Title: The Travels of Marco Polo — Volume 1

Author: Marco Polo

da Pisa Rusticiano

Editor: Henri Cordier

Translator: Sir Henry Yule

Release date: January 1, 2004 [eBook #10636]

Most recently updated: June 11, 2025

Language: English

Credits: Charles Franks, Robert Connal, John Williams and PG Distributed Proofreaders, updated and HTML created by Robert Tonsing

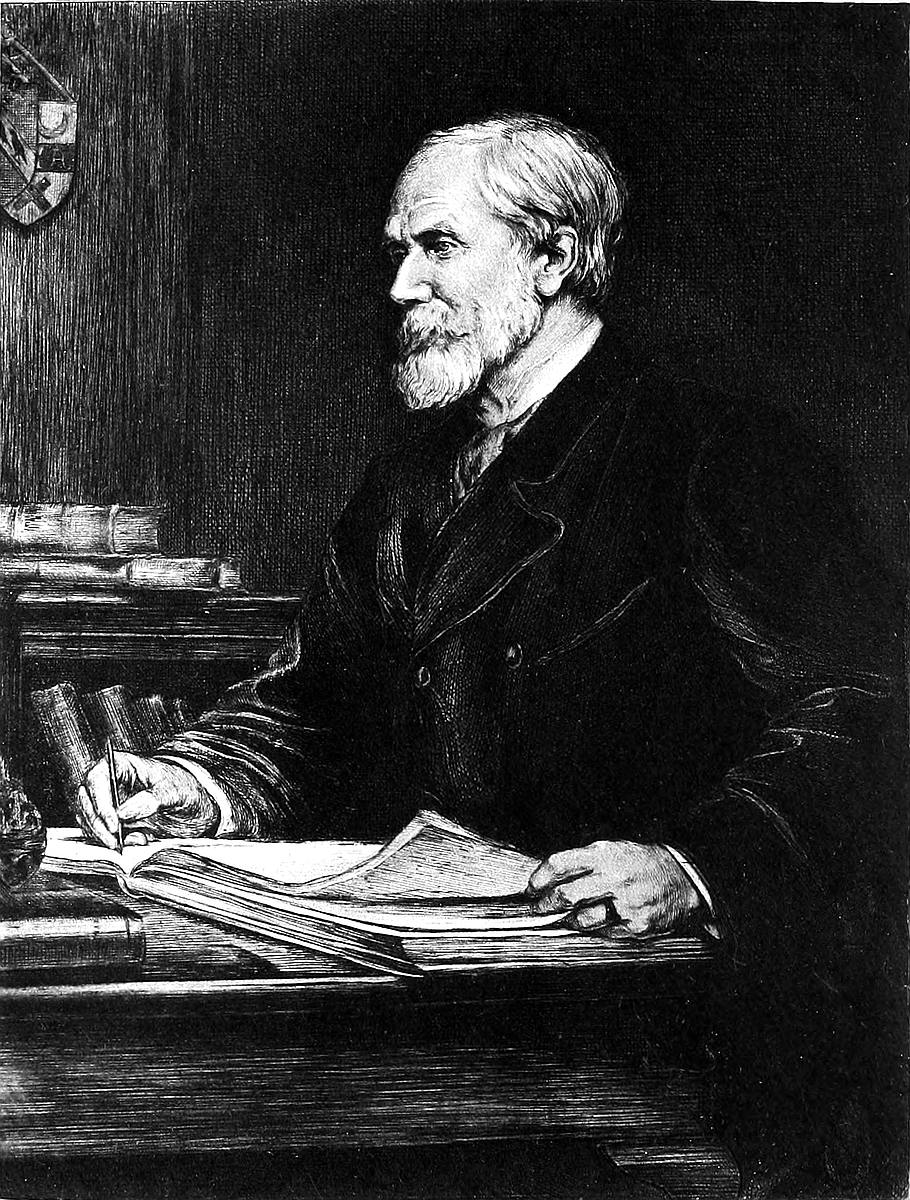

I desire to take this opportunity of recording my grateful sense of the unsparing labour, learning, and devotion, with which my father’s valued friend, Professor Henri Cordier, has performed the difficult and delicate task which I entrusted to his loyal friendship.

Apart from Professor Cordier’s very special qualifications for the work, I feel sure that no other Editor could have been more entirely acceptable to my father. I can give him no higher praise than to say that he has laboured in Yule’s own spirit.

The slight Memoir which I have contributed (for which I accept all responsibility), attempts no more than a rough sketch of my father’s character and career, but it will, I hope, serve to recall pleasantly his remarkable individuality to the few remaining who knew him in his prime, whilst it may also afford some idea of the man, and his work and environment, to those who had not that advantage.

vi

No one can be more conscious than myself of its many shortcomings, which I will not attempt to excuse. I can, however, honestly say that these have not been due to negligence, but are rather the blemishes almost inseparable from the fulfilment under the gloom of bereavement and amidst the pressure of other duties, of a task undertaken in more favourable circumstances.

Nevertheless, in spite of all defects, I believe this sketch to be such a record as my father would himself have approved, and I know also that he would have chosen my hand to write it.

In conclusion, I may note that the first edition of this work was dedicated to that very noble lady, the Queen (then Crown Princess) Margherita of Italy. In the second edition the Dedication was reproduced within brackets (as also the original preface), but not renewed. That precedent is again followed.

I have, therefore, felt at liberty to associate the present edition of my father’s work with the Name Murchison, which for more than a generation was the name most generally representative of British Science in Foreign Lands, as of Foreign Science in Britain.

