This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Young Book Agent

or Frank Hardy's Road to Success

Author: Horatio Alger

Release Date: March 16, 2018 [eBook #56756]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE YOUNG BOOK AGENT***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/youngbookagentor00alge |

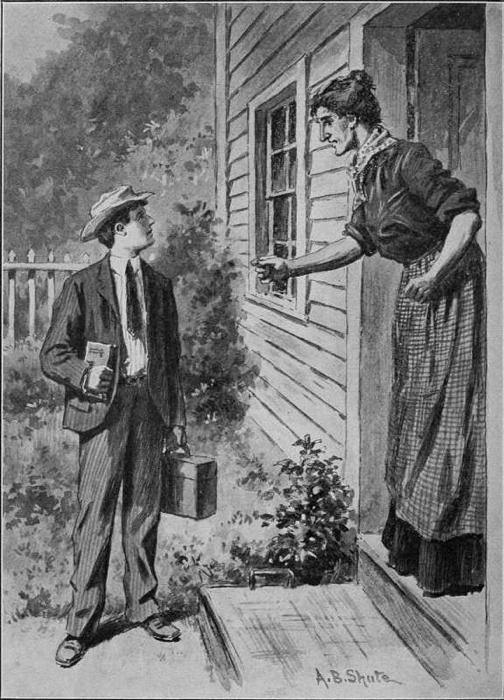

“BOOKS! YOU GET RIGHT OUT OF THIS DOORWAY!”–P. 112.

Many years ago the author of the present volume resolved to write a long series of books describing various phases of village and city life, taking up in their turn the struggles of the bootblacks, the newsboys, the young peddlers, the street musicians—the lives, in fact, of all those who, though young in years, have to face the bitter necessity of earning their own living.

In the present story are described the ups and downs of a boy book agent, who is forced, through the misfortunes of his father, to help provide for the family to which he belongs. He knows nothing of selling books, when he starts, but he acquires a valuable experience rapidly, and in the end gains a modest success which is well deserved.

It is the custom of many persons in ordinary life to sneer at a book agent and show him scant courtesy, forgetting that the agent’s business is a perfectly legitimate one and that he is therefore entitled to due respect so long as he does that which is proper and gentlemanly. A kind word costs nothing, and it often cheers up a heart which would otherwise be all but hopelessly depressed.

After reading this volume it may be thought by some that the hero, Frank Hardy, is above his class in tact, intelligence, and perseverance. This, however, is not true. A book agent, or, in fact, an agent of any kind, must possess all of these qualities in a marked degree, otherwise he will undoubtedly make a failure of the undertaking. As in every other calling, to win success one must first deserve it.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Frank at Home | 1 |

| II. | Down at the Wreck | 9 |

| III. | Disagreeable News | 17 |

| IV. | The Hunt for a Missing Man | 25 |

| V. | Frank at the Store | 34 |

| VI. | The Rival Merchants | 42 |

| VII. | A Fourth of July Celebration | 50 |

| VIII. | Frank Looks for Work | 58 |

| IX. | Frank Meets a Book Agent | 67 |

| X. | Frank Goes to New York | 76 |

| XI. | Frank as an Agent | 86 |

| XII. | A Bright Beginning | 96 |

| XIII. | Frank on the Road | 108 |

| XIV. | A Boy Runaway | 118 |

| XV. | Caught in a Storm | 127 |

| XVI. | An Important Sale | 136 |

| XVII. | A Curious Happening | 145 |

| XVIII. | The Would-be Actor | 153 |

| XIX. | Giving an Autograph | 162 |

| XX. | Frank’s Remarkable Find | 171 |

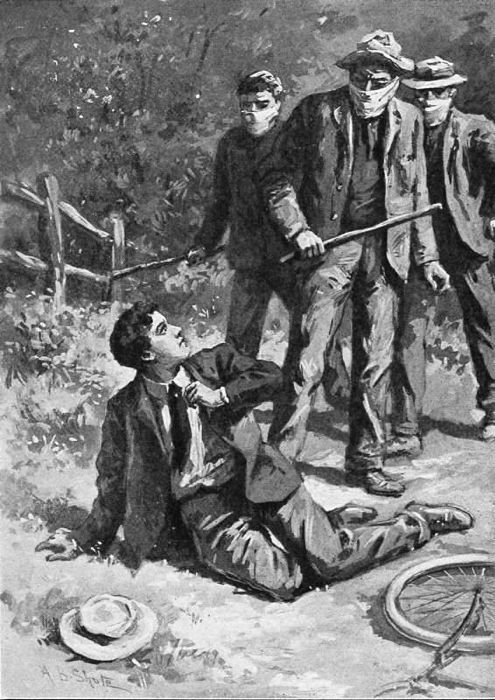

| XXI. | Gabe Flecker Shows His Hand | 180 |

| XXII. | The Rival Book Agent | 189 |

| XXIII. | News from Home | 197 |

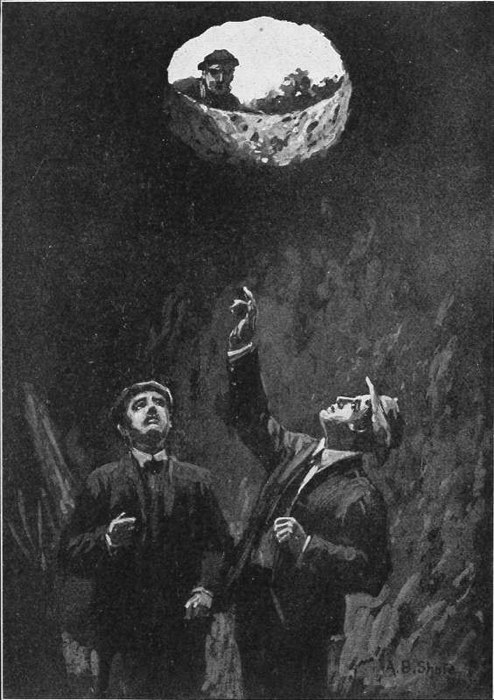

| XXIV. | Lost in a Coal Mine | 205 |

| XXV. | Frank Meets Flecker Again | 214 |

| XXVI. | An Escape | 224 |

| XXVII. | At Home Once More | 232 |

| XXVIII. | Frank Starts for the South | 242 |

| XXIX. | A Scene on the Train | 249 |

| XXX. | Frank Meets His Brother Mark | 257 |

| XXXI. | A Clever Capture—Conclusion | 264 |

Frank Hardy came up the short garden path whistling merrily to himself. He was a tall, good-natured looking boy of sixteen, with dark eyes and dark, curly hair.

“One more week of school and then hurrah for a long vacation in the country!” he murmured to himself as he mounted the piazza steps. “Oh, but won’t we have a dandy time swimming and fishing when we get to Cloverdale!”

His little dog Frisky was at the door to greet him with short, sharp barks of pleasure. Frank caught the animal up and began to coddle him.

“Glad to see me, eh?” he cried. “Frisky, won’t you be glad when we get to the country and you can roam all over the fields?”

For answer the dog barked again and wagged his tail vigorously. Still holding the animal, Frank entered the dining room and passed into the kitchen, where his mother was assisting the servant in the preparation of the evening meal.

“Mother, is father back from Philadelphia yet?” he asked, as he hung up his cap and slipped into the sink pantry to wash his hands.

“Not yet, Frank,” answered Mrs. Hardy.

“He must have quite some business to attend to, to stay away so late. I thought I was late myself.”

“You are late, Frank—it is quarter after six. I expected your father in on the half-past five train, but he must have missed that.”

“Then he won’t be here until nearly eight o’clock. Must I wait for my supper?”

“No; we can have our supper directly. I know you must be hungry.”

“I am, mother. Baseball gives a fellow an appetite, especially if he runs bases and plays in the field, as I did. We played the Hopeville Stars and beat them 12 to 7. I made three runs.”

“You must certainly love the game?”

“I do. Sometimes I wish I could be a professional ball player.”

“I shouldn’t wish you to be that, Frank. I want you to go to college and be a professional man,” added Mrs. Hardy, with a fond smile.

“Oh, I was only talking, mother. But some professional ball players are college men.”

Frank entered the dining room and sat down to the table. He was soon joined by his little brother, Georgie, and his sister, Ruth, who was twelve years of age.

“How do you get along with your lessons?” he asked of Ruth, who had been practicing on the piano in the parlor.

“I think I am doing real well,” returned the sister, who was very fair, with golden hair and bright blue eyes. “Professor Hartman says I will make a good player if I do plenty of practicing. And, oh, I love it so!” added the girl, enthusiastically.

“The one who loves it is the one who is bound to make a good player,” said Frank. “Now, there is Dan Dixon. His folks want him to learn to play the violin, and he takes lessons. But he doesn’t like it at all, and I am sure he will never make a player.”

