This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Journal of a Cavalry Officer

Including the Memorable Sikh Campaign of 1845-1846

Author: W. W. W. (William Wellington Waterloo) Humbley

Release Date: March 27, 2018 [eBook #56853]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JOURNAL OF A CAVALRY OFFICER***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/journalofcavalry00humbrich |

JOURNAL

OF A

CAVALRY OFFICER;

INCLUDING

THE MEMORABLE SIKH CAMPAIGN OF

1845-1846.

BY

W.W.W. HUMBLEY, M.A.

TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE;

FELLOW OF THE CAMBRIDGE PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY;

CAPTAIN, 9TH QUEEN'S ROYAL LANCERS.

LONDON:

LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, AND LONGMANS.

1854.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WERTHEIMER AND CO.

FINSBURY CIRCUS.

TO

LORD STANLEY, M.P.

THIS VOLUME

IS

BY PERMISSION DEDICATED

AS A

SMALL TOKEN OF ADMIRATION AND REGARD,

BY HIS

FRIEND AND SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR.

CONTENTS.

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

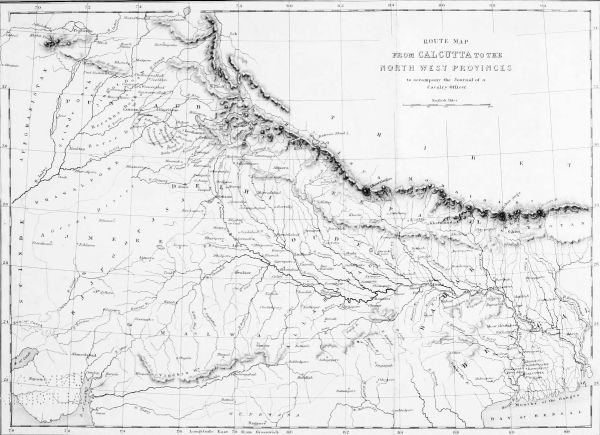

| Voyage to India—Advantages of Sailing with Troops on Board—Regulations at Sea—March from Cawnpore to Meerut—Return from Nougawa Ghât to Meerut—March to Ferozepore—Cantonments at Kurnaul—Colonel Campbell's Force—Number of Cattle required on a March—Sunday—Rev. W.J. Whiting, M.A.—Distribution of Prize-Money—Advanced Guard—Governor-General—Major Broadfoot and Captain Nicolson—Suspicions of the Sikhs—Sir David Ochterlony—The Sikh Army—The Battle of Moodkee—Tej Singh. | 18 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Colonel Campbell's Advance—Provisions required—Camp Followers—Samana—The Doabs—Gooroo Govind—The Akalees, their Quoits—Sikhs attack Ahmed Shah—Maha Singh—Maharattas—General Thomas—Runjeet Singh—Holcar—Sir Charles Metcalfe—Ochterlony's Proclamation—The Akalees routed—Generals Allard and Ventura—Treaty with Runjeet—Runjeet's Army—Runjeet's Death—Shere Singh Murdered—Dhuleep Singh—Ajean Khan—Battle of Moodkee. | 46 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Nidampore—Christmas-day—Munsorepore—Kotla Mullair—Phurawallee —Bussean—Surrender of Wudnee—Cession of Ferozepore—Bhaga Poorana—False Alarms—Roree Bukkur—Sir John Littler—Sir H.M. Wheeler—Ferozeshah—Aliwal—Sikh Forces—British Forces—Sikh Entrenchment—Returns of Killed and Wounded—Sir H. Hardinge—Battle of Ferozeshah—Sudden Attack by Tej Singh—His Blunder—Appearance of a Field of Battle—Fate of the Wounded. | 83 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Return to Bussean—Sir John Grey's Detachment—Battle of Assaye—Sindiah's Troops—Generals Allard and Ventura—General Lloyd's Observations on the Art of War—Tactics of the Sikhs—Runjeet Singh's Discipline—Sikh Artillery—Goojerat —Moodkee—Sir Joseph Thackwell—Bootawalla—Pontoons—Their Value to an Army—Great Rise in the Price of Food. | 109 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Hurrekee Ghât—Chain Bridles—Sir Thomas Dallas—Victory of Sir Harry Smith at Aliwal—Umballa—Preparations of the Sikhs—Capture of Dhurmkote—Loodianna—Runjoor Singh—Buddiwal—Sirdar Ajeet Singh—Invalids at Loodianna—The Pattiala Rajah—Alarm at Loodianna—Siege-train in Danger—Convoy inadequately protected—Sikh Artillery at Aliwal—Major Lawrenson—Singular Formation of the Sikh Infantry at Aliwal—16th Lancers—Desperation of the Sikhs—Colonel Cureton—Charge of Lancers—Marshal Marmont's Opinion—Sikhs evacuate Buddiwal—Rapid Movements of the Sikhs—Brigadiers Godby and Hicks. | 131 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Richard Bond, the Messman—Sikh Grass-cutters—Choice of Camps—General Lloyd's Opinions—Lieut.-Colonel Irvine and Sir H. Maddock—Position at Sobraon—Brigadier E. Smith's Plan—Colonel Irvine's Plan—Goolab Singh's Policy—Sir Robert Dick's Division—Major-General Gilbert's Division—Sir Harry Smith's Division—Brigadier A. Campbell—Sir Joseph Thackwell—Brigadier Scott—British Batteries—Rockets—Sikh Batteries—Assault on the Sikh Entrenchments—Brigadier Stacey—Captain Cunningham's Account—The 10th Foot—Lieut.-Colonel Franks—Sikh Entrenchments stormed—Sirdar Sham Singh destroys the Pontoon—Sikh Retreat cut off—Great Loss of the Sikhs—Peace Principles inapplicable to India—Sikhs driven across the Sutlej—Tej Singh. | 151 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Advanced-guard cross the Sutlej—Burial of Sir Robert Dick—Bridge of Boats—Kussoor—Surrender of the Sikhs—Dhuleep Singh—Lulleanee—Lahore—Runjeet Singh's Monument—The Summer Palace—The Governor-General's Address. | 181 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Review of the Army—Eastern Mode of Adoption—Cashmere assigned to Goolab Singh—Defeat of Affghan Cavalry—Major John Cameron Campbell—Security of the North-west Frontier—Fertility of the Punjaub—Infantry introduced into the East—Hyder Ali's Notion of English Power—Runjeet's Craftiness—Improvement in the Punjaub—Dhuleep Singh professes Christianity—Dr. Login—Dhuleep Singh baptized by the Rev. W.J. Jay—Dhuleep Singh's Sincerity. | 197 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Army of the Sutlej broken up—Set out on a Tour—Dhool —Ferozepore—Grandeur of the Himalayas—Misri-Wala—Ferozeshah —Moodkee—Bhaga Poorana—Bussean—Phurewallee—Kotla Mullair —Munsorepore—Samana—Goelah—The River Cuggur—Pehoah—Khol —Kurnaul—Military Stations—Transport of Artillery—Ali Merdan's Canal—English Church—Malaria—Sir David Ochterlony—Gurounda—Minarets—Somalka—Paniput—Battles of Paniput—Baber—Ibrahim Lodi—Ahmed Shah—Defeat of the Maharattas—Nadir Shah—Capture of Delhi—Mahomed Shah—Troops engaged—Native Armies—Sunput—Change in the Weather. | 218 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Delhi—Mahmood of Ghuznee—Shah Jehan—Gates of Delhi—Mosques—The Palace—Hall of Audience—Chapel of Aurungzebe—The Gardens—The Jumma Musjeed—Khoonee Durwaza—Protestant Church—The Observatory—Tomb of Zufder Jung—The Cootub Minar—Allah-ud-Deen —Gheias-ud-Deen—Mahomed Togluk—Humayoon—Nizam-ud-Deen—The Cantonments—Mahomedan College—Delhi—Produce of Delhi—Shah Allum II.—Lord Lake—Monsieur Louis Bourgion—Sir David Ochterlony—Holcar.—Lieut.-Colonel W. Burn—Mr. E. Thornton —Allahabad—Marquis Wellesley—Defence of Delhi—Mahomedan Population—Colonel Ochterlony's good Generalship. | 260 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Ghazenuggur—Secundra—Allyghur—The Fort—The Church—Monuments—The Gaol—Akbarabad—-Meerun-ke-Serai—Kanoge—Tombs—Ancient Coins—Language of Kanoge—Supposed Site of Palibothra—Population of Benares—Streets of Benares—Singers and Musicians—Productions of Kanoge—Poorah—Cawnpore—Court Etiquette at Lucknow—Nawab of Oude—His Regal Rank—Military Depôt at Cawnpore—Saddlery—Sirsole —Dâk Bungalows—Arapore—Lohunga—Allahabad. | 281 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Allahabad—Pilgrimages—The River Jumna—Hurdwar—Akbar—Allum II.—Fortifications—Inscriptions on Column—Military Depôt —Lieut.-Colonel A. Abbott, C.B.—Colonel Kyd discovers a Cave—Ancient Palibothra—Arrian's Account—Megasthenes—Dr. Adams—Heeren—Chundragupta—Patna—The Sacred Rivers—Bhaugulpore —The Mandara Hill—The Chundun—Palibothra—Rajmahal—Antiquity of Kanoge—Allahabad—Extent of Asiatic Cities—Mahomedan Invasion—Extent of Hindoostan. | 300 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Steamers on the Ganges—Native Pilots—Course of the River—Mr. Sims proposes Shields to the Banks—Shoals—Tributary Streams—Rapids—The Jumna—Mirzapore—Benares—Trimbuckjee Danglia—Chunar—Sultanpore. | 333 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Benares—Bathing in the Ganges—Water-carrying by Women—Extent and Population of Benares—Attempted Tax—Mosque of Aurungzebe—Observatory of Rajah Jey Singh—Bazaars—Jewellery —Cultivation of Sugar—Secrole—Murder of Mr. Cherry—State Prisoners—The Maharannee of Lahore. | 353 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Ghazepore—The Opium Trade—Marquis Cornwallis's Mausoleum—Sand-banks—Buxar—Cossim Ali Khan—Sir Hector Munro—Battle of Buxar—Nawab of Oude—Emperor of Delhi—Revelgunge—The Sonus—The Ganges and Jumna—The Indus—The Berhampooter—Arrian—Dr. Alexander Adam—Dinapore—Captain Strachan—Bankipore—H.M. 16th Lancers—Deegah—Grain Golah—Earl of Munster—Patna—Buildings of Patna—Population of Benares—Magistrates—E.I. Company's Charter—Products of Patna—Walter Reinhard—Snowy Mountains—Tirhoot—Juggernauth—Gyah Proper—Cave of Nugur-jenee—Sir Charles Wilkins—Futwa—Phoolbarea—Bar—Beggars. | 373 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Monghyr—Wells of Seetacoond—The Fort of Monghyr—Storms on the Ganges—Cossim Ali Khan—Monghyr the Birmingham of India—Employment of Women—The Gaol—A Sacred Bathing-place—Bhaugulpore—Its Population—Hill Rangers—The Bheels—Mr. Cleveland—Lieut.-Colonel Tod—Colonel Francklin—Colgong—The Jungheera Rocks—The Fakeers—The Rajmahal Hills—Sickreegullee—Boatmen of the Ganges—Rajmahal—Ruins of Gour—The Bhauguretty—Soottee—The Sunderbunds—Bogwangola—Jungepore. | 402 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Moorshedabad—Cossimbazar—"Eina Mahal"—The Nawab Cowar Krishnath Roy—"Snake-boats"—Population of Moorshedabad—Berhampore—Ivory and Silk Manufactures—Kulna—The Tidal-bore—English Factory at Kulna—Hoogly—Chinsurah —Chandernagore—Ishapore—Barrackpore—Serampore—Dum-Dum —Garden Reach—Calcutta. | 430 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Project of a Railway to Calcutta—Calcutta a Six Months' Trip from England—The Strand Road—The Mint—Professor Weidemann—The Strand Mills—The General Post Office—Custom House—Auditor General's Office—Military Board—The Commissariat—The Ice House—Metcalfe Hall—The Public Library—Bank of Bengal—The Oriental Bank—Indian Failures—Chandpaul Ghât—Baboo Ghât—Docks of Howrah—Prinsep's Ghât—Kidderpore Ghât—Fort William—Mir Jaffier—Arsenal —Chowringhee Road—Ochterlony Monument—Government House—Entertainments at Government House—Policy of Marquis Wellesley—Hotels at Calcutta—Theatricals—The Town Hall—Concerts—Fancy Fairs—The Mayor's Court—Newspapers—Merchants—Agency Business—Railways—Asiatic Society—Martinière Charity—College of Fort William—Haileybury College—Military Seminary at Addiscombe—College—Schools—Mesmeric Hospital—Chloroform—Sailors' Home—Alms Houses—Masonic Lodges—Botanical Garden—Charter of 1834—Lunatic Asylums—Law Courts—Police Office—Provident Funds. | 450 |

