The Project Gutenberg EBook of The English Rogue: Described in the Life of Meriton Latroon, A Witty Extravagant, by Francis Kirkman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The English Rogue: Described in the Life of Meriton Latroon, A Witty Extravagant Author: Francis Kirkman Release Date: November 9, 2015 [EBook #50416] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ENGLISH ROGUE *** Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Beloved Country-men,

Had I not more respect to my Countries good in general, than any private interest of mine own, I should not have introduc’d my Friend upon the common Theatre of the World, to act the part of a Rogue in the Publick view of all. Rogue! did I call him? I should recal that word, since his Actions were attended more with Witty Conceits, then Life-destroying Stratagems. It is confest, the whole bent of his mind tended to little else then Exorbitancy; and Necessity frequently compelled him to perpetrate Villany: And no wonder, since he lived in the infectious Air of the worst of most Licentious Times. But still I blame my self for stigmatizing him with such an Opprobrious Title, since in the declination of his days, the consideration of his former Wicked Courses hath wrought (I have so much charity for him to believe it) in him cordial contrition, and unfeigned repentance: and the truth of it is, Man should be regarded not for what he was, but what he is.

Since his Reformation, I have taken very great delight in his Conversation, and never went from him but with great satisfaction in the Ingenious Relation of the transactions of his youthful days: And frequently revolving them in my mind, Reason suggested to me, the History of his Life could not but be as profitable as pleasant, if made publick. For herein you may see Vice pourtrayed in her own proper shape, the ugliness whereof (her Vizard-Mask being remov’d) cannot but cause in her (quondam) Adorers, a loathing instead of loving. Wherefore, with my Friends free consent, and being instigated thereunto by many persons inferiour to few, either for Birth, Education, or Natural Parts, I attempted this Essay.

If any be so curious to know what the (Actors you have in the Title) Authors name is, let me crave his pardon for his concealment, and answer him with Plutarch to an inquisitive Fellow, Quum vides velatum, quid inquiris in rem absconditam? It was therefore covered, because he should not know what was in it. It is enough that the Actor hath shown himself willing to declare freely, and without mincing the truth of what he hath done, without knowing who writ it; if the Contents shall as well please as admonish, no matter what I’m call’d. But if you are so desirous to know what the Writer is, I shall briefly inform your curiosity: But I doubt I have undertaken what I cannot perform; for if to know a mans self be more then an Herculean Labour, then without doubt it is beyond the limits of my power to tell you what I am; neither can any man truly know another, unless he first knows himself.

For some few years, the World and I have had a great falling out; and though I have used all probable and possible means, we remain yet unreconcil’d.

My only comfort is, I have a small treasure in Minerva’s Tower, by which I subsist; and by the benefit thereof, can walk abroad, not without taking Observation both from what I hear and see; and returning home, Tam Aulæ vanitatem, quam Fori ambitionem ridere mecum soleo. I can with Democritus laugh at the Actions of men, extracting Wisdome from their Follies, and afterwards lash them with a Rod of Experience made of their own fond inconsiderateness.

As for my part, I am onely a Wise-acre, (a Retort once put upon Ben Johnson), for I have no Acres of Land. But therefore don’t be so unadvised, (as too many are of late) to regard not so much the worth of the Work, as the dignity of the Person. Qui similiter in legendos libros atq; in salutandos homines irruunt, non cogitantes quales, sed quibus vestibus induti sint. They mind not so much what, as who writ it; not the Quality of the Thing, but the Quality of the Author, and a Person of Honour (now adays) being set in the place of the Writer, makes the Book received with a general applause. Pardon as well my Satyrical as Cynical Humour. If any dislike what I have writ, let them let it alone, or publish themselves something of a better Composition. I shall not value any ones Censure, for I have already Antidoted my self against it, by my own dis-esteem I have hereof. I am so far from being Opinionative, that you cannot speak worse then what I judge of it.

Thus you see, as I will not arrogate, so I shall not derogate: for as I am so many Parasanges after such a one, yet I may be an Ace above thee, if thou art too Censorious.

But some may say, That this is but actum agere, a Collection out of Guzman, Buscon, or some others that have writ upon this subject; Crambem bis coctam apponere; and that I have onely squeez’d their Juice, (adding some Ingredients of mine own) and afterwards distill’d it in the Lymbeck of my own Head. Non habes confitentem reum, I ne’er extracted from them one single drop of Spirit. As if we could not produce an English Rogue of our own, without being beholding to other Nations for him. I will not say that he durst vye with either an Italian, Spanish, or French Rogue; but having been steept for some years in an Irish Bogg, that hath added so much to his Rogue-ships perfection, that he out-did them all by out-doing one, and that was a Scot; I need not use the Epithite Roguish, since the very name proves it a Tautologie. If I have borrowed any thing, it was not from what past the Press; but what I have taken upon the score in Discourse, &c. I here repay with Usury, but not in the same Commodity. Etiamsi apparet unde sumptum sit, aliud tamen quam unde sumptum fit, apparet. I have not done as the Romans, who robb’d the whole Universe to enrich their ill-sited City; Rome I mean. I skimm’d not off the Cream of other mens Wits, nor Cropt the flowers in others gardens to garnish my own Plots; neither have I Larded my Lean Fancy with the Fat of others Ingenious Labours; but from the dictation of my own Genius, I have exprest quicquid in buccam venerit, what came next, without much premeditation or study. Gramercy Sack, if happily I have hit the mark.

I am no Aquæ potor, an implacable Enemy to Small Beer; all the Purchases I can boast of, lies in Wine, which is by Moderns highly esteemed for improving good Wits, infusing Elogies and Hyperbolical Exornations, forming such hard Words in the Brain, as shall, like Acesta’s arrows, catch fire as they flie. But I have wandered from that common rode, respecting more the matter then words. For my Stile is plain and familiar, rejecting bombast Expressions, thinking them most happy when most easily to be understood.

As for the Matter it self, if it be faulty, or the Method rude and indigested, consider, Quod nihil perfectum vel singulari consummatum industria, No man can observe all things; neither is it to be imagined that all Rogueries can be perform’d by one man. Not but that when you have read him, you will find him Notorious enough.

Some men are not content to commit Villany themselves, and boast of it too, but they will rob others of that which they should be asham’d to own. In this there is little or no Fiction, I’ll assure you; and there is no Story therein which doth not carry with it more then the bare probability of truth. Should I speak much more, it is to be fear’d some will argue from hence, that I am conscious to my self of its various defects; and therefore I shall desist from Apologizing for it, or my self.

Sensible I am, that if ought be omitted or added, which the Reader likes or dislikes, he will account me Mancipium pancæ lectionis, an Idiot, an insipid Asse; nullus sum, vel Plagiarius, a very Thief, and that I stole other mens Labours. Thus do I know I shall be vilified and undervalued even by such, that are so far from being capable of judging of Ingenuity, that they know not how to write Orthographically six words of sence in their own Mother-tongue. Yet I must confess, what is writ, is neither as I would, nor as it should, it being usher’d into the world as it was first written; whereas I should have done with this, as a Physitian advised should be done with Lapis Lazuli, to be washt fifty times before used: had not immergent Affairs hindred me, I would have licked this Cub into a more comely Form. But since ’tis otherwise, I shall onely complain with Ovid:—

All the favour that I shall desire, is, That the Reader would not account the Printers literal or verbal Escapes mine; and withal pass a candid interpretation on each Line; and I shall endeavour in a short time to become more satisfactory, and study how I may be always serviceable to my Country.