“That is true in all things,” came from Mrs. Hardy, as she sat down to pour the tea. “If one wants to do well at anything, one’s heart must be in the work. I once knew a girl whose family wanted her to learn how to paint. She hadn’t any talent for it, and though she took lessons for two years she never drew or painted anything really worth showing.”

“I know what I like real well,” came from little Georgie. “I’m going to keep a candy store when I grow up. I like that real well.”

“Good for you, Georgie!” laughed Frank. “Only don’t eat up all the stock yourself.”

“Will you buy from me when I keep the store?” continued the little fellow.

“To be sure, I will—or, maybe, I’ll be a salesman for you—and Ruth can be the cashier.”

“What’s a cashier?”

“The one who takes in the money.”

“No, I want to take in the money myself,” came from Georgie, promptly.

Thus the talking went on, and while it is in progress and the family are waiting for the return of Mr. Hardy from his business trip, let me take the opportunity of introducing them more specifically than I have already done.

The Hardy family were six in number, Mr. Thomas Hardy and his wife; Mark, who was three years older than Frank, and the children already introduced.

Mr. Hardy was a flour and feed dealer, and at one time had had the principal store in that line in Claster, the town in which the family resided. He had made considerable money, and the family were counted well to do. But during the past two years two rivals with capital had come into the field, and trade with the flour and feed merchant had consequently fallen off greatly.

Mr. Hardy had expected to send his oldest son, Mark, to college, but the youth had begged to be allowed to take an ocean trip, and had at last been allowed to ship on a voyage to South America. He was to return home in seven or eight months, but during the past three months nothing had been heard of him.

Frank, Ruth, and little Georgie all attended the same school in Claster, Georgie being in the kindergarten, and Ruth in one of the grammar grades. Frank was in the graduating class, and after a vacation in the country, expected to prepare himself for high school. He was just now deep in his final examinations at the grammar school, and so far had done well, much to his parents’ satisfaction.

“Mother, what took father to Philadelphia?” asked Frank, after a spell of silence, during which he had devoted himself to the viands set before him.

At this question a shade of anxiety crossed Mrs. Hardy’s face.

“He went on very important business, Frank. I cannot explain to you exactly what it was. He was to see Mr. Garrison, the man he used to buy flour from.”

“Jabez Garrison?”

“Yes.”

“I never liked that man, mother; did you?”

“I really can’t say, Frank—I never had much to do with him.”

“I saw him at the store several times—doing business with father. He somehow put me in mind of a snake.”

“Oh, Frank!” burst in Ruth.

“A man don’t look like a snake,” was little Georgie’s sober comment.

“That is not a very complimentary thing to say, Frank,” said Mrs. Hardy, somewhat severely.

“I can’t help it, mother. He has such an oily, smooth manner about him.”

“Your father has spoken of him as a very good friend in business. I believe he gave your father prices which were better than he could get elsewhere.”

“Well, he didn’t look it. If I were father, I’d keep my eyes on him.”

“He went to Philadelphia to make inquiries about Mr. Garrison. I cannot tell you more than that just now.”

“Didn’t father loan him some money?”

“Not exactly that; but he went his security when Mr. Garrison was made treasurer of a certain benevolent order in Philadelphia.”

“How much security?”

“Ten thousand dollars.”

“That’s a big sum of money.”

“Yes, Frank—but I was told that it was more a matter of form than anything else.”

“I don’t see it, mother. If Jabez Garrison had a lot of money to handle, he could steal it if he wanted to.”

“Frank, you are certainly not in love with Mr. Garrison. Did he ever say anything to you?”

“Not a word. Only I don’t like his looks, that’s all.”

Further talk on this subject was cut off by Ruth, who chanced to look out of the bay window of the dining room.

“There goes the hospital ambulance,” she cried. “Somebody must be hurt.”

Frank, filled with curiosity, leaped up and ran to the front door, and then down to the gate.

“What’s the trouble?” he asked of a boy who was running past.

“Big accident on the railroad, down at Barber’s Cut,” answered the boy. “Freight train ran into the Philadelphia local, and about a dozen passengers have been killed or hurt.”

“The Philadelphia local!” echoed Frank, and for the moment his heart almost stopped beating. “Can father have been on that train?”

He ran back into the house and told his mother the news. Mrs. Hardy was almost prostrated, but quickly recovered.

“I will go down and see if your father is in that wreck,” she said. “Frank, you can go along.” And a moment later they set out for the scene of the disaster.

Claster was a thriving town of four thousand inhabitants, with several churches and schools, a bank, two weekly newspapers, and six blocks of stores. There was a neat railroad station at which two score of trains stopped daily, bound either north or south, for the line ran from Philadelphia to Jersey City.

Barber’s Cut was a nasty curve on the line, just south of the town. Here there was a rocky hill, and in one spot the cut was twenty feet deep. At the end of the cut was a hollow where a railroad bridge crossed Claster Creek.

Frank and his mother found a great many of the townspeople hurrying to the scene of the wreck. All sorts of rumors were afloat, and it was said the passenger cars were on fire, and the helpless inmates were being roasted alive. The local fire department was called out, but fortunately the fire was confined to a freight car loaded with unfinished wagon wheels, so but comparatively little damage was done through the conflagration.

The rumor that a dozen passengers had been killed or hurt was false. But four people on the passenger train had been injured, and only one severely—this man having several ribs crushed in and an arm broken.

“I don’t see anything of father,” said Frank, after he and his mother had looked at three of the injured persons. “I guess he wasn’t on this train after all.”

“It is very fortunate.”

“Your father was on this train,” said a man standing near. “I was talking to him just a short while before the smash-up occurred.”

“Oh!” ejaculated Mrs. Hardy. “Then where is he now?”

“There he is!” burst out Frank, and pointed to a form which four men were carrying from a wrecked car. “Mother, he is—is hurt. You had better go back and I’ll—I’ll tend to him.” Frank found he could scarcely speak, he was so agitated.

“My husband!” murmured Mrs. Hardy, and ran forward with Frank at her side. “Oh, tell me, he is not—not dead?”

“No, ma’am, he isn’t dead,” came promptly from one of the men. “He got his foot crushed, and he’s fainted, that’s all.”

“Thank Heaven it is no worse!” murmured Mrs. Hardy, and when the men laid her husband on the grass above the cut, she knelt beside him, and sent Frank down to the creek for some water with which to wash Mr. Hardy’s face, for it was covered with dust and dirt.

As Frank ran down to the creek for the water he saw something shiny lying in the grass. He picked the object up, and was surprised to learn that it was a silver spectacle case, containing a fine pair of gold-rimmed spectacles.

“Somebody dropped those in the excitement,” he reasoned. “I’ll have to look for the owner later;” and he shoved the case into his pocket.

Of the four that had been hurt two were removed to the hospital and the others were taken to their homes. Mr. Hardy was carried to his residence, and there his physician and his family did all they could to make him comfortable.

“The foot is in rather bad shape,” said Doctor Basswood. “Yet I feel certain I can bring it around so you can walk on it as before. But it will take time.”

“How much time, doctor?” questioned Mr. Hardy, faintly.

“Four or five months, and perhaps longer. But that is much better than having your foot amputated.”

“True. But I can’t afford to lay around the house for six months.”

At this the physician shrugged his shoulders.

“It’s the best I can do, Mr. Hardy.”

“Oh, it is not your fault, doctor. But——” Mr. Hardy paused.

“You are thinking of your store?”

“Yes.”

“It is a pity your son, Frank, isn’t older. He might be able to run it for you.”

“Unfortunately, Frank knows little or nothing about the business. I have kept him at school.”

“Perhaps you can get a good man to run it for you.”

“Perhaps. I don’t know what I’ll do yet.”

“What do you do when you go away, as you did to-day?”

“I lock the place up, and leave a slate out for orders. Trade is not as brisk as it used to be.”

“You mean as it was before Benning and Jack Peterson started in the business?”

“That’s it. The town can’t support three flour and feed stores.”

“Won’t your old customers stick by you?”

“A few of them do; but both Benning and Peterson are doing their best to get the trade away from me. They offer all sorts of inducements, and sometimes sell at less than the goods cost, just to get a customer.”

“Nobody in business can afford to do that very long.”

“They want to drive me out, and each wants to drive out the other. Then the one who is left will make prices to suit himself;” and here Mr. Hardy had to stop talking, for he felt very much exhausted.

In the meantime Frank had been sent down to the drug store for several articles which the doctor had said were needed for the injured man. While he was waiting for the articles a burly and rather pleasant-faced man came in and purchased a handful of cigars.

“Is there an optician in town?” questioned the man of the druggist. “I was in that wreck, and somehow I lost my glasses, and I want to get another pair.”

“The watchmaker across the way keeps spectacles,” answered the druggist. “But if he can fit you or not I don’t know.”

“I’ll try him,” said the man, and started for the door.

“Excuse me,” put in Frank, stepping up. “What sort of spectacles did you drop?”

