'Yes, Cissie, I Understand Now'

Title: Birthright: A Novel

Author: T. S. Stribling

Release date: January 1, 2004 [eBook #10621]

Most recently updated: December 20, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Robert Shimmin and PG Distributed Proofreaders

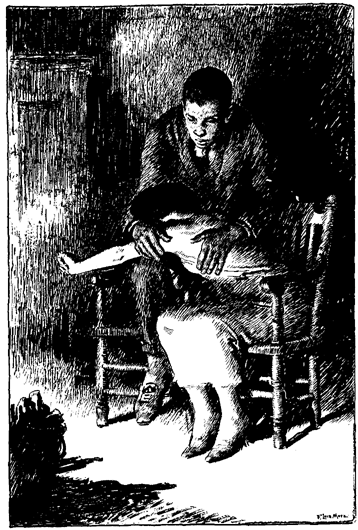

"Yes, Cissie, I understand now"

Peter recognized the white aprons and the swords and spears of the Knights and Ladies of Tabor

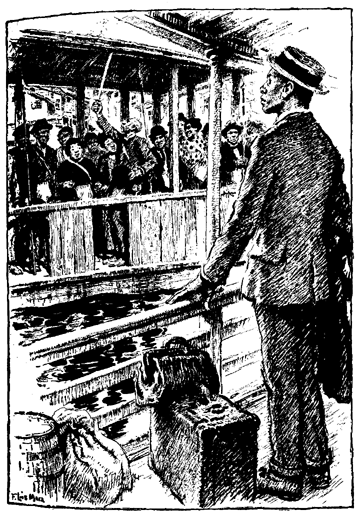

Up and down its street flows the slow negro life of the village

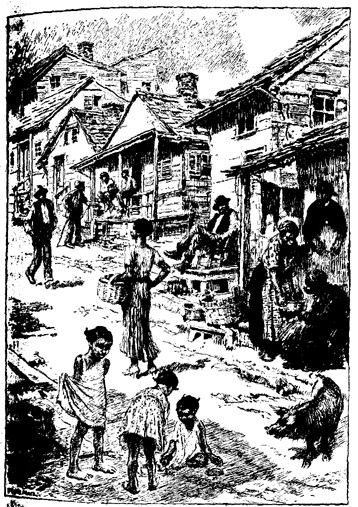

In the Siner cabin old Caroline Siner berated her boy

The old gentleman turned around at last

"You-you mean you want m-me—to go with you, Cissie?" he stammered

"Naw yuh don't," he warned sharply. "You turn roun' an' march on to Niggertown"

The bridal couple embarked for Cairo

At Cairo, Illinois, the Pullman-car conductor asked Peter Siner to take his suitcase and traveling-bag and pass forward into the Jim Crow car. The request came as a sort of surprise to the negro. During Peter Siner's four years in Harvard the segregation of black folk on Southern railroads had become blurred and reminiscent in his mind; now it was fetched back into the sharp distinction of the present instant. With a certain sense of strangeness, Siner picked up his bags, and saw his own form, in the car mirrors, walking down the length of the sleeper. He moved on through the dining-car, where a few hours before he had had dinner and talked with two white men, one an Oregon apple-grower, the other a Wisconsin paper-manufacturer. The Wisconsin man had furnished cigars, and the three had sat and smoked in the drawing-room, indeed, had discussed this very point; and now it was upon him.

At the door of the dining-car stood the porter of his Pullman, a negro like himself, and Peter mechanically gave him fifty cents. The porter accepted it silently, without offering the amenities of his whisk-broom and shoe-brush, and Peter passed on forward.

Beyond the dining-car and Pullmans stretched twelve day-coaches filled with less-opulent white travelers in all degrees of sleepiness and dishabille from having sat up all night. The thirteenth coach was the Jim Crow car. Framed in a conspicuous place beside the entrance of the car was a copy of the Kentucky state ordinance setting this coach apart from the remainder of the train for the purposes therein provided.

The Jim Crow car was not exactly shabby, but it was unkept. It was half filled with travelers of Peter's own color, and these passengers were rather more noisy than those in the white coaches. Conversation was not restrained to the undertones one heard in the other day-coaches or the Pullmans. Near the entrance of the car two negroes in soldiers' uniforms had turned a seat over to face the door, and now they sat talking loudly and laughing the loose laugh of the half intoxicated as they watched the inflow of negro passengers coming out of the white cars.

The windows of the Jim Crow car were shut, and already it had become noisome. The close air was faintly barbed with the peculiar, penetrating odor of dark, sweating skins. For four years Peter Siner had not known that odor. Now it came to him not so much offensively as with a queer quality of intimacy and reminiscence. The tall, carefully tailored negro spread his wide nostrils, vacillating whether to sniff it out with disfavor or to admit it for the sudden mental associations it evoked.

It was a faint, pungent smell that played in the back of his nose and somehow reminded him of his mother, Caroline Siner, a thick-bodied black woman whom he remembered as always bending over a wash-tub. This was only one unit of a complex. The odor was also connected with negro protracted meetings in Hooker's Bend, and the Harvard man remembered a lanky black preacher waving long arms and wailing of hell-fire, to the chanted groans of his dark congregation; and he, Peter Siner, had groaned with the others. Peter had known this odor in the press-room of Tennessee cotton-gins, over a river packet's boilers, where he and other roustabouts were bedded, in bunk-houses in the woods. It also recalled a certain octoroon girl named Ida May, and an intimacy with her which it still moved and saddened Peter to think of. Indeed, it resurrected innumerable vignettes of his life in the negro village in Hooker's Bend; it was linked with innumerable emotions, this pungent, unforgetable odor that filled the Jim Crow car.

Somehow the odor had a queer effect of appearing to push his conversation with the two white Northern men in the drawing-room back to a distance, an indefinable distance of both space and time.

The negro put his suitcase under the seat, hung his overcoat on the hook, and placed his hand-bag in the rack overhead; then with some difficulty he opened a window and sat down by it.

A stir of travelers in the Cairo station drifted into the car. Against a broad murmur of hurrying feet, moving trucks, and talking there stood out the thin, flat voice of a Southern white girl calling good-by to some one on the train. Peter could see her waving a bright parasol and tiptoeing. A sandwich boy hurried past, shrilling his wares. Siner leaned out, with fifteen cents, and signaled to him. The urchin hesitated, and was about to reach up one of his wrapped parcels, when a peremptory voice shouted at him from a lower car. With a sort of start the lad deserted Siner and went trotting down to his white customer. A moment later the train bell began ringing, and the Dixie Flier puffed deliberately out of the Cairo station and moved across the Ohio bridge into the South.

Half an hour later the blue-grass fields of Kentucky were spinning outside of the window in a vast green whirlpool. The distant trees and houses moved forward with the train, while the foreground, with its telegraph poles, its culverts, section-houses, and shrubbery, rushed backward in a blur. Now and then into the Jim Crow window whipped a blast of coal smoke and hot cinders, for the engine was only two cars ahead.

Peter Siner looked out at the interminable spin of the landscape with a certain wistfulness. He was coming back into the South, into his own country. Here for generations his forebears had toiled endlessly and fruitlessly, yet the fat green fields hurtling past him told with what skill and patience their black hands had labored.

The negro shrugged away such thoughts, and with a certain effort replaced them with the constructive idea that was bringing him South once more. It was a very simple idea. Siner was returning to his native village in Tennessee to teach school. He planned to begin his work with the ordinary public school at Hooker's Bend, but, in the back of his head, he hoped eventually to develop an institution after the plan of Tuskeegee or the Hampton Institute in Virginia.

To do what he had in mind, he must obtain aid from white sources, and now, as he traveled southward, he began conning in his mind the white men and white women he knew in Hooker's Bend. He wanted first of all to secure possession of a small tract of land which he knew adjoined the negro school-house over on the east side of the village.

Before the negro's mind the different villagers passed in review with that peculiar intimacy of vision that servants always have of their masters. Indeed, no white Southerner knows his own village so minutely as does any member of its colored population. The colored villagers see the whites off their guard and just as they are, and that is an attitude in which no one looks his best. The negroes might be called the black recording angels of the South. If what they know should be shouted aloud in any Southern town, its social life would disintegrate. Yet it is a strange fact that gossip seldom penetrates from the one race to the other.

