NOTE BY THE EDITORS

The Château de Vaux le Vicomte is a translation of the text of a sumptuously illustrated volume descriptive of this wonderful monument of human frailty and ambition, published in 1888 by Lemercier et Cie with plates by Rodolphe Pfnor. Although the text has not been published apart from the plates in France, it seemed only fitting to include a translation of The Château de Vaux le Vicomte in a complete edition of Monsieur Anatole France's works.

CONTENTS

CLIO

THE BARD OF KYME

KOMM OF THE ATREBATES

FARINATA DEGLI UBERTI

THE KING DRINKS

"LA MUIRON"

THE CHÂTEAU DE VAUX-LE-VICOMTE

PREFACE

NICOLAS FOUCQUET

THE CHÂTEAU DE VAUX

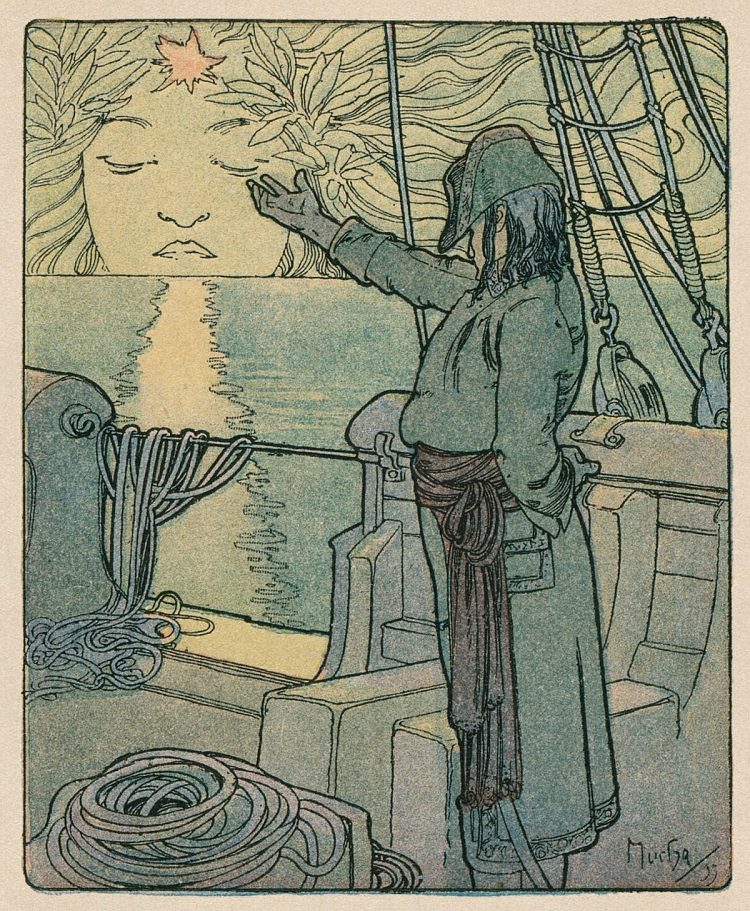

[To this English translation of Clio we added 12 plates by Mucha, who illustrated the French 1900 edition, which is also available at Project Gutenberg.—Transcribers' Note.]

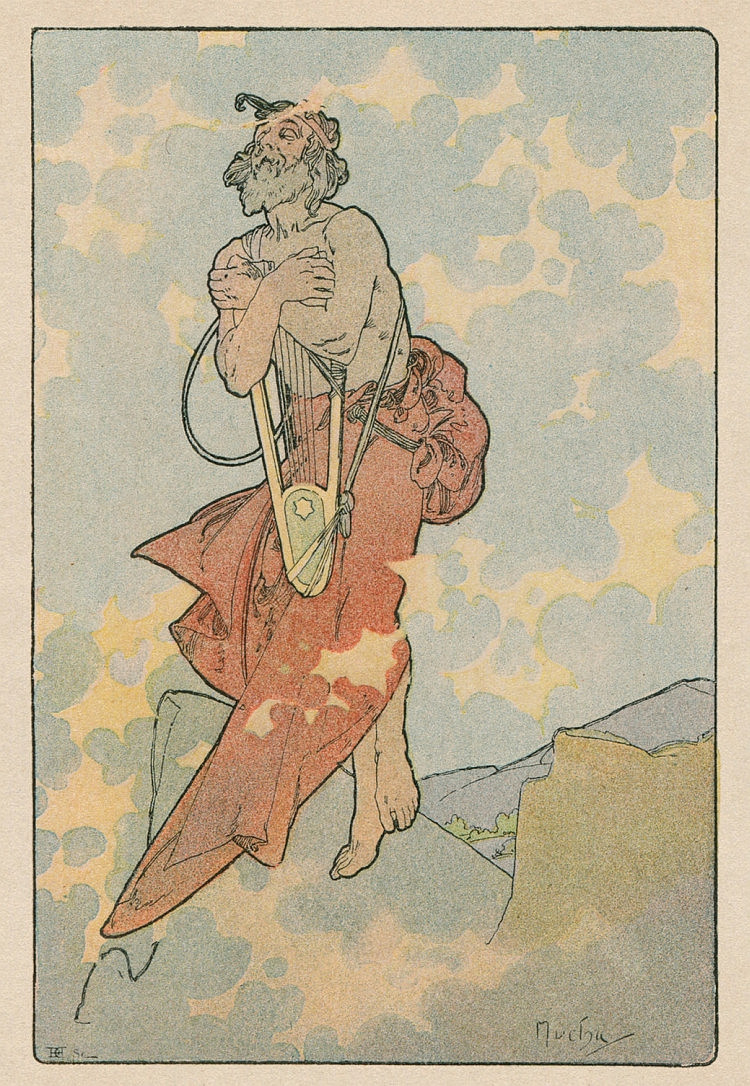

Along the hill-side he came, following a path which skirted the sea. His forehead was bare, deeply furrowed and bound by a fillet of red wool. The sea-breeze blew his white locks over his temples and pressed the fleece of a snow-white beard against his chin. His tunic and his feet were the colour of the roads which he had trodden for so many years. A roughly made lyre hung at his side. He was known as the Aged One, and also as the Bard. Yet another name was given him by the children to whom he taught poetry and music, and many called him the Blind One, because his eyes, dim with age, were overhung by swollen lids, reddened by the smoke of the hearths beside which he was wont to sit when he sang. But his was no eternal night, and he was said to see things invisible to other men. For three generations he had been wandering ceaselessly to and fro. And now, having sung all day to a King of Ægea, he was returning to his home, the roof of which he could already see smoking in the distance; for now, after walking all night without a halt for fear of being overtaken by the heat of the day, in the clear light of the dawn he could see the white Kyme, his birthplace. With his dog at his side, leaning on his crooked staff, he walked with slow steps, his body upright, his head held high because of the steepness of the way leading down into the narrow valley and because he was still vigorous in his age. The sun, rising over the mountains of Asia, shed a rosy light over the fleecy clouds and the hill-sides of the islands that studded the sea. The coast-line glistened. But the hills that stretched away eastward, crowned with mastic and terebinth, lay still in the freshness and the shadow of night.

The Aged One measured along the incline the length of twelve times twelve lances and found, on the left, between the flanks of twin rocks, the narrow entrance to a sacred wood. There, on the brink of a spring, rose an altar of unhewn stones.

It was half hidden by an oleander the branches of which were laden with dazzling blossoms. The well-trodden ground in front of the altar was white with the bones of victims. All around, the boughs of the olive-trees were hung with offerings. And farther on, in the awesome shadow of the gorge, rose two ancient oaks, bearing, nailed to their trunks, the bleached skulls of bulls. Knowing that this altar was consecrated to Phœbus, the Aged One plunged into the wood, and, taking by its handle a little earthenware cup which hung from his belt, he bent over the stream which, flowing over a bed of wild parsley and water-cress, slowly wound its way down to the meadow. He filled his cup with the spring-water, and, because he was pious, before drinking he poured a few drops before the altar. He worshipped the immortal gods, who know neither pain nor death, while on earth generation follows generation of suffering men. He was conscious of fear; and he dreaded the arrows of Leto's sons. Full of sorrows and of years, he loved the light of day and feared death. For this reason an idea occurred to him. He bent the pliable trunk of a sapling, and drawing it towards him hung his earthenware cup from the topmost twig of the young tree, which, springing back, bore the old man's offering up to the open sky.

White Kyme, wall-encircled, rose from the edge of the sea. A steep highway, paved with flat stones, led to the gate of the town. This gate had been built in an age beyond man's memory, and it was said to be the work of the gods. Carved upon the lintel were signs which no man understood, yet they were regarded as of good omen. Not far from this gate was the public square, where the benches of the elders shone beneath the trees. Near this square, on the landward side, the Aged One stayed his steps. There was his house. It was low and small, and less beautiful than the neighbouring house, where a famous seer dwelt with his children. Its entrance was half hidden beneath a heap of manure, in which a pig was rooting. This dunghill was smaller than those at the doors of the rich. But behind the house was an orchard, and stables of unquarried stone, which the Aged One had built with his own hands. The sun was climbing up the white vault of heaven, the sea wind had fallen. The invisible fire in the air scorched the lungs of men and beasts. For a moment the Aged One paused upon the threshold to wipe the sweat from his brow with the back of his hand. His dog, with watchful eye and hanging tongue, stood still and panted.

