Project Gutenberg's Teen-age Super Science Stories, by Richard M. Elam This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Teen-age Super Science Stories Author: Richard M. Elam Illustrator: Frank E. Vaughn Release Date: October 24, 2017 [EBook #55801] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TEEN-AGE SUPER SCIENCE STORIES *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Teen-Age Library

Teen-Age Stories of Action

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Adventure Stories

By Charles I. Coombs

Teen-Age Aviation Stories

Edited by Don Samson

Teen-Age Baseball Stories

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Boy Scout Stories

By Irving Crump

Teen-Age Companion

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Football Stories

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Historical Stories

By Russell Gordon Carter

Teen-Age Mystery Stories

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Victory Parade

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Champion Sports Stories

By Charles I. Coombs

Teen-Age Super Science Stories

By Richard M. Elam, Jr.

Teen-Age Science Fiction Stories

By Richard M. Elam, Jr.

Teen-Age Sea Stories

Edited by David Thomas

Teen-Age Sports Stories

Edited by Frank Owen

Teen-Age Stories of the West

By Stephen Payne

Teen-Age Animal Stories

By Russell Gordon Carter

Teen-Age Cowboy Stories

By Stephen Payne

Teen-Age Basketball Stories

By Josh Furman

Teen-Age Dog Stories

Edited by David Thomas

Teen-Age Sports Parade

By B. J. Chute

Teen-Age Horse Stories

Edited by David Thomas

Teen-Age Gridiron Stories

Edited by Josh Furman

Teen-Age Stories of the Diamond

Edited by David Thomas

Teen-Age Humorous Stories

By A. L. Furman

Teen-Age Frontier Stories

Edited by A. L. Furman

Teen-Age Treasure Chest of Sports Stories

By Charles I. Coombs

Teen-Age Baseball Jokes and Legends

By Mac Davis

Teen-Age Treasure Hunt

By Richard M. Elam

Teen-Age Nurse Stories

Edited by A. L. Furman

Teen-Age Nature Stories

Edited by A. L. Furman

The Teen-Age Library

By RICHARD M. ELAM, Jr.

Illustrated by Frank E. Vaughn

Grosset & Dunlap Publishers

NEW YORK

Copyright © 1957 by Lantern Press, Inc.

BY ARRANGEMENT WITH LANTERN PRESS, INC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 57-8908

PUBLISHED SIMULTANEOUSLY IN CANADA BY

GEORGE J. MCLEOD, LIMITED, TORONTO

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Cadet Marshall Farnsworth woke from a nightmare of exploding novae and fouling rockets. After recovering from his fright, he laughed contemptuously at himself. “Here I was picked as the most stable of a group of two hundred cadets,” he thought, “and chosen to make man’s first trip into space, yet I’m shaking like a leaf.”

He got out of bed and went over to the window. From his father’s temporary apartment, he could see distant Skyharbor, the scene of the plunge into space tomorrow night. He had been awarded the frightening honor of making that trip.

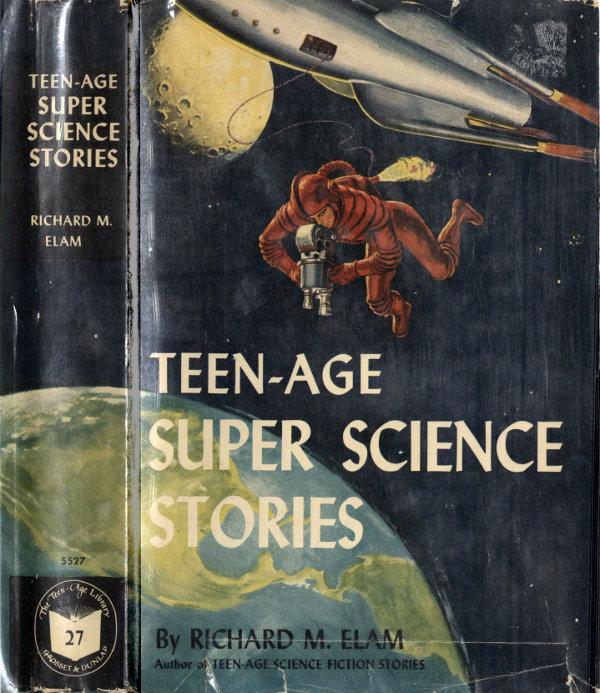

As he watched teardrop cars whip along Phoenix, Arizona’s, double-decked streets, elevated over one another to avoid dangerous intersections and delaying stop lights, he thought back over the years; to the 1950’s, when mice and monkeys were sent up in Vikings to launch mankind’s first probing of the mysterious space beyond Earth, and the first satellites were launched; to the 1960’s, when huger, multiple-stage rockets finally conquered the problem of escape velocity; to 1975—today—when man was finally ready to send one of his own kind into the uninhabited deeps.

Marsh climbed back into bed, but sleep would not come.

In the adjoining room, he could hear the footsteps of mother and father. By their sound he knew they were the footsteps of worried people. This hurt Marsh more than his own uneasiness.

The anxiety had begun for them, he knew, when he had first signed up for space-cadet training. They had known there was an extremely high percentage of washouts, and after each test he passed, they had pretended to be glad. But Marsh knew that inwardly they had hoped he would fail, for they were aware of the ultimate goal that the space scientists were working for—the goal that had just now been reached.

Marsh finally fell into a troubled sleep that lasted until morning.

He woke early, before the alarm rang. He got up, showered, pulled on his blue-corded cadet uniform, and tugged on the polished gray boots. He took one final look around his room as though in farewell, then went out to the kitchen.

His folks were up ahead of time too, trying to act as though it were just another day. Dad was pretending to enjoy his morning paper, nodding only casually to Marsh as he came in. Mom was stirring scrambled eggs in the skillet, but she wasn’t a very good actor, Marsh noticed, for she furtively wiped her eyes with her free hand.

The eggs were cooked too hard and the toast had to be scraped, but no one seemed to care. The three of them sat down at the table, still speaking in monosyllables and of unimportant things. They made a pretense of eating.

“Well, Mom,” Dad suddenly said with a forced jollity that was intended to break the tension, “the Farnsworth family has finally got a celebrity in it.”

“I don’t see why they don’t send an older man!” Mom burst out, as though she had been holding it in as long as she could. “Sending a boy who isn’t even twenty-two—”

“Things are different nowadays, Mom,” Dad explained, still with the assumed calmness that masked his real feelings. “These days, men grow up faster and mature quicker. They’re stronger and more alert than older men—” His voice trailed off as if he were unable to convince himself.

“Somebody has to go,” Marsh said. “Why not a younger man without family and responsibility? That’s why they’re giving younger men more opportunities today than they used to.”

“It’s not younger men I’m talking about!” Mom blurted. “It’s you, Marsh!”

Dad leaned over and patted Mom on the shoulder. “Now, Ruth, we promised not to get excited this morning.”

“I’m sorry,” Mom said weakly. “But Marsh is too young to—” She caught herself and put her hand over her mouth.

“Stop talking like that!” Dad said. “Marsh is coming back. There’ve been thousands of rockets sent aloft. The space engineers have made sure that every bug has been ironed out before risking a man’s life. Why, that rocket which Marsh is going up in is as safe as our auto in the garage, isn’t it, Marsh?”

“I hope so, Dad,” Marsh murmured.

Later, as Dad drove Marsh to the field, each brooded silently. Every scene along the way seemed to take on a new look for Marsh. He saw things that he had never noticed before. It was an uncomfortable feeling, almost as if he were seeing these things for the last as well as the first time.

Finally the airport came into view. The guards at the gate recognized Marsh and ushered the Farnsworth car through ahead of scores of others that crowded the entrance. Some eager news photographers slipped up close and shot off flash bulbs in Marsh’s eyes.

Skyharbor, once a small commercial field, had been taken over by the Air Force in recent years and converted into the largest rocket experimental center in the United States.

Dad drove up to the building that would be the scene of Marsh’s first exhaustive tests and briefings. He stopped the car, and Marsh jumped out. Their good-by was brief. Marsh saw his father’s mouth quiver. There was a tightness in his own throat. He had gone through any number of grueling tests to prove that he could take the rigors of space, but not one of them had prepared him for the hardest moments of parting.

When Dad had driven off, Marsh reported first to the psychiatrist who checked his condition.

“Pulse fast, a rise in blood pressure,” he said. “You’re excited, aren’t you, son?”

“Yes, sir,” Marsh admitted. “Maybe they’ve got the wrong man, sir. I might fail them.”

