CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.—THE NEPHEW OF A MARQUIS.

CHAPTER IV—AT MR. FINKELSTEIN'S.

CHAPTER VI—MY UNCLE FLORIMOND.

Both of my parents died while I was still a baby; and I passed my childhood at the home of my father's mother in Norwich Town—which lies upon the left bank of the river Yantic, some three miles to the north of Norwich City, in Eastern Connecticut.

My father's mother, my dear old grandmother, was a French lady by birth; and her maiden name had been quite an imposing one—Aurore Aline Raymonde Marie Antoinette de la Bourbonnaye. But in 1820, when she was nineteen years old, my grandfather had persuaded her to change it for plain and simple Mrs. Brace; from which it would seem that my grandfather must have been a remarkably persuasive man. At that time she lived in Paris with her father and mother, who were very lofty, aristocratic people—the Marquis and Marquise de la Bourbonnaye. But after her marriage she followed her husband across the ocean to his home in Connecticut, where in 1835 he died, and where she had remained ever since. She had had two children: my father, Edward, whom the rebels shot at the Battle of Bull Run in July, 1861, and my father's elder brother, my Uncle Peter, who had never married, and who was the man of our house in Norwich.

The neighbors called my Uncle Peter Square, because he was a lawyer. Some of them called him Jedge, because he had once been a Justice of the Peace. Between him and me no love was lost. A stern, cold, frowning man, tall and dark, with straight black hair, a lean, smooth-shaven face, thin lips, hard black eyes, and bushy black eyebrows that grew together over his nose making him look false and cruel, he inspired in me an exceeding awe, and not one atom of affection. I was indeed so afraid of him that at the mere sound of his voice my heart would sink into my boots, and my whole skin turn goose-flesh. When I had to pass the door of his room, if he was in, I always quickened my pace and went on tiptoe, half expecting that he might dart out and seize upon me; if he was absent, I would stop and peek in through the keyhole, with the fascinated terror of one gazing into an ogre's den. And, oh me! what an agony of fear I had to suffer three times every day, seated at meals with him. If I so much as spoke a single word, except to answer a question, he would scowl upon me savagely, and growl out, “Children should be seen and not heard.” After he had helped my grandmother, he would demand in the crossest tone you can imagine, “Gregory, do you want a piece of meat?” Then I would draw a deep breath, clinch my fists, muster my utmost courage, and, scarcely louder than a whisper, stammer, “Ye-es, sir, if you p-please.” It would have come much more easily to say, “No, I thank you, sir,”—only I was so very hungry. But not once, in all the years I spent at Norwich, not once did I dare to ask for more. So I often left the table with my appetite not half satisfied, and would have to visit the kitchen between meals, and beg a supplementary morsel from Julia, our cook.

Uncle Peter, for his part, took hardly any notice whatever of me, unless it was to give me a gruff word of command—like “Leave the room,” “Go to bed,” “Hold your tongue,”—or worse still a scolding, or worst of all a whipping. For the latter purpose he employed a flexible rattan cane, with a curiously twisted handle. It buzzed like a hornet as it flew cutting through the air; and then, when it had reached its objective point—mercy, how it stung! I fancied that whipping me afforded him a great deal of enjoyment. Anyhow, he whipped me very often, and on the very slightest provocation: if I happened to be a few minutes behindhand at breakfast, for example, or if I did not have my hair nicely brushed and parted when I appeared at dinner. And if I cried, he would whip all the harder, saying, “I'll give you something to cry about,” so that in the end I learned to stand the most unmerciful flogging with never so much as a tear or a sob. Instead of crying, I would bite my lips, and drive my fingernails into the palms of my hands until they bled. Why, one day, I remember, I was standing in the dining-room, drinking a glass of water, when suddenly I heard his footstep behind me; and it startled me so that I let the tumbler drop from my grasp to the floor, where it broke, spilling the water over the carpet. “You clumsy jackanapes,” he cried; “come up-stairs with me, and I'll show you how to break tumblers.” He seized hold of my ear, and, pinching and tugging at it, led me up-stairs to his room. There he belabored me so vigorously with that rattan cane of his that I was stiff and lame for two days afterward. Well, I dare say that sometimes I merited my Uncle Peter's whippings richly; but I do believe that in the majority of cases when he whipped me, moral suasion would have answered quite as well, or even better. “Spare the rod and spoil the child” was one of his fundamental principles of life.

Happily, however, except at meal hours, my Uncle Peter was seldom in the house. He had an office at the Landing—that was the name Norwich City went by in Norwich Town—and thither daily after breakfast and again after dinner, he betook himself. After supper he would go out to spend the evening—where or how I never knew, though I often wondered; but all day Sunday he would stay at home, shut up in his room; and all day Sunday, therefore, I was careful to keep as still as a mouse.

He did not in the least take after his mother, my grandmother; for she, I verily believe, of all sweet and gentle ladies was the sweetest and the gentlest. It is now more than sixteen years since she died; yet, as I think of her now, my heart swells, my eyes fill with tears, and I can see her as vividly before me as though we had parted but yesterday: a little old body, in a glistening black silk dress, with her snowy hair drawn in a tall puff upward from her forehead, and her kind face illuminated by a pair of large blue eyes, as quick and as bright as any maiden's. She had the whitest, daintiest, tiniest hands you ever did see; and the tiniest feet. These she had inherited from her noble French ancestors; and along with them she had also inherited a delicate Roman nose—or, as it is sometimes called, a Bourbon nose. Now, as you will recollect, the French word for nose is nez (pronounced nay); and I remember I often wondered whether that Bourbon nose of my grandmother's might not have had something to do with the origin of her family name, Bourbonnaye. But that, of course, was when I was a very young and foolish child indeed.

In her youth, I know, my grandmother had been a perfect beauty. Among the other pictures in our parlor, there hung an oil painting which represented simply the loveliest young lady that I could fancy. She had curling golden hair, laughing eyes as blue as the sky, ripe red lips just made to kiss, faintly blushing cheeks, and a rich, full throat like a column of ivory; and she wore a marvelous costume of cream-colored silk, trimmed with lace; and in one hand she-held a bunch of splendid crimson roses, so well painted that you could almost smell them. I used to sit before this portrait for hours at a stretch, and admire the charming girl who smiled upon me from it, and wonder and wonder who she could be, and where she lived, and whether I should ever have the good luck to meet her in proper person. I used to think that perhaps I had already met her somewhere, and then forgotten; for, though I could not put my finger on it, there was something strangely familiar to me in her face. I used to say to myself, “What if after all it should be only a fancy picture! Oh! I hope, I hope it isn't.” Then at length, one day, it occurred to me to go to my grandmother for information. Imagine my surprise when she told me that it was a portrait of herself, taken shortly before her wedding.

“O, dear! I wish I had been alive in those days,” I sighed.

“Why?” she queried.

“Because then I could have married you,” I explained. At which she laughed as merrily as though I had got off the funniest joke in the world, and called me an “enfant terrible”—a dreadful child.

This episode abode in my mind for a long time to come, and furnished me food for much sorrowful reflection. It brought forcibly home to me the awful truth, which I had never thought of before, that youth and beauty cannot last. That this young girl—so strong, so gay, so full of life, with such bright red lips and brilliant golden hair—that she could have changed into a feeble gray old lady, like my grandmother! It was a sad and appalling possibility.

My grandmother stood nearly as much in awe of my Uncle Peter as I did. He allowed himself to browbeat and bully her in a manner that made my blood boil. “Oh!” I would think in my soul, “just wait till I am a man as big as he is. Won't I teach him a lesson, though?” She and I talked together for the most part in French. This was for two reasons: first, because it was good practice for me; and secondly, because it was pleasant for her—French being her native tongue. Well, my Uncle Peter hated the very sound of French—why I could not guess, but I suspected it was solely for the sake of being disagreeable—and if ever a word of that language escaped my grandmother's lips in his presence, he would glare at her from beneath his shaggy brows, and snarl out, “Can't you speak English to the boy?” She never dared to interfere in my behalf when he was about to whip me—though I knew her heart ached to do so—but would sit alone in her room during the operation, and wait to comfort me after it was over. His rattan cane raised great red welts upon my skin, which smarted and were sore for hours. These she would rub with a salve that cooled and helped to heal them; and then, putting her arm about my neck, she would bid me not to mind it, and not to feel unhappy any more, and would give me peppermint candies and cookies, and tell me long, interesting stories, or read aloud to me, or show me the pictures in her big family Bible. “Paul and Virginia” and “The Arabian Nights” were the books I liked best to be read to from; and my favorite picture was one of Daniel iii the lion's den. Ah, my dear, dear grandmother! As I look back upon those days now, there is no bitterness in my memory of Uncle Peter's whippings; but my memory of your tender goodness in consoling me is infinitely sweet.

No; if my Uncle Peter was perhaps a trifle too severe with me, my grandmother erred in the opposite direction, and did much to spoil me. I never got a single angry word from her in all the years we lived together; yet I am sure I must have tried her patience very frequently and very sorely. Every forenoon, from eight till twelve o'clock, she gave me my lessons: geography, history, grammar, arithmetic and music. I was neither a very apt nor a very industrious pupil in any of these branches; but I was especially dull and especially lazy in my pursuit of the last. My grandmother would sit with me at the piano for an hour, and try and try to make me play my exercise aright; and though I always played it wrong, she never lost her temper, and never scolded. I deserved worse than a scolding; I deserved a good sound box on the ear; for I had shirked my practising, and that was why I blundered so. But the most my grandmother ever said or did by way of reproof, was to shake her head sadly at me, and murmur, “Ah, Gregory, Gregory, I fear that you lack ambition.” So very possibly, after all, my Uncle Peter's sternness was really good for me as a disagreeable but salutary tonic.