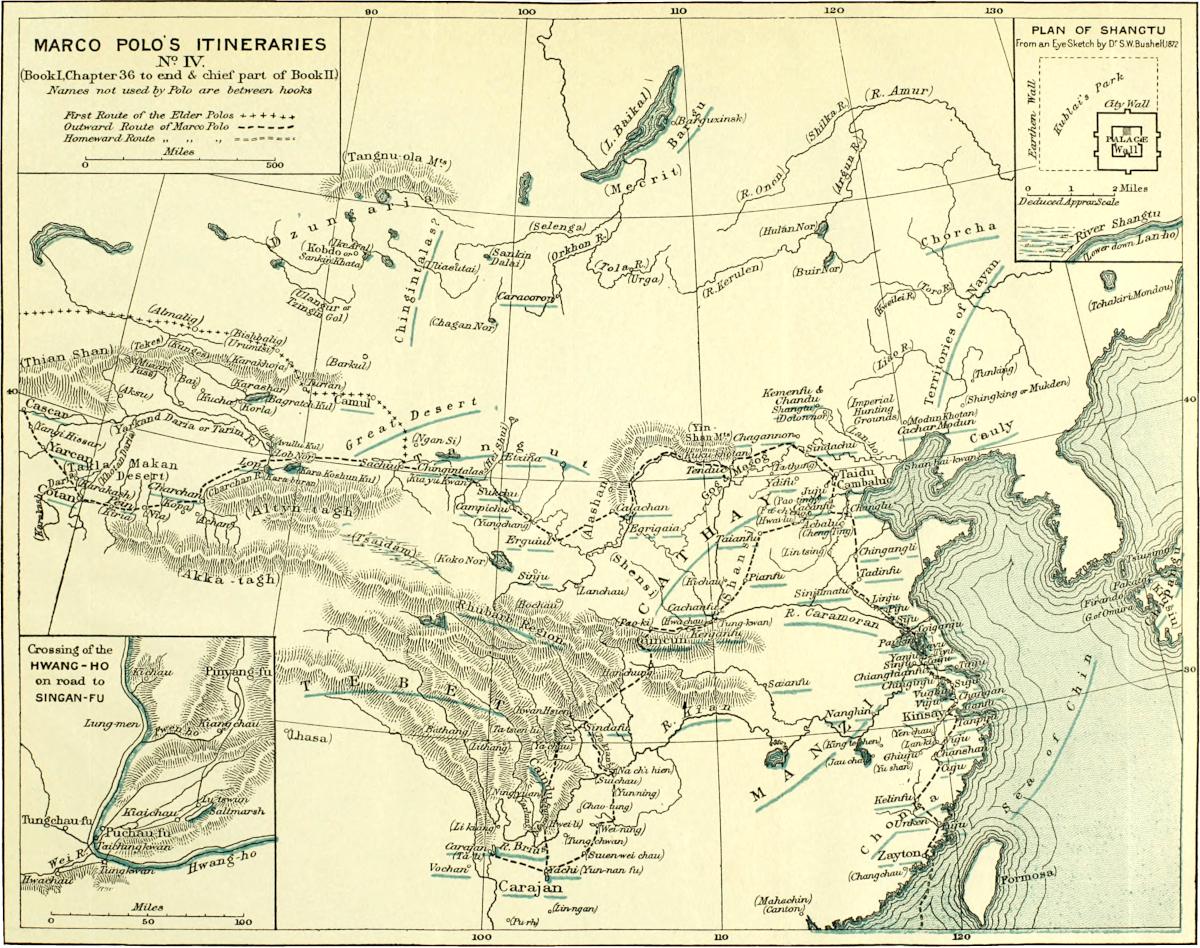

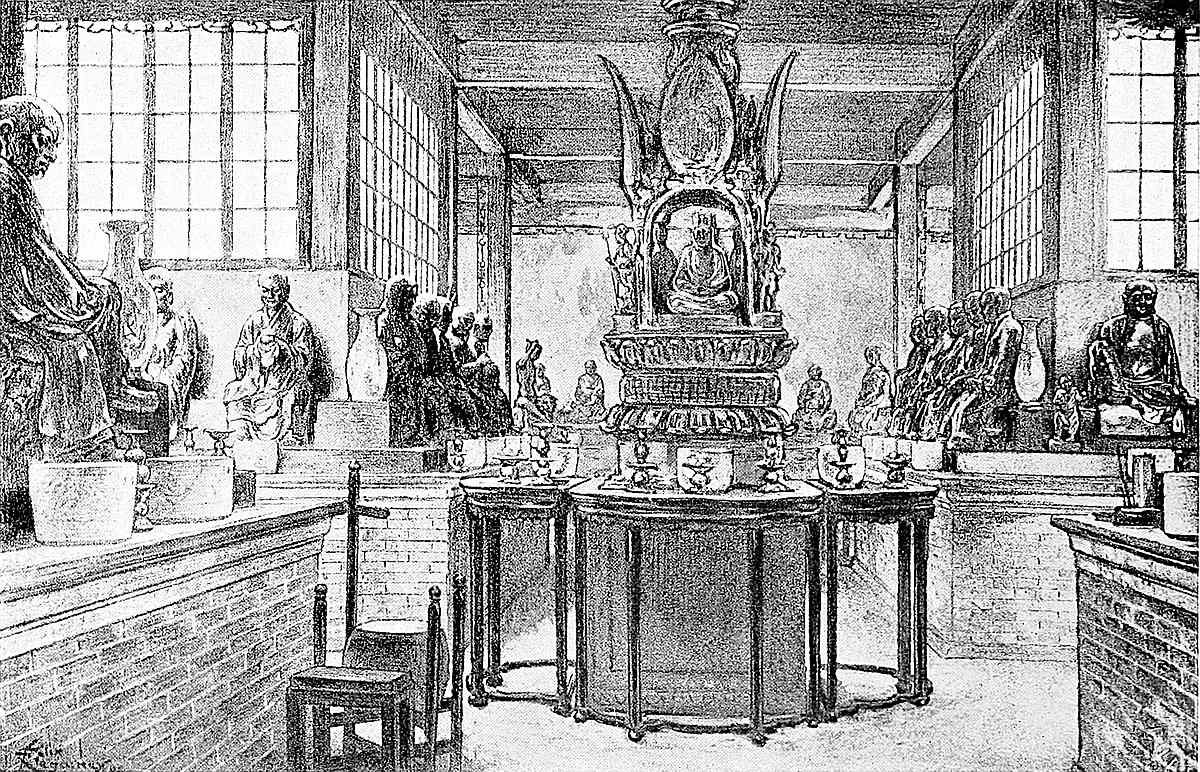

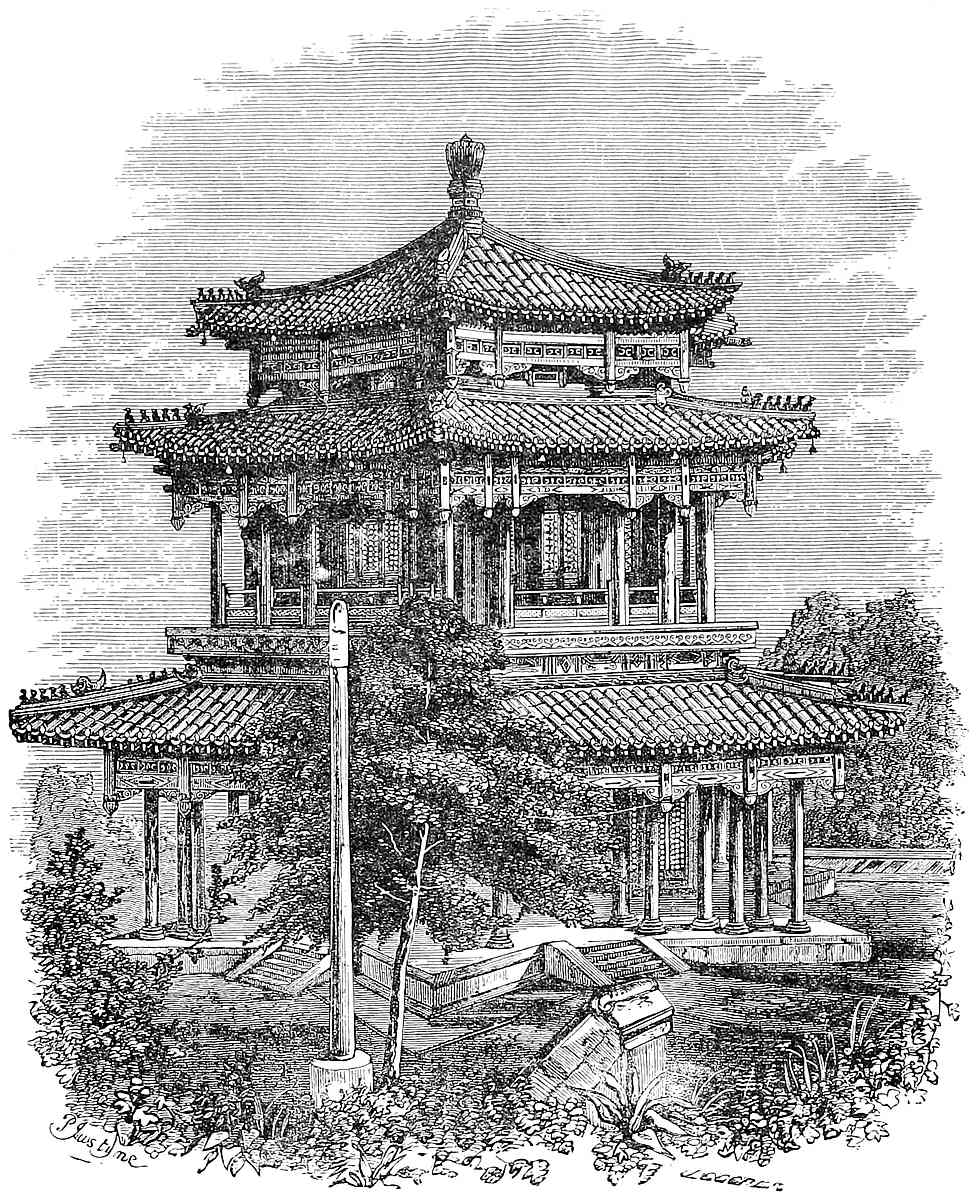

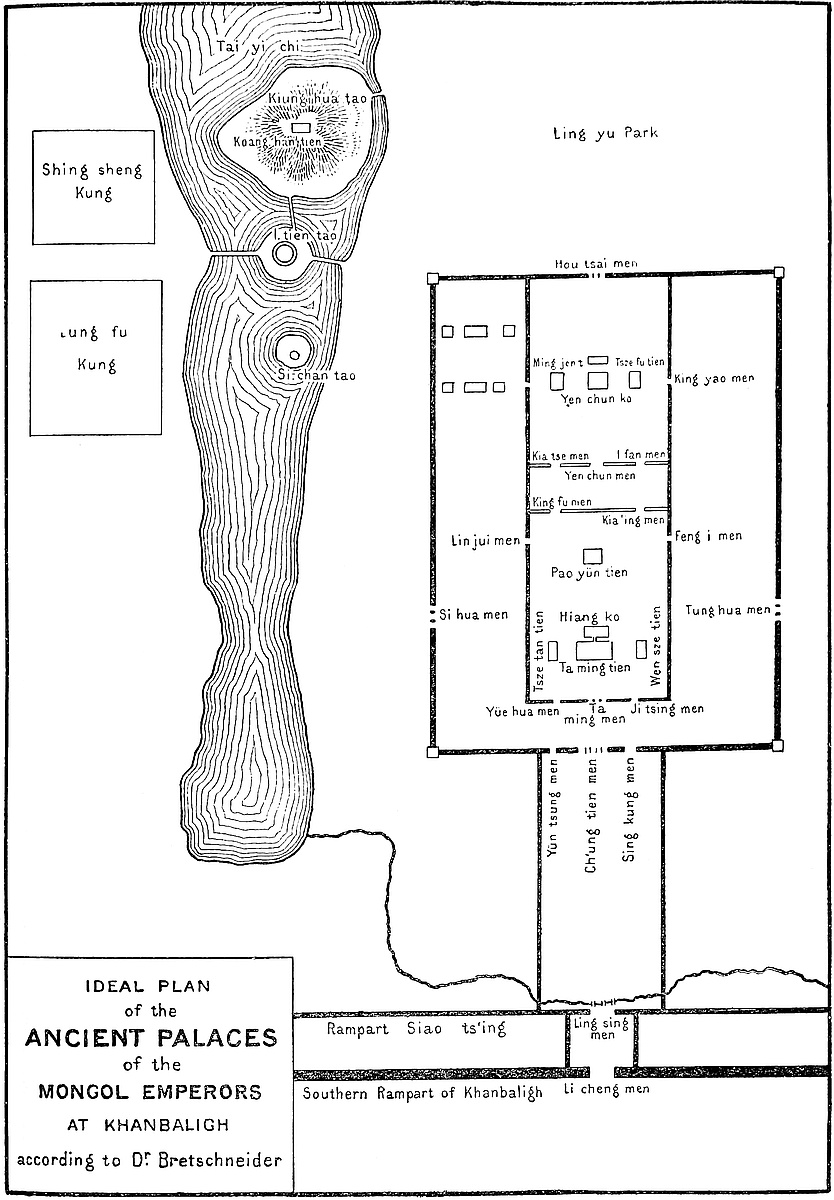

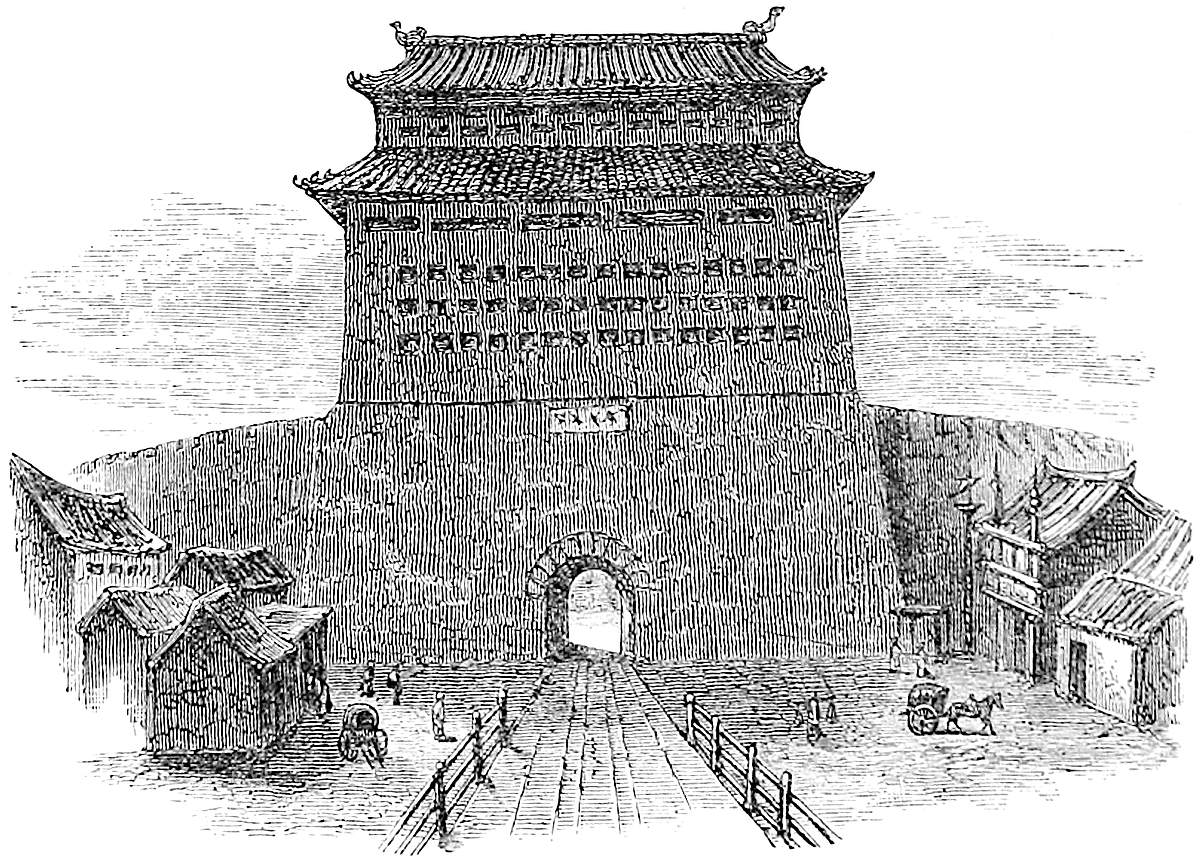

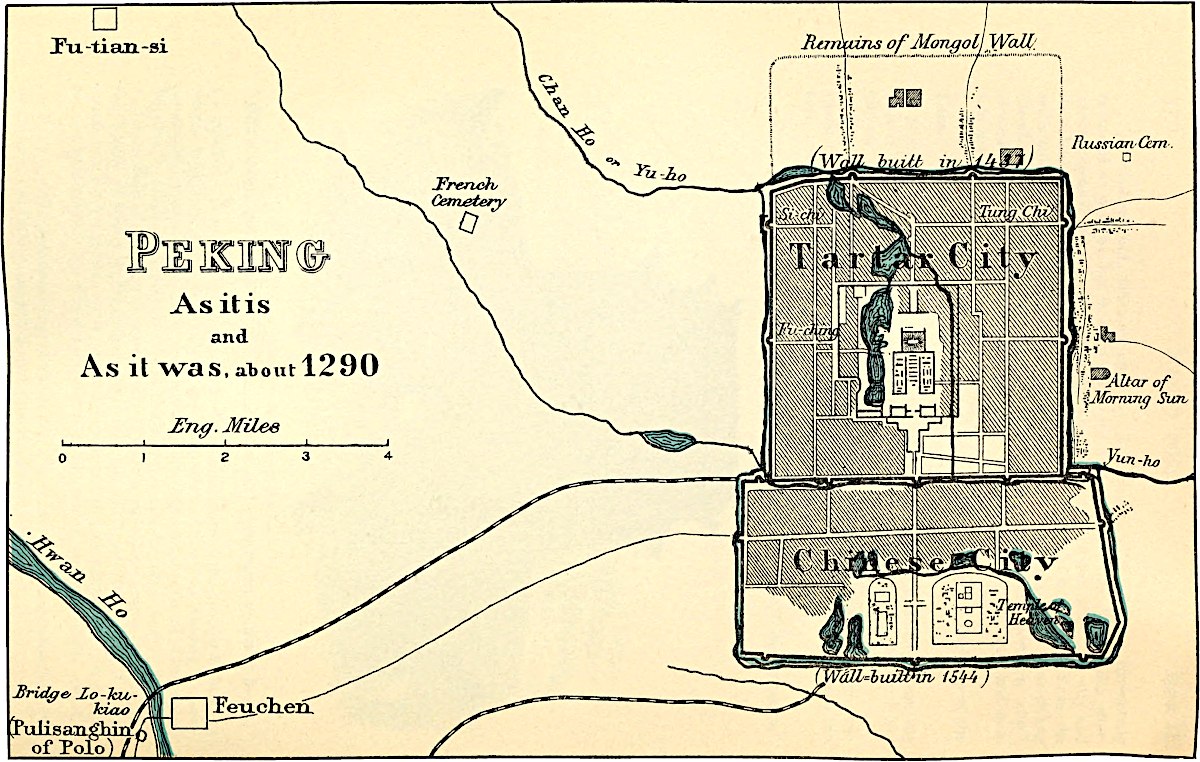

Little did I think, some thirty years ago, when I received a copy of the first edition of this grand work, that I should be one day entrusted with the difficult but glorious task of supervising the third edition. When the first edition of the Book of Ser Marco Polo reached “Far Cathay,” it created quite a stir in the small circle of the learned foreigners, who then resided there, and became a starting-point for many researches, of which the results have been made use of partly in the second edition, and partly in the present. The Archimandrite Palladius and Dr. E. Bretschneider, at Peking, Alex. Wylie, at Shang-hai—friends of mine who have, alas! passed away, with the exception of the Right Rev. Bishop G. E. Moule, of Hang-chau, the only survivor of this little group of hard-working scholars,—were the first to explore the Chinese sources of information which were to yield a rich harvest into their hands.

When I returned home from China in 1876, I was introduced to Colonel Henry Yule, at the India Office, by our common friend, Dr. Reinhold Rost, and from that time we met frequently and kept up a correspondence which terminated only with the life of the great geographer, whose friend I had become. A new edition of the travels of Friar Odoric of Pordenone, viiiour “mutual friend,” in which Yule had taken the greatest interest, was dedicated by me to his memory. I knew that Yule contemplated a third edition of his Marco Polo, and all will regret that time was not allowed to him to complete this labour of love, to see it published. If the duty of bringing out the new edition of Marco Polo has fallen on one who considers himself but an unworthy successor of the first illustrious commentator, it is fair to add that the work could not have been entrusted to a more respectful disciple. Many of our tastes were similar; we had the same desire to seek the truth, the same earnest wish to be exact, perhaps the same sense of humour, and, what is necessary when writing on Marco Polo, certainly the same love for Venice and its history. Not only am I, with the late Charles Schefer, the founder and the editor of the Recueil de Voyages et de Documents pour servir à l’Histoire de la Géographie depuis le XIIIe jusqu’à la fin du XVIe siècle, but I am also the successor, at the École des langues Orientales Vivantes, of G. Pauthier, whose book on the Venetian Traveller is still valuable, so the mantle of the last two editors fell upon my shoulders.

I therefore, gladly and thankfully, accepted Miss Amy Francis Yule’s kind proposal to undertake the editorship of the third edition of the Book of Ser Marco Polo, and I wish to express here my gratitude to her for the great honour she has thus done me.[1]

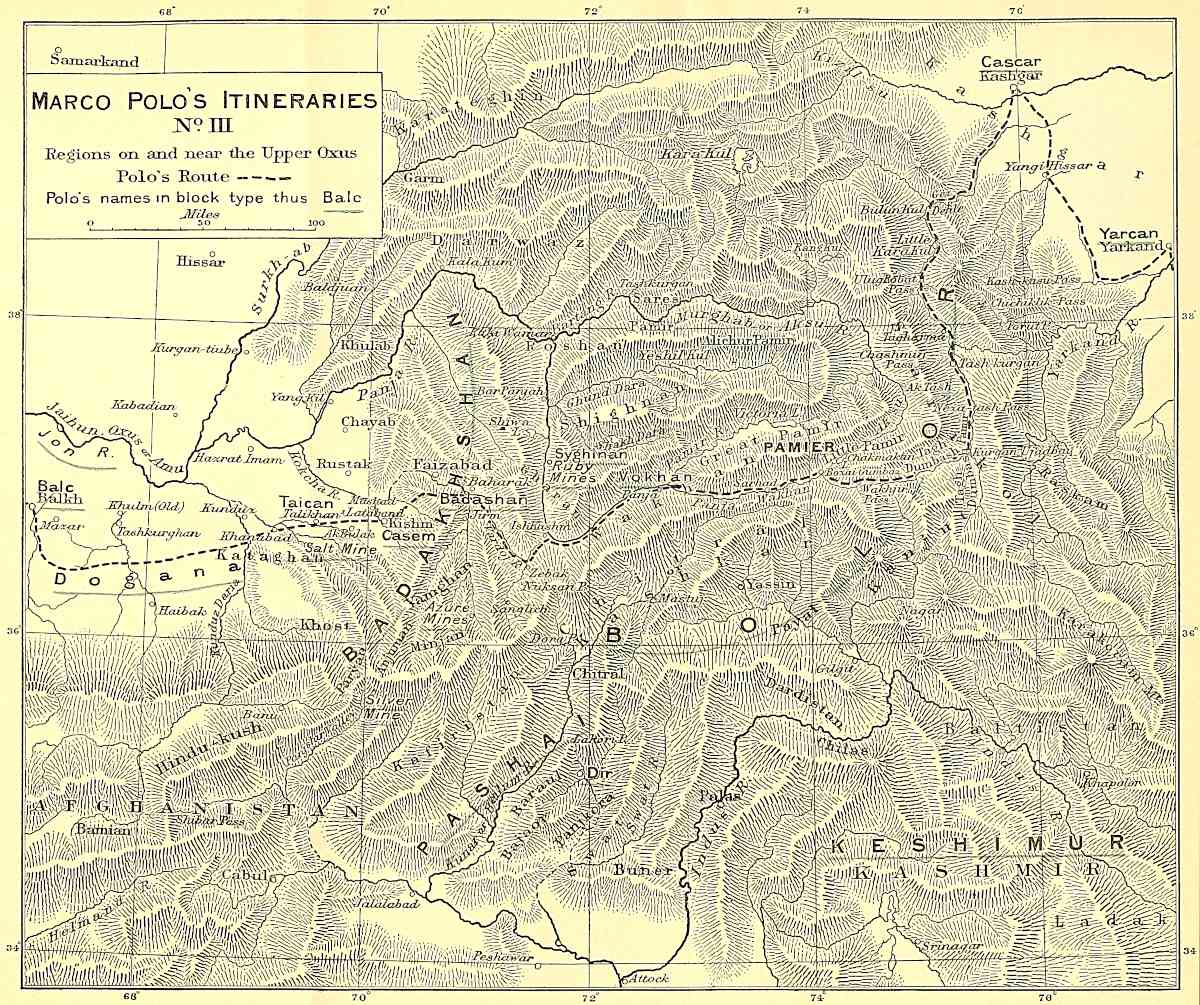

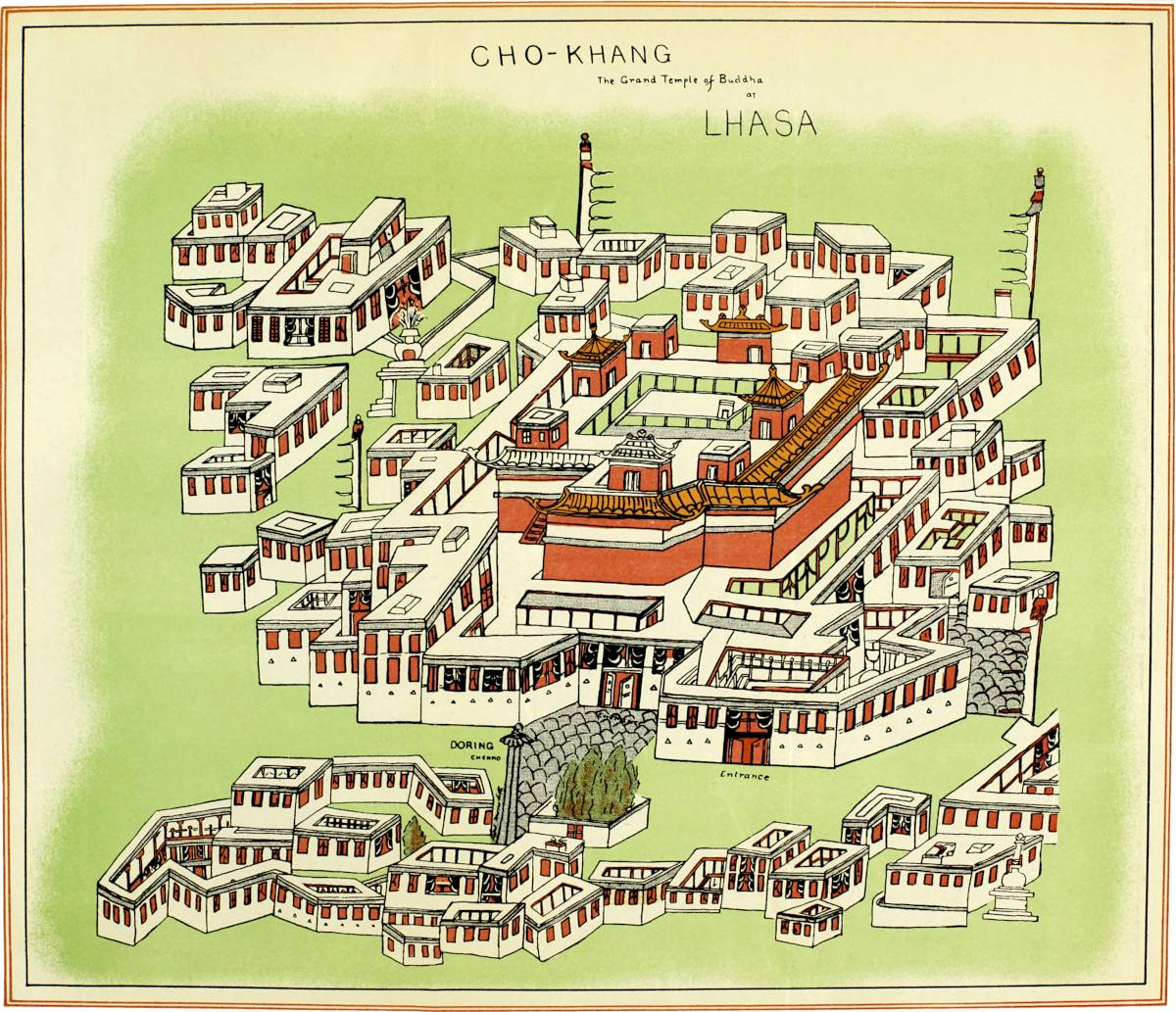

Unfortunately for his successor, Sir Henry Yule, evidently trusting to his own good memory, left but few notes. These are contained in an interleaved copy obligingly placed at my disposal by Miss Yule, but I luckily found assistance from various other ixquarters. The following works have proved of the greatest assistance to me:—The articles of General Houtum-Schindler in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, and the excellent books of Lord Curzon and of Major P. Molesworth Sykes on Persia, M. Grenard’s account of Dutreuil de Rhins’ Mission to Central Asia, Bretschneider’s and Palladius’ remarkable papers on Mediæval Travellers and Geography, and above all, the valuable books of the Hon. W. W. Rockhill on Tibet and Rubruck, to which the distinguished diplomatist, traveller, and scholar kindly added a list of notes of the greatest importance to me, for which I offer him my hearty thanks.