The doctor grinned. “They don’t have the wrong man,” he said. “They might have, with a so-called iron-nerved fellow. He could contain his tension and fears until later, until maybe the moment of blast-off. Then he’d let go, and when he needed his calmest judgment he wouldn’t have it. No, Marshall, there isn’t a man alive who could make this history-making flight without some anxiety. Forget it. You’ll feel better as the day goes on. I’ll see you once more before the blast-off.”

Marsh felt more at ease already. He went on to the space surgeon, was given a complete physical examination, and was pronounced in perfect condition. Then began his review briefing on everything he would encounter during the flight.

Blast-off time was for 2230, an hour and a half before midnight. Since at night, in the Western Hemisphere, Earth was masking the sun, the complications of excessive temperatures in the outer reaches were avoided during the time Marsh would be outside the ship. Marsh would occupy the small upper third section of a three-stage rocket. The first two parts would be jettisoned after reaching their peak velocities. Top speed of the third stage would carry Marsh into a perpetual-flight orbit around Earth, along the route that a permanent space station was to be built after the results of the flight were studied. After spending a little while in this orbit, Marsh would begin the precarious journey back to Earth, in gliding flight.

He got a few hours of sleep after sunset. When an officer shook him, he rose from the cot he had been lying on in a private room of General Forsythe, Chief of Space Operations.

“It’s almost time, son,” the officer said. “Your CO wants to see you in the outside office.”

Marsh went into the adjoining room and found his cadet chief awaiting him. The youth detected an unusual warmth about the severe gentleman who previously had shown only a firm, uncompromising attitude. Colonel Tregasker was past middle age, and his white, sparse hair was smoothed down close to his head in regulation neatness.

“Well, this is it, Marshall,” the colonel said. “How I envy you this honor of being the first human to enter space. However, I do feel that a part of me is going along too, since I had a small share in preparing you for the trip. If the training was harsh at times, I believe that shortly you will understand the reason for it.”

“I didn’t feel that the Colonel was either too soft or strict, sir,” Marsh said diplomatically.

A speaker out on the brilliantly lit field blared loudly in the cool desert night: “X minus forty minutes.”

“We can’t talk all night, Marshall,” the colonel said briskly. “You’ve got a job to do. But first, a few of your friends want to wish you luck.” He called into the anteroom, “You may come in, gentlemen!”

There filed smartly into the room ten youths who had survived the hard prespace course with Marsh and would be his successors in case he failed tonight. They formed a line and shook hands with Marsh. The first was Armen Norton who had gotten sick in the rugged centrifuge at a force of 9 G’s, then had rallied to pass the test.

“Good luck, Marsh,” he said.

Next was lanky Lawrence Egan who had been certain he would wash out during navigation phase in the planetarium. “All the luck in the world, Marsh,” he added.

Each cadet brought back a special memory of his training as they passed before him, wishing him success.

When they had gone and the speaker outside had announced: “X minus thirty minutes,” the colonel said that he and Marsh had better be leaving. Colonel Tregasker was to be Marsh’s escort to the ship.

Photographers and newspapermen swarmed about them as they climbed into the jeep that was to take them to the launching site farther out on the field. Questions were flung at the two from all sides, but the colonel deftly maneuvered the jeep through the mob and sped off over the asphalt.

At the blast-off site, Marsh could see that the police had their hands full keeping out thousands of spectators who were trying to get into the closed-off area. The field was choked with a tide of humanity milling about in wild confusion. Giant searchlights, both at the airport and in other parts of Phoenix, directed spears of light on the towering rocket that held the interest of all the world tonight. There was one light, far larger than the rest, with powerful condensing lenses and connected to a giant radar screen, which would guide Marsh home from his trip among the stars.

A high wire fence surrounded the launching ramp and blockhouses. International scientists and dignitaries with priorities formed a ring around the fence, but even they were not allowed inside the small circle of important activity. The guards waved the colonel and Marsh through the gate.

Marsh had spent many weeks in a mock-up of the tiny third stage in which he was to spend his time aloft, but he had never been close to the completely assembled ship until this moment. The three stages had been nicknamed, “Tom,” “Dick,” and “Harry.” Marsh swallowed as his eyes roved up the side of the great vessel, part of a project that had cost millions to perfect and was as high as a four-story building.

The gigantic base, “Big Tom,” was the section that would have the hardest job to do, that of thrusting the rocket through the densest part of the atmosphere, and this was a great deal larger than the other sections. Marsh knew that most of the ship’s bulk was made up of the propellant fuel of hydrazine hydrate and its oxidizer, nitric acid.

“We’re going into that blockhouse over there,” Colonel Tregasker said. “You’ll don your space gear in there.”

First a multitude of gadgets with wires were fastened to the cadet’s wrists, ankles, nose, and head. Marsh knew this to be one of the most important phases of the flight—to find out a man’s reaction to space flight under actual rocketing conditions. Each wire would telemeter certain information by radio back to the airport. After a tight inner G suit had been put on to prevent blackout, the plastic and rubber outer garment was zipped up around Marsh, and then he was ready except for his helmet, which would not be donned until later.

Marsh and the colonel went back outside. The open-cage elevator was lowered from the top of the big latticed platform that surrounded the rocket. The two got into the cage, and it rose with them. Marsh had lost most of his anxiety and tension during the activities of the day, but his knees felt rubbery in these final moments as the elevator carried him high above the noisy confusion of the airport. This was it.

As they stepped from the cage onto the platform of the third stage, Marsh heard the speaker below call out: “X minus twenty minutes.”

There were eleven engineers and workmen on the platform readying the compartment that Marsh would occupy. Marsh suddenly felt helpless and alone as he faced the small chamber that might very well be his death cell. Its intricate dials and wires were staggering in their complexity.

Marsh turned and shook hands with Colonel Tregasker. “Good-by, sir,” he said in a quavering voice. “I hope I remember everything the Corps taught me.” He tried to smile, but his facial muscles twitched uncontrollably.

“Good luck, son—lots of it,” the officer said huskily. Suddenly he leaned forward and embraced the youth with a firm, fatherly hug. “This is not regulations,” he mumbled gruffly, “but hang regulations!” He turned quickly and asked to be carried down to the ground.

A man brought Marsh’s helmet and placed it over his head, then clamped it to the suit. Knobs on the suit were twisted, and Marsh felt a warm, pressurized helium-oxygen mixture fill his suit and headpiece.

Marsh stepped through the hatch into the small compartment. He reclined in the soft contour chair, and the straps were fastened by one of the engineers over his chest, waist, and legs. The wires connected to various parts of his body had been brought together into a single unit in the helmet. A wire cable leading from the panel was plugged into the outside of the helmet to complete the circuit.

Final tests were run off to make sure everything was in proper working order, including the two-way short-wave radio that would have to penetrate the electrical ocean of the ionosphere. Then the double-hatch air lock was closed. Through his helmet receiver, Marsh could hear the final minutes and seconds being called off from inside the blockhouse.

“Everything O.K.?” Marsh was asked by someone on the platform.

“Yes, sir,” Marsh replied.

“Then you’re on your own,” were the final ominous words.

“X minus five minutes,” called the speaker.

It was the longest five minutes that Marsh could remember. He was painfully aware of his cramped quarters. He thought of the tons of explosive beneath him that presently would literally blow him sky-high. And he thought of the millions of people the world over who, at this moment, were hovering at radios and TV’s anxiously awaiting the dawn of the space age. Finally he thought of Dad and Mom, lost in that multitude of night watchers, and among the few who were not primarily concerned with the scientific aspect of the experiment. He wondered if he would ever see them again.

“X minus sixty seconds!”

Marsh knew that a warning flare was being sent up, to be followed by a whistle and a cloud of smoke from one of the blockhouses. As he felt fear trying to master him, he began reviewing all the things he must remember and, above all, what to do in an emergency.

“X minus ten seconds—five—four—three—two—one—FIRE!”

There was a mighty explosion at Skyharbor.

The initial jolt which Marsh felt was much fiercer than the gradually built up speed of the whirling centrifuge in training. He was crushed deeply into his contour chair. It felt as though someone were pressing on his eyeballs; indeed, as if every organ in his body were clinging to his backbone. But these first moments would be the worst. A gauge showed a force of 7 G’s on him—equal to half a ton.

He watched the Mach numbers rise on the dial in front of his eyes on an overhead panel. Each Mach number represented that much times the speed of sound, 1,090 feet per second, 740 miles an hour.

Marsh knew “Big Tom” would blast for about a minute and a half under control of the automatic pilot, at which time it would drop free at an altitude of twenty-five miles and sink Earthward in a metal mesh ’chute.

Marsh’s hurting eyes flicked to the outside temperature gauge. It was on a steady 67 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, and would be until he reached twenty miles. A reflecting prism gave him a square of view of the sky outside. The clear deep blue of the cloud-free stratosphere met his eyes.