When this piece was first published it was ushered into the World with the usual ceremony of a Preface, and that a large one, whereby the Authour intended and endeavoured to possess the Reader with a belief, that what was written was the Life of a Witty Extravagant, the Authours Friend and Acquaintance. This was the intent of the Writer, but the Readers could not be drawn to this belief, but in general concurred in this opinion, that it was the Life of the Authour, and notwithstanding all that hath been said to the contrary many still continue in this opinion. Indeed the whole story is so genuine and naturally described without any forcing or Romancing that all contained in it seems to be naturally true, and so i’le assure you it is, but not acted by any one single person, much less by the Authour, who is well known to be of an inclination much different from the foul debaucheries of the Relations, & if the Readers had read the Spanish Rogue, Gusman; the French Rogue, Francion; and several other by Forraign Wits, and have upon examination found that the Authors were persons of great eminency and honour, and that no part of their own writings were their own lives; they had happily changed their opinion of the Authour of this; but they holding this opinion caused him to desist from prosecuting his story in a Second Part, and he having laid down the Cudgels I took them up, and my design in so doing was out of three considerations, the first and chiefest was to gain ready money, the second I had an itch to gain some Reputation by being in Print, and thereby revenge my self on some who had abused me, and whose actions I recited, and the third was to advantage the Reader and make him a gainer by acquainting him with my experiences. This were the reasons for my engaging in the Second part, and the very same reason induced me to joyn with the Authour in composing and Writing a third and fourth Part, in which we have club’d so equally, and intermixt our stories so joyntly, that it is some difficulty for any at first sight to distinguish what we particularly Writ and now having concluded the Preface, which should never have been begun but that I had a blank page, and was unwilling to be so ill a husband for you, but that you should have all possible content for your money, and withal to tell you that I would not have you as yet to expect any more parts of the book, for although a fifth and last part is design’d, yet i’le assure you there is never a stitch amiss, nor one line Written of it, and if you desire that, you must give me encouragement by your speedy purchasing of what is already Written; and thereby you will ingage

Gentlemen,

It hath been too much the humour of late, for men rather to adventure on the Forreign crazy stilts of other mens inventions, then securely walk on the ground-work of their own home-spun fancies. What I here present ye with, is an original in your own Mother-tongue; and yet I may not improperly call it a Translation, drawn from the Black Copy of mens wicked actions; such who spared the Devil the pains of courting them, by listing themselves Volunteers to serve under his Hellish Banners; with some whereof I have heretofore been unhappily acquainted, and am not ashamed to confess that I have been somewhat soiled by their vitious practices, but now I hope cleansed in a great measure from those impurities. Every man hath his peculiar guilt, proper to his constitution and age: and most have had (or will have) their exorbitant exiliencies, erronious excursions, which are least dangerous when attended by Youthfulness.

This good use I hope the Reader will make with me of those follies, that are so generally and too frequently committed every where, by declining the commission of them (if not for the love of virtue, yet to avoid the dismal effects of the most dangerous consequences that continually accompany them.) And how shall any be able to do this, unless they make an introspection into Vice? which they may do with little danger; for it is possible to injoy the Theorick, without making use of the Practick.

To save my Country-men the vast expence and charge of such experimental Observations, I have here given an accompt of my readings, not in Books, but Men; which should have been buried in silence, (fearing lest its Title might reflect on my Name and Reputation) had not a publick good interceded for its publication, far beyond any private interest or respect.

When I undertook this Subject, I was destitute of all those Tools (Books, I mean) which divers pretended Artists make use of to form some Ill-contrived design. By which ye may understand, that as necessity forced me, so a generous resolution commanded me to scorn a Lituanian humour or Custom, to admit of Adjutores tori, helpers in a Marriage-bed, there to engender little better than a spurious issue. It is a legitimate off-spring, I’ll assure yee, begot by one singly and soly, and a person that dares in spight of canker’d Malice subscribe himself

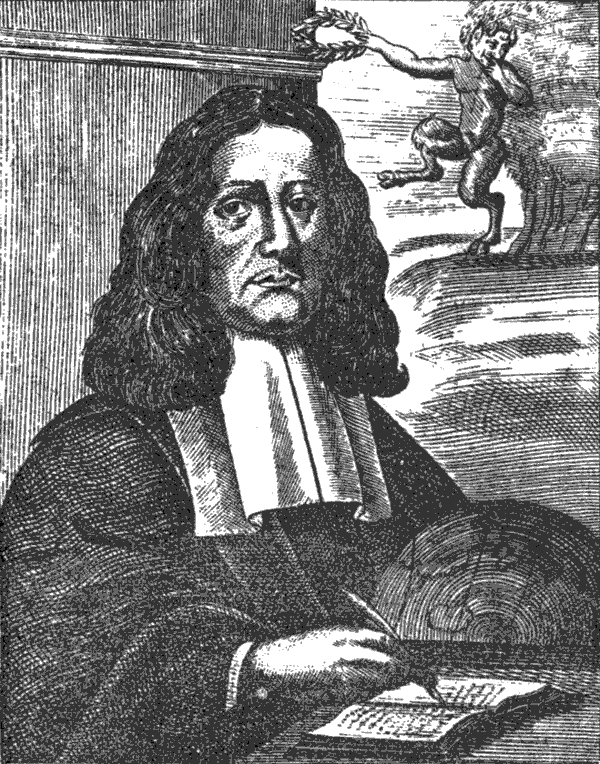

On the approvedly-ingenious, and his loving Friend, Mr. Richard Head, the Author of this book.

What his Parents were. The place of his own Nativity. His miraculous Escape from the hands of Irish Rebels. His brother being at that very time murdered by the merciless hands of those bloody Butchers.

After a long and strict Inquisition after my Fathers Pedegree, I could not find any of his Ancestors bearing a Coat: surely length of time had worn it out. But if the Gentle Craft will any wayes ennoble his Family, I believe I could deduce several of his Name, Professors of that lasting Art, even from Crispin. My Fathers Father had by his continual labour in Husbandry, arrived to the height of a Farmer, then the Head of his Kindred: standing upon one of his own Mole-Hills, Ambition so swelled him, that he swore by his Plow-share, that his eldest Son (my Father) should be a Scholhard: and should learn so long, till he could read any printed or written hand; nay, and if occasion should serve, write a Bill or Bond.

It was never known that any of the Family could distinguish one letter from another, neither could they speak above the reach of their Horses understandings. Talk to them in any other Dialect but that of a Bag-pudding of a Peck, or a piece of Beef, (in which their teeth might step wet shod) and a man were as good to have discoursed with them in Arabick. But let me not abuse them; for some understood something else that is to say, The Art of Whistling, Driving their Team and to shoo themselves as well as their Horses; how to lean methodically upon a Staff and through the holes of their Hat, tell what it is a Clock by the Sun.