The aged Melantho, emerging from the house, appeared on the threshold and spoke a few pleasant words. Her coming had been slow, because a god had sent an evil spirit into her legs which swelled them and made them heavier than a couple of wine-skins. She was a Carian slave and in her youth the King had bestowed her on the bard, who was then young and vigorous. And in her new master's bed she had conceived many children. But not one was left in the house. Some were dead, others had gone away to practise the art of song or to steer the plough in distant Achaian cities, for all were richly gifted. And Melantho was left alone in the house with Areta, her daughter-in-law, and Areta's two children.

She went with the master into the great hall with its smoky rafters. In the midst of it, before the domestic altar, lay the hearthstone covered with red embers and melted fat. Out of the hall opened two stories of small rooms; a wooden staircase led to the upper chambers, which were the women's quarters. Against the pillars that supported the roof leant the bronze weapons which the Aged One had borne in his youth, in the days when he followed the kings to the cities to which they drove in their chariots to recapture the daughters of Kyme whom the heroes had carried away. From one of the beams hung the skin of an ox.

The elders of the city, wishful to honour the bard, had sent it to him on the previous day. He rejoiced at the sight of it. As he stood drawing a long breath into a chest which was shrunken with age, he took from beneath his tunic, with a few cloves of garlic remaining from his alfresco supper, the King of Ægea's gift; it was a stone fallen from heaven and precious, for it was of iron, though too small for a lance-tip. He brought with him also a pebble which he had found on the road. On this pebble, when looked at in a certain light, was the form of a man's head. And the Aged One, showing it to Melantho, said:

"Woman, see, on this pebble is the likeness of Pakoros, the blacksmith; not without permission of the gods may a stone thus present the semblance of Pakoros."

And when the aged Melantho had poured water over his feet and hands in order to remove the dust that defiled them, he grasped the shin of beef in his arms, placed it on the altar and began to tear it asunder. Being wise and prudent, he did not delegate to women or to children the duty of preparing the repast; and, after the manner of kings, he himself cooked the flesh of beasts.

Meanwhile Melantho coaxed the fire on the hearth into a flame. She blew upon the dry twigs until a god wrapped them in fire. Though the task was holy, the Aged One suffered it to be performed by a woman because years and fatigue had enfeebled him. When the flames leapt up he cast into them pieces of flesh which he turned over with a fork of bronze. Seated on his heels, he inhaled the smoke; and as it filled the room his eyes smarted and watered; but he paid no heed because he was accustomed to it and because the smoke signified abundance. As the toughness of the meat yielded to the fire's irresistible power, he put fragments of it into his mouth and, slowly masticating them with his well-worn teeth, ate in silence. Standing at his side, the aged Melantho poured the dark wine into an earthenware cup like that which he had given to the god.

When he had satisfied hunger and thirst, he inquired whether all in house and stable was well. And he inquired concerning the wool woven in his absence, the cheese placed in the vat and the ripe olives in the press. And, remembering that his goods were but few, he said:

"The heroes keep herds of oxen and heifers in the meadows. They have a goodly number of strong and comely slaves; the doors of their houses are of ivory and of brass, and their tables are laden with pitchers of gold. The courage of their hearts assured them of wealth, which they sometimes keep until old age. In my youth, certes, I was not inferior to them in courage, but I had neither horses nor chariots, nor servants, nor even armour strong enough to vie with them in battle and to win tripods of gold and women of great beauty. He who fights on foot with poor weapons cannot kill many enemies, because he himself fears death. Wherefore, fighting beneath the town walls, in the ranks, with the serving men, never did I win rich spoil."

The aged Melantho made answer:

"War giveth wealth to men and robs them of it. My father, Kyphos, had a palace and countless herds at Mylata. But armed men despoiled him of all and slew him. I myself was carried away into slavery, but I was never ill-treated because I was young. The chiefs took me to their bed and never did I lack food. You were my best master and the poorest."

There was neither joy nor sadness in her voice as she spoke.

The Aged One replied:

"Melantho, you cannot complain of me, for I have always treated you kindly. Reproach me not with having failed to win great wealth. Armourers are there and blacksmiths who are rich. Those who are skilled in the construction of chariots derive no small advantage from their labours. Seers receive great gifts. But the life of minstrels is hard."

The aged Melantho said:

"The life of many men is hard."

And with heavy step she went out of the house, with her daughter-in-law, to fetch wood from the cellar. It was the hour when the sun's invincible heat prostrates men and beasts, and silences even the song of the birds in the motionless foliage. The Aged One stretched himself upon a mat, and, veiling his face, fell asleep.

As he slumbered he was visited by a succession of dreams, which were neither more beautiful nor more unusual than those which he dreamed every day. In these dreams appeared to him the forms of men and of beasts. And, because among them he recognized some whom he had known while they lived on the green earth and who having lost the light of day had lain beneath the funeral pile, he concluded that the shades of the dead hover in the air, but that, having lost their vigour, they are nothing but empty shadows. He learned from dreams that there exist likewise shades of animals and of plants which are seen in sleep. He was convinced that the dead, wandering in Hades, themselves form their own image, since none may form it for them, unless it were one of those gods who love to deceive man's feeble intellect. But, being no seer, he could not distinguish between false dreams and true; and, weary of seeking to understand the confused visions of the night, he regarded them with indifference as they passed beneath his closed eyelids.

On awakening, he beheld, ranged before him in an attitude of respect, the children of Kyme, whom he instructed in poetry and music, as his father had instructed him. Among them were his daughter-in-law's two sons. Many of them were blind, for a bard's life was deemed fitting for those who, bereft of sight, could neither work in the fields nor follow heroes to war.

In their hands they bore the offerings in payment for the bard's lessons, fruit, cheese, a honeycomb, a sheep's fleece, and they waited for their master's approval before placing it on the domestic altar.

The Aged One, having risen and taken his lyre which hung from a beam in the hall, said kindly:

"Children, it is just that the rich should give much and the poor less. Zeus, our father, hath unequally apportioned wealth among men. But he will punish the child who withholds the tribute due to the divine bard."

The vigilant Melantho came and took the gifts from the altar. And the Aged One, having tuned his lyre, began to teach a song to the children, who with crossed legs were seated on the ground around him.

"Hearken," he said, "to the combat between Patrocles and Sarpedon. This is a beautiful song."

And he sang. He skilfully modulated the sounds, applying the same rhythm and the same measure to each line; and, in order that his voice should not wander from the key, he supported it at regular intervals by striking a note upon his three-stringed lyre. And, before making a necessary pause, he uttered a shrill cry, accompanied by a strident vibration of strings. After he had sung lines equal in number to double the number of fingers on his two hands, he made the children repeat them. They cried them out all together in a high voice, as, following their master's example, they touched the little lyres which they themselves had carved out of wood and which gave no sound.

Patiently the Aged One sang the lines over and over until the little singers knew every word. The attentive children he praised, but those who lacked memory or intelligence he struck with the wooden part of his lyre, and they went away to lean weeping against a pillar of the hall. He taught by example, not by precept, because he believed poesy to be of hoary antiquity and beyond man's judgment. The only counsels which he gave related to manners. He bade them:

"Honour kings and heroes, who are superior to other men. Call heroes by their own name and that of their father, so that these names be not forgotten. When you sit in assemblies gather your tunic about you and let your mien express grace and modesty."

Again he said to them:

"Do not spit in rivers, because rivers are scared. Make no change, either through weakness of memory or of your own imagining, in the songs I teach you, and when a king shall say unto you: 'These songs are beautiful. From whom did you learn them?' you shall answer: 'I learnt them from the Aged One of Kyme, who received them from his father, whom doubtless a god had inspired.'" Of the ox's shin, there yet remained a few succulent morsels. Having eaten one of them before the hearth and smashed the bone with an axe of bronze, in order to extract the marrow, of which he alone in the house was worthy to partake, he divided the rest of the meat into portions which should nourish the women and children for the space of two days.

Then he realized that soon nothing would be left of this nutritious food, and he reflected:

"The rich are loved by Zeus and the poor are not. All unwittingly I have doubtless offended one of those gods who live concealed in the forests or the mountains, or perhaps the child of an immortal; and it is to expiate my involuntary crime that I drag out my days in a penurious old age. Sometimes, without any evil intention, one commits actions which are punishable because the gods have not clearly revealed unto men that which is permitted and that which is forbidden. And their will remains obscure." Long did he turn over those thoughts in his mind, and, fearing the return of cruel hunger, he resolved not to remain idly in his dwelling that night, but this time to go towards the country where the Hermos flows between rocks and whence can be seen Orneia, Smyrna and the beautiful Hissia, lying upon the mountain, which, like the prow of some Phœnician boat, plunges into the sea. Wherefore, at the hour when the first stars glimmer in the pale sky, he girded himself with the cord of his lyre and went forth, along the sea-shore, toward the dwellings of rich men, who, during their lengthy feasts, love to hearken to the praise of heroes and the genealogies of the gods.