JOURNAL

OF

A CAVALRY OFFICER IN INDIA.

The remark has often been made, that India is but little known to persons in England and on the continent of Europe. That there is ample ground for such a remark none can deny. For, whether we consider its vast territorial extent, covering an area of upwards of a million of square miles, with a population of more than 150 millions; its commercial wealth and enterprise, from the remotest ages of antiquity, and its immense natural resources; or, whether we regard India in a more intimate point of view, as forming an integral part of our own[Pg 2] dominions, owing allegiance to one sovereign ruler, bound up with us by social relations and family ties, and consider what an El Dorado it has proved to the British empire for upwards of two centuries and a half; it is indeed a matter of no small surprise, that India should be so little, and so imperfectly, known by us.

We can scarcely comprehend how, until recently, the Emperor of China and his subjects should have looked upon the celestial empire as the most important in the world; but it is yet more astonishing that we, to whom the whole world lies open, should be contented to remain in ignorance of what it is so obviously our interest to understand.

Nearly six centuries have elapsed since that enterprising Venetian, Marco Polo, first visited India, and revealed to Europe the treasures of the Eastern Hemisphere; nay, they are familiar to us from the earliest records of the sacred writers; and, in later ages, Herodotus and other Greek authors dwelt upon the wonders of the East, its history, its resources, and its races. It is true that Marco Polo gained little credit for the marvels he related; but, we must bear in mind that he did not always speak from personal[Pg 3] observation: he not only noted down what he saw, but eagerly collected all the information which he could obtain respecting those regions which he was unable to visit himself. His "Maraviglie del Mondo da lui descritte" were sneered at and discredited by many, in former times, as the visions of an enthusiast. People, indeed, believed in the existence of such cities as Agra and Delhi, because it was corroborated by the Chinese and Arabic maps which he brought home; while the fact of there being such an individual as the Great Mogul, was demonstrated by the painted representation of his Sublime Majesty on the royal court cards, which are supposed to have been then first introduced. More accurate investigations, however, have proved his veracity; and the researches of Klaproth, and other distinguished travellers, of modern times, have amply verified the truth of his statements.

The discredit at first thrown upon Marco Polo's narratives, may, in a great measure, be attributed to the Jesuit missionaries in India and China, who followed in his track, and who, while they availed themselves of the valuable information which he had supplied, scrupled not to add[Pg 4] the most unblushing and incredible falsehoods. These Jesuits, though the most learned men of their time, composed a class of writers whose object it was to appear to surpass all other European travellers in information; and who sought to acquire an ascendancy in Asiatic countries, for the benefit of their master, the Pope, and the sovereigns of the European States.

The maps brought home by Marco Polo, and the information which he communicated, proved invaluable to the Pope's missionaries, and to the Venetian and Portuguese traders and navigators who succeeded him, and aided the gallant Vasco di Gama in discovering the passage to India by the Cape of Good Hope. The Jesuits, however, did not make full use of the advantages which they possessed; for, while employed in constructing their excellent map of the Empire of China, which gained them free access to every part, they lost an opportunity for investigating and describing its natural productions, which might never have occurred again, but for the present movement in China. In the reign of Kang-hi they obtained permission to establish a college for the promotion of Christianity; but his[Pg 5] successor regarded the institution with different feelings; and, being jealous of the influence which it was calculated to produce, ordered it to be broken up, and thus deprived us of the means of obtaining much valuable information.

Among the few Oriental works which modern scholars have been able to obtain, the only one that has as yet been translated into English, from the Sanscrit, is, a History of the Kings of Cashmere, down to the Mahomedan conquest, entitled, "Raja Tarengini," published in 1835.

It was not till about seventy years ago, during the war with Hyder Ali, and the subsequent hostilities between the sovereigns of Mysore, from 1792 to 1799, that the English became acquainted with the state of Southern India; when (to our shame be it spoken) the capture at Seringapatam of the Sultan's library, revealed the fact of an extensive political correspondence with Napoleon Bonaparte, the Directory, and the French governor of the Isle of France; also with the Shah of Persia, with Shah Zeman of Affghanistan, the Maharattas, and many other native princes of India.

With so many salient points of tangible danger to defend, it might have been expected[Pg 6] that the Government of India would have employed—as Russia does, and as France has ever done—competent officers in their service to travel in Persia, Afghanistan, and, in fact, in all the countries from whence the danger of an invasion was to be apprehended: especially as it was well known that Zeman Shah of Affghanistan had, in 1796, '97, and '98, made attempts to invade India.