The symmetricall proportion, sweetness of features, and acuteness of my Fathers wit, were such (though extracted out of this lump of red and white marle) that he was belov’d of all. As the loveliness of his person gain’d always an interest in Female hearts; so the quickness of apprehension and invention, and the acquired quaintness of his expressions; procured him the friendship of such as converted with him. A Gentleman at length taking notice of more then ordinary natural Parts in him, at his proper charge sent him to School contrary to the desire of his Father, who was able enough to maintain him at School; and to say the truth this Gentleman offered not my Father his patronage upon any charitable account, but that he might hearafter glory in the being the chief instrument of bringing up such a fair promising Wit, which he questioned not with good cultivation would bring forth such lovely fruit as would answer cost, and fully satisfie his expectation. Being admitted into the Grammar-School, by the strength of his memory, to his Masters great amazement, in a very short time he had Lillies Rules by heart, out-stripping many that for years had been entred before him; his Master perceiving what a stupendious proficiency he had made, was very glad that this fair opportunity offered it self, that he might be idle, and in order thereunto would frequently appoint my Father to be his Usher or Deputy, when he intended to turn Bacchanalian, to drink, hunt, or whore, to which vices he was over-much addicted. My Father having now conquered in a manner the difficulties of that Schools learning began now to lay aside his Book, and follow the steps of his vicious learned Master, the examples of a Superior proving oftentimes guides to inferior actions,

Besides his springing Age (wherein the blood is hot and fervent) spur’d him on, and the natural disposition of his mind, gave him wings to flye whither his unbounded, licentious, self pleasing will would direct. His Youth introduced him into all sorts of vanity, and his Constitution of body, was the Mother of all his unlawful pleasures. His Temperament gave Sense preheminence above Reason. Thus you see (which experience can more fully demonstrate) how the heat of Youth gives fewel to the Fire of Voluptuous Enjoyments; but without a supply of what may purchase those delights, invention must be Tenter-hooked, which ever proves dangerous, most commonly fatal. My Grand-father too indulgent to his son, supply’d him continually with mony; which he did the more freely, since he was exempted from such charges which necessity required for my Fathers maintenance, he having now more than a bare competency, he not only consents to the commission of evil, but tempts others to perpetrate the like. And now following his own natural proneness to irregular liberty, diurnaly suggests matters of innovation, not onely to his own, but others reasons, Lectum non citius relinquens quam in Deum delinquens, non citius surgens quam insurgens. No sooner relinquishing his bed, but delinquishing his Creator, No sooner rising than rising against his God. In short, I know not whether he prevailed more on others, or others on him, for he was facile; the best Nature is most quickly depraved, as the purest flesh corrupts soonest, and most noisom when corupted. Yet notwithstanding these blooming debaucheries, he neglected not his Study so much, but that he capacitated himself for the University, and by approbation was sent thither by his Patron. He applyed himself close to his Book for a while, till he had adapted himself a companion for the most absolute critick could be selected out of any of the Colledges: in the assured confidence of his own parts, he ventured among them, and left such remarks of his cutting wit in all companies he came into, that the Gallants and most notable Wits of Oxford, coveted so much his company that he had not time to apply himself to his Study, but giving way to their sollicitations, being prompted thereunto by his own powerful inclinations, plunged himself over head and ears in all manner of sensuality. For his lewd carriage, inimitably wicked practises, and detestable behaviour, he was at last expelled the Colledge.

Now was he forc’d to return to his Father, who with much joy received him, but would not tell him the true cause of his coming down: But to palliate his villanies, informed his father that he had learned as much as he could be instructed in; and now and then would Sprinkle his discourse with a Greek or Latine Sentence; when talking with the poor ignorant old Man; who took wonderful delight in the meer sound thereof. When my father spake at any time, they were all as silent as midnight, and then would my Grandfather with much admiration becken to the standers by, to give their greatest attention, to what the Speaker as little understood as his Auditors, not caring what non-sense he utter’d, if wrapt up in untelligable hard words, purposely to abuse those brutish Plough-jobbers. In ostentation he was carried to the Parson of the Parish to discourse with him; who by good fortune understood no other Tongue but what his mother taught him; My father perceiving that, made Shoulderamutton and Kapathumpton serve for very good Greek; which the Parson confirm’d: telling my Grandfather further, that his Son was an excellent Scholar; protesting that he was so deeply learned, that he spake things he understood not; this I have heard him say, made him as good sport, as ever he receiv’d in the most ingenious Society.

He had not been long in the Country, before a Gentlewoman taking notice of his external and internal Qualifications, fell deeply in love with him; and preferring her own pleasure before the displeasure of her wealthy Relations, she incontinently was married to him. I shall wave how it was brought about in every particular, but only instance what is therein remarkable. Doubtless the gestures he used in his preaching (when she was present) might something avail in the conquest of her affections; beginning with a dearly beloved passionately extended, looking full in her face all the while, and being in the time of the Kingdomes alteration and confusion, a temporizing Minister, he had learned all those tricks by which those of his Sect and coat used to bewitch a female ear. But that which chiefly effected his desires, was the assurance of an old Matron, that lived near my mother, who for profit scrupled not to officiate as Bawd; this good old Gentlewoman contrived waies to bring them together, unsuspected by any, by which means they obtain’d the opportunity to perform Hymens rites, Sans Ceremonies of the Church. My mother finding impregnation, acquainted my Father therewith, who (glad to hear how fast he had tied her to him) urged her to the speedy Consummation of a Legal marriage, which she more longed for than he did himself, but knew not how to bring it to pass, by reason of those many Obstacles which they saw Obvious, and thwarting their intentions. As first the vast disproportion between their Estates; Next, the Antipathy her Parents bore to his Function. Joyning these to many other Obstructions, with Fancy and Knowledge presented to them, they concluded to steal a Wedding and accordingly did put it in execution: much troubled her Parents were at first, to hear how their daughter had ship-wrackt her fortune (as they judged it) in the unfortunate loosing her maiden-head but time, with the intercession of Friends, procured a Reconciliation between them, and all parties well pleased. The old people took great delight in their fortune, hopeful thoughts and expectations of their Son in law, but he more in the reception of a large Sum of Money they paid him, and my mother most of all (as she thought) in the continual conversation and enjoyment of my Father, which she equally ranked with what might be esteemed the best of things.

His eminent Parts natural, (and what he attain’d unto by his country studies, being asham’d to have lost so much time) introduc’d him as a Chaplain to a Noble man, with whom he travel’d into Ireland. He took shipping at Myneard, and from thence sayled to Knock fergus, where he lived both creditably and comfortably. Experience had then so reformed his Life to so strict a religious course, that his Observers gain’d more by his example than his Hearers by precepts. Thus by his piety in the purity of his practice, he soon regain’d his lost credit.

By this time my mother drew near her time, having conceiv’d me in England, but not conceiving she thus should drop me in an Irish Bog. There is no fear that England and Ireland will after my decease, contend about my Nativity, as several Countreys did about Homer; either striving to have the honour of first giving him breath. Neither shall I much thank my Native Country, for bestowing on me such principles as I and most of my Country-men drew from that very air; the place I think made me appear a Bastard in disposition to my Father. It is strange the Clymate should have more prevalency over the Nature of the Native, than the disposition of the Parent. For though Father and Mother could neither flatter, deceive, revenge, equivocate, &c. yet the Son (as the consequence hath since made it appear) can (according to the common custom of his Country-men) dissemble and sooth up his adversary with expressions extracted from Celestial Manna, taking his advantage thereby to ruine him: For to speak the truth, I could never yet love any but for some by-respect, neither could I ever be perswaded into a pacification with that man who had any way injured me, never resting satisfied till I had accomplisht a plenary revenge, which I commonly effected under the pretence of great love and kindness. Cheat all I dealt withal, though the matter were ever so inconsiderable. Lie so naturally, that a Miracle may be as soon wrought, as a Truth proceed from my mouth. And then for Equivocation, or Mental Reservations, they were ever in me innate Properties. It was alwayes my Resolution, rather to dye by the hand of a common Executioner, then want my revenge, though ever so slightly grounded. But I shall desist here to characterize my self further, reserving that for another place.

Four years after my Birth, the Rebellion began so unexspectedly, that we were forced to flee in the night, the light of our flaming Houses, Ricks of Hay, and Stacks of Corn guided us out of the Town, and our Fears soon conveyed us to the Mountains. But the Rebels, wandering too and fro, intending either to meet with their friends, (who flockt from all parts to get into a Body) or else any English, which they designed as Sacrifices to their implacable malice, or inbred antipathy to that Nation, met with my Mother, attended by two Scullogues, her menial servants, the one carrying me, the other my brother. The Fates had decreed my brothers untimely death, and therefore unavoidable, the faithful Infidel being butchered with him. The surviving servant who carried me, declared that he was a Roman Catholick, and imploring their mercy with his howling Chram a Cress, for St. Patrick a gra, procured my Mothers, his own, and my safety.