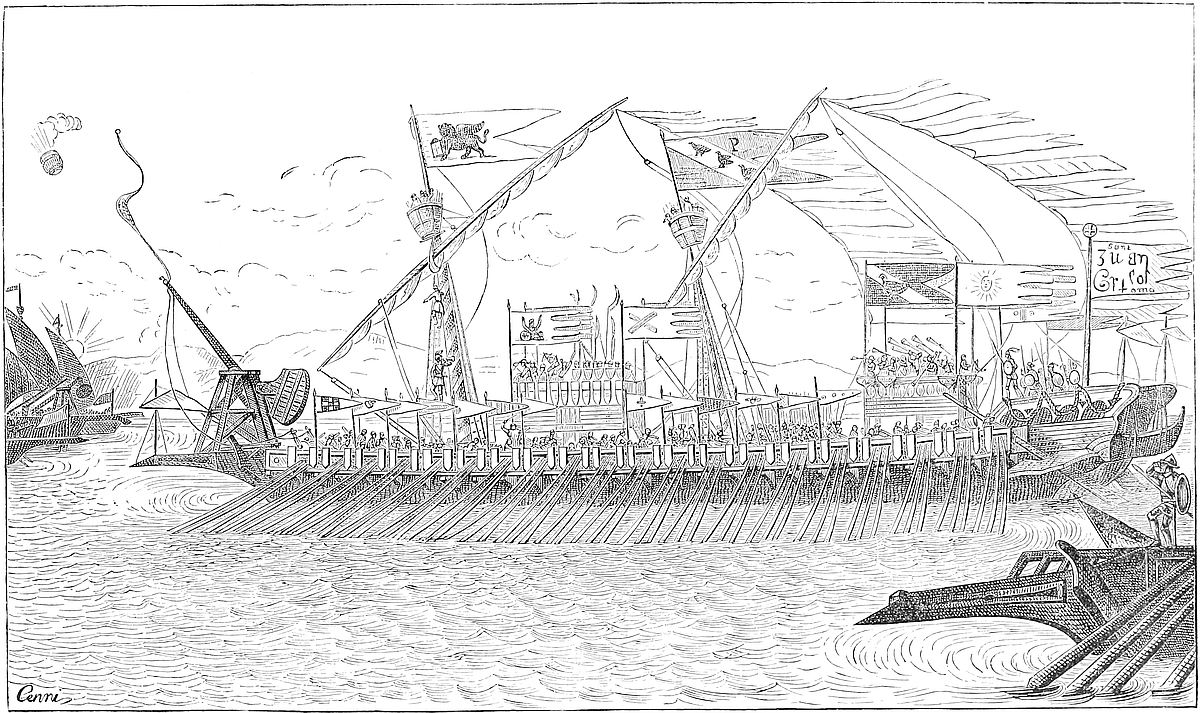

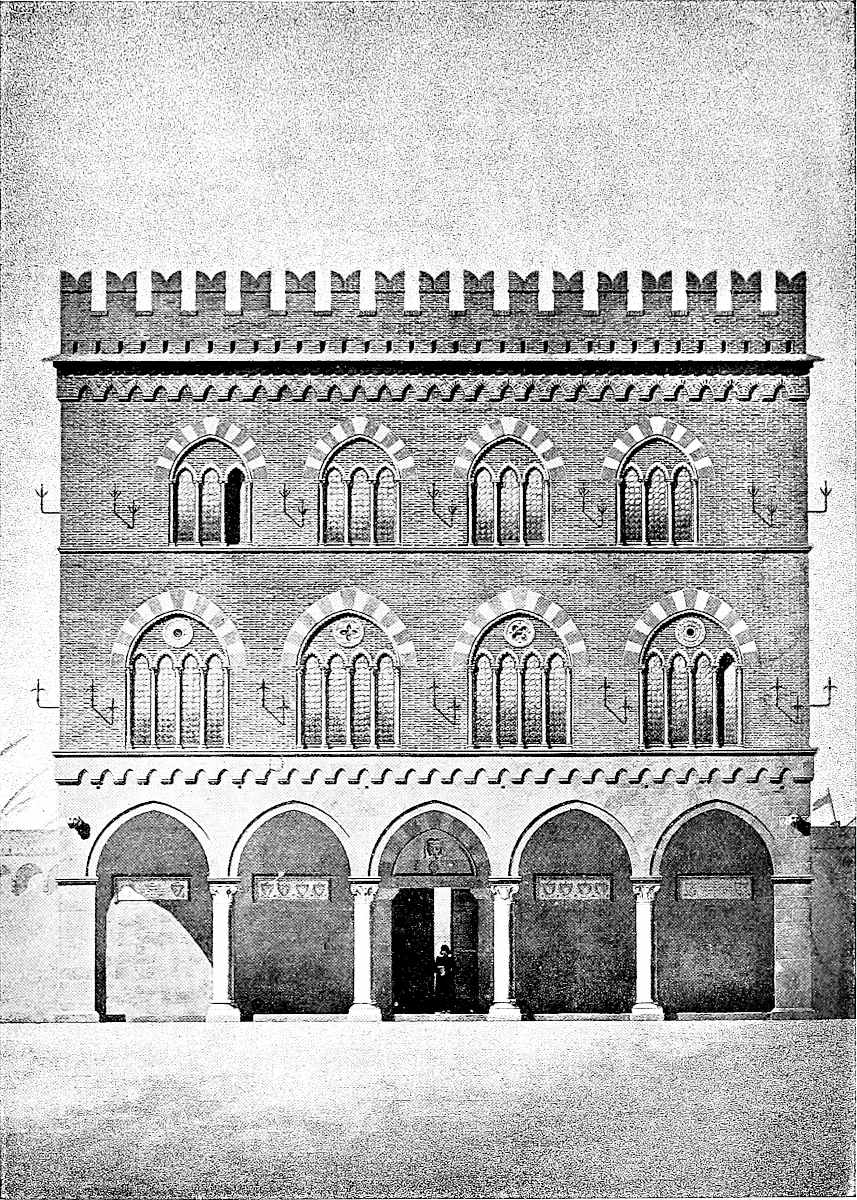

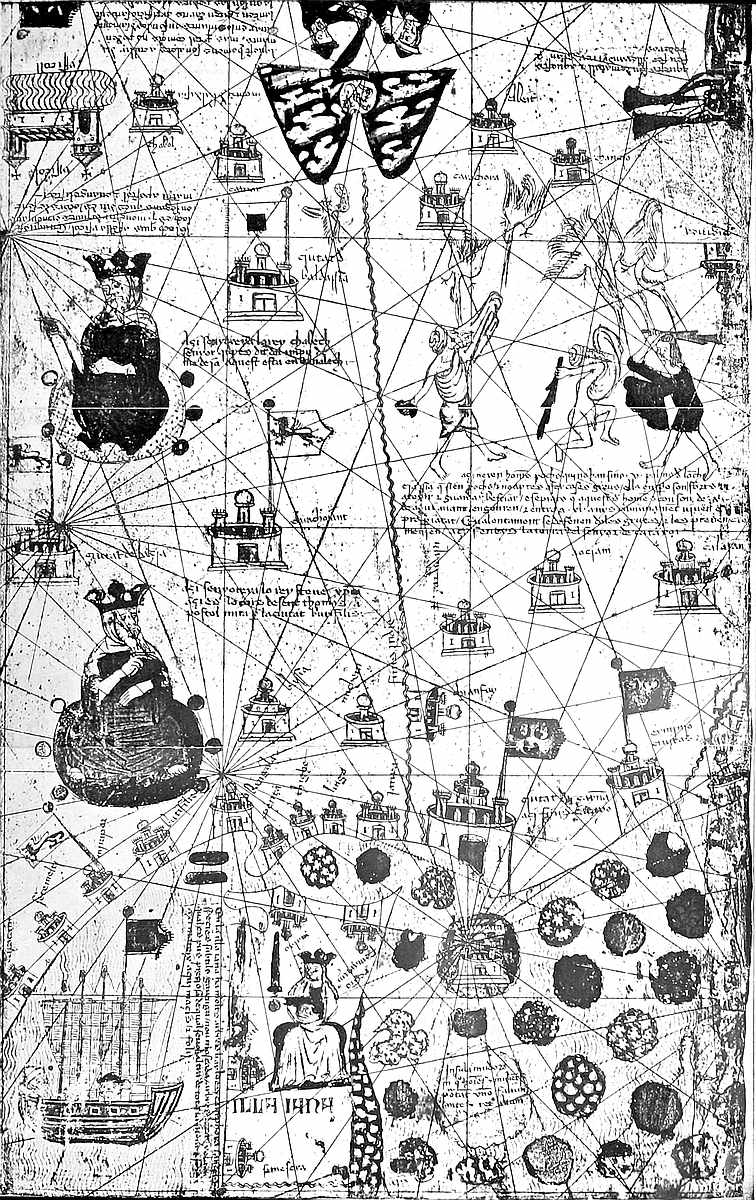

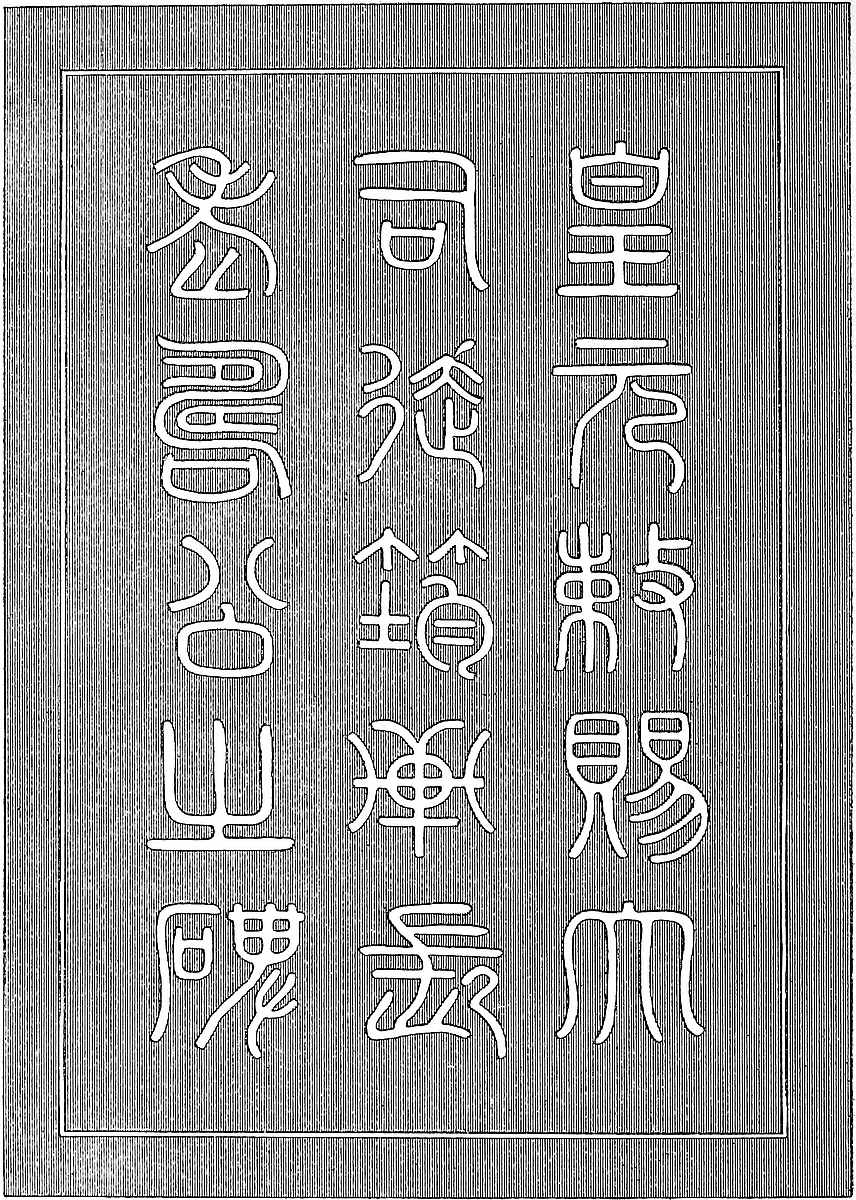

My thanks are also due to H.H. Prince Roland Bonaparte, who kindly gave me permission to reproduce some of the plates of his Recueil de Documents de l’Époque Mongole, to M. Léopold Delisle, the learned Principal Librarian of the Bibliothèque Nationale, who gave me the opportunity to study the inventory made after the death of the Doge Marino Faliero, to the Count de Semallé, formerly French Chargé d’Affaires at Peking, who gave me for reproduction a number of photographs from his valuable personal collection, and last, not least, my old friend Comm. Nicolò Barozzi, who continued to lend me the assistance which he had formerly rendered to Sir Henry Yule at Venice.

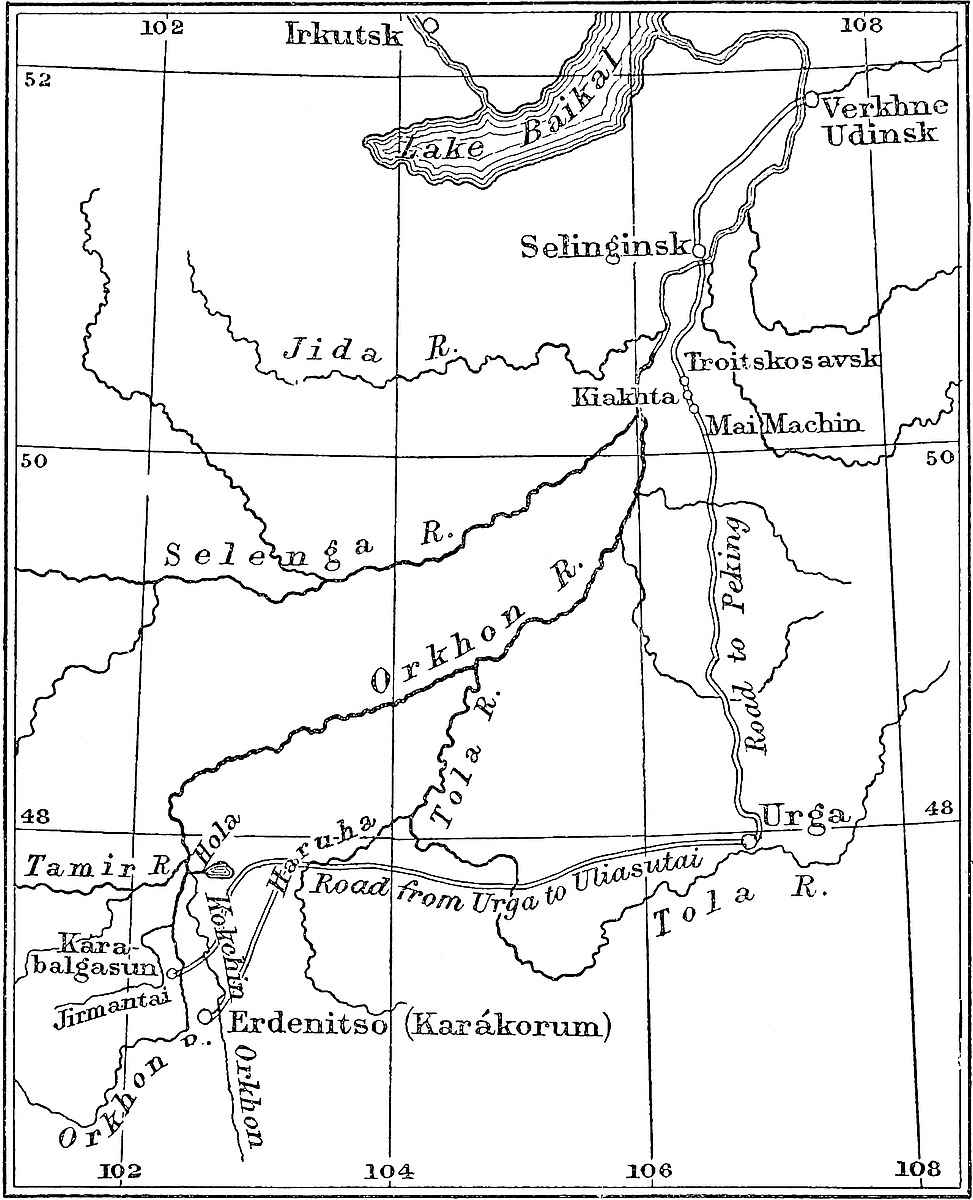

Since the last edition was published, more than twenty-five years ago, Persia has been more thoroughly studied; new routes have been explored in Central Asia, Karakorum has been fully described, and Western and South-Western China have been opened up to our knowledge in many directions. The results of these investigations form the main features of this new edition of Marco Polo. I have suppressed hardly any of Sir xHenry Yule’s notes and altered but few, doing so only when the light of recent information has proved him to be in error, but I have supplemented them by what, I hope, will be found useful, new information.[2]

Before I take leave of the kind reader, I wish to thank sincerely Mr. John Murray for the courtesy and the care he has displayed while this edition was going through the press.

The unexpected amount of favour bestowed on the former edition of this Work has been a great encouragement to the Editor in preparing this second one.

Not a few of the kind friends and correspondents who lent their aid before have continued it to the present revision. The contributions of Mr. A. Wylie of Shang-hai, whether as regards the amount of labour which they must have cost him, or the value of the result, demand above all others a grateful record here. Nor can I omit to name again with hearty acknowledgment Signor Comm. G. Berchet of Venice, the Rev. Dr. Caldwell, Colonel (now Major-General) R. Maclagan, R.E., Mr. D. Hanbury, F.R.S., Mr. Edward Thomas, F.R.S. (Corresponding Member of the Institute), and Mr. R. H. Major.

But besides these old names, not a few new ones claim my thanks.

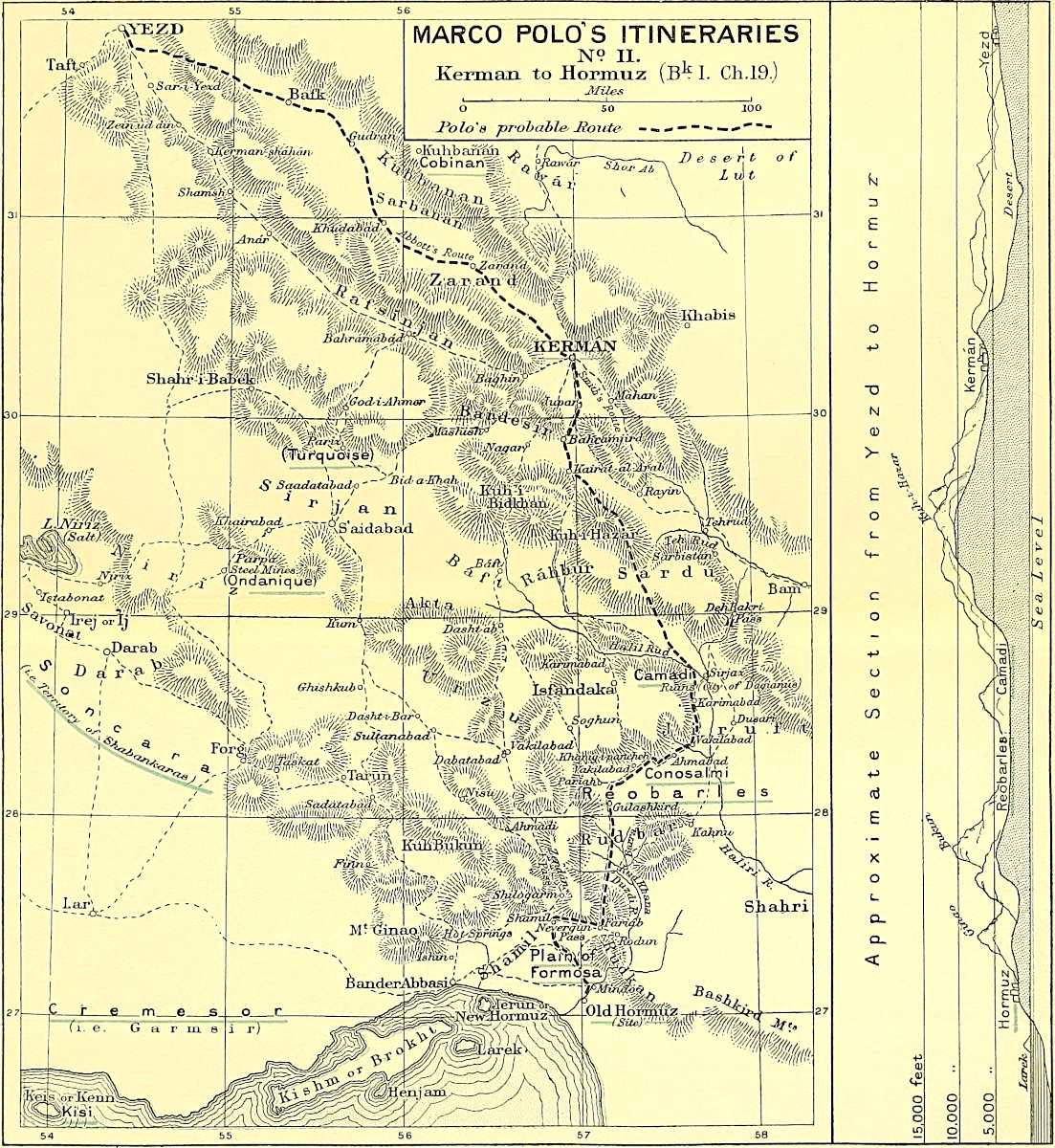

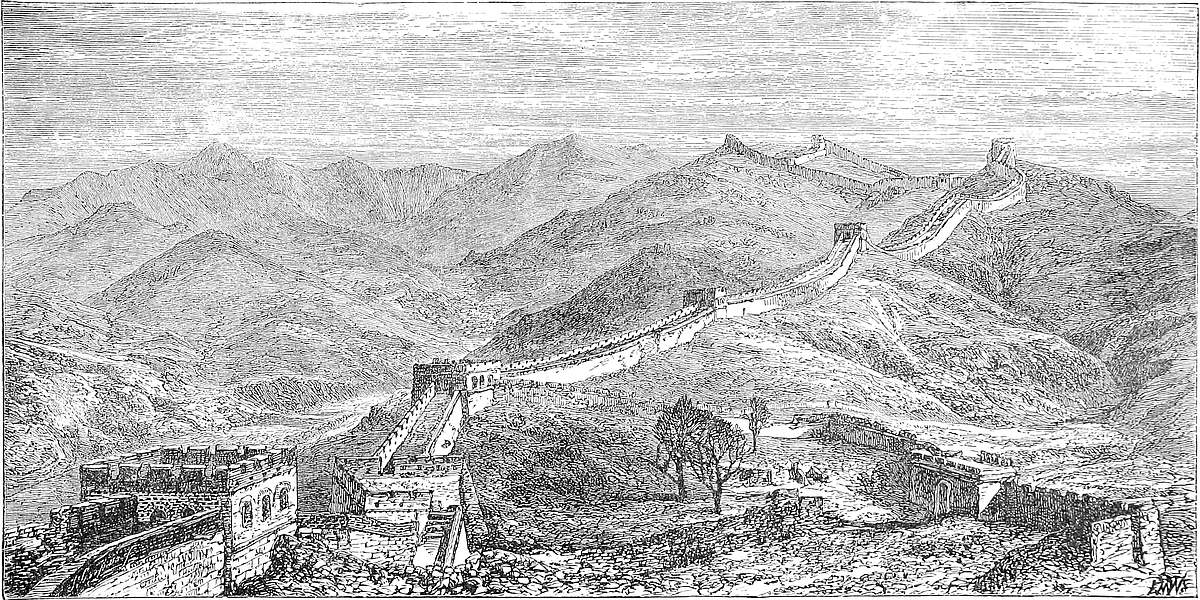

The Baron F. von Richthofen, now President of the Geographical Society of Berlin, a traveller who not only has trodden many hundreds of miles in the footsteps of our Marco, but has perhaps travelled over more of the Interior of China than Marco ever did, and who carried to that survey high scientific accomplishments xiiof which the Venetian had not even a rudimentary conception, has spontaneously opened his bountiful stores of new knowledge in my behalf. Mr. Ney Elias, who in 1872 traversed and mapped a line of upwards of 2000 miles through the almost unknown tracts of Western Mongolia, from the Gate in the Great Wall at Kalghan to the Russian frontier in the Altai, has done likewise.[1] To the Rev. G. Moule, of the Church Mission at Hang-chau, I owe a mass of interesting matter regarding that once great and splendid city, the Kinsay of our Traveller, which has enabled me, I trust, to effect great improvement both in the Notes and in the Map, which illustrate that subject. And to the Rev. Carstairs Douglas, LL.D., of the English Presbyterian Mission at Amoy, I am scarcely less indebted. The learned Professor Bruun, of Odessa, whom I never have seen, and have little likelihood of ever seeing in this world, has aided me with zeal and cordiality like that of old friendship. To Mr. Arthur Burnell, Ph.D., of the Madras Civil Service, I am grateful for many valuable notes bearing on these and other geographical studies, and particularly for his generous communication of the drawing and photograph of the ancient Cross at St. Thomas’s Mount, long before any publication of that subject was made xiiion his own account. My brother officer, Major Oliver St. John, R.E., has favoured me with a variety of interesting remarks regarding the Persian chapters, and has assisted me with new data, very materially correcting the Itinerary Map in Kerman.

Mr. Blochmann of the Calcutta Madrasa, Sir Douglas Forsyth, C.B., lately Envoy to Kashgar, M. de Mas Latrie, the Historian of Cyprus, Mr. Arthur Grote, Mr. Eugene Schuyler of the U.S. Legation at St. Petersburg, Dr. Bushell and Mr. W. F. Mayers, of H.M.’s Legation at Peking, Mr. G. Phillips of Fuchau, Madame Olga Fedtchenko, the widow of a great traveller too early lost to the world, Colonel Keatinge, V.C., C.S.I., Major-General Keyes, C.B., Dr. George Birdwood, Mr. Burgess, of Bombay, my old and valued friend Colonel W. H. Greathed, C.B., and the Master of Mediæval Geography, M. D’Avezac himself, with others besides, have kindly lent assistance of one kind or another, several of them spontaneously, and the rest in prompt answer to my requests.