So Peter Siner sat in the Jim Crow car musing over half a dozen villagers in Hooker's Bend. He thought of them in a curious way. Although he was now a B.A. of Harvard University, and although he knew that not a soul in the little river village, unless it was old Captain Renfrew, could construe a line of Greek and that scarcely two had ever traveled farther north than Cincinnati, still, as Peter recalled their names and foibles, he involuntarily felt that he was telling over a roll of the mighty. The white villagers came marching through his mind as beings austere, and the very cranks and quirks of their characters somehow held that austerity. There were the Brownell sisters, two old maids, Molly and Patti, who lived in a big brick house on the hill. Peter remembered that Miss Molly Brownell always doled out to his mother, at Monday's washday dinner, exactly one biscuit less than the old negress wanted to eat, and she always paid her in old clothes. Peter remembered, a dozen times in his life, his mother coming home and wondering in an impersonal way how it was that Miss Molly Brownell could skimp every meal she ate at the big house by exactly one biscuit. It was Miss Brownell's thin-lipped boast that she understood negroes. She had told Peter so several times when, as a lad, he went up to the big house on errands. Peter Siner considered this remembrance without the faintest feeling of humor, and mentally removed Miss Molly Brownell from his list of possible subscribers. Yet, he recalled, the whole Brownell estate had been reared on negro labor.

Then there was Henry Hooker, cashier of the village bank. Peter knew that the banker subscribed liberally to foreign missions; indeed, at the cashier's behest, the white church of Hooker's Bend kept a paid missionary on the upper Congo. But the banker had sold some village lots to the negroes, and in two instances, where a streak of commercial phosphate had been discovered on the properties, the lots had reverted to the Hooker estate. There had been in the deed something concerning a mineral reservation that the negro purchasers knew nothing about until the phosphate was discovered. The whole matter had been perfectly legal.

A hand shook Siner's shoulder and interrupted his review. Peter turned, and caught an alcoholic breath over his shoulder, and the blurred voice of a Southern negro called out above the rumble of the car and the roar of the engine:

"'Fo' Gawd, ef dis ain't Peter Siner I's been lookin' at de las' twenty miles, an' not knowin' him wid sich skeniptious clo'es on! Wha you fum, nigger?"

Siner took the enthusiastic hand offered him and studied the heavily set, powerful man bending over the seat. He was in a soldier's uniform, and his broad nutmeg-colored face and hot black eyes brought Peter a vague sense of familiarity; but he never would have identified his impression had he not observed on the breast of the soldier's uniform the Congressional military medal for bravery on the field of battle. Its glint furnished Peter the necessary clew. He remembered his mother's writing him something about Tump Pack going to France and getting "crowned" before the army. He had puzzled a long time over what she meant by "crowned" before he guessed her meaning. Now the medal aided Peter in reconstructing out of this big umber-colored giant the rather spindling Tump Pack he had known in Hooker's Bend.

Siner was greatly surprised, and his heart warmed at the sight of his old playmate.

"What have you been doing to yourself, Tump?" he cried, laughing, and shaking the big hand in sudden warmth. "You used to be the size of a dime in a jewelry store."

"Been in 'e army, nigger, wha I's been fed," said the grinning brown man, delightedly. "I sho is picked up, ain't I?"

"And what are you doing here in Cairo?"

"Tryin' to bridle a lil white mule." Mr. Pack winked a whisky-brightened eye jovially and touched his coat to indicate that some of the "white mule" was in his pocket and had not been drunk.

"How'd you get here?"

"Wucked my way down on de St. Louis packet an' got paid off at Padjo [Paducah, Kentucky]; 'n 'en I thought I'd come on down heah an' roll some bones. Been hittin' 'em two days now, an' I sho come putty nigh bein' cleaned; but I put up lil Joe heah, an' won 'em all back, 'n 'en some." He touched the medal on his coat, winked again, slapped Siner on the leg, and burst into loud laughter.

Peter was momentarily shocked. He made a place on the seat for his friend to sit. "You don't mean you put up your medal on a crap game, Tump?"

"Sho do, black man." Pack became soberer. "Dat's one o' de great benefits o' bein' dec'rated. Dey ain't a son uv a gun on de river whut kin win lil Joe; dey all tried it."

A moment's reflection told Peter how simple and natural it was for Pack to prize his military medal as a good-luck piece to be used as a last resort in crap games. He watched Tump stroke the face of his medal with his fingers.

"My mother wrote me; about your getting it, Tump. I was glad to hear it."

The brown man nodded, and stared down at the bit of gold on his barrel- like chest.

"Yas-suh, dat 'uz guv to me fuh bravery. You know whut a skeery lil nigger I wuz roun' Hooker's Ben'; well, de sahgeant tuk me an' he drill ever' bit o' dat right out 'n me. He gimme a baynit an' learned me to stob dummies wid it over at Camp Oglethorpe, ontil he felt lak I had de heart to stob anything; 'n' 'en he sont me acrost. I had to git a new pair breeches ever' three weeks, I growed so fas'." Here he broke out into his big loose laugh again, and renewed the alcoholic scent around Peter.

"And you made good?"

"Sho did, black man, an', 'fo' Gawd, I 'serve a medal ef any man ever did. Dey gimme dish-heah fuh stobbin fo' white men wid a baynit. 'Fo' Gawd, nigger, I never felt so quare in all my born days as when I wuz a- jobbin' de livers o' dem white men lak de sahgeant tol' me to." Tump shook his head, bewildered, and after a moment added, "Yas-suh, I never wuz mo' surprised in all my life dan when I got dis medal fuh stobbin' fo' white men."

Peter Siner looked through the Jim Crow window at the vast rotation of the Kentucky landscape on which his forebears had toiled; presently he added soberly:

"You were fighting for your country, Tump. It was war then; you were fighting for your country."

At Jackson, Tennessee, the two negroes were forced to spend the night between trains. Tump Pack piloted Peter Siner to a negro cafe where they could eat, and later they searched out a negro lodging-house on Gate Street where they could sleep. It was a grimy, smelly place, with its own odor spiked by a phosphate-reducing plant two blocks distant. The paper on the wall of the room Peter slept in looked scrofulous. There was no window, and Peter's four-years régime of open windows and fresh- air sleep was broken. He arranged his clothing for the night so it would come in contact with nothing in the room but a chair back. He felt dull next morning, and could not bring himself either to shave or bathe in the place, but got out and hunted up a negro barber-shop furnished with one greasy red-plush barber-chair.

A few hours later the two negroes journeyed on down to Perryville, Tennessee, a village on the Tennessee River where they took a gasolene launch up to Hooker's Bend. The launch was about fifty feet long and had two cabins, a colored cabin in front of, and a white cabin behind, the engine-room.

This unremitting insistence on his color, this continual shunting him into obscure and filthy ways, gradually gave Peter a loathly sensation. It increased the unwashed feeling that followed his lack of a morning bath. The impression grew upon him that he was being handled with tongs, along back-alley routes; that he and his race were something to be kept out of sight as much as possible, as careful housekeepers manoeuver their slops.

At Perryville a number of passengers boarded the up-river boat; two or three drummers; a yellowed old hill woman returning to her Wayne County home; a red-headed peanut-buyer; a well-groomed white girl in a tailor suit; a youngish man barely on the right side of middle age who seemed to be attending her; and some negro girls with lunches. The passengers trailed from the railroad station down the river bank through a slush of mud, for the river had just fallen and had left a layer of liquid mud to a height of about twenty feet all along the littoral. The passengers picked their way down carefully, stepping into one another's tracks in the effort not to ruin their shoes. The drummers grumbled. The youngish man piloted the girl down, holding her hand, although both could have managed better by themselves.

Following the passengers came the trunks and grips on a truck. A negro deck-hand, the truck-driver, and the white master of the launch shoved aboard the big sample trunks of the drummers with grunts, profanity, and much stamping of mud. Presently, without the formality of bell or whistle, the launch clacked away from the landing and stood up the wide, muddy river.

The river itself was monotonous and depressing. It was perhaps half a mile wide, with flat, willowed mud banks on one side and low shelves of stratified limestone on the other.

Trading-points lay at ten- or fifteen-mile intervals along the great waterway. The typical landing was a dilapidated shed of a store half covered with tin tobacco signs and ancient circus posters. Usually, only one man met the launch at each landing, the merchant, a democrat in his shirt-sleeves and without a tie. His voice was always a flat, weary drawl, but his eyes, wrinkled against the sun, usually held the shrewdness of those who make their living out of two-penny trades.

At each place the red-headed peanut-buyer slogged up the muddy bank and bargained for the merchant's peanuts, to be shipped on the down-river trip of the first St. Louis packet. The loneliness of the scene embraced the trading-points, the river, and the little gasolene launch struggling against the muddy current. It permeated the passengers, and was a finishing touch to Peter Siner's melancholy.