Thus was I preserv’d, but I hope not reserv’d as a subject for Divine Vengeance to work on. Had I then died, no other guilt could have rendered me culpable before Gods Tribunal, but what was derivative from Adam. But since, the concatenation of sins various links hath encompassed the whole series of my life. Now to the intent I may deter others from perpetrating the like, and receive to my self Absolution (according as it is promised) upon unfeigned Repentance, and ingenious Confession of my nefarious Facts, I shall give the Readers a Summary Relation of my Life: from my Non-age to the Meridian of my dayes, hoping that my Extravagancies and youthful Exiliences, have in that state of life, their declination and period.

A short Account of the general Insurrections of the Irish, Anno 1641.

But though the mercy of these inhumane Villains extended to the saving of our lives; yet they had so little consideration and commiseration, to expose our bodies (by stripping us) stark naked to the extremity of a cold winter night, nor so much as sparing my tender age. Thus without Shooes or Stockings, or the least Rag to cover our nakedness, with the help of our Guide, we travelled all night through Woods as obscure as that black darkness that then environed our Horizon. By break of day we were at Belfast; about entering the skirts of the Town, this honest and grateful servant, (which is much in an Irish man) being then assured of our safety, took his leave of us, and returned to the Rebels.

Here were we received with much pitty of all, and entertain’d, and cloth’d and fed, by some charitable minded Persons; to gratifie their souls for what they had done for my mothers body, and those that belong’d to her, my Father frequently preacht, which gave general satisfaction, and continued thus in instructing his hearers, till the Sark or Surplice, was adjudged by a Scotish Faction, to be the absolute Smock of the Whore of Babylon. Then was he constrain’d to flee again to Linsegarvy taking his charge with him.

Before I proceed, give me leave to digress a little in giving you a brief account of the Irish Rebellion. Not two years before it broke out, all those ancient Animosities, Grudges, and Hatred, which the Irish had ever been observed to bare unto the English, seemed to be deposited and buried in a firm Conglutination of their Affections, and National Obligations, which passed between them, for these two had lived together forty Years in peace, with such great security and comfort, that it had in a manner consolidated them into one body, knit and compacted together with all those Ligatures, of Friendship, Alliance, and Consanguinity, as might make up a constant and everlasting Union betwixt them there. Their Inter-marriages were near upon as frequent as their Gossippings and Fosterings, (relations of much dearness among the Irish) together with all Tenancies, Neighborhoods and Services interchangeably passed among them. Nay, they had made as it were a mutual Transmigration into each others manners, many English being strongly degenerated into Irish Affections and Customes, and many of the better sort of Irish studying as well the Language of the English as delighting to be Apparrel’d like them. Nay, so great an advantage did they find by the English Commerce and Cohabitation, in the profits and high improvements of their Lands, as Sir Phelim O Neal, that Rebellious Ringleader, with divers others eminent in that bloody Insurrection, had not long before turn’d off their Lands, their Irish Tenants, admitting English in their rooms; who are able to give far greater Rents, and more certainly pay the same. So as all those circumstances duly weighted & considered with the great increase of Trade, and many other evident Symptoms of a flourishing Commonwealth; it was believed even by the wisest and most experienced in the affairs of Ireland, that the Peace and Tranquility of that Kingdom was fully settled, and most likely in all humane probability to continue, especially under the Government of such a King as Charles the First, whom after-ages may admire, but never match. Such was the serenity and security of this Kingdom, as that there appeared not any where any Martial preparations, nor reliques of any kind of disorders, no nor so much as the least noise of War whisperingly carried to any ear in all this Lands.

Now whilst in this great calm, the Brittish continued in the deepest security, whilst all men sat pleasently enjoying the fruits of their own labors, sitting under their own Vines, without the least thoughts of apprehension of Tumults, Troubles, or Massacres; there brake out on October the Twenty third, in the Year of our Lord, sixteen hundred forty and one, a most desperate, dierful, and formidable Rebellion, an Universal Defection and Revolt, wherein not only the meer Native Irish, but almost all those English that profess the Name of Roman Catholicks, were totally involved.

Now since it is resolved by me to give you a particular account of the most remarkable Transactions and passages of my life, it will be also necessary to acquaint you with the beginning and first motions. Neither shall I omit to trace the Progress of this Rebellion, since therein, I shall relate summarily my suffering, and what others under went, the horrid cruelties of the Irish, and their abominable murders committed, as well without number, as without mercy, upon the English Inhabitants of both Sexes, and all Ages.

It was carried with such secresie, that none understood the Conspiracy, till the very evening that immediately preceeded the night of its general execution. I must confess there was some such thing more than suspected by one Sir William Cole, who presently sent away Letters to the Lord Chief Justices, but miscarried by the way. Owen O Conally (though meer Irish, was notwithstanding a Protestant) was the first discoverer of this general Insurrection giving in the Names of some of the chief Conspirators. Hereupon the Lords convened and sat in Council, whose care and prudence at that time was such, that some of the Ringleaders were instantly siezed, and upon examination, confest that on that very day of their surprizal, all the Ports and Places of strength in Ireland, would be taken; that there was a considerable number of Gentlemen and others, twenty out of each county, were come up expresly to surprize the Castle of Dublin. Adding further, that what was to be done in the Country (where Mercury the swift Messenger) could neither by the wit of man, or by Letter, be prevented. Hereupon a strict search was made for all strangers lately come to Town, and all Horses were seized on, whose owners could not give a good account of them. And notwithstanding, there was a Proclamation disperst through all Ireland, giving notice of a horrid Plot designed by Irish Papists, against English Protestants, intending thereby a discouragement to such of the Conspirators, as yet had not openly declared themselves. Yet did they assemble in great number, principally in the North, in the Province of Ulster, taking many Towns, as the Newry Drummoor, &c., burning spoiling, and committing horrible murthers every where. These things wrought such a general consternation and astonishment in the minds of the English; that they thought themselves no where secure, flying from one danger into another.

In a very short time, the meer Irish Northern Papists by closly Persuing on their first Plot, had gotten into their possession most of the Towns, Forts, Castles, and Gentlemens Houses within the Counties of Tyron, Donegal, Fermanah, Armah, Cauan, &c. The chief that appeared in the Execution of this Plot, within the Province of Ulster, were Sir Phelim O Neal, Tourlough his Brother, Ronre Mac Guire, Phillip O Rely, Sir Conne Mac Dennis, Mac Brian, and Mac Mahan, these combining with their Accomplices dividing their Forces, and according to a general Assignation, surprised the Forts of Dongannon and Montjoy, Carlemant, with other places of considerable strength. Now began a deep Tragedy: The English having either few other than Irish Landlords, Tenants, Servants, Neighbours, or familiar Friends, as soon as this fire brake out, and the whole Country in a general Conflagration, made their recourse presently to some of these, lying upon them for protection and preservation, and with great confidence trusted their lives and all their concerns in their powers. But many of these in short time after, either betrayed them to others, or destroyed them with their own hands. The Popish Priests had so charged and laid such bloody impressions on them, as it was held according to their Doctrine they had received, a deadly sin to give an English Protestant any relief.