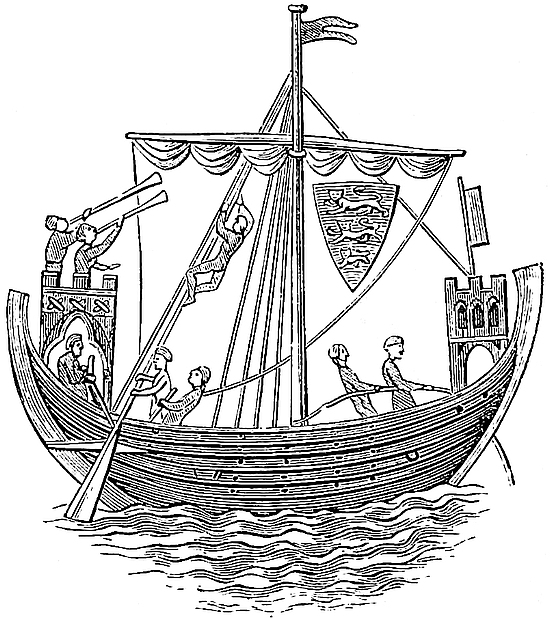

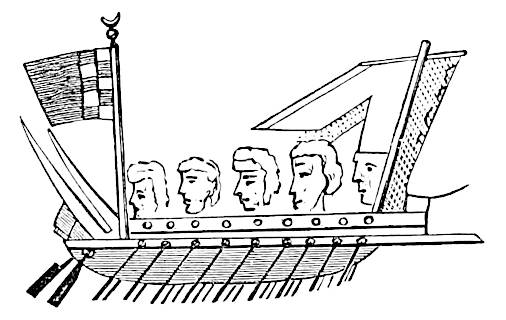

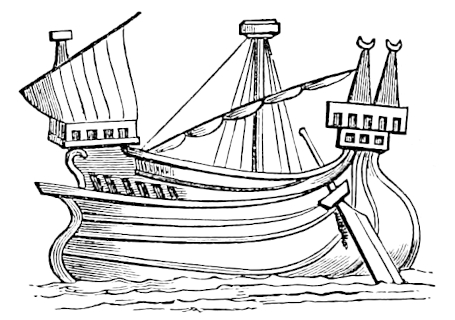

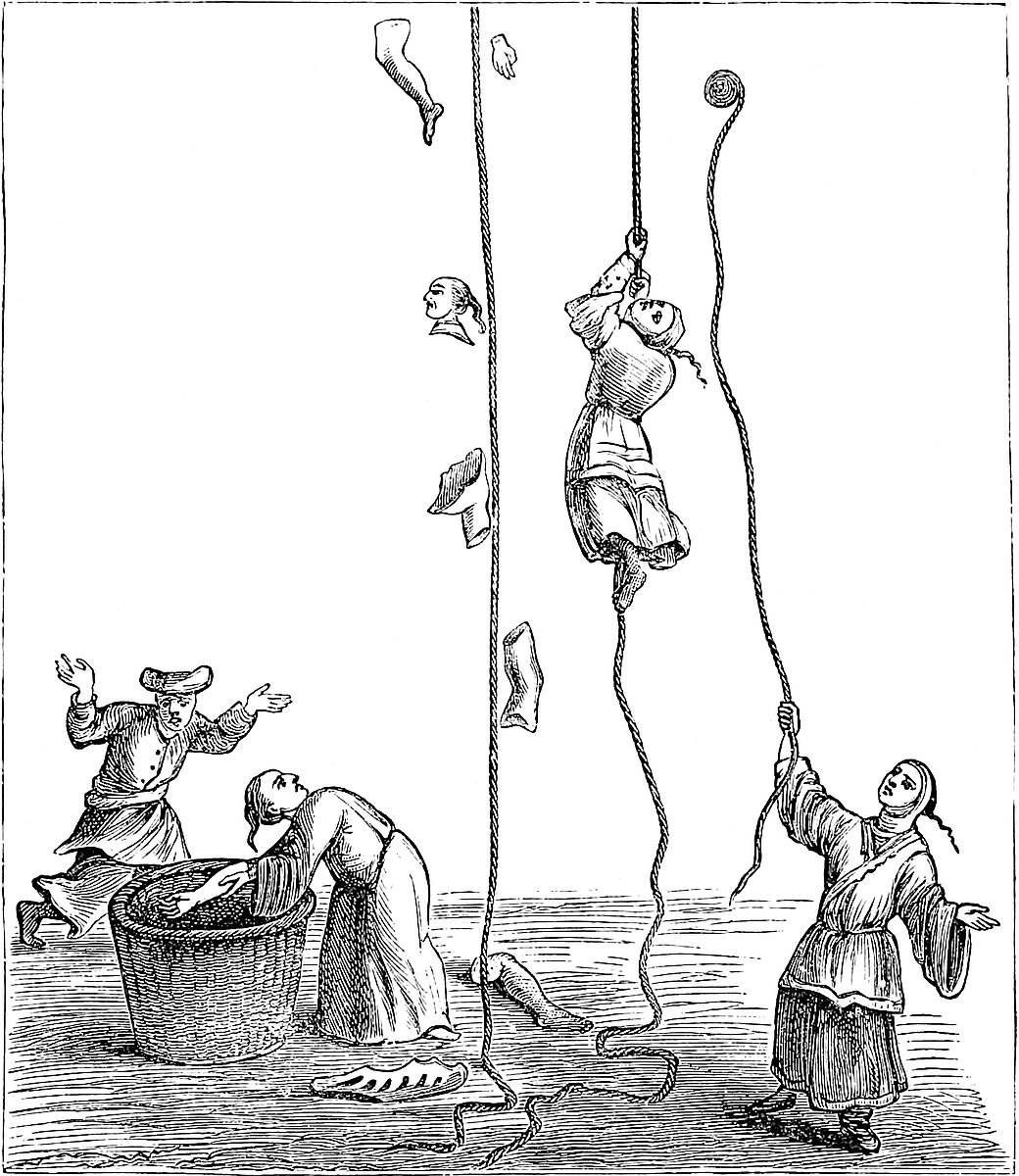

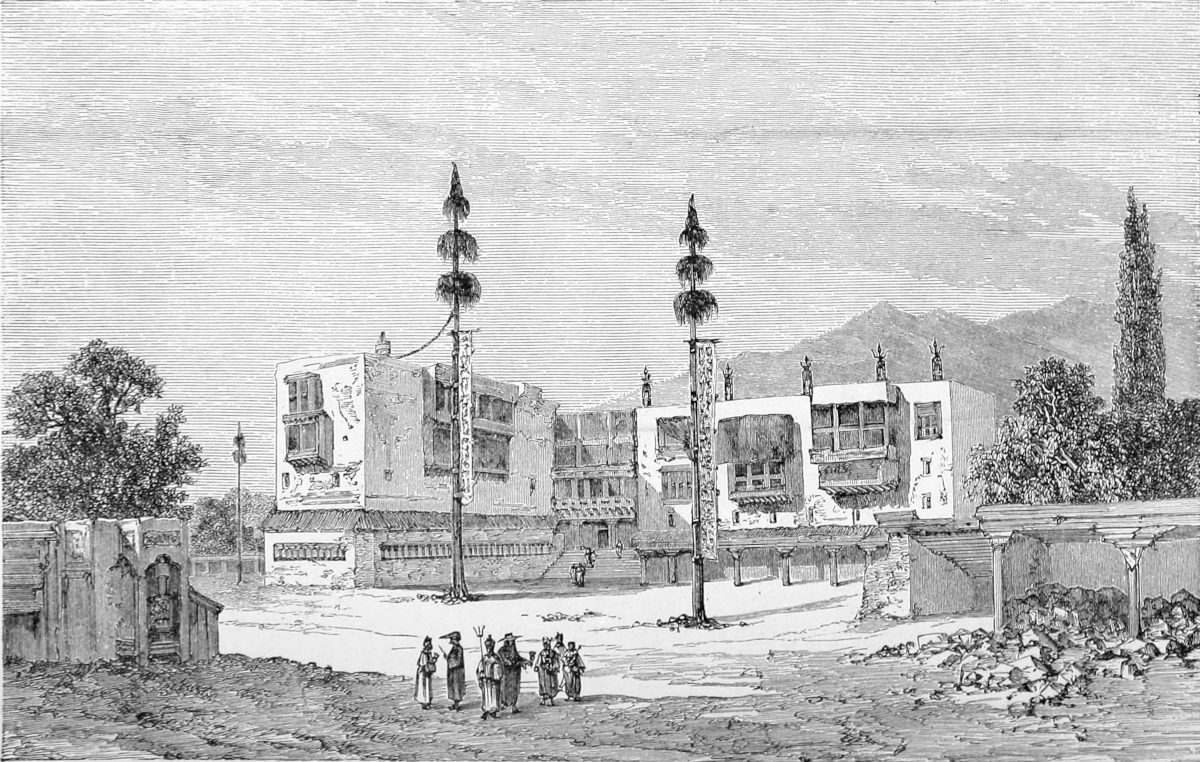

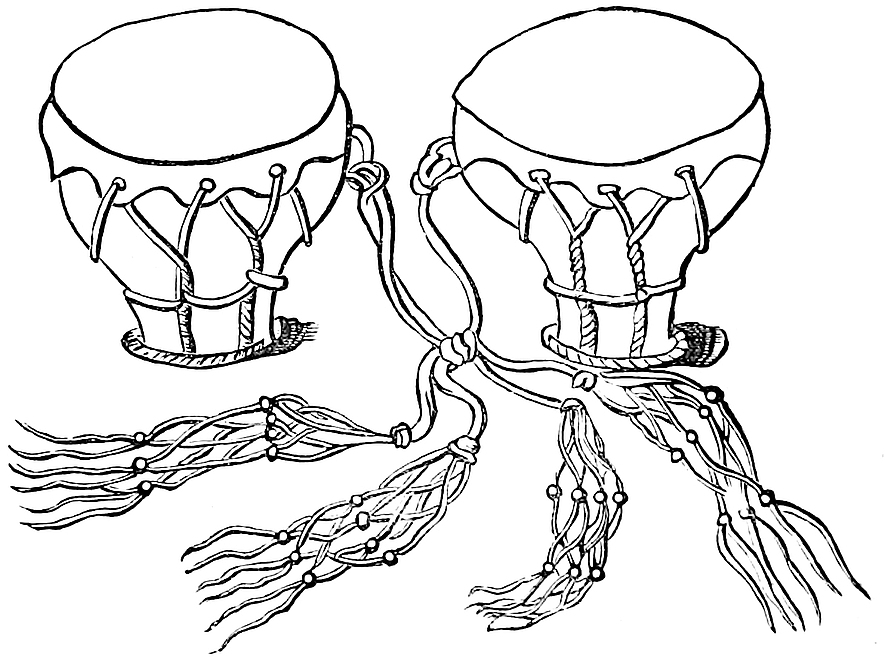

Having always attached much importance to the matter of illustrations,[2] I feel greatly indebted to the liberal action of Mr. Murray in enabling me largely to increase their number in this edition. Though many are original, we have also borrowed a good many;[3] a proceeding which seems to me entirely unobjectionable when the engravings are truly illustrative of the text, and not hackneyed.

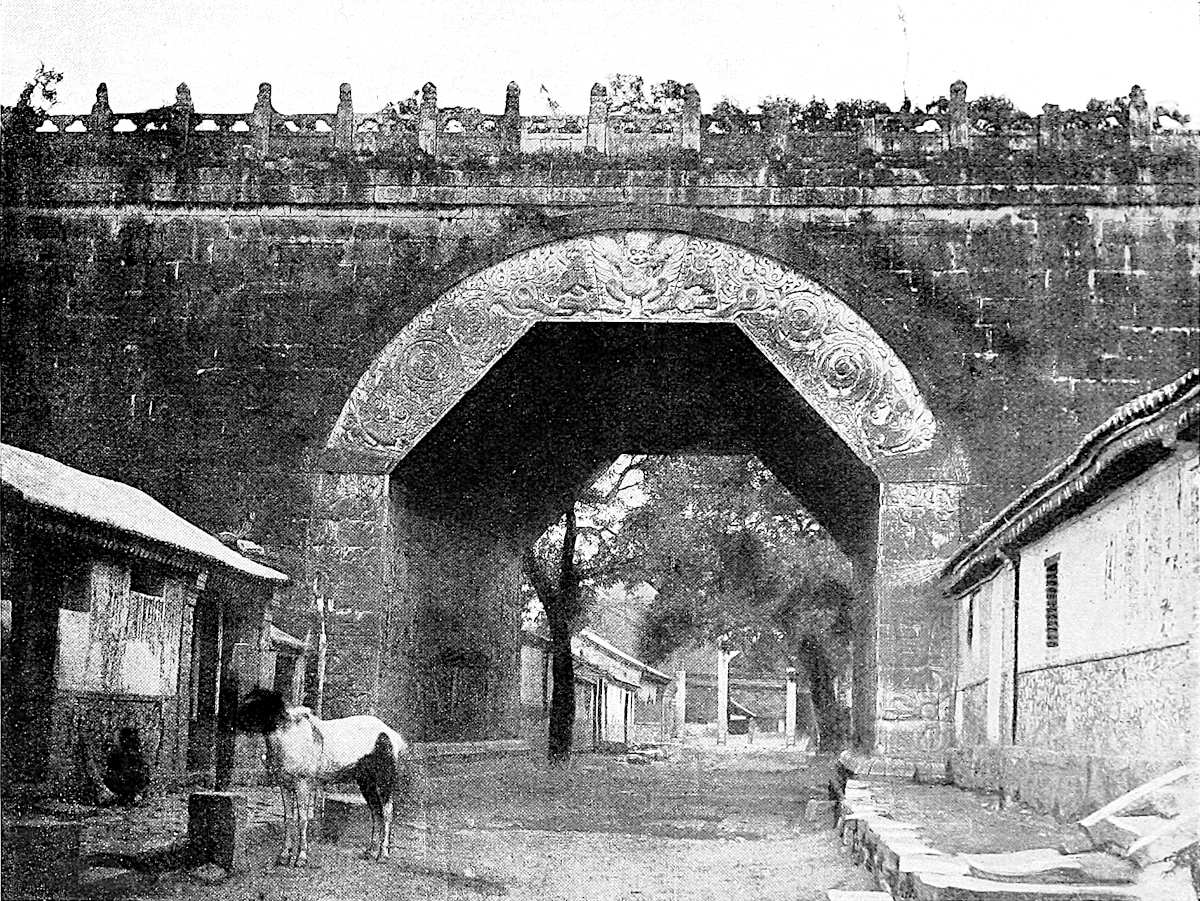

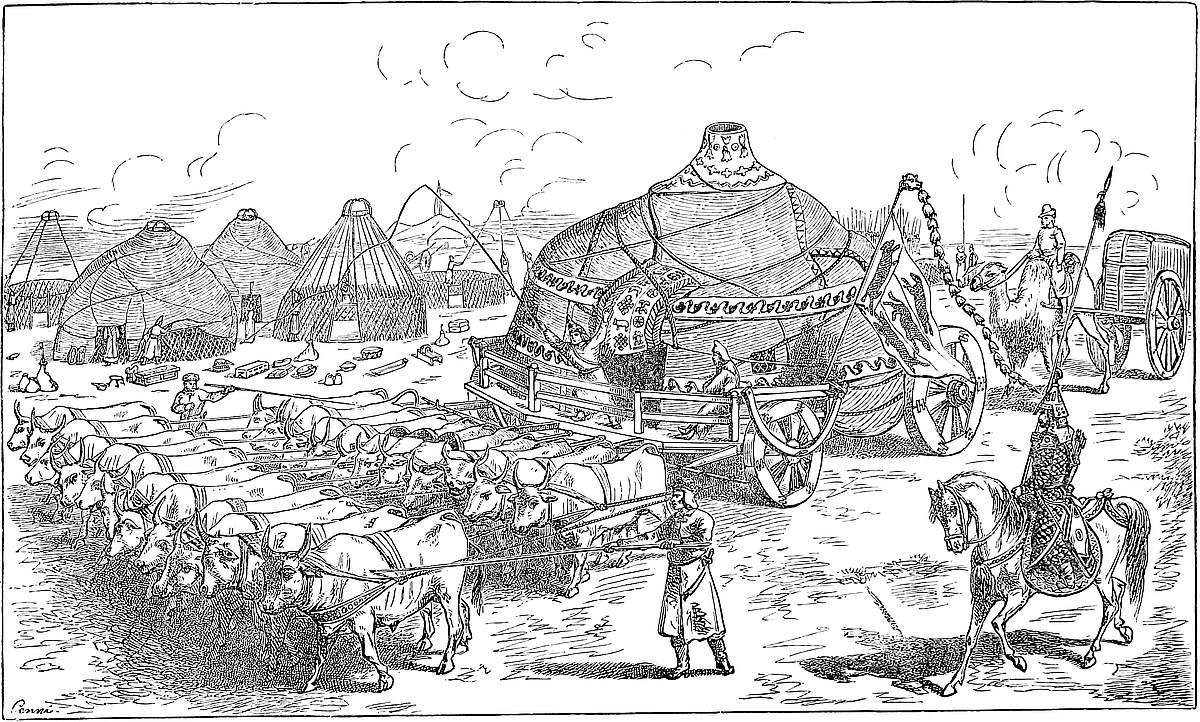

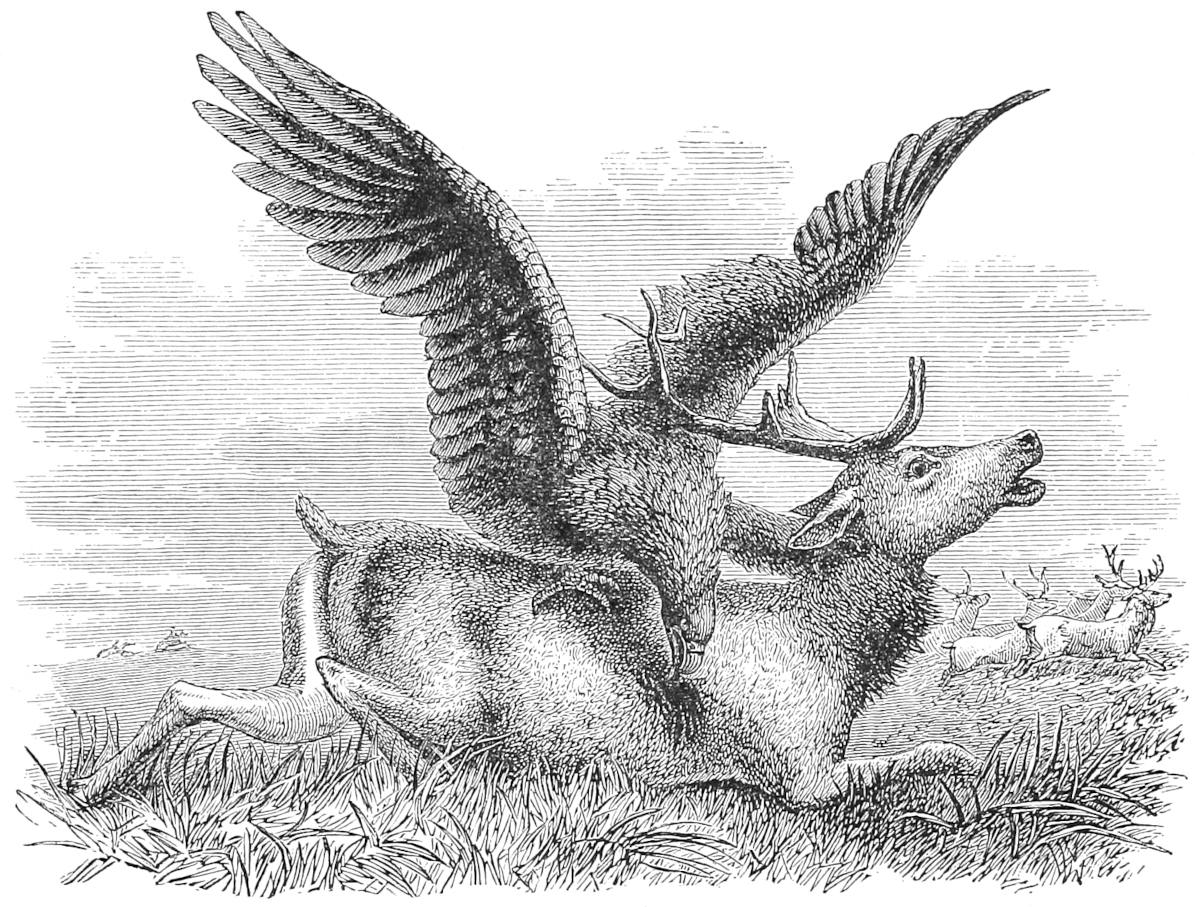

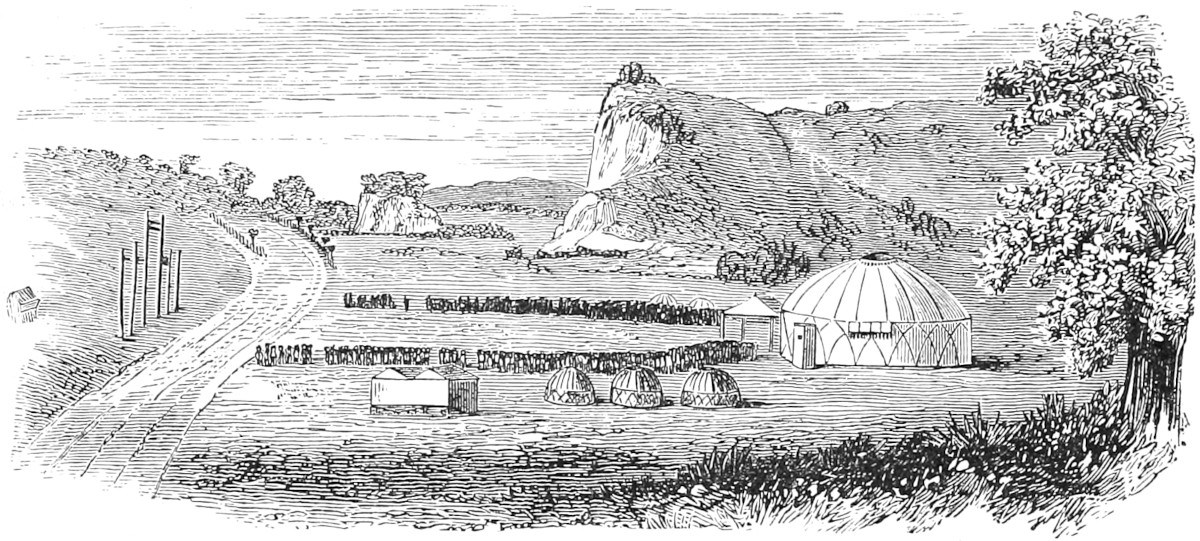

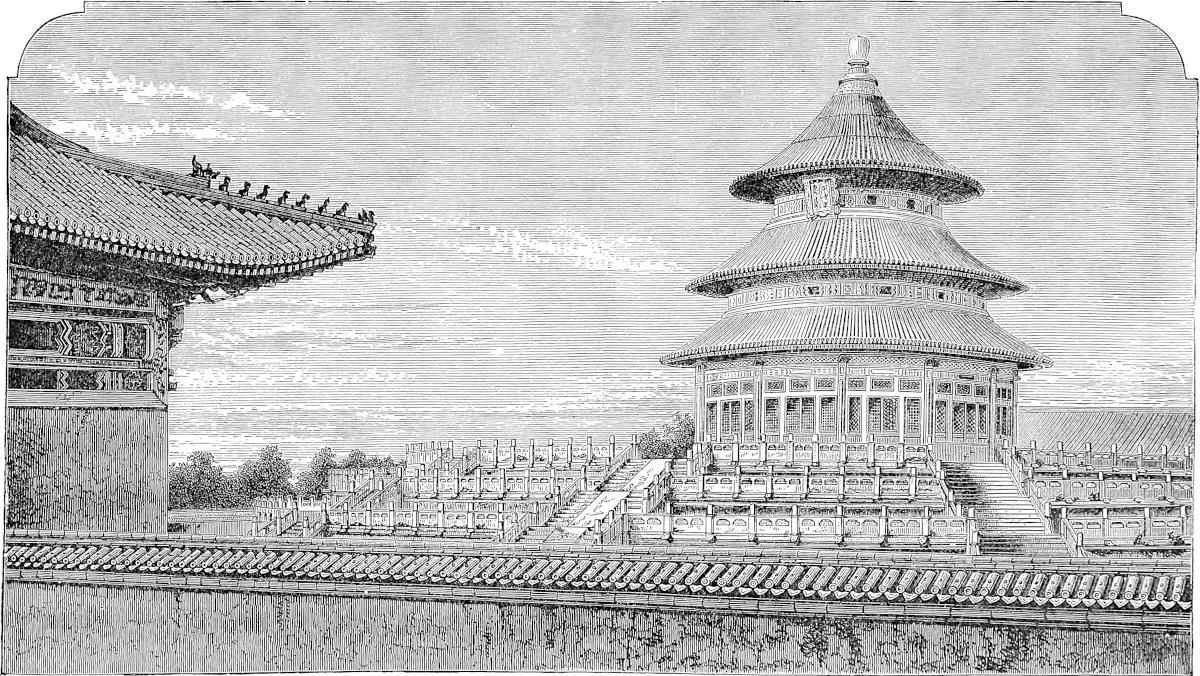

I regret the augmented bulk of the volumes. There xivhas been some excision, but the additions visibly and palpably preponderate. The truth is that since the completion of the first edition, just four years ago, large additions have been made to the stock of our knowledge bearing on the subjects of this Book; and how these additions have continued to come in up to the last moment, may be seen in Appendix L,[4] which has had to undergo repeated interpolation after being put in type. Karakorum, for a brief space the seat of the widest empire the world has known, has been visited; the ruins of Shang-tu, the “Xanadu of Cublay Khan,” have been explored; Pamir and Tangut have been penetrated from side to side; the famous mountain Road of Shen-si has been traversed and described; the mysterious Caindu has been unveiled; the publication of my lamented friend Lieutenant Garnier’s great work on the French Exploration of Indo-China has provided a mass of illustration of that Yun-nan for which but the other day Marco Polo was well-nigh the most recent authority. Nay, the last two years have thrown a promise of light even on what seemed the wildest of Marco’s stories, and the bones of a veritable Ruc from New Zealand lie on the table of Professor Owen’s Cabinet!