Foreigners have asked the question: "How is it that you English, who have so long possessed a considerable portion of India, know so little of that country, that, in our day, Baron Humboldt, a foreigner, should contemplate a visit to India, to explore the Himalaya mountains?" It is true, that nearly forty years ago, Lieutenant Webb and others had ascertained that the highest peak was about 27,000 feet above the level of the sea, and that it was the loftiest in the world; but doubts were expressed as to the amount of scientific knowledge possessed by a Bengal subaltern. Captain Fraser and other Englishmen have since visited those snowy regions; but it still remains to be seen what enterprising nation will equip an expedition to explore the character and resources of India.

That the English, as a commercial nation, have not as yet ascertained all the products of India, is a matter of yet greater astonishment to all foreign travellers. It is a fact, that the existence of that useful article, coal, has only been known within the last few years; and the same may be said in regard to other natural productions. The truth is, that, till the year 1814, the East India Company, who possessed the exclusive right of trade within the limits prescribed by their Charter of 1660, were the chief merchants of India; and their investments were almost wholly confined to the exportation of silk, and the usual cargoes of tea from China. It is to private enterprise that we are indebted for the commerce in indigo, sugar, and other articles of modern exportation; till the free trade with China, since the year 1834, opened up a more extended commerce.

Since that period, both India and China have become better known to us; and the wars in the latter country have naturally made us acquainted with the eastern portions of its vast dominions.

It cannot, however, be expected that persons pursuing commercial speculations should have leisure or inclination to write on Indian subjects,[Pg 8] beyond the facts relating to their own traffic. Some men will not even take the pains to learn the language of the people, but trust to such natives as speak English. Though some of these gentlemen have certainly acquired a colloquial knowledge of the language, and made themselves acquainted with the localities in their immediate vicinity—yet, as they have never travelled much in India, their statements are of course imperfect and superficial. It is from the pen of the civil, military, and other servants of the East India Company, and from officers in Her Majesty's service, that we must look for accounts descriptive of different parts of India, and of the various tribes and races of its inhabitants.

The removal of the army from place to place, affords an observant officer not only an opportunity of investigating the geological formation, natural history, and productions of the country, but also gives him great facilities for studying the history, religion, and civilization of the people, from the various monuments and inscriptions, both ancient and modern, which lie on his route.

The rapid extension of our Eastern empire since our first occupation of Hindoostan may, in some measure, account for our imperfect[Pg 9] acquaintance with the productions and natural resources of the several great Presidencies under our jurisdiction at the present day. Great Britain, in self-defence, rather than from choice, or from a policy of self-aggrandizement, such as she might reasonably be excused in adopting, has been forced to extend her sway, and to annex numerous native territories; for a long time, indeed, she only assumed a passive military tenure of dominions thus acquired, while her natural reluctance to obtrude or infringe upon the rights and prerogatives of others has not only influenced her general policy, but even led her subjects invariably to observe the same caution in indulging their natural bent for investigation and discovery. This, coupled with an apprehension for personal safety, and a want of confidence in native integrity and honour, has greatly impeded a free and frequent intercourse, and damped the ardour of enterprising and scientific enquiry.

The well-known faithlessness of the native character, and the internal disaffection existing among various tribes, have also tended to interrupt or preclude the possibility of travelling about among the people, for the purpose of[Pg 10] investigating their manners and customs, and the general state of the country.

The wars with the Sikhs afforded many opportunities of becoming practically acquainted with the perfidy and duplicity of the natives. The treachery of Tej Singh at the battle of Ferozeshah, the artful and wily conduct of Goolab Singh, in his negotiations with the Maharannee and the British, and the subsequent perfidy of our professed friend and ally, Shere Singh, at the siege of Mooltan, where he caused the defection of the Sikh army from the British to Moolraj, and thereby prevented our taking the fortress, are indisputable proofs of this trait. It is a painful peculiarity in the Oriental character, which will ever stamp it in the eyes of a European with an indelible stigma. This inherent vice, and our cognizance of it, have hitherto checked, and will continue to check, the ardour of all enquiry and enterprise, even where pecuniary gain, and still more, scientific information, are the objects in view.

We may also refer to the history of Moolraj, his confederates, and their diabolical schemes; but, thanks to an over-ruling Providence, the arch-traitor and his base accomplices were[Pg 11] defeated; their designs were marred, and fell upon themselves. Truly it is said, "Man proposes, but God disposes." Who could have foreseen or anticipated the results of the deliberations within the walls of Mooltan? Who could have foretold that Moolraj would be dethroned and immured in a British prison, and his rich and extensive territories revert to a British Queen? His treachery, however, led to the wanton murder of two of our officers, and to an immense sacrifice of the lives, both of natives and Europeans.

Our unwillingness to invade, or to annex to the British dominions, even partial portions of frontier countries, virtually in our possession before, has proved, as we have seen, a great barrier to enterprising researches; and our officers, generally speaking, had more work upon their hands, than allowed of much leisure or inclination for scientific expeditions into adjacent, and still less into more distant localities. We feel justified in offering this explanation, in order to do away with the reproaches to which the civil and military officers in India, have been subjected in regard to this question.

With respect to the Punjaub, our Government[Pg 12] was perfectly justified in its annexation; and the act was quite consistent with wise policy, and compatible with our previous and general mode of dealing with Indian rulers. No other power except Great Britain would so long have abstained from punishing a local authority, which had so shamefully and recklessly disregarded and violated its own solemn pledges and engagements, upon the faith of which, and which only, the rule of the Sikhs rested and eventually depended. Great Britain ought to have annexed this country long before, even as early as 1845. She relied on the gratitude and fidelity of the Sikh rulers, and was betrayed and disappointed.

What is applicable in one case, as in that of the Punjaub, may apply equally to all or any of our Indian acquisitions, and account, in a great measure, for our still imperfect knowledge of the products and vast resources of India.

We will not conceal from ourselves, nor leave the public in ignorance of the fact, that while all classes at home are unanimous as to the benefit and vast importance of steam communication, the case is far otherwise in India. The imperative necessity for improvement in facilitating the means of communication in the interior of India,[Pg 13] by means of roads, bridges, canals, railways and river navigation, has not obtained that fair share of attention and support which the past and future wants of India, her products, resources, and trade demand. These reforms are only in their infancy. India, strange to say, is still as backward as Turkey in these respects. It is extraordinary that in a country like India, and under such a rule as the British, no line of railway should have been laid down till the year 1851, when the attempt was made in the short line from Bombay.

Any contributions, however scanty, respecting India will be better appreciated now that a more judicious system has been adopted with regard to the qualification of candidates for Indian affairs. There are few families who have not friends and relations in some part of India, and these are now beginning to give their attention to subjects bearing upon its history, its people, products, institutions, and religion.

If we have been remiss in the past, and of this there is no question, we must endeavour, in the future, to regain our credit as a nation by progressive reform, and the promotion of civilization. India and her riches, her mountains of[Pg 14] light and her hills of gold, must not blind us to our duties, nor cause us to forget the true though trite saying, that, "Property and its possession have their duties as well as their rights." We must not lose sight of the well-being of the country and her people, in the pursuit of personal aggrandizement, and thus expose ourselves to the world's obloquy, our children's detriment, and our disgrace as a nation whose glorious destiny it was to elevate India to a high and proud position, compared with that state in which we found her.

It must not be supposed, from the foregoing remarks, that the author of these pages intends to write a history of India; all he presumes to do is to give information respecting that part of the country in which his regiment was on active service, and which is perhaps the most imperfectly known, namely, the vast district in the north west of India, where the Sikh battles were fought. Moreover they are not written for the scrutinizing eye of the public, but only for the amusement of his friends, and of those who have a personal interest in the war.

The author left England in the year 1836, and served with H.M.'s 4th (Queen's own) Light Dragoons for seven years. He studied both the[Pg 15] Oordoo and Maharatta languages, passed his examination, and became Interpreter to the regiment, and was therefore able to converse with the natives. Returning to England in 1842, he joined the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers, and was engaged in the Sikh campaign in 1845-46, which prostrated the power of that people, and exhibits a series of the most triumphant successes ever recorded in the military history of India.

The author has endeavoured to delineate scenes presented in a time of war, which could not be familiar to the general traveller, because the presence of two hostile armies exhibits the people in their native character, calling forth their hopes and fears as to the issue of the combat. In times of peace, the minds of the inhabitants repose upon the prospects of a good harvest and a fruitful season. The grand features of an Indian life are comprehended in the expressive phrase: "āb aur hawa humaree bustee kee achchha huen; mi khoob khata aur khoob sota hon:" i.e.; "The climate (air and water) of our village is good; I eat well and sleep well." If the Indian has plenty of good water and food, his family share it with him, and he is content; he is no politician, but when war rages between hostile parties[Pg 16] close to his own door, he can be no longer indifferent, and all his energies are aroused in estimating the issue. In losing his old masters, the English, he would fall under the iron rule of the Sikhs; or should the Sikhs suddenly attack his village and carry off his grain, he would have reason to apprehend that this act might be construed into "aiding the enemy," while a refusal to give up his corn to the Sikhs would involve the burning of his village.