All bonds of Faith and Friendship now fractur’d, Irish Landlords now prey’d on their English Tenants; Irish Tenants and Servants, made a Sacrifice of their English Landlords and Masters, one Neighbor murthering another; nay, ’twas looked on as an act meritorious in him that could either subvert or supplant an English man; The very Children imitating the cruelty of their Parents, of which I shall carry a mark with me to my Grave, given me with a Skene by one of my Irish Play-fellows. It was now high time to flie, although we knew not whither; every place we ari’vd at we thought least secure, wherefore our motion was continual; and that which heightened our misery, was our frequent stripping thrice a day, and in such a dismal stormy tempestuous season, as the memory of man had never observ’d to continue so long together. The terror of the Irish and Scotch incomparably prevailed beyond the rage of the Sea, so that we were resolved to use all possible means to get on Shipboard. At Belfast we accomplisht our desires, committing ourselves to the more merciful Waves. This Relation being so short, cannot but be very imperfect, if I dare credit my mother, it is not stain’d with falshood. Many horrid things (I confess) I purposely omitted, as desiring to wave any thing of aggravation, or which might occasion the least Animosity between two, though of several Languages, yet I hope both united in the demonstration of their constant loyalty to their Soveraign Charles the Second.

After his arrival in Devonshire, he briefly recounts what waggeries he commited, being but a Child.

Being about five years of age, Report rendred me a very beautiful Child, neither did it (as most commonly) prove a Lyar. Being enricht with all the good properties of an handsome face, had not pride in that my tender age, depriv’d me of those graces and choise ornaments which compleat both form and feature. Thus happen’d, my Father kept commonly many Turkeys; one amongst the rest could not endure the sight of a Red Coat, which I usually wore. But that which most of all exasperated my budding passion, was, his assaulting my bread and butter, and instead thereof, sometimes my hands; which caused my bloomy Revenge to use this Stratagem: I enticed him with a piece of Custard (which I temptingly shewed him), not without some suspition of danger which fear suggested, might attend my treachery, and so led me to the Orchard-gate, which was made to shut with a pulley; he reaching in his head after me, I immediatly clapt fast the Gate, and so surprized my mortal Foe: Then did I use that little strength I had, to beat his brains out with my Cat-stick; which being done, I deplum’d his tayl, sticking those feathers in my Bonnet, as the insulting Trophies of my first and latest Conquest. Such then was my pride, as I nothing but gazed up at them; which so tryed the weakness of mine eyes and so strain’d the Optick Nerves, that they ran a tilt at one another, as if they contended to share with me in my victory. This accident was no small trouble to my Mother, that so doated on me, that I have often heard her say, She forgot to eat (when I sate at Table) for admiring the sweetness of my complexion. After she had much grieved her self to little purpose, she consulted with patience, and applyed her self to skilful Occulists, to repair the loss this face blemishing had done so sweet a countenance, though for the present it eclipsed my Mothers glory and pride, yet Time and art reduced my eyes to their proper station; so that within six years their oblique aspects were hardly discernable. When I was about ten Years old, I have heard some say that this cast of my eyes was so far from being a detriment, that it became my ornament. Experience confirm’d me in this belief; for they prov’d as powerful, as the perswasive arguments of my deluding tongue, both which conjoyn’d, were sufficient (I speak it not vain gloriously) to prevail even over the Goddess of Chastity, especially when they were backt on with ardent desires, and an undaunted resolution. But to my purpose: being driven out of Ireland, there being at that time no place of safety in that Kingdom, my Mother taking me with her, being compelled to leave my Father behind, barbarously murdered by the Rebels for being a protestant Preacher, she adventured to Sea not caring whether she went. Foulness of weather drove us upon the coast of France, where we were forced to land, to repair what damage the Ship had sustained in stress of weather. From hence we set sail, and landed in the West of England, at a place called Barnstable in the County of Devon. Here we were joyfully received, and well entertained by some of my Mothers kindred at first; but lying upon them, they at length grew weary; so that we were forced to go from thence to Plymouth, so called from the River Plime, unto which the Town adjoyneth: at that time it was strongly fortyfied by new raiz’d Works, a Line being cast about it, besides places of strength antiently built; as the Castle, the Fort of an hundred pieces of Ordnance, that commands Cat-water, and over-looks the Sound, Mount Batten, and the islands in the Sound, well furnished with Men and great Guns impregnable; had they been never built or demolished raced assoon as raised on their Basis, it had been much better then to have prov’d the Fomenters of Rebellion in the late Wars for a whole year, daily thundring Treason against their lawful Soveraign. We being here altogether unacquainted both with the people and their profession, my Mother having an active brain, casts about with her self how she should provide for her charge, but found no way more expedient, than the pretention of Religion. Zeal now and Piety were the only things she seem’d to prosecute, taking the litteral sence of the Text; Without doubt Godliness is great gain: But she err’d much in the profession and seasonable practise thereof; Hers being according to the menu of the true Church, the Church of England, whereas the Plymotheans were at that time Heterodox thereunto and led away as the rest of their Brethren called Roundheads, by the spirit of delusion. Finding how much she was mistaken, she chang’d quickly her Note and Coat; a rigid Presbyterian at first, but that proving not so profitable, instantly transform’d her self into a strict independant. This took well, which made her stick close to the brethren, which rais’d their spirits to make frequent contribution in private to supply her want: Here we had borrowed so much of the Sister-hood, who vilely suspected my Mother to be too dearly beloved by the brother-hood, that it was high time to rub off to another place, lest staying longer, the holy Mask of Dissimulation should fall off; and she being detected be shamefully excluded their Congregation, and so delivered up to be buffeted by Satan. Before I leave the Town, give me leave to take a short view thereof. Formerly it was a poor smal fishing Village, but now so large and thron’d with inhabitants (many whereof very wealthy Merchants) that as it may be compared with, so may it put in its claim for the name of a City. Havens, as there are many so commodious, which without striking sail, admit into the bosome thereof the tallest Ships that be, harbouring them very safely, and is excellently well fortyfied against hostility. It is scituate alike for profit and pleasure in brief, it wants little that the heart of man would enjoy, from the various productions of the whole Universe. Now farewell Plymouth, no matter whither we went, for whereever we came; we found still some or other that gave us entertainment for those good parts they found in my Mother she being very well read both in Divinity and History, and having an eloquent tongue, she commonly apply’d her self to the Minister of the Town; who wondering to see so much learning and perfection in a Woman, either took us to his own house for a while; or gathered some contributions to supply our present necessities, with which we travelled to the next Town: And in this manner we strouled or wandered up and down, being little better then mendicant Itinerants, Staying so little time in a place, and my mother being more careful to get a subsistance, than to season my tender years with the knowledge of Letters, I was ten years old before I could read. Travelling through many towns unfit for our purpose, we at last took our seat for a while at Biraport in Dorsetshire, here being ashamed to go to School in this ignorance, I applyed my self to my Mother, who taught me to apprehend the Alphabet in less hours than there are letters; so that in a short time, I could read distinctly, and immediately introduc’d into the Grammar School, where I had not been long, before I became a Book-worm securing as many as lay in my way, if convenient privacy serv’d. And to the intent that my Thefts might pass undiscovered, before I would vend what Book I had stolen, I usually metamorphozed them: if new, I would gash their skin, and if the leaves were red, I would make them look pale with the wounds they received; If much used, tear out all the remarks, and paint their old faces, and having so done, make sale of them. This course I followed a long time undiscovered, which cost many a Boy a Whipping at home by their Parents, as well as Master. I had various uses for my money I made thereof (you must think) but principally to bribe some of the upper Form to make my Exercises, which were so well liked of by my Master, that I still came off with applause; and in a short time so advanced, that I was next to the highest Form, when I understood not the lowest Author we read. I was forced to imploy my wits in the management of my hands, to keep touch with my Pensioners, least they failing me for want of encouragement, my Master should discover how much my dunceship was abused. Frequent were my truantings, which were always attended with some notorious fact besides small faults as robbing of Orchards, pulling the first and seconds of forty or fifty Geese at a time, milking the Cows or Goats into my Hat, and so drink the milk: And then for poultry, there was seldome a day escaped wherein I had not more or less, usually I took them thus. At night I haunted the Hen-roosts taking them off so quietly from what they stood on, that their keckling noise seldome alarum’d the rest; if I could not conveniently carry them off, I made their Eggs compound for their heads. If I meet with any Geese at any time, then out came my short stick with a string fastned to a bullet, and tyed to the end thereof, with this would I fetch in my Game by the neck, the weight of the bullet twirling the string so many times about the neck, that they could not disengage themselves from inevitable destruction. I used to fish for Ducks, baiting my Hook with a gut or some such trash, and laying it on a piece of Corke, that swimming it might be the sooner perceived, I could catch in a short time as many as I pleased: Nay, I have not only thus deceived the tame fowl, but the same way with a longer time, I have caught Gulls and other Sea-birds. What I had gotten by these cunning & so much to be approved tricks, I carryed to a house that encouraged me in my Roguery, participating of the cheer, and so feasting me for my pains: if I had stolen any thing, I had my recourse to them, who would give me two pence for what was worth a shilling, and render me good content. I knew my punishment for my rambling and valued it not; therefore little hope of reformation from thence. Nay for very small faults I wished to be whipt, knowing the rod would then be laid on gently, which carried with it a tickling pleasure. As for my Thefts and Rogueries abroad I was careful they should not be discovered. If any Boy had injur’d me whose strength exceeded mine, so that I durst not cope with him, I would exercise my revenge upon him privately, concealing the resentment of the injury he did me. For to grin and not bite, doth but perswade an Adversary to knock out those teeth that may prove some time or other injurious. One common trick I had, was to stick a pin on the board whereon he was to sit: in this manner did I serve several, in which fact I was at last taken. The punishment my Master inflicted on me, was, to sit by his desk alone and complete a copy of Verses; there was great likelihood I should perform my task, when I knew not how many feet an Hexameter required and yet I then read Virgil. However some thing I must attempt, and thinking Saphicks and Iambicks too difficult, I ventur’d upon Heroicks, supposing them the easier composition. But Lord into what an access of laughter did my Master fall into, when he perused my hobling strains. Surely said he, these Verses are running a race altogether, the first did not start fairly, or else is a very nimble Gentleman, for he hath out run all his fellows four feet, the second comes two foot short of him, yet too forward for a true pace; here is another lame in a foot, and halts most scurvily, here is another whose quantity is short, and hath gotten upon stilts to seem long, and one (in contradiction to him) which is long, because he will be short hath cut his own Legs off: With these and the like speeches did he please himself in his own wit, (which I understood but little) and after he had tired himself and me too, with prodigal talk: He then spake to me in a harder dialect, making me understand how ignorant I was, and how much precious time (irrecoverably) I had lost, which so much seiz’d on my spirits, that I was much griev’d and troubled, so that he made Vermilion tears run down my cheeks, &c. After he had bestowed so much correction as he thought might work in me penitence for my egregious truanting he degraded me, and made me begin a new. The shame whereof and reproach I daily received from my School-fellows, I could not bear; wherefore I prevailed on my Mothers indulgence, to let me regain what I had lost at home, which she consented to. But perceiving my Lecherous inclinations, by my night practises with her Maid, resolved to send me to a Boarding School: For our Family being but small, I lay with the Maid: beeing so young, my Mother did not in the least suspect me; but my too forward Lechery would not let me lie quiet, putting her frequently to the Squeak. In fine, I was sent away a great distance to a very severe and rigid Master, I no sooner commenced Scholar to this Tyrant pedagogue, but I was kept close to my Book, and lest my Wit should be any ways dulled, my stomack was always kept sharp; which quickned my invention to supply what was deficient. There is no complaint so insufferable as the grumbling of empty and dissatisfied Guts. My greatest care was to insinuate my self into the favour of the Servant Maids, knowing they loved to play at a Small Game rather then stick out. I performed my business so well that my stomack was always satiated, when the rest of the Boarders were dissatisfied, often going to bed in a manner supperless. Here I was depriv’d of my old pilfering way, because I had no convenience for the disposal of what I stole, it being but a very small Village. However to keep my hand in use, I daily practised on Fruit. Sometimes with a Spar sharpned at one end, I pickt the Apples out of the Baskets: other times I took with me a Comrade, and then thus would we do. I would go to the Fruiterer and bargain with him for a penny worth or more of Apples, receiving them into my Hat, pretending to draw my mony out, I did clap my Hat between my Legs my partner perceiving that (as we had afore plotted it would be) behind, snatcht it through my Legs and ran away with it, I thereupon did use to roar out as if I had been undone, and pretending to run after him to regain my Hat, we got out of sight and then shared the booty. One time coming a long the Market, I saw a small basket of Cherries, I demanded of the woman that sold them, what she would have for as many as I could take up in my hand; she looking upon it and seeing it was but a very small one; proportionable to my Stature, two pence said she; with that, I laid her down her Price, and took up basket and all the Cherries therein contain’d, and in a sober pace carried them away. The woman amazed that she should be thus surprized by such a Younker followed me; and making a great noise, gathered a conflux of people about us, and among the rest a Gentleman of quality, who was very earnest to know what the matter was; Holding my purchase fast in my hands (for nothing could perswade me to let go that booty I had so fair obtained, I desired the Gentleman that he would be judge of my cause, whereupon I related to him in what manner I bargained with the woman, and that I had done nothing unjustly, but what was according to our contract; the Gentleman wondering at the Pregnancy of wit in so tender an age, laught heartily, and condemned the Cherries for my own proper use, but withal paid the woman for them. I was naturally so prone to please my sences so that I cared not what course I took that I might obtain my desires, I appli’d my self more to my wit and invention, than I should have done, had I had anything allowed me from a Friend for a moderate expence. But my Mother thought otherwise, knowing by infallible symptomes, the extravagantness of my inclinations, and therefore debarred me as much as she could the very sight of money. A River confined within some made Bank, deterring its natural course, will (when that is overthrown which impeded its progress) flow with the greater impetuosity: Youth may for a while be circumscribed as to its desires: but if his inclination prompt him to the enjoyment of sensual delights, sooner or later he will taste their relish; and better early than late. Before the Noon of his days approach, Experience may reform his Life and Conversation though from the dawning Morning thereof, till the Meridian his Actions have been nothing else but the Extract of all manner of Debauchery. But (it is commonly observed): That Man which in the Declination of his Age tracks the bypaths of Vice and Licentiousness seldom desists till Death cuts off his passage; never leaving off doting on such false and imaginary pleasures, till the Grim Pale-faced Messenger takes him napping. Thus much by way of digression.