The launch clacked on and on interminably. Sometimes it seemed to make no headway at all against the heavy, silty current. Tump Pack, the white captain, and the negro engineer began a game of craps in the negro cabin. Presently, two of the white drummers came in from the white cabin and began betting on the throws. The game was listless. The master of the launch pointed out places along the shores where wildcat stills were located. The crap-shooters, negro and white, squatted in a circle on the cabin floor, snapping their fingers and calling their points monotonously. One of the negro girls in the negro cabin took an apple out of her lunch sack and began eating it, holding it in her palm after the fashion of negroes rather than in her fingers, as is the custom of white women.

Both doors of the engine-room were open, and Peter Siner could see through into the white cabin. The old hill woman was dozing in her chair, her bonnet bobbing to each stroke of the engines. The youngish man and the girl were engaged in some sort of intimate lovers' dispute. When the engines stopped at one of the landings, Peter discovered she was trying to pay him what he had spent on getting her baggage trucked down at Perryville. The girl kept pressing a bill into the man's hand, and he avoided receiving the money. They kept up the play for sake of occasional contacts.

When the launch came in sight of Hooker's Bend toward the middle of the afternoon, Peter Siner experienced one of the profoundest surprises of his life. Somehow, all through his college days he had remembered Hooker's Bend as a proud town with important stores and unapproachable white residences. Now he saw a skum of negro cabins, high piles of lumber, a sawmill, and an ice-factory. Behind that, on a little rise, stood the old Brownell manor, maintaining a certain shabby dignity in a grove of oaks. Behind and westward from the negro shacks and lumber- piles ranged the village stores, their roofs just visible over the top of the bank. Moored to the shore, lay the wharf-boat in weathered greens and yellows. As a background for the whole scene rose the dark-green height of what was called the "Big Hill," an eminence that separated the negro village on the east from the white village on the west. The hill itself held no houses, but appeared a solid green-black with cedars.

The ensemble was merely another lonely spot on the south bank of the great somnolent river. It looked dead, deserted, a typical river town, unprodded even by the hoot of a jerk-water railroad.

As the launch chortled toward the wharf, Peter Siner stood trying to orient himself to this unexpected and amazing minifying of Hooker's Bend. He had left a metropolis; he was coming back to a tumble-down village. Yet nothing was changed. Even the two scraggly locust-trees that clung perilously to the brink of the river bank still held their toe-hold among the strata of limestone.

The negro deck-hand came out and pumped the hand-power whistle in three long discordant blasts. Then a queer thing happened. The whistle was answered by a faint strain of music. A little later the passengers saw a line of negroes come marching down the river bank to the wharf-boat. They marched in military order, and from afar Peter recognized the white aprons and the swords and spears of the Knights and Ladies of Tabor, a colored burial association.

Siner wondered what had brought out the Knights and Ladies of Tabor. The singing and the drumming gradually grew upon the air. The passengers in the white cabin, came out on the guards at this unexpected fanfare. As soon as the white travelers saw the marching negroes, they began joking about what caused the demonstration. The captain of the launch thought he knew, and began an oath, but stopped it out of deference to the girl in the tailor suit. He said it was a dead nigger the society was going to ship up to Savannah.

The girl in the tailor suit was much amused. She said the darkies looked like a string of caricatures marching down the river bank. Peter noticed her Northern accent, and fancied she was coming to Hooker's Bend to teach school.

One of the drummers turned to another.

"Did you ever hear Bob Taylor's yarn about Uncle 'Rastus's funeral? Funniest thing Bob ever got off." He proceeded to tell it.

Every one on the launch was laughing except the captain, who was swearing quietly; but the line of negroes marched on down to the wharf- boat with the unshakable dignity of black folk in an important position. They came singing an old negro spiritual. The women's sopranos thrilled up in high, weird phrasing against an organ-like background of male voices.

But the black men carried no coffin, and suddenly it occurred to Peter Siner that perhaps this celebration was given in honor of his own home- coming. The mulatto's heart beat a trifle faster as he began planning a suitable response to this ovation.

Sure enough, the singing ranks disappeared behind the wharf-boat, and a minute later came marching around the stern and lined up on the outer guard of the vessel. The skinny, grizzly-headed negro commander held up his sword, and the Knights and Ladies of Tabor fell silent.

The master of the launch tossed his head-line to the wharf-boat, and yelled for one of the negroes to make it fast. One did. Then the commandant with the sword began his address, but it was not directed to Peter. He said:

"Brudder Tump Pack, we, de Hooker's Ben' lodge uv de Knights an' Ladies uv Tabor, welcome you back to yo' native town. We is proud uv you, a colored man, who brings back de highes' crown uv bravery dis Newnighted States has in its power to bestow.

"Two yeahs ago, Brudder Tump, we seen you marchin' away fum Hooker's Ben' wid thirteen udder boys, white an' colored, all marchin' away togedder. Fo' uv them boys is already back home; three, we heah, is on de way back, but six uv yo' brave comrades, Brudder Pack, is sleepin' now in France, an' ain't never goin' to come home no mo'. When we honors you, we honors them all, de libin' an' de daid, de white an' de black, who fought togedder fuh one country, fuh one flag."

Gasps, sobs from the line of black folk, interrupted the speaker. Just then a shriveled old negress gave a scream, and came running and half stumbling out of the line, holding out her arms to the barrel-chested soldier on the gang-plank. She seized him and began shrieking:

"Bless Gawd! my son's done come home! Praise de Lawd! Bless His holy name!" Here her laudation broke into sobbing and choking and laughing, and she squeezed herself to her son.

Tump patted her bony black form.

"I's heah, Mammy," he stammered uncertainly. "I's come back, Mammy."

Half a dozen other negroes caught the joyful hysteria. They began a religious shouting, clapping their hands, flinging up their arms, shrieking.

One of the drummers grunted:

"Good God! all this over a nigger getting back!"

At the extreme end of the dark line a tall cream-colored girl wept silently. As Peter Siner stood blinking his eyes, he saw the octoroon's shoulders and breasts shake from the sobs, which her white blood repressed to silence.

A certain sympathy for her grief and its suppression kept Peter's eyes on the young woman, and then, with the queer effect of one picture melting into another, the strange girl's face assumed familiar curves and softnesses, and he was looking at Ida May.

A quiver traveled deliberately over Peter from his crisp black hair to the soles of his feet. He started toward her impulsively.

At that moment one of the drummers picked up his grip, and started down the gang-plank, and with its leathern bulk pressed Tump Pack and his mother out of his path. He moved on to the shore through the negroes, who divided at his approach. The captain of the launch saw that other of his white passengers were becoming impatient, and he shouted for the darkies to move aside and not to block the gangway. The youngish man drew the girl in the tailor suit close to him and started through with her. Peter heard him say, "They won't hurt you, Miss Negley." And Miss Negley, in the brisk nasal intonation of a Northern woman, replied: "Oh, I'm not afraid. We waste a lot of sympathy on them back home, but when you see them—"

At that moment Peter heard a cry in his ears and felt arms thrown about his neck. He looked down and saw his mother, Caroline Siner, looking up into his face and weeping with the general emotion of the negroes and this joy of her own. Caroline had changed since Peter last saw her. Her eyes were a little more wrinkled, her kinky hair was thinner and very gray.

Something warm and melting moved in Peter Siner's breast. He caressed his mother and murmured incoherently, as had Tump Pack. Presently the master of the launch came by, and touched the old negress, not ungently, with the end of a spike-pole.

"You'll have to move, Aunt Ca'line," he said. "We're goin' to get the freight off now."

The black woman paused in her weeping. "Yes, Mass' Bob," she said, and she and Peter moved off of the launch onto the wharf-boat.

The Knights and Ladies of Tabor were already up the river bank with their hero. Peter and his mother were left alone. Now they walked around the guards of the wharf-boat to the bank, holding each other's arms closely. As they went, Peter kept looking down at his old black mother, with a growing tenderness. She was so worn and heavy! He recognized the very dress she wore, an old black silk which she had "washed out" for Miss Patti Brownell when he was a boy. It had been then, it was now, her best dress. During the years the old negress had registered her increasing bulk by letting out seams and putting in panels. Some of the panels did not agree with the original fabric either in color or in texture and now the seams were stretching again and threatening a rip. Peter's own immaculate clothes reproached him, and he wondered for the hundredth, or for the thousandth time how his mother had obtained certain remittances which she had forwarded him during his college years.

As Peter and his mother crept up the bank of the river, stopping occasionally to let the old negress rest, his impression of the meanness and shabbiness of the whole village grew. From the top of the bank the single business street ran straight back from the river. It was stony in places, muddy in places, strewn with goods-boxes, broken planking, excelsior, and straw that had been used for packing. Charred rubbish- piles lay in front of every store, which the clerks had swept out and attempted to burn. Hogs roamed the thoroughfare, picking up decaying fruit and parings, and nosing tin cans that had been thrown out by the merchants. The stores that Peter had once looked upon as show-places were poor two-story brick or frame buildings, defiled by time and wear and weather. The white merchants were coatless, listless men who sat in chairs on the brick pavements before their stores and who moved slowly when a customer entered their doors.

And, strange to say, it was this fall of his white townsmen that moved Peter Siner with a sense of the greatest loss. It seemed fantastic to him, this sudden land-slide of the mighty.

As Peter and his mother came over the brow of the river bank, they saw a crowd collecting at the other end of the street. The main street of Hooker's Bend is only a block long, and the two negroes could easily hear the loud laughter of men hurrying to the focus of interest and the blurry expostulations of negro voices. The laughter spread like a contagion. Merchants as far up as the river corner became infected, and moved toward the crowd, looking back over their shoulders at every tenth or twelfth step to see that no one entered their doors.

Presently, a little short man, fairly yipping with laughter, stumbled back up the street to his store with tears of mirth in his eyes. A belated merchant stopped him by clapping both hands on his shoulders and shaking some composure into him.

"What is it? What's so funny? Damn it! I miss ever'thing!"

"I-i-it's that f-fool Tum-Tump Pack. Bobbs's arrested him!"

The inquirer was astounded.

"How the hell can he arrest him when he hit town this minute?"

"Wh-why, Bobbs had an old warrant for crap-shoot—three years old— before the war. Just as Tump was a-coming down the street at the head of the coons, out steps Bobbs—" Here the little man was overcome.

The merchant from the corner opened his eyes.

"Arrested him on an old crap charge?"

The little man nodded. They gazed at each other. Then they exploded simultaneously.

Peter left his obese mother and hurried to the corner, Dawson Bobbs, the constable, had handcuffs on Tump's wrists, and stood with his prisoner amid a crowd of arguing negroes.

Bobbs was a big, fleshy, red-faced man, with chilly blue eyes and a little straight slit of a mouth in his wide face. He was laughing and chewing a sliver of toothpick.

"O Tump Pack," he called loudly, "you kain't git away from me! If you roll bones in Hooker's Bend, you'll have to divide your winnings with the county." Dawson winked a chill eye at the crowd in general.

"But hit's out o' date, Mr. Bobbs," the old gray-headed minister, Parson Ranson, was pleading.

"May be that, Parson, but hit's easier to come up before the J.P. and pay off than to fight it through the circuit court."

Siner pushed his way through the crowd. "How much do you want, Mr. Bobbs?" he asked briefly.

The constable looked with reminiscent eyes at the tall, well-tailored negro. He was plainly going through some mental card-index, hunting for the name of Peter Siner on some long-forgotten warrant. Apparently, he discovered nothing, for he said shortly:

"How do I know before he's tried? Come on, Tump!"

The procession moved in a long noisy line up Pillow Street, the white residential street lying to the west. It stopped before a large shaded lawn, where a number of white men and women were playing a game with cards. The cards used by the lawn party were not ordinary playing-cards, but had figures on them instead of spots, and were called "rook" cards. The party of white ladies and gentlemen were playing "rook." On a table in the middle of the lawn glittered some pieces of silver plate which formed the first, second, and third prizes for the three leading scores.

The constable halted his black company before the lawn, where they stood in the sunshine patiently waiting for the justice of the peace to finish his game and hear the case of the State of Tennessee, plaintiff, versus Tump Pack, defendant.

On the eastern edge of Hooker's Bend, drawn in a rough semicircle around the Big Hill, lies Niggertown. In all the half-moon there are perhaps not two upright buildings. The grimy cabins lean at crazy angles, some propped with poles, while others hold out against gravitation at a hazard.

Up and down its street flows the slow negro life of the village. Here children of all colors from black to cream fight and play; deep-chested negresses loiter to and fro, some on errands to the white section of the village on the other side of the hill, where they go to scrub or cook or wash or iron. Others go down to the public well with a bucket in each hand and one balanced on the head.

The public well itself lies at the southern end of this miserable street, just at a point where the drainage of the Big Hill collects. The rainfall runs down through Niggertown, under its sties, stables, and outdoor toilets, and the well supplies the negroes with water for cooking, washing, and drinking. Or, rather, what was once a well supplies this water, for it is a well no longer. Its top and curbing caved in long ago, and now there is simply a big hole in the soft, water-soaked clay, about fifteen feet wide, with water standing at the bottom.

Here come the unhurried colored women, who throw in their buckets, and with a dexterity that comes of long practice draw them out full of water. Black mothers shout at their children not to fall into this pit, and now and then, when a pig fails to come up for its evening slops, a black boy will go to the public well to see if perchance his porker has met misfortune there.

The inhabitants of Niggertown suffer from divers diseases; they develop strange ailments that no amount of physicking will overcome; young wives grow sickly from no apparent cause. Although only three or four hundred persons live in Niggertown, two or three negroes are always slowly dying of tuberculosis; winter brings pneumonia; summer, malaria. About once a year the state health officer visits Hooker's Bend and forces the white soda-water dispensers on the other side of the hill to sterilize their glasses in the name of the sovereign State of Tennessee.

The Siner home was a three-room shanty about midway in the semicircle. Peter Siner stood in the sunlight just outside the entrance, watching his old mother clean the bugs out of a tainted ham that she had bought for a pittance from some white housekeeper in the village. It had been too high for white people to eat. Old Caroline patiently tapped the honeycombed meat to scare out the last of the little green householders, and then she washed it in a solution of soda to freshen it up.

The sight of his bulky old mother working at the spoiled ham and of the negro women in the street moving to and from the infected well filled Peter Siner with its terrible pathos. Although he had seen these surroundings all of his life, he had a queer impression that he was looking upon them for the first time. During his boyhood he had accepted all this without question as the way the world was made. During his college days a criticism had arisen in his mind, but it came slowly, and was tempered by that tenderness every one feels for the spot called home. Now, as he stood looking at it, he wondered how human beings lived there at all. He wondered if Ida May used water from the Niggertown well.

He turned to ask old Caroline, but checked himself with a man's instinctive avoidance of mentioning his intimacies to his mother. At that moment, oddly enough, the old negress brought up the topic herself.

"Ida May wuz 'quirin' 'bout you las' night, Peter."

A faint tingle filtered through Peter's throat and chest, but he asked casually enough what she had said.

"Didn' say; she wrote."

Peter looked around, frankly astonished.

"Wrote?"

"Yeah; co'se she wrote."

"What made her write?" a fantasy of Ida May dumb flickered before the mulatto.

"Why, Ida May's in Nashville." Caroline looked at Peter. "She wrote to Cissie, astin' 'bout you. She ast is you as bright in yo' books as you is in yo' color." The old negress gave a pleased abdominal chuckle as she admired her broad-shouldered brown son.

"But I saw Ida May standing on the wharf-boat the day I came home," protested Peter, still bewildered.

"No you ain't. I reckon you seen Cissie. Dey looks kind o' like when you is fur off."

"Cissie?" repeated Peter. Then he remembered a smaller sister of Ida May's, a little, squalling, yellow, wet-nosed nuisance that had annoyed his adolescence. So that little spoil-sport had grown up into the girl he had mistaken for Ida May. This fact increased his sense of strangeness—that sense of great change that had fallen on the village in his absence which formed the groundwork of all his renewed associations.

Peter's prolonged silence aroused certain suspicions in the old negress. She glanced at her son out of the tail of her eyes.

"Cissie Dildine is Tump Pack's gal," she stated defensively, with the jealousy all mothers feel toward all sons.

A diversion in the shouts of the children up the mean street and a sudden furious barking of dogs drew Peter from the discussion. He looked up, and saw a negro girl of about fourteen coming down the curved street, with long, quick steps and an occasional glance over her shoulder.

From across the thoroughfare a small chocolate-colored woman, with her wool done in outstanding spikes, thrust her head out at the door and called:

"Whut's de matter, Ofeely?"

The girl lifted a high voice:

"Oh, Miss Nan, it's that constable goin' th'ugh the houses!" The girl veered across the street to the safety of the open door and one of her own sex.

"Good Lawd!" cried the spiked one in disgust, "ever', time a white pusson gits somp'n misplaced—" She moved to one side to allow the girl to enter, and continued staring up the street, with the whites of her eyes accented against her dark face, after the way of angry negroes.

Around the crescent the dogs were furious. They were Niggertown dogs, and the sight of a white man always drove them to a frenzy. Presently in the hullabaloo, Peter heard Dawson Bobbs's voice shouting:

"Aunt Mahaly, if you kain't call off this dawg, I'm shore goin' to kill him."

Then an old woman's scolding broke in and complicated the mêlée. Presently Peter saw the bulky form of Dawson Bobbs come around the curve, moving methodically from cabin to cabin. He held some legal- looking papers in his hands, and Peter knew what the constable was doing. He was serving a blanket search-warrant on the whole black population of Hooker's Bend. At almost every cabin a dog ran out to blaspheme at the intruder, but a wave of the man's pistol sent them yelping under the floors again.

When the constable entered a house, Peter could hear him bumping and rattling among the furnishings, while the black householders stood outside the door and watched him disturb their housekeeping arrangements.

Presently Bobbs came angling across the street toward the Siner cabin. As he entered the rickety gate, old Caroline called out:

"Whut is you after, anyway, white man?"

Bobbs turned cold, truculent eyes on the old negress. "A turkey roaster," he snapped. "Some o' you niggers stole Miss Lou Arkwright's turkey roaster."

"Tukky roaster!" cried the old black woman, in great disgust. "Whut you s'pose us niggers is got to roast in a tukky roaster?"

The constable answered shortly that his business was to find the roaster, not what the negroes meant to put in it.

"I decla'," satirized old Caroline, savagely, "dish-heah Niggertown is a white man's pocket. Ever' time he misplace somp'n, he feel in his pocket to see ef it ain't thaiuh. Don'-chu turn over dat sody-water, white man! You know dey ain't no tukky roaster under dat sody-water. I 'cla' 'fo' Gawd, ef a white man wuz to eat a flapjack, an' it did n' give him de belly-ache, I 'cla' 'fo' Gawd he'd git out a search-wa'nt to see ef some nigger had n' stole dat flapjack goin' down his th'oat."

"Mr. Bobbs has to do his work, Mother," put in Peter. "I don't suppose he enjoys it any more than we do."

"Den let 'im git out'n dis business an' git in anudder," scolded the old woman. "Dis sho is a mighty po' business."

The ponderous Mr. Bobbs finished with a practised thoroughness his inspection of the cabin, and then the inquisition proceeded down the street, around the crescent, and so out of sight and eventually out of hearing.

Old Caroline snapped her chair back beside her greasy table and sat down abruptly to her spoiled ham again.

"Dat make me mad," she grumbled. "Ever' time a white pusson fail to lay dey han' on somp'n, dey comes an' turns over ever'thing in my house." She paused a moment, closed her eyes in thought, and then mused aloud: "I wonder who is got Miss Arkwright's roaster."

The commotion of the constable's passing died in his wake, and Niggertown resumed its careless existence. Dogs reappeared from under the cabins and stretched in the sunshine; black children came out of hiding and picked up their play; the frightened Ophelia came out of Nan's cabin across the street and went her way; a lanky negro youth in blue coat and pin-striped trousers appeared, coming down the squalid thoroughfare whistling the "Memphis Blues" with bird-like virtuosity. The lightness with which Niggertown accepted the moral side glance of a blanket search-warrant depressed Siner.

Caroline called her son to dinner, as the twelve-o'clock meal is called in Hooker's Bend, and so ended his meditation. The Harvard man went back into the kitchen and sat down at a rickety table covered with a red- checked oil-cloth. On it were spread the spoiled ham, a dish of poke salad, a corn pone, and a pot of weak coffee. A quaint old bowl held some brown sugar. The fat old negress made a slight, habitual settling movement in her chair that marked the end of her cooking and the beginning of her meal. Then she bent her grizzled, woolly head and mumbled off one of those queer old-fashioned graces which consist of a swift string of syllables without pauses between either words or sentences.

Peter sat watching his mother with a musing gaze. The kitchen was illuminated by a single small square window set high up from the floor. Now the disposition of its single ray of light over the dishes and the bowed head of the massive negress gave Peter one of those sharp, tender apprehensions of formal harmony that lie back of the genre in art. It stirred his emotion in an odd fashion. When old Caroline raised her head, she found her son staring with impersonal eyes not at herself, but at the whole room, including her. The old woman was perplexed and a little apprehensive.

"Why, son!" she ejaculated, "didn' you bow yo' haid while yo' mammy ast de grace?"

Peter was a little confused at his remissness. Then he leaned a little forward to explain the sudden glamour which for a moment had transfigured the interior of their kitchen. But even as he started to speak, he realized that what he meant to say would only confuse his mother; therefore he cast about mentally for some other explanation of his behavior, but found nothing at hand.

"I hope you ain't forgot yo' 'ligion up at de 'versity, son."

"Oh, no, no, indeed, Mother, but just at that moment, just as you bowed your head, you know, it struck me that—that there is something noble in our race." That was the best he could put it to her.

"Noble—"

"Yes. You know," he went on a little quickly, "sometimes I—I've thought my father must have been a noble man."

The old negress became very still. She was not looking quite at her son, or yet precisely away from him.

"Uh—uh noble nigger,"—she gave her abdominal chuckle. "Why—yeah, I reckon yo' father wuz putty noble as—as niggers go." She sat looking at her son, oddly, with a faint amusement in her gross black face, when a careful voice, a very careful voice, sounded in the outer room, gliding up politely on the syllables:

"Ahnt Carolin'! oh, Ahnt Carolin', may I enter?"

The old woman stirred.

"Da''s Cissie, Peter. Go ast her in to de fambly-room."

When Siner opened the door, the vague resemblance of the slender, creamy girl on the threshold to Ida May again struck him; but Cissie Dildine was younger, and her polished black hair lay straight on her pretty head, and was done in big, shining puffs over her ears in a way that Ida May's unruly curls would never have permitted. Her eyes were the most limpid brown Peter had ever seen, but her oval face was faintly unnatural from the use of negro face powder, which colored women insist on, and which gives their yellows and browns a barely perceptible greenish hue. Cissie wore a fluffy yellow dress some three shades deeper than the throat and the glimpse of bosom revealed at the neck.

The girl carried a big package in her arms, and now she manipulated this to put out a slender hand to Peter.

"This is Cissie Dildine, Mister Siner." She smiled up at him. "I just came over to put my name down on your list. There was such a mob at the Benevolence Hall last night I couldn't get to you."

The girl had a certain finical precision to her English that told Peter she had been away to some school, and had been taught to guard her grammar very carefully as she talked.

Peter helped her inside amid the handshake and said he would go fetch the list. As he turned, Cissie offered her bundle. "Here is something I thought might be a little treat for you and Ahnt Carolin'." She paused, and then explained remotely, "Sometimes it is hard to get good things at the village market."

Peter took the package, vaguely amused at Cissie's patronage of the Hooker's Bend market. It was an attitude instinctively assumed by every girl, white or black, who leaves the village and returns. The bundle was rather large and wrapped in newspapers. He carried it into the kitchen to his mother, and then returned with the list.

The sheet was greasy from the handling of black fingers. The girl spread it on the little center-table with a certain daintiness, seated herself, and held out her hand for Peter's pencil. She made rather a graceful study in cream and yellow as she leaned over the table and signed her name in a handwriting as perfect and as devoid of character as a copy- book. She began discussing the speech Peter had made at the Benevolence Hall.

"I don't know whether I am in favor of your project or not, Mr. Siner," she said as she rose from the table.

"No?" Peter was surprised and amused at her attitude and at her precise voice.

"No, I'm rather inclined toward Mr. DuBois's theory of a literary culture than toward Mr. Washington's for a purely industrial training."

Peter broke out laughing.

"For the love of Mike, Cissie, you talk like the instructor in Sociology B! And haven't we met before somewhere? This 'Mister Siner' stuff—"

The girl's face warmed under its faint, greenish powder.

"If I aren't careful with my language, Peter," she said simply, "I'll be talking just as badly as I did before I went to the seminary. You know I never hear a proper sentence in Hooker's Bend except my own."

A certain resignation in the girl's soft voice brought Peter a qualm for laughing at her. He laid an impulsive hand on her young shoulder.

"Well, that's true, certainly, but it won't always be like that, Cissie. More of us go off to school every year. I do hope my school here in Hooker's Bend will be of some real value. If I could just show our people how badly we fare here, how ill housed, and unsanitary—"

The girl pressed Peter's fingers with a woman's optimism for a man.

"You'll succeed, Peter, I know you will. Some day the name Siner will mean the same thing to coloured people as Tanner and Dunbar and Braithwaite do. Anyway, I've put my name down for ten dollars to help out." She returned the pencil. "I'll have Tump Pack come around and pay you my subscription, Peter."

"I'll watch out for Tump," promised Peter in a lightening mood, "—and make him pay."

"He'll do it."

"I don't doubt it. You ought to have him under perfect control. I meant to tell you what a pretty frock you have on."

The girl dimpled, and dropped him a little curtsy, half ironical and wholly graceful.

Peter was charmed.

"Now keep that way, Cissie, smiling and human, not so grammatical. I wish I had a brooch."

"A brooch?"

"I'd give it to you. Your dress needs a brooch, an old gold brooch at the bosom, just a glint there to balance your eyes."

Cissie flushed happily, and made the feminine movement of concealing the V-shaped opening at her throat.

"It's a pleasure to doll up for a man like you, Peter. You see a girl's good points—if she has any," she tacked on demurely.

"Oh, just any man—"

"Don't think it! Don't think it!" waved down Cissie, humorously.

"But, Cissie, how is it possible—"

"Just blind." Cissie rippled into a boarding-school laugh. "I could wear the whole rue del Opera here in Niggertown, and nobody would ever see it but you."

Cissie was moving toward the door. Peter tried to detain her. He enjoyed the implication of Tump Pack's stupidity, in their badinage, but she would not stay. He was finally reduced to thanking her for her present, then stood guard as she tripped out into the grimy street. In the sunshine her glossy black hair and canary dress looked as trim and brilliant as the plumage of a chaffinch.

Peter Siner walked back into the kitchen with the fixed smile of a man who is thinking of a pretty girl. The black dowager in the kitchen received him in silence, with her thick lips pouted. When Peter observed it, he felt slightly amused at his mother's resentment.

"Well, you sho had a lot o' chatter over signin' a lil ole paper."

"She signed for ten dollars," said Peter, smiling.

"Huh! she'll never pay it."

"Said Tump Pack would pay it."

"Huh!" The old negress dropped the subject, and nodded at a huge double pan on the table. "Dat's whut she brung you." She grunted disapprovingly.

"And it's for you, too, Mother."

"Ya-as, I 'magine she brung somp'n fuh me."

Peter walked across to the double pans, and saw they held a complete dinner—chicken, hot biscuits, cake, pickle, even ice-cream.

The sight of the food brought Peter a realization that he was keenly hungry. As a matter of fact, he had not eaten a palatable meal since he had been evicted from the white dining-car at Cairo, Illinois. Siner served his own and his mother's plate.

The old woman sniffed again.

"Seems to me lak you is mighty onobsarvin' fuh a nigger whut's been off to college."

"Anything else?" Peter looked into the pans again.

"Ain't you see whut it's all in?"

"What it's in?"

"Yeah; whut it's in. You heared whut I said."

"What is it in?"

"Why, it's in Miss Arkwright's tukky roaster, dat's whut it's in." The old negress drove her point home with an acid accent.

Peter Siner was too loyal to his new friendship with Cissie Dildine to allow his mother's jealous suspicions to affect him; nevertheless the old woman's observations about the turkey roaster did prevent a complete and care-free enjoyment of the meal. Certainly there were other turkey roasters in Hooker's Bend than Mrs. Arkwright's. Cissie might very well own a roaster. It was absurd to think that Cissie, in the midst of her almost pathetic struggle to break away from the uncouthness of Niggertown, would stoop to—Even in his thoughts Peter avoided nominating the charge.

And then, somehow, his memory fished up the fact that years ago Ida May, according to village rumor, was "light-fingered." At that time in Peter's life "light-fingeredness" carried with it no opprobrium whatever. It was simply a fact about Ida May, as were her sloe eyes and curling black hair. His reflections renewed his perpetual sense of queerness and strangeness that hall-marked every phase of Niggertown life since his return from the North.

Cissie Dildine's contribution tailed out the one hundred dollars that Peter needed, and after he had finished his meal, the mulatto set out across the Big Hill for the white section of the village, to complete his trade.

It was Peter's program to go to the Planter's Bank, pay down his hundred, and receive a deed from one Elias Tomwit, which the bank held in escrow. Two or three days before Peter had tried to borrow the initial hundred from the bank, but the cashier, Henry Hooker, after going into the transaction, had declined the loan, and therefore Siner had been forced to await a meeting of the Sons and Daughters of Benevolence. At this meeting the subscription had gone through promptly. The land the negroes purposed to purchase for an industrial school was a timbered tract tying southeast of Hooker's Bend on the head-waters of Ross Creek. A purchase price of eight hundred dollars had been agreed upon. The timber on the tract, sold on the stump, would bring almost that amount. It was Siner's plan to commandeer free labor in Niggertown, work off the timber, and have enough money to build the first unit of his school. A number of negro men already had subscribed a certain number of days' work in the timber. It was a modest and entirely practical program, and Peter felt set up over it.

The brown man turned briskly out into the hot afternoon sunshine, down the mean semicircular street, where piccaninnies were kicking up clouds of dust. He hurried through the dusty area, and presently turned off a by-path that led over the hill, through a glade of cedars, to the white village.

The glade was gloomy, but warm, for the shade of cedars somehow seems to hold heat. A carpet of needles hushed Siner's footfalls and spread a Sabbatical silence through the grove. The upward path was not smooth, but was broken with outcrops of the same reddish limestone that marks the whole stretch of the Tennessee River. Here and there in the grove were circles eight or ten feet in diameter, brushed perfectly clean of all needles and pebbles and twigs. These places were crap-shooters' circles, where black and white men squatted to shoot dice.

Under the big stones on the hillside, Peter knew, was cached illicit whisky, and at night the boot-leggers carried on a brisk trade among the gamblers. More than that, the glade on the Big Hill was used for still more demoralizing ends. It became a squalid grove of Ashtoreth; but now, in the autumn evening, all the petty obscenities of white and black sloughed away amid the religious implications of the dark-green aisles.

The sight of a white boy sitting on an outcrop of limestone with a strap of school-books dropped at his feet rather surprised Peter. The negro looked at the hobbledehoy for several seconds before he recognized in the lanky youth a little Arkwright boy whom he had known and played with in his pre-college days. Now there was such an exaggerated wistfulness in young Arkwright's attitude that Peter was amused.

"Hello, Sam," he called. "What you doing out here?"

The Arkwright boy turned with a start.

"Aw, is that you, Siner?" Before the negro could reply, he added: "Was you on the Harvard football team, Siner? Guess the white fellers have a pretty gay time in Harvard, don't they, Siner? Geemenettie! but I git tired o' this dern town! D' reckon I could make the football team? Looks like I could if a nigger like you could, Siner."

None of this juvenile outbreak of questions required answers. Peter stood looking at the hobbledehoy without smiling.

"Aren't you going to school?" he asked.

Arkwright shrugged.

"Aw, hell!" he said self-consciously. "We got marched down to the protracted meetin' while ago—whole school did. My seat happened to be close to a window. When they all stood up to sing, I crawled out and skipped. Don't mention that, Siner."

"I won't."

"When a fellow goes to college he don't git marched to preachin', does he, Siner?"

"I never did."

"We-e-ll," mused young Sam, doubtfully, "you're a nigger."

"I never saw any white men marched in, either."

"Oh, hell! I wish I was in college."

"What are you sitting out here thinking about?" inquired Peter of the ingenuous youngster.

"Oh—football and—women and God and—how to stack cards. You think about ever'thing, in the woods. Damn it! I got to git out o' this little jay town. D' reckon I could git in the navy, Siner?"

"Don't see why you couldn't, Sam. Have you seen Tump Pack anywhere?"

"Yeah; on Hobbett's corner. Say, is Cissie Dildine at home?"

"I believe she is."

"She cooks for us," explained young Arkwright, "and Mammy wants her to come and git supper, too."

The phrase "get supper, too," referred to the custom in the white homes of Hooker's Bend of having only two meals cooked a day, breakfast and the twelve-o'clock dinner, with a hot supper optional with the mistress.

Peter nodded, and passed on up the path, leaving young Arkwright seated on the ledge of rock, a prey to all the boiling, erratic impulses of adolescence. The negro sensed some of the innumerable difficulties of this white boy's life, and once, as he walked on over the silent needles, he felt an impulse to turn back and talk to young Sam Arkwright, to sit down and try to explain to the youth what he could of this hazardous adventure called Life. But then, he reflected, very likely the boy would be offended at a serious talk from a negro. Also, he thought that young Arkwright, being white, was really not within the sphere of his ministry. He, Peter Siner, was a worker in the black world of the South. He was part of the black world which the white South was so meticulous to hide away, to keep out of sight and out of thought.

A certain vague sense of triumph trickled through some obscure corner of Peter's mind. It was so subtle that Peter himself would have been the first, in all good faith, to deny it and to affirm that all his motives were altruistic. Once he looked back through the cedars. He could still see the boy hunched over, chin in fist, staring at the mat of needles.

As Peter turned the brow of the Big Hill, he saw at its eastern foot the village church, a plain brick building with a decaying spire. Its side was perforated by four tall arched windows. Each was a memorial window of stained glass, which gave the building a black look from the outside. As Peter walked down the hill toward the church he heard the and somewhat nasal singing of uncultivated voices mingled with the snoring of a reed organ.

When he reached Main Street, Peter found the whole business portion virtually deserted. All the stores were closed, and in every show-window stood a printed notice that no business would be transacted between the hours of two and three o'clock in the afternoon during the two weeks of revival then in progress. Beside this notice stood another card, giving the minister's text for the current day. On this particular day it read:

Half a dozen negroes lounged in the sunshine on Hobbett's corner as Peter came up. They were amusing themselves after the fashion of blacks, with mock fights, feints, sudden wrestlings. They would seize one another by the head and grind their knuckles into one another's wool. Occasionally, one would leap up and fall into one of those grotesque shuffles called "breakdowns." It all held a certain rawness, an irrepressible juvenility.

As Peter came up, Tump Pack detached himself from the group and gave a pantomime of thrusting. He was clearly reproducing the action which had won for him his military medal. Then suddenly he fell down in the dust and writhed. He was mimicking with a ghastly realism the death-throes of his four victims. His audience howled with mirth at this dumb show of the bayonet-fight and of killing four men. Tump himself got up out of the dust with tears of laughter in his eyes. Peter caught the end of his sentence, "Sho put it to 'em, black boy. Fo' white men—"

His audience roared again, swayed around, and pounded one another in an excess of mirth.

Siner shouted from across the street two or three times before he caught Tump's attention. The ex-soldier looked around, sobered abruptly.

"Whut-chu want, nigger?" His inquiry was not over-cordial.

Peter nodded him across the street.

The heavily built black in khaki hesitated a moment, then started across the street with the dragging feet of a reluctant negro. Peter looked at him as he came up.

"What's the matter, Tump?" he asked playfully.

"Ain't nothin' matter wid me, nigger." Peter made a guess at Tump's surliness.

"Look here, are you puffed up because Cissie Dildine struck you for a ten?"

Tump's expression changed.

"Is she struck me fuh a ten?"

"Yes; on that school subscription."

"Is dat whut you two niggers wuz a-talkin' 'bout over thaiuh in yo' house?"

"Exactly." Peter showed the list, with Cissie's name on it. "She told me to collect from you."

Tump brightened up.

"So dat wuz whut you two niggers wuz a-talkin' 'bout over at yo' house." He ran a fist down into his khaki, and drew out three or four one-dollar bills and about a pint of small change. It was the usual crap-shooter's offering. The two negroes sat down on the ramshackle porch of an old jeweler's shop, and Tump began a complicated tally of ten dollars.

By the time he had his dimes, quarters, and nickels in separate stacks, services in the village church were finished, and the congregation came filing up the street. First came the school-children, running and chattering and swinging their books by the straps; then the business men of the hamlet, rather uncomfortable in coats and collars, hurrying back to their stores; finally came the women, surrounding the preacher.

Tump and Peter walked on up to the entrance of the Planter's Bank and there awaited Mr. Henry Hooker, the cashier. Presently a skinny man detached himself from the church crowd and came angling across the dirty street toward the bank. Mr. Hooker wore somewhat shabby clothes for a banker; in fact, he never could recover from certain personal habits formed during a penurious boyhood. He had a thin hatchet face which just at this moment was shining though from some inward glow. Although he was an unhandsome little man, his expression was that of one at peace with man and God and was pleasant to see. He had been so excited by the minister that he was constrained to say something even to two negroes. So as he unlocked the little one-story bank, he told Tump and Peter that he had been listening to a man who was truly a man of God. He said Blackwater could touch the hardest heart, and, sure enough, Mr. Hooker's rather popped and narrow-set eyes looked as though he had been crying.

All this encomium was given in a high, cracked voice as the cashier opened the door and turned the negroes into the bank. Tump, who stood with his hat off, listening to all the cashier had to say, said he thought so, too.

The shabby interior of the little bank, the shabby little banker, renewed that sense of disillusion that pervaded Peter's home-coming. In Boston the mulatto had done his slight banking business in a white marble structure with tellers of machine-like briskness and neatness.

Mr. Hooker strolled around into his grill-cage; when he was thoroughly ensconced he began business in his high voice:

"You came to see me about that land, Peter?"

Yes, sir."

"Sorry to tell you, Peter, you are not back in time to get the Tomwit place."

Peter came out of his musing over the Boston banks with a sense of bewilderment.

"How's that? why, I bought that land—"

"But you paid nothing for your option, Siner."

"I had a clear-cut understanding with Mr. Tomwit—"

Mr. Hooker smiled a smile that brought out sharp wrinkles around the thin nose on his thin face.

"You should have paid him an earnest, Siner, if you wanted to bind your trade. You colored folks are always stumbling over the law."

Peter stared through the grating, not knowing what to do.

"I'll go see Mr. Tomwit," he said, and started uncertainly for the door.

The cashier's falsetto stopped him:

"No use, Peter. Mr. Tomwit surprised me, too, but no use talking about it. I didn't like to see such an important thing as the education of our colored people held up, myself. I've been thinking about it."

"Especially when I had made a fair square trade," put in Peter, warmly.

"Exactly," squeaked the cashier. "And rather than let your project be delayed, I'm going to offer you the old Dillihay place at exactly the same price, Peter—eight hundred."

"The Dillihay place?"

"Yes; that's west of town; it's bigger by twenty acres than old man Tomwit's place."

Peter considered the proposition.

"I'll have to carry this before the Sons and Daughters of Benevolence, Mr. Hooker."

The cashier repeated the smile that bracketed his thin nose in wrinkles.

"That's with you, but you know what you say goes with the niggers here in town, and, besides, I won't promise how long I'll hold the Dillihay place. Real estate is brisk around here now. I didn't want to delay a good work on account of not having a location." Mr. Hooker turned away to a big ledger on a breast-high desk, and apparently was about to settle himself to the endless routine of bank work.

Peter knew the Dillihay place well. It lacked the timber of the other tract; still, it was fairly desirable. He hesitated before the tarnished grill.

"What do you think about it, Tump?"

"You won't make a mistake in buying," answered the high voice of Mr. Hooker at his ledger.

"I don' think you'll make no mistake in buyin', Peter," repeated Tump's bass.

Peter turned back a little uncertainly, and asked how long it would take to fix the new deed. He had a notion of making a flying canvass of the officers of the Sons and Daughters in the interim. He was surprised to find that Mr. Hooker already had the deed and the notes ready to sign, in anticipation of Peter's desires. Here the banker brought out the set of papers.

"I'll take it," decided Peter; "and if the lodge doesn't want it, I'll keep the place myself."

"I like to deal with a man of decision," piped the cashier, a wrinkled smile on his sharp face.

Peter pushed in his bag of collections, then Mr. Hooker signed the deed, and Peter signed the land notes. They exchanged the instruments. Peter received the crisp deed, bound in blue manuscript cover. It rattled unctuously. To Peter it was his first step toward a second Tuskegee.

The two negroes walked out of the Planter's Bank filled with a sense of well-doing. Tump Pack was openly proud of having been connected, even in a casual way, with the purchase. As he walked down the steps, he turned to Peter.

"Don' reckon nobody could git a deed off on you wid stoppers in it, does you?"

"We don't know any such word as 'stop,' Tump," declared Peter, gaily.

For Peter was gay. The whole incident at the bank was beginning to please him. The meeting of a sudden difficulty, his quick decision—it held the quality of leadership. Napoleon had it.

The two colored men stepped briskly through the afternoon sunshine along the mean village street. Here and there in front of their doorways sat the merchants yawning and talking, or watching pigs root in the piles of waste.

In Peter's heart came a wonderful thought. He would make his industrial institution such a model of neatness that the whole village of Hooker's Bend would catch the spirit. The white people should see that something clean and uplifting could come out of Niggertown. The two races ought to live for a mutual benefit. It was a fine, generous thought. For some reason, just then, there flickered through Peter's mind a picture of the Arkwright boy sitting hunched over in the cedar glade, staring at the needles.

All this musing was brushed away by the sight of old Mr. Tomwit crossing the street from the east side to the livery-stable on the west. That human desire of wanting the person who has wronged you to know that you know your injury moved Peter to hurry his steps and to speak to the old gentleman.

Mr. Tomwit had been a Confederate cavalryman in the Civil War, and there was still a faint breeze and horsiness about him. He was a hammered-down old gentleman, with hair thin but still jet-black, a seamed, sunburned face, and a flattened nose. His voice was always a friendly roar. Now, when he saw Peter turning across the street to meet him, he halted and called out at once:

"Now Peter, I know what's the matter with you. I didn't do you right."

Peter went closer, not caring to take the whole village into his confidence.

"How came you to turn down my proposition, Mr. Tomwit," he asked, "after we had agreed and drawn up the papers?"

"We-e-ell, I had to do it, Peter," explained the old man, loudly.

"Why, Mr. Tomwit?"

"A white neighbor wanted me to, Peter," boomed the cavalryman.

"Who, Mr. Tomwit?"

"Henry Hooker talked me into it, Peter. It was a mean trick, Peter. I done you wrong." He stood nodding his head and rubbing his flattened nose in an impersonal manner. "Yes, I done you wrong, Peter," he acknowledged loudly, and looked frankly into Peter's eyes.

The negro was immensely surprised that Henry Hooker had done such a thing. A thought came that perhaps some other Henry Hooker had moved into town in his absence.

"You don't mean the cashier of the bank?"

Old Mr. Tomwit drew out a plug of Black Mule tobacco, set some gapped, discolored teeth into corner, nodded at Peter silently, at the same time utilizing the nod to tear off a large quid. He rolled tin about with his tongue and after a few moments adjusted it so that he could speak.

"Yeah," he proceeded in a muffled tone, "they ain't but one Henry Hooker; he is the one and only Henry. He said if I sold you my land, you'd put up a nigger school and bring in so many blackbirds you'd run me clean off my farm. He said it'd ruin the whole town, a nigger school would."

Peter was astonished.

"Why, he didn't talk that way to me!"

"Natchelly, natchelly," agreed the old cavalryman, dryly.—"Henry has a different way to talk to ever' man, Peter."

"In fact," proceeded Peter, "Mr. Hooker sold me the old Dillihay place in lieu of the deal I missed with you."

Old Mr. Tomwit moved his quid in surprise.

"The hell he did!"

"That at least shows he doesn't think a negro school would ruin the value of his land. He owns farms all around the Dillihay place."

Old Mr. Tomwit turned his quid over twice and spat thoughtfully.

"That your deed in your pocket?" With the air of a man certain of being obeyed he held out his hand for the blue manuscript cover protruding from the mulatto's pocket. Peter handed it over. The old gentleman unfolded the deed, then moved it carefully to and from his eyes until the typewriting was adjusted to his focus. He read it slowly, with a movement of his lips and a drooling of tobacco-juice. Finally he finished, remarked, "I be damned!" in a deliberate voice, returned the deed, and proceeded across the street to the livery-stable, which was fronted by an old mulberry-tree, with several chairs under it. In one of these chairs he would sit for the remainder of the day, making an occasional loud remark about the weather or the crops, and watching the horses pass in and out of the stable.

Siner had vaguely enjoyed old Mr. Tomwit's discomfiture over the deed, if it was discomfiture that had moved the old gentleman to his sententious profanity. But the negro did not understand Henry Hooker's action at all. The banker had abused his position of trust as holder of a deed in escrow snapping up the sale himself; then he had sold Peter the Dillihay place. It was a queer shift.

Tump Pack caught his principal's mood with that chameleon-like mental quality all negroes possess.

"Dat Henry Hooker," criticized Tump, "allus was a lil ole dried-up snake in de grass."

"He abused his position of trust," said Peter, gloomily; "I must say, his motives seem very obscure to me."

"Dat sho am a fine way to put hit," said Tump, admiringly.

"Why do you suppose he bought in the Tomwit tract and sold me the Dillihay place?"

Asked for an opinion, Tump began twiddling military medal and corrugated the skin on his inch-high brow.

"Now you puts it to me lak dat, Peter," he answered with importance, "I wonders ef dat gimlet-haided white man ain't put some stoppers in dat deed he guv you. He mout of."

Such remarks as that from Tump always annoyed Peter. Tump's intellectual method was to talk sense just long enough to gain his companion's ear, and then produce something absurd and quash the tentative interest.

Siner turned away from him and said, "Piffle."

Tump was defensive at once.

"'T ain't piffle, either! I's talkin' sense, nigger."

Peter shrugged, and walked a little way in silence, but the soldier's nonsense stuck in his brain and worried him. Finally he turned, rather irritably.

"Stoppers—what do you mean by stoppers?"

Tump opened his jet eyes and their yellowish whites. "I means nigger- stoppers," he reiterated, amazed in his turn.

"Negro-stoppers—" Peter began to laugh sardonically, and abruptly quit the conversation.

Such rank superiority irritated the soldier to the nth power.

"Look heah, black man, I knows I is right. Heah, lonme look at dat-aiuh, deed. Maybe I can find 'em. I knows I suttinly is right."

Peter walked on, paying no attention to the request Until Tump caught his arm and drew him up short.

"Look heah, nigger," said Tump, in a different tone, "I faded dad deed fuh ten iron men, an' I reckon I got a once-over comin' fuh my money."

The soldier was plainly mobilized and ready to attack. To fight Tump, to fight any negro at all, would be Peter's undoing; it would forfeit the moral leadership he hoped to gain. Moreover, he had no valid grounds for a disagreement with Tump. He passed over the deed, and the two negroes moved on their way to Niggertown.

Tump trudged forward with eyes glued to paper, his face puckered in the unaccustomed labor of reading.

His thick lips moved at the individual letters, and constructed them bunglingly into syllables and words. He was trying to uncover the verbal camouflage by which the astute white brushed away all rights of all black men whatsoever.

To Peter there grew up something sadly comical in Tump's efforts. The big negro might well typify all the colored folk of the South, struggling in a web of law and custom they did not understand, misplacing their suspicions, befogged and fearful. A certain penitence for having been irritated at Tump softened Peter.

"That's all right, Tump; there's nothing to find."

At that moment the soldier began to bob his head.

"Eh! eh! eh! W-wait a minute!" he stammered. "Whut dis? B'lieve I done foun' it! I sho is! Heah she am! Heah's dis nigger-stopper, jes lak I tol' you!" Tump marked a sentence in the guaranty of the deed with a rusty forefinger and looked up at Peter in mixed triumph and accusation.

Peter leaned over the deed, amused.

"Let's see your mare's nest."

"Well, she 'fo' God is thaiuh, an' you sho let loose a hundud dollars uv our 'ciety's money, an' got nothin' fuh hit but a piece o' paper wid a nigger-stopper on hit!"

Tump's voice was so charged with contempt that Peter looked with a certain uneasiness at his find. He read this sentence switched into the guaranty of the indenture:

"Be it further understood and agreed that no negro, black man, Afro- American, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, or any person whatsoever of colored blood or lineage, shall enter upon, seize, hold, occupy, reside upon, till, cultivate, own or possess any part or parcel of said property, or garner, cut, or harvest therefrom, any of the usufruct, timber, or emblements thereof, but shall by these presents be estopped from so doing forever."

Tump Pack drew a shaken, unhappy breath.

"Now, I reckon you see whut a nigger-stopper is."

Peter stood in the sunshine, looking at the estoppel clause, his lips agape. Twice he read it over. It held something of the quality of those comprehensive curses that occur in the Old Testament. He moistened his lips and looked at Tump.

"Why that can't be legal." His voice sounded empty and shallow.

"Legal! 'Fo' Gawd, nigger, whauh you been to school all dese yeahs, never to heah uv a nigger-stopper befo'!"

"But—but how can a stroke of the pen, a mere gesture, estop a whole class of American citizens forever?" cried Peter, with a rising voice. "Turn it around. Suppose they had put in a line that no white man should own that land. It—it's empty! I tell you, it's mere words!"

Tump cut into his diatribe: "No use talkin' lak dat. Our 'ciety thought you wuz a aidjucated nigger. We didn't think no white man could put nothin' over on you."

"Education!" snapped Siner. "Education isn't supposed to keep you away from shysters!"

"Keep you away fum 'em!" cried Tump, in a scandalized voice. "'Fo' Gawd, nigger, you don' know nothin'! O' co'se a aidjucation ain't to keep you away fum shysters; hit's to mek you one 'uv 'em!"

Peter stood breathing irregularly, looking at his deed. A determination not to be cheated grew up and hardened in his nerves. With unsteady hands he refolded his deed and put it into his pocket, then he turned about and started back up the village street toward the bank.

Tump stared after him a moment and presently called out:

"Heah, nigger, whut you gwine do?" A moment later he repeated to his friend's back: "Look heah, nigger, I 'vise you ag'inst anything you's gwine do, less'n you's ready to pass in you' checks!" As Peter strode on he lifted his voice still higher: "Peter! Hey, Peter, I sho' 'vise you 'g'inst anything you's 'gwine do!"