“Did you find them?”

“Perhaps I did.”

“Mine were in a silver case. They are thick glasses, with a gold frame.”

“Then these must be yours,” and Frank drew the case from his pocket and passed it over.

“They are mine!” cried the burly man, and looked well pleased to have his property returned to him. “Where did you find them?”

“In the grass between the wreck and the creek. I was down at the creek getting some water for my father, who was hurt. I almost stepped on the case.”

“I see. So your father was hurt. Which one was he?”

“He had his foot crushed.”

“Oh, yes, I remember. They took him to your home up the street.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I hope the hurt isn’t serious?”

“It’s bad enough. But Doctor Basswood says he can save the foot.”

“Well, that’s a great consolation. It’s no fun to have a foot cut off. May I ask your name?”

“Frank Hardy.”

“Mine is Philip Vincent. I am very much obliged for returning the glasses to me.”

“Oh, that’s all right, Mr. Vincent. I was going to hunt up the owner as soon as everything was all right at our house.”

“These glasses are a very fine pair, and I prize them exceedingly. Let me reward you for returning them,” and Philip Vincent put his hand in his pocket.

“I don’t want a reward, sir,” said Frank, promptly.

“But I want to show you that I appreciate having them returned,” insisted the burly gentleman.

“It’s all right.”

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’m in the book business in New York. I’ll send you a good boy’s book. How will that suit you?” and the gentleman smiled blandly.

“I must say I never go back on a good story book,” answered Frank, honestly.

“Most boys like to read. I suppose you go to school here?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, I shan’t forget you,” concluded Philip Vincent, and shaking hands, he left the drug store.

“What a pleasant kind of a man,” thought Frank. “I’d like to see more of him.” And then he wondered what sort of a story book Mr. Vincent would send him.

A little later Frank obtained the articles needed from the druggist, and then he started for home. He did not dream of the disagreeable surprise which was in store for him.

“How is father feeling?” asked Frank, when he entered the house with his packages under his arm.

“I think he is a little feverish,” answered Mrs. Hardy.

“Does his foot hurt him much?”

“He says not. Doctor Basswood put something on to ease the pain.” Mrs. Hardy paused for a moment. “Your father brought bad news from Philadelphia,” she continued.

“What bad news, mother?”

“It is about Mr. Garrison. He has got into trouble with that benevolent order.”

“What kind of trouble?”

“There is a shortage in the funds of the order.”

“For which Jabez Garrison is responsible?”

“So they claim.”

“What does Mr. Garrison say about it?”

“He told your father that it would all be straightened out in a week.”

“Does father believe it?”

“He won’t say. He is much worried, and I don’t wish to ask too many questions for fear it might make your father worse.”

“Didn’t I say Garrison was a snake?” went on Frank. “I am sorry father trusted him.”

“So am I—now. But it can’t be helped.”

“Do you know what father was going to do about it?”

“He said he had intended to go to Philadelphia again next Monday. But of course, he can’t go now.”

“Can’t I go for him?”

“Possibly, although I don’t see what you can do.”

“I could have a talk with Mr. Garrison and also with the other men who are interested in the order.”

“Well, we’ll wait and see how matters turn,” said Mrs. Hardy, with a sigh.

The accident had happened on Saturday, and during Sunday Mr. Hardy was decidedly feverish, so that the doctor had to come and attend him twice. The night to follow was an anxious one for the whole family, but by Monday noon the sufferer felt much better, although, on account of his crushed foot, he did not dare to move.

The store had been closed, but before and after school Frank delivered the orders that were left on the slate, and also went to such customers as his father mentioned. Trade was indeed slow, and the boy could readily see that the two rivals of his parent were doing the larger portion of the business. And this was not to be wondered at, since each had a fine location and made a very attractive display. If the truth must be told, Mr. Hardy was a bit old-fashioned in his ways, and he allowed his rivals to go ahead of him without much of a protest.

“I wish I knew all about the store,” thought Frank. “I’d go in for all the business there was.”

A letter had been sent to Jabez Garrison by Mrs. Hardy—the letter being dictated by her husband—but Wednesday passed without any answer being received. On this day Frank returned from school, stating that the final examination was at an end.

“And I received ninety-three per cent. out of a possible hundred,” said he, with just a little pride.

“You have certainly done very well,” answered Mrs. Hardy, and gave him a fond kiss. “Then you are sure of your grammar-school diploma?”

“Of course.”

“I am very glad to hear it, Frank.”

“How is father?”

“No different from what he was this morning. He is very anxious to hear from Mr. Garrison.”

“Then you have no word yet?”

“None whatever.”

“I don’t like that.”

“Neither do I.”

“Perhaps I’d better go to Philadelphia for him after all.”

“He says he will wait another day.”

The next day passed and still no word was received.

“Frank, do you think you could talk to Mr. Garrison?” questioned the boy’s father.

“Yes, sir—if you’ll tell me about what you’ll want me to say.”

“I want to find out just how he stands in relation to that benevolent order. If you can’t find out from him I want you to go to Mr. Bardwell Mason, the secretary. Here is his address on a card. I want to know exactly how matters stand.”

“What shall I do if I find Mr. Garrison has used up some money that doesn’t belong to him?”

“Tell him for me that he must straighten out the matter at once. If he does not I shall apply to the authorities for protection.”

“Could the authorities make you pay that ten thousand dollars if Jabez Garrison didn’t pay it?”

“Certainly, if he was in arrears that amount.”

“It’s a big sum of money, father.”

“To lose that amount would ruin me, Frank.”

“Ruin you?”

“Yes. Business is so bad that I need the money to help matters along. If I lose the cash I’ll have to close up or sell out.”

“Then I think you ought to get after Mr. Garrison without delay—or let me get after him.”

“I do not wish to appear too forward—in case everything turns out right, Frank. Mr. Garrison has done me some good turns in business in the past.”

Father and son had a talk lasting the best part of an hour, and then Frank came up to his room to prepare himself for the journey.

The youth had been to Philadelphia several times during the past two years, so he knew he would not feel as strange as though the city was totally new to him.

The wreck on the railroad had been cleared away in a few hours after it occurred, so there was nothing to hinder the trains from going through on time. Frank left home at ten in the morning and promised to be back by eight o’clock in the evening, or else to send a telegram stating why he was detained. If necessary he was to stop over night at a hotel his father mentioned to him.

The day was a bright, clear one in late June, and had our hero not had so much on his mind he would have enjoyed the trip very much. As it was, however, he could not help but think of what was before him, and of just how he should approach Mr. Jabez Garrison when he met that individual.

“I mustn’t say too much,” he reasoned. “And yet it won’t do to say too little. My opinion of it is, that father is altogether too easy on him. A man who can’t act on the square when he is handling money belonging to others doesn’t deserve nice treatment.”

It was some time before noon when Frank reached the Quaker City, as Philadelphia is often called. The ride had made him hungry, but he determined to call on Jabez Garrison before hunting up a restaurant for lunch.

The office of the wholesale flour and feed merchant was on Broad Street, and hither Frank found his way.

“Is Mr. Garrison in?” he asked of the clerk who came forward to meet him.

“What name, please?”

“Frank Hardy. I was sent here by my father, Thomas Hardy, of Claster.”

“I’ll see if Mr. Garrison will see you. He is very busy at present.”

“Tell him it is very important.”

The clerk walked to the rear of the place and entered a private office, closing the door behind him.

Frank heard some strong conversation for several minutes and then the clerk returned.

“Mr. Garrison is very sorry, but just now he cannot see you, as he has an important account to look after. He says if you will call at three o’clock this afternoon he will see you, and explain everything to your father’s entire satisfaction.”

“At three o’clock,” repeated Frank.

“That’s it. Just now he has got to look after an account that is worth something like fifteen thousand dollars to him.”

“All right then. I’ll call at three o’clock sharp,” said our hero, and left the place.

The statement the clerk had made was rather reassuring, for if Jabez Garrison had an account of fifteen thousand dollars coming to him he certainly could not be in a very bad condition financially.

“Perhaps this unpleasantness will all blow over after all,” thought Frank. “Father may be right, and I may be misjudging this man.”

He found a restaurant that suited him, and as he had a long time to wait, took his leisure in eating. Then he visited several department stores, spending a full hour in the picture and book departments. Books particularly interested him, and as he had a quarter to spend he let it go in the purchase of a volume which was slightly soiled, and therefore sold to him at one-third of its real value.

“I wouldn’t mind owning a bookstore of my own,” he said to himself, as he set out once again for Jabez Garrison’s offices. “It’s a business that would just suit me. I wonder if Mr. Philip Vincent has a place as large as that department I just visited?” And then he wondered when the gentleman from New York intended to send the book he had promised.

When Frank arrived at the flour dealer’s offices the clerk met him with rather a troubled look on his face.