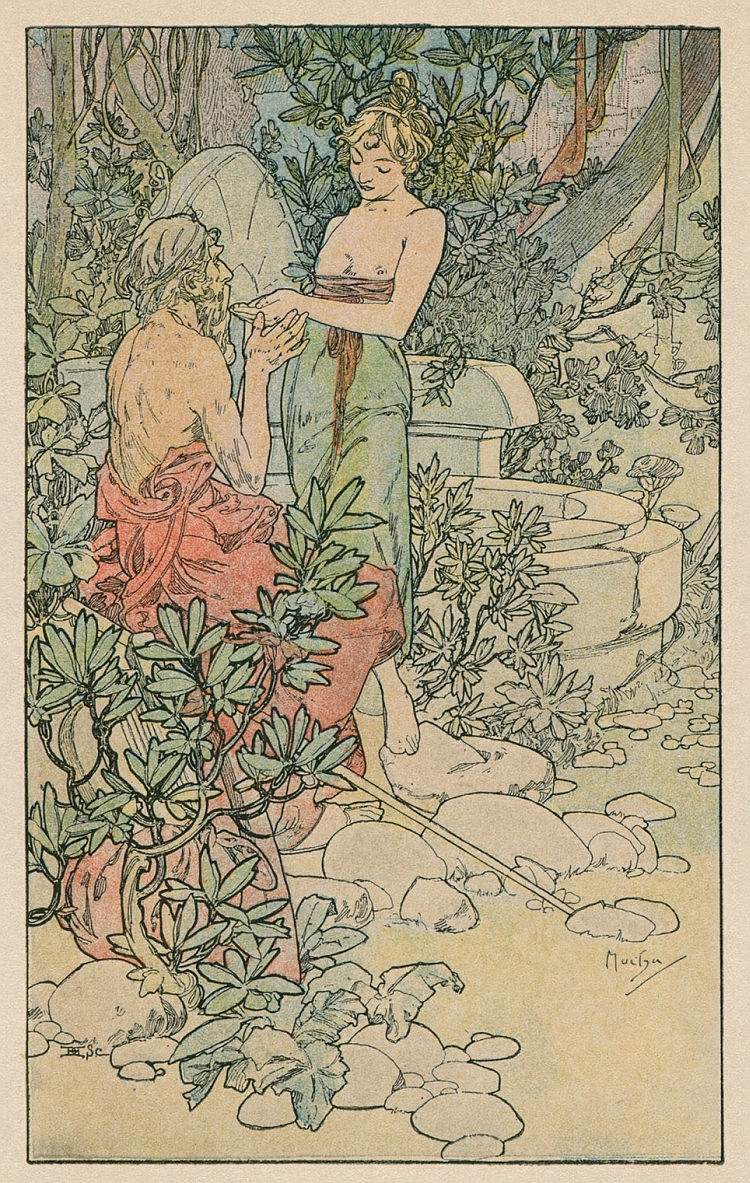

Having, according to his custom, journeyed all night, in the rosy dawn of morning he descried a town perched upon a high headland, and he recognized the opulent Hissia, dove-haunted, which from the summit of her rock looks down upon the white islands sporting like nymphs in the glistening sea. Not far from the town, on the margin of a spring, he sat down to rest and to appease his hunger with the onions which he had brought in a fold of his tunic.

Hardly had he finished his meal when a young girl, bearing a basket on her head, came to the spring to wash linen. At first she looked at him suspiciously, but, seeing that he carried a wooden lyre slung over his torn tunic and that he was old and overcome with fatigue, she approached him fearlessly, and, suddenly, seized with pity and veneration, she filled the hollows of her hands with drops of water with which she moistened the minstrel's lips.

Then he called her a king's daughter; he promised her a long life, and said:

"Maiden, desire floats in a cloud about thy girdle. Happy the man who shall lead thee to his couch. And I, an old man, praise thy beauty like the bird of night which cries all unheeded upon the nuptial roof. I am a wandering bard. Daughter, speak unto me pleasant words."

And the maiden answered:

"If, as you say and as it seemeth, you are a musician, then no evil fate brings you to this town. For the rich Meges to-day receiveth a guest who is dear to him; and to the great of the town, in honour of his guest, he giveth a sumptuous feast. Doubtless he would wish them to hear a good minstrel. Go to him. From this very spot you may see his house. From the seaward side it cannot be approached, because it is on that high breeze-swept headland, which juts out into the waves. But if you enter the town on the landward side, by the steps cut in the rock, which lead up the vine-clad hill, you will easily distinguish from all the other houses the abode of Meges. It has been recently whitewashed, and it is more spacious than the rest." And the Aged One, rising with difficulty on limbs which the years had stiffened, climbed the steps cut in the rock by the men of old, and, reaching the high table-land whereon is the town of Hissia, he readily distinguished the house of the rich Meges.

To approach it was pleasant, for the blood of freshly slaughtered bulls gushed from its doors and the odour of hot fat was perceptible all around. He crossed the threshold, entered the great banqueting-hall and, having touched the altar with his hand, approached Meges, who was carving the meat and ordering the servants. Already the guests were ranged about the hearth, rejoicing in the prospect of a plenteous repast. Among them were many kings and heroes. But the guest whom Meges desired to honour by this banquet was a King of Chios, who, in quest of wealth, had long navigated the seas and endured great hardship. His name was Oineus. All the guests admired him because, like Ulysses in earlier days, he had escaped from innumerable shipwrecks, shared in the islands the couch of enchantresses and brought home great treasure. He told of his travels and his labours, interspersing them with inventions, for he had a nimble wit.

Recognizing the bard by the lyre which hung at his side, the rich Meges addressed the Aged One and said:

"Be welcome. What songs knowest thou?"

The Aged One made answer:

"I know 'The Strife of Kings' which brought such great disaster to the Achaians, I know 'The Storming of the Wall.' And that song is beautiful. I know also 'The Deception of Zeus,' 'The Embassy' and 'The Capture of the Dead.' And these songs are beautiful. I know yet more—six times sixty very beautiful songs."

Thus did he give it to be understood that he knew many songs; but the exact number he could not tell.

The rich Meges replied in a mocking tone:

"In the hope of a good meal and a rich gift, wandering minstrels ever say that they know many songs; but, put to the test, it is soon seen that they remember but a few lines, with the constant repetition of which they tire the ears of heroes and of kings."

The Aged One answered wisely:

"Meges," he said, "you are renowned for your wealth. Know that the number of the songs I know is not less than that of the bulls and heifers which your herdsmen drive to graze on the mountain." Meges, admiring the Old Man's intelligence, said to him kindly:

"A small mind would not suffice to contain so great a number of songs. But, tell me, is what thou knowest about Achilles and Ulysses really true? For many are the lies in circulation touching those heroes."

And the bard made answer:

"All that I know of the heroes I received from my father, who learned it from Muses themselves, for in earlier days in cave and forest the immortal Muses visited divine singers. No inventions will I mingle with the ancient tales."

Thus did he speak, and wisely. Nevertheless to the songs he had known from his youth upward he was wont to add lines taken from other songs or the fruit of his own imagination. He himself had composed wellnigh the whole of certain songs. But, fearing lest man should disapprove of them, he did not confess them to be his own work. The heroes preferred the ancient tales which they believed to have been dictated by a god, and they objected to new songs. Wherefore, when he repeated lines of his own invention, he carefully concealed their origin. And, as he was a true poet and followed all the ancient traditions, his lines differed in no way from those of his ancestors; they resembled them in form and in beauty, and, from the beginning, they were worthy of immortal glory.

The rich Meges was not unintelligent. Perceiving the Aged One to be a good singer, he gave him a place of honour by the hearth and said to him:

"Old Man, when we have satisfied our hunger, thou shalt sing to us all thou knowest of Achilles and Ulysses. Endeavour to charm the ears of Oineus, my guest, for he is a hero full of wisdom."

And Oineus, who had long wandered over the sea, asked the minstrel whether he knew "The Voyages of Ulysses." But the return of the heroes who had fought at Troy was still wrapped in mystery, and no one knew what Ulysses had suffered in his wanderings over the pathless sea.

The Old Man answered:

"I know that the divine Ulysses shared Circe's couch and deceived the Cyclops by a crafty wile. Women tell tales about it to one another. But the hero's return to Ithaca is hidden from the bards. Some say that he returned to possess his wife and his goods, others that he put away Penelope because she had admitted her suitors to her bed, and that he himself, punished by the gods, wandered ceaselessly among the people, an oar upon his shoulder."

Oineus replied:

"In my travels I have heard that Ulysses died at the hands of his son."

Meanwhile Meges distributed the flesh of oxen among his guests. And to each one he gave a fitting morsel. Oineus praised him loudly.

"Meges," he said, "one can see that you are accustomed to give banquets."

The oxen of Meges were fed upon the sweetsmelling herbs which grow on the mountain-side. Their flesh was redolent thereof, and the heroes could not consume enough of it. And, as Meges was constantly refilling a capacious goblet which he afterwards passed to his guests, the repast was prolonged far into the day. No man remembered so rich a feast.

The sun was going down into the sea, when the herdsmen who kept the flocks of Meges upon the mountain came to receive their share of the wine and victuals. Meges respected them because they grazed the herds not with the indolence of the herdsmen of the plain, but armed with lances of iron and girded with armour in order to defend the oxen against the attacks of the people of Asia. And they were like unto kings and heroes, whom they equalled in courage. They were led by two chiefs, Peiros and Thoas, whom the master had chosen as the bravest and the most intelligent. And, indeed, handsomer men were not to be seen. Meges welcomed them to his hearth as the illustrious protectors of his wealth. He gave them wine and meat as much as they desired.

Oineus, admiring them, said to his host:

"In all my travels, I have never seen men with limbs so well formed and muscular as those of these two master herdsmen."

Then Meges uttered injudicious words. He said: "Peiros is the stronger in wrestling, but Thoas the swifter in the race."

At these words, the two herdsmen looked angrily at one another, and Thoas said to Peiros:

"You must have given the master some maddening drink to make him say that you are the better wrestler."

Then Peiros answered Thoas testily:

"I flatter myself that I can conquer you in wrestling. As for racing, I leave to you the palm which the master has given. For you who have the heart of a stag could not fail to possess his feet."