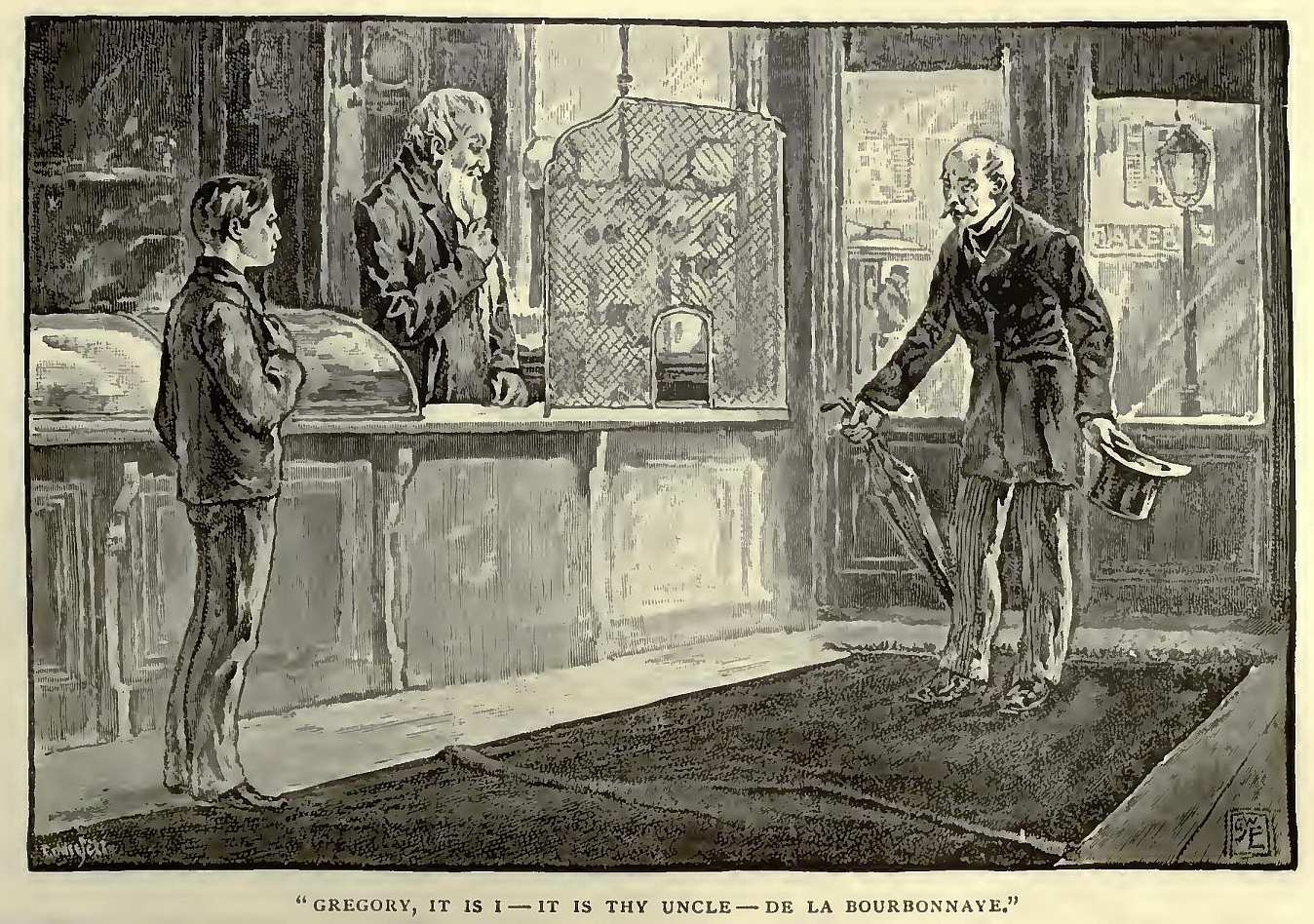

My Uncle Florimond was my grandmother's only brother, unmarried, five years older than herself, who lived in France. His full name was even more imposing than hers had been; and to write it I shall have to use up nearly all the letters of the alphabet: Florimond Charles Marie Auguste Alexandre de la Bourbonnaye. As if this were not enough, he joined to it the title of marquis, which had descended to him from his father; just think—Florimond Charles Marie Auguste Alexandre, Marquis de la Bourbonnaye.

Though my grandmother had not once seen her brother Florimond since her marriage—when she was a blushing miss of nineteen, and he a dashing young fellow of four-and-twenty—I think she cared more for him than for anybody else alive, excepting perhaps myself. And though I had never seen him at all, I am sure that he was to me, without exception, the most important personage in the whole wide world. He owed this distinguished place in my regard to several causes. He owed it partly, no doubt, to the glamour attaching to his name and title. To my youthful imagination Florimond Charles Marie Auguste Alexandre de la Bourbonnaye made a strong appeal. Surely, any one who went through life bearing a name like that must be a very great and extrordinary man; and the fact that he was my uncle—my own grandmother's brother—stirred my bosom with pride, and thrilled it with satisfaction. Then, besides, he was a marquis; and a marquis, I supposed, of course, must be the embodiment of everything that was fine and admirable in human nature—good, strong, rich, brave, brilliant, beautiful—just one peg lower in the scale of glory than a king. Yes, on account of his name and title alone, I believe, I should have placed my Uncle Florimond upon a lofty pedestal in the innermost shrine of my fancy, as a hero to drape with all the dazzling qualities I could conceive of, to wonder about, and to worship. But indeed, in this case, I should most likely have done very much the same thing, even if he had had no other title than plain Mister, and if his name had been homely John or James. For my grandmother, who never tired of talking to me of him, had succeeded in communicating to my heart something of her own fondness for him, as well as imbuing my mind with an eager interest in everything that concerned him, and in firing it with a glowing ideal of his personality. She had taught me that he was in point of fact, all that I had pictured him in my surmises.

When, in 1820, Aurore de la Bourbonnaye became Mrs. Brace, and bade good-by to her home and family, her brother Florimond had held a commission as lieutenant in the King's Guard. A portrait of him in his lieutenant's uniform hung over the fireplace in our parlor, directly opposite the portrait of his sister that I have already spoken of. You never saw a handsomer young soldier: tall, muscular, perfectly shaped, with close-cropped chestnut hair, frank brown eyes, and regular clean-cut features, as refined and sensitive as a woman's, yet full of manly dignity and courage. In one hand he held his military hat, plumed with a long black ostrich feather; his other hand rested upon the hilt of his sword.

His uniform was all ablaze with brass buttons and gold lace; and a beautiful red silk sash swept over his shoulder diagonally downward to his hip, where it was knotted, and whence its tasseled ends fell half-way to his knee. Yes, indeed; he was a handsome, dashing, gallant-looking officer; and you may guess how my grandmother flattered me when she declared, as she often did, “Gregory, you are his living image.” Then she would continue in her quaint old-fashioned French:—“Ah! that thou mayest resemble him in spirit, in character, also. He is of the most noble, of the most generous, of the most gentle. An action base, a thought unworthy, a sentiment dishonorable—it is to him impossible. He is the courage, the courtesy, the chivalry, itself. Regard, then, his face. Is it not radiant of his soul? Is it not eloquent of kindness, of fearlessness, of truth? He is the model, the paragon even, of a gentleman, of a Christian. Say, then, my Gregory, is it that thou lovest him a little also, thou? Is it that thou art going to imitate him a little in thy life, and to strive to become a man as noble, as lovable, as he?”

To which I would respond earnestly in the same language, “O, yes! I love him, I admire him, with all my heart—after thee, my grandmother, better than anybody. And if I could become a man like him, I should be happier than I can say. Anyway, I shall try. He will be my pattern. But tell me, shall I never see him? Will he never come to Norwich? I would give—oh! I would give a thousand dollars—to see him, to embrace him, to speak with him.”

“Alas, no, I fear he will never come to Norwich. He is married to his France, his Paris. But certainly, when thou art grown up, thou shalt see him. Thou wilt go to Europe, and present thyself before him.”

“O, dear! not till I am grown up,” I would complain. “That is so long to wait.” Yet that came to be a settled hope, a moving purpose, in my life—that I should sometime meet my Uncle Florimond in person. I used to indulge my imagination in long, delicious day-dreams, of which our meeting was the subject, anticipating how he would receive me, and what we should say and do. I used to try honestly to be a good boy, so that he would take pleasure in recognizing me as his nephew. My grandmother's assertion to the effect that I looked like him filled my heart with gladness, though, strive as I might, I could not see the resemblance for myself. And if she never tired of talking to me about him, I never tired of listening, either. Indeed, to all the story-books in our library I preferred her anecdotes of Uncle Florimond.

Once a month regularly my grandmother wrote him a long letter; and once a month regularly a long letter arrived from him for her—the reception of which marked a great day in our placid, uneventful calendar. It was my duty to go to the post-office every afternoon, to fetch the mail. When I got an envelope addressed in his handwriting, and bearing the French postage-stamp—oh! didn't I hurry home! I couldn't seem to run fast enough, I was so impatient to deliver it to her, and to hear her read it aloud. Yet the contents of Uncle Florimond's epistles were seldom very exciting; and I dare say, if I should copy one of them here, you would pronounce it quite dull and prosy. He always began, “Ma sour bien-aimee”—My well-beloved sister. Then generally he went on to give an account of his goings and his comings since his last—naming the people whom he had met, the houses at which he had dined, the plays he had witnessed, the books he had read—and to inquire tenderly touching his sister's health, and to bid her kiss his little nephew Gregory for him. He invariably wound up, “Dieu te garde, ma sour cherie”—God keep thee, my dearest sister.—“Thy affectionate brother, de la Bourbonnaye.” That was his signature—de la Bourbonnaye, written uphill, with a big flourish underneath it—never Florimond. My grandmother explained to me that in this particular—signing his family name without his given one—he but followed a custom prevalent among French noblemen. Well, as I was saying, his letters for the most part were quite unexciting; yet, nevertheless, I listened to them with rapt attention, reluctant to lose a single word. This was for the good and sufficient reason that they came from him—from my Uncle Florimond—from my hero, the Marquis de la Bourbonnaye. And after my grandmother had finished reading one of them, I would ask, “May I look at it, please?” To hold it between my fingers, and gaze upon it, exerted a vague, delightful fascination over me. To think that his own hand had touched this paper, had shaped these characters, less than a fortnight ago! My Uncle Florimond's very hand! It was wonderful!