“Mr. Garrison isn’t here,” he said. “He went out about two hours ago, and I can’t say how soon he’ll be back.”

On entering the offices Frank had glanced at a clock on the wall and found it was five minutes past three.

“You don’t know how soon he will be back?” he queried.

“No.”

“If you will remember, I had an appointment at three sharp.”

“I remember it very well.” The clerk hesitated. “Would you mind telling me what your business was with Mr. Garrison?”

“It was a private matter.”

“Relating to money matters?”

“In a way, yes. Why do you ask?”

“Oh, I have reasons. Perhaps you had better sit down and wait for him.”

“That is what I intend to do. If necessary, I’ll wait for him until you shut up,” added our hero, as he dropped into a chair.

“Then you are bound to see him.”

“I am.”

The clerk said no more, but turned to a set of books and began to write. Frank remained silent for perhaps ten minutes.

“Did Mr. Garrison say where he was going?” he asked.

“Out to collect a bill.”

“Near by?”

“He didn’t say.”

“Did he go out alone?”

“Yes.”

There was another spell of silence, and then the outer door opened quickly, and two well-dressed men stepped in.

“We wish to see Mr. Garrison,” said one, while he looked about to see if that individual was in sight.

“Sorry, sir; but he’s out,” said the clerk.

“When will he be back?” put in the second man.

“I can’t say.”

The two men exchanged glances, and one uttered a low whistle.

“Reckon we’re too late,” muttered the latter of the pair.

“It looks like it, Mason,” was the answer.

“What’s to do next?”

“Find him—if we can—and do it right away.”

“But it’s like looking for a pin in a haystack.”

“That’s true, too.” The man turned again to the clerk. “You are sure you don’t know where to find Mr. Garrison?”

“I haven’t the least idea where he has gone to.”

The other man had walked to the rear and glanced into the private office.

“Did Mr. Garrison have a satchel with him when he left?” he asked.

“He has a dress-suit case with him.”

“Humph!”

Frank listened to the talk with close attention. Then he arose and turned to the man who had been addressed as Mason.

“Excuse me, sir, but is your name Bardwell Mason?” he questioned.

“It is. Who are you?”

“I am Frank Hardy. My father is Thomas Hardy, of Claster.”

“Phew! Then you are after Garrison, too, eh?”

“I wish to see him. He was here this morning and promised to see me at three o’clock. It is now half-past three.”

“When did you call this morning?”

“About half-past eleven.”

“And you had a talk with him?”

“No, sir; I sent my name into the private office by this clerk.”

“Of course you want to see him about this security business.”

“Yes, sir. My father told me that if I couldn’t get any satisfaction here I should call upon you.”

Bardwell Mason nodded. Then he bent forward and lowered his voice.

“I’m afraid the fat’s in the fire here,” he whispered.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that Jabez Garrison knows he is found out and that he has flown.”

“You mean that he has run away?” whispered Frank, in horror.

“It certainly looks that way. We have had an expert on his books for two days, and it is a fact beyond question that he has swindled our benevolent order out of at least thirty-five thousand dollars.”

“Then he ought to be locked up.”

“If we can lay our hands on him.”

“Why don’t you notify the police?”

“That’s what we will do—if he doesn’t come back pretty soon.”

“We must catch him by all means—for my father’s sake as much as for yours.”

“True, my boy; but if he has really run away he has probably covered his tracks well.”

A half-hour went by, and leaving Frank to watch at the office, Bardwell Mason and his companion went off to interview the police.

“I guess the boss is getting himself in hot water,” said the clerk to Frank, when the two were again left alone.

“It begins to look that way,” answered our hero. “But I don’t feel like saying too much.”

“It’s over that benevolent order affair, isn’t it?”

“Yes. Do you know anything about it?”

“Oh, I heard the boss and Mr. Mason talking about it one day in the office. They had it pretty hot. I made up my mind then matters were coming to a head.”

“What will you do if Mr. Garrison doesn’t come back?”

“Shut up and go home at six o’clock.”

“Will you open up in the morning?”

“The boy does that. He’s out on an errand for me now.”

“Have you any stock on hand—I mean flour and feed?”

“We don’t keep stock any more. We simply sell on commission.”

At this announcement Frank felt more depressed than ever. There would then be nothing to attach, in case Jabez Garrison had really fled. He looked at the office furniture. It was old and dilapidated, and if put up at auction would probably not fetch over twenty or thirty dollars.

“Does Mr. Garrison own any property?”

“Not that I know of. He used to have a house on Walnut Street, but he sold that about a year ago.”

Here was more cause for regret, and Frank heaved a deep sigh. He felt that the news he would carry home would nearly prostrate his parents.

“And just when father is helpless with that crushed foot,” he thought. “It’s too bad! Oh! if only I could catch this Jabez Garrison and make him give up what he has stolen.”

It was after five o’clock when Bardwell Mason returned.

“Have you seen anything of him?” he asked, briefly.

“Nothing whatever,” answered Frank.

“He has flown beyond a doubt.”

“What have you done, Mr. Mason?”

“I have placed the police and a first-class detective on his track.”

At these words the clerk looked up in wonder.

“Do you mean to say Mr. Garrison has run away?” he demanded.

“We think he has, young man—anyway, he is not to be found, and at the place where he boarded he removed the best of his clothing this noon.”

“Was he married?” asked Frank.

“No, he was a bachelor.”

The clerk was now all attention, and asked for some details, which were given to him. He asked what he had best do regarding the offices.

“Better consult the police about that,” said Mr. Mason, and the clerk promised to do so.

“This is rough on me,” he said. “I haven’t been paid last week’s salary, and now I’m out of a job without a minute’s warning.”

“It certainly is rough on you,” said Frank.

The clerk locked up the place and walked off, and Frank and Bardwell Mason also took their departure.

“Mr. Mason, if Mr. Garrison is not found will my father have to make good the amount of the bond on which he went security?” asked our hero, as the pair took themselves to the gentleman’s office.

“Certainly; and he’ll have to make good anyway, unless Garrison pays back what he has appropriated.”

“It will be a great blow to my father.”

“I presume it will be. But that is not my fault, nor the fault of anybody in our order. Your father made a great mistake when he went security for such a slick rascal as Jabez Garrison.”

“Do you think the police will catch him?”

“Possibly. But he may have taken a steamer to some foreign land from which it will be impossible to bring him back.”

Frank hardly knew what to do next, but decided to call on the police himself. At headquarters he was informed that everything possible would be done to find Jabez Garrison.

“Mr. Mason has placed a very shrewd detective on the track,” said an officer to our hero. “He will probably learn something sooner or later.”

Before leaving Philadelphia Frank called at the house where the missing man had boarded. He was met at the door by a sharp-faced woman with a high-pitched voice.

“Yes, I guess he has run away and for good,” she said, tartly. “They say he stole fifty thousand dollars. He owed me for two weeks’ board, and seventy-five cents that I paid only two days ago for his laundry. He was a villain if ever there was one.”

“Didn’t he leave anything behind?”

“Yes, a lot of old clothing and worn-out shoes worth about fifty cents to the junkman. Oh, I wish I could catch hold of him! I’d tear his eyes out!”

“I wish I could get hold of him, too,” returned Frank, and there being nothing more to say he withdrew.

When Frank returned home and told of what had occurred in Philadelphia, there was consternation in the Hardy family. Mr. Hardy shook his head over and over again, and Mrs. Hardy shed bitter tears.

“I was a fool to trust Garrison,” said the disabled husband. “Now, here he is running away while I cannot even make a search for him.”

“I am afraid that such a search would be useless,” responded his wife. “And even if he were captured what good would it do, if he has squandered the money?”

“No good, so far as I am concerned, my dear.” Mr. Hardy heaved a long sigh. “Do you realize what this means for me?” he went on, bitterly.

“You will have to pay that ten thousand dollars.”

“Assuredly.”

“How much money have you in the bank, Thomas?”

“Nine thousand five hundred dollars.”

“Indeed! I thought you had more.”

“I used to have more, but the competition in business has forced me to put in additional capital, which I took from the savings bank.”

“Then you will have to take all the money in the bank and make up five hundred dollars besides?”

“Yes, if they call on me to make good the amount for which I went security.”

“Can you spare the five hundred out of the business?”

At this question Mr. Hardy hung his head.

“I am afraid I cannot, Margy. Business has been very bad lately, and I have many bills coming due inside of thirty and sixty days.”

At this candid statement Mrs. Hardy grew very pale.

“Oh, Thomas, do you mean that we—we——”

“This will drive me to the wall.” Mr. Hardy gave another sigh and his voice shook. “I am ruined.”

“Ruined!”

“That is the one word to use. Competition has almost forced me out of business, and this affair will take away nearly every cent I possess.”

After this confession the matter was discussed freely until Mr. Hardy grew so feverish that his wife told him he must be quiet and left to himself. She passed down into the sitting room and there met Frank.