But the wise Oineus checked the herdsmen's quarrel. He artfully told tales showing the danger of wrangling at feasts. And, as he spoke well, he was approved. Peace having been restored, Meges said to the Aged One:

"My friend, sing us 'The Wrath of Achilles' and the 'Gathering of the Kings.'"

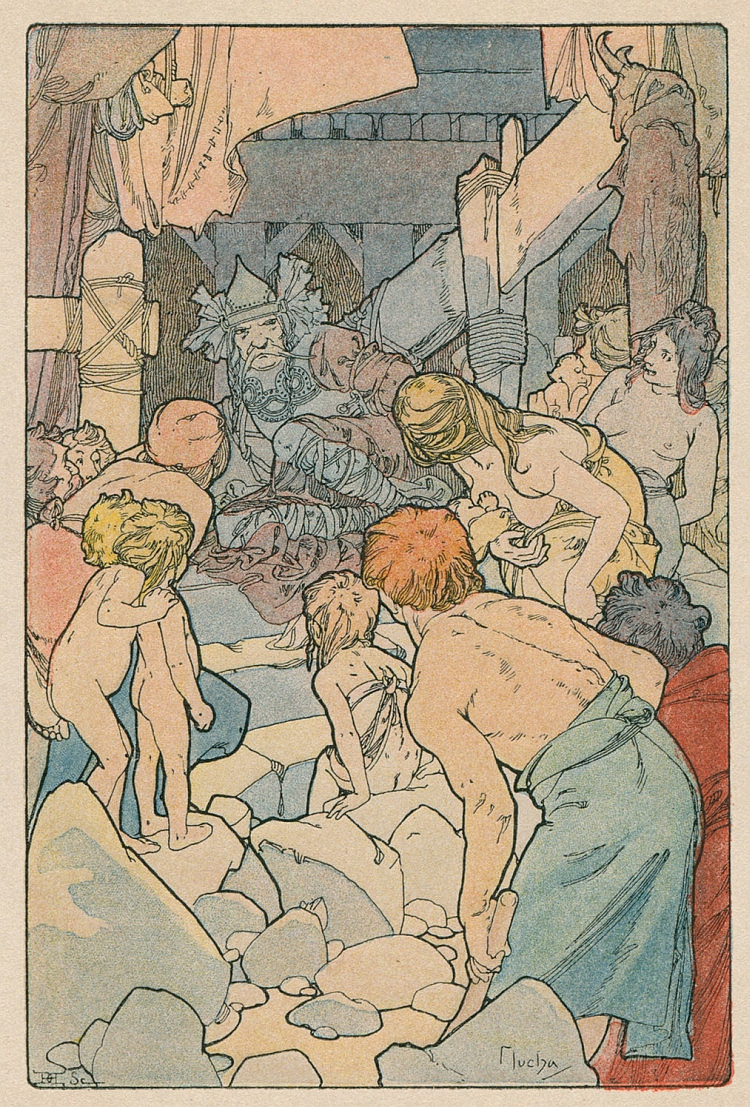

And the Aged One, having tuned his lyre, poured forth into the thick atmosphere of the hall great gusts of sound.

He drew deep breaths, and all the guests hearkened in silence to the measured words which recalled ages worthy to be remembered. And many marvelled how so old a man, one withered by age like a vine-branch which beareth neither fruit nor leaves, could emit such powerful notes. For they did not understand that the power of the wine and the habit of singing imparted to the musician a strength which otherwise would have been denied him by enfeebled nerve and muscle.

At intervals a murmur of praise rose from the assembly like a strong gust of wind in the forest. But suddenly the herdsmen's dispute, appeased for a while, broke out afresh. Heated with wine, they challenged one another to wrestle and to race. Their wild cries rose above the musician's voice, and vainly he endeavoured to make the harmonious sounds which proceeded from his mouth and his lyre heard by the assembly. The herdsmen who followed Peiros and Thoas, flushed with wine, struck their hands and grunted like hogs. They had long formed themselves into rival bands which shared the chiefs' enmity.

"Dog!" cried Thoas.

And he struck Peiros a blow on the face which drew blood from his mouth and nostrils. Peiros, blinded, butted with his forehead against the chest of Thoas and threw him backwards, his ribs broken. Straightway the rival herdsmen cast themselves upon one another, exchanging blows and insults.

In vain did Meges and the Kings endeavour to separate the combatants. Even the wise Oineus himself was repulsed by the herdsmen whom a god had bereft of reason. Brass vessels flew through the air on all sides. Great ox-bones, smoking torches, bronze tripods rose and fell upon the combatants. The interlaced bodies of men rolled over the hearth on which the fire was dying, in the midst of the liquor which flowed from the burst wine-skins.

Dense darkness enveloped the hall, a darkness full of groans and imprecations. Arms, maddened by frenzy, seized glowing logs and hurled them into the darkness. A blazing twig struck the minstrel as he stood still and silent.

Then a voice louder than all the noise of combat cursed these impious men and this profane house. And, pressing his lyre to his breast, he went out of the dwelling and walked along the high headland by the sea. To his wrath had given place a great feeling of fatigue and a bitter disgust with men and with life.

A longing for union with the gods filled his breast. All things lay wrapped in soft shadows, the friendly silence and the peace of night. Westward, over the land which men say is haunted by the shades of the dead, the divine moon, hanging in the clear sky, shed silver blossoms upon the smiling sea. And the aged Homer advanced over the high headland until the earth, which had borne him so long, failed beneath his feet.

In a land of mists, near a shore which was beaten by the restless sea and swept by billowy waves of sand raised by the Ocean winds, the Atrebates had settled on the shifting banks of a broad stream. There, amid pools of water and in forests of oak and of birch, they lived protected by their stockades of felled tree-trunks. There they bred horses excellent for draught-work, large-headed, short-necked, broad-chested and muscular, and with powerful haunches. On the outskirts of the forest they kept huge swine, wild as boars. With their great dogs they hunted wild beasts, the skulls of which they nailed on to the walls of their wooden houses. They lived on the flesh of these creatures and on fish, both of the salt-water and the fresh. They grilled their meat and seasoned it with salt, vinegar and cumin. They drank wine, and, at their stupendous feasts, seated at their round tables, they grew drunken. There were among them women who, acquainted with the virtue of herbs, gathered henbane, vervain and that healing plant called savin, which grows in the moist hollows of rocks. From the sap of the yew-tree they concocted a poison. The Atrebates had also priests and poets who knew things hidden from ordinary men.

These forest-dwellers, these men of the marsh and the beach, were of high stature. They wore their fair hair long, and they wrapped their great white bodies in mantles of wool of the colour of the vine-leaf when it grows purple in the autumn. They were subject to chiefs who held sway over the tribes.

The Atrebates knew that the Romans had come to make war on the peoples of Gaul, and that whole nations with all their possessions had been sold beneath their lance. News of happenings on the Rhone and the Loire had reached them speedily. Words and signs fly like birds. And that which, at sunrise, had been said in Genabum of the Carnutes was heard in the first watch of the night on the Ocean strand. But the fate of their brethren did not trouble them, or rather, being jealous of them, they rejoiced in the sufferings which they endured at Cæsar's hand. They did not hate the Romans, for they did not know them. Neither did they fear them, since it seemed to them impossible for an army to penetrate through the forests and marshes which surrounded their dwellings. They had no towns, although they gave the name to Nemetacum,[1] a vast enclosure encircled by a palisade, which, in case of attack, served as a refuge for warriors, women and herds. As we have said, they had throughout their country other similar places of refuge, but these were smaller. To them, also, they gave the name of towns.

It was not upon their enclosures of felled trees that they relied for resistance to the Romans, whom they knew to be skilled in the capture of cities defended by stone walls and wooden towers. But they relied rather on their country's lack of roads. The Roman soldiers, however, themselves constructed the roads over which they marched. They dug the ground with a strength and rapidity unknown to the Gauls of the dense forest, among whom iron was rarer than gold. And one day the Atrebates were astounded to learn that the Roman road, with its milestones and its fine paved highway, was approaching their thickets and marshes. Then they made alliance with the people scattered through the forest which they called the Impenetrable, and numerous tribes entered into a league against Cæsar. The chiefs of the Atrebates uttered their war-cry, girded themselves with their baldrics of gold and of coral, donned their helmets adorned with the antlers of the stag, or the elk, or with buffalo horns, and drew their daggers, which were not equal to the Roman sword. They were vanquished, but because they were courageous they had to be twice conquered.

Now among them was a chief who was very rich. His name was Komm. He had a great store of torques, bracelets and rings in his coffers. Human heads he had also, embalmed in oil of cedar. They were the heads of hostile chiefs slain by himself or by his father or his father's father. Komm enjoyed the life of a man who is strong, free and powerful.

Followed by his weapons, his horses, his chariots and his Breton bulldogs, by the multitude of his fighting men and his women, he would wander without let or hindrance over his boundless dominions, through forest or along river-bank, until he came to a halt in one of those woodland shelters, one of those primitive farms of which he possessed a great number. There, at peace, surrounded by his faithful followers, he would fish, hunt the wild beasts, break in his horses and recall his adventures in war. And, as soon as the desire seized him, he would move on. He was a violent, crafty, subtle-minded man excelling in deed and in word. When the Atrebates shouted their war-cry, he forbore to don the helmet which was adorned with the horns of an ox. He remained quietly in one of his wooden houses full of gold, of warriors, or horses, of women, of wild pigs and smoked fish. After the defeat of his fellow-countrymen, he went and found Cæsar and placed his brains and his influence at the service of the Romans. He was well received. Concluding rightly that this clever, powerful Gaul would be able to pacify the country and hold it in subjection to Rome, Cæsar bestowed upon him great powers and nominated him King of the Atrebates. Thus Komm, the chieftain, became Commius Rex. He wore the purple, and coined money whereon appeared his likeness in profile, his head encircled by a diadem with sharp points like those of the Greek and barbarian kings who wore their crowns as tokens of their friendship with Rome.