In this way I shall, therefore, endeavour to represent the character of these people as I myself observed them in peace and in war, that the reader may judge whether there exists among the natives of her north-western provinces any peculiarity of character, or whether we have any reason to conclude that the actions of human nature there are much the same as in similar countries in the East; for we must not judge them by those of the West.

It is to be hoped that better days are in store for the East; and, in that comprehensive term, I would include China, and countries nearer home, Asiatic Turkey, Persia, etc. I am sanguine that the bright dawning of a happy future is awaiting these interesting countries. If the[Pg 17] British people have conquered India, it is their imperative obligation to promote the welfare of their possessions; and we are glad to notice a laudable spirit in recent legislative measures to promote many desirable improvements. India, under an improved system, and with greater facilities of intercourse, will more than recompense any effort, or application of capital, on our part. Its internal resources are beyond our conception, and its people will unquestionably advance and improve in proportion to its elevation as an empire. Schools, industry, and commerce, if based on a solid foundation, will be the quick harbingers of peace, good-will, and prosperity to the people and their rulers, both native and European.

May this happy era be expedited in the good Providence of God!

Eynesbury, St. Neots,

Huntingdonshire,

May, 1, 1854.

Voyage to India—Advantages of Sailing with Troops on Board—Regulations at Sea—March from Cawnpore to Meerut—Return from Nougawa Ghât to Meerut—March to Ferozepore—Cantonments at Kurnaul—Colonel Campbell's Force—Number of Cattle required on a March—Sunday—Rev. W.J. Whiting, M.A.—Distribution of Prize-Money—Advanced Guard—Governor-General—Major Broadfoot and Captain Nicolson—Suspicions of the Sikhs—Sir David Ochterlony—The Sikh Army—The Battle of Moodkee—Tej Singh.

The circumstances of a voyage to or from India are so well known, from their frequent occurrence, that I will not even allude to them. Our voyage, however, offered some variety to the usual monotony of a mere passenger ship, from our having troops on board. This naturally gave rise to numerous incidents which afford topics of interest, especially to military men. We, of course, had regular parades both for the sake of discipline, and to ascertain that the men[Pg 19] were sober and clean. The men had, too, specific duties assigned to them—keeping watch, etc.

The object of placing the troops in watches, in time of peace, is, that they may assist in pulling and easing the ropes. They are confined to duties on deck only. If there should be an old sailor among them he may, of course, occasionally reef and unfurl sail. It is obvious that the addition of some fifty or sixty men to the crew of a merchant vessel of 600 or 700 tons burthen, is a great advantage in bad weather, as it enables almost the whole of the ship's crew to be employed aloft. In case of necessity a soldier or two will also assist the man at the wheel, or those at the pumps, by order of the quarter-master, or of the officer on duty, or of the captain himself.

Another advantage from having soldiers on board is in the case where the crew might be inclined to mutiny; when they would be restrained by the military. The troops being told off in watches, those on the morning watch assist in cleaning, or, what is called swabbing, the quarter-deck; but the rules for merchant ships are very imperfect in this respect.

Having troops on board necessarily adds much to the safety of the vessel.

It will probably be in the recollection of many of my readers, that two ships taken up in Australia as transports, were wrecked on the Great Andamans, islands on the east side of the Bay of Bengal, in the year 1844. These vessels would have been totally lost, but for the assistance rendered by the officers and men of the 80th Foot, the regiment which so nobly distinguished itself, the following year, at the battle of Ferozeshah, where many of those brave fellows who helped to save these vessels, yielded up their lives for their country.

To ensure regularity and a perfect understanding between the commanding officers of troops and captains of ships, a copy of rules for the guidance of the commanders of merchant-ships, should be given to the officer commanding the troops; and a copy of the regulations for troops of Her Majesty's forces, and the East India Company's service, given to the commander of the ship. The captain of a free-trader is not allowed to flog his men; but he may stop a sailor's grog and his pay for any crime of which he has been guilty. He may also put a culprit in irons, and lose the man's services.

Without stopping to describe my first impressions of India, or the countries which I traversed, after landing upon its far-famed shores, I will proceed at once to Cawnpore, where I found that my regiment was quartered, and where I first joined it.

On the 17th of October, 1845, my regiment, the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers, set out on its march from Cawnpore to Meerut, a distance of 266 miles. The Artillery received orders, at the same time, to hold themselves in readiness to proceed to the north-west. We reached Meerut on the 12th of November, and encamped near the lines of the 16th Lancers, to await further orders. We stayed only a few days in this place, which is situated in the province of Delhi. It is a very large town, of some antiquity, lying about forty miles to the north-east of the city of Delhi, and is one of our principal civil and military stations.

On the 23rd, our corps received orders to march the next day to Umballa, a large military station, a distance of 126 miles. We accordingly set out on the morning of the 25th, and marched to Sirdhana, eleven miles. On the 26th we encamped on the right bank of the river Hindon, at Nougawa Ghât, nineteen miles from Meerut.[Pg 22] On the 27th, just as the corps was about to proceed onwards—for the trumpet to boot and saddle had already been sounded—we received a sudden order, by an express camel, to return and encamp on our old ground at Meerut. On the 28th, the regiment halted; the following day it re-crossed the river, and encamped at Sirdhana; and on the 30th returned to Meerut.

Here we were quartered till the 10th of December, when the Queen's Royal Lancers received an unexpected and peremptory order, at half-past eight P.M., to march immediately to Umballa. We accordingly again set out for Sirdhana, which we reached the next morning; and whilst at Shamlee, four marches from Meerut, and twenty-eight miles from Kurnaul, we received, between three and four o'clock P.M., an express direct from the Commander-in-Chief, with the following important intelligence:—

"That the 9th Lancers were to proceed at once to Ferozepore, agreeably to an enclosed route; and that the 43rd and 59th regiments of Native Infantry, which were to leave Meerut the same day as the Lancers, were to proceed thither also: the whole to be under the command of Colonel Campbell, of the latter corps."

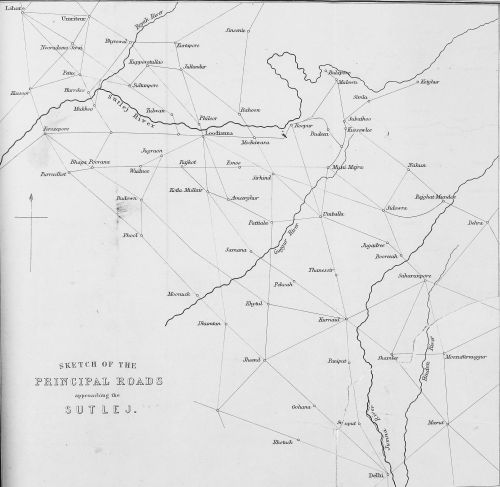

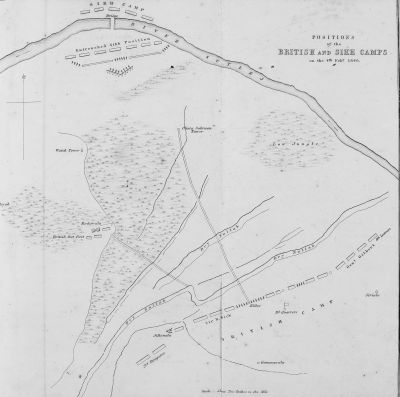

SKETCH OF THE

PRINCIPAL ROADS

approaching the

SUTLEJ.

On reaching Kurnaul, we halted on the 18th, in order to make preparations for forming a depôt at Umballa; to which place all the superfluous heavy baggage, and the young horses, were immediately sent, under the charge of Cornet R.W. King, with instructions to rejoin head-quarters as soon as he had reported himself to the officer commanding at Umballa.

At this time, it was not yet known at Kurnaul that the Sikhs had crossed the Sutlej—an event which took place as early as the 13th of this month.

I may here remark, that the extensive cantonments of Kurnaul had been abandoned about three years before, by order of Lord Ellenborough, then Governor-General. The officers' bungalows were now nearly all roofless, and the neat little church going to decay. In 1852 it was entirely dismantled, and the materials conveyed to Umballa, to assist in building a station-church there. The immense parade-ground, large enough to allow for the exercise of 12,000 men, is about the best in India.

The route of the 9th here changed; for instead of proceeding to Umballa, we marched as follows:—

On the 19th of December to Suggah, 10 miles.

" 20th

" Khol, 14½ "

" 21st

" Pehoah 14 "

These three villages were in the protected Sikh states: the two former are small and insignificant; the latter is larger, and of more importance.

The whole tract of country, on either side of our line of march, was one continued jungle, and as level as a bowling-green.