M. Vivien de St. Martin, during the interval of which we have been speaking, has published a History of Geography. In treating of Marco Polo, he alludes to the first edition of this work, most evidently with no intention of disparagement, but speaks of it as merely a revision of Marsden’s Book. The last thing I should allow myself to do would be to apply to a xvGeographer, whose works I hold in so much esteem, the disrespectful definition which the adage quoted in my former Preface[5] gives of the vir qui docet quod non sapit; but I feel bound to say that on this occasion M. Vivien de St. Martin has permitted himself to pronounce on a matter with which he had not made himself acquainted; for the perusal of the very first lines of the Preface (I will say nothing of the Book) would have shown him that such a notion was utterly unfounded.

In concluding these “forewords” I am probably taking leave of Marco Polo,[6] the companion of many pleasant and some laborious hours, whilst I have been contemplating with him (“vôlti a levante”) that Orient in which I also had spent years not a few.

And as the writer lingered over this conclusion, his thoughts wandered back in reverie to those many venerable libraries in which he had formerly made search for mediæval copies of the Traveller’s story; and it seemed to him as if he sate in a recess of one of these with a manuscript before him which had never till then been examined with any care, and which he found with delight to contain passages that appear in no version of the Book hitherto known. It was written in clear Gothic text, and in the Old French tongue of the early 14th century. Was it possible that he had lighted on the xvilong-lost original of Ramusio’s Version? No; it proved to be different. Instead of the tedious story of the northern wars, which occupies much of our Fourth Book, there were passages occurring in the later history of Ser Marco, some years after his release from the Genoese captivity. They appeared to contain strange anachronisms certainly; but we have often had occasion to remark on puzzles in the chronology of Marco’s story![7] And in some respects they tended to justify our intimated suspicion that he was a man of deeper feelings and wider sympathies than the book of Rusticiano had allowed to appear.[8] Perhaps this time the Traveller had found an amanuensis whose faculties had not been stiffened by fifteen years of Malapaga?[9] One of the most important passages ran thus:—

“Bien est voirs que, après ce que Messires Marc Pol avoit pris

fame et si estoit demouré plusours ans de sa vie a Venysse, il

avint que mourut Messires Mafés qui oncles Monseignour Marc

estoit: (et mourut ausi ses granz chiens mastins qu’avoit amenei dou

Catai,[10] et qui avoit non Bayan pour l’amour au bon chievetain

Bayan Cent-iex); adonc n’avoit oncques puis Messires Marc nullui,

fors son esclave Piere le Tartar, avecques lequel pouvoit penre

soulas à s’entretenir de ses voiages et des choses dou Levant. Car

la gent de Venysse si avoit de grant piesce moult anuy pris des

loncs contes Monseignour Marc; et quand ledit Messires Marc

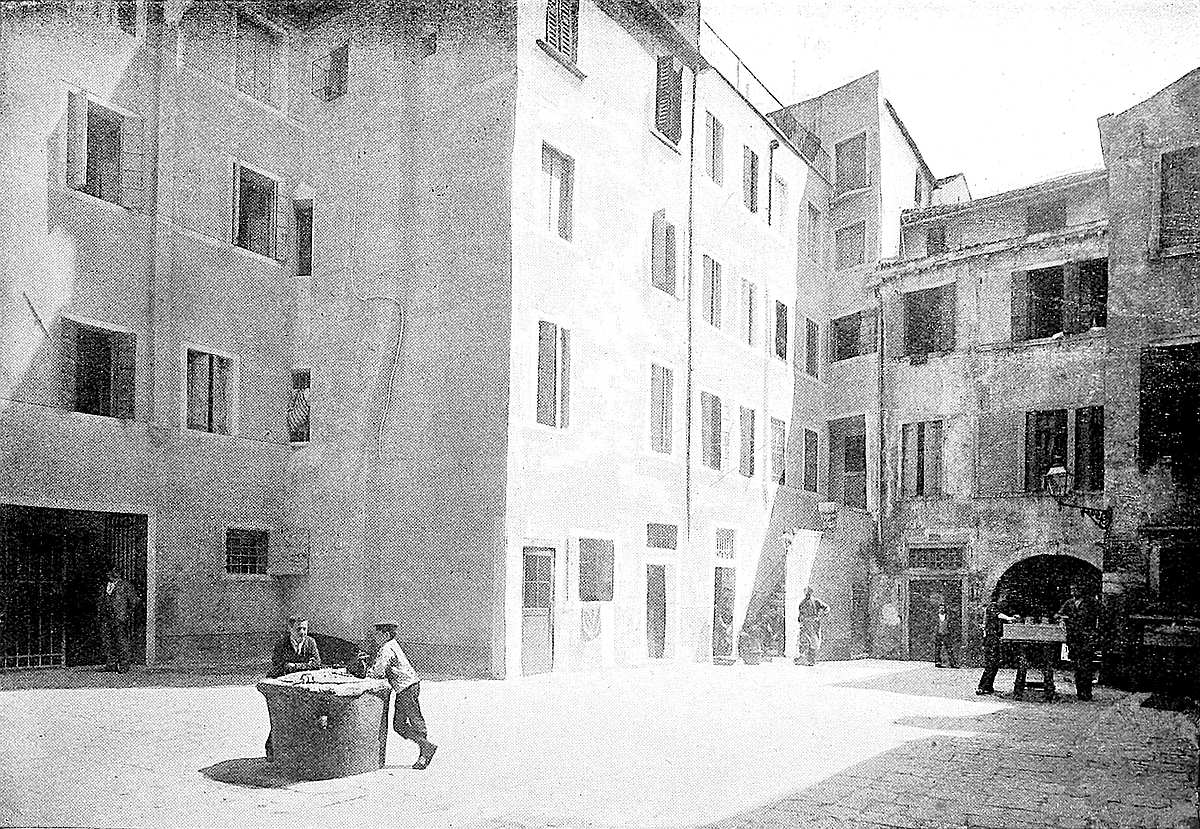

issoit de l’uys sa meson ou Sain Grisostome, souloient li petit

marmot es voies dariere-li courir en cryant Messer Marco Miliòn!

cont’a nu un busiòn! que veult dire en François ‘Messires Marcs

des millions di-nous un de vos gros mensonges.’ En oultre, la Dame

Donate fame anuyouse estoit, et de trop estroit esprit, et plainne

de convoitise.[11] Ansi avint que Messires Marc desiroit es voiages

rantrer durement.

“Si se partist de Venisse et chevaucha aux parties d’occident. Et

demoura mainz jours es contrées de Provence et de France et puys

fist passaige aux Ysles de la tremontaingne et s’en retourna par la

Magne, si comme vous orrez cy-après. Et fist-il escripre son voiage

atout les devisements les contrées; mes de la France n’y parloit mie

grantment pour ce que maintes genz la scevent apertement. Et pour

ce en lairons atant, et commencerons d’autres choses, assavoir, de

Bretaingne la Grant.

xvii

Cy devyse dou roiaume de Bretaingne la grant.

“Et sachiés que quand l’en se part de Calés, et l’en nage xx ou

xxx milles à trop grant mesaise, si treuve l’en une grandisme Ysle

qui s’appelle Bretaingne la Grant. Elle est à une grant royne

et n’en fait treuage à nulluy. Et ensevelissent lor mors, et ont

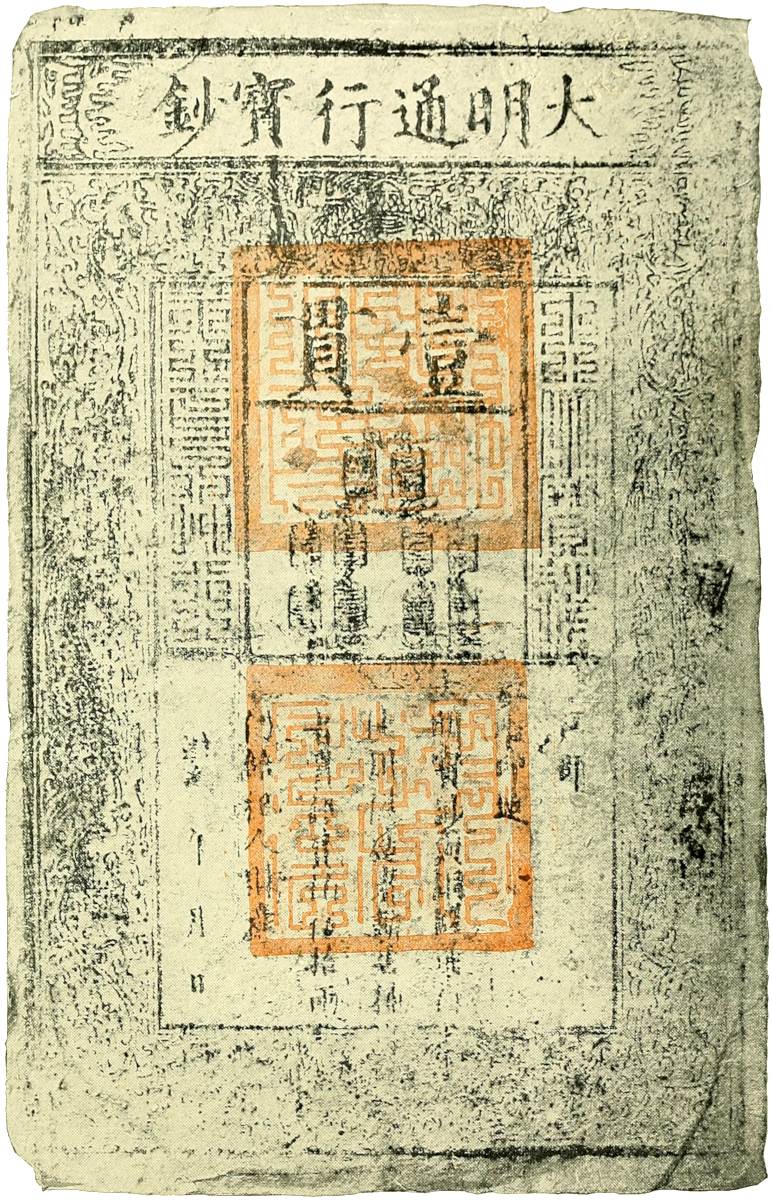

monnoye de chartres et d’or et d’argent, et ardent pierres noyres,

et vivent de marchandises et d’ars, et ont toutes choses de vivre en

grant habondance mais non pas à bon marchié. Et c’est une Ysle de

trop grant richesce, et li marinier de celle partie dient que c’est

li plus riches royaumes qui soit ou monde, et qu’il y a li mieudre

marinier dou monde et li mieudre coursier et li mieudre chevalier

(ains ne chevauchent mais lonc com François). Ausi ont-il trop bons

homes d’armes et vaillans durement (bien que maint n’y ait), et

les dames et damoseles bonnes et loialles, et belles com lys souef

florant. Et quoi vous en diroie-je? Il y a citez et chasteau assez,

et tant de marchéanz et si riches qui font venir tant d’avoir-de-poiz

et de toute espece de marchandise qu’il n’est hons qui la verité

en sceust dire. Font venir d’Ynde et d’autres parties coton a

grant planté, et font venir soye de Manzi et de Bangala, et font

venir laine des ysles de la Mer Occeane et de toutes parties. Et si

labourent maintz bouquerans et touailles et autres draps de coton et

de laine et de soye. Encores sachiés que ont vaines d’acier assez, et

si en labourent trop soubtivement de tous hernois de chevalier, et de

toutes choses besoignables à ost; ce sont espées et glaive et esperon

et heaume et haches, et toute espèce d’arteillerie et de coutelerie,

et en font grant gaaigne et grant marchandise. Et en font si grant

habondance que tout li mondes en y puet avoir et à bon marchié.

Encores cy devise dou dyt roiaume, et de ce qu’en dist Messires Marcs.

“Et sachiés que tient icelle Royne la seigneurie de l’Ynde majeure

et de Mutfili et de Bangala, et d’une moitié de Mien. Et

moult est saige et noble dame et pourvéans, si que est elle amée de

chascun. Et avoit jadis mari; et depuys qu’il mourut bien XIV ans

avoit; adonc la royne sa fame l’ama tant que oncques puis ne se voult

marier a nullui, pour l’amour le prince son baron, ançois moult maine

quoye vie. Et tient son royaume ausi bien ou miex que oncques le

tindrent li roy si aioul. Mes ores en ce royaume li roy n’ont guieres

pooir, ains la poissance commence a trespasser à la menue gent. Et

distrent aucun marinier de celes parties à Monseignour Marc que

hui-et-le jour li royaumes soit auques abastardi come je vous diroy.

Car bien est voirs que ci-arrières estoit ciz pueple de Bretaingne

la Grant bonne et granz et loialle gent qui servoit Diex moult

volontiers selonc lor usaige; et tuit li labour qu’il labouroient et

portoient a vendre estoient honnestement labouré, et dou greigneur

vaillance, et chose pardurable; et se vendoient à jouste pris sanz

barguignier. En tant que se aucuns labours portoit l’estanpille

Bretaingne la Grant c’estoit regardei com pleges de bonne estoffe.

Mes orendroit li labours n’est mie tousjourz si bons; et quand l’en

achate pour un quintal pesant de toiles de coton, adonc, par trop

souvent, si treuve l’en de chascun C pois de coton, bien xxx ou

xl pois de plastre de gifs, ou de blanc xviiid’Espaigne, ou de choses

semblables. Et se l’en achate de cammeloz ou de tireteinne ou d’autre

dras de laine, cist ne durent mie, ains sont plain d’empoise, ou de

glu et de balieures.

“Et bien qu’il est voirs que chascuns hons egalement doit de son

cors servir son seigneur ou sa commune, pour aler en ost en tens

de besoingne; et bien que trestuit li autre royaume d’occident

tieingnent ce pour ordenance, ciz pueple de Bretaingne la Grant

n’en veult nullement, ains si dient: ‘Veez-là: n’avons nous pas

la Manche pour fossé de nostre pourpris, et pourquoy nous

penerons-nous pour nous faire homes d’armes, en lessiant nos gaaignes

et nos soulaz? Cela lairons aus soudaiers.’ Or li preudhome entre

eulx moult scevent bien com tiex paroles sont nyaises; mes si ont

paour de lour en dire la verité pour ce que cuident desplaire as

bourjois et à la menue gent.

“Or je vous di sanz faille que, quand Messires Marcs Pols sceust

ces choses, moult en ot pitié de cestui pueple, et il li vint à

remembrance ce que avenu estoit, ou tens Monseignour Nicolas et

Monseignour Mafé, à l’ore quand Alau, frère charnel dou Grant

Sire Cublay, ala en ost seur Baudas, et print le Calife et sa

maistre cité, atout son vaste tresor d’or et d’argent, et l’amère

parolle que dist ledit Alau au Calife, com l’a escripte li Maistres

Rusticiens ou chief de cestui livre.[12]

“Car sachiés tout voirement que Messires Marc moult se deleitoit

à faire appert combien sont pareilles au font les condicions des

diverses regions dou monde, et soloit-il clorre son discours si

disant en son language de Venisse: ‘Sto mondo xe fato tondo, com

uzoit dire mes oncles Mafés.’

“Ore vous lairons à conter de ceste matière et retournerons à parler

de la Loy des genz de Bretaingne la Grant.

Cy devise des diverses créances de la gent Bretaingne la Grant et de

ce qu’en cuidoit Messires Marcs.

“Il est voirs que li pueples est Crestiens, mes non pour le plus

selonc la foy de l’Apostoille Rommain, ains tiennent le en mautalent

assez. Seulement il y en a aucun qui sont féoil du dit Apostoille et

encore plus forment que li nostre prudhome de Venisse. Car quand

dit li Papes: ‘Telle ou telle chose est noyre,’ toute ladite gent si

en jure: ‘Noyre est com poivre.’ Et puis se dira li Papes de la dite

chose: ‘Elle est blanche,’ si en jurera toute ladite gent: ‘Il est

voirs qu’elle est blanche; blanche est com noifs.’ Et dist Messires

Marc Pol: ‘Nous n’avons nullement tant de foy à Venyse, ne li

prudhome de Florence non plus, com l’en puet savoir bien apertement

dou livre Monseignour Dantès Aldiguiere, que j’ay congneu a Padoe

le meisme an que Messires Thibault de Cepoy à Venisse estoit.[13]

Mes c’est joustement ce que j’ay veu autre foiz près le Grant Bacsi

qui est com li Papes des Ydres.’

“Encore y a une autre manière de gent; ce sont de celz qui

s’appellent filsoufes;[14] et si il disent: ‘S’il y a Diex n’en

scavons nul, mes il est voirs xixqu’il est une certeinne courance des

choses laquex court devers le bien.’ Et fist Messires Marcs:

‘Encore la créance des Bacsi qui dysent que n’y a ne Diex Eternel

ne Juge des homes, ains il est une certeinne chose laquex s’appelle

Kerma.’[15]

“Une autre foiz avint que disoit un des filsoufes à Monseignour

Marc: ‘Diex n’existe mie jeusqu’ores, ainçois il se fait

desorendroit.’ Et fist encore Messires Marcs: ‘Veez-là, une autre

foiz la créance des ydres, car dient que li seuz Diex est icil

hons qui par force de ses vertuz et de son savoir tant pourchace

que d’home il se face Diex presentement. Et li Tartar l’appelent

Borcan. Tiex Diex Sagamoni Borcan estoit, dou quel parle li

livres Maistre Rusticien.’[16]

“Encore ont une autre manière de filsoufes, et dient-il: ‘Il n’est

mie ne Diex ne Kerma ne courance vers le bien, ne Providence,

ne Créerres, ne Sauvours, ne sainteté ne pechiés ne conscience de

pechié, ne proyère ne response à proyère, il n’est nulle riens fors

que trop minime grain ou paillettes qui ont à nom atosmes, et

de tiex grains devient chose qui vive, et chose qui vive devient

une certeinne creature qui demoure au rivaige de la Mer: et ceste

creature devient poissons, et poissons devient lezars, et lezars

devient blayriaus, et blayriaus devient gat-maimons, et gat-maimons

devient hons sauvaiges qui menjue char d’homes, et hons sauvaiges

devient hons crestien.’

“Et dist Messires Marc: ‘Encore une foiz, biaus sires, li Bacsi

de Tebet et de Kescemir et li prestre de Seilan, qui si dient

que l’arme vivant doie trespasser par tous cez changes de vestemens;

si com se treuve escript ou livre Maistre Rusticien que Sagamoni

Borcan mourut iiij vint et iiij foiz et tousjourz resuscita, et à

chascune foiz d’une diverse manière de beste, et à la derreniere

foyz mourut hons et devint diex, selonc ce qu’il dient.’[17] Et

fist encore Messires Marc: ‘A moy pert-il trop estrange chose se

juesques à toutes les créances des ydolastres deust dechéoir ceste

grantz et saige nation. Ainsi peuent jouer Misire li filsoufe atout

lour propre perte, mes à l’ore quand tiex fantaisies se respanderont

es joenes bacheliers et parmy la menue gent, celz averont pour toute

Loy manducemus et bibamus, cras enim moriemur; et trop isnellement

l’en raccomencera la descente de l’eschiele, et d’home crestien

deviendra hons sauvaiges, et d’home sauvaige gat-maimons, et de

gat-maimon blayriaus.’ Et fist encores Messires Marc: ‘Maintes

contrées et provinces et ysles et citéz je Marc Pol ay veues et

de maintes genz de maintes manières ay les condicionz congneues, et

je croy bien que il est plus assez dedens l’univers que ce que li

nostre prestre n’y songent. Et puet bien estre, biaus sires, que li

mondes n’a estés creés à tous poinz com nous creiens, ains d’une

sorte encore plus merveillouse. Mes cil n’amenuise nullement nostre

pensée de Diex et de sa majesté, ains la fait greingnour. Et contrée

n’ay veue ou Dame Diex ne manifeste apertement les granz euvres

de sa tout-poissante saigesse; gent n’ay congneue esquiex ne se

fait sentir li fardels de pechié, et la besoingne de Phisicien des

maladies de l’arme tiex com est nostre Seignours Ihesus Crist, Beni

soyt son Non. Pensez doncques à cel qu’a dit uns de ses xxApostres:

Nolite esse prudentes apud vosmet ipsos; et uns autres: Quoniam

multi pseudo-prophetae exierint; et uns autres: Quod venient in

novissimis diebus illusores ... dicentes, Ubi est promissio? et

encores aus parolles que dist li Signours meismes: Vide ergo ne

lumen quod in te est tenebrae sint.