He was not execrated by the Atrebates. His sagacious and self-interested behaviour did not discredit him with a people devoid of Greek and Roman ideas of patriotism and citizenship. These savage, inglorious Gauls, ignorant of public life, esteemed cunning, yielded to force and marvelled at royal power, which seemed to them a magnificent innovation. The majority of these people, rough woodlanders or fishermen of the misty coast, had a still better reason for not blaming the conduct and the prosperity of their chieftain; not knowing that they were Atrebates, nor even that Atrebates existed, the King of the Atrebates concerned them but little. Wherefore Komm was not unpopular. And if the favour of Rome meant danger to him, that danger did not come from his own people.

Now in the fourth year of the war, towards the end of summer, Cæsar armed a fleet for a descent upon Britain. Desiring to secure allies in the great Island, he resolved to send Komm as his ambassador to the Celts of the Thames, with the offer of an alliance with Rome. Sagacious, eloquent and by birth akin to the Britons—for certain tribes of the Atrebates had settled on both banks of the Thames—Komm was eminently fitted for this mission.

Komm was proud of his friendship with Cæsar. But he was in no hurry to discharge this mission, of the dangers of which he was fully aware. To induce him to undertake it Cæsar was compelled to grant him many favours. From the tribute paid by other Gallic towns he exempted Nemetacum, which was already growing into a city and a metropolis, so rapidly did the Romans develop the countries which they conquered. He somewhat relaxed the rigorous rule of the conquerors by restoring to it its rights and its own laws. Further, he gave Komm to rule over the Morini, who were the neighbours of the Atrebates on the sea-shore.

Komm set sail with Caius Volusenus Quadratus, prefect of cavalry, appointed by Cæsar to conduct a reconnaissance in Britain. But when the ship approached the sandy beach at the foot of the bird-haunted white cliffs, the Roman refused to disembark, fearing unknown danger and certain death. Komm landed with his horses and his followers and spoke to the British chiefs who had come to meet him. He counselled them to prefer profitable friendship with the Romans to their pitiless wrath. But these chiefs, the descendants of Hu, the Powerful, and of his comrades in arms, were proud and violent. They listened impatiently to Komm's words. Anger clouded their woad-stained countenances, and they swore to defend their Island against the Romans.

"Let them land here," they cried, "and they will disappear like the snow on the sand of the sea-shore when the south wind blows upon it."

Holding Cæsar's counsel to be an insult, they were already drawing their daggers from their belts and preparing to put to death the herald of shame.

Standing bowed over his shield in the attitude of a suppliant, Komm invoked the name of brother by which he was entitled to call them. They were sons of the same fathers.

Wherefore the Britons forbore to slay him. They conducted him in chains to a great village near the coast. Passing down a road bordered by huts of wattle-work, he noticed high flat stones, fixed in the ground at irregular intervals, and covered with signs which he thought to be sacred, for it was not easy to decipher their meaning. He perceived that the huts of this great village, though poorer, were not unlike those of the villages of the Atrebates. In front of the chiefs' dwellings poles were erected from which hung the antlers of deer, the skulls of boars and the fair-haired heads of men. Komm was taken into a hut which contained nothing save a hearthstone still covered with ashes, a bed of dried leaves and the image of a god shapen from the trunk of a lime-tree. Bound to the pillar which supported the thatched roof, the Atrebate meditated on his ill luck and sought in his mind for some magic word of power or some ingenious device which should deliver him from the wrath of the British chieftains.

And to beguile his wretchedness, after the manner of his ancestors, he composed a song of menace and complaint, coloured by pictures of his native woods and mountains, the memory of which filled his heart.

Women with babes at the breast came and looked at him curiously and questioned him as to his country, his race and his adventures. He answered them kindly. But his soul was sad and wracked by cruel anxiety.

[1] The modern Arras.—Trans.

Detained until the end of summer on the Morini shore, Cæsar set sail one night about the third watch, and by the fourth hour of day had sight of the Island. The Britons awaited him on the beach. But neither their arrows of hard wood nor their scythed chariots, nor their long-haired horses trained to swim in the sea among the shoals, nor their countenances made terrible with paint gave check to the Romans. The Eagle surrounded by legionaries touched the soil of the barbarians' Island. The Britons fled beneath a shower of stone and lead hurled from machines which they believed to be monsters. Struck with terror, they ran like a herd of elks before the spear of the hunter.

When towards evening they had reached the great village near the coast, the chiefs sat down on stones ranged in a circle by the road-side and took counsel. All night they continued to deliberate; and when dawn began to gleam on the horizon, while the larks' song pierced the grey sky, they went into the hut where Komm of the Atrebates had been enchained for thirty days. They looked at him respectfully because of the Romans. They unbound him. They offered him a drink made of the fermented juice of wild cherries. They restored to him his weapons, his horses, his comrades, and, addressing him with flattering words, they entreated him to accompany them to the camp of the Romans and to ask pardon for them from Cæsar the Powerful.

"Thou shalt persuade him to be our friend," they said to him, "for thou art wise and thy words are nimble and penetrating as arrows. Among all the ancestors whose memory is enshrined in our songs, there is not one who surpasses thee in sagacity."

It was with joy Komm of the Atrebates heard these words. But he concealed his pleasure, and, curling his lips into a bitter smile, he said to the British chiefs, pointing to the fallen willow leaves that were driven in eddies by the wind:

"The thoughts of vain men are stirred like these leaves and ceaselessly carried in every direction. Yesterday they took me for a madman and said I had eaten of the herb of Erin that maddens the grazing beasts. To-day they perceive in me the wisdom of their ancestors. Nevertheless I am as good a counsellor one day as another, for my words depend neither upon the sun nor upon the moon, but upon my understanding. As the reward of your ill-doing, I ought to deliver you up to the wrath of Cæsar, who would cut off your hands and put out your eyes, so that begging bread and beer in the wealthy villages you would testify to his might and justice throughout the Island of Britain. Notwithstanding I will forget the wrong you have done me. I will remember that we are brethren, that the Britons and the Atrebates are the fruit of the same tree. I will act for the good of my brethren who drink the waters of the Thames. Cæsar's friendship, which I came to their Island to offer them, I will restore to them now that they have lost it through their folly. Cæsar, who loves Komm, and has made him to be King over the Atrebates and the Morini who wear collars of shells, will love the British chiefs, painted with glowing colours, and will establish them in their wealth and power, because they are the friends of Komm, who drinketh the waters of the Somme."

And Komm of the Atrebates spake again and said: "Learn from me that which Cæsar shall say unto you when you bend over your shields at the foot of his tribunal and that which it behooveth you in your wisdom to reply unto him. He will say unto you: 'I grant you peace. Deliver up to me noble children as hostages.' And you will make answer: 'We will deliver up unto you our noble children. And we will bring you certain of them this very day. But the greater number of our noble children are in the distant places of this Island, and to bring them hither will take many days.'"

The chiefs marvelled at the subtle mind of the Atrebate. One of them said to him:

"Komm, thou art possessed of a great understanding, and I believe thy heart to be filled with kindness toward thy British brethren who drink the waters of the Thames. If Cæsar were a man, we should have courage to fight against him, but we know him to be a god because his vessels and his engines of war are living creatures and endowed with understanding. Let us go and ask him to pardon us for having fought against him and to leave us in possession of our sovereignty and of our riches."

Having thus spoken, the chiefs of the Island of Fogs leapt upon their horses, and set forth towards the sea-shore where the Romans were encamped near the cove where their deep-keeled ships lay at anchor, not far from the beach up which they had drawn their galleys. Komm rode beside them. When they beheld the Roman camp, which was surrounded by ditches and palisades, traversed by wide and regular thoroughfares and covered with tents over which soared the Roman eagles and floated the wreaths of the standards, they paused in amazement and inquired by what art the Romans had built in one day a town more beautiful and greater than any in the Isle of Mists.

"What is that?" cried one of them.

"It is Rome," replied the Atrebate. "The Romans bear Rome with them everywhere."

Introduced into the camp, they repaired to the foot of the tribunal, where the Proconsul sat surrounded by the fasces. His eyes were like the eagle's; and he was pale in his purple.

Komm assumed a suppliant's attitude and entreated Cæsar to pardon the British chiefs.

"When they fought against you," he said, "these chiefs did not act according to their own heart, the dictates of which are always noble. When they drove against you their chariots of war, they obeyed, they commanded not. They yielded to the will of the poor and humble tribesmen who assembled in great numbers against you; for they lacked understanding and were incapable of comprehending your might. You know that in all things the poor are inferior to the rich. Deny not your friendship to these men, who possess great wealth and can pay tribute."

Cæsar granted the pardon which the chiefs implored, and said unto them:

"Deliver up to me as hostages the sons of your princes."

The most venerable of the chiefs replied:

"We will deliver up unto you our noble children. And some of them we will bring to you this very day. But the children of our nobles are most of them in the distant places of our Isle, and to bring them hither will take many days."

Cæsar inclined his head as a sign of assent. Thus, by the Atrebate's counsel, the chiefs surrendered but a few young boys and those not of the highest nobility.

