue. WE are not the persons to deny this; for WE are but too proud of being able to call ourselves her contemporary; but we do dislike (and her ladyship will, forgive us for saying so)—we do dislike the seeming vanity of proclaiming this herself. She is a very great woman; an extraordinary woman; an Irish prodigy; popes and emperors have trembled before her; all Europe, all Asia, all America, from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico, ring with her praises; there never has been such "a jewel of a woman," as her own countrymen would say. She knows this, and we know it; and "our husband" knows it; every body knows it; then why need she tell us so a hundred times over in her "Book of the Boudoir?"

There is another little circumstance which we would take the liberty of mentioning. It is, that she is much too scrupulous, much too delicate in naming [pg 399] individuals, unless they happen to be dead. When she mentions a civil thing said to her by a prince, a duke, or a marquess, we never get at the person. It is always the Prince of A——, or the Duke of B——, or the Marquess of C——, or Count D——, or Lady E——, or the Marchioness of F——, or the Countess of G——, or Lord H——, or Sir George I——, and so on through the alphabet. Now we say again, that we have no doubt all these are the initials of real persons, and that her ladyship is as familiar with the blood royal and the aristocracy of Europe, as "maids of fifteen are with puppy-dogs;" but the world, my dear Lady Morgan—an ill-natured, sour, cynical, and suspicious world, envious of your glory, will be apt to call it nil fudge, blarney, or blatherum-skite, as they say in your country; especially when it is observed that you always give the names of the illustrious dead, with whom you have been upon equally familiar terms of intimacy, at full length; as if you knew that dead people tell no tales; and that therefore you might tell any tales you like about dead people. We put it to your own good sense, my dear Lady Morgan, as the Duke of X—— would call you, whether this remarkable difference in mentioning living characters, and those who are no longer living, does not look equivocal? For you know, my dear Lady Morgan, that Prince R—— and Princess W——, by standing for any body, mean nobody.—Blackwood's Magazine.

We find the following curious anecdote translated from a German work, in the last Foreign Quarterly Review:—

A poor protestant who had fallen from his horse and done himself some serious injury which had obviously ended in derangement, came to a Catholic priest, declaring that he was possessed, and telling a story of almost dramatic interest. In his sickness he had consulted a quack doctor, who told him that he could cure him by charms. He wrote strange signs on little fragments of paper, some of which were to be worn, some to be eaten in bread and drunk in wine. These the poor madman fancied afterwards were charms by which he had unknowingly sold himself to the devil. The doctor, he fancied, had done so before, and could only redeem his own soul by putting another in the power of Satan. "I know that this is my condition," said the poor madman, "by all I have seen and heard, by all I have suffered, by the change which has taken place in me, which has at length brought me to my present condition. All I cannot reveal; the little I can and dare tell must convince you. Often has my tormentor pent me up in the stove, and let me lie among the burning brands through the live long night. Then I hear him in my torment talking loud, I know not what, over my head. All prayer he forbids me, and he makes me tell whether I would give all I have or my soul for my cure. Then he speaks to me of the Bible; but he falsifies all he tells me of, or he tells me of some new-born king or queen in the kingdom of God. I cannot go to church; I cannot pray; I cannot think a good thought; I see sights of horror ever before me, which fill me with unutterable fear, and I know not what is rest; my one only thought is how soon the devil will come to claim his wretched victim and carry me to the place of torment." The poor creature had a belief that a Roman Catholic priest had the power of exorcism. The priest was most kind to the poor maniac, and tried to convince him of the power and goodness of God, and his love to his creatures. It need not be said that this was talking to the wind. In fine, he said, "Well, I will rid you of your tormentor. He shall have to do with me, and not with you, in future." This promise had the desired effect; and the priest followed it up by advising the maniac to go to a good physician, to avoid solitude, to work hard, to read his Bible, and remember the comfortable declarations of which he had been just reminded, and if he was in any doubt or anxiety, to go to his parish minister.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE.