Commant Messires Marcs se partist de l’ysle de Bretaingne et de la

proyère que fist.

“Et pourquoy vous en feroie-je lonc conte? Si print nef Messires

Marcs et se partist en nageant vers la terre ferme. Or Messires

Marc Pol moult ama cel roiaume de Bretaingne la grant pour son

viex renon et s’ancienne franchise, et pour sa saige et bonne Royne

(que Diex gart), et pour les mainz homes de vaillance et bons

chaceours et les maintes bonnes et honnestes dames qui y estoient.

Et sachiés tout voirement que en estant delez le bort la nef, et

en esgardant aus roches blanches que l’en par dariere-li lessoit,

Messires Marc prieoit Diex, et disoit-il: ‘Ha Sires Diex ay merci

de cestuy vieix et noble royaume; fay-en pardurable forteresse de

liberté et de joustice, et garde-le de tout meschief de dedens et de

dehors; donne à sa gent droit esprit pour ne pas Diex guerroyer de

ses dons, ne de richesce ne de savoir; et conforte-les fermement en ta foy’ ...”

A loud Amen seemed to peal from without, and the awakened reader started to his feet. And lo! it was the thunder of the winter-storm crashing among the many-tinted crags of Monte Pellegrino,—with the wind raging as it knows how to rage here in sight of the Isles of Æolus, and the rain dashing on the glass as ruthlessly as it well could have done, if, instead of Æolic Isles and many-tinted crags, the window had fronted a dearer shore beneath a northern sky, and looked across the grey Firth to the rain-blurred outline of the Lomond Hills.

But I end, saying to Messer Marco’s prayer, Amen.

Palermo, 31st December, 1874.

The amount of appropriate material, and of acquaintance with the mediæval geography of some parts of Asia, which was acquired during the compilation of a work of kindred character for the Hakluyt Society,[1] could hardly fail to suggest as a fresh labour in the same field the preparation of a new English edition of Marco Polo. Indeed one kindly critic (in the Examiner) laid it upon the writer as a duty to undertake that task.

Though at least one respectable English edition has appeared since Marsden’s,[2] the latter has continued to be the standard edition, and maintains not only its reputation but its market value. It is indeed the work of a sagacious, learned, and right-minded man, which can never be spoken of otherwise than with respect. But since Marsden published his quarto (1818) vast stores of new knowledge have become available in elucidation both of the contents of Marco Polo’s book and of its literary history. The works of writers such as Klaproth, Abel Rémusat, D’Avezac, Reinaud, Quatremère, Julien, I. J. Schmidt, Gildemeister, Ritter, Hammer-Purgstall, Erdmann, D’Ohsson, Defrémery, Elliot, Erskine, and many more, which throw light directly or incidentally on Marco Polo, have, for the most part, appeared since then. Nor, as regards the literary history of the book, were any just views possible at a time when what may be called the Fontal MSS. (in French) were unpublished and unexamined.

Besides the works which have thus occasionally or incidentally xxiithrown light upon the Traveller’s book, various editions of the book itself have since Marsden’s time been published in foreign countries, accompanied by comments of more or less value. All have contributed something to the illustration of the book or its history; the last and most learned of the editors, M. Pauthier, has so contributed in large measure. I had occasion some years ago[3] to speak freely my opinion of the merits and demerits of M. Pauthier’s work; and to the latter at least I have no desire to recur here.

Another of his critics, a much more accomplished as well as more favourable one,[4] seems to intimate the opinion that there would scarcely be room in future for new commentaries. Something of the kind was said of Marsden’s at the time of its publication. I imagine, however, that whilst our libraries endure the Iliad will continue to find new translators, and Marco Polo—though one hopes not so plentifully—new editors.

The justification of the book’s existence must however be looked for, and it is hoped may be found, in the book itself, and not in the Preface. The work claims to be judged as a whole, but it may be allowable, in these days of scanty leisure, to indicate below a few instances of what is believed to be new matter in an edition of Marco Polo; by which however it is by no means intended that all such matter is claimed by the editor as his own.[5]

xxiii

From the commencement of the work it was felt that the task was one which no man, though he were far better equipped and much more conveniently situated than the present writer, could satisfactorily accomplish from his own resources, and help was sought on special points wherever it seemed likely to be found. In scarcely any quarter was the application made in vain. Some who have aided most materially are indeed very old and valued friends; but to many others who have done the same the applicant was unknown; and some of these again, with whom the editor began correspondence on this subject as a stranger, he is happy to think that he may now call friends.

To none am I more indebted than to the Comm. Guglielmo Berchet, of Venice, for his ample, accurate, and generous assistance in furnishing me with Venetian documents, and in many other ways. Especial thanks are also due to Dr. William Lockhart, who has supplied the materials for some of the most valuable illustrations; to Lieutenant Francis Garnier, of the French Navy, the gallant and accomplished leader (after the death of Captain Doudart de la Grée) of the memorable expedition xxivup the Mekong to Yun-nan; to the Rev. Dr. Caldwell, of the S. P. G. Mission in Tinnevelly, for copious and valuable notes on Southern India; to my friends Colonel Robert Maclagan, R.E., Sir Arthur Phayre, and Colonel Henry Man, for very valuable notes and other aid; to Professor A. Schiefner, of St. Petersburg, for his courteous communication of very interesting illustrations not otherwise accessible; to Major-General Alexander Cunningham, of my own corps, for several valuable letters; to my friends Dr. Thomas Oldham, Director of the Geological Survey of India, Mr. Daniel Hanbury, F.R.S., Mr. Edward Thomas, Mr. James Fergusson, F.R.S., Sir Bartle Frere, and Dr. Hugh Cleghorn, for constant interest in the work and readiness to assist its progress; to Mr. A. Wylie, the learned Agent of the B. and F. Bible Society at Shang-hai, for valuable help; to the Hon. G. P. Marsh, U.S. Minister at the Court of Italy, for untiring kindness in the communication of his ample stores of knowledge, and of books. I have also to express my obligations to Comm. Nicolò Barozzi, Director of the City Museum at Venice, and to Professor A. S. Minotto, of the same city; to Professor Arminius Vámbéry, the eminent traveller; to Professor Flückiger of Bern; to the Rev. H. A. Jaeschke, of the Moravian Mission in British Tibet; to Colonel Lewis Pelly, British Resident in the Persian Gulf; to Pandit Manphul, C.S.I. (for a most interesting communication on Badakhshan); to my brother officer, Major T. G. Montgomerie, R.E., of the Indian Trigonometrical Survey; to Commendatore Negri the indefatigable President of the Italian Geographical Society; to Dr. Zotenberg, of the Great Paris Library, and to M. Ch. Maunoir, Secretary-General of the Société de Géographie; to Professor Henry xxvGiglioli, at Florence; to my old friend Major-General Albert Fytche, Chief Commissioner of British Burma; to Dr. Rost and Dr. Forbes-Watson, of the India Office Library and Museum; to Mr. R. H. Major, and Mr. R. K. Douglas, of the British Museum; to Mr. N. B. Dennys, of Hong-kong; and to Mr. C. Gardner, of the Consular Establishment in China. There are not a few others to whom my thanks are equally due; but it is feared that the number of names already mentioned may seem ridiculous, compared with the result, to those who do not appreciate from how many quarters the facts needful for a work which in its course intersects so many fields required to be collected, one by one. I must not, however, omit acknowledgments to the present Earl of Derby for his courteous permission, when at the head of the Foreign Office, to inspect Mr. Abbott’s valuable unpublished Report upon some of the Interior Provinces of Persia; and to Mr. T. T. Cooper, one of the most adventurous travellers of modern times, for leave to quote some passages from his unpublished diary.

Palermo, 31st December, 1870.

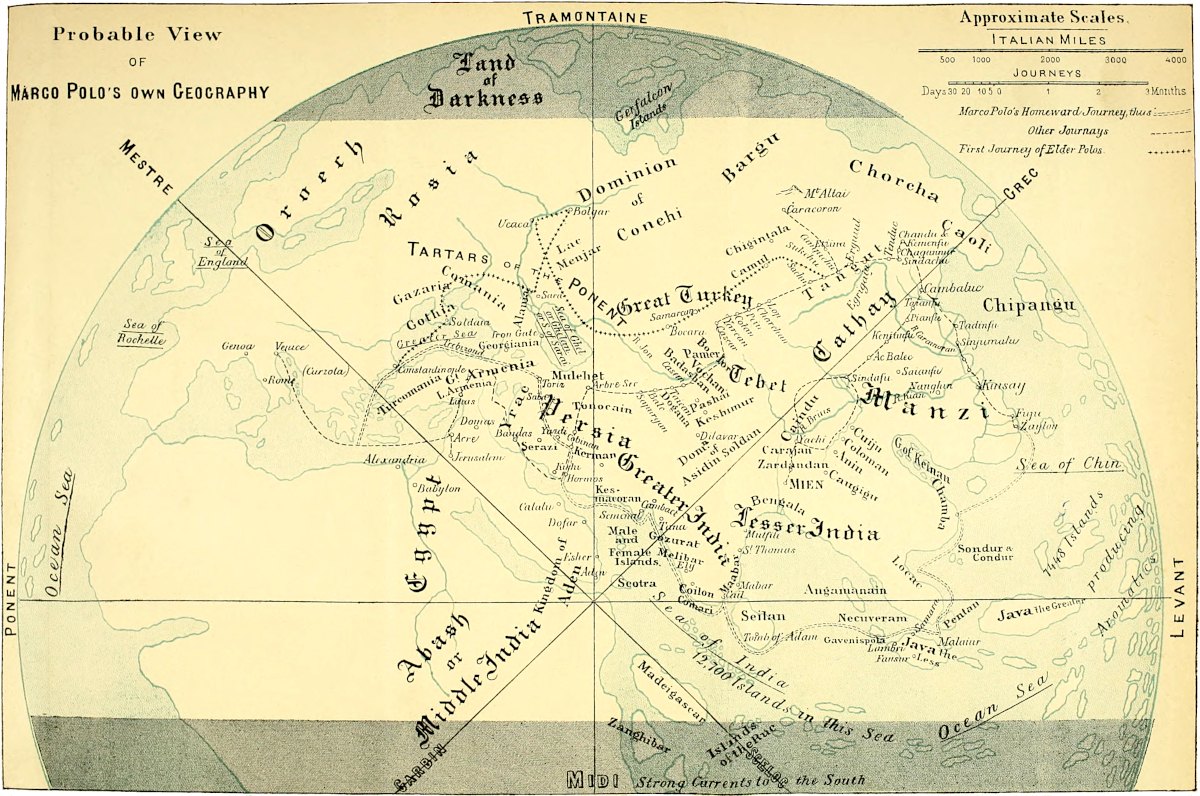

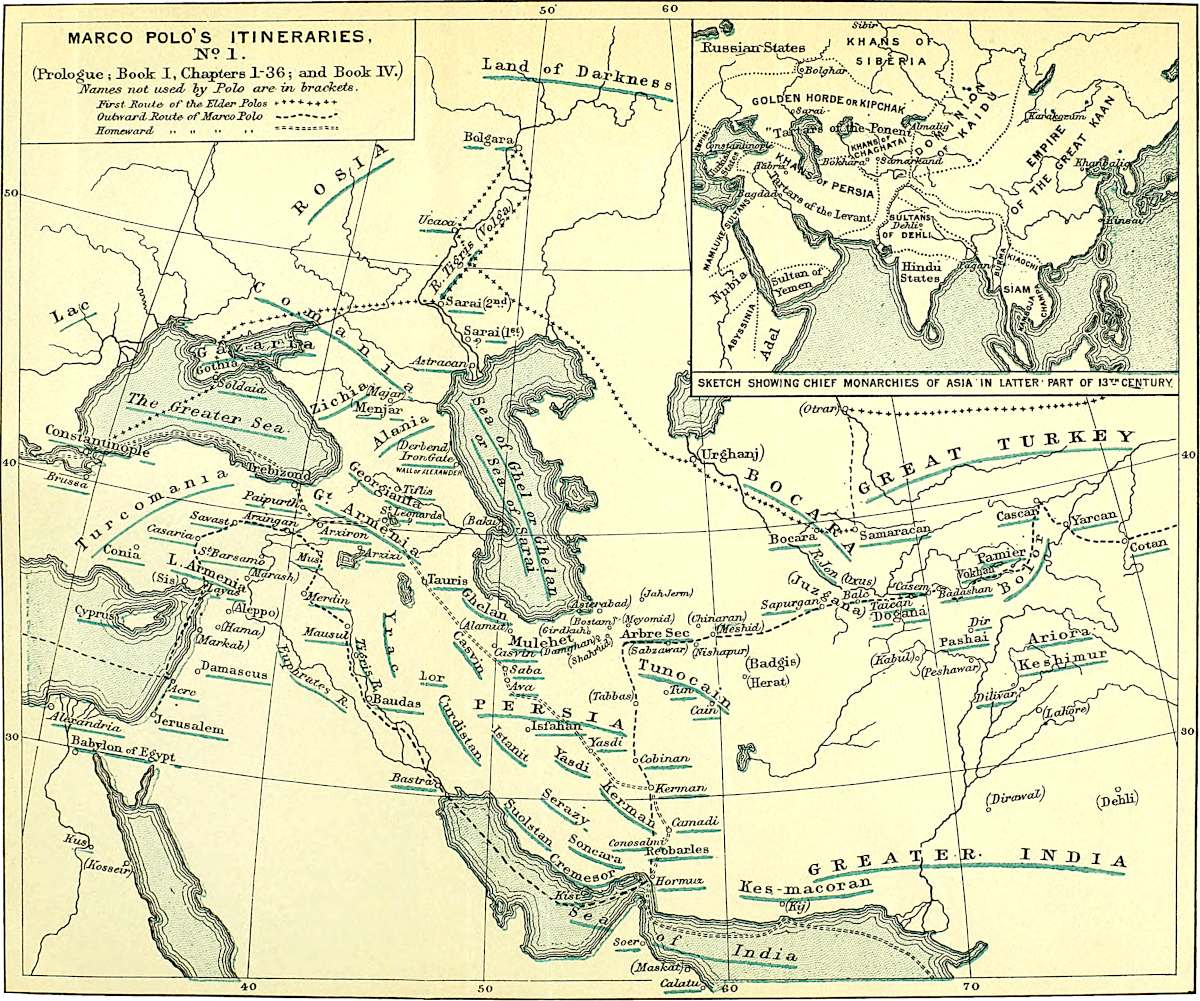

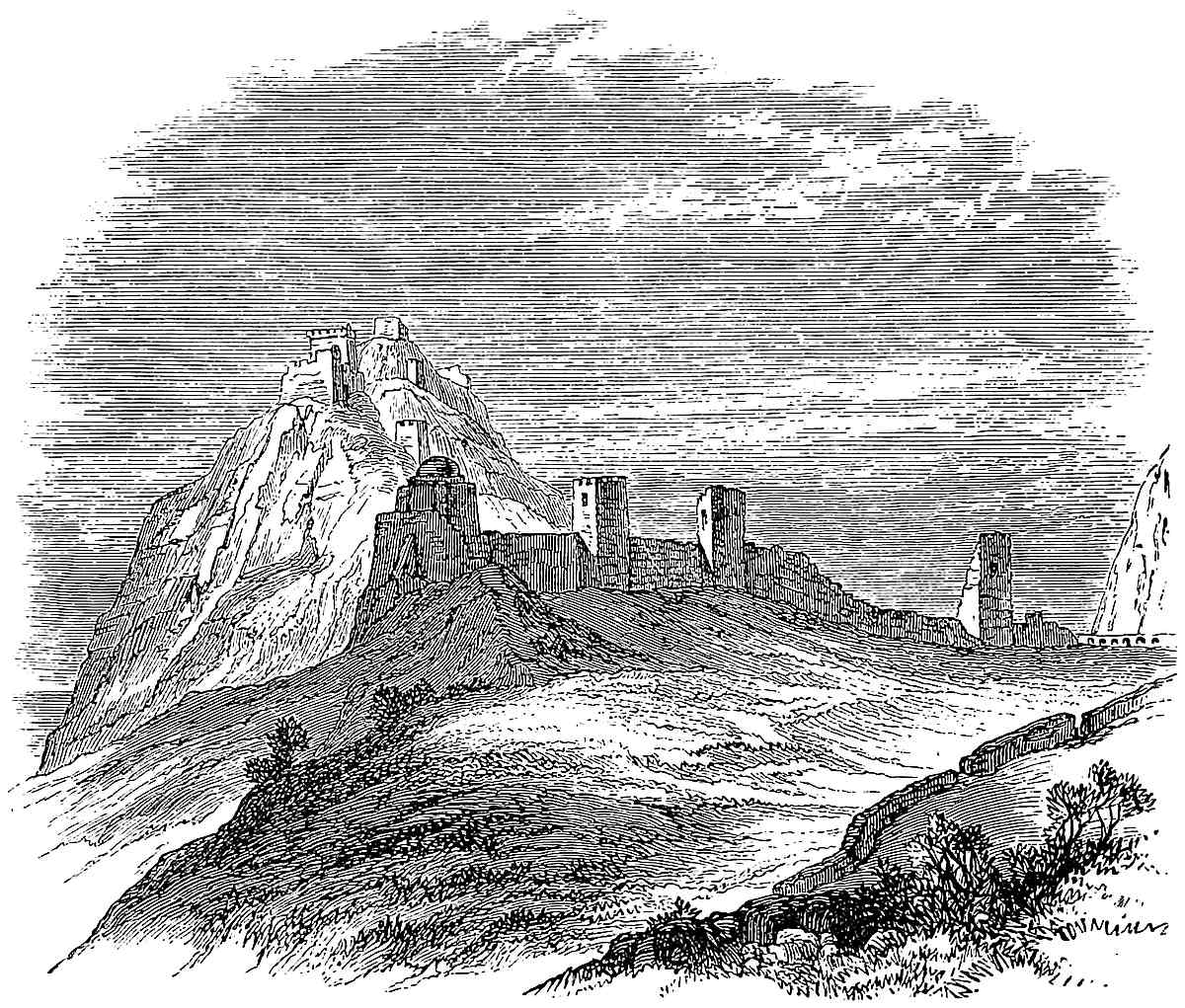

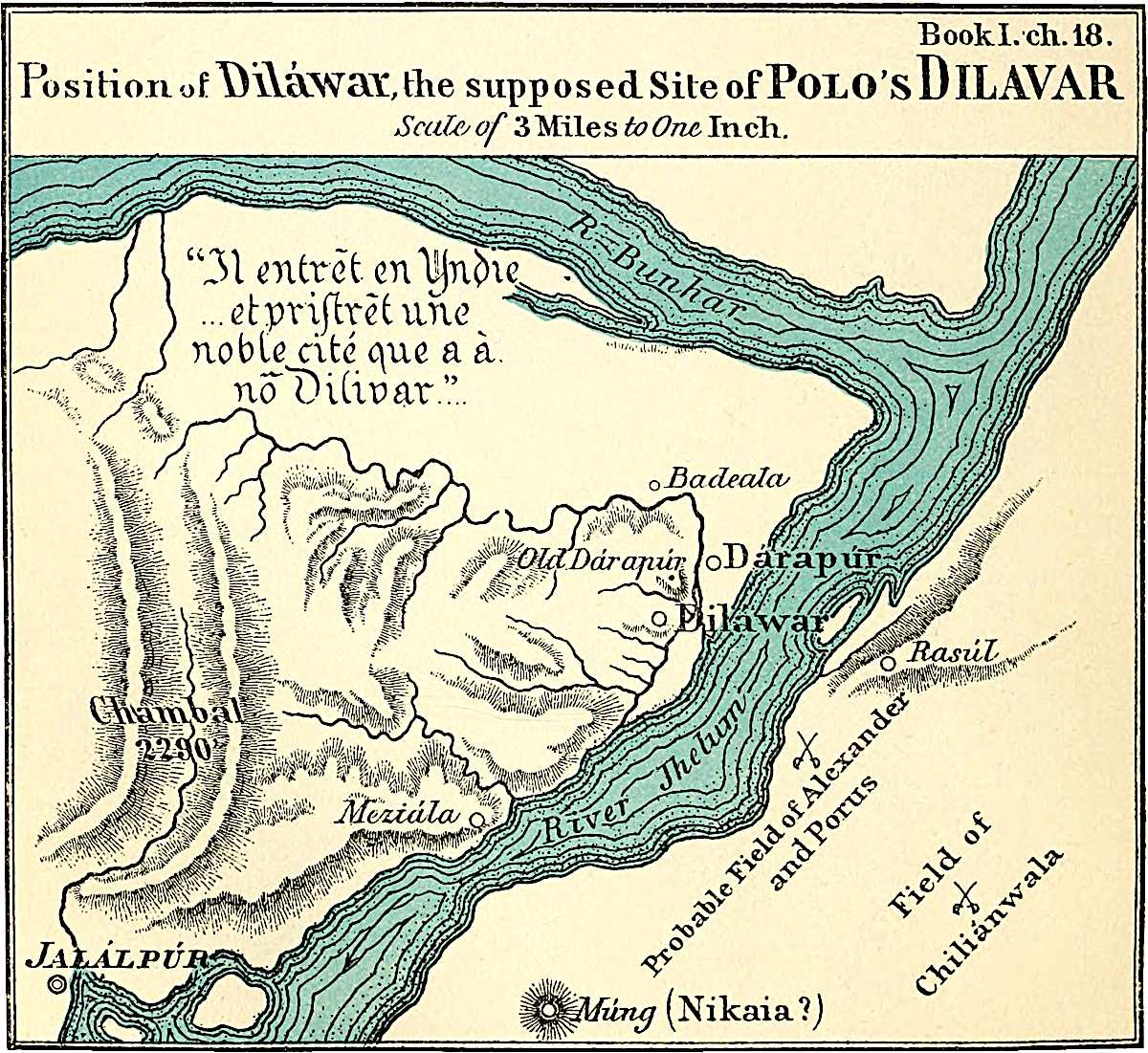

As regards geographical elucidations, I may point to the explanation of the name Gheluchelan (i. p. 58), to the discussion of the route from Kerman to Hormuz, and the identification of the sites of Old Hormuz, of Cobinan and Dogana, the establishment of the position and continued existence of Keshm, the note on Pein and Charchan, on Gog and Magog, on the geography of the route from Sindafu to Carajan, on Anin and Coloman, on Mutafili, Cail, and Ely.