Mach 5, Mach 6, Mach 7 passed very quickly. He heard a rumble and felt a jerk. “Big Tom” was breaking free. The first hurdle had been successfully overcome, and the ship had already begun tilting into its trajectory.

There was a new surge of agony on his body as the second stage picked up the acceleration at a force of 7 G’s again. Marsh clamped his jaws as the force pulled his lips back from his teeth and dragged his cheek muscles down. The Mach numbers continued to rise—11, 12, 13—to altitude 200 miles, the outer fringe of the earth’s atmosphere. There was a slight lifting of the pressure on his body. The rocket was still in the stratosphere, but the sky was getting purple.

Mach 14—10,000 miles an hour.

“Dick” would jettison any moment. Marsh had been aloft only about four minutes, but it had seemed an age, every tortured second of it.

There was another rumble as the second stage broke free. Marsh felt a new surge directly beneath him as his own occupied section, “Harry,” began blasting. It was comforting to realize he had successfully weathered those tons of exploding hydrazine and acid that could have reduced him to nothing if something had gone wrong. Although his speed was still building up, the weight on him began to ease steadily as his body’s inertia finally yielded to the sickeningly swift acceleration.

The speedometer needle climbed to Mach 21, the peak velocity of the rocket, 16,000 miles per hour. His altitude was 350 miles—man’s highest ascent. Slowly then, the speedometer began to drop back. Marsh heard the turbo pumps and jets go silent as the “lift” fuel was spent and rocket “Harry” began its free-flight orbit around Earth.

The ship had reached a speed which exactly counterbalanced the pull of gravity, and it could, theoretically, travel this way forever, provided no other outside force acted upon it. The effect on Marsh now was as if he had stopped moving. Relieved of the viselike pressure, his stomach and chest for a few seconds felt like inflated balloons.

“Cadet Farnsworth,” the voice of General Forsythe spoke into his helmet receiver, “are you all right?”

“Yes, sir,” Marsh replied. “That is, I think so.”

It was good to hear a human voice again, something to hold onto in this crazy unreal world into which he had been hurtled.

“We’re getting the electronic readings from your gauges O.K.,” the voice went on. “The doctor says your pulse is satisfactory under the circumstances.”

It was queer having your pulse read from 350 miles up in the air.

Marsh realized, of course, that he was not truly in the “air.” A glance at his air-pressure gauge confirmed this. He was virtually in a vacuum. The temperature and wind velocity outside might have astounded him if he were not prepared for the readings. The heat was over 2000 degrees Fahrenheit, and the wind velocity was of hurricane force! But these figures meant nothing because of the sparseness of air molecules. Temperature and wind applied only to the individual particles, which were thousands of feet apart.

“How is your cosmic-ray count?” asked the general.

Marsh checked the C-ray counter on the panel from which clicking sounds were coming. “It’s low, sir. Nothing to worry about.”

Cosmic rays, the most powerful emanations known, were the only radiation in space that could not be protected against. But in small doses they had been found not to be dangerous.

“As soon as our recorders get more of the figures your telemeter is giving us,” the operations chief said, “you can leave the rocket.”

When Marsh got the O.K. a few minutes later, he eagerly unstrapped the belts around his body. He could hardly contain his excitement at being the first person to view the globe of Earth from space. As he struggled to his feet, the lightness of zero gravity made him momentarily giddy, and it took some minutes for him to adjust to the terribly strange sensation.

He had disconnected the cable leading from his helmet to the ship’s transmitter and switched on the ship’s fast-lens movie camera that would photograph the area covered by “Harry.” Then he was ready to go outside. He pressed a button on the wall, and the first air-lock hatch opened. He floated into the narrow alcove and closed the door in the cramped chamber behind him. He watched a gauge, and when it showed normal pressure and temperature again, he opened the outside hatch, closing it behind him. Had Marsh permitted the vacuum of space to contact the interior of the ship’s quarters, delicate instruments would have been ruined by the sudden decompression and loss of heat. Marsh fastened his safety line to the ship so that there was no chance of his becoming separated from it.

Then he looked “downward,” to experience the thrill of his life. Like a gigantic relief map, the panorama of Earth stretched across his vision. A downy blanket of gray atmosphere spread over the whole of it, and patches of clouds were seen floating like phantom shapes beneath the clear vastness of the stratosphere. It was a stunning sight for Marsh, seeing the pinpoint lights of the night cities extending from horizon to horizon. It gave him an exhilarating feeling of being a king over it all.

Earth appeared to be rotating, but Marsh knew it was largely his own and the rocket’s fast speed that was responsible for the illusion. As he hung in this region of the exosphere, he was thankful for his cadet training in zero gravity. A special machine, developed only in recent years, simulated the weightlessness of space and trained the cadets for endurance in such artificial conditions.

“Describe some of the things you see, Marshall,” General Forsythe said over Marsh’s helmet receiver. “I’ve just cut in a recorder.”

“It’s a scene almost beyond description, sir,” Marsh said into the helmet mike. “The sky is thickly powdered with stars. The Milky Way is very distinct, and I can make out lots of fuzzy spots that must be star clusters and nebulae and comets. Mars is like an extremely bright taillight, and the moon is so strong it hurts my eyes as much as the direct sun does on earth.”

Marsh saw a faintly luminous blur pass beyond the ship. It had been almost too sudden to catch. He believed it to be a meteor diving Earthward at a speed around forty-five miles a second. He reported this to the general.

As he brought his eyes down from the more distant fixtures of space to those closer by on Earth, a strange thing happened. He was suddenly seized with a fear of falling, although his zero-gravity training had been intended to prepare him against this very thing. A cold sweat come out over his body, and an uncontrollable panic threatened to take hold of him.

He made a sudden movement as though to catch himself. Forgetting the magnification of motion in frictionless space and his own weightlessness, he was shot quickly to the end of his safety line like a cracked whip. His body jerked at the taut end and then sped swiftly back in reaction toward the ship, head foremost. A collision could crack his helmet, exposing his body to decompression, causing him to swell like a balloon and finally explode.

In the grip of numbing fear, only at the last moment did he have the presence of mind to flip his body in a half-cartwheel and bring his boots up in front of him for protection. His feet bumped against the rocket’s side, and the motion sent him hurtling back out to the end of the safety line again. This back-and-forth action occurred several times before he could stop completely.

“I’ve got to be careful,” he panted to himself, as he thought of how close his space career had come to being ended scarcely before it had begun.

General Forsythe cut in with great concern, wondering what had happened. When Marsh had explained and the general seemed satisfied that Marsh had recovered himself, he had Marsh go on with his description.

His senseless fear having gone now, Marsh looked down calmly, entranced as the features of the United States passed below his gaze. He named the cities he could identify, also the mountain ranges, lakes, and rivers, explaining just how they looked from 350 miles up. In only a fraction of an hour’s time, the rocket had traversed the entire country and was approaching the twinkling phosphorescence of the Atlantic.

Marsh asked if “Tom” and “Dick” had landed safely.

“‘Tom’ landed near Roswell, New Mexico,” General Forsythe told him, “and the ’chute of the second section has been reported seen north of Dallas. I think you’d better start back now, Marshall. It’ll take us many months to analyze all the information we’ve gotten. We can’t contact you very well on the other side of the world either, and thirdly, I don’t want you exposed to the sun’s rays outside the atmosphere in the Eastern Hemisphere any longer than can be helped.”

Marsh tugged carefully on his safety line and floated slowly back toward the ship. He entered the air lock. Then, inside, he raised the angle of his contour chair to upright position, facing the console of the ship’s manual controls for the glide Earthward. He plugged in his telemeter helmet cable and buckled one of the straps across his waist.

Since he was still moving at many thousands of miles an hour, it would be suicide to plunge straight downward. He and the glider would be turned into a meteoric torch. Rather, he would have to spend considerable time soaring in and out of the atmosphere in braking ellipses until he reached much lower speed. Then the Earth’s gravitational pull would do the rest.

This was going to be the trickiest part of the operation, and the most dangerous. Where before, Marsh had depended on automatic controls to guide him, now much of the responsibility was on his own judgment. He remembered the many hours he had sweated through to log his flying time. Now he could look back on that period in his training and thank his lucky stars for it.

He took the manual controls and angled into the atmosphere. He carefully watched the AHF dial—the atmospheric heat friction gauge. When he had neared the dangerous incendiary point, with the ship having literally become red-hot, he soared into the frictionless vacuum again. He had to keep this up a long time in order to reduce his devastating speed.

It was something of a shock to him to leave the black midnight of Earth’s slumbering side for the brilliant hemisphere where the people of Europe and Asia were going about their daytime tasks. He would have liked to study this other half of the world which he had glimpsed only a few times before in his supersonic test flights, but he knew this would have to wait for future flights.