Our Master was very ancient, however resolved that his Age should not hinder his Teaching: for if he found himself indisposed, he would send for us all into his bed-chamber, instructing us there: A man of so strange a temper, that he delighted to invert the course of Nature, lying in bed by day, and walking in the night, the rain seldome deterring him. On a time above the rest, a Gentleman had sent his Son five pieces of Gold to give his Master for Diet, &c. Our Master receiving them, called for a small Cabinet that stood in the room, which I (more officious than the rest) brought him. Having put in the Gold, he commanded me to carry it from whence I had it: which I did, well considering the weight thereof, being, though small, very heavy. The Devil presently became my Tutor, suggesting to my thoughts various ways for the gaining this money. At last I resolved to take the impression of the Key in wax: which with much difficulty I obtained and carried it to a Smith four miles distant. The old Fellow (immediately upon my proposal) suspected me; (doubtless he was acquainted with such kind of devices) and questioning me what I intended thereby, I was forced to betake my self to my Legs for safety, not knowing what answer to make him. The Smith seeing me run, thinking to benefit himself by apprehending me persued after, with a red hot iron in his hand which his haste had made him forget to lay aside, one standing by me, (just as the Smith had almost overtaken me) seeing him come running with a hot iron in his hand, and fearing lest his blind passion might prompt him to mischief me, struck up his heels who in the fall gave himself a burnt mark in the hand which no doubt he had long ago deserv’d; my unknown friend would not suffer him to rise till I was out of sight. My first stratagem not suiting with my purpose, I try’d a Pick-lock of mine own invention; but that would not effect my design neither: so that I concluded to take Cabinet and all, and in order thereunto watcht my opportunity when he should walk abroad according to his custom at night. It was not long ere I enjoyed my wishes. My masters custom was to walk abroad at nights, and sleep in the day time; inverting the course of Nature: foreknowing his intention, I got into the Chamber and conceal’d my self under the Bed: So finding my way clear, I convey’d my self and purchase out of the House; and travelled all night. In the morning I found my self near a small Town, about sixteen miles distant from the place whence I came. Thinking my self now secure, I thought it very requisite here to repose my wearied Limbs and solace my self with the sight of what I had gotten; but it was not long after that I was so laced for it, that comparatively to my punishment Bridewell whipping is but a pastime. The first Bush I came at I went in and called for Sack, having never tasted any, & hearing much talk thereof; at which the people of the house much admired that so small an Urchin as I should call for such costly liquor, they viewed me very attentively, but more especially the Cabinet, which caused them to suspect me. The Master of the house was acquainted herewith, who as the Devil would have it was a Puritan, & a Constable too, officious and severe. Without craving pardon for his bold intrusion, he desired me I would admit him into my Boy-ships society. I confess his gray hairs and sower countenance made me at first sight, very much fear what the event of his visit would prove. However with a seeming undauntedness I drank to him, but what a difference of taste there was in that and the first glass I drank Solus: at length he came to ask me divers questions, Whence I came? Whither I was going? What was contained within that Cascanet? and the like. Before I could give the resolution of what they demanded, the Hue and Cry overtook me: presently I was laid hold on, and my treasure taken from me: that which vext me as much as my Surprizal was, I had no further time to try what kind of taste the Sack had. Various were the talk of the people, every one spending his Verdict on me. This is a prime young rogue indeed, to begin thus soon, said one, could he have seen, when in his Mothers belly, surely he would have stoln something thence. Another said, Forward fruit was soon rotten, and since I began to steal whilst a child, I should be hanged before I should write Man. Ready to die with fear, I was sent back to the place whence I came and from thence to the place of execution, had not the tenderness of my age, and fewness of years procured pitty from my injur’d Master. Confin’d I was within his house, lockt up close Prisoner in a Chamber, till that he could acquaint my mother with what had past. In this time I was not debarred of my sustenance though my Commons were Epitomized, neither was I altogether deprived of society, for I was daily visited by my master attended with a Cat of Nine-tails (as he called it) being so many small cords, with which he fleyd my buttocks; and when he found me stubborn, or not penitent enough as he thought, after he had skinned my podex, he would wash it with vinegar, or water and salt. Within a week my Mother arrived, who hearing of my Rogueries, was so impatient, that she would needs take me to task her self; But when she had untrust me, and saw me in so woful a plight, my shirt being as stiff as Buckram with blood and my tender breech ploughed and harrowed, fell down as if she had been about to expire: recovering my Master endeavour’d to satisfy her, by telling her that great offences required great punishments; and the way to bend an oak, is to do it whilst it is young, I had once when young (said he) a Spaniel which would find out the Hens nest, and breaking the eggs suck them, so that we could never have any Chickens, at last discovering who was the malefactor; I be thought my self of this punishment which should hinder him for ever doing the like. I got an egg roasted so hard till the shell was ready to burn, then did I first show the Egg to the dog, and then clapt it hot into his mouth holding his jaws close, this so tormented him by burning, that ever after he could not indure the sight thereof but if shown run away crying as if he had been beaten. Thus for the notorious fact your Son must be so sharply chastized, that when he thinks of stealing he shall remember those torments he once endured for it, & so frighten him from executing any such crime. Many more arguments he alledg’d to that purpose, which had satisfied her well in his severity, had not natural affection interposed. What to do with me she knew not; wherefore she consulted with my Master, who told her, He durst not keep me longer, the Country people bringing in daily complaints against me. And to aggravate my Mother the more, he briefly summ’d up my faults in this manner; having had justly various accusers who drew up my indictment, Thus.