As regards historical illustrations, I would cite the notes regarding the Queens Bolgana and Cocachin, on the Karaunahs, etc., on the title of King of Bengal applied to the K. of Burma, and those bearing upon the Malay and Abyssinian chronologies.

In the interpretation of outlandish phrases, I may refer to the notes on Ondanique, Nono, Barguerlac, Argon, Sensin, Keshican, Toscaol, Bularguchi, Gat-paul, etc.

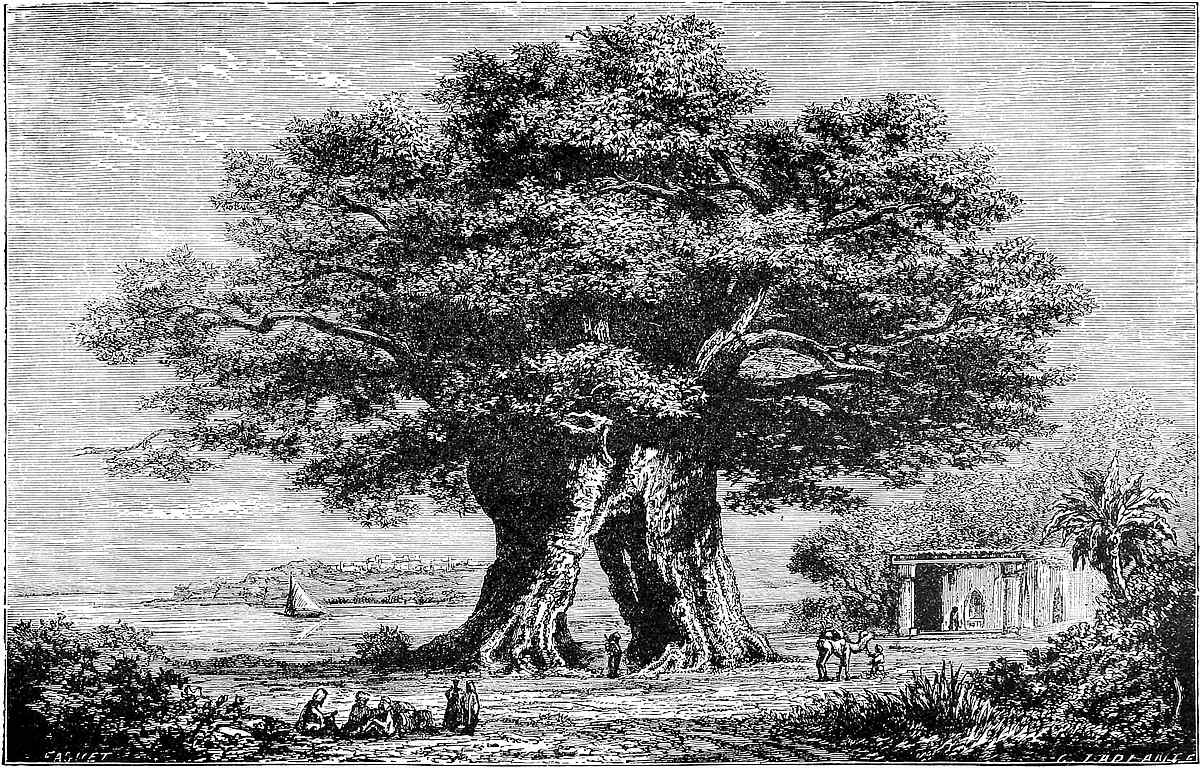

Among miscellaneous elucidations, to the disquisition on the Arbre Sol or Sec in vol. i., and to that on Mediæval Military Engines in vol. ii.

In a variety of cases it has been necessary to refer to Eastern languages for pertinent elucidations or etymologies. The editor would, however, be sorry to fall under the ban of the mediæval adage:

and may as well reprint here what was written in the Preface to Cathay:

“I am painfully sensible that in regard to many subjects dealt with in the following pages, nothing can make up for the want of genuine Oriental learning. A fair familiarity with Hindustani for many years, and some reminiscences of elementary Persian, have been useful in their degree; but it is probable that they may sometimes also have led me astray, as such slender lights are apt to do.”

Henry Yule was the youngest son of Major William Yule, by his first wife, Elizabeth Paterson, and was born at Inveresk, in Midlothian, on 1st May, 1820. He was named after an aunt who, like Miss Ferrier’s immortal heroine, owned a man’s name.

On his father’s side he came of a hardy agricultural stock,[1] improved by a graft from that highly-cultured tree, Rose of Kilravock.[2] Through his mother, a somewhat prosaic person herself, he inherited strains from Huguenot and Highland ancestry. There were recognisable traces of all these elements xxviiiin Henry Yule, and as was well said by one of his oldest friends: “He was one of those curious racial compounds one finds on the east side of Scotland, in whom the hard Teutonic grit is sweetened by the artistic spirit of the more genial Celt.”[3] His father, an officer of the Bengal army (born 1764, died 1839), was a man of cultivated tastes and enlightened mind, a good Persian and Arabic scholar, and possessed of much miscellaneous Oriental learning. During the latter years of his career in India, he served successively as Assistant Resident at the (then independent) courts of Lucknow[4] and Delhi. In the latter office his chief was the noble Ouchterlony. William Yule, together with his younger brother Udny,[5] returned home in 1806. “A recollection of their voyage was that they hailed an outward bound ship, somewhere off the Cape, through the trumpet: ‘What news?’ Answer: ‘The King’s mad, and Humfrey’s beat Mendoza’ (two celebrated prize-fighters and often matched). ‘Nothing more?’ ‘Yes, Bonaparty’s made his Mother King of Holland!’

“Before his retirement, William Yule was offered the Lieut.-Governorship of St. Helena. Two of the detailed privileges of the office were residence at Longwood (afterwards the house of Napoleon), and the use of a certain number of the Company’s slaves. Major Yule, who was a strong supporter of the anti-slavery cause till its triumph in 1834, often recalled both of these offers with amusement.”[6]

xxix

William Yule was a man of generous chivalrous nature, who took large views of life, apt to be unfairly stigmatised as Radical in the narrow Tory reaction that prevailed in Scotland during the early years of the 19th century.[7] Devoid of literary ambition, he wrote much for his private pleasure, and his knowledge and library (rich in Persian and Arabic MSS.) were always placed freely at the service of his friends and correspondents, some of whom, such as Major C. Stewart and Mr. William Erskine, were more given to publication than himself. He never travelled without a little 8vo MS. of Hafiz, which often lay under his pillow. Major Yule’s only printed work was a lithographed edition of the Apothegms of ’Ali, the son of Abu Talib, in the Arabic, with an old Persian version and an English translation interpolated by himself. “This was privately issued in 1832, when the Duchesse d’Angoulême was living at Edinburgh, and the little work was inscribed to her, with whom an accident of neighbourhood and her kindness to the Major’s youngest child had brought him into relations of goodwill.”[8]

Henry Yule’s childhood was mainly spent at Inveresk. He used to say that his earliest recollection was sitting with the little cousin, who long after became his wife, on the doorstep of her father’s house in George Street, Edinburgh (now the Northern Club), listening to the performance of a passing piper. There was another episode which he recalled with humorous satisfaction. Fired by his father’s tales of the jungle, Yule (then about six years old) proceeded to improvise an elephant pit in the back garden, only too successfully, for soon, with mingled terror and delight, he saw his uncle John[9] fall headlong into the snare. He lost his mother before he was eight, and almost his only remembrance of her was the circumstance of her having given him a little lantern to light him home on winter nights from his first school. On Sundays it was the Major’s custom xxxto lend his children, as a picture-book, a folio Arabic translation of the Four Gospels, printed at Rome in 1591, which contained excellent illustrations from Italian originals.[10] Of the pictures in this volume Yule seems never to have tired. The last page bore a MS. note in Latin to the effect that the volume had been read in the Chaldæan Desert by Georgius Strachanus, Milnensis, Scotus, who long remained unidentified, not to say mythical, in Yule’s mind. But George Strachan never passed from his memory, and having ultimately run him to earth, Yule, sixty years later, published the results in an interesting article.[11]

Two or three years after his wife’s death, Major Yule removed to Edinburgh, and established himself in Regent’s Terrace, on the face of the Calton Hill.[12] This continued to be Yule’s home until his father’s death, shortly before he went to India. “Here he learned to love the wide scenes of sea and land spread out around that hill—a love he never lost, at home or far away. And long years after, with beautiful Sicilian hills before him and a lovely sea, he writes words of fond recollection of the bleak Fife hills, and the grey Firth of Forth.”[13]

Yule now followed his elder brother, Robert, to the famous High School, and in the summer holidays the two made expeditions xxxito the West Highlands, the Lakes of Cumberland, and elsewhere. Major Yule chose his boys to have every reasonable indulgence and advantage, and when the British Association, in 1834, held its first Edinburgh meeting, Henry received a member’s ticket. So, too, when the passing of the Reform Bill was celebrated in the same year by a great banquet, at which Lord Grey and other prominent politicians were present, Henry was sent to the dinner, probably the youngest guest there.[14]

At this time the intention was that Henry should go to Cambridge (where his name was, indeed, entered), and after taking his degree study for the Bar. With this view he was, in 1833, sent to Waith, near Ripon, to be coached by the Rev. H. P. Hamilton, author of a well-known treatise, On Conic Sections, and afterwards Dean of Salisbury. At his tutor’s hospitable rectory Yule met many notabilities of the day. One of them was Professor Sedgwick.

There was rumoured at this time the discovery of the first known (?) fossil monkey, but its tail was missing. “Depend upon it, Daniel O’Conell’s got hold of it!” said ‘Adam’ briskly.[15] Yule was very happy with Mr. Hamilton and his kind wife, but on his tutor’s removal to Cambridge other arrangements became necessary, and in 1835 he was transferred to the care of the Rev. James Challis, rector of Papworth St. Everard, a place which “had little to recommend it except a dulness which made reading almost a necessity.”[16] Mr. Challis had at this time two other resident pupils, who both, in most diverse ways, attained distinction in the Church. These were John Mason Neale, the future eminent ecclesiologist and founder of the devoted Anglican Sisterhood of St. Margaret, and Harvey Goodwin, long afterwards the studious and large-minded Bishop of Carlisle. With the latter, Yule remained on terms of cordial friendship to the end of his life. Looking back through more than fifty years to these boyish days, Bishop Goodwin wrote that Yule then “showed much more liking for Greek plays and for German than for mathematics, though he had considerable geometrical xxxiiingenuity.”[17] On one occasion, having solved a problem that puzzled Goodwin, Yule thus discriminated the attainments of the three pupils: “The difference between you and me is this: You like it and can’t do it; I don’t like it and can do it. Neale neither likes it nor can do it.” Not bad criticism for a boy of fifteen.[18]

On Mr. Challis being appointed Plumerian Professor at Cambridge, in the spring of 1836, Yule had to leave him, owing to want of room at the Observatory, and he became for a time, a most dreary time, he said, a student at University College, London.

By this time Yule had made up his mind that not London and the Law, but India and the Army should be his choice, and accordingly in Feb. 1837 he joined the East India Company’s Military College at Addiscombe. From Addiscombe he passed out, in December 1838, at the head of the cadets of his term (taking the prize sword[19]), and having been duly appointed to the Bengal Engineers, proceeded early in 1839 to the Headquarters of the Royal Engineers at Chatham, where, according to custom, he was enrolled as a “local and temporary Ensign.” For such was then the invidious designation at Chatham of the young Engineer officers of the Indian army, who ranked as full lieutenants in their own Service, from the time of leaving Addiscombe.[20] Yule once audaciously tackled the formidable Pasley on this very grievance. The venerable Director, after a minute’s pondering, replied: “Well, I don’t remember what the reason was, but I have no doubt (staccato) it ... was ... a very ... good reason.”[21]

“When Yule appeared among us at Chatham in 1839,” said his friend Collinson, “he at once took a prominent place in our little Society by his slightly advanced age [he was then 18½], but more by his strong character.... His earlier education ... gave him a better classical knowledge than most of us possessed; xxxiiithen he had the reserve and self-possession characteristic of his race; but though he took small part in the games and other recreations of our time, his knowledge, his native humour, and his good comradeship, and especially his strong sense of right and wrong, made him both admired and respected.... Yule was not a scientific engineer, though he had a good general knowledge of the different branches of his profession; his natural capacity lay rather in varied knowledge, combined with a strong understanding and an excellent memory, and also a peculiar power as a draughtsman, which proved of great value in after life.... Those were nearly the last days of the old régime, of the orthodox double sap and cylindrical pontoons, when Pasley’s genius had been leading to new ideas, and when Lintorn Simmons’ power, G. Leach’s energy, W. Jervois’ skill, and R. Tylden’s talent were developing under the wise example of Henry Harness.”[22]

In the Royal Engineer mess of those days (the present anteroom), the portrait of Henry Yule now faces that of his first chief, Sir Henry Harness. General Collinson said that the pictures appeared to eye each other as if the subjects were continuing one of those friendly disputes in which they so often engaged.[23]

It was in this room that Yule, Becher, Collinson, and other young R.E.’s, profiting by the temporary absence of the austere Colonel Pasley, acted some plays, including Pizarro. Yule bore the humble part of one of the Peruvian Mob in this performance, of which he has left a droll account.[24]

On the completion of his year at Chatham, Yule prepared to sail for India, but first went to take leave of his relative, General White. An accident prolonged his stay, and before he left he had proposed to and been refused by his cousin Annie. This occurrence, his first check, seems to have cast rather a gloom over his start for India. He went by the then newly-opened Overland Route, visiting Portugal, stopping at Gibraltar to see xxxivhis cousin, Major (afterwards General) Patrick Yule, R.E.[25] He was under orders “to stop at Aden (then recently acquired), to report on the water supply, and to deliver a set of meteorological and magnetic instruments for starting an observatory there. The overland journey then really meant so; tramping across the desert to Suez with camels and Arabs, a proceeding not conducive to the preservation of delicate instruments; and on arriving at Aden he found that the intended observer was dead, the observatory not commenced, and the instruments all broken. There was thus nothing left for him but to go on at once” to Calcutta,[26] where he arrived at the end of 1840.

His first service lay in the then wild Khasia Hills, whither he was detached for the purpose of devising means for the transport of the local coal to the plains. In spite of the depressing character of the climate (Cherrapunjee boasts the highest rainfall on record), Yule thoroughly enjoyed himself, and always looked back with special pleasure on the time he spent here. He was unsuccessful in the object of his mission, the obstacles to cheap transport offered by the dense forests and mighty precipices proving insurmountable, but he gathered a wealth of interesting observations on the country and people, a very primitive Mongolian race, which he subsequently embodied in two excellent and most interesting papers (the first he ever published).[27]

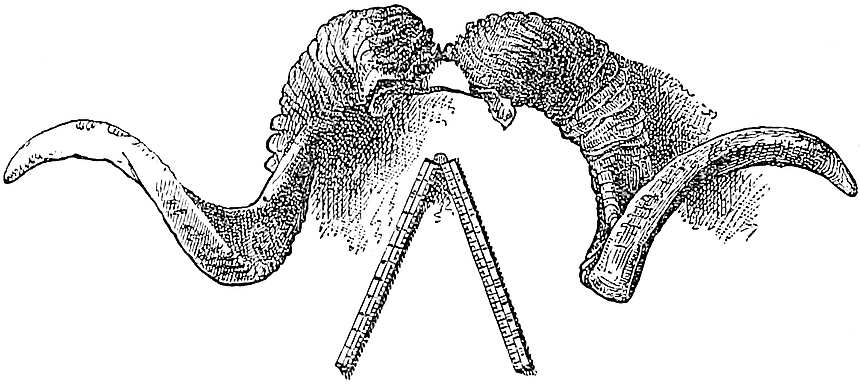

In the following year, 1842, Yule was transferred to the xxxvirrigation canals of the north-west with head-quarters at Kurnaul. Here he had for chief Captain (afterwards General Sir William) Baker, who became his dearest and most steadfast friend. Early in 1843 Yule had his first experience of field service. The death without heir of the Khytul Rajah, followed by the refusal of his family to surrender the place to the native troops sent to receive it, obliged Government to send a larger force against it, and the canal officers were ordered to join this. Yule was detailed to serve under Captain Robert Napier (afterwards F.-M. Lord Napier of Magdala). Their immediate duty was to mark out the route for a night march of the troops, barring access to all side roads, and neither officer having then had any experience of war, they performed the duty “with all the elaborate care of novices.” Suddenly there was an alarm, a light detected, and a night attack awaited, when the danger resolved itself into Clerk Sahib’s khansamah with welcome hot coffee![28] Their hopes were disappointed, there was no fighting, and the Fort of Khytul was found deserted by the enemy. It “was a strange scene of confusion—all the paraphernalia and accumulation of odds and ends of a wealthy native family lying about and inviting loot. I remember one beautiful crutch-stick of ebony with two rams’ heads in jade. I took it and sent it in to the political authority, intending to buy it when sold. There was a sale, but my stick never appeared. Somebody had a more developed taste in jade.... Amid the general rummage that was going on, an officer of British Infantry had been put over a part of the palace supposed to contain treasure, and they—officers and all—were helping themselves. Henry Lawrence was one of the politicals under George Clerk. When the news of this affair came to him I was present. It was in a white marble loggia in the palace, where was a white marble chair or throne on a basement. Lawrence was sitting on this throne in great excitement. He wore an Afghan choga, a sort of dressing-gown garment, and this, and his thin locks, and thin beard were xxxvistreaming in the wind. He always dwells in my memory as a sort of pythoness on her tripod under the afflatus.”[29]

During his Indian service, Yule had renewed and continued by letters his suit to Miss White, and persistency prevailing at last, he soon after the conclusion of the Khytul affair applied for leave to go home to be married. He sailed from Bombay in May, 1843, and in September of the same year was married, at Bath, to the gifted and large-hearted woman who, to the end, remained the strongest and happiest influence in his life.[30]

Yule sailed for India with his wife in November 1843. The next two years were employed chiefly in irrigation work, and do not call for special note. They were very happy years, except in the one circumstance that the climate having seriously affected his wife’s health, and she having been brought to death’s door, partly by illness, but still more by the drastic medical treatment of those days, she was imperatively ordered back to England by the doctors, who forbade her return to India.

Having seen her on board ship, Yule returned to duty on the canals. The close of that year, December, 1845, brought some variety to his work, as the outbreak of the first Sikh War called nearly all the canal officers into the field. “They went up to the front by long marches, passing through no stations, and quite unable to obtain any news of what had occurred, though on the 21st December the guns of Ferozshah were distinctly heard in their camp at Pehoa, at a distance of 115 miles south-east from the field, and some days later they came successively on the fields of Moodkee and of Ferozshah itself, with all the recent traces of battle. When the party of irrigation officers reached head-quarters, the arrangements for attacking the Sikh army in its entrenchments at Sobraon were beginning (though suspended till weeks later for the arrival of the tardy siege guns), and the opposed forces were lying in sight of each other.”[31]

Yule’s share in this campaign was limited to the sufficiently arduous task of bridging the Sutlej for the advance of the British army. It is characteristic of the man that for this xxxviireason he always abstained from wearing his medal for the Sutlej campaign.

His elder brother, Robert Yule, then in the 16th Lancers, took part in that magnificent charge of his regiment at the battle of Aliwal (Jan. 28, 1846) which the Great Duke is said to have pronounced unsurpassed in history. From particulars gleaned from his brother and others present in the action, Henry Yule prepared a spirited sketch of the episode, which was afterwards published as a coloured lithograph by M‘Lean (Haymarket).