“Mother, you have been crying,” said the boy, coming up and embracing her.

“I cannot deny it, Frank; this blow is an awful one.”

“Perhaps it won’t be so bad as you think.”

The lady of the house shook her head.

“It won’t take all of father’s money, will it?”

“Every dollar, Frank.”

“But he will still have the business, won’t he?”

“Not free and clear. He will have to take out of it five hundred dollars, and pay some bills besides.”

“That’s bad.”

“Your father says he is ruined, and I really think he is. The business will have to be sold for what it will bring.”

“And what will father do then?”

“I am sure I don’t know. He will have to get well first.”

“I wish I could catch Jabez Garrison. I’d—I’d strangle him!”

“Frank, you mustn’t speak like that!”

“I don’t care, mother. See what mischief he has created.”

“Well, we must face the truth, Frank.” Mrs. Hardy wrung her hands. “I am sure I do not know what we shall do.”

“I know what I am going to do, mother,” he returned, quickly. “I’ve been thinking it over ever since I got home.”

“What is that?”

“I’m going to work.”

The fond mother smiled faintly.

“Yes; I’m afraid we shall no longer be able to support you unless you do something.”

“I shall find something to do just as soon as I can, and bring all my wages home to you. Maybe they won’t be much, but they’ll be something.”

The mother embraced him again.

“Frank, you are truly a son worth having. But it will be too bad to keep you from high school.”

“Never mind; perhaps I can study at night.”

“If you do that, I’ll help you all I can. But I am sure I do not know where you can get a position.”

“Oh, I’ll get something. But first of all, I’m going down to father’s store and do all I can to sell what goods he has on hand.”

“Yes; I was going to ask you to do that.”

True to his word, Frank opened the store bright and early the next morning. He felt that he must do something, and during the day cleaned the windows and arranged the goods on the shelves and in the big storeroom. He also called on several regular customers and asked if they did not wish fresh supplies.

“So you are going to help your father out, eh?” said one old gentleman. “I’m glad to see it. Yes, you can send me two bags of oats and a bushel of corn, and also a barrel of that best flour for the house. I’ll help you all I can.” And Frank went away delighted with the order.

But the work was not all so agreeable. Some found fault, and others said they were buying elsewhere. Looking over the old store books, the boy soon learned that the receipts had been falling off steadily for six months—ever since the opposition had started.

“I guess it needs an experienced man with more capital than we now have to make a success of this,” he reasoned, and he was correct in his surmise. The two rivals carried big stocks, and both were very active, consequently more than three-quarters of the business of the town and vicinity went to them.

A few days later Mr. Hardy received a formal notification of what Jabez Garrison had done and was told that he must “make good” without delay or the benevolent order would sue him. Following this, Mr. Bardwell Mason paid him a visit.

“I am very sorry this has occurred,” said the gentleman from Philadelphia. “But business is business, and the order looks to me to have this matter straightened out.”

“I do not see what I can do excepting to give the bank notice to hold that money for you until we have time to look for Jabez Garrison,” answered Mr. Hardy.

“Have you the whole amount in the bank?”

“I have it, less five hundred dollars.”

“Where is that to come from, if I may ask?”

“I own my business and this house.”

“I see. Then there will be no trouble, Mr. Hardy. I am sorry to bother you at such a time as this. It looks like hitting a man when he is down. But you know what these orders are. They look to me to do my duty, and if I don’t do it some of the members will be sure to make trouble for me.”

“They are not very benevolent in my case.”

“Well, you see, you are not a member.”

The talk was continued for a good hour, and in the end, Mr. Hardy sent a note down to the bank introducing Mr. Mason, and relating the object of that gentleman’s call. By this means, the account was, for the time being, tied up so that Mr. Hardy could not touch it.

On Monday of the following week, Frank was in the store packing up a small order for delivery, when a dapper young man entered.

“Is Mr. Hardy around?” questioned the newcomer.

“No, sir; my father is at home with a crushed foot,” answered our hero.

“How did he crush it, in the store?”

“No; he had it crushed on the railroad.”

“Oh, was he in that wreck near here?”

“He was.”

“Then I suppose he’ll soak the railroad company good for it?”

“I think he expects them to pay something.”

“I’d soak them for all I was worth,” went on the dapper young man, sitting down across the counter. “They can stand it, and he can put in any kind of an old bill he wants to.”

To this Frank did not answer, but continued to put up the order upon which he had been working.

“I suppose you don’t know who I am,” went on the young man, after he had lit a cigarette.

“I do not.”

“I’m the representative of the Blargo-Leeds Flour Company. There’s a bill due us and I want to find out why it hasn’t been paid. Your father promised to pay it some time ago.”

“How much is it?” asked Frank uneasily, although he knew something of the bill already.

“Two hundred and sixty-eight dollars. It’s been due now for three weeks.”

“Well, I’ll try to find out for you.”

“Can’t you pay it now?”

“No.”

“My firm says that bill has got to be paid inside of the next ten days.”

“Very well; we’ll try to pay it.”

“If you don’t they will sue.” The young man leaped down from the counter. “Sure you can’t pay it now?”

“No; I haven’t the money.”

“I’ve heard your father is in a peck of trouble over some bond he went on. I’m sorry for him. But that bill must be paid, remember that. In ten days, or it’s a suit at law.” And lighting another cigarette, the dapper young man hurried out as quickly as he had entered.

When Frank went home to dinner he expected to tell both his father and his mother about the visit from the dapper young man; but he found both of them so much worried that he did not say a word. He ate his meal in silence, and hurried back to the place of business as soon as he could.

“I’ll tell them to-night or to-morrow,” he thought. “One thing is certain: we can’t pay that bill, for we haven’t the money on hand with which to do it.”

The youth worked hard during the afternoon, and made several sales which were rather gratifying—one of some middlings which had become slightly spoiled and which his father had despaired of selling. Frank sold the stuff for just what it was, so that no fault might be found later.

He was placing the nine dollars he had received in the transaction in the money drawer, when a dark, middle-aged man came in, and looked around.

“I suppose Mr. Hardy isn’t here?” he said.

“No, sir; my father is at home with a crushed foot,” answered Frank, telling what he had repeated many times before.

“I am Jackson Devore, the feed man. I have a bill of ninety dollars that has been running for some time. I want to know when your father intends to pay it.”

“I guess he’ll pay it as soon as he can, Mr. Devore.”

“That is what he told me when I saw him last. This bill has got to be paid at once.”

“I can’t pay it now.”

“Well, if it isn’t paid by the day after to-morrow, I’ll bring suit.”

“The day after to-morrow is the Fourth of July.”

“Well, then, the next day,” snarled Jackson Devore. “And tell your father I won’t wait a minute longer. He has let his business run down and go to pieces, and it looks to me like he didn’t intend to pay anything.” And out of the store bounded the man, shaking his head and his fist at the same time.

“This is certainly getting interesting,” said Frank to himself. “We will have to do something soon; that is certain.”

He had exactly twenty-seven dollars on hand, and this cash he took home at supper time. Then he told his parents of what had happened during the day.

“I expected it,” groaned Mr. Hardy. “To keep the store going longer would be folly. I may as well sell out as best I can, and settle these bills as best I can, too.”

“Who will you sell out to?” asked Frank.

“I’m sure I don’t know. I might offer the place to my rivals.”

“They wouldn’t buy anything but the stock.”

“They might be able to use the fixtures, such as they are.”

“I’ll tell you what I can do,” said Frank. “I can go to each of our rivals and get them to submit offers. Perhaps they will bid pretty well against each other—for each wants the business in this town, and they know your good will is worth something.”

“That is a good idea!” said Mr. Hardy, brightening. “You might go and see both of them this evening, if you wish.”

“Frank looks tired,” interposed his mother.

“Never mind, mother, I’ll go anyway. Perhaps Mr. Benning and Mr. Peterson will walk over here and see father.”

“Yes, you might ask them to call,” said the sick man.

A little later Frank went to see Andrew Benning, who lived but a short distance from the Hardy homestead. He found the storekeeper, who was a shrewd Yankee, reading the local weekly paper.

“Your father would like to see me, eh?” said the man. “What about, Frank?”

“He is going to sell out and thought you might like to buy.”

“Hum! Has he set any figger?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, I’ll call an’ see him first thing in the morning. I don’t reckon as how the place is wuth much—it’s so run down.”

“Oh, there is quite some stock,” answered our hero. “What time shall I say you will call?”

“About nine o’clock. I’ll take a look at the place first. Will you be around there early?”

“At seven o’clock.”

“All right.”

From the Benning home, Frank hurried to the place where Mr. Peterson, the other rival, boarded.

“I’m sorry for your father,” said Mr. Peterson, who was a young man and rather pleasant. “I might buy him out if he’ll sell cheap enough.”

“He’ll sell at a fair figure.”

“Do you know what he has on hand?”

“Yes, sir, in a general way.”

“Very well. I’ll go up with you now and see him.” And in a minute more the two were on the way. When they reached the Hardy home the rival flour and feed man shook hands cordially with Mrs. Hardy and also with the sick man.

“So you are going to sell out,” said he to Frank’s father. “Well, I thought one of us would have to give up pretty soon. The town can’t support three dealers.”

The matter was talked over, and it soon developed that John Peterson was as shrewd as Andrew Benning. The best offer he would make was seventy per cent. of the wholesale value of the stock and a hundred dollars for the fixtures and good will.

“Seventy per cent. is not enough,” said Mr. Hardy. “I think I can get more elsewhere.”

“I think Mr. Benning will give more,” said Frank.

“Is he going to have a chance to buy it?” cried John Peterson.

“I shall sell to the highest bidder,” answered Mr. Hardy.

“Oh, then you want us to bid against each other, eh?”

“Can you blame me?”

“Not exactly, Mr. Hardy—but it don’t just look right either. I’ll tell you what I’ll do—I’ll give you seventy-five per cent. of the value of the stock.”

“Make it ninety and I’ll take you up.”

“No, that is my best figure.”

“Then I’ll let you know by to-morrow night.”

“Very well,” answered John Peterson, and soon after this he left.

“Do you think that is a fair price, father?” asked Frank, after the visitor had departed.

“No, my son. But what shall I do?”

“Perhaps Andrew Benning will make a better offer.”

“Let us hope so.”

Early the next morning Frank went to the store and arranged the stock to the best possible advantage. He was just finishing the work when the rival dealer came in and began to look around.

Although Frank did not know it, Andrew Benning had, late the evening before, met John Peterson, and the rivals had talked over the matter of buying Mr. Hardy out, and reached an agreement by which neither was to outbid the other. If either got the place he was to divide the goods with the other and also the fixtures, and both were to settle jointly for the good will—and then each was to catch what customers he could as in the past.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do, and you can tell your father,” said Andrew Benning. “I’ll give him sixty per cent. of the value of his stock at wholesale and fifty dollars for his fixtures and good will.”

“Thank you, but my father can get more than that,” answered Frank, coldly.

“All right then, he had better do it,” was Andrew Benning’s retort, and he stalked out without another word.

But our hero had not reckoned on the plot the rivals had hatched out. On going to dinner he learned that his father had just received a note from John Peterson, which ran as follows:

“Mr. Thomas Hardy,

“Dear Sir: I have thought over the matter of buying your store out and have come to the conclusion that the best I can offer you is sixty per cent. of the regular wholesale value of the stock, and fifty dollars for all the fixtures. As the place is run down I do not consider that the good will is worth figuring in the transaction. This offer is open for one week. Yours ob’t’ly,

“John Peterson.”

“He has dropped to the very figures that Andrew Benning offered,” said Frank, in dismay.

“I believe they are in league with each other,” sighed Mr. Hardy. “They know they have me down and that I cannot help myself.”

“Perhaps we can sell the goods elsewhere, father.”

“Possibly, but it will cost money to transport the goods, and few people want to buy goods that they consider are second-hand.”

“Supposing I try to sell the goods to Mr. Fardale, of Porthaven?”

“You might try it. But Mr. Fardale is as close as Benning, if not closer.”

“If he would only give ten per cent. more it would be something.”

“That is true. Well, you can see him the day after the Fourth of July.”

“I will,” answered Frank. “I can go up on the stage,” he added, for Porthaven was six miles from Claster.

The people of Claster had arranged for a Fourth of July celebration, and early in the morning folks began to pour in from the surrounding farms until the place took on the liveliness of a fair-sized city.

Knowing that some folks would take the opportunity to order or buy supplies, Frank kept the store open until noon and did quite a fair business. When he closed up he had twenty-six dollars on hand, which he took home for safe keeping.

There was a short parade in the afternoon and all of the young folks went to see this. Little Georgie was particularly enthusiastic and wanted to follow the brass band all over the line of march.

“I’d like Fourth of July to come every day,” he told his brother and sister.

“I fancy you’d get tired of it soon enough,” said Ruth.

“I’d never get tired of it,” answered the little fellow, positively. “When I grow up I want to be a drummer in the band.”

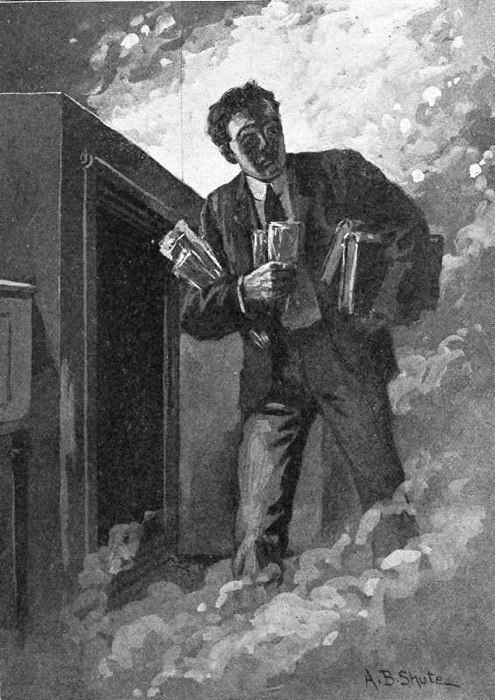

“THE SMOKE WAS SO THICK HE COULD NOT SEE WHERE HE WAS GOING.”–P. 54.

“Do you think you want to carry around the bass-drum, Georgie?” questioned Frank, with a smile.

“No, I want the little drum—the one that rattles and has two little sticks,” returned Georgie.

The town people had collected almost a hundred dollars which a committee had expended in fireworks. These were to be set off at the public square, only a short distance from Mr. Hardy’s store. At the appointed time the square was crowded, and the display of fireworks was begun amid great enthusiasm.

“I love those rockets and Roman candles,” said Ruth, enthusiastically.

“And I like the big pin-wheels,” answered Frank.

With Georgie they had taken a place in front of the store. But they could not see extra well, on account of a wagon being in the way, and so moved on to another part of the square.

A flight of rockets was followed by some colored fire and a very handsome set piece. Then came triangles and flower pots, and another set piece, and then some of the largest rockets the committee had purchased. The latter went up with a rush and a roar that made Ruth shrink back in momentary alarm.

“I don’t like that—it looks dangerous,” said she.

“It is not as dangerous as it is for those boys to be running around with blazing brushwood,” answered her brother. “The constable ought to stop them. They may set something or somebody on fire.”

“Wouldn’t one of those rockets set something on fire if it came down while it was still burning, Frank?”

“To be sure. We haven’t had rain in so long all the roofs around here are pretty dry.”

For the end of the celebration there was a set piece of the President of the United States, and as this lit up there was a wild cheering and hurrahing, which was changed to a sudden cry of alarm as a man yelled “Fire!” at the top of his lungs.

“Fire? Where is the fire?” asked several.

“He means the fireworks,” said one onlooker, and several laughed at the joke.

“Fire! fire!” continued the other man. “The feed store is on fire!”

“The feed store?” repeated Frank, with a start. “Can he mean our place?”

“He does!” shrieked Ruth. “See, the smoke is coming out of the upper window!”

“It is our place, true enough!” groaned Frank. “Here, Ruth, take care of Georgie. Don’t you come over to the fire.”

“Oh, what are you going to do, Frank? Don’t go into the place, please! You’ll be burnt up!”

“I’ll take care of myself. Now, keep back as I told you.”

Thus speaking Frank darted into the crowd and made his way to the front of the store, which was located in a small two-story frame structure, having a flat roof. The upper floor was filled with feed and grain, and through the front window the flames could readily be seen. As Frank drew closer there was a crash of glass, and then the flames shot out of the window, and began to lap the roof.

“Don’t go in there, Frank!” cried several. “The place is a goner. You can’t save anything.”

“I’m going to save the papers,” answered our hero, determinedly. “Why don’t you call out the fire department?”

“Bill Wilson did that already.”

Unlocking the front door, Frank made his way inside. All was dark and filled with smoke. He felt his way to his father’s safe and desk. Soon he had some papers from the desk in his pocket, and then he knelt down to open the safe.

The strong box had a combination lock, and as yet Frank was hardly accustomed to it. In his excitement it was not easy to remember the proper numbers, and the first time he tried the knob the safe refused to come open. Then he tried to work the combination again.

By this time the entire lower floor of the building was thick with smoke, and the flames were already beginning to show themselves in the vicinity of the back stairway. Frank’s eyes were swimming in tears, and it was all he could do to get his breath.

“I certainly can’t stand this any longer,” he thought, and gave the knob of the safe a final turn. Then the door came open and he pulled out the account books and some private papers in all haste. He had heard his father say that the safe was worn out, and in no condition to stand the test of a hot fire.