Finally, after a long time, his velocity was slowed enough so that the tug of gravity was stronger than the rocket’s ability to pull up out of the atmosphere. At this point, Marsh cut in “Harry’s” forward braking jets to check his falling speed.

“There’s something else to worry about,” he thought to himself. “Will old Harry hold together or will he fly apart in the crushing atmosphere?”

The directional radio signals from the powerful Skyharbor transmitter were growing stronger as Marsh neared the shores of California. He could see the winking lights of San Diego and Los Angeles, and farther inland the swinging thread that was the beacon at Skyharbor. All planes in his path of flight had been grounded for the past few hours because of the space flight. The only ground light scanning the skies was the gigantic space beacon in Phoenix.

When Marsh reached Arizona, he began spiraling downward over the state to kill the rest of his altitude and air speed. Even now the plane was a hurtling supersonic metal sliver streaking through the night skies like a comet. He topped the snow-capped summits of the towering San Francisco Peaks on the drive southward, and he recognized the sprawling serpent of the Grand Canyon. Then he was in the lower desert regions of moon-splashed sand and cactus. Although the fire-hot temperature of the outer skin had subsided, there had been damage done to the walls and instruments, and possibly to other parts, too. Marsh was worried lest his outside controls might be too warped to give him a good touchdown, if indeed he could get down safely at all.

A few thousand feet up, Marsh lowered his landing gear. Now the only problem left was to land himself and the valuable ship safely inside the narrow parallels of the airstrip. He circled the airport several times as his altitude continued to plummet.

The meter fell rapidly. His braking rocket fuel was gone now. From here on in, he would be on gliding power alone.

“Easy does it, Marshall,” the general said quietly into his ear. “You’re lining up fine. Level it out a little and keep straight with the approach lights. That’s fine. You’re just about in.”

The lights of the airport seeming to rush up at him, Marsh felt a jolt as the wheels touched ground on the west end of the runway. He kept the ship steady as it scurried along the smooth asphalt, losing the last of its once tremendous velocity. The plane hit the restraining wire across the strip and came to a sudden stop, shoving Marsh hard against the single safety belt he wore. Finally, incredibly, the ship was still and he was safe.

He unfastened his strap and removed his space helmet. The heat of the compartment brought the sweat out on his face. He rose on wobbly legs and pressed the buttons to the hatches. The last door flew open to admit the cool, bracing air of Earth which he had wondered if he would ever inhale again.

His aloneness was over then, suddenly and boisterously, as men swarmed over him with congratulations, eager questions, and looks of respect. Reporters’ flash bulbs popped, and he felt like a new Lindbergh as he was pulled down to the ground and mobbed. Finally the police came to his rescue and pushed back the curiosity seekers and newspapermen. Then only three men were allowed through the cordon.

The first to reach him was General Forsythe, who almost seemed to have ridden with him the whole way. He grabbed Marsh’s hand and clapped him on the shoulder. He said briefly, “You’ve launched the age of space travel, Marshall. Congratulations, son. Now go home with your father and get a good night’s rest. We’ll see you tomorrow.”

“Thank you, sir,” Marsh replied.

Colonel Tregasker came forward, and there was moisture visible in the eyes of the cadet officer. “Now that one of my boys has made the first trip into space and fulfilled a career-long dream, I can retire in peace,” he murmured. “I’m proud to have been associated with you, Marshall Farnsworth. Congratulations, my boy.”

Then Dad had his turn. He stood for a moment in front of his son as though undecided what to do, hat in hand, the night breeze ruffling his hair. Mr. Farnsworth seemed embarrassed by the grandeur of the moment and reluctant to accept a part in one of the greatest accomplishments of modern times.

Marsh moved forward and clasped his shoulders. “I did it, Dad,” he said.

“Thank God for bringing you back safely,” his father murmured huskily. “Are you ready to go home, son?”

Suddenly Marsh was terribly weary, and he felt as if he could sleep for days. “I am kind of tired,” he said. “Let’s go home and see Mom.”

The people around seemed to realize that this was not their moment. They parted ranks quietly as the father and his son walked through them and got into their car. As they drove off, even the stars and planets seemed to be standing silent and watchful, in respect for the dawn of space travel on the tiny pebble that was Earth.

Dr. Myron Lowenthal, gaunt, keen-eyed, and sixty, shuffled over to the receptionist’s desk in an office in the Pentagon. Clutched tightly beneath one spidery arm was a worn brief case.

“May I see Mr. Goodnight, miss?” Dr. Lowenthal asked.

“Who shall I say is calling, sir?” the young woman asked mechanically, not looking up.

“Lowenthal.”

The young woman’s eyes lighted alertly as if the name were of great significance to her. “Of course, Dr. Lowenthal. Mr. Goodnight is expecting you. Go right in.”

At the sight of Dr. Lowenthal and his brief case, Mr. Goodnight rose slowly to his feet, his face reflecting deep interest not unmixed with apprehension.

“You—you have finished the translation?” he asked.

Dr. Lowenthal placed the brief case on the desk, and Goodnight’s fingers were far from steady as he opened the case and pulled out top-secret manuscripts.

First he laid aside the sheaf of strange, charred papers, each protected by a cellophane envelope. The sheets were of very thin, amazingly tough material of unknown substance, and they were covered with tiny, neat hieroglyphics. The papers had been found by a farm boy twelve months before in Wickenburg, Arizona, and Dr. Lowenthal, archaeologist and cryptographer, had been all this time trying to decipher the hidden message.

Before reading the translation, Goodnight asked, “Is it your belief that this sheaf of papers was dropped from a flying saucer, as we first thought?”

“Undoubtedly,” Lowenthal replied.

“Is it good—or bad?” Goodnight asked tremulously.

“Perhaps you had better read it, sir, and judge for yourself.”

Mr. Goodnight began reading the manuscript translation:

FROM: Kal-Pota-Tekkala, Observer 13-J07, Group 507.

TO: Grand Council, Federation of the Triple Suns, Planet Ykaa, Takarala Sector GZ-5000-7076, Milky Way Galaxy.

SUBJECT: Planets of Sun 00836-Y, Specifically, Third Takarala Sector GZ-5000-7070.

Planet Called Earth, Charaan Year 37,811.

It is now my tenth year of observation in the planetary group called the solar system. In this brief report I shall review somewhat randomly a few of the things I have witnessed on Earth, only planet of intelligent life in this system and therefore the only world of interest to us in the Federation.

I arrived in the Earth year 1947. (What a youthful civilization this is, but about average in their development as compared to some 28,000 other worlds the Federation has so far observed.) I pride myself on being among the first of us (Group 507) to be detected by Earthmen in recent times. This was, of course, the sighting by one Kenneth Arnold near Mt. Rainier in America, the most advanced country of Earth. Our receivers picked up the newscast of the sighting and translated. Arnold’s description of having seen what looked like “saucers” led to our craft being thereafter named “flying saucers.”

Soon after this sighting, our receivers told us that nearly all the nations of Earth had taken up the cry of “Saucers! Saucers!” Indeed, the men of Earth must truly have been overwhelmed by the abundance of our craft in the sky at this time when our greatest concentration of observers viewed the planet.

It is hard to realize that many Earth inhabitants still doubt that there are other planets of habitation beside their own in the universe. (This is an opinion formed from reports of news commentators.) Yet how they can close their minds to such a fact, when they know that there are many billions of suns and planets, is beyond my comprehension. Of course, Earth has been an island to itself since the beginning of its civilization, and since they have not even yet ventured into space, I can understand their skepticism somewhat.

Incidentally, this skepticism of Earthmen is remarkable. Yes, even after the evidence of our heavy concentration of craft in their skies for ten years (at our latest visit), many even now doubt our reality. This is in spite of our near collisions with Earth craft reported by reputable witnesses (especially the Chiles-Whitted episode near Montgomery, Alabama, United States of America). Yet those who do believe in us are very stanch supporters, and I have heard newscasters say there have been some convincing books written on the subject. Some day—when we make contact—all must surely believe.

Earth is a planet of many races and different political groups. Although an effort is being made for co-operation through an organization called United Nations (not to be confused with United States), there is no real, enforceable unity among the countries of Earth. The planet has not even advanced to the point of a common tongue! Without being able to speak the same language, there is too much opportunity for misunderstanding, and this must be one of the causes of the deplorable bloodshed this planet has gone through in its history.

It is good to know that democracy presently seems to hold the balance of power on Earth. The world leader, America, has been a champion of democracy since its colonization by Europeans, and perhaps it has saved Earth from total disaster by intervention on two occasions in recent years.