At the close of the war, Yule succeeded his friend Strachey as Executive Engineer of the northern division of the Ganges Canal, with his head-quarters at Roorkee, “the division which, being nearest the hills and crossed by intermittent torrents of great breadth and great volume when in flood, includes the most important and interesting engineering works.”[32]

At Roorkee were the extensive engineering workshops connected with the canal. Yule soon became so accustomed to the din as to be undisturbed by the noise, but the unpunctuality and carelessness of the native workmen sorely tried his patience, of which Nature had endowed him with but a small reserve. Vexed with himself for letting temper so often get the better of him, Yule’s conscientious mind devised a characteristic remedy. Each time that he lost his temper, he transferred a fine of two rupees (then about five shillings) from his right to his left pocket. When about to leave Roorkee, he devoted this accumulation of self-imposed fines to the erection of a sun-dial, to teach the natives the value of time. The late Sir James Caird, who told this legend of Roorkee as he heard it there in 1880, used to add, with a humorous twinkle of his kindly eyes, “It was a very handsome dial.”[33]

From September, 1845, to March, 1847, Yule was much occupied intermittently, in addition to his professional work, by service on a Committee appointed by Government “to investigate the causes of the unhealthiness which has existed at Kurnal, and other portions of the country along the line of the Delhi Canal,” and further, to report “whether an injurious xxxviiieffect on the health of the people of the Doab is, or is not, likely to be produced by the contemplated Ganges Canal.”

“A very elaborate investigation was made by the Committee, directed principally to ascertaining what relation subsisted between certain physical conditions of the different districts, and the liability of their inhabitants to miasmatic fevers.” The principal conclusion of the Committee was, “that in the extensive epidemic of 1843, when Kurnaul suffered so seriously ... the greater part of the evils observed had not been the necessary and unavoidable results of canal irrigation, but were due to interference with the natural drainage of the country, to the saturation of stiff and retentive soils, and to natural disadvantages of site, enhanced by excess of moisture. As regarded the Ganges Canal, they were of opinion that, with due attention to drainage, improvement rather than injury to the general health might be expected to follow the introduction of canal irrigation.”[34] In an unpublished note written about 1889, Yule records his ultimate opinion as follows: “At this day, and after the large experience afforded by the Ganges Canal, I feel sure that a verdict so favourable to the sanitary results of canal irrigation would not be given.” Still the fact remains that the Ganges Canal has been the source of unspeakable blessings to an immense population.

The Second Sikh War saw Yule again with the army in the field, and on 13th Jan. 1849, he was present at the dismal ‘Victory’ of Chillianwallah, of which his most vivid recollection seemed to be the sudden apparition of Henry Lawrence, fresh from London, but still clad in the legendary Afghan cloak.

On the conclusion of the Punjab campaign, Yule, whose health had suffered, took furlough and went home to his wife. For the next three years they resided chiefly in Scotland, though paying occasional visits to the Continent, and about 1850 Yule bought a house in Edinburgh. There he wrote “The African Squadron vindicated” (a pamphlet which was afterwards re-published in French), translated Schiller’s Kampf mit dem Drachen into English verse, delivered Lectures on Fortification at the, now long defunct, Scottish Naval and Military Academy, wrote on Tibet for his friend Blackwood’s xxxixMagazine, attended the 1850 Edinburgh Meeting of the British Association, wrote his excellent lines, “On the Loss of the Birkenhead,” and commenced his first serious study of Marco Polo (by whose wondrous tale, however, he had already been captivated as a boy in his father’s library—in Marsden’s edition probably). But the most noteworthy literary result of these happy years was that really fascinating volume, entitled Fortification for Officers of the Army and Students of Military History, a work that has remained unique of its kind. This was published by Blackwood in 1851, and seven years later received the honour of (unauthorised) translation into French. Yule also occupied himself a good deal at this time with the practice of photography, a pursuit to which he never after reverted.

In the spring of 1852, Yule made an interesting little semi-professional tour in company with a brother officer, his accomplished friend, Major R. B. Smith. Beginning with Kelso, “the only one of the Teviotdale Abbeys which I had not as yet seen,” they made their way leisurely through the north of England, examining with impartial care abbeys and cathedrals, factories, brick-yards, foundries, timber-yards, docks, and railway works. On this occasion Yule, contrary to his custom, kept a journal, and a few excerpts may be given here, as affording some notion of his casual talk to those who did not know him.

At Berwick-on-Tweed he notes the old ramparts of the town: “These, erected in Elizabeth’s time, are interesting as being, I believe, the only existing sample in England of the bastioned system of the 16th century.... The outline of the works seems perfect enough, though both earth and stone work are in great disrepair. The bastions are large with obtuse angles, square orillons, and double flanks originally casemated, and most of them crowned with cavaliers.” On the way to Durham, “much amused by the discussions of two passengers, one a smooth-spoken, semi-clerical looking person; the other a brusque well-to-do attorney with a Northumbrian burr. Subject, among others, Protection. The Attorney all for ‘cheap bread’— ‘You wouldn’t rob the poor man of his loaf,’ and so forth. ‘You must go with the stgheam, sir, you must go with the stgheam.’ ‘I never did, Mr. Thompson, and I never will,’ said the other in an oily manner, singularly inconsistent with the xlsentiment.” At Durham they dined with a dignitary of the Church, and Yule was roasted by being placed with his back to an enormous fire. “Coals are cheap at Durham,” he notes feelingly, adding, “The party we found as heavy as any Edinburgh one. Smith, indeed, evidently has had little experience of really stupid Edinburgh parties, for he had never met with anything approaching to this before.” (Happy Smith!) But thanks to the kindness and hospitality of the astronomer, Mr. Chevalier, and his gifted daughter, they had a delightful visit to beautiful Durham, and came away full of admiration for the (then newly established) University, and its grand locale. They went on to stay with an uncle by marriage of Yule’s, in Yorkshire. At dinner he was asked by his host to explain Foucault’s pendulum experiment. “I endeavoured to explain it somewhat, I hope, to the satisfaction of his doubts, but not at all to that of Mr. G. M., who most resolutely declined to take in any elucidation, coming at last to the conclusion that he entirely differed with me as to what North meant, and that it was useless to argue until we could agree about that!” They went next to Leeds, to visit Kirkstall Abbey, “a mediæval fossil, curiously embedded among the squalid brickwork and chimney stalks of a manufacturing suburb. Having established ourselves at the hotel, we went to deliver a letter to Mr. Hope, the official assignee, a very handsome, aristocratic-looking gentleman, who seemed as much out of place at Leeds as the Abbey.” At Leeds they visited the flax mills of Messrs. Marshall, “a firm noted for the conscientious care they take of their workpeople.... We mounted on the roof of the building, which is covered with grass, and formerly was actually grazed by a few sheep, until the repeated inconvenience of their tumbling through the glass domes put a stop to this.” They next visited some tile and brickworks on land belonging to a friend. “The owner of the tile works, a well-to-do burgher, and the apparent model of a West Riding Radical, received us in rather a dubious way: ‘There are a many people has come and brought introductions, and looked at all my works, and then gone and set up for themselves close by. Now des you mean to say that you be really come all the way from Bengul?’ ‘Yes, indeed we have, and we are going all the way back again, though we didn’t exactly come from there to look at your brickworks.’ ‘Then you’re not in xlithe brick-making line, are you?’ ‘Why we’ve had a good deal to do with making bricks, and may have again; but we’ll engage that if we set up for ourselves, it shall be ten thousand miles from you.’ This seemed in some degree to set his mind at rest....”

“A dismal day, with occasional showers, prevented our seeing Sheffield to advantage. On the whole, however, it is more cheerful and has more of a country-town look than Leeds—a place utterly without beauty of aspect. At Leeds you have vast barrack-like factories, with their usual suburbs of squalid rows of brick cottages, and everywhere the tall spiracles of the steam, which seems the pervading power of the place. Everything there is machinery—the machine is the intelligent agent, it would seem, the man its slave, standing by to tend it and pick up a broken thread now and then. At Sheffield ... you might go through most of the streets without knowing anything of the kind was going on. And steam here, instead of being a ruler, is a drudge, turning a grindstone or rolling out a bar of steel, but all the accuracy and skill of hand is the Man’s. And consequently there was, we thought, a healthier aspect about the men engaged. None of the Rodgers remain who founded the firm in my father’s time. I saw some pairs of his scissors in the show-room still kept under the name of Persian scissors.”[35]

From Sheffield Yule and his friend proceeded to Boston, “where there is the most exquisite church tower I have ever seen,” and thence to Lincoln, Peterborough, and Ely, ending their tour at Cambridge, where Yule spent a few delightful days.

In the autumn the great Duke of Wellington died, and Yule witnessed the historic pageant of his funeral. His furlough was now nearly expired, and early in December he again embarked for India, leaving his wife and only child, of a few xliiweeks old, behind him. Some verses dated “Christmas Day near the Equator,” show how much he felt the separation.

Shortly after his return to Bengal, Yule received orders to proceed to Aracan, and to examine and report upon the passes between Aracan and Burma, as also to improve communications and select suitable sites for fortified posts to hold the same. These orders came to Yule quite unexpectedly late one Saturday evening, but he completed all preparations and started at daybreak on the following Monday, 24th Jan. 1853.

From Calcutta to Khyook Phyoo, Yule proceeded by steamer, and thence up the river in the Tickler gunboat to Krenggyuen. “Our course lay through a wilderness of wooded islands (50 to 200 feet high) and bays, sailing when we could, anchoring when neither wind nor tide served ... slow progress up the river. More and more like the creeks and lagoons of the Niger or a Guiana river rather than anything I looked for in India. The densest tree jungle covers the shore down into the water. For miles no sign of human habitation, but now and then at rare intervals one sees a patch of hillside rudely cleared, with the bare stems of the burnt trees still standing.... Sometimes, too, a dark tunnel-like creek runs back beneath the thick vault of jungle, and from it silently steals out a slim canoe, manned by two or three wild-looking Mugs or Kyens (people of the Hills), driving it rapidly along with their short paddles held vertically, exactly like those of the Red men on the American rivers.”

At the military post of Bokhyong, near Krenggyuen, he notes (5th Feb.) that “Captain Munro, the adjutant, can scarcely believe that I was present at the Duke of Wellington’s funeral, of which he read but a few days ago in the newspapers, and here am I, one of the spectators, a guest in this wild spot among the mountains—2½ months since I left England.”

Yule’s journal of his arduous wanderings in these border wilds is full of interest, but want of space forbids further quotation. From a note on the fly-leaf it appears that from the time of quitting the gun-boat at Krenggyuen to his arrival at Toungoop he covered about 240 miles on foot, and that under immense difficulties, even as to food. He commemorated his tribulations in some cheery humorous verse, but ultimately fell seriously ill of the local fever, aided doubtless by previous exposure and privation. His servants successively fell ill, xliiisome died and others had to be sent back, food supplies failed, and the route through those dense forests was uncertain; yet under all difficulties he seems never to have grumbled or lost heart. And when things were nearly at the worst, Yule restored the spirits of his local escort by improvising a wappenshaw, with a Sheffield gardener’s knife, which he happened to have with him, for prize! When at last Yule emerged from the wilds and on 25th March marched into Prome, he was taken for his own ghost! “Found Fraser (of the Engineers) in a rambling phoongyee house, just under the great gilt pagoda. I went up to him announcing myself, and his astonishment was so great that he would scarcely shake hands!” It was on this occasion at Prome that Yule first met his future chief Captain Phayre—“a very young-looking man—very cordial,” a description no less applicable to General Sir Arthur Phayre at the age of seventy!

After some further wanderings, Yule embarked at Sandong, and returned by water, touching at Kyook Phyoo and Akyab, to Calcutta, which he reached on 1st May—his birthday.

The next four months were spent in hard work at Calcutta. In August, Yule received orders to proceed to Singapore, and embarked on the 29th. His duty was to report on the defences of the Straits Settlements, with a view to their improvement. Yule’s recommendations were sanctioned by Government, but his journal bears witness to the prevalence then, as since, of the penny-wise-pound-foolish system in our administration. On all sides he was met by difficulties in obtaining sites for batteries, etc., for which heavy compensation was demanded, when by the exercise of reasonable foresight, the same might have been secured earlier at a nominal price.

Yule’s journal contains a very bright and pleasing picture of Singapore, where he found that the majority of the European population “were evidently, from their tongues, from benorth the Tweed, a circumstance which seems to be true of four-fifths of the Singaporeans. Indeed, if I taught geography, I should be inclined to class Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee, and Singapore together as the four chief towns of Scotland.”

Work on the defences kept Yule in Singapore and its neighbourhood until the end of November, when he embarked for Bengal. On his return to Calcutta, Yule was appointed xlivDeputy Consulting Engineer for Railways at Head-quarters. In this post he had for chief his old friend Baker, who had in 1851 been appointed by the Governor-General, Lord Dalhousie, Consulting Engineer for Railways to Government. The office owed its existence to the recently initiated great experiment of railway construction under Government guarantee.

The subject was new to Yule, “and therefore called for hard and anxious labour. He, however, turned his strong sense and unbiased view to the general question of railway communication in India, with the result that he became a vigorous supporter of the idea of narrow gauge and cheap lines in the parts of that country outside of the main trunk lines of traffic.”[36]

The influence of Yule, and that of his intimate friends and ultimate successors in office, Colonels R. Strachey and Dickens, led to the adoption of the narrow (metre) gauge over a great part of India. Of this matter more will be said further on; it is sufficient at this stage to note that it was occupying Yule’s thoughts, and that he had already taken up the position in this question that he thereafter maintained through life. The office of Consulting Engineer to Government for Railways ultimately developed into the great Department of Public Works.

As related by Yule, whilst Baker “held this appointment, Lord Dalhousie was in the habit of making use of his advice in a great variety of matters connected with Public Works projects and questions, but which had nothing to do with guaranteed railways, there being at that time no officer attached to the Government of India, whose proper duty it was to deal with such questions. In August, 1854, the Government of India sent home to the Court of Directors a despatch and a series of minutes by the Governor-General and his Council, in which the constitution of the Public Works Department as a separate branch of administration, both in the local governments and the government of India itself, was urged on a detailed plan.”

In this communication Lord Dalhousie stated his desire to appoint Major Baker to the projected office of Secretary for the Department of Public Works. In the spring of 1855 these recommendations were carried out by the creation of the Department, xlvwith Baker as Secretary and Yule as Under Secretary for Public Works.

Meanwhile Yule’s services were called to a very different field, but without his vacating his new appointment, which he was allowed to retain. Not long after the conclusion of the second Burmese War, the King of Burma sent a friendly mission to the Governor-General, and in 1855 a return Embassy was despatched to the Court of Ava, under Colonel Arthur Phayre, with Henry Yule as Secretary, an appointment the latter owed as much to Lord Dalhousie’s personal wish as to Phayre’s good-will. The result of this employment was Yule’s first geographical book, a large volume entitled Mission to the Court of Ava in 1855, originally printed in India, but subsequently re-issued in an embellished form at home (see over leaf). To the end of his life, Yule looked back to this “social progress up the Irawady, with its many quaint and pleasant memories, as to a bright and joyous holiday.”[37] It was a delight to him to work under Phayre, whose noble and lovable character he had already learned to appreciate two years before in Pegu. Then, too, Yule has spoken of the intense relief it was to escape from the monotonous scenery and depressing conditions of official life in Bengal (Resort to Simla was the exception, not the rule, in these days!) to the cheerfulness and unconstraint of Burma, with its fine landscapes and merry-hearted population. “It was such a relief to find natives who would laugh at a joke,” he once remarked in the writer’s presence to the lamented E. C. Baber, who replied that he had experienced exactly the same sense of relief in passing from India to China.

Yule’s work on Burma was largely illustrated by his own sketches. One of these represents the King’s reception of the Embassy, and another, the King on his throne. The originals were executed by Yule’s ready pencil, surreptitiously within his cocked hat, during the audience.

From the latter sketch Yule had a small oil-painting executed under his direction by a German artist, then resident in Calcutta, which he gave to Lord Dalhousie.[38]

xlvi

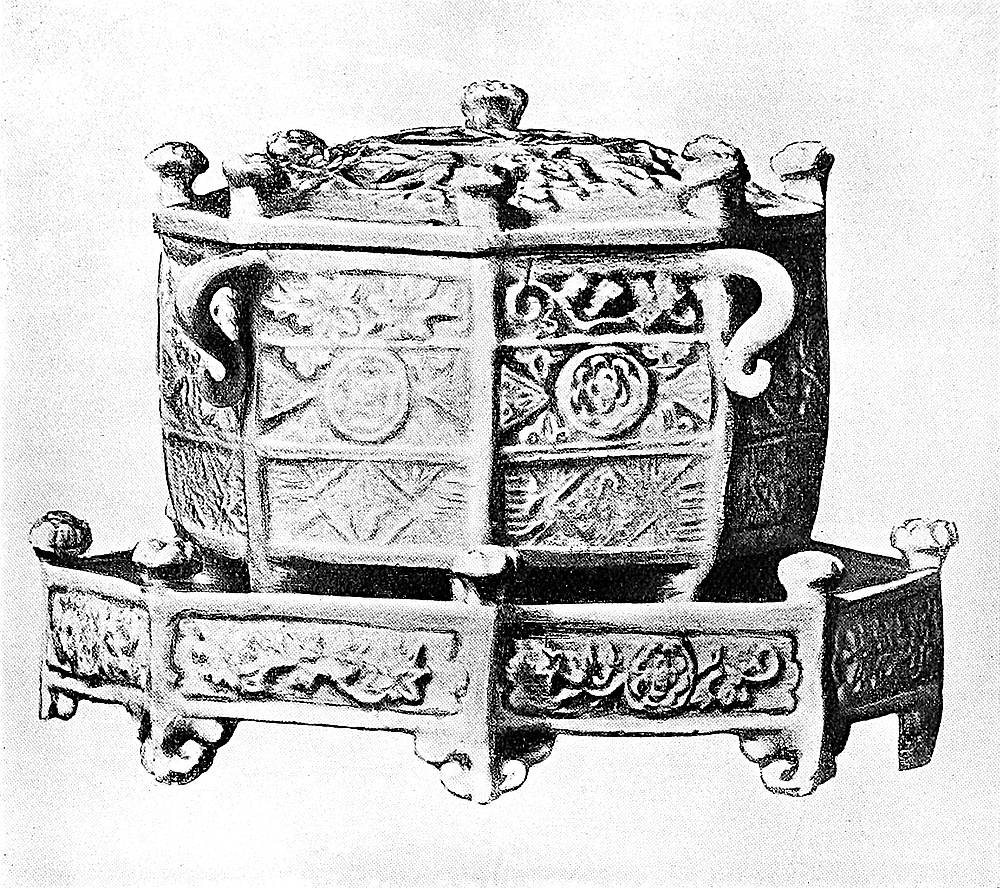

The Government of India marked their approval of the Embassy by an unusual concession. Each of the members of the mission received a souvenir of the expedition. To Yule was given a very beautiful and elaborately chased small bowl, of nearly pure gold, bearing the signs of the Zodiac in relief.[39]

On his return to Calcutta, Yule threw himself heart and soul into the work of his new appointment in the Public Works Department. The nature of his work, the novelty and variety of the projects and problems with which this new branch of the service had to deal, brought Yule into constant, and eventually very intimate association with Lord Dalhousie, whom he accompanied on some of his tours of inspection. The two men thoroughly appreciated each other, and, from first to last, Yule experienced the greatest kindness from Lord Dalhousie. In this intimacy, no doubt the fact of being what French soldiers call pays added something to the warmth of their mutual regard: their forefathers came from the same airt, and neither was unmindful of the circumstance. It is much to be regretted that Yule preserved no sketch of Lord Dalhousie, nor written record of his intercourse with him, but the following lines show some part of what he thought:

“At this time [1849] there appears upon the scene that vigorous and masterful spirit, whose arrival to take up the government of India had been greeted by events so inauspicious. No doubt from the beginning the Governor-General was desirous to let it be understood that although new to India he was, and meant to be, master; ... Lord Dalhousie was by no means averse to frank dissent, provided in the manner it was never forgotten that he was Governor-General. Like his great predecessor Lord Wellesley, he was jealous of all familiarity and resented it.... The general sentiment of those who worked under that ἄναξ ανδρῶν was one of strong and admiring affection ... and we doubt if a Governor-General ever embarked on the Hoogly amid deeper feeling than attended him who, shattered by sorrow and xlviiphysical suffering, but erect and undaunted, quitted Calcutta on the 6th March 1856.”[40]

His successor was Lord Canning, whose confidence in Yule and personal regard for him became as marked as his predecessor’s.

In the autumn of 1856, Yule took leave and came home. Much of his time while in England was occupied with making arrangements for the production of an improved edition of his book on Burma, which so far had been a mere government report. These were completed to his satisfaction, and on the eve of returning to India, he wrote to his publishers[41] that the correction of the proof sheets and general supervision of the publication had been undertaken by his friend the Rev. W. D. Maclagan, formerly an officer of the Madras army (and now Archbishop of York).

Whilst in England, Yule had renewed his intimacy with his old friend Colonel Robert Napier, then also on furlough, a visitor whose kindly sympathetic presence always brought special pleasure also to Yule’s wife and child. One result of this intercourse was that the friends decided to return together to India. Accordingly they sailed from Marseilles towards the end of April, and at Aden were met by the astounding news of the outbreak of the Mutiny.

On his arrival in Calcutta Yule, who retained his appointment of Under Secretary to Government, found his work indefinitely increased. Every available officer was called into the field, and Yule’s principal centre of activity was shifted to the great fortress of Allahabad, forming the principal base of operations against the rebels. Not only had he to strengthen or create defences at Allahabad and elsewhere, but on Yule devolved the principal burden of improvising accommodation for the European troops then pouring into India, which ultimately meant providing for an army of 100,000 men. His task was made the more difficult by the long-standing chronic friction, then and long after, existing between the officers of the Queen’s and the Company’s services. But in a far more important matter he was always fortunate. As he subsequently recorded in a Note for Government: “Through all consciousness of mistakes and shortcomings, xlviiiI have felt that I had the confidence of those whom I served, a feeling which has lightened many a weight.”