Imprimis, That one of his Maids having crost me (to be reveng’d of her; knowing she was a drowsie wench, when asleep not easily wak’d) as she slept by the fire, I took my opportunity, to melt some glew, and gently toucht the closure of both her eye-lids with a pencil, which well I knew would lock up her sight. Against the time I intended to wake her I placed all about her Chairs and Stools. The Plot being ripe, I pretended her Mistress called; The wench starting up running and rubbing of her eyes turn’d topsie turvy over the chairs, getting up the ingag’d her self with the stools and so entangled her self therein, that indeavouring to free her self her coats acted the parts of Traytors in discovering the hidden secrets and Arcanas belonging to her sex, and that with much satisfaction I had seen the execution of my revenge. That this wench could not be perswaded by any means, but that as a judgement she was stricken blind for some sin she had committed privately, which then her conscience did whisper in her ear; and undoubtedly had turn’d Lunatick had she not been speedily restored to her sight by taking off the glew, which was done with much difficulty. That he going about to correct me for this unlucky and mischievous fact, was by me shown a very Shitten trick, which put him into a stinking condition, for having made my self laxative on purpose squirted into his face upon the first lash given. That being upon boys backs, ready to be whipt, I had often bit holes in their ears. That another time sirreverencing in a paper, and running to the window with it, which lookt out into the yard, my aged Mistress looking up to see who opened the Casement, I had like to have thrown it into her mouth; however for a time deprived her of that little sight she had left, that another time I had watcht some lusty young Girls, that used in Summer nights about twelve a clock to wash themselves in a small brook near adjacent, and that I had concealed my self behind a Bush, and when they were stript, took away their cloaths, making them dance home after me stark naked to the view of their sweet hearts whom I had planted in a place appointed for that purpose, having given them before notice of my design. A great many more such tricks he recounted which he knew, but not the tenth of what he knew not. As for example, on Christmass-day, we had a pot of Plumb-broth. I askt the Maid to give me a taste to see how I lik’d them, I that I should, she said (this was the Maid I had so serv’d before with glew) and with that takes up a ladle full and bid me sup, she holding the ladle in her own hand, I imprudently opening my mouth somewhat larger then I should she poured down the scalding pottage through my throat: at present I could not tell the jade (that laught till she held her sides) how I lik’d them; but I verily believ’d I had swallowed the Gunpowder-Plot, expecting every moment to be blown up. I took as little notice of this passage as possibly I could, resolving to retalliate her kindness when she least thought on’t. I observed the maid to carry this plum-pottage pot into the yard, and taking notice that the weight of the Jack was in the same yard, wound up a great height under a small pent-house, the Jack being down I suddenly removed the weight, and fastned the pot to the line, so going into the Kitching, wound it up to the top, and then stopt it, for the meat was taken up. The house was all in an uproar instantly about the Pot, every one admiring what should become of it: The Maid averred that she saw it even now, and none could remove it but the Devil. Others asserted (which were infected with Puritanism) that it was a Judgment shown for the superstitious observation of that festival day; but the next day, roasting Meat, this seeming miracle vanished by the descending of the pot fastened to the Jack-line. Another time my Master had reserved in his Garden some choise Aprecocks, not above an half-score; which he purposed for some friends that intended to visit him shortly: The daily sight of this delicate fruit, being forbidden, tempted me more strongly to attempt their rape; but I made choice of an impropitious hour to accomplish my design in; for my master looked out of his window and saw me gather them, though he knew not absolutely whether it was I or no. Whereupon; he instantly summoned us together, being met, I quickly understood his intention: therefore I conveyed the Aprecocks into the next boys pocket, I had no sooner done it, but we were commanded to be searched; I was very forward to be the first though I was most suspected, but none was found about me, so that I was acquitted. But to see with what amazement the poor boy gazed, when they were discovered about him, how strangely he looked, distorting his face into several forms, produced laughter even from my incenc’d Master, but real pity from me, for he was severely whipped for that Crime I my self committed. I could recite many more such like childish Rogueries, did I not fear I should be tedious in their relation, and burden the Reader with juvenile follies; fore I shall return where I left off. Whilst my Mother was in a serious consultation with her Reason, how she should dispose of me, I had not patience to wait the result, but gave her the slip, resolved to run the risk of Fortune, and try whether mine own endeavours would supply my necessities.