The force under the personal command of Colonel Campbell, exclusive of officers, amounted at this time to 2,833 men, with twelve iron twelve-pounders, each drawn by an elephant. Brass guns of this description are usually drawn by ten, or even twelve, bullocks; brass eighteen-pounders by fourteen bullocks; and brass twenty-four-pounders by eighteen bullocks. An iron twenty-four-pounder is drawn by twenty-six bullocks; an iron eighteen-pounder by twenty-two bullocks; and an iron twelve-pounder by eighteen bullocks. Singly, therefore, that noble animal, the elephant, will draw a gun for which ten or even more bullocks are allowed.

These and the following remarks regarding cattle, are given for the purpose of showing the[Pg 25] number used in dragging guns and carrying loads. By the regulations of the service in Bengal, it is directed that no elephant shall be taken into the service under twelve years of age, nor under seven feet in height. A committee is appointed to examine and report whether the animals are fit for service; but it not unfrequently happens that infantry or cavalry officers, or both, are put upon these committees, who know nothing at all of the matter. Sometimes, however, the animals are so palpably inefficient and diseased, that, as one of the committee-officers exclaimed, "This camel speaks for itself." No elephant is employed unless the committee can report that he is capable of carrying at least 20 maunds of 80 sicca weight, or 1,600 pounds = 14 cwt. 32 lbs.

Camels admitted into the service by a committee, must never be under five, nor more than nine, years old; and capable of carrying a load of at least 6 maunds, or 480 lbs. Bullocks are admitted into the service not under five, nor above eight, years of age. Draught-bullocks must be fifty inches in height; those for carriage, not under forty-eight inches. The former must be capable of carrying 210 lbs. avoirdupoise[Pg 26] weight, besides the gear. The comparative value of these animals will be seen by the following scale:—

An elephant carries 1,600 lbs.

A camel

" 480 "

A bullock

" 210 "

In wet weather a camel, which, in dry weather, carries six maunds of tents, etc., will carry only four maunds, one-third being allowed for the difficulty which the camel finds of keeping on his legs in wet ground.

A six-pounder gun is drawn by six horses, and when bullocks are used, by six of these animals. This shows the relative value as to draught. Now a single elephant pulled along by himself one of the iron twelve-pounder guns, or, as they were more properly styled, "nine-pounders reamed up to twelves," which may be thus explained. Knowing that the Sikhs used guns of large calibre, the Government had ordered that these guns should be sent to the Delhi magazine, to be re-cast and reamed up for the occasion; and they did good service. They were a fraction lighter by this process than the nine-pounders were before.

On the 21st of December our troops halted at Pehoah. It is a large town, containing a succession of brick-built houses, the high walls of which, without any apertures, face the back streets, being evidently intended as a defence against marauders.

It will be seen, by reference to the map, that the original route by which the troops were ordered to march to Umballa, would have caused us to make a considerable détour, indeed, one of about thirty or thirty-five miles, for Umballa is nearly direct north of Kurnaul, while Ferozepore is north-west.

The Sunday at Pehoah was not kept as is customary on the Lord's-day in cantonments. We had no chaplain with us; and hence divine service was not performed. It would appear proper that, in the absence of the chaplain, some officer should take his place. This is the case in several European regiments, where the commanding or some superior officer reads the service to the troops. As on board of ship, when there is no chaplain, the purser reads the service, so I think, in the army, the paymaster should discharge this duty. A graduate of either University, if there be one in the corps, would be,[Pg 28] from his education and training, the most desirable person to read a selection of prayers from the church service. A chaplain accompanied the Bengal and Bombay columns, which went to Afghanistan in 1838-39.

We have a noble instance of voluntary dedication to the duties of chaplain to an army on active service, in the case of the Rev. W.J. Whiting, M.A., during the second Sikh campaign. The arduous and invaluable services which this excellent clergyman rendered during that campaign called forth the grateful thanks of the Governor-General, the Commander-in-Chief, the Bishop of Calcutta, and the Court of Directors. He has left an indelible impression, on all engaged in that war, of the importance of his benevolent, as well as spiritual ministrations.

By the warrant for prize-money for the navy, dated 1846, naval chaplains share in the prize money. There appears to be no positive regulation for army chaplains; but the analogy between the two services will point out the propriety of its existing in the latter case; and the warrant being by royal authority, no doubt ought to exist on the subject. It is pleasing to hear that the Rev. George Robert Gleig, M.A.,[Pg 29] Chaplain-General to the Forces, formerly a subaltern during the Peninsular war, and author of several entertaining and instructive military works, has not only received his medal, with two bars, but has worn it at Court over his canonicals, and does wear it at all times in the pulpit.

By the navy warrant, passengers on board a man-of-war, if they desire to join in an action, receive a share of the prize money. The navy prize rules are fairer than those of the army. The army rules were made—I am speaking of India—by the Prize Committees, assembled at Seringapatam, Agra, etc., in 1799 and 1803; and, being composed of senior officers, they took good care of their own grade, while the juniors got a very disproportionate share.

I return from this digression to the bellicose signs of the times. Colonel Campbell's detachment marched, on the 22nd December, to Goelah, sixteen miles distant. Here, in consequence of rumours that the Sikhs had crossed the Sutlej, and having heard, in the afternoon, a distant noise resembling the sound of cannon (which subsequently turned out to be the explosion of mines), Colonel Campbell ordered all the troops[Pg 30] under his immediate command to join and march together.

On the following morning the advanced guard consisted of a troop of the Royal Lancers—the light companies of the 43rd and 59th regiments of Native Infantry—some sappers and miners—and four 12-pounders. The main body consisted of the 9th Lancers—43rd and 59th regiments of Native Infantry—and six 12-pounders. The rear-guard consisted of a troop of the 9th—one company from each of the Infantry regiments—and two 12-pounders: Captain Spottiswoode, 9th Lancers, an able and most intelligent officer, acting as major of brigade. Here was a respectable force of nearly 3,000 men and twelve guns, or four to each thousand men, being above Napoleon's proportion, which was only three to 1,000.

It will be seen that we began the campaign with an artillery very inferior to that of the Sikhs. In fact, if calibres are reckoned, we, probably, were in the minority as one to three. I shall, in the sequel, prove these facts. But to proceed:

It will appear strange to the European reader when he hears that the whole tract of country between the Sutlej and the Jumna, including the[Pg 31] protected Sikh states, which were under our control, as well as our protection, had been in the possession of the East India Company since the year 1809, or for thirty-six years before this period; and that, nevertheless, troops marching to join the army, in a direct line, sixty miles off, were not even aware that the Sikhs had crossed the Sutlej; and that, moreover, two battles had been fought, that of Moodkee, on the 18th, and that of Ferozeshah on the 21st and 22nd of December, the latter being one of the most deadly contested actions ever fought in India. I have before stated that the 9th Lancers had been ordered from Meerut, and did march on the 25th of November; that this line corps, being unfortunately ordered back, did not leave Meerut the second time until the 11th of December. Here was a loss of sixteen days: hence it is clear, that, as the regiment heard firing, or sounds arising from the explosion of powder mines on the 21st of December, it would have been present in the battles of Moodkee and Ferozeshah, had not its march been countermanded.

Now the order to return to Meerut was received on the 27th of November. To what cir[Pg 32]cumstance was this to be attributed? The Sikhs did not cross the Sutlej until the 13th of December, or sixteen days after the 27th of November; and, allowing the order for the return to be dated the 25th of November, there certainly was not any crossing of the Sikhs at that time. It is positively stated, by a staff officer, that Lord Hardinge did not send the order. Although a Governor-General can send such an order direct, yet all military men here know that the Commander-in-chief is the channel for transmitting such orders. At the same time it is an established rule in the Indian army that a Commander-in-chief cannot order any troops on service without the sanction of the Governor-General, or of the government. Even in the common biennial or triennial relief the order is prefaced with the words: "With the sanction of government." The Governor-General being, in the present instance, on the field, was, de facto, the government. As Louis XIV. said: L'état? C'est moi.

Great uncertainty if not mystery prevailed in our army as to the probability of the Sikhs crossing the Sutlej. The Blue Book comes to our aid in deciding upon such a probability. It[Pg 33] was argued that in 1843 the Sikhs did threaten to cross, but thought better of it and forebore; and therefore they might do the same now. But all the politicals knew well enough that the Punts and Punchees were no longer under the control of the Durbar as they were in 1843, but were more likely than not, to act in open defiance of it.

There were two officers, however, of great political talent, whose official position enabled them to know more of the feelings of the Sikhs, and of the probability of such a step than most others; one was Major G. Broadfoot of the 34th Madras Native Infantry, who had held the office of British Agent for Sikh affairs since November 1844, and who had acted as engineer in the celebrated defence of Jellalabad, the heroes of which obtained the well merited Roman distinction of a mural crown; the other was Captain P. Nicolson, 28th Bengal Native Infantry who had been appointed his assistant. Captain Nicolson was in Affghanistan in 1838-39, and was deputed to conduct the traitor Dost Mahomed Khan to Calcutta, and afterwards to Saharunpore. This officer had had seven years' experience of the politics of the Affghans and the Sikhs. At[Pg 34] this juncture he was with Major General Sir John H. Littler at Ferozepore. He was in the daily receipt of intelligence from Lahore, and knew that the Sikhs would cross, for he wrote to Calcutta on the 9th of October, 1845, that "he believed the Sikhs would cross." What! because Major Broadfoot knew that the Sikhs had made an empty threat to cross in 1843, was it therefore improbable, that, being encamped for a long time, on the right bank of the Sutlej, menacing the Durbar at Lahore, from whence they marched in defiance of their government and of their chief, whom they compelled to join them, they would execute their threat under these circumstances?

Major Broadfoot was the Governor-General's agent, and as such was the officer to whom he looked for intelligence, Captain Nicolson was his subordinate; the Major doubted the Captain's intelligence, because he had received no other information to induce him to believe that the rebellious and infatuated Khalsa (or royal) troops would dare to cross. If they threatened to cross in 1843 without carrying that threat into execution, why might they not do the same in 1845? But this was not good logic; the in[Pg 35]ference was against him; because in 1843 they were obedient to the Durbar, and in 1845 they acted in defiance of it.

It would be useless at this distant period to enter into the discussion which arose in India, and was afterwards taken up with much warmth in England, as to the correctness of the views entertained by these officers on the crossing of the Sutlej by the Sikhs. The relative views of those two officers were then and are still sustained by their respective friends; but as far as we can individually offer an opinion, and as it seemed to many at the time, there is great difficulty in arriving at a decision as to the rights of the question at issue. It is true that Major Broadfoot, as the superior officer, might be presumed to be in a position for obtaining access to sources of information from which his subordinate was debarred. In a military point of view, this position must always carry its due weight in the scale of probable authentic intelligence, and should have a preponderating influence in ultimate proceedings, especially in such a country as India, and among such a people as we were then dealing with.

On the other hand, it is by no means uncom[Pg 36]mon for a subordinate in an important position, to have access directly, and indirectly, to authentic intelligence from which his superior may be shut out, and such a subordinate, knowing his duties and his means of intelligence, can constantly elicit facts in a variety of ways, especially from a hostile source, from which his superior is excluded.

Now, in reference to the position of Captain Nicolson at this juncture, and for a long period antecedent, we are decidedly of opinion that his information and impressions were correct: at the same time we do not consider that the admission of this circumstance can warrant any one to seek, or in justice desire, to disparage the opinions of Major Broadfoot. He, no doubt, had strong grounds for arriving at the conclusion that he did, as the information upon which he acted coincided with his own predilections, and for persisting in these views, even in the face of equally strong opinions on the part of Captain Nicolson.

Officers will, and must, differ on points like the one at issue; but we do not hesitate to say, that Major Broadfoot's views have subjected him to no small share of obloquy and censure. It is,[Pg 37] however, important to bear in mind, that in no country, and among no class of people in the world, is there so much cause for a difference of opinion as among military men in India, especially on such a question as that under consideration. The character of the Sikhs, their former empty and vacillating tactics, made the crossing of the Sutlej a matter of uncertainty, even up to a few days of their actual transit; and, to the very last moment, some of their own people were doubtful on the point. This has always been a piece of oriental policy.

It cannot be denied, that the Sikhs had considerable cause for provocation. The sequestration of the two Sikh villages near Loodianna, by the British government, early in November, was the culminating point, and left no doubt of our aggressive intentions on the minds of the Sikhs. Their suspicions had long been awakened by our proceedings—by the rumours of boats preparing at Bombay, to form pontoons across the Sutlej—of our equipping troops in Scinde, for a march on Mooltan—and reinforcing our frontier stations with men and ammunition. They persuaded themselves that the policy of our government was territorial aggrandizement, and that[Pg 38] war was inevitable. This feeling was shared by the mass of the Sikh population. The Durbar sitting at Lahore, however, knew well enough that the British government would not take the initiative; but it had completely lost the confidence and allegiance of the army by its internal dissensions, and the supine weakness and luxurious indolence of the chiefs of the Punjaub. The Sikh soldiery used to assemble in groups round the tomb of Runjeet Singh, vowing to defend with their lives all that belonged to the commonwealth of Govind—that they would never suffer the kingdom of Lahore to be occupied by the British strangers, but stand ready to march, or give the invaders battle on their own ground.

Thus, led on from one step to another, the Sikhs declared war on the 17th of November, and by an overt act broke the solemn treaty of alliance with our government; they crossed the Sutlej on the 13th of December, and on the 14th took up a position in the immediate vicinity of Ferozepore.

This treaty of alliance between the British government and the Maharajah had been concluded in April, 1809; being occasioned by the[Pg 39] aggressions of Runjeet Singh upon the territories of the chiefs of the Cis-Sutlej provinces, who claimed the British protection.[1]

In Sir David Ochterlony's proclamation,[2] which was issued at the same time, it was especially stated, "That the force of cavalry and infantry which may have crossed to this side of the river Sutlej, must be recalled to the other side, to the country of the Maharajah. This communication is made solely with the view of publishing the sentiments of the British, and of ascertaining those of the Maharajah. The British are confident that the Maharajah will consider the contents of this precept as redounding to his real advantage, and as affording a conspicuous proof of their friendship; that with their capacity for war, they are also intent on peace."

There can be no question, that so long as Runjeet Singh held the government, this and subsequent treaties would have remained inviolate. He knew the power and influence of the English well enough to desire their friendship, rather than their enmity. But this was not the case with his successors, whose policy was guided[Pg 40] by views of self-aggrandizement, rather than by the weal of their people, by which they lost their hold over them.

Up to this time, the British had adopted only precautionary measures for the protection of their frontier states. The Governor-General, Lord Hardinge, had joined the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Hugh Gough, at Umballa, early in December; and as soon as the rumour gained ground, that the Sikh forces were marching towards the Sutlej, the troops in the upper provinces received marching orders, and all were speedily on the move. The corps stationed at Umballa, Loodianna, and Ferozepore, amounted to about 30,000 men, with 70 field-guns; and as Ferozepore, which was then occupied by Sir John Littler, was the most exposed, the troops from Umballa were sent to his support, and only a small garrison was left at Loodianna, in order that as large a body of available men as possible, should be placed at the disposal of Sir H. Gough to give battle to the Sikhs, should they carry out their threat of crossing the Sutlej.

This, as we have seen, they actually did on the 13th; but so great was the influence which Captain Nicolson exercised over some of their[Pg 41] chiefs, that he prevailed upon Lall Singh to divide his forces; and it was only a division of the Sikhs which fought at Moodkee on the 18th of December.

The Sikh army numbered from 35,000 to 40,000 men, with 50 pieces of heavy artillery, besides a reserve force stationed near Loodianna, to act according to circumstances. The army of invasion consequently more than doubled that of the British. Notwithstanding the jealousy, mistrust, and treachery which prevailed in the Sikh army, in one thing they were agreed, that they would rid the commonwealth of Govind, of their hated British allies; and that in order to accomplish this, it behoved every individual to act as if the result depended upon himself alone. The Sikhs were commanded by Tej Singh, an officer of considerable talent. They took up an entrenched position at Ferozeshah, an inconsiderable village about 10 miles from Ferozepore and the same distance from Moodkee.

General Sir John Littler was, as we have stated, lying at Ferozepore with a garrison of about 10,000 men. As the Sikhs appeared to threaten the town, the gallant general immediately led out his men, and offered them[Pg 42] battle; this they declined, mainly it would appear, from the double dealing and artful conduct of Lall Singh and Tej Singh, who, uncertain as to the result of the present movement, were anxious to remain friends with both parties.

The head-quarters of the Commander-in-Chief were at Umballa about 150 miles from Moodkee. His Excellency[3] broke up his camp on the 11th, and by forced marches arrived at the village of Moodkee on the 18th. The Governor-General was a little in advance of his Excellency, and rode over to Loodianna to inspect the troops. Finding that post secure from an attack, he dispatched about 5,000 of the garrison to guard the important grain depôt of Bussean.

On the 18th of December, the Commander-in-Chief, with the Umballa division of the army arrived at Moodkee, and was immediately joined by the Loodianna division. On reaching Moodkee there was no longer any doubt as to the whereabouts of the Sikh forces. Orders were immediately issued by the deputy adjutant-general to a brigadier, that he should be ready for duty next[Pg 43] day; in other words, that he should command the advance guard. This was about twelve o'clock in the day, when the officers were in the mess tent at tiffin. Two young officers of the 16th Native Grenadiers overheard the order: "You are brigadier for to-morrow; the army will march early in the morning to attack the Sikhs, who are known to be ten miles off." They were still discussing the glorious prospect of an encounter with the Sikhs, when orders arrived in camp for "all hands to turn out," Major Broadfoot having received intelligence that the Sikhs were near. The order had been sent by Lord Hardinge,—every inch a soldier, but who at that time had not yet been appointed second in command to the Commander-in-Chief.

The cavalry and horse artillery darted off to the right front; the infantry followed; it was a short affair. Lord Gough did not at first credit the report: "The Sikhs are coming!" Like a true Irish soldier, he would have a view of them before he could make up his mind—but he was soon convinced of the reality of the rumour. Major Broadfoot, galloping up to their position, was fired on; both the Governor-General and the Commander-in-Chief were, it is said, at one time[Pg 44] nearly captured. The Governor-General, on the other hand, promptly put the troops in motion: being himself an old Peninsular officer, he was an excellent judge of the matter. His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief could not have done otherwise, but there was not time to send to him: the urgency of the occasion satisfies the mind of all military men; by a delay the Sikhs might have attacked the British.

Napoleon and other great generals "always anticipated the attack." They who attack have the advantage of deciding on the form of attack; those who await it, have no certainty where it may be made.

The battle of Moodkee was, as we have said, a short affair. The Sikhs headed by Lall Singh, opened with a heavy cannonade, but were answered by a brisk fire from the English; the enemy's rear was then attacked by a brilliant cavalry movement which routed him; and night put a stop to the carnage. The Sikhs were defeated with a loss of 17 guns. That of the British was very great; they had 215 killed, and 657 wounded. Among the killed were Sir Robert Sale and Sir John McCaskill. It is doubtful whether the addition of the 9th Lancers would have been of service at the battle[Pg 45] of Moodkee, because there was no extended field for cavalry movements: at Ferozeshah, however, they would have been of eminent use, for on the the second day (December 22nd,) Tej Singh advanced with a large force of horse artillery; and I have heard it deeply regretted by officers present in this action, that we were not at hand to complete the rout of the brave Sikhs.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] See Appendix I.

[2] See Appendix, II.

[3] The Commander-in-Chief is always so styled; the Governor-General never.

Colonel Campbell's Advance—Provisions required—Camp Followers—Samana—The Doabs—Gooroo Govind—The Akalees, their quoits—Sikhs attack Ahmed Shah—Maha Singh—Maharattas—General Thomas—Runjeet Singh—Holcar—Sir Charles Metcalfe—Ochterlony's Proclamation—The Akalees routed—Generals Allard and Ventura—Treaty with Runjeet—Runjeet's Army—Runjeet's Death—Shere Singh Murdered—Dhuleep Singh—Ajean Khan—Battle of Moodkee.

In the meanwhile the force under Colonel Campbell was rapidly advancing to the scene of action. It was as we have stated, nearly 3,000 strong, and attended by about 10,000 or 11,000 camp followers, so that we were in all 13,000 or 14,000 assembled in camp, besides numerous elephants, camels, bullocks, horses, ponies, &c. I will here remark for what purposes camp followers are allowed. Every officer, according to his rank,[Pg 47] will have from ten to twenty or twenty-five servants; the Bengal officers and others have more than those of Madras and Bombay; but the latter servants cost as much as the Bengalese. If a polki (or palanquin) be kept, then six bearers well be required; for every horse two servants, namely a groom and a grass-cutter;[4] for every elephant, two; for camels, one to every three is the usual number; for every two bullocks, one servant is allowed. Besides these there is a host of tent pitchers, store Lascars, etc.

Let us next consider the quantity of provisions required for our force; calculating the 9th Lancers at 800 horses (including officers' chargers,) the consumption of gram, a kind of vetch, daily would be, 800 × 5 = 4,000 seers, or 8,000 lbs. = 71 cwt. 48 lbs. The reader may hence form some idea of the quantity of corn required for 3,000 or 4,000 cavalry horses, or including horse artillery, waggon and private horses, say 5,000, and there would be a consumption of about 440 or 450 cwt. of gram daily. Then each elephant consumes 30 lbs. of atta (flour)[Pg 48] cakes;[5] each camel public and private is allowed 6 lbs. of gram, and a bullock 5 or 6 lbs. daily. The elephant likewise gets forage, such as the leaves of trees; and if he can meet with the branch of a tree he is all the happier, for with it he gracefully fans away the flies from himself or his driver: the poor animal suffers greatly from the mosquito bite. The Mahāwat, or elephant-keeper puts the rice in a whisp of rice straw, making a kind of bowl for the food, which is boiled. The camels, too, get bhoosa, or split straw, when it can be procured, otherwise the leaves of trees: they prefer those of the Imlee, Peepul, Babool, and Burh (fig-tree). The bullocks eat bhoosa or karbi, the stalk of Joar or Bajra (the Holcus Sorgum and Spicatus). If we calculate the quantity of grain consumed in an army of 10,000, 30,000, or 40,000 men, the result will be enormous, and we can only marvel where such supplies are obtained.

The Duke of Wellington[6] when in India, often marched with 30,000, or 40,000 bullock-loads of [Pg 49]grain, or 600,000, or 800,000 lbs. or 53,571, or 71,428 cwt. His grace's plan was never to open these grain bags so long as he could get supplies from the villages.

Let the reader imagine an Indian army of 20,000 men with its 60,000, 70,000, or even 80,000 camp followers, all of whom must be fed daily. Again, the number of hackeries, or carts, with an army of 20,000 or 25,000 men, varies from 700, to 12,000 or more, (for much depends upon whether there is a siege train), drawn by two, three, or four bullocks each, carrying shot, shells, and stores, and moving at the rate of two miles an hour, the whole line of march from the old to the new ground. Allowing 10 doolies, or light palanquins, for every European troop or company, for the conveyance of the sick or wounded men, there would be 80 required for the 9th Lancers, and as each dooly needs 6 bearers we had 480 bearers in our corps alone. In a European infantry regiment of 10 companies there will be 10 × 10 = 100; 100 × 6 = 600 bearers. A native corps is allowed only one for a troop or company, but some extra ones accompany the field hospital. Now such an army would have at least 5,000 dooly bearers, besides those which[Pg 50] are required for luxurious officers, who have been seen, though, I am happy to say, rarely, to ride in palanquins.

The English waggon train establishment is said not to be good. A veterinary surgeon has published a work on the use of a light cart, with cross seats on springs; but before it can be generally adopted, the roads must be improved. In the Affghan war they used Kajawahs, that is a frame-work on each side of the camel, for two men.

On the 23rd of December, our force marched to Samana, a large old town, now completely in ruins, in the province of Delhi. It is in the Rajah of Pattiala's country, and is about seventeen miles distant from Pattiala, and seventy miles from Kurnaul. It was a very fatiguing march; the road during the last few miles being bad, rough and sandy; this greatly impeded the elephants who dragged the guns, and our progress was very slow; so slow indeed that at six o'clock in the afternoon the men had not dined. In cantonments one o'clock is the usual hour, but in marching to meet an enemy the dinner hour is uncertain. Yesterday and to-day we were obliged to breakfast upon what chance threw in our way.

On service with Lord Lake, it is said that frequently neither officers nor men got any breakfast at all, but broke their fast at sunset; similar privations no doubt often occurred in the Peninsula; but this is very undesirable when it can be obviated, for especially in hot countries, European soldiers require more nourishment than in colder climates.

Samana contains a large brick-built fort; it appears at one time to have been very strong, but is now falling to decay. There are many of these forts, and their origin is long anterior to 1809, when the British obtained possession of the protected Sikh states. They were built by Runjeet Singh, when he was lord and master of the country on the left bank of the Sutlej, governing, in fact, the whole district between the Jumna and the Sutlej. At that time he fortified all the towns and villages, to defend not only the inhabitants against the attacks of their neighbours, but also to prevent the cattle sheltered under the walls, from being carried off by marauders.

Before proceeding further on our route, we will take a brief survey of the territory of the[Pg 52] Sikhs, and of the history of the singular race whom we were marching to encounter.

The Punjaub, or country of five waters, from punj, "five," and āb, "water," forms the northern portion of the plain of the Indus. It covers an area of 6,000 geographical miles, and extends from the lower ranges of the Himalaya mountains to the confluence of the Chenāb with the Indus. The four streams or arms of the Indus which rise in the Himalayas, namely, the Jelum, the Chenāb, the Rāvee and the Sutlej, intersect the country, and, with the Indus, divide it into four Doabs or Provinces.

The first Doab ("country between two rivers"), lying between the Indus and the Jelum, is 147 miles in breadth; this Doab is intersected with defiles and mountain chains, and covered with thickets. It is the worst cultivated, the most barren and thinly peopled of all the Doabs.