Komm remained in the camp. At night, being unable to sleep, he climbed the cliff and looked out to sea. The surf was breaking on the rocks. The wind from the Channel mingled its sinister moaning with the roaring of the waves. The wild moon, in its stately passage through the clouds, cast a fleeting light on to the water. The Atrebate, with the keen eye of the savage, piercing through the shadow and the mist, perceived ships, surprised by the tempest, toiling in the waves and the wind. Some, helpless and drifting, were being driven by the billows, the foam of which shone upon their sides like a pale gleam; others were putting out to sea. Their sails swept the waves like the wings of some fishing bird. These were the ships that were bringing Cæsar's cavalry, and they were being scattered by the storm. The Gaul, joyfully breathing the sea air, paced awhile along the edge of the cliff; and soon he descried the little bay, where the Roman galleys which had alarmed the Britons lay dry upon the sand. He saw the tide approach them gradually, then reach them, raise them, hurl them one against the other and batter them, while the deep-keeled ships in the cove were tossed to and fro at anchor by a furious wind which carried away their masts and rigging like so many wisps of straw. Dimly he discerned the confused movements of the panic-stricken legionaries running along the beach. Their shouts reached his ear like the noise of a storm. Then he raised his eyes to the divine moon, worshipped by the Atrebates who dwell on river-banks and in the deep forests. In the stormy British sky she hung like a shield. He knew that it was she, the copper moon at the full, that had brought this spring tide and caused the tempest, which was now destroying the Roman fleet. And on the cliff, in the majestic night, by the furious sea, there came to the Atrebate the revelation of a secret, mysterious force, more invincible than that of Rome.

When they heard of the disaster that had overtaken the fleet the Britons joyfully realized that Cæsar commanded neither the Ocean nor the moon, the friend of lonely shores and deep forests. They saw that the Roman galleys were not invincible dragons, since the tide had shattered them and cast them, with their sides rent open, on the sand of the beach. Filled once again with the hope of destroying the Romans, they thought of slaying a great number by the arrow and the sword, and of throwing those that were left into the sea. Wherefore every day they appeared more and more assiduous in Cæsar's camp. They brought the legionaries smoked meats and the skins of the elk. They assumed a kindly expression; they spoke honeyed words, and admiringly they felt the muscular arms of the centurions.

In order to appear more submissive still, the chiefs surrendered their hostages; but they were the sons of enemies on whom they wished to be revenged, or uncomely children not born of families who were the issue of the gods. And, when they believed that the little dark men confidently relied upon their friendliness, they gathered together the warriors of all the villages on the banks of the Thames, and, uttering loud cries, they hurled themselves against the camp gates. These gates were defended by wooden towers. The Britons, unacquainted with the art of carrying fortified positions, could not penetrate through the outer circle, and many of the chiefs with woad-stained visages fell at the foot of the towers. Once again the Britons knew that the Romans were endowed with superhuman strength. Therefore on the morrow they came to implore Cæsar's pardon and to promise him their friendship.

Cæsar received them with a passive countenance, but that very night he caused his legions to embark in the hastily repaired ships and made for the Morini coast. Having lost hope of receiving his support of his cavalry which the tempest had scattered, he abandoned for the time the conquest of the Isle of Mists.

Komm of the Atrebates accompanied the army on its return to the Morini shore. He had embarked on the vessel which bore the Proconsul. Cæsar, curious concerning the customs of the barbarians, asked him whether the Gauls did not consider themselves the descendants of Pluto and whether it were not on that account that they reckoned time by nights instead of by days. The Atrebate could not give him the true reason for this custom. But he told Cæsar that in his opinion at the birth of the world night had preceded day.

"I believe," he added, "that the moon is more ancient than the sun. She is a very powerful divinity and the friend of the Gauls."

"The divinity of the moon," answered Cæsar, "is recognized by Romans and Greeks. But think not, Commius, that this planet, which shines upon Italy and upon the whole earth, is especially favourable to the Gauls."

"Take heed, Julius," replied the Atrebate, "and weigh your words. The moon that you here behold fleeing through the clouds is not the moon which at Rome shines on your marble temples. Though she be big and bright, this moon could not be seen in Italy. The distance is too great."

Winter came and covered Gaul with darkness, with ice and with snow. The hearts of the warriors in their wattle huts were moved as they thought on the chiefs and their retainers whom Cæsar had slain or sold by auction. Sometimes to the door of the hut came à man begging bread and showing his wrists with the hands cut off by a lictor. And the warriors' hearts revolted. Words of wrath passed from mouth to mouth. They assembled by night in the depths of the woods and the hollows of the rocks.

Meanwhile King Komm with his faithful followers hunted in the forests, in the land of the Atrebates. Every day, a messenger in a striped mantle and red braces came by secret paths to the King, and, slackening the speed of his horse as he drew near to him, said in a low voice:

"Komm, will you not be a free man in a free country? Komm, will you any longer submit to be a slave of the Romans?"

Then the messenger disappeared along the narrow path, where the fallen leaves deadened the sound of his galloping horse.

Komm, King of the Atrebates, remained the Romans' friend. But gradually he persuaded himself that it behooved the Atrebates and the Morini to be free, since he was their King. It annoyed him to see Romans, settled at Nemetacum, sitting in tribunals, where they dispensed justice, and geometricians from Italy planning roads through the sacred forests. And then he admired the Romans less since he had seen their ships broken against the British cliffs and their legionaries weeping by night on the beach. He continued to exercise sovereignty in Cæsar's name. But to his followers he darkly hinted at the approach of war.

Three years later the hour had struck: Roman blood had flowed in Genabum. The chieftains allied against Cæsar assembled their fighting men in the Arverni Hills. Komm did not love these chiefs. Rather did he hate them, some because they were richer than he in men, in horses and in lands; others because of the profusion of the gold and the rubies which they possessed; others, again, because they said that they were braver than he and of nobler race. Nevertheless he received their messengers, to whom he gave an oak-leaf and a hazel twig as a sign of affection. And he corresponded with the chiefs who were hostile to Cæsar by means of twigs cut and knotted in such a manner as to be unintelligible save to the Gauls, who knew the language of leaves.

He uttered no war-cry. But he went to and fro among the villages of the Atrebates, and, visiting the warriors in their huts, to them he said:

"Three things were the first to be born: man, liberty, light."

He made sure that, whenever he should utter the war-cry, five thousand warriors of the Morini and four thousand warriors of the Atrebates would at his call buckle on their baldrics of bronze. And, joyfully thinking that in the forest the fire was smouldering beneath its ashes, he secretly passed over to the Treviri in order to win them for the Gallic cause.

Now, while he was riding with his followers beneath the willows on the banks of the Moselle, a messenger wearing a striped mantle brought him an ash bough bound to a spray of heather, in order to give him to understand that the Romans had suspected his designs and to enjoin him to be prudent. For such was the meaning of the heather tied to the ash. But he continued on his way and entered into the country of the Treviri. Titus Labienus, Cæsar's lieutenant, was encamped there with ten legions. Having been warned that King Commius was coming secretly to visit the chiefs of the Treviri, he suspected that his object was to seduce them from their allegiance to Rome. Having had him followed by spies, he received information which confirmed his suspicions. He then resolved to get rid of this man. He was a Roman, a son of the divine City, an example to the world, and by force of arms he had extended the Roman peace to the ends of the earth. He was a good general and an expert in mathematics and mechanics. During the leisure of peace, beneath the terebinths in the garden of his Campanian villa, he held converse with magistrates touching the laws, the morals and the customs of peoples. He praised the virtues of antiquity and liberty. He read the works of Greek historians and philosophers. His was a rare and polished intellect. And because Komm was a barbarian, unacquainted with things Roman, it seemed to Titus Labienus good and fitting that he should have him assassinated.

Being informed of the place where he was, he sent to him his master of horse, Caius Volusenus Quadratus, who knew the Atrebate, for they had been commissioned to reconnoitre together the coasts of the isle of Britain before Cæsar's expedition hither; but Volusenus had not ventured to land. Therefore, by the command of Labienus, Cæsar's lieutenant, Volusenus chose a few centurions and took them with him to the village where he knew Komm to be. He could rely upon them. The centurion was a legionary promoted from the ranks, who as a sign of his office carried a vine-stock with which he used to strike his subordinates. His chiefs did what they liked with him. As an instrument of conquest he was second only to the navy. Volusenus said to his centurions:

"A man will approach me. You will suffer him to advance. I shall hold out my hand to him. At that moment you will strike him from behind, and you will kill him."

Having given these orders, Volusenus set forth with his escort. In a sunken way, near the village, he met Komm with his followers. The King of the Atrebates, aware that he was suspected, would have turned his horse. But the master of the horse called him by name, assured him of his friendship and held out his hand to him.

Reassured by those signs of friendship, the Atrebate approached. As he was about to take the proffered hand a centurion struck him on the head with his sword and caused him to fall bleeding from his horse. Then the King's followers threw themselves upon the little band of Romans, scattered them, took up Komm and carried him away to the nearest village, while Volusenus, who believed his task accomplished, crept back to the camp with his horsemen.

King Komm was not dead. He was carried secretly into the country of the Atrebates, where he was cured of his terrible wound. Having recovered, he took this oath:

"I swear never to meet a Roman save to kill him." Soon he learnt that Cæsar had suffered a severe defeat at the foot of the Gergovian Mount and forty-six centurions of his army had fallen beneath the walls of the town. Later he was told that the confederates commanded by Vercingétorix were besieged in the country of the Mandubi, at Alesia, a famous Gallic fortress founded by Hercules of Tyre. Then, with a following of warriors, Morini and Atrebates, he marched to the frontier of the Edni, where an army was assembling to relieve the Gauls in Alesia. The army was numbered and was found to consist of two hundred and forty thousand foot and eight thousand horse. The command was entrusted to Virdumar and Eporedorix of the Edni, Vergasillaun of the Averni and Komm of the Atrebates.