There is one major threat to the democratic life of Earth. This is the nation of Russia, located in the Eurasian area. Its leaders have taken to the archaic system of totalitarianism. But at the present time the democracies are so strong that Russia appears hesitant to take the path of conquest. Besides this, I believe all realize that Earth cannot stand another world war because of the frightful nuclear weapons that would be used. In such a war there would be no victor, only losers and world destruction.

If Earth avoids the pitfall of major warfare, I believe she is on the threshold of great things. Even now she is launching satellites into space in the first step toward space travel. The aircraft of Earth are attaining greater speed, height, and maneuverability. They are still slow and awkward, of course, compared to the craft we have, but the engineers are learning, even as we had to do thousands of years ago.

Since Earthmen have still not gone into space, there has been no experimentation on craft utilizing force fields, but after observing our craft for the past ten years, I am sure the scientists have come up with some theories as to how we get about. They are baffled by our motions that seem to defy the laws of physics. They report that no living person can withstand the abrupt turns and acceleration of which we are capable. When they have utilized the cosmic rays of space and understand that a force field will permit a flyer to spin and soar with his craft, without distress of any kind, then they will have unlocked the key to what they believe to be a dark mystery.

Their attempts to overtake us in their jet craft have been laughable. I often wonder what they would do if we should suddenly stop and dare them to approach closer. Should they fire on us, it would undoubtedly fill them with fear and dismay to see their shots bounce harmlessly off our force field.

It is my opinion that the more prosperous races of the planet are not the leaders that they could be. There is much frivolity and lack of emotional discipline about them, and few seem to employ their fullest mental capabilities. Their radio and picture-radio are entirely in the realm of entertainment, and formal education seems to be largely abandoned after an Earthman has passed his school years. Our receivers constantly pick up, day in and day out, music of definite rhythms which seem to be enjoying current popularity. These melodies survive for only a few weeks, then new ones take their place and are, in turn, played to their deaths. There is a noble class of music that is heard less frequently and usually at late hours. This never seems to lose popularity, for some of our recorded pickups of these long compositions have been compared with recordings made some two hundred years ago by our prior observers, and they are identical.

Regarding the subject of frivolity, there is a deadly “game” being played unceasingly across the pathways of Earth, particularly in prosperous America. Although not really a game, of course, I am reminded of one as I see it going on. Each player is in control of a free vehicle (or “guided missile” as I think of it), and he attempts to survive by avoiding collision with another player. Some are indifferent to the game and drive their cars unexcitedly and with caution. Other players—and there are many of them—appear to enjoy the game very much and drive their “weapons” with reckless haste and seeming indifference to their own safety and the safety of others. Many of these players lose the game, and their remains are carried away systematically. It is very disturbing to see this bloody game going on without end, and I should feel better if America would abandon it in favor of travel of a less dangerous nature. But they seem years away from a truly safe, fully automatic car of our type with the electronic protection shield.

While on the subject of fatality, it is with regret that I heard of the disintegration of Paltaa-Vezek and his craft some days ago. Paltaa and I were boys together barely three hundred (Earth) years ago on the Symphony Lake plantation. We went through sleep-absorption education together for twenty years, and he was my dear friend. Paltaa’s force field collapsed when he was escaping a fleet of Earth craft which were rising into the sky in pursuit. At an acceleration of some 5,000 miles an hour, his craft collided with air in inertia, and he and his “saucer” were vaporized in a blinding flash and thunderous roar. The radio commentators calmly informed the world that it was merely a large meteor burning itself up in the atmosphere. (The stubborn refusal of Earthmen to accept our existence continually baffles me.)

From what I have heard these radio spokesmen say, Earthmen who believe in us seem to regard us with a sort of awe. They rightly consider us much farther advanced than themselves, but you should hear the outlandish descriptions some have given us. And after the weird appearance they present to us, too!

I have judged the people of Earth to be excitable and unpredictable. Therefore I can understand the Federation’s reluctance to have us make contact. Earthmen undoubtedly regard us as invaders and would treat us as such, although they must realize we have shown no acts of aggression. Nevertheless, there have been a few unfortunate instances that might tend to make them think we are belligerent (namely, the Mantell case in 1948). Kaal-taa-ar, pilot of the involved craft, I understand, has been recalled to Ykaa because of his mistake in permitting an Earth craft to venture into his force field, thereby destroying the alien craft and violating our strict orders to avoid any incidents with Earth craft.

In spite of the obvious risk, it is my greatest anticipation to meet these Earth folk face to face. Our observations have been from afar and therefore lacking much that we could really know about these people. I’m sure there are things they could teach us, and of course there is much that we could do to make happier their own existence. Some day, I know, the Federation will give the word to land on Earth soil. Should I be one of those fortunate ones, I am ready, and if it costs me my life I shall be satisfied to have first enjoyed making contact with other men who live so many light-years from our own Ykaa.

When will this contact be, my friends?

Today?

Tomorrow?

When?

As he concluded his reading of the report, Mr. Goodnight’s eyes reflected the relief he felt.

“It is reassuring, Doctor, isn’t it?” he asked, huskily.

“I think so,” Dr. Lowenthal replied. “Even with my liberal translation, the nonaggressive attitude comes through continually.”

“This is the final proof we needed as to the authenticity of the saucers,” Goodnight remarked. “This couldn’t possibly be a hoax, could it?”

“Not a chance. The substance of the original paper is completely alien in its composition and manufacture, and the language is undoubtedly the creation of minds farther advanced than our own.”

Mr. Goodnight sighed as if a great burden had been lifted from him. “Well, our part in this is closed, Dr. Lowenthal,” he said. “It is out of our hands.”

“And now?” Lowenthal prompted.

“It is the job of others to determine if the manuscript is to be made public. This thing could be revolutionary in impact, Dr. Lowenthal. It could change the thinking and living of every person on Earth.”

The scientist nodded in agreement. “You know, Mr. Goodnight,” he said after a meditative pause, “I believe that Kal-Pota-Tekkala would be a rather nice fellow to know. I should really like to meet him.”

“So would I,” Goodnight replied, then added significantly with a sparkle of anticipation in his eyes, “Who knows? Perhaps some day, Doctor, not too distant, we shall.”

Steve Gordon stared out of the forward port of the Condon Comet, which was streaking toward the sun. A dense filter protected his eyes from the searing brilliance of the star, looming ever larger by the day and hour as the rocket devoured the miles at a speed never before equaled by a space flyer.

“We’ll whip Dennis easily if we can keep up this pace!” exclaimed Steve’s older brother, Bart, in his clipped way.

Steve saw a gloating, almost fanatical, expression on Bart’s face. Bart’s one passion in life was to beat a Dennis ship with a Condon craft. The rivalry extended back eighteen years to 2003, when the youths’ fathers had first started their competing light-space-craft companies.

“Take a look out back, Steve, and see if we’re still gaining,” Bart said.

Steve left his seat and at the rear of the compartment searched the TV screen, which showed the star-filled darkness behind the ship. A small silvery mote, the Dennis Meteor, moved against the immobile stars.

“We’re well ahead,” Steve reported, turning back. “Why don’t you let up, Bart? We’ll burn out our jets at this speed!”

Bart’s expression was grimly set. “This is the moment Dad wished for all his life, Steve. A Condon ship has always played second best to a Dennis. Now that we seem to have broken through, do you think I’m going to let up?”

Steve realized that an eventual victory for Bart would not settle anything, for then Jim Dennis would strike back with an even better ship next year, and the fight would continue. On and on it would go until one of them took a foolhardy chance. Then disaster would be the final victor in the feud.

“We’re going a hundred miles a second!” Steve protested. “We’re already ahead of Jim’s last year’s record!”

“I’m going to set a record around the sun that no Dennis ship will ever top!” Bart asserted stubbornly.

Steve had come along as Bart’s assistant mainly in the hope of somehow calming his brother’s hotly competitive spirit and restraining him from over-stepping the bounds of common caution in this race that held the interest of the entire world.

Steve looked over the strain dials on the control panel. The needle was wavering toward the danger point.

“Bart, slow down!” Steve burst out. “We’ll shake ourselves to pieces! This refrigerator gauge has been acting funny too!”

Bart checked the panel dials. “I guess we can afford to coast a little,” he admitted.

They pushed levers, and Steve felt the little ship bucking gently as her forward jets braked to slower speed.

“Why do you and Jim have to keep going on like this year after year?” Steve asked. “A Dennis-Condon merger would make for a terrific space ship.”

Bart grinned tolerantly. “Still trying, aren’t you, Steve?” Then he frowned. “If Jim Dennis wants peace, let him come to us. Then we’ll incorporate his best points in our machines and call them Condons.”