How he ran from his Mother, and what courses he steered in one whole years Ramble.

It was in August when I undertook this my Knight-errantry; the fairness of the Season much favoured my enterprise: thinking I should always enjoy such weather, and never be pincht with necessity, I went on very couragiously. The first dinner I made was on Blackberries and Nuts, esteemed by me very delicious fare at first, which delighted me so much the more, having not my liberty controul’d. When night approached it seemed very uncouth & strange, finding instead of a feather-bed, no other thing to lie on but a Haycock, and no other coverlid but the Canopy of Heaven. But considering with my self that I had no task to con over night, nor fear of over-sleeping my self next morning, and so be fetcht to School by a Guard of my fellow Schollars with a Lanthorn and Candle, though the Sun appear’d at that time in his full lustre; I laid my self down and slept profoundly, not without some affrighting dreams: The last was of the Cat of Nine Tails, which my Master laid so home me thought that the smart thereof made me cry out, and so I awaked; as then the early Larke, the winged Herald of the morning, had not with her pretty warbling Notes, summon’d the bright watchmen of the Night to prepare for a retreat; neither had Aurora opened the Vermillion Oriental Gate, to make room for Sols radiant Beams, to dissipate that gloomy darkness that had muffled up our Hemisphere in obscurity. In the morning I went on in my progress as the day before; then began a shower of tears to fall from my eyes, considering how I had left my disconsolate, and almost heart-broken Mother, lamenting my loss, and fearing what fatal courses I might take: it was no less trouble to me to think that I was travelling I knew not whither, moneyless, having nothing but hazel, and Brambles to address my self for the appeasing of hungers approaching gripes. Now me thought I began to loath my aforenamed Manna, Blackberries, Nuts, Crabs, Bullies, &c., and longed to taste of the Flesh-pots again, but the Devil a bit could I get but what the hedges afforded me. All day I thus wandred about, not daring to come near any Town, having had such bad success in the last when I first rambled, and now night came on, which put me in mind of procuring a lodging somewhat warmer than the other. A Barn presently offered it self to my sight, which I accosted, and without delay or fear, entred into the inchanted Castle, where I found accommodations for the most faithful and valiant Knight that ere strode Saddle for Ladies sake. Here might I take my choice of variety of fresh straw, but my weariness would not permit to complement my good fortune one jot, and I so tumbled over head and ears; I had not lain there above an hour before I heard a noise, and peeping out of the straw, being in a great fear, I saw a many strange Creatures come into the Barn, for the day was not yet shut in. My thoughts presently reminded me, that I had heard talk of Hobgoblings, Fairies and the like, and judged these no other; and that which confirmed me in this belief, was their Garb and talking to one another in a Language I understood not, (but since, I understand it to be Canting.) I lay still as long as my fear would permit me, but they surrounding me, I was not able to contain my self longer, but cryed out aloud, Great God have mercy on me, and let not these Devils devour me; and with that, started out from among them: They amazed as much as I, ran for it too, leaving their children behind them, every one esteeming him the happiest man which was the foremost. I looking behind me, seeing them following me, imagined these Devils ran upon all four, and having started their game were resolved to hunt a sinful Leveret to death: Concluding them long-winded Hell-hounds, I judgd praying a safer way than flying, and so fell instantly on my knees: The Gypsies quickly overtook me, and finding me in that posture, soon understood whence their fear proceeded. They then spoke to me in a Language I understood, bidding me not be afraid; but I had heard the Devil was a Lyar from the beginning, therefore I would not believe them. They would have rais’d me from my devotion, telling me it was enough, and that made me suspect them the more; thinking they designed to get me out of a praying posture, that they might have the more power of me. Nothing prevailing with me, they vowed and protested they would not injure me in the least, and if I would go along with them, I should share as deliciously as they did, this was a potent argument to perswasion, and so I agreed to go along with them back again. All their cry was now for Rum-booz (i. e.) for Good Liquor. Their Captain not induring to hear so sad a Complaint, and not endeavour the supplying the want complained of, immediately commanded out four able Maunders, (Beggars) ordering them to stroule (wander) to the next Town, every one going apart. Some Countrey-men gave them drink fearing they might fire the houses in the night, out of revenge, others (out of the more ignorant sort) thought they could command infernal spirits, and so harm them that way, or else bewitch their Cattle, and therefore would not deny them: in so much, that in a short time these four return’d laden with bub and food. It was presently placed in the middle of us, who sate circularly; then out came the Woodden dishes, every one provided but my self, but I was soon suppli’d by a young Rum-Mort that sate next me intended for my sporting mate. A health went round to the Prince of Maunders, another to the Great Duke of Clapperdogeons, a third to the Marquess of Doxy Dells, & Rum Morts, a fourth, to the Earl of Clymes; neither did we forget, Haly, Abbas, Albumazar, Arcandam, with the rest of the Waggoners, that strive who shall be principal in driving Charles his Wain. Most part of the night we spent in Boozing, pecking rumly or wapping, that is drinking, eating, or whoreing, according to those termes they use among themselves. Jealousie was a thing they never would admit of in their Society, and to make appear how little they were tainted therewith, the males and females lay promiscuously together, it being free for any of the Fraternity to make choice of what Doxie he liked best, changing when he pleased. They plyed me so oft with their Rum-booz (as they called it) and pleased me so well in giving me a young Girle to dally with, who (though in Rags, and with a skin artificially discolloured tawny) yet I was not so ignorant, as not to understand good flesh, and what properties went to the compleating a votaress for Venus service. I was so tickled in my fancy with this pretty little wanton Companion, that for her sake, I was very well content to list my self one of that Ragged Regiment. And that which added to the induceing me to this resolution, was my want of money, and what I suffered in those two foregoing hard dayes fare among the Nut Trees. I first acquainted my Doxie with my intent, who glad to hear thereof, gave it vent, and broacht it to the rest, who unanimously with joy imbraced me; and to gratify my inagravation tipt to each other a Gage of Booz, and so went round. The fumes of drink had now ascended into their brain, wherefore they coucht a Hogs-head, and went to sleep.

Wherein he relates what manner of People they were in whose Society he entered himself, division of their Tribes, Manners, Customes, and Language.

As soon as I had resolv’d to travel the Country with them, they fitted me for their company by stripping me, and selling my proper garments, and cloathing me in rags, which they pinn’d about me, giving a stitch here and there, according as necessity required. We used not when we entered our Libkin or Lodging to pull off our clothes; which had I been forced to do, I could never have put them on again, nor any, but such who were accustomed to produce Order out of a Babel of Rags. Being now ale mode Taterdemallion, to compleat me for their purpose, with green Walnuts they so discoloured my face, that every one that saw me, would have sworn I was the true Son of an Egyptian. Before we marched on, let me give you an account of our Leaders, and the rancks we were disposed in. Our chief Commander was called by the name of Ruffeler, the next to him Upright-man, the rest in order thus: