The Project Gutenberg EBook of Trout Flies of Devon and Cornwall, and How and When to Use Them, by G. W. Soltau This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Trout Flies of Devon and Cornwall, and How and When to Use Them Author: G. W. Soltau Release Date: January 11, 2019 [EBook #58674] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TROUT FLIES OF DEVON AND CORNWALL *** Produced by F E H and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

All punctuation errors repaired.

Page 12—ancle is an obsolete spelling of ankle, so has been retained.

The corrections listed in the Errata have been applied to the text.

These are noted at the end of the book.

TROUT FLIES

OF

DEVON AND CORNWALL,

AND

WHEN AND HOW TO USE THEM.

BY G. W. SOLTAU, Esq.

LITTLE EFFORD, DEVON.

LONGMAN & CO. PATERNOSTER ROW;

WALLIS AND HOLDEN, EXETER; BRIGHTWELL, BARNSTAPLE; LIDDELL,

BODMIN; HEARD AND SONS, TRURO; AND

EDWARD NETTLETON, WHIMPLE STREET,

PLYMOUTH,

PRINTER TO HER MAJESTY.

1847.

NOTE.

It will be remarked that the Flies furnished by the makers, do not, in all cases, exhibit the same tints as those shown in the drawings; this arises from the difficulty of colouring exactly from the original Flies. I have examined the patterns manufactured by the parties referred to in p. 40, and find they correspond precisely with my own. I would therefore recommend those persons, who are in the habit of making their own flies, to procure patterns from the makers and imitate them, rather than take those in the lithographed sketch for their guide.

ERRATA.

Page 9, line 16, for to apt, read too apt.

Page 15, line 7, for variest, read veriest.

Page 20, line 10, for aught, read naught.

Page 35, line 8, for lace, read Laced.

Page 99, line 8, for falshood, read falsehood.

I am induced to offer the following pages to the youthful aspirant after piscatory fame, from the belief, that the various treatises, which have appeared from time to time on Fly-Fishing, do not contain those minute details, which are so essential to the ready acquirement of the art, and which are generally learnt by slow degrees; either from some experienced angler, or by the accidental discovery of the noviciate.

My chief object however, is to furnish the sportsman, who for the first time is about to wet his line in the west, with a list of flies; which, for a period of twenty years, I have found the most effective, in the Rivers of Devon and Cornwall. I have no doubt, they would be equally successful in Somerset, in the smaller Rivers of Wales, and in some of the Irish Lakes; but, as I cannot vouch from personal experience, I must leave to others the task of testing their more general application.

My remarks are restricted to Fly-Fishing; partly, because I hold this to be the most skilful and pleasing of the various ways by which man secures the wily fish; and also, from the length to which this paper would extend, if I were to enlarge on the numerous other devices adopted to entrap the finny tribe.

Worms, kill-devils, salmon-roe, minnows, cock-chafers, &c. &c. &c., are to be met with in the catalogue of the fisherman’s stock in trade; and, [7]if we extend our researches to distant climes, we find even birds are classed among the fishing implements.

The Cormorant, an aquatic bird of China, and other countries, is an excellent swimmer and diver, and also flies well. It is very voracious, and as soon as it perceives a fish in the water, it darts down with great rapidity, and clings its prey firmly, by means of saw like indentations on its feet. The fish is brought up with one foot; the other foot enables the bird to rise to the surface, and by an adroit movement, the fish is loosened from the foot and grasped in the bird’s mouth.

Le Comte, a French writer, describes the mode in which the Chinese avail themselves of this angling propensity on the part of the cormorants: “to this end,” says he, “cormorants are educated as men rear up spaniels or hawks, and one man can easily manage one hundred. The fisher carries them out into the lake, perched on the [8]gunnel of his boat, where they continue tranquil and expecting his orders with patience. When arrived at the proper place, at the first signal given, each flies a different way to fulfil the task assigned it. It is very pleasant on this occasion, to behold with what sagacity they portion out the lake or the canal where they are upon duty. They hunt about, they plunge, they rise a hundred times to the surface, until they have at last found their prey. They then seize it with their beak by the middle, and carry it without fail to their master. When the fish is too large, they then give each other mutual assistance; one seizes it by the head, the other by the tail, and in this manner carry it to the boat together. There, the boatman stretches out one of his long oars, on which they perch, and being delivered of their burden they then fly off to pursue their sport. When they are wearied he lets them rest for a while: but they are never fed till their work is over. In this manner they supply a very plentiful [9]table—but still their natural gluttony cannot be reclaimed even by education. They have always, when they fish, a string fastened round their throats, to prevent them from devouring their prey, as otherwise they would at once satiate themselves and discontinue the pursuit the moment they had filled their bellies.”

Local information, is at all times, most valuable to the fisherman; without it, his money is often wasted, and his patience, sorely taxed. He purchases flies, which frighten, rather than attract, the fish. A sportsman should seek instruction from every quarter, and not take for granted that the experience he has acquired in his own neighbourhood, will serve him when he roams from home. But many are too apt to rely on their own judgment; they procure flies, which are totally inapplicable to our rivers; they sally forth on a piscatory trip well provided with these monsters; they have little or no sport; are disgusted with our rivers; and seek in some distant land that [10]amusement, which under more favorable auspices, they might have obtained in these counties. Not that our fish generally run so large, as in some parts of the kingdom—they are however very strong, and one of a half pound, will afford better sport, than one of double the weight in some of the more popular streams.

Let not the reader flatter himself, that the closest attention to the suggestions I shall shortly offer; nay, that all the information contained in the numerous books, which have been written upon this interesting subject; will, at once, enable him to supply the larder or gratify a friend; they are only facilities to the acquirement of the science; practice and patience, are required in large proportion to form the expert fisherman. The days, the weeks, which he must devote to the attainment of his wishes, will not however be unprofitably passed, if he avail himself of the numerous opportunities which will offer for the study of those works of nature, with which his [11]path will be abundantly strewed. He will find opportunities for acquiring an insight into the natural history of the finny tribe; into the natural history of the busy fly, or beauteous moth, that tempt the wily fish. The lichen and the moss—the thousand plants that line the rivers bank, or the stately trees and shapeless rocks that shade its waters; all, are subjects, which the more he contemplates, the more he will wonder and admire. And, when by practice, he finds himself an adept in the art, and looks with pleasure on his captured prey; it may suggest the fate of those, who attracted by the glittering tinsel and allured by the gaudy show, follow these dangerous snares and fall a sacrifice to the pomps and vanities of life.

The expert fisherman must be temperate in all things: the steady hand and quick eye are indispensable; the drunkard must quit our ranks,—the feverish temperament,—the blood-shot eye,—the giddy head, bespeak the peril of the man—not [12]of the fish. The epicure must follow his boon companion;—the bloated cheek—the shortened breath—the gouty ancle, are more likely to furnish food for fish, than fish, for food. That temperance has characterised many of our best artists, is evidenced, from the extreme age that several have acquired; for it cannot have been from mere accident, or from their having originally stronger stamina than other mortals, that so many have lived to an age far exceeding the ordinary term of human existence.

Henry Jenkins, who lived to the age of 169, and who boasted when giving evidence in a court of justice, to a fact of one hundred and twenty years date, that he could dub a fly as well as any man in Yorkshire, continued angling for more than a century, after the greater number of those who were born at the same time, were mouldering in their graves.

Dr. Nowell was a most indefatigable angler, allotting a tenth part of his time to his favorite [13]recreation, and giving a tenth part of his income and all the fish he caught to the poor. He lived to the age of 95, having neither his eyesight, hearing, or memory impaired.

Walton, lived to upwards of 90.

Henry Mackenzie, died in January, 1831, aged 86.

These and many others that might be named, were remarkable for their temperate habits: there is no doubt however, that their pursuits by the side of the running streams, whose motion imparts increased activity to the vital principle of the air; and, that composure of mind (so necessary to the perfect health of the body), to which angling so materially contributes, must also have had an influence on their physical constitutions.

We boast in our ranks, some of England’s bravest warriors, her most experienced statesmen, her best divines, and her cleverest philosophers. Our princes have substituted the rod for the [14]sceptre, and have endeavoured to vie with their subjects in the capture of the wily trout.

George the Fourth, was much attached to this amusement, though he was not particularly successful. His fishing apparatus was of the most costly character: the case, containing the various requisites, was covered with the best crimson morocco leather; the edges, sloped with double borders of gold ornaments, representing alternately, salmon, and basket; the outer border, formed a rich gold wreath of the rose, thistle, and shamrock, intertwined by oak leaves, and acorns; the centre of the lid, presented a splendid gold impression of the Royal Arms of Great Britain and Ireland. The case was fastened with one of Bramah’s patent locks, handles, eyes, &c., all double gilt; whilst the interior was lined with the finest Genoese sky-blue velvet. The hooks for angling and fly-fishing were of the most chaste and beautiful description.

That majesty is not famed for proficiency in [15]the art, may be partly accounted for from the circumstance, that fly-fishing is one of the few occupations which depend entirely on the individual skill of the sportsman. Keepers may rise pheasants by the score, and drive hares by the dozen before the well-placed gun; offering shots which the veriest tyro cannot fail to kill: the huntsman by a judicious cast, may exhibit the hounds and their quarry, in the most accommodating proximity to the royal group—the highland deer may be driven within the limits of the rifles range—but, no keeper’s art can oblige a trout to rise; or, compel the salmon to quit its darkened haunt, even for the amusement of princes, or sport of kings. The finny tribe acknowledge no allegiance, and will not be tempted, though the fly be proffered by royal hands. Prompt obedience is expected by kings; a ready compliance with their wishes, is their behest.

Nelson, was an excellent fly-fisher; and, as a proof of his passion for it, continued the pursuit even with his left hand.

Dr. Paley, was ardently attached to this amusement, so much so, that when the Bishop of Durham enquired of him, when one of his most important works would be finished; he said, with great simplicity and good humour, “My Lord, I shall work steadily at it when the fly-fishing season is over;” as if this were a business of his life.

To the list of eminent characters who have been lovers of angling, may be added the name of Robert Burns.

Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd, may be noticed as an expert angler.

Professor Wilson, is one of the best fly-fishers that ever threw a fly.

Wordsworth, is an angler, and in many of his poems may be traced images which have reference to, or have been suggested by this delightful art.

Emerson, the mathematician, was a fly-fisher.

Dr. Birch, formerly Secretary to the Royal Society, was a lover of angling; and Dr. Wollaston and Sir Humphrey Davy, are instances of [17]men of the highest philosophic attainments, finding pleasure in the rod and line.

Chantrey, was much attached to this amusement, and prided himself on the superiority of his equipment.

A sport which is thus seen to be so universally popular, has naturally been selected as a subject upon which some of our ablest men have written many instructive and interesting pages. The first treatise in our language appeared in 1496 but the earliest allusion to the art, is by Elian, who flourished in the year 225. In the fifteenth book of his History of Animals, he says, “that a fish of various color is taken in the River Austræum, between Beræa and Thessalonica.” He also describes a fly which frequents the river, which is greatly preyed on by this fish; he states, that the skilful fisherman, dresses an imitation of it on his hook, forming the body of purple coloured wool, and adding two yellow feathers of a cock’s hackle for wings.

The work which appeared in 1496, was printed by Wynkyn de Worde, and is known by the name of the “Book of St. Albans,” from its having been first printed in the monastery there in 1486. This book is a small folio of seventy-three leaves, and contains short treatises on hawking, hunting, fishing, &c. How long the latter art had been practiced in England before this publication, is not known; but the directions for dressing the twelve different kind of flies, (which even Walton, writing a hundred and fifty years later, availed himself of) are not such, as were likely to be suggested in the infancy of the art.

The treatise commences with the following expositions:—

“Solomon in his parables saith, ‘that a good spirit maketh a flourishing age;’ that is, a fair age and a long.” “If a man lack leech and medicine, he shall make three things, his leech and medicine, and he shall need never no more. The first [19]of them is, a merry thought,—the second is, labour not outrageous,—the third is, diet measurable.”

The writer then proceeds to a comparison of angling, with hunting, hawking, and fowling, and after enumerating the inconveniences attendant on the three last, thus recounts the pleasures and advantages of angling.

“Thus me seemeth, that hunting and hawking, and also fowling, are so laborious and grievous, that none of them may perform, nor be the means to induce a man to a merry spirit; which is the cause of his long life, according unto the said parable of Solomon.

“Doubtless then it followeth that it needs must be the desport of fishing with an angle, for all other manner of fishing is laborious and grievous, often making folks full wet and cold, which many times hath been cause of great infirmities.

“But the angler may have no cold, nor no disease, nor anger, except he be the cause himself. [20]For he may not lose at the most, but a line and a hook, of which he may have store plenty of his own making, as this simple treatise shall teach him. So then his loss is not grievous, and other griefs may he not have, saving if any fish break away, after that he is taken on the hook, or else that he catch nought. Which is not grievous. For if he fail of one, he may not fail of another, if he doeth as this treatise teacheth; except there be naught in the water.

“And yet, at least he has his wholesome walk and merry at his ease, and hath a sweet air of the sweet savour of the mead flowers that maketh him hungry. He heareth the melodious harmony of fowls. He seeth the young swans, herons, ducks, coots, and many other fowls with their broods: which seemeth to me, better than all the noise of hounds, the blast of horns, and the cry that hunters, falconers, and fowlers, can make.

“And if the angler take fish, surely then, there is no man merrier than he is in his spirit.

“Also, whoso will use the game of angling, he must rise early; which thing is profitable to man in this wise, (that is to wit) most to the health of his soul, for it shall cause him to be holy. And to the health of his body, for it shall cause him to be whole. Also to the increase of his goods, for it shall make him rich, as the old English proverb says, in this wise, ‘whoso will rise early, shall be holy, healthy, and wealthy.’

“Thus, have I proved in my intent, that the sport of angling is the very means and cause that induceth a man unto a merry spirit. Which after the said parable of Solomon, and the said doctrine of physic, maketh a flowering age and a long.

“And therefore to all you that be virtuous, genteel, and free born, I write and make this simple treatise following, by which ye may have the full craft of angling to desport you at your pleasure, to the intent that your age may be the more flower and the more longer to endure.”

From the first publication of this book to the [22]appearance of “Walton’s Complete Angler,” there seems to have been no improvement of the original work; on the contrary, the “doers” of new editions of the book under new titles seem to have had but little skill in the art of fly-fishing, and their alterations, as Pinkerton said of Evelyn’s amendments of his work on medals, “are for the worse.”

In 1653, appeared the first edition of “Walton’s Complete Angler; or, Contemplative Man’s Recreation:” in small duodecimo, adorned with cuts of most of the fish mentioned in it. It came into the world attended with laudatory verses by several writers of the day, and had in the title page, (though Walton thought proper to omit it in future editions) this apposite motto, “Simon Peter said, I go a fishing, and they said, we also will go with thee.” John xxi. 3.

Isaac Walton, was born at Stafford, in August, 1593. He settled in London as a shopkeeper, in the Royal Exchange; and, as in the year 1624, [23]he was fixed in a different part of the city, it is supposed, he was one of the first inhabitants of that building; and being then but twenty-three years, was perhaps one of those industrious young men whom, as we are told, the munificent founder himself, Sir Thomas Gresham, placed in the shops erected over that edifice. We next hear of him in Chancery Lane, where he carried on the trade of a linen draper. About 1643, he left London with a fortune, very far short of what would now be called a competency; we are told he subsequently “lived at Stafford and elsewhere, but mostly in the families of the eminent clergymen of England, of whom he was much beloved.” He employed his time in writing several biographical works, and at the advanced age of eighty-three, (which, to use his own words) “might have procured him a writ of ease, and secured him from all further trouble in that kind,” he undertook to write the life of Dr. Robert Sanderson, Bishop of Lincoln, which was published in 1677. In [24]1683, when he was ninety years old, he published “Thealma and Clearchus,” a pastoral history, in smooth and easy verse. He lived but a short time after the publication of this poem; for, as Wood says, “he ended his days on the fifteenth day of December, 1683,—in the great frost at Winchester, at the house of Dr. William Hawkins, a prebendary of the church there, where he lies buried.”

The “Complete Angler” has passed through several editions; and, although the art has greatly improved since Walton’s day, its perusal will afford much information and amusement, as well to the sportsman as the general reader; for, in the words of one of the editors, “let no man imagine, that a work on such a subject, must necessarily be unentertaining, or trifling, or even uninstructive; for the contrary will most evidently appear, from a perusal of this excellent piece, which, whether we consider the elegant simplicity of the style; the ease, and unaffected [25]humour of the dialogue; the lovely scenes which it delineates; the enchanting pastoral poetry which it contains; or, the fine morality it so sweetly inculcates; has hardly its fellow in any of the modern languages.”

These remarks are very applicable to other treatises which have appeared on the same subject, more especially those of Shaw, Scrope, and Sir H. Davie; indeed, there are few works more beautifully written than “Salmonia,” wherein the talented author thus alludes to his favorite recreation.

“The search after food, is an instinct belonging to our nature; and from the savage in his rudest and most primitive state, who destroys a piece of game, or a fish, with a club or spear—to man in the most cultivated state of society, who employs artifice, machinery, and the resources of various other animals to secure his object, the origin of the pleasure is similar, and its object the same; but that kind of it requiring most art, may be said [26]to characterise man in his highest or intellectual state; and the fisher for salmon or trout with the fly, employs not only machinery to assist his physical powers, but applies sagacity to conquer difficulties; and the pleasure derived from ingenious resources and devices, as well as from active pursuit, belongs to this amusement. Then as to his philosophical tendency; it is a pursuit of moral discipline—requiring patience, forbearance and command of temper. As connected with natural science, it may be vaunted as demanding a knowledge of the habits of a considerable tribe of created beings—fishes, and the animals that they prey upon; and an acquaintance with the signs and tokens of the weather and its changes, the nature of waters and of the atmosphere. As to its poetical relations, it carries us into the most wild and beautiful scenery of nature; amongst the mountain lakes, and the clear and lovely streams that gush from the higher ranges of elevated hills—or that make [27]their way through the cavities of calcareous strata.

“How delightful in the early spring, after the dull and tedious time of winter, when the frosts disappear, and the sunshine warms the earth and waters, to wander forth by some clear stream, to see the leaf bursting from the purple bud, or scent the odours of the bank perfumed by the violet, and enamelled, as it were, with the primrose and the daisy;—to wander upon the fresh turf below the shade of trees, whose bright blossoms are filled with the music of the bee,—and on the surface of the waters to view the gaudy flies sparkling like animated gems in the sunbeams, whilst the bright and beautiful trout is watching them from below;—to hear the twittering of the water-birds, who, alarmed at your approach, rapidly hide themselves beneath the flowers and leaves of the water-lily;—and as the season advances, to find all these objects changed for others of the same kind, but better and brighter, [28]till the swallow and the trout contend as it were for the gaudy May fly, and till, in pursuing your amusement in the calm and balmy evening, you are serenaded by the songs of the cheerful thrush and the melodious nightingale, performing the offices of maternal love, in thickets ornamented with the rose and the woodbine.”

Sir H. Davie’s researches in natural history, are exhibited in many parts of this interesting work, and his suggestions with reference to the migration of animals, will account for those phenomena, which direct the operations of the sportsman whether armed with gun or rod. He is of opinion that the two great causes of the change of place of animals is the providing of food for themselves and resting places and food for their young. The great supposed migrations of herrings from the poles to the temperate zone, he considers to be only the approach of successive shoals from deep to shallow water, for the purpose of spawning.

The migrations of salmon and trout are evidently for the purpose of depositing their ova—or of finding food after they have spawned.

Swallows and bee-eaters, decidedly pursue flies half the globe over; the snipe tribe in like manner, search for worms and larvæ—flying from those countries where either frost or dryness prevents them from boring—making generally small flights at a time, and resting on their travels where they find food. A journey from England to Africa is no more for an animal that can fly with the wind one hundred miles in an hour, than a journey for a Londoner to his seat in a distant province.

The migration of smaller fishes or birds always occasions the migration of larger ones, that prey on them:—thus, the seal follows the salmon in summer, to the mouths of rivers—the hake follows the herring and pilchard—hawks are seen in great quantities in the month of May, coming into the east of Europe after quails and landrails—and locusts are followed by numerous birds, [30]that fortunately for the agriculturists, make them their prey.

The reason of the migration of sea-gulls to the land is their security of finding food. They may be observed, at this time, feeding greedily on the earth worms and larvæ, driven out of the ground by severe floods, and the fish, on which they prey in fine weather in the sea, leave the surface when storms prevail, and go deeper.

The different tribes of the wading birds always migrate, when rain is about to take place. The vulture, upon the same principle, follows armies, and there is little doubt, that the augury of the ancients was a good deal founded upon the observation of the instinct of birds. There are many superstitions of the vulgar, owing to the same cause.

For anglers, in spring, it is always unlucky to see single magpies, but two may be always regarded as a favorable omen; and the reason is, that in cold and stormy weather one magpie [31]alone leaves the nest in search of food, the other remaining sitting upon the eggs or the young ones; but when two go out together, the weather is warm and mild, and thus favorable to fishing.

I shall dismiss Sir H. Davie for the present, with the following remarks which he offers on the whale, as they may be interesting to those who have remarked the comparatively easy capture of an animal, possessed of such enormous strength and activity.

The whale, having no air-bladder, can sink to the lowest depths of the ocean; and mistaking the harpoon for the teeth of the sword fish or a shark, he instantly descends, this being his manner of freeing himself from these enemies, who cannot bear the pressure of a deep ocean: and from ascending and descending, in a small space, he puts himself in the power of the whaler; whereas, if he knew his force, and were to swim on the surface in a straight line, he would break or destroy the machinery by which he is arrested, [32]as easily as a salmon breaks the single gut of a fisher, whose reel is entangled.

Mr. Scrope’s work entitled “Days and Nights of Salmon fishing,” is most interesting; his description of this enticing sport is so vivid, and given with such spirit, that even those who never saw a rod, except that in Oxford-street with a golden perch hanging from its point and for ever turning on its axis; or whose knowledge of fish is confined to the unfortunate inmates of a glass globe, are led to take a lively interest in his various piscatory adventures, and cease to wonder that some of the wisest and best of men have been enthusiastic admirers of the art. His apology for fly fishing is ingenious, and may be quoted when the angler is rallied by his tender-hearted neighbour.

“I take a little wool and feather, and tying it in a particular manner on a hook, make an imitation of a fly; then I throw it across the river, and let it sweep round the stream with a lively motion. This I have an undoubted right to do; for the [33]river belongs to me or my friend,—but mark what follows. Up starts a monster fish, with his murderous jaws, and makes a dash at my little Andromeda. Thus he is the aggressor, not I; his intention is evidently to commit murder. He is caught in the act of putting that intention into execution. Having wantonly intruded himself on my hook, which I contend he had no right to do, he darts about in various directions, evidently surprised to find that the fly, which he hoped to make an easy conquest of, is much stronger than himself. I naturally attempt to regain this fly, unjustly withheld from me. The fish gets tired and weak, in his lawless attempts to deprive me of it. I take advantage of his weakness, I own, and drag him, somewhat loth, to the shore; where one rap at the back of the head ends him in an instant. If he is a trout, I find his stomach distended with flies. That beautiful one called the May fly, who is by nature almost ephemeral—who rises up from the bottom of the shallows, [34]spreads its light wings, and flits in the sunbeam, in enjoyment of its new existence—no sooner descends to the surface of the water to deposit its eggs, than the unfeeling fish, at one fell spring, numbers him prematurely with the dead. You see, then, what a wretch a fish is; no ogre is more blood thirsty, for he will devour his nephews, nieces, and even his own children, when he can catch them, and I take some credit for having shown him up. What a bitter fright must the smaller fry live in! They crowd to the shallows, lie hid among the weeds, and dare not say the river is their own, I relieve them of their apprehensions, and thus become popular with the small shoals.”

I must now hasten to offer those suggestions which I deem so requisite for the attainment of that popularity to which Mr. Scrope alludes; and although I may in some respects appear tedious, I beg to assure the novice that a good day’s fishing is often lost for lack of some trifling [35]appendage, and many a leviathan has escaped from the neglect of some simple rule.

The dress of a fisherman should be as sombre as possible—a darkish grey or lightish brown is probably the best, as these colours assimilate with that of the bark of trees, and the mosses and lichens which encrust the rocks. Shining metal buttons must be avoided. Laced boots or shoes and stout leather gaiters are needed, as vipers resort to the rivers in warm weather, and their teeth readily penetrate the unprotected stocking. By the bye, if the sportsman should unfortunately be bitten, a little carbonate of soda, or sweet oil should be applied to the part as speedily as possible. I have found the former most efficacious when my dogs have been bitten by those reptiles. Our moors abound with them in August and September; it is well therefore to be provided with a bottle of these simple antidotes, if a lengthened excursion is contemplated by the angler or shot. A drab hat is preferable to black, [36]especially in hot weather, when the latter will be found to heat the head considerably more than the former. Worsted socks are less apt to chafe the feet than cotton, and a small portion of yellow soap rubbed on the instep and heel will keep the feet in good order during the longest day’s fag.

The next question is, what is the fitting time for adopting this costume? Fishing may be pursued from the first week in March until the last week in October. During the months of March, April, September, and October, from ten to three or four, will be found the most profitable hours; during the intervening months it is necessary, to ensure sport, to be early on the banks—from six to eleven, and from three till dusk, are generally the best hours. Before starting, be careful that your tackle is complete and in good order. The rod, the fly-book, the reel, the basket, must be examined, that nothing be left behind. It is justly considered one of the greatest miseries of life to find oneself, after a long ride or walk, minus [37]either the above articles. These necessary appendages should be of the best quality, to ensure which, purchase them from a maker of known celebrity. In the first place, procure a twelve-foot rod, which has a uniform even play; avoid a cheap, second rate article, nine times out of ten it will be found to warp, crack, or snap off; or if it escapes these calamities, the ferrels will become loose, or the rings through which the line passes will check or chafe it at every throw. Let your reel and line be of the best workmanship, the size of the former and length of the latter the maker will inform you; the twelve-foot rod indicates a narrow river, requiring the other articles in proportion. The casting lines should be seven or even eight feet long, made of round gut, small by degrees, and beautifully less to the end, where the stream-fly is attached. They must be stained light blue, for clear; brown, for red or pale ale coloured water: our rivers are frequently of this colour, occasioned by the rain percolating through [38]the bogs with which our moors abound. Never use more than two flies, one at the end of the collar, called the “stream-fly,” the other about three feet from it, called “the bob.” It may be as well to observe that when our rivers present the beerish appearance above described, and the day is fine, with occasional clouds, a good day’s sport may generally be depended on. The wind however must be consulted as well as the water—if the weathercock indicates any portion of East wind, relinquish the rod, and seek some other occupation. Fish have a peculiar aversion to cold wind, and will not be tempted to expose their noses within some distance of the surface; the fly, therefore, though thrown with skill and judgment, will sport on the water in profitless gambols. A Southerly wind and a cloudy sky are as welcome to the fisherman as the fox-hunter: indeed the wind in that quarter generally promises well for all field sports. West, if the weather is settled, is also good; but from W. by N. to N. by E. it becomes less and less favorable.

The choice of flies is the next consideration: as a general rule, when the day is bright, use a dark fly, when gloomy, a bright one. The Devonshire and Cornish fish are particular in their food—preferring simple, plain viands; hence I have often seen sportsmen unsuccessful in their efforts to move our trout—they present them with food which instinct tells them is not congenial; they rise probably, look at the monster, and depart to rise no more.

Neither do our fish desire much change of diet: the flies enumerated on the annexed leaves are sufficient for all their wants, and if thrown with skill, will surely repay the labour.

Purchase a Russia leather fishing book for the reception of these gay deceivers. I recommend this material, because the moths will not intrude within its folds. Let the article be no larger than sufficient to carry a small collection of flies, four casting lines, a penknife, and scissors to repair damages, a skein of strong black silk, and forget [40]not a small piece of Indian rubber, with a piece of white tape attached thereto; the former to pass your casting line over, twice or thrice, which immediately straightens it, the latter enables you to recover the former, if through carelessness it falls to the ground.

Immediately above the flies, when placed in their respective loops, write their numbers and the period when they are to be used; this will save you much trouble, and your friend also should he borrow the book.

Each fly is entitled to a distinct appellation, but it frequently happens that the dun of Mr. A. differs materially from that of Mr. B.; thus the sportsman is disappointed in his application—when the packet arrives he scarcely recognises one of his old acquaintances. To avoid this inconvenience, I have adopted figures, and have furnished Mr. W. H. Alfred, No. 54, Moorgate Street, and 41, Coleman Street; Messrs. Ben. Chevalier and Co. Bell Yard, Temple Bar, [41]London; and Mr. J. N. Hearder, 28, Buckwell Street, Plymouth; with full particulars. Those persons have engaged to keep a good stock on hand, so by sending to either of them for any No. required, no mistake can arise.

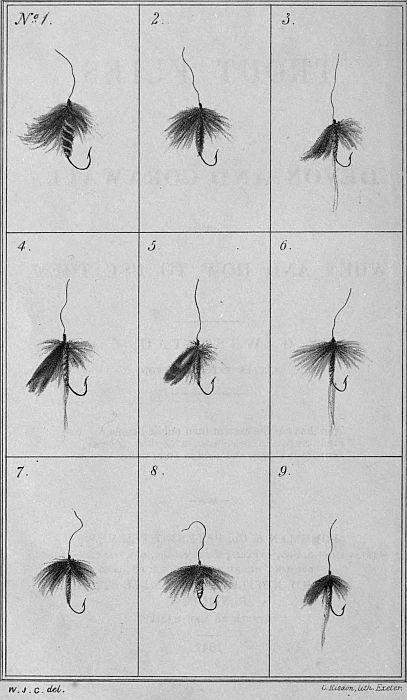

February, March, and April, at all times; after rain, at any time throughout the season.

February, March, and April.

A good fly through the season, especially on windy days. Makes an excellent bob.

Latter end of February, the entire of March, and the early part of April.

From the second week in April to the end of the season, particularly under bushes, and on the moors.

For dark, gloomy, windy days, from the middle of March to the end of the season.

Good fly from the last week in April to the first of August, in hot days especially.

In hot weather, during the months of May, June, and July, no fly will equal it.

Excellent moor fly at all times. Makes a good bob, particularly on chilly days.

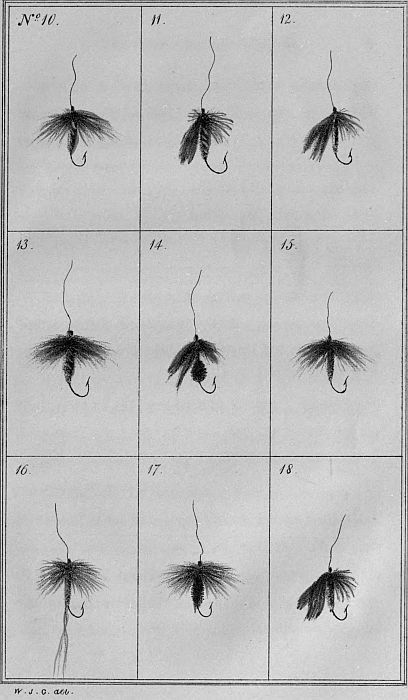

After rain throughout the season. Take this for the stream fly, and No. 1, for the bob, where the waters are the colour of small beer.

Latter end of August, all September, to the third week in October.

Very good moor fly, especially in March, April, and August. Use this for bob, and No. 5, for stream.

From the latter end of May to the last week in August. Later in the season if the weather is warm.

In hot days, in May and June, a most killing fly.

A very superior fly in June and July, or hot sultry days. A good bob, with No. 8, as stream.

In sultry weather, after rain in June, July, and beginning of August.

From the second week in June, to the second week in August, a very certain killer in hot days.

A good fly from the second week in July to the end of the season. A superior bob on the moors.

A black fly with silver twist may occasionally be substituted for No. 13. They are sold at all tackle makers.

The white moth is sold at all tackle makers, and is a good fly on moon-light nights in June and July.

Although Eighteen sorts are enumerated, it is by no means necessary that the occasional fisherman should be provided with the full complement.

It will generally be found that Nos. 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 17, are certain killers. The others, however, must be procured by the more indefatigable sportsman; especially if he is undaunted by wind or weather.

Every thing being now in readiness for a start, be careful to commence fishing with the sun in your face, and if possible, keep it so during the day. By adopting this precaution, the shadow of yourself and rod will not be cast upon the water, and [46]your presence consequently is less likely to be observed by the fish than if a contrary position were adopted. Let me urge the great importance of keeping out of sight of your prey as much as possible. If the banks are high and open, crouch down, and if needs be, creep on, as you would if a duck and mallard were the object of your pursuit, until you find you can command the pool in your prostrate position. If bushes intervene, of course you may approach with boldness: less caution is also needed when the banks are nearly even with the surface of the water.

As a general rule, I am in favour of fishing up the stream for trout; the heads of the fish being always against the current, their eyes are pointed in the same direction, looking for flies, &c., which may be floating down on the surface; your approach therefore is not so readily perceived, and your fly when taken is pulled against the jaw, and not from it as is often the case when fishing [47]down the stream. The casting the fly well and lightly is a knack which can only be acquired by experience. The spring of the rod should do the chief work, and not the labour of your arms. To effect this, you should lay the stress as near the hand as possible, and make the wood undulate from that point, which is done by keeping the elbow in advance, and doing something with the wrist which is not very easy to explain. Thus, the exertion should be chiefly from the elbow and wrist, and not from the shoulders.

A little practice will enable you to determine the length of line required to reach a given spot: until this knowledge is acquired, rather throw too short than too long a line. In the latter case, it will bag in the water and scare the fish, or if per chance one rises, it will most probably escape, before you have power to strike.

The stream fly should fall lightly on the desired spot, and the line, being just of sufficient length [48]to allow of the exact point being reached, the bob fly will rest on the surface of the water, and by imparting to the rod a slight tremulous motion, from right to left, the stream fly will appear to be struggling in the stream, whilst the bob will occasionally bob up and down, (from which circumstance its name is derived) exhibiting the movement of the natural fly, when it alights, rises, and again alights.

After some experience, the eye will apprize you when the fish rises to seize the hook; you are doubly prepared to strike, if your line is on the stretch, in which case, you feel, as well as see your prey.

Striking, signifies a sudden jerk of the rod, at the instant the fish has taken the hook, and forms a very important feature in the art of fishing. If the jerk is too violent, the hook will probably be torn from its hold, or if it be too slight, the hook will not enter the jaw, and the fish escapes. The happy medium must be aimed at, [49]remembering that our small fish require gentler treatment, than those of greater weight, whose capacious mouths afford a firmer hold, and may be treated with less ceremony.

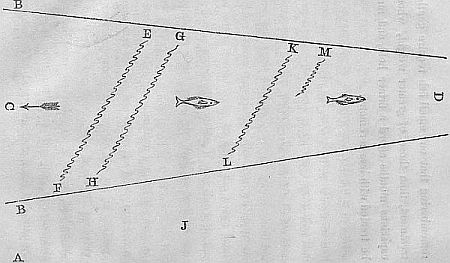

Commence by throwing the fly across the tail of the stickle, thus:—A. is the fisherman, B. B. the banks of the river, C. the tail of the stickle, D. its commencement. A. first throws his fly across to E. then draws it with a kind of tremulous motion to F. then to G. and back to H. A. then moves on, and takes up his position at J. casts over to K. and across to L. tries again at M. and hooks a fish. If it is small, as too many of our West Country fish happen to be, it may be raised instanter, gently out of the water, and deposited in the basket. A. then advances a few paces, and finishes the pool between M. and D.

If by good luck a large fish is hooked, don’t attempt to jerk him out of the water, which frequently snaps the gut or tears the hook from its hold; but to use a technical term, “play him,” that is, let him swim about with your fly well embodied in his jaw, until he is sufficiently exhausted to enable you to take him out, either by lifting him over the bank, by taking the casting [52]line in your hand, or by drawing him upon the sand or gravel. Whilst the fish is engaged in endeavouring to rid itself of the disagreeable customer in its mouth, be careful to maintain a steady, uniform strain, upon the line; don’t jerk at one time and slack at another. If the fish is unusually large, the butt of your rod must be held forward, which throws the point back; and thus the line presses against the entire length of the rod, and offers greater opposition to the fish than if the top were kept down and the butt up. The following hints, from the pen of an experienced fisherman, are deserving special notice.

“If your fish misses the fly in making his offer, wait awhile before you throw a second time, and if he rises at all, he will come more greedily for this delay. When he returns to his seat, after the unsuccessful sortie, he will say mentally, ‘What a donkey I was to be so awkward! By St. Antonio, if he comes again, I’ll smash him!’ But if you keep lashing away at him immediately, [53]he will probably treat you with contempt, and will have no intercourse with your gay deluders for the rest of the day. It is some time, perhaps, since he has taken up his seat in the water, without ever having seen an animal like that which you are so obliging as to tender him; all of a sudden come a swarm of locusts, as it were, one after another over his nob, which astonish and alarm him exceedingly. Thus, it is apparent that you do not do justice to his sagacity, or instinct, or whatever you please to call it, if you set to work in such an intrusive manner.”

The preceding hints on trout fishing may with some exceptions, be adopted by the salmon and salmon peal fisher; before I proceed however to offer a few observations on the mode of fishing for these fish, a brief notice of the natural history of the trout may not be unacceptable.

The common trout is an inhabitant of most of the rivers and lakes of Great Britain. It is a voracious feeder and is vigilant, cautious, and [54]active. During the day, the larger sized fish move little from their accustomed haunts, but towards evening and during the night, they rove in search of small fish, insects, and their various larvæ, upon which they feed with eagerness.

The young trout fry may be seen throughout the day, sporting in the shallow gravelly scours of the stream, where the want of sufficient depth of water, or the greater caution of larger and older fish prevent their appearance. Though vigilant and cautious in the extreme, the trout is also bold, and active. A pike and a trout put into a confined place together, had several battles for a particular spot, but the trout was eventually the master. This fish varies considerably in appearance in different localities; so much so, as to induce a belief that several species exist. Lord Home, however, who has paid much attention to the subject, remarks, “I am much inclined to think there is but one kind of river trout; the large lake trout may be different.”

Sir Wm. Jardine, in a paper on Salmonidæ, has described at considerable length, the variations observable in the trout of some of the lakes of Sutherlandshire. The fish in these lakes are reddish, dark, or silvery, according to the clearness of the water.

Mr. Neil, in his tour, notices the black moss trout of Loch Knitching, and Loch Katrine, is said to abound also with small black trout; an effect considered to be produced in some waters by receiving the drainage of boggy moors. In streams that flow rapidly over gravelly or rocky bottoms, the trout are remarkable for the brilliancy and beauty of their spots and colours. Thus, in our immediate neighbourhood, we find that the trout caught between Shaugh Bridge and Plym Steps, on the river Cad, are generally very dark, approaching in some instances almost to a black; whilst on the Tavy, below Denham Bridge, they will be found of a light silvery hue; so also on the Yealm—those taken below Lee Mill [56]Bridge, are of a bright sparkling appearance, whilst others caught in Horns and Dendles, or on the moor above, are generally very dark, and in some of the pools which seldom enjoy the rays of the sun, are almost black.

The author of the “Wild Sports of the West of Ireland” remarks, “I never observed the effect of bottom soil upon the quality of fish so strongly marked as in the trout taken in a small lake, in the county of Monaghan. The water is a long irregular sheet, of no great depth: one shore bounded by a bog, the other, by a dry and gravelly surface. On the bog side, the trout are of the dark and shapeless species peculiar to moory loughs, while the other affords the beautiful and sprightly variety, generally inhabiting rapid and sandy streams. Narrow as the lake is, the fish appear to confine themselves to their respective limits: the red trout being never found upon the bog moiety of the lake, nor the black where the under surface is hard gravel.”

Sir H. Davie gives the following account of their spawning; and his remarks on some of the flies upon which they feed will be found interesting.

“Trout spawn or deposit their ova and seminal fluid in the end of Autumn or beginning of Winter, from the middle of November till the beginning of January: this materially depending upon the temperature of the season, their quantity of food, &c. For some time (a month or six weeks) before they are prepared for the sexual functions, or that of reproduction, they become less fat, particularly the females, the large quantity of eggs and their size, probably affecting the health of the animal, and compressing generally the vital organs in the abdomen. They are at least six weeks or two months after they have spawned before they recover their flesh, and the time when these fish are at the worst, is likewise the worst time for fly fishing, both on account of the cold weather and because there are fewer flies on [58]the water than at any other season. Even in December and January there are a few small gnats, or water flies on the water in the middle of the day, in bright days or when there is sunshine. These are generally black, and they escape the influence of the frost, by the effects of light on their black bodies—and probably, by the extreme rapidity of the motions of their fluids, and generally of their organs. They are found only on the surface of the water, where the temperature must be above the freezing point.

“In February a few double winged water flies, which swim down the stream, are usually found in the middle of the day—such as the willow fly, and the cow-dung fly is sometimes carried on the water by winds. In March there are several flies found on most rivers, and in April, the blue and browns come on—the first in dark days—the second in bright. These lay their eggs in the water, which produce larvæ that remain in the state of worms, feeding and breathing in the water, till [59]they are prepared for their metamorphosis, and quit the bottoms of the rivers, and the mud, and stone, for the surface, and the light and air.

“The brown fly usually disappears before the end of April—but of the blue dun there is a succession of different tints, or species, or varieties, which appear all the summer and autumn long. The excess of heat seems equally unfavorable, as the excess of cold, to the existence of the smaller species of water insect, which during the intensity of sunshine seldom appear in summer, but rise morning and evening. Towards the end of August the ephemera appear again in the middle of the day. To attempt to describe all the variety that sport on the surface of the water at different times of the day, throughout the year, would be quite an endless labour. Some of them appear to live only a few hours, none have their existence protracted to more than a few days. Of the beetle, there are many varieties fed on by fishes.—These insects are bred from eggs, which [60]they deposit in the ground, or in the excrement of animals. The cock-chafer, the fern fly, and gray beetle, are common in our meadows in the summer, but there is hardly any insect that flies, including the wasp, the hornet, the bee, and the butter-fly, that does not become at sometime, the prey of fishes.”

Mr. Stoddart mentions an interesting experiment made with trout some years ago, in the South of England, in order to ascertain the value of different food. “Fish were placed in three separate tanks, one of which was supplied daily with worms, another with live minnows, and the third with those small dark coloured water flies, which are to be found moving about on the surface, under banks, and sheltered places. The trout fed with worms grew slowly, and had a lean appearance; those nourished on minnows, which it was observed they darted at with great avidity, became much larger; while, such as were fattened, upon flies only, attained in a small time, prodigious [61]dimensions, weighing twice as much as both the others together, although the quantity of food swallowed by them was in nowise so great.”

In the new Sporting Magazine for Nov., 1840, a writer on fishes says, “An acutely-observing friend of mine, who has paid great attention to the growth of trout, states that they are rarely visible the first year, that they congregate with minnows and other small fry; the second, are found on shallows; the third summer, about seven or eight inches long; and subsequently increase rapidly to a pound or a pound and a half, dependent on the quantity and quality of their food, the season, and other circumstances.”

This gentleman has for years kept trout in a kind of store stream, and having fed them with every kind of food, has had some of them increase from one pound to ten pound in four years.

Steven Oliver, in his agreeable scenes and recollections of fly fishing, mentions a trout taken in the neighbourhood of Great Driffield, in [62]September, 1832, which measured thirty-one inches in length, twenty-one in girth, and weighed seventeen pounds.

A few years since, a notice was sent to the Linnæan Society, of a trout that was caught on the 11th January, 1822, in a little stream, ten feet wide, branching from the Avon, at the back of Castle-street, Salisbury. On being taken out of the water, its weight was found to be twenty-five pounds. Mrs. Powell, at the bottom of whose garden the fish was first discovered, placed it in a pond, where it lived some time.

The age to which trout may arrive, has not been ascertained. Mr. Oliver mentions that in August, 1809, a trout died which had been for twenty-eight years an inhabitant of the well, in Dumbarton Castle.

A trout died in 1826, which had lived 53 years in a small well in the orchard of Mr. William Mossop, of Board Hall, near Broughton, in Furness.

The trout in our streams rarely exceed a pound in weight: this may, in some degree, be accounted for from the circumstance, that the Devon and Cornish rivers are very rapid, consequently, the insects which fall from the bushes, are carried so swiftly down the stream, that whilst a fish is engaged in seizing on one, the others pass rapidly by: the same remarks may, in times of flood, apply to worms, &c. In more tranquil rivers a fly seldom escapes; it lights, or is blown on the water, is immediately espied, and the fish, whilst occupied in seizing one, has half-a-dozen in his eye, each awaiting his leisure in calm repose. That our trout will increase rapidly, under favorable circumstances, I can testify from my own experience. I knew several that were placed in a pond, in August, which averaged from eight to ten ounces; in the July following, I caught the same fish with a fly, which averaged from one pound to one pound and a half.

Before taking leave of trout, I must notice a fly [64]which may be used with success after sunset, in the months of July and August. It is called the white moth, and has often given me sport as late as ten and eleven on fine moon-light nights. Choose an open place on a tranquil portion of the river; the fly may be thrown with less nicety than in the day-time, and catching a fish does not alarm the neighbouring fry, who will frequently seize the moth immediately after the water has been disturbed by the efforts of the captured fish to rid itself from the hook.

Fly-fishing for salmon is seldom pursued in these counties. The fish meets with such a host of formidable enemies as soon as it quits the sea, that comparatively few ascend our rivers. The intent of the proprietors of our fisheries appears to be the annihilation of this prince of fishes. The most impracticable weirs are constructed, over which it is almost impossible for a fish to leap; in the pools immediately below, the rapacious fisherman casts his net every tide; whilst [65]above, if perchance a fish does succeed in evading the cunning of his netting foes, a host of spearmen are on watch by night, as well as by day, to immolate the persecuted wanderer.

Laws exist, restricting the capture of salmon, within certain months; but that which in this case is truly everybody’s business, is considered nobody’s; consequently, in season and out of season are they caught, sold, and devoured, as openly as if no penalties were incurred by the act. That food, which under proper regulation would soon become abundant and reasonable, can only now be placed on the tables of the affluent.

The preservation of salmon I hold to be a question of national importance; so much so, that I consider conservators should be appointed to protect them, as well from the unlawful proceedings of the owners of fisheries, as from the unscrupulous acts of the poacher. Weirs should be so constructed as to admit of their ascending whenever the waters are swollen by floods; hutches [66]should be kept open at least forty-eight hours during the week.

Besides the perils which await the parents on their journey from the sea, their young are also in imminent danger on their route towards the sea. The millers take them in traps, by thousands, and dispose of them by the gallon to the neighbours; indeed, at times they are taken in such vast quantities that pigs are regaled upon their delicate flesh.

Man is not content with employing his own ingenuity in capturing this delicious fish, he calls to his aid the sagacity of the dog, which we find becomes, by practice, as expert a fisherman as his master: numerous instances of this are on record. The following are well-established facts:—In the work by the Reverend William Hamilton, an interesting account is related of the assistance afforded by a water-dog to some salmon fishermen, when working nets in shallow pools. The dog takes his post in a ford where the water [67]is not very deep, and at a distance below the net; if a salmon escapes the net, the fish makes a shoot down the river, in the direction towards the sea; the dog watches, and marks his approach by the ripple on the water, and endeavours to turn the fish back towards the net, or catch him; if he fails in both attempts, the dog then quits the water, in which the pace of the fish is too fast for him, and runs with all his speed down the bank to intercept the fish at the next shallow ford, where another opportunity, and a second diverting attempt, occurs.

Dogs are occasionally used in Glamorganshire, when trying for salmon. They appear to take great pleasure in the pursuit, exhibiting by turns the most patient watchfulness, persevering exertion, or extraordinary sagacity, as either quality may best effect the wishes of the master.

In some parts of Wales, where the rivers are narrow, the salmon are caught in a net drawn by men on each bank; dogs are trained to swim over [68]from side to side, with the head and ground lines of the net, as required.

A clever poacher at Totnes, allows that he has killed many salmon in the night, on the Dart, by setting a trammel net at the lower end of the deep pools, by sending in a dog at the upper end of the pool, which dog he had trained to dive like an otter. The fish, as soon as the dog dived, immediately dashed down the stream, and were taken in the net at the lower end of the pool.

The Earl of Home, in a letter to the Earl of Montague, dated 10th January, 1837, relates the following history of a Newfoundland dog, which belonged to his uncle. He knew the Monday mornings as well as the fishermen themselves, and used to go to the mill dam at Fireburn Mill, on these mornings. He there took his station, at the opening in the dam, to allow the salmon to pass, and has been known to kill from 12 to 20 salmon in a morning: the fish he took to the side. The then Lord Tankerville instituted a process against [69]the dog. This case was brought before the Court of Session, and the process was entitled, “The Earl of Tankerville versus a dog, the property of the Earl of Home.” Judgment was given in favor of the dog.

Hoping the time may arrive, when the salmon in our rivers will afford similar opportunities for the display of canine sagacity, I shall, in anticipation of such good days, proceed to offer a few brief hints, which our grand-children may find useful, when tempted by a strong breeze and a dark gloomy sky, to cast the fly over a salmon run.

Follow the advice given with reference to the purchase of trout tackle; go to the best, which you will find the cheapest market.

Let the manufacturer know the average width of the river, and he will provide the rod, &c., accordingly.

In the selection of your flies, be guided by the suggestions of a local fisherman—obtain patterns, and get them fac-similied by a well-reputed maker, [70]whose hooks are known to stand a long-contested struggle.

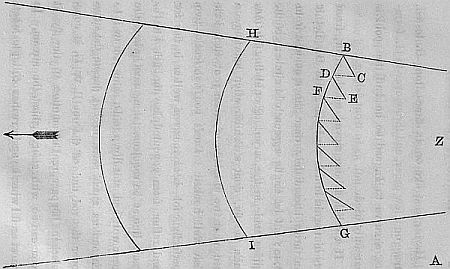

Commence fishing at the head of the pool Z., instead of at the tail, as in trout fishing.

Throw the fly directly across the river, from where the fisherman stands at A., to B. Let it sink a little below the surface; then guide it from B. to G., forming the segment of a circle; give it, during this passage, a jerking or sliding motion, such as water-spiders exhibit when sporting on still pools by the side of rivers; at each jerk draw the fly gently towards you, two feet or two and a half for salmon, seven or ten inches for peal. For instance, your fly having lighted at B., draw it to C., then pause a moment, when the stream will carry it down to D. again; draw it to E., and let it fall back to F.; pursue the same process until the curve from B. to G. is completed. By giving this motion to the fly, it appears to be struggling against the stream. In drawing it towards you the wings collapse, when you pause they expand.

Having cast five or six times from B. to G., move on a few paces, and throw over to H., forming a curve to I., and so on until the pool is carefully tried.

If a fish has been moved, note the place, and try him again in a few minutes. Be careful, not to throw immediately over the spot where he rose; but let the fly approach him in one of the glides made in the curve. Should the fish then take the fly, don’t strike directly, but allow a second or two to intervene, when you will find the fish well hooked. Don’t be frightened—keep perfectly cool—hold your rod well back, the butt end rather from you; indulge the fish with as much line as he requires, taking care however to bear well and steadily against him, so that he encounters much resistance in drawing the line over the rod and off the reel. When the fish slackens his pace, reel up as much of your line as you can do with safety; this economy may be most useful when he again rushes off. The length [73]of time occupied in playing the salmon depends somewhat upon the nature of the adjacent banks, and also upon the size and disposition of the fish, some being more lively than others; and a small fish will frequently afford better sport than one of twice or thrice its weight.

A gaff, or landing net, is necessary, as no gut will stand the strain of lifting a large fish out of the water. The foregoing remarks will be found applicable to peal fishing, which may be obtained in some of our rivers, and is justly considered very excellent sport.

To enter more into the detail of this amusement is not my present intention, I must be content with this rough sketch, leaving others to complete the picture. It is proper however to remark, that the flies used in peal fishing are about twice the size of those used for trout: they should be purchased under the advice of an experienced fisherman, as they differ materially from these which are applicable to the Irish and other rivers.

The ingenuity of the sportsman has been taxed to vary the means of capturing the salmon. Sometimes they are shot whilst leaping the weirs, at others they are speared by torch lights from the banks of rivers, or from boats. The otter has been trained to catch and bring the fish to his master; and, in “Red Gauntlet,” we find a lively sketch of a salmon chase, which is thus described by Darsie Latimer, in one of his letters to Allan Fairford.

“The scene was animated by the exertions of a number of horsemen, who were employed in hunting salmon. Aye, Alan, lift up your hands and eyes as you will, I can give their mode of fishing no name so appropriate, for they chased the fish at full gallop, and struck them with their barbed spears, as you see hunters spearing boars in the old tapestry. The salmon, to be sure, take the thing more quietly than the boars; but they are so swift in their own element, that to pursue and strike them is the task of a good horseman [75]with a quick eye, a determined hand, and a full command both of his horse and weapon. The shouts of the fellows, as they galloped up and down in the animating exercise—their loud bursts of laughter, when any of their number caught a fall—and still louder acclamations, when any of the party made a capital stroke with his lance—gave so much animation to the whole scene, that I caught the enthusiasm of the sport, and ventured forward a considerable space on the sands.”

In the Arms of the city of Glasgow, and in those of the see, a salmon, with a ring in its mouth, is said to record a miracle of St. Kentigern, the founder of the see, and the first Bishop of Glasgow.

“They report,” says Spotswood, “that a lady of good place, in the country, having lost her ring in crossing the Clyde, and her husband waxing jealous, as if she had bestowed the same on one of her lovers, she did mean herself unto Kentigern; entreating his help for the safety of [76]her honour; and that he, going to the river after he had used his devotions, willed one, who was making to fish, to bring him the first fish that was caught, which was done. In the mouth of this fish, he found the ring, and sending it to the lady, she was thereby freed of her husband’s suspicion.”

The classical tale of Polycrates related by Herodotus, a thousand years before the tale of St. Kentigern, is perhaps the earliest version of the fish and the ring. “This ring,” says Herodotus, “was an emerald set in gold, and beautifully engraved;” and this very ring Pliny relates, was preserved in the Temple of Concord, in Rome, to which it was given by the Emperor Augustus.

It is somewhat singular, that the Natural History of a fish, which constitutes so important an article of commerce—that adds so much to the wealth of a country where it abounds—that forms so nutricious and delicate a food—that affords an amusement which rivals that truly British sport of [77]fox-hunting, should have remained for centuries in considerable obscurity.

Of late, Jardine, Shaw, Scrope, and others, have investigated the subject with much success; still, many points require further elucidation, especially with reference to the causes which induce this fish to quit its more congenial quarters, and resort to the fresh water, which is evidently distasteful to them, as they decrease in weight and become much weakened after they have frequented the rivers a few months.

Some of the recent experiments, touching the young of the salmon, are very curious, and exhibit much patient and minute enquiry.

Mr. Scrope, in his very interesting work entitled “Days and Nights of Salmon Fishing,” observes, “This splendid fish leaves the sea and comes up the Tweed at every period of the year, in greater or lesser quantities, becoming more abundant in the river as the summer advances. It travels rapidly, so that those salmon which leave the [78]sea, and go up the Tweed on the Saturday night, at twelve o’clock, (after which time no nets are worked till the sabbath is passed) are found and taken on the following Monday, near St. Boswell’s, a distance, as the river winds, of about forty miles. When the strength of the current is considered, and also the sinuous course a fish must take, in order to avoid the strong rapids, this power of swimming is most extraordinary.”

As salmon are supposed to enter a river merely for the purpose of spawning, and as that process does not take place till September, one cannot well account for their appearing in some rivers so early as February, and March, seeing that they lose in weight and condition during their continuance in fresh water. Some suppose it is to get rid of the sea louse, but this supposition must be set aside, when it is known that this insect adheres only to a portion of the newly run fish, which are in the best condition. I think it more probable they are driven from the coasts near the [79]river by the numerous enemies they encounter there—such as porpoises, and seals, which devour them in great quantities; however this may be, they remain in the fresh water till the spawning months begin. In the cold months, they lie in deep and easy water, and as the season advances, they draw into the principal rough streams, always lying in places, where they can be least easily discovered. They prefer lying upon even rock, or behind large blocks of stone, particularly such as are of a colour similar to themselves. At every rise of the river from floods, the fish move upwards, nearer the spawning places, so that no one can reckon on preserving his particular part of the river, which is the chief reason of the universal destruction of those valuable animals. Previous to a flood, the fish frequently leap out of the water, either for the purpose of filling their air bladder, to make them more buoyant for travelling; or from excitement; or perhaps to exercise their powers of ascending heights and [80]cataracts in the course of their journey upwards. Mr. Yarrell places their power of leaping at ten or twelve feet perpendicularly, but I do not think I ever saw one spring out of the water above five or six feet. Large fish can spring much higher than small ones; but their powers are limited or augmented, according to the depth of water they spring from. They rise rapidly from the bottom of the water to the surface, by means of rowing and sculling, as it were, with their fins and tails; and this powerful impetus bears them upwards in the air, on the same principle that a few tugs of the oar make a boat shoot onwards, after one has ceased to row.

The fish pass every practicable obstruction till they arrive at the spawning ground; some early, some late in the season. The principal spawning months are December, January, and February; but in some rivers the season is much earlier.

Salmon are led by instinct to select such places for depositing their spawn, as are least likely to [81]be effected by the floods. These are the broad parts of the river, where the water runs swift and shallow, and has a free passage over an even bed. Here they either select an old spawning place, or form a fresh one, which is made by the female. Some fancy, that the elongation of the lower jaw in the male, which is somewhat in the form of a crook, is designed by nature to enable him to excavate the spawning trough; certainly it is difficult to divine what may be the use of this very ugly excrescence, but observation has proved that this idea is a fallacy, and that the male never assists in making the spawning place. When the female first commences making her spawning bed, she generally comes after sun set, and goes off in the morning: she works up the gravel with her snout, her head pointing against the stream, and she arranges the position of the loose gravel with her tail. When this is done, the male makes his appearance in the evenings, according to the usage of the female; he then [82]remains close by her, on the side on which the water is deepest. When the female is in the act of emitting her ova, she turns upon her side, with her face to the male, who never moves. The female runs her snout into the gravel and forces herself under it as much as she possibly can, when an attentive observer may see the red spawn coming from her. The male, in his turn, lets his milt go over the spawn, and this process goes on for some days, more or less, according to the size of the fish, and consequent quantity of the eggs.

If a strange male interferes, the original one chases him with great fury, and in their combats, frequently inflict great injury upon each other. When the female has spawned, she sets off and leaves the place; the male remains, waiting for another female, and if none comes in twenty-four hours, he goes away in search of another spawning place.

When the spawning is finished, the fish become very lank and weak, and fall into deep easy [83]water. Here, after a time, their strength is recruited, when as the spring advances, the strongest fish leave the depths and draw into the streams. They now move down the river in their passage to the sea. When they arrive in the deep pools, near the mouths of the rivers, they take rest for a few days; here they may be caught by anglers, as they take the fly and other baits freely. March is usually the best month for this sport—if indeed, it can be called sport, to kill an animal that is worth a mere trifle and resists but little.

Having now dispatched the salmon to the sea, it remains to explain what becomes of the spawn, and how, and when, the young fry arrive at maturity; and as there have been various doubts and contradictions on this subject, I think it more prudent to lead the reader to a consideration of the following pages, than to make a positive assertion on my own unsupported authority.

Up to a late period, it was universally thought that the spawn deposited, as described above, was [84]matured in a brief time, and that the young fry of the winter grew to six or seven inches long; were silver in colour; and went down to the sea in this state with the first floods, early in the May of the coming spring.

Mr. Shaw’s ingenious experiments, which have been continued with the greatest care and attention for a long period, disprove the correctness of this opinion. This gentleman constructed three ponds, the banks so raised, and otherwise formed in such a manner, that it was impossible for any fish to escape, or for any other fish to have access to them. On the 4th of January, 1837, some fresh spawn was deposited in one of these ponds, on the 28th of April, one hundred and fourteen days after impregnation, the young salmon were excluded from the egg. On the 24th of May, twenty-seven days after being hatched, the young fish had consumed the yolk which remains attached to the lower part of the body, and which serves them for nourishment; [85]the characteristic bars of the parr had then become distinctly visible. From an unforeseen accident, his experiments upon this brood were abruptly terminated. With a second, however, he was more fortunate. On the 27th January, 1837, he deposited some spawn in one of his ponds; on the 21st March, the embryo fish were visible to the naked eye. From a minute inspection, he found that they had some appearance of animation, from a very minute streak of blood which appeared to traverse for a short distance the interior of the egg, originating near two small dark spots, not larger than the point of a pin. These two spots ultimately turned out to be the eyes of the embryo fish. On the 7th May, (one hundred and one days after impregnation) they had burst the envelope, and were found among the shingle in the stream; at this period the head is larger in proportion to the body, which is exceedingly small, and measures about five-eighths of an inch in length; of a pale [86]blue or peach blossom colour. But the most singular part of the fish is the conical, bag like appearance, which adheres by its base to the abdomen. This bag is about two-eighths of an inch in length, of a beautiful transparent red, very much resembling a light red currant. The body also presents another singular appearance, namely, a fin or fringe, resembling that of the tail of the tadpole, which runs from the dorsal and anal fins to the termination of the tail, and is slightly indented. This little fish does not leave the gravel immediately after its exclusion from the egg, but remains for some time beneath it, with the bag attached, which contains its supply of nourishment.

On the 24th June, Mr. Shaw found the bag had disappeared, but the symmetry of the form was as yet but imperfect. At the end of two months, (7th July) the shape was much improved. At the age of four months (7th September) the characteristic marks of the parr or samlet were partly developed. Two months later (six months old 7th November) the average length was three [87]inches. On the 10th May, 1838, the fish being then twelve months old, were improved in condition, and measured four inches: they had changed their winter coating for that which may be called their summer dress. On the approach of autumn, the whole of the salmonidæ, while resident in fresh water, acquire a dusky exterior, accompanied by a considerable increase of mucus or slime. As the summer advanced, they continued to increase in size; and on the 14th November, being then eighteen months old, they measured six inches in length, and had attained that stage, when all the external markings of the parr are strikingly developed. On the 20th May, 1839, the fish being then two years old, they measured six inches and a half long, and had assumed the migratory state.

This change commenced about the middle of the previous April; the caudal, pectoral, and dorsal fins assuming a dusky margin, while the whole of the fish exhibited symptoms of a silvery [88]exterior, as well as an increased elegance of form.

The specimens in question, so recently a parr, exhibited a perfect example of the salmon fry, or smolt. Mr. Shaw having thus traced the spawn of the salmon up to this point, it will now be necessary to pursue our inquiries until we find the matured fish. The descent of these little fish takes place much about the same time in all rivers, commencing in March, and continuing through April, and part of May. They first keep in the slack water, by the side of the river; after a time, as they become stronger, they go more towards the mid-stream; and when the water is increased by rain, they move gradually down the river. On meeting the tide, they remain for two or three days, in that part where the water becomes a little brackish from the mixture of salt water, till they are inured to the change, when they go off to the sea all at once. There their growth is very rapid, and many return to the brackish water, increased [89]in size, in proportion to the time they have been absent. Fry, which were marked in April and May, have been caught on their return at the end of June, weighing from two to three pounds in weight. These are sold in our markets as salmon peal, when of a larger size they are called gilse. A second visit to the sea gives these another increase, when they return to the rivers as salmon.