A certain author was introduced one day by a friend to Mr. Addison, who requested him at the same time to peruse and correct a copy of English verses. Addison took the verses and found them afterwards very stupid. Observing that above twelve lines from Homer were prefixed to them, by way of motto, he only erased the Greek lines, without making any amendment in the poem, and returned it. The author, seeing this, desired his friend who had introduced him to inquire of Mr. Addison the reason of his doing so. "Whilst the statues of Caligula," said he, "were all of a piece, they were little regarded by [pg 400] the people, but when he fixed the heads of gods upon unworthy shoulders, he profaned them, and made himself ridiculous. I, therefore, made no more conscience to separate Homer's verses from this poem, than the thief did who stole the silver head from the brazen body in Westminster Abbey."3

A furious wife, like a musket, may do a great deal of execution in her house, but then she makes a great noise in it at the same time. A mild wife, will, like an air-gun, act with as much power without being heard.

L—W—R M.

In Time's Telescope for 1825, we are told that the few fine days which sometimes occur about the beginning of November have been denominated, "St. Martin's Little Summer." To this Shakspeare alludes in the first part of King Henry the Fourth (Act. I, Scene 2), where Prince Henry says to Falstaff, "Farewell, thou latter spring! farewell, All-hallowen summer!" And in the first part of King Henry the Sixth, (Act I, Scene 2), Joan La Pucelle says,

"Assign'd am I to be the English scourge—

This night the siege assuredly I'll raise:

Expect St. Martin's Summer, halcyon days,

Since I have entered into these wars."

W.G.C.

(For the Mirror.)

M.F. Cuvier has found that all marshy countries are remarkable for the small number of births in autumn, or the period when the influence of the marshes is most dangerous. Consequently, the marshes do not diminish the population by adding to the number of deaths alone, but by attacking the fecundity.

In Guiana balls are made of caoutchouc, for children to play with; and so elastic are they, that they will rebound several times between the ceiling and floor of a room, when thrown with some force.

In turtles' eggs, the yolk soon becomes hard on boiling, whilst the white remains liquid: a fact in direct opposition to the changes in boiling the eggs of birds.

There are 330 varieties and sub-varieties of wheat said to be growing in-Britain, perhaps scarcely a dozen of which are generally known to farmers.

Is made with cream alone, and is best preserved in casks or tubs, with a pickle made of salt, which is removed from time to time.

The moral precepts of the Siamese are comprised in the following Ten Commandments:—

1. Do not slay animals.

2. Do not steal.

3. Do not commit adultery.

4. Do not tell lies nor backbite.

5. Do not drink wine.4

6. Do not eat after twelve o'clock.

7. Do not frequent plays or public spectacles, nor listen to music.

8. Do not use perfumes, nor wear flowers, or other personal ornaments.

9. Do not sleep or recline upon a couch that is above one cubit high.

10. Do not borrow, nor be in debt.

The Supplement published with the present number contains a Fine Large Engraving of the Leaning Towers of Bologna; humorous cuts from the Comic Annual; and interesting Notices and Unique Extracts from the Keepsake, Landscape Annual, Forget-Me Not, Bijou, Emmanuel, &c. and with No. 400, forms the SPIRIT OF THE ANNUALS FOR 1830.

LIMBIRD'S EDITION OF THE

Following Novels is already Published:

s. d.

Mackenzie's Man of Feeling 0 6

Paul and Virginia 0 6

The Castle of Otranto 0 6

Almoran and Ham et 0 6

Elizabeth, or the Exiles of Siberia 0 6

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne 0 6

Rasselas 0 8

The Old English Baron 0 8

Nature and Art 0 8

Goldsmith's Vicar of Wakefield 0 10

Sicilian Romance 1 0

The Man of the World 1 0

A Simple Story 1 4

Joseph Andrews 1 6

Humphry Clinker 1 8

The Romance of the Forest 1 8

The Italian 2 0

Zeluco, by Dr. Moore 2 6

Edward, by Dr. Moore 2 6

Roderick Random 2 6

The Mysteries of Udolpho 3 6

Peregrine Pickle 4 6

Footnote 1: (return)Switzerland; or a Journal of a Tour and Residence in that country, in 1817, 1818, and 1819. By L. Simond, 2 vols. 8 vo. Second Edit. 1823 Murray.

Footnote 2: (return)The utility of such a Tour as the present is greater than may appear at first sight. Londoners are so absorbed with the wealth and importance of their own city, as to form but very erroneous notions of the extent and consequence of the large towns of the empire—as Liverpool, Manchester, &c.; find those who live in small country towns are as far removed from opportunities of improvement. The social economy of different districts is therefore important to both parties.

Footnote 4: (return)The punishment for drinking wine is to have a stream of melted copper poured down the throat; but wine is drunk, and all classes feed upon flesh.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.