After a long and arduous march, Komm, with his chiefs and fighting-men, reached the mountainous country of the Edni. From the heights surrounding the plateau of Alesia he beheld the Roman camp and the earthworks dug all around it by those little dark men, who waged war with the mattocks and the spade rather than with the javelin and the sword. This seemed to him to augur ill, for he knew that against trenches and machines the Gauls were of less avail than against human breasts. He himself, though well versed in the stratagems of war, understood little of the engineering art of the Romans. After three great battles, during which no break was made in the enemy's fortifications, the terrific rout of the Gauls carried off Komm as a blade of grass is whirled away in a storm. In the mêlée he had perceived Cæsar's red mantle and taken it for an omen of defeat. Now he fled furiously down the track cursing the Romans, but content that the Gallic chieftains, of whom he was jealous, were suffering with him.

For a year Komm lived in hiding in the forests of the Atrebates. There he was safe, because the Gauls hated the Romans, and having themselves submitted to the conquerors they had a great respect for those who refused them obedience. On the river-bank and in the green-wood, accompanied by his followers, he led a life not differing greatly from that he had lived as the chief of many tribes. He gave himself up to hunting and fishing, devised stratagems and drank fermented drinks, which, though depriving him of the knowledge of human affairs, enabled him to understand those that are divine. But his soul had suffered a change, and it pained him to be no longer free. All the chiefs of his people had been killed in battle, or had died beneath the lash, or, bound by the lictor, had been led away to a Roman prison. No longer did a bitter envy of them possess him; for now all his hatred was concentrated upon the Romans. He bound to his horse's tail the golden circlet which he, as the friend of the Senate and the Roman people, had received from the Dictator. To his dogs he gave the names of Cæsar, Caius and Julius. When he saw a pig he stoned it, calling it Volusenus. And he composed songs like those which he had heard in his youth, eloquently expressing the love of liberty.

Now, it happened that one day, absorbed in the chase, having wandered away from his followers, he climbed the high, heather-clad table-land which commands Nemetacum, and, gazing thence, he saw with amazement that the huts and stockades of his town had vanished, and that in a wall-encircled enclosure rose temples and houses of an architecture so prodigious as to inspire him with the horror and fear caused by works of magic. For he could not believe that in so short a time such dwellings could have been constructed by natural means.

He forgot the birds on the moorland, and, prone on the red earth, he lay and gazed long upon the strange town. Curiosity, stronger than fear, kept his eyes wide open. Until evening he gazed upon the spectacle. Then there came to him an overpowering desire to enter the town. Beneath a stone on the heath he hid his golden torques, his bracelets, his jewelled belts and his weapons of chase. Retaining only his knife, hidden under his mantle, he descended the wooded hill-side. As he passed through the moist undergrowth, he gathered some mushrooms, so that he might appear as a poor man coming to sell his wares in the market. And in the third watch of the night he entered the town through the Golden Gate. It was kept by legionaries who allowed peasants bringing in food to pass. Thus the King of the Atrebates, disguised as a poor man, was readily enabled to penetrate as far as the Julian way. This was bordered by villas; it led to the Temple of Diana, the white façade of which was already adorned with interlacing arches of purple, azure and gold. In the grey morning light Komm saw figures painted on the walls of the houses. They were ethereal pictures of dancing girls and scenes drawn from a history of which he was ignorant: a young virgin whom heroes were offering up as a sacrifice, a mother in her fury plunging a dagger into her two children as yet unweaned, a man with the hoofs of a goat raising his pointed ears in surprise, when, unrobing a sleeping and reclining virgin, he discovers her to be at once a youth and a woman. And there were in the courtyard other pictures representing modes of love unknown to the peoples of Gaul. Though passionately addicted to wine and women, he had no idea of Ausonian voluptuousness, because he had no clear idea of the variety of human forms and because he was untroubled by the desire for beauty. Having come to this town, which had once been his, in order to satisfy his hatred and inflame his wrath, he filled his heart with fury and loathing. He detested Roman art and the mysterious devices of the Roman painters. And in all these census figures on the city portals he saw but little, because his eyes lacked discernment save in observing the foliage of trees or the clouds in a dark sky.

Bearing his mushrooms in a fold of his mantle, he passed along the broad-paved streets. Beneath a door over which was a phallus illuminated by a little lamp he saw women wearing transparent tunics, who were watching for the passers-by. He approached with the intention of offering them violence. An old woman appeared, who in a squeaky voice said sharply.

"Go thy way. This is not a house for peasants who reek of cheese. Return to thy cows, herdsman." Komm replied that he had had fifty women, the most beautiful of the Atrebates, and possessed coffers full of gold. The courtesans began to laugh, and the old woman cried:

"Be off, drunkard!"

And it seemed to him that the duenna was a centurion armed with a vine-stock, with such splendour did the majesty of the Roman people shine throughout the Empire!

With one blow of his fist Komm broke her jaw and serenely pursued his way, while the narrow passage of the house was filled with shrieks, howls and lamentations. On the left he passed the temple of Diana of the Ardeni and crossed the forum between two rows of porches. When he recognized the goddess Roma standing on her marble pedestal, wearing a helmet, with her arm outstretched to command the peoples, in order to insult her, he performed before her the most ignoble of natural functions.

He was now coming to the end of the buildings of the town. Before him extended the stone circle of the amphitheatre as yet barely outlined, but already immense. He sighed:

"O race of monsters!"

And he advanced among the shattered and trampled vestiges of Gallic huts, the thatched roofs of which once extended like some motionless army and which were now degraded into less even than ruins—into little more than a heap of manure spread upon the ground. And he reflected:

"Behold what remains of so many ages of men! Behold what they have made of the dwellings wherein the chiefs of the Atrebates hung their arms!"

The sun had risen over the grades of the amphitheatre, and with insatiable and inquisitive hatred the Gaul wandered among the vast enclosures filled with bricks and stones. His large blue eyes gazed on these stony monuments of conquest, and he shook his long fair locks in the fresh breeze. Thinking himself alone, he muttered curses. But not far from the stone-masons' yard he perceived, at the foot of an oak-crowned hillock, a man seated on a mossy stone in a crouching position, with his mantle thrown over his head. He wore no insignia; but on his finger was the knight's ring, and the Atrebate knew enough of a Roman camp to recognize a military tribune. This soldier was writing on tablets of wax and appeared wrapt in thought. Having long remained motionless, he raised his head, pensive, with his style to his lips, looked about him vacantly, then gazed down again and resumed his writing. Komm saw his full face and perceived that he was young, and that he had a gentle, high-born air.

Then the Atrebate chief recalled his oath. He felt for his knife beneath his cloak, slipped behind the Roman with the agility of the savage and plunged the blade into the middle of his back. It was a Roman blade. The tribune uttered a deep groan and sank down. A trickle of blood flowed from one corner of his mouth. The waxen tablets remained on his tunic between his knees. Komm took them and looked eagerly at the signs traced thereon, thinking them to be magic signs the knowledge of which would give him great power. They were letters which he could not read and which were taken from the Greek alphabet then preferred to the Latin alphabet by the young littérateurs of Italy. Most of these letters were effaced by the flat end of the style; those which remained were Latin lines in Greek metre, and here and there they were intelligible:

TO PHŒBE, ON HER TOMTIT

O thou, whom Varius loved more than his eyes,

Thy Varius, wandering beneath the rainy sky of Galata ...

And the couple sang in their golden cage of gold.

. . . . . . . . .

O my white Phœbe, with prudent hand give

Millet and fresh water to thy frail captive.

She sits, she is a mother: a mother is timid.

. . . . . . . . .

Oh! come not to the misty Ocean's strand,

Phœbe, for fear ...

... Thy white feet and thy limbs

So nimbly moving to the crotalum's rhythm.

. . . . . . . . .

And neither the gold of Crœsus nor the purple of Attala,

But thy fresh arms, thy breasts....

A faint sound ascended from the waking town. Past the remnants of the Gallic huts where a few barbarians, fierce though of humble rank, were still lurking in the trenches, the Atrebate fled, and through a breach in the wall he leapt into the open country.

When, through the legionaries' sword, the lictor's lashes and Cæsar's flattering words Gaul was at length completely pacified, Marcus Antonius, the quaestor, came to take up his winter quarters in Nemetacum of the Atrebates. He was the son of Julia, Cæsar's sister. His functions were those of paymaster to the troops. It was for him, also, to apportion the booty captured, in accordance with established rules. This booty was immense; for the conquerors had discovered bars of gold and carbuncles under the stones of sacred places, in the hollows of oaks and in the still water of pools; they had collected golden utensils from the huts of exterminated tribes and their chiefs.

Marcus Antonius brought with him many scribes and land surveyors who set to work upon the apportionment of lands and movable goods, and would have perpetrated many useless writings had not Cæsar prescribed for them simple and rapid methods of procedure. Merchants from Asia, workmen, lawyers and other settlers came in crowds to Nemetacum; and the Atrebates who had quitted their town returned one by one, curious, astonished, filled with wonder. The Gauls, for the most part, were now proud to wear the toga and to speak the tongue of the magnanimous sons of Remus. Having shaved off their long moustaches they had resembled Romans. Those who had succeeded in retaining any wealth employed a Roman architect to build them a house with an inner porch, rooms for the women and a fountain adorned with shell-work. They had paintings of Hercules, Mercury and the Muses in their dining-room, and would sup reclining on couches.

Komm, though himself illustrious and the son of an illustrious father, had lost most of his followers. Nevertheless he refused to submit, and led a wandering, warlike life in company with a few fighting-men who were addicted to plunder and rape, or who, like their chief, were possessed of a keen desire for liberty or of hatred for the Romans. They followed him into impenetrable forests, into marshes and even into those moving islands which occur in the broad estuaries of rivers. They were entirely devoted to him, but they addressed him without respect, as a man speaks to his equal, because they were actually his equals in courage, in the extremes of continual hardships, of poverty and wretchedness. They dwelt in trees or in the clefts of rocks. They sought out caverns worn in the friable stone by the water gushing down narrow valleys. When there were no beasts to hunt, they fed on blackberries and arbutus berries. They were excluded from towns by their fear of the Romans or by the vigilance of the Roman guards. In few villages were they readily received. Komm, however, always found a welcome in the huts scattered over the wind-swept sands which border the lazy waters of the Somme estuary. The dwellers on these dunes fed on fish. Poor, dishevelled, buried among the blue thistles of their barren soil, they had had no experience of Roman might. They received Komm and his companions into their subterranean abodes, which were covered with reeds and stones rounded by the Ocean. They listened to him attentively, having never heard any man talk so well. He said to them:

"Know who are the friends of the Atrebates and the Morini who live on the sea-shore and in the deep forest.

"The moon, the forest and the sea are the friends of the Morini and the Atrebates. And neither the sea nor the forest nor the moon loves the little dark men who follow Cæsar.

"Now the sea said to me: 'Komm, I am hiding the ships of the Veneti in a lonely cove on my shore.'

"The forest said to me: 'Komm, I will provide a secure shelter for thee who art an illustrious chieftain, and for thy faithful companions.'

"The moon said to me: 'Komm, thou hast seen me in the isle of the Britons shattering the Roman ships. I command the clouds and the winds, and I will refuse to shine upon the drivers of the chariots which bear victuals to the Romans of Nemetacum, in order that thou mayest take them by surprise in the darkness of the night.'

"Thus spoke unto me the sea, the forest and the moon. And this I bid you:

"Leave your boats and your nets and come with me. You will all be chiefs in war and of great renown. We shall fight great and profitable battles. We shall win victuals, treasure and women in abundance. Behold in what manner:

"I know so completely the whole country of the Atrebates and the Morini that there is not a single river, nor pool, nor rock with the situation of which I am unacquainted. And likewise every road, every path with its exact length and its precise direction lies as clear in my mind as upon the soil of our ancestors. Great and royal indeed must be my mind thus to encompass the whole land of the Atrebates. But know that many another country is likewise contained in it—the lands of the Britons, the Gauls and the Germans. Wherefore, had it been given me to command the peoples, I should have conquered Cæsar and driven the Romans out of this country. Wherefore we, you and I who speak, shall surprise the couriers of Marcus Antonius and the convoys of food destined for the town which has been reft from me. We shall surprise them without difficulty, for I know along which roads they travel, and their soldiers will not discover us since they know not the roads we shall take. And were they to follow on our tracks, we should escape from them in the ships of the Veneti, which would bear us to the isle of the Britons."

With such words Komm inspired his hosts with confidence on the misty sea-shore. And he finally won them over by giving them pieces of gold and iron, the last vestiges of the treasure which had once been his. They said to him:

"We will follow thee wherever it please thee to lead us."

He led them by unknown ways to the edge of the Roman road. When he saw horses grazing on the bush grass near the abode of a rich man, he gave them to his companions.

Thus he gathered together a body of horsemen which was joined by those of the Atrebates who desired to wage war for the sake of booty, and by some deserters from the Roman camp. The latter Komm did not receive, in order not to break the oath which he had sworn never again to look a Roman in the face save to slay him. But he had them questioned by some one of intelligence, and dismissed them with food for three days. Sometimes all the male folk of a village, young and old, entreated him to receive them as his followers. These men had been completely despoiled by the tax-gatherers of Marcus Antonius, who in addition to the imposts which Cæsar levied had demanded others, which were not due, and had fined chiefs for imaginary offences. In short, these publicans, after filling the coffers of the State, took care to enrich themselves at the expense of barbarians whom they thought a stupid people, and whose importunate complaints could always be silenced by the executioner's axe. Komm chose the strongest of these men. The others were dismissed, despite their tears and their entreaties not to be left to die of hunger or at the hands of the Romans. He did not wish for a great army, because he did not wish to wage a great war as Vercingétorix had done.

In a few days he had, with his little band, captured several convoys of flour and cattle, massacred isolated legionaries up to the very walls of Nemetacum and terrified the Roman population of the town.

"These Gauls," said the tribunes and centurions, "are cruel barbarians, mockers of the gods, enemies of the human race. Scorning their plighted word, they offend the majesty of Rome and of Peace. They deserve to be made an example. We owe it to humanity to chastise these criminals."

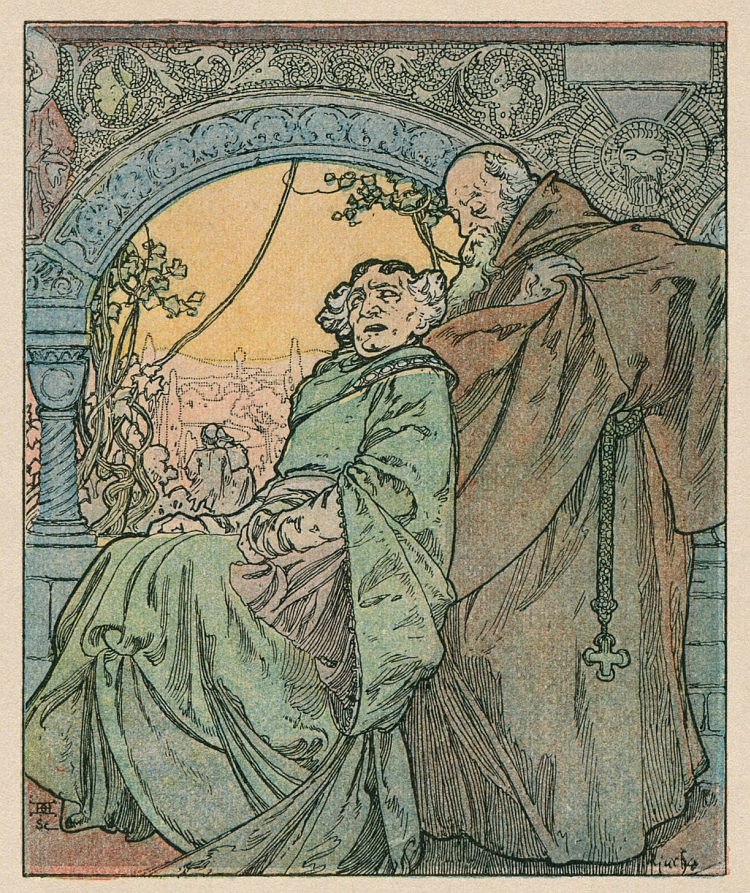

The complaints of the settlers and the cries of the soldiers penetrated into the quæstor's tribunal. At first Marcus Antonius paid no heed to them. In well-heated, well-closed halls he was busied with actors and courtesans who were representing on the stage the works of that Hercules whom he resembled in feature, in the cut of his short curly beard, and in the vigour of his limbs. Clothed in a lion's skin, club in hand, Julia's robust son threw fictitious monsters to the ground and with his arrow pierced a false hydra. Then, suddenly exchanging the lion's pelt for Omphale's robe, he likewise changed his passion.

Meanwhile convoys were being intercepted, bands of soldiers surprised, harried and put to flight, and one morning the centurion, G. Fusius, was found hanging disembowelled from a tree near the Golden Gate.

In the Roman camp it was known that the author of this brigandage was Commius, formerly king by the grace of Rome, now a robber chieftain. Marcus Antonius commanded energetic action to be taken in order to assure the safety of soldiers and settlers. And, foreseeing that the crafty Gaul would not easily be captured, he bade the Proctor straightway to make some terrible example. In order to carry out his chief's design, the Proctor caused the two richest Atrebates in the city of Nemetacum to be brought before his tribunal.

One was by name Vergal, the other Ambrow. Both were of illustrious birth, and they had been the first of their tribe to make friends with Cæsar. Poorly rewarded for their prompt submission, robbed of all their honours and of a great part of their wealth, ceaselessly annoyed by coarse centurions and covetous lawyers, they had ventured to whisper a few complaints. Imitating the Romans and wearing the toga, they lived in Nemetacum, vain and simple-minded, proud and humiliated. The Proctor examined them, condemned them to suffer the traitors' death and on that very day handed them over to the lictors. They died doubting Roman justice.

Thus did the quaestor by his firmness banish fear from the hearts of the settlers, who presented him with a laudatory address. The municipal councillors of Nemetacum, blessing his paternal vigilance and his piety, decreed that a bronze statue should be raised in his honour. After this several Roman merchants, having ventured out of the town, were surprised and slain by Komm's horsemen.

The prefect of the body of cavalry stationed at Nemetacum of the Atrebates was Caius Volusenus Quadratus, the same who had formerly enticed King Commius into a trap and had said to the centurions of his escort: "When I hold out my hand as a sign of friendship you will strike from behind." Caius Volusenus Quadratus was held in high esteem in the army because of his obedience to the call of duty and his unflinching courage. He had received rich rewards and enjoyed the honours due to military virtue. Marcus Antonius appointed him to hunt down Commius.