Scarcely able to stand, Frank felt his way toward the front door. The entire back and upper part of the building were now ablaze and he could plainly hear the crackling of the flames above him.

“Frank Hardy, where are you?” called a voice through the smoke.

Frank did not answer, but staggered toward the sound, for the smoke was so thick he could not see where he was going. Then, just as he felt he must drop, he received a dash of water in the face, thrown by a member of the local bucket brigade, for as yet the town boasted of nothing better than one engine and a company of men, who possessed sixty leather fire buckets.

The water did much toward reviving our hero and in a second more he almost fell through the front door and out on the stoop of the store. As he came into view a shout went up.

“There he is!”

“He has had a narrow escape!”

“Did he get burnt?”

“No, he is all right.”

Assisted by willing hands, Frank made his way to a bench in the public square. Close at hand was a town pump, where men and boys were filling the leather buckets. Down the square was the hand engine, drawing water from a nearby cistern. As weak as he was our hero had brought his books and papers with him, and these he now placed at his side.

“Oh, Frank, are you hurt?” It was Ruth who asked the question, as she came up with little Georgie.

“No, I’m all right,” Frank answered. “But I guess I’m pretty well smoked,” he added, coughing and wiping his eyes.

“You should not have gone in such a place.”

“I wanted to save father’s books and papers. The desk will be burnt, I know, and the old safe isn’t of any account.”

“Do you think they’ll put the fire out?”

“It doesn’t look like it now.”

“It must have been set on fire by the fireworks,” went on Ruth.

“More than likely.”

The firemen were working with a will, and before long Frank started in to aid them, telling Ruth and Georgie to take the books and papers home.

“Tell mother not to worry about me—that I’ll keep out of danger,” said our hero.

He had scarcely spoken when Mrs. Hardy rushed up, all out of breath and with her face full of fear.

“They told me you had gone into the store,” she gasped. “Are you unharmed?”

“Yes, I’m all right, mother.”

“Thank Heaven for that!”

“Here are father’s papers and account books. I’m afraid the whole place is doomed.”

“Yes, it looks like it—and the next place, too,” answered Mrs. Hardy.

She remained at the fire for only a few minutes and then returned home, to tell her husband that Frank was safe. Georgie went with her, but Ruth stayed to see the end of the conflagration.

It was a full hour before the fire was under control. By that time not only the feed store was gone, but also the butcher shop next door, and a barn in the rear. Yet many felt that the firemen had done well to save the surrounding property, considering how dry everything was and what a breeze was blowing.

“That’s the end of the feed business,” thought Frank. “I hope father is insured. If he isn’t, the loss will be a heavy one for him—especially after this Garrison disaster.”

When Frank arrived home he found that his father had been given all the particulars of the conflagration by the other members of the family and by several neighbors who had dropped in to tell him the news and sympathize with him.

The exact origin of the fire was a mystery, but it was generally accepted as being due to the Fourth of July celebration.

“I hope you are insured, father,” said Frank, after the last of the neighbors had departed.

“I am insured, Frank, but I have forgotten the exact amount,” was the reply. “I want you to look over the papers for me.”

“The papers call for twenty-five hundred dollars on stock and two hundred dollars on fixtures,” said our hero, after a careful reading of the insurance papers, three in number.

“Then I am fully covered. The stock on hand did not amount to over eighteen hundred dollars.”

“Then for stock and fixtures you ought to get two thousand dollars.”

“Yes—if I can make the insurance companies toe the mark.”

“That is more than you would have gotten from Mr. Benning or Mr. Peterson.”

“Yes, Frank; I doubt if they would have given me over twelve hundred dollars—perhaps not over a thousand.”

“In that case—if you can make the insurance companies pay up—the fire won’t have been such a bad happening after all.”

“No, it will be quite a good thing for us.”

Early on the following morning two insurance men put in an appearance, and surveyed the ruins carefully. Nothing had been saved of Mr. Hardy’s belongings, even the safe being rendered absolutely worthless by the intense heat. After looking around, the insurance men called upon the sufferer at his home.

“Well, Mr. Hardy, you seem to be suffering in more ways than one,” said one of the men.

“That is true, Mr. Lane. The town celebrated yesterday at my expense.”

“I should say at our expense,” put in the second insurance man, with a grim smile. “We are the ones to foot the bill.”

“Well, I am glad, Mr. Watson, that the loss does not fall on me, for it would ruin me utterly.”

“What do you figure your loss at?”

“I have been looking over the accounts with my son, Frank, who has been running the store lately, and we figure the stock at eighteen hundred and forty dollars, and the fixtures at the figure in the papers.”

“Then you claim two thousand and forty dollars?”

“Isn’t that fair?”

“Will you let us go over the stock sheet with you?”

“Certainly.”

This was done, and at the end of an hour the insurance men said they would recommend that the company pay Mr. Hardy nineteen hundred dollars in full for his claims. As this was not such a big cut as he had feared, Frank’s father said he would accept the amount if the sum was forthcoming inside of thirty days.

“I am sure I have made a good bargain with the insurance people,” said Mr. Hardy to his wife, when they were alone. “I have done much better than if I had sold out to any of my rivals.”

“Yes, and the best of it is, you are now under no obligations to your rivals,” returned Mrs. Hardy.

“I did not get exactly what I think the stock was worth, but one cannot expect to get that when one is burnt out.”

“What will you do, Thomas, when they pay the money?”

“Settle the Garrison matter first of all, and then put the balance of the money in the bank.”

“And after that?”

“I’ll have to get well before I make up my mind. I can do nothing so long as I am tied down to the house.”

With the store burnt out, Frank scarcely knew what to do with himself. When the débris was cleared away by the owner of the property, he went around to hunt for anything of value, but nothing was forthcoming.

Frank was very thoughtful when he came home the following Saturday. He chopped a big pile of wood, and cleaned up the garden and the cellar.

“I’m going to find something to do next week,” he told his mother. “With father laid up and the store gone, it won’t do for me to remain idle.”

“I am afraid you’ll not find it easy to get a position in Claster,” answered Mrs. Hardy, as she placed an affectionate hand on his shoulder.

“I was thinking of looking for a place in Philadelphia, mother.”

“What, away from home!”

“I’ve got to strike out for myself some day.”

“But I hadn’t thought of your leaving home yet, Frank,” his mother went on, in dismay.

“Well, I’ll look around in Claster first.”

“I wish you would, and in Porthaven, too.”

Frank was enthusiastic about doing something, and that very Saturday night he asked half a dozen persons he knew for a situation.

But as his mother had intimated, it was next to impossible to find an opening. Only at one store was anything offered, and the pay there was but two dollars a week.

“I cannot afford to work for such an amount, Mr. Grimes,” said Frank.

“Well, that’s all I am willing to pay,” returned the storekeeper. “Plenty of boys would jump at the chance. I thought I’d give you a trial on your father’s account.”

“Thank you, but I’ll look further.”

Early Monday morning Frank went to Porthaven. As he did not want to pay the stage fare, which was twenty cents each way, he determined to walk the distance. But he was scarcely out of town when a boy in a grocery wagon came up behind him.

“Hullo, Frank!” called out the boy. “If you are going my way, jump in.”

“I am bound for Porthaven, Joe.”

“So am I. Glad I met you,” replied Joe Franklin, who worked for a local grocer. “I hate to travel such a distance all alone. Where are you going?”

“I am going to look for work,” answered Frank, as he took a seat beside the grocer’s boy.

“Can’t you get anything to do in Claster?”

“Yes, one job. Mr. Grimes wants me to work for him for two dollars a week.”

“Don’t you work for him, Frank.”

“I don’t intend to. I must earn more.”

“Old Grimes is the hardest man in town to get along with. All of his clerks are in hot water with him every day.”

“Mr. Wilkins must pay you more than two dollars, Joe?”

“He pays me three and a half, and I am to have four after New Year’s.”

“That is something like. But I want to earn even more—if I can.”

“I suppose you’ve got to do it, now your dad is out of work and laid up.”

“Yes.”

“Somebody told my dad you folks had lost a lot of money on some rascal in Philadelphia.”

“It is true, and that’s all the more reason I want to earn something.”

“Can’t your father get anything out of the railroad company for the accident?”

“I trust so. But it is pretty hard to fight a big railroad company.”

“Will your father start in the feed business again?”

“I don’t think so. Still, he doesn’t know what he will do. He wants to get well first.”

So the talk ran until the outskirts of Porthaven were reached. Then Frank left the wagon and thanked his comrade for the ride.

“When are you going back?” asked Joe.

“I can’t tell you.”

“I’m going back in half an hour. You can ride with me if you will.”

“Thank you, Joe, but I guess I’ll have to stay a little longer,” answered Frank; and then the two boys separated.

Porthaven was a town considerably larger than Claster and consequently Frank had a great many more stores and offices to visit. But his quest for employment here was even less encouraging than at home. Not a single opening of any kind presented itself.