I was born on the first of March, 1860; so that on the first of March, 1870, I became ten years of age. On the morning of that day, after breakfast, my grandmother called me to her room.

“Thou shalt have a holiday to-day,” she said; “no study, no lessons. But first, stay.”

She unlocked the lowest drawer of the big old-fashioned bureau-desk at which she used to write, and took from it something long and slender, wrapped up in chamois-skin. Then she undid and peeled off the chamois-skin wrapper, and showed me—what do you suppose? A beautiful golden-hilted sword, incased in a golden scabbard!

“Isn't it pretty?” she asked.

“Oh! lovely, superb,” I answered, all admiration and curiosity.

“Guess a little, mon petit, whom it belonged to?” she went on.

“To—oh! to my Uncle Florimond—I am sure,” I exclaimed.

“Right. To thy Uncle Florimond. It was presented to him by the king, by King Louis XVIII.”

“By the king—by the king!” I repeated wonderingly. “Just think!”

“Precisely. By the king himself, as a reward of valor and a token of his regard. And when I was married my brother gave it to me as a keepsake. And now—and now, my Gregory, I am going to give it to thee as a birthday present.”

“To me! Oh!” I cried. That was the most I could say. I was quite overcome by my surprise and my delight.

“Yes, I give it to thee; and we will hang it up in thy bed-chamber, on the wall opposite thy bed; and every night and every morning thou shalt look at it, and think of thy Uncle Florimond, and remember to be like him. So thy first and thy last thought every day shall be of him.”

I leave it to you to fancy how happy this present made me, how happy and how proud. For many years that sword was the most highly prized of all my goods and chattels. At this very moment it hangs on the wall in my study, facing the table at which I write these lines.

A day or two later, when I made my usual afternoon trip to the post-office, I found there a large, square brown-paper package, about the size of a school geography, postmarked Paris, and addressed, in my Uncle Florimond's handwriting, not to my grandmother, but to me! to my very self. “Monsieur Grégoire Brace, chez Madame Brace, Norwich Town, Connecticut, Etats-unis d'Amérique.” At first I could hardly believe my eyesight. Why should my Uncle Florimond address anything to me? What could it mean? And what could the contents of the mysterious parcel be? It never occurred to me to open it, and thus settle the question for myself; but, burning with curiosity, I hastened home, and putting it into my grandmother's hands, informed her how it had puzzled and astonished me. She opened it at once, I peering eagerly over her shoulder; and then both of us uttered an exclamation of delight. It was a large illustrated copy of my favorite story, “Paul et Virginie,” bound in scarlet leather, stamped and lettered in gold; and on the fly-leaf, in French, was written, “To my dear little nephew Gregory, on his tenth birthday with much love from his Uncle de la Bourbonnaye.” I can't tell you how this book pleased me. That my Uncle Florimond should care enough for me to send me such a lovely birthday gift! For weeks afterward I wanted no better entertainment than to read it, and to look at its pictures, and remember who had sent it to me. Of course, I sat right down and wrote the very nicest letter I possibly could, to thank him for it.

Now, as you know, in that same year, 1870, the French Emperor, Louis Napoleon, began his disastrous war with the King of Prussia; and it may seem very strange to you when I say that that war, fought more than three thousand miles away, had a direct and important influence upon my life, and indeed brought it to its first great turning-point. But such is the truth. For, as you will remember, after a few successes at the outset, the French army met with defeat in every quarter; and as the news of these calamities reached us in Norwich, through the New York papers, my grandmother grew visibly feebler and older from day to day. The color left her cheeks; the light left her eyes; her voice lost its ring; she ate scarcely more than a bird's portion at dinner; she became nervous, and restless, and very sad: so intense was her love for her native country, so painfully was she affected by its misfortunes.

The first letter we received from Uncle Florimond, after the war broke out, was a very hopeful one. He predicted that a month or two at the utmost would suffice for the complete victory of the French, and the utter overthrow and humiliation of the Barbarians, as he called the Germans. “I myself,” he continued, “am, alas, too old to go to the front; but happily I am not needed, our actual forces being more than sufficient. I remain in Paris at the head of a regiment of municipal guards.” His second letter was still hopeful in tone, though he had to confess that for the moment the Prussians seemed to be enjoying pretty good luck. “Mais cela passera”—But that will pass,—he added confidently. His next letter and his next, however, struck a far less cheery note; and then, after the siege of Paris began, his letters ceased coming altogether, for then, of course, Paris was shut off from any communication with the outside world.

With the commencement of the siege of Paris a cloud settled over our home in Norwich, a darkness and a chill that deepened steadily until, toward the end of January, 1871, the city surrendered and was occupied by the enemy. Dread and anxiety dogged our footsteps all day long every day. “Even at this moment, Gregory, while we sit here in peace and safety, thy Uncle Florimond may be dead or dying,” my grandmother would say; then, bowing her head, “O mon Dieu, sois miséricordieux”—O my God, be merciful. Now and then she would start in her chair, and shudder; and upon my demanding the cause, she would reply, “I was thinking what if at that instant he had been shot by a Prussian bullet.” For hours she would sit perfectly motionless, with her hands folded, and her eyes fixed vacantly upon the wall; until all at once, she would cover her face, and begin to cry as if her heart would break. And then, when the bell rang to summon us to meals, “Ah, what a horror!” she would exclaim. “Here are we with an abundance of food and drink, while he whom we love may be perishing of hunger!” But she had to keep her suffering to herself when Uncle Peter was around; otherwise, he would catch her up sharply, saying, “Tush! don't be absurd.”

And so it went on from worse to worse, my grandmother pining away under my very eyes, until the siege ended in 1871, and the war was decided in favor of the Germans. Then, on the fourteenth of February, St. Valentine's Day, our fears lest Uncle Florimond had been killed were relieved. A letter came from him dated February 1st. It was very short. It ran: “Here is a single line, my beloved sister, to tell thee that I am alive and well. To-morrow I shall write thee a real letter”—une vraie lettre.

My grandmother never received his “real letter.” The long strain and suspense had been too much for her. That day she broke down completely, crying at one moment, laughing the next, and all the time talking to herself in a way that frightened me terribly. That night she went to bed in a high fever, and out of her mind. She did not know me, her own grandson, but kept calling me Florimond. I ran for the doctor; but when he saw her, he shook his head.

On the morning of February 16th my dear, dear grandmother died.

I shall not dwell upon my grief. It would be painful, and it would serve no purpose. The spring of 1871 was a very dark and dismal spring to me. It was as though a part—the best part—of myself had been taken from me. To go on living in the same old house, where everything spoke to me of her, where every nook and corner had its association with her, where every chair and table recalled her to me, yet not to hear her voice, nor see her face, nor feel her presence any more, and to realize that she had gone from me forever—I need not tell you how hard it was, nor how my heart ached, nor how utterly lonesome and desolate I felt. I need not tell you how big and bleak and empty the old house seemed.

Sometimes, though, I could not believe that it was really true, that she had really died. It was too dreadful. I could not help thinking that it must be some mistake, some hideous delusion. I would start from my sleep in the middle of the night, and feel sure that it must have been a bad dream, that she must have come back, that she was even now in bed in her room. Then, full of hope, I would get up and go to see. All my pain was suddenly and cruelly renewed when I found her bed cold and empty. I would throw myself upon it, and bury my face in the coverlet, and abandon myself to a passionate outburst of tears and sobs, calling aloud for her: “Grand'-mère, grand'mere, O ma grand'mère chérie!” I almost expected that she would hear me, and be moved to pity for me, and come back.

One night, when I was lying thus upon her bed, in the dark, and calling for her, I felt all at once the clutch of a strong hand upon my shoulder. It terrified me unspeakably. My heart gave a great jump, and stopped its beating. My limbs trembled, and a cold sweat broke out all over my body. I could not see six inches before my face. Who, or rather what, could my invisible captor be? Some grim and fearful monster of the darkness? A giant—a vampire—an ogre—or, at the very least, a burglar! All this flashed through my mind in a fraction of a second. Then I heard the voice of my Uncle Peter: “What do you mean, you young beggar, by raising such a hullaballoo at this hour of the night, and waking people up? Get off to your bed now, and in the morning I'll talk to you.” And though I suspected that “I'll talk to you” signified “I'll give you a good sound thrashing,” I could have hugged my Uncle Peter, so great was my relief to find that it was he, and no one worse.

Surely enough, next morning after breakfast, he led me to his room, and there he administered to me one of the most thorough and energetic thrashings I ever received from him. But now I had nobody to pet me and make much of me after it; and all that day I felt the awful friendlessness of my position more keenly than I had ever felt it before.

“I have but one friend in the whole world,” I thought, “and he is so far, so far away. If I could only somehow get across the ocean, to France, to Paris, to his house, and live with him! He would be so good to me, and I should be so happy!” And I looked up at his sword hanging upon my wall, and longed for the hour when I should touch the hand that had once wielded it.

I must not forget to tell you here of a little correspondence that I had with this distant friend of mine. A day or two after the funeral I approached my Uncle Peter, and, summoning all my courage, inquired, “Are you going to write to Uncle Florimond, and let him know?”

“What?” he asked, as if he had not heard, though I had spoken quite distinctly. That was one of his disagreeable, disconcerting ways—to make you repeat whatever you had to say. It always put me out of countenance, and made me feel foolish and embarrassed.

“I wanted to know whether you were going to write and tell Uncle Florimond,” I explained with a quavering voice.