The second Doab is formed by the rivers Jelum and Chenāb. At its narrowest breadth it is forty-six miles across; this country is flat, except the low range of hills terminating the beds of rock salt that run through the Jelum. It is capable of very improved cultivation.

The third Doab lies between the Chenāb and the Rāvee. This Doab might with the greatest ease be converted into a most fertile country, were the land irrigated by the mountain streams, which could be conveyed in artificial canals. It is seventy-six miles in breadth at its widest part.

The fourth Doab is considerably the smallest, being only forty-four miles in breadth. It, however, comprises some of the most important cities, namely, Lahore, Umritsur and Kussoor. It lies between the Rāvee and the Sutlej.

Besides this fine country, the rule of the Sikhs at this time extended over the rich Province of Mooltan, on the right bank of the Indus. The territory under the sway of the Maharajah might be estimated at 8,000 geographical square miles, with a population of about 5,000,000 inhabitants, and an annual revenue of between £2,000,000 and £3,000,000 sterling.

The Sikhs, or "Disciples," were originally a religious sect, which arose among the inhabitants of the Punjaub as late as the close of the fifteenth century. Their leader was Nānak, who succeeded in drawing thousands of enthusiasts after him. He was a disciple of Kahir, and consequently a Hindoo deist; he upheld the principle[Pg 54] of universal toleration, calling upon his followers to worship the one invisible God, and to lead a virtuous life. He died at the age of seventy, in 1539. His doctrines and writings tended greatly to elevate the mind, and reform the morals of his disciples. The Sikhs believe that the soul of Nānak has transmigrated into the body of each succeeding Gooroo, or teacher.

The spirit of religious toleration adopted by the Sikhs, was odious in the eyes of the bigoted Mahomedans, and Arjoon, their chief, who was celebrated not only for his piety, but for his wisdom and skill as a legislator, was falsely accused, and put to death, by the Mogul, in 1606. Arjoon converted the obscure hamlet of Umritsur into a city of great importance, by making it the seat of his disciples, and the place of the Sikhs' pilgrimage. His cruel death transformed the quiet and peaceable Sikhs into a warlike nation; their spirit was roused, and, led on by Hur Govind, the son of their murdered priest, they determined to avenge themselves upon his assassins. The Mogul, however, was too mighty for them; and they were forced to retreat into the mountain districts beyond Lahore.

After a series of sanguinary engagements, in[Pg 55] which the Mahomedans were successful, a powerful opponent to the infidel faith and arms, was raised up, in the person of Gooroo Govind, grandson of Hur Govind, in 1675. He effected a radical change in the character, laws, and institutions of the Sikhs, by the abolition of caste, and the introduction of religious, social and military reforms. Amidst the surrounding spiritual darkness, Govind had comparatively enlightened views of the Deity; he abhorred idol worship, and declared that there was but one Lord, and that the invisible God, the Creator of heaven and earth, could not be represented by any painted or graven image; and that as He could be seen only by the eye of faith, He must be worshipped in sincerity and truth. Fearful that he himself might hereafter become an object of religious adoration, Govind denounced all who should regard him as a divinity, alleging that it was his highest ambition that his spirit should return to God after his death.

In the full persuasion, that the only hope of successfully opposing the Mahomedan power was by throwing open the ranks of the army to men of every grade and profession, he adopted the wise and politic measure of abolishing the[Pg 56] system of caste. This step was at first highly offensive, especially to the Brahmins, and many quitted the community; but the majority of the Sikhs rejoiced at the breaking down of this barrier to all social and religious intercourse. His expectations, however, were more than realized; vast multitudes joined his ranks, he caused each of his followers to wear a peculiar dress, to adopt the name of Singh, or soldier, and to suffer their beard and hair to grow; he completely reorganized the army, divided his followers into troops and bands, and placed them under the command of able and confidential men.

A special corps was formed of the "Akalees," the Immortals, or Soldiers of God, they wore a blue dress and steel bracelets, and were provided with a quoit, which they carried either round their pointed turbans or at their side; this quoit is a flat iron ring, from eight to fourteen inches in diameter, the outer edge is extremely sharp; they twirl this weapon round their finger or on a stick, and fling it to a distance with such dexterity and precision, that the head of the destined victim is often severed from his body.

In proportion as the Mahomedan power de[Pg 57]clined, that of the Sikhs rose into importance. They were bound together by the strong ties of a fervid common faith; and this gave them unity of purpose, and consequent strength in operation.

After various struggles for independence, in which they displayed heroism amounting even to martyrdom, they boldly attacked Ahmed Shah, the king of Affghanistan on his first invasion of India, in 1747. They were, however, dispersed by Mere Munroo, and expelled from Umritsur by Timoor, the son of Ahmed Shah, who was appointed governor of the Punjaub. Strong in the faith of Govind, and in his all-prevailing name they rallied their forces, drove out the Affghans, and re-occupied Lahore in 1756.

About this time they called in the aid of the Maharattas, gained several victories, and fortified their towns. In 1762, they were again attacked by Ahmed Shah, who completely routed them, but with their native energy and warlike prowess, they once more gathered their scattered forces, and in 1763 slew the Affghan governor, and defeated his army in the plains of Sirhind, when they took undisputed possession of the[Pg 58] country from the Sutlej to the Jumna, and partitioned it among their chiefs.

They successfully defeated a seventh attack made by Ahmed Shah; and after ejecting the governor of Lahore, they took possession of the territory from the Jelum to the Sutlej. Like the former acquisition, it was divided among their chiefs.

During the brief period of peace which now intervened, the Sikhs settled the boundaries of their respective districts, and more firmly established their federal government, which, properly speaking, may be styled a theocratic feudal confederation, inasmuch as they considered God as the Head and Leader of their confraternity. They held stated councils, or conclaves, which they called "gooroo-moottas," in which they settled their civil and religious affairs. The nation was divided into twelve confederacies or "misls," from an Arabic word signifying "equal," each "misl" being under the control of a sirdar or chief.

Their respite from war was not, however, of long duration; for in 1767, Ahmed Shah made an eighth and last attempt to reconquer the Punjaub. Being, however, deserted by 12,000 of[Pg 59] his own troops, he was compelled to retire, and had scarcely re-crossed the Indus when he was besieged at Rhotas, by the grandfather of Runjeet Singh; and the Sikhs took possession of this stronghold in 1768.

Timoor, the son of the veteran Shah, had various conflicts with the Sikhs; and in 1779 reconquered the city of Mooltan, which they had taken seven years before. He died in 1793, leaving the Sikhs undisputed masters of the Upper Punjaub.

Maha Singh, though originally an obscure sirdar, soon rose by his military skill to be the most influential chief in the Punjaub. With the view of cementing his power, he espoused his only son, Runjeet Singh, to the daughter of Sudda Kour. Maha Singh died at the early age of twenty-seven, leaving Runjeet Singh to succeed him in the government. He was a boy of only eleven years of age, having been born in 1792, at Gujeranwalla, forty-seven miles from Lahore.

From a very early age, Runjeet Singh began to display that wisdom and valour, combined with prompt decision and firmness of character, which distinguished him through life. He carved[Pg 60] out with his sword his own colossal position in the Punjaub; and, at the age of twenty, expelled the Sikh chiefs, Ischet Singh, Muhuc Singh and Sahib Singh, who opposed him. On the second invasion and retreat of Shah Zeman, king of Cabool, Runjeet Singh acquired the object of his ambition—the wealthy kingdom of Lahore, with the royal investiture and title of Maharajah.

About this time the star of the Maharattas again rose in the Northern Provinces, under their able leader, Madhajee Sindhia, who, in 1785, formed an alliance with the Sikhs, and threatened the kingdom of Oude, then under the protection of the British. Runjeet, however, soon became jealous of his allies; and finding that they were likely to prove troublesome, he had recourse to the strongest measures to check their growing influence.

One of the generals of the Maharatta forces was an English adventurer, named George Thomas. He came to India in 1781, in a British man-of-war; he was originally a common sailor, but rose to be quarter-master, and on his arrival in India entered the service of the native chiefs. He was sent to oppose the combined forces of the Sikhs. Leaving a competent force for the[Pg 61] defence of Jeypore, which was then threatened with an attack from another quarter, he marched to Kurnaul, where the Sikhs lay encamped. Here four successive engagements took place, in which the Maharattas lost 500 men, and the Sikhs about 1,000. Both parties at last inclining to peace, a treaty was concluded, by which the Sikhs agreed to evacuate the Province. In 1800, General Thomas again entered the Sikh country, with a body of 5,000 men and sixty pieces of artillery. He was now opposed by the youthful Maharajah, Runjeet Singh; but the issue was adverse to the Sikhs. Nor was it surprising that General Thomas with a well disciplined army of 5,000 men, and sixty guns[7] should defeat a young chief of twenty-two years of age.