“It would have to be a fifty-fifty proposition, Bart,” Steve reminded him. “Jim has as much pride as we do.”

The younger man studied the slowly enlarging yolk of Sol in front of them. In spite of the heavy filter over the port, it seemed as though the terrific light and heat were burning through his eyes.

This was Steve’s first trip, but he had been told by Bart that the celestial furnace had an aura about it that seemed to penetrate clear to one’s bones. Their refrigerating unit and heat-repulsing hull would be taxed hard to keep them from bursting into flame.

“Better check on Jim again,” Bart said impatiently.

“He’s holding back; I know he is. He won’t try to overtake us yet,” Steve replied. Nevertheless, he got up to take another look at the screen. He was glad to see that his assumption was correct.

He returned to his seat at the panel and carefully kept tab on the readings, covering first one dial and then another. Some minutes later the refrigerator-gauge needle unexpectedly soared above the subzero mark. Almost at the same moment, Steve felt encroaching heat pressing in on him from all sides. The sweat popped out. The heat filled his nostrils, burned his lungs.

“The refrigerator has broken down!” Steve gasped.

His gaze shifted to Bart, who was rubbing a moist hand over his crimsoning face. Bart’s fingers jerked instinctively from the levers that had quickly grown too hot to handle. In the motion, Bart’s arm carelessly brushed against one of the side jet levers. The ship veered on its gyroscopic balance and plunged out of control.

Steve bumped against the far corner of the compartment, feeling bruises all over him, but he was not really hurt, although it seemed as though he were breathing fire. Bart’s head had struck the fire drill, a big welding machine for repairing breaks in the hull, stupefying him.

Steve shook his head to clear it and scrambled to his seat, righting the ship again and putting it on automatic pilot. Then he got up and hurried down the corridor to the garb room. His magnetic shoes clacked along the metal floor. Hurriedly, Steve donned space suit, oxygen tank, and helmet.

The insulated gear momentarily cut out the oppressive heat. But in another few minutes he and Bart would be sizzling like steaks on a griddle, for even the insulation of their suits could not withstand raw heat for long. The only way out, as Steve saw it, was to call on Jim Dennis.

Steve carried another set of gear down the corridor and shook Bart. “Put this on, Bart,” he said. “It’ll protect you from the heat.”

Bart was gasping in the hot air of the compartment, his face scarlet and shining, but he took the gear. Next, Steve went outside onto the skin of the Condon Comet. The vault of starlight closed in all about him, and the deep web of midnight space seemed to extend endlessly. There was the sweeping veil of the Milky Way galaxy and here closer the pulsing, blinding sphere of Sol. There was another startling light, a driving streak of firestreams and silvery glow—the Dennis Meteor.

Jim and his co-pilot, Pete Rogers, could hardly miss seeing them. Quickly the Dennis Meteor drew abreast of the Condon Comet, but then it swept on past overhead!

Steve felt bitterness and disappointment well up in him. He had always thought Jim to be a “right guy.” Could it be that the winning of the race was more important to him than two persons’ lives?

The only hope now was a hasty repair of the refrigerator unit. Steve hustled back into the ship and made his way to the rear where the cooling machinery was located. He found Bart working there, his helmet off. Steve removed his own helmet, for apparently Bart had repaired the trouble. The customary blandness of the atmosphere had been restored.

“What happened to it?” Steve asked.

“The dynamo burned out,” Bart answered. “I just coupled in the spare one. Where have you been?”

“Out on the skin,” Steve said. “I was trying to signal Jim Dennis.”

Bart’s face went red again, and he muttered to himself.

“I didn’t think there was any chance of repairing the trouble,” Steve went on.

“I’d rather burn than take help from Jim Dennis!” Bart snapped. “Did Dennis see you?”

“He must have. He went right overhead.”

“Obviously he didn’t stop, though.”

“No, he didn’t,” Steve said frankly.

“I wouldn’t have believed that of Dennis,” Bart murmured. “I thought he was a better man than that.”

“He may not have seen me, Bart. Let’s give him the benefit of the doubt.”

“I’ll give him nothing!” Bart rapped. “If Jim Dennis wants a fight to the finish, we’ll give it to him!”

Bart began immediately to battle to regain their lead. It was a frenzied, closely fought contest for many hours, the lead seesawing back and forth. It took the top speed Bart’s craft was capable of to gain the lead he was finally able to maintain.

Only when Jim Dennis appeared content to linger behind again did Bart cut their driving velocity. Once more Steve felt he could breathe easier—for a while at least.

In the days that followed, there were no changes in position. Steve and Bart took turns at the controls during the sleeping periods. They could see the planet Venus at a distance. Their flight had been planned to avoid close proximity with Earth’s twin because of the retarding effect of her gravity.

The sun steadily dominated the sky, an enormous cottony ball of atomic fury with a surface temperature of 6000 degrees centigrade and an interior heat around 20,000,000 degrees. The red leaping flames of the chromosphere were like the mountainous waves of a gigantic cosmic ocean as they lapped millions of miles out into surrounding space. Magnetic storms—sunspots—all of them large enough to swallow the Earth, were seen as whirling dark cyclones in the sea of gas.

As the Condon Comet moved around and behind the star, it began to close in on the planet Mercury. The ship was actually overtaking the miniature world even though it was circling the sun at a rapid thirty miles a second.

On the fifth day away from Earth, the Condon Comet reached its apogee, the farthest point of its orbit from the mother planet. It was “behind” the sun now, the dominant ball eclipsing the Earth. By now Mercury had grown hugely, a big pebbly world that literally shimmered with the frightening heat that poured down upon it. It was a startling sight, halved into hemispheres of darkness and extreme brilliance. The closer side was so hot that streams of molten tin and lead flowed, while that side away from the sun approached the arctic cold of absolute zero.

“I hope we don’t have to land there, Bart,” Steve spoke uncomfortably, looking out the port.

They began to feel the gravitational attraction of the miniature world, and they had to bolster rocket fire to combat it. Unlike Venus, Mercury could not be avoided in this flight.

Steve watched the gauges, especially the refrigerator dial. The latter was holding up well under this maximum barrage of heat from Sol, but there was still an oppressive hotness that reached through the laboring artificial coolness and penetrated Steve’s pores like insidious rays.

“If the Comet isn’t superior to Dennis’s in any other way, it’s made of better heat-resistant alloy,” Bart had said with self-assurance before leaving Earth. Steve wondered now if the proof of this assertion would be settled before both ships were beyond the sun’s reach.

Hours later, when the Condon Comet had passed Mercury, Steve was impelled to check on their rivals behind. For a moment he couldn’t find the ship on the TV screen. When he spotted it at last, by changing the direction of the movable screen, he was amazed to find the craft far below, hovering over the planet.

“Bart!” Steve called. “It looks as if Jim and Pete are in trouble! They’re diving for Mercury and seem to be heading for the terminator line between the dark half and the light!”

Steve wished there were some kind of radio communication between the ships, but electrical interference from the sun made radio impossible on these round-the-sun races.

“We’ve got to go down there, Bart,” Steve said.

“We haven’t won yet, Steve. There’s still the record to beat.”

“Will you stop thinking about records!” Steve retorted. “There are a couple of men down there in trouble!”

“Did they stop for us?” Bart bit out. “It’s probably only a trick to lure us down so that Dennis can make a quick getaway!”

But Steve knew that his brother was not as cold-hearted as he pretended to be. Bart proved it in the next few minutes when he reluctantly turned the Comet’s nose downward with a savage thrust of the upper tail jets.

“You’ll never regret this,” Steve said.

“I wonder,” Bart grunted, without satisfaction.

As the ship moved strongly into Mercury’s gravitation field, Bart lined the automatic pilot up with the tiny speck on the rocky world below that was the Dennis Meteor. Then he and Steve strapped down on their protective couches for the grueling landing.

Steve felt as though his chest were crushed under the rapid deceleration. It was the effect of a swiftly dropping elevator multiplied hundreds of times as the Comet’s forward jets thrust against Mercury’s crust to brake the hurtling speed. Steve finally blacked out; he always did. When he came to, they had landed, and through blurry eyes Steve saw his brother struggling to release himself from his straps.

They went to the port. The Dennis Meteor was in bad shape, its prow crumpled into a huge face of rock. Its occupants could have been killed by the concussion, although there was a good chance that they were still alive if they had had time to strap down.

Steve noted their rugged surroundings, where strange rock pillars thrust into the black sky from a shimmering, white-hot plain. Snaky rifts of incalculable depth split the torrid landscape.

“The ship landed on its side,” Bart observed, speaking over his short-range helmet radio. “The escape port is underneath!”

There was no point of exit from the ship for the trapped occupants if they were still alive, Steve observed. Even the rocket tubes had been crushed flat. Actually the Dennis Meteor was a complete ruin, its entire glossy surface warped and corrugated.

“You can see the ship broke down under the heat,” Bart said. “That’s why they had to crash-land.”

“Look here on the other side!” Steve’s voice suddenly crackled in alarm over his helmet radio.

Bart joined him. Only now did they see that the craft had nearly rolled down a precipitous incline into a canyon stream of molten lead far below. The ship was balanced precariously on the ledge. It seemed as if the slightest jar would send it hurtling down the slope.

“We’ve got to get them out of there before the ship falls!” Steve said. “The precipice looks so crumbly it may give way at any minute!”

“I don’t see how we can get them out,” Bart commented.

Steve thought a moment. “The fire drill! We can cut a hole in the top of the ship!”

Bart frowned. “The force of the drill or even our weight on top of it may cause the ship to go. But if you’re game, I am.”

They brought the fire drill out of the Condon Comet, and as they climbed up onto the warped hull of the other ship with it, Bart smiled wryly. “I never thought I’d see the day that I’d risk my neck for a Dennis,” he remarked.

A moment later, when Bart was about to start the drill, he asked, “Ever try swimming through molten metal, Steve? You’d better think about it. We may be doing it in a second.”

Steve felt weak in the knees as he looked down into the plunging gulf where the metallic river tossed against blackened rocks. A person flung into that stream would be a cinder in scant moments.

Steve gritted his teeth. “Start it up, Bart.”

The machine whined into action, pouring a thin stream of blue-hot biting energy against the heat-resistant alloy. The rocket shuddered under the drill’s action, and Steve felt waves of fear course through him. The drill moved in an arc that was to be a circle barely large enough for the two men inside to squeeze through in their space suits.

When the job was halfway done, the ship ground forward several feet. Steve saw Bart’s face drain whitely. Steve could almost feel the scorching bite of liquid metal against his body. Yet the ship somehow clung stubbornly to its precarious support.

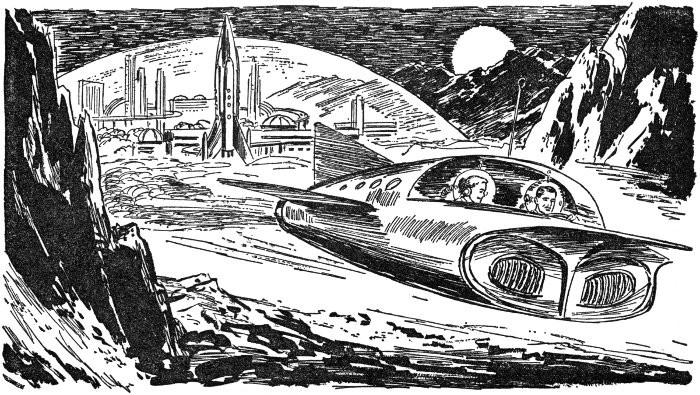

They renewed their efforts, and the arc grew. Finally the circle was full round. Bart stood up and jammed a foot against the isolated ring, and it dropped inside. Steve held his breath as he looked in, afraid of what he might see. He felt immeasurable relief as Jim and Pete came up to the opening attired in space gear. They shoved a ladder into place and started up. Steve gave Pete a hand, for he seemed to be shaken up. Suddenly the ship rumbled a foot or two. It was going any instant. The four of them carefully walked the length of the craft and made their way down the flattened rocket tubes.

Bart was the last to jump to the ground. His movement affected the delicate balance of the ship, and it slid forward, its stern arching straight up as it dipped over the gulf. The ground shook, and a moment later the Dennis Meteor had thundered to oblivion into the river of lead.

After Jim and Pete had expressed gratitude for their rescue, the four fell into silence as they trooped back to the Condon Comet. Although no one spoke, Steve felt that the others, like himself, must be thinking many things. Would this mark the end of the long feud, or would it be only a temporary truce?

Jim Dennis walking with a limp, studied the Condon ship. He circled the rocket completely and closely examined the smooth hull, still undamaged by the abnormal heat bombardment it was taking.

When they were inside, Jim was the first to speak. “This ship is terrific,” he said simply.

“You admit that?” Bart asked incredulously.

“I’ve never seen a craft stand up so perfectly under extreme heat,” Jim continued. “I think you’ve done it, Bart. It’s the finest light space ship ever built.”

“An engineer who started out with Dad made this alloy,” Bart declared. “He told me he thought he had finally come up with the ideal metal.”

“The Meteor rattled like an old freighter the whole way!” Jim complained. “We spent a lot of time in the rear checking on the rocket tubes. We were afraid they’d shake loose. I guess we must have been back there when we passed you, for the last time I looked out you were ahead of us.”

That explained why they hadn’t seen his wave, Steve thought.

“It sure was a lucky break for us that you brought your drill along,” Jim went on. “I had so much confidence in the Meteor I was sure we wouldn’t need it.”

“I felt the same way,” Bart admitted, “but Steve insisted we bring it. That kid brother of mine always did have more practical sense than I.”

“I’ve been doing a lot of thinking since we crash-landed, Bart,” Jim said. “I’ve been thinking that maybe this feud has gone on long enough and that you must be as sick of it as I am. Together, we could turn out ships that would be just about perfect. What do you say, Bart?”

Bart’s face grew stern and thoughtful. Finally he answered, “I’ll have to think it over first, Dennis.”

“While you’re thinking, we may as well have a look-see,” Jim said. He went over to the panel and checked the readings. “You seem to be way ahead of my old record, Bart. You’re still going to try to beat it, aren’t you?”

Steve knew this remark had broken down the last of Bart’s stubborn pride and reserve. His brother smiled and thrust out his hand to Jim Dennis. “You’re a good loser, Jim,” he said.

“I’m no loser,” Jim answered, grinning. “I’m a winner—we both are.”

Young Steve Condon sighed contentedly. He glanced at Pete Rogers, who winked at him. Jim and Bart sat down side by side at the control panel of the Condon Comet. Steve didn’t doubt for a moment that the long feud was finally at an end. He was satisfied that his father would have liked it this way.

Spacemaster Brigger came into the navigation compartment of the Centaurus, which was thrusting into the starry night of space far beyond Saturn. Rob Allison, junior officer, looked up from the desk where he sat, wondering at the frown on the skipper’s face.

“It’s just as I feared, Allison,” Mr. Brigger said gravely. “The men are sorry they signed on for Titania and are grumbling already. They think they’ll be ridiculed when they get back.”

“Because of Dr. Franz’s being discredited by all the scientists, I suppose?”

The skipper nodded. “They’re sure they’re on a wild-goose chase. I’m afraid I’m inclined to agree with them.”

“I guess you and the crew, sir, are only reflecting the opinion of almost everyone else on Earth,” Rob mused bitterly.

The spacemaster of the Centaurus dropped onto a plastic bench beside a port that overlooked the star fields of the outer solar system. “Exactly why did your brother Grant authorize this expedition, Allison? Does he really believe we’ll find animal life on Uranus’ satellite or is it something else?”

Grant Allison, an illustrious front-rank explorer of several years before, was now president of Interplanet Exploration, which controlled research space travel.

Rob relaxed as he prepared to answer. “You probably didn’t know, sir, that Dr. Franz put my brother through space school when our father couldn’t afford it. He was Grant’s teacher in space mechanics in high school and thought he showed unusual promise.”

“That would explain President Allison’s interest in Dr. Franz,” Mr. Brigger agreed, “but I can’t understand an intelligent man like your brother falling for a harebrained story such as Dr. Franz told.”

The facts of Dr. Franz’s amazing discovery were known to the whole world. While studying the planet Uranus a distance of two and a half years before, the research ship blew a rocket tube and was forced down on Titania, Uranus’ largest moon. While the crewmen repaired the craft, Dr. Franz went prospecting. After he returned, he reported that he saw fish life swimming beneath Titania’s solid ice sheet, where the temperature was 300 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. The crewmen were too interested in their work and, not having a scientific curiosity anyhow, did not bother to verify the scientist’s claim.

Upon returning to Earth, Dr. Franz, who was in the early stage of a fatal illness, told the scientific world of his remarkable discovery. He was totally unprepared for the rebuff he received from all quarters. No scientist on Earth would admit that Dr. Franz’s preposterous tale could possibly be true. Those people who would not go as far as calling Dr. Franz a dishonest publicity seeker (as some did) were nevertheless agreed that the ordeal he had gone through must have been too much for him. Dr. Franz died six months later of his illness—a brokenhearted man.

“Grant truly believed Dr. Franz found life on Titania,” Rob said to the skipper of the Centaurus. “He’s so sure of it that he has risked his own career on this expedition. If this fails, he says public sentiment will force him out of office.”

“Your brother must have a lot of confidence in you, Allison,” Mr. Brigger said, “making you head of this research trip which is so important to him. But from what I hear of your exploits on other planets, he has reason to trust you.”

“Thank you,” Rob murmured. “I couldn’t do a good job, though, if I didn’t believe as whole-heartedly in this as Grant does. I believe, as Grant does, that Dr. Franz spoke the truth.”

“It will certainly be a revolutionary discovery for science if you find and bring back evidence of that,” the skipper admitted.

Before leaving the compartment, Mr. Brigger added, “Let’s hope we don’t have a mutiny on our hands before this thing is over.”

Alone, Rob got up and stared out of the port into the perpetual black deeps where the star points glowed like polished gems.

Some minutes later a young spaceman with sandy, disordered hair that even space regulations could do nothing with, came into the compartment. Jim Hawley was Rob’s best friend and had flighted a number of expeditions with him. There was a sober look on Jim’s customarily jovial face.

“The men are complaining like babies, Rob,” Jim said. “Do you think they’ll be any good to us?”

“They’ll have to be, Jim,” Rob answered grimly. “They’re all we have.”

Jim looked at his stalwart young friend in admiration. “You and Grant are all right, Rob. Not many men would risk their careers on an old man’s whims. Aren’t you scared—just a little bit?”

“I’m plenty scared,” Rob told him, with a nervous smile. “I’m only a subofficer of five months, and here I am in charge of an expedition. Don’t think that isn’t frightening. In a sense, the lives of all men aboard the ship will be in my hands after we land.”

“If you need me,” Jim assured him, “here’s one buddy you can count on.”

Two days later the Centaurus had intercepted the orbit of Titania and was beginning to barrel surfaceward. Rob, looking outside from the officer’s platform up forward, saw a huge rocky world filling the port, its mantle of ice shimmering in the reflected light of the unseen primary body.

The Centaurus dropped lower over a plateau that Rob had pointed out to Mr. Brigger as the spot where Dr. Franz had visited. The underjets threw out pencils of braking power to check the plunge of the space ship.

Finally the Centaurus touched down on its tail fins and then Spacemaster Brigger said to Rob, “It’s all yours now, Allison.”

Looking out over the hoary wilderness, completely airless because of the little world’s inability to retain an atmosphere, Rob felt suddenly incompetent. Only now did he realize fully his youthful inexperience. It was one thing to be an idle witness on a journey; it was another to be in charge of a crew of men.

Rob heard footsteps on the platform and turned to see Jim Hawley walking up. Jim grinned in his engaging fashion, and it was like a tonic to Rob’s spirits.

“What do you say we get started, Rob?” he said. “We’ve got a lot to do.”

Rob had the skipper round up the crew in the orientation compartment as soon as he had made his own plans. Then he laid before them the order of procedure. On a flannel board he tacked an enlarged map he had copied from one owned by Dr. Franz.

“Here’s a sketch of this area,” Rob explained. “Dr. Franz neglected to mark where he had seen the fishlike animal swimming beneath the ice. He did report that he was only able to find one after days of searching. They must be very scarce.”

“So scarce there probably aren’t any at all,” retorted one of the subofficers in a low voice.

Rob ignored the remark and went on with his explanation. “We’ll scatter out over the area and begin searching. It won’t be an easy job because the ice isn’t completely clear but is streaked through with ammonia and other opaque solubles.”

“Just how long will we have to keep up this search?” another crewman demanded. “I don’t want to spend Christmas in this forsaken place.”

Spacemaster Brigger spoke up then. “We can spend seven days on searching and still have enough supplies and fuel to get us home again. If we don’t find anything in that time, we start back just the same. Is that clear, Mr. Allison?”

“Yes, sir,” Rob said. Seven days sounded like ample time, but the area they had to cover was several square miles. From Dr. Franz’s description of the place, the liquid medium beneath the ice was wide and deep, a veritable ocean. Beneath this solution the ice began again and extended into the core of the small planet.

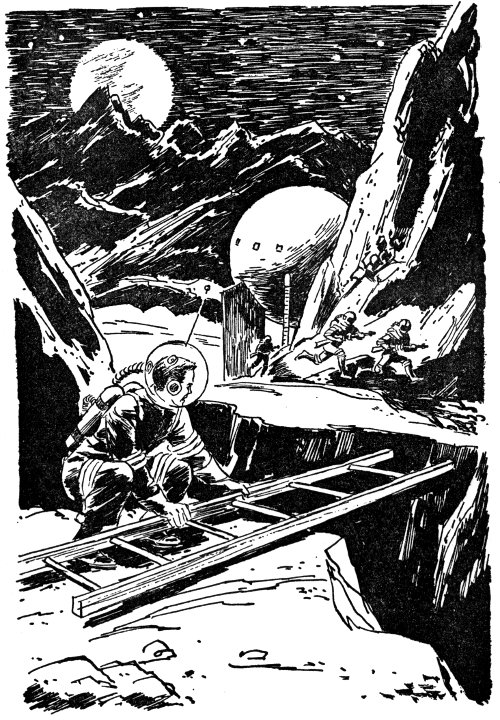

Explanations over, the majority of the crew, about twenty spacemen, climbed into their space gear, Rob and Jim with them. Mr. Brigger and a few key personnel would remain aboard to attend the operational facilities of the ship. The suits were triple-reinforced against the exceeding cold and were electrically heated. The helmets, with inside radio sets, were frost-free types, and the shoes were doubly weighted and spike-soled for navigating over the icy, low-gravity surface.

The men descended to the ground on an escalator dropped from the side of the Centaurus. Rob had the men spread out, two by two, as safety buddies. He concentrated on the farther corners of the ice field to begin with, intending to bring the searchers closer and closer to the ship each day.

As the men began hiking over the glacier, Rob and Jim talked together through their helmet radio sets.

“I don’t understand how the water under the ice flows without freezing in this superlow temperature,” Jim remarked.

“It can’t be water,” Rob answered. “It’s something else, probably a liquefied gas with an extremely low freezing point. Wherever it is, it must contain all the elements needed to support its strange life forms.”

“Let’s start looking too, Jim,” Rob suggested.

The first “day” passed without success. Then the second. Night was only a relative term, for Uranus, Titania’s main source of light, was never out of the sky. On the third day, some of the men complained about having to spend ten hours at a time in biting cold weather searching for something they were sure did not even exist. Despite the men’s heavily insulated suits, the ultralow temperature that frosted the suits like mold could not be entirely kept out. Rob sympathized with the men, but there was no other way to do the job.

It was on the fifth day that one of the searchers spotted a small thick-bodied shape several feet beneath the ice. The cordon of searchers had closed in more than halfway to the ship by now.

“Jim, will you supervise operation of the ice saw?” Rob asked, when they had joined the men who had made the discovery.

Jim nodded and left.

“Has it moved yet?” Rob asked one of the crewmen, trying to curb the almost overpowering excitement he felt.

“No,” one of them replied. “It seems to be dead and embedded in the ice.”

Presently the ice saw came trundling up on its ski runners, being pushed along by Jim and two others. It was a boxlike machine, heavily insulated against the cold. Jim dropped the blade and turned on the machine, guiding it along an invisible outline around the imprisoned thing. He went over the cuts several times, lowering the blade each time until a depth of several feet was reached. Then he gave the saw a side-to-side motion, and there was a sharp crack as the block of ice was snapped off beneath the surface.

By now all the searchers had come over. Jim worked the lifters on the machine and the block of ice, containing its inanimate prisoner, was raised and set down. The men crowded close and looked. Then Rob looked, and Jim. Rob felt a sickening disappointment as he realized their failure. There was no creature inside the ice at all. It was nothing but a slab of rock.

One of the men snorted contemptuously. Another laughed openly in scorn.

Rob bit his lips and regretfully ordered the ice saw back to the ship. Then he sent the men back to their positions of search.

The young officer felt little hope. The ring was closing in toward the Centaurus. There wasn’t much more area that hadn’t already been examined. Rob, realizing the attitude of the men, knew they hadn’t probed as diligently as they were supposed to have. Very likely large areas had been only carelessly examined. But that couldn’t be helped.

Rob went through the last day with the slow resignation of defeat settling within him. In only a few hours the searchers would have covered the entire area, and their own moment of victory would be at hand.

When the search was finally over and still no one had found anything moving beneath the ice, Rob knew how it felt to taste defeat.

Jim clapped Rob sympathetically on the shoulder. “I’m sorry, Rob,” he said. “Perhaps later on there will be another expedition.”