By way of retort, he half-shut his eyes, and gave me a queer, quizzical glance, which seemed to be partly a sneer, and partly a threat. He kept it up for a minute or two, and then he turned his back upon me, and went off whistling. This I took to be as good as “No” to my question. “Yet,” I reflected, “somebody ought to write and tell him. It is only fair to let him know.” And I determined that I would do so myself; and I did. I wrote him a letter; and then I rewrote it; and then I copied it; and then I copied it again; and at last I dropped my final copy into the post-box.

About five weeks later I got an answer from him. In a few simple sentences he expressed his great sorrow; and then he went on: “And, now, my dear little nephew, by this mutual loss thou and I are brought closer together; and by a more tender mutual affection we must try to comfort and console each other. For my part, I open to thee that place in my heart left vacant by the death of my sainted sister; and I dare to hope that thou wilt transfer to me something of thy love for her. I attend with impatience the day of our meeting, which, I tell myself, if the Lord spares our lives, must arrive as soon as thou art big enough to leave thy home and come to me in France. Meanwhile, may the good God keep and bless thee, shall be the constant prayer of thy Uncle de la Bourbonnaye.”

This letter touched me very deeply.

After reading it I came nearer to feeling really happy than I had come at any time before since she died.

I must hasten over the next year. Of course, as the weeks and months slipped away, I gradually got more or less used to the new state of things, and the first sharp edge of my grief was dulled. The hardest hours of my day were those spent at table with Uncle Peter—alone with him, in a silence broken only by the clinking of our knives and forks. These were very hard, trying hours indeed. The rest of my time I passed out of doors, in the company of Sam Budd, our gardener's son, and the other village boys. What between swimming, fishing, and running the streets with them, I contrived to amuse myself after a fashion. Yet, for all that, the year I speak of was a forlorn, miserable year for me; I was far from being either happy or contented. My first violent anguish had simply given place to a vague, continuous sense of dissatisfaction and unrest, like a hunger, a craving, for something I could not name. That something was really—love: though I was not wise enough to know as much at the time. A child's heart—and, for that matter, a grown-up man's—craves affection as naturally as his stomach craves food; I did not have it; and that was why my heart ached and was sick. I wondered and wondered whether my present mode of life was going to last forever; I longed and longed for change. Somehow to escape, and get across the ocean to my Uncle Florimond, was my constant wish; but I saw no means of realizing it. Once in a while I would think, “Suppose I write to him and tell him how wretched I am, and ask him to send for me?” But then a feeling of shame and delicacy restrained me.

Another thing that you will easily see about this year, is that it must have been a very unprofitable one for me from the point of view of morals. My education was suspended; no more study, no more 'lessons. Uncle Peter never spoke of sending me to school; and I was too young and ignorant to desire to go of my own accord. Then, too, I was without any sort of refining or softening influence at home; Julia, our cook, being my single friend there, and my uncle's treatment of me serving only to sour and harden me. If, therefore, at the end of the year in question I was by no manner of means so nice a boy as I had been at the beginning of it, surely there was little cause for astonishment. Indeed, I imagine the only thing that kept me from growing altogether rough and wild and boisterous, was my thought of Uncle Florimond, and my ambition to be the kind of lad that I believed he would like to have me.

And now I come to an adventure which, as it proved, marked the point of a new departure in my affairs.

It was early in April, 1872. There had been a general thaw, followed by several days of heavy rain; and the result was, of course, a freshet. Our little river, the Yantic, had swollen to three—in some places even to four—times its ordinary width; and its usually placid current had acquired a tremendous strength and speed. This transformation was the subject of endless interest to us boys; and every day we used to go and stand upon the bank, and watch the broad and turbulent rush of water with mingled wonder, terror and delight. It was like seeing an old friend, whom we had hitherto regarded as a quite harmless and rather namby-pamby sort of chap, and been fearlessly familiar with, suddenly display the power and prowess of a giant, and brandish his fists at us, crying, “Come near me at your peril!” Our emotions sought utterance in such ejaculations as “My!” “Whew!” and “Jimminy!” and Sam Budd was always tempting me with, “Say, Gregory, stump ye to go in,” which was very aggravating. I hated to have him dare me.

Well, one afternoon—I think it was on the third day of the freshet—when Sam and I made our customary pilgrimage down through Captain Josh Abingdon's garden to the water's edge, fancy our surprise to behold a man standing there and fishing. Fishing in that torrent! It was too absurd for anything; and instantly all our wonder transferred itself from the stream to the fisherman, at whom we stared with eyes and mouths wide open, in an exceedingly curious and ill-bred manner. He didn't notice us at first; and when he did, he didn't seem to mind our rudeness the least bit. He just looked up for a minute, and calmly inspected us; and then he gave each of us a solemn, deliberate wink, and returned his attention to his pole, which, by the way, was an elaborate and costly one, jointed and trimmed with metal. He was a funny-looking man; short and stout, with a broad, flat, good-natured face, a thick nose, a large mouth, and hair as black and curling as a negro's.

He wore a fine suit of clothes of the style that we boys should have called cityfied; and across his waistcoat stretched a massive golden watch-chain, from which dangled a large golden locket set with precious stones.

Presently this strange individual drew in his line to examine his bait; and then, having satisfied himself as to its condition, he attempted to make a throw. But he threw too hard. His pole slipped from his grasp, flew through the air, fell far out into the water, and next moment started off down stream at the rate of a train of steam-cars. This was a sad mishap. The stranger's face expressed extreme dismay, and Sam and I felt sorry for him from the bottom of our hearts. It was really a great pity that such a handsome pole should be lost in such a needless fashion.

But stay! All at once the pole's progress down stream ceased. It had got caught by an eddy, which was sweeping it rapidly inward and upward toward the very spot upon the shore where we stood. Would it reach land safely, and be recovered? We waited, watching, in breathless suspense. Nearer it came—nearer—nearer! Our hopes were mounting very high indeed. A smile lighted the fisherman's broad face. The pole had now approached within twenty feet of the bank. Ten seconds more, and surely—But again, stay! Twenty feet from the shore the waters formed a whirlpool. In this whirlpool for an instant the pole remained motionless. Then, after a few jerky movements to right and left, instead of continuing its journey toward the shore, it began spinning round and round in the circling current. At any minute it might break loose and resume its course down stream; but for the present there it was, halting within a few yards of us—so near, and yet so far.

Up to this point we had all kept silence. But now the fisherman broke it with a loud, gasping sigh. Next thing I heard was Sam Budd's voice, pitched in a mocking, defiant key, “Say, Gregory, stump ye to go in.” I looked at Sam. He was already beginning to undress.

No; under the circumstances—with that man as a witness—I could not refuse the challenge. My reputation, my character, was at stake. I knew that the water would be as cold as ice; I knew that the force of its current involved danger to a swimmer of a sort not to be laughed at. Yet my pride had been touched, my vanity had been aroused. I could not allow Sam Budd to “stump” me with impunity, and then outdo me. “You do, do you?” I retorted. “Well, come on.” And stripping off my clothes in a twinkling, I plunged into the flood, Sam following close at my heels.

As cold as ice! Why, ice was nowhere, compared to the Yantic River in that first week of April. They say extremes meet. Well, the water was so cold that it seemed actually to scald my skin, as if it had been boiling hot. But never mind. The first shock over, I gritted my teeth to keep them from chattering, and struck boldly out for the whirlpool, where the precious rod was still spinning round and round. Of course, in order to save myself from being swept down below it, I had to aim diagonally at a point far above it.

The details of my struggle I need not give. Indeed, I don't believe I could give them, even if it were desirable that I should. My memory of the time I spent in the water is exceedingly confused and dim. Intense cold; desperately hard work with arms and legs; frantic efforts to get my breath; a fierce determination to be the first to reach that pole no matter at what hazard; a sense of immense relief and triumph when, suddenly, I realized that success had crowned my labors—when I felt the pole actually in my hands; then a fight to regain the shore; and finally, again, success!

Yes, there I stood upon the dry land, safe and sound, though panting and shivering from exhaustion and cold. I was also rather dazed and bewildered; yet I still had enough of my wits about me to go up to the fisherman, and say politely, “Here, sir, is your pole.” He cried in response—and I noticed that he pronounced the English language in a very peculiar way—“My kracious! You was a brave boy, Bubby. Hurry up; dress; you catch your death of cold standing still there, mitout no clodes on you, like dot. My koodness! a boy like you was worth a tousand dollars.”

Suddenly it occurred to me to wonder what had become of Sam. I had not once thought of him since my plunge into the water. I suppose the reason for this forgetfulness was that my entire mind, as well as my entire body, had been bent upon the work I had in hand. But now, as I say, it suddenly occurred to me to wonder what had become of him; and a sickening fear lest he might have got drowned made my heart quail.

“O, sir!” I demanded, “Sam—the other boy—where is he? Has anything happened to him? Did he—he didn't—he didn't get drowned?”

“Drownded?” repeated the fisherman. “Well, you can bet he didn't. He's all right. There he is—under dot tree over there.”

He pointed toward an apple-tree, beneath which I descried Sam Budd, already nearly dressed. As Sam's eyes met mine, a very sheepish look crept over his face, and he called out, “Oh! I gave up long ago.” Well, you may just guess how proud and victorious I felt to hear this admission from my rival's lips.

The fisherman now turned his attention to straightening out his tackle, which had got into a sad mess during its bath, while I set to putting on my things. Pretty soon he drew near to where I stood, and, surveying me with a curious glance, “Well, Bubby, how you feel?” he asked.

“Oh! I feel all right, thank you, sir; only a little cold,” I answered.

“Well, Bubby, you was a fine boy,” he went on. “Well, how old was you?”

“I'm twelve, going on thirteen.”

“My kracious! Is dot all? Why, you wasn't much older as a baby; and yet so tall and strong already. Well, Bubby, what's your name?”

“Gregory Brace.”

“Krekory Prace, hey? Well, dot's a fine name. Well; you live here in Nawvich, I suppose—yes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Maybe your papa was in business here?”

“No, sir; my father is dead.”

“Oh! is dot so? Well, dot's too bad. And so you was a half-orphan, yes?”

“No, sir; my mother is dead, too.”

“You don't say so! Well, my kracious! Well, den you was a whole orphan, ain't you? Well, who you live with?”

“I live with my uncle, sir—Judge Brace.”

“Oh! so your uncle was a judge. Well, dot's grand. Well, you go to school, I suppose, hey?”

“No, sir; I don't go to school.”

“You don't go to school? Oh! then, maybe you was in business already, yes.”

“O, no, sir! I'm not in business.”

“You don't go to school, and you wasn't in business; well, what you do mit yourself all day long, hey?”

“I play.”

“You play! Well, then you was a sort of a gentleman of leisure, ain't you? Well, dot must be pretty good fun—to play all day. Well, Bubby, you ever go to New York?”

“No, sir; I've never been in New York. Do you live in New York, sir?”

“Yes, Bubby, I live in New York when I'm at home. But I'm shenerally on the road, like I was to-day. I'm what you call a trummer; a salesman for Krauskopf, Sollinger & Co., voolens. Here's my card.”

He handed me a large pasteboard card, of which the following is a copy:—

“Yes,” he went on, “dot's my name, and dot's my address. And when you come to New York you call on me there, and I'll treat you like a buyer. I'll show you around our establishment, and I'll give you a dinner by a restaurant, and I'll take you to the theayter, and then, if you want it, I'll get you a chop.”

“A chop?” I queried. “What is a chop?”

“What is a chop! Why, if you want to go into business, you got to get a chop, ain't you? A chop was an embloyment; and then there was chop-lots also.” At this I understood that he meant a job. “Yes, Bubby, a fine boy like you hadn't oughter be doing nodings all day long. You'd oughter go into business, and get rich. You're smart enough, and you got enerchy. I was in business already when I was ten years old, and I ain't no smarter as you, and I ain't got no more enerchy. Yes, Bubby, you take my advice: come down to New York, and I get you a chop, and you make your fortune, no mistake about it. And now, Bubby, I want to give you a little present to remember me by.”

He drew a great fat roll of money from his waistcoat pocket, and offered me a two-dollar bill.

“O, no! I thank you, sir,” I hastened to say. “I don't want any money.”

“O, well! this ain't no money to speak of, Bubby; only a two-tollar pill. You just take it, and buy yourself a little keepsake. It von't hurt you.”

“You're very kind, sir; but I really can't take it, thank you.” And it flashed through my mind: “What would Uncle Florimond think of me, if I should accept his money?”

“Well, dot's too bad. I really like to make you a little present, Bubby. But if you was too proud, what you say if I give it to the other boy, hey?”

“Oh! to Sam—yes, I think that would be a very good idea,” I replied.

So he called Sam—Sem was the way he pronounced it—and gave him the two-dol-lar bill, which Sam received without the faintest show of compunction.

“Well, I got to go now,” the fisherman said, holding out his hand. “Well, good-by, Bubby; and don't forget, when you come to New York, to give me a call. Well, so-long.”

Sam and I watched him till he got out of sight. Then we too started for home.

At the time, my talk with Mr. Solomon D. Marx did not make any especial impression on me; but a few days later it came back to me, the subject of serious meditation. The circumstances were as follows:—

We had just got through our supper, and Uncle Peter had gone to his room, when all at once I heard his door open, and his voice, loud and sharp, call, “Gregory!”

“Yes, sir,” I answered, my heart in a flutter; and to myself I thought, “O, dear, what can be the matter now?”

“Come here, quick!” he ordered.

I entered his room, and saw him standing near his table, with a cigar-box in his hand.

“You young rascal,” he began; “so you have been stealing my cigars!”

This charge of theft was so unexpected, so insulting, so untrue, that, if he had struck me a blow between the eyes, it could not have taken me more aback. The blood rushed to my face; my whole frame grew rigid, as if I had been petrified. I tried to speak; but my presence of mind had deserted me; I could not think of a single word.

“Well?” he questioned. “Well? ''

“I—I—I”—I stammered. Scared out of my wits, I could get no further.

“Well, have you nothing to say for yourself?”

“I—I did—I didn't—do it,” I gasped. “I don't know what you mean.”

“What!” he thundered. “You dare to lie to me about it! You dare to steal from me, and then lie to my face! You insufferable beggar! I'll teach you a lesson.” And, putting out his hand, he took his rattan cane from the peg it hung by on the wall.

“Oh! really and truly, Uncle Peter,” I protested, “I never stole a thing in all my life. I never saw your cigars. I didn't even know you had any. Oh! you—you're not going to whip me, when I didn't do it?”

“Why, what a barefaced little liar it is! Egad! you do it beautifully. I wouldn't have given you credit for so much cleverness.” He said this in a sarcastic voice, and with a mocking smile. Then he frowned, and his voice changed. “Come here,” he snarled, his fingers tightening upon the handle of his cane.

A great wave of anger swept over me, and brought me a momentary flush of courage. “No, sir; I won't,” I answered, my whole body in a tremor.

Uncle Peter started. I had never before dared to defy him. He did not know what to make of my doing so now. He turned pale. He bit his lip. His eyes burned with a peculiarly ugly light. So he stood, glaring at me, for a moment. Then, “You—won't,” he repeated, very low, and pausing between the words. “Why, what kind of talk is this I hear? Well, well, my fine fellow, you amuse me.”

I was standing between him and the door. I turned now, with the idea of escaping from the room. But he was too quick for me. I had only just got my hand upon the latch, when he sprang forward, seized me by the collar of my jacket, and, with one strong pull, landed me again in the middle of the floor.

“There!” he cried. “Now we'll have it out. I owe you four: one for stealing my cigars; one for lying to me about it; one for telling me you wouldn't; and one for trying to sneak out of the room. Take this, and this, and this.”

With that he set his rattan cane in motion; nor did he bring it to a stand-still until I felt as though I had not one well spot left upon my skin.

“Now, then, be off with you,” he growled; and I found myself in the hall outside his door.

I dragged my aching body to my room, and sat down at my window in the dark. Never before had I experienced such a furious sense of outrage. Many and many a time I had been whipped, as I thought, unjustly; but this time he had added insult to injury; he had accused me of stealing and of lying; and, deaf to my assertion of my innocence, he had punished me accordingly. I seriously believe that I did not mind the whipping in itself half so much as I minded the shameful accusations that he had brought against me. “How long, how long,” I groaned, “has this got to last? Shall I never be able to get away—to get to France, to my Uncle Florimond? If I only had some money—if I had a hundred dollars—then all my troubles would be over and done with. Surely, a hundred dollars would be enough to take me to the very door of his house in Paris.” But how—how to obtain such an enormous sum? And it was at this point that my conversation with Mr. Solomon D. Marx came back to me:—

“Why, go to New York! Go into business! You'll soon earn a hundred dollars. Mr. Marx said he would get you a job. Start for New York to-morrow.”

This notion took immediate and entire possession of my fancy, and I remained awake all night, building glittering air-castles upon it as a foundation. The only doubt that vexed me was, “What will Uncle Peter say? Will he let me go?” The idea of going secretly, or without his consent, never once entered my head. “Well, to-morrow morning,” I resolved, “I will speak with him, and ask his permission. And if he gives it to me—hurrah! And if he doesn't—O, dear me, dear me!”

To cut a long story short, when, next morning, I did speak with him, and ask his permission, he, to my infinite joy, responded, “Why, go, and be hanged to you. Good riddance to bad rubbish!”

In my tin savings bank, I found, I had nine dollars and sixty-three cents. With this in my pocket; with the sword of my Uncle Florimond as the principal part of my luggage; and with a heart full of strange and new emotions, of fear and hope, and gladness and regret, I embarked that evening upon the Sound steamboat, City of Lawrence, for the metropolis where I have ever since had my home; bade good-by to my old life, and set sail alone upon the great, awful, unknown sea of the future.

I did not feel rich enough to take a stateroom on the City of Lawrence; that would have cost a dollar extra; so I picked out a sofa in the big gilt and white saloon, and sitting down upon it, proceeded to make myself as comfortable as the circumstances would permit. A small boy, armed with a large sword, and standing guard over a hand-satchel and a square package done up in a newspaper—which last contained my Uncle Florimond's copy of Paul et Virginie—I dare say I presented a curious spectacle to the passers-by. Indeed, almost everybody turned to look at me; and one man, with an original wit, inquired, “Hello, sword, where you going with that boy?” But my mind was too busy with other and weightier matters to be disturbed about mere appearances. One thought in particular occupied it: I must not on any account allow myself to fall asleep—for then I might be robbed. No; I must take great pains to keep wide awake all night long.

For the first hour or two it was easy enough to make this resolution good. The undiscovered country awaiting my exploration, the novelty and the excitement of my position, the people walking back and forth, and laughing and chattering, the noises coming from the dock outside, and from every corner of the steamboat inside, the bright lights of the cabin lamps—all combined to put my senses on the alert, and to banish sleep. But after we had got under way, and the other passengers had retired to their berths or staterooms, and most of the lamps had been extinguished, and the only sound to be heard was the muffled throbbing of the engines, then tired nature asserted herself, the sandman came, my eyelids grew very heavy, I began to nod. Er-rub-dub-dub, er-rub-dub-dub, went the engines; er-rub-dubdub, er-rub-er-rub-er-er-er-r-r...,

Mercy! With a sudden start I came to myself. It was broad day. I had been sleeping soundly for I knew not how many hours.

My first thought, of course, was for my valuables. Had my fears been realized? Had I been robbed? I hastened to make an investigation. No! My money, my sword, my satchel, my Paul et Virginie, remained in their proper places, unmolested. Having relieved my anxiety on this head, I got up, stretched myself, and went out on deck.

If I live to be a hundred, I don't believe I shall ever forget my first breath of the outdoor air on that red-letter April morning—it was so sweet, so pure, so fresh and keen and stimulating. It sent a glow of new vitality tingling through my body. I just stood still and drew in deep inhalations of it with delight. It was like drinking a rich, delicious wine. My heart warmed and mellowed. Hope and gladness entered into it.

It must have been very early. The sun, a huge ball of gold, floated into rosy mists but a little higher than the horizon; and a heavy dew bathed the deck and the chairs and the rail. We were speeding along, almost, it seemed, within a stone's throw of the shore, where the turf was beginning to put on the first vivid green of spring, where the leafless trees were exquisitely penciled against the gleaming sky, and where, from the chimneys of the houses, the smoke of breakfast fires curled upward: Over all there lay a wondrous, restful stillness, which the pounding of our paddle-wheels upon the water served only to accentuate, and which awoke in one's breast a deep, solemn, and yet joyous sense of peace.

I staid out on deck from that moment until, some two hours later, we brought up alongside our pier; and with what strange and strong emotions I watched the vast town grow from a mere distant reddish blur to the grim, frowning mass of brick and stone it really is, I shall not attempt to tell. To a country-bred lad like myself it was bound to be a stirring and memorable experience. Looking back at it now, I can truly say that it was one of the most stirring and memorable experiences of my life.

It was precisely eight o'clock, as a gentleman of whom I inquired the hour was kind enough to inform me, when I stepped off the City of Lawrence and into the city of New York. My heart was bounding, but my poor brain was bewildered. The hurly-burly of people, the fierce-looking men at the entrance of the dock, who shook their fists at me, and shouted, “Cadge, cadge, want a cadge?” leaving me to wonder what a cadge was, the roar and motion of the wagons in the street, everything, everything interested, excited, yet also confused, baffled, and to some degree frightened me. I felt as though I had been set down in pandemonium; yet I was not sorry to be there; I rather liked it.

I went up to a person whom I took to be a policeman, for he wore a uniform resembling that worn by our one single policeman in Norwich City; and, exhibiting the card that Mr. Marx had given me, I asked him how to reach the street and house indicated upon it.

He eyed me with unconcealed amusement at my accoutrements, and answered, “Ye wahk down tin blocks; thin turrun to yer lift four blocks; thin down wan; thin to yer roight chew or thray doors; and there ye are.”

“Thank you, sir,” said I, and started off, repeating his instructions to myself, so as not to forget them.

I felt very hungry, and I hoped that Mr. Marx would offer me some breakfast; but it did not occur to me to stop at an eating-house, and breakfast on my own account, until, as I was trudging along, I presently caught sight of a sign-board standing on the walk in front of a shop, which advertised, in big conspicuous white letters upon a black ground:—

Merely to read the names of these good things made my mouth water. The prices seemed reasonable. I walked into the ladies' and gents' dining parlor—which was rather shabby and dingy, I thought, for a parlor—and asked for a beefsteak and some fried potatoes; a burly, villainous-looking colored man, in his shirt-sleeves, having demanded, “Wall, Boss, wottle you have?” His shirt-sleeves were not immaculately clean; neither was the dark red cloth that covered my table; neither, I feared, was the fork he gave me to eat with. To make sure, I picked this last-named object up, and examined it; whereupon the waiter, with a horrid loud laugh, cried, “Oh! yassah, it's sawlid, sawlid silvah, sah,” which made me feel wretchedly silly and uncomfortable. The beefsteak was pretty tough, and not especially toothsome in its flavor; the potatoes were lukewarm and greasy; the bread was soggy, the butter rancid; the waiter took up a position close at hand, and stared at me with his wicked little eyes as steadily as if he had never seen a boy before: so, despite my hunger, I ate with a poor appetite, and was glad enough when by and by I left the ladies' and gents' dining parlor behind me, and resumed my journey through the streets. As I was crossing the threshold, the waiter called after me, “Say, Johnny, where joo hook the sword?”

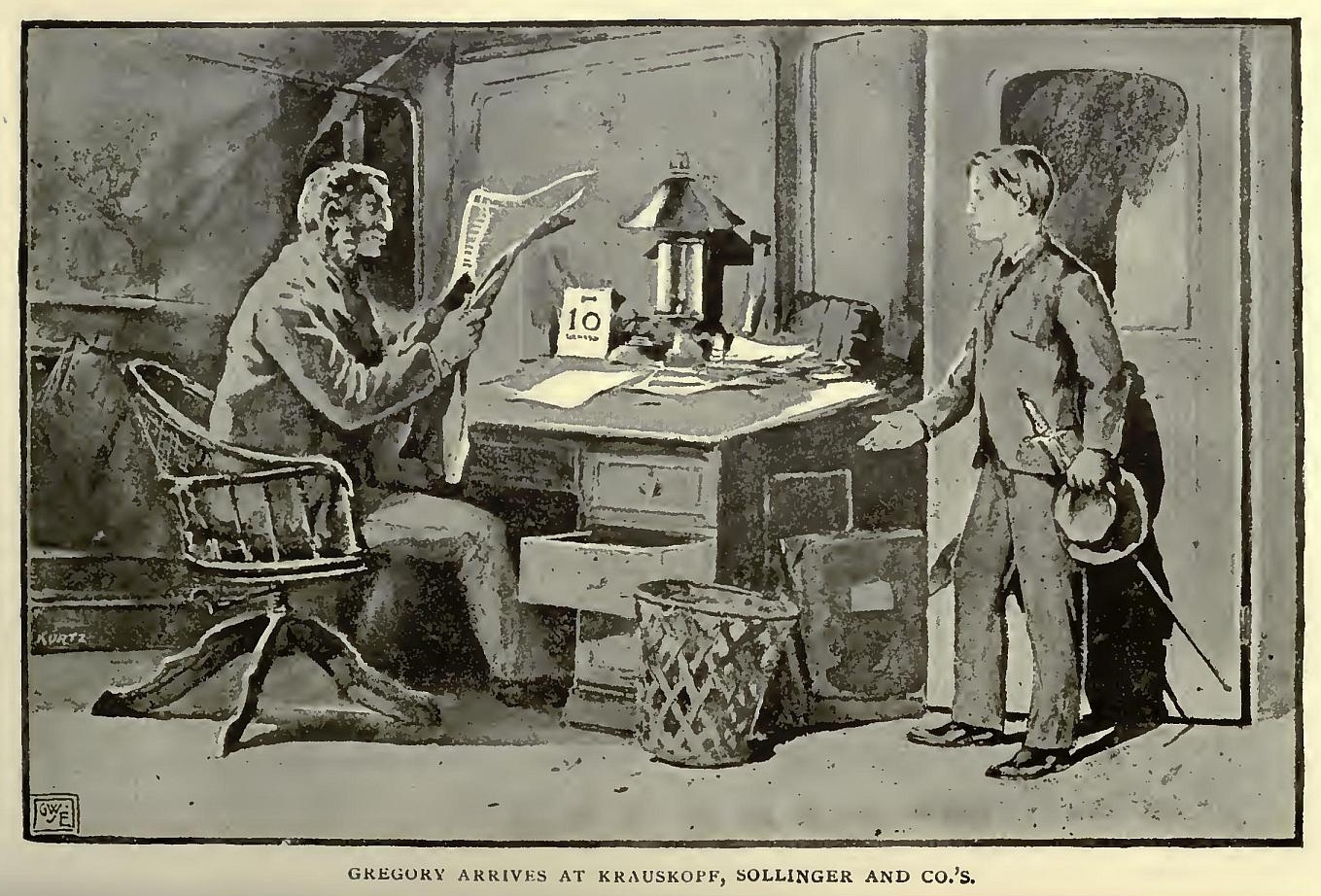

Inquiring my way of each new policeman that I passed—for I distrusted my memory of the directions I had received from the first—I finally reached No. ——, Franklin Street and read the name of Krauskopf, Sollinger & Co., engraved in Old English letters upon a shining metal sign. I entered, and with a trembling heart inquired for Mr. Marx. Ten seconds later I stood before him.

“Mr. Marx,” I ventured, in rather a timid voice.

He was seated in a swivel-chair, reading a newspaper, and smoking a cigar. At the sound of his name, he glanced up, and looked at me for a moment with an absent-minded and indifferent face, showing no glimmer of recognition. But then, suddenly, his eyes lighted; he sprang from his chair, started back, and cried:—

“My kracious! was dot you, Bubby? Was dot yourself? Was dot—well, my koodness!”

“Yes, sir; Gregory Brace,” I replied.

“Krekory Prace! Yes, dot's a fact. No mistake about it. It's yourself, sure. But—but, koodness kracious, Bubby, what—how—why—when—where—where you come from? When you leave Nawvich? How you get here? What you—well, it's simply wonderful.”

“I came down on the boat last night,” I said.

“Oh! you came down on de boat last night. Well, I svear. Well, Bubby, who came mit you?”

“Nobody, sir; I came alone.”

“You came alone! You don't say so. Well, did your mamma—excuse me; you ain't got no mamma; I forgot; it was your uncle—well, did your uncle know you was come?”

“Oh! yes, sir; he knows it; he said I might.”

“He said you might, hey? Well, dot's fine. Well, Bubby, what you come for? To make a little visit, hey, and go around a little, and see the town? Well, Bubby, this was a big surprise; it was, and no mistake. But I'm glad to see you, all de same. Well, shake hands.”

“No, sir,” I explained, after we had shaken hands, “I didn't come for a visit. I came to go into business. You said you would get me a job, and I have come for that.”

“Oh! you was come to go into pusiness, was you? And you want I should get you a chop? Well, if I ever! Well, you're a great feller, Bubby; you got so much ambition about you. Well, dot's all right. I get you the chop, don't you be afraid. We talk about dot in a minute. But now, excuse me, Bubby, but what you doing mit the sword? Was you going to kill somebody mit it, hey, Bubby?”

“O, no, sir! it—it's a keepsake.”

“Oh! it was a keepsake, was it, Bubby? Well, dot's grand. Well, who was it a keepsake of? It's a handsome sword, Bubby, and it must be worth quite a good deal of money. If dot's chenu-wine gold, I shouldn't wonder if it was worth two or three hundred dollars.—Oh! by the way, Bubby, you had your breakfast yet already?”

“Well, yes, sir; I've had a sort of breakfast.”

“A sort of a breakfast, hey? Well, what sort of a breakfast was it?”

I gave him an account of my experience in the ladies' and gents' dining parlor. He laughed immoderately, though I couldn't see that it was so very funny. “Well, Bubby,” he remarked, “dot was simply immense. Dot oughter go into a comic paper, mit a picture of dot big nigger staring at you. Well, I give ten dollars to been there, and heard him tell you dot fork was solid silver. Well, dot was a. pretty poor sort of a breakfast, anyhow. I guess you better come along out mit me now, and we get anudder sort of a breakfast, hey? You just wait here a minute while I go put on my hat. And say, Bubby, I guess you better give me dot sword, to leaf here while we're gone. I don't believe you'll need it. Give me dem udder things, too,” pointing to my satchel and my book.

He went away, but soon came back, with his hat on; and, taking my hand, he led me out into the street. After a walk of a few blocks, we turned into a luxurious little restaurant, as unlike the dining parlor as a fine lady is unlike a beggar woman, and sat down at a neat round table covered with a snowy cloth.

“Now, Bubby,” inquired Mr. Marx, “you got any preferences? Or will you give me card blanch to order what I think best?”

“Oh! order what you think best.”

He beckoned a waiter, and spoke to him at some length in a foreign language, which, I guessed, was German. The waiter went off; and then, addressing me, Mr. Marx said, “Well, now, Bubby, now we're settled down, quiet and comfortable, now you go ahead and tell me all about it.”

“All about what, sir?” queried I.

“Why, all about yourself, and what you leaf your home for, and what you expect to do here in New York, and every dings—the whole pusiness. Well, fire away.”

“Well, sir, I—it—it's this way,” I began. And then, as well as I could, I told Mr. Marx substantially everything that I have as yet told you in this story—about my grandmother, my Uncle Florimond, my Uncle Peter, and all the rest. Meanwhile the waiter had brought the breakfast—such an abundant, delicious breakfast! such juicy mutton chops, such succulent stewed potatoes, such bread, such butter, such coffee!—and I was violating the primary canons of good breeding by talking with my mouth full. Mr. Marx heard me through with every sign of interest and sympathy, only interrupting once, to ask, “Well, what I ordered—I hope it gives you entire satisfaction, hey?” and when I had done:—

“Well, if I ever!” he exclaimed. “Well, dot beats de record! Well, dot Uncle Peter was simply outracheous! Well, Bubby, you done just right, you done just exactly right, to come to me. The only thing dot surprises me is how you stood it so long already. Well, dot Uncle Peter of yours, Bubby—well, dot's simply unnecheral.”

He paused for a little, and appeared to be thinking. By and by he went on, “But your grandma, Bubby, your grandma was elegant. Yes, Bubby, your grandma was an angel, and no mistake about it. She reminds me, Bubby, she reminds me of my own mamma. Ach, Krekory, my mamma was so loafly. You couldn't hardly believe it. She was simply magnificent. Your grandma and her, they might have been tervins. Yes, Krekory, they might have been tervin sisters.”

Much to my surprise, Mr. Marx's eyes filled with tears, and there was a frog in his voice. “I can't help it, Bubby,” he said. “When you told me about dot grandma of yours, dot made me feel like crying. You see,” he added in an apologetic key, “I got so much sentiment about me.”

He was silent again for a little, and then again by and by he went on, “But I tell you what, Krekory, it's awful lucky dot you came down to New York just exactly when you did. Uddervise—if you'd come tomorrow instead of to-day, for example—you wouldn't have found me no more. Tomorrow morning I start off on the road for a six weeks' trip. What you done, hey, if you come down to New York and don't find me, hey, Bubby? Dot would been fearful, hey? Well, now, Krekory, now about dot chop. Well, as I got to leaf town to-morrow morning, I ain't got the time to find you a first-class chop before I go. But I tell you what I do. I take you up and introduce you to my fader-in-law; and you stay mit him till I get back from my trip, and then I find you the best chop in the market, don't you be afraid. My fader-in-law was a cheweler of the name of Mr. Finkelstein, Mr. Gottlieb Finkelstein. He's one of the nicest gentlemen you want to know, Bubby, and he'll treat you splendid. As soon as you get through mit dot breakfast, I take you up and introduce you to him.”

We went back to Mr. Marx's place of business, and got my traps; and then we took a horse-car up-town to Mr. Finkelstein's, which was in Third Avenue near Forty-Seventh Street. Mr. Marx talked to me about his father-in-law all the time.

“He's got more wit about him than any man of my acquaintance,” he said, “and he's so fond of music. He's a vidower, you know, Bubby; and I married his only daughter, of the name of Hedwig. Me and my wife, we board; but Mr. Finkelstein, he lives up-stairs over his store, mit an old woman of the name of Henrietta, for houze-keeper. Well, you'll like him first-rate, Bubby, you see if you don't; and he'll like you, you got so much enerchy about you. My kracious! If you talk about eating, he sets one of the grandest tables in the United States. And he's so fond of music, Krek-ory—it's simply wonderful. But I tell you one thing, Bubby; don't you never let him play a game of pinochle mit you, or else you get beat all holler. He's the most magnificent pinochle player in New York City; he's simply A-number-one.. . . Hello! here we are.”

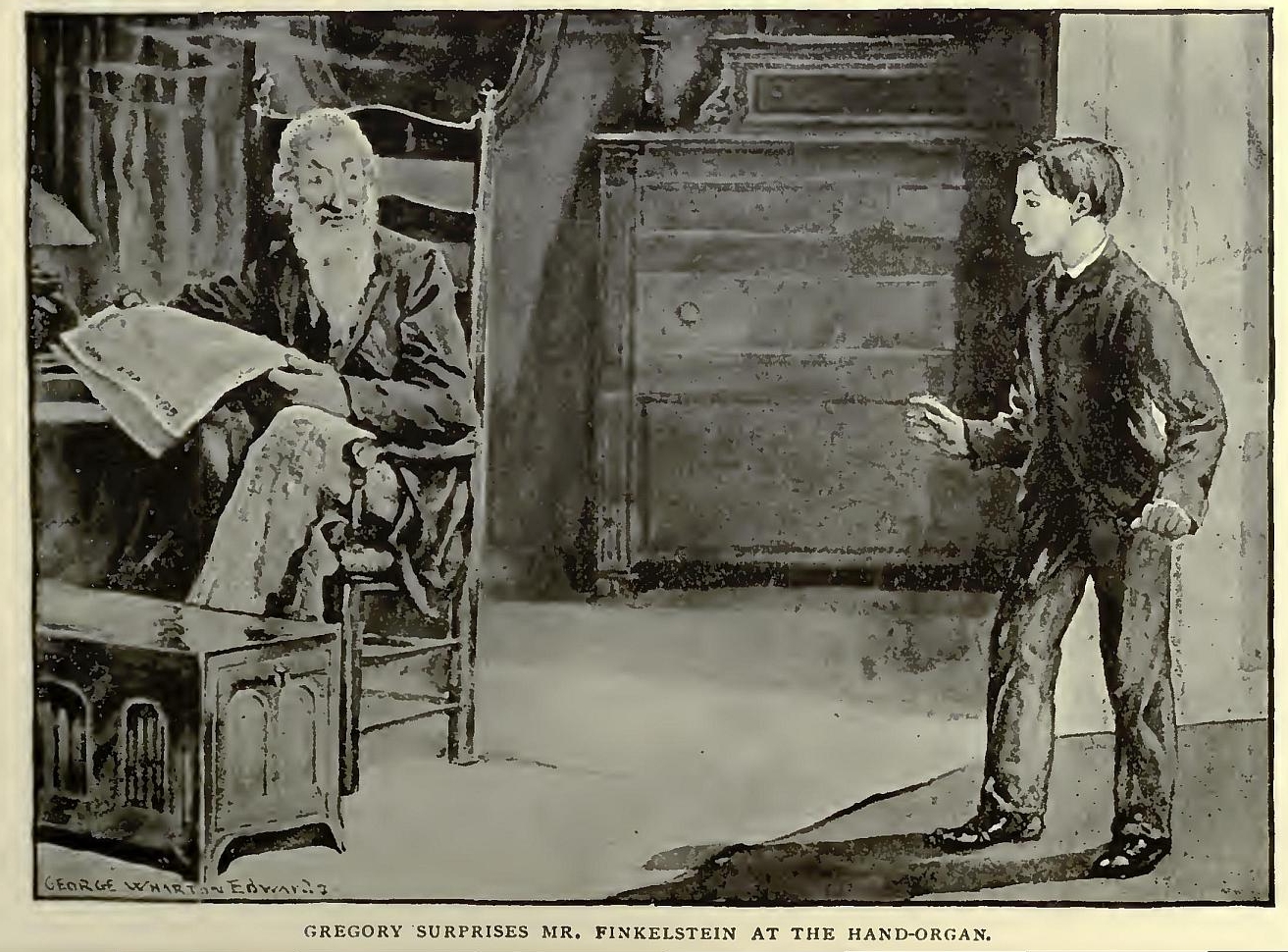

We left the horse-car, and found ourselves in front of a small jeweler's shop, which we entered. The shop was empty, but, a bell over the door having tinkled in announcement of our arrival, there entered next moment from the room behind it an old gentleman, who, as soon as he saw Mr. Marx, cried, “Hello, Solly! Is dot you? Vail, I declare! Vail, how goes it?”

The very instant I first set eyes on him, I thought this was one of the pleasantest-looking old gentlemen I had ever seen in my life; and I am sure you would have shared my opinion if you had seen him, too. He was quite short—not taller than five feet two or three at the utmost—and as slender as a young girl; but he had a head and face that were really beautiful. His forehead was high, and his hair, white as snow and soft as silk, was combed straight back from it. A long white silky beard swept downward over his breast, half-way to his waist. His nose was a perfect aquiline, and it reminded me a little of my grandmother's, only it was longer and more pointed. But what made his face especially prepossessing were his eyes; the kindest, merriest eyes you can imagine; dark blue in color; shining with a mild, sweet light that won your heart at once, yet having also a humorous twinkle in them. Yes, the moment I first saw Mr. Finkelstein I took a liking to him; a liking which was ere a great while to develop into one of the strongest affections of my life.

“Vail, how goes it?” he had inquired of Mr. Marx; and Mr. Marx had answered, “First-class. How's yourself?”

“Oh! vail, pretty fair, tank you. I cain't complain. I like to be better, but I might be vorse. Vail, how's Heddie?”

“Oh! Hedwig, she's immense, as usual. Well, how's business?”

“Oh! don't aisk me. Poor, dirt-poor. I ain't made no sale vort mentioning dese two or tree days already. Only vun customer here dis morning yet, and he didn't buy nodings. Aifter exaiming five tousand tol-lars vort of goots, he tried to chew me down on a two tollar and a haif plated gold vatch-chain. Den I aisked him vedder he took my establishment for a back-handed owction, and he got maid and vent avay. Vail, I cain't help it; I must haif my shoke, you know, Solly. Vail, come along into de parlor. Valk in, set down, make yourself to home.”

Without stopping his talk, he led us into the room behind the shop, which was very neatly and comfortably furnished, and offered us chairs. “Set down,” said he, “and make yourself shust as much to home as if you belonged here. I hate to talk to a man stainding up. Vail, Solly, I'm real glaid to see you; but, tell me, Solly, was dis young shentleman mit you a sort of a body-guard, hey?”

“A body-guard?” repeated Mr. Marx, “how you mean?”

“Why, on account of de sword; I tought maybe you took him along for brodection.”

“Ach, my kracious, fader-in-law, you're simply killing, you got so much wit about you,” cried Mr. Marx, laughing.

“Vail, I must haif my shoke, dot's a faict,” admitted Mr. Finkelstein. “Vail, Soily, you might as vail make us acqvainted, hey?”

“Well, dot's what brought me up here this morning, fader-in-law. I wanted to introduce him to you. Well, this is Mr. Krekory Prace—Mr. Finkelstein.”

“Bleased to make your acqvaintance, Mr. Prace; shake hands,” said Mr. Finkelstein. “And so your name was Kraikory, was it, Shonny? I used to know a Mr. Kraikory kept an undertaker's estaiblishment on Sixt Aivenue. Maybe he was a relation of yours, hey?”

“No, sir; I don't think so. Gregory is only my first name,” I answered.

“Well, now, fader-in-law,” struck in Mr. Marx, “you remember dot boy I told you about up in Nawvich, what jumped into the water, and saved me my fishing-pole already, de udder day?”

“Yes, Solly, I remember. Vail?”

“Well, fader-in-law, this was the boy.”

“What! Go 'vay!” exclaimed Mr. Finkelstein. “You don't mean it! Vail, if I aifer! Vail, Shonny, let me look at you.” He looked at me with all his eyes, swaying his head slowly from side to side as he did so. “Vail, I wouldn't haif believed, it, aictually.”

“It's a fact, all de same; no mistake about it,” attested Mr. Marx. “And now he's come down to New York, looking for a chop.”

“A shop, hey? Vail, what kind of a shop does he vant, Solly? I should tink a shop by de vater-vorks vould be about his ticket, hey?”

“Oh! no shoking. Pusiness is pusiness, fader-in-law,” Mr. Marx protested. “Well, seriously, I guess he ain't particular what kind of a chop, so long as it's steady and has prospects. He's got so much enerchy and ambition about him, I guesss he'll succeed in 'most any kind of a chop. But first I guess you better let him tell you de reasons he leaf his home, and den you can give him your advice. Go ahead, Bubby, and tell Mr. Finkelstein what you told me down by the restaurant.”

“Yes, go ahead, Shonny,” Mr. Finkelstein added; and so for a second time that day I gave an account of myself.

Mr. Finkelstein was even a more sympathetic listener than Mr. Marx had been. He kept swaying his head and muttering ejaculations, sometimes in English, sometimes in German, but always indicative of his eager interest in my tale. “Mein Gott!” “Ist's moglich?” “You don't say so!” “Vail, if I aifer!” And his kind eyes were all the time fixed upon my face in the most friendly and encouraging way. In the end, “Vail, I declare! Vail, my kracious!” he cried. “Vail, Shonny, I naifer heard nodings like dot in all my life before. You poor little boy! All alone in de vorld, mit nobody but dot parparian, dot saivage, to take care of you. Vail, it was simply heart-rending. Vail, your Uncle Peter, he'd oughter be tarred and feddered, dot's a faict. But don't you be afraid, Shonny; God will punish him; He will, shust as sure as I'm sitting here, Kraikory. Oh! you're a good boy, Kraikory, you're a fine boy. You make me loaf you already like a fader. Vail, Shonny, and so now you was come down to New York mit de idea of getting rich, was you?”

“Yes, sir,” I confessed.

“Vail, dot's a first-claiss idea. Dot's de same idea what I come to dis country mit. Vail, now, I give you a little piece of information, Shonny; what maybe you didn't know before. Every man in dis vorld was born to get rich. Did you know dot, Shonny?”

“Why, no, sir; I didn't know it. Is it true?”

“Yes, sir; it's a solemn faict. I leaf it to Solly, here. Every man in dis vorld is born to get rich—only some of 'em don't live long enough. You see de point?”

Mr. Marx and I joined in a laugh. Mr. Finkelstein smiled faintly, and said, as if to excuse himself, “Vail, I cain't help it. I must haif my shoke.”

“The grandest thing about your wit, fader-in-law,” Mr. Marx observed, “is dot you don't never laugh yourself.”

“No; dot's so,” agreed Mr. Finkelstein. “When you get off a vitticism, you don't vant to laif yourself, for fear you might laif de cream off it.”

“Ain't he immense?” demanded Mr. Marx, in an aside to me. Then, turning to his father-in-law: “Well, as I was going to tell you, I got to leaf town to-morrow morning for a trip on the road; so I thought I'd ask you to let Krekory stay here mit you till I get back. Den I go to vork and look around for a chop for him.”

“Solly,” replied Mr. Finkelstein, “you got a good heart; and your brains is simply remarkable. You done shust exaictly right. I'm very glaid to have such a fine boy for a visitor. But look at here, Solly; I was tinking vedder I might not manufacture a shop for him myself.”

“Manufacture a chop? How you mean?” Mr. Marx queried.

“How I mean? How should I mean? I mean I ain't got no ready-mait shops on hand shust now in dis estaiblishment; but I might mainufacture a shop for the right party. You see de point?”

“You mean you'll make a chop for him? You mean you'll give him a chop here, by you?” cried Mr. Marx.

“Vail, Solomon, if you was as vise as your namesake, you might haif known dot mitout my going into so much eggsblanations.”

“My kracious, fader-in-law, you're simply elegant, you're simply loafly, and no mistake about it. Well, I svear!”

“Oh! dot's all right. Don't mention it. I took a chenu-wine liking to Kraikory; he's got so much enterprise about him,” said Mr. Finkelstein.

“Well, what sort of a chop would it be, fader-in-law?” questioned Mr. Marx.

“Vail, I tink I give him de position of clerk, errant boy, and sheneral assistant,” Mr. Finkelstein replied.

“Well, Krekory, what you say to dot?” Mr. Marx inquired.

“De question is, do you accept de appointment?” added Mr. Finkelstein.

“O, yes, sir!” I answered. “You're very, very kind, you're very good to me. I—” I had to stop talking, and take a good big swallow, to keep down my tears; yet, surely, I had nothing to cry about!

“Well, fader-in-law, what vages will you pay?” pursued Mr. Marx.

“Vail, Solly, what vages was dey paying now to boys of his age?”

“Well, they generally start them on two dollars a week.”

“Two tollars a veek, and he boards and clodes himself, hey?”

“Yes, fader-in-law, dot's de system.”

“Vail, Solly, I tell you what I do. I board and clode him, and give him a quarter a veek to get drunk on. Is dot saitisfaictory?”

“But, sir,” I hastened to put in, pained and astonished at his remark, “I—I don't get drunk.”

“O, Lord, Bubby!” cried Mr. Marx, laughing. “You're simply killing! He don't mean get drunk. Dot's only his witty way of saying pocket-money.”

“Oh! I—I understand,” I stammered.

“You must excuse me, Shonny,” said Mr. Finkelstein. “I didn't mean to make you maid. But I must haif my shoke, you know; I cain't help it. Vail, Solly, was de proposition saitisfaictory?”

“Well, Bubby, was Mr. Finkelstein's proposition satisfactory?” asked Mr. Marx.

“O, yes, sir! yes, indeed,” said I.

“Vail, all right; dot settles it,” concluded Mr. Finkelstein. “And now, Kraikory, I pay you your first veek's sailary in advaince, hey?” and he handed me a crisp twenty-five-cent paper piece.

I was trying, in the depths of my own mind, to calculate how long it would take me, at this rate, to earn the hundred dollars that I needed for my journey across the sea to my Uncle Florimond. The outlook was not encouraging. I remembered, though, a certain French proverb that my grandmother had often repeated to me, and I tried to find some consolation in it: “Tout vient à la fin à qui sait attendre”—Everything comes at last to him who knows how to wait.

So you see me installed at Mr. Finkel-stein's as clerk, errand boy and general assistant. Next morning I entered upon the discharge of my duties, my kind employer showing me what to do and how to do it. Under his supervision I opened and swept out the store, dusted the counter, polished up the glass and nickel-work of the show-cases, and, in a word, made the place ship-shape and tidy for the day. Then we withdrew into the back parlor, and sat down to a fine savory breakfast that the old housekeeper Henrietta had laid there. She ate at table with us, but uttered not a syllable during the repast; and, much to my amazement, Mr. Finkelstein talked to me about her in her very presence as freely and as frankly as if she had been stone deaf, or a hundred miles away.