“This is certainly hard luck,” he thought, as he found himself at the end of the main street. “I did think there would be at least one opening.”

He had brought a lunch with him, and now walked down to the edge of the small river which ran through Porthaven.

At a beautiful spot bordering the river somebody had placed a bench, and here he sat down to enjoy the sandwiches and piece of pie his mother had thoughtfully provided for him.

Frank’s appetite, like that of most growing boys, was good, and it did not take him long to dispose of his meal.

“Wish I had another sandwich,” he thought, after it was gone. “Tramping around gives one a very hungry feeling, especially if he doesn’t get any work.”

Not knowing what to do next, Frank remained where he was, and presently a young man, carrying a small, square hand-bag of black leather, came strolling towards him.

“Can you tell me how much further it is to Porthaven?” the young man asked, as he came to a halt, and rested his bag on the end of the bench.

“You are on the outskirts of the town, now,” was our hero’s reply.

“Good! I was afraid I had still a mile or so to go. I missed the stage from River Bend, and I did not want to waste the time, so I walked over. It’s pretty hot, isn’t it?”

“Yes.” And now Frank made room so the stranger could sit down, which he did.

“Are you acquainted in Porthaven?”

“Pretty well.”

“Then perhaps you won’t mind telling me where some of these folks live,” and the young man brought out a notebook from his pocket.

“I’ll tell you what I know willingly.”

“Live around here, I suppose?”

“No, sir; I come from Claster. I’m looking for work.”

“Oh!” The young man gazed at Frank curiously. “Hard job, isn’t it?”

“It is.”

“Struck anything yet?”

“Nothing.”

“I can sympathize with you. I was out looking for work, myself, last summer, and I couldn’t get a single thing that was worth anything.”

“But you are working now?”

“Well, yes; but I haven’t got anything steady. I’m a book agent, and I get paid for what orders I get, that’s all.”

“So you are a book agent?” said Frank, and now looked at the young man with increased interest. “May I ask what books you sell?”

“I am taking orders for three works—a new and beautifully illustrated set of Cooper’s works, an Illustrated History of the United States, and a new cook-book. Here are some samples,” and the young man brought them forth from his bag.

“They certainly look very fine,” answered Frank, after inspecting the volumes.

“Perhaps I can sell you a set of the Cooper.”

“Thank you; I can’t afford them.”

“Or a cook-book for your wife,” and the book agent laughed. “Get her a cook-book and she won’t kill you off when she cooks for you.”

“I’ll have to get the wife first—and means to support her,” and now Frank laughed, too. “May I ask if there is much money in selling books? If I can’t get a steady job I might take it up,” he went on, seriously.

“Selling books is a great speculation, my friend. You might make fifty dollars a week at it, and you might not make a dollar. It all depends on what you have to sell, what territory you cover, and what your abilities as a salesman are.”

“Yes, that must be true. But, somehow, I think I could sell books, if I had the right kind.”

“Many think they can do the same, but out of a hundred who try, not a dozen succeed. It’s very discouraging at the start. To make a success you’ve got to have lots of ‘stick-to-it’ in you.”

“May I ask what firm you represent? Or, perhaps you don’t care to tell?”

“Oh, I’m perfectly willing to tell you, and if you want to try your luck with them go ahead. My name is Oscar Klemner, and I represent the Barry Marden Publishing Company, of Philadelphia—one of the largest publishing houses in the subscription book business. Here is their card,” and Oscar Klemner handed it over.

“Thank you. My name is Frank Hardy, and I come from Claster.”

“Glad to know you, Hardy, and if you take up books I hope you make a big success of it.”

“Will you tell me how they pay for the work?”

“Certainly. An agent gets twenty per cent. for getting an order, and twenty per cent. more if he delivers and collects.”

“Do you do both?”

“Sometimes; but at other times I merely take orders, and when I can’t get orders I take to delivering the orders some fellow more lucky than myself has obtained.”

“You wanted me to tell you about some folks here.”

“Yes. Here is a list of names. I want to visit the people in regular order, according to where they live, if I can. I don’t want to waste my time skipping from one end of the town to the other and back.”

Frank looked over the list carefully.

“I know all these people, and if you wish it, I’ll go around with you.”

“Won’t it be too much trouble?”

“No. And besides, it will give me a little insight into the business.”

“All right, then. Come ahead, Hardy. I’ll give you a practical lesson in both the art of delivering books and in taking new orders. You see, some of these people have merely asked about the books, not ordered them.”

Having rested himself, Oscar Klemner said he was ready to start, and Frank offered to carry the leather hand-bag for him.

“Never mind; I’ll carry it myself. I’m so used to it, I’d feel lost without it.”

They were soon at the first house, where the book agent delivered a cook-book and collected three dollars for it. The transaction was quickly over, and they passed on to the next place.

“That was certainly a quick way to make sixty cents,” thought our hero.

“We don’t always have it so easy,” said the agent, as if reading what was in Frank’s mind. “Sometimes folks won’t take the books they have ordered.”

“What do you do then?”

“It depends. If it’s a written order, we show it, and demand that it be honored.”

The next place to stop at was one where a minister had written that he wished to look at the illustrated history. The book agent showed the history and dilated eloquently on its worth and cheapness, but the man of the church refused to order just then, although he said he might do so later.

“That was a disappointment,” said Frank, as they hurried off, after half an hour had been wasted in the effort.

“Oh, you’ll get used to them, if you ever get into this business,” answered Oscar Klemner, cheerfully.

Frank remained with the agent until dark, visiting twelve homes and three places of business. He took note of the fact that Oscar Klemner collected eight dollars, and took orders for twenty-eight dollars’ worth of books. This made thirty-six dollars in all, upon which the agent’s commission, at twenty per cent., was $7.20.

“That is certainly a good day’s wages,” thought our hero. “I’d like to do half as well.”

“How do you like it?” asked the book agent, when the work was over.

“I like it first-rate,” answered Frank. “I’m going to try it, if they’ll let me.”

“If you do, I wish you luck. But I wouldn’t work around here. Our men have been through this territory pretty thoroughly.”

On parting with Frank, Oscar Klemner offered our hero a fifty-cent piece.

“You’ve earned it,” he said.

“I don’t want the money. I am glad I got the experience,” said Frank, and refused to accept the coin. Soon they parted; and it was many a day before our hero saw Oscar Klemner again.

Frank did not relish the walk back to Claster, after his tramp all over Porthaven. But there seemed no help for it, and he struck out as swiftly as his tired limbs would permit.

“If I’m going to be a book agent, I may as well get used to walking first as last,” he told himself. Yet, when a lumber wagon bound for Claster came along, he was glad enough to hop up beside the driver and ride the last half of the journey. Even then, it was nearly ten o’clock when he got to his home.

“So you’ve had no luck, Frank?” said Mrs. Hardy. “I am sorry for you. Have you had any supper?”

“No, mother. But don’t worry; I’ll find a couple of slices of bread or so.”

“There is some tea on the stove, and some beans and rice pudding in the pantry, and some cake and berries. You must be very hungry.”

“I’ve got a plan,” said Frank, when he was eating. “I’ll tell you about it in the morning. It’s too late now.” And as soon as he had satisfied his hunger he went to bed.

When our hero told his father and his mother of his plan, on the following morning, both were much surprised.

“A book agent!” cried Mr. Hardy. “I don’t think they earn their salt.”

“Father, you are mistaken,” Frank answered, and then told of his experience of the day previous. Both of his parents listened with keen interest.

“That agent must be a remarkable man to earn so much,” said Mrs. Hardy. “I knew a man here who tried it once, old Randolph Winter. He earned only a few dollars a week.”

“I guess he wasn’t cut out for an agent,” answered Frank, who knew the man mentioned to be very lazy and shiftless.

“And so you think you are cut out for an agent, Frank?” demanded his father.

“Oh, I wouldn’t say that. But I thought it might be worth trying—more especially as I can’t get anything else to do.”

“Oh, it won’t do any harm to try. But don’t fill your head with any false hopes, for you may be sadly disappointed.”

“If I try it, I’ll make up my mind to do my level best, and then take what comes. But I’d like to go to Philadelphia and see those book publishers first.”

“Very well; I’ll give you the necessary money.”

While Frank was talking the matter over with his parents, Ruth came in with several letters, and a big package from the post office.

“Here are some books for Frank!” she called out. “And a letter, too.”

“The package is from Mr. Philip Vincent, the gentleman whose spectacles I picked up at the wreck,” said Frank. “And one of the letters is from him, too.”

“What does he say, Frank?”

“I’ll read his letter out loud, mother,” answered our hero, and proceeded to do so.

“My Dear Young Friend [so ran the communication]: I must ask you to pardon me for the delay in sending you the story book I promised. The fact of the matter is, I had a sudden call to Chicago on business, and just arrived in New York again yesterday.